Leaflet

MARCH - APRIL 2025

From the EDITOR

As the clock “springs forward” and the weather (hopefully) does the same, the staff and volunteers at Massachusetts Horticultural Society look forward to welcoming existing members and new visitors (starting on April 1st) to the Garden at Elm Bank, which were significantly renovated and enhanced last year. After a long, cold winter, there is nothing more uplifting than walking through a garden and seeing colorful flowers, beginning with the earliest bulbs and flowering shrubs highlighted in Catherine Cooper’s article.

Spring is a time to cultivate new plants and new gardens and perhaps new knowledge or skills. Please note the Upcoming MHS Classes and Botanical Art Spring & Summer Courses to get a few ideas. Mark your calendar for the New England Fall Flower Show in September, which will be building and expanding upon the success of our first Fall Flower Show last year. If you are looking to enhance your composting efforts to improve the health of your own garden, make sure you read Libby Wilkinson’s article about the worm bin and vermicomposting. And as always, Maureen O’Brien highlights some of the interesting historical information available in the MHS archives and library.

Gardens and plants have always been great cultivators of friendships, and I am pleased to highlight my friend and professional colleague Warren Leach in this issue’s “In First Person” article. I have also thoroughly enjoyed working with Julie Moir Messervy on many projects over the years, and she is now introducing a new and readily accessible/friendly way for homeowners to design and make their own garden more beautiful. And by now, thanks to John Lee, everyone should feel like Bert and Brenda are old friends. I know I do!

Dave Barnett Editor-in-Chief

UPCOMING CLASSES

Seed Starting & Growing From Seed

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

6:30-7:30pm

Nature in Ceramics: Designing with Sgraffito

Saturday, March 22, 2025 10am-1pm

Terrarium Workshop Saturday, March 29, 2025 10-11:30am

Rethinking Your Lawn: Sustainable & Smart Wednesday, March 26, 2025 6:30-7:30pm

Design Tips for LowMaintenance Gardens Saturday, March 22, 2025 11am-12pm

Introduction to Companion Planting Wednesday, April 23, 2025 6:30-7:30pm

Green Partner Spotlight

Shop at Green Partner businesses to receive 10% off with your MHS Membership card!

East Bridgewater North Attleboro Rowley

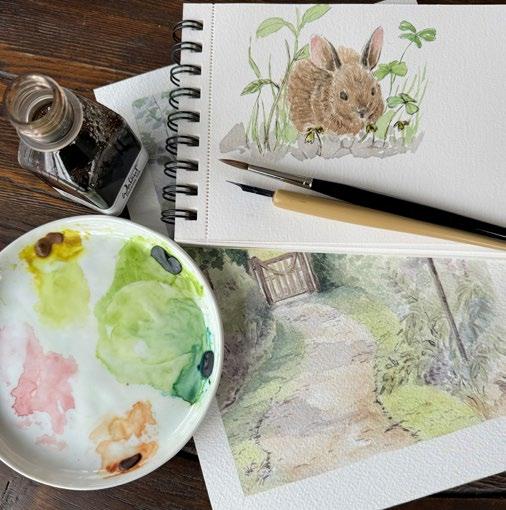

Botanical Art Program

SPRING & SUMMER 2025 COURSES

GREAT FOR BEGINNERS

Color Mixing for Artists

March 31 - April 4

from 10am-1pm

Introduction to Botanical Art: Foundations in 3 Days June 2-4 from 9:30am-3:30pm

© Elizabeth Pyle

The Art of the Floral Flat Lay

Saturday, April 12 from 10am-12pm

Botanical Sketchbook: Inspired by Beatrix Potter June 12, 17 & 19 from 10am-2pm

SPRING FLOWERS

Capturing Seasonal Color: Spring Blooms

April 15 & 17 from 10am-2pm

Spring Studio Focus: Painting Pansies

Tuesdays May 6-27 from 10am-1pm

Introduction to Botany Through Drawing

Thursdays May 1-June 5 from 9:30am-1:30pm

Learning From the Masters June 24 & 26 from 10am-1pm

© Lauren Meier

© Sarah Roche

© Susan T. Fisher

© Tara Connaughton

© Tara Connaughton

© Pierre Joseph Redouté

Marianne Orlando is a landscape architect turned freelance illustrator who loves plants, and does commissioned drawings of homes, pets and people. You can see samples of her work at www.marianneorlando.com

- April 2025

Amateur Competitions Schedule

for Exhibiting at the 139th New England Fall Flower Show

2025 Theme: World in Bloom

Amateur Horticulture

Junior Horticulture

Floral Design

Botanical Arts (+ New Junior BA Classes!)

Photography

Registration for Floral Design, Botanical Arts, and Amateur Horticulture - Kokedama is now open!

In First Person

Warren

Leach

Warren Leach is a life-long gardener and educator with a passion for sharing his knowledge of plants and design with others. He is an avid plant collector, nurseryman, horticulturist, and landscape designer. He has decades long relationships with his landscape clients and their gardens. He has received national and local recognition for his landscape designs. Images of his garden design at Brigham Hill Farm in North Grafton, MA, are archived at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In 2010, Massachusetts Horticultural Society honored Warren with a Gold Medal for his horticultural expertise and landscape design as well as years of forcing plants and creating exceptional displays at the New England Spring Flower Show. Here is Warren’s story in his own words

My passion for gardening developed early, starting at the age of five. I grew up on a farm in rural Holden, Maine. My first flower garden was a border of summer-blooming annuals started from seed and planted in front of existing herbaceous perennial peonies, delphiniums, and daylilies. A fragrant lilac anchored the back of the border. I learned the skills of gardening at the nurturing hands of my mother. She instilled in me a love for both cultivated and wild landscapes and a discerning eye for seeing subtle beauty. I count myself fortunate to have first experienced the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden in Seal Harbor and Thuya Garden and the Asticou Azalea Garden in Northeast Harbor as a young adolescent. They were a significant influence on my formative horticultural education. Fast forward in time fifty-plus years, and these gardens and the magnificent landscape of Mt. Desert Island are still my favorite places to visit and to be inspired.

Upon graduating from the University of Maine in 1976, I found work with a renowned nurseryman, Ludwig Hoffman, whose nursery was in Bloomfield, Connecticut. My down-to-earth horticultural education became engaged, expanded, and flourished. Lud was one of the prominent, pioneer hybridizers of red-bud mountain laurel. While in his employment, I was also introduced to a milieu of other prominent nurserymen and members of the Connecticut Horticultural Society.

One of many nursery skills that Lud taught me was the art of hand-digging trees in preparation for transplanting them into new gardens. This involves digging a circumferential trench around the correct diameter for the tree’s root ball. The tree is then undermined at an acute angle, wrapped in burlap, and secured with a drum-laced-knotted network of sisal rope. Digging trees in this manner brings focus to the physical and practical reality of Euclidean geometry.

The late 1970s was a time when the mechanized tree spade was fast changing the harvesting practices of field-grown trees. It is now standard in the nursery industry. This modern mechanization provides economic incentives but is also a horticultural concession. The tradeoff is a root ball bound in a wire cage with a compromised geometry that conforms to the angle of the hydraulically powered tree spade blades, rather than the configuration of the tree’s root system. Planting trees these days requires compensation for the shortfall of roots, bolt cutters to remove the wire cage, and often the removal of an overburden of soil against the trunk. To this day, I still practice the artisan skill of tree digging and drum-lacing root balls that Lud taught me years ago.

The communal connectedness of the horticultural world is appreciable and a source of many cherished relationships. The connecting links form a chain that spans and unites the past with contemporaries and over geographical distances. My horticultural retrospective points to a sequence of ties: Lud Hoffman to The Arnold Arboretum and Jack Alexander (now retired propagator), nurseryman and horticulturist, Wayne Mezitt and Massachusetts Horticultural Society, and to my wife Debi Hogan.

After working as a landscape designer in a West Hartford garden center, I relocated in 1981 from Connecticut to Jackson Nursery in Norton, Massachusetts. I wanted to be connected with a landscape design firm

Drum-Lacing root ball of three-flowered maple (Acer triflorum)

that had a relationship with the soil and field-grown plants. Soon after moving to Massachusetts, I met Charlie Trommer, a dye chemist by profession, but also a plant geek collector who, with his school teacher wife, Edy, ran a mail-order plant business, Tranquil Lake Nursery. The growing fields on this twenty-two-acre Rehoboth nursery offered a few thousand different cultivars of Hemerocallis, as well as Siberian and Japanese iris. My previously obscure link to Charlie was that he had sold daylilies to Philip White, proprietor of Hermitage Gardens in Monroe, Maine. It was there, as a teenager, that I purchased my first daylily hybrid, ‘Gay Troubadour’. After Edy’s untimely death, serendipity ensued, and in 1986 I became the co-owner of Tranquil Lake Nursery.

Straightaway I started making new gardens and transplanting Charlie’s collection of dwarf conifers. In 1988, encouraged by the collaboration of a stone-sculpture friend, I heeded the siren’s call of flower shows. That first garden display at Massachusetts Horticultural Society's New England Flower Show garnered the Trustee’s Trophy, Ruth Thayer Prize, and a Silver Medal. At the Gala Preview Party, I met Debi Hogan, who was the Children’s Program Coordinator for MHS. That Flower Show encounter was kismet; we married in 1991.

A double rainbow over the daylily fields at Tranquil Lake Nursery

Debi and I kept our connection to the New England Spring Flower Show, both exhibiting and judging. I foolishly once remarked that I was a better flower arranger than her. In response, she signed us both up to create floral designs in The Federated Garden Club’s challenge category at the 1993 New England Spring Flower Show. We exhibited in different categories and both received yellow ribbons. I call that a draw! The next year, we worked together, collaborating on a miniature garden, a Lilliputian garden with a scale of one inch to one foot. For many years afterward, we created and exhibited miniature garden designs and even co-chaired the category in later years. Over the years we received many gold medals and twice were awarded the Superlative Award for Historic Gardens and Landscapes for our Chinese Scholar's Garden and a Fletcher Steeleinspired garden. This is an award that is given to only one landscape exhibit in the entire flower show! We were hooked.

In the fall semester of 2010, I taught a Planting Design class at the University of Rhode Island. On October 10th, six students and my coinstructor Andy Balon gathered in Hopkinton, MA, at Wayne and Beth Mezitt’s garden. Wayne wanted to donate a sizable three-flowered maple (Acer triflorum) to Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston, so I volunteered to teach a very hands-on ‘artisan’ tree-digging workshop. The maple is still thriving in the winter garden at Tower Hill and is now a fitting and poignant memorial to Wayne and The Horticultural Club of Boston.

Miniature Chinese Scholar's Garden

Tree-digging workshop in Wayne Mezitt's garden

The artisan digging of trees continues to follow me. In the spring of 2023, Jack Alexander, the retired propagator from the Arnold Arboretum, was now engaged at the Heritage Museum and Gardens in Sandwich. Jack and the Director of Horticulture, Les Lutz asked me if I could dig and transplant a rare collection of fifty-year-old Dexter hybrid Rhododendrons. The plants were in the way of the construction of a new visitor’s center. The rhododendrons were growing closely together and amongst oaks and pitch pines with no room for machine access. Always up for a challenge, in late November, my crew and I hand-dug seven-foot-diameter root balls, roped and laced them to be air-lifted, and moved by crane. They are now thriving in their new garden location.

Digging and moving Dexter hybrid Rhododendrons at Heritage Museum and Gardens in Sandwich, MA

I have been speaking and teaching horticultural subjects and landscape design to garden clubs and horticultural institutions for more than forty years. Several years ago, while attending a horticultural trade show, I was greeted by a person who told me I had changed their life! Quite a flattering statement. She told me that she had participated in a landscape design class that I had taught at the Arnold Arboretum. My style of teaching landscape design is to bring abstract principles to life with down-to-earth, concrete examples and to illustrate them in a solution-based, visual context. In that class we used model forms and miniature trees in pots and also re-arranged the classroom furniture, using the entire room as a design tool. I focus on teaching critical thinking as opposed to drafting and representational drawing skills. She told me the class had empowered her to find her niche in the garden design business.

Circular Bower of Crabapple (Malus 'Sugar Tyme') at Brigham Hill Farm in May (above) and December (right)

I have had the good fortune of a life and career that both fulfills my love of plants and provides the opportunity to design and create landscapes for clients who share a passion for plants and gardens. Debi and I are lifelong gardeners. We are also devoted to the protection of our natural environment and particularly to the protection of farmland. Life is indeed transient, but we have secured the future use of our twenty acres of farmland with an (APR) deed restriction. We are still actively engaged in making gardens as well as extending our horticultural links into the future.

In November 2017, I received a phone call from an editor at Timber Press in Oregon. She asked me to write a book on the winter garden! The publisher was in search of a different approach to the winter garden season than previous books written by British authors. I guess my Maine and New England creds made an impression. It was an arduous task, photographing and writing in my self-limited time of only two months of the year. A seven-year feat was accomplished thanks to the patience of my editors and especially Debi. My new book, Plants for the Winter GardenPerennials, Grasses, Shrubs, and Trees to Add Interest in the Cold and Snow, was published on November 5th, 2024, by Timber Press. I hope it will inspire current and future gardeners.

Last year, I was visited by a plant-geek friend. Pete was wearing a black sweatshirt emblazoned with a stylized, green Echeveria bordered by the logo “Gardening is Life.” I thought, what a simple but true statement! Though humble in the status of its source, I found the message profound as well as personally reflective.

Life is gardening; may you always find joy in your garden.

For “In First Person,” Leaflet Editor-in-Chief Dave Barnett interviews people who have made their mark in horticulture and adjacent fields by asking a standard set of questions about their work and career. This column offers an opportunity for them to share their passions and tell the story about what motivates them and how they define and measure success

Appreciation of Early Flowers

By Catherine Cooper

Here in New England we look forward to the arrival of spring for it not only heralds warmer weather, but also a burst of color which banishes the subtle muted palate of mostly browns and dark green which is winter. This is particularly welcome as we have spent four months in which nothing has been blooming and such a color scheme can become wearing on the spirits, especially if the sky is also gray.

The transition is slow at first but gives opportunity to cultivate an appreciation of even the smallest changes, savoring the gradual

Witch hazel (Hamamelis x 'Jelena')

△Snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis)

▷ Winter aconite (Eranthis hyemalis)

transformation that creeps over the landscape. Many of our early bloomers are small and without competition from the showier plants that will burst forth at the height of spring so we are forced to get up close and personal to appreciate the gems that early spring delivers. One of the earliest groups of plants to flower is spring bulbs. Snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis) are so named not only for their flower color and shape, but also because they can be in bloom while snow is still on the ground. Similarly crocus can be found poking their buds up through wintery ground and with their flowers in shades of white, yellow, purple and orange they add a pop of color. They also provide food for the earliest pollinators as do winter aconite (Eranthis hyemalis), a gorgeous yellow flower whose shape betrays its membership of the buttercup family. A little later they will be joined by grape hyacinth (Muscari spp.), Siberian squill (Scilla siberica), glory of the snow (Chionodoxa luciliae) and dwarf iris, all of which add shades of blue to the mix and before long the earliest of daffodils, such as the variety 'Tete a Tete' will augment the landscape along with hyacinth and species tulip.

Perennial plants are a little slower to come into flower, although winter heather (Erica carnea) produced some flowers as early as December in my garden only to go into suspended animation, so to speak, with the cold that January brought. Generally it doesn’t flower quite that early just as Christmas rose (Helleborus niger) isn’t normally in bloom outside at the end of December. Still, they both bloom early in the season and as both plants are evergreen they provide all year interest, which peaks in early spring.

Cultivated plants are not the only ones to bring a splash of color. For example, I have patches of ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea), which isn’t always growing where I wish, but whenever I see its purple-blue flowers frequented by queen carpenter and bumble bees, I forgive it for being an aggressive non-native plant. One of the earliest native perennials to flower is skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus). Growing in wetlands, it does not inhabit my sun-baked patch, but walks in conservation land reveal swaths of these gothic-like flowers which have an eerie beauty upon close inspection. Perfectly adapted to capitalize on an early start it can warm the soil around itself in order to start growing so early, and smelling as it does of carrion, it attracts flies as pollinators. They are one of the earliest native flowers and the sight of them is always welcome, even if they do not conform to conventional ideas of beauty.

In fact, New England has several native perennials that bloom in early spring in order to take advantage of a lack of leaf canopy, which later on will also serve to shade these plants from the intensity of the summer sun. These include trillium, hepatica, trout lily (Erythronium americanum) and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) and all of them bring delicate beauty that can be found in our woodlands.

Left: Eastern carpenter bee on ground icy (Glechoma hederacea)

Right: Skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus)

Small perennials and bulbs are not the only plants that inch us into the growing season. Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas) and witch hazel (Hamamelis spp.) are small trees that produce their flowers before their leaves emerge, allowing these delicate flowers to be better appreciated. Witch hazels have the added bonus of scented flowers and come in shades of yellow through burnt orange. Native maples are also an early harbinger of spring with red maples turning a delicate wine red from their flowers, while sugar maples offer a jaunty yellow-green before each type of tree then unfurls its foliage. Another sign that spring is arriving are the fluffy catkins on pussy willow, which is popular decor in spring containers.

As time progresses these early heralds of spring cede their crowns to more exuberant plants and by the time we are into April dogwood trees, ornamental cherries, pears and apples as well as magnolias are all vying for our attention, but before that moment arrives, nature provides plenty to whet the horticultural appetite.

Winter heather (Erica carnea)

Born in England, Catherine learned to garden from her parents and from that developed a passion for plants. Catherine works assisting customers at the newest Weston Nurseries location in Lincoln. When not at Weston Nurseries, she can often be found in her flower beds or tending to an ever-increasing collection of houseplants.

Dwarf iris (Iris pumila)

Crocus

Tales from the Worm Bin

By Libby Wilkinson

As a child, I would delight my family each summer by filling our portable cooler not with sodas, but with live frogs. Inside the cooler, the little guys would be swimming in the pond water, ready to pounce on my unsuspecting mother. Again, this was the delightful half of my summer antics. On any given day, I was just as likely to hand my uncle a mason jar filled to the brim with….leeches. Picture it now—a little girl with her front teeth missing, dirty little hands holding a sealed jar filled with brown pond water mixed with writhing, wriggling, black leeches. I loved them and hated them! I wanted to stare at them and never look away… that mix of delight and disgust and awe at another way of life. The frogs were cute, but the leeches were aliens.

Fast forward 20 years, and now I am paid to feed a bin of one thousand writhing, wriggling worms that live under my desk. Worms are, admittedly, cuter than leeches. For one, they don’t drink our blood. Even so, most adults, at best, shy away from worms, but more often, jump back in audible disgust when a worm ball is presented to them. (A worm ball is when 10+ worms get tangled together to form, well, a ball.) What is it about a slimy, tube creature with no eyes that really seems to freak us out? I’m convinced this is a learned behavior. Almost every child that meets a worm leaves that interaction feeling delighted and in awe of the humble worm. Some are staring at the worms the same way I looked at the leeches—like an alien has arrived at school. Most kids try to leave with one or two in their pockets.

Earthworms are decomposers. So, unlike the leech, they will never bite us in hopes of a tasty meal. Their mouth parts are so small, we wouldn’t even feel it if they did try to bite us. In short, earthworms are our helpers and friends - in comparison to the rest of the creepy crawly world, worms are our heroes. This part of the world used to be covered by glaciers, and places that were covered in glaciers do not have native earthworm species. I will say that again: there are no native earthworms to New England. Every worm you see comes either

from the American south, Europe, or Africa. The settlers who came over from Europe unknowingly brought earthworms to New England in the soil used for their potted plants or the mud tracked in on the hooves of their animals. The earthworms entered a new world filled with leaf litter and decomposing garden plants and forest critters. Thankfully, a worm is a delicious and easily eaten snack, so their populations have never become invasive. A lot of earthworms (like the composter extraordinaire, the Red Wiggler), cannot survive a New England winter. The forest floors of New England used to look a lot different before the humble earthworm—there used to be inches of thick fluffy leaf litter on the ground, slowly decomposing and only leaching out small amounts of nutrients at a time. Enter the earthworm! They digested those leaves and pooped out fertile soil—creating an increasingly fertile landscape for plants and animals to exploit (in a good way!) We owe a lot to these little creatures! Okay, if you’ve made it this far, you’re probably wondering when I’ll get to the good stuff: vermicomposting! That bin of worms I told you about isn’t just for fun - it is a functioning soil ecosystem in a box. For a long time, people regarded soil as just dirt, the lifeless substrate that plants grow in. It wasn’t until quite recently that we realized that the soil is filled with a complex, vibrant, and diverse ecosystem made up of plants, animals, fungi, and raw materials. Composting is how humans mimic this soil ecosystem that recycles all the world’s waste and turns it into something new.

Vermicomposting is the science of using animals (worms specifically) to break down the waste themselves, instead of relying on microbes and time as in a regular compost pile. This comes with its own set of challenges and benefits - the challenge of simply keeping living creatures alive through feeding and habitat management, versus the benefit of delegating the decomposition work to another critter.

Worms create much more potent compost than a regular pile - so much so that worm poop is called worm castings, and it's sold for good money at your local garden store. With a worm bin, worm castings are the gold at the end of the rainbow. Although you will create far less compost by volume, you can dilute the castings and use this to water your plants to the same effect as sprinkling on the soil. We used the worm castings here at MHS to give all the indoor plants a refresh, and kids even take some home in ziplock baggies for their own gardens!

Plantmobile students learn about decomposers.

Worm castings are made up of humus—that rich, spongy, dark soil created when things decompose. It is filled with available nutrients like nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, zinc, iron and so many more. There are whole colonies of beneficial bacteria and fungi that get passed from the worm’s gut to the soil. These microorganisms help protect plants from disease and infection. When we explore the worm bin with students we can see the digestive tract of the worms. The dark line is the waste (dead leaves, apple cores) going through the system, then at the end it is a fully formed casting ready to be dropped in the soil. Their poop is nontoxic to humans, and it is totally safe to touch, smell, even taste. I tell the kids: the worms eat the yucky stuff and poop out the good stuff—the opposite of most animals!

True to their roots, worms are recyclers. So, after you have harvested all that golden poop from your worm bin, you simply add more materials (dead leaves, small sticks, pinecones, newspaper, brown paper bags, cardboard, rotten apple, smooshed banana, etc.) and plop your hundreds of worms back into their house. I clean out our worm bin every few months with the students.

Even if you were not the type of kid to catch frogs and jar up leeches, I hope you’ve learned enough to befriend a worm, or five-hundred, and create some rich soil for your gardens this spring!

HOW TO MAKE A WORM BIN

Materials:

• 2 plastic bins same size, 1 lid (the bins will nest inside each other)

• Electric drill or hammer and nails

• Recycled materials:

• Brown corrugated cardboard

• Black and white printed newspaper

• Brown paper bags

• Natural materials:

• Dead leaves

• Sawdust or coco coir

Pine cones

Small sticks

Dead flowers, old fruit (no citrus), seeds or nuts

Spray bottle with clean tap water

Worms! We ordered our worms from Uncle Jim’s Worm Farm. They arrive in a burlap sack in a box. They will need to be fed right away, so gather your supplies before the shipment arrives.

Instructions:

1. Rinse out the plastic bins.

2. Use the electric drill to drill holes around the bins and the lid. These are air and drainage holes. I drilled about 24 holes in each bin in random spots, and about 20 in the lid in a nice uniform style. Use a drill bit that is the same size as a standard nail. Nothing too big or the worms WILL get out.

a. If using a nail and hammer, hammer in the nail and pull it out over and over to make your air and drainage holes. Nest the bins - put one bin in the other. This will help air flow and keep the mess off your floor or tabletops. Make sure the lid can still fit securely - there should be no gaps or the worms WILL get out.

Create the bedding:

a. Layer your materials in the bin like you are mimicking a forest floor.

b. Break/tear up big pieces of materials so the worms can digest it easier.

c. Spritz the materials as you are making the habitat. Worms like damp, but not wet, environments.

d. When the bin is ¾ full, add your worms. Place a few food items near

e. Cover the worms with more layers of materials and water spritz so they have a nice dark and damp place to settle in.

f. Stop filling the bin about an inch and a half below the lip of the bin.

g. Put the lid on the bin and store your bin in a dark and warm place.

• What CAN’T worms eat? NO: citrus, garlic or onions, meat, dairy, eggs (rinsed egg shells are ok), fats and oils like butter and coconut oil, diseased plants, fruit stickers, alcohol, soda, or highly acidic foods

• Spritz the bin when it seems to be drying out. After a while your bin will reach an equilibrium where it can maintain its own moisture, but keep an eye on it until then.

• Don’t add too much food at one time. Save a separate smaller compost bin to collect a few worm friendly items per day (apple core, rinsed egg shell, pistachio shells etc) then bury the food in a corner of the worm bin.

• You can always add more dead leaves! Always spritz the dry leaves.

• Your worm population will double in size in 6 months. When the bin reaches its equilibrium, the worm population will control itself. If there are too many worms, give some to a friend!

• There will be other creatures living in the bin. Popular residents include roly-poly bugs, mites, snails, centipedes, and even small spiders. The diversity in your bin is an indication that you are creating a vibrant decomposer ecosystem.

The home in Elm Bank, Wellesley, was being built and in the Spring of 1876, we moved out there, … We enjoyed “Elm Bank” for many years.

Elizabeth Stickney Clapp Cheney (1839-1922) Excerpt from her Memoir

Elm Bank – The Cheney Era 1874-1905

Benjamin and Elizabeth Cheney were enthusiastic and active members of Massachusetts Horticultural Society (MHS). Benjamin contributed his valued business acumen to MHS while Elizabeth was an active committee member and participant in MHS’s exhibitions. In 1874, the Cheneys acquired Elm Bank at an auction for $10,000. Immediately, they began to transform Elm Bank from a gentleman’s farm to a summer retreat for relaxation, play and entertainment. They hired architect John Andrews Fox to design a new Queen Anne Victorian Mansion and the landscape.1 In the mid-19th century, landscape design for estates in the United States featured dramatic drives, foliage plants, geometric patterns and large lawns, all evident at Elm Bank.

Image: Elizabeth Stickney Clapp Cheney (1839-1922). MHS Archives.

1In the mid-19th century, it was not unusual for an architect to handle the design of both the house and landscape. The profession of landscape architecture did not come into existence until the late 19th century. The American Society of Landscape Architects was founded in 1899 and in 1900, Harvard introduced the first landscape architecture program.

Image: Benjamin Pierce Cheney (1818-1895). MHS Archives.

Elm Bank’s location on the Charles River and the topography of the land provided the ideal setting for the Cheneys’ country place. Fox’s design included a leisurely drive along the river, gardens, bridle paths, lawns, meadows, woodlands and a golf course. In addition to the mansion, there were out-buildings and massive greenhouses where Elizabeth and her gardener, John Barr, grew their prize-winning plants. Some of these features are extant today.

After Benjamin’s death in 1895, and several personal tragedies, Elizabeth Cheney believed that Elm Bank “had proved to be very malarial being on the banks of the Charles River.” She built a new summer residence in Peterborough, New Hampshire and transferred Elm Bank to her daughter Alice Steele Cheney in 1905. When Alice married William Hewson Baltzell in 1907, the Mansion was razed and the Manor you see today at the Garden at Elm Bank was built a short distance away.

In 1996, MHS entered a 99-year lease of 36 acres at Elm Bank with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for its new headquarters. In 2001, MHS moved its headquarters to Elm Bank after a major investment to revitalize the landscape and buildings. When MHS took possession of the property, it received a photograph album from the Commonwealth that depicted the Cheney Estate in the late 19th century. A brief history of Elm Bank that features images from that album is found on the Library’s webpage.

Top: Eighteenth century Jones farmhouse was on the highest plateau at Elm Bank. It was surrounded by five elms. C. 1870. Courtesy of Natick Historical Society. Bottom: The Jones farmhouse was razed in 1874 and the Cheney Mansion was built on the same site. It was designed so that every window had a view over the landscape. The five elm trees that surrounded the Jones farmhouse were retained. MHS Archives.

MHS Book Club

During the cooler months, the Book Club meetings take place on the third Tuesday of the month at 1:30 pm in the Dearborn Room in the Education Building.

All are welcome to attend.

Here are the books for the Club’s upcoming discussions:

March 18

Nature’s Best Hope by Doug Tallamy

April 15

Onward and Upward in the Garden by Katherine S. White

May 20

Elements of Garden Design by Joe Eck

COME VISIT!

The Library is open by appointment until the Garden opens on April 1, 2025. Please email Library & Archives Manager Maureen O’Brien for an appointment if you want to schedule a visit.

Something to Make the World More Beautiful…and Resilient

By Julie Moir Messervy

I’ve spent my life trying to make the world around me more beautiful. I started by designing public and private gardens through our landscape design firm, JMMDS. One of the special spaces we created was the Garden at Elm Bank's Weezie’s Garden for Children, a one-acre children’s garden whose theme was the image of a fern frond unfurling like the growth of a child. I’m thrilled that my own young grandchildren are of an age to explore its many treasures, including the Treehouse, the Bluebird Garden, the Butterfly Garden and the Tortoise Sandbox.

The original design plan of Weezie's Garden for Children © Julie Moir Messervy Design Studio

Twelve years ago, my team and I realized that we could use technology to help more people create a beautiful garden. So we developed a 2D design app that’s now called Yard Planner and recently launched Home Outside® 3D Landscape & Garden Designer, the only 3D Augmented Reality (AR) design app created by landscape design experts.

In just minutes, you can visualize and design your garden right in your own yard, using our AR feature and our beautifully rendered 3D plants and predesigned garden collections.

You can choose different shade trees, privacy hedges, corner and border gardens, edible gardens and container plantings commonly available in nurseries, with pre-designed collections created by Home Outside's expert designers for your hardiness zone (currently available for Zones 5-9), each with a scaled planting plan.

With the AR feature, you can walk around your yard and see your design from all angles, then move and rotate the elements to get everything just right. Then save your design and get a plant list. You can also filter for sun and shade, deer resistance, flower color, as well as native plants and collections. Home Outside has also created a 3D AI tool that creates a digital twin of a homeowner’s property and designs the landscape for them. We hope to release this feature sometime later this year.

Together with our partner Homegrown National Park, Home Outside has been nominated for Prince William’s Earthshot Prize (Home Outside for the second year in a row), the world’s most prestigious environmental award. With funding, we plan to develop a native plant app that helps people around the world make their home landscape more resilient, sustainable, and biodiverse. And, of course, more beautiful!

WASTE NOT, WANT NOT

BY JOHN LEE

John shares stories of Bert and Brenda and their gardening wisdom. These chronicles feature recipes, tried-and-true gardening practices, and seasonal struggles and successes. Bert and Brenda were first introduced in the March 2022 issue of Leaflet.

In the dead of winter, Bert and Brenda sometimes got a little testy. If last summer’s green bean harvest was truly exceptional then by now both were, frankly, sick and tired of green beans once, if not twice a day for what seemed like months on end. Yankees to their very core, those beans were not to go to waste. Brenda’s winter

mantra (preached when need be) was ‘waste not, want not’ and produce put up at home could not be shared at the food pantry (they had rules about what was acceptable!) and would not, could not go to the compost (although that was arguably not ‘wasted’). So, both felt a keen, if unwelcome, sense of obligation, a marriage if

you will, to the larder. While this did take a bit of shine off their past summer’s travails, this momentary disdain was instructive: maybe a few feet less string beans this coming summer. In the meantime, Brenda wracked her brain about some different, more delectable green bean preparation that might get Bert to be a little cheerier at mealtimes. The problem was that once put up, there wasn’t much

gab sessions but more often than not, it was to no avail. The ladies of her generation threw their hands in shared consternation; the younger gals’ tastebuds were far too gregarious for her husband’s more than mundane sense of an acceptable offeering. The lesson this winter was less string beans (green or waxed) and more shell beans, perhaps. Bert was never too keen on Limas for some reason

one could do to make a string bean any different than what it already was. Wistfully (and without sharing) each came to the same conclusion: too much of anything was kind of akin to something else otherwise unthinkable (like getting in each other’s way at times). She had broached the subject down at the Homemaker’s

– maybe too many in his earliest life although shelling beans while listening to the Red Sox or the Patriots lose made a rainy day more bearable. Of all the shellable varieties, they both generally preferred Tongue of Fire/French Horticultural varieties. When they were dried, she used them like any other dried bean. She did

Tools from Bert's work bench

not discriminate that way and beans on the back burner always made her feel right at home. Bert liked them because whatever was not consumed were replanted the next season along with fresh seed.

This was his idea of a noble scientific experiment: would the leftover seeds be true to type? Only time would tell. He would plant late in spring training (once referred to as the ‘grapefruit league’) and by harvest time, he really could not likely tell the difference if the game was at all close.

Not to change the well-worn subject, but in her kitchen garden, her bay plant was now a tree and becoming too big to manage comfortably (she brought it into the house before the first freeze and set in a north window), the rosemary was suffering, her thyme was a bit played out and wouldn’t it be nice if there were a few more edible flowers to decorate a salad if she (or they) had a meeting that was unavoidable? A dressy salad was always welcome and a pleasant alternative to

the dreaded pasta salads and/ or molded creations that some folks still trundled down to the Community Center. Often as not, they were reason enough to stay home. Such were never going to help recruit new members if the best they could dish up was ‘old’ food!

When the cold weather set in hard, and even the woodshed seemed too cold to dally in, Brenda would find herself chomping at the bit. Even in the best of times, sitting on her hands was not her cup of tea. Bert feared for lost what-nots. She’d get to putting things away on a shut-in afternoon and who knew when they’d come to light again. Were he to remonstrate, Brenda’s standard retort was always along the lines of “if you’d done it, I wouldn’t have to”. Some days she seemed like a run-away train. He’d best stay out of the way and keep an eye out for what went where. As often as not there was no reason as far as he was concerned to her

squirrelling. It seemed like ‘out of (her) sight, out of mind’ was her modus operandi. End of story.

There was but one exception to her compulsion: cookbooks. Over the years of their long marriage, whether or not a 1,000 piece jigsaw puzzle was their evening’s post prandial amusement, she would usually retire with a cookbook to browse. It was not like she was looking for new recipes (maybe just a little inspiration). She was pretty happy with what she already knew how to prepare and would please Bert. But the pictures were entrancing even if Bert said he would not eat whatever she was admiring in those moments and she would often admit to herself that there was such a thing as too much butter. Suffice it to say, almost all of these tomes were, in fact, just bedtime reading. They had been ‘gifts’ usually from younger acquaintances who sometimes thought her cuisine was what one might call antediluvian. Bert’s mea culpa were his seed catalogues and ‘too many’ hammers. There was no winning the argument

about who had too many of what. He also knew where his next meal would be coming from. He oughtn’t want to get her too riled up lest she take it upon herself to clean up his work bench. Better to keep the peace than put his foot where it didn’t belong.

PS: Despite her nocturnal meanderings, it turns out there’s not much new she could do to bring new life to all those canned or frozen green or wax beans. Brenda had sauteed them with peppers and god knows what else, added slivered almonds, herbs and/or spices (which were hit or miss with her fussy husband). Fresh green bean casseroles were great in the summer. But even the best canned or frozen green bean recipes were old hat even if Bert were to be a fan of garlic or parmesan cheese (which he barely countenanced). What’s a woman to do when faced with such an intractable dilemma?

John Lee is the retired manager of MHS Gold Medal winner Allandale Farm, Cognoscenti contributor and president of MA Society for Promoting Agriculture. He sits on the UMASS Board of Public Overseers and is a long-time op-ed contributor to Edible Boston and other publications.