Silicon Valley as Innovation Landscape

Martyn Smith

© Martyn Smith, 2020, 2023 Published in the United States

Preface

In any experience of travel we encounter a place at a particular point in time, and that place can never be revisited. This visual essay was formed out of two trips to Silicon Valley in the spring and summer of 2016. In hindsight this was the peak of Silicon Valley confidence. The people we met were certain that Donald Trump would be defeated in the fall election, and they had no doubt that tech and innovation could be anything but a positive force in the world. The election of Donald Trump along with the Covid pandemic a few years later shook that confidence.

Silicon Valley is often referred to as an ecosystem. The word thus loses any relation to ecology, but serves as a metaphor for the complex, interlocking institutions that make up this region. It would be easy to point to the major corporate players like Apple, Google (Alphabet), and Facebook (Meta). But any exploration of Silicon Valley will bring to light other contributing institutions, such as Stanford University and UC San Francisco (two institutions of higher education mentioned in this essay). Then there’s civic museums like the Tech Interactive in San Jose or the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. We could add public sculptures and murals, along with restaurants and places of worship. These institutions spoke in one

voice in praise of this dominant worldview of our time. It’s a worldview that has gained a foothold around the world, so that while it’s first crystalization might well be in the United States (designed in California?) it defines global spaces. What is distinctive about this worldview? First, it sets up a specific relationship between Self and Society. The Self no longer finds meaning through association with traditional social configurations (church, state, class) that in the past gave it meaning, but welcomes the illusion of being a free chooser of symbols and associations. Second, the Self is told that it should liberate itself from the Past and its dogmas, and should become oriented toward the Future. The correct attitude toward the Future is defined by the words Creativity and Innovation. The former if one is speaking within an individually expressive context, the latter in the context of for-profit endeavors. If enough out-of-the-box thinking is devoted to any subject, the end result will be sooner or later be Success (though failures might pile up in the process). The ethical expression of this worldview will be defined not by traditional virtues of limitation, but by principles of Self expansion. Shared systems of thought seek expression in a physical landscape, and some human landscapes manage to represent those systems with particular clarity and force.

Silicon Valley, California

Facebook HQ

Stanford University

Apple HQ

Google HQ

This small advertising card was there for the taking at the entrance to Hacker Dojo, a tech hub where members get space to work and collaborate (all while connected to fast Wi-Fi). In 2016 we sensed around Silicon Valley an ongoing gold rush. In the same way that aspiring musicians once gathered in Nashville to sell a hit song, young techies now came to Silicon Valley with the goal of developing an app that would make it big. Wherever we went this summer we encountered the Innovation Ideology, either implicit or directly stated. The future was right there waiting to be created by innovative individuals, and the profits would be beyond belief. At the time we couldn’t have guessed that this was the peak of Silicon Valley techno-optimism. With

1

the election of Donald Trump in the coming fall and then the increased scrutiny on the major tech corporations, Silicon Valley would pass into an era of skepticism about the future it proposed. At the Mountain View headquarters of the networking platform LinkedIn (acquired by Microsoft just a few months later), we came across pinball machines and open ping-pong tables in its central space. Both serve as markers for a playfulness that’s common in Silicon Valley (though we never saw people actually playing ping-pong at these tables). An image of the moon loomed, and text on another wall explained: “...inside each of us is a moonshot/ An ambitious undertaking that stirs the soul/ One we’d embark on if only we had more time/ ...that

2

moonshot is your purpose..” There’s veiled religious sentiment there in that linking of tech work to a larger “purpose.” I sometimes get asked why as a religious studies professor I’ve become interested in technology. A short answer is that the set of values that revolve around technology and innovation constitute an invisible religion. These values give many people meaning in their experience of contemporary life and provide a basis for social connection. A tenet of this invisible religion is that all the serious problems of our time can be solved with a deep dump of data and a dash of “thinking outside the box.” The past is most likely what holds us back. The Tech Museum in San Jose was aimed at kids, and hands on displays got them into the mindset

3

that they could help solve the world’s problems. Any successful religion (even an invisible one) must be supported by interlocking institutions. The weave of a religion gets tighter and feels more certain as the core message is taken up and affirmed from multiple perspectives within a society. In Silicon Valley the Innovation Ideology is set out at every turn. This was the entrance of the Tech Museum of Innovation (now “The Tech Interactive”). In this photo children from a martial arts summer camp are lining up at the entrance. As I walked through the museum it was crowded with children in families or extra-curricular groups like this one. Although innovation is a soft cultural concept, it feels more solid when presented as the topic at the heart

4

of an expensive civic museum. The main exhibit at the Tech Museum was this “Innovation Gallery.” The room was filled with interactive examples of tech advances brought about by Silicon Valley based corporations. The examples ranged from the past (microchips) to current breakthroughs (facial recognition). The central takeaway from the exhibit was that innovation in the tech sector is exciting and making life better all the time. The museum’s large donors (listed on its website) included Cisco, Dell, Mozilla, Adobe, and Gilead (a biopharmaceutical company). The older authority and format of the traditional museum was thus transformed into a mouthpiece for the Innovation Ideology. Silicon Valley is often referred to as an ecosystem, and

5

the point of that word from environmental studies is that Silicon Valley contains a web of interlocking institutions that make it a unique economic zone. Looked at from the standpoint of their online presence on our screens, these institutions are just a set of common words, but within Silicon Valley itself these institutions sit in close physical proximity. This is a photo of Stanford University’s Hoover Tower as visible from a hill overlooking the Google Campus in Mountain View. Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergei Brin attended graduate school at Stanford, and they were able to launch their search engine only because of the resources they had access to there. As Google flourished and grew, they established a corporate campus near their former

6

university. It’s not just Google, the headquarters of Apple and Facebook are nearby as well. Looking in the other direction from that same hill overlooking Google’s campus it’s possible to see NASA’s Ames Research Center and Moffett Airfield. The massive scaffolding in the distance is Hangar One (outer panels removed at this time for restoration). The hangar was built in 1930 to house the USS Macon, a massive airship or zeppelin. The large rectangular structure to its right (looking like a flatscreen TV) is the intake for the world’s largest wind tunnel for testing aircraft. These structures stand as lasting evidence of the long-term investment in Silicon Valley on the part of the US defense industry. And we should remember that the internet itself had its

7

origin as a defense project in the 1960s. Those past institutional connections continue to be represented throughout this landscape. The Main Quad sits at the heart of Stanford University. The original layout was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the 19th century landscape architect responsible for classic American spaces such as Central Park. A well-known architectural firm then designed the red-tiled stone buildings with their distinctive Romanesque arches. When it comes to Silicon Valley, the peninsular land that stretches from San Francisco in the north to San Jose in the south, the Stanford campus is the paradigmatic public space. When Steve Jobs spent his last years designing the new Apple headquarters, he was striving to recreate the feel of

8

walking around Stanford’s Main Quad. The Memorial Church has a lovely Byzantine-style mosaic on its exterior, facing the Quad. The scene depicts Jesus teaching a crowd, but my attention was drawn more to the background, which with palm trees, low rolling hills, and distant mountains looked a lot like California! Leland Stanford was the 19th century industrialist who founded Stanford with a slice of his personal wealth, and his wife Jane dedicated this church to his memory. One of the plaques inside the church urges students to find the “power of personal religion” and to avoid the “narrowing of man’s horizon of spiritual things.” The church doesn’t represent an orthodox point of view, rather it pushes toward the spirituality of beauty. At

9

one time wealthy donors might’ve had a statue of themselves erected in a public place. Realistic statues like that now strike us as gauche. Nothing has more prestige than a named building. The Stanford campus goes back to the 19th century, but the campus has expanded ambitiously, especially when it comes to the sciences. The names of the new science buildings are a roll call for tech innovators of the past decades. Jerry Yang was a co-founder of Yahoo! and he and his wife gave $75 million to Stanford. Other notable tech figures with named buildings include Bill Gates and David Packard. Stanford has encouraged a dynamic relationship with corporations, and its campus reflects that coziness. One strong line of criticism is that Stanford is too

10

comfortable with these corporate connections. Stanford’s “Discovery Walk” was opened in 2012. It lies alongside the medical school and tells the story of medical research at Stanford by means of laser-etched black granite panels. Anyone who stops to read these panels (they are quite wordy) will be impressed with the scientific advances associated with the university. There are panels explaining the Human Genome Project, advances in stem cell research, and many other projects. There won’t be many people who stop to read through all these panels (there are more than just the two sections pictured above), but the investment in this public installation is a major statement about what is valued here. There is a drive within institutions to

11

represent and celebrate the stories that matter the most to them. The Burghers of Calais is a sculpture group completed by Auguste Rodin in the 1880s, the same decade in which Stanford University was planned. The city of Calais first commissioned the sculpture group as a civic monument commemorating the bitter loss of the city back in 1346 and the self-sacrifice of its leaders. The statue group by Rodin turned out to be a human statement that could easily be dislodged from that particular setting. One of the several sites where the group can now be seen is Memorial Court at Stanford, where the figures are approached at ground level just as Rodin had imagined. Institutions like Stanford that cultivate an international reputation

12

strive to dislocate themselves from a particular place, and embrace art that’s perceived as universal rather than regional. A cast for Rodin’s Gates of Hell stands outside the Center for Visual Arts at Stanford. “The Thinker” is an iconic statue, but its conceptual origin was on this sculpted gateway crowded with contorted figures (as one might expect at the Gates of Hell). The only figure in repose is this Thinker, and it’s an open question how he relates to the rest of the composition. It felt strange to admire this gate on the sunny and wealth-reflecting campus. Just as the death-resignation of the Burghers of Calais seems miles from the future-think of Silicon Valley, so this individual man lost in contemplation and abstract thought speaks of some ideal that’s

13

been lost with the social sharing that built the internet. Not many apps induce that pose of thoughtful attention. San Jose is the major city at the southern end of Silicon Valley. Its state university is close to the polar opposite of Stanford. It has an undergraduate student body of 33,000 and an admission rate of about 60%. Its endowment is minuscule in comparison to Stanford’s $27 billion. When it comes to public art visitors don’t stumble across internationally famous Rodin sculptures, rather representations like this one of Tommie Smith and John Carlos (both alums of San Jose State University) raising their fists at the 1968 Olympics to protest racial inequality. The theme of this statue group, along with the scale and architectural style of the

14

administration building behind, speaks of more directly egalitarian educational goals. I saw these banners hanging everywhere on the campus of SJSU. “Share Your Story” they urged us. I couldn’t imagine Stanford putting up similar banners. Stanford is extraordinarily selective (only 4% of applicants accepted), so the message can’t be: “This is a place where everyone can share their story!” On the campus of San Jose State it doesn’t matter if you are 50 years old or if you struggled in high school, you can attend college here. That openness allowed for banners like this that affirmed the value of everyone’s story. We can’t ignore that this is exactly the ethos (share your photos, post your thoughts) that has powered the success of the major tech platforms of

15

Silicon Valley. The CEOs of the large tech companies are most likely to have attended an exclusive university like Stanford, but their broad appeal is all San Jose State: everyone’s story is worth sharing. Stanford University is smack in the middle of Silicon Valley, and a significant portion of its endowment is related to holdings in tech companies spun out of work done on its campus. One purveyor of the Innovation Ideology is the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, commonly known as the d.school. Its website carried what amounted to a statement of belief: “We believe design can help create the world we wish for. Design can activate us as creators and change the way we see ourselves and others. Design is filled with optimism, hope, and the joy that comes

16

from making things change by making things real.” As it happened, one of the founders of the d.school had recently published a book: The Achievement Habit. The idea is that achievement isn’t the domain of geniuses, but is the result of specific habits. Everyone can be creative, and everyone can “follow their dreams” to their imagined life. What’s stands in the way is something related to each person’s mindset. This book represents a further step into the Innovation Ideology. We’re seeing an approach to life defined by the orientation of the Self toward the Future. This orientation includes an emphasis on personal creativity, a positive mindset regarding life, and holding onto the hope of finding personal filfillment at the end (“follow your dreams”). The

17

d.school at Stanford University prominently asks people to “reset” the seats and tables in its atrium. The idea is that there’s no perfect setup for this space, and the arrangement can always be varied and made new. This highlights the anxiety that must come with the Innovation Ideology. In every part of existence humans are urged to think again about what would be best and

18

to design it anew. Everything’s open for change. But it would often be such a relief to have things just be given, and accepted as they are. Terry Winograd (one of the d.school’s founders) was the academic advisor to Google co-founder Larry Page. Winograd’s big idea was that software should be designed with the same obsessive care as the physical things that matter to us. Software design should be oriented toward intuitive functionality (think of Google’s minimalist search box). Since Winograd was a graduate from one of the liberal arts colleges in our Midwestern liberal arts college consortium, we got the chance to sit down with him. What I remember most was his idea that we can’t wait for our administrations to come along before we shake

19

things up and innovate in our classes. Resetting and trying something new should be a habit. Many internet companies exist for people only as an app on a screen. It’s surreal to drive along a freeway in Silicon Valley and see a plain building with the corporate logo for “Evernote” or some other app. Then it clicks: the service I make use of online is housed in that building. In San Francisco, along the Embarcadero, we walked past the corporate offices for the web browser Firefox, and I had that reaction of surprise. Much of the vocabulary of the internet is intent on casting a veil over the spatial reality of corporations, pushing us to imagine them as existing “in the cloud.” But the work of designing and maintaining these apps and services was a real

20

enterprise, and people we met commuted across the nearby Bay Bridge in order to work in buildings just like this. Donald Trump’s election at the close of 2016 brought a shock to the assumptions of Silicon Valley—a shock that’s still being processed. During our visit in the summer of 2016 it was clear that people at all levels considered their work in tech as a net positive for the wider world. People were doing good for society at the same time as they were doing well for themselves. The Firefox corporate space in San Francisco put this sense of “doing good” into words on this sign, and it would’ve been difficult at this time to find any corporation in Silicon Valley that didn’t see the world through this same lens. Google had put it in the negative—“Don’t

21

Be

Evil”—but it came to the same thing. Much of what we expect about sacred space within a religious tradition is mirrored in Silicon Valley. The area has an origin story, connected to a series of garages located next to private houses. In 1937 a Stanford professor urged students to start their own electronics firms in the area, and the two students who first took him up on this were William Hewlett and Dave Packard, whose names were linked in the tech corporation Hewlett-Packard (now just “HP”). In 1938 they moved into a portion of a Palo Alto house, and the garage became the site for their electronics tinkering. Their work proved successful enough that it could be thought of as the “birthplace” of Silicon Valley. So their garage was recognized by the

22

state of California as a place to be preserved. In the 2000s Hewlett-Packard bought this property and restored the garage. It’s now maintained as a private museum, though without knowing the right people visitors can only view the garage from the sidewalk (as seen in this photo). In an online statement Hewlett-Packard calls this garage “the enduring symbol of innovation and the entrepreneurial spirit.” The garage in Silicon Valley is something like the manger scene in Christianity. It draws intense responses because of the contrast between these humble spaces and the multi-billion dollar corporations they gave rise to. A garage isn’t a house or residence, but represents a kind of makeshift space for capitalist enterprise that implies risk taking and

23

personal initiative. It symbolizes the pursuit of a hunch or an idea, when there isn’t enough money to fund a laboratory or workshop. The house where Steve Jobs grew up in Los Altos isn’t a national landmark, though no doubt it will be. Signs outside warn against trespassing, hinting at its popularity with out of town visitors. It was in this garage that Apple, which has become the world’s most valuable corporation, got its start when the friends, and then business partners, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak assembled fifty Apple I computers. It was a shoestring venture, as is evident from the need to use this garage in the first place. In talks with his biographer Jobs raved about the design of the house in which he grew up: “[the] houses were smart and cheap

24

and good. They brought clean design and simple taste to lower-income people.” Partly as a result of the wild global success of the company he founded, these houses are now worth over $2 million apiece—so out of reach for working class people like his parents were. Jobs came to see his work in designing personal computers as parallel to the work that went into these homes: “I love it when you can bring really great design and simple capability to something that doesn’t cost too much... It was the original vision for Apple.” A suburban way of thinking about value and design was crucial for Apple’s success. If the garage is the Silicon Valley equivalent of the manger scene, then the area’s tech headquarters are the grand cathedrals set up as beacons

25

for the Innovation Ideology. Visitors aren’t welcomed into these spaces, as was the case in many ancient temples that walled off their central sacred rooms to anyone but priests. I imagine that in 100 years some of these tech cathedrals will be preserved and open for tours, and visitors will hear about the theories of personal creativity and corporate secret-keeping that explain the interior design. In 2016 Apple was still located here at its older campus, with its address “1 Infinite Loop.” That name is a coding joke, but also pushes toward the unplaced transcendence that tech corporations love to claim. Arguably, among all the major tech corporations, Apple has the finest sense of place. Steve Jobs grew up right around here, and on all its products Apple

26

makes sure to note that they were “assembled” in China, but “designed” in California. The new Apple headquarters was under construction in Cupertino at the time of our visit. This was as close as we could get, and even here we were approached by security guards and asked to explain what we were doing. Already the pure perfect curve of the building was clear. Steve Jobs had insisted on creating the exterior out of curved glass, so that the curve of the building wouldn’t be an illusion of distance but grow out of the material itself. It was a perfectionism of design that mirrored the care that went into all Apple products. Every detail about the look and the experience mattered, and Jobs spent the last two years of his life working instensely on the design

27

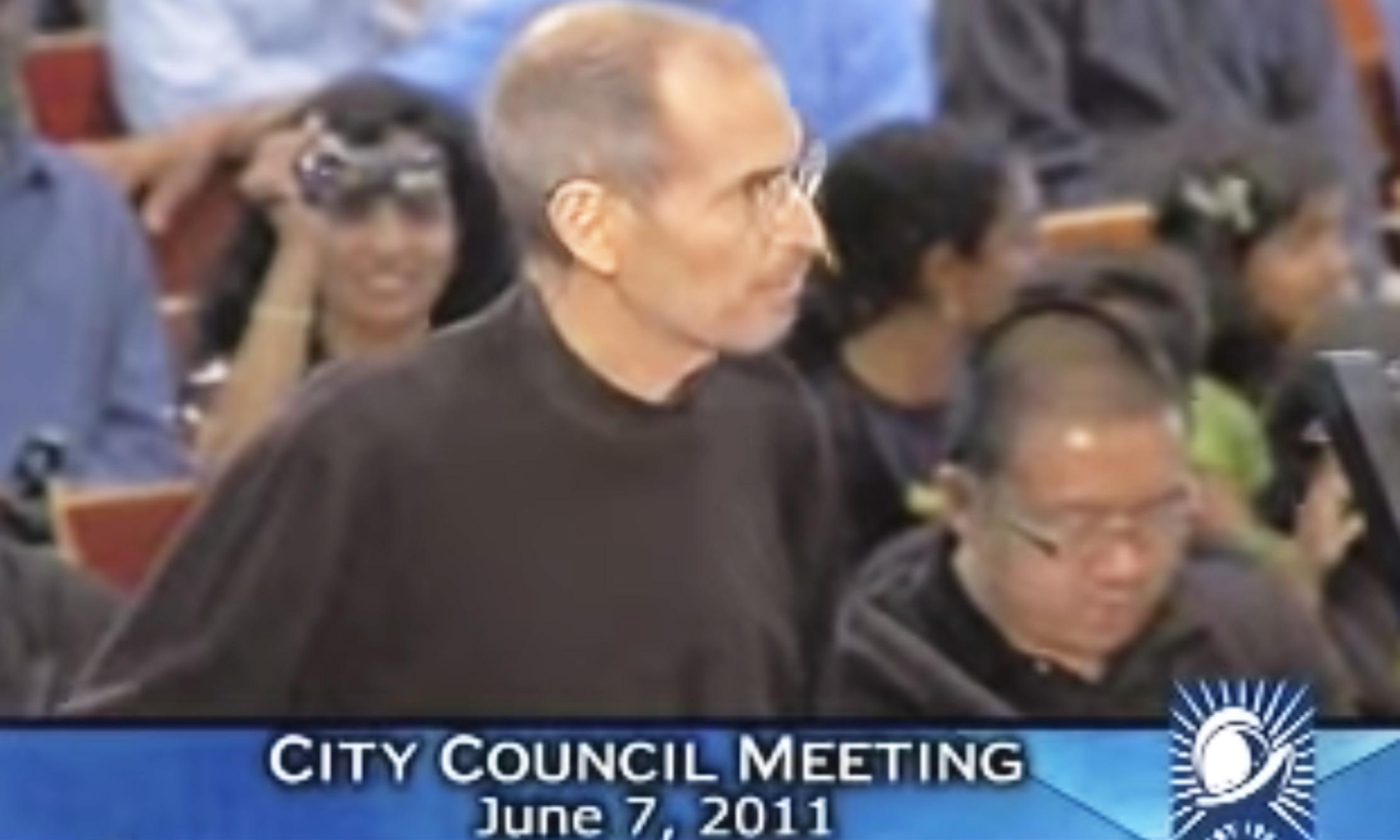

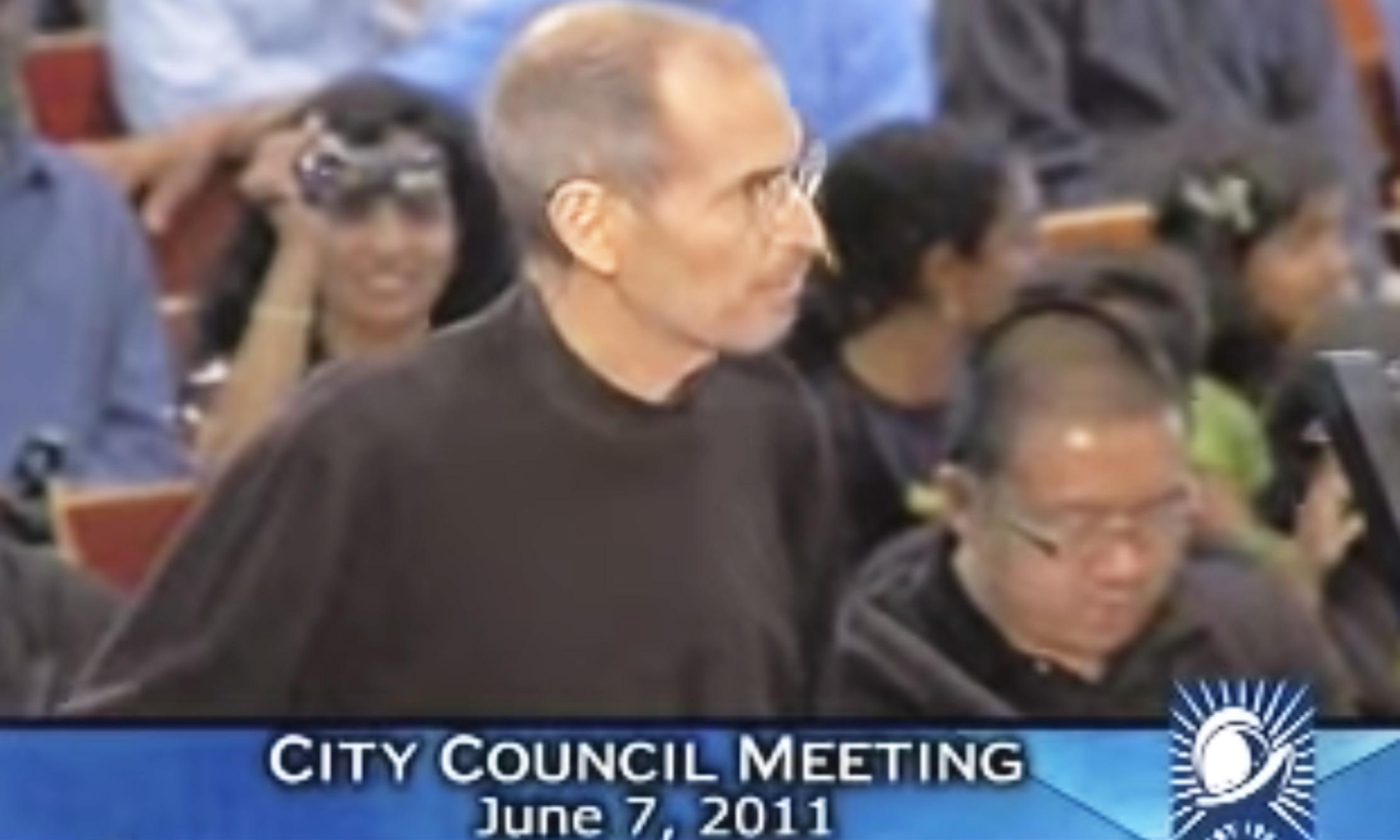

of this headquarters. If Steve Jobs had a native genre it was the keynote speech introducing a product. Examples of his keynotes for the original Macintosh and later products like the iPhone and iPad are marvels of controlled rhetoric as they convince us that this is an insanely great thing. In front of the Cupertino city council a visibly weak Jobs sketched his vision for the new Apple headquarters. He told the city council in his intense colloquial style: “I think we do have a shot of building the best office building in the world.” That also happens to be the best critique of this building: it’s envisioned too much like another perfect Apple product, and not allowed to be a living, breathing—messy!—structure (as so many architectural wonders are). From a

28

distance the major tech corporations (Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon) share major assumptions about the nature of innovation. Prostestant denominations like Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists also share lots of assumptions about Christianity, but close up these denominations differ in important matters like baptism or salvation. We could say that tech corporations function something like these denominations. In their campus designs we’re best able to see how their sectarian emphases about innovation result in different physical structures. In the case of Apple the need to design “the perfect thing” pretty much shouts up at us once the finished headquarters is viewed from above. The parish church of this corporation is the

29

Google Earth image

Apple store. Steve Jobs was always reticent about letting people fidget with Apple’s perfect things. This applies to its devices, which are difficult to customize or repair, and it applies to their headquarters, which can’t be casually visited. There are always well-defined angles of approach to Apple, such as by turning on one of their perfect devices and entering the world of that screen. When it comes to its old headquarters in Cupertino, there’s an Apple Store at the front that welcomes visitors. With its glass walls, wooden tables and shelves, and polished sandstone floor, it’s an experience that’s every bit as thought through as the devices for sale inside. Lots of t-shirts were available in this Apple Store, so while there was no going into the headquarters,

30

you could still make the pilgrim’s claim to presence. The t-shirt designs were crisply displayed in rectangular boxes. T-shirt images and all forms of advertising reflect the values and story of an organization. On the left is Isaac Newton, with the mythical apple about to fall and make him think of gravity. This old-timey image calls to mind the “Think Different” advertising campaign, and hints at Apple’s role in innovative progress. On the right is a shirt with a succession of devices, arranged by size. This isn’t a line of evolutionary development, but an aesthetically pleasing presentation of Apple’s basic set of screens. Many people who visit the Apple Store will likely own several of these interlocking screens, each with their own practical use. Apple Stores are

31

present around the world at locations that have both symbolic importance and the convenience to draw visitors with spending money. This is a view through the glass walls of the Apple Store in New York’s World Trade Center Transportation Hub. The store sits in the now iconic white-ribbed station designed by architect Santiago Calatrava. The Apple Store fits right in with this modernist setting and makes zero concessions to its particular place. The same wooden tables, the same burnished silver logo, and the polished sandstone floors—not to mention the walls constructed with oversized panes of glass—these are part of the standardized Apple consumer space. The Mall of America might score low on cultural resonance (in comparison to New York’s

32

World Trade Center), but visitors find a lively Apple Store here in the mall too. The upside for Apple was the fact that many people come with the intention of spending money. Of all the Apple Stores I’ve visited, this one was the least designed in appearance. It maintains the canonical forms (glass, wood, whiteness), but can’t hide the fact that this is ordinary mall space. From this vantage outside the entrance it seemed that the store itself functioned as a screen, offering within a collection of further screens to be entered and then purchased. The “genius bar” provided technical support, but also put a name on the implied end for those who enter Apple’s world: “you too will become one of the crazy ones who change our world for the

33

better.” The influence of Apple and Steve Jobs is visible around the world. Gramedia is the Barnes & Noble of Indonesia. While browsing its two floors of books and magazines, I came across this banner with a quotation attributed to Steve Jobs. That phrase is linked to Jobs because it was the conclusion to his 2005 Stanford commencement speech, though in the speech it’s attributed to the Whole Earth Catalog. Jobs uses that phrase “stay hungry, stay foolish” to describe the ideal mental state for innovation. It’s not an intuitive phrase, since its literal meaning is confusing, to say the least. But it apparently had resonance for Indonesians since it was posted so prominently. Silicon Valley is the capital of technology, but it has been the center for

34

broadcasting the Innovation Ideology. If I were to choose a single statement of this invisible religion it’d be the 2005 Stanford commencement by Steve Jobs. It was delivered in the heart of Silicon Valley, by a figure whose career bridged the major eras of the tech industry. One passage captured this worldview: “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.” To be captured by dogma and received opinions is to be locked in the Past. This is a religion marked by a willingness to rethink everything. At a kiosk in

35

Lima, Peru I found Steve Jobs peering out at me from the covers of several books. That Walter Isaacson biography was for all intents and purposes his authorized biography, though Jobs was hands-off as to the final text. Isaacson had written biographies about Benjamin Franklin and Albert Einstein, and Jobs must have seen himself in that line since he set out to persuade Isaacson to write his biography. There’s plenty to criticize about Jobs in his personal life, and in the way he treated employees, but there’s something about his vision of creativity that makes him a positive icon around the world, and the true apostle of the global Innovation Ideology. While traveling in Istanbul I saw these women posing for a collective selfie at the grand Suleimaniye

36

Mosque. This photo likely went up immediately onto Instagram or some other social media site. We have witnessed the development of a shared global experience of physical space under the influence of the technology emanating from Silicon Valley. Steve Jobs visited Istanbul and saw only the flatness: “All day I had looked at young people in Istanbul. They were all drinking what every other kid in the world drinks, and they were wearing clothes that... were bought at the Gap, and they were all using cell phones. It hit me that.. the whole world is the same now.” In the 2010s Silicon Valley felt like a latter day gold rush. Wealth from angel investors swirled through start-up companies and young people dreamed of striking it rich with an idea that

37

might even change the world to boot. This young man was another graduate from a college in our liberal arts college consortium, and he had immediately headed to Silicon Valley and found a marketing position at Moxtra, an app for digital collaboration (a competitor with Slack). During our visit we received an introduction to the app and how it might be a good fit for our classes, but mostly we asked about whether his liberal arts education had given him useful skills for this tech environment. Mostly, yes, he appreciated the skill he’d acquired in writing and communication, but he could’ve used more coding. He was working at Moxtra in the less-respected side of tech work—sales and marketing. That corporate name Moxtra struck me as a mashup of

38

“moxie” and “extra,” two positive, forward-leaning words. The name didn’t mean anything in itself, but the logo showed two blue dots linking up with each other, and that gave one overly broad clue as to Moxtra’s goal: something to do with connection. The font had a playfully futuristic look. Tech start-ups are dependent on a “look” far more than other corporations since their success or failure is directly related to how lots of people respond at first sight when the name and logo pop up in a digital app store. I can only imagine the money and effort (the endless brainstorming sessions!) that go into developing these names and logos. At Moxtra I got my first view of a typical office layout for a start-up. When I use a new app on my cell phone I now imagine

39

it coming together in space just like this. I didn’t come away from this experience wishing I worked here. The windows were completely covered by white plastic so that there was no way to see outside (except from side offices). The workers sat together in this open space, staring intently at their computer screens. The claim is that this open office layout allows for face-to-face interaction and stirs creativity. I’m not sure it works out that way. Toward the back the chief technical officer talked through issues that had come up, and a white board displayed all the intense plans in the works. There’s little aesthetic appeal in tech offices. That is, until the company makes it big and has Frank Gehry design their headquarters (like Facebook). The tech

40

product only truly exists within the screen portals, and so the office space itself has no real value. This office was a suite located within a building that was itself completely nondescript. There’s no foothold in this Innovation Ideology for place (at least once you get past the sacred garages). When I visited tech offices I tried to notice instances where at least a motion had been made toward aesthetic appeal, and at Moxtra I found this tree and those pine cones underneath (collected during some outdoor team-building event, no doubt), all sitting on a classic and cheap IKEA display shelf. Visitors were gifted one of the figurines on a lower shelf—a cute squeezable monkey in a Moxtra t-shirt. The figurine didn’t seem destined to become a collectible, but

41

underscored the difficulty in making a tech business into something concrete. Silicon Valley is now linked with San Francisco, a city graced with beautiful physical landmarks like the Golden Gate Bridge. Most of San Francisco’s history has nothing to do with technology, and on one view it was simply fortuitous (or the opposite!) that this city became aligned with the tech sector. From another view there was something characterological about its people and local culture that enabled tech corporations to thrive in this area. In 1866 Frederick Law Olmsted reflected on the people in and around the city, and saw “...a general readiness and disposition to turn one’s hand rapidly & frequently from one thing to another and to hold to nothing ploddingly or with

42

long forecast.” That’s not a bad foundation for the Innovation Ideology with its orientation toward the future. The pop art sculpture “Cupid’s Bow” sits along the waterfront of San Francisco, in the shadow of the Bay Bridge. The sculpture, funded by the Gap, the globally ubiquitous clothes company, emphasizes San Francisco as a city of love. The orientation of the bow and arrow, shooting into the ground instead of romantically into the sky, allows the sculpture to echo the nearby suspension bridge. This orientation also provides an exclamation point for this spot of ground: “This is the Place!” The economy that radiates out from Silicon Valley to the globe is marked by placelessness, but on site there are nods to physical space, a pride in the fact that

43

this is the region where a large share of the global economy originated. Growing up in the Bay Area, I associated San Francisco with the Transamerica Pyramid. The building was completed in 1972, so it was just a decade old when it gained a place in my consciousness. It seemed to me then a futuristic building, though now the reinforced concrete and small windows

44

makes it look dated in comparison to the gleaming glass exteriors of more recent buildings. Current photos of the skyline displace the Transamerica Pyramid from the center of San Francisco’s cityscape, demoting it to the margins. The Beat Museum houses a collection of books and memorabilia associated with the Beat poets of the 1950s and 60s. The museum opened in 2006 and occupies space near the former hangouts of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. It has a pleasant low-fi vibe, the emphasis being on actual things (books, posters, handwritten letters) and not digital representations of their world. Visitors are greeted at the entrance by this clunky model of the Golden Gate Bridge (built in 1937). It all hearkens back to an older San

45

Francisco. And the question now is to what extent the creative ferment of the Beats can even be preserved in a city redefined by tech CEOs and their unlimited wealth. Another question: how does the tech world relate to the psychedelic efflorescence of the Sixties? The intersection of Haight and Ashbury has come to stand for ground zero of hippie culture, and today that past is both consumed and reimagined by tourists. On the surface level it looks like San Francisco is being overrun by the tech industry and its shiny new buildings. At a deeper level there’s a consilience between these points of view. In his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture (2010) Fred Turner traced this developing invisible religion of the Self. There was a time when tech visionary

46

Stewart Brand was hanging around with Jerry Garcia and his new band the Grateful Dead. The Castro is a prominent gay district in San Francisco. Today LGBTQ pride is displayed by rainbow pedestrian walks and flags hanging from street lamps. Pedestrians can follow the “rainbow honor walk” that memorializes gay activists and artists associated with the area. I stopped to read the memorial for poet

47

Allen Ginsberg. Yet as the symbolic embrace of this identity becomes more visible, the neighborhood is becoming gentrified, leading to worries that the area is losing its LGBTQ identity. At the time of our trip the Salesforce Tower was still under construction, but pedestrian signs gave a view of this skyscraper going up in downtown San Francisco. Unlike many tech corporations, Salesforce is not a household name since it provides behind-the-scenes aid for businesses. Its logo emphasizes its presence in the cloud, but this building, then on its way to being the tallest in San Fancisco, would serve as a physical stake for a corporation that mostly wants to be an invisible force. Images of the future building didn’t emphasize its context in the

48

city, but rather its ability to deliver people from that city to the natural landscape of the region. Other images showed idealized interior scenes. In the background an open table is filled with a row of Apple computers. Young people face each other, working industriously. It is a racially and ethnically mixed group of young workers. The furnishings are a solid step up from Moxtra, but this is still recognizable tech office space. The furniture is quirky and modern. Various angular lighting fixtures hang from the ceiling. The maker of this idealized image seems intent on emphasizing a youthful workplace, but the space has nothing to do with its urban setting. It appears that this work is taking place in a green forest but really we could be anywhere.

49

Tech Longings for Place

The positive reception of Google over the past twenty years is at least in part due to its whimsical corporate presentation. The logo has evolved over time, but it always exemplifies playfulness in its font, with a subtle lean and primary colors plus green (no one would confuse these colors with a rainbow). Despite being the most intellectually ambitious of the Silicon Valley tech companies, Google avoids anything that appears overly serious, and this carries through to its campus (note those Adirondack chairs). This playful feel marks out a contrast with the sleek and serious minimalism of Apple. Google doesn’t strive to feel perfect, and thus unapproachable; it wants to feel fun. This is the platform you go to when you’re feeling lucky! The work

53

environment fostered by Google has become a legend. My students are usually impressed with the concept of free gourmet meals as well as with the 20% rule where workers devote one day each week to a passion project. Google’s workplace ethos is so striking that in 2013 a comedy with major stars was set on the campus. This central building of the Googleplex was originally built in 1994 by Silicon Graphics in Mountain View. The sprawling headquarters was taken over by Google in 2003 and then bought outright in 2006. Unlike Apple and Facebook, Google has largely adapted its corporate spaces from previously existing structures, adding touches like this Android statue to signify its identity. The central building of the Googleplex is identified

54

with the corporation, but it’s far too small to house all the work of the corporation (now officially known as Alphabet). Google has taken over a broad swath of office buildings in Mountain View, many of which are as boring as can be imagined (like this one). It’s impossible to tell from the outside what’s being worked on inside, and so a kind of opacity reigns in this landscape of nondescript buildings. Google, perhaps accidentally, arrived at a de-centered corporate campus with no sense of architectural unity. This opens up a question: why be located in a place at all? There’s a kind of corporate posturing that comes with a sprawling headquarters, but the actual value of such a campus isn’t clear. The decentralized structure of the Googleplex is often

55

Google Earth image

main building

compared to a college campus, but buildings on a college campus have labels (Earth Sciences, Humanities, Admissions). This tech campus is anchored by the main building, but that’s only one of this sprawling set, whose individual structures are often surrounded by old-fashioned parking lots. It was curious that a Google search for “Google campus map” brought up how-to articles for creating campus maps, but there appeared to be no publicly available map of Google’s campus (again, in contrast to any college). Whatever the inspiration for this decentralized layout, Google’s campus has nothing of the academic spirit when it comes to unity of design. No high profile college could afford to inhabit such a disunified campus assembled out of

56

forgettable buildings. In 2015 Google released future plans for its Mountain View campus. According to its promotional video its team had scoured the world and come up with two architectural firms that could translate its values into design. This image represents a rendering of the proposed campus. The major change would be to replace the sea of boring office buildings with those “transparent membranes.” All those parking lots would give way to greenery (with parking underground?). Only one of these membranes is being built—and it’ll no longer be see-through. With proposed campuses in other cities, it looked for a while as if Google was moving back toward a distributed model of corporate space, only now covering a much wider geographical

57

image from Google promotional video, 2015

area. Silicon Valley corporations still need to figure out how the screen relates to place. This is the classic screen form in which a generation of internet users encountered Google. The font for Google’s name has changed over time and that search bar has gone from a rectangle to a more friendly oval, but still this is basically what I saw when I first tried out Google in 1999. For a while it seemed that all I was getting back from my search queries was spam, but then Google gave me exactly what I wanted. The internet became transparent. Their search bar provided a service that made the internet usable, and its success would eventually (somehow!) lead to revenue. But how could anyone make architecturally visible the values of simplicity and un-

58

placedness that this search screen represents? Each of the big three tech corporations of Silicon Valley (Apple, Google, Facebook) put an unexpected emphasis on nature in the design of their headquarters. In this case Google wholly reimagines its Mountain View setting. Why would tech corporations that mostly live on screens align themselves with nature? One answer is that nature represents a way to reject any specific cultural past. The emphasis on nature cloaks a rejection of designs and structures from the human past. It’d be fascinating to ask tech CEOs in what ways their products and platforms have led people to greater connection with the natural world. It’s not concern for nature that’s present in these tech cathedrals, but concern to

59

image from Google promotional video, 2015

recruit nature as a symbol for their goodness. Going north from the Googleplex we came to the Facebook headquarters in Menlo Park, designed by the architect Frank Gehry and opened in 2015. While I appreciate how Gehry works with reflection and light, I dislike that isolated roof-top natural space—especially since all this spending comes at the expense of care for the natural world right out its windows! Gehry was the obvious choice a young guy would make who wanted a “really cool” headquarters, and so this is the choice we could have predicted from Mark Zuckerberg. As I’ve mentioned, from a distance the major tech corporations espouse a single ideology of innovation, but up close they function more like religious denominations.

60

Facebook has also tried to translate its social media screen presence into a suitable physical space. At their headquarters in Menlo Park we came to this sign, which included a blown-up version of the “thumbs up” that over a billion people use to “like” things on Facebook. In order to keep the site vibe positive, for years no “thumbs down” or “dislike” option existed. In a nod to the self-image of Mark Zuckerberg, the address for Facebook is 1 Hacker Way. Since hackers “move fast and break things” and “apologize rather than ask permission,” it could be that a conflict exists between the institutionalization of a tech headquarters and the rebel spirit of hackers who operate in the fluidity of online life. But I don’t want to get bogged down with Facebook, and

61

so I’ll return to the Google Headquarters back in Mountain View. The buildings on Google’s campus are unremarkable, which is why Google harbored dreams of constructing a headquarters that would better captures its ethos. But while the corporation searches for the perfect look, these old office buildings must persist. The problem becomes how to establish a sense of unity on a stitched-together campus. Google has learned to get a lot of mileage out of ornament and external decoration. The campus was rich in add-ons like playful sculptures and colorful furniture like Adirondack chairs in bright colors. The office buildings gave no hint of ownership, but the simple presence of these chairs made clear the corporate association. At the entrance to

62

many of the buildings around the Google headquarters we saw these distinctive bikes. They aren’t rainbow bikes, but rather Google bikes since their parts reflect the logo colors. These bikes are another example of external aids that help build unity for an otherwise atomistic campus. Any place with these bikes is marked as Google-connected, even if it’s a restaurant in downtown Mountain View or some independent tech start-up. An extended Google corporate space is defined by these bikes. They have a practical use too, of course, since there’s no easy way to move between buildings, and since it was so tempting my friend and I grabbed a bike and rode around the campus. Besides this convenience, I’m more interested now in their clear place-building

63

role. In the courtyard of the Googleplex visitors will notice this iron cast of a T-Rex fossil. There are chairs nearby and a volleyball court, so the atmosphere isn’t educational but whimsical. The Google founders Larry Page and Sergei Brin left the high sculptural art to their alma mater Stanford University. The public art at Google always had a sense of play (as with everything else). It seemed that art in the serious museum-quality sense didn’t exist. So far as Google is concerned, the value of art was to express a sense of fun and to be mentally refreshing. It should stir a smile. At its most searching this art represented the discovery of surprising connections, and so represented an allegory of the creative coder’s mind, which should avoid getting into a well-

64

worn rut or following tired dogma. Another sculpture within the Googleplex is “No Swimming “ by Oleg Lobykin. That title stirs up pop-culture memories of the movie Jaws, but the artist statement proposes something more serious: “This project represents deep concern about the impact of human activity and progress on nature.” Yet there’s nothing about this setting that makes the fin a site for serious meditation on the natural world. In context it’s just another playful courtyard piece. The sculpture was first exhibited on the flat desert playa at Burning Man in 2008. The annual Burning Man festival in the empty Black Rock desert of Nevada is the most important point of reference. With a desert setting in mind the arch jokiness of “no swimming” becomes

65

obvious. Again, the highest response would be a knowing smile. Major updates to the Android operating system go by the names of popular sweets (side-stepping the seriousness of Apple’s iOS updates that reference natural areas or parks in California like Big Sur or Yosemite). Google created a foam statue as each named Android update came along. In 2016 these older operating systems were arranged together behind the small visitor center on Google’s campus. We see above, from left to right, Froyo, Ice Cream Sandwich, Cupcake, Donut, Gingerbread, and Honeycomb. These statues represent one answer to the challenge of how to translate a screen presence into a physical place. Google has taken notional items or words and instantiated

66

them into colorful physical objects. This raises a nod of recognition from visitors and makes visible Google’s screen history. These operating system statues are set in an inconspicuous part of the campus. At this time they were grouped together near a parking lot with the Bayshore Freeway running at its back. The big tech corporations give the impression that they are uncomfortable with the demands of place. Their everyday presence in our lives makes many people want to visit these corporate campuses, but they make scant concessions to this human desire for physical experience. Their campuses are built to be cool places for employees to work, and not to be sites for pilgrimage or tourism. But visitors like us search for (and inevitably find)

67

the corners where this human need for place can be at least partly satiated. Just outside the visitor center (near those Android statues) was this car, sitting on an uneven patch of ground. No signage explained why this car was on display. My assumption was that it represented an early Street View car. It was even possible that this was the very first such car, but there was no way to know. The choice of putting it on display showed that it was an innovation in which Google took some pride. Someone had recognized that this car and its mounted camera would please visitors. The car wasn’t much different in effect than those Android statues. Lots of resources were invested in the online presentation of Street View, but almost no thought had gone into

68

telling the story of its real-world development (which entailed real cars and real drivers on real streets). In The Mathematical Theory of Communication (1949) Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver presented a way of thinking about communication that excluded meaning from consideration. What was important was only the transmission of “information.” The transmission of a voice would not be an exact transfer of that sound, but a breaking down of the voice into the lowest possible number of “bits” of data, which could then be reassembled on the receiving end. This insight represented the birth of the digital. The process of converting not just voice but everything into data is already hinted at in their book. There would be no rational place to halt the

69

transformation of the physical world into bits of information. In its small visitor center, Google offered a booth labelled “Explore Your World.” The lighting was ordinary and the furnishings cheap (too cheap!), but what was on offer was stupendous. The entire world could be browsed on a semi-circle of linked screens by means of the data set of Google Earth. Simple controls allowed visitors to sit and explore the Earth for a few minutes. I sometimes imagine all the past explorers and geographers who wondered about places far away, gazing at the blank spaces of the map, and how this booth would have appeared to them like a miracle. Even now the presence of the whole Earth can stop us in our tracks, though I doubt that all this digital “exploring”

70

increases the passion for getting to real places. Did this little booth spur these young people to daydream about study abroad in college? Mark me down as doubtful. The Explore Your World booth provided not only a birds eye view of places, but in many cases users could zoom in on a 3D scene. I don’t understand the technology that enables satellite imagery and street level photos to be stitched together, but it creates the ability to visit sites around the world. Even at the time this booth felt like a stopgap rather than a finished product. It was itself a simulation of the more immersive VR headsets that would soon be coming out. Embedded in these ever-improving representations of the world is a faith that people have no need for a teacher or guide

71

to get meaning out of these images of places around the world. I didn’t get the sense that Google had devoted much time or effort to planning its visitor center. The finest minds at the company hadn’t come together for this. There was a problem to be solved: lots of visitors come to the campus for some reason. Some group was tasked with putting together a place to which those visitors could be pointed. The visitor center had some displays, such as this sample room, hilariously labelled “Googlers at Work.” A sign explained that Google workers don’t get their own cubicle, but work together in order to “promote idea sharing and collaboration.” The presence of memes, cartoons, and photos on the wall point to “fun” personalization in the group work

72

space. In the exhibit a small Lego creation sat on the edge of one desk. Perhaps the square began as a model for some imagined plan, but visitors had nicked too many blocks? More likely it was just thrown together to symbolize the playfulness of work at Google. Another sign invited visitors to try on the cap of a “Noogler” ( = New Googler). According to the sign, the reason for these beanie-like caps was that they were “a reminder to everyone that no one at Google is allowed to take themselves too seriously.” I’m in favor of not taking oneself too seriously, but at Google and elsewhere there can be a kind of high seriousness about demonstrating how playful everything is. They could be a little less serious about how un-serious they are. Apple stores

73

are stocked with products that give the feeling they’ve been carefully considered and vetted. Steve Jobs paid careful attention to every Apple product. The gift shop—whether in an old church or modern tech cathedral—is a marker for contemporary pilgrimage. These shops exist to meet the demand of pilgrims to return with something that symbolizes their visit to a place. At a smaller site a gift shop might provide a line of revenue, Google had no need for revenue (with its advertising business it was basically printing money at this point). It saw some value in popularizing its corporate logo and the Android icon. So it had on offer items for personal use stamped with its corporate symbols. It’s the Capitalist exchange we know well: money goes one

74

direction and brand identity in the other. If visitors had come looking for tokens that are more place-based (like a poster of the Googleplex), they were disappointed. Apple is the corporation that designs perfect devices, and the t-shirts and small things are intended to bolster that reputation. Google doesn’t have so much at stake with its gear. Like the visitor center as a whole, it doesn’t seem like anyone really cared about the backpacks, notebooks, pens, and water bottles that had Google’s name stamped on them. They needed to be of decent quality—they weren’t cheap! But there’s no sense that places or things in the actual world had access to the attention of the engineers who mind the functioning of Google’s online tools. One section of Google’s visitor

75

center was devoted to Chade-Meng Tan (who goes by Meng), and included this life-size cutout of Google’s celebrity greeter. Since Google’s co-founders Larry Page and Sergei Brin (seen with Meng in the top left photo) prefer to keep under the radar, they have delegated photo-ops to Meng, an early engineer at Google. In these photos he stands with celebrities as different as the Dalai Lama, former US president Bill Clinton, and pop singer Lady Gaga. Always Meng has a beaming smile, and in 2012 he published a book on achieving happiness and world peace, based on a seminar he’d long offered at Google. I found myself looking closely at Chade-Meng Tan on this wall of celebrity portraits. The range was remarkable, from models to news anchors

76

to film stars to comedians, giving a fine sense of how wide the American concept of celebrity had become. Anyone seen in a positive light on a mass market medium becomes a person who carries a positive spiritual energy that’s contagious to others. Tech corporations tend to be stacked with people who don’t have this spiritual energy (Steve Jobs being an exception), and so it’s imperative to allow for open channels between tech corporations and celebrities in the hope that some of that charisma might be harnessed to draw people to online products. And celebrities want some of the Google power, which is more like controlled magic than the spiritual attraction of a saint. Chade-Meng Tan’s book Search Inside Yourself was on display in the

77

Google visitor center, and I later bought a copy for myself. We’ll perhaps never get anything closer to a religious statement from a major tech corporation than this book. With its mention of “search” and its adoption of Google’s colors right on the cover, this becomes more than a book on happiness by a Google worker, but an actual Google doctrinal statement. Google’s former CEO Eric Schmidt even has a blurb on the front cover. It turns out that the concept of “search” not only works for discovering information on the internet, but is a method for inquiring within the Self and getting the emotional data that draws us to happiness. Let’s get some clarity on the basic argument. Chade-Meng Tan argues that the human “factory setting” is happiness.

78

Daily anxieties and demands get in the way of feeling happy, but if we practice mindfulness and clear our minds then we can get back to the factory setting of the human being. There’s no place in his book for the unwellness or addictions that could make happiness impossible for some, nor for a cast of mind that just isn’t happy. It’s a kind of constant smile that’s reflected in the Google campus itself, in all its public art and furniture. This breezy confidence in happiness is surely one reason the tech industry as a whole hasn’t come to terms with the Earth-destroying reality of bad actors ready and willing to use these platforms for conflict. Tech corporations have a systematic unwillingness to recognize the dark side of our global system. No one confuses

79

Silicon Valley with the Bible Belt. Leaders in the tech industry have little use for formal religious institutions. But many religious “deliverables” (to borrow corporate-speak) are widely sought after. Apps like Headspace and Calm deliver what appear to be neutral methods for controlling anxiety, and we’ve seen how Chade-Meng Tan offered “Search Inside Yourself” courses on personal happiness on Google’s campus. The techniques of mindfulness have their ultimate source in Buddhism, and it’s not hard to find casual references to this tradition throughout Silicon Valley. The connection was bolstered by Steve Jobs, who went on retreats at the Tassajara Zen Center in the coastal mountains south of Silicon Valley. At points the casual Buddhism of

80

Silicon Valley even takes on institutional form. That’s the case with the Insight Meditation Center in Redwood City. The Center purchased this building from the First Christian Assembly in 2001 (the church building itself was constructed back in 1950). On its website the center described itself as an “urban refuge for the teachings and practice of insight meditation, also known as mindfulness or vipassana meditation. We offer Buddhist teachings in clear, accessible and open-handed ways.” For a Sunday meditation dozens were in attendance, but even this religious institution hadn’t broken through to become a real popular force in this Silicon Valley community. Apps remained far more palatable. Gil Fronsdal was co-leader at the Insight Meditation

81

Center at the time of our visit, and it turned out he’d written several books exploring Buddhism as a path to contentment and happiness in the modern world. We attended a meditation and listened to a Dharma Talk one Sunday, and thankfully this talk was preserved on the center’s website so I could go back and hear the talk again. Fronsdal began by discussing what holds us back: “We have a preconception about how to interpret what our experience is... we carry with us ideas that we maybe inherited from society, or our family, or past ideas.” This re-states a key point of the Innovation Ideology: the past must be cut away. One idea that gets repeated everywhere in Silicon Valley is that innovators have to be prepared to fail. Being a tech entrepreneur

82

means cultivating a willingness to fail big. Fronsdal spoke of the lesson on failure contained within every meditation exercise:

“I’m supposed to follow my breath, and I didn’t. I tried again and the same thing happens. So here in a conventional sense you’ve failed at what you’ve tried to do. Note first of all what your mind’s doing. To see it as a failure is a choice. It’s a perspective that’s not necessary. Maybe you have a tendency to look for success and failure.” Whether Fronsdal meant it or not, many of his listeners would quickly translate those words into the tech speak of Silicon Valley. His message was that while learning to be mindful of breathing during meditation, there is a need to accept constant failure. Perhaps innovation too could finally become

83

so natural and unconscious of a personal practice as breathing—that seems to be what Steve Jobs heard in the Zen tradition. At the Insight Meditation Center we sat in an open, high-ceilinged room (once part of the sanctuary for the older church). At the front was this small stand for the leader to sit, and a series of objects: a Tibetan bowl for transitions, a sitting Buddha, and an indoor plant. One part of the Dharma Talk helped to interpret this setting: “Being in contact with something very simple helps in the process of settling, calming, and clearing. One way to do this is to focus on breathing. Come back to breath and forget the premature cognitive commitments.” Physical objects in this setting function like breath: they are places where the

84

attention can come to a point of rest again after distraction. What is it that makes the casual practice of mindfulness attractive to those in tech? The Innovation Ideology relies on seeing things with fresh eyes. A recent book on design in Silicon Valley was entitled “Make It New” (echoing the high modernist aesthetic). Tech innovators cultivate a similar mindset that asks at every view of the world how this or that could be re-thought. This idea was also taken up in this Dharma Talk: “An important value of mindfulness is that it teaches us to question the perspective we have on our world, question the concepts put on top of it, the judgments we have. It starts with the ability to just stop and look. Cultivate the ability to see clearly.” Following our visit to the

85

Insight Meditation Center and lunch at a farm-to-table restaurant that exemplified the spirit of innovation in the culinary realm, we headed over the coastal mountains to a popular beach. It was overcast, and I sat on some rocks and waited for the small shore crabs to emerge from the rocks they’d scurried under at my approach. Mindfulness techniques might be a natural fit for the needs of the tech office, but attention to living things seemed to come from a different place. What would it take to know something about this shore crab? No doubt many hours of world-observation. A person with a love for the natural world would quickly find their mind pulled away from total devotion to any tech corporation. Tech defines one approach to modern

86

life: the Self cuts itself off from the Past and uses Innovation to fashion the ideal Future. The problem with this tech religion is that it generates anxiety for those who fear they might fail at this effort, perhaps for lack of creative insight. The main counterpoint to this tech approach to life is one we might call ecological. The ecological Self is understood to exist within a web of other living things and cultures. The goal is not to maximize the Self but to determine its limitations. This approach to life also faces a devastating problem: the global decline of the web of life. With this threat there arises an urgent need to convince others to care for life on Earth. The dark green religion of the ecological Self doesn’t project an image of humanity attaining its godlike future,

87

but of human beings learning to accept limitation and death. Ray Kurzweil is a serial inventor, but best known today for his speculations about the coming technological Singularity. He was employed by Google in 2012. The documentary Transcendent Man (2009) presents his vision of a future in which humans do what they’ve dreamed of doing for millennia: transcending their bodies. At one point Kurzweil looks out at the ocean, and the documentary maker asks him what he’s thinking: “Well, I was thinking about how much computation is represented by the ocean. I mean it’s all these water molecules interacting with each other... that’s computation. It’s quite beautiful. I’ve always found it very soothing.” Computation might be the way we would

88

now explain or reproduce the complexity we experience at the shore, but waves crashing on rocks are no simulation in some mega computer, but brute physical interactions. Silicon Valley is located in a rich natural environment. Two of its big tech corporations front the endangered ecosystem of a rich estuary. Drive a short ways and you reach beautiful beaches like this. Environmentalism is almost indigenous to the Bay Area since the Sierra Club was founded in San Francisco in 1892. But the staggering wealth of the major tech corporations has cast an unexpected new meaning over the physical world: all of this—the waves to the barnacles to the crabs—has become an expression of information. In the days after visiting the coast we stopped

89

for a tour of QB3, an incubator for biotech startups. QB3 is in a partnership with UC San Francisco, so it was another example of the ties between the academic and tech worlds. During a tour of shared labs I stopped in front of a large device that had “life” punched onto its plastic-cased side. This machine turned out to be the Quant Studio6, and I learned later that it does real time PCR (Polymerase Chain Reactions), allowing for the replication in large numbers of specific bits of

90

DNA. This is the point where Life and Data meet, and the possible merging of tech and bio-systems is seen as a high growth endeavor. At the entrance to QB3 was a board containing the brand logos for all the hopeful startups that made their home here. This is just a detail from a larger board, but it’s clear from these logos that there’s plenty of work here for graphic designers. I looked over these names and imagined how every one of them would have a founder with a smart elevator talk quickly sketching the work and its world-changing implications. From the names it was clear that these startups were addressing easily monetized health issues. This work is quite distinct from the distracting effort of observing the natural world, which isn’t nearly

91

so well funded. Before moving its headquarters to a trendier address, the tech company Prezi was located on one floor of a nondescript highrise in downtown San Francisco. Visitors went up an elevator, followed signs down a hall, and then entered the offices. Prezi was known for providing an artsy replacement for Microsoft’s ubiquitous Powerpoint, and its offices were a reflection of that creative mission. That app-ready logo appeared immediately, both on the wall and the surface of the repurposed blackjack table that served as the welcome desk. The pillows up against the highrise windows said “Hello” in dozens of languages, letting us know that Prezi was a corporation with a global mission. At the entrance to the Prezi offices was

92

this drink cooler. Visitors were free to grab a Coke or La Croix sparkling water. With the addition of that simple head the cooler became a welcoming robot. This initiates visitors to the whimsy at the heart of the Prezi’s aesthetic. It’s not so different from the dinosaur or shark fin of the Googleplex. What Prezi adds is a sense of creative re-purposing. It’s not a corporation with billions

93

in profits, but it makes use of office design to demonstrate its culture of innovation. At the entrance to the San Francisco headquarters of Prezi was a timeline set on a blue background. The years going back to its founding in 2009 were marked on a straight line, and then playful white badges were set onto the line. The badges marked milestones, awards, and any sort of forward leap. In this section of the timeline we learn that somewhere in the early part of 2014 Prezi had reached 50 million users, and shortly after that they received a 3rd round of investment funding. The next badge marks their move into this office building on Folsom Street in San Francisco. Corporations are ultimately like any other human group, and to be successful they

94

must build a feeling of common history and purpose. Prezi was founded in 2009 in Budapest, Hungary. A few months later it hired its first employee in San Francisco. Since 2009 Prezi has grown as a corporation with two centers. At the entrance to these offices we came across two clocks, one with the local time and the other for the time in Budapest. On the wall in the breakroom were likewise two painted squares that at first looked like abstract art, but on closer inspection turned out to be maps of its two cities. The one for Budapest is distinctive with the Danube rolling through its heart. Always this tension exists in tech companies: they are organizations with real people who need to belong in a group that builds a common story, but they offer products that

95

exist on screens and claim indifference to space and place. Tech work spaces looked basically the same everywhere in Silicon Valley. No matter the company, large or small, the workspace was laid out as long tables with a series of individual workstations. A main computer screen anchored each station, and workers supplemented that with laptops and other devices. There’s a belief in tech that workers should not be isolated in cubicles, but be able to see each other and so easily ask questions and collaborate. There is also a counter belief that workers need to “get into the zone” and escape into themselves to code, so there were always headphones lying around too. Prezi sees itself as a creative company, so they made various motions toward

96

making the office aesthetically pleasing in that familiar playful way. Tech corporations recognize that workers shouldn’t sit in place all day at a desk. They are happy to supply alternate spaces where workers can sit comfortably by themselves or talk informally. At Prezi it was possible to see all the typical corporate spaces within one bounded floor, these being 1) computer workstations, 2) open sitting areas, 3) a break room for food, 4) glass-enclosed side rooms for breakout meetings, and 5) a seating area for company-wide meetings. The philosophy behind these varied corporate spaces was to give employees reason to stay for long periods within the corporate domain. Common needs are addressed so that workers stay present and productive.

97

These work spaces don’t presume a fulfilling social life outside the corporation, but assume that real life happens here in the workspace. At one far end of the Prezi office is this open space defined by two bleachers. Many tech companies—like Facebook— have a weekly “all-hands” meeting where the CEO stands in front of employees and reports on milestones and challenges, and workers get a chance to ask questions. Although tech corporations are well-equipped to handle such meetings virtually, they’ve mostly insisted on doing this group interaction in-person (at least until the Covid outbreak). Right along with this insistence on physical presence, we see a fascination with global reach, as can be glimpsed in the world maps projected on the screens up

98

front, which tout “75 million users” and “260 million Prezis.” One thing that came up often at Prezi and other tech corporations was Agile collaboration. This work philosophy came from a “manifesto” published in 2001, which emphasized fast, teamoriented software development. Two Agile principles have a particular impact on spatial layout: “Projects are built around motivated individuals, who should be trusted.” This sets up spatial flows that give workers options (desk, couch, etc.). Then this: “Face-to-face conversation is the best form of communication.” This underlies not only the “all-hands” space, but also the “daily scrum” meetings where workers report to each other about what they’re up to and any problems (“What is blocking

99

me?”). The rooms set off from the main open area of the Prezi office mostly served as meeting rooms, with table, chairs, and screen making their function clear. But one of these side rooms was an under-construction green room. There were indoor plants around the entire floor, but here they were given a special prominence. Other details of this space hinted at nature, and since the soft recliner faced blank walls, the room promised to offer a sensory palate cleansing for anyone who’d been staring at a screen for hours on end. The room mirrored the common use of the natural world in tech spaces: it’s not present as something worthy of engaging the mind, but rather as a signal to turn off the mind. This green room was officially known as the

100

“wellness room.” It was open for all workers to enter, and when they did they were prompted to mark with that arrow what they were doing. The choices represented standard mindfulness practices. Meditation and Yoga are accepted as neutral (and so non-religious) parts of work in a tech corporation since productivity is closely tied to mindset in the Innovation Ideology.

101

Traditional religious practices aren’t even an option. The permanent exhibit at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View (right down the street from the Googleplex) consisted of a wandering path through the historic machines and devices that extended the computational skill of human beings. This museum is perhaps the one must-see public institution in Silicon Valley. The permanent exhibit’s title mirrored the belief among tech innovators that they were participating in an ongoing “revolution.” The need for such a museum arose because in the midst of this revolution the physical things that were once cutting-edge were always being replaced by the next new thing, and so the museum gained value as a reference library for tech

102

machines. Early on in the Computer History Museum is this visual representation of Moore’s Law from 1975. The law simply states that the transistors on a chip will double about every 24 months. This sets up the exponential growth of computer memory, and that in turn means that devices and gadgets that would be unimaginable a few years earlier will all of a sudden become

103

possible. This incline sets up a steady stream of new machines, rolled out to the public as the revolutionary products of genius minds. It’s strange to see an everyday object that came out in my memory sitting behind a plastic box in a museum. Putting an iPhone on display transforms it into a purely aesthetic object, but in this setting the iPhone looked both bulkier and cheaper than I remember it being when it came out in 2007. My eyes have become accustomed to the ever slimmer and more powerful iPhones. That difference would only be magnified with the screen turned on. All things that embody sleek modernity inevitably fall back into bulky history, revealing just how much about tech modernity is a product of mass media expectation and

104

advertising rhetoric. The lesson for us should be to cast a colder eye on the new things we pick up. Web pages are perhaps the single hardest artifact of our time to preserve. The Computer History Museum makes a valiant attempt to show what various web browsers looked like (and for good measure connects them to their place of development on a world map). But it’s not possible to try them out or get a feel for how they worked—or know what the internet was like in these years. No doubt those browsers would feel clunky now, and the screens and operating systems on which they depended are long gone. That old internet is gone too, flooded by an ever-expanding deluge of web pages. Much time and effort goes into making sure websites

105

work smoothly on our various screens, but the actual pages and the experiences they represent are the most ephemeral of ephemeral things. Twice a week visitors to the Computer History Museum were able to watch this IBM 1401 Data Processing System in operation. This medium-sized mainframe computer gives a sense of what tech was like before computers became “personal” and were instead resolutely “institutional.” Most Americans in 1959 would’ve had difficulty imagining how a computer would ever have anything to do with their own lives. To run a mainframe like this took several trained experts in the room. Our distance from this past makes it imperative to preserve these old IBMs, so that we can imagine the conceptual leaps