inspire

Summer 2024

Editorial

This issue of Inspire (which is the magazine of Marlborough College’s academic scholars) is the last edition of the year and truly demonstrates the breadth of interest and love of learning that the academic scholars have. Inspire encourages scholars of all ages to look into areas of subject interest beyond the curriculum so that they can extend and further their knowledge to eventually become experts in their particular fields.

It is also with great sadness that we now say goodbye to our Upper Sixth scholars, but we thank them for all their hard work over their time at Marlborough and wish them good luck in their future endeavours. This edition also brings our time as Editors to an end. We have thoroughly enjoyed our time in this position and have learned so much from all of the scholars and we look forward to reading next year’s editions.

Thank You

We would like to thank Mrs. Doxford and Mrs. Jordan for working beside us this year and helping us to produce the impressive and high-quality articles that you receive every term. We would also like to thank Mr. Moule for giving us this wonderful opportunity and for his support and guidance throughout the year. Finally, thank you to all of the scholars who go out of their way to produce all of the fascinating articles that make Inspire what it is.

Dani, Tilly, Xanthe and Milly.

Endless Boundaries

This year’s themed publication, spearheaded by the academic scholars, is titled Endless Boundaries: Games, Competition and Play in the Human Experience. Articles in this publication have been building on a dedicated webpage which can be found here: https://www.marlboroughcollege.org/games-a-new-college-publication

Wonderfully broad in scope, Games as a theme allows for multi- and inter-disciplinary contributions, from both pupils and staff, that highlight not only the universality of games and its centrality to the human experience, but the diverse interests of the College community. We would highly recommend this publication to you for what it reveals about the presence and power of games, and also for how it reflects the engaged intellectual community at Marlborough.

2

3 Contents Can we effectively predict the effects and patterns of demographic change? 4 Arabella M (L6) The scientific harmony between China and the UK 6 Danielle L (L6) Why do people kill for religion? 8 Virginia M (Re) What are the benefits and drawbacks of AI in our society? 10 Rhea S (Sh) Was the Congress of Vienna successful? 12 Edward G (L6) The SAT question everyone got wrong 14 Imp P (Sh) Tulip or bust! - A short summary of Tulip Mania in 17th Century Holland 15 Annabel S (Re) Dance of the Giants 17 G K W James (CR, Director of the Blackett Observatory, Astronomy Department) Unhealthy school meals are the main reason for obesity in children 21 Eloise J – (Sh) Some strange stories of art on the move 22 C A F Moule (CR, Head of Academic Scholars, Head of History) Nuclear weapons as a deterrent in modern geopolitics 28 Matilda B (Sh)

Can we effectively predict the effects and patterns of demographic change?

Arabella M (L6)

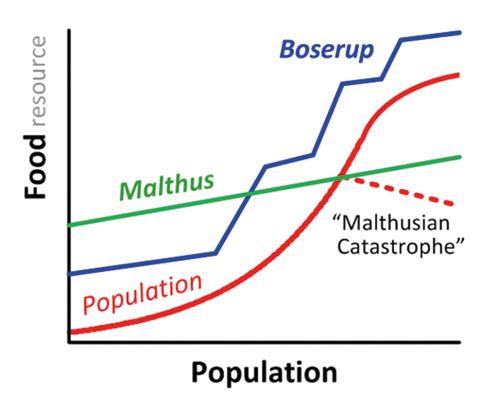

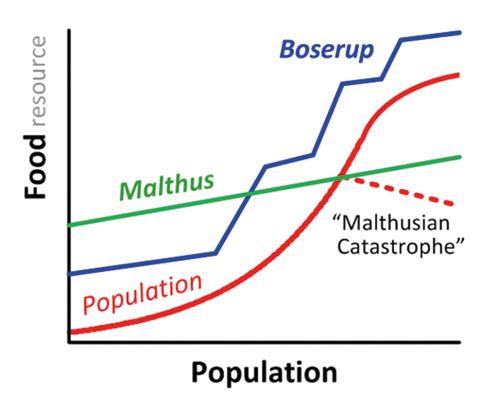

The world’s population is an exponentially growing, and continually developing, resulting in a multitude of implications for global systems, governance, and resources. Across centuries economists and demographers have been straining to grasp an understanding of the next demographic steps and what this will mean for us worldwide. I will be looking at the perspectives of Thomas Malthus, Neo-Malthusians, Ester Boserup and Julian Simons to argue whether we can truly predict the effects and patterns of demographic change?

Thomas Malthus was an 18-19th century economist, who suggests population growth is exponentially unsustainable and should be slowed down. Neo-Malthusians have taken a modernized perspective on his original ideas, arguing it is necessary to slow down population to a certain extent, as well as evenly distributing resources. Whereas, Ester Boserup, a 20th Century Economist, argues that people will always produce sufficient resources to support growth, agreeing with Julian Simons perspective that as populations grows there are more opportunities for development. Their contrasting views perspectives can be explored regarding the rapid global population growth of 1 billion since 2010, the sustainability of countries as they managed resource, and continue to develop.

Malthus argues that populations will exceed carrying capacity as population grows exponentially and food supply increases arithmetically, therefore populations will decline due to famine, war, disease. This is also believed by Neo-Malthusians due to rapid development in the 20th century leading to

the perspective that population would exceed resource production rates. Neo-Malthusians have utilised Malthus’ theory to create the 1970s Club of Rome Computer models predicting exponential population growth and declining economic productivity within 100 years. This is evident in many LICs in Northern, central Africa as rapid population growth has led to food shortages and famine, as demonstrated by Ethiopia, where food shortages have led to around 1 million famine deaths. Malthus’ theory is replicated in the demographic transition model where populations reaching stage 5 will no longer support large populations and populations will see a natural decline. Although Malthus’ perspective can be utilised to a certain extent in the 21st century to predict future patterns, it is primarily based on an 18th century impossibility that food production cannot increase. However, due to technological advances and the agricultural mechanization of the Green revolution food production has rapid increased and remains relatively sustainable. As Malthusian theory is based off of no technological advances, I believe this perspective can be applied to demographic prediction to a certain extent but is not completely relevant to the modern world and will subsequently be ineffective in prediction. Whereas Neo-Malthusians agree with the premise of his theory in a more relevant ways to deal with population growth through resource management, creating a more applicable perspective.

On the other hand, Boserup and Simon take a more positive perspective arguing that however large a population reaches there will remain sufficient food and resources to

4

support a sustainable growth as the “ultimate resource is the human mind” (Simon). Their theories argue that technological advances and innovation will allow populations to grow exponentially, as population grows, new methods and technology will develop, therefore farming will become more intensive and able to support the population. This is evident in HIC areas such the Netherlands who are leading advances in technological agriculture through storage technology, vertical farming and seed technology allowing more efficient food production able to support larger populations.

Human innovation can fix demographic and resource issues as seen with food production or housing, through multistorey buildings, or marine land expansion. Some areas have seen natural resources become less scarce and quality of life improved as countries increase in population due to new ways to support the population. Technology has seen many developments in supporting population growth in the 21st century, however, this is mainly in HICs suggesting populations in LICs cannot continue to grow even in the 21st century until they develop enough to sustainably develop resources.

To conclude, stage 5 of the demographic transition model agrees with Malthus’ perspective of limiting population growth as a natural course. Population change does not have to be forced change through governmental control, but a natural decrease as contraceptive education and women’s emancipation become a prevailing theme in the patterns of population growth. However, stage 2-4 in the demographic transition model show larger populations can be supported by new technologies therefor grow exponentially. Therefore, I do not believe population change can be successfully predicted on a global scale. I take the argument that Boserup and Simon’s perspectives are more relevant in the developing world. However, this is not applicable to undeveloped countries where technological lag will struggle to keep up with exponential population growth, nor the developed world where natural decrease will occur, and Malthusian perspectives may become increasingly more relevant.

5

The scientific harmony between China and the UK

China and the UK are among the world’s great scientific superpowers. China has a great history of scientific discoveries, most notably, gunpowder, paper making, printing and the compass; however, recently they are the leading nation with their innovation in earth and environmental sciences. In addition, the UK has made many very important discoveries ranging from the discovery of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, to penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming in 1928.

There have been many discoveries made by the two countries separately over the course of history, and it still continues to this day. My personal favourite development has been made by China. China is currently in the process of creating an artificial sun. Many protypes have been made, and China is currently home to the world’s largest artificial sun at the ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor). This discovery is very important as it could revolutionise China’s future in nuclear fusion, and this is why China is a leading scientific figure, as nuclear fusion is one of the solutions to reducing our carbon emissions, as it generates huge amounts of energy without a cost to the environment. In fact, ITER’s artificial sun produces 500 megawatts from 50 megawatts of power input (so the output is 10 times larger than the input) and this is enough energy to power 4 million light bulbs all year round!

These two countries have been very successful separately, but what happens when they work together? The UK and China are well established science and innovation partners (with the UK bringing science and China bringing innovation) and the beginning of their scientific harmony began in November 1988,

Danielle L (L6)

when the First Bilateral Scientific Treaty was signed between the two nations. This would have happened due to their mutual interests in scientific research and their desire to address global challenges collaboratively. What makes this relationship so unique, is that the UK was the first Nation that China had made a collaboration with for scientific development. Every year, under the UK-China Research and Innovation Fund, China has helped address the UN’s global sustainability goals, so not only are we achieving harmony between two nations, but science is bringing the world together, as it should, as we all need to help save our planet. This union has helped to promote scientific discoveries by having more access to expertise, resources and allowing an exchange in knowledge, as well as different perspectives due to the difference in culture.

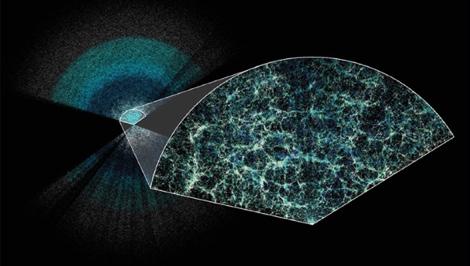

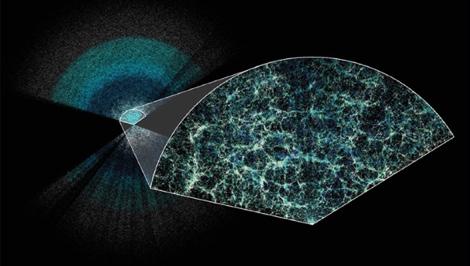

An organisation that was born out of this partnership is UKRI China, which stands for United Kingdom Research and Innovation China. It has funded over 804 joint innovation projects and has an investment value from the UK of £440 million which was matched by China. On the 12th of April 2024, UKRI China announced their results from a study that gave the most precise measurements of the expanding universe. The team used the Dark Energy

6

Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) to create the largest 3D map of the universe. This discovery may seem to be less important than those to do with the climate, however, understanding the universe will only open more doors to humanity, so this alliance will, and is creating scientific history. Professor Carlos Frenk says, “Never before has mankind measured the basic properties of our Universe with such precision.” This shows us the depth of the discoveries that are being made in this collaboration, and how it is the future of science.

UKRI China is not only aiding the environment and developing physics, but it is also advancing medicine. On the 18th of April 2024, UKRI China published a trial that they had been undertaking in finding a drug to help gut damage from malnutrition. The trial took place in Zambia and Zimbabwe, so once again this union between China and the UK is connecting countries all over the world, even third world countries that wouldn’t have access to drugs like these. They have now identified a drug called teduglutide that promotes intestinal healing by repairing mucosal membranes (the lining of the stomach) and reducing inflammation. This study gave the first evidence in three decades showing that by treating malnutrition enteropathy (inflammation caused by poor hygiene) can reduce the effects in children experiencing severe acute malnutrition (SAM). 3.1 million children die a year of malnutrition, and this is almost half the number of deaths in children under the age of 5, so UKRI China is helping save the lives of children all over the world.

So far, the alliance between China and the UK has been very successful, but how can we secure this relationship in the future? This is very important as the two countries have made and can make, ground breaking scientific discoveries that could change the course of science for the better. We can do this be ensuring that there are ongoing diplomatic efforts between the two nations, continued collaboration between research institutions, regular progress reviews

and a mutual commitment to the goals outlined in the treaty. This is an alliance that is crucial to sustain, as it is not only going to benefit the two nations involved, but it will also benefit the whole world.

Organisations such as UKRI China and the UK-China Research and Innovation Fund have helped benefit the world and have demonstrated the positive outcome of this collaboration. However, now we have to ask ourselves the question, “What can we expect from them in the future?” This is a difficult question to answer as it is hard to see where the world will be in the next few years, but the most probable issue that the world will still be facing is climate change. I recently attended a talk on “The life of an Engineer” given by Dr. Robert Witty who is a very successful engineer, and he mentioned that the future of science would be in the hands of anyone who would be able to invent a way to extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. I also believe that if China can perfect their artificial sun by reducing its power intake, this could solve the worlds energy crisis while producing energy with a green method. In my opinion the above two solutions need to happen together, as we need to be able to generate electricity without producing more carbon dioxide, but we also need to fix the current issue of there being too much carbon dioxide in our atmosphere before it is too late. Separately these two countries have been successful, but it is the harmony and collaboration between them that could lead them into dominating the scientific world and solving some of our planets most pressing problems.

7

Why do people kill for religion?

Religion is a great power in the world and has been all throughout history, from the Pope in medieval era to the terrible conflict that is happening now in Gaza. So, why do people need to use religion to justify dreadful crimes like manslaughter and genocide. But it’s not as simple as a fear of another religion or a fundamental tendency to violence. It is the long battle of conflicting claims of superiority based on the ideas of a deity or deities’ supremacy, however they cannot be ever proven to exist. To explain the abnormal tendency for violence in religion there are many different fields including psychology, theology, politics, history, and religious studies.

Political institutions include tribes, dynasties, empires, and states in which a multitude of religions may clash or harmonize over any detail and create a complex, unstructured web to be untangled. In the modern era it is easier to separate a state’s politics from its own religion/religions however this was not always the case and when it first

Virginia M (Re)

became so, it was separable primarily in the West. In earlier times, what was separating the religion or politics of human sacrifices in the Aztec culture? Or the politics and religion of the Roman and Greek empires.

The psychology of violence is often linked to an incredibly strong emotion that drives someone to commit a crime such as murder, this topic is particularly popular in our culture, for example the author Agatha Christie, who has no obvious religious theme in her books as she explains to the reader that the motives for murder are universal and manifold. This interests many people who specialise in Neuroscience and Psychology for example Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The main emotions that drive a person to violence or murder are jealousy, anger, revenge, love, greed, and hate. In relation to religion any of these emotions can be applied and produce a violent result. The hate of a different religion may drive someone to kill to prove a point.

A common theme in murder is psychopathy and sociopathy. Although there are people in history that have already been predisposed to murder in the working of their brain, in the modern day we can tell when the person in question is caught, for example Lucy Letby. In relation to psychology, Douglas Fields an American neuroscientist wrote a book called “Why we snap”. He says, “Every day the news is filled with fights and murders—and they’re not committed by psychopaths—it’s the everyday snapping response.” He explains that the brain is predisposed to violence, but the twist is that the neuropathways are the same that enable us to act heroically. He explains it with a simple mnemonic which stands for the triggers that cause this reaction in the brain, LIFEMORTS. This stand for life or limb, insult, family,

8

environment, mate, order (in society), resources, tribe, and stopped (escaping restraint or imprisonment). His point is that the human brain is wired to react violently as aggression is a defence mechanism, this means that the human response makes anyone able to kill in the right or even more crucially the wrong circumstance.

In the book, “When religion becomes evil” written by Charles Kimball, he opens by saying that “Religion is arguably the most powerful and pervasive force on earth.” I agree with him, the instinct to be safe in a group of people that share your beliefs is a very appealing for most people. And the great majority of people would never abuse this power because religion is an amazing thing for billions of people around the world. Contrary to this, there are people that take advantage. They can sway the group of people to believe what they want. This has been seen all throughout the 20th century with the rise of dictators. One of these people was Adolf Hitler, a man who moved a country to believe that their nationality and race was superior to another, and of course it wasn’t everybody but over six million jews were killed because one man could sway the ideology of nearly an entire country.

This has happened earlier in history as well, the persuasive power of a couple of people to change a nation. The Catholic-Protestant relations have been shaky with some conflict through the time of The Reformation and

continued in the troubles in Ireland, it was fuelled on the protestant side by Martin Luther and John Calvin. Famously in 1555 Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, and John Hooper were condemned as heretics and burned at the stake in Oxford. ‘Bloody’ Queen Mary known for her attempt to reverse the English reformation, and after her vigorous attempt to reinstate Roman Catholicism, her successor Elizabeth I reversed it, converting England to a primarily protestant state. This is also demonstrated in Ireland, by the IRA who committed mass murder and the most famous of that being Lord Mountbatten. This then led to the Good Friday agreement.

In conclusion, a facet of religion is not and should never be an underlying hate for another religion or a propensity to kill. It is the genetic makeup of humans that tips some of us closer to violence and in doing so using religion as another excuse as they go. For example, the conflict happening now, the Israel-Palestine war, has again brought ancient hatreds, partly based on religion, to the fore.

Therefore, it is not only religion by itself that sparks violence, it tends to be the tipping point to a war or a hate crime or even just a small reason that is blown up by the media in modern days, but usually there are many other reasons that are in the background that drive people involved to kill.

9

What are the benefits and drawbacks of AI in our society?

Rhea S (Sh)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has recently emerged as a transformative force with both positive and negative implications for our modern world. This essay explores the various properties of AI, highlighting its potential benefits and drawbacks.

Positive aspects of AI:

One of the most significant advantages of AI lies in its ability to automate repetitive tasks, thereby enhancing efficiency and productivity across various industries. This allows human workers to focus on more complex and creative aspects of their jobs. AI systems also have remarkable precision and accuracy in executing tasks, minimizing errors that may arise from human work. This characteristic is particularly valuable in fields where precision is key, such as medical diagnostics and manufacturing.

The capability of AI to swiftly process vast amounts of data from many sources across the internet simultaneously has drastically improved data analysis. By extracting meaningful insights and patterns, AI contributes to informed decision-making, research, and development. Its applications in collecting and comparing information from enormous amounts of data have made knowledge discovery far more accessible to all.

AI serves as a catalyst for innovation, propelling the development of ground breaking technologies. For example, machine learning algorithms have made important advancements in creating self-driving cars, revolutionizing transportation. This innovative property of AI is evident in various sectors, making advancements that were once deemed

impossible. AI-powered translation tools play a crucial role in facilitating communication across languages and cultures. This not only breaks down linguistic barriers but also fosters global collaboration and understanding, extending the boundaries of innovation and progress.

Negative aspects of AI:

One of AI’s most common features is personalization. While this may seem like a great idea, it can be considered a breach of privacy and requires consent from the user. However, most people consent without reading any terms or conditions, so they do not know what they are consenting to. AI can recall previous activity on your account and save information without your knowledge, using it to target recommendation and ads etc., In turn promoting consumerism and needless spending.

The rise of AI also brings forth ethical questions that demand careful consideration. Issues like the use of autonomous weapons, widespread surveillance, and the invasion of privacy underscore the need for ethical guidelines and regulations to govern the development and deployment of ai technologies.

While AI automation contributes to cost reduction, it may simultaneously lead to job displacement in certain industries. The efficiency gained through automation can reduce the demand for human labour, necessitating a shift in workforce dynamics and skill requirements. The people whose jobs have been replaced by ai work will not necessarily have the right skillset to work in a job created by AI.

10

AI algorithms, when trained on biased data such as social media platforms, can demonstrate and extend existing biases in society. This raises concerns about fairness and equity, especially in applications like hiring processes, where biased algorithms can lead to discriminatory outcomes.

As well as this, the rapid advancement of AI technology often outpaces the development of appropriate legal and regulatory actions and guidelines. The absence of comprehensive laws

can lead to potential misuse and ethical lapses, necessitating a regulatory response that could be avoided if AI had been more thoroughly controlled from its creation.

Finally, AI lacks emotion and compassion. It tends to prioritize solutions that are most effective in problem-solving, rather than considering the broader well-being of all involved. This can raise concerns about the alignment of ai decisions with human values, for example the utilitarian principle of ‘the greatest happiness for the greatest number’.

In conclusion, the positives and negatives of AI underscore the importance of responsible development and utilization. Striking a balance between taking advantage of increased automation, innovation, and efficiency, while mitigating the negative impacts on employment, fairness, ethical considerations, and addressing legal and regulatory challenges, is crucial for a harmonious integration of AI into our rapidly evolving society.

11

Was the Congress of Vienna successful?

Edward G (L6)

The Congress of Vienna was the peace treaty at the end of the Napoleonic wars, a conflict lasting 12 years and killing 3 million soldiers – with many more civilian deaths as well. Napoleon was first defeated at Leipzig in 1814. However, after he escaped his imprisonment, the subsequent 100 days of Napoleon followed ending with the famous Battle of Waterloo – a joint effort from British, Prussia, and Russian forces. The 8-month long Congress of Vienna was the meeting between Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria – called the Quadruple Alliance - which decided how to restructure the destroyed European order.

The main aim of it was maintaining the balance of power, which is to make sure no country controls so much land or people that they become too powerful and become ‘undefeatable’. This is what happened with Napoleonic France and therefore there was real impetus to make sure that the balance of power was fair for everyone and thus maintained by everyone. In real terms, power was controlling the whole of Germany and its resources, people and economic output. The solution was that Germany would be a collection of independent states with no Prussian hegemony there. The Congress went further by creating a German confederation that bound the member states to mutual assistance in the case if an invasion.

This was, in theory, to make sure that an invading country such as France or Russia could be defeated by the combined military of all of Germany but that this combined military would only be used for defence – not attack. Furthermore, many smaller German were given to the larger states like Bohemia or Bavaria to enhance each states military just enough to counter both Prussian and outside aggression but not enough to be able to develop any real threats of invasion to another state. However, the Congress’ solution to the German problem was not entirely successful as in fact, being the largest state and therefore having the largest military, Prussia ended up being the guardian against outside aggression as they contributed the most to defence. What this did was to create a new Great Power and enhance calls for German unity under the powerful Prussia as the German people wanted to and saw a way in which they would be able to. Therefore, the solution created was ultimately a short-term success as no power did control the whole of Germany. However, it did lead to German states constantly turning to Prussia for defence and thus accelerated the dangerous rise of nationalism in Germany.

The other monumental problem of the Congress was France. A balance needed to be struck where France would be strong enough to balance out the growing threat of Russia and especially their growth into Europe but also keep France both weak enough and content enough so that it would not get its own ambitions again and kickstart a second European conflict. The solution was for France to lose all of its territories, such as Naples and Belgium, that it had gained since 1789. The creation of these new states also meant that they could be used as buffer states to prevent direct conflicts between the great powers. However,

12

the new France needed to have both stability and legitimacy, so the old French monarchy was re-established but with a constitution. In that sense, the Congress had been successful as France stopped a lot of their aggression into Europe, and was a successful defence against Russian aggression, as shown in the Crimean war.

In conclusion, the Congress of Vienna’s aim was to create a fair system where no nation gained too much power but was satisfied enough to keep the peace. In the short term, it did that as Germany was independent; Russia had been taken out of Germany but satisfied with influence in Poland; Austria was satisfied with parts of Italy; France was not treated too harshly but was diminished in population and size; many independent buffer states had been created to prevent direct conflicts and

Britain had kept its colonial possessions as well as the spreading of liberalism like with the constitutional monarchy in France. However, in the long term, it did not account for the rise in nationalism and in fact enhanced it by making Germany rely on Prussia. Also, it did not secure any real stability in France as the monarchy was very unpopular and overthrown 15 years later and then again after another 18 years. This meant that France was always a threat as the first action of any new government system was always to try and expand its borders to make itself more popular. However, overall, one cannot look past the fact that the systems put in place by the Congress kept Europe out of large-scale war for almost a century and when war came, it was only because the actions of the congress had been undone such as Germany uniting in 1871 and Russia advancing into the Balkans.

13

The SAT question everyone got wrong

The SAT is a standardised test widely used for college admission in the United State. It had a reputation for determining people’s entire career. As a newspaper from the 80s stated: ‘If you mess up on your SAT tests, you can forget it. Your life as a productive citizen is over. Hang it up, son.’ SAT questions are designed to be quick. The exam gave students 30 minutes to solve 25 problems; therefore, it is expected for each question to used up one minute.

However, in 1982, there was one question in which every single student answered incorrectly. Here is the question.

The intuitive and general answer was B as the circumference of a circle is just 2Πr and since the radius of circle B is 3 time of circle A, the circumference must also be 3 times the circumference of A. Logically, it should take 3 full rotation of circle A to roll around circle B. This is incorrect but so are answer A, C, D and E. The reason why nobody answered question 17 correctly was because the test writer themselves made a mistake, also thinking that the answer was 3. The actual correct answer was not listed in this option.

Of 300,000 test takers, only 3 students responded about the error to the College Board, a company which administers the SAT. The intended answer to this problem was choice B, 3. However, the motion of the small circle is not in a straight line, but rather around the large circle. This revolving action around the large circle contributes an extra revolution. Thus, the answer to this question should have been 4, not 3. This is known as the coin rotation paradox. This result in all 300,00 tests, being rescored and recalculated. With the removal of question 17, the final score was moved up or down by 10 points out of 800.

This is how the paradox work: place two identical disk of the same size, for instance a coin. While holding one of the coin stationaries, rotate the other coin around it, keeping the edge contact without slipping. When the coin returns to its original position it should have rotated twice.

The extra rotation occurred because of the circular path. The general solution toward this is to find the ratio between Circle A and Circle B and then add one to account for the circular path traveled. However, as the wording of this question is extremely ambiguous, it could also be interpretated as in different way giving out two other solution, 1 and 3.

The astronomical definition of a revolution is the object’s orbital motion around another object. By this definition of a revolution, circle A only revolve around circle B once. However, if counting from the perspective of circle B looking out at circle A, it only revolves three times. Using the perspective of the circle is just like turning the circle’s circumference into a straight line. It’s only as external observer that see the circular path travelled.

14

Imp P (Sh)

Tulip or bust! – A short summary of Tulip Mania in 17th century Holland

Annabel S (Re)

Tulips are a part of the lily family and are originally native to central Asia. During the 16th Century they became so popular that a functioning ‘economy’ was formed on trade of the flower. This short time period was named Tulip Mania.

Tulips began to be cultivated in Persia, which is now Iran and were not introduced to the West and to Europe until 1551, when Augier Ghislain de Busbecq brought seeds to Constantinople. Tulips then became extremely popular within the Ottoman Empire and later became the symbol of the great nation. Shortly after the flower species was introduced to Turkey, Ghislain de Busbecq also sent some seeds to Austria and by 1562 a large cargo ship

full of tulip bulbs was arriving in Antwerp, Belgium. From here the avid horticulturist and doctor, Carolus Clusius began to develop different variants of tulips and the plant grew further in popularity and began to demand higher prices. In 1596 Clusius had developed ‘broken tulips’ a name given due to their streaks of colour, however there is speculation to whether this unique colouring is a result of disease. Burglars broke into Clusius’ green house and stole the new variant of tulips. This led to the creation of many other variants and the wider spread of tulip trade in Northern Europe and later ‘Tulip Mania’.

Following this continental spread in favour the flower eventually became arguably the most popular in Holland, a country that is now extremely famous for their tulips. During the 17th century it reached they reached their peak and the craze became known as ‘Tulip Mania’ . Since the mid 1500s, when they were first brought to the Netherlands the flowers were always in high demand as they were a desirable item to display one’s wealth. Prices constantly rose over many years and the sales increased dramatically once the broken tulip was launched within the market and by 1610 a single bulb of a new variety was considered more than acceptable as a dowry for a bride. From 1633 to 1637 the craze reached its prime. This was a result of gradual price increase but also prior to 1633 the heavy majority of tulips were bread by professionals and experts, however many members of the public saw that tulips were reasonably easy to grow and began to make new variants and colours of tulip from their garden. Price and demand for new types of tulips increased so much that many families,

15

businessmen and others bought tulips as a form of investment, and some became more expensive than acclaimed art and even houses. Over only a few years tulips had formed their own respective economy.

It is thought by some that during Tulip Mania, bulbs were used as an alternative currency to money. Although this is an interesting vantage point of the craze, tulips were used alongside ‘normal’ currency and should be viewed as more of an investment. Despite this tulip bulbs were often traded for other valuables, but we must remember that in the 17th century trading for items, opposed to modern conventional retail, was a lot more common.

Many members of the public applied for mortgages just to buy tulip bulbs, risking their houses and financially stability. For many years this was a relatively safe and sensible investment, however in 1937 there was an inevitable crash within the tulip market. As doubt rose about how many new variants could be created and further price increase, almost overnight the price structure collapsed. This left many ordinary Dutch families in financial disrepair. However, without an extortionate price tag, tulips still remained a very popular flower in Holland and continue to be today.

Tulips remained very popular in Europe and Asia and one hundred years later they became extremely popular again but especially in the Ottoman Empire. Between 1718 and 1730 during the latter half of Sultan Ahmed III’s reign the empire saw a rise in culture and this short period of time marks a turning point for elite consumerism becoming present. This caused art, architecture, and literature to flourish within the nation. This brief era obtains its name, ‘The Tulip Era’ from the flower that was used, yet again, as an asset to show wealth. The tulip then became the emblem of the Ottoman Empire.

Throughout hundreds of years tulips were extremely popular, desirable, and certainly expensive items particularly in Europe but also in other continents. It is interesting to consider how an object that we now consider small and irrelevant was once so significant in history and caused people to lose their homes and finances. Crazes such as Tulip mania present themselves throughout history and indeed today, closer to the time fruits like pineapples became extremely expensive and today it could be argued that investing in things such as tech stocks are a craze that will rise until it crashes. However, I believe that Tulip Mania remains the most severe investment craze, relative to the flowers original purpose and size. The Tulip Mania shows us that financial speculation and its inevitable fallout is nothing new.

16

Dance of the Giants

G K W James (CR, Directory of

the Blackett Observatory, Astronomy Department)

How the Gas Giants formed and how they may have migrated through the Solar System. With particular attention to evidence provided by recent studies of exoplanetary systems.

1. Introduction

This essay investigates how today’s Solar System came into being. First, we consider the accepted solar nebula theory that explains the differentiation between the inner rocky planets and the outer gas planets. We go on to examine the possible mechanisms by which the planets took up their current locations and how the asteroid and Kuiper belts came to be where they are found today; the two principal theories, the Nice Model and the Grand Tack Hypothesis, involve radial migration of the gas giants in the Solar System. We end by considering how the modern field of exoplanet investigation can corroborate or refute these theories.

Formation of the Gas Giants

2.1 The Solar Nebula Theory

The first theories that attempted to explain how the Solar System formed were proposed in the late 18th Century, with Leclerc (17071788) suggesting that the collision of a giant comet with the Sun caused the ejection of sufficient material to form the planets. Other theories suggested that a close encounter with a passing star created tidal forces that drew off material from the Sun. All these theories were superseded by theories proposed by René Descartes (1596-1650), Immanuel Kant (17241804) and Pierre-Simon Marquis de Laplace (1749-1827), who independently proposed that

the Sun and the planets were all formed at the same time from the same nebula. (Carroll & Ostlie, 2017; Horner, et al., 2020).

The solar nebula theory suggests that about 4.6 billion years ago, the collapsing solar molecular cloud heated up as the gravitational potential energy was converted to thermal energy. The Sun developed at the centre of the cloud, using up about 99.9% of the material, which was made up of about 71% hydrogen, 27% helium and 2% metals. The remaining 0.1% of the cloud formed a protoplanetary disk orbiting in a plane around the Sun; within this disk the material coalesced to form planetesimals, which would collide and coalesce to form the planets.

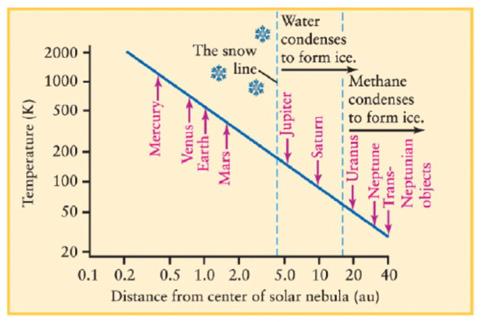

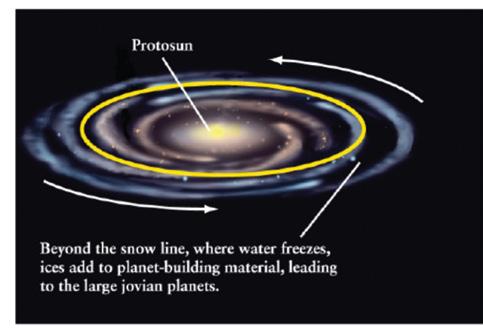

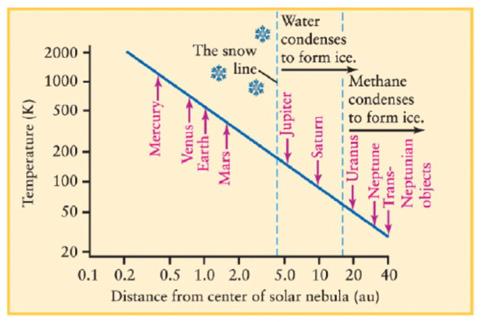

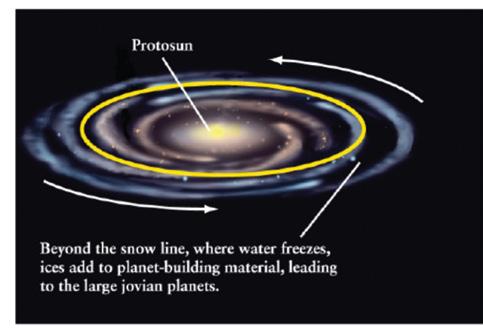

Today we see four inner rocky planets and four outer gas planets. How did this segregation occur? The effect of radiation from the Sun drops off with distance, meaning that the temperature decreases with increasing distance. Close to the Sun, within the Frost Line, also called the Snow Line, which is at about 4.5 AU from the Sun, the temperature is high enough that hydrogen compounds such as water, methane and ammonia could not condense into solids, whereas heavier metals such as iron were in solid form (see Figure 1). Planets within the Frost Line accreted the solid heavier elements to form their cores. Beyond the Frost Line, the temperature had dropped sufficiently that the lighter molecules could condense to form ices; these ices coalesced with the heavier metals to form the more massive cores of the outer planets. The radiation from the Sun also pushed the lighter molecules out towards the forming outer planets. The large mass of their cores accreted the lighter hydrogen and helium

17

gases, and the vast atmospheres of the gas giant planets were formed. (Geller, et al., 2019; Horner, et al., 2020).

geller, et al., 2019).

3. Inconsistencies in the Solar System

The solar nebula theory accounts neatly for the differences in planetary composition across the Solar System and does lead to the planets all orbiting in the same plane in the same direction around the Sun. However, there are multiple issues that still need to be resolved:

• The asteroid belt located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter and the Kuiper belt found beyond the orbit of Neptune contain thousands of rocky and icy bodies, but how did those bodies accumulate in those zones?

• The Ice Giants, Uranus and especially Neptune are located at great distances from

the Sun; the solar nebula theory cannot account for their large size as there would be insufficient molecules at those distances for them to accrete in their atmospheres.

• Why is Mars smaller than the other rocky planets, what stunted its growth?

• What caused the Late Heavy Bombardment, the abundance of collisions that occurred several hundred million years after the Solar System had formed?

(Carroll & Ostlie, 2017; Geller, et al., 2019; Horner, et al., 2020).

The possible solutions to these problems have come from research into extra solar planetary systems, especially through the discovery of Hot Jupiters, massive gas planets that orbit extremely close to their host stars. Computer simulations can create the Solar System as we see it, including all these features, if the migration of the gas giants is included. (Horner, et al., 2020).

4. Migration of the Gas Giants

Two theories propose the radial migration of the gas giants within the Solar System, the Nice Model and the Grand Tack Hypothesis. It is likely that the Solar System evolved through a mixture of the two. (Horner, et al., 2020).

4.1 The Nice Model

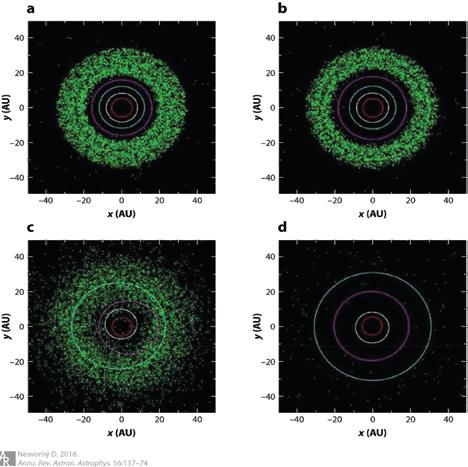

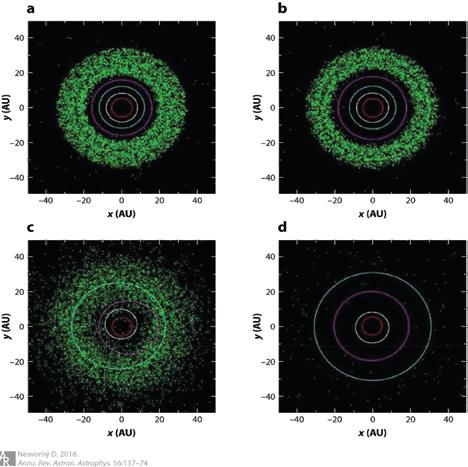

Observations of extra solar planetary systems indicate that systems can evolve dramatically over time and giant planets can be found much closer to their host stars than where the Solar System giants formed. The Nice Model, named after the southern French city where the astronomers who constructed the model worked, is a computer simulation that shows the development of the Solar System (Figure 2), starting with the four gas giants forming in a region between about 5 and 17 AU from the Sun, placing Neptune significantly closer to the Sun than its current position of 30 AU. The planets are surrounded by a large mass

18

Figure 1: illustration oF how temperature drops with distance From the sun, causing the Frost line at about 4.5 au, where water and other hydrogen compounds can condense into ice (image credit:

of planetesimals, with which they interact. At each interaction there is an exchange of angular momentum, so as a planetesimal is sent inwards progressing past Neptune, Uranus and Saturn, each interacting planet moves outwards. This explains the migration of the three outer gas giants away from the Sun. When the inbound planetesimals reach the massive Jupiter, its greater gravitational force ejects the bodies to the outer reaches of the Solar System and the exchange of angular momentum causes Jupiter to move inwards. Over time, Saturn and Jupiter form a 2:1 orbital resonance, which perturbs their orbits and increases their eccentricities, leading to a chaotic period where planetesimals are ejected inwards and outwards through the Solar System. Eventually the system settles down with the gas giants in their current configuration. (Horner, et al., 2020; Nesvorny, 2018; Armitage, 2020).

2: the original nice model simulation which shows the Four gas giants surrounded by planetesimals (a), an early conFiguration (b), scattering oF planetesimals (c) and the Final conFiguration (d). (image credit: nesvorny, 2018).

Gomes, et al (2005) suggest that this mechanism accounts for the Late Heavy Bombardment as the planetesimals are perturbed and travel across the Solar System

causing the myriad cataclysmic collisions. Furthermore, the disruption and distribution of planetesimals can explain the composition and position of the Kuiper belt at its distance beyond Neptune (Levison, et al., 2011) and the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter (Morbidelli, et al., 2010).

4.2 The Grand Tack Hypothesis

In the Grand Tack Hypothesis, Jupiter develops earlier than Saturn and migrates radially inwards towards the Sun. As Saturn develops it too migrates inwards, but more quickly as it is lighter, and encounters Jupiter. They fall into a 3:2 orbital resonance which halts the inwards migration, changing to an outer migration to their current positions. The disruptive influence of Jupiter at about 1.5 AU from the Sun is significant, moving material to the asteroid belt and depleting the planetesimals available for the formation of Mars, thereby explaining Mars’s smaller size. (Armitage, 2020; Walsh, et al., 2011; Masset & Snellgrove, 2001).

5. Exoplanetary Systems

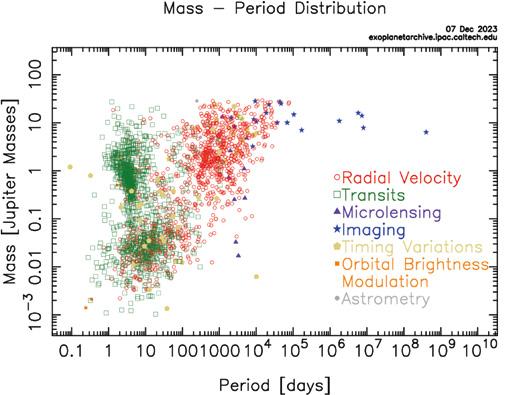

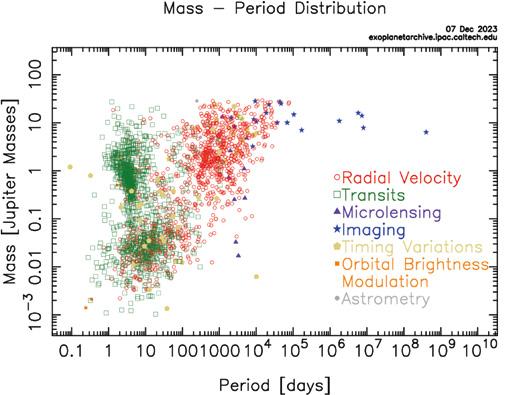

Since the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1992, over 5,500 exoplanets have been discovered in more than 4,000 exoplanetary systems (NASA, et al., 2023); Figure 3 shows the distribution of these exoplanets by period and mass, detailing their discovery method. There is a clear bias in each method for the kind of planet that it can detect. However, myriad planets exist in multiple configurations, and they are not all like those found in the Solar System. The discovery of massive gas planets orbiting close to their host star (Hot Jupiters) challenged the quiescent solar nebula theory, forcing new methods of evolution to be formulated (Dawson & Johnson, 2018; Heller, 2019; Zink & Howard, 2023). Systems at all stages of development are observed, some planets have highly eccentric planetary orbits, and there are a range of densities and sizes,

19

Figure

with super-Earths and mini-Neptunes being commonplace (Horner, et al., 2020).

3: plot to show exoplanets discovered to 07-12-2023 by discovery method. (image credit: nasa exoplanet archive, 2023).

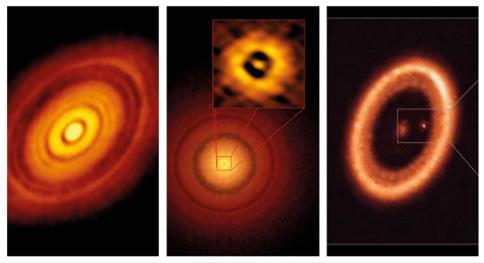

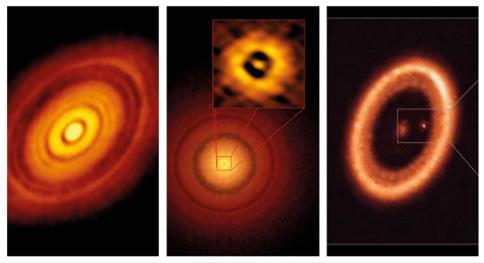

Observations in optical wavelengths with the Hubble Space Telescope and in infrared with ALMA (Figure 4) have shown the widespread existence of protoplanetary and debris discs around stars. These serve to confirm elements of the solar nebula theory and show that the asteroid belt and Kuiper belt are not unusual. (Horner, et al., 2020).

6. Conclusion

This brief roundup of theories to explain how the Solar System has come to be in its current configuration illustrates the constant evolution of ideas. Whilst the solar nebula theory remains at the root of our understanding, it is through more recent observations of extra solar planetary systems that theories have been forced to evolve. The main element to be introduced is the migration of gas giants, without which exoplanet observations are hard to explain. The evolutionary model of the Solar System improves with migration, as it can account for the multiple inconsistencies that hitherto were mysteries. Further observation of all planetary systems will only serve to enhance our understanding.

20

Figure

Figure 4: dust disks captured by alma around stars. (image credit: alma, 2021)

Unhealthy school meals are the main reason for obesity in children

Eloise J (Sh)

The numbers in childhood obesity have sky-rocketed in recent years, with 10% of reception children being obese and a further 12.1% being overweight. Studies have shown that two-thirds of school meal are ultraprocessed foods which, without proper exercise, could largely contribute to obesity and excessive weight gain. Moreover, packed lunches are made up of nearly 84% of these foods. The increase in ultra-processed food is thought to be due to rising food costs resulting in cheaper, unhealthier food being served to the children by schools and in packed lunches. So, is this rise in processed food in children’s lunches the reason for higher rates of obesity in children?

One would think that the government are not trying to increase the obesity in children as the foods that schools provide are often marketed as healthy, whereas in reality they are high in salt, fat, and other additives which contribute to a poor diet. As the foods school serve are thought of as to be healthy, there is no idea that these meals are contributing to childhood obesity, making it all the more likely to be the main reason for obesity in children. The main reason for these ‘healthy’ unhealthy foods are thought to be the soaring energy costs

and supply chain disruption caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In addition, current school regulations do not mention ultra-processed foods, so there is no awareness of how this unhealthy food could cause obesity in children.

In addition, it is not just school served meals that are the issue, 84% of children have packed lunches at school, and only 1 in 100 of this 84% have lunches that meet nutritional standards. Packed lunches at school often insist of white bread sandwiches, but the processed flour and additives can lead to heart problems, and the crips often served with said sandwiches are high in salt and unhealthy fats. It is proved that eating a single packet pf crisps per day, as these children are, leads to many long-term health problems, one of which being obesity. Fruit is sometimes added, but it is almost always paired with a chocolate bar, and it is nowhere near a child’s 5 a day.

In conclusion, the school served meals are made up of too much ultra–processed foods to allow children to maintain healthy lifestyles. Other reasons for obesity in children could be not enough exercise at school, but smaller amounts of exercise would not cause nearly 25% of children to be obese without significantly unhealthy foods being fed to them every day. Schools have tried to limit the amount of sugar that parents put in their children’s packed lunches, but teachers are saying it is not enough and more action needs to be taken. Majority of a child’s dietary journey as they grow up cannot be made up of excessive amounts of salts and fats as that will not help future generations to combat obesity. Therefore, the ultra-processed foods making up children’s diets needs to be managed to fight childhood obesity.

21

Some strange stories of art on the move

C A F Moule (CR, Head of Academic Scholars, Head of History)

The Parthenon (or Elgin) Marbles held by the British Museum appear regularly in the news these days. Greece wants them back, to be united with other parts of the Ionic frieze of the Parthenon in the lovely airy museum just below the Acropolis within sight of the great temple. Meanwhile, Nigeria wants the Benin Bronzes back.

And in 1998 the question of repatriating those equivalent, if rather softer, English national treasures Winnie the Pooh, Piglet, Tigger, Kanga and Eeyore from their exile in New York’s Public Library was raised in Parliament and discussed publicly by Tony Blair and Rudi Giuliani. Nothing came of this, and they languish far from home. I’ve seen the soft toys in New York: they look a bit bewildered, but then they often are like that in the stories too.

Some art hasn’t travelled much, and that’s especially true of architecture, though if you go up 5th Avenue from the library to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you’ll find a whole Egyptian temple inside (a ‘realio trulio’ temple, as Ogden Nash might have said – it is actually authentic), and there’s another equally incongruous one in a park in Madrid. They were moved in the 1960s to save them from the rising waters of the new Lake Nasser in Egypt. They are solid, chunky things. But it would be pretty hard to shift delicate masterpieces like the Forbidden City or the Taj Mahal to a western city.

However, a great deal of art was actually made to travel: Titian’s beautiful Poesie were painted in Venice but intended for Philip II of Spain. Meanwhile, Leonardo travelled round the place with some of his paintings (like the Mona

Lisa) touching them up from time to time. That’s why the Mona Lisa is now in Paris, not very far from where Leonardo died. Tens of thousands of works have been commissioned by people living in countries separate from those of the artists, and tens of thousands of works of art have moved country having been bought (though not, it seems, including Winnie the Pooh).

And then there are all the tricky cases of works of art which weren’t intended to move anywhere, but which nevertheless has done so. In modern times that art has tended to move west and north, from Mediterranean shores or the exotic Orient to chilly European or American cities, and it’s well-known that moral integrity wasn’t always uppermost in the minds of the removal men of Paris, London, Berlin or New York. Nor did The Rest of the World get much of a chance (or have much inclination) to pinch antique treasures from New Jersey, Lancashire or the Pas de Calais. It’s not really been a fair exchange.

I’m not going to whinge about all that unfairness here – there’s enough of that sort of thing all over the press, often couched in terms of national debates which bear no relation whatever to the societies which created the works. After all, the greatest Greek leader, Alexander the Great, was a Grade A* looter, robber and wrecker who made Lord Elgin look like a bumbling amateur, and who – in spite of his vigorous approach to cultural appropriation – has happily appeared on Greek bank notes, stamps and statues in square and parks. He’d probably have given Elgin advice on how to do a bigger, better job of it. And I admit a sneaking admiration for people like Charles Fellowes: the latter, risking life and limb in Turkey in the early 19th century,

22

managed to spot carved stones from among the mountains of rubble at the Lycian city of Xanthos. He then proceeded to direct rowdy disgruntled sailors to shift these delicately to London, and then to reassemble them (for the first time in more than a thousand years) into the fabulous Nereid Monument, one of the most beautiful ensembles in the British Museum.

Instead, I want to point to a few curious cases of ‘art which has moved’. In each case, you might consider whether or not it should have moved (sometimes the answer is obvious), whether its reputation has increased or decreased because of the move, and (perhaps most interesting) whether or not it’s become more powerful and potent as a result of the move. The backdrop of these stories – which are the tiniest tip of a gigantic iceberg – include greed, vainglory, patriotism and nationalism, internationalism, and even altruism. They also all share the sense of works of art as profoundly valuable, but in different ways.

Let’s start with the relatively simple case of the Mona Lisa itself, whose occasional and slight wanderings have helped to catapult its fame. The painting ‘moved’ in 1911 when it was stolen by an Italian who was himself outraged by what he considered its earlier theft from Italy: he thought Napoleon had grabbed it from Florence and put it in the Louvre. National outrage about wandering artwork was already alive and well; but in this case Napoleon, grand thief though he was, hadn’t stolen it – it had been acquired perfectly legally in 1519. It was quite a celebrated portrait before its 1911 theft, but very much more so afterwards. It might be said that its theft, and the subsequent publicity, is at the very root of its status as the most famous painting in the world.

A few years before the theft of the Mona Lisa Gustav Klimt had painted Adele BlochBauer, an Austrian Jew, surrounding her radiant figure with shimmering gold brimming with beautiful patterns. The painting was stolen by

the Nazis and subsequently displayed in the Belvedere Gallery in Vienna. This museum refused for a long time to acknowledge the claims on it by members of Adele’s family who survived the Holocaust. After several years of increasingly bitter wrangling (1998-2004) it was awarded to the family, who sold it to a New York gallery for 135 million dollars (a record at that time). It was a famous picture but the intensity of this story – and especially its connection with the Holocaust and lingering injustices resulting from that – has made it much more so: and not least because it is the star of four films, including a major Hollywood one (The Woman in Gold (2015)). Moreover, this portrait is merely the tip of the iceberg: tens of thousands of paintings, sculptures and buildings were stolen from Jews and others in the 30s and 40s, and – for obvious, tragic reasons – only a fraction have been returned. (The Washington Post, a couple of months

23

ago, estimated that there are around 100,000 paintings and objets d’art that have never been returned to the Jewish families from whom they were stolen; and this doesn’t include the plethora of buildings, many of them great – and many now destroyed by bombs or developers).

The physical destruction that potentially awaited works of art had they stayed put has been a frequent excuse for their removal. Indeed, the Egyptian government actually gifted those Nubian temples now found in New York and Madrid to the countries in question, to save them from flooding by the new reservoir (others are now underwater). Of course, they also then serve as popular – even much loved – advertisements for Egyptian civilization. It’s often claimed that Elgin’s purchase of the Parthenon Marbles ostensibly saved them from the worse fate of weathering, neglect and vandalism, and a great many eastern antiquities were picked carefully from rubble and ‘saved’ before locals could use them to build houses or burn the marble for lime. More iniquitous still has been the threat of war and especially iconoclasm, visible recently in Syria and Afghanistan, where, alongside the human tragedy, Islamists have been wantonly blowing up spectacular antique art such as the Bamiyan Buddhas or the temples of Palmyra. Would that they had been transported to Swindon – or indeed pretty much anywhere else – in good time!

Given his rather destructive tendencies, there was little chance of Saddam Hussein successfully claiming Assyrian and Mesopotamian antiquities from western museums. But just for a moment, he was interested in Canford School, which discovered in 1994 that it had a major Assyrian palace relief sculpture on a wall in its tuck shop, the Grubber. The relief shows King Assurnasirpal II, a 9th century BC king. It had been plastered over and was largely undamaged except by some stray darts from the nearby darts board. The school was once a Victorian mansion, inhabited by a sponsor of the great Victorian expeditions

who took Assyrian reliefs from Iraq, and Henry Layard, the leader of the expedition, had donated it. King Assurnasirpal might have been quite surprised to find himself in the Grubber with darts thrown at him, though I’m sure he sympathized with that kind of approach when dealing with his enemies, and he certainly would have understood and respected the business of looting objects in large quantities. But he might have been even more surprised (and indeed relieved) to know that, after being sold for £7 million at Christies, he would wind up in a New Age cultic museum near Kyoto in Japan. As for Canford, it built a new sports centre and theatre with the money and awarded a Mars Bar to every pupil. Saddam, who liked to identify with the likes of Assurnasirpal and who apparently claimed the relief, got nothing. But in 2002 Saddam also made a bolder (if equally hopeless) claim for the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, whose fragments had been gathered by German archaeologists before World War One and placed in a special new museum of antique architecture, the Pergamon Museum, right in the heart of the city. When this Berlin museum is open (which is rare these days), one can have the thrilling and rather dislocating experience of walking through the greatest gate of Babylon straight into the Roman marketplace of Miletus.

A couple of galleries away stands the immense Pergamon Altar, one of the largest and greatest survivals of the ancient Greeks. The latter, naturally, has been claimed by Turkey (whose government and population has nothing to do with the Greeks of ancient Pergamon except that the Turks conquered and today inhabit that land – perhaps, the Turkish government’s logic indicates that the land too should be returned?). It’s likely that Germany ‘saved’ the monument, or at least gave us a more thorough scholarly display and treatment, though of course it’s had its vicissitudes because of Berlin’s own terrible 20th century history. (Much of the altar, having been treated by the Nazis pretty much as a holy icon, was then carted off as war loot by Soviet Russia and taken

24

to Moscow in 1943 – it was returned in 1958).

But even if Germans ‘saved’ the Pergamon Altar, altruism was clearly not the only motive for moving the huge monument to Berlin: in 1871 the Prussian culture minister had addressed Kaiser Wilhelm I thus: ‘It is very important for the museums’ collections, which are so far very deficient in Greek originals […] to now gain possession of a Greek work of art of a scope which, more or less, is of a rank close to or equal to the sculptures from Attica and Asia Minor in the British Museum’. The hunt for Greek antiquities was a 19th century national arms race.

The ugly building that houses these things, built under Kaiser Wilhelm II at the beginning of the 20th century, is now in serious trouble. Apart from leaks and rotten metalwork, its sheer weight, and that of the treasures inside, is

resulting in it sinking – it’s on the move again. Berlin is built on a bog, and this island part in the middle of the city is particularly prone. The altar closed in 2014 for renovation; and now the whole museum has closed and will only fully reopen (we hope) in 2037. Turkish calls for repatriation have grown louder. But it’s worth noting this response from one of the museum bosses in Berlin: ‘We need to show visitors that collections’ histories are inseparable from political history,’ he said, but added: ‘The future cannot be that German museums only show German art.’ Surely this depends, from case to case.

In Gdansk, a city with an especially chequered modern history, there’s a painting with a particularly curious and perambulatory past, and nobody, I think, is claiming that it should ‘go home’ – wherever that may be.

25

Memling’s huge Last Judgement is the star of the show in the picture gallery. Memling would have known about Gdansk, which, as Danzig, was one of the most important trading partners of his native Bruges. But the painting was commissioned by an Italian agent of the Medici of Florence, probably on the occasion of his wedding. It was to travel from Bruges to Pisa via Southampton, and was destined for a family chapel in the Badia Monastery close to the centre of Florence. But on its way to Southampton on a boat richly laden with luxury goods, it was captured (along with everything else) by pirates, who subsequently sold it in Danzig. There was a legal wrangle, involving Florence, England, Burgundy and Danzig, but it remained in Danzig and graced the main church. Thereafter it was coveted by the Habsburg Emperor Rudolph II and later by Tsar Peter the Great of Russia but somehow managed to escape their clutches. But Napoleon took it to Paris, after which it spent time in Berlin; and, during World War II, Stalin took it to Moscow. After all that, it is almost

incredible that it is not only back in Gdansk, but also in extremely good condition: a resilient treasure indeed. And, given all the momentous and devastating things that it’s witnessed, its eerie and atmospheric treatment of its subject, the Last Judgement, feels especially apt and powerful.

Finally, nobody reacts in outrage and disgust, so far as I know, at the display or war loot that adorns Venice and especially its most beautiful building, St Mark’s Basilica. Much of it was stolen from the Byzantine Empire in 1204 (and subsequent years) when Venice helped to conquer that city for the crusaders. There are some choice pieces, most notably the Four Bronze Horses and the Tetrarchs, as well as a lot of beautiful relief panels, exotic columns (such as the serpentine one propping up the church of S. Giacomo dell’Orio), and brilliant metalwork. There are no nuances or legal niceties in most cases here: this stuff was stolen, and Venice benefited and continues to benefit, while Constantinople and its empire suffered

26

and eventually collapsed (partly because of Venice’s aggression in 1204). Should it be given back, to the monks of Athos, or somewhere where Byzantium lingers? Or to the Turks who now rule and inhabit Constantinople? The trouble is that the Bronze Horses of Venice were themselves taken from somewhere else and put in Constantinople; where does one stop? And what about the Egyptian temple obelisks that occupy the centres of Rome’s piazzas? Should there be returned to Egypt, along with the granite columns that prop up the portico of the Pantheon?

Should stolen art be repatriated? The answer to the Venice and Gdansk thefts is pretty clear, as is the answer to the Adele Bloch-Bauer and Mona Lisa thefts. The Ishtar Gate is better off in Berlin than Iraq, for obvious reasons. And the Elgin Marbles debate will rage. There seems to be an arbitrary cut-off date for the acceptability of pinching art, and that cut-off date seems to be moving backwards. No one minds now much about Venice’s looting spree of 1204, or those North Sea pirates who grabbed Gdansk’s Memling in the 1480s. On the other hand, the modern

theft of Jewish property in World War II horrifies us, while that of the Mona Lisa just looks mad. But opinions have been shifting about the big archaeological projects of the 19th century: we can be relieved that the Ishtar Gate is in Berlin not Baghdad (even if it’s sinking), but more vexed about Benin bronzes and Greek reliefs.

What all these strange stories demonstrate is how the movement of works of art and architecture has always been heavily charged and indeed remains so. That’s often for their familial, political, national, or purely monetary value, as well as the sense of righting injustices. In other instances, it’s apparently just for their association with vaunted, semi-worshipped artists, and sometimes because of worthy efforts to save them from possibly destruction. Today’s changing attitudes to this movement of art and to the display of such things mark merely the latest chapter in a very long and extraordinary narrative. But the present spotlight on historical ownership, legal rights and indeed the very purpose of museums may in due course have spectacular consequences and it’s worth watching this space.

27

Nuclear weapons as a deterrent in modern geopolitics

Nuclear weapon technology was invented during World War II in an American led effort to quickly develop powerful weapons, known as the Manhattan Project. To this day, nuclear and atomic weaponry have only been used on two occasions, both by the US against Japan in 1945. The war had ended in Europe; however, Japan was refusing to surrender. In order to end the war, the US dropped two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This caused absolute devastation and catastrophic loss of life, prompting the surrender of Japan and the end of the war on the second of September 1945. At that time, the USA was the only country to have possession of atomic weapons so there was no fear of retaliation.

This changed in the years after the war. Other nations quickly developed their own nuclear weapons for reasons of national security, prestige, and given domestic political dynamics. (from article by MIT, Jan 2022). The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) became the second country to detonate a nuclear bomb in August 1949. The United States in turn responded to this by attempting to develop even more advanced weapons. The Cold War arms race had begun.

Matilda B (Sh)

This completely altered the way nuclear weapons were viewed. Before they had been a means to end a war, however, they became a symbol of strategic conflict, where each side built up an ever larger and more advanced stock to essentially try and dominate their enemies. During the Cold War, the United States, and the USSR stockpiled tens of thousands of nuclear warheads.

The closest the world has come to nuclear war was in October 1962 when the Soviet Union had installed missiles in communist Cuba, an island only 90 miles from America. This caused a 13-day military and political standoff known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Fortunately, disaster was avoided when the United States agreed to an offer proposed by the Soviets which meant that the USSR would remove the missiles if the US promised not to invade Cuba.

During the Cold War the United States and the Soviet Union built up a cache of warheads so large that they could have easily wiped-out all humanity in the event of war. The amount was so excessive and the risk to the world so great that the major protagonists and the international community introduced the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The treaty went into effect in 1970 and it separated countries into two groups – nuclear weapons states and non-nuclear weapons states. Nuclear weapons states agreed not to use nuclear weapons or help non-nuclear states acquire nuclear weapons. They also agreed to gradually reduce their stockpiles. Non-nuclear states agreed not to acquire or develop nuclear weapons. The period following this saw the

28

threat of nuclear war diminish, and the US and the USSR both greatly reduced their nuclear arsenals as the Cold War ended.

Despite this, nuclear weapons remain a fundamental part of the military arsenal of both the established nuclear powers and, worryingly, a growing number of errant states. North Korea has dozens of warheads, and Iran has enough enriched uranium for its first bomb (United Nations).

When Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine on 24th February2022, he warned of a nuclear strike. He threatened countries which may have interfered with consequences “such as you have never seen in your lifetime” (Economist). His invasion of Ukraine was already the biggest attack on a European country since the Second World War, but he was invoking a nuclear threat to support a conventional war, which is more like World War Two than other military threats in modern times. In recent years warnings have only been issued against countries, such as North Korea and Iraq, that have threatened to use weapons of mass destruction themselves. This makes what Putin has done both different and more corrosive.

The key to nuclear deterrent is that it only works if the countries threatened believe that the weapons could actually be used. Although many analysts and officials are dismissive of these threats, suggesting these are merely meant to intimidate the West, the threat still limited support from NATO reaching Ukraine, showing the deterrent did work. Anders Sanberg, who researches risk at the University

of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, said ‘The risk of nuclear war is probably much higher than many of us might want to assume.’

The issue is, even if Russia does not decide to use nuclear weapons, Putin has already upset the nuclear order on a large scale. Putin’s threats limited the help NATO was prepared to offer to Ukraine. This creates two main problems. The first being that vulnerable states now may believe that the best defence against a nuclear armed attacker is to have nuclear weapons of their own. Secondly, nuclear armed aggressors will believe they can benefit in the same way Russia has by following Putin’s tactics. Although over the last 12 months the threat of nuclear action has diminished by a huge amount, the impact on the nuclear order may still stand.

Russia’s threat to use nuclear weapons was met with no retaliation from Western powers. This raises the question of whether any of the NATO countries would be willing to resort to the use of nuclear weapons if the situation called for it. As stated previously, the nuclear deterrent only works if it is plausible to believe nuclear weapons would be used. If errant states do not believe that NATO and the West would use their nukes if it came to it, then the deterrent does not work. As time goes on and more countries develop their own nuclear weapons, the nuclear order continues to change drastically, as does the role of nuclear weapons as a deterrent in geopolitics.

29

May 2024

Marlborough College, Wiltshire SN8 1PA www.marlboroughcollege.org