ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF

TELEVISION

Reflections on the development and impact of this influential medium

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF

Reflections on the development and impact of this influential medium

This year’s themed publication is titled One Hundred Years of Television, and our academic scholars have been busy delving into all that this remarkable milestone entails. 2025 marks one hundred years since the first television image was transmitted by Scottish inventor John Logie Baird. The first television picture was a greyscale image featuring the head of a ventriloquist’s dummy nicknamed ‘Stooky Bill’ (featured on our cover). Later, Baird fetched office worker William Edward Taynton to demonstrate how a human face would look in the same picture: Taynton became the first person to be televised. Baird could scarcely imagine that from this modest beginning would grow a medium that permeates almost every aspect of modern life.

From its mechanical origins, television has evolved into a sprawling network of content delivery: from wallmounted Smart TVs to handheld phones, VR headsets to gaming consoles. Today, television is a fixture of every day life, whether it’s morning news, afternoon antiques, or the nightly scroll through a streaming platform’s offerings. It educates, informs, entertains, provokes, distracts and occasionally transforms us. To those of us fortunate enough, television is not just a luxury but a backdrop to our lives, and has become a shared reference point which shaped – and continues to shape – generations.

The 21st century is frequently dubbed ‘The Golden Age of Television’, and with good reason. The technological leaps in digital broadcasting and streaming platforms have revolutionised how we consume content. Critically acclaimed series such as The Wire, Breaking Bad, and Game of Thrones have demonstrated that television can now rival, and in many cases surpass, film in terms of narrative depth, production quality, and cultural impact. With the introduction of streaming services in particular, binge-watching has become a cultural phenomenon, encouraging the public to spend even more timeconsuming media than before. In response, this media has become widespread across every conceivable genre: whether it is comedy, drama, documentaries, thrillers, science fiction or more, there is some form of television for everyone.

In light of this century of innovation, the breadth of topics our students cover reflects the incredible diversity of television itself. Whilst some have chosen to delve into its early days, with investigations into the pioneering work of John Logie Baird and the intense rivalries that played out in the so-called Colour War, others have examined the influence of television on public perception and culture, with articles covering television’s role in encouraging historical bias and shaping attitudes through Russian propaganda. Other responses consider the commercial side of the industry, with discussions ranging from the use of subliminal messaging in advertising, to the evolving models of how television is financed. In addition, some pupils have chosen to explore more contemporary concerns such as the neurological impact of consuming short-form content on platforms such as TikTok, to the medical accuracy of the show Grey’s Anatomy. Together, these articles demonstrate that the influence of television, in all its evolving forms, remains as compelling and far-reaching today as ever.

This publication would not be possible without the tireless work of Jackie Jordan, who determinedly worked through injury to ensure that all submissions were the highest quality. Without her editorial precision and attention to detail, this publication would not be brought together so beautifully. Thanks must also go to C A F Moule for organising and leading the academic scholars programme, and providing pupils with the structure and inspiration to produce work of such quality and scope.

Like the medium of television itself, this publication embraces variety: a vivid tapestry of analysis, curiosity, and insight. Each contribution reflects both an area of interest and broader engagement with the world around us. The scholars have approached their chosen topics with both intellectual rigour and personal flair, revealing that television is not just a passive form of entertainment, but can be a cultural mirror; commercial machine; social commentary; and psychological force. Whether our pupils have examined the past, reflected on the present, or speculated about the future, each author invites us to consider how this invention continues to shape our lives, and what the next hundred years might hold. We are delighted to share their work with you.

In the last 100 years television has become a huge part of our lives. Roughly 5.4 billion people watch televisions worldwide. This is around 68% of the 8 billion strong population of the world. Usage varies from country to country but, in 2023, in the UK the average person would watch around 4.5 hours of television and video content per day. Yet this pillar of our lifestyles was invented less than 100 years ago. The first television was made in 1926, by John Logie Baird, and it wasn’t until 1936 that the BBC were making regular transmissions. So where did television come from?

John Logie Baird was born on the 13th of August in 1888. He was born in the Scottish county of Dunbartonshire to John Baird and Jessie Inglis. John Baird was a priest, but his son did not take up his faith. Logie Baird went to boarding school, Larchfield Academy, before going to college at the Glasgow and West of Scotland Technical College. The College gave him his first taste of engineering in a variety of apprentice jobs. To finish his education, he went to Glasgow University where he studied engineering. Unfortunately, his education was cut short by the World War which started during his first year in 1914.

After leaving university, Baird initially applied to join the army but failed because he had been declared unfit for active service. When he was young, Baird had suffered from a near fatal illness. This had left him with a ‘weak constitution’ which meant that he was never at full health and was always susceptible to illness. So, instead he was sent to work at Clyde Valley Electrical Power Company. To help the war effort, Clyde Valley was working as a munitions factory.

After the war, John Logie Baird had many different business ideas few of which succeeded. For example, he moved to Trinidad in 1919 and seeing the vast array of fruit available, he attempted to set up a jam factory which shortly failed. His most successful idea was a water absorbent sock which he marketed and sold. In 1923, his weak constitution struck again and Baird moved to Hastings. Increasingly, he turned his thoughts towards becoming an inventor.

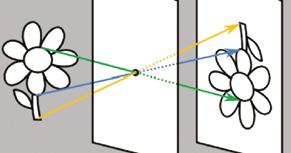

When John Logie Baird was born, the camera had been around for more than 70 years and in 1923, it was 107 years old. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had invented his heliograph in 1816. This was a camera which used a light sensitive substance called bitumen. The bitumen would be dissolved in lavender oil before being spread on a polished metal plate in a thin layer. This plate would then be placed inside a dark box with a small hole facing outwards. This device is known as a pinhole camera or camera obscura. It would project the image upside down but clearly onto the plate. The bitumen side of the plate would face outwards towards the hole. Niépce would leave this contraption on his windowsill for days before taking the plate out. On exposure to light, the bitumen would harden. This meant that Niépce could dissolve and wash off the unhardened

bitumen, leaving an impression of the scene on the plate. 23 years later, Louis Daguerre created a camera which was much closer to something we might see today. He used treated silver to leave an impression of the image in a very similar way to Niépce. In his later models, even though the process of preparing the chemicals on the plate was much more complex, the process could be used to take pictures in under a minute. So, by the time Baird was born, the public were used to seeing photos.

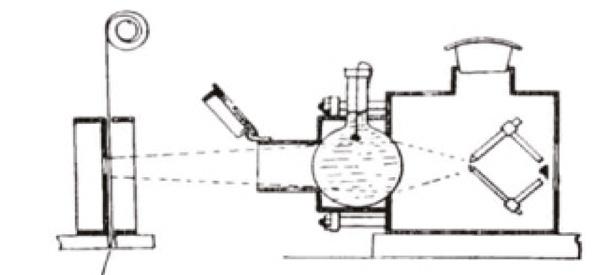

John Logie Baird had also grown up with film. In late 1895, when Baird was six, the Lumière brothers had hosted the first public screening of a moving picture. They used their cinématographe to show a film of the workers leaving the Lumière factory. It lasted just under a minute and was watched by an audience of 30. These early films have since become iconic, for example the Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station and The Sprinkler Sprinkled which both lasted around a minute. The cinématographe worked using photographic film. By using shutters, the film would

rotate very quickly in front of a light source with no deceivable separation between images. The Lumières based their device on the kinetograph which was an early form of projector but was very heavy and impractical. They were trying to make a smaller more portable version of it. They used a handle which could be turned to move the film in front of the camera. In later versions, the Lumières incorporated a spherical glass which could be placed in front of the light. The water inside the glass would refract the light inwards. This meant that at certain distances the light would converge in the same spot and be very concentrated. This meant that the film could be put at that distance and exposed to much higher amount of light making the image clearer and more defined.

It is estimated that there were already 10,000 movie theatres in 1910. Films were becoming available to the wider public and were no longer seen as an experiment. They were already estimated to be one of the most popular forms of entertainment despite the fact that the films were silent and black and white. As they became longer, the rich began to see them as more than just a cheap novelty because the films could now tell stories. Some actors and directors were becoming household names and were gaining recognition from the wider public.

There were sceptics who were beginning to raise questions - some thought that films were rotting children’s brains and wasting their time. Others were more worried about theatre fires from the flammable nitrate photographic film which could sometimes catch fire if the light from the projector made them too hot. Other arguments included that films could damage your eyes and the view that actors were social rejects and they did not deserve the publicity. In spite of this, the film industry was booming and the filmmakers were charging more for the longer, higher quality movies, further inflating the worth of the industry.

In 1923, with the film industry still booming, Baird was in ill health. He decided to put his wider business interests aside and focus on developing his legacy. The media and other inventors were beginning to discuss the idea of a machine that could turn transmissions into pictures, the television. The television could not use photographic film or light reactant chemicals which meant that the inventors were going to have innovate. John Logie Baird had very little funding or resources. To make the first television, which he called the televisor, he used what he had at hand including a hatbox, bicycle light lenses and a tea chest. The televisor eventually incorporated many other designs by other inventors. Baird used Paul Nipkow’s disks to make his transmitter and receiver. These disks when spun would direct the light onto a light sensitive cell as a strip of light. The disks had 30 holes meaning that there were 30 strips on Baird’s first television. The light sensitive cell would turn the light strips into electrical signals which could then be transmitted. At the television end, the electrical signals would be amplified and plugged in to a neon gas discharge lamp. The lamp had a variable brightness depending on how much electricity ran through it. The light from the gas lamp could then be focused onto another Nipkow disk rotating at the same speed as the other one. This one would also have 30 holes and would then shine the light onto and through a screen. This process worked at five images per second and gives a black and white image in 30 very slightly separate vertical lines. This system was exhibited for the first time on the 26th of January 1926 to a few select members of the Royal Institution of Science. The screening took place in Baird’s new lab in Soho, London. The observers initially watched a moving dummy (it was called Stooky Bill) being filmed downstairs. Because this was going so well, an office boy was then added to the set.

Following the success of Baird’s first television, he founded his business, Baird Television Development Company Ltd. By 1927, Baird had improved his system enough to allow it to show 12.5 images per second. To keep up with the quickly moving market, Baird kept developing his idea. By 1928, he had attempted to make a colour television. This used three Nipkow disks and two gas discharge lamps. He added a lamp full of mercury vapour and helium for green and blue to the neon lamp which was red. The same year, Baird demonstrated the first stereoscopic (3D) television. 1930 marks the first sound and picture television transmissions. In 1931, Baird televised the first outside broadcast for the BBC - the Derby. In 1936, the BBC began regular broadcasts but, by 1937, Baird’s television was abandoned for the MarconiEMI system. By the time the Second World War started, there were roughly 20,000 television sets in Britain. Baird’s final invention is the telechrome. This device should have been able to show pictures in colour and 3D. The system created light beams by firing electrons at cyan and red phosphor which created a beam that could be directed at a screen. This could create a variety of colours that was wider than any other television of its time. The process of integrating the telechrome was still underway when Baird died in 1946 of a stroke. This may have been caused by his weak constitution.

In the past 100 years, the television has continued to evolve from the televisor, yet its heritage still lies with Baird. He is remembered through various memorials including the television awards (the Logie Awards) in Australia and a plaque to him in Helensburgh, his home town in Scotland. He certainly wouldn’t recognise the enormous flat screen televisions that adorn our walls today!

FCC:

Short for ‘Federal Communications Commission.’ It is an independent agency of the United States government that holds authority over most areas of the electronics and communications industry.

RCA:

Short for ‘Radio Corporation of America.’ In the early 1920s, RCA became the dominant electronics and communication firm in the US. However, in 1986, GE - General Electronic – acquired RCA and sold or liquidated most of its assets.

CBS:

Short for ‘Columbia Broadcasting System.’ It was once the largest radio network in the US and is now one of the ‘Big Three’ American broadcast television networks. At present, it no longer directly owns or operates radio news stations.

NTSC:

The first American standard for analogue television. It was developed and published in 1941. In 1953, the ‘second NTSC’ standard was adopted and became one of the three major formats for colour television.

After World War I, a worldwide economic boom not only increased television’s manufacturing capability but also provided a huge amount of excess funds, which allowed the television industry to invest in a new medium. In around 1939, the United States only had about 10 experimental TV stations nationwide, each of which was only testing broadcasting ranges and receptions. Being in the experimental stage meant they were prohibited from broadcasting commercial messages; therefore, there was no solid funding for the project. All TV industries were waiting for the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) to settle on a television standard and regulations. Since there was no television standard yet, every company wanted to get their system adopted. They were aiming for the profits that they could get from being able to license that technology. The war for Colour TV involved many parties, but I will describe the situation from these two big corporal giants’ perspectives:

Radio Corporation of American – RCA headed by David Sarnoff.

Columbia Broadcasting System – CBS headed by William S. Paley

At first, in 1940, RCA’s (Radio Corporation of America) black-and-white standard for television was considered by the FCC as a standard. But on August 29th, CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) unexpectedly announced that they had been developing a sequential colour system – created by Dr Peter C. Goldmark - which used a standard monochrome CRT display behind a synchronised rotating colour heel. They claimed that if the wheel were spun fast enough, the primary colours would blend to form a colour television.

+On the other side, RCA was also working on a colour system, but it was barely in the experimental state. Ultimately, the pressure on the FCC to act was too great. So, in June of 1941, the FCC compromised by announcing their black and white NTSC television standard. Unfortunately, despite CBS’s big campaign on their new colour system, they did not meet this standard.

CBS lost the first round

World War II kept everybody preoccupied and there was not much progress during the war years. In December 1946, CBS was still trying to convince the FCC to adopt their system for colour. With Charles Denny, the new FCC chairperson, expressing his staunch support for CBS’s system, it seemed like everything was going well for CBS. However, in March 1947, the FCC finally announced that CBS’s colour system was still too premature.

CBS lost the second round

In mid-1947, a problem occurred. People who lived between stations of the same channel, or adjacent channels, could not watch their television normally as their television’s screen would show a scrambled display. This is because different signals from different stations were interfering with each other. To fix this problem, on September 30, 1948, the FCC halted all new TV station licenses.

Then, in 1949, RCA displayed their newly modelled television set, composed of three vacuum tubes, each projecting an image onto frosted glass (the full set weighed close to a ton). The FCC suggested RCA’s system to be dropped immediately without even field evaluating it. This was a public embarrassment for the RCA. On May 26, 1950, the FCC ruled in favour of the CBS mechanical colour system - approving it on September 1, 1950.

CBS took the win in the third round

To recover from their previous failure, RCA’s David Sarnoff put in all effort toward improving the shadow mask concept, while also leading others in the industry to formally establish the “second NTSC.”

On June 25, 1951, CBS commenced colour broadcasting with Premiere on a five-city network. Three months later, the first CBS sequential colour television went on sale: the CBS-Columbia Model 12CC2. Unfortunately, with only two hundred sets shipped and one hundred sold, most of the public ignored this overpriced television ($500). At that time, TVs were selling in their millions a year. Compared to that, CBS could only sell a hundred. This shows the degree to which CBS’s television failed to attract customers.

CBS lost the fourth round

Senator Charlie E. Wilson of the Defence Production Administration issued an order on November 20, 1951, instructing CBS to abandon production and development of colour television because it might lead to a shortage of vital electronic components needed on the war front. That was considered the unofficial end of CBS’s sequential mechanical colour. Two years later, CBS officially revoked their colour standard. In contrast, on July 22, 1953, the second NTSC committee submitted their new colour standard to the FCC. This time RCA was leading the way with their electronic colour system that separates luminance and chrominance and a CRT screen with Red, Green, and Blue coloured phosphors.

In December of 1953, the new NTSC Colour standard was unanimously adopted.

The RCA took the final win

Black and white TVs continued to outsell colour TVs for yet another decade after that. It was only in 1972 that the colour sets started taking over. The ‘Colour War’ happening in the United States was not the only occasion that promoted the development of the colour system. For example, in 1956, the first alternative colour system was developed in France by Henri France which would later become SECAM. SECAM was a politically motivated colour system; it was made to counter the Americans and protect French Television industries. SECAM uses the same principle of separating luminance from chrominance as the NTSC; however, SECAM fixed a phase problem that the NTSC had. The NTSC could potentially lead to phase distortions over exceptionally long distances which could make the colours go a bit off – e.g. turning green to blue. In 1959 Walter Bruch, working at Telefunken in Germany, developed a hybrid of NTSC and SECAM. His system was called PAL, and, unlike NTSC and SECAM, it would not be backward compatible. It took Europe about 20 years after World War II to adopt the German system. In 1967, the UK implemented the PAL system on BBC2, the second and more high-end channel of BBC. Then, on November 15, 1969, BBC started broadcasting in PAL.

Although now both NTSC and PAL have been abandoned for digital broadcast; nevertheless, the effect of the war of Colour Television also paved the way to how we make television and video today. If you are interested in more information about the history of Television around the world, you can try exploring the ‘Early Television.org’ website.

Bibliography: EarlyTelevision.org by Bob Cooper Inventionandtech.com ‘The Color War’ by Marshall Jon Fisher

Bertie F (Sh)

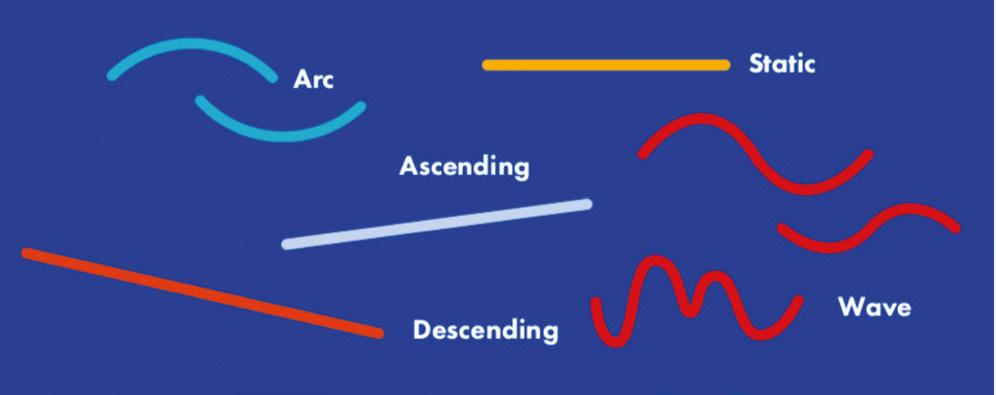

Digital television was first researched as early as the 1960s but due to requiring bandwidths of 200 Megabits per second for SD (Standard Definition) and 1 Gigabit per second for HD (High Definition), it only became a viable possibility around the 1990s. Digital signals are preferred for a variety of reasons, primarily because analogue signals are susceptible to interference. This is primarily because analogue signals are continuous, smooth waves of which amplitude and frequency dictate the brightness of the pixels and so can be negatively affected by distance or obstacles in the transmission path; whereas digital signals are binary (values of zero and one), with each signal being on or off, known as a bit. Since the system must discern between only two values with digital, as opposed to a continuous range of values with analogue, the television presents the user with less distorted images and audio as a result.

Digital systems also have more advanced error-correction techniques such as Reed-Solomon coding, Turbo code, and Viterbi algorithms, all of which can be employed by television systems to “fill in the gaps” of information lost in transmission. An additional reason as to why digital signals are clearer and less prone to distortion is more advanced digital modulation technology. Analogue systems use FM (Frequency Modulation) and AM (Amplitude Modulation), using one path to encode information, whereas digital systems use QAM (Quadrature Amplitude Modulation) and OFDM (Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing), which encodes information in multiple parts of the signal, spreading the data over a variety of frequencies. This makes the signals more robust against interference as even if one part of the signal is corrupted, the other parts of the signal can be preserved, and used to restore the missing signal using the aforementioned error-correction techniques.

However, to make the transition to this superior technology, great levels of research had to be done in fields such as digital signal processing, compression algorithms to lower file sizes of the video and audio involved in television, telecommunications and networking -such as expanding broadband networks and the development of satellite communications-, and devising broadcasting standards such as the ATSC (Advanced Television Systems Committee) in the United States, the ISDB (Integrated Services Digital Broadcasting) in Japan and the DVB (Digital Video Broadcasting) in Europe. These groups helped to establish and define the technical standards of digital television such as aspect ratio and resolution, frame rates, audio formats, and more. To do this, further levels of scientific research were conducted around visual perception, to find the most optimal resolution levels (e.g. 1080p, 1440p/2k, and 4k) for a realistic and immersive experience.

Digital television also employed flat panel displays such as LCD, LED, and OLED as their primary form of display as opposed to analogue, which employed CRT (Cathode Ray Tube) as its primary form of display. Scientists also had to carefully plan the electromagnetic spectrum to make sure that television did not interfere with other forms of communication, developing new antenna technology to ensure the reliability of the new signals. During the transition, the social and economic impacts also had to be investigated, as well as providing information to the public and ensuring that digital converters could be employed so that older analogue televisions could utilise the signals. DRM (Digital Rights Management) and HDCP (HighBandwidth Digital Content Protection) had to be set up to ensure that intellectual property was protected, and that piracy was prevented, and ensure that content was securely transmitted.

Additionally, stronger encryption systems had to be put in place to prevent unauthorised access to premium content such as pay-to-view and subscription-based channels. Software such as EPGs (Electronic Programme Guides) also had to be developed to be user-friendly, as well as smart TV interfaces and transporting software only available for computers such as games and applications. Multi-Platform Distribution such as streaming and VOD (Video on Demand) were developed to transmit television

services via the internet with platforms such as Netfix and YouTube becoming increasingly popular with the rise of digital television. HbbTV (Hybrid broadcast broadband Television) was developed to offer both traditional television broadcast and smart TV services to work harmoniously in the same television system.

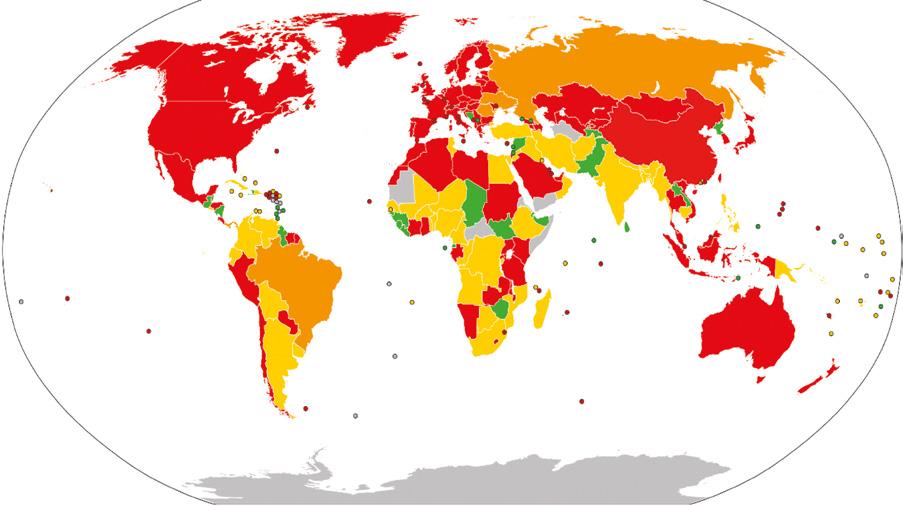

The map illustration above depicts stages of digital television transmission, red indicating “Transition completed; all analogue signals terminated”, orange depicting “Transition partially completed; some analogue signals terminated”, yellow depicting “Transition in progress; broadcasting both analogue and digital signals”, green depicting “Transition has not been planned or started, or is in early stages” and grey depicting no information available.

Today, many countries have fully switched over from analogue to digital, with Luxembourg being the first country to complete its terrestrial switchover on September 1st 2006, and Albania being the most recent, completing the switchover on December 29th 2020. The United Kingdom began the switchover on the 17th of October 2007 and completed the switchover on the 24th of October 2012.

In conclusion, the switchover from analogue to digital television, despite requiring intense research and technological requirements, has already shown itself to be an incredible advancement in society, and a pivotal moment in the history of television. It required research in a variety of scientific fields, including data transmission, coding and algorithms, error-correction techniques, telecommunications and networking; new methods of signal processing; analysis on new resolutions and display types to yield realistic results; protection of televised content; new software to give users a choice between on demand video and content spread by the internet, and allowing users to use both forms of software with the same system; satellite development; organising, planning, and regulating all forms of the new technology, as well as providing information to the public and making sure that the technology could be available to people regardless of their current system. As TV continues to develop with new technologies, allowing for even more content and clearer images and audio, the research that has been going on for multiple decades, and been theorised for even longer, will surely continue to be enhanced and improved in the future.

3-Dimensional Television was so popular in the 2010s that some may even call 2010 ‘the year of 3D TV’. 3D TV sounds like a modern concept – however, the idea of stereoscopic films has been around since the mid19th century. So why, after so many decades of development, has it failed to maintain its popularity?

The first ideas of stereoscopic films include the invention of the stereoscope. In 1832, Charles Wheatstone developed the idea of the stereoscope – a device in which two photos of the same subject taken at slightly different angles are viewed together, creating an impression of 3-dimensional depth. The stereoscope was the starting point for 3D technology; later in the late 1890s, British film pioneer William Friese-Greene filed a patent for the making of a 3D film. This patent described the concept as two videos that were projected side by side, and the viewer would look through a stereoscope to combine the two images into one to achieve the ‘3-dimensional’ effect. Although this plan was never conducted, many more 3D films were released in the next couple of decades.

In December 1922, Laurens Hammond premiered the Teleview system – the first alternating-frame 3D system ever exposed to the public. The left and right frames viewed in the glasses that came with it were projected alternately. Later on in the 20th century, 3D filming evolved from stereoscopes to projecting films with two projectors. This, however, would result in some minor viewing issues, such as the possibility of one frame becoming uncoordinated on one side of the screen, thus jumbling the final video.

Modern 3D televisions work similarly – from the fancy, futuristic glasses to the two alternating images that converge into a 3D one. In 1981, Matsushita Electric (now Panasonic) launched their 3D televisions into stores, and the technology was quickly adapted in preparation for the first 3D stereoscopic video game, SEGA’s Sub-Roc3D. However, it was only after decades of development that 3D technology gained popularity and interest from the public. This was marked by the release of Avatar in 2009 which became the highest-grossing film of all time, which was shot in 3D as well as the traditional format.

After Avatar’s surge in popularity, more major manufacturers began producing 3D technology, along with special 3D glasses. At the Consumer Electronics Show in 2011, a vast range of 3D TVs were unveiled by numerous different tech giants. This was a wide range of novel technology, which included Mitsubishi’s 92-inch model of its new ‘theatre-sized 3D Home Cinema TV’ lineup. Toshiba’s ‘Glasses-Free 4K 3D TV’ prototype was unveiled, and Samsung and LG also announced their 3D TV series. Soon, 3D TVs were the new craze, and their sales had never been better - according to DisplaySearch, 3D television shipments totalised a staggering 41.45 million units in 2012.

Unfortunately, this craze was short-lived, and many buyers soon discovered (possibly too late) that the television sets they had bought had several drawbacks. The one in particular that dissuaded customers from purchasing was the hassle of setting up the 3D television. A BBC article (by Dan Whitworth) covering the first 3D TVs sold in the UK from April 2010 says: “The price of the first TV released is £1,799 - and there are lots of other bits of kit needed to get the right set-up. A pair of the 3D glasses this system uses cost £150, a 3D Blu-ray DVD player is around £350, and a compatible HDMI cable is £50.” These TVs required expensive new 3D gear the public did not already have, as listed in the article. This was a nuisance to most of the public, and some were unwilling to spend the vast sum of money on equipment they were only going to use for an equally expensive 3D TV.

Furthermore, two different kinds of 3D televisions were sold – passive and active, but they also each required a specific pair of glasses only compatible with its own brand and type. This was both confusing and vexing for customers, as this meant that they would have to buy multiple pairs of glasses if they were viewing as a group, which meant more costs. Moreover, the range of Blu-ray movies available to buy and watch was extremely limited, many of which had poor quality 3D and low frame rates.

In addition to the mounting frustrations, buyers of stereoscopic 3D glasses also discovered that there were potential side effects to wearing them, such as dizziness, headache, and nausea. This was because of the flickering caused by the shutters of the 3D glasses opening and closing, despite some TVs labelling themselves as ‘flicker-free’. Warnings were even issued out occasionally on consumer sets, advising the pregnant and elderly to avoid watching 3D movies. Many had also complained online that the glasses were heavy as well, making them even more off-putting to new customers.

Now that the public was slowly finding out that 3D TV sets were not only pricy, cumbersome, but potentially even harmful, sales began to decline. In 2013, sales plummeted and suddenly, nobody was buying 3D television sets. TV manufacturers caught on, and quickly discontinued their 3D lines. By 2016 only a few premium TV models supported 3D movies, but even that did not last long. The last 3D TVs were sold by LG and Panasonic in 2016, but no more were ever produced. Although 3D in cinemas remained intact throughout the late 2010s (as of my experience), movies shown dropped from 102 in 2011 to 33 in 2017 – a significant drop. 3D home TVs died as quickly as they came to life. However, there is still a slither of hope for 3D television. The popularity of 3D films and movies flickered on and off throughout its lifetime – could the 2016 decline of 3D TV just be another one of those flickers? Only time will tell.

Televisions: they’ve become a normal aspect of life. But how much do you actually know about TVs? They show images, you can watch the football on them. But how do they work? Why are they the shape they are? These are just some of the questions that almost no one knows the answer to, and I hope I can provide some explanation.

Why are TV screens rectangular? It’s the kind of thing you don’t ever think about, isn’t it? Of course, it is not just TVs, but other visual representations of the world, people, and places: movies, photographs, paintings. Also, windows and mirrors are mostly rectangular, etc.

Some reasons are:

• TVs are shaped like books, windows, or paintings because we’re used to those shapes. A rectangle feels “normal” to look at.

• TV companies might have stuck with rectangles to make their designs consistent across brands so people wouldn’t get confused.

• Other shapes might have caused issues, like blurry images at the edges or harder production, so rectangles were the easiest solution.

• People got used to rectangular screens over time. Even if other shapes were possible, companies might have avoided them because viewers prefer what they already know.

Another thing most people never think about is how do TVs actually work? TV technology has evolved massively, starting with mechanical TVs, advancing to cathode-ray tube (CRT) TVs, and leading to today’s modern displays. But whilst you may have an idea about how modern TVs work, do you know how mechanical TVs and cathode-ray tube (CRT) TVs work?

Mechanical TVs relied on a Nipkow disk (Invented by Paul Nipkow), a spinning disk with holes arranged in a spiral pattern that scanned images line by line. Light passed through the holes and was captured by a photodetector, which converted it into an electrical signal. At the receiver, a synchronised Nipkow disk recreated the image by modulating light intensity. These TVs were limited by low resolution, dim images, and mechanical inefficiency, but they were a vital first step in TV history.

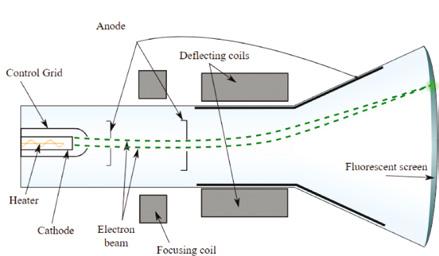

CRT TVs, dominant from the 1930s to the 2000s, used a cathode-ray tube where an electron gun emitted a beam of electrons directed onto a phosphorescent screen. Deflection coils guided the beam in a raster pattern, with its intensity controlling the brightness of each point. Phosphors emitted light when struck, forming the image. Colour CRT TVs used red, green, and blue phosphors, with a shadow mask ensuring correct alignment. While CRTs improved image quality and reliability compared to mechanical TVs, they were bulky, heavy, and consumed significant power. Interestingly curved screens were briefly introduced in 2013, but their popularity declined in 2017 due to increased glare and difficult wall mounting.

Modern TVs, including LED, OLED, and QLED technologies, revolutionised the viewing experience. LED TVs are LCD displays with LED backlights, where liquid crystals modulate light to form images, enhanced by colour filters. OLED TVs use pixels as individual light sources, offering perfect blacks and stunning contrast. QLED TVs enhance LED technology with quantum dots, providing brighter and more saturated colors.

Next, another thing people don’t consider. The sound that comes out of TVs. It comes from speakers, right? But speakers have evolved along with the TV as well. Here’s a brief timeline of how sound has evolved in TVs.

1920s: TVs began as a silent device in 1927, just a picture. The technology to synchronise audio and video had yet to be developed.

1930s and 1940s: By the 1930s, mono sound was introduced, transmitted via amplitude modulation (AM). In the 1940s, frequency modulation (FM) improved audio clearness, allowing matching audio and visuals.

1950s: The black-and-white TVs then set up mono sound as standard. Built-in speakers provided basic audio, and the NTSC standard ensured smooth audio-video synchronisation.

1960s: Stereo experiments began, hinting at richer soundscapes. Though mono sound prevailed, external speaker connections allowed some viewers to enhance their experience.

1970s: The 1970s introduced dual-speaker TVs, making stereo sound more accessible. External outputs enabled connection to home stereo systems for improved audio.

1980s: NICAM (Near Instantaneous Compounded Audio Multiplex) technology debuted in Europe, offering high-quality stereo. Dolby Pro Logic brought multi-channel surround sound, boosting home theatre popularity.

2000s: Flat-panel TVs sacrificed audio quality for sleek designs. HDMI enabled uncompressed digital sound, while soundbars and surround systems compensated for smaller speakers.

2010 – Present Day: Dolby Atmos and DTS:X brought 3D sound to Smart TVs, which also integrated streaming services. Advanced algorithms and multi-directional speakers optimised sound for modern setups.

So, at its core, the invention of television was driven by human curiosity and the desire to send moving images across vast distances. Early pioneers experimented with electrical signals, blending science with creativity to develop a medium that could bring communication and entertainment to life in a completely new way. Fast forward to today, and TVs have evolved into sleek, high-definition devices that are as much about design as they are about technology. From their bulky, boxy beginnings with tiny, flickering screens to the ultra-thin, wall-mounted panels of today, the shape of TVs has been reimagined time and again. Alongside their visual advancements, the sound has undergone a similar revolution. Early models offered tinny, basic audio, while modern TVs deliver immersive surround sound experiences that make you feel like you’re in the middle of the action.

Television has become more than a way to access information or enjoy entertainment—it’s a device that seamlessly blends form and function. From the hum of the earliest black-and-white sets to the crystal-clear images and vibrant soundscapes of today, TVs have transformed how we experience the world. They remain a testament to human ingenuity, shaping not just our living rooms but also our understanding of culture and connection.

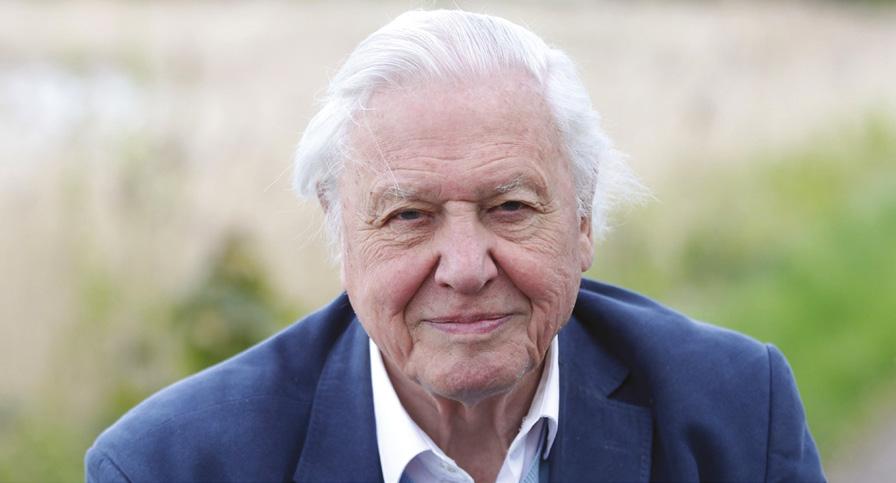

Sir David Attenborough, renowned for his recognisable voice and unparalleled contributions to the broadcasting of Natural History, is an iconic figure whose life has been dedicated to uncovering the wonders of the natural world. Attenborough’s journey from an inquisitive boy to a world-renowned environmentalist and nature broadcaster is a story that greatly interests me, and one that I have thoroughly enjoyed researching and writing about.

David Attenborough was the second of three brothers and was raised in an educationally stimulating and thriving household. His father, Frederick Attenborough, was the principal of University College, Leicester. He was a keen academic, running the scholars’ programme at the College, and he often embarked on research and projects himself. It is no doubt that his father’s intellectual prowess impacted David’s early interest in learning. As a child, Attenborough displayed fascination with the natural world. He used to collect fossils and explore the countryside. He also loved reading books on Natural History and participating in local wildlife expeditions.

Attenborough attended Wyggeston Grammar School, where he excelled in the Sciences. He ended up studying Geology and Zoology at Cambridge, where he was consistently the top of his class. Following his degree, he served two years in the Royal Navy. During these years he travelled and explored new wildlife, deepening his passion for the natural world.

In 1952, Attenborough joined the BBC as a trainee producer. He was initially assigned to work on factual programmes. However, his smarts and passion were soon recognised, and he quickly began rising through the system. In 1954, he launched the show, Zoo Quest. In Zoo Quest, David and his team travelled to exotic countries to capture animals to bring them back to a zoo in the UK (which was legal at the time). In addition, they filmed animals and local people exploring their customs. The programme was immediately successful. It was groundbreaking for its time and captivated audiences, establishing Attenborough as a pioneer in wildlife documentaries.

Throughout the early 1960s, Attenborough continued to develop programmes that explored the beauty of the natural world. He was then promoted to Controller of BBC Two in 1965. During his time, the channel was extremely successful. He helped air incredible shows such as Civilisation, The Ascent of Man, and Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Despite his success, Attenborough wanted to return to the field and write and produce more television series. As such, in 1972 he resigned from his position to return to filmmaking and broadcasting.

Attenborough’s work after this moment went to monumental heights. His series of documentaries began with Life on Earth in 1979 and continued with The Living Planet and The Trials of Life, to name a few. Each programme was meticulously researched and filmed, and Attenborough’s iconic and passionate narration brought information and entertainment to audiences. These series set new standards for programmes and are widely known as the best nature documentaries of all time.

During Attenborough’s time creating his documentaries, his awareness of the threats facing the natural world deepened. In the latter part of his career, he shifted from being solely a presenter of Natural History to becoming an influential advocate for environmental conservation. Recent documentaries such as The Blue Planet and Planet Earth not only showcased breathtaking visuals and spectacular animals, but also highlighted the threats facing ecosystems and the dangers posed by human activity.

In recent years, Attenborough’s message has become more urgent. Works such as Climate Change – The Facts, and A Life on Our Planet are a call to action for our generation and future generations to act on the issues facing our planet. In these films, Attenborough outlines the dramatic changes he has witnessed in the natural world, emphasizing the critical need for sustainable practices to mitigate climate change and preserve biodiversity.

Despite his global fame, David Attenborough has led a relatively private life. He married Jane Elizabeth Ebsworth Oriel in 1950 and they had two children, Robert and Susan. Unfortunately, Jane passed away in 1997, which did deeply affect Attenborough. Nevertheless, Attenborough’s work remained consistently brilliant and a source of inspiration for many.

Sir David Attenborough’s career, spanning over 70 years, leaves an immense legacy. His documentaries have generated hundreds of millions of views and caused countless people to think sustainably and consciously about the state of our world. His work is inspiring and enjoyable for all generations. Attenborough once said that ‘No one will protect what they don’t care about, and no one will care about what they have never experienced’. Attenborough’s work has given people the experience and means to care, so that we can now hopefully act.

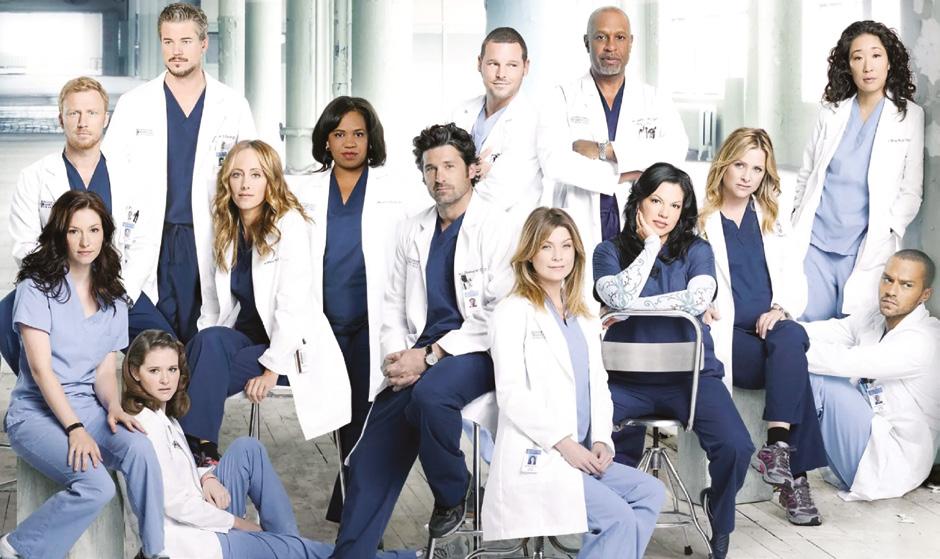

Grey’s Anatomy is a popular medical drama TV series that intertwines the world of healthcare with your typical Hollywood drama. The show premiered in 2005 and recently released its 21st season in late 2024 despite the star of the show, Meredith Grey herself, leaving the show in 2023. The show has sparked many young people’s interest in the medical field and has become an influential platform, raising awareness of the world of healthcare. Grey’s Anatomy’s ability to strongly influence society derives from the fact that Shonda Rhimes, head writer and executive producer of the show, has been able to incorporate real-world issues into the storyline, covering a large breadth of topics, and therefore reaching a wider audience.

Whilst it is such a popular show, suspicion has been raised about the accuracy and how realistic the show actually is. It’s obvious that a real functioning hospital wouldn’t burst into song and conduct a fullblown musical as they did in the controversial episode called “Songs Beneath the Song,” season 7, episode 18; however, how accurate is the medical aspect of it? Are the medical procedures, diagnoses, and protocols all just a load of fictitious, fancy-sounding words that the scriptwriters threw in there to give a false sense of reality?

Grey’s Anatomy has often faced criticism throughout its time under the spotlight for the degree to which the featured content is accurate. There almost always seems to be a rare, unsolvable case with a 0.001% survival rate every few episodes that somehow, more often than not, ends up a success. Shonda Rhimes, alongside the show’s writers, consults with real-life physicians, so why are there still inaccuracies? Those who watch the show but are also in the medical field themselves have stated that the terms and actual procedures are real and are used and practiced in the real field of medicine but are also oversimplified or exaggerated. The operating rooms are presented as extremely fast-paced and high-pressure when in reality it is a slow process that requires delicate precision and a calm environment.

The show gives off an overall sense that the information discussed and the terminology used is accurate; however, to a trained medical eye, there are subtle details that seem almost impossible to overlook. Dr. Kailey Remien, a physician from Ohio who recently discussed in an article the inaccuracies of Grey’s Anatomy, stated that she often noticed the inappropriate and improper use of certain instruments. She says that it drives her crazy when actors put their stethoscopes on backwards and still discover a heart murmur! The meticulous details that doctors have engrained into themselves since medical school seem like second nature to them as they know the consequences if steps are missed, but in the show, it seems that those little details don’t have any sort of disastrous effects on the outcome.

The doctors on the show are portrayed as impulsive and always willing to bend the rules to get the preferable outcome. Protocol is often broken, which jeopardises patient safety, and decisions are made in those high-stakes crises that seem reckless and spontaneous. In real settings, this would be heavily frowned upon and often illegal due to the strict guidelines and ethics that doctors must follow. The punishments that the doctors in Grey’s Anatomy face are, needless to say, lenient. For example, when Izzie Stevens (an intern) cut a patient’s LVAD wire in the interest of her love for him, not only was she still able to retain her license to practice, but also her place in the residency program. In reality, this would have most likely landed the physician in jail as well as having them stripped of their privilege to practice medicine for the rest of their life.

Grey’s Anatomy also inaccurately depicts the hierarchy and the relationship between the different seniorities of doctors, or ‘the surgical food chain,’ as described in the show. Interns normally don’t address or contact the attending, let alone the chief of surgery, as often as the interns in the show do, and this is because, under normal, realistic circumstances, the senior residents act as the bridge between them.

Lastly, something Grey’s Anatomy is infamous for is the extent to which all characters get romantically entangled. It is a frequent question asked of physicians who discuss the show, and the responses are all very similar. Hospitals are incubators, exposed to any and maybe every type of bacteria, so any self-respecting, educated physician would not involve themselves in a sex scandal in the on-call rooms. Additionally, the bottom line is that doctors realistically wouldn’t have the time for such activities when on call. There is always someone to help or something to do because, after all, hospitals are places for people in need and seeking help.

Conversely, some may argue that Grey’s Anatomy is somewhat accurate. Those who are criticising the show often forget that it is a TV show. To a certain extent, everything needs to be dramatised and exaggerated to attract an audience, and at the end of the day, the goal is for the show to achieve that. An inaccuracy that has been brought up by critics is how the show seems to ‘conceal’ the administrative aspects of the job. This may be true, and critics make a valid point that a lot of the job does involve large amounts of administrative work; however, if one thinks about it, as accurate as it may be, no one wants to sit around and watch a show that is just mainly doctors sitting on a laptop or filling in charts.

Some residents have actually commended the writers of the show, saying that they were able to accurately show the reality of working in the field of medicine. The seasons in which MAGIC (the acronym used to describe the 5 interns: Meredith Grey, Alex Karev, George O’Malley, Izzy Stevens, and Christina Yang) were interns were portrayed as brutal, long working days, which is the reality. The writers didn’t sugarcoat it to give a false sense of a fantasy perfect world; instead, it is slightly dramatised so that viewers aren’t led to believe that it’s an easy job. Residents have said that the show was able to encapsulate the emotions of being an intern perfectly. The overwhelming feeling that you are holding someone’s life in your hands but you don’t exactly know what you are doing. It is a terrifying feeling that the show has been able to subtly portray and get across to the viewers.

What viewers often find shocking is that many of the cases featured on the show were based on realworld people and events! For example, it may be hard to believe that the episode where a man walks into the hospital with hands resembling tree branches was anywhere close to being real, but it’s actually a disease called Epidermodysplasia where warts grow on the body that looks a lot like branches or tree bark. Seems more believable now, doesn’t it?

So, in conclusion, just how accurate is Grey’s Anatomy? To the normal eye, Grey’s Anatomy is your typical drama series with crisis after crisis, scandal after scandal, but to a trained medical eye, it is riddled with inaccuracies. From the frequent romantic involvement between characters to the improper use of medical equipment, Grey’s Anatomy does not seem to rank high on the list of most realistic medical shows. However, what people have seemed to lose sight of is the fact that this is Hollywood! Writers most likely consciously left out information to not bore the audience and to make time for other, more engaging storylines. Without the drama and exaggeration, there is no show, and Grey’s Anatomy would not be what it is today: a medical inspiration, an encapsulation of the medical field, and, of course, a prime-time American television medical drama.

City Hospital, which aired in 1951, is often considered to be the first televised medical drama. Since then, hundreds of medical dramas have been produced in Western countries alone, with varying degrees of success. Even after all this time, this specific genre of television is still hugely popular among a wide range of people. A few famous medical dramas include: House, Scrubs, ER, Casualty, with the most notable being Grey’s Anatomy, a series which first aired on 27th March 2005 and which is still going 19 years later. The series is the eighth highest grossing series of all time1, and, according to ABC’s president Ben Sherwood, roughly 200,000 people watch the pilot episode on Netflix each month2. However, what makes this genre so popular, and does it affect real life health-care expectations in a positive or negative way?

On the surface, medical dramas do not seem all that appealing. They feature a location and topic which to most people should seem mundane and relatively familiar. Furthermore, upsetting, gory scenes do not sound particularly great for daytime watching. Despite this, not only the huge number of medical dramas but also the equally large quantity of seasons of these shows, prove they remain very popular.

One reason for this is that they are largely relatable. The shows feature a high level of suspense and drama while remaining tangible to the viewers. This, in a way, makes them all the more tense and the situations are plausible to those watching. Scientifically, our brains find it hard to look away from disaster. Dr David Henderson, who is a psychiatrist explains that ‘witnessing violence and destruction, whether it is in a novel, a movie, on TV or a real life scene playing out in front of us in real time, gives us the opportunity to confront our fears of death, pain, despair, degradation and annihilation while still feeling some level of safety […] We watch because we are allowed to ask ourselves ultimate questions with an intensity of emotion that is uncoupled from the true reality of the disaster: “If I was in that situation, what would I do? How would I respond? Would I be the hero or the villain? Could I endure the pain? Would I have the strength to recover?” We play out the different scenarios in our head because it helps us to reconcile that which is uncontrollable with our need to remain in control’. 3 Medical dramas feature a huge number of disaster-like situations, thus keeping viewers engaged for large periods of time.

While being unarguably popular, medical dramas do not always affect patients and doctors in positive ways. The so called ‘Grey’s Anatomy Effect’ is defined by The National Library of Medicine as unrealistic expectations, like those caused by misleading and unrealistically optimistic medical stories, which often lead to worse health outcomes; as a result, mortality rates increase4. Shows such as Grey’s Anatomy and ER do strive for accuracy by having physician consultants; however, inaccuracies are still common. CPR, a vital part of first aid, has been found to be performed highly inadequately on TV, while resuscitation is successful a lot more than in real life5

As well as this, a 2018 study was conducted screening 269 Grey’s Anatomy episodes versus 4,812 patients from the National Trauma Data Bank National Program Sample6. The results showed that, in Grey’s Anatomy, mortality after injury was notably higher than in real life, with 22% of patients dying in the show compared to just 7% in real life. This makes viewers more anxious about hospital visits, and makes the doctors appear far less competent. The study also found that after arrival to the ER, a massive 71% of TV patients were taken directly to the operating room, compared with a relative minority of 25% in the NTDB sample. This can cause frustration in real life patients when they are not taken to the operating room as quickly as they believe they should be.

It is fair to say that these factors do massively add to the drama and watchability of the series, however because so many people get health information from television (for example a survey of geriatric patients demonstrated that 42% of older adults named television as their primary source of health information7), inconsistencies such as these can have a negative effect on both the patients and the medical professionals involved. This is proved by a study by Dr. Brian L. Quick, a University Professor of Communication and Medicine, which found that viewing Grey’s Anatomy had negative effects on patient satisfaction8.

Opposingly, medical dramas can provide awareness to people who otherwise would have incredibly limited medical knowledge. A study has found that 17% of viewers were inspired to speak to their doctors about an issue they had seen on Grey’s Anatomy9. The show can also help to discourage prejudices which are caused by ignorance to medical facts. This is demonstrated in an episode of Grey’s Anatomy in which a young HIV-positive woman who is pregnant asks for an abortion, before learning that with proper treatment she has a 98 percent chance of delivering a baby who is HIV-free. A study surveyed a random group of viewers before the watching of the episode, a week after watching the episode, and then six weeks after watching the episode. One of the questions asked in the survey was ‘is it irresponsible for a woman who knows she is HIV positive to have a baby?’. Before watching the show, 61 percent answered yes, a week after watching the show, only 34 percent said it was irresponsible and six weeks after the show aired, 47 percent of viewers said it was irresponsible9. Lack of knowledge leads to unfair judgement and prejudices, and shows such as Grey’s Anatomy have helped to tackle this issue in the past, proving that they can have positive effects on watchers.

In conclusion, medical dramas are a genre which has been popular for five decades, and which continue to be widely and frequently watched to this day. It is important for viewers to remember that the shows are not documentaries, and that this should be taken into account when medical ‘facts’ are mentioned. At the same time, viewers should make sure that they talk to doctors or other medical professionals about any issues discussed within the series which concern them. As a species, we love drama so I am sure shows such as these will remain popular into the future.

1 The Billion-Dollar Shows: The TV Shows That Made the Most Money | Brand Vision ( brandvm.com)

2 The Grey’s Anatomy Effect: Unraveling the | Mysite (dukemedicalethicsjournal.com)

3 The Science Behind Why We Can’t Look Away From Tragedy (nbcnews.com)

4 Beyond the Drama: The Grey’s Anatomy Effect and Medical Media Misrepresentation – The Monarch (amhsnews.org )

5 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on television: are we miseducating the public?* | Postgraduate Medical Journal | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

6 Grey’s Anatomy effect: television portrayal of patients with trauma may cultivate unrealistic patient and family expectations after injury | Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open ( bmj.com)

7 The Grey’s Anatomy Effect: Unraveling th | Mysite (dukemedicalethicsjournal.com)

8 The Effects of Viewing Grey’s Anatomy on Perceptions of Doctors and Patient Satisfaction | Request PDF (researchgate.net)

9 Grey’s Anatomy Raises Health Awareness - CBS News

The Hunger Games trilogy is a series of dystopian films based on the books by author Suzanne Collins. The story is based around the annual games that take place in a civilisation called Panem. The Hunger Games are essentially a fight to the death of 24 people, two people randomly selected from each of 12 Districts, leaving one survivor who is showered in riches. This is all led by the Capitol, Panem’s equivalent of a government. The district system is a harsh scale of wealthy to poor, with each being in charge of a particular resource starting at District 1 and ending at District 12.

In an interview with Scholastic Media, Suzanne Collins mentioned that her inspiration for the storyline was the result of channel surfing one night, flipping between a reality TV programme and footage from the war in Iraq. She said ‘the lines began to blur in this very unsettling way, and I thought of the story’. Most dystopian novels may focus on unrealistic or imaginary scenarios to make their book fit into the genre. However, the fact that her idea stemmed from a disconcerting view of reality shows how the storyline of The Hunger Games is primarily focused on the similarities between less fortunate, corrupted countries and a more fortunate countries idea of a nightmare.

Overall, the dystopian trilogy follows three main themes; the District system and economic divide; the exploitation of resources and labour; and control and manipulation of the media. The events in The Hunger Games series are strongly influenced by the segregation between districts and the unjust living conditions that follow. In District 1, where the most common source of work is producing luxury goods, the population is stereotypically wealthy and very comfortable. The same goes until District 3 or 4, the technology and fishing industries. However, lower down the scale is poverty and struggle within District 11, agriculture, and 12, coal mining. These areas deal with notably prejudiced conditions, and it is easy to notice the famine and homelessness in the movies.

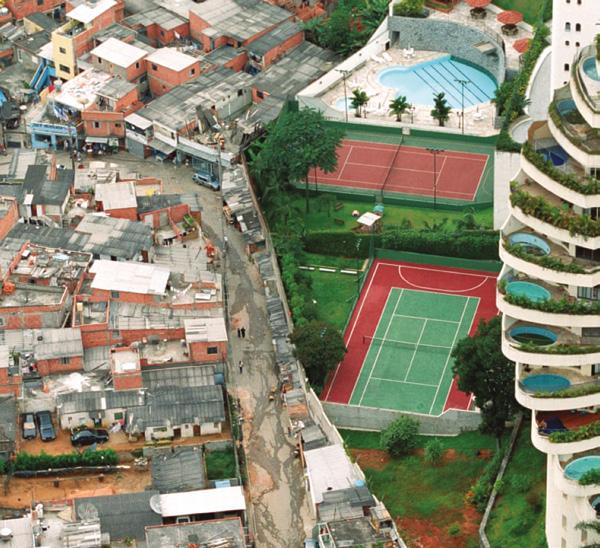

Conditions like these are equally as destructive in the current world, directly mirroring circumstances that support the rich getting richer and evidently allowing the lower classes to struggle. The popular image on the left shows the border between the Paraisópolis favela and the affluent district of Morumbi in São Paulo, Brazil. The immediate distinction between wealth is obvious, yet nothing is done about it. At the moment nobody feels the need to change anything, however a further similarity between fact and fiction is that down the line a large-scale revolution ended up happening. The Russian revolution started as a result of dissatisfaction from peasants, workers and soldiers towards Tsar Nicolas, and ended up with them murdering their Tsar, almost parallel to the eventual revolution in the Games.

Likewise, exploitation of labour and resources is a common theme throughout the trilogy. Whilst District 11 supplies the rest of the population with food, they barely have enough for themselves. There is a general resource scarcity in The Hunger Games, and even though most are earnt by hard working labourers, food is passed off to higher Districts. It is easy to compare this to hard working labourers in Africa, specifically Botswana. Botswana has the biggest yield of diamonds in Africa, and yet its economy still suffers. The reason for this is the foreign owned multi-million-dollar extraction companies managing the sites take the bulk of the profit and get away with paying workers a minimum wage. This is yet another parallel between fictional dystopias and legitimate environments.

Many countries around the world are familiar with surveillance, as it is a secure way to prevent crimes such as theft. However, some governments have harnessed cameras with the intent of preventing freedom of expression. For instance, in North Korea, cameras and CCTV seem to be a standard practice around the country. Moreover, it has been noted that even private conversations can be recorded and examined in a way that completely defies any freedom of speech. Yoshihiro Makino, an author within the book Inside Pyongyang wrote, ‘seemingly, every aspect of a person’s existence in North Korea is monitored. There is a general sense that it is dangerous to engage in any serious conversation about sensitive topics’. This alone proves that with bad intent, even a surveillance system used to prevent crime can become a terrifying concept. In Panem, the country that The Hunger Games takes place in, the Capitol uses cameras in a similar way. What this leads to is an authoritarian government, and a complete lack of free speech. The constant surveillance is a factor that further confirms the dystopian environment that civilians in Panem are living in.

Furthermore, a similarity between worldwide dystopian-like governments and The Capitol is the use of propaganda and media manipulation. Propaganda is now and always has been an alarmingly influential method of promoting a point of view. Displaying posters with information, true or not, or spreading rumours via radio broadcasts, tends to get a point across and support various theories and opinions. Likewise, something as simple as click-bait nowadays is a prime example of media manipulation. However, The Capitol manipulate their media in stronger forms. Every year the games are televised to every District, supposedly to share the ‘entertainment’. Although it may seem innocent, the Capitol subtly benefit from using this as an opportunity to show their population the authority that they hold. Having the ability to make the 24 subjects compete in the first place and being able to force the Districts to watch the games play out show just how much power they possess. The annual game itself was initially created as a form of punishment in order to remind civilians of the cost of rebellions, and to prevent any from every happening again. Overall, it can be said that there are a surprising amount of similarities between a work of fiction with intent to be disorderly, and government systems with an intent to keep order.

Televised football has undergone an exceptional journey, going from a simple broadcast in the ‘30s to a worldwide display that generates billions annually. However, alongside this remarkable growth, the industry has become more and more monopolised with only a few corporations dominating television rights and hiking up prices for the average consumer. The monopolisation of the televised football industry is a worrying, topical issue that has been shaped by modernisation and football as a whole over the course of the past century.

Starting in 1937, the first football game to be broadcasted on TV was a practice match featuring Arsenal’s first team and reserve team in London at Highbury stadium by the BBC. Despite this being a momentous occasion in hindsight, the match reached a very limited audience. However, the stage was set for more to come; in 1938, the first competitive match was televised – the FA Cup Final – between Huddersfield Town and Preston North End. The progression of televised football was then disrupted by World War II yet once that had passed, by the mid ‘50s, football on TV was back up and running. At first, many clubs feared that by televising games match attendance would be reduced which led to an extremely cautious approach with only certain matches being played on TV.

By 1960, ITV took the leap to sign the first contract with the Football League worth £150,000 at the time. This was then followed up by the creation of Match of the Day by the BBC in 1964. This programme featured weekly highlights which quickly attracted thousands of fans, turning it into a cultural phenomenon. Although, it wasn’t until the 1970 football World Cup in Mexico where televised football truly changed. After the BBC’s first colour TV broadcast in the UK in 1969, this was the first tournament to be broadcast in colour providing a live viewer experience that captivated the vibrancy of matches in a way that had never been done before. During this decade, paying leagues and clubs money for broadcasting rights emerged which marked the start of commercial agreements between television and football albeit the sums were very modest compared to what was to come.

The true turning point of televised football came about in the ‘80s. Through the introduction of cable and satellite TV, paired with worldwide economic growth, new opportunities opened for companies. Particularly, in England, attendance in stadiums was declining due to a number of issues including the Heysel Stadium disaster of 1985 and the Hillsborough disaster in 1989 as well as a general decline in the game’s reputation due to hooliganism. From this, teams struggled financially and television was seen as a lifeline by offering clubs new forms of revenue through broadcasting deals. Furthermore, it was through such financial motives that led top clubs to break away and create the English Premier League in 1992 which allowed for their own negotiating of broadcasting rights. Through this, Sky Sports was able to acquire exclusive rights in a massive £304 million deal which included never before seen multi-camera angles, expert analysis and even pre-match entertainment. Seeing this, other leagues and competitions across Europe followed suit negotiating new, lucrative deals. By the year 2000, Sky paid £1.1 billion for a Premier League deal alone.

As the industry expanded, only a few key companies were able to keep up with the rising prices of buying rights. Sky Sports dominated English football although other regions across the world have been monopolised by other giants like ESPN and BT Sports. The shift towards a monopolised industry is down to a few reasons and has many consequences for fans, clubs and the sport itself.

For one, the driving prices for broadcasting deals has begun to reach astronomical levels. In 2015, Sky and BT Sports alone paid £5.1 billion for only three years of Premier League rights. Such costs are passed on to their customers who face rising subscription fees. Moreover, the monopolised industry has led to restricted access for fans across the world. Originally, matches were available on free channels such as the BBC or ITV but now are locked behind paywalls.

Another consequence is that broadcasters have begun prioritising international markets due to the inability for overseas fans to go to matches live and their reliance on televised football. Premier League clubs generate significant revenue from overseas broadcasting deals yet this focus neglects the domestic audience who have to pay more for the service. Lastly, the revenue generated from TV deals has created financial disparity among teams making football less competitive and more ‘pay-to-win’. This is largely due to the fact that bigger clubs are paid more for rights to air their games which simply allows for the gap to grow.

The future of televised football is uncertain in many aspects. The monopolisation of the industry has led to higher and higher prices for the average consumer and there are fears that the average football fan may be priced out of watching weekly games. Fans have voiced frustration and many have begun to turn to piracy. Illegal streams across the internet draw millions of viewers from across the world. To combat this, many teams have started their own TV channels that directly play their games to fans for cheaper prices; however, this comes with many risks that could further disrupt the market.

Overall, the history of televised football is an interesting and important story that describes the rise of football from a simple past-time hobby to a global commercial enterprise. While TV has exponentially grown the game, it has also created a concentrated market in the hands of a few broadcasters that marginalises fans and smaller clubs. This raises large concerns and questions between commercial interests as well as the accessibility and integrity of the game. The sport needs to remain inclusive to all fans across the world and is struggling to do so at this very moment. In conclusion, the future of televised football and the sport as a whole is very uncertain.

Archie D (Re)

The Indian Premier League (IPL) is an Indian cricket competition that was founded in 2008 and has since grown its way to have television rights worth over $6.2bn for a five-year period. While there are many other similar competitions across the world, there are a number of reasons that mean it is unlikely that any of them will ever come close to having such valuable rights, such as India’s vast population and the way that their ownership works.

Before answering this question, we have to understand how TV rights work and how their value is estimated. A TV right is the rights for a broadcasting corporation to show an event live or even at a later date, in the form of highlights or replays. These can be extremely valuable, the NFL having deals worth over $100bn for the next 11 years1, and their value is determined by a variety of factors. These include the number of customers likely to watch a certain event, the amount that they are willing to pay in subscriptions and the amount that advertisers are willing to pay to advertise during these events.

The fact that over 1 billion people live in India means that while TV companies are paying many times more for these rights, they are also streaming to many more paying customers, meaning that while they are paying a lot to get the rights in the first place, Star India (the TV company broadcasting the IPL) is also likely to make more money from more subscriptions. This can be demonstrated by the fact that the Hundred’s (England’s T20 competition) TV rights are worth £251m a year, compared to £1.026bn for the IPL. In India, cricket has an audience of 612m people2 compared to only 13m in the UK3 meaning that broadcasters in India, even though they are paying four times more for rights, are reaching over forty-seven times more customers. This just shows that the population of India, compared to any other cricketing nation, is so large that broadcasting companies like Star India will always be willing to pay more for an Indian competition than its competitors.

Additionally, the way that franchise cricket has developed has meant that the owners of IPL franchises have also ended up buying teams in South Africa, USA, the UAE and the Caribbean and these teams all share players with their linked franchises especially the original teams in India. This means that these competitions will never outgrow the IPL because most if not all of the best players in these other leagues will also play in

the IPL. But many will play IPL and not other leagues for various reasons such as the fact that in the IPL they are being paid extravagant amounts so they have no need to play smaller leagues for the rest of the year. Furthermore, the profits from these sister franchises will either go back to the owners of be pumped straight back into the IPL teams, meaning they can pay more for wages and therefore attract better players.

Some have also begun to wonder if the same is about to happen to England, as the owners of the Delhi Capitals (an IPL franchise) have just made a landmark purchase of Hampshire CCC for £120m and the Hundred franchises have just been put up for sale. If many of these are bought by IPL owners, it seems likely that the Hundred will just turn into another secondary league, and while this would provide financially stability and maybe even some better players (currently the Indian cricket board blocks Indian players from playing in oversees leagues), it would mean that the possibility of this competition being the most valuable in the world would be zero because as soon as there appears to be any risk of it becoming more valuable than the IPL, owners would return their focus to India to make sure it stays the premier cricketing competition in the world.

On the other hand, there are a few reasons why the Hundred could attract large TV deals. Firstly, it is held during August, and this is a time in the year where not only are there no other T20 competitions in August, but also in June and July meaning that there will be more people wanting to watch it. Secondly, the fact that a Hundred game is 40 balls shorter than a regular T20 fixture means that it is even more accessible to new spectators, and it is less of a commitment for someone to watch more often. This will be appealing to TV companies as they are always looking for new spectators to broaden their audiences. The Hundred also has the chance to attract new large sponsors as it is not only a popular, widely viewed competition but it is fresh and new and sponsors may want to be associated with this.

To conclude, for the foreseeable future, the IPL will remain the premier T20 competition due to its high quality of matches and the vast population of its audience. However, there is hope as the Hundred grows for it to solidify its spot at number two and maybe at some point challenge the IPL. Additionally, if the Hundred does continue to grow, if handled correctly, it could start to challenge the IPL, although currently the league is way off even thinking about this.

1 https://www.grandprix247.com/2024/08/01/top-sports-with-the-most-expensive-broadcast-rights/#

2 https://www.business-standard.com/cricket/news/india-s-sport-audience-base-678-mn-2-cricketers-are-most-liked-report-124032000232_1.html

3 https://www.ecb.co.uk/news/3334603/new-figures-show-health-of-cricket-in-england-and-wales#:~:text=13%20million%20people%20describe%20themselves,Inspiring%20Generations%20strategy%20in%202020.

Kerry Packer, a media magnate, never played cricket seriously but few people have made a bigger impact on the game. Kerry Packer opened cricket up to thousands more spectators through the medium of television. In 2005, Kerry Packer and Sir Donald Bradman were named as Australian cricket’s most influential men of the past 100 years. In this article, I will examine how Kerry Packer helped transform the sport and the fortunes of its players by launching his own World Series competition.