GASTROENTEROLOGY

Patients and families often feel most comfortable with their primary care provider and prefer to get their mental health care in the primary care setting. The Missouri Child Psychiatry Access Project (MO-CPAP) was created to help ensure PCPs have the resources, tools and support they need, including same-day phone consultations, referral services and ongoing education.

BOARD CHAIR John Paulson, DO, PhD, FAAFP (Joplin)

John Burroughs, MD (Kansas City)

PRESIDENT-ELECT Kara Mayes, MD, FAAFP (St. Louis)

VICE-PRESIDENT Afsheen Patel, MD (Kansas City)

SECRETARY/TREASURER Lisa Mayes, DO (Macon)

DISTRICT 1 DIRECTOR Arihant Jain, MD (Cameron)

ALTERNATE Mike Feuerbacher, MD (Maryville)

DISTRICT 2 DIRECTOR Robert Schneider, DO, FAAFP (Kirksville)

ALTERNATE Vacant

DISTRICT 3 DIRECTOR Emily Doucette, MD, FAAFP (St. Louis)

DIRECTOR Dawn Davis, MD (St. Louis)

ALTERNATE Lauren Wilfling, MD (St. Louis)

DISTRICT 4 DIRECTOR Jennifer Scheer, MD, FAAFP (Gerald)

ALTERNATE Jennifer Allen, MD (Hermann)

DISTRICT 5 DIRECTOR Natalie Long, MD (Columbia)

ALTERNATE Amanda Shipp, MD (Versailles)

DISTRICT 6 DIRECTOR David Pulliam, DO, FAAFP (Higginsville)

ALTERNATE Justin Cramer, MD, FAAFP (Marshall)

DISTRICT 7 DIRECTOR Beth Rosemergey, DO, FAAFP (Kansas City)

DIRECTOR Afsheen Patel, MD (Kansas City)

ALTERNATE Jacob Shepherd, MD (Lees Summit)

DISTRICT 8 DIRECTOR Andi Selby, DO (Joplin)

ALTERNATE Barbara Miller, MD (Buffalo)

DISTRICT 9 DIRECTOR Douglas Crase, MD (Licking)

ALTERNATE Vacant

DISTRICT 10 DIRECTOR Gordon Jones, MD (Sikeston)

ALTERNATE Jenny Eichhorn, MD (Jackson)

DIRECTOR AT LARGE Wael Mourad, MD, FAAFP (Kansas City)

Josephine Glaser, MD (St. Louis)

Krishna Syamala, MD (St. Louis)

Wesley Goodrich, MD, UMKC

Kelly Dougherty, MD, Mercy (Alternate)

Karstan Luchini, KCU Joplin

Abby Crede, UMKC (Alternate)

Keith Ratcliff, MD, FAAFP, Delegate

Kate Lichtenberg, DO, MPH, FAAFP, Delegate

Sarah Cole, DO, FAAFP, Alternate Delegate

Peter Koopman, MD, FAAFP, Alternate Delegate

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Kathy Pabst, MBA, CAE

ASSISTANT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Bill Plank, CAE

MEMBER COMMUNICATIONS AND ENGAGEMENT Brittany Bussey

The information contained in Missouri Family Physician is for informational purposes only. The Missouri Academy of Family Physicians assumes no liability or responsibility for any inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete information, nor for any actions taken in reliance thereon. The information contained has been provided by the individual/organization stated. The opinions expressed in each article are the opinions of its author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of MAFP. Therefore, Missouri Family Physician carries no respsonsibility for the opinion expressed thereon.

Missouri Academy of Family Physicians, 722 West High Street Jefferson City, MO 65101

p. 573.635.0830

Website: mo-afp.org

Gastroenterology and Digestive Health

Inhibitor-Induced

Tract

Vitamin B12: A Family Practice Perspective

the

Familial Colorectal Cancer Syndromes: A Practical Approach

Review of Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Fatty Liver Disease

Equity in Gastrointestinal Diseases

Rise of Alpha Gal

Chronicles of the 2022 Summer Externs

MAFP Promotes Family Medicine at HOSA International

AFP Participates in National Conference

in the News

f. 573.635.0148

office@mo-afp.org

2022

Self-Assessment

MAFP

MAFP

13-14,

-

Marriott,

MAFP Board of Directors Meeting

City,

City,

Recently, a medical student and I reviewed a new patient’s chart together before entering the room. This was a 40-something-year-old female whose problem list spanned two pages, but the reason for her visit that day was abdominal pain. I noted before we entered the room that, statistically, this young woman had likely been sexually abused at some point in her life. Her medical history offered many clues to inquire about previous trauma. I told the student that since this was our first time to meet, this might not likely come up but that I would eventually have an opportunity to ask. That opportunity came sooner than expected and occurred during that first visit. She described physical and sexual abuse from her stepfather to the point that I was sick to my stomach. This was a very memorable patient for me, and I did not want to miss the opportunity to highlight how elusive abdominal pain can be and how connected our gut is with our emotions.

Looking back on my career in law enforcement, working in crime labs, and now as a physician, I’m astonished at the substances we put in our bodies as well as the physical and emotional trauma that the human body can withstand.

Sometimes, it’s clear why a patient’s stomach might be hurting. Other times it can be one of the most elusive symptoms we encounter.

In this issue, we will focus on GI issues, not emotional trauma. I’m frequently amazed at the variety of disease states involved with GI distress and feel like it is a never-ending topic of study. A brief review of the range of topics in this issue are a reminder of how

interconnected our patients’ lives are to their GI health. I hope everyone will learn something from each of these articles that will help deliver better care to our patients.

On a personal note, my time as Board Chairman is concluding. I am thankful to God for the people I have met and the privilege I have had to serve. Thank you, MAFP members, for allowing me to lead, learn, and grow in this capacity. It is so important to recognize the efforts of Kathy, Bill, and Brittany. Many do not know their significant level of commitment to family medicine, advocacy, and our MAFP members, but they are such hard workers and so committed to our cause. I am certain our organization will grow and succeed with that team behind the wheel. I’m excited about our next strategic plan and the focus on pipeline, education, and advocacy. I think our members can really get behind our students and residents. As we ALL know, they are truly the future of family medicine. To my family, Crissy and Ella, I owe the most heartfelt thank you for allowing me the time for meetings, calls, and for all the conferences and functions you have attended with me. Our family has a lot of memories from MAFP events, and I know we will continue to make more. I have seen and experienced the burnout in society today and how it affects family medicine physicians. In this next season of my career, I hope to become a wellness resource, educating on burnout recognition and helping others develop tools to address burnout and improve their well-being. Thank you for all you do, and may God bless each of you and your families!

PS - I’d be remiss if I didn’t again take the opportunity to ask my colleagues to share their stories with the MAFP about how their gut feeling led them to become a family medicine physician or how FM has positively impacted their life. We are still collecting stories for our anniversary edition! (See back cover for details)

Creighton University Department of Family and Community Medicine Omaha, NE

Sudehsna Dutta, MD, PGY-1

Creighton University Department of Family and Community Medicine Omaha, NE

Gary N. Elsasser, PharmD, BCPS

Creighton University Department of Family and Community Medicine Omaha, NE

Angioedema is a well-known complication of heart failure and hypertension treatment with an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACEI). The estimated incidence is between 0.1 and 0.2%.1 ACEI induced angioedema (ACEI-AE) has a predilection for patients greater than 65 years of age, a history of drug rash or allergic history and African American ancestry.2 Most often the manifestation is orolingual in nature and patients may present with subcutaneous swelling of the tongue, larynx and pharynx. Lingual involvement can produce obstruction and life-threatening asphyxia. Isolated gastrointestinal angioedema is a rare presentation but often misdiagnosed due to the commonality of symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting) with other more common gastrointestinal disorders. We report a case of a rarely encountered occurrence of ACEI-AE involving the small bowel.

This 47-year-old Caucasian female with a past history of gout, iron deficiency anemia and hypertension, presented to the ED with epigastric abdominal pain for one day that she described as crampy and colicky in nature. She rated the pain as 8 of 10 that radiated to both flanks and improved with rest. She admitted to nausea but denied vomiting. She denied any other acute complaints. She had no history of abdominal surgery. Medications prior to admission included twice daily ferrous sulfate, once daily atenolol, once daily ethinyl-estradiol/norgestimate and once daily lisinopril for hypertension that was initiated 3 weeks prior to admission. In the ED, she was afebrile, blood pressure 146/99 mmHg, respirations 16/minute with an oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, and a heart rate 67 beats/minute. On exam, the abdomen was distended, soft but tender without guarding. Bowel sounds were normal. All other physical findings were within normal limits. A computed tomographic (CT) scan with intravenous contrast of the abdomen demonstrated a small volume of intraperitoneal free fluid with distal jejunal wall thickening, mucosal enhancement and adjacent mesenteric vascular engorgement consistent with ACEIinduced intestinal angioedema. The lisinopril was replaced with amlodipine and the patient improved over the next 3 days and was able to tolerate oral intake at discharge.

ACEI-AE of the small bowel should be considered in any patient presenting with severe acute onset of abdominal pain and concurrent treatment with an ACEI. It can present within hours to months after initiation and can occur independent of the dose. The abdominal pain is usually associated with nausea (78%) and/or diarrhea (65%).3 Failure to promptly remove the offending agent can lead to additional unnecessary diagnostic studies with an inherent potential for increased morbidity.4,5 CT-scan characteristically demonstrates mucosal wall thickening and intraperitoneal fluid as in our patient.6 This is consistent with a bradykinin-mediated reaction and increased vascular permeability with leakage of fluid into the intraperitoneal space. C1-esterase is useful to delineate hereditary angioedema but is not necessary to confirm the diagnosis of ACEI-AE. CT findings coupled with a history of concurrent ACEI use is sufficient to solidify the diagnosis. Management dictates prompt discontinuation of the offending agent and supportive care. Treatment is primarily supportive. The administration of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant successfully improved symptoms in 13 patients with ACEI-AE involving the airway.7 Whether similar benefit can be achieved in patients with intestinal angioedema is yet to be determined.

Shailendra K. Saxena, MD, PhD Health Care For The Family Omaha, NE

Ashlee J. Denny, BSN, RN

Nebraska Methodist College DNP Student Omaha, NE

Vi

tamin B12 deficiency is a condition exhibited by a wide spectrum of clinical sequelae allowing for it to be frequently overlooked or misdiagnosed in its early stages. This article describes the complex physiology of vitamin B12, describes various etiologies of vitamin B12 deficiency and interprets recent research distinguishing the relationship of the western diet on malnutrition and vitamin B12 deficiency. In a primary care clinic, vitamin B12 deficiency was evaluated and treated in settings that were not characteristically associated with deficiency.

Vitamin B12 deficiency is a condition that frequently presents in the primary care setting. However, due to its broad and often indefinable clinical sequelae, it is a condition that is frequently overlooked or misdiagnosed. This article describes the complex physiology of vitamin B12, clinical manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency and provides an analysis of the various etiologies for B12 deficiency while elucidating recent research distinguishing the relationship of the western diet on malnutrition and B12 deficiency. Given these relations, recognizing vitamin B12 deficiency could lead to better patient outcomes through further examination of a patient’s medical history and their dietary pattern.

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin. Vitamin B12 is a vitamin that is only synthesized by microorganisms. In humans, B12 is synthesized naturally in the colon by bacteria; however, the site of absorption in the small intestine is significantly distant from the site of synthesis, manifesting insufficient bioavailability of the naturally synthesized B12 in humans.1,2 Consequently, vitamin B12 must be sequestered from food products that contain the essential vitamin. Sources containing B12 other than fortified foods (e.g., breakfast cereals) and supplements, are restricted to animal products such as fish, meat, egg and dairy. Vitamin B12 is generally not present in plant foods.

Vitamin B12 in animal products is bound to a protein. After ingestion, B12 is separated from the protein by hydrochloric acid in the stomach allowing for the release of free vitamin B12.

The free vitamin B12 then binds to R-protein (transcobalamin I), a glycoprotein found in saliva and gastric juice.3–6 In the duodenum, degradation of the B12-R-protein complex occurs by pancreatic enzymes allowing B12 to bind to intrinsic factor (IF). The resulting vitamin B12-IF complex is absorbed in the distal ileum by receptor-mediated endocytosis.7 Once taken

up, vitamin B12 is released to the plasma where it is bound to its transport proteins, haptocorrin and trancobalamin II which are responsible for the delivery of B12 to peripheral tissues and the liver.6,7

In its role, cobalamin acts as a coenzyme for various cellular enzymatic reactions within the body including the conversion of methylmalonic acid to succinyl coenzyme A, the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, and the conversion of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate.6,8–10 In humans, B12 is essential in formation of hematopoietic cells, specifically red blood cells and DNA synthesis. Its purpose is also dynamic in the structure and function of the central and peripheral nervous system. In this aspect, B12 has a function in production of myelin generating oligodendrocytes and the synthesis of myelin.2,6,8–10

These intricate absorption mechanisms facilitate numerous ways in which vitamin B12 deficiency can develop. Many individuals are predisposed to vitamin deficiencies due to having an associated health condition. A well-known origin of B12 deficiency is pernicious anemia, an autoimmune disease in which the parietal cells of the stomach lining fail to secrete IF, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12.7 Although pernicious anemia is well acknowledged as a cause of B12 deficiency, it actually accounts for a marginal number of all cases.7 Similarly, atrophic gastritis is an autoimmune disease in which vitamin B12 deficiency may occur as a result of the body making insufficient hydrochloric acid and IF. Another established basis for B12 deficiency is the exposition in response to poor dietary intake in individuals who adhere to a strict vegan or vegetarian diet, the elderly and those with alcohol excess. Likewise, certain pharmaceuticals including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and the antidiabetic metformin, have proven to reduce circulating vitamin B12 concentrations with prolonged use. 6,10,11 Evidence also suggests micronutrient deficiencies are commonly associated with inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease due to malabsorption from underlying alteration in intestinal activity.12 Clinicians should also keep in mind that patients with a past medical history of certain types of stomach or intestinal surgery may also be at risk for micronutrient deficiencies. Recognizing these associations is key to correcting the deficiency. In some circumstances, these

conditions may be appreciated after the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency has been made. However, clinicians may suspect a patient to be low in B12 in absence of the common causes. Theories recognizing the need for further investigation suggest that perhaps B12 deficiency may in fact be influenced by one’s lifestyle including the consumption of a western (American) dietary pattern.

Currently, guidelines do not suggest routine screening of average-risk adults for vitamin B12 deficiency. However, screening may be warranted in patients with one or more risk factors or those who present with suspected clinical indicators.8 High risk patients include but are not limited to vegetarians or vegans, bariatric or any gastrointestinal surgical patients, patients who receive medications that can alter vitamin B12 absorption, patients with gastrointestinal disorders, patients with an imbalanced diet, and the elderly.13 When the provider deems appropriate, laboratory testing should include a complete blood count and serum vitamin B12 level.10 Folate level may also be drawn, but this may be omitted if the patient is consuming a diet containing folate-supplemented grains and has normal functioning gastrointestinal anatomy.10 A folate level would be warranted in individuals with known gastrointestinal conditions, excess alcohol use, or dietary patterns known to cause both deficiencies.10 Vitamin B12 deficiency can be further confirmed by testing for high levels of methylmalonic acid and homocysteine assays.10 Pernicious anemia can be diagnosed by evaluating anti-IF antibody and serum gastrin and pepsinogen levels. Recognition of the cause of vitamin B12 deficiency is beneficial with treatment, preventing further complications, diagnosing additional vitamin deficiencies, and determining route of supplementation.13

Laboratory interpretation is as follows: 10,14,15 •Less than 150 pg/mL Diagnostic for deficiency •200 to 300 pg/mL Borderline deficiency •Above 300 pg/mL Normal

In a family practice clinic, patients were customarily screened for vitamin B12 insufficiency due to having a high index of suspicion. Many patients demonstrated B12 deficiency unaccompanied by classic origins and despite observing a typical western diet high in meat and animal product consumption. A specific factor that has changed in the American diet over the last several decades is the increasing amount of sodium-containing salt and fat intake. 11,12 The typical western diet is low in fruits and vegetables, and high in fat and sodium.12 Malnutrition due to physiopathology can occur in a western diet because the foods typically consumed are stripped of their natural nutrients.13 The western diet is considered to be the chief contributor to the increasing rate of obesity epidemic in the United States and one of the leading causes for the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and some cancers.12,13 There has recently been increasing interest on the effect that dietary patterns have on the network of the gastrointestinal system. One theory proposed to explain B12 deficiency occurring in the privation of the commonly known causes includes the adverse effects of a high salt diet (HSD) and high fat diet (HFD) on the gastrointestinal tract.

Recently, several studies have established that a diet high in sodium directly alters the composition and function of the gut microbiome.16,17 A case series study on mice fed a diet supplemented with 4% NaCl for 3 weeks revealed histologic secretions suggestive of inflammation in the colonic mucosa with depletion of goblet cells, cellular infiltration, erosion, ulceration, and destruction in muscularis mucosa layer, as well as edema in submucosal layer.18 These observations are suggestive that a HSD provokes micronutrient deficiencies due to inflammation and alteration of absorption cascades.

Likewise, another recent case series study utilized a mouse model of obesity to investigate gastric epithelial homeostasis. In the study, mice were fed a HFD consisting of formulas of linoleic acid-rich and stearic acid-rich diets, both 54.8% kcal fat for 8-20 weeks.19 Histological investigation of the gastric mucosa in the mice were notable for both necrosis and apoptosis pathways of HFD-

Clinical features seen in practice among patients with low serum B12 level in absence of predisposed conditions

Alopecia in males and females

Fragile/brittle nails

Numbness/tingling in lower extremities

Low libido Gait instability

Depressed mood and mood instability

Low energy

Cognitive impairment/memory loss/ brain fog

fed parietal cells.19 This result implies that a HFD damages parietal cells. Because parietal cells are highly differentiated to efficiently secrete hydrochloric acid, parietal cell damage and hydrochloric acid insufficiency reduce the liberation of vitamin B12 from food proteins. The findings of this study support the theory that HFD damages parietal cells thereby precipitating B12 insufficiency.

Given this analysis, nutrition can be used as a way towards treatment and mitigation of some of the most common diseases of our time, including vitamin B12 deficiency. Primary care clinicians are well positioned to help guide patients in integrating nutritional modulation as an adjunct in treatment plans.

Vitamin B12 deficiency affects multiple body systems, and the manifestations vary from mild to severe. Hepatic storage of vitamin B12 can delay clinical presentation for up to 10 years after the onset of deficiency.10,20 The classic neurologic features seen in B12 deficiency are caused by progressive central nervous system demyelination.10,20

Improved hair growth and thickness

Nail growth, improved nail thickness

Decreased or complete cessation of numbness/tingling

Libido was improved in relation to an increased mood

Decreased falls, decreased dizziness, and decreased weakness

Mood improvement, decreased depression symptoms, mood stability

Increased energy and endurance, decreased fatigue, improved sleep

Improved memory, decreased forgetfulness, clearer thought processes

It is apparent that vitamin B12 deficiency exhibits a wide spectrum of symptoms. The primary care provider is at the foundation of preventative care and is uniquely qualified to help guide patients in incorporating parenteral or oral vitamin B12 supplementation as an adjunct in treatment plans. Evaluation and treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency may be beneficial for patients seen in primary care clinics.

Shailendra K. Saxena, MD, PhD, is family practice physician at Health Care For The Family in Omaha, Nebraska.

Ashlee J. Denny, BSN, RN, is a family focused doctor of nursing practice (DNP) student at Nebraska Methodist College in Omaha, Nebraska.

Nicholas O. Davidson MD, DSc

Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

David A. Rudnick MD, PhD Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Nicholas O. Davidson MD, DSc

Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

David A. Rudnick MD, PhD Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the leading causes of cancer related deaths in the western world. Among adults with CRC, one quarter to one third will have a familial component, with approximately 5% affected with a defined, actionable genetic variant. While CRC is rare in pediatric populations, there has been a striking increase in early onset CRC in young adults over the last decade, and parents of children in families with CRC are understandably concerned. Patients with early onset CRC (age <45y) are more likely to harbor genetic variants, but the increased incidence of early onset CRC is only partially attributable to inheritable factors. Because of the multifactorial nature of CRC susceptibility even within families with a predisposing genetic condition it is important to recognize alarm symptoms and signs in patients encountered in the primary care setting. Here we review some of the underlying genetic causes of familial CRC and provide practical guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation and management of familial colon cancer.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer related death in the US and western world, with up to a third of patients having a family history suggestive of a hereditary susceptibility. Suggestive features of familial cancer risk include a first degree relative (FDR, i.e. parent, sibling or child) with CRC or uterine, ovarian or gastric cancer and family members with colon adenomas diagnosed before age 50. The estimated risk for CRC within families increases with the number of FDRs affected.1 Among patients with CRC, those with defined genetic variants account for ~5% of all colon cancers. Although much less common than sporadic colon cancer, these genetically-based diseases are important because they predispose affected people to increased incidence and rate of progression of colon cancer and extra-intestinal malignancies. Furthermore, because almost all these conditions are inherited as autosomal dominant diseases (the exception being MUTYH (MYH) associated polyposis, reviewed below), first degree relatives of index cases have a 50% chance of possessing the familial pathogenic gene mutation and being affected by the syndrome. These syndromes are broadly binned into so-called ‘polyposis’- and ‘non-polyposis’-types, with the ‘non-polyposis’ type characterized by fewer (but not absent) polyps compared to the ‘polyposis’ syndromes. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is the most common of the ‘polyposis’ colon cancer syndromes, and Lynch syndrome, which is in the ‘non-polyposis’ category, is the most commonly diagnosed familial colon cancer syndrome overall. In this report, we (i) briefly review the genetic basis and many of the important intestinal and extraintestinal clinical manifestations of these colon cancer syndromes, (ii) provide readers with recent references to polyposis syndrome-specific disease surveillance and management recommendations and the website link for a publicly available Lynch syndrome risk assessment tool, and (iii) discuss the important contributions primary care providers make to these patients and their families.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP, see table on page 13): The clinical manifestations of FAP are highly variable. In some patients with FAP, colonic polyps with tubular adenomatous histology may develop in late childhood or adolescence. Without a family history of FAP, those patients may present to their pediatrician with diarrhea or rectal bleeding. Such polyps may be discovered in people that undergo screening colonoscopy recommended after testing positive for a known familial FAP-associated pathogenic mutation

in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, or as noted above, identified incidentally at colonoscopy for persistent hematochezia in the absence of an FAP family history. APC gene mutations are inherited in autosomal dominant fashion and it is important to elicit a detailed family history to include grandparents, aunts and uncles. Many patients with FAP do not develop polyps until their late teens or twenties but 95% will develop polyps by the age of 30. Adenomatous polyps that are not removed have very high (>95%) potential for becoming malignant, and colon cancer may even be diagnosed in children and teenagers with FAP. Thus, when polyp load is no longer manageable by colonoscopic polypectomy, patients should be referred for colectomy. In addition to the very high risk of colorectal cancer, FAP can also cause upper-gastrointestinal tract disease, including duodenal/periampullary polyposis, which often show adenomatous histology, that can progress to carcinoma, and whose management may require specialized procedural expertise. Most adult patients with FAP exhibit gastric fundic gland polyps, which have a very low malignant potential and rarely (1%) progress to cancer. FAP patients are also at increased risk for extraintestinal cancers, including hepatoblastoma in infants and young children, papillary thyroid cancer, desmoid-, and central nervous system (CNS)-tumors, and other manifestations (soft tissue tumors, epidermal cysts, extranumerary teeth) in older children and adults. Desmoid tumor-associated FAP gene

mutations have been reported, and family histories of those tumors have been incorporated into cancer surveillance recommendations. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) is identified by fundoscopic examination in some FAP patients, and if discovered in people with known or suspected FAP family histories should prompt referral for FAP diagnostic testing. Pre- and post-colectomy gastrointestinal and extraintestinal cancer surveillance recommendations for pediatric2 and adult3 patients have been reported. An attenuated form of FAP is characterized by later age of onset (40-60) with reduced (and more endoscopically manageable) polyp burden (typically 20-40 lifetime versus >100-1000 in classical FAP). While specific APC gene mutations have been associated with the attenuated phenotype, most patients with the attenuated form of FAP do not exhibit a specific genetic signature. This is important because relatives of patients with attenuated FAP cannot be screened with a simple blood test, but rather require referral for colonoscopy with the first encounter 10 years younger than the youngest familial case of FAP-associated colon cancer.

Other polyposis syndromes: MUTYH (MYH)-associated polyposis is recessively inherited and caused by bi-allelic mutations in the MUTYH gene (see Table). Like FAP, polyps exhibit adenomatous histology, with the clinical phenotype generally attenuated but with increased lifetime colon cancer risk. Peutz-Jeghers (PJS) and Juvenile Polyposis

(JPS) syndrome are autosomal dominant syndromes, characterized by gastrointestinal polyps with hamartomatous type histology, often times with histopathological structure that permits distinction between PJS- and JPS-type polyps (see table on page 13). PJS is almost always caused by loss-of-function mutations in the STK11 gene, and this condition is associated with risks of gastrointestinal, gynecological, and testicular tumors, as well as significant risk for intestinal polyp-induced intussusception which can require emergent evaluation and management to prevent ischemic bowel injury. JPS is caused by mutations in BMPR1A or SMAD4 in a subset of patients, and also associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal tumors. JPS also carries significant risk for polyp-induced intestinal intussusception. Some JPS-associated SMAD4 mutations cause hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which, when identified, should prompt additional evaluation and monitoring by appropriate specialists. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) is caused by mutation in the PTEN gene, and includes Cowden, BannayanRiley-Ruvalcaba, and PTEN-related Proteus syndromes. PHTS is also inherited as an autosomal dominant disease, and is associated with significant risks of gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis and associated complications4 as well as high risk for benign and malignant tumors affecting other organ systems.5 GI and other cancer surveillance recommendations for pediatric patients with MAP, PJS, and JPS have also been published.2 Finally, Juvenile Polyposis of Infancy is an extremely rare condition caused by a de novo genetic 10q23 microdeletion spanning BMPR1A through PTEN, and characterized by massive colonic and gastrointestinal polyposis, with significant associated complications.6

The term ‘hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer’ (HNPCC, see table on page 13) was first coined in reference to recognition of an autosomal dominant hereditary colon cancer syndrome that is distinct from classical FAP based on detection of significantly fewer colonic polyps in HNPCC vs. FAP.7 This disease was subsequently renamed ‘Lynch syndrome’ in 1984 in honor of Dr. Henry Lynch’s seminal contributions defining this condition, including his characterization of the extensive gastrointestinal and gynecological cancers diagnosed in living relatives of Andrew Warthin’s ‘Cancer Family G’ first described in the late 19th century. The research enabled by the HNPCC/Lynch syndrome classification schema led to the discovery that mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MSH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) and, later, in the EPCAM gene (that silences MSH2) cause this most common of the heritable colon cancer syndromes. Subsequent studies identified high rates of ‘microsatellite instability’ (MSI) in DNA from Lynch syndrome cancers caused by mutation-induced disruption of DNA MMR. Based on those results, diagnostic testing is now commonly used to assess for MMR gene mutations and MSI in tumors from colon cancer patients. Those advances have also led to recognition that Lynch syndrome is the most common familial colon cancer syndrome, and is estimated to account for ~3% of all newly diagnosed colon cancers and ~8% of those cancer diagnosed in patients under 50 years of age. Lynch syndrome also causes endometrial and ovarian cancers and has been implicated as a cause of many other extraintestinal malignancies. In addition, Lynch syndrome has rarely been reported to occur in children. Finally, pediatric patients with biallelic germline mutations in MMR genes have also been described.8 This very rare condition, which is designated Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency (CMMRD),

1. Familial colon cancer syndromes predispose affected individuals to early onset colon cancers and extrahepatic malignancies. Most of these conditions are inherited as autosomal dominant diseases. Thus, 1st degree relatives of affected patients have a 50% chance of having inherited the pathogenic disease causing gene mutation.

2. An online Lynch syndrome prediction model tool, based on information about cancers in the index subject and 1st and 2nd degree relatives is available at: https://premm.dfci.harvard.edu/.

3. Testing for gene mutations in index cases is increasingly available. Identification of specific causal gene mutations permits definitive testing (of 1st degree and more distant relatives) for the familial pathogenic mutation. Whole gene sequencing and cancer gene panels can also inform such disease risk.

4. Patients affected by these syndromes should be referred to tertiary care centers for GI and extraintestinal tumor surveillance and management. Young adulthood is a particularly vulnerable time of risk of loss of continuity of care and subsequent poor disease outcomes.

5. Young patients with unexplained rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, change in bowel habits and particularly those with a family history of CRC should be referred for evaluation and endoscopy.

6. Polyposis syndromes also carry risk of intestinal intussusception, which can affect pediatric as well as adult patients, and when suspected, should be emergently evaluated.

exhibits a distinctly severe presentation with development of a wide range of malignant neoplasms in childhood and most children reportedly not reaching adulthood.

CRC diagnosed under the age of 50 is referred to as early onset and now accounts for 10% of all new CRC diagnoses.9 The impact of this rise in early onset CRC has shifted the average age of diagnosis of all cases of CRC in the last two decades from 72 to 66. There are several distinctive clinical features of early onset CRC, including the majority being

left sided, predominantly rectal cancer. In addition, 30% of patients with early onset CRC have a family history of CRC and the prevalence of a defined causative variant ranges from 1625%, which is much higher than noted for patients with CRC diagnosed at age >50. Lynch syndrome-associated variants are the most commonly associated genetic conditions in people with early onset CRC. It is important to recognize that both genetic and environmental causes are likely responsible for the alarming increase in early onset CRC, including factors such as obesity, metabolic syndrome and other associated comorbidities.10

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) (Gardner’s*, Turcot’s**)

Adenomatous

papillary thyroid, hepatoblastoma, desmoid*, cysts*, lipomas*, osteomas*, fibromas*, brain tumors (medulloblastoma, glioma)**

Attenuated FAP

MUTYH-associated polyposis

Juvenile polyposis

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

PTEN hamartomatous tumor syndrome

APC MUTYH

BMPR1A, SMAD4

STK11

Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome (HNPCC)

PTEN MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM

Adenomatous Adenomatous

Hamartomatous (Juvenile type)

Hamartomatous (Peutz-Jeghers type)

Hamartomatous Adenomatous

HHT in those with SMAD4 mutations

ovary/cervix, testes

Breast, endometrial, renal cell, melanoma, thyroid (papillary, follicular)

Endometrial, ovarian

St. Louis, MO

Brian R. Odum, DO Department of Laboratory Medicine Medical Director, Anatomic Pathology Mercy Hospital

St. Louis, MO

PGY3 – Mercy Family Medicine Residency

Hospital

St. Louis, MO

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an inclusive term for both nonalcoholic fatty liver and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) is defined by the presence of at least 5% hepatic steatosis without hepatocellular injury seen on liver biopsy.3 On the other hand, the definition of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the appearance of at least 5% of hepatic steatosis and mostly lobular inflammation, hepatocyte injury (ballooning), apoptotic hepatocytes, and sometimes (even without alcohol) Mallory’s hyaline. While liver fibrosis is often seen in the setting of NASH, such fibrosis is not essential for the diagnosis.

In March 2020, an expert consensus from an international team recommended changing the name from NAFLD to metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD).1 MAFLD is based on histopathological examination, imaging, and blood biomarkers to show evidence of hepatic steatosis in association with one of the following three conditions: BMI greater than 25 kg/m2, type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic dysfunction. Metabolic dysfunction was measured by the present of at least two metabolic risk factors, including high waist circumference, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterolemia, prediabetes, insulin resistance, and highsensitivity C-reactive protein level.

The prevalence of MAFLD is increasing. MAFLD now affects up to 25% in the adult population worldwide; it is the most common liver disease in the United States affecting 30% of adults.2,7 MAFLD can progress to cirrhosis and result in portal hypertension, hepatic failure, and a significantly increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Studies have shown higher-liver related mortality among NASH, and it is putting a further strain on the already present limited supply of transplantable livers. Therefore, NASH resolution has become one of the main goals when developing treatment strategies of MAFLD. In addition, MAFLD patients have higher risk of cardiovascular mortality, which should be considered when deciding in regard of statin therapy duration. In fact, for affected patients these cardiovascular risks may exceed the liver related risks so efforts should be taken to ensure aggressive management for cardiovascular risks including the use of statins.

Mercy Clinic Hepatology Mercy HospitalThe onset of MAFLD is insidious and often asymptomatic. A small number of patients may have non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, dull pain in the right upper quadrant, or upper abdominal distension.3, 4 In the decompensated stage of MAFLD-related liver cirrhosis, the clinical manifestations are like those of liver cirrhosis caused by other causes.9 Overlapping issues of diabetes, and sleep apnea also add to clinical manifestations.

The routine screening for MAFLD is often recommended for those with metabolic syndrome or other risk factors; however, the benefits and cost-effectiveness of such screening remains unproven.8 Serum aminotransferase levels may be normal (or elevated) in patients with MAFLD. Caution should be used before attributing elevated alkaline phosphatase to MAFLD, especially in male patient, on the other hand screening tools such as liver ultrasound has limited sensitivity and specificity.

When MAFLD is suspected the initial evaluation starts with history. Assessment for dietary indiscretions, poor diet perhaps especially the consumption of sugared beverages, food insecurity, lack of exercise, risks or history for sleep apnea, alcohol consumption, the use hepatotoxic medications.8, 11 Laboratory work up which should include screening for viral hepatitis B and C. Testing may be extended to check for less-common causes for chronic liver disease (Table 1).10 However primary care physicians should be cautious and consider the referral to gastroenterology or hepatology when suspected stage 2 or greater fibrosis or when there are substantial concerns of other liver disease. Some liver disease specific markers can lead to confusion. Often patients with NASH can have very elevated serum ferritin levels but often with normal transferrin saturation, still caution must be applied to avoid missing hemochromatosis. Wilson’s disease may also present with findings of hepatic steatosis (sometimes with a low alkaline phosphatase level).

Table 1

Less common causes of chronic liver disease

Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

Autoimmune hepatitis

Alpha1-antitrypsin level, liver biopsy

Antinuclear antibody, smooth muscle antibody, liver/kidney antibody testing

and without fibrosis (Figure 3 and 2), NAFLD Cirrhosis (Figure 4 and 5). In case of alcoholic steatosis histological findings are marked hepatocyte ballooning and prominent Mallory hyaline (Figure 6). However, routine biopsy is not recommended because the inherent risks [12]. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease recommends liver biopsy for patients with MAFLD who are young, are at increased risk of NASH or advanced fibrosis based on noninvasive test results and in those cases when the etiology of liver disease is unclear.

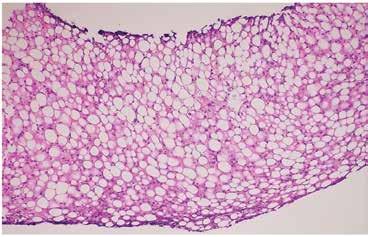

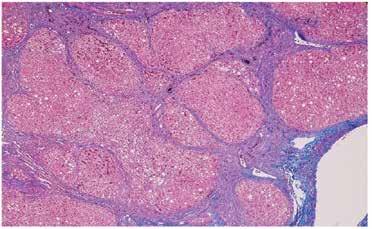

Figure 1. Diffuse steatosis (H&E stain, 10x) panacinar macrovesicular steatosis without overt steatohepatitis.

Hereditary hemochromatosis

CBC, ferritin level, transferrin saturation, genetic testing (HFE gene), liver biopsy with staining iron, MRI

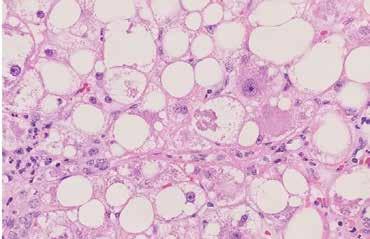

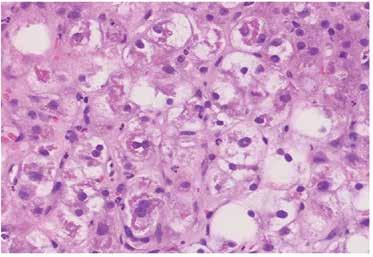

Figure 2. Steatohepatitis (H&E stain, 40x) patchy lobular inflammation, steatosis, and ballooning degeneration.

Wilson Disease

Ceruloplasmin level, liver biopsy, genetic testing, 24-hours urinary cooper measurement

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for defining NAFLD and for distinguishing bland steatosis from NASH [8, 10]. Below are shown the histological findings of diffuse steatosis (Figure 1), steatohepatitis with

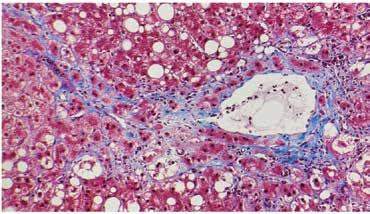

Figure 3. Steatohepatitis with perisinusoidal fibrosis (trichrome stain, 20x) perisinusoidal and pericellular fibrosis in a predominately centrilobular (zone 3) distribution.

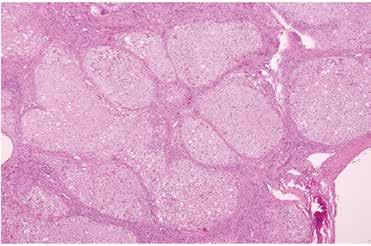

Figure 4. NAFLD cirrhosis (H&E, 4x) liver wedge biopsy with micronodular cirrhosis and only mild residual steatosis.

Figure 5. NAFLD cirrhosis (trichrome, 4x) liver wedge biopsy with micronodular cirrhosis. The fibrous septa (blue) are highlighted by a trichrome stain.

An evolving field is non-invasive liver disease assessments (NILDA). NILDA can be helpful to assess the likelihood for the development of hepatic fibrosis. These tests include AST:ALT ratio, APRI (AST:platelet) ratio, Fibrosis-4 Score, NAFLD Fibrosis score. In addition, transient elastography FibroScan, magnetic resonance elastography, and shear wave elastography are now considered useful but still imperfect approaches for the assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis.13, 14 Ultrasound is the most recommended and widely used diagnostic method for the identification of hepatic steatosis due to its sensitivity, non-invasiveness, inexpensive and its widespread availability. The ultrasound findings usually consist of visual decrease in the vascular margins, loss of definition of the diaphragm, hepatomegaly, and increased echogenicity of the liver parenchyma. If hepatocyte steatosis is greater that 30%, the transabdominal ultrasound is felt more effective.15, 16 On the other hand, it can miss the diagnosis when the fat hepatic content is <20% because the sensitivity of abdominal ultrasound among patients with morbid obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) is low. Nevertheless, the gold standard for evaluating and quantifying hepatic steatosis and detecting the amount of liver fat as low as 5-10% is magnetic resonance imaging, although it is not commonly used in the clinical practice despite its accurate precision, because of its limited availability, high costs and long execution time.

Currently, proven medical therapeutic agents for MAFLD are very limited. Some data has advocated for the use of pioglitazone or vitamin E for a small subset of patients with NASH. The most effective therapy for MAFLD remains lifestyle modification. It is shown that, for many, a 10% reduction of weight can resolve steatohepatitis and can improve liver fibrosis by one stage. Weight loss it is also very important to reduce cardiovascular and diabetes risks. The Mediterranean diet is often suggested as a healthy diet since it can not only help to increase weight loss but also enhance heart health, reduce inflammation, and promote better blood sugar control. The role of ketogenic diets, and intermittent fasting is limited because of concerns for sustainability. Lifestyle changes can include initiating an exercise regimen with an ideal goal include a 60-70 minute daily exercise regimen and at least twice weekly resistance exercises. In case of no response to lifestyle treatment potential options include weight reducing medicines, bariatric surgery, and research protocols.

Figure 6. Alcoholic steatohepatitis (H&E, 40x) patchy macrovesicular steatosis with marked hepatocyte ballooning and prominent Mallory hyaline (ropy eosinophilic material within ballooned hepatocytes).

By replacing terminology from NAFLD to MAFLD, the drug development strategy has changed. The research and pharmacology world are currently focused on two outcomes. These include the resolution of steatohepatitis or NASH and the improvement of fibrosis stage. Drugs with potential benefits include thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone)17-19 and vitamin E20 , supported by both randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses. From the current recommendation, pioglitazone has been established in both diabetic and nondiabetic MAFLD patients with significant fibrosis (≥F2), whereas vitamin E (preferably the d-enantiomer only) is recommended in nondiabetic MAFLD patients with ≥F2 non-cirrhosis. Statin therapy is considered important for prevention of CVD. Metformin has not shown any benefits. GLP-1 agonists are yet to be studied but so far, the outcomes have been promising since they have played an important role on weight management and help to control type 2 diabetes. In case everything has failed the last but not the least to consider based on risks and benefits in MAFLD patients is bariatric surgery.

n June of 2020, 4 leading organizations in gastroenterology pledged to “advocate for diversity in our staff and governance, grant awards to research health care disparities, ensure quality care for all, and work tirelessly to reduce inequalities in health care delivery and access”.1 In August of that year, the American Gastroenterological Association formed its Equity Project which was designed as a 3-year strategic plan to achieve a broad vision of equity across 6 domain areas.2 Then, in February 2021, the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists was formed with the purpose of being “a space to discuss health conditions that disproportionately affect Black communities and a place to engender community among Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists”.3

In January of 2022 the journal Gastroenterology added a section titled “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Gastroenterology”. The purpose was to highlight research in health equity and inclusion, with a strong focus on work conducted by researchers who are underrepresented in medicine and science. A few months later a similar section was added to Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.4 All of this highlights the significance of looking at various aspects of gastroenterology through the lens of health equity.

Health equity has been the focus of numerous initiatives within healthcare recently. Healthy People 2030 defines health equity as “the attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and health care disparities”.5

Healthy People 2030 goes on to define health disparities as: “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion”.5 This article will examine some of the issues of health equity in gastroenterology through the framework of these definitions. While there are aspects of health equity in gastroenterology that relate to sex and gender issues, this article will focus on aspects of health equity related to race and ethnicity.

There are significant health disparities in a number of gastrointestinal diseases. This may be due to a variety of factors including access to care, type of insurance, genetics, differences in rates of comorbidities, bias of heath care workers, misperceptions of disease risk, and insufficient participation in clinical trials by members of historically marginalized groups. Regardless of the cause, examples of the disparities in various gastroenterological diseases abound.

Health disparities in colorectal cancer is particularly concerning for Blacks, who have the highest rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality of all major ethnic/racial groups in the United States (US).6 Black males have 24% higher rates and Black females have 19% higher rates of CRC compared to White males and females respectively.7 Of note, in 1989 the rates of CRC were higher for White men than Black men, and the rates for women were similar in both races.7 While there has been a decline in the incidence of CRC for both Blacks and Whites, it has been more significant for Whites, which may be due to differential rates of screening. Screening for CRC may be influenced by access to care or other factors related to social determinants of health, which adversely affect Blacks in greater proportion than Whites. Another factor affecting mortality rates was highlighted by an analysis using data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which found longer time to intervention following a diagnosis of CRC for all groups compared to nonHispanic Whites.8 Blacks also have higher rates of incidence and mortality for pancreatic cancer and liver cancer.7 It is also worth noting the group with the second highest rates of CRC is American Indian/Alaskan Native.6

BLACK MALES HAVE 24% HIGHER RATES AND BLACK FEMALES HAVE 19% HIGHER RATES OF CRC COMPARED TO WHITE MALES AND FEMALES, RESPECTIVELY

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is another area where there are significant health disparities. Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are often thought of as something that primarily affects individuals of Western and Northern European ancestry.9 Recent data show it is increasing both in developed countries as well as developing countries across the globe.9-11 In the US, differences have been reported in how Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis manifest clinically in Blacks compared to Whites, as well as in the treatment each group recieves.12 A cross sectional study at a major academic medical center found Blacks with IBD were less likely to be under the care of a gastroenterologist, more likely to have required an Emergency Department visit in the prior 12 months, and amongst those with Crohn disease treated with chronic corticosteroids, less frequently treated with infliximab.13 A systematic review examining heath disparities in surgical management of IBD found Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to be treated with abdominal surgery when hospitalized, and when they did have surgery, were more likely to have complications.14 In particular, Black patients were more likely to have postoperative bleeding, infection, and sepsis compared to White patients.14

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has also been studied for health disparities. This is complicated by the fact that NAFLD is closely associated with other conditions, such as obesity15-18 and diabetes18-20, which are themselves associated with health disparities. A systematic review found the prevalence of NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) was highest in

Hispanics, intermediate in Whites, and lowest in Blacks. Interestingly, there were no significant differences found in rates of liver fibrosis.

There are differences across racial and ethnic groups in the prevalence of autoimmune liver disorders, including primary biliary cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis.21 It is not known how much of this is due to genetics, socioeconomic status, or other contributing factors. This is an area needing more research to elucidate what are modifiable risk factors, and how to improve prognosis.

Celiac disease is another condition in which there appear to be some health disparities, but the research to date has been quite limited. It is another condition often thought of as affecting primarily people of European extraction, but Celiac disease affects all populations worldwide.22 Celiac disease is known to be underdiagnosed, and patients with lower income are less likely to be diagnosed with celiac disease if they do not have classic gastrointestinal symptoms.23 A recent oral presentation of an analysis of medical claims data found the highest rates of celiac disease in the Northeast and Midwest, and the lowest rates in the Southeast.24 Rates of claims for irritable bowel syndrome had the opposite geographic distribution, suggesting there may misdiagnosis in parts of the country with a larger proportion of Blacks in their population.24

Recognizing health disparities exist and signify a shortfall from health equity leads to the question of what can be done to improve things. There have been many ideas proposed and what follows is meant to showcase the variety of activities that can be undertaken. It is not meant to be an exhaustive review.

One area increasingly in focus is the racial and ethnic backgrounds of gastroenterologists. For example, Blacks constitute approximately 13% of the US population but only 4% of practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists3. Mentorship has been proposed as an effective means to recruit, retain, and promote underrepresented minorities into academic gastroenterology and hepatology.25 The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists has proposed the target, establish, acquire, and measure (TEAM) approach, which is a set of proactive behaviors for institutions wishing to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion.26

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) has indicated its intention to support various initiatives, including engaging various communities and stakeholders, developing greater understanding of how social determinants of heath impact health equity, and mitigating these factors along with addressing upstream causes.28 The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) plans to incorporate more health disparities research into its scientific sessions.29

Finally, the use of race-based or ethnicity-based recommendations in clinical practice guidelines has been questioned.29 Does such a practice advance or hinder health equity? For example, race and ethnicity may be proxies for social risk factors and being more explicit in what the risk actually is may improve health equity.29 This may be more likely to occur if there is appropriate diversity of the membership of guideline development panels.

Health equity is a challenge in managing gastrointestinal disorders. Having an awareness of some of the examples that have been highlighted here can help individual clinicians in the treatment of their patients. In particular, clinicians need to be aware of the extent to which social determinants of health need to be kept in mind in order to optimize the clinical outcomes for their patients.

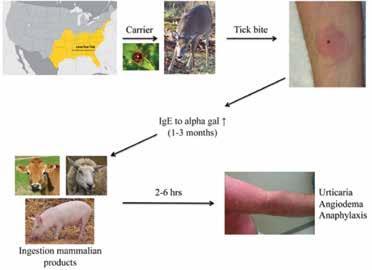

Not to be confused with the female counterpart to an alpha male, “AlphaGal” (galactose-α-1,3-galactose) allergy is the furthest thing from primordial depictions its name may conjure, and is nothing to be scoffed at. Though still unfamiliar to many, this condition is no longer isolated to the unfortunate few, as its prevalence and incidence, especially in Missouri, is increasing at an alarming rate.

performed the alpha gal antibody test. Sure enough, the patient was positive.

After diagnosing my first patient, my heightened awareness made me more likely to test patients for alpha gal allergy any time they complained of vague or specific food intolerances, which could be linked to red meat and history of tick bites. Since then, I have diagnosed an average of three patients a year and have had multiple others come in to my office reporting that they were diagnosed elsewhere. I work for Citizens Memorial Healthcare, which serves approximately 150,000 patients, and a recent search of our system’s medical records indicated that we have had 43 positives over the past 365 days. It is important to note that this is for a condition that is not frequently tested for and hence, often underdiagnosed.

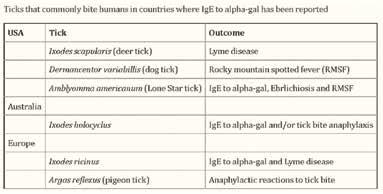

Evoking images of the Lone Texas Ranger (.e.g. Lone Wolf McQuade), this mammalian meat allergy (MMA) is transmitted by bites from the Lone Star tick (Amblyomma americanum) in the United States. Known colloquially as “red meat allergy,” Alpha-Gal single-handedly topples homosapiens from their omnivorous perch as an apex predator atop the planetary food chain, making them allergic primarily to pork, beef, and lamb. In some cases, individuals may also develop allergies to venison, rabbit, and products made from mammals including gelatin, cow’s milk, and milk products.

I must admit, before moving to Missouri from New York, I had never heard of the alpha gal allergy. Being from the Northeast, I was familiar with concerns regarding potential transmission of tick-borne disease, most notably Lyme disease. After beginning practice in the Midwest, I immediately became aware of the high regional prevalence of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, caused by Rickettsia rickettsii. It wasn’t until about five years into my practice in Missouri that I read an article about another tick-borne illness that causes meat intolerance. I came to understand that alpha gal syndrome was very variable in nature, ranging from asymptomatic or mild itching, to sudden allergic rashes or a life-threatening anaphylactic response. Fortuitously, my education on alpha gal syndrome occurred just a few weeks before a patient entered my clinic reporting feeling sick with each time he consumed hamburger meat. Recalling what I had recently learned, I

According to an HHS subcommittee report, accumulating data suggest that the incidence of Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS) is on the rise, with the highest number of incidences reported in the southeast region of the United States, which correlates with the expanding geographic distribution of lone star ticks (Commins, 2016; Commins et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2019; Pattanaik, Lieberman, Lieberman, Pongdee, & Keene, 2018). In 2009, there were 24 reported cases of alpha-gal syndrome; however, by 2018 case estimates had exploded into the thousands and AGS was identified as the leading cause of anaphylaxis in a southeastern registry of patients (Pattanaik et al., 2018). AGS has been diagnosed throughout the world and in each population ectoparasitic ticks (or other parasitizing exposures) have been implicated, which demonstrates a scope beyond the lone star tick and beyond the United States (Chinuki et al., 2016; Commins et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2019; Van Nunen et al., 2009).

Alpha Gal’s rise from obscurity has been noticed by national news outlets, including the New York Times, which wrote about this tickborn allergy in 2017, 2018, and twice in May 2022 (5/9/22 & 5/13/22). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 2004 and 2019, the total number of tick-borne diseases in the United States more than doubled.

According to some maps, the lone star tick has advanced as far west as parts of Nebraska, and as far northeast as Maine. Other models indicate that climatic conditions are also suitable for the ticks to establish populations along the coast of Washington, Oregon and California.

According to a May 8th, 2022 article in the Springfield Newsleader, data obtained from CDC via the nation’s leading provider of the Alpha-gal antibody test since 2010, Viracor-IBT Laboratories, in Lee’s Summit Missouri, reported 34,256 positive cases in Missouri between 2010-2018, revealing that Missouri is among the top five states with the highest number of cases: Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Virginia. Referenced in the same article, is Dr. Tina Merritt, who is reported to be co-owner of the patent for the alpha-gal test owns the Allergy & Asthma Clinic of NWA in Bentonville, Arkansas, is an expert on the topic and has the syndrome herself. During her allergy & immunology fellowship from 1999-2001 she trained with the man responsible for discovering AGS, Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, professor of medicine and microbiology and head of the division of allergy and clinical immunology at University of Virginia (UVA). Dr. Merritt is said to have more than 1,000 alphagal patients from the Arkansas area, but as she also sees patients via telemedicine, many of these remote visits are with patients from Missouri.

Around 2006, scientists first began noticing allergic reactions which were eventually attributed to alpha-gal, but it was not until several years later that they understood it was likely caused by the bite of the lone star tick. According to one study, by 2012 alpha-gal had already been found in 39 states.

According to UVAToday (news.virginia.edu), it all started in the early 2000s, when cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody, was being trialed by ImClone and Bristol Meyers Squibb in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Despite the hopeful outlook of having a new chemotherapeutic agent on the market, cetuximab was noted to illicit a hypersensitivity reaction in a small number of patients, escalating to anaphylaxis. Upon realization of this troublesome immune response, Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, a British physician specializing in allergy, asthma, and immunology, was contacted and his insight on the situation was requested. In 2007, Dr. Platts-Mills discovered the galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose sugar as an ingredient in cetuximab. He also discovered that there was a specific geographical area, mainly the southern United States, where these anaphylactic reactions were concentrated. On the same note, Dr. Platts-Mills and his team realized the region having a severe reaction to cetuximab heavily overlapped with a region suffering from an unknown red meat allergy. Through research and testing, Dr. Platts-Mills and his team concluded that these allergies went hand in hand and were a result of being bitten by the lone star tick.

Early work by Karl Landsteiner discovered that all humans had antibodies to a blood group “B-like” oligosaccharide found on nonprimate red blood cells. That antigen was subsequently identified as galactose-alpha-1,3- galactose (alpha-gal) and represents a major transplantation barrier between primates and other mammals. Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, also known as alpha gal, is a sugar

molecule found on the cell surface of most mammals with the exception of primates, including humans. It is thought that the lone star tick bites these mammals and ingests the alpha gal sugar. When the tick bites a human, it transfers the sugar and the alpha gal allergen is officially introduced into the body. This elicits an IgE immune response to the sugar.

As reported by Mayo Clinic, Signs and symptoms of an alpha-gal allergic reaction are often delayed compared with other food allergies. Most reactions to common food allergens peanuts or shellfish, for example happen within minutes of exposure. In alpha-gal syndrome, reactions usually appear about three to six hours after exposure. Signs and symptoms of alpha-gal syndrome may include:

• Hives, itching, or itchy, scaly skin (eczema)

• Swelling of the lips, face, tongue and throat, or other body parts

Wheezing or shortness of breath

A runny nose

Stomach pain, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting

Sneezing

Headaches

Severe, potentially deadly anaphylaxis

According to CDC, many foods and products contain alpha-gal; you will need to work with your patients to understand which products they need to avoid. Some evidence suggests that products may be safely reintroduced in patients after long periods of avoiding alpha-gal and tick bites.

• Most patients with AGS must stop eating mammalian meat (e.g., such as beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit). Organ meats and those with high mammalian fat typically contain high amounts of alpha-gal.

•

Depending on the sensitivity and the severity of their allergic reaction, patients may need to avoid other products, such as cow’s milk, milk products, and gelatin, which may contain alpha-gal.

• Although very rare, patients with severe AGS may react to ingredients in certain vaccines or medications. There is no comprehensive list of alpha-gal-containing medications, but providers can look for products containing ingredients such as gelatin, glycerin, magnesium stearate, and bovine extract.

• Patients with AGS should avoid tick bites. New tick bites may reactivate allergic reactions to alpha-gal.

Because of these limitations to the diet, it is important to educate your patients on alternatives and potential need for supplementation. Discuss other protein options such as poultry, fish, and plant-based proteins such as lentils, beans, and soy products. Similarly, patients with AGS may now struggle maintaining adequate levels of calcium, iron, or B12 so supplementation may be needed if diet alone is not enough. Consider routinely checking these levels in AGS patients.

Providers may also consider testing IgE levels in AGS every 6-12 months to evaluate total IgE percentage, as IgE levels greater than 2% is clinically significant and likely to be symptomatic.

Medication management for AGS includes antihistamines including H2 antagonists such as famotidine, corticosteroids, and others. Because AGS is an immune mediated mechanism, it should be managed like other potentially life-threatening allergies. An example management plan is as follows:

• Provided patient education about Alpha-gal allergy (handout given)

• Recommended patient avoid red meat (beef, pork, and lamb) as well as dairy products and gelatins (including gel capsules)

• Discussed with patient the importance of adequate protein intake from plants (soy and other legumes), fish, chicken, and other meal replacement sources

• Recommended patient take calcium, iron, and B12 supplements

• Cetirizine 20mg PO BID

• Famotidine 20mg PO BID

• Diphenhydramine 25-50mg PO q6-8 PRN allergy symptoms

• Consider addition of montelukast 10mg PO QD if symptoms persist

• Patient provided with epinephrine autoinjector

• Obtain alpha gal/gelatin/bovine IgE titers q6-12 months

• Placed referral to allergist

For patients, a food allergy and anaphylaxis emergency care plan can be found on the Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE) site at www.foodallergy.org. FARE also provides resources for patients such as food allergy precautions and recipes. Providing your patients with these tools is crucial for navigation around this new onset allergy.

“In October of 2017, my wife took me out to dinner at a local Mexican restaurant where I enjoyed a beef taco, beef enchilada, and a cold beer.” J goes on to explain he spent the next four or five hours shopping with nothing unusual happening until he returned home for the day and began experiencing abdominal pain. “I thought food poisoning,” states J. At the same time, J noticed the palms of his hands were red and itchy. A short time later, J noticed this rash moving up his arms and legs and noted his lips were also swelling. J showed his wife who immediately gave him Benadryl and took J to the emergency department.

“They gave me some IV cocktail and after my symptoms started to subside, one of the ER nurses suggest that I might have the ‘red meat allergy caused by a tick bite.’” J, who was at the time

unfamiliar with alpha gal syndrome, did some research of his own on this “red meat allergy” after being discharged from the emergency department. Previously, J had not made the connection between his food and his symptom onset as it was much later on during the day; however, J’s research confirmed this is a typical course of alpha gal syndrome.

J soon saw his PCP, Dr. Bravata, who ordered some preliminary testing and referred J to an allergist. “He told me that if I did have alpha gal syndrome, that I needed to carry two Epi-Pens because if I was more than 15 minutes from the hospital and only have one, I probably wouldn’t make it.”

Several weeks later, J heard back from his allergist who told J that he did in fact have alpha gal syndrome. “My number was so high I’d probably never eat red meat again. I haven’t,” he reported. “Unfortunately, it isn’t just limited to red meat; for me, cream cheese can cause excruciating intestinal pain.”

Patient J concluded, “One important final note if you ever go out to eat, explain your condition to the wait staff. You probably won’t be the first and should you not tell them […], you will regret not speaking up.”

Until now, alpha gal syndrome has been a relatively obscure condition and its emergence demands more investigation. One has to wonder if the incidence is indeed on an exponential rise, or has increased testing become a confounding factor in the rise in cases, potentially skewing the data, making it appear as though alpha gal syndrome is becoming more prevalent. Either way, it not a condition to be taken lightly and the good news is that Snopes confirms that despite what 2013 April Fool’s Day hoaxers allegedly posted to the PETA Webpage, there is no grand conspiracy to spread red meat allergy by releasing Lone Star ticks into the environment.

Healthcare providers need to be careful not to overlook vague GI symptoms or food intolerances and should always consider a history of tick bites as red flags for a potential case of alpha gal. Chigger bites have also been implicated. Because of this, it is critical that we educate our colleagues and our patients about this emerging potentially severe condition and that we are quick to get our patients tested when indicated. It would be reasonable to consider adding Alpha-gal testing to standard tick panels and to have food allergy tests reflex to Alphagal antibody assays if red meat allergies are positive.

Avoidance is key in the management of a patient with alpha gal syndrome. It is recommended that patients completely eliminate the biggest offenders from their diet, such as all mammalian meats. Elimination of other animal products from the diet such as dairy products and gelatin will depend on a patient’s specific sensitivity.

In terms of prognosis, although not well studied, there is some evidence that IgE antibodies to alpha gal decrease in some patients over time, but it is not clear that this necessarily results in decreased allergic response to red meat products. To complicate matters, additional tick and chigger bites appear to increase the antibody level. Therefore, red meat avoidance is always recommended. Although dairy products may not cause as severe of reaction, it is reasonable to consider limiting or avoiding them as well.

In the case of emergencies, patients with alpha gal syndrome must be equipped with an epinephrine autoinjector along with instructions. Patient education regarding early recognition of an allergic reaction and next steps is crucial in the management of those with alpha gal syndrome. Other management includes antihistamines, corticosteroids, and other medications.

With the recent acquisition of NORCAL Group, ProAssurance is now the nation’s third largest medical professional insurance carrier with claims and risk management expertise in every major healthcare region.

Meet the new best-in-class, where the principle of fair treatment guides every action we take in defense of our medical professionals.

The Family Health Foundation of Missouri (FHFM) and the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation sponsored six medical students to participate in the MAFP Summer Externship Program. Because of your financial support, we can continue this program for medical students interested in family medicine each year. Learn more about the FHFM by visiting https://www.mo-afp.org/foundation/. If you are a student interested in participating in the program, visit https:// www.mo-afp.org/join/residents-students/externships/ for more information. Below are the stories about each of the extern’s experiences this summer.

This summer, I was selected to be an extern for the Research Family Medicine Residency program with Goppert Trinity Care Clinic in Kansas City. Through this program, I was paired with both faculty physicians and residents during their outpatient clinics, hospital rotations, prenatal clinics,

and OB hospital rotations. After spending a year hitting the books and studying for hours on end, this experience was just what I needed to reignite my passion for medicine and serving the community. Seeing some of the concepts I had spent so much time learning in real-life scenarios was thrilling. Going into this program, I knew family medicine was a specialty focused on primary care and preventative medicine. Through this experience, I learned it is this and so much more.

I started out shadowing attendings and residents during their outpatient clinics. Visits ranged from physicals, acute injuries, well-woman exams, well-child exams, and more. The diversity in visit types throughout the day kept me on my toes and made each encounter a wonderful learning experience. I loved going from a hospital follow-up in one room to seeing a little baby in the next. As someone very interested in patient education, I particularly enjoyed celebrating with a patient who had followed their doctor’s advice, worked hard on their diet and exercise, and then learned they were no longer pre-diabetic. Seeing how much the family med team had impacted their health and life was truly inspiring. I also loved witnessing many different types of procedures, like knee injections, pap smears, and endometrial biopsies, only further showing the wide range of family medicine’s abilities.

For my second week, I was placed with the residents doing their in-hospital rotations. Since most of my background is in the outpatient field, this was a very new experience for me. Compared to most clinic visits where you do not see a patient for a few weeks or months, getting to see patients every day and witness more immediate results was a big change of pace. It was gratifying when you got to see people improve throughout the week. This experience opened my eyes to the fact that family medicine doctors can be trained to take care of patients in these inpatient settings as well.

Last but not least, I was on the OB floor and in prenatal clinics. I am passionate about women’s health, so this was one of my favorite parts of the externship. I loved witnessing the care of those before, during, and after their deliveries. To be present at such pivotal moments in families’ lives was heartening. We also cared for the newborns, which felt truly encompassing of the “family” in family medicine. I find the physician’s role so special in these scenarios because they get to take care of their patients and share in their excitement of a new baby.

The more I learn about family medicine, the more I get excited about it. Participating in this program only clarified that. It was a privilege to spend my summer with Research Family Medicine and further my experience within the field. I am beyond thankful to the program director, Dr. Kavitha Arabindoo, the other attendings, and all the residents who took me under their wing during this time. Everyone I interacted with was so welcoming and happy to teach me, further demonstrating the supportive atmosphere of family medicine. I am excited to take what I have learned from this externship and use it as I go forward in my career and to help educate my peers further about family medicine and all the things it can be.

University of Missouri Kansas City Site: Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis