Where's the Mate?

by Captain Niels A. Nielsen

by Captain Niels A. Nielsen

Afterguard

Capt. Rod Leland, President

Cheri Folk, Past President

Don Magnusen , Treasurer

Jerry L. Ostermiller, Executive Directo r

Board of Trustees

George F. Beall

Dennis Bjork

Peter Brix*

Richard T. Carruthers * Thomas V. Dulcich

Fred Fields

Walter Gadsby, Jr

Alan C. Goudy * W. Dennis Hall

E H. (Ted) Halton, Jr.

Jonathan Harms

Don M. Haskell

Senator Mark Hatfield *

Rep. Betsy Johnson

Dr. Russell Keizer

S. Kenneth Kim

W. Louis Larson

Robley Mangold *

Thomas F. Martin

James Mcclaskey

John McGowan *

Prudence M. Miller

Ken M. Novack

Lany Perkins

David W. Phillips

Hugh Seppa

June Spence

Joe Tennant

Willis Van Dusen * Bruce Ward

Samuel C. Wheeler Bill Wyatt

Ted Zell

* Trustee Emeritus

From the Wheelhouse

The Museum's physical upgrades are very close to being completed with the paving of our parking lot. This spring n~w landscaping will provide the warm and friendly setting that our fine Museum deserves. The final pieces of our campus upgrade will include the relocation ofthe railroad tracks between the Museum building and the old depotto create badly needed overflow parking.

These projects are highly visible and therr value is obvious, yet the Museum is also undergoing internal growth as well. To cont.inu~ o~ development as a nationally signilicant ll1S1:ltu1:lon, our professional staff is expanding their roles and activities. Programs featuring nationally recognized scholars or subjects ofsignificance are bringing greater acclaim to the Museum. Our institution is beginning to be seen as an intellectual crossroads, bringing together scholars, researchers, writers and heritage organizations from throughout the country. This year the Museum hosted a two week seminar for the National Park Service, which brought the newly appointed Superintendents to Astoria. These leaders will manage the country's National Parks. The meetings were designed to explore challenging issues and to prepare these administrators for their new roles as the next managers ofthis nation's history.

The Museum was also this year's site for theNation'sannualgatheringofmaritime museums, bringing together Curators, Educators, Executive Directors and interested professional maritime museum staff. The Council ofAmerican Maritime Museums annual meeting is a powerful and important gathering. The Council boasts a membership ofthe 74 finest maritime institutions in North and South America. Attendees from as for away as Australia and Nova Scotia came to the Museum for this week-long conference. CRMM staffput together a comprehensive program focusing on the changing nature of exhibits by bringing in nationally recognized educators. These educators explored cutting edge strategies such as "free choice learning,"

and one ofthe nation's best exhibit designers provided numerous examples for discussion. At the conclusion ofthis conference, our staffwas flooded with compliments. Not only was this conference seen as one of the best ever, but the general consensus from our many colleagues was that CRMM's new approach to exhibits may have resulted in our Museum being "the best interpreted maritime museum in the nation."

Our professional staffhas also expanded their roles to meet our new leadership goals. Currently, our Curator is President ofthe Astoria Historic Landmarks Commission and the Gateway Design Review Committee, our Fiscal Officer is a member of the Clatsop County Fair Board, our Librarian is a member of the Astoria Planning Commission, our Development Officer is Vice President ofthe Astoria Music Festival, our Associate Curator is Chair of the Astor Library Advisory Board, and our new Volunteer Coordinator is a member of the Seaside Library Siting Committee.

The Museum's emerging leadership role as a sienificant heritage institution in Oregon was made even more apparent when the Governor appointed me as one ofthe nine State Heritage Commissioners. On a national level our Store Manager served as the NW Chapter President ofthe Museum Store Association, our Education Director is the District Coordinator for National History Day, and I was just elected President of the Council ofAmerican Maritime Museums.

Our Board ofTmstees recognizes these initiatives as a vital part ofthis Museum's commitment to transform itselffrom an inwardfocusedmuseum into an institution ofhighly visible and respected leadership. The Museum's growth and development has been an extraordinary success story, blessed with good f~rtun~ and the benefits of outstanding leadership. With the completion of our campus infrastructure and our historic commitment to a sound financial policy, the Museum is now setting a new course to its rightful place as one ofthe nation's most signilicantmaritime institutions.

-Jerry Ostermiller, Executive DirectorWhere's the Mate?

by Captain Niels A . Nielsen"Where's the mate?" is probably the most often asked question aboard a merchant vessel. He is in demand by almost everyone who has business aboard the ship, from agents to stevedores, port officials, and union representatives.

I will be attempting to describe the job and duties of a chief officer aboard a U.S. merchant vessel during the period from the end ofWorld War II until the early to mid 1960s. I admit my perspective may be limited, to some extent, as I spent my entire working career with one company. On the other hand, I was there long enough and under enough different conditions to become familiar with most of the situations confronting the chief mate. I know nothing about tankers, as I never had the opportunity nor desire to work on one. I have no experience on passenger

The QuarterDeck, Vol 29 No 2

vessels because the company I worked for operated none, and quite frankly, I'm not a passenger ship type of guy.

A ship's officer's first assignment as chief mate is usually the result ofluck. Ifhe has been a long time steady employee of a company, he gets his chance either when the chief mate on his ship is fired or promoted, or ifhe is available in the close proximity of a vessel that is in the immediate need of a mate. The company will promote the man that is closest rather than spend money travelling someone from a distant vessel and then having to replace that man. If the company has nobody available from their roster they will ship the man from the union hall lucky enough to hold the oldest shipping card.

We have now touched upon the first of several differences between chief officers: the

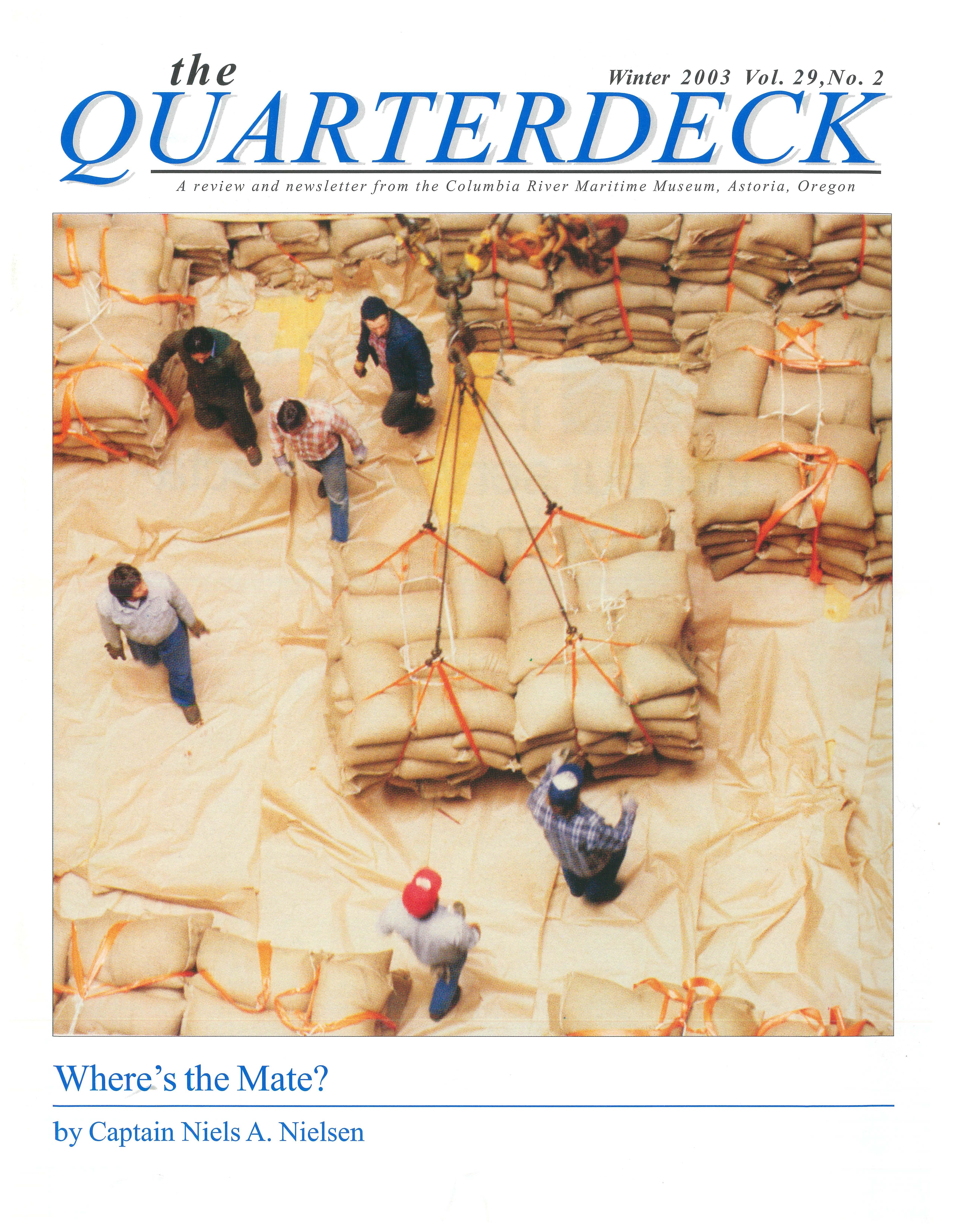

Cover:

man who works his way up within the company over a period of years and the one who ships out of the union hiring hall taking the first job he can get. I think the company mate has an advantage because he has had the opportunity to become familiar with the company's trade route, the cargos they carry, their shore personnel and the stevedore superintendents who work their vessels. The advantage that the man shipping out ofthe hall may have is more experience in a diversity of situations. A second difference in mates is their perception of the job. Some mates have the attitude that they are in charge of ship maintenance and cargo operations and don't need or want any input or interference from the captain. Other mates feel that the captain has a huge stake in what happens aboard the vessel and, in the normal course of events, keep him advised. I always tried to have a close relationship with the captain and frequently discussed any subject with him. Who knows? I might learn something. An important question is what qualities a chief mate must have. My feeling is that he needs a lot ofknowledge, experience, confidence and courage. Obviously, he needs to know a lot about cargo stowage, vessel maintenance and union contracts. If he has the knowledge, experience will temper his decisions because he will understand that everything is not either black or white and sometimes you have to settle for something less than perfect. No matter how much knowledge or experience you have, you will fail if you aren't confident enough to tell everyone what you want. You need to be able to express yourself in such a manner that your orders are unquestioned; in fact, you need such respect that people around you will assume that it is the correct thing to do or you wouldn't have said it. If a situation gets to the point where your orders are ignored, you need the courage to do something about it. For example, if the longshoremen refuse to stow cargo in the manner you instruct, you have to realize that you hold the ultimate

hammer You can turn off the power to the winches. Nothing gets such quick action as a gang oflongshoremen standing around idle while still on the payroll. This is a case where you must be confident that you are right and have the courage to take an extreme action. It is also a case where you had better be correct or the ship owner won't support your decision and you have lost a lot of respect and, possibly, your job.

It's almost a necessity that you have a good sense of humor and it doesn't hurt if you don't care to eat breakfast. Your sense of humor comes into play in your dealings with the sailors' delegate and the bos'n. When the mate joins a ship, he has to be prepared to play a little game with the sailors. They have to determine how far they can go and what they can get away with The delegate will try to pad the overtime sheet with an extra hour here and there or make an effort to convince the mate that some established custom is in place such as paying someone an hour overtime per week to polish the binnacle. The bos 'n will attempt to use more men than are needed when he is allowed to call out men on overtime. The best thing the mate can do is laugh and kid them a little for thinking that he would fall for such preposterous proposals. It's helpful for the mate to get along well with the sailors in the deck department. You have to be honest and truthful in all your dealings and play a game of give and take. If you don't, somewhere you're going to get burned and it will be absolutely within the rules of the sailors' agreement. You sometimes let an extra half-hour of overtime slip by because there could be some doubt as to the actual time worked. Other times you may cut some overtime because it will look bad when someone from the office checks the time. You protect yourself by adding an hour here and there which makes it possible to cut some time without causing resentment. If you don't have to cut time, you have a little reserve built up which you can toss in when the crew has done something exceptionally well. So you play the

game and if you do it well, there will be no problems with the sailors at the voyage payoff and the union patrohnan and the port captain will be happy. There is nothing a port captain hales more lhan lo have lo argue wilh lhe union patrohnan, because he usually has to concede something. The mate likes to see things proceed smoothly as well, but within limits. The last thing he wants is to be mentioned as a good mate in the patrolman's report in the West Coast Sailor, the union paper. Too much praise in the union paper was considered "The Kiss of Death."

As for not caring about eating breakfast, that is only mentioned because the chief mate is probably going to miss a lot of breakfasts. It is not uncommon for a ship to arrive at her berth and be tied up around 7:30 A.M. As soon as the vessel is fast there is a stream of agents, stevedores, ship chandlers and port officials coming aboard looking for the mate.

By the time he takes care of all of them, the longshoremen are aboard and the mate finds himself on deck making sure that the chain rails are taken down and that the longshorerneu aie 1iggi11g ll1e geai cuueclly. He has lo pretty much stay on deck until he is certain the longshoremen are loading the proper cargo in each hatch. When he finally gets a free moment, breakfast time is long gone.

At the end ofWorld War II the steamship companies found themselves in a state of confusion that led to a wild scrambling attempt to reestablish their pre-war business. Pope & Talbot was no exception. The ships they had been operating before the war were either sunk or had been sold; many of their top managers and officials were still in the military and their traffic department, which had not been needed for four years, was mostly nonexistent. By early 1946 they had a patchwork fleet of intercoastal vessels made

up mostly ofVictory ships and Liberties that they had been operating for the War Shipping Administration. They also found a ship or two to service Puerto Rico. Under the old McCormick name, Pope & Talbot became a partner with Coastwise Line to reestablish the Pacific Coast steam schooner trade using six small vessels. This venture lasted perhaps a year more and then faded out of the picture. I never saw any of the coastwise vessels in operation nor heard any discussion about them.

The frequent changing of vessels due to government sales and War Shipping Administration involvement further hampered returning to normal operations. There were too few of the old hands, familiar with prewar commerce, available to man the vessels. During the hostilities, labor unions had been unable to voice their demands and took full advantage of the situation presented them during the period of restructuring. Both the 1946 and '48 strikes contributed mightily to the confusion and struggle associated with the rebuilding ofthe industry.

In 1947 Pope & Talbot purchased six C-3 type vessels for placement in the South American trade route that had been granted them. The intercoastal fleet was not stable until 1951 when the last of four Victory ships were purchased and in service with, I think, one Liberty. Somewhere in the mid 1950s the fleet was firmly established and consisted of 10 ships, six C-3s and four Victory Ships. They operated their intercoastal service with the four Victories and one C-3, which was sometimes chartered in order to adjust the schedule. The Pacific Argentine Brazil Line was their service to the East Coast of South America and operated with four C-3 s, although a fifth was sometimes used when necessary to achieve the number of voyages required under their subsidy agreement. The voyage assignments frequently left one C-3 that was chartered either to another steamship company or the Military Sea Transportation Service. Since I was a mate who

remained with one company for my entire career (company stiff), I sailed on vessels in each type of service. I suppose the job description of chief mate would be the same for each type of employment, but in actual practice, there are many differences.

Most voyages ended in San Francisco, as that was the home port and the location of the main office. That was convenient for the voyage payoffs as well as the loading of ship's stores for the next voyage. From San Francisco, the intercoastal ships usually sailed north on coastwise articles and then signed articles for the intercoastal voyage in Washington or Oregon. The South American ships paid off in San Francisco and signed foreign articles for the coastwise trip as they called at Vancouver, B.C. They completed their northern loop and paid off and signed on for the South American voyage. The chartered vessels paid off and signed on most anywhere.

The intercoastal ships loaded lumber in Puget Sound, Columbia River and Coos Bay for East Coast ports from Fort Lauderdale, Florida to Boston, Mass. They usually loaded general cargo and steel in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, Charleston, and sometimes Puerto Rico for Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle. The company tried to limit loading lumber to a maximum of four ports of discharge but sometimes ended up with five in order to fill the vessel.

To reduce the number of ports of call, they set up a schedule where they would load one ship on the East Coast with general cargo for Seattle and the next with cargo for Portland. The Seattle ship would load all her lumber and pulp in Puget Sound and the Portland ship would load in the Columbia River and Coos Bay. These schedules were not set in stone because, during times that cargo was scarce, a ship could be sent anywhere in order to get a full load.

North bound, in San Francisco, would be as good a place as any to pick up a ship in the intercoastal service. The vessel had already discharged in Wilmington, California. While

there, the various union patrolmen had visited the ship; huddled with the men they represented and attempted to settle overtime disputes. They usually looked the ship over and, after talking with the crew, came up with some new demands These could be anything from a new coffee pot to a television set. What couldn't be resolved would be referred to San Francisco for final settlement.

The vessel's captain would phone the paymaster in San Francisco and they would determine the day the vessel would be paid off; generally the day after arrival in San Francisco On the trip north to San Francisco the captain would complete the payroll , usually with the assistance of the chief mate, and wire in the amount of each denomination of bills and change that would be necessary for the payoff That was very simple as every man was paid in $100 00, $10 00 and $1.00 bills and dimes and pennies. It made putting

the money into the pay envelopes easy as well.

Sometimes, the day of payoff was pretty hectic as we were also receiving ship's stores. Taking on stores required the attention of the chief officer and chief engineer as some of the providers would want to know if they could substitute for some item that had been requisitioned but they were unable to supply. A third mate, the first assistant engineer and the chief steward were usually on the dock checking the delivery of the stores for their departments against the purchasing orders. The sailors hoisted the stores ahoar<l usine the eear at No 1 hatr,h for the deck department and the after gear at No. 3 hatch for the engine and steward department stores. Members of the steward department usually rigged a series of roller conveyors and chutes from the forward in shore side of the midship house down to the

Close up of a lifeboat aboard P&T Seafarer. Company photo ca.1947-49.

Wiper- The per son r esponsible for general cleaning and painting of the engine room .

Dunnage- Material used in holds to protect goods and their packaging .

storeroom flat. The messmen and room stewards moved the packages of meat, canned goods, fruits and vegetables along this track until they reached the storeroom area where others picked up the boxes and stowed them in the proper place, as directed by one of the cooks. The engine department stores were normally landed on the offshore side and taken from there by the wipers. Most of the deck department stores were put away in the forepeak under the direction of the bos'n. Longshoremen would hoist the stores if they were working with the preferred set of cargo gear. They would hoist a pallet of ship's stores between loads of cargo as the sailors brought them under the hook. As the years progressed, the longshoremen began to claim that handling ship's stores was their work and gradually were able to take over a large part of it. It reached the point where a few companies that had used the ship's crew to take stores for many years were granted "Grandfather Rights" and could continue to use the crew. Everyone else was required to use longshoremen.

Sometimes the call at San Francisco required shifting the ship to Oakland in time for the night shift and then shifting back to San Francisco to go back to work the next morning. If a shift to the East Bay was required, we always hoped that it would be after completing the San Francisco discharge and that we could sail from there. That made life a lot easier.

On the first day out of San Francisco, it was a good idea to sit down with the deck delegate and reach agreement on the number of overtime hours each member of the deck department worked since the payoff. If the delegate was new to the vessel, it put him on notice that the overtime was going to be closely watched and he would be unable to be creative in his claim for hours.

In the early to mid 1950s, it was not unusual for the intercoastal vessels to discharge cargo at Portland and Seattle and load in Puget Sound and then Columbia

River. This gave the mate a little more time to complete some of the work that was necessary, but regardless of the port rotation, there was a certain amount of work that had to be done.

The first task was to concentrate on cleaning holds and the extent to which this was completed depended greatly upon the weather. Under ideal conditions, the mate would tell the bos 'n to call out all hands. There were usually three or four dirt slings on deck full of broken dunnage and debris and possibly a few sling loads of used shoring material. When the sailors turned to, they immediately hoisted the dirt slings over the side and dumped the contents. Then, if the ocean was calm enough, they opened one of the hatches and proceeded to clean whatever space was free of cargo.

Good dunnage was stacked into loads, on stickers, with an endless rope sling secured around it. Broken dunnage, hold sweepings and used shoring material was placed in dirt slings, hoisted out of the hold and dumped over the side. Shoring material was not saved because it was hardwood and almost impossible to pull the nails. Longshoremen loved these hardwood 4x4s as they made wonderful firewood, giving off a tremendous amount of heat. Frequently we would stack them into loads and leave them in the hatch, ready for the longshoremen to hoist out and dump in the back of someone's pickup truck.

It was always a judgment call whether it was calm enough to pull a couple of pontoons, remove a hatch beam and hoist debris. It was one thing that I was never comfortable with because sailors always seemed to overestimate their ability to drive winches. It was sometimes a heart-stopping event when a sailor had a hatch beam or pontoon on the hook and it started swinging wildly. You held your breath, hoping that he would get it under control, and were afraid to say anything for fear that he would panic.

You worked at hold cleaning until all the hatches were completed or you ran out of

time. You tried to finish the forward end first so that you could continue after dark, especially when underway with a pilot aboard.

At one time, hold cleaning was considered sailor's work, even in port, and sometimes they would be cleaning a 'tween deck while the longshoremen were discharging the lower hold. It was bound to happen that a few times some dirt or dunnage got away from the sailors and fell down to where the longshoremen were working . That caused a change in the rules and soon the sailors were only allowed to clean cargo spaces below the deck where the longshoremen were working. It wasn't long before that changed and the sailors weren't allowed to work in the same hatch. Eventually, the longshoremen negoti ated an agreement with the ship owners making hold cleaning their work while a vessel was in port. It seemed as if the disputes over work jurisdiction, between the longshoremen and the sailors, were an endless occurrence.

Breaking out the deck chain lashings was another operation that needed to be completed as soon as possible. This consisted of dragging the chains out of their storage boxes and shackling one end into a pad eye on deck and piling the chain against the fish plate The The QuarterDeck, Vol. 29 No. 2

'

pad eyes were approximately eight feet apart and it was up to the chief mate to designate where the d1aim; were to be located. You usually liked to have an extra chain across No. I hatch and in the area of the shrouds between No. 2 and No. 3. Turnbuckles, pear links and shackles were usually stowed on top of the mast houses where they would be available when lashing.

From our arrival on the coast until our final port of departure for the Panama Canal, the cargo gear almost always remained "flying." It would only be lowered and secured when heavy weather was expected.

There were times when a vessel arrived at her berth and there were four or five gangs oflongshoremen standing around waiting for the ship. The message was delivered loud and clear. "Get that damned gangway on the deck in a hurry." Under favorable conditions, the gangway would be completely rigged with safety net m place and ready to be lowered immediately. Other times, when the ship was deep or the river or tide was low, there might be a question as to whether the gangway would clear the dock, in which case it remained in the stowed position. In either case, the chief mate had better make

P&T Adventurers

Eastbound cargo plan. Side profile of ship is simplified, showing the loading layers and the deck loads. Courtesy Captain Nielsen.

certain that the gangway be in place on the dock in record time.

It was common practice for the mate to send a sailor from the bow back to the gangway as soon as they had a couple of lines ashore. When the second mate had a stem line in place he would send a man forward and the mate on the bridge would send the helmsman down to help. If the gangway was ready to be lowered, these three would have it in place in a very short time and if it had to be rigged, they would have it well under way by the time the rest of the sailors arrived to help. It would be a safe bet that iflongshoremen were waiting on the pier, so was the port captain or office manager. Failure to get the gangway lowered in a timely fashion was a very visible and costly mistake and could be one that had demotion to second mate written all over it. If you can't get the gangway down, what the hell can you do?

There was enough activity while discharging cargo at either Portland or Seattle to keep all the deck officers busy. Before discharge started, the stevedore foreman would usually get together with the mate in order to find out anything that might be a problem or if it mattered which end of a hatch should be rigged. The chief mate took the forward end of the ship and the second mate, or the mate on watch, the after end while the longshoremen rigged the cargo gear. The Victory ships had very simple gear so there was very seldom any problem with them. On the other hand, the C-3s were a little more complicated and there was always the possibility that longshoremen would get careless and drop a boom. They had double drum winches with the cargo fall secured on one and the topping lift on the other. The drums were on a common shaft and were engaged or disengaged by means of a lever that moved a notched collar along the shaft to fit it into a matching fixed collar, which was part of the shaft. When a drum was disengaged, a break operated by a wheel pre-

vented the drum from running free. We had so much trouble with longshoremen releasing the topping lift break, to lower a boom, and then losing control and allowing the boom to fall that we secured the brake with a length of chain and a padlock. This made it impossible for a longshoreman to raise or lower a boom without a mate, who had a key, in attendance. The topping lift also had a patent brass stopper that was secured to the deck. The jaws, grooved to fit the lay of the wire, were clamped in place by means of a turn screw. This was intended to prevent accidental dropping of the boom when disengaging the drum, but sometimes the longshoremen left it in place with the weight of the boom on it and then proceeded to work cargo. This could easily wear down the brass grooves on the jaws of the stopper and render it unsafe. All the mates were instructed to make certain that his stopper was used properly.

When listing the duties of the chief mate, safety is seldom mentioned except as an afterthought. My guess is that maintaining safe working conditions aboard the vessel is usually delegated to the junior mates and the bos 'n and reflects the attitude and interest of the chief mate in promoting safety. There is a hazard connected with just about every shipboard operation and the attention paid to safety by the crew depends upon how hard the mate presses the issue. While maybe not a direct issue of safety, the mate had to be ready to handle the problems brought up by the longshoremen. The main problems were cargo falls that were either kinked or had a lot of fish hooks, cargo stowed within the three foot clearance around the hatch square or hatch boards that were damaged in some manner. All the deck officers had to be alert when the vessel was loading and make certain that the three-foot clearance was maintained. The condition of the cargo falls was a pet complaint of the longshoremen in the northwest. In Los Angeles, the longshoremen loved to find fault with the hatch boards. You saved time and trouble by granting their

wishes, even if you put the cargo falls and hatch boards back in service for the next port.

It didn't matter much if the ship was discharging in Portland or Seattle; the mate had plenty to do. At the initial rigging of cargo gear and opening of hatches, he needed a mate to take care of the after deck while he presided over the forward deck. Without the supervision of a couple of mates, there was an excellent chance that chain railings would not be removed or that hatch beams would be landed on pontoon covers without dunnage between.

Pope & Talbot delivered large shipments ofliquor to both the Oregon and Washington Liquor Commissions. Liquor possibly created the greatest problem in the never-ending fight against pilferage. When we loaded it on the East Coast, a mate was stationed in the hatch where the booze was stowed and checked it aboard. It was loaded in special cargo lockers, over-stowed with other cargo, and, in the Victo1y ships, stowed in the former gun crew quarters. Regardless of what we did, we were unable to prevent pilferage. Our only success was to make the game a little harder.

Ships discharging in Portland usually had steel plate that had been loaded directly from gondola cars in Philadelphia or Baltimore. They had to be discharged into rail cars exactly as they had arrived at the ship's side at the port ofloading. We never could find a satisfactory way to mark-off between the carloads. We tried paper, chalk, paint, dunnage, tape and nets; all to no avail. The mark-offs disappeared from cargo being dragged over them, rain dissolving them, people walking over them or by magic. At any rate, it was time consuming and largely ineffective.

In port, the second mate was busy correcting charts and publications because a couple of month's worth of"Notice to Mariners" had been delivered aboard in San Francisco. If the vessel was one of the Victory ships he need only correct charts

pertaining to the intercoastal service. If it was a C-3, he might also take care of the charts for the South American run as that ship could possibly change services.

In addition to his duties relating to cargo, the chief mate had to think about laying out the work for the deck department. Two or three sailors might be assigned to splice the eye in a new mooring line and then cut and splice wire for cargo runners. If the weather was good, the paint punt would be put in the water and as much of the hull as possible would be painted. They would work in way of the bow and stem as the rest of the vessel might easily be painted from the dock at a later time. Maintaining the lifeboats and davits was a never-ending program as the provisions, water and equipment had to be inspected periodically. The releasing gear had to be inspected and checked and the davits and falls had to be lubricated. Historically, taking care of the lifeboats was the responsibility of the third mate uut, uve1 time, this became another job that wound up under the direction of the chief mate. Ifnothing else, the midship house usually could stand a good soogie job, the storerooms could be cleaned or the chain locker painted. Of course, there were always holds that needed to be cleaned before the vessel went on loading berth.

The company provided a booking list, which showed the loading and discharge rotations along with the quantity oflumber at each loading berth for each discharge berth. We could usually maintain the discharge rotation but our loading sequence was frequently turned completely around. There were several reasons for this, all of which were beyond the control of the vessel. First, the traffic department sometimes had not fully booked the vessel when the loading commenced so they were looking for an additional booking at an unknown berth for an unknown port of discharge. Second, we might prefer to start loading at a certain mill but there was only one berth there and it was

Soogie- Cleaning the inside of the ship with soap and ,vater.

Docking the P&T Seafarer.

occupied by another vessel. Third, a mill was in the process of cutting the lumber we were to load but hadn't produced enough for us to start loading Usually they were cutting to obtain the best utilization of the logs They might have sufficient lumber to start loading but hadn't completed production for the last port of discharge. This situation resulted in loading a partial deck load in the wings abreast and securing it with a minimum of chain lashings. Until the holds were full we had to climb over the deck load and work our way around the pontoons and hatch beams that were landed on top of the deck load . It happened so frequently that we began to believe that this was the proper way to load a ship.

When it came to lashing a deck load, there was no hard and fast rule except that you had better provide close supervision. How the deck load was secured depended upon the chief mate and what he wanted done . Generally speaking, the amount of securing depended upon the size, weight, shape, number ofitems, and value of the pieces. My goal in securing the deck load was to temporarily make the deck load part of the vessel, as solid as the mast houses, winches and masts. This was impossible to achieve with rubber-tired vehicles because there was no way to take the bounce out of them. On the other hand, the tread on rubber tires provided a strong grip on the deck and when a vehicle was in gear with the brake set, it was hard to move. I never felt comfortable lashing the deck load with wire for two reasons. Longshoremen often did not properly apply cable clamps; they would put them on in the wrong direction or not tighten them sufficiently. Also the weight of a turnbuckle tends to make a wire lashing bounce and loosen the turnbuckle if it is not properly stopped off My first choice was always to lash with chain and the regular deck lashing turnbuckles (1 114" dia. xl 6" take-up with pelican hook and pear link). Before the loading and lashing begins, the mate should take the time to explain to the stevedore superintendent and the ship

foreman exactly where he wants each unit landed and how it is to be lashed. If the mate doesn't plan to supervise the lashing himself, he should thoroughly explain what he wants to the mate assigned to the job.

When large, out of the ordinary commodities such as railroad locomotives or very large pieces of machinery were to be loaded, there were special arrangements made for their securing. This could include welding pad eyes on deck, in the proper locations, to facilitate the lashing. In some cases small pieces of steel plate were used to weld the cargo directly to the deck. It was usually not sufficient to just weld the lift in place and it was also blocked and lashed. In the case of exceptionally heavy pieces, the deck was shored up from the deck below with heavy timbers.

Ordinary deck loads required no special attention other than what the chief mate required. There is no question that there could be a big difference between what one mate would require compared to what would satisfy another. All I could do is explain what I required, knowing full well that it probably exceeded what satisfied many other mates. I also know that I made out better than lots of

others because I never lost any part of a deck load nor did I ever receive a complaint from the company for spending too much money lashing.

The voyage westbound was the time that we tried to make everything look pretty for the home office. This was when we chipped the main deck and painted it with a special deck preserver The main deck paint was special because every mate had his own formula which he was positive was better than any other. Just about all the formulas contained the same ingredients. These were fish oil, lampblack and Japan drier. The main difference was in the proportions. Some mates mixed in used lube oil or diesel and, in some cases, even fuel oil. I had my own mix, but after a few disasters, gave it up in favor of commercial deck coating. Too much fish oil and it smelled awful forever and never dried. Too little lampblack and it dried a crummy looking gray. The commercial deck coating dried a dark black and looked great.

Just about everything else we did was to improve the appearance of the vessel for her arrival on the West Coast. The midship house was partially painted or touched up to make it look fresh and clean. The outside decks of the midship house were painted either red or black, depending upon their location, and the inside passageway decks were coated with bright red deck paint. Inside passageway bulkheads were either washed or painted if they were soiled and crew mess rooms and quarters were painted as needed. Deck coating was applied to the entire main deck except where cargo stowed on deck prevented it. If we knew of any "beefs" the crew had that could be taken care ofby the carpenter or deck department, we would try to get it done.

From the Canal Zone, we mailed our requisition for deck department stores, for the next voyage, and a copy of the disputed crew overtime to the port captain in San Francisco.

With our arrival at Los Angeles, we were getting ready to complete the voyage and start

all over again on the next. As you finished the voyage, you felt rested and could look back with satisfaction knowing that you had worked hard, earned your money and hoped that you had helped the company make a profit. In some respects, the deck department could almost be considered a family. Usually only the best sailors in the union shipped out on the intercoastal ships. Many of them were family men with wives and children to support and they sailed intercoastal because they worked a lot of overtime and the voyages were short. If they wanted to spend some time at home, they could leave the vessel knowing that there would be another along shortly. It was a comfortable feeling when the ship changed crews, at the end of a voyage, and you realized that you knew several members of the new crew.

The post-war Intercoastal Trade was at its peak for about ten years from the early 1950s to the eaily 1960s. All ufthc: cumva1iic:s engaged in the trade fell on hard times due to higher wages, frequent labor strikes, and the railroads offering low freight rates on selected cargoes . Also affecting their profit possibilities was their inability to obtain a reduction in the cost of the Panama Canal transits

Editors Note:

Both Nielsen 'sfather and grandfather were captains engaged in the Pacific Coast Lumber Trade. Nielsen would become a ship 's officer during World War II. After the war Nielsen continued his career in merchant shipping with Pope & Talbot working his way to Chief Mate inl952, then Captain in 1954. Captain Nielsen would go ashore in 1959 and retire in 1986.

Full text for the story of Where ' s the Mate? is available at the Columbia River Maritime Museum Library A special thanks to Captain Niels Nielsen for his assistance in making this article possible .

Museum Staff:

Barbara Abney

Kim Bakken

Russ Bean

Celerino Bebeloni

Chris Bennett

Ann Bronson

Cheryl Cochran

Betsey Ellerbroek

John Gibbens

Helen Hon!

Arline LaMear

Jim Nyberg

Jerry Ostermiller

David Pearson

Molly Saranpaa

Hampton Scudder

Jeff Smith

Cynthia Svensson

Patric Valade

Shelley Wendt

RnrhP1 Uj 1nnP