2022 Changemakers dismantle food insecurity through hands-on job training and urban farms

By Clare Hintz

By Clare Hintz

At the turn of the millennium, urban farming was just becoming popular. Nonpro t organizations in Chicago realized that if something happened to the highways owing into the midwestern city, there was perhaps a day’s worth of food in the whole town.

Laurell Sims, co-founder of the Urban Growers Collective re ects that food security is still a major issue in Chicago more than two decades later, made even worse by the pandemic.

“Two days of food in the city is a terrifying prospect,” Laurell says, “With the pandemic, more people have started to lack food security, and public consciousness around the issue has grown tremendously.”

e Urban Growers Collective is this year’s MOSES Changemaker of the Year. e purpose of the MOSES Changemaker designation is to recognize emerging leaders in the organic farming and food movement who creatively overcome systemic challenges in order to nurture a thriving agricultural future for all.

e Urban Growers Collective provides hands-on job training and career laddering at eight urban farms for youth, beginner Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian farmers, and men who are at high risk for gun violence. e impact of this organization far outstrips its 11 acres, making it a natural MOSES Changemaker. Food insecurity is just one dimension of the system that the Urban Growers Collective is trying to dismantle.

“For so long we siloed food insecurity, lack of housing or unstable housing, access to employment, lack of quality education, and economic development all as separate problems,” says Laurell. “But they are all interconnected. Addressing them as one system also helps tackle issues like gun violence.”

“ e Urban Growers Collective works to create solutions with Chicago communities to get folks what they need,” she continues. Produce from the farms is available at farmers’ markets, in their Collective Supported Agriculture program, and through their Fresh Moves Mobile Market. Job training e orts directly help tackle systemic instabilities in the city.

e results are impressive. In 2021 alone, the Collective employed 188 teenagers, who together earned more than eighty thousand dollars for their e orts. e organization grew, packed, and distributed more than ve thousand food security boxes and made 13,626 hot meals for folks with limited means to cook. e organization underwrote $169,686 worth of vouchers for people to use at the Fresh Moves Mobile Market sites, providing even better access to the produce grown locally. Despite the pandemic, Urban Growers Collective was able to hold 38 workshops, with nearly four hundred attendees and thirteen thousand dollars given as scholarships. Fourteen incubator farmers helped grow the produce that owed through all of these e orts. Chicago’s city motto is “city in a garden,” and the Collective is making that vision a reality for all residents.

Ag Solidarity Network: connection and collective action, we have

By Lori Stern

So much of agricultural knowledge has been passed from person to person, with direct experience of hands in dirt, witnessing the cycle of life and death, standing in for any credentials or earned certi cates. Making a living on a small or medium-sized farm, o en with diversi ed production, also comes with challenges that are equally complicated. Because attending training and education o -farm can be costly, time consuming, and o en not serendipitous to when problems arise, many farmers have turned to social media and electronic mailing lists to learn and connect with peers when they need it most.

e many production-focused Facebook groups, the multiple mailing lists, and the organizational job and classi ed boards demonstrated a desire to reach other Midwestern farmers who were farming in similar ways. In fall 2021, MOSES convened stakeholders across the Midwest, all working directly with farmers. We recognized that in addition to advice on agronomy, equipment, seeds, and breeds, human scale farmers are facing systemic challenges. Policies that proliferated during Sonny Perdue’s tenure to support the ‘go big or get out’ approach to the food and farming systems have gutted many rural communities. e conversations in small co ee shops or bodegas over post-chores breakfast, co ee, and house-made pie are rarer. Still, small and medium-scale farmers need a way to organize and share their stories.

According to Regi Haslett Marroquin, the Vice President of MOSES, through education, mentorships and publications, MOSES “is fundamentally a movement builder, it is what people expect, that is why they come to the annual gathering.”

To step further into this role, we are collaborating with partners to create a platform of knowledge exchange, advancement, and sharing of practices that work for farmers to succeed. e platform will facilitate those exchanges and ensure that they are captured and exponentially shared. rough this process, we can upli knowledge and wisdom from communities.

ese form the foundation of the future of agriculture, validating indigenous knowledge, agrarian traditions, and ensuring that all of this is shared for both current and future farmers.

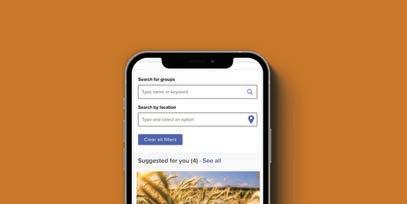

With a portion of a foundation grant for technology, the communications team at MOSES started interviewing platform companies that host online communities. A er talking to stakeholders, we

an app for that!

prioritized the following:

• Space for multiple groups, each with their own identities and control of their data and information that could interact with the main site

• Easy navigation that was familiar for social media users with all the ease and functionality that comes with Facebook and Instagram but did not feed the “Meta-Monster”

• Ability to host multiple languages

• Shared space for events, job boards, classi eds, and messages

• Searchable content across the site

• An app and/or single sign-on so there is no need for unique passwords or extra steps to get on the platform

Because we wanted to build a platform that was collectively conceived and owned, the rst two bullet points were most critical. e platform we chose o ered the greatest exibility for various groups. Farmer a nity groups or organizations are able to be administrators and even create custom looks for their pages. Several partner organizations indicated that they were exploring the costs associated with hosting a platform, but the price was o en out of reach. By working together, committing to the site always being free for farmers, we chose the platform and the Ag Solidarity Network (ASN) became a reality.

e Ag Solidarity Network is on its face a social networking platform. ere will be an app available so that farmers can receive noti cations, post questions, and pictures. It looks very similar to Facebook and Instagram, making it easy to navigate. However, we are hoping that it will become much more. Unlike Facebook groups that have no relationship to each

March | April 2022 Midwest Organic & Sustainable Education Service Volume 30 | Number 2 TM PO Box 339,

54767 Ag Solidarity Network continues on 8

Spring Valley, WI

6

2022

Changemakers

continues on

Teen farmers selling their harvest.

Perennial Pastures Page 11 BIPOC Farmer Listening Session Page 15 Selling Directly with REKO Ring Page 9

Photo submitted

Editor Hannah Westfall Advertising Coordinator Tom Manley Digital Content Producer Stephanie Co man

The Organic BroadcasterTM is a bimonthly newspaper published by the Midwest Organic & Sustainable Education Service (MOSES), a nonprofit that provides education, resources, and practical advice to farmers.

Opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher. Inclusion of an advertisement does not imply endorsement of a product. We reserve the right to refuse inappropriate advertising.

©2022 MOSES

Content may be reprinted with permission. Contact organicbroadcaster@mosesorganic.org

Content Submissions or Inquiries: organicbroadcaster@mosesorganic.org

Display Advertising: Thomas@mosesorganic.org or 888-90-MOSES

Classified Advertising: Sophia@mosesorganic.org or mosesorganic.org/organic-classifieds

Subscription: mosesorganic.org/sign-up or 888-90-MOSES

MOSES is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit qualified to receive tax-deductible donations.

Support resilient organic, sustainable, and regenerative farms by donating: MOSES, P.O. Box 339, Spring Valley, WI 54767 Online: mosesorganic.org/donate

MOSES educates, inspires, and empowers farmers to thrive in a sustainable, organic system of agriculture.

Together we move into spring with

By Lori Stern, MOSES Executive Director

As I am writing this column for a pre-conference print deadline, I am literally dreaming about the conference. Just like those nightmares we all had as summer was winding down to the start of school, the annual conference is looming large during my waking hours and in sleep as well. Not all of my dreams were related to oversleeping the general sessions or feeding almost 2,000 people peanut butter and jelly for three days. Some were celebratory dreams of an event lled with learning, meaning, movement building, and community.

As you read this, you will know how it all turned out. Whether you were in La Crosse with us, joined during streamed sessions, or listened to recorded workshops and keynotes, I hope you were inspired to try something new on your farm or take collective action on behalf of a more just agricultural system.

With the conference in the rearview mirror, we head toward spring, starting plants, sowing seeds, witnessing the birth of countless calves, lambs, kids, and piglets. At MOSES we will continue to work on behalf of a strengthened regenerative and organic farming movement. Our mentor program has new pairings, we are building an expanded Wisconsin land access hub of real estate, farming, and conservation professionals, and we are planning for an exciting eld day season.

I hope the conference also gave you the opportunity to hop on to the Ag Solidarity Network. We have created this collectively with other organizations and farmers to be a space of social networking and movement building that we own together, void of the tracking and ads of the “Meta-Monster.” If you have not gotten the chance to go onto the platform and create a pro le, check it out at https://agsolidaritynetwork.com

“Cultivating Community,” the theme of the Organic Farming Conference this year, will hopefully be what guides us in 2022. e past two years have been marked by so much separation and loss. I hope

MOSES Team:

Lori Stern, Executive Director | lori@mosesorganic.org

Chuck Anderas, Program Specialist | chuck@mosesorganic.org

Sarah Broadfoot, Project Manager | sarahb@mosesorganic.org

new hope and new

strength

in the coming months we will all nd opportunities to make connections with friends, family, and maybe folks with whom you would not normally connect. We need to hear each other’s stories, struggles and joys. I know there will be common ground and shared understanding.

One of our initiatives this year trains farmers as Peer Support Specialists to improve farmer mental health. e many years of dwindling farm income, dairy closures, and the ongoing isolation of the pandemic have taken their toll. In the spirit of farmer-led e orts that are at our core, we know that creating a network of trained farmers will make mental health support more accessible.

As farmers and food system advocates all centering people and the planet, more connects us than divides us. I hope the conference was a reminder of what we have in common. As I type this column, it looks like the pandemic is poised to become more endemic, another virus that lives in the background rather than taking a central role in errands, schools, planning gatherings, or running businesses. I also know that we are likely forever changed. I can only hope that we keep what we learned about the fragility in our food system due to consolidation and the importance of small and medium sized local farms.

at we recognize our power in mitigating, and then reversing climate change as we saw clearer skies with fewer commuters. And that the rapidity in which the coronavirus covered the globe, surge and variant a er surge, reminds us that there is no separation, only connection.

We are also moving into the cycle of a new Farm Bill. anks to all of you who attended sessions at the conference designed to engage farmers in essential agricultural policy creation. All that we learned during this pandemic about food and farming, climate and community health should be re ected in a Farm Bill that a rms the critical role of human-scale, organic farming. Hop on the Ag Solidarity Network, share your story and knowledge, and listen to those from others. In 2022, we cultivate community!

Board of Directors:

Katie Bishop | PrairiErth Farm, IL

Dela Ends | Scotch Hill Farm, WI

Regi Haslett-Marroquin | Northfield, MN

Sophia Cleveland, Administrative Coor. | sophia@mosesorganic.org

Jenica Caudill, Dir. of Development & Marketing | jenica@mosesorganic.org

Stephanie Coffman, Presentation Coor. | stephanie@mosesorganic.org

Tom Manley, Partnership Director | thomas@mosesorganic.org

Jennifer Nelson, Land Access Navigator | jennifer@mosesorganic.org

Hannah Westfall, Comm. & Marketing Specialist | hannah@mosesorganic.org

Sarah Woutat, Farmer Advancement Coor. | sarahw@mosesorganic.org

On-Farm Organic Specialist Team | specialist@mosesorganic.org

Clare Hintz | Elsewhere Farm, WI

Charlie Johnson | Johnson Farms, SD

David Perkins | Vermont Valley Farm, WI

Sara Tedeschi | Dog Hollow Farm, WI

Darin Von Ruden | Von Ruden Family Farm, WI

Volume 30, #2 March | April 2022

CONTROL WEEDS. INCREASE YIELD. VERY SAFE + FUEL EFFICIENT + VERSATILE HOODS + ELECTRONIC IGNITION + FLAME DETECTION + CALL NOW TO PLACE AN ORDER 402.326.8086 WWW.AGFLAME.COM

Minnesota establishes Emerging Farmer Office

By Patrice Bailey and Lillian Otieno

By Patrice Bailey and Lillian Otieno

My name is Patrice Bailey, and I am the Minnesota Department of Agriculture Assistant Commissioner. In that role I oversee outreach, agricultural marketing and development, dairy and meat inspection, and food and feed safety. I am the rst assistant commissioner of color ever in MDA’s history. I have served the Twin Cities in several positions focused on bridging underrepresented communities of color to various available resources and advocating for them legislatively at the Capitol.

In 2021, we experienced another turbulent year, with climate change and fall-out from the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to a ect the agricultural sector and access to food. In addition, it was a very tough year for farmers all over the country, but especially in Minnesota, due to a severe drought, worker shortages, and supply chain issues, which all posed a major upset for our farmers. However, the farm economy in agriculture has been and continues to be a foundation for Minnesota’s economy.

Minnesota ranks h in the nation in terms of agricultural production, and there are over 430,000 agriculture-related jobs in the state. Minnesota has 68,500 farms covering 25.5 million acres. Agriculture also plays a large role in Minnesota’s culture and heritage, and many Minnesotans feel connected to agriculture even if they themselves have no formal role in the industry. Since the death of George Floyd, Minnesotans have come together to address food deserts in urban communities and mobile food hubs. However, the agricultural opportunity is not equally available to all Minnesotans.

According to the McKinsey and Company article, “Black farmers in the US: e Opportunity for addressing racial disparities in farming,” “Today, just 1.4 percent of farmers identify as Black or mixed race compared with about 14 percent 100 years ago. ese farmers represent less than 0.5 percent of total U.S. farm sales.”

e history of land ownership in the state has been a ected by the Homestead Act (1862), Bonanza Farms (1875), and well-documented racial bias in USDA grant and loan programs (Keepseagle v. Vilsack, Pigford v. Glickman). Limited access to capital and the lack of legal protections like wills that transfer property to the next generation means that communities of color and

INSIDE ORGANICS

Viewpoints from members of the organic community

emerging farmers have been unable to fully participate in the land market.

Emerging farmers continue to grow beyond urban areas and within refugee and immigrant populations in Minnesota despite the ongoing e ects of the COVID-19 pandemic. e Emerging Farmers’ Working Group and the MDA achieved major success during the last legislative session. Many of the 2021 legislative requests and successes put forth by the MDA came as recommendations from EFWG members. ese included the establishment of an Emerging Farmer O ce.

Because of the Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) farmers, women farmers, veteran farmers, and other farmers from historically underrepresented and underserved communities who are contributing their voices and ideas as part of the Emerging Farmers Work Group, we are creating an agricultural future where it is easier for all new farmers to take their first steps into the field. It is with a deep appreciation for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture for their continued dedication to this important conversation and bringing people’s voices to the table.

-Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan

e function of the Emerging Farmer O ce is to focus on advocating and championing the e orts and recommendations of emerging farmers both internally at the MDA and externally. e coordinator will engage with emerging farmers, stakeholders/partners, and report directly to the assistant commissioner. is includes outreach, communication, analysis, and developing a workplan based on the recommendations of the working group. e coordinator will also be the lead public facing gure for the o ce and the working group.

Lillian Otieno (she/her) is the current Emerging

Farmer Outreach and Engagement Coordinator for the new o ce. Lillian has worked with the MDA in other outreach roles, most recently with the Produce Safety Program. Before joining the MDA Commissioners’ O ce, Lillian brie y served as a Public Engagement Liaison with the O ce of Governor Tim Walz and Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan. She is also a 2021 graduate of the state of Minnesota Emerging Leaders Institute (ELI). Her background spans several years in the food safety industry both in retail and manufacturing. Lillian is also a member of the MDA’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Committee and serves on several community leadership roles and board memberships.

Lillian’s vision for the Emerging Farmer O ce is shaped by feedback from the many listening sessions with emerging farmers from across Minnesota and the Emerging Farmer Working Group members:

• Serving all emerging farmers in a way that meets their needs and acting as a liaison between farmers and all the MDA divisions. e o ce will be a one-stop shop for emerging farmers – responsive to questions on how to start a farm business.

• Listening, engaging, and learning from emerging farmers to continue to inform the structure, evolution, and development of the Emerging Farmer O ce, and to enable the MDA to have an impact in addressing equity and justice in agriculture for all.

• Addressing language barriers to include translation/interpretation of materials and resources, with intentional language access at inception, development and delivery of materials and services.

• Assisting farmers to navigate public-private partnerships in agriculture and connecting with nonpro ts. Supporting and collaborating with allies who are not emerging farmers and are interested in sharing their expertise and resources.

• Advocating for emerging farmers with other Minnesota state agencies and programs. Building connections externally and internally to leverage access, and address equity in policies, processes, procedures, and programs.

“I am very hopeful that we can all boldly begin to intentionally address the structural and institutional

| 3 mosesorganic.org | 888-90-MOSES TM

of

it

the yield, quality and

line of organic and natural

fruits, flowers, grains,

and known worldwide as... Simply the

TOP QUALITY ORGANICS FOR ANY CROP FROM SUSTÅNE’S FAMILY OF FERTILIZERS AND SOIL BUILDERS VISIT US AT BOOTH 401/414 www.sustane.com (507) 263-3003 1-800-352-9245

Suståne’s 33 years

independent field trials prove

enhances

profitability in a variety of growing

zones.

Suståne’s full

soil builders and amendments nurture the soil to grow world class

herbs, and

vegetables. Safe, simple, effective;

Best.

Patrice Bailey (top) and Lillian Otieno

Inside Organics continues on 14

Minnesota’s rst agriculture-themed license plate Photo submitted

Think outside the box for weed management

By Carmen Fernholz

Invariably the most frequently asked question from transitioning organic eld crop farmers, inexperienced organic farmers, and yes, even veteran long time organic farmers, always seems to center on weed management. Part of the reason this question is uppermost in any gathering of these farmers is that the e ectiveness of weed management protocol is highly dependent on a number of factors, some of which we have limited control over and others we do not.

Factors we have at least some control over include the equipment we have available to us, the variety of crops we grow, the fertility levels we are able to enhance and maintain, our care for the soil itself, and the rotations we utilize. Most important in this list however is the honing of our management skills which are learned over time and through education.

e factors we have very little control over include the soil types we are given, and the area of the country we live in, including the speci c seasonal characteristics and ultimately the weather patterns we live with. Adding to the complexity of the weather patterns is what appear to be climate surfacing with each passing season.

Since much of the e ciency in our weed management is both site speci c and management speci c, I would like to focus on the management side of things. Many of you experienced farmers reading this know that robust rotations are a key factor. Incorporating warm and cool season crops, perennials and single season crops, and row crops and non-row crops is paramount to combat the many and varied species of weeds. It becomes our responsibility as e cient managers to learn and understand the characteristics of the weeds on our farms. roughout the growing season, observe, take notes, take pictures, and read about weeds. A er all, if you do not know your opponent, how are you going to counter their actions?

Weeds like any other growing plant are directly impacted by the weather. Some are early risers while others wait until things warm up. How does knowing that impact which crops you will plant? How will this impact the equipment that you have in mind to deal with these weeds? How does your soil disturbance a ect all of this? Only you can determine this cropweed relationship and how to approach it. It takes time, study, and lots of experience; hands-on, in-theeld experience. Experience that I call tuition.

Over the years I have come to learn just how e ective good soil fertility can be in weed management. is may seem counterintuitive because most weeds thrive equally well in good fertile soils. What I have experienced, however, is that in fertile soil crops can be much more competitive with weeds. And in the case of row crops, weed competition is better managed because I am able to use my weed management equipment earlier and more e ectively with a more vigorous corn or soybean plant rather than a plant struggling to

MOSES Organic Specialists answer your questions about organic production and certi cation.

CALL: Organic Answer Line 888-90-MOSES (906-6737)

SUBMIT: Click “Ask a Specialist” button at mosesorganic.org/ask

READ: Browse answers to questions at mosesorganic.org/ask

DOWNLOAD: Fact Sheets at mosesorganic.org/ organic-fact-sheets

emerge and grow because of a lack of fertility.

One of the most challenging aspects of highly e ective weed management is the gi of patience. is is especially true for transitioning growers, many of whom have been operating in a world where earlier is always better. In an e ective organic weed management world, it is a matter of both patience and timeliness. In an organic weed management protocol, earlier really most e ectively applies to the planting of spring grains and other crops like peas. In this instance earlier is always better both for the crop and for getting ahead of the cool season grasses that are just waiting in the wings.

But that is where it ends. Warm season crops, including corn and soybeans because they allow more open spaces in the elds, need a more level playing eld; that is, they need to emerge quickly and have adequate early growth and fertility to allow them to compete with the many weeds which also have an ideal seed bed because of the more open spaces they are given. Allowing the soils to warm levels this playing eld.

So how do we deal with this row crop challenge. Many of you who have visited with me and have seen my presentations over the years know that planting row crops later is the most e ective option. Warm soils mean quicker emergence of the crop. Warm soils mean less compaction, a condition that creates an environment favorable for weeds to ourish. Warm soils mean more e ective results from the equipment that will be used to manage the weeds.

Giving the soils time to warm allows something else; the elimination of a rst ush of weeds. And here is where you as an operator can have the weeds do

some multitasking. Consider these weeds as a cover crop, especially the early emerging cool season species. In western Minnesota where we have eliminated any fall tillage and have also delayed corn and soybean planting until the middle of May, we are seeing lamb’s quarters germinating and emerging as early as the last week in March. ink about it. is lamb’s quarter plant, allowed to grow until May twentieth will then have ful lled its task as a spring cover crop keeping the soil protected while providing root exudates to feed the microbes which are coming to life as the soil is warming. Once the weed, like any other cover crop, is terminated, you have eliminated a signi cant amount of weed seed, and the eld is ready for corn or soybeans.

One nal item relating to outside-the-box management of weeds. I mentioned earlier that we have eliminated any fall tillage of our corn and soybean elds. Besides the signi cant fuel savings and using the crop residue as a type of nonliving cover crop, we have provided additional time for weed seed predation from birds and other ground insects. And in the springtime weed seed is again subject to predation from birds and germinates earlier because the warmed-up soil allows the weed seed to germinate earlier.

In the end, this entire conversation really centers around each of us using our creative skills; skills which will increase and become more e ective in proportion to the time we spend closely observing what is happening each and every day on our farms and in our elds. Skills shaped with each note or picture we take each growing season that we walk our elds, and skills sharpened with each conference and workshop we attend.

If you have questions or just want to talk about some ideas give me a call anytime. (320-212-3008)

4 | March | April 2022 TM

Carmen Fernholz is a MOSES Organic Specialist and has grown organic grain and forage crops at A-Frame Farm in Madison, Minnesota, since 1975.

Rejuvenation through connection

By Sarah Woutat

By Sarah Woutat

I have spent every birthday of mine since 2009 at the MOSES Organic Farming Conference as a certi ed organic vegetable farmer attendee — with the sole exception of 2021 due to the pandemic. is year, I spent my birthday at the conference as a member of the MOSES sta .

My role with MOSES is working with beginning and intermediate farmers. But beginning in August, it’s all hands on deck for conference planning. We begin gathering input from our farming community in July about what they’d like to learn at the next year’s conference. (If you’re interested in sharing your thoughts for next year, check our monthly eNews beginning in June!)

From there, our team hits the ground running — planning 60 workshops, seven Organic University courses, and two keynote speakers, collaborating with sponsors and exhibitors, organizing Roundtables, In Her Boots meetings, and the Organic Research Forum, organizing volunteer shi s, marketing the event, creating a conference website, and designing the program, guring out how best to o er a virtual option, working jointly with the caterer and food donors, overseeing scholarships and registration — and the list goes on. is is all while continuing to do our other work serving farmers. We are well-known for the Organic Farming Conference, but we stay busy throughout the entire year. roughout all of this planning, I kept saying to our team “I can’t believe a sta of 9 does all of this!”

Each year as an attendee, I would plan out which workshops I’d attend in advance, drive three and a half hours to La Crosse the evening before the conference started, check in early to avoid crowds, pile into a cheap hotel room with farmer friends I only got to see at the conference, and show up bright-eyed and bushytailed in my conference plaid at 7:30 a.m. on Friday ready to soak it all in.

is year, I arrived in La Crosse on Tuesday a ernoon to unload the U-Haul we rent to bring what feels like our entire o ce to La Crosse and start setting up. Volunteers show up rst thing on Wednesday morning and we all spend all day transforming the La Crosse Center for the MOSES Organic Farming Conference! Instead of lingering a er workshops to connect with other attendees about production systems and farm business management, I spoke with attendees in hallways about their conference experience: some folks who were experiencing the conference for the rst time and others who have been to every conference for the past 33 years.

is year, we worked with DATCP to provide a Hmong Farmer Resource Room, a networking event, and translation services. I connected with a Hmong farmer who had never been to the conference; he hadn’t even known about it. He attended the Vegetable Plant Pathology Organic University and was so unbelievably happy to be there — sharing that he learned

so much and would be encouraging his friends to join him at next year’s conference.

I spoke to a man who thought he was going into a roundtable discussion about rye, but ended up in the In Her Boots Meet & Greet. He stayed to learn about the woman-identi ed perspective of farming. He le the session thanking the host for letting him attend because he learned so much.

I reconnected with the exhibitors I used to buy from and bought two bags of potting mix, instead of the nine totes I used to have delivered. I saw friends I haven’t seen in two years, I hugged people I was meeting in person for the rst time, and I laughed harder than I have in recent memory.

I manage the MOSES Farmer-to-Farmer Mentorship Program. Each year at the conference, we host a program kick-o meeting to welcome the new group and say goodbye to the old one. Because of the pandemic, I had not met any of the mentors or mentees in person, but I have spent a lot of time on the phone with them. It was great to hear about the connections folks have made over the past year or two. Some of them hadn’t met in person, but hearing how they had formed their relationships virtually and then seeing those relationships come to fruition in person was simply inspiring.

I had an ongoing disagreement with someone on my hotel oor, every time we ran into each other. e conversation was open and honest and we each got to hear each other’s di ering perspectives. Neither of us changed our minds, but it felt good to engage.

I had hard conversations about masks, equity, our agricultural system that was built on the backs of folks for whom the system is designed to exclude, and our organizational role in that system. But hard conversations are something that the MOSES sta and board have committed to engaging in and I am proud to be on a team that is doing its best to own and re ect on where we have missed the mark and make changes. ese hard conversations help us move forward as a farming community and help us all do better for each other.

ere were hiccups with tech and audio/video— and all kinds of other things as there always are at such a large event—but we powered through. e goal of the conference is for people to connect, learn, and grow, and that’s what happened.

I am no longer farming and joined the MOSES team in November 2020. I didn’t meet anyone on sta until the following spring. is conference was the rst time that I really got to spend time with these amazing people, a small sta of 9 who put on this gigantic conference every year. eir passion and commitment to providing this space for learning and connecting, bridging gaps and having hard conversations, is truly inspiring. ey’re also a lot of fun, they love to laugh, and they love what they do.

Over the years, I have attended the conference with

a scholarship, as a volunteer, as a mentee, as a mentor, and as just a regular attendee. Seeing behind the curtain of the conference was awe-inspiring.

As I drove the two and a half hours back to Minneapolis where I now live, I couldn’t stop smiling. I had the warm fuzzies about the whole experience. It was hard work, my feet are still killing me, and I’m exhausted. I walked about 100,000 steps between Wednesday and Saturday night, but it was worth it. I feel more invigorated than I have in the past two years.

I have always loved the conference as an attendee as it’s been a place a place to learn, grow, and meet new people. It has always served as my jump start to the farming season. e day I’d get home, I would re up the greenhouse and start seeding. I always le feeling inspired and ready to tackle the upcoming season. is year was no di erent in that regard, except that I le feeling hopeful for our farming community and the future of our food system, and even more committed to my work with this amazing team than I was before.

We know we are ghting for the livelihood of ALL farmers committed to continuous improvement, land stewardship and healthy soils. As keynote Adae Briones pointed out, we are all ‘of this land’ and need to work together to protect and steward it. is year’s conference, more than ever, was a re ection of this. We need to keep this fresh energy and forward momentum owing in programs, resources, and until we meet again next February.

A huge thank you to presenters, Roundtable and In Her Boots hosts, our Board of Directors, the MOSES sta , exhibitors, sponsors, volunteers, food donors, the audio and video team, the La Crosse Center, and every single attendee who came to make this event so special! I am already counting down the days to next year’s Organic Farming Conference.

Sarah Woutat is a Farmer Advancement Coordinator for MOSES. She operated her own certi ed organic vegetable farm in Minnesota for nine years.

| 5 mosesorganic.org | 888-90-MOSES TM

Norfolk,NE AGlobalEquipmentCompany,Inc. www.henkebuffalo.com 800-345-5073

Sarah Woutat

Photo submitted

Laurell is inspired by the teens she works with in the Youth Corps job training program, which is based on science, technology, engineering, art, and math curriculum. “We generally have them for their whole high school career, which means we have the time to be real mentors to youth. We get to watch teens grow as they explore how to be adults. ey learn in so many ways from their farming experience, from cooking quesadillas to taking care of the goats. ey know how important it is to be connected to community.”

Laurell also loves the mobile markets run by the Urban Growers Collective. “Senior citizens want fresh produce but they can’t always access it nancially, or they may have limited mobility. Sharing produce at

the Fresh Moves Mobile Market and seeing customers light up when they are told produce is grown in the neighborhood is always such a joyful event.” ere is still much work to be done. “It’s been a lot of trial and error over many years,” says Laurell. “Nonpro t organizations in Chicago have slowly become more and more coordinated and e ective.”

“We were operating on a scarcity model, with everyone competing for the same funding or working in a fractured way from neighborhood to neighborhood. As we became more educated on anti-racist practices and as we gained more Black and Latinx leadership, we realized that we were just perpetuating problems. Now we’re working more systematically to weave this security blanket for everyone.”

e Urban Growers Collective has deliberately cultivated a distinctive style of management: decisions are made as a team and there is much more horizontal leadership. e organization also set up a plan for change as people progress in their careers, making room for the next generation of leaders.

“Having the focus be on one leader distracts from the mission and does not celebrate the incredible team we have cultivated at Urban Growers Collective,” re ects Laurell. “It’s also really important to have voices from the community on our board so that our actions are directly responding to the vision of the neighborhoods.”

What’s on the horizon for the Urban Growers Collective? A capital campaign will soon be launched for a new green era campus which will serve as the organization’s headquarters. e campus will have

space for important new initiatives, including a worker-owned composting operation. Compost is critical for a healthy and safe garden because high organic matter helps bind the heavy metals found in city soils. Currently it is very expensive to bring compost into the city. Adequate compost not only feeds the crops, it also protects the gardeners. e compost operation is one example of the start-up businesses the organization intends to develop.

“Having more start-up businesses in our plan gives more opportunities to our sta and the people we work with to grow and thrive,” says Laurell.

e Collective recognizes the signi cant lessons of the pandemic, and the heightened iniquities it has caused. e challenges further demonstrate the need for new opportunities to build stability and resilience while dismantling structural inequalities.

“I hope we hold onto the lessons of the pandemic. We’ve gotten used to making do without so many things. Not like my grandparents during World War II, but at least in a small way. And that makes us more creative. We’ve had to build better systems of resilience. We’ve gotten better at relying on each other. But we need to keep empowering people, growing food, and investing in the neighborhoods that have been le behind,” concludes Laurell.

Clare Hintz is a MOSES board member and runs Elsewhere Farm in Herbster, Wisconsin, a production perennial polyculture supporting winter and summer Community Supported Agriculture groups (CSAs) and other markets. She is also the Editor-in-chief of the Journal of Sustainability Education.

6 | March | April 2022 TM 2022 Changemakers — from page 1

Your trusted buyer of organic grains. We’re in the market for organic and non-GMO grains. Corn • Soybeans • Wheat Connect with one of our traders to learn more. 833.657.5790 www.sunrisefoods.com

Tony Schiller

Luke Doerneman Nick Nelson

Adult job training participants harvesting for fried green tomatoes.

Photo submitted

Terrance Glenn, Urban Growers Collective Incubator Farmer.

Photo submitted

Youth Corps Participant at Urban Growers Collective Youth Farm.

Photo submitted

Creating a fair and sustainable farm labor force

By Jacob Taylor

By Jacob Taylor

For many small- and medium-scale growers, it is the love of the cra and art of farming that keeps them in the work despite nancial pressures and difcult conditions. Many folks choose to keep farming because it is life-a rming, humane work. ere is beauty and deep satisfaction in working with the land to bring forth food to nourish our loved ones and communities, all the while regenerating soil, sequestering carbon, and strengthening the local foodshed.

But we must consider whether we can rightly use the term “sustainable” to describe the arrangement which does not allow farmers and farm laborers to support themselves and a family in modest comfort. Social equity for farmers and farmworkers is too o en overlooked, but it is an essential part of a truly sustainable, regenerative food and farm system. We need what Margaret Gray calls in her book Labor and the Locavore a “comprehensive food ethic” which encompasses all the ecological and social relations, from soil to farmhand, to farmer, to retailer, to eater, and maximizes justice and equity between them.

Despite the importance of social relations on farms, there has been little investment in outreach and education in this critical topic in the North Central Region. Labor issues have received some attention, though it is typically focused on increasing management control and e ciency. To respond to the need for increased social equity in our local food and farm systems, Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association’s new Fair Farms Program works in collaboration with the Agricultural Justice Project to tend to the interlocking concerns of fair wages and labor standards for farmworkers, and fair pricing for farmers. By supplying free help and educational opportunities around these issues for family-scale farmers through a recent NCR-SARE grant, this program contributes to a more socially just and resilient food system.

e Fair Farms Program works from a recognition that many small- and medium-sized famers are committed to sustainability principles and aspire to pay better wages and uphold fair labor standards. However, many, if not most, of these operations nd themselves balancing season a er season on a tightrope of nancial pressure as they try to make ends meet with tiny margins, increasing debt, and a highly unstable work force. Farmers have trouble keeping workers, covering costs of production, and

many cannot, or do not, pay themselves a living wage. Farmworkers are compensated little for their labor on the farm and are o en subjected to dangerous working conditions without signi cant legal protections.

Our goal is to equip farmers with the resources they need to achieve actual social and nancial sustainability. ese resources might include guidance on optimum pricing of farm products, and strategies for increasing revenues, as well as methods for calculating living wages. We can suggest ways to diversify products and extend the working season to make jobs more attractive. Templates for creating clear written labor policies, safety plans, and training protocols are also important resources.

By providing farmers with knowledge and tools that bring about greater equity, we foster development of a skilled and stable workforce, more able to contribute to the long-term sustainability of farms.

We believe that fair labor practices bene t everyone. Farmworkers are treated and compensated well and are more likely to return season a er season, not only for love of the work but because it o ers nancial stability and a potentially viable career path. Farmers have the advantage of a well-trained work force, which enhances productivity, care for the environment, and the long-term resilience of the farm. Having fair labor standards in place also provides eaters with the satisfaction of knowing the people who grew their food received a just compensation for their work and were treated with the dignity and respect they deserve.

Receiving this support from OEFFA is simple. When a farmer lls out our short self-assessment on labor and pricing standards, and sends us any written documentation they have on employment policies, we send back an individualized report with resources to help strengthen their commitment to social integrity. ose resources include ready-to-adapt templates and excellent model policies and procedures on:

• Creating a thorough employee handbook and farm health and safety plan

• Calculating full production costs and living wages, fair pricing, and negotiating with buyers

• Working through grievances and con icts on the farm

• Creating learning programs, and working with interns and apprentices

• Implementing on-boarding, and employee evaluation forms

Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association offers free labor and pricing help to farmers in the North Central Region

is program supports farmers in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. Receiving support is easy: ll out our 30-minute self-assessment on labor and pricing standards and send any written employment policies your farm uses. We’ll send back an individualized report with resources to help strengthen your farm’s commitment to social integrity. ose resources include ready-to-adapt templates and excellent model policies and procedures for an employee handbook, farm health and safety plan, ways to calculate full production costs, and more. Take the self-assessment at www.surveymonkey.com/r/fairfarms

To provide the best support, we work with farms one-on-one and carefully consider their speci c context and needs to produce a personalized report at no cost to the farmer. Many of the resources we’re able to supply have been developed over the past twenty years through the Agricultural Justice Project’s e orts to transform the existing agricultural system through education and their Food Justice Certi cation. eir stakeholder-driven certi cation is considered the gold standard for domestic fair trade for farm products, and their wealth of time-tested resources help equip farmers to implement food justice principles in their operations.

In addition to providing this technical assistance, we are also o ering a series of educational events taught by farmers. ese events dig deeper into many of these topics—moving from legal to fair employment, creating a health and safety plan, improving

| 7 mosesorganic.org | 888-90-MOSES TM CARBON NUTRIENTS MICROBES MICROwww.ohioearthfood.com - info@ohioearthfood.com Call or write for free 2022 catalog! 5488 Swamp St. NE Hartville, OH 44632 330-877-9356 612 Enterprise Dr. Hilsboro, WI 54634 608-489-3600 OHIO WISCONSIN ReVita The root-zone supply chain KELP COMPOST HUMATE MANURE LISTED products available ™ Viking Corn & Soybeans • Cover Crops • Forages Small Grains • Conservation • Lawn 800.352.5247 | ALSEED.COM ORGANIC SEED FOR THE WHOLE FARM FROM PEOPLE COMMITTED TO ORGANIC AGRICULTURE

Farm labor force continues on 14

Ag Solidarity Network — from page 1

other, the ASN will centralize conversation threads between the various groups. In this way, a group of small ruminant farmers can connect with a group focused on grazed cattle over shared interests related to meat processing. In this way, there is potential for individual farms to collectivize their voice, identifying their needs and goals to nd shared solutions or make demands of the larger food system.

e login form was also developed in partnership with other organizations. It captures information about geography and production types along with interests and expertise. Farmers will be able to search for others who may be nearby, but also learn about who is in conversation threads and whether their advice is relevant based on latitude and farming systems.

ere seems to be a growing awareness of how consolidation has made our food system fragile and untenable for human scale farms. Groups of farmers are more regularly coming together to have control over aggregation and vertical integration. ey are forming cooperatives and opening meat processing facilities. ey are selling directly to consumers and wholesaling.

Our current consolidated food system is not broken, it is functioning as it was intended. With farmers

now seeing less than 20% of the food dollars paid by consumers, the time has come to co-create a more localized, fair, and sustainable system that both feeds and nourishes people and the planet. e ASN was so named with this in mind. It will enable farmers to nd each other. A nity groups on the platform can organize and give voice to their stories, both successes and challenges.

For those of us in farmer education, agricultural research, and policy organizations, doing advocacy work on behalf of farmers, what we can gain from the ASN is invaluable. We will be able to share those stories. As we head into Farm Bill 2023, we can let farmers know of opportunities to amplify their experiences and posit solutions that may be based on local innovation. As we try to explain the critical nature of Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grants to elected o cials, we can use the platform to ask any farmers to share how these funds improved their farm operations. Or if a group of farmers nd each other through conversation on the platform and want to organize a message for policy makers, the organizational partners on the ASN can facilitate access to make it most impactful.

Before life on farms gets too busy, or while you are

‘on call’ during lambing and calving, we hope you will take a moment and hop onto the platform. It will only be as good as the number of farmers on it. MOSES is committing the time of our On Farm Organic Specialists to facilitate some of the a nity groups. In this way the MOSES Ask a Specialist will be available through ASN in addition to calling one of them directly. is means both the questions and answers will be available to many farmers.

Let us know what content or resources you would like to see on the Ag Solidarity Network. We will work to make content that would have required clicking through our websites more accessible through the ASN app.

We recognize that most farmers just want to raise food and be good stewards of the land. e making of farm policy and legislation tends to breed more cynicism than hope. For most this platform will hold value for production and business knowledge. But democracy requires that we show up. at we organize. We can do that, too!

Lori Stern is the Executive Director of MOSES. She lives with her wife, LeAnn, on a small farm near Monticello, Wisconsin, where they grow vegetables and raise chickens and goats.

FlexibleLoans for RegenerativeFarms &FoodProducers

8 | March | April 2022 TM

Applyonline gosteward.com

COLLECTIVELY LAUNCHED BY MOSES, FAIRSHARE CSA COALITION, OGRAIN, ARTISAN GRAIN COLLABORATIVE, AND ORGANIC FARMERS ASSOCIATION.

WHICH BCS TRACTOR MODEL IS RIGHT FOR YOUR FARM? Follow three easy steps on BCS America’s new BUILD YOUR BCS configurator to find the optimal tractor setup based on the attachments you need: www.buildyourbcs.com

Sell directly with REKO ring

By Thelma Heidel-Baker

REKO is a direct farm-to-consumer online market model. It works like a pre-paid and pre-ordered farmers’ market. Within the ring farmers and food producers sell only what they produce (grow, raise, or make), and customers have the opportunity to purchase what they want directly from local producers. e system supports small-scale farmers and businesses in their community, keeping dollars and food local.

e beauty of REKO is its simplicity and e ciency. For customers, REKO is a local food online ordering system where you can connect directly with farmers in your area. All ordering is done through a closed Facebook group. e customer agrees to meet the farmer(s) at the designated pick up location at a specied time to collect their pre-ordered produce. Farmers convene at that location to deliver the pre-paid produce directly to the customer. e farmers only need to pack and deliver produce that was pre-ordered and prepaid for by the customers, making this a very ecient market model for busy farmers.

REKO is an acronym for the Swedish phrase “rejäl konsumtion,” which means “fair consumption” or “real consumption.” e REKO ring concept was started in 2013 bv organic Finnish farmer omas Snellman. He was looking for a simple way to connect farmers directly with local consumers. Since that rst market in June 2013, the REKO ring model has exploded to hundreds of rings across Scandinavia and beyond. In 2021, an estimated 600 REKO rings in 14 di erent countries provide the means to get food from farmers to local consumers.

My journey with REKO rings began in April 2020, when nearby farmer and friend Vanessa Quinones of e Victory Garden Farm sent me a podcast about the REKO ring model. Like so many other farmers when COVID-19 rst struck, she needed to nd alternate outlets for the surplus of produce on her farm, and she had just learned about REKO rings. I listened to the podcast and was hooked. I wondered why I’d never heard of this farm marketing model that was so simple, so farmer friendly, so feasible, and so popular in other parts of the world.

One week later, the Ozaukee Area REKO Ring group was created online, and on April 30, 2020, we held Wisconsin’s rst REKO ring pickup in Gra on,

Wisconsin, with three participating farms and 300 members in our Facebook group. Within one week, we outgrew the parking lot we had used as our rst delivery point. My suggestion when identifying a pickup location is to think bigger.

No one in our area knew what a REKO ring was when we began, but farmers needed to nd new customers, and people were looking locally for food they couldn’t nd in more traditional places like grocery stores. e timing was ideal, and our REKO ring really took o in the rst year. Participating farms shared the REKO ring idea with their customer bases and social media outlets, and our REKO customers shared this new local food option with their friends, family members, and coworkers on Facebook.

We now have an established local REKO food community here in southeastern Wisconsin where more than 20 farms and food producers have sold their locally grown, o en organic, produce to a continually growing customer base of over 2500 members. In any particular week, our REKO ring averages seven participating farms with a diversity of produce that varies seasonally, but includes vegetables, apples, pastured meats, eggs, owers, herbs, jams, breads, and ke r.

ree basic rules guide the REKO ring model:

• ere are no intermediaries. Producers can only sell what they grow, raise, or make.

• e whole system is free of charge for both farmers and customers. e only charge is the price paid for the products themselves.

• e farmers/producers are responsible for making sure what they sell is legal and meets food safety laws in their area.

Beyond these basic rules, there’s the exibility to make the REKO ring work for you. For example, in our Ozaukee

Area REKO Ring, we decided to focus our group on locally grown organic and sustainably raised produce, and we have limited producers to within 40 miles of our pickup point. Our REKO customers know we have done the work to source high quality, local produce for them.

REKO rings are managed and run through a closed Facebook group. Facebook provides a free platform that is designed to connect people without having to create a whole new system. While Facebook works well to host the REKO group, it is also one of the limitations of the REKO ring model. REKO will not work for you or your farm if you are not on this social media platform. But if you are on Facebook, then the opportunity is there and available to you.

Each REKO ring has one or several admins that guide the group behind the scenes. ese may be farmers and/or customers. e REKO ring group admins decide on a date, time, and location to hold their REKO ring deliveries. ey also decide what the focus of the REKO ring may be and who will be selling through the ring. e admins also run and moderate the Facebook group. One person could do this, but having more people helps spread the responsibilities, and means you have several people who really

| 9 mosesorganic.org | 888-90-MOSES TM

REKO ring

continues on 10

understand how your REKO ring operates.

Farmers sell their produce by posting what they have to o er that week to the Facebook group. Each post states who they are, what products they have available, and the product pricing. Customers order by commenting on a farmer’s Facebook post with what they would like to purchase such as “1 dozen eggs, 2lbs

ground beef.” e farmer then likes or acknowledges that order, sending the customer a message with further details on their order, and payment options.

While still relatively few, a growing number of REKO rings are popping up across the U.S., and at least three exist today in the Midwest. Because REKO is such a grassroots e ort (started from the farmer up), there is no limitation or trademark to using the REKO name or starting a REKO in your area. All that is really needed to start a REKO ring is a motivated group of people (either farmers and/or consumers) to start the conversation and nd some willing farmers.

A great way to get started is to join an active REKO ring and see how their group operates. Most REKO rings have a general shared set of guidelines that are then customized for the needs of that particular group. I have personally reached out to REKO ring admins around the world to get advice on what worked for them, and all were more than willing to share what they had to help us get started. Most REKOs worldwide are named a er their pickup location. For example, the Duluth,Minnesota/ Superior,Wisconsin area has the Twin Ports REKO Ring that has been going strong since spring 2021.

REKO rings are inherently farmer and family friendly. On my family’s farm, Bossie Cow Farm, I do all the farm marketing and sales. We sell 100% grass-fed beef, organic eggs, and pastured pork directto-consumer, and being involved with the Ozaukee REKO Ring has completely changed the way I market our farm’s produce. Prior to the Ozaukee REKO Ring, sales were done on-farm, via Facebook, and through word of mouth. I have never sold at traditional farmer’s markets because I simply didn’t have the time. With REKO, I sell and post from the comfort of my own home. I only o er for sale what I have available, and I know exactly what I need to pack for a delivery day. I still get to know my customers, and I still get to be a part of larger local food community. It’s a win on so many levels.

From a broader perspective, one of the most rewarding assets of running a REKO ring is seeing

the community of local food supporters that develops around it. Our Ozaukee REKO Ring will be two years old in April 2022, and we have dedicated “REKO ringers” who have been with us since the beginning. We have new people and new families joining our group every week. As customers share their REKO ring experience with others, the REKO group continues to grow. Many of the farmers know the regular customers personally, and the customers get to know their farmers by rst name. Customers recommend other farmers they think would be a good t for our group, and our REKO ring and the in uence it holds in our local food community continues to grow.

Thelma Heidel-Baker and her husband Ricky Baker run Bossie Cow Farm, their family run certi ed organic diversi ed dairy farm near Random Lake, Wis. Thelma is also a founder, group admin, and participating farmer in the Ozaukee Area REKO Ring located in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin.

Resources

• “What is the Ozaukee County REKO Ring?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iOQ4XuVzig

• REKO: Fair Consumption Since 2013 https:// www.pedersore. /assets/Dokumentarkiv/ Om-Pedersoere/REKO/Reko_engelska_komprimerad.pdf

(888) 337-8246

(608) 637-7080

10 | March | April 2022 TM Whether your farm is a non-traditional operation marketing directly to consumers – or through local and regional food systems – our dedicated and experienced team can provide financial solutions designed to help you succeed. And we’ll guide you every step of the way. COMPEER.COM/EmergingMarkets Compeer Financial can provide assistance with financing and operations based on historical data and industry expertise. Compeer Financial does not provide legal advice or certified financial planning. Compeer Financial, ACA is an Equal Credit Opportunity Lender and Equal Opportunity Provider and Employer. ©2020 All rights reserved. Sai Thao Sr. Lending Specialist (612) 597-4086 Sai.Thao@compeer.com Paul Dietmann Sr. Lending Specialist (608) 963-7763 Paul.Dietmann@compeer.com (844) 426-6733 | #CHAMPIONRURAL LET’S MAKE YOUR PLANS A REALITY, TOGETHER. Healing the Earth and Feeding the World - Better Naturally! Fertilizer Blends for your Farm & Garden Feed Supplements for Cattle, Swine, Goats, Sheep, Horses, Chickens and more! CALL FOR A COPY OF CATALOG: 800-347-1566 | WWW.FERTRELL.COM PRODUCER OF NATURAL & ORGANIC FEED SUPPLEMENTS & FERTILIZERS REKO ring — from page 9

Vanessa Quinones of The Victory Garden Farm at Ozaukee REKO, October 2021.

Act for a Sustainable World +1

www.naturesinternational.com An Ecocert Group Company Organic Certification & More with People You Trust +1

www.ecocertusa.com

Photo by Thelma Heidel-Baker

Finding hope in perennial pastures: the potential of well-managed grazing to sequester carbon

By Ashley Becker

By Ashley Becker

With the prospect of payments to farmers for storing soil carbon long-term, or ‘sequestering’ soil carbon, who wouldn’t be excited about the nancial bene ts and recognition for the work farmers have done in prioritizing soil health? is seems like a win-win scenario: farmers continue to care for the land, which bene ts society at-large, and are rewarded for doing so.

Quantifying how soil carbon changes across di erent agricultural practices is necessary for making that scenario work. So, what do we know about the potential for soil carbon sequestration across di erent farming practices in Wisconsin? My own work shows that grazed pastures o er the greatest potential to accumulate carbon in agricultural soils. If you are a farmer grazing livestock on perennial pasture, you may already be optimistic about this potential outcome of well-managed grazing, and in that, you wouldn’t be alone.

While I grew up on a farm in eastern Iowa, I was not introduced to rotational grazing until meeting Ron Schoepp, a Wisconsin grazier, who inspired me to study grazing systems and soil carbon in Wisconsin. Ron hosted UW-Madison’s Nelson Institute graduate student eld trip in 2018, which takes incoming graduate students on a brief tour to introduce them to Wisconsin’s landscapes. We visited his home farm to learn about his family’s mob grazing operation. Mob grazing involves putting more animals in a smaller area of pasture for a shorter amount of time followed by a longer rest period for that pasture area. Ron’s passion for grazing led me to a research project aimed at measuring the soil carbon responses to managed grazing.

In that project, I compared soil samples from 33 rotationally grazed pastures paired with nearby rowcrop sites to examine soil carbon di erences between these approaches in southern and central Wisconsin. I worked to ensure these paired sites were as similar as possible with respect to proximity, soils, and slopes. Results showed that perennial pastures had a lot more soil carbon. In the top 6 inches of soil, the pasture sites averaged 5.5 more tons of soil carbon per acre than the row crop sites.

at large di erence was observed despite lots of variability in rotational grazing practices, including di erences in rest period, residual plant biomass a er grazing, and the type of grazing animals. ese were important results because they suggest that graziers have exibility in how they manage their operation with respect to the intensity and frequency of grazing management. ey can adapt their practices to the needs of their land and livestock – an important part of well-managed grazing – while still working towards soil carbon sequestration goals.

Even though there was more soil carbon in the pastures than the row crop sites between most of the pairs, and quite a bit more in some of them, that

was not true for all 33 sites. In a handful of the sites, there was actually more soil carbon measured in the row-crop eld (see Figure 1). ere are several reasons that might have happened. e pastures could have been younger, so the soil carbon didn’t have much time to build up, while those row-crop elds might have used all best management practices (no-till, cover crops, crop rotations, etc.). ere also could have been historic di erences in management between the paired elds that were a ecting the soil carbon measurements today. at said, I observed no consistent pattern for why those row-crop elds had more soil carbon. ey appeared to be the exception to the rule. For example, the pastures with less soil carbon had been established for several years or more, and best management practices were not used on all those row-crop elds. If there were di erences in the historic management of the paired sites, that didn’t seem to impact these results: the paired pasture and row-crop sites had no di erence in soil carbon at the 6 to 12-inch depth. I think these results show that soil carbon can vary, but despite these few exceptions, the pastures still had much greater soil carbon on average in the surface 6 inches of soil.

Now, nding 5.5 more tons of soil carbon in the pastures is not to say that pastures have gained 5.5 tons. e row-crop systems likely were losing soil carbon over time too, which could be entirely driving that soil carbon di erence. Both soil carbon losses under row-crop agriculture and a lack of change in soil carbon under rotationally grazed pastures have been observed in other Wisconsin sites previously (“Researchers use 30-year cropping systems experiment to evaluate if farm elds can serve as carbon sinks,” March/April 2021 Broadcaster, https://mosesorganic.org/publications/broadcaster-newspaper/ farms-as-carbon-sinks/). So, rather than pastures gaining soil carbon, they might just be holding on to what they already have. Either way, my ndings support the value of pasture systems,

estimates of the annual soil carbon change from this research suggest that soil carbon is building in pasture systems, although slowly.

Speci cally, I estimated soil carbon gains of 0.14 tons/acre each year in pastures. One important takeaway here was that soil carbon estimates for pastures vary considerably. Some work has suggested accumulation rates ten times higher while others estimate even lower rates. Even slow accumulation contributes to increased soil carbon over time, but to achieve it, pastures need to be kept without tillage. is is particularly important when we look at what kind of soil carbon is accumulating.

First, two types of soil carbon can be described: mineral-associated organic matter-carbon (MAOM-C) and particulate organic matter-carbon (POM-C). MAOM-C is derived from dead soil microbes and is more stable because it sticks to soil minerals, making decomposition more di cult and allowing it to stay in the soil for longer amounts of time on average. POM-C is just tiny plant particles that are more available for soil microbes to consume and tends to be broken down over shorter periods in the soil. I found that POM-C was present in higher

Soil Carbon Difference (tons/acre)

20

10

0

Sites

Figure 1. The di erence in soil carbon between the paired pasture and row-crop sites (pasture carbon – row-crop carbon). All points that are above the zero line represent sites where the pasture had more soil carbon than the row-crop eld.

amounts as pastures got older while the amount of MAOM-C did not change with pasture age. Because POM-C is less stable, this nding shows why it’s critical that pasture soils remain undisturbed. Breaking up these soils with tillage or discs makes more POM-C available for microbial decomposition, which sends a large part of the POM-C to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. at means that instead of building soil

| 11 mosesorganic.org | 888-90-MOSES TM

fortunately, Perennial pastures continues on 12 We Buy Organic & Conventional Non-GMO: •Oats •Corn •Wheat •Barley •Soybeans •Rye Grain Millers is a privately held, family-owned company. We depend on direct farmer relationships and offer farm gate pricing and contracted grower production. We also offer a Sustainable Grower Program – our Crop Science Team is here to help you with any agronomy questions you may have so you can get the best return on your production. BUILT ON FARMER Relati ships. grainmillers.com | 800.328.5188 IT’S MORE THAN PROCESSING. IT’S OUR Pr ise

though

Ashley Becker doing eldwork.

Photo submitted

carbon, you could be losing it from your elds.

Even with uncertainty in estimating and maintaining soil carbon changes, the greater amounts of soil carbon in pastures o ers many co-bene ts aside from potential payments for carbon sequestration. More soil carbon can help farms to be more resilient during droughts and heavy rainfall by increasing water in ltration and retention. ose who have watched a rainfall simulator demonstration know the di erences in in ltration can be striking. More soil carbon can also improve productivity overall because increasing organic matter, which is made up of 50% carbon, helps reduce nutrient losses and soil erosion. at can also play a role in improving water quality.

e bene ts of well-managed grazing can even extend beyond environmental impacts, which is exactly what I heard when chatting with graziers throughout Wisconsin. ey mentioned that grazing improved their quality of life, bringing fun to farming and creating opportunities for families to farm together. One grazier summed up the many bene ts that grazing provided by saying it helps his family achieve a “triple bottom line” through its combined social, economic, and environmental impacts. ese experiences seem to explain why many of the graziers expressed such a strong commitment to continue

their grazing practices. And it’s the addition of these positive impacts on farmer livelihoods that have me convinced about the need for more perennial pastures with managed grazing on the landscape.

If all these bene ts are linked to well-managed grazing, what does “well-managed” look like? Even though I found that management can be exible and adaptive, there are still guiding principles for managed grazing. First, the rotational aspect is key. Rotating livestock between sections of fenced-o pasture helps you to better manage other important factors: the rest period and the residual plant biomass. Rest between grazing events and leaving behind some plant residual a er grazing are important for giving the plants an opportunity to continue photosynthesis and regrowth (for more details on pasture systems and management, see https://greenlandsbluewaters.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/10/GLBW-Soil-carbon-pastures-factsheet-LPaine-RJackson-Sep2020-FINAL.pdf). e practices that best support your animals and the soil can support healthy, diverse pastures. Overall, maintaining pastures long-term without

tillage provides the greatest chance of soil carbon sequestration. As a result, well-managed perennial pastures o er the best, and perhaps only, opportunity for so-called climate-smart agriculture. While this may lead to payments to farmers for soil carbon sequestration, well-managed grazing also provides other important bene ts both on- and o -farm. For that reason, this work renews my sense of hope about our future agricultural landscapes, with farmers who care for the land making the change we need.

Acknowledgments

is research was made possible thanks to support, guidance, and a willingness to collaborate from many people, including my advisors, Randy Jackson and Leah Horowitz. I would like to extend a huge thank you to all the Wisconsin farmers who partnered in this research, as well as Ron Schoepp for inspiring this work with a tour of his family farm and continued conversations.

Ashley Becker is an environment and resources doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. She received an environment and resources Master of Science from UW Madison and a bachelor’s degree in biology and behavioral neuroscience from St. Ambrose University.

12 | March | April 2022 TM

Perennial Pastures— from page 5 CORNSOYBEANSALFALFAFORAGES GoOrganic.GowithConfidence. GowithBlueRiver.® Copyright©2014-2021Farmer'sBusinessNetwork,Inc.AllrightsReserved."BlueRiver"isaregisteredtrademarkofBlueRiverOrganicSeeds,LLC.ProductsavailablebyBlueRiver OrganicSeeds,L.L.C.areavailableonlyinstateswhereitislicensed.Individualresultsmayvaryandaredependentuponadditionalfactors,includingbutnotlimitedtoweather,agronomic conditionsandpractices,andcommodityprices.Termsandconditionsapply.“FBN”andthesproutlogoaretrademarksorregisteredtrademarksofFarmer'sBusinessNetwork,Inc. BLUERIVERORGSEED.COM A soil sample.

Photo submitted

Reviewed by Rachel Henderson

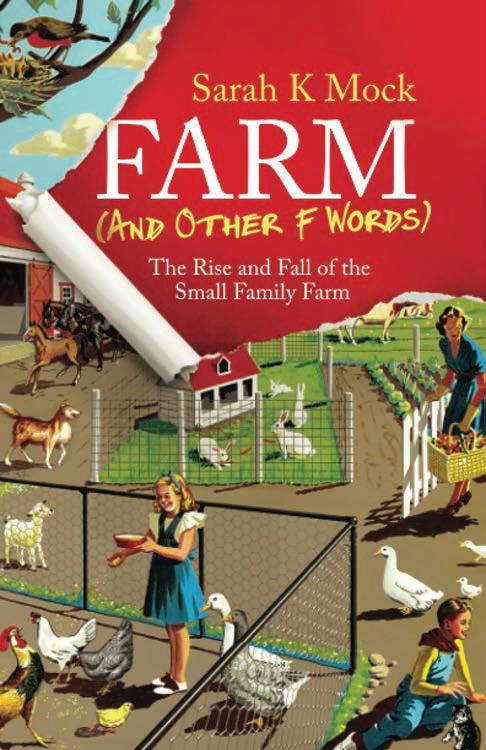

First, I should make some disclaimers. I did not enjoy this book. As a farmer, I got defensive. I wanted to shout back at Sarah Mock, over and over, “What do you want from me?!” In the introduction, she addresses this, and asks the reader to approach the difcult parts with an open mind. I’ve tried to do that so I could make it through and parse the important messages in the book. Despite my frustration, I learned from this study of what we think we want from family farms, and how we might get there.

e other part of my disclaimer: It turns out my own farm is not, as laid out here, a “Good Farm.” e rst part of the book focuses on de ning this term, and suggests a number of ways to assess if our favorite farm is “Good.” Mock explores whether being small, diversi ed, a product of passion, scalable, “poor,” “wealthy,” sustainable, multi-generational, brand new, or focused on feeding the community are the right ingredients to make a farm the kind of business we want to maintain at all costs. For each of these, she explores an example, a farmer she has worked with and gotten to know, and attempts to assess if their farm is “Good.”

Spoiler: most of them aren’t, or at least not completely. She features farmers who have closed up shop, who have seen their markets inundated with competition, who have been unable to make money at the crops they are best at producing, or have been unable to secure land tenure that would make their farms economically viable. ese stories are familiar — everyone reading this can name someone who experienced each of those, and each one feels like a heartbreaking loss to our community. She also features farmers who are entirely reliant on government programs for their annual income, who have almost unbelievable land wealth, who have non-farm sources of revenue and

support, or who, in other ways, don’t depend on farm production to make ends meet. We all know them, too — I’m one of them.

For each of these criteria, Mock lays out why the farms that don’t pass muster aren’t what we’re looking for in a “Good Farm.” She treats the search as an obvious one, but failed to convince this reader that it’s important. What does it mean that most of our country’s small family farms aren’t “Good”? Do we conclude that we don’t need them? And if so, where does our food come from, and what happens to our rural communities? While we all know farms that haven’t made it, we also can all name someone who is at least surviving, and maybe even thriving. I have friends whose farms DO support their families, and know farmers who use government programs as a supplement, but derive most income from production. If a farm is “Good Enough,” can we keep it? is book is well researched, and heavy on citations. e author has pored over decades of agricultural statistics in an attempt to understand the landscape of family farms. e existing data turns out to be woefully inadequate. When we look at data from the US Census of Agriculture, our top source of information, we have to remember that it relies on self-reporting, and that response rates are perennially low. (Fill out that ag census, farmers.) I was surprised to learn how much the USDA back lls information. Mock explains the agency’s published method for accounting for non-responsive farms. She interviews

Harvard researcher Nathan Rosenberg, who is skeptical of the results of that formula, but points out that there is no more useful alternative. at data, incomplete and unreliable, drives USDA decision making, and is used to develop programs to keep US agriculture going. Mock e ectively makes the case that this is why our farm programs are such a mess.

Mock dives into the history of how commodity markets came to dominate, and the ways that state and federal policy, that once ensured a healthy agriculture sector and reliable food supply, now perpetuate extractive practices, and encourage farms to get larger and larger. Some of these policies are familiar to anyone who spends time thinking about farms. We know that crop insurance guarantees income for the largest grain producers, regardless of their practices, while failing to provide a meaningful safety net for specialty crops. It’s important to put this information in any study of US farming. Mock examines other policies that keep farms a oat, including the way that agricultural land is taxed. I found this study to be a little more muddying than clarifying. It might have been my defensiveness, but I wondered if it’s right to equate those two types of policies. e book does not dig into which have a bigger impact on the way land use decisions are made. anks to the complications of studying farm data, which might not even be possible.