AUDIOVISUAL PRODUCTION SCHOOL

2023 MEMOIRS

In partnership between APAN (Association of Black Audiovisual Professionals) and Manos Visibles

Elaborated by: Laura Asprilla, Paula Moreno and Valeria Brayan

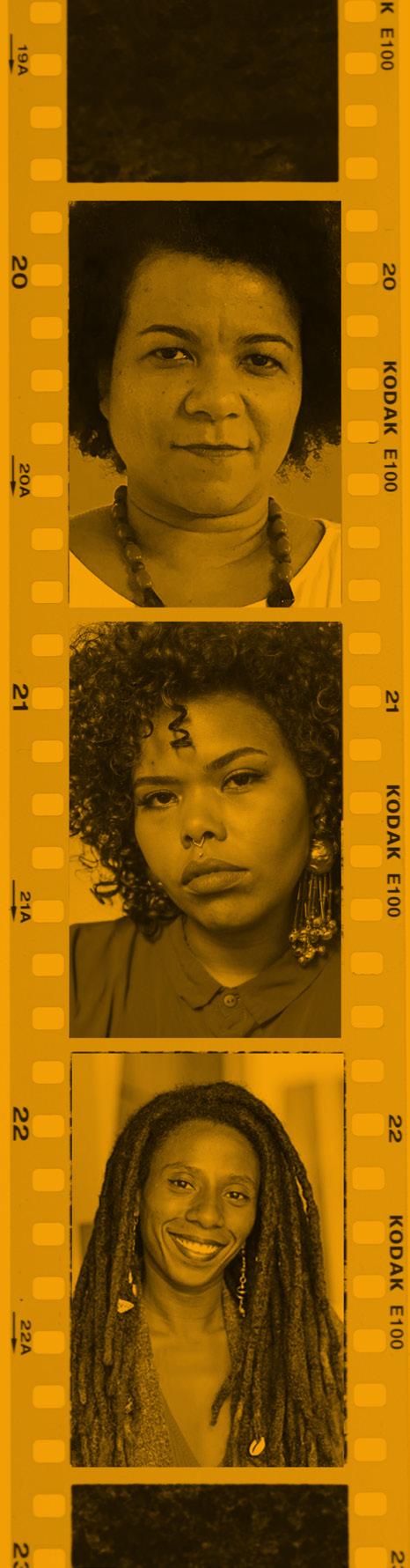

FOCO TEAM

Tatiana Carvalho President, APAN

Paula Moreno, President, Manos Visibles

Melina Bonfim, Training Coordinator, APAN

Valeria Brayan, Culture and New Narratives Manager, Manos Visibles

Laura Asprilla, Gestora Audiovisual Manos Visibles

Daniel Rumana, Translator APAN apan.com.br

APAN is the largest network of audiovisual professionals of Afro-descendancy in Latin America, with a strong presence in Brazil since its founding in 2015. It has over 1,000 affiliated associations and individuals across different regions and the organization’s courses of action include: (i) advocacy for systemic transformations with the public and private sectors; (ii) training for the audiovisual sector (e.g., labs, schools); and (iii) circulation and market platforms such as the International Black Audiovisual Film Festival (FIANB) and the TodesPlay platform.

Manos Visibles manosvisibles.org

Since 2010, the non-profit organization Manos Visibles has impacted more than 25,000 people in building a network of leadership and cutting-edge organizations that empower identities and generate systemic solutions that reduce cultural, educational, and economic inequalities from a racial and territorial perspective. One of its areas of specialization is culture and new narratives. Since 2020, it has developed the Ethnic Audiovisual Power strategy, which seeks a principal role for Afro-Colombian audiovisual leadership in Colombian cinema, in dialogue with the African diaspora through its AFROINNOVA strategy. To this end, it has empowered production companies and community organizations, awarded graduate-level scholarships in audiovisual management and production, supported script labs and co-production initiatives, and actively lobbied the Ministry of Culture and the Film Development Fund to establish a feature film category dedicated to racial equity.

OUR FOCO

The chronicle of the FOCO Audiovisual Production School are structured like a three-act story consisting of a beginning (Act I), a middle (Act II), and an end (Act III). These acts reflect a character’s transformation from point A to point B. And although the FOCO story continues with no end in sight, it has undoubtedly been a path of transformation for its participants, who themselves have been transformed since the beginning of their journey.

PRELUDE

Brazil and Colombia - A Photo Album of a Latin America that Denies Its Own Image

ACT I

Another Academy: FOCO School

ACT II

What cinema made by Black filmmakers do we want to see in Colombia and Brazil?

ACT III

The Characters and their Stories

AN OPEN-ENDED QUESTION: WHAT’S NEXT?

“The past becomes our source of inspiration, the present a stage for breathing, and the future our collective aspiration.” Ngugi wa Thiago

PRELUDE

Brazil and Colombia: A Photo Album of a Latin America

that Denies Its Own Image

Brazil and Colombia are the two countries with the largest Afro-descendant populations in Latin America, and both share a common history of narrative invisibility. Moving images can exercise a lasting effect on inequality and the stagnation of Afrodescendant populations on the continent, notwithstanding some advances in representation in recent years. Still, Latin America is home to over 150 million Afro-descendants who are not represented in their diversity or with the appropriate level of dignity. In Colombia, Afro-descendants are estimated to make up 20% of the population, while in Brazil, this percentage stands at 56%.

Our focus is on the power of Black imagery in the Americas, not only to change narratives but to transform realities. This is why an essential part of the training process involved analyzing and discussing images, texts, sounds, and power relationships that shape and perpetuate these realities, as well as studying

the ancestral technologies of Black movements, their methods, their achievements, and their demands to map the future of Afro-Latino audiovisual production.

During the FOCO sessions, participants from Colombia and Brazil learned about their countries’ histories, which often came in direct contrast with Eurocentric narratives. This was undertaken by revisiting the pioneers and freedom fighters who reclaimed the first narratives and representations of Black people. In Brazil, we studied the important work of Zozimo Bulbul and the Black Experimental Theater. Meanwhile in Colombia, we explored the first feature film script written by Manuel Zapata Olivella. In both countries, we recognized the efforts of artists and the Afro social movement in the arts and cinema. Naiara Leite from ODARA (Black Women’s Institute in Brazil) and historian Francisco Floréz posed questions that remain open-ended: What is the current panoramic of Brazil’s Black movement? What is the current panoramic of this movement in Colombia? What stories still need to be told? What is the future we’re building? Audiovisual production should be understood as a political decision that influences and transforms, and when thinking in images, it is essential to consider the feelings and power we wish to generate in the mind, body and soul of Black people, giving them the value and recognition they deserve in Latin America.

ACT I

ANOTHER ACADEMY - FOCO SCHOOL

The purpose of the FOCO School is to zero in on audiovisual storytelling from and with a Black perspective to encourage audiovisual works that carry a real possibility of participating in a competitive market, where the racial focus and everyday stories resonate with an ever-growing audience in Latin America and across the globe. FOCO seeks to open perspectives, expand narratives, and pursue approaches that are systematic and renewed with a purpose. In this way, FOCO as a school has been, and will continue to be, a space for the exchange of experiences, where mentors and modules align with an urgent, necessary, and disruptive perspective, in contrast with traditional audiovisual schools that have perpetuated inequalities based on who creates the narratives and whose narratives are told by others, all determined by those who enjoy access to resources and those who do not. FOCO has created its own academy, which, with universal and specialized knowledge, values experience, history, and subjectivity, and this approach challenges the storytelling landscape to expand by including more Afro-Latino audiovisual imaginaries.

FOCO references a diverse generation of cinema and images from an Afro-Latino perspective. Beyond the idea of niche cinema which leads to pigeonholing, our grand commitment is to universalize the presence of Afro-descendants in cinema. Although our work is based on cultural elements, it does not confine itself to them; from there, it envisions Colombian or Brazilian cinema with an expansive perspective towards the African diaspora—1.5 billion people on the African continent and abroad—as well as the world in general. This expands aesthetic boundaries that engage in dialogue and fill spaces of relevance on the global audiovisual sphere.

The school addressed perspectives on the political culture of audiovisual production from the standpoint of racial equity in Latin America and the African continent, and it also delved into topics such as scriptwriting, production, industry, and distribution. Each module had a conceptual framework that opened a space to pose deep ethical, aesthetic, and practical dilemmas. For example, demystifying the documentary, understanding its origins as a colonialist practice, and exploring how we can appropriate that format beyond colonial ideologies. Likewise, the myth of the Hero’s Journey was analyzed as a universal method for character creation based on the universality of the European white man; even the Aristotelian structure in our stories was questioned, as our narratives do not come from there. They begin with our grandmothers and mothers, our ancestry, our daily lives,

and our modernity as trans-Atlantic people. FOCO invited us to create our own theories, narrative models, and to cite our own philosophers in the work we do.

In terms of distribution, the challenges to reduce the gap in cinema and audiovisual content in territories that are predominantly Afro-descendant or lie on the margins of society were analyzed. What is the point of making cinema if communities do not have access to it? How can we reach more commercial spaces such as movie theaters, streaming platforms, network and subscription television, niche audiences on public television, websites and social media, libraries, and schools, among others?

Many questions were posed with the intention that, over time, the answers will diversify through the creative and disruptive leadership of each participant, as they are the ones who build their own experiences from the learning shared by the mentors and other members of the program.

“I have a cultural role as a filmmaker. If I am not interested in my history, who else will be?”

Sarah Maldoror

A TRAINING MODEL TO STRENGTHEN AUDIOVISUAL LEADERSHIP FOR RACIAL EQUITY

From FOCO, we envisioned the next level of diasporic, more specifically, Afro-Latino audiovisual production. We sought to explore the possibilities of audiovisual construction found in Brazilian and Colombian ethnic identities, aiming to explore narratives with renewed aesthetic foundations and with an agenda and advocacy for visual and audiovisual matters in Latin America. For this reason, our model was built upon three pillars:

AWARENESS: We created awareness through direct questions and reflections on the production of cinema and audiovisual content that grow from within the concept of Blackness, drawing from the diversity of perspectives that live on the African continent and its diaspora. How has Blackness been conceptualized in cinema made in Brazil and Colombia? What are those referents from Africa and the African diaspora? From where is Colombian and Brazilian cinema made by Black filmmakers being envisioned? We opened a dialogue on the comparatives and contrasts within Black creative communities in both countries.

QUALITY: The aim was to create and produce works that, due to their quality, can gain global positioning for AfroLatino audiovisual content. What are the stories we need to tell? How do we narrate what is ancestral while keeping an eye on the future? What are the key elements of these stories that can reach a global audience? How can we find new forms of production that achieve the quality necessary for finished products to become increasingly visible? How can we make our careers an exercise in dignity while maintaining professional well-being that is sustainable?

IMPACT: Through the exchange and collaborative work among creators, technicians, and audiovisual entrepreneurs from Brazil and Colombia, we encourage greater positioning of Afro-Latino cinematography with transnationally oriented products that reach a wider audience.

ACT II

WHAT KIND OF CINEMA MADE BY BLACK

FILMMAKERS DO WE WANT TO SEE IN COLOMBIA AND BRAZIL?

What topics do our proposed narratives still need to explore? What are the spaces, themes, and proposals not yet addressed in Colombian and Brazilian audiovisuals? How do we establish ourselves as an ethnic community of creatives? What are the possibilities for building new imaginaries that are truly inclusive in ethnic and gender issues? What audiovisual creations are of interest to diverse audiences in Colombia and Brazil, and around the world?

A Perspective of Opposition that Generates a Revolution

Reflections by Rodrigo Antonio, Director of Training and Innovation, Ministry of Culture, Brazil

The first session was led by Rodrigo, who shared the long journey of his career and the motivations that gradually contributed to the creation of the FOCO School in partnership with Manos Visibles. “It was important to think about building an annal of the Black movement—the archives, the preservation, and the very lack of physical documents—to understand where we come from and who we are. We face the need for a physical archive about ourselves, confronting a capitalist and colonial system that has denied our existence and our ways of affirming ourselves in the world. Right now, we are in a process of rediscovery.”

During this session, reflections were built around Black representation in audiovisuals, the role of art in building community meanings, the

construction of the collective self of Black artists, and pathways toward the systematization of Black references in favor of Afro-centered methodologies in creative fabulation. What does Colombian cinema made by Black filmmakers look and sound like? What does Brazilian cinema made by Black filmmakers look and sound like? What are the characteristics of contemporary Colombian literature written by Black people? Images enhance memory—so, How do we rescue that image that has been so often distorted and stereotyped? For this reason, it is vital to change the focus and analyze where stories come from and how far they can take us. To close the reflection, we read “Letters to a Young Poet” by Rainer Maria Rilke, and our mentor adapted it into “Letters to a Young Filmmaker,” that included the following excerpt:

Letters to a Young Filmmaker

You are so young, you are going through it now, so I would like to ask you to be patient with everything that is still unresolved in your heart, to seek answers that cannot yet be given, because you are not yet able to live them, and everything must be lived.”(…)

Extract from: “Letters to a Young Poet” by Rainer Maria Rilke

of knowledge so they may bloom into future responses. This is a space to celebrate those questions and the paths that will arrive at our feet, from the ancestral and from the gift we have of being a community. We are going to make the films we want to see and create the physical archives we do not yet have. We will place our feet upon this creative path, carrying the load but also the freedom of our multifaceted existence as Black people in the world—and the beauty and the contradictions of having to deal with that responsibility.

Rodrigo invited us to embody the questions from an Afro-centered perspective and vision, anticipating that FOCO participants will soon be able to experience the answers for themselves. He summonsed us to confidently accept everything that is to come, respecting the timing of processes and the path already traveled. At FOCO, we are here to raise those questions, planting the seeds

“What we seek is not in the archives but at the bottom of the ocean.”

Sarah Maldoror

DECOLONIZING SCREENS

HISTORY AND CRITIQUE OF AFRICAN CINEMA

Reflexiones Janaina Oliveira, Investigadora

The history of African cinemas and their singularities contribute to a critical understanding of current discourses and images about Africa, African identities, and the world. The trajectory of African cinematography helps us understand contemporary productions and how cinema functions on the continent. Analyzing African cinema through the lens of aesthetic vanguard conquests, such as Afro-futurism, is fundamental. Janaina indicates that the camera, from an African or Africanist perspective, constitutes a spiritual and communal tool.

The repeated narrative of a timeless Africa is not part of history, much less part of art history. With the understanding that cinema is a structure that generates historical imaginaries, Janaina asks: What would cinema be like if it were not a colonial practice? Are we part of the cinematic histories of Colombia or Brazil? This requires a critical reading of history, to chisel intentionality into the future and to write the history of that future. This implies a grammar of intervention in cinema—a cinema that has often romanticized poverty and perpetuated traumas that we go through but do not define us. Janaina invited us to analyze the transition from a “cinematographed Africa” to a “cinematographic Africa.” She

then offers us a historical overview of this evolution through moving images, summarized as follows:

• Cinematographed Africa: Colonialism and the organization of the visible world. Cinematic experiences, the first anti-colonialist films, and the pioneers of African cinema.

• Cinematographic Africa I: Early African cinemas, film circulation and distribution, the first film festivals, and African cinema made by women.

• Cinematographic Africa II: Contemporary dimensions of cinematic production on the African continent, Nigeria and Nollywood, queer African stories, Afrofuturism, and avant-garde aesthetics.

[...] “Africa is immensely rich in cinematic potential. It is good for the future of cinema that Africa exists. Cinema was born in Africa because the image itself was born in Africa. The instruments are European, yes, but the creative and rational need exists within our oral tradition. As I told the children before, to make a film, you simply close your eyes and see the images. Open your eyes, and the film is there. I want these children to understand that Africa is a land of images not only because African masks have revolutionized art worldwide but, simply and paradoxically, because of the oral tradition. Oral tradition is a tradition of images and it’s stronger than what is written; words go directly to the imagination, not to the ear. Imagination creates the image, and the image creates, which is why we are in direct lineage as a country of cinema.” (Ukadike, 2)

After this analysis, Janaina poses further questions: What is diasporic, non-African construction of audiovisuals? What are the African questions? What are the diasporic questions? Drawing a parallel with Brazil, she mentions the films of Zozimo Bulbul and his contributions to the development of Black cinema in Brazil and asks: What is the repertoire, archive or repository are we building? For what purpose? She deepens the importance of audiences, urging us to know our public and to ask continually: Why do people not go to the movies? Her final reflection connects to the decolonization of the curator’s position, emphasizing: “I see curation as an offering; I started taking movies to schools, universities, classrooms…I offered cinema to everyone.”

QUILOMBO CINEMA AND AQUILOMBARSE.

REFLECTIONS BY TATIANA CARVALHO

President of APAN, University Professor, Researcher

Based on the formulations of Maria Beatriz Nascimento and Abdias do Nascimento, the Quilombo Cinema course proposed an approach to film culture and audiovisual production through the concept of a “quilombo” in its conceptual dimension and its consequences for understanding the disruptive dimension of Black actions in contemporary Brazilian cinema. Short-, medium-, and feature films—as well as research, criticism, curation, and other fields of reflection—were explored through Black think tanks composed of intellectuals from Brazil and other countries. These gatherings emphasized the place of the “universal subject” and pointed to the possibilities of decolonization in culture, applying this thinking to practices in and with film and audiovisuals.

Tatiana established the genealogy of the word “Quilombo”: “No matter which social system dominates, it is possible to create a differentiated system within it, and that is the quilombo.” She highlighted the various meanings it has acquired in Brazil over the years. The term quilombo originated as a concept of resistance brought by African peoples to the Portuguese colonies. Contrary to the notion of family, quilombo focused on the idea of the collective, defining any dwelling of runaway Black people housing more than five individuals as a space of resistance. This concept is

often expressed alongside other terms such as “Palenques,” “Cumbés,” and “Cimarrones,” representing the Black fugitives who freed themselves from colonial oppression.

The history of the Black audiovisual movement in Brazil has been a search for freedom through the affirmation of the self as a Black entity. This has involved the systematization of works and reflections within the Black and feminist movements, translating them into stories, scripts, and films. Through this work, the aim is to reclaim self-image with the intention to reconstruct and make one’s identity visible. In the words of Beatriz Nascimento, “Body fiction” becomes an aesthetic-political statute that encompasses the complex and fluctuating Black existence, historically represented and often excluded by cinema. Living in the Black diaspora becomes an act of self-fiction, where personal experiences intertwine with a broader narrative of resistance and empowerment. Here, the concept of “Quilombismo” is introduced, representing a project of social emancipation for Black people by immersing themselves in their own history and culture, and building a society where Black people are the protagonists. This movement also included an ideological component related to instating nationality and fighting for full citizenship in a context where civil rights were nonexistent for many.

At the end of this module, the need for “Aquilombamento” was emphasized, connecting the history of quilombos in Brazil with the process of uniting Black peoples throughout Latin America by way of an artistic approach and audiovisual collective. “The collective then overrides the individual, as an operator of forms of social and cultural resistance that reactivate, restore, and reterritorialize us,” Tatiana emphasized. She also posed the question: Are we going to remain in a narrative of pain and suffering? Our existence is not only permeated by violence. What do we do with violent images? We have a hyper-presence of violence, and we are hyper-exposed to images of death and destruction. How can we propose narratives that convoke images of life, and not those that invoke those dark, historically constructed places? Tatiana calls on us to explore the art of “aquilombarse,” which involves renewing our ways of conceptualizing and making audiovisual content. Because we are not just spectators. Reclaiming the image becomes a communication revolution that changes the ways we produce and consume audiovisual content.

MAPA DE LA DIFUSION DEL CINE NEGRO EN BRASIL

“Imagine what cannot be verified.” (Hartman, 2018)

AM I A SCREENWRITER? NARRATING A BETTER WORLD REFLECTIONS

BY MAÍRA OLIVEIRA Screenwriter

¿Acaso soy guionista? es la pregunta “Am I a screenwriter?” This is the question answered in this module, which delves into narratives and useful techniques from the conception of an idea to the writing of a script. Maíra Oliveira’s answer is yes, emphasizing that the main challenge for Black screenwriters in various spaces is to change the stereotypical view that exists about Black people and to move from being mere objects to becoming the actual creators of our own stories. Maíra highlighted the power of the script,

which defines the impact of the story and its ability to reach the audience. She explored terms such as the concept in audiovisuals that describes the tone of the project and its aesthetic proposal. She also addressed the importance of characters, plots, locations, iconography and the music, all drawing attention to the need to develop these elements in detail for each genre. Finally, Maíra explained script parameters, writers’ rooms, and the structure for developing a story, noting that each screenwriter has their own method. But the key is to organize the best ideas, starting with a strong logline and later building a solid outline. She shared the code of honor of screenwriters and filmmakers, reminding us that film is like writing with the camera: the camera is the eye, and there is a code between the viewer and what is viewed.

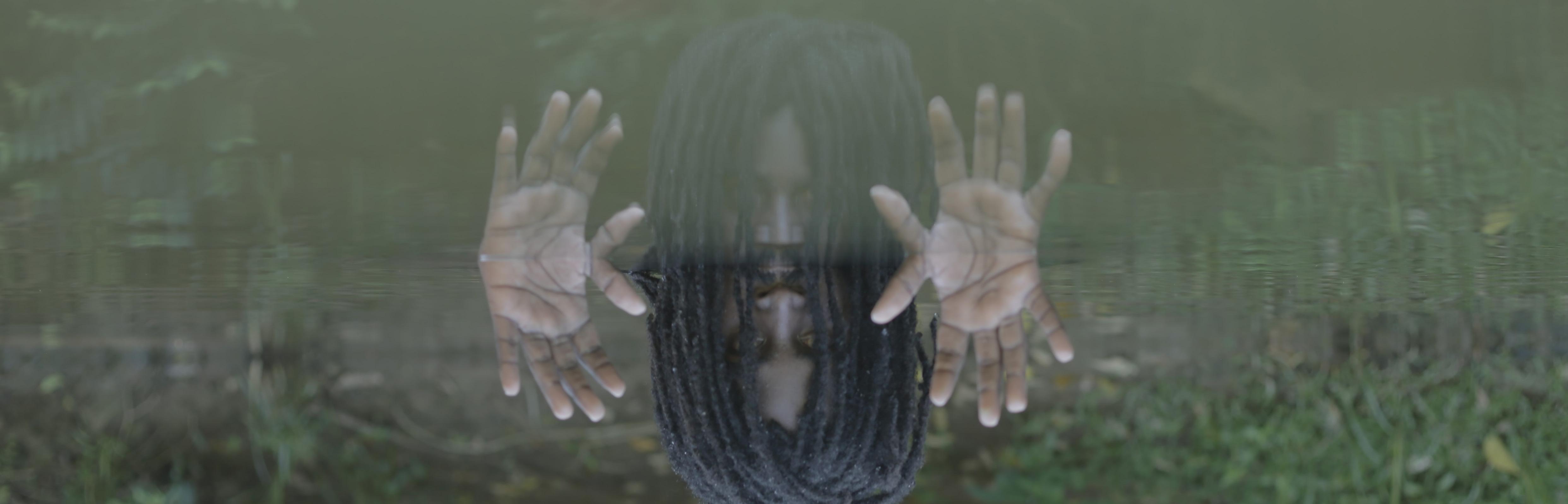

PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION AS A WAY OF AFFIRMING THE WORLD I CLAIM

REFLECTIONS BY FLÁVIO REBOUÇAS

Photographer

Together with Flávio, we engaged in a reflective process on why cinema is made of images (visual and sound). The visual image is born from the apprehension of the limited relationship between shadow and light. In this gradation of tones, generated by this connection, cinema has been used for over a century as a medium for representing and expressing cultural ideals, values, and concepts of beauty. Therefore, this workshop emphasized the importance of photography in cinema, articulating the roles of aesthetics, ethics, and technique as a tripod in the image creation process and the construction of memory.

Flávio shared his experience as Director of Photography and Post-production Image Editor on films such as Murciélago, Praia Formosa, and the documentary on

Racionais MC. He simultaneously made a comparative analysis with Brazil’s visual arts and the traditional representations of Blackness, emphasizing how we need to transform art history and its traditional royalties schema in our countries.

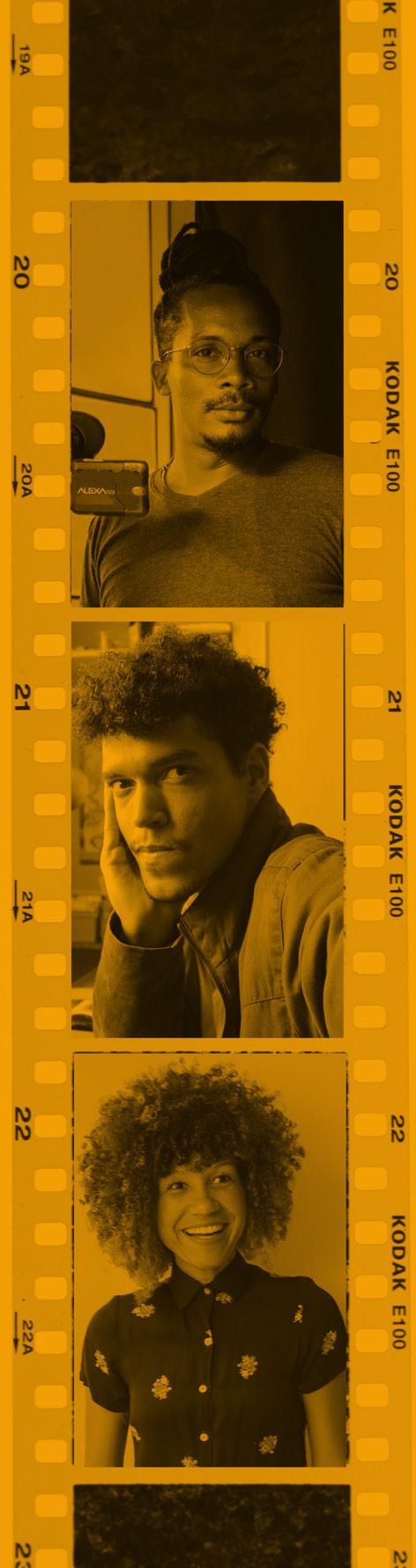

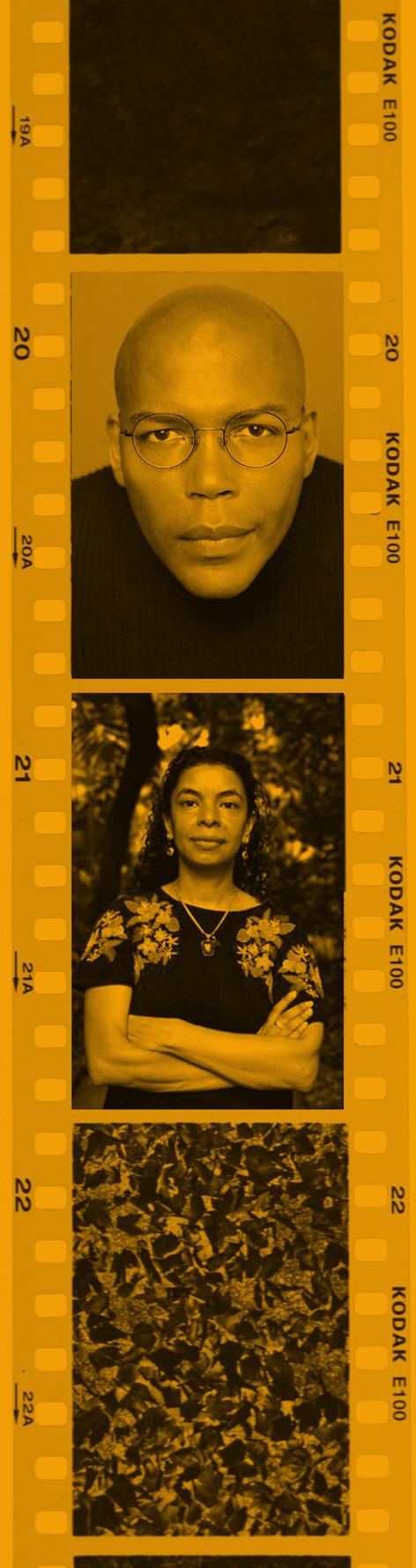

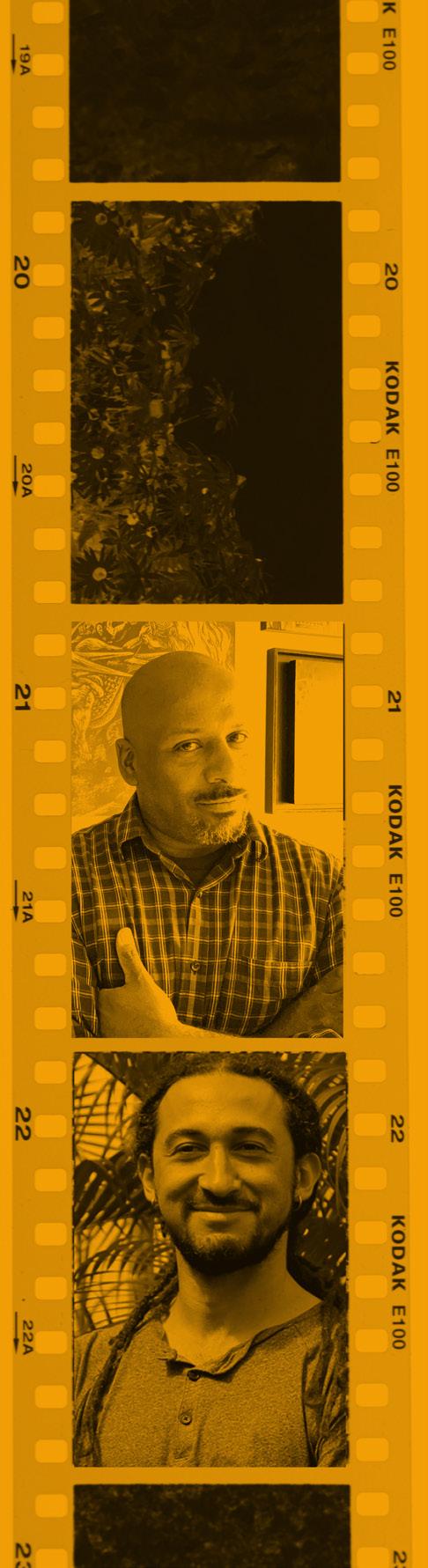

As part of this module, each FOCO member shared a synthesis image of their audiovisual work, and these images are included in this chronicle.

DIRECTING, CREATIVE PROCESSES, AND LATIN AMERICAN DIALOGUES

REFLECTIONS BY EVERLANE MORAES

Director and Producer

The dialogue with Everlane brought to light building new perspectives from the standpoint of nonhegemonic cinema that represents different spaces and experiences shaped by the context of the colonization that still surrounds us. The intention was to navigate the ways and the elements that compose a film, and the concepts surrounding filmmaking. How do we conceptualize theme? How do we materialize that theme in a project? How do we develop a method for filming, for choosing the characters and everything else? Everlane’s perspective addressed philosophical issues in cinema and documentaries, aiming to provide an approach to the questions surrounding the author’s/director’s universe, as well as the ethical, aesthetic, and political decisions that must be made while filming.

Everlane emphasized the importance of understanding and addressing the concepts of aesthetics, ethics, and politics to provide a comprehensive approach to our audiovisual projects, stating, “Every aesthetic decision is a moral decision.” This implies understanding how all the elements that make up our films interact beyond the final product, as this is a process that develops before, during, and after production. Accordingly, Everlane highlighted the importance of understanding cinema from an inter-, trans-, and multidisciplinary perspective, as it is the only artform that brings together all artistic languages in one space. It is a demonstration of the myriad possibilities for constructing messages and the many aesthetic, moral, and ethical decisions taken when addressing and narrating stories that are produced in specific historical contexts with a serious consideration to race, class, and gender.

Everlane invites us to link artistic practice with political factors, understanding that our productions will be seen by others. And from this perspective, there is an intention to convey a concept. For this to take place, it is necessary to use aesthetics as a bridge that helps translate ideas into form, to understand aesthetics as a path to the translation of thought. This is especially important when intentions and gestures play a leading role, opening new possibilities for interpretation and modifying perceptions, where the universality and specificity of themes and experiences generate a new narrative, a new vision.

TRACES OF MEMORY

REFLECTIONS BY FABIO RODRIGUES

Researcher and Audiovisual Creator

During this session, Fabio shared a method in development designed to forge a tool capable of implementing justice for Black actors and actresses in Brazilian cinema. How do we compose scripts and stories specifically for Black actors and actresses? How do we see and think about agencies, acts of resistance, or even counterstrategies of subversion of meaning on the part of Black artists? How do we weave a story that honors the legacy of Black actors?

Fabio proposed the notion of “TRACE” to think about this tension in opening the narrative fabric, which, once amplified and put into relation, reveals a historical struggle around images. This method involves working with reassembling archives and analyzing works guided by actors (i.e., trajectory, performance, and testimonies). Throughout the session, discussions were held on building archives, ways to approach editing as a project of justice and dignity, and interventions in history through Black recollections.

CREATIVITY AS A WAY OF OPTIMIZING PRODUCTION RESOURCES

REFLECTIONS BY JOYCE PRADO

Director and Screenwriter

oyce invited us to reflect on the importance of integrating the creative process within the practice of audiovisual production, understanding that access to resources that guarantee autonomy in executing projects presents various challenges, keeping in mind that optimization is key to success. Joyce prompted us to reflect on our role as directors and producers, the alignment of the stories we want to tell, the audiences we aspire to reach and impact, and the debates our productions will spark on both a local and global level.

Joyce presented these elements as foundational aspects for designing our productions, questioning: How do we want to create our stories? From the answer to this question, we can develop creative decisions that build critical awareness within our productions. It is essential to focus on one of the core functions within the audiovisual field and to clearly identify the stakeholders in the audiovisual ecosystem with whom we can collaborate as allies to optimize resources

“FOCO, with its class titles alone, already promised it would be an interesting process. For me, it was inspiring to participate in a process with structured methodologies, classes delivered with care, and the total dedication of each person who made it possible. The school is a meeting of dreams, ideas, and perspectives that begin to envision our image in a decolonized way.” Leonardo Rua , Bogotá Colombia

and broaden perspectives. Throughout the session, creativity was positioned as an integral element from the development stage to distribution, directly guiding and intersecting with executive production decisions that influence the trajectory of the work and directly impact the quality of narrative development and its execution.

SHARING TO EXIST: BLACK MOVIES IN DIALOGUE WITH THEIR AUDIENCES

REFLECTIONS BY TALITA ARRUDA AND MARINA TARABAY

Talita and Marina proposed a structure for developing new spaces for the circulation and distribution of audiovisual pieces created by Black filmmakers. It is necessary to develop and innovate distribution schemes that allow these projects to reach new and wider audiences. In their practice as a distribution agency, they emphasized audience design as a process that begins in the creation stage, stating that “the audience is the compass.” What this means is that once the audiovisual product is complete, what is critical for its distribution and communication is the potential audiences. Talita and Marina analyze the current crisis in traditional distribution formats such as movie theaters and festivals, stressing the educational, representational, and entertainment roles of audiovisual works, which enable the creation of new spaces.

CASE STUDY: THE FILM MARTE UM (MARS ONEMARTE UNO)

GABRIEL MARTINS

Film Director and Partner at “Filmes de Plástico”

Gabriel Martins invited us to explore various creative universes that tell the stories of Afro-descendant populations from a perspective that embraces their daily lives while aiming for the universality of their narratives.

Gabriel described Marte Um as a film that portrays other Brazilian realities, exploring who we are and who we can become, with an expansive image of a family in transformation. It tells the story of a boy who wants to go to another planet, seeking his promise beyond soccer to become an astrophysicist, highlighting the value of backyards in Brazilian neighborhoods as spaces for dreaming and construction. In his cinematic work, he naturally brings forth the reality of being Black as something that does not need to be explained, as something as commonplace as being white. These are stories that go beyond trauma. They are new stories that do not aim to defend or dispel any social paradigms, but by way of their creation, they allow freedom to simply exist on its own merit.

FREE LANDSCAPES FOR INVENTIVE SENSIBILITIES ¿ WHAT IS OUR COMMITMENT TO BLACK CHILDREN?

REFLECTIONS BY MELINA BOMFIM AND ÉLLEN CINTRA

In this space, Melina and Éllen guided us to reflect on the importance of developing safe spaces for children, youth, and communities. Through the analysis of various spaces such as the home, school, and open areas, they propose curatorial and pedagogical strategies in presenting images and methodologies that expand the limitless and free imaginaries of Black children and communities. This conversation served as a call to antiracist action, informed by Brazil’s Law No. 10.639/03. From this platform, they propose challenging established optics for Black futures and imagining new ones.

MIRROR COLOMBIA

HOW TO PRODUCE MOVIES FROM BLACK PERSPECTIVES FOR COLOMBIAN CINEMA

Reflections by Jhonny Hendrix

Jhonny Hendrix, Colombian director and producer known for his films Chocó, Candelaria, and Saudo, shared insights about his career as a pioneer in Afro cinema and the long journey of both producing and directing in Colombia. He emphasized aesthetic quality in terms of photography and art as a potential barrier that prevents films from transcending. This includes sound quality. In terms of the industry, he reflected on the need to occupy decision-making spaces within the audiovisual power structures in Colombia and globally, considering the economic resources needed to make films, and exploring investment strategies in cinema to achieve greater creative freedom.

REPRESENTATIONS AND INTERNATIONAL PROJECTION OF AFRO-COLOMBIAN UNIVERSES

REFLECTIONS BY SALYM FAYAD

“How do we build a nation? Cinema becomes a key tool for nation-building.” In recent years, cinema in Africa has been shaped by national identities and Pan-Africanism. During this session, Salym discussed the importance of connecting diaspora films internationally and weaving dialogues among them. He also expanded the discussion to the process he has developed with MUICA (Muestra Itinerante de Cine Africano).

BLACK IMAGERY IN COLOMBIA AND ITS PRESENCE IN NATIONAL CINEMA

Astrid Gonzales, Visual Artist, and Gerylee Polanco, Producer

Astrid Gonzales and Gerylee Polanco, both participants in the school, shared their work and productions within the artistic and audiovisual fields, contextualizing their perspectives on the representation of Black populations in Colombia.

Astrid reviewed her body of work, explaining how her creative process begins with reflecting on the historical processes of Afro-descendant communities in the Americas and graphically grounding these in the colonial context, structural racism, the birth and consolidation of maroon and Palenque towns, and, finally, the whitening processes as a paradigm of progress and mestizaje in the Americas. Astrid shared how her work articulates various disciplines such as video, photography, and sculpture to give form to discourses of racism, invisibility, and cultural hybridity that, since the 16th century, have used Afrodescendant bodies to perpetuate racist notions.

Gerylee Polanco shared her experience as a producer of major Colombian films such as El Vuelco del Cangrejo, Perro Come Perro, and La Sirga, explaining how she has understood the importance of generating representations that dignify and reflect the ethnic diversity present in the country. She shared her vision of executive production in Colombia by outlining the importance of opening more spaces for stories written and directed by Afro-descendant communities while recognizing the technical and financial challenges involved in developing and materializing these works. Additionally, she shared the strategies she has employed for the development and circulation of these projects and emphasized the importance of integrating a gender perspective into her work, noting that while a racial focus is a priority, it is also essential to understand the importance of incorporating a gender perspective to help reduce social gaps present in the field.

“FOCO has a political spirit that many training processes I have attended lack. That is precisely why I connected deeply, because in my pedagogical efforts, I instill this same spirit.”

Gerylee Polanco Cali, Colombia

ACT III

THE CHARACTERS AND THEIR STORIES

“I am not the person who left Salvador, but I am also not the temporality of the harsh experiences of the city of São Paulo either. I am a connection of both temporalities and energies. I almost always narrate audio-visually in first person. When I make a film, I do not make it only for others; I make it for myself. Films must transform me.”

Viviane Ferreira

OUR PIONEER MENTORS

Rodrigo Antônio Audiovisual Producer, Audiovisual Coordinator at the Audiovisual Secretariat, Ministry of Culture of Brazil

Janaina Oliveira Researcher and Curator

Naiara Leite Journalist, Master’s in Communication, Executive Coordinator at Odara Institute for Black Women

Tatiana Carvalho Costa University Professor, Researcher

Maíra Oliveira Screenwriter, Playwright, Writer, and Educator

Everlane Moraes Director and Producer

Gabriel Martins Director

Viviane Ferreira Lawyer and Filmmaker

Joyce Prado Director, Screenwriter

Flávio Rebolças Photographer

Fabio Rodrigues Researcher, Filmmaker, and Curator

Melina Bomfim Filmmaker, Researcher, Curator, and Producer of Showcases and Festivals

Talita Arruda Distributor, Researcher, and Curator

Marina Tarabay Distributor

Francisco Javier Flores Historian and Researcher

Jhonny Hendrix

Hinestroza

Film Director and Producer

Astrid Liliana

Angulo Cortés

Visual Artist

Wilson Andrés

Borja Marroquín

Graphic Designer

“I would describe FOCO as the backyard of a house on a sunny day. The guest mentors sat at the same level as us, and we addressed the topics like those who grind corn to prepare a delicious meal.”

Milena Andrade da Rocha, Teresina, Brazil

Salym Fayad Freelance journalist and documentary photographer

FOCO 2023 COHORT

A QUILOMBO-PALENQUE OF AFRO-DESCENDANT FILMMAKERS AND ARTISTS TRANSFORMING COLOMBIAN AND BRAZILIAN CINEMA

• Alfredo Manuel Marimon Carcamo (Cartagena, Bolívar)

• Allan David Guerrero Moreno (Cali, Valle del Cauca)

• Ana María Jessie Serna (San Andrés y Providencia)

• Angélica María Pérez Vega (Riohacha, Guajira)

• Astrid González (Bello, Antioquia)

• Carlos Alberto Mera Jiménez (Santander de Quilichao, Cauca

• Daniel Mauricio Rodríguez Guzmán (Tumaco, Nariño)

• Diego Armando Casseres Navarro (San Basilio de Palenque, Bolívar)

• Fray Miguel Blanco Palacio (Manaure, La Guajira)

• Gerylee Polanco Uribe (Cali, Valle del Cauca)

• Gustavo Antonio Cabezas Tenorio (Tumaco, Nariño)

• Harold Enrique Tenorio Quiñones (Tumaco, Nariño)

• Jorge Aldair Pérez Cáceres (Barranquilla, Atlántico)

• José Luis Guzmán Alvear (Villa Rica, Cauca)

• Katherine Ortiz Sánchez (Cali, Valle del Cauca)

• Laura Camila Flórez Castellanos (Santa Marta, Magdalena)

• Laura Yineth Asprilla Carrillo (Bogotá D.C)

• Leonardo Rua Puertas (Bogotá D.C)

• Sara Johana Asprilla Palomino (Bahía Solano, Chocó)

• Yaqueline Esthefanía Preciado Ordóñez (Yumbo, Valle del Cauca)

• Zulay Karina Riascos Zapata (Bogotá D.C)

• Ruan Jones Souza Ribeiro Assaggi Piá Conceição do Almeida - BA

• Milena Andrade da Rocha Teresina - PI

• Gustavo Monção Carneiro Faria Rio de Janeiro - RJ

• Nataraney Nunes Recife - PE

• Sandra Alves Florianópolis - SC

• Christiane Da Dilva Gomes Krika Niterói - RJ

• Cledison da Conceição Pereira Planaltina-DF

• Daianade Souza Macaé - RJ

• Rafael Anaroli Condado - PE

• Carlos Eduardo Marques Mendes São Luís - MA

AN OPEN ENDING: WHAT S NEXT?

Without a doubt, FOCO was a space for gathering, learning, and interchange for members of the diaspora, where audiovisual art was the reason to meet and connect from new perspectives. We aim to empower a new generation of AfroLatino filmmakers, schools, and production companies with high-level products that reflect the critical execution and ethnic responsibility we have encouraged throughout this training process—a generation that dialogues with its peers and finds spaces for exchange and promotion both nationally and internationally. Our vision is to continue supporting and creating incentives for Afro-Latino filmmakers to connect and strengthen their narrative processes through dialogue, mentoring, and funding. Our goal now is to continue developing these spaces and to strengthen participants through mentorships and guidance that allow us to materialize their works. Here is a list of their projects:

Participant

Country Project

Format

Alfredo Manuel Marimon Carcamo Colombia Agua de la Virgen Dramaturgical Documentary

Allan David Guerrero Moreno Colombia Ruts of da bit Short Documentary

Ana María Jessie Serna Colombia El hombre Coral Ethno-fiction Documentary

Angélica María Pérez Vega Colombia Frontera Negra Short Documentary

Astrid González Colombia Drexciya Fiction Short Film

Carlos Alberto Mera Jiménez Colombia DÍAS DE GLORIA Fiction Feature Film

Daniel Mauricio Rodríguez Guzmán Colombia Rostros Documentary

Diego Armando Casseres Navarro Colombia Catalina Loango: La historia que nunca te contaro Drama/Suspense/Mysticism Short Film

Fray Miguel Blanco Palacio Colombia Sal Negra Pueblo Blanco Short Documentary

Gerylee Polanco Uribe Colombia El Nido de las Alas Fiction Feature Film

Gustavo Antonio Cabezas Tenorio Colombia La Tunda Fantasy/Mythological Short Film

Harold Enrique Tenorio Quiñones Colombia Videoclip animado, La Visita Animated Music Video

Jorge Aldair Pérez Cáceres Colombia El Cuento de las Almas Drama/Fantasy Feature Film

José Luis Guzmán Alvear Colombia EL VUELO CAPITÁN Drama Short Film

Katherine Ortiz Sánchez Colombia El Precio de Crecer Drama Short Film

Laura Camila Flórez Castellanos Colombia El bullerengue es del cielo Fictionalized Short Documentary

Laura Yineth Asprilla Carrillo Colombia El retiro de la Ninfa Fiction Short Film

Leonardo Rua Puertas Colombia Estilo libre Fiction Musical Short Film

Yaqueline Esthefanía Preciado Ordóñe Colombia Revelaciones Fiction/Fantasy Short Film

Sara Johana Asprilla Palomino Colombia Mis amigos están bien lejos. Fiction/Drama/Comedy Short Film

Zulay Karina Riascos Zapata Colombia Nos dejaron ir al mar Fiction Feature Film

“It was a ‘Buen Viaje’ of discoveries through narratives told in Brazil and Colombia. An immersion that stimulates cinematic thinking, where we shape imaginaries based on our experiences and memories. It referenced African cinema, and our own movies made in the countryside and peripheries of Brazil, with stories so much our own that they are becoming part of the Brazilian and Colombian diasporic cinematic experience.”

Milena Andrade da Rocha, Teresina, Brazil