Shaping the Future Through Growth

From Founders to Futures

planning, with best practice in HR, to secure long term organisational resilience.

September / October 2025 Edition

Publications and Financial Officer:

Fabrizio Gerada MCIOB Vice President

Being a Construction Project Manager is, in many ways, akin to holding a General Management role within an organisation. In a world that is constantly evolving, one of the most critical functions for any business is Human Resources Management. For the built environment industry in Malta, it is increasingly vital to develop this function beyond the traditional monthly salary routine. Instead, it should be transformed into a comprehensive employee satisfaction strategy that becomes a genuine competitive advantage.

This edition of our magazine delves deeply into this topic, with a particular focus on succession—a pressing issue in an industry comprised mainly of family-run businesses. The responsibilities of a project manager extend across a variety of roles, and it is clear that leadership and management abilities are central to the quality of service delivered. We also provide an in-depth exploration and clarification of the latest Health and Safety laws, which have now come into effect and are shaping industry practices.

Driven by a steadily growing audience, our publication is shifting its lens to address the built environment as a broad industry, rather than concentrating exclusively on construction project management. The industry itself is experiencing a paradigm shift; sustainability is no longer an optional add-on. Both governmental authorities and private developers are showing a strong willingness to set higher standards. We urge project managers to actively embrace change, incorporate low-carbon materials, apply life-cycle analysis, and implement energy efficiency measures in their projects.

Ultimately, innovation and conservation need not be at odds. Through the use of advanced technological tools, open dialogue, and inventive design, it becomes possible to harmoniously integrate our heritage into the infrastructure of tomorrow, ensuring that progress respects and preserves our rich past while building a sustainable future.

Photo Credit: David Thomas

Photo edits: Luke Graham Cassar

Editorial enquiries: info@mccm.org.mt

Advertising: info@mccm.org.mt

Who We Are

The Chamber is the voice of the construction managers at the various levels operating in Malta and beyond. We promote and expect, high standards in, quality, ethics, integrity and to be at the forefront of innovation of the local built environment. Through our input we strive to influence policies and regulations that impact the industry and their impact on the common good.

Mission Statement

To promote science and technological advancement in the process of building and construction for the public benefit.

To be at the forefront of public education, encouraging research and sharing the outcome from this research.

To make sure that advancement in the built technology is aimed at improving the quality of life of the public in general.

To enhance professionalism, encourage innovation and raise quality in construction management.

To promote high standards and professional ethics in building and construction practices.

To promote the highest levels of integrity in every decision that we take that affect others.

To respect all those affected by our decisions

TO BE THE DRIVER OF A CULTURAL AWARENESS CAMPAIGN STRIVING FOR PROFESSIONALISM IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY.

September/OCtober 2025

Message from THE PRESIDENT

Welcome to the 15th edition of our publication.

This article marks my fourth contribution and as I look back over the past few months, I am encouraged by the strength of our community and the momentum we continue to build. From new members joining our ranks to important national engagements, the past weeks have shown once again the value of working with purpose and unity.

One of the most rewarding moments was our certificate presentation event in June. Bringing together professionals, students and company affiliates reminded us of the shared commitment that drives MCCM forward. Having Hon. Minister Dr. Jonathan Attard present, reaffirming government’s support for our vision, recognition within the Building Codes initiative and commitment to our profession’s legal recognition, gave the occasion added weight and meaning.

Equally significant was our courtesy visit to H.E. President Dr. Myriam Spiteri Debono at San Anton Palace. Together with some members of the Council, we outlined MCCM’s mission and our determination to secure formal recognition for the role of Construction Project Managers. This visit reinforced our ongoing engagement with national institutions, as we continue to push for higher standards across Malta’s built environment.

Outreach and education remain core to our efforts. At the I Choose Post Secondary Education Fair in Valletta, our team introduced young students to the exciting pathways offered by construction project management, promoting both the profession and our student membership pathway. Similarly, the launch of the new University of Malta Diploma in Construction

Management, developed with MCCM, UoM and BCA, is a landmark moment in professionalising the sector. In parallel, MCCM has been actively participating in the BCA-led discussions on the new Building Codes, ensuring our members’ voice is heard in shaping these important reforms.

Looking ahead, the Council is also working on new initiatives which, if brought to fruition, will open up valuable opportunities for collaboration with our partners—initiatives that promise to be both important and beneficial for every member of the Chamber.

Each of these moments adds to a larger picture: a profession gaining recognition, opportunities opening for the next generation and stronger foundations being laid for Malta’s construction industry. There is more work ahead, but with your continued support, I am confident in the direction we are heading.

Wishing you an insightful read.

Key Duties under Malta’s Construction Health and Safety Regulations

• Liability: Failure to comply may result in inspections, penalties, prosecution, or site shutdowns.

The Role and Impact of the Client Representative

• Delegation of Duties: Clients may appoint a client representative, who then assumes all legal, health and safety obligations in place of the client. This is especially useful for organisations with boards of directors.

• Appointment Process: Appointment requires notification to OHSA, with signed declarations from both client and representative regarding acceptance of responsibilities and data processing consent.

• Change of Representative: If the representative resigns or changes, written notice must be given to OHSA. Until acknowledged, the outgoing representative remains responsible.

• Domestic Clients: For home projects, proposals require that client representatives be permanent residents and registered with OHSA.

• Ultimate Responsibility: The appointment of a representative or project supervisor does not absolve the client (or the representative) of overarching health and safety responsibilities.

The client representative is the legally designated person handling daily adherence to these regulations on behalf of the client.

Project Supervisor: Central Authority for Construction Safety

Project Supervisors are critical to ensuring compliance with health and safety requirements throughout all project stages.

Duties at the Planning and Design Stage

• Integrate general principles of prevention regarding health and safety, as stipulated by the OHSA Act (Cap. 646).

• Collaborate with designers and planners to integrate safety requirements into both technical and organisational aspects.

• Draft a site-specific Health and Safety Plan for both

design and execution stages.

• Coordinate sequencing and scheduling of work to minimise risk.

Duties at the Execution Stage

• Coordinate the implementation of all health and safety provisions on site.

• Regularly inspect site conditions and work practices, adjusting the Health and Safety Plan and File as work progresses.

• Issue written inspection reports and monitor corrective actions, including conducting follow-up inspections.

• Submit prior notification to OHSA for large projects. General Powers and Responsibilities

• Unrestricted access to the construction site at any time and authority to take photographs, measurements, and recordings as needed.

• Power to halt works posing serious or imminent risks, with immediate notification to all duty holders and OHSA.

• Investigate complaints regarding health and safety breaches, recommend corrective actions, and report findings.

• Prepare and update the Health and Safety File, which is handed over on project completion.

• Must be suitably qualified (e.g., MQRIC level 5) and experienced, and registered with OHSA as competent.

The Project Supervisor’s authority is extensive—enabling them to enforce and coordinate safety throughout the project.

Contractor Duties on Construction Sites

Contractors are responsible for day-to-day site safety and must cooperate with the Project Supervisor and comply with all regulations and directives.

• Cooperation and Compliance: Actively cooperate with and follow all directives from the Project Supervisor regarding health and safety.

• Adherence to Plans and Laws: Implement the site-specific Health and Safety Plan and comply with all relevant laws, particularly the Health and Safety at Work Act and its subsidiary legislation.

• Risk Assessments: Submit written risk assessments before work, identifying hazards and proposing preventive measures, prioritising collective protections.

• Safe Procedures: Establish safe work procedures and ensure proper demarcation and storage of materials, especially hazardous ones.

• Site Management: Keep work areas orderly and safe; ensure safe placement of workstations, proper access, and safe routes for equipment movement.

• Maintenance and Equipment: Carry out technical maintenance and inspections of installations and equipment to address safety faults.

• Qualified Workforce: Ensure all workers have necessary qualifications and certifications (e.g., Level 4 for Demolition Plant Supervisors from Jan 1, 2025).

• Information and Training: Provide thorough safety information, training, and emergency instructions to all workers.

• Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Supply PPE where risks remain and ensure workers use the equipment properly.

• Coordination Among Contractors: Facilitate cooperation and information-sharing with other contractors and self-employed persons on site.

• Licensing and Insurance: All contractors in demolition, excavation, and construction must hold a valid BCA licence from Jan 1, 2025, and have appropriate insurance cover for risks to persons and property.

• Accident Reporting: Promptly report any accidents or dangerous occurrences to the relevant authorities.

• Obeying Stop-Work Orders: Comply with any instructions from the Project Supervisor, particularly when work is halted for safety reasons.

Contractors are therefore at the forefront of daily site

safety management.

Key Duties of Employees and Workers

While employers, clients, and supervisors carry primary responsibility, employees and workers have important obligations:

• Personal Responsibility: Take reasonable care for their own safety and that of others who may be affected by their actions or omissions at work.

• Cooperation: Actively cooperate with the Project Supervisor and comply with any directives related to health and safety, as well as established safety protocols and procedures.

• Proper Use of Equipment and PPE: Use machinery, equipment, dangerous substances, and PPE correctly. Never tamper with or disable safety devices.

• Reporting Hazards: Immediately report any situation they believe poses a serious or immediate health and safety risk to their employer or supervisor, as well as any shortcomings in safety arrangements.

• Behaviour: Refrain from reckless or irresponsible actions at work that could endanger health and safety.

In summary, workers are expected to help maintain safety by adhering to procedures, using equipment properly, and reporting problems promptly.

Conclusion

Legal Notice 52/2025 establishes a comprehensive framework for protecting health and safety on construction sites in Malta. Strict obligations are imposed on clients, representatives, project supervisors, contractors, and workers, with the aim of reducing risks and fostering a culture of safety. The regulations emphasize clear lines of responsibility, mandatory planning and risk assessment, and the authority to enforce corrective actions, with enforcement mechanisms ranging from inspections to shutdowns and penalties for non-compliance. All parties on a construction site are expected to collaborate actively to ensure these standards are consistently met.

MCCM Strengthens Its Collaborative Ties

Strategic Partnerships and Growth

Amanda Williams Head of Environmental Sustainability at CIOB

Earlier this year, there was a piece here in the MCCM magazine about CIOB’s three current headline themes, one of which is sustainability. To examine that theme, CIOB recently held our annual sustainability conference.

I believe that the need to act has never been greater, not just to tackle climate change but the interconnected nature and pollution crises too, which are linked to community wellbeing and impact us all. It is perhaps unsurprising that our industry, which makes a significant contribution to the climate crisis, faces calls to go beyond doing ‘less bad’ to doing ‘more good’.

This led to our event headline of “Shifting the narrative”, with Pooran Desai OBE as keynote speaker. Pooran delivered on the theme with a plea to think about this issue differently. Pooran has a track record of delivering in practical ways too - he put together the

world’s first zero carbon urban village development, Beddington Zero fossil Energy Development (BedZED) in London, and created the framework on which the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are based.

Among the thought-provoking questions he posed: “Do we want to live in ways which promote our health and happiness, at the same time as allowing other people and the rest of nature to do the same?” He also talked about creating “a regenerative future” and “imagination-led, science-informed and technology-enabled” sustainability solutions.

This is highly complex issue and one that’s a challenge to summarise in a short article. But there is reason to be positive and there are resources out there to support construction professionals (many of which are produced by CIOB and available for free). Embedding sustainability in everything we do is a must – and I want to thank MCCM members for your efforts in supporting education around sustainable construction.

Engagement and Vision

People are the always the key

Nick Smith

I was 49 years old when I left my native England and landed in Muscat, the Sultanate of Oman, to manage the biggest ever construction project I had ever been involved with. I was greeted by people from over 20 nationalities - different backgrounds, cultures, beliefs, education and skills. And our task? To design and develop the biggest tourism scheme that the country had ever envisaged. We were pioneers.

I’d never worked outside of the UK before so it was a massive learning curve for me. I realised, very early on, that the secret was to mould these wonderful people into a cohesive team that could face all the tasks ahead with excitement, vigour and professionalism. Maybe I just had to be the catalyst to achieve this.

It took a year to refine the masterplan for 4000 homes, 3 hotels, a marina, a golf course, commercial and shopping, entertainment and the necessary infrastructure. We achieved the required permissions, and started to build in early 2007. I am so pleased that the Al Mouj mega project now boasts thousands of people living in and enjoying the world class places the team brought to life.

I left Oman for Spain in 2014 with some important

lessons learned about human capital and in particular the role of project managers involved in changing or creating the environment around us. We build bridges between the vast array of professionals involved, with effective communication being the major key. We must respect and use to advantage the unique characteristics of those from different countries in the world. Simple language; clear and achievable objectives; being firm but fair; and celebrating success are crucial components.

There is no substitute for talented, capable people with a positive attitude. Computers and AI can’t do this. For everyone already in one of our professions, or training to be so, I encourage you to push to your limits. It is the best feeling ever to be able to say ‘I helped create that building in that place.’ The sense of pride will stay with you for ever. Above all, we owe it to all those who will follow us in the generations to come.

Nick Smith

Previous President and then Executive Officer of ICPMA I can be contacted at nicksmith21c@gmail.com

The story of my time in Oman can be found at Amazon books entitled ‘Oman, My Dear’

Are Legal Changes Safeguarding Architects against Future Potential Liability?

When designing a building in Malta, a developer is legally required to appoint a warranted architect to apply for a building permit through the Planning Authority. Once the permit is granted, numerous laws and procedural changes introduced in recent years also require clearances from the Building Construction Authority. Without these, it is no longer lawful to proceed with works, even if a valid planning permit has been issued.

However, compliance with these requirements does not absolve the architect of potential future liability, particularly in cases involving works on or near adjoining properties, where permits and clearances have otherwise been properly obtained.

Dr Maria McKenna

Designing and constructing a building in full accordance with regulations does not automatically eliminate the architect’s liability—especially when buildings are directly abutting each other. In such cases, the stability of a structure often depends on the lateral support provided by adjoining buildings. These site conditions would have significantly influenced how the works were designed and directed.

It follows that if these conditions change—such as when a contiguous building is demolished and its lateral bracing removed—the stability of the remaining building may be seriously compromised. In such situations, temporary structural measures become essential to preserve the safety and stability of adjacent buildings.

Accordingly, the architect demolishing a building should take an active role in addressing the stabilisation of adjoining properties and building sites. Failure to do so could result in dangerous incidents. While it may not be necessary to enshrine this obligation formally in law, it remains a matter of professional diligence and responsibility. A true understanding of this duty, and how to execute it, is fundamental to the role of the architect.

Dr. Ivan Mifsud LLD PHD

The above question requires qualification: what value do solar panels covered by a Development Notification Order have in the eyes of the Planning Authority, when a neighbour applies to build a block of apartments which will result in these PV panels becoming non-functional?

The above is a very real issue; all one has to do is look around them and they will find many examples of non-functioning PV panels, thanks to later development which rose higher thus blocking out the sun. Keeping in mind that generally speaking:

i. said panels were at least part-financed by the government; ii. said panels are covered by a Development Notification Order;

iii. said notification order grants a legal right not only to place the panels on the roof, but to also enjoy the fruit one’s endeavours;

iv. granting a planning permission which renders someone else’s PV panels effectively useless amounts to a de facto withdrawal of the DNO which in itself is illegal;

v. SPED and other policies expressing themselves in favour of renewable energy sources

then the Planning Authority should give weight to an objection raised by a neighbour as occurred in PA6670/24, which is currently pending appeal. Regrettably when the objecting neighbour raised the matter before the Development Commission, the latter would have none of it and merely contended that since there are other blocks in the area then said area was committed to blocks of apartments and therefore the application was acceptable.

The reality is otherwise; Maltese planning legislation was originally based on English planning law, and one dares say that despite all the changes to the local planning legislation over the last thirty years, English planning law is still a source. And the English courts have made it amply clear come out in favour of the above arguments, in The Queen (on the application of William Ellis McLennan and Medway Council Ken Kennedy [2019] EWHC 1738 (Admin) which concerned an application for development permission which, if granted, would have led to the objecting neighbour’s photovoltaic panels’ considerable loss in efficiency. It probably comes as no surprise that the English planners like their Maltese counterparts, considered the matter to be a private interest, preferring to give weight to the fact that the application under consideration was similar to other approved proposals in the same street, but the Courts had other things to say and quashed the permit specifically stating that the effect of the proposal on the neighbour’s PV panels was a material consideration and the local planning authority must have regard to it. The English Administrative Court therefore found “an erroneous approach to materiality”.

It is submitted that this should be the correct way forward in Malta. Loss of solar power is a material planning consideration which should be given its due when the issue is raised; concurrently the Planning Authority should seek advice on whether, and to what extent, it can issue a planning permit which negatively impacts on an earlier permit.

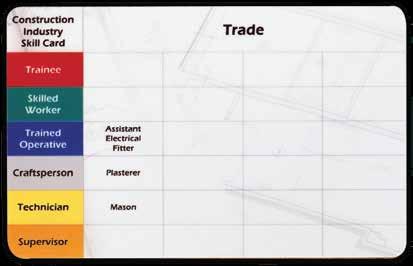

Top Build Seminar

Jade Boye

On Saturday, 20 September 2025, Malta witnessed a pivotal moment for its building and construction industry as Jade Bøye hosted Top Build.

The event brought together a rare mix of voices — government ministers, policy makers, regulators, architects, engineers, developers, tradesmen, project managers, and academics. For the first time, stakeholders from every level stood on the same platform to address the sector’s pressing challenges and map out a shared vision for the future.

At the heart of the discussion was a central truth: there is a widening gap between legislation and on-site realities. Project managers and contractors continue to struggle with outdated practices, while new regulations, though necessary, often feel far removed from the practicalities of day-to-day building. The result is an industry caught in transition — burdened by bureaucracy, yet desperate to modernise.

Speakers highlighted how tradesmen in particular are under increasing pressure. With legislation advancing

rapidly, many lack access to the continuous training needed to keep up. Without targeted education and upskilling, workers risk becoming demotivated or

construction methods, engineered materials, and

New Rules. Smarter Builds. Safer Futures. Sparks National Dialogue on Malta’s Construction Future

advanced technologies already available on the market. These include sustainable materials with stronger performance, healthier indoor qualities, and lower environmental impact; energy-efficient design tools;

and streetscapes must strike a careful balance: preserving the country’s rich heritage while embracing modern, greener architecture. Tall buildings, if designed thoughtfully with vertical greenery and solar glass façades, can both reduce land use and enhance urban aesthetics.

Top Build’s mission is clear: to bridge the gap between legislation and practice by creating a neutral platform where decision-makers and on-site experts can learn from each other. This seminar marked the first step in a series of engagements that will shape the future of Malta’s built environment.

As one participant concluded, “We cannot keep building with yesterday’s mindset for tomorrow’s Malta.” With Top Build driving the conversation, the industry now has the momentum to move from outdated methods to an innovative, sustainable future.

BIM Guidelines in Europe Cont’d – CEN/TS 18113:2024

Clarabel Zahra Versace

This article focuses on one of the European guideline documents written by the Technical Committee CEN/TC 442 “Building Information Modelling (BIM)”. CEN/TS 18113:2024 is a European technical specification that translates the EN ISO 19650 series into practical, Europe-facing guidance. It explains the concepts, roles, documents and workflows of the ISO 19650 (parts 1–5) standards and gives concrete examples and implementation advice such that owners, contractors and public authorities can make the standards operational

This document is intended as a supporting document to the ISO19650 series which aims to create a common understanding of these standards in Europe. The objectives of this guidance document are:

• To provide an appropriate and adaptable framework for Europe.

• To deliver a common and consistent interpretation of the standards across Europe.

Although this is a supporting document to ISO19650 standards, it can also be read as a standalone document. Very often industry stakeholders find standards abstract and ask,

‘How do we actually implement these clauses in a European project, with European contractual and regulatory contexts?’

CEN/TS 18113:2024 fills this gap by offering supporting text, worked examples and recommended approaches aligned to EN ISO 19650 parts 1-5, without changing their normative requirements. In short: it’s a bridging document — normative standards on one side, local practice and project delivery on the other.

Guidance on how to implement EN ISO 19650-series in Europe in particular parts 1,2,3,4, and 5.

What are the practical implications of this document for Construction Managers?

• Standardise procurement language:

By using the mappings in CEN/TS 18113 to tighten EIRs and appointment clauses, bidders will know exactly what to deliver and when. This reduces ambiguities at tender stage and eases verification at a later stage.

• Turn information requirements into measurable checklists:

The worked examples included in this document help translate the OIR (Organisation Information Requirements), PIR (Project Information Requirements), and AIR (asset information requirements) into exchange schedules and acceptance criteria which

can be very helpful to site managers and QA teams.

• Draft EIR/Exchange Plan using CEN/TS examples as a template.

• Assigning clear information roles (Appointing Party, Lead Appointed Party, Information Manager) and include them in contracts.

• Create a project information delivery schedule tied to acceptance criteria not just dates.

This document help the industry stakeholders in understanding the ISO19650 standards and implement it in projects in a common way across Europe.

Archaeologist Charlene Ader, Perit Charlene Jo Darmanin, Perit Jurgen Vassallo

Construction production in Malta has grown exponentially over the last two decades, with output quadrupling from 2000 to 2021 (Eurostat, 2022). This surge has brought increased excavation activities, such as for the construction of foundations and basements. In the rich heritage context of Malta, excavations frequently expose archaeological remains, often extending beyond the boundaries of currently recognised historical centres. In 2024 alone, development-led excavations uncovered notable discoveries: burials, military structures, and agricultural features in Gżira; sets of cart ruts and an air-raid shelter in Attard; another set of cart ruts and a catacomb in Żejtun; air-raid shelters in St Paul’s Bay; and classical cisterns in Qormi and Luqa (Superintendence of Cultural Heritage, 2024). The same year, the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage (SCH) received twelve thousand and nine (12,009) consultation requests on development applications (SCH, 2024), issuing Terms of Reference (TOR) for archaeological surveillance during excavation works for three hundred thirty-nine (339) of said applications (SCH, 2024). A total of one hundred forty-two (142) archaeological discoveries were recorded in the same

year, including fifteen (15) accidental finds (SCH, 2024). These discoveries enrich our understanding of the past, while offering opportunities for education and tourism. Moreover, these discoveries enhance the distinctiveness of the new development and encourage community recognition (European Archaeological Council, 2024).

The growing intersection between development and archaeology in Malta is evident, bringing both benefits and challenges. The two disciplines, however, could not be more diverse, resulting in various challenges for construction projects and archaeological preservation. Project timelines are a major challenge in excavations, particularly when archaeological investigation is required. In the case of archaeological discoveries, delays may also result from the redesign of the proposed development, for the integration of discoveries. This often brings unpredictable project costs, with the eventual treatment of archaeological discoveries being one of them (whether these are preserved in situ, reburied or integrated into the project). Historical research, pre-planning consultations with SCH and early archaeological investigations may

Development-Led Archaeology: Balancing Preservation & Development

be a mitigation measure in sensitive areas, supporting well-informed decisions on schedules and budgets.

While development can threaten archaeological heritage, a shift in mindset reveals opportunities for integration, with the potential to create a balance that supports both modern infrastructure needs and preservation. Increasingly, multidisciplinary dialogue between the construction and heritage sectors has produced developments that celebrate the inherent value of discoveries through development-led archaeological exercises. Locally, historic remains have been integrated into hotel amenities, schools, and public squares. Internationally, significant discoveries have become part of metro stations, museums, and commercial centres. In this manner, the public has been granted their right to access archaeological remains that contribute to their communal identity. What may initially appear as a burden becomes an added value to a new development. Weaving archaeology into contemporary projects may be a daunting task, but it offers the opportunity to create a built environment that honours the past, serves the present, and inspires the future.

Eurostat (2022). Key Figures of European Business. European Union. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/15216629/15230677/K S-06-22-075-EN-N.pdf/930f2188-48cb-ef84-678e-e6f96682 b072?t=1672841155329

European Archaeological Council (2024): The Benefits of Development-Led Archaeology in Europe and Beyond (EAC Guidelines 5). European Archaeological Council. Available at: https://zenodo.org/records/10696865

Superintendence of Cultural Heritage (2024), Superintendence of Cultural Heritage Annual Report for 2024, Valletta: Superintendence of Cultural Heritage: Available at: https://schmalta.mt/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/SCH-Annual-R eport-2024.pdf

Building with Purpose:

Turning Insights into Impact: Why Good Governance Matters in Construction

Gabriella Borda

In the world of construction, bricks and mortar are only part of the story. Behind every structure lies a web of decisions, trade-offs, and responsibilities that ultimately shape the quality, safety, and sustainability of the built environment. This is where good governance comes in, not as a theoretical concept reserved for boardrooms, but as a practical compass that guides teams, companies, and entire industries toward better outcomes.

Good governance in construction is about leadership. It is about setting a clear vision that aligns commercial objectives with societal needs and environmental realities. Strong leaders establish the culture that permeates project teams: a culture where transparency, accountability, and integrity are not negotiable. In this environment, site managers, architects, engineers, and subcontractors understand their role in delivering not just a building, but a lasting contribution to the community.

The stakes are high. Buildings today account for nearly 40% of global carbon emissions. Construction is also one of the sectors most vulnerable to economic shocks, regulatory change, and reputational risk. Without effective governance, projects can falter, leading to cost overruns, safety incidents, and missed opportunities to innovate. With good governance, however, risks are managed, opportunities are seized, and sustainable value is created.

At the company level, governance translates into clear processes for decision-making, procurement, and risk management. It ensures that supply chains meet ethical and environmental standards, that financial structures are sound, and that teams are empowered to speak up when issues arise. It is the invisible scaffolding that supports the visible work on site.

But governance also speaks to the end product. A sustainable building is not the outcome of technical excellence alone, it reflects the strength of the decisions taken along the way. From material choices to stakeholder engagement, from design reviews to safety protocols, every stage is influenced by the quality of governance. Well-governed projects deliver buildings that stand the test of time, both physically and socially.

Looking ahead, governance will only grow in importance. As climate commitments tighten, as investors demand transparency, and as communities

expect higher standards, construction companies will need to demonstrate not just what they build, but how they build it. Leadership in governance will distinguish those who adapt and thrive from those who struggle to keep pace.

In this edition, we explore governance as the backbone of sustainable construction. We look at how leadership can set the tone, how companies can integrate risk and opportunity into their strategies, and how governance ultimately shapes the buildings that define our skylines.

The message is clear: governance is not bureaucracy; it is the key to building with purpose. And in construction, purpose is what transforms projects into legacies.

Governance and the added value of sustainability

Good governance is the bridge that turns sustainability from aspiration into action. It ensures that environmental and social goals are not just side notes but central to how projects are designed, procured, and delivered. By embedding accountability in planning and monitoring, governance reduces waste, improves resource efficiency, and lowers emissions throughout the construction process. It also creates the clarity and transparency needed for innovation, allowing new methods to be adopted responsibly.

At the same time, governance strengthens resilience. It compels teams to anticipate climate, regulatory, and social risks, ensuring buildings remain valuable and functional for decades to come. Perhaps most importantly, it builds trust. Transparent reporting and clear leadership reassure clients, investors, and communities that sustainability commitments are genuine, not just promises on paper. In this way, governance adds lasting value, delivering buildings that are not only completed, but truly resilient.

Drivers for good governance

When we speak about governance in construction, it is tempting to place the end user at the center of change. After all, the ultimate purpose of a building is to serve those who inhabit and use it. Yet the reality is that end users rarely have the power to influence the governance frameworks that determine how projects are conceived, financed, and delivered. Their preferences for greener, safer, or smarter buildings may

shape market demand, but on their own, they are insufficient to drive the systemic change required. The real drivers of good governance sit higher in the value chain. Authorities and policymakers set the regulatory frameworks that establish standards of transparency, accountability, and sustainability. Financial institutions and investors act as gatekeepers of capital, requiring governance structures that protect value, reduce risk, and deliver long-term resilience. Together, these forces create the enabling environment where governance becomes non-negotiable.

This does not mean that consumer preferences are irrelevant. On the contrary, they can amplify pressure on industry and regulators alike, especially as awareness of climate and social impacts grows. But consumer demand functions best in collaboration with regulatory and financial drivers. It is when these elements align, policy mandates, financial expectations, and user preferences, that governance becomes embedded across the construction sector, ensuring that the end product truly reflects the values of sustainability and resilience.

Bridging the Green Premium: Governance and Finance for Sustainable Buildings

Good governance in finance is as critical as governance in construction. Nowhere is this clearer than in the affordability gap faced by end users who aspire to live or work in sustainable buildings.

A green-certified home, for instance, may cost 15% more upfront than a conventional one. While this premium can often be recovered within a few years through lower utility bills, reduced maintenance, and healthier indoor environments, the reality is that many families and businesses cannot afford the extra cost at the time of purchase. The promise of long-term savings does little to ease the immediate burden of higher down payments or loan sizes.

Compounding this is the principal–agent barrier: developers are asked to invest in sustainability features that they may never recover, since it is the eventual owner or tenant who benefits from lower running costs. Without targeted mechanisms, developers have little incentive to take on the risk of higher upfront

investment, even when the long-term case is clear. This is where sustainable finance can change the equation. Green mortgages with preferential rates, higher loan-to-value ratios that reduce the upfront cash requirement, or public–private incentive schemes can all help bridge the gap. Purpose-built financial products can share the cost and distribute the value more fairly across the chain of actors, developers, investors, and end users.

Without such mechanisms, green buildings risk remaining a premium product rather than the new standard. With them and with governance to ensure transparency, accountability, and alignment, finance becomes a true enabler of sustainability, unlocking access to healthier, more resilient buildings for all.

Aligning Policy, Finance and Industry

“Good governance is the invisible framework that transforms construction projects into sustainable, resilient, and trusted outcomes. It ensures that leadership decisions cascade into practices that reduce risk, unlock innovation, and add value for generations to come. Yet governance is not the responsibility of companies alone. The alignment of policy, finance, and industry practice is what ultimately determines whether sustainable construction becomes the norm or remains a niche.

Here, regulators play a decisive role. In the built environment, regulators set the standards, from building codes to energy efficiency requirements, that define the minimum thresholds for safety, quality, and sustainability. In financial services, regulators guide capital flows by shaping disclosure rules, green taxonomies, and prudential requirements that determine how markets price risk and reward sustainability. When both sectors move in tandem, governance becomes systemic: developers have clearer incentives, financiers have greater confidence, and end users gain better access to sustainable buildings.

The message is clear. End users alone cannot drive this change, but in collaboration with policymakers, regulators, and financial institutions, the construction industry can close the gap between aspiration and reality. By embedding governance into both how we build and how we finance, we can ensure that the built environment of tomorrow is not only delivered, but delivered with resilience, responsibility, and purpose.

Succession:

Turning Insights into Impact:

Robert Cassar Founder & Executive Recruiter, Heroix

Succession has been popularised by the acclaimed HBO drama series of the same name, yet for Malta’s entrepreneurs, it is a real life concern. Many of the companies that have transformed our economy were established in the closing decades of the last century, and their founders now face the challenge of passing on the baton. The stakes are high: some 75% of Malta’s registered businesses are family-owned, and these enterprises employ roughly 40% of the workforce. Despite this prevalence, only 30% of family businesses transition to the second generation and about 13% to the third, a pattern first documented by John L. Ward and often summarised as ‘30/13/3’.

Why Succession Matters Now

Demographic And Labour Market Pressures

Malta’s population trends place additional pressure on succession. The Central Bank of Malta projects that the native population will decline by about 14% by 2050, and that foreign nationals will account for around 46% of the working-age population by 2035. All of this is further exacerbated by a tight labour market in which

local family businesses compete with multinationals for talent.

Tight Labour Market And Governance Challenges

Professional executives value clear structures, visible progression and stable governance. Making these explicit and delegating authority with transparent processes supports both hiring and retention. On the other hand, when delegation is unclear, lines of authority blur and favouritism may be perceived. Family preference, if unmanaged, can end up sidelining capable people and weaken accountability, which can affect decision making and limit diversity. Therefore, clear role definitions, merit based selection and independent oversight help to prevent this and proactively build trust.

Family enterprises are also advised to seek external perspectives by engaging with peer networks, participating in industry associations and drawing on trusted advisors; such exposure helps avoid becoming too insular, supports cross-pollination of ideas and keeps the business connected to evolving market trends. Transparent governance and a willingness to embrace external ideas are therefore essential for attracting and retaining top talent.

Understanding The Scale

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) dominate Malta’s economy. European Commission figures for Malta for 2025 show SMEs make up 99.8% of enterprises, employ over 75% of people, and generate nearly 73% of value added; out of these SMEs, nearly 94% of companies are actually micro, with fewer than 10 staff. The building and infrastructure sector alone comprises roughly 5,750 registered businesses employing an estimated 24,000 people. Succession

From Founders to Futures, Building Malta’s Next Generation of Leaders

(this article is the first of a two-part series)

planning is therefore an economy wide imperative, equally so in construction.

Options For Passing The Baton

Handing Over To Family Members

Entrusting the business to children or other relatives can preserve heritage and maintain long term relationships. However, recent research points to a perception gap between generations: current leaders often believe successors are more involved in decision making than the younger generation reports. Using accredited tools such as Hogan assessments, together with numerical and critical reasoning tests, helps evaluate whether prospective successors have the required competencies and motivations. Training and mentoring programmes can prepare the next generation to take on responsibility gradually.

Advantages: continuity of family values, stronger bonds with long-standing clients and employees. Disadvantages: risk of perceived nepotism and limited external perspective.

Appointing An Interim Leader

Some boards choose to appoint an interim chief executive while the next generation gains experience. Studies note that, increasingly, young family members are working outside the family business before returning. A caretaker leader can maintain stability and mentor successors during such a period. Yet this approach requires clear time frames and open communication to avoid prolonged uncertainty.

Advantages: buys time for successors to develop; brings professional practices; mentors the next generation; preserves family ownership.

MALTA CHAMBER OF CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT

BENEFITS

Instil professionalism, innovation and quality - Continuing Professional Development Opportunies - Affiliation with the Chartered Insitute of Building Preparation for the Cosntruction Project Manager Warrant An active community willing to improve the industry Built around the busy schedules of professionals www.mccm.org.mt

Disadvantages: potential cultural mismatch; risk of stagnation if the interim phase drags on.

Recruiting An External Leader

Bringing in a non-family CEO or managing director can add sector expertise, new perspectives and impartiality. Success depends on clarity and support. Set a written mandate, decision rights and the reporting line. Agree twelve month priorities and KPIs. Pair the leader with an independent chair or senior non-executive as a sounding board. Use a family charter to define reserved matters and how the family engages. Plan structured onboarding and clear communication with staff, clients and banks.

Advantages: fresh perspective, faster change, wider talent pool, stronger governance signal. Disadvantages: cultural-fit and control concerns. Mitigate with clear expectations, conflict rules and 90and 180-day reviews.

Steps To Prepare

Start Early: Where time allows, develop a succession plan five to ten years ahead to support mentoring, training and gradual transfer.

Formalise Governance: Establish a board (ideally with one or more independent members). Boards remain male dominated, which raises the risk of groupthink and blind spots across customers, staff and markets, and can lead to discrimination, including within families. Widen searches and set clear goals so that qualified women and candidates from under represented groups are considered on merit; appointments should be skills based and evidence led, not tokenistic or made to signal superficial diversity. Adopt a family

END OF SECOND QUARTER NETWORKING EVENT

constitution that defines roles, ownership rights and dispute resolution. Malta’s Family Business Act (Cap. 565) encourages good governance and intergenerational transfer. Registration with the Family Business Office provides access to incentives, including Malta Enterprise support for succession advisory and mediation. Separately, inter vivos donations within the family of company shares or qualifying business property may attract reduced duty, subject to conditions and filing deadlines.

Assess Leadership Objectively: Use accredited psychometric tools together with numerical and critical reasoning tests to evaluate internal and external candidates. Combine these with structured interviews, 360 degree feedback and role simulations, then translate the findings into clear, measurable development plans.

Invest In Education And External Experience: Enrol future leaders in professional courses on family business governance and encourage them to work in other organisations to gain broader perspectives.

Leverage Expert Advisers: In our case, we work with a multidisciplinary team – independent experts each specialising in executive recruitment, mentoring, family succession, financial planning, grants and training. We coordinate with lawyers, accountants and training providers to develop a holistic plan, including access to government grants and educational programmes.

Communicate Transparently: Start early and share the succession plan with employees, clients and partners to build confidence and reduce rumours.

Run A Structured Executive Recruitment Process: Assess internal and external candidates, including family members, against the same criteria, and pass them through the same auditable process. Define the role and success criteria; issue a public call and run targeted outreach; apply blind screening; hold

structured interviews and case tasks; use accredited assessments; convene an independent panel and manage any conflicts; carry out reference and background checks; keep scored decision notes; conclude with a board resolution. This builds confidence for the board, leadership team, employees, external stakeholders and, above all, the selected person.

Final Thoughts

Succession must for sure not be about ego or maybe even in preserving a surname; it is about safeguarding livelihoods and ensuring a business’s longevity, and its contribution to Malta’s prosperity. Significant changes in demographics, labour-market constraints, and regulation mean the next decades will look very different from the previous ones, this goes for the construction sector as much as the Maltese economy in general. By combining structured governance, objective assessment and a collaborative team of experts, family-owned companies can navigate the handover successfully and ensure that the next generation has the skills and support to thrive well into the next three-quarters of the 21st century.

About Robert Cassar

Robert Cassar is the Founder of Heroix Recruitment & HRM (https://www.heroix.eu), DIER Agency Licence No. 00412-2025. He has 30 years’ management experience, including Head and CEO roles, and focuses on executive recruitment and mentoring. He is a visiting lecturer at Master’s level and an accredited practitioner of Hogan psychometric assessments. Robert holds an MBA from Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge; a Bachelor’s in Human Resources Management from Global College Malta; and a Higher Diploma in Business Administrationfrom the University of Malta.

Contact: robert.cassar@heroix.eu LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com /in/robertcassar/ Further contact details via the QR code.

Two-Way Slabs in Masonry Structures

Milan Zdravkovic

In building construction, especially for low- to mid-rise structures, masonry walls paired with reinforced concrete slabs create practical and economical solutions. Two-way slabs, which span in both directions, are effective for square or nearly square bays with support on all sides—seen often in residential, school, and small commercial buildings.

What Is a Two-Way Slab?

Unlike one-way slabs that bend in a single direction, two-way slabs experience bending in both axes, letting them cover larger areas with less depth and more balanced reinforcement. In masonry buildings, these slabs usually rest on load-bearing walls or on beams integrated into the wall system.

Structural Behaviour in Masonry Systems

Masonry walls offer vertical support for the slab, which transfers loads in both directions. These continuous walls provide ideal bearing conditions, but reinforcement anchorage, wall stability, and temperature movement must be considered in design.

Cost-Effective Spans and Depths

Two-way slabs are most economical for spans between 3 and 6 metres (10–20 feet). In this range, slabs can remain thin and reinforcement efficient. Recommended thickness is about Span/30 to Span/35, so a 5-metre span would call for 150–170 mm (6–7 inches) of thickness. Beyond 6 metres, slabs require more depth and steel, making them less efficient.

Advantages

• Efficient Load Distribution: Loads are shared in both directions, lowering peak moments and reducing required reinforcement.

• Material Savings: Better load sharing allows for

thinner slabs and less steel.

• Design Flexibility: No need for beams in one direction provides cleaner ceilings and design freedom.

• Crack Control: Dual-direction reinforcement controls shrinkage and thermal cracks.

• Natural Compatibility: Masonry walls naturally provide the four-side support that two-way slabs need.

Disadvantages

• Complex Design: Biaxial bending requires more advanced analysis than one-way slabs.

• Construction Precision: Slab must bear evenly on all sides; uneven walls may cause cracks or imbalances.

• Formwork Costs: Flat, beamless construction needs careful formwork and sometimes extra support during curing.

• Thermal Expansion: Different expansion rates for concrete and masonry can cause interface cracks if not addressed.

Reinforcement Detailing

Two-way slabs require reinforcement in both directions. Bottom steel handles positive moments at the centre, while top steel covers negative moments near supports. Steel is arranged in a grid, with extra bars near openings or stress areas. Care is needed for proper anchorage, corrosion protection, and to avoid congestion.

Practical Applications

Common uses include multi-storey residences, schools, warehouses, and low-rise offices. These slabs are ideal for repetitive layouts where formwork can be reused.

While design and execution require care—especially regarding wall movement and reinforcement details—the benefits in terms of material savings, performance, and integration with masonry systems make two-way slabs a valuable choice. Proper design and site coordination are key to their success.

A Net Zero Economy

A Building Industry that needs an Uplifted set of Skills

Part 14

David Xuereb

Younger and older workers will both be needed to transition Malta’s built environment into a low-carbon, resilient sector — but they’ll need different entry points, different training pathways, and shared hands-on experience. This time, I take the liberty to suggest concrete green skills Malta should prioritise, tangible on-the-ground examples, and practical international best practices that can be adapted locally.

Why this matters now

The EU’s “Renovation Wave” targets a dramatic scaling up of energy renovations across the bloc — roughly 35 million buildings by 2030 — which creates urgent demand for new trades, upskilling and quality assurance across the construction chain. Malta will need a trained workforce to capture its share of the work, access incentives, and avoid poor retrofits that lock in future costs.

Core green skills Malta needs

Low-energy retrofit trades (insulation, airtightness, windows)

What to learn: external and internal insulation installation, detailing to avoid thermal bridges, airtightness testing, moisture risk management. Tangible example: a local builder trained to upgrade party walls, install external insulation and perform airtightness tests can convert a typical terraced Maltese apartment into a high-performing unit while avoiding condensation damage. Best practice: EnerPHit/Passivhaus retrofit protocols emphasise airtightness testing, staged quality checks and accredited installers—models that Maltese training centres can adopt.

Heat-pump and HVAC installers / technicians

What to learn: sizing and installing air-to-water and ground-source heat pumps, system commissioning, controls integration and routine maintenance. EU demand projections show a steep need for heat-pump installers and many existing technicians will require reskilling. Plumbing/electrical apprenticeships with a heat-pump module produce installers who can both retrofit and service systems. Coordinated installer certification and consumer guidance will help build trust and demand.

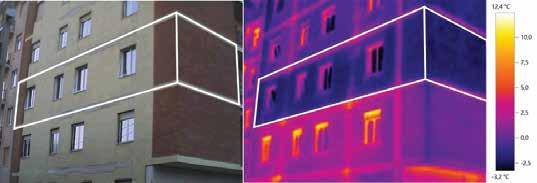

Building performance diagnostics & energy auditing

What to learn: energy auditing, thermography, data logging, simple modelling, and post-works performance verification. Tangible role: an independent auditor for a social-housing retrofit who certifies energy savings and ensures grant conditions are met. Best practice: EU projects fund diagnostic toolkits and curricula that Malta can import.

Digital & design skills: BIM, retrofit sequencing, materials traceability

What to learn: basic BIM for small projects, digital

record keeping for materials and embodied-carbon estimates, and planning modular retrofit sequences. Any architect-led firm using BIM to coordinate scaffolding, insulation, installation of facade system and apertures and PV installation to minimize disruption and cost overruns.

Circular-economy and sustainable materials handling

What to learn: deconstruction rather than demolition, materials reuse, low-carbon mortars and breathable systems suitable to building materials used in our country. On the ground: training masons in compatible lime mortars and reuse practices to protect heritage buildings.

show how to knit formal FET provision to industry needs. Malta’s Jobsplus and VET providers can scale modular courses to match local demand.

2. Short upskill bootcamps and recognition of prior learning for experienced tradespeople:

Offer intense 1–4 week heat-pump, airtightness or energy-auditing courses with practical assessment and certification so experienced workers can transition without losing income.

3. Mobile training units and demo-projects:

Use live retrofit pilot projects (social housing, public buildings) as teaching sites — hands-on experience accelerates competence and builds local case studies for homeowners. The EuroPHit and deep-retrofit pilots across Europe demonstrate the power of pilot projects to transfer skills and validate techniques.

Practical Pathways on how to train players of all ages working in the Industry

1. Apprenticeships + stacked micro-credentials for young entrants:

Combine classroom modules (building physics, sustainable materials) with on-site mentor placements. Ireland’s and other national “Green Skills” strategies

4. Certification + quality assurance:

Link training to a national register of certified installers and mandatory commissioning checks for rebate eligibility. This prevents poor workmanship and builds public confidence.

Policy levers and immediate actions for Malta

It is recommended to fund a small number of high-visibility retrofit pilots (social housing, schools and public buildings) with embedded training quotas. It is also suggested to launch modular heat-pump and airtightness credentials with Jobsplus and industry partners, recognizing prior skills for fast reskilling. Malta should also create a national apprenticeship uplift that includes digital (BIM) and sustainability units so new entrants have both craft and green competencies.

Conclusion

Transforming Malta’s building and real estate sector is as much a skills challenge as a technical one. By combining apprenticeships for young people, fast-track reskilling for experienced trades, demonstration projects, and accredited certification linked to incentives, Malta can build a workforce capable of high-quality, low-carbon retrofit and new build that respects local heritage and climate realities.

Art in Interiors is not an Afterthought

Vera Sant Fournier

In well-considered interiors it is a decisive, emotive layer that completes the architecture, anchors daily life and gives a space it’s voice. For construction managers, developers and design professionals in Malta, treating artwork as an integral element of the build — rather than as decorative icing — raises the quality, longevity and cultural value of a project.

In the best interiors it reads as a natural extension of the architecture, a considered response to light, proportion and program. In Malta, where pale limestone and Mediterranean light are themselves part of a room’s palette, artwork should feel inevitable: the quiet, human story that completes a space rather than an ornament bolted on at the end.

When selecting a piece, begin with intent. Ask what the work will do within the room — to ground a double-height entrance, to animate a dining wall, to offer a quiet companion above a bedside console. The answers need not be prescriptive, but they should inform scale and material. A large wall will ask for a confident, generous work; a grouping of smaller pieces

composition rather than an accidental scatter. Colour can either echo the scheme, reinforcing tonal subtleties, or provide a deliberate counterpoint that enlivens a neutral interior. Equally important is the artwork’s material presence: oil and acrylics withstand everyday life, watercolours and pastels demand glazing and careful siting, and textiles or mixed media bring tactility — as well as particular conservation needs.

Placement is an act of architecture. The eye finds a room’s rhythm through sightlines and approach; artwork should sit within that rhythm. A painting’s visual centre often aligns around standing eye height, but this is a guideline rather than a rule — seating walls invite a slightly lower hang, and rooms with lofty ceilings can accommodate higher, more theatrical compositions. Above furniture, the relationship between piece and furnishing must feel intentional: the work should form a dialogue with the object beneath it, neither swallowing nor shrinking from it. Consider how people move through the space and where they pause; a well-placed work rewards a moment of stillness, revealed at a natural stopping point rather than in a hurried glance.

Commissioning living artists shifts the conversation from acquisition to authorship. A commission gives the space something it cannot otherwise have: a work conceived to converse with its specific setting, the client’s brief and the project’s materiality. There is a

practical economy to commissioning locally too — shorter lead times, lower transport risk, and a constructive relationship with the local creative community. For Maltese projects this also means embedding narratives specific to place. The process itself benefits from clarity: a concise brief with elevations, palette intentions and scale expectations; an honest budget that recognises the artist’s time and materials; and a contract that sets out scope, payments, delivery and rights. Beyond the paperwork, commissioning is an ethical act. It sustains practice, nurtures cultural life and leaves a legacy that traces back to an individual maker rather than an anonymous supply chain.

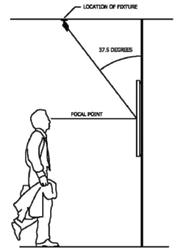

Light is where art truly comes alive. The same piece can appear wildly different under changing illumination; a painting that sings under a soft, warm wash of light can become flat or washed out under a harsher spectrum. Choose light sources with a high Colour Rendering Index so pigments retain their fidelity, and select colour temperatures that harmonise with the interior — warmer tones for traditional palettes, neutral for contemporary schemes. Lux levels should respond to the material’s sensitivity: works on paper and delicate textiles benefit from lower light exposure, while robust oils tolerate higher intensities. Pay attention to beam angles and glare, and design lighting so it reveals texture without creating distracting reflections. Integrate lighting early in the project’s engineering stage so wiring, dimming and maintenance access are resolved before finishes are signed off.

A frame does more than contain; it clarifies intention. A minimal, floating frame can allow a contemporary canvas to breathe; a hand-carved moulding can add dignity to a classical composition. But framing is also a conservation decision. Use archival materials, spacers where glazing is present, and museum-grade glazing for fragile works. These choices protect investment

and ensure the work will age gracefully within its environment.

Practical responsibilities accompany good taste. Document provenance and condition at acquisition, obtain certificates of authenticity where possible, and keep a clear record of any conservation work. Insurance should cover transit, installation and on-site risks; for projects in shared or commercial buildings, contractual clarity on liability is essential. Be mindful of legalities too: contracts should address ownership transfer, reproduction rights and moral rights retained by artists. When sourcing internationally, factor in customs, VAT and specialist freight handling — art is both fragile and valuable, and its logistics deserve specialist attention.

A seasoned interior designer acts as the project’s cultural translator: vetting galleries, brokering relationships with artists, overseeing framing and specifying lighting that respects both art and architecture. For construction managers and developers, early collaboration with a designer saves time and cost, ensuring structural provisions for heavy works, coordinated lighting runs and a coherent handover. Engaging a designer from concept stage moves art from an afterthought to an integral layer of the design strategy.

Art, when selected and sited with intention, elevates a room into something memorable — an enduring conversation between material, maker and occupant.

Chadwick Lakes Ecological Rehabilitation: Challenges Faced by Construction Companies

Noel Zahra Diacono

The construction industry, often described as the backbone of economic growth, plays a critical role in shaping our built environment. From high-rise to vital infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and hospitals, the industry’s output is visible in almost every facet of daily life. Yet, beneath the impressive steel frameworks and polished architectural designs lies a world fraught with complex challenges. These obstacles, if not addressed effectively, can derail projects, cause financial strain, and even damage reputations.

According to Abass and Al-Mharmah (2000), one of the most significant hurdles faced by construction organisations during the life cycle of a project is the challenge of coordinating and communicating effectively with the many stakeholders involved. These stakeholders include clients, architects, engineers, subcontractors, and suppliers—each with their own priorities, expectations, and working styles. Miscommunication, or worse, a complete breakdown in dialogue, can lead to misunderstandings, costly mistakes, and delays.

Recognising this, the Project Management Institute (2008) stresses the importance of establishing a robust communication system that fosters openness and transparency. By ensuring that every party understands not just their role, but also the project’s broader objectives, teams can work more cohesively and reduce the risk of conflicts or missed opportunities.

Balancing Time, Budget, and Client Satisfaction - While delivering a project on time and within budget has long been seen as a measure of success, Iman and Siew (2008) argue that these metrics alone are not enough. If a project meets its cost and time targets but fails to meet the client’s expectations, it is ultimately considered a failure. One common reason for this is the lack of active client involvement throughout the project. Without regular input, the final product may diverge from what the client truly envisioned.

This sentiment echoes earlier research. Abdullah et al. (2006), as cited in Frefer et al. (2018), noted that as early as the mid-20th century, the link between successful project management and the “triple constraint” of time, cost, and quality was already being recognised. Wit (1988) further reinforced this connection, highlighting that these three factors must be balanced carefully to achieve project success.

However, as Professor Bassam A. Hussein (2012) points out, even when success criteria are identified, failure to actively apply them throughout the project can lead to

problems. Frequent changes in project requirements or a lack of clarity in success measures can result in poor execution, client disappointment, and significant financial loss.

The Pressure of Speed and Accuracy - Time is money in construction—sometimes quite literally. Love (2002) observed that clients increasingly demand faster project delivery, both in terms of design and construction phases. While speed can be a competitive advantage, it comes with its own risks. Rushed work increases the likelihood of oversights or errors in documentation, which often leads to rework. Such rework not only delays the project but also inflates costs, undermining the very efficiency that faster delivery was meant to achieve.

The Skilled Labour Shortage: A Global and Local Concern - The construction industry is one of the largest sectors of the global economy (Ahmed et al., 2008), and skilled labour is one of its most vital assets. Yet, many countries are facing a severe shortage of qualified workers, and Malta is no exception.

An extract from a typical Finishes’ BOQ

Oseghale and Ata (2018) highlight the critical role of skilled workers in driving a country’s economic development. However, Healy et al. (2011) describe the shortage of such workers as a complex phenomenon that can significantly reduce the efficiency of construction projects. Windapo (2016) adds that a lack of “skilled manpower” is a major contributor to project failures, with the issue often stemming not from a complete absence of talent, but from a shortage of workers trained in the latest techniques and technologies.

Akomah et al. (2020) attribute the shortage to multiple factors: an ageing workforce, insufficient training programmes, an increasing number of simultaneous projects, and a waning interest among younger generations in pursuing careers in construction. This last point is particularly concerning, as it raises questions about the long-term sustainability of the industry’s talent pipeline.

Bennett and McGuinness (2009) suggest that the industry’s reputation is partly to blame. With its physically demanding work, exposure to hazards, and association with accidents, construction is often perceived as a less attractive career choice. Such perceptions discourage potential recruits, exacerbating the labour shortage.

The Maltese Context: Rising Vacancies and Growing

Pressures - In Malta, the shortage of skilled labour in construction has become increasingly pronounced in recent years. The problem affects not only current projects but also future developments, as contractors struggle to find the expertise required to meet rising demand.

Data from Jobsplus, Malta’s Public Employment Services, shows a significant increase in job openings in the construction sector between 2013 and 2022. Vacancies jumped from 922 in 2013 to 2,588 in 2018, before easing slightly to 1,915 in 2022. The rise in managerial roles is even more striking: from just 5 vacancies in 2013 to 28 in both 2021 and 2022 (Jobsplus, 2022). This growth reflects the industry’s expanding scope and the increasing need for experienced leaders capable of overseeing complex projects.

Figure 1:Vacancies notified to Jobsplus (Jobsplus, 2022).

However, the challenge is that many of these positions remain unfilled for extended periods, slowing project progress and putting added strain on existing staff. For an industry already under pressure to deliver high-quality work quickly and cost-effectively, such shortages can have cascading effects on timelines, budgets, and client relationships.

The Cost of Delay - The consequences of these challenges are extensive. Poor communication and coordination can result in design errors, supply delays, and contractual disputes. Insufficient client engagement risks delivering a product that fails to meet expectations, potentially leading to costly modifications or even litigation. Labour shortages can slow progress, reduce productivity, and increase reliance on less experienced or inadequately trained workers—further impacting quality and safety.

Over time, these issues can damage the reputation of construction firms, making it harder to secure new contracts and retain skilled employees. In a competitive

market, even a single high-profile failure can have lasting repercussions.

Turning Challenges into Opportunities - While the obstacles are formidable, they are not insurmountable. Solutions often lie in proactive management, strategic investment, and a willingness to adapt to changing conditions.

Strengthening Communication Systems: Investing in digital collaboration tools and regular stakeholder meetings can help keep everyone aligned. Open communication not only prevents misunderstandings but also fosters trust among team members.

Enhancing Client Engagement: Encouraging clients to be actively involved throughout the project ensures their needs are met and reduces the risk of costly late-stage changes.

Investing in Skills Development: Establishing partnerships with vocational institutions, offering apprenticeships, and providing ongoing training can help address the skills gap. By promoting career pathways within the industry, companies can also attract younger workers.

Improving Industry Image: Highlighting the innovation, sustainability, and problem-solving aspects of construction can help reshape public perceptions and make the field more appealing to new entrants.

Leveraging Technology: Adopting tools such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) and advanced project management software can increase efficiency, reduce errors, and make the industry more attractive to tech-savvy professionals.

A Critical Moment for the Industry - The construction sector is at a crossroads. As demand for infrastructure and development grows, so too does the need to address the underlying challenges that threaten project success. Malta’s situation mirrors global trends, but it also offers an opportunity for the country to take a proactive stance. By investing in communication, training, and technology, and by improving the industry’s image, stakeholders can create a stronger, more resilient construction sector capable of meeting the challenges of the future.

In the end, the true measure of success in construction is not just in meeting deadlines or staying within budget—it is in delivering projects that meet the highest standards of quality, safety, and client satisfaction. Achieving this requires not only skill and dedication but also a willingness to confront and overcome the obstacles that stand in the way.

The Main Causes of Disputes in Construction Contracts

Mohamed Elaida MCIOB

What is a Dispute

The construction industry is one of the most dynamic and vital sectors of any economy. It creates infrastructure, shapes cities, and provides livelihoods for millions. Yet, behind the impressive iconic and landmark projects lies an undeniable reality: construction is also one of the most dispute-prone industries. Projects often involve numerous stakeholders, large sums of money, tight deadlines, and complex technical requirements. This mix makes disagreements almost inevitable.

A dispute in a construction contract arises when parties disagree on the interpretation, performance, and/or obligations under the agreement. It typically involves issues such as misinterpretation of contract clauses: payment, delays, variations, and/or defects. When negotiation fails, the disagreement escalates into a formal dispute requiring a form of resolution. The process of the latter is usually defined under the contract.

“Time

is money”;

“Construction

contracts are fertile grounds for disputes”;

“Claims are not disputes, but disputes are often claims gone wrong.”;

“Most construction disputes arise not from what the contract says, but from what it fails to say.”

The above represents essentially a collection of sayings, proverbs, and industry wisdom that capture the nature of disputes in construction projects. They are not strict legal principles but rather widely acknowledged truths in the construction law and contract management community.

Disputes, if not well managed, can derail projects, inflate costs, strain relationships, damage reputation and even lead to lengthy legal battles. To avoid these pitfalls, it is essential to understand the main causes of disputes. While every conflict has unique elements, most disputes in construction stem from five core areas: contractual issues, management and communication problems, technical challenges, time-related pressures, and external factors.

The Main Causes of Disputes in the Construction Industry

1. Contractual Related Issues

Contracts should provide clarity, allocate risks fairly, and support smooth project delivery, yet they often spark disputes. Ambiguity is a key cause: vague or conflicting clauses allow differing interpretations, such as unclear scope of work or responsibilities, leading to claims for extra payment. Variation orders are another trigger, since projects inevitably change; disagreements arise over validity, costs, or time impacts. Payment issues remain persistent, with late payments, underpayment, or disputes on valuation causing tension between contractors and clients. Ultimately, poor drafting, unclear terms, and ineffective contract administration turn routine project challenges into disputes that disrupt delivery.

2. Management and Communication Problems

Even with a sound contract, poor management and weak communication frequently cause disputes. Construction projects rely on collaboration among clients, contractors, consultants, engineers, and subcontractors. Any breakdown in coordination can lead to misunderstandings.