maine farms

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2022

maine farms

5 field

Snippets from the farming landscape

7 future

Here Comes the Sun

KATE OLSON

16 business

The People who Feed You VIRGINIA WRIGHT

25 food

Capturing Convenience KATE COUGH

31 people

Yes, we can do that and we can do more

MICHELE CHRISTLE

40 land

Farming Begins Again: New Roots Cooperative Farm

DANI WALCZAK

45 recipe

Harvest Time Borscht

LOUANNA PERKINS

editor Ellen Sabina

design

Might & Main

writing

Michele Christle

Kate Cough

Amy Fisher

Kate Olson

Louanna Perkins

Dani Walczak

Virginia Wright

photography

Zack Bowen

Molly Haley

Kelsey Kobick

Ian Maclellan

Tara Rice

Greta Rybus

publisher

Maine Farmland Trust

97 Main Street, Belfast, Maine 04915 (207) 338-6575 | mainefarmlandtrust.org info@mainefarmlandtrust.org

Printed on 80# Finch Opaque Bright

White Smooth by J.S. McCarthy Printers, Augusta, Maine

All material © 2022 Maine Farmland Trust

The Maine Farms journal is a publication of Maine Farmland Trust, a statewide nonprofit that protects farmland, supports farmers and advances the future of farming.

Where We Are Now

A note from Maine Farmland Trust’s President & CEO, Amy Fisher

I left Maine shortly after college, missing Maine Farmland Trust’s rise to prominence in the state alongside the local food movement. So it was only in 2021 when I came across the job posting for MFT’s CEO and President that I looked deeply at MFT’s mission for the first time.

The first two elements of MFT’s mission seemed fairly straightforward: “to protect farmland, support farmers.” But the third element, to “advance the future of farming,” really caught my eye. There’s nothing that can capture my imagination like a good challenge, and the challenges that we face in food, farming, conservation, energy, and equity are immense. A future-oriented mission like MFT’s is an invitation to creativity, visioning, flexibility, and boldness in action, and upon seeing this potential, I was sold. I crossed my fingers and hoped that I could at least get a first-round conversation. As I reflect on my first year at MFT, what I see is that the landscape of farming in Maine is abundant and mutli-faceted. It’s new farmers wanting to farm here because they see Maine’s resilience in the face of climate change; it’s people who choose to live in Maine simply to be closer to the food they want to eat and the farmers that produce it; it’s a

sophisticated local market with customers willing to pay for value-added products and prioritize the local economy; it’s thriving agricultural hubs that a lay person might pass through and refer to as “the middle of nowhere” but that Mainers are savvy enough to treat as strategically critical to all of our futures; it’s nonprofits and entrepreneurs experimenting with how to help address food processing and distribution; and it’s a community of farmers, government officials, nonprofit agencies, businesses, and consumers that will join together to mobilize at an unprecedented scale when farming is threatened. This abundance was clear to me from the start of my tenure, and my time here has only reinforced my belief that all of the stars are aligning for Maine agriculture. Maine has all the right goals—from the New England Food Vision, to the Maine Won’t Wait climate plan, to the national 30 by 30 conservation

1 2

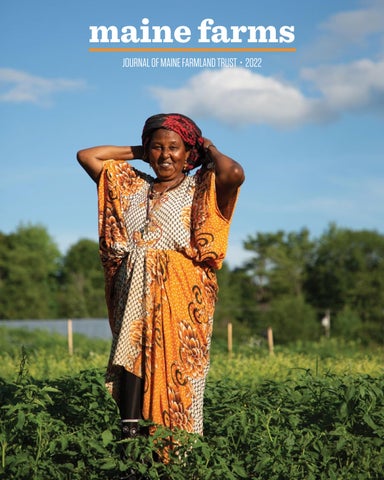

Cover Khadija Hilowle at New Roots Cooperative Farm in Lewiston, Maine.

plan, to the goal for Mainers to be eating 30 percent local foods by 2030. The community here collectively shares a vision of Maine as a place with more conserved agricultural acreage and more land in food production, more viable and thriving farms and farmers, more fresh and healthy local food serving more Mainers and New Englanders. The stories in this year’s journal reflect the fullness of Maine’s farming landscape, and the momentum, talent, and ingenuity we have here, all of which will serve us well as we meet the challenges ahead.

I was just four months into my role at MFT when the PFAS crisis hit Maine farms for the second time. This time, Maine was prepared to act. One reason I am excited to include in this journal the photo essay of remarkable women leaders in agriculture by Tara Rice and Michele Christle is to highlight some of the many leaders who collaborated to meet the challenge of PFAS for Maine farmers. These women—and many more, such as Nancy McBrady, Melanie Loyzim, Tricia Rouleau, Ryan Dennett, Heather Spalding, Ellen Griswold, Ellen Sabina, Sarah Woodbury, Sharon Treat, Diane Rowland and Ellen Mallory—are the people who mobilized and built PFAS emergency supports for farmers in real time, centering farmer voices and experiences. Representative Bill Pluecker was also a key leader in creating and championing legislation to respond to the needs of Maine farmers. I am grateful to work alongside all of these people. MFT has always taken a “forever” approach to our work, as the easements that are at the core of our farmland protection work are intended to safeguard agricultural land in perpetuity, so a challenge posed by “forever chemicals” was

one that we had to meet head on. We’ve taken the position from day one that PFAS will only last forever if we allow it to do so by failing to act and writing off this farmland and these farmers. That’s not acceptable, and based on the strength of MFT’s advocacy work on solar siting, solar was one of the first tools we looked to for solutions for farmers impacted by PFAS contamination.

We’re interested in seeing robust solar energy growth in Maine and we’re interested in that growth occurring in ways that protect Maine’s agricultural resources and provide economic relief and opportunity to PFAS-impacted farmers. As Kate Olson and Greta Rybus explore in Here Comes the Sun, it’s not a given that Maine will strike a balance between protecting our natural resources and pursuing renewable energy development in a way that sustains our thriving food system—it’s going to take thoughtful planning. In the coming year, solar siting will be a hot topic in the Maine legislature and in municipalities across the state. To support towns in navigating solar siting we released an advance chapter of our Municipal Planning Guide and as opportunities to influence solar siting arise we will be sure to let you know how you can get involved.

While I’m happy that joining the great resignation brought me back to Maine, the upheaval in the labor landscape across the country has compounded issues around labor on Maine farms. Many farmers are being squeezed by the tight labor market and rising prices and they are struggling to find help. Legislation has been moving for several years in Maine around farmworker pay and been vetoed— but, why? In The People Who Feed You , Virginia Wright and Kelsey Kobik found farmers who are getting the labor equation right for their farms, but keep in mind that these folks aren’t necessarily

representative. For every farm that has been able to make this equation work there are others who haven’t and those farmers have longer workdays, thinner margins, longer deferred maintenance, and may have trouble imagining a day when they can ever stop working.

Despite labor issues, rising prices, and numerous challenges, the pandemic also brought new opportunity by changing the way people eat.

Kate Clough and Ian MacLellan’s story, Capturing Convenience, examines the impact of and opportunities posed by how people changed their habits once they had to stay at home day after day preparing their own meals, through the stories of the Daybreak Growers Alliance and Good Shepherd Food Bank—two entities that used the pandemic to rethink supply chains and figure out how to get more local food out to more customers. This growth is exciting because one of the most commonly cited frustrations that I hear from farmers is the lack of processing infrastructure in the state. Similar to Good Shepherd’s response to the processing issue, this year MFT creatively applied our farmland protection skills to convert the former Coastal Blueberry Services building in Union into a processing hub in partnership with dozens of Midcoast farmers. The facility will include a shared chicken processing enterprise, a shared retail storefront where Mainers can purchase locally grown produce, and shared cold and dry storage for crops and meat.

The profile of New Roots Cooperative Farm by Dani Walczak and Molly Haley highlights another recent MFT project, and might be my favorite story in this issue. In 2015, this group of farmers worked with us to find a farm that would fit their needs. We used our Buy Protect Sell program, in which MFT

purchases a farm, protects it with an easement, and sells the farm to the farmers at a lower price. The farmers have had a lease-to-own agreement with MFT, and this year raised the remaining funds to purchase the farm outright. Because the land is protected with an easement, MFT will forever have a relationship with these farmers and the land. As we look towards making our farmland protection and other programming more equitable and more attuned to the diverse needs of farmers, we hope this project with New Roots will be the first of many that help facilitate more affordable farmland access for all farmers.

The stories in this issue represent many facets of agriculture in Maine, and help orient us to our future work. What we need in order to achieve our goals and cultivate this abundance are people who will come together to do the work, to fund the work, and to make sure that all of the organizations and institutions that Maine relies on to make these goals happen are strong and resilient. At the core, the future of farming in Maine is about people, it’s about you and me—the choices we make today with our farmland, our habits, our money, and our influence have longterm impacts. As farmer Bethany Allen reminds us in The People Who Feed You, “when you put people and their humanness at the fore, your possibilities are endless.”

Amy Fisher, President & CEO

ART

3 4

field snippets from the farming landscape

the

explore: fairs everywhere

by the numbers: top six challenges for young farmers nationally

We’re digging into the National Young Farmer’s Coalition’s new report, Building a Future with Farmers 2022. The report compiles the results of the Coalition’s recent survey of 10,000 young farmers throughout the country. Here’s what the survey revealed:

what to cook this winter:

A new second volume of the Maine Community Cookbook celebrates Maine home cooking and reminds readers that culinary traditions— soothing, quirky, unexpected, and fun—continue to connect us. Compiled of more than 200 recipes, crowdsourced from contributors in all 16 counties, the Maine Community Cookbook, Volume 2, provides a warm glimpse into kitchens across Vacationland. One of those kitchens belongs to LouAnna Perkins, who was MFT’s first executive director and spent many years on staff as lead counsel. LouAnna retired in 2021, but her legacy at MFT lives on in myriad ways, not the least of which is through her recipe for borscht, which you can find in the Maine Community Cookbook and in the back of this issue.

Maine has a long tradition of agricultural fairs, and each year 26 fairs crop up across the state to celebrate Maine agriculture. Though each fair has its own flair, all feature things like farm products, livestock and agricultural exhibits, and many host a wide-range of tastings, classes and demonstrations showcasing Maine products and livestock.

on our reading list: Foodtopia: Communities in Pursuit of Peace, Love & Homegrown Food by Margot Anne Kelley

In Foodtopia, Maine author Margot Anne Kelley tells the story of five back-tothe-land movements, beginning in the 1840s when tens of thousands of people, including cultural icons such as Thoreau, participated in more than eighty food-centric utopian communities. She then looks at a second “groundswell of utopian experiments” between 1890 and 1910; the legacy of Helen and Scott Nearing; the “seeds of Moosewood’s world” in the early 1970s; before examining how today’s young farmers—now growing heirloom pigs, culturally appropriate foods, and newly bred vegetables—along with others working in coalitions, advocacy groups, and educational programs are working to extend the reach of this era’s Good Food Movement.

Access to Land

Land access is the top challenge cited by current farmers, aspiring farmers, and those who have stopped farming, and proves even more challenging for BIPOC farmers. Responses highlighted the ability to buy land as a key concern (compared to leasing or other methods of access).

Cost of Production

of young farmers named that “the cost of production being greater than the price they receive for their products” is very or extremely challenging.

Student Loan Debt

of young farmers named finding affordable land to buy as very or extremely challenging.

of young farmers named finding available land to buy as very or extremely challenging.

of young, BIPOC farmers shared that maintaining access to land was very or extremely challenging, compared to 17.4% of White farmers.

Access to Capital

survey respondents said that finding access to capital to grow their businesses was very or extremely challenging. That number was even higher for farmers of color: 59% for Black farmers // 54% for all BIPOC farmers.

Health Care Costs

59% 45% 33% 41% 40% 21%

of young farmers named personal or family health care costs as very or extremely challenging.

said family, business partner, or other health care costs were a top challenge.

Read the full report: www.youngfarmers.org/22survey

35% 38%

Student loan debt can prevent farmers from qualifying for additional financing needed to launch their businesses.

of young farmer respondents carry some student loan debt. Student debt burden is much higher for BIPOC farmers, and particularly Black young farmers.

62% 20%

of Black young farmers have student loan debt, compared to only 36% of White farmers.

of young farmers did not take out additional loans to support or grow their farm businesses.

Housing

Finding an affordable place to live is a major challenge for young farmers and a leading reason why former farmers quit. Land access and housing are closely intertwined:

83% 33%

of farmers who own land purchased a property that included housing, compared to 29% of farmers leasing land.

of young farmers reported that finding or maintaining affordable housing was very or extremely challenging. For BIPOC young farmers, that number jumps to 42%

5 6

HERECOMESTHE SUN

BY KATE OLSON | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

As the demand for solar energy grows, solar arrays on farms are cropping up around the state. But do the opportunities for combining agricultural production with solar generation outweigh the drawbacks?

FUTURE

7 8

Afew years ago, Michael Dennett, a sheep farmer and middle school science teacher in Gardiner, had an idea. He loved sheep and animals but couldn’t afford the amount of land they required for grazing. He knew that solar energy was about to expand in a big way, and he imagined the acres of grass underneath solar panels that would need mowing. What if his sheep could eat that grass? On a gray, muggy day in late August, Michael walks on a 31-acre solar plot outside of Augusta. Several curious sheep come over to say hello, while others rest underneath solar panels. The 63 sheep will graze roughly two acres every few days, then move over to a new paddock. They have fresh grass, they have water, and most importantly: they have shade. The panels provide the cooling shade for the sheep, and the sheep keep the grass beneath the panels short, which increases air flow and helps the panels stay cool and more efficient. It looks, at least in this moment, like a

mutually beneficial arrangement. Of course, there are issues. These particular panels are ground-mounted, very low to the ground, and occasionally the sheep bump into some of their wires. Although seeing the sheep rubbing up against the panels is incongruous at first, the longer they happily chew their cud, play, and rest, it becomes almost idyllic. As another summer of drought-like conditions and heat waves has driven home the necessity of mitigating the climate crisis and transitioning to renewable energy, solar production is expanding across the state. Although renewable energy production hit an all-time high in the U.S. last year, it still accounts for only 12% of total energy consumption, a far cry from what will be needed to transition to a net-zero economy. In Maine, the Maine Won’t Wait climate plan aims to transition the state to 80% of renewable energy by 2030. For solar production to be profitable in a traditional sense, developers seek wide open spaces with no shade, such as farmland. Enter agrivoltaics and solar grazing, the practices of integrating solar panels with crops or livestock. The idea behind these projects is that farmland can be used to produce food and energy at the same time,

in ways that are potentially better than doing each separately. Dual-use projects modify solar panels by raising them or increasing spacing between them so that primary agricultural activities such as animal grazing or crop production can still take place simultaneously. Co-location projects use traditionally-mounted solar panels—called ground-mount— with either grazing, non-agricultural plantings such as pollinator plants, or arrays on only a portion of the farmland, reserving the rest of the land for agriculture. Some studies have suggested that growing plants underneath panels lowers the panel temperatures by 3-4 degrees, allowing the panels to produce energy more efficiently. Crops grown beneath solar panels also require less water, a major benefit given the growing unpredictability of precipitation, and may even have higher productivity. When it comes to grazing, using sheep instead of mowers to keep pasture grasses low can reduce greenhouse gas emissions on-site, while the sheep’s manure can nourish the land for future agricultural use. The nexus of renewable energy production and agricul-

ture has inspired many new possibilities. Yet, as ground-mounted solar production is expected to triple by 2030, the question for many farmers in Maine is: Will solar development help support farm viability, or will it out-compete agricultural production altogether and gobble up the best soils in the state?

When Bussie York first got into farming 65 years ago, on Sandy River Farm in Farmington, canned corn was a major local export, so he invested in mechanical shucking equipment to supply the local “corn shops.” Then, he observed that there was demand for sugar beets so he began growing those, along with dry beans. They did bulk squash to be canned in Waldoboro for a while, then turnips, then beef. He was always tinkering with things, trying to find the right mix to remain profitable. “In all the years I’ve been farming there’s always been multiple opportunities to change and if you don’t plan ahead in farming then you’re always ten years behind.”

•••

10

Opposite Page Michael Dennett runs Crescent Run Farm in Jefferson, Maine, with his wife Ryan and daughter Maine. He has begun to pasture his sheep herd at solar array sites. Above Bussie York’s family farm in Farmington, Maine, has leased out land for solar use for a site that is now considered the largest solar array in New England.

Sometimes he would increase the herd, other times he would diversify into another crop, always seeking a balance between sustaining long-term health of the farm and meeting his family’s needs. Despite this continual adjusting, “the paychecks never seemed to come soon enough,” he says. Eventually they moved into dairy and their herd grew bigger. When the conventional dairy market bottomed out, they transitioned to organic dairy in 2000, a new market which “saved the small Maine dairy farmer, at least for a while,” he says. Things were steady for a while. In 2019, Bussie found out that Horizon Organics, to whom he had been selling his organic milk for 19 years, was going to drop him in 6 months if he didn’t close his farm store. The farm store allowed his family a steady income stream, provided direct, organic, local raw milk to his community, not to mention delicious ice cream and yogurt, as well as a cornucopia of vegetables from corn to pumpkins, and dry beans.

But Horizon didn’t like the store. So he had 6 months. Bussie was heartbroken and nervous. He couldn’t afford to lose his contract with Horizon. But the farm store was important to him, his family, his community. He had been contacted by a solar company that was interested in putting up a large array on his land. “They’re talking big bucks and I don’t know if they’re serious but I may have to look into it,” he told me then. Three years later, it’s hard to miss Sandy River Farm. As the road crests, rows and rows and rows of solar panels, stark against the ground, undulate through the fields and nooks surrounding the farm. Inside the farm store, Bussie and I sit at a formica table in the back as customers come and go, and talk about the decision to develop solar. As a farmer, he has ridden several successive waves of change as the markets shifted, and managed to grow his farm besides, by adapting and planning ahead. But in the end, he needed to ensure his

farm remained profitable and kept going for the next generation, and ultimately, “When you lose your market, you don’t have many alternatives.”

Andy Smith, of The Milkhouse Dairy Farm and Creamery in Monmouth, empathizes with dairy farmers across the state who are in vulnerable positions due to the challenge of keeping a dairy farm profitable. “I would say that pretty much every dairy farmer around, their economic reality is, it’s not really working that great. Almost all of them are in their 60s and 70s and most of them don’t have the exit strategy figured out,” he says. Smith served on the state’s Agriculture Solar Siting Stakeholder Group, which was convened in June, 2021 to gather public input and provide guidance on solar siting. He has a 72 KW solar array on the roof of his barn, and is supportive of solar development, but has grown concerned about balancing protection of the state’s agricultural lands with the rush of interest from solar developers whose short-term interests are not necessarily aligned with maintaining access to valuable agricultural lands. He and other farmers have been inundated with fliers and calls

from solar developers. In time, his opinion has shifted from “This is going to be great! To, what have we done? What have we unleashed here?”

Producing solar on farmland, while having potential, also has drawbacks and unintended consequences. In Maine, demand for solar production is unfolding at a moment of unprecedented rural development pressure and concerns over loss of prime farmland. Although solar development has emerged as a potential tool to support farmers like Bussie through supplemental income, there is a risk that this development could out-compete traditional agricultural uses, and once farmland is developed for solar, it isn’t always clear if it can or will be returned to agricultural use down the line. According to American Farmland Trust, Maine was one of the top five states with declines in farmland between 2012 and 2017. Between 2016 and 2021, electricity in Maine generated from solar panels increased more than tenfold. This is good news for beginning the

•••

Left Bussie York’s family farm has operated along the Sandy River in Farmington for decades, growing crops like soybeans, sugar beets, and corn, although their main product was milk. As the dairy industry shifted, York and his family pivoted to lease much of their land to solar use. Right Bussie York’s farm still reserves acreage for growing staple crops, although the hillsides beyond their barns are lined with solar arrays.

11

Cascova Gregory and Gavrin Simpson harvest wild blueberries around solar panels in Rockport.

energy transition. But so far, solar producers favor flat, open spaces—such as farmland—which are more cost-effective for them to develop. That makes farmland particularly appealing, and might imperil it. Last year, the Governor’s Energy Office and the Maine Department of Agriculture & Forestry convened an Agricultural Solar Siting Stakeholder Group. Through their public comment process, the committee heard from farmers across the state who are both interested and cautious about solar development on farms. Many Maine farmers lease land, for increased hay or vegetable production, or because they cannot afford to own quality farmland. This land is often owned by aging non-farmers who may be interested in the significant economic return on solar leases. This presents yet another barrier to new and aspiring farmers, who are struggling to access land to begin with, even without solar production inflating land values. Sara Hodges of SparkPlug Farm in Leeds notes that “In the past year we have seen 170 acres of open farmland that is zoned prime

agricultural land be approved for solar development in our town. I cannot express how frustrating this feels as a young farmer trying to build out a business. I cannot afford to compete with the leases these solar companies are presenting to land owners.” For farmer Dave Asmussen of Bowdoinham, solar should go on marginal lands first: “I am an advocate for solar power, but I believe that panels should be on every rooftop and parking lot and brownfield before we cover farmland. It is obviously cheaper to use a big empty field, but I worry that we will all be sacrificing long term sustainability and resiliency for quick profits.” Still, other Maine farmers are collaborating to explore whether with some creativity and foresight, solar and farming can be compatible in Maine. On a test plot in Rockport, a collaboration between UMaine Extension, BlueWave Solar, and a private landowner seeks to measure the impact of solar panel construction on wild blueberries. Dr. Lily Calderwood, UMaine Extension Wild Blueberry Specialist, and her team, are measuring soil compaction, plant

heights, diseases and pests, and berry counts, among other things, in three sections that were installed on a spectrum from standard installation to being “mindful” of the plants. Calderwood notes that because wild blueberries are rhizomes and 75% of the plant lives underground, they may be resistant to the impact of installation. The study will take four years, and in addition to measuring blueberries it seeks to determine how viable blueberry management underneath solar panels is for farmers and what kinds of harvest practices and equipment are optimal. Studies such as these will inform our understanding of the potential for solar projects to be compatible with various forms of agricultural uses. They also demonstrate how, just as Maine agriculture is diverse, solar development that is truly compatible with agriculture in Maine must also be diverse. There is no one size fits all solar project that will work across the state. Ellen Griswold, Deputy Director and Vice President of Maine Farmland Trust, notes that “there

are lots of different models that we need to be thinking about, from development on marginal lands and the built environment, to the role of dual-use projects and solar grazing.” Maine Farmland Trust is currently exploring with the University of Maine, BlueWave, and other partners, opportunities for dual-use projects involving PFAS phytoremediation and solar development on contaminated lands. One thing is certain: the imperative to transition our energy system to renewable energy has never been more clear. By centering the experiences and concerns of Maine farmers, Maine has the potential to strike a balance between protecting our natural resources and pursuing renewable energy development in a way that sustains our thriving food system.

kate olson, phd is a writer and sociologist based in Freeport. Her work explores people, places, and livelihoods in a changing climate. | kate-olson.com

@livingchangeme

14

From left to right: Jordan Ramos, Lily Calderwood, Brogan Tooley, Mara Scallon, Abby Cadorette, and Julian Lascala conduct studies on blueberry growth on a midcoast solar site. The group worked to quantify weed, insect, and disease pressure and measured soil moisture and chlorophyll.

13

Left Lily Calderwood, PhD, measures wild blueberry cover in the sun vs. shaded areas on a solar site in Rockland. Right Lily Calderwood, PhD, is an assistant professor of horticulture at the University of Maine and is the university’s extension wild blueberry specialist. Her work includes research and education programs focused on Maine’s blueberry production, including recent studies about blueberry production at solar sites.

FEED YOU PEOPLE THE WHO

BY VIRGINIA WRIGHT | PHOTOGRAPHS BY KELSEY KOBICK

Beth Schiller easily filled 12 full- and part-time jobs at Dandelion Spring Farm in Bowdoinham this year, which is saying something given a labor shortage so severe it’s closed businesses across the country. “I feel lucky to have a full team,” Schiller says. “I’m a small employer. If I were hiring 20 people, this might be a different conversation.”

Schiller, who grows organic vegetables on seven of her 75 acres, may make some of her own luck. She pays a minimum of $16 an hour—nearly $2 more than the average pay for Maine farmworkers and

$8.75 more than the federal minimum wage, their legally required base pay. She’s flexible too. “In the last three or four years, I’ve found that the people I’ve hired are very engaged in agriculture but want to balance that with other interests,” she says. “If someone tells me they want to work only three days a week because other things are important to them, then we’ll work that out.”

Those other interests are evident in Schiller’s dooryard this humid July morning. It’s Maine Open Farm Day, and some of her crew, including Portland potter

BUSINESS 16 15

Julia Michael and Wiscasset weaver Hilary Crowell, are displaying their crafts in a grove of trees. “Work flexibility is important to me,” says Michael, who carpools to Dandelion Spring two days a week. “I like the balance of being outside and then going to my studio and being a hermit. I’ve worked at farms where you’re just a set of hands. It feels like more than that here.”

Crowell echoes those sentiments. “I feel valued,” she says. “I’m more than just a person making the wheels in the farm machinery turn. It’s reflected in my pay and in conversations around my pay.” Crowell, who works alongside Schiller at two farmers markets, admires the way her boss talks with customers about the land and the people who feed them.

“There are a couple ways to look at farms: you can look at them as businesses, and you can look at them as educational resources,” Schiller explains. “We have to figure out how to have a dialogue about the price of food so it can include a living wage for employees, and that circles back to what the labor pool can look like.”

Maine’s 13,440 paid farmworkers work on about

one-third of Maine’s 7,600 farms, most of them for less than half the year, according to the USDA’s 2017 Census of Agriculture (another 10,000 workers, presumably owners and their families, are counted as unpaid). Farmworkers have in common physically demanding jobs and modest pay, but they’re otherwise a diverse lot. They range from teenagers earning pocket money, like the Brodis and Howard cousins who spend three weeks in summer picking twigs and leaves from winnowed blueberries at their family’s farm in Hope, to the hundreds of foreign-born migrant workers who harvest and pack broccoli at Smith’s Farm in Presque Isle. Some are apprentices jumpstarting a farming career, others adventurers immersing themselves in the local culture as they work their way around the world. There are new backto-the-landers determined to build more equitable and just communities, and older, lifelong farmhands for whom a bountiful harvest is satisfaction enough.

When Maine’s potato industry was struggling in the mid-1980s, cousins Lance and Greg Smith gambled on reorienting their Presque Isle farm for large-scale broccoli and cauliflower production, unheard of in New England at the time. “It was a huge leap of faith,” says Lance’s daughter, Tara Smith Vighetti, a sixth-generation member of the Smith’s Farm leadership team. “Even in 2004, when I started working in sales, people were still saying, ‘I don’t buy eastern. I buy California.’ So it was cool and innovative that they learned how to do it.”

As their business took off, the Smiths looked for workers experienced in hand-cutting broccoli and cauliflower to help them grow their volume. They found them in California, a team of about 100 men, most of them Mexican immigrants, headed by foreman Antonio Garcia. The Smiths paid for their flight to Boston and bussed them to Maine, a routine they’ve repeated every July since. That was the first time the Smiths had hired migrant workers, and their need for them, in both the field and the packing facility, has only increased.

Smith’s Farm is now the largest broccoli grower in the east, with about 3,500 acres of broccoli and 600 acres of cauliflower in production from April to late October (Smith’s manages more than 10,000 acres of fields that are worked in a three-year rotation with potatoes and other crops raised by partner farms). “Between 100,000 and 120,000 cases of broccoli and cauliflower go through our cooler every week for 16 weeks,” Vighetti says. “That’s a lot of product in a short period of time, and it takes a lot of people to get that done.”

The farm’s 300-plus person seasonal Maine workforce includes locals who do the planting; immigrants who live in the U.S.; and guest workers from Mexico and other countries who contract with the Smiths through the U.S. Department of Labor’s H-2A visa program.

Vighetti is proud of Smith’s Farm’s employee retention record. “North of 90 percent of our seasonal workers have worked for us before, even the people who come straight from Mexico on the H-2A program, and many of them, like Antonio and his crew, have worked for us for decades,” she says. Fieldworkers are paid a piece rate of $1.15–$1.20

•••

Previous Page Carlos Johnson hauls a bin of head lettuce out of the field at Harvest Tide Organics. Left Katiana Selens picks sweet lunchbox peppers and poblanos for Harvest Tide's weekly farm shares. Right Miguel Valentine works on a green bean crew. Large crews on tedious tasks like picking beans can make the work more efficient.

17

Devon Williams fills buckets one handful of beans at a time at Harvest Tide Organics in Bowdoinham.

per carton of broccoli crowns or at least $14.99 an hour, according to Department of Labor records. They live on the farm in group housing equipped with industrial kitchens. “There are a number of regulatory hurdles [related to housing], but we don’t use that as a benchmark,” Vighetti says. “We want it to be a place where people want to come and stay.”

Migrant workers, the only sub-group that the Census of Agriculture separates out, accounted for 13 percent of Maine’s hired farm workforce, or 1,789 people, in 2017 (the Department of Labor defines a migrant farmworker as an individual whose employment requires travel that prevents the worker from returning to his or her permanent place of residence on the same day). Most of them—about 1,600 people—worked for growers of broccoli, blueberries, and, to a lesser extent, potatoes in Aroostook, Washington, and Hancock counties, a phenomenon that started in the late 1980s in response to steep population declines that decimated local labor pools. Aroostook farmers still rely heavily on local people to dig potatoes in September, including high-schoolers on a two- to three-week harvest break.

The immigrant workers who harvest and pack wild blueberries in Hancock and Washington counties represent a different demographic than Aroostook’s broccoli pickers. Most of them are part of the East Coast Migrant Stream, which originates in Florida in winter and works its way up to Maine by July. Unlike H-2A visa holders, whose numbers are recorded annually, these migrants are difficult to count, but noticeably fewer of them are making it DownEast compared to a decade ago, says Jorge Acero, the state monitor advocate at the Maine Department of Labor. Back then, several thousand migrant workers would come through a welcome center set up in Columbia Falls by social-service providers and staffed six hours a day for two weeks. Today, he estimates there are around 1,000. “The primary reason is mechanization. Owners of large stands of blueberries have cleared rock from the land, so machines can go in and smoothly harvest. They fill 10 to 15 of these huge tractors a day. It would take 50 to 60 people two to three days to rake that amount.”

•••

20

Below Crew leader Jon Graziano and veteran worker Carlos Johnson finish head lettuce harvest. Opposite Page Lydia Baker bunches rainbow swiss chard for Harvest Tide CSA shares. The white plastic mulch reflects heat to keep cooler-season crops from bolting, and greatly reduces the labor hours to produce the crop because it suppresses weeds.

The decline in the blueberry harvest workforce has in turn affected the vegetable farms and orchards that are next on the migrants’ route, and that partially accounts for the increase in Maine businesses looking to hire workers through the H-2A program. In 2021, 51 agriculture businesses requested guest workers for 742 jobs, up from 26 businesses looking to fill 649 jobs in 2015. Their pay ranges from $14.29 to $23 an hour. “The majority of H-2A workers are from Mexico, but we’re seeing more and more from Honduras and Guatemala,” Acero says.

On this sunny mid-July afternoon, Acero is in Milbridge to attend the first welcome center of the 2022 blueberry harvest (the welcome centers are now offered once a week for a few hours during harvest season). He’ll introduce himself to workers and let them know he’ll advocate on their behalf if they have any concerns about their pay, housing, or working conditions. “If there’s, say, a wage issue, and I can’t resolve it with a face-to-face with their employer, then I would refer it to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage-

and-Hour Division, which administers the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act.” Workers trickle in and head directly to several tables brimming with free food boxes and neatly folded clothing provided by the welcome center’s lead organizer, Mano en Mano. Founded by former migrants who settled in the Milbridge area, Mano en Mano supports itinerant farmworkers and immigrants with education, housing, childcare, and other services, including a three-week-long Blueberry Harvest School focused on migrant children’s social, emotional, and academic growth. Eighty children enrolled in the school this year. Education is a priority for Mano en Mano executive director Juana Rodriguez Vazquez, whose own schooling was disrupted as her family migrated between Florida, where they picked vegetables, and Michigan, where they picked apples. About 20 years ago, at the suggestion of a family friend, they came to Maine for the blueberry harvest and ended up staying. “My parents found a way to make a year-round living here

between seafood processing, wreath making, and blueberry harvesting,” she says. Her memories of raking blueberries as a teenager are not fond: she recalls hours in the hot sun bent over a rake seven days a week. “All of the services we provide here at Mano en Mano—it’s not charity, it’s solidarity,” she says. “We’re filling a gap we shouldn’t have to fill. If folks had the services they need to survive, we wouldn’t need to exist. We’re trying to work ourselves out of a job.”

Vazquez was among the immigrant advocates who joined farm owners and business leaders at an August press conference in Dayton to draw attention to the Workforce Modernization Act. The proposed federal legislation aims to ease the labor shortage by creating a pathway to citizenship for migrant workers in the U.S. and by expanding and streamlining the H-2A visa process. "We need to create paths to permanent status and fully welcome immigrants who are already here and who are coming, contributing each and every day to our communities," Vazquez said.

Vazquez also supported a 2022 bill that would have given farmworkers the right to organize, join unions, and engage in collective bargaining. Farmworkers are excluded from protection of the National Labor Relations Act, “a vestige of systemic racism” dating to 1930, says state representative Thom Harnett, who introduced the bill. Had Governor Janet Mills not vetoed it, Maine would have become the 11th state to allow agricultural workers collective bargaining rights, but Mills said she feared the legislation would discourage the growth of farms. “So people can be lawfully fired for talking to each other and then going to their employers, saying, ‘We don’t think we’re making enough money,’ or ‘The working conditions are dangerous’ or ‘The housing is subpar,’” Hartnett says. “It’s unethical and unjust, but it’s perfectly legal.”

Hartnett also sought to reverse a state law that exempts farmworkers from the state minimum hourly wage (currently $12.15) and from overtime-pay requirements. “Even in a Democratic-controlled house, I couldn't get it out of committee,” he say. Discouraged, Hartnett is not seeking another term but says he’ll continue to advocate on behalf of farmworkers. “Why can’t we treat them with dignity and respect?” he asks.

just thrown out in the field to work,” Jorge Acero says. “Some develop a really good rapport with the farmer and want to come back after they graduate, because the money for farm work is better here than at home.” More common are apprenticeships on organic farms, which post their openings with MOFGA, the National Center for Appropriate Technology’s ATTRA program, and WWOOF (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms). That’s how Los Angeles resident Lucy Brooke landed at Apple Acres in Hiram, the only organic apple orchard in New England that offers apprenticeships—and unusual ones, at that. Apple Acres apprentices can supplement their compensation ($250 a week, plus housing and unlimited produce from a sister farm) with hourly wage jobs in owners Molly McKenna and Bill Johnson’s other ventures, such as building tent platforms and treehouses for vacation rentals and organizing the Ossipee Valley Music Festival. “That’s what drew me,” says Brooke, who previously worked as a server for a catering company. It’s the first day of picking, and she’s standing on a stepladder under a McIntosh tree, a harvest bag slung over her shoulder. “It felt more well-rounded. It wasn’t just fieldwork. Molly makes sure to stop every now and then to have a little sit-down about, say, pest lifecycles. And the music festival was a giant lesson in event prep, finances, carpentry, and plumbing. I’m learning things that are relevant and useful to my life.”

Izzy sought a 6½-month apprenticeship at Apple Acres to give meaning to the environmental- and agricultural-policy studies she pursued in college (at Izzy’s request, we only use her first name). “I felt very disconnected from my schoolwork,” she says. “It was instantly more rewarding to come here and see the policies I’d been reading about put into practice and see how profit and environmental consciousness interact.”

Recently, a small number of Brazilian, Columbian, and Venezuelan students have come to Maine farms through the U.S. State Department’s summer work travel program. “It’s supposed to be more of an internship where they learn all aspects of farm management, but they can get taken advantage of and

That’s how an apprenticeship is supposed to work: the apprentice works in exchange for hands-on experience, one-on-one instruction, housing, and a stipend. Sometimes, though, the instruction is lacking. That was true for Emma, who was one of eight apprentices on a three-acre mixed-vegetable farm last year (Emma likewise asked that we use only her first name). “I hoped to get experience and mentorship in farming no-till because I’m looking to start my own farm and that’s the only type of farming I didn’t know how to do,” she says. “Our host farmer wasn’t as present as I thought he’d be, and that was disappointing. I assumed that because he was offering apprenticeships, he’d be there more day-to-day and tell us about the systems he’d got

•••

21 22

Left Eli Beckford and Right Juniper Hathaway work all day in the wash/pack building, rinsing crops and preparing them for Harvest Tide's wholesale customers and CSA members.

in place and why he does things a certain way.”

Instead, she and her fellow apprentices, all new to the farm and its only workers, brainstormed their way through clearing and prepping beds, starting plants, and other no-till techniques. “In the end, I learned a lot, but not from the person I thought I’d be learning from,” Emma says. “Overall, it was a positive experience, but my perspective on apprenticeships has changed. In theory, they’re great, but it’s a huge responsibility for the host/mentor. I don’t know if I would have the mental space to work with an apprentice while running a business and managing a crew.”

Managing any crew is a huge responsibility, as Bethany Allen has discovered. Before founding Harvest Tide Organics in Bowdoinham with her partner, Eric Ferguson, she worked for several years as a farmhand herself. “I’m not sure which I prefer,” she says with a laugh. “If you have a good boss, you know what’s going on and you’re learning a lot. The work is really hard, but when it’s done, you’re done. When you own it, it feels like it never ends.”

She and Ferguson started the farm with two employees in 2016. Today they have 16, including

four men from Jamaica with H-2A visas who are guaranteed, by contract, at least 50 hours a week. “They’ve left their families and lives behind, and they don’t want to waste their time,” Allen explains. The men live in barracks on the farm from May through October. Once or twice a week, they pile into a car with Allen, Ferguson, and their 3-year-old daughter, Iona, and go shopping. “It’s very social—not like family, I wouldn’t claim that, but you get close.” The rest of the crew works 40–42 hours a week in summer, and anyone who wants to work through the winter is accommodated. In fact, the main reason Allen and Ferguson added a spring CSA to their offerings was to retain employees. “When we started this, I didn’t think a lot about what it meant to manage people on this scale. It's been a learning process,” Allen says. “I’ve come to the conclusion that our employees are at the forefront of what we do. They’re the ones making everything happen. That’s where we see the most return on our investments. When you put people and their humanness at the fore, your possibilities are endless.”

virginia m. wright is the former senior editor of Down East and Maine Homes magazines. Her current projects include a history of the town of Carrabassett Valley.

23

Opposite Page Bethany Allen takes 10 minutes to organize a plan for the four workers packing tomatoes before jumping in to help sort cherry tomatoes. Left Shoshanna Weiner, another apprentice at Apple Acres, picks into a bushel-size fruit harness bag. Right Apple Acres' certified organic fruit is coated in a light dusting of kaolin clay, an effective treatment to prevent pest damage as the fruit ripens.

capturing convenience

Can Maine businesses meet the growing demand for more convenient food?

BY KATE COUGH PHOTOGRAPHS BY IAN MACLELLAN

During the pandemic, Americans went to the grocery store and found something many had never before encountered: bare shelves.

Some of the reasons for those bare shelves were clear-cut: panic buying, knowledge workers who were camped out at home and dining in three meals a day, processing plants operating at diminished capacity as workers fell sick. Others were farther up the chain, and less visible. A shortage of styrofoam trays for packing meat products. A lack of childcare. The pandemic exposed the bones of the global food system, making it clear that the abundance we enjoy is dependent upon a vast, elaborate web, whose threads, under strain, were ready to snap. But those challenges also presented opportu-

nities, as consumers became more comfortable shifting tasks once conducted in-person—classes, birthdays, meetings, and grocery shopping—into the digital world.

“It was a long enough period of time that it changed people's eating habits and got them used to an online platform,” said Adrienne Lee, co-owner of Daybreak Growers Alliance, a distribution business based in Unity that delivers both direct-to-consumer farm boxes and wholesale to businesses around central Maine. “It opened us up to a broader, not-as-typical CSA [Community Supported Agriculture] customer base.”

Daybreak began to see shoppers who, before the pandemic, might have made one stop at the grocery store, now turning to customizable farm shares and CSA boxes. The reasons varied: a desire

FOOD 26 25

to avoid crowded spaces, a lack of certain products on grocery store shelves, and an increase in price (particularly in the meat department) that put local products on par with those from outside the state.

“It also opened their eyes to trying to source more locally and getting into a rhythm with their purchasing in a different way,” said Lee. Grocery and meal-kit delivery services existed before the pandemic. But their rise during it was explosive: the Brookings Institution found that online grocery spending more than quadrupled between August 2019 and November 2021.

Daybreak was able to capture some of those customers, said co-owner Colleen Hanlon-Smith, and it’s likely many will stay, having grown accustomed to fresher products and supporting local food systems. The company’s boxes, which start at $35 for a butcher box and $30 for a farm box, are

customizable and include many typical grocery store offerings: fresh produce, of course, as well as meat, cheese, tofu, bread, sauerkraut, jams, jellies and maple syrup. Delivery is weekly or biweekly, to homes and pickup sites around central and southern Maine. But some slice of the grocery delivery market will always be out of reach, said Hanlon-Smith. “I think there are going to be those that don’t want to be limited to seasonal eating no matter what.” Those customers might stay with Daybreak, supplementing with online delivery of foods such as citrus and tropical fruits. Others will return (if they haven’t already) to shopping in-person, or switch to larger online delivery services such as Amazon Fresh, Whole Foods and Walmart that offer more variety. Daybreak has yet to conduct in-depth research on their new customer base, said Hanlon-Smith (“We've put the energy into just sort of responding to that

increase more than reflecting on where exactly it's coming from”), but sensed that the company had captured shoppers who previously “were going to Whole Foods and were satisfied by an organic label on their food, but maybe hadn’t taken the time to get to know the immediate farms around them.”

It’s unclear how long online grocery shopping will last: a study published in February by researchers at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute found that more than 90 percent of people who use delivery services would likely revert back to their original way of pre-pandemic shopping. But Lee and Hanlon-Smith said that although growth has slowed somewhat compared to the rapid rise at the beginning of the pandemic, it’s still holding steady.

“We've got super loyal customers that really weren't pandemic dependent,” said Hanlon-Smith, “and we've also seen those that gave us a try go back to the grocery stores as they can. Our growth—I wouldn't put it as having leveled off, but it's at a more modest pace now than that dramatic growth that we saw when the pandemic first hit.”

Nationwide numbers bear that out. Groceries are now 8.9 percent of the digital economy, up from 6 percent in 2019 and down slightly from 9.1 percent in 2020, according to recent research by Adobe.

The pandemic also opened doors for other small and medium scale food processing ventures in Maine, said Kristen Miale, president of Good Shepherd Food Bank, which recently launched the frozen food processing venture Harvesting Good.

“There really are no food production facilities— not only in Maine, but anywhere in the Northeast,” said Miale. Entering the processing business is expensive, requiring millions in upfront investment, she added, “which is probably why it's dominated by very large companies.” Those companies have little interest in working with small and mid-size farmers, said Miale, which typically can’t provide

Previous Page Jamie Edwards packs an end of the summer farm box at Daybreak Growers Alliance office in Unity, ME. Above Adrienne Lee, left, moves a pallet of flowers and vegetables from New Beat Farm in Knox and Jamie Edwards, center, helps unload vegetables from Villageside Farm in Freedom during the primary receiving day. Opposite Page (top) Plums from The Apple Farm in Fairfield on the receiving dock at Daybreak Growers Alliance. (bottom) Jess Carey moves a box of heirloom slicer tomatoes during packing day.

Previous Page Jamie Edwards packs an end of the summer farm box at Daybreak Growers Alliance office in Unity, ME. Above Adrienne Lee, left, moves a pallet of flowers and vegetables from New Beat Farm in Knox and Jamie Edwards, center, helps unload vegetables from Villageside Farm in Freedom during the primary receiving day. Opposite Page (top) Plums from The Apple Farm in Fairfield on the receiving dock at Daybreak Growers Alliance. (bottom) Jess Carey moves a box of heirloom slicer tomatoes during packing day.

27

“Yes, we can grow food here, keep it local, and have it available all year round, and affordable at the same time.”

the volume, consistency and low prices large processors demand to keep turning a profit.

The pandemic didn’t change any of that. But it did change the way many consumers interacted with their food system.

Good Shepherd already gives out more than two million pounds of fresh produce in the state, but that’s really the maximum amount of fresh food it’s able to distribute during Maine’s relatively short growing season. “There's only so much zucchini all of us can take in these two months,” Miale joked.

Extending the season by expanding into frozen or processed foods was the logical next step, said Miale, but it quickly became clear that the associated costs—refrigerated trucks for transport, cold storage warehouses, industrial equipment for peeling, blanching, chopping and freezing—would run into the millions of dollars.

As Miale tells it, Good Shepherd was about to give up on the idea when “we ended up getting connected to some blueberry processors in Maine,

and we learned that they have significant capacity and capability and generations of experience of freezing and packaging and distributing frozen fruit.” They also had a business entirely focused on a single product, an inherently risky model, and were looking to diversify.

Harvesting Good, Good Shepard’s newly-minted for-profit processing business, will begin its “proof-of-concept” season this fall.

The company is starting with just a single vegetable, broccoli, which they chose for a few reasons: it’s the top-selling frozen vegetable in the Northeast, Maine grows a lot of it, and it comes into season right after blueberries, allowing W.R. Allen, which will be processing the crowns at its facility in Orland, to keep its equipment running and workers in place with minimal disruption.

The first round of crowns went into the ground this summer at Circle B Farms in Caribou, which has added fields to increase its yield and meet Harvesting Good’s demand, said Miale. Blanching, floreting and freezing is being done at W.R. Allen

in Orland, while packaging will be handled by Jasper Wyman & Sons in Milbridge, and Native Maine and Sodexo will handle distribution.

Hannaford has agreed to carry the broccoli in all of its New England stores, said Miale, while Native Maine will also distribute to smaller grocery stores and grade schools through the state.

“I'm just really excited about this model,” said Miale. “Rather than creating something from scratch, it's really leveraging expertise that has already been here in Maine.”

That doesn’t mean it will be cheap. Between an expansion of the farm in Caribou, machines for floreting, blanching and cooling the broccoli, upgrading electrical and water equipment, and building an addition onto the W.R. Allen building, Miale estimated Harvesting Good required $6 million to get up and running.

Harvesting Good will begin with 500,000 pounds, with the goal of scaling up to 2 million pounds and eventually expanding into other vegetables.

“That's really the scale that's needed for a venture like this to break even because of the expense of the equipment,” said Miale, and why the company needed large distribution partners such as Hannaford and Sodexo, which put the broccoli on shelves throughout the Northeast, as Maine doesn’t have enough customers to support frozen food processing at this scale.

Both Daybreak and Harvesting Good emphasized a desire to localize and bring transparency to a supply chain that, until recently, has been far-flung and opaque.

“We've all realized how quickly we can lose access to food because we rely on a global system,” said Miale, of the upheaval during the pandemic. “All of a sudden those supply chains got jammed up and we all lost access to certain products. So a lot of people are starting to say, ‘Why isn't my food coming from closer to home? And can I get food that's closer to home?’ Hopefully we’ve found a solution that really does show, yes, we can grow food here, and keep it local, and have it available all year round, and have it be affordable at the same time.”

kate cough is an eighth generation Mainer and graduate of Bryn Mawr College and Columbia University. She lives with her family in Downeast Maine, where she writes about energy and environmental issues.

29

Below Colleen Hanlon-Smith unloads a container of heirloom tomatoes onto the receiving dock from New Beat Farm in Knox. Opposite Page (top) Adrienne Lee unloads farm boxes at the Casco Bay Lines Ferry Terminal in Portland, ME. (bottom) Husk cherries from Dig Deep Farm in South China on the receiving dock at Daybreak Growers Alliance.

Yes, we can do that and we can do more

Seven Remarkable Minds Leading Maine’s Food and Agricultural Sectors into the Future

BY MICHELE CHRISTLE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY TARA RICE

BY MICHELE CHRISTLE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY TARA RICE

For the first time in Maine’s history, women are leading all of the most recognizable and established agricultural organizations in the state. While this dynamic is remarkable in and of itself, it’s also notable that these women have led through remarkable times that continue to call for remarkable leadership in action: the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the PFAS crisis, the increasingly destabilizing impacts of climate change. It’s not just what they’re doing to address these issues; it’s how they’re doing it. These leaders are decisive, passionate, enthusiastic, empathetic listeners who know how to synthesize feedback into action and work together to support the people (and land) of Maine. Through their thoughtful collaborations, big things are happening. For this project, we asked seven leaders to share their perspectives on what the future of leadership

in Maine food and farming might look like, as well as what needs to happen to cultivate a more inclusive community of leaders and farmers.

Many of the women interviewed mentioned the importance of role models and mentors and seeing people that look like ourselves in leadership roles.

One interviewee asked, “When does the term ‘women leaders’ just become ‘leaders?’ That, to me, is the future, when it’s not unusual to have a woman in any of these positions. All the people who want to be a part of agriculture need to see a place for themselves within it.”

These conversations have been condensed and edited.

michele christle is a freelance writer who writes about ecology, people, places, and abandoned houses.

| michelechristle.com

SARAH ALEXANDER

Executive Director at Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association

Over the last couple of years, first with the pandemic, and then the PFAS crisis, I’ve seen how the women in these leadership positions are willing to come together and collaborate. Sure, we all have our own missions and programs but the way we’ve been able to meet the moment for our agricultural communities has been really impressive. We all have limited resources but we can always accomplish more when we work together than we can individually.

MOFGA is the lead on a professional development program that provides diversity, equity, and inclusivity training to agricultural service providers,

funding for individual consultants for improving internal DEI within seven organizations, and convening a space for cross-organizational learning around equity and inclusion. We have to learn from these crisis moments, tackle these issues together, and bring forward leaders from across the lived experiences of all the people in Maine to represent our agricultural community. The future of our planet and our communities depend on having healthy food for everybody—I can’t imagine any greater privilege than getting to work on this.

PEOPLE

31 32

AMANDA BEAL

Commissioner of Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry

My philosophy is that people can be leaders in any role they hold. To that end, I already see many bright leaders in our farmers of all ages, as well as throughout agricultural businesses and organizations that serve farmers in Maine and beyond. This gives me great hope and optimism for the future of our state, as does the growing appreciation for the importance of farmers and the hard work they do that impacts our everyday lives.

Ensuring that the whole ecosystem related to our work reflects diversity of all types is important, including organizations from which leaders are likely to be recruited. This goes even further back to ensuring diversity among those asked to serve on boards and committees. The same pertains to recruiting students for agriculture-related tracks in trade schools, community colleges, and universities. The more we can work to cultivate pathways to leadership that enhance diversity, the more readily we will all benefit.

STACY BRENNER

State Senator and Farmer of Broadturn Farm

Women have been engaged in agricultural activity as long as men have but without recognition; it only makes sense that it's time for us to also be given opportunities to take leadership roles. We just need to be sure not to shut the door behind us. It’s incumbent upon us to shine a light on others when we see potential and to cultivate leadership. The only wrong way to be a leader is when we're not inclusive and we're not making room for all the different types of farmers to be present and deemed important and valuable in the story of Maine’s agricultural economy.

As fires encroach and extreme weather events increase in other parts of the country, Maine stands to be a place for climate migration and climate refugees. Our capacity to be the breadbasket of New England will only become more important going forward. This leadership team is willing to embrace that growth, inclusively. I love this group of women because they approach problems with “Yes, we can do that and we can do more.”

33 34

HANNAH CARTER

Agriculture is going to be the foundation of the future for the state of Maine. We’ve gotten a lot better about taking apart our silos. What we need to continue to do is be open and share. There are a lot of different crops grown in Maine and a lot of different philosophies on how to grow them. My goal is to ensure that there’s a place for everybody.

Whether you’re leading an organization or a farmer wanting to live your dream and buy a little

piece of land and raise your family on it, there’s room for everybody. There isn’t a right way and a wrong way or a right person and a wrong person to do it. It’s collective. How do we do this together? How do we ensure that everyone feels like their voice is heard and that if they come to us for help they’re going to be helped in whatever way we can help them? We can always find a commonality.

AMY FISHER

President and CEO at Maine Farmland Trust

From what I’ve seen, this is a very decisive group of leaders. We’re collaborative, fast-moving, and committed to our constituencies. When the PFAS crisis arose, we were all on the same page. We knew we needed to be led by the farmers and that we needed to coordinate our operations such that the experience for affected farmers is as smooth and supportive as possible. It’s exciting to see this level of cooperation—and, speed.

When you’re in a leadership role, it’s important to look for opportunities to welcome more people in. As well as listen to criticism. There's a lot of really fair criticism out there of food, farming, land trusts, and conservation groups. We have to be able to listen, take it in, and figure out what we do with it. That doesn’t mean we have to change our whole business model but we do need to make moves that acknowledge these criticisms—which are grounded in people’s experiences with all these different systems and organizations—and do better.

35 36

Dean of University of Maine Cooperative Extension

JULIE MARQUIS

President and CEO at Five County Credit Union

When I was first approached with the idea of Maine Harvest Credit program merging with Five County Credit Union, my wheels really started turning. I knew this would take us in a new direction as we’re not normally in the agricultural space. I like puzzles and I was excited to figure this one out. I got into the credit union movement because I love the idea of people helping people. I love that if we hear that farmers are struggling we can immediately turn around and provide them with some relief and support.

I’m proud to be a part of this group of leaders. The urgency of the situations farmers and people in food production are facing requires leaders who can get things done—quickly—which I think we’re all very capable of. We know we can’t just sit around and think. We need actionable solutions. The relief we can provide small farms, their families, and generations of future farmers through collaboration like this is wonderful. There’s so much we can offer in this space, not just on land but in aquaculture, too.

KRISTEN MIALE

President and CEO of Good Shepard Food Bank

For a period of time, Maine entrepreneurs were a little too connected to the quaintness of Maine; little shops and cottage industries. But fundamentally, we need thriving businesses that can hire workers and provide good jobs so that every person has an opportunity to thrive here in Maine. I’m excited about the shift we’re seeing in some food companies to think bigger and bolder—“I’m not just going to sell to my neighbors in town, I’m going to sell to the entire east coast!” This is why Harvesting Good is so exciting to me. We want to be processing vegetables year-round to

feed the northeast so that people who live here can have a much greater percentage of their food grown locally. Sometimes Mainers can almost stand in our own way by thinking we need to stay hyperlocal. We're not going to have thriving communities if we stay hyperlocal—we don't have enough consumers to support the jobs. With this group of leaders in place, the possibility that we could move the needle on expanding the economic impact of Maine’s agricultural economy has never been greater.

37 38

FARMING BEGINS AGAIN:

New Roots Cooperative Farm

BY DANI WALCZAK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY MOLLY HALEY

Each year in Southern Somalia, after a heavy rain, the rivers rise and flood the ravine between the Juba and Shabelle rivers where Seynab Ali learned to farm from her parents when she was seven years old. With the river water comes silt and nutrient-dense material. The river recedes, the soil is replenished with nutrients, farming begins again. These farming cycles and practices have been passed down for generations in Somalia and Ali continues the farming tradition now but on much different farmland—an old dairy farm in Lewiston, Maine, where the soil is rocky, fertilizer is brought in, cover crops planted, and water is pumped from a well with a generator.

New Roots Cooperative Farm is an intergenerational farm comprised of Ali, Batula Ismali, Mohamad Abukar, and Jabril Abdi—all African, Somali Bantu, Black, Muslim farmers from different regions of Somalia.

The paths at the Lewiston farm are lined with magenta amaranth, or ambaqa in Maay Maay, the farmers’ shared language. Beets protrude from the soil, tomatoes lay their straggly vines along the dry ground. African corn, sabuul, stands tall with tougher and starchier kernels, unlike the sweet variety grown on nearby farms, and softer than dent varieties grown for cornmeal. High tunnels are filled with roselle, a plant in the hibiscus family. Water Spinach, baareyle, one of the semi-aquatic plants that would grow in Ali’s childhood river valley, also finds a home in the tunnel.

The crops grown at the farm go to six farmers markets or the farm’s 250 CSA members, and three local food pantries. For many community members and friends, New Roots Cooperative is often the only source of culturally familiar crops.

Community members from Somalia often buy these crops in bulk, to freeze for the Maine winter when availability all but disappears.

LAND 39 40

“Some of the communities we know here have been in need of that [African vegetables], they never used to get it,” Ali said. “The soil in the land where we used to live changed itself, we didn’t have fertilizer. [In Maine] we have to build the soil up. The history for the vegetables, for the land, a lot of that, people remember what they used to have and they want to see a taste of it.”

The way Ali and her co-farmers weave knowledge of past and present, and hold space for their cultural traditions and their new home is evident in all their work.

The four met in the mid-2000s at refugee camps, fleeing civil war in Somalia. The farmers began farming in Lisbon, Maine in 2006. During the next 10 years they studied American farming, navigating how to incorporate their generational farming expertise into a totally

new environment with different local challenges. They studied business and marketing and graduated from Cultivating Community’s New American Sustainable Agriculture Program. In 2015, the farmers worked with Maine Farmland Trust to find suitable farmland in the Lewiston area. MFT purchased a 30-acre former dairy farm on the outskirts of the city and by 2016, New Roots Cooperative Farm had set their roots on the land, leasing the property from MFT with the option to eventually buy the farm. With the help of community members and fundraising partners, New Roots Cooperative purchased their farmland from MFT in 2022.

“At the beginning, you know, we were scared, we came from a country that was broken down and we never thought we would own land, especially a farm. When we started we thought

we’d just be leasing it and renting every year, but when the opportunity came we were a little bit afraid,” Ismali said.

“Maine Farmland Trust encouraged us, and lots of folks said ownership is good. It’s a different dynamic, it's a lot of tax stuff and lease, we were just afraid,” Ismali continues. “Once we got it, a lot of tensions went away, we were afraid of stuff that didn’t happen. We are so excited, owning this land is like you’re at your own house, rolling around, that’s how I feel—just excitement.”

This July the Cooperative celebrated land ownership with a gathering, inviting the broader community to celebrate the farm with food and tours of the property.

Cars kicked up a dry July dust as they parked among greenhouses abundant with a variety of crops. At the top of the hill there was another hoop house, this one teeming with human life. Mesh-topped tables were covered with casserole dish pans set out

corner-to-corner with steamy food like sambusa, vegetable and meat wrapped in a fried dough. The other side of the greenhouse was lined with tables, folding chairs were shuffled around to make room for friends. The tent was boisterous with celebration. People sat in corners of shade under pop-up tents.

Hussein Muktar, son of Seynab Ali, spoke on a megaphone, “Sitting down eating together, sharing together, this is what it’s all about as a community and we couldn’t do it without you guys,” he said.

The community that supports New Roots Cooperative is diverse: CSA members, fellow Somali Bantus, community partners, city government, and nonprofits. The farmers are quick to show gratitude for the support they receive, but they are also the very people creating a community that helps support them. They do this by cultivating a place to coalesce, leading by example, and showing in-practice that collaboration builds energy and momentum.

Previous Page Seynab Ali harvests amaranth at New Roots Cooperative Farm in Lewiston, Maine Above Seynab Ali, Jabril Abdi, Batula Ismail, and Mohamed Abukar, founders of New Roots Cooperative Farm. Opposite Page Community members take a tour of New Roots Cooperative Farm during the Farm Purchase Party in July.

Previous Page Seynab Ali harvests amaranth at New Roots Cooperative Farm in Lewiston, Maine Above Seynab Ali, Jabril Abdi, Batula Ismail, and Mohamed Abukar, founders of New Roots Cooperative Farm. Opposite Page Community members take a tour of New Roots Cooperative Farm during the Farm Purchase Party in July.

42 41

“The main reason [we’re a cooperative] obviously, is doing things alone is very challenging,” Ali said. “If you don’t have all of your teeth you can’t really chew. Maybe you have one or two you won’t be able to do much, it’s going to be an endless struggle for you, but if you have a group—together, ready to do work together, that itself is strength.”

Cooperation and community care are central to the farmers’ ethics, whether it’s 70 no-cost CSA boxes for newly settled low-income individuals and asylum seekers, food pantry donations, welcoming new people to the farm, or expanding field use to four potential new cooperative members this season.

“It’s an opportunity to be engaged with your own community,” Ismali said. “I feel like we’re fighting food hunger, especially folks who are like me, who came to this country, it’s hard to find known crops from back home and that’s what we’re trying to provide. We know it’s difficult but seeing them buy those crops just makes us happy and we feel proud of it.”

After the dinner celebration the farmers led a farm tour. The farm is situated at the top of a hill, and unlike the river valley they farmed in Somalia, water is scarcer here. The farmers installed a new well pump this year but it’s still not enough to meet

the needs of the farm. Water is only one of the challenges the New Roots farmers are learning to adapt to.

“First of all, if you were not born here, that in itself brings in so many variables for you,” Abukar said. “But if you want to be successful in farming—in where we’re at I don’t know if we’re successful right now—you have to be really patient. You have to be committed to being patient and you have to be willing and ready to learn and adapt to all those variables or you won’t make it. It’s tough for us.”

The farmers keep adapting though.

“Back home there’s a big difference, the high tunnels don’t exist,” Abdi said. “We were trained on how to use them and how helpful they are, our hope is to take this knowledge and give it to our kids, maybe someday they can train other folks like us.”

On the tour, Muktar picked some Roselle—a leafy, sour plant—from the tunnel and passed it around for us to try. The Roselle and other Somali crops are planted in high tunnels to keep the flea beetles and other pests out.

“What is important,” he said, “we put inside.”

dani walczak is a farm worker turned gardener. She writes, cooks, and lives in Portland, Maine. .

44

Opposite Page Mantanow Holbow bunches onions for market. Left Mohamed Abukar washes new potatoes destined for sale at market the next day. Right Batula Ismail harvests amaranth at the farm.

Harvest Time Borscht from the Maine Community Cookbook

“I have adapted this recipe from one in my mother’s box of family favorites. The partially grated, partially julienned veggies are a traditional touch, but the ‘throw in whatever the garden offers’ reflects my own style, developed once I became a gardener. It was in Alaska that I first tried using moose meat (terrific!). After that, I began experimenting with whatever meats came along. (It’s great to have a family of game harvesters!) Never the same twice, this borscht begs to be tinkered with—herbs, seasonings, bone broth, wild mushrooms…whatever. It’s also good as a pot pie with biscuit topping.”

For 4 servings

Approximately 1 pound meat, cut into small cubes (any kind of meat will work, venison is terrific, but then, so is beef, pork, chicken, rabbit…)

2 teaspoons salt, divided

2 medium carrots

2 medium beets

2 medium potatoes

2 each turnips, parsnips, onions, whatever else is in the garden that wants to come in!

2 celery ribs

Quarter of a medium cabbage

1 tablespoon olive oil

2-3 garlic cloves, pressed

8-10 paste tomatoes, diced, or 4 tablespoons

tomato paste

1 bay leaf or 3 sage leaves

2 cups (more or less) chopped beet greens

¼ cup chopped parsley

Sour cream and sourdough bread, for serving