Macaranga

Readers who contributed to keep our stories free for all

CENGAL RM1,000

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz Cengkih & Vela Daphne Choy Ee Phin Wong Fiona Bodipalar Gayathry Venkiteswaran Groundcontroldotcom Jay Rosenheim Izwan & Partners Sandra Laxmana

KAPUR RM200

Aini Mutalib

Andrew Merwin Cengkih & Vela Chern Yunn Yee Choon Chyuan Low Crystal Ch’ng Dayaneetha De Silva Evelyn Teh Hilary Kung Isad Chung Jeeva Jen Tan Jia Yaw Kiu Jo Lim Ju Lian Chong Juliet Jacobs June Rubis June Tan

Justine Chew Kai Hui Wong Kaixiang Chin Kelly Wilkinson

Kevin Albin Khairil Yusof Kiah Chun Heng Kumitaa Das Latifah Hamzah Leong Aik Lim Mui-Yun Wong Nicholas Chan Nuradilla Mohamad Fauzi Premesh Chandran Pui May Wong Pushpa Nair Sheryl Lee Siti Syaliza Mustapha Sumei Toh Ting Hui Ng Toyoaki Fujiwara Tze Ni Yeoh Veronica Yow Yen Yen Sam YS

MERBAU RM500

Chee Yew Goh Dylan Ong Ginny Ng Kar Yin Tham Kim Fun Leong Min Law Pui Yi Wong Shao Loong Yin Steven Khoo

TUALANG RM50

Alexandra Wong Alvin Kah Wei Hee Anil Ramachandren AQ Koh Balqis Tajalli Biow Ming Sim Chai Ming Lau Chong Chin Heo Darsh Kanda Eyad Hasbullah Fitri Baderulnizam Grace Yeo Joshua Pandong Kevin Bathman Kuang Keng Kuek Ser Lee Lim Norida Mazlan Norman Goh Puteri Nizar Sharifah Tahir SJ Zahiid S Kamal

Sue Law TS Koh Wan F. A. Jusoh WL Law Yoke Mooi Liew Shaua Fui

Thary Gazi Yao Hua Law Yee Pheng Wu Yin Foong Lim Anonymous 1

Anonymous donor II Contributors to the Sprouts New Journalists Fund

Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network Earth Journalism Network Internews in Malaysia The Habitat Foundation

004 Letter from the Editors

Macaranga is an independent journalism portal covering the environment, climate and sustainability in Malaysia through in-depth features and knowledge building.

Run by specialist environmental and science journalists, our objective is to be relevant, insightful and accurate, and to fill a gap in producing local content for Malaysian and global readers.

We also train and mentor journalists in these areas, and provide a platform for voices and experts on the ground.

macaranga.org

editorial@macaranga.org

@macarangatweets

@macaranga.org

006 Tree Farming Gone Wrong: #Ladanghutan Series 008 When Birds Flock to A Bornean Bay 010 Building Arks for Corals 012 Drains Dug, Trees Cut; Now Let’s Get It Approved 014 Living Next to A Paper Recycling Behemoth 016 When Laws Put the Brakes on Pig Farm Pollution 018 Three Stories on Land and Water: #Tanahair Series 020 Cutting the Chini-Bera Forests for Oil Palm that Can’t Sell 022 Locals Protest Sandmining in Sabah 023 Where’s the Green in GE15?

024 Landscapes in Limestone 025 Villagers Restoring Mangroves Destroyed by Failed Shrimp Farm

REMARKS

026 Lapangan Terbang Baru Tioman Perlu Difikirkan Semula 027 Now or Never for Malaysian Coral Reefs

028 Where Are All the Sabah Pigs? 030 The True Value of Limestone 031 Lessons Learned from #Hutanpergimana 032 An End to the Culture of Eating Turtle Eggs 033 City Farms Growing Resilience

034 Heath Soil is Far from Basic

035 Translations 037 Radio & Social Media 038 Engagements & Awards 040 Looking Ahead

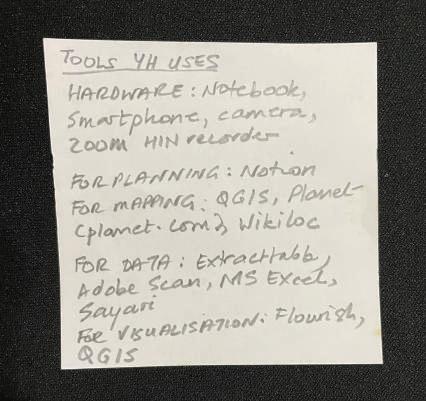

Welcome to our first Annual. We figure this is a good way to encapsulate all we did in the past year and encourage you to re-read (or read) our stories. Here, we present each story from 2022 in one or two visuals, a summary, and links so you can go to the full stories or listen to podcasts.

Some highlights (though we love and value every single one of our stories):

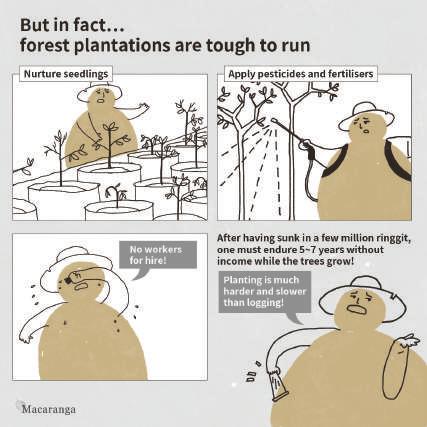

Following from our first series on drivers of deforestation in 2021, we dived into another key driver this year: forest plantations. Most - if not all - of these monoculture estates have been approved in forest reserves. But Yao Hua found that developers have cleared twice more the area than they have replanted; meanwhile, existing projects are poorly managed (p6).

Yao Hua also flagged anomalies in other deforestation projects. One had cleared forest before submitting its Environmental Impact Assessment report (p12), and another wants to convert forest for oil palm when the oil palm cannot be certified for sale (p20).

We also embarked on an ambitious Special Project which comprised training, mentoring

YEAR 2022

and producing 3 stories in 3 languages by 3 writers and as many editors, our largest team ever (p18).

In an election year, series editor Siew Lyn wanted to prompt a rethink of tanah air. As Malaysians, we are bound to land and water in so many ways: as a nation and citizens, through the actual and imaginative, the collective and the personal.

The series looks at food security and the climate crisis; reclamations and ecosystems; and small island pollution as the proverbial tip of the waste iceberg.

Among our firsts this year, we finally covered a Sarawak story, on the migratory bird haven of Bako-Buntal Bay (p8); we featured our first video interviews in an article (by a Sprouts new journalist, no less) (p30); and we produced our first animation condensing a story point, for our social media.

Collaborations are important to provide readers with the rich and varied perspectives needed for complex issues.

This year, we are pleased to have collaborated with Taiwan’s Commonwealth Magazine on the climate crisis and water (p10), and with Earth Journalism Network (Asia-Pacific) on meat consumption and One Health (p16). In conjunction with the Climate COP27, the Guardian UK invited us to co-publish a 30-newsroom global joint editorial on the urgency for climate action.

Our stories, either in full or abridged, were republished in Al Jazeera, Oriental Daily, Sin Chew Daily, and South China Morning Post.

We remain passionate about and committed to training and mentoring environmental journalists. From pages 30—34, we highlight the pieces painstakingly produced by our Sprouts new journalists. Read what they say about their own stories.

We also believe in creating a groundswell of environmental journalism. We therefore conducted lots of environmental media training for working journalists this year, with Siew Lyn leading 2 multi-day workshops, and a several-month long climate mentorship.

So, all this and much more in the following pages. We hope you enjoy the Annual!

Siew Lyn and Yao Hua READ

Hyperlink Glossary Tell us what you think of the Macaranga Annual 2022!

Radio interview TV interview Also appeared in Webinar Training Story link

Macaranga Annual 2022

Areas in forest reserves approved for forest plantations are clearfelled to be replanted with fast-growing trees. While approvals to clear sped up in Peninsular Malaysia, replanting slowed.

Cumulative change in area (hectare): 200,000

Forest plantations are meant to provide a reliable source of wood and reduce the need to log natural forests. They are essentially farms that grow one species of trees cut for timber every 7—15 years.

But in Peninsular Malaysia, forest plantations have fuelled forest loss, destroyed biodiversity and wrecked Orang Asli lives. And despite hundreds of millions of ringgit invested, neither planters nor regulators can guarantee timber supply.

Between 2012—2020, developers cleared 185,413 ha inside forest reserves to be turned into forest plantations. But more than two-thirds of that have not been replanted. Worse, some developers bagged profits from logging and then abandoned the land. The problem is most obvious in Kelantan, but Pahang is emerging as a bigger concern.

Abdul Khalim Abu Samah, the then Kelantan state forestry director said: “When we started in 2006, 2007, we had no SOP (standard operating procedures) to check if [the applicants] were interested in logging or planting.”

So, were forest plantations used as an excuse to clear-fell forest reserves? Abdul Khalim replied with a grunt: “Yes.”

BFM89.9 Radio Earth Matters

Macaranga webinar

South China Morning Post, Al-Jazeera

Migratory bird numbers have been plunging everywhere – but not in Sarawak’s beautiful Bako-Buntal Bay. There, numbers have been stable or increasing.

Bako-Buntal Bay is Malaysia’s only site on the long-distance East Asian–Australasian Flyway, which supports more species of bird than any of the world’s other major flyways. It is also the most threatened by land reclamation and degradation.

Maintaining and protecting this special coastal wetland is critical for the country and the world, say the citizen scientists who have been monitoring birds there for 22 years.

“The birds depend on a bunch of sites as they move from one point to the other point. If one very important site is badly impacted then downstream (sites) will be affected to some extent.” – Dr Yong Ding Li, Asia-Pacific regional flyway coordinator for BirdLife International

Tangshan, China

Yalujiang, China

Chongming Island, China

Kamchatka, Russia

Hong Kong, China

IMPORTANT WETLANDS FOR MIGRATORY SHOREBIRDS LINKED TO BAKO-BUNTAL BAY

Bako-Buntal Bay

80 Mile Beach, Australia

In collaboration with China Dialogue

Sources: Batrisyia Teepol/MNS and Yong Ding Li/Birdlife International

When Birds Flock to a Bornean Bay Hyperlinks Malaysiakini, Sin Chew Daily

Checking on the growth of corals on a floating nursery, Pulau Lang Tengah.

by Mok Man Ying

by Mok Man Ying

“I had to change my mind. I had to realise that now, coral restoration or coral rehabilitation was one of the only ways that we can save our coral reefs. Because if we don’t buck up and find out the best way, what chance do our reefs have?”

– Affendi Yang Amri, coral reef ecologist

Coral reefs worldwide are in big trouble. By 2030, global warming might kill up to 90% of coral reefs in tropical seas, scientists warn. Already, coral reefs are suffering more frequent bouts of bleaching.

These are events where corals stressed by prolonged heat spikes eject their internal algae partners. Without the colourful and food-producing algae, the corals turn white, starve, then die.

In response, scientists scramble to grow corals and restore reefs. Even those who had preferred to protect the remaining corals and dismissed restoration as a defeatist approach, are slogging to find the best ways to grow corals.

AA Sawit’s EIA report was published for public feedback in July, but before that, the company had already planted oil palm.

Photo by Law Yao Hua

by Law Yao Hua

Photo by Law Yao Hua

by Law Yao Hua

Projects in forests can start only with an approved environmental impact assessment (EIA) report. But in Johor, AA Sawit Sdn Bhd started cutting forest for a plantation two years before it submitted an EIA report.

The project sits on a 3,775 ha site in Endau, owned by one of the company’s shareholders, the Sultan of Johor. Satellite images show that in 2020–2021, the company had cleared more than 600 ha of forests there and dug kilometres of irrigation drains.

The company’s EIA report was published in July for public feedback. By then, AA Sawit had already planted oil palm on the site.

The forest used to house elephants, barking deer, gibbons, and hornbills, locals said. Forest loss had led to violent conflict between elephants and villagers, river pollution, and floods.

Macaranga’s report prompted the federal Department of Environment to investigate the project. Results of the investigation have not been disclosed.

“It shows how EIAs are too often an afterthought…A box to tick after the project has already been approved…The question should be directed to the state and local authorities: why did they allow logging to commence without an EIA?” – Lim Teckwyn, forestry consultant

In collaboration with Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network Hyperlinks READ

→ Drains Dug, Trees Cut; Now Let’s Get it Approved

→ Between Floods, Elephants, and Jobs

BFM89.9 Radio Earth Matters

South China Morning Post

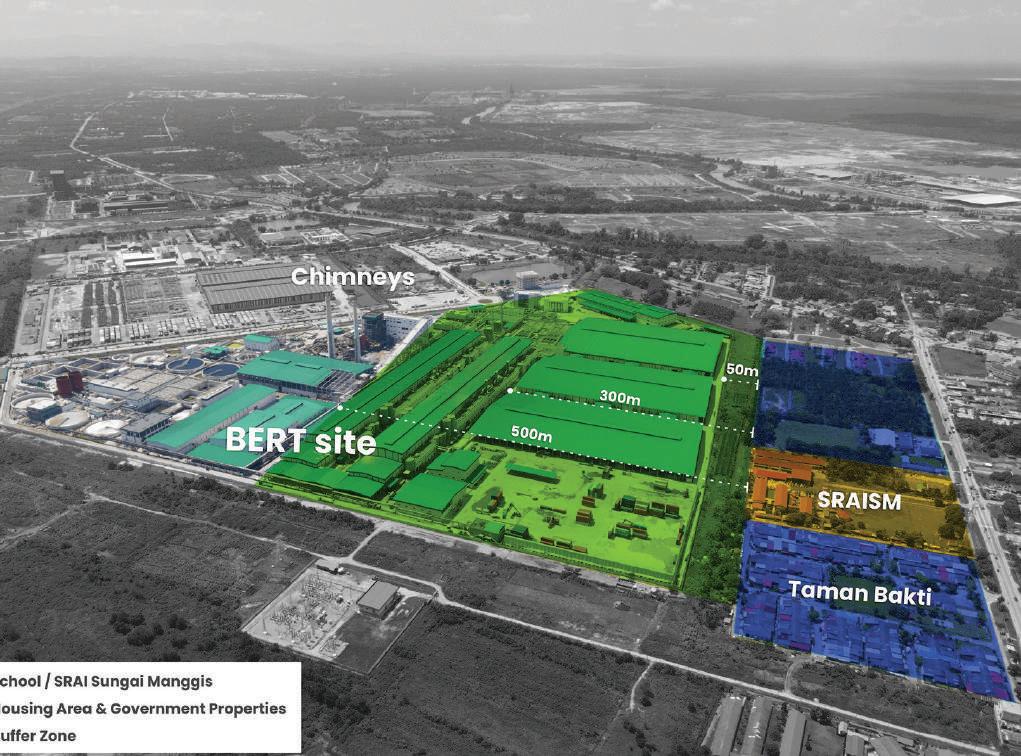

The BERT facility is as close as 50 metres to schools and houses, though the pollution-emitting chimneys are 500 metres away. Residents argue that the facility violates the municipal local plan’s buffer zone condition of 500 metres. Image by Long Long

“We work so hard on the BERT case because what happens here will set an example for other communities. Our documents may be used as a reference. That’s what we hope for. People must understand that we have the right to live peacefully and get clean water and air. If we don’t do anything now, [the] same issue will happen on a larger scale later.” – Suhaizam Mohd Kassim, Klang resident protesting the BERT facility

Klang is on the cusp of becoming a paper recycling hub. While that would mean billions of ringgit in foreign investment, the potential health and environmental impacts are worrying some residents.

One such facility in Klang is owned by Best Eternity Recycle Technology Sdn Bhd (BERT) and, ultimately, by a Hong Kong-listed company. It imports more than 1.7 million tons of waste paper every year. These materials contain metal, plastics, and debris that cannot be recycled.

Residents contest that the facility violates various rules, including buffer and environmental impact assessment conditions. These complaints have led the authorities to penalise the facility. But operations are expanding.

Environmentalists argue that recyclers are importing waste disguised as waste paper and dumping it in the country. They question if Malaysia can enforce the strict policies needed to minimise pollution from paper recycling facilities.

by SL Wong

by SL Wong

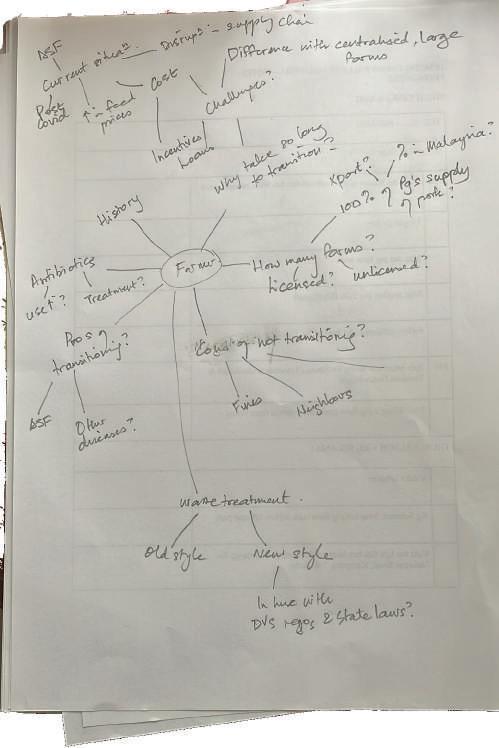

Stench clogs the nose, sludge fills canals, and green algae blooms in stagnant water. Penang’s small, traditional pig farms are notorious for polluting rivers. But the state is finally mandating its farms modernise or shut down.

Still, pig farms might not be the only, or main polluters along whole river systems. It is unclear if modernisation will bring relief to the ecosystem and impacted communities.

Moreover, modernisation is expensive. Large, closed-house farm systems with zero discharge and biosecurity measures cost millions to set up. Farmers have no access to loans. Meanwhile, feed prices have escalated and the deadly African Swine Fever threatens entire farms. To modernise, both farmers and consumers are paying the price.

The Department of Environment says “polluted rivers can be rehabilitated, provided a holistic approach is applied. This includes implementing laws and regulations, enforcement and monitoring, awareness raising among farmers and the public, and implementing waste disposal solutions such as waste-to-energy biogas systems.”

In collaboration with Earth Journalism Network’s “More Than Meats the Eye” project on One Health and meat in the Asia Pacific

→ When Laws Put the Brakes on Pig Farm Pollution

→ Costs Rise For All to Green Pig Farms

#MoreThanMeatsTheEye: Collaborative Journalism in Action

This Macaranga Special Project looks at tanahair. While literally land and water, tanahair is also love of country, connection, identity as regards our ‘tanah’ and ‘air’ and each other as citizens, community and nation.

We use #Tanahair to look at 3 key environmental issues, not definitively but rather, a gateway to questions about governance, drivers and solutions for Malaysia’s many issues.

Rice is every Malaysian’s staple food but extreme heat, heavy winds and floods due to the climate crisis are affecting rice production and stressing paddy farmers. (Climate Crisis Stirring a Storm in a Rice Bowl

By Lee Kwai Han)

By Lee Kwai Han)

Inland deforestation is often seen as the biggest threat to Malaysia’s ecosystems but land reclamation is quietly destroying critical coastal mosaics of land and water.

(Reclamations Gateway to Ecological Disaster By Ashley Yeong)

Islands are creaking under the weight of mismanaged rubbish, a snapshot of Malaysia as her pollution grows unwieldy due to lack of funding, infrastructure and space. (Trashed Islands a Snapshot of Polluted Malaysia By Ushar Daniele)

Macaranga inhouse training

BFM89.9 Radio Earth Matters

Astro Awani Consider This

by Law Yao Hua

by Law Yao Hua

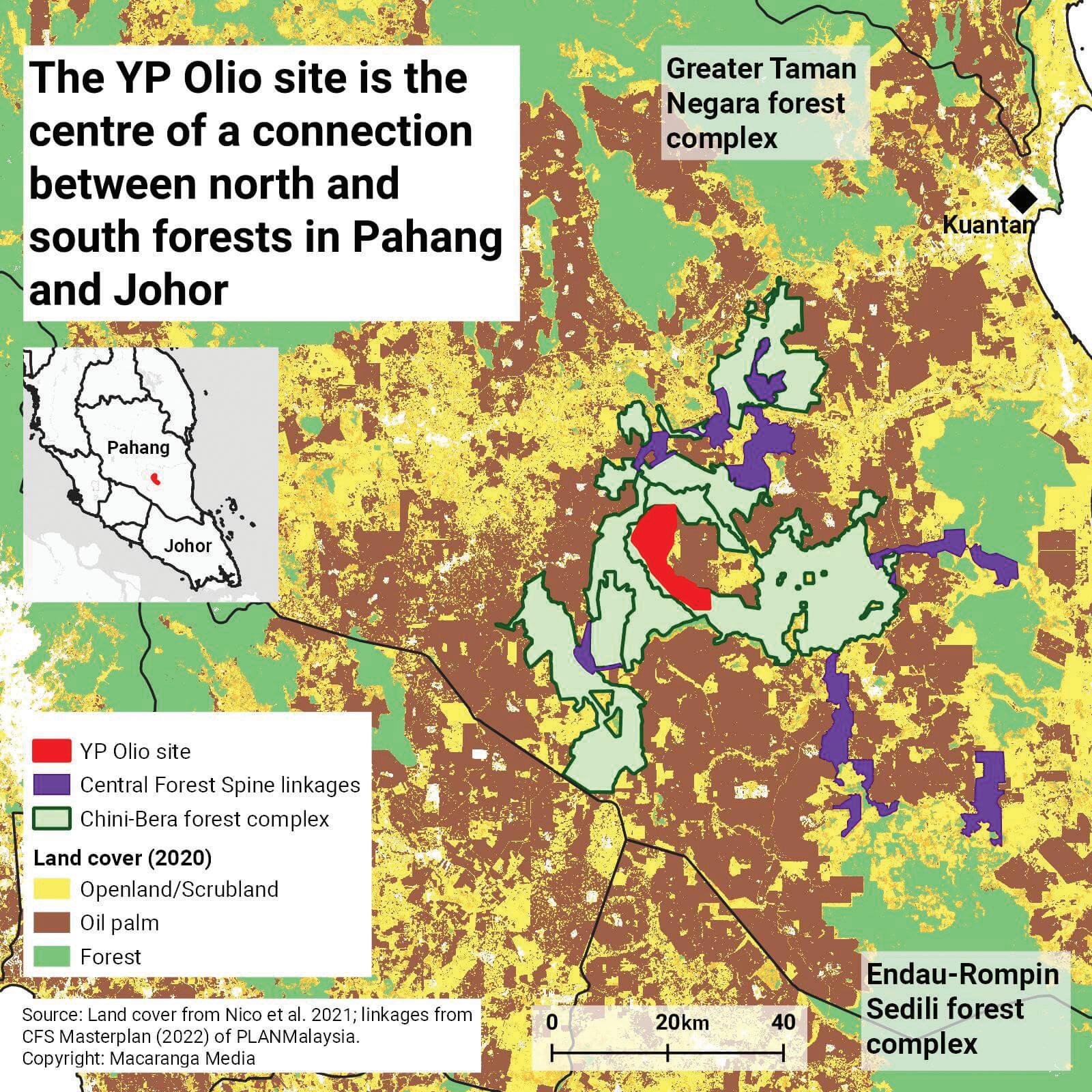

We highlighted yet another project approved by the authorities despite questionable merits. The developer, YP Olio Sdn Bhd, wants to grow oil palm on a 8,500 ha site in Rompin, Pahang. The project would remove a key piece of the Central Forest Spine network of forests across the peninsula.

Last year, YP Olio’s environmental impact assessment report was rejected, partially because Macaranga revealed that the locals were allegedly

misled by the company into signing consent letters. But in September, the Department of Environment approved the project.

The point is, the oil palm plantation has no future. That is because the mandatory Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification standard prohibits clearing forests after 2019. In effect, palm oil harvested from YP Olio’s site cannot be sold.

What need is there to clear the rest of the forest?

The YP Olio project “is a classic example of the lack of awareness by decision makers and agencies on the Central Forest Spine Masterplan.”

– Christine Fletcher, forestry consultant

Speeding trucks, washedup turtles, disrupted water supply, and inadequate consultation – those were some of the complaints lodged against a 400ha sand mining operation in Bangau Beach, Kudat, Sabah. Concerned villagers want the state government to stop the project.

“Don’t get us wrong,” says Mohd Khair Abdullah, local villager and Save Bangau Beach committee member. “We welcome development in our village with open arms, for example if any companies want to develop our tourism. But not development that will harm the environment and our lives.”

From declaring a climate emergency to stopping deforestation, different groups demanded that political candidates and parties in the 15th General Election (GE15) include environmental and climate commitments in their manifestos.

Macaranga put together a resource page of these demands and campaigns by CSO/NGOs. These included Gabungan

Darurat Iklim Malaysia, Gabungan Bertindak Malaysia/CSO Platform for Reform and Greenpeace, as well as senior conservation scientists.

We also plucked out the green components of political coalitions’ manifestos, as well as templates for voters to lobby their respective candidates.

Over two years, a scientist took over 2,000 drone photos of limestone hills in Peninsular Malaysia. The stories they tell are fascinating. [Text by SL Wong. Images by Foon Junn Kitt/ ‘Conservation of Limestone Ecosystems of Malaysia’ (2021)]

Stories told through powerful images and captions

In Pitas, Sabah, a mega shrimp farm shut down during the pandemic. That, after having cleared more than 900 ha of mangroves. But nearby villagers are taking it upon themselves to restore the damaged mangroves and fight to protect what forests remain. [Text and portraits of villagers by Chen Yih Wen, with support from the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Journalism Fund]

→ Landscapes in Limestone

→ Pitas Villagers Restoring Mangroves Destroyed by Failed Shrimp Farm

Curated commentaries by experts on the ground

Suhami Awang, a local anak jati Tioman pens our first commentary in Bahasa Malaysia. It is about the proposed enlarged airport on the Pahang island: “Sekiranya lapangan terbang ini dijayakan, industri pelancongan di Pulau Tioman akan mati dengan serta-merta.”

Sebastian Szereday is a marine ecologist whose nonprofit organisation Coralku focuses on resilience-based management and restoration of coral reefs. “Climate change has become the grim reaper of coral reefs.”

→ Lapangan Terbang Baru Tioman Perlu Difikirkan Semula

→ Now Or Never For Malaysian Coral Reefs

Mentorship is an integral part of Macaranga. Our Sprouts programme for new journalists comprises media training and mentorship to produce environmental articles. In two years, the programme has produced 15 Sprouts and 16 stories.

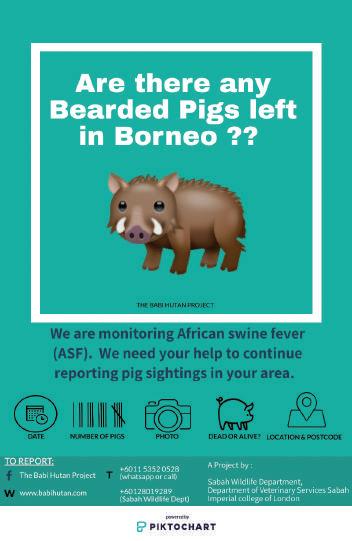

Above: Catch me if you can: the last remaining babi kampung in Kampung Pangasaan, Sabah (Photo by: Alven Chang). Above, right: Scientists crowd-sourced to determine how badly hit wild pigs were (Poster by Babi Hutan Project Borneo)

African Swine Fever (ASF) hit wild pigs in Sabah in December 2020. Over a year later, 20 of Sabah’s 23 districts had been declared outbreak districts. ASF can decimate up to 95% of pig populations.

While actual numbers were hard to confirm, scientists were concerned about the impact to forests, should wild Bornean Bearded pigs be decimated. The animals are important for forest regeneration and they shape tree diversity too.

Meanwhile, Kadazandusun communities have also been affected; pigs are key to traditional hunting, ceremonies and feasts. Moreover, local backyard farmers lost supplementary incomes when ASF wiped out their babi kampung, a hybrid of wild and commercial pigs.

Hyperlinks

→ Where Are All The Sabah Pigs?

Supported by the European Union in the form of a grant from Internews Malaysia. Kymberley Chu also received training under the Macaranga Sprouts programme. BFM89.9 Radio

→ Locals Feeling Loss of Wild Pigs

From ancient elephant fossils to unique biodiversity and tourism, limestone hills are valuable in multiple ways. However, in actual ringgit and sen, extracting limestone for cement earned the major cement producing state of Perak RM457.5 mil in 2020, and the major cement conglomerate Malayan Cement, RM2 bil in revenue a year (2016, 2017 and 2018).

This feeds the hungry cement consumer that is Malaysia, with its outsized cement consumption of 600 kg per capita, higher than the US. But conservationists argue in favour of biodiversity and ecosystem services, cultural and historical heritage as well as religious and spiritual purposes.

Natasha: “I learned that good stories are those with different voices being heard and stitched together with accurate facts & passion for the environment. One thing I wish to highlight about my story is that the

actual value of limestone is dependent on one’s priorities – either cashing in 0.6% of a state’s GDP that is finite or unleashing opportunities that are more infinite…”

This story examined how environmental NGOs banded and drove public discourse to save the degazetted Kuala Langat North Forest Reserve in Selangor from development. The Malaysian public almost always has no say over that one thing that covers one-third of their country – forest reserves.

Undeterred, a coalition of environmental NGOs and activists carried out an extended #HutanPergiMana campaign. They debunked misinformation put out by the government, using different messaging platforms and tools. Because they came together across generations, they reached out to different audiences. They also strategically targeted politicians.

Over a year later, the state decided to regazette the forest reserve.

Michelle: “The experience of writing this story on PHSKLU has taught me to write economically and think objectively. My biggest lesson learned was the urgency of publishing stories. As a rookie

journalist, I was too focused and nervous about getting the first draft right. I hope that my story highlighted the potential and power of activism in Malaysia.”

This is a follow-up story on the announcement of the June 1 ban on commercial sales of turtle eggs in Terengganu. It dived into whether culture would derail the ban. Not banning consumption of the eggs safeguards culture, say conservationists. And coupled with tourism overtaking turtle egg sales as a source of livelihood, locals increasingly appreciate the value of turtle conservation.

This is the first time video interviews feature in a Macaranga article.

Bryan: “Through Sprouts, I experienced first-hand the competition with mainstream media that freelancers face to publish stories on a time-sensitive topic. I also understood the challenges of

unbiased writing covering turtle egg trade in Terengganu. Siew Lyn and Yao Hua taught me well on planning, storyboarding, and reporting for my first official journalist assignments.”

With food prices ever increasing, community farming for food security among lower income city-dwellers is ever more critical. But many attempts have failed.

However, among Kuala Lumpur’s 63 public housing schemes, 3 are impressive models of success. This is largely thanks to farming champions within residents’ associations as well as KL City Hall who run this programme.

At Seri Perlis 2A, farming efforts now feed the 40 resident farmers, have extra to sell at the coop and local pasar malam, and boast tech like a self-watering system, dehydrating machine to produce dried food, and a fertigation system for irrigation.

Kai Ren: “Getting to know the personal stories of the different farmers in the public housing was the most important experience… All of them volunteered their personal time and for some, money,

to contribute to this communal effort. They have built their own support system and an extended community by helping each other through knowledge sharing.”

Mei Mei: “Having trekked in heath forests, I find the ecosystem fascinating. However, translating that into a story is not easy as the information

The sandy, acidic soil of heath forests make it difficult for plants to grow, but that in turn, means a huge role for decomposers like bacteria and mushrooms. These organisms break down organic materials on the forest floor, releasing nutrients which plant roots eagerly absorb.

Hyperlinks

READ

Heath soil is far from basic

and conversation about heath forests are limited. I have learnt that finding the right experts is important to present reliable and interesting perspectives.”

To have our stories reach as wide a readership as possible, they are translated whenever the budget permits. Our core translators are Adriana Nordin Manan and Mun Yee San.

→ Penduduk Pitas Memulih Bakau yang Dimusnah Kolam Udang Gagal → Pulau Sampah Petanda Malaysia Tercemar

Reklamasi: Gerbang kepada Bencana Ekologi

Krisis Iklim Menyebabkan Porak Peranda dalam Periuk Nasi → Tiga Cerita Tentang Tanah dan Air → Lagi Satu Ladang Kelapa Sawit di Endau, Johor

Tebang, Tarah, Tebas: Perginya Hutan Besar

This is an Ecosystems story. This section features the various ecosystems in Malaysia, from mangroves to limestone. The stories are of the natural living and non-living components, including human ones. Presented in text, voice and photos, guided by the experience of those who know it well.

Macaranga has a regular segment on ‘Earth Matters’ with Juliet Jacobs on BFM89.9 Radio. It is a 20-minute discussion of key environmental news and issues in Malaysia at the end of each month. December sees a review of the year that was. All podcasts are available on our blog and on www.bfm.my

Tune in every last Monday of the month at 3.30pm on BFM89.9 Radio or www.bfm.my.

We use comic panels to tell our deforestation stories on social media, and ventured this year into short animation.

Follow and engage with us on Twitter and Facebook.

Macaranga Annual 2022

Macaranga Annual 2022

Macaranga turns 4 next year, in 2023. We have worked hard, and our reporting has generated more responses, reach, and impact than we had expected.

This is heartening, but there is still much we need to do to get onto firmer footing. We are relooking at our direction, working on strengthening our finances, exploring partnerships and revamping our website. And we want to hear your thoughts more than ever.

But do not worry that the above commitments will distract us from Macaranga’s core purpose: in-depth, insightful, and accurate reporting.

Already, we have several major projects confirmed and in development. We will report the findings of our investigation into the huge difference – several hundred thousands of hectares –between satellites’ and government records of forest loss.

We also go beyond forests. Look out for our series of multimedia stories on how Malaysia manages our seas, coasts, and all the interdependent lives and livelihoods.

At the same time, Macaranga will continue to train environment journalists, current and new. We realise that while funding is challenging, the bigger gap here is the talent and skill pool. And we can help to fill that gap.

We hope 2023 will be transformational for Macaranga. Thank you for standing by us, and here’s to another year of great stories!

Tell us what you think of the Macaranga Annual 2022!

Macaranga Annual 2022

Published by Macaranga Media Sdn Bhd., Kuala Lumpur, 2022 Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Editorial: SL Wong & Law Yao Hua

Design and layout: Sharon Yap macaranga.org editorial@macaranga.org @macarangatweets @macaranga.org

Macaranga Annual 2022