15 minute read

2020-2021 Paideia Texts and Issues Lecture Series: Building Community in a Changing Society

from Agora Spring 2021

Amish Genetic Health Needs and an Innovative Community Response

by ANGELA KUENY, Associate Professor of Nursing; PHILIP IVERSEN, Associate Professor of Mathematics; and LEE ZOOK, Associate Professor Emeritus of Social Work

This year’s Paideia Text & Issues Series, entitled Building Community in a Changing Society, inspired us to submit a presentation and article summarizing our work with Amish and Mennonite (jointly referred to as the “Plain Population”) communities across Minnesota and Iowa. This series asks, “What can we learn from the past and the present about different ways that communities survive, adapt, and flourish in periods of drastic change?” Given the very high risk for serious and sometimes lethal genetic conditions, Amish and Mennonite families innovatively collaborated with health care providers to provide community-based treatments that allow them to survive and flourish. We have much to learn from this work. This presentation and article follow Angela Kueny’s sabbatical project described in a previous Agora article, “A Different View of Health Advocacy in Amish Country” (Kueny, 2020). The purpose of this article is to describe our work in assessing the genetic health needs of Amish families in Iowa, and situate these findings within a national clinic initiative to address genetic needs in Amish populations. Background: Amish Genetic Condi-

tions

Dr. Holmes Morton writes in his essay “Through My Window” from the Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania:

I have also watched the sun rise over the field in all seasons after long worried nights at work because of a sick child. I especially like to watch Jake Stoltzfoos or his son-in-law work in the field with a team of mules. Jake and Sam plow, plant, and harvest with four small red mules. You may think, such a contrast, the work of a doctor, analytical chemistry, biochemistry, efforts to understand how an inherited disorder injures the brain of an infant, all within 100 feet of an Amishman’s fieldwork with mules. Such contrast, you say. Yes, I say, but these people and their way of life have much to teach us. (Morton, 2012) Only through understanding Amish social and historical underpinnings does it become more clear how complex the health care concerns, networks, and decisions for children with genetic illnesses are. The Amish religious community has roots in the Anabaptist tradition that continues to grow in population size across 31 of the United States and four Canadian provinces (Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, 2020). Amish families typically reside in rural settlements, geographically and culturally separate from the dominant culture. The core tenets of the Amish religion limit the use of technology, automobiles, public telephones, or indoor plumbing in order to maintain self-reliance and prevent dependency on public utilities (Kraybill et al., 2013). A particular concern in the Plain communities are genetic conditions that necessitate family outreach to biomedical health services. Plain populations experience a heightened risk for genetic illnesses because of historical practices of marrying within their tight-knit religious groups, large family sizes, and founder genetic illnesses within members. Genetic illnesses are widely varied and extensive from settlement to settlement, many of which are life limiting without early intervention (Payne et al., 2006). The result of these genetic conditions for years was the loss of too many children. In a community that does not ascribe to public or private health insurance and lives remotely to any genetic specialist (Kraybill et al., 2013), a significant challenge is to make the connection between these families and life-saving health care.

Amish Clinic Model and the Ethics of Care

Dr. Holmes Morton, the physician who founded the Clinic for Special Children in 1989 and now the Central Pennsylvania Clinic in 2015, inspired a network of clinics to address the health care needs of Plain families with genetic illnesses. It is timely to highlight the significance of his work as he was recently the recipient of the 2020 Pennsylvania Pediatrician of the Year award (PCAAP, 2021). The Plain Population clinic model is described in more length in Kueny (2020). In this article we will

Angela Kueny, Philip Iversen, and Lee Zook

draw upon Dr. Morton’s from the families in his inspiring work to situate practice. our work in assessing the needs of the local Iowa and Minnesota Plain communities toward establishing a possible local clinic to serve the needs of families who have children with genetic illnesses. To set the stage, the extended family is gathered in the bedroom where the young boy died, and Morton is there in the bedroom with them. The adults are sitting shoulder to shoulder on chairs Dr. Morton’s ethical around the bed and the stance is clear, and is young boy’s siblings are written clearly in one at the foot of the bed of his early reflections, where the deceased is “Death and Life” (Mor- lying. Morton reflects: ton, 2012, p. 11): Special children hope to suffer less and lead fulfilled lives through the help of others. Within their families and communities they are not merely the object of compassion and love but often are the very source. Such children IMAGE COURTESY OF SARAH MCRAE MORTON I talked about how difficult it is to care for children who have illnesses that are not understood and cannot yet be treated. I said that as a doctor and scientist when each new therapy fails I must somehow renew my efforts to learn more. Then the boy’s shape the Amish and Of Kings and Fishers by Dr. Morton’s daughter Sarah McRae Morton grandfather spoke. As

Mennonite cultures he spoke he smiled and and inspire work such as that clinics it seemed that both are informed looked first at me then the chilat the Clinic in important and by the ethics of care (EoC). EoC is an dren on the bed. He said, “We will forceful ways. We should not ethical framework formulated by Carol be glad if you can learn to help underestimate the value of their Gilligan (1982), who contends that these children but such children lives, however brief or however empathy and compassion, which are will always be with us. They are difficult. We should not assume not addressed in many ethical theories, God’s gifts. They are important to that the Plain cultures, or our are essential aspects of moral decision all of us. Special children teach a own cultures, would be better making, and that reasoning without family to love. They teach a family without them. these characteristics comes up short. how to help others and how to

These special children are not just interesting medical problems, subjects of grants and research. Nor should they be called burdens to their families and comWhile Gilligan emphasized that women portray these characteristics more than men, subsequent authors seemed to find her work important regardless of gender (Tronto, 1987). accept the help of others.” (The Death of Enos Fisher, Morton, 2012, p. 10, 11). Elsewhere in his writings Morton refers various times to William Carlos munities. They are children who The ethics of care seem to be part and Williams, a physician and writer who need our help and, if we allow parcel of Morton’s work and writings. In lived in the early part of the twentieth them to, they will teach us com- the first essay in Roads Taken, Morton century. Williams also seemed to have a passion. They are children who describes his visit to an Amish house- keen understanding of the culture where need our help, if we allow them hold where the extended family had his patients lived. Williams (1967) to, they will teach us to love. If gathered to grieve the loss of the young wrote, “We catch a glimpse of somewe come to know these children, boy Morton had been treating. In that thing, from time to time, which shows as we should, they will make us essay Morton shows his understanding us that a presence has just brushed past better scientists, better physicians, of the culture as well as his empathy and us, some rare thing ... For a moment we and thoughtful people. compassion for the families and individ- are dazzled.” As we learned more of Morton’s work and writing and the work of the genetic uals who are his patients. He refers to children with genetic illnesses as “special children,” a term apparently borrowed Additionally, the clinics that have come about because of Morton’s work operate

on a different basis than Other contacts were made typical medical clinics. with Amish bishops using They are non-profit entities Raber’s Almanac which is and their boards of direc- found in many Amish homes tors have at least 50% of (Raber, 2020). Typical of their members from Plain information found in almapopulations that they serve. nacs, this almanac lists all the The Plain populations they Amish bishops, ministers, and serve are important in the deacons in the Old Order initiation and ongoing Amish settlements across the operation of the clinics and United States and Canada by in formulating policy about state, county, and church dishow they operate. trict. In addition to the names In summary, it appears that empathy and compassion inform Morton’s work and the work of the clinics. Further, Morton (2012) says that special children have been his most important teachers and that, “The secret of caring for the patient is in caring for the patient. Caring is the important work of a Doctor” (p. 93). Method of Gathering Data To assess the genetic health needs of Amish families, IMAGE COURTESY OF SARAH MCRAE MORTON of individuals, their birthdates and the dates of ordination are listed. Thus we were able to identify the eldest of the elders in a given settlement; usually this is the individual who convenes the group of bishops in a settlement. Typically, when first contacting a bishop in a given settlement and after explaining our intentions to do a health needs assessment focused on genetic issues to see if a clinic might be established, the response of the bishop was that he would take the matter data gathering was accom- Ruthie’s Prayer by Sarah McRae Morton up with his fellow bishops in plished by adapting a survey that particular settlement and used by the WeCare Clinic, a recently Iowa Amish population. The number they would together decide whether established genetic clinic in Kentucky of surveys returned in Minnesota is to assist in the endeavor. In 10 of 15 serving Amish and Mennonite families much smaller and not included in this settlements where we contacted bishops with genetic disorders (Hunt et al., report. We extrapolated the number face to face the answer came back in the 2018). The survey asked families to list of individuals from household data affirmative; five settlements declined. members with diagnosed and undiag- in consultation with Professor Joseph It should also be noted that surveys nosed genetic disorders, undiagnosed Donnermeyer, an expert in Amish were distributed to several conservamedical disorders, and deaths in the Population studies at The Ohio State tive Mennonite churches in Iowa; these household. Our survey was intended to University (Personal communication, were either Old Order Mennonites or reach as many of the Amish and Plain January 25, 2021). Holdeman Mennonites. Mennonites in Iowa and Minnesota as possible. As of June 2020, the estimated population of Amish in Iowa was 9,780, in Minnesota 4,740 (Young Center, 2020). The population of Plain Mennonites is unknown, though we know there are fewer than 1,000 Old Order Mennonites in Iowa (Young Center, 2020). The first several contacts with settlements were made through personal acquaintances with Amish elders, or bishops, in several of the larger settlements. Additionally, those first contacts provided names of specific bishops in other settlements they suggested should be contacted. In this manner trust was established as the process unfolded. It How the surveys would be distributed to the households was left up to the bishops; most were distributed after Sunday services, returned to a central location, and then mailed to the research team. In Iowa, an overall return rate of those surveyed where face to face contacts were established was 54%. Surveys were completed by an indiAt this point we have surveyed 554 was thought that involving the bishops vidual for each household; all surveys households which represent an es- in the early discussion of completing were voluntary. Human Subjects Review timated 3,324 individuals. Of those the survey was important as they are the Board approval from Luther College households, 436 households, represent- “chief authority” of the church district was obtained for each settlement where ing an estimated 2733 individuals, are (Hostetler, 1993). Furthermore, they we had face-to-face contacts. Amish living in Iowa, about 28% of the gave valuable feedback about how to proceed in a variety of instances.

By March of 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic was a concern. Therefore, we stopped face to face contacts and sent each bishop who had not been a part of a previously contacted settlement a letter explaining our project. Several bishops responded to these letters and surveys were sent to them for distribution. As of this writing few of those have been returned and none are included in the data discussed below.

Findings

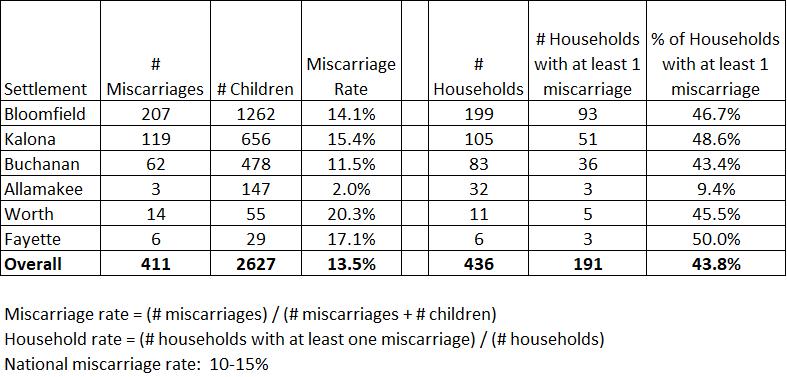

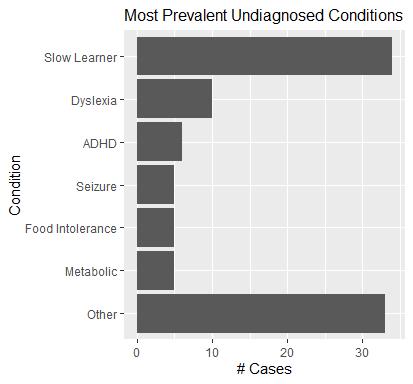

These findings are presented with a few disclaimers. First, the surveys were sent to all households in the participating settlements, but those returned represent a self-selected sample. Therefore, we cannot do any formal statistical inference to generalize these results to these settlement populations or beyond. Our hope is to share these initial results with the settlements and work toward a more complete census in Iowa and Minnesota. Table 1 outlines the Iowa Amish settlements surveyed with genetic disease prevalence. Based on our sample across six settlements, an average of 3.4% of people surveyed were diagnosed with a genetic disease. Although it is tempting to compare this to a national average of individuals living with genetic conditions across the United States, this comparison has little value because of the different genetic conditions within each population sub-set. Figures 1 and 2 outline the most prevalent genetic conditions across settlements. Within the survey, families identified diagnosed genetic conditions and undiagnosed genetic conditions. Outlining the undiagnosed genetic conditions is helpful to understand some of the symptoms that may be underlying genetic conditions which could be diagnosed and treated in the future. It is important to note that “other” categories in the diagnosed and undiagnosed categories represent 17 and 18 different conditions, respectively, signaling the diverse genetic conditions across the settlements. We also explored the rate of miscarriages reported on the form, as that can be representative of complications due to genetic conditions (Table 2). Overall, across the settlements, approximately 43.8% of households reported at least one miscarriage. The miscarriage rate of 13.5% of all pregnancies (ranging from 2.0-20.3%) is reflective of the national miscarriage rate of 10-15% (March of Dimes, 2021).

Conclusion

Working with Amish community leaders, we distributed genetic health needs surveys to Amish settlements across Iowa and Minnesota. The surveys highlight genetic trends within and across settlements, allowing us to discern Amish health needs that will inform the development of an innovative community-based clinic. Dr. Morton’s essays bring to practical life the call for compassion and empathy found in Carol Gilligan’s ethics of care (EoC). These Amish clinics for families with genetic conditions are a community based and collaborative response to increasing medical costs and complexity in the mainstream health care system. It is the hope of this presentation to inspire the audience to consider collaborative community efforts in other underserved communities in response to an everadvancing health care delivery system.

Table 2. Miscarriages

Figure 2

References

Clinic for Special Children (2021).

Retrieved from, https:// clinicforspecialchildren.org/ Cooksey, E. & Donnermeyer, J. (2013) A

Peculiar People Revisited: Demographic

Foundations of the Iowa Amish in the 21st Century. Journal of Amish and Plain

Anabaptist Studies, 1, 110-126. Gilligan, C. (1982) In a different voice.

Harvard University Press. Hostetler (1993) Amish society. The Johns

Hopkins University Press. Hunt, M., Jones, S., Main, M.E., Carter, D.,

Cary, K, & Hall, M. (2018). Genetic medical clinic in Kentucky: A needs assessment of Anabaptist households.

Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist

Studies, 6(2), 159-173. Kraybill, D. B., Johnson-Weiner, K., &

Nolt, S. M. (2013). The Amish. Johns

Hopkins University Press. Kueny, A. (2020) A different view of health advocacy in Amish Country. Agora, 32(2), 20-25. March of Dimes (2021). Miscarriage.

Retrieved from, https:// www.marchofdimes.org/ complications/miscarriage. aspx#:~:text=Miscarriage%20(also%20 called%20early%20pregnancy,15%20 percent)%20end%20in%20miscarriage. Morton, D.H. (2012) Roads Taken:

Recollections, words, and images from meaningful work. Retrieved from, https://www.etown.edu/ centers/young-center/files/hmortonreferences/Roads%20Taken.pdf Morton, D. H., Morton, C. S., Strauss, K.

A., Robinson, D. L., Puffenberger, E.G.,

Hendrickson, C. & Kelley, R. I. (2003).

Pediatric medicine and the genetic disorders of the Amish and Mennonite people of Pennsylvania. American

Journal of Medical Genetics Part C:

Seminars in Medical Genetics, 121C(1), 5-17. Payne, M., Rupar, C. A., Siu, G. M., & Siu,

V. M. (2011). Amish, Mennonite, and

Hutterite Genetic Disorder Database.

Paediatrics & Child Health, 16(3), e23–e24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ pch/16.3.e23 Pennsylvania Chapter of the American

Academy of Pediatrics (PCAAP) (2020). Pediatrician of the Year Award.

Retrieved from: https://www.paaap.org/ recognition.html Raber, A. & Raber, M. (2020). The new

American almanac. Ben J. Raber, Ohio. Strauss, K. A., Puffenberger, E. G., & Morton, D. H. (2012). One community’s effort to control genetic disease. American Journal of Public

Health, 102(7), 1300–1306. https://doi. org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300569 Tronto, J.C. (1987) Beyond gender difference to a theory of care. Signs, 12(4), 644–663. Williams, W.C. (1967) The autobiography of Williams Carlos Williams. New

Directions Publishing Company. Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist

Studies (2020). Amish population, 2020. Retrieved from, https://groups. etown.edu/amishstudies/statistics/ population-2019/. The paintings in this article are courtesy of Dr.

Holmes Morton’s daughter, Sarah McRae

Morton: https://mcraemorton.com/home. html.