23 minute read

How Did We Get Here? Reflections on the Capitol Insurrection Todd Green, Susan Schmidt, and Orçun Selçuk

from Agora Spring 2021

How Did We Get Here? Reflections on the Capitol Insurrection

by TODD GREEN, Associate Professor of Religion; SUSAN SCHMIDT, Assistant Professor of Social Work; ORÇUN SELÇUK, Visiting Professor of Political Science

Introduction

On January 6, 2021, an angry and aggressive mob descended on the US Capitol, spurred on by what media outlets increasingly have labeled “The Big Lie,” or the belief that the presidential election was rigged and ultimately stolen from Donald Trump. Protestors breached Capitol security, violently assaulted Capitol police officers, and penetrated the innermost chambers of the Capitol. Their ostensible purpose was to halt the verification of the electoral college count and to prevent the ratification of Joe Biden’s electoral victory. While the Capitol was eventually cleared of rioters, and while the counting of electoral votes resumed that evening, the end result was not just damage to government property but the loss of life. Five people died in the riots, one a Capitol police officer. Five days after the insurrection, three Luther faculty members—Todd Green (Religion), Susan Schmidt (Social Work), and Orçun Selçuk (Political Science)—participated in a panel discussion hosted by the Center for Ethics and Public Engagement. They addressed a question that permeated media and political discourse in the days following the attacks: How did we as a nation get to this point? What follows are reflections from all three faculty members based on the formal remarks they made on the January 11 panel.

The Violent Attack on the US Capitol was Not an Aberration

Todd Green It is important to recognize that what was on display at the US Capitol on January 6 was not an anomaly or an aberration. Many journalists and politicians have expressed shock and dismay at what happened. A common thread is that this was out of character for the United States. This was not who we are. I have lost count of the number of instances in which media commentators have pointed out that this was something that we would normally see in some other part of the world, such as the Middle East or Latin America. Trump’s authoritarianism, violent mobs, efforts to overturn legitimate elections—these are things we are accustomed to seeing those uncivilized people “over there” doing. But not here. Not in America. Or at least that was the prevailing assumption in public discourse in the days following the insurrection. As Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-California) stated: “It felt like a coup in a third-world country” (Ruhl, 2021). Such commentary is possible only because of a collective failure in this nation to come to terms with the fact that violence and opposition to democracy are also part of who we have been and who we still are as a nation. Far from being out of character, the violent mob at the Capitol was the actualization of beliefs and attitudes that have existed for quite some time in this nation. That applies not just to the past four years but stretches back to before the nation’s founding. We would do well to remember several things as we process and contextualize what happened on January 6. First, we would do well to remember that White Americans’ opposition to full democratic participation and inclusion has existed since the very beginning of this nation’s history. Women, slaves, indigenous peoples, non-propertied men—none of these groups were allowed to hold public office in the earliest chapters of this history. While these groups were eventually enfranchised in the course of history, it wasn’t without opposition – at times, fierce opposition. Even with enfranchisement, efforts to limit or undermine full civic and political participation of all Americans have proliferated. Gerrymandering and voter suppression are just two of many tactics in modern American history employed to exclude groups, particularly communities of color, from having their voices fully heard in the democratic process. We would also do well to remember that violence and hostility from White and White Christian Americans toward racial and religious minorities were integral parts in the formation of this nation. Native American genocide was perpetrated largely by White and White Christian Americans, often in the name of Christianity. Closer to our own time, White Christians have defended segregation and Jim Crow. More recently, from exit polling from 2016 and 2020, we know that more than any other faith

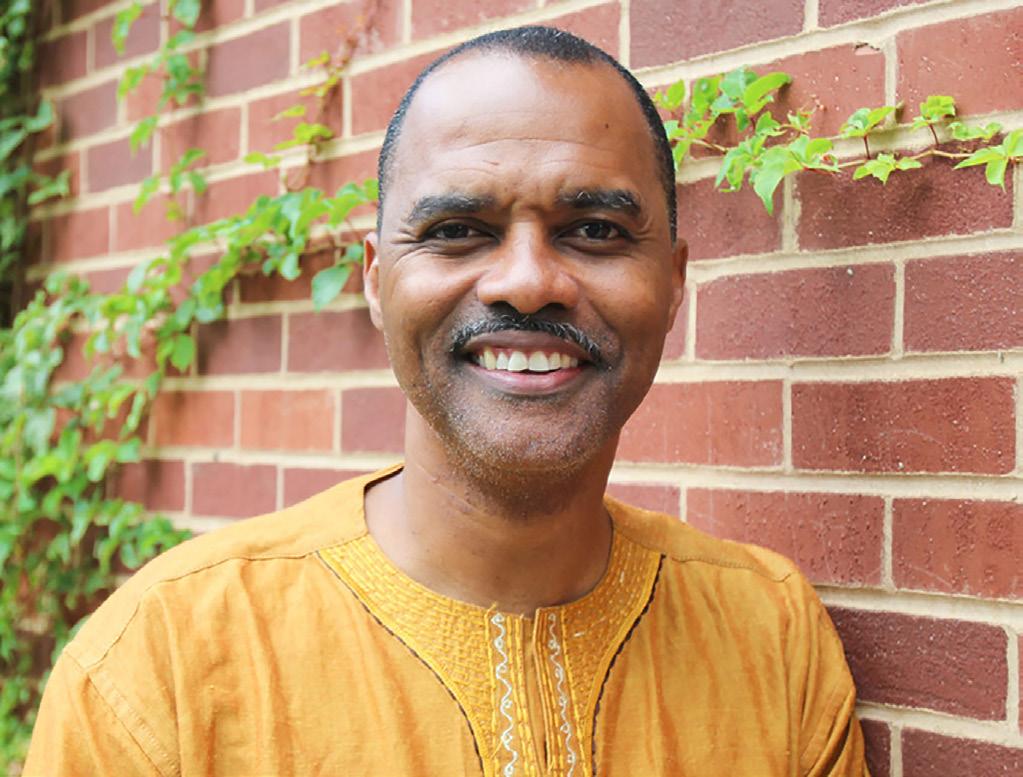

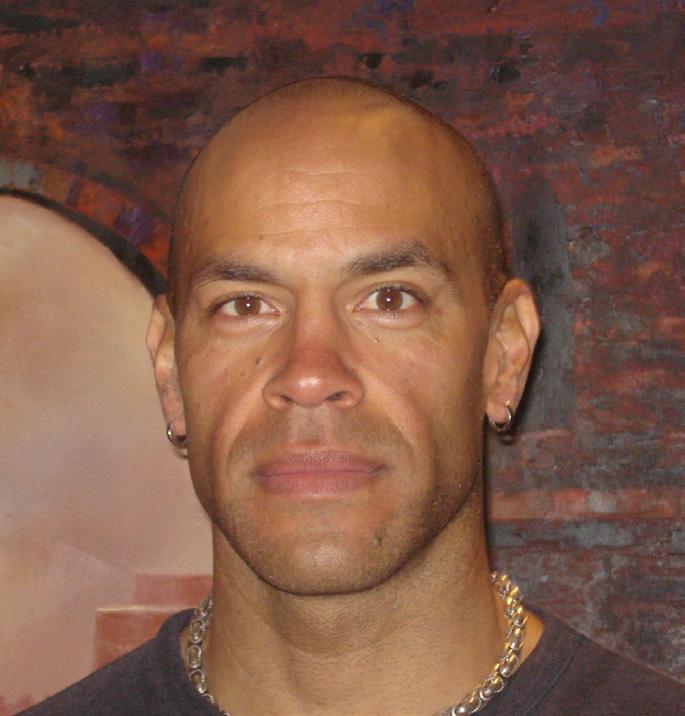

Todd Green, Susan Schmidt, and Orçun Selçuk discuss the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol during a virtual campus gathering on January 13, 2021

US Capitol, January 6, 2021

community, White Christians are the most likely to support President Trump, despite and at times because of his targeting of racial and religious minorities in his rhetoric and policies (Chew, 2020). That support has persisted even as hate crimes targeting Jews, Muslims, and people of color have risen significantly. On January 6, we saw some White Americans appropriating symbols of Christianity and White supremacy as they attacked the Capitol. Signs reading “Jesus Saves” and “God, Guns, and Guts Made America” were on full display. Other rioters yelled: “Shout if you love Jesus!” Alongside of these shouts and signs were Confederate flags. My point is not that the Christians in the mob were representative of the attitudes of all American Christians. My point is that the symbolism and the intertwining of Christian and White supremacist attitudes and rhetoric in the insurrection has a long history in the United States. This didn’t simply materialize in the last four years. It has been part of the effort to build and solidify a White Christian America for centuries. There is a religious context to the insurrection as well as a racial one. We ignore this context and this history at our peril. Finally, we would do well to remember that labeling the Capitol insurrection as a form of “domestic terrorism” itself points to the utter hypocrisy involved in exceptionalizing this violence instead of recognizing that violence by White Americans targeting either the government or other civilians has been commonplace for many years. It’s simply that the word “terrorism” has not been applied in any meaningful way to White American violence. I believe the word “terrorism” has become so racialized, so tied to Muslims, that it has lost any power to describe what extremist White Americans have done or will do in the future. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, right-wing and White supremacist violence accounts for the majority of all terrorist incidents in the United States since 1994. In 2019 alone, right-wing and White supremacist individuals or groups perpetrated two-thirds of terrorist attacks or plots in the United States. (Jones, Doxsee & Harrington, 2020). Yet journalists and politicians have often been reluctant to use the “t” word to describe White violence. The word only seems “natural” when applied to Muslims (Green, 2017). I don’t think the Capitol insurrection will easily reverse or erase any of this. Journalists and politicians should stop patting themselves on the back for calling the insurrection an act of terrorism as if this reflects how enlightened we have become as a nation to the fact that White people can be terrorists too. What’s more, the use of the word “terrorists” to describe the rioters who stormed the Capitol will never lead to racial and religious profiling of White and White Christian Americans, not in the way that the use of this word has led to racial and religious profiling of Muslim Americans. Our nation suffers from historical amnesia in terms of the role that violence and anti-democratic movements have played in our past and in our present. As we ask the question—“How did we get here?”—perhaps we should formulate our answers to this question much more carefully, with much more humility, than has been the case in our public discourse. The Capitol insurrection does not represent some alternate reality or alternate universe. The insurrection is a mirror into the soul of this nation, and we would do well to remember that.

WIKIMEDIA IMAGE BY TYLER MERBLER, DSC09170

Our House

Susan Schmidt How did we get here? By “here” I refer to the storming of the US Capitol by a mob loyal to former President Donald Trump, resulting in the deaths of four rioters, a Capitol police officer, two subsequent suicides by police officers who had been at the scene, and the suicide of a rioter after being charged in connection with the siege (McEvoy, 2021). There are many dynamics that contributed to this toxic stew that culminated in a violent mob breaching, damaging, and defacing “the people’s house,” sending Vice President Pence, his family, and Congressional lawmakers into hiding, interrupting the certification of Joseph Biden’s election, and resulting in death. The official “Congressional Record” is spare in its documentation of the events of January 6, 2021: apart from law-

makers’ own words, the official record merely notes that the Senate recessed from 2:30 p.m. and reassembled at 8:06 p.m., (Senate, 2021) and that the House stood in recess from 2:29 PM until called to order by the Speaker at 9:02 p.m. (House of Representatives, 2021). Faculty from each of the disciplines at Luther College could contribute a different perspective on how we as a nation got here. As a social worker, here is a non-exhaustive list of significant dynamics that I identify: • Hubris • Inequality • Racism • Social media I’ll say a few words about each of these. Americans often view our government through a lens of “American exceptionalism.” Indeed, in the comments made by our Congressional lawmakers on January 6 before and after the Capitol siege, at least seven representatives and senators, both Republicans and Democrats, referred to the United States as “the greatest democracy this world has ever known” (Congressional Record, 2021, H83, H90), “the greatest democracy human kind has ever known” (H87), “the greatest power on earth” (H86), “the greatest nation in the history of the world” (H108), “the greatest country on Earth” (S21), and “the most exceptional nation in the history of the world” with the US Constitution as the “greatest political document that has ever been written” (S22). We are socialized to believe that the US is different from other countries, that it is the best version of democracy, and that the US therefore has a responsibility to share our version of democracy with the world. In some sectors, this set of beliefs is mixed with the religious view that the US has been chosen by God (Rodgers, 2018) and by extension for some a belief that Donald Trump was chosen by God (Pew Research Center, 2020). Yet this hubris may prevent us from facing and addressing our flaws, while also spurring some of our brethren to elevate nation above all else. One of those flaws we avoid addressing is growing inequality. US inequality is higher than in most other developed nations due to wage stagnation, lowering taxes on the rich, and reduced prospects for people without college degrees combined with the rising cost of college, among other things (Siripurapu, 2020; Institute for Policy Studies, n.d.). Inequality has traditionally been higher in rural areas, but it has been increasing in urban areas over the last decade (Thiede, Brown, Butler & Jensen, 2020). Inequality can contribute to a sense of alienation from societal systems, which may make a candidate like Donald Trump seem like a savior. The economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton have written about the rise in “Deaths of Despair” as the life expectancy of White Americans between 45 and 54 has declined due to suicide, opioid overdoses, and alcoholrelated deaths (Zarroli, 2020).

Inequality in the United States builds on a foundational history of slavery and systemic racism that has been persistent in our policies and practices (Carten, 2016), including in ways illuminated by the pandemic (USA Today, 2020; Scott, Johnson & Ibemere, 2020). The storming of the US Capitol on January 6 was not carried out by those most directly affected by systemic racism (though there are convincing arguments that systemic racism makes us all losers; (McGhee, 2021). Instead, the largely White crowd on January 6 included groups who espouse explicitly or implicitly an ideology of White supremacy—a belief that White people are superior and should therefore control society— evident in visible symbols (e.g. the Confederate flag, a noose, anti-Semitic slogans), behavior towards African American law enforcement officers at the scene (Bowden, 2021), and views espoused by groups identified in the crowd (Farivar, 2021).

As the US becomes more multiracial, some White individuals and groups find this threatening and seek ways to hold onto power and societal dominance. Political science researcher Larry Bartels explains the “antidemocratic sentiments,” identified in January 2020 interviews with Republicans and right-leaning Independents, as: …not primarily products of social isolation or insufficient education or political interest. Rather,

[these views] are grounded in real political values—specifically, and overwhelmingly, in Republicans’ ethnocentric concerns about the political and social role of immigrants, African-Americans, and

Latinos in a context of significant demographic and cultural change (Bartels, 2020). The organizational vehicle for these events was social media, which facilitated the online connections, propagated the spread of toxic ideas, and cultivated misinformation into identity groups and communities of grievance. These platforms, run by largely unregulated

Insurrectionists outside the US Capitol, January 6, 2021

WIKIMEDIA IMAGE BY TYLER MERBLER, DSC09402-2

Insurrectionists and tear gas outside the US Capitol on January 6, 2021

technology behemoths, have managed to simultaneously expand communities of identity while also contracting access to contradictory information systems, creating polarized echo chambers that feed and cater to our latent beliefs (Seneca, 2020). The documentary “The Social Dilemma” (Orlowski, 2020) raises disturbing questions about the algorithms controlling our media feeds, the personal data being harvested from our online activities, the financial interests guiding ethical technology decisions, and the larger societal impact of the sector on which much of our lives depend. How do we rein it in, for both individual and collective good? As we get farther from the unsettling yet crystallizing melee of January 6, 2021, I wonder what lasting impact it will have on our democracy. Will we recognize it as a cautionary tale and seek ways to build bridges and rein in sources of misinformation? Will we downplay its significance and seek to move past it, rather than examining its causes? Will we ignore the evident risks and continue as if nothing unusual happened? Initially, I thought this event might present opportunities for collective examination, but lately I am wondering if we as a nation have the willingness to face the uncomfortable dynamics within our shared democracy. In her article applying the concept of caste to the racial hierarchies of the United States, Isabel Wilkerson uses the metaphor of a house to help readers grasp our shared responsibilities:

We in this country are like homeowners who inherited a house on a piece of land that is beautiful on the outside but whose soil is unstable loam and rock, heaving and contracting over generations, cracks patched but the deeper ruptures waved away for decades, centuries even…We are the heirs to whatever is right or wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars or joists, but they are ours to deal with now (Wilkerson, 2020). By the time you read this article, what will you see as the lessons from January 6, 2021, and more importantly, what are you willing to invest in repairing this civic house that we share?

Challenges to American Democracy

Orçun Selçuk Building on the reflections of Professors Todd Green and Susan Schmidt, I would like to offer three comparative themes to understand the current state of American democracy, which are directly linked to the events of January 6, 2021. As a political scientist whose work is at the intersection of populism, polarization, and democratization, my goal is to situate the United States within a global context. Rather than analyzing the US as an exceptional or unique country, I would like to illustrate some patterns that can help us make sense of the last five years and beyond. The first theme that would answer the question “How did we get here?” is the rise of populism and nativism around the world. From a

WIKIMEDIA IMAGE BY TYLER MERBLER, DSC09523-2 comparative perspective, it is not surprising that the Capitol attack was directly tied to then President Donald J. Trump, a right-wing populist who claims to represent the real American people against the corrupt Washington elite. In the 2016 presidential elections, Trump not only positioned himself against Hillary Clinton but also establishment figures within the Republican Party such as Jeb Bush, whom he called “Crooked Hillary” and “Low Energy Jeb” respectively. When Trump announced his candidacy in 2015, his style of politics was considered marginal, fringe, and unpresidential (Ostiguy and Roberts, 2016). As he started to win key primary races and became the Republican nominee, this perception within the GOP quickly changed. After his surprise victory against Clinton in 2016, Trump soon consolidated his grip over the Republican Party and gradually turned it into a far-right movement that revolved around fiscal conservatism, cultural nativism, and personalism. During his four-year presidency, Trump delivered to establishment Republicans like Mitch McConnell and Lindsey Graham judicial appointments and tax cuts. At the same time, he mainly appealed to his core constituency, who were predominantly White, non-college educated, and lived in rural areas. As a populist leader, Trump opened up the political space to “angry patriots” who saw themselves as the owners of the country and the president as their savior. Under Trumpism, far-right ideas like building a wall on the Mexican border and conspiracy theories like QAnon have found themselves a place in the mainstream (Mudde, 2017). From a comparative perspective, Trump’s brand of right-wing populism is similar to other populist leaders like Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Viktor Orban in Hungary, Jair Bolsonoro in Brazil, Alberto Fujimori in Peru, Narendra Modi in India, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and Recep

Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey (Norris and Inglehart, 2016). All of these populist leaders have positioned themselves against the establishment in their own countries and claimed to represent the authentic people, who felt marginalized, victimized, and silenced. Populist figures like Le Pen and Wilders have not won a national election yet, but they have pushed centrist political actors to consider their xenophobic and Islamophobic agenda. More successful populist leaders like Fujimori and Erdoğan have used authoritarian tactics to undermine civil liberties and weaken checks and balances in their country (Selçuk and Arrarás, 2017). Thus, for observers who look beyond the borders of the United States, Trump’s brand of populism is far from novel. Trumpism is a successful application of an already existing right-wing populist playbook from Europe, Latin America, and Asia into the American context. Like Trump, the above-mentioned populist leaders subscribe to democracy as long as they are on the winning side. The moment they lose an election or a referendum, the most common explanation is to call it fraudulent or a heinous conspiracy against the will of the people. Another variable that explains the crisis of American democracy is the multiple types of polarization that undermine the political center and reward extremist behavior. The first type of polarization that erodes democracy in the United States is partisan polarization between Democrats and Republicans. The growing divide between the two parties has ideological and affective origins. From a comparative point of view, both political parties in the United States subscribe to free-market capitalism and do not offer any structural alternatives to neoliberal globalization. Regardless, in the last decade, the Democratic Party has shifted to the left and the Republican Party has moved to the right, which reduces the likelihood of bipartisan legislation and incentivizes gridlock. At the citizen level, Democrats and Republicans increasingly dislike and distrust one another. They tend to live in echo chambers that reinforce their existing beliefs and attitudes, thus minimizing their social interactions with the members of the out-group (Iyengar et al., 2019). Populist leaders like Donald Trump not only benefit from these polarizations but deliberately deepen them to consolidate their base and capitalize on pre-existing fears. In the age of negative partisanship (Abramowitz and Webster, 2016), for millions of Democratic voters the 2020 presidential election was less about voting for Joe Biden but more about voting against Trump and Republicans. The possibility of the other party winning elections is a feeling that dominates American politics. In polarized countries like the United States, Venezuela, Brazil, and Turkey, every election is seen as “the most important election of our lifetimes.” One of the main challenges of President Joe Biden is to keep the diverse anti-Trump coalition (from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on the left to the Lincoln Project on the right) together while trying to govern with a slim majority in the Senate, which makes Biden’s progressive agenda depend on centrist senators like Joe Manchin. Lastly, I would like to reflect on the contemporary challenges to American democracy with a focus on its outdated institutions that need urgent reform. Unlike the mainstream media outlets like CNN and politicians on the both sides of the aisle who believe in American exceptionalism or leadership of the free world, according to well-known measures of democracy, the United States is far from being the best democracy in the world. According to Freedom House, a global watchdog of democracy in the world, the United States has a score of 83 out 100, which classifies the country “free” but ranks way behind Norway (100), Canada (98), Uruguay (98), Japan (96), and Germany (94). Other countries that also have a score of 83 include South Korea, Romania, and Panama, which all share a legacy of authoritarianism during the Cold War period (Freedom House, 2021). As a scholar of comparative democratization, I cannot think of another country where the winner of the popular vote (i.e., Al Gore in 2000 and Hillary Clinton in 2016) would lose the presidential elections. The United States is the only country that I know that lacks a national electoral body and uses an archaic institution called the Electoral College to pick its powerful head of state. The current winner-take-all system not only favors smaller, Whiter, and rural states at the expense of highly diverse population centers but also disenfranchises millions of Republicans living in California and millions of Democrats living in Texas. Given Trump’s rural appeal, it is not a coincidence that he questioned the integrity of the vote in urban areas like Detroit, Philadelphia, and Atlanta with significant Black populations instead of the Whiter parts of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Georgia. If the United States is serious about fixing its democracy, it should start with abolishing the Electoral College and restoring the integrity of elections in all fifty states and territories, which would force the Republican Party to appeal to a larger segment of voters who are racially and geographically more diverse than the current narrow base. According to the Bright Line Watch initiative, besides abolishing the Electoral College and instituting a national popular vote, political scientists also support campaign finance transparency, flexibility on when and how to vote, redistricting commissions, same-day voter registration, suffrage for ex-felons, public funding of campaigns, ranked-choice voting, eighteen-year Supreme Court terms, eliminating the filibuster, multi-member districts, and enlarging the House of Representatives (Bright Line Watch, 2021). A comprehensive reform package is the only way to revitalize democracy in the US and minimize the risk of violent events like the one on January 6.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of US elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12-22. Bartels, L. (2020, September 15). Ethnic antagonism erodes Republicans’ commitment to democracy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(37). https://www.pnas.org/content/ pnas/117/37/22752.full.pdf

Bowden, J. (2021, February 25). Capitol

Hill officer details racist abuse during mob attack. The Hill. https://thehill. com/homenews/news/540576-capitolhill-officer-details-racist-abuse-duringmob-attack Bright Line Watch. (2021). American democracy at the start of the Biden presidency. Bright Line Watch

January-February 2021 surveys. http://brightlinewatch.org/americandemocracy-at-the-start-of-the-bidenpresidency/ Carten, A. (2016, August 21). How racism has shaped welfare policy in America since 1935. The Conversation. https:// theconversation.com/how-racism-hasshaped-welfare-policy-in-americasince-1935-63574 Chew, Cassie M. (2020, November 5). Have

White Christians Changed Since 2016?

Not Much, Early Data Says. Sojourners. https://sojo.net/articles/have-Whitechristians-changed-2016-not-muchearly-data-says Congressional Record—House of

Representatives. (2021, January 6). “Recess,” p. H85, Vol. 167, No. 4. https://www.congress.gov/117/ crec/2021/01/06/CREC-2021-01-06. pdf Congressional Record—Senate. (2021,

January 6). “Recess subject to the call of the chair,” p. S18, Vol. 167, No. 4. https://www.congress.gov/117/ crec/2021/01/06/CREC-2021-01-06. pdf Farivar, M. (2021, January 16). Researchers:

More than a dozen extremist groups took part in Capitol riots. VOA News. https://www.voanews.com/2020usa-votes/researchers-more-dozenextremist-groups-took-part-capitolriots Freedom House (2021) Freedom in the

World 2021: Democracy under Siege. https://freedomhouse.org/report/ freedom-world/2021/democracy-undersiege Green, Todd. (2017, October 12). It’s Time to Abandon the Word ‘Terrorism.’

Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost. com/entry/its-time-to-abandon-theword-terrorism_b_59dc350de4b060f0 05fbd67f Institute for Policy Studies. (n.d.) Income inequality in the United States. https:// inequality.org/facts/income-inequality/ Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M.,

Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United

States. Annual Review of Political

Science, 22, 129-146. Jones, S. G., Doxsee, C. & Harrington,

N. (2020, June 17). The Escalating

Terrorism Problem in the United States.

Center for Strategic & International

Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/ escalating-terrorism-problem-unitedstates McEvoy, J. (2021, January 27). Another officer who responded to Capitol attack dead by suicide. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ jemimamcevoy/2021/01/27/ another-officer-who-respondedto-capitol-attack-dead-bysuicide/?sh=7f5dd0e21782 McGhee, H. C. (2021, February 13).

The way out of America’s zero-sum thinking on race and wealth. The

New York Times. https://www. nytimes.com/2021/02/13/opinion/ race-economy-inequality-civil-rights. html?smid=url-share Mudde, C. (2017). The far right in America.

Routledge. Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge

University Press. Orlowski, J. (2020). The social dilemma [documentary]. Netflix. https://www. netflix.com/ Ostiguy, P., & Roberts, K. M. (2016).

Putting Trump in comparative perspective: Populism and the politicization of the sociocultural law. Brown J. World Aff., 23, 25. Rodgers, D. T. (2018). As a city on a hill:

The story of America’s most famous lay sermon. Princeton University Press. Ruhl, Ashleigh. (2021, January 6). Rep.

Lowenthal on U.S. Capitol riot: ‘felt like a coup in a third-world country.

Daily News. https://www.dailynews. com/2021/01/06/rep-lowenthal-onu-s-capitol-riot-felt-like-a-coup-in-athird-world-country/ Scott, J., Johnson, R. & Ibemere, S. (2020,

September 21). Addressing health inequities re-illuminated by the

COVID-19 pandemic: How can nursing respond? Nursing Forum, 56(1). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/10.1111/nuf.12509 Selçuk, O. & Arrarás, A. 2017. Here’s what Peru can teach Turkey about presidential power grabs. Washington

Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/ news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/05/02/ heres-what-peru-can-teach-turkeyabout-presidential-power-grabs/ Seneca, C. (2020, September 17). How to break out of your social media echo chamber. Wired. https://www.wired. com/story/facebook-twitter-echochamber-confirmation-bias/ Siripurapu, A. (2020, July 15).

Backgrounder: The U.S. inequality debate. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/usinequality-debate Smith, G. A. (2020, March 12). About a third in U.S. see God’s hand in presidential elections, but fewer say

God picks winners based on policies.

FactTank, Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2020/03/12/about-a-third-inu-s-see-gods-hand-in-presidentialelections-but-fewer-say-god-pickswinners-based-on-policies/ Thiede, B., Brown, D. L., Butler, J., & Jensen,

L. (2020, April 14). Income inequality is getting worse in US urban areas. The

Conversation. https://theconversation. com/income-inequality-is-gettingworse-in-us-urban-areas-132417 USA Today. (2020, October 12). Deadly discrimination: ‘An unbelievable chain of oppression’: America’s history of racism was a preexisting condition for

COVID-19 (6-part series). https:// www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/ nation/2020/10/12/coronavirusdeaths-reveal-systemic-racism-unitedstates/5770952002/ Wilkerson, I. (2020, July 1). America’s enduring caste system. New York Times

Magazine. https://www.nytimes. com/2020/07/01/magazine/isabelwilkerson-caste.html Zarroli, J. (2020, March 18). ‘Deaths

Of Despair’ Examines The Steady

Erosion Of U.S. Working-Class

Life. NPR News. https://www. npr.org/2020/03/18/817687042/ deaths-of-despair-examines-thesteady-erosion-of-u-s-working-classlife#:~:text=Much%20of%20the%20 decline%20stems,or%20shooting%20 or%20hanging%20themselves.%22