8 minute read

Sabbaticals

from Agora Spring 2021

Julian of Norwich and “The Showing of Love”

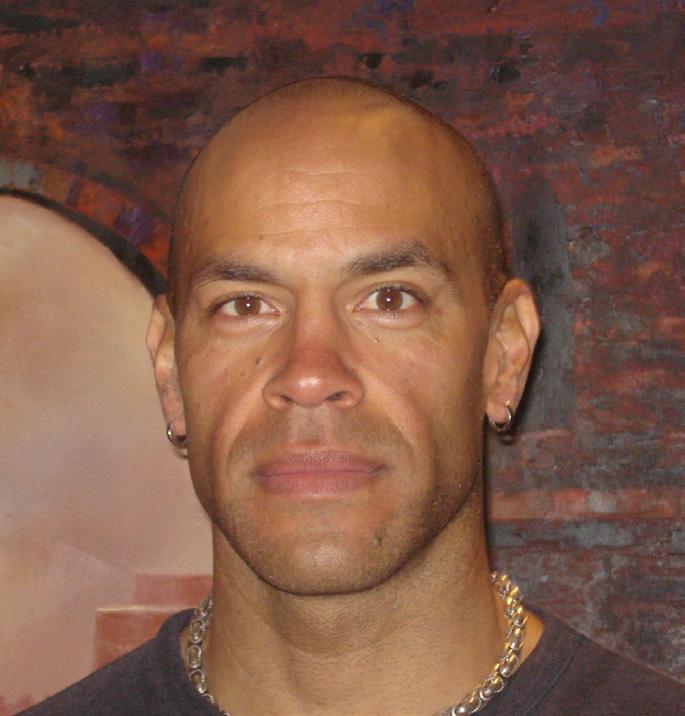

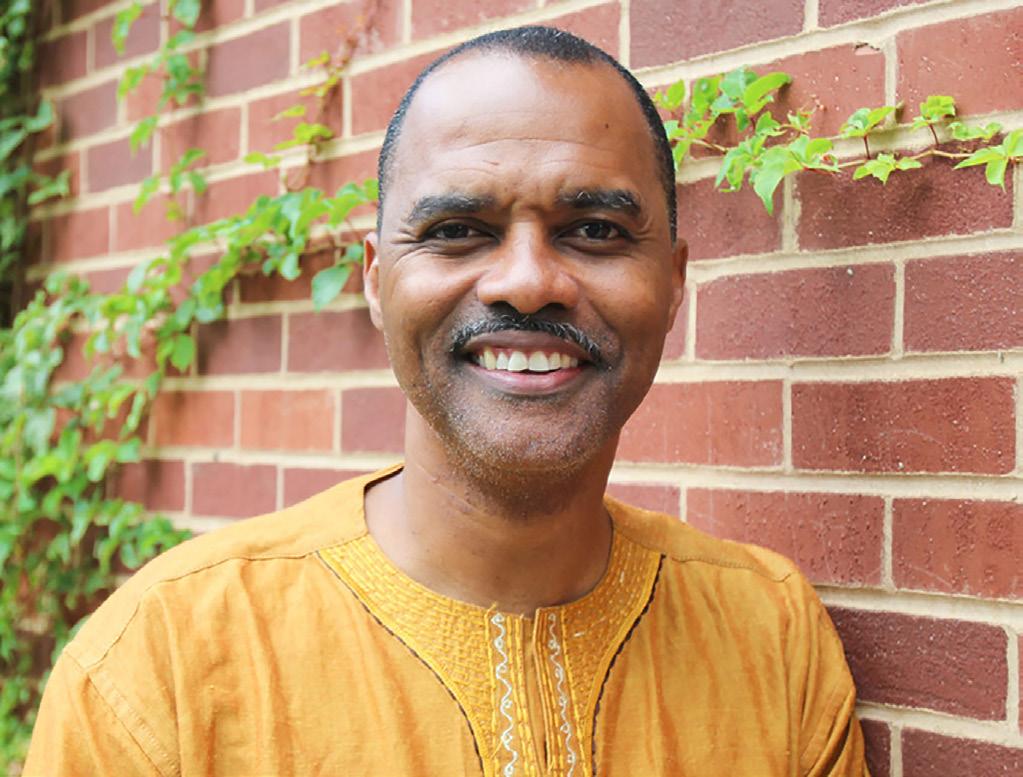

by BROOKE JOYCE, Professor of Music

As I write this essay in late winter, 2021, it’s been one year since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. Although I couldn’t have known it at the time of my sabbatical in fall 2019, my research and the creative work based on the life and work of Julian of Norwich—“The Showing of Love,” a dance-opera for solo voice, electronics, and dancers—became even more meaningful as the year of the pandemic progressed. Julian was a fourteenth century theologian and the first woman to write a book in the English language. As an anchoress, she lived most of her life in a kind of self-imposed solitary confinement, as she was literally walled into the corner of her parish church in England, with one window providing her a view of the outside world and another window that allowed her to see into the church’s sanctuary and participate in worship services. During her life, several waves of the bubonic plague ravaged England, one of which may have been responsible for an illness that almost cost Julian her life when she was in her 20s. A pandemic, self-isolation, income inequality, social upheaval—these were important facets of Julian’s life and times, not so different from our own. Shortly after the concert performance of “The Showing of Love” at Good Shepherd Church here in Decorah on March 1, 2020, most of the world went into a lockdown, and it seemed as though Julian was speaking to us across time and space. But even before I settled on creating a large-scale theater work, Julian’s writings, theology, and legacy had been important touchstones for me for many years. One of the first pieces I composed after arriving at Luther in 2005 was a choral setting of one of her most famous writings, “Revelations of Divine Love,” where God reveals the vastness of creation in the form of a hazelnut. In the fall of 2019, I returned to Julian’s writings and created a theater piece for solo voice, dancers, and electronics based on her work. In preparation for this project, I reread Julian’s “Revelations of Divine Love” and traveled to Julian’s church in Norwich. As I told a number of people I met during my visit, I wasn’t quite sure why I traveled to Norwich, or what I hoped to learn. I suppose I simply had a desire to see the place where she lived, and that, perhaps, some idea, image, or sound would come my way and aid in my creative process. Mostly, what I learned is that Julian’s church is quite small, very plain, and these days surrounded by homes and businesses. In some ways, it feels like a typical “neighborhood” church—it blends in with its surroundings and doesn’t really call attention to itself. It reminded me, in fact, of Good Shepherd in Decorah! And yet, Julian’s church is a place of pilgrimage, attracting hundreds of visitors every year.

St. Julian’s Church in Norwich

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

A bowl of hazelnuts inside Julian’s cell in Norwich, England, with her text “Revelations of Divine Love,” which Brooke Joyce used in his composition of two choral works

Mother Julian’s cell, recreated inside her church

Mostly, what I learned in Norwich is that Julian’s writings have engendered a devoted following, and that many people, from both Christian and nonChristian backgrounds, find wisdom and guidance in her words. For me, I am drawn, in particular, to this passage:

And these words, Thou shalt not be overcome, was said full sharply, and full mightily, for secureness and comfort against all tribulations that may come. God said not, thou shalt not be tempested; God said not, thou shalt not be travailed;

God said not, thou shalt not be diseased; but God said, thou shalt not be overcome. God wills that we take heed at these words, and that we be ever mighty in secure trust in well and woe, for God loveth us, and so wills that we love God, and mightily trust in God, and all shall be well, and all shall be well, And all manner of thing shall be well. The love wherein God made us was in

God from without beginning, in which love we have our beginning.

And all this shall be seen in God without end. I recently shared these words with a group of students at a virtual Sunday evening worship service on campus. We had an opportunity to spend a few minutes in small group discussion, and I asked the students, “What has God done to let you know that you will not be overcome?” This is a difficult question for many to answer—for some, their lives have been relatively free of strife, and they haven’t felt close to the point of being overcome. For others, tragedy or hardship may be ever present, and for them, they may feel constantly overcome, that perhaps they are barely hanging on, that God doesn’t seem to intervene when most needed. I pay particular attention to the word “diseased”—we are living in a time when invisible diseases run rampant in the world, both in the physical realm, such as COVID, and in the societal, such as racial injustice. We are diseased, and those diseases cause all manner of tempest and travail. And yet, Julian offers comfort, and a challenge. Earlier in her book, she describes a “great deed” that God will do. She doesn’t describe or define it, because she doesn’t know what it is. None of us do. Her faith in God is such that she knows the love of God, and the power of God’s love to heal, or, as she says, “all shall be well, all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” We can be comforted in the knowledge of God’s love, but that knowledge can only come through faith and trust. That’s the challenge. I also asked the students, “Do you think that Julian’s vision of a world in which ‘all shall be well’ is possible? In our deeply polarized world, what would that look like?” This is another difficult question to answer. My version of wellness may be very different from yours. I may pursue my goal of wellness in ways that feel threatening to you. How can we find common ground, and pursue a kind of wellness that benefits all of creation? I think Julian gives us a tiny clue. When she says “all manner of thing shall be well,” I think she is pointing beyond the world of things, that is, the world we can see and understand, to the world beyond our understanding, “all manner of thing.” There is a world beyond, a world of love and beauty, that we can’t even imagine. That’s the world that only God can create. Theological and philosophical conversations can be wonderful and engaging… but can they also be theatrical? After all, part of what drew me to Julian was the idea of folding her words and ideas into a musical work that might be performed in a theater, worship space, or some other venue that worked both as a performance as well as meditative space. I decided to start by imagining the sounds that Julian might have heard from her cell. Having little to look at beyond her windows, I imagined that sound played an important part in her life, giving meaning and context to her limited experience of the world around her. I imagined she heard voices, bells, birds, water, air, fire, and the sounds of the earth. These sounds, both real and

Brooke Joyce

imaginary, found their way into my composition, and form the primary structural elements that demarcate each section of the piece. One other important structural element I incorporated was both a theatrical as well as practical one: in order to sustain a one-hour long work for solo voice, sung episodes alternate with dance interludes. Dramatically, this allows for Julian’s words to be heard in a musical setting as delivered by the singer, and then for dancers to offer a visual reflection of those words through movement. Practically, it allows the singer time to rest and hydrate. Other than the singer, all other musical and sonic elements are present as prerecorded sounds that are heard through loudspeakers in the performance space; no additional musicians are necessary for performance. This decision was made both for creative purposes (essentially forcing me to create a dynamic soundscape that could be sustained for an hour without the benefits of collaborative performers) as well as practical ones (without the need for piano or additional musicians, the piece can be performed with just a singer, a dancer, and a technician). As we continue to live through the pandemic, the small-scale production requirements allowed the piece to take on a new form. This spring, “The Showing of Love” became a filmed dance piece, directed by Jane Hawley and performed by a corps of student dancers. The audience saw a physical manifestation of Julian in the form of a solo dancer and heard the vocal music as recorded by my collaborator, mezzo-soprano Lisa Neher, who is based in Portland, Oregon. It was a performance scenario we wouldn’t have imagined prior to the pandemic, and yet, it allowed us to bring this work into its next stage of development without having all members of the creative team present in one location. We hope that when it is safe to sing and dance for an audience, we’ll be able to share this work as a live dance-opera. My thanks to Luther College for supporting my creative work, both through the gift of sabbatical as well as the Paideia Endowment grant that aided my research.