10 minute read

The Wisdom of the Fool (March 10, 2021) Gereon Kopf

from Agora Spring 2021

The Wisdom of the Fool

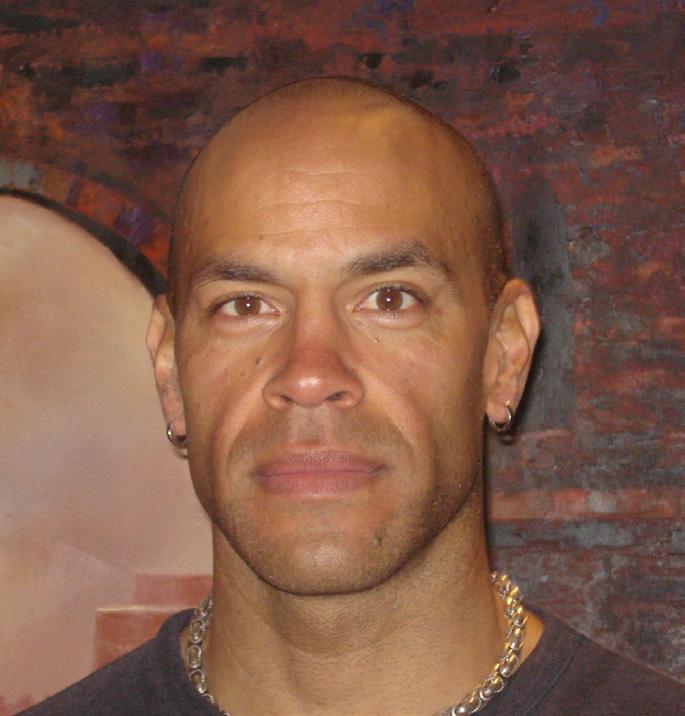

by GEREON KOPF, Professor of Religion

MARCH 10, 2021

Good morning, I would like to thank the college ministries team for inviting me to share some reflections on interfaith cooperation and civil rights. Reading from Ecclesiastes 1:12, 16-18:

I, the Teacher, was king over

Israel in Jerusalem. I applied my mind to study and to explore by wisdom all that is done under the heavens.…

I said to myself, “Look, I have increased in wisdom more than anyone who has ruled over

Jerusalem before me; I have experienced much of wisdom and knowledge.”Then I applied myself to the understanding of wisdom, and also of madness and folly, but I learned that this, too, is a chasing after the wind. For with much wisdom comes much sorrow; the more knowledge, the more grief. Having grown up in a German Catholic home, I have always had a fondness for the Book of Ecclesiastes because of its air of existentialism and its vicinity to the general feeling of the transience. The lines from chapter 1 that I have read today also have an appeal for us at Luther College or any other academic institution, especially us professors. The first-person voice of this passage speaks as someone who has “experienced much wisdom and knowledge.” As members of an institution in higher education I assume, nay I hope, that all of us can relate to this sentiment. The speaker, however, immediately puts a damper on our enthusiasm and suggests that both wisdom and madness are “chasing after the wind.” This is of course depressing for people like us college teachers who have dedicated our whole lives to education and the pursuit of knowledge. But not to worry: the author does not discourage knowledge per se. In chapter 9, right after making some rather problematic political claims (at least from our perspective today) which deserve reflection in their own right, he clearly values wisdom over folly. In addition, verse 18—“For with much wisdom comes much sorrow; the more knowledge, the more grief”—seems to be descriptive rather than normative, suggesting something along the line of “ignorance is bliss” and knowledge implies responsibility. If I know about injustice, it is harder for me to ignore it. I need to do something about it. In Buddhism, wisdom/prajñā and compassion/karuna are inseparable. But there is another take on this disclaimer to wisdom. If you read the whole book of Ecclesiastes you will see that, to the author, wisdom—just like pleasure, wealth, and all the things we value—is meaningless. Everything is transient, nothing last forever, nothing can be owned. Therefore, chapter 7 suggests, “The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning, but the heart of fools is in the house of pleasure.” A wise person is aware that, to cite George Harrison, “all things must pass,” while the fool is deluded and distracted by pleasure. Most of all, transience seems to be a major theme in Ecclesiastes as well as the question of how the awareness of it shapes our outlook on wisdom and life in general. So, what I want to talk about today is the epistemological fool—the fool who is not certain of the possibility and infallibility of knowledge. This terminology is inspired by a rather provocative book of a friend of mine, Hans-Georg Moeller. In this book, Moeller introduces what he calls the “moral fool.” The moral fool is not someone who is immoral but someone who is not attached to moral beliefs, someone who is not attached to morality to the degree of falling into moralism. Similarly, the fool I am talking about is not a person who devalues knowledge or wisdom but who is not obsessed with people’s IQ, with knowing everything, with always being right. The epistemological fool is a person who is not attached to being right and therefore not obsessed with proving other people wrong. I am talking about persons cognizant of their own fallibility, of their own limitations, who have the ability to forgive others who are as imperfect as we are ourselves. I was asked to talk about civil rights and interfaith cooperation. Thus, I would like to explore how epistemological fools who, while learned are neither convinced about not obsessed with their own infallibility, enact social justice and interfaith collaboration. Isn’t it ironic that a Roman Catholic is talking to a mostly Protestant audience about the impossibility of infallibility? But that’s

Gereon Kopf

a different story. To talk about our topic, I would like to introduce another such fool, Vimalakīrti. Vimalakīrti is introduced to us by the Vimalakīrti Sūtra, a Mahāyāna Buddhist text that inverts a couple of social norms and hierarchies of the early Buddhist communities. Among others, it breaks the gender norms and the institutional hierarchies of its time. Its protagonist is Vimalakīrti, a layperson who is spiritually more advanced than even the disciples of Buddha themselves. He, not unlike the author of Ecclesiastes, was wise yet appeared foolish. The author of Ecclesiastes seems to reject knowledge and a lot of socially accepted values and wisdom. Vimalakīrti similarly remained silent when asked about his knowledge and led a life that was scandalous for either a layperson or a monastic. Chapter 2 of the Vimalakīrti Sūtra reads:

He wore the white clothes of the layman yet lived impeccably like a religious devotee. He lived at home, but remained aloof from the realm of desire, the realm of pure matter, and the immaterial realm. He had a son, a wife, and female attendants, yet always maintained continence.

He appeared to be surrounded by servants yet lived in solitude.

He appeared to be adorned with ornaments, yet always was endowed with the auspicious signs and marks. He seemed to eat and drink, yet always took nourishment from the taste of meditation. He made his appearance at the fields of sports and in the casinos, but his aim was always to mature those people who were attached to games and gambling.

He visited the fashionable heterodox teachers, yet always kept unswerving loyalty to the Buddha. He understood the mundane and transcendental sciences and esoteric practices, yet always took pleasure in the delights of the

Dharma. He mixed in all crowds yet was respected as foremost of all.

In order to be in harmony with people, he associated with elders, with those of middle age, and with the young, yet always spoke in harmony with the Dharma.

He engaged in all sorts of businesses yet had no interest in profit or possessions. To train living beings, he would appear at crossroads and on street corners, and to protect them he participated in government. To turn people away from the Hinayana and to engage them in the

Mahayana, he appeared among listeners and teachers of the

Dharma. To develop children, he visited all the schools. To demonstrate the evils of desire, he even entered the brothels. To establish drunkards in correct mindfulness, he entered all the cabarets. I keep telling myself the last sentence whenever I go to Pulpit Rock or other bars, “It is okay, I am just doing the work of the Buddha.” Be that as it may, in the text, the life of Vimalakīrti is neither that of layperson nor of a monastic. He does layperson things, having a family, engaging in business, going to bars and brothels, yet he possesses the attitude of a monastic: he is detached, he does not get involved. Vimalakīrti accepts his body, his profession, his social role, his identity, but he is not attached to anything. Detachment provides us with liberation from ourselves; compassion, however, requires a bit more. Chapter 8 suggests that some “become food and drink to alleviate hunger and thirst,” “become courtesans to convert those stricken by desire,” and “remain impartial in military conflict.” This is a radical message. Those are tough passages for good Christians as well as for good Buddhists. Many serious Mahāyāna Buddhists I know would feel uneasy hearing words like these. But this is what the epistemological fool, i.e., the person who understands the transience and the emptiness of everything, does out of compassion for those who suffer. The goal is not to be wise, not to be moral, not to be best, but to give oneself for others in need. This sentiment should sound familiar to both Buddhist and Christians. This kind of behavior may not imply civil rights but it lifts up the downtrodden. It is not easy but this is radical compassion. And now, it might become clear why I called such a person a fool. In the last part of my reflections, I would like to explore how the epistemological fool would approach interfaith collaboration. We could start with the above-cited line, “He visited the fashionable heterodox teachers, yet always kept unswerving loyalty to the Buddha.” If one replaces “Buddha” with whatever religious authority one chooses, we encounter a frequent attitude towards interfaith work. Even for many Buddhists there is an assumption that one’s orthodoxy or orthopraxy is “ortho,” i.e., “correct.” I have to admit that I feel uneasy with such an approach. And I say this as a person who has organized two interfaith forums at Luther in the past five years. First, “hetero” means “different” not “false.” We construct our identity vis-à-vis others. Both our identities and that of others are constructed. Identity constructions like these are explored in our new program in Identity Studies. Second, when we use terms such as “Christianity,” “Buddhism,” or “Islam” we talk about traditions. Religious truth claims can be analyzed, religious institutions have clear membership criteria, but traditions are fluid, diverse, and ever-changing amalgams. They are not monolithic. Our texts would say those terms are “meaningless” or “empty.” I would say that when we use them as identity markers we endow them with specific meaning that may or may not be shared by others. Interreligious dialogue is not a dialogue between traditions such as Christianity and Buddhism, but between individuals who identify as “Christian” and “Buddhist.” This is a big difference. What a representative of one identity claim says might ring true for the representative of another, but not for a representative of one’s own imagined community. How can anyone represent a “tradition”? Participants in these dialogues represent their own beliefs, their own identify and perhaps their institution. Finally, I would argue, a lot of what we do is syncretic: Christian Yoga? We may call it “praise moves” but it is inspired by Hindu Yoga. Buddhist ghost weddings? They are Buddhist

rituals, based on Shinto beliefs to fulfil a Confucian need. Third, and this returns us to Ecclesiastes or the Vimalakīrti Sūtra, if wisdom is meaningless and all truths are empty, why am I so convinced that my beliefs are true? The older I get the less I understand the obsession with proving other beliefs to be false, besides the ego boost such an exercise might give us. Do we really feel comfortable claiming that we know it all? In addition, dogmatism seems to be harmful more often than not. To illustrate this sentiment, I turn to a Buddhist thinker who “remained impartial in conflict” to use the words of the Vimalakīrti Sūtra: Thich Nhat Hanh – who was banned by both Vietnams in 1966, because he was neutral and refused to take sides in their conflict. He went to France and founded the Order of Interbeing in the Plum Village. This order has 14 precepts. The first four commit the members of the order to “openness,” “non-attachment to views,” “freedom of thought,” and “awareness of suffering.” In the interest of time, I will limit myself to the second precept here. It reads:

Aware of the suffering created by attachment to views and wrong perceptions, we are determined to avoid being narrow-minded and bound to present views. We are committed to learning and practicing non-attachment to views and being open to others’ experiences and insights in order to benefit from the collective wisdom. We are aware that the knowledge we presently possess is not changeless, absolute truth.

Insight is revealed through the practice of compassionate listening, deep looking, and letting go of notions rather than through the accumulation of intellectual knowledge. Truth is found in life, and we will observe life within and around us in every moment, ready to learn throughout our lives. This is the wisdom of the epistemological fool. This is the way to understanding across traditions and to compassion for all living being. Amen.