YOU MAY WONDER in an issue with the grand-sounding theme “worldbuilding” why we chose for the cover an ordinary image of grandparents sharing a meal at a modest little kitchen table, surrounded by the familiar objects of home. The scene is intimate. And private. The grandparents don’t seem to notice anyone watching at all.

When I first saw “La Casa de Los Abuelos” in the submissions folder, the whole issue, and in truth the whole of the last two years, both of educating and living through the pandemic, came into focus. “Worldbuilding” is often asso ciated with fiction that challenges convention and oppressive forms of life with newly imag ined futures. These new worlds exist not because the past has been destroyed or denied, but because worldbuilders understand how to

perceive what is worth saving: warmth, memory, home. In her video discussing the inspira tion for her piece “La Casa de los Abuelos,” the artist, first-gen Education major Mercedes Barriga, reminds us that we are all moved forward by our sense of home.

I am so grateful to Mercedes and all of the first-gen students who submitted to this multimedia “worldbuilding” issue. And I hope our readers can begin to imagine a new univer sity built on the “home” languages of students who came of age during a season of profound trauma and loss, and are becoming empow ered now through their work to shape not only their own but all of our futures.

Sincerely, Rachael Collins, editor-in-chief

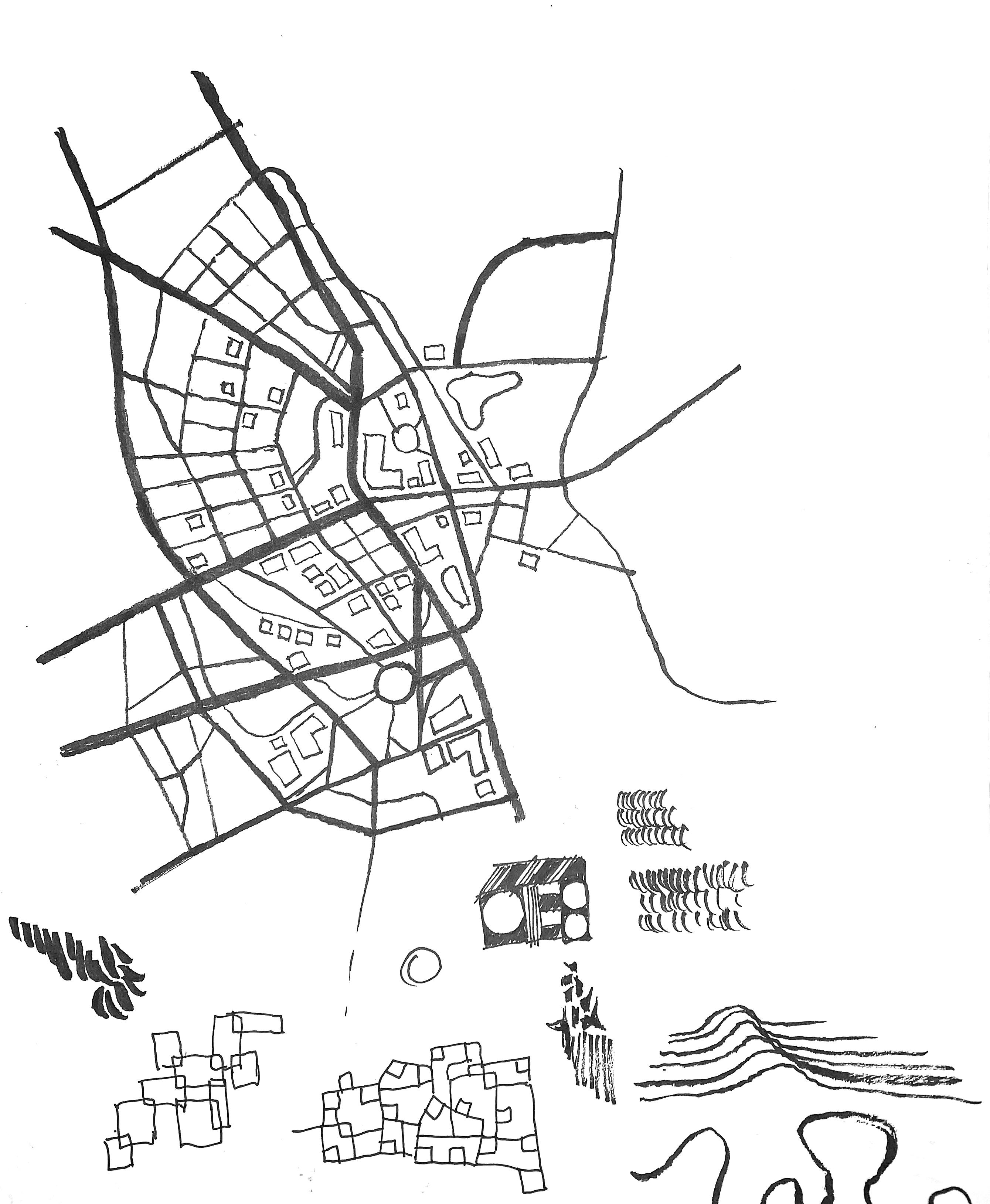

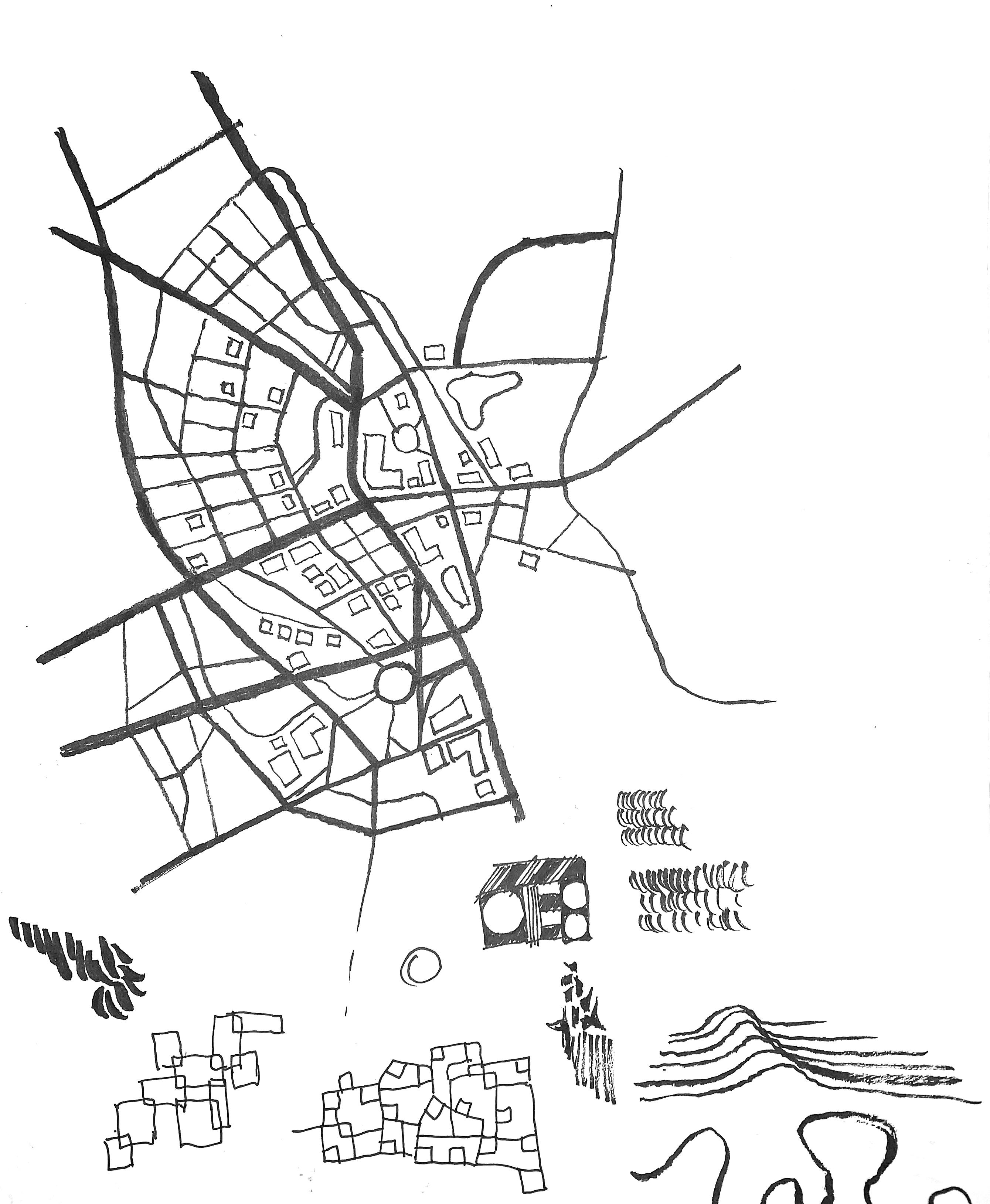

No. 3 September 2022 RACHAEL COLLINS JACKIE WAY STEPHANIE MOORE CHRIS VARELA ALEJANDRO CABRERA-MALDONADO AUTUMN HOFF MERCEDES BARRIGA STEPHANIE MOORE Editor-in-chief Managing editor Designer Audio/video editor Intern Spiritual laborer & artistic advisor Cover illustration Interior illustrations

WHITE & JESSICA LOPEZ

CABRERA-MALDONADO

FLORES

CASSANDRA FLORES

HERNANDEZ

SAN ROQUE

CRISTOPHER CASTILLO

10 BEATRICE

Interconnected (dance/video) 14 CASSANDRA

Mi Castigo Por Ser Hija (creative nonfiction) 26

Three Poems: Clavel, Niña Sufrida, & Borrowed Approval 30 DONNA

Matilda (poem) 32 HELENA

Cubed House (creative nonfiction) 12 ALEJANDRO

What does first-gen mean to you? (interviews) 36

My Name is Cristopher Castillo (video)

JIN YANG

Teaches

IRIS KIM

CAO

Valediction

TRAN

Minutes

EL JAMRAH

Poverty in America” by the New York Times (creative nonfiction)

AYESH

nonfiction)

SELAH GARRETT

Bursting

Insomnia

nonfiction)

58

A

of Balloons (fiction) 62 SILVIA CHAVARIN Chronic

(creative

44 XUÂN

30

(poem) 46 CINDY

“Mapping

38 JOY

Dad

Joy to Play the Guitar (video) 40 ISABELLA

Chopin, Piano Concerto No. 2, 2nd Movement (music recording) 50 DEENA

Pressure (creative

42

Part-Time 사랑시, Part-Time

(poem)

FELIZ AGUILAR

The Inevitability of the Gun

nonfiction)

TEFFINA ZHU ZHENG

Kiss

nonfiction)

DONNA HAKIMBABA

as i watch the curtains breathe in and out to the rhythm of the gentle breeze (poem)

DAYANA HERNANDEZ RODARTE

Chilaquiles de la Abuela (creative nonfiction)

LETICIA ESPINOZA

Nopalera

nonfiction)

Bringing It Home: A First-Gen First-Year Looks For His Path

76

(creative

88

The

(creative

92

94

100

La

(creative

108 ALEJANDRO CABRERA-MALDONADO

(multimedia project) 124 CONTRIBUTORS

F

IRST AND FOREMOST, we would like to thank all of the students who submitted (those we published and those we did not) and all of the students who participated in Lucid work shops and events last year–without you, there is no Lucid; there isn’t even a UCI. We would also like to thank the staff from English and Composition who helped process a ton of paperwork and throw a massively fun open mic party: Brianna Brown, Jasmine Diaz, and Jason Kwock–we simply couldn’t have done it without you. Thanks to Scott Lerner and Ryan Chang for helping us kick off the year with the zine workshop and to Stacy Brinkman for putting on the podcasting workshops and just for being a constant support of this work. Your attitude and skillz constantly inspire us. We are grateful to the Composition Program and the English Department for funding Lucid; and to the Humanities Center and Illuminations for their generous support of our workshops and open mic party. Thanks to proof readers: Jung Soo Lee, Yolanda Venegas, and Patrick McBurnie. A special thanks to everyone who donated to and helped fund raise for the Zotfunder campaign, especially Sandy Oh and Julie Schulte. And thank you to Sean Fischer and Xochitl Ramirez for their patience and support while we learned how to fundraise! Thank you always to Kevin Huie and the folks in SSI, the First

LUCID 8

Gen Committee, the Latinx Resource Center, the Dream Center and everyone else who helped with advertising last year. A special thanks to Sharon Stead with first gen housing for your enthusiasm about this work. It means a lot. Thanks to Ballet Folklorico for performing during our Lucid Open Mic Party. Thanks to Micherlange Francois-Hemsley for the beautiful photographs of the blackout poetry workshop and the Lucid open mic party. Thanks to Autumn Hoff for her editing of the advertising video on Instagram “First Generation at UCI” and the amazing art slideshow and black and white photographs at the open mic party. We would also like to extend a special thanks to all of the supportive graduate students and lecturers in Composition who continue to give their precious time and money to the important work of first gen student success. Thanks to Angel, Lesli, and Angel Jr. for being part of Alejandro’s world. We feel we got to know you through the process of help ing to construct his piece. We would like to thank all the moms who gave their time to help make your first gen baby’s piece truly beautiful (especialmente tú, Rosalva. Alejandro es unico en su clase). Finally, congratulations to all of the first gen stu dents from all of our issues who graduated last year! We are so proud of you!

No. 3 9

LUCID 8

No. 3 9

What does first-gen mean to you?

Alejandro Cabrera-Maldonado interviews first-gen UCI students at Lucid’s first spring open-mic celebration, May 2022

Aracely

Mariana Daniel

Kimberly

No. 3 13

MI VIDA COMENZÓ en el momento en que pensamos en huir de esa casa. The shame I felt in that house. We hardly invited anyone over. A dirty sort of white paint slathered the walls and the yard stayed littered with my dad’s mecánica and bottles of cerveza. The dirt from the barren yard clouded the air on your way to the patio donde más cochinero estaba amontonado.

Cuando entrabas la casa olía a Fabuloso después de que mi madre mapiaba. Pero la misma basura from outside snuck its way onto the floor in heaps and piles.

To the left of the door was a stack of mecánica hoarded and stacked to the ceiling where I made sure to watch my feet so I didn’t trip.

The tiles and planks of wood on the floor were worn down. Tracing to the kitchen, the worn floor en la cocina was con cealed by car mats, but when lifted, revealed la tierra y madera from the tears on the floor.

My poor mami tried to keep the house tidy because she liked a nice home for us.

My two brothers were both older than me, pero mas calla dos. A mi hermano mayor, le llamábamos Lito, short for Angelito; eight years older than me and six years older than Bryan. He taught us to love anime and Pokemon. I picked up English from him before I got into school.

LUCID 14

Mi hermano, Bryan, y yo eramos más cerca en edad, just two years apart, but growing up, he felt like a younger brother. He never spoke Spanish but he’s smart enough to get by with what he understands. We always suspected he had autism, but the doctors never took us seriously. Would you, if you were confronted with a mother who relied on her five-year old daugh ter as a translator?

As kids, I took care of him at school, but his teachers urged me to step back and give him chances at independence. He was my dad’s favorite because he never dared to stand up to him. Born out of his mispronunciation of my name, came my nickname, Sany, always pronounced with a Mexican accent.

Mis hermanos y Ma shared a room con literas and I used to sleep there too growing up but I got a room to myself after my primo and his family moved out. But ever since I could remember, mi padre ha dormido en la sala, where his couch sat to the left of my bedroom door, guarding any chance of my escape without his permission.

A night where I would have usually followed our routine. Mi madre y hermanos ya se metieron al cuarto. La hora ya toco 6. It was my turn to head in for the night pero no obedecí.

Instead, I stayed up on the phone with a boy. My worst offense. Mi Pa le decía a mi Ma que iba a quedar embarazada si me dejaban tener novios. I was twelve. Como pude ser así de mensa. De puta. I knew the rules. I was hurting my mom. Mis hermanos.

LUCID 16

As routine followed, mi padre llego en la noche, alarming the dogs as he stumbled into the house drunk. The second he heard a noise coming from mi cuarto, he pounded on my door.

I let the echoes of his fist fade, hoping he’d let it slide for the night. He never did but I just hoped. “Cassandra abre la pinche puerta.” La sangre se me subió ala cabeza, y la piel se me enchino. Words slurred. It was the only way I’d heard his voice. Temblando, abrí la puerta and I handed him my phone.

“Quédate aquí.” I kept still behind the door as it slammed in my face. Through routine, Lito was the first to come out of the room.

In this house, these traditional roles almost felt primal. The way mis hermanos traumados tenian que ser los primeros en protejer. And when I try to stand up for even myself, soy malcriada. Calladita te ves más bonita.

Mi madre followed after my brother in a panic, but at that point, all I could grasp was snippets of the escan dalo outside my door.

“¿Asi la querias verdad. Como tú?”

“¿No le pones atención o que?”

He blamed my Ma for the way I craved validation y la atención que nunca me dio. Now my mom is a puta for my mistakes. Pero la culpa no es de ella. Es tuya y ahora es mi problema. Mi castigo.

No. 3

Holding my head up to my door, I heard his heavy steel-toed work boots trace out of the living room and into the kitchen. Taking my chances, I rushed out of my room and knocked on the door to the cuarto with a frantic sense of danger.

“Abre la puerta. Soy yo,” I pleaded in a forceful hush. My Ma opened the door in an instant. “Apurate.”

That night, I slept in my mom’s room and we held each other.

I sobbed and couldn’t find the words to tell her how much I dreaded my existence on this planet. How if I had my way, the last place where she could see my face would be in a coffin. I knew it would shatter her heart and her grief shatters my own. So I wrote her a letter. I left it on her tocador and left to the restroom. I couldn’t bear to read her face.

Walking back into the room, I couldn’t help but shoegaze, pero I felt los ojos de mi madre esperandome con paciencia. Una paciencia, tan pura, tan linda que nomas biene de una madre. Cuando estuve lista, I picked up my head, joining her gaze, eyes welling up with tears.

A sob choked out of my throat, erupting into a llanto when I heard mi madre join me. She held me and we sobbed, yo ni encuenta que fui la ultima de mis her manos en decirle este tipo de noticia.

Después de esa noche, mi madre supo que su terror de ese hombre nos dañaba. When all your kids want to die, you’ve failed. Estás aquí porque te dejaste. Se propuso que esta iba a ser la última vez. My mom felt responsible for the pain we felt. Como madre nos quiso cuidar. No la culpo por el daño, but the moment she chose to fix the burdens of el abuso de mi padre es cuando se convirtió en mi héroe.

LUCID

Esa noche de Octubre, the still wind that night warned that we had to brace ourselves. Not only for my father’s arrival from a barra, pero para cambio. En vez de correr del enemigo, we had to face him. Ya estuvo. My Madre has just started working, though my Pa didn’t allow it, and she was out working a late shift. When it hit 8, I joined my brothers in their room in our routine for when our Pa hadn’t arrived yet.

Waiting into the night, the anticipated pounding on the bedroom door shook the fragile frame of the house. My brothers and I quickly looked to each other for reassurance and my oldest brother opened the door.

My dad stumbled into our room, yelling drunken gibberish. We sat back in our positions and ignored his attempts at confron tation. The three of us stared at the TV hoping he would settle down pero ese hombre no tiene límite.

“What the fuck do you think I am?” mi Pa asked in his thick Mexican accent.

“Pa relax,” my older brother Lito told him dismissively. Mi Pa can’t handle that. Being patronized. Bryan and I looked at each other and were ready for the worst.

“Relax? Fuck you hijo de tu pinche madre . . . Don’t disrespect me . . . Vete de mi casa.”

“Pa, please por favor calmate,” I pleaded.

“Callate niña. No te estoy hablando.” I knew he would say that but I still tried.

A silence fell over the room that felt comfortable yet tense with my father’s glare. We stared back at the TV, wishing for peace.

“¿Me vas a ignorar? Look at me,” he demanded from Lito. My brother sighed and kept avoiding eye contact, with his attention still focused on the screen. “Yo compré esta tele,” and after a brief pause, he grabbed the TV and began to carry it out of the room. My brothers and I looked at each other startled. Jumping out of the beds with a frantic pace, we followed him out the door, yelling for what the hell he was doing. Once outside, the man flung it off the patio, slapping it onto the concrete. The screen shattered as pieces of glass fell to our feet. In shock, we stared at each other, my father

No. 3 19

included. Heaving, sus ojos me dieren terror. They starved for attention. For reverence so deep. Quería respeto como hombre. Pero como va a ser hombre if he’s throwing childish tantrums. In silence, my brothers and I backed up and were ready to head inside. “Cassandra. Quédate aquí.” I held my breath waiting for Lito to object but he didn’t. I looked at him and he gave me a look of reassurance and turned around with Bryan to go inside. I shuffled closer to my dad as we’re left alone outside, filling the gap where I stood away from him in fear. I stared at the pavement beneath my feet to avoid the glare of my father’s confrontational eyes. They begged to be loved yet I couldn’t betray myself and mi Madre and let the man have that. The cold breeze of that night felt sharp and painful. Me dijo, “Cassandra, sabes que te amo.” The silence crawled into my breath y envolvio sus manos sobre mi cuello, donde mis lagrimas se

“Yo sé,” I choked. I have to tiptoe around this man knowing he won’t hurt me. He’ll hurt my mom for raising me. When it was

Just then, el candado de la puerta empezó a sonar as I look to see my mom arriving from her shift, her face filled with confu sion, her eyes analyzing the situation. The shattered TV on the floor. My drunken dad with piercing red eyes. Nervous at first, I rushed to help her open the fence and try to guide her into the

LUCID 20

“¿Que le haces?” mi mom confronted him, fronting a look of boldness, yet she was exhausted from limpieza at the motel she worked at.

“No te metas,” he told her and grabbed me by the shoulder. I felt tense and tried shrugging him off. My brothers had heard the escandalo outside and rushed outside to help.

“Sany, go inside,” Lito told me and I scurried up the steps of the patio, not looking back because I knew I would have stayed. I hurried to my room where I started packing like we did when we would spend the night at a motel. Putting the bag down, I laid down on my bed, my breath tense, holding back lagrimas with every inch of my will. My heavy eyes sank as I fell into the escape of sleep.

Banging began on my bedroom door, and I woke up anxious, fearing it was my father. I glanced at the clock, reading it at 3 am en punto. Mi Madre empieza a hablar through the door, “Alistate. Ya nos vamos.” I let out a sigh of relief, unlocking my door and joining my family as we walked out the door of the house, down the steps of the patio, and out the fence for the last time.

We cramped into the car with little, but a new sense of dignity began to form. We never acknowledged it but we knew we were leaving para siempre. Mi Ma silently drove us to the motel she worked at.

After checking into a room, we flicked on the lights and settled down into the beds while my mom headed straight towards the restroom. I heard my mom get onto the phone with who I assume was one of my tías. I heard her begin to sob uncontrollably. She could hardly speak on the phone. It was the second time I ever heard my mom cry. Just at the sound of my mom, I began sobbing too and Lito sat down next to me, trying to hug me. That was the first time he hugged me. It felt awkward but never in my life have I felt so much comfort. My vision grew blurry through my tears as I thanked him and laid myself to rest for the night. The lights stayed on as I drifted to sleep en la segu ridad de nuestro nuevo hogar.

Sometimes I have to wonder if I was doomed from the start. I was raised in fear and silence. Mi padre treated me like I belonged to him. He claimed to protect me but he was protecting his own image of me. He demanded my respect in the way I lived. In the way, I should listen and keep callada. In the way, I was obligated to avoid boys and stay out of platicas que no me pertenecían. The entitlement of machismo belittles me to an object. Pero no soy sirvienta. No soy objeto. Soy mujer. Y el castigo por ser hija is unjust but I’ll endure hell to safeguard my latinidad.

With love, Cassandra Flores

LUCID 22

CASSANDRA

Clavel

Eres mi razón de ser Mis raíces y mis sueños Cuando bailo, tu alma resuena entre mis pasos

Amo al clavel

Casi tanto como amo compartir un hogar contigo Tomando nuestro cafecito y llegando tarde del trabajo

Aunque te nombras Rosa Siempre serás mi clavel Eres la flor en mi apellido Mi ramo hecho de orgullo

Te amo Mami

FLORES LUCID 24

Niña Sufrida

Niña Sufrida.

Víctima de mis propios pecados

De mi propia conciencia

My fatal finger Points and claims burdens carried for me that I dare to not live Of voyages across el Rio Grande that yearn for a foot to wet

Por ser pura Nayarita, me adorno en artesanía

Y me llenará de asco si me llaman Americana. Yet I still defend the name of land I dare to not be born in.

I’m pushed onto a stage where even the floors are a looking glass

Where I’m stared at with the beady eyes of mi Madre and my peers

I tend to a soil not belonging to my name

A garden made of plastic that feeds me white lies

Of the promises that I reluctantly follow pero ni tengo fe en este systema

Is this tierra mine to claim or do I fail to conquer? Do I fail to belong?

No. 3 25

Borrowing Approval

I yearn to bask in the familiarity of Chicanas,

In the sorrow of poetry,

In the rage and filth of my own reflection.

Holding out for life

So passively, so hopelessly, so carelessly

Blanketed by the comfort of my traumas

They keep me afloat

I’ve been through worse? I don’t even get up to brush my teeth anymore.

I force truths whispered from the mirror down my throat

Hacking and gagging wet phlegm

Until I vomit an image of myself

That I love so much, I frame.

I’m a collection of chapters with twine stabbed through my pages.

1.… Chicana.

14…. Willingly fatherless girl.

18.… Self-proclaimed víctima de la sociedad.

LUCID 26

Estos capítulos son puertas altas y pesadas

Encierran llanos tan vacíos que lloran por lo romántico

Lloran por lo que me faltó mi padre.

Atención.

¡Atención! ¡Atención!

Esta hija de puta es chillona. Es noviera y va a caer embarazada.

When I first saw my dad after our escape.

Me miró con novio caminando por mi ciudad.

He busted a U and our eyes locked.

“Tu madre no sabe criarte.”

He floored the gas, quemó llanta, and left me.

Porque yo ya no era su problema.

Yo ya no quise ser su propiedad

Y con eso, él ya no me quiso a mi.

No. 3 27

Your daddy’s drunk but its not your fault He’s had a long life This is a consequence of the toll Not yours to pay but you’re here anyway You can’t join in, so why don’t you just watch one drink become three THREE! turns into that special glass that can fit a whole bunch Magic show but you’re too old to wait for the reveal Lost count of how many times you’ve gotten up, now the cans have folded up into lawn chairs We don’t have company.

Tipsy teetering about Giggling like an adult, breaking down like a child He’s on the floor catching his breath When will it be my time to rest? When will it be his?

DONNA HERNANDEZ LUCID

Papi, it’s been a long night Papi, I’ve had a short life But it feels long to me. I turned 21 two nights ago, ur taking my shots for me again Mija, I’m not a drunk; I’m drinking So That’s that I stay for the reveal, But I know how it goes.

No. 3 29

HELENA SAN ROQUE

WHEN I WAS TOO LITTLE and too scared to sleep by myself, my mother and I would always sing “Bahay Kubo,” before we went to bed. It was a song about vegetables growing around a stilt nipa hut.

“Bahay kubo kahit munti, ang halaman doon, ay sari sari . . .”

And she would tell me about how she had a big backyard with a fish pond that got destroyed because of the road widening. One of the many things she left behind to come to a place that wasn’t any better. With the military owning over 90,000 hectares of land and around 10 naval bases, the Philippines is America’s playground. In the 60s and 70s, the Marcos regime spread propaganda, promising a better Philippines, yet pushed more Filipinos to work abroad in the U.S. Like my mom, who had clocked in more hours taking care of elderly white women or little white kids than her own daughter.

But I always had this song. We took turns saying the Lord’s Prayer and Hail Mary. And, of course, sang “Bahay Kubo.”

Every time I prayed, I’d look at the picture of Christ holding a lamb across the room. This Christ had pale skin and light hair, even though the Bible said his skin was bronze and his hair was like black wool.

At St. Catherine of Sienna Catholic Church, I prayed with my mother in the lower room. The air smelled like roses and frankincense. There were people lighting rows of candles in front of Jesus of Nazareth and mother Mary. There were statues of the saints kneeling in front of Her. One of them, my mother told

No. 3

me, was a Filipino saint, San Pedro, who clutched his sombrero in his right hand and prayed. The afternoon sun peeked through the stained glass window panes. We kneeled in front of Her. My mother prayed, but I just closed my eyes and tried not to think about how much I didn’t want to be there.

It occurred to me that my faith was fading when I spent more time looking at the clock than paying attention to the sermon. And that my best friend snuck in her DS one time and we played it until our mothers got annoyed. Looking back, I think it’s funny that only our mothers went to church. The only time my dad came to mass was when I was sick. And then he got sick. And he died.

I would dream about my life outside of this apartment. I would think about Heaven. I wouldn’t think about the neighbor screaming at his wife downstairs to “shut the fuck up.” I prayed so I wouldn’t have to look up at the same asbestos ceiling. I prayed to God to let me see my dad again. I prayed for an SAT score over 1400. And when I finished, I was greeted with silence.

LUCID 32

“If it’s His will, it’s His will,” my mom would say.

And when she said that, I knew—that my mom didn’t really believe in God.

I remember walking down the street and wishing someone was walking me home. I wished my parents could pick me up. I didn’t want to go home because there wouldn’t be anyone there. No God. No Mother Mary. No father. No mother.

When I think about “Bahay Kubo,” it’s not just a song about vegetables. I think about all the times my life could have been better. In my mother’s version of a perfect life, where we all lived in a nipa hut with vegetables growing around it. If there was a God watching over us. If my dad was alive to watch me graduate high school. If I had a graduation in the first place. If I had someone to walk me home. If my best friend and I went to the same college together like we promised. But every time I close my eyes. I don’t know if there’s a God, but I still like to think there is and pray. Even if I will never have a house with vegetables growing around it, I still like to imagine there is one. For my mom, at least.

No. 3 33

From Lucid editor Rachael Collins:

During the school closure of winter, 2022, I asked students in my composition course “Education as the Practice of Freedom” to make a self-introduction video in which they talk about their relationship to education. Christopher beautifully articulates much of what we hear from first-generation college students at UCI, especially about the immense pressure to succeed that can rob them of the simple joys of learning.

35

When I was in eighth grade, my English teacher assigned my class a project where we had to try something new and record our progress. I chose to learn to play the guitar from my dad. This video is from the beginning of my project when I was first learning to play the chords for a song I had chosen to play. The guitar was a little big for me because it had been my mom’s guitar. So, it was difficult for me to stretch my hand out to play the different chords. Memorizing the chords wasn’t so easy either. I stopped playing the guitar after that because I couldn’t get used to the pain in my fingertips where blisters were just about to form. However, it was a meaningful time for me being able to spend time with my dad. It had also been my dream to learn to play the guitar from my dad as I had grown up watching him play. Although I did end up dropping it, I’m glad I took up the guitar through him.

JOY JIN YANG

LUCID 36

No. 3 37

ISABELLA CAO LUCID 38

No. 3 39

geomijul.

half-cold tteokbokki in white bowls. i pick out the fish cakes and lay them in my brother’s bowl a pile of abandoned words—actions will suffice as an apology. “is this enough?”

green onions going down the drain. crocodile hands, chicken skin. fingers gathering hair into three dark rivulets. she doesn’t remember how to braid.

wiping dust off the floors with a rag. forever fan. my birthday, tomorrow. i’m not expecting much. summer birthdays are like that. my friends and i might go out, share popsicles in the july heat ignore the fact that we’re speedrunning towards our twenties. quiet.

i miss the boys i used to love. the hum of summer insects. the conversations, social networks, acknowledgement. i want to hang out with you. are you free this weekend? lip gloss tastes exactly how it smells: bad.

IRIS KIM LUCID 40

Hear Iris read “Part-Time 사랑시, Part-Time Valediction”

lying on the floor again. humming the same chorus line. i’m suddenly feeling inspired. sweating it off. the stench of crab sticks, mayonnaise, and wasabi: underneath a layer of bergamot and plum blossoms. sometimes it’s ck one, sometimes it’s clean cotton, i spray one, two, three times to keep the sea at bay.

be safe, kids. boram.

sun on my arms. my lungs hurt from laughing. i’m gonna miss you so much. an era has ended. the words are leaving me as quickly as they come and i swear i try to catch them, desperately scooping at them with both arms. train rides back home. re-reading dms from 4 years ago: thank you for existing! a new age has arrived.

No. 3 41

On my lunch break, thumbing through the web, my McDonald’s crispy chicken sandwich box, teeter-tottering on my left thigh, I read a study conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in the comfort of my Corolla. It claimed: Americans spend 74 minutes eating each meal— the quickest time compared to Turkey (162 minutes) and France (135 minutes). I scrolled some more and saw a picture of two cream Korean poodles, @spicedogsss, confettied in pink bows, a rhinestone collar cuffing their cotton necks. Caption poorly translated: It’s so cold that my face just keeps getting ugly. Batter-nugget crumbs drop into the box, nearly tipping over. Instagram’s algorithm tallies how long it hypnotizes me and then, suggests more dog photos and lipgloss. My life suggests: more dog photos and lipgloss. Inevitable timer tings. I toss three bites into the garbage. Dust my fingertips on faded black jeans. Clock in the last four digits of your social and swipe a damn hairnet.

XUÂN TRAN

No. 3 43

“Mapping Poverty in America” by the New York Times

CINDY EL JAMRAH

THIS IS MY ASSIGNED READING at my $15,000-a-year university in Irvine.

At a university where 45% of the students are working part-time jobs to pay rent and using CalFresh to afford a meal, they want us to study poverty.

The reading says low income is under $23,283. The cities in California include Oakland, Oxnard, Panorama City, South Gate, Santa Ana, Adelanto, Victorville, etc. My hometown makes the list with a 53% population of low income and I’m starting to understand why my hometown is listed instead of Irvine.

At my high school 95% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch, eating school-provided meals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

School lunch included microwaved pizzas where the cheese stuck to the plastic, overdone taquitos that you needed to use your molars to bite on, foil-wrapped steamed burgers with soggy buns, and frozen orange juice for dessert.

Besides the state-of-the-art meals that we must be appreciative of, we were constantly watched over by the care of authorities.

No. 3 45

6 Police Officers are spread across campus hovering over any sudden movement of Black and Brown students trying to get an education, 8 Army Officials stalk students to con vince them to use their life for endless and pointless wars, 2 Political Representatives track our education to ensure 12.7 billion dollars are spent on prisons instead of schools, and 40 students are packed into a classroom where teachers have shifted their focus on measuring the length of our skirts to be lower than the tips of our three fingers. All of this is happening while we wonder what the SAT is?

We unknowingly run around these obstacles, and when we make it to a college with a 2% Black population in Irvine or we become a part of the 13% of Latines with a Bachelor’s Degree we are reminded that any success is from the color of our skin rather than our own accomplishments. Our privilege comes from “Affirmative Action” because there is no way we can actually succeed.

But as children running around these obstacles we never thought anything of it; besides doesn’t everyone want the same thing? To not be woken up by helicopters roaming around at night after the sound of fireworks or 5 gunshots that have gone off. Instead we want to be woken up to 4 stacks of pancakes topped with cajeta and fresas in the morning, not a bullet through the window again. We sit at our table that seats 4 but always has 2 empty seats; we sit wishing our parents could join us for these meals, but they’ve already left for 1 of their 3 jobs of the day.

But we never saw ourselves as different; until we are in our parents’ shoes paying bills we can barely afford, and learning our life is defined by The New York Times as Poverty.

LUCID 46

Hear Cindy read from “‘Mapping Poverty in America’ by the New York Times” No. 3 47

Pressure

4:29AM. My sister wakes me up from a deep slumber to pray Fajr.

I think I’m twenty minutes late. If I had woken up earlier, maybe I’d have the luxury of going back to bed.

I go to the bathroom to perform wudū, and drench my face with cold water to wake up. This gives me a frigid shock of energy that lasts about ten minutes. It’s enough to get through prayer and maybe pick an outfit to wear, but once my face is fully air-dried, I can sense the looming lethargy heavily weighing down my eyes as I sit in bed, waiting for my day to start.

5:00AM. Chime! *buzz* chime! Chime—THUMP. I’m already up.

I shower, brush my teeth, do my skincare routine and style myself in the dark.

I’m wearing gray-plaid slacks with a streak of pink in them, matching it with a pink puffed-sleeve blouse, a black sleeveless

DEENA AYESH

No. 3 49

blazer, a diamond necklace, and some fake silver rings. I hide the dark circles under my eyes—the battle scars of my fatigue— with concealer. I then color my face with primer, contour, foundation, highlighter, eyeshadow, eyeliner, mascara, lipliner and lip gloss. I put on my black platform heels, despite how impracti cal they’d be to wear for an outdoorsy university. I tighten my poofy hair to a ponytail and tuck it away with the crown that is my pink hijab.

I must dress with no flaws. I must embody perfection.

The only way I can be acknowledged, respected, and accepted is if I present myself in a way palatable to every expectation imposed on me by the world’s superficiality.

I have to showcase my femininity, but not too much, or else I do not have respect for myself. I have to exhibit a sense of fashion, but not too excessively, or else my priorities are oriented towards materialism and minimize how smart I actually am. I have to

Some of my boots. Fashion is often a tool people use for leaving an impression on others, and with time it became one of my outlets of self-expression.

LUCID 50

dress modest, but not too modest, or else I’m a Muslim woman oppressed by some fictional man dictating what I can and can not wear. I have to put in the effort, but convey an impeccability that is effortless.

Of course I have enough confidence to ensure my self-image and esteem is intact, but why risk all that I’ve sacrificed to be here by rebelling through indifference in the name of pride?

I have to care what others think even if I internally don’t, because if I show that I am noncompliant to faulty standards then I delay my opportunities for connections and success. It’s like the sub missivity of wearing an uncomfortable suit for a job interview; it’s socially unacceptable to wear sweats or pajamas. “Dress for success”—or else forget getting the job. This discomfort is mostly temporary for others; but I have to live with it everyday. I want a better life. I must refine every detail of myself to show the world how much I want it and deserve it.

I look in the mirror wondering if I should practice my smile. I must constantly beam and swallow my frustrations or else my sharp facial features will reify the historically discriminatory narrative against me as an Arab and a Muslim, that I am inher ently angry/violent/uncivilized/capable of terrorism.

No. 3 51

Taken during a drive to UCI. It was 6:18 on the interstate 110, so I was tired, but it was nice because I was able to watch the sun starting to rise while the road was quiet.

I don’t feel like smiling right now.

I should be allowed to feel that way.

I guess I’m ready to go.

6:05AM. A calm rush of wind strokes my face as I cross the street to my car.

It’s too early to be out. But if I were to leave at 7:00AM, I would not arrive at school until 9:00AM because of the traffic of overpopulated Los Angeles. I leave now, and it will take me 45 minutes to get to school on an empty freeway, with an hour to spare before my 8:00AM class.

Commuting makes life a little more tiresome, but any other option would be impossible for me to afford.

Helping my family with the rent at home is less financially strenuous than it would be for myself and for them if I were on my own. My wage as a barista isn’t livable. Even when I used to work full-time (I changed to part-time because I could not fit the right availability with my school hours), I would not be able to finance an apartment, my car payment, insurance, gas, food, and tuition simultaneously. I’m lucky I managed to have some money saved from the years of work I put in while I was in community college for free. When it comes up in conversation that I com mute from the South Bay to Irvine, I receive pity as they recall the one time they engaged in a similar commute for a trip of leisure.

“How can you do that everyday?” they ask.

They never ask why I have to—or why the world is constructed in a system where I have to.

At least commuting gives me time for myself to contemplate in silence.

8:00AM. My heart cannot stop hammering in my chest. My anxiety is heightened from my Monster energy drink. Today is the day we get our exam scores back for thermodynamics. If I get a C, then maybe with supplemental work and a curve, I could get a B in the class if I’m lucky.

The TA hands me back my exam without mak ing eye contact.

A big red 28% is written at the top. I failed.

I open the Canvas app on my phone to see the grading scale and overall class average. Class average is 70%. Lowest score is 28%.

I was not anticipating stellar performance, but I certainly was not expecting such a massive failure either. How could I have performed so badly? How am I supposed to fix my grade now? How am I supposed to get accepted to medical schools with such a tainted GPA? How am I supposed to go home to my parents—who have fought tirelessly to show me love and care, to keep the roof over my head, to make sure there’s food on the table, to ensure I never drop out of school because my potential is the only way we can

My car after hitting a semi-truck on the 405 freeway. I was on my way to class, and after this accident I wasn’t able to attend class for three weeks. It was disheartening to have a new factor outside of my control get in the way of my potential success.

Taken one night while I was studying for a quantum mechanics exam. I was pulling an all-nighter because I had to work right after my classes that day and found no time to study beyond staying up all night.

climb out of the poverty we’ve suffered from for over a decade—and look them in the eye to tell them that the daughter they’re so proud of might not have what it takes to succeed? That all this hard work we invested is in vain?

I can feel my cheeks burning with red, my throat tightening, and my vision is suddenly blurred by tears beginning to form.

My support system at school likes to tell me that one bad exam isn’t the end of the world, and one failure won’t hurt my potential for success. They like to tell me that everything is going to be okay. Maybe that’d make me feel better if this was my first failure. But this is the third exam I failed for this class. I’m failing my other two classes as well. I use all my free time to read, study, and learn the material.

Is it even my fault? If I didn’t have to commute for so long, I’d have more time to study. If I didn’t have to work, I could attend the randomly scheduled tutoring sessions and professor office hours. Could it be that I don’t have enough time?

Or could it be the lack of foundational knowl edge that I missed by having a community college education?

Could it be the fault of my calculus professor that refused to deliver lectures during remote learning? Or my chemistry professor that only focused on giving us shortcuts without explain ing concepts? What about my physics professor that graded us on nothing but the one project he assigned us?

Could it be the fault of my university professors that don’t have supplementary material to help me transition? Or the fault of the professors that assume I already know everything?

Am I supposed to be upset with myself for not succeeding with my struggles (despite the many others that have overcome worse), or should I be upset with the world for inhibiting my success by not preparing me or not accom modating me?

I shouldn’t dodge responsibility. I knew that I didn’t know my calculus, chemistry, or physics very well before coming here. I just thought that despite this, maybe I could still fight for my goals. Maybe I had some intelligence and talent to offer that could outweigh my shortcomings.

I think I still do. But maybe if I didn’t have to prove it to the world first, I could prove it to myself.

My notes and some photos of my grades during my first quarter, as I do put in some effort to learn the material but sometimes I don’t see the results I want.

A Bursting of Balloons

E

VERYDAY, IT’S ALWAYS the same thing . . . wake up in the morning and stare at the bulbous red shoes and the speckled blue suit and the white face paint that smears the bedpost and the walls and the mirror. They stare back—the shoes and the suit and the paint—they stare back and mock me with a this isn’t what you expected to be doing with your life by your mid 30’s, huh, Joe. Everyday, I have to stare into their mocking gaze, and swallow it all. Down it like medicine or a shot of cheap tequila or news that your grandma’s in the hospital again. It’s a living, I plead back; although really, it’s embarrassing I feel as though I owe this stuff, this meaningless, pointless stuff, any explanation at all. But after all, they’re part of me now. I wrap the blue suit around my arms and legs like it’s my own skin, like I’m a gift ready to be tossed aside at any snot-nosed, little kid’s birthday party within the county. Slip my feet into the shoes, paint my face in white. It’s all just a mask at the end of the day. It’s all just a mask, but it’s the mask I’ve chosen. One time, my mother called me and she said, Joe, what you’re doing with your life . . . the clown thing

don’t even like clowns

. . . well . . . people

No. 3 57

58

roaches. All the world’s a stage, they say, and roaches need a good laugh too. Maybe one day, I’ll write one of those infomercials. Have scenes in black and white of a party where no one is having fun—smushed cake, awkward silence—and I’ll juxtapose those against colorful scenes of children and their families surrounding me in endless squeals of laughter, laughing so hard they cry, laughing so hard they nearly piss themselves. Everyone loves TV these days. Maybe if Ma saw me on TV like that, mak ing everyone smile and laugh, she’d change her mind. I had a partner once, Delilah. She knew it was a dying gig, same as Ma, but she loved it. Her suit was pink and covered in daisies. The kids loved her. She never scared them. She knew how to make them feel warm. One day, we were on our way to a party for this rich family that lived down south and we were on the freeway and we were in a hurry and we were going too fast and she told me to slow down but we needed the money and they were going to pay us so well and we couldn’t afford to be late and I yelled at her, I yelled at her, We get paid by the hour, Delilah, we can’t miss a single minute, and then she turned away from me and one of the tires popped and I lost control of the wheel and the car spun like a top, spun like a ballerina on steroids, and we slammed into a wall and the bricks crushed her, and the sound of her bones crunching beneath them was like the sound of fireworks crack ling and popping on the Fourth of July. The ambulance came, screaming like children’s laughter, but it was too late. She was gone. Her body mangled beyond recognition. I think of her too, every morning. Remember the way her cheek bone shot out from her face, covered in blood. I broke my arm that day. That was it. Just a broken arm, and a bit of trouble with my spine. But, I can still make a blue bird out of a single balloon. I can make you any bird you want. That’s got to count for something, right?

No. 3 59

Chronic Insomnia

SILVIA CHAVARIN

CONVERSATION WITH ANDREA

Andrea: “You know, some people are just biologically meant to be night owls.”

Me: “Oh really? –Well, go on, enlighten me.”

Andrea: “Just think about it. Back in hunter-gatherer times, some people had to stay up all night to keep the group safe.”

Me: “So I can’t sleep at night because my ancestors decided to take the graveyard shift?”

Andrea: “Yes, you’re genetically predisposed to be an insomniac.”

SLIGHT MISCONCEPTION

To most people’s understanding, insomnia is a sleep disorder that prevents individuals from falling asleep at night. And although that interpretation is fairly accurate, it does not encompass all aspects of insomnia.

CLARIFICATION

Better explained by Thomas Roth, the director of the Sleep Disorders and Research Center at Henry Ford Hospital, a more accurate and concentrated description of insomnia would be, “the presence of a long sleep latency, frequent nocturnal awak enings . . . or even frequent transient arousals.”

In other words, insomnia is not only the inability to fall asleep, it also extends to the inability to stay asleep. Some sources, such as Stanford Health Care, even include “wak[ing]

No. 3 61

Figure 1. My first sleep-aid bottles.

up too early the next morning” as another indicator of insomnia disorder.

Insomnia is generally classified by its duration. If the disorder presents itself for less than a month then it would be classified as transient insomnia. Insomnia that lasts between one to six months is referred to as short-term insomnia. And if the disorder persists for more than six months it is labeled as chronic.

Certain factors may contribute to the development of an insomniac disorder. These factors are environmental, physiolog ical, and psychological. And while some individuals have a higher risk of developing insomnia than others, a great number of people suffer from sleep disorders in general. As Matthew Walker, a neuroscientist who specializes in the study of slumber, noted, “the ‘sleep aid’ industry, encompassing prescription sleeping medications and over-the-counter sleep remedies, is worth an astonishing $30 billion a year in the USA.” Walker’s research goes on to argue that this “is perhaps the only statistic one needs in order to realize how truly grave the problem is.”

4 DAYS WITHOUT SLEEP

I didn’t always struggle with chronic insomnia. My unhealthy relationship with sleep began sometime around my sophomore

LUCID 62

year of high school. What started as sacrificing a few hours of sleep has now led to the slow deterioration of my health. A chronic problem that has followed me well into my college life. And although I’ve endured many of the side effects that accompany severe sleep deprivation (such as concentration issues, mood changes, a weak ened immune system, etc.) there is only one side effect that has left me in fear:

The light coming from the sunrise touched my face. Just a few minutes ago the only illuminating fixture was the blue light coming from my computer. Now you could see the sleep deprivation on my face. This is the third sunrise I have witnessed consecutively. Unlike me, my roommate has a “normal” sleeping schedule.

“Why are you still awake, Silvia?” my roommate asked suddenly.

I replied with: “I have a test to finish in 12 hours. I can’t waste a second.”

“You’re crazy,” she replied.

“Mentally unstable,” I corrected her.

After our brief conversation, she got up. To presum ably use the restroom. I vividly remember my roommate struggling to free herself from her blanket. I remember her struggling to find her glasses; their black frame often blended in with our mini fridge.

“Can you pass me a water bottle?” I asked.

“Yeah, when I come back,” she replied. As she got up to leave, I don’t recall whether she put her sandals on, but I do remember the loud locking sound that followed the slamming door. I found that to be out of character. She is very considerate of our hallmates and does not let the door slam.

I finished reading a chapter and realized that she still had not returned. Reasonably, I begin to worry. The restroom is two doors down the hall, she should’ve been back already. That’s when something caught my eye.

“It’s actually fairly common for sleepdeprived people to hallucinate when sleep-deprived for long enough.”

Brandon Peters, M.D.

No. 3 63

“I try to live every day but the fact doesn’t change”

Aaron Taos, “Control”

“We can’t change the things we can’t control” Foster the People, “Imagination”

LUCID 64

My roommate, sound asleep, turns over in her bed. Her glasses, still on top of our mini fridge.

“How did I not see or hear her come back? How do I know that’s really my roommate? Did she ever leave the room?”

Several questions such as these raced through my head. Shock turned into fear. “How do I know what’s real and what isn’t?

Would I still have gone through that if I had just slept?”

ACCOUNTABILITY?

Sometimes I don’t know who to blame. Myself? The school system? My parents? Is there anyone to blame?

“Going to college [is] not a choice for first-generation stu dents, it [is] necessary in attempt to push their families to a higher economic standing” (Hernandez). Growing up my parents made it excessively clear that the only “right” pathway for me was that of a college education. It seemed as if “no querás terminar como yo” became my father’s catchphrase whenever we started a conversation. He never missed the opportunity to lecture me on the importance of obtaining a higher education.

Due to certain circumstances, my parents never went to college, let alone finished high school. Their unfinished educa tion has proven to be detrimental to their livelihood and has made it an obstacle in providing for my siblings and me. Although we are more economically stable now, it is still not enough to make a comfortable living.

For this reason, I was expected to enter a respected college. I was expected to further my education. I am expected to do better in life than they ever could.

It took me a few years to understand why. Why they would express great disappointment if my grades dipped to a B. Why they would view my breaks as lazy and unproductive rather than resting.

Although they meant well and only had my best interest in mind, the mentality they instilled in me was “place your educa tion above anything else.” Unfortunately, to my interpretation,

No. 3 65

this included my health. So that’s what I did; my sole focus became school. If I could fit a club or some community service hours on top of my eight-class schedule, I would. If I had to sacrifice a few hours of sleep, I would. Annually, I would create strict schedules that revolved around school. I would choose whichever program I believed would look better on my college applications. I chose Cajon High School (CHS) over Middle College High School (MCHS).

• MCHS is a relatively small high school that integrates some of its classes with the local community college. Each grade level consists of 100 students or less.

• CHS is a much larger high school that provides stu dents with the option of entering the International Baccalaureate program (IB). Each grade level holds about 600 – 700 students.

Lo Siento Madre. Saboteé las dos entrevistas para Middle College High School.

By choosing Cajon, I was choosing IB. I put myself in this situation. I was the one who consented to it all. What I didn’t realize at the time was the cult-like environment that IB creates. At least that was the case for my graduating class. Rather than generating a supportive environment that allowed room for growth, IB was devised with toxicity and high competitiveness within those who had high ranks. You were seen as nothing but competition to other high-ranking students.

Besides the cut-throat environment, IB classes tended to be over-demanding. The assignments themselves were manageable; it was the load in which these assignments came that was truly terrifying. In the blog Nail IB, dedicated to helping IB students, one of the authors wrote, “Every IB student that I have ever met on this planet has pulled a lot of all-nighters. I once remember a time when I drank almost 8 cans of Red Bull to make it through the night for

“[F]irst generation college students report getting fewer hours of sleep and would prefer to get more sleep at night compared to their colleagues.”

Lhia Hernandez

LUCID 66

the sake of finishing assignments. Interestingly, I was only a little dosage of caffeine away from being hospitalized.”

I regrettably positioned myself in a place where I couldn’t change my school environment, therefore, by destroying my sleeping schedule it felt as if I were regaining some control. But now I can’t help but feel like the villain of my own story.

WORSE THAN BEFORE

My troubles with sleep started around my sophomore year of high school. However, at the time these problems were justified due to the environment that I was in. Now that I’ve begun college I no longer carry such an immense burden. I learned to let go of the mindset that was contributing to my deteriorating health.

Despite this my insomnia persists, worse than before. Why?

When Andrea and I had that conversation about my insom nia I didn’t place as much significance in her words. If my insom nia was inherited, then why didn’t I experience trouble with sleep earlier in life? Why did it have to start at the most crucial point of my high school career? Turns out there was some truth to her words, as I’ve recently discovered I have a handful of family members who also struggle with insomnia. But none have reached the extremities that I have.

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID, PETER TRIPP, AND RANDY GARDNER

There was a point in time when I tried scaring myself into sleep ing. I read research suggesting that during deep sleep there’s a moment where our brain releases Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) through itself to conduct a deep clean of the brain tissue. Studies suggest that “the CSF provides buoyancy, nourishment” (Spector) and it removes waste that is accumulated when we are awake. It has been speculated that if this process were to be disrupted, such as not entering deep sleep, our brain will

Figure 2. My Apple Sleep Tracker

No. 3 67

begin to build up waste. Even the idea of having unhealthy waste piling up in my brain can’t put me to sleep.

I also read up on the case of Peter Tripp, a radio host who stayed up for 8 days as a stunt that would help him raise money for charity. During the fourth day, he too began experiencing hallucinations. After the stunt, he claimed to feel the same, but he “continued to show psychotic symptoms . . . lost his job, divorced his wife, and was rarely heard of by the public ever again” (Medium).

Randy Gardner later went on to beat the world record of days without sleep. In the name of science, Gardner spent eleven days awake. By the end of the experiment, Gardner had been experiencing moodiness, paranoia, problems with concen tration and short-term memory, and hallucinations.

As unhinged as this may sound, my initial thought after reading about these two was, “as a female, I need to defeat both of them.” I won’t do it, mainly for health purposes but also because Guinness World Records no longer accepts entries for the longest time without sleep.

THE WANDERER

Staying up during the night is never the hard part, at least not for me. The real struggle begins at sunrise when the golden sun rays expose my dark circles to the world. I’ve found that the real challenge is to keep my brain stimulated throughout the day, especially during classes.

12:00 AM

It was around midnight when I had left my dorm. Now I found myself wandering through my housing community. Strolling around campus has become my nightly routine. A soothing feeling accompanies the calm and refreshing night.

LUCID 68

I also picked up this habit because I didn’t want to disturb my roommate. She’s a light sleeper and I don’t want my problem affecting her.

I cross the School of Art and use the bridge to make my way to the School of Humanities.

12:30 AM

When people find out I have insomnia they usually question all the ways it affects me. They question my mental health, physical health, and academic performance. Then they question the steps I’ve taken to possibly resolve this problem. Whether I take medication, talk to a sleep specialist, anything. But they never consider how it affects the people I’m close to.

I have woken up my roommate on numerous occasions when I return in the morning. Although she’s told me that it’s okay, I can’t help but feel guilty.

I have lashed out at certain friends, more than I’d like to admit when I experience mood changes from the lack of sleep.

I reach the School of Humanities and briefly admire the light academia aesthetic.

1:00 AM

I begin walking on the outer ring road, with the School of Biological Sciences as my destination. I breathe in the crisp air and Andrea’s voice travels through my head: “You know the temperature is good once you start going numb.”

The sprinklers go off and I stop in front of the Anteater Learning Pavilion. My attention travels towards the water. The aroma emitted from the sprinklers reminds me of the smell found at Disneyland’s Pirates of the Caribbean ride. I’ve always liked that smell.

I come out of the nostalgic haze and begin my walk toward the Science Library. I don’t stop to look at the statues behind the

No. 3 69

Figure 3. Photo taken at BioSci bridge.

library because my destination is a pink-colored wall in the BioSci School.

1:30 AM

For the most part, Irvine is a relatively safe space. I had found comfort in the night, a false sense of security. I suppose that’s why I didn’t take any of the safety precautions most people would have. As I crossed the bridge connecting the science library to the school of Biological Sciences there was a white van conveniently taking a stroll underneath. The only reason I noticed was because I dropped my phone and had to look around to find it.

When I saw the van, my heart sank to my stomach. What were the chances that a van had stopped exactly when I stopped at relatively the same area at nearly 2am? Perhaps, whoever was in that van had no ill intentions and it truly was a pure coincidence. However, I weighed my options; if I were to continue to my destination, I would probably have a very low chance of survival. That night I found out how fast I could really run: pretty darn fast. I made it back to my dorm; I did not sleep that day.

LUCID 70

CONVERSATION WITH A RESIDENTIAL ADVISOR

RA: You do know the health complications that come with not sleeping, right?

Me: Yeah, I’m actually writing a paper about my problem right now?

RA: If you know what can happen, why don’t you just sleep?

Me: It’s not that simple.

RA: Have you ever heard of melatonin?

Me: Yeah, and Unisom. And Kirkland’s sleep aid. My mom had me try some vitamins, she thought those would help, but they didn’t. A friend gave me a mild tranquil izer once. That didn’t work either. Yes, I have also tried those sleep hygiene routines, like not drinking coffee, not using my bed for anything other than sleep; I tried not using my phone before sleeping. I’ve tried some recreational stuff too. My brain just refuses to let me sleep.

RA: Silvia, you worry me. What are you going to do?

Me: The only thing I can do. Learn to be productive at night.

Figure 4. Accidental photo taken as phone fell.

No. 3 71

WORKS CITED

Gardner, Kate. “What It’s Like To Be So Sleep Deprived That You Hallucinate.” https://www.self.com/story/sleep-deprivation-hallucinations.

Hernandez, Lhia. “Past Your Bedtime? How Much Sleep Are First Generation Students Getting Compared to Their Peers?” (2019). Sociology Senior Seminar Papers. 34. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/socio_stu_stu_schol/34.

“How Sleep Deprivation Drove One Man Out Of His Mind.” Medium, 2022, https://medium.com/@sleepybears/how-sleep-deprivation-drove-one-man-out-of-his-mind-7fd44722c7d0.

“Insomnia.” Stanfordhealthcare.org, 2021, https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/sleep/insomnia.html.

“Is IB Worth It: 5 Ways IB Program Can Ruin High School For You - Nail IB.” Nailib.com, 2021, https://nailib.com/blog/is-the-ib-program-worth-it.

Roth, Thomas. “Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine vol. 3.5 Suppl (2007): S7-10.

Spector, Reynold. “A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans.” Experimental Neurology vol. 273 (2015): 57-68. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.07.027.

Vedantam, Shankar. “The Haunting Effects Of Going Days Without Sleep.” Npr.org, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/12/27/573739653/the-haunting-effects-of-going-days-without-sleep.

Walker, Matthew. 2017. Why We Sleep. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

LUCID 72

Hear Silvia discuss “Chronic Insomnia”

No. 3 73

Inevitability of the Gun

The

FELIZ AGUILAR

STANTON, CA – As soon as the door to the FT3 Tactical gun range swung shut behind me, I lost all control and compo sure. Terrified, I could only hear gunshot after gunshot, BANG! BANG! BANG! With every shot, my entire body perspired, my heart rate increased, my cheeks reddened, and my stomach dropped. With every shot I saw flashes of victims’ faces, followed by their killers. BANG! Uvalde. BANG! Sandy Hook. BANG! Columbine. A mixture of grief, terror, and regret seeped over me, as I entered a room full of the objects that have aided in the massacre of thousands. I was being led by my gun safety instructor, Paul, to our reserved stalls on the gun range. It was a busy evening, around 6:30pm, I imagine many folks had just clocked out of work. People were chattering, everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. It was a diverse group of people; I even saw a woman with kitty cat ears over her headgear. And there I was literally shaking in my boots. I wanted to leave. I wanted to fire one shot, just to write this article, and leave. It felt like when I was too little to be on roller coasters and my stomach flipped as the chain of the motor pulled us higher and higher. In those moments I wondered if it would be worth the theatrics to halt everything and retreat to my comfort. But in both moments, on the roller coaster and at the gun range, my main motivation to stay was the experience I’d walk away with, which could only be achieved by doing the thing I feared most.

I.

No. 3 75

my main motivation to stay was the experience I’d walk away with, which could only be achieved by doing the thing I feared most.

II.

The first mass shooting I remembered vividly was Virginia Tech. I was in third grade at Oscar Loya Elementary and my teacher, Mr. Goularte, encouraged us to talk about current events. My mom kept the news on at home, and I remember consuming too much of the shooting coverage at my tender age. For the first time in my life, I felt a deep sorrow and darkness form within me. I attribute this mass shooting as the trigger that began my battle with depression. I gained 100 pounds that year and didn’t leave our two-bedroom apartment for those twelve months. That same year, while I was in third grade, my home town of Salinas, CA was experiencing a surge in gun-related homicides, mostly due to gang wars. We lived in the East Side, known as the most dangerous part of our town. I remember there were murders every single weekend for months. I smelled the gun powder in the air. Whenever I thought I heard shots nearby, I’d hit the floor.

Over the years, my fear of gangs and gun vio lence transferred to an anger with white supremacy and unchecked police power. In 2014, the political event that began my devotion to social justice was the murder of Michael Brown, and his killer’s acquittal. In that same year, Carlos Mejia was murdered by the Salinas Police Department one block down the street from my house. In the viral video of his death, I recog nized the neighborhood bakery that I’d pass every day. Mejia was murdered down the street from my middle school, in the light of day. He was severely mentally ill and holding garden shears. The police were certain that their lives were in danger.

LUCID 76

Since 2014, I have remained committed to advocating against police violence. As the mass shootings continued to occur, I began to view gun control as something that the United States would unfortunately never meaningfully or effectively implement. There are too many obstacles to make it happen, especially as it is the Second Amendment to what many con sider our nation’s most important document. My focus has moved from gun reform to the obliteration of white supremacy. To me, white supremacy is the uniting ideology and “reason” for most, if not all mass shootings.

III.

The recent mass shooting in a predominantly Black part of Buffalo, NY was perpetrated by a white supremacist who had a slur etched in his killing weapon. The El Paso shooting of 2019 was carried out by a white man who drove out of his way to shoot people in the majority Mexican town. Dylan Roof murdered several worshippers at a historic Black church. The Columbine shooters were revealed to have been racist bullies before they killed themselves. Some shooters act out of misog yny, which I would argue is an arm of patriarchal white supremacy. The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence published a study that claimed “two-thirds of mass shooters [are] linked to domestic violence.” The Uvalde shooter shot his grandmother and frequently harassed women online. The Sandy Hook

No. 3 77

78

shooter killed his mother. The Isla Vista shooter went on a rampage because he claimed that women did not want to sleep with him. While the gun control debate centers around the availability of guns, I see less people outright pointing to white supremacy and misogyny as the fundamental problems.

Since these mass murderers are misogynistic racists, I do find it somewhat empowering when women and People of Color elect to learn how to defend themselves with a firearm. If they are being targeted by people with guns, why not know how to use them against the people who want to kill them? In fact, there have been diverse pro-gun groups forming across the nation, such as the Socialist Rifle Association, created by and for social ists who want to defend themselves and their communities, or Arm the Girls, a Black, Indigenous, and PoC-led project that aims to equip members of the LGBTQ+ community, but specifically transgender women, with firearms. Black transgender women are murdered at a higher rate than any other LGBTQ+ demographic and arming them could aid in preventing another life lost. With these progressive groups among the ranks of gun enthusiasts, I felt less controversial about choosing this topic for my article. But during the process, I was met with valid reasons to hesitate.

This article was assigned to me on May second. According to the Gun Violence Archive which classifies a mass shooting as the death of four people or more, there have been 75 mass shootings. In the last week, there have been sixteen. The Uvalde shooting occurred right in the middle of the writing process, and I seriously contemplated picking a different topic. I ultimately decided to follow through because I felt that my unique experience with gun violence would allow different perspectives on the use of firearms in the U.S., and the diverse groups who might take an interest in their proper use.

IV.

Back at FT3 Tactical, I settled in the classroom upstairs from the range. I arrived first and talked with the instructor, Paul, who told

LUCID

me a lot about himself. Paul was a direct and confident person.

In his late-thirties, Asian-American, with a bulky, muscular build. He said he had been in the military for nine years, having toured Iraq twice. Though I surmised from his demeanor that we had chasms between our political affiliations, I respected him for the expert knowledge he brought to the course. The first question I asked him, since our meeting took place days after the Uvalde shooting, was whether interest in gun safety increases or decreases after a mass shooting. “It actually goes up,” he alleged. He pivoted to talking about the high murder and rob bery rates in California, claiming that the increase in crime was the driving force behind a rise in gun purchases. The Public Policy Institute of California corroborates Paul’s claim that homicide is increasing. Additionally, the SF Chronicle wrote in 2021 that gun sales in California “skyrocketed.” Paul’s information was correct, but I found it troubling that that was his response to my question about mass shootings. The second, and last, person to join us was a middle-aged Filipino man named Michael who brought his own gun and ammo. We introduced ourselves and Paul began his slideshow presentation.

Paul described firing a gun like the yin and yang of Taoism—it requires as much gentleness as strength. “You’ve got to be gentle with your hands, but firm with your arms.” The first part of the presentation detailed the various parts of the firearm. Paul claimed that movies portrayed inaccurate depictions of guns, such as referring to the cylinder in the gun chamber as a “bullet” when it wasn’t. “This one really annoys me,” began Paul. “The bullet is only the tip of the object, the whole thing is called the cartridge.” He proceeded to draw a diagram of the parts of the cartridge: bullet at the very end, followed by gun powder, wrapped by a bullet casing. The next part of the course covered the fundamentals of gun safety. Paul introduced to us the 4 Points of gun safety: “Always treat firearms as if they are loaded,”

“Always keep your finger off the trigger and alongside the frame until ready to fire,” “Always be aware of your surroundings when using a firearm; this includes what lies beyond your intended

79

No. 3

target,” and finally: “Never have your firearm pointed at anything you are unwilling to destroy.” Paul’s philosophy was that in order to have a well-rounded firearm safety course, the student must understand the consequences of using this weapon. “Accidents happen when you get lazy, so education is key.”

As we moved on to the next part of the presentation, I felt a succession of vibrations beneath my feet. POP! POP! POP! For a second, I forgot that our class room, the first location where we would be taking our gun safety course, was upstairs from the shooting range. My nervous system went into survival mode, and I dissociated out of reality. I thought to myself, This is what it sounds like when your classmates are being murdered in the other room. I snapped myself out of it and continued to pay attention to Paul’s slides. The next portion detailed the various laws of deadly force. He read the first law: “You must be in reasonable fear of death or great bodily harm.” Examples of great bodily harm he offered were bone fractures, permanent loss of a limb, loss of consciousness, and rape. The second law: “Potential threat(s) must have the ability to carry out death or great bodily harm.” He adds, “Threats alone, without the capacity to follow through, does not authorize the use of deadly force.” Third law: “There must be intent to cause death or great bodily harm.” Paul includes two important legal terms: Reasonable Man Standard, which means that a person must act “reasonably” when using deadly force; and Disparity of Force, which justifies using deadly force if the person attacking you is significantly bigger than you. Underneath all three laws of deadly force is written: “Ignorance

LUCID 80

of the law is not an excuse!” Paul referenced CA Penal Code 23515, subsection 197, which contains the laws of legally defending oneself. He also referenced two different court cases, People vs. Ceballos (1974) and People vs. Piorkowski (1974). The former case sets precedent that a burglary is not enough reason to use deadly force. The latter case sets precedent that using deadly force during a robbery at a place of work is still punishable.

We reached the end of the presentation, and the final part of our classroom training required us to practice holding a gun and aiming. Paul provided a gun replica for us to practice with in place of the real thing. As the time grew closer to the moment in which I’d pull the trigger, the lump in my throat grew heavier. The process of shooting a gun, as Paul instructed, was Sight, Trigger Press, and Follow Through. First, I had to form the proper shooting stance while holding the gun correctly, looking through the front sight (located at the tip of the weapon) towards my desired target. The next step was to gently pull the trigger with out releasing it. Lastly, follow through meant that I had to watch the bullet travel. Follow through, like in basketball or archery, means that you must watch your projectile until it reaches its destination to ensure an accurate launch. Paul had us practice our shooting stance: “Pull with your left, push with your right! Put your feet shoulder-width apart and bend your knees! Lean forward! Keep your finger off the trigger!” I was overwhelmed, but I got into position, took a deep breath, and set my eyes on the front sight of the practice gun in my hands. Before I felt ready

As the time grew closer to the moment in which I’d pull the trigger, the lump in my throat grew heavier.

No. 3 81

82

to shoot, Paul instructed us to take our belongings and walk downstairs to the shooting range with him. It was time. We made our way downstairs. I picked up my rental gun, ammunition, and ear protection. We walked through the large metal doors that lead to the range. After my initial shock mildly dissipated, I stood in my designated stall. Paul loaded the gun for me, a Glock with .22 caliber cartridges—about as wide as a pencil eraser. He clamped the target, the outline of a body with a bullseye for the head and the heart, to a moveable wire that ran from us all the way to the back of the range, the length of a semi truck. He adjusted it to five yards away from me, saying that most gun fights occur within this short range, gave me the gun, and asked me to shoot. Overwhelmed with stimulation, I got into my shooting stance. Paul was behind me reminding me to aim, release, and pull. I focused on the rear sight, looking through it towards the bullseye. Beads of sweat formed on my brow and upper lip as I took a deep breath and pulled the trigger. The small bullet instantly shot out, releasing a warm casing that ricocheted and hit me on the arm. I didn’t flinch. “Great job, another one,” Paul told me. I kept shooting until the magazine emptied. My hands were shaking, and the sweat continued to secrete. Paul noticed and said, “You’re sweating!” I answered, “I am, I’m very nervous,” and I let out a weak chuckle. He had me put my weapon down. “Have you ever heard of the Box Breathing Method?” He told me he used it in the military when his mates would get shell-shocked. “Inhale for four seconds, hold for four, exhale for four, hold for four, and repeat,” he guided me as I tried the breathing exercise. We completed a couple

LUCID

cycles, and then I was ready to keep shooting. “Ready?” he asked me. I gave him a thumbs-up and he reloaded the Glock. I did not expect to be com forted in the middle of a shooting range by this prob ably-Republican war veteran, but life is full of surprises. I wasn’t as nervous anymore, and I continued shooting. Paul would alternate between me and my classmate, adjusting our stances along the way. After I got more accustomed to shooting, Paul came back and gave me reassuring feedback: “You have a better shot than half the people in this range!” My confidence soared as Paul affirmed that I had skills better than some of the regulars.

I fired sixty rounds of cartridges, and our time in the range had come to a close. I’d been there for about one hour shooting. My terror never went away, but the guidance of Paul helped me avoid a fullblown panic attack. Paul, my classmate, and I exited the range and returned our equipment. We then sat at some tables in a resting area of the building. I thanked Paul for calming me down and asked if he had to use the Box Breathing Method often with his students. “There was one guy who was violently, nervously shaking. It was dangerous for him to hold a gun moving like that,” he told me. “I pulled him aside and had him do the breathing technique with me, and by the end of the class he had the best shot out of everyone,” Paul alleged. While I have no confir mation that his student really did have the best shot at the end of that class, it was evident that many people of varying backgrounds signed up for Paul’s class. I imagined that the nervous student felt like me—he couldn’t shake the fatality associated with the object in his hand.

I did not expect to be comforted in the middle of a shooting range by this probablyRepublican war veteran, but life is full of surprises.

No. 3

V.

After completing the firearms safety training, I am more confident in my ability to protect myself and others. Knowing that I have good aim reassures me that if I were to ever find myself in a situation in which I had to protect my or anyone else’s life with a firearm, then I could do it. Nonetheless, this doesn’t mean I want to go out and purchase a gun. I am still terrified of them and the damage they can cause. I am devastated that the nihilistic attitude in this country towards gun control has led me to the shooting range.

I did not pursue this activity because I like guns, but because I am deeply afraid of them.

I did not pursue this activity because I like guns, but because I am deeply afraid of them.

Hear Feliz talk about

“The Inevitability of the Gun”

No. 3 85

TEFFINA ZHU ZHENG

WHEN I TRY TO LOOK BACK

memory works like an old roll of film—the images dam aged by too much exposure to light.