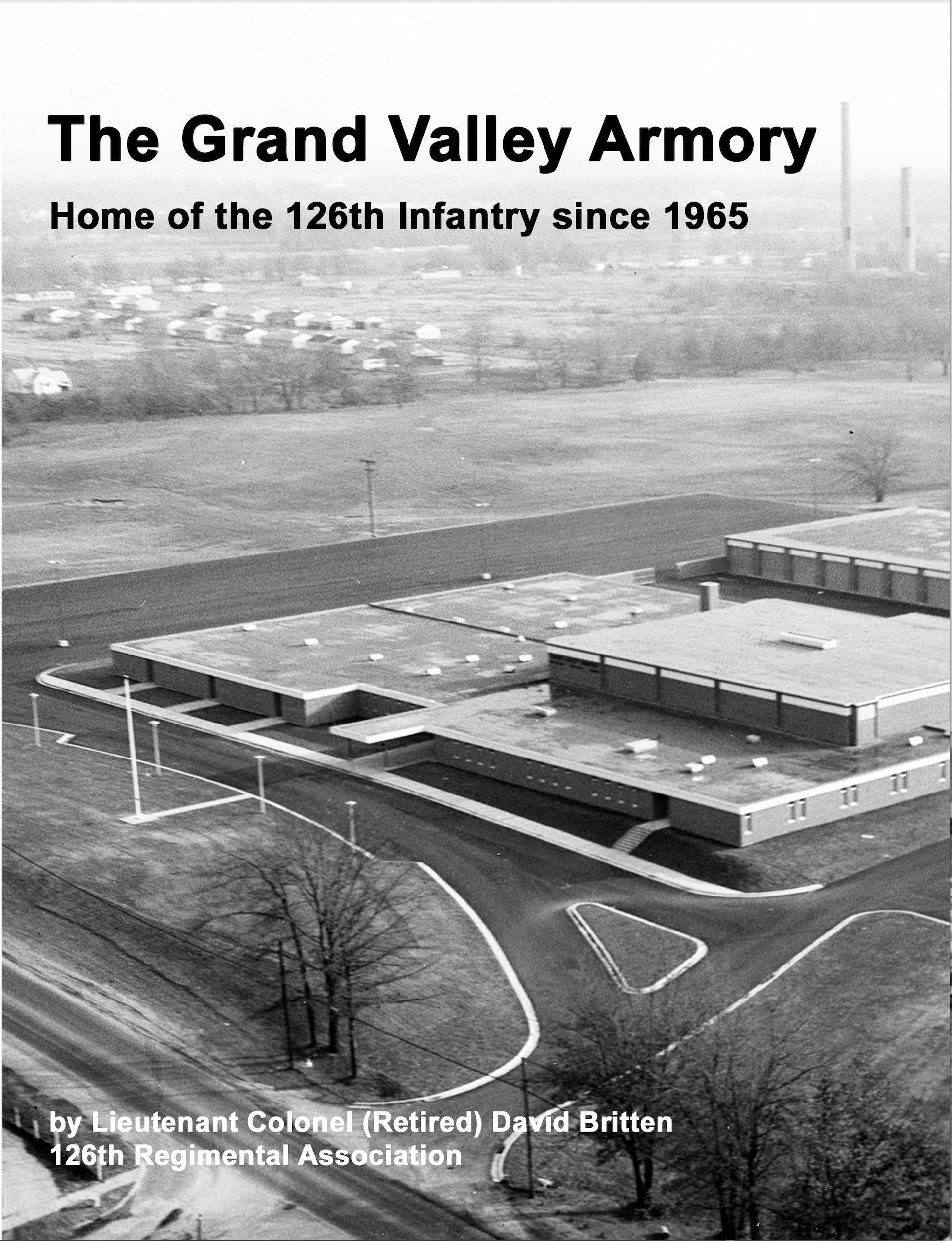

Since the organization of local militia companies, beginning with the Grand Rapids Light Guard on July 12, 1855, each company was responsible for providing an armory either by building one or, as most often was done, renting space around the downtown area. One of the very first armories we are aware of was the No. 1 Fire Engine House where on July 12, 1855, at 8 o’clock that evening, a group of civic-minded men met in Wright L. Coffinberry’s office and agreed to organize the Light Guard with Coffinberry as their captain. It soon moved to an armory in the Abel Block on Monroe Street, while the Grand Rapids Artillery met on the top floor of the new West Side Union School on Turner Avenue.

In 1859, the Light Guard had moved to an armory in Taylor & Barn’s Block. By the Civil War, there were four companies each meeting in its own location. Besides the two already mentioned, the Grand Rapids Rifles met above the John W. Pierce store on Canal Street.

Beginning with the post-war organization of the Grand Rapids Guard in 1872, the armory for this company was in the Old Randall Block, which was later occupied by police headquarters. One year later, the Guard moved to Armory Hall at 36-1/2 Ionia Avenue in the new Godfrey Block. The company would remain there until 1897.

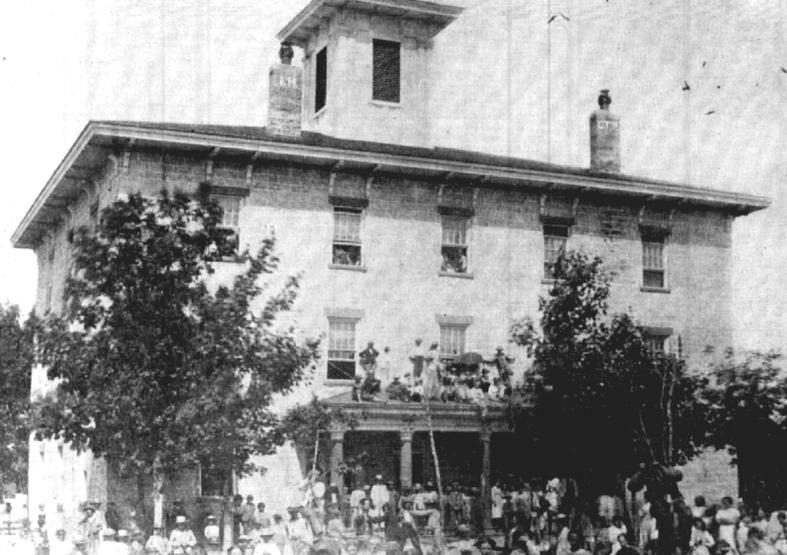

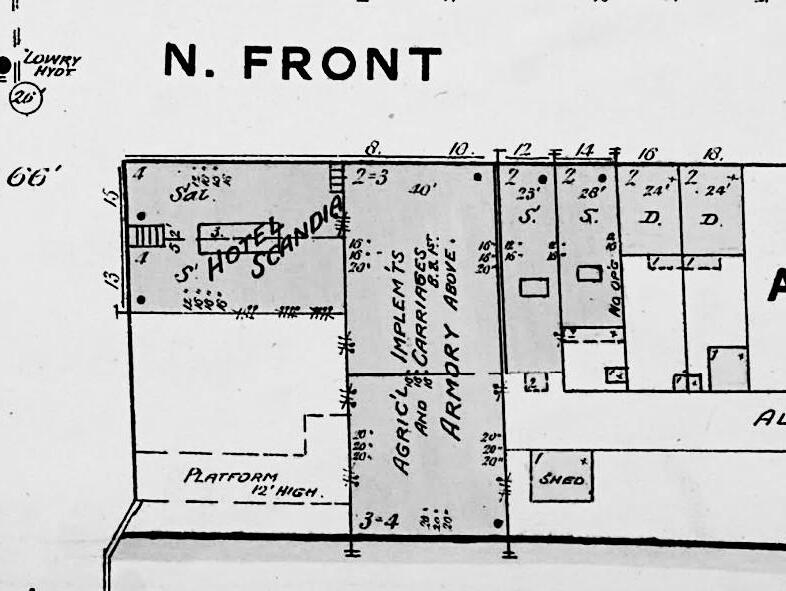

It wasn’t until 1882 that a second company joined what had become the 2nd Regiment of Michigan State Troops, and it did not list an armory of its own until 1885. Known affectionately as the “Custer Guard,” this company settled into the second floor of an agricultural implements building on North Front Street, just north of Bridge Street

on the west side of Grand Rapids. It too remained there until 1897.

The Custer name was in honor of Major General George Armstrong Custer whose wife, Elizabeth Bacon, was a cousin to Rebecca Richmond of the Grand Rapids Richmond family. The company was considered elite in Michigan for its ability to conduct drill and ceremony, winning several prizes. Later at the Michigan Street Armory, Mrs. Custer would provide the battalion with a forage cap originally worn by her husband and a portrait. The cap is still in the association’s possession today.

A third Grand Rapids company joined the 2nd Regiment in 1884 calling itself the “Innes Rifles,” using the old skating rink at 55 North Division for an armory. The name was in honor of General William P. Innes of Civil War fame. The company remained there for the next four years, moving to the Powers Building on Pearl Street by 1888.

Another four years later, the Rifles moved to a new Armory Hall on the northeast corner of S. Division and Cherry Street. It would later become the site of the Moose Lodge and would be substantially altered when South Division was widened. The Innes Rifles remained in that location until 1897 when it was mustered out of service for failing inspections. A new Company H known as the “Grand Rapids Cadets” took its place.

It was expensive for each company to provide for its own armory, so a decision was made by the three companies to merge as a battalion in one location. By 1897, the battalion – dubbed the Grand Rapids Battalion – had relocated to leased space on the 4th and 5th floors of the Clark Building on South Ionia Avenue, across from today’s VanAndel Arena The Clark Building armory was considered the finest in the state at the time, with furnishings and equipment valued at $11,000. It featured a large drill hall, classrooms, billiards, an 80-foot indoor target range, a café, and elegant parlors.

A fourth company simply known as Company H soon joined the battalion. It was from here the local units mobilized and departed Grand Rapids with the 32nd Regiment for the 1898 War with Spain, as Companies B, E, G and H. These letter designations would change periodically with exception of Company B, the original Grand Rapids Guard

By December 1909, the Grand Rapids battalion’s officers were calling for a new armory large enough for the companies and other gatherings. If the City of Grand Rapids were to provide the land and turn the deed over to the state, Michigan would provide funding for construction. The first plan called for using the city museum site or even a portion of it, but city leaders and the school board which had jurisdiction over the museum were cool to that idea.

In early 1910, it was decided the city would purchase the Kusterer property on the northeast corner of Michigan Street and Ionia Avenue Northwest. This would provide 200 feet along Ionia Avenue and 150 feet on Michigan, large enough to erect an armory with a drill hall of 22,500 square feet, large enough to allow the four companies with adequate drill facilities, and ample space for holding banquets and occasional conventions. Major Earl Stewart, battalion commander, estimated the hall and surrounding gallery would hold more than 8,500 persons. Besides the four companies, the battalion included a band and a hospital corp. Meanwhile, the Second Regiment was called out and deployed to the Upper Peninsula for the Copper Strike of 1913

It would take several more years and considerably more funding to erect the armory. In the meantime, not wanting to extend the lease on the Clark Building, the Grand Rapids Battalion temporarily moved into the 4th and 5th floors of the Cadillac Building on LaGrave Avenue, where it would eventually mobilize and deploy for the 1916-17 Mexican Border War. While they were away, work began in earnest on the new armory. The Battalion was fortunate

to secure the two top floors since the owner of the building originally intended to use the entire structure for the automobile business. He consented only when assured that at the end of the lease, a new state armory would be ready for occupancy by the Battalion.

The Cadillac Building on the immediate left along LaGrave Avenue also had other names and uses over the years, but the top two floors served as a temporary armory for the Grand Rapids Battalion from 1914 until 1917.

The state guaranteed $90,000 but the cost of a new armory was put at $150,000 so a local bond issue was put up for election in the spring of 1915. This called for the ability of the city to utilize the armory for conventions and other programs. When completed, it would boast the largest drill floor in Michigan (150 feet square) with a gallery on three sides, tripling the seating capacity of the local convention hall being used at the time.

The cornerstone for the new armory was laid in April 1916 with an impressive parade led by Colonel Louis C. Covell and ceremony led by Masonic Grand Master George L. Lusk. The local third battalion of the 32nd Infantry regiment (the designation of the local units at that time) followed as well as the regimental band, the new machine gun company and Field Hospital No. 1. A wide variety of historical documents and photos were placed in the cornerstone.

Constructed on a site 150 x 200 feet in dimensions (a parcel that very soon would prove to be far too limiting), the armory would have a 65 x 45-foot main floor with a

gallery surrounding three sides and a stage along the fourth. The Grand Rapids community saw this new armory, which would be built and maintained by the State of Michigan, as a chance to finally have a convention hall for a large variety of civic purposes beyond the military intent.

Completed and turned over to the National Guard in midDecember 1916, the new armory was considered “architecturally superb in perspective and detail” providing facilities for club, recreation, and instruction purposes. Several parlors flanking the sides of the drill floor included spiral staircases that led to the company rooms along the second-floor gallery. Each parlor was assigned to a company, one for each of the four infantry companies, one for machine gun company, and one for the regimental band. Special offices and parlors on the first floor were included for officers.

At its dedication, The Grand Rapids Press noted the basement of the armory as being “perhaps the most interesting part of the building.” On the west end were several bowling alley lanes in a room that opened to a club office containing a tobacco stand. A separate entrance was provided for access without disturbing events on the main floor.

On the east side of the basement was the rifle range, 100 feet in length. It included a ventilating system for gun smoke and a dirt floor to allow for digging of trenches. In the front of the basement was “the best lighted and probably the best swimming pool in Grand Rapids.” It was 20 x 60 feet with diving board and had showers and a locker room adjacent. On the east side of the building in the first floor, space was provided for a billiard and pool room that opened into card and reading rooms. A room for “veterans” or retired members of the battalion was provided as well as a kitchen.

Aside from three minor contracts, the local population took pride in the fact the new armory was “made in Grand Rapids.” When it was dedicated in December 1916, the Guard was on the Mexican Border. Colonel Covell returned to Grand Rapids to participate and accept the building, but a formal “housewarming” would not take place until the units returned.

The reading and card room was a popular spot in the new armory.

They weren’t there for very long when mobilization for the World War came along and by the time the units did return and were re-organized in 1919-21, they were part of the 126th Infantry Regiment, 32nd “Red Arrow” Division.

This new post-war organization led to overcrowding in the armory and talk of a new armory or significant expansion began almost immediately.

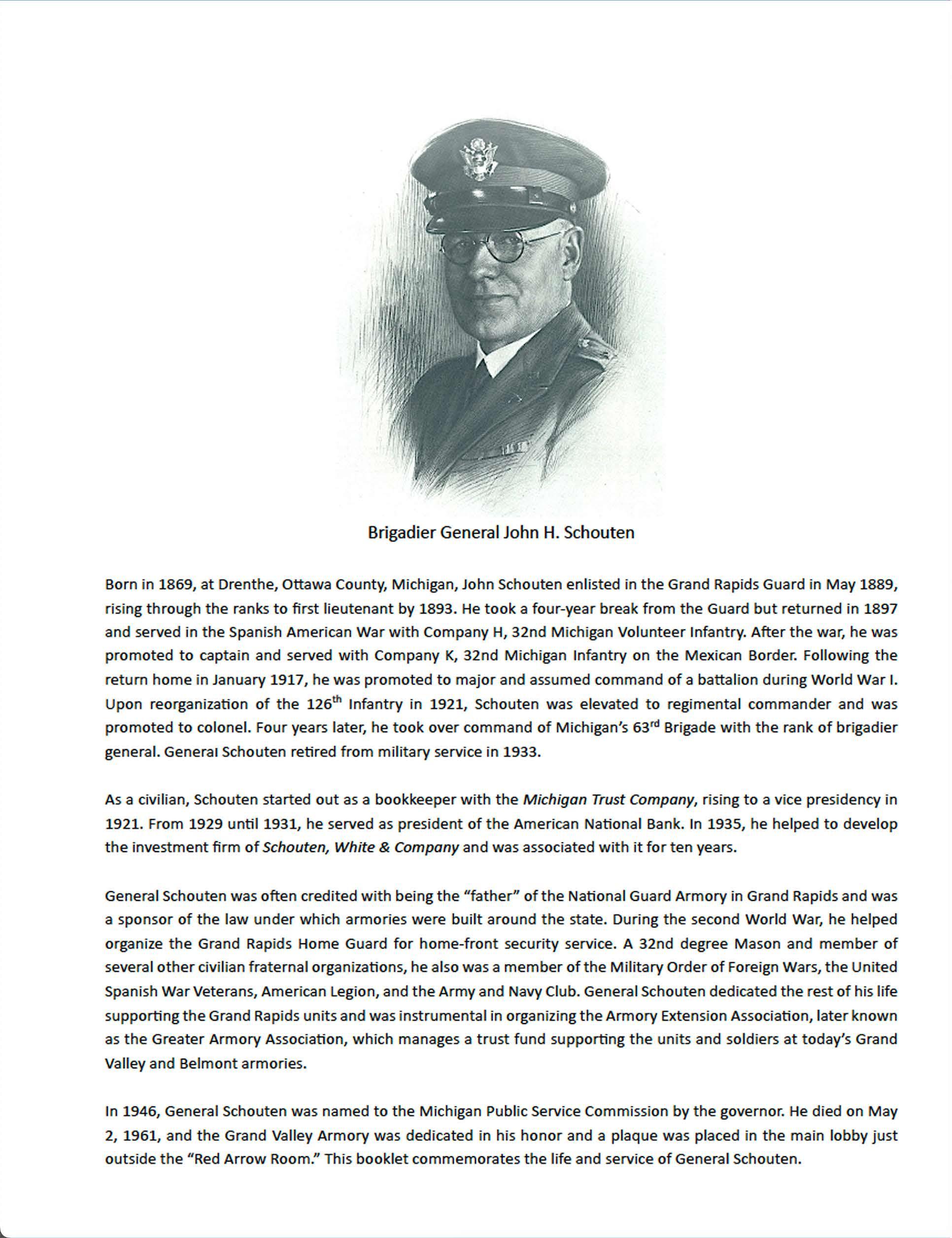

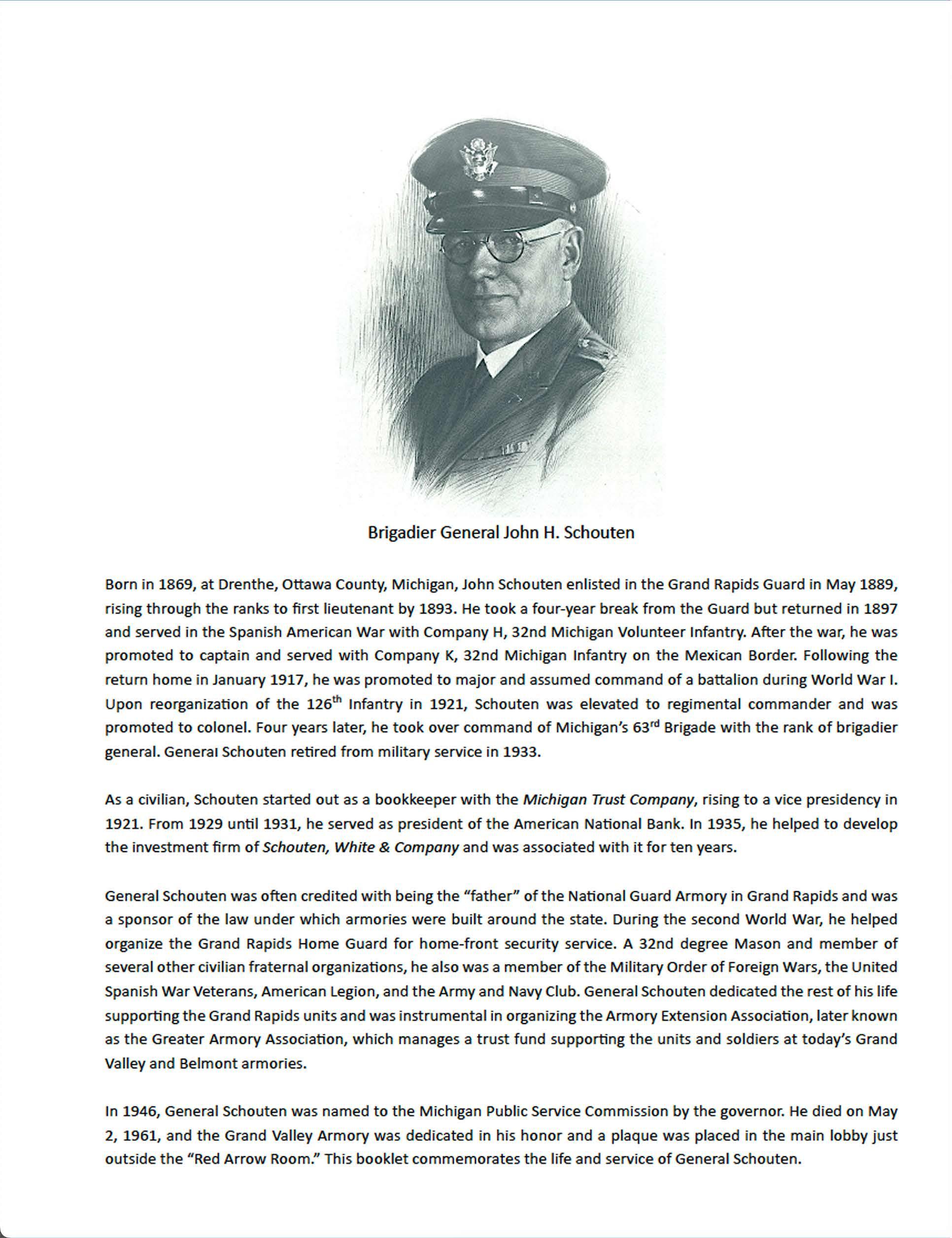

By 1923, Colonel John H. Schouten, an investment banker with the Grand Rapids Trust Company, made public plans for doubling the size of the armory on Michigan Street. The planned addition would cost around $100,000 and would include “one of the largest auditoriums in the state.” The expansion, however, did not materialize. Even worse, plans by the city in 1931 to extend Division Avenue north of Michigan Street tightened the squeeze on the Guard’s property and eliminated virtually any room for expansion of the armory. That expansion likely would not have occurred anyway since by the early 1930s, most large civic functions and conventions were moved to the new Civic Auditorium near the Grand River.

During the winter of 1940, Kent County requested the State of Michigan turn over 360 acres of the old Picric Acid plant site after no person or group bid on it during the state land board’s “scavenger sale.” The state had come into ownership when a local group promoting the sale of the abandoned site defaulted on its taxes after little luck finding buyers for the site. The state land board act provided for parcels that were not bid on were to be made available to government units, provided the lands were guaranteed to be used for at least ten years for public purposes. There was no cost to the transaction and the acreage, particularly in Section 26 of Wyoming Township, was characterized as ideal for a county park. George Tilma, Wyoming’s supervisor, had sought to have the land purchased for a township park but he died suddenly before any actions were taken.

In March 1940, the state land board notified Leonard E. Kaufman, secretary for the Kent County Road Commission, that the county would get the deeds to the 360 acres. Kaufman noted that seedlings would be planted to reforest the parts of the acreage that were bare due to the World War I construction work on the uncompleted plant. However, little work was done on the new park at first owing primarily to demands for work on the older parks. Five years later, as World War II was coming to an end, the Grand Rapids Round Table Club endorsed a proposed development of the park as a county war memorial project. The Round Table Club was a local service organization with membership primarily in Grand Rapids that had been in existence since 1926 (and still is today). It was part of a larger organization of the

International Knights of the Round Table founded in 1922 in Oakland, California.

The following year, the Kent County Park Commission requested that the board of supervisors dedicate the property as the county’s newest park. In response the board appropriated $5,000 to prepare the land for picnic grounds and Kaufman indicated it could be ready for public use by the next season. The park commissioners were also considering the placement of a monument in the park in tribute to the memory of Kent County’s World War II dead. On August 14, 1946, the county board of supervisors officially christened the park as Veterans Memorial Park. Work continued but the park would not formally open for another nine years.

By October 1954, Lieutenant Colonel (abbreviated as LTC)

Clarence C. Schnipke, the full-time officer at the Michigan Street armory, was planning to write a letter to the Kent County Road commission requesting ten acres of county property on 44th Street, one-half mile west of Clyde Park Avenue, for use as a site for an additional armory costing in the neighborhood of $1 million to construct. Schnipke pointed out that the present armory in Grand Rapids was inadequate and had been since the 1920s.

While Veterans Memorial Park was still not officially opened, Kaufman predicted it should be ready in about a year. He saw no problem with Schnipke’s request since the new armory would still be available for public use citing the possibility that it would include recreational facilities such as basketball and volleyball courts and could be made available to the public for meetings and social events.

One month later, the road commission approved the request. The plan at that time called for the Grand Rapids armory to be remodeled as an additional structure to the new one in Wyoming Township. In other words, two National Guard armories instead of one. The Wyoming armory would be built large enough to house three full Guard companies plus the 126th Infantry regimental headquarters. The federal government would pay sixty percent of the cost. The ten acres would be deeded outright by the county to the State of Michigan, representing a small return to the state of property it once owned.

The county board of supervisors approved the ten-acre request in January 1955. Of course, the action was subject to approval by the state. The approved plan included a clause which stated that if the land was not used for the armory within five years after the deed was given to the state, the property would automatically revert to the county. It would be another ten years before the site was occupied by the Guard.

In the meantime, U.S. Representative Gerald R. Ford conferred with the senior officers of the Michigan National Guard on the armory plans. At the time, Ford was a member of the Army Appropriations Committee that would need to approve the funding. A month after that, a national test mobilization of National Guard forces, dubbed “Operation Minuteman,” demonstrated the severity of a lack of space at the Grand Rapids armory. LTC Schnipke was forced to plan for use of space in the old brewery across Michigan Street since not knowing how long the test alert would require the assembly of troops, he had to consider housing and providing meals for as many as 1,000 men. In addition, guards were posted at every door for the first time since prior to World War II, just to keep members of the public from wandering into an already over-crowded situation. Conditions were so bad that the four companies of the 3rd Battalion were forced to move outdoors during the alert.

Wyoming was not yet sold on a new armory in its area. Township supervisor George Sietsema indicated he was taking a cautious approach to the project, indicating he wanted to determine the sentiment of the township residents before he made any commitment. There was no rush since Guard officials had noted that the necessary appropriations for the second armory could take as long as two or three years. Later that year, the Armed Services Committee in the U.S. House voted to authorize the start of a billion-dollar expansion of armories and training areas to keep pace with the expected growth of the military

reserve forces throughout the country, but only $250 million was approved for use over the next three years, a more limited amount that the Pentagon had requested. This was just the first of many steps that would be needed to make the new 44th Street armory a reality.

During the winter of 1956, a county-wide armory finance committee, which included representatives of Kent County residents and the Michigan National Guard armory, began a drive to raise at least $250,000 from city, county, and township governments to help with the proposed armory in Wyoming. The drive was announced at Wyoming Park’s Parkview School by Major John P. Brown, supply officer for the 126th Infantry regiment and assistant to the state quartermaster general. The goal of the committee was to obtain pledges by June 1.

Brown noted that local communities traditionally contributed to the cost for such facilities as a basketball court, women’s restrooms, locker rooms, dining space, kitchen, blacktopped driveways, off-street parking, landscaping, and extension of sewer and water mains. Such facilities would serve as a benefit to the entire community. He went on to point out that the federal government would likely contribute half the total cost and the state, which would own the armory, another $300,000. Later that year, the Kent County Board of supervisors approved changing the name of the park from Veterans Memorial Park to the Linus C. Palmer Park, in honor of the county park superintendent and forester. This change was pushed by backers for changing Grand Rapids’ Fulton Street Park to Veterans Park.

By 1958, there was still no plans or designated funding for building the Wyoming armory. That April, it was announced that the Guard would use approximately $43,000 in federal funding to build a new garage, underground gasoline storage tank, and gas pump at the armory on Michigan Street NW. This would require approval by the state legislature. One thing that was holding up progress on the Wyoming armory was a substantial reorganization of the National Guard under a new “Pentomic” structure designed to create streamlined organizations that could operate independently as a striking force. This was in response to the Cold War threat of nuclear conflict that might cut off communications and support, leaving commands to depend solely on their own systems of support. The 126th Infantry Regiment that existed since 1917 was reorganized into two of Michigan’s five new battle groups. The Grand Rapids armory became the home base for the 1st and 2nd Battle Group 126th Infantry headquarters along with Companies A, B, and C

of the 1st Battle Group and Company E and support units for the 2nd Battle Group.

Overcrowding persisted, with military vehicles stored offsite and the Guard’s facilities stretched thin. At the same time, the armory was also housing the 46th Division Band (soon to be known as the 126th Army Band) and the 46th Division Trains, a detachment consisting of ordnance, transportation, and medical contingents. It was also announced that the $1.125 million armory in Wyoming was still on the “desired list” due to the overcrowding of the downtown armory, but local contributions of at least 25 percent would be required for construction. Plans for the new armory would have to be altered to support the new organization of the Guard.

During the summer of 1960, a meeting of senior commanders was held at Camp Grayling to discuss proposals for the new armory in the Grand Rapids area. Colonel Robert T. Williams, commander of the 1st Battle Group 126th Infantry, with a goal of coming up with an agreement on the type and size of facilities needed to either augment the Michigan Street armory or replace it. The old armory was so overcrowded that most of the military vehicles were being kept in rented garage space off site. But another issue was also on the table and that was the desire by the State Highway Department to obtain the Michigan Street armory property as part of the planning and construction of the Interstate 96 downtown penetrator route (later known as I-196). Moving the Guard out of that armory would allow it to be demolished to make room for realignment of N. Division Avenue through the site as it passed under I-196. Such a move would reduce costs by eliminating extensive retaining walls necessary if the thoroughfare was routed around the armory as previously planned.

The armory property was valued at $700,000, however the Guard offered it to the highway department for

$400,000. This would allow the Guard to seek a similar amount from in federal matching funds along with $200,000 from local governments for the new 44th Street armory. It was noted that the federal payroll for 1,000 men training out of the armory at the time was approximately $500,000. By February 1962, the Guard and the highway department finally agreed on the purchase of the Michigan Street armory with funds from the sale to be designated for construction of the new armory. The Michigan legislature agreed to the deal, but a new wrench was thrown into the works.

Major General Cecil L. Simmons, commander of the state’s 46th Infantry Division and traffic engineer for Grand Rapids, was investigating other possible armory sites besides the 44th Street site. These included a 20-acre site on the east side of Fuller Avenue NE, north of Sweet Street (which was nixed because it was left as a trust for perpetual care of a neighboring cemetery), and a ten-acre parcel at the site for the new Kent County Airport in Cascade Township. While the site on 44th Street was already owned by the state, Simmons felt the Guard’s first obligation was to Grand Rapids where the units had existed since 1855. In the meantime, because demolition of the Michigan Street armory was set for the coming fall, space in the old Berkey & Gay terminal on Ottawa Avenue NW was rented to serve as a temporary armory, and the State Military Board was pressing Simmons for speed in making a site selection.

Now came the back-and-forth between the Guard and the City of Grand Rapids on where to place a new armory. City commissioners wanted to look at sites where rejuvenation is needed and construction of an armory would be an

asset. However, the city planner noted they could not find any other sites under city control that could be acquired at reasonable cost and meet the minimum site specifications necessary. The state Guard Headquarters noted that the clock was running out and any further delay beyond September 1 would push the availability of federal funds out for one even two more years. Simmons set August 21 as the deadline for a Grand Rapids site and failure to come up with a workable proposal would default the site to the 10-acre Wyoming location. The state had already retained an architect but could not proceed with planning until a final decision was made. Simmons also note that a group in Wyoming had already offered to raise the necessary funds for local participation. The Wyoming location ultimately gained favor, with local support for funding. The 10-acre site offered a viable solution to alleviate the overcrowding and facilitate the Guard’s evolving needs, culminating in the construction of a modern facility to meet community and military demands.

Not so fast, according to Wyoming Commissioner Louis Vos who was not happy that it appeared a site in Grand Rapids was more desirous than Wyoming. That wasn’t blocking his support, however. Mayor David Visser was concerned about the $80,000 local dollars needed, but if it could be raised particularly from private sources, he felt the armory would be a good investment for the young city. But he added the caveat that the city would not go begging for the new armory. Vos also suggested that perhaps funds could be subscribed locally for installation of a swimming pool for community use.

At the August 21 deadline, in what appears to be a desperate last attempt to keep the armory in Grand

Rapids, a 40-acre site being acquired from the state along the riverfront near the Michigan Veterans Facility was suggested. However, General Simmons had reported earlier that that site was unacceptable because it did not meet federal criteria. When it was inspected back in March, the site was under water, but the federal requirement states the site must be free from low-lying areas. In a heated debate, city commissioners appeared to pile on in defense of the site but to no avail.

On August 28, 1962, the State Military Board acted to award the new armory to the City of Wyoming by default, but one more delay by Simmons to give Grand Rapids fifteen more days suggest a site, kept preliminary planning on hold. He had sought the delay at the request of the Army-Navy Club of Grand Rapids. The city commission used the delay to go through the motions of formally voting on a site already rejected by the state and appeared resigned to losing the armory to Wyoming.

The final decision was stamped in September and the announcement read: “The Military Establishment congratulates the City of Wyoming on the future construction of this $1,200,000 Armory. It was the sincere expressed desire of the City of Wyoming to support the Michigan National Guard and the construction of the Armory in your community that determined this final decision.”

Preliminary engineering in the physical layout of the location on the Palmer Park site began with the next two weeks. The communication from the state’s quartermaster general continued, “I am looking forward to your cooperation and a very pleasant relationship in the construction of this Armory building which will serve the National Guardsmen in your area and will provide Wyoming with an excellent facility for community usage.”

The armory would be the second largest such facility in the state with approximately 1,000 soldiers assigned to it. General Simmons also noted that the new Wyoming Armory would house the “largest indoor swimming pool” in Western Michigan, and an auditorium with a banquet capacity to accommodate up to 1,000 diners at one time. “The People of Wyoming will, I am sure, be very proud of their National Guard. Our men can be relied upon to participate in such events as Memorial Day, Veterans’ Day, and other patriotic occasions which may be scheduled observances in their home community, in years to come.”

Much work was left regarding the details of the City of Wyoming’s financial support for the new armory. A meeting of city and National Guard officials was held at the Holiday Inn on 28th Street SW to discuss Wyoming’s share of the $1.289 million armory. The cost to the city would be about $80-85,000. The quartermaster general noted that if the suburb desired any facilities beyond those paid for by the federal and state government, it would have to foot the bill. He requested Mayor Visser appoint a three-member committee to work with the local armory board of control and architects, claiming “we have no preconceived idea how the building is going to look; we want the community to help us build it.”

The Guard’s state engineer estimated the use of city crews to install water and sewage lines and make other site improvements might cut the city’s share of costs by $15,000. Extras that would be covered by Wyoming’s $80,000 were listed as expanded kitchens, public toilets, classroom space, and a “face brick” façade used in all Michigan armories. In a September 1962 address to the Army -Navy Club in Grand Rapids, Michigan’s adjutant general noted the new armory would handle about the same complement of men and material as the former Michigan Street armory, however it would be larger especially in training and storage areas and would include improved military facilities. Other items included in the planning were advanced training aids such as returns on the rifle range, improved classroom and teaching facilities, and greater indoor space for training and working.

Much to the chagrin of the Guard, the enthusiasm of bringing the new armory to the City of Wyoming was

being tempered by the $80,000 cost towards the building and any additional money needed for “extras” as requested by the city. One of those extras not included in the basic plans of the armory was a cost of $250,000 for a swimming pool. Enlargement of the drill hall from 14,000 to 24,000 square-feet to bring its seating capacity up to 4,000 for use as a combination gymnasium-auditorium would cost another quarter million from local sources.

One Wyoming spokesperson who was not identified said that since the Guard afforded extra time to Grand Rapids to decide if it could provide a suitable site, they should afford a similar amount of time to explore our own resources and to determine what our own community contribution might be possible and within the city’s means.

By November, it was determined by City Manager John H. Kennaugh that the price tag for the extra features the city might want in the new armory would cost an additional $379,400. The mayor indicated that if the city can come up with almost $400,000 through a subscription fund, it would go along with the whole program. Otherwise, the basic $80,000 is the most the armory control board could expect. A five-member committee of the Wyoming Community Council, chaired by Lloyd C. Fry, Superintendent of Godfrey-Lee Public Schools, planned to meet with the city commission to discuss the possibility of the city underwriting the costs of the armory project. The committee noted that representatives from civic groups and its own members were not in favor of public subscription.

Meanwhile, the 126th Infantry units began moving their vehicles from the temporary armory at 947 Ottawa Avenue NW to the new site at Palmer Park. Fencing for the new motor pool was under construction at the 10-acre site and expected to be ready the following Saturday. Most of the vehicles consisted of “jeeps” (1/4-ton trucks), trailers, and half-ton trucks according to the report. Five “jeeps” mounted with 105-mm recoilless rifles were kept indoors at the temporary armory.

The struggle for local support continued throughout the first months of 1963. The City of Wyoming was considering taxes instead of a community-wide solicitation of funds to finance its participation in the construction of the new armory at the recommendation of the Wyoming Community Council committee. Meanwhile, General Simmons noted that the $800,000 federal share of the armory costs had cleared the National Guard Bureau and the Department of Defense, but final

plans for the facility was on hold pending a February 11 announcement of how another National Guard reorganization would once again affect the local units.

Mayoral candidate Edward Wiest chided city officials for an informal pledge to contribute $80,000 towards construction of the new armory. He noted concern that the city would be investing funds in a “building over which you have absolutely no control or voice in its use.” The higher amount of up to $450,000 for extras brought out his admonition that if the city had that much to invest, why not invest it in the city’s own Civic Center where citizens and youth could use it any time? He also noted that the city tax increased fifty percent in the last year, calling for holding the line for a while.

Another dispute arose over Wyoming’s contribution towards the new armory when Guard officials disagreed with Mayor David Visser’s denial that the city had pledged informally to give $80,000 towards construction costs. Visser made this statement after a visitor to the City

Commission meeting questioned spending city funds for the installation. General Simmons said it had been his impression following past meetings that the city tacitly agreed to contribute the $80,000. He went on to claim “We thought they were going to have more than that. They indicated to the state adjutant general they would have more than that.”

Simmons pointed out that lack of Wyoming funds would close the armory to civilian use. The state adjutant general in Lansing noted it would present a problem the Guard has not faced before and would be a bitter blow. Visser conceded at the meeting that it would not be wise for Wyoming to contribute beyond the $80,000 towards more extensive refinements since the Guard uses would have precedence over civil functions and neighboring communities or groups from outside the city also could lease the installation.

How to raise the money had been recently handed off to commissioners Thomas K. Eardley Jr. and Earl Robson. Meanwhile, Mayor Visser took umbrage with the statements that were made by General Simmons and the adjutant general to the Grand Rapids Press. He felt they had given a false impression of what was said at the commission meeting. Visser claimed he never said that Wyoming was not going to contribute to the cost of the armory. He merely responded to the citizen’s request from the floor that there was nothing to rescind since the city had made no formal commitment. He also stated that Wyoming citizens should understand that it would cost the city much more than $80,000 to building its own community building instead of using the armory. Visser felt the Grand Rapids Press was overtly attempting to embarrass Wyoming. The local community Wyoming Advocate weekly newspaper devoted most of a page to laying out the facts and disputing any myths associated with the construction of the new armory, paying particular attention to Grand Rapids Press’s effort to stir up questions. At the conclusion, it had recommended that Wyoming stick to the $80-85,000 even though it will likely limit the public use of the facility.

As May 1963 rolled around, Governor George Romney finally signed the bill authorizing an appropriation to cover the state’s share in the cost of constructing the new armory in Wyoming. Now the process of building a new armory began speeding up. Preliminary drawings were revealed in a public meeting held at Wyoming City Hall and it was noted the next step would be to go into greater detail on inside planning. If the final design was completed by the coming fall, bidding on construction would likely be

in January or February 1964. The preliminary plans called for a building of two major sections, one being the drill hall-classroom-office space area fronting along 44th Street, and the other a 38,000 square-foot unheated garage. Space for five classrooms, a rifle range, and kitchen facilities for both military and public use were included. Office space and classrooms were to be included in the second-floor area protruding above the drill hall (this was never built).

The preliminary plans for the new armory gained approval of the National Guard Bureau in January 1964. Daverman Associates was then authorized to proceed with final plans subject to review in Washington, Lansing, and by the local armory board of control. Federal funds totaling $684,000 were formally made available for the new armory with an announcement made to Congressman Gerald R. Ford Jr. by the Chief of the National Guard Bureau. Lansing State Headquarters indicated that bids were to be opened on March 19 in Lansing and contracts would be awarded March 30 or 31. He noted it was possible that construction could begin that April.

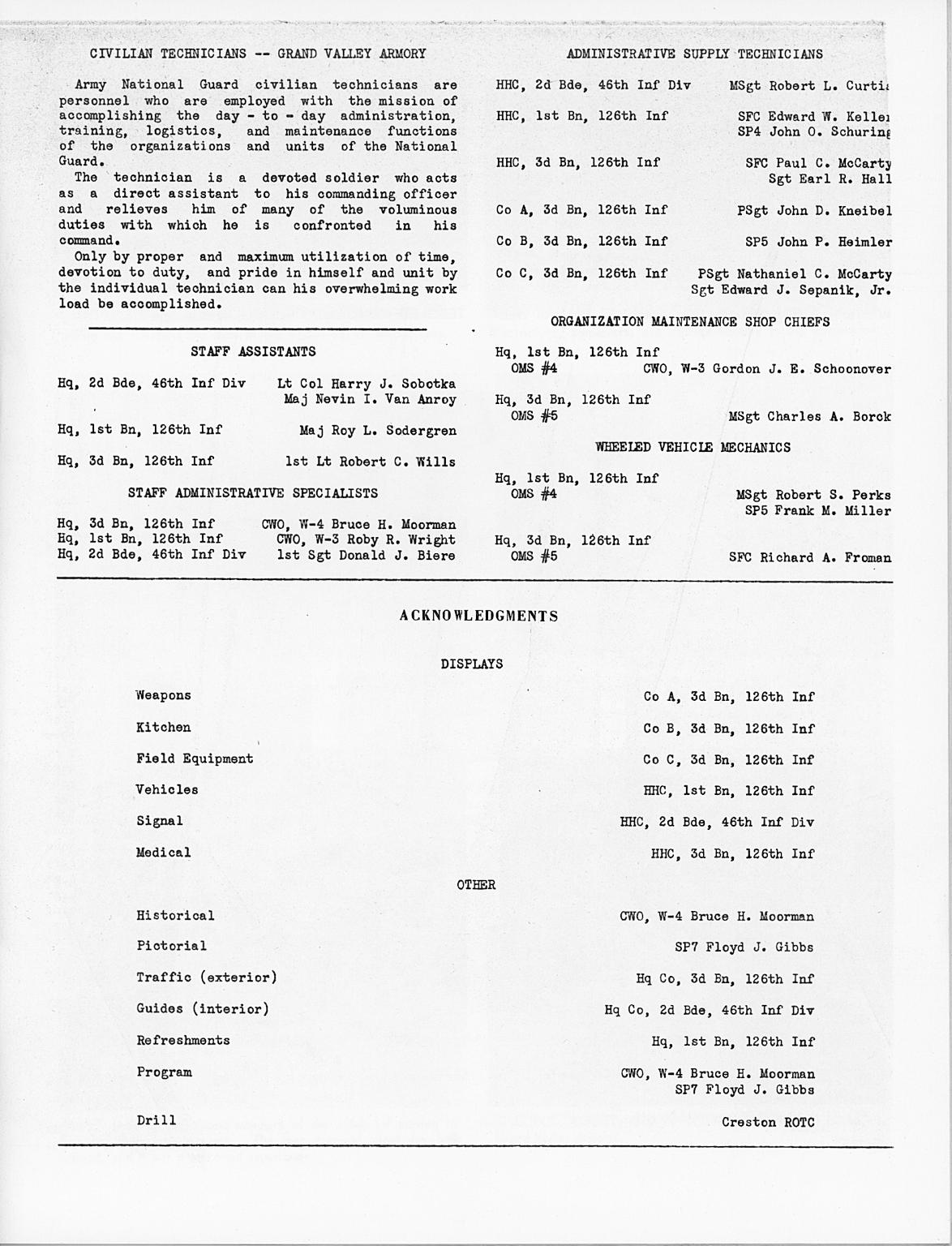

On April 1, 1964, it was announced that groundbreaking ceremonies for the armory would be held the following Thursday at 4 pm. The construction contract had been awarded to Omega Construction Company. On week later, the Guard’s 130 vehicles, that had been stored in the fenced compound on the 10-acre site, were moved to a new temporary compound on Wyoming’s well fields located at 36th Street and Clay Avenue SW. By then the contract had begun preparing the site for construction. By April 10, the new armory had received a construction permit from the city and a groundbreaking ceremony was held that day.

Another slight hiccup occurred when Wyoming resident Albert H. Dochstader requested to know why the new armory was not named the “Wyoming Armory” instead of the Grand Valley Armory. Commissioner Thomas K. Eardley Jr. responded by claiming the name came from an advisory council consisting of county residents and was certainly appropriate given the 10-acre site in Palmer Park had been donated by the Kent County. Actual excavation on the site of the World War I picric acid plant began for the new Grand Valley Armory began on April 17, 1964.

In just six weeks, it was noted that the armory was rising swiftly with construction running about three weeks ahead of schedule. Completion was expected the following February. By the end of July, construction was

running six weeks ahead of schedule with installation of additional steel roof beams and flooring to complete the drill hall-basketball court. While this was going on, the first county-owned public golf course neighboring the armory site was taking shape as it was carved out of the Palmer Park landscape over the top of the old Picric Acid plan ruins. The course had been started the previous fall and by now the seeding of greens and some fairways was well underway, according to Leonard E. Kaufman, secretarymanager for the Kent County Road Commission.

On October 7, General Simmons led the ceremony laying the armory’s cornerstone. Two months later, following final inspection of the Grand Valley Armory, the facility was turned over to the Guard when on December 2, keys were handed to the new armory’s manager, Chief Warrant Officer Paul P. Garland. At that point it became the home for the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 126th Infantry, and the 2nd Brigade, 46th Infantry Division headquarters.

The actual occupancy by the units was still awaiting arrival of lockers and company storage equipment. By the middle of December, National Guard vehicles could be seen moving into the armory’s vehicle storage building but the two battalions had not begun to shift from the rented space on Ottawa Avenue NW. They were scheduled to begin moving into the new armory beginning January 16,

starting with the 3rd Battalion, followed by the 2nd Brigade headquarters on January 23, and the 1st Battalion on January 24.

On February 13, 1965, the Kelvinator Division of American Motors Company became the first outside group to debut the exhibit hall at the new armory. It made use of the 14,000 square-foot drill hall to display more than $100,000 worth of autos and appliances for Kelvinator employees and the public. AMC’s new sports car, the Marlin, was one of the featured exhibits.

Despite temperatures dipping below ten degrees, the companies of 3rd Battalion 126th Infantry moved their equipment from the rented factory to the new armory. More than 450 men made the move on a scheduled drill weekend. For the most part, the move was completed by Sunday afternoon. At the start of the move, it was noted coincidentally that the new armory had 126 first floor rooms. Today, the 126th Regimental Association’s history archive room occupies Room 126.

Not long after moving into the Armory, Companies A and C of the 3rd Battalion 126th Infantry were called out on April 11 to aid during the Palm Sunday tornadoes that slashed across the southern portion of Michigan’s lower peninsula. The two companies were rushed into the Comstock Park and Westgate areas to secure the area and prevent looting, among other responsibilities. In the hours following, the 2nd Brigade and 3rd Bn 126th Infantry headquarters were both engaged in the disaster.

The newly complete drill hall in the Grand Valley Armory. It would later be dedicated to the 126th Infantry's own Dirk J. Vlug, recipient of the Medal of Honor while serving in the Leyte Campaign during World War II. Today it’s simply known as “Vlug Drill Hall.”

In May, the Grand Valley Armory hosted a large-screen, paid admission showing of the World Heavyweight Championship Fight between Cassius Clay and Sonny Liston. Tickets were $5 and were available at several area stores including Wurzburg’s at the Southland Plaza. However, the showing was a qualified disaster with only 450 to 500 paid admissions in attendance. In addition, the promoter had to erect a special tower to get good reception at a cost of $1,200 he wasn’t counting on. The fight itself wasn’t very good according to patrons. Among the boiling mad customers was “huge Buster Mathis,” the 290-pounder who had recently signed a contract to get into professional boxing himself.

On Monday, May 31, 1965, the Grand Valley Armory’s public dedication began with a traditional Memorial Day Parade. The Wyoming Advocate newspaper noted the “spectacle was most impressive, not only in the turnout which it attracted, but in the quality and magnitude of the production.” The column of considerable length marched from 36th Street south along 44th Street the new armory, where the parade participants, including all the armory’s military units, passed the official reviewing stand, before breaking up for the ceremony that followed.

Conservatively it was estimated that at least 10,000 spectators lined the parade route to view the military vehicles, soldiers, civic organizations, youth groups and religious sponsors, displaying an all-out patriotic memorial to the nation’s defenders of freedom.

Before the parade even began, excitement broke out when the 126th Infantry’s units set out from the armory and marched northward along Milan Avenue toward the point of formation. Families, aroused by the strains of the 46th Infantry Division’s band, scurried from neighboring streets, often in bare feet, pajamas, slippers, and dusters, just to watch the uniformed ranks and olive-drab vehicles go by.

From that point on, it was a holiday celebration in the southern sector of Wyoming, with parked cars lining the streets in all directions and strolling crowds populating the area, “out to see one of Wyoming’s outstanding sightseeing attractions, with its numerous facets of interest.”

Approximately 5,000 attended the dedication and open house on May 31. Heading the list of dignitaries for the event were Major General Cecil L. Simmons of the 46th Infantry Division, Colonel Clarence C. Schnipke, Acting Adjutant General for Michigan, and Mayor Edward F.

Wiest, as well as other representatives of city and state government.

In the keynote address, Colonel Schnipke, who had started the whole ball rolling back on Michigan Street, noted how the new armory, which will house units of the famed 126th Infantry; the 2nd Brigade 46th Infantry Division, and the 46th Infantry Division Band, was the realization of a dream which had its beginning nearly fifteen years ago. The Acting Adjutant General, who had returned to his hometown for the occasion, stated that the site for the new armory was selected in 1950 and came about only through the cooperation of the city (of Wyoming) officials and federal and state agencies.

He paid tribute to the men of the 126th Infantry by stating that the new armory would serve as a memorial to those who gave the last full measure of devotion to their country and their state, and said that it will also serve as an inspiration to those men (and since then, women) who will serve the cause of freedom and justice in the future.