In the nine months since I've started as Dean of LSU Law, every day I see amazing examples of how hardworking, creative, and impactful our students, teachers, staff, and alumni are. You have warmly welcomed me and embody everything good and noble in the legal profession. Your contributions to law, government, business, and public service have improved the lives of the citizens of our state and beyond.

We’ve already celebrated many milestones this academic year, and we’re looking forward to cheering on the LSU Law Class of 2024 at our May 18 commencement. This past August, I had the pleasure of welcoming 206 first-year students to the Law Center. Hailing from more than 70 different undergraduate institutions, our first-year class is filled with highly accomplished aspiring lawyers, including a former U.S. Army interrogator, a registered nurse, the reigning Miss Louisiana Collegiate USA, and a youth pastor.

Just before the fall semester began, I also welcomed many alumni and friends of the Law Center who taught in our outstanding Trial Advocacy Program for third-year students. Our students raved about their experience in the program, which is one of the many things that makes our community and curriculum unique.

In October, we celebrated the Class of 2023 on their 92% Louisiana bar passage rate, making LSU Law the state leader in bar passage rates once again. I am exceedingly proud of all our graduates—and of our ability to offer an affordable, high-quality legal education that prepares students for a lifetime of success. And speaking of our graduates, I had the great pleasure of meeting with hundreds of you at special events we held in Shreveport, Lafayette, Houston, and Washington D.C. between October and January. I hope to meet even more of you at similar events we’re planning throughout this year.

The future is very bright at the Law Center. This academic year, we also welcomed two outstanding new faculty members—Nikolaos Davrados and John Lovett—who will strengthen our civil law curriculum. We are also celebrating the myriad successes of our faculty. They have published books, received national awards, and successfully secured interdisciplinary grants for research projects.

The Law Center has an exceptionally strong foundation, and I am beyond excited for the future. We’re hiring additional new faculty, upgrading classrooms, creating new clinics and programs, and reviewing and expanding the curriculum. None of these initiatives would be possible without your support. So, I ask that you please remain engaged with your alma mater in any way that suits your interests and availability. Whether it’s attending alumni events, volunteering as a guest speaker, mentoring current students, or financially supporting our programs and scholarships, your involvement makes a significant difference in the lives of our students and the continued success of LSU Law.

In closing, I want to express my heartfelt gratitude for your ongoing support and dedication to the Law Center and our students. You are an integral part of our vibrant community, and your achievements are a testament to the enduring strength, character, and excellence of our institution. Please do not hesitate to reach out to us if you have any questions, suggestions, or simply wish to reconnect. I am confident that together, we will continue to uphold LSU Law’s proud tradition of excellence.

Geaux Tigers!

LSU Law Dean and Professor of Law

LSU Law Dean and Professor of Law

Dean Alena M. Allen poses with the Hon. Darrel Papillion ('94), Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Piper Griffin ('87) and retired Judge Trudy White ('81) at the Louisiana State Bar Association Annual Conference, which was held in Destin, Florida, on June 4-9, 2023.

Dean Allen meets with LSU Law alumni in Lafayette on Jan. 18, 2024. Additional events have been held in Shreveport, Houston, and Washington, D.C. for LSU Law alumni and

Dean Allen welcomes more than 200 members of the Class of 2026 to orientation at the Law Center Friday, Aug. 11, 2023.

Dean Allen participates in a roundtable discussion with third-year LSU Law students Brock McKiness and William “Grey” Fitzgerald, as well as LSU Law alumni and past presidents of the Baton Rouge Bar Association Judge Fred Crifasi (’92), Leo Hamilton (’77), and Christine Lipsey (’82), on Dec. 8, 2023. On Nov. 30, 2023, she was the featured speaker at the BRBA luncheon, where she discussed the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to end raceconscious college admission policies.

LSU Law student leaders meet with Dean Allen on Nov. 15, 2023.

Dean Alena M. Allen poses with the Hon. Darrel Papillion ('94), Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Piper Griffin ('87) and retired Judge Trudy White ('81) at the Louisiana State Bar Association Annual Conference, which was held in Destin, Florida, on June 4-9, 2023.

Dean Allen meets with LSU Law alumni in Lafayette on Jan. 18, 2024. Additional events have been held in Shreveport, Houston, and Washington, D.C. for LSU Law alumni and

Dean Allen welcomes more than 200 members of the Class of 2026 to orientation at the Law Center Friday, Aug. 11, 2023.

Dean Allen participates in a roundtable discussion with third-year LSU Law students Brock McKiness and William “Grey” Fitzgerald, as well as LSU Law alumni and past presidents of the Baton Rouge Bar Association Judge Fred Crifasi (’92), Leo Hamilton (’77), and Christine Lipsey (’82), on Dec. 8, 2023. On Nov. 30, 2023, she was the featured speaker at the BRBA luncheon, where she discussed the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to end raceconscious college admission policies.

LSU Law student leaders meet with Dean Allen on Nov. 15, 2023.

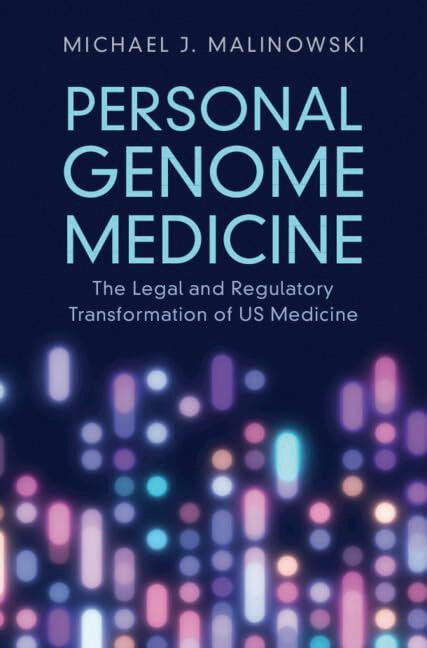

US Medicine by LSU Law Professor Michael J. Malinowski has been honored with the 2023 Best in Law award from the American Book Fest. Published by Cambridge University Press in August, Personal Genome Medicine is a groundbreaking examination of the ethical, legal, and social implications of direct-to-consumer genetic health risk testing services such as 23andMe’s Personal Genome Health Service.

“In the roughly 30 years that I have been researching and writing about these important topics, I have witnessed an explosion in the use of these emerging technologies far beyond anything I could have imagined when I began my career. Personal Genome Medicine represents the culmination of my scholarship on this issue to date, and my hope is that it will elevate and advance the conversation in a meaningful way.”

LSU Law faculty are actively researching artificial intelligence, using it in the classroom, and teaching law students, law professors, and practicing lawyers how to begin incorporating AI into their personal and professional lives to maximize productivity, efficiency, and creativity.

This past fall, Professors Will Monroe and Aimee Self Pittman taught the first course focused on using AI in legal research at the Law Center, and additional classes will be offered in legal writing and other AI-related areas moving forward. LSU Law Professors Tracy Norton and Marlene Krousel incorporate generative AI into their teaching, and all four faculty members have shared new ideas about using the technology in legal education and the practice of law at events across the country over the past year.

Professors Monroe and Norton—along with former LSU Law Professor Susan Tanner—were awarded a teaching grant by the Association of Legal Writing Directors to develop and launch PRISM, a generative AI toolkit for law professors. PRISM will assist law professors in improving their generative AI literacy, whether a professor is just getting started with generative AI (called an “AI Explorer” in PRISM) or already proficient with generative AI (called an “AI Innovator” in PRISM).

“At LSU Law, we’re not just keeping pace with the evolving legal technology landscape—we’re leading it. With faculty members immersed in the study and application of generative AI, our students gain a competitive edge, learning to harness this pivotal technology in their legal education and future careers. We are committed to keeping our graduates at the forefront of innovation in the practice of law.”

How Jason St. Julien (’11) shifted gears, discovered a new career path, and got re-engaged with his alma mater

By Jennifer Tran

By Jennifer Tran

After a long night of studying at the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center, Jason St. Julien liked to clear his mind by jumping on his motorcycle and cruising across the Mississippi River bridge, away from the hustle and bustle of Baton Rouge.

“My mind was always racing when I was in law school,” he recalled, “so those were really meditative rides.”

Rural roads have always been St. Julien’s favorites to ride along, mostly due to the minimal traffic. But in both his personal and professional life, St. Julien seldom selects the path of least resistance.

After earning his Juris Doctor and Graduate Diploma in Comparative Law from LSU Law in 2011, the St. Martinville native served as a law clerk for Judge Mary Ann Vial Lemmon in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, before moving to Denver to clerk for the late Chief Judge Wiley Y. Daniel in the U.S. District Court of Colorado. He then joined the U.S. Attorney’s Office as an Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Criminal Division prosecuting violent crime.

St. Julien was a highly driven and effective prosecutor, earning two U.S. Attorney Awards of Excellence during his tenure. While acknowledging that representing the United

States as a federal prosecutor was “the biggest honor of my life,” St. Julien knew when it was time to leave.

“I got tired of my sole job being to put people in prison,” he said.

In 2021, St. Julien joined Airbnb as Lead Counsel of Community Trust. In his role, he supports trust and safety for the San Francisco-based company, working with their regional and global counterparts on emerging issues.

“A lot of the issues I deal with are emergencies, so there really is no typical day,” he said. “I could come into the office and there may be an issue with law enforcement in the United States, Australia, or France. I’m always coordinating with regional counterparts and colleagues to figure out how we can help protect the community.”

St. Julien credits his bijural studies in both civil and common law, as well as his professors at LSU Law, for helping prepare him to successfully launch his career and transition to a new role that involves international law.

But before he was ever a law student, St. Julien was a middle school Texas History and Reading teacher in Pearland, Texas, where he was named New Teacher of the Year in Secondary Education in 2007.

“Economics,” he said with a chuckle when asked why he decided to quit teaching to attend law school. “At the end of the day, when I have a family, I want to be able to provide for them like my parents did for my brother and I—and I couldn’t do that with the salary I had at that time.”

St. Julien doesn’t look back on his time at LSU Law through rose-colored glasses or sugarcoat the challenges he faced. As a Black student during a period when there was considerably less diversity among the students and faculty at the Law Center, the already intense pressures of law school felt amplified for St. Julien.

“I didn’t have some grand time at LSU Law,” he said, “and for the longest time I didn’t want to be associated with the law school due to my experiences there. But that was the easy way out. That was safe. By turning away, I didn’t have to deal with what happened and what I made that mean about law school, life, and my place in the legal field.”

Rather than disengaging with his alma mater, St. Julien has decided to take a proactive approach by joining the Dean’s Council and mentoring LSU Law students with hopes of helping foster a more welcoming and inclusive environment for all current and future LSU Law students.

He was encouraged to join the Dean’s Council by his former classmate, David Fleshman (’11), who is an LSU Law adjunct professor and was among a handful of alumni who served as ambassadors for the Law Center during LSU Giving Day 2023. Fleshman and St. Julien were roommates when they studied abroad in Lyon, France, during their time at LSU Law, and they’ve remained close friends ever since.

“I demand that the world have an authentic conversation about race. Not the type where you prance around with vagueries,” reads the op-ed. “The type where you tell the truth, wade into the muck, and confront the un-confrontable. That is where possibility lives. That is where mastery lives.”

Several years later, St. Julien describes progress on issues surrounding race and equality in our country as a “push and pull.”

“I see juries holding law enforcement officers accountable for killing people who look like me, and I also see people fighting for me who do not look like me,” he said. “At the same time, I see people in power enacting legislation that denies certain people the dignity of what it is to be human. I see people in power banning critical race theory, as if students are neither sufficiently self-aware nor possess the intellectual capacity to grapple with this thing we call race. So, I see advancements, but I also see a population of people who have a death grip on the status quo. There has been change, but this isn’t over and there still needs to be more change.”

During the 2020 football season, when many NFL players began wearing helmet decals featuring the names of victims of racism and police violence in support of social justice initiatives, Lomando—who was then serving as Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Denver Broncos—honored his friend’s courage by wearing St. Julien’s name on his hat.

“I would not be where I am, doing what I’m doing, without LSU Law and the people who supported me. So, if I don’t do what I can to further the institution and help create a greater sense of belonging for diverse students, then that’s a dereliction of my duty.”

St. Julien also remains in touch with former classmates

Ashley (Mayes) Guice (’11), Sydney Jakes (’11), and Leisa Lawson (’11), who he became close friends with while serving in the Black Law Students Association, as well as Professor Darlene Goring, who was elected the 2023 Professor of the Year by the Student Bar Association at LSU Law.

“Professor Goring was like my second mother,” he said. “She was not only an outstanding professor, but a mentor and true friend.”

Professor Goring also serves as an inspiration, said St. Julien, and was among the mentors who helped him develop the courage to act and speak out when he encounters injustice. Another mentor is Anthony Lomando, who serves as Director of Sports Performance for the Los Angeles Chargers football team. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Lomando encouraged St. Julien to make his views public by penning an op-ed for The Denver Post, titled “The unrelenting, frustratingly delicate balancing act of being Black.”

The op-ed details some of the racial injustices St. Julien encountered while growing up in rural South Louisiana, and discusses how those experiences continue to impact him to this day. He also used the platform to challenge everyone to engage in honest conversations about race relations and equal justice, rather than disengaging out of fear, mistrust, or frustration.

“There are hundreds of thousands of people who have risked their lives or lost them for the cause, and he could have chosen any of them,” St. Julien said. “And for him to choose to have my name on his hat for every game during that season still boggles my mind. What an honor. I am forever indebted to him for seeing me, trusting me, and having my back—and I’ll always have his.”

These days, St. Julien still enjoys taking to the open road to clear his mind and relax in his free time. He recently upgraded to a Harley-Davidson Road Glide, which he enjoys riding along Colorado’s country roads and mountain passes. Although he’s lived in the area long enough now to have become familiar with most of the roadways, St. Julien said he “really enjoys just figuring out which country roads I haven’t been down before,” adding, “and then after I ride them, I just turn around and look for more.”

Vinson & Elkins’ latest gift to LSU Law establishes yet another scholarship and brings total giving by the firm to more than $600,000

By Steve Sanoski

By Steve Sanoski

After graduating from LSU Law in 1980 as the top student in her class and serving as a judicial clerk at the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the Hon. Alvin B. Rubin (’42), Marie Yeates had plenty of options on where to launch her career as an attorney. After careful consideration, the Metairie native chose to go to work for Vinson & Elkins at the firm’s Houston office in 1981 for two primary reasons.

“My goal was to become a great lawyer, so I wanted to join a firm where I could work alongside and learn from great lawyers—and V&E has always been known for having truly outstanding lawyers,” said Yeates, who also served as Editorin-Chief of Louisiana Law Review and was selected for the

Order of the Coif at LSU Law. “The other main reason I went to V&E was that there were so many LSU Law alumni there. It just felt like home.”

The history of Vinson & Elkins dates back more than 100 years, and its reputation as a thriving, international law firm with deep roots in energy, which now include renewables and green energy—among the other complex areas in which it practices—has made it a natural fit for LSU Law graduates for just as long. Though the exact number of LSU Law alumni who have worked for Vinson & Elkins since its inception is not known, records show the firm has hired more than 120 graduates of the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center since 1965. Five of the firm's partners are LSU Law alumni and fourteen of its associates proudly wear their Tiger stripes.

In recognition of the role LSU Law alumni have played in the continued success and growth of the firm—which today has roughly 700 lawyers at 12 offices worldwide—Vinson & Elkins has generously supported the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center over the past four decades, establishing a professorship and a program endowment to support trial advocacy. Additionally, the firm has recognized LSU Law students annually since 1987 with scholarship awards and a case note award.

In September 2022, Vinson & Elkins announced its latest major gift to LSU Law, committing $110,250 over the next decade to financially support four students each academic year. The gift brings the total amount of financial support that the firm has provided the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center since 1984 to more than $600,000.

Keith Fullenweider started his career with Vinson & Elkins in 1988, has been a partner for more than 25 years, and was named Chair in the spring of 2021. Shortly after Fullenweider

and a new senior leadership team assumed their roles, they decided to further invest in LSU Law and other flagship law schools from which the firm routinely recruits, which led to the most recent gift announcement. Fullenweider said Vinson & Elkins has long scouted for new talent from flagship law schools, among others, because they tend to produce graduates who already have some real-world legal experience and are ready to the hit the ground running.

“LSU Law has always been a very important law school for us. Obviously, we’ve always shared a geographical connection, with it being right next door, but it really goes far beyond that,” he said. “One of the things that we do a really good job of at V&E is putting young lawyers in the courtroom or on the frontlines of business transactions. You get responsibility here from a very early age, and that tends to appeal to young lawyers who graduated from state law schools like LSU Law due to their focus on providing a hands-on legal education. Their graduates are selfstarters who want to work where the action is.”

“The Trial Advocacy Program gift was made because the firm had benefited from a significant contingent fee decision,” explained Yeates, “and after we decided to set aside a large portion of the money for philanthropy, LSU Law was at the top of the list of places that we wanted to invest in.”

Along with establishing the Trial Advocacy Program, the firm made an additional gift in 1987 to create the Vinson & Elkins Endowed Professorship in honor of the late Judge James Anderson Elkins, a founder of the firm and distinguished lawyer who was very involved in his community, setting a standard for future lawyers at the firm.

“As someone who has spent their entire career at this incredible law firm and who credits LSU Law for providing me with a legal education that has served as the foundation for everything I’ve achieved in my career, I am thrilled that our senior leadership has further cemented our relationship with LSU Law for the long term with this most recent scholarship gift.”

–Marie YeatesAside from legal clinics, field placements, simulations courses, moot court competitions, and externships, another way that LSU Law provides its students with real-world legal training is through the Vinson & Elkins Trial Advocacy Program. The intensive, three-day training session for third-year law students takes place each year just before the start of the fall semester and covers every aspect of trial practice, from jury selection to closing arguments. It regularly features some of America’s top trial lawyers and judges who work in small groups with students, and was established with a major gift from Vinson & Elkins in 1987.

For example, Vinson & Elkins Partner Chris Popov, a Baton Rouge native and undergraduate alumni of LSU (’98), served as 2022-23 Houston Bar Association president.

Since 1987, Vinson & Elkins has contributed more than $250,000 in non-endowed scholarship support to LSU Law. It has made major gifts in support of the Centennial Fund, an endowed fund that produces about $60,000 annually in unrestricted revenue for the Law Center, as well as the Rubin Visiting Professorship, a fund providing about $8,000 each year for special programming at LSU Law. Through the years, the firm has also hosted receptions and recruitment events at its Texas offices for LSU Law alumni and students.

In short, the contributions from Vinson & Elkins support virtually every aspect of teaching and learning at LSU Law, which in turn helps the firm ensure that it will have a reliable source of top talent to recruit from for generations to come.

“We have always looked to LSU Law for new talent, and my great hope is that we always will,” said Yeates, who continues

Lanny Yeates met his future wife, Marie, on the LSU campus in the summer of 1977 as the two were nearing graduation.

“While she completed her undergraduate work in August, I graduated in December after serving in the United States Navy,” said Lanny, an Arkansas native who was born in Pine Bluff and graduated from high school in El Dorado. “During that summer, we discussed our hopes and plans for the future, married a year later and then attended LSU Law.”

Lanny earned his degree from LSU Law a year after Marie, in 1981, having served as Associate Editor of Louisiana Law Review and being selected for The Order of the Coif, and the young couple relocated to Houston to launch their legal careers. Though they have practiced at different firms—Marie at V&E, and Lanny at Gordon Arata McCollam Duplantis & Eagan—each has distinguished themselves among the nation’s leading attorneys in oil and gas law throughout their accomplished careers. They also have a shared passion for giving back to the university and law school that they credit for their success.

“Our undergraduate and law degrees from LSU have provided us with an enormous advantage,” Lanny said. “High in importance is the understanding that, with hard work, personal and professional accomplishments of LSU graduates are limited only by their desire to make a better future for themselves.”

Lanny is a longstanding Law Center Dean’s Council member and a past president of the LSU Law Alumni Association. He is a former interim director of the Louisiana Mineral Law Institute at LSU Law, and he has also served as a member and past chairman of the Advisory Council of the Institute. LSU Law recognized him with its Distinguished Service Award in 2006.

Lanny has served as Chairman of the Board of Directors of the LSU Foundation from 2007-08, during which he played a key role in the success of the Forever LSU Campaign that was launched in 2006 and surpassed its goal of raising $750 million in just four years.

In recognition of her husband’s distinguished academic career at LSU Law and professional career as an oil and gas transaction lawyer, in 2018 Marie initiated the J. Lanier Yeates Endowed Scholarship in Law benefiting LSU Law students. “LSU and the Law Center provided us with opportunities that absolutely transformed our careers, and the lifelong friendships that we made on the LSU campus continue to be a big part of our lives today,” Marie said. “Lanny and I have always made it a priority to give back to LSU and LSU Law because we want current and future students to enjoy the same opportunities that we had.”

to practice from the firm’s Houston office as Partner— Appellate. “LSU Law teaches its students to be diligent and thorough in everything they do, and its rigorous scholastic program produces highly skilled graduates who are very able and who know how to work.”

And because LSU Law is one of the only law schools in America offering a comprehensive legal education that includes both civil law and common law, graduates of the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center bring a little lagniappe to the table when compared to most of their peers.

“Having a firm understanding of two legal systems is like being bilingual,” Yeates said, “and as we continue to expand our firm globally, it will only make LSU Law grads even more valuable to us.”

Yeates’ impressive career is a perfect example of how an ambitious LSU Law graduate can take advantage of the opportunities offered at Vinson & Elkins to grow into a great attorney and reach their highest professional goals. Over her 43 years with the firm, she has presented more than 135 appellate oral arguments in federal and state courts across the country and argued dozens of cases before the Texas Supreme Court. Yeates has particularly enjoyed her opportunities to argue in the Louisiana appellate courts. Representing clients across diverse industries, she has

successfully obtained appellate results worth hundreds of millions of dollars, earning her a much-deserved reputation as one of the nation’s leading appellate lawyers.

Among the many accolades and awards she has received throughout her career, Yeates is a two-time recipient of the Texas Lawyer Lifetime Achievement Award and has been named one of the country’s Top 50 Women Litigators by The National Law Journal. She credits her success in the courtroom to her collaborative approach and ability to simplify complex concepts—skills she began honing as a law student and has steadily sharpened throughout her career.

“The culture at LSU Law and V&E are very similar in many ways. Our firm’s culture is an inclusive one that’s based on mutual respect. We’re a diverse, international firm where characters are welcome, and we celebrate what makes each of our team members unique. At LSU Law and V&E, it doesn’t matter where you’re from or who you happen to know—the only thing that matters is who you are and what you bring to the table,” she said. “As someone who has spent their entire career at this incredible law firm and who credits LSU Law for providing me with a legal education that has served as the foundation for everything I’ve achieved in my career, I am thrilled that our senior leadership has further cemented our relationship with LSU Law for the long term with this most recent scholarship gift.”

As a law firm that proudly counts its people as its greatest asset, Vinson & Elkins has always made investing in students one of its highest philanthropic priorities.

“Whether it’s for high school, undergraduate, or law school students, investing in the next generation of leaders is something that we have just sort of built into our DNA,” said V&E Chair Keith Fullenweider.

Over the past four decades, V&E has provided more than $250,000 in non-endowed scholarship support to the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center, and its total support exceeds $600,000. The firm’s latest major gift to LSU Law will provide direct financial support to four students at the Law Center every year for the next decade.

Recent recipients of the V&E Scholarship support include Zachary Ryan Crawford, Paige Meno, Elise Diebold, and Tyson D. Lee.

Zachary Ryan Crawford is a 3L who hails from Baton Rouge and plans to pursue a career in commercial litigation, corporate transactions, and/ or bankruptcy. “I’ve been a Tiger my whole life,” said Crawford, who also earned his undergraduate degree at LSU. “I know that LSU Law will set me up for a fantastic career.” Crawford would like to launch his career by clerking for a federal judge. “I’m incredibly grateful for the generous donors at V&E who made my scholarship possible. The financial assistance means I can turn my full attention to becoming the best lawyer I can be.”

Paige Meno is from Springfield, Virginia, but she decided to attend LSU Law because she wants to live in Houston and practice for a Big Law firm one day. Now in her third year of studies at LSU Law, Meno has earned academic honors, served as a Junior Associate on Louisiana Law Review, and been a summer associate for Baker Donelson, and she is currently a research assistant. “My V&E scholarship means so much to me, especially since it’s coming from a firm with a long history of helping young attorneys grow.”

Elise Diebold is a 3L and Baton Rouge native who has served as a Junior Associate on Louisiana Law Review. She has earned Dean’s Scholar and Paul M. Hebert Scholar honors, has externed with Judge Brian A. Jackson of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana, and has served as an LSU Law research assistant. “My time at LSU Law has provided me with countless opportunities, both inside and outside the classroom. Coming to LSU Law has been my dream for my entire life, and the scholarship from Vinson & Elkins has helped make my dream a reality.”

Tyson D. Lee discovered his passion for public service while serving in Student Government as an undergraduate at LSU Shreveport. That passion grew in the summer of 2020, when he was selected for the prestigious Governor’s Fellows Program. “I exclusively applied to law schools in Louisiana and LSU Law was at the top of my list,” said Lee, who hopes to use his law degree to help Louisiana address some of its most pressing problems. “I have thoroughly enjoyed law school, and I will be forever grateful for the V&E Scholarship and the opportunities I’ve been provided.”

LSU Law alumni helped bring the state's high court into the modern era and have come to dominate the current bench

By Steve Sanoski

By Steve Sanoski

When the 26 students in the first class of the newly opened LSU Law Department met on Sept. 24, 1906, the Louisiana Supreme Court had already been in operation for 93 years. But in terms of form and function, the state’s high court was a fledgling, inefficient institution in dire need of modernization.

The court comprised five elected justices who worked from inside the cramped, dark, and structurally unsafe Cabildo building along New Orleans’ Jackson Square. They were sworn to adhere to and uphold the Louisiana Constitution of 1898, a massive document of some 326 articles that effectively served to legitimize white supremacy as the constitutional rule of the land.

But external forces and emerging technologies were slowing bringing about change in Louisiana at the outset of the 20th century. As industry continued to pull people away from rural areas and into the cities, oil and gas corporations were building immense power and wealth as the state’s mineral rich lands and waterways were exploited with reckless abandon. Meanwhile, the advent of the radio, automobile, moving pictures, and mass advertising were spurring their own societal evolution.

‘modern,’ and ‘businesslike,’ which would reduce popular discontent with them … For the court the challenge was how to cope.”

By the time the Louisiana Supreme Court celebrated its centennial in 1913, a campuswide reorganization at LSU had established colleges and schools within, meaning the Law Department had formally become the “LSU Law School.” Although the first LSU Law alumnus wouldn’t join the court for another 22 years, graduates of LSU Law would eventually become some of the most influential justices in the court’s long history. They would succeed in reforming the court and bringing it into the 21st century, during which LSU Law alumni would achieve several historical firsts and come to dominate the bench.

Since Fournet took his seat on the bench nearly 90 years ago, 22 of his fellow LSU Law alumni have presided over the state’s high court. All have made significant contributions to the court and our state, and several have made history while doing so.

“In social terms, Louisianans remained rigidly divided along the color line, largely uneducated, and extremely poor,” wrote historian Warren M. Billings in “The Supreme Court of Louisiana, 1813-2013: A Bicentennial Sketch.” “Catching whiffs of the national Progressive Movement, deeply conservative politicians advocated structural reforms to make a state government that was at once honest, efficient,

John B. Fournet was our first alumnus to win a seat on the state’s high court. A St. Martinville native, Fournet became a schoolteacher after earning his undergraduate degree at the Louisiana State Normal School (now Northwestern State University). He enrolled in law school at LSU but withdrew to enlist in the Army and fight in World War I. Upon his return home, Fournet resumed his legal studies and graduated from LSU Law in 1920. He served in the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1928 to 1932, at which point he became lieutenant governor.

Fournet’s election to the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1934 was clouded by charges of cronyism. The controversy was far too complex to unpack here, but it stemmed from Fournet being a close ally of Gov. Huey Long and his opponent, Tom Porter, having the support of the Louisiana

State Bar Association—which Long and his supporters disdained and would eventually work to destroy through the State Bar Act of 1934. The race sparked several lawsuits by Porter and the LSBA, but Fournet—who had no prior judicial experience—took his seat on the bench on Jan. 2, 1935.

“With the exception of the judge’s intimates and Huey Long, no one held great expectations for John Fournet when he went to the court,” Billings wrote. “To the bitterest of his enemies, he was merely a hack politician who had stolen the seat that rightfully belonged to Tom Porter. To his less virulent opponents, he was a legal nobody. To other critics he was little more than an undistinguished journeyman lawyer.”

Over the next 35 years, Fournet would silence his critics as he led sweeping efforts to modernize the court. By the time he stepped down from the bench on July 31, 1970, he had served as chief justice for 21 years and was the longest serving justice in the court’s history (Pascal Calogero Jr. would subsequently serve 36 years and currently holds the distinction).

“Chief Justice Fournet set in motion a revolution in the way the Supreme Court operated and related to the rest of the judiciary,” reads the “Brief History of the Louisiana Supreme Court” written as part of The Bicentennial of the Louisiana Supreme Court celebration in 2013. “He created the Judicial Council, gained legislative appropriations, and appointed a judicial administrator, who with his staff compiled data on all aspects of the judicial branch. The court system was restructured, and the Supreme Court docket was cleared.”

Fournet is credited with establishing law clerks at the court, drafting its first comprehensive cannons of judicial ethics, revising and improving bar admission requirements, revising the Code of Criminal Procedure, and structuring a deal to establish what is now the Law Library of Louisiana at the court.

He also impacted the Louisiana Supreme Court in a very tangible way, leading the effort to construct a new courthouse at 301 Loyola Street in New Orleans, where it would remain in use from 1958 to 2004. Fournet remarked that the old courthouse in the French Quarter “was a fitting symbol of the old order,” while the new building “of the most modern and advanced design, became, upon its completion in 1958, a fitting symbol of the new.” In May 2004, the court returned to its restored original home at 400 Royal Street.

“By his hand, the high bench turned into a potent entity featuring a collection of related agencies that supervise every phase of the entire judicial branch and made the chief justice the system’s premier administrator,” Billings wrote. “Put another way, Fournet convinced Louisianans that better administration through the judiciary resulted in the speedier, more honest and equitable dispensation of justice, while infusing the court with a marked willingness to experiment with new ways of improving its expanded responsibilities.”

Since Fournet took his seat on the bench nearly 90 years ago, 22 of his fellow LSU Law alumni have presided over the state’s high court. All made significant contributions to the court and our state, and several made history while doing so.

In 1992, Catherine “Kitty” Kimball (’70) became the first female to be elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court and in 2009 she succeeded Calogero Jr. as chief justice, making history again as the first female to lead the court. Bernette Joshua Johnson—who was among the first Black females to earn a degree at LSU Law in 1969—became the first Black female to be elected to the court in 1994. In 2013, Johnson became the first Black chief justice.

Today, LSU Law alumni dominate the court, with six of the seven current justices. To celebrate their distinguished careers, we sat down with each to discuss their journeys to the state’s high court, their memories of LSU Law, and their hopes for the future of our state’s high court and Louisiana’s flagship law school. We are proud to share their stories, all of which were written by Steve Sanoski, on the following pages.

LSU Law alumni who have served as Louisiana Supreme Court Justices

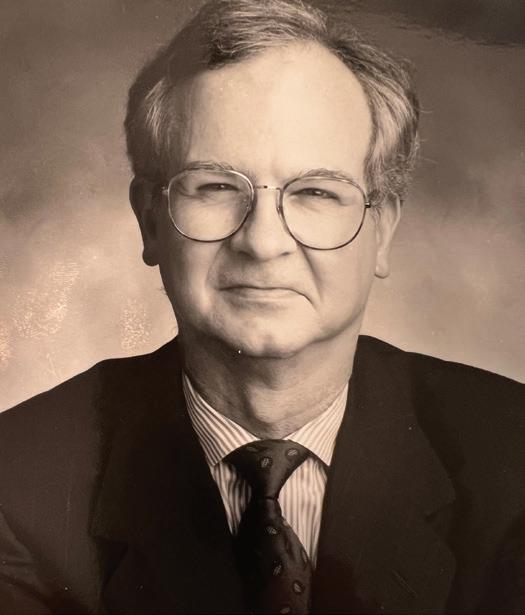

John B. Fournet (1920)

1935-1970*

Amos L. Ponder Jr. (1912)

1937-1959

Joe B. Hamiter (1923)

1943-1970*

Frank W. Hawthorne (1924)

1945-1968

Robert F. Kennon (1925)

1945-1946

Joe W. Sanders (1938)

1960-1978*

Mack E. Barham (1946)

1968-1975

James L. Dennis (1962)

1975-1995

Fred A. Blanche Jr. (1948)

1979-1986

Jack C. Watson (1956)

1979-1996

Luther F. Cole (1950)

1986-1992

Pike Hall Jr. (1953)

1990-1994

Catherine “Kitty” D. Kimball (1970)

1992-2013*

Bernette J. Johnson (1969)

1994-2020*

Joseph E. Bleich (1973)

1996-1996

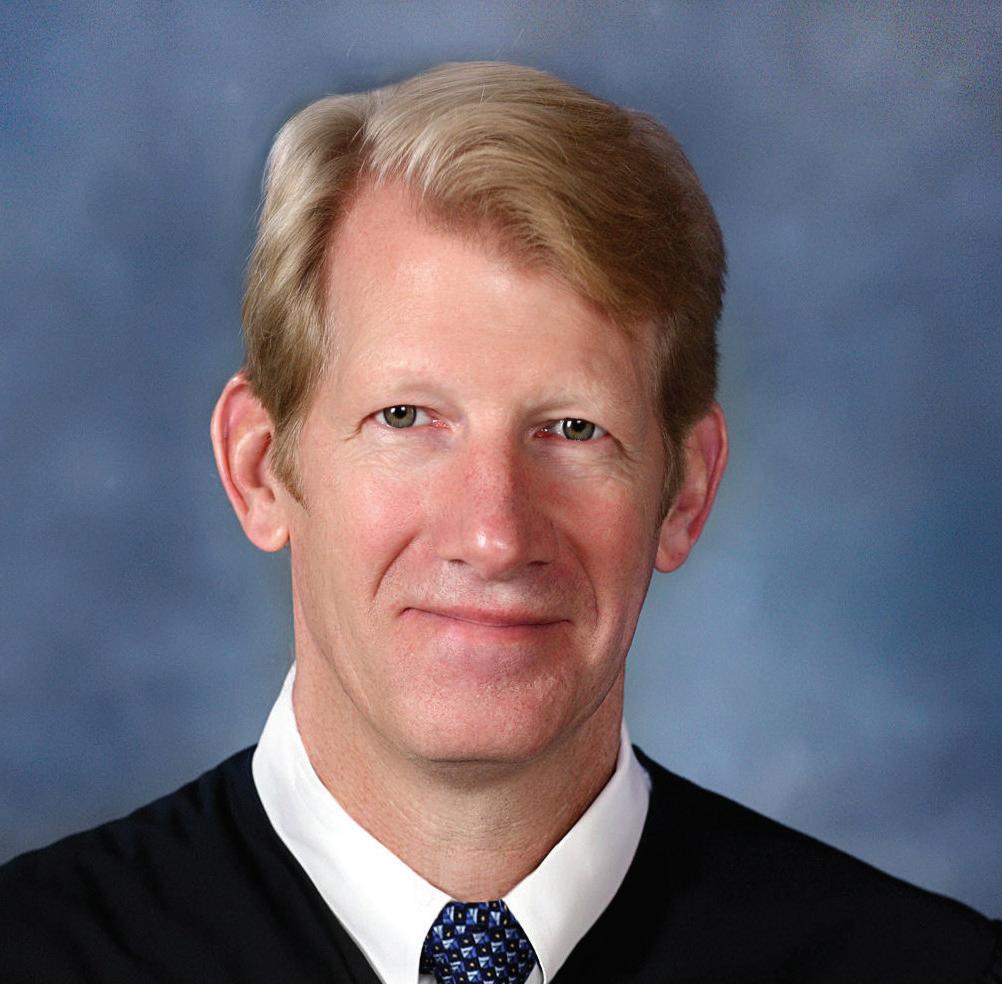

John L. Weimer (1980)

2001-Present*

Greg Guidry (1985)

2009-2019

Marcus R. Clark (1985)

2009-2020

Jefferson D. Hughes III (1978)

2013-Present

Scott J. Crichton (1980)

2015-Present

William J. Crain (1986)

2019-Present

Jay B. McCallum (1985)

2020-Present

Piper D. Griffin (1987)

2021-Present

* Served as chief justice

Thibodaux, Louisiana

EDUCATION

Thibodaux High School ('72), Nicholls State University ('76), LSU Law ('80)

FAMILY

Married to Penny Hymel, and together they have three daughters: Jacqueline ('20), Katherine, and Emily.

• 1993: Appointed by the Louisiana Supreme Court to serve as Judge pro tempore, Division D, of the 17th Judicial District.

• 1995: Elected to serve as Judge, Division A, of the 17th Judicial District Court and reelected in 1996 without opposition.

• 1998: Elected to serve on Louisiana’s First Circuit Court of Appeal.

• 2001: Elected as Louisiana Supreme Court Associate Justice, District 6.

• 2002 and 2012: Re-elected to a 10-year term on the Louisiana Supreme Court without opposition.

• 2021: Becomes the 26th Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

OFF THE BENCH

In his free time, Weimer enjoys spending time with his family, riding motorcycles, painting, kayak fishing, and playing basketball. He is also a longtime volunteer with the Thibodaux Volunteer Fire Department, Fire Company No. 1, and is an active member of his church.

Long before he arrived at LSU Law in the fall of 1976, Louisiana Supreme Court Chief Justice John L. Weimer began learning some of the valuable life lessons that would later serve as the cornerstone of his judicial philosophy in an unlikely place: His father’s small service station in Thibodaux, Louisiana.

“The virtue of honesty, the value of hard work, and the importance of treating everyone with dignity and respect, regardless of their station in life—these are all things that I learned while working at my dad’s service station,” Weimer said. “His clientele was an extremely diverse group of people, so it was also an incredible place to meet, get to know, and learn how to interact with people from all walks of life.”

Weimer is the first to admit that his ascent to the top seat on the state’s highest court was as unlikely as it was unconventional. Growing up in a family of few means, it was expected that he and his four siblings would contribute by working at the service station. After his mother passed away when Weimer was just nine years old, times got even tighter for the family and his father was left to raise the children with help from their grandparents.

“My father was a working-class guy. He was an impeccably honest and hardworking mechanic, but he was not a big proponent of education. Work was mandatory. School was optional,” he said. “Most of us took off from school as much as we could, but when I graduated high school—barely—I decided to go to college.”

He enrolled at his hometown college, Nicholls State University, where he entered with a “seventh grade education at best” by his own calculation.

“People often ask me, ‘Why Nicholls?’ and I always tell them, ‘With my grades, it was Nicholls or nothing,’” Weimer said. “But it really turned out to be one of the greatest blessings in my life because it has impacted me in so many positive ways.”

By the time Weimer started his undergraduate studies, his family had been forced to sell the service station and “everything we owned, literally, to put food on the table” after his father had fallen ill. Weimer didn’t have a vehicle, so he borrowed a bike from his brother and spent his days peddling between home, campus, and his job at a washing machine repair shop, which helped pay his tuition and expenses.

“I would show up to classes filthy, stinky, and nasty from working on washing machines and riding a bicycle across town two or three times a day,” said Weimer. “I looked like a wretch—probably was one.”

Because he had previous experience serving as editor of his high school newspaper (“It was about the only accomplishment of my high school career”), he began working at the Nicholls Worth as a reporter and editor, which helped him learn how to write concisely and clearly. It was among the experiences that led him to start thinking that he might be suited to pursue a law degree.

“I struggled as a student in high school and when I got to college, I knew that if I wanted to do something different, I would have to make better grades, so I just studied all the time,” he said. “I developed a knack for talking to people, for writing, and analyzing problems and solving them, and it just seemed like the skills the Lord had blessed me with were consistent with going to law school.”

During his summers as an undergrad, Weimer began working for local state Sen. Harvey Peltier Jr. at the Louisiana State Capitol, which provided him with a new perspective on how he might be able to serve the public.

“I was exposed to a whole different world working at the capitol in Baton Rouge and meeting people who were involved in the law-making process,” he said.

After earning a business degree from Nicholls in 1976, Weimer began saving money to attend LSU Law, which he recalls having a tuition of about $500 per semester. While searching for a job, he got a call from his cousin, Dan Borné, who’s also from Thibodaux and would go on to become a household name among LSU fans as “The Voice of Tiger Stadium.” Borné was working with Sen. Russel Long (’42) and floated the idea of Weimer taking an internship with the senator in Washington, D.C. Weimer was intrigued, but declined the offer after running a rough calculation and realizing he wouldn’t be able to save enough money for law school. He took a job as a deckhand on an offshore supply boat instead, making $40 a day, working 30 days on and two days off.

“Back then, you could work your way through law school without going into debt if you were willing to work hard enough—and I was willing to,” Weimer said. “Unfortunately, young people today don’t have that opportunity.”

When the time came to find a place to live in Baton Rouge, Weimer was equally practical and financially prudent. Instead of renting a place, he bought a dilapidated trailer home without a heater or air conditioner for $850 from a couple in Choctaw and “prayed the whole way that it would make it to Baton Rouge without collapsing.” His prayer was answered, and Weimer settled in at a trailer park on Nicholson Drive—on property where condominiums full of LSU students now stand. The move turned out to be fortuitous, as two of his neighbors were also LSU Law students. Charlie Riddle III (’80), who now serves as district attorney of Avoyelles Parish, lived next door, and Gary Bowers (’79), who has a law firm in Shreveport and formerly served as a district judge for the First Judicial District Court in Caddo Parish, lived across the street.

“We live in a civil law system and that was burned into my brain at LSU Law by so many wonderful professors who were incredibly bright, articulate, and scholarly. They were not only a major influence on me, but I was fortunate to maintain relationships with them throughout my career,” he said. “The people I met at LSU Law and became close friends with are still my close friends and confidants all these decades later. In my estimation, that’s the real advantage of going to LSU Law, because it’s a wonderful community of so many people who are Louisianans first and foremost—or who want to be.”

After graduating from LSU Law in 1980, Weimer passed the bar and returned to Thibodaux to work as an attorney with U.S. Rep. Billy Tauzin (’67). When Tauzin was elected to Congress, Weimer began practicing alongside Randy Parro (’67) and Jerald Block. For the next eight years, he practiced law full time while teaching part time at Nicholls, and also teaching law and banking through the American Institute of Banking and notary prep classes.

“It was a wonderful experience, and I thoroughly enjoyed those years,” he said of teaching at his alma mater, which he ultimately would do for 16 years. “I taught roughly 3,000 students during the time I was there and so many of them went on to become successful in their lives. I feel so fortunate to have had the opportunity to touch the lives of people in a positive fashion and reciprocally have those students touch my life in a positive fashion.”

“The people I met at LSU Law and became close friends with are still close friends and confidants all these decades later. In my estimation, that’s the real advantage of going to LSU Law, because it’s a wonderful community of so many people who are Louisianans first and foremost—or who want to be.”

Though he has been honored with many awards and accolades throughout his career, Weimer said being honored by Nicholls students with the Presidential Award for Teaching Excellence is “probably the accomplishment that I’m most proud of because it was based on consumer opinions, the students that I taught.” He also credits his teaching years for preparing him to serve as a judge.

“After all, you sit in judgment of your students, you have to have command of the classroom, you have to interact with a wide variety of people,” he explained, “and the position is all about service—giving back, treating people with dignity and respect, sharing your knowledge and thoughts, and educating them.”

“Charlie and I could have a conversation without opening the windows of our trailers,” Weimer recalled with a laugh. “When I ended up on the Supreme Court, he sent me a note saying, ‘I guess I can’t call you trailer trash anymore,’ and I said, ‘No, you can, that’s a badge of honor that I wear proudly.’”

Weimer said his classmates and professors at LSU Law— which included Frank Maraist ('58), Paul Baier, George Pugh ('50), Alston Johnson ('70), Mike Rubin ('75), Cheney Joseph ('70), Bill Crawford ('55), and Alain Levasseur—had a profound impact on him, professionally and personally.

While teaching at Nicholls, Weimer had yet another life altering event: He met his future wife, Penny Hymel. The two would go on to have three daughters—one of whom, Jacqueline W. Sanchez, graduated from LSU Law in 2020.

In the spring of 1993, while grading papers and posting grades, Weimer received a call from his friend and former colleague Randy Parro that would forever alter his career path. Parro had just been elected to the 1st Circuit Court of Appeal in Baton Rouge and would soon be vacating his seat as a state district judge for Lafourche Parish before the term expired. He called to let Weimer know that he planned

to recommend the Louisiana Supreme Court make him the interim appointee for the state district court seat.

“I said, ‘Randy, I’m not remotely interested. Thank you for thinking of me, but please don’t,’” Weimer recalled. “We discussed it for a while, and he wouldn’t let me tell him no. Long story short, two or three days later he convinced me to serve, and the Louisiana Supreme Court voted unanimously to allow me the opportunity to serve.”

Weimer was granted a sabbatical from Nicholls, and he served for just under eight months on the state district court bench.

“I went back to teaching after my judicial service and I thought that was the end of my judicial career. I had no hopes, goals, or beliefs that I would ever go back to being a judge,” he said. “In fact, the president of the university and the dean of the business college called me in when I came off the bench and they said, ‘We want to start moving you through the academic ranks. We believe that you have a future here at the university as either a dean, vice president, or president one day.’ So, I was all in. That sounded like a plan to me.”

Shortly thereafter, however, another unexpected vacancy on the state district court was created when a local judge, Sidney Ordoyne Jr. ('71), passed away. Weimer began receiving calls from people in the area encouraging him to run, and he was eventually persuaded. In 1995, he was elected District Judge for the 17th Judicial District Court, and three years later he was elected as an Appellate Judge for the Louisiana Court of Appeal, First Circuit. He served in that capacity until 2001, when Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Harry T. Lemmon retired with a year left on his term and Weimer successfully ran to fill his seat for the remainder. In 2002 and 2012, he was reelected to 10-year terms without opposition.

Weimer was sworn in as the 26th Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court on Jan. 7, 2021—one day after the attack on the U.S. Capitol shocked the nation.

“John Weimer is the right person to lead this court during these challenging times,” Gov. John Bel Edwards (’99) said at the investiture ceremony, which featured heightened security due to the events of Jan. 6 and limited attendance due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Weimer filled the seat vacated by Bernette Joshua Johnson (’69), who retired after serving 26 years on the high court, both as the second female and the first Black person to serve as chief justice.

“When I took the oath, I was very sincere when I said that I was overwhelmed by a sense of humility and the understanding that this is a position of service,” Weimer said. “I concluded my remarks by citing the biblical passage in which God tells Solomon that he could have anything he wished for—a long life, riches, anything—and Solomon asked for an understanding heart; that he could discern right from wrong and treat his people well. Again, that’s very sincere. I don’t pray for myself. I pray for a lot of wisdom, guidance, and the ability to come to the right decision based on the law and the facts.”

Reflecting on his life and journey to the Louisiana Supreme Court, Weimer credits his LSU Law degree for giving him the opportunity to have four distinct and rewarding careers as an attorney, mediator, teacher, and judge. Going forward, Weimer said he wants to continue doing what he’s always done, regardless of his official job title: Work hard and serve others.

“It’s incredibly gratifying to be of service to others and to give back to the community,” Weimer said, “and, again, that’s something that I first learned at my father’s service station.”

HOMETOWN

Madisonville, Louisiana

EDUCATION

Bogalusa High School (‘79), LSU (‘83), LSU Law (‘86)

FAMILY

Married to Cheri Hackett Crain and together they have four adult children: William, Michael, Matthew ('16), and Elizabeth.

• 2008: Elected without opposition to the 22nd Judicial District Court.

• 2012: Elected without opposition to the First Circuit Court of Appeal, where he served until 2019.

• 2019: Elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court in a contested election.

In his free time, Crain enjoys working outside, fishing, hunting, golf, and spending time with his family. He is a parishioner at St. Timothy United Methodist Church.

A few months after William J. Crain was sworn in as a justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court in December of 2019, the rapidly accelerating COVID-19 pandemic brought unexpected and unprecedented disruption to the judicial system and courthouse operations statewide.

“After practicing law and serving as a judge at every level for more than 30 years, I came to the court expecting to make some momentous decisions— and we certainly have,” said Crain. “I just didn’t anticipate that some of the most important decisions we’d make would be administrative, not adjudicative.”

When it comes to the judiciary, landmark rulings on hot-button issues such as abortion, religious freedom, and voting rights naturally garner the greatest public interest. Most people don’t pay nearly as much attention to another primary function of the state’s highest court: Managing the operations of Louisiana’s 42 judicial districts, which encompass 42 district courts, five courts of appeal, five family or juvenile courts, 48 city courts, and three parish courts. At the same time, the court is responsible for holding legal professionals accountable by administering discipline for the more than 25,000 lawyers who practice in Louisiana, as well as hearing petitions for discipline and removal relative to the state’s roughly 350 judges.

“We run the legal system in the state of Louisiana and that is a weighty responsibility. The public might not think about it all that much when everything is working normally, but they certainly pay attention when it isn't,” Crain said. “And, quite frankly, there isn’t much you can do to prepare for that part of the job—managing the legal profession in the state—before you join the court, other than honoring your oaths as a lawyer and judge and remembering that the public’s trust is built on how good (or bad) we do our jobs.”

As the effects of the global pandemic reached Louisiana in early March 2020, Crain and his fellow justices had to act fast to ensure the work of the state’s courts could continue with as minimal disruption as possible. With the number of COVID-19 cases spiking across Louisiana, it became clear that courthouses would need to be physically closed. On March 26, 2020, the justices ordered that all essential court functions be conducted via video and phone conferencing, with extremely limited exceptions for in-person proceedings to address emergency matters that could not be resolved virtually.

“One of the first things we did as a court was form a technology commission so we could quickly assess our technology infrastructure statewide and determine what was needed to keep our courts operational,” Crain explained. “That was a very important decision because we didn’t know at that time how long we would have to physically close our courthouses, but we recognized that it could be a very long time. And, unfortunately, just because our normal interactions stopped around the world, peoples' legal problems did not."

Working in tandem with the Louisiana District Judges Association and the Louisiana Judicial College, the Supreme Court began overseeing technological upgrades in each judicial district, rebuilding and enhancing court websites, creating an online forms platform, increasing cybersecurity, and providing technology training for judges, among other initiatives.

"We faced some significant challenges,” Crain acknowledged, “but I can guarantee you the work we’ve done over the past three years to enhance our technology infrastructure and procedures has helped move our courts forward by at least 10 years.”

While the justices can be commended for their effective and efficient decision making in the early days of the pandemic, Crain said, the lion’s share of the credit is owed to the many dedicated judges and court staff members across Louisiana, who ensured the important work of the courts continued throughout the pandemic.

Just as many companies developed new ways of doing business during the pandemic that they've since retained, so, too, has the state's high court.

“Technology is here to stay and not only from the functionality side for the courts, but also from the access and service side for the public. For example, we conducted oral arguments remotely in 2020 for the first time in the court’s 200-plus year history. Another example is the development of an e-filing system, which we are working to get unified in all 64 parishes,” he said. “Not everything that we’re working on is going to be implemented in the short term, but the fact that we have an eye on these important issues surrounding technology is a step in the right direction. Going forward, I’m very hopeful that we’re going to make some significant technological improvements that will help us address larger issues in the funding, size, access, and overall efficiency of our courts and districts.”

Along with Justice Jay McCallum, Crain is one of two Supreme Court members who serve on the Louisiana Supreme Court Technology Commission. The other commission members are judges from the state’s appeal, district, juvenile, family, and city courts. While Crain has established himself as a leading advocate on the court for advancing the judicial system’s technical capabilities, he is the first to admit that he is much more comfortable using a chainsaw than a computer.

Ultimately, Crain earned an accounting degree from LSU in the spring of 1983. Soon after beginning his studies at LSU Law that fall, he immediately knew he was on the right path. “I had never experienced the Socratic method of teaching in any of my classes before, it was a new universe to me, and I absolutely embraced it. I enjoyed reading the cases, analyzing them, and the discussion that would follow. The cases were about real people needing real answers to real life issues. I knew a career in the law was what I wanted to do,” he said. “The demands on students at LSU Law were incredible. The professors made sure that it was very challenging, but looking back on it, I can see just how instrumental the focus of my professors on the civilian tradition and methodology has been on my education and career. My professors at LSU Law had a huge influence on the way I now judge and decide cases.”

Just before the start of his final year of law school, Crain and Cheri Hackett were married. The two had begun dating during their undergraduate years at LSU, and they would go on to have four children. One of their sons, Matthew, followed in his father’s footsteps, graduating from LSU Law in 2016 and joining the same firm where his father launched his career.

"Going forward, I'm very hopeful that we're going to make some significant technological improvements that will help us address larger issues in funding, size, access, and overall efficiency of our courts and districts."

After earning his law degree in 1986, Crain began practicing law with Jones Fussell LLP in Covington. He would practice at the firm for the next 22 years, specializing in medical malpractice cases, both on the plaintiff and defense sides, and in complex judge and jury trial cases. In 2009, he began his judicial career after winning a seat on the 22nd Judicial District Court bench. In 2012, he was elected to the First Circuit Court of Appeal, where he served until being elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court.

“Ever since I was a child, I’ve always loved being in the outdoors and working with my hands,” said Crain, who was born and raised in Bogalusa, the small Washington Parish town of some 12,000 people near the Louisiana-Mississippi border. “Being idle was not an option when I was growing up, primarily because my mother wouldn’t allow it, and that was just fine by me.”

Crain was familiar with the courts from an early age because his father, Hillary J. Crain (’61), was an attorney and judge who served on the benches of the 22nd Judicial District Court and the First Circuit Court of Appeal for nearly 30 years before his retirement in 1994.

“I worked construction through my second year of college, and I can distinctly remember telling my dad I really liked the work,” he said, “But, I also remember him looking at me and saying, ‘Son, you won’t like it when you’re 50.’ He may have been right. But, while my career did take a different direction, I still have a passion for working outside and that’s usually what you can find me doing whenever I can get a little break from our work at the court.”

As he enters the fifth year of his term on our state’s highest court, Crain approaches his work on the bench with the same expectation that he had when he was sworn in just before the pandemic started: He wants to make decisions on meaningful issues.

“Nobody elected me to be an administrator. They elected me to decide cases. That said, administering justice necessarily requires working through administrative issues to guarantee that justice is served. Working out those logistical matters ensured the courts were open and available to all—and I’m very proud of the work we’ve done,” he said.

The pandemic also ushered in a host of new cases ripe for consideration, including opinions addressing the scope of the right to privacy under the Louisiana constitution, the scope of liability for protest organizers, and the protection of religious liberties.

“I recently told one of my staff members that with all the changes made during and after the pandemic, it really feels like I’m just starting to get my legs under me here, and I’m excited about the important work we are doing and have ahead of us,” Crain said.

HOMETOWN

Minden, Louisiana

EDUCATION

The Webb School (’72), LSU (’76), LSU Law (’80)

FAMILY

Married to Susie Crichton and together they have two sons: Stuart (’13) and Sam (’14).

• 1990: Elected to the First Judicial District Court, and served on the bench until his election to the Louisiana Supreme Court.

• 2014: Elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Crichton is an active member of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Shreveport, where he served on the vestry. He is also a member of The Webb School Board of Trustees, for which he has served on the Executive, Governance, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, and Excellence in Teaching and Learning committees.

In the fall of 1977, Scott J. Crichton found himself among the roughly 375 firstyear law students at orientation in the LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center, feeling a little uneasy about the journey he was embarking upon.

“My dad influenced my decision to attend LSU Law—and it was not a negotiation,” Crichton explained, “but I really wasn’t sure about being a lawyer.”

Though his first day of law school did little to assuage any apprehension, it certainly left a lasting impression on the young man.

“When Acting Dean Francis Sullivan gave us the old, ‘Look to your left, look to your right, one of you won’t be here next year’ speech, I paid close attention,” Crichton remembered. “My thought was, ‘To hell with that. I’m staying. If I leave, it will be on my own terms.’ I accepted what he was saying as a direct challenge to stay in and survive.”

Luckily for Crichton, he already had significant experience adapting to survive in completely new and extremely challenging environments. He was just 14 years old when his parents informed him that he’d soon be leaving Minden, Louisiana—the small town of some 15,000 people in northwest Louisiana where he’d grown up—to attend an all-boys boarding school in the mountains of middle Tennessee.

“It was absolutely terrifying at first,” he recalled of his arrival at The Webb School in 1968. “My parents drove me the 10 hours there and helped me move into my dorm room, and when they were leaving my dad said, ‘We’ll see you at Christmas.’ This was in August.”

Founded in 1870, The Webb School had a well-earned reputation for molding young men into future leaders of academia, politics, business, military, and the law. Its motto, “Noli Res Subdole Facere”—Latin for “Do Nothing on the Sly”— reflected its strict honor code.

To Crichton, the prep school “felt a lot like the Army, without the uniforms.” Students were expected to adhere to a highly regimented daily schedule that was scant on idle time.

“The older students supervised the younger students. That was part of the leadership model, and for the most part it worked,” he said. “But there were a lot of big, strong upperclassmen, and you had to be worried about how you’d fit in as a new kid who wasn’t nearly as big. The first few years were especially tough.”

By his third year, Crichton had made some close friends and was beginning to feel more comfortable on campus. But his junior year would also bring his greatest test in survival yet, which came after Crichton signed up to partake in the North Carolina Outward Bound School.

“They called it a survival school, and it was easily the most physically grueling and torturous experience of my life,” he said. “The whole experience only lasted three weeks but by the end of it I had lost 15 pounds, which I really didn’t think I had to lose.”

Located in Morganton, North Carolina, the adventure-based, experiential education program was designed to help young people discover their strength of character, ability to lead, and desire to serve. The school’s motto: “To Serve, To Strive, and Not To Yield.”

“That has always stuck with me, along with the motto for The Webb School,” Crichton said. “I mean, what a great way to live. You put those two mottos together and what else do you need?”

By the time Crichton graduated from The Webb School in 1972, he had unknowingly taken the first steps in a journey that would reach professional heights far beyond the imagination of the boy who had left Minden just four years earlier.

“It took me a little time to adjust,” he reflected, “but the time I spent there turned out to be one of the greatest blessings of my life. My experiences there set the tone for the path I would continue to travel on until this very day.”

Roughly 46 years after leaving home for The Webb School, Crichton’s path would wind its way to the summit of his judicial career—thus far, at least. The date was Monday, Dec. 14, 2014. The setting was the Caddo Parish Courthouse.

“I had presided in that very courtroom a number of times during my 24 years as a district court judge,” he noted, “and I had tried cases in it as a litigator early in my career.”

The occasion was Crichton’s induction as an associate justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court. His brother, Tom Crichton IV, an LSU Law Class of 1972 alumnus, read the official commission. His sons, Stuart and Sam—who earned their LSU Law degrees in 2013 and 2014, respectively—assisted with the official robing ceremony.

“A glorious moment for me,” Crichton said, “and I remember it like it was yesterday. It was almost surreal. I mean, you can’t help but think, ‘Is this really happening to me?’”

His father, Tom, was a plainspoken cattle rancher and hardware store owner who was uncompromising when it came to his children’s education, work ethic, and honor. “Dad was a country boy who emphasized hard work and education. You could usually find him in khakis and overalls, working outside or in the hardware store, but he could also transform himself into a gentleman with plenty of polish and etiquette when he was called upon to do so,” Crichton said. “His brother had graduated from LSU Law—John Hayes Crichton Sr. ('49), but Dad couldn’t go to law school because he had to run the family business. He mapped out my education path early. It was the path he insisted my brother and I take, and it included The Webb School and higher education—and that was non-negotiable.”

Crichton returned home to Louisiana to attend LSU after graduating from The Webb School. But after spending four years at an all-boys prep school, he was ready for a little less regimen and discipline in Baton Rouge.

“I was just sort of meandering through my undergraduate years, partying and dating and catching up on some of the things I had missed out on during my high school years,” he explained. “I had a lot of fun as an undergraduate—and probably too much fun at times—but that wasn’t the case as a law student.”

"Our parents taught us that with education and hard work, anything was possible. And it was that gift of education–including law school–that would make all the difference for a purpose-driven professional life in service of the law."

After the oath was administered by Chief Justice Bernette Joshua Johnson (’69), it was Crichton’s turn to speak. He presented his wife, Susie, with a bouquet of flowers, thanking her for her endless support and tireless work on his campaign. He then thanked the dozens of family members, longtime friends, and colleagues who had traveled to Shreveport from all corners of Louisiana to help make the occasion even more special for Crichton. And then he turned his thoughts to the two people who had set him on his unlikely path, instilling in him the virtues of humility, education, and community service along the way.

“Our parents taught us that with education and hard work, anything was possible,” Crichton told the packed courtroom. “And it was that gift of education—including law school— that would make all the difference for a purpose-driven professional life in service of the law. Sadly, my parents would not live long enough to see me elected judge. They both died more than 25 years ago, but with this commission and in accordance with the 5th Commandment, I honor them today. Every day, I strive to carry their lessons forward.”

Crichton credits his mother, Mary—a “master bridge player and voracious reader” with a fondness for mystery novels— for his analytical mind.

“She would have been a tremendous lawyer. She had that keen analytic ability,” he said. “But she grew up at a time when women did not have the opportunity to go to law school.”

At LSU Law, Crichton eschewed all potential distractions to improve his chances of survival.

“I broke up with my girlfriend, I had no pets, and I kept a small group of friends. I didn’t participate in any student organizations or extracurriculars, and I was proud of it,” he recalled. “Interestingly, I never participated in moot court, but I’ve had a career in the courtroom since 1980—and I credit the great teachers at LSU Law for providing me with a strong academic foundation on which I learned how to operate in the courtroom after I left law school.”

Three months after earning his J.D. in the spring of 1980, Crichton began serving as the sole clerk for eight judges at the Caddo Parish District Court. The experience provided him with a 360-degree view of the court’s day-to-day operations, through which he began to see a future in litigation.

“It required me to bring all the knowledge that I learned from (Professors) Cheney Joseph (’70), George Pugh (’50), Alston Johnson (’70), and so many others to the courthouse,” Crichton said. “Plus, I had to know protocol, and luckily I had learned a lot about that from (Professor Athanassios N.) Yiannopoulos and (Adjunct Professor) Mike Rubin (’75). All of that came together for me in that position, and I was growing more passionate about the work every day.”

In 1981, he joined the Caddo Parish District Attorney’s Office as an assistant district attorney, a position in which he would remain for the next decade.

“I especially enjoyed bringing justice and closure to the family members of victims. It became another passion,” he said. “The role appealed to my sense of community service and jury trials appealed to my competitive nature.”

By 1990, at the age of 36, Crichton felt he had enough courtroom experience to make a run for the bench. He was just waiting for the right opportunity. At the time, he was prosecuting the most important case of his career to that point, which involved a serial killer accused of murdering eight people in the Shreveport area between 1984 and 1987.

“I was the lead prosecutor, it was a very complex case with a volume of circumstantial evidence, and we were seeking the death penalty. It doesn’t get any more serious than that,” Crichton recalled. “The pressure to secure a conviction was tremendous.”

As the trial was unfolding, a federal injunction was suddenly lifted that resulted in every judge’s term on the First Judicial District Court in Caddo Parish to unexpectedly end in two short months, creating a unique opportunity for Crichton to take his first run at the bench.

“The only problem is I’m in this extremely serious trial with a sequestered jury,” he remembered. “So, I called up Susie and said, ‘I want to run, but I need your OK.’”

He received much more than his wife’s approval.

“She organized my campaign, launched it, and operated it entirely for the first 10 days while the trial was wrapping up,” Crichton explained. “And then I went straight from the death penalty verdict to the campaign, and it was a very tough race.”

His first campaign turned out to be his most hotly contested. In fact, Crichton hasn’t even drawn an opponent in any of his subsequent races, due in no small part to the strong trust and stellar reputation he has earned from his constituents and neighbors through the years. Though he wasn’t exactly an unknown candidate, he was far from the frontrunner in a race that included three well-known opponents.

“I had been the underdog, but I also had grassroots support and the backing of law enforcement,” said Crichton, who eventually won in a runoff election, with 56% of the vote. “That experience prepared me to run for the Supreme Court, though that wasn’t on my mind at the time.”

Crichton served as a First Judicial District Court judge for 24 years, presiding in both the civil and criminal division, before joining the Louisiana Supreme Court. When he wasn’t on the bench in those years, he spent a great deal of time creating and assisting with the development of several extremely successful educational programs for legal professionals as well as high school students—one of which came about as a direct result of his experiences in the courtroom.

“One day, we had an unusually large number of young people charged with really violent crimes, including rapes and murders, and one case in particular really stuck with me,” he explained. “It was a 15-year-old kid who was charged with armed robbery with a firearm, the minimum sentence for which was 15 years of hard labor.”

The evidence against the teenager was overwhelming. When it came time for sentencing, Crichton took no joy in performing his judicial duty.

“His mother was in the audience, weeping uncontrollably, and this 15-year-old kid looked like a deer in the headlights as the gravity of the situation was finally setting in,” he recalled. “I’m thinking: ‘My God, he really had no idea of what the consequences of his actions would be, but we can’t undo this. I mean, I can’t send him to a social program or The Webb School or Outward Bound, and I can’t bring him home with me.’ It was heartbreaking.”

The moment inspired Crichton to develop a program that provides high school students with a comprehensive understanding of the penalties that accompany serious crime convictions. In the nearly 20 years since Crichton began personally presenting the program at Shreveport area churches and schools, “Crime, Consequences and the Power of Choice” has been incorporated in high schools across the state.

“That’s the sort of thing that keeps me going,” he said. “My attitude has always been that I really don’t need this job—or any job, for that matter—as much as I need to make a positive impact in the community I serve. That’s my priority in life.”

For the first time in a long time, Crichton has been giving some thought to his next job. He’ll celebrate his 70th birthday about seven months before his Louisiana Supreme Court term ends on Dec. 31, 2024, and the state constitution restricts anyone 70 or older to qualify for a judicial election. But even if Crichton were able to run for another term on the bench, he said he wouldn’t.

“This is the summit,” he said during an extensive interview inside the Louisiana Supreme Court. “I’ve been on the judiciary now for 32 years and I’m ready to be a little bit more private. My extremely loving and supportive wife would also