AUTHOR Dr. Alessandro Morganti M.D., Ph.D in collaboration with LS3P

We live in a world in constant evolution, and we experience driving forces of change that are both under and outside of human control. Most of these forces impact the health of our communities, defining the current and future needs of our diverse populations and influencing our ability to achieve physical, social, and mental wellbeing for all.

Design can play a fundamental role in responding to these changes and supporting health improvements for every individual.

The “Future of Healthcare in the Southeast” white paper aims to match current and future trends in healthcare with optimal healthcare design strategies, learning from scientific evidence and experiences from across the industry.

This research was conducted in collaboration with LS3P, an architecture, interiors, and planning firm with a unique regional focus on the Southeast US. The firm is deeply committed to creating architecture that enriches community through a culture of design excellence, expertise, innovation, and collaborative engagement. This white paper integrates LS3P’s commitment with leading-edge medical insights from an academic research perspective to build knowledge for the Southeastern communities.

METHODOLOGY & SOURCES

The white paper is grounded on extensive analysis of peer-reviewed scientific papers, reviews, big data from government and NGO sources, and industry research. The interpretation of these sources and dialogues with experts in the field has guided authors to delineate how specific trends impacting healthcare in the US Southeast are likely to evolve, and which are the most probable challenges that healthcare design will face in the near future.

A full list of bibliographic sources can be found at the end of the document.

HOW TO READ THIS DOCUMENT

The white paper is divided into three key parts:

One Environment

Multiple Communities Whole Individual

Each part is articulated into three chapters. Each chapter includes an analysis of one healthcare trend, followed by a section called “The Power of Design” addressing the related design implications. Infographics and charts enrich the document, helping the reader understand at a glance what the data communicate. Many international case studies are featured in the chapters as well, highlighting best design practices that have been thoughtfully integrated into buildings all around the world.

At the end of each section, a “Too Long; Didn’t Read” (TL;DR) column summarizes the main takeaways from chapters, providing busy readers with a taste of what they will find in the previous pages.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Alessandro Morganti, MD, PhD, is a medical design research consultant working with LS3P’s Healthcare team. Dr. Morganti earned his MD from the University of Milano-Bicocca and his MS from Politecnico di Milano. Over the course of his medical training, he became passionated in how space impacts the patient experience, leading him to pursue a PhD in architecture after medical school. He served as a visiting scholar in Stanford Medicine’s Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Department in 2021-2022, and was recently selected for a Joseph G. Sprague New Investigator Award by the Center for Health Design. His applicative research work focuses on Healthcare Design and Design for Neurodiversity, with projects across the US and Italy.

ABOUT LS3P

LS3P is an architecture, interiors, and planning firm celebrating 60 years of design excellence. With deep regional roots and a national reach, we offer large-firm expertise and resources with small-firm relationships and service. In everything we do, we’re guided by our vision: In our commitment to the Southeast, we create architecture that enriches community through a culture of design excellence, expertise, innovation, and collaborative engagement.

Core Team: Ron Smith, AIA, ACHA, ACHE, LEED AP; Katherine Ball, AIA, LEED AP; Autumn Delfino; Megan Bilgri; Chelsea Heitzman; Willy Schlein, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP.

Subject Matter Experts: Espy Harper, EDAC, Six Sigma GB; Jeff Mural, AIA, NCARB, EDAC; Steven Johnson, AIA; Leigh Pfeifer, AIA, LEED AP, ILFI_ LFA, NCARB, EcoDistricts AP; Helen Byce, AIA, EDAC, LEED AP BD+C, GGP.

1 2 3

01One Environment 02Multiple Communities 03Whole Individual 1.1 Public Health Trends 04 1.2 Climate Change 08 1.3 Preparedness & Resilience 11 2.1 Two Growing Populations 15 2.2 Urbanization 20 2.3 Rural Communities 23 3.1 Evolution of Care 27 3.2 Central Role of Behavioral Health 32 3.3 Prevention & Health Education 36

01

One Environment

The health challenges of a growing and aging society living in a transformed natural environment.

4

Public Health Trends

Advancements from the last decades in science and technology have extended life expectancy in upper-income countries tremendously. In the US, life expectancy now averages 76.1 years overall. While this achievement has been made possible by revolutionary solutions in acute and chronic care, our biggest opportunity is now in addressing health challenges introduced by longevity.

In fact, chronic conditions have now surpassed acute illnesses as the leading cause of death, and this trend has accelerated over the last 20 years. Chronic diseases (non-communicable diseases or NCDs) are also the leading driver of healthcare costs, with more than 6 in 10 adults living with at least one chronic condition. In the US Southeast, for example, higher national rates of diabetes and obesity impact the physical and mental health of the population, and are also known risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. The incidence of cancer is higher in the Southeast as well, with some states having over a 10% higher rate compared to the national rate.

Many factors such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, and poverty influence the rise of chronic health conditions. These factors are all part of the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) identified by the World Health Organization (WHO). Health education plays a central role in guiding populations towards healthier lifestyles and building awareness of the importance of daily behaviors in disease prevention.

Healthcare systems can support patients in reaching the “Good Health and Wellbeing” goals that the United Nations has set for 2030 as part of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (United Nations 2015). As the infographic shows, the projected results of a diffused awareness and public health interventions in 90% of the US population would far exceed the UN’s target of a 1/3 reduction of NCDrelated deaths in the US (Watkins et al. 2022).

Certain populations present a higher risk for NCD; healthcare systems should target effective public health interventions for

these vulnerable populations. Data from the Southeast have shown an increase in chronic diseases and worse health outcomes in young adults, mothers, children, and specific ethnicities compared to other regional populations. As Chapter 3 will explain, prevention and health education are powerful resources for addressing the needs of vulnerable populations, and now more than ever the evolution of technology is making broader adoption of preventive public health actions possible.

Effective public health interventions empower patients who actively embark on a continuum of care, meant as a cohesive care system that oversees and monitors patients throughout their journey. An integrated continuum of care benefits a wide spectrum of healthcare services, ranging from prevention to all levels of intensity of care.

1.1 PUBLIC HEALTH TRENDS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

2 0M 2.5M 3 0M 3 5M 2030 2025 2020 2015 2010 2005 2000 1995 1990 Optimal Adoption of SDG SDG Goal Projected Deaths Actual Deaths The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 5

F1 Deaths related to NCDs in the US population. The yellow continuation of the chart marked as “Projected Deaths” estimates the deaths between 2020 and 2030 if the measures for prevention adopted as of today remain unchanged. The dotted red line projection shows, instead, how the effects of NCDs can be significantly reduced if a healthy lifestyle and preventive measures are broadly adopted by citizens (90% of them), with a greater reduction of NCD-related deaths compared to the goal set by the United Nations in the 2030 SDGs target (marked by the blue line)

Power of Design

Advances in technology have the potential to amplify preventive health measures through non-invasive, fast, and costeffective diagnostics. The use of screening procedures is likely to increase: an aging population will require care for more years, and may experience a higher prevalence of chronic diseases. The number of diagnostic procedures per person and overall volumes may rise along with ease of access to emerging diagnostic technologies as well.

As a recent analysis from Deloitte shows (Deloitte 2022) the evolution of diagnostic technologies is very likely to benefit from many disruptive innovations like AI, blockchain, or digital twins, multiplying the investigation opportunities based on instrumental diagnostics.

Thanks to faster image acquisition and interpretation, shorter investigation time, and reduced costs, an increased use of diagnostic machines for preventive purposes will increase the number of visitors to healthcare facilities, with a higher turnover. As an example, wholebody MRI scans are benefiting from these evolutions, transitioning from limited use due to the high cost and acquisition time to more widespread use for population screening and disease evolution tracking (Tunariu et al. 2020).

This higher patient volume will impact the building masterplan for patient access, facility layout, the organization of waiting areas, and patient flow. Evolving layouts will need to provide the best efficiency in patient flows and avoid crowded spaces. This trend will mostly impact ambulatory care facilities like medical office buildings (MOBs). Higher patient demand will increase the number, size, and technological complexity of MOBs, supporting the important “ambulatory shift” that healthcare in the Southeast is experiencing for outpatient services.

Diagnostic machines are also increasingly – and rapidly – being integrated into operating rooms, and hybrid operating rooms are paving the future of surgery in almost every medical field, including emergency medicine. In certain fields, the overall rate of hybrid surgical procedures increased from 6.1% to 32% in just 7 years (Fereydooni et al. 2020). Bigger room sizes, adequate structures to sustain heavier equipment, and the need for more electrical power all impact the design of the entire building.

1.1 PUBLIC HEALTH TRENDS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F2 The technologies diagnostics companies

introduce over the

5 years

Unlikely Somewhat Likely Highly Likely 0% 50% 100% Digital Twins 23% 56% 20% Quantum Computing 26% 49% 25% Virtual Reality 35% 56% 10% Nanotechnology 36% 48% 16% Blockchain-Like Technology 40% 49% 11% Artificial Intelligence 60% 37% Cloud Computing 64% 33% 4% 3% 6

expect to

next

(Deloitte 2022).

While specialized hospitals and outpatient facilities are seeing a remarkable increase in technology integration, a more holistic approach to patient care is humanizing the future of healthcare processes, services, and facilities. A consolidated example can be seen in the evolution of cancer care. Innovative cancer centers are increasingly modeled on the famous Maggie’s Centres in the United Kingdom. These independent facilities give respite and mental support to patients who are undergoing hard times while they fight the disease.

The positive results from this integrated approach to treatment are impacting other medical fields, recognizing that providing patients with a sense of identity, community, and tailored support can have a significant impact on improving their wellbeing.

F3 Centre For Cancer And Health, Copenhagen. This Cancer Centre is located within the city center, easily accessible by public transport and cycling paths. Its modern design of wood and glass encloses a central courtyard that protects the privacy of patients and caregivers, providing a connection with nature in a quiet and home-like atmosphere.

Design: NORD Architects | Photography: Bo Bolther & AdamMørk

1.1 PUBLIC HEALTH TRENDS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 7

Climate Change & Environmental Health

The environment in which we live is a fundamental determinant of health outcomes, and the impacts of climate change are increasingly impacting the lives of populations worldwide.

While solutions to slow and mitigate climate change will need to happen at the individual, regional, national, and international scales, healthcare systems also bear a responsibility to work towards innovative strategies that can reduce the impacts of climate change on the health of the population.

In fact, the scientific community has identified climate change as a significant environmental risk factor for chronic diseases. Rising temperatures, poor air quality, and extreme weather events such as hurricanes and floods represent important concerns for the human health of the US population, ranging from limitations in access to healthcare facilities to the rise of chronic diseases.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Southeastern US is particularly vulnerable to the health effects of climate change, including heat-related illnesses, respiratory disease, and vector-borne diseases (CDC 2021).

The impact of the natural and built environment on health, also called Environmental Health, is equally important in urban and rural settings. In cities, rising temperatures caused by the urban heat island effect can increase the vulnerability of older populations and exacerbate the effects of air pollutants and airborne allergens that greatly impact air quality. The American Lung Association reports that Georgia, Florida, and Tennessee experience some of the worst air quality in the country; contributing factors are traffic congestion, urban sprawl, and environmental degradation (The American Lung Association 2023). Particularly in bigger cities, climate change is therefore worsening respiratory disorders,

cardiovascular issues, and kidney diseases. In rural areas, outdoor workers in industries such as agriculture, fishing, and construction are particularly vulnerable to heat and cold wave threats.

Climate change is also having a significant impact on food and nutrition. Food insecurity increases in the wake of natural disasters, often causing rising food prices when crops fail. In such situations, people cope by turning to nutrient-poor, calorie-rich foods, with consequences ranging from micronutrient malnutrition to obesity, which is especially observed in the Southeastern population.

Finally, the impact of climate change on the mental health of the population is undeniable. Especially during heat waves,

adverse effects include a parallel increase in suicide rates, depression, and other episodes of mental illnesses, as well as increased hospitalization rates and the risk of negative outcomes for people with dementia.

Extreme weather events which have impacted the region in recent decades including hurricanes, tornadoes, extreme heat, and wildfires have highlighted the need for immediate emergency response and maintaining access to health services. Overwhelmed health systems and damaged infrastructures represent a threat to access to essential health services, especially for chronic patients, older adults, and pregnant women.

1.2 CLIMATE CHANGE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

8

F4 Impact of climate change on human health. From CDC.

Power of Design

Design can play a significant role in reducing the carbon footprint generated by the built environment: in fact, concrete, steel, and plastic production account for 31% of the total world emissions of CO2 (Gates, Bill 2021). A hospital’s life cycle is continuously impacted by evolutions in technology and medicine which require frequent space reorganizations, equipment updates, and expansions.

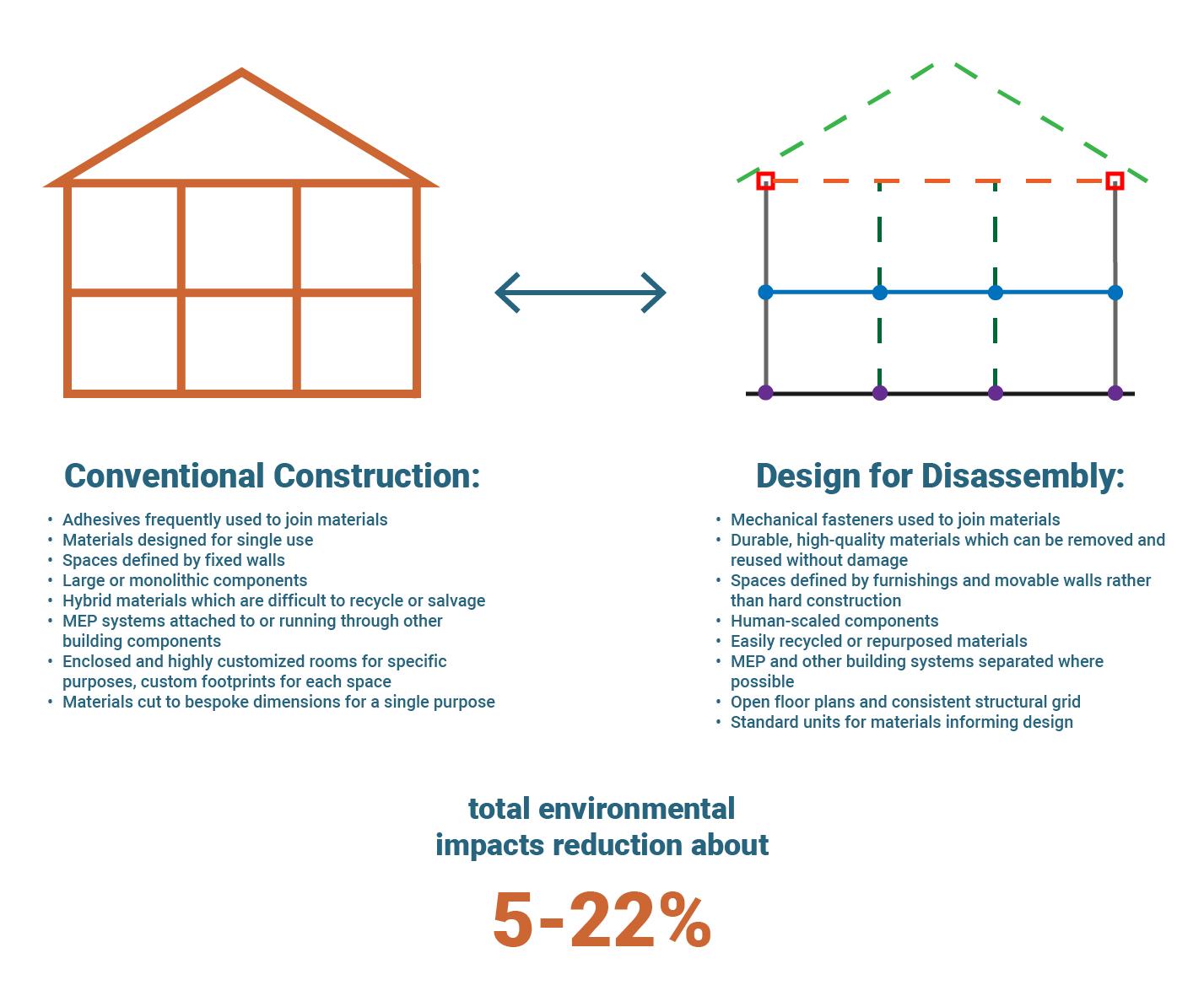

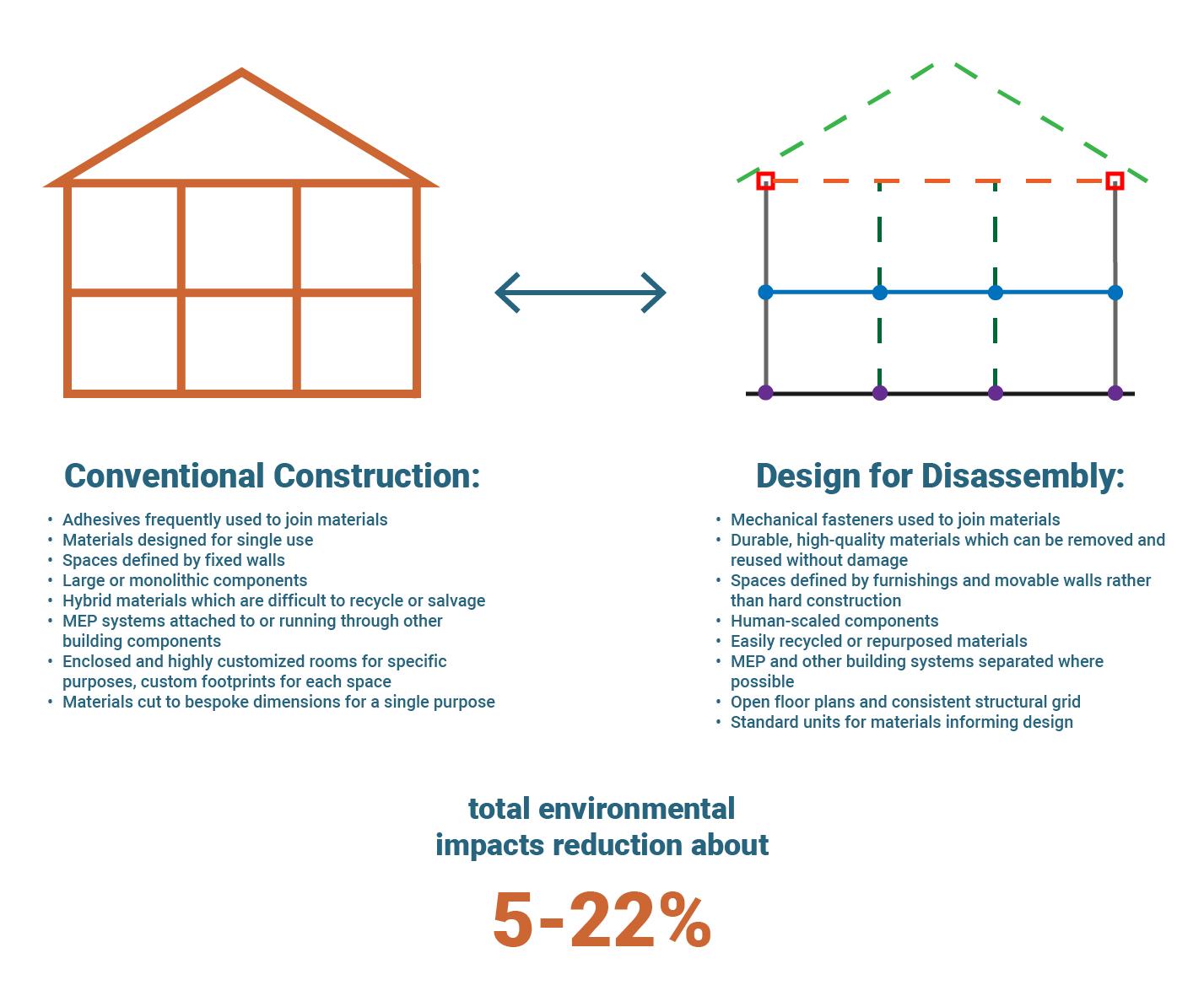

Changing space needs in healthcare facilities can create opportunities to reduce carbon emissions while designing for energy efficiency, improved function, and occupant health. Instead of demolition followed by another cycle of new construction, healthcare systems should explore alternative methods for meeting facilities needs over the life cycle of a building. Designing for easy deconstruction, using prefabricated and modular building components, and considering closed-loop cycles for materials and recovery can substantially reduce the environmental impacts of a building.

Strategies for ease of deconstruction include specifying mechanical fasteners instead of adhesives, and using demountable walls and furniture systems to divide spaces instead of built-ins and hard construction. Prefabricated components which are factory-assembled and installed onsite can reduce CO2 emissions up to 22% compared to a conventional building. If recycled steel components are used, the energy savings can be up to 81% (Aye et al. 2012).

A closed-loop process that repurposes existing reusable building components can reduce carbon impacts by up to 70% over new construction (Eckelman et al. 2018) At a time when reducing carbon emissions is imperative for global human health, these strategies will be critical in achieving carbon reduction goals.

These principles have been adopted in the design and construction of the Martini Hospital in Groningen, Netherlands, with plans for a second life for many of its components.

1.2 CLIMATE CHANGE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F5 Environmental impact reduction of buildings designed for disassembly compared to conventional construction. (From Caroli, Lavagna, e Campioli 2019)

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 9

F6 The Martini Hospital in Groningen, Netherlands, incorporates numerous industrial, flexible and demountable (IFD) building principles. The blocks which form the structure can be easily demounted for future expansions, renovations, and recycling of components, allowing for the highest flexibility possible and significantly reduced carbon impacts over the life cycle of the materials. Design: SEED Architects | Photography: Rob Hoekstra

While hospitals are called to reduce their environmental impact, they also need to increase their resilience to the consequences of climate change. Design can play a fundamental role in protecting key areas of hospitals (like EDs, ORs, or diagnostics) and help to minimize service interruptions during and after natural disasters.

A higher complexity of care also reflects the higher value of what’s inside the building: as the graph above shows, hospitals can have up to 92% of their value in non-structural elements and contents such as diagnostic equipment, specialized furniture, and medical supplies (The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 2012). It is therefore crucial to adopt design solutions to avoid or mitigate the risks of flooding, wind, and seismic damage. Strategies include selecting sites in areas of lower hydro-geological risk, elevating the building well above potential flood levels, incorporating dedicated

technologies such as anti-seismic devices in the building, and providing designated landscape or hardscape areas which are designed for water infiltration during high water events.

Healthcare facilities also need emergency spaces that can accommodate greater and more frequent peaks of ED access related to the health consequences of environmental factors and natural disasters, and which are able to bear emergencies without interrupting ordinary care services. Flexible spaces that rapidly increase the capacity of an ED are fundamental for lean and resilient healthcare facilities. The location of the ED within the facility is also crucial, as it should provide multiple safe access points for cars and ambulances during extreme weather events.

92% of construction value derives from nonstructural building elements

Contents

Non-structural elements

Structure

1.2 CLIMATE CHANGE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F7 Value breakdown of structural, non-structural, and content elements for three building typologies (FEMA E-74 Damage Breakdown).

10

Preparing for Emergencies

The global COVID emergency put healthcare systems under extreme pressure, exposing many vulnerabilities. As a globalized world faced an unexpected pandemic emergency that crossed geographical boundaries within a few days, healthcare facilities in the US also became a vector of the disease. Crosscontamination among patients and healthcare staff in overcrowded hospitals contributed to the exponential spread of the disease. A medical staff shortage increased the workload of nurses and MDs, leading to staff burnout and increased exposure to infection risk. Spaces to divide patients in the EDs and wards were lacking, as well as flexible settings able to accommodate intensive care patients while maintaining adequate levels of safety.

The pandemic not only had a tremendous direct impact on infection-related deaths in the population, but can also be seen as a major cause of non-direct public health issues related to interruptions of care access and delivery. Delayed cancer diagnoses and treatments during COVID will impact the outcomes of an estimated 38,000 patients in the next 10 years in the United States (Chen et al. 2021). Postpandemic studies have also estimated that 41% of US adults delayed or avoided medical care during the pandemic, and this phenomenon was significantly more common among vulnerable patients and their caregivers.

The mental health impacts of the pandemic cannot be denied: according to the CDC, the percentage of adults with symptoms of anxiety or depression increased from 36.4% to 41.5% between August 2020 and February 2021. An even more significant increase was measured among healthcare staff (Biber et al. 2022), increasing the risk of burnout.

During COVID, we learned that it is sometimes impossible to predict a health crisis or its trajectory. For this reason, we are called to anticipate possible scenarios based on our best available knowledge, and to integrate emergency preparedness and resilience into our communities, cities, and systems of the future, starting today.

1.9x

more common amongst individuals with 2+ medical conditions

2.9x

more common amongst caregivers

4 in 10

adults avoided medical care because of concerns related to COVID-19

1.3x more common amongst individuals with disabilities

1.3 PREPAREDNESS & RESILIENCE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F8 Reported delays in medical care during COVID and most impacted patients – US adult population (Czeisler et al. 2020). 4 in 10 adults reported avoiding medical care because of concerns related to COVID-19. Delaying or avoiding urgent or emergency care was more common among: caregivers of people with disabilities (2.9x), patients with two or more underlying medical conditions (1.9x), and persons with a disability (1.3x).

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 11

Rapid Discharge Activities

Capacity Expansion Activities

Power of Design

The role of healthcare design has been confirmed as crucial to support healthcare systems in their resilience to extreme events, from a pandemic to natural disasters.

The challenge for hospitals and clinics (as identified by the WHO) is to follow the same shift that we’re seeing in healthcare: we must not just be reactive to emergencies but must act proactively before they manifest. This proactive approach should be integrated not only at the macro and the micro scales of any building project, but also in the network that connects facilities.

The hub and spoke model has proved to be efficient in limiting infectious disease spread by concentrating higher complexity of care in the hub while providing capillary territorial care access with spokes placed in strategic geographical locations to serve the population (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2023). At the building level, a “satellite layout” can be seen as the evolution of the old pavilion typology, maintaining some strategic areas of the hospital still connected to the main

building, but also with the ability to run independently if a high risk of hospitalacquired (nosocomial) infections arises (Capolongo et al. 2020). Satellites may offer multiple independent access points for patients and staff, dedicated diagnostics (especially in the case of EDs), and also dedicated horizontal and vertical connections.

This resilient and flexible satellite layout can preserve ordinary hospital activities while allowing rapid expansion during emergencies. The New York City Department of Health and Hygiene (NYC Health) has created a Hospital Toolkit identifying three main healthcare response actions in a public health emergency. These actions were tested and confirmed during the COVID pandemic: 1) Emergency bed expansion requires expanded staffing, facilities, equipment, and supplies; 2) rapid discharge from hub to spokes is key to avoiding overcrowding, and 3) capacity expansion may require strategies utilizing both existing and temporary spaces.

In the wake of the intense COVID spread in northern Italy in early 2020, a study

conducted by Politecnico di Milano University (Capolongo et al. 2020) explored the most effective strategies for space flexibility used by multiple hospitals. Shell space – flexible, unfinished space which could quickly be adapted to expand ICU bed capacity or other uses within a few days – was found to be one of the most effective ways to meet evolving needs.

Buffer indoor spaces for programmed expansions, emergency expansions, or backup systems have also proved to be effective in reducing immediate consequences of hazardous events. These spaces can be easily reconfigured depending on patient needs, advances in care, and changing programs. A flexible and neutral platform with modular and open floor plans, prefabricated components, movable walls, and demountable systems support continuous changes in space use. These strategies form the basis of a “Process Neutral Approach” developed in a recent research conducted by MetroHealth’s Lean team, led by Walter B. Jones, to support the new Acute Care Hospital campus in Cleveland, Ohio.

1.3 PREPAREDNESS & RESILIENCE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

Facilities, Equipment & Supply Expansion

Bed Expansion

Staffing Expansion Bed Management

F9 The three pillars of the Bed Surge Capacity Expansion Tool to guide hospitals in health emergencies response (NYC Health 2013).

»

»

»

12

Sometimes the need to respond to a public health emergency occurs far from an established medical facility. Where rapidresponse temporary facilities are needed, designers can apply their expertise to mobile structures such as modular tents tailored to healthcare uses. Following a collaborative and intensive COVID hospital design process, the WHO began working on prototype emergency treatment modules that can be quickly delivered to a site by truck and assembled rapidly by a local team, like satellites of existing facilities. The separation of patients, staff flow, and working spaces reduces contamination while enabling continuous monitoring of patients and interventions on them from behind a transparent wall. The flexibility of the modular design, together with easy transportability, could represent a strategic, itinerant tool for healthcare groups to deploy rapidly in place for disease outbreaks and other emergent situations.

Design: Sharon Architects- Arad Sharon, Sharon Gur-Zeev L.T.D. | Photography: Bea Bar Kallos

for human contact between patients and their families. Following human-centered design principles, dedicated external access allows families to visit patients using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) while keeping healthcare and visitor flows separate. Dedicated restrooms for patients have a separate plumbing system to treat hazardous waste.

1.3 PREPAREDNESS & RESILIENCE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F10 During the peak of the COVID pandemic, the Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa, Israel used an underground parking lot as an overflow emergency hospital. The structure is equipped with capillary electrical and gas systems for medical use during emergencies. This strategy could be applied to auditoriums, offices, dining halls, and other flexible spaces that could accommodate patients during a widespread public health emergency.

F11 LS3P’s Healthcare Practice Leader Willy Schlein, as a volunteer with the International Federation of Healthcare Engineers (IFHE), participated in the prototyping process of the WHO reusable Infectious Disease Treatment Module (IDTM), conceived through a Design Thinking approach. Green zones for staff allow safe, continuous monitoring of infected patients with intensive care needs, providing physical access to the patient through a transparent wall with vacuum-like gloves. The design also creates opportunities

FAMILY PORCH FAMILY PORCH

TRANSPARENT SCREEN TRANSPARENT

WASHROOM

SCREEN

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 13

WASHROOM

TL;DR Chapter 1

People are living longer. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are now the leading cause of death and a significant driver of healthcare costs in the US. Vulnerable populations are at a higher risk for NCDs due to Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), and our biggest opportunity is now in addressing health challenges introduced by longevity.

» A higher volume of screening and diagnostic procedures will require evolving building layouts for more efficient patient throughput.

» The “ambulatory shift” towards more outpatient diagnostic and treatment procedures will require increasingly complex medical office buildings (MOBs).

» More hybrid procedures involving diagnostic equipment in the operating room (OR) will require changes in OR room size and structural/electrical capacity.

» A more holistic approach to patient care is humanizing the future of healthcare processes, services, and facilities, like Maggie Centers have done in cancer care.

Our changing climate is having real and immediate health impacts in the Southeast. Increasing heat, poor air quality, severe weather events, and food insecurity disproportionately affect vulnerable populations and are detrimental to physical and mental health.

» Construction and renovation of healthcare facilities creates opportunities – and a responsibility – for healthcare systems to reduce carbon emissions, design for energy efficiency, and support occupant health.

» Buildings should be designed with the life cycle of the facility in mind including ease of deconstruction, prefabricated and modular building components, and flexibility for evolving uses.

» Resilient design is increasingly important in a changing world. Healthcare facilities must be designed to withstand and recover from natural disasters, minimize service disruptions, safeguard highly technical equipment, and accommodate surges in emergency department demand.

Lessons from COVID-19 can prepare us for future emergencies. The pandemic revealed vulnerabilities in the healthcare system including cross-contamination among patients and staff in an airborne disease outbreak, the need for greater flexibility in healthcare facilities, and a crisis in medical staffing and burnout.

» A “hub and spoke” model and “satellites” layout are helpful in a variety of scenarios, including limiting infectious disease spread and providing care for multiple acuity levels.

» A “Process Neutral Approach” can support a more resilient healthcare design to enable space reconfiguration depending on patient needs, advances in care, and changing programs.

» Rapidly deployable spaces with the infrastructure for emergency expansion as medical units can allow healthcare systems and communities to pivot and provide services during a disaster.

14

02

Multiple Communities

How age and geography define different communities and their needs.

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 15

Two Growing Populations

The southeastern US is home to approximately 68 million people, making it the third-most populous region in the country.

This region is experiencing rapid growth, with a population increase of over 20% in the past two decades, and the region is projected to continue to grow. This growth is driven by both natural increases (births minus deaths) and migration from other parts of the country.

Two rapidly expanding populations are defining the landscape of healthcare in the Southeast: older adults and young families. As the region experiences significant demographic shifts, understanding the health implications for these distinct groups is essential for improving healthcare systems in these states.

The first group, older adults, represents a significant portion of the population in the Southeast. The growth in this population is due not only to the aging of local residents, but also to the region’s popularity among retirees from other parts of the US. By 2030, estimates are that one in five residents of the Southeast will be aged 65 or older.

Older adults tend to have more chronic health conditions than younger individuals and the two populations need different volumes and typologies of healthcare services. These divergent needs can place a strain on the healthcare system. Additionally, the increasing number of older adults requires an expansion of social services to meet their needs, such as housing, transportation, and home care services.

The second group, young families, represents another expanding demographic in the Southeast. Economic growth in the region, employment opportunities from big corporations moving to the region, diverse geography, and prestigious universities attract young professionals to the area.

An example of this trend is seen in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, where the median age (35.6) is lower than the median age for both NC (39.2) and the US (38.9). Nevertheless, even in this exceptionally young county, trends of an increasing older population are visible: according to the US Census 2022 data, the population of residents over 50 years old increased to 30% in 2022, compared to 25% in 2010, and residents in the 60-80 age group doubled (US Census Bureau 2023).

North Carolina is also experiencing a decline in fertility rates in both rural and urban settings (Center for Women’s Health Research (CWHR) at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine 2022). Healthcare programs must take a comprehensive approach to supporting the wellbeing of mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum as well as supporting the ongoing heath requirements of children and teenagers.

Younger adults are also the principal consumers of technology services that innovate and simplify every process: online shopping, home delivery, real-time services, reduction of waiting times, online reviews, and videocalls are examples of well-established habits that patients are also looking for in healthcare. These trends represent a tremendous opportunity for stakeholders in the healthcare industry to develop and boost the adoption of telehealth, retail health, and home care.

2.1 TWO GROWING POPULATIONS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

16

F12 The 4Ms framework that defines the main needs of older adults, compared to the four main health needs for young families. Modified from the John Hartford Foundation, IHI, AHA, and CHA (The John A. Hartford Foundation; Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI); American Hospital Association (AHA); Catholic Health Association of the United States (CHA), s.d.).

Older Adults

What Matters

Align care with each adult’s specific health goals and preferences across various healthcare settings

Mentation

Prevent, identify, treat, and manage dementia, depression, and delirium across healthcare settings

Medication

Use age-friendly medication that does not interfere with goals, mobility, or cognitive abilities across healthcare settings

Mobility

Ensure older adults can move safely every day in oder to maintain function and achieve health goals

Young Families

Maternal & Child Health

Ensure a flow of information and simplified access to healthcare for women before and during pregnancy, favoring perinatal care regardless of socioeconomic status or location

Education & Prevention

Provide effective tools to elevate the health literacy of young adults and children, emphasizing the importance of prevention and creating a network that includes healthcare providers, workplaces, and schools

Behavioral & Neurodevelopmental Health

Support healthcare providers, caregivers, and teachers in the early detection of behavioral and neurodevelopmental diseases of both parents and children to offer support and solutions for early access treatments

What Matters

Know and align care with each family member’s health needs and relationships to increase adherence, prevention, and healthy psycho-physical development of parents and children

2.1 TWO GROWING POPULATIONS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 17

Power of Design

For decades, solutions for accommodating senior citizens who need different levels of assistance have been limited. As an attractive option, community housing can create entire neighborhoods specifically tailored to the needs of senior citizens. These neighborhoods promote social interaction, encourage active aging, and support people in daily activities and care, integrating the concepts of “aging in place.”

Specialized senior living facilities can now integrate evidence-based design principles to improve the wellbeing of patients, such as in “dementia villages” designed to provide safe, welcoming places for people with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Recent estimates suggest that the prevalence of dementia will double in the next two decades, and the need for caring environments for this population will continue to grow.

To maintain connections between aging residents and the wider community, senior living solutions should ideally be integrated within the surrounding community and share a variety of amenities and services such as fitness options, healthy food, and transportation. The urban integration of senior living facilities is an important opportunity to build multi-generational societies that can transition between different typologies of independent living as people age, from age-restricted communities to multi-age, mixed occupancy communities.

While the cost of land for new construction can be cost-prohibitive for new developments, adaptive reuse of existing buildings can help with both financial and social sustainability for senior living facilities. Adaptive reuse may reduce construction costs and allow owners to invest more capital on modern amenities, sustainability, and environmental controls, while providing proximity to urban settings with well-developed transportation networks.

Technology will also be an important element in the design of facilities for aging populations. High technology integration and related infrastructure are key to power domotics (smart home systems), personal remote connections, continuous learning, and remote working for users of any age.

The broader adoption of telehealth, reliable and secure remote monitoring of patients via the “Internet of Things” (IOT), and the growing concept of “Hospital at Home” will reduce the needs for the displacement of older patients to healthcare facilities. At the same time, however, new spaces and staff will be needed to support remote care integration into a coordinated network of medical and social assistance.

Technology for remote healthcare services will also benefit the growing population of young families in the Southeast. Smarter facilities will be able to provide both in-person and remote services focusing on maternal and child health. Technology integration in the healthcare process should also target developmental and mental health disorders that are

increasingly prevalent among the pediatric population such as obesity or autism. The design of these facilities should support the diagnosis and therapy processes to improve the patient journey and reduce the barriers to treatment posed by the design of traditional outpatient clinics.

2.1 TWO GROWING POPULATIONS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

A

5.2

and

(Estimation

and

2019 5.2 2050 10.5 18

F13

recent study published in The Lancet Journal in 2022 estimates that the number of people in the US with dementia in 2019 is more than

million,

is expected to double before 2050 to 10.5 million, with women at higher risk

of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019

Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. 2022).

THE GIESSEREI COMPLEX

The Giesserei complex in Oberwinterthur, Switzerland combines participatory housing structures with ecological living in timber constructions. In addition, a smart metering system shows the residents their hot and cold water and heat consumption. Overall, numerous details ensure an engaging and lively residential structure. The modular system allows a variety of different unit layouts and sizes, so that one-room apartments could be created in addition to cluster apartments with 10 rooms. The modular system also allows for adaptation to changing housing needs. A decentralized nursing care group ensures medical assistance for the occupants. On the long sides of the building, the total of 155 flats can be reached via loggias which invite people to socialize. In addition, the lively ground floor area with restaurant, bicycle shop, workshops, community room, laundry, clinics, and much more offers space for encounters. The neighborhood is self-managed and organized by an association and various working groups. An interactive website enables additional contacts and uncomplicated customer service.

F14 A once-abandoned industrial site has been revitalized into a thriving community of Bijgaardehof in Ghent, Belgium, featuring co-housing groups and a community health center. The renovation utilized materials salvaged from the original factory building, and the community is powered by local geothermal energy for heating, with passive cooling methods in place for the summer months.

Design: &bogdan | Photography: Laurian Ghinitoiu

F15 The Giesserei complex in Oberwinterthur, Switzerland, combines multigenerational, participatory housing structures with ecological living in timber constructions. The modular system allows a variety of different unit layouts and sizes, so that one-room apartments could be created in addition to cluster apartments with 10 rooms, also allowing for adaptation to changing housing needs. A decentralized nursing care group ensures medical assistance for the occupants. In addition, the lively ground floor area with restaurant, bicycle shop, workshops, community room, laundry, clinics, and much more offers space for encounters.

Design: Galli Rudolf Architekten | Photography: Ralph Feiner, Malans

2.1 TWO GROWING POPULATIONS THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F14 F15 The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 19

Urbanization in the Southeast

Urbanization is another growing phenomenon in the US and the Southeast. Major cities are growing fast, attracting people from smaller towns and rural areas and other geographic regions. Data shows that around 84% of the total US population is now living in urban areas, and the growing trend is expected to reach 89% in 2045 (UN DESA 2018).

Despite the attractive economic opportunities that bigger cities can offer, urbanization has repeatedly been associated with undesirable health effects among specific populations, such as minority and economically vulnerable residents with low incomes. A low income normally determines the urban area where people can afford to live, and housing choices can impact everything from indoor air quality to educational opportunities to social inclusion to healthcare access - all of which have been recognized among the SDOH (WHO 2003).

Rapid growth is also a major contributor to gentrification. Recent investigations from the American Community Survey (ACS) show that gentrification primarily occurs in major cities boasting thriving economies,

but it also manifests in smaller cities and particularly affects neighborhoods near central business districts that offer abundant amenities (Jason Richardson, Bruce Mitchell, e.g. Juan Franco 2019). Gentrification can drive up prices in established neighborhoods, make it increasingly difficult for residents to find affordable housing, and disrupt social support systems.

Many studies from the last decade have shown how life expectancy varies depending on the zip codes and neighborhoods within a city (Arias et al. 2018), with a linear decrease from wealthy downtowns to rural areas with fewer resources. Populations living in less affluent contexts are, therefore, more exposed to health disparities, with a gap that increases in cities that are experiencing rapid economic growth (for example, Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill, NC, which form the prosperous Research Triangle).

Other areas of the US such as the San Francisco Bay area have also faced the complex problem of economic and health disparities as a consequence of rapid

economic development. Recent events have shown that populations living in urban settings with a higher cost of living are particularly vulnerable to the economic burdens of health emergencies; for example, the cities of Oakland, Seattle, and Phoenix experienced a significant increase in homeless populations between 2020 and 2022 (The US Department of Housing and Urban Development 2022). during the COVID crisis. These experiences are key to informing healthcare providers, planners, and designers about risks and opportunities that urban areas will deal with in the near future, highlighting the need to pair the growth of urban economies with the growth of healthcare and social safety networks to protect vulnerable populations.

In the city center, functionally integrated facilities should be available to provide an advanced level of health services including primary care, prevention, and health promotion services on a neighborhood scale. Telehealth and mobile health will also be relevant tools to promote equitable access to healthcare, especially for individuals with limited resources.

F16

2.2 URBANIZATION THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

Life expectancy at birth for North Carolina, differences between counties. While coastal and urban areas reflect a higher life expectancy, the population living in rural areas more frequently faces lower life expectancy ranges. (CDC 2023).

- 75.1 Life Expectancy (in Quintiles) 75.2 - 77.5 77.6 -79.5 79.6 - 81.6 81.7 - 97.5

56.9

20

Power of Design

As previously introduced, the hub and spoke model has proved to be effective in managing different levels of care and ensuring healthcare access in urban settings. Multi-specialty and primary care hubs providing advanced levels of health services, including primary care, can be strategically located in city areas that are easy to reach, serving as reference points for prevention and health promotion services. Hubs should be central to the spoke facilities, which can cover primary care needs, lower complexity health services, and social services for urban and suburban neighbors. The hub and spoke model could be equally effective in rural areas to decrease travel distance to healthcare options for lower acuity services or in urban areas to provide better access and build trust between patients and providers at the neighborhood level.

Design: RSHP | Photography: Morley von Sternberg

2.2 URBANIZATION THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F17 The Cancer Centre at Guy’s Hospital, in the London city center, features a thoughtfully designed layout with organizes services into four interconnected “villages” fostering a human-centric atmosphere that is both uplifting and devoid of institutional sterility for patients. These distinct blocks encompass a welcoming area, radiotherapy, chemotherapy services, respite spaces for patients and caregivers, and an outpatient unit, all at a smaller and more human scale than a traditional facility.

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 21

Urban areas have witnessed a rapid expansion of the urgent care model for lower-complexity healthcare needs. A typical urgent care visit costs 10 times less, on average, than a trip to the ED, with significantly shorter wait times. However, though the urgent care model may reduce unnecessary ED visits with higher initial costs, a recent Harvard study found that reliance on urgent care centers ultimately results in a 6-fold increase in urgent care center costs and out-of-pocket expenses (Wang, Mehrotra, e Friedman 2021) due to the need for multiple visits. It’s worth noting that urgent care facilities are often run by Physician Assistants (PAs) or Nurse Practitioners (NPs), while the presence of MDs in urgent care facilities has decreased, on average, from 70% to 16% since the first urgent care facilities opened in 2009.

Urgent care facilities are typically located near wealthier communities and urban areas, and are less represented in rural areas. These facilities primarily serve insured patients, and do not often accept Medicaid. Due to the geographical and

economic challenges, reliance on urgent care is not a viable option for underserved populations. Urban residents are often forced to choose between insufficient alternatives to the challenges of healthcare access.

Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) models are also strongly contributing to addressing the care needs of underserved and uninsured populations at a local and regional level. The adoption of temporary clinics that occupy spaces like firehouses, pharmacies, or offices for a few hours per week requires maximum flexibility of rooms and equipment to rapidly transform these settings. Similarly, mobile health solutions with medically equipped trucks are effective in bringing healthcare to underserved neighbors, where health disparities are greater. These new models also reshape the design of brick-and-mortar facilities, where dedicated spaces to park, sanitize, equip, and refurbish mobile health trucks are needed.

Design plays a key role in enabling facilities to increase access to care. Especially in urban settings, extended working hours and longer transportation times are significant barriers that prevent patients from seeing a doctor, getting lab tests, or attending a radiodiagnostic appointment during the day. Many healthcare providers (including urgent care centers) are now offering selected healthcare services afterhours, and the cost effectiveness of these services should be supported by online admission processes, better efficiency for reduced waiting times, and facilities that are designed to run with a reduced staff presence.

Finally, the increase in the adoption of remote work has opened up an important opportunity to accommodate other personal needs in between working hours, including healthcare appointments. Healthcare design should accommodate patients and caregivers who might need to work during waiting times by integrating solutions from office design into common spaces and waiting areas.

Around

2.2 URBANIZATION THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

80% of the US population is within a 10-minute drive of an urgent care center. 80 75 75% of Communities with urgent care centers are in urban areas (Le e Hsia 2016) 60 Urgent Care centers Patient volume has jumped 60% 2019-2022 55 A shortage of up to 55,000 primary care physicians is expected by 2033 in the US (Association of American Medical Colleges 2020) 22 F18 Meaningful numbers depicting the primary care physicians shortage and urgent care market phenomena in the US.

Rural Communities

Rural communities grapple with a range of complex issues that significantly impact their overall health and wellbeing. A socioeconomic gap can be found between urban vs. rural settings, and also between wealthy coastal cities with robust tourist economies and under resourced areas further inland. Understanding these challenges is critical for devising effective healthcare strategies tailored to the unique needs of these populations.

One of the primary health challenges for many rural communities is the limited access to nutritious and healthy food options. Healthy dietary choices are harder to pursue because of longer travel distances to a full-service grocery store and reduced buying power compared to populations living in urban settings. When the closest food options are convenience stores or fast-food restaurants, fresh produce and affordable, nutritious options are more difficult to acquire. Longer travel distances also contribute to vehicledependent lifestyles and less walkable neighborhoods, increasing sedentary behaviors.

Limited access to healthcare is another major contributing factor to poorer health outcomes in rural areas of the US. Rural areas typically have fewer healthcare facilities and medical professionals compared to urban areas, which can make it more difficult for individuals to access medical care when they need it. According to the UNC Center for Health Services Research, over 80 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, leaving many rural communities without access to essential healthcare services (UNC - The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research 2023). This can lead to longer wait times for appointments, fewer options for specialized care, and a greater reliance on emergency medical services for routine healthcare needs. Long travel distances can also hinder timely access to healthcare, and reimbursement barriers for lowerincome individuals (such as providers who do not accept Medicaid patients) further limit access to care.

One of the main reasons for the limited access to healthcare in rural areas is the shortage of healthcare providers,

particularly physicians and specialists, who often experience higher rates of stress and burnout due to the high workload, long travel distances, and the emotional loads they bear without the support of a larger healthcare team. Telemedicine and mobile health are fundamental tools to help bridge these disparities and provide rural populations with essential medical attention when needed. Nevertheless, a broader diffusion of telehealth in rural areas will necessitate an adequate upgrade of broadband and internet infrastructures, which are often lacking in rural spaces.

Addressing the major health challenges faced by rural communities in the Southeast demands a comprehensive approach that involves collaboration between healthcare providers, policymakers, and community stakeholders. By recognizing and responding to the unique needs of rural populations, healthcare providers and designers in the Southeast can strive towards greater inclusivity, accessibility, and improved health outcomes for all residents.

2.3 RURAL COMMUNITIES THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 23 1-25 26-50 51-75 76-100 1-12 13-23 24-35 36-46 1-40 41-80 81-119 120-159 1-17 18-34 35-50 51-67 Nort h Carolina South Carolina Georgia Florida

F19 Number of deleterious health factors by county, including unhealthy behaviors, limited access to insurance, limited access to care, adverse socioeconomic factors, and environmental threats. A higher number of harmful health factors is documented for inhabitants of rural areas compared to urban areas and coastal areas (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, s.d.)

Power of Design

Given the challenge of access to care in rural areas, the localization of clinics is a crucial element that design and urban planning can help address. Clinics and hospitals should be strategically located depending on the actual and future infrastructure that will allow them to be easily reached. Such buildings should also be included in a synergistic network of mobile health and telehealth solutions, based on the needs of the communities, in order to “meet people where they are.”

To improve healthcare access, the ideal distance to a healthcare facility should account for both mileage and time.

A successful point-of-care access must provide convenient opening hours based on travel distances from where patients live and work. Similarly, tailored primary care solutions should be designed for large populations of workers in the farming, fishing, and mining sectors living in rural areas, which are often the most vulnerable populations. Difficulty in accessing primary care and outpatient care can push patients to wait longer to address their healthcare problems. Delaying care might mean that patients eventually require hospitalization to address their care needs, with negative impacts on both health outcomes and life expectancy.

F20 Preventable hospital stays that might have been avoided by outpatient treatment, differences between counties. Darker colors indicate a higher number of preventable hospital stays out of the total registered, index of a worse performance of the healthcare ecosystem. Similar to previous data showing geographical differences, rural areas experience more preventable hospital stays compared to urban areas and coastal areas (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, s.d.)

2.3 RURAL COMMUNITIES THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

24

Less Preventable Hospital Stays

More Preventable Hospital Stays

The shortage of healthcare staff is another crucial challenge that design can help tackle.

Advanced practice nurses and resident MDs are becoming increasingly involved in rural healthcare, and are specifically trained from the early stages of their careers. Evidence-based design studies can inform the organization of rural clinics, helping to prevent staff burnout and increase the attractiveness of rural working settings for young professionals. These providers also tend to be more familiar with technologies that telehealth brings into the practice.

Lastly, rural hospitals and clinics must transform their identities to become physical reference points for health education and social support. By closely partnering with non-profit organizations in mitigating the effects of the SDOH that impact these communities, rural hospitals and clinics can be key players in building an integrated care ecosystem.

A prime example of integrated care encourages a proactive approach to

nutrition and wellness. Healthy diet education programs and healthy food access can be key elements in creating a stronger trust between hospitals and rural communities, which is fundamental to lowering the barriers to healthcare access.

ECU Health Beaufort Hospital in rural North Carolina is a successful example, where a community garden that models healthy habits that promote well-being has been the starting point to involve the community in educational programs

The Harvard School of Public health identifies dietary education provided by hospitals and clinics as one of the most powerful tools to reduce childhood obesity (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, s.d.). Healthcare facilities are also one of the earliest sources of maternal and child nutrition education, starting from their very first days of life with breastfeeding awareness. A recent CDC survey found that newborns living in the Southeast are less likely to be breastfed at 6 months than infants living in other areas of the US, and infants in rural areas are less likely to ever breastfeed than infants living in urban

areas (CDC 2022). Access to qualified health education can help overcome some of the most significant reasons women stop breastfeeding earlier than desired; strategies include lactation training, neonatal nutrition support, and medication management (Odom et al. 2013).

Supporting young families with vital health information offers a powerful opportunity to create positive health impacts at the individual, family, and community levels.

The Southeast is witnessing promising signals for an evolution of rural healthcare. Many rural hospitals have recently integrated with larger healthcare groups, bringing the promise of more efficient management while preserving the identity of these local facilities for the community. A renewed and greater focus on addressing the SDOH through prevention can reduce the need for costly acute and chronic access to care, which is one of the main reasons behind the deterioration of the network of care in rural areas.

2.3 RURAL COMMUNITIES THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 25

F21 ECU Health Beaufort Hospital in Washington, NC serves as a reference point for prevention, health education, and community engagement in addition to being a trusted point of care for this rural community. A new community garden and outdoor classroom are often the first point of contact between residents and ECU Health. Photography: ECU Health

TL;DR Chapter 2

The demographics of the Southeast are changing. The region as a whole is experiencing rapid growth, with older adults and young families comprising a large share of the growth. Healthcare systems will need to address the unique needs of these expanding populations to have the greatest impact.

» Integrated, thoughtfully designed communities for older adults can fill a critical need for healthcare access across the continuum of care, and foster the growth of multigenerational neighborhoods that respond to housing and services needs for all ages.

» Adaptive reuse may provide exciting opportunities to maximize land and facilities investments and provide connectivity and access to local amenities.

» Expanding telehealth options can provide better access to care for older adults, young families, rural patients, and others who benefit from the convenience and expanded care options. Upgrades to broadband infrastructure in rural areas will be critical for equitable access.

The Southeastern population is becoming more urban. Urbanization brings both benefits and challenges; a limited supply of affordable housing in urban areas creates ripple effects within the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) which can affect both health outcomes and healthcare access.

» Hub and spoke models can provide better healthcare access at the neighborhood level. Urgent care facilities dispersed in strategic locations can serve as a more economical and accessible alternative to help reduce unnecessary trips to the emergency department, but often remain unviable as a point-of-care access

» Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) can be an effective strategy to meet underserved populations where they are, and can provide flexible healthcare delivery options outside of traditional brick-and-mortar facilities.

» Healthcare providers are addressing the lifestyle needs of their patients through afterhours options, streamlined admissions procedures, and workspaces integrated into waiting rooms.

Rural communities have unique health needs. Greater travel distances, fewer healthy food options, vehicle-dependent lifestyles, hospital closures, and a healthcare provider shortage create challenges to optimal health outcomes.

» Healthcare facilities must provide better access to care through a strategic network of facilities accounting for mileage (distance to the facility), time (convenient opening hours), and community needs (such as large populations working in farming, fishing, or mining).

» Evidence-based design can guide better work settings, including the integration of telehealth options, to retain healthcare professionals specializing in rural populations and reduce the shortage of qualified providers.

» Integrated care for rural patients may include health and lifestyle education projects as a first or ongoing point of contact for patient engagement in public health and health prevention interventions.

2.3 RURAL COMMUNITIES THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

26

A

03

Whole Individual

human-centered, holistic approach to the health of every individual.

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 27

Evolution of Acute, Chronic & Long-Term Care

As individuals, we’re evolving our relationship with technologies that can be easily tailored to each user: we wear them, talk to them, communicate through them, and benefit from services that respond to our needs in any field. Healthcare providers are taking advantage of the same innovations, pushing the boundaries of telehealth further for broader and easier access to primary care, follow-ups, health monitoring, and prevention thanks to an integrated network of digital services.

Prevention and early diagnosis are increasingly benefiting from the use of complex diagnostic machines like PET and MRI systems, thanks to the fast pace of their technological evolution. The reduction in costs and acquisition time, the increase in precision, the minimal need for doses of radiation, and the match between radiodiagnostics and genomics information are opening the doors to a new concept of prevention.

Discoveries in medicine and biology such as in the “-omics” fields (e.g., genomics, proteomics, etc.) have embraced computing power, allowing the investigation of single molecules of a patient to understand the root causes of diseases and fine-tune prevention plans.

Such data, paired with powerful diagnostic machines and biological engineering techniques, are driving the revolution of treatments for millions of patients where precision medicine can overtake the onesize-fits-all approach.

As an example, the new era of biological therapies like immunotherapies is revolutionizing cancer treatment, already reducing the need for surgical interventions and long hospital stays for surgery recovery for some patients (Cercek et al. 2022). The promising evolution of immunotherapy suggests that, in the near future, many treatments will be tailored to every single patient to improve health outcomes and survival rates in the field of oncology and beyond.

Due to these evolutions in healthcare and the demographic trends discussed in Chapter 1, the number of chronic patients is likely to increase. The growth of this patient population will require increased efforts in chronic and long-term care management programs, whose economic and social sustainability will be made possible by solutions that are not hospital-based.

Recent studies by Kaiser Permanente and Mayo Clinic estimate that 30% of patients currently admitted to hospitals could be treated at home (Mayo Clinic News Network 2021), and healthcare groups globally are investing billions into the evolution of “hospital at home” models for chronic and long-term care needs of populations of every socioeconomic status.

Between November 2020 and September 2022, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) granted approval to 114 healthcare systems and 256 hospitals spanning 37 states to offer acute hospital care in home settings. The home healthcare industry is projected to increase its workforce by almost 30% from 2019 to 2029, including registered nurses, MDs, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and occupational therapist, and home care aides (Kacik e Devereaux 2022).

In fact, less invasive treatments and the ability to effectively monitor patients at home can shorten acute patients’ stay in hospitals and reduce hospitalization rates. This trend shifts the concept of general hospitals towards hub facilities that address medical emergencies and highintensity care, create networks of spoke facilities, and integrate deeply with virtual care.

This transformation of health systems towards a wider integration of capillary services places a higher importance on the homogeneity of quality of care delivered by hospital networks, which is often inconsistent across affiliated hospitals and clinics (Sheetz et al. 2019).

3.1 EVOLUTION OF CARE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

28

Reduced Admissions

36 fewer hospital episodes/100 people over 12 months via remote patient monitoring (RPM)

Australia Remote Dialysis Program

Acute Care Costs

Total costs of acute care episode + the 30 days after:

$17,937 Hospital at Home

$22,991 Inpatient

Mt. Sinai Study

HOSPITAL + VIRTUAL CARE

Reduced Falls

21% experienced falls in home group vs. 39% in conventional pathway

Telerehabilitation Program in Italy

Reduced Patient Suffering

18% of time spent lying down at home vs. 55% conventional

3 labs needed at home vs. 15 labs conventional

7% readmission rate for patients at home vs. 22% conventional

Acute Care US Study

3.1 EVOLUTION OF CARE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F22 An integration of virtual care and hospital care can improve patient health outcomes and recovery, reduce patient suffering, and reduce overall acute care costs. (Ernst&Young (EY) Global Health 2022).

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 29

Power of Design

Acute care hospitals in particular will have to react proactively to new exigencies like shorter recovery times, acuity adaptable patient rooms for optimal utilization, increased bedside diagnostic procedures, and dedicated space for caregivers.

Modular design is a key strategy for flexible adaptation of spaces over time: transforming patient rooms into outpatient areas, expanding diagnostic spaces, or installing new services within a few days without paralyzing a hospital wing with extensive renovation work is now a standard required by healthcare management.

The evolution of acute care hospitals is closely connected to the decentralization of healthcare, and also results in higher cost effectiveness. Lower-complexity facilities typically have lower construction and operating costs, and should be dedicated to hosting lower-intensity care like rehabilitation hospitals with post-acute patients who are recovering.

Lower-complexity buildings can optimize cost effectiveness and construction schedules through maximizing modular design and prefabrication: recent market data (Dodge Data & Analytics 2021) shows that 82% of healthcare facilities will use “a high frequency” of prefabrication and modular construction in the coming years.

As hospital stays shorten, the appropriate transfer of patients will be crucial to improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare costs. Designing the most effective patient journeys increases the inherent organizational complexity, and technology will be fundamental to supporting clinicians in the process. AI models that predict patient trajectories beginning with the earliest medical records and lab test results are already being developed (Allam et al. 2021). This technology optimizes the opportunity for shorter patient hospitalization times in acute care settings while also anticipating potential complications. The AI tools can also coordinate with predictive bed occupancy for hub and spoke facilities and assist with programming for flexible space use.

F23 The Rigshospitalet patient hotel in Copenhagen, Denmark. The hotel is part of the medical campus, serving the general hospital, the pediatric hospital, and the research campus across the street. Patients coming to the campus for assessment, therapies, and follow-ups that require multiple days can stay at the hotel, as well as families of inpatients. Based on availability, the room can also be used for short stays for visiting specialized healthcare staff and researchers. Wood finishings and private balconies provide visitors with a cozy feeling and a sense of privacy.

Design: 3XN

Photography: Adam Mørk

Complementing changes in the delivery of acute, chronic, and long-term care, increasing evolving hospital designs will provide better flexibility and support to patients and their families.

Additionally, hotels connected to numerous hospitals are already hosting patients and caregivers coming for periodic assessments. The success of this organizational and design model is bringing more frequent requests for the integration or expansion of hotels within medical campuses. This “patient hotel” model has already been broadly adopted in Europe, with these healthcare/hospitality facilities accommodating self-reliant patients undergoing hospital treatment, families, visiting medical specialists, or researchers for short stays in hotel-like rooms.

3.1 EVOLUTION OF CARE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

30

For patients who are able to receive care and support from their homes, healthcare design is also called to support telehealth integration for chronic care management by providing efficient physical spaces in existing clinics and hospitals. Practitioners will need specialized settings for safe, private video consultations and data exchange with patients. Patients, likewise, may need dedicated spaces for home health devices and may require tailored therapies to be prepared and delivered to the patient’s home.

One example is biologic therapies, which are influencing the design of cancer centers. For the immediate future, the administration of these therapies is likely to remain in medical facilities, requiring adequate settings. In the long run, however, the evolution of telehealth and the delivery of therapies could be served by medical drones that travel from a physical clinic to the patient’s home. These drones have the potential to safely deliver tailored therapies, reduce patients’ transportation time, and provide better access to healthcare services. These drones will require specialized support spaces for storage, programming, loading, charging, and maintenance.

Blood Units

Lab Test Samples

Medicines

Vaccines

Antibiotics

Antivenoms

Pathology Specimens

Human Organs

Automatic External Defibrillators (AEDs)

Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs)

Medical Waste

3.1 EVOLUTION OF CARE THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

F24 The UN reports that many types of medical supplies can be transported by drones in various settings, including those routinely used by UNICEF in support of their missions. Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Sustainable Development (United Nations 2023).

The Future of Healthcare in the Southeast 31 F24 F25

F25 Residential designs should be ready to support home healthcare needs.

The Central Role of Behavioral Health

Mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse disorders have become a pressing concern across the United States, with over 50 million American adults experiencing mental illness in a given year (National Institute of Mental Health 2023). The Southeast region is no exception, facing significant mental health challenges that warrant focused attention. The recent World Mental Health Report from the WHO has underlined the prevalence of anxiety disorders (31%) and depressive disorders (28.9%) in the population, exacerbated by the recent pandemic with a notable increase of 28% in depressive disorders and 26% in anxiety disorders. These disorders particularly impact females and younger age groups (Amerio et al. 2020) (Freeman 2022).

Higher rates of suicide and substance abuse in parts of the Southeast – areas that are most impacted by the opioid crisis and economic disparity – also remain a mental health concern (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2023), but these regions are actively

working to provide necessary resources for prevention and rehabilitation focusing on education, community support, and building a stronger safety network for mental illnesses. These emergencies also require a multilevel effort at the community scale to address mental health issues as early as possible. Early intervention can reduce stigma, increase the awareness of available tools (such as mental health hotlines), and provide police training in the management of mental health crises to avoid dangerous escalations.

Additionally, the emergence – and better understanding – of neurodevelopmental disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) poses further challenges in the field of mental health. ASD prevalence has surged by 241% since 2000, with recent CDC estimates indicating that approximately 1 in 36 children is on the spectrum (Maenner et al. 2023).

Healthcare services that promote early detection and diagnosis and provide parent support have proved to be fundamental

3.2 CENTRAL ROLE OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH THE FUTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN THE SOUTHEAST

32

F26 Sandhills Child & Adolescent Crisis Center in Greensboro, NC. Design: LS3P | Photography: Keith Isaacs

to reducing the burden of these diseases and ensuring the best health and social outcomes for neurodivergent individuals through their entire lifespan.

Thanks to a reduced stigma around diagnosis and treatment, the role of mental health in overall wellbeing is increasingly recognized at both the individual and community level. Innovative mental health solutions to improve public health are flourishing, especially those empowered by telehealth and digital therapies.

However, healthcare systems in the Southeast must still improve their capacity to address the wide range of mental health needs of the population, from outpatient services that can intercept early symptoms of mental diseases to inpatient beds for patients who need acute behavioral health care. Mental health inpatient beds are consistently lacking after years of disinvestment; as an example, North Carolina has approximately 22 psychiatric inpatient beds per 100,000 residents, but requires 30-60 beds per 100,000 residents to meet current needs (North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research 2012).