Fall Issue

Volume 1 CTLR Official Online Magazine Issue 1

October 20th & 21st

At the Farr Cross Ranch

9223 CR 314 Terrell, Texas 75161

We would like to invite you to join us for this fun and educational event. It is open to anyone who has an interest in Texas Longhorn cattle. You will gain valuable knowledge about the historic Texas Longhorn Breed, the CTLR and it’s conservation efforts. Since the formation of the CTLR in 1990 it has been dedicated to preserving the heritage genetics of the Texas Longhorn Breed.

Schedule of Activities

Friday October 20th Social Gathering

Join your fellow Longhorn enthusiast to talk about the cattle, the history & the future. At Farr Cross Ranch @ 5pm Ribeye Steak Dinners are $20 per person RSVP Required click the link in this email

Saturday October 21st Cow Camp Gathering

At James & Debby Farr’s Farr Cross Ranch Gates open at 8:30 am Actives start @9 am

Topics and Activities

Background about the Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry

Update on the new CTLR DNA test

How to register cattle with CTLR

How the required visual inspections are done

How to evaluate Texas Longhorn Cattle

How to pull the required DNA sample

Update on New Registry Database

Round Table Q&A with seminar presenters

Breakfast & Lunch will be available

Viewing of the Farr Herd

Door Prizes and much more

This event is open to anyone interested in Texas Longhorn Cattle.

Click Here RSVP or Email: russellh@longhornroundup.com Text or Call 409-381-0616

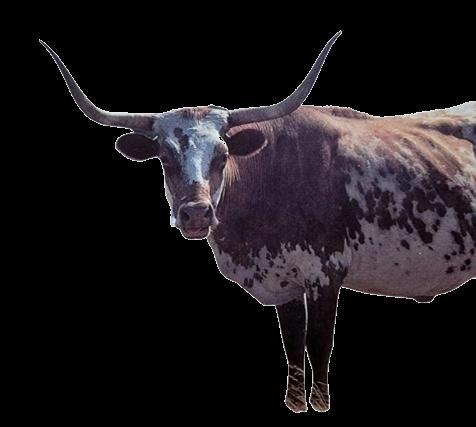

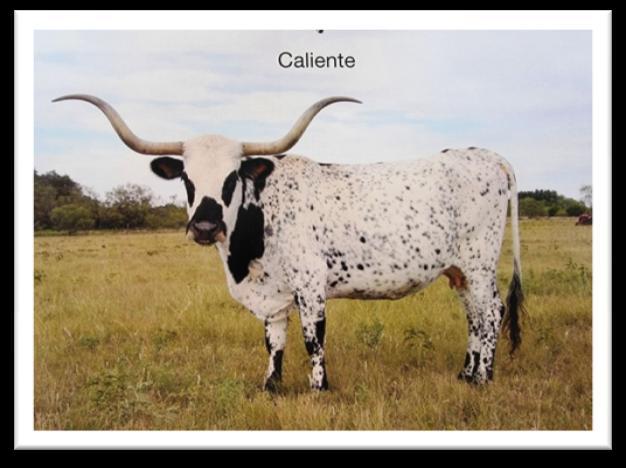

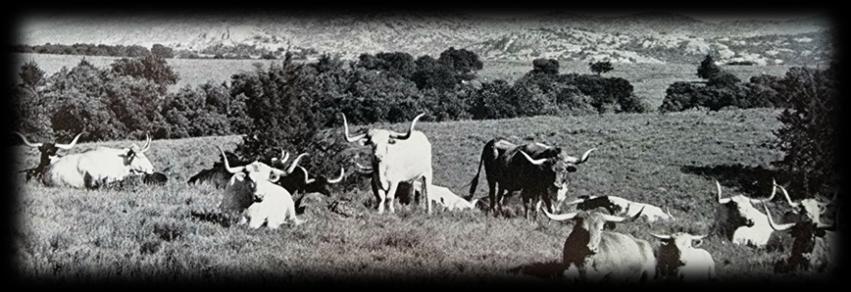

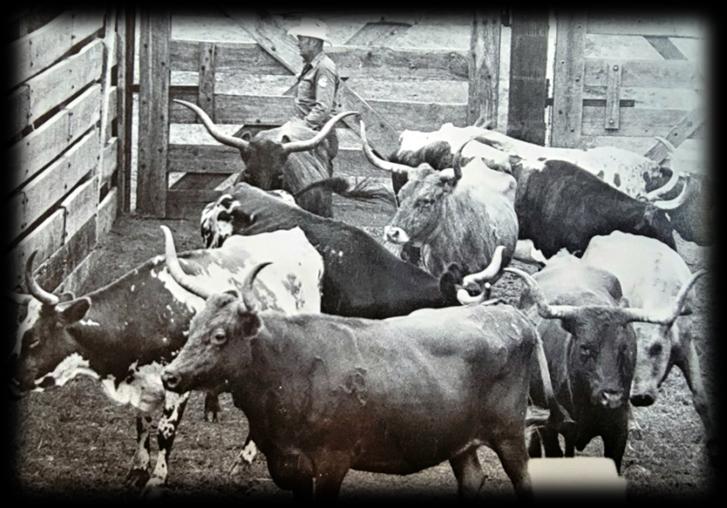

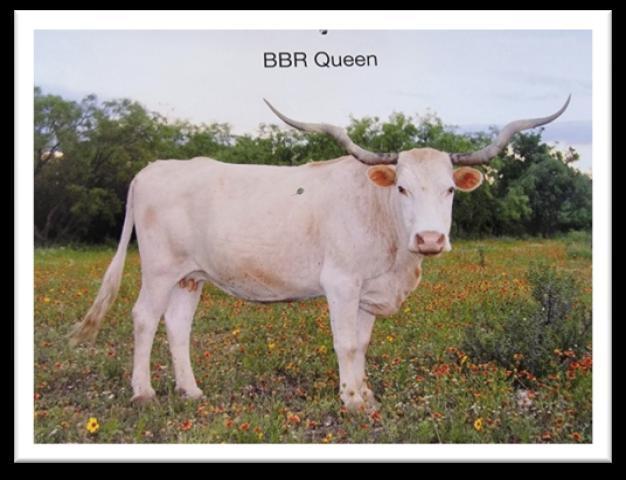

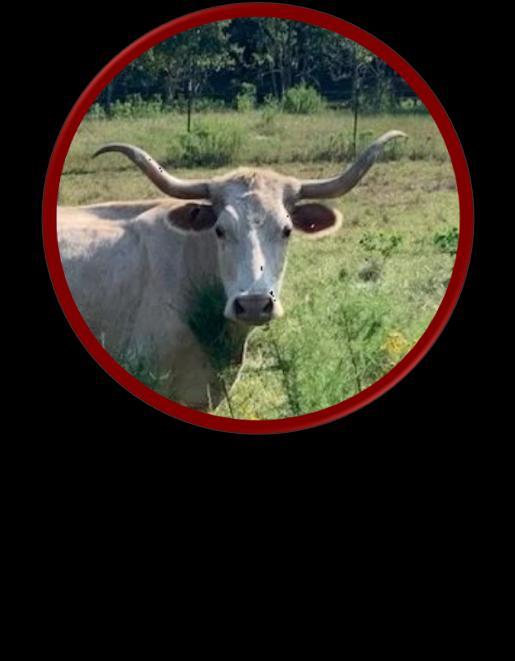

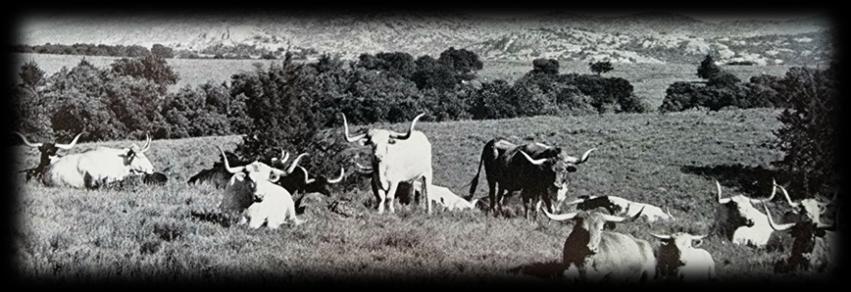

About the cover: CTLR Registered cattle at DWD Longhorns owned by Don & Debbie Davis.

Page 3 – Welcome to CTLR online magazine

Page 4 - CTLR Mission Statement & Officers & Directors

Page 5 – Poem “Cattle”

Pages 6-8 Why Raise Texas Longhorns

Page 10-15 Texas Longhorn History

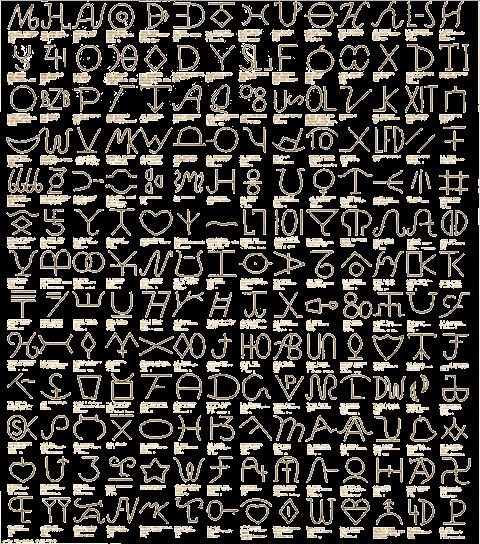

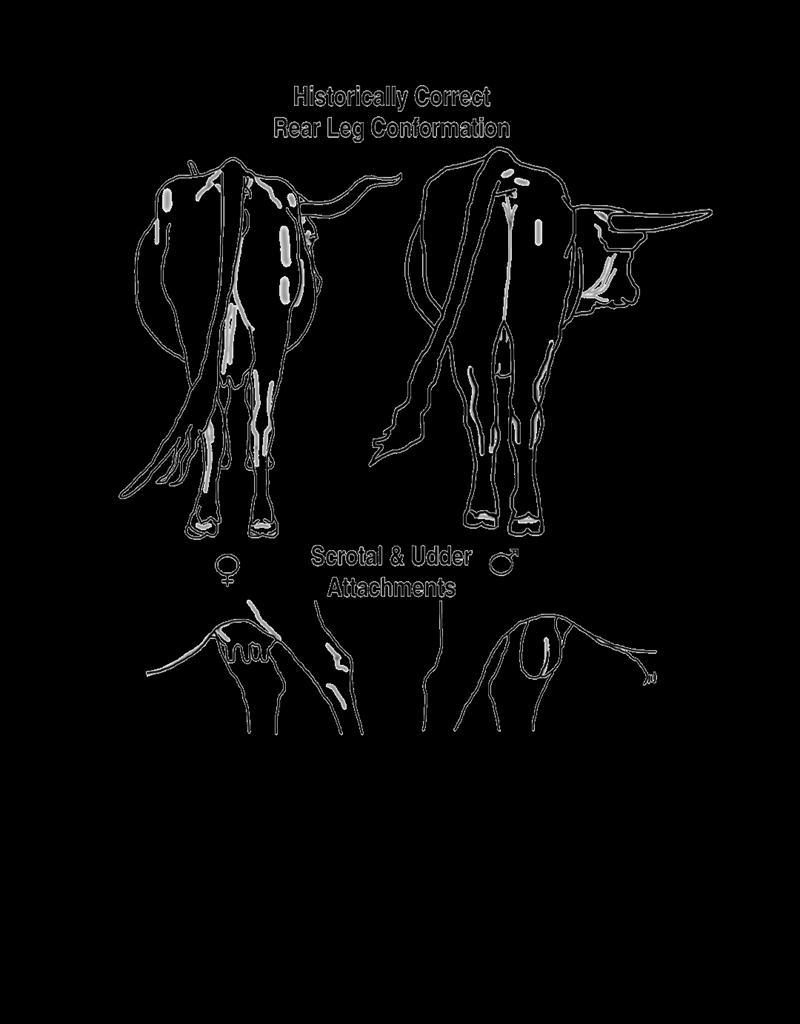

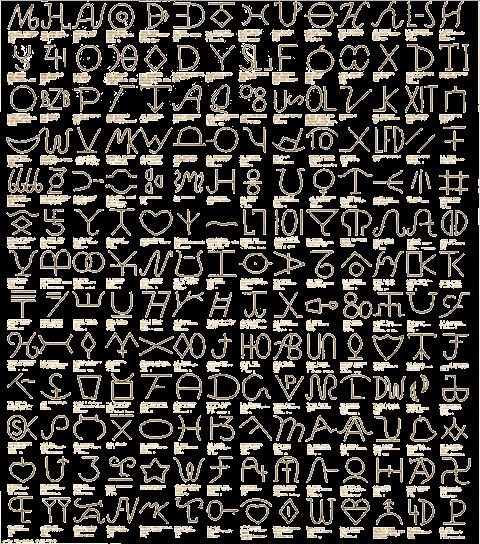

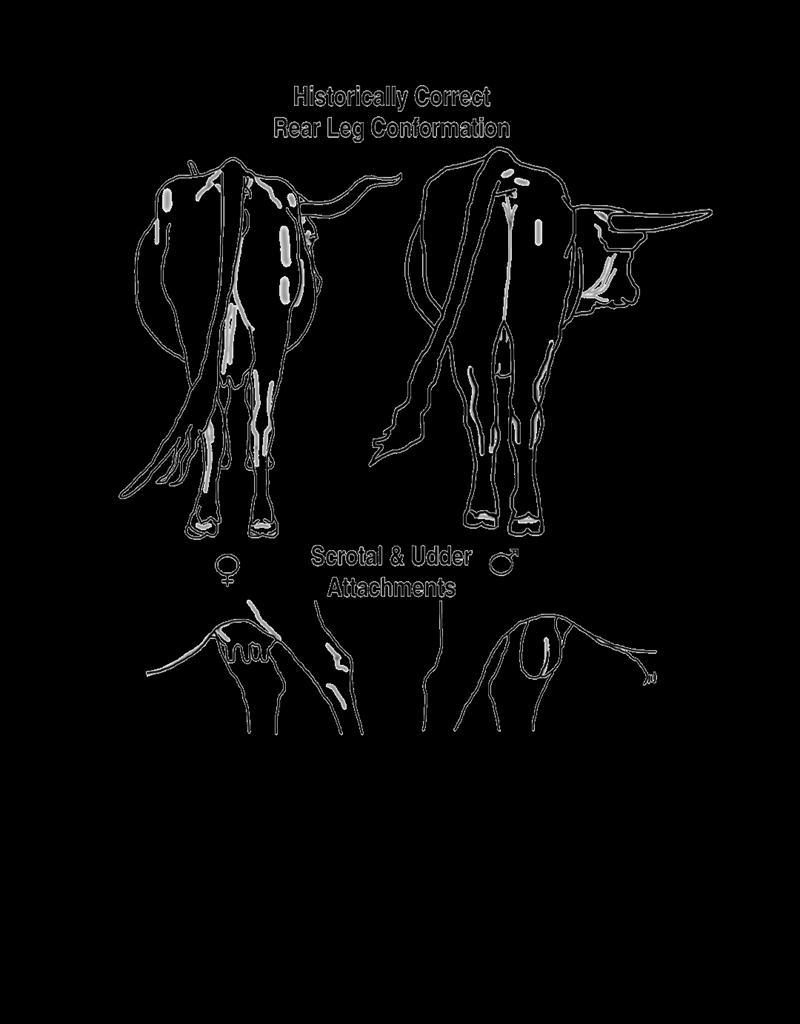

Pages 17-22, 24-25 - Longhorn Characteristics Educational Drawings

Page 28-29 CTLR DNA Testing Explained

Page 33- About CTLR DNA Testing

Page 34- Membership Requirements

The Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry is pleased to share our first edition of our online magazine. The new magazine will be quarterly starting with this fall addition.

The goals of this publication is to create a greater public awareness of the heritage genetics of the Texas Longhorn breed. It is also a way for CTLR to share information with our members, other Texas Longhorn breeders and the general public about the conservancy efforts of the CTLR. The association was founded on the principle of preserving, protecting and promoting the heritage genetics of the Texas Longhorn breed for future generations. These founding principles are why the association has requirements for registration in place that make them uniquely different from other breed registries. Unlike other registries the CTLR requires a DNA test and a visual inspection before the animal can be officially entered into the association herd books. These requirements are an important part of the CTLR’s efforts to maintain the integrity of the Herd Books of the registry to insure that the heritage genetics of the Texas Longhorn are preserved for future generations to enjoy and benefit from.

3

OUR MISSION : Conserve The Original Texas Longhorn

History shows us all the Texas Longhorns contribution to the Lone Star State. The breed’s unique adaptability provided the much-needed means of survival during Reconstruction through the post-Civil War era.

The key role Longhorn cattle played traveling the long trails North by the millions paved a way for Texas to become the economic leader it is today. It’s hard to imagine any other animal having made as large an impact on its state as has the iconic Texas Longhorn.

The Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry was formed by one simple goal: to conserve the “original” type of Texas Longhorn.

2023 Officers & Directors

James Farr - President

Debbie Adams - Vice President

Debbie Davis - Treasurer

Debby Farr - Secretary

Tim Aycock - Director

Will Cradduck - Past President

Markham Dossett - Director

Robert Lemmon - Director

Vivian Page - Director

Monroe Sullivan - Past President

Eric Woster - Director

Founding Members

Walter Scott

Enrique Guerra

David Karger

Fayette Yates

Shelby King

Alice King

Ed Paynter

Joel Carslile

John Galle

Maudeen Marks

Lawrence Wallace

For additional information call the CTLR

(512) 975-0777.

4

Cattle

by Berta Hart Nance

by Berta Hart Nance

Other states were carved or born, Texas grew from hide and horn.

Other states are long or wide, Texas is a shaggy hide,

Dripping blood and crumpled hair; Some fat giant flung it there,

Laid the head where valleys drain, Stretched its rump along the plain.

Other soil is full of stones, Texans plow up cattle-bones.

Herds are buried on the trail, Underneath the powdered shale;

Herds that stiffened like the snow, Where the icy northers go.

Other states have built their halls, Humming tunes along the walls.

Texans watched the mortar stirred, While they kept the lowing herd. Stamped on Texan wall and roof

Gleams the sharp and crescent hoof.

High above the hum and stir

Jingle bridle-rein and spur. Other states were made or born, Texas grew from hide and horn.

5

Texas Longhorn Breeders get asked a lot of questions. However, I would have to say the most often asked question is “why do you raise Longhorns”. This question is not a simple single answer but rather a question with multiple answers.

First off, they are one of the easiest breeds of cattle to raise and do not require a lot of cattle knowledge or experience working with cattle. One of the factors that makes Longhorns a “no hassle” breed is their natural resistance to numerous diseases and parasites. Longhorns seem to have a natural immunity developed over centuries of having to make it on their own with little too no help from mankind. This seems to continue to be the case with the heritage true to type Texas Longhorns being registered with CTLR. These qualities translates into fewer veterinarian bills and less maintenance cost for an individual choosing to raise Texas Longhorns.

Another reason as to “why Longhorns” is their browse utilization. Longhorn cattle will take advantage of whatever type of forage is available thus requiring less supplemental feed to maintain an adequate body condition. Most Longhorn cows weight less than1000lbs which means less cost to maintain the cows.

They also put less stress on your pastures by their lower forage requirements and by their willingness to consume different types of vegetation. This allows the rancher to possibly increase his carrying capacity, which increases the number of calves produced thus increasing the potential profits.

6

Continued on pg 7

Adaptability is another good reason for raising heritage Longhorn cattle. Unlike many of the other cattle breeds the heritage Longhorn thrives in climates from the hot, damp coastal regions to the harsh cold of the far north.

When considering a breed of cattle to raise and own, production is a key factor in making a breed selection. Longhorns excel in the two very important production traits, fertility and reproductive efficiency. These are two very solid reasons for “why Longhorns”. The heritage Longhorns fertility is exemplified by the cattle’s ability to breed at a young age, then to breed back quickly after calving and calve into their teenage years. Longhorn cattle have been known for their reproductive efficiency for many years, which has been a key to their survival. They have a larger pelvic opening than most breeds and low birth weights which almost guarantees a live calf at birth. This also means no sleepless nights sitting up waiting to see if you’re going to have to help with the delivery of the calf or call the vet. These traits were developed over time and fine tuned by God and Mother nature in order to insure the survival of the Longhorn when they roamed freely across the states. The CTLR heritage Longhorns still carry these traits today.

Heritage Longhorn cows will not only deliver a live calf but a good Longhorn cow will generally wean a calf that weights at least 40-50% of cow’s weight at weaning. This is a good example of the Longhorns efficiency in production and is another benefit of raising Longhorns over other breeds of cattle.

When most other breeds of cattle are being culled from the herd at the ages of 6 to 8 years of age a Longhorn is just hitting its prime. Longhorns are known for their longevity which is another sound business reason for raising Longhorn cattle. Texas Longhorns will breed and calve well into their teenage years with some continuing into their twenties. Their longevity results in more live calves over the years and means more dollars in the producer’s pocket. It also means that fewer replacement heifers need to be retained for the herd.

We have covered some of the business reasons for “why Longhorns” but now let’s discuss some of the more personal reasons for choosing Heritage Texas Longhorns. For some folks it is the history and nostalgia of the legendary Texas Longhorn that first catches their interest. After all the Texas Longhorn is one of the main symbols of the old west and stirs up images of cowboys, horses, cattle drives, big ranches, cattle barons, outlaws and gunfights. When you think about it the cattle drives which moved Longhorns that were roaming free in Texas up the trails to the northern market places were actually laying the

7

Longevity Functional Udders Fertility Continued on pg 8

foundation for our current livestock market. Today’s cattle industry was built by the Texas Longhorn and the American Cowboy. A breed registry was established in 1964 to preserve the genetics and history of the Texas Longhorn cattle which were near extinction. However in 1991 the Cattleman’s Texas Longhorn Registry (CTLR) was formed by a concerned group of individuals, several who's families had been instrumental in working to save the original iconic Texas Longhorn from extinction by establishing their own family herds of Texas Longhorns. They believed that more needed to be done to preserve the valuable heritage genetics of the original Texas Longhorn. They felt like the other organizations were not doing enough to safeguard the genetics of the historic Texas Longhorn. So they formed CTLR to fill the gap.

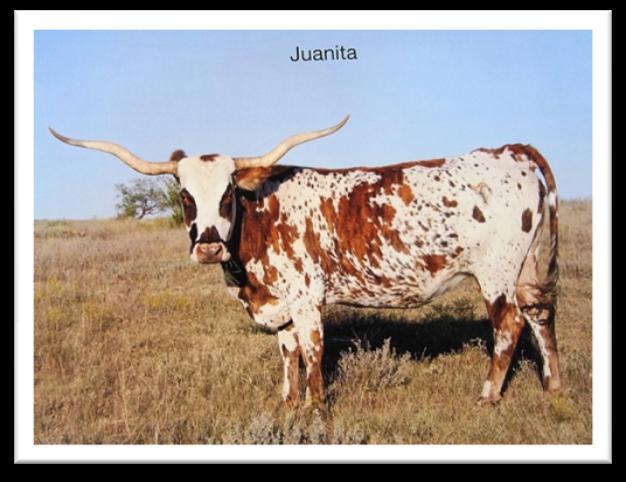

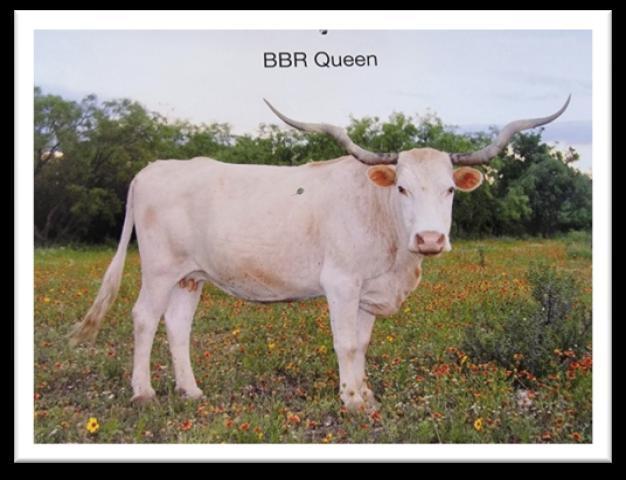

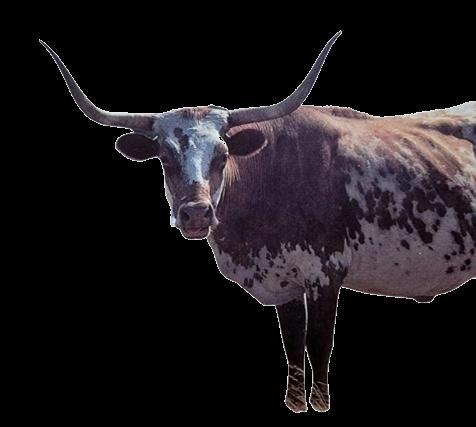

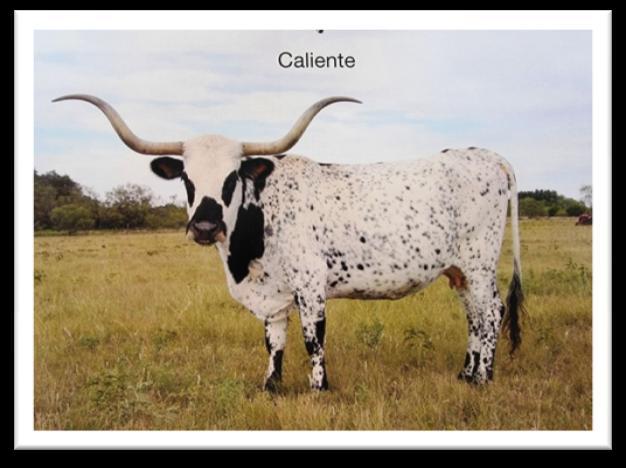

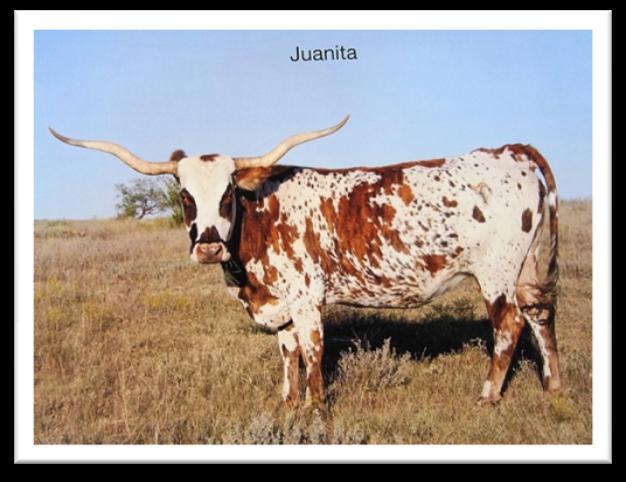

As you look at a lot of today’s breeds of cattle you will find that most are very similar in look and type almost like they came from the same cookie cutter mold. Most breeds are working to have this consistent look in their cattle. But it is the uniqueness of the Texas Longhorn that draws some people to the Longhorn breed. They are all truly one of a kind because no two are alike in color, body or horn shapes which makes for a beautiful pasture setting. Yet even with all these differences the CTLR cattle all have the same phenotype which shows their strong ties to the original Texas Longhorns.

As you spend time around Longhorn cattle you will soon learn that they all have their own individual personality which makes them a joy to be around. They are a very intelligent breed with a good memory and are easy to train and work. They will respond to positive treatment or handling in a positive way but will also respond in a negative way to rough or negative treatment.

The Texas Longhorn is basically a good all-around breed of cattle because they are a multipurpose breed. They will work for just about anyone from the serious cattleman to the recreational rancher. Prospective buyers can find cattle that will fit their budget, lifestyle and goals. You can even raise Longhorns for meat. Yes, I am saying you can eat Longhorns. Most people at first are surprised by the fact that you can eat Longhorn meat. They are generally more surprised to find out how tasty it is and that it is healthier for you. Longhorn beef is some of the healthiest meat you can eat. It is lower in cholesterol than chicken and turkey. If you need to watch your cholesterol or calorie intake you may not have to give up eating beef if you start eating Longhorn beef. Healthy beef for your family is another reason as to “why Longhorns”.

If you are looking at getting involved in raising cattle, adding to your cattle operation or looking to raise beef for your family’s table then you should take a serious look at the heritage Texas Longhorn Breed.

8

Browse Utilization Natural Mothering Instinct Hardiness

Dedicated to scientific and historical research and education associated with heritage Texas Longhorn cattle, we recognize the value of this national treasure in its original phenotype (appearance) and genotype (genetics). We provide ongoing resources toward research and education pertaining to the conservation of this naturally evolved, historic breed. We work closely with the Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry to insure the preservation of the heritage genetics of the breed.

Our mission is to safeguard the integrity of the old-time, traditional Texas Longhorn for future generations by educating the public about the value of conserving this naturally evolved breed of cattle and providing resources for continued research into understanding their unique, genetic traits.

Help Support our efforts by making a Donation.

Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Conservancy is a nonprofit, tax-exempt charitable organization (EIN 05-0618099) under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Donations are tax-deductible as allowed by law.

www.ctlc.org

Ancestors of the Texas Longhorn were first brought to the North American continent in 1521 by Gregoiro de villalobos, just six months prior to the subjugation of Mexico City and the establishment of New Spain for the crown of Emperor Charles V. The cattle originated around the salt marshes of the Guadaiquivir River valley in the Andalusian Mountains of southwestern Spain. Transplanted to the New World, the estimated thirty heifers and three bull calves that landed on the banks of the Pánuco River near Tampico, on the eastern coast of Mexico, were to influence the history of North America no less profoundly than did the Industrial Revolution three centuries later.

Spanish explorers continued to bring cattle on subsequent trips to the New World, populating what is now southern Mexico, all of Central America and the northern Countries of South America. Beginning in 1682 and continuing through 1793, twenty-six Spanish Catholic Missions were established to spread their faith among the Native Americans and lay Spanish claim to the land. Shipped from ports in Sevilla and Cádiz, those Missions introduced cattle and livestock handling techniques from several regions in Spain to the territory now known as Texas. Andalusia (southern Spain including Sevilla, Córdoba, Jaen and Granada) was home to the solid red Retinto breed. Near Córdoba, there was a breed called Berrenda that was white with black points (ears, nose, legs and sometimes black markings around the neck). Extrema Dura (Estremadura) was home to the solid white Cacereño breed. The mountains of central Spain were home to solid black Andalusian cattle. As the Spanish abandoned the Missions or local Native people killed the Spanish, the livestock were left to fend for themselves.

Wild cattle roamed across Mexico and the southwestern United States unencumbered by mankind for more than two hundred years. Natural Selection created a hearty breed that was lean and able to travel long distances in search of forage and water. The breed had laterally twisting horns for fighting predators. With cunning and disease-resistance, the cattle thrived in the arid wilderness. Descendants of cattle from various regions in Spain commingled in the wild, creating offspring in a rainbow of colors. These animals possessed immunity to tick fever. Cattle brought by early settlers did not have this immunity and died from the disease, thus minimizing crossbreeding and preserving the Spanish ancestry of the Texas Longhorn.

The ranchers of Spain and Mexico provided the basis for most of our laws, equipment, procedures and terminology used in cattle ranching today. The 1529 Mesta (cattleman’s organization) rules soon became laws that evolved to today’s codes that are applied to the livestock industry in the U.S. The original Spanish military saddle lacked an effective saddle horn. The lasso (lariat) was put on the end of a lance or pole and dropped over the cow’s horns, with the end usually tied to the horse’s tail. The saddle horn was developed in the latter part of the 17th century and is similar to what is used today. The high-topped Spanish military boot was adapted to the cowboy boot of today. The wide brimmed Mexican sombrero was suited to the Mexican climate and was the basis of the many styles of cowboy hats today. The vaquero’s leather legging became the chaps and chinks now in use.

10

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain and began colonizing the Texas region. Mexico offered land grants to US citizens. Moses Austin was awarded a land grant and entitled Impresario. He was assigned the task of settling three hundred families in his colony. Other impresarios were granted land in the same way and soon, thousands of US citizens flocked to Texas. Settling farmers domesticated the wild cattle in their areas, using them for draft animals and a source of beef. After his death, Moses Austin’s son Stephen F. fulfilled his father’s contract of introducing three hundred new settlers to his colony in San Antonio de Bexar. “According to the Mexican Constitution of 1824, these settlers were granted land, allowed to own slaves, and were to be free of taxes for seven years. The only requirements were that they become Mexican citizens, practice the Roman Catholic religion, and secure Texas for the Mexican government.” Mexico wanted Texas as a territory, not a state of Mexico with full representation, so settlers found themselves without a government or a militia to protect them from Indian raids. The state was the ancestral home to near fifty Indian Nations, some quite hostile toward the newcomers. Another one of the many factors that contributed to the desire for Texas’s independence from Mexico was a tax Mexico imposed on owners of cattle.

Stephen F. Austin became the leading spokesperson for the "Texians" for all affairs with Mexico. Texas was a part of the territory known as Coahuila y Tejas. Many times Austin petitioned the government for separate statehood for Texas, all to no avail. Formed to protect the colonies, Committees of Safety later became the Texas militia that took up battle with Mexico to gain independence. Austin traveled to Mexico in 1834 to petition the government once again. He was imprisoned there for three months. At home in Texas a revolution was being planned. In January 1835, the Mexican government ordered its citizenry be disarmed in Texas’s neighboring state of Zacatecas, due to disturbances for reasons similarly experienced by Texans. Troops that were dispatched to expel dissidents by occupying Texas were recalled for use in Zacatecas. Later that year Mexico again assigned troops to Texas. “The Mexicans commenced their warlike movements at Goliad by jailing the Mexican Colonel Ugartachea assigned to oversee the territory, and extorting from the administrator the sum of five thousand dollars, under the penalty of being sent on foot a prisoner to Bexar in ten hours. Martial law was imposed; the town stripped of its arms, the people pressed into the ranks as soldiers, and given notice that the Mexican troops would be “quartered upon the citizens five to a family and should be supported by them. Mexico intended to overrun and disarm all of Texas and drive out all Americans who had come into the territory since 1830.

The spring of 1836 witnessed Texas’s bloodiest battles and the formation of the independent Republic of Texas. The new government of Texas voted to concede to annexation by the United States. Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna warned

11

annexation would equal a declaration of war. In the following nine years before annexation by the United States, young Texas struggled as an agricultural nation through savage battles between Texas Rangers, the Texas Army, and farming settlers against raiding native Indians determined to reclaim their ancestral lands. Political unrest continued between Texas and Mexico over boundary lines. Texas incurred huge debts, which the United States agreed to assume upon annexation. Annexation resulted in Mexico declaring war against the United States that was waged from 1846 until 1848 when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed that allowed the U.S. to purchase California and other areas from Mexico on the condition that Americans would honor Mexican culture and values. The annexation of Texas was highly controversial amongst the states and contributed to widening American sectionalism leading up to the Civil War. In 1851, Federal frontier forts were established to assist pioneer farmer settlers from assaults by Indians and Mexicans. In 1852, in return for its assumption of Texas’s debt, a large portion of Texas-claimed territory, now parts of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Wyoming, was ceded to the Federal Government. Texas having joined the Union as a slave state, in 1861 seceded with ten other states from the Union to form the Confederacy. The War Between the States continued for four years, devastating the fragile Texas economy. Federal troops from forts were called away to fight for the Union Army, so Comanches and Kiowas reclaimed as much as one hundred miles of frontier. Many settlers left to fight the war and others fled from raiding Indians. Livestock again was left to roam wild on the open range. With few enterprises available in Texas’s depressed economy after the war, and scarcity of supplies and hard currency, Texans were left to their own ingenuity. The one commodity they enjoyed in abundance was beef. From the brush country of South Texas to the grassy rolling plains of Northwest Texas, the lean, hardy breed of longhorn cattle proliferated. "Cow hunters," as the early-day cowboys called themselves, at last found a use for the land that Brig. Gen. Belknap had declared unfit to inhabit. The frontier shaped Texas history as well as the practicality, energy, and individualism of its people.

Thus began the legendary trail drives. The migration of Texas Longhorn cattle from south Texas to the northern plains and the Kansas railheads in the decade following the War Between the States was the largest movement of animals under the control of man in the history of the world. Some nine million head of Texas cattle were driven up the trails by men who, returning to Texas in 1865 after losing a war, found nothing in their new and vast state from which to make a living but millions of rangy, free-roaming and rancorous cattle hiding in the brush and the arroyos of the brasada country and the coastal plains of south Texas. The Texas Longhorn saved the Texas economy from imminent ruin. The money from the sale of the Texas Longhorn for the stocking of the northern plains and the feeding of the meathungry east was the foundation for the development of the Texas economy. An infrastructure of roads and railroads quickly developed to serve the cattle trade and enable further economic development. The greatest and longest lasting impact of the Texas Longhorn was its cultural impact on the Wild West, which would not have existed without these cattle. The trail drives, cowboys and cow towns of the southwest expanded in legend first in the dime novel and later on the silver screen, changed us as a people.

12

Charles Goodnight was one of the brave men to blaze cattle trails and he established one of the most revered cattle ranches in Texas history the JA Ranch in Palo Duro Canyon. Responsible for inventing the chuckwagon from an army surplus Studebaker wagon in 1866, he facilitated meal preparation for cowboys on cattle drives. Oxen or mules drew the chuckwagons. They are still used in varying forms today on large ranches.

Prior to the invention of the water-pumping windmill in 1854, human habitation, farming and livestock production were limited to areas in close proximity to a constant supply of flowing water. The advent of the windmill was a precursor to the ranching industry across the Southwest.

By the end of the 1870s, the national economic depression had mostly run its course, and the long awaited southern transcontinental route soon became a reality. The Texas & Pacific Railroad that had stood frozen between Dallas and Fort Worth since 1873, suddenly burst across West Texas in 1880 and 1881. By the time it connected with the Southern Pacific near Sierra Blanca, any number of tent and clapboard railroad towns sprang up along the tracks. Abilene, planned by the T&P as its market hub, signaled the beginning of a new era. European livestock shipped on rail cars began to populate the lush farming communities in Texas. Gone now were the days of driving herds of cattle on horseback, walking hundreds of miles. Gone too, was the frontier. The frontier did live on first in the Wild West shows and later in the rodeos of today. The term rodeo comes from the Spanish word rodear. The rodear started in the mid 16 century as a roundup of the wild cattle to get them used to humans and easier to handle. The ranchero was the center of social activity and probably the scene of many vaquero contests. Buffalo Bill Cody started the Wild West show in 1883 followed by Pawnee Bill in 1886. Bill Pickett was one of the early rodeo stars who invented bulldogging (steer wrestling). The Wild West shows spread the cowboy craft around the world, and the early vaquero contest was the first step toward the PCRA, the Professional Cowboy Rodeo Association of today. Rodeo is the official sport of the state of Texas.

Barbed wire became commercially available in the late 1870’s. It was an inexpensive fence capable of restraining cattle. It became affordable to fence large areas. Massive ranches were established. The Texas Legislature, in 1879 appropriated three million acres to finance building a new state capitol building. The contract was awarded to the Farwell Brothers out of Chicago to build our red granite capitol in Austin, still the largest state capitol on the North American Continent. Their payment was the land that became the XIT Ranch. Over thirty miles wide and encompassing part of ten counties in the panhandle, the XIT range was the largest in the world under fence. Hundreds of miles of wire was stretched across Texas in the 1880’s, forever halting roaming of wild herds of grazing animals and taming the West. Cattle became the backbone of the economy, supplying beef to the nation. Mining towns sprang up westward along the railroads, supplied with food by area ranches.

13

The growing urban population of the country realized the need to preserve scenic areas of the West. First Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872, then Yosemite in 1890. The Sierra Club was founded in 1892. Big Bend National Park was not established until 1933. It became a National Park ten years later. Prior to acquisition by the state, the land was used for ranching. Sheep and hearty Texas Longhorn cattle dotted the landscape.

By the end of the 1880’s, all peaceful Indians had been relocated to Oklahoma Reservations. Federal troops and Texas Rangers had exterminated the last of the hostile Comanches. Cities were developing across the state with commerce of all kinds. Herds of cattle behind barbed wire fences replaced the once massive herds of roaming bison.

In 1901 the first oil well, Spindletop, gushed oil one hundred feet into the Texas sky, propelling the Texas economy from its agricultural roots and flung headlong into the petroleum and industrial age. Landowners across the state became wealthy over the next one hundred years by selling the mineral reserves under their ranches. Cattle were no longer the primary source of income for the state.

Importation of fat cattle from England and Bos Indicus cattle from India became commonplace by 1900. Consumers favored English cattle for their beef’s fat content. Indian cattle, shipped into Texas ports, were better adapted to insect resistance so ranchers along the coast crossed them with their English cattle. The Texas Longhorn fell from favor of ranchers for several reasons: its horns made it difficult to pack tightly into rail cars, its meat was lean, its tall, slim athletic frame made it more difficult to contain in fences, and its independent nature did not conform to the organized group grazing habits of English cattle. Many ranchers “bred up” their herds of range cattle to fancy imported bulls. At the turn of the twentieth century, on the brink of extinction through crossbreeding, the U.S. Congress revived the Texas Longhorn in 1927 with the establishment of a national herd at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Cache, Oklahoma. This herd endures today as a leading source of seedstock. Where the Texas Longhorn once carried the dreams of westward expansion into a new century, today the breed's future lies in redefining the beef industry as a source of naturally grown, high-quality, savory beef with the fat and cholesterol content of the leanest of seafood. The first cattle to set foot in North America and the only breed of cattle to evolve without human management,

14

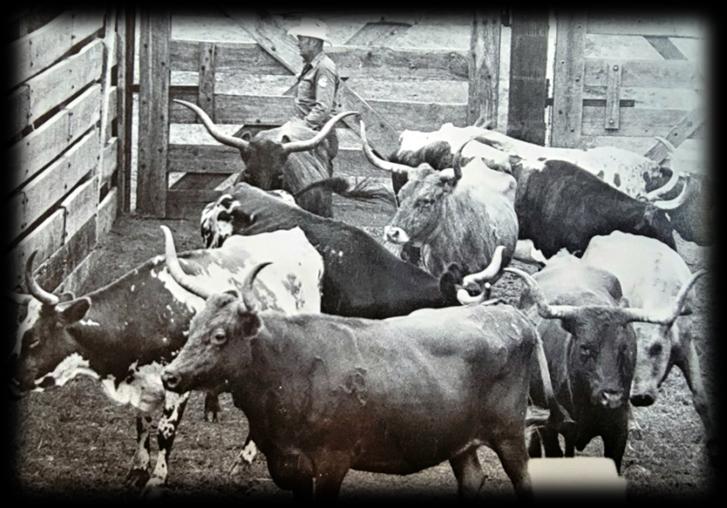

Cattle in the pens at Wichita Wildlife Refuge

the Texas Longhorn can thrive in country where no other breed can live; subsist on weeds, cactus and brush; range days away from water; and stay fit and fertile whether it's living in the scorching, parasite-infested tropics or in the arid, subzero winters of Montana. As our society continues to multiply and the most desirable agricultural land is developed for human habitation, Texas Longhorn genetics are in greater demand for their qualities that enable them to live on marginal terrain with little maintenance from man. Their lean, healthful beef qualities are now in demand. The Texas Longhorn having evolved in this land is well adapted to grass finishing without grain supplementation making the breed environmentally sustainable and in high demand by educated, health-conscious consumers.

Thanks to: Texas Heroes website is recommended for teaching aid ideas. San Antonio Charro Association Bozeman curriculum

1. Dallas Historical Society

2. Son of the South

3. Wikipedia

4. Texas Beyond History l

5. Dary David Cowboy Culture, A Saga of Five Centuries, University Press of Kansas 1981,1989

6. Jordan Terry G. North American Cattle-Ranching Frontiers, Origins, Diffusion, and Differentiation University of New Mexico Press 1993

7. Jackson Jack Los Mestonios, Spanish Ranching In Texas 1721-1821 Texas A&M University Press 1986

8. Rouse John E. The Criollo Spanish Cattle in the Americas University of Oklahoma press 1977

9. Atherton Lewis The Cattle Kings University of Nebraska Press 1961

15

Est. in 1991

Working to preserve the heritage genetics of the Texas Longhorn Breed

The Texas Longhorn made more history than any other breed of cattle the civilized world has known…

J. Frank Dobie

If you are interested in joining CTLR’s efforts to preserve the heritage Texas Longhorn please call the CTLR at or visit our website.

What is a heritage Texas Longhorn?

Lets look at Phenotype. What is Phenotype? It is the observable physical or biochemical characteristics of an organism, as determined by both genetic makeup and environmental influences.

17

18

19

20

21

In the coming months CTLR will be launching our new online store, Longhorn Mercantile. The online store will offer a wide verity of items with a Historic Texas Longhorn theme. These items will be of interest not only to our members but also to any one with an appreciation for the Heritage Texas Longhorn Breed.

The new online store is a great way for any Longhorn enthusiast to show their support for CTLR’s conservancy efforts. Profits from the sell of the online merchandise will be used to advance these efforts. The proceeds will also be used to create a greater awareness of the importance of the Heritage Texas Longhorn and the work of the Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry. Help us tell the Longhorn story with your purchasing of Longhorn merchandise offered at our new online store. Announcement of Grand Opening coming soon.

Monroe & Debbie Sullivan Midland, Texas (432) 210-9391 sullivanlonghorns@gmail.com Proud Member of

24

25

A valuable Tool to CTLR’s Efforts

English/Continental breeds and 4 Indicine; African Sanga/Middle East /India Zebu breeds. The UC Davis report for both males and females include the percentage of genetics grouping with conservation Texas Longhorn cattleand/or the percentage an animal groups with hybridized horned cattle.Y-chromosomes haplotypes in males are associated with specific regions (Y1 northernEurope and British Islands, Y2 Iberian Peninsula and Southern Continent, Y3 Zebu (all humped cattle), and reveal percentage of introgression of any of the 17 breeds on file. Bos taurus (includes all European cattle) or Bos indicus (includesall Zebu or Indian cattle), mtDNA lineages are classifiedaccording to major Bos taurus families(haplogroups T1, T1a, AA (or T1c), T2, T3, Q) and Bos indicus families (I1, I2). Results to expect for conservation Texas Longhorn cattleare rankings of 80% or greater with conservation control group. Less than 1% of Hereford, Shorthorn,Angus, British White, and Zebu are not uncommon in conservation Texas Longhorn cattle.Low percentages reflect historic introgression from the 1800s and early 1900s. Animals possessing markers found only in Iberian breeds with 0% introgression of other referenced breeds do exist. In combination with 90+% conservation genetics, these animals are considered elite. Many conservation Texas Longhorn bulls possess a Yhaplotype indicating historic admixture of Hereford, Shorthorn or Angus due to the introduction of those breeds in 1885 to west Texas. Read an articlefrom 1920 in The American Hereford Journal.

https://www.ctlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Herefords-inWestTexas.pdf

Cattle gathered along coastal regions possessed historicadmixture of Nelore and Gyr; Zebu breeds that were imported to the US in the 1885 to become the foundationof the American Brahman breed. We must accept less than 1% admixture from other breeds as part of the evolution of the Texas Longhorn breed. We do not consider introgression from other breeds introducedin the last sixty years to be natural evolution. Animals possessing greater than 1% of other detectable breeds are excluded from conservationstatus. We have learned by experimentation offspring can be ‘bred up” from parents possessing unacceptable genotypes, when one grandparent possessedconservation genetics, the calf has a 50/50 chance of inheriting the conservation alleles or the hybrid alleles. For this reason, we include eight bulls that fall below our minimum acceptablerange of 80% conservation score. These are available for experimentation in effort to increase diversity but are not guaranteed to produce an offspring that will be acceptable for CTLR registration.

29

dwdlonghorns.com

David Holmgren

Deep Well, Nevada (775) 455-5671

James & Debby Farr

Terrell, Texas (214) 202-8141

farrcrosslonghorns.com

Running M Longhorns Giles & Becky Madray

Ozona, Texas (325) 392-5801

Monroe & Debbie Sullivan

Midland, Texas (432) 210-9391

sullivanlonghorns@gmail.com

Ron & Janet Fowler

Wayne, OK (309) 333-5693

DCS Livestock

Gil & Judy Dean

Bastrop, Texas (512) 940-1676

gilbertodean@gmail.com

Ted, Todd & Tim Aycock 13012 Seaman Rd.

Van Cleave, MS 39565

Ted: (228) 861-4029

Todd: (228) 365-4594

Tim: (228) 365-8751

Sunny K Longhorns

Bonnie & Ian Kuecker

Verhelle, Texas (832) 212-4323

burnsgrant626@gmail.com

Les Mallory Round Top, Texas (979) 208-9387

Vivian Page

Bar V Ranch

Driftwood Texas

Barvlonghorns.Com

vivianpage06@gmail.com

Debbie Adams

Wimberley, TX 713-416-9740

bosslady1961@icloud.com

To be listed on this page please contact Russell at russellh@longhornroundup.com

31

Fort Griffin Historical Site

Home of THE OFFICIAL TEXAS LONGHORN HERD

1701 N. U.S. Hwy. 283, Albany, TX 76430 325-762-3592

visitfortgriffin.com

The official state Longhorn herd is co-managed by the Texas Historical Commission and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. The herd is based at Fort Griffin State Historic Site, although portions of the state herd also reside at Copper Breaks, San Angelo, Palo Duro Canyon, and LBJ state parks.

Coppers Breaks State Park

777 Park Road 62 Quanah, TX 79252-7679

https://tpwd.texas.gov/stateparks/copper-breaks

Lyndon B. Johnson State Park

199 Park Road 52 Stonewall, TX 78671

https://tpwd.texas.gov/stateparks/lyndon-b-johnson

Palo Duro Canyon State Park

11450 Park Road 5 Canyon, TX 79015

https://tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/paloduro-canyon

San Angelo State Park

362 S. FM 2288

San Angelo, TX 76901

https://tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/sanangelo

32

The official Registry of the Texas State Herd

These cattle continue to represent the unique and once-abundant animals that made a critical contribution to the development of Texas’ economy in the 19th century.

In 1991 the Cattleman’s Texas Longhorn Registry (CTLR) was formed by a concerned group of individuals, several who's families had been instrumental in working to save the original iconic Texas Longhorn from extinction by establishing their own family herds of Texas Longhorns.

They believed that more needed to be done to preserve the valuable heritage genetics of the original Texas Longhorn. They felt like the other organizations were not doing enough to safeguard the genetics of the historic Texas Longhorn. So they formed CTLR to fill the gap.

They formed the CTLR with strict requirements for acceptance into their registry database. Which includes the use of scientific DNA testing as a tool to insure genotype, as well as visual inspections to insure phenotype. These steps were not & have not been taken by other breed organizations. Both of these requirements help to insure that the CTLR registered cattle are as close to the original heritage Texas Longhorn cattle as possible.

It is important to Preserve the Past to Protect the Future. Because of the work of the CTLR, the cattle they register still maintain a strong genetic linked to the heritage and profitable survival traits of their ancestors. Thus insuring that the CTLR Heritage Texas Longhorns continues to possess these important breed traits and characteristics which were so important to it’s survival as well as it’s value the cattlemen.

33

Cattle on the Wichita Wildlife Refuge

Type Cost

Lifetime* $1,500 (one time fee)

Estate* $700 (one time fee)

Breeder* $75 (annual)

Participant $35 (annual)

Youth $10 (annual)

Corporate $150 (annual)

Membership Application is available at www.ctla.org

Must own at least two CTLR registered breeding animals and receive unanimous approval of the Board of Directors.

34

DWD Longhorns, LLC 3361 CR 211 Hondo, TX 78861 office (830) 562-3650 cell (830) 796-1057

Outside Briscoe Art Museum

On they famed San Antonio River Walk

T.D. Kelsey Bronze Statue

T.D. Kelsey Bronze Statue

T.D. Kelsey Bronze Statue

T.D. Kelsey Bronze Statue