RAFAEL SORIANO

RAFAEL SORIANO

Transcendentalism, Distilled

by Richard Blanco

RAFAEL SORIANO: THE LAST DECADE by Alejandro

Anreus, Ph.D.

PLATES

RAFAEL SORIANO: A LIFE OF ART

Chronology by Carol Damian, Ph.D.

—ANATOMY OF LIGHT— for Rafael Soriano

—across your canvases, my bones’ mortal ache softens like your glimmers into the immortal— —worries wrinkled across my forehead dissolve into the gossamer sheen of your sapphire hues— —I inhale the language of your gusty colors until my mouth exhales words that heal me— —you redraw my ribs as a divine staircase I climb back toward to the brilliant heavens you brushed for me— —my eyes peer within your eyes into the shadows of the time before and after my earthly time— —the losses of my rock-heavy heart float amid the translucence of your sienna-blood clouds— —in the flesh of your brilliant colors I see myself as more than merely flesh, for I am the light of— —your light that renders the infinite and lets me see god as the glow of your god in all humanity—

Richard Blanco was born in Madrid and immigrated to the United States as an infant with his Cuban-exile family. He was raised in Miami and earned a BS in civil engineering and MFA in creative writing from Florida International University. Blanco has been a practicing engineer, writer, and poet since 1991. In 2013, Blanco was chosen to serve as the fifth inaugural poet of the United States. Blanco performed “One Today,” an original poem he wrote for the occasion, becoming the youngest, first Latino, immigrant, and openly gay writer to hold the honor. Blanco has taught at Georgetown University, American University, Writer’s Center, Central Connecticut State University, and Wesleyan University. He is currently Distinguished Visiting Professor at Florida International University. He lives in Bethel, Maine.

- Richard Blanco

Photograph of the newly inaugurated Rafael Soriano Foundation space, offering a Curator in Residence Program to further the scholarship of Soriano’s works

Rafael Soriano: The Last Decade

by Alejandro Anreus, Ph.D.

“My work began to change; it was something spiritual that cannot be measured in material terms.

I believe that art is a means through which the spiritual side of our being evolves.”

- Rafael Soriano1

Introduction

In 2000 Rafael Soriano completed his last oil painting. Although the artist would live for another fifteen years, heart-related health issues and memory loss would keep him from creating any more paintings. In the 1990s, his last decade as a working painter, Soriano completed not only some of his largest canvases, but also some of his most poignant. This essay will attempt to contextualize Soriano’s production in his last decade as a painter, not only within his native milieu but beyond it, exploring his life-long spiritual and metaphysical pursuits, as well as framing the work within notions of “late style” or “old age style.”

Soriano was born November 23, 1920, to a family of modest means in the small town of Cidra, province of Matanzas, Cuba. When he was nine years old the family moved to the city of Matanzas, historically known as the “Athens” of the island due to its rich cultural milieu. His father was a barber and his mother a homemaker; both were very supportive of young Rafael’s artistic sensibility, which manifested itself since childhood. By the age of fifteen, he was attending the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts in Havana; in 1939 he would complete a degree in sculpture and drawing, and two years later his degree in painting and drawing.2 Soriano’s generation included key figures that would contribute to the modern art of the island starting in the late 1940s, painters and sculptors such as Roberto Diago, Agustín Cárdenas, Roberto Estopiñán, Servando Cabrera Moreno, José Nuñez Booth, Manuel Rodulfo

Tardo and others. They were also among the last group of students to be taught by painter Leopoldo Romañach (1862-1951), a leading artist of the turn of the century, and sculptor Juan José Sicre (1898-1974), perhaps the one advocate of modern art that taught at the school. During his years at the academy Soriano absorbed the rigorous and traditional course of study; and would possess an extraordinary craftsmanship for the rest of his life. During his years as an art student in the city, Soriano befriended the avantgarde painters Fidelio Ponce (1895-1949) and Víctor Manuel García (18971969). These two offered living examples of artists committed to a modern visual language, as well as being marginal figures that were never part of the conventional art establishment. Of the two, Ponce was the most significant influence, considering the religious/spiritual aspect of his work and Soriano’s own pursuit of the metaphysical and spiritual in his canvases. During these years Soriano was briefly involved with the Rosicrucians, whose synthesis of Christian and Asian spiritualities also influenced his work.3

After graduating from San Alejandro, Soriano, and other fellow graduates (Diago, Nuñez Booth, Tardo) founded the School of Fine Arts in Matanzas, where they taught introducing elements of modern art. He would be associated with the school as both a teacher and director until his exile in 1962. In the summer of 1947 Soriano visited Mexico, where he encountered the monumentality of both PreColumbian art and the modern mural movement. He was particularly affected by the forceful qualities of David Alfaro Siqueiros’ forms and compositions, and the painterly and metaphysical qualities of Rufino Tamayo’s canvases.4 Later in the same year, Soriano visited New York City with a group of art educators, but apart from a handful of photographs there is no documentation of his brief time there or the art he might have seen.5

Soriano’s paintings of these years already exemplify a cosmopolitan sensibility: his subjects are neither tropical nor cliché, his forms synthesize the organic and the geometric, his palette favors warm and dramatic contrasts, and he incorporates surrealist elements with originality. In the 1950s Soriano developed a geometric, concrete language of angular and rectilinear compositions charged with strong flat colors. He would join the group of Pintores Concretos, who introduced concrete abstraction in Cuba.6 But I would argue that Soriano

stood apart from these artists who were exploring a purely rational, optical, and materialistic vision. In his evocation of the fourth dimension in his painting, Soriano was pursuing the metaphysical, the transcendent. His painterly, sensual application of pigment is also different from the other concretos Soriano is closer to Piet Mondrian’s painterly approach and mystical strain more than any of his Cuban contemporaries.

In January 1959 the Cuban Revolution triumphed, deposing the regime of Fulgencio Batista. The new government promised a return to democratic and constitutional rule, yet it quickly soured into a totalitarian system allied with the Soviet Union. Rafael Soriano very quickly understood that his vision of life and art and the new government could not reconcile. In 1962 with his wife Milagros and daughter Hortensia, he went into exile in Miami.7 With exile, Soriano left behind an entire life; family, vocation, job, and nation. This traumatic experience would affect him profoundly, and he would not be able to paint for over two years. By 1965 he was back at his easel, searching for and constructing a visual language. Between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s his painting went through a series of transformations, geometry being replaced by organic forms, colors becoming richer, darker, and applied in a modulated manner. By the mid-1970s Soriano’s work had achieved an extraordinary new language, where both monumental and delicate forms resemble a synthesis of figure and landscape and his compositions represent deep space with rich colors, evoking a tranquil infinity.8

Contexts

Rafael Soriano belongs to the third generation of the avant-garde in Cuba. The first generation consisted of artists that came of age in the late 1920s, many of whom experienced modernism in Europe, and returned to live and work on the island. Stylistically diverse, their preferred subjects included genre scenes and still-lives, peasant life, and the Afro-Cuban. The second generation, which emerged in the late 1930s and early 1940s, looked to modern Mexican art for inspiration, as well as Picasso’s neo-classical phase, and favored the figure in environments executed with a neo-baroque sensibility in a colorful palette.9 By the time the third avant-garde emerged in the late 1940s and early 1950s, its

artists had little interest in the styles and subjects of its predecessors (Wifredo Lam and Amelia Peláez being the exceptions), and specifically themes of national identity. They were decidedly cosmopolitan, more concerned with abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction, and neo-figuration. Soriano is a breed apart within the trajectory of Cuban modernism and his own generation due to the specifics of his identity and concerns as an artist. First there is the lifelong concern with craftsmanship, the thoughtfully and well-made painting, where sound technique is essential in the creation of a modern pictorial language. Then there is the spiritual and metaphysical content, which is not that frequent in Cuban art with a few exceptions.10 In this Soriano is linked to a significant trend within twentieth-century art beyond Cuba. This trend includes artists as diverse as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, Rufino Tamayo and Roberto Matta, Mark Rothko, and Fernando de Szyszlo, to mention the leading figures. Their art has spiritual and metaphysical concerns – what Alberto Savinio defined as “the total representation of spiritual necessities within pictorial limits.”11 These painters, whether working gesturally, geometrically or with biomorphic forms, are reflecting a transcendent concern, the pictures becoming meditative moments in themselves. Soriano is very much a part of this family tree, for the obvious spiritual and metaphysical dimensions, as well as the painterly exploration of form and space.

The works in this exhibition reflect another significant context within Soriano’s artistic production, that of Late Style or Old Age Style, since they were made during the last decade in which he worked as a painter. Soriano was in his seventies during the 1990s. Late Style/Old Age Style is a term that began to be used by art historians in the 1920s, to refer to the work of long-lived artists. It can refer to sharp and unexpected changes in subject matter, treatment, and other features of later works. It can also refer to a deepening of the artist’s vision to further reflect mystery, farewells, and end-of-life visions. 12 It is this last aspect of Late Style/Old Age Style that is very evident in Soriano’s last pictures.

Last Paintings

This exhibition consists of fourteen paintings from the 1990s. These works have the poetic names so usual in Soriano, and in particular these titles

contain evocations of night, eclipses, twilight, dreams, and mirrors. Worlds of mystery, evoking transcendence in what is transient, what is finishing, yet moving forward while conjuring a listlessness. These pictures are charged with deep blues and purples, delicate earth, and pink tones, as well as shapes that summon figures and landscapes that are never literal. They fill the space with a solidity that simultaneously moves back and forth and across the surface. While earlier work can be life affirming through the sensuality of the forms, the late works evoke a different transcendence exploring a serene acceptance.

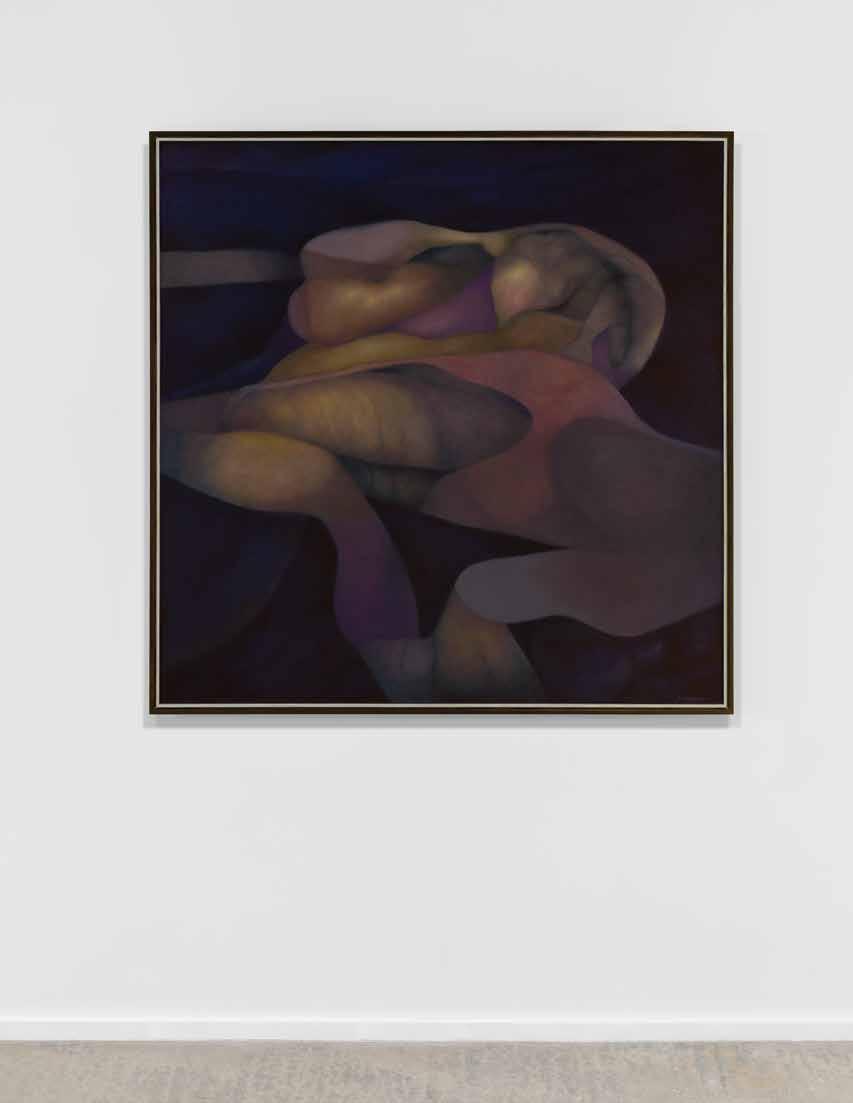

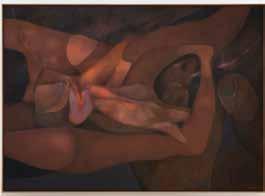

Espejismos de Agua (Water Mirages), 1990, is one of the largest canvases Soriano painted. A horizontal work, its very dark background is blue and purple, while the foreground and middle ground contain forms that seem fragments of torsos, coral reefs, or enormous bones. These range in color from delicate, pale violets and blues to matte beige and grays. The forms are moving, pushing, and pulling on the pictorial surface. Parts of the forms become transparent, allowing the other forms behind to be seen, therefore creating the illusion of a vast body of water moving. Water is the main constituent of the earth’s hydrosphere, the most vital element of all known forms of life. It is also the seas, which human, and animal life traverse to escape, to somewhere else. It is also mystery and danger, where death is met. Soriano embodies all these possibilities in this enormous work, the enigma of life and its end. Sueño Guardado (Guarded Dream) of the following year, is another painting of considerable size. Its palette of browns, oranges, and ochres constructs shapes that suggest a cave, and figures laying and standing, and again a dark background surrounds these elements and pushes them to the foreground. Obviously, the title reminds us of the subconscious, but what is this dream guarding? Not knowing precisely helps to create the mystery of the work. Ave Inventando la Ausencia (Bird Inventing Absence), 1992, represents a large bird flying across the evening sky. The bird is not literally depicted, yet we can see its head, body and wings. Soriano subtly models the fowl in ochre, pink and blue tones. A shadowy form appears beneath the animal, seeming to disappear into the dark sky. In European art, birds can represent love and truthfulness, and specifically within Christian iconography, they can represent the soul. With his knowledge of art history as well as spiritual and mystical concerns, Soriano was very aware of these meanings, which fed pictures like

this one. The mention of inventing absence in the title, adds another dimension calling to mind loss, farewell, and even exile.

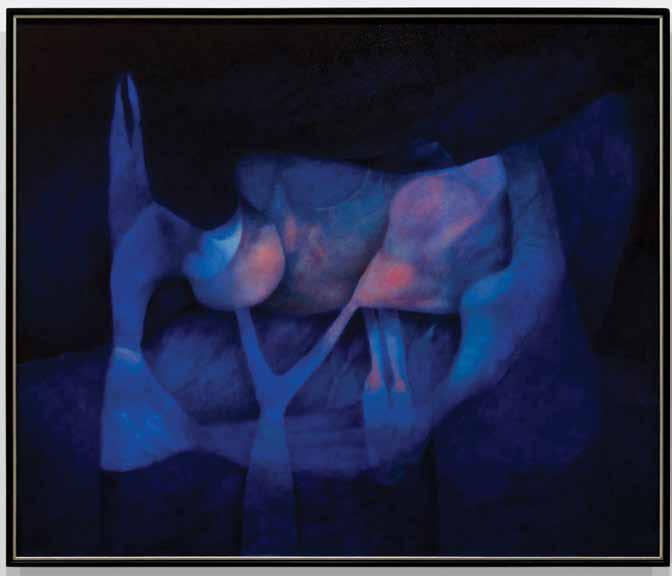

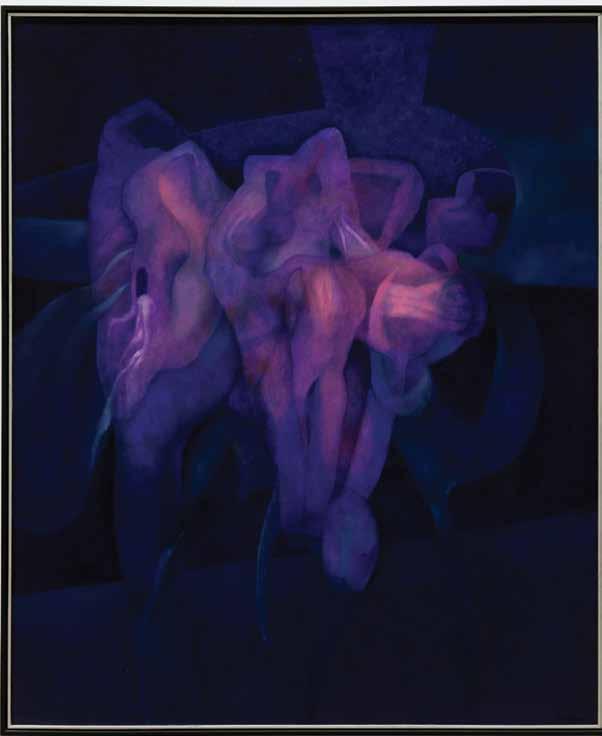

Recondita armonía (Hidden Harmony) and Umbral de la noche (Threshold of the Night) are both canvases of 1994 yet could not be more different in their color structures. Recondita armonía is a sober study of browns and ochres with minimal yet distinctive touches of pink and blue. The shapes remind us of fragments of a stone wall and of bodies, seemingly floating against darkness. Perhaps the harmony is the fusion of stone and flesh, or the tender bits of blue and pink. Umbral de la noche is an explosion of blue, mostly cerulean, with diaphanous touches of rose and pink. The elements that congeal into the central blue form seem pieces of landscape, plants, animals that have come together into a puzzling entity; a gate or entrance to the vast night beyond it. The totemic El vigía del estío (The Watchman of Summer), 1995, is a figure that is both animal and vegetable. Its soft palette of terra cotta, pink, yellow and ochre contrast with the solid, sculptural quality of the shapes. We see Soriano’s adaptation of the biomorphic figuration of surrealism into his own language; the mysterious is present without the conventional uncanny. The solid forms that create the body are not dense, but rather evoke agility, movement, as it inhabits the vertical canvas with its shamanistic presence.

All fourteen paintings in this exhibition have dark backgrounds as well as the range of Soriano’s palette with its blues and purples, pinks, and ochres. These are distinctive elements of his mature pictorial language, which he chooses to deepen and expand in his late work. He also continues to disrupt the conventional picture plane, creating an infinite space that projects the cosmos. Since 2011 Rafael Soriano’s paintings have been the subject of two major retrospectives (one which traveled nationally), and of a smaller exhibition focused on his pictures of heads. Why is he an artist that we keep rediscovering and seeing? And I write “seeing” because his art is not meant for the glance, for just looking; it demands the subtle and meditative act of seeing, where his paintings reveal themselves to the viewer in a thoughtful process. He is a magnificent painter’s painter who loved, worked, and expanded a tradition which encompasses Titian, Rembrandt, Zurbarán and Velázquez, Matta and Tamayo, Rothko and Szyszlo. These artists are masters of the craft of

painting, and go beyond it, applying their sheer pictorial force to exploring the metaphysical and spiritual dimensions. Soriano’s mature paintings, especially works of his last decade of production, affect the viewer slowly, obsessing and haunting us as they reveal themselves and we see. The splendid cosmic space that he constructs in his canvases provides the atmosphere where mystical forces manifest their presence. His forms convey a luminosity as if transfused with inner light.

Years ago, I wrote that his paintings were meditative moments which projected visionary journeys13 – he achieves this with a pictorial imagery that is neither illustrative nor literary. His is a visual vocabulary of allusive forms and complex, shifting colors. Soriano’s last paintings are reflections of profound sensations, and profound can signify both the eternal and mysterious: life, end of life, death, transcendence. Soriano’s pictorial universe confronts us with victories through struggles, offering us rescue and redemption.

Alejandro Anreus was born in Havana, Cuba in 1960. He and his family went into exile in 1970. He received his PhD in art history at the Graduate Center, CUNY. He was the curator at the Jersey City Museum from 1993 to 2001, and professor of art history and Latin American Studies at William Paterson University from 2001 to 2023. He is the author of seven books of art history, and more than 60 articles and catalogue essays. His articles have appeared in Art Journal, Third Text, Art Nexus, Encuentro de la Cultura Cubana and Commonweal. A poet in the Spanish language, he has published five books of poetry, all of them with covers and illustrations by Arturo Rodriguez. His book Havana in the 1940s. Artists, Critics and Exhibitions is forthcoming. In the fall of 2023 Dr. Anreus will be a Mellon fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery, Washington, DC.

Endnotes

1 Rafael Soriano in Ileana Fuentes-Pérez, et al, Outside Cuba. Contemporary Cuban Visual Artists, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University and The University of Miami, 1989), p. 186.

2 Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta, “The Heart That Lights from Inside: Rafael Soriano’s Struggle for his Artistic Vision,” in Rafael Soriano: The Artist as Mystic, ed. Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta, exhibition catalogue (Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2017), p. 22.

3 Hortensia and Milagros Soriano, questionnaire from the author, November 2015 (unpaginated). According to the artist’s widow, Milagros, Soriano ceased his involvement with the Rosicrucians by the time they were married, but there is no doubt that their mysticism influenced the painter’s work.

4 Ibid., The study trip was sponsored by the Cuban Ministry of Education of the Auténtico government of President Grau. Although Tamayo lived in New York City at the time, his work was regularly exhibited in Mexico.

5 Ibid., It is very possible that Soriano visited both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Museum of Modern Art, there is no evidence that he visited galleries and saw contemporary art.

6 Sandu Daríe, José Mijares, Luis Martínez Pedro, Soriano and others, would informally gather in the late 1950s and exhibit together as “concretos.” See Abigail McEwen, Revolutionary Horizons: Art and Polemics in 1950s Cuba (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016) and Beatriz Gago, ed. Más que 10 Concretos (Madrid: Fundación Arte Cubano, 2015).

7 Hortensia and Milagros Soriano, questionnaire from the author, November 2015 (unpaginated). Rafael Soriano arrived in Miami April 16, 1962. His wife, daughter and father-in-law arrived on May 22, 1962.

8 The most complete and in-depth discussions of Soriano’s life and work are Rafael Soriano: Other Worlds Within; A Sixty Year Retrospective, ed. Jesús Rosado, exhibition catalogue (Coral Gables: Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, 2011), and Rafael Soriano: The Artist as Mystic, ed. Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta (Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2017). The 2011 publication contains essays by Jesús Rosado, Paula Harper, and Alejandro Anreus; the 2017 publication has essays by Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta, Roberto Cobas Amate, Claude Cernuschi, Roberto Goizueta and Alejandro Anreus. An earlier publication is Ricardo Pau-Llosa’s monograph Rafael Soriano and the Poetics of Light (Coral Gables: Ediciones Habana Vieja, 1998).

9 The first generation consists of Víctor Manuel García, Antonio Gattorno, Eduardo Abela, Carlos Enríquez, Amelia Peláez, Fidelio Ponce, and others. Of these artists Ponce did not travel outside of Cuba. Generationally Wifredo Lam, the country’s leading surrealist, belongs with the first group, but he did not return to Cuba from Europe until the early 1940s. The leading figures of the second generation are René Portocarrero, Cundo Bermúdez, Mario Carreño and Mariano Rodríguez.

10 As noted earlier, there are the paintings of Fidelio Ponce, the urban New York landscapes of Daniel Serra-Badué, some pen and ink abstractions by Raúl Milián. Plenty of Cuban artists have depicted religious subjects, but this is not what I am referring to here, but rather the sensibility towards the mysterious, the other-worldly.

11 Metaphysical Painting entry, in The Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Art, Harold Osborne, ed. (Oxford, New York, Toronto, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 368. Savinio (1891-1952) was a poet and musician and brother of painter Giorgio de Chirico, the founding figure of metaphysical painting in Italy.

12 The German art historian A. E. Brickman was among the first to use this term in the 1920s, since then Julius Held contributed significantly to this concept in his studies of Rubens and Rembrandt. Theodor Adorno and Edward Said added substantial contributions in the fields of literature and music. Much has been written on Late Style/Old Age Style. An important recent contribution is Carel Blotkamp, The End: Artist’s Late and Last Works (London: Reaktion Books, 2019).

13 See my essay in the 2011 catalogue, “Rafael Soriano: A Painter’s Painter,” pp. 12-14.

PLATES

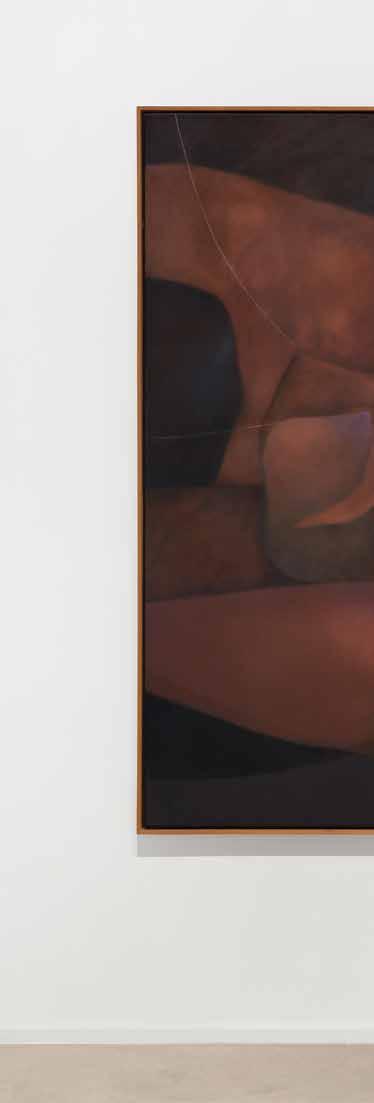

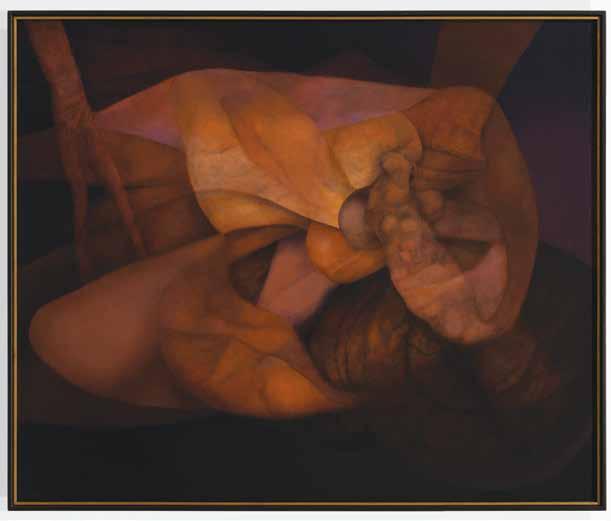

Guarded Dream (Sueño guardado), 1991 oil on canvas, 68 x 96 inches

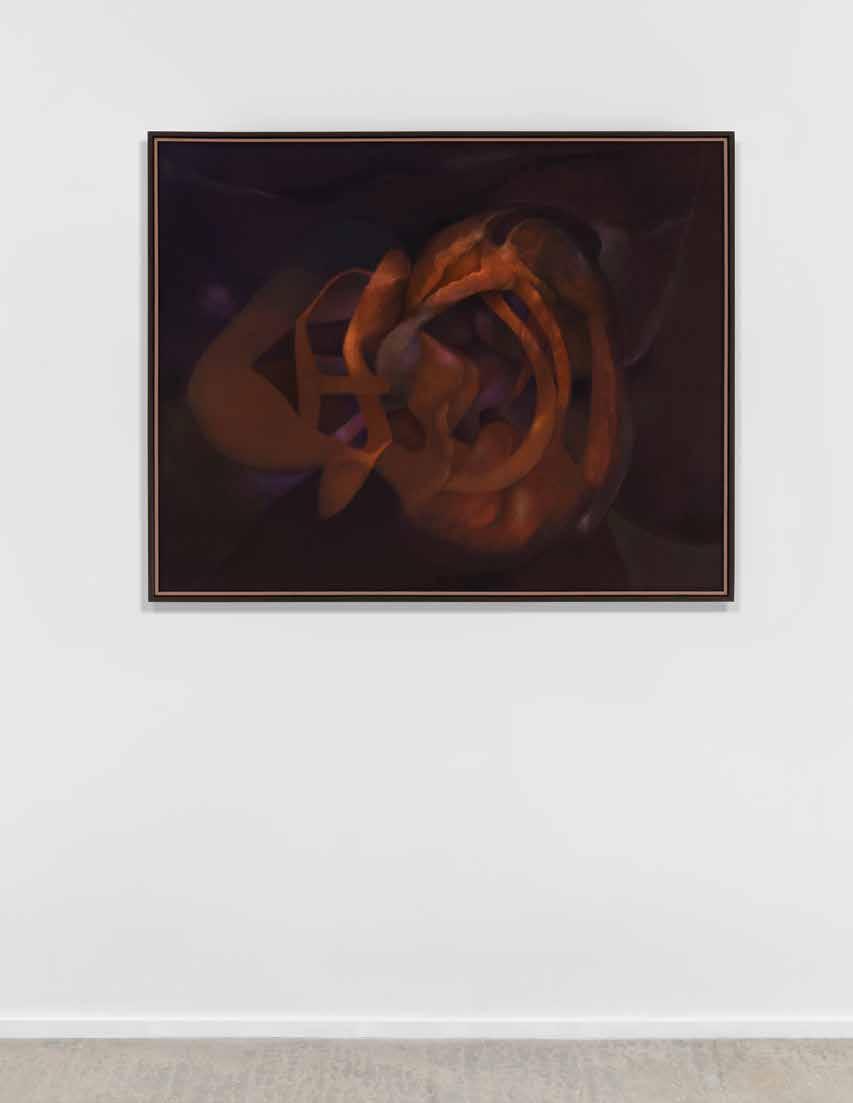

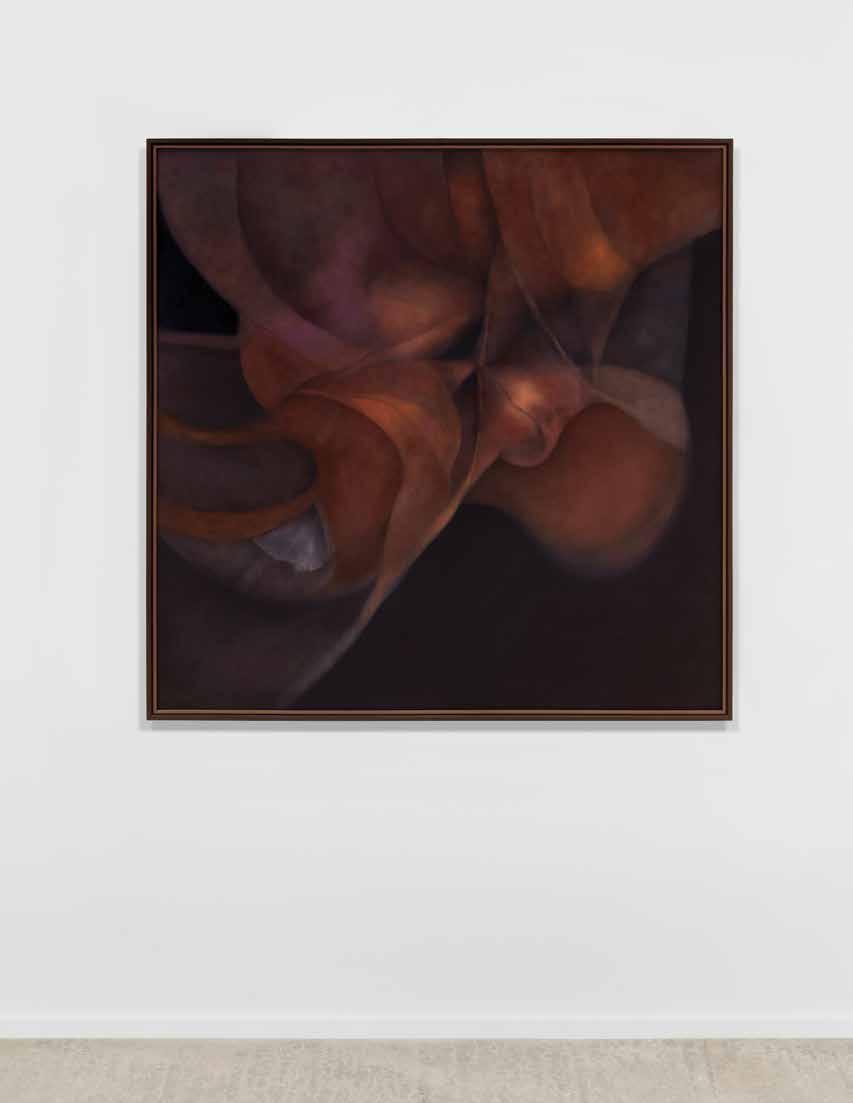

Forma en expansión (Expanding Form), 1994, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

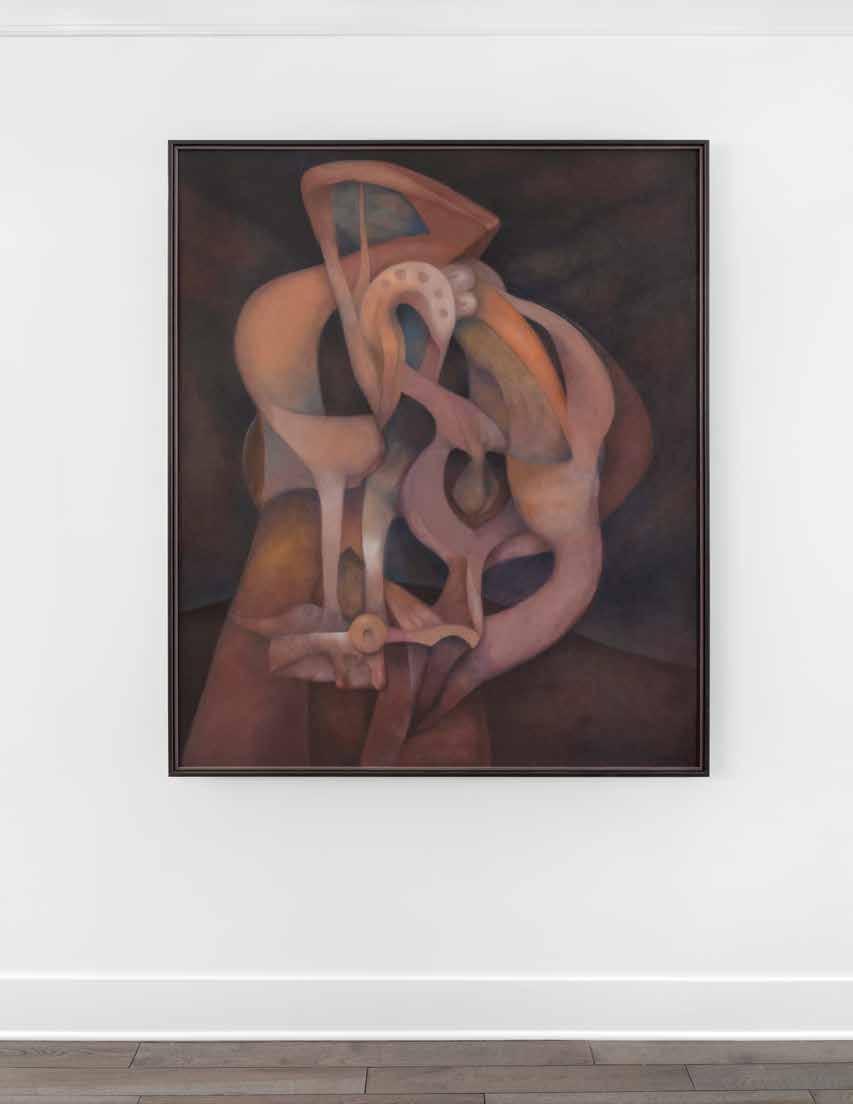

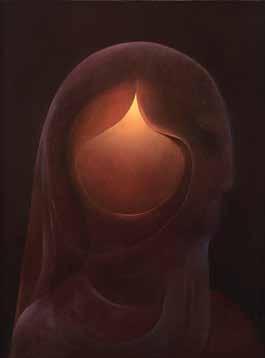

La identidad del silencio (Identity of Silence), 1995, oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Opposite page |

Umbral de la noche (Threshold of the Night), 1993, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

El hechizo de la noche (Enchantment of Night), 1990, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

El candor del estío (Candor of Summer), 1990, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches

Espejismos de agua (Water Mirages), 1990 oil on canvas, 68 x 98 inches

Inefable quimera (Ineffable Chimera), 1993, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches

Opposite page |

Untitled, c. 1990s, pastel on paper, 22 x 30 inches

Cautiva ternura (Captive Tenderness), 1997, oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

El vigía del estío (The Watchman of Summer), 1995, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches

Untitled, c. 1990s, mixed media on paper, 22 x 30 inches

Opposite page |

Preludio de un eclipse (Prelude to an Eclipse), 1996, oil on canvas, 54 x 50 inches

Opposite page |

Umbral del otoño (Dawn of Autumn), 1991, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

Languidez (Languor), 1995, oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches

Dimensión nocturna (Nocturnal Dimension), 1994, oil on canvas, 40 x 40 inches

Opposite page |

La fuga de la soledad (Escape from Loneliness), 1997, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches

Ave inventando la ausencia (Bird Inventing Absence), 1992 oil on canvas, 68 x 98 inches

Opposite page |

Monumento al crepúsculo (Monument to Twilight), 1996, oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches

Barca de fantasía (Fantasy Boat), 1997, oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches

Jirones de la noche (Fragments of Night), 1996, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches

Opposite page |

Crisálidas del alba (Chrysalis of Dawn), 1994, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches

Cadencia nocturna (Night Cadence), 1999, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches

page |

El Ilusionista (The Illusionist), 1995, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

Opposite

Mágico encuentro II (Magical Encounter II), 1995, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

Opposite page |

Untitled, c. 1990s, charcoal on paper, 22 x 30 inches

Visión sobre el peñasco (View Over the Cliff), 1994, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches

Opposite page |

Recóndita armonía (Hidden Harmony), 1994, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

Forma ondulante (Undulating Shape), 1993, oil on canvas, 30 x 50 inches

Obelisco (Obelisk), 1996, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches

Rafael Soriano

A Life of Art

Chronology by Carol Damian, Ph.D.

Rafael Soriano was born in the small town of Cidra in the Province of Matanzas, Cuba, in 1920. From a humble family, he showed an early interest, and talent, in art and creativity, and his parents were supportive of his artistic inclinations. After the family moved to Matanzas, the young artist began with lessons in the private art academy of Spanish artist Alberto Tarascó and continued at the highly respected Academy of San Alejandro in Havana. Only 15 years of age, he quickly befriended avant-garde painters as he mastered the academic curriculum under its prestigious faculty. The first exhibition of his works took place in Matanzas in 1934 at the Ateneo de Matanzas Exposición de Pinturas, Dibujos y Caricaturas and featured drawings that were an early indication of a skill set that would prevail throughout his career, including work as a graphic designer during the early years of exile. After San Alejandro, he returned to Matanzas in 1941, where he helped found the School of Fine Arts in 1943 with other San Alejandro graduates. He served as a teacher and the director of the school until he left Cuba in 1962, influencing an entire generation with his unique and independent approach to painting that was vastly different from the accepted traditions of other island artists who were focused on figuration and naturalism descriptive of the Cuban landscape.1

THE 1940s

Soriano created his own spiritual and metaphysical style that was personal and subjective and inspired by Surrealism and

Rafael Soriano, Lyceum Exhibition, Havana, 1947, Exhibition Catalog Cover

La Emoción (Emotion), c.1948-9 oil on wood, 72 x 48 inches (182.9 x 121.9 cm) Dominic and Cristina Veloso Collection

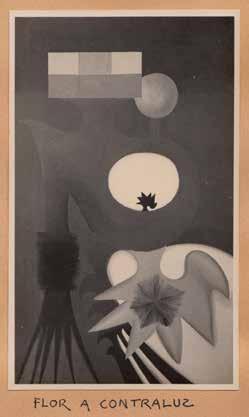

other spiritual movements (“the truth of his inner world and reality of his inner psyche”2) familiar to him and his colleagues. Among the many influences that informed his paintings of this period and his move in the direction of mysticism was Rosicrucianism, the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, from which is derived the acronym “AMORC.” In Cuba, a small group of followers studied the vast collection of knowledge and philosophical concepts expressed by the great thinkers of ancient Greece, India, and the Arab world to enrich their cultural and spiritual heritage.3 His interest in Rosicrucianism was more syncretic than devout, as was his version of Catholicism, which was a rare subject for his work, despite his devotion to the spiritual and transcendental. His first exhibition at the Lyceum in Havana in 1947 introduced his drawings and gouaches to the art community. Soon a focus on painting elevated his trajectory, evident immediately for its unique approach technically and conceptually. His first major painting, La Emoción (The Emotion), 1949, later known as Flor a contraluz (Flower Against the Light), exhibited at La Union in Matanzas, was already demonstrating an interest in light and soft brushwork describing abstract forms, very different from early drawings and paintings that were academically competent rather than the expression of a personal vision. A trip to Mexico in 1947 sponsored by the Cuban Ministry of Education and Culture introduced him to the muralists, and Siqueiros was particularly influential for the expressive quality of his work, as was Tamayo who inspired an interest in mythology and the cosmos. The presence of a group of Rosicrucians continued his interest in the mystical world, while the highly active group of Surrealists in Mexico also contributed to the development of a new approach to otherworldly subjects guided by his subconscious, rather than formal principles. Soriano’s work was already associated with

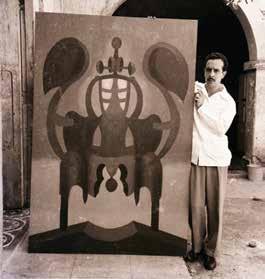

Rafael Soriano at his patio in Matanzas, with La Emoción, preparing for the 1950 exhibit at the Caseta del Parque Central, Havana

Flor a contraluz (Flower Against the Light), c.1949–50, oil on wood, 96 x 72 inches (243.8 x 182.9 cm)

Latin American Surrealism, often described in art and literature as “magical realism.” It differed from European Surrealism with its focus on the artist’s psychic reality. In Latin America, artists draw the viewer into a world beyond images, a cosmic environment “where the intimate and the cosmic converge.”4 By 1948, he finally breaks completely with a realistic approach to figuration to explore new methods of creating transcendental subjects. He became recognized as a “painter of metaphors” with the inclusion of watercolors in the exhibitions Historia del Traje (History of Fashion) in the Ateneo de Cárdenas (October 1948) and at the Colegio de Abogados (November 1948), both in Matanzas, that stood out for their ethereal qualities with flowers elevating nature to meaningful images expressive of his inner vision and imagination. This set him apart from the artists of the Havana School who had developed a tropical Cuban language of color as he continued to abstract to minimal geometric shapes. This was an indication of a time devoted to experimentation resulting in styles ranging from realistic to expressive to geometric abstraction – all of which will become fully developed in the following years.

THE 1950s

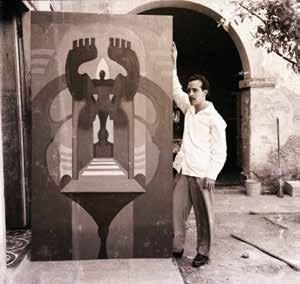

Rafael Soriano with Presencia mística (Mystical Presence), 1949-50

Presencia mistíca (Mystical Presence), c. 1949–50 oil on wood, 96 x 72 inches (243.8 x 182.9 cm)

Rafael Soriano at Palacio Nacional, Mexico, 1947

This is the last oil on wood, thought to be Construcción metafísica that is photographed in the July 1952 Boletín from the School of Fine Arts of Matanzas (La Escuela de Artes Plásticas de Matanzas). Soriano

V

Pintura,

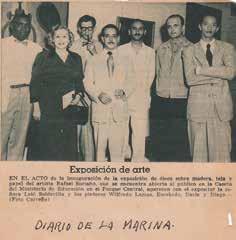

The 1950s saw significant developments in Soriano’s work as he moved away from the surreal to geometric abstraction, only one of the many innovative stylistic approaches influenced by the complex visual language of New York and Paris, led by the arrival of Hans Hofmann and the Action Painters. Always exploring and experimenting, Soriano became a key figure in the group Pintores Concretos with their promotion of a new aesthetic. An exhibit at the Caseta del Parque Central, Havana, in 1950 marked the first introduction of Soriano’s new move toward abstraction, with only remnants of past figuration evident. The chromatic intensity that would distinguish his future work is now apparent. By 1951, exhibitions in Havana and Matanzas saw the transformation to what has been described as “geometric construction metafísica,”5 perhaps inspired by the title of a major rigorously geometric oil on wood: Construción metafísica (Metaphysical Construction), 1951, exhibited at the Fifth Painting, Sculpture, and Printmaking National Salon held at the Asturian Center. His career received critical acclaim as a member of the 3rd Generation Vanguardia – a group of young artists intent on pursuing abstraction as the key element in their work. In 1952, he continued to travel from Matanzas to Havana where he exhibited with Grupo los Once and participated in a major solo exhibition at La Rampa in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana in 1954. The chromatic intensity coupled with geometric forms in Amanecer (Dawn), 1955, and Motivo del mar (Sea Motif), 1953, demonstrate that his work was approaching full maturity with a firm grasp of the tenets of abstraction while maintaining a personal, non-dogmatic vision. In the Galería

Photo at Parque Central Exhibition, Havana, 1950 Motivo del mar (Sea Motif), 1953, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches (91.4 x 121.9 cm), Rafael Soriano Family Collection

Construcción metafísica (Metaphysical Construction), early 1951, oil on wood, 72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm)

exhibited Construcción metafísica at the

Salón Nacional de

Escultura y Grabado, July - August 1951.

de Matanzas, he presided over an exhibition with a group of young painters and sculptors for the IV Exposición Anual de Obras de Profesores de la Escuela de Artes Plásticas de Matanzas (March 6, 1954) that established his artistic dominance. A solo exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Havana in September 1955 marked a pivotal year for Soriano as he moved beyond Cuba to exhibit in Mexico and Miami and participated in international fairs. His novel approach to the representation of his subjects was readily apparent in a mural painted for the Matanzas Adelante Newspaper offices in 1958 (it no longer survives). The figures were reduced to their most minimal and geometric, extremely “modern” for Cuba at the time. As the end of the decade approached and the anti-abstraction, anti-progressive dictates of the flailing Batista government threatened artistic independence, the rationalist, universalist attitudes of the young Vanguardia of concretos became a mark of rebellion.6 The seminal exhibition of the Grupo de Los diez pintores concretos in Havana, 1959, collided with the socio-political environment, a harbinger of things to come when artists were forced to comply with the directives of the dictatorship of Fidel Castro’s revolution of 1959.

THE 1960s

His last exhibitions in Cuba were with los diez pintores concretos, installed in Matanzas in the Biblioteca Publica “Ramon Guiteras” (January 9-16, 1960) and in what would be his final participation in his School of Plastic Arts, the Exposición Anual de Profesores y Graduados de la Escuela de Artes Plasticas de Matanzas (March 6, 1960). By May 1962, Soriano knew it was time to leave and a new chapter would begin in the decade of the 1960s. The trauma of displacement in the new cultural environment of Miami affected his work and its production stopped for two years (1962-1964). To support his family, he worked as a graphic designer and taught at the Catholic Welfare Bureau.

This was one of the first geometric paintings acquired after Hortensia Soriano started searching for this period of her father’s paintings.

Mural at Adelante Newspaper Offices, 1958 (it no longer survives)

Luciérnaga (Firefly), 1955 oil on canvas, 50 x 33 in. (127 x 83.8 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

Exhibition catalog cover of Rafael Soriano, Pinturas, a solo exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Havana, 1955

From 1967-1970 he was a Professor of Design and Composition in the Cuban Culture Program at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, continuing the academic and administrative skills he had established in Matanzas and with a new awareness of the local art scene, its artists, and institutions. With the realization that the family would not return to Cuba in the near future, Soriano painted at night and revived the trajectory of a personal visual language with light as a key element. More introspective, he abandoned the hard-edge geometric structures of previous works and moved toward figuration informed by spiritual expressionism. Described as saturated with color and light in a style called “oneiric luminism,”7 the paintings feature phantasmagoric imagery marked by a return to surreal overtones that now suited his aesthetic direction more than the geometric and may have been a product of the times. Soriano was exposed to the popularity of science fiction and space travel of the era, which was influential to the creation of his alien-like images emerging from the darkness of the void and titles referring to galactic travel such as Galaxia (Galaxy), 1968. In El profeta (The Prophet), 1969, the flame of mysticism subsumes all effects from reality and will become stronger as time progresses.

The 1960s were pivotal for Soriano. Concerned for his future and that of his wife and daughter

Catalog cover, los diez pintores concretos, 1960

Galaxia (Galaxy), 1968 oil on canvas, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm) Zelaya Rodríguez Collection

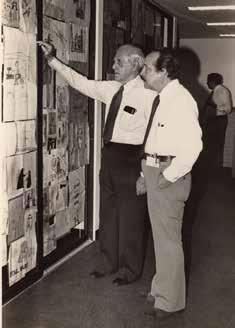

Photo of Rafael Soriano as Graphic Designer, Miami, FL

Ventana cósmica (Cosmic Window), 1966 oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

and adjusting to a different path to produce art in Miami, it was a relatively slow period for an artist accustomed to considerable attention to his work and his professional career. Solo exhibits at the Bacardi Art Gallery and the Pan American Bank in downtown Miami served as an introduction to the public to a new master in its midst and he was quickly included in group shows that traveled to other cities in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and New York, and outside of the United States to the Netherlands and Guatemala. Soon, the significance and quality of his work were recognized with awards, honors, and invitations to prestigious American art venues. Although the 60s saw some of the most noteworthy developments and upheavals in the production of art in Europe and New York, with Abstract Expressionism still dominating the world scene and Surrealism maintaining its role in revealing subjective expressive content, Soriano stayed true to his vision during this period of adjustment. Having abandoned Geometric Abstraction for his expressive techniques, he chose not to follow the bold spontaneity of the New York School represented by Jackson Pollack, Wilhelm de Kooning, Rauschenberg, and others, and focused on color for his creative process, closer to the work of Mark Rothko.

THE 1970s

The decade of the 1970s may be considered the period of full maturity for the artist, with his total dedication to paintings imbued with his unique biomorphic and luminous imagery now recognized as quintessential Soriano. In the United States, the 70s featured eclectic and quite individual paintings, and Soriano maintained his focus on creating works that were distinctly his own, unencumbered by the trends. His works featured a darker, richer palette and deep space for floating ephemeral shapes and created a mysterious atmosphere that is one of organic simplicity. This is particularly evident in a series of works that begins in the late 1960s and continues into the 1990s called Cabezas (Heads). The repetition of the head motif throughout his various stylistic explorations over the years traces the image from its most geometric and

El profeta, (The Prophet), 1969 oil on paper, 40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

El collar mágico (The Magic Necklace), 1970 oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

solid to its most elusive; from Cabeza de una reina mistica (Head of a Mystical Queen), 1967, to Cabeza hechizada (Bewitched Head), 1994, that are especially expressive and emotional.8 In the 1970s, the Cabezas appeared in a uniquely spiritual and Catholic subject: La Virgen (The Virgin), 1974, marking the tendency toward natural simplicity and muted tonalities. The works have come to exemplify Soriano’s method of applying layers of pigment for velvety effects that will last well into the future. It is his version of “neosurrealism” with light as the most important factor to illuminate and dramatize the mysteries within each composition as it enhances the reality of a fantasy. Just as Surrealism used imaginative and innovative methods to express a new reality of the mind, Soriano revised its tenets to serve his own aesthetic and stylistic purposes.

His work was included in over 70 group exhibitions, from galleries and banks to museums and annual events in Miami and beyond. Noted among the many notable venues was his participation in Arte Actual de Iberoamerica , Instituto de Cultura Hispanica, Centro Cultural Villa de Madrid, Spain (1977); Contemporary Latin American Art, the Esso Collection of the Lowe Art Museum , University of Miami (1978); Hispanic-American Artists of the United States , Museum of Modern Art of Latin America, Organization of American States, OAS, Washington, DC (1978).

THE 1980s

The decade of the 1980s establishes a total mastery of a painting technique that reveals attention to spatial constructs in which only mere allusions to figures, landscapes, the mysterious terrain of the mind, and the cosmos appear. Forms are created out of light with its shifting and fluid hold on diaphanous colors and the bare remnants of shapes and forms. The luminous works produced during this

La virgen (The Virgin), 1974 oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

Cabeza (Head), 1977 oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm) Zelaya Rodriguez Collection

time continued his interest in the transcendent and the mystical as inspiration. The works were stunning and evocative, inviting the viewer to share in the mysteries they held within the distinctive application of paint that had become his trademark. As his reputation and popularity grew, Soriano was included in numerous exhibitions in Miami and the United States, participated in the IV Bienal de Arte de Medellin Galería with work in the Museo de Arte de Antioquía, Medellín, Colombia (1981), and in the same year, the V Bienal Iberoamericana de Arte, Instituto Cultural Domecq, México, DF and in other international venues in México, El Salvador, Switzerland, and Italy. In 1981, the painting, Nave flotante (Floating Ship), 1979, was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art of Latin America, OAS, Washington, DC. Several traveling exhibitions validated Soriano’s recognition as an artist of note as the invitations continued for the next ten years. One significant and groundbreaking exhibition for Cuban artists in the United States was Outside Cuba/Fuera de Cuba, showcasing five generations of contemporary Cuban visual artists responding to the new circumstances and artistic conditions after their exodus from the island. It opened at the Zimmerli Art Museum of Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (1987) and embarked on a national tour until April 1989 which brought it to the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art (MoCHA), New York City; the Art Museum, Miami University, Oxford, OH; Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico; the Center for the Fine Arts, Miami and the College of Fine Arts, Atlanta, GA. In 1989, Mira! Canadian Club Hispanic Art Tour, III, opened at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery) followed by a National Tour that included the Meadows Museum, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX; Bass Museum of Art, Miami Beach, FL; Terra Museum of Art, Chicago, IL; and Museo del Barrio, New York, NY; That same year, he won First Prize with

Rafael Soriano painting Flotando el astral, 1981

Catalog cover, Fuera de Cuba (Outside Cuba), 1987

Nave flotante (Floating Ship), 1979 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm) Collection OAS Art Museum of the Americas

a painting titled, The Liturgy of Silence in the exhibition, Expresiones Hispanicas, The Coors National Hispanic Art Exhibit & Tour, which opened at the Mexican Cultural Institute, San Antonio and traveled to Southwest Museum, Los Angeles; Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities Arvada, CO; Triton Museum of Art, Santa Clara, CA; Millicent Rogers Museum, Taos, NM; and Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, FL.

This remarkable exposure and recognition over a short ten-year period kept the already prolific artist occupied as he created drawings and paintings to respond to the demand for his work. He had established a style that was uniquely his own.

THE 1990s

At the age of 70, Soriano continued to paint, but the challenges of illness and time led to what may be described as a “late style” often encumbered by foreboding images and dominated by a dark background. His biomorphic shapes turn inward, struggling for an existence that reveals a mood of solitude and introspection. They writhe in space as if searching for breath in the confines of the night. They are also ethereal, in constant movement, appearing and disappearing

into the shadows. These are some of his most dramatic and powerful images – fitting for a master artist who has perfected his style and can rest on his accomplishments. However, Soriano continued to work and exhibit and receive numerous awards for the rest of his long life.

In 1995, an important retrospective exhibition was presented at the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale: Rafael Soriano: Light’s Way. He continued to be included in group exhibitions in Miami and beyond, including the international Tour of Latin American Masters III that traveled to Galería Tomás Andreu, Santiago, Chile; Museo Pedro de Osma, Lima, Perú; Galería Gary Nader, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; and Museo de las Américas, San Juan, Puerto Rico (1996); Latin American Artists , that originated in East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, (1997), and traveled extensively. His work was featured in Breaking the Barriers: Selections from the Museum of Art’s Permanent Collection , Museum

Naturaleza onírica (Oneiric Life), 1991 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

Naturaleza onírica (Oneiric Life), 1991 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm)

Rafael Soriano Family Collection

of Art, Fort Lauderdale (1997), among many others in galleries, art fairs, and biennials.

THE YEARS 2000-2020

Into the 21st century, there were key events and exhibitions during the last years of his life and after his passing in 2015. Among his most important accomplishments was recognition by city proclamations. In 2008, he was presented the Key to the City of Doral, FL during the exhibition, Rafael Soriano: The Mystic and Spiritual, Miami Dade College, West Campus, Miami, FL. In 2008, he also received proclamations from Miami Mayor, Tomas Regalado, Doral Mayor, Juan Carlos Bermúdez, and Hialeah Mayor, Julio Robaina.

Group exhibitions continued well until the time of his passing in 2015. In 2001, Cuban and Cuban-American Art, Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL. América Fría, Geometric Abstraction in Latin America, at the Fundación Juan March, Madrid, Spain (2011), followed by Rafael Soriano | Other Worlds Within, A Sixty Year Retrospective at the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL; Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC (2013) with a national Tour (October 2013-May 2016) beginning in Miami at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum; Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA; Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, Utah, and the Arkansas Art Center.

In 2014, he was presented with the Cintas Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award in Miami, FL.

Exhibits in 2015 included Concrete Cuba, David Zwirner Gallery, London, England; Streams of Being: Selections from The Art Museum of The Americas, The Art Gallery, University of Maryland, College Park, MD; Pan American Modernism, Avant-Garde Art in Latin America and the United States, Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL. Recognition continued in numerous gallery and museum exhibitions. Between the Real and the Imagined: Abstract Art from Cintas Fellows, Coral Gables Art Museum, Coral Gables, FL (2017); Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art since 1950, Museum of Fine Arts of Houston (MFAH), Houston, TX. A major exhibition honored him in death in 2017: The Artist as Mystic at the McMullen Museum, Boston College, Boston, MA is an important summation of a long and prolific career. Among the most recent and most prestigious exhibits, Rafael Soriano: Cabezas (Heads) was presented at the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora, Miami, FL (2019-20) and traveled to the Art Museum of the Americas (AMA), Washington, D.C. During the exhibition Rafael Soriano: Cabezas (Heads), at the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora, Miami Mayor, Xavier Suarez, declared December 1st as “Rafael Soriano Day” in Miami, FL, and Coral Gables, Vice Mayor, Vicente Lago, declared

December 1st as “Rafael Soriano Day” in Coral Gables, FL.

Currently, an exhibition at the Casa de Americas in Madrid is in the planning stages for 2023.

Rafael Soriano passed away on April 9, 2015, in Miami, FL.

Although he is gone, he is not forgotten, and his work is still included in group exhibitions, catalog references, auctions, and other events. A catalog raisonné of his work is presently in production. It will document the career of a dedicated artist who created over 1200 paintings, prints, drawings, pastels, and watercolors, and will long be recognized as one of the great masters of Cuban and Cuban American art.

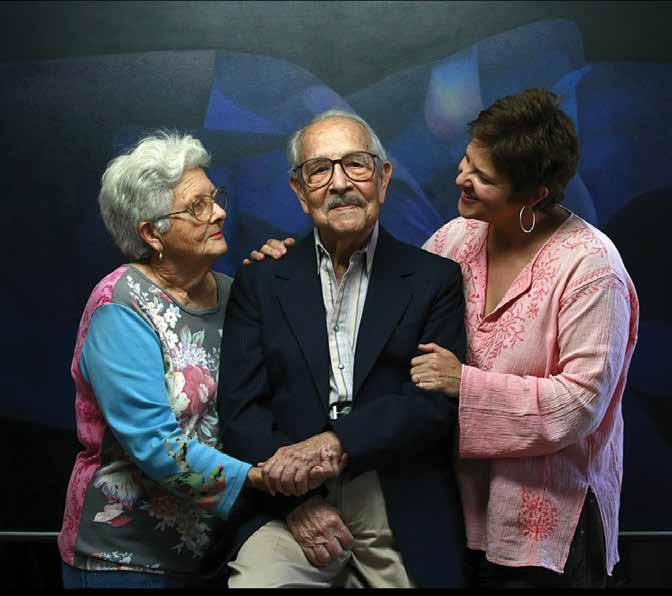

Rafael Soriano, 2011

Photo by Pedro Portal

Carol Damian, Ph.D., Art Historian, Professor of Art History and former Director and Chief Curator of the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum at FIU. A specialist in the Art of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Endnotes

1 Biographical and archival information kindly shared by the Soriano Foundation, Miami, September 2022.

2 Rafael Soriano, quoted in Rafael Soriano Exposición, Exhibition Catalogue, Colegio de Abogados, Matanzas, January 1947.

³ https://www.rosicrucian.org/

4 Roberto Goizueta, “Where the Intimate and the Cosmic Converge: Art as Icon” in Rafael Soriano | The Artist as Mystic, Exhibition Catalog (English/Spanish). McMullen Museum (Boston: Boston College, 2017), 81.

5 Roberto Cobas Amate. “Rafael Soriano: Invention and Drama,” Ibid., 3. For a discussion of the metaphysical presence in Soriano’s work in the 1950s, see also Abigail McEwen, “Rafael Soriano: 1950s.” unpublished essay, August 2022.

6 Alejandro Anreus, “Rafael Soriano and His Generation: Exile and Transcendence,” in Rafael Soriano | The Artist as Mystic, 75.

7 Ricardo Pau-Llosa, Rafael Soriano and The Poetics of Light. (Coral Gables: Ediciones Habana Vieja, 1998).

8 For a discussion of the series, see Rafael Soriano: Cabezas (Heads), exhibition catalog (New Jersey: William Paterson University Galleries, William Paterson University, January 28-May 8, 2019).

Bibliography

Anreus, Alejandro. “Las Cabezas (Heads),” in Rafael Soriano: Cabezas (Heads). Exhibition Catalog. William Patterson University Galleries, William Patterson University, New Jersey, 2019.

Pau-Llosa, Ricardo. Rafael Soriano and the Poetics of Light. Coral Gables: Ediciones Habana Vieja (English/Spanish) edition, 1998.

Rosada, Jesus. Rafael Soriano | Other Worlds Within, A Sixty Year Retrospective. Exhibition Catalogue (English/Spanish). Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, 2011. Essays by Alejandro Anreus, Ph.D., Paula Harper, Ph.D., and Jesus Rosado. January 29- March 27, 2011.

Thompson-Goizueta, Elizabeth, ed. Rafael Soriano | The Artist as Mystic. Exhibition Catalog (English/Spanish). McMullen Museum, Boston College, Boston, MA, 2017. Essays by Roberto Cobas Amate, Claude Cernuschi, Ph.D., Roberto Goizueta, Ph.D., Alejandro Anreus, Ph.D., and Elizabeth Goizueta.

Sueño guardado (Guarded Dream), 1991 oil on canvas, 68 x 96 inches | 172.7 x 243.8 cm

Forma en expansión (Expanding Form), 1994 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches | 127 x 152.4 cm

La identidad del silencio (Identity of Silence), 1995 oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches | 127 x 127 cm

Umbral de la noche (Threshold of the Night), 1993 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches | 127 x 152.4 cm

El hechizo de la noche (Enchantment of Night), 1990 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches | 127 x 152.4 cm

El candor del estío (Candor of Summer), 1990 oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches | 152.4 x 127 cm

Espejismos de agua (Water Mirages), 1990 oil on canvas, 68 x 98 inches | 172.7 cm x 248.9 cm

Inefable quimera (Ineffable Chimera), 1993 oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches | 101.6 x 127 cm

Untitled, c. 1990s, pastel on paper 22 x 30 inches | 55.9 x 76.2 cm

Cautiva ternura (Captive Tenderness), 1997 oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches | 127 x 127 cm

El vigía del estío (The Watchman of Summer), 1995 oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches | 152.4 x 127 cm

Untitled, c. 1990s, mixed media on paper 22 x 30 inches | 55.9 x 76.2 cm

Preludio de un eclipse (Prelude to an Eclipse), 1996 oil on canvas, 54 x 50 inches | 137.2 x 127 cm

Umbral del otoño (Dawn of Autumn), 1991 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches| 127 x 152.4 cm

Languidez (Languor), 1995 oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches | 127 x 127 cm

LIST OF WORKS

Dimensión nocturna (Nocturnal Dimension), 1994 oil on canvas, 40 x 40 inches | 101.6 x 101.6 cm

La fuga de la soledad (Escape from Loneliness), 1997, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches

Ave inventando la ausencia (Bird Inventing Absence), 1992, oil on canvas, 68 x 98 inches | 172.7 cm x 248.9 cm

Monumento al crepúsculo (Monument to Twilight), 1996, oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches | 91.4 x 91.4 cm

Barca de fantasía (Fantasy Boat), 1997 oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches | 127 x 101.6 cm

Jirones de la noche (Fragments of Night), 1996 oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches | 101.6 x 127 cm

Crisálidas del alba (Chrysalis of Dawn), 1994 oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches | 152.4 x 127 cm

Cadencia nocturna (Night Cadence), 1999 oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches | 76.2 x 101.6 cm

El Ilusionista (The Illusionist), 1995 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches | 127 x 152.4 cm

Mágico encuentro II (Magical Encounter II), 1995 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches | 127 x 152.4 cm

Untitled, c. 1990s, charcoal on paper 22 x 30 inches | 55.9 x 76.2 cm

Visión sobre el peñasco (View Over the Cliff), 1994 oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches | 76.2 x 101.6 cm

Recóndita armonía (Hidden Harmony), 1994 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches | 127 x 152.4 cm

Forma ondulante (Undulating Shape), 1993 oil on canvas, 30 x 50 inches | 76.2 x 127 cm

Obelisco (Obelisk), 1996, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches | 91.4 x 121.9 cm

LnS GALLERY

would like to thank:

Hortensia Soriano

Lisa Faquin

The Rafael Soriano Foundation

Alejandro Anreus

Carol Damian

Richard Blanco

Sofia Guerra

Estefania Escobar

Zachary Balber

Michelle and Joel Rodríguez

Bellak Color

Manny Fernandez

Alex Amador

David Fique

Raiman Rodríguez

rafael soriano | Transcendentalism, Distilled

catalogue essay | Alejandro Anreus, Ph.D.

chronology | Carol Damian, Ph.D.

poem | Richard Blanco

graphic design | Luisa Lignarolo

artwork photography | Zachary Balber

archive photos | Courtesy of the Rafael Soriano Foundation

editorial consultant | Sofia Guerra

printing | Bellak Color

exhibition dates | December 2, 2022 - January 28, 2023

isbn | 978-1-7346065-8-4

publication copyright 2022 | LnS GALLERY

LNS GALLERY

2610 SW 28th Lane | Miami, FL 33133

+1 305 781 6164

WWW.LNSGALLERY.COM INFO@LNSGALLERY.COM

Dedicated in Loving Memory of Milagors Soriano

Milagros, Rafael, and Hortensia Soriano