jer o nimo villa

22 nov11 jan

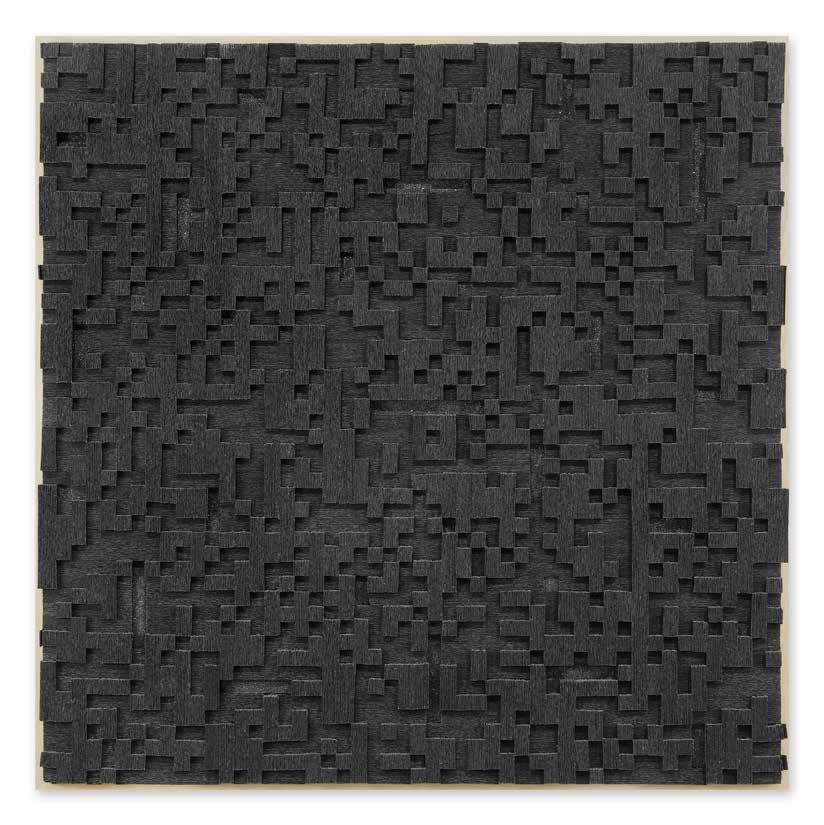

Entroque Op. 06

(Opus Junction 06), 2024, sandpaper and wood, 54 x 42 ½ inches, 137 x 108 cm.

moksha

Debuting his first solo exhibition at LnS Gallery, Jerónimo Villa invites us to explore Moksha , a deeply introspective series inaugurating on November 22, 2024. Rooted in the Hindu concept of spiritual liberation, this profound exhibition guides visitors on a journey of self-reflection, with each work representing a facet of the universal quest for balance, transcendence, and inner peace.

Villa’s choice of materials, including wood and sandpaper, underscores the raw yet meditative quality of his compositions. These works reveal an intricate interplay of dualities—life and death, fragility and strength—rendered through abstraction to capture the essence of spirituality.

Drawing inspiration from music and Eastern philosophies, Villa imbues his art with a rhythm and sensitivity to light that invites continuous discovery. Each shift in perspective unveils new dimensions, urging viewers to delve into the intricate layers of his compositions and engage with themes that resonate deeply with the soul.

We welcome you to Moksha , where material and space are redefined, transcending boundaries and creating a sanctuary for contemplation and spiritual exploration.

MOKSHA by Christian Padilla

Since the late 1940s and early 1950s, there has been talk of Rothko’s work having the power to evoke a religious experience in viewers, a curious assertion supported by the emotional reaction, sometimes tears, of those encountering his abstract forms. But if it's possible to feel melancholy, sadness, or joy when listening to music, which is even more abstract and ethereal, why not when viewing a painting with no recognizable figures? Rothko is just one of many examples of seeking spirituality through the images of intuition—like the ancient oracles, preHispanic American art, Byzantine art, or African tribal art—created from expressions of ecstasy and spirituality rather than representation. While today we may think that art and religion have always been linked by narrating stories through naturalism, historian Wilhelm Worringer warned in 1908 that this Western notion represents only a small fraction of humanity’s history, compared to thousands of years when divinity took the form of abstract images across hundreds of civilizations. Ironically, this narrow view of art became the doctrine. However, expressing the divine continues in our time, and perhaps we find a good answer to why abstraction remains relevant in contemporary art in Barnett Newman's words:

"The painter is concerned...with the presentation of mystery in the world. His imagination, therefore, tries to dig into metaphysical secrets. To that extent, his art is concerned with the sublime. It is religious art that, through symbols, captures the fundamental truth of life."

Jerónimo Villa is the heir of a legacy of abstract

Desde finales de los años cuarenta e inicios de los años cincuenta se hablaba de la capacidad que tenía la obra de Rothko de producir en los espectadores una experiencia religiosa, una curiosa aseveración sustentada en la reacción conmovida y emotiva, a veces con llanto, de algunas personas frente a sus formas abstractas . Pero si es posible reaccionar con melancolía, tristeza o alegría frente a la música, que es aún más abstracta y etérea, por qué no frente a una pintura sin figuras reconocibles. Rothko es solo uno de los numerosos ejemplos de la búsqueda de la espiritualidad a través de las imágenes de la intuición, como los antiguos oráculos, el arte americano prehispánico, el arte bizantino o el arte tribal africano, creadas desde las manifestaciones del éxtasis y la espiritualidad, y no desde la representación. Aunque hoy creamos que el arte y la religión siempre han estado ligados por la forma de narrar historias a partir del naturalismo, el historiador Wilhelm Worringer advertía en 1908 que esa noción occidental es solo una parte mínima de la historia de la humanidad comparada con miles de años en que lo divino ha tomado forma de imágenes abstractas en cientos de civilizaciones alrededor del mundo . Irónicamente, esta mínima visión del arte se convirtió en el dogma. Sin embargo, la expresión de lo divino se prolonga a nuestro tiempo, y tal vez tenga una buena respuesta al porqué de su proceder abstracto en el arte contemporáneo en las palabras de Barnett Newman:

“The painter is concerned . . . with the presentation into the world mystery. His imagination is therefore attempting to dig into metaphysical secrets. To that extent, his art is concerned with the sublime. It is a religious art which through symbols will catch the basic truth of life.”

artists in Colombia who have addressed these metaphysical and existential questions through order and geometry, like Edgar Negret, Carlos Rojas, and Danilo Dueñas. At the same time, his language and search align with the innovative perspectives of contemporary artists like Bill Viola, Shirin Neshat, or James Turrell, who extend these concerns into the 21st century through diverse perspectives and mediums. Villa turns to abstraction because the concepts he wants to address and the things he seeks to express in his work lack defined physical forms, and only through that language, which ends up appearing abstract, can he symbolically bring these complex ideas to life. This approach is similar to Kandinsky or John Cage, a comparison that is not arbitrary if one considers that Villa's initial training was in music. Thus, instead of representation, realism, or expressionism, Villa is closer to the descriptions of sound concepts that may have an equivalent in the visual arts (rhythm, repetition, canon, silences). Kandinsky and Cage broke down traditional music methods to bring sound closer to concerns that existing systems could not express, such as synesthesia, jazz, and spirituality (in Kandinsky), or Eastern philosophies and Zen Buddhism (in Cage). Villa embraces both visions, transforming them into an intimate and original body of work.

This comparison, moving from the musical to the visual, is pertinent not only due to Villa’s background in visual production but also because of the mathematical rhythm, geometry, and compositional method: the planes and sketches composed as complex instructions, like scores, and sometimes even the titles of his pieces. Music surrounds and defines his work. Jerónimo Villa’s obsession with giving physical form to the indefinable stems from his questioning of how religions have tried to create images of a common concept: the creation of an afterlife. What is, for some, the image of a sacred space floating among the clouds, is

Jerónimo Villa es heredero de una saga de artistas abstractos que en Colombia han abordado aquellas preguntas metafísicas y existenciales a través del orden y la geometría, como Edgar Negret, Carlos Rojas y Danilo Dueñas. Pero a la vez, su lenguaje y búsqueda se alinea con la novedosa mirada de artistas contemporáneos, que como Bill Viola, Shirin Neshat o James Turrell, amplían estas preocupaciones al siglo XXI desde ópticas y medios diversos. Villa acude a la abstracción porque los conceptos que quiere abordar y las cosas que quiere decir en su obra carecen de formas físicas definidas y solo a través de aquel lenguaje, que termina siendo en apariencia abstracto, puede simbólicamente darle vida a esas complejas ideas. De esta forma se aproxima Kandinsky o John Cage, una comparación que no es caprichosa si se tiene presente que la formación inicial de Villa proviene de la música, y que por tanto, en vez de la representación, el realismo o el expresionismo, el artista está más próximo a aquellas descripciones de conceptos sonoros que pueden tener equivalencia en las artes visuales (el ritmo, la repetición, el canon, los silencios). Kandinsky y Cage desintegraron las maneras tradicionales de la música para acercar el sonido a preocupaciones que los sistemas vigentes no podían expresar como la sinestesia, el jazz y la espiritualidad (en Kandinsky), o las filosofías orientales y el budismo zen (en Cage). Villa acoge ambas visiones y las transforma en un trabajo íntimo y original.

Esta comparación que nos traslada de lo musical a lo visual se hace pertinente no solo por la educación que precede la producción visual de Villa, pero además, por el ritmo matemático, la geometría y su método compositivo: los planos y bocetos compuestos a manera de complejas instrucciones como partituras, y a veces los nombres de sus piezas. La música rodea y define su obra.

La obsesión de Jerónimo Villa por darle forma física a lo indefinible proviene de su cuestionamiento por la manera en que las religiones se han esforzado en crear imaginarios sobre un aspecto común: la creación de un supuesto del más allá. Lo que para unos es el

better revealed to others through words and oral transmission. All cultures have sought to leave behind a system of representation that embodies their dogmas and precepts, even when dealing with ethereal, shapeless, or immaterial topics. There are as many religions as there are ways to seek an understanding of life, human destiny, and death. Villa's search for a personal sense and representation system for these existential reflections drives him to create his visual universe, one detached from and resistant to organized religions (particularly Western notions of guilt, sin, and condemnation) but deeply aligned with the poetry of Eastern beliefs. After a life journey that has led him to study all these perspectives, Villa concluded that the one best representing and aligning with his vision is Moksha, a Sanskrit term from Hinduism that refers to spiritual liberation. The term also appeals to the artist for its musicality: both for the phonetic sound of the word and because this liberation it refers to culminates in the cessation of all activity, in silence (another reference to John Cage).

What makes the representation of spirituality in art important? Kandinsky explored this need of the individual to feel ecstatic before a work of art in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, proposing a response regarding the significance of art in relation to the soul:

"These two kinds of similarities between new art and forms from past stages are radically different. The first is external and, therefore, has no future. The second is spiritual and thus carries within itself the seed of the future...The artist has a complex, subtle life, and the work that arises from him will necessarily produce, in an audience capable of feeling them, emotions so nuanced that words cannot express them...All these genuinely artistic forms serve a purpose and are spiritual nourishment, especially when the viewer finds a connection with his soul."

imaginario de un recinto sagrado que flota en medio de las nubes, para algunos se revela mejor en la palabra y la transmisión oral. Todas las culturas han procurado dejar un sistema de representación que contenga sus dogmas y preceptos, aun cuando se trate de temas etéreos, informes o inmateriales. Hay tantas religiones como formas de querer entender el sentido de la vida, el devenir humano y la muerte. La búsqueda de un sentido propio y de un sistema de representación de estas reflexiones existenciales es lo que lleva a Villa a crear su universo visual, uno desligado y reticente de las religiones (especialmente de las nociones de culpa, pecado y condena de las occidentales) pero con profunda afinidad por la poesía de las creencias orientales.

Tras un proceso de vida que le ha llevado a estudiar todas aquellas perspectivas, Villa ha concluido que la que representa y coincide mejor con su visión es Moksha, un término sánscrito proveniente del hinduismo que hace referencia a la liberación espiritual, pero que también atrae al artista por su musicalidad: por un lado, por la sonoridad fonética de la palabra; por el otro, porque aquella liberación a que se refiere concluye en el cese completo de actividad, el silencio (nuevamente una referencia a John Cage).

¿Y que hace que sea importante la representación de lo espiritual en el arte? Kandinsky exploraría aquella necesidad del individuo por sentirse en éxtasis ante una obra de arte en su libro De lo espiritual en el arte, en el que proponía una respuesta frente a la importancia del arte en relación con el alma:

Estas dos clases de semejanzas entre el arte nuevo y las formas de etapas pasadas, son radicalmente diferentes. El primero es externo y, por lo tanto, no tiene porvenir. El segundo es espiritual y por eso lleva en sí la semilla del futuro. […] El artista tiene una vida compleja, sutil, y la obra surgida de él originará necesariamente, en el público capaz de sentirlas, emociones tan matizadas que nuestras palabras no las podrán manifestar. […] Todas estas formas de ser auténticamente artísticas, cumplen una finalidad y son alimento espiritual,

and positive spaces, diptychs juxtaposing opposing colors, and compositions contrasting inside with outside. Like the yin and yang—the complementary opposing forces present in all things according to another Eastern existential view—the composition, elements, and forms of the works present a meticulously calculated balance.

This precise arrangement of all the works reveals a slow, meticulous, sometimes repetitive creation process, like a mantra. Sandpapers are stacked, cut, and folded by the thousands, then grouped on the support to give them form. The lightness of sandpaper, condensed in dozens of meters in each work, paradoxically sometimes becomes heavy blocks framed in wood. In other cases, the lightness of the piece comes from the organic shape of an irregular frame that resembles a mantra in Sanskrit. Thus, color and form complement compositions requiring breaking the traditional rectangular format to link ideas like the cyclical, the mythical ouroboros biting its tail, and the curved and dancing shapes Villa confers to wood.

The journey is always accompanied by the sparkle of carbide, the bright stone grain embedded in the paper, producing a mystical aura akin to the presence of gold in sacred iconography. Moksha never looks the same, as the effect of light on it constantly changes. Furthermore, as if it were an analogy of the human condition, the sandpaper reveals its ambiguity: beneath its abrasive function of violently wearing down wood, it hides fragility in the shining carbide grains peeling off its surface. Violence and fragility, other opposites needing balance to achieve the spiritual peace Villa seeks to represent.

Thus, we move through Villa's works as we journey through the seven stages in his pursuit of fulfillment. This sequence is structured like a symphony, with various movements, variations,

opuestos y los junto como adversarios, oponiéndose pero conviviendo, sin anularse”, dice Villa. Y en esa misma analogía otros opuestos se hacen visibles en Moksha, espacios negativos y positivos, dípticos que enfrentan colores contrarios, composiciones en las que el adentro contrasta con el afuera. Como el yin y el yang -las fuerzas opuestas complementarias presentes en todas las cosas según otra visión existencial oriental-, la composición, los elementos y las formas de las obras presentan un balance plenamente calculado.

Aquella milimétrica disposición de todas las obras revela un proceso de creación lento, minucioso, a veces reiterativo como un mantra. Las lijas, una por una, se apilan, se cortan y se doblan por miles, para luego ser agrupadas en el soporte en que les da forma. La levedad del papel de lija, compendiado por decenas de metros en cada obra, termina convirtiéndose, paradójicamente a veces, en pesados bloques contenidos en marcos de madera. En otras ocasiones la levedad de la obra la da la forma orgánica de un marco irregular que asemeja a un mantra en sanscrito. Así, color y forma complementan composiciones que requieren romper el formato tradicional rectangular para poder enlazar ideas como lo cíclico, el mítico uróboro que muerde su propia cola y las formas curvadas y danzantes que el artista le confiere a la madera.

Al recorrido lo acompaña siempre el destello del carburo, el brillante grano de piedra que se aloja en el papel, y que produce un halo místico, semejante a la presencia del oro en la iconografía sacra. Moksha nunca se ve igual porque el efecto de la luz sobre ella es siempre cambiante. Además, como si se tratara de una analogía sobre la condición humana, la lija expone su ambigüedad: detrás de su función abrasiva de desgastar violentamente la madera, esconde su fragilidad en el esplendente grano de carburo que se va desprendiendo de su superficie. Violencia y fragilidad, otros opuestos que requieren ser equilibrados para lograr la paz espiritual que el artista busca representar.

Así transitamos a través de las obras de Villa al mismo tiempo que lo hacemos por las siete etapas con que

and tempos. A subtle and slow overture in To Be in Space is introduced early through small-format drawings, setting forth the abstract nature and elements of order and geometry that will progressively guide and expand throughout the journey. The final movement culminates in an apotheosis, with two monumental pieces representing spiritual liberation and the arrival at Moksha. Villa invites us into the intimacy of his beliefs and the ethereal music that permeates his work, and in doing so, he frees the abstract form from its most ornamental qualities to move us with works that speak to the soul.

1Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists, Capricorn Books. New York, 1961, pp. 93-94.

2James Elkins. Pictures & Tears A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings. Routledge, London. 2007.

3Wilhelm Worringer. Abstraction and Empathy – A Contribution to the Psychology of Style. International Universities Press, New York, 1953. p.132.

4Citado en: Pamela Schaeffer. “Spirituality in Abstract Art”, en Christian Century, Septiembre 30 de 1987, p. 819.

5Wassily Kandinsky. De lo espiritual en el arte. Premia Editora de libros, México. 1989. pp. 9 – 10.

persigue la plenitud. Este orden propone una estructura semejante a una sinfonía, con distintos movimientos, variaciones y tiempos. Una obertura sutil y lenta en Ser en el espacio, que va anunciando tempranamente, en dibujos de pequeño formato, el cariz abstracto y los elementos de orden y geometría que irán guiando y paulatinamente abarcando el recorrido, y un cierre apoteósico en el último movimiento con las dos piezas monumentales que representan la liberación espiritual y la llegada a Moksha. Villa nos ofrece entrar a la intimidad de sus creencias y de esa música etérea que domina su obra, y al hacerlo libera la forma abstracta de su carácter más ornamental para conmovernos con obras que le hablan al alma.

Christian Padilla, Ph.D., Cum Laude in Society, Culture, and Heritage, also earned a Master’s in Advanced Studies in Art History from the University of Barcelona. Padilla has curated distinguished exhibitions including El joven maestro. Fernando Botero, obra temprana: 1948-1963 (Museo Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, 2018) and Un arte propio: convergencias entre México y Colombia, with the FEMSA Collection and Banco de la República (Museo de Arte del Banco de la República, Bogotá, 2019). Padilla is recognized as a specialist on the work of Fernando Botero.

Moksha

2024 sandpaper and wood

½ x 112 ½ inches, 250 x 286 cm.

Parcelas (Plots) 2024 sandpaper and wood

71 x 60 ½ inches, 183 x 59 cm.

Entroque Op. 03 (Opus Junction 03)

2024 sandpaper and wood

43 ⅛ x 57 inches, 110 x 145 cm.

Entroque Op. 05 (Opus Junction 05)

2024 sandpaper and wood

54 x 42 ½ inches, 137 x 108 cm.

Atman I

2024 sandpaper and wood

55 ⅞ x 55 ⅞ inches, 142 x 142 cm.

Atman III

2024 sandpaper and wood

55 ⅞ x 55 ⅞ inches, 142 x 142 cm.

Atman IV

2024 sandpaper and wood

55 ⅞ x 55 ⅞ inches, 142 x 142 cm.

JERÓNIMO VILLA

(b. 1990, Bogotá, Colombia)

Jerónimo Villa’s artistic practice delves into the profound transformation of materials, challenging traditional notions of functionality and purpose. By repurposing utilitarian objects, Villa elevates them from their everyday roles into elevated geometric compositions that transcend their original forms. Through his work, he highlights the latent potential of the obsolete, creating a dialogue that invites viewers to reconsider the inherent properties of materials and the ephemeral nature of utility.

Born in Bogotá, Colombia, Villa grew up surrounded by creativity, with a sculptor father and a fashion designer mother. This rich environment fostered an early fascination with materiality, as he witnessed firsthand the transformative process of turning raw substances into refined works of art. These formative experiences are intricately woven into his practice, where three-dimensional components are reimagined as wall-mounted compositions that seamlessly merge craftsmanship with conceptual depth. Villa’s keen understanding of material treatment enables him to create works imbued with timeless resonance.

Initially trained as a musician at the University of Los Andes in Bogotá, where he graduated in 2008, Villa carries a rhythmic sensibility into his visual art. His transition from music to art was characterized by a bold embrace of experimental textiles and an exploration of art historical canons in his innovative creations. His achievements include residencies at the Prairie Center of the Arts (Schaumburg, IL, 2012), Artula Environmental Arts (Salem, OR, 2011), and the DC Art Foundation Residency (Miami, FL, 2022). Villa has exhibited widely across Colombia and the United States, continually pushing the boundaries of fiber art and material exploration.

Destruktion I (Destruction I) 2024 sandpaper, carborundum, and wood 59 x 59 inches, 150 x 150 cm.

Destruktion II (Destruction II) 2024 sandpaper, carborundum, and wood 59 x 59 inches, 150 x 150 cm.