Sherron Francis: Splash of Serenity

1973-77 Paintings

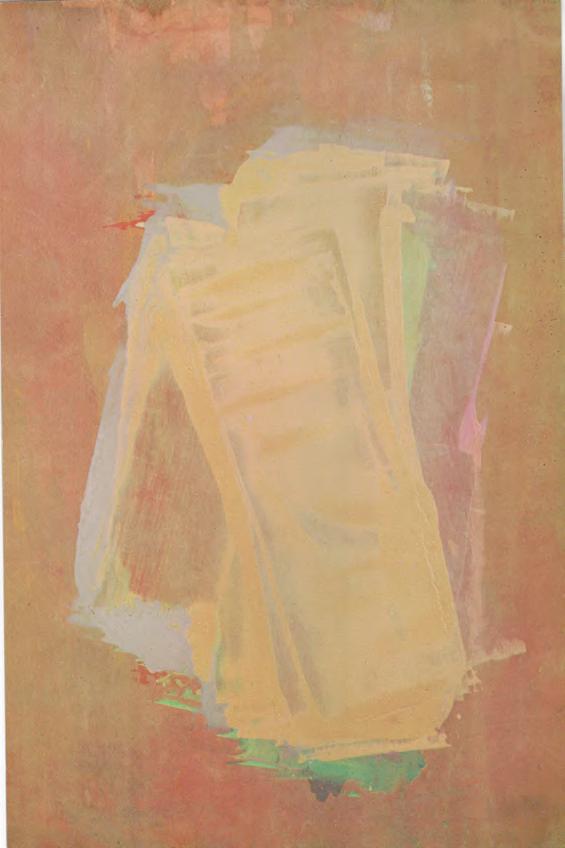

Cover illustration:

Strawberry 5, 1977

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

56 1/2 x 22 inches

Signed, titled and dated on the reverse

All rights reserved, 2024. This catalog may not be reproduced in whole or in any part, in any form or by any means both electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of Lincoln Glenn.

Catalog design and select photography by Clanci Jo Conover

Sherron Francis in her loft at 16 Waverly Place, New York, circa 1982

Foreword

What is a “rediscovery?” One dictionary defines a rediscovery as “the act of finding or remembering something or someone again after losing or forgetting about them for a long time.” Today, the word is freely tossed around in our field of 20th century American art, but Sherron Francis’s paintings and biography are distinguished amongst the sea of rediscoveries.

Our journey with Sherron began in 2021, when we had the privilege of meeting the artist and viewing her paintings for the first time. Instantly captivated, we knew we wanted to present her work (and live with examples ourselves!). In the following year, we unveiled our first gallery space in Westchester and honored Sherron with our inaugural exhibition and her first one-person exhibition in 37 years. As our gallery has grown and expanded to two locations in New York, we are delighted to share Sherron Francis’ story and work with a wider audience than the successful exhibition that we originally staged in 2022.

Sherron Francis was once a fixture in the downtown New York art scene, and her distinctive style and approach to color left a mark on those who encountered her work. Yet, as she chose to step away from the city and the art world, she embarked on a unique journey rejecting gallery representation for decades. With Splash of Serenity, we extend a warm and heartfelt welcome back to Sherron, inviting her to reclaim her place in the artistic tapestry of New York. May this event, Francis’s first solo exhibition in over four decades in Manhattan, serve as a celebration of her enduring legacy and a testament to those who march to the beat of their own drum.

We would like to recognize the efforts of Michael Mahon for assistance with moving monumental canvases on the North Fork of Long Island. We are grateful for Clanci Jo Conover's brilliant photography of these shimmering paintings, and Alex Grimley for his poetic expertise on color field artists.

Warmly,

Doug Gold & Eli Sterngass“A Plenitude of Riches” : Sherron Francis in the 1970s

by Alex GrimleyThe 1970s saw a flourishing of abstraction. Propelled by the momentum of Color Field painting, a new generation of artists developed a style of abstract painting focused on expressive color and the creation of new and individualized techniques to realize it. Sherron Francis was among the second generation of Color Field painters that emerged in that decade. Early in the 1970s, the hard edged geometry of the previous decade, exemplified by artists like Kenneth Noland and Frank Stella, gave way to gestural markmaking, looser paint handling, and thick surface textures. The development of acrylic pastes and gels helped spur painterly experimentation. Along with Walter Darby Bannard, Peter Bradley, Dan Christensen, Darryl Hughto, Jules Olitski, and Larry Poons, Sherron Francis revitalized painterly abstraction.

“Painterliness redefined,” announced a December 1972 article by John Elderfield. “A certain materiality in the use of pigments has reentered ambitious painting,” he wrote. “Color remains [its] primary concern: the turn toward painterliness is but an attempt to give [color] a new freedom and amplitude of effect.”i

The paintings in the current exhibition date from the middle of the 1970s, when debates about the status and future of abstract painting preoccupied artists and critics alike. Reductive and austere minimalist painting continued throughout the decade and found champions who appreciated its conceptual content. By contrast, Sherron Francis’s art emerged in a aesthetic milieu in which “a calm, Matissean resplendence [and] soft, untormented loveliness prevailed.”ii While her work was championed by fellow artists—Peter Bradley, for one, wrote of his enjoyment of Francis’s paintingsiii —it divided critics, some of whom, seemingly unable to see past its obvious lusciousness, were unwilling to acknowledge the formal experimentation and innovation her paintings presented. Nearly fifty years after their initial appearance, these works remain vital and ravishing, beautiful at first glance but also rewarding prolonged attention with their nuances of color and surface. The selection of paintings on view in the current exhibition expands upon the Sherron Francis retrospective organized by Lincoln Glenn Gallery in 2022, showing both the depth of her engagement with painterly abstraction as well as her stylistic versatility.

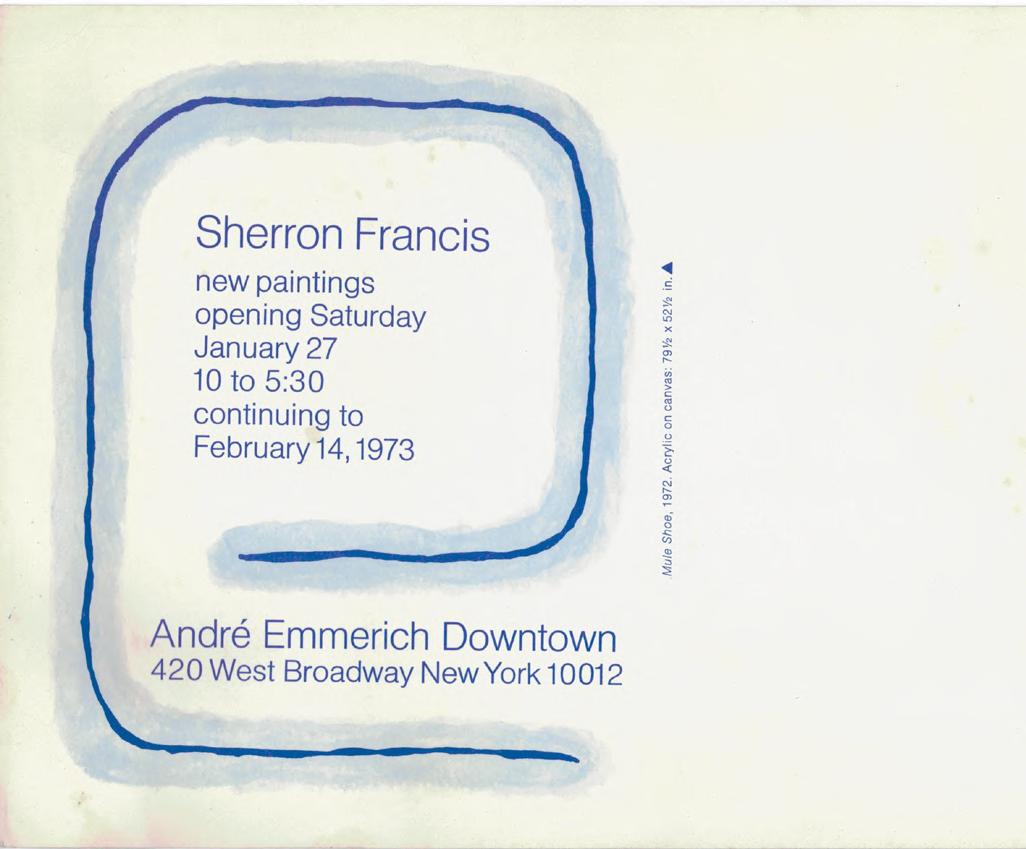

Paintings by Sherron Francis could be seen in two New York exhibitions early in the winter of 1973. The Whitney Biennial opened on January 10th. She was one of the eight exhibited artists—five of them in their 30s—represented by the André Emmerich Gallery, who lent Francis’s 1972 painting, Mule Shoe

These young Color Field artists represented the main contingent in the “resurgence of abstraction” observed by critic Hilton Kramer in his review of the show. Just over two weeks later, on the blustery Saturday evening of January 27th, Francis’s first solo exhibition with Emmerich opened at the gallery’s SoHo outpost at 420 West Broadway. On the building’s top floor, above branches of the Leo Castelli and John Weber galleries, were showcased about a dozen of her recent works. By chance, Peter Schjeldahl’s review of Francis’s solo show appeared on the same day, and on the same New York Times Sunday arts page as Kramer’s commentary on the Biennale. The contrast between the two reviews illuminates how ’70s Color Field panting was understood and misunderstood in its time.

“What dominates the Biennale,” Kramer wrote, “is the sheer profusion of abstract painting.” Singling out Dan Christensen and Larry Poons, both of whom had recently adopted gestural, painterly styles, as well as “many of the newer artists,” he continued: “What [this work] suggests is a new wave of nostalgia for the abstract painting of the Fifties. There is nothing (so far as I can see) esthetically new in this new abstraction.”iv Further down on the page Peter Schjeldahl lamented this response to contemporary painting, with Francis as a case study. Describing her as an artist of “taste and skill,” he found her paintings “at once as gorgeous and as delicate as possible.”

Commenting on their large scale and bodily proportions, Schjeldahl noted that they “confront the viewer with a satisfying firmness, inviting delectation.” He was confounded by the listless response that such paintings seemed to elicit. “It has become fashionable to express boredom in the face of this plenitude of riches,” he wrote. “Evidently many of us are either very spoiled or otherwise benumbed in our capacities for enjoyment.”v

The difference in focus between abstract art of the 1950s and ’70s brings to mind the divergence between the mid-19th century landscapes of the Barbizon School and those of the Impressionists. The older painters imbued landscape with pathos, drama, and the suggestion of narrative; for Monet and his contemporaries, the landscape was a vehicle for capturing effects of color and light. In a similar manner, for many of the Abstract Expressionist artists of the 1950s, the painterly gesture was loaded as much with existential content as it was with impasto.

Critic Harold Rosenberg voiced the ethos of this generation in his essay on “action painting,” writing, “The gesture on the canvas [is] a gesture of liberation. Form, color, composition, drawing, are auxiliaries, any one of which—or practically all… can be dispensed with. What matters always is the revelation contained in the act.”vi

By contrast, in a painting like Francis’s Untitled, 1975 [p. 10], the broad, sweeping gestures are layered to create modulations in hue, tone, surface, and translucency. A zone of stained red appears dark, nearly brown at the top of the canvas, gradually accumulates warmth in the center, and shifts to purple near the bottom. The thicker, more translucent pigment that Francis amplifies both the changes in hue and the visual speed of the picture. Though they shared the pictorial language of abstraction, painters of the 1950s and the 1970s spoke very differently through it.

Kyle Morris (1918-1979) Pendant Greens, 1958, Oil on canvas, 72 x 48 inches, Lincoln Glenn, New York

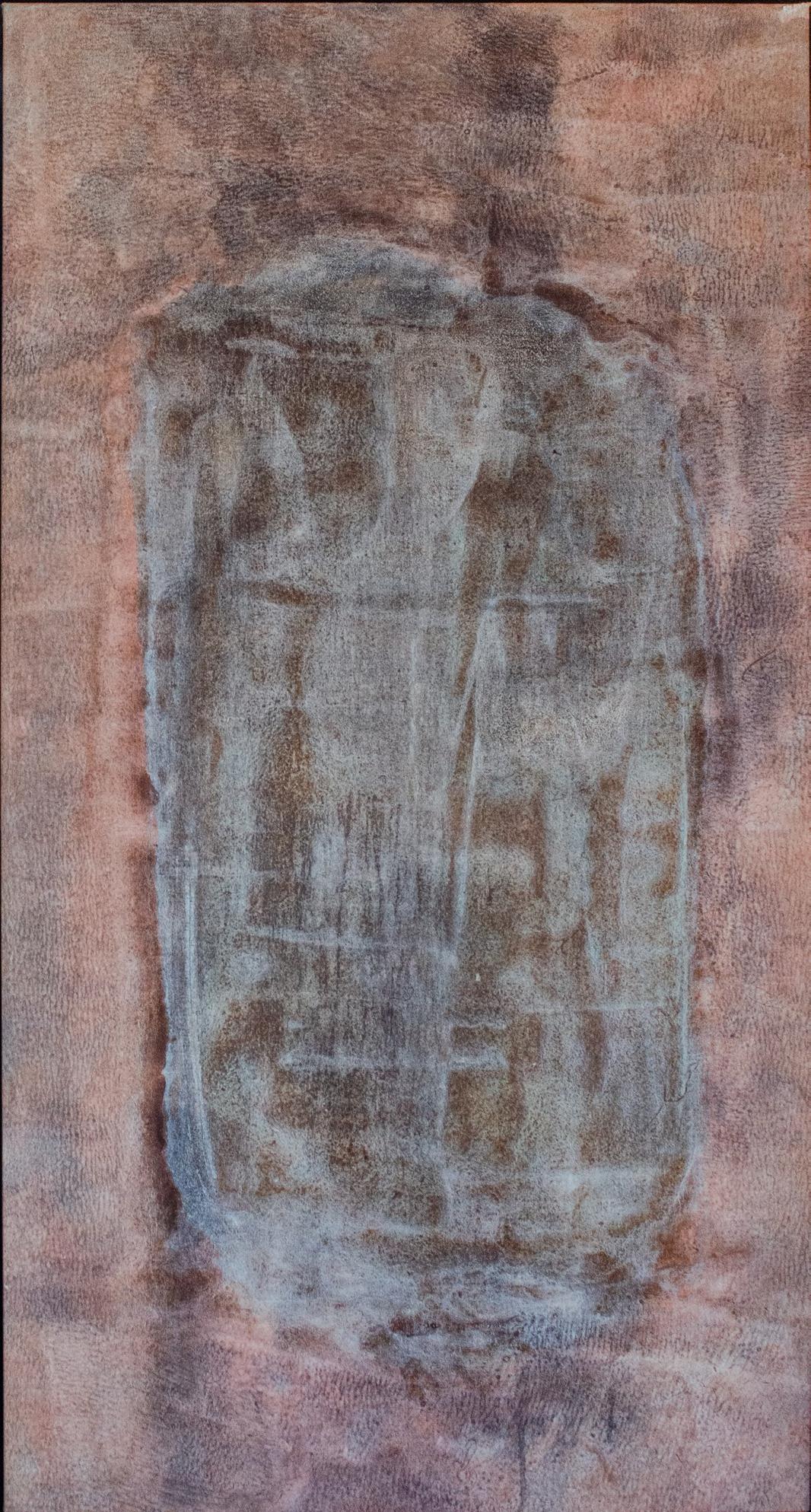

With their rugged surfaces and painterly markmaking, Sherron Francis’s works of the ’70s bear a passing resemblance to the Abstract Expressionism of the ’50s, but the range of nuances and effects in her art is distinct. Naturalism pervades her paintings. Their atmospheric surfaces radiate warmth and coolness, often in the same picture. Her gestures accumulate in floating forms, suspended cloudlike upon the canvas; elsewhere she creates dense, crackling textures that erupt and surge

forth. In some paintings, she’s scraped paint from the surface, leaving only ghostly traces that resemble weathered cliff sides. In others, ropes of impastoed pigment appear to cut through the colored ground. Though resolutely abstract, sensations of nature can be felt throughout these works.

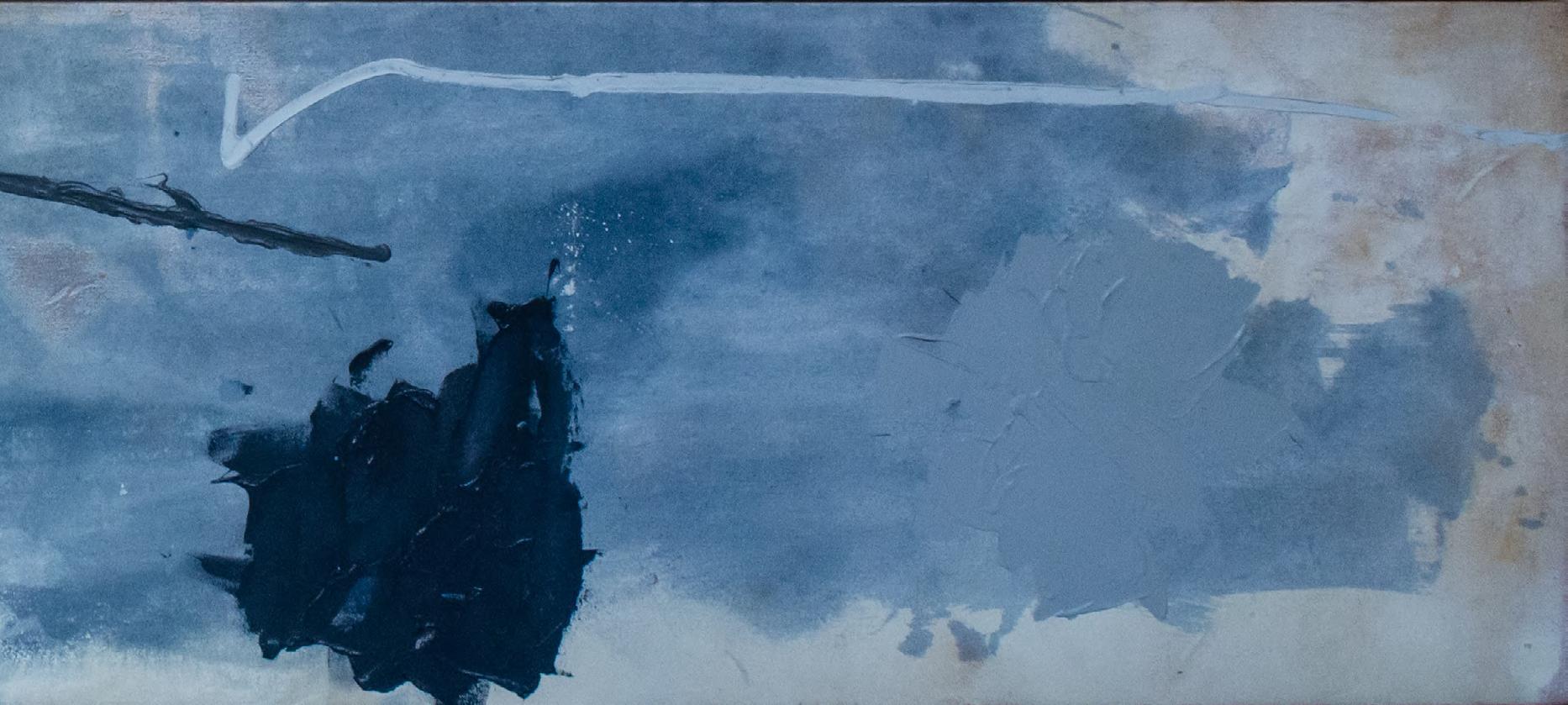

What appear to be sweeping gestures cover Titled Out, 1973 [p. 11],and Untitled, 1973 [p. 10]. In both paintings, however, Francis scraped away at the canvas, removing any build up of texture and instead depositing layers of color into the surface, where they blend and overlap. The sum total of her markmaking is a spectral image, departing from the canvas ground to leave a fading surface of silt like a stone slab eroded over time. A similar play of painterly residue and receding space occurs in the subtly luminous Untitled, 1977 [p. 24], where a stained ground of dark blue-gray gradually softens near the center and casts a nocturnal glow that illuminates a zone of sedimentary pigment on the left.

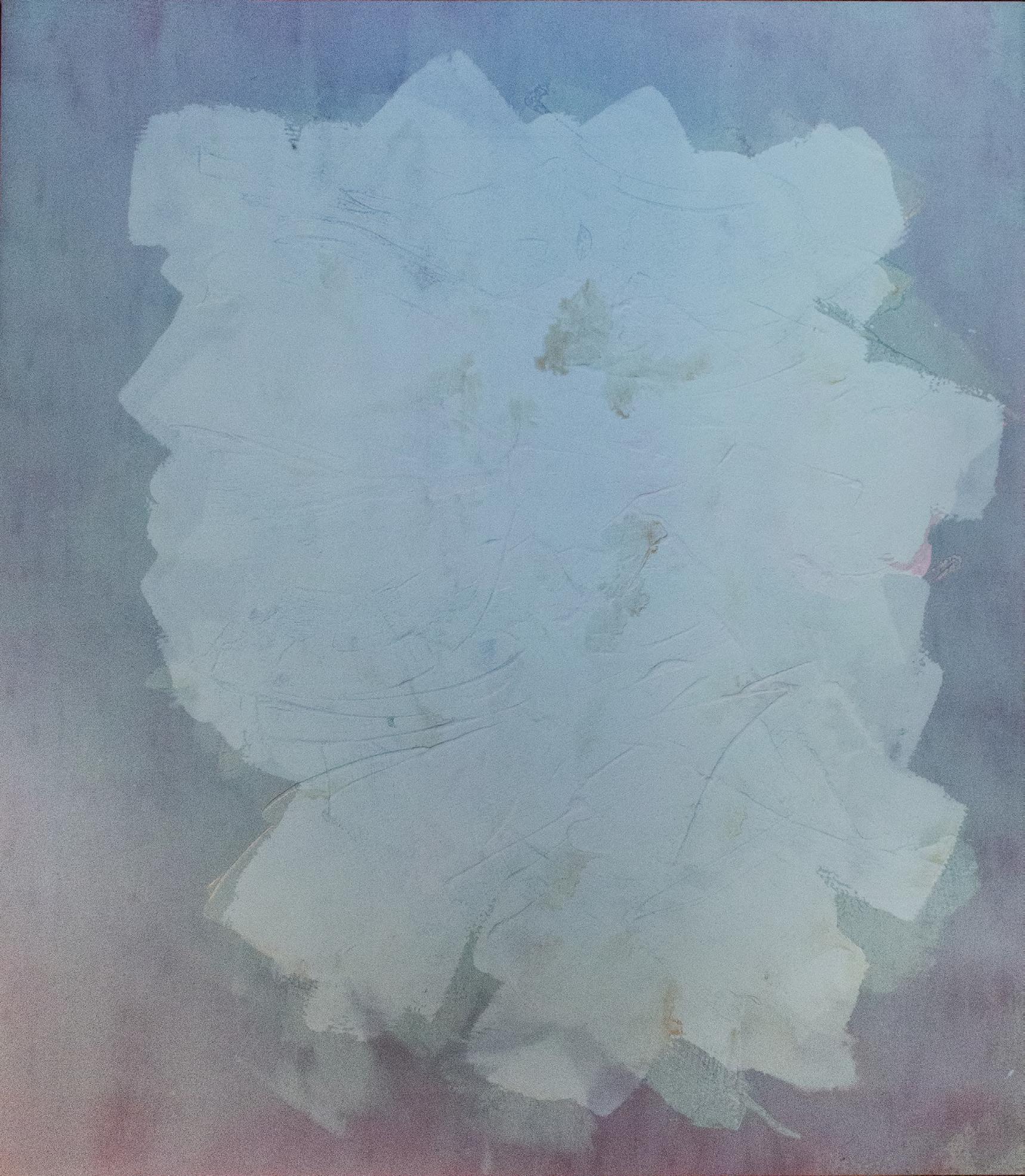

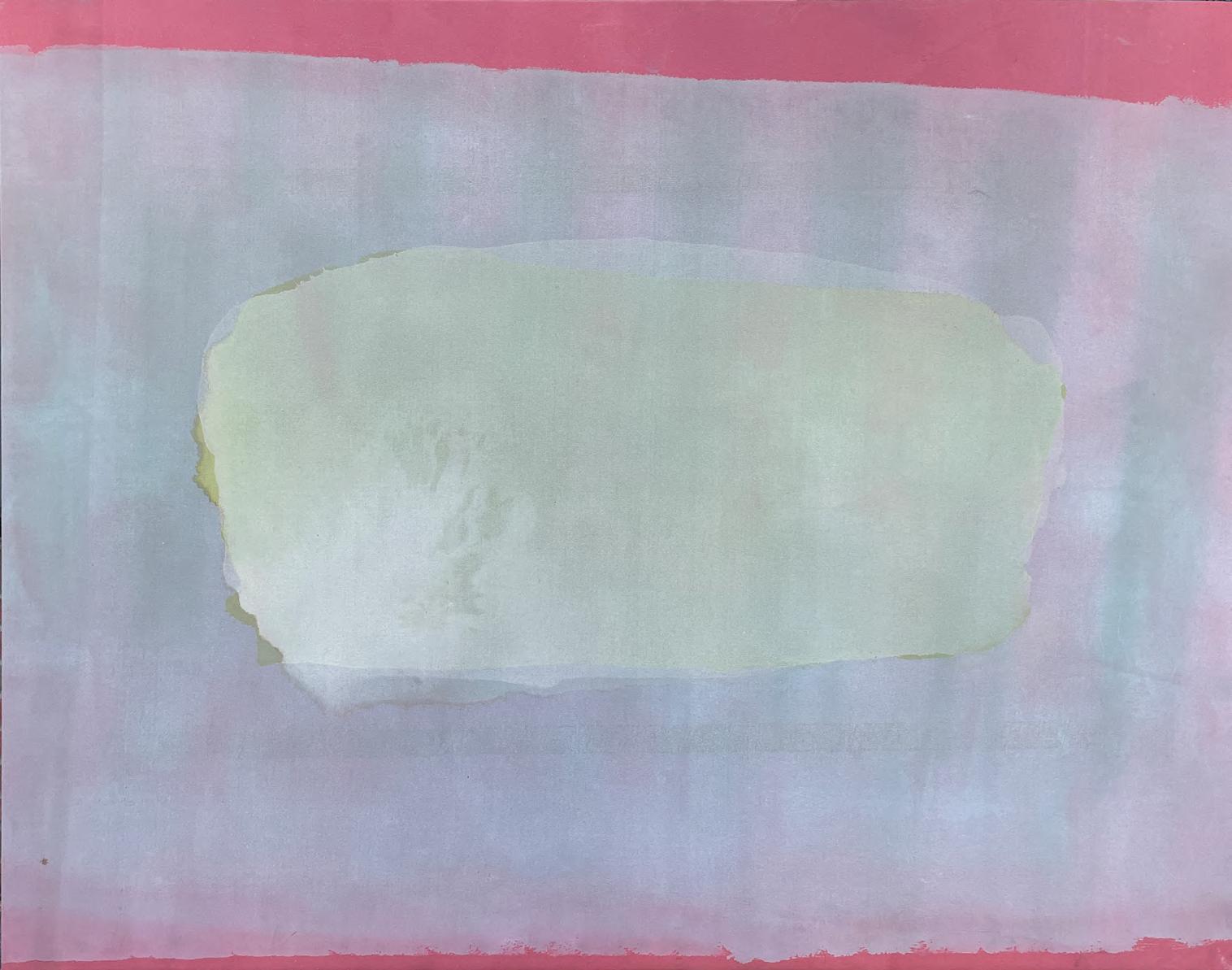

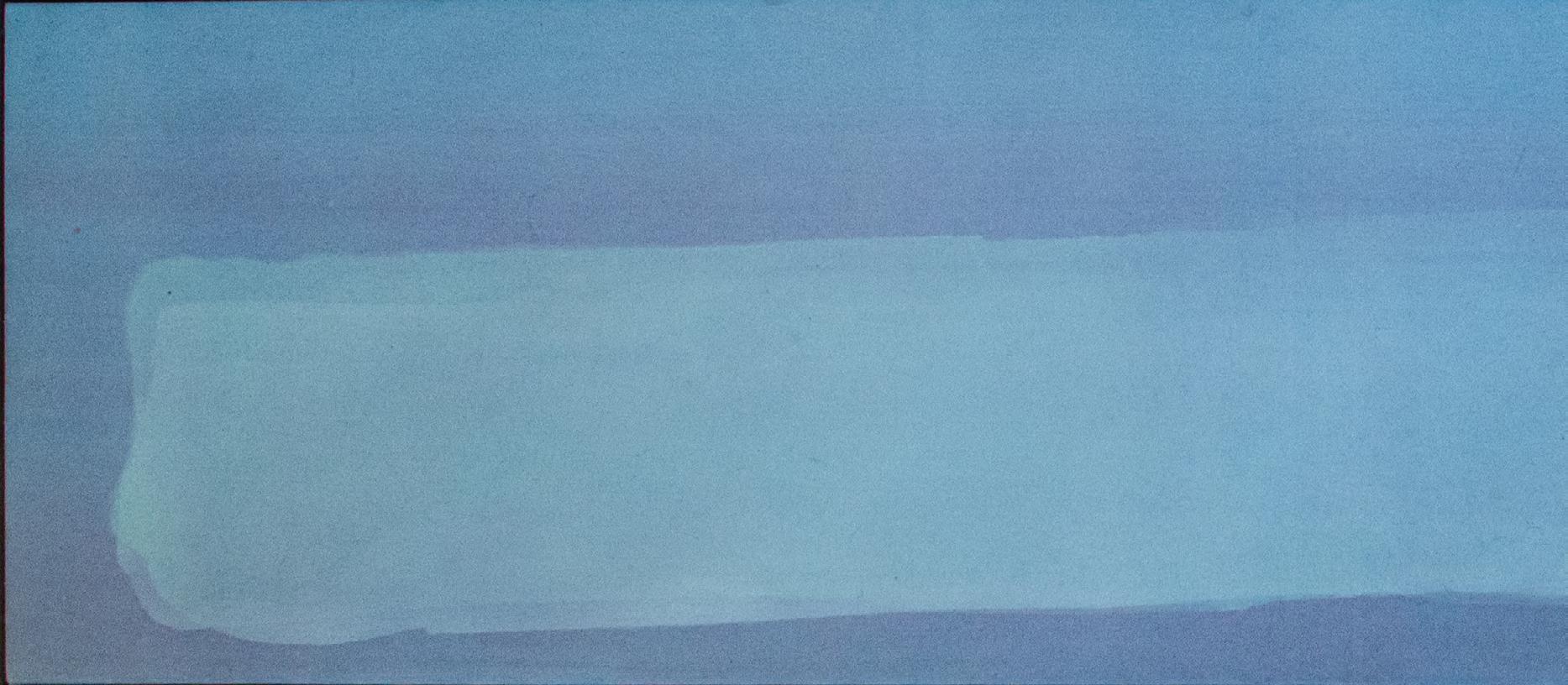

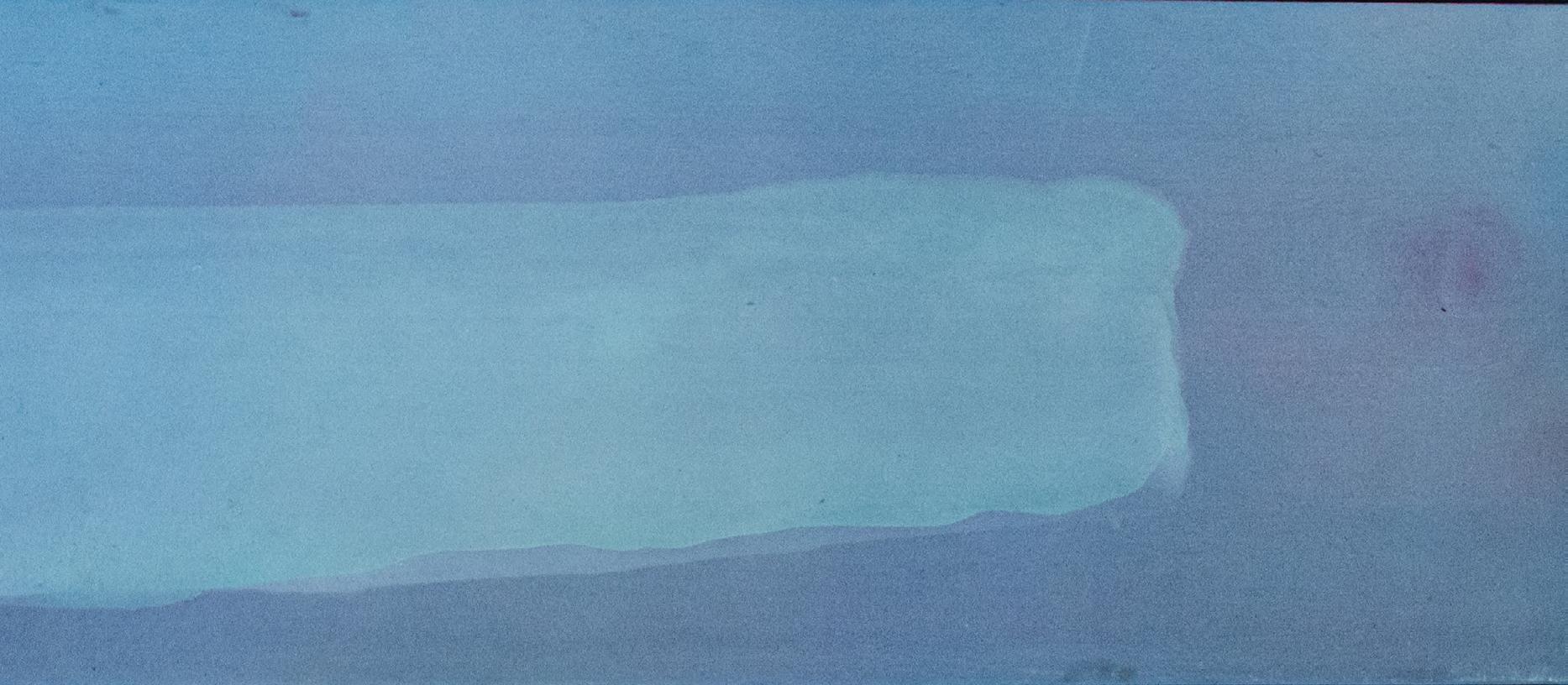

If in Titled Out and Untitled, 1973 [p. 10], Francis’s mixtures and removals yield a surface that is difficult to fix visually, a related effect is achieved through different means in Sonic Lark, 1974 [p. 19]. Painted in shades of limpid blue that shift almost imperceptibly, Sonic Lark contains a lighter, luminescent blue band that hovers, suspended in space. Ostensibly the “figure” in this painting, the band reads negatively, not placed atop the ground but further from it, like an opening or a portal. In Grey II, 1975 [p. 12], Francis has spread broad swathes of thicker paint into a cluster that blossoms from the middle of the picture, creating a form not unlike the “Burst” paintings of Abstract Expressionist Adolph Gottlieb; but unlike his tempestuous calligraphy, Francis’s marks are tranquil, defined by small ridges that flow into one another as if blown by a gentle gust of wind, with a shroud of blue pigment sprayed atop the form pushing it away in space.

One of the most unique characteristics of Francis’s paintings is her understated, pastel palette, an array of pale hues that she modulates in temperature with extraordinary subtlety. Take for example Untitled, 1976 [p. 14], where a pair of lines wander down the middle of the vertical canvas. Together with a small area of peach colored scribbles near the bottom, these lines are the only solidly defined elements in the picture. The main aspect of the painting is an expansive field of light, neutral pink marked by pressure points of greater or lesser accumulations of paint. On the right center of the canvas, the pink has pooled into a richly saturated zone. Near the top and bottom edges, and at moments along the central lines, the pink tone fades almost to a mist and reveals both blues and greens underneath. All the while, the painting’s surface texture—thin, coarse, grainy—remains unbroken.

In paintings near the end of the decade, in works like Noble O, 1976 [p. 15], and Untitled, 1977 [p. 6], Francis began building up emphatic surface textures. Paint and

mixed media surge down the surface of the former picture, accumulating around the middle in a coarse, crackling mass. Despite the craggy, tactile quality of the surface, traces of the artist’s hand are hard to discern; the painting seems to have erupted into being, like a force of nature. The crusty texture of Untitled, 1977, is similarly impenetrable, with only minute fissures in the frigid white ground revealing icy blue tones underneath.

Sherron Francis (b. 1940) Untitled, 1977, Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 33 x 27 1/2 inches, Lincoln Glenn, New York

Endnotes

Taken together, the works in this exhibition show the trajectory of Sherron Francis’s work as it developed throughout the 1970s. As soon as she’d refined a given style or technique, she pushed forward to the next one. From the lightly colored stain paintings with which she began the decade, through her scraped and darkly patinated pictures, to the warm and atmospheric series of the mid-70s, and finally the thick textures that closed out the decade, the outward appearance of her paintings changed dramatically. What remained consistent was her dedication to aesthetic quality and expressive color. With the critical debates about ColorField painting now in the distant past, all that remains for subsequent generations of viewers is the plenitude of riches that Sherron Francis’s art affords us.

i John Elderfield, “Painterliness Redefined: Jules Olitski and Recent Abstract Art, Part I,” Art International, vol. XVI, no. 10 (December 1972), 22.

ii Marilyn Friedman Hoffman, “Painterly Abstraction,” in Aspects of the 70’s: Painterly Abstraction (Brockton, MA: Brockton Art Museum, 1980), 2. Hoffman was in these quotations describing the general tenor of early 1970s abstract painting.

iii Peter Bradley, “Statement,” Studio International, vol. 188, no. 968 (July/August 1974), 33.

iv Hilton Kramer, “A Nostalgia for the Fifties?” The New York Times, Feb. 4, 1973, D23.

v Peter Schjeldahl, “Abstract Painting—The Crisis of Success,” The New York Times, Feb. 4, 1973, D23.

vi Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters,” The Tradition of the New (New York: Horizon Press, 1959), 30; 26.

Untitled, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

Untitled, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

Titled Out, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

66 3/4 x 38 1/2 inches

Signed, titled and dated on the reverse

Grey II, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

80 x 69 1/2 inches

Signed, titled and dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1976

Acrylic on canvas

52 x 28 inches

Signed and dated on the reverse

Noble O, 1976

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

57 x 21 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Acrylic & mixed media on canvas

56 1/2 x 22 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 90 inches

Dated on the reverse

Sonic Lark, 1974

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 109 1/2 inches

Signed, titled and dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1976

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 87 inches

Signed and dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1977

Acrylic & mixed media on canvas | 93 x 42 inches

Signed & dated on the reverse

List of Works

Untitled, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

96 x 66 inches

Untitled, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 48 inches

Titled Out, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

66 3/4 x 38 1/2 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Grey II, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

80 x 69 1/2 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Untitled, circa 1975

Acrylic on canvas

90 x 56 inches

Untitled, 1976

Acrylic on canvas

52 x 28 inches

Signed & dated on the reverse

Noble O, 1976

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

57 x 21 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Strawberry 5, 1977

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

56 1/2 x 22 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 90 inches

Dated on the reverse

Sonic Lark, 1974

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 109 1/2 inches

Signed, titled & dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1976

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 87 inches

Signed & dated on the reverse

Untitled, 1977

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

93 x 42 inches

Signed & dated on the reverse

Selected Solo Exhibitions

Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, 1966

Bowery Gallery, NYC, 1970

Andre Emmerich Gallery, NYC, 1974, 1973

Janie C. Lee Gallery, Houston, TX, 1974

B. Kornblatt Gallery, Baltimore, MD, 1977

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, NYC, 1978, 1980

Bell Gallery, List Art Ctr, Brown Univ, Providence, RI 1979

Watson/de Nagy & Co., Houston, TX, 1980, 1984

Douglas Drake Gallery, Kansas City, MO, 1981

Clayworks Studio Workshop, NYC, 1982

Rubiner Gallery, Detroit, MI, 1985

Lincoln Glenn, Larchmont, NY, 2022

Selected Group Exhibitions

Speed Museum, Invitational Exhibition, Louisville, Kentucky, 1964

Evansville Museum, Midstates Exhibition, Evansville, Indiana, 1965-1966

University of North Dakota, North Dakota Annual, Grand Forks, North Dakota, 1966

Bowery Gallery, New York, New York, 1969

Galleria 11 Fante Di Spade, Rome, Italy, 1972

Andre Emmerich Gallery, New Talent Show, New York, New York, 1972

Whitney Museum of American Art, Whitney Biennial, New York, New York, 1973

Janie C. Lee Gallery, Houston, Texas, 1973, 1975

Gallerie Andre Emmerich, Zurich, Switzerland, 1973, 1975

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Three Young American Painters, 1974

Dootson/Calderhead Gallery, Seattle, Washington, 1975

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Modern Painting: 1900 to the Present, 1975

Edmonton Art Gallery, New Abstract Art, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, 1977

American Academy & Institute of Arts and Letters, New York, New York, 1978

Traveling Exhibition, Clayworks, Squires Art Gallery, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, 1981

Douglas Drake Gallery, Abstract Paintings, Kansas City, Missouri, 1981

Watson/de Nagy & Co., New Work New York, Houston, Texas, 1981

Clayworks Studio Workshop, Visiting Artists, New York, New York, 1981

Traveling Exhibition, Broken Surface, Virginia State, Bennington College, Tibor de Nagy, 1981

Rubiner Gallery, Selected Paintings of Contemporary Abstractionists, Detroit, Michigan, 1982

C.D.S. Gallery, Artists Choose Artists, New York, New York, 1983

Watson/de Nagy & Co., Clayworks, Houston, Texas, 1984

Douglas Drake Gallery, Toot, Kansas City, Missouri, 1985

Douglas Drake Gallery, Wood, New York, New York, 1989

Douglas Drake Gallery, Small Paintings: Big Issues, New York, New York, 1993

Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia, South Carolina, 2001

Portland Art Museum, Clement Greenberg: A Critics Collection, Portland, Oregon, 2001

Art Museum of South Texas, Modernism of the 1970s, Corpus Christi, Texas, 2008

Art Museum of South Texas, Looking Back and to the Now, Corpus Christi, Texas, 2020-21

Museum Collections

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX

Portland Art Museum, OR

Everson Museum, Syracuse, NY

Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Museum of Southern Texas, Corpus Christi, TX Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI

Sherron Francis, Bandoline, 1978, Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 46 ½ x 71 in., Art Gallery of Alberta Collection, purchased in 1978 with funds donated by Stuart Olson Construction Ltd. and the Women's Society of the Edmonton Art Gallery

Sherron Francis, Bandoline, 1978, Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 46 ½ x 71 in., Art Gallery of Alberta Collection, purchased in 1978 with funds donated by Stuart Olson Construction Ltd. and the Women's Society of the Edmonton Art Gallery

Sherron Francis, Green DeVille, circa 1972-73, Acrylic on canvas, 62 x 87 ½ inches. Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi. Gift of C. Frederick Stimpson. To the right, paintings by Paul Jenkins and Walter Darby Bannard.

Sherron Francis, Green DeVille, circa 1972-73, Acrylic on canvas, 62 x 87 ½ inches. Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi. Gift of C. Frederick Stimpson. To the right, paintings by Paul Jenkins and Walter Darby Bannard.