THE MATERIAL ALCHEMY OF GENE HEDGE:

ORGANIZED CHANCE IN ABSTRACT FORM

by Clanci Jo Conover

Gene Hedge (1928-2017) was an heir to the trailblazing artists who bucked convention in the first part of the 20th century, carrying on his own unique style born out of experimentation and curiosity. Known for his collage work but an equally skilled painter, Hedge was constantly developing his relationship to and understanding of materials, organizing and reorganizing shapes and forms to create almost mystic abstractions. His work can be viewed as an intersection of art, nature, and technology, harmoniously uniting these elements across his oeuvre.

Growing up in Indiana, Hedge served in the military when he completed high school from 1946-1947, using tuition assistance from the G.I. Bill to study art at Ball State University. After only one year there, the writings of Lászlo MoholyNagy (1895-1946) inspired him to move to Chicago in 1949 and enroll at the Institute of Design, founded as The New Bauhaus by Moholy-Nagy in 1937. This was a pivotal moment in Hedge’s artistic development, as the school had embraced the precepts of its namesake, The Bauhaus. Founded in Weimar by architect Walter Gropius in 1919, the epochal school’s manifesto was to redesign the material world in a way that unified all forms of art, propelling Gropius’ vision for a new artistic synthesis—one that would merge architecture, sculpture, and painting into a compatible and holistic creative endeavor. After the Bauhaus was closed in response to Nazi hostilities and intolerance, many of its teachers, including Moholy-Nagy, relocated to the United States and began teaching a new contingent of students that eventually included Hedge.

At the Institute of Design, Moholy-Nagy would continue to teach the foundation course he developed with Joseph Itten at The Bauhaus, a systematic introductory course in visual thinking that revolutionized how students understood art and design.1 The goal was to make students conscious of their creative power, maintaining the energy and clarity of a child while working as an adult. Assignments were meant to emphasize different dimensions of the senses to elevate one’s understanding of materials. Students were required, for example, to create “hand sculptures,” the primary purpose not to be seen with the eyes but felt with the hands.2 Looking at Hedge’s dynamic collages, one can recognize a clear connection between his unconventional education at the Institute of Design and his masterful employment of industrial materials.

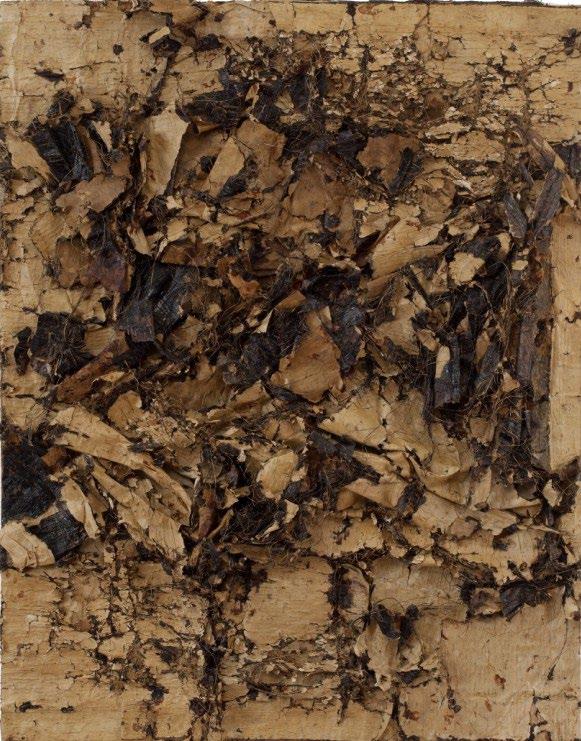

When Hedge moved to New York in 1956, three years after graduating from the Institute, he found new material he was eager to work with: a thick, industrial paper used in the construction of roads and highways. He explained that “it consists of two layers of very tough paper with monofilament reinforcing threads between and bound together with tar. I was able to collect large amounts of this

paper, and the more it was exposed to weather, the more it changed… it became a very flexible material that I could organize in many different ways. The collages got larger and more three-dimensional. They are glued, overlapping, pushed together; the reinforcing threads made it possible to anchor certain parts and let others take care of themselves.”3 A collage from 1953 featured in the present exhibition, Untitled (C1), provides an example of Hedge’s earlier, two dimensional collages that allude to the artist’s grasp on composition, becoming fully realized in his later brown-toned industrial works.

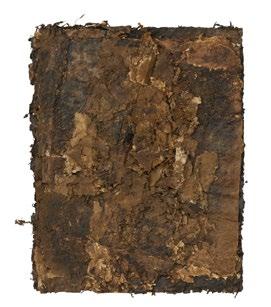

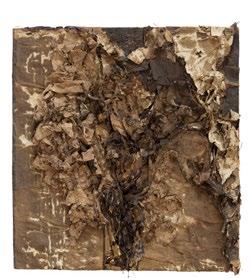

Hedge’s use of industrial construction materials in collage demonstrates a compelling transformation of the synthetic into the organic. In the exhibited collages from 1956 onward, what may begin as heavy-duty materials—tar paper, fiberglass mesh, adhesives, and other industrialgrade substances—are manipulated into a composition that evokes the textures and tones of the natural world. The layered browns and ochres recall autumn leaves or peeling

Figure 1: Gene Hedge showing industrial materials used in his collages, 2013 bark, apparent in Untitled (C35), 1958 (p. 11), while the rough, tactile surface mimics the slow processes of decay and renewal found in nature, exemplified in Untitled (C30), 1958 (p. 17). Hedge’s method blurs the boundary between the built and the organic, suggesting that even the most artificial materials can, through artistic intervention, mirror the irregular beauty and quiet complexity of the environment. Hedge described in 2013 that when he was originally creating these pieces, he wondered about their longevity given their unusual materials.4 Decades later, after traveling both nationally and internationally, he confirmed that the pieces have maintained their quality.5

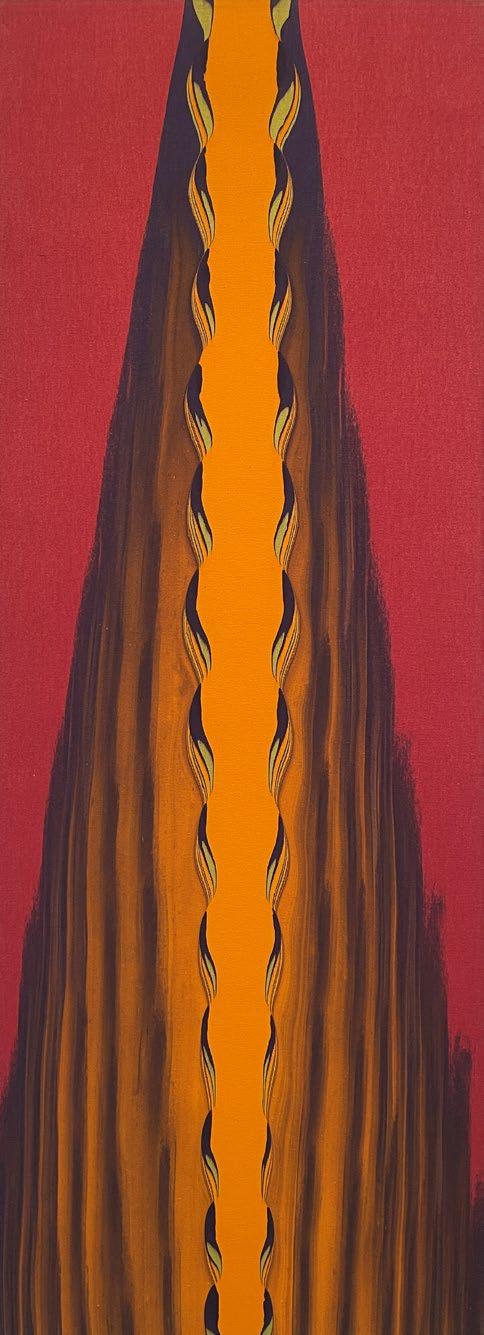

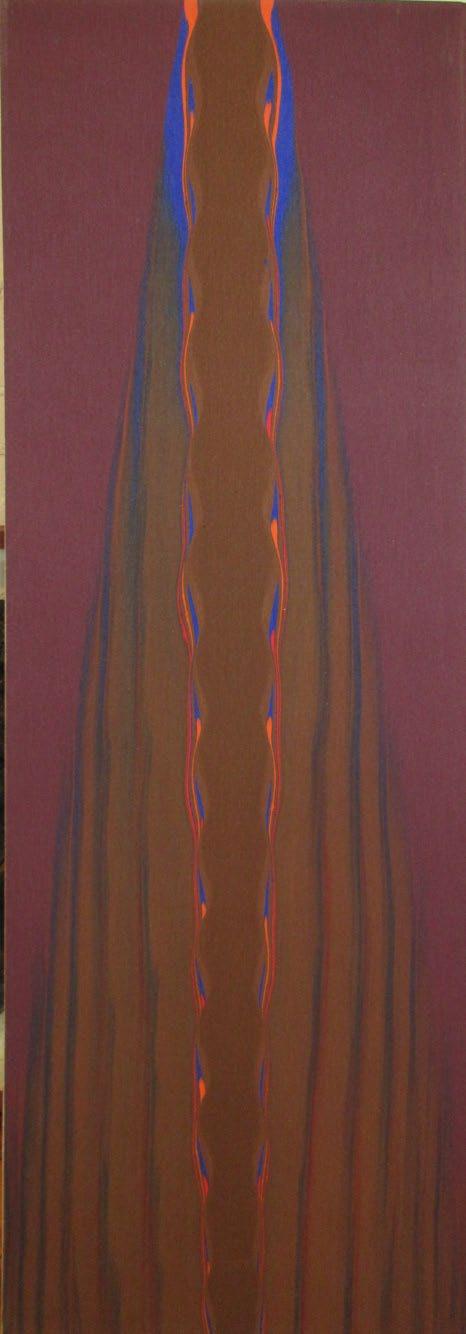

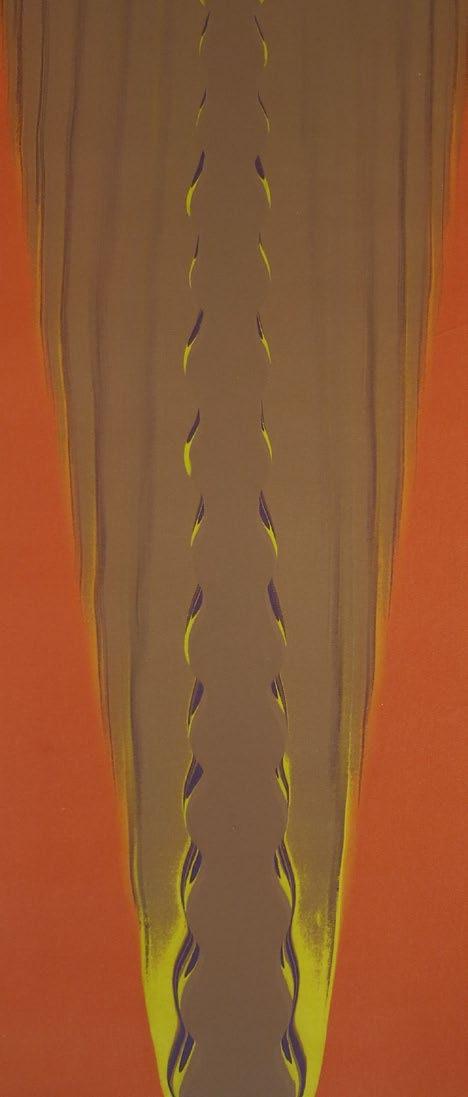

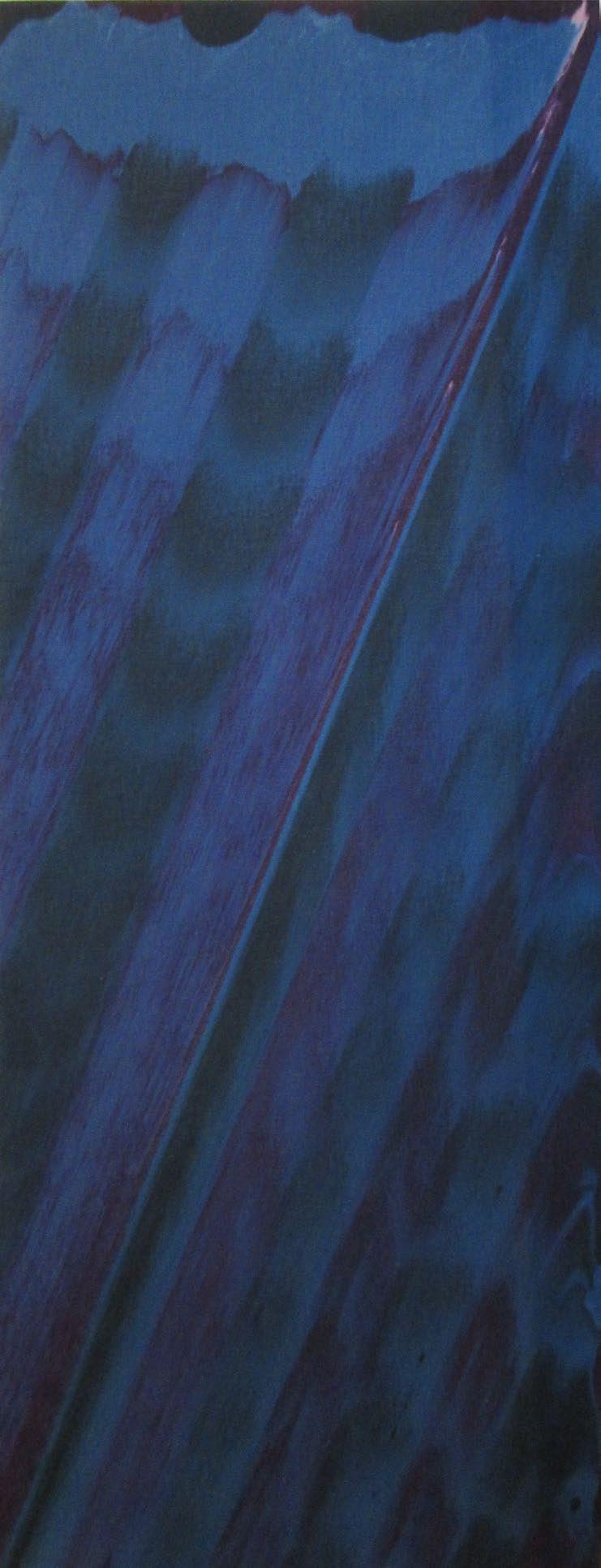

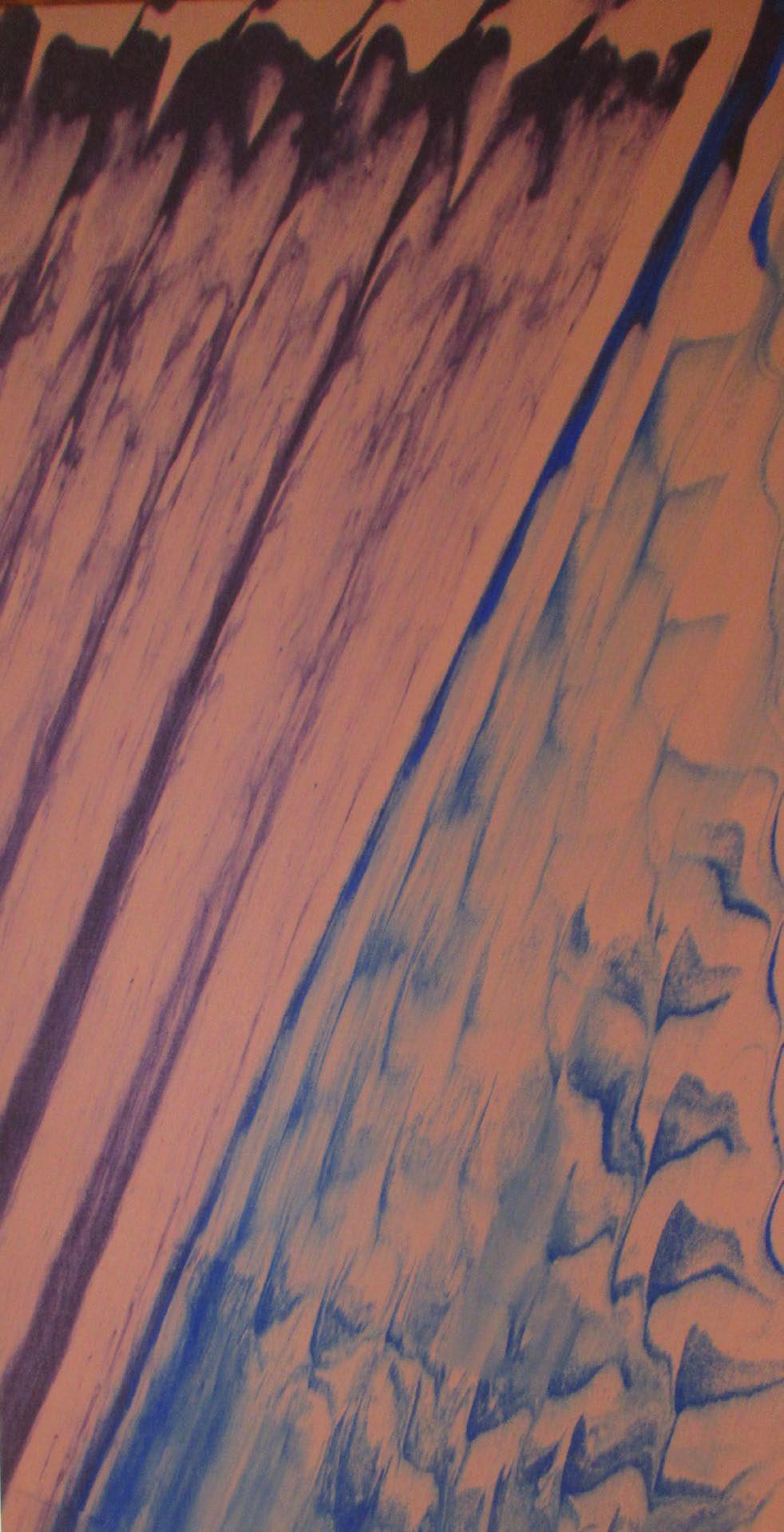

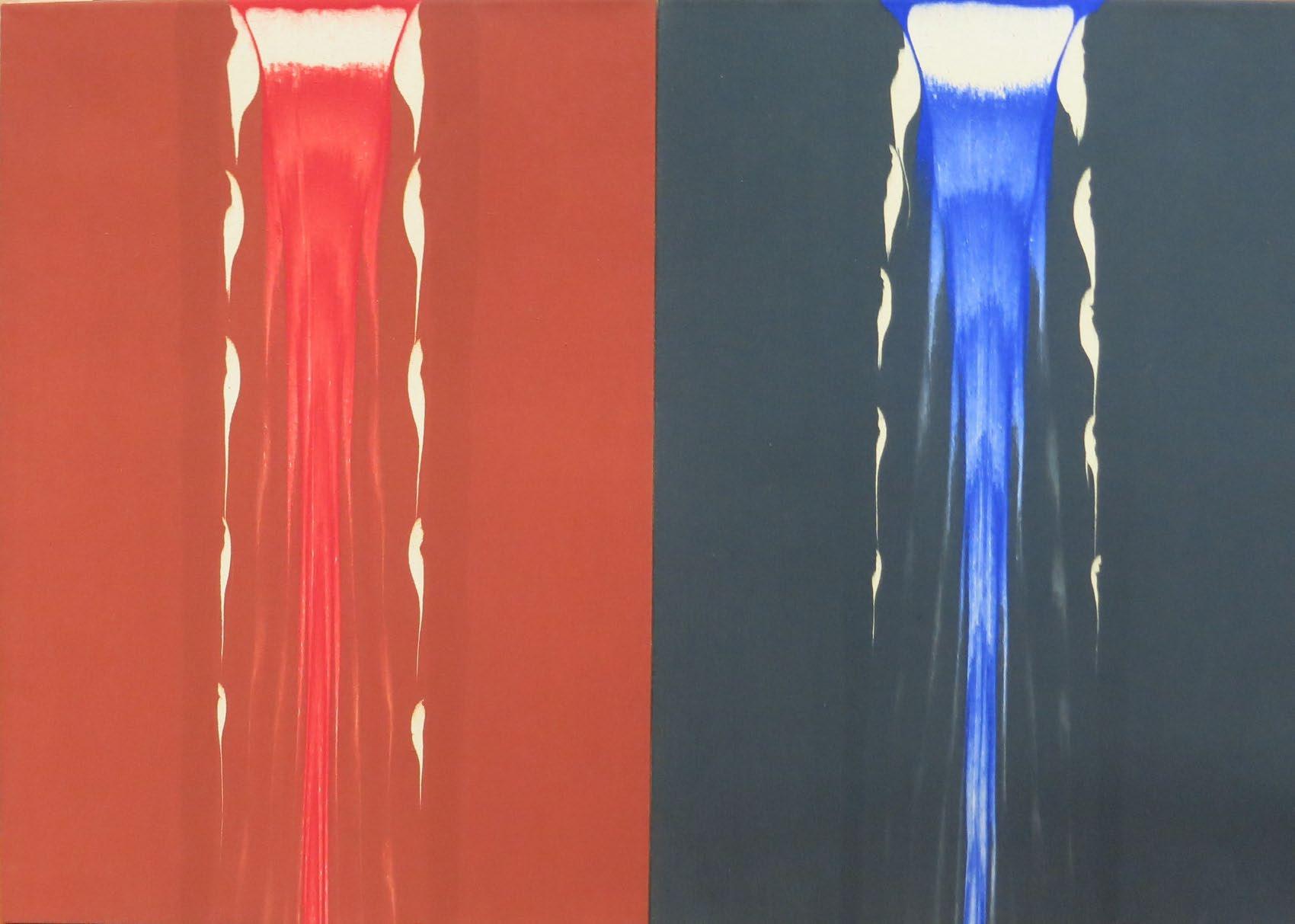

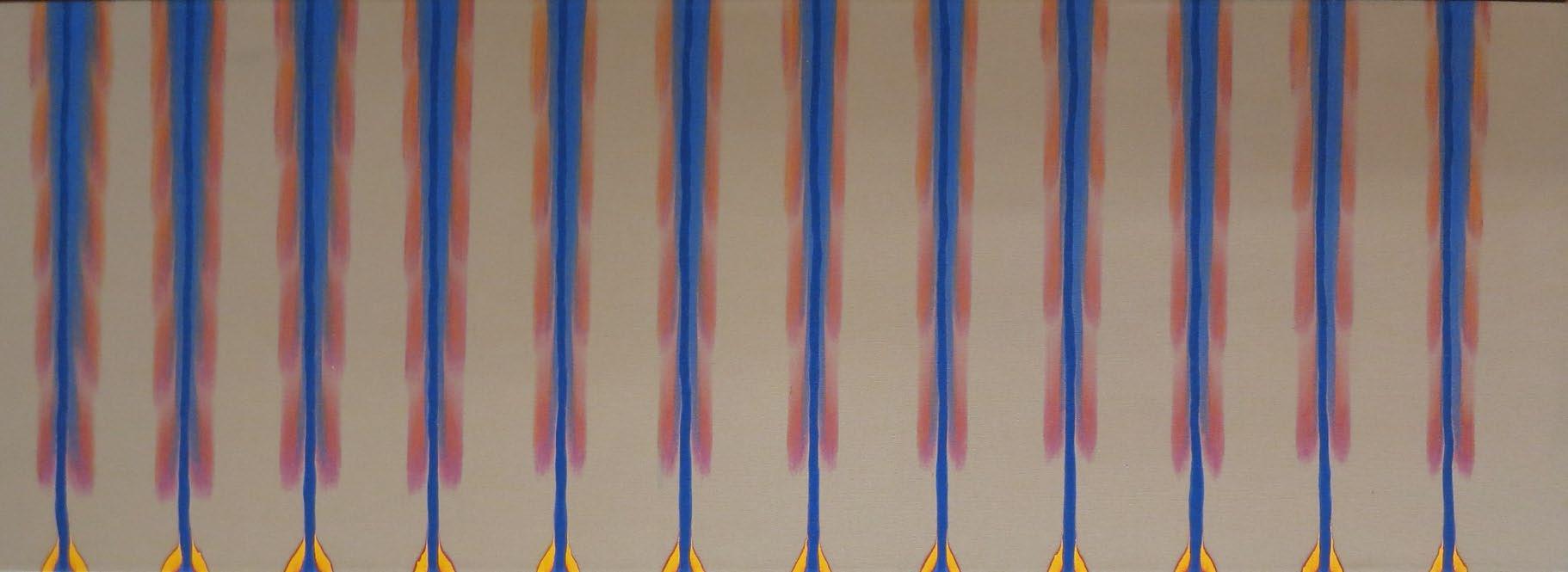

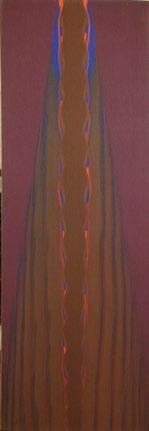

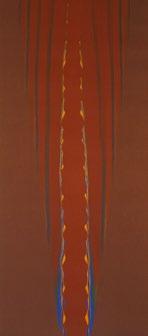

Painting with oil had been part of Hedge’s practice as long as collage, but he initially struggled to identify a visual language with the medium. In 1965, he essentially reinvented his approach to painting by experimenting with acrylic. Hedge discovered an aesthetic through variations of repeated forms he created by pouring paint onto canvases and coaxing it into biomorphic shapes with tools like squeegees. He produced these paintings in batches, finding a general outline that interested him and exploring the similarities and variations he could produce within that outline. In Figure 2, these batches are clearly delineated: the pair of large works on the left wall and the four slender works on the right wall would fall into two distinct batches. Whenever some new outline would present itself, the artist would begin a new batch.

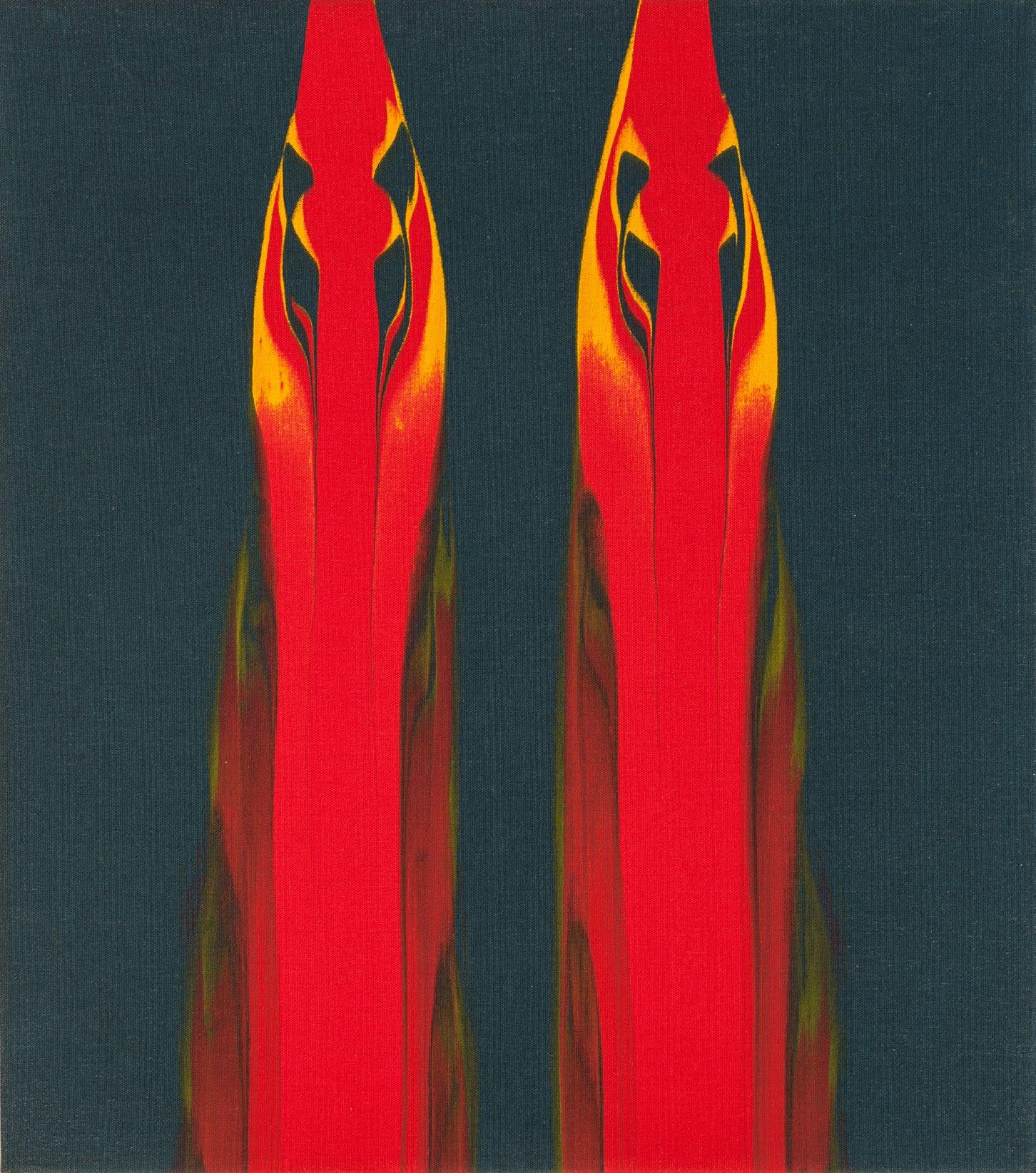

Although repetition was an important component of Hedge’s painting practice, it was never his goal to produce perfect replicas of the forms within the paintings. Instead, he isolated the forms to see how they are varied even when executing them through the same process. At first glance, works like Vanda, 1981 (p. 9), Double (p. 33), and Numerical (p. 38), appear to be symmetrical, but on closer inspection,

2: Gene Hedge:The Pattern of Nature at Lincoln Glenn, 2023, installation view irregularities between the forms are undeniable. By abandoning the sharp lines and regulated symmetry found in movements like De Stijl or hard edge abstraction, Hedge imbues his canvases with a sense of effusive freedom and childlike curiosity. He explained that his method “is sort of a dialogue between control and lack of control. I don’t think these paintings could be produced in any other way. What I enjoy in this painting (Fig. 3) is the way these thin slivers develop as they repeat and become this wonderful ribbon of form, twisting in space.”

Hedge’s alternative practices reveal a unique way of seeing the world—an approach that injected his work with an intrinsic sense of depth and dimension. Early in his career, Hedge was featured in a juried show presented by the independent Chicago group Exhibition Momentum in 1954. Artists were selected by New York art dealer Betty Parsons (1900-1982), painter Robert Motherwell (1915-1991), and Guggenheim Museum director James Johnson Sweeney (1900-1986); over 225 artists submitted work for the exhibition, but only 14 were chosen.6 One of Hedge’s nascent collages made the cut, heralded in ARTnews as “the towering monarch” of the group.7 From there, he earned a place in Allan Frumkin’s inaugural gallery opening in 1955 and was selected the following year for inclusion in the 62nd American Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago by a jury consisting of sculptor Theodore Roszak (1907-1981) and Museum of Modern Art curator Dorothy Miller (1904-2003). The opening of Frumkin’s gallery was significant because

Figure

Figure 3: Gene Hedge, Untitled (P056), c. 1970, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 18 in.

“it represented an effective alternative to the tedious annual pilgrimage to New York which Chicago artists had forever been obliged to make if they wanted to see something more real than pictures in the magazines.”8 Nevertheless, Hedge relocated to New York by 1956.

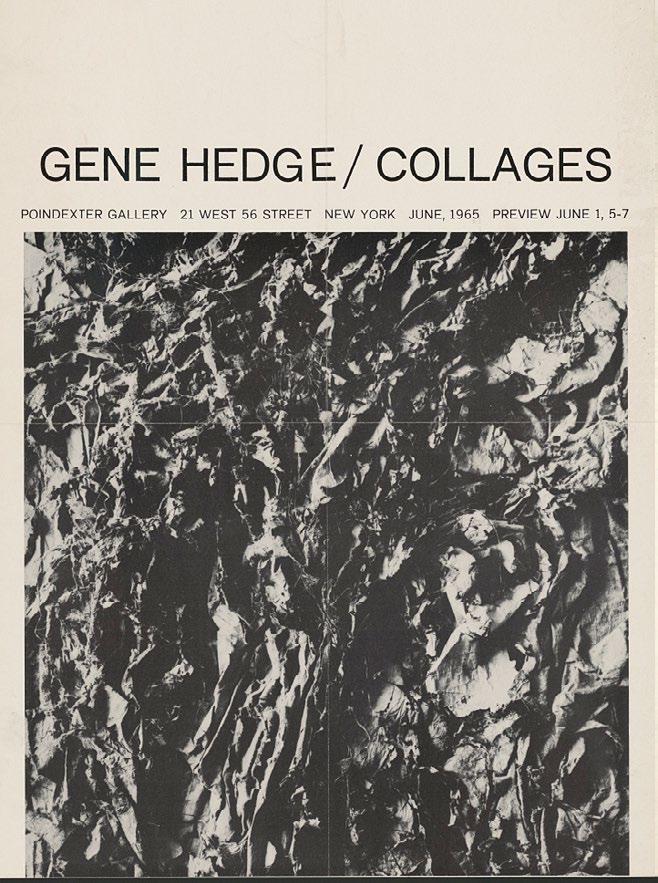

Young American Artists of 1957, presented at the Museum of Modern Art Guest House, would be Hedge’s first showing in New York. He continued to exhibit at notable institutions around the city such as the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Stable Gallery, and secured multiple shows with Poindexter Gallery in the late 1960s (Fig. 4). A seminal exhibition in the field of collage, and for Hedge personally, was the traveling American Collages (1965-1967), which was organized by the Museum of Modern Art and exhibited at 16 museums across the United States and Europe. American Collages brought four of Hedge’s industrial assemblages into conversation with work by thirteen other artists: Leon Polk Smith, Joseph Cornell, Alfred Leslie, Conrad Marca-Relli, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, Alex Katz, Esteban Vicente, Angelo Ippolito, Jess, Charmion von Wiegand, Robert Goodnough, and Nicholas Krushenick. Curator for the exhibition Kynaston McShine was quoted in the exhibition’s accompanying press release, confirming the ascension of collage as medium: “[Collage] has been a means of creative liberation, leading us to recognize not only the beauty of ephemera but also that of texture and spatial effects… It has added much to what we accept as art – severe and formal juxtapositions of everyday scraps of paper as well as arrangements of pristine materials arrived at by accident or chance.”9 Given the care with which Hedge approached collage work, it is no surprise that he was featured in this exhibition alongside well-known artists of the day.

Even after Hedge settled in New York, his ties to Chicago persisted. He gained representation with B.C. Holland Gallery in the early 1960s, presenting the solo exhibition Gene Hedge: Collages. Holland later wrote a letter of recommendation on Hedge’s behalf that confirmed he had known the artist since his days at the Institute of Design, and that “he has always been regarded by those of us with a professional interest, as a lyrical and sensitive artist. His style is entirely unique, and I believe him to be the sort of serious artist who would most benefit from the help a fellowship would provide.”10

Beyond his studio practice, Hedge held two college-level teaching positions over the course of his career. From 1968 to 1973, he taught at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, and later, from 1980 to 1986, at the University of Illinois, Chicago. Teaching came naturally to Hedge, whose spirit of experimentation and curiosity made him a dynamic educator

Figure 4: Gene Hedge / Collages Exhibition Flyer, Poindexter Gallery, 1965

and mentor to young artists. His influence extended beyond the classroom, as well. Dorothea Rockburne—who, like Hedge, had studied under Bauhaustrained instructors at Black Mountain College—cited her time living with him as an important influence on her own assemblage practice.11 A mutual friend and colleague Hedge had in common with Rockburne was Susan Weil, a collage artist in her own right who was once married to Robert Rauschenberg.12 Hedge also maintained a close friendship with artist Cora Kelley Ward until her death – he recalled that, as she approached the conclusion of her battle with cancer, she was spending less time on art and more time thinking about the spiritual realm.13 She had asked: “Is painting still enough for you?” He answered: “Yes.”14

In the 2013 video Gene Hedge Unscripted (Fig. 5), the artist can be seen pensively looking at a number of his collages and paintings lined up, considering them carefully and taking in each detail. It is in this moment that we glimpse the depth of Hedge’s inner world—a fleeting view into his extraordinary way of seeing. Indeed, he confirmed in his own words: “It starts with visual experience. And seeing something is the greatest pleasure. I make things I want to look at.” Through a career defined by experimentation and sensitivity to material, Gene Hedge forged a body of work that bridges the industrial and the organic, the intellectual and the intuitive. His practice stands as a testament to the power of perception, reaffirming his belief that the act of seeing itself is the artist’s greatest pleasure.15

Endnotes

1 Christopher Lyons, “From The Monster Roster to The Hairy Who to The Neoexpressionists ” Chicago Magazine, May 1984, 160.

2 Ibid.

3 Gene Hedge Unscripted. Video, 2013.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Marilyn Robb Trier, “Summer in Chicago,” ARTNews, Summer 1954, 59.

7 Ibid.

8 Franz Schulze, Fantastic Images; Chicago Art Since 1945 (Chicago: Follett Publishing Co., 1972), 19.

9 The Museum of Modern Art, press release for the exhibition American Collages, no. 43, May 11, 1965.

10 B. C. Holland Gallery records, 1942-1991, bulk 1959-1965. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

11 Christopher Lyons, “System and Sensibility: Dorothea Rockburne at DIA:Beacon,” Hyperallergic, April 19, 2019, https://hyperallergic.com/492679/dorothea-rockburne-dia-beacon/

12 Mary Marshall Clark, The Reminiscences of Susan Weil: Rauschenberg Oral History Project, Columbia Center for Oral History, Columbia University (transcript, July 17, 2015), 12, https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/sites/default/files/Weil1-8-5-15-FINAL.pdf

13 John Ed Bradley, “Outside the Lines: A Cache Of Paintings By The Unsung Louisiana Artist Cora Kelley Ward Leads The Author Onayearslong Journey To Fill In The Details Of Her Unconventional Life—And Understand Why Her Work Grabbed Him And Wouldn’t Let Go,” Garden & Gun, February/March 2021, 111.

14 Ibid.

15 For a comprehensive biography on the artist, see Lisa N. Peters, “Gene Hedge (1928–2007),” in Gene Hedge: The Pattern of Nature (New York: Lincoln Glenn, 2023).

Figure 5: Gene Hedge inspecting his paintings, 2013

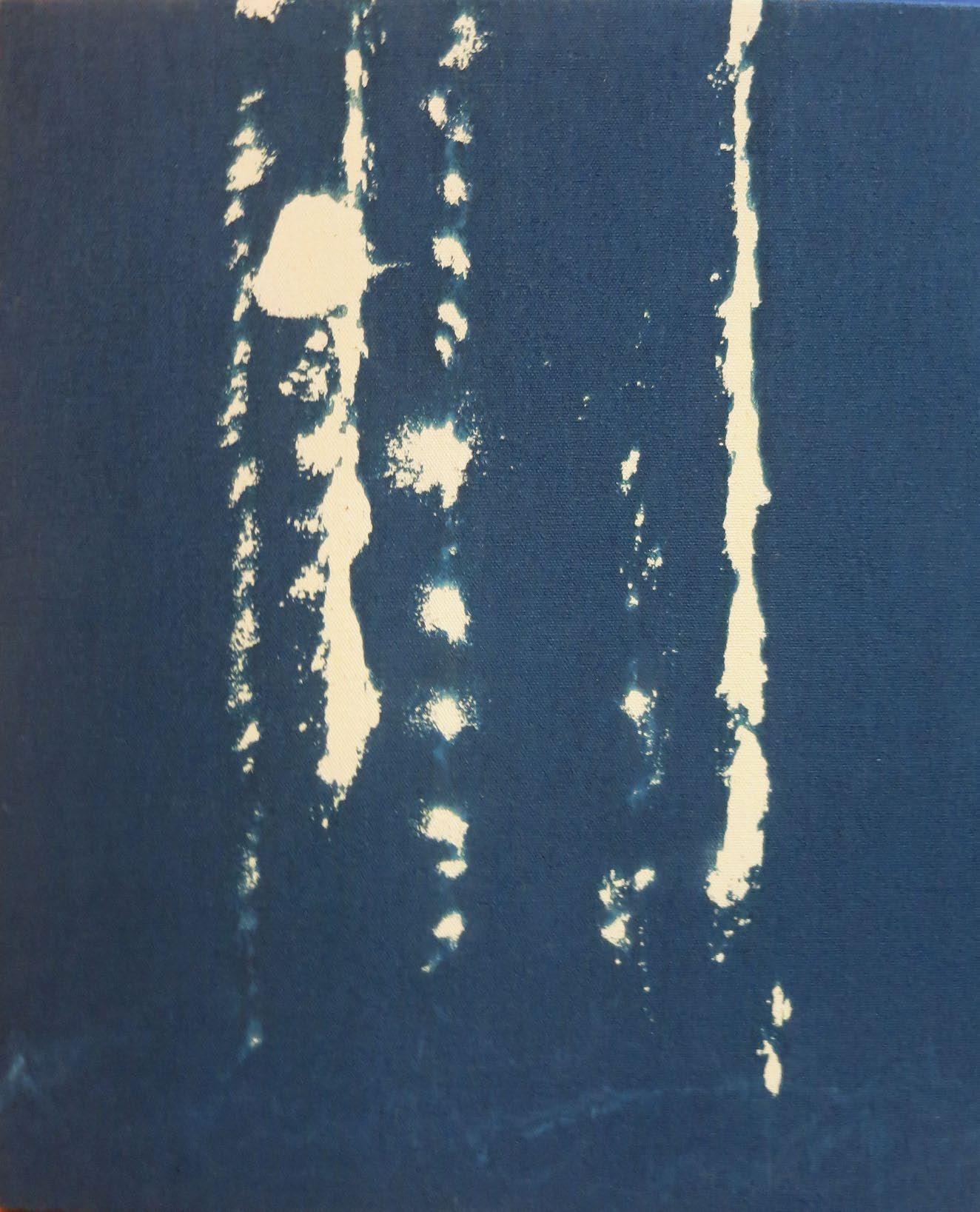

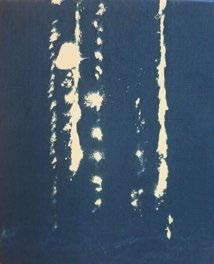

Untitled, c. 1955

Mixed media 21 1/4 x 17 3/4 inches (C25)

Untitled, c. 1956

Mixed media 14 3/4 x 14 inches (C27)

Vanda, 1981

Acrylic on canvas | 31 x 40 1/2 inches

Signed, dated, titled and inscribed on the reverse (P048)

Untitled

Acrylic on canvas mounted on board 15 x 12 1/2 inches (P016)

Untitled, c. 1958

Mixed media | 47 x 33 1/2 inches

With Art Institute of Chicago and B.C. Holland Gallery labels on the reverse (C35)

Untitled

Mixed media | 15 1/2 x 12 inches

Museum of Modern Art label from ‘American Collages’ exhibition, 1966 on reverse (C28)

Untitled, c. 1970

48 x 18 inches (P051)

Untitled, c. 1970

48 x 18 inches (P054)

Untitled, c. 1970

48 x 18 inches (P254)

, c. 1970

48 x 18 inches (P252)

Acrylic on canvas

Untitled

Acrylic on canvas

Acrylic on canvas

Acrylic on canvas

Breath

on canvas 43 1/4 x 16 1/4 inches (P055)

Acrylic

Untitled, c. 1958

Mixed media

22 1/2 x 18 inches (C30)

Untitled, c. 1958

Mixed media

36 x 33 inches (C29)

on canvas

30 1/8 x 22 7/8 inches (P099)

Saga

Acrylic

on canvas 19 5/8 x 17 inches (P029)

Trace

Acrylic

Mixed media

48 x 32 1/2 inches (C37)

Untitled, c. 1958

Untitled, c. 1962

Mixed media on board | 23 x 18 1/2 inches

Signed, dated, titled and inscribed on the reverse (C33)

Tactile

Acrylic on canvas

38 x 21 inches (P065)

Untitled Acrylic on canvas

47 x 18 inches (P057)

Untitled, 1963

Mixed media | 14 1/2 x 12 inches

Initialed and dated “H63” lower left (C26)

Untitled Mixed media

8 x 7 1/2 inches (C17)

Untitled, 1966

Acrylic on canvas

60 x 43 inches (P276)

Acrylic on canvas

28 1/8 x 25 1/8 inches (P067)

Parrot’s Poem

Untitled, 1956

Mixed media | 22 1/2 x 12 inches

Signed with initial and dated “H56” upper center; artist label on the reverse (C13)

Untitled, 1953

Mixed media | 15 x 11 inches

Signed with initial and dated “H 53” center right; artist label on the reverse “Gene Hedge C-1-1953” (C1)

Untitled

Mixed media

10 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (C18)

20 3/8 x 18 inches

Double

Acrylic on canvas

(P030)

Untitled, 1975

Acrylic on canvas | 14 1/2 x 18 1/2 inches

Signed ‘Gene Hedge 1975’ verso, upper center (P014)

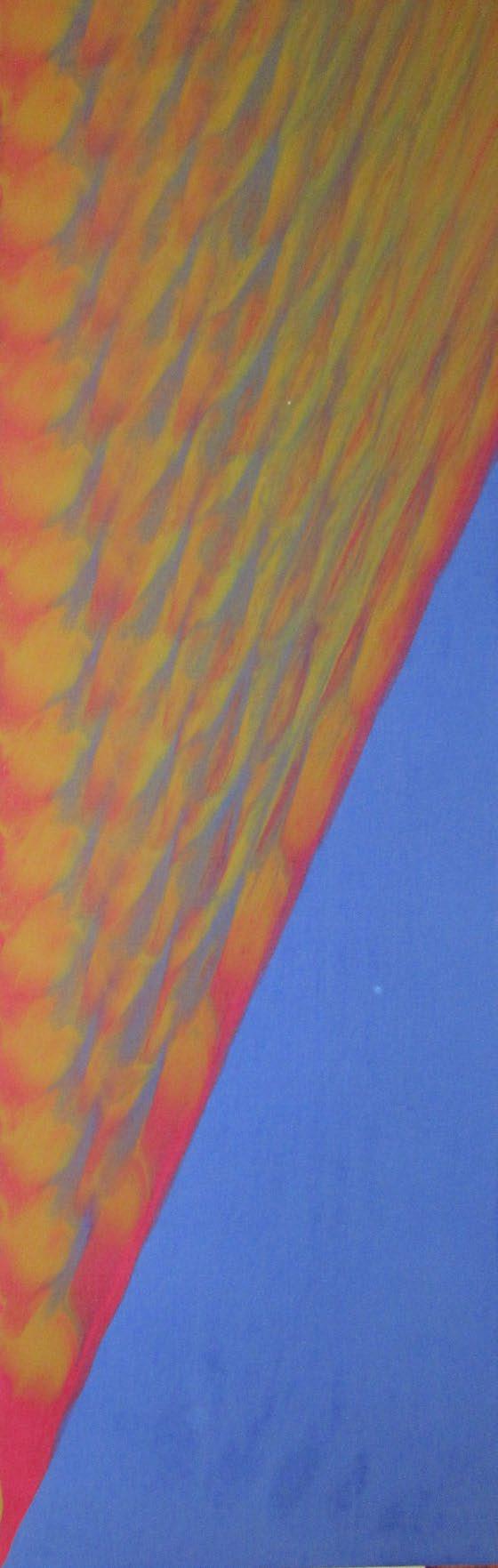

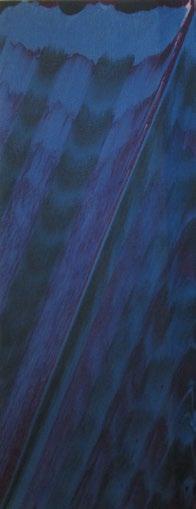

Oblique, 1970

68 1/4 x 22 1/4 inches (P131)

Acrylic on canvas

Here Now, c. 1968

Overall: 30 3/4 x 45 3/4 inches (P052)

Acrylic on canvas

83 1/2 x 61 1/2 inches

Untitled

Acrylic on canvas

(P103)

Numerical

Acrylic on canvas 20 x 58 1/2 inches (P059)