Thirty Years, Two Worlds EDWARD ZUTRAU

Cover illustration: Edward Zutrau

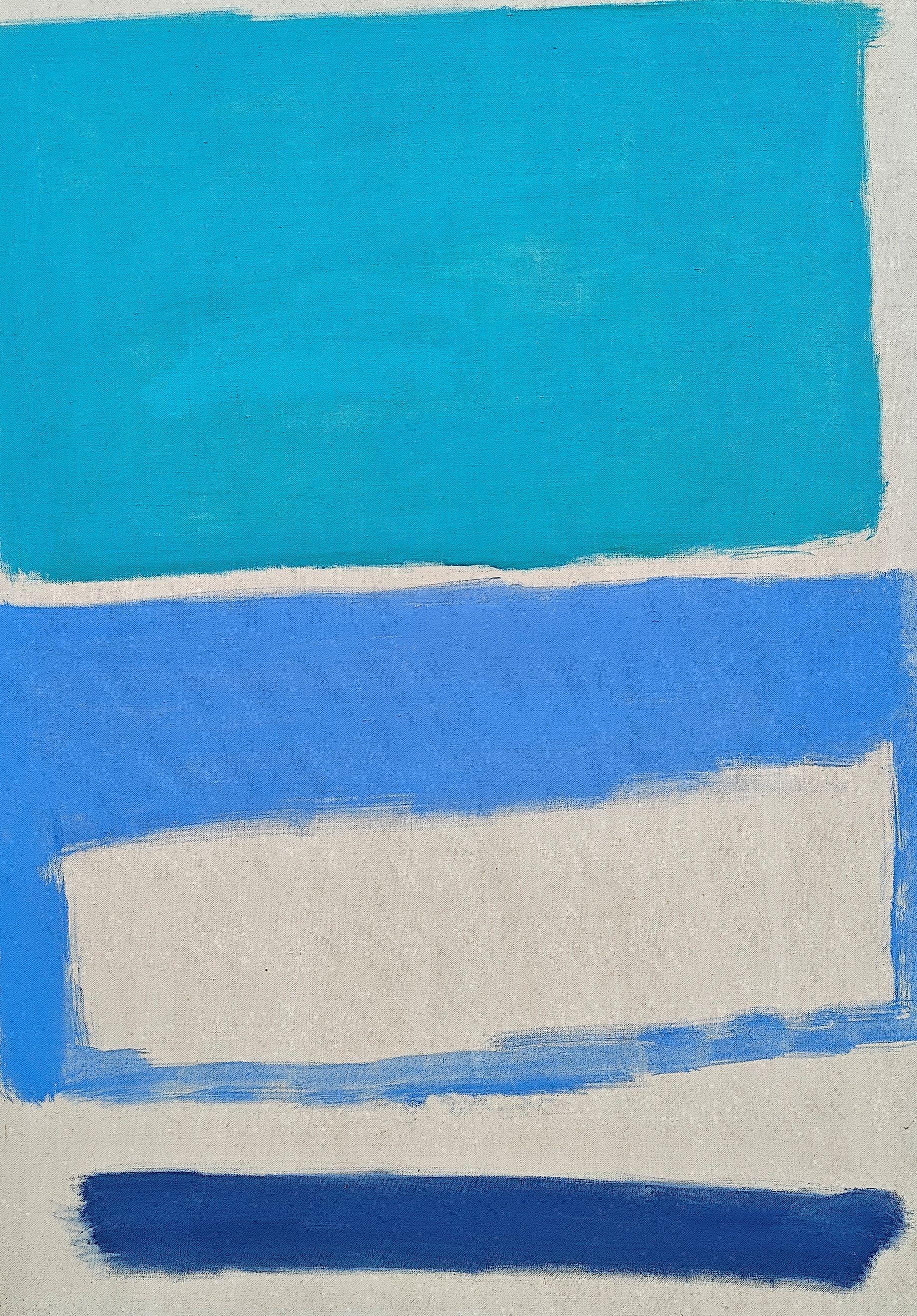

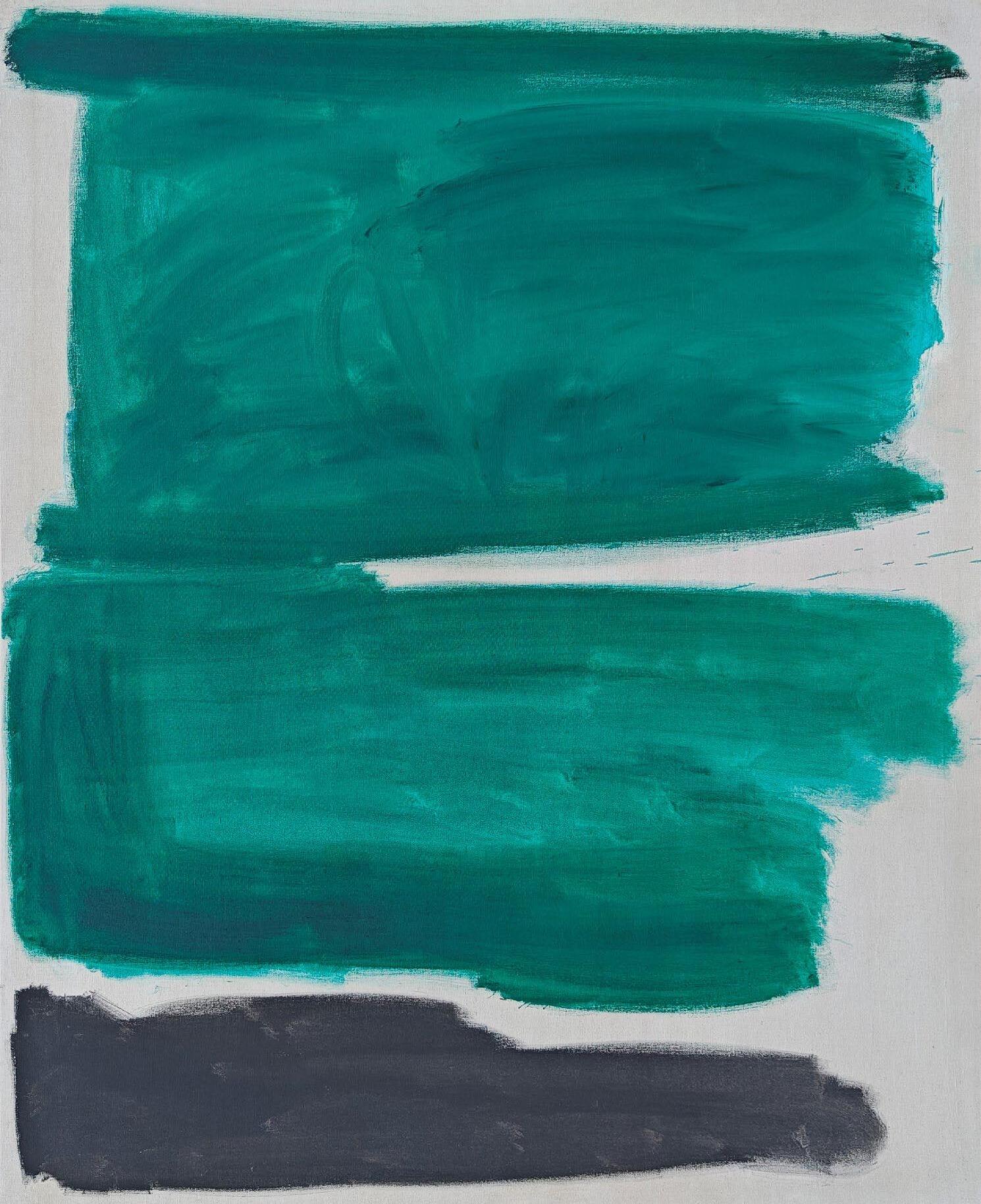

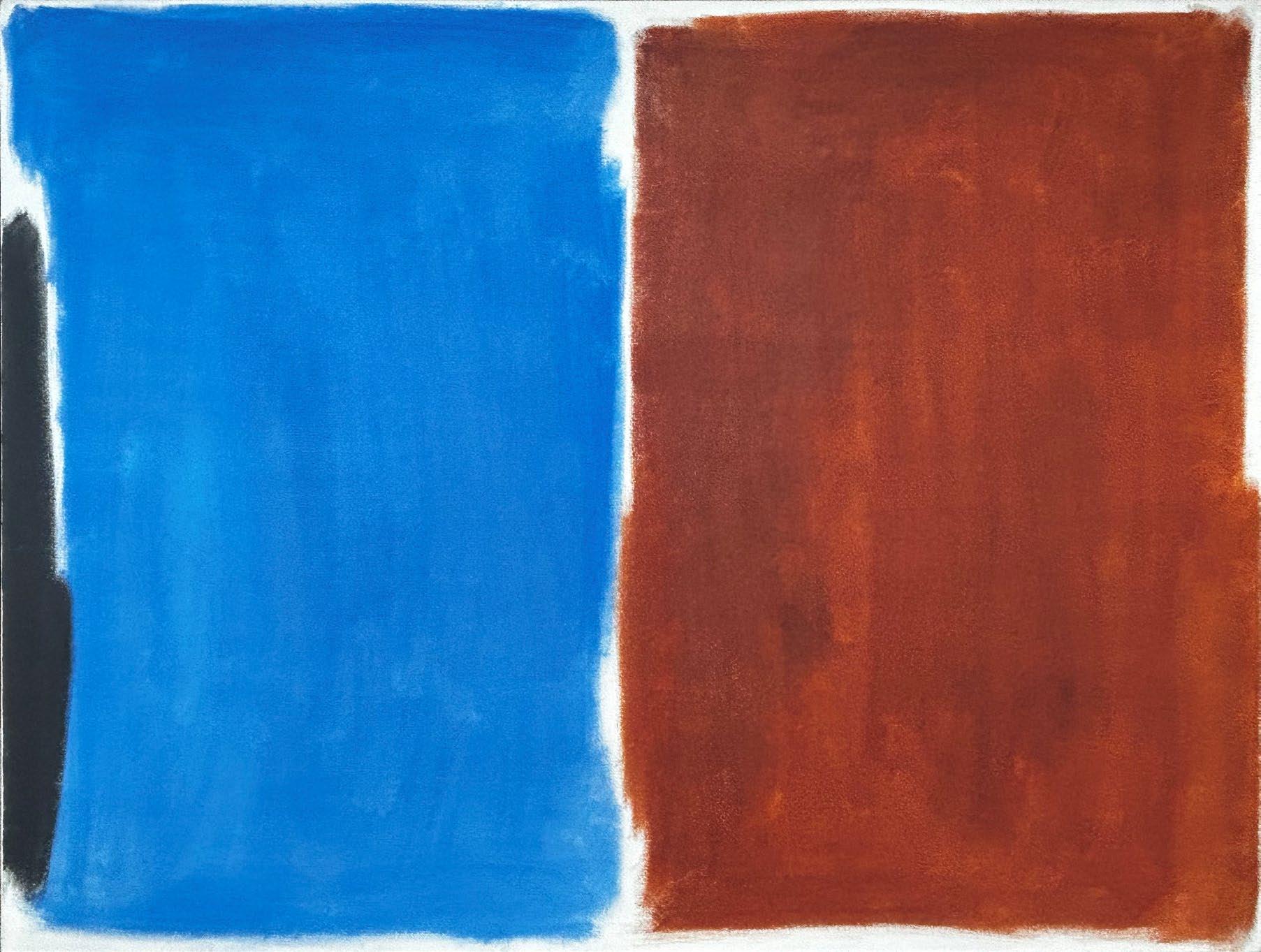

Untitled, 1968

Oil on canvas

51 1/2 x 38 inches

All rights reserved, 2025/2026. This catalog may not be reproduced in whole or in any part, in any form or by any means both electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of Lincoln Glenn.

Catalog design by Clanci Jo Conover

January 8 - February 21, 2026

542 West 24th Street New York, NY 10011

(646) 764 - 9065

gallery@lincolnglenn.com www.lincolnglenn.com

Foreword

As we begin 2026 with Edward Zutrau: Thirty Years, Two Worlds, we find ourselves reflecting not only on the remarkable arc of Zutrau’s career, but also on the growth of our gallery, our relationships with the artists we champion, and the evolution of their practices over time. This exhibition marks our second dedicated solo presentation of Zutrau’s work since establishing our current location and beginning our representation of the artist’s estate.

What we started in 2022 has steadily expanded into a two-location program with a clear curatorial vision and a commitment to meaningful, long-term engagement with artists and their legacies. When we concluded our previous exhibition—focused on Zutrau’s transformative years in Japan—we knew we wanted to revisit his work with a broader lens.

Even before opening the gallery, we imagined bringing artists back into public view, reintroducing bodies of work that had been tucked away for decades, and engaging with art history in an intimate, renewed way. Zutrau embodies the very spirit of that mission. Since we began representing his estate, his work has entered museum collections across the United States and private collections around the world, reaffirming his relevance and resonance today.

Like Zutrau, our own commitment to abstraction has only deepened over time. Presenting this expansive selection of his paintings—many unseen for years—is both a privilege and a responsibility we approach with care and gratitude.

We are proud to share Edward Zutrau: Thirty Years, Two Worlds with a new generation of collectors, curators, and admirers, and to continue building the legacy of an artist whose work has profoundly shaped our vision.

Sincerely,

Douglas Gold & Eli Sterngass

A NEW YORKER IN JAPAN: EDWARD ZUTRAU

by Clanci Jo Conover

In the 1950s and 60s, Edward Zutrau (1922-1993) inhabited two worlds on opposite sides of the globe: Tokyo and New York. The experience of straddling different cultures and residing in a foreign country during a time of great transformation – both personally for the artist and nationally for Japan – had a profound, lasting impact on his style and approach. Zutrau developed a distinct version of abstraction that could only come into being through multicultural exchange and intense introspection, coalescing in subtle calligraphic lines, distilled structures, and fields of created or perceived space.

A Brooklyn native, Zutrau began creating art at age 4 under the tutelage of his grandfather Michael Gunderson, a designer for the National Can Company.1 He recalled in a letter from 1972 “I spent all the time I could with him making drawings while he sat working at his drawing board doing much of his designing at home after regular hours. We listened to a crystal set (a radio with headphones) while working.” Zutrau progressed through a number of art schools, studying with artists such as Victor Candell, Will Barnet, and Julian Levi, receiving his first solo exhibition at Regional Arts Gallery by 1951.2 His second solo show came in 1955 at Perdalma Gallery, receiving recognition in The Art Digest – the sentiment about Zutrau’s particular brand of abstraction lacking a formal language resounds to the present day, refusing to be pigeonholed:

“Abstract in viewpoint, Zutrau precariously balances clean-edged planes of flat colors along unstable, tilting pictorial axes. The results often combine a curious fussiness of detail with an overall emptiness. In some works, his vocabulary switches from these precise shapes to the idiom of [Franz] Kline or [Clyfford] Still… The general effect of these canvases, however, is of an artistic personality which has not yet found its appropriate formal language.”3

In addition to exhibiting, Zutrau took on commercial jobs and advertised in a 1950 edition of The Art Digest (Fig. 1) that he was offering classes in drawing and painting at Studio 11, 58 W. 57th Street – the historic Sherwood Studio Building designed as artist apartments with studio spaces. The artist married model Kikuko Miyazaki in 1955, and the pair relocated to Japan by 1958 with their young family.

Zutrau received considerable attention during his years living in Japan, earning five solo exhibitions and gaining popularity in the local art scene. This period would be critical to his development as an artist, exposing him not just to a different culture and artistic styles, but to cities and landscapes that inspired his compositions. The title Kamakura appears on a number

of his works, denoting the seaside Japanese city and the rich colors and forms it contains. Both paintings in the present exhibition bearing this title are composed of two large forms surrounded by rivuletlike borders (p. 8 and p. 17). These could dually represent manmade structures and the surrounding hills, blurring the line between organic and artificial by obscuring the subject itself.

Beyond the sights Zutrau was exposed to during his time abroad, the time at which he arrived in Japan undoubtedly impacted his philosophical approach to art. Japan was on a journey of reconstruction following the devastating toll of World War II, which sparked a desire to regain a national/cultural identity. Artists and creatives were a critical part of this conversation, with some believing a return to traditional arts and craftsmanship, often referred to as kōgei, would strengthen a sense of identity rooted in history and precedence. The history of kōgei is marked by continual reinterpretation, and in postwar Japan the term’s meaning was, and in many ways still is, actively debated. Advocates of Meiji period (1868-1912) craftsmanship argued that an adherence to special, fine crafts inaccessible to the common citizen best represented a national aesthetic, while proponents of industrial design and folk art styles saw kōgei as encompassing the applied arts.4

More progressive Japanese movements – such as the Gutai Art Association (1954-1972) and the Experimental Workshop (1951-57) – appeared, as well, keen to find a new style and way of interacting not just with material, but interdimensional, multimedia creativity.5 The Gutai manifesto, published in 1956 by Yoshihara Jirō (1905-1972), offers praise for the explorative work of Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) and Georges Mathieu (1921-2012), and claims: “In Gutai Art, the human spirit and matter shake hands with each other while keeping their distance. Matter never compromises itself with the spirit; the spirit never dominates matter… To make the fullest use of matter is to make use of the spirit. By enhancing the spirit, matter is brought to the height of the spirit. Art is a site where creation occurs; however, the spirit has never created matter before. The spirit has only created spirit. Throughout history, the spirit has given birth to life in art. Yet the life thus born always changes and perishes.”6

Outside of the artistic sphere, the country’s economy was beginning to stabilize with improved production of exports like cameras, motorcycles, and television sets – this is the landscape Zutrau entered when he relocated to Japan in 1958. The outpouring of ideas and philosophical debates around subjects like aesthetic, design, functionality, and the avant-garde provided fertile ground for Zutrau, then in his mid-30s, to develop his own philosophies around painting. Interestingly, two separate reviews of his solo exhibitions in Japan mention the quality of space within his paintings – a 1959 review on his show at Chuo Koron Gallery states Zutrau’s work has a decorative yet romantic quality that culminates in an “East Asian space feeling,”7 while another review for his exhibition at Tokyo Gallery reads “The work consists of paintings with flat color composition and caliagraphic [sic] lines. The essential qualities of this painter is mostly made clear by the former, and is made of bright clear colors painted broadly and by the relationship of various shapes, space is created.”8

The concept of space is mentioned repeatedly in the Gutai manifesto, seen in the following passage: “When the individual’s character and the selected materiality meld together in the furnace of automatism, we are surprised to see the emergence of a space previously unknown, unseen, and unexperienced. Automatism inevitably transcends the artist’s own image. We endeavor to achieve our own method of creating space rather than relying on our own images.”9 It is unclear if this thinking influenced the journalists who noted the endearing qualities of “space” in Zutrau’s paintings, or if Zutrau himself admired these principles at the time, but the coincidence can not be overlooked.

When considering the paintings presented in the current exhibition, a progression starts to emerge in Zutrau’s style: his work from 1956 (p. 19-20) predating his residence in Japan has more

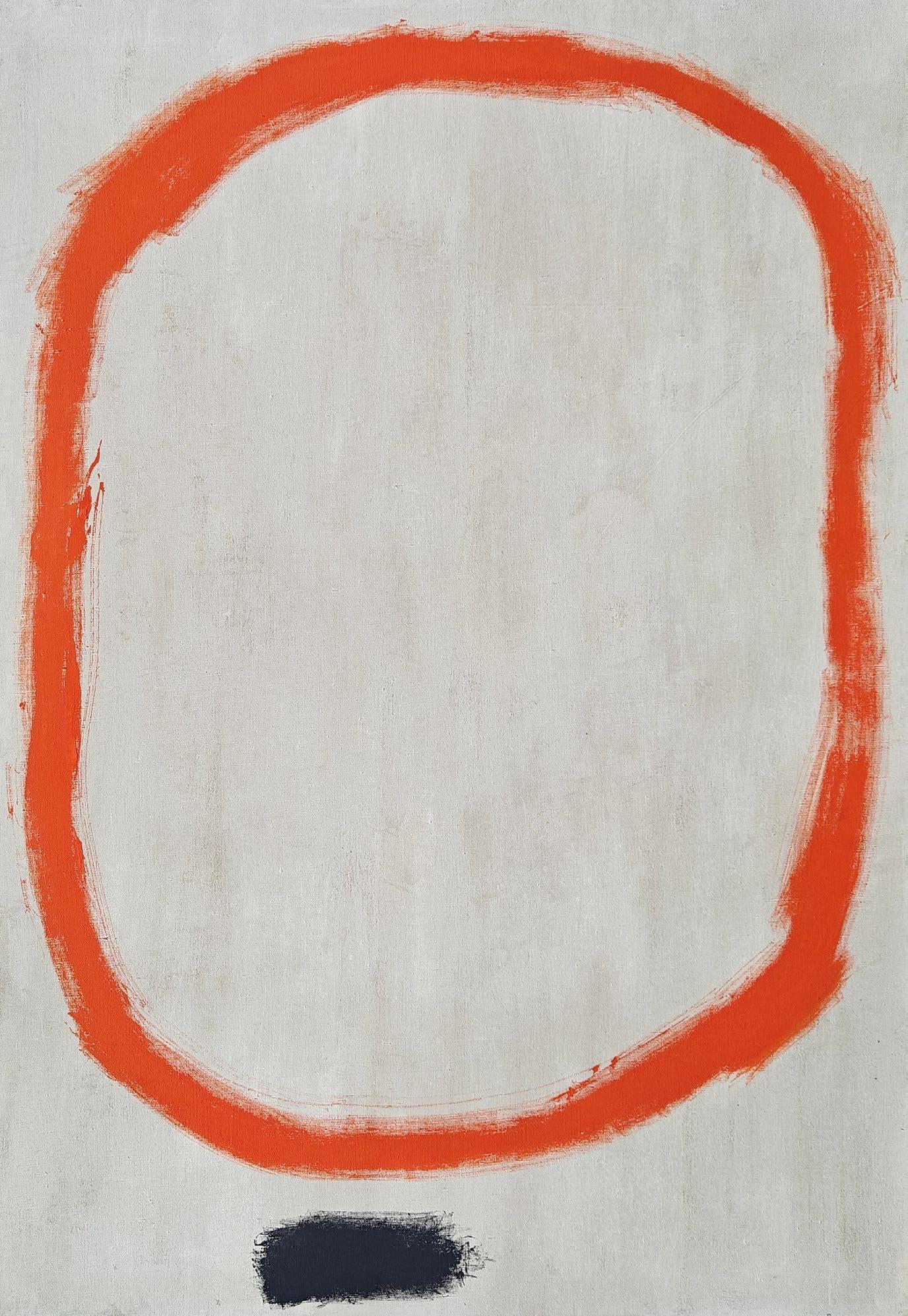

of an expressive tribal, almost cubist, inclination with its various forms and colors. These forms are gradually edited in the paintings from 1958 (p. 14) and 1960 (p. 16), until they finally reach maturity in the pared down, subtle compositions of 1963 and beyond. Although Zutrau’s style was distinctly unique, it is worth noting that Yoshihara produced his own series of circle paintings around this time, not dissimilar to Zutrau’s 1969 work featured in Thirty Years, Two Worlds (p. 13). Yoshihara’s creed about creating space rather than relying on selfmade images aligns with the philosophies Zutrau taught his students after returning to New York in the 1960s – space (see: Untitled, 1971, p. 11) and calligraphical elements (see: Untitled, 1963, p. 18) remaining frequent priorities within his work.

In Zutrau’s lecture notes from a painting course taught at New York University in 1978, he explains that an artist’s tools can not simply be something to pick up and use as a part of the self, but must be an extension of the self as a whole. He implored his students:

“The materials you use for painting (and drawing) must become a part of you and your attitude toward your work… Your attitude and approach to these materials will to a great extent determine the outcome of your painting… Your brushes and palette knife cannot remain separate objects that you pick up in your hand to work with. They must become an extension of your arm and essentially of you both physically and psychologically - in other words, your brushes, knife, and paint are not just a part of you, they are you. And must express you creatively. Otherwise, your painting will merely be the carrying out of a ritual - and no matter how well done, it will not be creative art, and this is what we are after…

Your work will have its identity and be known by the way you compose a painting and the space concept you develop (as your own) and in the way you use your materials in arriving at this way of working or ‘style” as it is more popularly called. I caution you, do not become a slave to… style or her sister - technique - these are just elaborate wordsand all they refer to is a way of working. Style and technique are nothing more than the way one works, they grow out of the way we work. Pascal the French philosopher once said: ‘Never Mind the Word, Give me the Definition.’”

A review of Zutrau’s last show in Japan at Nihonbashi Gallery in 1963 called his work “obviously American” and compared it to that of [Mark] Rothko, Still, and [Barnett] Newman.10 The article contrasted Zutrau from these older artists, stating that his “combinations and emphases add up to a new freshly realized original work. This is enhanced by means of certain conscious or perhaps unconscious addition of quiet subtle qualities of space and color probably achieved through knowing about the arts of our tradition.”11 Here, the author outright claims that Zutrau gleaned a subtle quality of space by way of exposure to Japanese art and aesthetics.

The years Zutrau spent in Japan from 1958 to 1963 marked a kinetic period as the country reckoned with their own artistic and national identity, providing a concentration of experimentation, debate, exploration and problem solving in myriad aspects of life and culture. Zutrau was a capable, compelling artist when he left New York. It was not until he sojourned in Japan, however, that he would develop a fully realized, mature style based on his own artistic vocabulary that synthesized his training in New York, his foray into the Japanese modern art scene, and personal priorities such as philosophy and psychology.12

Following his return to New York in 1963, a host of artistic movements like minimalism and conceptual art would overtake the city, yet none appear to have outweighed the aesthetic and philosophical priorities he had already established for himself. Spatial reverence and psychological nuance cultivated during his years in Japan continued to guide him, allowing his work to maintain a consistent internal logic even as the world around him was in a state of flux. Zutrau would continue exhibiting, notably earning three solo shows with Betty Parsons (Fig. 2), and inclusion in her annual Christmas exhibitions from 1972-1979.

Teaching became an equally important arena where Zutrau could develop and define his philosophies, imparting them onto young artists. Having taught students of all ages for much of his career, he eventually transitioned into university-level instruction in the 1970s, first at the Fashion Institute of Technology and later at NYU. His lecture notes reveal an artist who believed creativity was not tied to any one style or process, but that it came from an intentional integration of mind, body, and medium. By encouraging his students to approach their materials as extensions of themselves rather than tools to manipulate, he echoed, consciously or not, certain Japanese philosophies that had profoundly shaped his own thinking.

In the final decades of his life, settled with a family in the town of Mineola on Long Island, Zutrau continued to pursue this vision with steady commitment. Removed from the pressures of shifting artistic trends, he remained focused on the elemental concerns that had long driven him: the creation of space, the interplay of form and color, and the psychological immediacy of interacting with materials. Betty Parsons said that his paintings were “timeless, as if they stop time, itself.”13 Zutrau’s legacy endures in the clarity of his vision: an art unfixed to trends, yet profoundly shaped by the worlds he inhabited and transformed.

Clanci Jo Conover has worked with the Estate of Edward Zutrau through her company Fine Art Donations to place his paintings in major museum collections such as the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, MA, and the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, IA, contributing to the ongoing visibility of his artistic legacy.

Endnotes

1 Edward Zutrau, unpublished biographical note, June 18, 1972.

2 Edward Zutrau, “Curriculum Vitae,” unpublished document.

3 R.R., “Edward Zutrau,” The Art Digest 29, no. 14 (April 15, 1955): 29.

4 Aleksandra Cieśliczka, “The Boundary Between the Art and Product: On the Meaning and Form of Kōgei in the Past and Present,” On the Intricacies of Aesthetics (Doctoral School of Humanities, University of Łódź), p. 7-9.

5 Doryun Chong, Michio Hayashi, Kenji Kajiya, and Fumihiko Sumitomo, From Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan, 1945–1989: Primary Documents (New York: The Museum of Modern Art/Duke University Press, 2012), 28–29.

6 Yoshihara Jirō, “Gutai Art Manifesto,” trans. Reiko Tomii, originally published as “Gutai bijutsu sengen,” Geijutsu Shinchō 7, no. 12 (December 1956): 202–4.

7 Yusuke Nakahara, “Edward Zutrau,” Yomiuri, March 19, 1959, English translation.

8 Kuwa, “Edward Zutrau One Man Show,” Tokyo Shimbun, March 1960, English translation.

9 Yoshihara Jirō, “Gutai Art Manifesto.”

10 Thomas Ichinose, “Edward Zutrau’s: Paintings on Exhibition,” Mainichi Daily News, December 1, 1960.

11 Ibid.

12 In addition to his education in the arts, Zutrau completed 210 hours of psychology credits at the New School in New York.

13 Betty Parsons Gallery, exhibition statement, 1980.

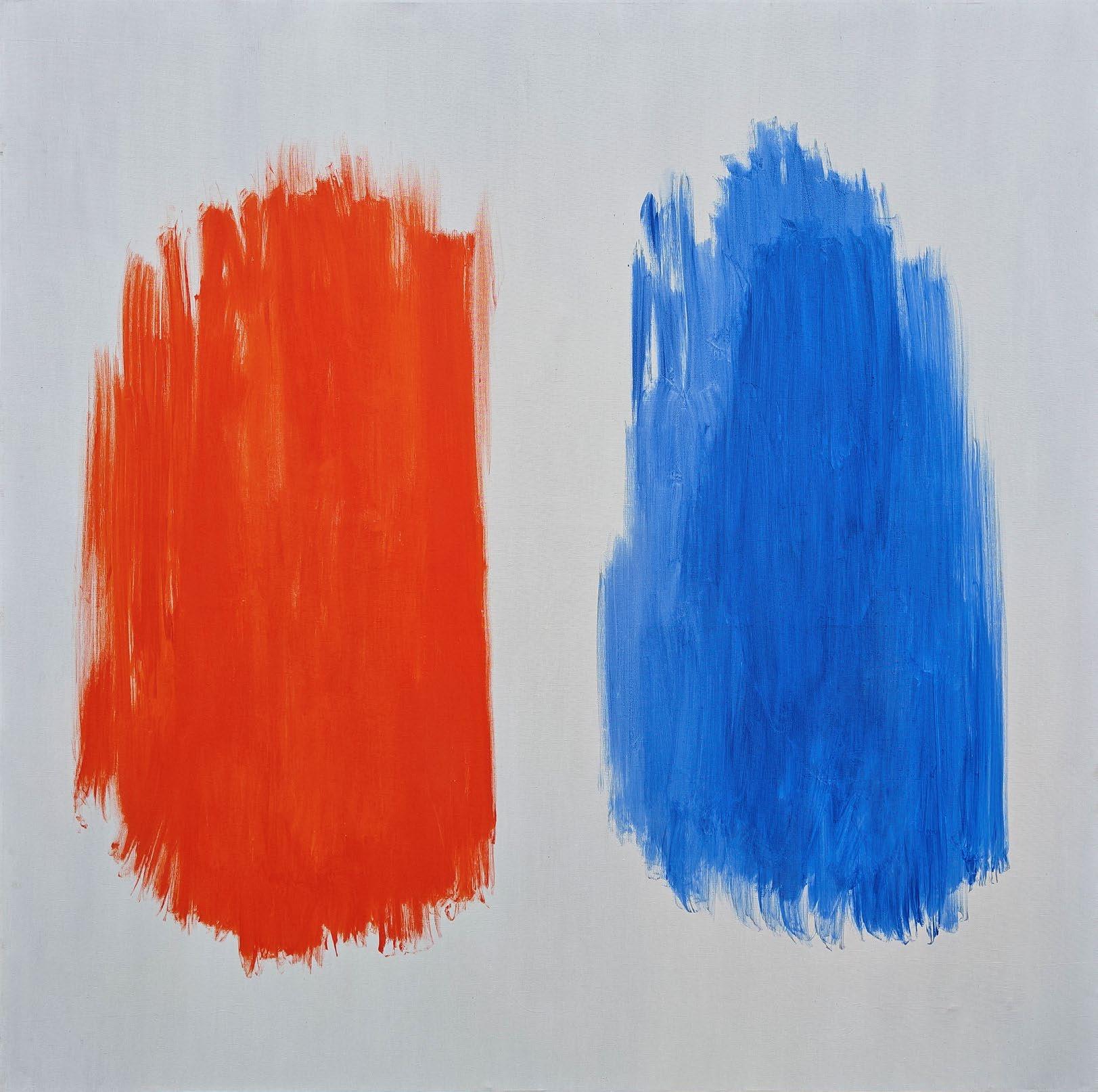

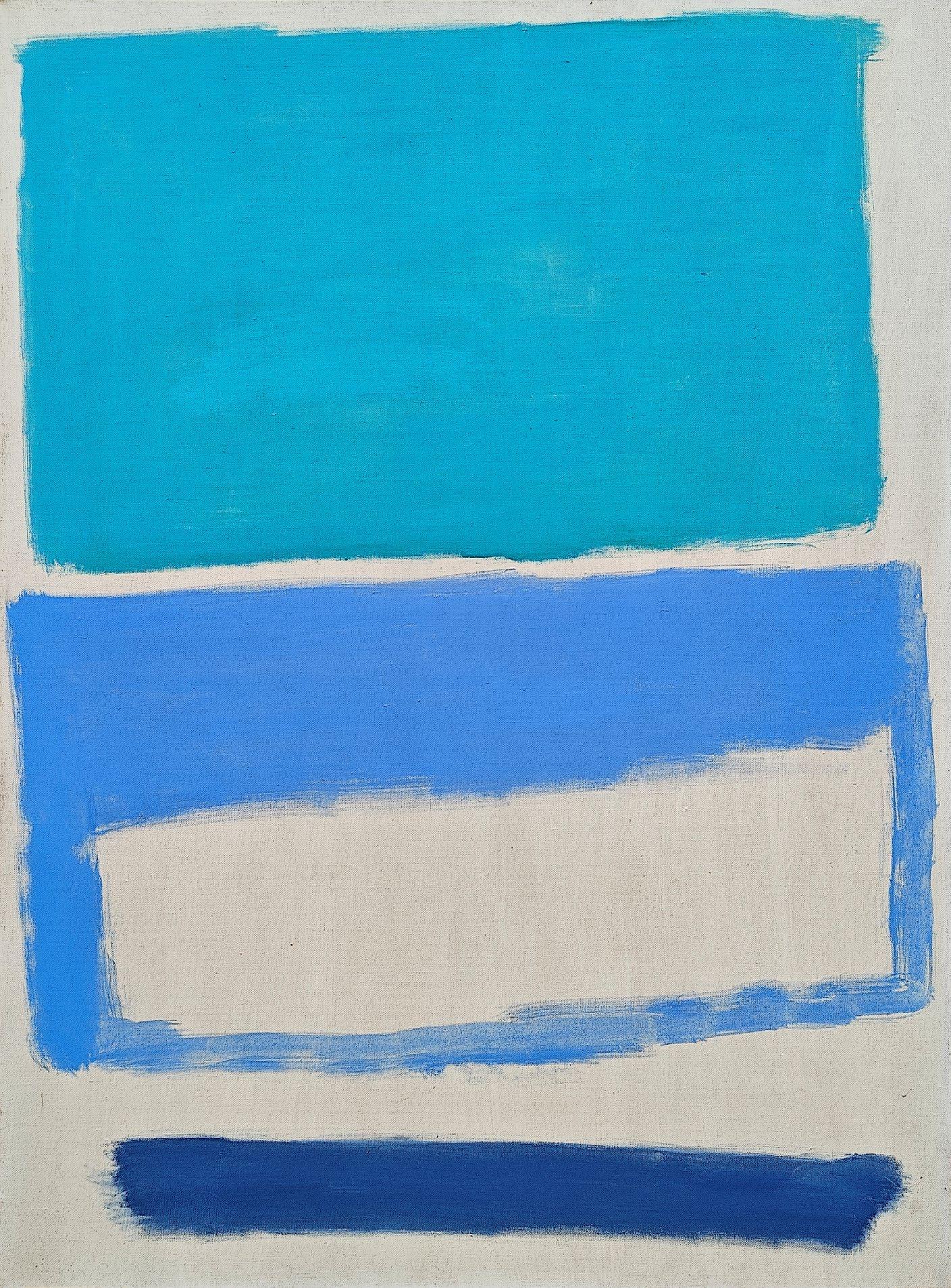

, 1984

66 x 66 inches

Signed and dated “5/7/84” on the reverse

1/2 x 63 3/4 inches

Signed and dated “2/63” on the reverse

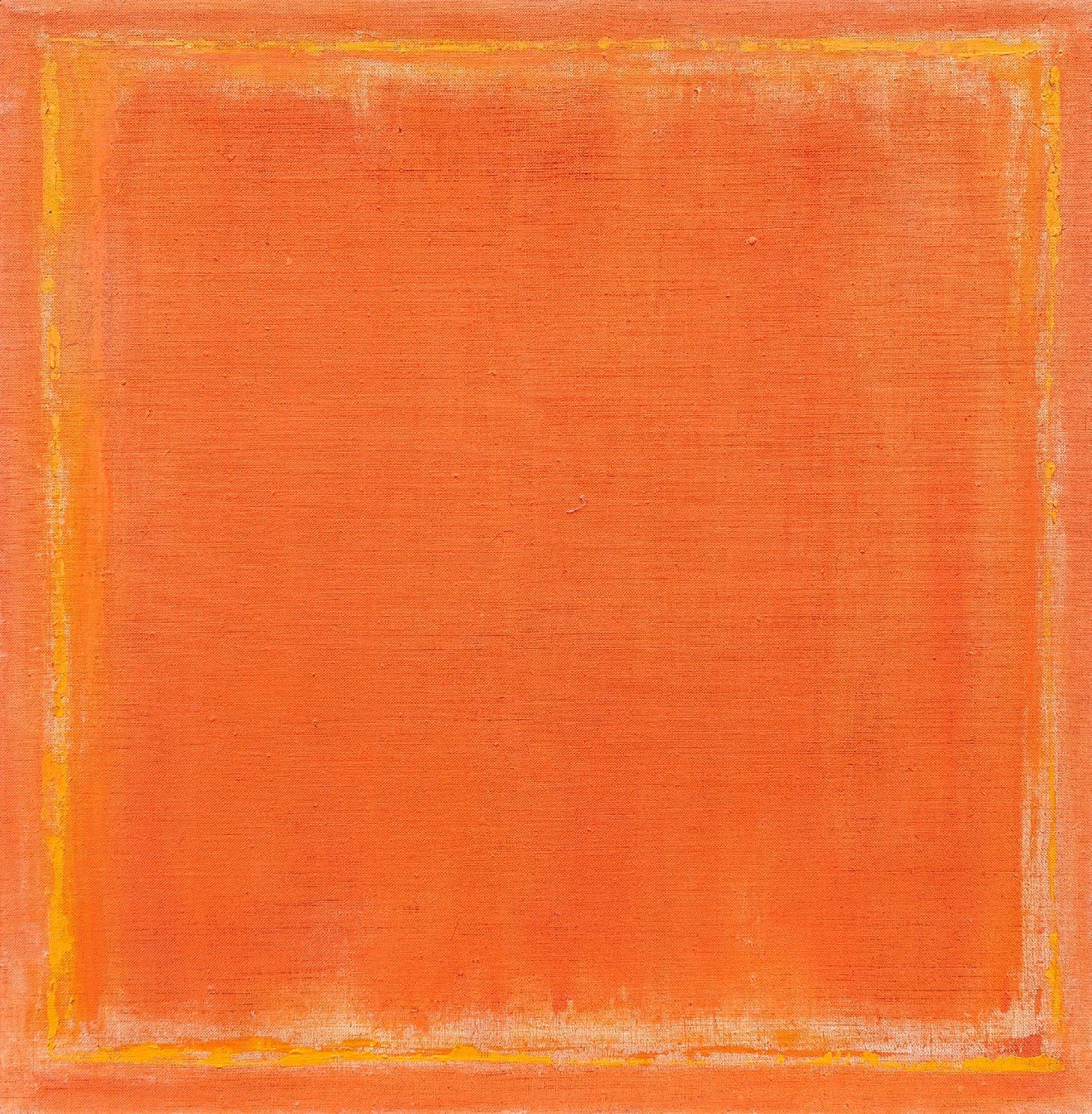

, 1980

22 x 22 inches

Signed and dated “5/4/80” on the reverse

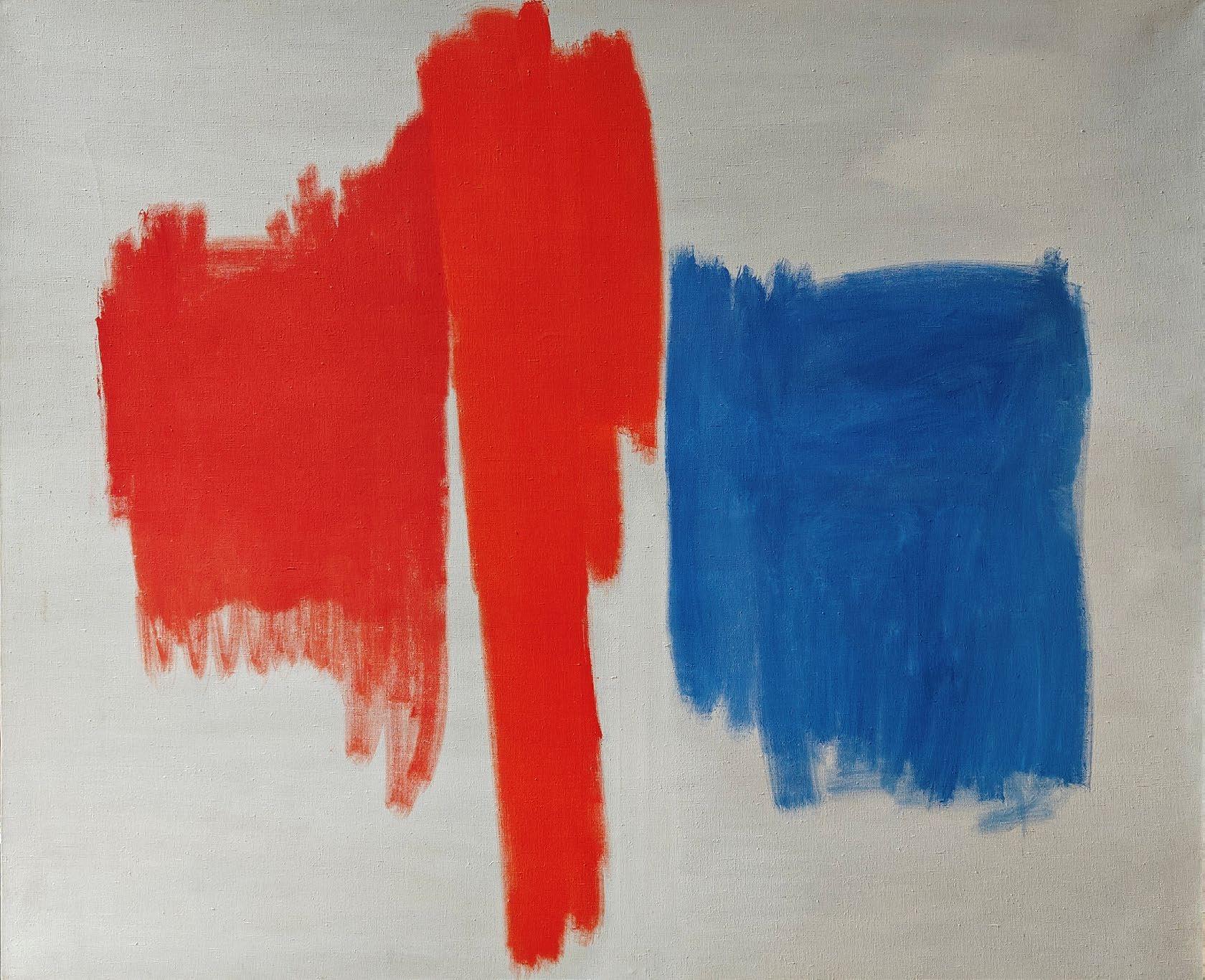

, 1963

63 3/4 x 51 1/4 inches

Signed and dated “4/63” on the reverse

Signed and dated “May 3 1971” on the reverse

Signed and dated “4/9/68” on the reverse

Signed and dated “10/25/58” on the reverse

51 1/4 x 35 1/4 inches

Signed and dated “5/18/1969” on the reverse

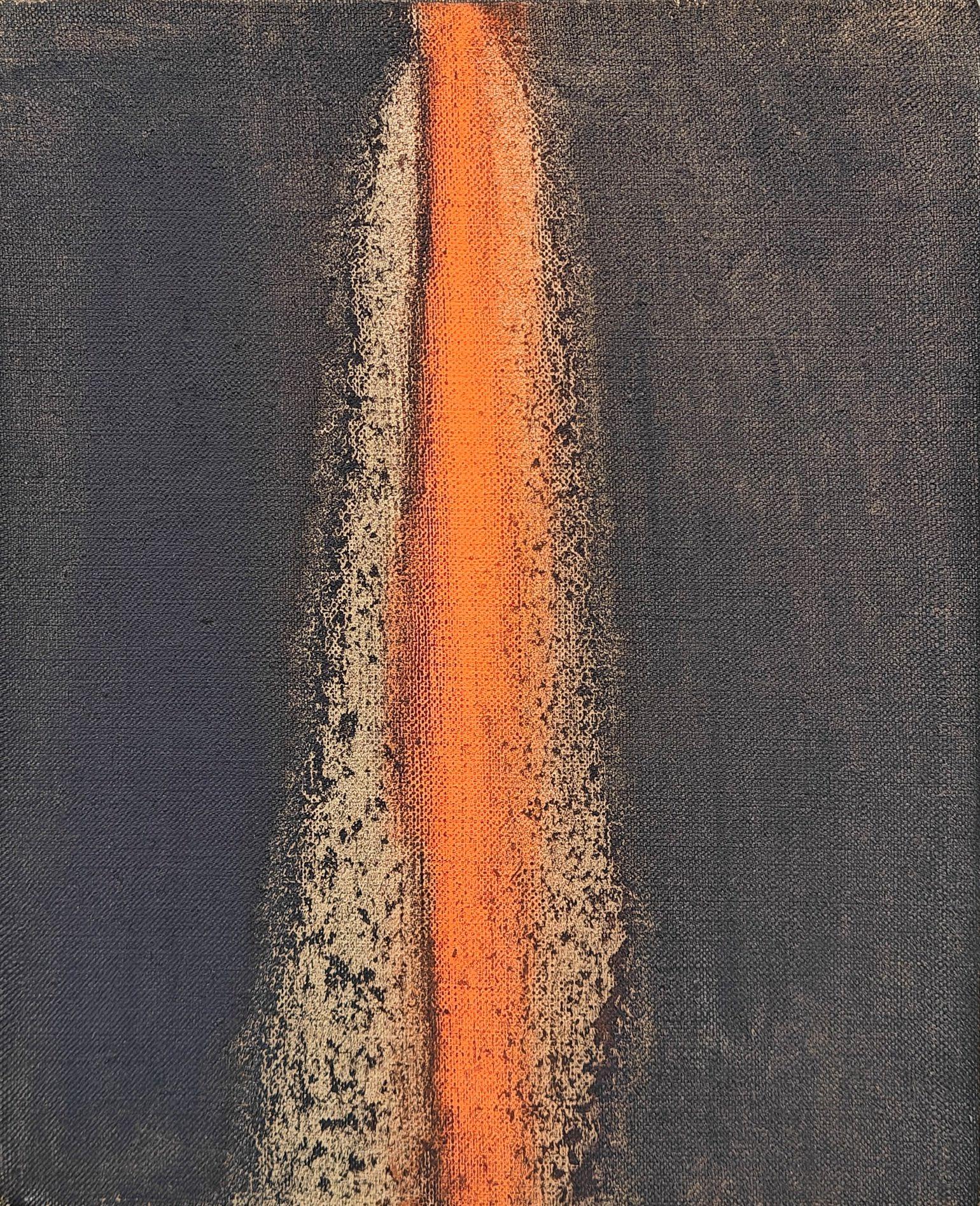

Untitled , 1963

10 3/4 x 8 3/4 inches

Signed and dated “5/63” on the reverse

9 3/4 x 13 1/4 inches

Signed and dated “11/60” on the reverse

38 1/2 x 51 inches

Signed and dated “May 1963” on the reverse

Signed and dated on the reverse