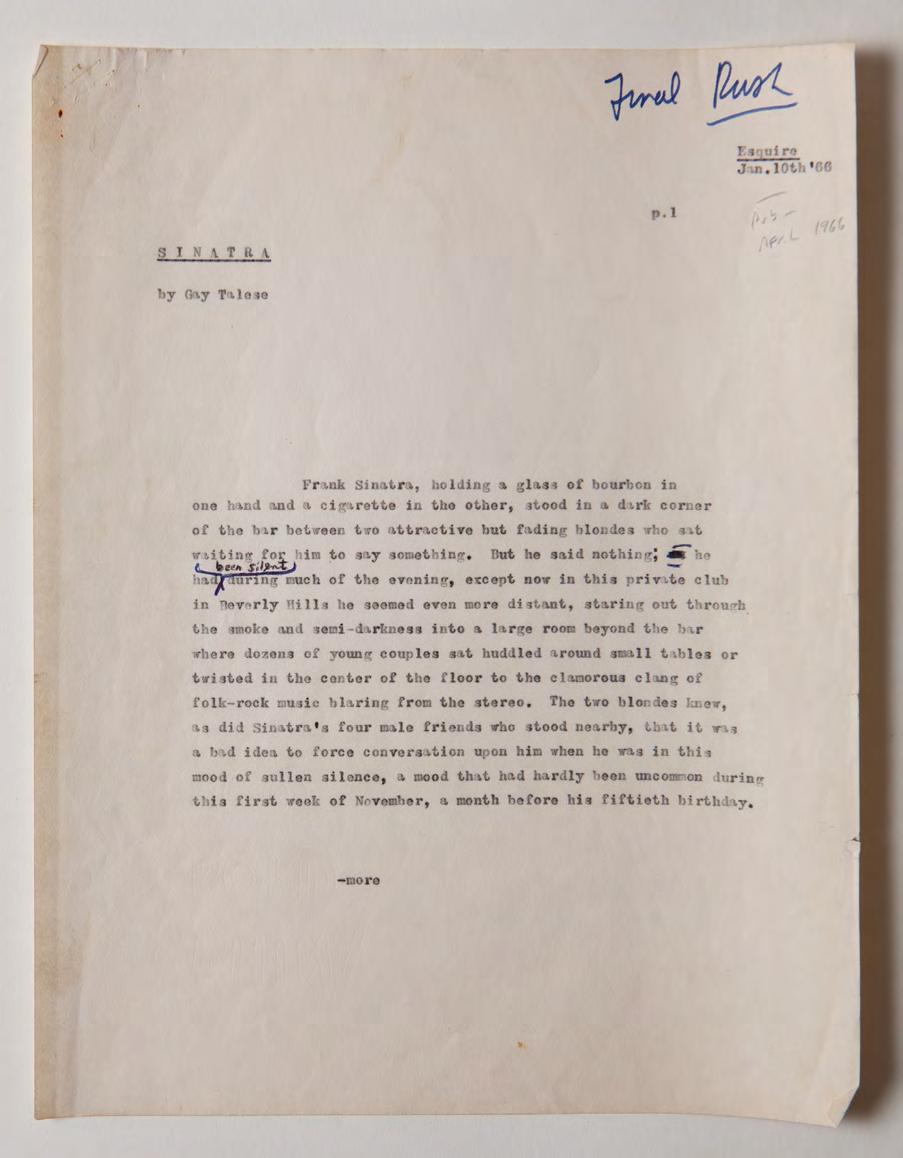

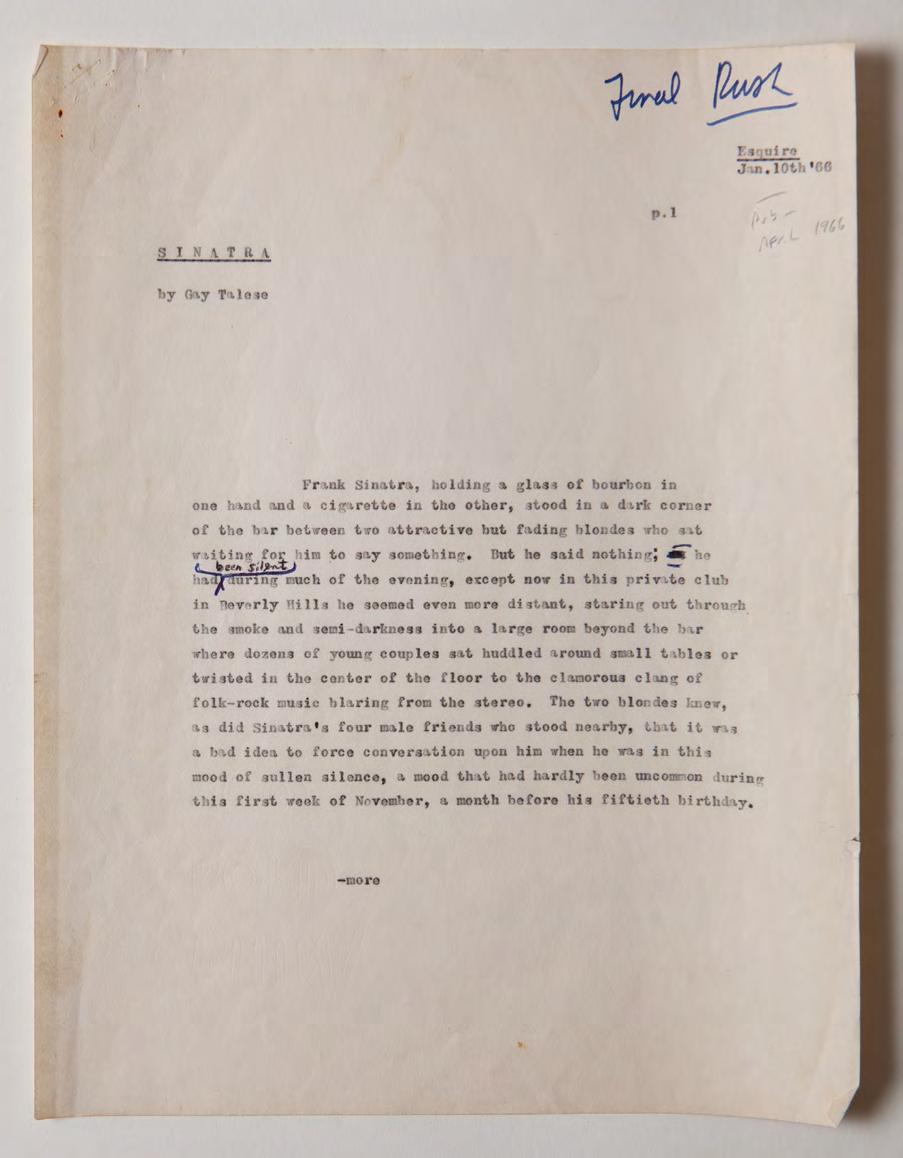

THE WORK OF ART Adam Moss

KARA WALKER

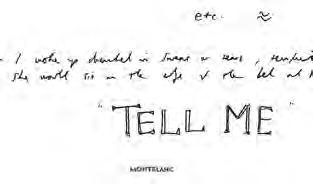

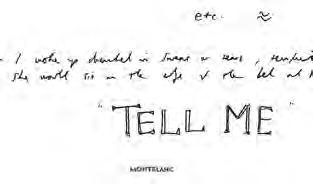

You, Where Are You?

born : 19TK

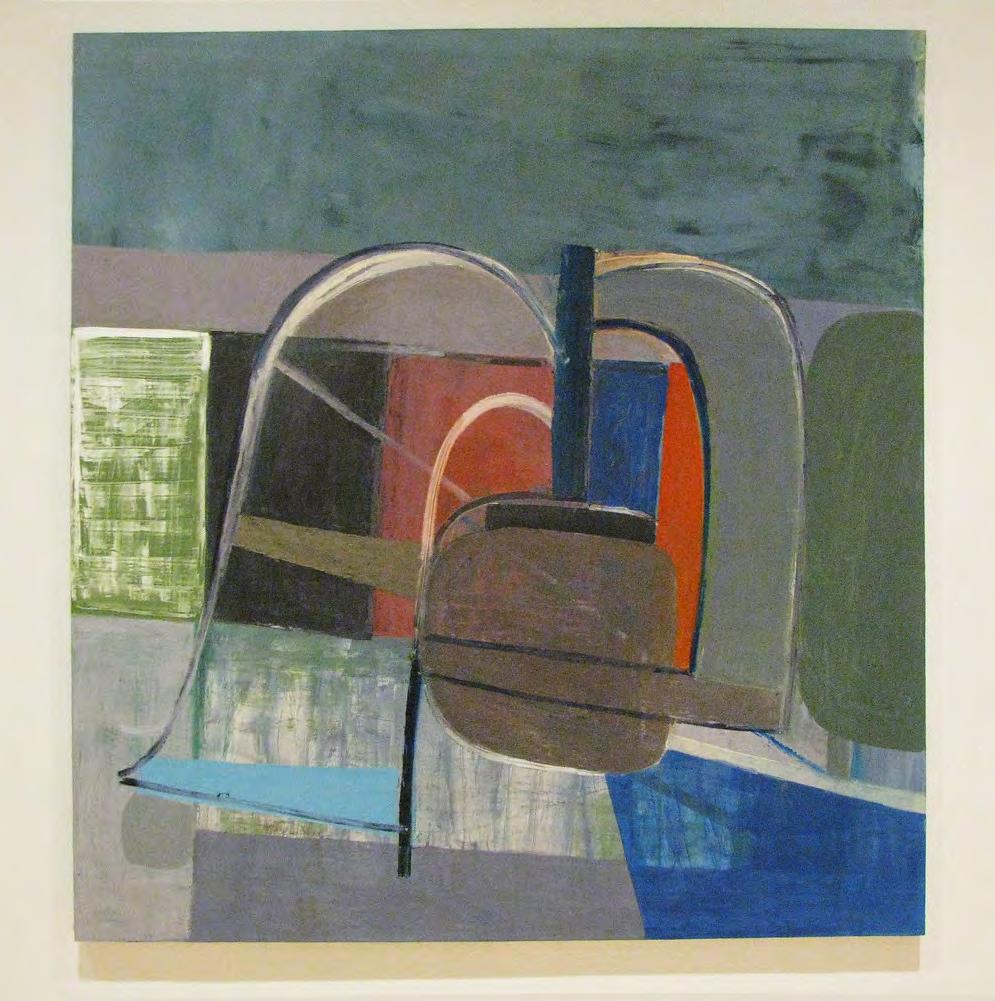

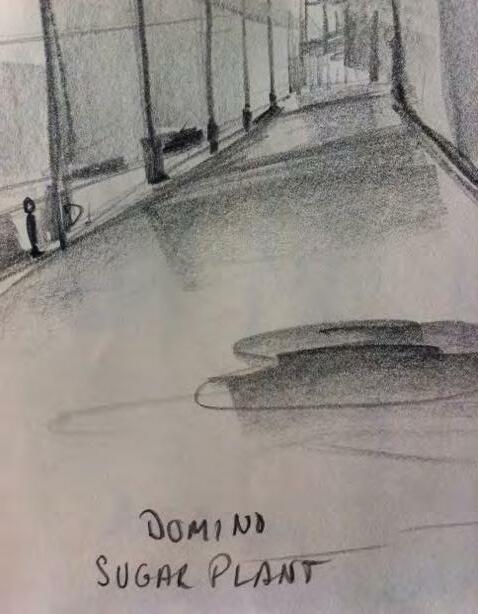

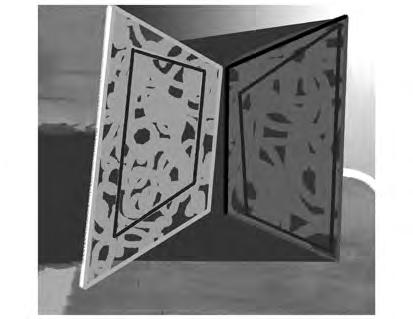

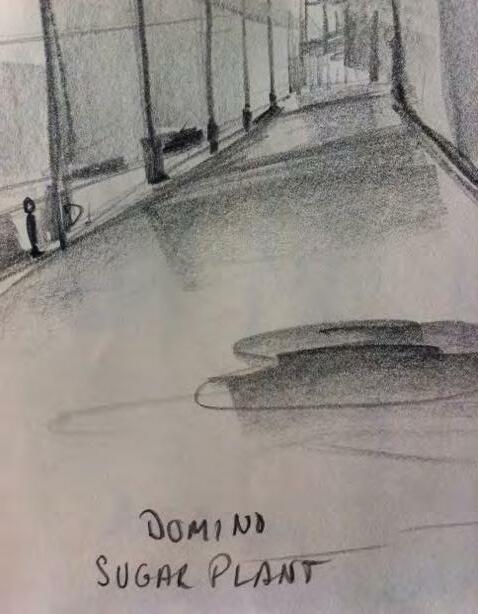

I’D READ ABOUT A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby – or as it was commonly referred to, the Sphinx – but I can’t say I was really prepared for it. I had biked there, to the old Domino Sugar Factory right by the Williamsburg Bridge. The factory was about to be destroyed, and I knew that they — Creative Time, a visionary arts organization devoted to public works, with funding from the developer [fn1] — had approached Kara Walker, an artist I revered, and invited her to make a public sculpture there.

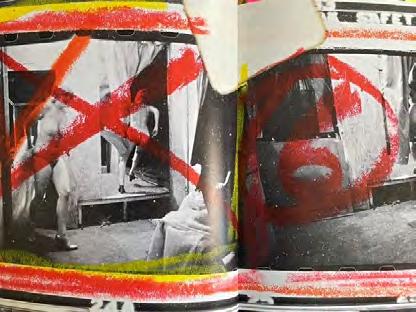

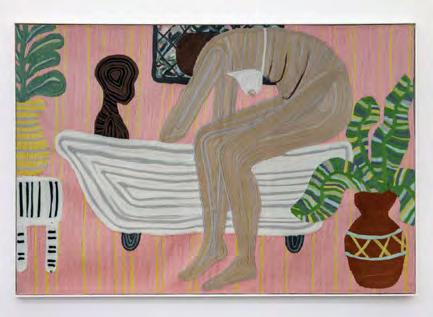

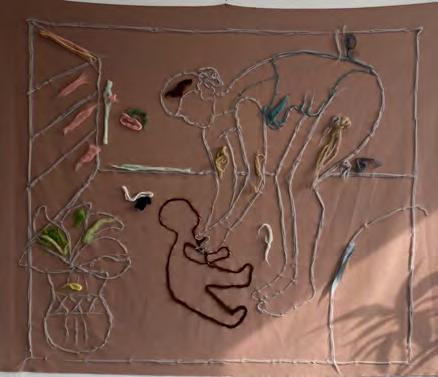

I entered the building, and if I remember right, it was a little twisty to get there, passing deserted rooms until suddenly you were in a vast cavernous space. And there you saw the giant face of a Mammy figure, perched forward with two giant breasts, Sphinx-like. Her body extended behind her. She was mammoth — 75 feet long, 35 feet high —and surrounding her were more life-sized figurines, boys with baskets, most of them. The Sphinx was white. She was covered in refined sugar- in fact it looked like she was made of the sugar entirely. It was at first almost comical to me, but I realized that was mostly a defensive reaction, since it very quickly became horrifying. Later I learned that was the frequent reaction – laugh/horror – to the sculpture, which was actually a set of sculptures: the Sphinx and the

2 KARA WALKER

Dolut eliciisqui te volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

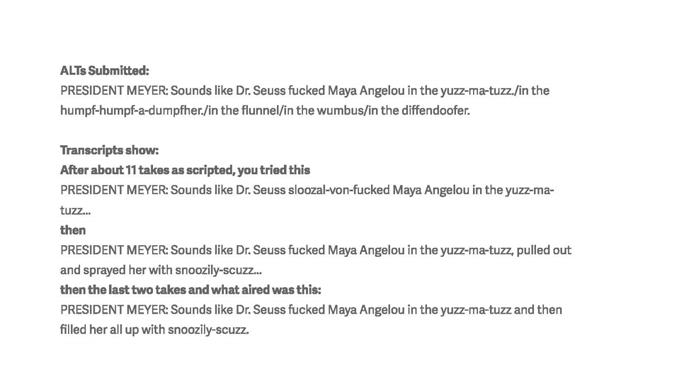

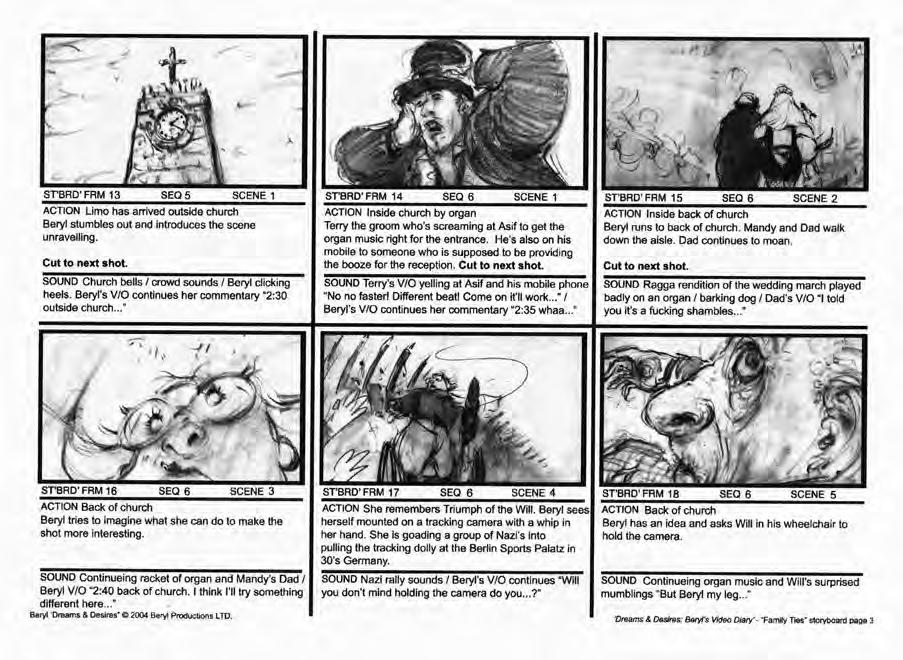

occupation : scultor work : A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby

1

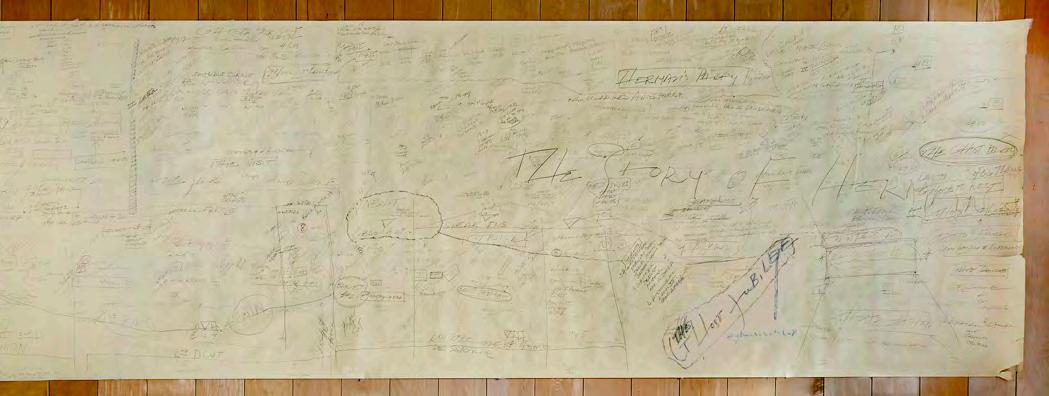

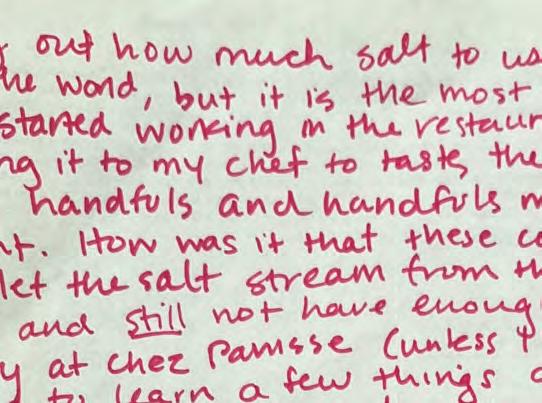

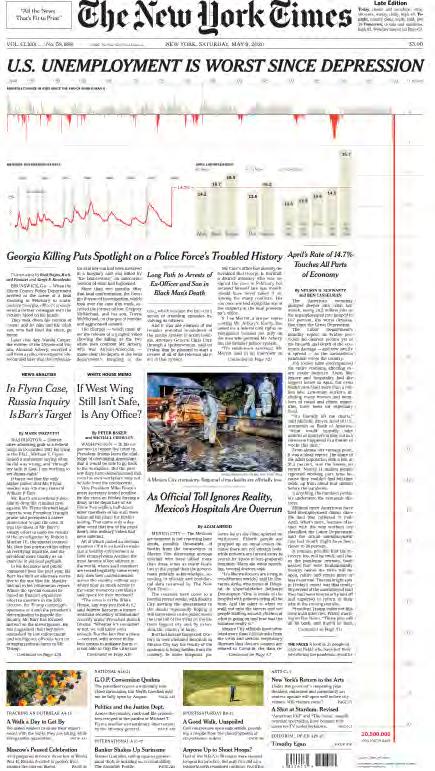

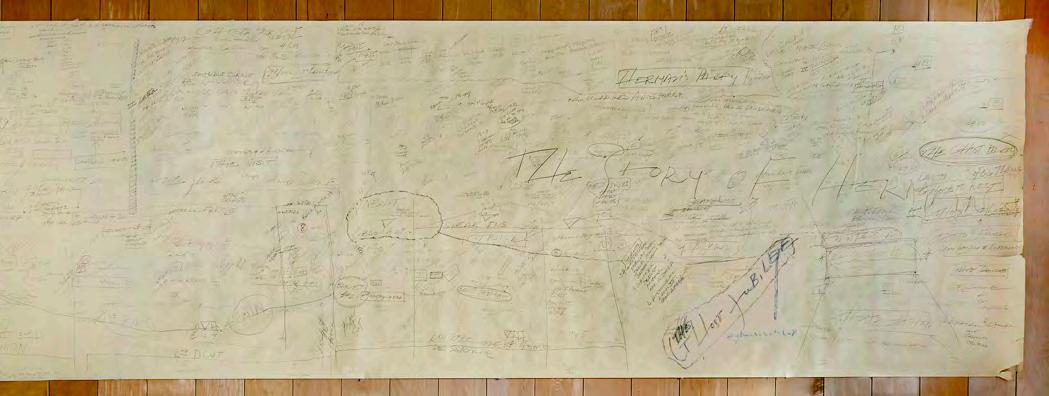

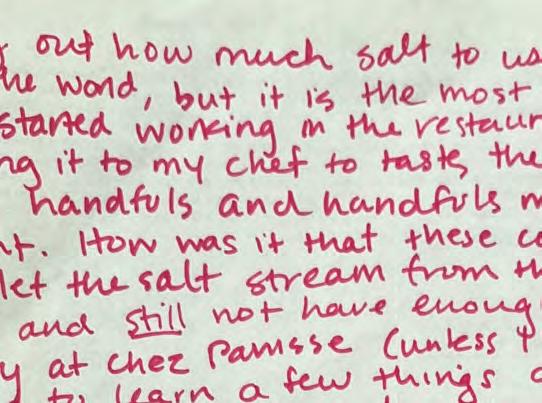

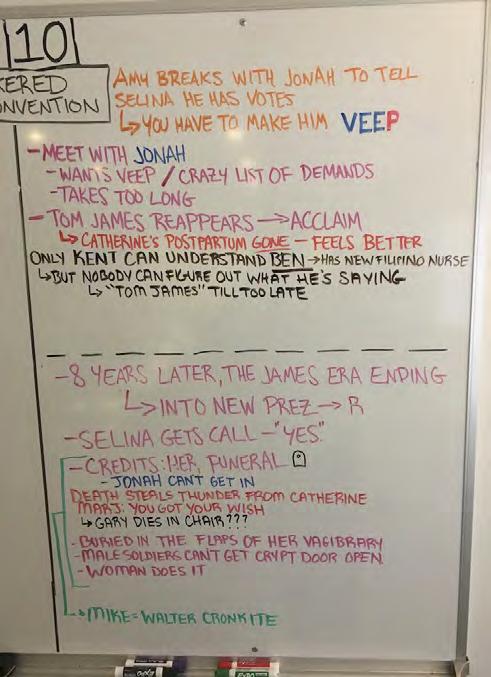

RE: FIRST THOUGHTS FROM 2013 ABOUT DOMINO I found an email that I sent to Anne Pasternak (the director of Creative Time) of the space after the initial visit. See below. ‑Kara

3

statues of boys with baskets. You could smell the sugar, smell the molasses, it was already (and this was the beginning of its run) a little rancid. I wandered back, taking in her whole length, until I was face to face with her exposed vulva. People, including several families, mostly white, were studying her, some taking pictures, some chattering, some agog. I went home, and found myself thinking about her a lot. Several weeks later, I went back. The figurines had largely melted. The stench was vile. The spectators were now mostly black.

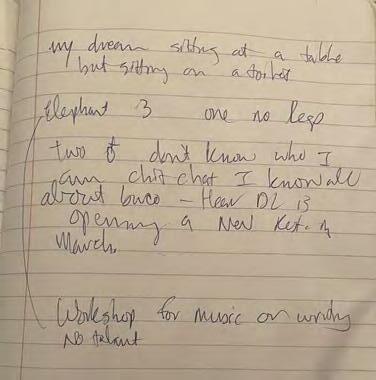

Between these visits, I dreamed about the Sphinx, and found myself in many conversations trying to divine her meaning, reading up about the history of sugar and slavery.

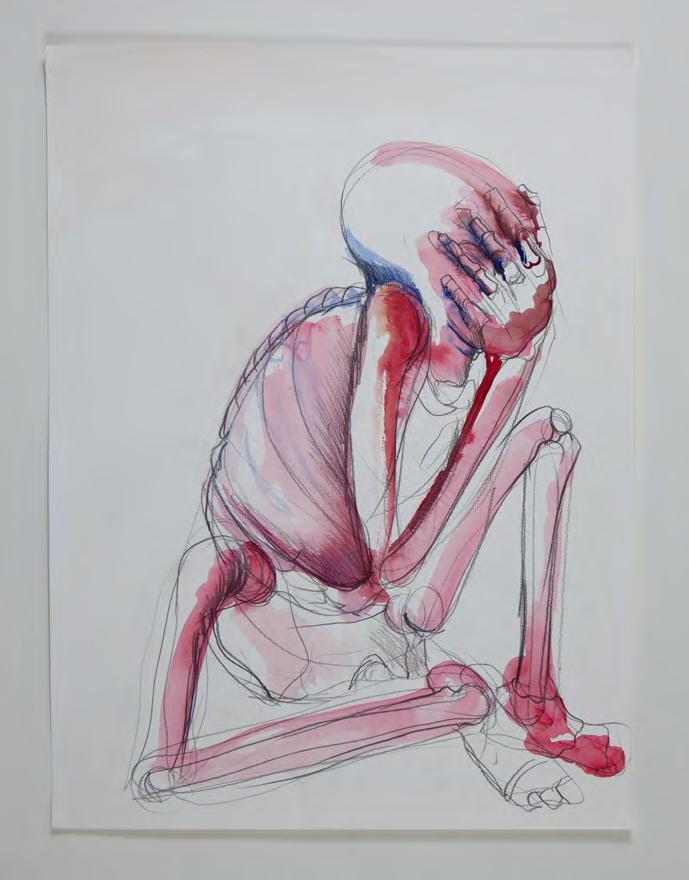

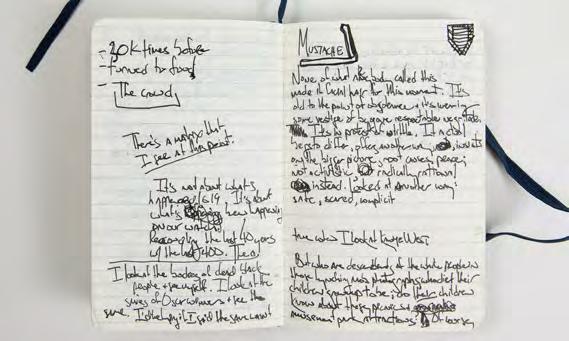

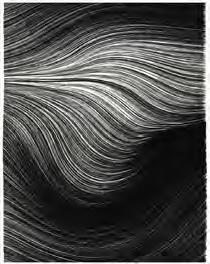

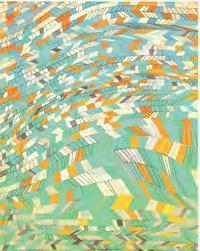

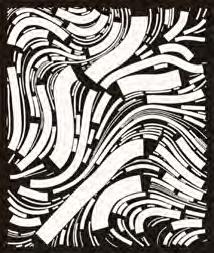

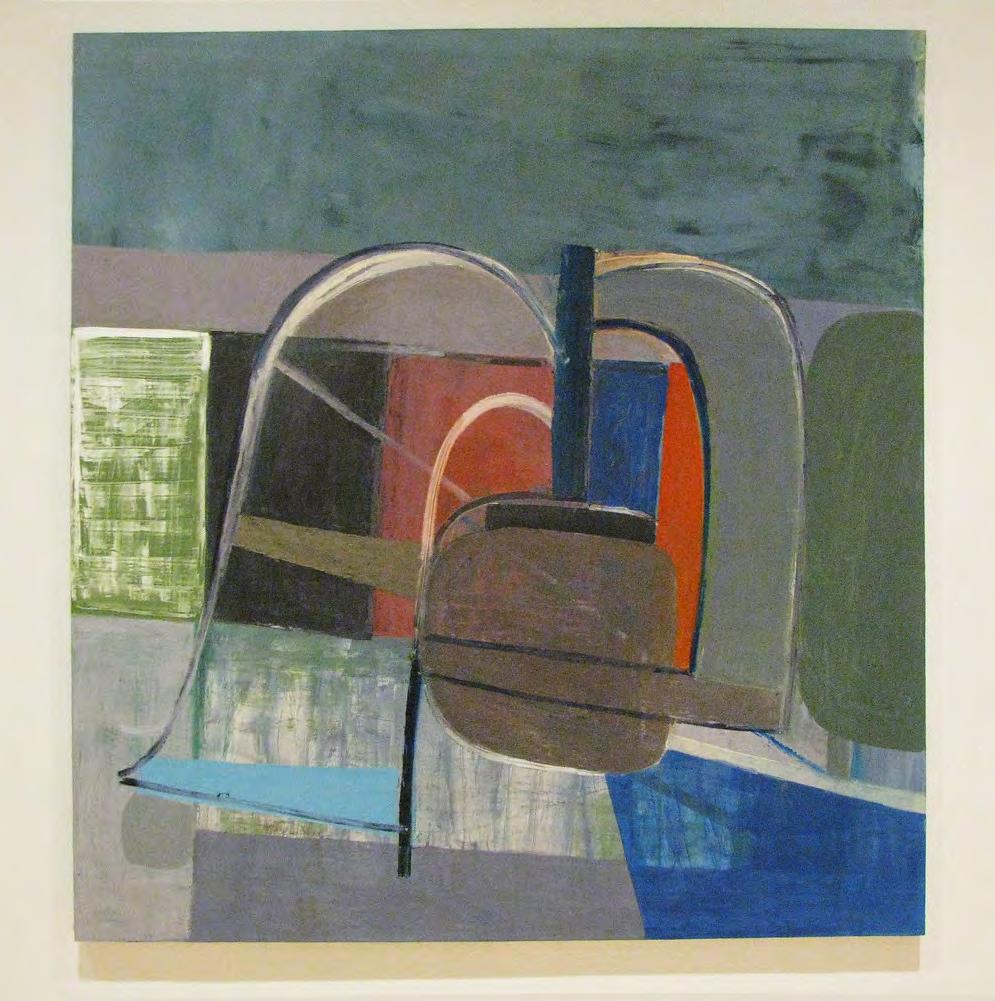

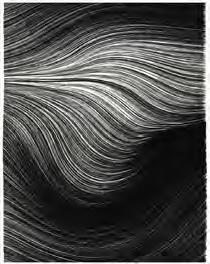

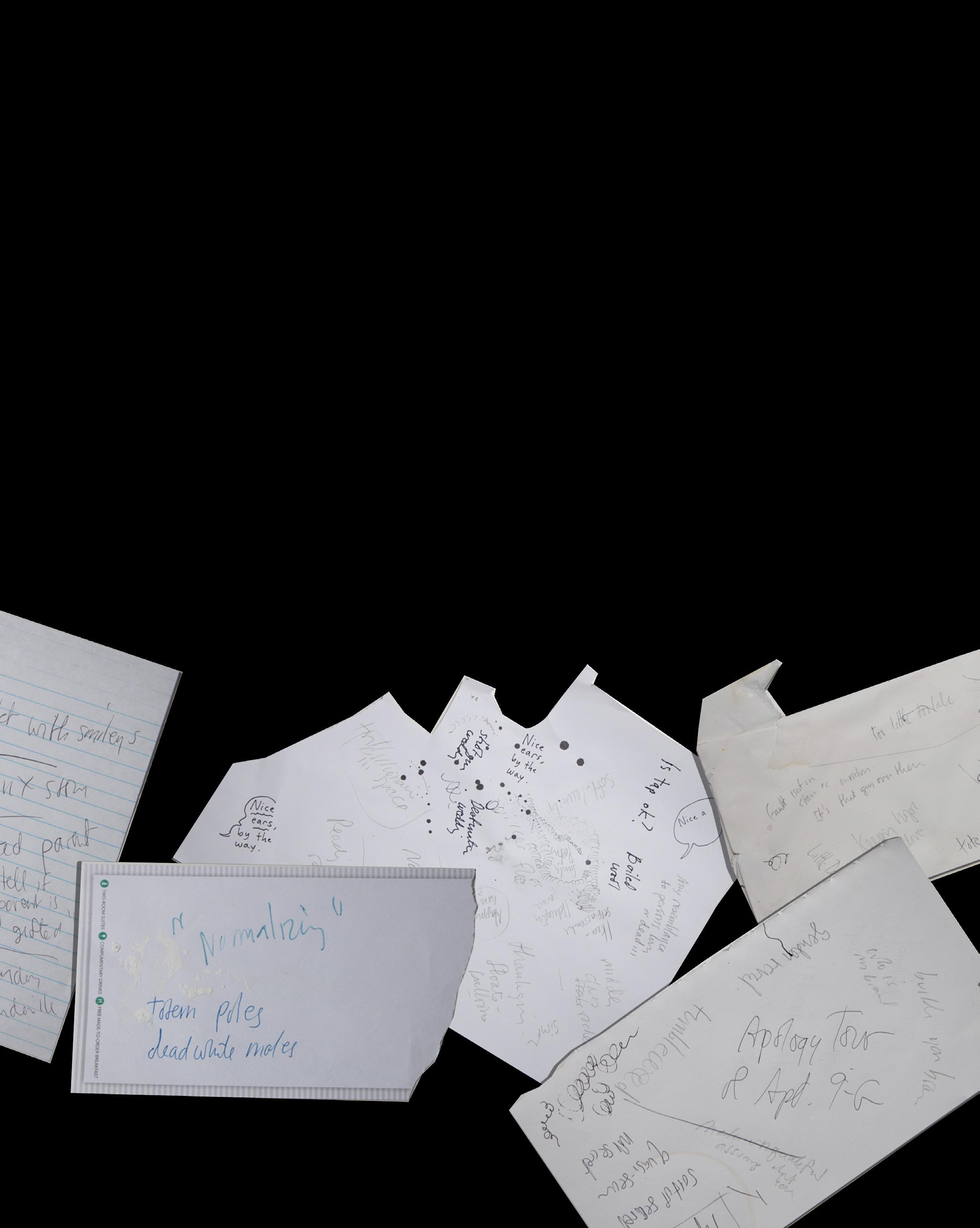

Walker was one of the first artists I spoke to. We spoke about what she’d been doing recently, and she was describing working through her struggle with a work she was then making, responding to the January 6th insurrection. “I was feeling very frustrated, she said, “I had been making a piece about white nationalism, or the origins of it, and I just started making a drawing with my feet because I had sat down to make a drawing and I was like, I can’t trust this hand not to make something very obvious, that we already know. So I took a cue from Trisha Brown [fn 2], put some paper on the floor and just let my body do the work [fn3]. And I thought, well, that’s better. It’s just a fucking mess, but it totally fit the mood.”

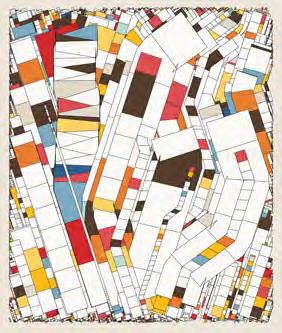

And we talked about the unusual creation story of A Subtlety, in which a PowerPoint and an epiphany on the Q train were pivotal to her making of the sculpture(s). The path is a cascading series of associations but she approached it like a research project. I was really surprised at how methodical her thinking was, maybe because I cling to the idea that artists are all instinct. The installation took over a year to take shape, from Walker’s first visit to the site until its opening on May 6, 2013. Walker, who had become well-known for her art, mostly about the Antebellum South and mostly comprising black and white silhouette cutouts of slaves, was just emerging from a fallow period

artistically. When Creative Time approached with the open-ended invitation to do whatever she liked in the vast, historically-fraught factory, she had been looking to move away from the silhouettes but hadn’t settled yet into a new project, or even a desired medium. She had never done a piece of public art before, or much sculpture, let alone a sculpture of this scale. But then it was not always obvious that a sculpture was what she would build. The site intimidated her, but she also found it difficult to resist. She reluctantly said yes.

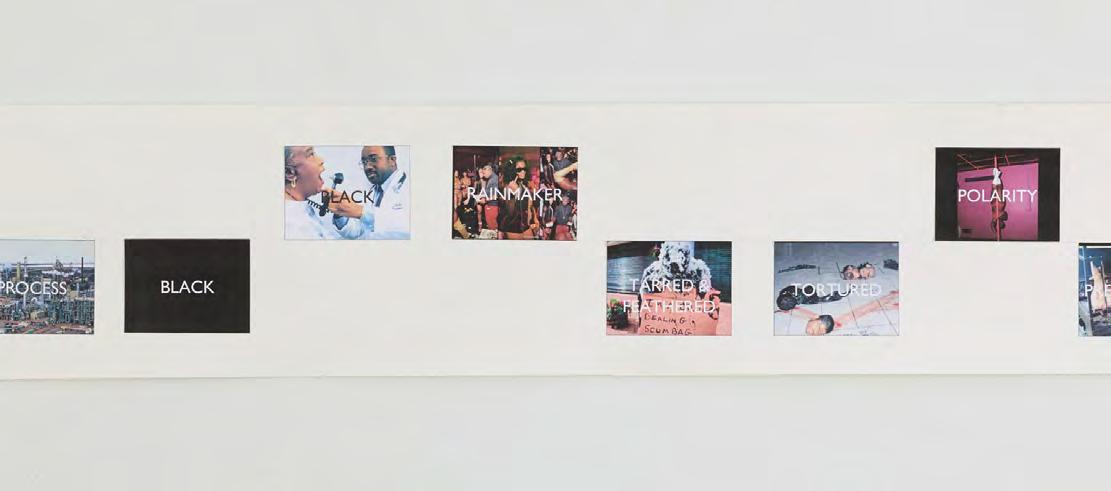

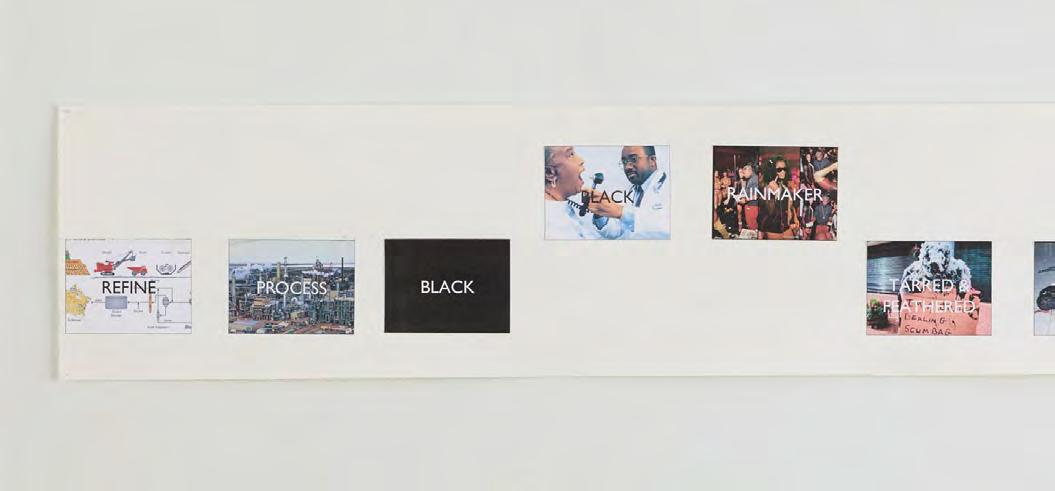

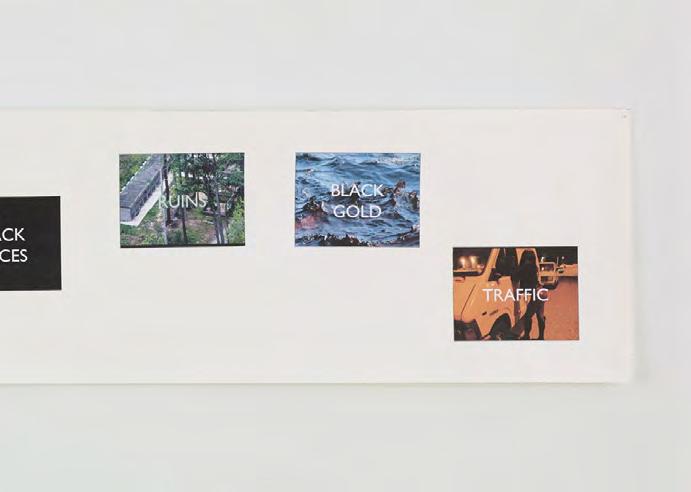

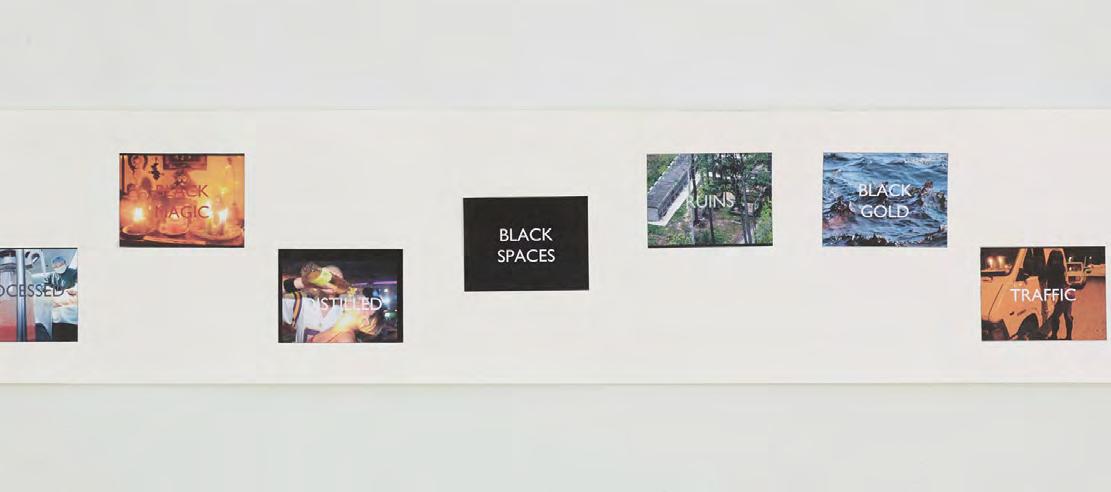

KARA WALKER:

“I have to go back in time to, what was it, early spring, late winter of 2013? In 2011 I had two shows that opened at the same time in Manhattan. I did a whole bunch of drawings and prints – big sort of block letter text pieces. And a shadow puppet film. I was trying to shift some focus away from the silhouette work into drawing and other material, trying to create a space for illustration, drawings of hidden moments, as if they could be book covers for all the possible dissertations on Black life and Black culture from like Reconstruction forward.

But what happened is I bought a house and so from 2012 to 2013 all I was doing was the house. I did not make anything. There was a year where I did a bunch of little cartoon drawings, like scrolls, but really it was like: why am I not working? I didn’t understand. It was the weirdest experience not to feel productive.

By 2013, I finally had a feeling of being settled. And that’s when Creative Time approached. You know, I ‘m sort of inclined to keep saying no to things, but then I just thought, why not, [I’ll look]. We went to the Domino Refinery and I was pretty floored. I felt I kind of got it, it felt kind of perfect. So saying yes was one thing.

And then – I was trying to think of an analogy earlier. It was like flood gates opened, dadada, but I can’t swim. It ushered in this huge flood of possibility. And then I was tumbling

4 KARA WALKER

around in that, trying to conjure magical sort of inflatables in order to survive.

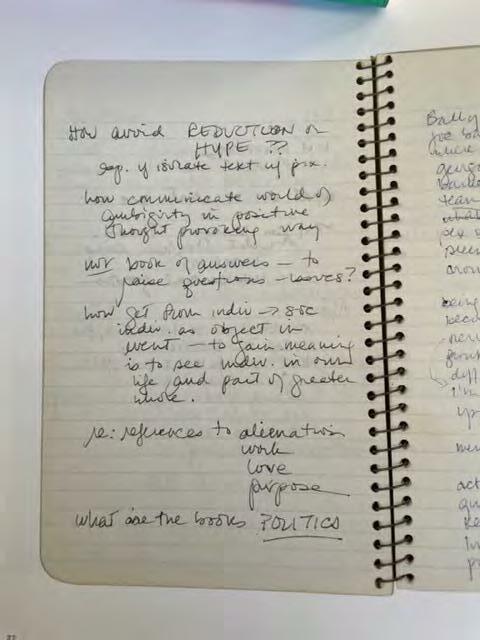

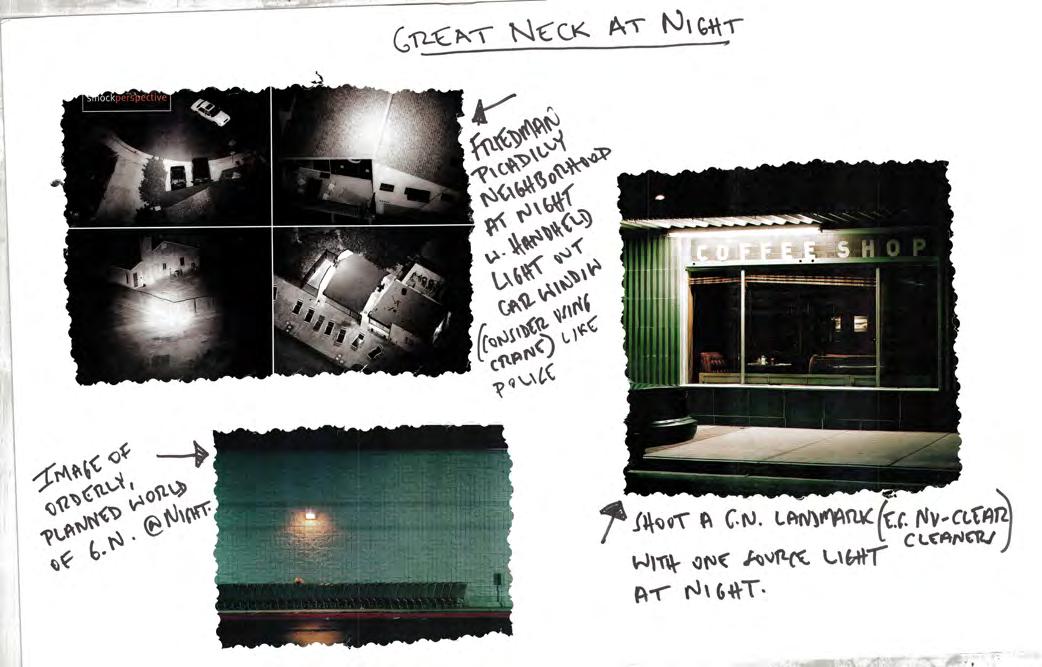

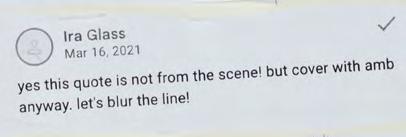

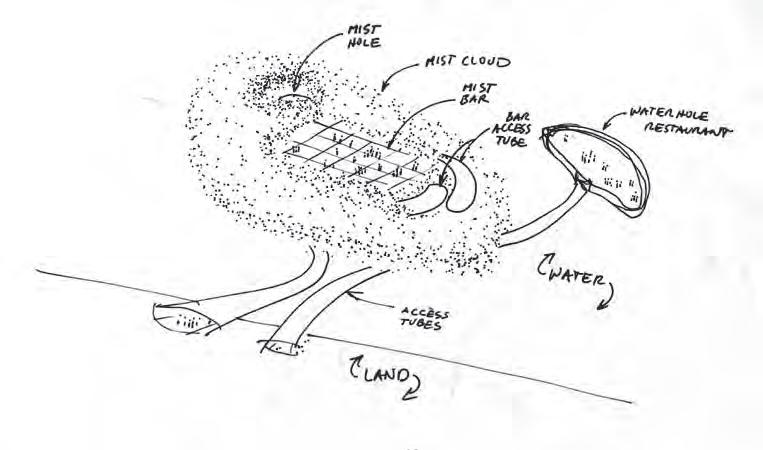

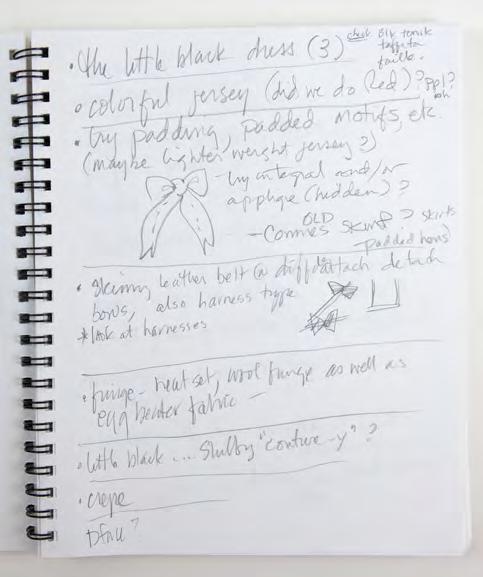

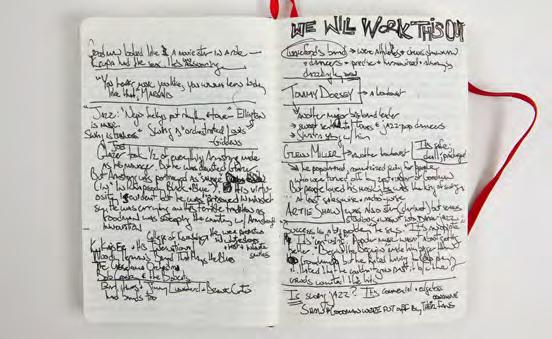

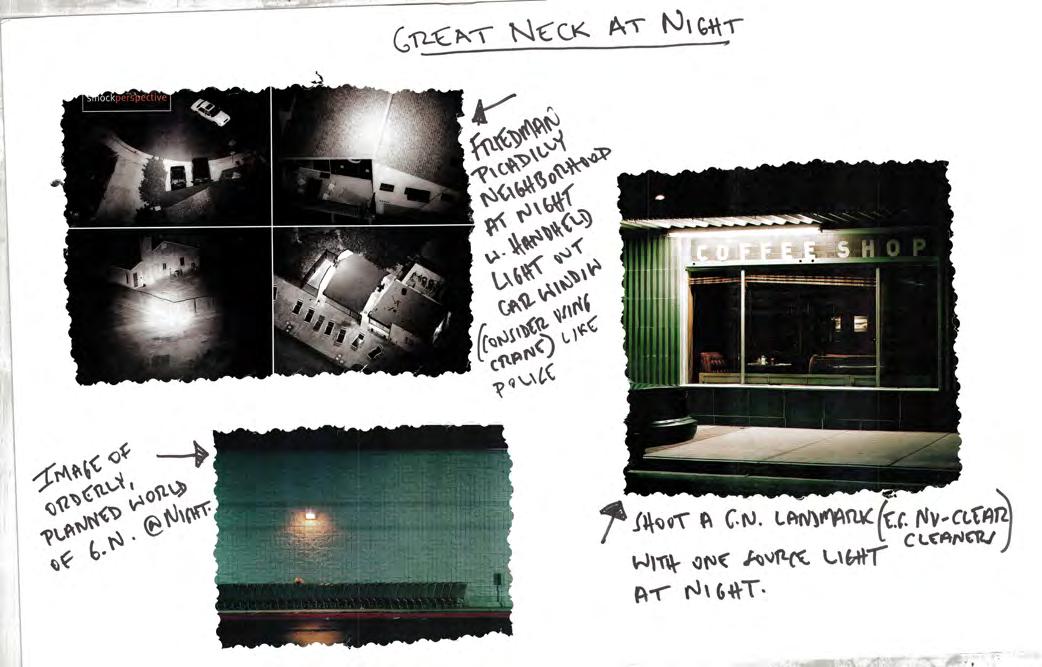

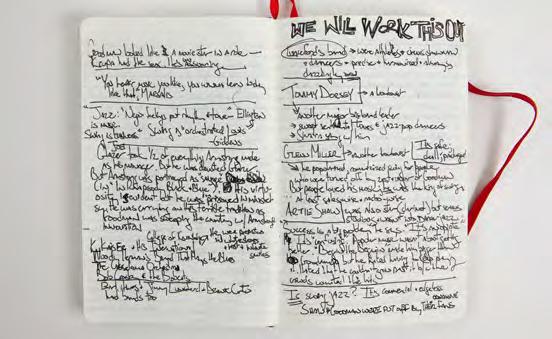

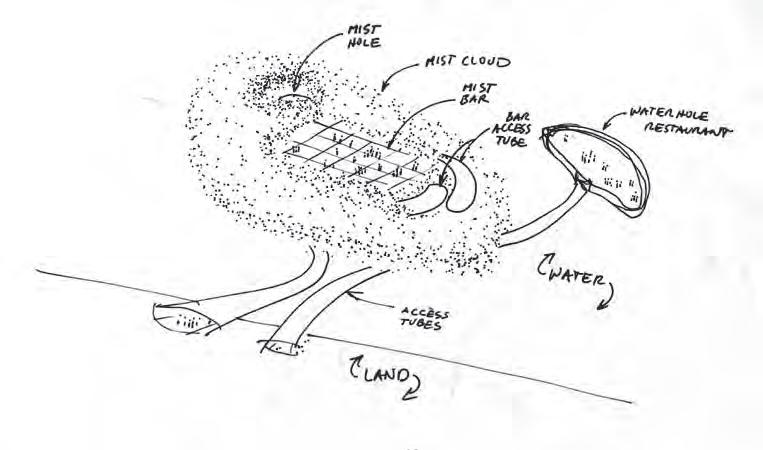

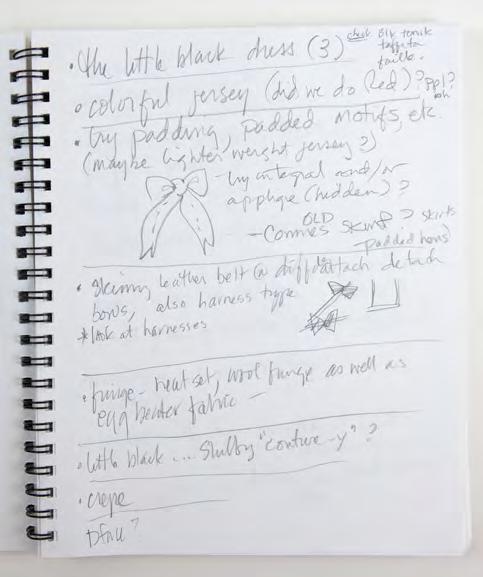

What About This? Creative Time didn’t

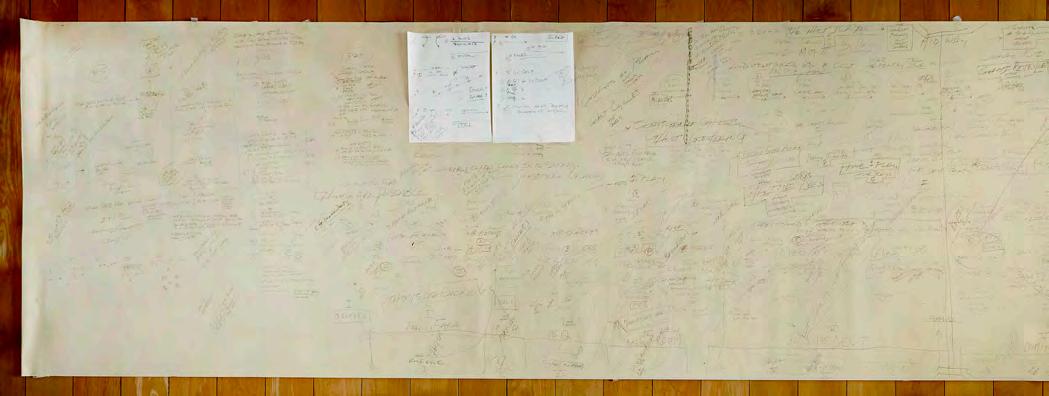

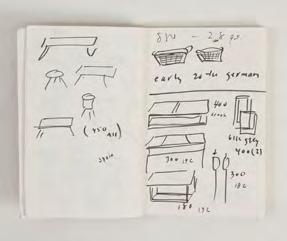

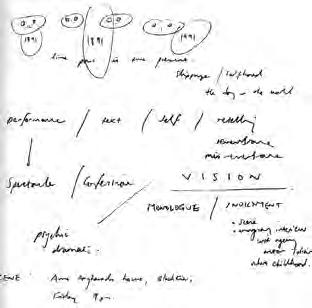

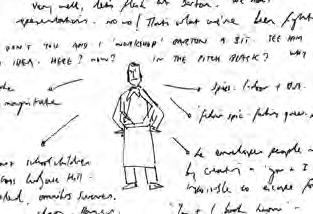

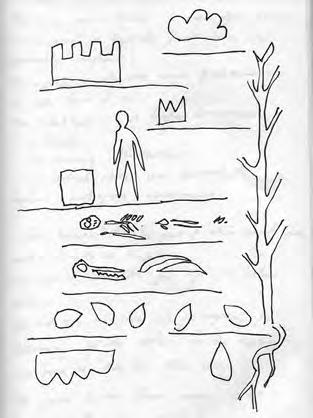

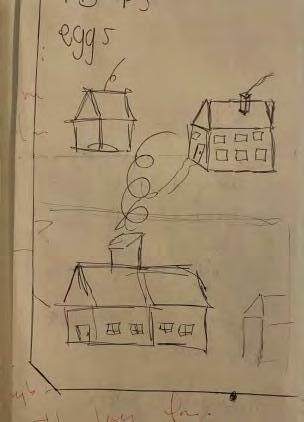

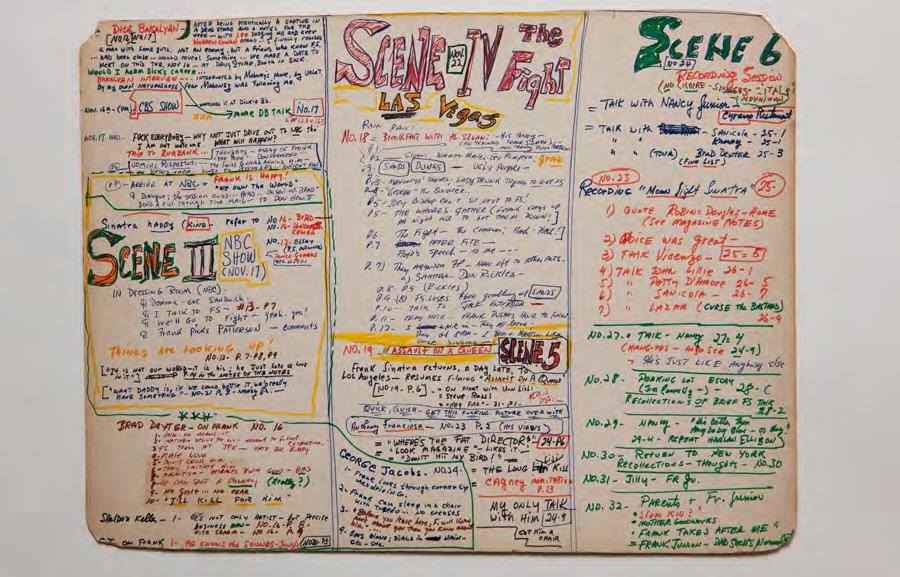

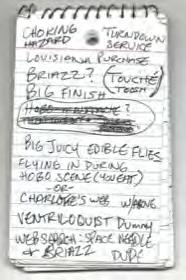

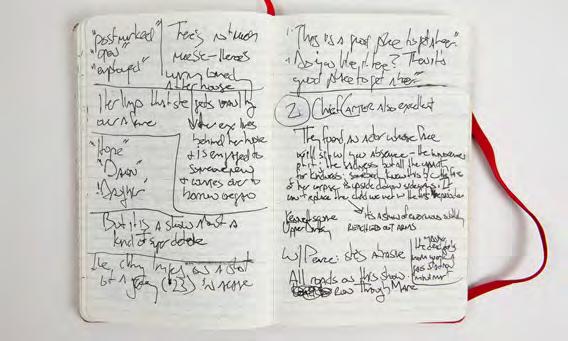

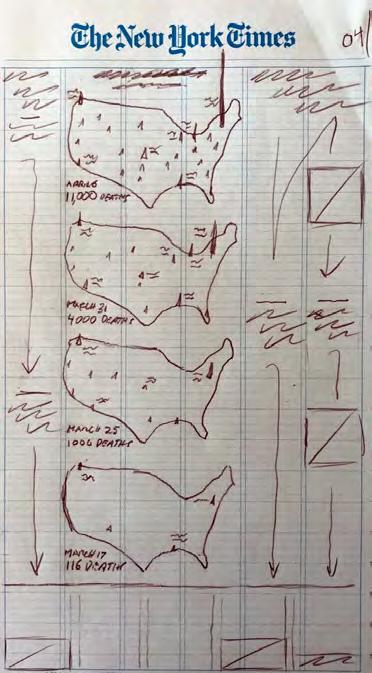

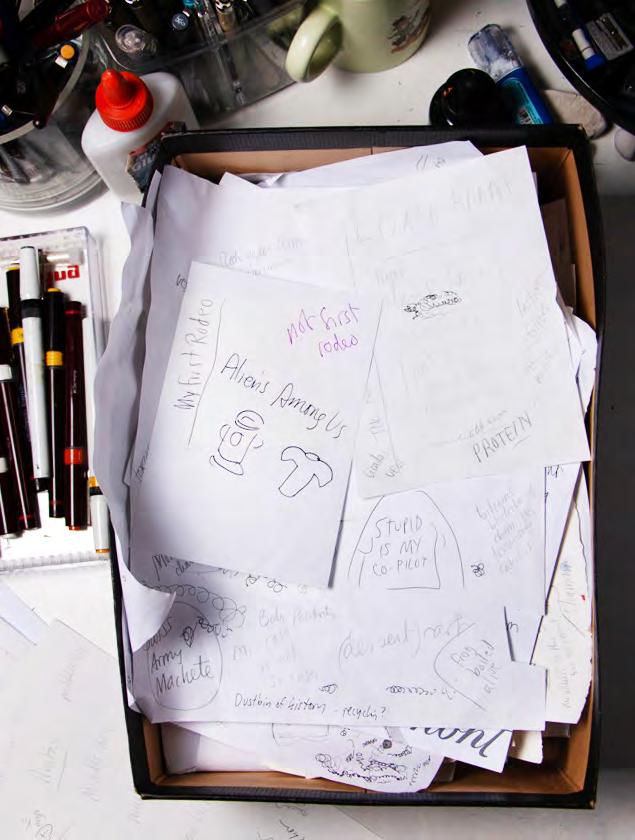

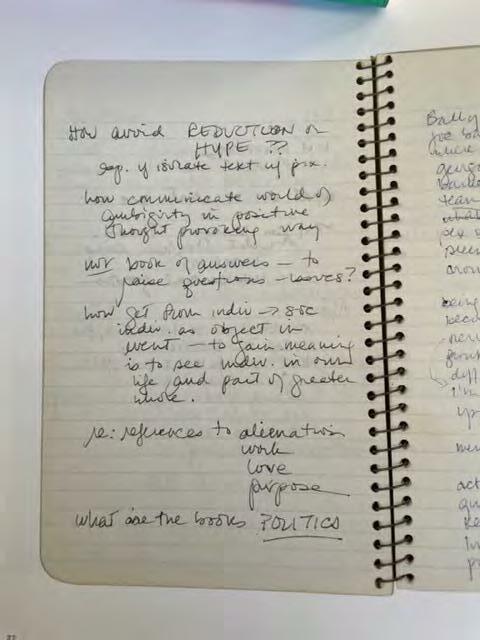

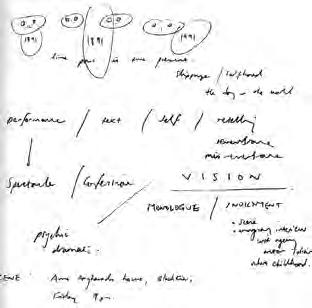

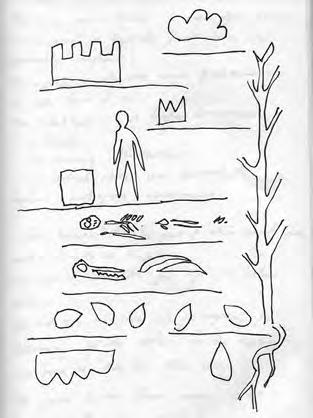

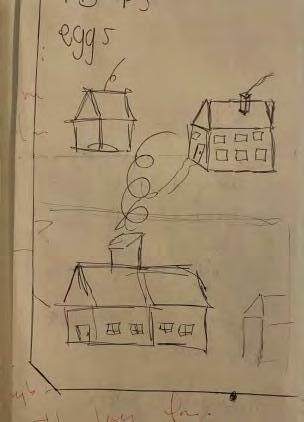

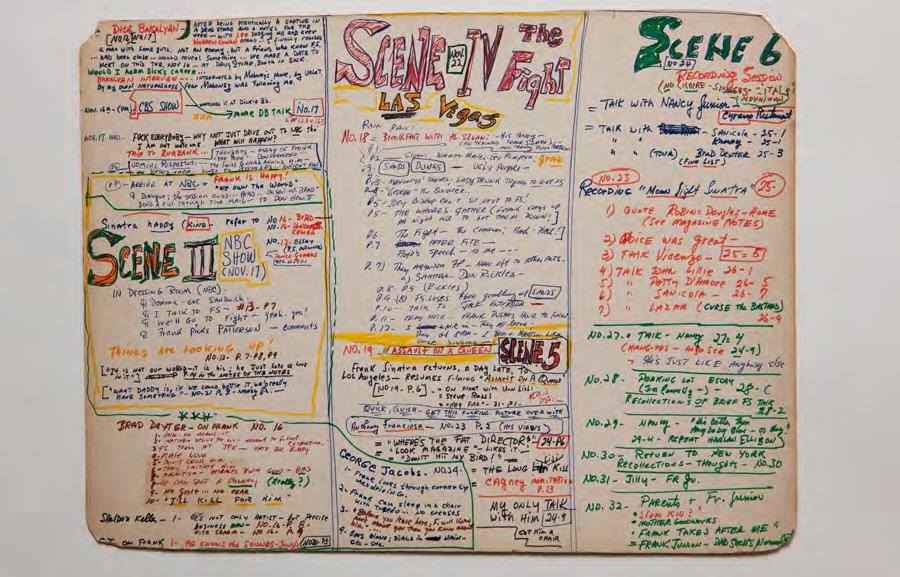

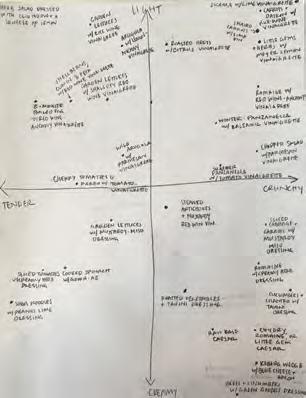

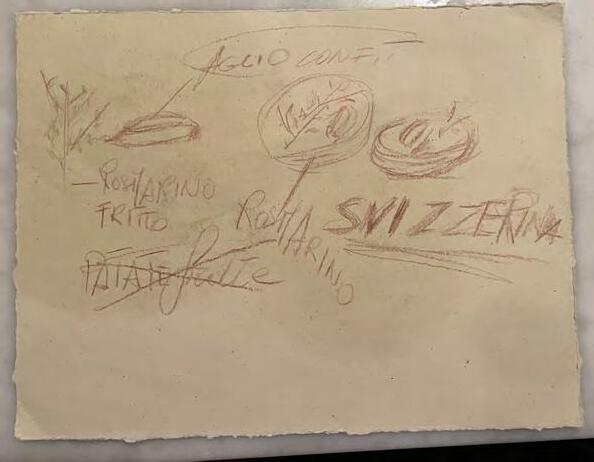

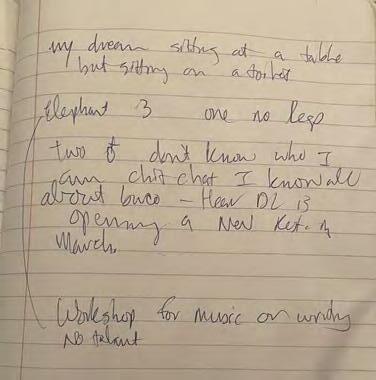

say anything about what they were looking for. So... I had a sketchbook, and I kept asking myself: what about this, or this, or this? That was what it was like for three months. I was hardly even drawing. How do I think about the volume of this space? And then, how do I think about the history of this location? And then, how do I think about the history of what this location has been processing? I was overwhelmed. For a couple of those months, I couldn’t figure out how to begin.

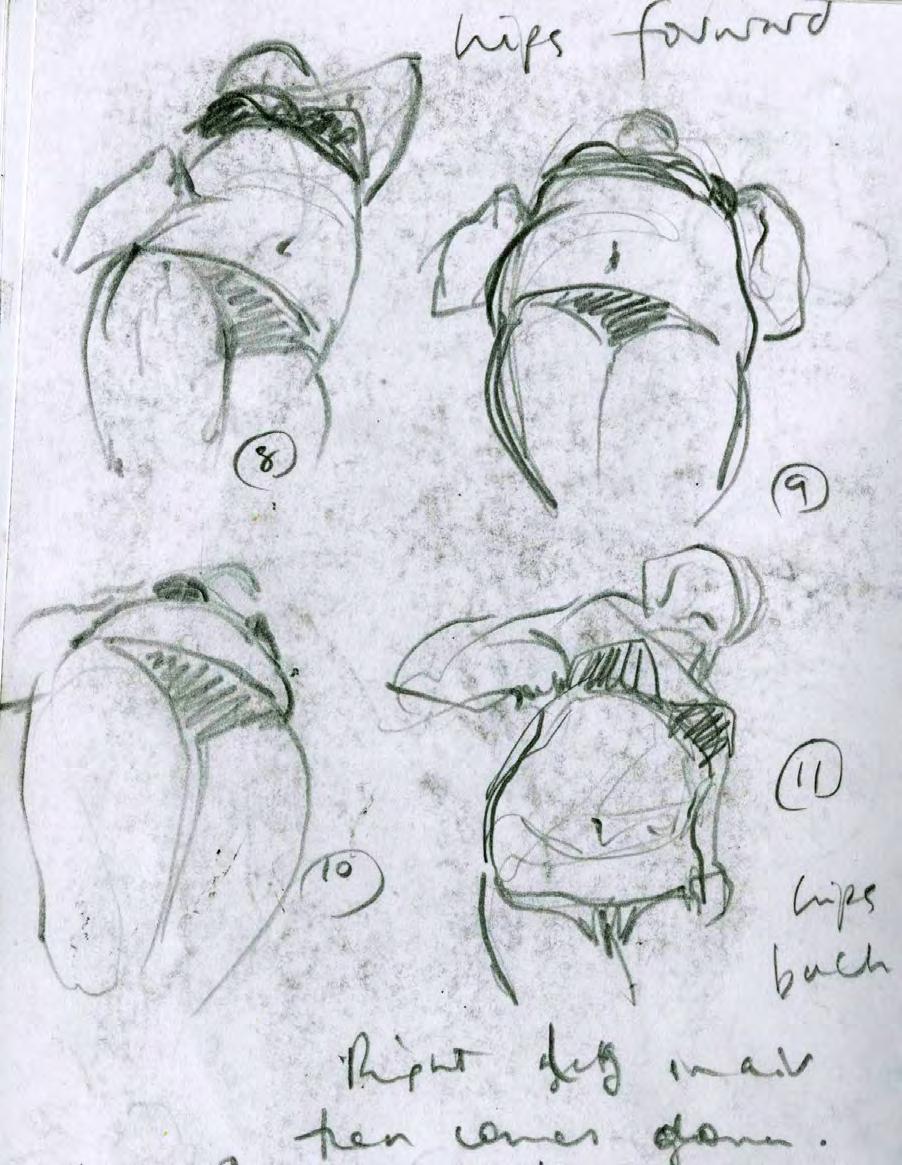

They weren’t really ideas, just sort of little bubbles, kind of like, how to traverse the space very quickly? Something that moves? Machinery? Image, video, multimedia? You can envision all kinds of things. It could be a group happening, for instance. And when I was sitting in my studio or my room, it was hard to really picture the volume that I was going to be working with for real. There was one moment – I’d done a bunch of figures in costume with balloons. But no, it was like smashing your head over and over because everything seems like a possibility. I’d see something on TV, and I’m like: what about that ? I was sketching people on roller skates! No, really. Stupid shit.

And then I finally said to myself: You, where are you? You know, like looking in the mirror, like who are you Kara, again? Stop sketching stuff! And the deadline for presenting my idea was [fast approaching].

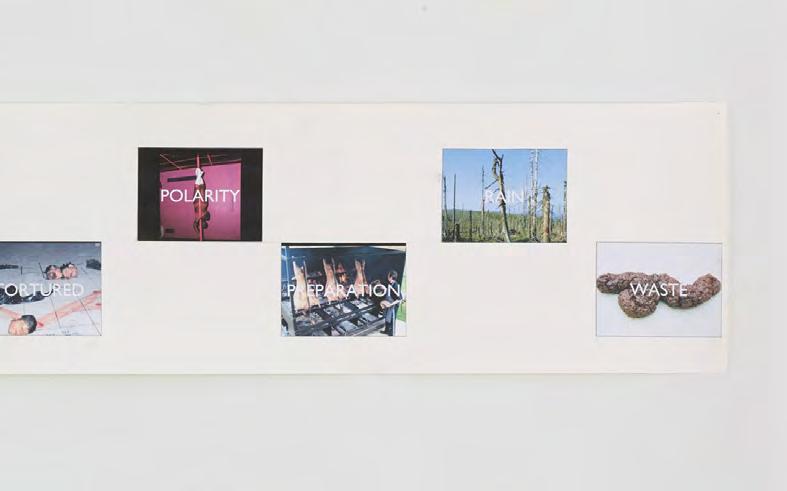

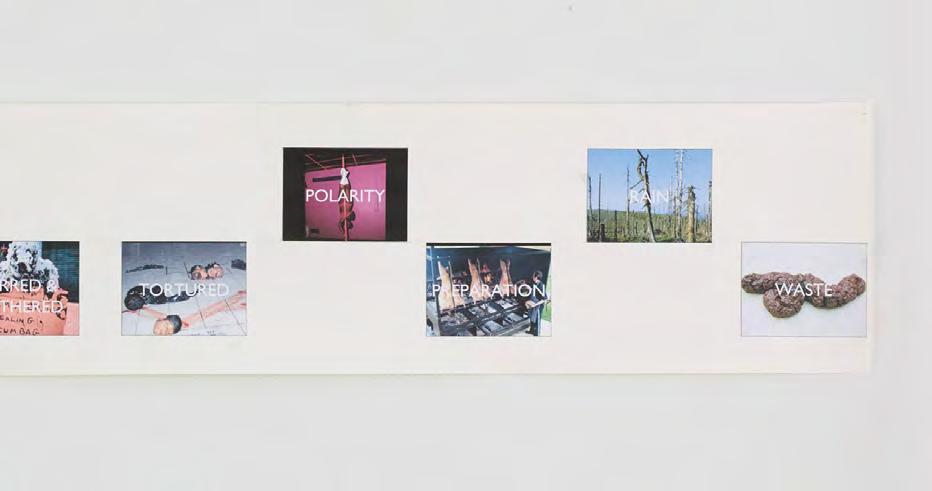

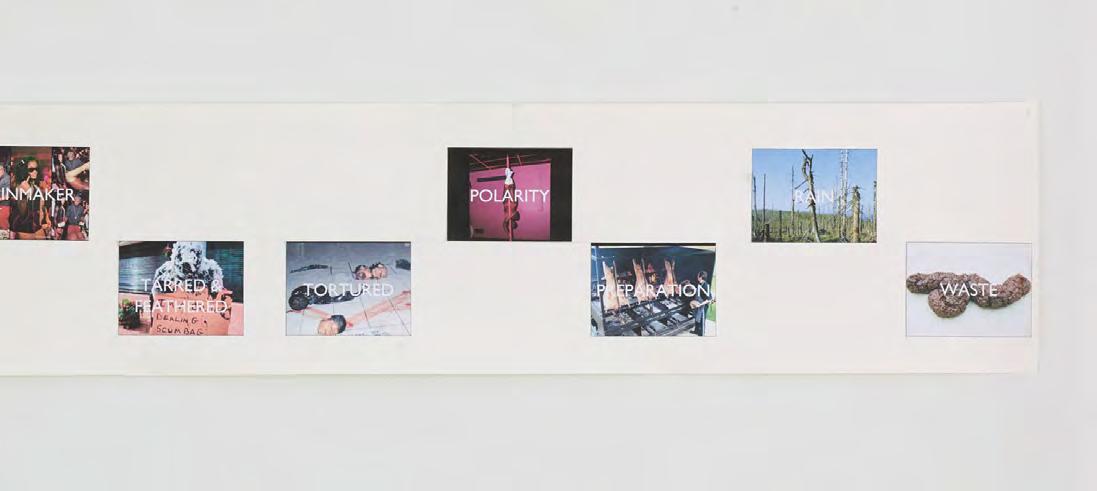

One of the lovely things about Creative Time was that they were at my beck and call. If I wanted to research something, they would say yes. So, for a while, I was thinking of some kind of conveyor, one material transforming to another material. And chickens. I don’t know why but I was thinking about chickens. And then I also was thinking about waste products, the effect of the sugar on the Domino plant, the heavy molasses smell – caked onto every surface was a kind of molasses. And about oil

and other byproducts and the over-reliance we have on things that are bad for us. And they did some research for me into chicken processing, slaughterhouses. And I thought, what if I do this? I won’t import raw Coke or whatever and put it in this space … that’s the wrong direction. But then I thought, wait, what is the right direction?

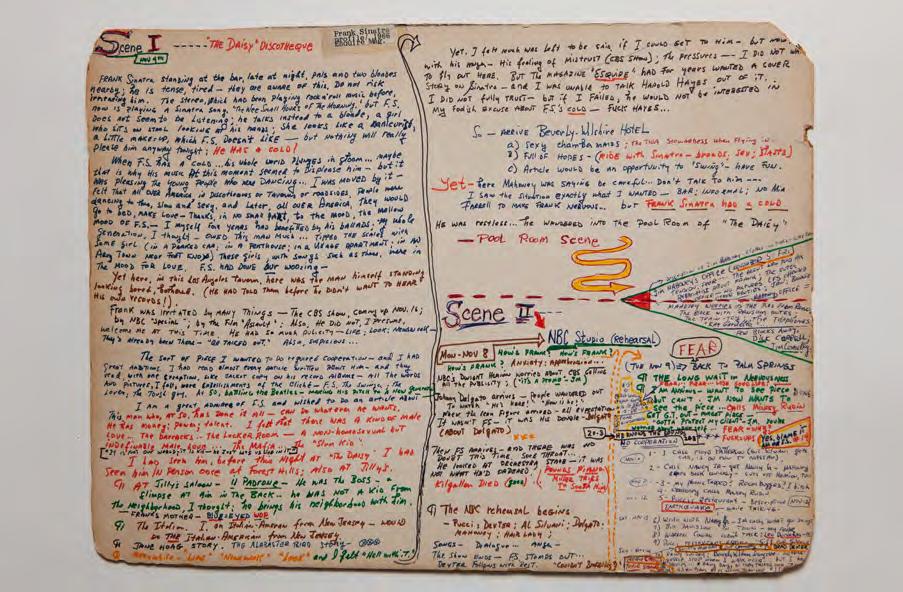

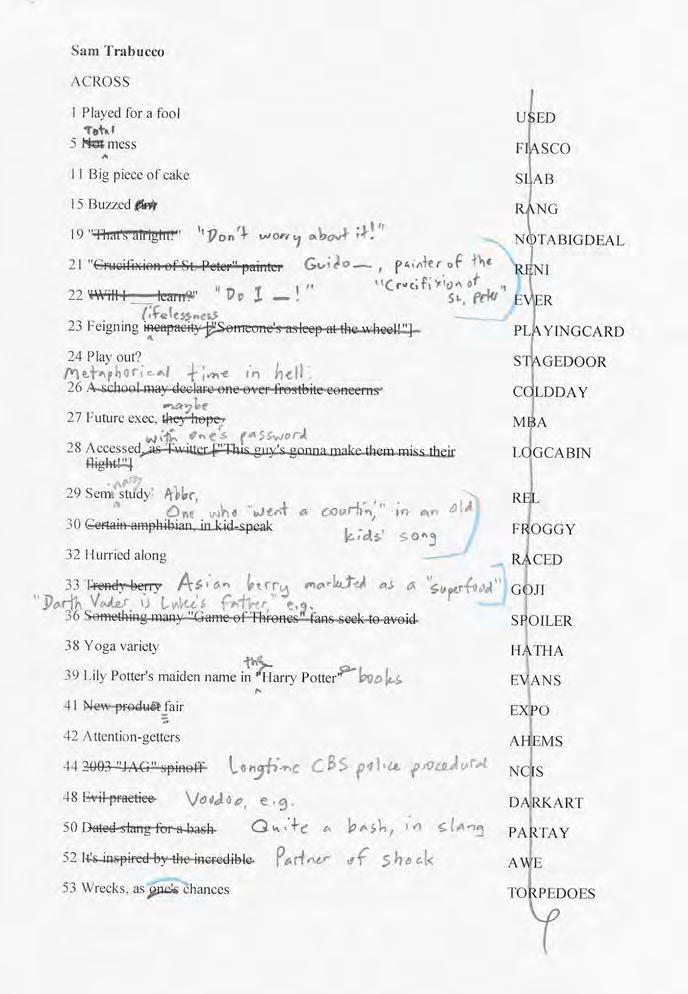

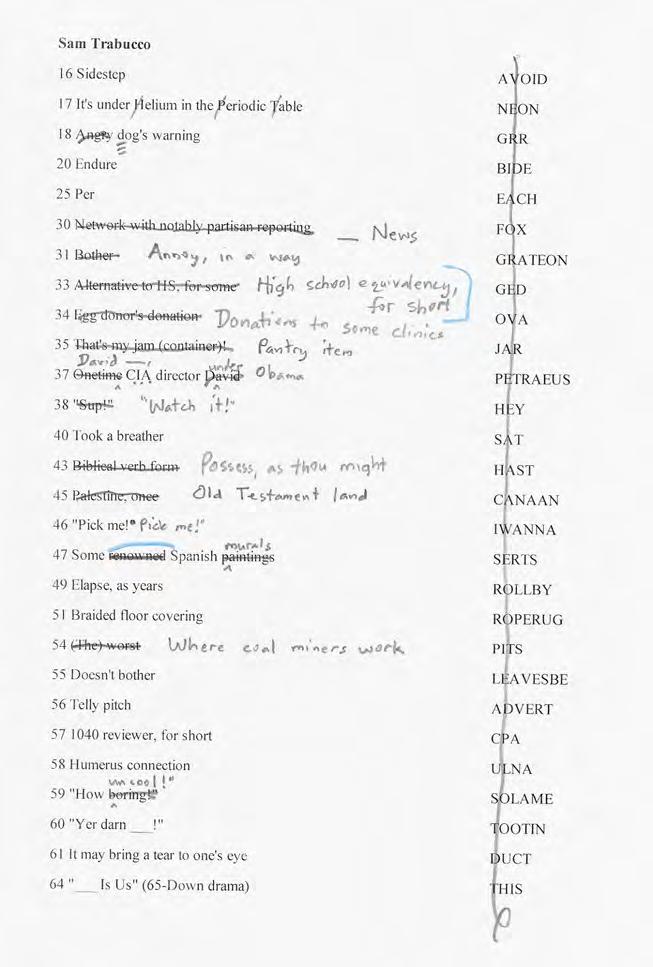

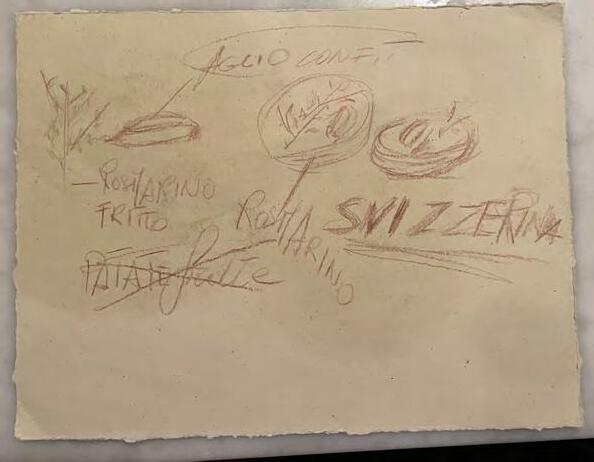

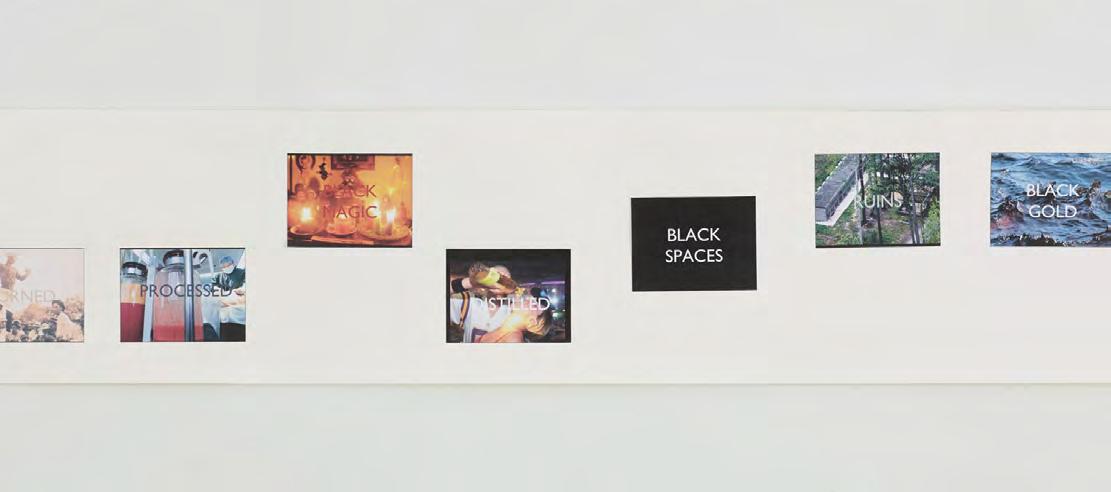

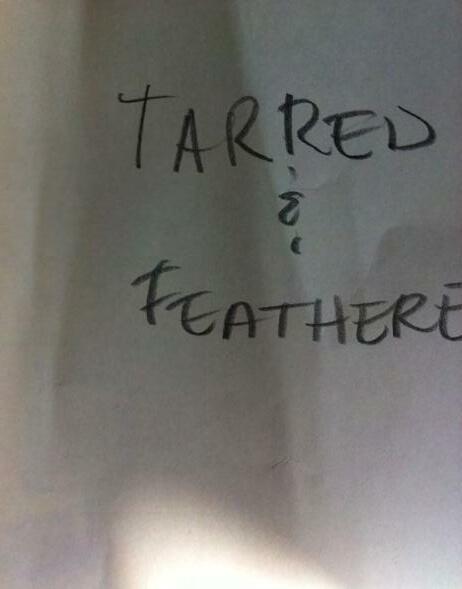

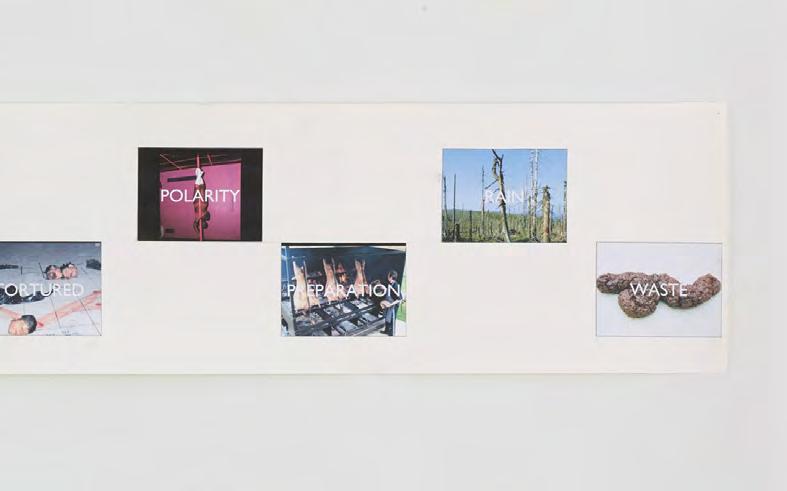

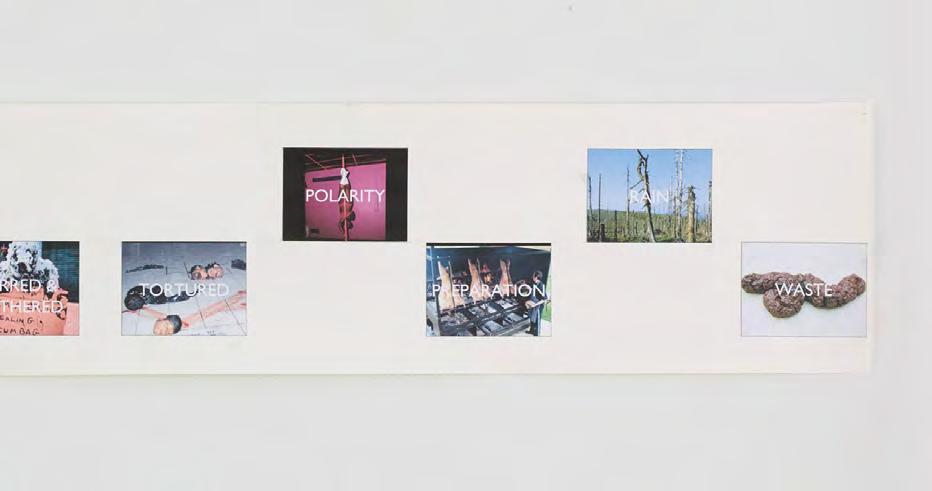

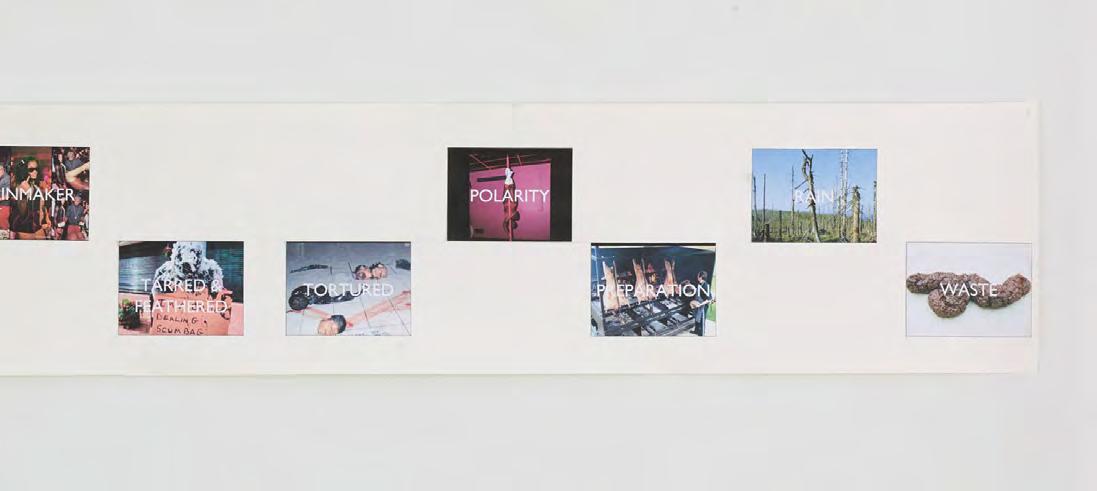

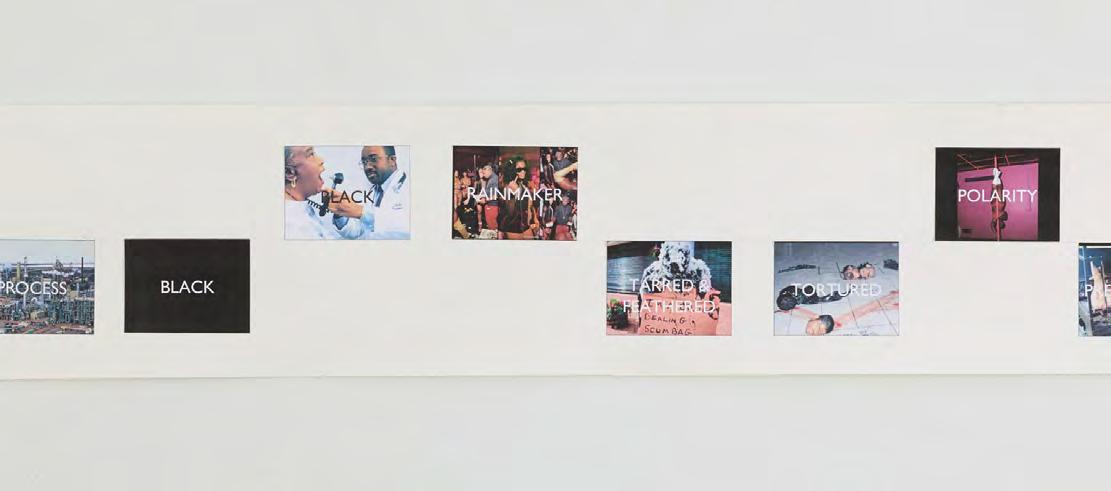

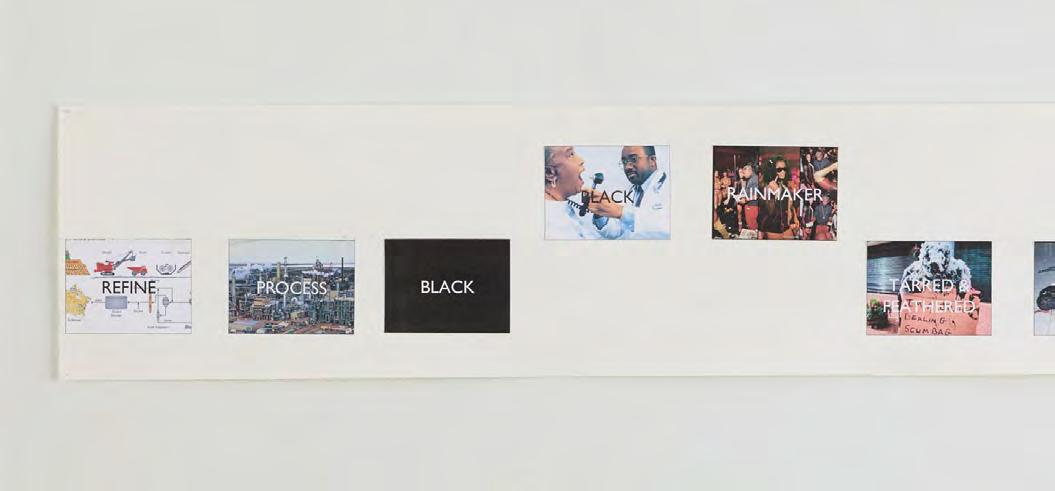

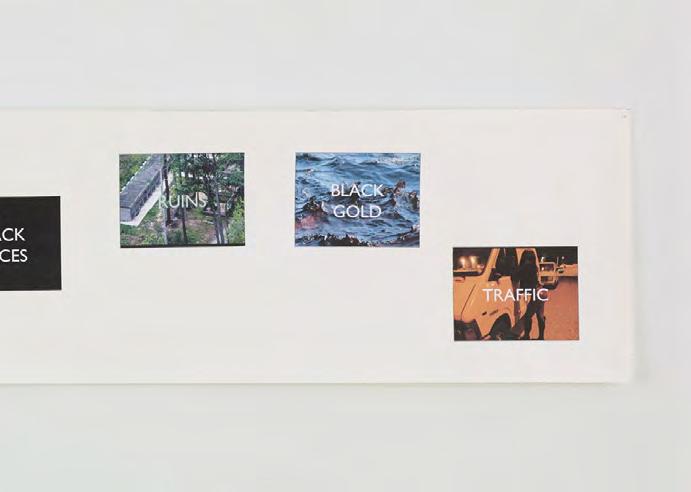

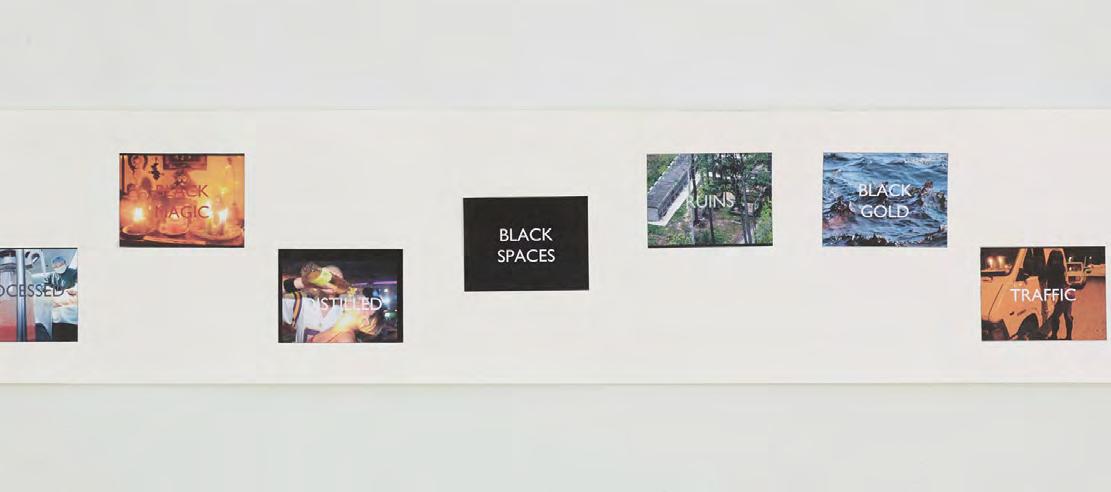

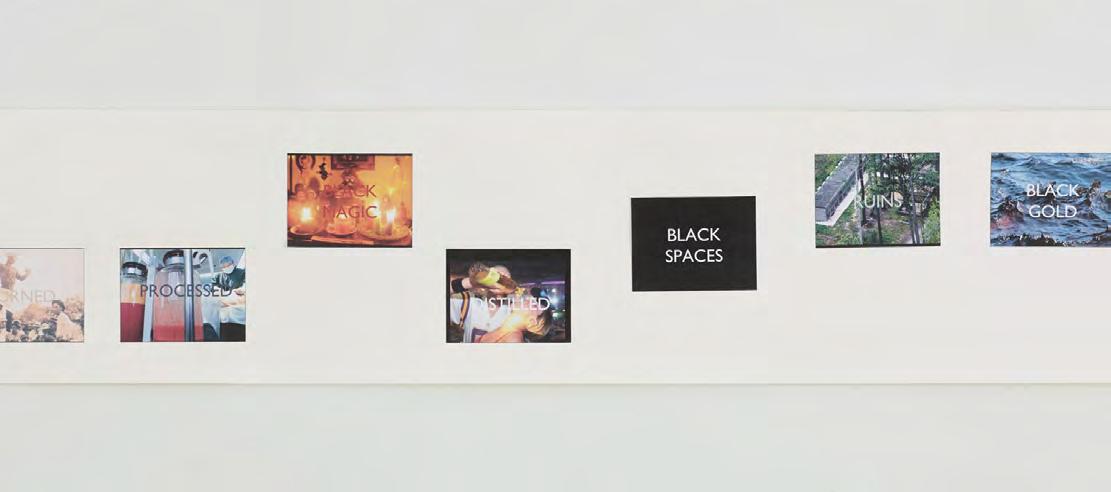

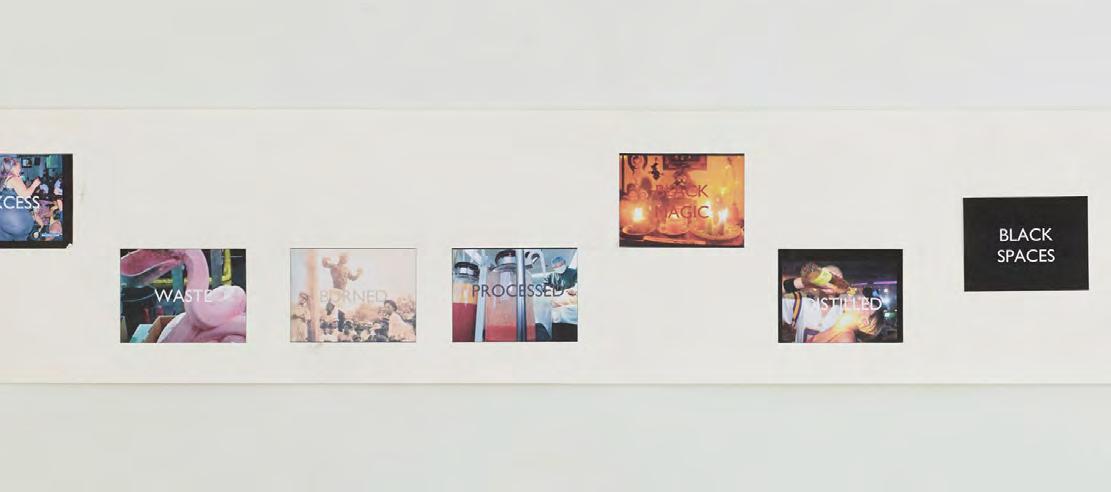

A PowerPoint So I put together this PowerPoint, which confused everybody at Creative Time. But the PowerPoint was the only sketch I approved of. I couldn’t trust my hand to draw the thing I was trying to articulate because it just wants to make things cute.

It’s funny. The PowerPoint was like my office life. It was a way of synthesizing material but it also has a rhythm and poetry to it. I was gathering images that included the chickens but then went into voodoo and rum and sugar and the transatlantic slave trade. I started to read about the process of sugar refining, and that it’s not a given that sugar should exist in the world. I started to think about my role as the artist in relation to doing a big public art project. I got interested in men like Henry Osborne Havemeyer [fn5], the guy that brought the sugar refining process to... foolish expression. Those are the gods of Industry. That’s really what I have to imagine myself to be.

We had a meeting scheduled for December 2013. I was trying to get a little thesis going.

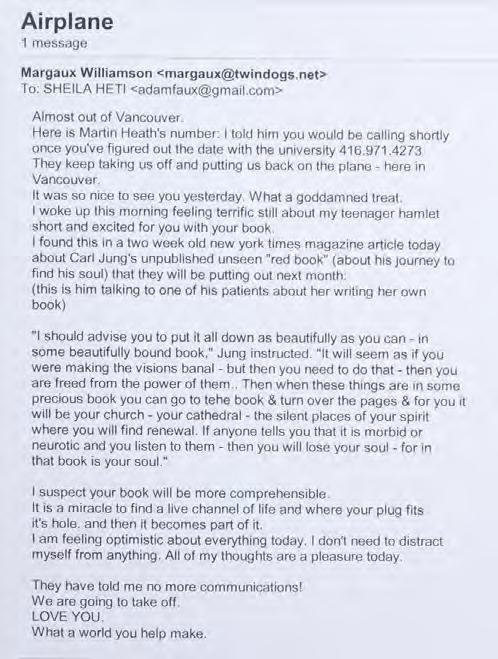

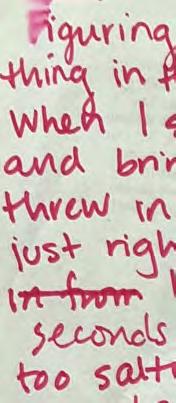

And I’m not talking to anybody about it. It’s sitting in my head. I don’t usually have people that I talk to about what I’m doing. I’m too secretive sometimes –but especially this one because it was top secret. So I’m jotting things down, scattered notes. But the one thing that really changed everything was Sidney Mintz’s [fn6] book on the history of sugar. I had my aha moment in the middle of that book on the Q train.

I mean, I had been getting there because the last piece of the PowerPoint involved text and images with words on them, started with sugar and brown sugar and then I added a pole

5

TKTKTKTKT

ne et fuga. Sit liciisqui te volupti ne eliciisqui te volupti ne equiae.

impulses and make some sort of icon, whether it’s like the silhouette or... it just has to fuse into one thing. And it has to be something like you have no choice about. The time for

And I’m feeling, now I know what the material is. I feel the material. It’s not just an intellectual pursuit. It lives in my body.

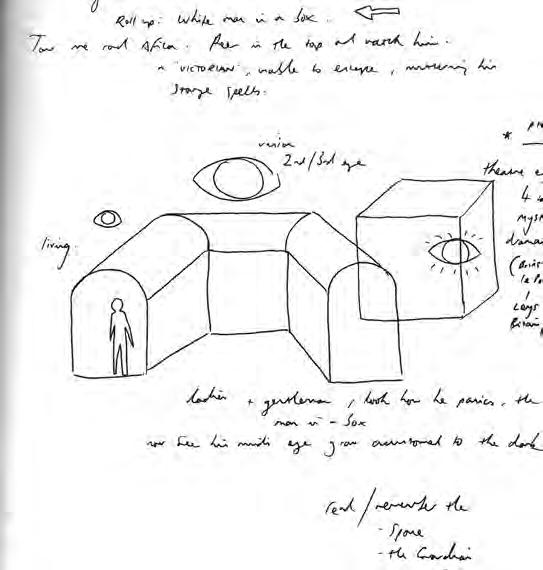

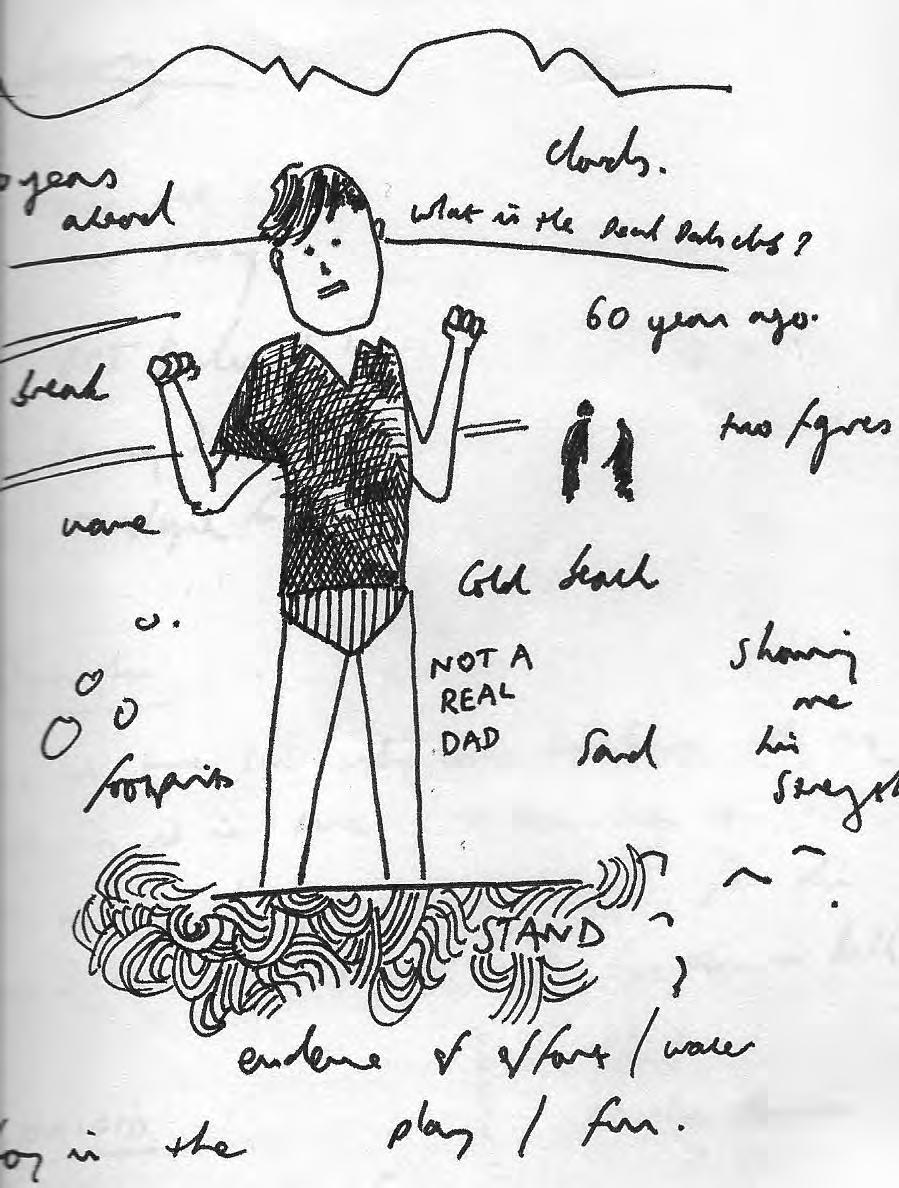

Revelation on the Q Train And here’s what happened: I was on the Q train. And I was reading the Sidney Mintz book. And there’s a section where he talks about the “subtleties” – these special decorative [sugar ornaments] exclusively for kings, for the celebration of weddings... and you know, we’re so used to fucking sugar we don’t even realize how special sugar is...

And I was just like: Oh, it’s a sugar sculpture! And I realized the Sphinx was the perfect sort of ruin. And that was the big moment.

From that point on, the drawings are drawn with molasses, stuck together.

And I thought, It can’t just be a Sphinx because then it only reads on that one note.

We have to open it up to all these other sorts of desires that sugar exploits and represents. And our covetousness for sugar is not

mammy figure. Mammy-like figures existed so much in my work already. Michael Jenkins

unlike sexualized covetousness. The power is hard to quantify. So it had to be a female, larger than life queen figure with everything open and bare and bare breasted.

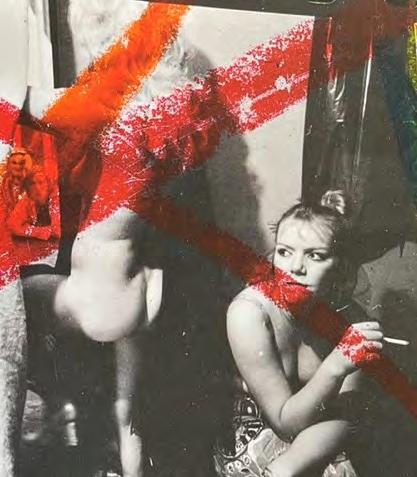

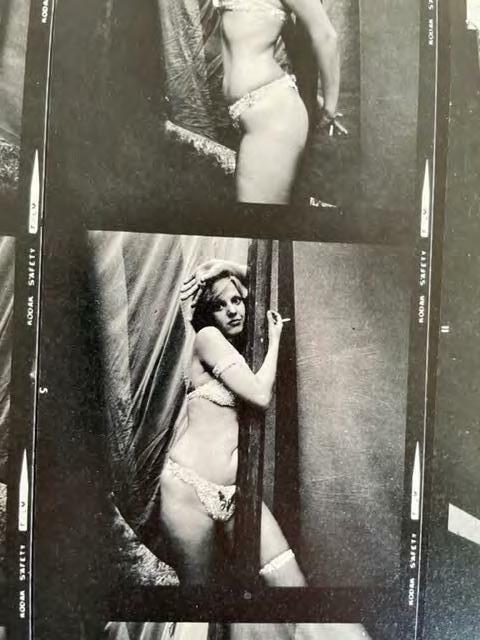

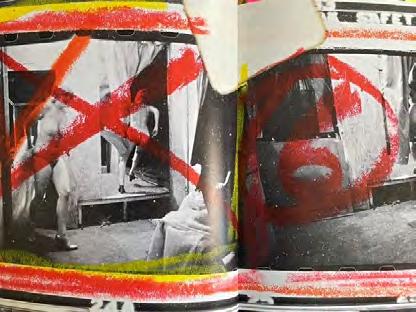

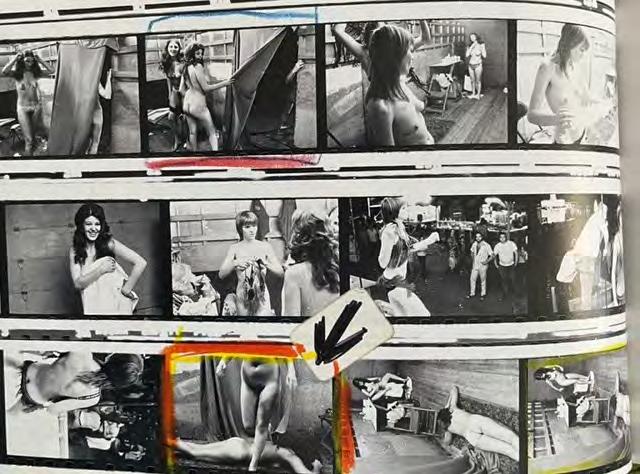

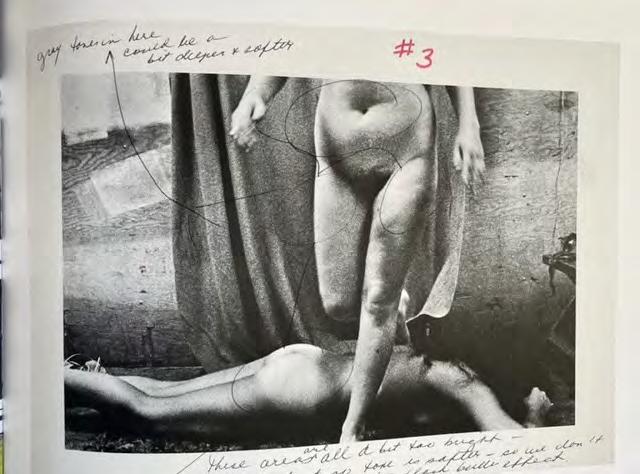

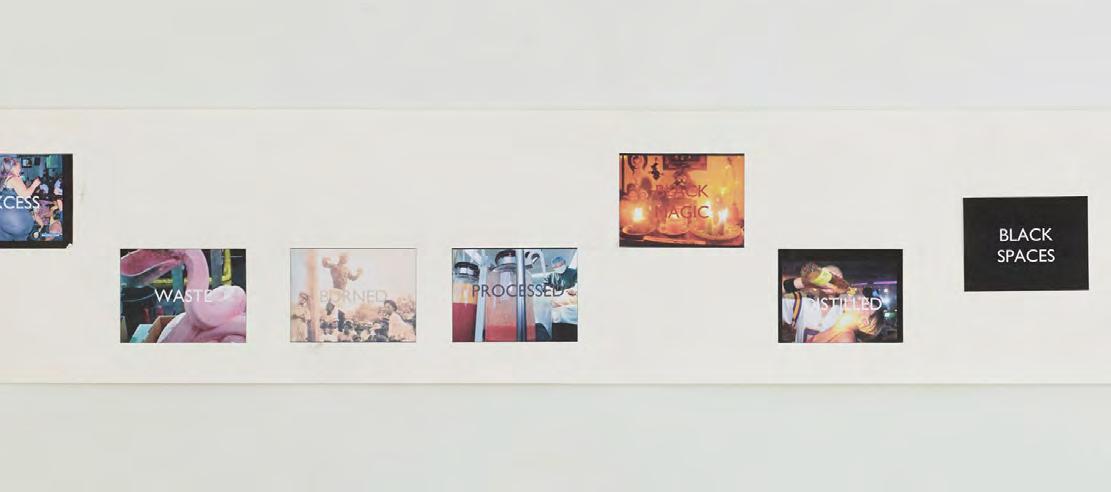

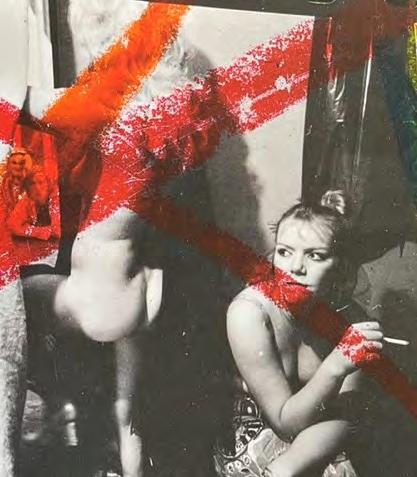

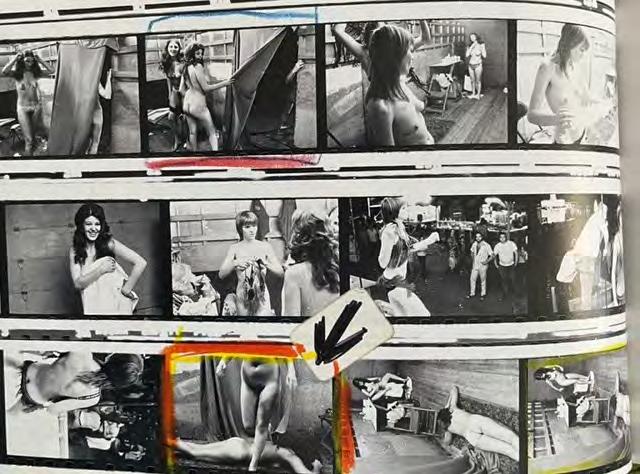

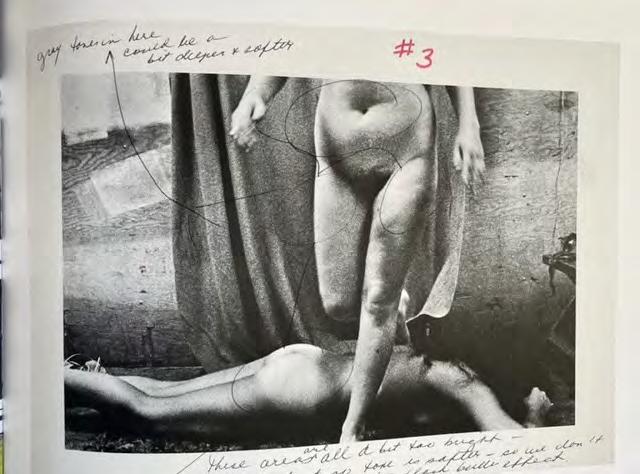

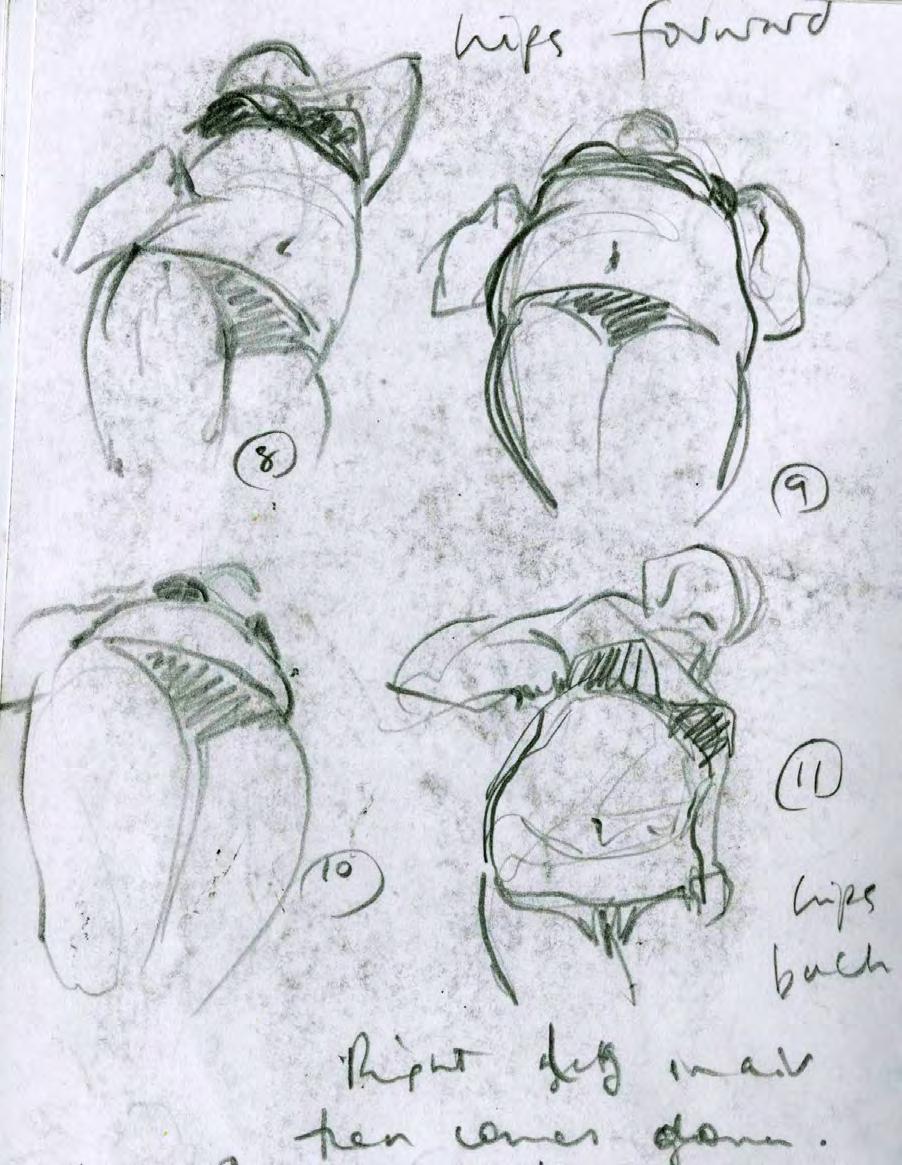

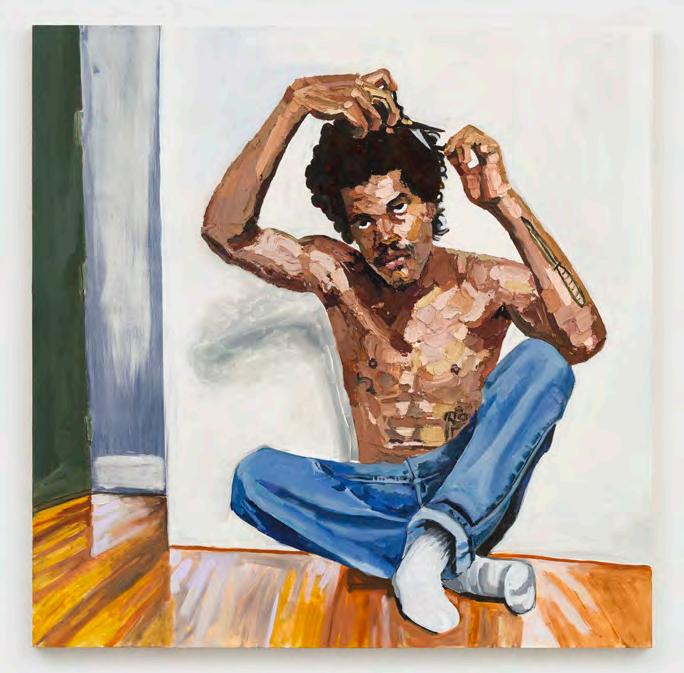

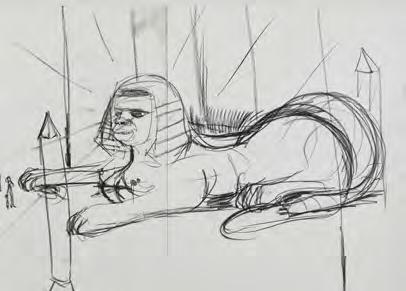

A Mammy Sculpture I’m not sure exactly when I got the idea to do the sculpture as a

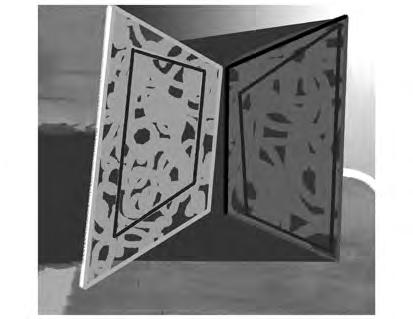

from the gallery found a drawing of mine from the late nineties or something with a mammy Sphinx on it. And there’s one sketch that was also kind of instrumental, it was a collage with the back end of the her butt in the air.

And so now I had to build a sculpture, and that was terrible. The first iteration at my studio, I was so embarrassed. I don’t know how to do sculpture. So let me just make a tablesized one, of papier mache. And the first one

collapsed. That kind of thing can be a big setback when you think you know how to do other things.

I felt, I don’t know how to do anything. Who do you think you are?

7

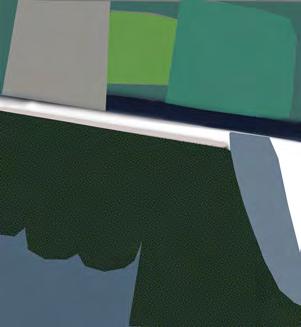

So then I made a smaller little clay sphinx figure, just kind of modeled on the Sphinx. And I took a little snapshot with the refinery behind it. And I had a model of space, like a little foam core model.

Creative Time helped me facilitate how it could get made, I just knew it should be an object, monumental, something grand. But then I was wondering if it should be something made by my hand. And I started looking stuff

point it became, what is possible, what is not possible? What is achievable in the timeframe? What is achievable financially? In physics? At a certain point everything was achievable. We just had to say what it was. So it was this giant sugar sculpture and these candy figurines at a human scale.

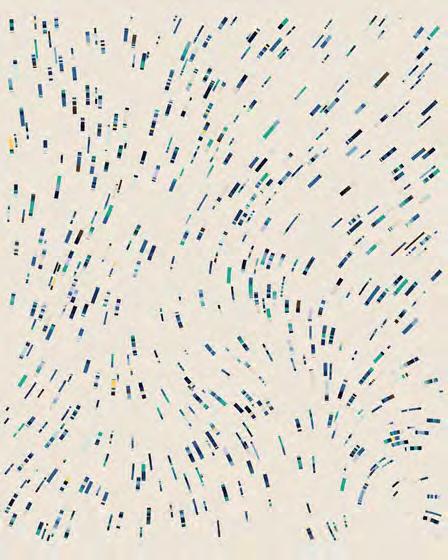

I didn’t ever have the specific notion that it would melt. That just sort of came with it. I knew it would be an unstable object. But we didn’t really know how unstable until we started making them.

up. And I found these little sugar boys sculptures online--candy dishes. And I thought these are appalling. I don’t know how I found those boysMy studio was in the Garment district for so long. So I always happened to pass by shops that had tchotchkes in the window, like African queen kind of figurines. And I thought, these are kind of strange, why are these being made. Who buys them --besides me apparently?

Logistics So the sphinx was going to be the main sculpture. And the challenge for me was how to make it solid. That was a bit of a challenge. And finally it was just, settle on a face or something, settle on a kind of body and then work with a model maker to make a figure that was a passing resemblance to the sketch. And then I thought these boys could be attendant figures.

I wanted them made as candy sculptures, made of sugar. I’m thinking everything is going to be made of sugar. And basically, at a certain

It was all trial and error because nobody had ever done it. People had made smaller sugar sculptures, and there were people in the candy business, of course, and bakers. But when we started asking around for how to do this, no one wanted to touch it. They said, it’s not going to work. The first one, when we made the molds – well, let me first explain that it’s easy to make candy — it’s just sugar and water and temperature. It just has to reach the hard ball stage, when you can pour it into the mold and let it sit. But for us, the molds were so big and the temperature was so hot, it never cooled in the interior. So the first one, we took it out of the mold, and at about six o clock that evening, it was a puddle.

Compromise Eventually, we thought maybe we have to do some of these in resin, some in resin and some in candy. Okay, compromise. Don’t love it, but maybe it will create the effect.

So we made as many of these sugar boys as we could. And then the day before the opening, a truck backed into one of them, maybe two of them got knocked over. Oh my god that was bad. I don’t know if you remember but some of the figures have figures inside their baskets. I just picked up the broken pieces of the ones that had fallen and put them in the baskets of the ones who were standing.

The building process, when that actually started, that was amazing. I’d have fits of giggles because I just couldn’t believe we’re doing this. The development was interesting, all of that was interesting, but just stepping into

8 KARA WALKER

Dolut eliciisqui te volupti ne et fuga. Sit liciisqui te volupti ne eliciisqui te volupti ne equiae.

9

table-sized one, of papier mache. And the first one collapsed. That kind of thing can be a big setback when you think you know how to do other things.

I felt, I don’t know how to do anything. Who do you think you are?

So then I made a smaller little clay sphinx figure, just kind of modeled on the Sphinx. And I took a little snapshot with the refinery behind it. And I had a model of space, like a little foam core model.

Creative Time helped me facilitate how it could get made, I just knew it should be an object, monumental, something grand. But then I was wondering if it should be something made by my hand. And I started looking stuff up. And I found these little sugar boys sculptures online-candy dishes. And I thought these are appalling. I don’t know how I found those boysMy studio was in the Garment district for so long. So I always happened to pass by shops that had tchotchkes in the window, like African queen kind of figurines. And I thought, these are kind of strange, why are these being made. Who buys them --besides me apparently?

Logistics So the sphinx was going to be the main sculpture. And the challenge for me was how to make it solid. That was a bit of a challenge. And finally it was just, settle on a face or something, settle on a kind of body and then work with a model maker to make a figure that was a passing resemblance to the sketch.

And then I thought these boys

1. Creative Time is a nonprofit that supports public art – with a particular focus on vacant spaces with historical resonance.

2. Trisha Brown is a choreographer who is also a visual artist; she makes drawings with her hands –and her feet.

3. KW’s drawing with her body because she is afraid of drawing too cute is a classic hack. Artist’s hacks are plentiful, and sometimes very odd. For their book Sketchbook with Voices, Eric Fischl and the art critic Jerry Saltz interviewed artists. “What I found so compelling was to hear how artists got themselves out of their dead spots” Fischl wrote me. “Richard Artschwager was overworking a painting. He decided to watch TV and only go into his studio to paint during commercials. That gave him about two minutes a time to work. He said it took him most of the afternoon soaps but eventually got passed whatever it was that was holding him back.” There’s a fun book on the subject, by Mason Currey called Daily Rituals. Among its findings: When Igor Stravinsky was blocked, he stood on his head. WH Auden would take a benzedrine every morning. John Cheever would get dressed in a suit, take the elevator to a room in the basement and then strip to his boxers to work.

4. She’s talking about the Rolling Stones song Brown Sugar.

5. Henry Osborne Havemeyer was President of the American Sugar Refining Company – which were once owners of the Domino Refinery.

6. The New York Times called Sidney Mintz the father of food anthropology. He wrote extensively on the link between sugar and slavery.

could be attendant figures.

I wanted them made as candy sculptures, made of sugar. I’m thinking everything is going to be made of sugar. And basically, at a certain point it became, what is possible, what is not possible? What is achievable in the timeframe? What is achievable financially? In physics? At a certain point everything was achievable. We just had to say what it was. So it was this giant sugar sculpture and these candy figurines at a human scale.

I didn’t ever have the specific notion that it would melt. That just sort of came with it. I knew it would be an unstable object. But we didn’t really know how unstable until we started making them.

It was all trial and error because nobody had ever done it. People had made smaller sugar sculptures, and there were people in the candy business, of course, and bakers. But when we started asking around for how to do this, no one wanted to touch it. They said, it’s not going to work. The first one, when we made the molds – well, let me first explain that it’s easy to make candy — it’s just sugar and water and temperature. It just has to reach the hard ball stage, when you can pour it into the mold and let it sit. But for us, the molds were so big and the temperature was so hot, it never cooled in the interior. So the first one, we took it out of the mold, and at about six o clock that evening, it was a puddle.

Compromise Eventually, we thought maybe we have to do some of these in resin, some in resin and some in candy. Okay, compromise. Don’t love it, but maybe it will create the effect. So we made as many of these sugar boys as we could. And then the day before the opening, a truck backed into one of them, maybe two of them got knocked over. Oh my god that was bad. I don’t know if you remember but some of the figures have figures inside their baskets. I just picked up the broken pieces of the ones that had fallen and put them in the baskets of the ones who were standing. The building process, when that actually

10 KARA WALKER

started, that was amazing. I’d have fits of giggles because I just couldn’t believe we’re doing this. The development was interesting, all of that was interesting, but just stepping into the space… I don’t know how to describe it really. It was intimidating. It was, is this mine? I had to go back in there and figure out and how to make it mine.

There were some things I literally couldn’t do. I wasn’t really capable of moving giant blocks of polystyrene. So I would go over there regularly and talk with the team who was shaping everything. It wasn’t until the last phase of it, the last four weeks, that I felt I was really doing something, I was running back and forth.

A Deadline We’re on a timeframe that was very tight. It was kind of clockworkish.

We decided to open early May, and then we just started an eight week run. So things are going to fall into place, or not. I had done what I could do.

As for destroying it after it was done, well, what is the purpose of a monumental sculpture on a grand scale but to be destroyed? I had my moments when I thought, well maybe I shouldn’t, but I felt ickier holding onto it than letting it go. I felt I was playing some sort of game with it. I had promised it, you’re going to come and then you’re going to go. And that’s just how it has to be.

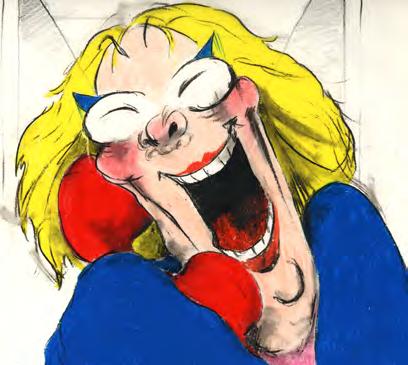

On May 10 it opened: My daughter went to see it a couple of days before. And there’s a picture of her when she first gets into the space, laughing. And that resonated for me because it reminded me so much of my first experience when I presented the work. There was the not-seeing of it. People walked into the factory and they were like wow, wow, wow, look at all the sugar boys. People walking and walking and walking, and then suddenly it was there. And they didn’t know there would be a big thing there. They were just like, Oh my God. And I found that very satisfying. So, my daughter walked in there, she’s a teenager and she’s looking around, and I sort of pointed to it. We were standing in front of it, just looking. And it wasn’t about the aha moment. It wasn’t just Oh, the breasts, Oh the sugar, it’s made of what? You know, you walk around. And it keeps changing shape and meaning in the viewer’s eye and mind – I mean hopefully. And maybe it sort of elicits some of those harder feelings that I was thinking about – I hope so.

All I can say is, I was trying to materialize and manifest the feeling of the histories I wanted to talk about. I had ingested that. I had done something that affected me, and I knew what it was. I knew the effect I wanted it to have. And that was it.

I don’t know about anything really. I always feel like I’m a novice and I’m just starting out

SIDEBAR TKTKTKT

I was very taken with the ephemerality of the project. I asked if that was always the plan.

KW: Well, what is the purpose of a monumental sculpture on a grand scale but to be destroyed? I had my moments when I thought, well maybe I shouldn’t, but I felt ickier holding onto it than letting it go. I felt I was playing some sort of game with it. I had promised it, you’re going to come and then you’re going to go. And that’s just how it has to be.

11

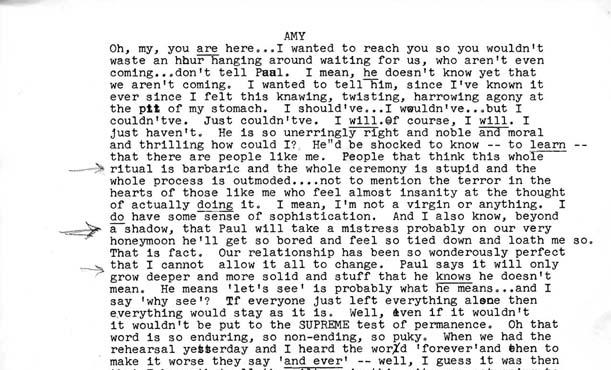

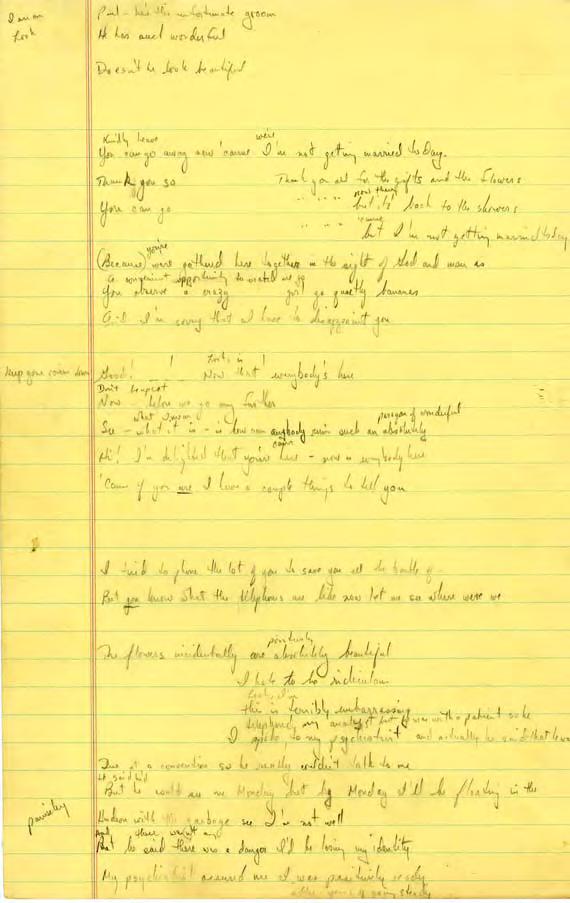

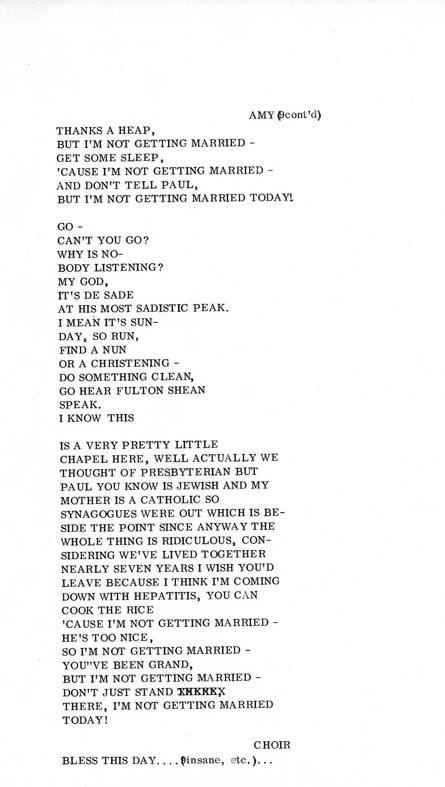

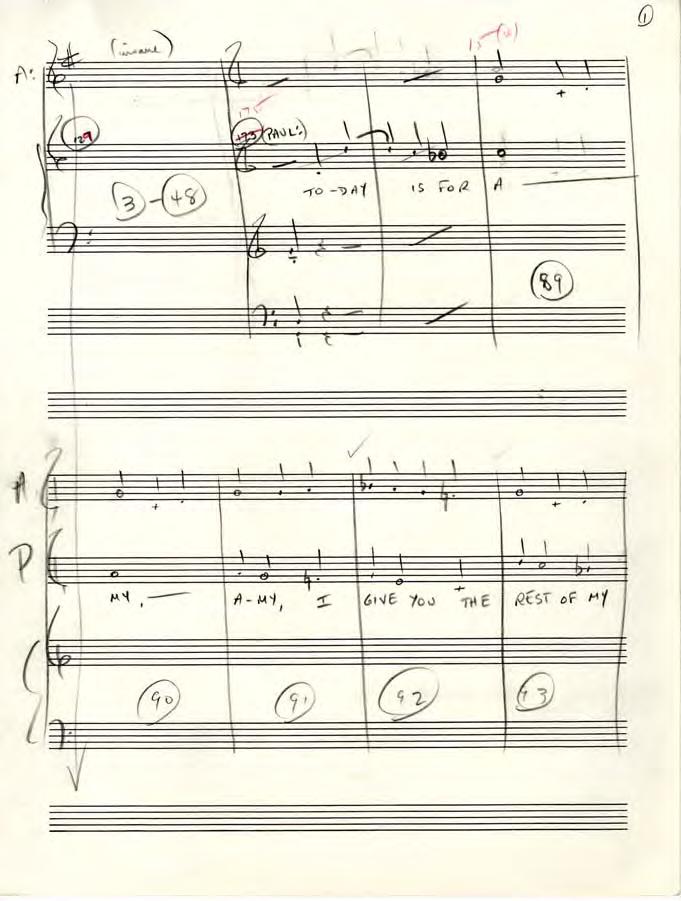

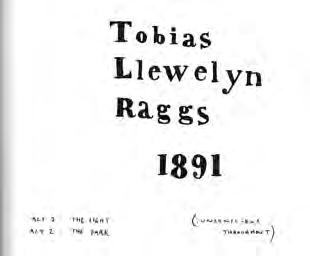

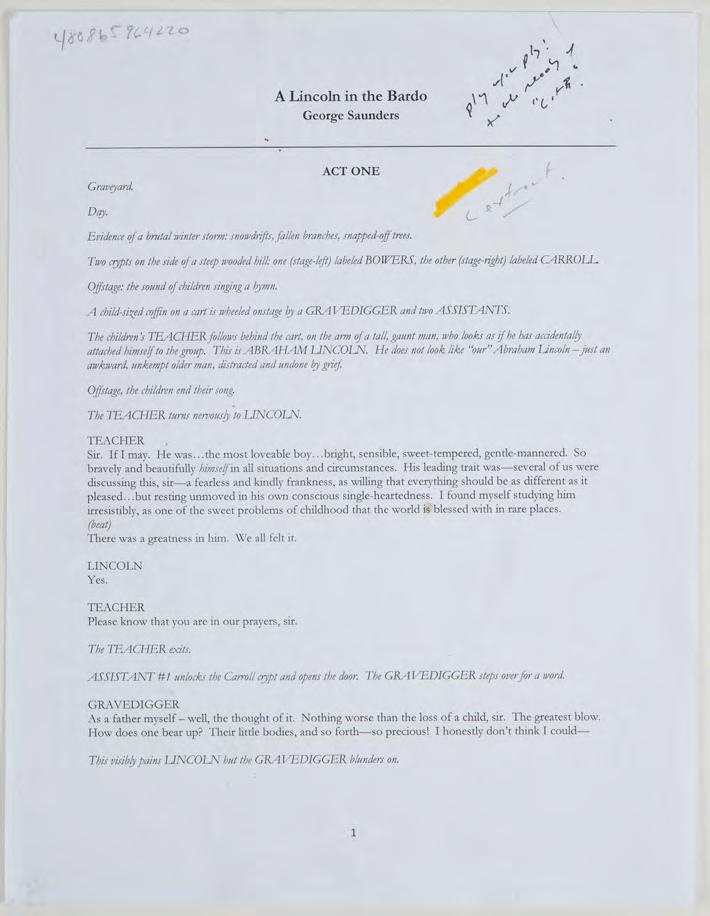

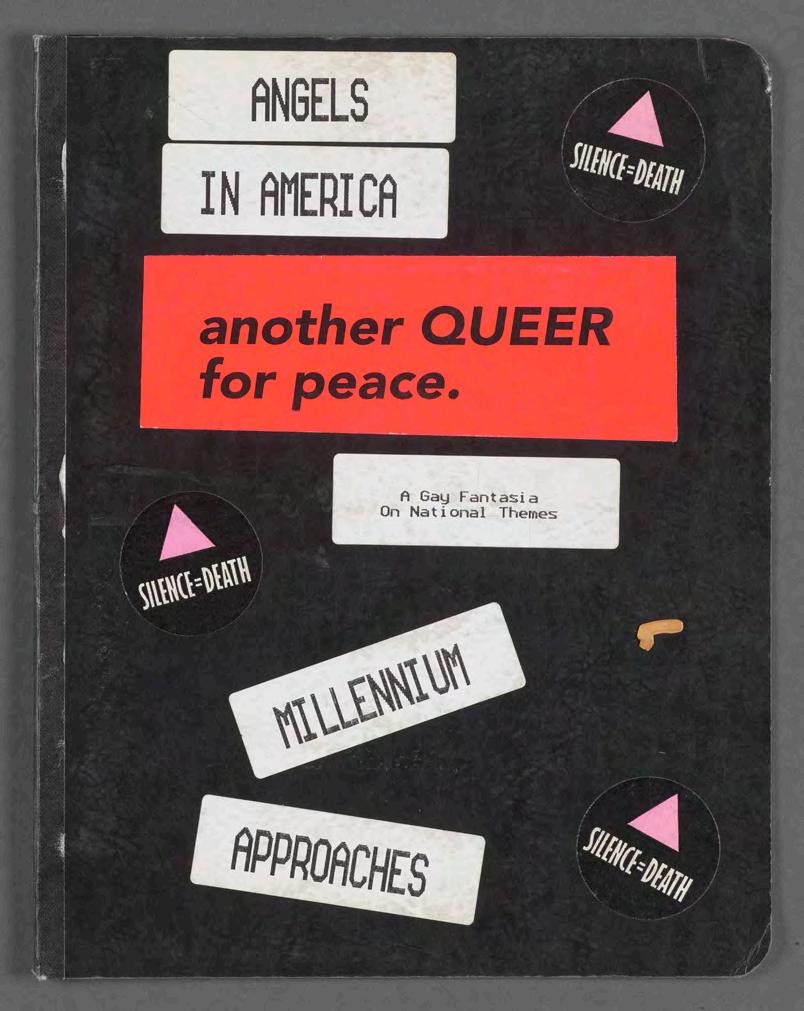

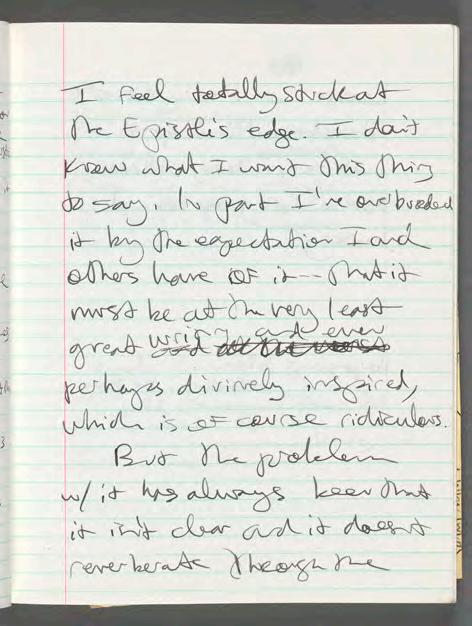

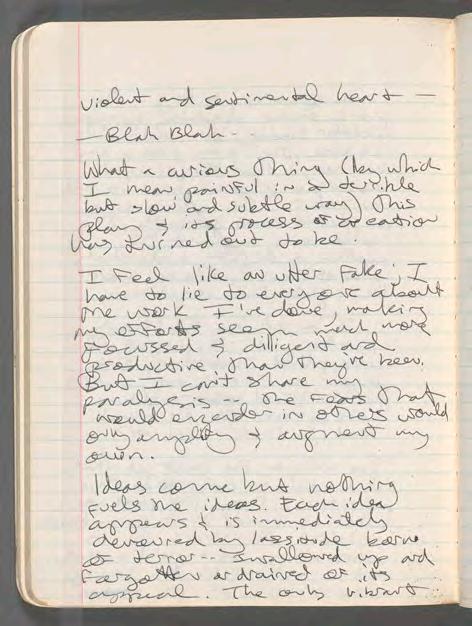

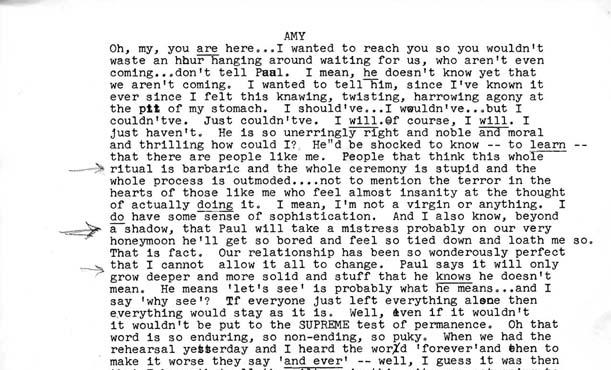

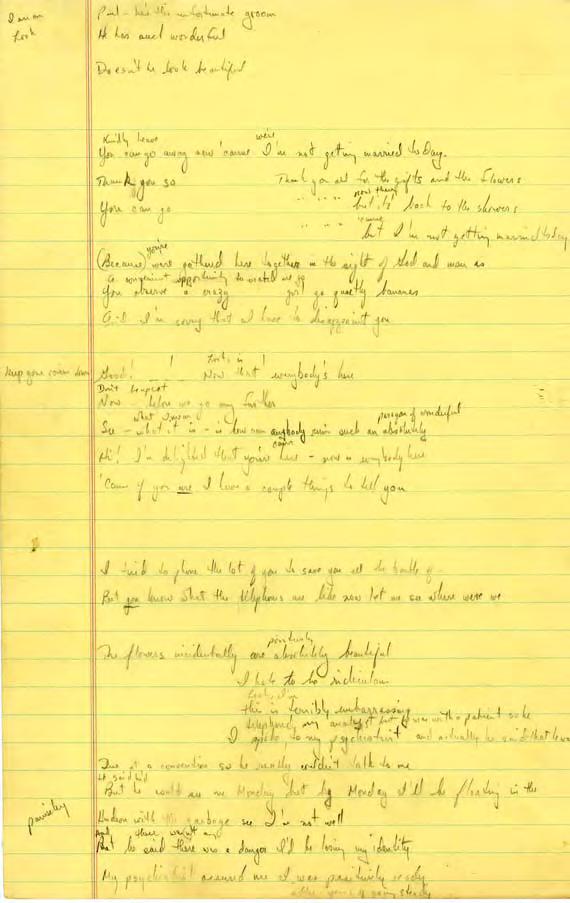

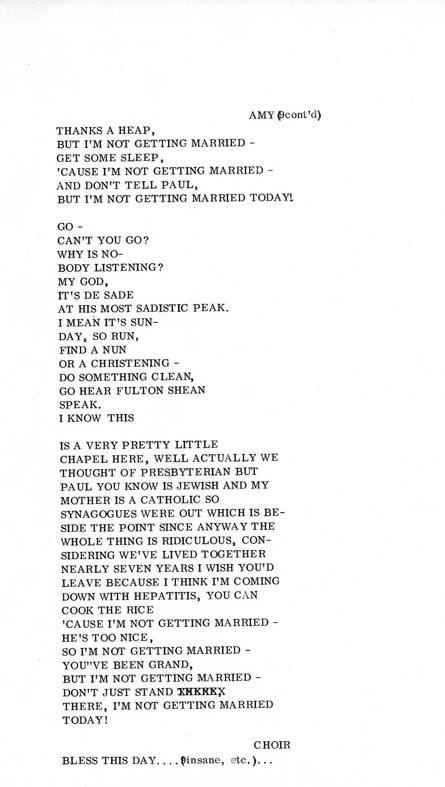

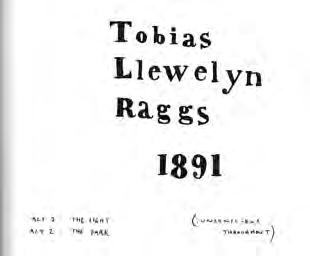

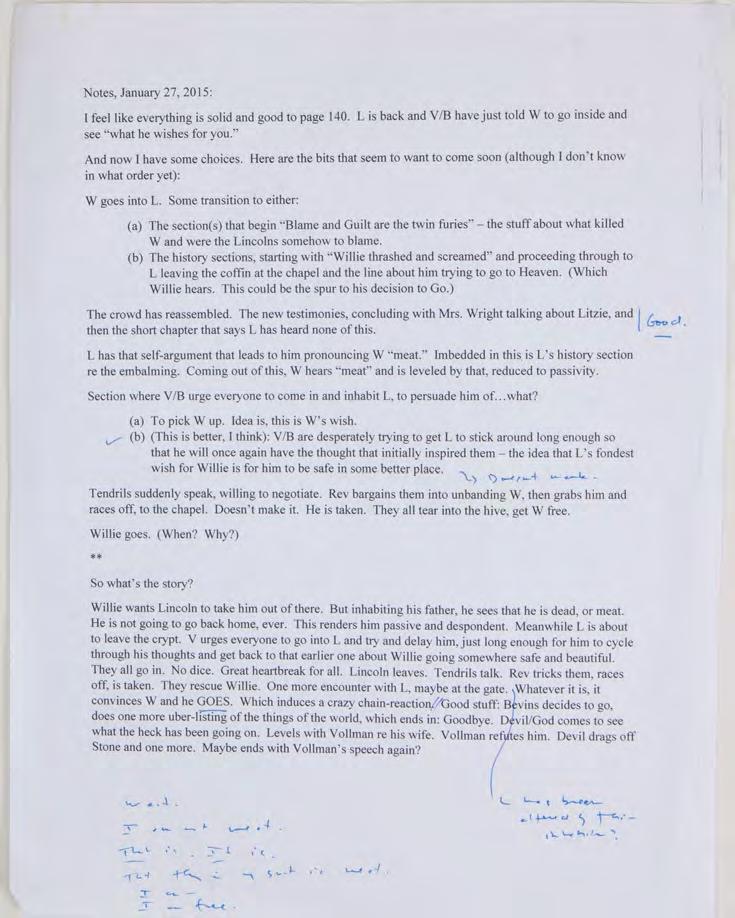

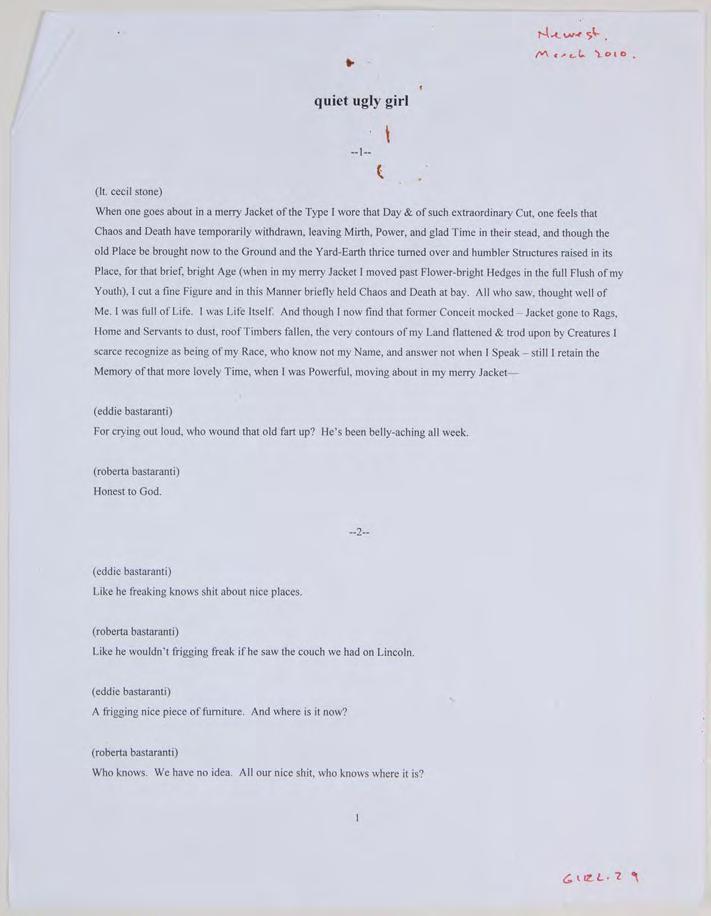

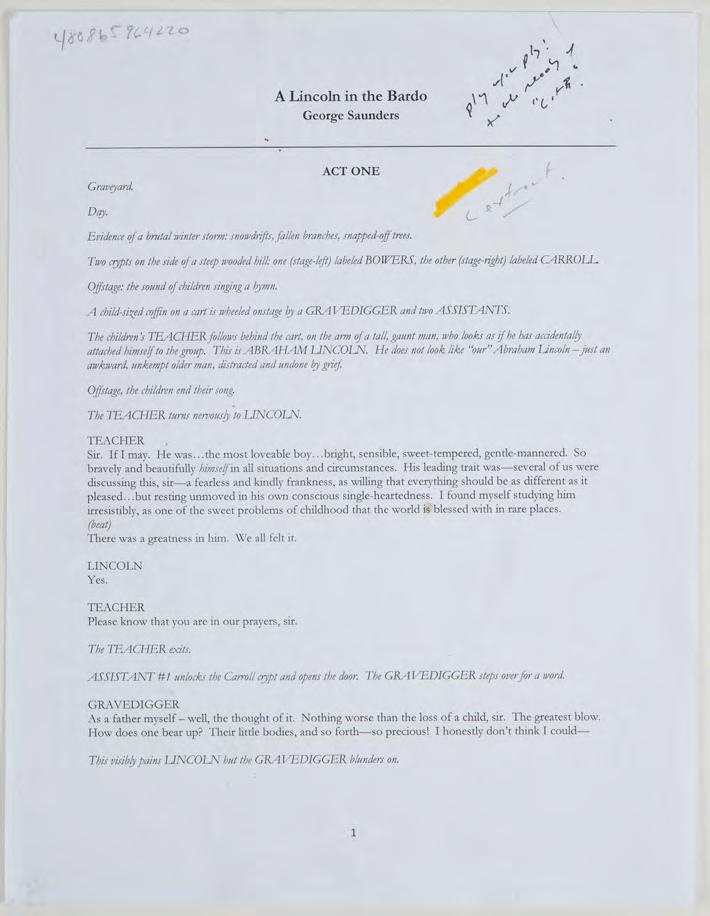

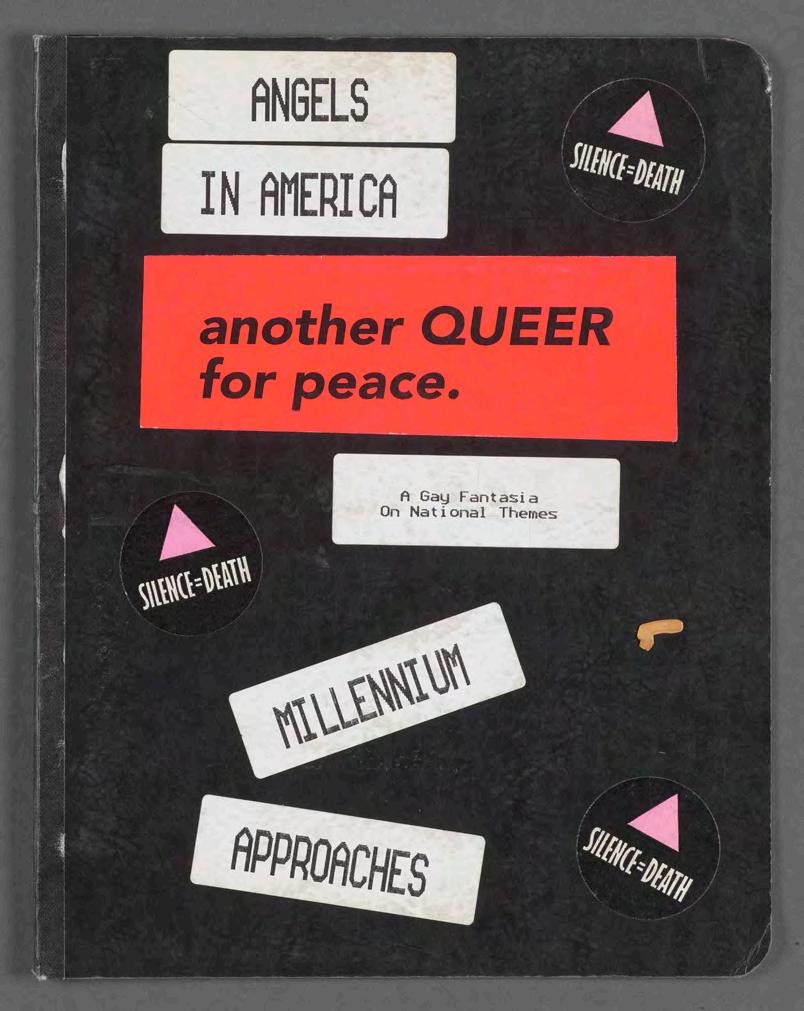

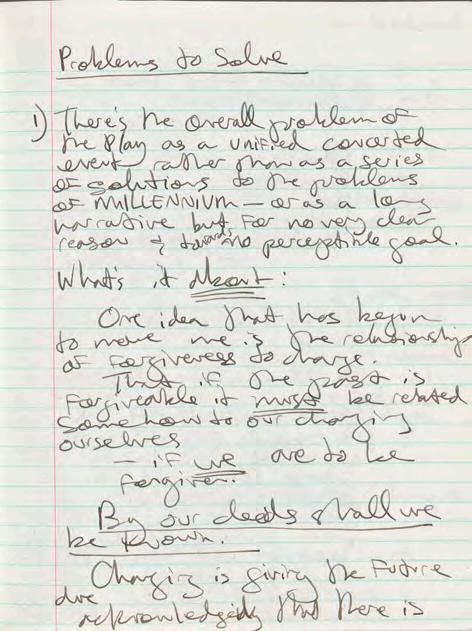

TONY KUSHNER

Breadcrumb

Traces Is What I Call Them

occupation : Playwright/screenwriter

work : Angels in America

born : 1956

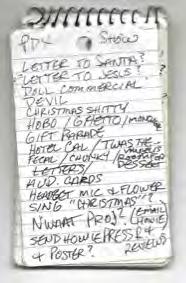

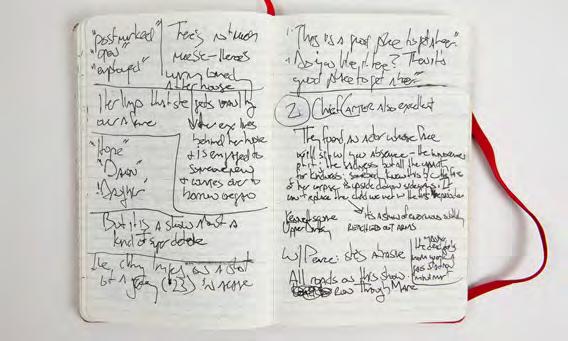

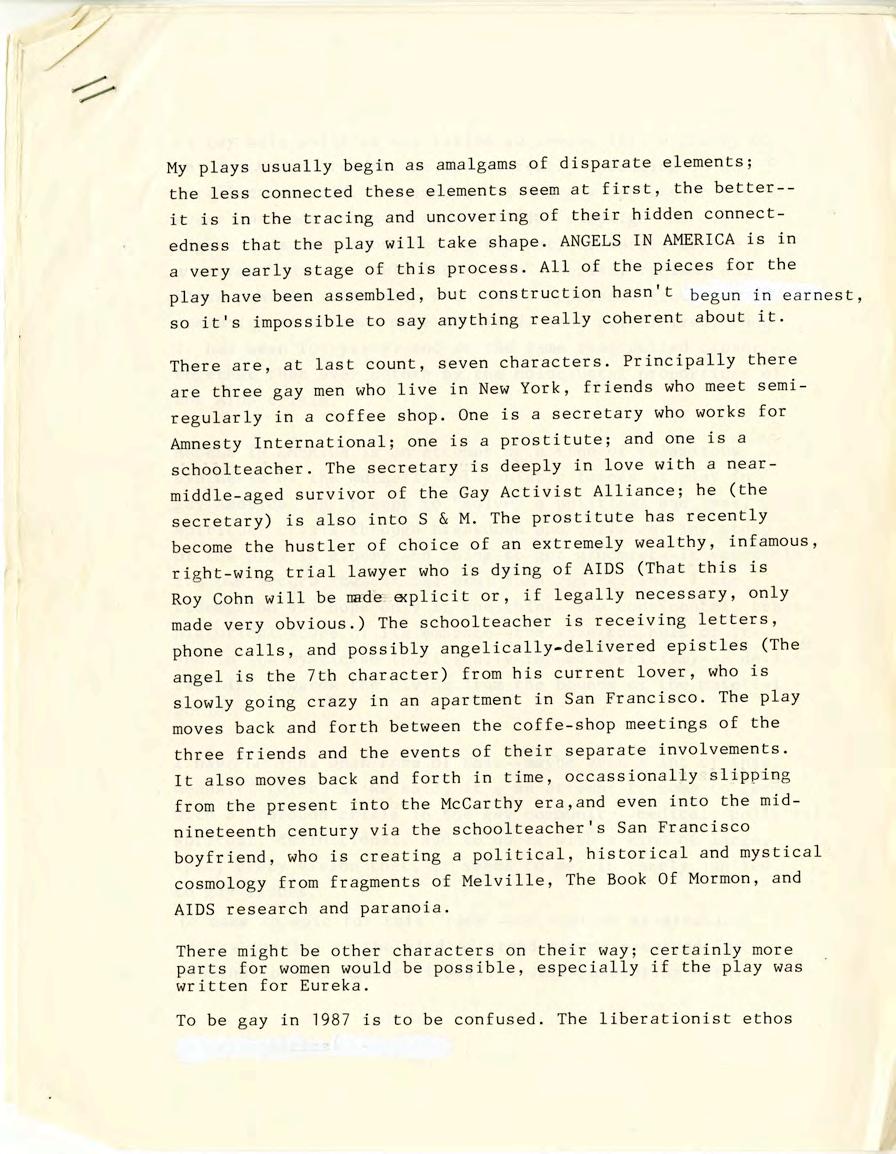

I MET TONY KUSHNER in his house in Provincetown. I was first greeted by his husband Mark Harris who I used to work with, and soon by his exuberant dog, who they both fussed with. Mark took off, and Tony and I settled in his living room, curled on the couches for a long conversation. It took place, like so many of these conversations, during the heart of Covid. The release of Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story , for which he had written the script, was still months away. West Side Story was finished a while ago, and now it was just waiting, we were all just waiting. A revival of the musical he wrote, Caroline, or Change (evidence of the broad nature of his talent, if some were needed), was also in suspended animation; it had been set to open just as the pandemic began. But Tony was hardly idle; he was furiously writing another movie with Spielberg [fn1] , and the speed with which it was coming surprised him, since he is very invested in his identity as a procrastinator. I told him the obvious, that he seemed plenty productive.

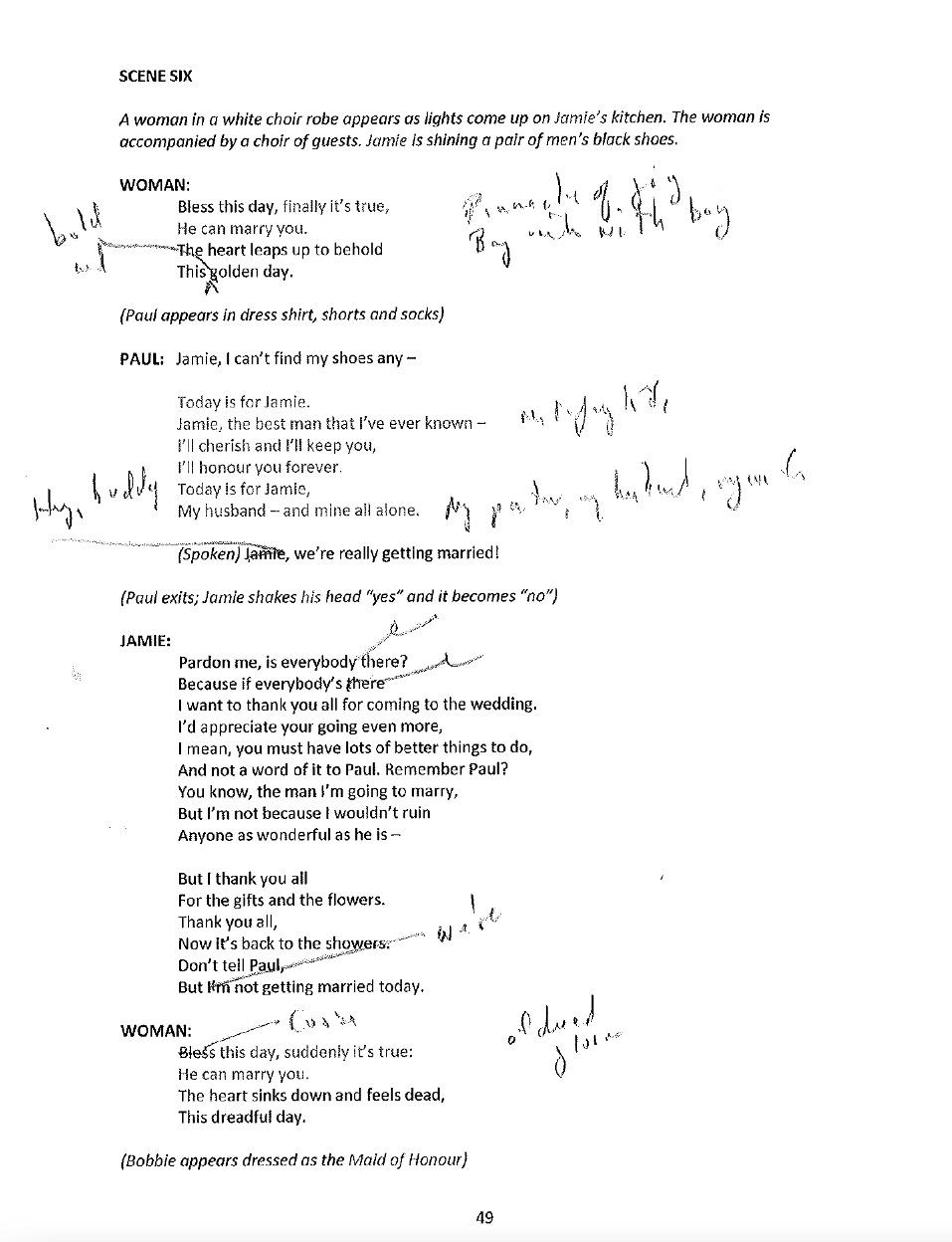

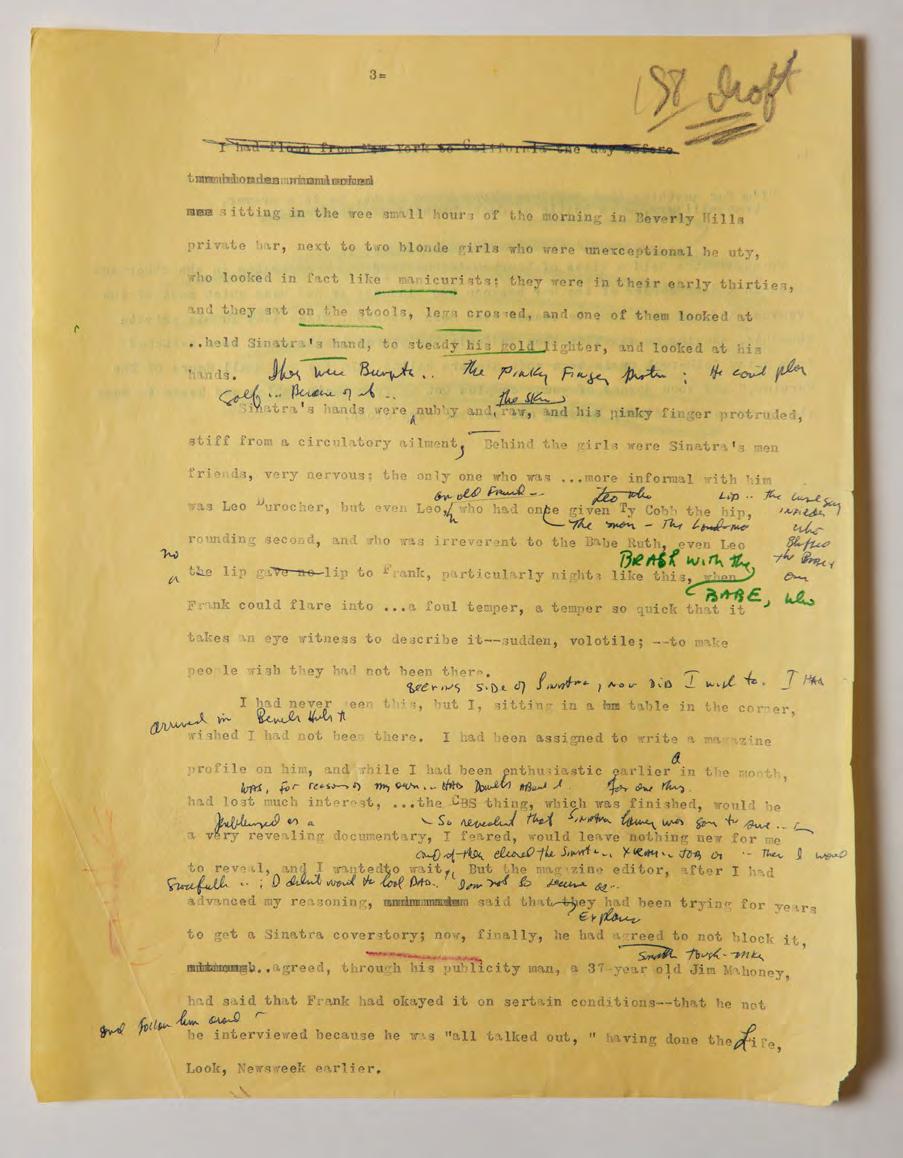

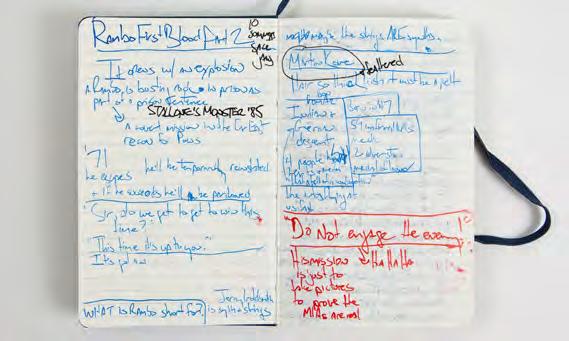

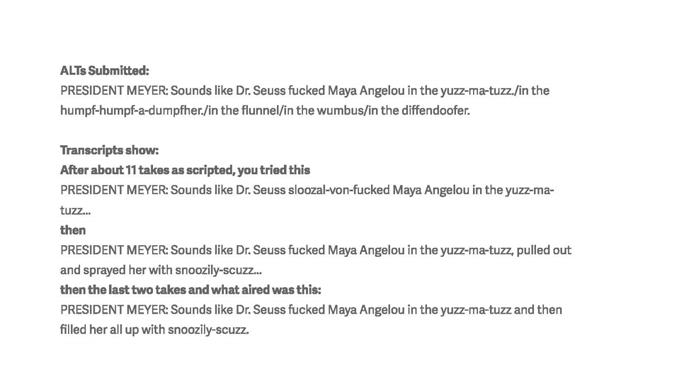

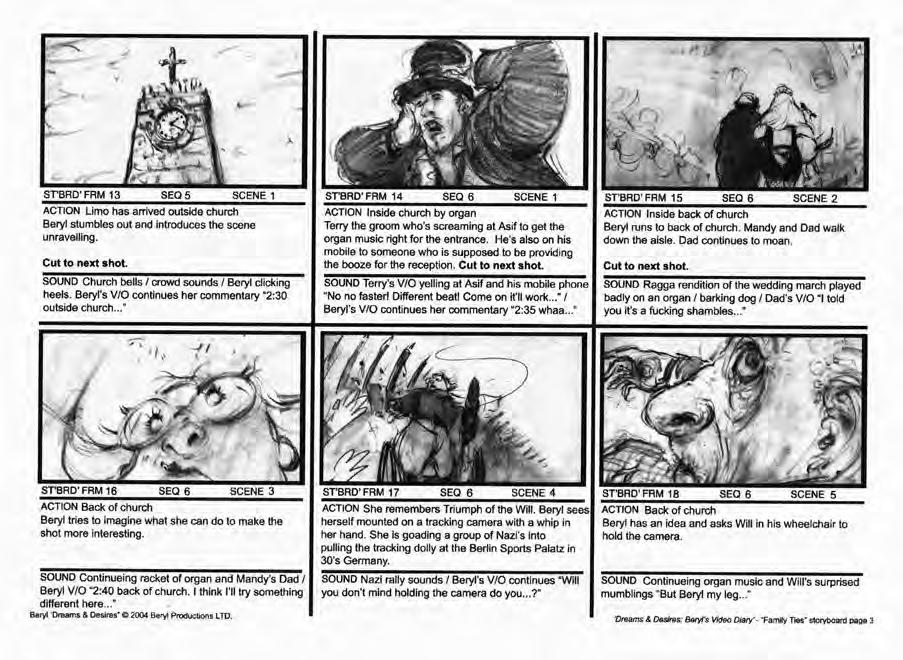

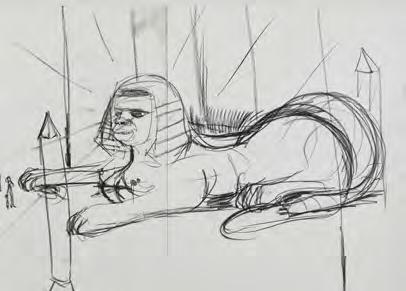

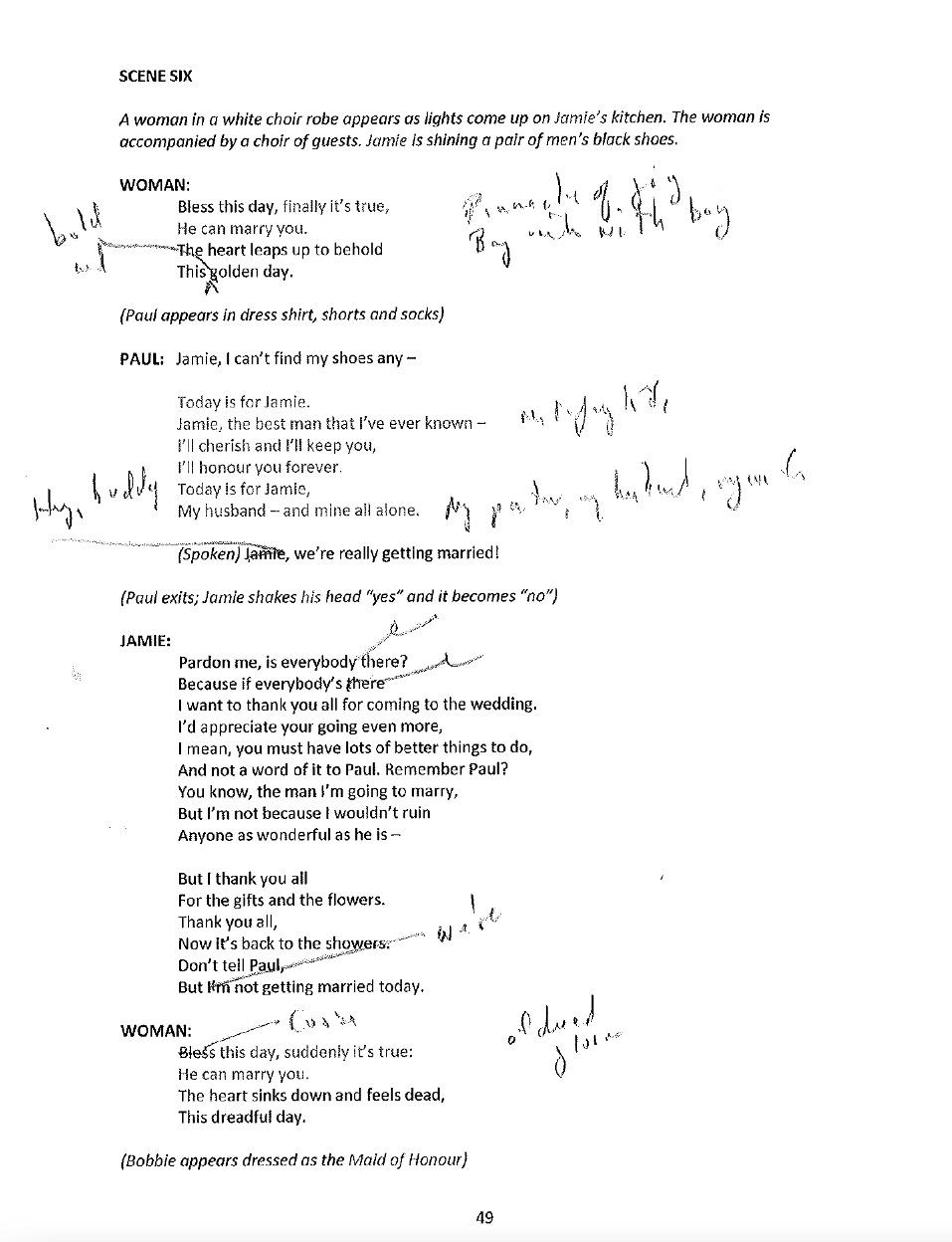

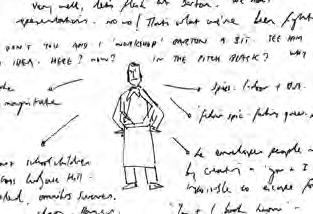

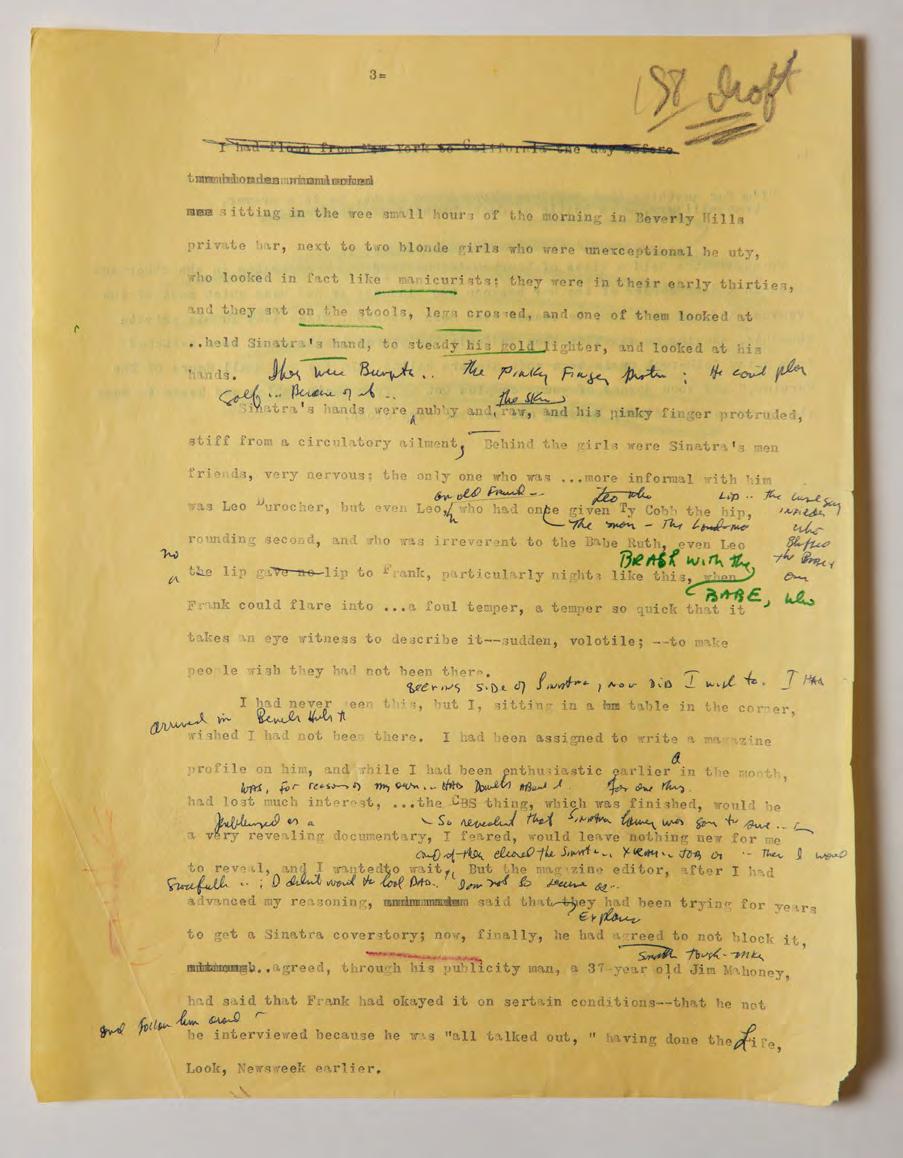

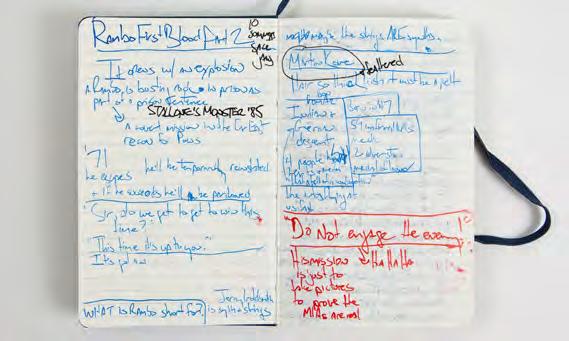

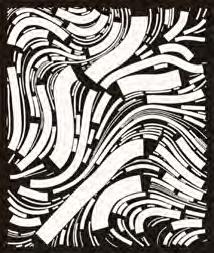

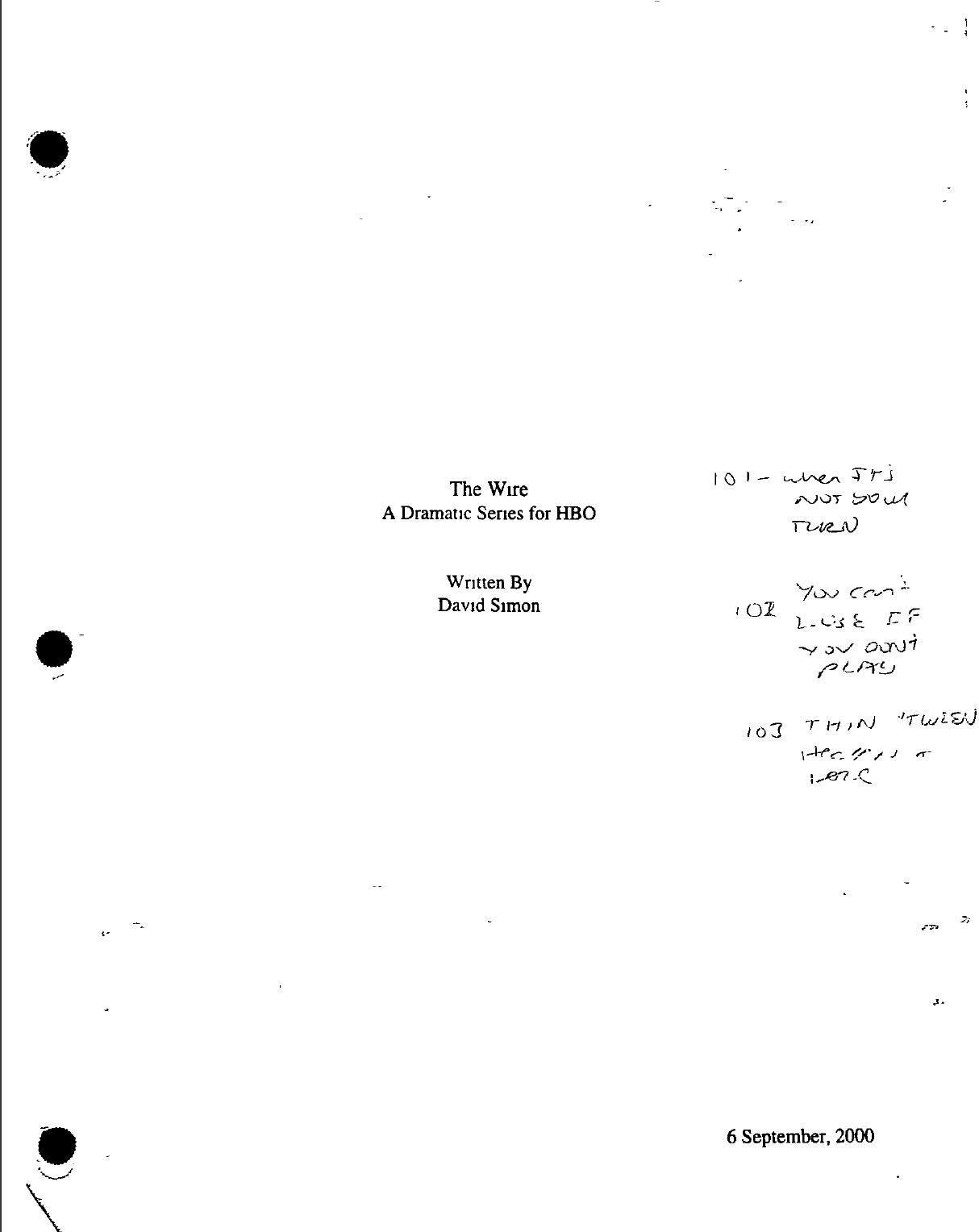

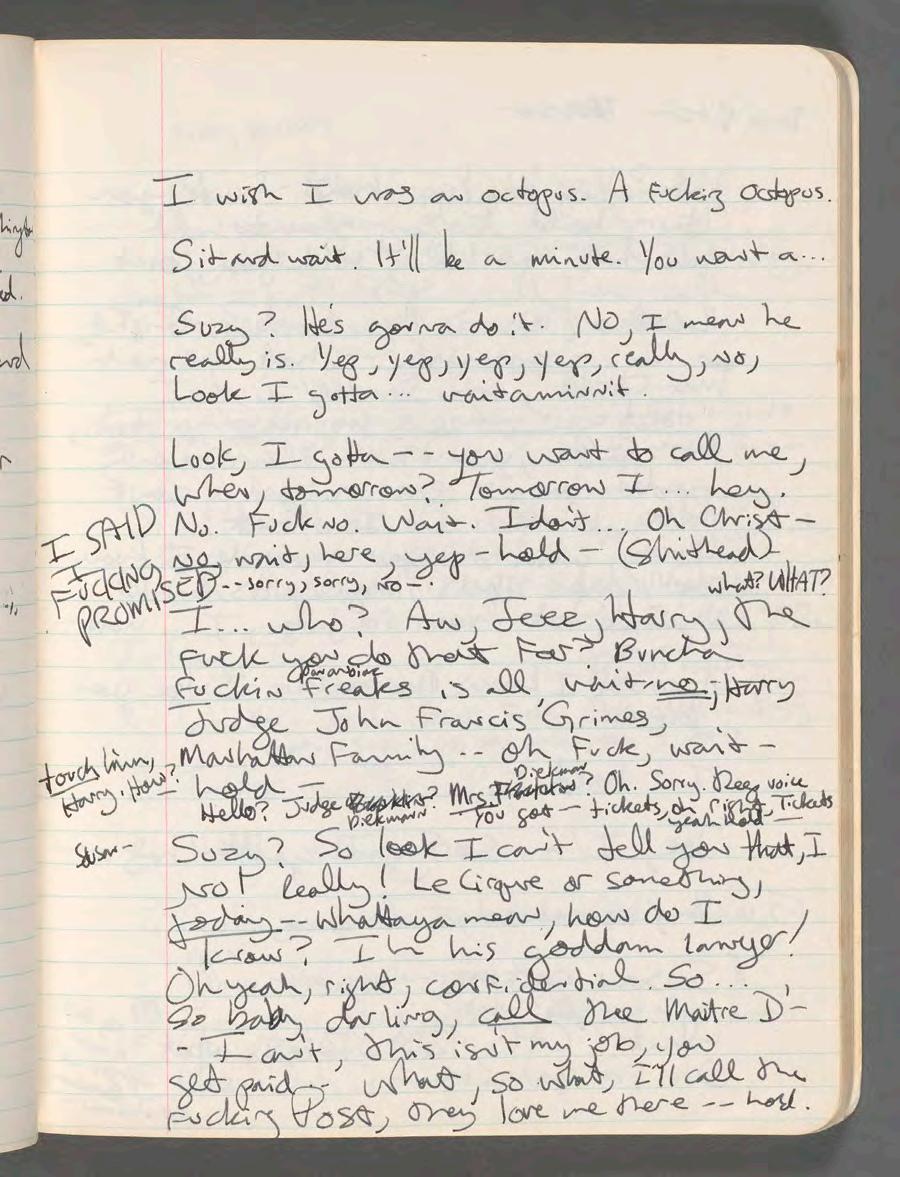

ROY COYN THE OCTOPUS, FINAL

Roy (Hitting a button): Hold. (To Joe) I wish I was an octopus, a fucking octopus. Eight loving arms and all those suckers. Know what I mean?

Joe: No, I . . .

Roy (Gesturing to a deli platter of little sandwiches on his desk): You want lunch?

Joe: No, that’s OK really I just . . .

Roy (Hitting a button): Ailene? Roy Cohn. Now what kind of greeting is. . . . I thought we were friends, Ali. . . . Look Mrs. Soffer you don’t have to get. . .

. You’re upset. You’re yelling. You’ll aggravate your condition, you shouldn’t yell, you’ll pop little blood vessels in your face if you yell. . . . No that was a joke, Mrs. Soffer, I was joking. . . . I already apologized sixteen times for that, Mrs. Soffer, you . . . (While she’s fulminating, Roy covers the mouthpiece

“I’m not though. It’s pathetic. Todd Haynes [fn2] called me a while back and said would you do this series with me, about Freud? It was so much up my alley I said yes immediately. And I never heard back from him. And then I saw him later and I said what are you working on? And he said, a miniseries about Freud with this British playwright. And I was aghast. I said, ‘what happened to me?’ And I tried not to have a reaction but I couldn’t resist. I said, ‘fuck, what happened to me?’ He said ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I forgot. I wanted to hire you. But Christine [Vachon, the producer fn 3 ] said absolutely not. You’re never going to get the script.’” I laughed. “Spielberg

2 TONY KUSHNER

2

3

ROY COYN THE OCTOPUS, FIRST TRY Tktktkt tktktk tktktktk tktktk

4 TONY KUSHNER

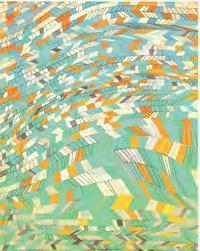

TKTKTKTKTT, Figure 1 – teekay

5

TKTKTKTTKTKT, Figure 2 – teekay

for some reason has been the soul of patience with me. I always have 700 reasons why I mustn’t start working right now: I don’t trust my instrument, I think I’m not really good.”

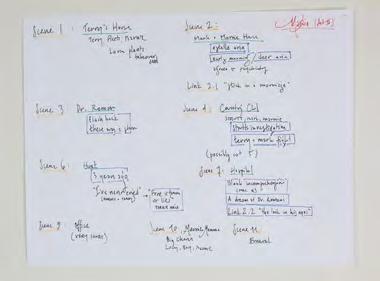

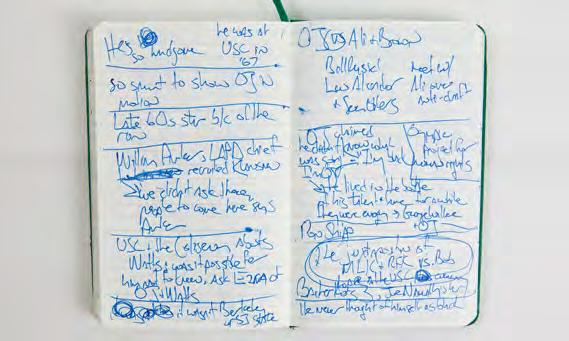

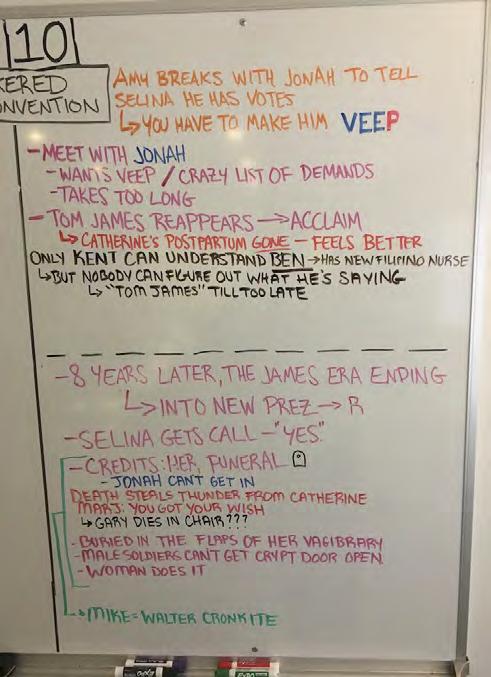

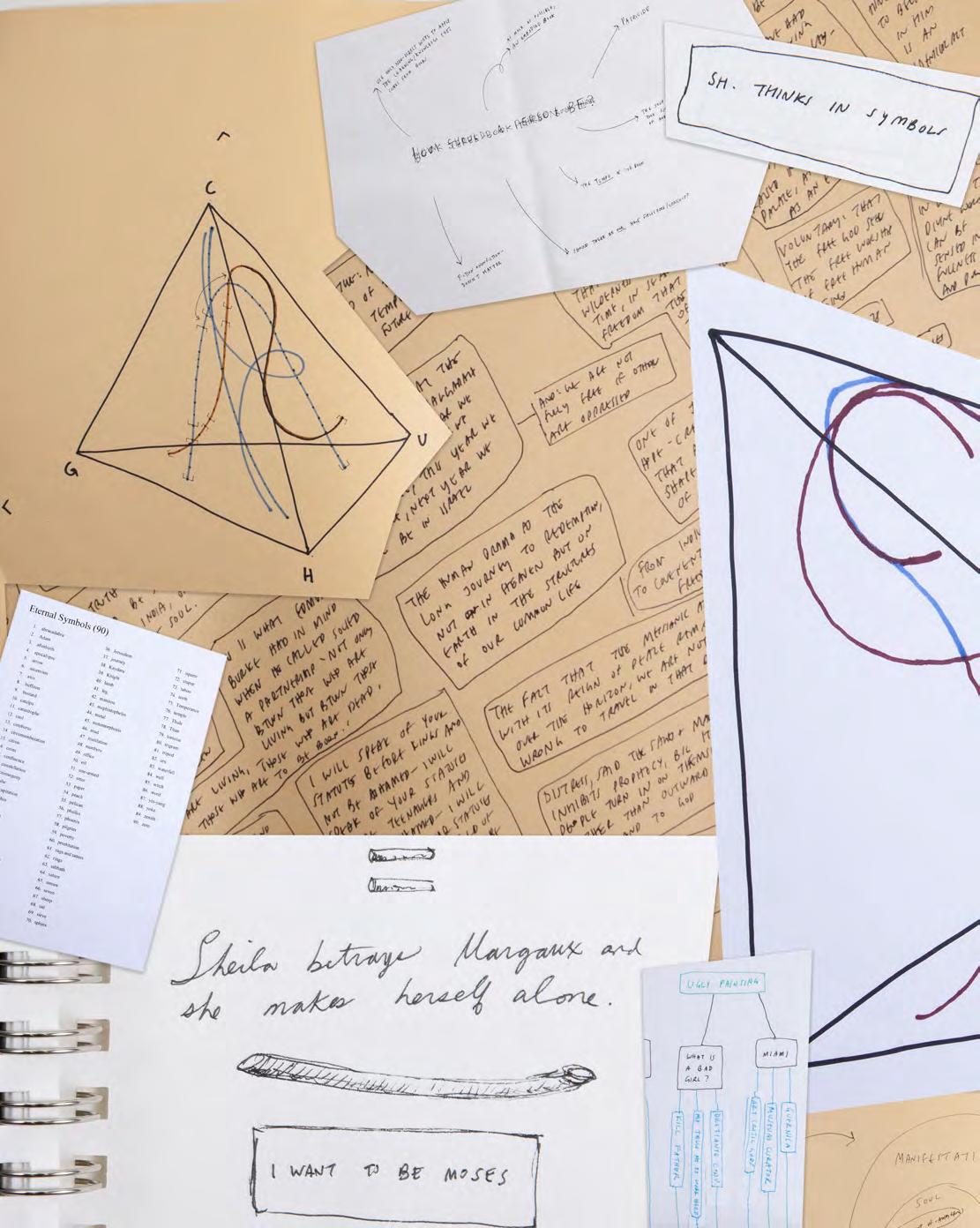

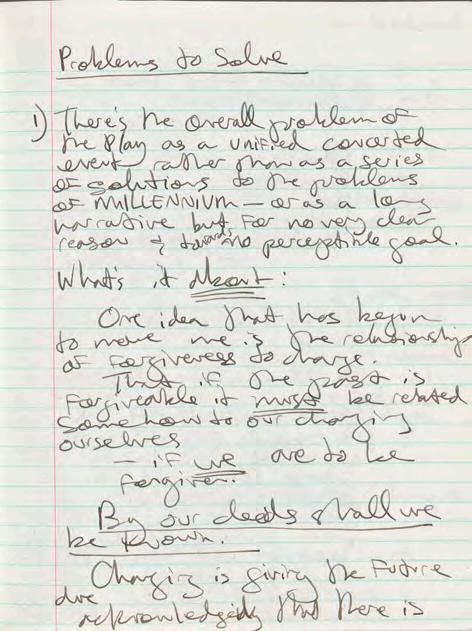

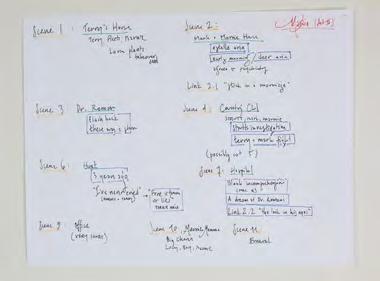

Freud hovered over our talk, which concerned his masterwork Angels in America, and how it came together, a story in which the unconscious, in the shape of a dream, plays a central part. I probably don’t have to explain how good it is, since it’s widely considered the most accomplished play of the last chunk of the twentieth century at least; it’s the winner of Tonys and the Pulitzer and all that. Just to give you some orientation, it’s actually two plays-- Millennium Approaches and Perestroika, written in succession but usually performed together. Its hero is a gay man named Prior, who is struck with AIDS and has hallucinations, but it is also a thickly plotted epic involving the Mormon Church (and Joe, a closeted Mormon who has an affair with Louis, Prior’s boyfriend that Louis has left; Joe’s wife Harper, a pill addict, who also has hallucinations; and his mother, Hannah Pitt, who comes to visit); and the notorious real-life lawyer Roy Cohn, who also has AIDS and also has hallucinations and has designs on Joe; and Belize a friend of Prior’s who is Roy’s nurse; and most crucially an Angel, who has descended from Heaven through Prior’s ceiling to take him back with her, since he is, she tells him, a Prophet, who is destined to rescue

the otherworld, which by the way is in tatters because it has been abandoned by God. Does that make sense? For our purposes here I suppose it must, since my conversation with Tony was a piece by piece account of how the epic emerged.

We got to that in a winding way that suggested the labyrinth of Tony’s mind, which is just as funny and thoughtful and honest as his plays. I’ve tried to straighten it out here. So we’ll just pick it up at the beginning of how he became a playwright in the first place:

ABOUT FORM

Experience Does Teach You “I

think I really always wanted to be a writer,” he said, “but I’ve always found writing scary. I have ADHD or something, I don’t know what it is. In any case, I didn’t actually know what I wanted to do. I came from this tiny town in Louisiana, both my parents were musicians, my father was very erudite – a great reader of poetry. My father, who was a Juilliard trained clarinetist, lived for art – music and poetry especially and had a kind of eidetic memory, could cite ‘Endymion’ by heart and Robert Burns and Shakespeare. He really loved language and loved words. And he wasn’t a mean person. But he couldn’t read a book that was badly written. It just made him angry. And it was sort of, if you weren’t a genius, if you weren’t Keats, what was the point? He and I clashed

As Tony was considering the sort of play he might want to write,. he found himself attracted to the possibilities of epic theater, thinking particularly about Shakespeare. “Shakespeare makes you want to come in and do what most people don’t know they have to do with works of art, which is, you are as capable of failing it as it is of failing you. You have to bring yourself to it. And somehow Shakespeare just makes that the thing you want to do–

“I love big long discursive things. I loved Moby-Dick. I just became obsessed with Melville, rejecting the idea that you had to exclude things. One of Brecht’s friends Walter Benjamin said that beneath the surface there are these tunnels constantly being made, that connect things. I loved that idea and because I’m Freudian and have been in analysis forever, I really believe in the unconscious as a schematic.--

“It sort of became my method of construction. I just had some vague intuition that there might be some way to join these things. I would write them down in a notebook and keep playing with them until I figured out how they join.”

6 TONY KUSHNER

blackly on my bar mitzvah sermon. For my bar mitzvah I was just young enough for him to stomp on it-- he took it away and wrote his own version of it. And that’s what I delivered.”

“It makes sense to me that that might make it terrifying to be a writer.” I said.

He nodded. “But part of it about writing also is that I’m an emotional coward, I become a little disarranged by having to go into painful places. So I have to trick myself into doing what you’re supposed to do, which is to go into difficult emotional terrain. And the more I’ve come to understand my writing, the harder it’s gotten, which I think is probably true of any kind of anxiety-based art, is that experience does teach you. One, you start to realize what human beings are actually capable of, what a great work of art is really-- I mean if you were an earthworm you’d probably be able to figure out that Hamlet is a great play. But the more times you see Hamlet , the more you realize this impossibly great thing lies so far beyond your capabilities. One starts to assume a proper level of awe for what a truly great work of art is, and how many shortcomings you bring to this enterprise.”

Tony’s modesty, his default stance, alternated with pride; it didn’t feel insincere, even if as he was pretty hard on himself –

“And the few times you’ve stumbled into something good,” Tony says, “you think, How did that happen? What if I had gone down this other road instead? Would I have ever gotten to this thing that I’ve accidentally come across? I mean there are a few things I’ve written, moments in some of the things I’ve written that I really rather proud of. Where did that come from?”

“That’s what this conversation is about,” I told him. “Also this book.”

“Good luck.” He laughed.

He returned to his chronology, or the pieces of it that would end up relevant to the evolution of Angels. The early years in a biography are often the dullest, but in Tony’s own account you could see how the strands – intellectual and otherwise – started to weave. He went to

Columbia. “In my junior year I took Edward Tayler’s [fn4] class in Shakespeare-- and his maxim was to really understand Shakespeare you have to be able to count to two because everything was was dyads and dialectics and antinomies. And I started to read Marx for the first time. And I was taking a modern drama class. I started reading Brecht – the theory as well as the plays. And I was a medieval studies major --”

“Why that?”

“Because I was a Jew and gay and the glory of the church and all that I am... am I just babbling?”

I assured him that he wasn’t, but he sped up. He fast-forwarded to NYU.

A Beautiful Boy Named Bill “I was a graduate student at NYU’s theater acting program. I was a directing student, not a playwriting student. Directing was sort of a way of getting into writing through the back door because I was terrified to own the identity of being a writer.” He met Stephen Spinella, an acting student there – that would become essential. The drama program did collaborations with the dance department – that was crucial too. “One of the first things I wrote was for one of these collaborations.” But also: “there was a dancer there named Bill who was unbelievably beautiful. I saw him once dancing in a studio without his shirt on and I was faint.”

He started to explore the cruising aspects of gay life of New York – situations that he would later integrate into Angels. And he wrote more. His first play was produced, A Bright Room Called Day , at a theater on 22nd street. A friend knew Oskar Eustis, who now runs the Public Theater, but was then running an avant-garde theater company in San Francisco; he was even at that point a formidable figure. “Oskar was this hot kind of red diaper baby guy. He spoke German, he had actually read Marx unlike most everybody else and really had theories. He was legendary.” Tony continues. “This friend brought Oskar to see the first performance. And Oskar asked to see the

7

script afterwards. He read the script, liked it, and then he [went] to back to the Eureka.”

Eureka would go on to produce Bright Room, but at one point, as they were eating hot dogs on the Embarcadero, Oskar had another question for Tony. He asked if he wanted to apply with Eureka for a commission for his next play.

So now in order to understand how Tony answered that question, we have to back up.

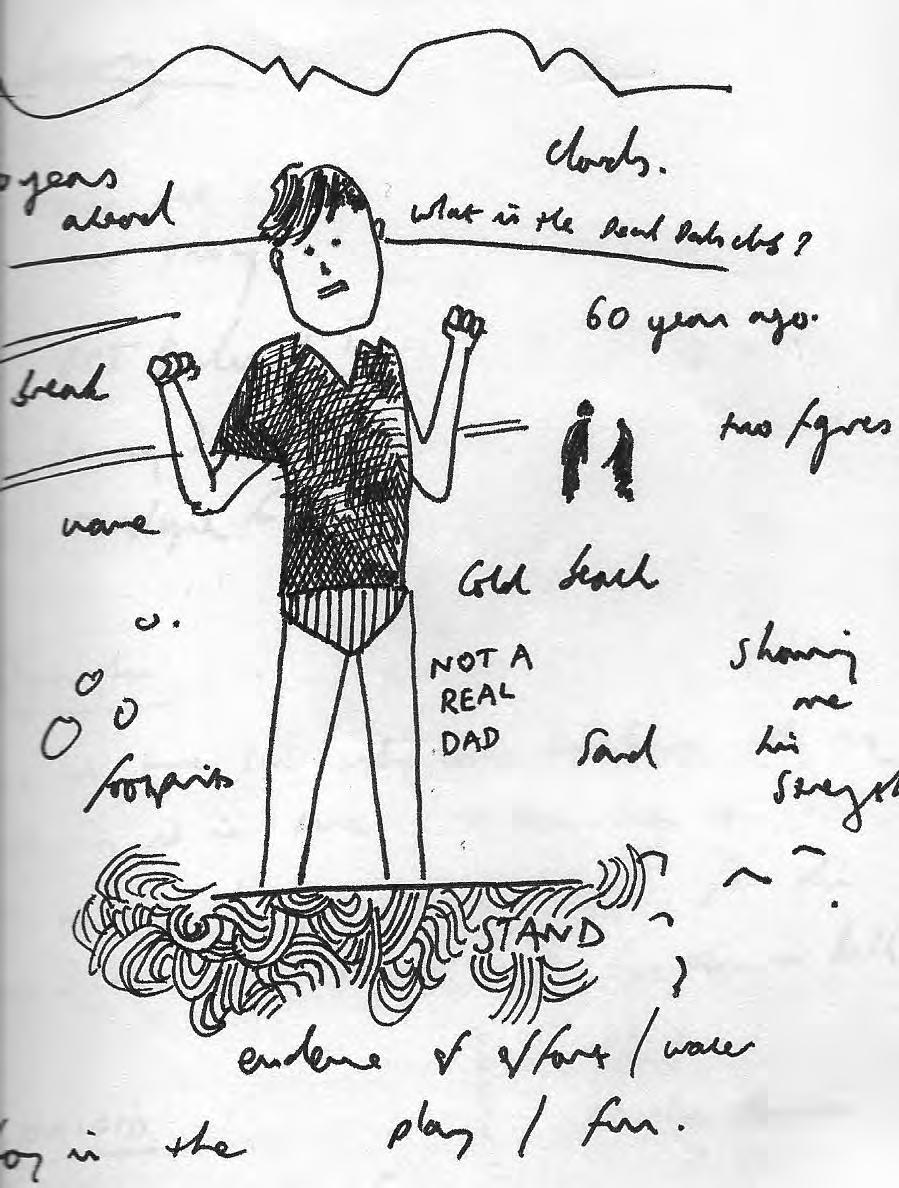

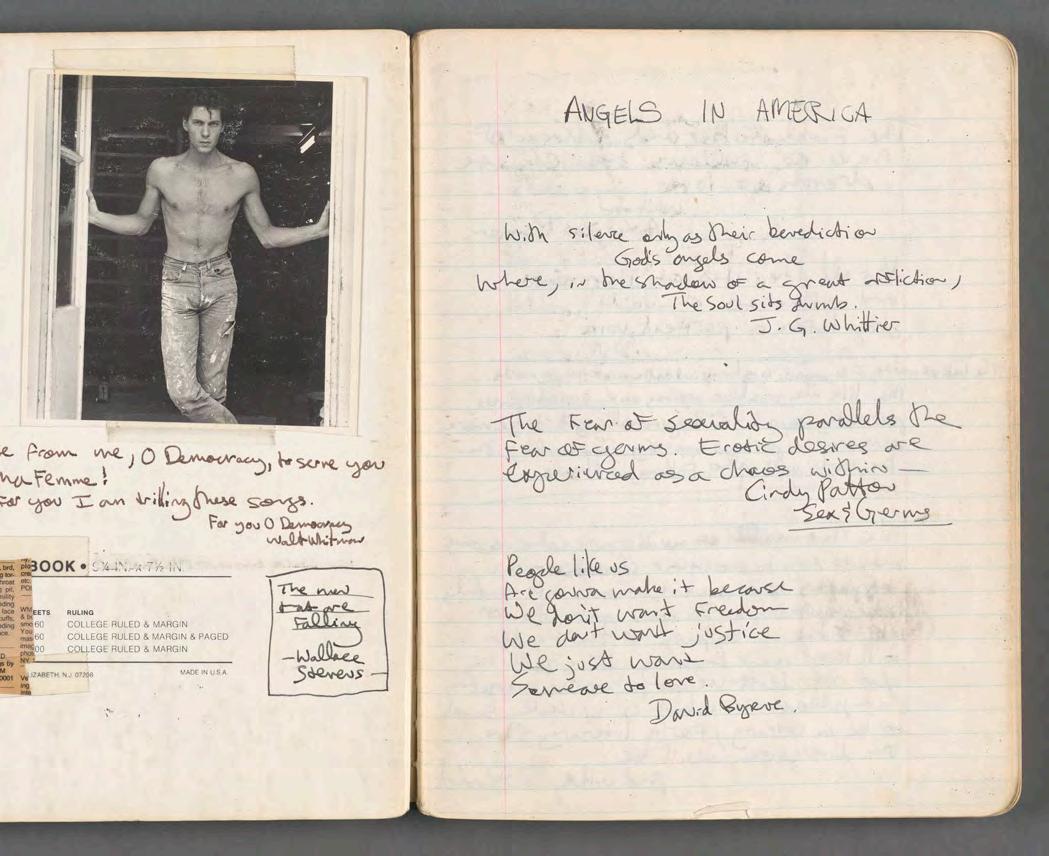

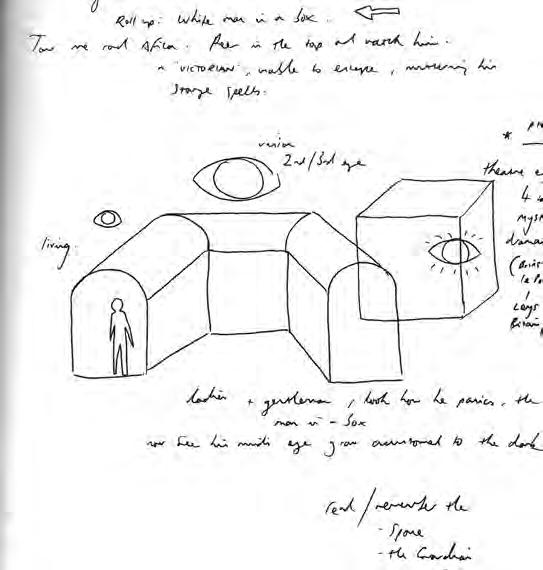

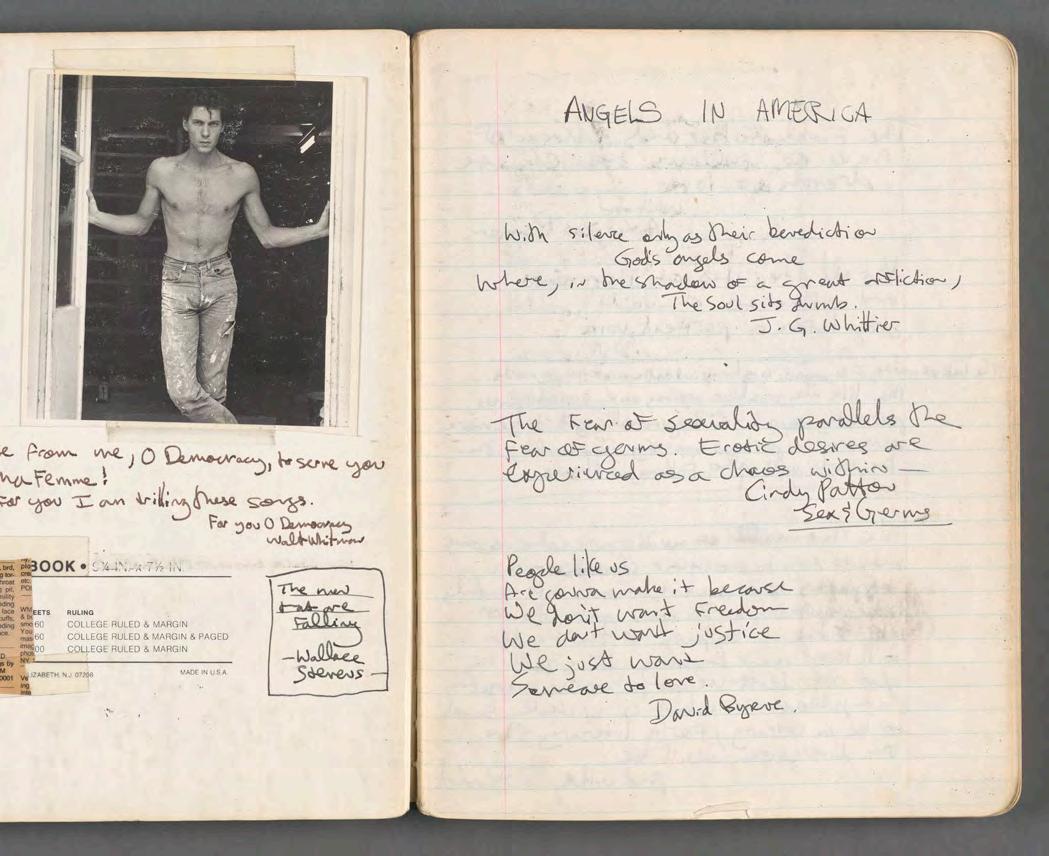

“Remember the dancer Bill I was telling you about?” Tony said. “I was in St. Louis on a NEA directing fellowship. And I heard that Bill was sick. He was the first person I knew fairly well who had gotten sick. Then I got a phone call from a mutual friend who said that Bill had died. I was in this weird little house in back of some rich drunk lady’s house in St .Louis I had rented. And I dreamt that Bill was in this room, in his pajamas. And he was screaming in terror. And looking up at the ceiling. The ceiling was starting to bulge like in a horror movie. The lights were flickering, he was cowering in the bed screaming. And then the ceiling collapsed and fell on the bed and covered him in plaster. And this angel came through the hole in the ceiling.”

Tony had dreamed “what turned out to be the punchline to the end of Millennium Approaches --”

Two Mormons on the Street “I wrote it down.”

he continued. “I went back to New York, there were two adorable Mormon guys on Carroll Street in Brooklyn, they were missionaries, they were not getting a lot of attention from angry Brooklynites on their way to work. And I asked one of them if I could have a copy of the Book of Mormon, which I’d read before. One of them was seriously hot so there was a level of erotic obsession. And I was doing a lot of driving back and forth in St Louis. Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA had just come out, I’d listen to the tape over and over again, thinking about his butt. And as I said, I was a medieval studies major and we were fifteen years from the Millennium, which is a very big deal if you’re a medieval studies major. And as I say, I was thinking about America, Born in the USA. And the Mormon angel Moroni is the only real homespun American angel. But he didn’t have wings. My angel had wings. And was a woman. Or Bill’s angel I guess I should say –“I went back to St. Louis, I was still thinking about this dream. And then I wrote a poem, which nobody’s ever seen except for me. And it was an attempt to fake my way through the epidemic and this dream about Bill and these boys and the Angel- and whatever else I stuffed in there. I’m not a poet –I’ve always had the good taste to know that –so I put it away.

“And this is when I was thinking, what

8 TONY KUSHNER

Dolut ete volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

would my next thing be? And that was when Oskar flew me to San Francisco to do a reading of Bright Room before they committed to do it –

“And when the play closed Oskar and I went out to the Embarcadero for hot dogs. The play hadn’t been particularly successful, but he said, we are really excited about your writing. We want to do a thing with you. They had a standing company of three straight woman and one straight man. And I had come out of the closet between 1982 and 1984, at a point when the epidemic was really starting to make its way through the community in that terrifying way – and you know, Reagan and all that stuff. So I decided that since it was for San Francisco, I should really write about being gay. And so that’s what I told Oskar. And we both scratched our heads a little bit over the fact that if we got the grant it was going to be for these four straight actors. And I said, I needed to think about it.”

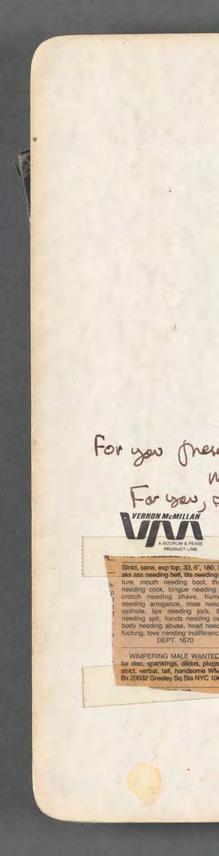

So he did. He thought about his dream, and the poem he’d written about it. In fact, he’d filled notebooks writing about it. He gave a title to it. “I called it Angels in America...” he said.

“And then I guess probably a year before that, Roy Cohn had died. And I had been interested in him since I was 10. I heard these terrifying stories about the McCarthy era from my parents, and the Rosenbergs and all the stuff

that one has heard about if you were born in 1956. My father had given me a copy of Fred Cook’s The Nightmare Decade to read in which he looms significantly as one of the great villains, as he should. Cook talks about him and David Schine [fn5] chasing each other naked through the Ritz in Paris and snapping each other’s butts with towels. I was this little closeted gay boy and I picked up all the signifiers.”

As he got older, Tony’s interest in Cohn had just grown.

“When I came to Columbia, at the beginning of Studio 54 [where Cohn was a regular] I was disgusted that this horrible man that any sane human being would turn away in revulsion suddenly was in the NY Post everyday with Liza Minelli and Halston. And then we all saw that bizarre Mike Wallace interview where he’s saying I don’t have AIDS. So he’s really beginning to loom for me as a gay Jewish man.”

When Cohn died, Tony found himself feeling some sympathy. He was particularly upset about an article in The Nation by Robert Sherrill

“one of the great old lions of the Left. He wrote this really venomous piece [building on] what Jack Anderson [fn6] had written about Cohn, about his body’s condition at the end, talking about the number of lesions around his anus. I mean, it was ugly. And this was quoted rather gleefully by Sherrill, who then also resorted to the old bromide, that there’s something about

9

Dolut ete volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

homosexuality that seems to have a natural affinity for fascism, and the lavender mafia around Ronald and Nancy Reagan. It was infuriating and enraging. I felt angry on his behalf. And I felt that meant I really should start to think about writing something.”

And then, in the meantime, Tony and Eureka had gotten their grant from the NEA, which Tony called “a command.”

“So you had to write it.” I said. Like with Kara Walker, Angels emerged from a commission. A prompt. Or a command.

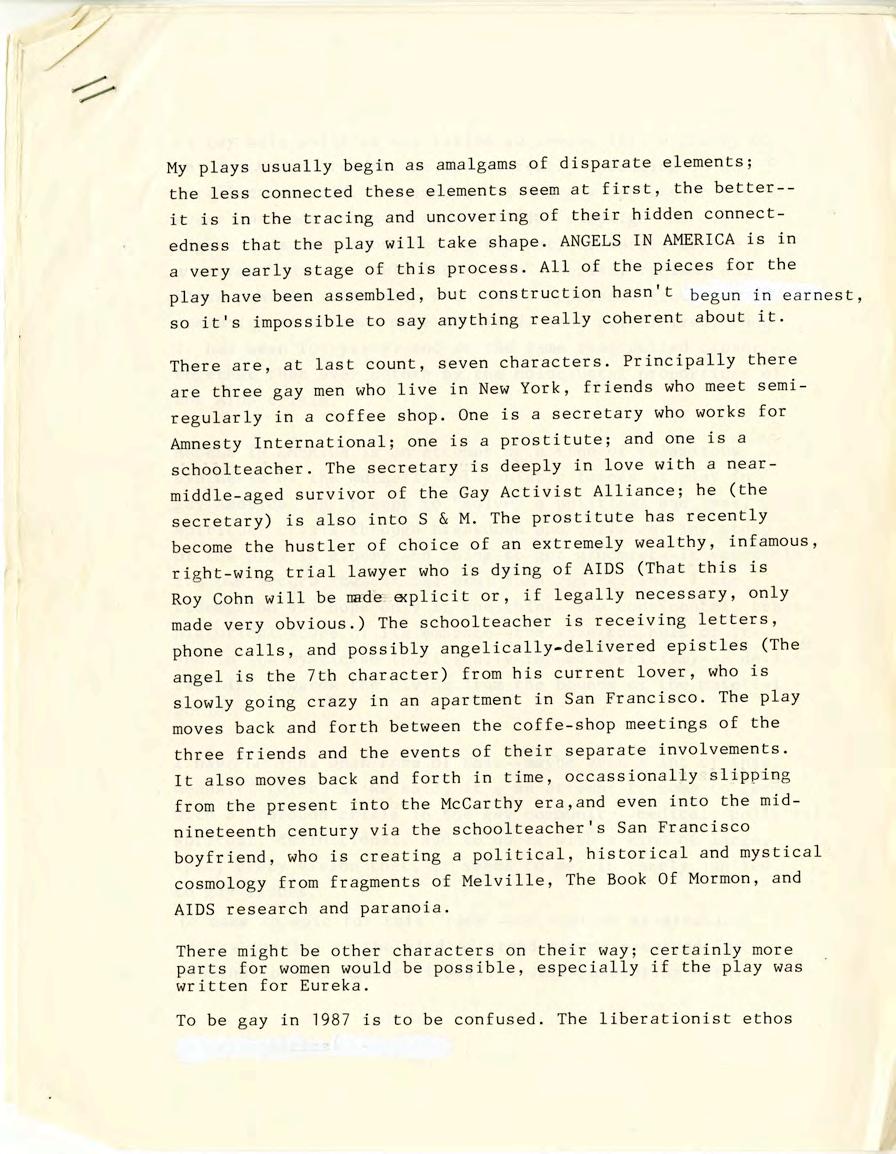

“Well, it was a command to write something, but because of the watermark on the check, it was the people of the United States of America-the federal government – who had commissioned this play. And I’m in my own way a very patriotic person. I have a belief that a combination of action on the street and representation in the halls of power would bring about transformation for everybody. And what Reagan was doing at that point... it just felt terrifying. And I’m sure that’s where a gay fantasia on national themes came from.--

Preaching to the Converted “The impulse is always, what do you feel most confused about and most unsure about. You can assume that others like you are having similar doubts. As I’ve always said, your job is to preach to the converted. That’s what preachers are supposed

to talk about. It’s not the things we know are true but the things we’re worried might not be true that contravene our faith. That’s the place to go. Anything good comes from a place of unknowing.--

“I pulled out the poem because I had it in the folder in a filing cabinet. And I said, Oskar I think I have a title. And I thought, why am I saying it to him, it’s a terrible title. And he said, ‘right the fuck on’ – when Oskar likes something you really can tell. So butch and manly and just a daddy guy.--

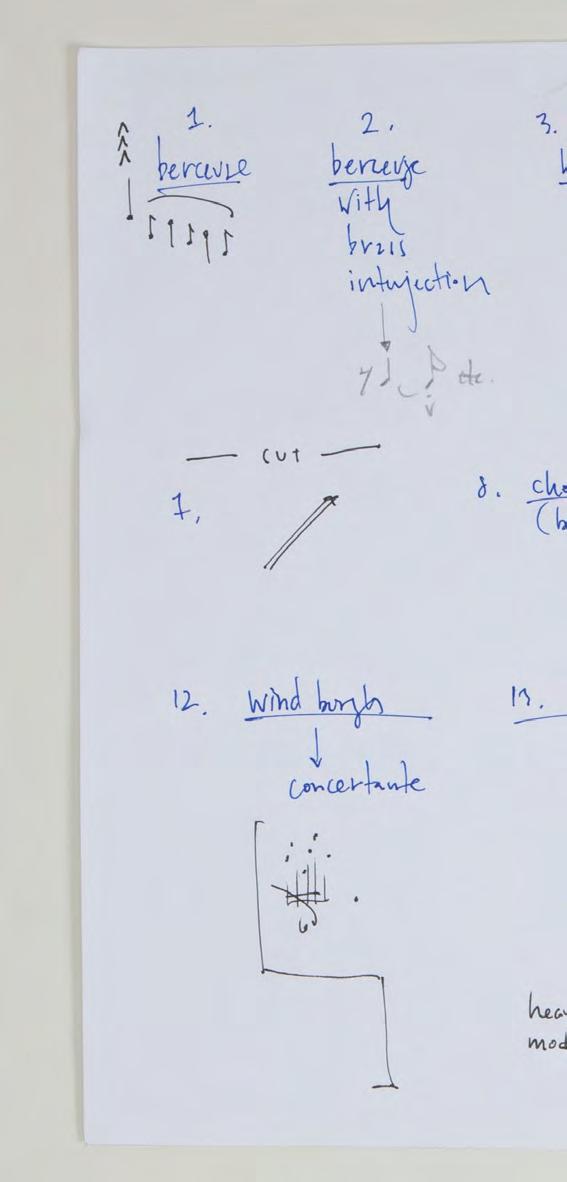

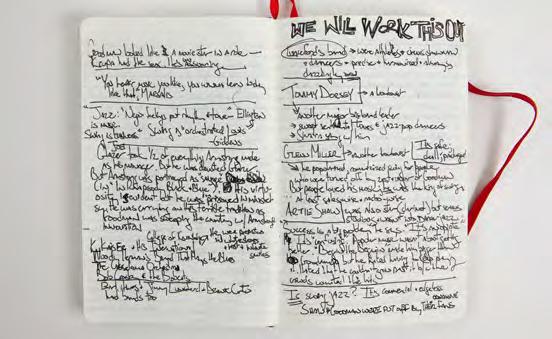

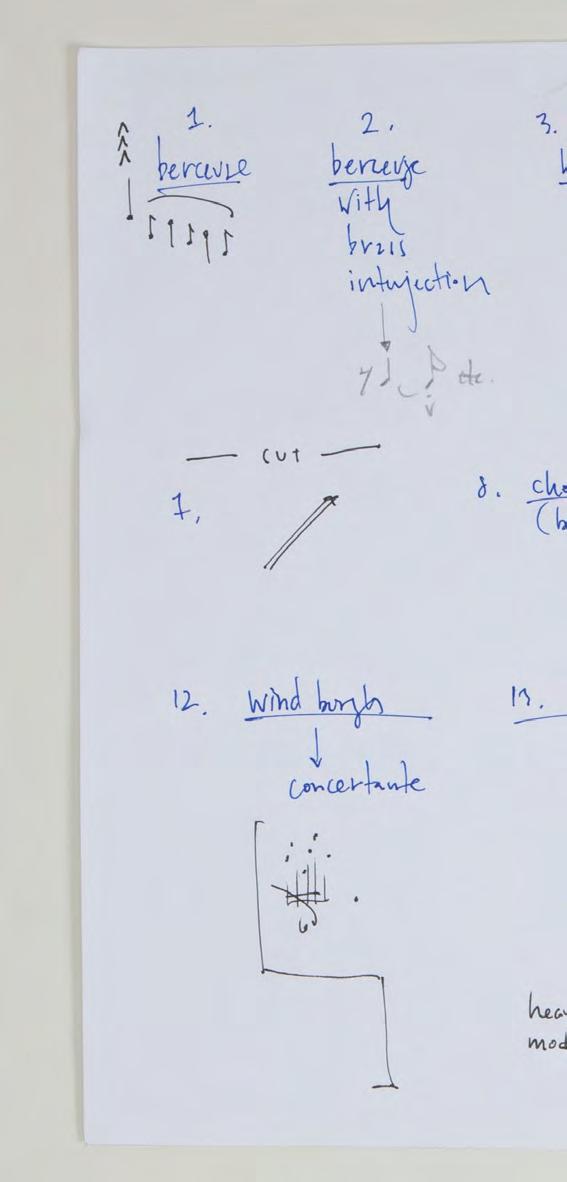

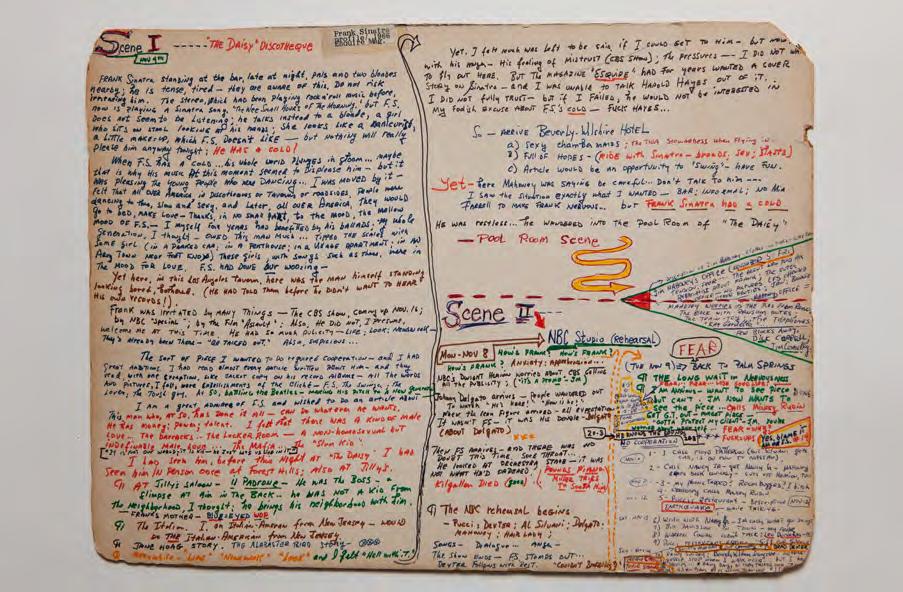

“And then I started writing. And I wrote, with very little trouble, 60 pages, which is an hour on stage. And Oskar made me sign a contract – he wanted the play to be two hours [max] because Bright Room had been three. And I said I wanted to have songs. Jazz with songs. And I did write lyrics, and a couple of the lines from them wound up in the play. But needless to say, it didn’t turn into a musical.”

The 60 pages began to have characters, and a shape.

“My friend Kimberly [fn5] had had a terrible accident. I was taking care of somebody who was catastrophically ill. That really fed into Louis [who would abandon his very ill boyfriend].” He considered the company, the three straight women actors and the fourth a man.

The Importance of Constraint For the man, Jeff King, “he was six foot two and looks like

10 TONY KUSHNER

Dolut ete volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

a linebacker, and I thought, there’s gonna be a Mormon guy. And he’d be a great closet case. What if he could be a Mormon missionary?”

He devised his characters around the available women as well. “So at first I thought I’m going to make the angel a man because it would be hotter and whatever. And then I thought no I can’t. I wanted Roy Cohn in there somewhere. And I made Jeff King Joe and I made Lorri [Holt] his wife because she was small and in her early 30s and a little bit nuts. And I’ll figure out something for Abigail. She was really sort of a roughhewn person. And I thought maybe Joe would have a mother who was a Mormon also. And then in the dream the angel was female. So I said, let’s make it female and I made it Sigrid.”

His thinking about Roy led him to a thought that Roy should have some sort of father-son thing with Joe. He’d read a lot about Cohn and his relationship with Joe McCarthy. “It started off as a paternal thing. Kind of s&m. Daddy and his boy. I will admit that I was somewhat attracted to those power dynamics.

“It [took me a while to] come up with a gay couple, I wanted to write a gay couple. Also at this point I knew anything I wrote needed to have Stephen Spinella in it.” Spinella, the actor he had so admired at NYU, would play Prior, “There was just no actor on earth who

has a better command than Stephen. He had already become sort of my avatar. And that voice, I just loved him.”

And he understood that their stories would have to intertwine, even as he wasn’t sure yet exactly how. “I’ve always loved chamber music. And if you listen to chamber music, if you’re paying attention you can start to understand how the music is constructed. I began very much in these terms. I thought of Roy as a kind of continuum, a line that went down the middle, and then the two couples would weave. And I knew Joe would connect to Roy and then Joe would connect to Louis.”

“And I really didn’t think Harper and Prior would meet. I think the play originally started with Harper’s monologue about when you look at the world from a spaceship. I had written it sitting on the Bethesda fountain [fn6] on a January day, this monologue. And then I just put it away, I said, maybe I’ll use that, that’s pretty good. And I think she opened the play first and then the rabbi and then Roy. And then I switched them around. I think Roy was in the first place at some points and then the rabbi became permanently first.”

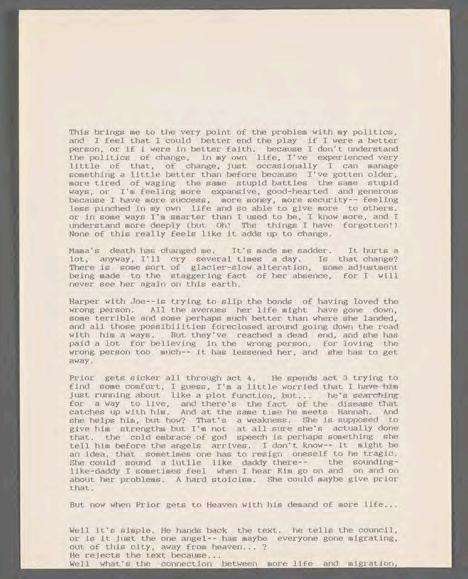

But one thing he absolutely knew was that at the turn of the play, which he had at first thought was the end of Act I, the Angel would appear. She hadn’t at the end of his sixty pages. He typed his pages up (“I write in longhand.

11

Dolut ete volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

[fn7] And then I type it. I always do that. So that my first draft is really my second draft. So that if anybody looks at your first draft, it’s not going to be as bad as your first, it gives you permission to be a terrible stupid idiot.”)

He gave the pages to Oskar Eustis. “‘I thought this is some sort of dumb soap opera.,” Tony said of this first effort. “I kind of loved it but I also thought it was kind of horrible. I sent it to Oskar, and he clearly wasn’t nuts about it. He’ll deny that. He said, there’s great stuff comrade, and we’ll just keep going. And we’ll edit. And this was clearly a lie.--

But there were others who were more excited by it. “People saying, ‘you’re doing something we didn’t know you could do.’ that sort of thing. And I was confused by the different reactions. And it was already so long! Surely in the next 60 pages the angel will have arrived. I always start with an outline. The outline said, the angel arrives by intermission. So an hour in. Sixty pages is an hour. All right the next 60 pages the angel will at least arrive somewhere. And we can cut.--”

And even if he wasn’t wild about the play, Oskar gave him useful insight about how to understand what seemed to be pouring forth. “Oskar said you know what you’re showing is that under really unbearable pressure, reality is going to start to crack. And that is in a sense the action of Millennium Approaches .”

He understood exactly what Oskar was saying. The play he seemed to be writing was fantastical; strange things kept happening. They were having a cumulative effect. “I read comic books when I was a kid, and I learned how to construct the science fiction fantasy thing. The reason the angel works is the escalation of supernatural events that happen to Prior in the first act. The play gets crazier and crazier. It really moves in on you until you know something is going to happen. And as Coleridge said about Shakespeare, his genius was that he always preferred expectation to surprise.”

All the while, Tony was unlocking boxes. He hadn’t meant for the Prior/Harper stories to converge but once he figured out how to do that, through their mutual hallucinations, “that was a big liberation.”

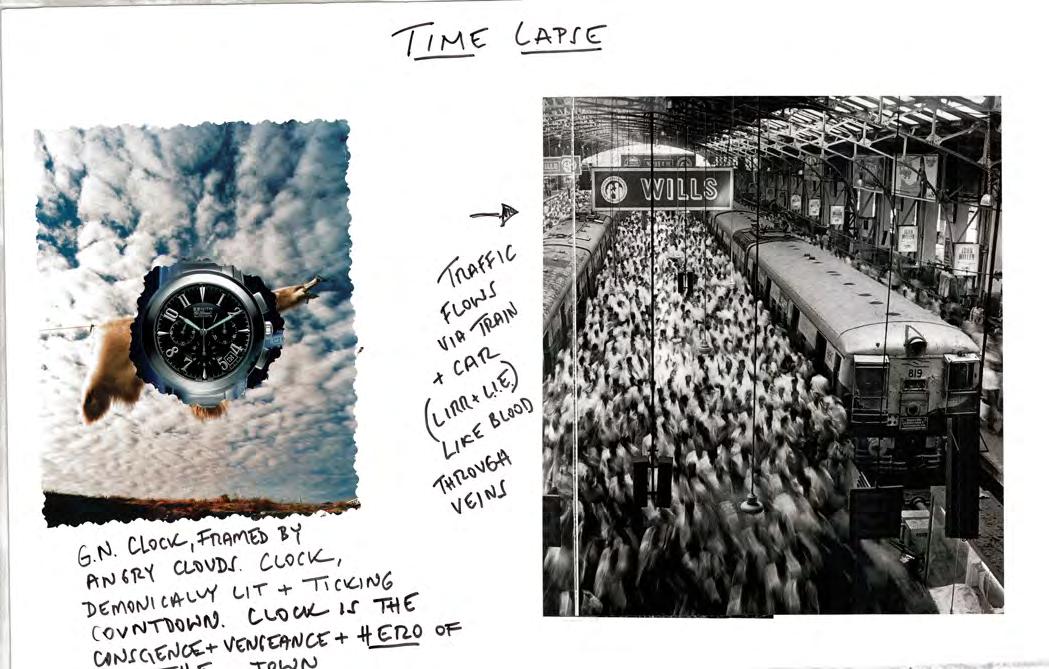

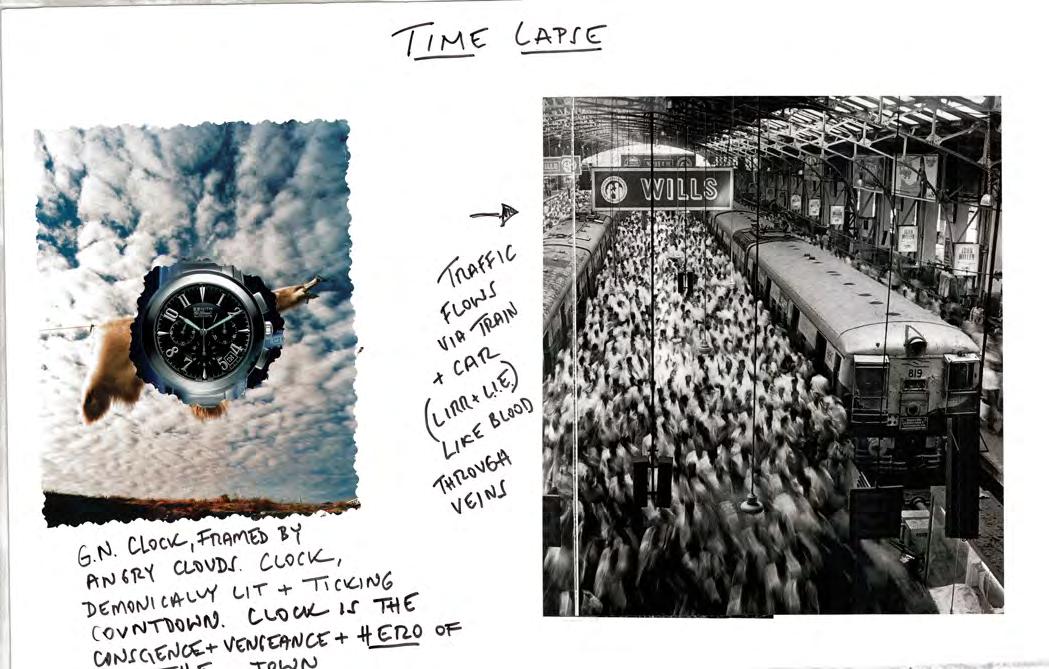

Writing on Vehicles [fn7] He began to write Act 2. “And still the angel wasn’t showing up. But I had more scenes that I thought were worth including.” Among these was another that felt like giving birth. The first scene of the act involved Prior collapsing in his apartment – “which is probably the hardest thing I ever had to write. And I got on the subway. I always write on the subways and airplanes really well. I went out towards Coney Island and I said, I’m not getting off this fucking train until I write this because I couldn’t go into the second act without it. I knew what the scene

12 TONY KUSHNER

Dolut ete volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

was. I was just such a chicken about it, because it’s about somebody having a psychotic break.

“I got the second act done and that’s when Oskar called and said okay we’re now really late. And you’re in breach of contract, and why don’t you come out and we’ll do a reading of the play. So I got on the plane and there was one other scene -- I knew that I wanted the ghosts to start showing up, so I wrote really quickly on the plane. I thought there’s only one other thing I know is going to happen-- Ethel Rosenberg is going to show up. So I quickly typed that out. And we did a reading of that.--

“In the reading, we got to Roy and Joe and Ethel and then the play just stopped. I didn’t have anything else, but we had already been reading for two hours and 45 minutes. And it had not been boring. It was working in this kind of exhilarating way-- so good that Oskar now thought it could be a two and half hour play! And I went out walking with Sigrid and she said what else are you thinking, and I said I don’t know all this stuff, na na, na. I’ve written tons of notes and one monologue. And it’s Harper’s and I don’t know when she would even say it. It was the night flight to San Francisco [that’s the one he wrote sitting at Bethesda fountain]. And she read it and then she handed it back to me, and she says, ‘you know I think you should make this two plays.’”

A Conversation with Louis Which of course is what actually came to pass. But meanwhile, the play was long – very long. “I became panicked that I didn’t know how I was going to cut the play down. The characters wouldn’t do the thing that they’re supposed to do in the outline. So I just had to ask a character. And the character I was closest with was Louis, and I said, you know, what’s this play about? And I felt like I was sort of taking dictation…

I noticed in our conversation that Tony would toggle between the mystical and the analytical to explain both how he worked and how he understood what was actually happening when he was working. He’s fond of dialectics; this one seemed core; and like all dialectics they resolve in synthesis. Here he wanted to talk to Louis (who was, of course, his proxy) – his description was striking, equal part séance and self-analysis. I was especially struck by it earlier in the conversation, when he was describing how he wrote a scene in another play The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures: “I was writing Lincoln at the same time, so I wrote this play in rehearsal, which is insane. There was no play. We designed it, we cast it, but the play [wasn’t really written until] the second day of rehearsal. And it sort of worked.--

“I was still trying to finish the third act and I’d done a really bad job. Everybody was sick of

WRITING BOY

Tony said that the toughest part of these first pages for him was writing a scene he knew he needed: the conversation between Roy and the doctor when the doctor tells him he has AIDS. Tony couldn’t figure it out.

“The last thing I wrote in Act One was Roy and his doctor, because I knew that’s how I wanted to end Act One. The scene didn’t work. I struggled for a week, two weeks, to think of what do I want to say? And then for some reason I went back and reread Billy Budd. And I came across this line about Claggart: He had perfected the use of the rationale as an ambidextrous instrument for effecting the irrational. In other words, a great order is a disorder and a great disorder is an order, these things are one. And it made me realize what I was getting at with Cohn, which is true of right wing thinking in general-- that reality is an activity of the imagination, they’re fundamentally idealists, they believe that the idea precedes matter. They reject the notion that you begin with material reality. You just demand that reality obey your fantasies.”

“Then I called my friend Kimberly and I think I’ve just written the best scene that I’ve ever written.”

13

me. In the play, there are a bunch of characters in a house in Brooklyn. And one of them is in labor. And in the first draft they call a car service and the car service is sitting outside and honking the horn. And when I was starting to type up the play from longhand, I thought, Oh this is weird. I’ve made a real deal about every time the car horn honks, I keep getting more descriptive about it. It blasts very loud, like the trumpets in the Book of Revelations. And I went back and counted – there were seven horn blasts. My father was in the later stages of kidney disease. I watched one of my father’s favorite movies, The Seventh Seal, and I just fell apart. And then I wrote what was probably the best scene in the play – a father and son scene. The father has tried to commit suicide several times, the son says you have to promise me you’re not going to do that. And the father says I promise. And the son says “as true as that you love me.” And the father says it’s true that I love you. And then the son leaves, knowing that the father’s just going to do it. And the car horns, I just cut out.” The story itself is full of the cosmic coincidence of the mystical but his explanation is analytical. Synthetic.

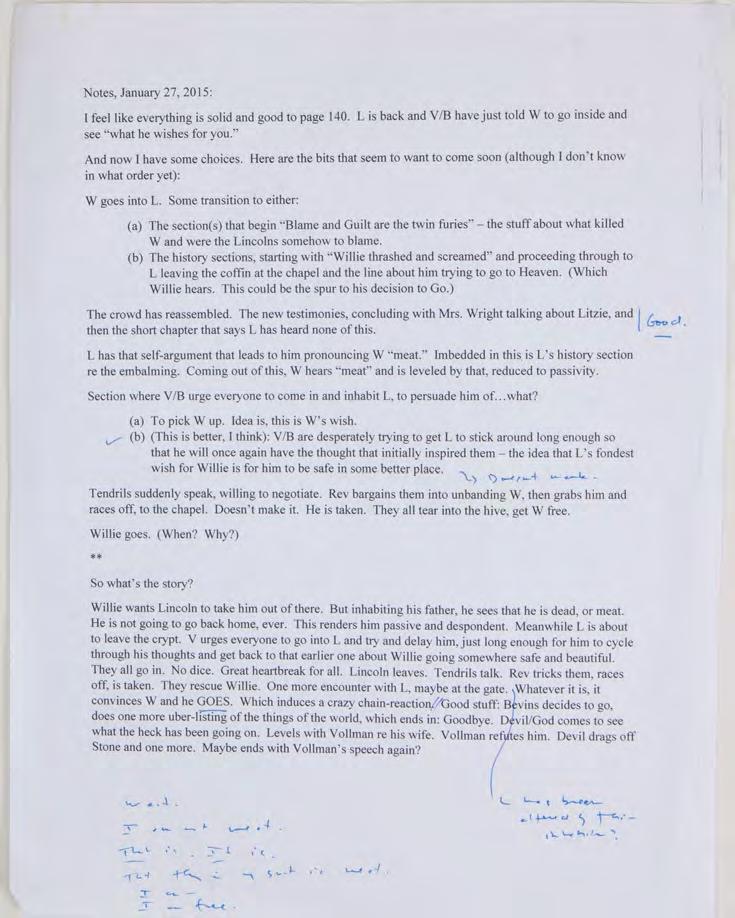

“It’s a thing your brain does all the time.”he said. ‘’The unconscious is leaving little puns and little jokes. Breadcrumb traces is what I call them.”

He returned to Angels . “So Louis started talking, then I realized that he was very nervous while he was talking, correcting himself a lot, especially when it comes to politically correct things. And I thought oh, he’s talking to someone else , and I started to see Belize. And so I put Belize in there. And then I started really having fun. By the time I was done I had this massive stack of paper. But the purpose of the writing was make the thing shorter!”

I had articulated some of the themes of this giant thing, but now they were watching and waiting. I call them “penny drop” moments -- moments in a play when something happens.and the audience starts having a singular experience and everybody bonds. And the energy that those moments can create is astonishing. There are some really good plays without them including Perestroika , which I think may be a better play than Millennium but it doesn’t have that moment.”

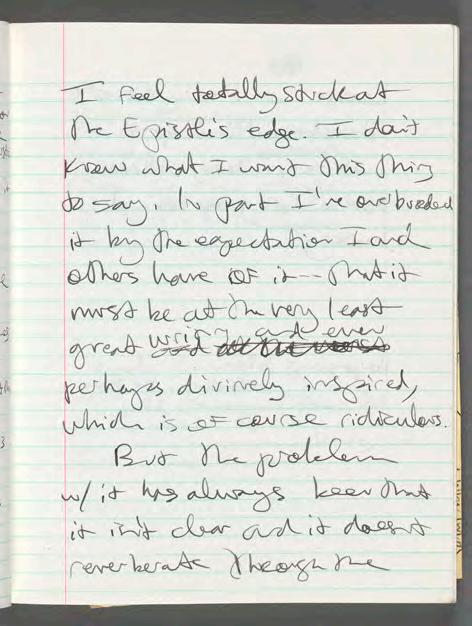

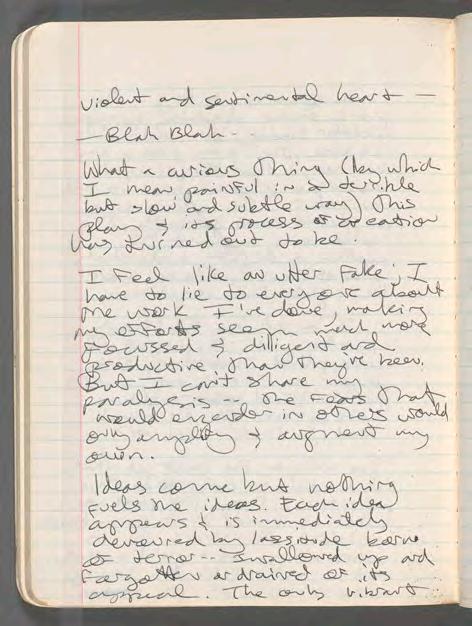

How Do You Write an Epistle?

There was another play to go, which would have its own struggles, most of which I won’t go into here. But there was one particular part of Perestroika I did want to talk to Tony about, because it was a part he has felt he never got right – the Angel’s “epistle,” which is a crucial scene in the second play: it is the Angel’s own nervous breakdown, her description of how Heaven has been devastated by the disappearance of the Creator, and sets in place Prior’s eventual visit there. To makes matters more difficult, it is relayed by Prior as he’s talking to Belize so it is acted out and described, back and forth. The Epistle delivers pivotal exposition, but it also requires pathos and is incidentally very, very funny. That balance makes it almost impossible to play. But when Tony and I first started talking, he had seen a version on Zoom for a benefit that he thought may have worked, so he’d been thinking about it. He set up the Epistle for me..

Pennies

Drop

Eventually he finished the play. Finally the angel does appear through the ceiling. But even as the play began actual performances, he wasn’t done. “The show went well,” said Tony. “The audience got it, and they were waiting for something to happen.

“I had gone up to Russian River and in ten days wrote hundreds of pages. And then I drove back with this gigantic stack of legal paper and turned on the – I’m not making this up – -car radio driving back from Napa Valley. The first thing that came on was Mozart’s Bassoon concerto, which was one of my mother’s big practice pieces. It was the sadness when she died. Then it went right from that to Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, one of my father’s big practice pieces! And then the Black Crowes song -- She lives an angel, she would sing with angels, something like, about angels. I finally got scared and I turned off the radio.” Cosmic coincidence

14 TONY KUSHNER

15

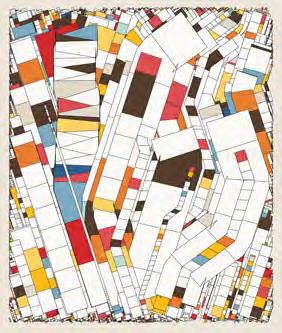

WORKING OUT ‘DOOMED’: TWO TRIES, Figure 1 – teekay

again. “But I had written most of the play.--

“Ok, so the angel crashes through the ceiling. I knew she going to crash into the ceiling because that happened in my dream. And when Millennium was done people in the audience were devastated at the end because they thought [the angel’s arrival] meant Prior was dead. I had even thought for a moment that Prior was dead.--

“But some people were exhilarated because – this is exactly what you used to say in the Middle Ages-- the kingdom of God is both the day of judgment and the day of wrath, it’s the end of history, the end of suffering and the beginning of the kingdom of God...”

“So you started to realize it has dramatic possibilities?”

“Well I kind of accidentally stumbled on it. Millennium Approaches is really beautifully constructed just in terms of its dramatic structures, where it goes, how it ends, what it leaves you wanting, I think it’s really really good. But all epic poems need fatigue. How do you know you’re on an epic journey if you’re not tired.”

The action of Perestroika had picked up quickly. He realized the second play would involve, in a sense, the exchanging of partners – Belize with Roy, Prior with Hannah, that sort of thing.

“I began to really play with this idea of the Angel as a kind of [agent of] failed revelations. I thought a lot about the prophet that rejects the vision then complains about it.”

He cited various theological examples to me. “And so I thought all this was interesting. And I was interested in perestroika and glasnost, watching this kind of miraculous thing happening in the Soviet Union. And Chernobyl -- and I thought that was apocalyptic and millennial.”

So that informed his thinking about needing the Epistle as the pivot of the second play. And he wrote it, and has kept rewriting it, long after the play was finished and performed.

“I’ve learned so much about being a playwright.” Tony said. “There’s this glob of text that I rewrite and rewrite but it never gets all that much easier. And in a certain sense, I’ve made my peace with it. The play’s doing fine. So I don’t worry too much about it.--”

“I’ve seen a couple of people get close to really nailing her,” he said, and we talked a bit about the Zoom version he’d recently seen, which altered his text some and in which the Angel is played by four actresses spookily layering parts of the speech on top of each other. But still–

“It’s hard to perform a being who is not human. And it’s very important that she not be human. And some of what she says is meant to be confusing to Prior. You want to make it as idiot proof as people read it, they think it’s a big joke. And then they turn her into a joke. But if you do that, it really guts the whole experience. So the speech - it just comes out as gobbledygook.”

16 TONY KUSHNER

Dolut ete volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

Seeking Magic We got to talking about various productions – one by the director Ivo van Howe which he thought worked pretty well and was deadly serious and very theatrical – and some aspects of the play he still thinks haven’t been realized. “When the angel pierces through the ceiling, nobody’s done what I really want. It’s to see what I saw in the dream – a heavenly visitation in plaster and lathe debris. She doesn’t appear in the room, she just punches through the membrane. That speaks to me in all these –.” He stopped. “And then what’s always bothered me, is that nobody vanishes. Harper vanishes, but she doesn’t – she just walks offstage, and this is theater so people understand the convention. I like the zizz of it, the magic trick. But also-- these things have deeper meanings. And this is a play about AIDS-- there one day and gone the next.”

“So that was subconscious for you--”

“That took me decades.”

“Do you find yourself understanding your subconscious by looking at your work in retrospect, seeing things you were working out that you didn’t realize at the time?”

“I think every writer would say that. There are themes that you come back to over and over again. There are specific things about myself that I’ve always been very unhappy about that I’m trying to figure out. I put them on stage to try and figure them out. I have to be careful because I tend to be very unsympathetic to those characters, and they can get beaten up a lot. That’s why Louis is hauled over the coals in a terrible way.”

“I’ve never been one of those people – like Mann and O’Neill I think – who don’t want to be analyzed because they thought

their magic will be taken away. I feel I got great value from being in analysis for myself. But I don’t know that I have ever really thought I could cure anything of myself in writing plays. I don’t think my plays, or my movies, will cure anything. You put these questions and visions in the world, and then you don’t know what is going to be made of them.

All Art Fails And eventually, inevitably, we got around to talking about failure. It had been a long conversation, and it would soon be time to go. He was forgiving of himself – and others – I couldn’t help but thinking his analysis had worked.

“All art fails,” he said, “because all art is essentially Orpheus, all art is meant to resurrect the dead and it will not succeed in doing that. The great model for all artists is Orpheus, and in his greatest work he bombed. He didn’t get her out.--

“Almost all playwrights are like physicists – we do our work from our late teens to about 33. And then we’re kind of garbage. And we generate some interesting things after that. But for some reason it seems to go that way.”

2.

3.

We talked about A Bright Room Called Day, which had been recently revived. “There are things I like in it, but for most people it didn’t work, and the play has never worked. But it keeps getting done, hey. And it never goes away. I sort of wish it would.--

4.

5.

6. Jack Anderson was another lefty journalist.

7. What is it about movement? Many of the book’s subjects – Gregory Crewdson, Cheryl Pope --mentioned feeling more creative when in motion. For what it’s worth (maybe not much), there’s some research that supports that.

8.

“There are flaws and problems and failures in every work that I love. A lot of people feel that the Epistle is the big mistake in Angels . [The critic] Michael Feingold just vomited all over it-- [all over Perestroika in fact] but then Robert Altman [who at one point had wanted to film Angels ] said he thought Millennium was just this kind of piffle, what you have to get through to get to the meat of the matter, which was Perestroika”

Art, Tony said “is always endurance. I don’t think you should ever feel like a failure unless you catch yourself in the habit of lying about something and telling yourself that you have to do this for money or safety. If you’ve really

17

1. The movie he was writing with Steven Spielberg was The Fablemans. Previously he’d written Lincoln and Munich for Spielberg as well.

Todd Haynes is the director of Safe and Far From Heaven, among other movies.

Christine Vachon is a well-known producer, mostly of independent movies.

Edward Tayler was a noted literary scholar.

David Schine was an hotel heir, vehement anti-communist and crony of Roy Cohn’s.

Tony has called Kimberly Flynn, a dramaturge, his closest friend.

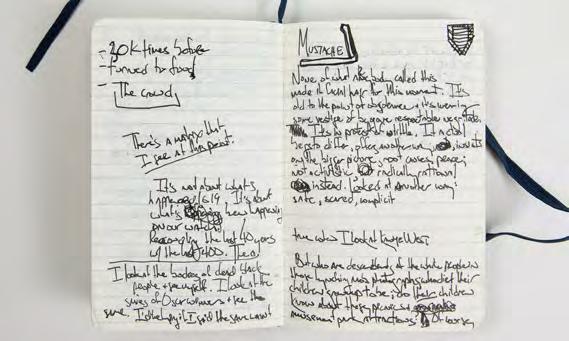

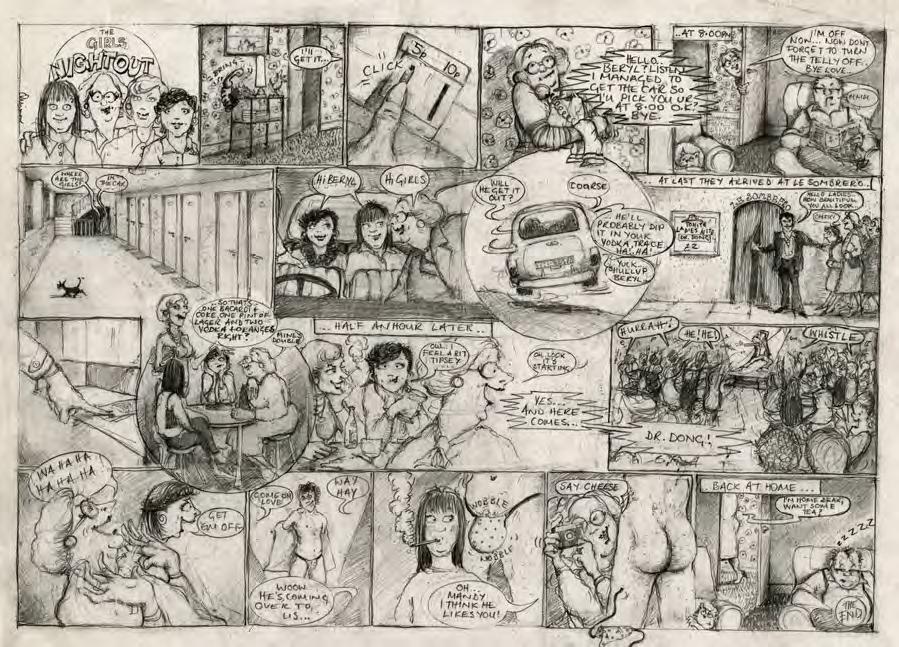

The Child’s Way

I LOVE ROZ CHAST, but then who doesn’t? Her demented cartoons appear regularly in The New Yorker, to which she has contributed for over forty years. She’s also written or illustrated over a dozen books, including the National Book Circle winner, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant , a soulful cartoon memoir of taking care of her aging parents. In it you see the more ‘grown-up’ artist she might have been, both because of the book’s depth and, interestingly to me, some glimpses of a drawing style that looks (and was) art-trained. Which isn’t to say that her cartoons are superficial. Far from it – and I was interested to see that she was elected to the American Philosophical Society, which seems apt. But she has very emphatically embraced a jubilant juvenile voice she calls “the child’s way.”

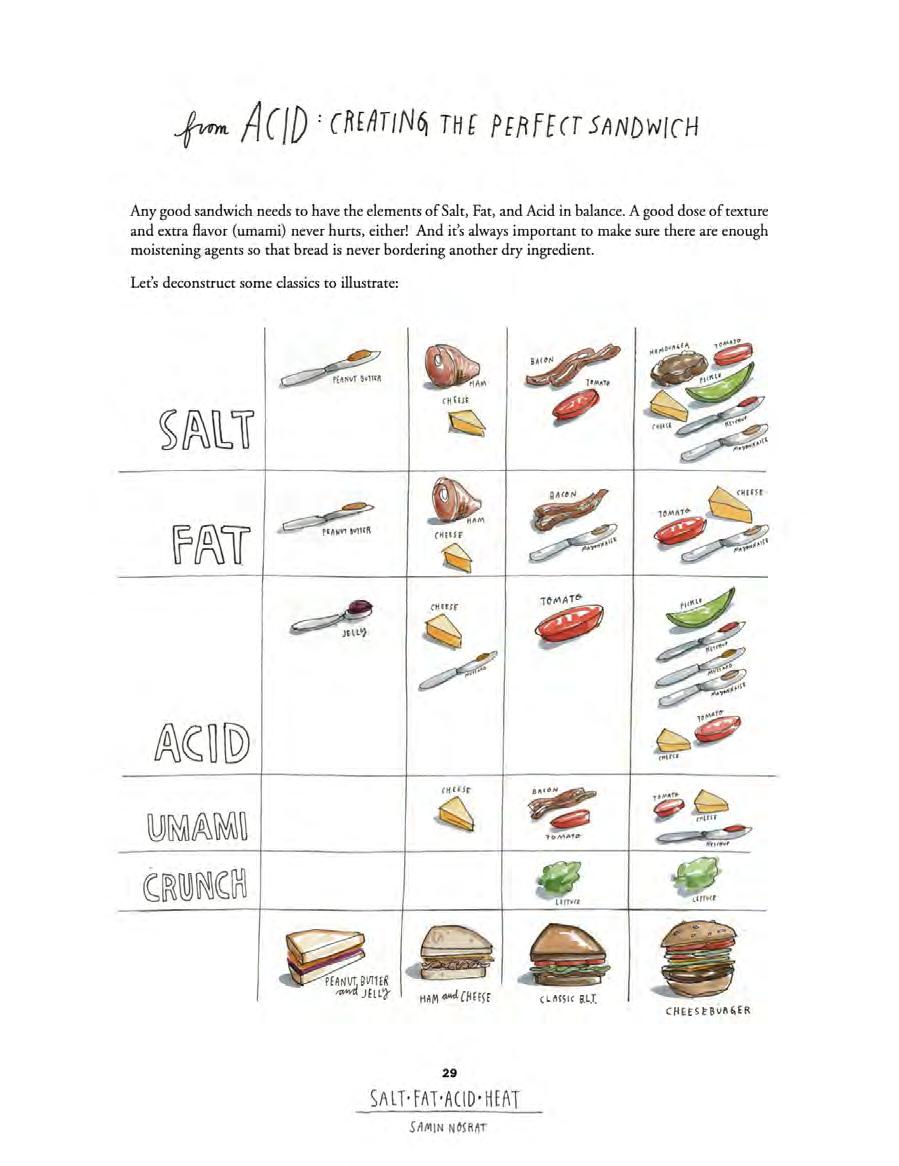

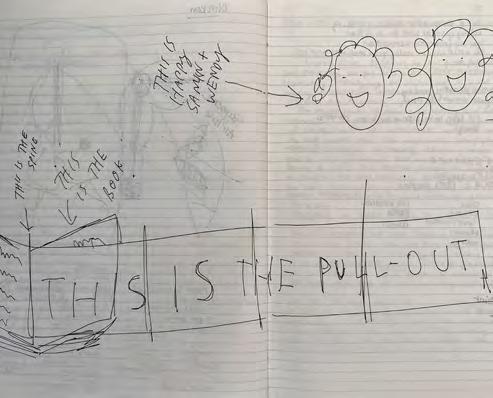

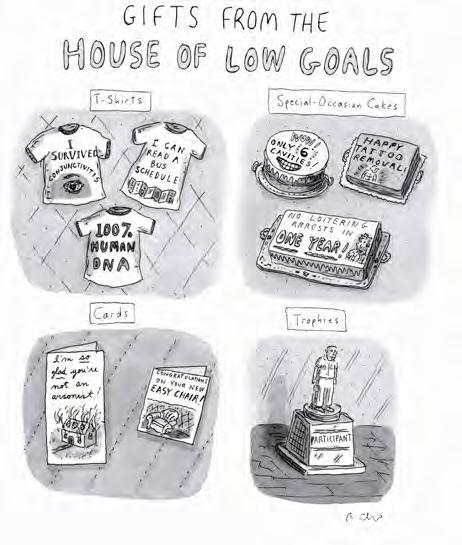

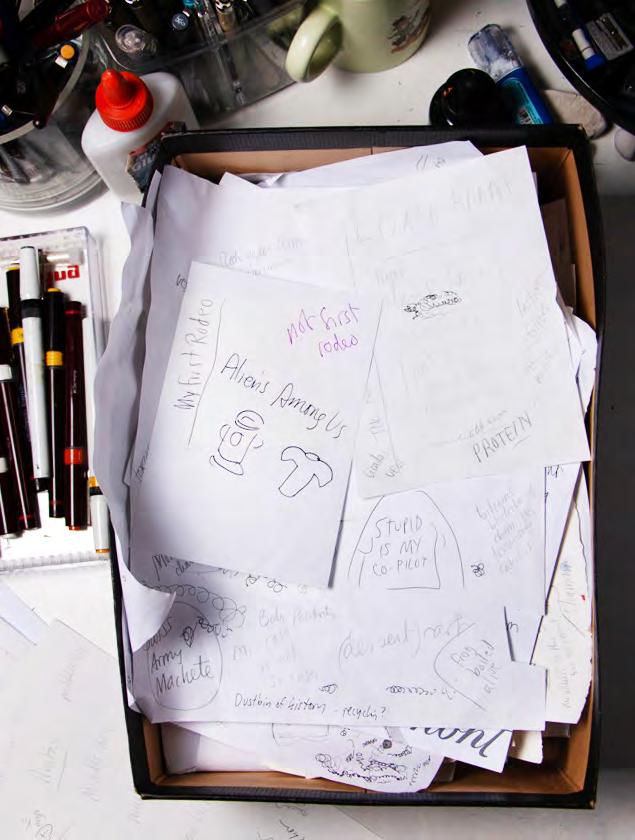

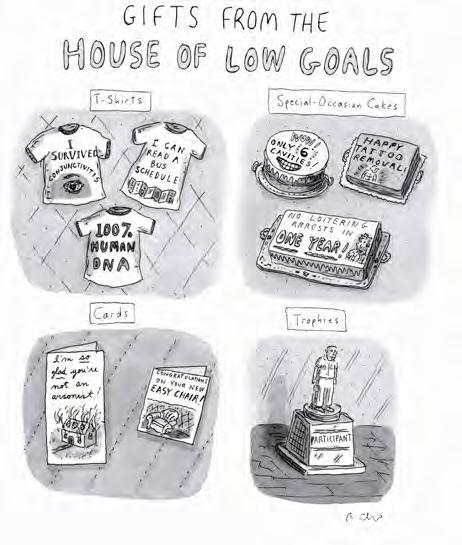

A mammoth sculpture, an epic play – those are projects of long gestation. A cartoon takes minutes. But how different is it really? I went to Roz to understand. It all happens so quickly it defeated the method of the project– she had no entrails of cartoons-in-progress. Still, she very kindly made a cartoon of how she makes cartoons, one especially called “Gifts From the House of Low Goals,” and offered it up. And she let me look into the box she throws her idea-bits into in a room in the Connecticut house where she lives with her husband and kids.

Associations are associations; hers are just a bit wackier than most. Turns out, the distance between her cartoon persona and her actual self is pretty tiny, maybe non-existent.

The Beginnings of an Idea

RC: I can give you a couple of examples of where cartoon ideas came from. There was a cartoon I did years ago, when my daughter – well, she’s not, she’s my son now she’s trans --- anyway, was about 16, and doing her homework in the living room. There was a boombox with music going. And if you’ve been around teenagers, you know that there’s nothing more disgusting in the eyes of a teenager than to watch a

2 ROZ CHAST

3

occupation : Cartoonist work : Gifts from the House of Low Goals born : 1954

ROZ CHAST

3

Dolut eliciisqui te volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

grownup dancing. I hate to dance, but I wanted to see if she was paying any attention. So I’m like doing my mom dance and it was, mom, stop. You’re hurting me. And it made me laugh. So I asked if I could use that in a cartoon.

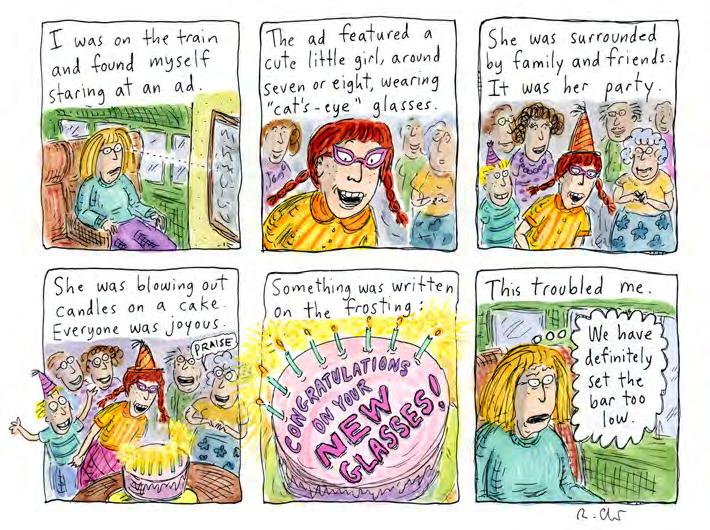

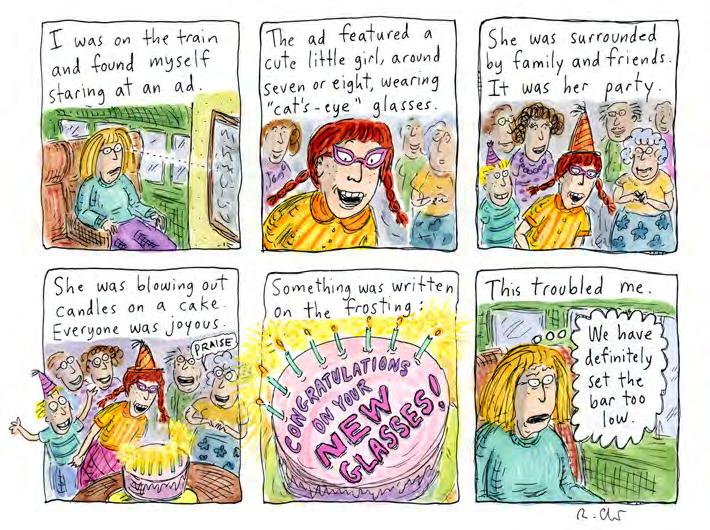

Another time I’m on Metro North, and there was an ad for –maybe it was Carvel – and there was a little girl, she’s wearing these cute cat-eye glasses, and she has a party hat on. And she’s blowing out the candles on the cake and on the cake it says, congratulations on your new glasses. And I just thought, we have set the bar low! So I had all these things, like ‘congratulations on your new armchair’ and ‘I’m so glad you’re not an arsonist.’

AM: Do these come to you fully blown? Or are you constantly revising these things once you’ve set them down?

RC: Depends. There are times – like when I saw an ‘End of the World’ guy. And I just wanted to draw one of those guys. So I did, and I thought: Oh, he needs a wife. So he has his the End is Near sign and she is next to him, looking like the female version of him. And she is carrying a sign that says, You wish.

AM: Do you keep these observations in a notebook?

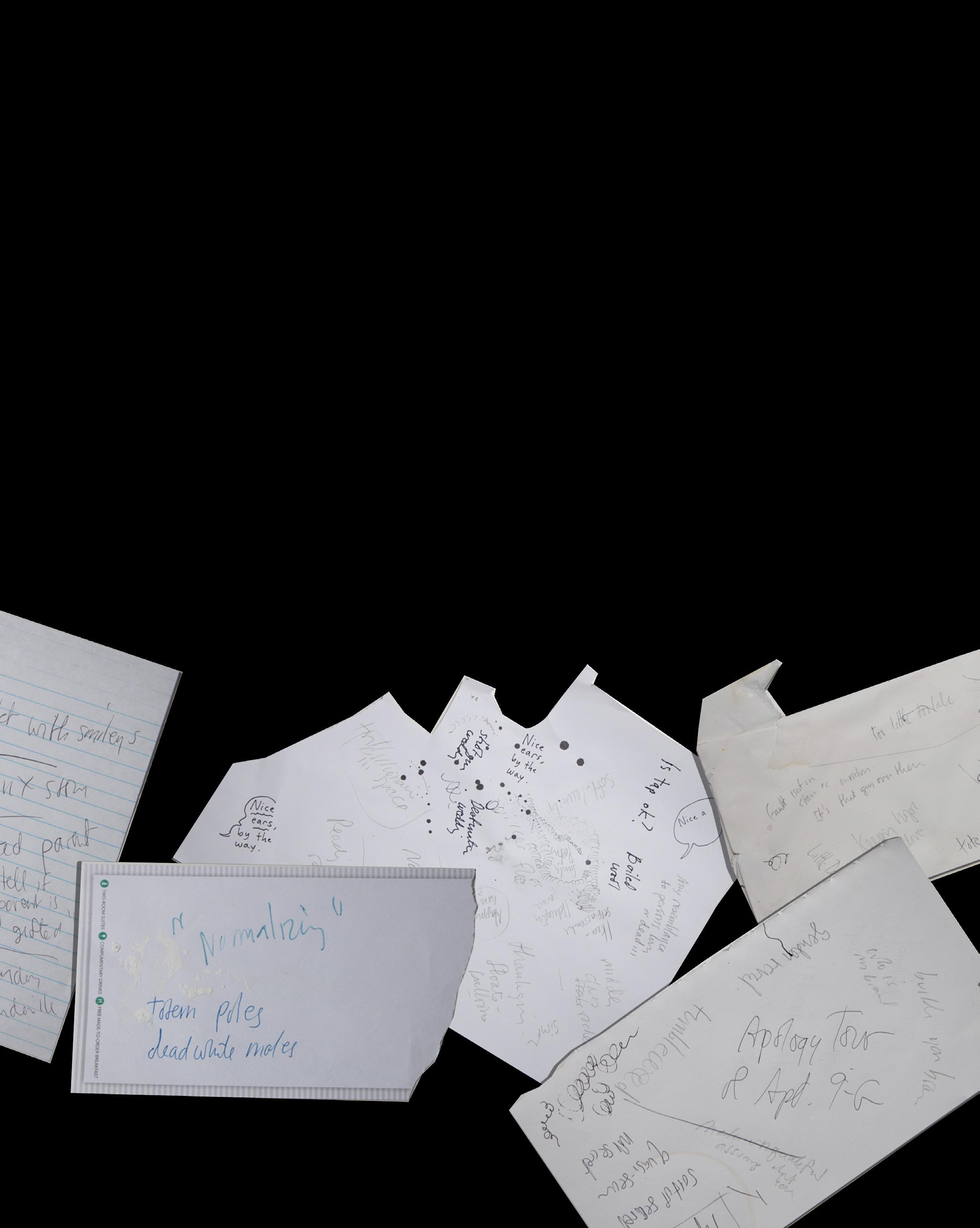

RC: I’m not organized enough to keep a notebook. But I have these kinds of slips of paper in an idea box. There’s like thousands of them. A whole box of Nope, Slow Pour Coffee, Choose Your Own Adventure. And then an arrow. The entire box is nonsensical. [She pours notes out on her desk] Here, I’ll read you: Okay,

Concierge . This is circled and underlined like five times. Hacks. Semi heirloom tomatoes, Bitcoin fairy.

[Keeps reading] This one just says Podiatrist. Hmm. Niche audience. Big Hair. I did sell a cartoon with that idea. Little Red Riding Hood is visiting her grandmother in bed. And I had just been in Texas, where the women had like helmet heads. And the grandmother has this giant hairstyle, and Little Red Riding Hood says, um, what big hair you have…

Let’s see: Uber. Compassion fatigue. Chief Happines s Officer.

AM: Whe n you go back to these things, do you know what you’re talking about?

RC: Sometimes yes, sometimes no. A lot of the ideas happen when I’m actually working. When I’m at my desk. The ideas begin to percolate.

AM: So you sit down. And one of your scraps says Concierge.

RC: It made sense at the time. But now it… AM: So what do you do, do you run through different scenarios in your head, are you working

4 ROZ CHAST

THIS THOUGHT BECAME... Caption here tktkt tktktk tktktk tktkt

out language, are you starting to draw?

RC: It all happens simultaneously. Once I decided that the End of the World guy needed a wife, I knew what was going to be on the sign. Boom, done. But that’s rare. Most times, I draw, I write, I figure it out. I’m kind of immersed in it. One time I was chewing gum and I forgot, and the gum just actually fell out of my mouth. That’s really kind of a moment that lives on in time for me.

Cut Anyway, then a lot of what I do is cut. If I can say something in ten words as opposed to 50, it helps the joke.

Comedy has a lot to do with rhythm and how you tell a story. I’m not the most analytical person about this, I’m usually feeling my way blindly through something, but you see something, it seems better, sometimes you realize the other version was better, but you just look it over and decide-- I’m going to go with that, you know.

AM: Bec ause you’re really generating a lot of

these?

RC: At The New Yorker , we submit a group of cartoons a week, batches we call them-for me, that’s usually six or seven. So a lot of stuff I do just gets shoved aside. But if something gets rejected that I think is a good idea, I’ll resubmit it multiple times.

AM: Alt ered?

RC: Sure. If I think there’s an idea there I’m going to see if I can find a better way to tell the story. It’s kind of like if you were telling somebody a story and their attention wandered, you’d go into the time machine and try to tell it a better way. A lot of times, if I think something’s funny I’ll just keep at it. Being a cartoonist really involves stubbornness coupled with a kind of stupidity.

Child Is Good

AM: Do you have rules that help you?

RC: I have a friend whose kid is an artist, and she told me something that her kid once said. She was trying to show her daughter how to do something, and her daughter said: I want you to do it the child way. And that’s how I feel about work. I want to do it the child way. I want to do it how I want to do it.

I’m bad at stuff like cartoon lettering. I’m bad at straight lines. I’m bad at like, do a drawing and have a gag line.

AM: But you can actually draw very well. I was looking at your book Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant, and there are some really moving, sophisticated drawings of your mother. And it occurred to me that the visual style that you describe as clunky is a kind of construct. How did you come upon the visual voice of your cartoons?

RC: Hmm, well, when I was like 12 or 13, I started to feel my way toward something like how I draw now. That’s when I started to think, I’m going to be a cartoonist.

AM: Bu t then you went to art school. And I presume that they were teaching you all sorts of ways to draw “better.” Was it hard to hold on to this more primitive style of expression?

RC: Well before going to RISD [Rhode

5

THIS CARTOON Caption here ttktktk tktkt

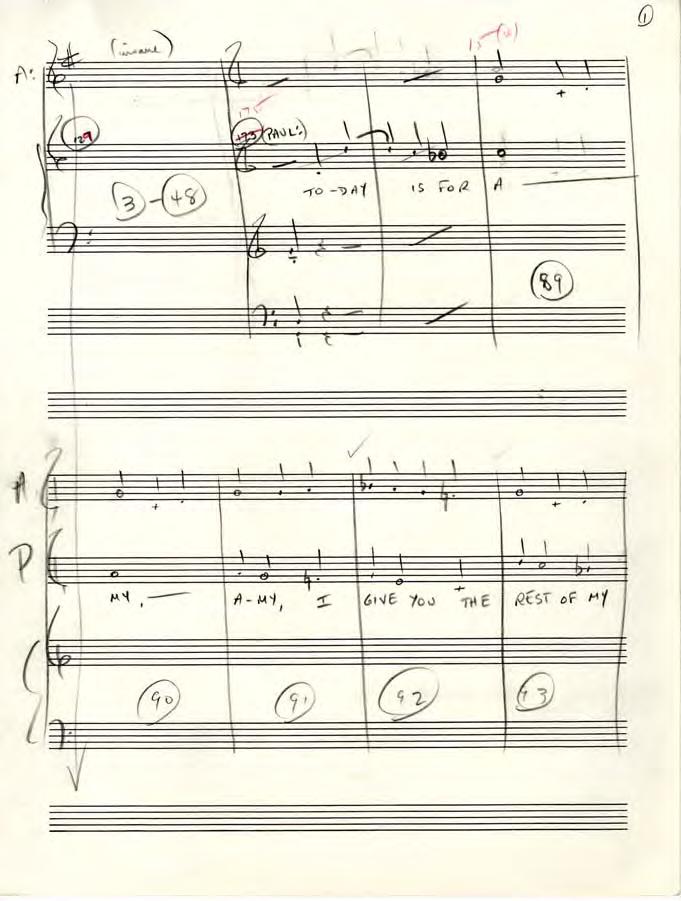

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

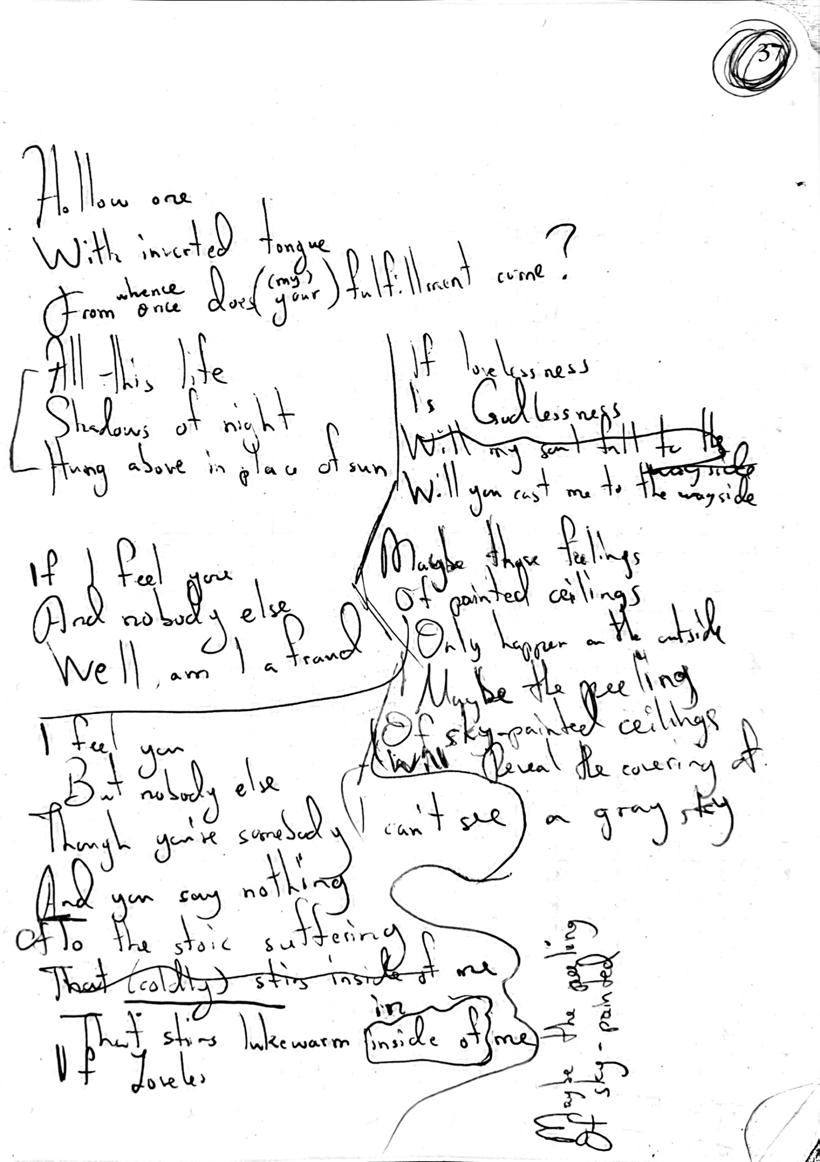

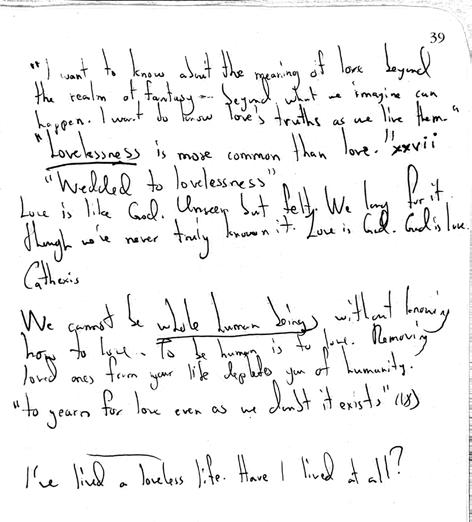

“ Will Your Hand Do the Thing Your Mind Wants?”

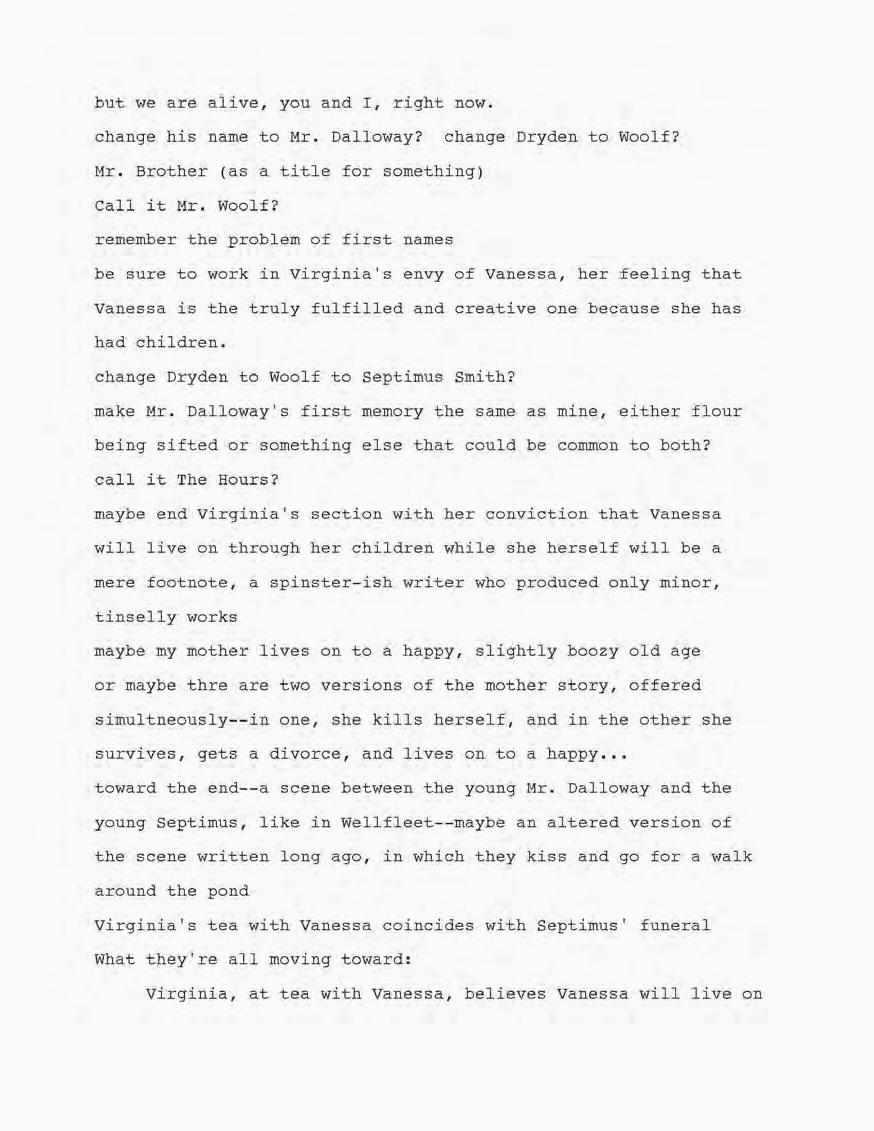

born : 1956

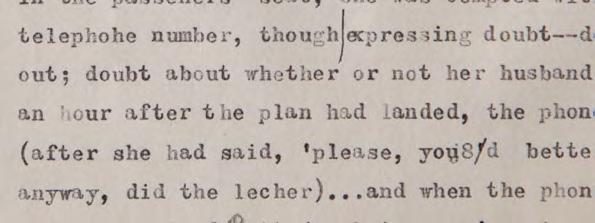

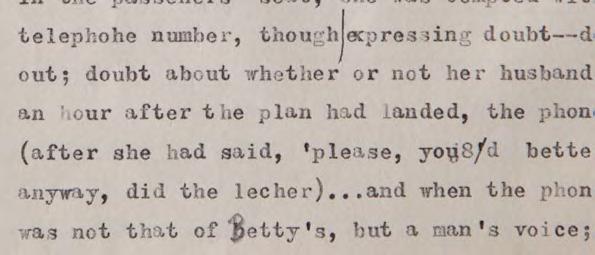

ONE AFTERNOON I WAS sitting with Michael Cunningham in his writing studio, ransacking bags of old documents and opening countless files looking for evidence of the origins of his novel The Hours . This was before I started. Michael is a close friend, and I was leaning on our friendship for an experiment. I had been thinking about doing this book, and I wanted to see if my conceit would work – that the artifacts of something’s beginnings might yield insight into how an artist’s mind works. He was game, though he warned me he wasn’t sure what he’d saved-- the record of his work was kind of a mess. But he remembered his early thinking about the book (which, for reference, is three interweaving stories related to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway – Virginia Woolf writing it; a homemaker reading it; a contemporary “Clarrisa” named after it.) He explained:

“Everything about The Hours was a surprise to me.

“Originally it was going to be a contemporary version of Mrs. Dalloway , set in NYC among gay men. At the time I started writing there was a kind of gay Chelsea society that felt disconcertingly like the London society in which Clarissa Dalloway lived. Clarissa was 52 I think and I thought okay, this is about a gay party boy who turns 52, the age in which you are not considered young when viewed through any possible lens. Mrs. Dalloway is quite specifically set after World War I – subtly but clearly it is about the war. And so maybe my book would be set against the AIDS epidemic. (Which is why the character Richard, the poet in the finished book, is a casualty of AIDS. Richard incidentally was originally a woman.) Anyway, eventually I realized this wasn’t a necessary book; it was a riff on a great book. Why in the world would anyone need my gay Mrs. Dalloway when we’ve got the original goods? I might have that original draft somewhere. You lose track of how many drafts you go through.

“I decided it just had to be a story about a woman, a contemporary version of Mrs.

2

CUNNINGHAM

MICHAEL

occupation : Playwright/screenwriter

work : Angels in America

4

3

SELF

Dolut eliciisqui te volupti ne et fuga. Sit quiae.

THE HOURS, NOTES TO

Dalloway in which Mrs. Dalloway has many more options that she did in Wolff’s time. But that too felt more like an idea for a book than a book. So I toyed with bringing Virginia Wolff in it somehow. There was a while when I thought on the right-hand pages was going to be the contemporary version of Mrs. Dalloway and on the left side was going to be the story of Virginia Wolff writing Mrs. Dalloway.

“But all that wasn’t coming together; it felt academic and insufficiently alive and I was really about to give it up. I remember sitting in my studio ready to abandon the book. But I had put a year into it! So I gave it another try. I tried to figure out what about Mrs. Dalloway was was so compelling to me and my mother drifted into my head. And I realized eventually that my mother, as a homemaker, has always seemed to me to be trapped in a life that was too small for her. And if you look at it like this: two women, my mother and Virginia Wolff who each in their way were trying to do more than wa possible –Virginia Wolff writing Mrs. Dalloway and my mother baking a cake – then my mother gets to be in the book just as surely as Virginia Wolff. And that’s when the book started to come to be what it was.”

Michael and I went hunting in a small closet through garbage bags and boxes of paper looking for the traces of The Hours beginnings. We found just about everything else. But then somewhere in his computer drive he found the “gay” draft he wasn’t sure existed. Here

is how the book once began: And here is what that turned into:

Michael was surprised to see the gay draft. Even he didn’t remember much about this early version of what would become a Pulitzer Prize winning book and a Renee Fleming opera, a Dutch play and a Hollywood movie that would win an Oscar for Nicole Kidman for playing a part that wasn’t even imagined at the start. It’s impossible to imagine The Hours without Virginia Wolff. But there you have it.

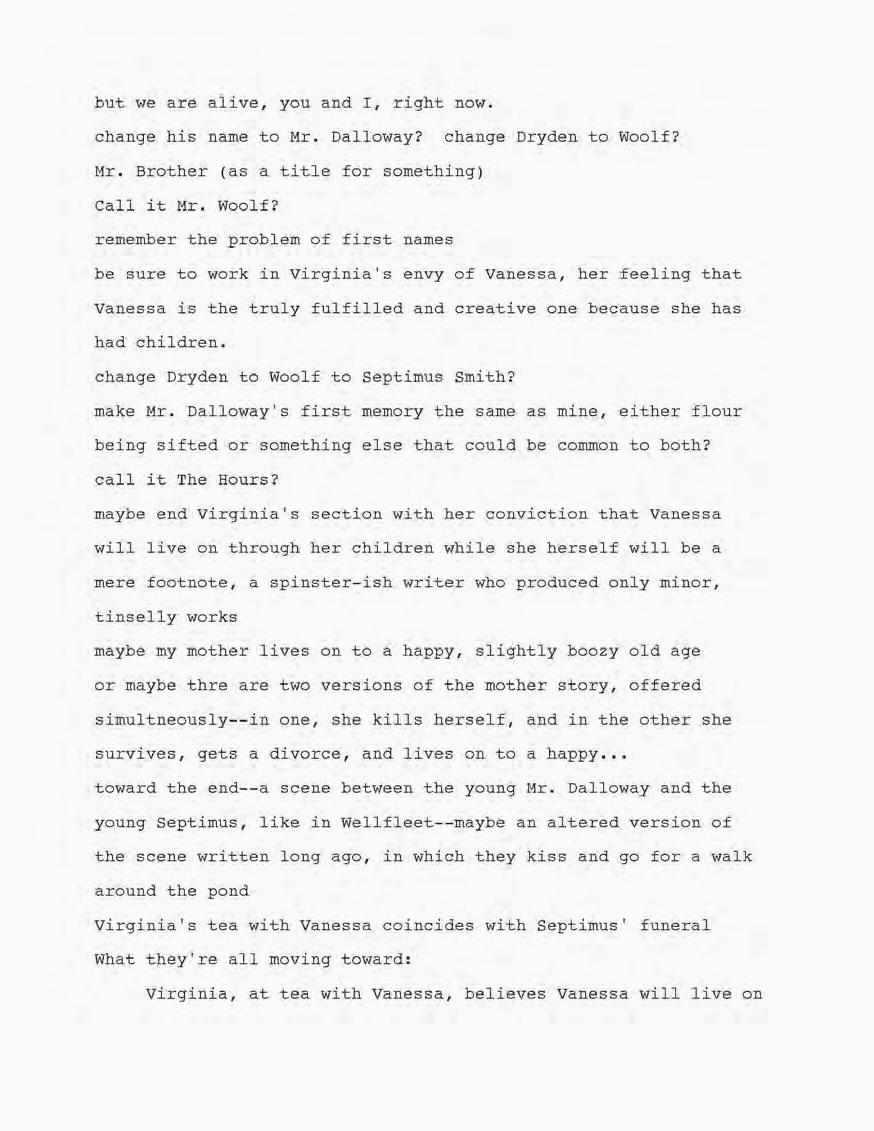

Incidentally, we also found in our rummaging this list of notes to himself midway between the gay draft and the finished book – a particularly clear glimpse of a novelist’s constantly revising mind at work. You can see it on

Persistence, endurance – much of the work we revere wouldn’t exist if the artist hadn’t been spectacularly tenacious; I am certain pretty sure much anybody else would have moved on when Michael didn’t. But as I was listening to him and reading over his notes, I was struck by another quality as well: a Martian-like ability to be outside and inside himself at the same time. To look at his own work undefensively but critically; to say, nah, this is crap, but somehow (and this is what seemed impossible to me), not to annihilate himself in the process.

On Not Giving Up A year or so later I went to visit Michael again, tape recorder in hand. We were going to have another conversation about the book to fill in the

4 MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

MR. DALLOWAY VERSION

gaps but also to talk this outside/inside

dynamic, why he doesn’t give up, the artist’s head, that sort of thing. It was an artificial conversation for us since we see each other often, though never on the record; the little red light of the tape gave structure to our usual meanderings (also, I cherry picked the conversation, though Michael does tend to speak in the perfectly formed paragraphs you see here).

This time we were in the apartment he shares with his husband the psychologist Ken Corbett. Michael had just given his new novel to Kenny to read. Kenny was visiting his mother so Michael was alone to fret. Michael often says that Kenny is his best reader, and he hadn’t shown this version of the novel to him (or anyone) for the years he’d been writing it. “I don’t worry, as I do with many people, that Kenny will read something bad and realize anything else I did was just a fluke, and this is terrible. It’s just, ‘God I hope he doesn’t effectively convince me that I have to rewrite the entire final third of it.’ But he might.”

THE HOURS, AS PUBLISHED

he had written the book in two parts, one set years after the other. And on that afternoon he’d just gotten off the phone with her. “She thought the second half of the book was just wrong,” he reported at the time, a little dazed. She told him he ought to junk it and start over. We were sitting on a beach. “Oh no,” I said, or something like that. I was devastated for him. But he took it in stride. “She was right,” he said, without a trace of self-pity. I was pretty sure that my response would have been to throw myself into the ocean.

To be typset tktktktktktkt

Sinum ipictin umquias susanih icimincimil molestiam aut et eos voluptate neseque cus, qui odignim aspiciis dolessitia voluptas molorectur?