23 minute read

The Child’s Way

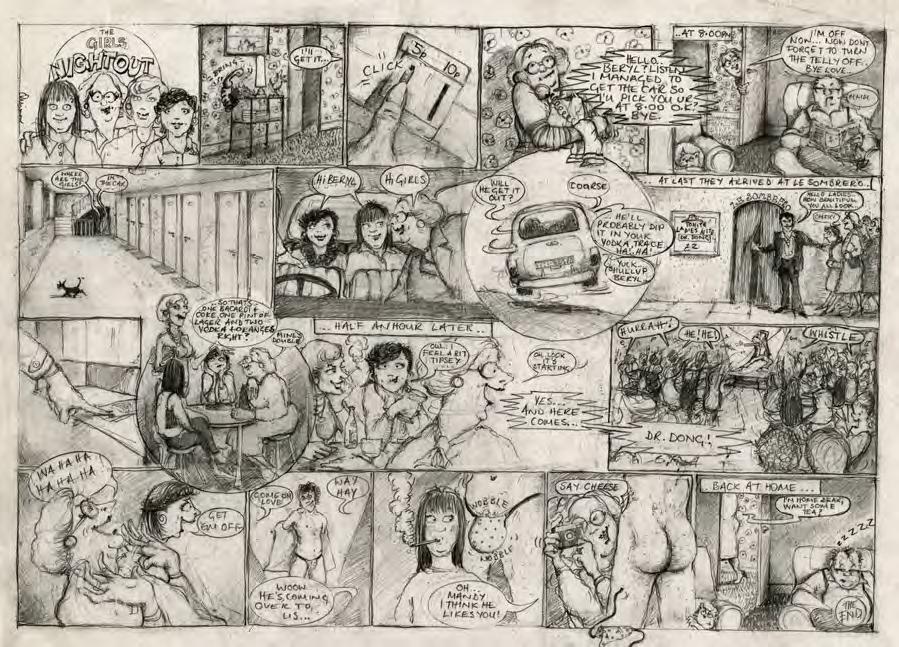

I LOVE ROZ CHAST, but then who doesn’t? Her demented cartoons appear regularly in The New Yorker, to which she has contributed for over forty years. She’s also written or illustrated over a dozen books, including the National Book Circle winner, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant , a soulful cartoon memoir of taking care of her aging parents. In it you see the more ‘grown-up’ artist she might have been, both because of the book’s depth and, interestingly to me, some glimpses of a drawing style that looks (and was) art-trained. Which isn’t to say that her cartoons are superficial. Far from it – and I was interested to see that she was elected to the American Philosophical Society, which seems apt. But she has very emphatically embraced a jubilant juvenile voice she calls “the child’s way.”

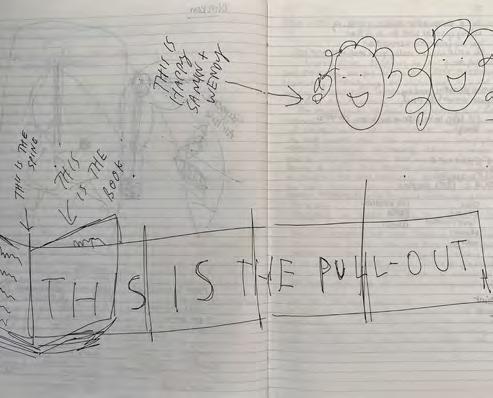

A mammoth sculpture, an epic play – those are projects of long gestation. A cartoon takes minutes. But how different is it really? I went to Roz to understand. It all happens so quickly it defeated the method of the project– she had no entrails of cartoons-in-progress. Still, she very kindly made a cartoon of how she makes cartoons, one especially called “Gifts From the House of Low Goals,” and offered it up. And she let me look into the box she throws her idea-bits into in a room in the Connecticut house where she lives with her husband and kids.

Advertisement

Associations are associations; hers are just a bit wackier than most. Turns out, the distance between her cartoon persona and her actual self is pretty tiny, maybe non-existent.

The Beginnings of an Idea

RC: I can give you a couple of examples of where cartoon ideas came from. There was a cartoon I did years ago, when my daughter – well, she’s not, she’s my son now she’s trans --- anyway, was about 16, and doing her homework in the living room. There was a boombox with music going. And if you’ve been around teenagers, you know that there’s nothing more disgusting in the eyes of a teenager than to watch a grownup dancing. I hate to dance, but I wanted to see if she was paying any attention. So I’m like doing my mom dance and it was, mom, stop. You’re hurting me. And it made me laugh. So I asked if I could use that in a cartoon.

Another time I’m on Metro North, and there was an ad for –maybe it was Carvel – and there was a little girl, she’s wearing these cute cat-eye glasses, and she has a party hat on. And she’s blowing out the candles on the cake and on the cake it says, congratulations on your new glasses. And I just thought, we have set the bar low! So I had all these things, like ‘congratulations on your new armchair’ and ‘I’m so glad you’re not an arsonist.’

AM: Do these come to you fully blown? Or are you constantly revising these things once you’ve set them down?

RC: Depends. There are times – like when I saw an ‘End of the World’ guy. And I just wanted to draw one of those guys. So I did, and I thought: Oh, he needs a wife. So he has his the End is Near sign and she is next to him, looking like the female version of him. And she is carrying a sign that says, You wish.

AM: Do you keep these observations in a notebook?

RC: I’m not organized enough to keep a notebook. But I have these kinds of slips of paper in an idea box. There’s like thousands of them. A whole box of Nope, Slow Pour Coffee, Choose Your Own Adventure. And then an arrow. The entire box is nonsensical. [She pours notes out on her desk] Here, I’ll read you: Okay,

Concierge . This is circled and underlined like five times. Hacks. Semi heirloom tomatoes, Bitcoin fairy.

[Keeps reading] This one just says Podiatrist. Hmm. Niche audience. Big Hair. I did sell a cartoon with that idea. Little Red Riding Hood is visiting her grandmother in bed. And I had just been in Texas, where the women had like helmet heads. And the grandmother has this giant hairstyle, and Little Red Riding Hood says, um, what big hair you have…

Let’s see: Uber. Compassion fatigue. Chief Happines s Officer.

AM: Whe n you go back to these things, do you know what you’re talking about?

RC: Sometimes yes, sometimes no. A lot of the ideas happen when I’m actually working. When I’m at my desk. The ideas begin to percolate.

AM: So you sit down. And one of your scraps says Concierge.

RC: It made sense at the time. But now it… AM: So what do you do, do you run through different scenarios in your head, are you working out language, are you starting to draw?

RC: It all happens simultaneously. Once I decided that the End of the World guy needed a wife, I knew what was going to be on the sign. Boom, done. But that’s rare. Most times, I draw, I write, I figure it out. I’m kind of immersed in it. One time I was chewing gum and I forgot, and the gum just actually fell out of my mouth. That’s really kind of a moment that lives on in time for me.

Cut Anyway, then a lot of what I do is cut. If I can say something in ten words as opposed to 50, it helps the joke.

Comedy has a lot to do with rhythm and how you tell a story. I’m not the most analytical person about this, I’m usually feeling my way blindly through something, but you see something, it seems better, sometimes you realize the other version was better, but you just look it over and decide-- I’m going to go with that, you know.

AM: Bec ause you’re really generating a lot of these?

RC: At The New Yorker , we submit a group of cartoons a week, batches we call them-for me, that’s usually six or seven. So a lot of stuff I do just gets shoved aside. But if something gets rejected that I think is a good idea, I’ll resubmit it multiple times.

AM: Alt ered?

RC: Sure. If I think there’s an idea there I’m going to see if I can find a better way to tell the story. It’s kind of like if you were telling somebody a story and their attention wandered, you’d go into the time machine and try to tell it a better way. A lot of times, if I think something’s funny I’ll just keep at it. Being a cartoonist really involves stubbornness coupled with a kind of stupidity.

Child Is Good

AM: Do you have rules that help you?

RC: I have a friend whose kid is an artist, and she told me something that her kid once said. She was trying to show her daughter how to do something, and her daughter said: I want you to do it the child way. And that’s how I feel about work. I want to do it the child way. I want to do it how I want to do it.

I’m bad at stuff like cartoon lettering. I’m bad at straight lines. I’m bad at like, do a drawing and have a gag line.

AM: But you can actually draw very well. I was looking at your book Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant, and there are some really moving, sophisticated drawings of your mother. And it occurred to me that the visual style that you describe as clunky is a kind of construct. How did you come upon the visual voice of your cartoons?

RC: Hmm, well, when I was like 12 or 13, I started to feel my way toward something like how I draw now. That’s when I started to think, I’m going to be a cartoonist.

AM: Bu t then you went to art school. And I presume that they were teaching you all sorts of ways to draw “better.” Was it hard to hold on to this more primitive style of expression?

RC: Well before going to RISD [Rhode

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

“ Will Your Hand Do the Thing Your Mind Wants?”

born : 1956

ONE AFTERNOON I WAS sitting with Michael Cunningham in his writing studio, ransacking bags of old documents and opening countless files looking for evidence of the origins of his novel The Hours . This was before I started. Michael is a close friend, and I was leaning on our friendship for an experiment. I had been thinking about doing this book, and I wanted to see if my conceit would work – that the artifacts of something’s beginnings might yield insight into how an artist’s mind works. He was game, though he warned me he wasn’t sure what he’d saved-- the record of his work was kind of a mess. But he remembered his early thinking about the book (which, for reference, is three interweaving stories related to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway – Virginia Woolf writing it; a homemaker reading it; a contemporary “Clarrisa” named after it.) He explained:

“Everything about The Hours was a surprise to me.

“Originally it was going to be a contemporary version of Mrs. Dalloway , set in NYC among gay men. At the time I started writing there was a kind of gay Chelsea society that felt disconcertingly like the London society in which Clarissa Dalloway lived. Clarissa was 52 I think and I thought okay, this is about a gay party boy who turns 52, the age in which you are not considered young when viewed through any possible lens. Mrs. Dalloway is quite specifically set after World War I – subtly but clearly it is about the war. And so maybe my book would be set against the AIDS epidemic. (Which is why the character Richard, the poet in the finished book, is a casualty of AIDS. Richard incidentally was originally a woman.) Anyway, eventually I realized this wasn’t a necessary book; it was a riff on a great book. Why in the world would anyone need my gay Mrs. Dalloway when we’ve got the original goods? I might have that original draft somewhere. You lose track of how many drafts you go through.

“I decided it just had to be a story about a woman, a contemporary version of Mrs.

Dalloway in which Mrs. Dalloway has many more options that she did in Wolff’s time. But that too felt more like an idea for a book than a book. So I toyed with bringing Virginia Wolff in it somehow. There was a while when I thought on the right-hand pages was going to be the contemporary version of Mrs. Dalloway and on the left side was going to be the story of Virginia Wolff writing Mrs. Dalloway.

“But all that wasn’t coming together; it felt academic and insufficiently alive and I was really about to give it up. I remember sitting in my studio ready to abandon the book. But I had put a year into it! So I gave it another try. I tried to figure out what about Mrs. Dalloway was was so compelling to me and my mother drifted into my head. And I realized eventually that my mother, as a homemaker, has always seemed to me to be trapped in a life that was too small for her. And if you look at it like this: two women, my mother and Virginia Wolff who each in their way were trying to do more than wa possible –Virginia Wolff writing Mrs. Dalloway and my mother baking a cake – then my mother gets to be in the book just as surely as Virginia Wolff. And that’s when the book started to come to be what it was.”

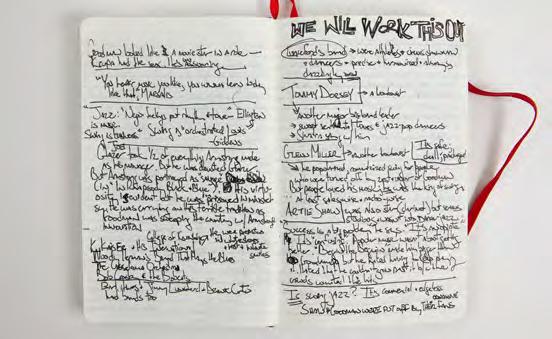

Michael and I went hunting in a small closet through garbage bags and boxes of paper looking for the traces of The Hours beginnings. We found just about everything else. But then somewhere in his computer drive he found the “gay” draft he wasn’t sure existed. Here is how the book once began: And here is what that turned into:

Michael was surprised to see the gay draft. Even he didn’t remember much about this early version of what would become a Pulitzer Prize winning book and a Renee Fleming opera, a Dutch play and a Hollywood movie that would win an Oscar for Nicole Kidman for playing a part that wasn’t even imagined at the start. It’s impossible to imagine The Hours without Virginia Wolff. But there you have it.

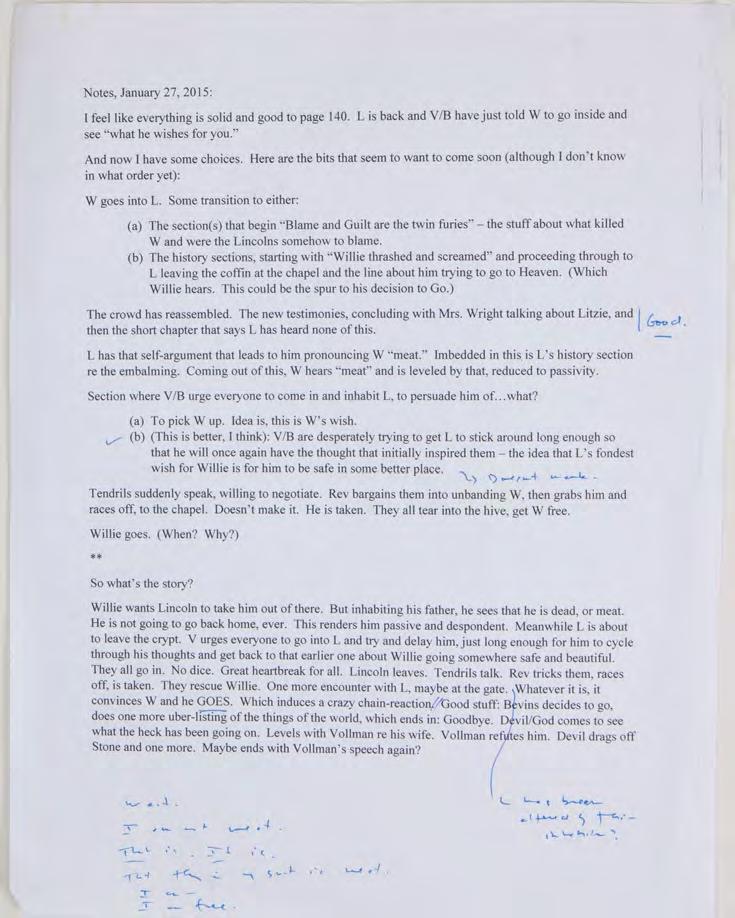

Incidentally, we also found in our rummaging this list of notes to himself midway between the gay draft and the finished book – a particularly clear glimpse of a novelist’s constantly revising mind at work. You can see it on

Persistence, endurance – much of the work we revere wouldn’t exist if the artist hadn’t been spectacularly tenacious; I am certain pretty sure much anybody else would have moved on when Michael didn’t. But as I was listening to him and reading over his notes, I was struck by another quality as well: a Martian-like ability to be outside and inside himself at the same time. To look at his own work undefensively but critically; to say, nah, this is crap, but somehow (and this is what seemed impossible to me), not to annihilate himself in the process.

On Not Giving Up A year or so later I went to visit Michael again, tape recorder in hand. We were going to have another conversation about the book to fill in the gaps but also to talk this outside/inside dynamic, why he doesn’t give up, the artist’s head, that sort of thing. It was an artificial conversation for us since we see each other often, though never on the record; the little red light of the tape gave structure to our usual meanderings (also, I cherry picked the conversation, though Michael does tend to speak in the perfectly formed paragraphs you see here).

This time we were in the apartment he shares with his husband the psychologist Ken Corbett. Michael had just given his new novel to Kenny to read. Kenny was visiting his mother so Michael was alone to fret. Michael often says that Kenny is his best reader, and he hadn’t shown this version of the novel to him (or anyone) for the years he’d been writing it. “I don’t worry, as I do with many people, that Kenny will read something bad and realize anything else I did was just a fluke, and this is terrible. It’s just, ‘God I hope he doesn’t effectively convince me that I have to rewrite the entire final third of it.’ But he might.”

THE HOURS, AS PUBLISHED

he had written the book in two parts, one set years after the other. And on that afternoon he’d just gotten off the phone with her. “She thought the second half of the book was just wrong,” he reported at the time, a little dazed. She told him he ought to junk it and start over. We were sitting on a beach. “Oh no,” I said, or something like that. I was devastated for him. But he took it in stride. “She was right,” he said, without a trace of self-pity. I was pretty sure that my response would have been to throw myself into the ocean.

To be typset tktktktktktkt

Sinum ipictin umquias susanih icimincimil molestiam aut et eos voluptate neseque cus, qui odignim aspiciis dolessitia voluptas molorectur?

Aque opta sendigene lacesti diatat. It magnimi, am quis minctur? Verat aut esto del ma dolupiet omnist ma pel et lamusam quam evelitio od que idit, conempor autaquas mos nonest laccaer ovitia volecatus, qui quaepre ptatiorectum aut ut expernat fuga. Itatus et, optas volut offic tet quid ut odio quistios eos experest, aut aute natem quae iliquib usandis quodio delest magnam hillent haris eum, et asped et et illacid eostrumque et accabori ut pos aspiduci con re sitia qui

“Yeah, it’s not what you want to hear.” he said, remembering. “But for me my fear of hearing ‘you have to throw out the whole second half’ is so overshadowed by the fear that no one will tell me it’s not working until it’s out in the world because you know, most books aren’t very good. I don’t feel very precious about it. I figure, well, there’s always more where that came from.”

I reminded him of an afternoon a couple, three, summers ago; he had just had a conversation with his agent about an earlier draft he’d given her to read. It was the same novel he’s just given to Kenny but only sort of – this one has taken a long time and gone through entire rethinks; in many ways he’d written several books searching for the right one. At that point,

I had known Michael for the sweep of his very accomplished career –met him was he was a struggling-ish writer (he did already have a published first novel he sort of didn’t acknowledge because he didn’t like it enough); celebrated with him when The New Yorker published his remarkable short story ‘White Angel’; and then again when that story became part of the much-loved book about a trio of friends called A Home at the End of the World; and again when he published his epic family novel Flesh and Blood; and especially when he won the Pulitzer Prize for The Hours. And then tried to console him when the Pulitzer actually threw him into a funk. (“I was happy for three days and then depressed about it –for a long time. Which I’ve never fully understood, only, you know, it’s only downhill from here. I was surprised how bad I felt about it, and then I just came out of it. It’s obviously nice to win a Pulitzer, even if you do have some bad days about it.”

The Freedom of Low Expectations On this day, we sat in his open Brooklyn loft, and ate burritos. I turned on the tape. “Let’s talk about The Hours a little bit and then we’ll move on.” I said. “My memory of your state of mind before you set out to write the book was that you had written Flesh and Blood with the intention for it to be popular. And then when it wasn’t in the way you’d imagined, it kind of freed you up to write a personal, and-- you thought -little book.”

“Yes, that’s right.” Michael said. “ I mean, Flesh and Blood was the book that I wanted to write. But it was my impression – and the impression of the publisher – that this would be my big book. The thought was that Home at the End of the World was my solid midlist book and then this family saga was gonna really sell. I don’t think anyone ever really knows why a book sells or doesn’t. But it didn’t. So I thought, well I’m not gonna be a best-selling writer. Which was disappointing and liberating at the same time. So when I wrote The Hours I thought, This will be a little arty book. That it will sell a few copies, then march with whatever dignity it can muster to the remainder’s table. Which was an opinion shared by the publisher.”

“All your many initial versions of The Hours involved Mrs. Dalloway in some fashion. You jettisoned one way to respond to the book after another, but you never departed from your intention to work off Mrs. Dalloway. What was so important to you about Mrs. Dalloway?”

“Well, Mrs. Dalloway was one of the first great books I read as a kid. Some girl I liked sort of urged me to read it. I’m not even sure I finished it because I couldn’t figure it out. What really struck me about it was the language. I had never seen language like that before. I didn’t know you could do that with a sentence. It was like you’ve grown up on the songs they sing in your village. And then someone takes you to a concert and they’re playing Beethoven, and you just think, what

“I need to write first thing in the morning. I need to segue from sleep and dreams directly into this invented world of mine because part of the deal is maintaining for several years your belief in this world and if I were to even run a few errands before I got to work I’d get derailed. I’d get so lost in the realness of the real world that when I turn on the computer and look at what I’ve been writing, I think well this isn’t as deep and mecurious as the dry cleaner – or the drug store, or wherever else I’ve just been. I write for about four, five hours, after which there’s nothing there anymore. But I also learned that for me it was gong to be much more helpful to think in terms of time spent as opposed to page limit – because if you just have to produce words and you write too much of what you know is crap-- and there are those days-- then you are in danger of losing faith in your book. But if I am in my chair, ready to write whatever arrives – 10 pages or one sentence-- I’ve fulfilled my commitment. The next day I read what I wrote, catch up with myself. For me it’s as much about the language as it is about the story, and I find myself needing a solid sentence to stand on in order to move forward. I usually have some idea of what I’m going to write that day. Although we have complicated feelings about Ernest Hemingway he said a great thing that I read early on: ‘always stop writing for the day when you feel you have more to write,’ so you’re eager to get back to it. I try to do that. As for writing environment, I have a studio that’s not where I live, that I go to everyday. I’m not one of those delicate creatures where if a dog barks that’s it, but I do need to be in a fairly familiar place so the background sort of fades away. I can’t write in a coffehouse for instance. I just need to be in a space capsule.” the fuck?”

“In high school were you dabbling with writing at all?”

“No, I was more of a visual arts kid.”

I said, “I remember from when we took a drawing class together that you were pretty good.”

“I guess. But it didn’t turn out to be a sufficiently driving passion. When I got to college, thinking I was going to study art, there were some people in the classes I took who were not only really gifted but who were bottomlessly interested in the fundamental proposition of trying to produce something that was alive. And I just wasn’t as indefatigable as they were. I would get discouraged and give up. The girl next to me would get discouraged and start over again.”

“Were you intimidated by their levels of prowess?” I asked. “Were they just more talented than you were at drawing and painting?”

Interest, Not Talent “I think it’s really hard to comfortably separate talent from this unquenchable interest in the problem presented by the task.” I hadn’t thought about it that way – as interest rather than talent. Michael continued. “Like they never got tired of trying to paint. And I started writing and realized that I felt that way about writing. That the fundamental question, can you do some sort of justice to life using only words and ink, was endlessly interesting to me. But then sure, some people are able to produce unthinkingly a squiggle that has a kind of life. That I couldn’t do. There’s a question of I guess I’ll call it athleticism. Will your hand actually do the thing that you have in your mind? So I’m starting to write and at the same time beginning to wonder if I really possess what a serious visual artist possesses.”

“And writing came easier to you?”

“I didn’t feel instantly brilliant at it. I was pretty good. I was good with language. My sense of my ability to write still comes and goes. It depends on the day. But I don’t know if I’ve ever in all these years lost that fundamental interest in the proposition, here’s ink, paper, words in a dictionary.”

We returned to The Hours. He’d made a lot of notes, some of which you’ve just seen. And he didn’t really mention his idea to anyone, including Kenny. . . “for the practical reason that no matter how intimate the person you might talk to about it, you need to maintain your faith in the story you are about to spend god knows how long writing, and there’s no surer way that I know to lose faith than by summing it up too soon. ‘It’s about a guy, a whale bit off his leg, he’s really mad.” Michael laughs in the big bellowing way he does.

“So we talked before about cycling through various versions--” He’d just told me another one, where his version of a day in a Mrs. Dalloway’s life would be accompanied by notes to himself, another device he soon realized “was pretentious and uninteresting.”

Getting Stuck “So many false tries.” We finally got around to the question. “Why didn’t you just give the book up?”

“You know, just this endless determination. By then I had written enough to know that most of the time you get to a certain point in a book you want to give it up. And to write another book that won’t cause me the same trouble. And it does. You just end up stuck all over again. So you might as well stay with the thing.”

“And you always get stuck?...”

“It took me a while to realize that if a novel is any good, it’s going to defeat what little idea that took you into it in the first place. And sometimes your experience of it not working out is it taking on a life of its own, going in a direction that’s more interesting and complicated than what got you there. And I suppose that’s what happened here. I realized it was really a book about women and I just felt like, lose the gay man thing, and then what we talked about before, about my mother’s labors set against Virginia Woolf’s.”

We got into a discussion of the novel’s particulars, which I was especially interested in because I had just reread the book before coming over – putting Virginia Woolf’s suicide at the beginning for instance, which he’d told me was a late decision he made so her eventual suicide (which he felt it was necessary to include) wouldn’t hang over the book. I asked him about another one (I suppose this requires a spoiler alert), a surprise plot device Michael employs at the end of his book which ties together two of the threads: the son of the mother character in one of the intertwined stories is revealed to be, grown-up, the suicidal poet in the other. I’d read the book maybe three times and seen the movie, but it still startled me reading the book again – and I wondered how that simple, effective narrative move came about.

“That came late too. I felt for the longest time like, I don’t how these strands are going to meet. And one day I just saw this, and I thought hmmm. And I thought you know, let’s give it a shot, even though I was sure everyone was going to see it coming. And I was surprised as anybody that people were surprised by it.”

“And when you come up with a solution like that, are you elated? I mean, emotionally, does it feel satisfying?”

“Oh, certainly not elation. An element of relief. But throughout this book – I always feel this but maybe more so with this one – I thought, this is probably terrible. And I showed it to a lot of people, waiting for someone to say, ‘this is just a contraption with an obvious ending. Don’t publish this.’ And people kept not saying that.”

“What were you so worried about, this contrivance?”

“Oh you know, I find it easiest just to worry about everything..—

“That I had Virginia Wolff wrong.” he continued. “That, you know, how dare I as a man... But also, the time it takes to write a novel inevitably requires a level of familiarity with it that makes it almost impossible to imagine that it could be interesting to anybody. Going over it the hundredth time, you can’t possibly know what it would be like reading it the first time.”

“And it is inevitable that a book will start to bore you?”

“No, that’s not it. I haven’t had a novel begin to bore me. And that’s probably because I keep thinking I will find a way to make it better. But you know it’s also true that you don’t want to take forever to write a novel because you don’t want to get to the point where the book ceases to be – I guess, you just don’t want to outgrow it.”

The Better Book in Your Head “I was really struck on rereading the book,” I said, “how much you underscore the theme of having something in your head that is impossible to realize. It comes up in a couple of contexts.” I wondered if that gulf was particularly frustrating to him as he was writing this book.

“You always have a better book in mind than you’re able to write. And one of the things you have to be able to do, if you’re going to write novels, is survive that discrepancy between the book you were able to write and the better book you imagined.”

“Is there a mood you’re in that you feels to you the most productive – or the most doomed for that matter?

“There are better days and lesser days. What varies the most is the degree to which the aperture is open or closed.”

“What do you mean – the aperture?”

“Whatever is coming through is either coming through in gushes or dribbles. But the dribbles are about as good as the gushes.”

“Let’s go back to what you called athleticism before.” In all my conversations I kept trying to understand where talent comes from, to no avail. I thought maybe Michael, who is fond of what he calls ‘crackpot theories’ might offer one. “You want to take a stab and describe what you think talent is, or where it comes from?” I asked. Michael didn’t really bite.

“As I mentioned before, it’s hard to separate talent from the almost spectrumy degree of endless interest in something.”

“All your years of teaching haven’t led to any theories as to why certain people have facility and others don’t?”

“Honestly my sense based on all the writers I’ve worked with is that the aliens aimed a beam of light at some of you, and I don’t know why. And I think the actual visceral experience of a lot of people who have some kind of gift is, What, everybody can’t do that?’”

I wanted to talk about age, since he’d mentioned it before in relation to Clarissa and he and I talk about the subject a lot in every possible context. “Do you feel anything gets different for you in your work as you age?”

“So far, I don’t feel a significant difference. I feel it lies ahead. It’s impossible to separate aging from the passage of time. So I find I’m a little less interested in lyricism for instance.”

“Just changing taste, then.” I said. “What about experience? Is experience always good --”

“Like do you sacrifice a kind of reckless --”

“Exactly. Are there things that come to you when you don’t know better?”

“Sometimes. And sometimes you’re writing pretentious shit. But take Walt Whitman. He spent all his life rewriting Leaves of Grass. And the first edition is on the one hand not as accomplished as the final edition. And yet the first edition has a kind of naive vigor that’s not in the ninth edition. I don’t know how you can fail not to be a little nervous about that. One of the reasons I love Philip Roth is those later books are some of the best stuff he’s written, it’s the work of a mature writer.”

I told him I was struck with the number of times in our conversations about writing that he swatted away feelings of satisfaction with his work. Didn’t he have any ? “Do you ever experience happiness in what you write?” I ask.

“I think if you didn’t, why would you do it? No, absolutely, the good moments range from ‘that’s a really good line’ to when you’re walking around, you think of something and you have to get back home to write it down.”

Happiness, it turned out, was all anticipation.

“Because the best times,” he said, “are while you’re working on it, you’re still imagining what it might be. And it feels like it could be anything.”