9 minute read

THE HOURS, NOTES TO SELF

Cheryl Pope

Advertisement

A Kind of Derangement

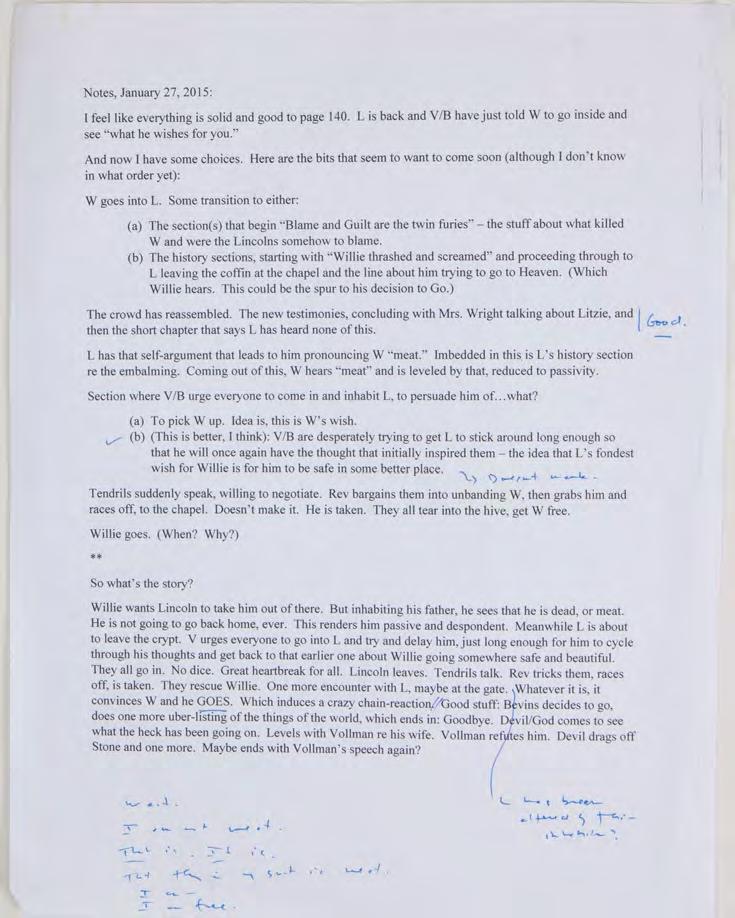

I WAS ON THE LOOKOUT for artists who kept minute iterations of their work, which few people actually do, and Mardee, the project manager of this book, sent me this unfinished image. Mardee was a big fan of Cheryl Pope, who’d made the work it was on the path to becoming. And she knew Cheryl had recorded the steps because she’d had a number of doubts along the way. Also that the work was very emotionally fraught for her, which piqued my interest.

I didn’t know Cheryl’s art, and I didn’t know the heartbreaking context of the image I was looking at, but I was drawn in by the beautiful emptiness of it – a consequence of it being essentially a study, but also, I later learned, because the work is itself about absence. And in fact, this simple gestural study of a mother and child in felt is actually my favorite version of the picture because it expresses that emptiness most poignantly.

Cheryl is a Chicago-based artist who traverses mediums (she moves from installation to sculpture and performance); this piece was a textile painting, an art form she taught herself. She is a disciple of the artist Nick Cave, who is best known for making Soundsuits, elaborate costumes that are part performance, fashion, part sculpture. You can certainly see the influence. Cheryl ran Cave’s studio, watched and sewed a lot.

She made Mother on a Blue Mat after her third miscarriage, and it was her way of responding to the growing evidence that she would never give birth. This conclusion devastated her. Art is often a kind of therapy but few pieces I’ve encountered are so directly and powerfully motivated in that purpose – to work through difficult feelings -- as this one. Making the work was, as she put it, “my way of painting through the motherhood” she would never have. She teared up as she was describing how she found her way through to the end, and then later said that the act of talking about it to me “unraveled an internal knot,” which made me think that art shrink maybe ought to be a profession. In any case, the work was deeply loaded for her.

She started to make art as a child, where she got encouragement from an art teacher, found herself studying fashion at School of the Art Institute, Chicago (“I would dream, I would see everyone in clothing I had never seen before. So when I woke up I would try and draw that out. That’s why I went into fashion.”), where she met her mentor Cave. What seems striking to me (because I spend so much effort/time/ agony trying to learn a craft) is that she hasn’t had a particularly rigorous skills training, but seems very unintimidated by the craft aspect of making art. She switches materials a lot, figures out how to make stuff by looking at YouTube or talking to knowledgeable salesmen at Home Depot. She is an avid boxer; she says that being in motion helps her to see things – it’s one of her hacks (a common hack, as it turns out.) She doesn’t particularly understand how she makes what she makes; she becomes obsessed and can’t let go, like pretty much everybody else in these pages. “The way an image comes forward, I don’t have a map for that. I have my mind just going and then all of a sudden, I start to visualize it. Sometimes I think about myself as an employee of this,” she said, pointing to her head. “Whoever up here comes up with the idea, I am just the laborer. It becomes a blur. I don’t even remember much because I’m in such a neurotic obsessive state.”

That was the case for this work, which first took hold right after she lost the last child. Her partner hadn’t wanted the child in any case, and she was distraught. Eventually she and the partner split, which gave her the freedom to go forward with making the work. I asked her to narrate her way through it, decision by decision – including, as you’ll see, regrets.

CHERYL POPE:

“Okay, to start, this work happened out of survival. I had a miscarriage – my third – and lost my mind. It felt like a volcano erupting, like tectonic plates shifting.” She started to “draw” the image on felt, which felt for her like the right medium though she didn’t know a thing about felt. “One of my students had used this felt-making technique five years earlier and that stayed in my mind. I thought, oh, that’s cool, I’m gonna remember that one.” The technique required her to punch through the felt. Maybe the punching was what drew her to the material.

As for how she figured out how to work in the medium, she says “I just did it. I was in a deranged state.”

1.“I took this picture a few days after the third miscarriage. I’m in a really messed up space here. One of my ways of coping I realized later was that I started amping up my plant life at home. Like: Yes I lost these babies but I can grow things. I was repotting everything.” She took the pictures because she intuited that the planting might “be telling me something.” But meanwhile, she was making other images.

2. “ This was the first one I did, maybe three days after. I’d had an image I’d been working on, of me sitting on the bath [when I was pregnant], and I took it out. And I see that she’s sitting on the bath because she’s washing someone – everything was composed for a child to be there. My partner had been very against me drawing any of these images with the child until I had the child. But then once I’d had that third miscarriage, I thought you know, I’ve imagined this so many times, I wanted to give myself the gift of seeing what I had imagined. My partner did not want the children. So I had been imagining myself as a single mom, seeing myself in these different moments -- the bath, or this other picture of me breastfeeding, which I did a year later. What I wanted to have happened, what I imagined would happen, what didn’t happen.”

3. “When I went to begin what became Women with Child on a Blue Mat, I couldn’t find the plant picture in my phone, but I remembered it. So I recreated the scene and took several pictures of it . What I liked about this version was this shape, with her leaning down. I’m starting to make an oval.”

4. As she began to work on the felt, she tentatively placed a child in the image, almost as an imagined witness to the mother and the plant. “When I looked at the photo it was almost like I was talking to this baby that wasn’t there. Where is the child – the child was absent but was it present in the plant? Do I put the child there? I’m asking myself these questions. And of course it was because I’m still revisiting motherhood in my own life. Those miscarriages were my motherhood. And when

I started to do some research, I realized that [the Impressionist painter] Mary Cassat, who is the go-to for mothers and children – she also didn’t have any children herself. So that was really critical. She gave me a freedom to say I can do this – This is my motherhood and people can hate me for it but that’s what it is. So I made this drawing. I love composition, composition makes any work work. The psychology, the feeling of a work for me, is in the composition. I was interested in this circle [the mother and plant] and this larger circle [including the child.] And I started to get this anxiety, like why is she picking up the plant? I want to pick up the baby –

“And I was going to leave it like that, but then I had a three hour call with a friend who also had a miscarriage. While I’m talking to her I’m looking at the image. And I got off the phone and I just -- work. “And so I start going back and forth and then I need to make a decision and I say okay I’m going to make the switch.” So she’ll move the baby, but put aside the two-baby picture.

“Okay I’m going to put him here and the plant there. And they still make this nice circle. But I know I will use that image [of the two children] again someday--I will return to it. And actually now I find I like that picture better than where I landed.”

5. “-- moved the baby over : let me just draw him over here. But I didn’t want to surrender the other drawing yet. This may be TMI, but I draw when I’m ovulating because I’m the most sensual. So my time window matters with these. And I record the image [of the two babies] because I think I really like this too. I like this echo, I like this as a misplace.” She plays with the introduction of an illogic to the

6. “Meanwhile, I’m just drawing these on my phone—I take a picture and draw on it with my finger – they’re stages of apprehension. Studies.”

7. She did a version with color swatches to see what would work. “I learned to do that during my fashion days,” she says..

“In the same way that with mothers there’s this ongoing relationship of the child disconnecting from the mother, I’m also thinking about connection and disconnection between the real and the imagined in my own situation with the child. This child did disconnect from me already.

“This happened three times. It’s a cycle. That’s why the composition is circular. I’m circling around this, I can’t get out of it... .Color has to start to work with composition, it controls the way I moved my eye. Because as Kerry James Marshall said, why did you make that rug a pattern? His answer was that otherwise it would be boring. Pattern keeps the eye irritated, active. So we stay engaged longer. I’m not following color theory, it’s just intuition.”

But she’s wrestling with decisions. “Should I leave the floor white? Do I want to leave her hair like this? How much do I keep telling and not telling in this image?” him look more like a mulatto looking child. But it doesn’t work for the painting. I’m well aware that a child is born lighter and can get darker.” But she’s worries that because she’s white, viewers will think she doesn’t know this. “I have to tell everything in this one image,” she says. “There’s no room for nuance in this political climate. And that’s suffocating.”

8. Of particular worry is the skin color of the child. Her partner, the baby’s father, is Black. She is white. “My anxiety is hyped up because I am worried about how people are going to read race in the picture.” It is 2021, Black Lives

Matters protests have heightened racial sensitivities, and they unnerve her. She tries to “put in a softer brown rather than black to make

9. Of all the decisions she has to make for this work, the hardest might be the decision to give faces to the mother and baby, or not –to make the picture specific or to generalize, to close it, in her words, or to open it. After much deliberation, “finally,” she says, “ I go all the way and give her a face.”

She notes that she put the face in because it frightened her to draw one on, and she knew if it scared her, she ought to try. She could always pull it back.

As she is talking to me, she uses that phrase so many other artists use” says that she is “listening” to the mother, waiting for it to tell her whether it wants a face or not. “Listening is at the ground of all of this...In those moments of debate, I just tried to stay very quiet, listening for which one she wants me to do.”

As for the baby, she says, “even at this moment I’m stopping because I don’t want to draw his face in. Because I can’t imagine his face. And I’ve never drawn a face. Am

I scared? In my own mind I’ve never been able to imagine the face of the babies I’ve lost.”

10. In the end, she gives the child a face. “So then I came into my studio and thought, just do it to see if you can do it. “ she says. She keeps the face.

11. Here is what the picture looks like finished: But even after she is done, she has regrets about having included the baby’s face. “Later when I looked at the piece I went back to the gallery to take it down because it just tells everything. Everything is told here. But it was too late. Because then it became public.”

“If you were to do the picture again, you’d do it without facial features on the child?” I ask her.