Jaune Quick-to-See Smith Summer Exhibition

Indian Market is a special time in Santa Fe. More than a thousand Native American artists, from more than two hundred tribes, are juried to participate in what is considered the world’s most prestigious Indian art show. For Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, one of the most celebrated Native American artists of the past century, it is particularly auspicious that, shortly before her death in January of this year, she requested that works of hers be on view during this period of time in Santa Fe.

The request was poignant because it was made not for any commercial reason but as a natural coda of her tribal heritage which she has described in past writings as “possessing a sharing cultural mandate.” Since the begining of her career, Smith has continually raised the voices and works of other Indigenous artists and focused on building a space for them. Always, she has placed others before herself. About this she said “The Crees have a word, wahkootowin, for this, meaning everything we do is for community, that we always take into account [that] our actions affect our family, our tribe, and our relations, friends, and acquaintances. You might say our community of humans.”

It is in this spirit that Smith, before her death, requested that her works be shown during this Indian Market season. Considering that she was a relentless champion and spent so much of her time and substantial energy promoting and opening doors for so many Indignous artists, her request to have her works on view in the midst of those of her fellow artists at this special time

was simply a natural and fitting dénouement to an extraordinary career. And, of course, there was no question that her request should be honored.

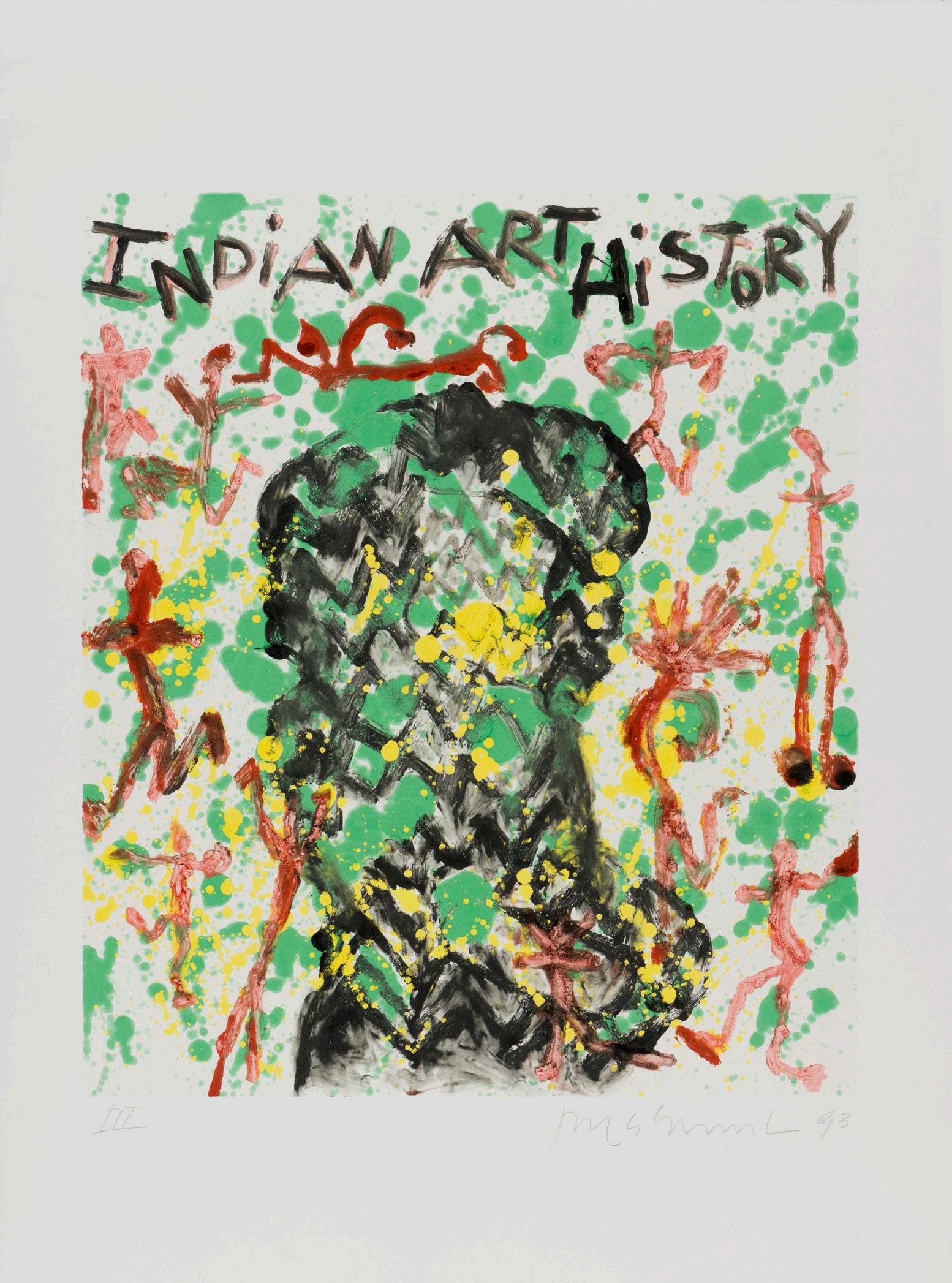

Smith was a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation and her voice has been a powerful presence in the art world calling people to action, curating Native exhibitions, and uplifting Native artists. Indeed, there is little question that over the course of five decades of her career, Smith has been a principal force to “break the buckskin ceiling” of long-overdue visibility of Native American art in U.S. museums and the culture generally.

Smith was the first Native American artist to receive a retrospective exhibition in the history of the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2023 and the first to have a work purchased by the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in 2020. She curated thirty exhibitions of works by Native artists including at the National Gallery and the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University just before her passing.

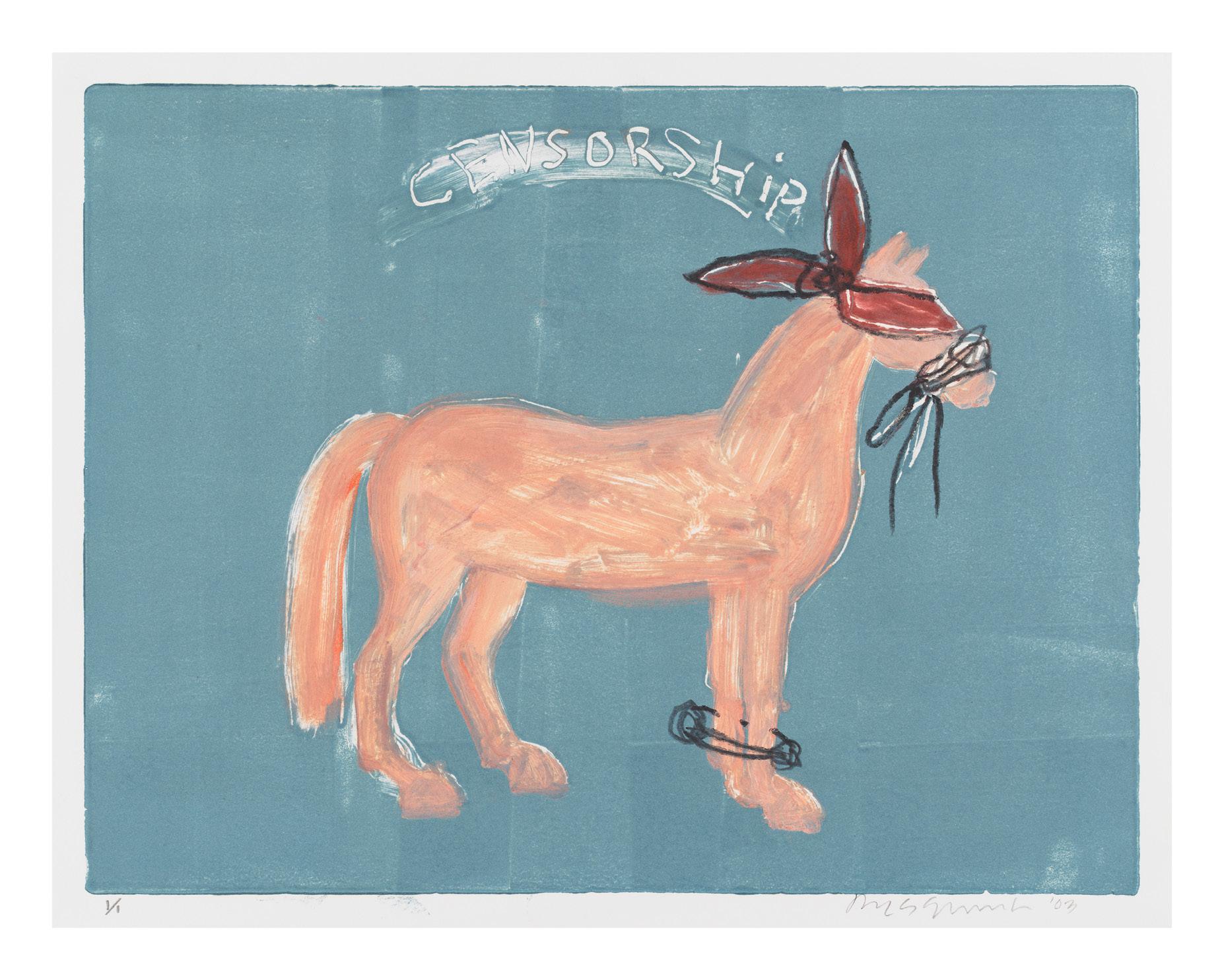

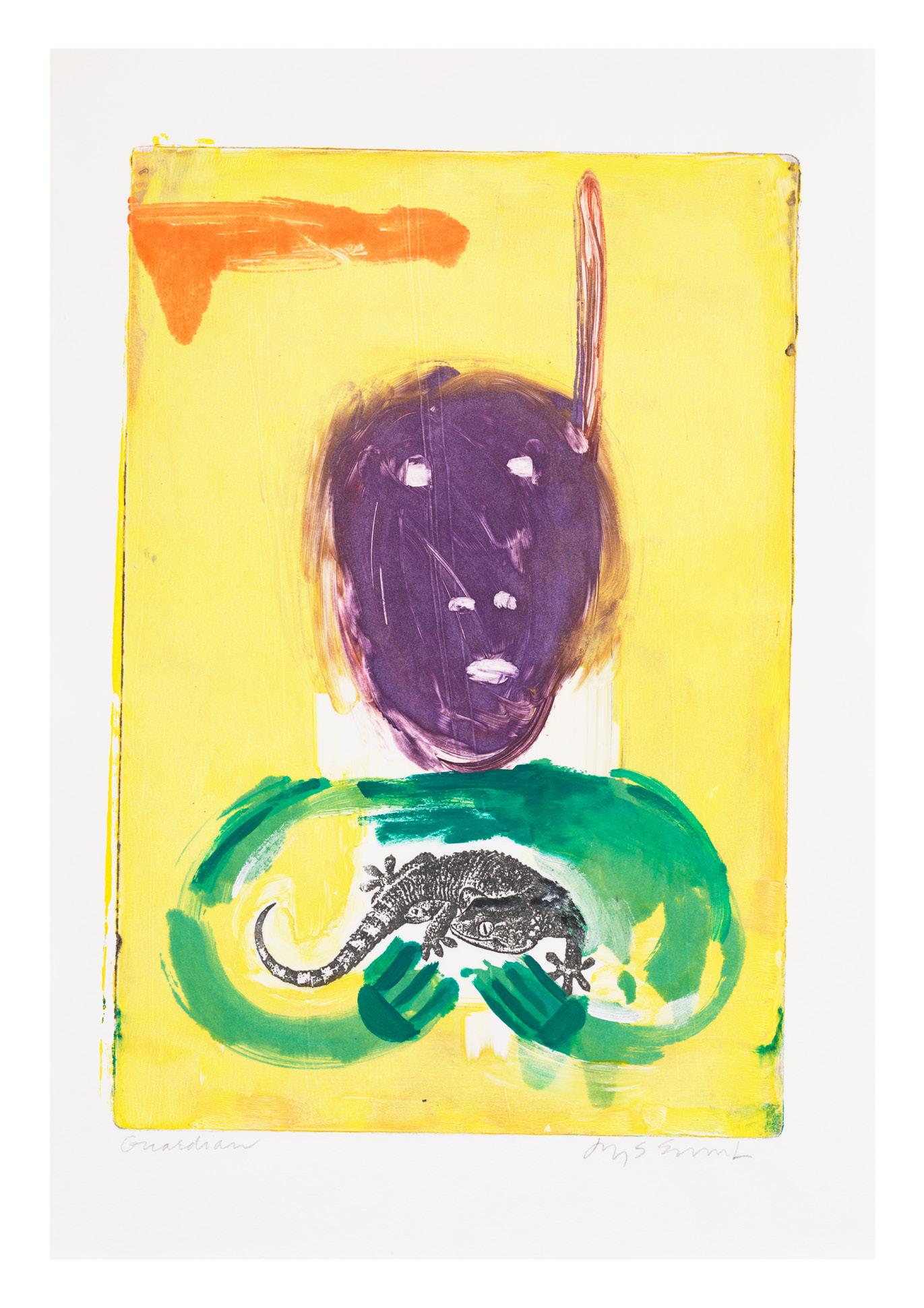

Throughout her career, Smith created a diverse body of work in varied media that deftly expressed Native American truths and identity, preserved cultural memories and reclaimed lost histories, and urged protection of ancestral lands and the environment through messages she embedded in her work and the storytelling she accomplished in her art. That art often used subtle humor or satire in taking on such difficult issues as displacement and violence against her people which she did

unflinchingly and with utter authenticity. Those efforts often had remarkable results.1

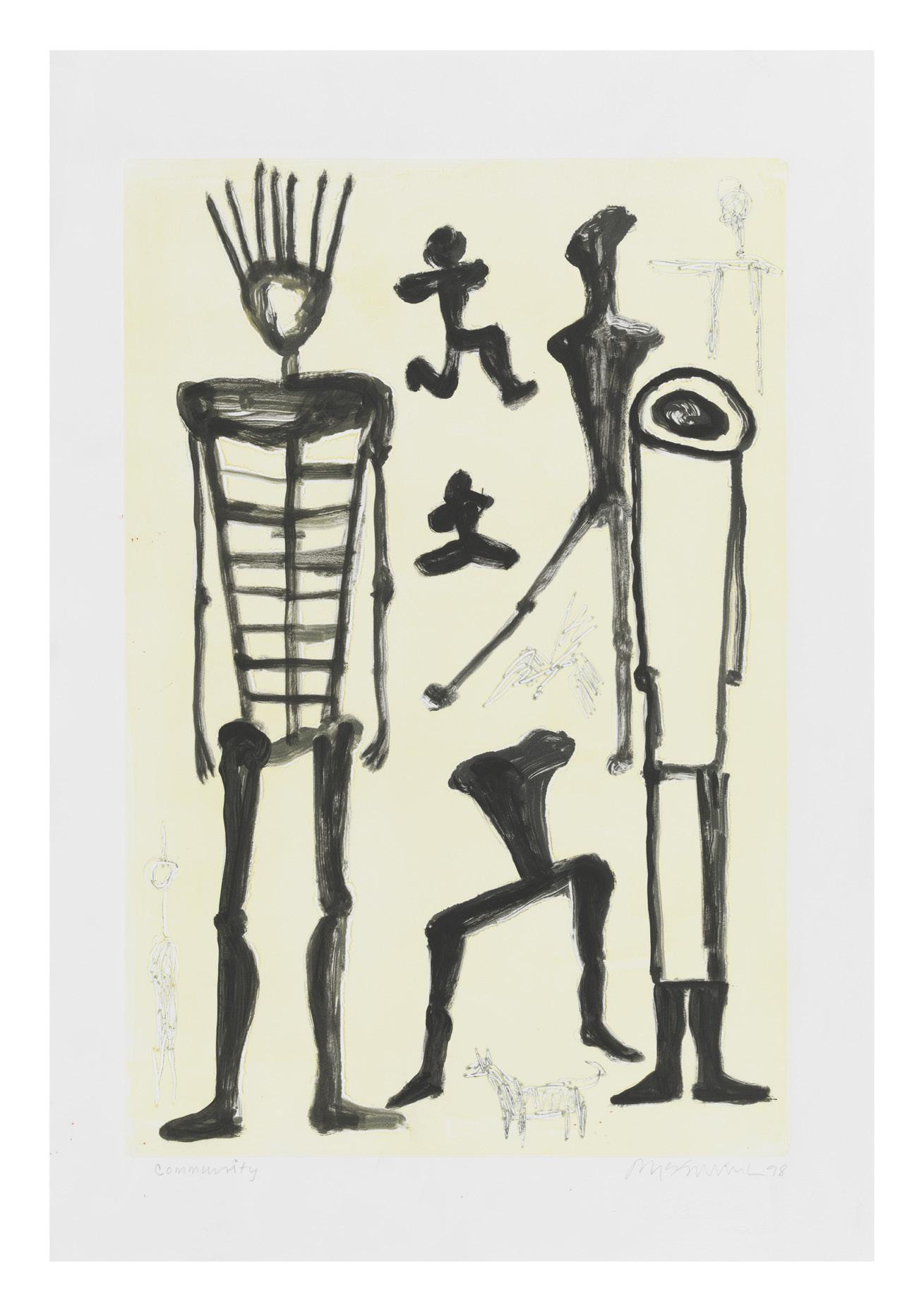

Born on the Flathead Reservation in Montana in 1940, Smith was raised by her father, an itinerant horse-trader. Smith, her father, and sister moved around the Pacific Northwest and Montana, where the artist’s father would do his trading and Smith would work on farms when school was out. She remembered fondly her father’s drawings, which sparked her interest in art. “He would draw pictures of animals on small pieces of paper for me and I would carry them for weeks in my pocket,” she recalled. Though she had practically no access to classes or supplies as a young girl, Smith made art. Using a stick as her brush, she would draw animals and people on the ground in dirt.

Smith’s works return to childhood, to land, to family, and to history. She uses references to all these to create her stories of a past, not just of her own but of her Native people, for the sake of those people, a past she insists be remembered, a past

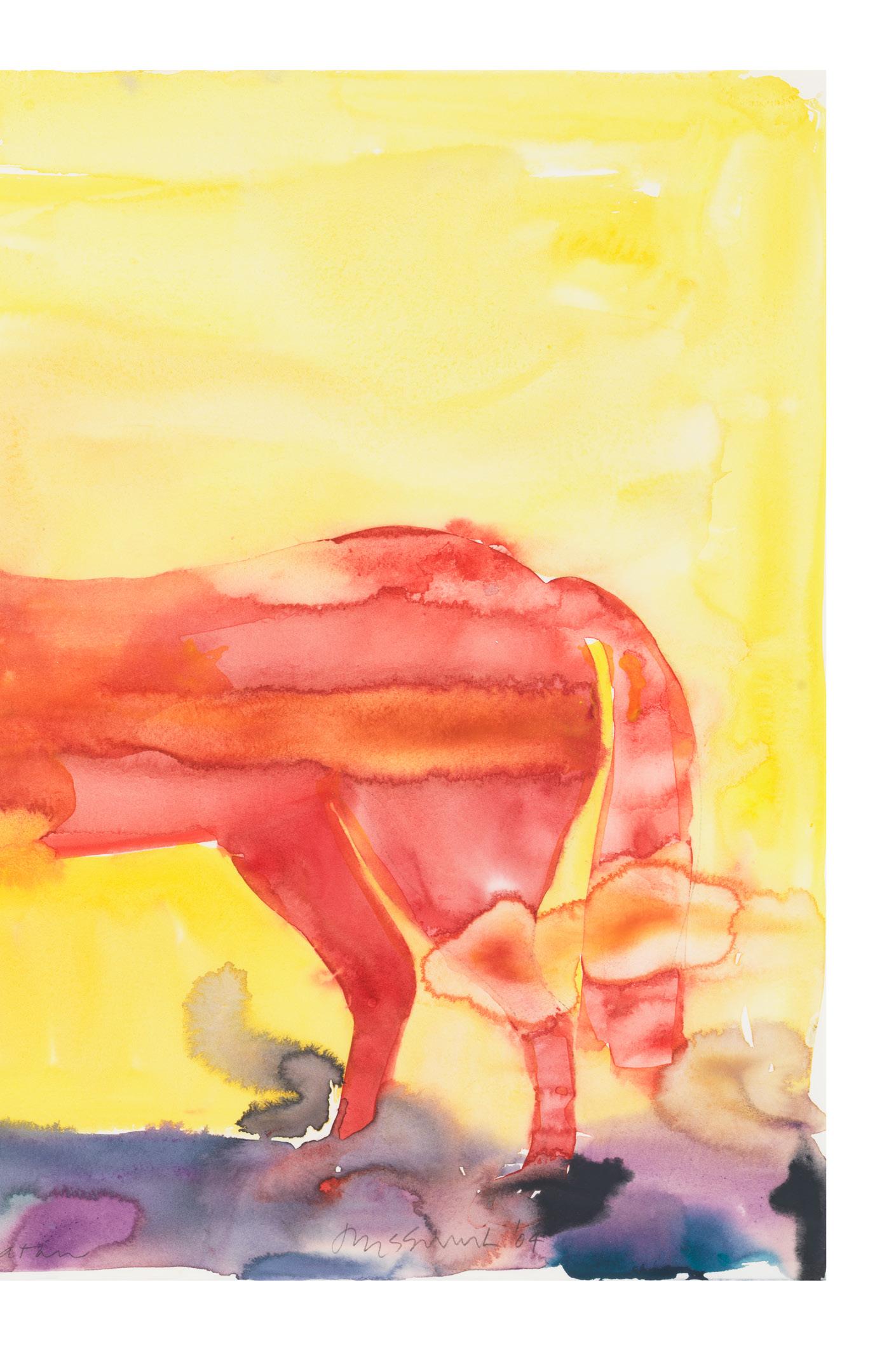

that has been made the subject of 200 years of erasure. The imagery of horses, for example, which appears in several works in this current exhibition, is important in her work. It is not only a manifestation of personal memory, or an homage to her father whose business was to trade in them, but also as a connection to the larger collective consciousness of Native people for whom the horse is a symbol of enduring resilience and freedom in the face of colonial oppression and erasure. The horse was the means for travel, mobility and escape. It was revered and honored.

So it is no coincidence that in the most significant work of this exhibition, the oil on canvas painting entitled Arlee Ledger Pony, the boldly outlined horse appears in the middle of this major painting and has both highly personal and powerful metaphorical significance. Not surprisingly, Smith kept horses as pets and companions throughout her life, even creating a series of works entitled Cheyenne after her beloved horse of the same name. But the horse also references the vital place of

1 See for example the discussion in the LewAllen Galleries catalog that accompanied the Art of Memories Told exhibition held in early Spring 2025 that discussed Smith’s art and efforts that materially assisted the establishmentby Congress of Petroglyph National Monument in 1990 saving dozens of ancient sacred Indian sites and more than 24,000 petroglyphs from destruction by commercial development in the West Mesa near Albuquerque, N.M.

the animal in Plains cultures and is the carrier of the warrior traversing both place and time. As a recurring form in Smith’s work, the horse acts as a literal and metaphorical image that travels through history and memory.

Depicted in this painting as steadfast among fragments of Native history, traditional symbols, and disruptive Western imagery, the horse traverses an ever-changing landscape of convoluted visual influences that Smith has inserted into the painting. As such, it makes Arlee

Ledger Pony one of Smith’s classic great paintings, reflecting her sensibilities in artmaking, addressing resistance, Western influence, and the continuity of Native American culture. History buried under drips of paint, cartoons, animal forms, references to home, and Native American symbols permeate this work. The animal’s body navigates the patchwork of grids, maps, and spectral traces—each element potentially invoking a fragmented archive of Indigenous experience.

Very interesting, too, Arlee Ledger Pony might be seen to have an aspirational or wishful diaristic aspect to it. Smith has written that “My work is a diary, or journal, of my life.” She has also written that “I ‘reside’ in other places, but Montana is always where I circle back to.” Arlee is a small town on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, less than 20 minutes from Smith’s birthplace of St. Ignatius. The genre of Native American ledger drawings clearly influenced Arlee Ledger Pony and has been a constant but quiet presence in Smith’s works.

Ledger drawings were originally developed in the late 19th century by Plains tribes who, lacking a written language, used pictures to record their battle results and other cultural events and history. Their small size and narrative imagery made ledger books diaristic — partially personal, partially reflective of the larger community. Ledger art became a powerful conceptual and aesthetic

framework in Smith’s art. She expanded on this tradition with her own contemporary vocabulary: gestural drips, collaged historical and pop imagery (from the collaged images of the buffalo to a smirking Bugs Bunny), and layered color fields, all of which appear in the Arlee Ledger Pony work.

Juxtaposed with the overarching presence of the horse in the work and its powerful symbolism as the figure of carrier who can transport through time and place, together with reference to the ledger drawings of the Plains Indians which were important, diary-like keepers of history for the Plains Indian ancestors of Smith, Arlee Ledger Pony can be seen as a kind of visual metaphor with significance for Smith’s own personal wishes and history — a desire to be transported back home to her birthplace in Montana, the place she “always circles back to,” further suggesting the special significance of this important work.

- KENNETH R. MARVEL

Bering Strait Theory

Internationally prominent for her groundbreaking artwork, Jaune Quick-toSee Smith combines contemporary issues and art movements with traditional Native American artmaking and myth. She is recognized as one of the most prominent Native American artists of the past century. Smith not only had an incredibly successful career as a maker, but was also an avid supporter and advocate for Native American arts and artists. Her work to “break the buckskin ceiling” has shaped contemporary Native American arts, and blazed a trail for other Indigenous artists looking to follow in her footsteps.

Education

1960 Olympic College, Bremerton, Washington

1976 Framingham State College, Massachusetts

1980 University of New Mexico

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2025 Special Summer and Indian Market Exhibition, LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NM

2025 Art of Memories Told, LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NMw

2023–24 Memory Map, Whitney Museum of Ameri can Art, New York, NY; Seattle Art Museum, WA

2017–19 In the Footsteps of My Ancestors, Yellow stone Art Museum, MT; Missoula Art Museum, MT; Loveland Museum, CO; Tacoma Art Museum, WA

2012 Landscapes of an American Modernist, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, NM

2007 Paintings, Drawings and Prints, Ellen Noel Museum, Odessa, TX

2005 Connections: Old Work/New Work, Flomenhaft Gal lery, New York, NY

2004 Continuum: 12 Artists, National Museum of the American Indian, New York, NY

2003 Made in America, Belger Arts Center, Kansas City, MO

2003 LewAllen Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

2002 200 Years: Change/No Change, Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, PA

2001 Poet in Paint, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, NY

2001 Anton Gallery, Washington, D.C.

2001 Longwood Center for the Visual Arts, Farmville, VA

2000 New Work, Jan Cicero Gallery, Chicago

2000 Art Museum of Missoula, MT

1999 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Bush Barn Art Center, Salem, OR

1998 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Sacred Circle Gallery of American Indian Art, Seattle, WA

1998 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Steinbaum Krauss Gal lery, New York

1997 Modern Times, New Mexico State University Art Gallery, Las Cruces, NM

1996–98 Subversions/Affirmations: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, A Survey, Jersey City Museum, NJ; Lehigh University Art Galleries, PA; Austin Museum of Art, TX; Missoula Art Museum, MT

1995 Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, New York

1994 Jan Cicero Gallery, Chicago, IL

1994 LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NM

1994 SITE, Santa Fe, NM

1993 Parameters Series, Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, VA

1993 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Steinbaum Krauss Gal lery, New York

1993 LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NM

1992 The Quincentenary Non-Celebration, Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, New York

1992 LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NM

1991 Works on Paper, LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NM

1990 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: New Paintings, Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, New York, NY

1990 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, LewAllen/Butler Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM

1988 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Marilyn Butler Fine Art, Scottsdale, AZ,

1987 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Marilyn Butler Fine Art, Scottsdale, AZ,

1986 Speaking Two Languages, Yellowstone Art Center, Billings, MT

1986 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Bernice Steinbaum Gal lery, New York, November

1985 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Marilyn Butler Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM

1984 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Bernice Steinbaum Gal lery, New York, February

1983 Galerie Akmak, Berlin, Germany

1983 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Marilyn Butler Fine Art, Santa Fe, July

1980 Galleria de Cavallino, Venice, Italy

1980 Marilyn Butler Fine Art, Scottsdale, AZ,

1979 Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Kornblee Gallery, New York, NY

1978 Clarke Benton Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Selected Public Collections

Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AK

Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY