NEW YORK ABSTRACTION

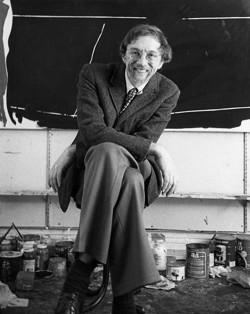

Norman Carton | Dan Christensen

Katherine Porter | Jack Roth | Edward Zutrau

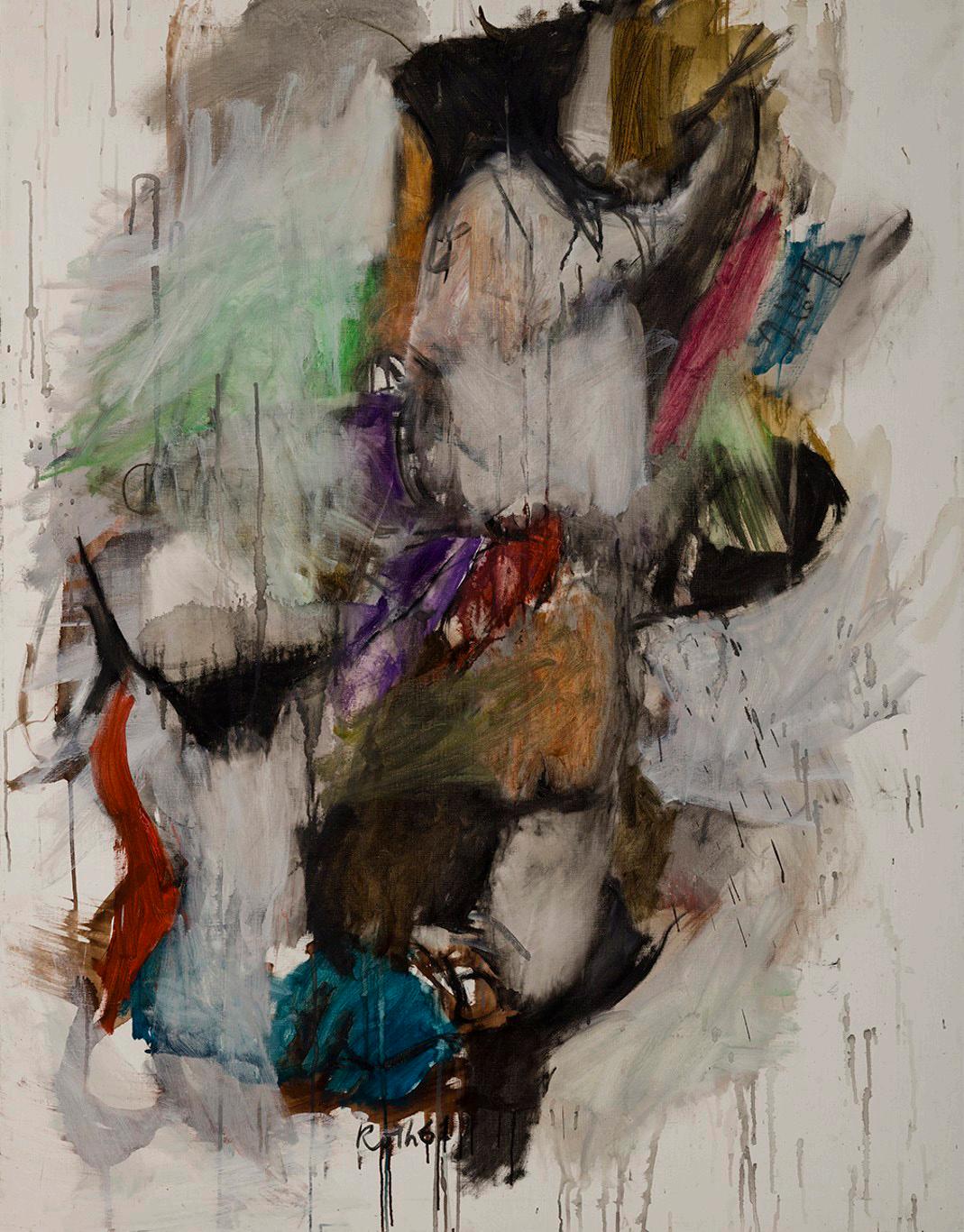

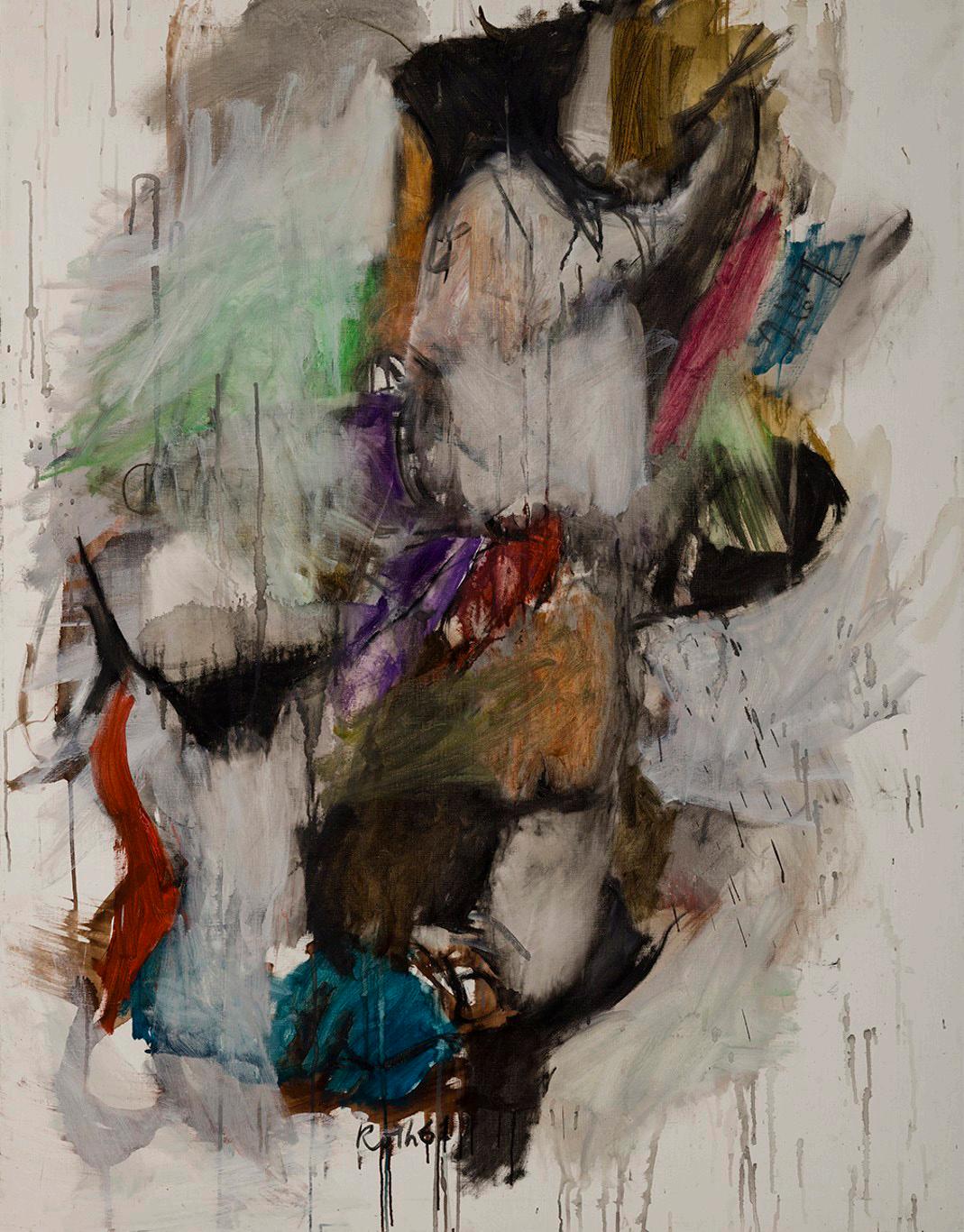

Jack Roth, Humpty Dumpty, circa 1961, oil on linen, 51.5” x 39.75”

Norman Carton | Dan Christensen

Katherine Porter | Jack Roth | Edward Zutrau

NEW YORK ABSTRACTION : N ORMAN C ARTON , D AN C

LewAllen Galleries 50th Anniversary Celebrating New York Abstraction

LewAllen Galleries initiates 2026 – its 50th anniversary year of being in the gallery business – with a group exhibition that focuses on New York Abstraction, featuring the work of Norman Carton (1908-1980), Edward Zutrau (1922-1993), Jack Roth (1927-2004), Dan Christensen (1942-2007) and Katherine Porter (1941 - 2024).

This illuminating presentation reflects on the broader significance of Abstraction in American art by looking at the works of these five very different artists who, at some point during their careers, worked in New York City. In various ways this show is indicative of the range and varied approaches of the larger group of renowned Abstract artists that LewAllen Galleries has also championed over the last quarter of a century in the dozens of exhibitions of abstract works it has staged.

In each of their own personal ways, the works of these artists demonstrate the basic tenets of abstract art. Their works are conceived to be singular and, as with all abstract art, do not strive to imitate a particular subject matter or attempt fidelity to a recognizable narrative. As scholars of abstraction have noted, abstract art is, finally, art that “looks like nothing but itself.”

Of course, the great hallmark of all abstraction is the liberation of creative artistic freedom as an approach to art making. Abstraction celebrates the freedom

K ATHERINE P ORTER ,

J ACK R OTH AND E DWARD Z UTRAU

from perceived orthodoxies of verisimilitude and particular subject matter in the creation of the artwork. First emerging in Europe out of movements that included Post-Impressionism and Cubism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, nonrepresentational Abstract art was generated by significant pioneering artists such as Vassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Hilma af Klimt.

Artists became free to express spontaneity, personal emotion, and subconscious response through non-representational marks, gestures, and expanses of color and material put onto canvas, linen, board, and also unconventional materials. In his 1911 treatise entitled On the Spiritual in Art – considered to be a foundational text on abstract art – Kandinsky advocated for the use of pure color and form to express inner emotional and spiritual truths, likening the process to creating music. In a similar fashion, art could now be liberated from discernible image or subject so that the artist could work from a spiritual or theoretical basis.

Correspondingly, viewers encountering the manifestations of such artistically personal forms of creative expressions are freed to experience their own personal sensations of emotion or exhilaration through non-representational art. It is that ineffable response, sometimes described as even “mystical” or “the abstract sublime” in intensity, experienced when viewing certain abstract art, that can cause the viewer to stand quietly and contemplatively and ponder as though looking at some incomprehensible but wondrous manifestation of transcendence. It is akin to the “awe” experience of seeing a magnificent sunset or an extraordinary mountain vista. It can trigger a flush of exhilaration that is intense.

After World War II, New York Abstract Expressionism had the distinction of being the first American school of art to gain international acclaim and significance –so much so that New York would supplant Paris, transforming New York into the premier city of the art world. This movement also became known as the “the New York School” characterized by two main styles: the gestural “action painting” of artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, who would dribble, pour, and energetically brush paint onto canvas, and the large-scale “Color Field” paintings of artists such as Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still, focused on the expressive potential of open fields of color, the materials and properties of paint, and the eloquence of their internal relationships.

Subsequently, other refinements and various other forms of New York abstraction would emerge, including what would be called “lyrical abstraction,” characterized by looser, flowing forms and brushwork and “stain painting.”

Throughout the various genres of abstraction, a profound sense of human agency is often present. There is a sense of the artist’s declaration of individuality evident from habits of gesture, marks, color relationships, and elements of composition apparent in a work of excellent abstract art. Because the work evinces the deepest feeling and thoughts of the artist, there should be traces of the artist’s hand discernibly charged in the materials. And of course, there is that wonderful, amazing, exhilarating sense of wonder from the experience of looking at the work. The “awe” factor.

These aspects of New York Abstraction are what LewAllen Galleries honors and celebrates in this exhibition. And it is these aspects – and the “awe” experience they have the capacity to produce in our audience – that the gallery has had the honor and privilege to present over the past 23 years, and it is these that it looks forward to continuing to seek and present to its audience in the years to come.

Kenneth R. Marvel

Katherine Porter, East Port, 2004, oil on canvas, 54” x 44”

KATHERINE PORTER

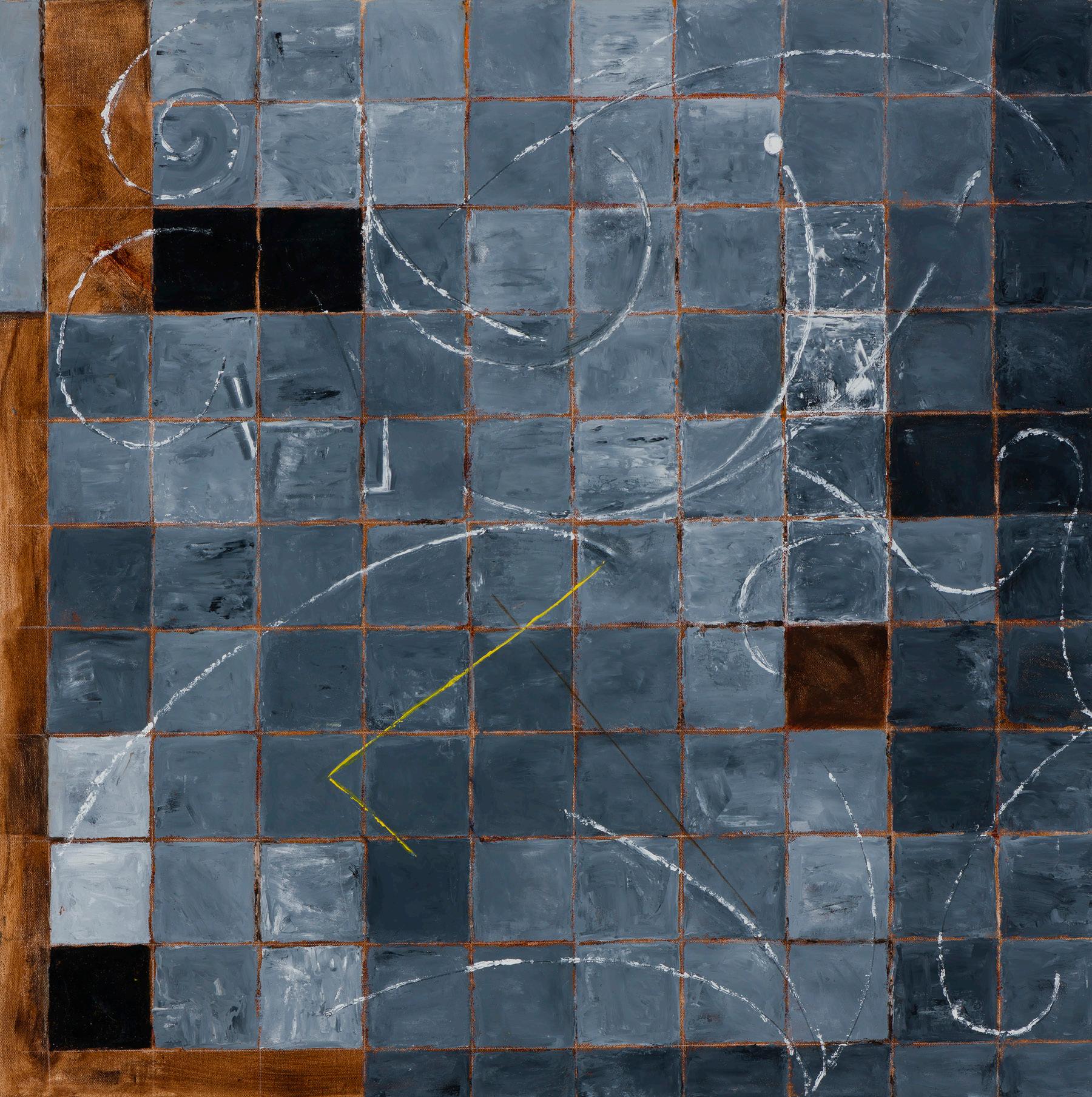

Katherine Porter’s (1941 - 2024) importance lies in the raw, kinetic interplay she forged between geometry and gesture. Over a remarkably distinguished career that spanned nearly six decades and with work in the permanent collections of more than forty important national and international museums, Porter stands as one of the great women of American Abstract Painting, with an enduring resolve that art should inherently maintain an integrative unity consistent with an artist’s aesthetic, social, political, and personal concerns. She built canvases that moved with a sense of wild spontaneity while always underpinned by rigorous compositional control. Her paintings are abundant with circles, triangles, rectangles, squares interposed with lines, spirals, arcs, scaffolds, and matrices, and fields of color, but these formal devices never feel ornamental—they serve as evidence of a painter wrestling with change, conflict and flux. The noted late art historian and Picasso scholar, Lydia Csato Gasman, described Porter’s protean body of work as ‘the vast domain of spontaneity untamed,’ which is ‘tempered, subjected to rational control by a supreme act of self-critical concentration.’ What made her distinctive is that she didn’t merely paint emotion in abstraction—she sought to manifest transformation itself: the clash of order and chaos, the visible and invisible, the psychic and the worldly. In doing so, Porter expanded the possibilities of abstraction for future generations—showing that bold color, disparate shapes, expressive mark-making, and the generative qualities of freedom could speak not just of an artist’s hand, but of the broader forces of change that shape our lives.

Katherine Porter, Opera 2012, oil on canvas, 40” x 40”

Katherine Porter, Arabesque 2014, oil on canvas, 42” x 42”

Katherine Porter, Joie de Vivre n.d., oil on canvas, 85” x 138”

Katherine Porter, Begin Again

2016, oil on canvas 41.75” x 38”

Katherine Porter, Sunset in Maine with Yellow Frame 2023, oil on canvas 48” x 42.25”

Katherine Porter, Blowup 2016, oil on canvas, 40” x 44”

Katherine Porter, Three Squares A Day 2016 - 2017, oil on canvas, 44” x 44 “

Edward Zutrau, Tokyo, 1958, oil on linen 63.75” x 51.25”

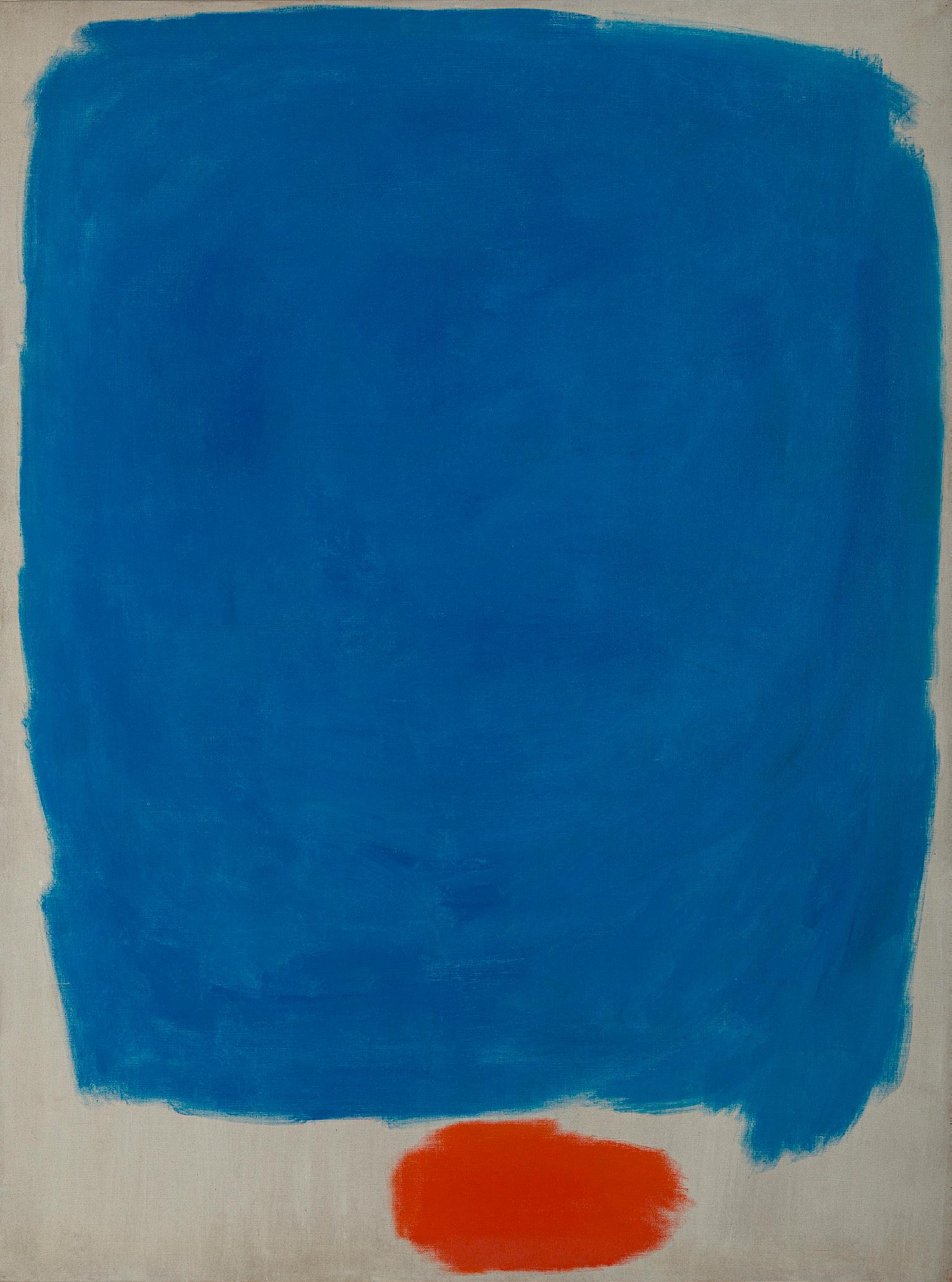

EDWARD ZUTRAU

Edward Zutrau (1922–1993), an American Abstract Expressionist painter whose career spanned four decades, was born in Brooklyn, New York. He developed a style of abstraction distinguished by its meditative stillness and balanced resonance, a quiet yet potent fusion of Western painting and Eastern sensibility. His formal training included studies at the Brooklyn Academy of Fine Art and the New York Art Students League. By the 1950s, Zutrau was actively exhibiting alongside major New York School figures. A significant turning point came in 1958 when he moved to Japan with his wife, Kikuko, a period that deepened his Zen and artistic influences. Zutrau’s visual practice links to the notion of “awakening” (satori) in Zen Buddhism, hinting that his art aimed to transcend the familiar boundaries of form and material. His works often revolve around large, softly delineated color fields, where subtle contours and harmonized tones evoke a contemplative space. The works explore relational dynamics of form and duality, with his soft geometric forms and simple brush movements seeming to arise and dissolve simultaneously. Zutrau articulated a still-point within color and form, inviting the viewer into a liminal threshold where shape recedes, hue expands, and time nearly pauses. In doing this, he questioned abstraction’s usual emphasis on action or expression, proposing instead that painting can serve as a space of presence and gentle revelation. His compositions seem to hover between painting and contemplation, their quiet surfaces charged with a subtle inner light, and his art becomes not merely visual but experiential. He was represented by the legendary art dealer Betty Parsons, who remarked of his paintings, “They are timeless, as if they stop time, itself.”

Edward Zutrau, Kamakura

1963, oil on linen, 38.25” x 51.62”

Edward Zutrau, Tokyo 1959, oil on linen 51.25” x 63.75”

Edward Zutrau, No. 3 (Blue Shape)

1965, oil on linen, 51.37” x 38.25”

Edward Zutrau, Untitled 1969, oil on linen, 36” x 28.75”

Edward Zutrau, Untitled 1954, oil on linen, 36” x 50”

Edward Zutrau, Abstraction (April)

1963, oil on linen 21” x 25.75”

Edward Zutrau, Untitled 1962, oil on linen 21” x 25.75”

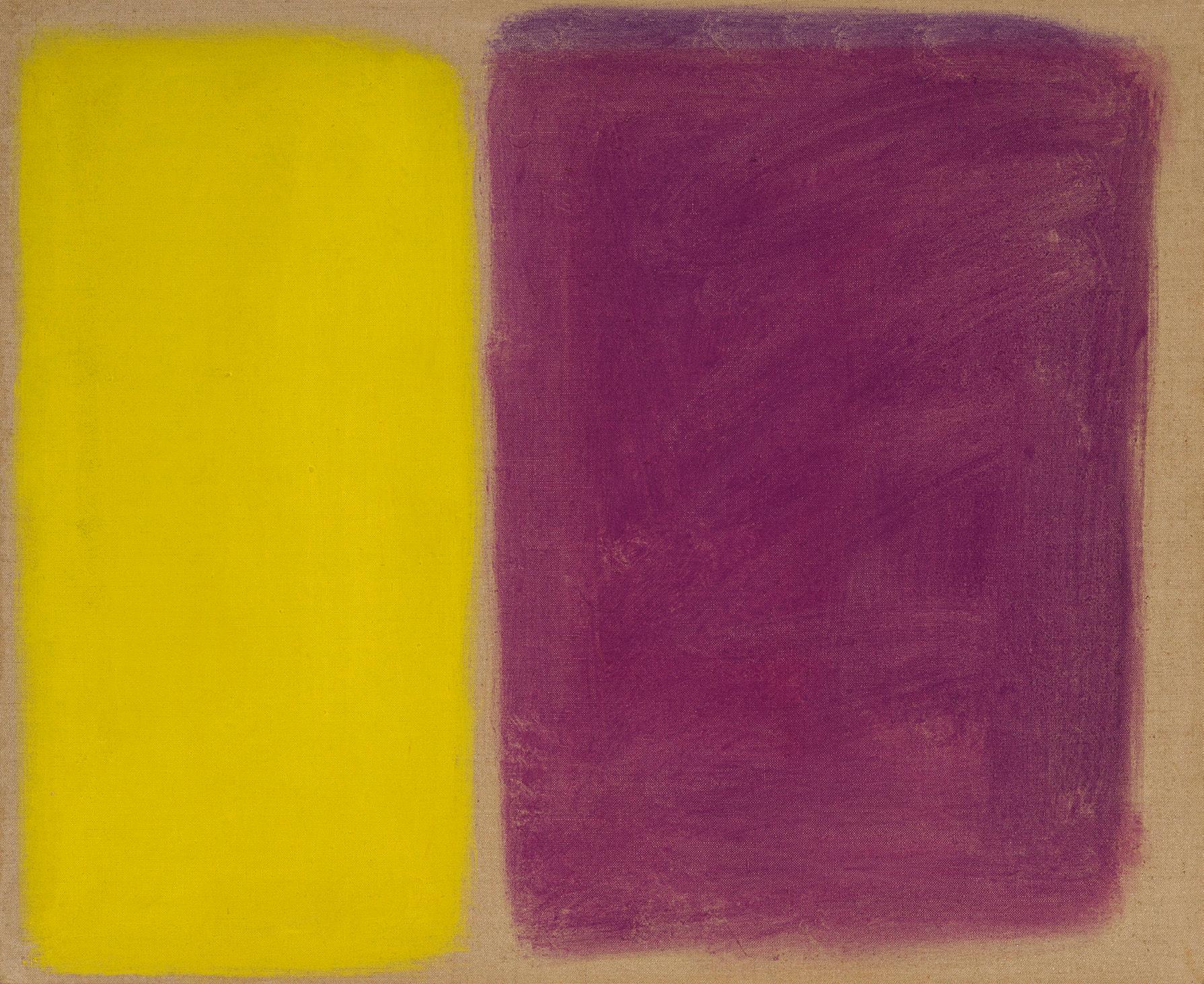

Norman Carton, Untitled #693, circa 1954, oil on canvas, 32” x 25.50”

NORMAN CARTON

Norman Carton (1908-1980), distinguished himself in the mid-20th-century American art scene through a forceful, deeply emotive approach to abstraction that placed color and gesture at the center of his visual language. Having fled the Russian pogroms as a child and settled in Philadelphia to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Carton used a 1934 fellowship to travel to Europe, where he was exposed to the work of masters like Matisse, Picasso, and Kandinsky. Although he began his career as an illustrator, he emerged as a superb colorist whose canvases wield rich, pulsating palettes and dynamic brushwork to evoke inner worlds of tension and release. Carton is particularly significant because his work bridges the modernist lineage—from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Surrealism, and Cubism—to the gestural dynamism of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, while retaining a personal signature built around luminous color fields that seem nearly spatial in effect. Carton described his practice as a “dialectical process” and the realization of “organic unity between color and plastic form,” reflecting a philosophical ambition to offer viewers the space for “free association” and a kind of contemplative immersion, often evoking the rhythmic complexity of improvisational jazz. This reflects not only his technical mastery—grinding his own pigments and exploring the materiality of paint—but also his commitment to re-frame the mid-century abstract movement by foregrounding color itself as subject and space. In addition to his many solo exhibitions, Carton’s legacy includes two decades on the faculty of the New School for Social Research, his advocacy for artists’ rights, and his work in public collections such as the Whitney Museum of American Art and the National Gallery of Art, solidifying his place as a singular interpreter of color’s emotional and spatial capacities.

Norman Carton, Island Within #1052 1963, oil on canvas, 26” x 41”

Norman Carton, Sierra Summer #1257

1964, oil on canvas 17” x 20”

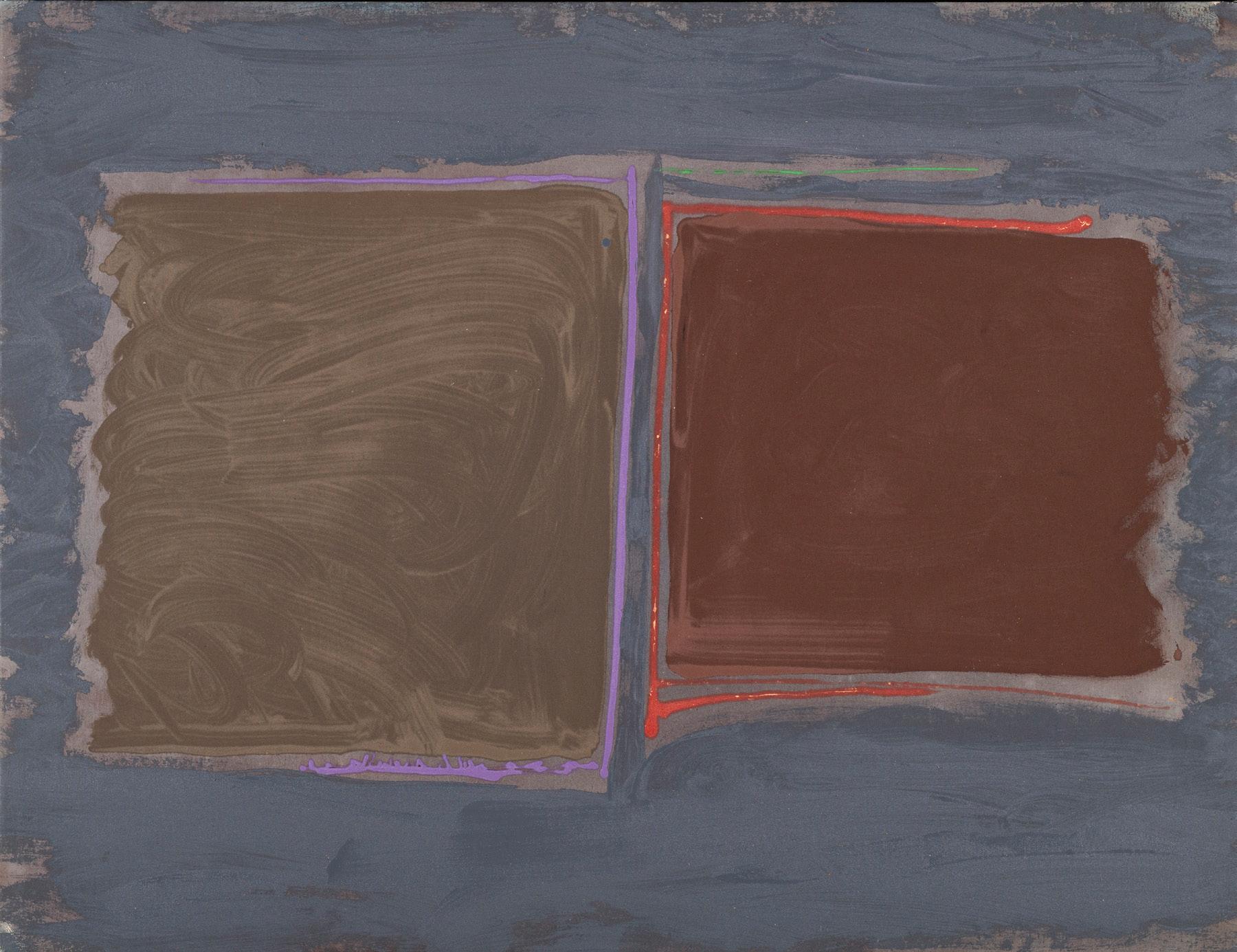

Norman Carton, The Gate #679 circa 1954, oil on canvas, 17.25” x 20.25”

Norman Carton, Turkey in the Straw #728

circa 1955, oil on canvas, 59” x 48”

Norman Carton, Untitled #680 circa 1954, oil on canvas, 24” x 30”

Norman Carton, Aegean Night #9536 circa 1960, watercolor on paper, 18.25” x 22.50”

Dan Christensen, Della Street, 1981, acrylic on canvas, 64.50” x 49”

DAN CHRISTENSEN

Dan Christensen (1942-2007) is a pivotal figure in post‐war American abstraction whose importance lies in the way he consistently challenged painting’s possibilities — its techniques, its energy, and its materials. The great critic Clement Greenberg anointed him in 1990 as “one of the painters on whom the course of American art depends” and viewed him as an exemplar of “post-painterly abstraction. Widely recognized as one of America’s foremost color abstractionists he emerged during the Minimalism-dominated 1960s but chose instead to explore a more exuberant sensibility: his signature spray works unleashed ribbon-like loops of color across vast canvases with a spray gun, allowing for a shimmering, all-over surface that seemed to physically pulse with motion. He fused the broad sweeps and spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism with the clarity and expanses of Color Field painting, yet resisted being pigeonholed thanks to his restless experiments with squeegees, spray guns, scraping tools and exotic pigment layering. He didn’t stay in one lane but kept pivoting—from minimalist bars to spray‐loops to scraped slabs to gestural stains—thereby showing that abstraction was not a closed chapter but an ongoing adventure. He achieved spectacular success at an early age, exhibiting in two Whitney Biennials before the age of 26 and winning awards such as a National Endowment Grant in 1968 and the Guggenheim Fellowship Theodora Award in 1969.

Dan Christensen, 5 or 6 P.M 1994, acrylic on canvas, 47” x 99 “

1982,

Dan Christensen, Untitled

acrylic on canvas, 83” x 79”

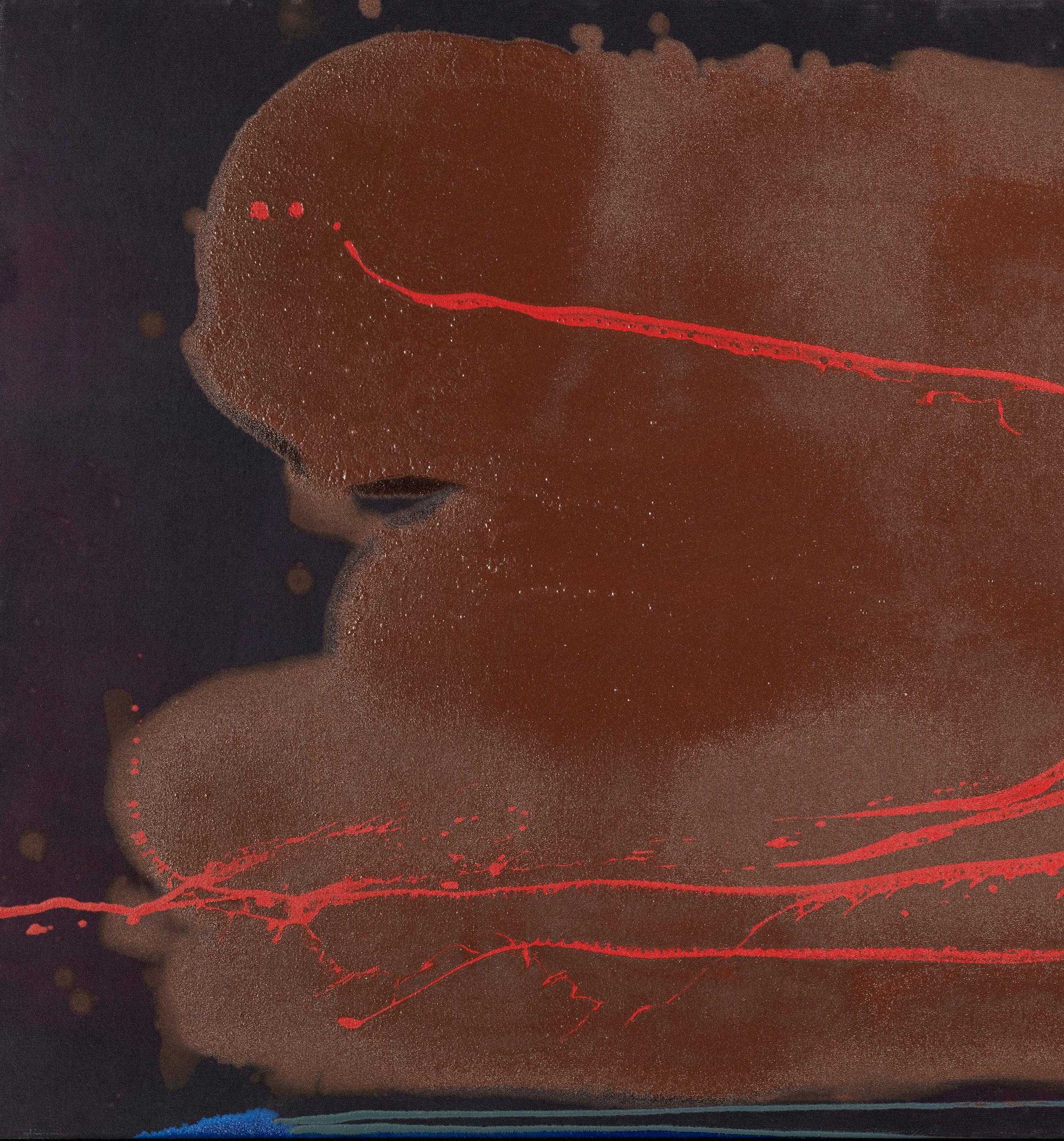

Dan Christensen, Rough Rider 1981, acrylic on canvas, 88.5” x 67”

Dan Christensen, Land's End 1971, acrylic & enamel on canvas, 78” x 116.50”

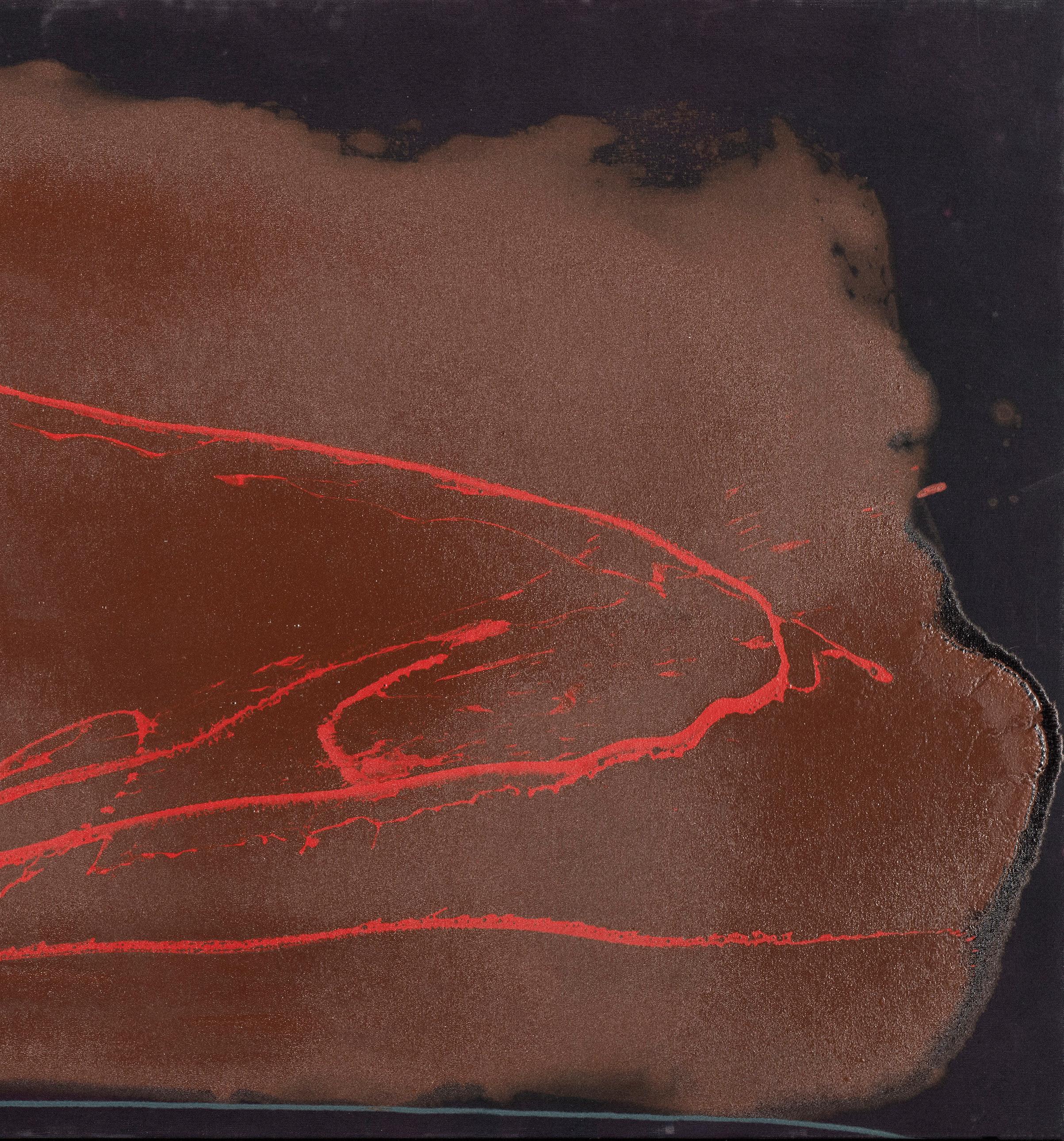

Dan Christensen, Changzhou 1981, acrylic on canvas. 68” x 58.5”

Dan Christensen, Electric Avenue 1983, acrylic on canvas, 66.5” x 55.5”

Dan Christensen, Creek Treaty 1982, acrylic on canvas, 28.5” x 81.5”

Dan Christensen, Doxy II, 1980, acrylic on canvas, 66.5” x 51”

Dan Christensen, Song of Ceylon 1977, acrylic on canvas, 73.5” x 91”

Dan Christensen, Dolphin Diver 1981, acrylic on canvas, 40.5” x 75.5”

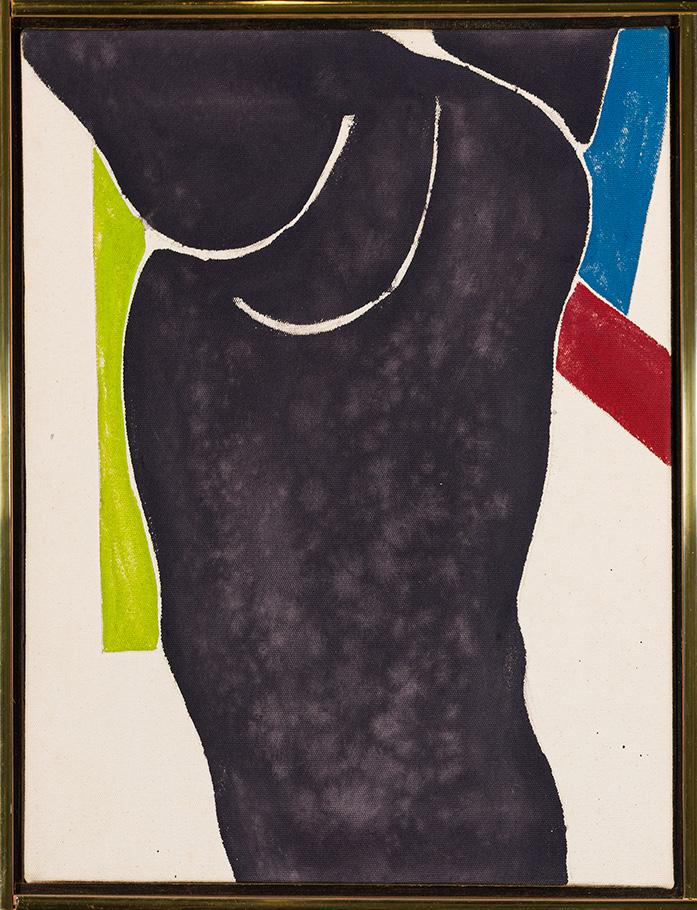

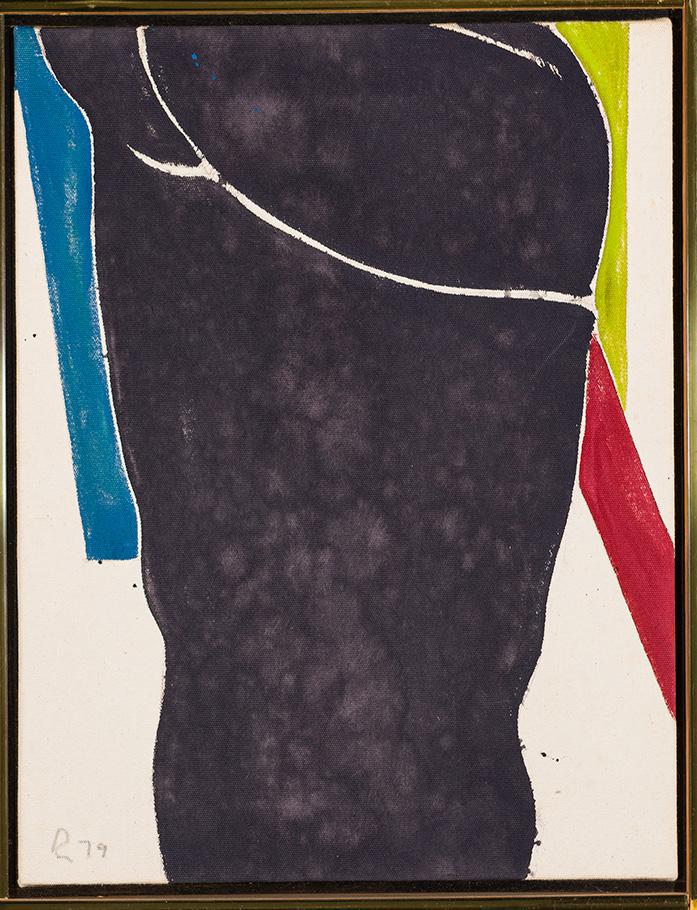

Jack Roth, Untitled (#13803), 1979, acrylic on canvas, 55” x 46”

JACK ROTH

Jack Roth (1927-2004) stands out in the narrative of American painting for his persistent melding of intellectual discipline and painterly freedom—an abstraction that is at once mathematically attuned and emotionally alive. Coming from a background in math and science, including a PhD in mathematics from Duke University in 1962, and a concurrent career as a longtime professor of mathematics who published two books on calculus, he carried into his canvases a rare fusion of analytic structure and lyrical gesture: his works often feature thin contour lines and soft forms set amid expanses of saturated color and subtle geometry, giving his abstractions both a shimmering immediacy and an underlying sense of order. Working initially within the realm of Abstract Expressionism—starting with his selection for the landmark Younger American Painters exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1954—and then moving into the arena of Color Field painting, Roth’s evolution from gestural marks toward more spacious, unified fields of pigment yields a body of work that both reflects and transcends mid-century abstraction. His later work, which often incorporated broad shapes of stained matte pigment on unprimed canvas and sometimes evoked the ‘cutout’ shapes of Matisse’s late paintings, underscores his importance in how he synthesized these traditions by structuring abstraction without making it sterile. He was also awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for painting in 1979. He treated canvas as a site of both discovery and control, where line, edge and color become vectors of thought rather than mere display. His work invites the viewer to read more than form—it invites a contemplation of process, structure, and sensation in concert. In his paintings, translucent layers of pigment appear to breathe, creating an almost atmospheric tension between spontaneity and containment. This delicate balance of intuition and intellect gives Roth’s work its enduring resonance— each canvas functioning as both a meditative space and a visual equation for how emotion can be structured through form.

Jack Roth, Rope Dancer #16 1980, acrylic on canvas. 32” x 67”

Jack Roth, Ibid #5

acrylic on canvas. 66” x 66”

Jack Roth, New Synthesis #11 1981, acrylic on canvas, 55” x 47.75”

Jack Roth, Untitled #2833 n.d., acrylic on canvas, 30 x 48

Jack Roth, New Synthesis #27

1981, acrylic on canvas, 92” x 65.75”

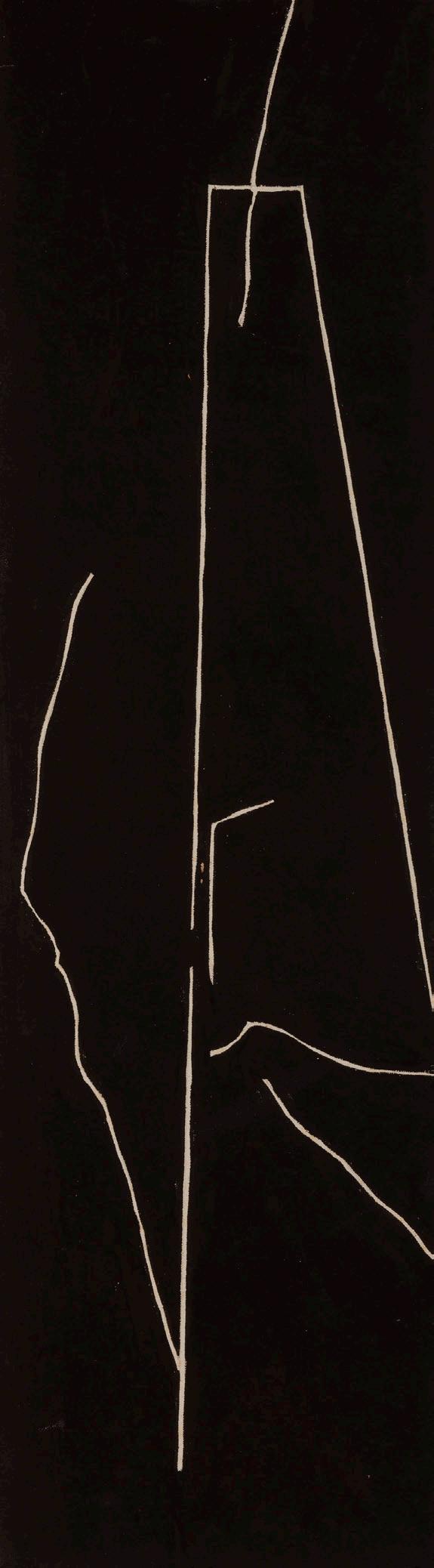

Jack Roth, Synthesis XXVII #32260 1981, acrylic on canvas, 36” x 10”

Jack Roth , Swy (diptych) 1979, acrylic on canvas, 18” x 28“

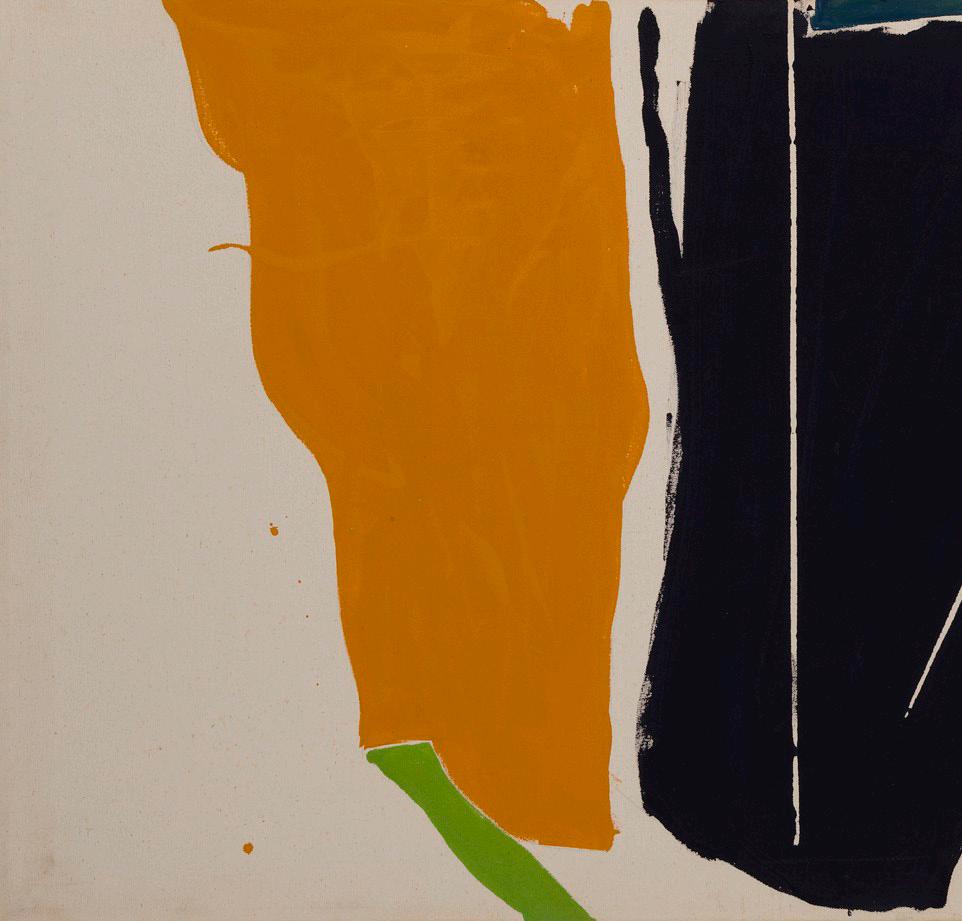

Jack Roth, Humpty Dumpty circa 1961, oil on linen, 51.5” x 39.75”

Front: