JAUNE QUICK-TO-SEE SMITH

ART OF MEMORIES TOLD

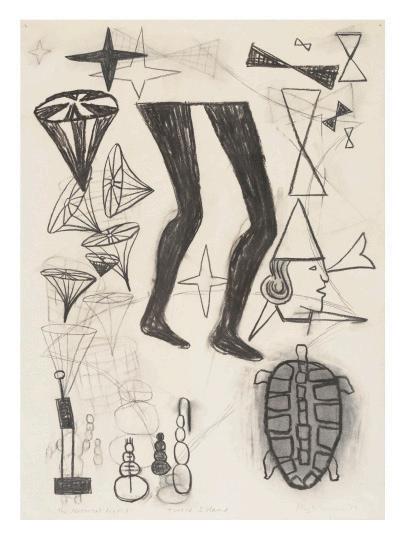

Monotype,

(Part of the 1998 Monotype series, page 18)

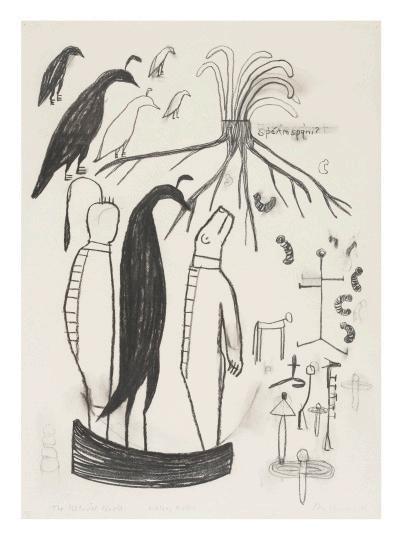

Monotype,

(Part of the 1998 Monotype series, page 18)

The world lost an extraordinary artist and person on January 24, 2025 with the passing of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith at the age of 85. Internationally prominent for her groundbreaking artwork that made visible the history and experiences of Indigenous people, Smith is today considered one of the most prominent Native American artists of the past century.

LewAllen Galleries is deeply honored to present this exhibition entitled Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Art of Memories Told. It is the first private gallery exhibition to honor the life and legacy of this extraordinary artist following her passing. Comprised of twentyfive major original works on paper including pastel paintings, monotypes, charcoal and graphite drawings, and mixed-media, the exhibition also has special significance for Santa Fe. Smith was a long-time resident of nearby Corrales and this is the first solo gallery show in New Mexico of her work in over two decades.

Smith’s career has been a profoundly important one in many ways. She was honored in 2023 with a major solo retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, the first Native American artist in the museum’s history to receive such an exhibition. That show traveled also to the Fort Worth Modern Museum and the Seattle Art Museum in 2023 and 2024. Works from the Whitney show are included in this LewAllen exhibition. The major 263-page catalog published by the Whitney to accompany the retrospective provides important insight into Smith’s art and career and reflects the esteem in which she is held in today’s art world.

Smith’s art transcends boundaries—both culturally and artistically—through her deep commitment to storytelling. She put messages in her art expressing Native American truths, includ-

ing about reclaiming lost histories, affirming Indigenous identities, and urging protection of the environment and ancestral lands, among other causes she pursued with tenacious resolve.

Over the course of more than five decades, her diverse range of works in a variety of media have served as powerful means for her voice to be heard and for her unflinching efforts to be expressed in behalf of redefining and preserving the history and identity of Indigenous people in American life. Her work has had a deep and abiding concern with memory and its importance for the life and legacies of the people and their land, as well as the sacred inter-relationship between the two as taught by her tribal culture. These have occupied her passionate energies for over fifty years of making art, giving more than 200 university, museum and conference lectures, and striving to enlighten minds and change hearts.

Smith’s art bridged the past to the present to ensure that the past is neither forgotten nor remembered erroneously. “Smith’s images bear witness. They are a recounting of truths… She only asks us not to forget … She reminds us what is sacred,” wrote Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Associate Curator of Native American Art, in her essay entitled “The Things She Carries” published in the catalog accompanying the Whitney Museum retrospective. Stated in Smith’s own words, her work exists to “remind viewers that Native Americans are still alive. This is always my interest … So there’s a historical continuity from something in the past, up to the present.”

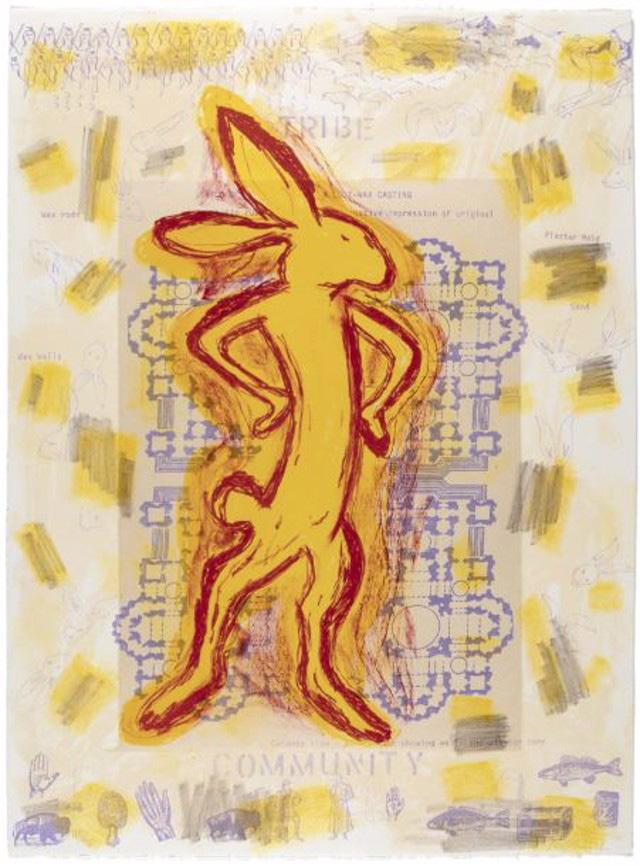

In her pursuit of this mission, Smith's work often cleverly blurred lines between polemic and poetry, engaging viewers with humor as well as directness. Perhaps it was the mythic “trickster” coyote in her - that aspect of her playful personality - that prompted her to encase her messaging in layers of imagery that was often unfamiliar or abstract, enticing viewers to unravel meanings. “All the better to be provocative but encourage people to look” she would say. Smith’s combination of imagery, drawing upon Native American symbols, Pop culture, and ancient petroglyphic characters, all within the context of American modernism, has operated to expand the confines of American art. The meanings in her works may be nuanced and complex but, as one engages with the work, the meanings become clearly present and significant.

Smith expressed her intention this way:

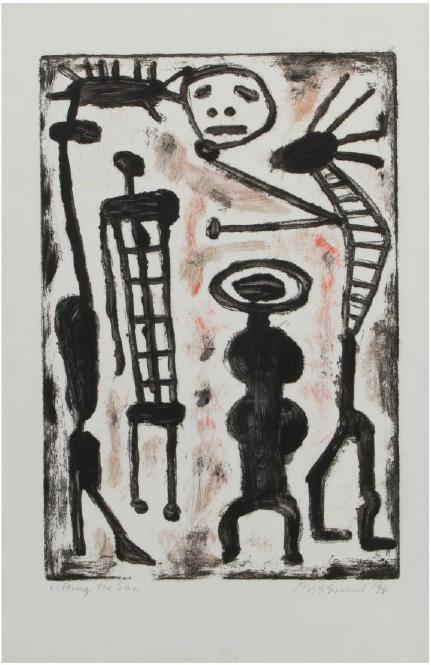

Lifting the Sun, 1996, monotype, 22.5" x 14.75"

Part of what I do in my work is using my work as a platform for my beliefs. Can I tell a story? Can I make it a good story? Can I add some humor to it? Can I get your attention? Those are all things that I try to do with my artwork. It's not always successful, but it's important to speak up when you believe in something so strongly, and I passionately believe in the life that I live. I think that my work will probably go on being political in some way.

There is little doubt that Smith achieved those goals over her career of more than fifty years. Her work became a powerful platform. It captured enormous attention including through the more than 100 solo exhibitions accorded to it and the thousands of viewers who attended them. With her art, Smith told her stories, and the stories she told were engaging and interesting and vastly more than just “good.” They spark curiosity, challenge perspectives, and push boundaries in American art, and they cemented her legacy as one of the most dynamic, provocative, and impactful artists of her generation.

Those stories are widely acknowledged to have been groundbreaking in their success to increase awareness of issues still

facing Native Americans and the environmental perils that threaten the land so deeply cherished by her. These are stories, that at various levels of specificity, are told by Smith to remember but also to change the ways of the past, the ways that have for so long dehumanized Indigenous people of America and created suffering where there could have been respect and caring.

Smith once described her art as a "diary" of her life which was itself a compelling story. An enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, Smith was born on January 15, 1940, in the St. Ignatius Mission on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana. Her teenage mother disappeared when Smith was still a toddler leaving her much older father, a horse trader, to raise her. They moved frequently, and between the ages of eight and fifteen, when she wasn’t in school, Smith worked in canneries and in fields, harvesting rhubarb and raspberries.

Though fascinated with art from an early age, she said that “I wasn’t inside of a museum until I was in my 20s.” Not yet able to afford crayons or paste – or the correspondence art course on the back of a matchbook she once sent away for - her first experiences with art as a child came with materials connected to her life in and among the earth and nature.

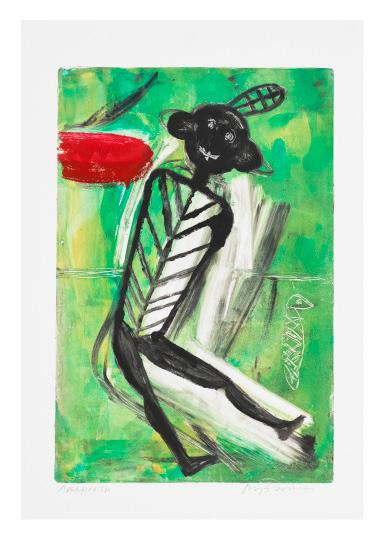

Rabbit, 1996, monotype, 22.5" x 18.5"

In an interview she recalls “I always drew. I remember drawing on dirt with a stick and with my hands. Drawing has always been natural to me.” Living on reservations where ancient petroglyphs and cave paintings were common, these influences, drawing and mark-making all became evident in her work throughout her career.

During high school, however, she was discouraged by teachers and administrators from pursuing an art career owing to her gender and Indigenous heritage. She was admonished by an adviser that “Indians don’t go to college.” Nevertheless, she enrolled at the two-year Olympic College in Bremerton, Washington where she was told “you draw better than all the men here, but you can’t be an artist, women cannot be artists.” Despite that, she pursued art anyway and – as her son Neal AmbroseSmith says, “following Coyote’s advice” - she received her associate's degree from there in 1960. For the next twenty years she persisted with her art education.

She worked her way through school and ultimately met her partner, Andy Ambrose, and had children. For years she struggled to fit her college studies in among the various jobs she was forced to hold to support her young family, including those of factory worker, waitress, veterinary assistant, and janitor. Smith earned a degree in art education, in 1976, from Framingham State College in Massachusetts, and received an MA in visual art from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in 1980.

Though her career struggles were many, her accomplishments

as measured by art world standards were astonishing. While still a student she had her first show in Santa Fe in 1978 followed by a show in New York in 1979. In addition to making and exhibiting her own art, Smith was, early on, a talented curator and a tireless advocate for Native American artists, including founding the Grey Canyon Group, a collective of Indigenous artists who exhibited their work together, both domestically and internationally. She subsequently organized more than thirty group exhibitions featuring Native artists. Among them was the highly regarded “Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar, and Sage” (1985). In 2023, she was chosen to be the curator of “The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans” at the National Gallery of Art, the first exhibition of contemporary Native American art ever held there. She had also been the first Native American artist to have a work purchased by the National Gallery in 2020.

Adding to these career firsts, Smith has also been recognized with numerous awards from leading arts organizations, and has been awarded with four honorary doctorate degrees. In addition, she was elected to the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York and was the recipient of the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. Despite these major distinctions, Smith retained a remarkable sense of humility, never losing sight of her important personal goal to open doors for other Indigenous artists. In an interview with The New York Times about the Whitney Museum retrospective, she noted “When I came through the door, I bring a community with me … I want there to be others after me.”

Her efforts have also helped save important cultural institutions. For example, after joining the Board of Trustees of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe in the 1980s and seeing that the school was suffering economically, Smith began a concerted advocacy campaign to persuade Congress to provide financial support for the IAIA which resulted in creating a solid fiscal foundation for the institution. In another famous example, after Smith moved to Albuquerque in the seventies, she became involved in bringing attention and successful local activist support to save from development the land now known as Petroglyph National Monument. In connection with it she created works including her iconic series Charlo, Petroglyph Park, and Goose Prairie series, examples of which are included in this exhibition.

Today Smith’s work is held in numerous permanent collections of important national and international museums including the Museum of Modern Art in Quito, Ecuador; the Museum of Mankind, Vienna, Austria; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC; the Museum of Modern Art; the Brooklyn Museum; the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Whitney Museum; and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; among others.

In promoting and generating opportunities for younger Native artists, Smith proved to be a paragon of generosity. Having played a major role in “cracking the buckskin ceiling” in the art world for Indigenous artists, she maintained a steadfast commitment to “raising their voices”. About this aspect of her work, Smith observed that this came as a natural part of her tribal heritage which possessed a “sharing cultural mandate.” As an example of this, in what has been described as her “most ambitious curatorial undertaking,” Smith curated the last major

project of her life, the important survey exhibition entitled “Indigenous Identities: Here, Now and Always” at the Zimmerli Art Museum of Rutgers University in New Jersey. It features the works of 97 artists from 74 Indigenous nations. It opened on February 1, 2025, just a week after her passing.

Smith’s strength as an artist derived from no ordinary source. “My work comes from a visceral place – deep, deep as though my roots extend beyond the soles of my feet in sacred soils.” She assembled elements that connect her to ancestors - elements such as petroglyphs and Indigenous symbols with powerful mythic significance – assembled, as she put it, “when the spirit moves me,” in order to tell her stories and work a new kind of magic that only art can do. It is the aggregation of these images and marks that has the feeling of a primal connection to a great spirit that will be the sustaining imprint of Smith’s intentions and labors.

The combination of elements placed in any of the works included in this exhibition attains the status of a kind of reliquary. They are repositories of the marks and images Smith has assembled to create meanings that now live as her legacy. A writer for The Times describes Smith’s art as possessing “a force” that is “urgent” and “unflinching.” From the grit of her experiences and the generosity of her spirit - both to use her art in service of elevating awareness of Indigenous people’s issues and the imperative for the voices of other Native artists to be heard – this constitutes the gravitas that courses beneath her legacy and will sustain her place both as a major figure in American art and as an extraordinary advocate for causes she believed in so passionately.

Her work in all its various forms will also be a reminder of the efficacy of that clever coyote, that brilliant trickster who knew how to balance subtle humor and clear-eyed icy clarity to visually articulate effective messages in her art. She put her heritage in her art and it will stand as mighty as a mountain.

Smith will be remembered too for her years of dedication of work for improving the lives of others and elevating the presence of those who otherwise might never be seen, and for her remarkable humility in the process of doing so. And in the process, she will be recognized as one of America’s greatest artists. In the final analysis, after all her struggles, incredible challenges and enormous work, that humility is astonishing and perhaps remains a glowing testament to her personal character. Her own words, spoken toward the end of her life to her son Neal, sums up her state of mind about it all: “Lucky Duck I am.”

KENNETH R. MARVEL

LewAllen represented Smith’s art for more than twenty years beginning in the early 1990’s and is deeply honored to present this exhibition of her work. The gallery is most grateful to Garth Greenan Gallery in New York with whom this exhibition is in collaboration.

At the heart of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s art is her connection with the land. The land is that which is immutable and spiritual, and connects all people back to their ancestors. In the legend of the Salish culture, the Creator sent Coyote to prepare the earth and taught man to respect the earth and all creatures that live upon it to live there in harmony. This spirit is alive in Smith’s work.

As Laura Phipps, the curator of the Whitney Museum retrospective exhibition of Smith’s work, wrote in the Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map catalog, "[Smith's] drawings, prints, paintings, and sculptures exist in conversation … with her own memory and, most importantly, with the legacies and life of the land. [...] These works engage Indigenous epistemologies of mapping as storytelling, rather than as geopolitical divisions".

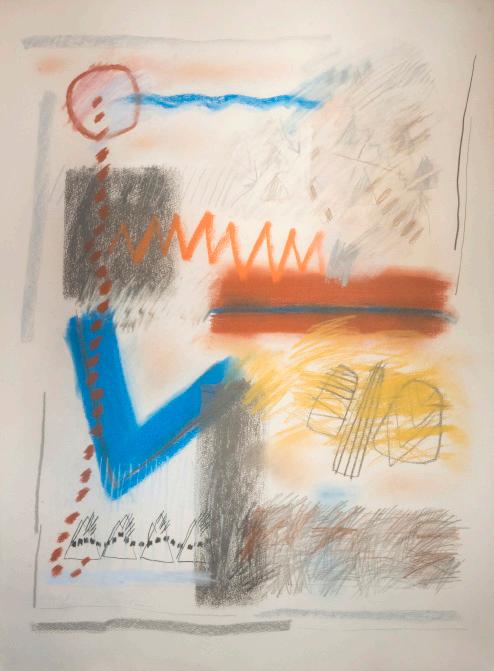

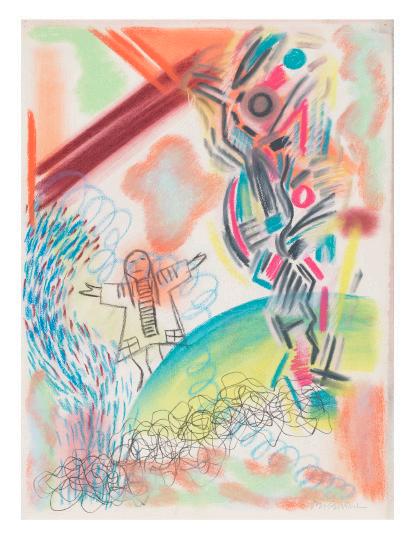

This is evident in Smith’s later map paintings but was showcased in her earlier works of the Wallowa Waterhole and Goose Prairie series included in this exhibition The visual language

Smith develops in these works include triangular forms representing tipis, and arrows and dashed lines signifying migration and movement. Her use of dotted lines represent fences, but in her vision these are mutable and varying, a view consistent with her belief that the “landscape is never static” corresponding with her the resistance evident in her work to colonial narratives of land use.

In these series of pastel and charcoal drawings, Smith divides the paper with planes of colors and exquisitely rendered lines that move around the page. The consistent sense of movement and openness in these works underscore the ideas of human and animal habitation and the land’s enduring embrace of freedom that sustains Smith’s journey in the ongoing story her art depicted along with Coyote.

On the cover:

Wallowa Waterhole: Spring Tracks, 1979

Charcoal and pastel on paper, 41½" x 30"

Prairie Series #12, 1978

In this series, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith follows Chief Charlo, Little Claw of the Grizzly Bear (1830–1910), Chief of the Salish Tribe in the Bitterroot Valley near Missoula, Montana. He became Chief in 1870 after his father, Chief Victor (Many Horses) died. Shortly after, in 1871, the U.S. government broke the Treaty of Hellgate that had been signed in 1855 with Charlo’s father as one of the signatories when he was Chief. That Treaty aimed to preserve Salish land and autonomy, but problems with language and translation worsened ever increasing infringements by non-Indian squatters asserting claims to Native lands and resources.

After the 1864 gold rush in the newly established Montana Territory, pressure upon the Salish increased both from illegal settlers and government officials. In 1870, Chief Victor died, and was succeeded as chief by his son, Chief Charlo. Like his father, Charlo adhered to a policy of nonviolent resistance. He insisted on the right of his people to remain in the Bitterroot Valley. But in 1871 territorial citizens and officials successfully lobbied President Ulysses S. Grant to declare that a land survey required by the Hellgate Treaty had been conducted and that it had found that the Flathead Reservation was better suited to the needs of the Salish Tribe than the Bitterroot Vallery. On the basis of Grant's executive order, Congress sent a delegation, to make arrangements with the tribe for their mandatory removal. Chief

Charlo ignored their demands and even their threats of bloodshed, and he again refused to sign any agreement to leave. U.S. officials then simply forged Charlo's "X" onto the official copy of the agreement that was sent to the Senate for ratification.

Conditions had become intolerable for the Salish by the late 1880s, after the Northern Pacific Railroad Bitterroot Branch Line was constructed directly through the tribe's lands in the Bitterroot, with neither permission from the native owners nor payment to them. With crop failures and buffalo extinction, Charlo finally signed an agreement to leave the Bitterroot Valley in November 1889. Inaction by Congress, however, delayed the removal for another two years, and according to some observers, the tribe's desperation reached a level of outright starvation. But in October 1891, a contingent of troops forced Charlo and the Salish out of the Bitterroot and roughly marched the small band sixty miles to the Flathead Reservation.

Smith’s Charlo series of pastel paintings on paper vividly depicts the rootedness of a people to their treaty-guaranteed land but also the emotional turmoil endured by them from the betrayal of that guarantee and their subsequent uprooting and forced relocation.

“Fiercely energetic, the works convey the emotive resistance of Native people, past, present, and future, as well as the agitated spirits of the land coming together at the escarpment of the West Mesa. The relevance of the series endures today, as we look back and ask ourselves if we are repeating the mistakes of the past, or if we are healing our futures.”

— LARISSA NEZ, in her essay entitled “Indigenous Power in Public Spaces” Whitney Museum catalog for Jaune Quick-toSee Smith: Memory Map

In her important and learned book entitled Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: An American Modernist, situating Smith’s work within historical and cultural movements of American Art, Dr. Carolyn Kastner, scholar and retired curator at the Georgia O’Keefe Museum in Santa Fe, notes that “The majority of Smith’s artwork expresses a personal sense of place and connection to the land of North America.”

This connection is especially manifest in Smith’s Petroglyph Park series created between 1985 and 1987. Smith’s home was near the West Mesa escarpment outside of Albuquerque where more than 24,000 petroglyphs and dozens of prehistoric and historic sites are situated representing more than 12,000 years of human history. It is estimated that about 90 percent of the petroglyphs were created during the period between CE

1300 until the end of the 17th century. Over this period, the Native population was increasing quickly and Pueblo adobe villages were being built along the Rio Grande River at the base of the Sandia Mountains. As Kastner notes, “The elders from the nearby pueblos located along the Rio Grande use the images to teach history, culture and spiritual beliefs. Many claim relationships to the site because they recognize the images as having deep cultural and spiritual significance.”

As early as 1970, developers had been attempting to build homes, commercial centers, and roads on the escarpment. Though various community groups and Native activists pushed back on development, encroachment occurred. Then in 1985, Smith began her series of paintings and pastels on paper, including those in this exhibition, in order to call attention to efforts to block development. Kastner’s book explains that Smith’s works from this series “reinvigorated reverence for the sacred and helped to transform the political landscape.”

In 1990 the Petroglyph National Monument was established by Congress after years of efforts by the Friends of the Albuquerque Petroglyphs and other groups aided in material ways by Smith’s generosity in contributing proceeds of sales of works from her Petroglyph Park series according to Kastner. Today the entire 17-mile escarpment, location of most of the petroglyphs, has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

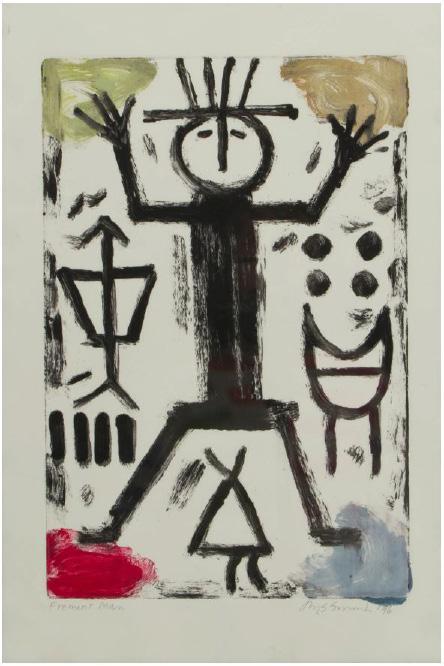

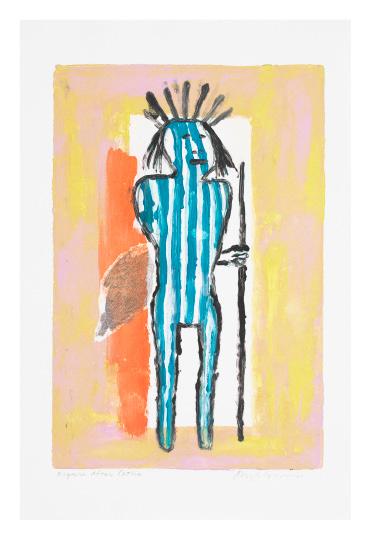

Although not a part of the Petroglyph Park series of 1985–1987, the monotype above, entitled Fremont Man, is an excellent example of how Jaune Quick-to-See Smith makes use of petroglyph images beyond those of the West Mesa in Albuquerque. This image is likely inspired from those of the Fremont people, a pre-Columbian archaeological culture. Large numbers of petroglyphs were discovered at Range Creek, Utah dating to a thousand years ago.

Man, 1996 Monotype, 22" x 15"

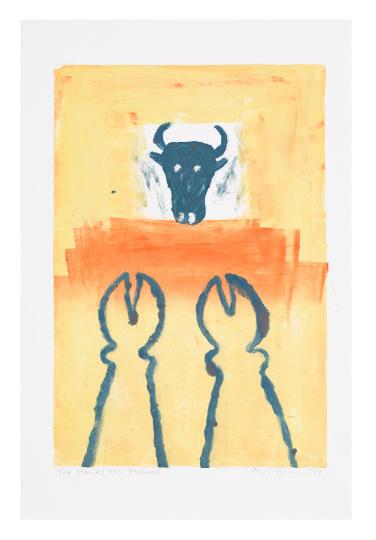

The 1998 monotypes by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, though not originally conceived as a cohesive series, form a distinctive body of work created through the monotype process. These pieces offer an unfiltered glimpse into the artistic process, marked by a raw and direct approach. While each work stands independently, they share common thematic ground, drawing on anthropological, art historical, pictographic, and photographic records related to Indigenous peoples and cultures.

In her essay "Printmaking as Resistance and Survival," published in the Whitney Museum catalog Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, Josie M. Lopez observes the powerful agency Smith’s prints possess within contemporary art. Lopez writes, “Her decades-long foray into printmaking highlights how her works exert power and agency within the context of contemporary art by incorporating historical perspective, the legacies of printmaking, and imagining a future that embraces Indigenous knowledge.” These monotypes, rich in historical references, exemplify how Smith’s work subverts and engages with diverse artistic movements, reflecting both historical specificity and a strong dialogue with the viewer.

Several of these monotypes reference specific sources that have become central to Smith’s exploration of Indigenous rep-

resentation. Figure After Catlin (1998) derives from an illustration in George Catlin's Illustrations of the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, a comprehensive 19thcentury work that documents Indigenous people. Wishram Man (1998) revisits the photographic portraits of the Wasco-Wishram tribe taken by Edward S. Curtis. Bering Strait Theory (1998) centers on an Inuit carving and draws from the theory that the ancestors of the Inuit people crossed the Bering Strait land bridge thousands of years ago. Arapoosh (1998) references the shield of Chief Arapoosh, held at the National Museum of the American Indian. These works convey Smith’s engagement with cultural archives while subverting their historical context and offering new meanings. As Smith herself reflected, "knowledge is what comes from books, and wisdom is a gift from our elders."

A recurring figure in Smith’s work is the coyote, seen prominently in Coyote Wears a Mask (1998). Often interpreted as a selfportrait, the coyote embodies qualities of the trickster, creator, and dissembler. In the essay “Coyote's Ransom: Jaune Quickto-See Smith and the Language of Appropriation” Erin Valentino notes, "Like Coyote, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith has turned on the light. It is up to you to see the power and inescapability of what she brought to light."

Buffalo Dancer, 1998

Monotype, 22" x 14"

Weather Dancer, 1998 Monotype, 22" x 14.75"

, 1998

Bering Straight Theory, 1998

Monotype, 22" x 15"

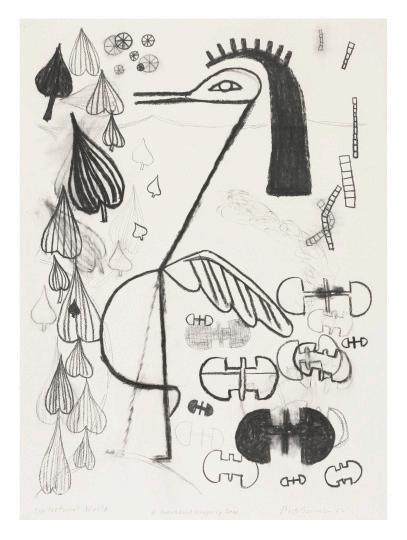

So much of the visual content of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s art draws from the remembered legends and ancient images of Native people that Smith seeks to preserve in her work and whose symbolic significance uses to give contemporary meaning as well as spiritual resonance in it. Specifically, in the Natural World series, Smith makes use of petroglyphic images and references from her own Salish tribal culture and mythology to suggest relationships between nature and the spiritual realm. As always, Smith refuses to create simple, romantic narratives and these drawings are especially loose and open for interpretation. The bird and animal symbols suggest insights into traditional stories, clan ties, and belief systems that her Salish culture has cultivated over many centuries. They fit into a larger creation story that, according to Salish legend, begins:

“When the Creator, the Maker, put the animal people on this earth, the world was not yet fit for mankind because of many evils. So the Creator sent Coyote first --with his brother Fox-- to this big island (as the Elders call this land) to free it of evils. ... However, Coyote –being Coyote– left many faults such as greed, jealousy, hunger, envy, anger and many other imperfections that we know of today. At the core of this story is the fact that we are all made by the Creator, and we must respect and love each other. All creation consists not only of mankind, but of all creations in the animal world, the mineral world, the plant world-- All elements and forces of nature. Each has a spirit that lives and must be respected and loved. The Elders tell us that Coyote and his brother are at the edge of this island, this land, waiting. When Coyote and Fox come back through here, it will be the end of our time. The end of this part of the universe if we do not live as one creation, one big circle.... ”

(Salish Culture Committee)

In each of the charcoal and graphite drawings that comprise this Natural World series, key figures possess important symbolic meanings that may be viewed to exist within the context of this legend and have relevance to its larger lessons. In the work entitled Thunderbird (2003), the image represents a guardian against evil spirits and is thought to hold the power to create thunder by flapping its wings. Its significance is profound, as it symbolizes the balance of nature–both destructive and protective forces. In many depictions, the Thunderbird is shown with lightning or snakes hidden beneath its wings, both elements being discernable in this work, further emphasizing its role as a harbinger of power and change within nature.

In the work entitled A Thousand Drops of Dew (2002), the primary image resembles an ibis, a bird that carries its own symbolic significance in various Native cultures. The ibis, with its distinct shape and presence might represent wisdom, peace, or transformation. The symbol may also carry dual meanings, such as representing both danger and optimism, which speaks to the complexities of life and the interconnectedness of seemingly opposing forces that must be contended with constructively by humankind in nature.

The image of a gushing geyser of water surrounded by animals and birds in the work entitled Water, Water (2003), suggest the essence of life and, in Indigenous cultures, it is revered as a fundamental element that births and nurtures all living beings. The phrase “’'s’pér’m spq'ni,”” that appears in the drawing is rooted in the Salish language and loosely translates to “Spokane Water.” The Salish language reflects the deep connection between people and water, a vital source that sustains life. Smith’s use of the term highlights the significance of water rights and the ongoing relationship Indigenous people have with water as both a physical and spiritual resource. The interplay between English and Salish also hints at the broader cultural dialogue, drawing attention to the way water has been a source of both life and conflict through American history.

Beyond the familiar meaning in Western culture of the phrase “birds and bees,” in the drawing Birds and Bees (2003), the symbolism is more profound based on Native American myth. Birds often symbolize the sky, spirituality, and the realms beyond, representing a connection to the heavens. Bees are symbolic of creation, fertility, and the interconnectedness of life. In Native American culture, the metaphor of pollination by bees and the hatching of bird eggs often represents the cyclical process of reproduction, creation, and the maintenance of life. This can be understood as a natural cycle that connects all living beings and generations watched over by Coyote and Fox.

In the Turtle Island (2003) drawing, a part of the creation story is signified according to legend by a turtle carrying the weight of the Earth on its back. This myth reflects a profound connection to the land and symbolizes a spiritual unity of the Earth, the sky, and all living beings. The turtle, a slow-moving creature, is a powerful symbol of endurance, wisdom, and stability. The story of Turtle Island defines the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Earth, emphasizing the sacredness of land, water, and life by the turtle carrying the weight of the Earth. As mandated in the Creation Myth itself, it reflects an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life forms and the importance of maintaining balance and respect for nature.

The Natural World: Water, Water, 2003

The Natural World: Birds and Bees, 2003 Charcoal and graphite on paper, 30" x 22"

Tribe/Community (from the Survival Suite, Ed. 45/50),1996

lithograph with chine-collé on paper, 35.75" x 24.75"

A Map to Heaven (Ed. 15/20), 2002 Original lithograph on paper, 39" x 34"