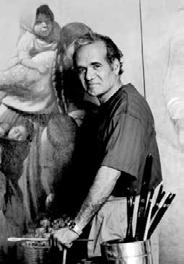

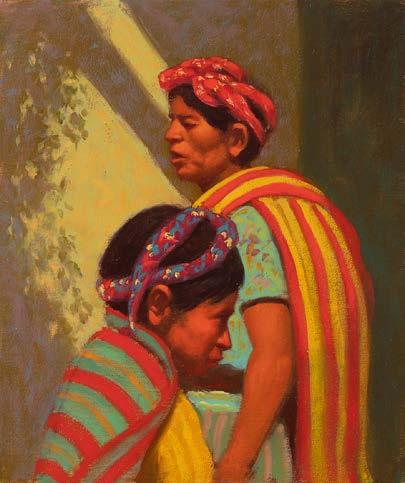

With a successful career spanning more than half a century, Elias Rivera was a renowned Santa Fe-based painter. In his vibrant works inspired by Dutch, Spanish, and Italian Old Master paintings, Rivera chronicles vivid scenes of life in New Mexico, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru. Eloquently distilling the essence of daily life in these Indigenous communities, Rivera’s striking canvases are brimming with figures bathed in radiant light and color. Capturing moments in time, almost cinematically, Rivera portrays bustling markets and the unique customs of these diverse peoples in his exquisite, original compositions.

Born in Bronx, NY, Elias Rivera attended the School of Industrial Arts from 1953 to 1954, and then the Art Students League from 1955 to 1961, where he studied with and was mentored by artist Frank Mason. Rivera moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1982, where he met his future wife, artist Susan Contreras, and lived and worked throughout the rest of his life. He received the Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts in 2004. A major monograph entitled Elias Rivera was published in 2006 with an essay by wellknown art critic and writer Edward Lucie-Smith. Following a tragic car accident in 2011, Rivera stopped working in 2015 and passed away in 2019 in Santa Fe.

FROM THE THREAD OF TIME

Art history’s enduring classicism is one tributary stemming from the river of time, and this flowing line unites era to era and continent to continent. It’s emphatic in the work of Elias Rivera (1937–2019), who maps a certain geography in his paintings, recalling, with intention, time-honored genres that lend prestige to even his most humble subjects.

Beneath the veneer of his contemporary subjects, allusions to still-life painting from the Dutch Golden Age, history painting, and neoclassical composition among other influences coalesce to recast ordinary scenes of everyday life in the grandeur that the Renaissance once afforded to the subjects of myth and religion.

Born in the Bronx to Puerto Rican parents, Rivera knew from a young age that he wanted to be an artist, and entered the Art Students League in 1955, eventually renting a cramped, unheated Manhattan railroad flat as a live-in studio space. He remained in that space for 19 years before eventually moving to Santa Fe, honing the skills that would bring him fame for his bright, bold scenes of daily life in New Mexico, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru.

In Elias Rivera (Hudson Hills, 2006) art historian and critic Edward Lucie-Smith wrote that the worlds of intellectual and artistic culture were not open to Rivera in his youth. It was his own determination and belief in his abilities as a figurative artist that carried him through the door. The same light of dignity in which he captured his subjects was also a reflection of self.

Lucie-Smith states that what Rivera “wanted to be was a figurative painter who belonged to an artistic tradition that had existed long before the rise of twentieth-century modernism, and which still seemed to him at least to possess its own validity.” The author traces a continuum from the work of American realist George Bellows (1882–1925), to the three Soyer brothers Moses (1898–1973), Raphael (1898–1987), and Isaac (1902–1981) to Rivera, who, like those older generations, created paintings that reflected social realism and the struggles of urban life.

From the late 1950s and over the next two decades, Rivera captured scenes of a quotidian nature, quietly (like Edward Hopper) distilling in unforgettable images the drama he saw through his observances along city streets, subways, and venues such as the Brooklyn hotspot Minsky’s Burlesque.

Perhaps it was the world-weary atmosphere of New York City, reflected in the somber tones and closed-in nature of the subjects of his work from the time, such as Untitled (Automat), an oil on canvas from 1970, and Subway #2, an oil from 1975, but the East Coast art scene was proving frustrating for a talented artist and skilled draughtsman committed to making such figurative work, and it wouldn’t sell.

“Potential clients often told him that, while they admired his skills, they found his work depressing,” writes Lucie-Smith. But, working from innumerable sketches and photographs, Rivera was painting what he saw around him. Feeling like “a fly in the ointment,” as he told Lucie-Smith, he was an outsider looking in. Other works from the era, including his Airport (triptych) from circa 1960, convey a potent feeling of subjects observed from a distance, at arms’ length, as though he was capturing a world he longed to understand. It was an unknown and mysterious world of shadow that could hardly match the exuberance of his later works, with their vibrant, jewel tones and dramatic contrasts.

“I knew I was doing good painting, because I worked hard at perfecting my process,” he said. “I knew it wasn’t personal I just didn’t fit with the time.”

A move to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1982 brought a new range of subjects and a new light into Rivera’s painting. Most notably, the very distance with which he regarded his earlier subjects became a defining feature, and, as Lucie-Smith points out, lent itself to his frieze-like compositions, which he perfected in scenes of Indigenous artists selling their wares under the portal of the Palace of the Governors.

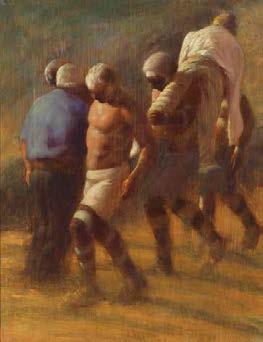

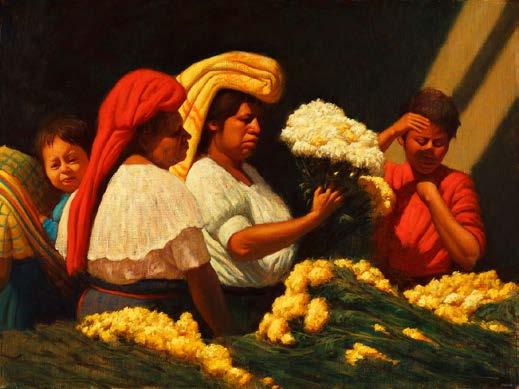

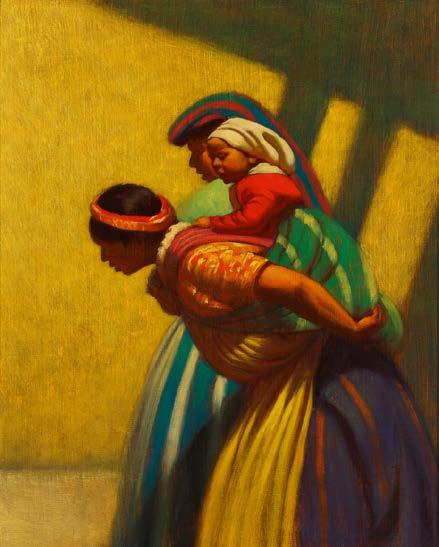

In From the Thread of Time , classical compositions such as his Oaxaca Midday Break reflect this dedication to a determinate style. In their seemingly candid nature, Rivera’s paintings offer an ideal image which, if brought to life, would appear as tableaux vivant exhibiting moments of extraordinary grace. And there’s something to each of these compositions that recalls not only the painting traditions to which they belong but even specific works of art from those traditions. It’s the iconography of the classical form itself that calls up, from some Platonic depths of the human psyche, a pose or a gesture known to us from other, older works. There’s something in the stance of the figures in White Onions (1995), for instance, that evokes depictions of the Three Graces, only here they’ve traded their apples for more savory fruits.

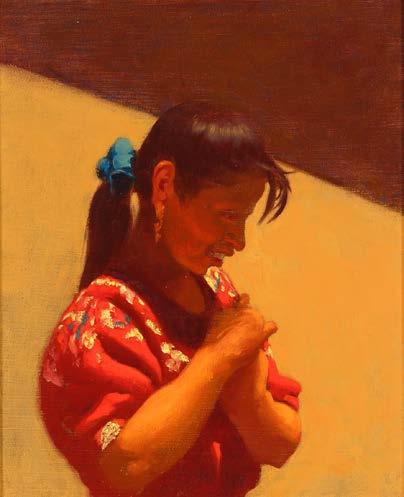

His treatment of chiaroscuro, as evident in Into the Light (1999) and Flowers of the Mind #5 (2002) may have beautiful resonance with the Baroque era of Caravaggio, but the loose, painterly brushwork echoes that of El Greco, although, with his New York works, the Ashcan School comes more readily to mind. It’s as though, in looking further back than the early modernists, Rivera came more singularly into his own.

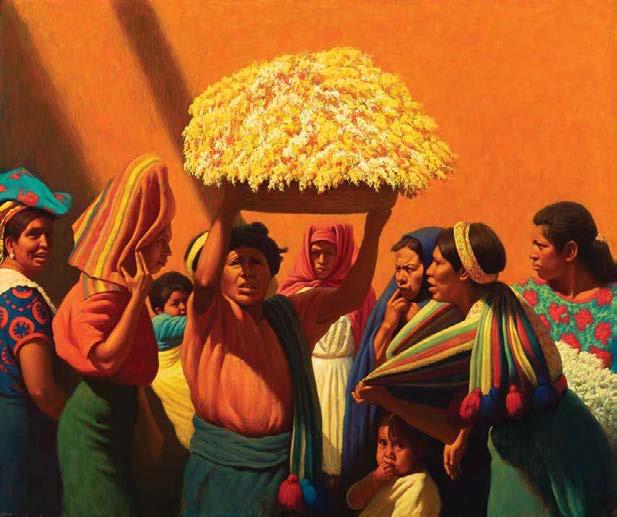

In addition to compositional elements that evoke the Dutch Masters comes the treatment of faces and personalities. Each is distinct, bringing a sense of individual inner life to each person, and a touch of wry humor. Flowers of the Mind #5, for instance, is an extraordinary map of such faces, and Rivera masterfully positions each figure so their faces can be seen while still providing an overall sense of a busy street scene. Rivera was, justifiably, an inheritor of traditions that included certain types of subject matter as well as the styles associated over the centuries with various movements. In the case of Dutch genre painting, transfer a street scene to an interior parlor, replace the marketplace with letter writing or needlework, and the purview is the same: the essence of timelessness and universality that pervades the familiar and the everyday.

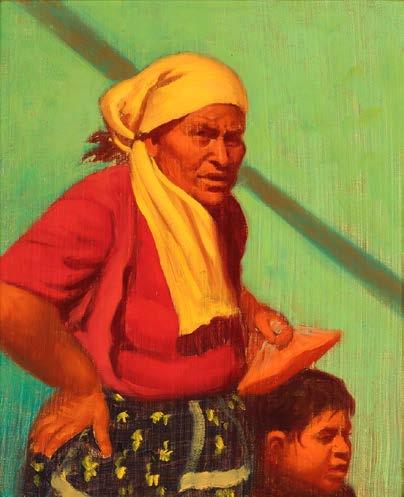

But is this practice of observance at a remove a kind of “othering,” like the artists of the late 19th and early 20 th centuries were wont to do in their encounters with Indigenous societies? Lucie-Smith mentions Rivera’s cool treatment of his subjects, but the constancy of his subject matter insists on another idea. Looking at recurrent themes of the Earth’s produce, the harvesters and sellers of these fruits and flowers are often strong women who carry not only the weight of their wares literally upon their heads, but their children upon their backs. In seeking out the places where time stands still, he strips away specificity to arrive at an essential spirit embodied in these people. In an appreciation of the artist that’s included in Elias Rivera, former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson writes, “Rivera shows us vivid depictions of Latin American culture filled with warmth and passion. His work captures the dynamic spirit of the Latino people, and his skilled technique and use of color embolden the senses and bring the images to life.” In 2004, Richardson presented Rivera with the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts.

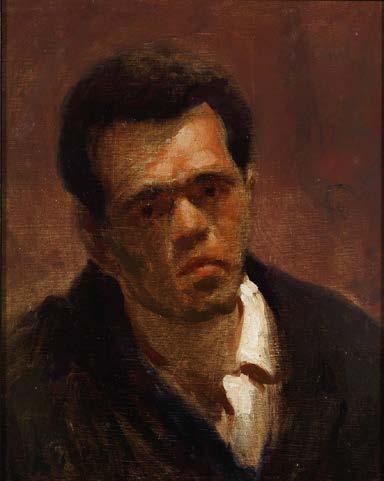

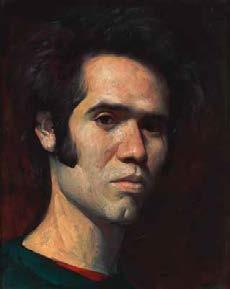

The light in his paintings is radiant. The glow divine, like a halo. It envelopes his subjects with warmth but doesn’t ask them for their names first. Hence, anonymous people are Rivera’s people. Even his own self-portrait from his days at the Art Students League is untitled. If his portraits, by some contemporary measure, stand outside of time, it is because the essential human spirit resides there.

This position is held regardless of the fact that Rivera was often less interested in painting a single human figure than he was in painting them in groups. The figure itself was less interesting in isolation than in relation to other figures. Form and color were his true subjects. But with human activity at the forefront of each composition, the figures become the repositors of an ageless relationship with the Earth, as they come bearing its bounty, and the sky, as they’re illuminated in its golden glow.

— Michael Abatemarco

— Michael Abatemarco

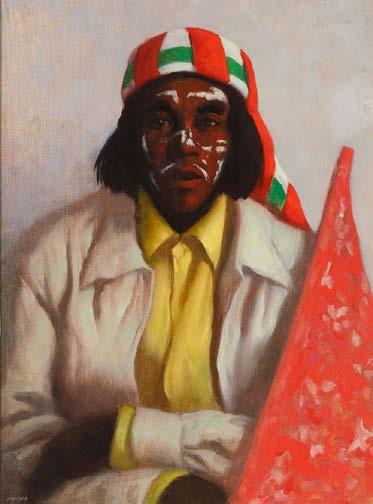

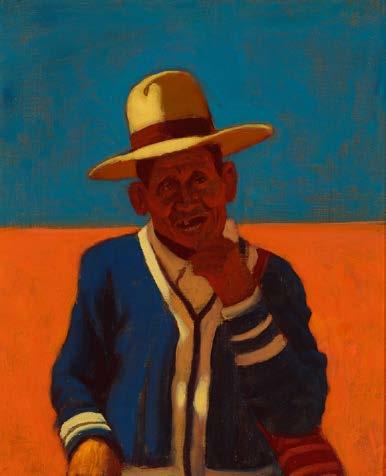

Tarahumara, n.d.

Oil on canvas, 16.25 x 12.25 inches

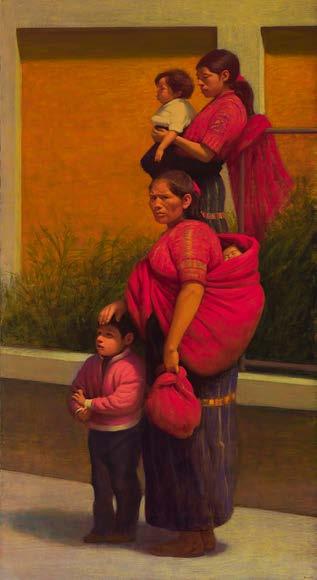

Baptismal Staurday, n.d.

Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches

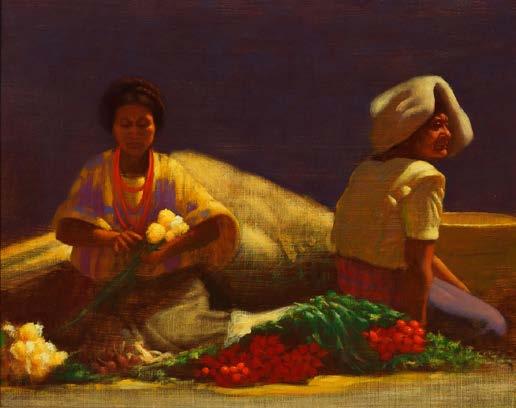

The Earth Provides, 2003 Oil on canvas, 48

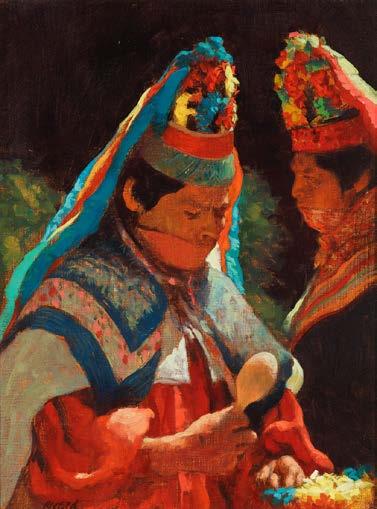

Matachine Dancers, n.d.

Oil on linen, 12 x 9.50 inches

Into the Light, 1999

Oil on canvas board, 20 x 16 inches

Airport (triptych), 1960

Oil on panel, 8.25 x 38.75 inches

1937

–2019 I b. 1937, Bronx, NY

EDUCATION

1953-54 Industrial Arts, Manhattan, NY

1955-61 Art Students League, New York City, NY

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2023 From the Thread of Time, LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe, NM

2006 Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, NM

National Hispanic Cultural Center, Albuquerque, NM

Riva Yares Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

2005 Surface, Exhibit 51, Albuquerque, NM

National Small Format Invitational, Exhibit 51, Albuquerque, NM

The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

Cacciola Gallery, New York City, NY

2003 Guatemala Revisited, Riva Yares Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

The Other Side of the Street, Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Oklahoma City, OK

2002 Artists of the Ideal: Nuovo Classicismo, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Verona, Italy

Ahora: New Mexican Hispanic Art, National Hispanic Cultural Center, Albuquerque, NM

The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

2001 The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

2000 The Americas: Central & South, Riva Yares Gallery, Santa Fe, NM and Scottsdale, AZ

A New Mexico Influence, Art in Embassies, Madrid, Spain

The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

1999 The Human Fabric , Riva Yares Gallery

Santa Fe, NM

The City Series–Taos, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Cedar Rapids, IA

1997 San Francisco el Alto, Riva Yares Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

1996 Elias Rivera: Retrospective, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY

1995 Visions of Solola , Riva Yares Gallery, Santa Fe, NM and Scottsdale, AZ

1993 Cacciola Gallery, New York City, NY

The Americas: A Latin Connection, Nevada Institute of Contemporary Art, Las Vegas, NV

The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

1992 Ventanas: Visiones Culturales / Contemporary Hispanic Art, Plains Museum, Moorehead, MN

University Art Museum, Northrup Gallery

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

1991 The Miniature Show, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM

1990 Munson Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Hispanic Invitational Show, Partners Gallery, Bethesda, MD

Lizardi & Harp, Pasadena, CA

1988 Munson Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

1987 E. S. Lawrence Gallery, Taos, NM

1986 Georgetown Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Munson Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

1985 Center for Contemporary Art, Santa Fe, NM

E. S. Lawrence Gallery, Taos, NM

1984 Santa Fe Festival of the Arts, Santa Fe, NM

Munson Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

1983 Santa Fe Festival of the Arts, Santa Fe, NM

1980 Harbor Gallery, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

1978 American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, New York City, NY

Hassam and Speicher Fund Purchase Prize

Allied Artists, New York City, NY

David Humphrey Memorial Award

1977 National Academy, New York City, NY

Harbor Gallery, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

1975 Harbor Gallery, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

1974 Kenmore Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

Allied Artists, New York City, NY, Gold Medal

1973 National Academy, New York City, NY

Henry W. Ranger Purchase Prize

1971 Quintana Gallery, Nantucket, MA

Park Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

Allied Artists, New York City, NY

1970 Harbor Gallery, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

Cordiner Gallery, East Hampton, NY

1969 Brooklyn Museum, Community Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

Glaisek Gallery, Provincetown, MA

1968 Glaisek Gallery, Provincetown, MA

Kenmore Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

1965 Lincoln Institute Gallery, New York City, NY

Harbor Gallery, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, NM

The Capitol Art Collection, Santa Fe, NM

Albuquerque International Sunport, Albuquerque, NM

Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA

Northland College, Ashland, WI

Early Self Portrait from Arts Student League n.d., oil on board, 11" x 9"

Early Self Portrait from Arts Student League n.d., oil on board, 11" x 9"