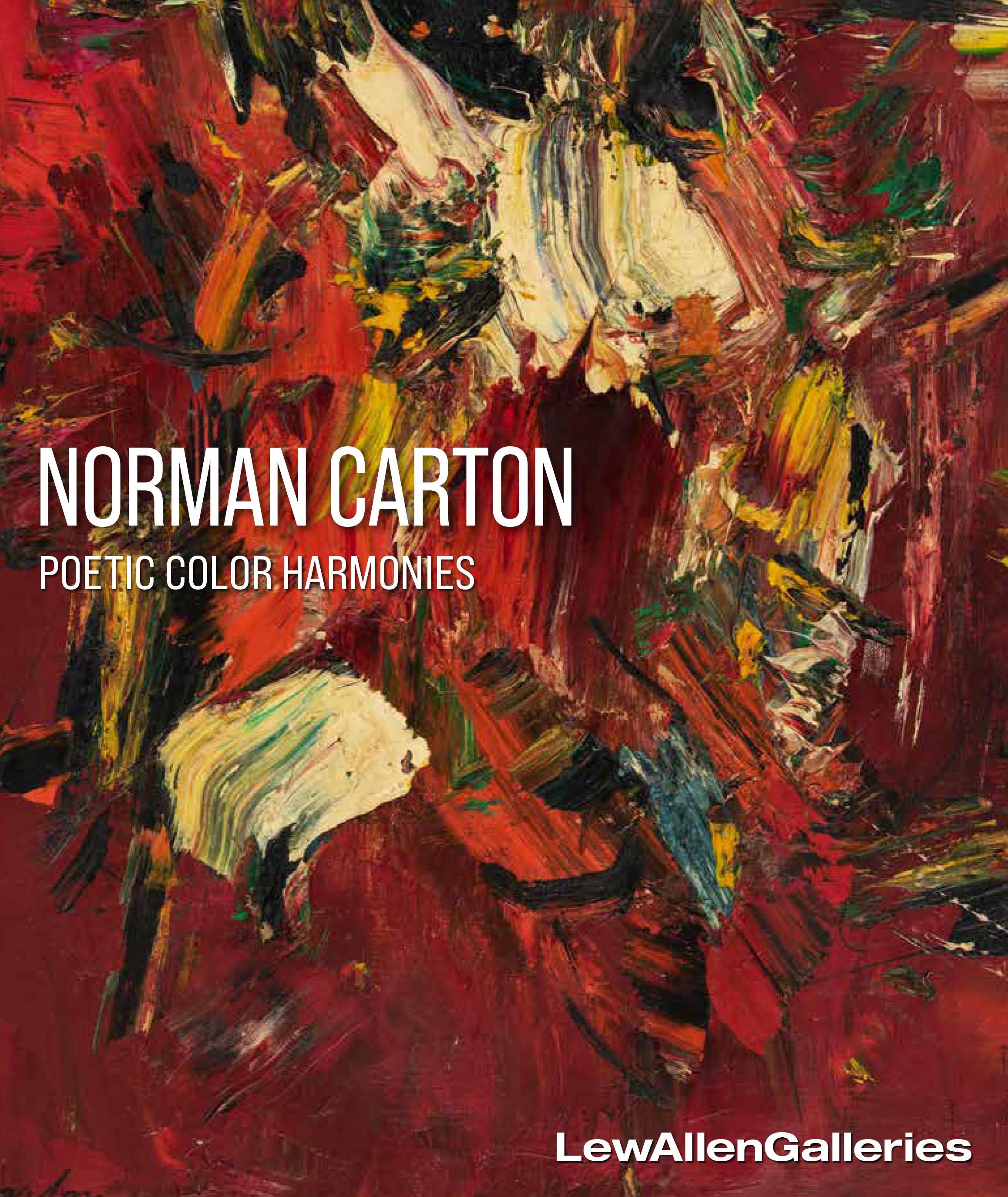

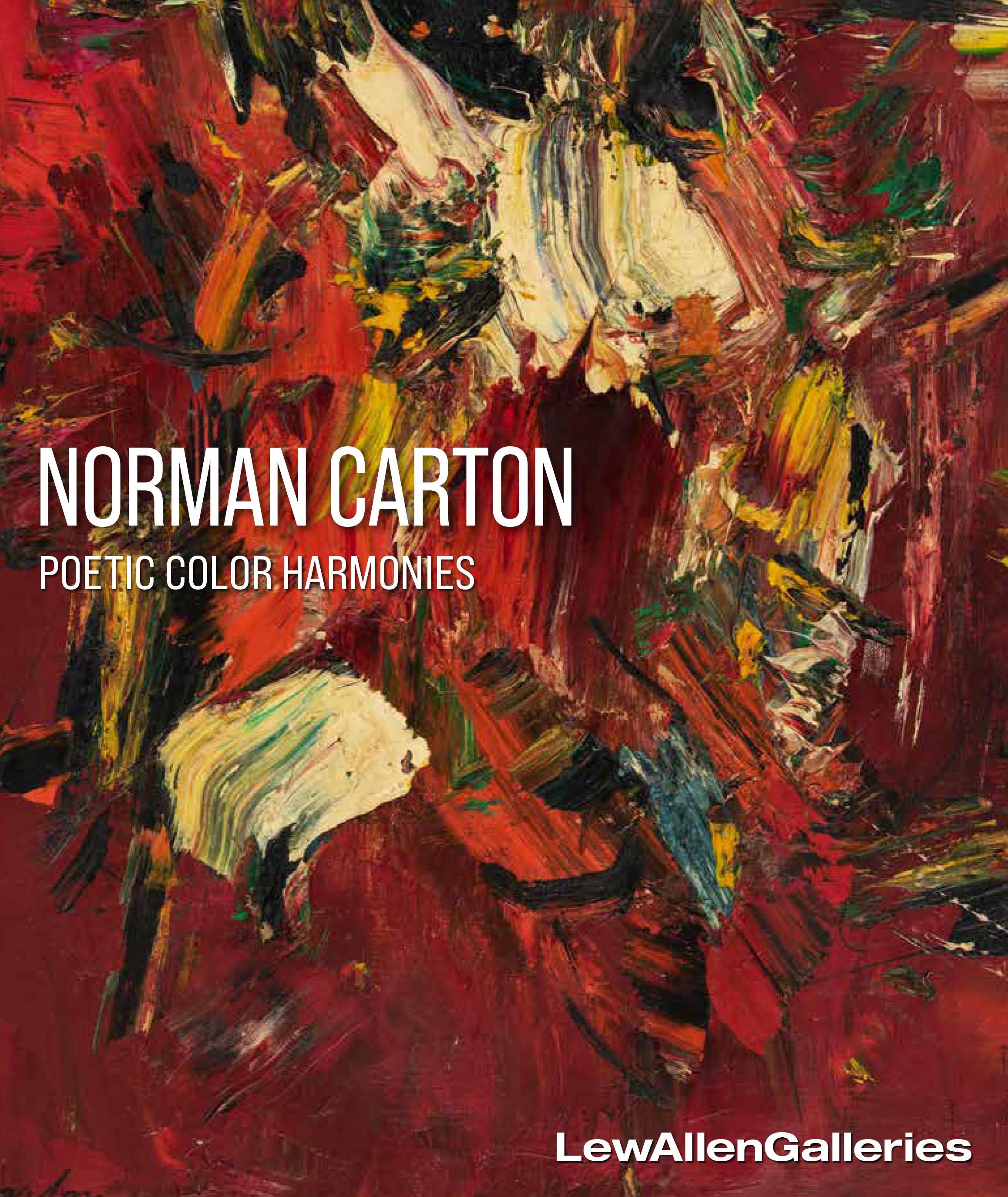

For the painting, all is contained within the picture frame. Conscious use of the rectangular frame as a limiting device keeps one’s focus on a composition that packs bold and emphatic statements in the form of bright swaths and ridges of color, energetically applied. But even as one assertive black ribbon appears as if it must continue past the picture frame, out into space, even it ultimately ends, abruptly truncated where the canvas meets the edge of the stretcher bar.

Many of the paintings of Ukrainian-American artist Norman Carton (1908–1980) seem self-contained in this way, as something whole and cohesive, like a dark universe undulating with a mysterious inner energy. One catches not so much a glimpse of this universe—an edge of it, like an inset rectangle on a larger view of outer space—but an entire universe itself, one in which the tension seems everready to burst into a supernova (and sometimes does).

But is that energy directed outward or inward?

Limited to the rectangular structure the way a thinking mind is contained within body, or a deep feeling to the human heart, Carton goes within. It shouldn’t be surprising that he was active in the age of the advent of television, a rectangular device which became a focal point of the family home and which also representations. There may be no irony that in America at mid-century, obsessed with TV, Abstract Expressionism was also hot.

intensities and darkness within. And Carton had seen darkness. He was born in the Dnieper Ukraine territory of the Russian Empire at a time of political and social upheaval, revolution, war, and economic strife. In his teen years, Carton and his family hid from the violent pogroms aimed primarily at Jews and other ethnic groups. According to Jillian Russo’s catalogue essay for the 2023 exhibition Norman Carton: Chromatic Brilliance, Paintings from the 1940s-60s, while his father was arranging asylum in Romania for his wife and son, they were captured by the Red Army and detained. But Norman escaped, getting word to his father, who secured their release along with that of 30 other refugees. A brother in Philadelphia arranged the family’s passage to the United States in 1922. Carton was 14.

Settling in Philadelphia, he attended the Pennsylvania Museum School and, in his early 20s, supported himself as a newspaper artist for the Philadelphia Record and as a set designer for local stage productions.

Enrolling at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1930, he studied under artist and illustrator Henry McCarter, who himself trained under renowned artists Toulouse-Lautrec and Thomas Eakins. Under McCarter, writes Russo, he was and American Modernists. Having been classically trained at the Museum School, this led to an infusion of color and abstraction into his work which emphasize color relationships and forms for emotional effect.

Essay continues on page 6

Norman Carton:

In 1935, Carton was granted a residency at the Barnes Foundation in Marion, Pennsylvania, where he studied painting withArthur B. Carles and developed many of his aesthetic and viewer-oriented ideas from John Dewey and Bertrand Russell who were then participating in the education programs at the Barnes.

Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism made their marks on his oeuvre he something more idiosyncratic. In his works from the 1940s, there are linear elements of Cubism and Expressionism, recalling styles and techniques honed by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Arshile Gorky, and Fernand Léger. But in the 1950s, Ab Ex had taken root as dominant American painting style. Carton’s work structure by the variegated patchwork application of short dabs and strokes.

While the word “chromatic” is used for all the tones of the musical scale of half steps, it also denotes phenomenon of color. There is a staccato, rhythmic sense to some of Catron’s compositions from this time, in which forms gravitate toward an invisible center, grabbing the viewer with an inward pull. Like visual they seem lost in their own apparent madness. All the varicolored elements are caught in a kind of static state between becoming and dissolving, form and no form, birth and death.

Essay continues on page 10

Norman Carton:

But the almost opalescent use of tones that mark him as a supreme colorist are like a voice crying out from the agony of despair as they’re framed within a surrounding atmosphere of black, blood red, or magenta. Sometimes the darkness is near total, and bits of color exist within the surrounding black like fragments of a shattered tapestry, the black void itself outlined by a swath of cream that loosely follows the contours of the picture frame.

LewAllen is featuring 22 abstract works from Carton’s career, during which he became known for his particular prowess with the interplay between light and color, or as one French critic described it “his intense poetry in color harmonies.” It was a career that became increasingly successful with numerous critical recognitions and museum and leading gallery exhibitions. These include the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Annual Exhibition of Contempoary American Painting in 1955 and at the legendary Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, as well as other solo shows in New York and throughout the U.S during the 1950s and ’60s. Today his work is in more than 25 museum collections. In the late 1950s certain context as being among a generation of artists who arrived as exiles and referencing Pablo Picasso’s Guernica as an example of art that documents the abstract impact of war on the human spirit.

tation of the inner emotional content, this is a body of work that feels almost like Guernica and at times more intimate. That’s the allure of their aesthetic arrest.

Viewing Carton’s work, there is a feeling of a sudden stopping of time, then a strong pull into their erratic interiors. That is the shock of the familiar but also the seduction of the strange. These canvases are mirrors, only the face staring back is no face at all, so there is nothing in them to love or fear save the unrecognized self.

Carton recognized this important connection between artists and their creations, that there really is no separation. In discussions of Abstract Expressionism where formal and material aspects of art are often emphasized, this conversation River Edge #751, 1957, oil on canvas, 16" x 13" is sometimes lost. Carton recognized and emphasized the material, compositional, and stylistic components of painting in service to the visual manifestation of its emotional content. Or perhaps more colors, light and gesture.

“My painting is the realization of organic unity between color and plastic form,” he wrote in a letter to the Dayton Art Institute, dated August 1, 1959. “It is a real organism; independent and free not only from obvious representational conventions, but is also apart from visual nature itself.”

Norman Carton:

Carton described painting as a “dialectical process.” But his intellectual investigations into composition, color theory, and medium are aimed, ultimately, at eliciting some unnamable truth—truth that must be experienced and realized perhaps in that moment before it’s spoken, and before words, by necessity of the limitations of language, come to paint an incomplete picture of it.

Carton’s paintings are the complete picture, self-contained yet so full of pictorial energy and exuberant color and thick impasto they might still burst into the great beyond.

— MICHAEL ABATEMARCO

LewAllen Galleries is grateful to Hollis Taggart with whom this exhibition is in collaboration.