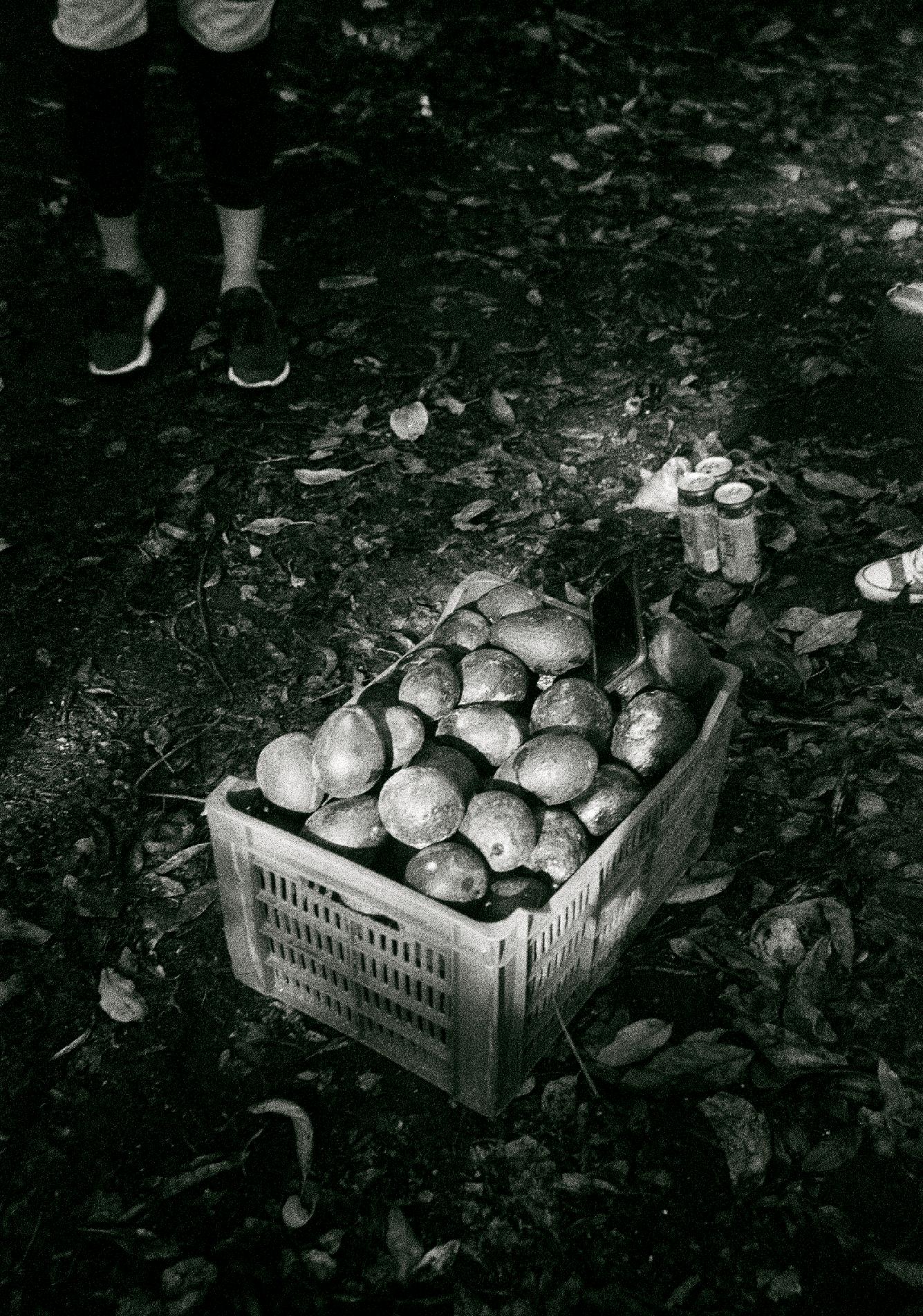

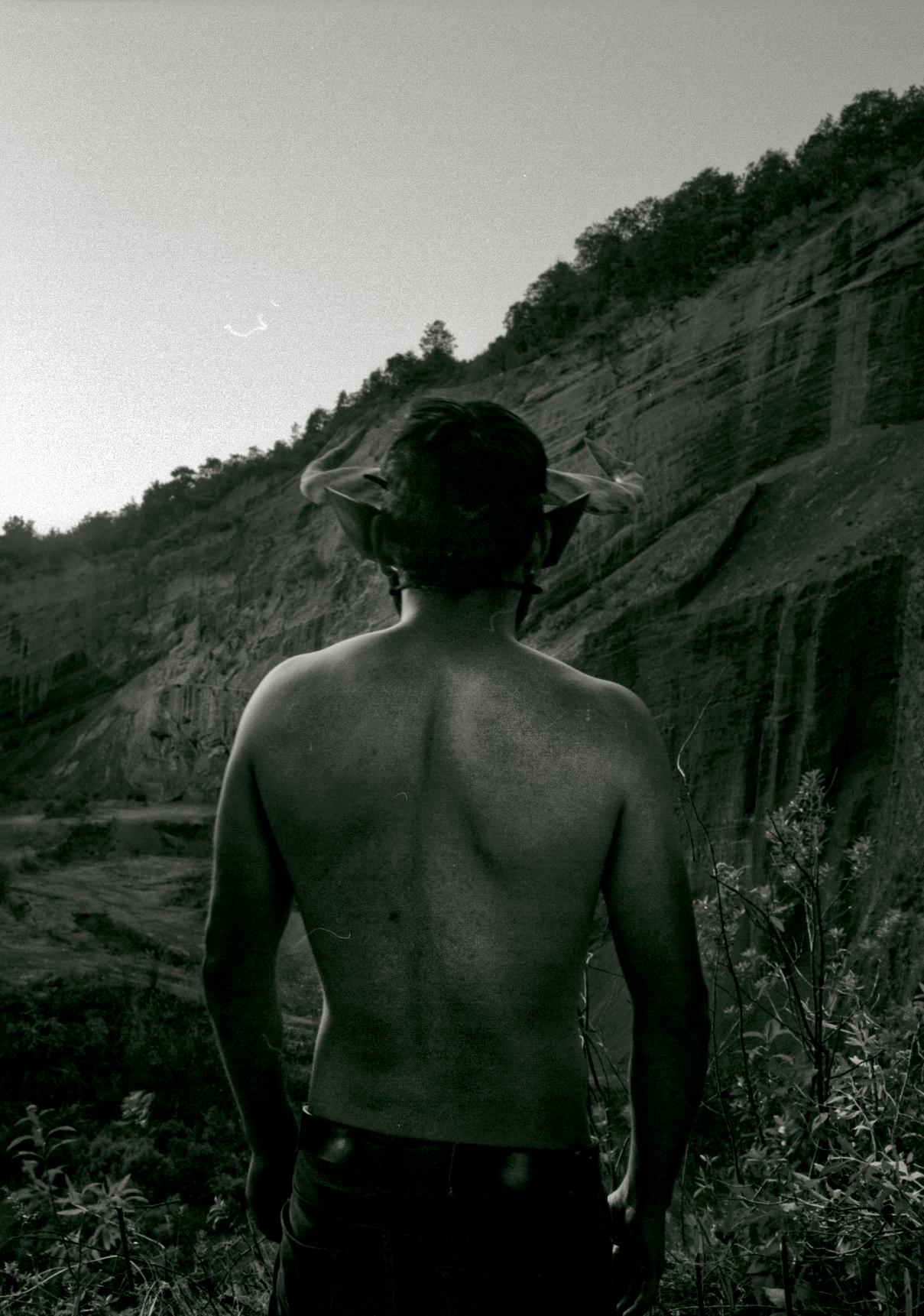

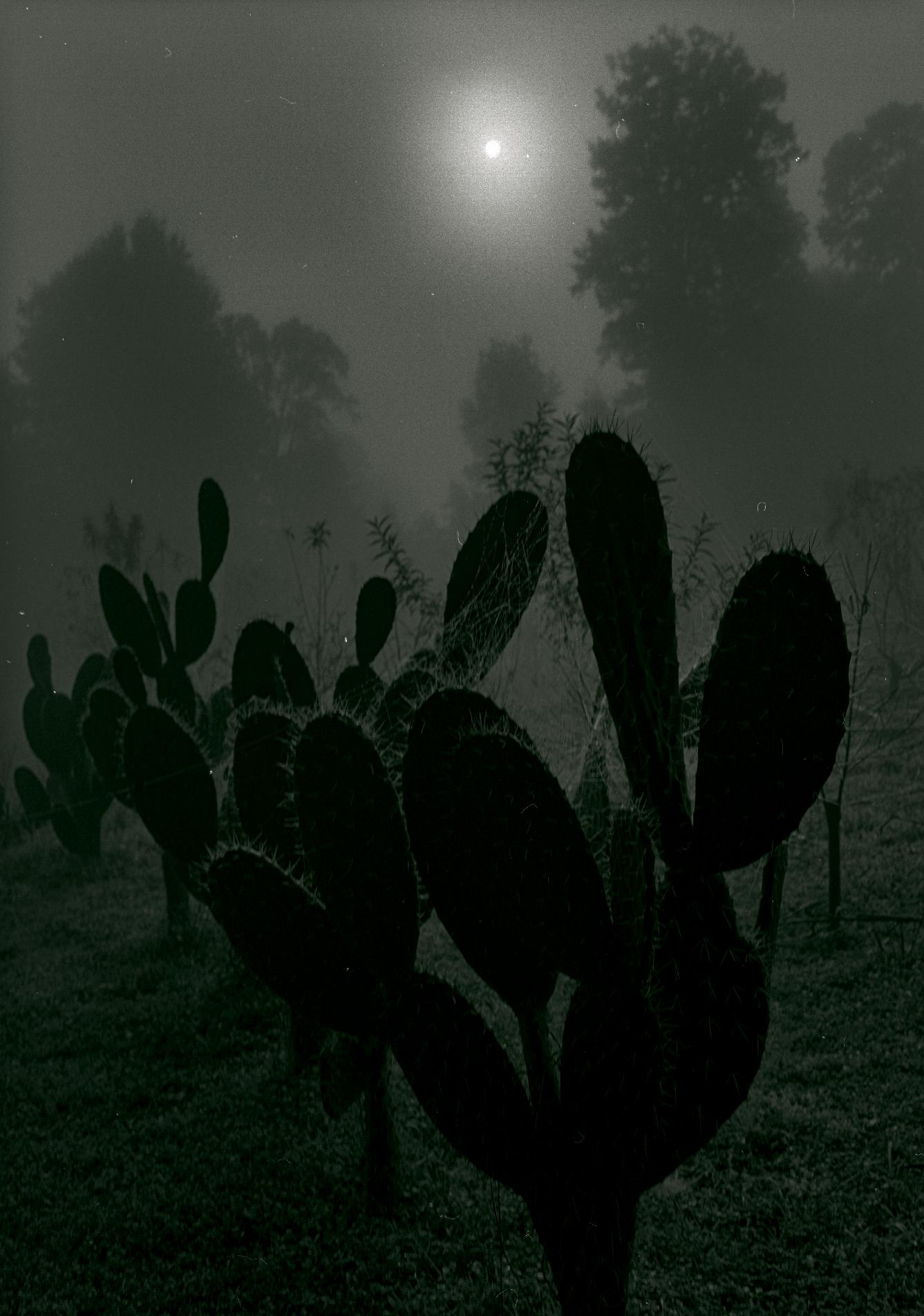

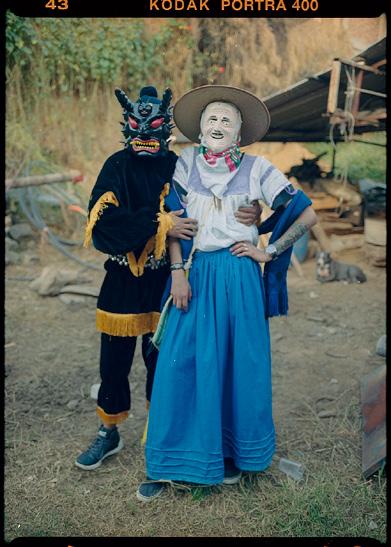

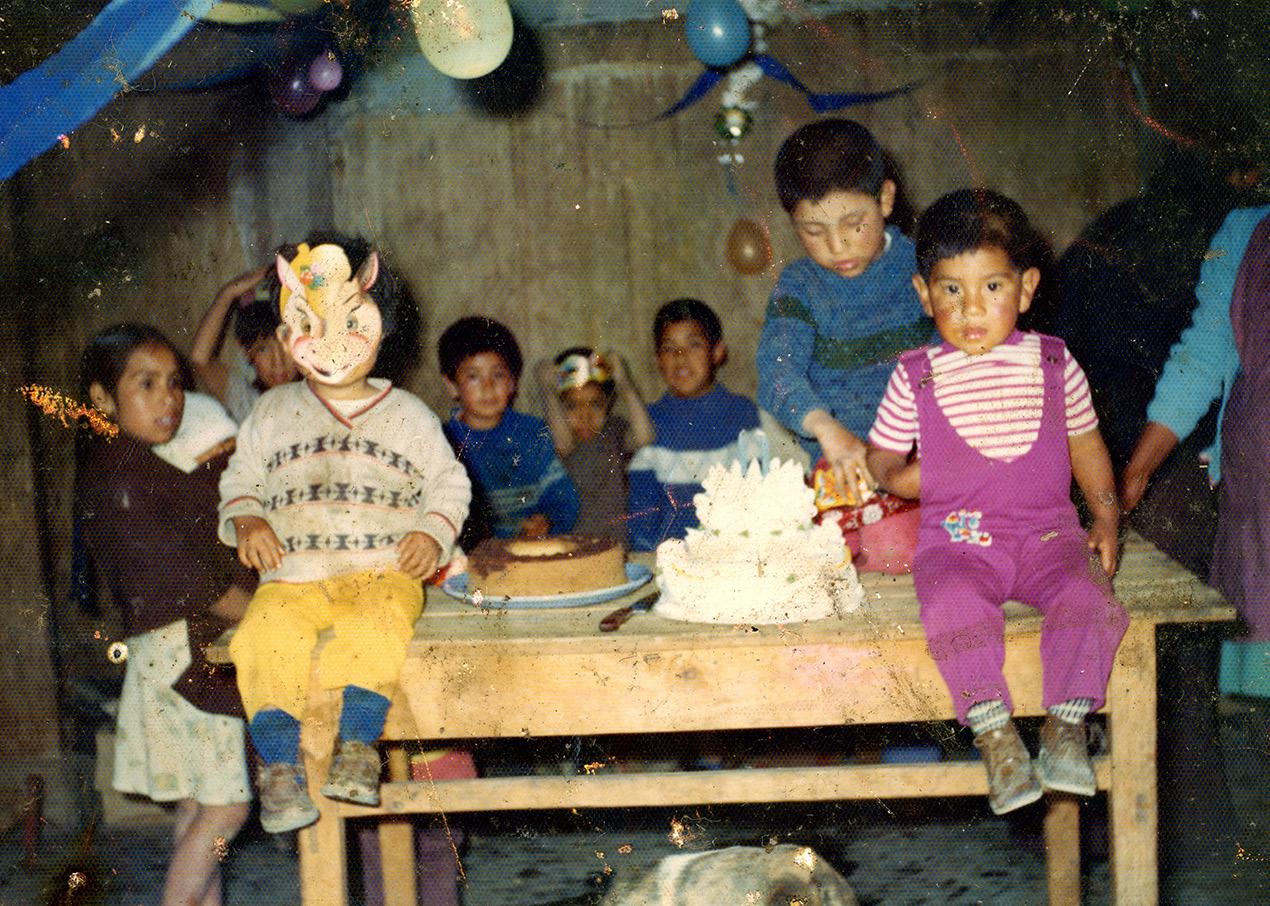

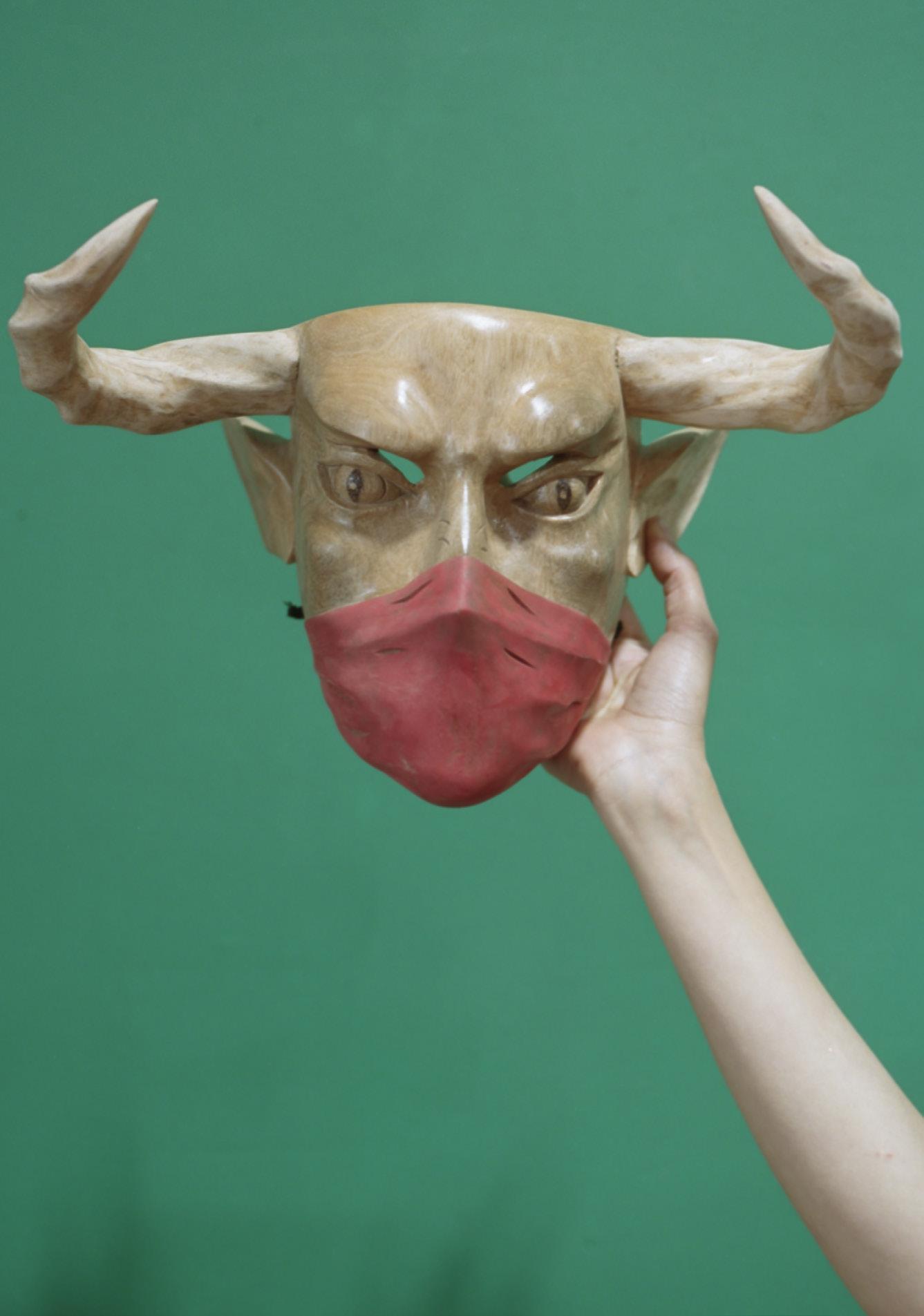

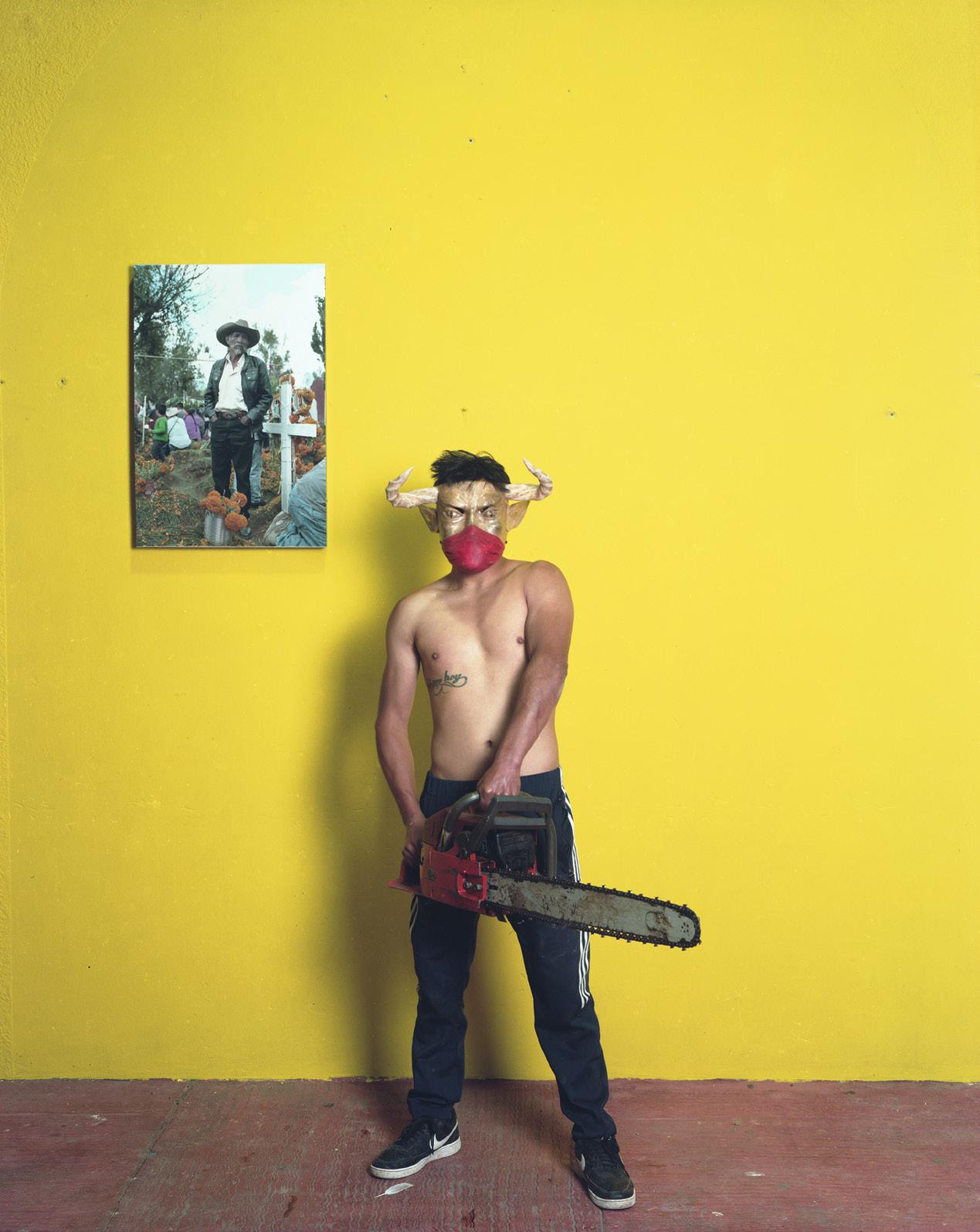

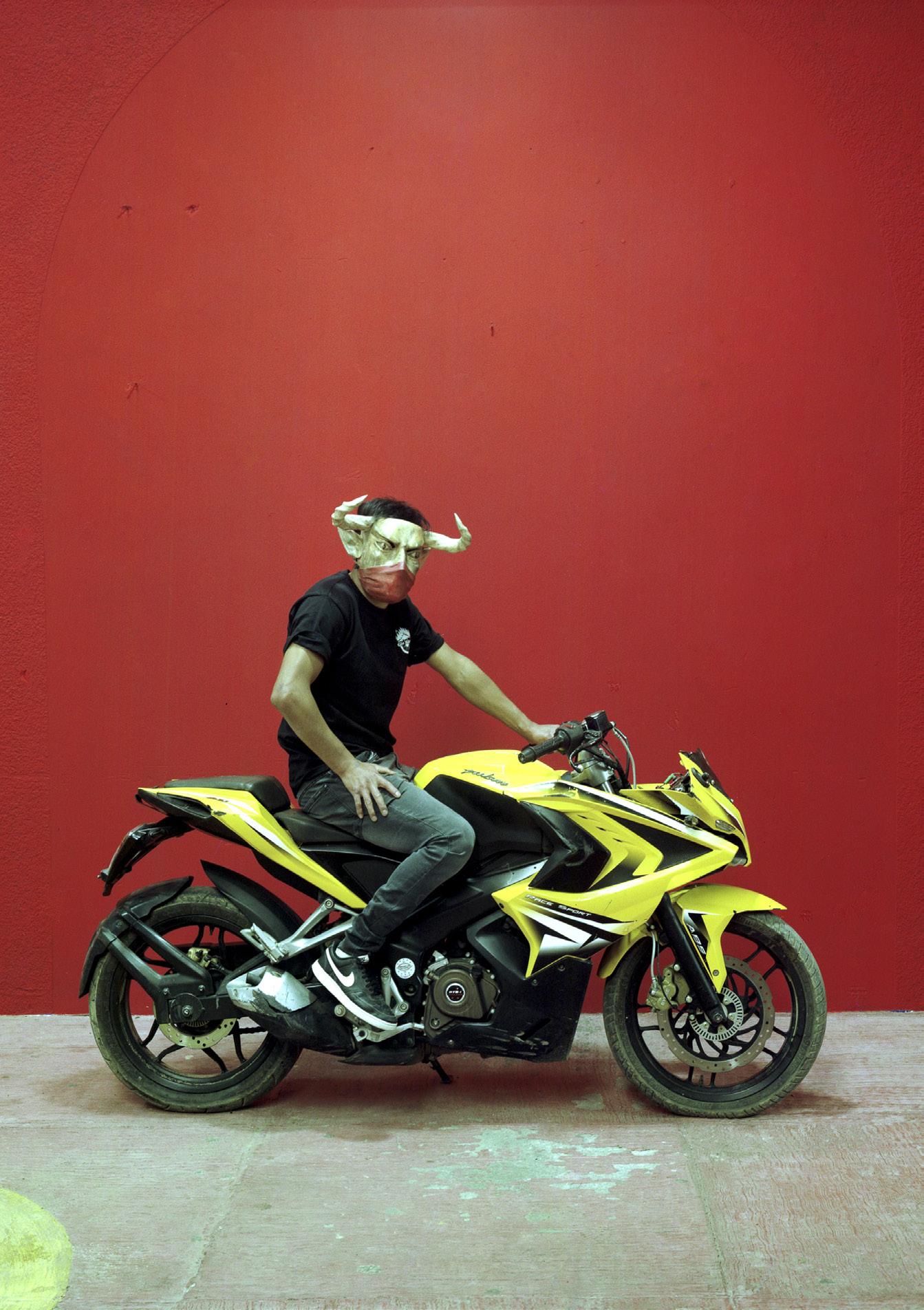

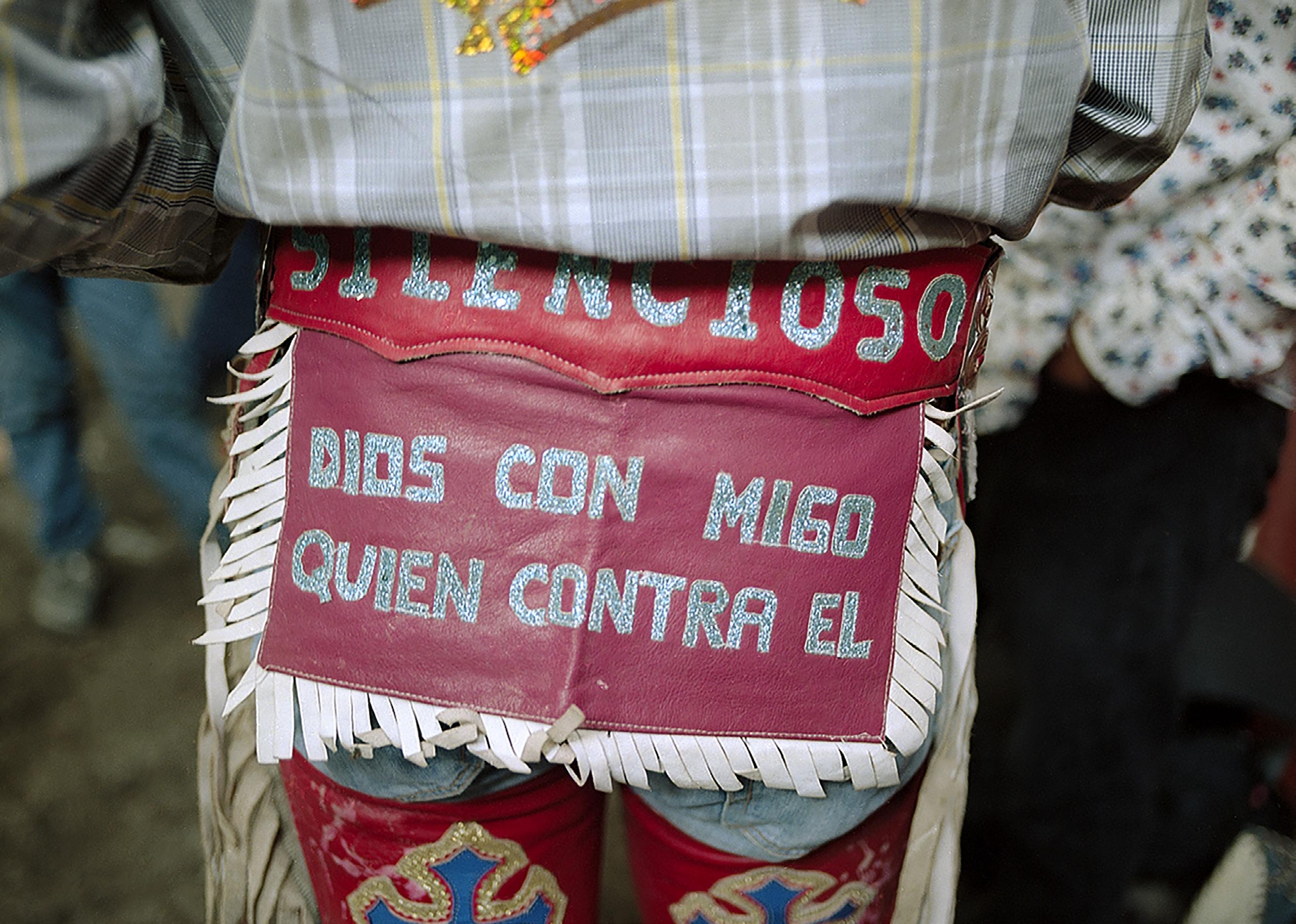

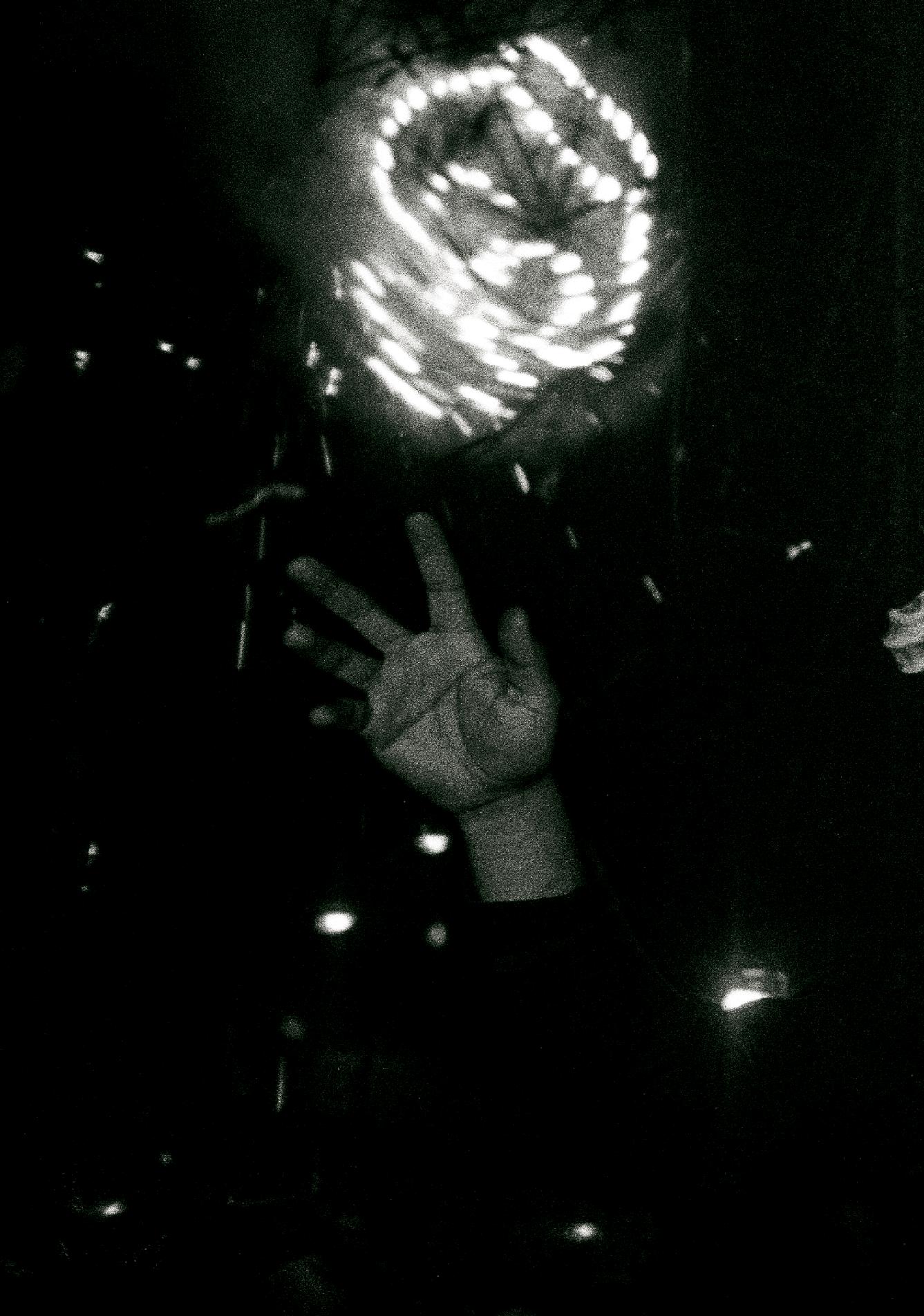

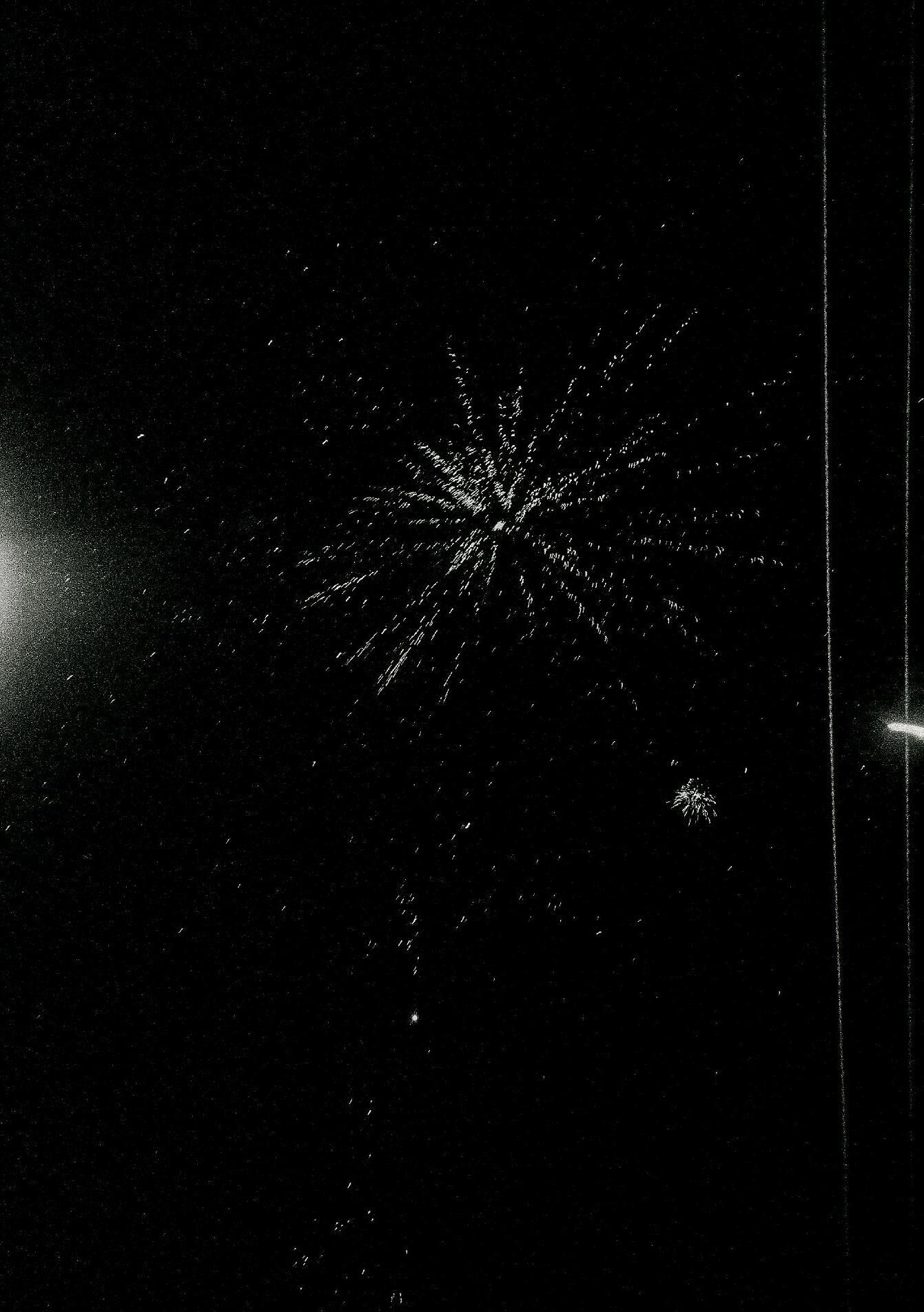

This photobook narrates the uprising of a Purepecha community in Cherán, Michoacán, Mexico, from an artistic perspective, based on an archive of 5,000 images created by the collective Ritual Inhabitual in collaboration with the community. For five years, they collected local photographic archives, objects, newspapers, and stories from community members. The multiplicity of versions of April 15th, 2011— the day Cherán rose up against organized crime —led the collective to abandon the idea of journalistic truth and create the “Mytho-Documentary”: a search for poetic and visual truth. Purepecha rituals and a body of work created in the studio they established in the town and on the streets, with three characters —the Wooden-Faced Boy, the Wasp, and the Narco-lumberjack— as protagonists, form the story.

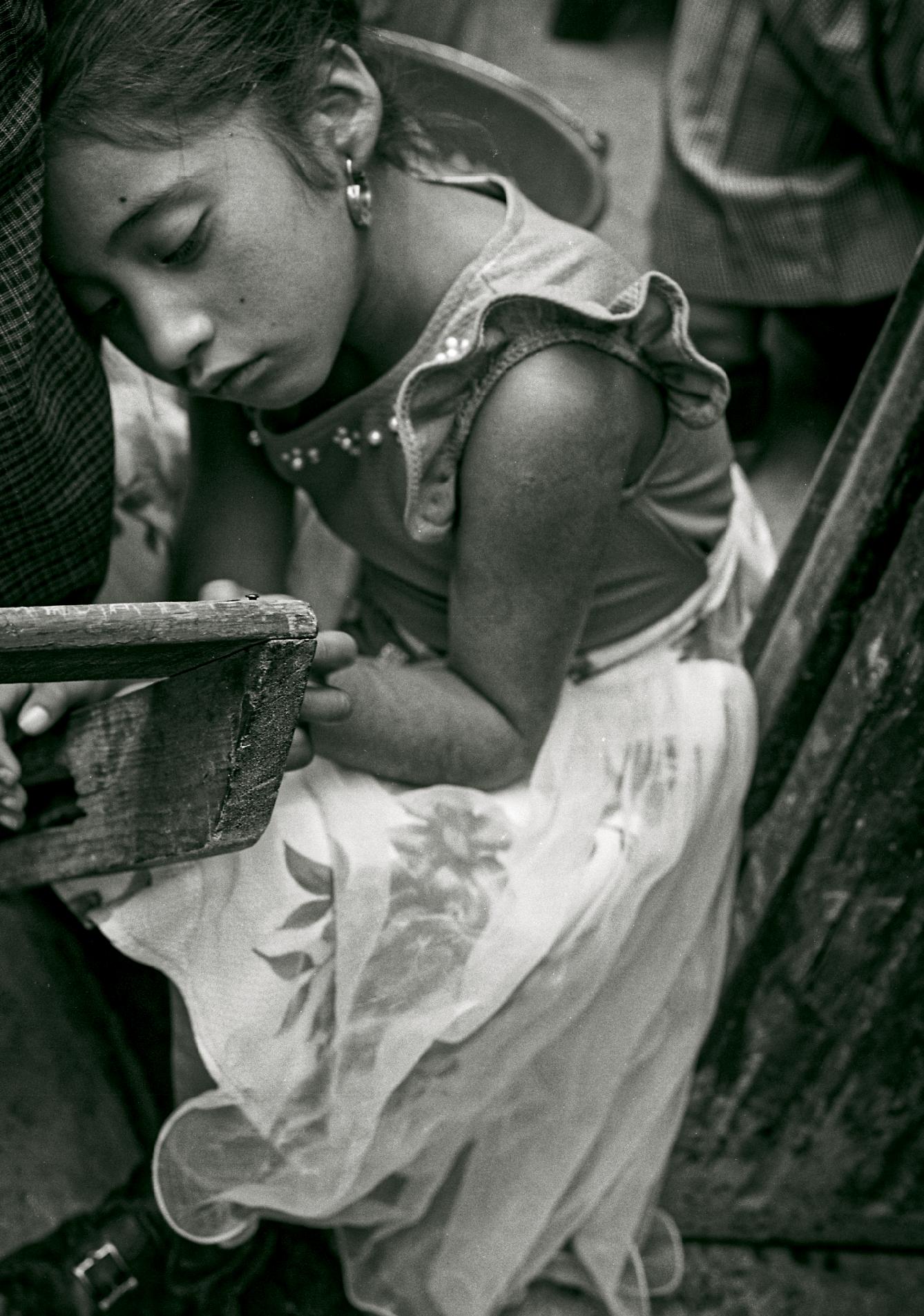

But make no mistake, in the notion of Mytho-Documentary there is also a deep desire for a Latin American art that rewrites its own history with its own codes and through its own actors and artists. Here, a photographic investigation, a scientific research, a pre-Columbian fairy tale and an encounter between the photographed and the artists converge. In this mixture of violence and existence, in these stories of lives devastated by the greed of industrialists and corrupt governments, and by the programmed destruction of the environment, the reader is immersed in the streets of Chéran, in the skin of revolutionary women, and in what it means to belong to an indigenous community in the 21st century. It is a journey that is not shameless, but the result of a rigorous investigation.

Ce livre raconte le soulèvement d’une communauté purépecha à Chéran, dans l’État du Michoacán, au Mexique, à travers une perspective artistique. Il s’appuie sur un fonds de 5 000 images constitué par le collectif Ritual Inhabitual en collaboration étroite avec les habitant·es. Pendant cinq ans, le collectif a rassemblé des archives photographiques locales, des objets, des journaux et des récits de vie. La multiplicité des versions sur les événements du 15 avril 2011 — jour où Chéran s’est insurgé contre le crime organisé — les a menés à renoncer à l’idée d’une vérité journalistique, pour forger un outil méthodologique inédit : le « Mytho-Documentaire », une quête de vérité poétique et visuelle. Les rituels purépechas, ainsi qu’un corpus d’images créées en studio et dans l’espace public, constituent l’ossature du récit, porté par trois figures centrales : l’Enfant au visage de bois, la Guêpe et le Narco-bûcheron.

Mais qu’on ne s’y trompe pas : derrière cette notion de Mytho-Documentaire se dessine le désir profond d’un art latino-américain capable de réécrire sa propre histoire, selon ses propres codes, à travers ses propres acteur·ices et artistes. Ici se rencontrent enquête photographique, recherche anthropologique, conte précolombien et alliance entre photographié·es et photographes. Dans ce tissage de violence et d’existence, dans ces récits de vies brisées par la cupidité des industriels, par la corruption des gouvernements et la destruction programmée de l’environnement, le lecteur est plongé dans les rues de Chéran, dans la peau des femmes en résistance, et dans ce que signifie appartenir à une communauté autochtone au XXI siècle. Un voyage sans tabou, qui est néanmoins le fruit d’une recherche sérieuse.

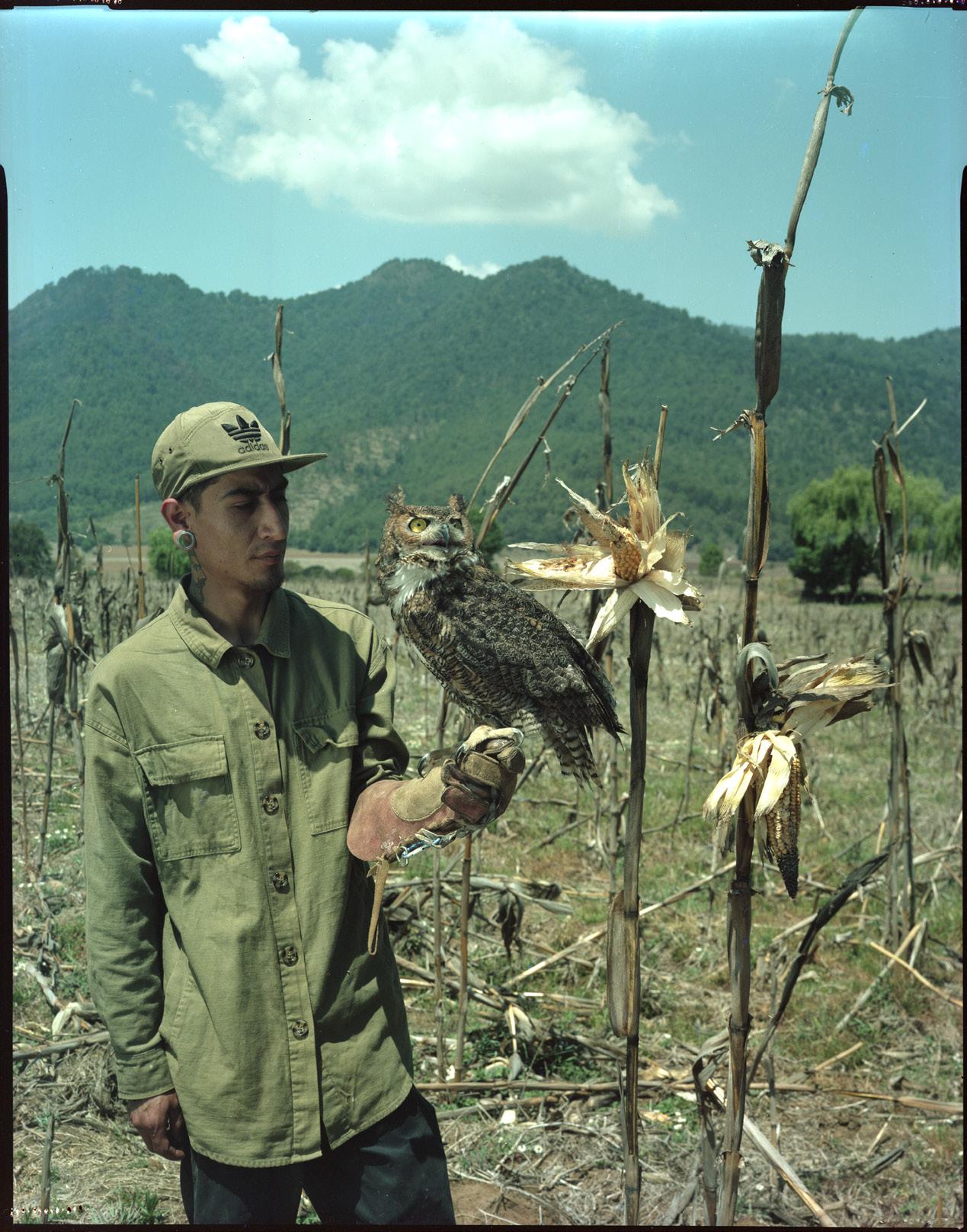

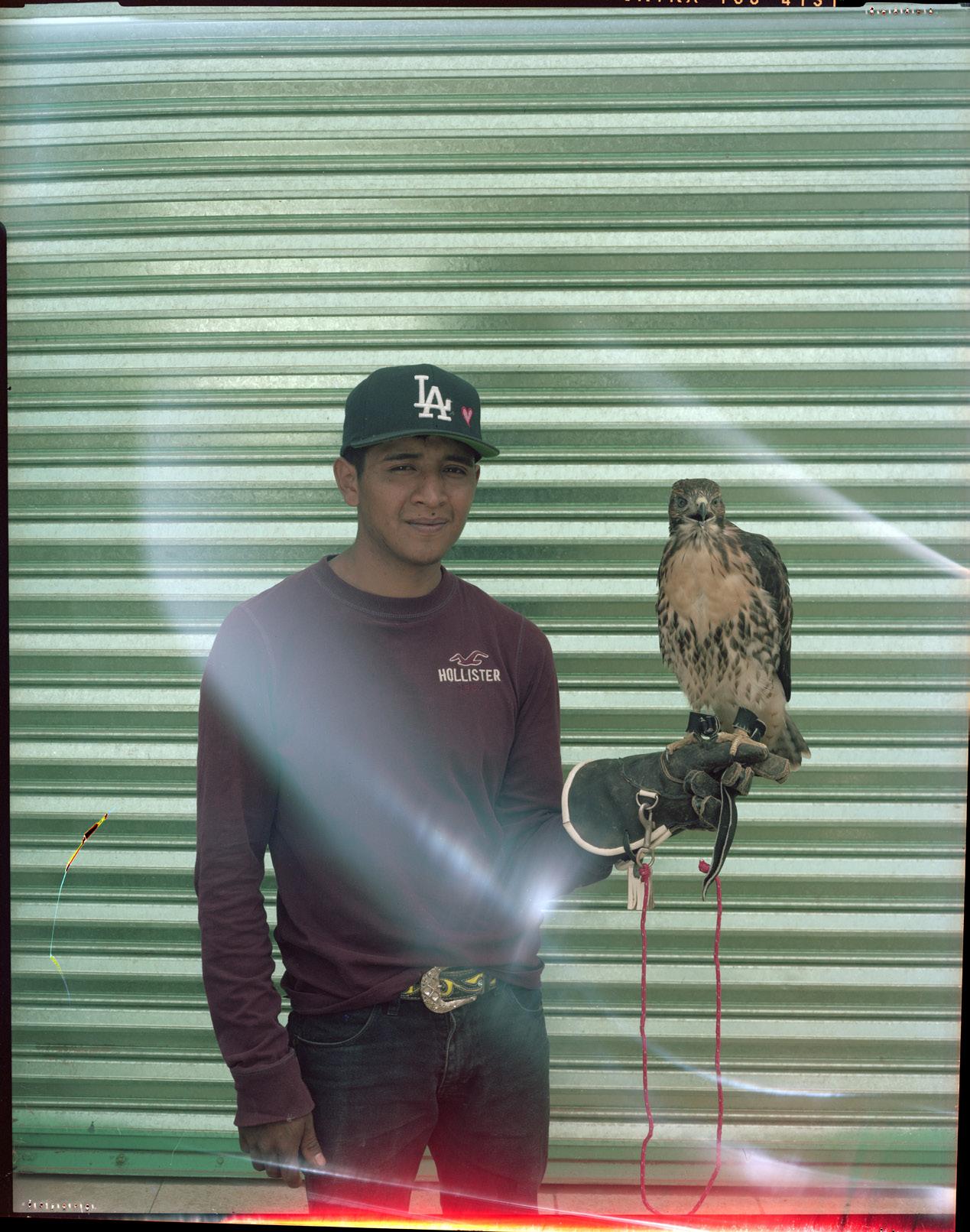

El niño de madera The Wooden-Faced Boy

1. Forest 50 2. Logging 100 3. Uprising 150 4. Reforestation 200

El talamonte The Narco-lumberjack

La avispa Uauapu Uauapu The Wasp

La comunidad The community

P’urhépecha nomadic populations migrate from the north of present-day Mexico and settle in the region of Lake Patzcuaro, in the current state of Michoacán.

Second migration of P’urhépecha populations from the north, who subdue their predecessors in the lake region.

Foundation of the Uacúsecha clan empire.

1519

Hernán Cortez lands in the current state of Veracruz.

1521

Fall of Tenochtitlan, end of the Aztec Empire.

1530

Execution of the last Uacúsecha king, end of the Tarascan Empire.

1532

Foundation of the first pueblohospital in Santa Fe de la Laguna by the Spanish Vasco de Quiroga.

1533

Charles V recognizes communal land ownership rights to the inhabitants of the indigenous pueblo of San Francisco Cherán.

1535

Establishment of the Kingdom of New Spain in the territory of present-day Mexico.

1537

Vasco de Quiroga appointed as the first bishop of the province of Valladolid, present-day state of Michoacán.

1530s-550s

Franciscan monks apply Quiroga’s doctrine in the foundation of pueblo-hospitals throughout the P’urhépecha region, forming the basic structure of indigenous communities.

1550

Epidemics ravage the indigenous population of the territories conquered by the Spanish.

1657

P’urhépecha population growth resumes after a century of epidemics.

17th C.

The P’urhépecha population, governed by the status of “Republica de indios,” confirms its autonomy in terms of internal organization and possession of communal agricultural and forest lands.

1750

Beginning of the Bourbon reforms in the Spanish Empire.

1766-1767

Rebellion of Patzcuaro against the Crown.

Expulsion of the Jesuits from New Spain.

1786

Creation of intendencias and subdelegaciones. Beginning of the dismantling of the Repúblicas de indios.

1810

Start of the Mexican War of Independence.

1821

Independence of Mexico.

1827

First law privatizing indigenous communal properties in Michoacán.

1856

Promulgation of the Lerdo Law as part of liberal reforms, obliging indigenous and ecclesiastical communities to sell their communal lands.

1858-1861

War of Reform between liberals and conservatives.

1868

The village of Cherán is named the head of the homonymous municipality.

1876

Beginning of Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship.

1894

Promulgation of the Regulations for the Exploitation of Forests and Public Lands.

1908

The Industrial Company of Michoacán S.A., owned by American Santiago Slade Jr., begins logging operations in the P’urhépecha plateau.

1910

Mexican Revolution breaks out.

1913

Casimiro Leco from Cherán organizes an expedition to expel the logging company of Sleade.

1916-1917

Cherán is ravaged by the revolutionary bandit Inés Chávez García.

1926

Promulgation of the anticlerical law by revolutionary president Plutarco Elías Calles. Beginning of the Cristero War.

1928

Lázaro Cárdenas becomes president of the State of Michoacán.

1929

Calles founds the National Revolutionary Party (PNR). End of the Cristero War.

1931

Creation of the legal status of comunidad agraria, replacing the comunidad indígena.

1932

First clash: Anticlerical sympathizers of Cárdenas beheaded in Cherán.

1924

Lázaro Cárdenas becomes President of Mexico.

1937

Cherán is integrated into the road network through the construction of the MexicoGuadalajara national highway. Second clash: Anticlerical sympathizers of Cárdenas executed in Cherán.

1940

Abolition of the indigenous cabildo, the communal civicreligious governing body.

1946

The PNR becomes the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

1950s-1970s

Jesús Hernández Toledo, a personal friend of Cárdenas, becomes the PRI leader in Cherán.

1963

Establishment of the communal pine resin processing plant in Cherán.

1976

Third clash: Military intervention in Cherán.

1984

The Secretary of Agrarian Reform legally recognizes communal lands in Cherán, primarily forested areas.

1989

Foundation of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) on a national scale. The PRD wins the municipal election in Cherán, ending the PRI’s hegemony.

1992

Reform of the Mexican Constitution, recognizing the multicultural nature of the nation and granting indigenous peoples the right to choose their representatives through usos y costumbres (customs and traditions).

1994

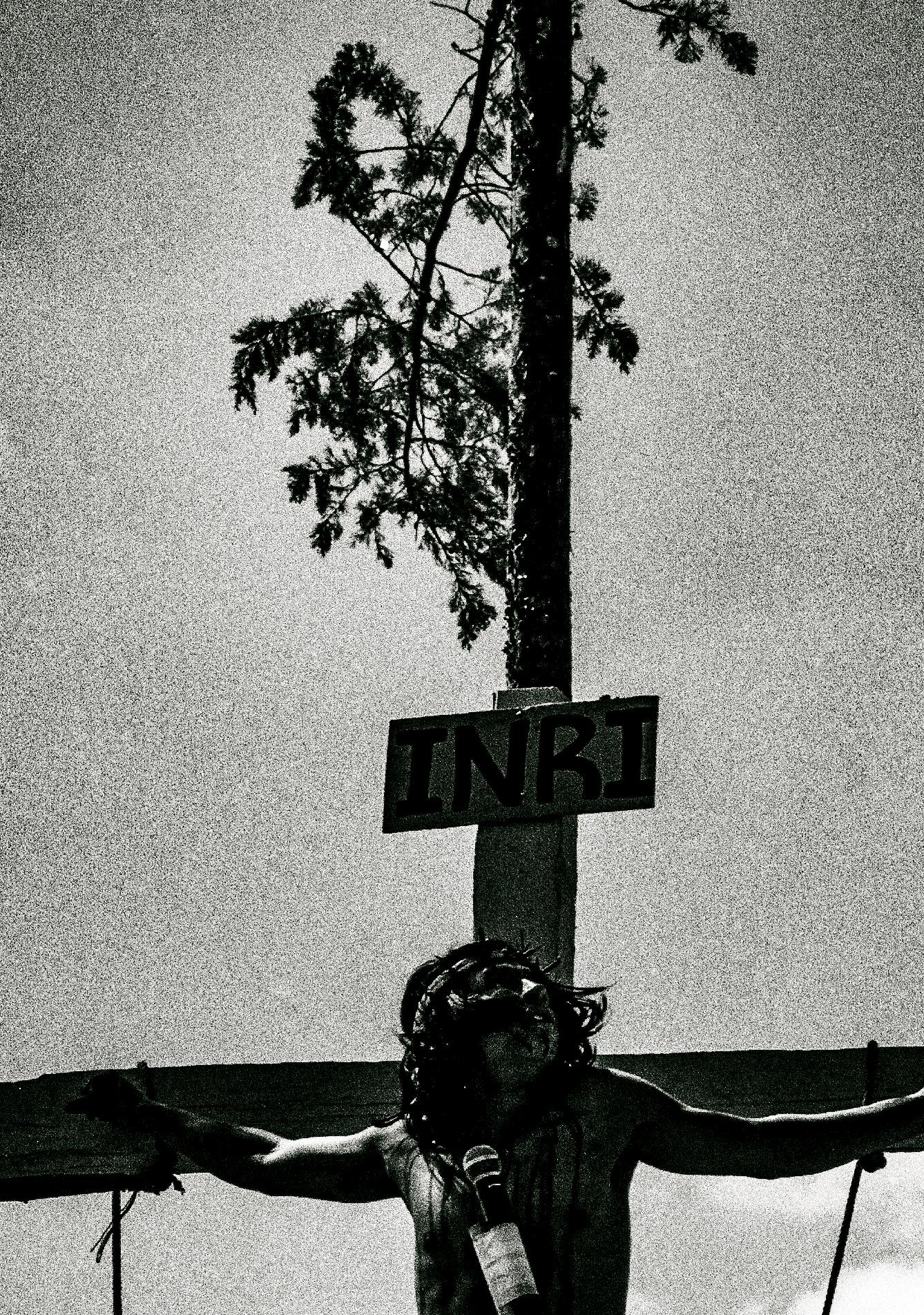

Zapatista uprising. Refoundation of the ecclesiastical cabildo in Cherán.

2007

The PRI regains the municipal presidency of Cherán. The municipal building is occupied by a faction of the PRD opposing the election of the new mayor, led by former mayor Leopoldo Juárez Urbina.

2008

Organized criminal groups begin clandestine exploitation of communal forests in Cherán.

Leopoldo Juárez Urbina is executed.

2011

Popular uprising in Cherán. All political parties and the national police are expelled from the village.

2012

Establishment of a government based on usos y costumbres and a municipal nursery for reforesting communal lands.7th Century

In Mexico, the plundering of natural resources has had significant consequences and generated countless territorial conflicts at the local level, as exemplified by the one that occurred in 2011 in the municipality of Cherán, Michoacán state. The devastation of forests and the inaction of the local government led the community to reaffirm itself and claim its territorial and political autonomy.

Firstly, we will provide an overview of the politicization of the Purépecha people in Cherán by discussing the historical process of the formation of their communal territory and the domination they have endured from agrarian reform to the present day. Secondly, we will examine how, realizing they were losing control over their lands, they engaged in a conflict that resulted in their reterritorialization and paved the way for their emancipation. Finally, we will analyze how autonomy is constructed through a process of self-institutionalization of the territory, which enables the collective production of a desired space that opposes the dominant social model.

Community, Agrarian Reform, and Local Conflicts: Territory as the Origin of the Struggle

The Cherán community is located in the northwest part of the Mexican state of Michoacán, on the Purépecha Plateau, highlands that were administered by encomenderos in the early years of the colonial period. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the intensive distribution of land in New Spain suppressed the revolts of the caciques who demanded rights to the territories taken from indigenous populations. The vice-royal administration issued property titles for lands,

forests, and watercourses, thereby establishing a new territorial order marked by differences between Castilians and indigenous peoples. However, certain indigenous territories were recognized as legitimate property of their inhabitants.

After the country's independence, foreign investments and industrialization triggered a new phase of plundering, which, combined with land grabbing and the cacicazgo inherited from the colonial period, generated significant social discontent in several indigenous regions. These factors constituted one of the main causes of the 1910 Revolution. In the case of the Purépecha Plateau, most of the conflicts during the revolutionary period revolved around forest exploitation. The arrival of the railroad at the beginning of the 20th century was accompanied by the establishment of the Michoacán Industrial Company, which engaged in intensive exploitation. It was in this context, in 1913, that Casimiro Leco López, a leader from Cherán, gathered men to fight against forest plundering and protect themselves from bandit attacks.

Between 1934 and 1940, during the golden age of land distribution, the Ministry of Agrarian Reform recognized communal properties and ejidos (communal lands) in a large part of the country. However, the Cherán community only obtained property titles for its communal lands in 1984. The verification of ancient records revealed that this community's property rights over the occupied lands had already been established in 1552, 1565, and 1575. By closing their agrarian case, the Ministry of Agrarian Reform recognized

and granted property titles to 2,100 comuneros (community members) of Cherán, covering a total area of 20,826 hectares of communal lands, free from conflicts, of imprescriptible, unseizable, and inalienable nature.

The agrarian redistribution policy should be seen as a mechanism that allowed the postrevolutionary state to establish its legitimacy in the rural world, satisfying popular demands for land without, however, breathing new life into local autonomies. The Cárdenas administration pursued a policy of reconfiguring the rural world, which led to territorial fragmentation in some areas. By institutionalizing land legalization procedures, agrarianism created new conditions for resolving disputes. It also opened up new avenues for expressing disagreements and demanding changes in land distribution.

In post-revolutionary Mexico, agrarian disputes primarily revolved around land demarcation, as well as the form and nature of local organizations responsible for land management, within a broader context of indigenous populations' autonomy in land regulation. In the 1940s, the federal government took the task of redefining ejidal rights through the National Agrarian Commission. Clientelism, as a practice that facilitated the negotiation of agrarian affairs, was reinforced, and the dissensions between rival factions were reaffirmed within and between communities.

It is in this context that the Cheranástico community separated from Cherán in 1939 and joined the municipality of Paracho. Forest companies gradually returned to the Purépecha Plateau - the cancellation of land leases and the forest prohibition policy implemented under Cárdenas had slowed their progress. Simultaneously, the encouragement given to local cooperatives through public assistance proved counterproductive: indigenous caciques eventually took control of them and, with the complicity of large national companies, sought to increase extraction for their own benefit.

The plundering of the forest escalated with the “ant theft” of wood and the clandestine leasing of forested lands: by 1946, the Meseta had fallen into the hands of forest companies. The following year, the state transformed cooperatives into Industrial Forest Exploitation Units to “rationalize” production, that is, optimize regional output to support the new national economic system based on exports. This reconfigured the national agrarian system over the following decades: communities engaged in the direct exploitation and sale of timber and resin to the regional company located in Cherán, with

some of the population abandoning agriculture to work in this sector. In Cherán, this stage was marked by the existence of agrarian power groups who, through clientelism at the local and state levels, pocketed the profits by controlling the Communal Property Commission. Thus, the resolution of Cherán's agrarian issue took forty years.

In the 1940s, Beals described Cherán as a selfsufficient indigenous and peasant community with little social contrast. However, what Castile observed in the 1970s was different: according to him, Cherán opened up to the modern world and imported new goods. Schools adhered to the modern national project, and faced with increasing social inequalities and land scarcity, the local youth began to emigrate. The population still had a sense of community, but in this context, its chances of persisting continued to weaken. Its autonomy had a flaw: its economic dependence, exacerbated by the “integrative” activities of the “big society,” not to mention the socio-economic and political consequences implied by integration into a national production system. In the eyes of the comuneros of Sevina, a locality in the neighboring municipality of Nahuatzen, this period in which the Purépechas turned the forest into a commodity marked the rupture of their pact with nature.

Ana Del Conde places the process of political subjectivation of the inhabitants of Cherán within a broad spatio-temporal framework that encompasses experiences of resistance to Spanish colonization and more recent influences from other Mexican sociopolitical movements. Throughout the 20th century, the state denied cultural diversity by implementing policies to integrate the “indigenous society” into the culture of the “national society.” These policies neither resolved conflicts between communities nor offered alternatives to resource plundering, which fostered a certain unity among Purépecha organizations whose discourse advocated for the defense of their territories and the recognition of their rights. Subsequently, the emergence of indigenous resistance in Latin America brought the valorization of communal assets to the forefront.

When forest bans were lifted in 1972, the state of Michoacán became one of the largest timber producers in the country within a few years. The amount extracted was so substantial that in 1983, the police shut down hundreds of clandestine sawmills, prompting communities to defend their forests against private exploiters. While some managed to limit extraction, illegal logging soared. In this context, also marked by the debate on legal reforms of communal property

in Mexico, the first Encounter of Indigenous Communities of Michoacán took place in Cherán in 1991, inaugurating a period of organization and indigenous struggles throughout the entire state. Through the P'urhépecha Nation Decree, several organized communities publicly expressed their opposition to the reform of Article 27 of the Constitution in 1992, which they believed opened the way to land privatization. Moreover, Cherán did not participate in the Land Certification Program (“Procede”) established by this reform. In 1994, the P'urhépecha Nation Organization was founded as an instrument of struggle and a manifestation of solidarity with the Zapatista National Liberation Army's insurgency. Three years later, increasingly engaged in political actions, the organization published the booklet Juchari Juramukua (Our Autonomy), which for the first time mentioned autonomy or the right to self-determination of peoples. Through their experiences, the Cherán community became one of the leaders of the indigenous movement in Michoacán, alongside other Purépecha organizations.

It is important to note that the process of politicization among the Purépechas is linked to a communal conception of resources, as their status as an agrarian community and their common assets have been officially recognized. Common assets, referring to the resources that a community has appropriated and manages collectively, also relate to the notion of territory, understood as the living space of a community and the culmination of a historical process that shapes its social organization and identity. Control over territory and common assets is therefore the condition for comuneros to ensure social reproduction and development while respecting their identity. Thus, Cherán mobilizes indigenous conceptions of territory and nature in its political discourse to oppose a utilitarian and market-driven vision of communal goods.

The dynamic of substituting a “nature” space with a “resource/product” space, the national and state situation of indigenous peoples, and the progressive reaffirmation of a discourse on Purépecha identity are all elements that have facilitated the construction of an indigenous political subject aware of its subordinate position. In addition to these factors, specific factors within the Cherán community, such as the electoral conflict in 2007 arising from suspicions of electoral fraud by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, also played a role. Furthermore, the initial acts of resistance by the Purépechas against the activities of loggers — filing public complaints with the municipality, hanging banners from windows, organizing public or secret meetings —

proved insufficient. The social climate became more oppressive when the local criminal group intensified its harassment of the community, going so far as to “disappear” and/or assassinate the initial opponents. Far from silencing the voices, these acts of repression, combined with the factors mentioned earlier, fostered the collective acceptance of an inevitable conflict.

Three years after the intensification of clandestine logging, the devastation of the forests surrounding the La Cofradía water source, a site of high environmental and cultural value, sparked outrage: Cherán rose up on April 15, 2011. While this event marked the transition from the experience of domination to that of conflict, it should not be considered the sole factor behind this spontaneous response, as we have seen earlier. However, the form of the insurrection informs us about a certain desire for community unity. In the early hours of April 15, a group of women and children went to the Templo del Calvario to block the passage of logging trucks, which had the habit of passing through that location. When they found and apprehended the thieves, the comuneras used the church bells to call upon the community to come to their aid.

According to Ojeda, this conflict expresses a breaking point and differs from previous conflicts in identifying a common external enemy that is much more dangerous than previous ones. Previously, internal conflicts within the community had weakened it, giving way to organized crime that generated this situation of violence. However, it was no longer just about theft of wood or threats to the physical integrity of a few comuneros: deforestation and pollution of the water source that supplied the majority of the community affected it as a whole. Finding witnesses who recognize the internal conflicts within the community spanning decades is particularly difficult. However, Juan Navarrete (member of the Execution, Oversight, and Justice Mediation Council) points out that since 2011, the community has acknowledged the need to overcome these conflicts: “Our condition [...] has led us to adopt a more understanding behavior, attitude, and this helps us avoid significant conflicts among comuneros.”

Living together in a common space enables both material transformation and the exchange of ideas, establishing a collective identity that, as in the studied case, can be oriented towards asserting a political stance. When the community of Cherán takes on this conflict, it is asserting its communal life. Even though its inhabitants had little

influence over political processes at the municipal level for decades, they would come together occasionally to participate in organizing traditional festivities and community work.

Their knowledge of the territory helped them prepare their defense, which materialized through the control of strategic points. It is no coincidence that their first action was to erect barricades at the city gates. Simultaneously, the residents organized themselves by occupying the streets of each neighborhood day and night, lighting fogatas (campfires) for their security. Some comuneros claim that these fires appeared spontaneously, but it is likely that they were inspired by the previous organization of manzanas. Beals, in the 1940s, and Castile, in the 1970s, had observed that manzanas, which brought families and neighbors together, were key locations for community organization. Additionally, due to the need to occupy the streets, women, who were usually responsible for household chores, brought stoves out of their homes and began cooking outside, fostering gatherings among families.

The 2011 conflict escalated into an armed insurrection when volunteers formed a civil security force and conducted what they called “rondes” (rounds). Although there are no historical sources attesting to the ancient existence of community rounds, it appears that they emerged during the post-revolutionary turmoil, taking the form of a nighttime guard composed of about ten voluntary men who patrolled the streets of their neighborhood. Furthermore, on the day of Cherán's insurrection, community members confiscated the weapons of the municipal police, whom they deemed corrupt, causing the mayor, a member of PRI, and his administration to flee.

The town hall was occupied, and a communal assembly was formed, supported by existing neighborhood assemblies and strengthened by the conflict. By mobilizing traditional practices and collectively reclaiming the spaces of official political power, the community residents reclaimed their living spaces and began contemplating the creation of an autonomous government inspired by local customs and traditions, with no ties to political parties.

As Zibechi pointed out - and as we have observed in the case of Cherán - in most autonomist struggles or insurrections that have taken place in Latin America over the past twenty years, it appears that the daily life of communities enables the deployment of practices of resistance. The historically woven social relations within a community facilitate its organization and the “emergence” of the movement. Collective actions require solidarity, participation, and numerous encounters among individuals to materialize. Hence, the spatial dimension of these processes is crucial, as space provides the necessary material and “ideational” conditions for social encounters. Thus, the more a social group is territorially grounded, the greater its capacity for organization and defense of its own territory. In this sense, territory can be understood as a socio-spatial device of struggle that, when activated, builds and consolidates a balance of power and participates in the reconfiguration of power relations at other scales.

According to a relational conception, territory does not correspond solely to the social space itself but rather to the power relations delimited within that space, operating based on a referential substrate. Speaking of territory as both the origin

and instrument of struggle thus entails evoking the process of reterritorialization, namely the reappropriation of a space necessary for the existence of the social group. By recognizing themselves as a community, the residents of Cherán managed to identify the destruction of a common good (the forest). In a context of conscientization, they established a connection between their subordination and the loss of control over their territory, progressively assuming the antagonism as their own. Territory, as an expression of a dense fabric of social relations inscribed in a given space, facilitated their collective action against the talamontes and political parties. This subjective development was fueled by the necessity of defending their territory and mobilization as an instrument of struggle, eventually becoming the commitment of the movement and the foundation for long-term emancipation.

The autonomy project of Cherán K'eri: the re-institutionalization of territory

The media and certain scientific research, such as Calveiro's [2014], tend to consider Cherán as an “autonomous municipality.” This confusion can be primarily explained by the overlapping of two territorial structures: one agrarian and the other municipal, both created at the foundation of the Mexican state. Each of these territorial divisions has its own legal framework and parallel authorities, often in competition with each other.

Research like Castro's reminds us that, for the Purépecha people, what is now referred to as a neighborhood already existed before the colonial period and was considered a cluster of dwellings based on personal relationships and kinship ties. Administratively, the neighborhood did not have official existence, but it seems to have always been a point of reference for organization and popular consultation, as was the case in Cherán in the 1940s. Therefore, it is not coincidental that neighborhood assemblies played a crucial role in the conflict.

The fogatas, on the other hand, have been institutionalized as the basic level for information dissemination and decision-making, replacing representation by manzanas (neighborhood units). Following the uprising, a fogata

In this institutional context, Cherán has the status of an agrarian nucleus and also functions as the municipal seat. While the 2011 uprising was a community effort, the Government of Usos y Costumbres (Government of Customs and Traditions) was validated at the municipal level after mobilizing international law. Federal entities were able to grant this right to Cherán because it obtained the status of an “indigenous municipality” [Official Gazette of the Federation, 2014]. On December 18, 2011, a popular consultation was held at the municipal level to validate or reject the proposal to govern based on usos y costumbres. Through this consultation, the Electoral Institute of Michoacán recognized the institutional validity of Cherán's community government [Flores, 2015; IEM]. Thus, Cherán has autonomy in choosing its authorities and exercising a relative self-determination. However, the situation is not without conflicts, as the community government also functions as the government of the municipality, which includes the localities of Santa Cruz Tanaco and Casimiro Leco.

Cuando los árboles empezaron a desaparecer, Uauapu transmitió a los hombres su secreto.

Del corazón de un pino Michoacano, nació un día el niño de Madera. Cuentan que fue entre las llamas de un incendio que lo vieron salir.

Los surcos de su cara portaban las marcas del Fuego, pero no las había dibujado Kurikheri, el Dios del Fuego de los Purépechas.

Este Fuego lo habían provocados los hombres tristes, los hijos de la violencia.

Sin dudas, sus cicatrices las había dibujado un artista genial o intoxicado.

Talamontes. Así los llamaron. Llegaron en vehículos pavorosos, con el rostro escondido. Armados y gritando al sonido de las motosierras. Nadie sabía con certeza de donde vinieron. Alguien dijo que probablemente venían de un pueblo vecino llamado “lugar de miel”, en Purépecha: Capacuaro. Otro dijo que no podrían ser más que los hijos de la Familia Michoacana, o de un bandido al que le decían “el Güero” que terminó acribilladlo por elegir la mujer equivocada.

El caso es que nunca nadie supo de donde llegaron ni quien los mandó. Pero si sabíamos a que habían venido. Habían venido a plantar el Oro Verde.

El Talamonte entraba en los bosques por rutas inventadas por el arquitecto del mal, dibujadas con balas en los acantilados. Muchos eran jóvenes, apenas adolescentes, aturdidos por el sonido del Oro. Se intoxicaban con humo, con liquido o con cristal.