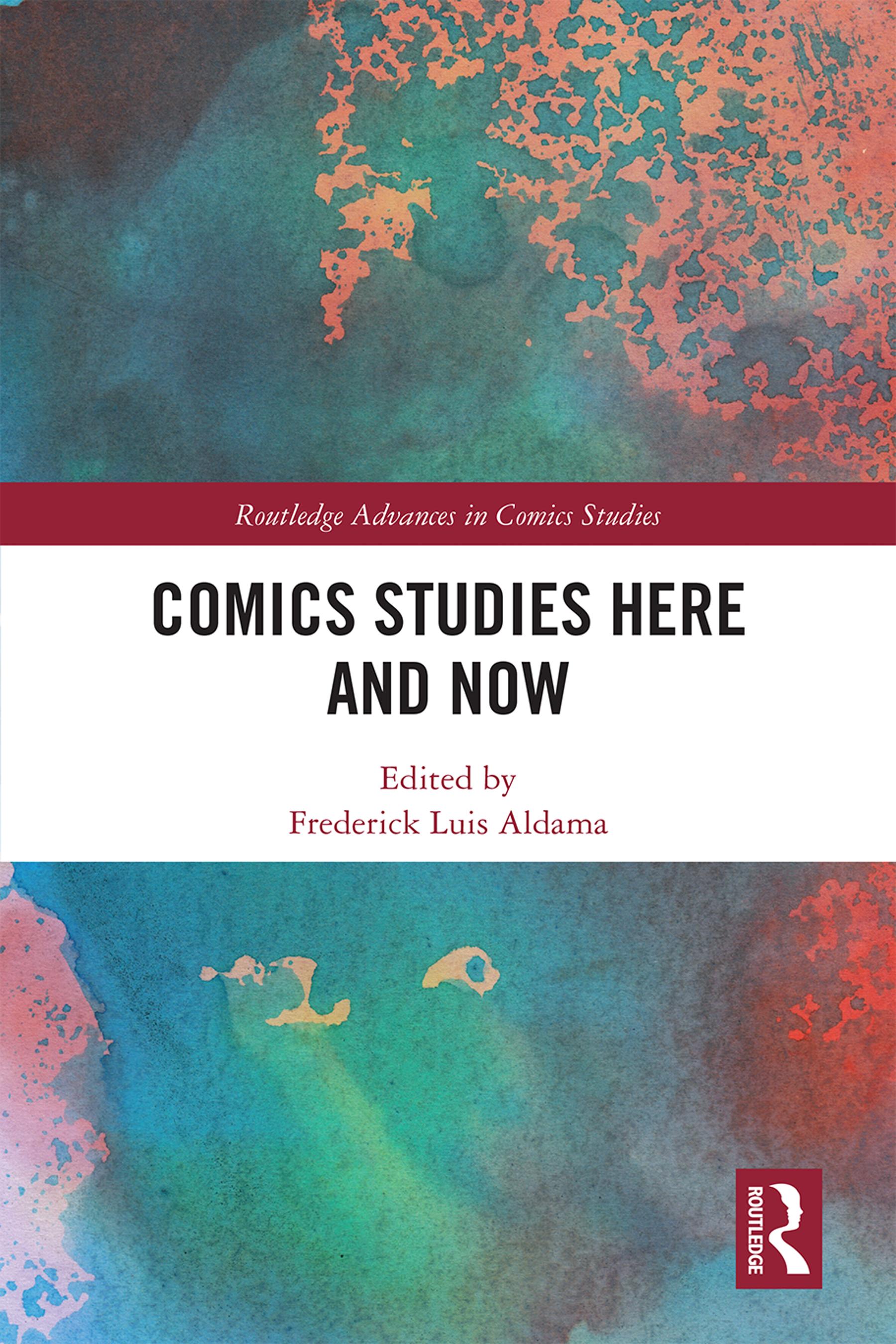

Comics Studies Here and Now 1st

Edition

Frederick Luis Aldama (Editor)Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmeta.com/product/comics-studies-here-and-now-1st-edition-frederick-lui s-aldama-editor/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Muy Pop Conversations on Latino Popular Culture 1st

Edition Frederick Luis Aldama

https://ebookmeta.com/product/muy-pop-conversations-on-latinopopular-culture-1st-edition-frederick-luis-aldama/

Graphic Borders: Latino Comic Books Past, Present, and Future 1st Edition Frederick Luis Aldama

https://ebookmeta.com/product/graphic-borders-latino-comic-bookspast-present-and-future-1st-edition-frederick-luis-aldama/

PERCEPTION in Architecture HERE and NOW 1st Edition

Claudia Perren Miriam Mlecek

https://ebookmeta.com/product/perception-in-architecture-hereand-now-1st-edition-claudia-perren-miriam-mlecek/

HR Here and Now The Making of the Quintessential People

Champion 1st Edition Ganesh Chella

https://ebookmeta.com/product/hr-here-and-now-the-making-of-thequintessential-people-champion-1st-edition-ganesh-chella/

Documenting Trauma in Comics: Traumatic Pasts, Embodied Histories, and Graphic Reportage (Palgrave Studies in Comics and Graphic Novels) 1st Edition Dominic Davies

https://ebookmeta.com/product/documenting-trauma-in-comicstraumatic-pasts-embodied-histories-and-graphic-reportagepalgrave-studies-in-comics-and-graphic-novels-1st-editiondominic-davies/

The Arabesque from Kant to Comics Routledge Advances in Art and Visual Studies 1st Edition Cordula Grewe

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-arabesque-from-kant-to-comicsroutledge-advances-in-art-and-visual-studies-1st-edition-cordulagrewe/

Introduction to Management Science A Modeling and Case Studies Approach with Spreadsheets 7th Edition Frederick Hillier

https://ebookmeta.com/product/introduction-to-management-sciencea-modeling-and-case-studies-approach-with-spreadsheets-7thedition-frederick-hillier/

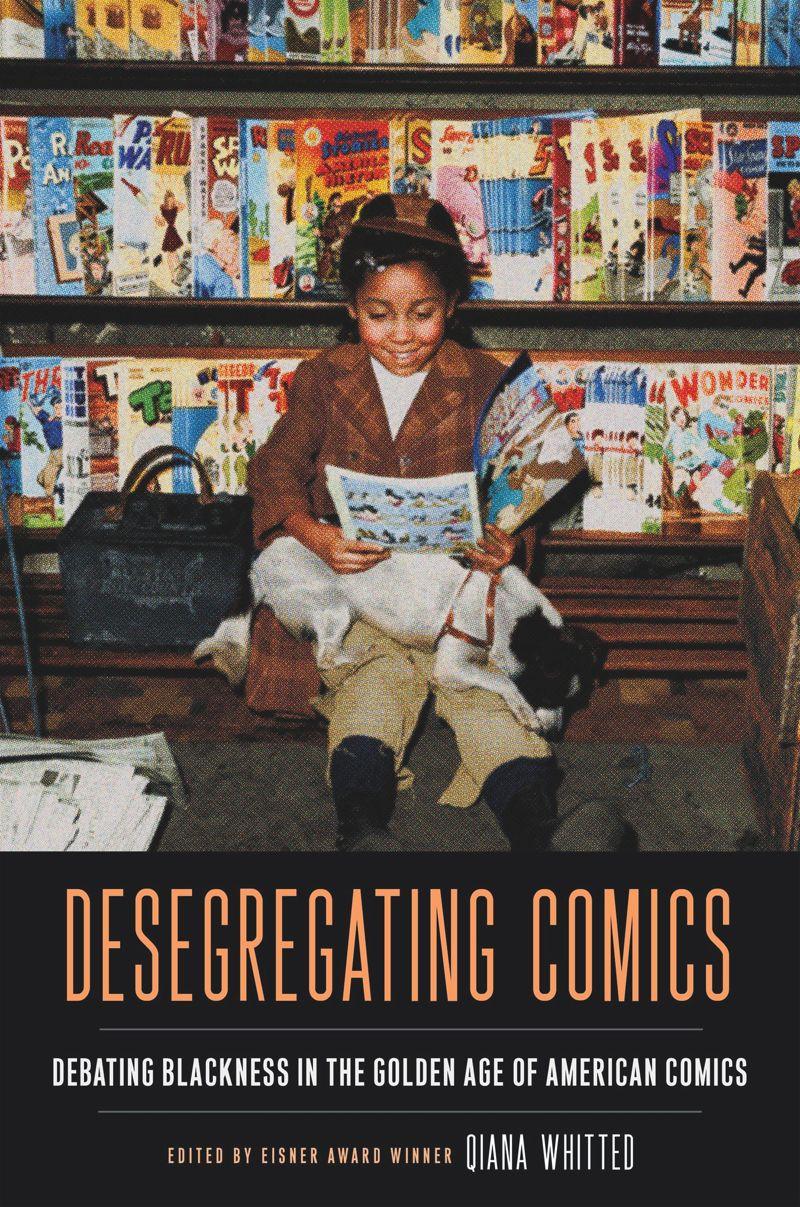

Desegregating Comics Debating Blackness in the Golden Age of American Comics 1st Edition Qiana Whitted

https://ebookmeta.com/product/desegregating-comics-debatingblackness-in-the-golden-age-of-american-comics-1st-edition-qianawhitted/

Case

Studies in Emergency Medicine Learn Evaluate Adopt Right Now Colin G. Kaide (Editor)

https://ebookmeta.com/product/case-studies-in-emergency-medicinelearn-evaluate-adopt-right-now-colin-g-kaide-editor/

Comic s Studies Here and Now

Comic s Studies Here and Now marks the arrival of comics studies scholarship that no longer feels the need to justify itself within or against other fields of study. The essays herein move us forward, some in their re-diggings into comics history and others by analyzing comics—and all its transmedial and fan-fictional offshoots— on its own terms. Comics Studies stakes the flag of our arrival—the arrival of comics studies as a full-fledged discipline that today and tomorrow excavates, examines, discusses, and analyzes all aspects that make up the resplendent planetary republic of comics. This collection of scholarly essays is a testament to the fact that comic book studies have come into their own as an academic discipline, simply and powerfully moving comic studies forward with their critical excavations and theoretical formulas based on the common sense understanding that comics add to the world as unique, transformative cultural phenomena.

Frederick Luis Aldama is the author, coauthor, and editor of over 30 books, including recently Latinx Superheroes in Mainstream Comics. He is Arts & Humanities Distinguished Professor, University Distinguished Scholar, and Director of the award-winning LASER (Latinx Space for Enrichment & Research) at The Ohio State University.

Routledge Advances in Comic s Studies

Edited by Randy Duncan

Henderson State University

Matthew J. Smith

Radford University

Reading Art Spiegelman

Philip Smith

The Modern Superhero in Film and Television

Popular Genre and American Culture

Jeffrey A. Brown

The Narratology of Comic Art

Kai Mikkonen

Comic s Studies Here and Now

Edited by Frederick Luis Aldama

Comic s Studies Here and Now

Edited by Frederick Luis AldamaFirst published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Taylor & Francis

The right of Frederick Luis Aldama to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging- in - Publication Data CIP data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-138 - 49897-6 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-351- 01527-1 (ebk)

Typeset in Sabon by codeMantra

6 Al fred Hitchcock’s Rear Window as “Cineromanzo”

7 Articulate This!: Critical Action Figure Studies and M aterial Culture

8 Singapore Cartoons in the Anti-Comics Movement of the 1950s and 1960s

9 The Institutional Support for Hong Kong Independent Comics

The Latina Superheroine: Protecting the Reader from the Comic Book Industry’s Racial, Gender, Ethnic, and Nationalist

12 The Page Is Local: Planetarity and Embodied Metaphor i n Anglophone Graphic Narratives from South Asia

ORSA G HO SAL 13 Hands across the Ocean: A 1970s Network of French

15 Service Dogs, Code-Switching, and Interracial Polyamory: Exploring the Reclamation Narratives of Comic Fandom

Erica Mass E y Pa Rt V

16 Once and a gain, ack!: Epimone, Recursion, and Variation in Guisewite’s Cathy

s usan Kirtl E y

17 Mapping transamerican Mestizaje in Love and Rockets

Brittany t ullis

18 Only a Chilling Elegy: a n Examination of White Bodies, Colonialism, Fascism, Genocide, and Racism in Dragon Ball

Zachary Micha E l lE wis D E an

19 From the Inner City to the Interstellar: Brian K. Vaughan’s Comix after 9/11

Ja ME s J. Donahu E

20 “a m I Doing the Right t hing?”: Milestone Comics, Black Nationalism, and the Cosmopolitics of Static

sE an Guyn E s-Vishniac

21 Juvenile, Cruel, and MAD : In Defense of Immature Comics

List of Figures

1.1 Krazy Kat, September 28, 1919

1.2 Krazy Kat, January 6, 1924

1.3 Krazy Kat, November 26, 1916

1.4 Krazy Kat, March 11, 1922

1.5 Krazy Kat, August 19, 1917

3.1 Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff strip from 12 February 1919. Printed from the original art from the collection of Craig Yoe

3.2 Sheldon Mayer’s Scribbly and the Red Tornado (December 1942). From All-American Comics 45 © DC

3.3

5.1 Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel (2010)

5.2 Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel (2010)

5.3 Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel (2010)

5.4 Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel (2010)

5.5 Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel (2010)

6.1 La Finestra sul cortile, 1955

6.2 La Finestra sul cortile, 1955

13.1 Barb Brown’s “Lords of Creation,” 1976

13.2 Melinda Gebbie’s “10 Cents a Dance,” 1976

13.3 (Top) Sharon Rudahl’s “Katy Cruel”; (bottom) Fêvre and Clodine “Fastasme et Réalité” (1978)

14.1 Magdy El Shafee’s Metro. Trans. Ernesto Pagano. Fagnano Alto, IT: Il Sirente, 2010

14.2 Comparison of the same pages from Magdy El Shafee’s Metro. Trans. Chip Rossetti. New York: Metropolitan, 2012 and Trans. Ernesto Pagano. Fagnano Alto, IT: Il Sirente, 2010

x List of Figures

14.3 Ma zen kerbaj’s “Suspended Time, Number 1: The Family Tree.” Samandal 1. Trans. Ghenwa Hayeck. Beirut, Lebanon: Dots Printing Press, 2008

22 2

16.1 Cathy. August 28th, 1979 245

16.2 Cathy. June 3rd, 1986

16.3 Cathy. September 24th, 1986

18.1 Akira Toriyama (2002)

18.2 Lef t: Toriyama’s artwork for Freeza in the 17th Kanzenban; Right: Freeza in the Dragon Ball Z anime with two of his generals 269

18.3 Lef t: Sketches of Commodore Perry’s Officers, by Hibata Osuke (1854); Right: The Warrior & the Lady, by Torii Kiyonobu I (1719) 270

18.4 From left to right: Dragon Ball, Chapter 315 & Chapter 314; Captain America Comics, Unknown Issue 273

18.5 Transformations (from left to right): 1st form; 2nd form; 3rd form; 4th form 276

18.6 Dragon Ball, Chapter 317; Toriyama’s artwork for Goku in the 22nd k an zenban as a Super Saiyan

20.1 Ju xtaposed family discussion of difference in Static #7 (December 1993) 312

List of Contributors

Frederick Luis Aldama is Arts & Humanities Distinguished Professor of English and University Distinguished Scholar at The Ohio State University. He is the author, coauthor, and editor of 30 books. He is editor and coeditor of 8 different academic press book series, including the world Comics and Graphic Nonfiction series. He is founding member of The Comics Studies Society and member of the Society of Cartoon Arts.

Jonathan Alexandratos is a New York City-based playwright and Professor at queensborough Community College. He is editor of Articulating the Action Figure: Essays on the Toys and Their Meanings (2017). He comanages Page 23, Denver Comic Con’s pop culture literary conference, and has presented on action figures and comics at numerous national conferences.

Jan Baetens is an award-winning poet and Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Leuven. He is author and editor of numerous books and journals on comics and text-image cultural phenomena generally, including the coauthored The Graphic Novel: An Introduction (2015).

Bart Beaty is Professor of English at the University of Calgary. He is author of more than a dozen books on comics, including recently Comics Versus Art (2012), Twelve-Cent Archie (2015), and The Greatest Book of All Time (2016).

Colin Beineke is an independent scholar whose writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, INKS: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, ImageText, and The International Journal of Comics Art.

Matthew Bolton is Assistant Professor of English at Gonzaga University. His work on adaptation across media has appeared in Adaptation , Diegesis, Miranda, and ImageText. His current book examines the intersection between narrative ethics and adaptation.

Kin Wai Chu is a PhD fellow of the Research Foundation of Flanders (F wO) at the University of Leuven, Belgium. She researches, teaches, and publishes on comics and cultural studies.

List of Contributors

Zachary Michael Lewis Dean holds a BA from the Ohio State University. He is cocurator of Planetary Republic of Comics. He plans to continue his work on comics as a PhD student at The Ohio State University.

James J. Donahue is Associate Professor at The State University of New York, College at Potsdam. He is author of Failed Frontiersman: White Men and Myth in the Post-Sixties American Historical Romance (2015) and coeditor of Post-Soul Satire: Black Identity after Civil Rights (2014) and Narrative, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States (2017).

Enrique García is Associate Professor of Hispanic visual Culture at Middlebury College. He is author of Cuban Cinema After the Cold War (2015) and The Hernandez Brothers: Love, Rockets, and Alternative Comics (2017).

Torsa Ghosal is Assistant Professor of English at California State University, Sacramento. Her articles have appeared in Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies 7.1, Media-N: Journal of the New Media Caucus 11.1, South Asian Review 36.1, Post Script 33.3, and anthologized in Latinos and Narrative Media (2013).

Jennifer Glaser is Associate Professor of English & Comparative Literature, and Director of Graduate Studies at the University of Cincinnati. She has published numerous articles and is author of Borrowed Voices: Writing and Racial Ventriloquism in the Jewish American Imagination (2016).

Richard Graham is Associate Professor at the University of NebraskaLincoln. He is author of the Eisner and Harvey award nominated book, Government Issue: Comics for the People (2011). He served as a judge for the Eisner awards in 2015 and is currently the managing editor of the online, academic journal SANE- Sequential Art Narratives in Education.

Sean Guynes-Vishniac is a PhD student in the Department of English at Michigan State University, where he writes and teaches about American science fiction, popular culture, and comics. He is coeditor of Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling (2017).

Robert Hulshof-Schmidt is a lifelong comics collector and amateur historian who obtained his certificate in Comics Studies from Portland State University. He works as a development director and runs an online comic store.

Katherine Kelp-Stebbins is Assistant Professor of English at Palomar College, San Marcos, California. Her work has been published in Media Fields, Studies in Comics, and a number of anthologies.

Susan Kirtley is Associate Professor of English, the Director of Rhetoric and Composition, and the Director of Comics Studies at Portland State University. She is author of the Eisner winning book, Lynda

List of Contributors xiii

Barry: Girlhood through the Looking Glass (2012). She served as a judge for the 2015 Eisner Awards and is currently the Secretary for the Comics Studies Society.

Andrew J. Kunka is Chair, the Division of Arts and Letters and the Division of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Education at University of South Carolina Sumter. He is the author of Autobiographical Comics (2017) along with numerous articles and chapters on comics.

Cheng-Tju LIM is an educator who writes about history and popular culture. He is coauthor of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya (2012) as well as numerous articles. He is the country editor (Singapore) for the International Journal of Comic Art and also the coeditor of Liquid City 2 (2010).

Matt Madden is a cartoonist, teacher, and translator. His work includes 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style, his comics adaptation of Raymond queneau’s Exercises in Style, as well as two comics textbooks written in collaboration with his wife, Jessica Abel. For six years he was series coeditor of The Best American Comics.

Erica Massey is a PhD student at Southern Methodist University where she researches, teaches, and publishes on comics and fandom studies.

Leah Misemer is a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow at Georgia Tech. She has published about teaching comics in Composition Studies and about transnational approaches to comics studies in Forum for World Literature Studies.

Ben Novotny Owen taught at the Ohio State University where he received his PhD. He has published articles on comics forms and the politics of history in the work of Joe Sacco, and the modernist aesthetics of mid-century animation in the Peanuts television specials. He is book review editor of INKS: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society.

Christopher Pizzino is Associate Professor of Contemporary US Literature in the Department of English at the University of Georgia. He is author of numerous articles on comics in journals as well as the author of the book, Arresting Development: Comics at the Boundaries of Literature (2016).

Brittany Tullis is Assistant Professor of Spanish and women and Gender Studies at St. Ambrose University. She is the coeditor of Picturing Childhood: Youth in Transnational Comics and author of numerous articles on Latin/x American comics. She currently serves as Academic Director of the International Comic Arts Forum (ICAF).

Daniel F. Yezbick is Professor of English & Communications at St Louis Community College at wildwood. Yezbick is the author of Perfect Nonsense: the Chaotic Comics and Goofy Games of George Carlson (2014).

Matt Madden’s Brief Comic Book Odyssey

A Foreword

w hen I began making comics in the late 1980s, the comics world was small and fairly isolated. On a given visit to the comics store you would find superhero comics, some indie fantasy titles, and a handful of underground or “alternative” comics from publishers like Fantagraphics Books or k itchen Sink Press. The authors were almost all American or Canadian, male, and white. The readers and cartoonists I got to know were aware of the large scene in Europe and the more adventurous ones were getting increasingly excited about rare glimpses of manga from Japan. But to actually get your hands on or read any of this stuff was difficult. we had to seek out oases like the early run of Heavy Metal, which featured translations of Moebius, Enki Bilal, and other European luminaries of the 70s; Fantagraphics’ sporadic printings of Muñoz & Sampayo or Jacques Tardi; and RAW magazine, which introduced us to more far out artists from around the world like Tsuge Yoshiharu or Pascal Doury.

If you flash forward to today, you get whiplash: two major developments of the last 20 years have opened up the Anglophone North American scene to the world in a massive way. The first is the snowballing popularity of manga and anime, which introduced us to whole new graphic and imaginary universes along with several toolkits’ worth of formal innovations, from dynamic layouts to creative screen-toning to inventive sound effects and “emanata.” As importantly, manga brought large numbers of women and girls into comics, first as readers and later as creators. The second sea change is, of course, the world wide web, which made manga, French BD, Italian porno comics, Mexican fotonovelas, forgotten American newspaper strips, and just about anything else you can imagine easily available to people all over the world. Better yet, it’s a two-way system, meaning that a young artist who may earlier have made a photocopied minicomic to sell at a local store (as I did) could now post her work on a blog or on a social media platform and find readers (if not royalties) all over the world. This online networking has transformed the sociocultural world of comics as well. I am able to communicate with a wide range of people, from former students to some of my personal heroes with an ease and informality that was impossible

xvi Matt Madden’s Brief Comic Book Odyssey

when I was a teenager. And while I admit that I miss the thrill of digging up a Moebius book in a used bookstore or discovering new artists through word of mouth, I will gladly trade in that exclusivity for the democratic access the web gives to me and others all over the planet.

An anecdote to illustrate just how far this networking can go: at some point around 2010 I started communicating with some young Colombians on Twitter, commenting on each other’s remarks about comics and retweeting their announcement about a new comics festival they were organizing called Entreviñetas. This polite interaction between strangers on different hemispheres led to me being invited to the second iteration of their festival as, I believe, their first non-South American guest. And since that wonderful experience I’ve informally advised them on foreign guests and have been able to easily put them in touch with artists from the US, France, and elsewhere—all of this done mainly over our smartphones. It’s remarkable when you stop to think about it. (It’s worth noting that “the old ways” still persevere: in Colombia I had a coffee with a Peruvian cartoonist who had bought a minicomic of mine years earlier in Mexico City where I had published it in 1999.)

I feel I should point out that I am skeptical about what all this means in terms of the comics market and the future livelihoods of cartoonists and other artists that are trying to wrangle a living out of this sprawling, liquid entity that is the Internet. However, I am unabashedly optimistic about the importance of the global comics culture the Internet has helped establish. You can see the cross-pollination in the work of younger artists (as well as early adopters like Paul Pope with his fusion of k irby, Otomo, and Hugo Pratt) all around the world: western artists freely incorporating manga tropes and genres in their work, manga-ka showing American and European influences. More and more comics festivals and residencies are popping up around the world, and their guest lists are increasingly international thanks to the ease of communication. And I believe that with that increased interaction, both online and “IRL” along with intermixing of comics traditions, young artists and readers are developing a larger sense of scope and ambition that I hope will lead to transformative work in the future. If you take into consideration the influence comics has on film and television around the world as well, it seems to me that this lowly art form—once dismissed by Daniel Clowes, one of its greatest practitioners, as being akin to professional badminton—has a rich and promising future ahead of it.

Matt Madden

Cartoonist, teacher, translator, and author of 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style

Comic s Studies Here and Now

An Introduction

Frederick Luis AldamaComics studies has arrived. By this I mean, comics scholars no longer feel the immediate compulsion to justify its existence. we si mply do the work of excavating and analyzing, to enrich our understanding of comics the world over. This is exactly what is done by the chapters that make up this volume, Comic s Studies Here and Now. wit hin academia’s hallowed halls, the study of comics is a rather recent phenomenon. w hi le Sol M. Davidson’s 1959 “Culture and the Comic Strips” was the first dissertation on comics, it is only in the twenty-first century that we begin to see dissertations and theses published more en masse. It’s during this period that we also begin to see the rise of scholarly journals on comics, faculty who teach comics, university special collections built around comics (Michigan State and The Ohio State University), and MA and PhD degree programs in comics studies (University of Dundee and University of Lancaster).

Further manifestations of this growth are the increasing number of courses that include comics in the high school, undergraduate, and graduate curricula as well as the writing of PhD dissertations that include chapters on comics (see comicsresearch.org). Perhaps the Benchmark here is Nick Sousanis’s publishing of his comic book dissertation, Unfl attening, with Harvard University Press in 2015. Sousanis is now a professor of comics studies at San Francisco State. And, with more students focused on the study of comics, more faculty are being hired into literature and arts departments who can teach in this area. The 600 faculty listed as founding members of The Comics Society all teach comics at the university level. Additionally, we’re seeing an extraordinary number of monographs and edited books published every year on the subject. I currently coedit the “world Comics and Graphic Nonfiction” series for the University of Texas Press where a steady flow of extraordinary manuscripts cross my desk every week. Additionally, there is “Comics Culture” (Rutgers), “Palgrave Studies in Comics and Graphic Novels” (Palgrave), “Studies in Comics and Cartoons” (OSU Press), “C omics and Graphic Novels” (Bloomsbury), “Studies in European Comics and Graphic Novels” (University of Leuven Press), “C omics and Popular Culture” (University of Mississippi Press), and “Graphic Medicine”

Frederick Luis

Aldama(Penn State). Besides the books, there have been a number of important academic journals dedicated to publishing scholarship on comic books, including INKS , ImageText, International Journal of Comic Art, as well as dozens of others from around the world. (See Comics Research Academic Resources.) And academic journals not focused on comics are dedicating increased space to their study. For instance, for the journal Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature I recently edited a special issue entitled, “A Planetary Republic of Comic Book Letters: Drawing Expansive Narrative Boundaries.”

I should indicate, too, that academic presses are now also publishing comic books. As already mentioned, Harvard University Press published its first comic book dissertation, Unflattening. Add to this Yale Un iversity Press’s publication of Ivan Brunetti’s autobiography Aesthetics: A Me moir HC (2013), Princeton University Press’s graphic narrative of seventeenth century anti-status quo thinkers Heretics! (2017), and my own Latinographix series with OSU Press—a comics venue for Latinx creators to push visual-verbal narrative boundaries.

The scholarly chapters that make up Comic s Studies Here and Now all simply study comics. They are testament to the fact that comic book studies has come into its own as an academic discipline. They move us beyond the debates and discussions (comics vs. literature, for instance) about the ontological and functional status of comics. They powerfully convey the deep understanding that comics demand careful study as unique, transformative cultural phenomena.

I divide the volume into seven sections. They include the following:

Chapters included in section “I: words, Pictures, and Borders” build on and revise what we already know about comics as built material objects made and consumed in time and place. I begin this section with Ben Novotny Owen’s chapter “A Touch of Irony and Pity: Krazy Kat in the Breaks” that sleuths out a significant shift in comics creation that took place in the early twentieth century when George Herriman was given a larger space to experiment with layout. Herriman’s use of vertical space in Krazy Kat (1913–1944) opened the possibility for the kind of complexity fully realized in the contemporary work of Los Bros Hernandez and Alison Bechdel. In “In Love with Magic and Monsters,” Richard Graham shines a much-needed spotlight on turn-of-the-twentieth-century comics of Rose Cecil O’Neil (1874–1944). w hi le her comics and illustration work were extraordinary and her contribution to the field significant, because yesteryear’s comics history and canon-making actively excluded women and promoted men, she was left out. In “Cranky Bosses, Rebellious

Characters, and Suicidal Artists” Andrew J. kun ka digs into the comics archive to identify the shaping of protean autobiographcal comics avant la lettre. Focusing on Sheldon Mayer’s Scribbly and Al Stahl’s Inkie, kun ka attends to how the labor conditions and market forces of the 1940s led to the making of these “proto-autobiographical comics.” I end this section with Robert Hulshof-Schmidt’s “How Lust was L ost.” He examines Matt Baker, Arnold Drake, and Leslie wal ker’s 1950 published “picture novel” It Rhymes With Lust that resisted categorization and, as a consequence, was not given its critical due till recently.

Section “II: New Transmedial Forms” brings together chapters that examine the exciting ways that comics have permeated other media forms such as literature and film. I begin this section with Jennifer Glaser’s “Comics, Race, and the Political Project of Intermediality in k aren Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel.” Glaser carefully teases out and analytically unpacks the “transformative exchange” that takes place between comic and novel in Yamashita’s I Hotel (2010). Following in the same transmedial and transformative spirit, in “Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window as ‘Cineromanzo’” Jan Baetens excavates and analyzes a rich archive of comic books made from film visual stills, scenarios, and scripts. These cine-comics at once work within and radically expand comics and film narrative conventions. Concluding this section is Jonathan Alexandratos’s and Daniel F. Yezbick’s “A rticulate This!” that analyzes how the transmedial move from comic book to action hero can shed light on how the private and public as well as communal and transnational intersect.

In section “III: Institutions and Movements,” I include chapters that excavate the rich and complex comic book traditions shaped by government censorship policies and government sponsorship programs—as well as those comic book creators that dare to cross nationally recognized comic book conventions and styles. I begin this section with Cheng Tju LIM’s “Singapore Cartoons in the Anti- comics Movement of the 1950s and 1960s” that focuses on Si ngapore’s 1960 anti- comics movement—a movement that went hand in hand with the government’s anti-colonial policy making. Ironically, perhaps, it was within this culturally restrictive space that, as LIM identifies, comics became complexly layered, antiauthoritarian, resistant critical narratives. In “The Institutional support for Hong kong Independent Comics” k in wai Chu focuses on Hong kong’s pro-comics policies that helped strengthen and solidify the making of a tradition of alternative manhua —comics that emphasized the visual aesthetics and the personal narratives. Further complicating the way external political and institutional forces have shaped comics from around the world, in “Jirō Taniguchi: France’s Mangaka” Bart Beaty analyzes the maverick career of Jirō Taniguchi. In biography

a nd style, Taniguchi crisscrossed continents and comic book conventions: French bande dessinée with Japanese manga. Indeed, as Beaty so aptly demonstrates, it is this cross-pollination that elevated the status of Japanese manga in France and transformed its comics tradition.

Section “I v: Resistant word-Drawn Acts & Transformative Reading Communities” includes chapters that analyze the way comic book creators skillfully use visual shaping devices (paneling, layout, perspective, angles, lettering, for instance) to complicate reader engagement. In addition to considering how comics are constructed, these chapters attune to how reading communities can and do shape individual comic book stories and comic book traditions. I begin this section with Enrique García’s “The Latina Superheroine” that analyzes how Latino creators such as George Pérez and Jaime Hernandez created intersectional comics that changed the independent and corporate perceptions of heroic women—and with this, shaped new comic book reading communities. I follow this with Torsa Ghosal’s “The Page is Local: Planetarity and Embodied Metaphor in Anglophone Graphic Narratives from South Asia.” Ghosal analyzes a series of Subcontintental Indian, Anglophone nonfiction comics that appear in First Hand (2016) to show how they complicate simplistic conceptions of local versus global. In “Hands across the Ocean,” Leah Misemer identifies American and Feminist comics communities in the 1970s that used the comics form to represent and critique the misogynist dominant culture. Also formulating a feminist comics framework, k at herine kelp-Stebbins analyzes transnational and translational reader communities in the making and consuming of comics such as The Adventures of Tintin, Magdy El-Shafee’s Metro, and the Beirut-based comics anthology Samandal. I end this section with Erica Massey’s “Service Dogs, Code Switching, and Interracial Polyamory: Exploring the Reclamation Narratives of Comic Fa ndom.” Here, Massey uses the concept of the borderlands to uncover then analyze how comic book fandoms work expansively within existing comic book storyworlds in ways that center-stage otherwise disenfranchised characters.

The section “v: Ma rgins Transforming Centers” brings together chapters that consider the ways that the marginal forms, subjects, and experiences infiltrate and transform centers in the making of inclusive storyworlds and reading communities. I open this section with Susan k ir tely’s chapter, “Once and Again, Ack!: Epimone, Recursion, and variation in Guisewite’s Cathy.” k ir tley analyzes how Cathy Gu isewite’s use of the rhetorical strategy of purposeful redundancy (epimone) conveys subtle political messages in her comic strip, Cathy (1976–2010). In “Mapping Transamerican Mestizaje in Love and Rockets” Brittany Tullis excavates a micro-history of Los Bros

Her nandez’s 1980s Love and Rockets to show how it traverses North and South American narrative traditions as well as how in form and content it transcends US Latino subjectivities and experiences. In a like decolonial mode of critical inquiry, z achary Michael Lewis Dean examines how Japanese mangaka (comic artists) like Akira Toriyama create storyworlds that work doubly: to entertain and to level radical critiques against American and European colonialism, genocide, and racial supremacy. In “From the Inner City to the Interstellar: Brian k . vaughan’s Comix after 9/11” James J. Donahue also considers the double narrative function in comics, in this case to entertain and draw critical awareness to historical and political facts of daily life. Donahue analyzes how contemporary comics such as Ex Machina, Pride in Baghdad, We Stand On Guard, and Saga work within sci-fi and militaristic narrative conventions and present a worldview critical of capitalism. In “Am I Doing the Right Thing?” Sean Guynes analyzes Robert L. wash ington’s “Louder than a Bomb” storyline that appeared in issues 5–7 of Static as representative of this comic book series’ that creates “transformative encounters between characters of different colors, creeds, genders, and sexualities” that reveals real racism in the world and that sidesteps black essentialist and nationalist ideological agendas. I end this section and the volume as a whole with Christopher Pi zzino’s “Juvenile, Cruel, and MAD: In Defense of Immature Comics” that provides a critical framework for evaluating deliberately juvenile, potentially offensive satirical comics. He does so by analyzing two boundary-pushing comics: John Layman and Rob Guillory’s Chew and Nicholas Gurewitch’s The Perry Bible Fellowship.

Comic s Studies Here and Now marks the moment of our arrival. That is, the arrival of scholars who no longer feel the need to justify how we choose to spend our scholarly time and attention. The chapters herein move us forward, some in their re-diggings into comics history and others by analyzing comics—and all its transmedial and fan-fictional offshoots— on its own terms. Comic s Studies Here and Now stakes the flag to mark our arrival—the arrival of comics studies as a full-fledged discipline that today and tomorrow excavates, examines, discusses, and analyzes our planetary republic of comics.

Works Cited

Aldama , Frederick L . Latinx Superheroes in Mainstream Comics. Tucson , A z : Un iversity of Arizona Press, 2017.

Babic , Annessa A. Ed. Comics as History, Comics as Literature: Roles of the Comic Book in Scholarship, Society, and Entertainment. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press/Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

6 Frederick Luis Aldama

Beaty, Bart. Comics Versus Art. Toronto: University of Toronto Press , 2012 . Brunetti, Ivan. Aesthetics: A Memoir HC . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press , 2013.

Karasik , Paul , and David Mazzucchelli. City of Glass: The Graphic Novel. La Cour, Erin. “Comics as a Minor Literature.” Image & Narrative 17.4 (2016): 79 –90. Web. 19 June 2017. < www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/ imagenarrative/article/view/1336/1081>.

Ledesma , Alberto. Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer. Columbus, OH : Ohio State Univerity Press , 2017.

Meskin , Aaron. “Comic as Literature?” British Journal of Aesthetics 49. 3 (2009): 219 –239.

Nadler, Steven, and Ben Nadler. Heretics!: The Wondrous Beginnings of Modern Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Pizzino , Christopher. Arresting Development: Comics at the Boundary of Literature . Austin, TX : University of Texas Press , 2016 . Simmonds , Posy. Gemma Bovary. New York: Pantheon , 2005.

———. Tamara Drewe. New York: Mariner Books , 2008.

Sousanis , Nick. Unflattening. Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press , 2015.

Part I

Words, Pictures, and Borders

1 A Touch of Irony and Pity Krazy Kat in the Breaks

Ben Novotny OwenThe 1913 Armory Show, which introduced large numbers of Americans to post-Impressionist art for the first time, inspired sophisticated mockery from cartoonists, who saw Cubism, Futurism, and their ilk as latecomers to the task of representing the experiences of modern life that already crowded the funny pages.1 According to George Herriman’s biographer, Michael Tisserand, the show also led to a quieter but equally momentous change—a small alteration to the format of the comics page in several of wil liam Randolph Hearst’s newspapers, the full significance of which would not become apparent until considerably later. “On Friday, April 4, 1913,” about a month and a half after the opening of the Armory Show, Hearst’s New York Evening Journal “launched a vertical strip along the right side of the page, which various cartoonists used for experimenting with vertical action, frequently offering direct parodies of (Marcel Duchamp’s) Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 ,” a painting whose abstraction infuriated and fascinated visitors to the show (241). The change to a vertical format was particularly significant for Herriman because, starting on October 28, the Krazy Kat strip became the regular occupant of the vertical space. The principal characters k ra zy and Ignatz Mouse had previously been confined to a narrow band running horizontally along the bottom of Herriman’s strip The Dingbat Family. Now, in a larger space, they “launched into a daily routine that was equal parts minstrel show and Socratic dialogue” (242).

Tisserand notes that the second of the Krazy Kat dailies in the vertical format featured k ra zy descending a staircase (242). 2 Like Duchamp’s painting, the strip plots a body moving through a fixed space over a span of time—in this case k ra zy walking down stairs at Ignatz’s urging, to meet a rock Ignatz has dropped out the window. But while the connection to modernist painting is significant, the vertical format was itself a major factor in Herriman’s conception of the new strip. He and other cartoonists treated the new format as a space for experiment, as we see in strips such as Hal Coffman’s Freddy Film, which ran in the San Francisco Call on November 5, 1913 (followed by a Krazy Kat in the next issue). Coffman’s comic shows a man in free fall, tearing through the gutters between panels as he goes. In the bottom panel, a cop asks

t he crumpled man, in the manner of Rube Goldberg’s contemporaneous “Foolish questions” cartoon, “S’matter did you fall?”

The sense of free fall persists in the Krazy Kat dailies even after the experiments with the format stop, preserving a sense of downwardmoving kinetic energy. Herriman draws k ra zy and Ignatz as bodies in a constant dance, changing poses each panel like a vaudeville double act. And during this vertical period, the settings of the strip began to change from panel to panel—Ignatz addresses k ra zy from an armchair while k ra zy lies on the floor, but in the next panel they stand on a block of ice floating in the sea. Cues suggesting downward fall remain scattered throughout these antic strips—one ends with Ignatz having fallen from a fence, struck senseless by the revelation that k ra zy’s real name is wil hemina, another features a penultimate panel of k ra zy and Ignatz falling head first, only to find them in the final panel next to each other in bed, as though awoken from a dream of falling (Herriman 42). The vertical layout of the strip seems to make possible new kinds of associations among pictures, less immediately available to strips that read left-toright, as though Krazy Kat were cutting through layers of other stories. Herriman’s sense of the strange associations that come from opening up comics to multidirectional reading is crucial to the experimental designs he brought to the larger-format Krazy Kat Sunday pages, which he began drawing for Hearst’s newspaper in 1916. Herriman’s fame as one of the greatest cartoonists in history rests on these Sunday strips.

Krazy Kat has gained the attention of critics since at least 1917, when Summerfield Baldwin wrote his appreciation “A Genius of the Comic Page” for Cartoons Magazine. Yet little of that criticism, including recent work by comics scholars, tends to pay close attention to Krazy Kat ’s design in general (though there are good readings of layout in individual strips). 3 This is understandable—the strip’s language and narrative structure are fascinating subjects in themselves, and the layouts of Herriman’s pages for the Sunday strip seem particularly difficult to generalize about because they are so various, changing pattern from week to week. However, without careful attention to the poetics of Herriman’s design, we lack the means to describe much of what makes Krazy Kat a continued object of fascination and centrally important to comics history (influential on the expressive layouts of Bill wat terson’s Calvin & Hobbes, as well as the complex, unresolvable temporal structures of long-form comics like Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen , Al ison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and Jaime Hernandez’s Locas stories in Love and Rockets, all of which resist conclusive endings and instead demand to be reread backwards, upwards, and through). Sarah Boxer suggests that critics take on the verticality at the heart of Herriman’s aesthetic (“k ra zy k riticism”). I respond with an account of how that vertical fall warps the strip’s temporality. Herriman’s complex design should also be central to our understanding of the strip’s very particular

A Touch of Irony and Pity 11

version of modernism, which rests on Herriman’s invention of a form of visual syncopation during the short period—from the mid-1910s through the 1920s—when “jazz” and “ragtime” were virtual synonyms for all that was modern in art and culture.4

Through the design of his pages Herriman constructed a layered story space, in which implied narratives and montage associations crisscross the page. Layout thereby functions as a companion to the verbal poetry of Herriman’s strip, which plays continually on the connotative associations of language to create suggestive connections. The design of Herriman’s pages produces loops and reframings, temporal eddies in which what comes later in a story seems to inflect what comes before. The overall shape of the page works as a visual companion to the strip’s fascination with repeat performance, via constant references to the vaudeville stage and the iterative repetition of altered versions of popular songs. The well-known emphasis on shifting origins and identities within Herriman’s cartoons finds its complement in a formal quality of origin-less-ness. w here nineteenth-century American comic strips were fascinated with unmasking social appearances, Krazy Kat presents the process of unmasking as continual and constitutive of comics reading. Ultimately, the ongoing shift off-beat within the strip creates a melancholic form. This melancholy is not so much a matter of consistent tone—though the strip is in part defined by a “touch of irony and pity,” as the critic and early champion of the comics Gilbert Seldes called it—as it is a way of designing the strip so that objects of desire remain present but slightly out of reach.

Herriman’s variations on the design of the Sunday strip (and, for a brief period in 1920, the daily strip as well) produced delays and offbeat movements, elaborating a form of visual syncopation, analogous to the ragtime music that, by the mid-1910s, was at the center of popular culture in the United States. He invented the mechanisms of this syncopated effect quite quickly during a period of rapid experimentation following the introduction of the Krazy Kat Sunday strip on April 23, 1916. The alternation between panels with drawn borders and panels without drawn borders was pivotal. This was certainly not Herriman’s only innovation, and he continued to experiment extensively with design and layout over the next 28 years. But the alternation of bordered and unbordered panels introduced a new flexibility in terms of panel layout, in tandem with a new means of creating patterns of visual stress.

Every panel in the first 10 Sunday strips has a drawn border. Already, however, Herriman experiments with panel layout as an expressive feature, as when he draws a thicker line around the final four panels of the April 30 strip to indicate k ra zy’s awaking from a dream or when he uses a panoramic first panel in the June 25 strip—along with odd narrative “intertitle” panels to indicate “cuts,” producing the comics-page equivalent of parallel editing (showing a clear instance of the formal

techniques of film entering the comics page). 5 Then, in the July 2 strip, most of the borders disappear; only the first panel has a line around it on all sides, while the final panel has defined edges created by a block of solid black background. Borders for every panel return for the next two strips (including an experiment with a sequence of three round panels on July 9), and then, on July 23, a new form appears, or rather an old form used to new effect. Only three of the strip’s 13 panels have borders on all sides, and one of those bordered panels—panel six—appears to float in the middle of the sequence of unbordered panels that composes the center of the page.

Herriman had used the alternation of bordered and unbordered panels before—in his 1906 Zoo Zoo strips (about a mischievous cat), for example. But it reemerged in Krazy Kat as a more clearly expressive tool. Most other comic strips at the time employed panels with regular, rectangular line borders. The first 14 Krazy Kat Sundays appear to be Herriman’s gradual shaking-off of arbitrary restrictions, first of shape and then of line. Dissolving the panel outlines was a gesture of artistic freedom—a literal move beyond a drawn border. Herriman was not the first cartoonist to manipulate the form of the panel for expressive ends—the first 15 years of Sunday newspaper cartoons afford many examples of experimentation with the size, shape, and layout of panels. 6 And indeed, Herriman’s manipulation of panel borders and arrangement marks a resumption and intensification of the artistic experimentation that had begun as soon as multi-panel stories became a regular feature of the newspaper comics page in the United States in the late 1890s, but which had trailed off by the 1910s, by which time most Sunday comics had become standardized in a three-across-by-four-tall grid. The Krazy Kat Sundays stood out as distinct from these strips, partly because they initially appeared in a separate part of Hearst’s newspapers, the “City Life” section (Tisserand 266). But they were also immediately visually distinct from the strips in the comics section because they very rarely conformed to the regular grid, the alternation of bordered and unbordered panels becoming central to their basic grammar.

This alternation allowed for an effect analogous to syncopation by creating a distinction between the implied beat of a standard page’s panel layout and the rhythm of its stressed and unstressed panels. The layout of panels of any comic strip, including Krazy Kat, suggests an underlying regular structure, even when there are no drawn panel borders. we ca n view this underlying structure as a kind of beat—an implied, regular distribution of panels over a page or section of a page. By frequently using panels without drawn borders, Krazy Kat leaned on its readers’ intuitive awareness of that beat. And by introducing bordered panels at unevenly spaced intervals, Herriman could draw panels that appeared visually off-beat, in that their borders and placement gave them a visual stress greater than that accorded them by their expected position in the

A Touch of Irony and Pity 13

underlying layout. (Needless to say, because visual stress can only be understood relatively, it is also possible to produce stress if the relationship is reversed—an unbordered panel breaking the regular pattern of a series of bordered panels.) Syncopated stresses in music depend on a regular beat, in that there can be no irregularity or alteration without a predictable underlying pattern. Krazy Kat found in the alternation between bordered and unbordered panels a means of creating that dialectic visually. These patterns of stress produce many of the commonplace but formally sophisticated expressive effects within the strip. On July 20, 1919, for example, a heavy black border marks k ra zy’s first appearance, and a wide unbordered panel depicts the passage of time over “the long midsummer day.” These techniques are now a routine part of many cartoonists repertoire, but in the late 1910s they set Krazy Kat apart from other comics.

Further, in coming to rely on the implication of a regular grid as a form of beat from which to produce syncopated variation, Herriman prefigured the work of Piet Mondrian by about three years. Mondrian abandoned the regular grid patterns that appear in his work of 1918 and 1919 in favor of the irregular grid patterns that characterize his work from 1920 on. Harry Cooper argues that this shift marks Mondrian’s use of jazz syncopation, of which he was newly aware, as a solution to a formal problem—the assertion of equilibrium among elements in the painting without a crushingly regular equality among them. The regular grid, overasserted in his paintings of 1918 and 1919, came to function in the paintings of 1920 as an implied beat, from which the actual grid structure varied (180–183).

Mondrian’s work needed to take a dialectic turn through the assertion of the regular grid as beat before it could arrive at visual syncopation because, of course, the overtly regular grid is an anomaly in traditional painting—basic to the principles of composition, but rarely depicted directly. In comics, the regular grid had become an established convention, and so Herriman could rely on the other strips in the newspaper to cultivate in his readers the understanding of a grid as the beat from which his own work could deviate in surprising ways. Indeed, it seems likely that Herriman’s reputation as a modernist rests partly on this breakup of regular rhythm. As Jared Gardner notes, comics could never really pull off the modernist break with the recent past performed by, say, the novels of James Joyce and virginia woolf, since they had no strongly felt tradition of victorian realism to kick against. Gaps and disjunctions were the norm for comics, not the new (Gardner xi–xii). But Herriman could push against the much more recently established conventions of the comics page, composing “in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of the metronome,” to use F.S. Flint’s and Ezra Pound’s phrase (199).

Krazy Kat had little obvious direct influence on high modernism, except on John Alden Carpenter’s 1921 “jazz pantomime” based on the