GARDNER

FAMILY HISTORIES

©2020 Suzanne Gardner Stott

Designed & published by Legacy Books® www.legacybooks.com

Because stories are forgotten if left untold.™

GARDNER

FAMILY HISTORIES

“Remember the days of old, consider the years of many generations.”

DEUTERONOMY 32:7

“I

come not with my own strengths, but bring with me the gifts, talents, and strengths of my family, tribe, and ancestors . . .”

MAORI SAYING

INTRODUCTION

Dear Family,

These ancestor histories are given to you with great joy! What began in 2013 as a simple Christmas gift to my siblings with the writing of Hannah Elida Baldwin Crosby’s history has mushroomed into this book. By compiling and writing these stories I have a deep kinship with these family members, and I want you to have the privilege to better know them.

Countless nights as I sat typing I glanced heavenward, hoping for assurance that I was on the right track in relating details of their heroic lives—a grandmother suffering from the last stages of cancer, yet determine to make it to “Zion” before she died; a grandfather who toiled months felling trees and turned over the desperately needed wages to the Church so others could make the trek across the plains; a grandmother who supported herself and her three sons by selling eggs and eating roots during her husband’s three-year mission to England; a grandfather who was miraculously healed after a tree fell on him; a grandfather pursued by a mob whose prayer of faith stopped an ice flow, allowing him to cross the river to safety; a grandmother who lived in abject poverty, but whose visitors always left her home with a treat. The list goes on and on.

When compiling a life sketch there is never-ending material available and the depth of research that can be done is formidable. There is always additional information. I have drawn from sources I thought would enhance our understanding of their lives.

These histories are just glimpses. How could I, living in this century, capture their time and circumstances in the context in which they lived? They lived in the past, and we are strangers to life back then. Fortunately through journals, histories, and other records, we are given the highlights of their lives and specific examples of their devotion and endurance. I marvel at the faith that compelled them to join the Church; leave familiarity, professions, property, and family; and endure unbelievably difficult living situations. They were tough folks.

Someday we will have greater understanding of their circumstances, and I think we will be even more amazed and grateful for the choices they made to give us a legacy of faith and hope.

I am indebted to Melanie Kirry Gardner for spending countless hours adding photos to enhance these histories. Her compassion and expertise are deeply appreciated.

Lastly, I express gratitude to my brother, Kem, who is a man who “notices such things,” and is the shining force behind assembling these histories into one book.

Suzanne Gardner Stott February 2020

CHAPTER 3: CROSBY FAMILY

George

CHAPTER 4: LINDSAY FAMILY

CHAPTER ONE GARDNER FAMILY

LINCOLN BLACKER GARDNER

PATERNAL PEDIGREE

BRIGHAM LIVINGSTON GARDNER

b: 6 June 1852, East Millcreek, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah, United States

m: 24 January 1874, Endowment House, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah

d: 19 March 1911, Afton, Lincoln, Wyoming, United States

LUCIA ADELL GARDNER

b: 1 June 1856, East Millcreek, Salt Lake, Utah, United States

d: 3 April 1936, Afton, Lincoln, Wyoming, United States

WILLIAM

GARDNER

b: 31 January 1803, Barony, Lanarkshire, Scotland, United Kingdom

m: 7 May 1841, Mosa, Middlesex, Ontario, Canada

d: 12 January 1880, Cottonwood, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah, United States

JANET LIVINGSTON

b: 20 November 1820, Quebec, Quebec, Canada

d: 24 February 1904, West Jordan, Salt Lake, Utah, United States

ROBERT GARDNER SR

b: 12 March 1781, Bogstown Farm, Houston, Renfrewshire, Scotland, United Kingdom

m: 25 May 1800, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland

d: 20 November 1855, East Millcreek, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah, United States

MARGARET CALLENDER

b: 24 January 1777, Falkirk, Stirlingshire, Scotland, United Kingdom

d: 28 April 1862, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah, United States

NEIL LIVINGSTON

b: 9 May 1784, Kilmory Scarba, Lochgilphead, Craignish, Argyll, Scotland, United Kingdom

m: 28 December 1813, Craignish Parish, Argyll, Scotland, United Kingdom

d: 1830

JANET MCNAIR

b: 7 December 1794, Glassary, Argyll, Scotland, United Kingdom

LINCOLN BLACKER GARDNER

b: 13 December 1911, Afton, Lincoln, Wyoming, United States

m: 14 January 1939, Billings, Yellowstone, Montana, United States

d: 25 July 1987, West Point, Davis, Utah, United States

BRIGHAM DELOS GARDNER

b: 18 September 1876, Cottonwood, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah, United States

m: 7 April 1904

d: 23 July 1936, Afton, Lincoln, Wyoming, United States

MARIA BLACKER

b: 25 May 1883, Streator, LaSalle, Illinois, United States

d: 5 October 1967, Ogden, Weber, Utah, United States

ARCHIBALD GARDNER

b: 2 September 1814, Kilsyth, Stirlingshire, Scotland, United Kingdom

m: 3 March 1851, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah, United States

d: 8 February 1902, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah, United States

LAURA

ALTHEA THOMPSON

b: 3 August 1834, Alexander, Genesee, New York, United States

d: 10 July 1899, Afton, Lincoln, Wyoming, United States

d: 4 July 1854, Alvinston, Middlesex, Ontario, Canada

GEORGE VAUGHN THOMPSON

b: 29 May 1798, Elizabethtown, Essex, New York, United States

m: 1 January 1822, Genesee, New York, United States

d: 9 November 1863, South Cottonwood, Salt Lake, Utah Territory, Utah, United States

LUCIA SPAULDING

b: 2 March 1796, Windsor, Berkshire, Massachusetts, United States

d: 9 February 1878, South Cottonwood, Salt Lake, Utah, United States

LINCOLN BLACKER GARDNER

DICTATED BY LINCOLN BLACKER GARDNER IN HIS OWN WORDS

I was born in the log house just a little way from where Papa later built a new house with a parlor and bedrooms upstairs, a dining room, a big kitchen, and one bedroom downstairs. I have 12 brothers and sisters: B. Delos, Althera Adell (Allie), Marguerite, Edward Harold (died at three months), Dorothy, Elna, Darrel, Kenneth, Cumora, Maxine, Genevieve, and Vern.

I don’t remember much of my early childhood. I do remember sitting out on the front porch. I must have been four or five years old, and Papa had a white-topped buggy waiting out in front to take me to the baseball game. We called our horses Bally and Bud. I also remember one day in the old home my mother was nursing a baby. It must have been Dorothy. Mother’s sister Fannie was there, and she said to me, “Do you want some?” I was so frightened I ran behind the rocking chair to hide.

Papa had a milk route. We had a big barn, and I helped milk from a very early age. I remember cleaning the barn out so well; water ran under the barn and we’d scoop the manure down a chute. We had 10 to 15 cows in the barn. I thought we were quite well to do.

Grandmother Althera came to see us often. She was a little Welsh lady and always wore black dresses. She was smaller than my mother, but they still looked alike. I vividly remember mother’s brothers: Uncles Hyrum, Will, Kem, Tom, and George. They were such fine people, and they supported our family in every way possible. They loved to sing, and I remember them walking up the lane singing when they lived in Afton. Uncle George moved to Rock Springs to work in the coal mines there. He often returned to the Valley in the summer in a big, fine car, and he always brought us candy. I used to think that he was really rich. I loved to hear his wife, Aunt Polly, laugh. Papa loved to play Rook and was a very good player. He and Mother liked to play with Aunt Polly and Uncle George. Papa was also a skilled checkers player and was champion of the Valley in tournaments for several years.

I was only a child, but I thought we were doing quite well in Star Valley. We had the cows, and Papa drove the milk wagon. He was superintendent of the MIA at this time. The threshers always liked to come to our place to thrash. I believe they actually tried to “break down” so they could stay longer because Mother was such a good cook! I well remember the threshing crew and the thresher. This was the kind that ten head of horses walking round and round would pull the worm that threshed the grain. We measured the grain, then stacked it.

Two of Mother’s brothers, Tom and Will, were living in Rupert. They were doing quite well and thought that our family would benefit by moving to Idaho. Since they were good farmers, our family decided to make the move. I helped drive the stock from Afton to Montpelier. I was in the fifth grade. We drove a team of horses and about five cows and mules to get them on the train and travel from Montpelier to Rupert.

While there I was picked on at school and got into a lot of fights in the neighborhood. Finally I made some good friends. Papa hauled gravel, and he always wore a copper band around his wrist because in Rupert he started to tremble. We noticed his hands first. We had a little black buggy pulled by one horse. We took this buggy into town, which was about a mile and a half away, and to things at night and to celebrations. Papa always drove. At that time he was a big strong fellow. Later, as the disease overtook him, he was stooped.

A horrible hail storm hit Rupert, and the hail was as big as hens’ eggs. It stripped our apples, broke windows, and destroyed our chicken coops. Our livestock was driven away and ended up at our neighbor’s. The hail was about six inches deep in the melon patch, and the melons were riddled with holes.

We moved back to Afton around Christmas because things didn’t work out for us in Rupert. Papa drove the team of mules from Montpelier, and I drove a team of white horses owned by Uncle George. We were in sleighs. We stayed at Aunt Fanny’s until we could get back in our house. I was only in the sixth grade; I had to stand on a box to do the harness on the top of the horses and mules. I was really too small to harness a horse, but I had to help.

The people who had rented our house had intended to buy it. They couldn’t make the payment, and they caused a lot of damage to our house, the granary, and part of our barn. Papa thought they had been making whiskey inside the house because of spots all over the ceiling that looked like bottles had exploded. It was such a sad sight. With so many children, Papa unwell, and no money, things looked bleak. We were very poor. We were able to buy one cow from Heber Burton, then we bought a team from Harold Papworth, named Dot and Dove. I don’t remember exactly how we got started back milking cows and farming a little. We had milk, butter, cheese, and a garden of sorts, and a little fruit. That was mainly out diet. My sisters and Mama would fix us a lunch of jelly sandwiches wrapped in newspaper or the Sears catalog. The jelly would seep through and embarrass me when I ate my lunch around other people.

Uncle George Williams, Aunt Merintha’s husband, worked on the railroad, and he bought Papa 200 head of sheep. Papa and I took a buggy and drove to Cokeville to get them. It took us two days to ride out there and a week to trail the sheep back. Papa was really trembling a lot during this time. When he was awake it was very noticeable, but when he was asleep he was perfectly calm. I remember sleeping with him

(left) Lincoln with seven of his siblings, Wyoming, ca. 1920

in an old log broken-down house. We slept together and the dog slept by me. They gave us an extra sheep who limped on its hind legs, and we didn’t know if it would be able to keep up with the herd. But when we were coming into the Valley that sheep was leading the way. What a valuable lesson! With determination one can overcome weaknesses and gain the strength to be a leader.

I had to stay out of school for two years to support the family by herding sheep and keeping the farm going. It was very lonesome in the hills, and I missed being in school with my friends and at home with my family, so I sent away for a little phonograph from the Sears catalog. I enjoyed listening to the music so much, but in the end I had to send it back because I couldn’t make the payments. One time while I was herding sheep I went fishing and tied my horse to a willow by the river. I went too far down the river and became lost, and it was getting dark. I knelt down and asked the Lord to bless me to find my horse. I got up and walked about 100 yards to my horse. This was a profound message to me that our prayers are answered.

In the winter I hauled hay from Dry Creek and the meadows on a sleigh. It was severely cold—42 degrees below zero many times and of course lots of snow. In summer I worked on the

binder, hauling, mowing, etc., wherever I could, often for $1.00 a day. My sisters worked too; everyone had to help. Mama and the girls did janitor work at the school, and they would still be there when I came in from football or basketball practice, and I would often stay to help them. Those were long days as I had got up early to milk cows before school!

In 1933 I was elected student body president. There was no way to get home from school but to walk. Some nights it was so cold my sisters and Mama stayed in town in a little cabin. But I would walk on home, and Darrel and Ken would be milking and doing other chores. Many times when I got home from school we had to go to the meadow to get a load of hay and it was cold as heck. The loads were so heavy the horses would walk slower and I would walk along beside them slapping my hands around my shoulders to keep warm. I did this about three times a week. I wouldn’t get home until 9 or 10 o’clock and could hardly move I was so frozen.

Going out on dates with young ladies I depended on neighbors for a ride. When I was a deacon, Ben Hale was an adviser. I remember one of his expressions so well: “Pret ni.” I remember the old ward chapel and sitting around the floor furnace. When I was baptized we drove to Uncle Bruce’s in a sleigh and picked him up and went on to Swift Creek. It was

(top left to right) Elna, Lincoln, Maxine, Kenneth, Marguerite, Dorothy, Darrel, Cumora, (front left to right) Allie, Vern, Maria, Delos, Genevieve, February 1943—all of Lincoln’s siblings and mother, mostly likely in Star Valley, Wyoming

the middle of December, and ice had formed in places. Uncle Bruce walked out on the ice and stood in water up to his middle. Then I went in and was baptized. It was freezing, but as soon as I got out Mama quickly put a quilt around me. Papa was there when I was baptized. We went to Uncle Bruce’s, and I dressed. Mama always made cakes for birthdays. I honestly don’t know how she found ingredients to make a cake, but they always tasted real good to me.

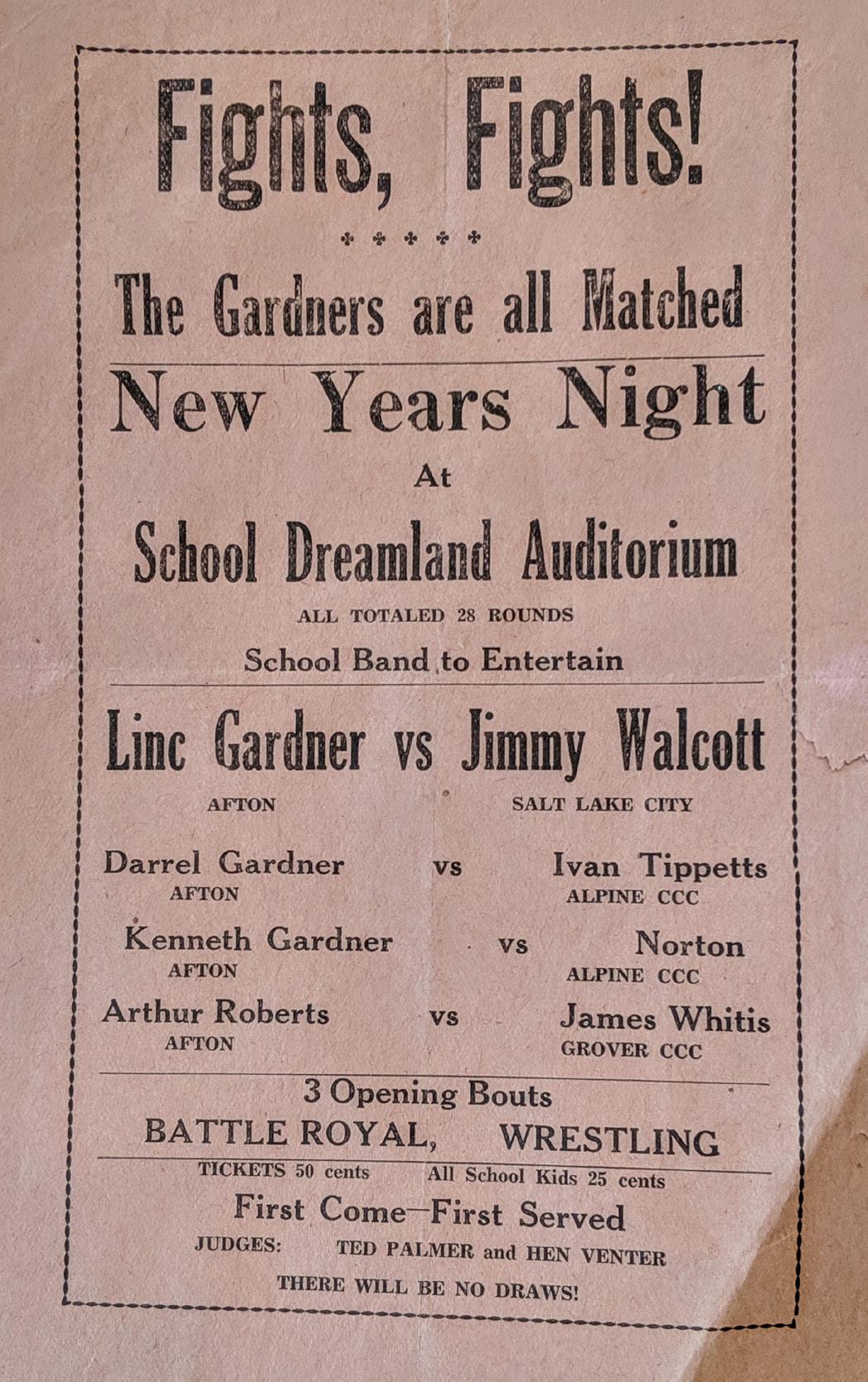

I went one night to watch Delos box. Even though I was young, I was asked to box that night with Art Roberts. I must have been in the seventh grade. Well, I nearly knocked Art out so they all thought I was pretty good. From that time on I was always called to box and considered a very good boxer in the Valley. There was never a celebration in Afton after that when I didn’t have to fight. I never intended to be a boxer. It just came naturally to me. Papa was very interested in his sons boxing, but I don’t remember anyone really showing me how to box.

I didn’t worry too much about what I wanted to be when I grew up. When I graduated from high school I did think seriously about what I was going to do. When I was out with the sheep for hours and hours alone, I distinctly thought that sheepherding was not the life I wanted, but I hadn’t figured out what my future would be. I never resented having to work so hard; I just wondered if I would have the opportunity to finish school.

I remember coming down the stairs as the first one up many and many a morning to make the fire in the stove, mostly the kitchen stove. We couldn’t afford the wood to keep the two front rooms heated all the time before we had electricity. I studied with a coal oil lamp for years. We didn’t get electricity until the thirties, when Franklin Roosevelt was president. We had three bedrooms upstairs, and each room had two double beds. Sometimes we slept three in a bed. But the one in the middle always kept warm!

Mama always prepared good meals for us. We had cooked cereal in the morning and occasionally eggs, potatoes, bread, and milk. Papa and I took a team of mules to Mink Creek, Idaho. I was out of school that fall, and we brought back a load of plums, apples, and pears, some of which we were able to sell. I have many vivid memories of that trip with Papa. I had to hitch up the team, but he would take care of the mules. I have seen him lead them to water and put harnesses on them. It was very hard for him to get up in the wagon, and he and I both drove, mainly Papa. It was so good to be with him even though he did not talk a lot. Sometimes we

Lincoln, 1934 or 1935

Lincoln, 1930s

would drive for hours without him saying a word. He was especially good at arithmetic and could figure hay and cords of wood in his head. He was a staunch Democrat. His mother, Grandmother Lucia Adell, was a Democrat, but her brother Ozro was a Republican. He was running for a state office, and Grandmother said she would rather vote for a yellow dog than a Republican!

The years I stayed out of school we received government wheat to feed our animals, but Mama would take some of it to town and have it ground for cereal. We sold 11 head of cows that year because feed was so scarce, but we didn’t receive anywhere near what they were worth. That must have been about 1933.

For entertainment we went to silent movies about cowboys. We also attended all the reunions and parties at church. We traveled in a sleigh and had such a good time. I especially remember Papa and Mama dancing—he was very light on his feet. I know he took several waltz prizes and he liked to twostep. Everybody knew Brig Gardner!

Bishop Frank Gardner was a great influence in my life. He was Afton First Ward bishop for 20 years. He was the last of great grandfather Archibald’s 48 children. I also admired Uncle Tom Blacker, Mama’s brother, and Uncles Bruce, Dell, and Oz from the Gardner side. Uncle Oz was a big fellow, and I loved to hear him pray. He spoke loudly when he prayed and always said he knew the gospel would roll forth till it would fill the whole earth. I sat up and took notice when Uncle Oz prayed.

I was blessed with good friends. My two best friends were Orrin Gardner—who had a car and drove me to dances, and Ted Kennington—our neighbor across the road. We hunted squirrels together many times. Ted was a good shot. Special girl friends were Bernice Michaelson and Bonnie Gardner. Bonnie and Orrin were children of Uncle Oz.

For family vacations we went to the hills and picked chokecherries and service berries. One time we all went fishing in the narrows in a Model T Ford. Papa was driving when he came to a huge rock in the road. He got out to move it and told Mama to back the car, which she did but went too far and ran off the road and tipped over! Once when we were going to a celebration in Bedford Papa let me drive, but he worked the gas shift, which was on the steering wheel. Thomas Call had a bigger and nicer car than ours and he would slow down for bridges, but Papa sped up for bridges and passed him. I was embarrassed because I danced with Thomas’s daughter Vivian at the dances.

Lincoln, Cowley, Wyoming, mid 1930s

Lincoln, Cowley, Wyoming, mid 1930s

We milked cows in the pasture about two miles from the house, and I always ran to and from the pasture. On July 4th and 24th we got up earlier than usual in the morning to get the milking done before daylight so we could go into town to the celebrations. We traveled back and forth in a little wagon. Sometimes the rims would come off and we wired them on with wire. We didn’t know we were poor, but as I look back we were. We borrowed Bert’s wagon to go to town, and we often borrowed his sleigh to take our girlfriends for a sleigh ride.

I stayed out of school seventh and eighth grades and returned as a freshman. I took advantage of the activities at school as much as I could. I took first place in speech contests throughout high school and traveled to Montpelier for competitions. I was also in many plays and theatrical productions in school and at church. I have always enjoyed dancing. I guess I take after Papa. In a church dance contest Vivian and I won in Star Valley and traveled to Salt Lake to the Saltair Resort representing our stake. Dancing was an important pastime. Everyone danced! I always went to the Saturday night dances, and to this day I love dancing!

We didn’t have a radio for a long time, but our neighbors the Kenningtons did. Back then you had to listen with earphones, so when the parents, Bert and Stella, weren’t listening to the radio, Ted and I would. When we finally got a radio, Papa loved to listen to baseball games. I remember him sitting on the front steps listening to games because he had become too ill to work anymore. He had been an outstanding athlete and was a good baseball player in the position of first baseman. Mama would squeal and holler for him and have a lot of fun at the games.

Papa served a mission in Wisconsin and was older when he was called. I remember him bearing his testimony and telling us about his missionary experiences. I was called in and interviewed by Uncle Frank about a mission, but I was never called, probably because Papa was so ill and I was needed to help with the family.

I loved to go to church and associate with the good people there. I enjoyed listening to testimonies. I was never a noisy kid and paid attention to speakers. I remember giving many talks, and there were certain speakers I enjoyed more than others. I took seminary at the old tabernacle in a side room. I didn’t even own a Bible. I was frightened when they asked me to pray. I guess I was rather timid. Even in the sacrament prayers I worried about messing up. The blessing on the bread is longer than the blessing on the water, so I always wanted the shorter one. I can still remember many of those who bore

their testimonies. I don’t remember Papa and Mama bearing theirs, but they were such good people I knew what they believed. Mama and Papa didn’t always go to Sunday School, but we kids always went rain or shine. I never had a desire to do anything else. The Church was a very important part of my life, and I always thought it was true and I never did doubt it. We had family prayer together in our home although it was hard in the mornings as we had to do our chores and then run to catch the school wagon. We were in such a hurry!

Uncle Oz’s children sang and played instruments. As I ran down their lane I could hear them singing, and that had a great effect on my life because I developed my own love of music and singing. Uncle Oz’s son Arch had a beautiful voice, and I longed to sing as well as he did. Orrin taught me how to lead a song, and I actually led the singing in Sunday School when I was young.

I was accepted at BYU and went there on a football scholarship. While there they found out that I was a boxer, so they offered me a job teaching boxing for $75 a month. That was more money than I had ever seen! It enabled me to graduate in four years. The summer after I graduated I was boxing at a match in Nephi, Utah. During the fight I went down with a severe pain in my side. They rushed me to Salt Lake City and operated on me for a ruptured appendix. This was 1937 and things were different back then, and I was in the hospital for nearly a month. During this time Elmer Eyre came down from Cowley, Wyoming, and offered me a coaching job at Cowley High School. I signed the contract and with a drain in my side I started my coaching career for $110 a month!

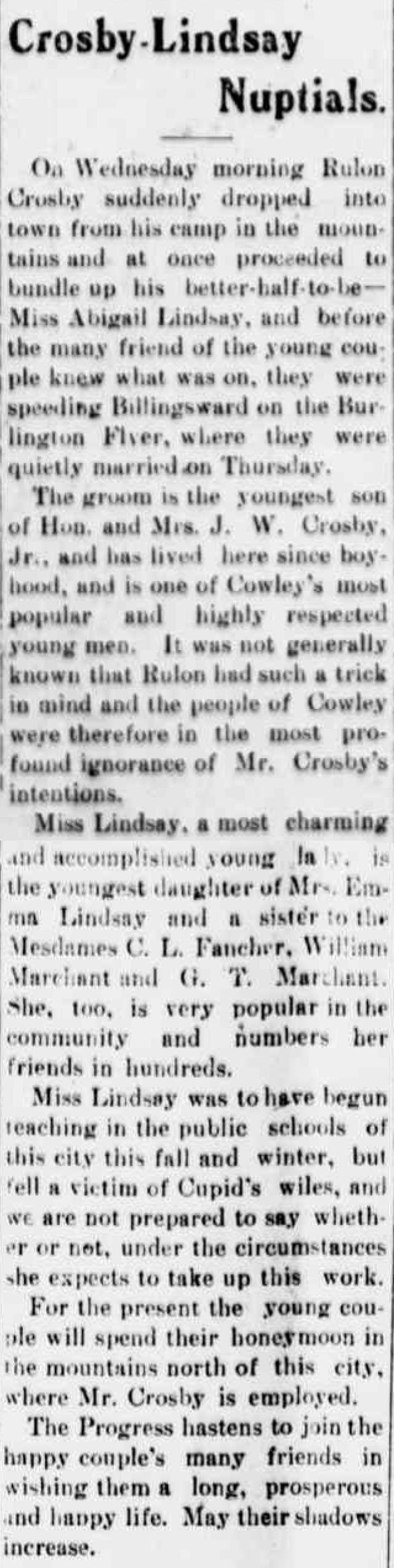

The first year I was in Cowley I attended many dances and socials. I was also asked to perform in a theater piece called “Mignonette” with a pretty redhead, Phyllis Crosby, as the leading lady. The high school drama teacher, Donnetta Willis, was the director. Consequently, Phyllis and I began dating that spring. I returned to Star Valley for the summer and continued seeing Phyllis to the exclusion of all other young women. I had dated so many girls in Afton and at BYU, and I felt Phyllis and I were meant for each other. We were married in Billings, Montana, on January 14, 1939. We lived in our little apartment until school ended that year and moved to Afton because the school board there had offered me a contract of $365 a month. I taught and coached at Star Valley High School beginning in the fall of 1939. Our first son, Gary, was born September 2, 1939.

On November 8, 1940, we traveled to Salt Lake City for our endowments and to be sealed together for time and eternity.

Lincoln and Phyllis dressed for a play they were in, Cowley, Wyoming, late 1930s

Phyllis and Lincoln at the home of her mother, Abigail, Cowley, Wyoming, late 1930s

Marriage certificate, Lincoln and Phyllis Crosby, sealed at Salt Lake Temple, November 8, 1940

Gary was sealed to us then. This was a very spiritual experience for us, and we were very happy we could go.

I really enjoyed the eight years at Star Valley High. Both football and basketball teams were winners. I was superintendent of the Sunday School and coached the church teams, along with helping out on the family farm during the summers and after school and on Saturdays.

World War II had begun, and the United States entered the war on December 7, 1941. The war years were sad and difficult because of lives lost and scarcity of food and gas.

Our second son, Kem, was born March 4, 1942. I was at tournament when he arrived, but Phyllis was well taken care of by family and friends. In the spring of 1944 I went to Salt Lake City for a serious gallstone surgery and was there almost a month. When I returned home I worked that summer as a forest ranger in LaBarge—a town in northern Lincoln County. Our first daughter, Suzanne, was born January 1, 1945. I was still coaching, and we moved several places in the Valley trying to better our circumstances. Our third son, Dan, was born December 2, 1946, when we were living by Swift Creek in Afton.

As is typical of Star Valley winters, at times it was 42 degrees below zero. I milked cows after school to improve our finances. Phyllis’s brother Elman called about that time to offer me a part ownership in a grocery store. He and Grandma Abigail and I would work together to run the CNG. In the spring of 1948 we moved back to the Big Horn, where we stayed for three years. The store was not a success, but fortunately we added two more sons to our family: Phil was born December 12, 1948, and Greg was born June 17, 1951, both in nearby Lovell.

In the fall of 1951 we picked up stakes and made a major move to Hooper, Utah. My brother Vern had been playing professional basketball, and he, with my brothers Darrel, Delos, and Ken, decided to build and operate a gas station in Clearfield, Utah. I was asked to join this promising venture.

Milas Johnson, my brother-in-law, let his hired man drive a big truck with our furniture and belongings to Utah. We followed in a car pulling a trailer with our chickens on top. Talk about The Grapes of Wrath! It was a colorful sight.

The first winter in Utah I was hired to drive a truck to Afton and headed back to Utah on a snowy road in Logan Canyon. A truck hit my truck, and I suffered a broken leg, dislocated hip, and cuts and bruises. I ended up staying in the Logan Hospital and was off work for about a month. I returned to work even though my leg hurt. This accident gave my family quite a scare.

In the fall of 1952 we moved to Clearfield on 500 East, just west of the highway separating Clearfield from Hill Air Force Base. We had so many happy memories in that little white frame home. We were cramped, but we loved the 5th Ward members, most all of our neighbors, and liked the schools the children attended. Again I was

Sunday School superintendent and later served on the high council of the North Davis Stake when George Haslem was president. We had such fun times serving in the stake, and I made lifelong friends. Our sixth son, Scott, was born September 18, 1952, and our seventh and last son, Rulon, was born June 18, 1956, while we were living there. Somehow that little house accommodated our growing family! During this time a teacher at North Davis Junior High unexpectedly passed away and I was asked to teach there, where I stayed for a few years.

In 1958 we began the construction of a new brick home in West Point and were thrilled with the space and lovely furnishings when we moved there in the fall of 1959. In 1960 Clearfield High School was built and I asked to transfer there. Gary and Kem attended Davis High, and Suzanne had her heart set on going there too. For so many years she had heard of the traditions and scholarship of Davis, but she was part of the first graduating class of CHS and it turned out to be a positive experience in her life.

After moving to West Point we attend a ward in Syracuse, and we grew to deeply love those members and treasure our friendships with them. I was still on the high council. Gary was called to serve a mission to the Central Atlantic States, and soon after Kem was called to the West German Mission with headquarters in Frankfurt. He served for two and a half years. Months before Kem left and while Gary was still on his mission, our second daughter and last child was born. Sally joined the family on July 28, 1960—five boys in a row and at last a daughter. Suzanne was overjoyed!

I taught at Clearfield High until Sally and the five boys had graduated and enjoyed watching them participate in sports and extracurricular activities. I never missed a basketball, football, or baseball game and traveled all over the state to support the boys. After her high school graduation Suzanne attended BYU. Dan was also serving in the Florida Mission, and Suzanne was called to serve in Northern Germany. I worked two jobs most of the time to support my missionaries and also had help from friends and family. Phil was called to the Eastern Atlantic States Mission, and Greg went to the California Spanish Mission. Scott attended the University of Arizona and played basketball for two years, then returned home and played for Weber State. Rulon was called to the Halifax Mission in Nova Scotia. Sally graduated from high school and moved to Idaho to attend Ricks College for one year and then transferred to BYU and graduated with a teaching degree.

In 1970 I was called to be a counselor to Russell Hanson and Elwood Johnson in the North Davis Stake presidency, where I served for five wonderful years and had many beautiful experiences. My hip had been bothering me for quite some time, and I was released from the stake presidency so I could have a hip replacement at the University of Utah hospital. After that I served as an ordinance worker in the Ogden Temple for three and a half years. I also retired as a school teacher. Then on February 12, 1973, I was called to be the stake patriarch and I was set apart by Elder Delbert L. Stapley. I loved this calling and was blessed to serve from 1973 to 1987.

Phyllis and Lincoln’s first home that they built and owned, West Point, Utah

Gary, Lincoln (holding Suzanne and Dan), Phyllis, and Kem, Abigail Crosby’s home, Cowley, Wyoming, ca. 1948

Lincoln, Dan, Phyllis, Gary, Kem, and Suzanne, ca. 1948, Wyoming

(back) Phyllis, Lincoln (holding Dan), (front) Suzanne, Gary, and Kem, Cowley, Wyoming, 1948

Gary, Lincoln, Phil, Suzanne, Dan, Kem, and Greg, outside their home in Hooper, Utah, ca. 1951—Lincoln is on crutches here because of a car accident

(front) Phyllis (holding Rulon), Lincoln, (middle) Greg, Phil, Scott, (back) Dan, and Suzanne—on a Sunday ride in the old model T, West Point, Utah, ca. 1959

Suzanne, Dan, Kem, and Gary, outside their house in Clearfield, Utah (64 South and 500 East), 1956—First day of school

Gary, Kem, Lincoln, Suzanne, Dan, Phil, Phyllis, Greg, and Scott, in front of their home in Clearfield, Utah, ca. 1953

Lincoln, mid 1960s

Rulon, Scott, Greg, Phil, Phyllis, Kem, and Dan, This is the Place Monument, Salt Lake City, Utah, early 1960s

After I quit teaching school, I sold real estate for Greg Higley and Lee Holt. I also helped from time to time doing the books at the station.

The fall that Rulon left for his mission a representative from Utah Power and Light came to our home to tell us that their company was putting in new power lines and, since our home would be directly under them, it would have to be moved. This was unhappy news, but fortunately we were able to stay in the immediate area because my brothers and I owned land just west of where we were living. The power company paid the expenses for digging a new basement, landscaping, etc. It was a lot of work and trouble for us. One night I was at the new location with Dan and I stepped on stairs going in the back door, but they weren’t solid and I fell to the basement floor. I was severely bruised, broke ribs, and was sore for a long time. Fortunately my hip was not damaged. A short time after this incident I was operated on again for gallbladder trouble and this time it was removed. The positive side of the hospitalization is that Greg met Debbie, who was my nurse.

Serving a mission had always been my desire. I mentioned before that even though I was worthy as a young man my bishop felt it was better for me to stay home and help the family because of Papa’s illness. Mother and I told our bishop that we were ready to go, but we couldn’t because Sally was still at home. When she and Keith married in February of 1981 we hurried to the bishop’s office and told him we were ready to go! I wanted to hurry because in December of that year I would turn 70 years old and at that time many felt that 70 would be a good cut-off age for senior couples. Bishop Flint was overjoyed, as we were the only couple that he had

interviewed to accept a mission call. We had requested serving at a visitors’ center, but we never dreamed that we would actually be called to serve in one. We just couldn’t believe our eyes when the call came and we were to serve in the New Zealand Visitors Center! We were overjoyed, but we had to look up on a map where it was located!

Then we received a telephone call from the missionary committee asking if we could be ready to go to the MTC in three weeks! We were excited but thought we had three months to prepare. We really had to hurry to get things in order prior to leaving for the Mission Training Center by July 8. We stayed there for one month and then we served for a memorable month in St. George before flying to New Zealand.

I had the best companion in the world! Mother and I enjoyed the routine of our mission. We studied the scriptures every morning, attended staff meeting once a week where we discussed and studied the scriptures together and also sang and had prayers. We opened the Center every morning and many days did service in the community, like visiting the cancer ward of a local hospital and socializing and singing songs for them. Another missionary couple, the Baileys, usually went with us. They joined us in singing old songs, and Sister Bailey played the piano and Mother and I would dance. Since we love to dance it was fun to share our talents and bring so much joy and fun to those patients. Many times we sang some of our favorites: “Let the Rest of the World Go By,” “Springtime in the Rockies,” and “Have You Ever Been Lonely?” On one occasion the ward we attended had an arts program and I recited some of the poems I had composed.

Gary, Scott, Phyllis, Kem, Suzanne, Sally, Lincoln, Greg, Dan, and Rulon, Sally’s wedding, Salt Lake Temple, February 13, 1981

(back) Suzanne, Gary, Lincoln, Phyllis, (front) Kem, Dan, Phil, Greg, Scott, Rulon, and Sally

We were thrilled that while we were serving in New Zealand we had visits from family members. Kem came first in March of 1982. He bought steaks for all of us at the Center, and we had a big party at Elder Julian’s home. It was so wonderful to visit with him. Then later that fall Mother’s sisters, Rula and Ramona, came to visit. We drove them around Auckland and saw all the interesting sites—harbor, town, homes, shopping centers, and a trip to Temple View. We took them to the ocean and had a picnic on the beach. It was so wonderful to show them and Kem all we loved in beautiful New Zealand. Before Rula and Ramona left, Brother Julian asked them to give talks. It was a very inspirational time. Two Maori boys visited us often. We couldn’t pronounce their names, so we called them Tutti and Frutti. When Rula and Ramona left these boys sang a sweet version of “Now is the hour when we must say goodbye. Soon you’ll be sailing far across the sea.” It was very emotional, and as they had done for Kem the missionaries at the Center had a party for them.

Near the end of our mission we had been attending a zone conference when President Chalker called us into his office because the Brethren in Salt Lake City had requested that Mother and I go to the Cook Islands for the last month of our mission. Because I was a patriarch, they were calling me to give patriarchal blessings to the Saints there. This was really a surprise, but we were told we would still be home by Christmas. We were so sad to leave the missionaries at the Visitors’ Center and our wonderful Maori friends, but we obeyed the call and prepared to leave. After a wonderful party and many tears and singing with our Maori friends, we went to Auckland to the mission home and our good friends the Ramseys took us to the airport.

If you look on the map the Cook Islands look like fly specks in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. When we landed we were greeted by a missionary couple, the Romeros, who were serving in that area. They happened to be from Layton, so it was nice to get to know them. We stayed with them for three weeks while I gave blessings to 30 members living there. They came to where we were staying, and Mother typed them as quickly as she could. We still had to bring 15 blessings home to type and send back. People were extremely kind to us; they couldn’t imagine having a patriarch on their island because there had never been a patriarch there. I was the first on the Cook Islands and was treated like I was the prophet. There were several branches in Rayatonga, so Elder Romero and I flew in a small plane to the island of Aitutaki and I gave blessings there. We were gone for two days, and it was fascinating to fly in a small plane over all that water! Again the Maori people were grateful I was there and were very gracious.

Kem, Suzanne, Sally, Phyllis, and Lincoln, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1970— Law school graduation of Kem and Master’s graduation of Sally, University of Utah

Lincoln and Phyllis, Rulon and Laurie’s wedding, 1979

They were practicing for some event at church and we were able to listen. I think everyone there could play a guitar and oh, how they could sing!

When it was time to leave, all of them came to the airport and put so many leis around our necks we could hardly walk on the plane! The stewardess put them in a plastic bag and they came home with us in good shape. First we flew to Fiji for a four-hour wait. It was miserable. Finally we were on our way to Hawaii and then to Los Angeles and then home. What a sight when we arrived! All of our family was there, and amid tears of joy and thankfulness we gave the adults the leis, which had held up well.

I don’t know how to describe the feelings we had as we neared home. Mother kept saying, “Look! There’s snow!” It was so wonderful to think we had been able to serve the Lord and all our children had been protected while we were away. Suzanne had adopted another child; Rulon had a baby boy; Phil a baby boy; and Scott a girl, the day before we arrived. How could we be so blessed! Our home was also protected, for which we were so grateful.

We couldn’t believe what the children had done in preparing our home. Dan drove us down the lane, and tree lights were shining through the front window and the house was warm, clean, freshly painted, food in the fridge, drapes cleaned, etc. It was all so beautiful. What a homecoming! We were so excited I’m not sure we slept. We were so grateful to be home in our own bed. I later remembered Kem calling us while we were still in the islands, telling us, “You can’t come home yet!” I told him that I didn’t care, we were coming anyway. Mother and I didn’t realize all the kids were trying to do to get the house ready.

We spoke in church, and many, many friends and family came. Mother took most of the time, so the bishop said I would have a whole meeting another time. We drove around the stake giving talks in sacrament meeting, encouraging couples to serve missions. We were soon back in the swing of things—going to ball games, serving in the Church, etc. Mother was called as a Relief Society teacher and visiting teacher, and I taught a missionary preparation class. We attended the temple as often as possible. In 1983, the first summer we were home, we traveled as a family to the Crosby reunion in Cowley on July 24. Mother rode in the parade with Rula and Ramona to represent the Crosby family that had settled the Big Horn Basin.

Since our mission release we have enjoyed countless parties with our missionary groups from the MTC, St. George,

and those in New Zealand. Some of the bishops and stake presidents from New Zealand have come in for General Conference, and it has been wonderful to reconnect with them. When you serve a mission you just love the people you serve and serve with. We had so many kisses and hugs from our dear Maori friends!

Our son Kem ran for governor of Utah in 1984. I was so proud of him and that he represented the Democratic Party. My Grandmother Gardner, being a staunch Democrat, wouldn’t even vote for her brother running for senate in Wyoming because he ran on the Republican ticket! All of the family supported Kem by putting up signs, going door to door, riding on floats, etc. He really fought a good fight, but in the end he lost. Then a few months after the election he was called to serve as mission president in the Massachusetts Boston Mission. Just a few days before the mission call, Kem called and asked, “How would you like to go to Israel?” What a surprise! That was as mind boggling as going to New Zealand to serve our mission!

Traveling to Israel with my family was a beautiful experience. I became aware of the troubles between the Israelis and the Palestinians and some of the causes of their conflict. On both sides they are willing to fight and willing to die. The

Lincoln, in front of their home, Clearfield, Utah, September 3, 1981

feelings they have are every deep, and I can’t believe they live like they do. I don’t understand why things can’t be resolved so they can live together in peace. Some parts of Israel are beautiful, but other parts are nothing but rocky hills. I was surprised to actually see the distances that Christ walked.

I remember one beautiful experience as we were walking down a path: my dad, or Papa as I always called him, came to me. I felt his presence there. No, I did not see him, but his presence was really plain to me. I wished I had thought to ask him how Mama and my brother Harold were doing.

The trip to Israel was truly a spiritual experience for our family. I don’t know of any other family that has gone all together on such a trip. Rula and Ramona, Mother’s sisters, came, and Jean Kennington, Sally’s friend. I was so proud of my family and that we could share together the places we had read about and walk in the places that the Savior had walked.

It was nice Rula and Ramona could go with us. Mother has a good family. Rula is a remarkable person, and I always wanted to live long enough to see Rula and Milas go to the temple, and Elman and Cleone. They are such good people and have always been kind to me. Ramona is such a gracious and lovely person. We have enjoyed visiting her and Don wherever they have lived. They have always been welcoming and hospitable to us. I can see why Mother is such a good woman. She is so beautiful and I love her to pieces. Talking about Elman reminds me of the fishing trip I took with him and Uncle Gib!

I don’t think you can find finer people than my brothers and sisters. I have enjoyed the many trips that the five brothers have taken with Big Vern’s paying the way—Denver, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, San Francisco—always to see ballgames and to golf and just enjoy being with each other. My brothers were always my friends. Seems like we went together if we ever went anywhere. Then my sons of course when they were older took me to ball games and my daughters to operas and more sophisticated events.

My sisters gained an education and have been able to take care of their families. Elna, Allie, and Cumora taught school, and I have heard so many compliments about their skills and concern for their students. Dorothy was a competent nurse, and Maxine and Gen achieved success in Business Education. Marguerite worked at Hill Air Force Base for a long time and took care of her family. I am so grateful for each one of them. Who would have ever imagined that as poor as we were when we were younger we would be able to go to college and provide for our families! Of course we have always been so proud of Vern to become an All-American. He really brought fame to the Gardner name.

Lincoln, passport, 1981

The Gardner Coat of Arms—designed for the Phyllis and Lincoln Gardner family newsletter

Phyllis and Lincoln, Jerusalem, March 1985

Phyllis and Lincoln, in front of replica of the old city, Jerusalem, 1985

(back) Scott, Paula, David, Lincoln, Suzanne, Phil, Linda, Carolyn, Kem, Laurie, Rulon, (front) Greg, Debbie, Phyllis, Dan, Nancy, Gary, and Ann Greg and Debbie’s wedding, December 1978

My heart is filled to overflowing as I contemplate my time on earth and what the future holds for me. I know I must trust that I am in the Lord’s hands, as I believe we all are. I would like to share the following thoughts with you, my family: I hope you will always obey the Word of Wisdom. I’ve felt added energy and endurance because I’ve always tried to keep this principle. And often it has been spiritual as well as physical strength. I’ve tried to pray each day of my life. I feel the power I’ve received from prayer has quietly sustained me through illness, discouragement, and financial worries. I hope you’ll never neglect your personal and family prayer.

I have also felt great power from reading the scriptures. Maybe I am not as versed in them as my children are, but I know that as I have read and studied my testimony of the Savior has grown. I have felt with assurance that God lives and that we have a purpose to be here. This is the great blessing of scripture reading! Another thing I’d like to mention is getting up early. I know this may not be as crucial as the other things I’ve mentioned, but I feel strongly that it’s a good habit to arise before your children so you can get a good start on your day. It’s a simple thing, but I think it has value. I know I have many weaknesses and maybe I’ll still have time to overcome some of them, but whatever happens I want each of you—my children and your families— to know that I love you. I love my son-in-law, Keith, and all my daughters-in-law and each grandchild. I thrill just thinking about how wonderful it will be to live with Mother and all of you for eternity.

MEMORIES OF “THE BIG GUY”

Written by Gary Gardner

ORGANIZER

Busco was great at keeping youth busy. He organized smokeless smokers (boxing matches) in three communities—Afton, Cowley, and Clearfield. These boxing matches were held at night during celebrations or other special occasions. They featured boys he had taught boxing against other clubs or towns. I, Gary, remember boxing Willie Smiun in Cowley at the July 24th celebration in a three-round event. Dad always had nicknames for the boxers. I was called DDT Gardner. I also boxed my brother Kem, because we were usually the same size.

Dad organized Little League baseball in Cowley and Clearfield. Later in his life he started the annual Fun Day at the Clearfield, Syracuse, West Point, and Clinton stakes of the Church. Fun Day was a way to raise money to support the stake camps. The stake members looked forward to it, and there were activities for all ages.

At the annual Gardner reunion Dad was the “whistle maker.” He arrived early and spent a good part of the day making whistles for all the kids. Then he led them in the much-anticipated Whistle Parade. Dad was very sociable and easily the life of the party. He was usually the master of ceremonies at ward events, Christmas parties, or high council socials, and he always led the dance promenades.

Lincoln, Utah State Senate run, late 50s or early 60s.

Lincoln, first run for Wyoming State Legislature

Lincoln making whistles for the family reunion whistle parade, 1980s— He just had such a wonderful knack for making whistles out of willow branches and carved one for each of the kids and grandkids

Lincoln, riding in a parade, Clearfield, Utah, 1969 or 1970

Lincoln, Utah State Senate run

BOXER

Dad began his boxing career one night while watching his brother Delos box. Because Dad knocked out his first opponent, he was considered to be quite good, and so his career started. He boxed in venues around the Valley and even into Idaho and Utah. He was featured on several cards with his two brothers Ken and Darrel. He was a Golden Gloves and an AAU Champion, making him the first amateur champion at BYU, where he was hired to teach boxing for $75 a month. This was in 1933 and more money than he had ever earned. He organized and taught the extra-mural BYU Boxing Club along with promoting various matches and sometimes participated in the matches himself.

After graduating in 1937 he went to Nephi to box in a big match and that is when his appendix ruptured. He was rushed to a hospital in Salt Lake City and was told by the doctors attending him that he would have died if he hadn’t been in such great shape. Even though his boxing career came to an abrupt halt, he continued organizing, teaching, and promoting boxing. He taught his sons to box and loved to see them put on the gloves against each other, much to the chagrin of Mother and Sally and Sue, who were doing chores at the time.

left: Lincoln, 1930s

right: Newspaper clippings, mid 1930s 26 | Gardner Family History | Gardner Family

(middle, third from left) Lincoln and (front row, third from left) Kenneth, Star Valley Boxing and Wrestling Champions, 1933

Star Valley Independent Newspaper, 1934

Newspaper clipping, ca. 1934

Newspaper clippings—Lincoln won the title for 175 pounds at BYU

ATHLETICS COACH

Dad’s interest in athletics began with his father, Brig Gardner, who gained fame in the Valley as a great athlete. It helped to have four brothers who were also considered to be very athletic. Dad had a terrific high school career playing football, boxing, running track, and especially cross country. He continued playing football and ran cross country at BYU.

His love for competition and athletics carried over into his choice of coaching for his career. He coached in schools and coached young men in Mutual, Scouts, and other church teams throughout his life. He coached and greatly contributed to the success of his brother Vern, who later became a three-year All-American in basketball at the University of Utah.

Dad’s love of sports was implanted in his own kids, as all of them excelled at sports—football quarterbacks, basketball guards, baseball players, track runners, high jumpers, golfers, ping-pong players, tennis players, and the sisters in belly dancing and pole vaulting. He was a proud follower of his kids and never missed sporting events in which they participated. Many of our teammates commented that they wished their dads would be as loyal a fan as Dad was to us.

(back row, left) Coach Lincoln with Cowley High School basketball team, Cowley, Wyoming, 1939

(back row, left) Coach Lincoln with Star Valley High School basketball team, April 1945—district champions

(back row, left) Coach Lincoln with Star Valley High School football team, 1941

(front, right) Coach Lincoln with Star Valley High School basketball team, early 1940s

Telegram to Coach Lincoln informing him his team won against Green River, March 5, 1942— Lincoln missed the game because Kem was born the day before on March 4, 1942

TEACHER

As a teacher Dad was a strict disciplinarian, and some students give him credit that they changed the direction of their lives. He didn’t put up with messing around.

He also taught classes at church. He loved reading and pondering the scriptures and expounding on them.

FINAL IMPRESSIONS OF BUSCO

Dad loved horses and rode until his health wouldn’t permit it. He liked to keep horses to ride, and he had a special way of talking to them. He never showed fear with horses because of his confidence around them.

He always had a dog!

Music was an important part of his life. He sang with his brothers and with Mother. He sang in choirs, at funerals, and in the mission field. He loved singing around the piano at home and listening to his children and Mother sing.

He was an outstanding dancer. He glided across the floor as if he were on skates! He and Mother won many dance contests.

He enjoyed writing poems and in the last years of life compiled them into a booklet to share with others.

He showed his love for siblings by taking loads of vegetables, melons, and fruit to Afton to share with them. He shared his produce with everyone.

He would drop anything for a game of Rook or checkers. He and his siblings were avid Rook players, and he enjoyed playing with his kids— checkers, Rook, Carom, and horseshoes.

He was active in politics and ran for office as a Democrat. He believed in the basic principles of the Democratic Party. He saw no conflict in being a member of the Church and a Democrat.

He was the first one in the car when it was time to leave for Church meetings and hated to be late. The phrase, “Come on, let’s go” echoes in the halls of our home.

Funeral program for Lincoln, West Point, Utah, July 28,1987

Funeral program for Lincoln, West Point, Utah, July 28, 1987

Maria Blacker Gardner, mostly likely in Star Valley, Wyoming, February 1943

MARIA BLACKER GARDNER

LINCOLN’S MOTHER

Maria Blacker (pronounced with a long i) was born May 25, 1883, in Streator, Illinois. Her parents, Edward Blacker and Merintha Althera Loveday, emigrated from Pontypool, Wales, to Wyoming. Her mother was a member of the LDS Church all her life because her parents, Isaac Loveday and Mary Danks, were baptized before she was born. Maria’s father joined the Church after living in Wyoming for several years.

Maria’s parents had lived briefly in Pennsylvania after Althera joined her husband in the United States. When they left Pennsylvania, they stopped in Illinois to live with other family members so they could earn money before continuing their journey west. Maria is the fifth child born to her parents, following Sarah Ann, Mary, George, and Thomas, who were born in Wales. Five of her younger siblings—Isaac, Will, Merintha, Hyrum, and Fannie—were born in Almy, and her youngest brother, Kem, was born in Star Valley.

Descriptions about what Maria’s youth might have been like in Almy are included in her parents’ and grandparents’ histories. She was 12 years old when the family left Almy to settle in Star Valley. Sarah Ann had married and Mary stayed behind in Almy to care for her sickly grandparents, so Maria was the oldest girl at home and she assumed a large share of the housework. In Almy she attended school to the fourth grade, and this was the extent of her schooling. As Aunt Allie recollects: “It is hard for us to realize just how much Mama missed. Imagine no school to go to after 4th grade, no fun in 7th and 8th grades, no graduations, no junior proms, no memories of high school.”

The family started for the Valley in the fall of 1895. Two friends of her father—Archesio Corsi and Archie Moffatt—lived in Star Valley and had been to different settlements selling cheese, eggs, and farm produce and agreed to use their freight wagons to take the family’s furniture to the Valley. They were to lead the way, and Edward, Althera, and the children were to follow. As the family reached Randolph, Utah, Hyrum, just four years old, became seriously ill, and in order for him to recover they decided to return to their home in Almy, which in the meantime was occupied by Maria’s brother George and his wife. Without furniture and much of their clothing, the family was very inconvenienced but felt they should stay in Almy that winter.

Salt Lake Herald, 9 June 1888 newspaper clipping about accident when Maria Blacker broke her shoulder

The second attempt to make it to Star Valley that next spring was challenging and cold! Snowfall had been heavy, and they made the trip in a sleigh with three horses—two pulling the sleigh and the third led behind. Again the trip was eventful, this time because their sleigh and horses slipped off the road and couldn’t get back on the road! The family walked for hours to reach a farm house near the entrance to the Valley. Uncle Will, Grandmother Maria’s brother, shares his observations about this difficult journey:

At first we didn’t have any trouble, but from Montpelier to Star Valley we had a terrible time. Dad was a green horn about horses. He didn’t know much about them. The roads were getting pretty soft. There was a lot of snow, and one of the horses stepped off the road. Of course the horse couldn’t get up because the other horses pulled the sleigh right on him. Instead of us going to work and pushing the sleigh back off him so he could get up, Dad just rolled him over and down into the gully. The horse was clear out in the snow and couldn’t get up. We tied a rope on him and tried to pull him out with the other horses. As we struggled, the downed horse pulled the other horses down. Instead of staying with the sleigh like we should have, we started to walk.

Fannie and Hyrum were little tots, and Mother and Dad were carrying them on their backs. The mail man came along, found the horses off the track, and brought our bedding and grub boxes to us. Dad told him to send someone to help, so Hy and Sam Kennington came up with a team and brought our sleigh down to us and took us to Star Valley. We landed in Afton on April 10, 1896.

They stayed at Archie Moffatt’s for a few days after reaching the Valley, then they moved to the land Edward had purchased. Maria remembers that the snow was up to the horses’ backs. They had to make steps so the horses could walk.

As noted, the Blacker family was pretty destitute when they arrived in Star Valley and Maria as the oldest daughter had to help with running the household, but she also worked cleaning and cooking for families in Afton, Almy, and even Evanston for $1.50 a week, plus board and room. She always sent her wages home. Sometimes she stayed at the homes of women having babies. She cried at nights because she was homesick and wanted to be home. All accounts concur that she was a fast worker, a good cook, pleasant and willing and was much sought after to do housework throughout the Valley. She had a beautiful soprano voice and as a young girl sang in the choir and many programs in the Church and the community. Even when she was a teenager ladies in the area called on her to make pies for them.

BRIGHAM DELOS GARDNER

LINCOLN’S FATHER

Brigham Delos Gardner is the first son and second child of Brigham Livingston Gardner and Lucia Adell Gardner, who are first cousins. Brigham, known as “Brig” was born September 18, 1876, in Big Cottonwood, Utah. Brigham and Lucia’s first child, two-year-old Laura Althea, died on September 17, 1876, just the day before Brig was born. Perhaps her death contributed to Brig’s premature birth. He was so tiny and fragile that he was carried on a pillow for several weeks. To keep him warm Lucia Adell wrapped him in a blanket and placed him on a big platter by the oven door of the old wood stove.

Brig attended grade school in Utah and was a keen student. His father was a miller and worked with his father-in-law, Archibald Gardner, who was also his uncle, in grist-and sawmill operations. Brig’s family moved to Woodruff, Utah, for a short time when his father operated a sawmill there. Then in 1889 when he was 13 years old the family made the trek to Star Valley, Wyoming. At that time only a few families were living there and it was frontier survival for the early inhabitants. Very rough!

Brig grew to become a husky young man, and because of his strength and stature he assisted materially in the milling business. Even in his teens his physical prowess was well known. Uncle Oz Gardner tells about times when he and Dave Williamson took one end of a saw log and Brig would shoulder the other and carry it. Once a green slab that two men could barely lift was shouldered and carried off by Brig. He gained notoriety in weight lifting and competed easily in contests and supposedly was never beaten. Along with working at the mill he herded sheep and completed other tasks to help supplement the family income. He attended Church meetings but was not too involved in ward activities. He was described as happy-go-lucky and good-natured. He was light on his feet and liked to dance. Most all accounts state that he was skilled in all physical pursuits and could run, jump, wrestle, box, play ball, and shoot as well as anyone.

One day, quite unexpectedly, Brig received a visit from his bishop and subsequently made a decision that likely changed the course of his life. He was 24 years old—typically too old to go on a mission—but he accepted the call, changed his undesirable habits, and on October 8, 1900, was ordained a Seventy and set apart to labor in the Northern States Mission. Brig’s diary is full of faith-promoting experiences, and his letters home, though few, reflect his concern for his family. From a letter to his sister Margaret he displays uncanny observations about his siblings:

I think your birthday is on the 10 of September, is it not? But don’t know whether you are 12, or 13 and I don’t know when Viola’s Pearl’s and Alice’s

Brigham Delos as a baby, ca. 1877

is and Georgie’s is the 27 of May, or near that. And Florence’s is in September, I believe. What color is the baby’s hair now and also her eyes? Ask Ma if Georgie’s disposition is anything like mine was at his age or is it more like Dean’s? Is he growing? Is Alice still that easy going, slow, good-natured, sweet kid yet, and Pearl must be getting a young lady now. Has she those

clear sparkling eyes yet and is she as quick as ever? How is Viola? Is she growing as fast as ever and just as nice and pretty with that willingness to help Ma, bless her. I am struck with the words from your letter very forcibly that Pap has prayers now. What do you do when Pap is at the mill? You don’t omit them, do you? You girls each want to pray in turn.

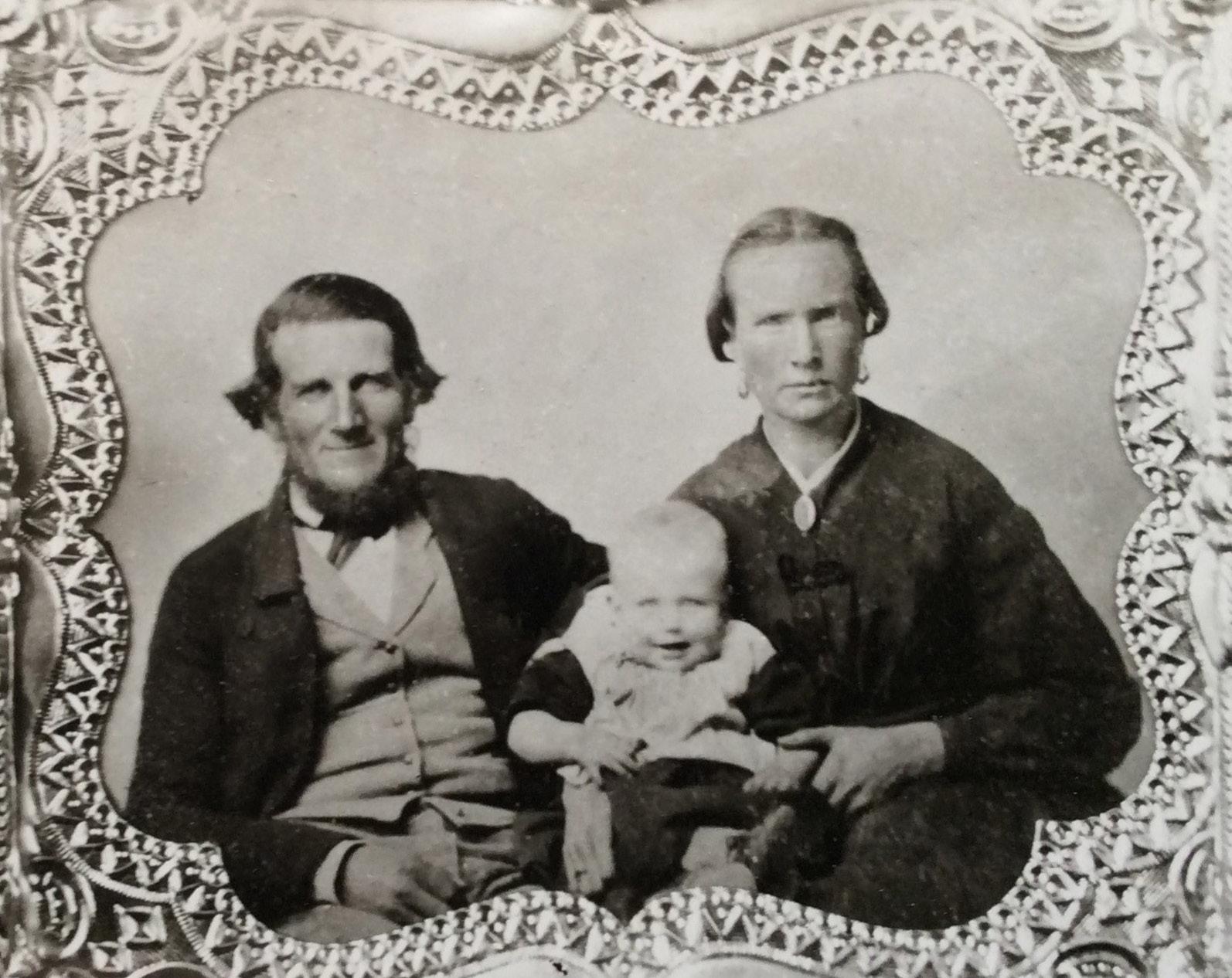

William, Janet Adell, and Brigham Delos Gardner ca. 1887

(back) William, Margaret, Brigham Delos, Janet, (front) Brigham Sr. (holding Pearl), Lucia (holding Alice), Viola, and Robert, Star Valley, Wyoming, 1896

(back) Brigham Gardner Jr., Afton, Wyoming; R. B. Gardner, West Jordan, Utah; (front) C. T. Kirst, Paradise, Utah; and William Atwood—Northern States Mission companions, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1901–1902

Brigham, Northern States Mission, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1901–1902

Brigham, Northern States Mission, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, July 28, 1902

Brigham, ca. 1900s

Brig was released from his mission on December 15, 1902. As soon as he returned home it appears that he didn’t waste any time contacting a young woman named Maria Blacker. Maria occasionally enjoyed going to dances at mining camps near Diamondville, Frontier, and Kemmerer. Reportedly the Blacker girls were excellent dancers and never lacked for partners. It was at dances in Star Valley that Maria first remembers Brig. She describes him as that “red-headed rough guy and his ‘bunch’ who used to ride horses and with their yells and even shooting out lights (sometimes) frightened all the girls.” She once referred to him as a “roust-a-bout.” She remembers that when Brig and his crowd came into a dance people “held their breath and figured things would soon start popping!” She always knew of him, but never had much to do with him until just before his mission. They went out together once before he left, and after he had been gone 11 months he wrote her a letter, and from then on she told her boyfriends in Kemmerer that she was waiting for her “redheaded missionary.” It appears that both were anxious to see each other again. But she was in Kemmerer when Brig came home. Brig asked about her and told the men driving the mail truck that he was going after “Miss Blacker.” When Maria came home, Elias Michaelson and Brig came to visit her. They played games, and Maria writes that outside, as he was leaving, Brig grabbed her and kissed her.

A really charming example of Brig and Maria’s relationship is captured in an excerpt from a newspaper article written about early baseball games in Afton. There was an intense rivalry among the teams from Etna, Fairview, and Afton, retold in the Star Valley Independent in the spring of 1979:

The lead went back and forth as the summer passed and it began to look like Afton was the team to beat. When they met, the rivalry between Afton and Etna was keen and the game was close, but Afton nosed them out by one run.

The cheering sections on both sides were working overtime.

Afton’s first baseman was tall and rawboned and had red hair. This made him a natural target for the Etna newcomers who were masters at getting a player’s goat.

One of them shouted out, ‘If it wasn’t for that flaming Yankee haybaler we could have an even break. He covers half the field.’ He directed this at a young woman who was actively pushing for Afton and for the carrot top in particular.

Not to be abashed she shot back, ‘If he had your mouth he could cover the whole diamond!’ This sort of entertainment was a part of the game and the spectators ate it up.

The many players on these teams are not forgotten, but few will remember them now. All deserve to be remembered, but I can name here only those I remember best.

The red-headed first baseman was Brig Gardner. The catcher was Bruce Gardner.

The girl who made up part of the Afton cheering section was one of the Blacker girls, either Brig Gardner’s wife or best girl. Maria!

A courtship ensued between Brig and Maria, and on April 7, 1904, they were married in the Salt Lake Temple. They traveled in a sleigh the 50 miles to Montpelier on their way to Salt Lake City. They tipped over three times going out and once coming back. They caught a train at Montpelier to Salt Lake City but had to stay in West Jordan with some of Brig’s Gardner relatives for a few days because the temple was closed! Maria admits that she was taken aback and a bit timid about all the teasing she got. She wondered what kind of a family she was marrying into! According to her son Delos:

Mama admits she was a little afraid and was timid about the teasing of the Gardner relatives, but the “Queen” in her coy, lovely way and with her pleasant, witty disposition assumed her role. Their gentility, hospitality and friendliness soon won her over and she knew that she had not done so badly after all.

Brig and Maria set up housekeeping in a small one-room house north of the Blacker ranch and three miles northwest of Afton. There their first child, Delos, was born on May 14, 1905. Brig was working for the Burton Creamery Company, located not far from where they lived. He was then transferred to the creamery at Muddy String about two miles from Thayne, where Althera (Allie), their second child, was born. That night there was a huge blizzard and the telephone lines were out. Brig hitched up the horses and in a sleigh went over to the closest neighbor to get someone to stay with Maria while he rode into Thayne to get a midwife. On his way he actually met the neighbor, who was riding to get the midwife himself as his own daughter was in labor. Brig took the neighbor to stay with Maria because he had the fastest team. He fetched the midwife, and Allie was born before the other baby.

(back, center) Brigham with Afton City baseball team

(left) Brigham, ca. 1900s

Maria Blacker and Brigham Delos Gardner wedding portrait, April 7, 1907

After Allie’s birth, the family moved two miles north of Afton to the Gardner homestead—40 acres that Grandfather Brigham Livingston had given to Brig—and they moved the house they had lived in by Grandmother Blacker’s to this new location. There are copies of the legal transfer of this land from Brigham L. to Brig at the end of this history.

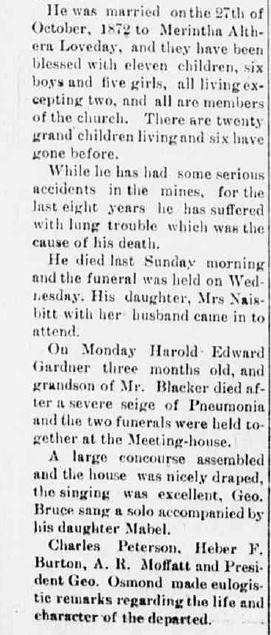

They added a little shanty onto the log house where Maria cooked and where they ate. She had a stove and washstand with a big bucket underneath it to catch the water. The children slept further back in the shanty. Allie remembers that typical of Maria the place was always tidy and clean. We can only imagine how they lived day to day in that enclosed space—especially in the winter! They lived there until just before Darrel was born: Marguerite, Harold, Lincoln, Dorothy, and Elna were born in that little house. Harold died on November 30, 1910, of pneumonia when he was three and a half months old. I think an account of his death is worth including in this history because it so poignantly describes the travail of sickness during that time and how deeply his passing impacted our grandmother, even with her many children.

Grandpa Edward was sick on Thanksgiving that year, so for the first time Maria and Brig stayed home with their family for Thanksgiving dinner. Harold was in his crib, well and happy. He coughed once, and Maria told Brig that if Harold took sick she knew he would die. She cried and cried. She called Dr. Groom to come check on him and the doctor reported that Harold was healthy and there was nothing wrong with him. About midnight Harold woke up with terrible congestion. Maria was so frightened about his condition she left Harold with Brig and ran all the way to her brother Tom so he and Brig could give Harold a blessing. At 4 o’clock they called the doctor and were told to put turpentine packs on him. At 7 o’clock they begged the doctor to come.

Saturday morning Harold had a temperature of 105 degrees. Mrs. Wollenstein and Dr. Groom worked with him all night to break the fever. When Harold began convulsing, the doctor thought the temperature had broken and Harold would be all right. But about 30 minutes later the baby was dead. It was about 7:30 Monday morning, November 28, 1910. The doctor cried like a baby because he had wanted so badly to save Harold. Grandfather Edward had died the evening before.

How heartrending for Maria to lose her father and a son within a few hours! A joint funeral was held, and grandfather and grandson are buried near each other in the Afton Cemetery. Maria always said that when Lincoln was born a year later in 1911 she had her baby back.

As noted above, in November of 1915 they moved to the new house. Darrel was born December 28, 1915, about a month later. Six months later Maria was operated on for gallstones, so her mother, Grandmother Althera, had to wean Darrel. He never would take a bottle, so he just drank from a cup. 14 months later, in June of 1917, Kenneth was born in the new house. Finally Star Valley had a hospital, converted out of an old building, and Cumora was the first child born in a hospital, the only one of the 13. Maria was very ill at the time and did not expect to live. She stayed in the hospital for a long time. Ironically, the hospital was torn down shortly after Cumora’s birth, so Genevieve and Vern were born in the new house.

Maria assisted Brig every way she could in building the new home, but Thomas Call was the main builder. It must have seemed palatial compared to where the family had been living. Allie, Marguerite, and Delos picked out the bedrooms they wanted upstairs. They would come after school and play in the house and loved the smell of new lumber. The wallpaper in the parlor had gold embossed flowers on it and also boasted a rolled-back black sofa and fancy curtains. A favorite spot for the children was a long upstairs passageway leading to a little room under the gable of the house. It was known as the “runway,” and it provided hours of fun. When the children were young they considered the house big and beautiful even though they had to sleep three in a bed, had no electricity, no indoor plumbing, and no water in the house. Wood had to be chopped, carried, and stacked on the porch. Several of them mention walking through the fields filled with abundant varieties of wild flowers. They played games outside, such as Kick-the-Can, Relevo, and Pomp-Pomp Pull-Away, and swung from a rope onto the hay in the barn.

The new home was considered one of the nicest homes in the Valley at the time it was built. Lincoln thought the family was doing quite well. They had animals and a huge garden. The children did all the work there is to do on a farm: milked cows, plowed, raked, ran the mower, and drove the hay rack for the hay loader before stakers and buck rakes were used. Threshers came to the farm to thrash. Lincoln thought they actually tried to break down to stay longer and enjoy Maria’s cooking.

Just providing water for the family and farm maintenance was a huge undertaking. In the summer water was needed for irrigation, and in the winter it froze. The family had “running” water, but it ran in a ditch outside in the yard, and there wasn’t even a faucet in the house! Water was carried to the house in pails or cans. On wash days and bathing days extra water had to be carried to the house. Fooling around and interference from teasing brothers caused a few tip-overs and spills. The

cans were hauled by wagons in the summer and sleds in the winter. In the winter a hole was cut in the ice and Brig pulled the sleigh while the children tried to hold the cans so they wouldn’t tip or slide off. The path was bumpy and icy. Sometimes in the winter they had to go to other ditches and streams for water. Many times they had to drive their cows and horses a half a mile away for water. Frostbite and frozen hands and feet were the norm during the winters.

It is important to note that before electricity Brig and Maria cared for their large family using coal oil lanterns, which were used for outside chores at night and carried from room to room when the family ate or the children did studies, etc. Allie writes a clever description of the day electricity finally came to the ranch: No more cows in the barn running over lamps and the danger of a fire!

Imagine Maria’s long wash day before electricity and gas: Maria and the girls filled boilers and tubs with water to be heated on the stove. Maria washed in an old shanty behind the house. The water was heated during breakfast and soap was cut up and put in the boiler. Lye was placed close by ready for use. The washer was pulled in from the porch, and as soon as the children left for school Maria started to wash by hand with a washboard. Clothes were wrung out by hand. When the children came from school Maria was still washing, and they helped her finish. The clotheslines were filled and refilled several times. Overalls, rugs, and socks were dried on the fences.

Years later Maria drove a Model A or T down the land to Grandmother Blacker’s to use her washing machine. She piled the clothes in the car, which had no top, and even though she was afraid to drive a gear-shift car, she drove quite fast. Genevieve was just a baby, and she had been put in a basket of clean clothes. Maria hit a bump and the car tipped over. No one was hurt, but there were a few anxious moments until Genevieve was found gurgling and laughing amid the clean clothes!

Brig spent most of his time on the farm, improving it and adding to it. However, he had time for other pursuits, too. He served as deputy sheriff of Uinta County—before Lincoln County had been established. He served under Sheriff Ward, who was headquartered in Evanston.

Delos remembers Brig riding out to Cokeville in search of a bank robber and riding over to Swan Valley to identify the body of a person who had drowned in the Snake River. Maxine remembers the stories of Brig picking up unruly fans at ballgames and singlehandedly depositing them outside of the field.

Brig also served as superintendent of the stake YMMIA (Young Men) and later in the presidency of the 103rd Quorum of Seventy in the Star Valley Stake. Around this time a National Guard unit was organized in Star Valley.

Brig’s spirit of adventure was demonstrated when he joined. This was during World War I and the government was concerned that Germany would forge an alliance with Mexico. A military presence was required at the border because of anticipated problems between the United States and Mexico. The Valley unit was mobilized and sent to Cheyenne. Delos remembers Brig leaving and Maria crying, “But Papa considered the whole affair quite a lark. He was not gone for long and things worked out.”

This was probably 1916, and Brig was in good health and very active. He was farming and operating the creamery. Lincoln remembers a big barn, and he helped milk and then clean the barn out. They had 10–15 cows.

Brig still played baseball and went hunting most every fall. He usually took a wagon to Brigham City or to the Snake River country and brought back peaches, apples, plums, etc. The children enjoyed climbing up into the wagon, getting under the cover, and sampling everything. Allie says when Brig went fishing he always caught the most fish in the shortest amount of time.