By

Foothills Forum is an independent, communitysupported nonprofit tackling the need for in-depth research and reporting on Rappahannock County issues.

The group has an agreement with Rappahannock Media, owner of the Rappahannock News, to present this publication and other awardwinning reporting projects. More at foothillsforum.org.

EDITOR’S NOTE

• Jan Makela (p. 5) is a former Foothills Forum board member.

• Mary Ann Kuhn (p. 36) Is an editor for Foothills Forum and the Rappahannock News.

• Chuck Akre (p. 41) is a longtime donor to Foothills Forum.

Written by: Bob Hurley

Edited by: Paul McGeough

by: Luke Christopher

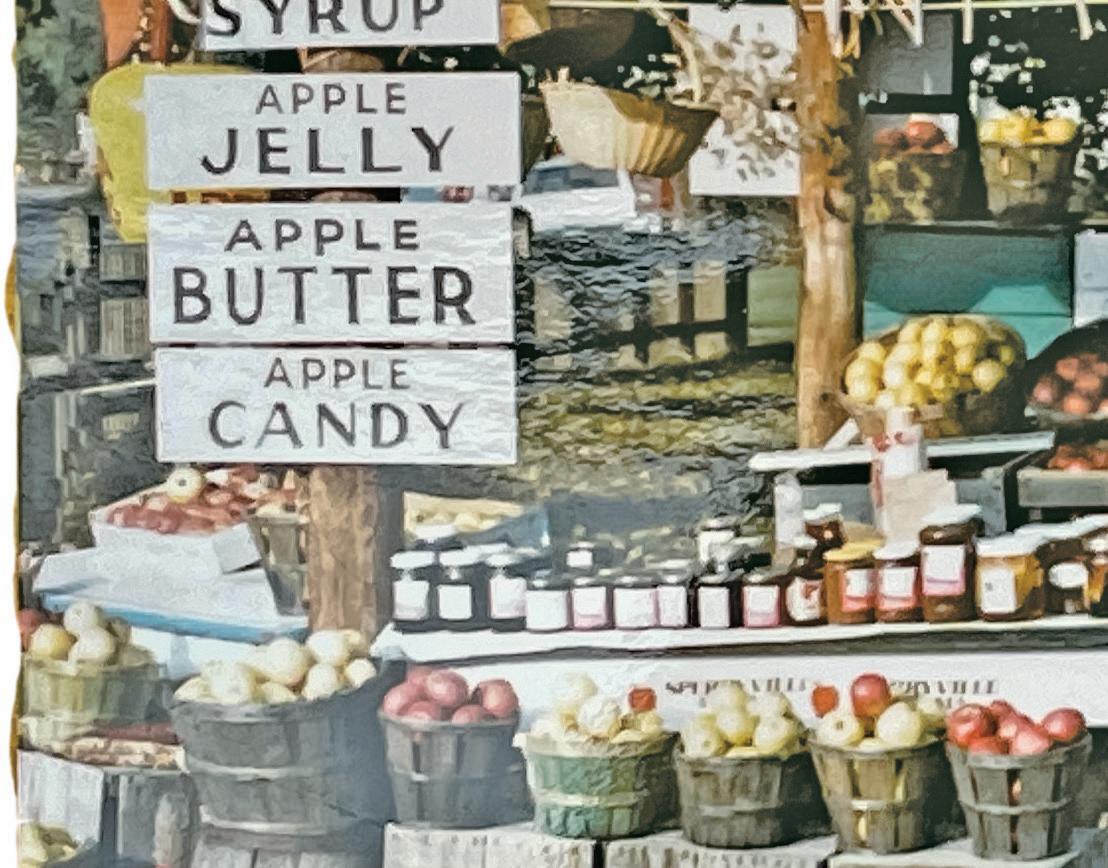

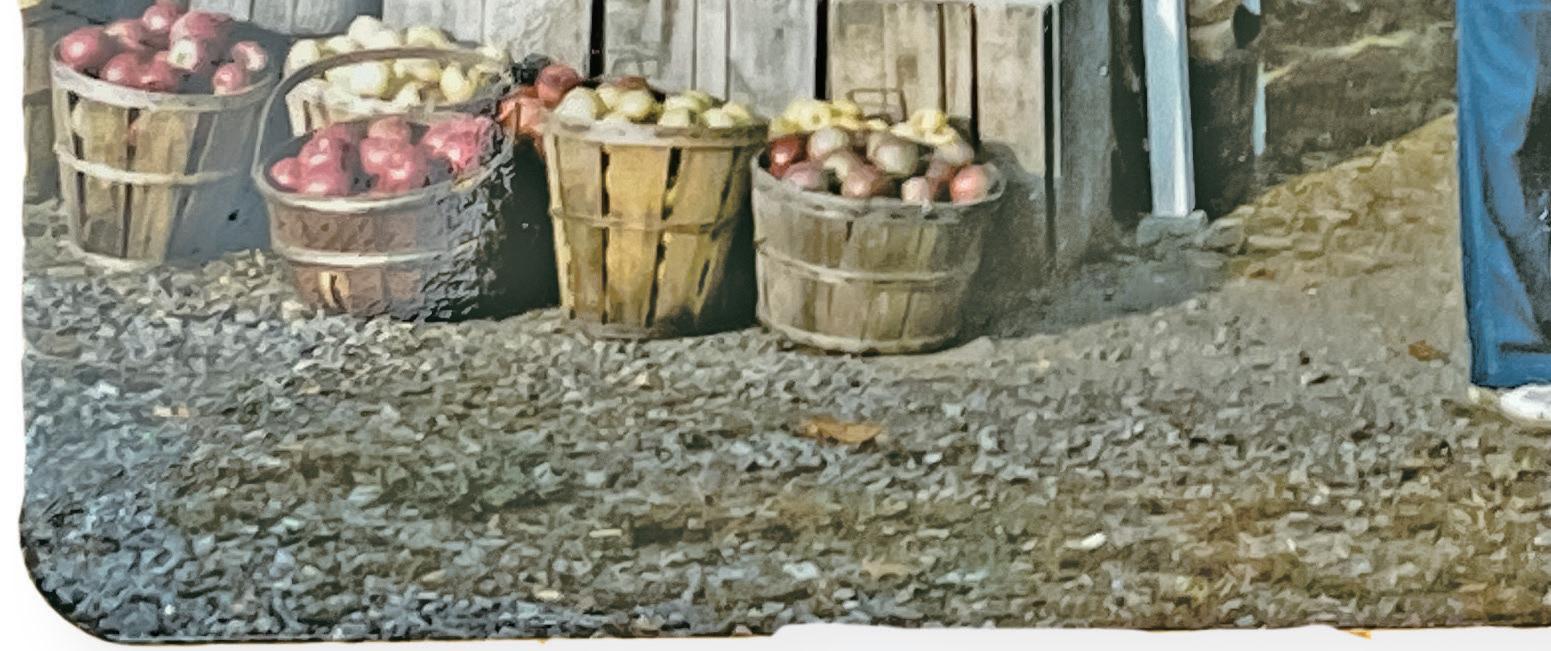

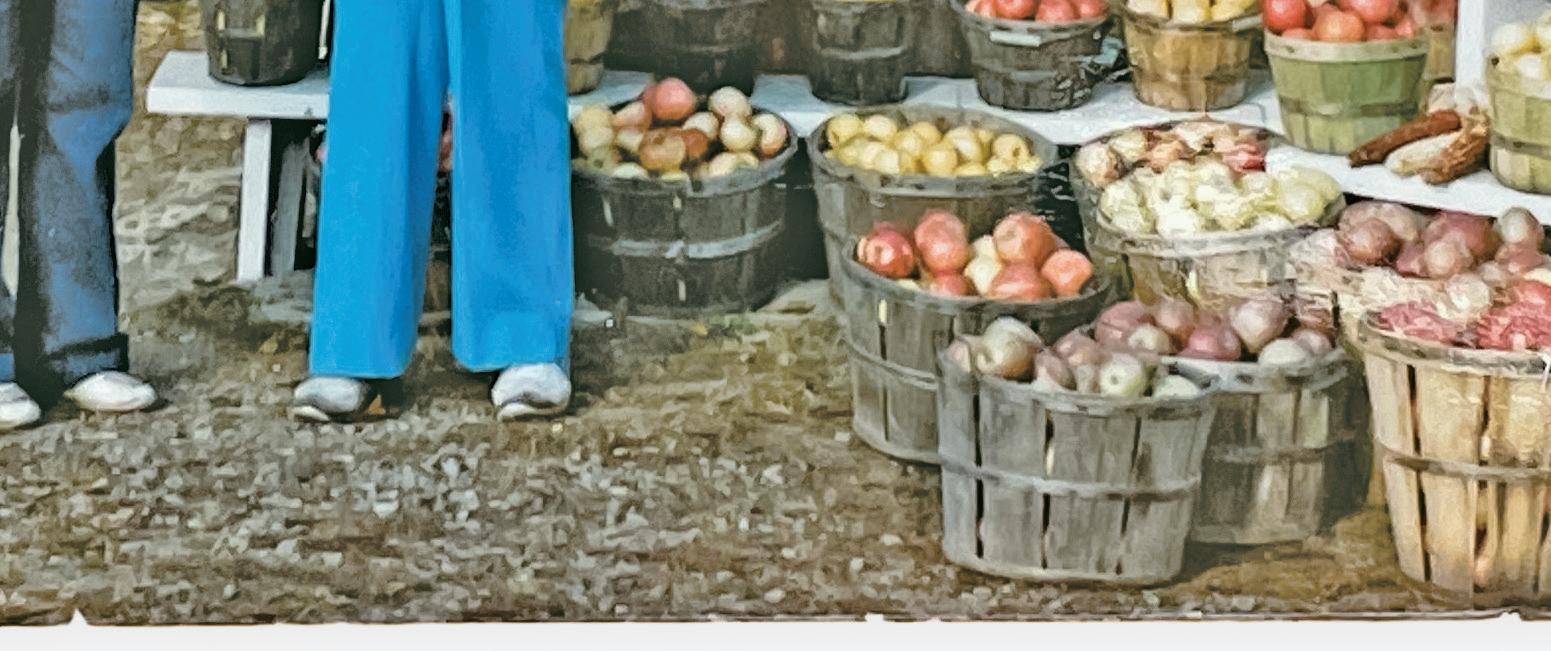

SPERRYVILLE REWIND: Emma Estes Swindler and Annabelle Estes Swindler at the Sperryville Fruit Stand, across the bridge near the Sperryville Rescue Squad. Circa 1980.

ADDITIONAL CREDITS

Above: Courtesy photo

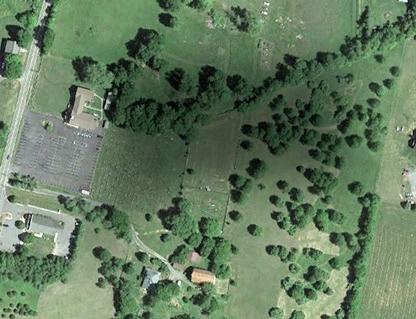

Pages 6, 36: Drone photos by Robert Stephens

Page 8: Courtesy Rapp-Culpeper Baseball

Pages 10, 21, 41: Library of Congress

Page 11: Hugh Kenny/Piedmont Environmental Council

Pages 22, 27: Rappahannock Historical Society

Page 46: Courtesy photo; Tom Pich/National Endowment for the Arts via Wikimedia

Page 47: Courtesy of Sharon Kilpatrick; NBC; U.S. Senate

© 2024 by Foothills Forum All rights reserved.

It’s often said that local news is the connective tissue that binds a community. We believe that. Through a unique partnership, the Rappahannock News and the nonprofit Foothills Forum work cooperatively to cover what’s happening each day in our community. But we also regularly step back and provide in-depth stories (with photos, video and informational graphics) that can take weeks or months to produce.

These stories might shine a spotlight on an important local issue, like the shortage of affordable housing or increased mental health struggles among area teens. They might examine inequities in local real estate taxes, or efforts to preserve our environment. Occasionally, they are moving remembrances, eulogizing those who had an impact on our community.

This publication – “The Villages of Rappahannock County” – is an example of how our journalism informs and

binds Rappahannock. It’s a compilation of in-depth stories that were produced by Foothills Forum and appeared intermittently in the Rappahannock News over the past several years. Through exhaustive reporting, Foothills’ journalist Bob Hurley captured the fascinating past – and previewed the future – of what Rappahannock County officially identifies as its villages: Sperryville, Amissville, Chester Gap, Woodville, Flint Hill and the Town of Washington.

The installments won awards from the Virginia Press Association for reporting, photography, videography and graphics. They also won praise from residents of the villages. For these reasons, we decided to compile them into this publication, which is being distributed free to the public.

We greatly appreciate the efforts of Bob, photographer Luke Christopher, veteran journalist Paul McGeough, graphic artist Laura Stanton and others for their initial work and then updating each installment

for this publication.

And special thanks to the Rappahannock Association for Arts and Community (RAAC), which helped underwrite “The Villages of Rappahannock County.”

We feel this provides a good example of how robust local journalism educates and instills civic pride. Sadly, this is no longer possible in much of America.

Across the nation, thousands of longestablished local newspapers have been shuttered over the past 20 years. Many others, facing daunting financial challenges in the Digital Age, have become “ghost newspapers” after gutting their news staffs. Small newspapers in rural areas are most at risk.

When local news outlets disappear, civic engagement declines. Voter participation drops. Misinformation spreads. Polarization grows. Without informed citizens, there’s less public discussion of governmental performance and proposals. The result: taxes, wasteful spending and corruption typically increase. And, studies show, community pride suffers.

The partnership between the Rappahannock News and Foothills Forum has helped to prevent that from happening in our community. Foothills Forum –marking its 10th anniversary in 2024 – is a nationally recognized news nonprofit that relies on donations to pay accomplished reporters, photographers and graphic artists who supplement the journalism of the short-staffed Rappahannock News. Together, their efforts have helped the Rappahannock News to be named by the Virginia Press Association as the best weekly of its size in the state for the past four years.

We hope you enjoy “The Villages of Rappahannock County.”

Andrew Alexander Foothills Forum Board Chair

Dennis Brack

Rappahannock News Publisher

FORWARD | By Janet Hackley Makela

Editor’s note: Like many residents with deep roots in the county, Janet Hackley Makela is a product of Rappahannock’s storied villages. Her family has been in Amissville for more than 150 years.

There’s something about growing up in a village in Rappahannock County that stays with you always, that pulls you back. It’s hard to explain, but it is something many of us have experienced.

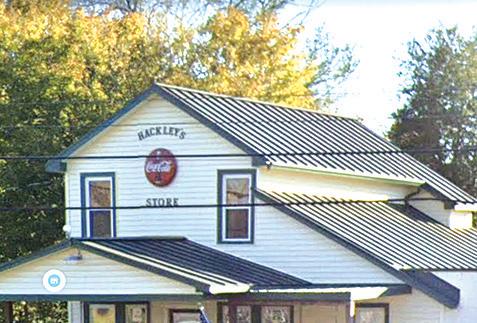

In a nostalgic moment a few years ago, my older brother Larry said he felt as if we’d been raised in a Norman Rockwell painting. I had to agree. We’d had the joy of growing up in our family-owned Hackley’s Store in Amissville, where we’d gotten to know almost all our neighbors.

After college, longing for a little more fun and excitement than I thought Rappahannock had to offer my 21-year-old self, I moved to Virginia Beach. Though I loved my community there, my heart was always in Amissville. Why? The people, of course. The closeness. The way we all looked out for one another.

When our son was born in 1989, we wanted to raise him in the same “Rockwellian” world I had experienced as a child. Loving neighbors. Safe places. Open spaces. We moved home to run our family’s general store. True, some things were different, but the spirit of the place was the same. Some faces were missing, but other familiar ones were still around.

Like Sam Riley, who’d built Hackley’s with his dad in 1934. He’d given me nickels whenever we crossed paths at the store when I was a child. When I returned years later, he was still a fixture on the front porch of Hackley’s and would give my young son Joshua quarters! Different, but the same.

New faces soon became familiar friends, and we began to realize that most of these people had grown to love Rappahannock as much as those of us whose families had

lived here for generations. It was just a matter of them getting to know this special place, in this bucolic setting, to appreciate its magic. My family has been in Amissville for well over 150 years, and I’ve seen businesses and people come and go. Yet life goes on. And we adapt.

So much of what happens in Rappahannock still revolves around its precious villages. They provide many opportunities to volunteer for good causes, like our fire and rescue units, our food pantry and our churches. Many of our traditional gathering places of the past, where neighbors met to share and discuss the news of the day, have disappeared. But some new places have appeared. And volunteerism (critical to life in a village) continues to create community, as we meet new friends and join forces to make this an even better place to live. We are all essentially the same; we just want to belong, to do good, to be accepted. That is the joy of village life.

Yes, we’ve lost some population, our mills, most general stores and orchards. But life does go on. Change IS inevitable, but not to be feared — rather embraced with open eyes, good research and intelligent planning. We

are ONE RAPPAHANNOCK and yes, we are adaptable. We are at our best when we remember and honor our past as we look ahead.

Foothills Forum, an independent citizen-supported nonprofit, produces award-winning journalism about our community in partnership with the Rappahannock News. Over the past several years, the weekly newspaper has published a series of deeply researched stories by Foothills reporter Bob Hurley that have captured the rich histories of the county’s villages. They are reprinted here, along with current and historical photos and helpful explanatory graphics.

The series reinforces the importance of community and preserving our village life. And it underscores how quality journalism is a critical component of life in a rural community. True, every story may not interest us, and some may not seem particularly important in the moment. But when urgent issues arise locally, it is our local journalists who will keep us informed. They are part of us, and care about their community. As a daughter whose dad read multiple newspapers (leftleaning, right-leaning and in between) daily, call me grateful.

Fifty years ago, motorists traveled through Amissville on a twolane road dotted with historic homes, small hardware and grocery stores, restaurants, tourist cabins, garages and a post office. Today, most travelers on four-lane U.S. Route 211 buzz past the village, hardly noticing the village’s big green welcome signs that read, “Ensuring our Future by Preserving Our Past.”

One of Rappahannock’s key villages, Amissville is the county’s eastern gateway. A handful of familiar landmarks remain along 211 – Hackley’s Store, Settle’s Cars & Trucks, Early’s Carpet, Mayhugh’s Store, the Gray Ghost and Narmada wineries and the Amissville Volunteer Fire and Rescue department.

But what lies beyond in a village that has no defined boundaries?

Just four miles east of a 1,443-acre housing and retail development being built at Clevengers Corner, Amissville residents will have to contend with increased traffic and the potential for new growth.

“With the expansion of U.S. Route 211 from two to four lanes in the 1970s, we lost what was considered our Main Street,” said Lorraine Early, a third-generation resident who, with her husband John, started Early’s Carpet in 1966. “Businesses, homes, even the fire department were lost or relocated. People used to congregate at places along the road, but now all that’s gone,” she said.

Lois Settle, a direct descendant of Joseph Amiss, of the family for which the village is named, is one of the residents who had her home moved across Route 211 to make way

for the new highway. “After they expanded (211) it was a whole lot different,” she said. “Before, there wasn’t nearly as much as traffic or as many houses.”

‘No village in the village’

Longtime resident Hal Hunter, who completed a project in 2000 to document Amissville through oral histories and photographs of historic buildings, recognizes the challenge of building a community where there is no central place to congregate. “The truth is there is no village in the village,” he said. “We need to continually look for ways to come together and talk with each other.”

In 1999, Hunter, along with Steve Miller, Jan Makela and others started an organization called the Amissville Area Community Association (AACA). Miller,

who is now a part-time Amissville resident and served as AACA’s president, said the organization’s goals were to better define the community, act as a forum to discuss local issues, and identify improvement projects.

“When Route 211 was expanded the village lost a lot of its identity and we were trying to help regain that,” he said.

In addition to sponsoring fall festivals, identifying historic structures and working on a community planning process, AACA was responsible for erecting the welcome signs now found along Route 211.

Less successful was a bid for funding for highway landscaping, historic markers, and a study of pedestrian access in the village area. In 2001, Miller presented the proposal to the Rappahannock County Board of Supervisors seeking support for state funding under the federal TEA-21 highway law. But it was dead on arrival — many in the village objected, citing safety and tax issues and worries about finding volunteers to sustain the proposed projects. Miller withdrew it and the AACA disbanded in 2002. “Perhaps we were a little ahead of our time,” said Miller.

Churches, fire and rescue, baseball

John Wesley Mills, is a technology consultant and Amissville resident who chairs the Rappahannock County School Board. An ordained minister, he is pastor of the Gathering Christian Church off Route 211.

‘When I think of what brings our community together, churches, the annual fireman’s carnival and parade, and baseball at Stuart Field immediately come to mind,” he said “Our village does not have a central gathering place, so these three things provide opportunities for residents to meet and enjoy each other’s fellowship,” he said.

As a child, J.B. Carter remembers music drifting from the windows of the fire hall on summer nights. “Our house was across the street from the old fire hall and they would host dances there once a month,” he said. “Growing up, there wasn’t a whole lot to do, so the fire department supported a lot of activities for kids, like basketball and softball.”

Now chief of the Amissville Volunteer Fire and Rescue company, Carter works to make sure the fire hall is a center of community life. “Covid suspended a lot of our activities like bingo, community dinners, and the big annual carnival,” he said, noting that the carnival and parade are held in June. “I know a lot of people enjoyed its return, as it is probably the village’s biggest annual event.”

Carter worries about the shrinking pool of young fire company volunteers. “I joined as a junior member when I was 14 years old,” he said. “Now the age has been upped to 16, just when kids are getting their driver’s license. Between that and the distractions of the internet, it is hard to recruit junior members who will eventually become full-fledged volunteers. Those that do join often go off to college and can’t return because it is so expensive to live here.”

Amissville has no shortage of churches — there are five in the village area. “There is a crossover among the churches for community and outreach projects,” said Frank Fishback, an ordained minister and president of the Amissville Community Foundation.

For more than 50 years, it has sponsored the Amissville Christmas Project which prepares food baskets and gifts for 100 local families each year. “This is a very successful

Peter Witkowski, pastor at the Baptist Church, also on Viewtown Rd., agreed, saying: “Since homes are spread out and somewhat secluded, people need places to enjoy fellowship and care for one another. Amissville’s churches provide those gathering places.”

Another large community event has been an annual Thanksgiving service. “Each Sunday before Thanksgiving, churches in the area would join together and host a community service of Thanksgiving,” said James Pittman, pastor of the Full Gospel Church, located on Viewtown Road. “We’ve had to postpone the service the past few years because of Covid, but hope to start it up again this fall.”

The community Thanksgiving service was restarted in November 2023.

Veterinarian Jana Froeling and spouse

Melissa Schooler operate Full Circle Equine Services in Amissville. “We have a business

“I joined as a junior member when I was 14 years old. Now, it’s harder to recruit young members. Those that do join go off to college and can’t return because it is so expensive to live here.”

J.B. CARTER

Amissville Volunteer Fire and Rescue chief event, held at the United Methodist Church, that is sponsored by many of our local churches with dozens of people from all walks of life participating,” said Fishback. “No doubt, churches in Amissville play an important role in bringing people together.”

here so it is much easier to meet and get to know people in the community,” Froeling said. Schooler, who also serves as treasurer of Businesses of Rappahannock, the nonprofit group that represents Rappahannock’s business community, added: “And of course, we’ve gotten to know people over the years through the Christmas project and fire hall activities.”

A few years back the two women were hauling a load of wood when their pickup truck broke down on Viewtown Road. “A sheriff’s deputy arrived on the scene. Shortly after that, volunteers from the fire

department were returning from a call and stopped to help us,” said Froeling. “They all pitched in to help us transfer the wood to another truck so we could have it towed. They couldn’t have been nicer or more helpful. It made us feel really good about the community here.”

In 1975, John Early and Clarence “Boosie” Dodson asked retired U.S. Navy Capt. Luther B. “L.B.” Stuart if the Amissville Little League Baseball team could play on his land. Stuart agreed, paving the way for what has become a five-field complex off Carter Lane hosting youth teams from Rappahannock and Culpeper counties.

Stuart passed away in 1980. A few years

later his wife, Maybel, deeded the field complex to the Amissville Ruritan Club which transferred ownership to the county in 2008. The complex is managed and funded primarily by the Rappahannock Athletic Association (RAA), with some funding contributed by the county.

Wayne Dodson, son of Boosie, who serves as RAA president, explained: “We started with just one field and now we have five. I grew up playing ball there and never left. There isn’t a better place for kids of all ages, families and friends to congregate during the baseball season. This place is our local ‘field of dreams’ and it adds so much to community life here.”

Amissville resident Donna Comer, who represents the community on the Board

JANA

“They couldn’t have been nicer or more helpful. It made us feel really good about the community here,” Froeling recalls when strangers stopped and helped out after their truck broke down on a local road.

of Supervisors, has been going to games at Stuart Field since her son, Mason, was just five. “I challenge you to find another spot anywhere in the county, between mid-March through the end of October, where you might find more children and families gathered,” she said. “We’ve bonded with many families over the years watching their kids grow up playing ball. And stopping at Hackley’s Store for ice cream after a game is always a treat.”

Perhaps the most familiar landmark in Amissville is the Hackley’s Store building, located at the intersection of Viewtown Road and Route 211.

“As a kid, I loved Hackley’s Store, especially the candy bins,” said Christina Loock, who lives nearby on Viewtown Road. “My sister and I would walk there to buy penny candy and Mrs. Hackley would scoop an eighth of a pound of spice drops and an eighth of a pound of jelly beans into little brown paper bags.”

Hackley’s sold more than penny candy. “It was once a full-fledged general store selling clothing, groceries, hardware, animal feed — just about anything anyone living in the country needed,” said Dorothy Hackley. Now deceased, she ran the store with her husband Graham for 57 years.

The original store was built in 1908 by Graham’s parents, L.E. and Rosalie Hackley, just across Viewtown Road from the current structure. It burned in the early 1930s and was rebuilt at its present location in 1934.

“It was a central meeting spot where members of the community could find items they needed, then sit around the old wood stove or on the porch and exchange news and gossip,” added Dorothy’s daughter, Jan Hackley Makela. “In later years, bluegrass bands and musicians would play on the porch and neighbors would come to listen or dance in the parking lot,” she said.

Bill Anderson, a former member of the Board of Zoning Appeals and an Amissville resident since 1965, said of the store’s founders: “Mr. and Mrs. Hackley were two of

Present-day Amissville was first settled in the mid-1700s on tracts of land granted by Lord omas Fairfax. Joseph Amiss and Edmond Bayse each purchased significant acreage from those tracts.

As the Amiss and Bayse families grew and acquired more land, and new settlers arrived in the area, a post o ce was needed. But there was no name for the new village. Legend has it, both the Amiss and Bayse families wanted to claim the name of the village. It was decided that landowners in the area should put it to a vote. e Amiss family won by one vote. Hence the name “Amissville.”

From 1889 until 1960. Tapp’s general store, located at the corner of Hinson’s Ford Road and Route 211, ran an undertaking business. Bodies were transported in a fringe-topped, horse-drawn hearse.

What is now Mayhugh’s store and gas station once housed the Bel-Air Restaurant, a popular bar and dance hall. It was also a general store and gun shop. e faint lettering “GUNS” is still visible on the roof.

Tapp’s

e two-room, one-story Amissville public school was built in the early 1900s. Ira Beatty, father of movie stars Warren Beatty and Shirley MacLaine, taught there around 1925. Amissville also had several “graded” schools” for African American students, built with financial assistance from the Rosenwald Foundation.

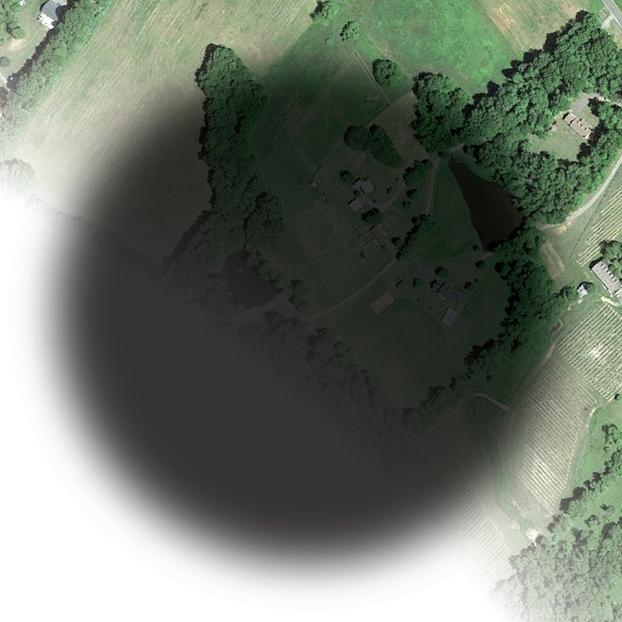

The Amissville post office on Viewtown Road serves portions of all three counties. Zip code 20106 stretches west from Clevengers Corner to Ben Venue, and north from Viewtown to Crest Hill Road.

Today, compared to other areas of the county, Amissville sends the most kids to Rappahannock public schools – some 25% of the student body. Some suggest housing in Amissville may be more a ordable, and working parents are able to live closer to their jobs in Warrenton, and areas in Northern Virginia.

Organized in early 1870s, Bethel Baptist Church on Viewtown Road was likely the first African American church in the county.

The heart of Amissville (Detailed below)

ree counties come together in the area. Many properties are split by county boundaries.

people think Battle Mountain is named for General George Custer’s attack on Confederate troops in 1863. Not so. e Batailles, a French Huguenot family that settled in Amissville, changed their name to “Battle” when they arrived in America.

and rescue station was

Present-day Amissville was first settled in the mid-1700s on tracts of land granted by Thomas Lord Fairfax. Joseph Amiss and Edmond Bayse each purchased significant acreage from those tracts.

As the Amiss and Bayse families grew and acquired more land, and new settlers arrived in the area, residents asked the government for a post office. But there was no name for the new village.

As the story goes, both the Amiss and Bayse families wanted to claim the name of the village. To settle the dispute, it was decided that landowners in the area should put it to a vote. The Amiss family won by one vote.

Thomas Amiss, one of four sons of Joseph Amiss, was appointed first postmaster of newly named Amissville in 1810.

Through the mid-1800s the village grew. The United Methodist Church on Route 211 was founded in 1829. Construction of the SperryvilleRappahannock Turnpike provided access for farmers to transport their goods by fourand six-horse wagons to canals on the Rappahannock River and roads to Warrenton and Falmouth near Fredericksburg.

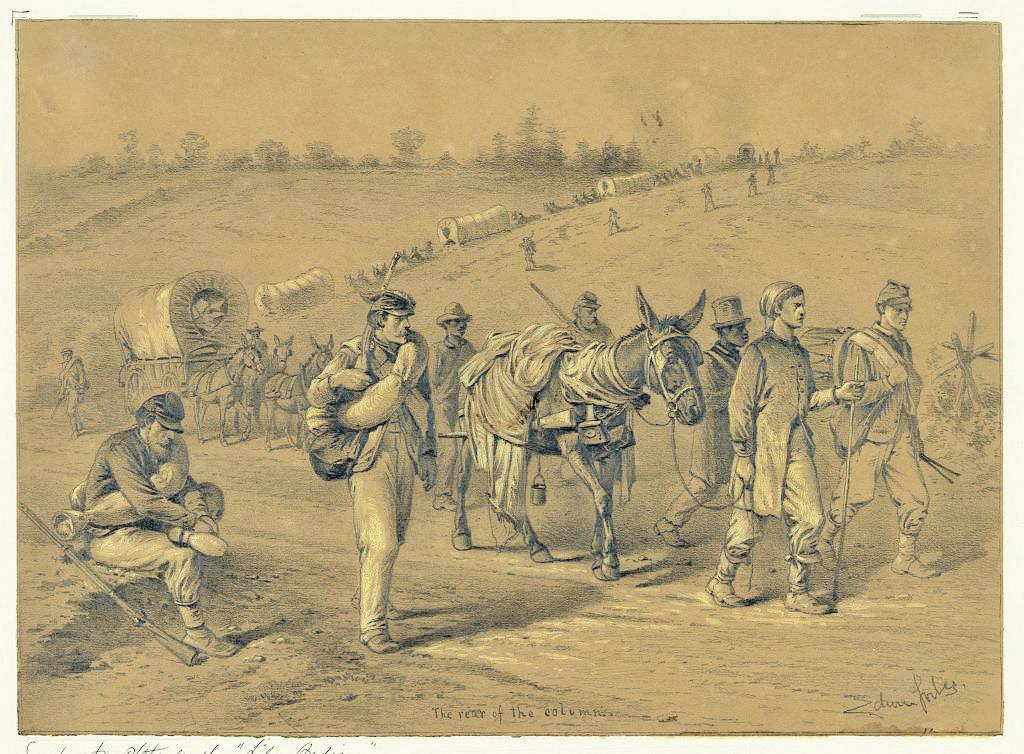

Although Amissville did not see major action during the Civil War, two minor engagements are worth noting.

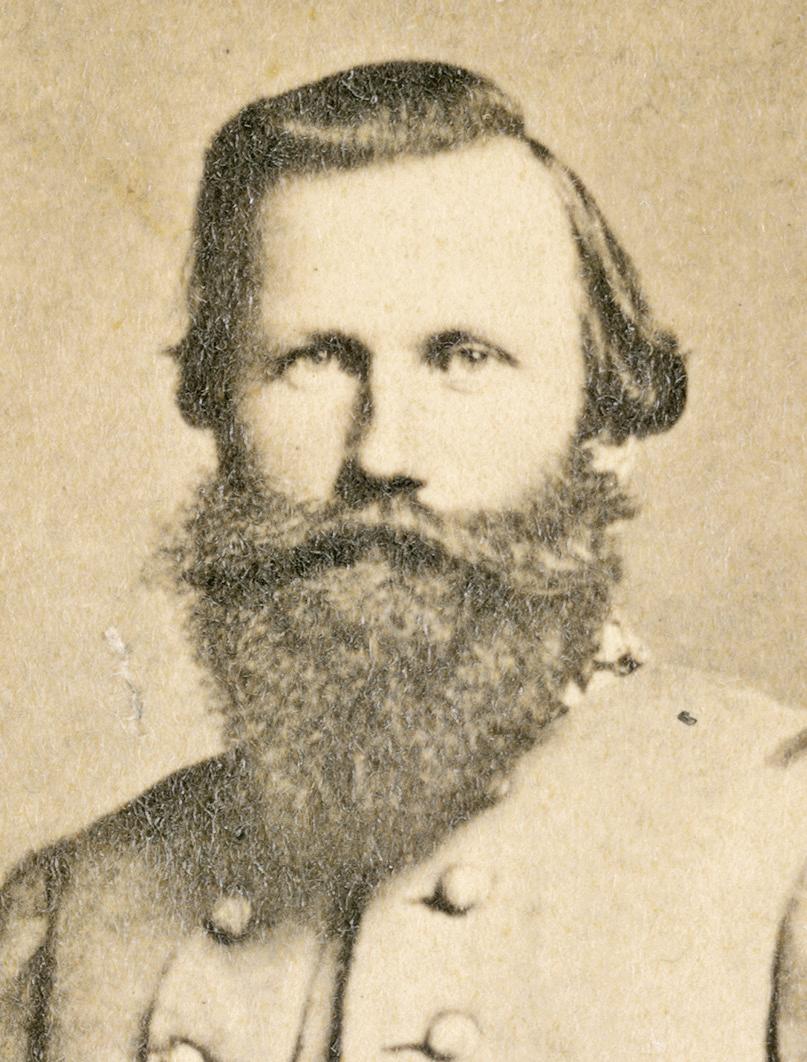

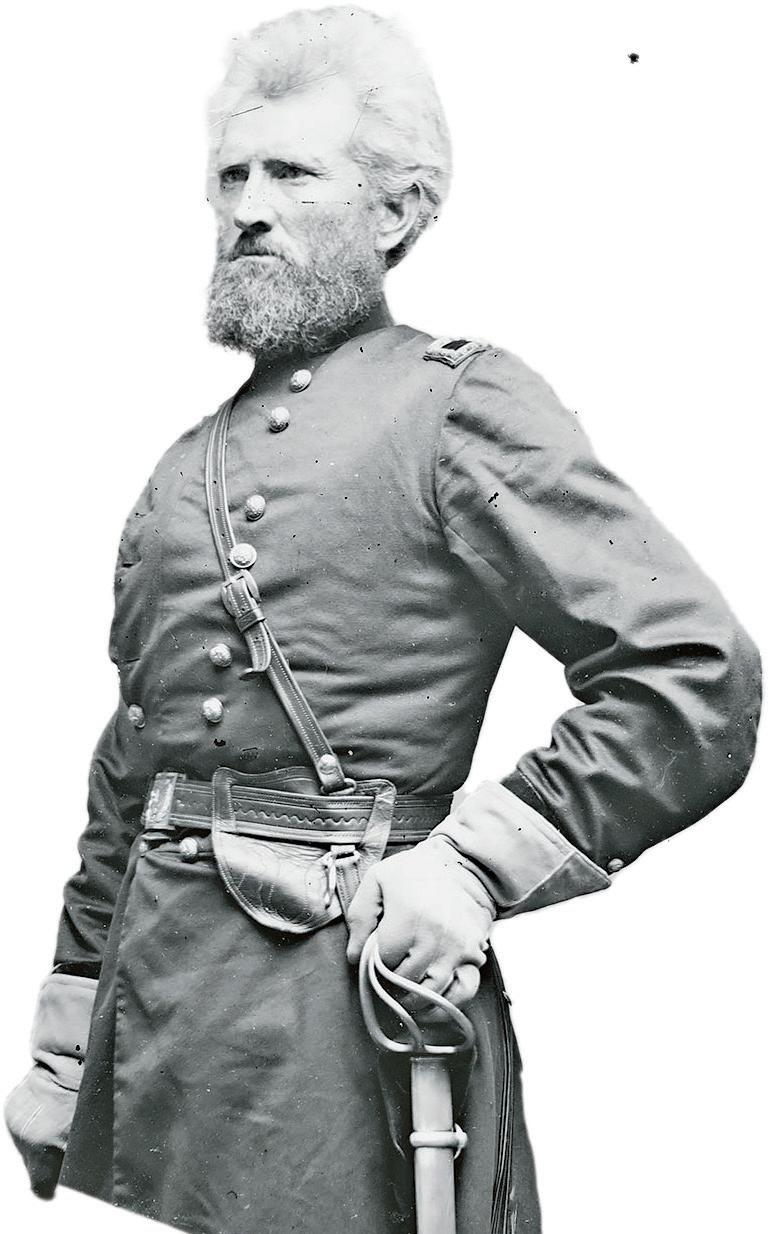

In November 1862, following the Battle of Antietam in Maryland, Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart and his cavalry units were in the vicinity of Amissville, traveling to Culpeper. At Corbin’s Crossroads (now the intersection of Seven Ponds Road and Viewtown

Road), about a mile south of Amissville, Stuart came upon Union cavalry forces. During the engagement he narrowly escaped death. Just as Stuart turned his head, a bullet whizzed past, clipping off half of his mustache.

Following the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, thousands of Confederate troops were retreating through Chester Gap and south to Culpeper on Richmond Road.

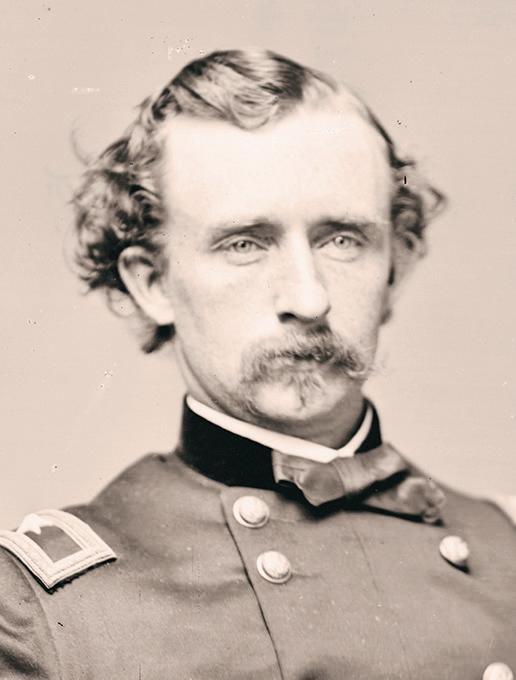

Union Gen. George A. Custer and his Michigan cavalry and artillery battery were camped in Amissville. They scouted the Confederate forces not realizing about two-thirds of the Army of Northern Virginia was moving through the area. Custer stationed his troops on the southern shoulder of Battle Mountain about five miles west of Amissville. As his cavalry and artillery units engaged the Confederate forces, Custer realized he was vastly outnumbered and retreated to Amissville, bushwhacking his way back to camp.

After the Civil War the village continued to grow. It boasted merchandise stores, sawmills, grist mills, carriage makers, wheelwrights, tanners, a doctor and a dentist.

Around the turn of the century, churches, small oneand two-room schools, homes, stores, garages — even an undertaker — sprouted along Viewtown Road and the old turnpike, which would later become U.S. Route 211.

With the opening of Shenandoah National Park in 1935, Rappahannock County was a primary access point to the park. Amissville became a major tourist stop along the way. Tourist homes and restaurants such as Lom-BarDy Tourist Court and Lunch Room, Bel Air Tourist Cabins, and Mountain View Tea Room and Tourist Cabins did a brisk business. As visitations to the park increased, especially in the fall months, Sunday traffic returning to Washington, D.C., would often back up all the way to Warrenton.

In the mid-1970s, Lee Highway was widened to four lanes. Many homes, businesses, and other buildings on the northern side of the road, were torn down or relocated to make way for the expansion, including the fire house which was rebuilt on its present location in 1974.

the finest people you could ever meet. They always helped anyone who needed it.”

In 2023, the store began operating as the Corner Deli Market, but closed after almost 18 months. The business owner, Ernesto Elias, did not cite a reason for closing but, in a Facebook post, he thanked past customers for their support. The Hackley family, which still owns the store, is in discussions with potential lessees interested in providing food service. “We have a lot of interest and I hope we can find a tenant with a good business plan and strong marketing skills,” said Makela.

Across Viewtown, on the site of the first Hackley’s store, Pam and David Jenkins opened 211 Veggies and More in August 2020. “We used our savings to set up a small outdoor market selling vegetables and plants mainly on weekends,” said Pam Jenkins. “We felt a market like this was needed at this end of the county. With more people visiting the country during the pandemic, we’ve been able to make a go of it,” she said.

The Jenkinses, who report business is going well, are working to update the adjacent building and expect to sell handicrafts and specialty items inside by late summer 2024.

A third-generation resident of Amissville, Pam Jenkins, who retired from Rappahannock County Public Schools, doesn’t feel there is enough for kids to do in the village. “If I hit the lottery, I’d build a recreation center for them,” she said.

McKenna Torosian, who recently graduated from Rappahannock High County School and lives on Goldfinch Lane, suggested a sidewalk along Viewtown Road. “Having a sidewalk where kids could stroll to Hackley’s Store or other places would be nice,” she said. “It is dangerous walking along the road.”

Just four miles east of Amissville sits Clevengers Corner — the intersection of Route 211 and Rixeyville Road in Culpeper County. Rising there now is Stonehaven, a mixed-use development with up to 776 housing units which are selling briskly. According to Saadeh Partners, responsible for building and leasing retail space, an initial phase with shops, restaurants and other services is expected by fall of 2025. A planned second phase of the development is to include bigger commercial businesses, such as a grocery store and hotel. Amissville residents have mixed views about the project’s impact on the village. Most worry about increased traffic and commute times to Warrenton and Northern

Virginia. Of less concern is the potential of future development that would compromise the rural nature of Amissville. Many welcome the possibility of commercial services available closer to home.

Donald Brown, who lives on Battle Mountain Road and whose family roots in Amissville go back to the 1800s, shared concern about the possible increase in traffic but is pleased that restaurants and other services may be a little closer.

“Traffic is going to be a problem but most of us will end up shopping there,” he said. “The project might even spur some additional development in the Amissville village area. That would be great for the county’s tax base, but the people in Amissville have to be included in any decisions affecting future growth. That hasn’t always been the case.”

Real estate agent Kaye Kohler, who lives on Sam Riley Lane off of Hinson Ford Road, isn’t overly concerned about development pressure migrating from Stonehaven to Amissville. “We have strong zoning laws and as long as we continue to follow them, we should be protected,” she said.

“Amissville is physically positioned such that growth, while at a slow pace, is coming,” said Donna Comer. “We need now, more than ever, to be very intentional and strategic in community planning,” she said. “As more folks move into Culpeper and Fauquier and discover the beauty of the Shenandoah National Park, Amissville becomes the gateway to the mountains. What happens when this ‘sleeping giant’ awakens depends

in large part on what county leaders do now.”

Noel Laing’s family moved to Amissville in the early 1920s and he grew up in the area. “It’s anybody’s guess on how property values will be affected, but it might put pressure on this end of the county for rezoning with reduced acreage requirements, or some moves to concentrate housing around what might be a village in Amissville,” he said.

Ron Makela, Amissville’s representative on the Board of Zoning Appeals, knows of at least two 100 acre-plus parcels along Route 211 near the village area that could be developed. “Although they are zoned for agriculture, given their proximity to 211, a developer could apply, or even sue, for rezoning on the basis of satisfying a need for affordable housing,” he said. “The law requires we take steps to provide affordable housing. We know there is a shortage of it in the county, and other than the Rush River Commons, not much is being done to encourage it,” he said.

In 2022, the Planning Commission brought in a consulting firm, The Berkley Group, to analyze the county’s zoning ordinances and make recommendations for updating land use rules. The group’s report can be found on the county’s website. Although the commission and BOS have had numerous briefings, meetings and hearings on the report, no final action has been taken to update the zoning ordinance.

“Residents should pay close attention to this process,” said Makela. “It could have significant impacts on how we plan for future development, not just in Amissville, but the entire county.”

Jan Makela continues to think about how a village center might be created in Amissville. “It would be wonderful to define the boundaries of Amissville so we could have a small commercial center, a place for people to meet,” she said. “Maybe start with something small like a walking trail from Stuart Field over to Hackley’s, and up to the post office. I’d like to start a conversation about it.

“Before my brother Larry passed away last year, he was reflecting on growing up in Amissville. He said, ‘I feel like we grew up in a Norman Rockwell painting.’ I had to agree. We were surrounded by friends and family who loved us, watched out for us, and really cared about us, and we always tried to return the favor. That’s the joy of living in a small village like Amissville.”

Originally published June 30, 2022

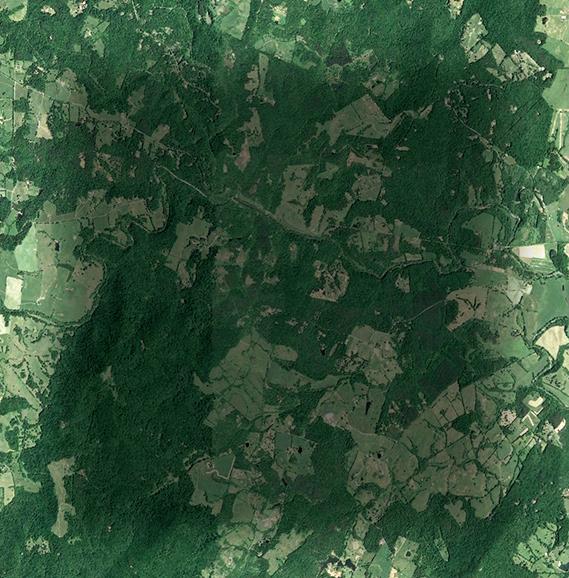

It is the most densely populated village in Rappahannock County. It has its own voting precinct. It adjoins Shenandoah National Park and is home to the headwaters of the Rappahannock River. At 1,670 feet it has the highest elevation of the county’s villages, thereby experiencing its own harsher weather.

It has more than 800 residents and about 300 homes. But with no shops or stores, and just one road in and out, chances are residents who live elsewhere haven't spent much time in this corner of the county.

Chester Gap – or “The Gap,” as many residents call it – snuggles up to the mountains where the boundaries of

Sisters Jesse Wines and Mattie Frazier, whose family has lived in Chester Gap for generations.

Rappahannock, Warren and Fauquier counties meet. Its main thoroughfare, Chester Gap Road, runs west from U.S. Route 522 to a dead end at a Shenandoah National Park (SNP) trailhead.

Newer residents and those whose families date back generations love the place. Housing is more affordable, they say; neighbors look out for each other; and access to services like groceries, medical care, restaurants and entertainment, including a movie theater and bowling alley,

are in Front Royal, just five miles down the north side of the mountain.

Trey Williams, with his wife Tiffany Matthews and two daughters, moved to a house on Skyway Lane in 2017. “We looked to purchase a place in the area for about three years,” he said. “We were looking for an area that we liked, had good schools, and a home we could afford. Finding that trifecta was difficult.”

Tiffany, who serves on Rappahannock’s nonprofit Family Futures board and advises the county’s Department of Social Services, added: “One of the benefits of living here is you have the option to go to close-by Front Royal for services, but also participate in school and social activities in Rappahannock.”

A key Civil War throughway to orchard powerhouse

Little has been written about the history of Chester Gap. Once inhabited by the Manahoacs, a Native American tribe, the village’s European settlement dates to the mid 1700s, when Thomas Chester purchased land on the western edge of what now is the village. Chester, who ran a ferry across the Shenandoah River near Riverton in the 1730s, was considered a founding father of Front Royal.

Over the years, a road was built from the ferry along current Route 522 to what was then known as “Chester’s Gap,” and eventually into Rappahannock County. An old highway toll house that stood along Route 522 near the top of the mountain was moved in 1995 to a private property in nearby Huntly.

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate armies fought for control of gaps in the Blue Ridge Mountains that led into and out of the strategically important Shenandoah Valley. Chester Gap was a key access point. During the war, soldiers from both sides camped in the area.

The first notable use of the pass was in July 1862, when Gen. Nathaniel Banks' corps of the Union Army of Virginia marched from Winchester through Chester Gap en route to its monthlong occupation of Rappahannock County.

At the time, Annie Gardner, who lived just below Chester Gap near Front Royal, observed in her diary:

July 5, 1862: “Cavalry went over toward Flint Hill this morning early, been coming back in small companies all the morning, have heard no news from Front Royal, suppose no fighting there as the Yankees look as consequential as ever.”

July 7, 1862: “Yesterday they (Union troops) drank up all the milk in the spring house, and took some of Pa's hay this morning, they have been all over the yard,

in the spring house, in the meadow, up the Cherrie trees, almost broke them to the ground…”

Almost a year later, in June of 1863, more than half of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia passed through on its way north to the Battle of Gettysburg. A few weeks later, after the Confederate forces lost that battle, Lee’s army retreated through the gap. Union forces tried to block Lee’s army on the Rappahannock County side of the pass, but were pushed back by Confederates in a 26-hour skirmish on July 21-22.

Longtime residents remember old family stories of subsistence farming, logging and blacksmithing. Two large families, the Williams, and the Wines, migrated to Chester Gap in the mid-1800s and many of their descendants still live in the village. At

one time, there were so many members of the Williams’ family living in the area, the community became two settlements: Chester Gap and Williamsburg.

Big apple orchards were planted in the early 1900s, most notably by the Wood and North families. The Wood orchard, near the end of Waterfall Road in the old Chester’s Gap, provided seasonal work for many locals. Covering almost 1,000 acres, it had its own store, private homes and numerous storage and processing facilities.

Ronnie Morris, whose Williams’ family lineage goes back five generations, said that those who didn’t work in the orchards found jobs in Front Royal. “A lot of folks worked in Front Royal, at the old American Viscose Corp. manufacturing plant or the horse breeding remount depot run by the U.S.

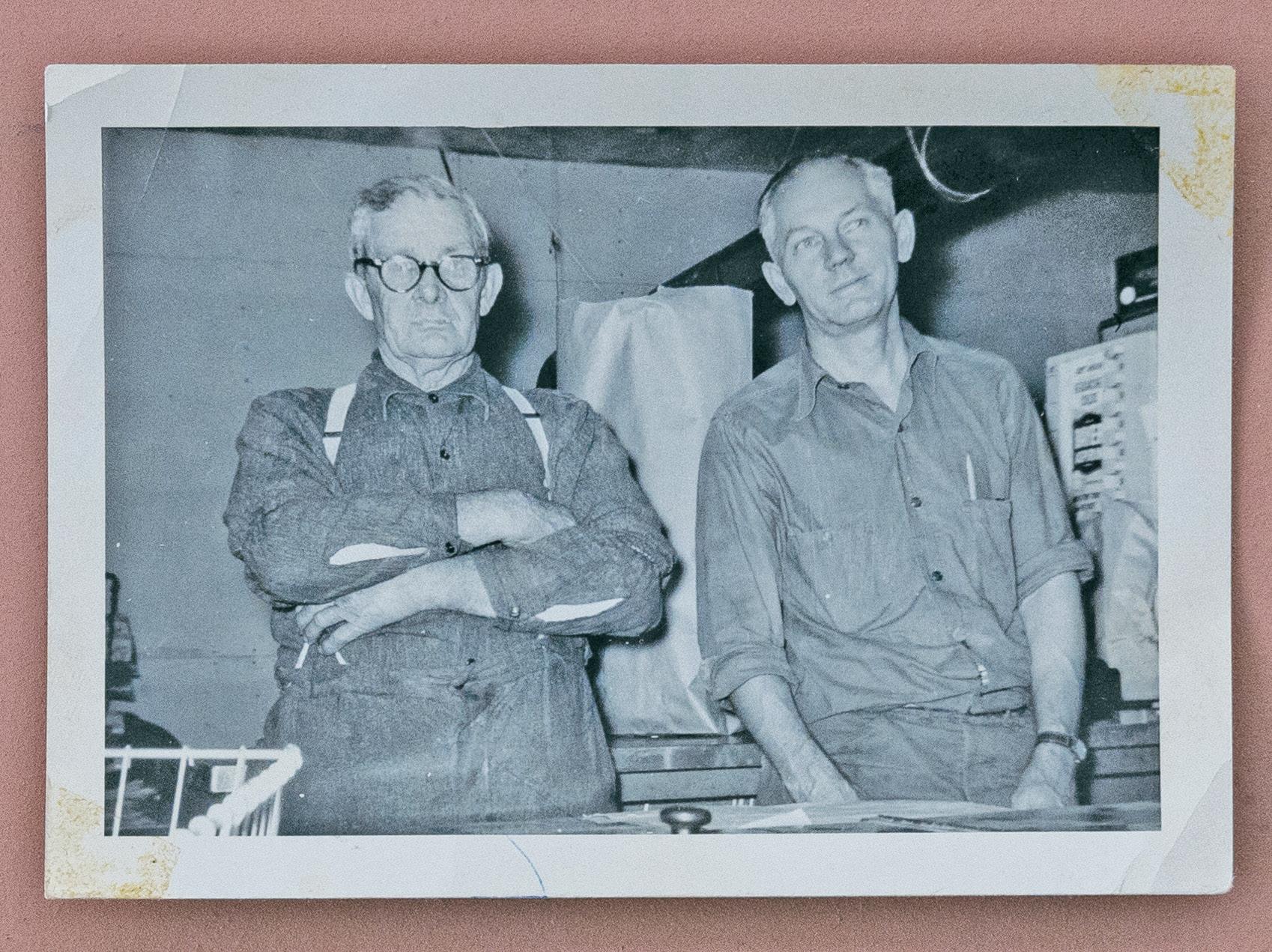

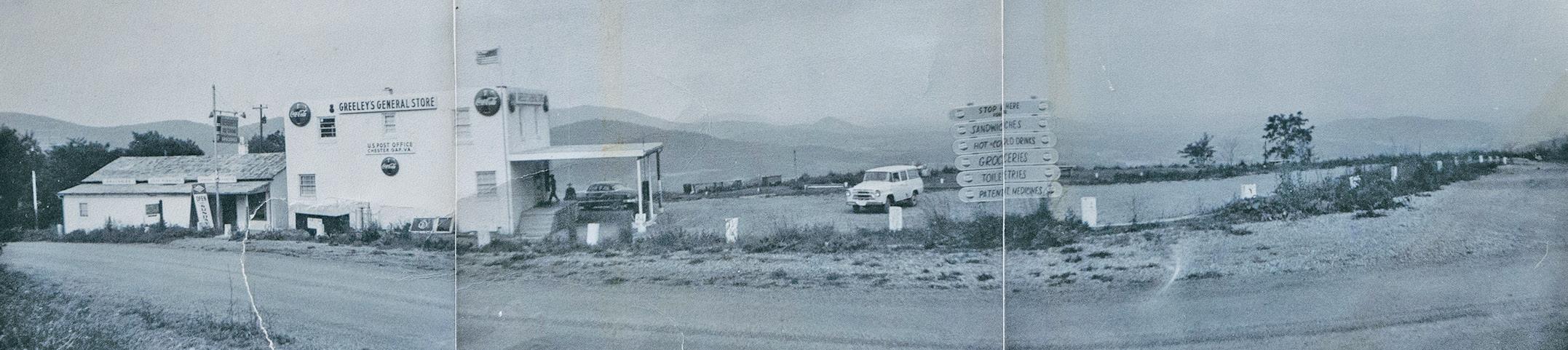

Merritt Greeley, pictured at right, served as the first postmaster. His general store, below, housed the post office. Greeley is standing with Kerry Williams, father of twins Mattie Frazier and Jesse Wines.

Ronnie Morris, whose Williams’ family lineage goes back five generations.

Army,” he said. “Most everybody had several acres for a garden and a few animals like hogs and cows.”

Chris Ubben, a descendant of the Wines’ family, represents the area on the Rappahannock County School Board and is a deputy sheriff. He recalled: “It was a little slice of Appalachia up there back in the day. It was a small, tight-knit community and folks made do with what little they had.”

A community leader from ‘The Gap’ paves way for county zoning laws

By the mid-20th century, Merritt Greeley, a resident of Front Royal, purchased land around what was then the Williamsburg area. Originally from Iowa, Greeley was a great, great grandson

postmaster and operated the post office out of his general store, where he kept a small room with a bed.

“In those days postmasters were required to live in the towns where they served,” recalled Morris. “But I’m not sure he stayed there very often. He’d let us kids sit in that little room and watch a small black-andwhite TV he kept there. It was the first TV I ever saw.”

Greeley also owned an apple orchard near his general store. In the mid-1950s he converted it into the village’s first residential subdivision, Skyverge Estates, which comprised about 70 lots.

As other open spaces were subdivided in the 1950s and 1960s, the village began its slow transformation into more of a

residential neighborhood.

of Horace Greeley, founder and editor of the New-York Tribune newspaper, an ardent abolitionist and a Republican Party organizer.

“He got the community together,” said Morris. “Mr. Greeley built a general store; got our first post office in 1954; helped form our first citizens’ association; organized the volunteer fire department in 1960; and donated land for both the fire department and the Chester Gap Baptist Church.”

When the post office was established, it was agreed to officially name the area Chester Gap. Greeley served as the first

A few years after the Skyverge subdivision, the Blue Ridge Mountains Estates, with about 400 lots at the top of the mountain, were carved from old orchards and woods bordering SNP. But these were little lots, some just 60 feet by 60 feet, and were marketed primarily to urban dwellers as campsites. Because they were so small, people seeking to build permanent homes needed to buy adjacent lots to have room for wells and septic fields.

Hubie Gilkey who represented Chester Gap on the county Board of Supervisors (BOS) from 1980 to 1998, recalls:

“Growth kept coming. First there were a few small seasonal places, then folks started

Ronnie Morris, retired, multi-generation Chester Gap resident: “Back in the day people who knew we were from Chester Gap asked us, ‘What are you, a Williams or Wines?’ Not so much anymore, though. There are so many names here now. I can sit on my back porch in the morning and nine out of 10 cars going by, I don't know who's in them.”

Morris recalled a favorite activity at the end of Waterfall Road. “We’d roll an old tire down the steep waterfalls of Foot of the Mountain stream and see how far it would go. Then we’d drag it all the way back to the top and do it again. It was a 10-second trip down and a 10-minute climb back up.”

Jesse Wines, retired, multi-generation Chester Gap resident: “Once school got out for the summer we couldn’t wait to go barefoot. We’d play in the mountains, swing on the vines, go to the waterfall. We’d stay out until dusk until we heard my mother call us home.”

Mattie Frazier, retired, multi-generation Chester Gap resident: “Growing up, there would be lawn parties on the open lot by the side of the church. Everybody would bring a dish and they would just sit and talk. Sit and talk for hours.”

Kevin Williams, multi-generation Chester Gap resident, firefighter and former county Emergency Management and Services coordinator: “As kids growing up, there wasn’t a whole lot to do, but we’d make our fun. We’d hang out at the fire department or walk up to the old Chester Gap Store. On the way we’d stop at the houses of people we knew and they’d invite us in and give us snacks. You might only see one or two cars on the road.”

Jim Vittitow, builder: “We moved here in 1998 and were warmly welcomed. People up here are ‘salt of the earth’. They don’t put on pretenses, are very accepting, look out for each other, and take a live-and-let-live attitude. To raise money during the winter months, the fire department would have shooting matches on Saturday nights. Winners would take home a quarter of beef, half a hog, turkeys, or bacon, all that good stuff.”

Settled in the early 1700s, Chester Gap, is located at the northern end of Rappahannock County. Farming and logging, and, later, apple orchards provided work. A section of the community was known as Williamsburg, named a er members of the Williams family who arrived in the 1850s.

A strategic pass into the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War, it was traversed by both Union and Confederate troops. By the mid 20th century, the village grew to include a well-supplied general store, post o ce, fire department and Baptist church.

Development of the Skyverge and Blue Ridge Mountain Estates subdivisions was the impetus for Rappahannock County’s first zoning ordinance in the 1960s. Today, with over 800 residents, Chester Gap is the most densely populated village in the county.

Sisters Mattie Frazier and Jesse Wines. Mattie was crowned the fireman’s carnival’s first queen 1962, and she still has her crown.

building permanent homes. All those lots were going to suck water out of the ground and then put sewage back in.

“All this potential growth was a cause for concern, since there was no subdivision or zoning ordinance in the county at the time. What was going on in Chester Gap was a big driver for the adoption of Rappahannock’s first zoning ordinance in 1966.”

A plane crash and a boundary change

Before 2002, the boundaries of Rappahannock, Warren and Fauquier counties cut through Chester Gap, splitting parcels and confusing residents. In 2001, the three counties filed a petition

in Rappahannock Circuit Court, stating that the uncertainty “resulted in real and personal property being taxed by a County other than the County where the property is located, in children attending school in a County other than the County in which they reside, and in confusion as to jurisdiction in the investigation and prosecution of criminal matters, the application of zoning and subdivision laws, and the proper place for the recordation of deeds.”

According to Peter Luke, Rappahannock County’s attorney at the time, government officials didn’t know for sure which property belonged in what county and which was the proper taxing authority. “The county revenue commissioners from the three counties would get together and decide who was going to tax what property," he said. “It worked, but in my view, wasn’t the best process.” Luke, who had to continually resolve

Jimmy Williams, retired, owner of apartments in the former Greeley general store, multi-generational Chester Gap resident: “It has changed a lot since I was a kid. The older members of the community are passing away.”

Tiffany Matthews, academic advisor, Laurel Ridge Community College, moved to Chester Gap in 2017: “Since there isn’t a general gathering place in Chester Gap, it would be nice to have a small park or playground where people could bring their kids and hang out. I think it would help people feel a little more connected.”

Helen Ordile, manager, Piedmont Nursery, lives in Skyverge Estates: “I grew up on a farm in Amissville and the closest house was my grandparents a mile up the road. Here families are closer, houses are closer. It makes for strong community bonds. My husband grew up here and his best friend lived just down the road. They still hang out together.”

Pastor Paul Strassner, Jr., Chester Gap Baptist Church: “Covid has taken a toll on attendance at a lot of churches. We hope to bring our membership back to 60, maybe 70 people. Our youth program is building, and there is a big desire to bring back adult Bible studies on Sunday mornings. We are here to build the Kingdom, and as we do, God will build the church.”

Dale Welch, owner of the Appalachian Inn, lives in Flint Hill: “It is a very interesting community. Growing up as a child in the 1960s, I remember if the older families liked you, they would do anything in the world for you. But if they didn’t, you’d better not go up there. It’s a much more diverse community today.”

Scott Schossler, retired teacher at Rappahannock County High School lives in Fox Pine subdivision across Route 522: “When we moved here in 1994, we weren’t sure if our home was in Fauquier County or Rappahannock County. We knew our water well was in Warren County. I was teaching at the high school and wanted to live in Rappahannock, so we were able to get the property lines adjusted.”

questions over voting locations, law enforcement jurisdiction, zoning and other local government issues, was the driver behind drawing a new boundary. “Although dealing with those issues was time consuming, the tipping point for me was a tragic plane crash that killed a whole family in Shenandoah National Park.

“No one knew for sure in which county the crash occurred and who had jurisdiction over it,” Luke said. “I figured it was high time we got the boundaries straightened out once and for all.”

The boundary adjustment process began in 1997 and ended with a proposal that virtually all of the Chester Gap village area be located in Rappahannock County. The Board of Supervisors adopted the changes in November 1999, and the new boundary line eventually was approved by the circuit court in 2002.

from where she grew up and was the fire department’s treasurer.

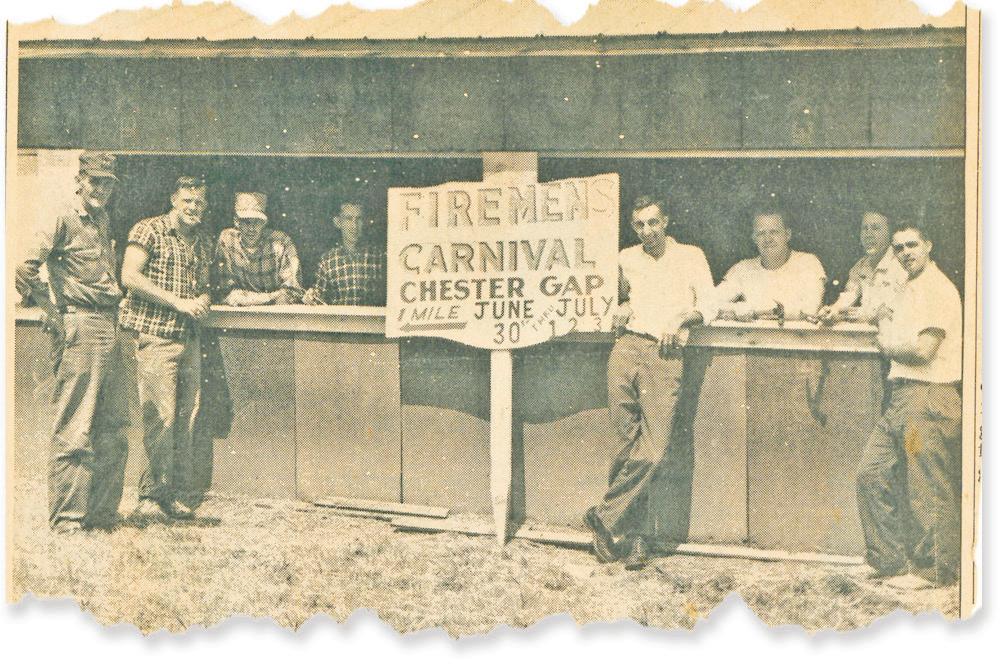

Working at the fireman’s carnival in July 1965 were Garfield Williams, Haywood Williams, John Williams, Albert Williams, Sherman Williams, Joe Williams, Ermand Morris and Hubie Gilkey.

‘You don't get connected now the way we used to’

For decades community life in Chester Gap centered around the fire hall, the general stores, the post office and the Baptist church.

“We started the fire department in 1960,” said Maybelle Gilkey, who served as the department’s treasurer for 20 years. “Back then, there weren’t any federal grants, so we

had to do a lot of fundraising to keep the operation running. That was a main focus of the community. The post office, the general store, and the Baptist church, of course, also provided lots of ways for folks to stay in touch.”

One of the big fundraising events was the annual fireman’s carnival. Jesse Wines, whose family lived in Chester Gap for generations, recalled: “Every summer, we’d have a carnival with rides, games, and good things to eat. It was a highlight of the summer. People came from all around.” Wines' sister, Mattie Frazier, was crowned the carnival’s first queen – and to this day she keeps her crown as a memento of the occasion.

Todd Brown, today’s fire chief, agrees the carnival was a big deal; he met his wife Sandra at the event in 1984. “Everybody in the community would help out baking pies, working in the kitchen, keeping the area clean,” he said. “It was a very communityoriented gathering.”

The fire department closed the carnival in 1995, around the time the county fire tax was levied. “Because of operating costs, insurance, and the fact that a lot of the older volunteers had passed on, it was becoming more and more difficult to run each year,” said Brown. “I would have preferred that we kept it running for a few more years. A lot of folks were upset they lost the carnival and, in its place, had to pay a new tax.”

More change came in the 1990s. The post office closed in 1996 and cluster mailboxes were erected around the village. Greeley's general store changed hands, finally closed in 1964, and later was converted into apartments. Other community stores opened and eventually closed – the last of them, Chester Gap Store, in 2014. New homes were constructed in the existing subdivisions, adding to the influx of new residents.

Residential growth has paused somewhat in the last two years. Of the 73 new construction permits issued in the county since the beginning of 2021, only four were for Chester Gap. An additional four new construction permits were issued since 2023. Still, as new homes go up, others are sold by old timers to new residents, and the village continues to see change.

“There are so many homes now you don't know who lives here. Folks wave or whatever, but you don't get connected now the way we used to,” said Wines.

“THE GAP” TODAY: The fire station and old country store and post office.

Maybelle Gilkey observed the lack of a central meeting place for village residents. “People aren’t able to gather around potbellied stoves or on the porches at community stores,” she said. “You can’t meet at a post office, and the community room at the fire hall was closed a while back to accommodate full time EMT staff. We have the Baptist church and youth activities, but our membership has declined from an average of about 130 people to around 40.”

‘A forgotten part of the county’

Today, the village has become something of a bedroom community with its relatively dense population and homes clustered on a close-knit patchwork of roads and lanes.

“A lot of folks who live on the mountain sort of consider it a world unto itself,” said Ubben, the deputy sheriff. “Because of its location, sometimes residents feel they are a forgotten part of the county.

“We are not landed gentry. Folks up here work hard to pay the bills and keep to themselves. Although some of the old families are still a little clannish, there is an acceptance between the newer residents and those whose family history go back generations. As long as people are decent, there is no reason to differentiate between the been-heres and the come-heres.” he said.

“It is by far the most densely populated area of Rappahannock County,” said Brown, the fire chief. “This area up here on the mountain, which is a little over a square mile, has half the population of the Wakefield district, and we provide a huge tax base

for the county. We’ve had our own voting precinct for close to 50 years.”

Brown, like many village residents, worries about the condition of the roads in the subdivisions where lot owners are responsible for maintenance.

“Some of these roads are just horrible,” said Brown. “They are rutted, have deep ditches, and are a real hazard. Try taking one of these fire trucks down one of these roads. It is a real challenge,” he said.

A homeowner’s association for Blue Ridge Mountain Estates, long disbanded, was established in the 1960s to collect fees for road upkeep. But as Hubie Gilkey explained: “It didn't have any bylaw requirements to pay maintenance fees, so it was toothless. If you lived on the road and didn't want to pay your dues, you didn't have to.”

Gilkey was on the Board of Supervisors when an arrangement was reached with the Virginia Department of Transportation to begin paving the roads. “VDOT started to take them over, maybe did one or two roads, and then the funding played out so the project just stopped,” he said.

Today, the situation leaves homeowners to fend for themselves, with some going doorto-door, asking neighbors to chip in for road repairs.

“We have had conversations with our neighbors, but it is really difficult to get folks organized to take charge of road repairs, especially if they are absentee landlords or just own vacant lots,” said Sheila Lamb, who lives in Blue Ridge Mountain Estates. “On our road, two or three families pay thousands of dollars for maintenance but we aren’t the

only ones who use it. We are subsidizing others,” she said.

Lamb has reached out to the county for guidance on how to address the problem but with little success.

Wakefield Supervisor and Chair Debbie Donehey, who represents the village, has been trying to find a way to help. “It’s been extremely frustrating,” she said. “VDOT came up with me in 2021, to take a look at some of the roads and give a ballpark cost for repairs and maintenance. I was shocked when they said it would cost over $600,000 to just bring one short road in Skyverge Estates into conformance with VDOT standards.

“It’s not for a lack of trying, but even if we got grant money and shared the costs with VDOT, upgrading the roads would still be a huge cost for our county,” she said.

“I know folks up on the mountain don’t always feel they have easy access to county services. That is particularly true about having to drive all the way to Flatwood or Amissville to dump their trash. I’m exploring ways to see if it might be possible for Chester Gap residents to take their trash to closer facilities in Warren County.”

To many residents, the harsh weather of Chester Gap relative to elsewhere in the county helps to define the village’s identity.

“We have the worst, and most diverse weather in the county,” said Brown. “Ice storms, heavy snow, fog that sticks around for days, you name it. It could be snowing up here and sunny in Flint Hill.”

‘If you were looking for trouble, you’d find it there’

The Appalachian Inn sat on the loop of Chester Gap Road, just off of U.S. Route 522. During the 1950s and 60s, it was a favorite haunt for drinking, dancing and the occasional brawl.

“It was a pretty rough place,” said Jimmy Williams, who lives near the now shuttered building. “If you were looking for trouble, you’d find it there.”

Local lore has it that the old county boundary line ran right through the inn. Back in the day, you could drink beer in Warren County on Sunday’s but not in Rappahannock. On Sundays, patrons would sit on the Warren County side of the inn to enjoy their brew. Others say the inn was just inside Rappahannock County, but to serve customers on Sundays, a concrete block building was constructed a few feet away in Warren County. The block structure is still there, but unfinished.

Whether the stories are true or not, the place had

quite a reputation. The inn was patronized mostly by people from the village. Dale Welch, who lives in Flint Hill and now owns the property, remembers a story his father told him. “It was the territory of the local folks. If someone from Flint Hill wanted to visit, before they could enter, they had to throw a hat through the door,” he said. “If the hat came back out it was a signal they had to move down to Front Royal to do their drinking. If the hat didn’t come out, they could go on in and

have a good time.”

Maybelle Gilkey remembers going there after school. “There was a little store in there and we’d get permission from our parents to stop by and get a Coke or snack after school,” she said. “But we’d never be allowed to go near the place at night.”

Asked if she had ever gone into the inn, Mattie Frazier laughed and said, “What! And die!”

Ronnie Morris recalls peeking through the windows. “Coming home from getting

Conditions in Chester Gap often were the determining factor as to whether Rappahannock County schools would close in bad weather.

“It would be rainy or a wet snow down below, but up here it was heavy snow or ice, and they would close schools because of the weather in Chester Gap,” said Ubben, the deputy sheriff and member of the School Board. “Some parents in other parts of the county would complain about having their kids stay home because students who lived on the mountain couldn’t make it in.”

That changed last year when the school administration adopted a policy which now allows Chester Gap students

excused absences if weather conditions on the mountain warrant. “It is kind of the compromise that keeps the schools open, while making sure our kids stayed safe. Now we can have our kids, or some of our kids, excused while everybody else is still going to class,” said Ubben.

Despite so much change, Mattie Frazier said parts of the community have retained the atmosphere of past decades. “Life in the old core part of the village around the Williamsburg area is pretty much the same. It hasn’t changed that much.”

groceries on summer nights we’d hear the music and see couples dancing,” said Morris. “One time my daddy had to go inside and took me and my brother. I was seven years old and had never seen a woman drink beer before. We were shocked to see that. My mama scolded Daddy for taking us in.”

Mac McGrail, who lives in Huntly, said Warren County sheriff's deputies often were staked out near the inn. “It was too far away for Rappahannock deputies to cover, but Warren County often had a patrol car close by,” he said. “Other than Route 522, there wasn’t an easy way for the Front Royal patrons to get back to town. So, the Warren County deputies had a fine time stopping people coming out. I’m sure they had a lot of court cases.”

The building still stands but needs repairs. Welch said he didn’t have any immediate plans for its future.

Born and raised in Chester Gap, Jimmy Williams, 77, loves the peace and quiet. “Even though you don’t know people like you used to know them, it’s a good community to live in.”

Maybelle Gilkey, the former fire department treasurer, still lives across the street from her childhood home. She summed up her feelings about the village. “My kids always said they were glad they grew up in Chester Gap. You had memories, you had family, and you were a community. Everybody knew everybody, and it was a fun place. I hope we can continue to have that kind of community into the future.”

Originally published April 13, 2023

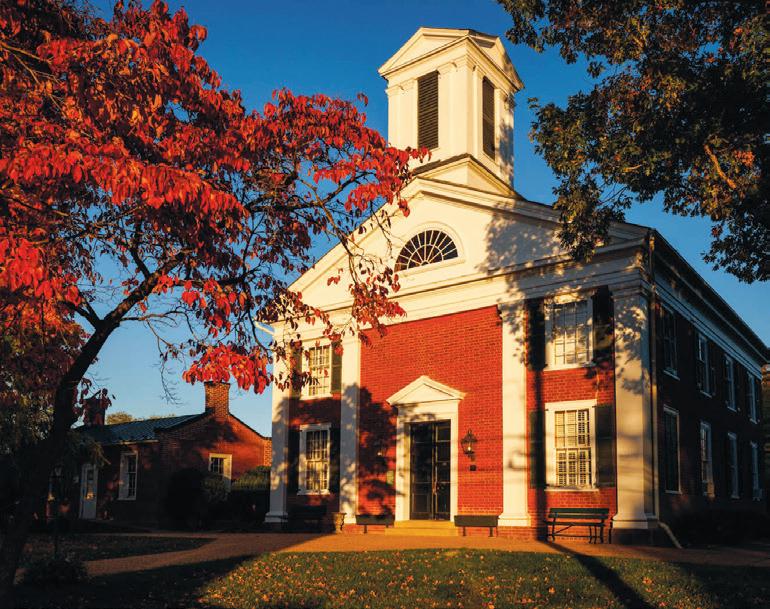

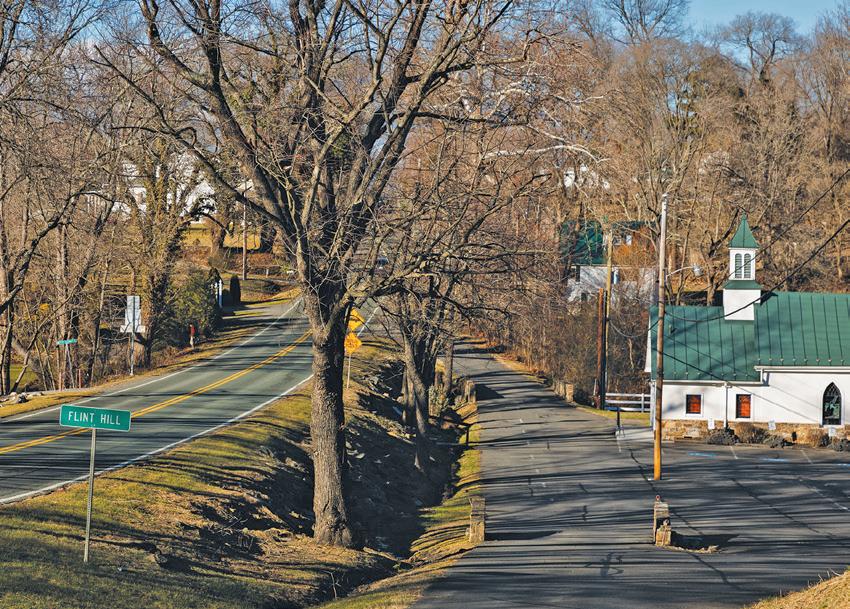

What’s to become of Flint Hill, a sleepy crossroads village, that now finds itself at a crossroads? Can new residents and businesses lead a village renaissance?

There was a time when Flint Hill's milelong historic district along Zachary Taylor Highway was one of Rappahannock County’s livelier economic hubs.

Hard to imagine now, but varied architectural styles – Greek Revival, Federal, Italianate and Craftsman – housed a bustling community of homes, schools, hotels, banks, shops, tea rooms, medical offices, and later,

Longtime resident Jean Lillard recalls village life in the mid-20th Century: “It was a great place to grow up.” She used to play on the merry-go-round at the Flint Hill School, now the Blue Door.

gas stations. Even a car dealership.

Today, with a population of about 360, Flint Hill is quiet. Many descendants of the old families have moved on. The general store closed years ago. The shuttered bank is up for sale – again. The Skyward Café closed recently. Ditto the Horse N Hound Saddlery. A short-lived Latin market also shut down..

Yet new residents and business owners are breathing energy and life into the village.

Will their spirit transform Flint Hill into a “destination” village, like Sperryville or Little Washington?

Flint Hill got its start in the mid-1700s near the intersection of two important routes: Chester’s Road (now U.S. 522/ Zachary Taylor Highway), connecting Front Royal and Culpeper, and Fodderstack Road, leading to the Town of Washington. Lore says the village actually was named “Flinn’s Hill,” after the local Flinn family. Others believe it was named for nearby deposits of flint rock. Through the first half of the 1800s, the hamlet grew to about 140 residents. A post office was established in 1823. Twenty years later the village was formally created by

an act of the Virginia General Assembly. During this period, the Baptist Church and the United Methodist Church were built, as were many homes and commercial buildings that still grace the historic district. Stores, millers, physicians, blacksmiths, wagon makers, saloon keepers and a deputy sheriff all thrived.

“...the beauty of the mountain scenery, of the mountain lassies, of the innumerable bouquets showered on us on all sides – of the waving of handkerchiefs, and the loud shouts of the soldiery…”

– Letter by a member of the 30th Regiment, North Carolina, marching through Flint Hill in June 1863.

Strategically located on the road north to Chester Gap and Front Royal, Flint Hill was a stop-off for tens of thousands of Union and Confederate troops during the Civil War. The village was spared any fighting, but citizens suffered looting and property destruction. Lore has it that residents hid their meat from Union soldiers upstairs in the Methodist Church, and at one point, the church served as a Confederate hospital.

Some residents joined the Flint Hill Rifles, part of the regular Confederate army. Others signed up with Colonel John Mosby’s Rangers who operated in the area.

As told by noted Civil War historian and Culpeper local, Clark Hall, Flint Hill in June 1863 witnessed the inauguration of the Gettysburg Campaign, considered by many a turning point of the Civil War.

Following the cavalry battle at Brandy Station near Culpeper, General Robert E. Lee ordered the Army of Northern Virginia to clear the northern Shenandoah of Union troops ahead of his planned invasion of Pennsylvania.

Hall explains: “The 2nd Corp of the Army of Northern Virginia left Culpeper and marched north on the Richmond Road, through Gaines Cross Roads (now the intersection of U.S. 211 and Ben Venue Road) into Flint Hill and over Chester Gap to Winchester, where they defeated a Union army garrison. Two weeks later, the corps arrived at Gettysburg, only to be routed by the Union army. Their retreat followed the same route back through Flint Hill.”

Another account from the period is noteworthy. In October 1864, Federal troops were in the area, seeking reprisal for the death of a Union soldier, reportedly at the

hands of Mosby’s men. The Union troops captured two of Mosby’s Rangers at the blacksmith’s shop at Gaines Cross Roads. One was Albert Gallatin Willis, who earlier had dined at Rose Cliff in Flint Hill and the other was a fellow fighter. Union officers ordered one of the two be put to death.

Willis’ companion, married with five children, was chosen, but pleaded for mercy. Willis, a Baptist lay minister who was single, offered himself instead. The next day, Willis was hung from a tree off U.S. 522 just below Chester Gap, near what is now Willis Chapel. His body was returned to Flint Hill and buried in the cemetery behind the Baptist Church.

Highway was widened, eliminating walking paths and leaving homes and shops close to the road. Filling stations and garages opened, as did the Russell Brothers’ Chrysler dealership, now occupied by Settles Grocery and Garage.

“This region was governed by people with common sense and experience,” said Bob Miloslavich, a local history buff who lives off Hillsborough Road, outside the village.

“There was a real sense of community in and around Flint Hill. Generation after generation, they took care of themselves

Flint Hill regained its footing and experienced a growth spurt after the Civil War. By the 1880s many new homes and commercial buildings were built, including two hotels, several general stores, an academy school (in what is now the Dark Horse Irish Pub) and a sawmill. The Macedonia Baptist Church was completed, bringing the number of churches to three.

The early 20th Century brought more growth, new businesses and more farming. A local bank, saddlery, barber and wheelwright served the village’s 350 residents.

As motorized transport became more common in the 1930s, Zachary Taylor

and had a wisdom that they earned the hard way. Many had been poor for generations. If anyone got a little ahead, they looked after the others.”

Jean Lillard, whose mother Mabel was Flint Hill’s postmaster for many years, recalls village life in the mid-20th Century. “It was a great place to grow up. There were so many kids and activities. We had Scouts, 4-H, youth groups, softball, roller skating and other activities. Every day, we walked to the school which is now the Blue Door restaurant.”

Lillard’s cousin, Richard Brady, a longtime resident, was raised near the village, off Aileen Road in the area then known as “Pullentown.”

“My mother raised 10 kids and had her hands full,” he said. “To make extra money she also raised and processed chickens and sold eggs. She ordered the baby chicks through mail. As a kid, I remember going to the tiny old village post office at the intersection of Fodderstack Road and U.S. 522 [and] hearing their ‘cheep, cheep’ coming from cardboard boxes.”

Just down the street from the post office was Bradford’s store, which sold groceries and home goods and had a small restaurant. Originally operated by the Carys in the late 1890s, the store’s potbelly stove was a place where locals gathered and shared conversation.

During the lead up to Christmas, Marvin “Boo” Bradford and his wife Francis would transform the upstairs level into “Toyland.”

“It was the biggest thing around,” said Brady. “All the kids would line up at the steps, then rush upstairs with their parents and see the toys. There was Santa in the corner handing out candy canes and oranges. It was a magical experience.” Parents would often return another day to make a purchase.

A popular hangout for the village men was the now vacant service station next to the Methodist Church. It had many operators over the years, including Clarence “Skindigger” Jones and Major Cowgill.

“The nice people congregated over at Bradford’s store and the rest of us hung out at Major’s station,” said Miloslavich. “Before TVs and air conditioning, all the men would go there in the evening. There’d be 40 or 50 guys sitting around spitting tobacco, telling lies to each other, and playing card games. Inside, that place was so smoky you couldn’t see a thing.”

Many families, including the Bradfords, Brownings, Reids, Easthams, Thorntons and Barksdales, contributed to the growth and livelihood of Flint Hill.

In the 1940s, 50s and 60s, the Foster brothers, Stanley and Herbert, farmed about 1,800 acres just north of Flint Hill, including cattle, orchard grass, corn as well as peach and apple orchards. Greg Foster, Stanley’s grandson, recalled: “To help run the operation, they employed a number of families who lived on the property, some

who moved down from the Shenandoah National Park. ”

For years, the brothers worked on construction projects in Washington, D.C., including the bomb shelter at the White House, returning to Flint Hill on weekends. “The farm wasn’t always profitable so their income from the city jobs kept folks employed and the operation running,” said Foster. “They were hard working and loyal to the people who worked for them.”

Herbert’s granddaughter, Sharon Dodson, remembers days on the farm as a child. “We worked 10-hour days and my grandfather would provide housing, transportation, and lunch for all of our farm workers,” she said. “Lunch consisted of a meal that today would be comparable to Thanksgiving or Christmas dinners, complete with at least three different pies for dessert.”

Firemen’s Parade and Carnival

The Flint Hill Volunteer Fire Department, organized in 1954, was another social hub. Like other

Richard Brady, raised off Aileen Road, remembers kids lining up for Christmas toys at Bradford’s store (left, in earlier days).

fire companies in the county, it sponsored an annual Firemen’s Parade and Carnival. Hubie Gilkey, who represented Flint Hill on the Board of Supervisors for several terms, reminisces: “It was a premier community event with people coming from miles around. Miss Virginia always participated. It was the biggest and best parade in the county.”

The carnival and parade, which ended in 2013, were an honored tradition for almost 50 years.

Dave Bailey, now president of Flint Hill Volunteer Fire & Rescue,, sees the company as a place where the community always could come together. “I feel a real responsibility to try to continue that tradition. There is a sense that people long for a place to gather, and in the future, we plan on hosting community events like dances,” he said.

Bailey was gratified by the attendance at a recent fish fry fundraiser at the fire hall where some 200 people from all over the county turned out. “Along with all that goodwill comes a sense of responsibility to make sure we are doing what’s right, not just in our ‘first due’ area, but also for the greater community.”

Originally published February 1, 2024

Once a bustling crossroads village, Flint Hill got its start in the mid-1700s near the intersection of Zachary Taylor Highway and Fodderstack Road. In its heyday, the designated Historic District of architecturally diverse buildings, housed a bustling community of homes, schools, hotels, banks, shops, tea rooms, medical of ces, and later, gas stations. Today the village is a quiet

Creel Toll House – Tolls were collected here to help pay to build the road from Ben Venue to Front Royal. It now houses ‘Raising Brain,’ a learning enrichment center Current owner Ann Pankow says a ghost cat once inhabited the building.

Dark Horse Irish Pub – Formerly the Grif n Tavern, it was built as an academy and later became the home of Marvin and Frances Bradford.

Flint Hill Methodist Church – Organized in 1832, the church was built in 1847. During the Civil War, it is said villagers hid their meat in the attic from Union soldiers. The church was reportedly used as a hospital for Confederate soldiers.

Wakefield Service Station – Once a blacksmith shop and later a garage with a movie theater upstairs, the original building was torn down and rebuilt into a service station in the 1930s. It had many renters including Clarence “Skindigger” Jones and Major Cowgill.

Maison Latouraudois – Built in 1837 as the home of James Latouraudois, a founding father of Flint Hill, his wife Elizabeth and seven children. It is now a private residence.

Bank/Post Office – Original home of the First National Bank of Flint Hill, it served as the post of ce from 1962 until 1967.

Althea Terrace – Originally a small log cabin built in 1742, the building has seen several renovations. A dependency building, now the Florence Room art gallery, once housed a blacksmith shop, dry goods store, Red Cross bandage rolling station, and a tack shop. Bradford’s store A general store since the 1890s, the popular gathering spot had a small restaurant. Upstairs the Bradfords staged “Toyland” during the holidays.

Grocery and Garage

from 1940 to 1972.

Flint Hill Square – Built in 1987, it houses the Flint Hill post of ce, four apartments, of ce space.

Skyward Café – Now shuttered, it was the site of 24 Crows Restaurant, Rector’s general store, a doctor’s of ce, and a beauty parlor.

Bank building – New branch o ce of Oak View National Bank, this building once housed branch of ces of a number of banks including, Truist Bank, BB&T Bank, and Farmers and Merchants National Bank.

Flint Hill Baptist Church – Built in 1854, its goes back to the beginnings of Baptist preaching in the county. Albert Willis is buried behind the church.

“Rose Cliff” – Part of the house dates to the late 1790s when it was used as a public meeting place. In the late 1800s, it was expanded on the south. It is said that Albert Willis had his last dinner at Rose Cliff before he was hanged for the killing of a Union soldier.

Rickett’s Hotel – Built around 1860, the hotel and rooming house fell into disrepair and burned down in the 1960s leaving only the foundation. Next door was Rickett’s Tavern which housed a saddlery and post of ce. It is now a private home.

Macedonia Church – Organized in 1865, it’s the oldest African American church in Rappahannock. Its rst pastor, the Rev. George Horner, founded several Baptist churches in the county. The 15 stained glass windows are by Sperryville artist, Patricia Brennan.

Michael Dennis

Over the last decade, Flint Hill has experienced an influx of residents bringing fresh ideas and new energy to the quiet community. Is renewal on the horizon for the village’s long and cherished history? Can residents overcome obstacles like pedestrian safety, speeding traffic and limited infrastructure?

Jean Lillard, whose family goes back several generations, has seen a big change since she grew up in Flint Hill. “I used to know everybody in every house,” she said. “Now a lot of new people have moved here. I think it is good to get a variety of residents with cultural differences, but the village is a much different place from my childhood.”

John Quido, a farrier who moved to the village 23 years ago, also notices changes. “I’d say adhere to country living, so we can stay like we are.”

Settle’s Grocery and Garage on the north end of the village has been a fixture in Flint Hill since Richard and Esther Settle started the business in 1972. Previously the store and garage had housed the Russell Brothers Chrysler dealership, which operated for 42 years.

“Thirty years ago, I knew 90% of the people who came in the store,” said Richard “Bubby” Settle, who took over the grocery and garage from his parents and started the used car and truck operation in the 1980s. “Today, I probably know about 10%. Still, we have a lot of loyal customers and great neighbors and we are grateful for that.”

Settle’s daughter, Kendra Hahn, now the general manager, remembers visitors sitting on the outside benches or inside around the wood stove. “A lot of that changed because of COVID,” she said. “We remodeled in 2020 and removed our gathering spaces so fewer people congregate in the store. Our breakfast business is still very brisk and a lot of the old regulars come in for that.”

Michael Dennis observes that the south end of the village, near Fodderstack Road, has several new residents who are renovating homes. Dennis, who lives in a bungalow-style home set back from the main road, said, “With new arrivals, you get the sense the village is moving into a new phase of its long and cherished history.”

Dennis, who moved to the village in 2010 with his spouse, Paul Smith, completed substantial remodeling of their home and constructed an art studio on the property.

Two years ago, they purchased the adjoining “Rose Cliff” parcel, and are renovating the main house and its outbuildings.

Across the street, Mark and Elena Kazmier purchased “Althea Terrace,” the origins of which date back to the 1740s. They are renovating the interior of the home, and Elena has opened a small art gallery, “The Florence Room,” in a building that has served many purposes, including a Red Cross center during World War I.

“We’ve been here three years and just love this place,” said Mark. “The quiet, stunning, rural environment is a great place to raise our children, but we are also excited about the enormous potential for it to become a more vibrant community for businesses, residents and visitors.”

The old post office where Richard Brady’s mother would pick up her mail-order chicks now is a private residence, recently purchased by Kristin Perper and Jeff Stiles. The home, once known as Rickett’s tavern and saddlery, sits next to the stone foundations of what was the Rickett’s Hotel. Built around 1860, the building fell into disrepair and burned down in the early 1960s.

“We were looking for a unique place to live and found this tiny house in Flint Hill,”

said Perper, who worked at the Freedom Museum in Manassas. “I love this community and the people who live here. It has a real ‘hometown’ feel.”

Perper is excavating the hotel’s foundation and wants to “showcase” its history. “People jokingly call us the Flint Hill archaeologists,” she said. “The old hotel is a lost treasure. We are finding lots of interesting artifacts and hope to incorporate them into an outdoor display recounting the hotel’s important history.

“I believe Flint Hill’s future is bright and shiny. There are a lot of new and creative folks here who want to make this more than a town people drive through to go somewhere else,” she said.

Milda Vaivada opened her store, HOME – Honoring Our Mother Earth – in 2022 in the old Bradford’s store building. The shop sells gifts and other items with nature-oriented themes.

“I have really great, loyal customers, but it isn’t always easy to get customers in the door,” she said. Vaivada blames the lack of sidewalks and vehicles often exceeding the 25-mph speed limit.

“It’s not safe to walk around the village. Cars and trucks speed through here at 50 or 60 mph. Motorists who might want to pull over are fearful. To make matters worse, the village doesn’t have a system of sidewalks, or crosswalks, and that creates serious safety issues for pedestrians,” she said.

In 2024 Vaivvada moved her store to the Sperryville Marketplace, where she reports there is better foot traffic.

Board of Supervisors chair Debbie Donehey, the former owner of Griffin Tavern, now the Dark Horse Irish Pub, represents Flint Hill. “Our problem as a village is that U.S. 522 runs right through it and the road is a major thoroughfare,” she said. “A lot of people speed through Flint Hill and don’t see what is available in the village.