LIVING DRYSTONE

Commoning the Peak District Moorlands through Convivial Wildness

Leela Keshav

How can methods of drystone vernacular construction become part of the repair, stewardship, and multispecies commoning of the Peak District moorlands?

“To design a commons is to see land through the lens of relationships; the points where connection occurs becomes sites of design. This view considers multiple scales at once – the links outward from the project into broader contexts as well as the spaces, devices and rituals that form intersections between landscape systems and everyday life.”

- Jen Lynch, “From Landscape to Commons”

PROJECT INTRODUCTION

Moss as Method: A Trans-scalar Guide to the Thesis

Project Ambitions

Thesis Strategies: An Overview

Strategy 01: Filmic Mapping

Strategy 02: Critical Mapping

Strategy 03: Imprints

Strategy 4: Making and Testing On-Site as Situated Practice

Strategy 5: Case Studies

Strategy 6: Quantifying Information and Questioning Quantification

An Introduction to the Peak District

The God-Trick Map

Blurring the Map

Dissolving the Picturesque Frame

Enclosing Landscape

Peak District Timeline: Ownership, Access + Conservation

Current Land Ownership

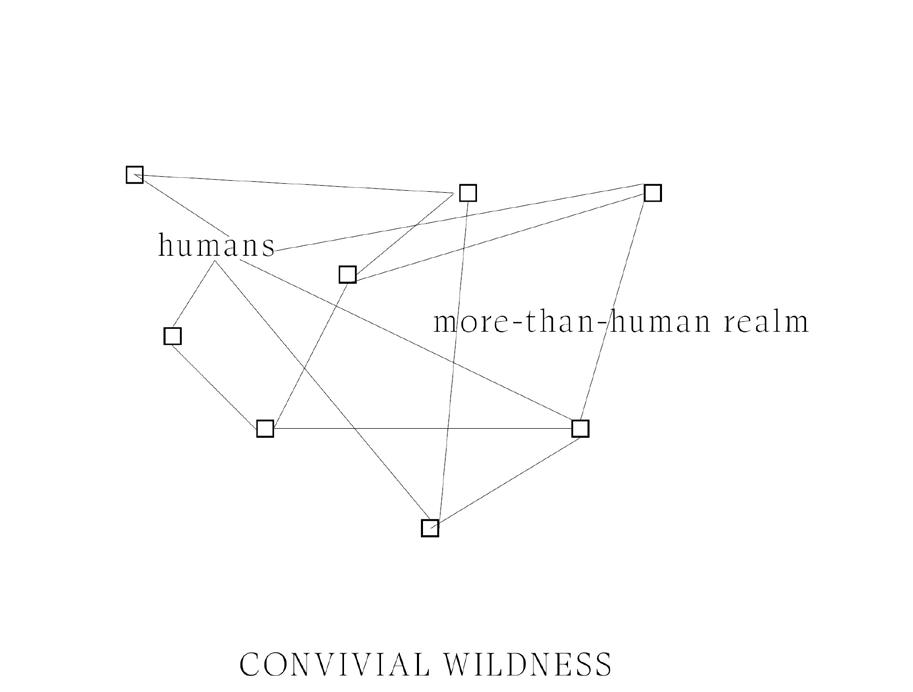

Thesis Terminology: What is “Convivial Wildness”?

Commoning as Experimental Geography Forms of Commoning

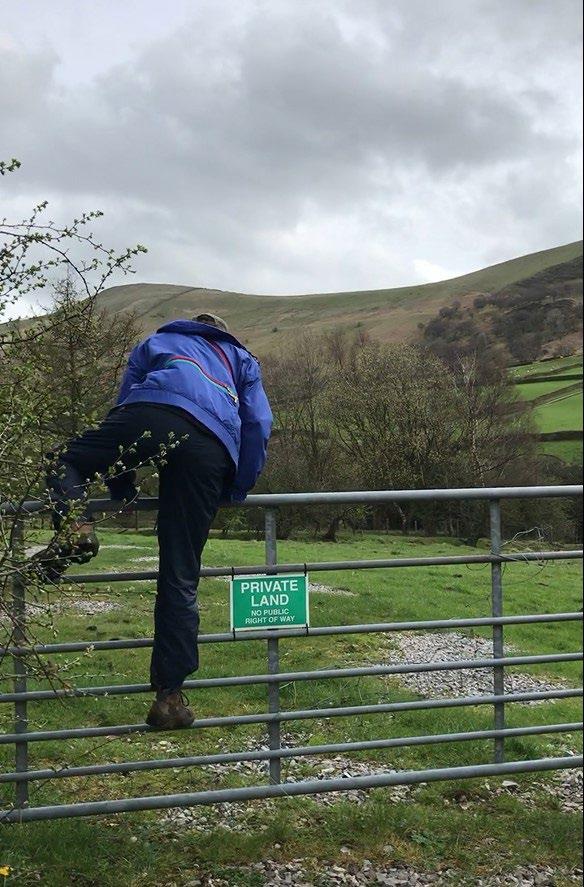

Trespass as a Commoning Catalyst

Shifting Stakeholders: Transient Commoners

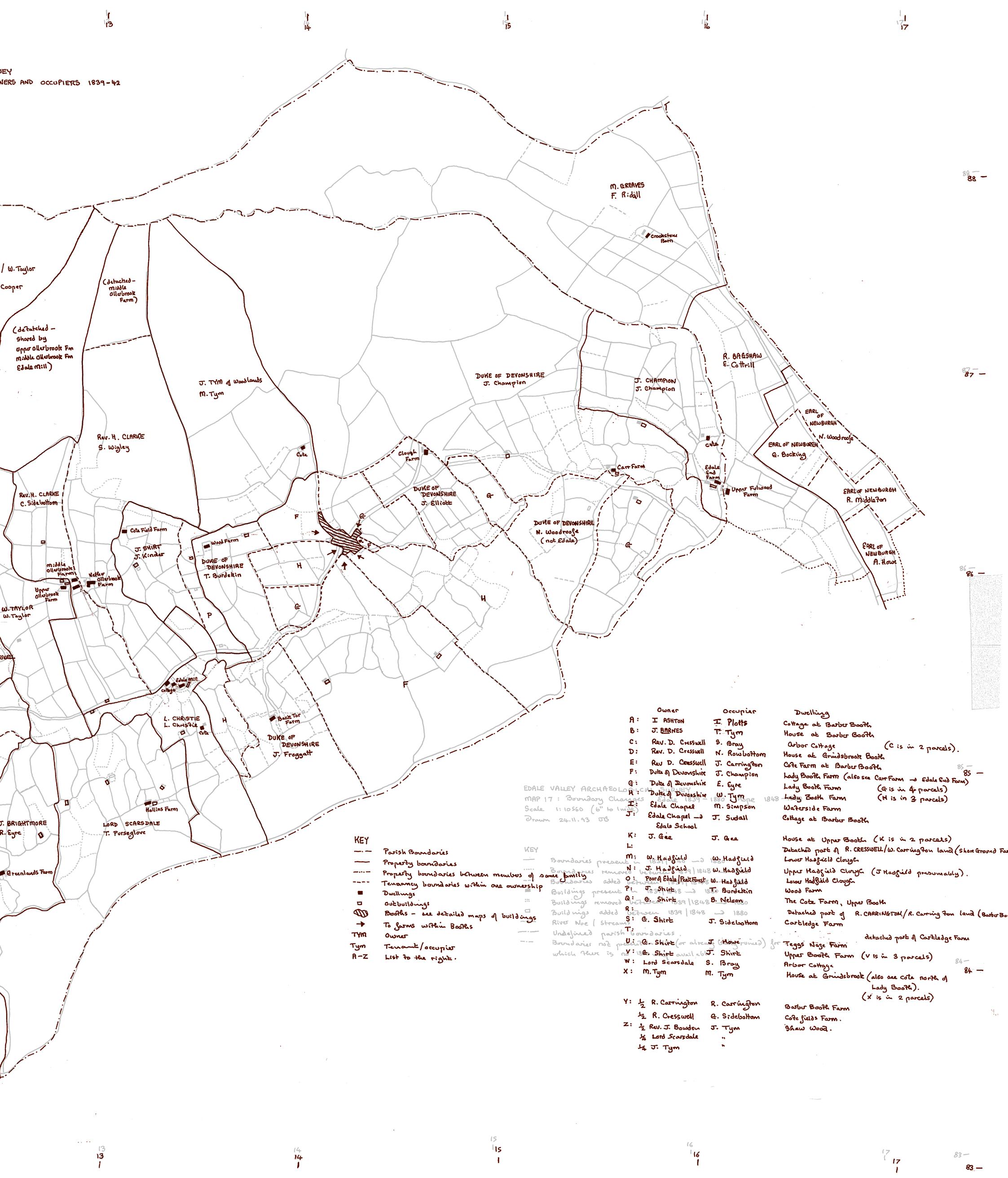

Region of Focus: Dark Peak Moorlands

Section through the Dark Peak

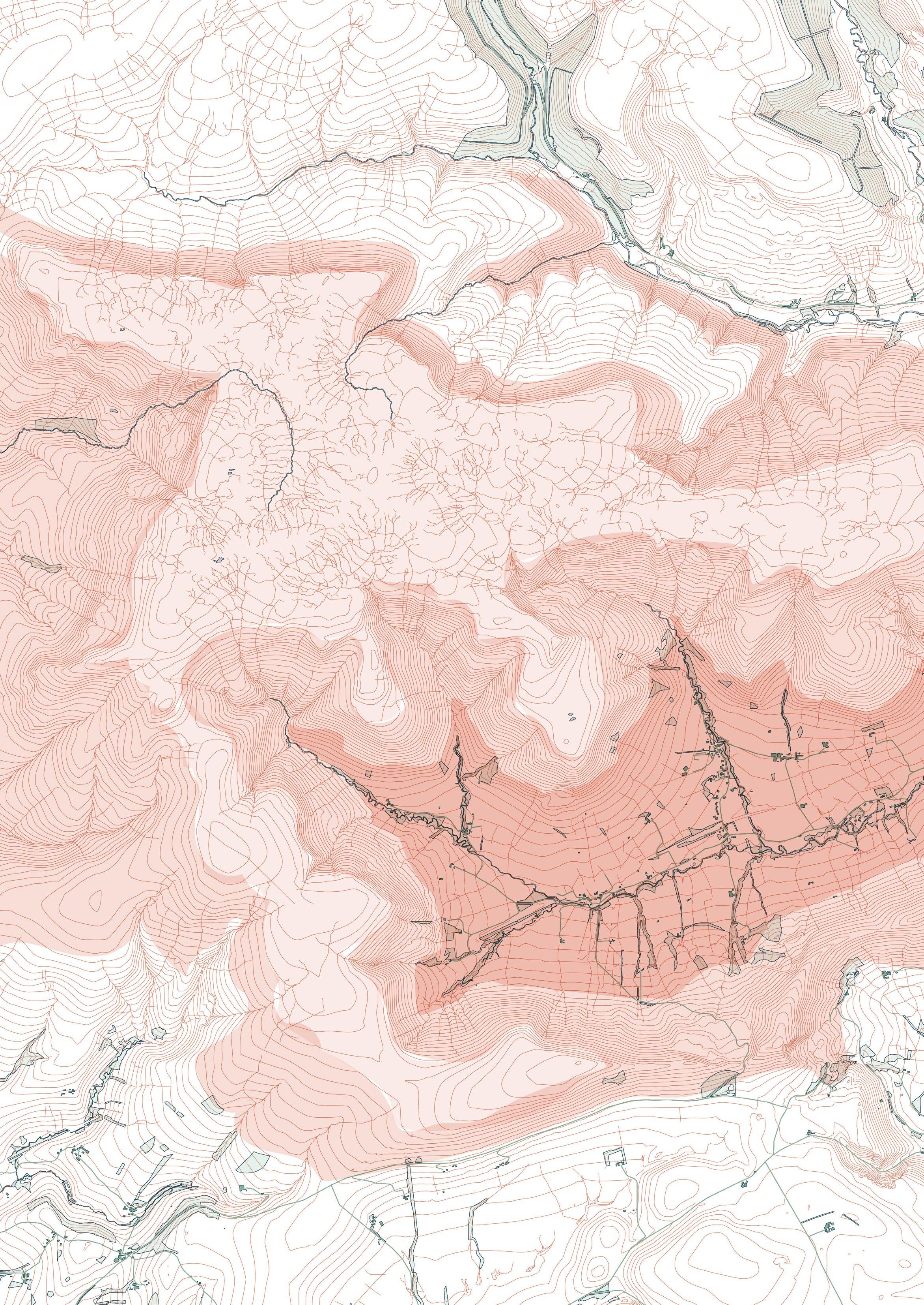

Fieldwork Site and Area of Focus: Edale Valley and Moors

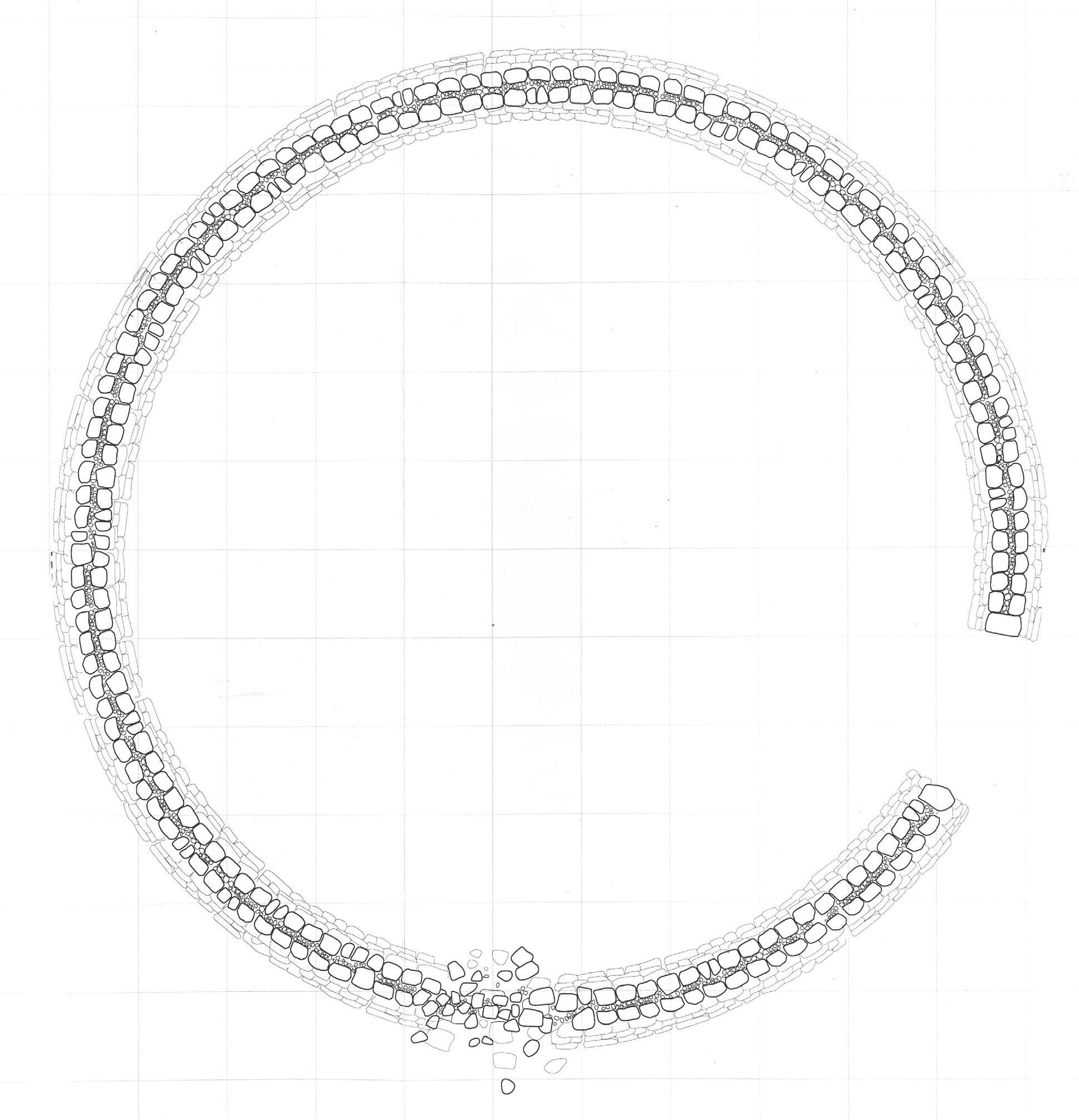

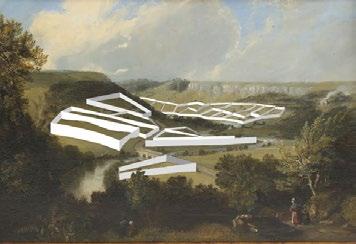

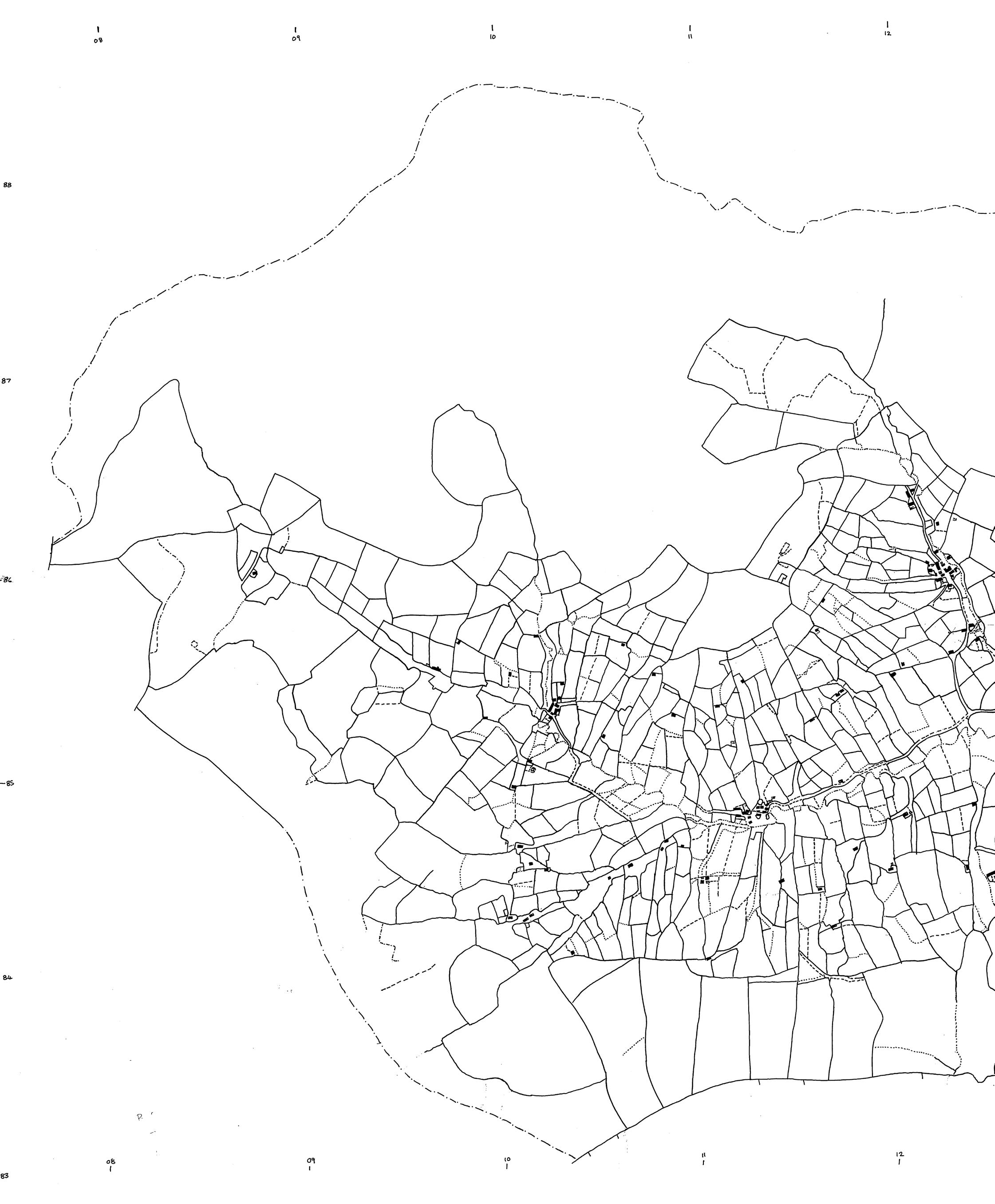

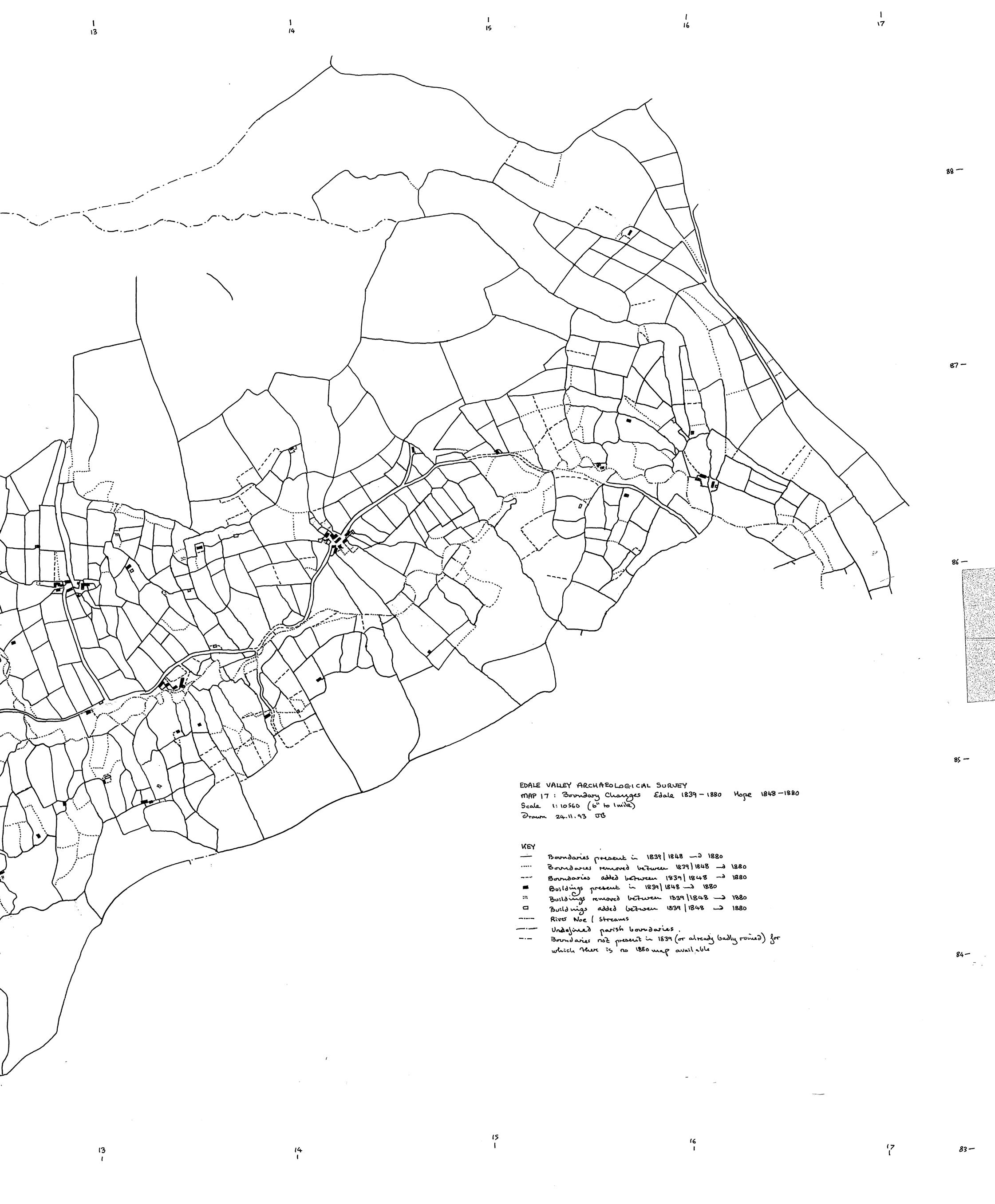

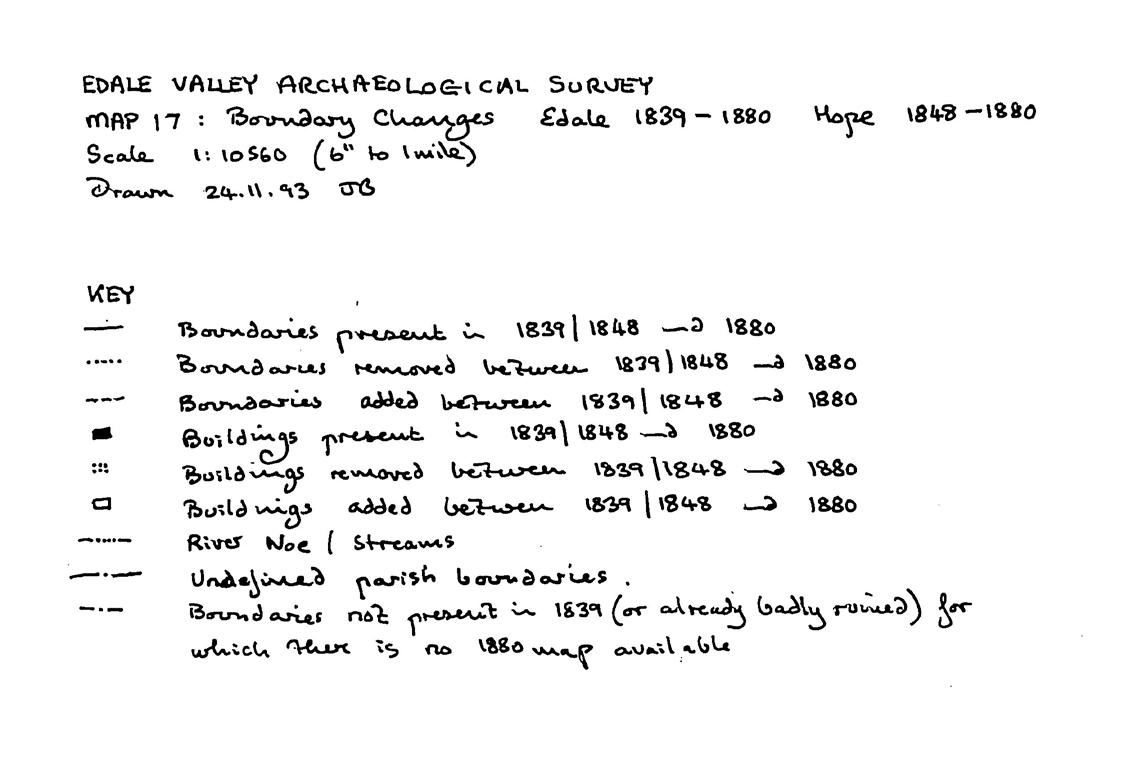

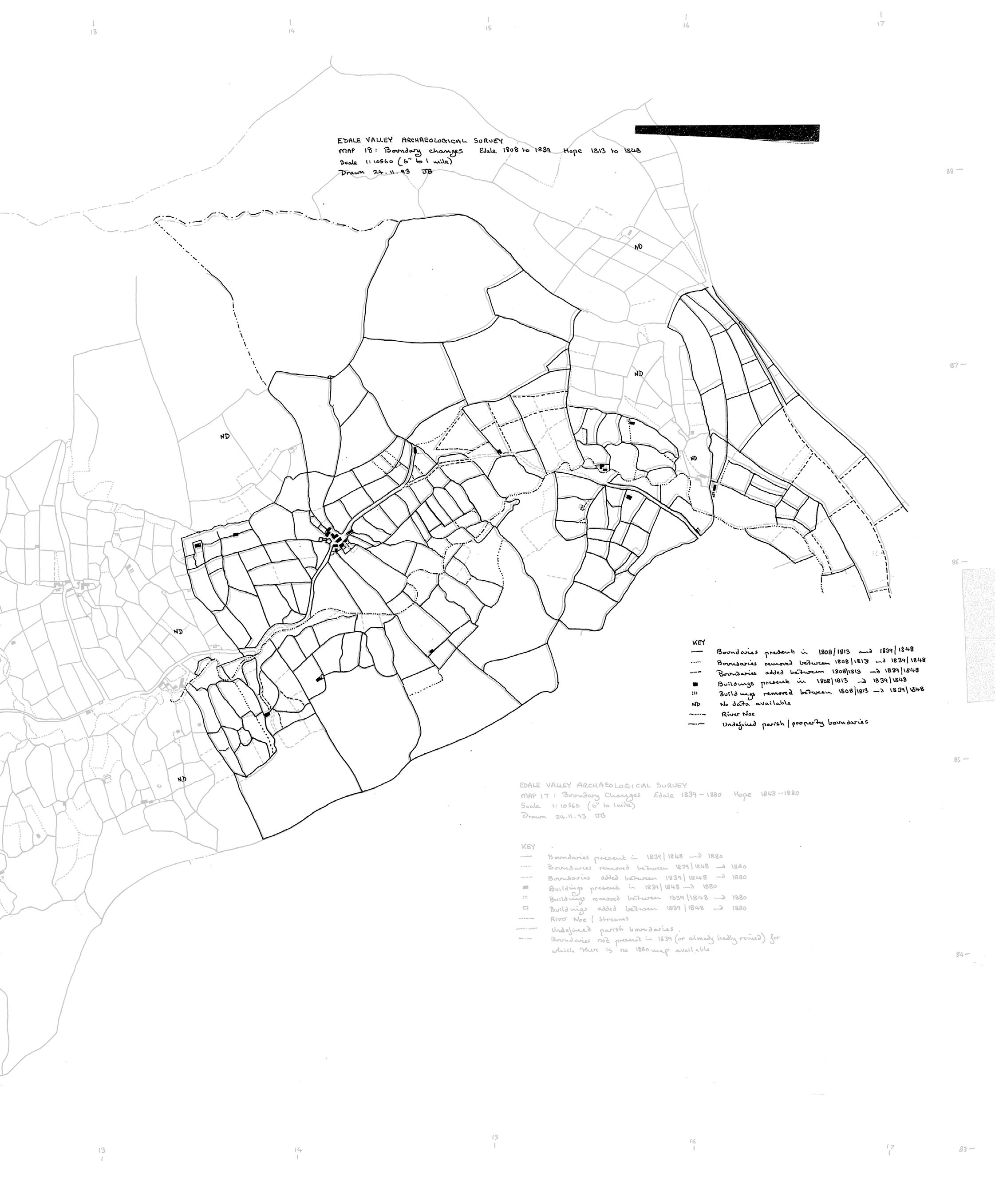

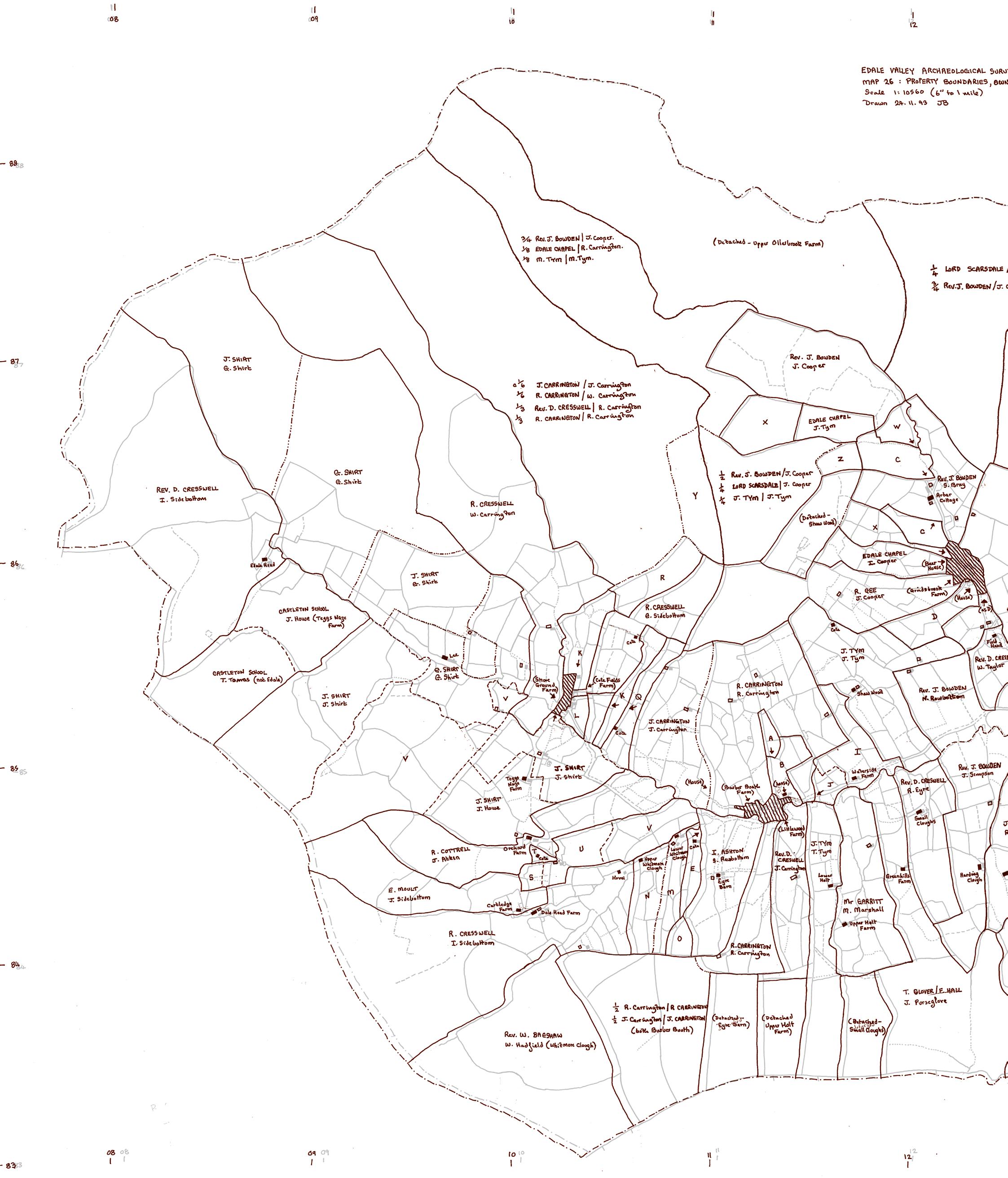

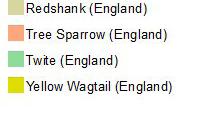

1993 Edale Boundary Walls Survey

Boundary Wall Emergence

1993 Edale Land Ownership Survey

Fieldwork

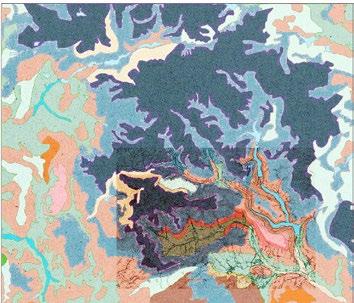

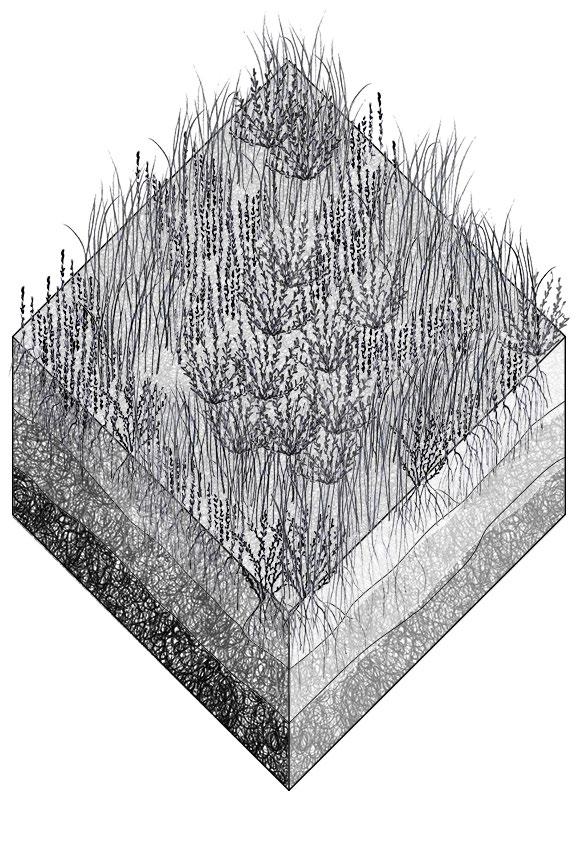

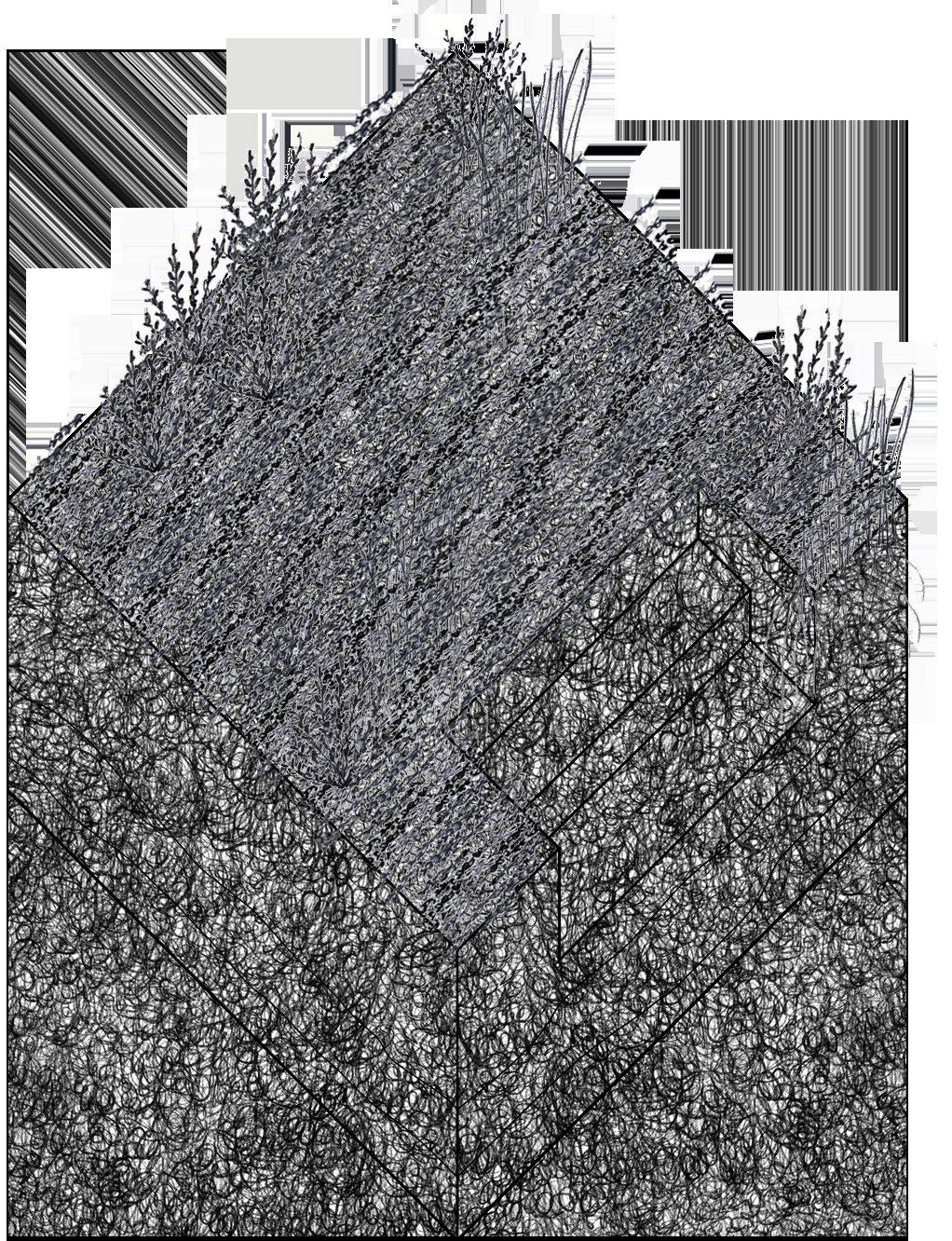

GEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY: INTERACTIONS BETWEEN SURFACE AND SUBSURFACE

Preamble: Becoming Geological

Dark Peak Geology

Dark Peak Ecology

Dark Peak Landforms and Lifeforms

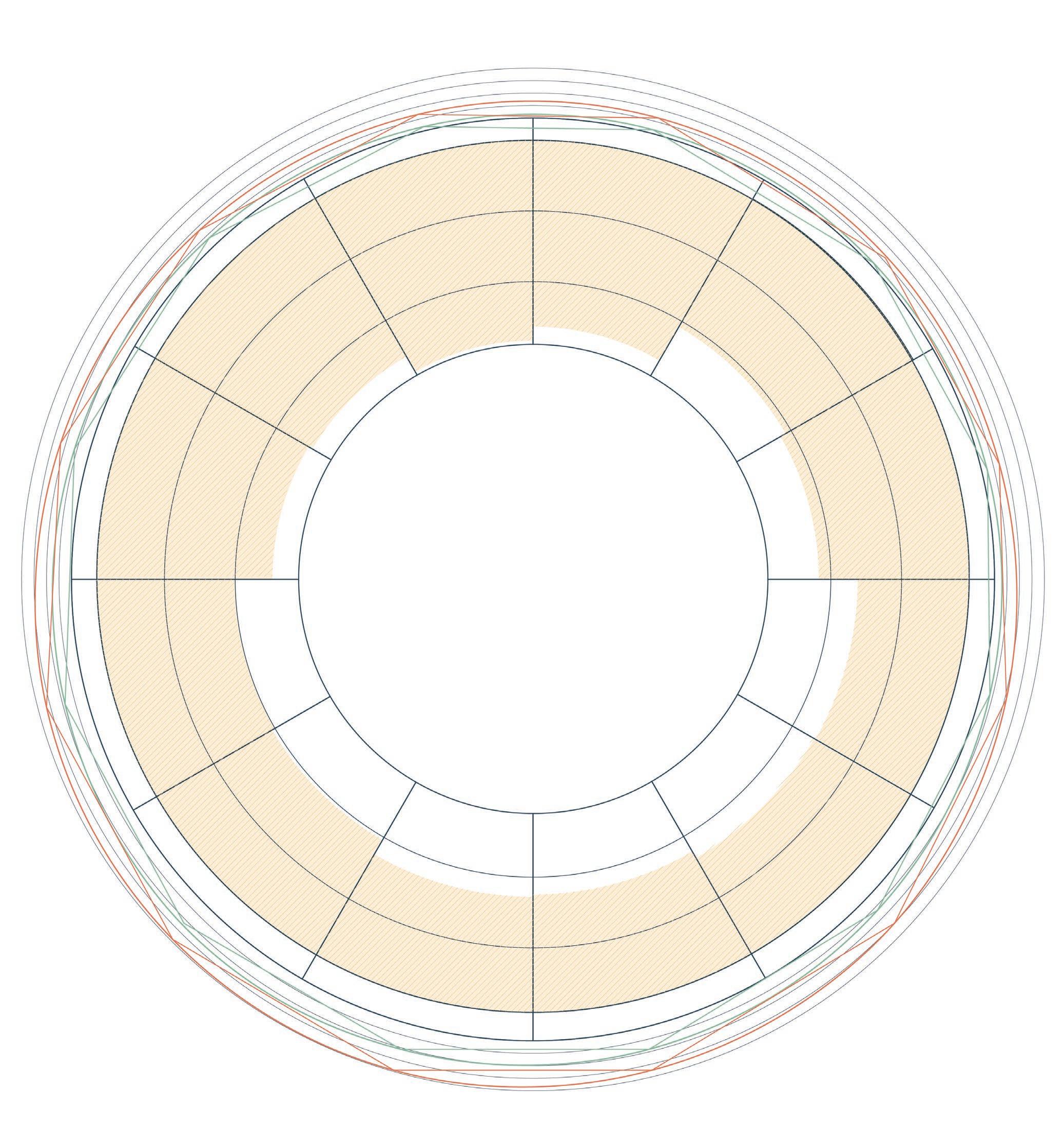

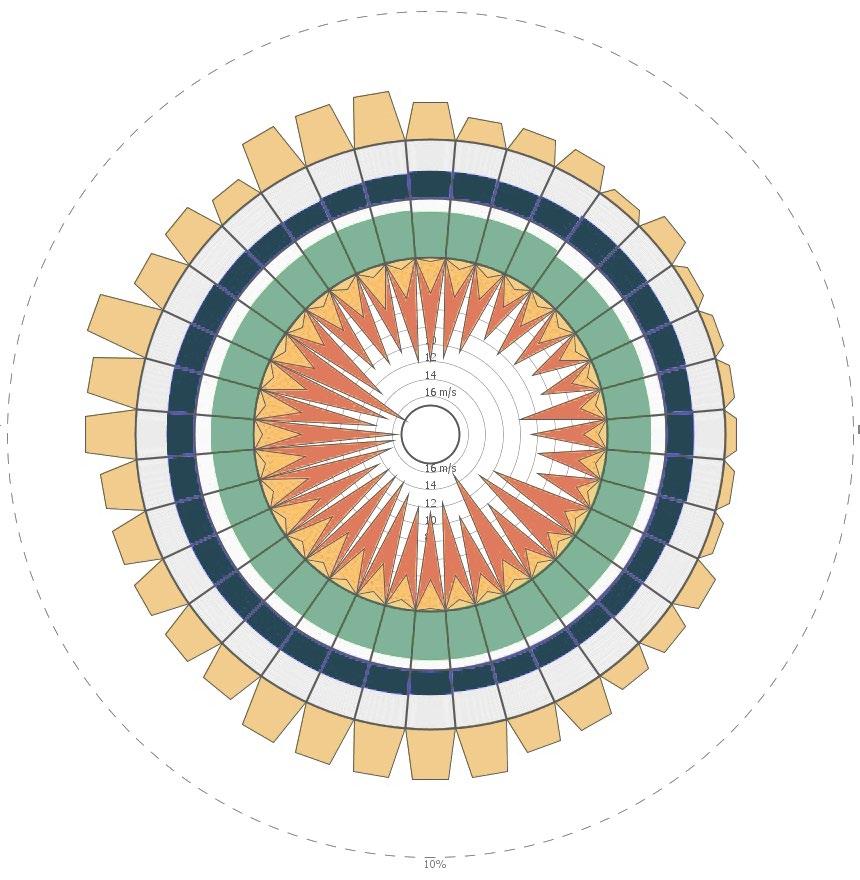

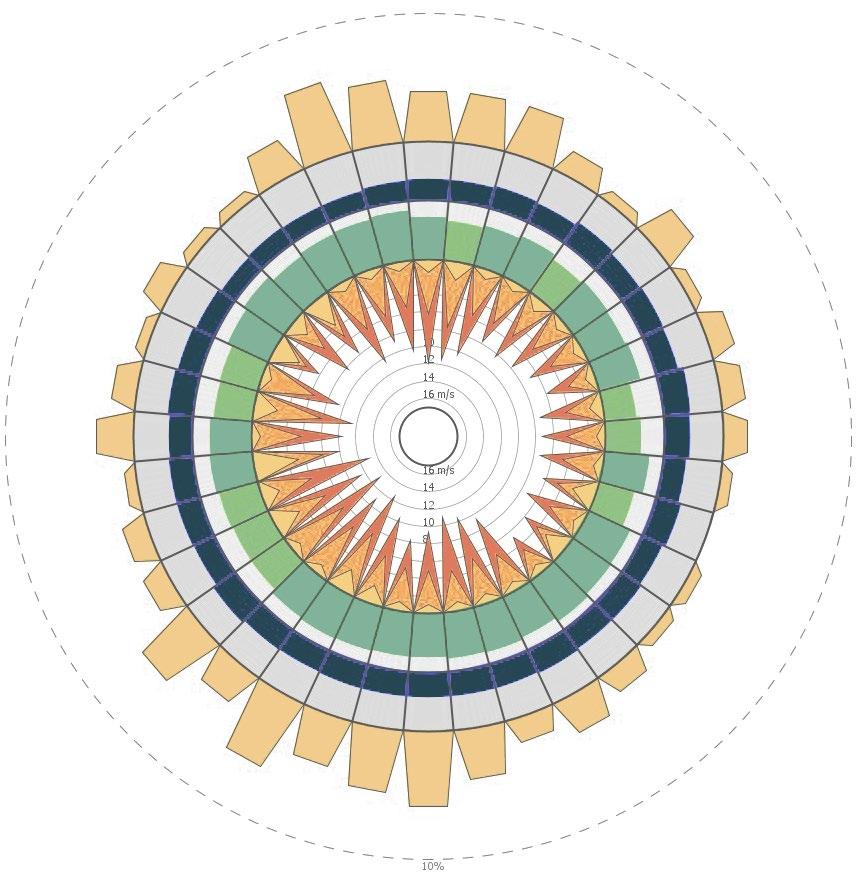

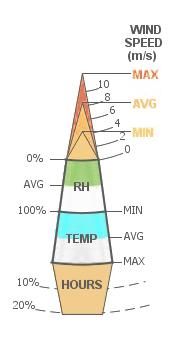

Landforms as Windforms

Moorland Peat Ecologies

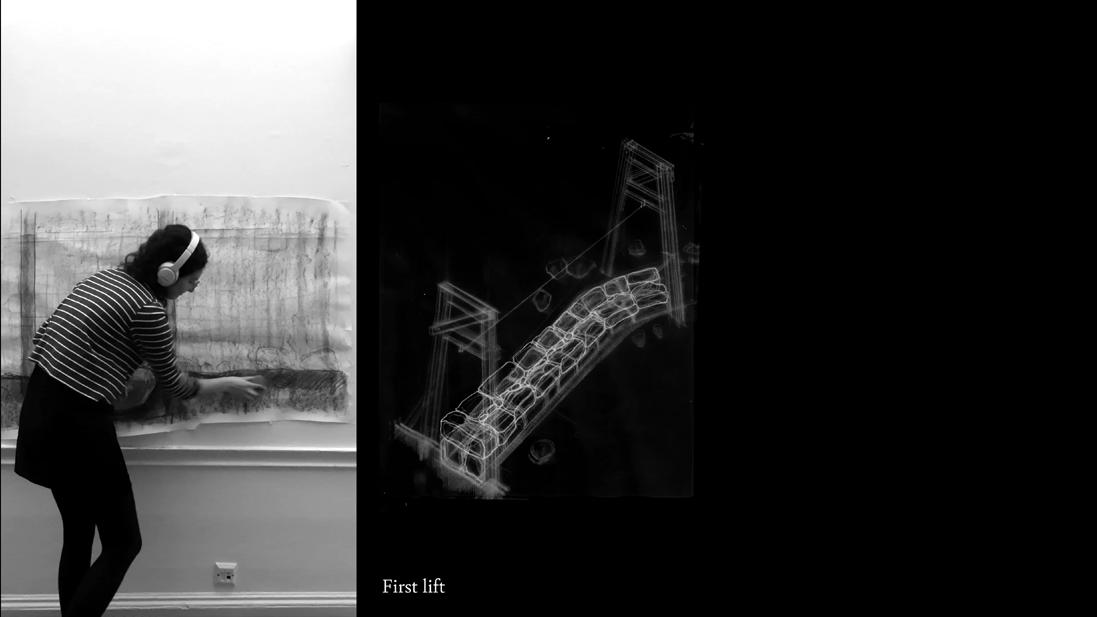

DRYSTONE CONSTRUCTION

Design Question

Case Studies + Context Analysis

Drystone Analysis

Site Criteria and Analysis

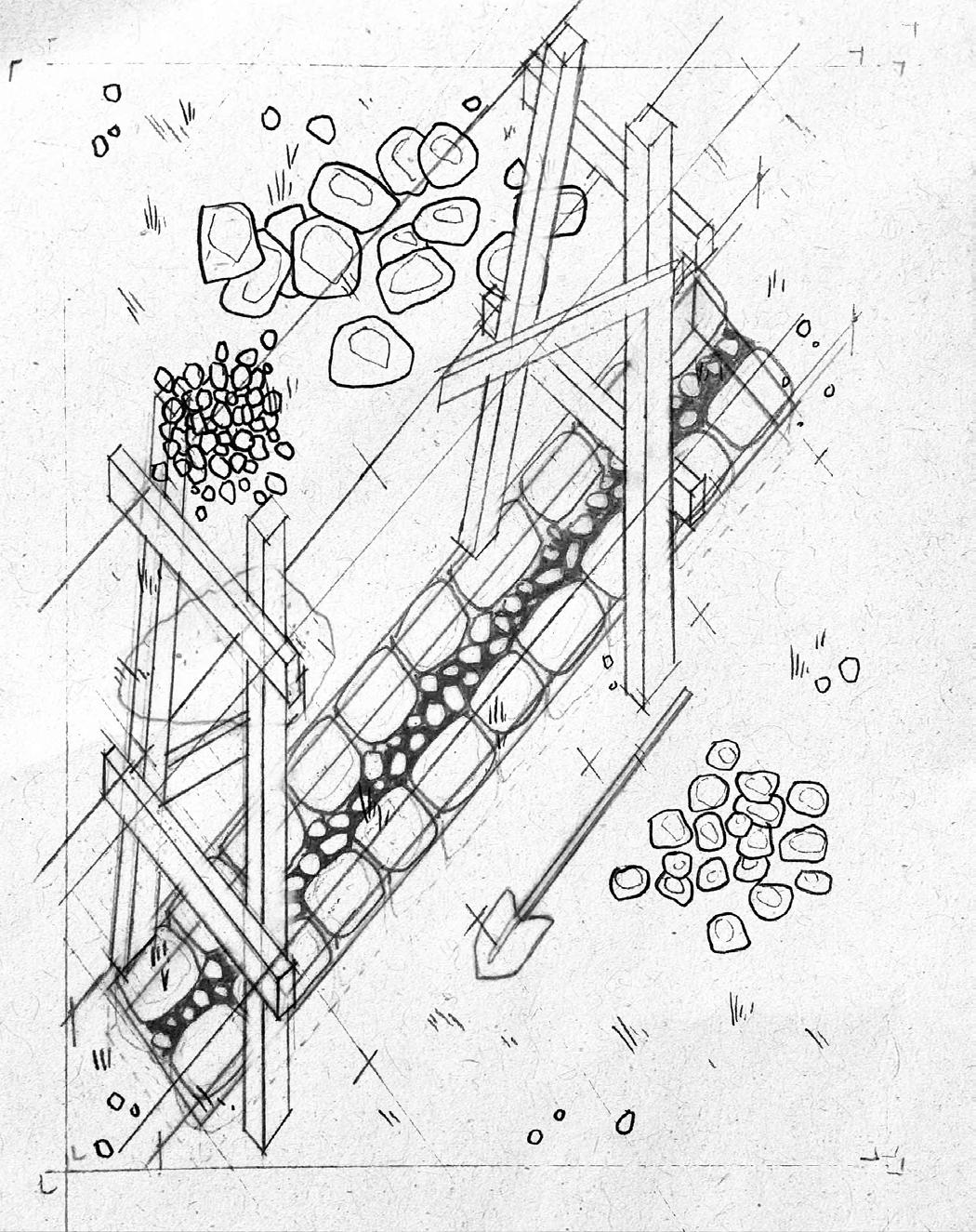

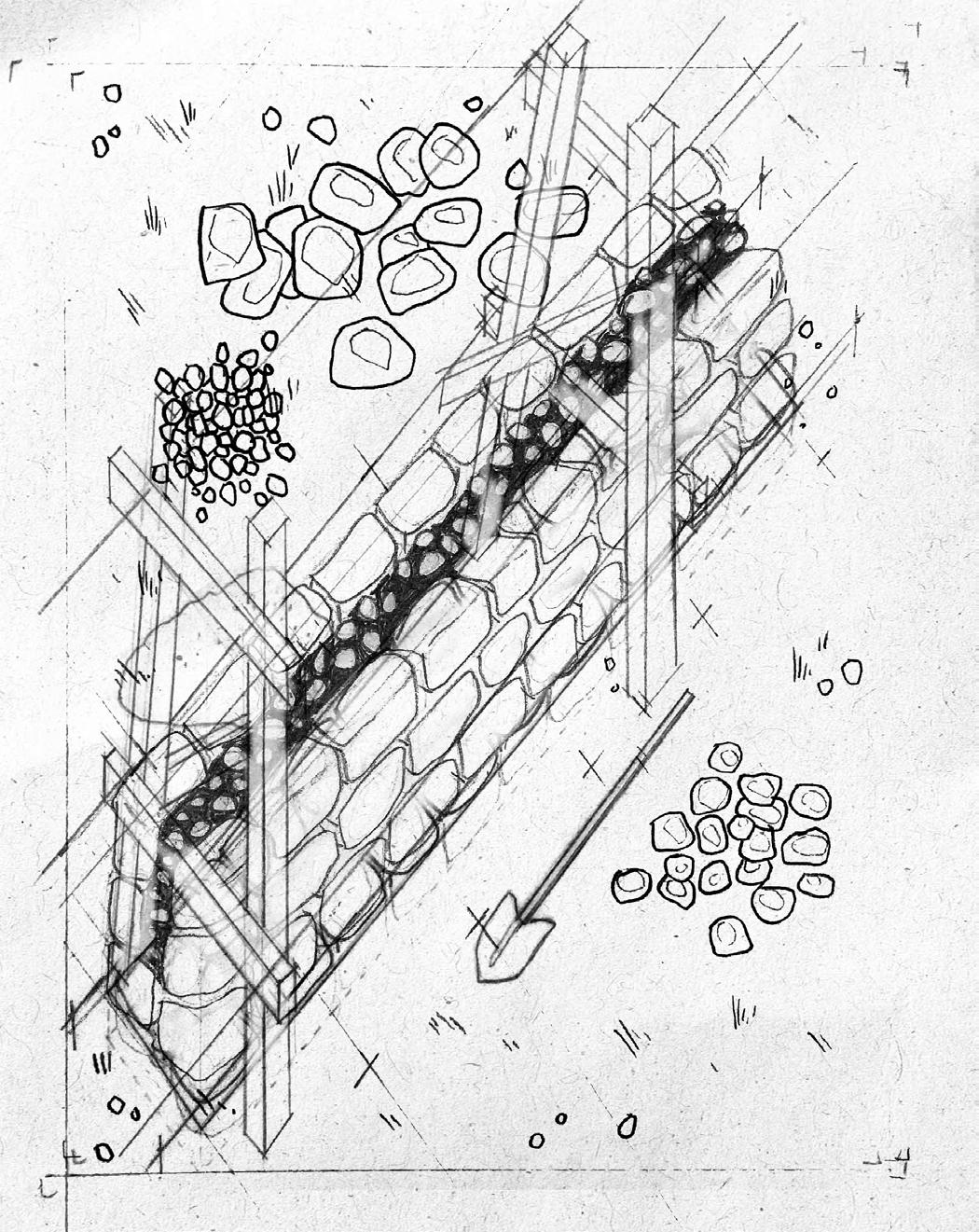

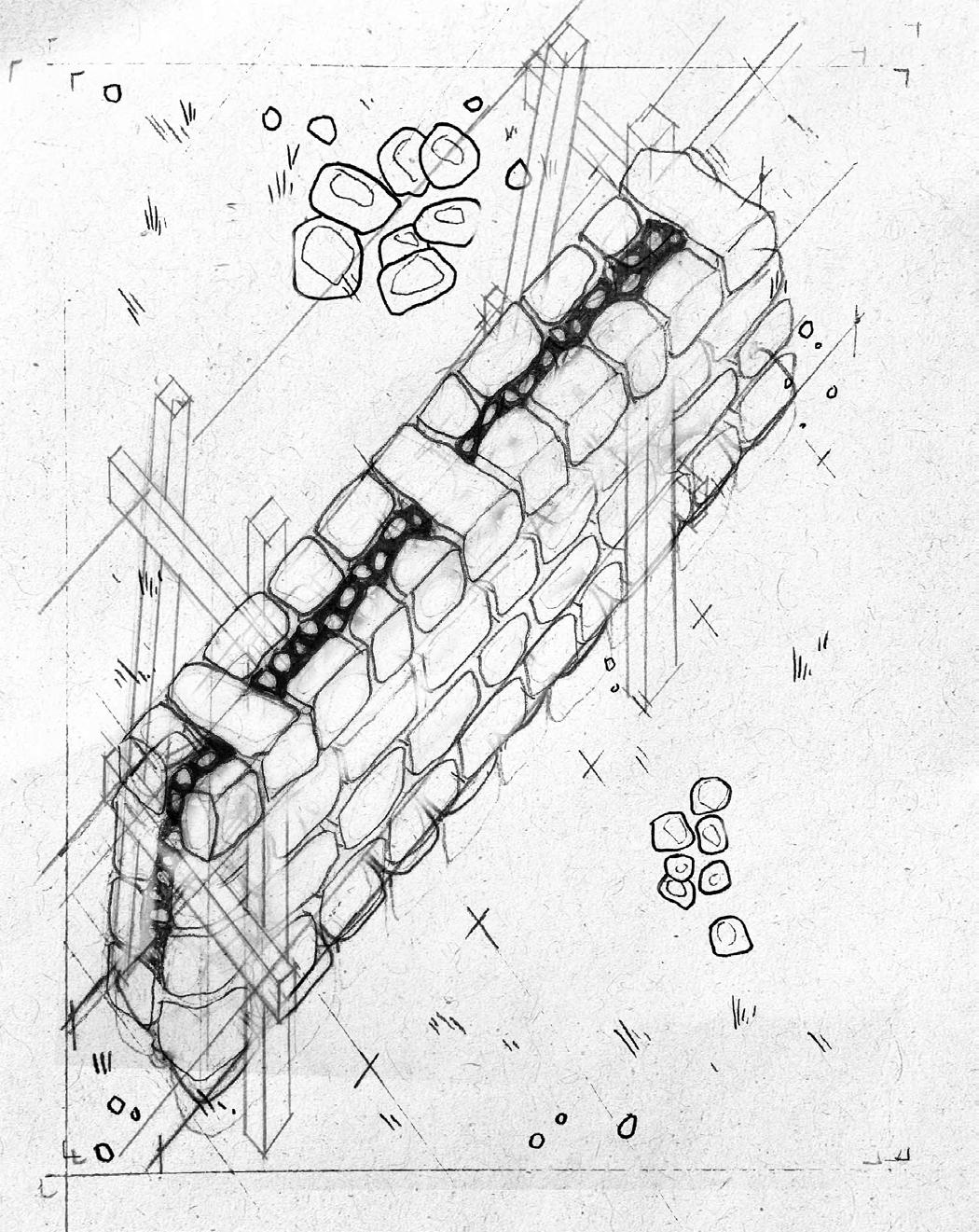

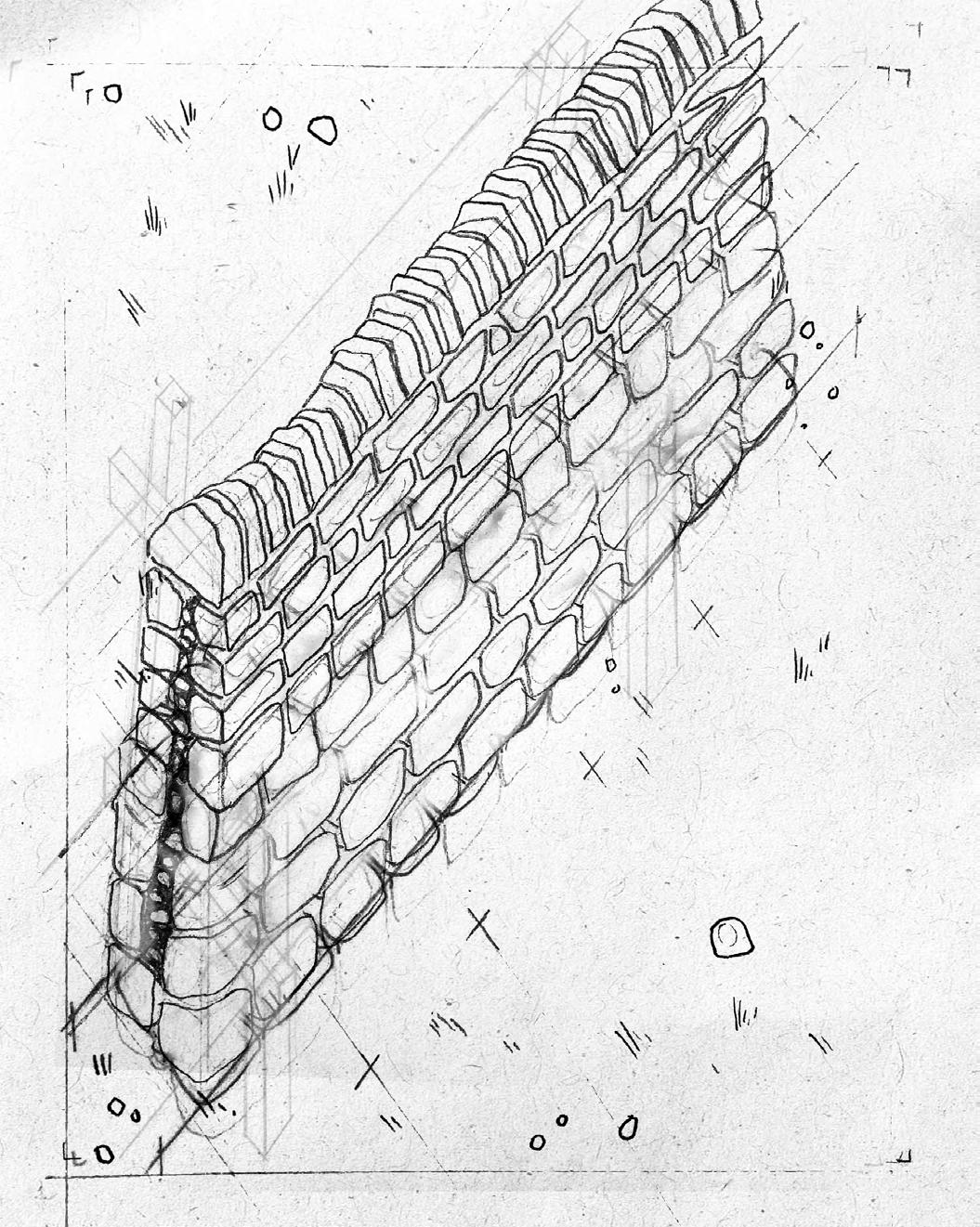

Drystone Construction Tests

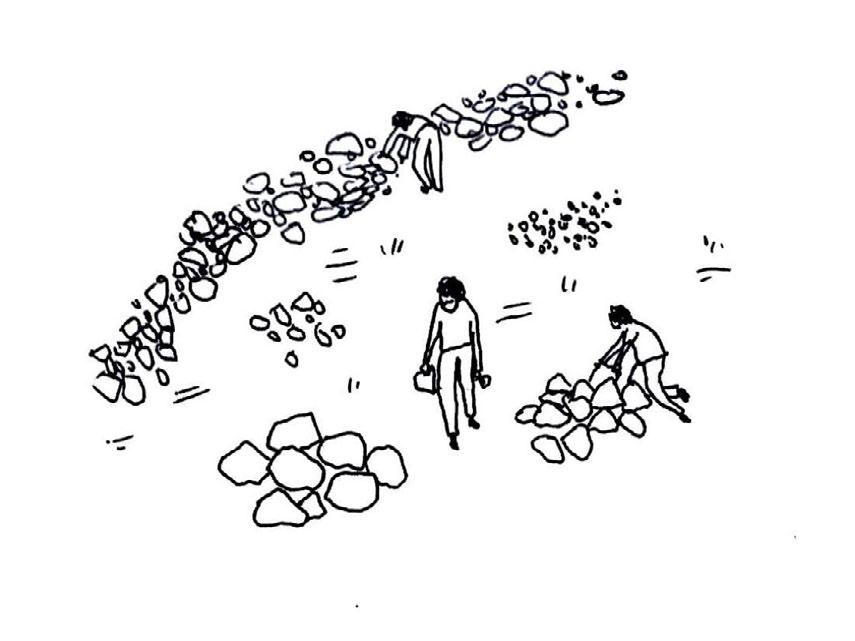

Constructing Drystone

Design Scenario

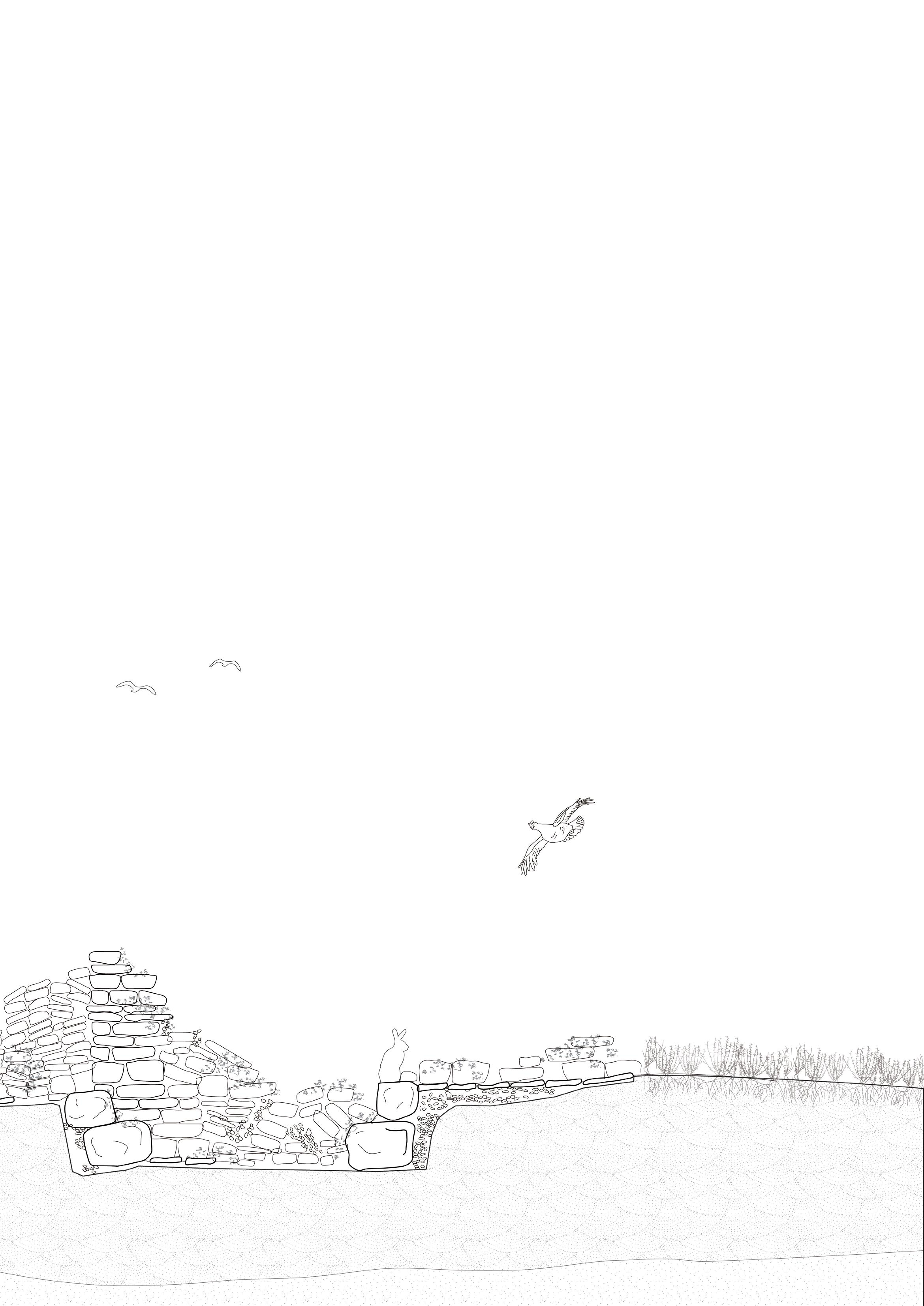

Drystone as . . . A collective design and construction process

Drystone as . . . A continual practice of repair and maintenance

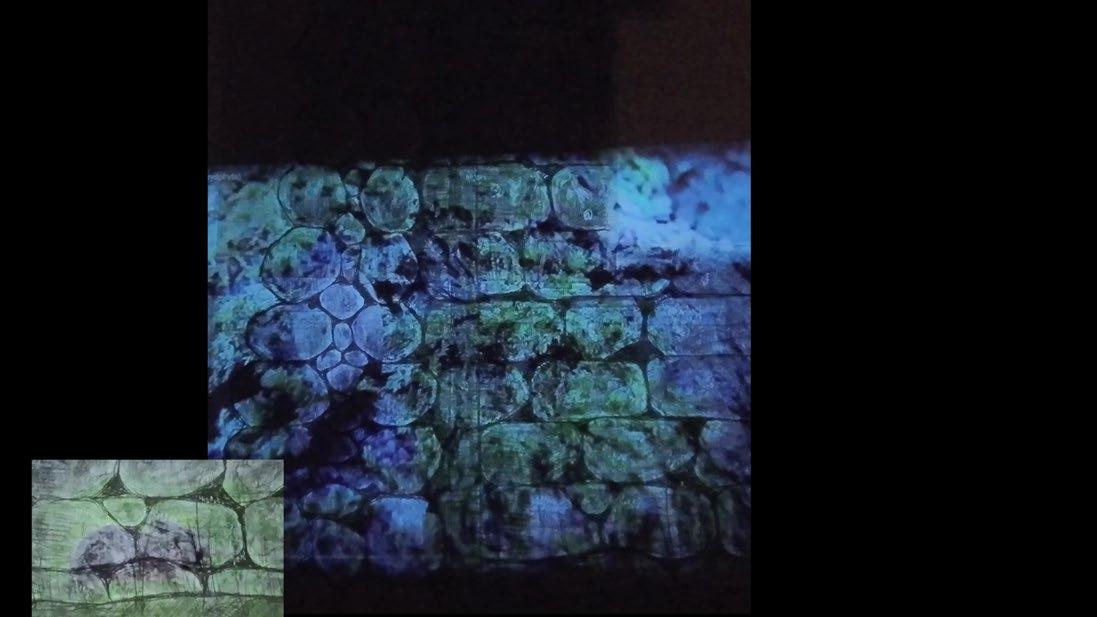

Drystone as . . . A site of multispecies interaction

CONVIVIAL WILDNESS IN DRYSTONE FIELD STATIONS

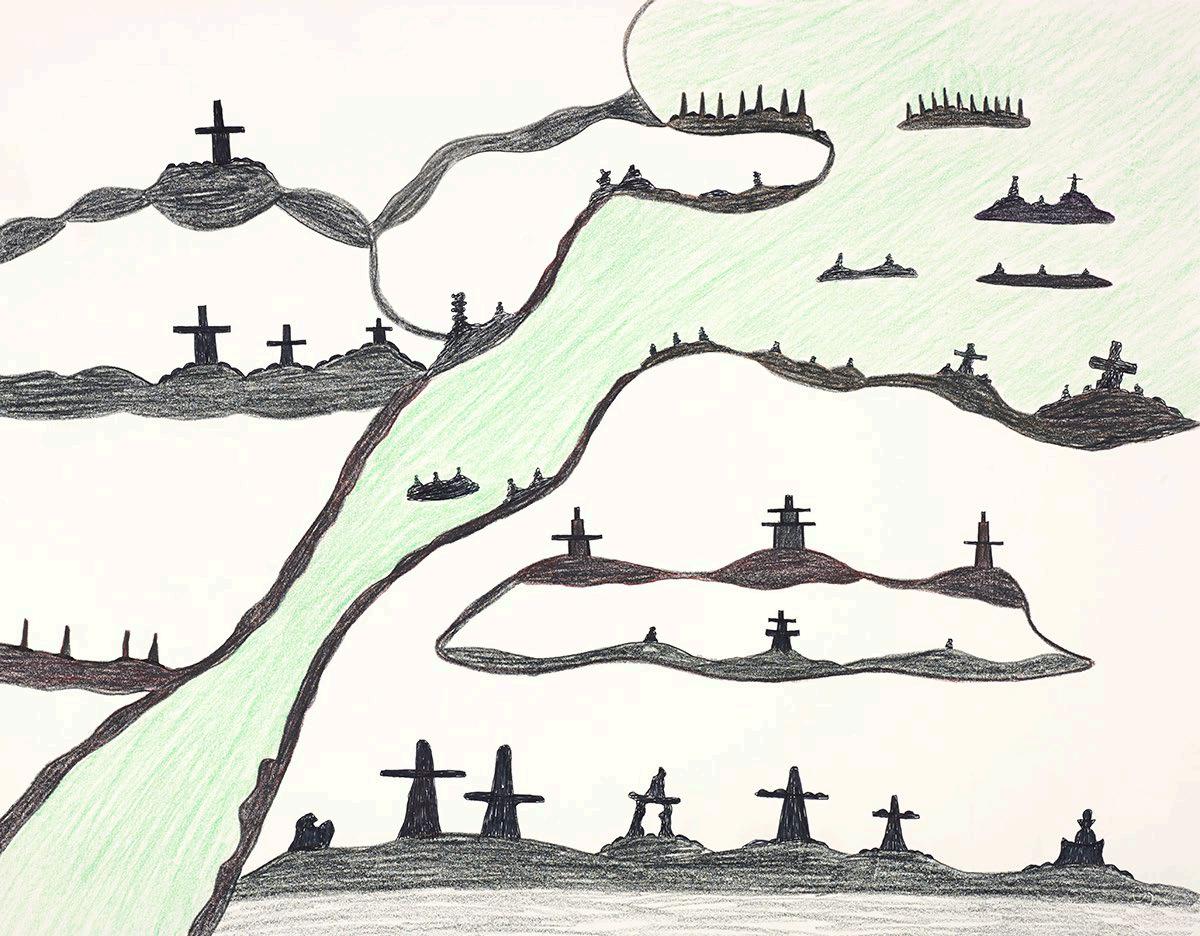

Drystone Navigation

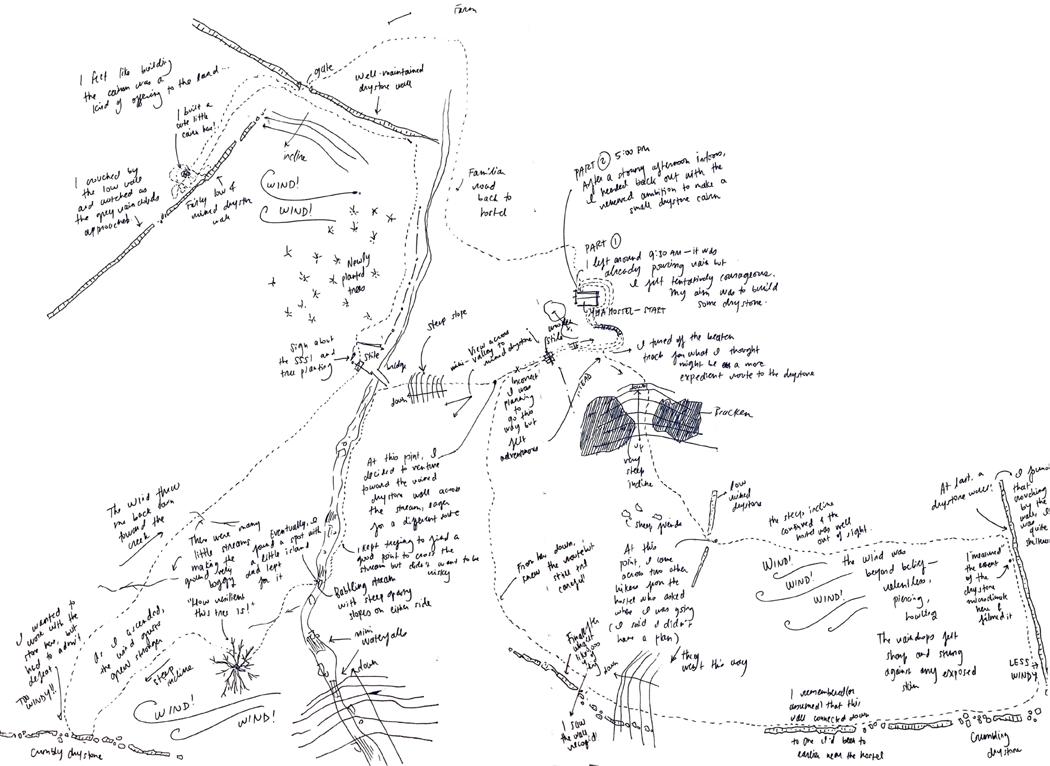

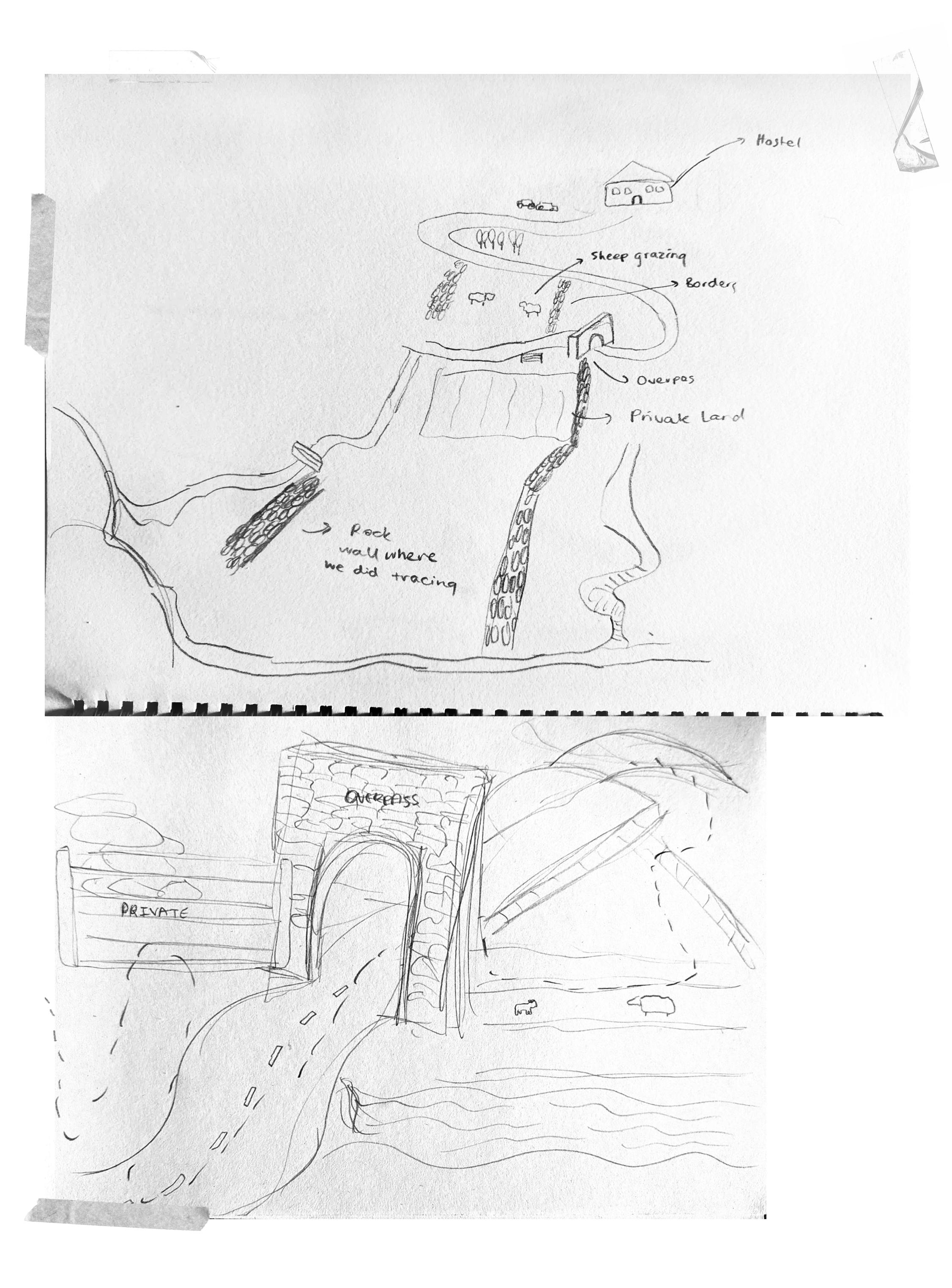

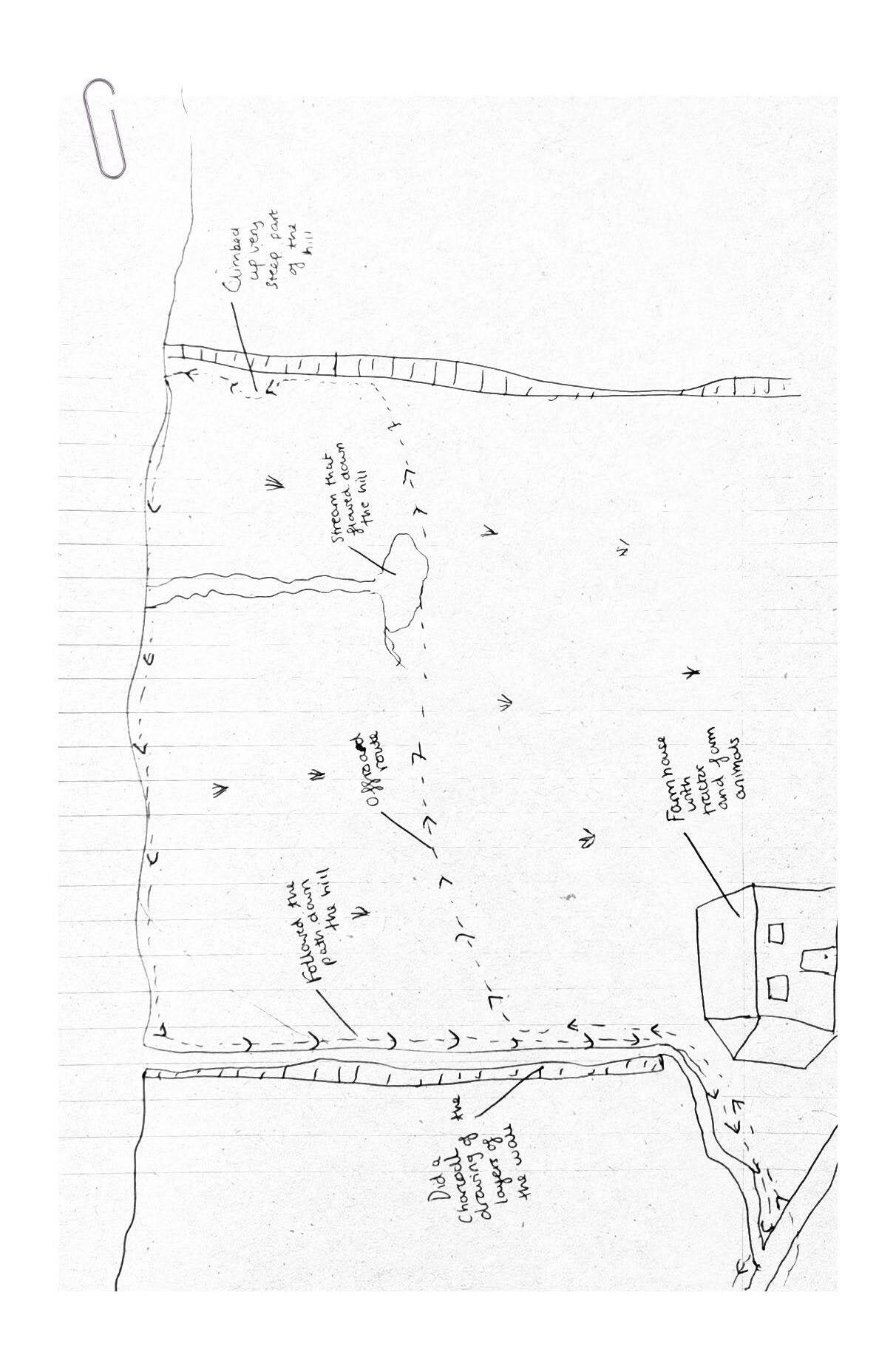

Navigating drystone by . . . Walking as mapping

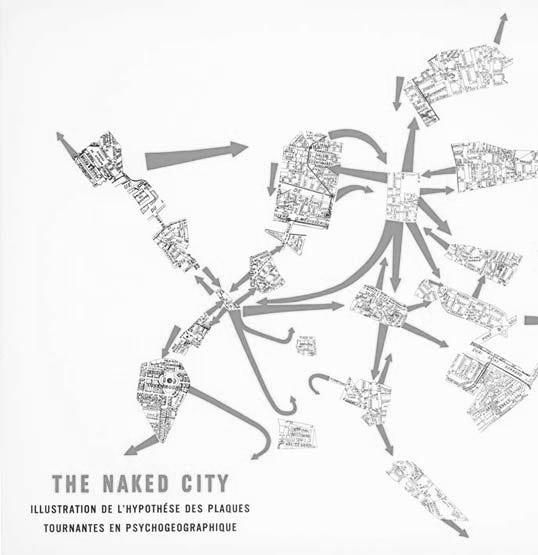

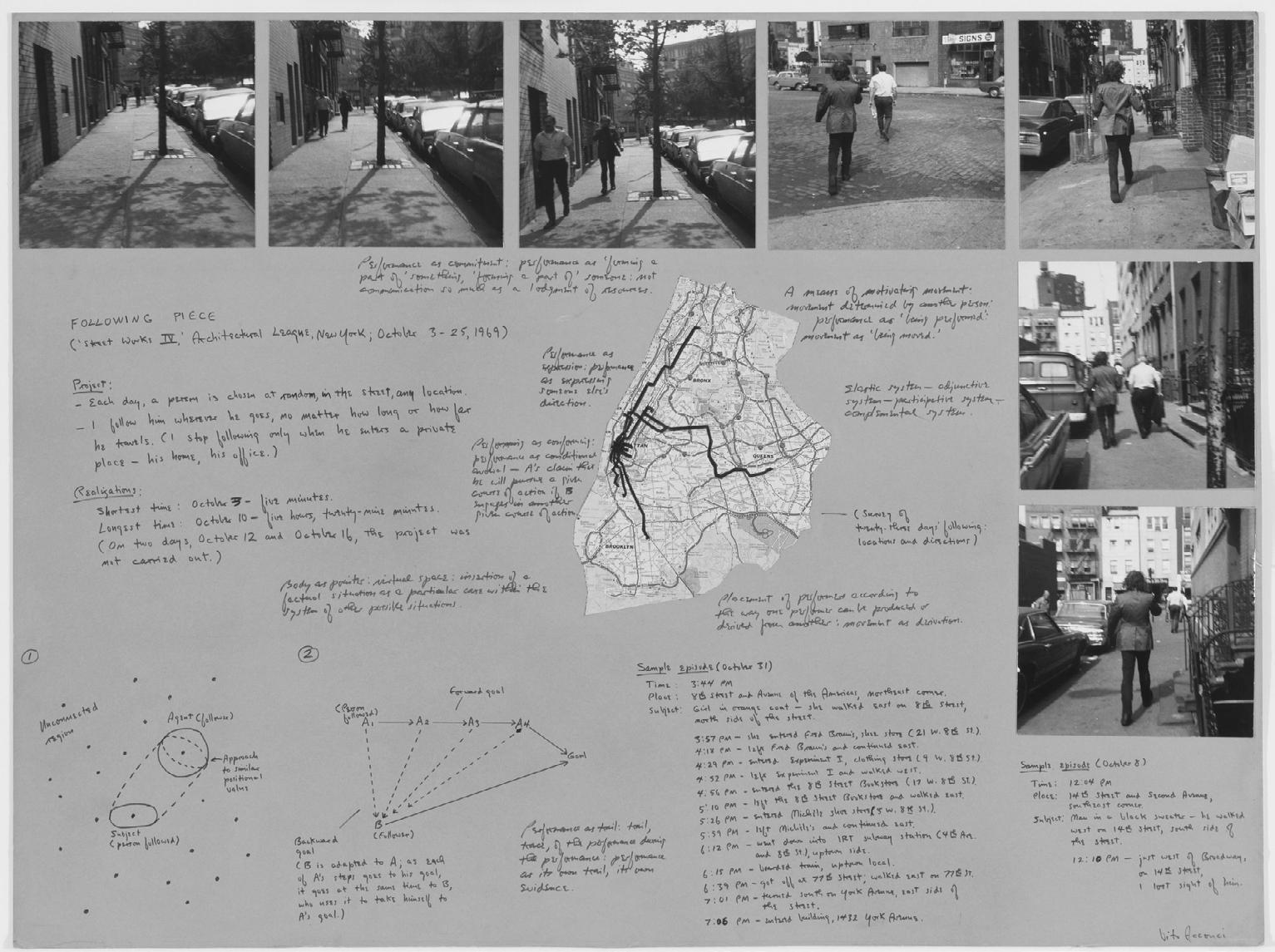

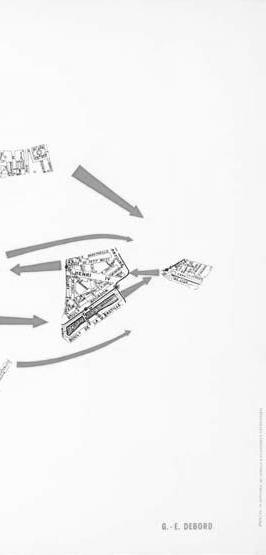

Walking as Mapping: Case Studies

Collective Walking as Commoning Practice

Navigating drystone by . . . Imprint-mapping

Drystone as Ecological Repair

Bibliography

Image credits

The thesis has three sections, each using a trans-scalar method to examine aspects of drystone, from the Dark Peak’s geology to the practicalities of construction to its potential to host multispecies inhabitation and invite commoning practices.

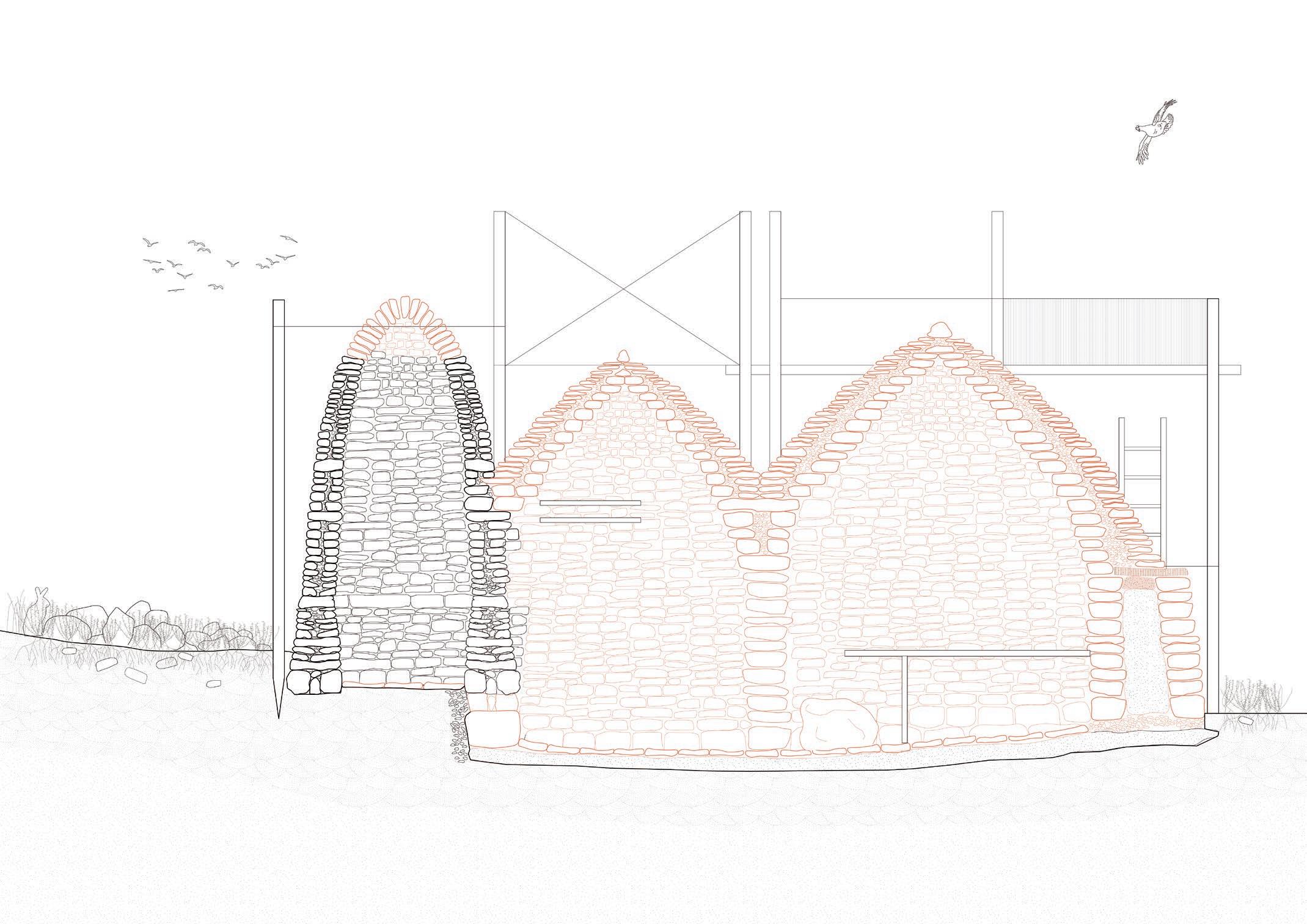

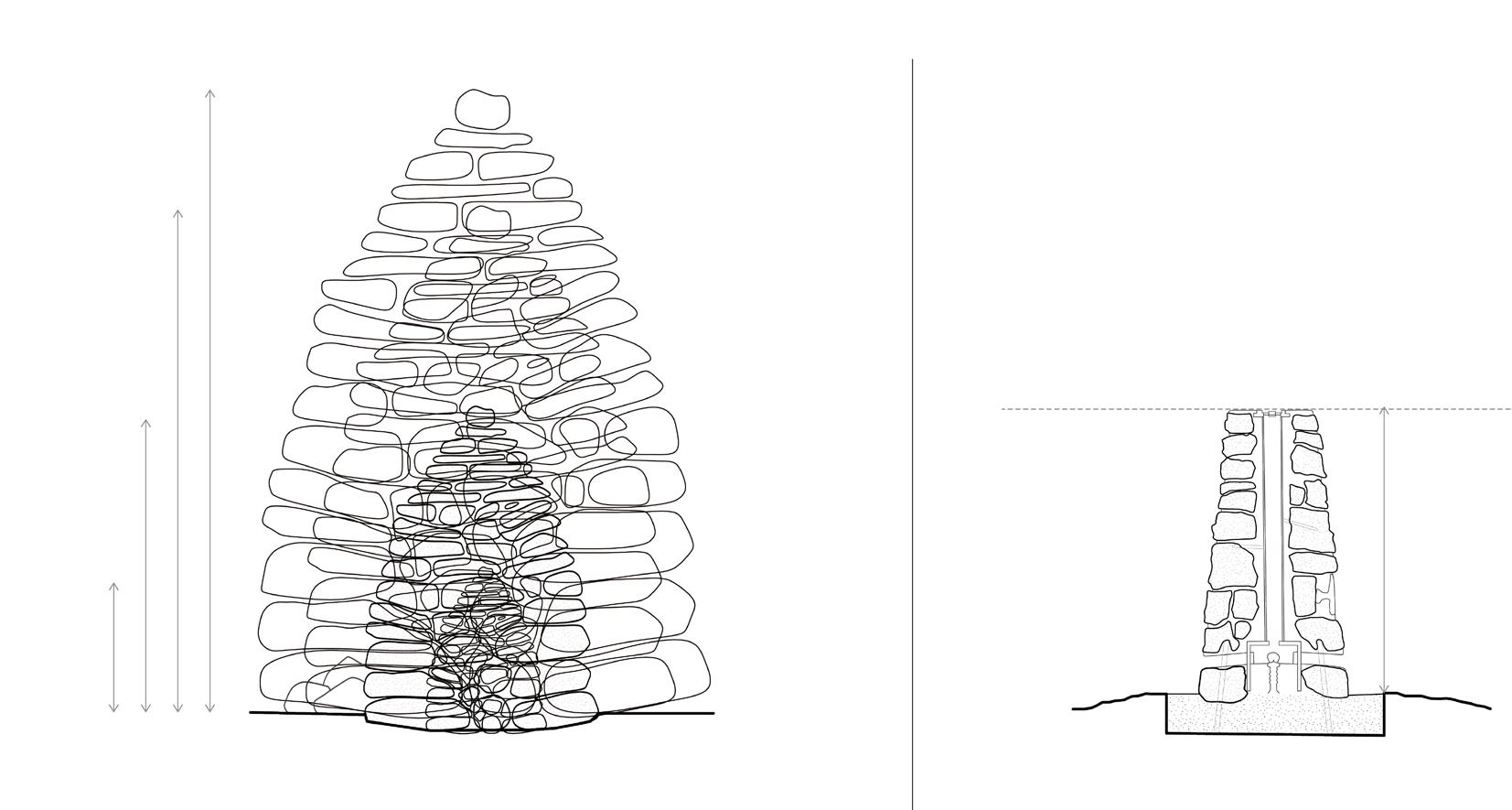

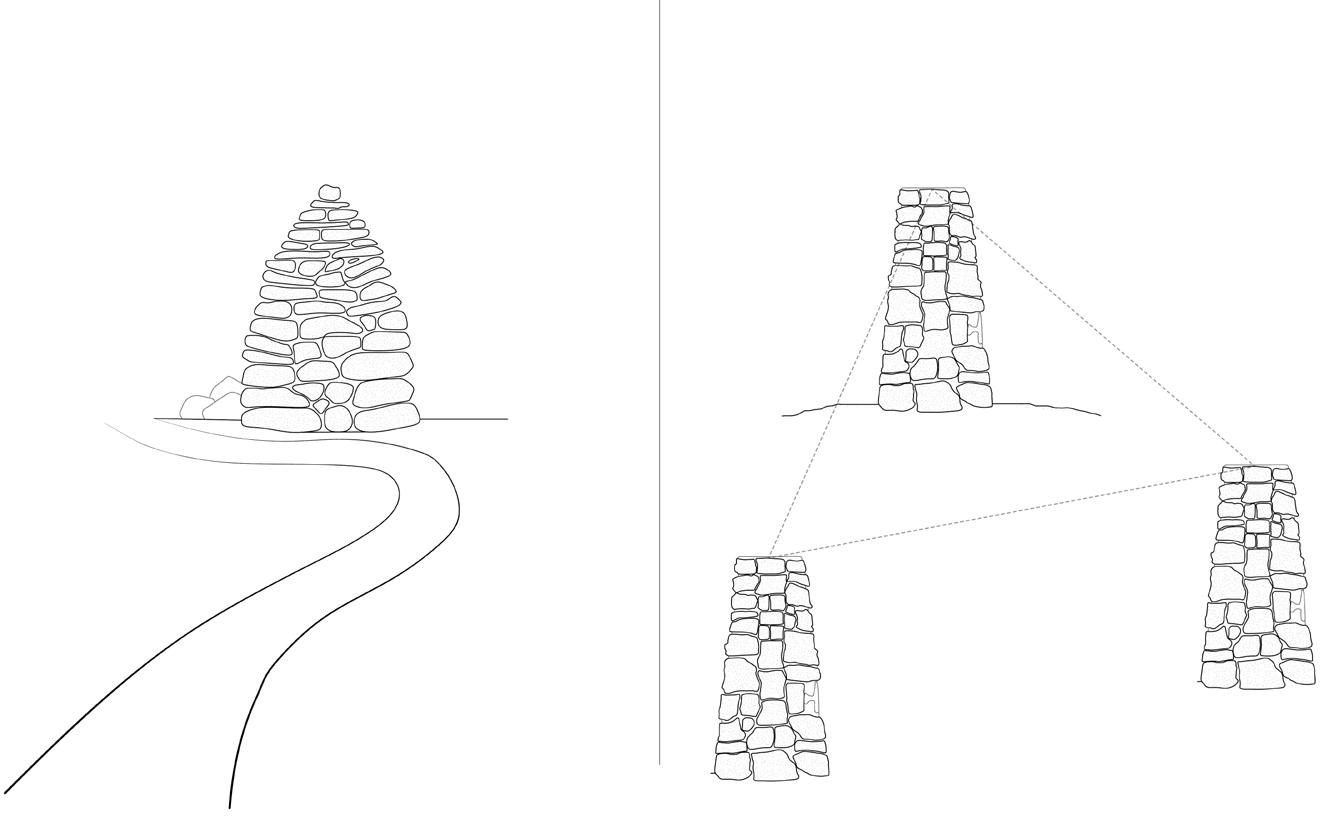

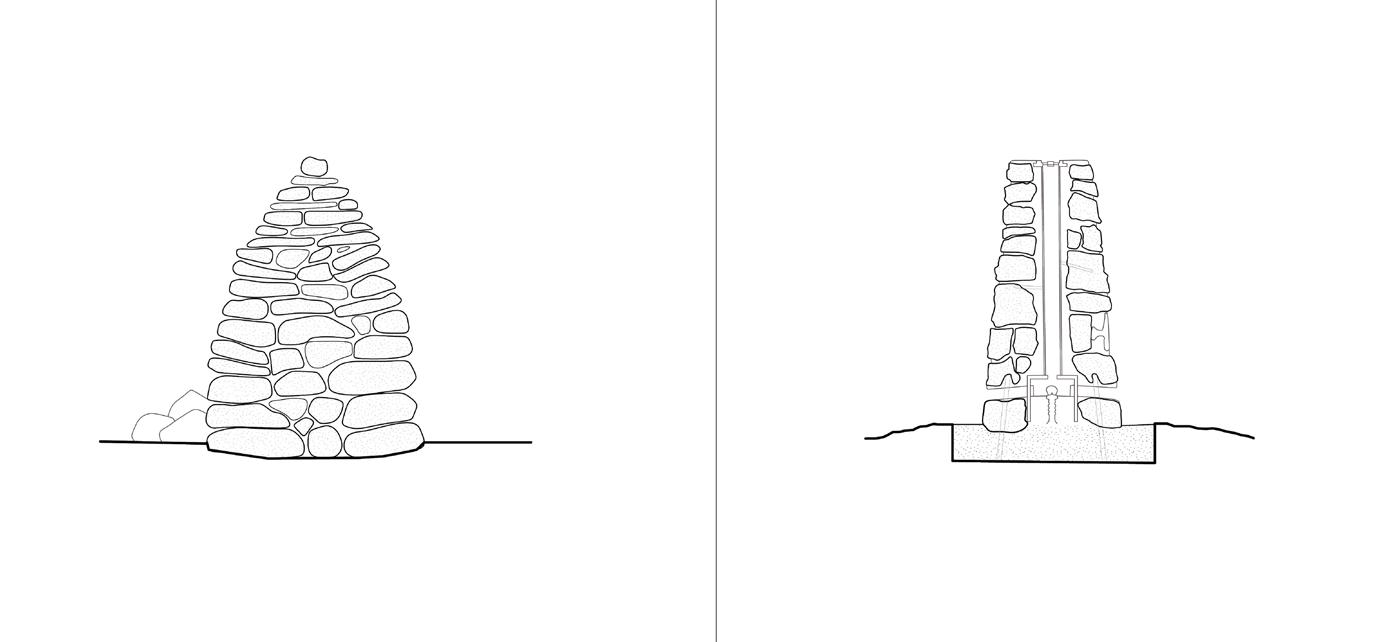

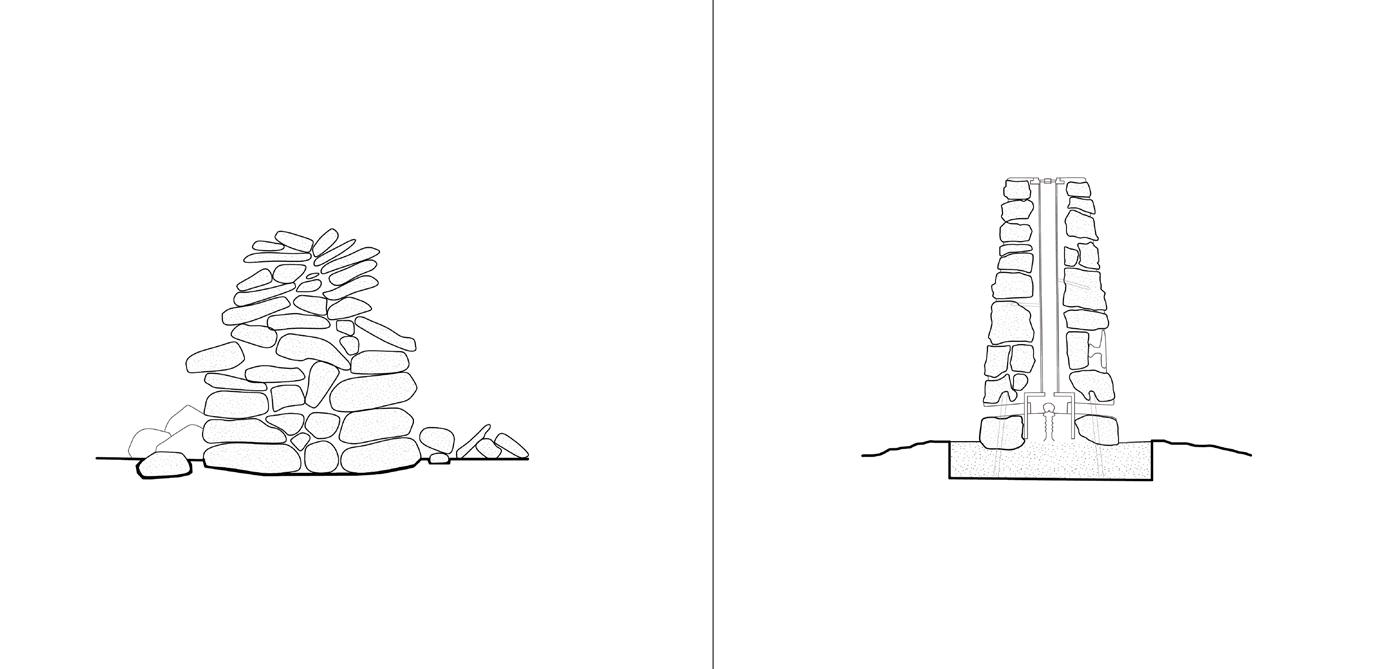

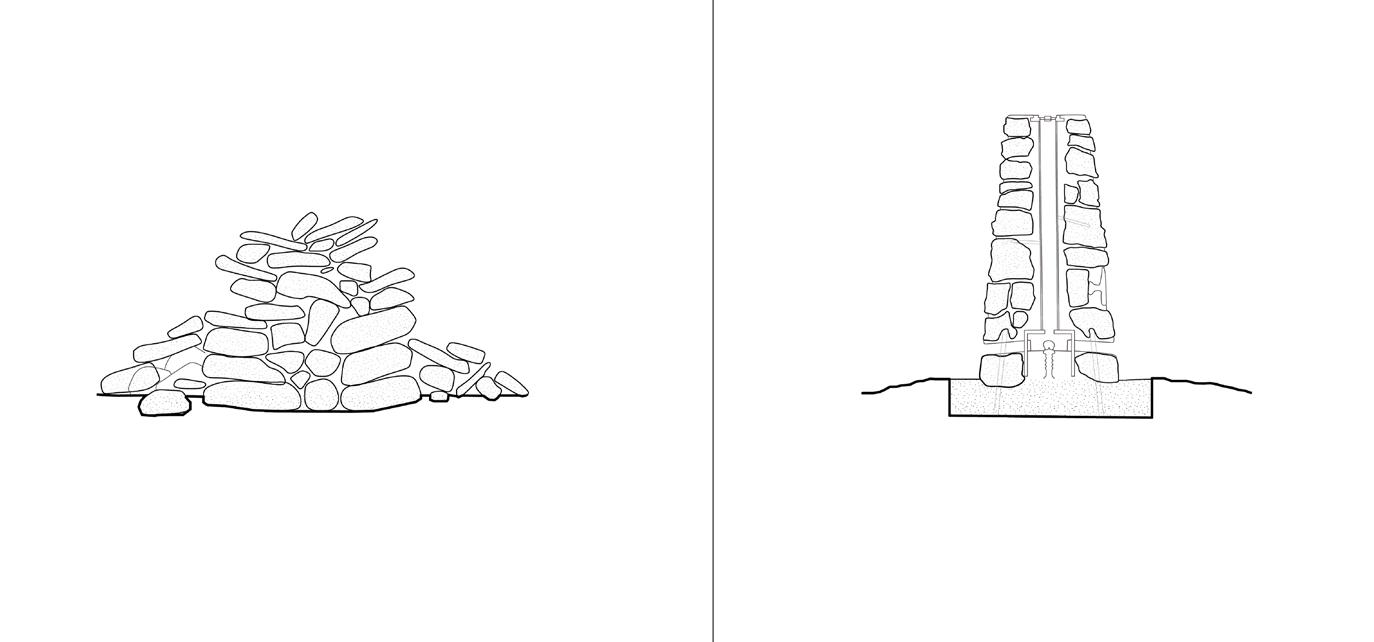

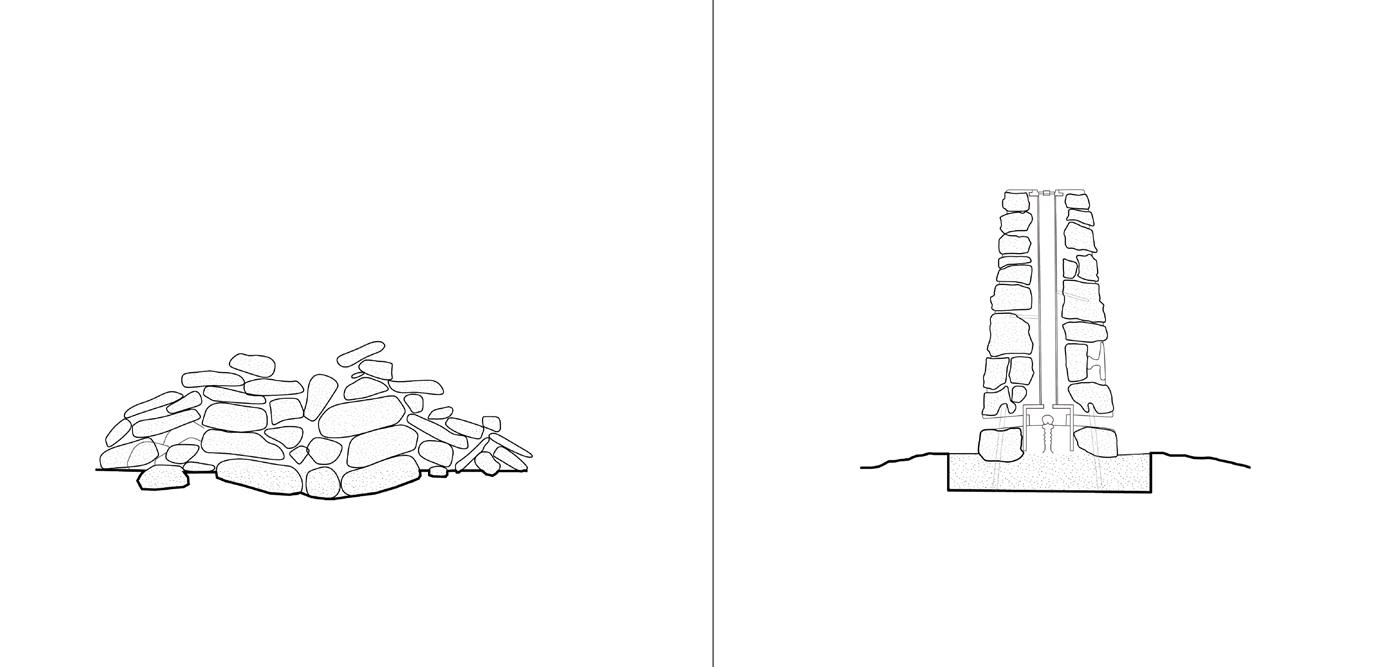

The first chapter looks at the geology and ecology of the Peak District, asking how the surface and subsurface interact. Here, geology is architectural, providing the building materials for drystone construction, the topic of the next chapter. This chapter provides an overview of existing stone structures and tests drystone building methods through the construction of three cairns, finally arriving at a 6-stage design for a field station. The final chapter zooms out from the single field station, speculating on commoning the moorlands through new wayfinding methods and forms of ecological repair.

PROJECT INTRODUCTION

This thesis is concerned with processes of commoning the Peak District moorlands, contesting legacies of privatisation toward new forms of embodied, situated, collective, and regenerative conservation practices .

It investigates this through the revival and reimagining of drystone , an ancient mode of construction.

ETS THESIS STATEMENT

Drystone construction has for thousands of years shaped the Dark Peak’s landscape as an architectural embodiment of the region’s geology. Often associated with the straight drystone walls that proliferated during the Enclosures Acts, I propose reimagining drystone as not a divisive force, but one that holds the potential to invite convivial practices of repair, ecological engagement, and landscape ritual. This technical thesis seeks to test new methods of vernacular drystone construction where the landscape and the rocks themselves become active agents in the design process.

The ETS proposal will examine the multi-scalar nature of stones in the Dark Peak, asking how drystone construction can become part of larger-scale ecological restoration practices, include sphagnum moss replanting, soil remediation, and forms of convivial rewilding.

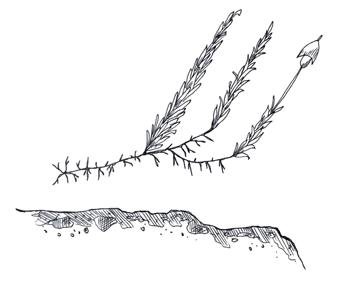

My method is informed by moss, a key non-human agent to whom a drystone wall is not a barrier but a home. Moss teaches us about trans-scalarity, wayfinding, and resilience.

The thesis tests methods of making 1-ingredient structures that constitute a moorland vernacular, focusing on the design of field stations that are both wayfinding devices and temporary inhabitations for transient commoners. The tests— involving both off-site and situated practice—investigate how these structures might:

1. Allow for short-term inhabitation by people as they take part in ecological restoration practices

2. Embrace a convivial construction process that is a collaboration between a group of people, the rocks, and the wider ecology

3. Allow for the cohabitation of people, moss, lichens, and other life forms

4. Register the temporality of the geologic landscape as the stones fall apart, allowing the structures to become sites of constant repair, maintenance, and reconfiguration

Note: As a rule, all colour photographs in the thesis are taken by the author and all black and white photographs are from online research. Image credits can be found at the end of the thesis.

Introduction Geology and Ecology: Interactions between Surface and Subsurface i A

+ How can methods of drystone vernacular construction become part of the repair, stewardship, and multispecies commoning of the Peak District moorlands?

Sub-question A:

+ How can drystone become a collective building practice that takes into account multispecies inhabitation, existing stone infrastructure, and a constantly transforming landscape?

Small scale

Drystone Construction

Convivial Wildness in Drystone Field Stations B

C

Sub-question B:

+ How does the geologic makeup of the moorlands provide the ‘ingredients’ for drystone construction?

Sub-question C:

+ How might an expanding network of drystone field stations create new modes of wayfinding and allow for the ecological repair of the moorlands?

This thesis proposes that drystone—as a craft, structure, and way of being in the landscape—has the potential to:

01. Blur the top-down “God-trick” map.

02. Dissolve the picturesque frame and the fixed view of landscape.

03. Challenge private land ownership regimes.

Additionally, it proposes that:

01. Geology is architecture.

02. Landscape is a construct.

03. Fixity is an illusion; dynamism is constant.

04. Land is living.

05. All matter is entangled and interconnected.

These positions frame and provoke the following research, speculations, and imaginings of commoning the Peak District’s moorlands.

How drystone in this project addresses these critiques:

+ Drystone as wayfinding network + Filmic mapping methodology

+ Embodied and situated construction and maintenance practices that view the reshuffling of stones as inherent to an everchanging landscape

+ Drystone as a living practice and a host for many forms of life.

+ Collective drystone construction as a commoning practice

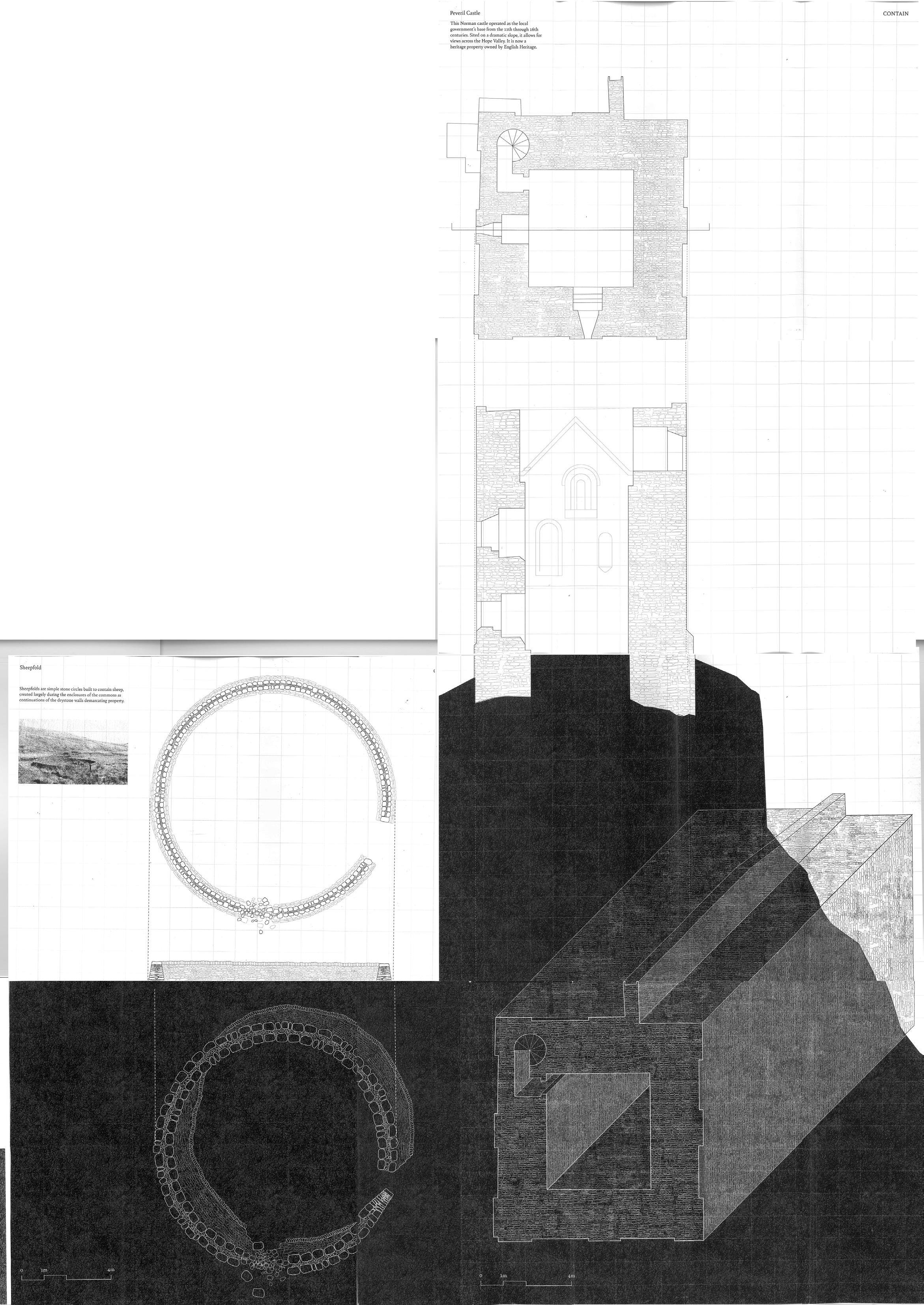

01. Cave Dale by Peveril Castle

Thesis Strategies: An Overview

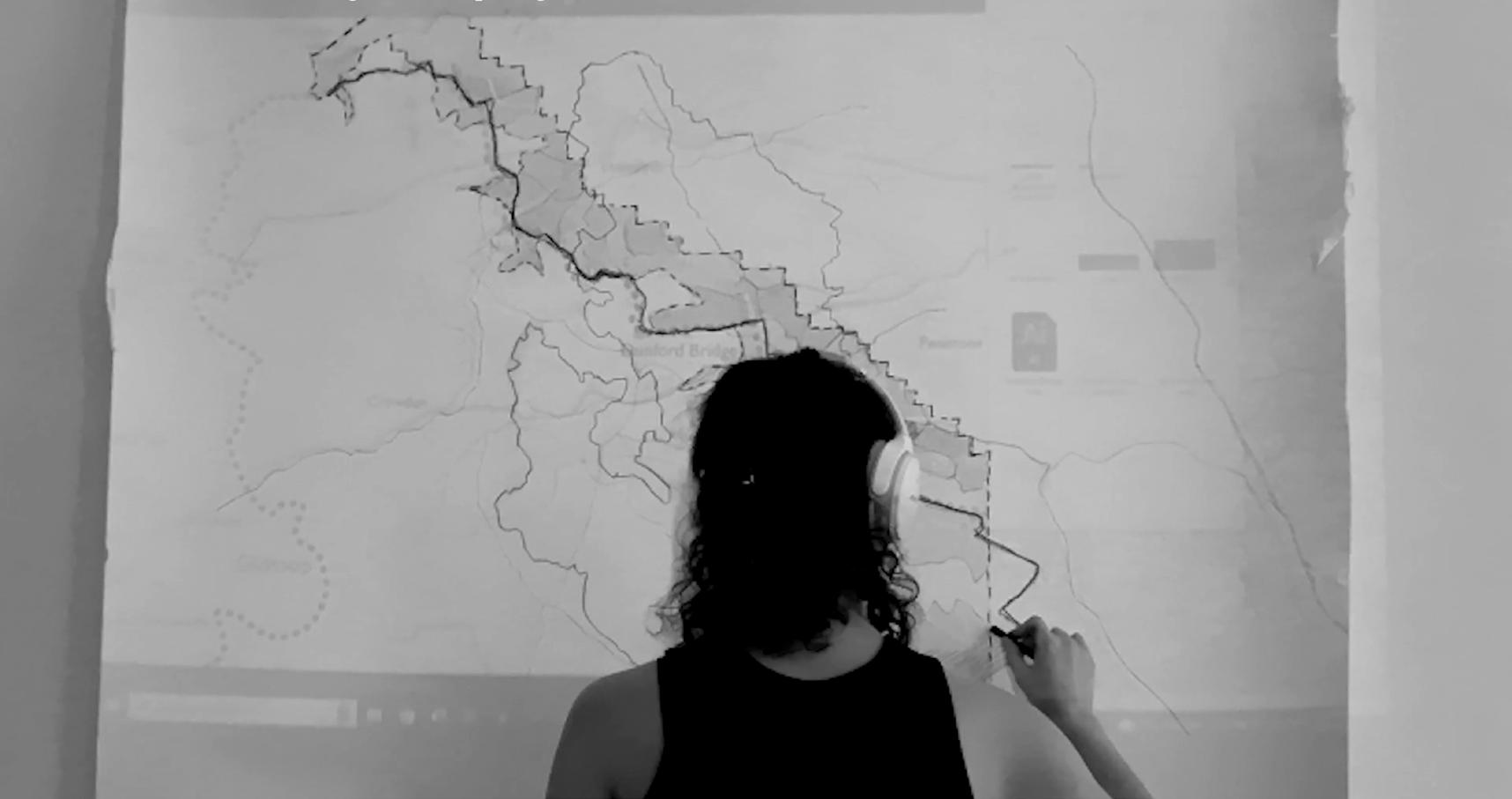

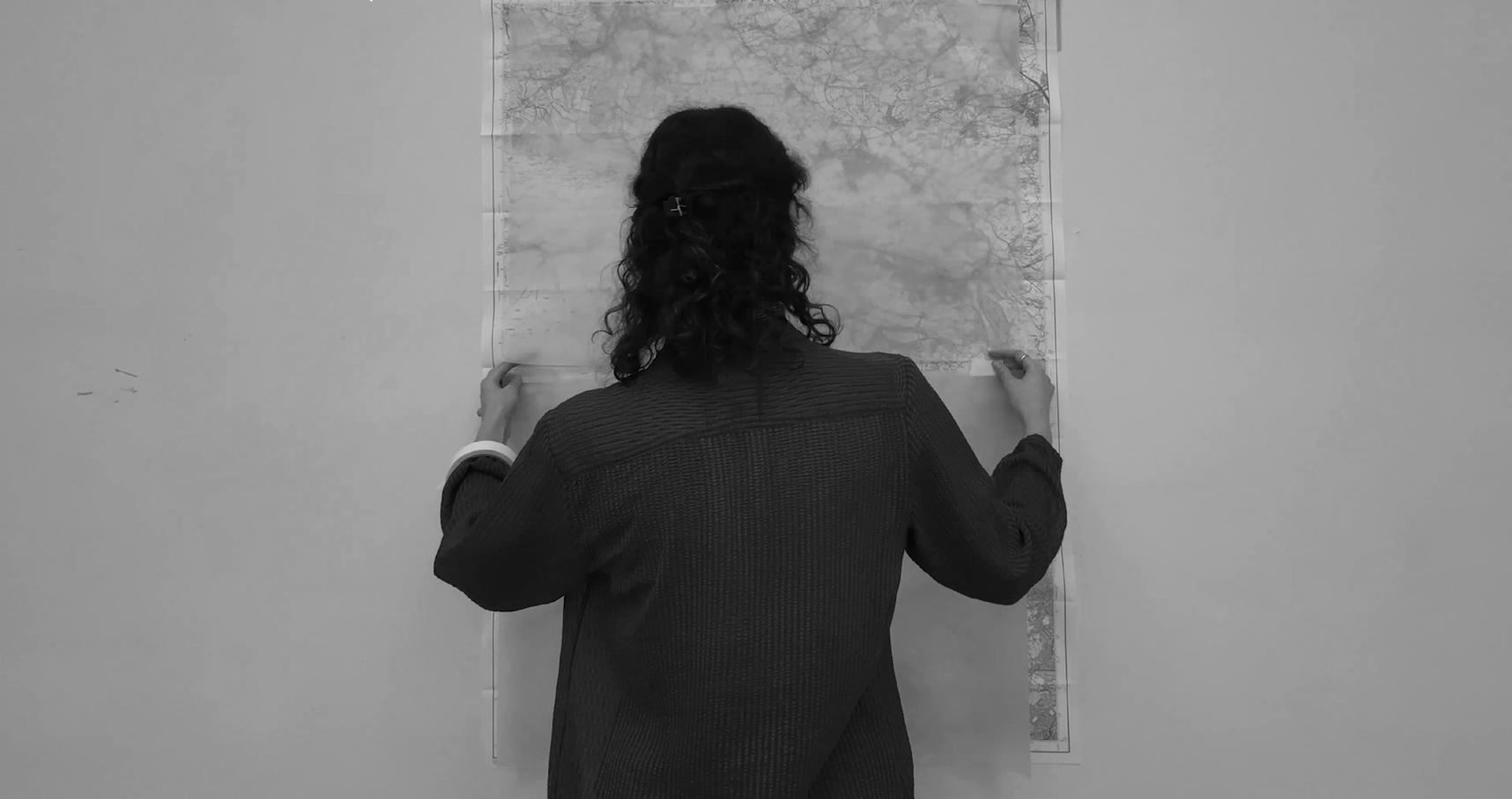

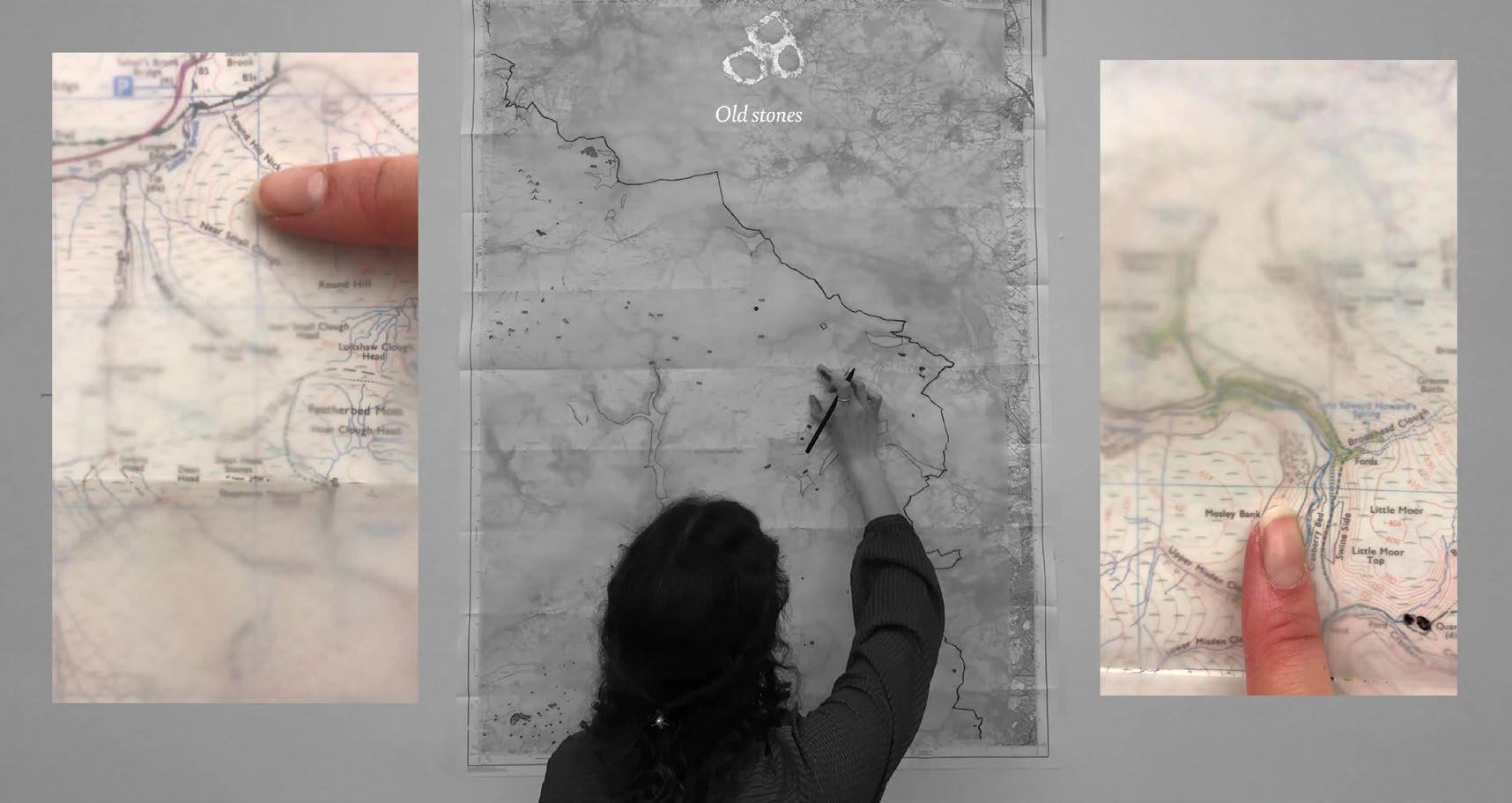

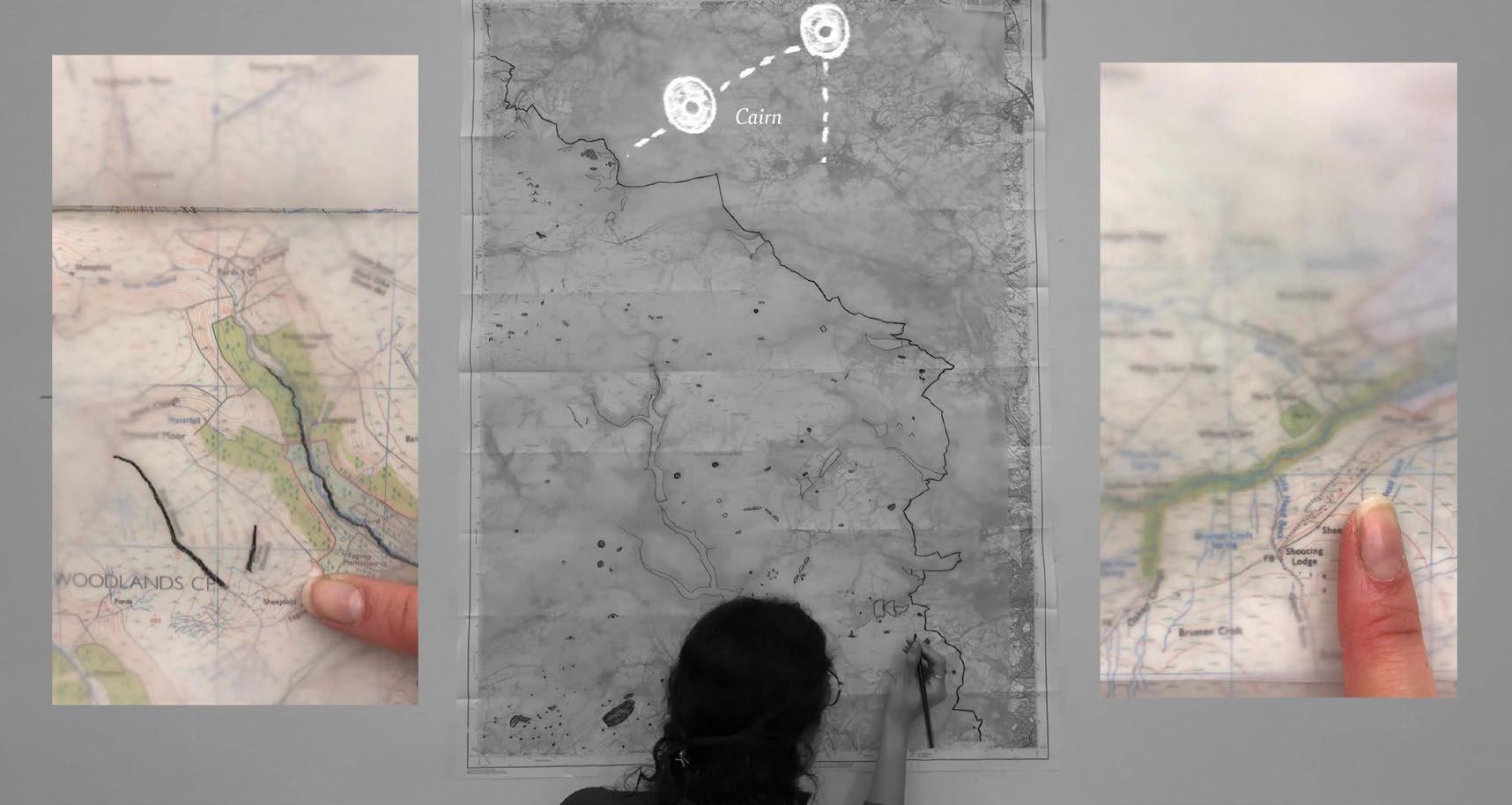

Strategy 1: Filmic Mapping

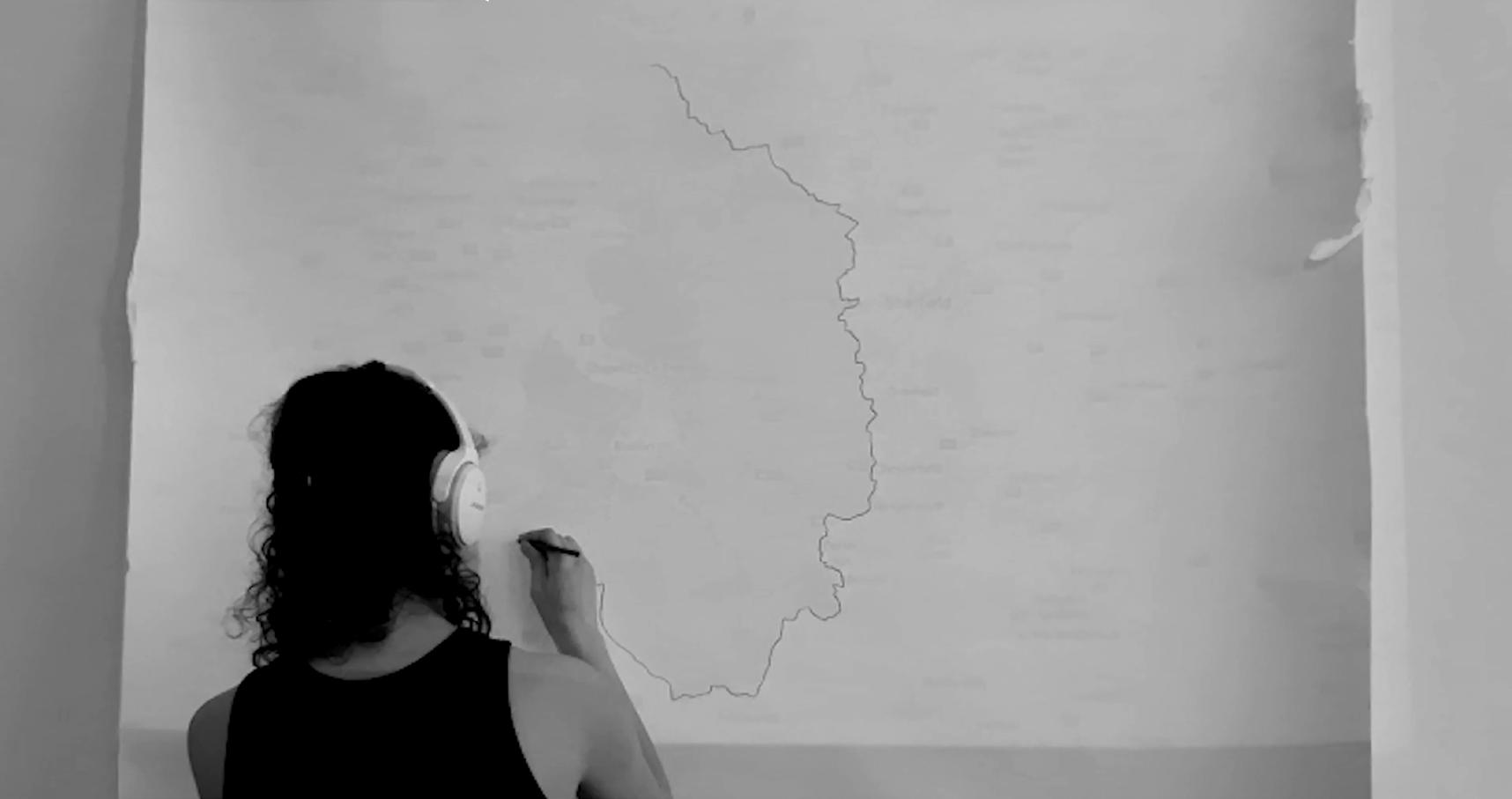

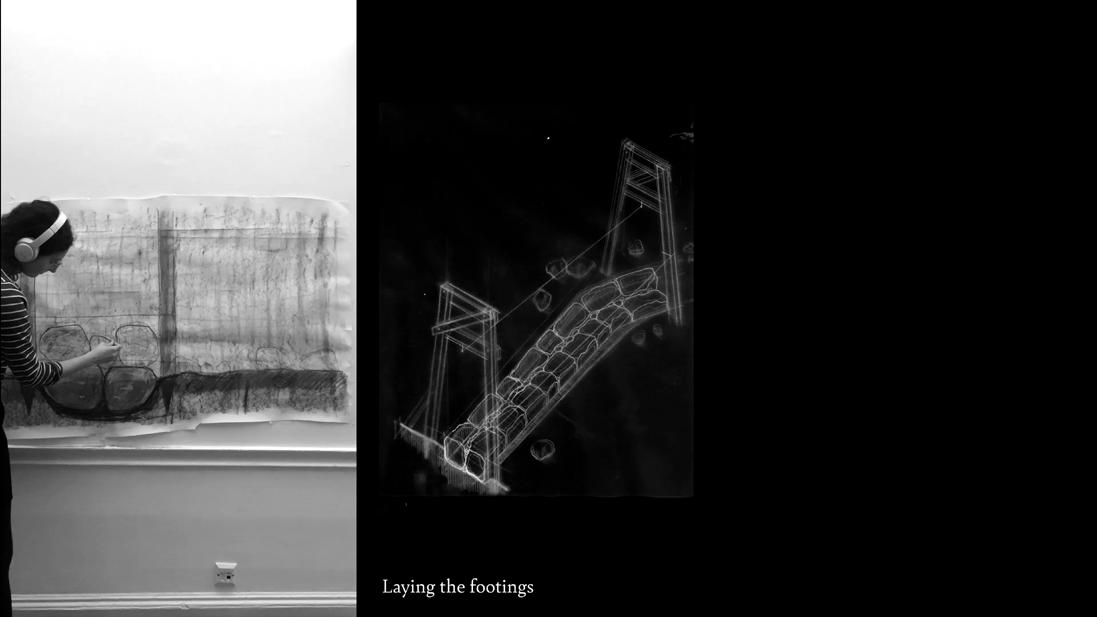

Filming landscape as experimental cartography

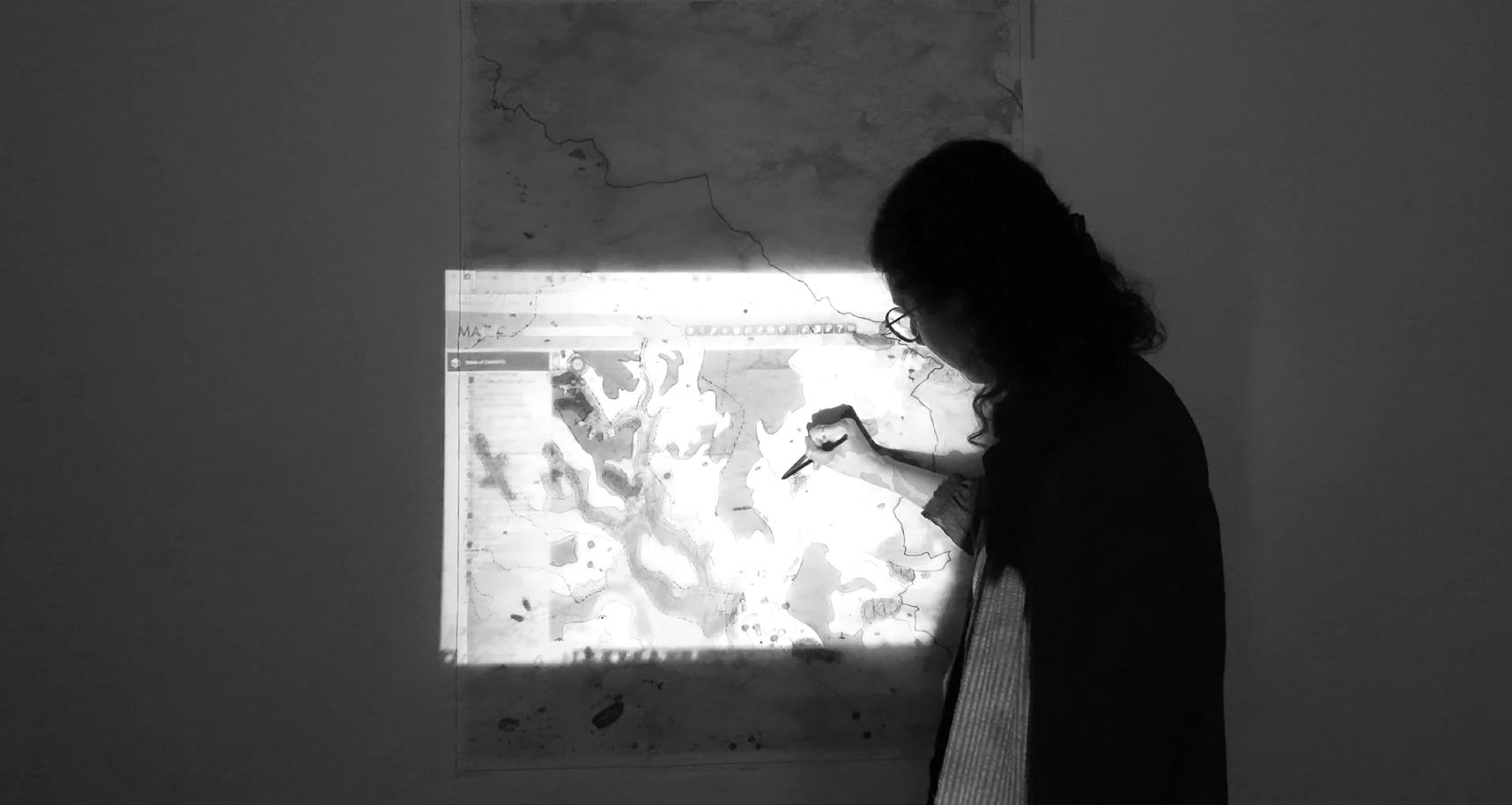

I came across the term ‘filmic mapping’ in Christoph Girot’s Landscript series, and the thesis adopts this way of representing and thinking about landscape. To film a landscape is to establish an embodied relationship to it and to recognise its temporality. To hold a camera and walk is to both affect the landscape and be affected by it. The camera follows the bounce of one’s steps and the disorientation of a rambling walk. It catches the splattering of rain, or in my case, has its lens partially obscured when wrapped in cling film as an attempt to protect it.

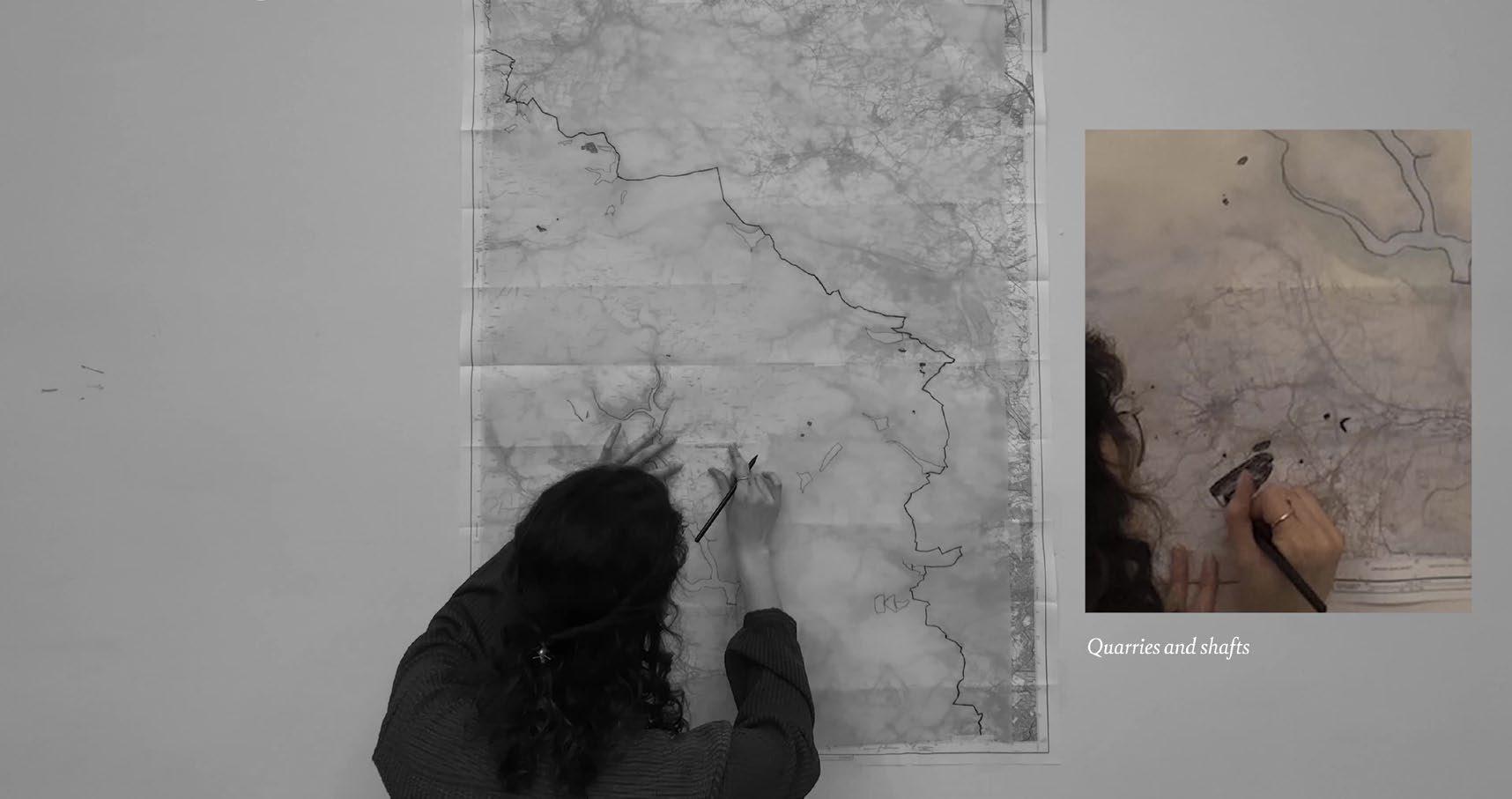

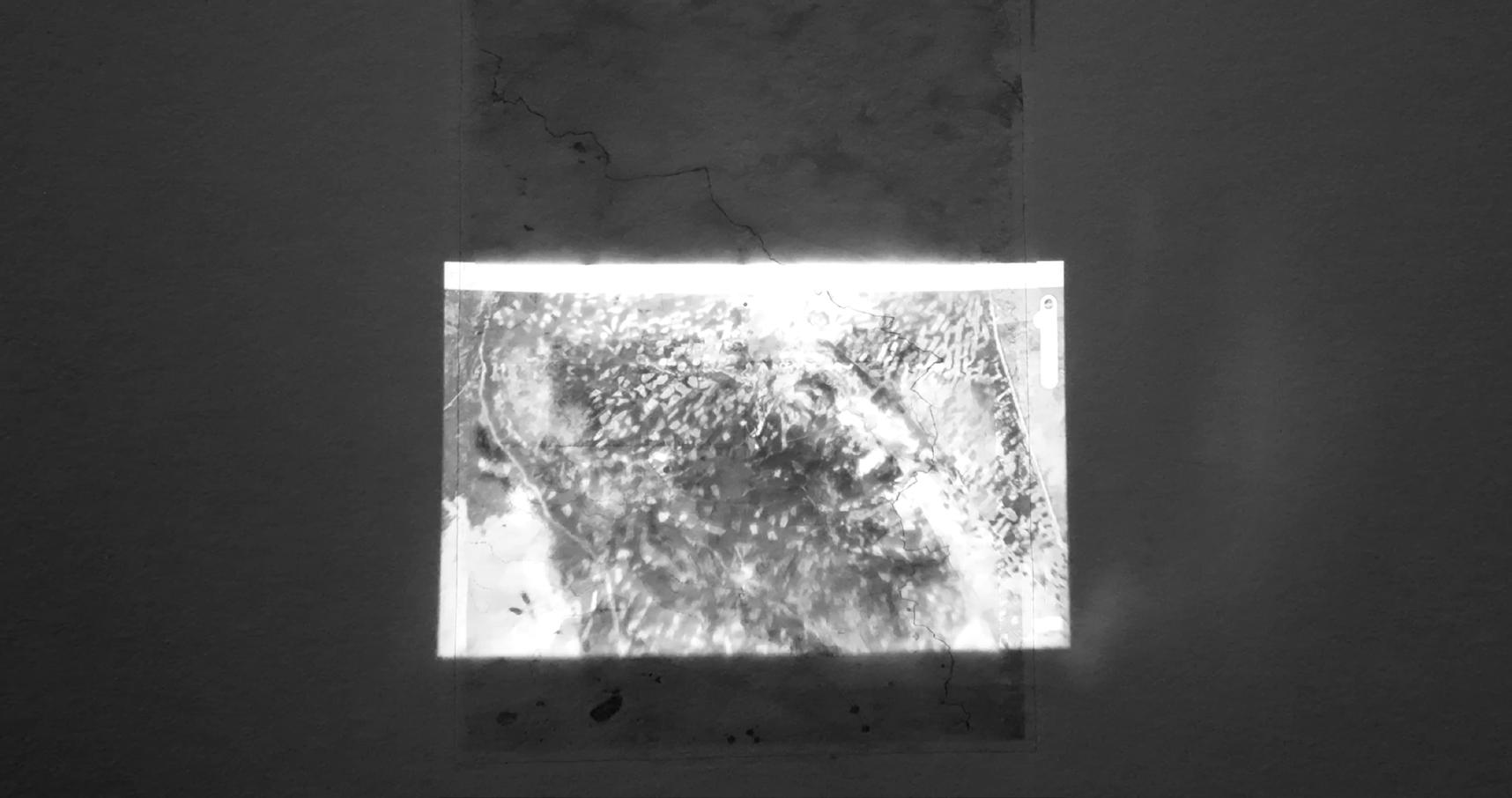

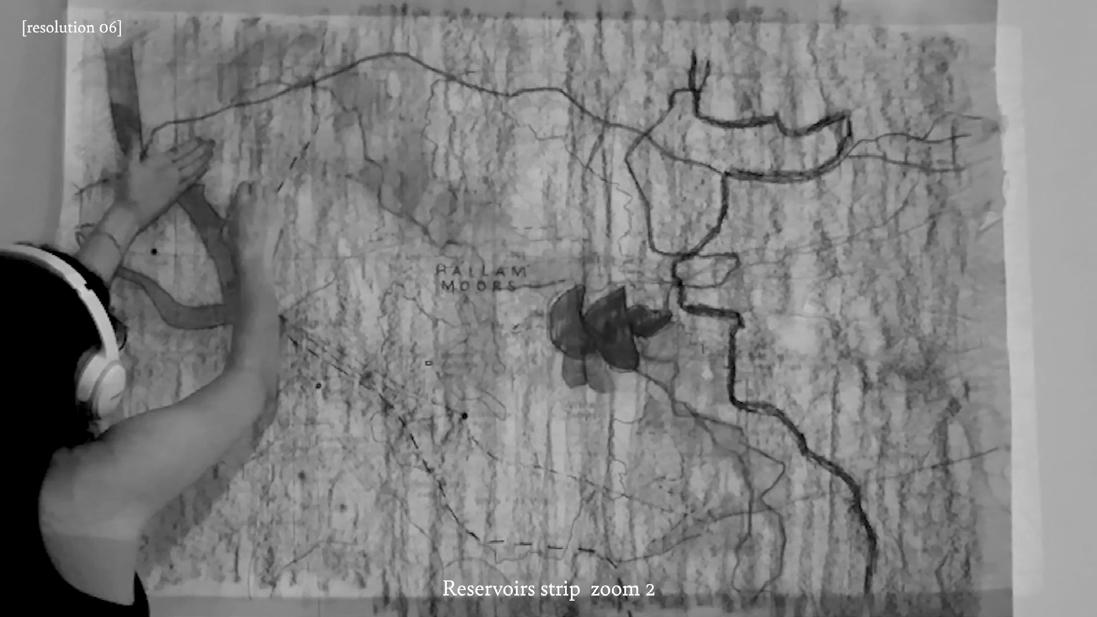

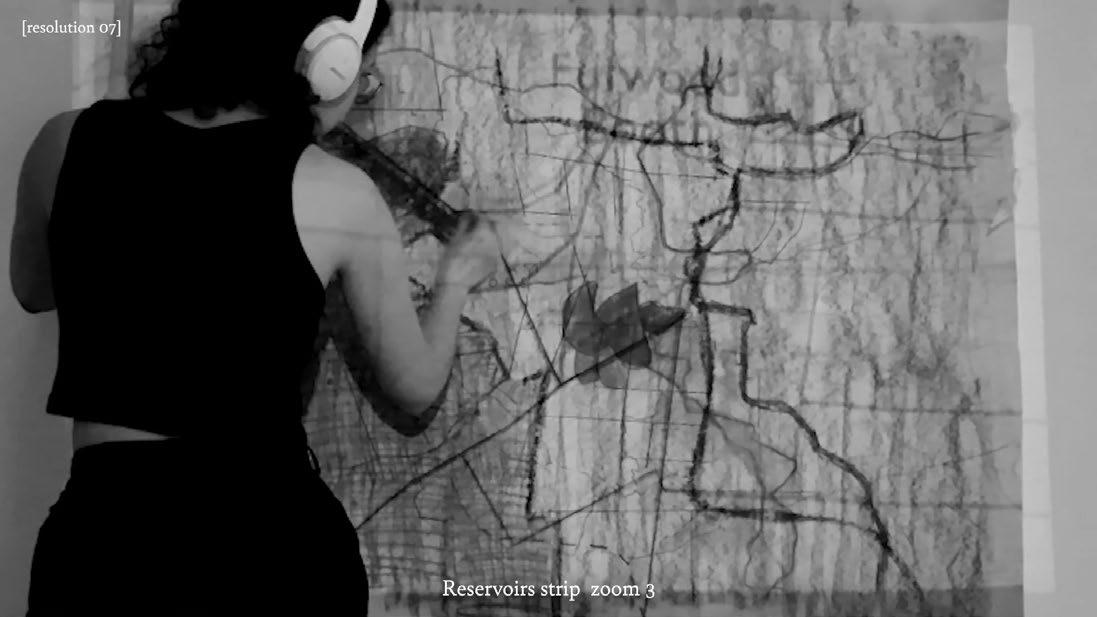

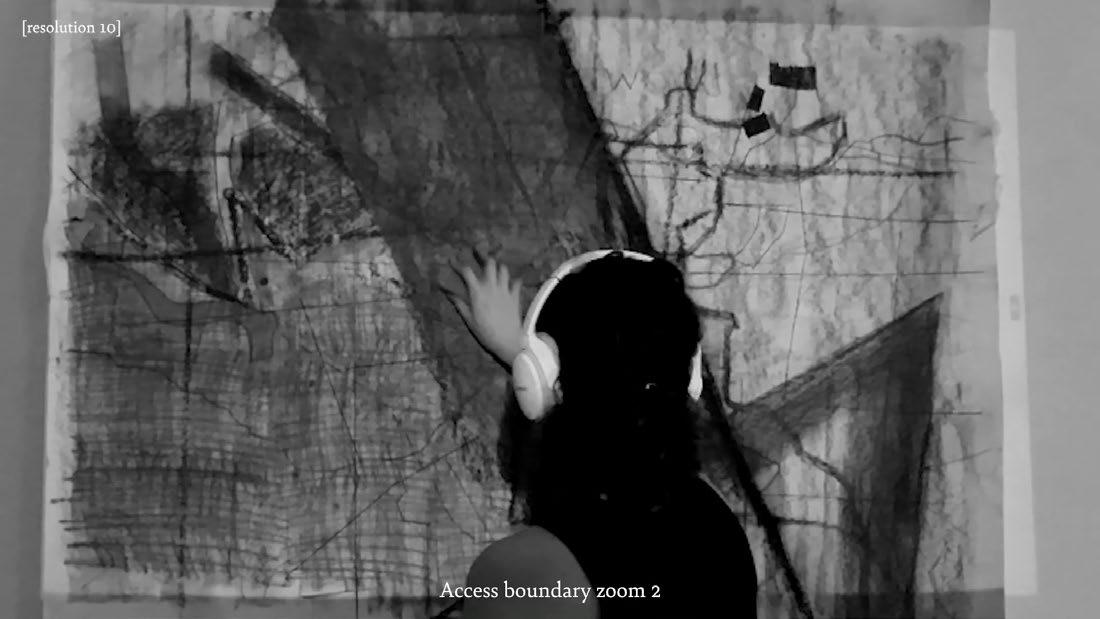

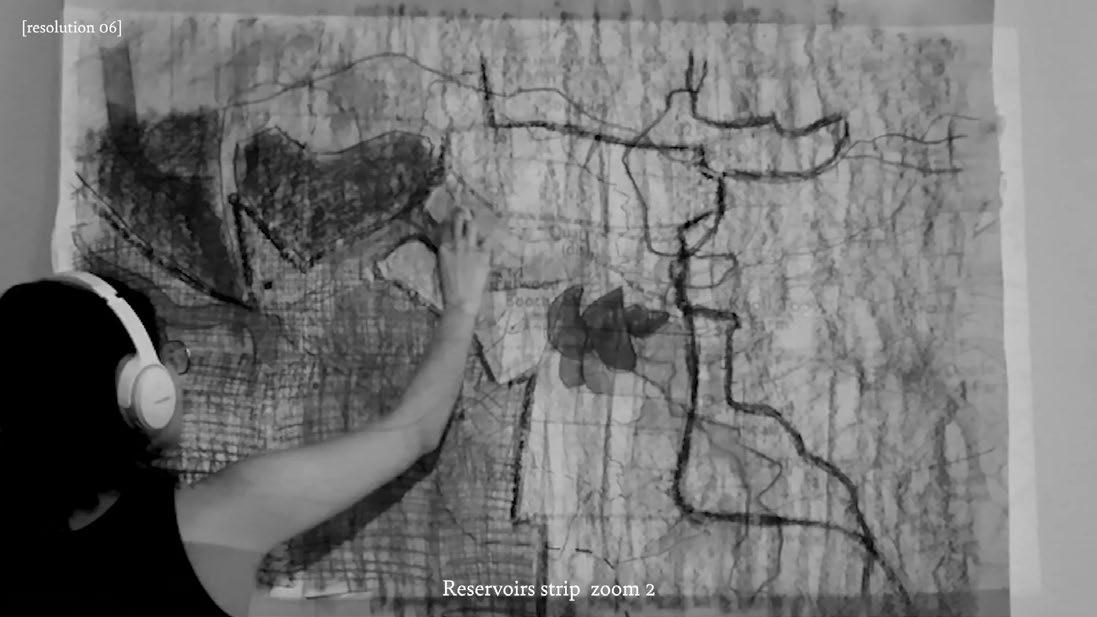

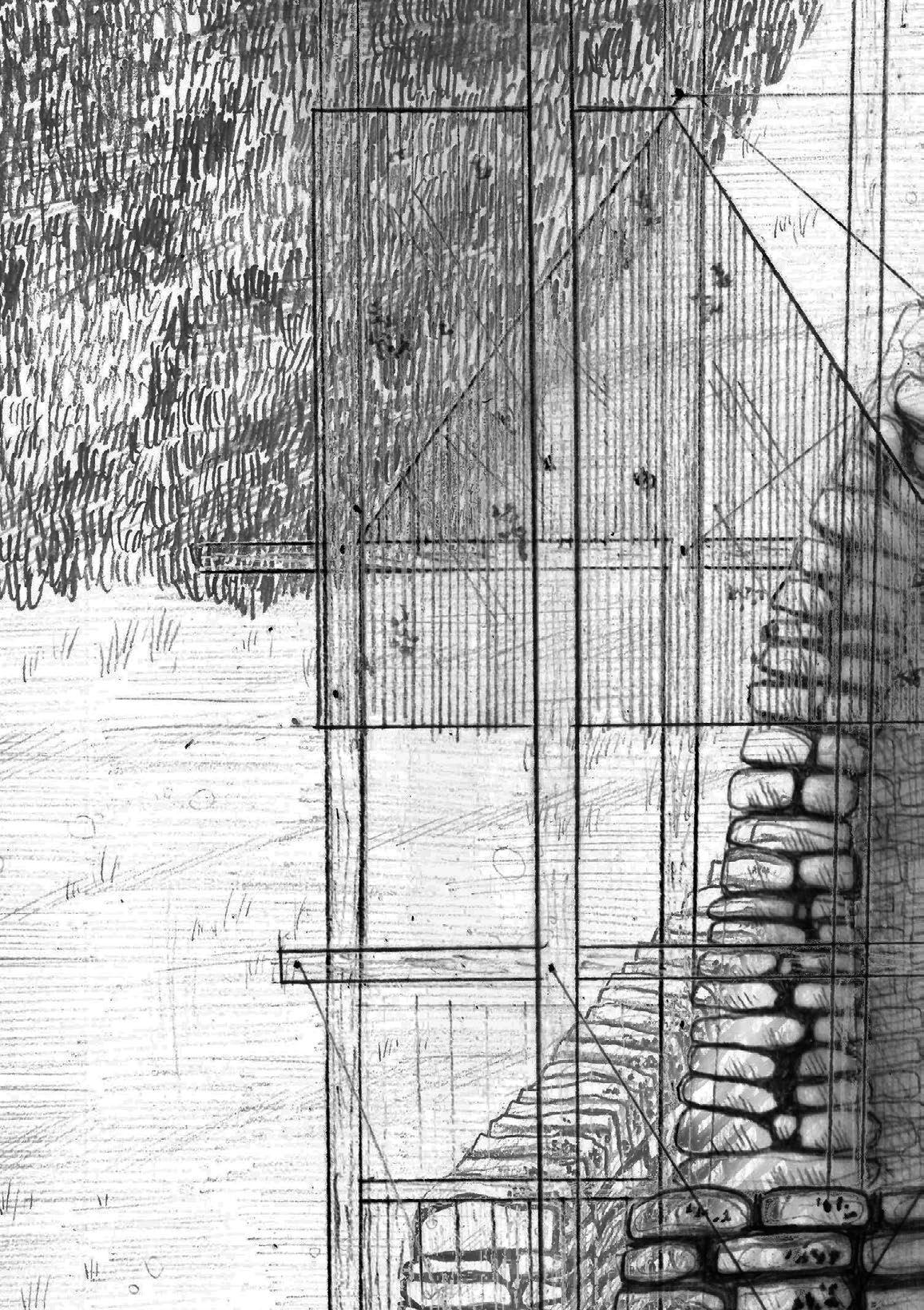

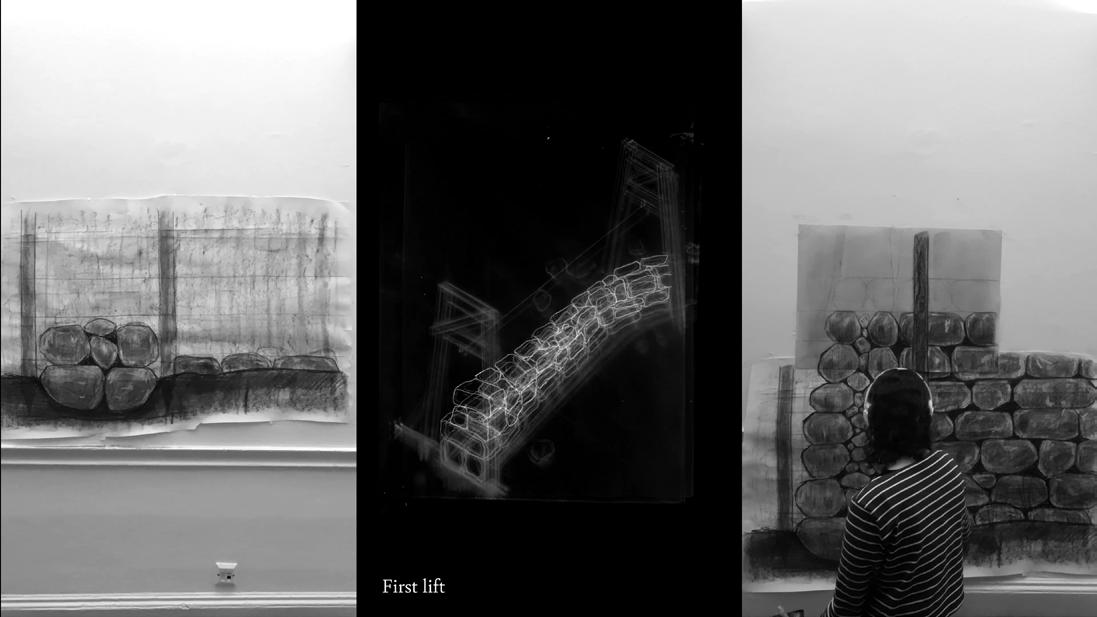

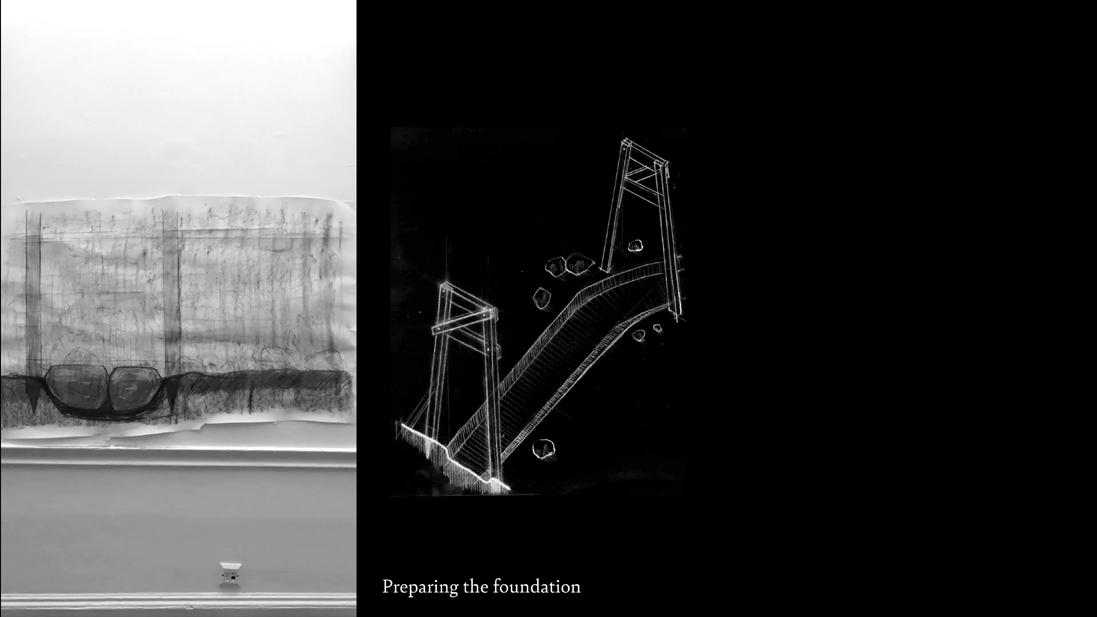

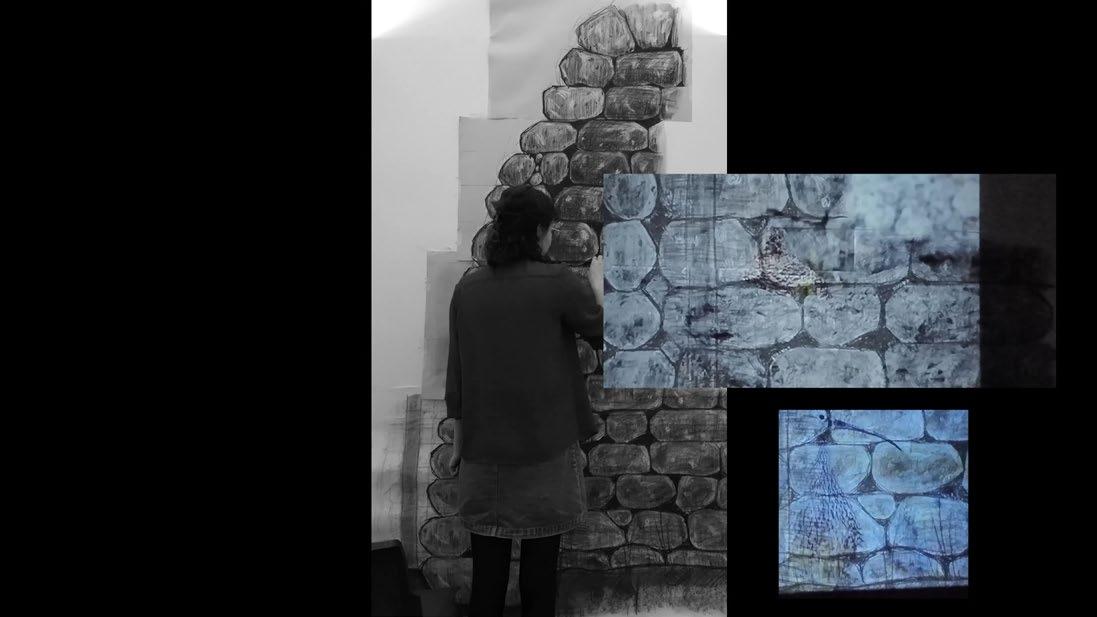

To film a drawing in the studio replicates this attention to temporality, but instead of both the camera and the ‘subject’ moving, the camera remains fixed, capturing the movement of making a large-scale drawing.

Both the filmed walk and the filmed drawing become forms of mapping, methods of recording space in time. These maps—unlike the ordnance survey or the satellite image—reject landscape as fixed and subvert the omniscient gaze to the bodily one, fluid and shifting with the charcoal smudged on the page and the walking feet leaving imprints on the peat.

The following six strategies are consistently employed throughout the thesis to provide various modes of understanding and designing within the Dark Peak moorlands.

Above: Filming in the field

Below: Filming in the studio

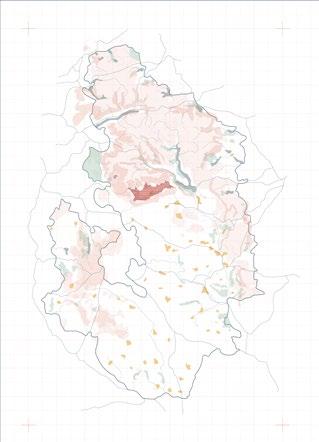

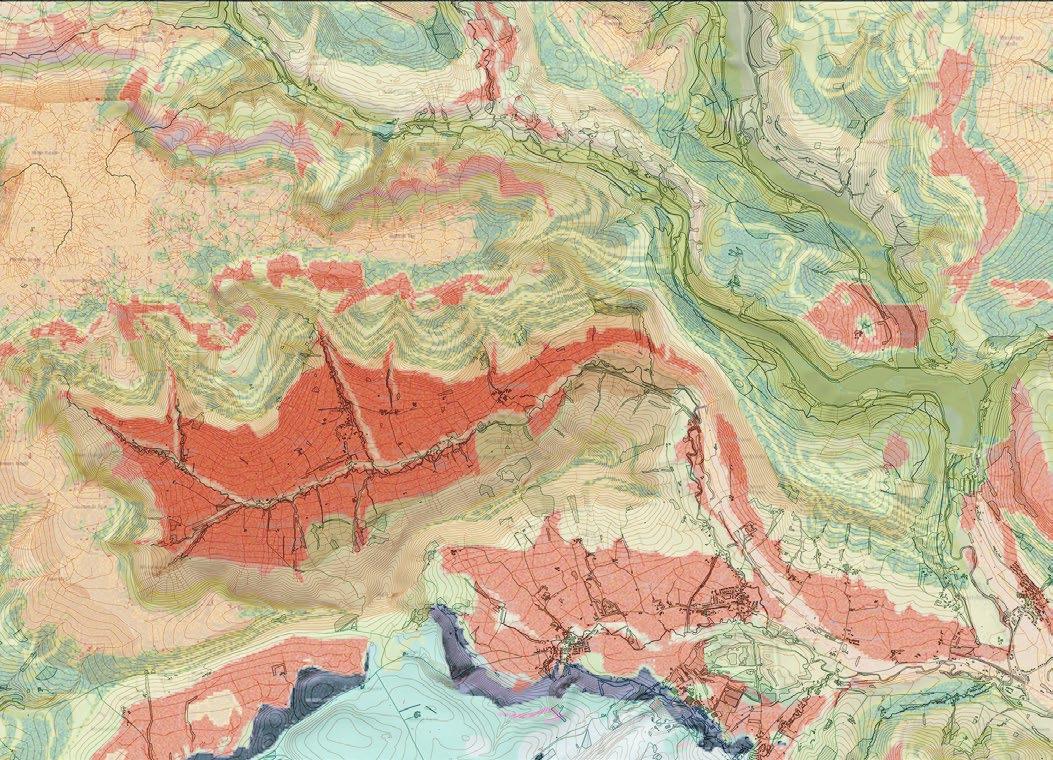

Strategy 2: Critical Mapping

The thesis can be read as a critique of the top-down, God’s eye map: or as Donna Haraway puts it, “the gaze from above, from nowhere.” As such, mapping is used in a critical manner throughout the thesis. As a tool, the top-down map can be useful in identifying regions or elements of study; thus, some more conventional maps are included. However, these maps should not be read as objective “views from nowhere”: they are situated, drawn from my hand, and up for interpretation and interrogation. Maps are always biased, curated selections of information, and the maps included in this thesis are no exception.

With its interest in new modes of navigation beyond the measured map or the satellite view, and in walking as a form of mapping, the thesis presents a series of alternative mapping strategies. These take into account sensorial and temporal factors, rejecting the fixed, static registration of landscape.

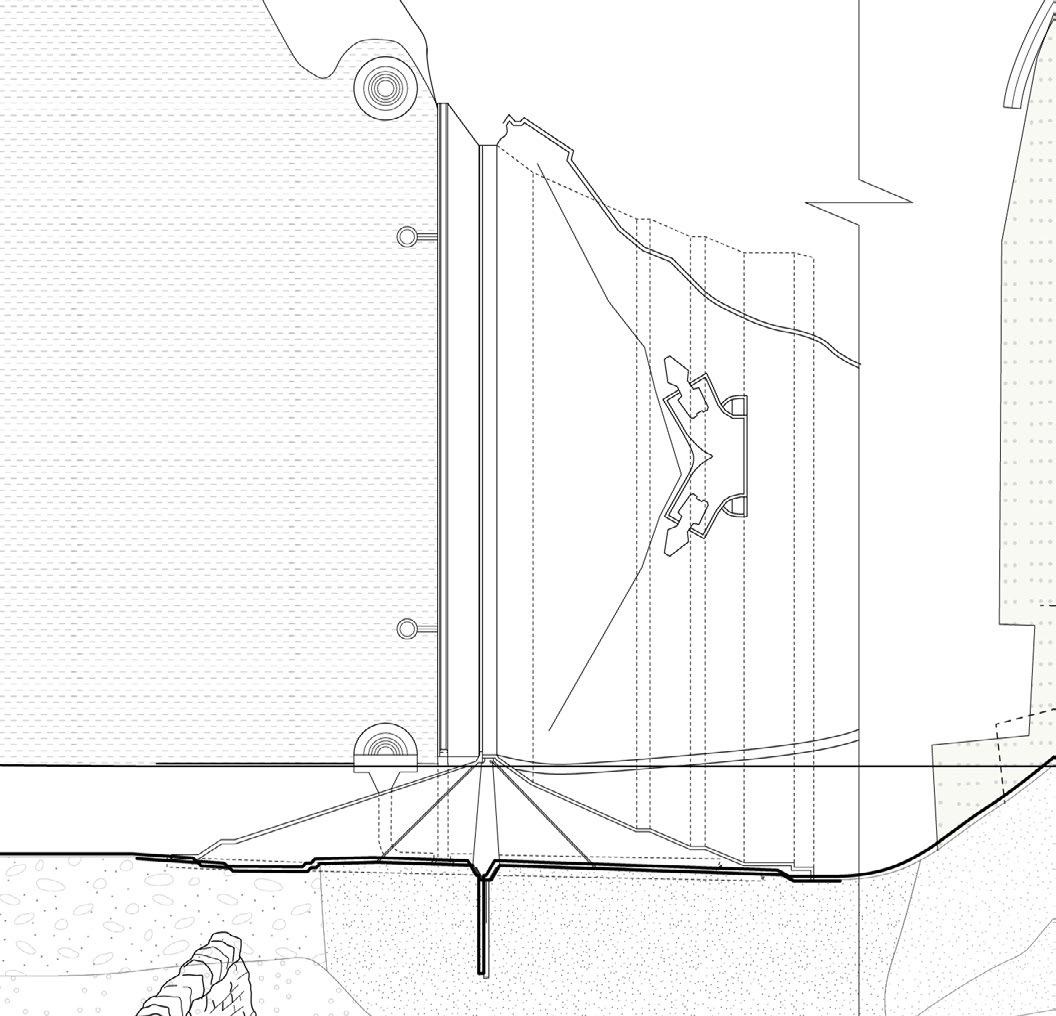

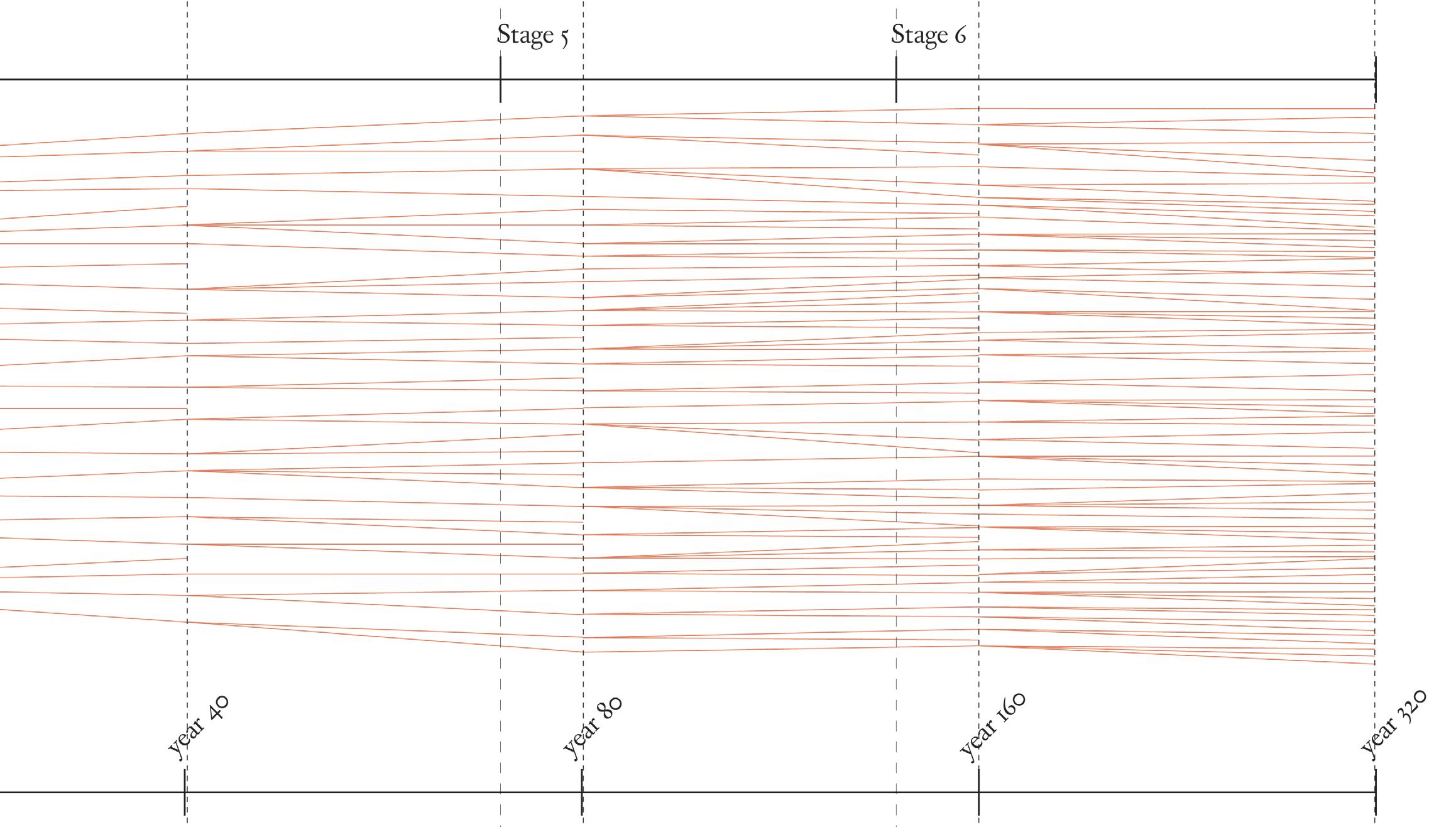

In Chapter B: Drystone Construction, the speculative design strategy presents sectional drawings as maps over six stages of time. By employing a series of mapdrawings, the thesis presents the construction process as continual and ongoing, rather than occurring at a single stage.

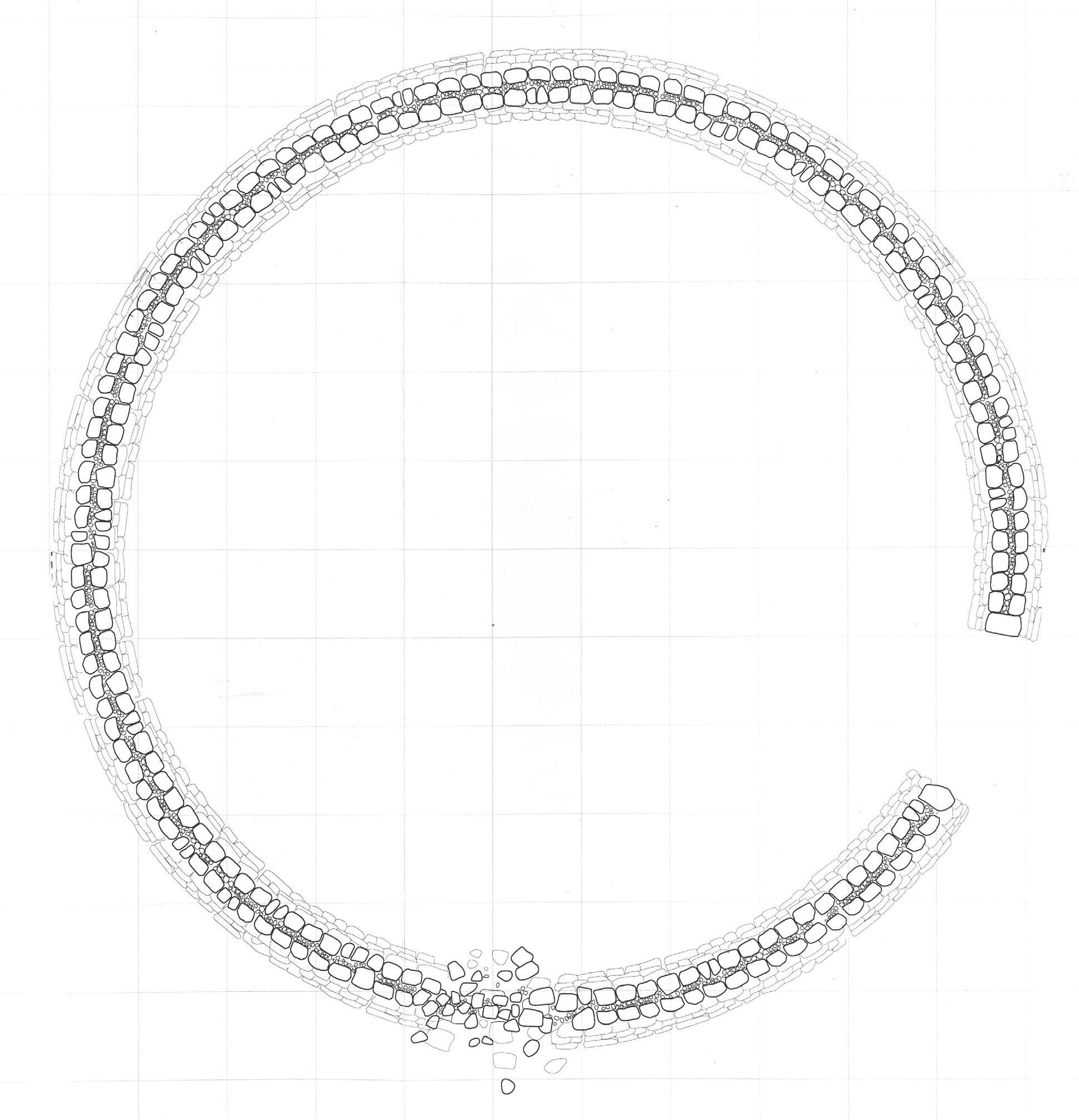

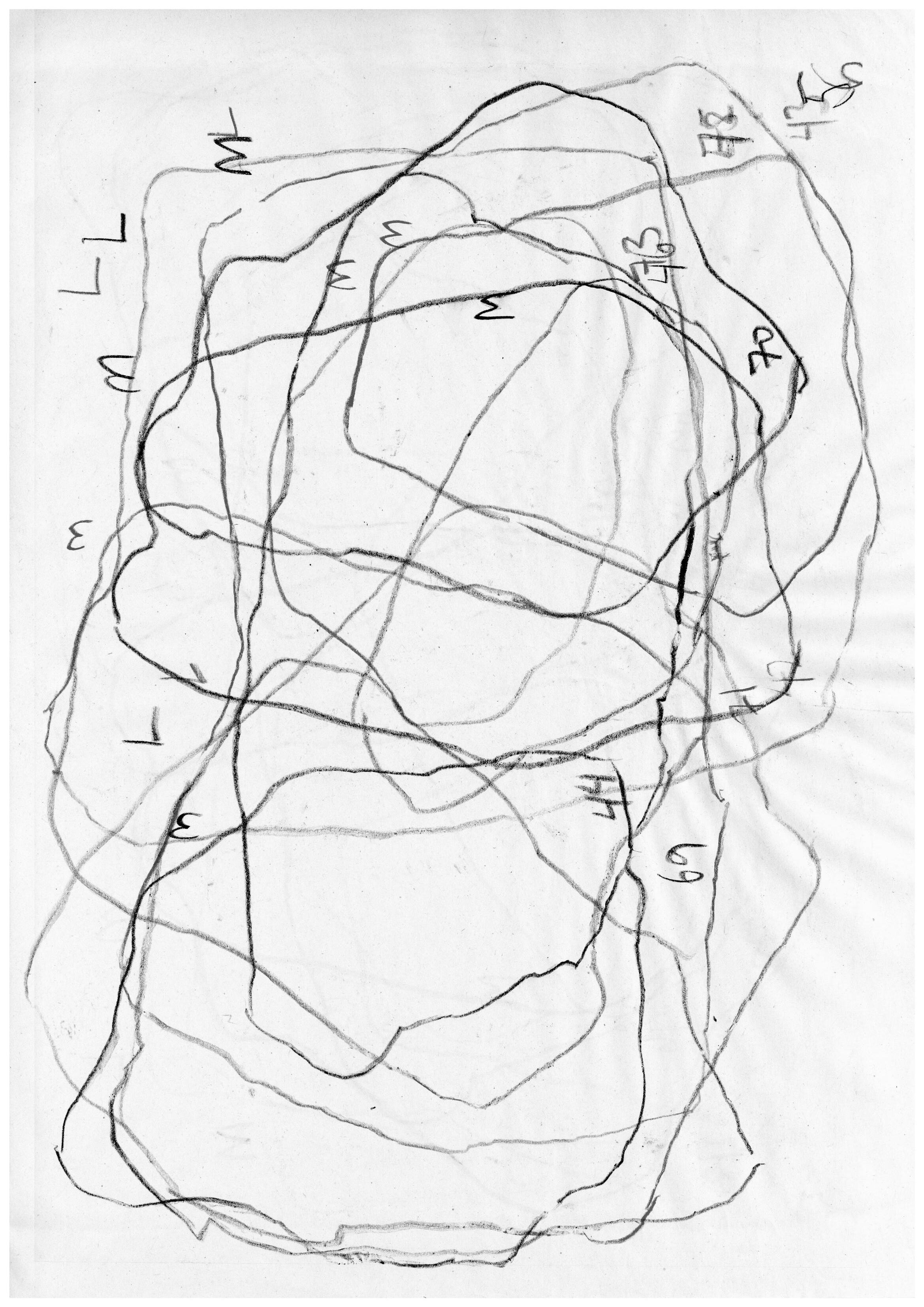

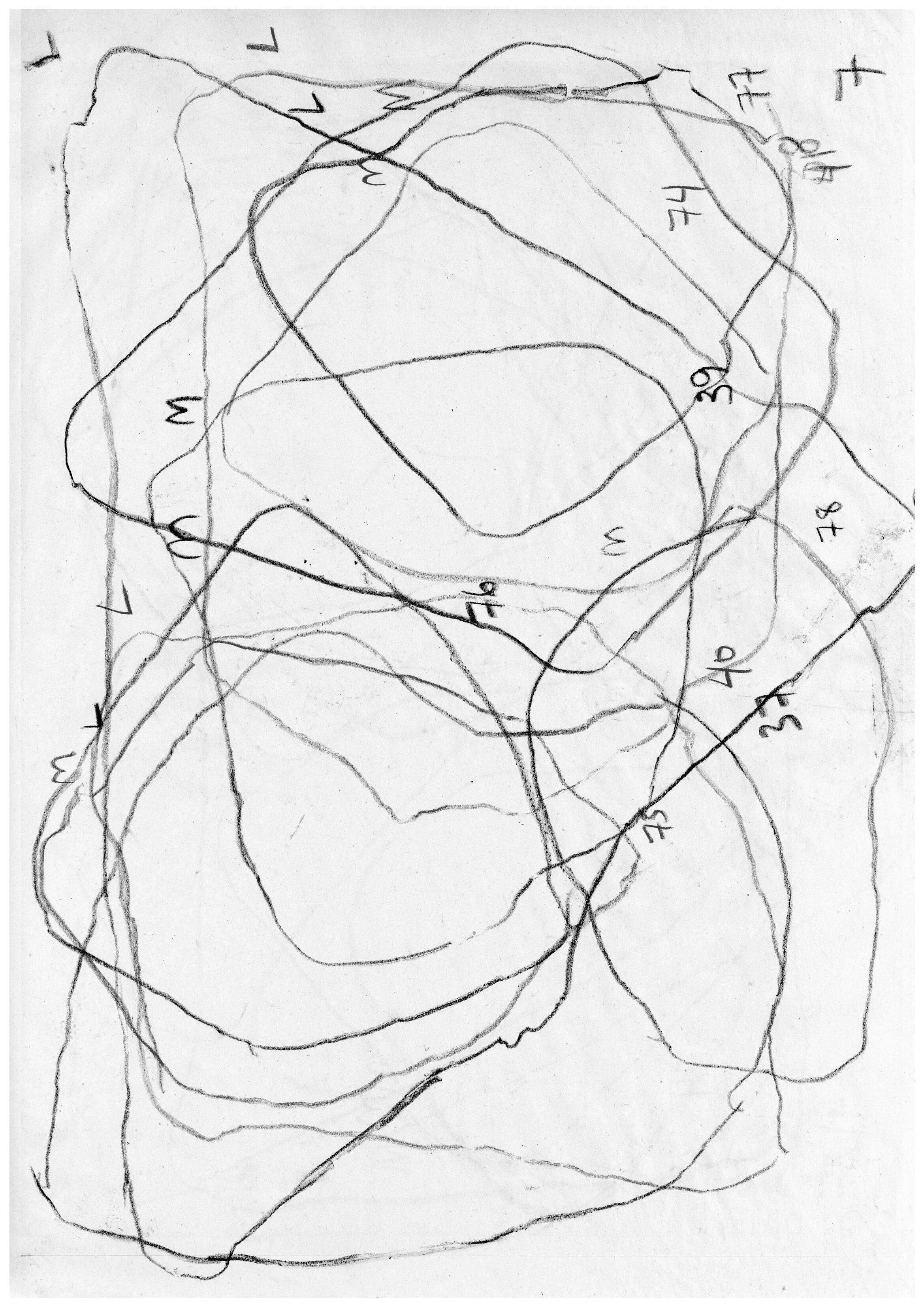

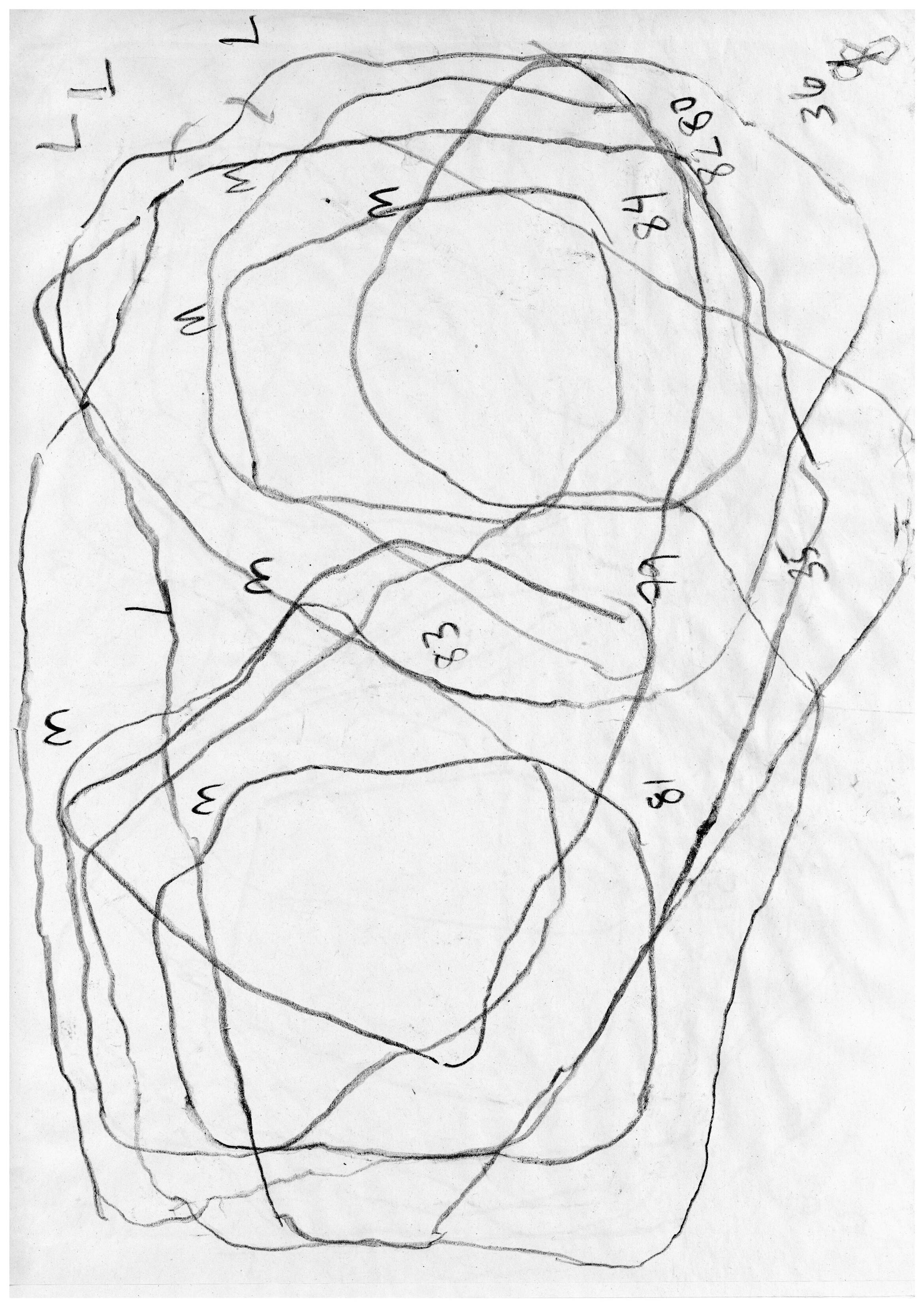

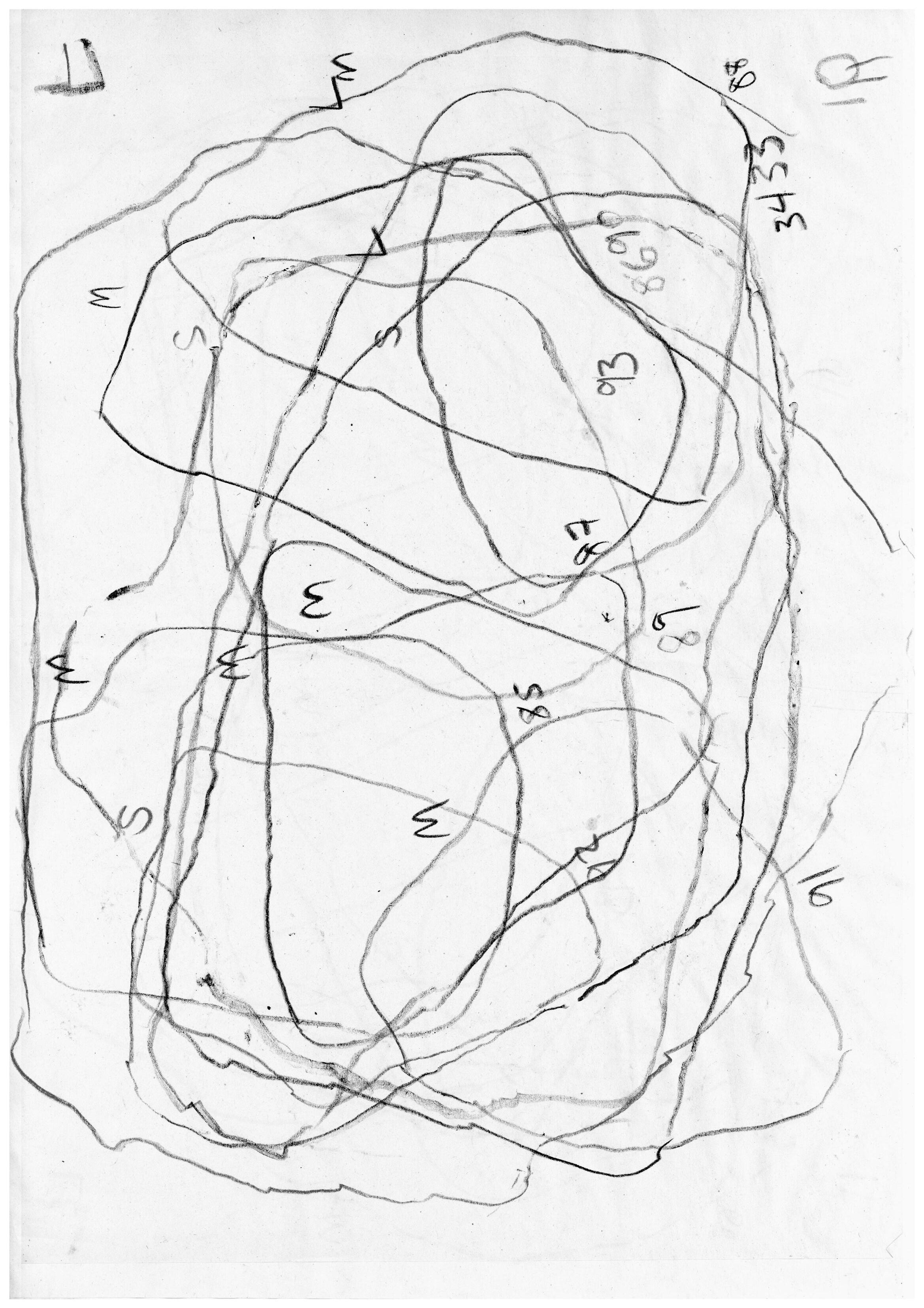

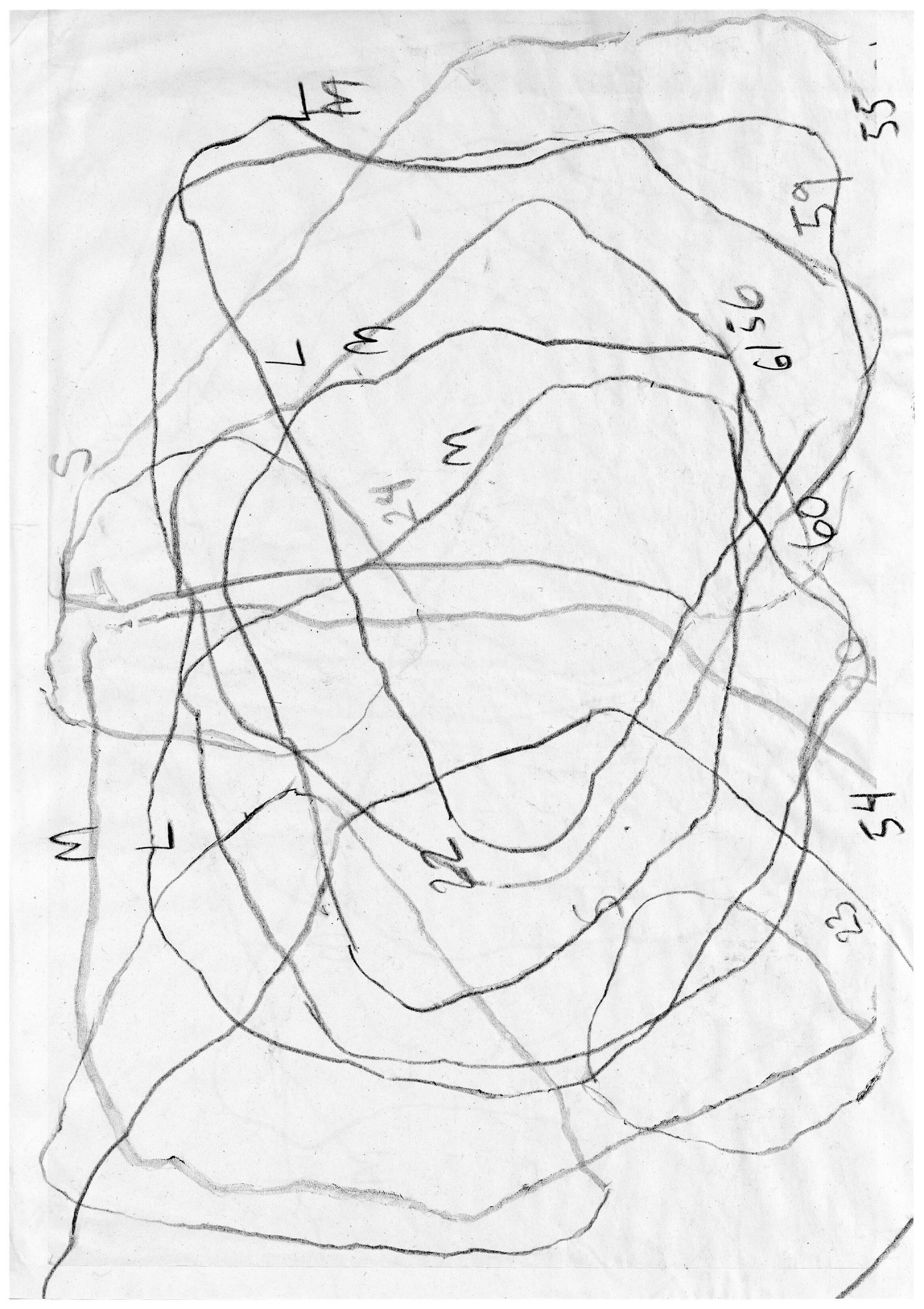

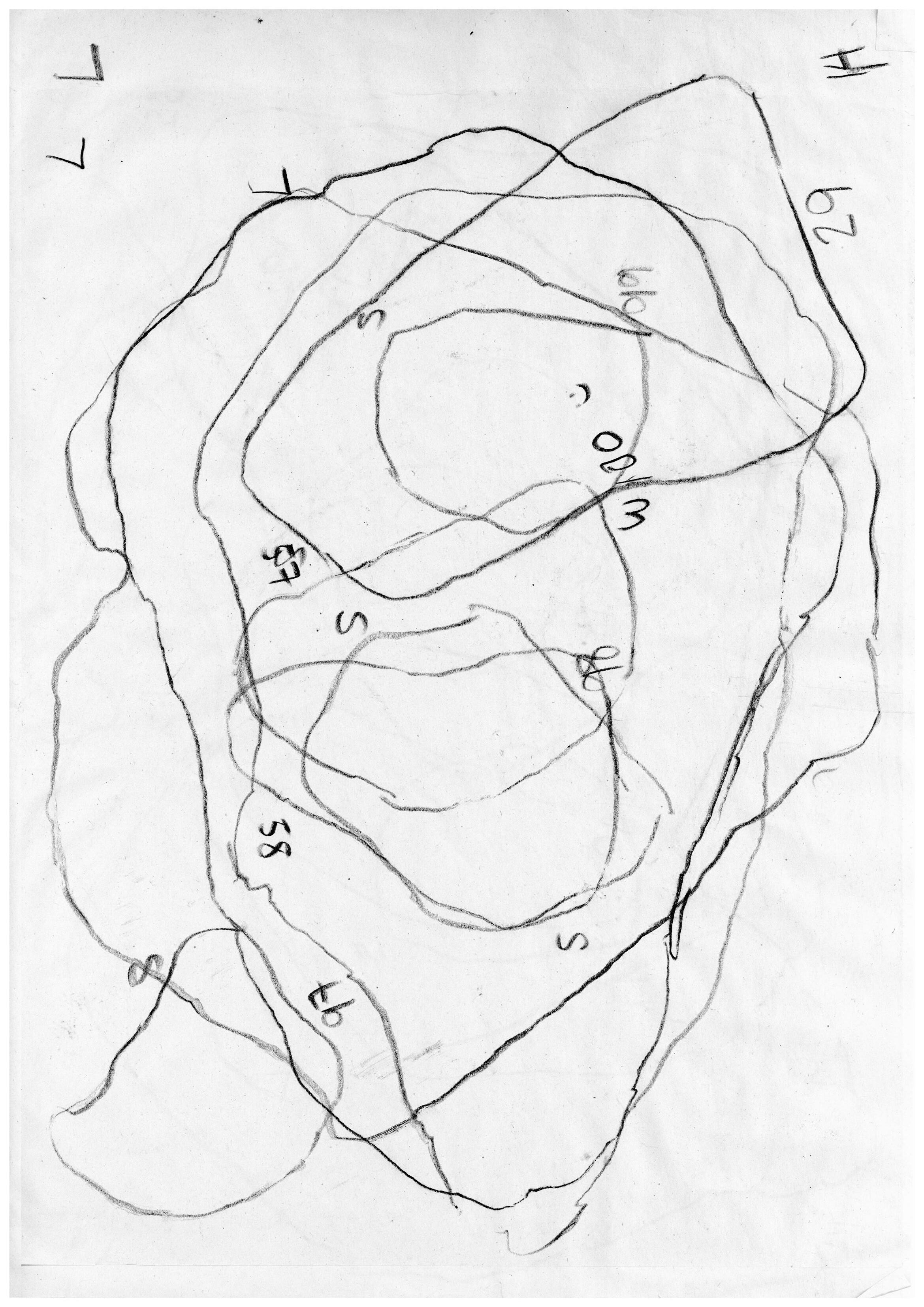

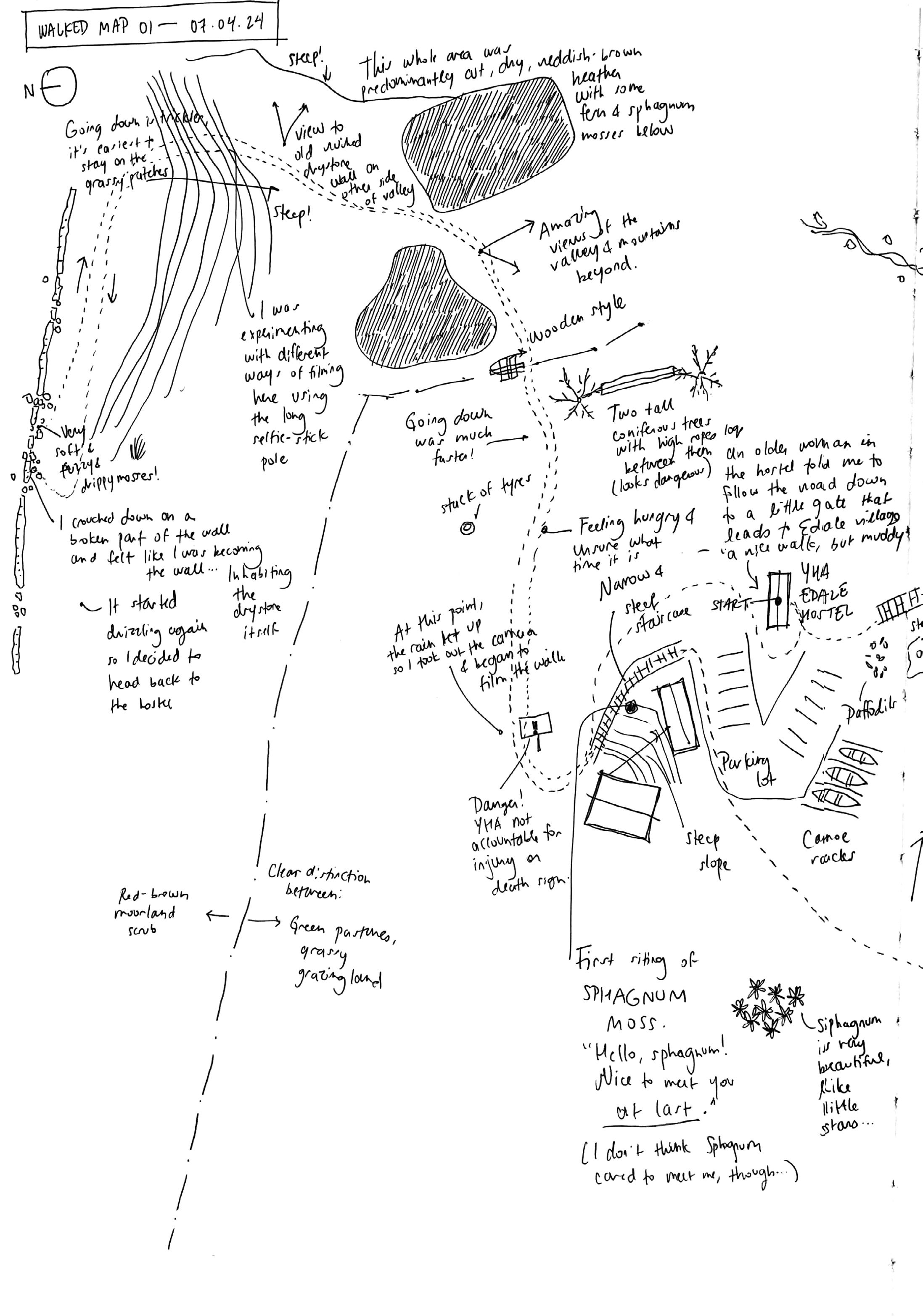

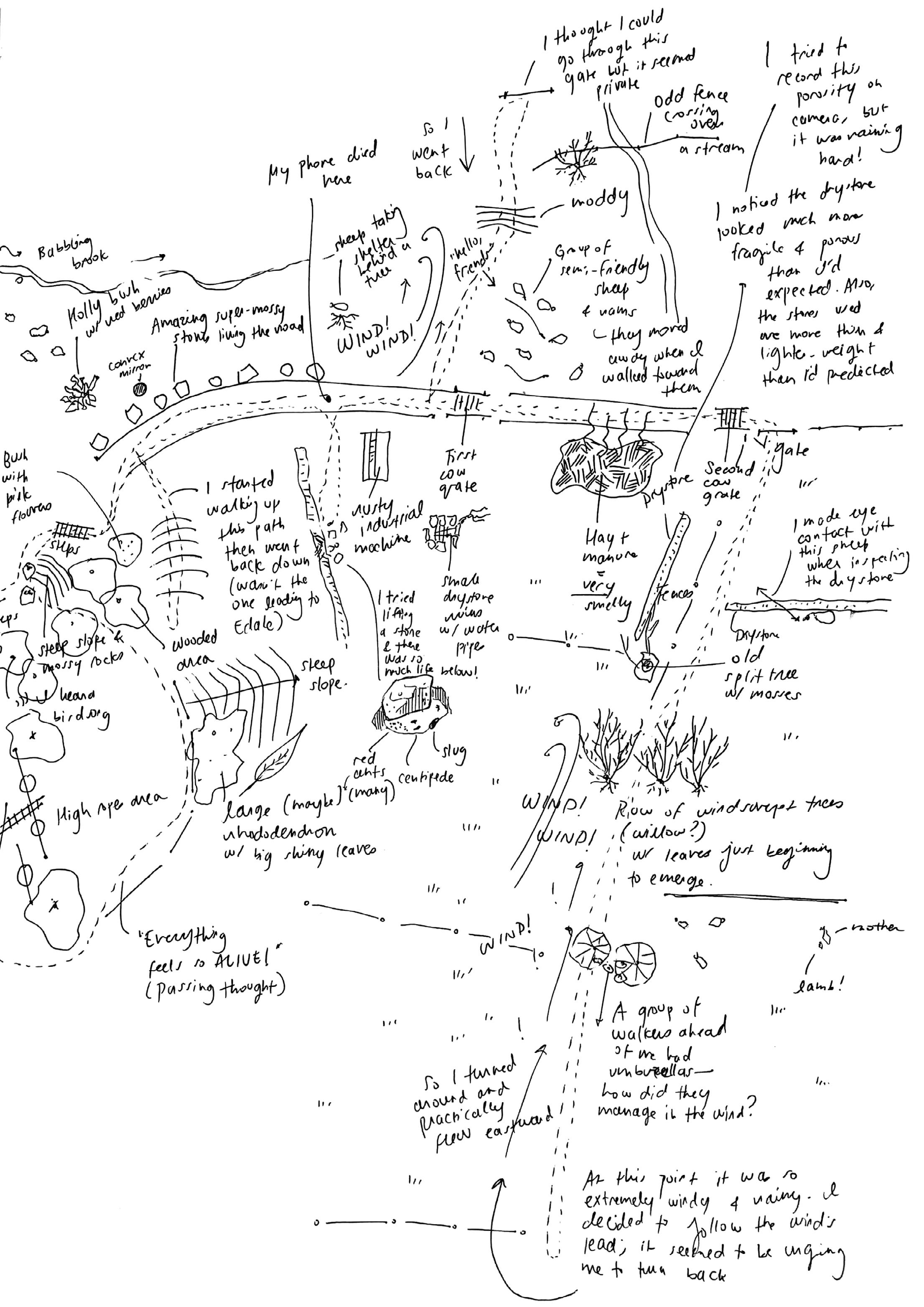

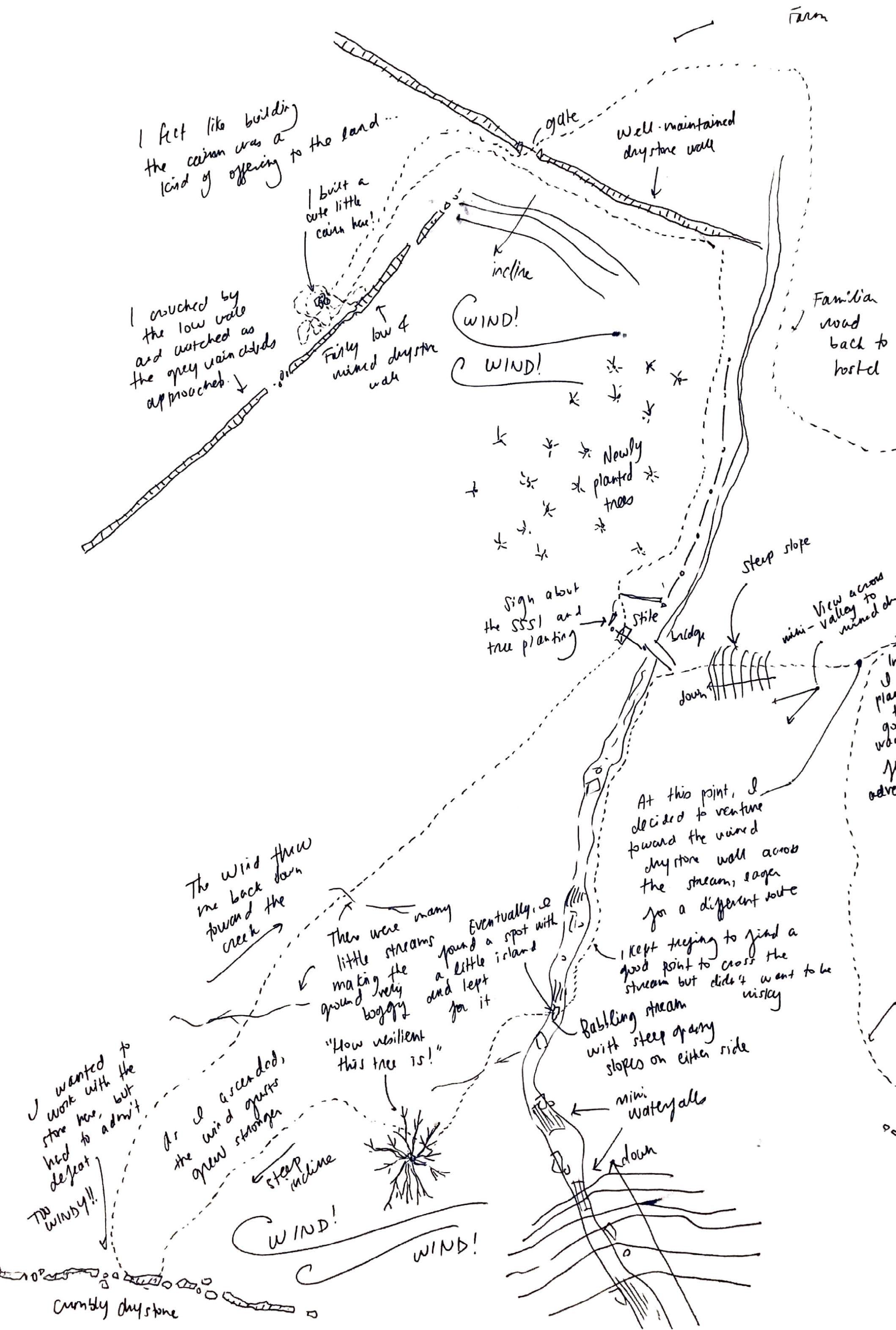

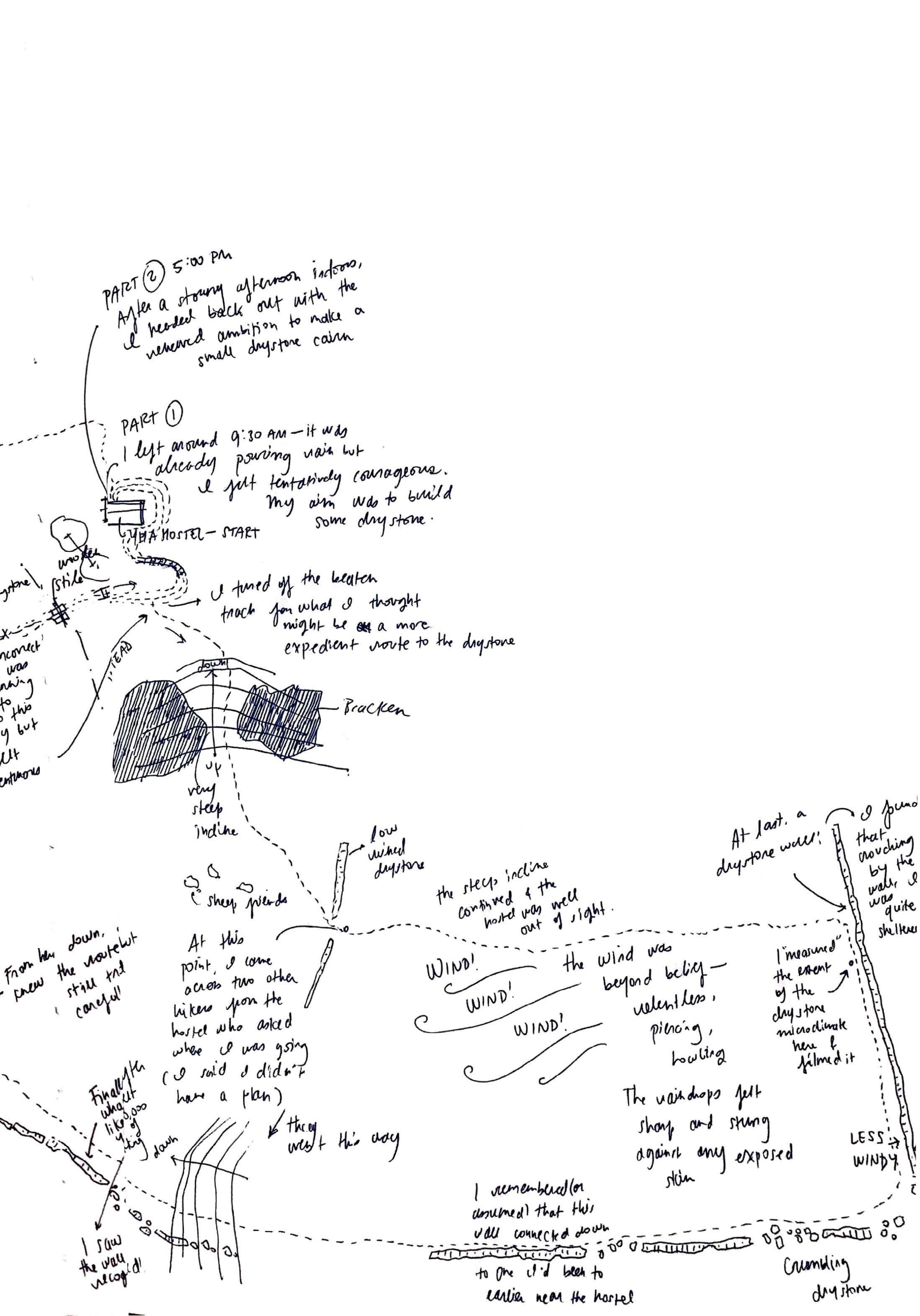

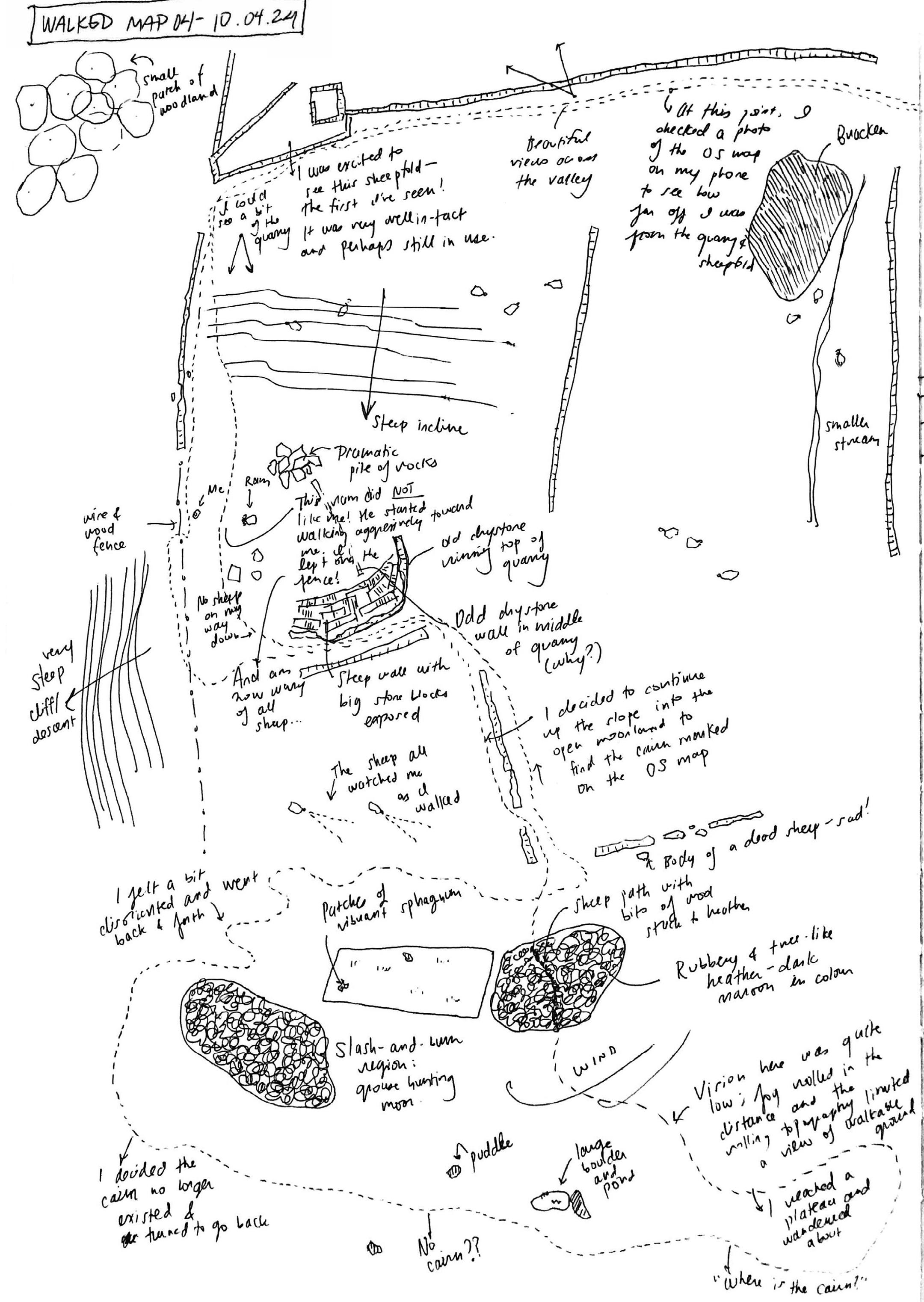

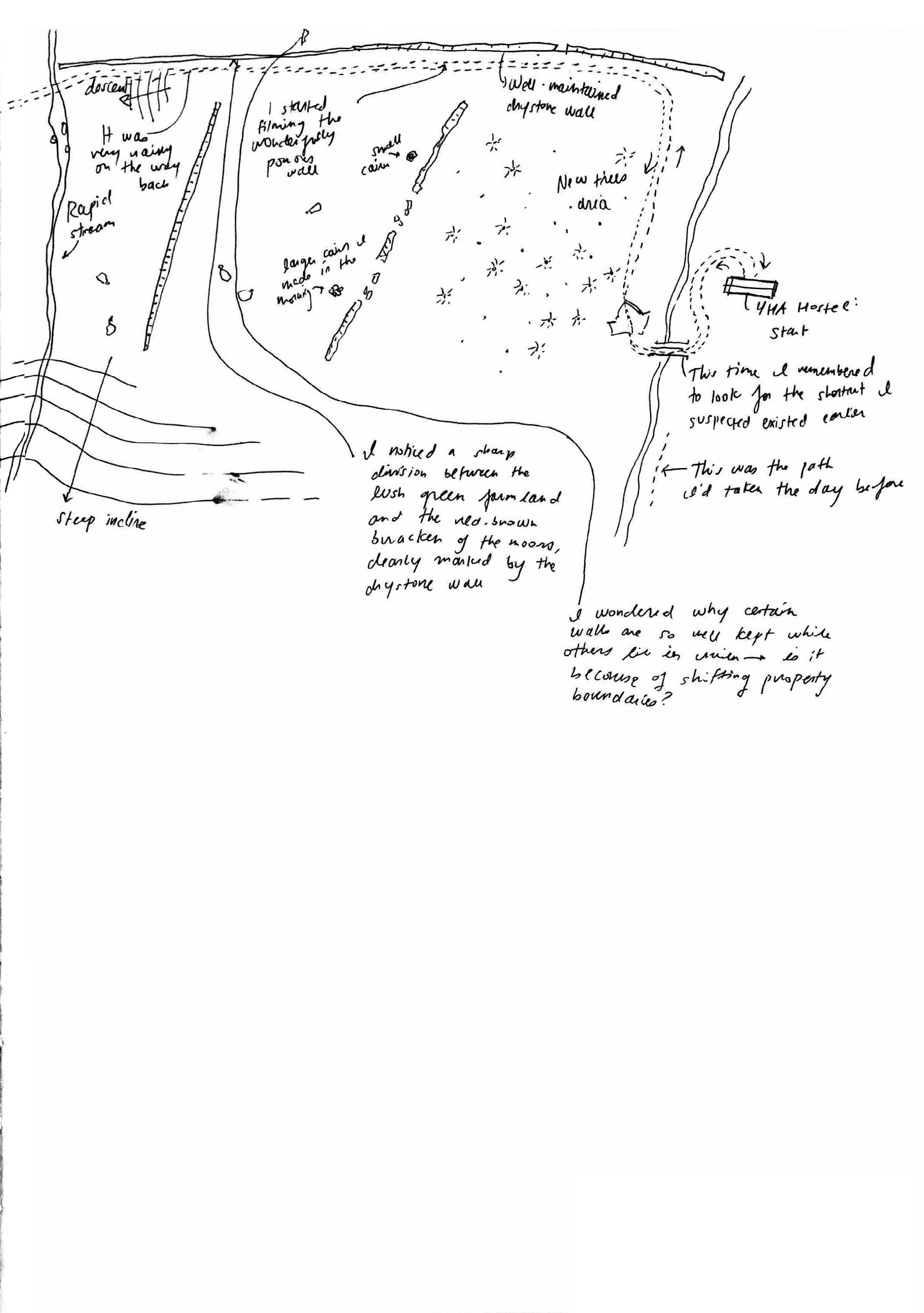

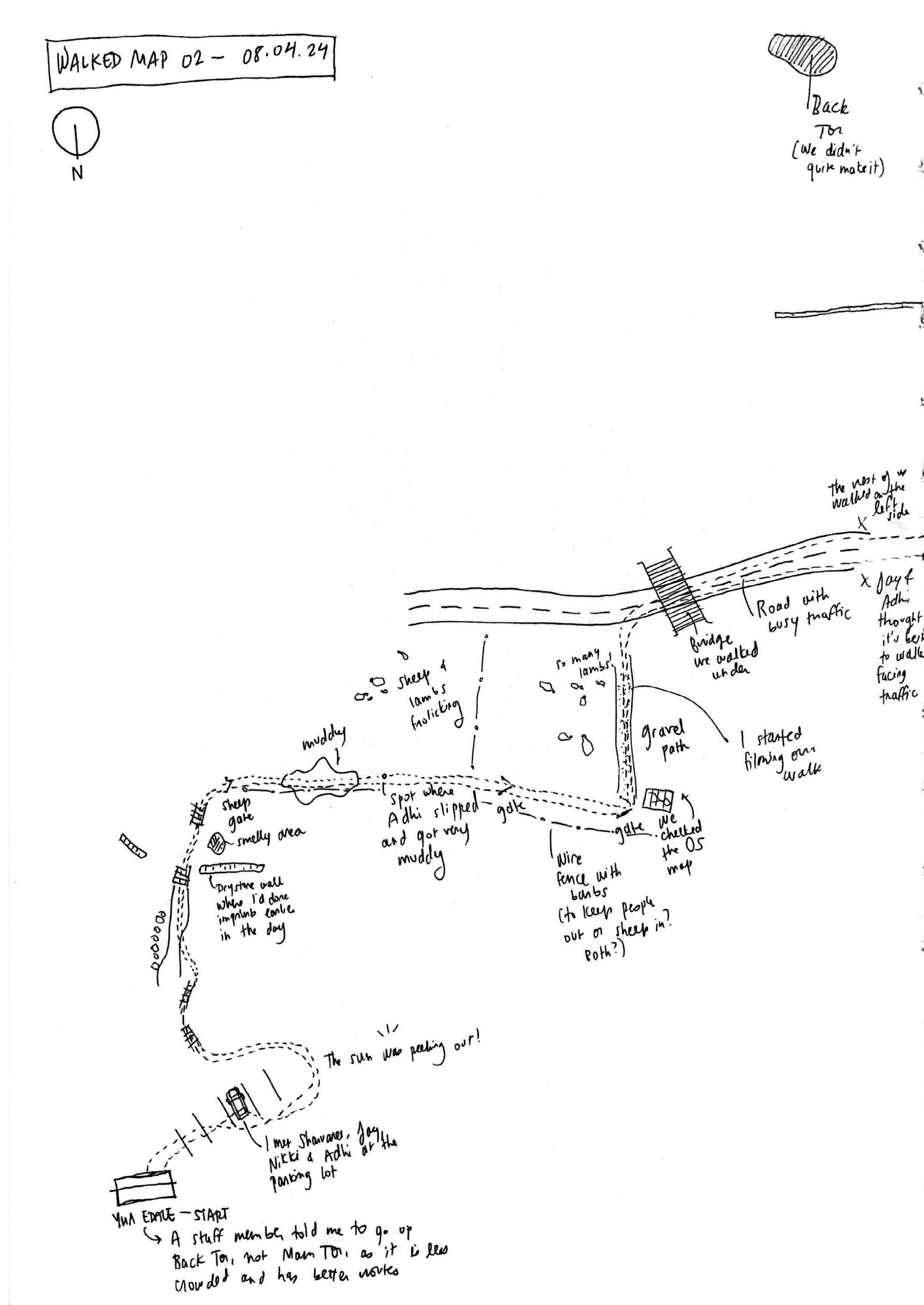

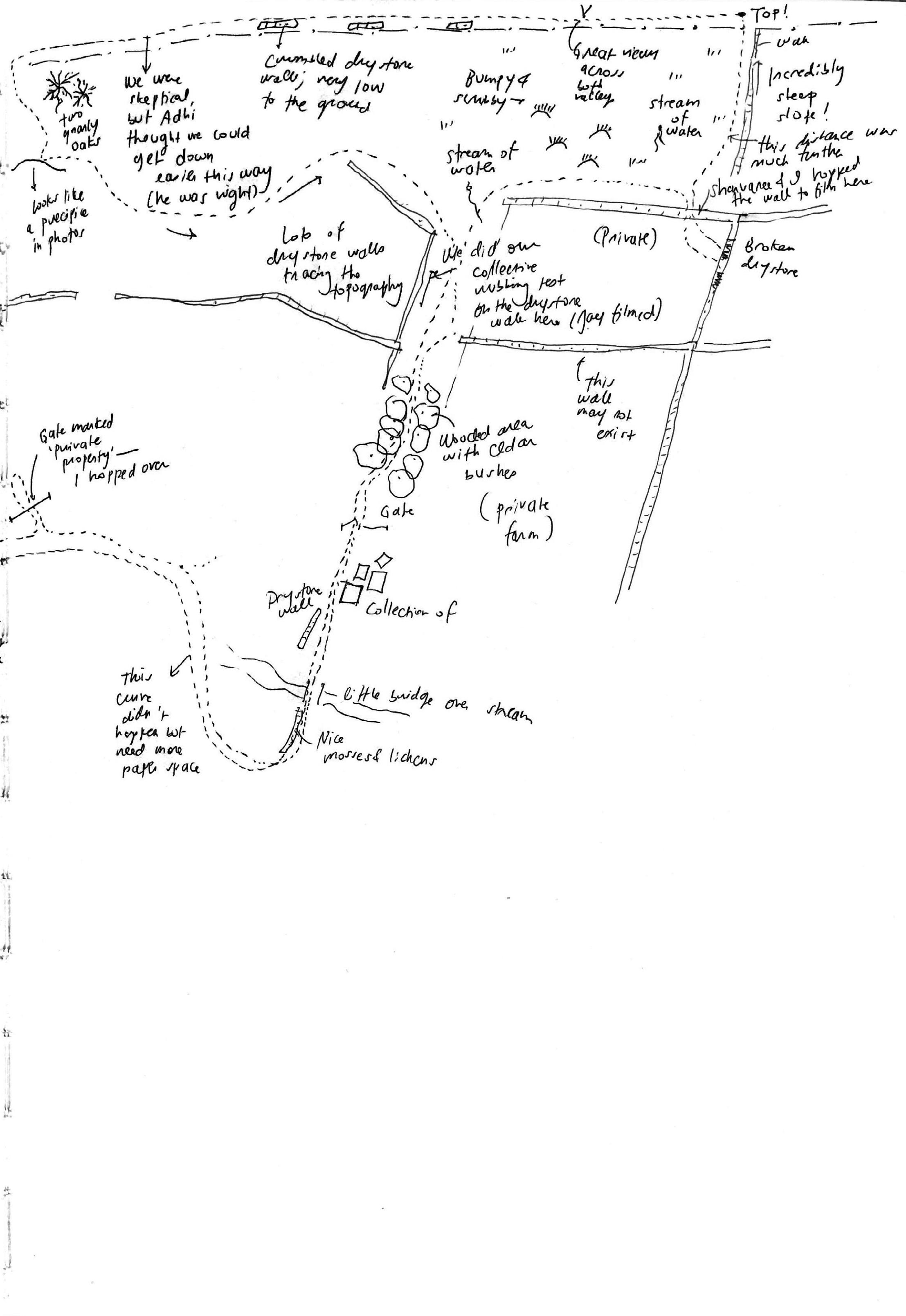

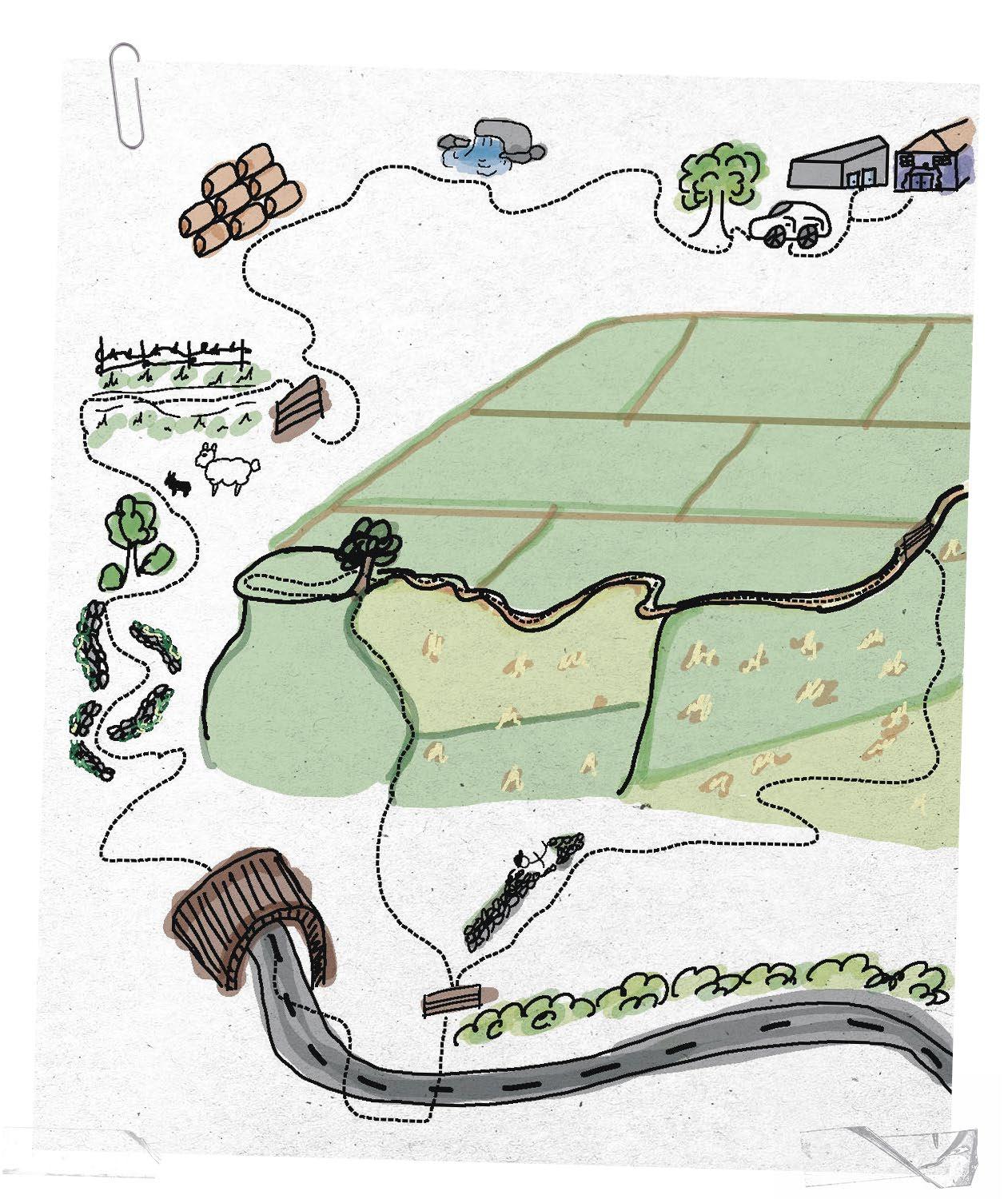

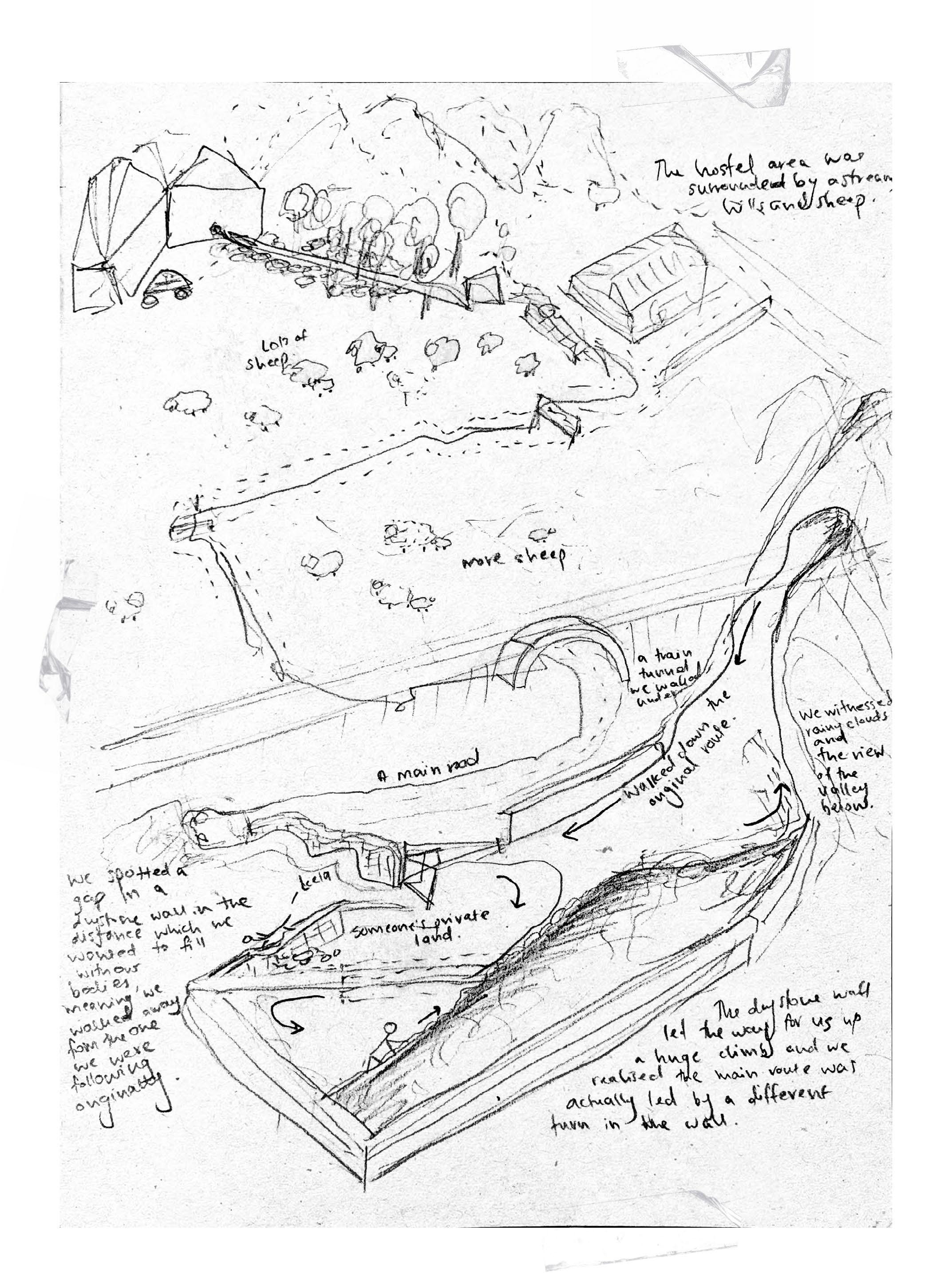

In Chapter C: Convivial Wildness in Drystone Field Stations, I present a series of ‘walked maps,’ mental maps drawn based on my memory of walks just taken. In these temporal and scalar collisions, I note particular moments and affects that remained with me, nearly all of which would be invisible in an ordinary map. Ultimately these mapping methods point to new forms of conservation and caretaking within the landscape through the lens of drystone.

Geological map from Chapter A: Geology and Ecology Walked map from Chapter C: Convivial Wildness in Drystone Field Stations

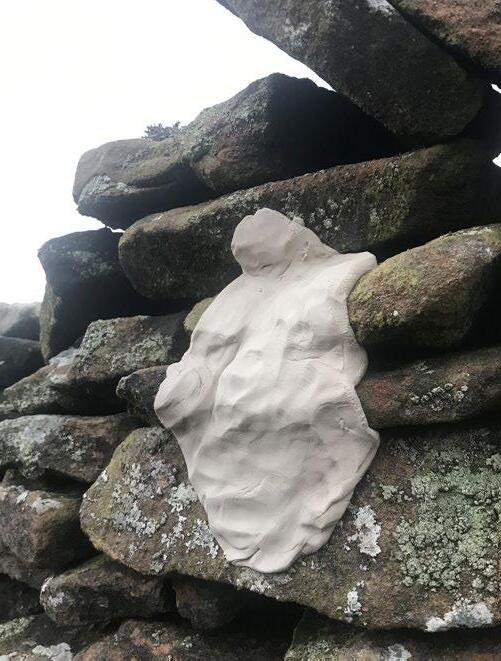

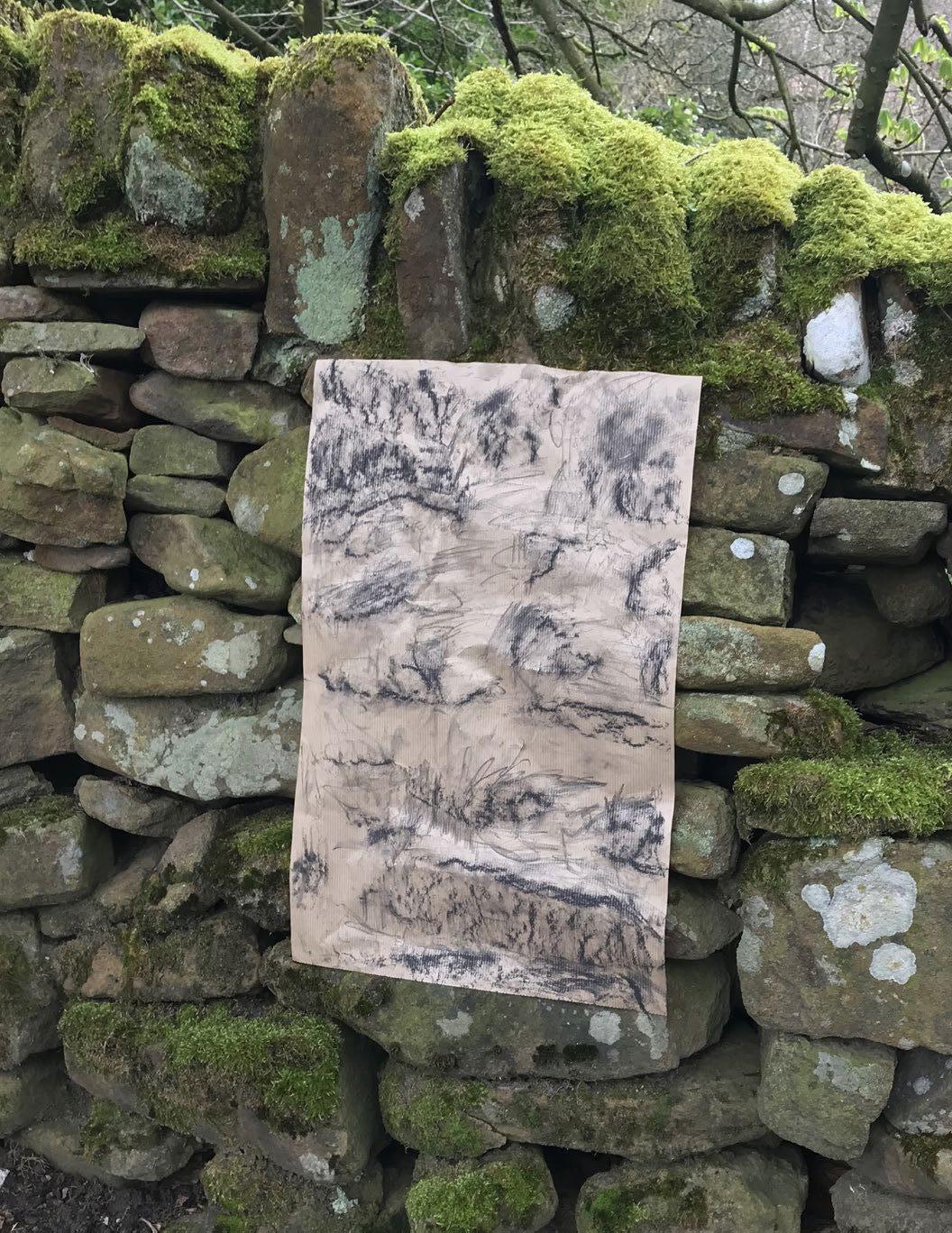

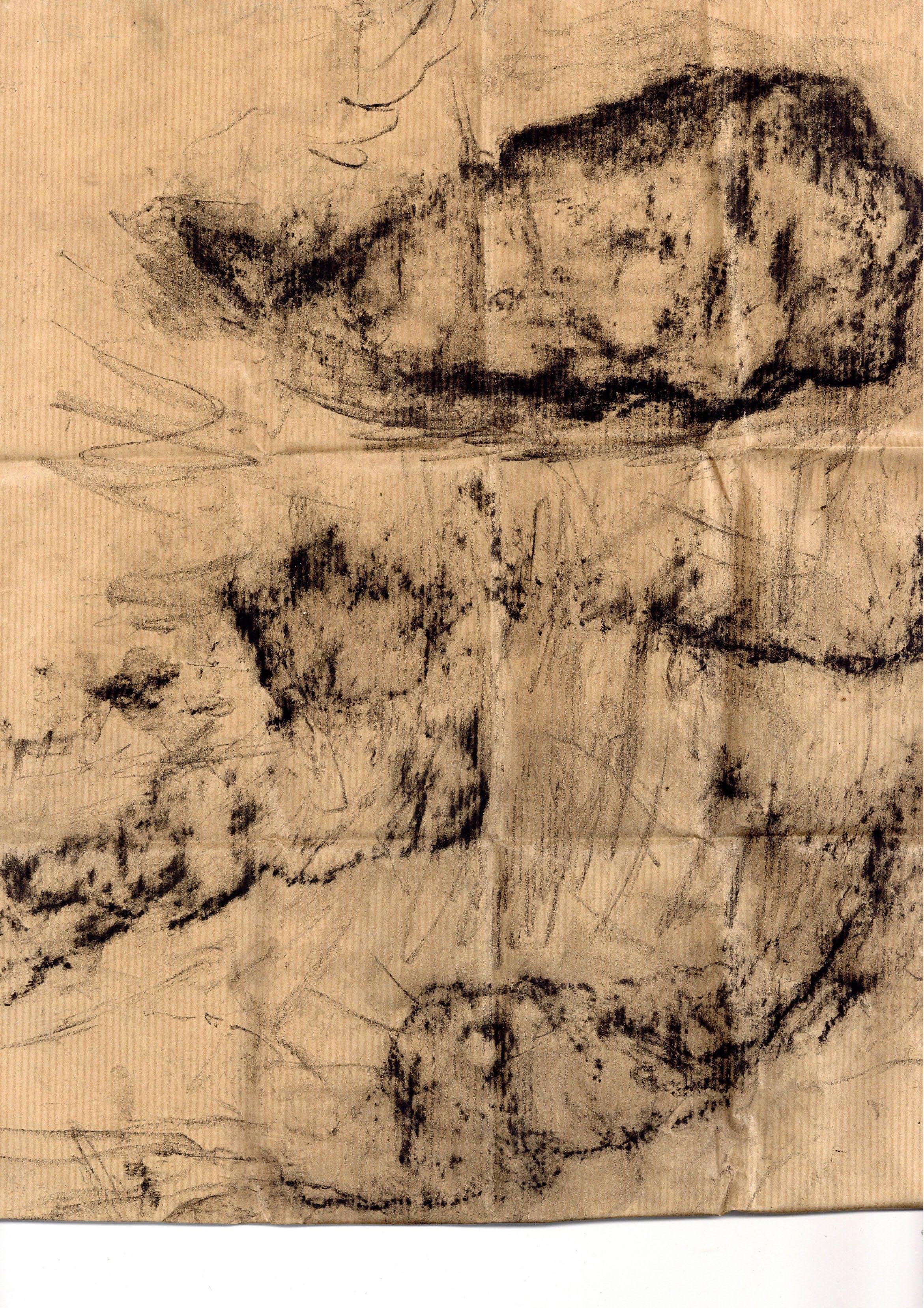

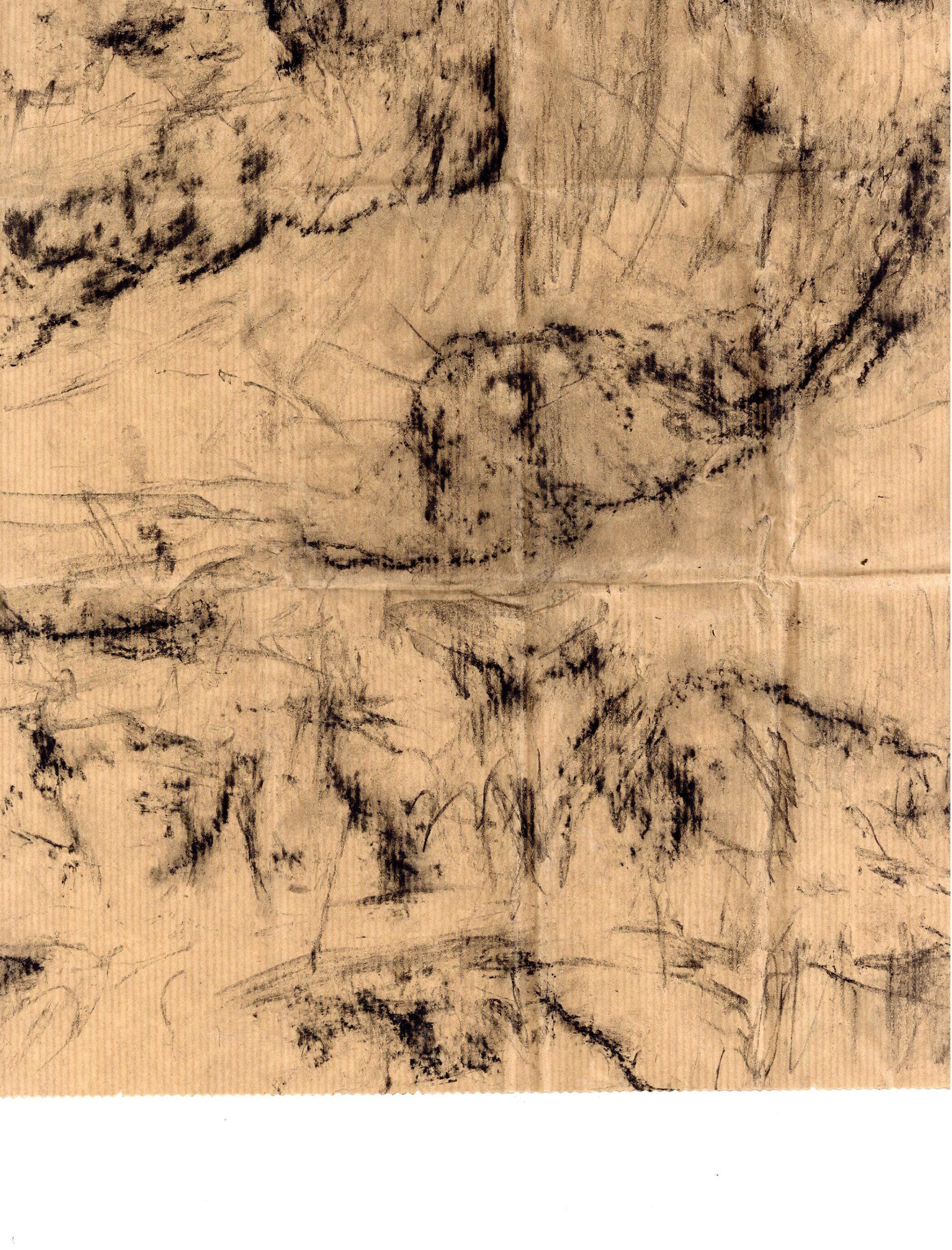

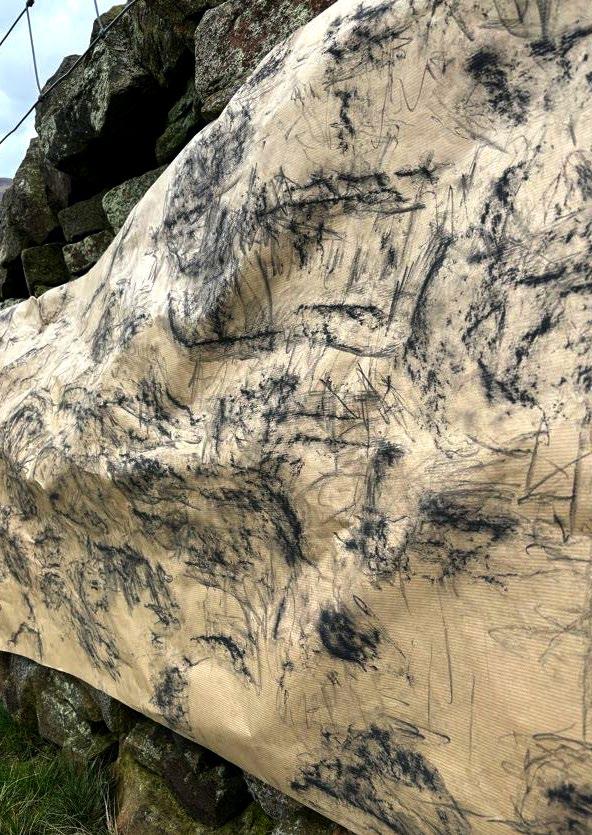

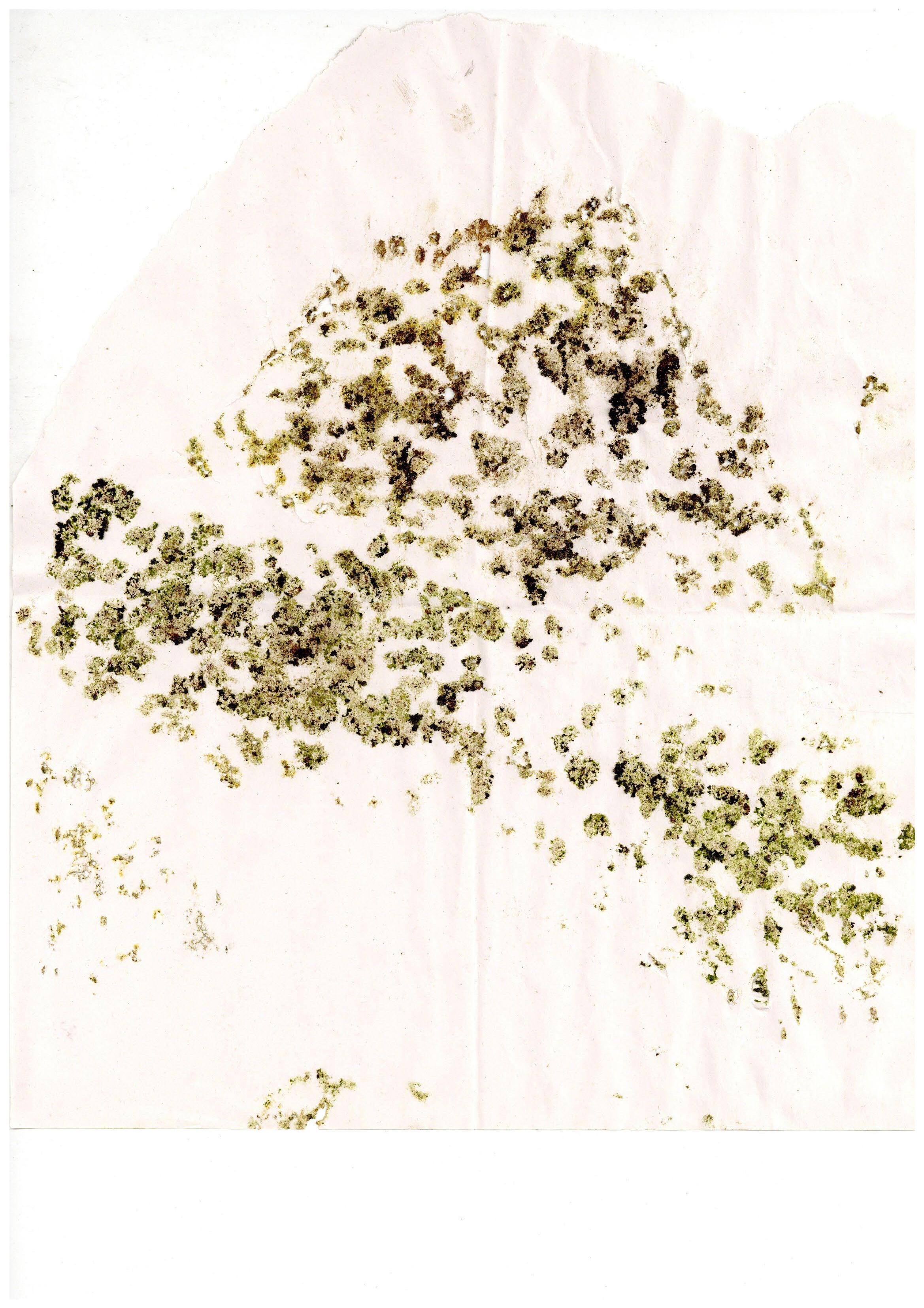

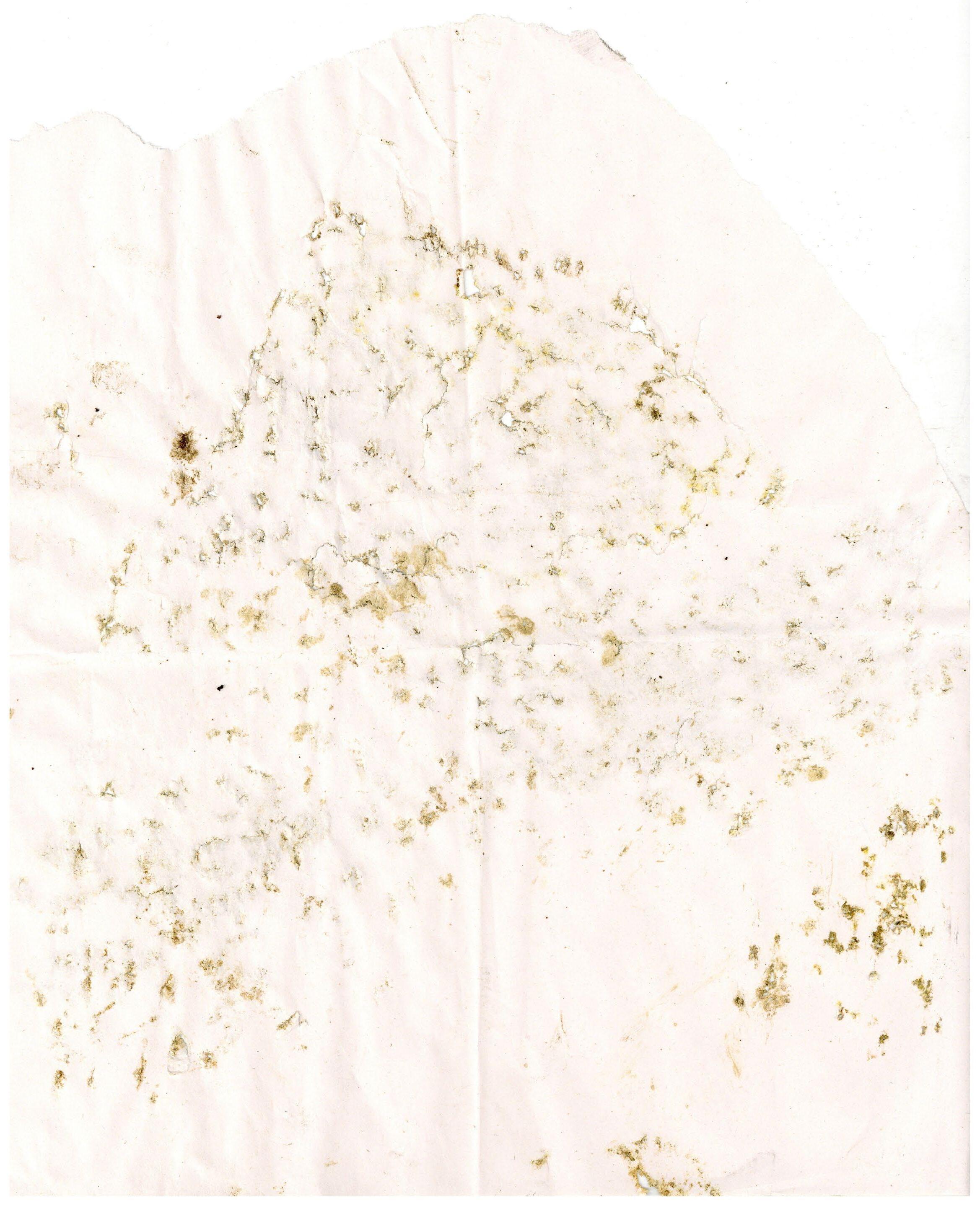

Imprints are another form of critical map that this thesis explores. Viewing landscape as an assemblage of beings and elements shows how different agents are constantly ‘imprinting’ on one another, leaving traces of their presence. For instance, rocks that fall from drystone walls leave imprints in the ground that in turn form habitats for insects.

To visit the landscape for even the shortest period of time leaves imprints: to be in a place is to affect it, and to be in relationship with it. To exhale is to imprint the air with carbon dioxide which may then be taken up by plants; to inhale is to intake the oxygen they create. To walk in a landscape is to compress the earth.

These temporary traces are fleeting and often unrecorded, yet they impact and create what constitutes ‘landscape.’ This thesis presents various strategies of both registering and creating imprints as 1:1 maps.

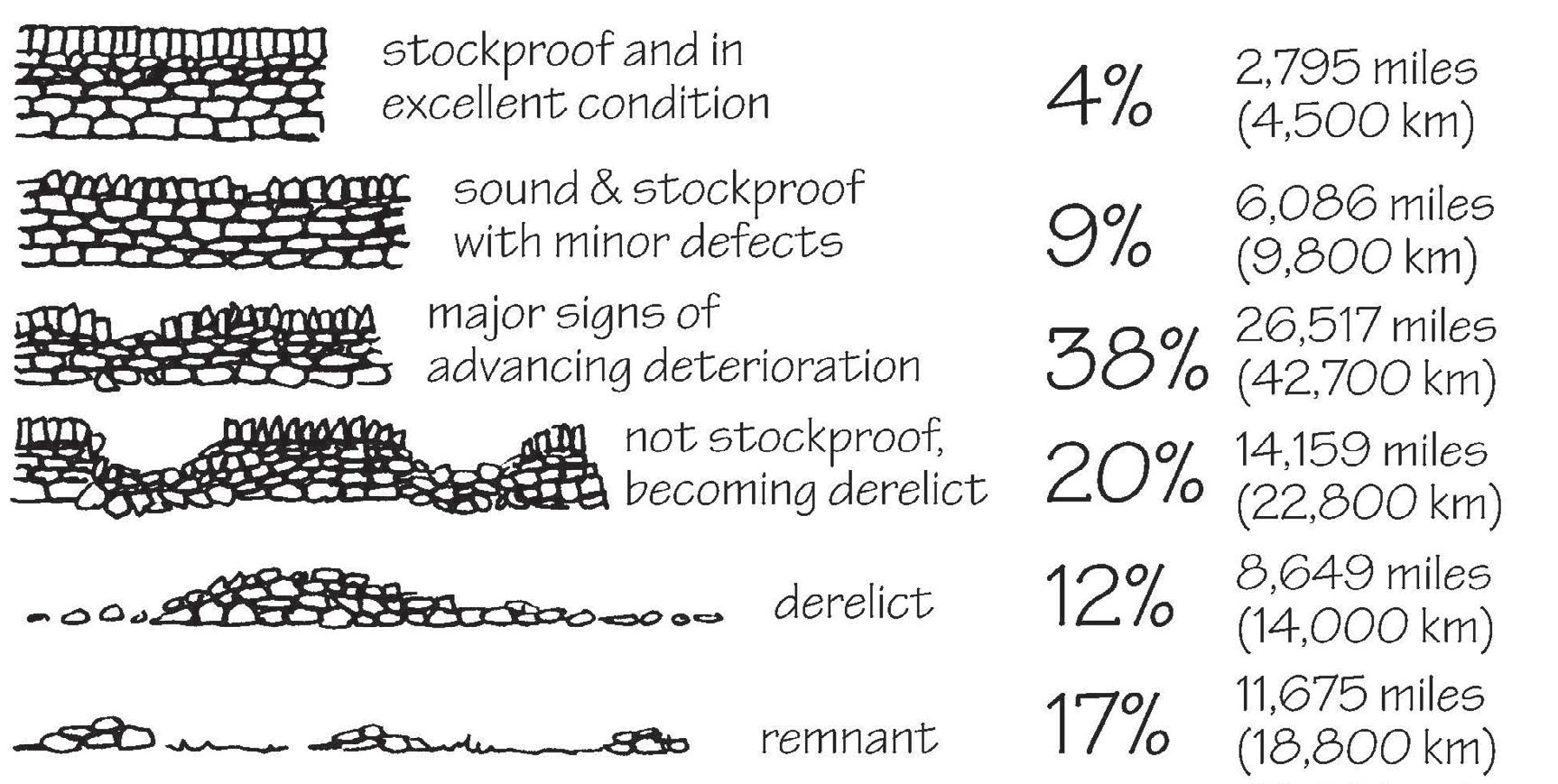

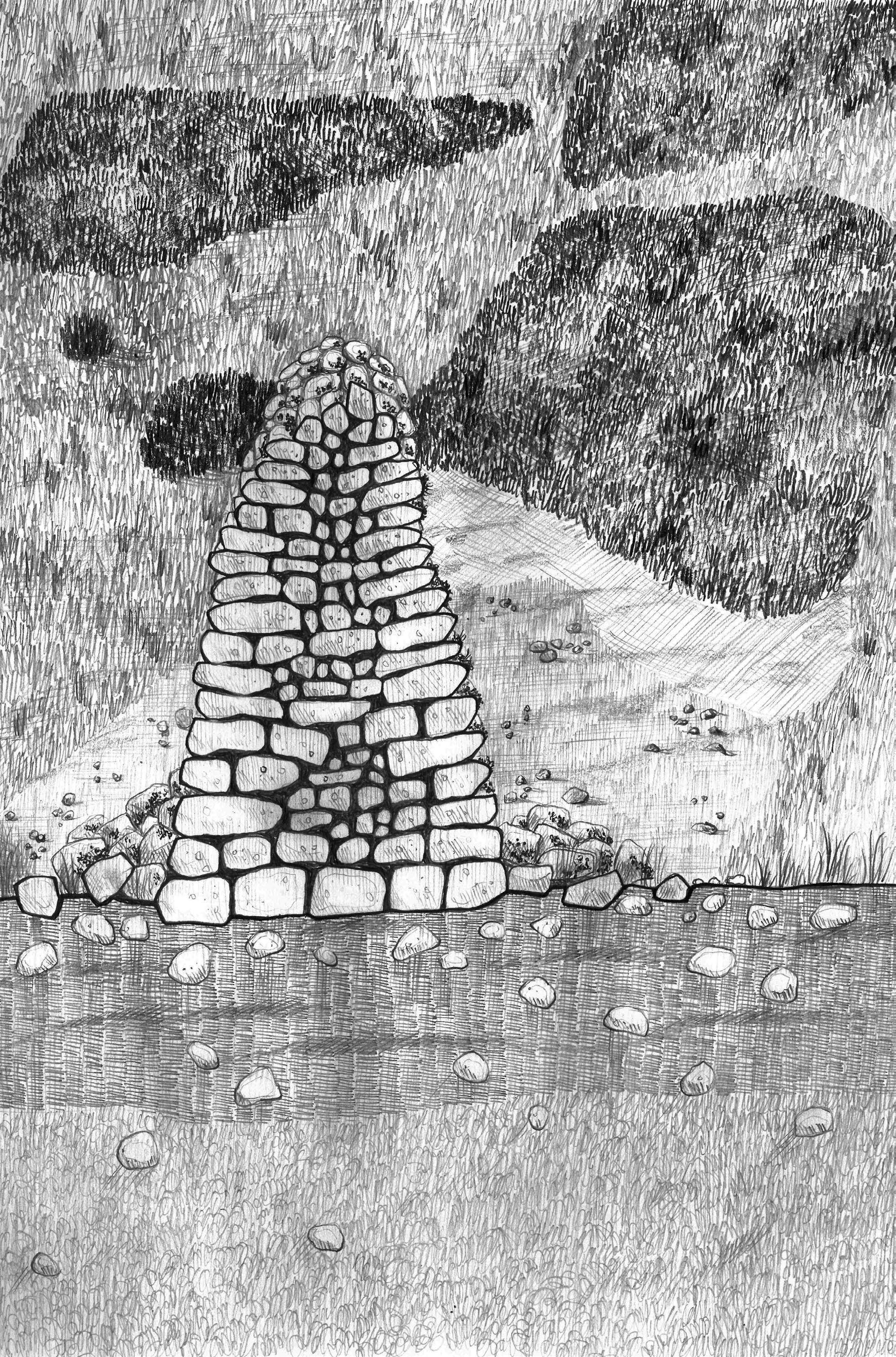

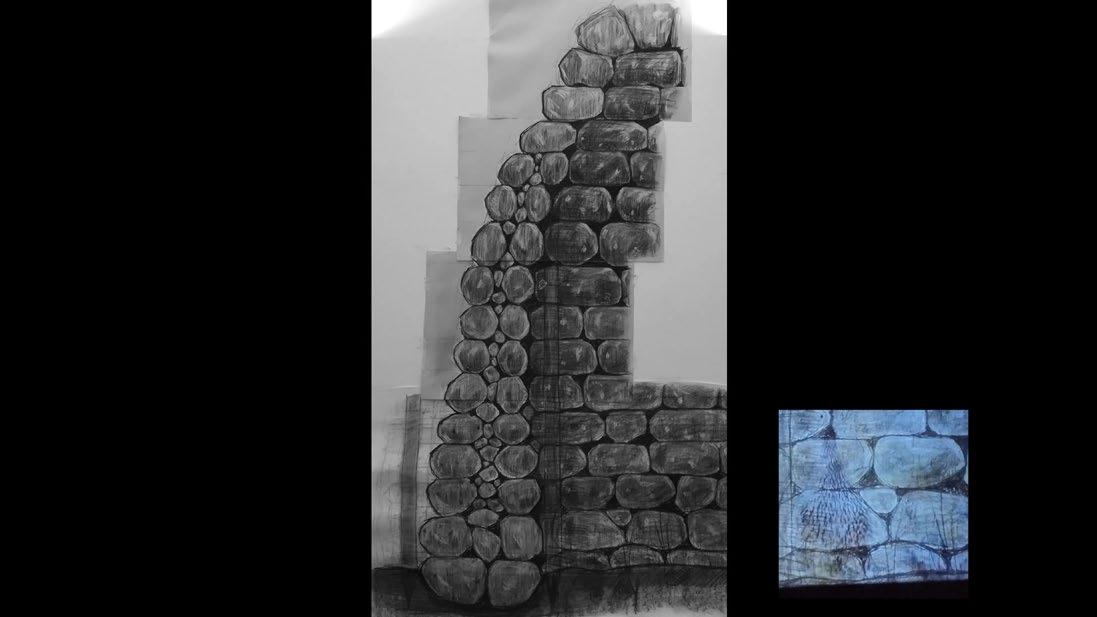

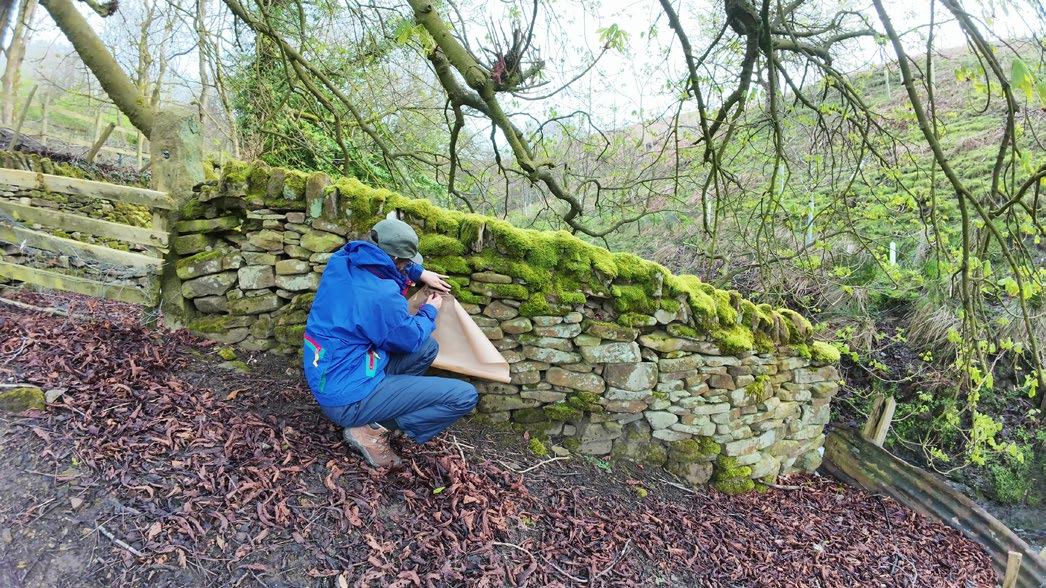

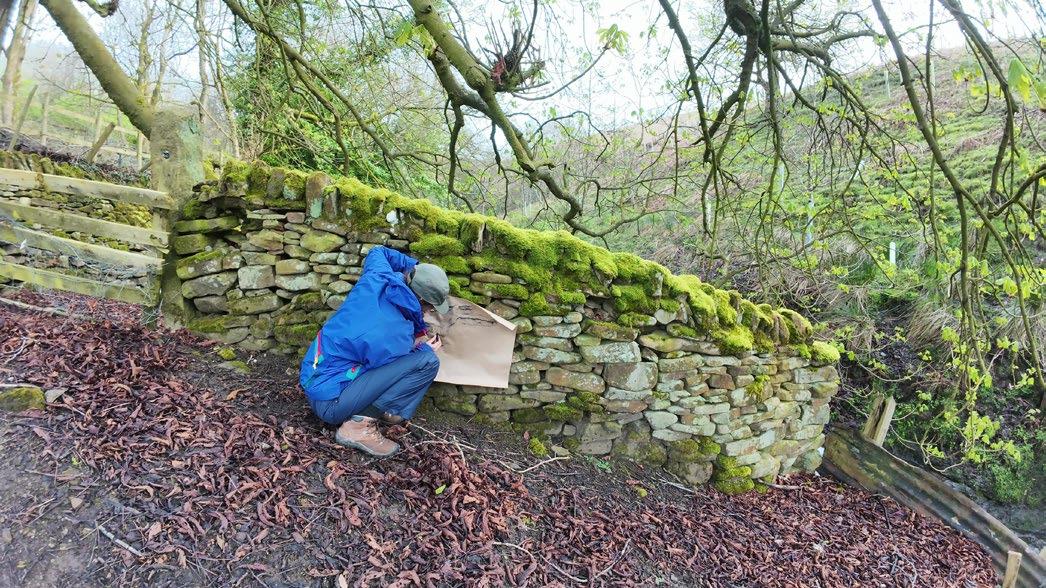

In building a series of small cairns in Chapter B: Drystone Construction, I imprint the landscape with temporary markers. In Chapter C: Convivial Wildness in Drystone Field Stations I further investigate imprint-making methods as maps of drystone walls I encountered, using charcoal rubbings, clay, and hammered paper as media that record imprints differently.

Lichen imprint from Chapter C: Convivial Wildness in Drystone Field Stations

Tracing stones as I build the 100-stone cairn, from Chapter B: Drystone Construction Filming

Strategy 4: Making and Testing On-Site as Situated Practice

Interacting with drystone walls and building cairns, from Chapter B: Drystone Construction

Learning-with drystone and walking in the landscape, from Chapter C: Convivial Wildness in Drystone Field Stations

Situated practice lies between fieldwork, on-site artistic practice, and simply being-in-place. It is a form of intentionally learning-with and becomingwith, to use Haraway’s term, the land and the morethan-human realm to foster situated knowledges. The thesis speculates on forms of ‘living’ conservation as situated practice, undoing the extractive gaze for one of reciprocity and the desire for control for obligations of care.

My five-day trip to the Peak District was a pivotal moment for this thesis: being within the landscape was a process of discovery and wonder, a reckoning with what I thought I knew to form new ideas of the place. Certain elements, such as the wind, became powerful characters within the landscape. In fact,

being immersed in the climatic conditions of Edale valley drove home how variable weather conditions can entirely shift one’s experience of place. These conditions, then, require a different attitude toward design, one that accommodates the unpredictable and makes space for the ambiguous.

Walking in the landscape—and spending hours in single locations in the building of the cairns—put me in relationship with the landscape in a way I had not felt earlier. Even for a moment, I felt part of the place: I cared for it and felt connected to it. This re-orientation to the Dark Peak allowed me to speculate on the design of drystone field stations in a far more realistic manner, making visible the drawbacks as well as the potentials of drystone.

Strategy 5: Case Studies

This thesis employs a series of case studies external to the Peak District region as a tool to learn from the wider context of drystone construction. Given that examples of drystone can be found across the world, in diverse climatic and social environments, there is a rich body of knowledge to draw from. The thesis selects specific studies that directly influence the design of the field stations.

Case studies are useful in providing ideas of the many possible ways of configuring drystone. The Scottish blackhouse, for instance, ingeniously packs peat between two drystone walls to provide thermal mass; this technique could easily be used in the Dark Peak moorlands. The Croatina kazun and the Italian trullo further provide ideas for building corbelled domes, again employing a double layer for durability and weatherproofing.

Strategy 6: Quantifying Information and Questioning Quantification

Quantifying drystone is difficult, given that it is not a standardised material and has no singular construction method. It is a learned craft that takes time and practice, and it is a process of working with rocks of specific and unique shapes, types, and sizes, varying on location. Given these limitations, in certain places within the thesis I attempted to measure or quantify data to give a more realistic idea of working with this material. Any attempt at quantification relies of a series of assumptions that could easily be disproven. For example, in Chapter B: Drystone Construction, I analyse the amount of labour required to construct a field station, estimating how large of a structure could be built over a certain number of days by a certain number of people. This exercise, though useful, shows the impossibilities of quantifying this information with any degree of accuracy. Drystone is necessarily sitespecific and time-specific, and its construction process varies greatly from person to person.

Measuring drystone heights, from Chapter B: Drystone Construction

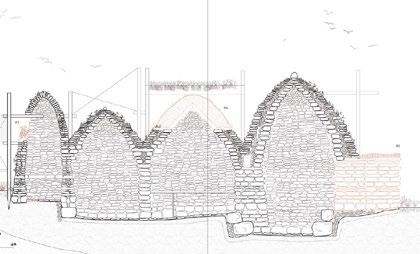

Kazun case study, from Chapter B: Drystone Construction

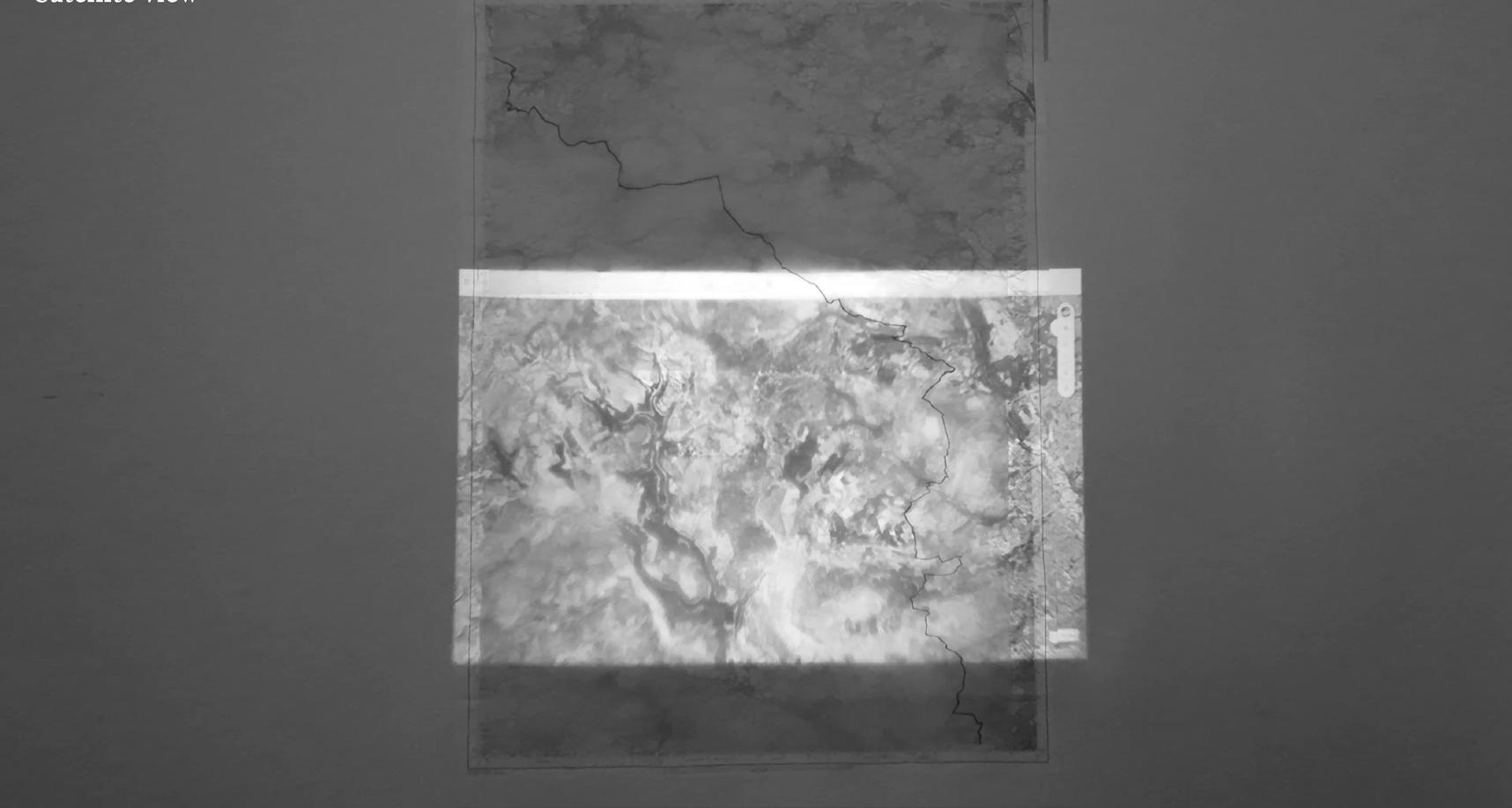

An Introduction to the Peak District

This first filmic mapping exercise enters the Peak District via the ordnance survey. Through this film, I challenge and blur the fixity of the survey by covering it in tracing paper and drawing over it in charcoal. By slowly revealing certain elements called out in the map, I animate the static map to set the scene for the project.

+ The Peak District is Britain’s first national park, officially designated in 1951 after decades of working-class led activism called for recreational access to the privatized countryside. In effect, the national parks attempted to reinstate access without the commons, where legacies of enclosures are prominent in the gritstone walls stitched across the landscape.

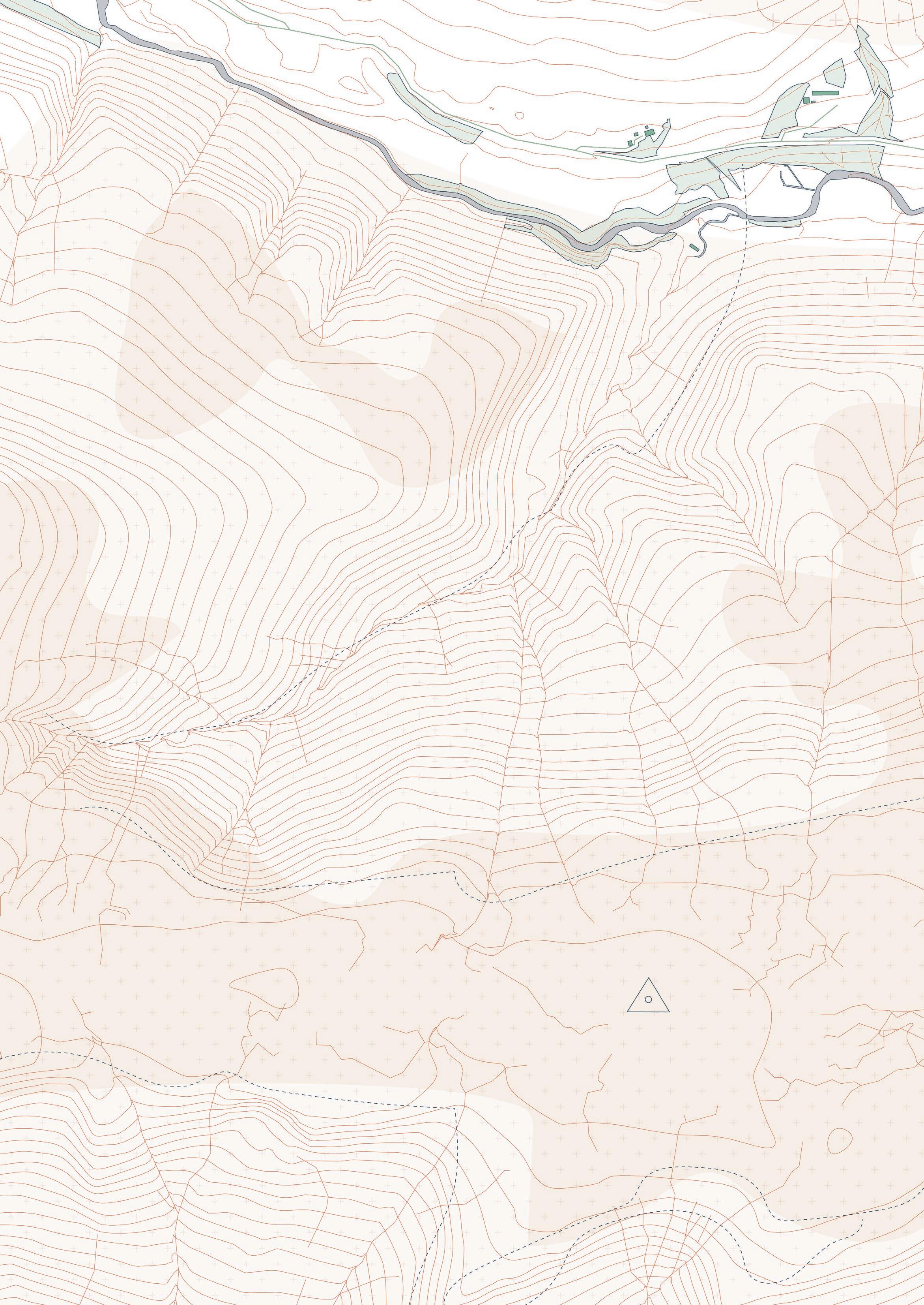

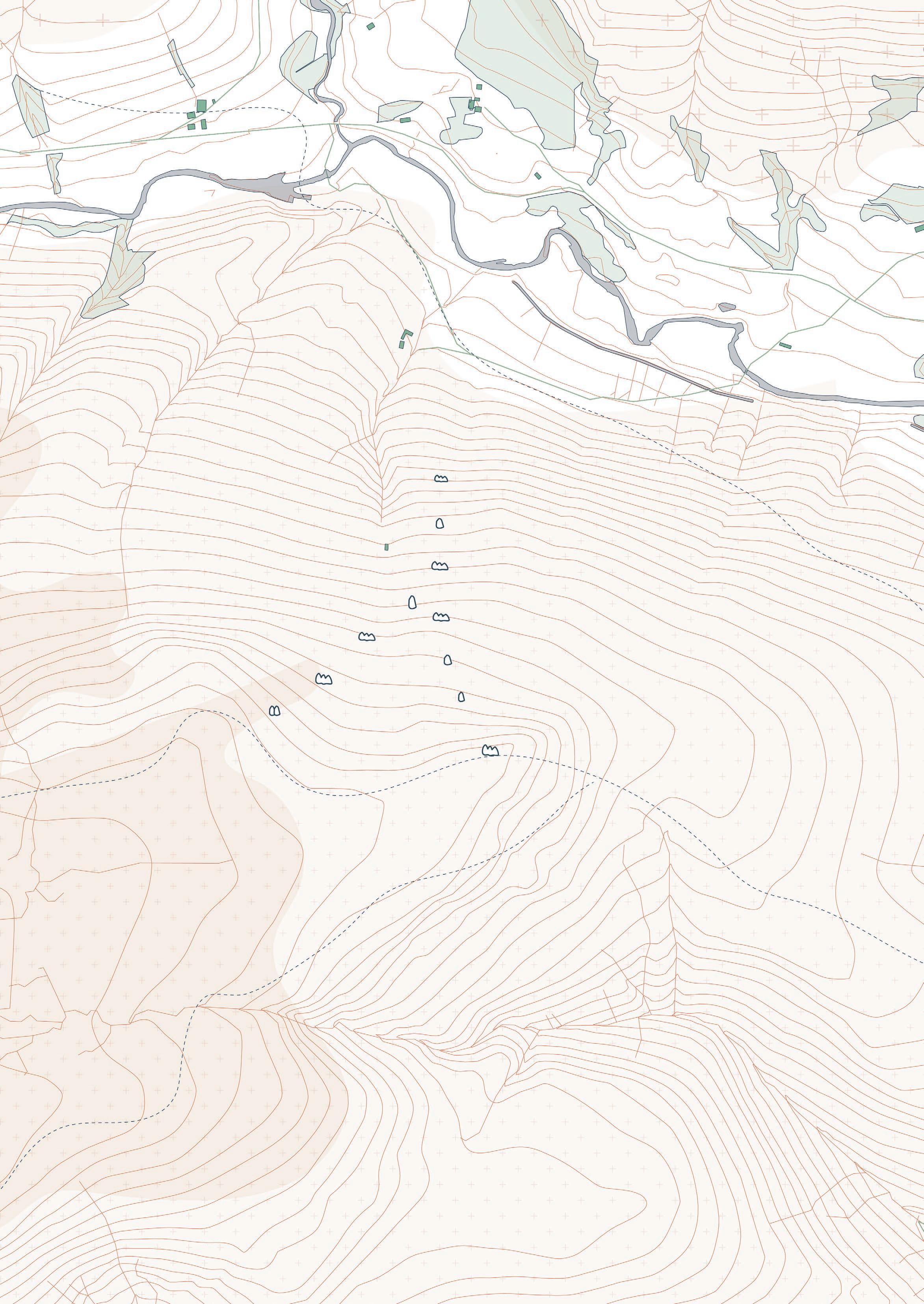

+ The project begins by zooming in to the northeastern region of the Peak District, designated by the National Parks authority as the Dark Peak Yorkshire Fringe landscape character region.

+ This region has been mapped by the Ordnance Survey as the “Dark Peak Region: Kinder Scout, Bleaklow, Black Hill & Ladybower Reservoir”

01. Peak District National Park

02. Dark Peak Yorkshire Fringe Landscape Character Region

03. Ordnance Survey “Dark Peak Region”

+ The national park boundary cuts through this region, shown as a red dashed line on the OS map.

+ If we switch to a satellite view of the landscape, the park boundary all but vanishes.

+ Situated between Manchester and Sheffield, the Peak District is an industrial landscape riddled with disused quarries, mills, and mineshafts.

04. Peak District National Park Boundary Line 05. Satellite imagery 06. Industrial markers

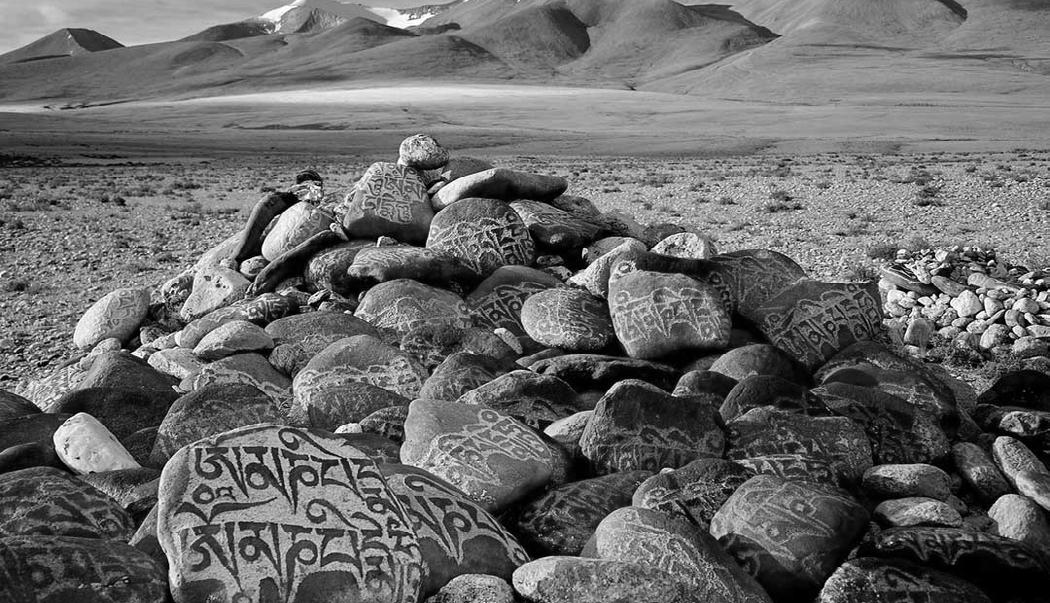

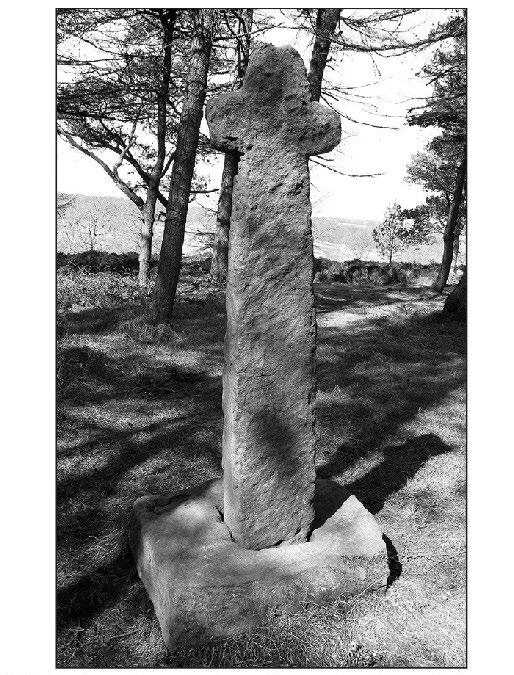

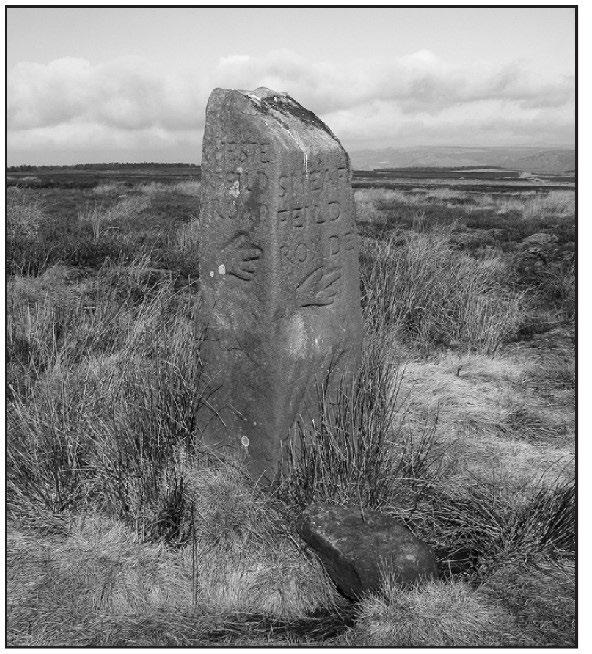

+ Human traces date back millenia in the landscape, where scattered marks on the OS map indicate lost rituals and lifeways in stone circles, burrows, cairns and tumuli.

+ These were olds modes of wayfinding, predating the map’s allknowing view.

+ The picturesque view creates the illusion of access, while in reality the landscape is privatized in a patchwork of enclosures. Much of land is owned by water companies, charitable bodies like the National Trust, grouse hunting estates, and private landholders. Under the private property regime, access to land is fraught territory, leading to ongoing right to roam activism.

07. Ancient markers: old stones

05. Ancient markers: cairns

06. Land ownership

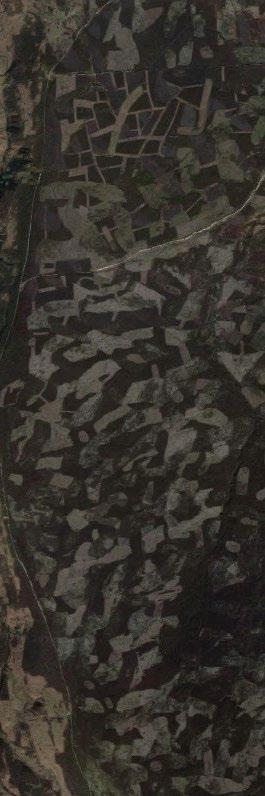

+ Moorland landscapes are scarred by grouse hunting, where slash-and-burn marks are made visible in the satellite view.

+ This is detrimental to the rich peat soil covering much of the region that acts as a carbon sink.

+ Though lending the illusion of a wild landscape, the moorlands are highly maintained and preserved toward a certain image. Much of the peak district is monocultural, a mosaic of grassland, heather, and conifer plantations. With much of the land dedicated to sheep grazing, plant, animal, and insect life is limited.

10. Grouse hunting scars

11. Peat soil

12. Conifer plantation

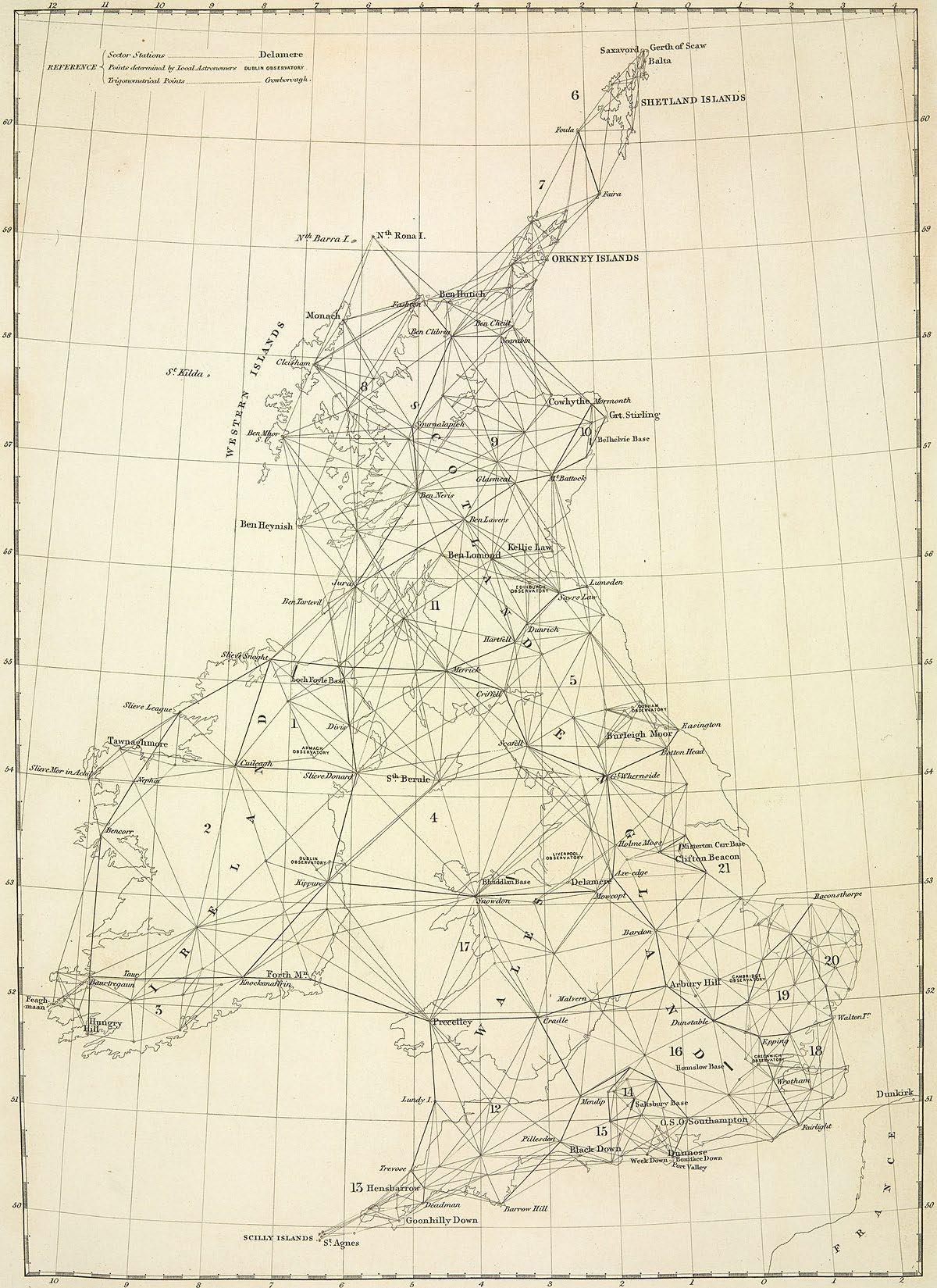

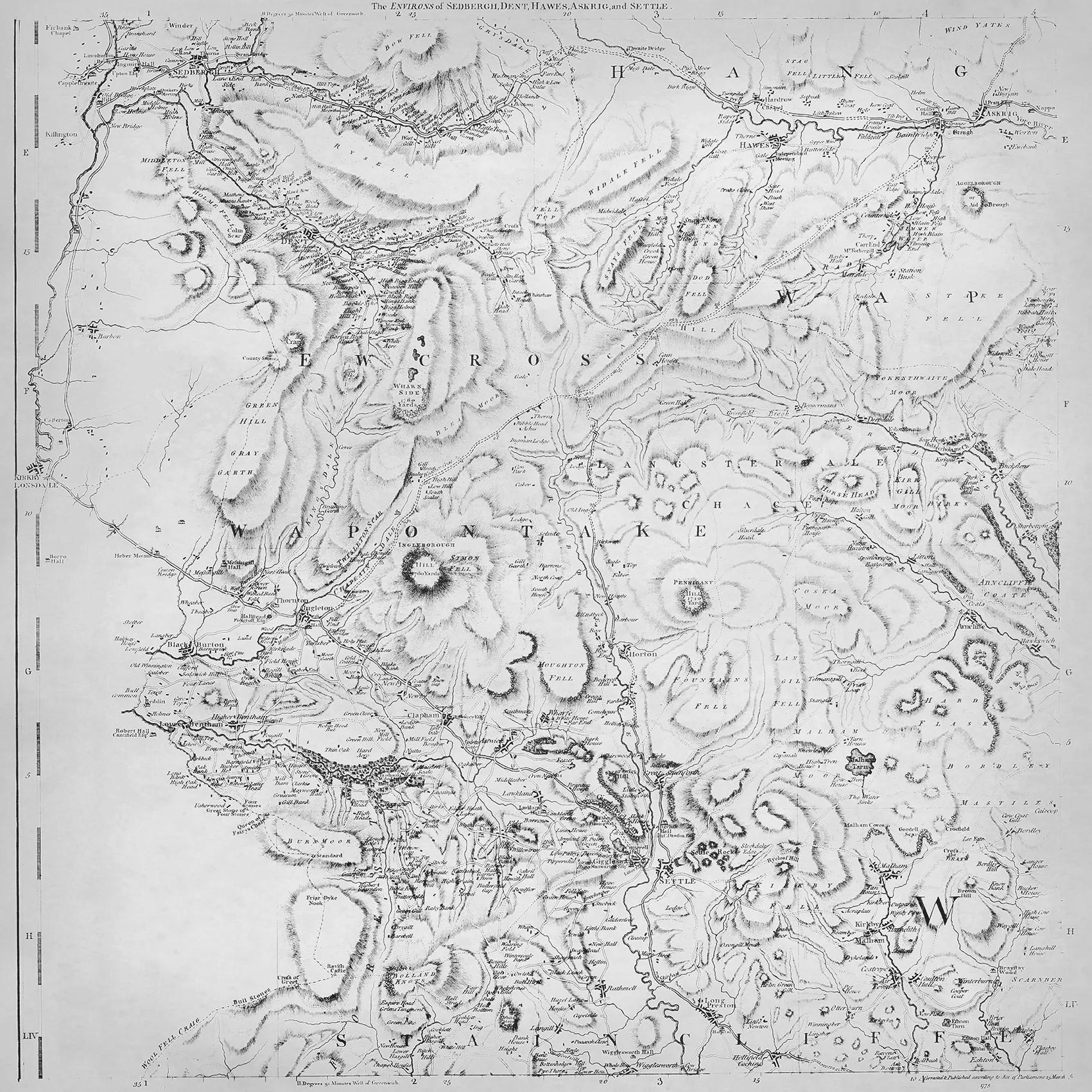

If wilderness is the most unmappable territory, the last British wilderness officially vanished in the mid-19th century when the first standardized mapping of the entire British Isles was completed. The Ordinance Survey, began as a military undertaking, represents the complete objectification of the English landscape.

The survey fabricates a relationship to landscape, one that operates using what Donna Haraway terms the ‘god trick’: the omniscient and objective gaze wearing a mask of neutrality. In its flattened aerial view, the god-trick map projects the division of property and demarcates conservation boundaries, drawing a line between landscapes deemed worthy and unworthy of saving from environmental harm.

In challenging the top-down map, this thesis speculates on alternative forms of mapping landscapes that are embodied, situated, and temporal, rejecting the static for the dynamic, the distant for the tactile, and the measured for the sensed. In doing so, ideas of conserving ‘nature’ shift from an administrative and legalistic approach to a new way of being-with the more-than-human realm, seeing ourselves as part of and with obligations to what we term ‘nature’ and the entanglements it entails. In dissolving the God-trick map, we must see ourselves as part of the land, not removed from it.

01. Ordnanace survey triangulation map

Blurring the Map

What happens when lineweight meets landscape? I enter the project by exposing the paradox of drawing lines demarcating publicly accessible land. In this filmic mapping exercise, I interrogate the boundaries that appear and disappear when zooming into the ordinance survey.

The projected map meets the fuzzy charcoal line drawn on paper hung in the AA, mirroring the abstracted way in which a map constructs landscape. Through a process of projecting and overlaying the same map as it increases in scale, boundaries begin to blur as they interrupt one another. This is a temporal drawing, which poses a counter-narrative to the god’s eye map, exploring a layered and multi-scalar mapping method.

As we zoom in, the boundary that marks publicly accessible land is revealed as a thick margin measuring 28m, blurring the binary conditions of private and public, trespass and right to roam. This mapping method is projective, exposing landscape as a construction so as to redefine relationships to it.

I start by projecting the ordnance survey map onto a wall in 33 Ground Floor Front on a Sunday in February. I begin by giving the paper a rough

as it appears almost as though I am drawing these lines out of thin air, as if I have somehow internalised the map rather than merely tracing where drawing a charcoal line is fuzzy, thick, and smudgy: an expression of my hand holding charcoal pressing on cartridge paper. I draw the boundary becomes larger and the object of my attention. It gradually grows, dominating the page, before swallowing it entirely. In this dark

rough charcoal texture, then realise that this makes the projected map washed out are hard to see. This adds an unexpected layer to the film,

it. I can’t draw all the lines, so I must select certain ones to focus on. I make clear this process of selection that the God-trick map obscures,

the fine straight lines of the OS quadrants with a ruler, and shade in the reservoirs to indicate their relative depth. As I zoom in, the access

void - inside the lineweight - is a liminal zone, devoid of signifiers, upon which we can begin to project our alternative imaginaries of the

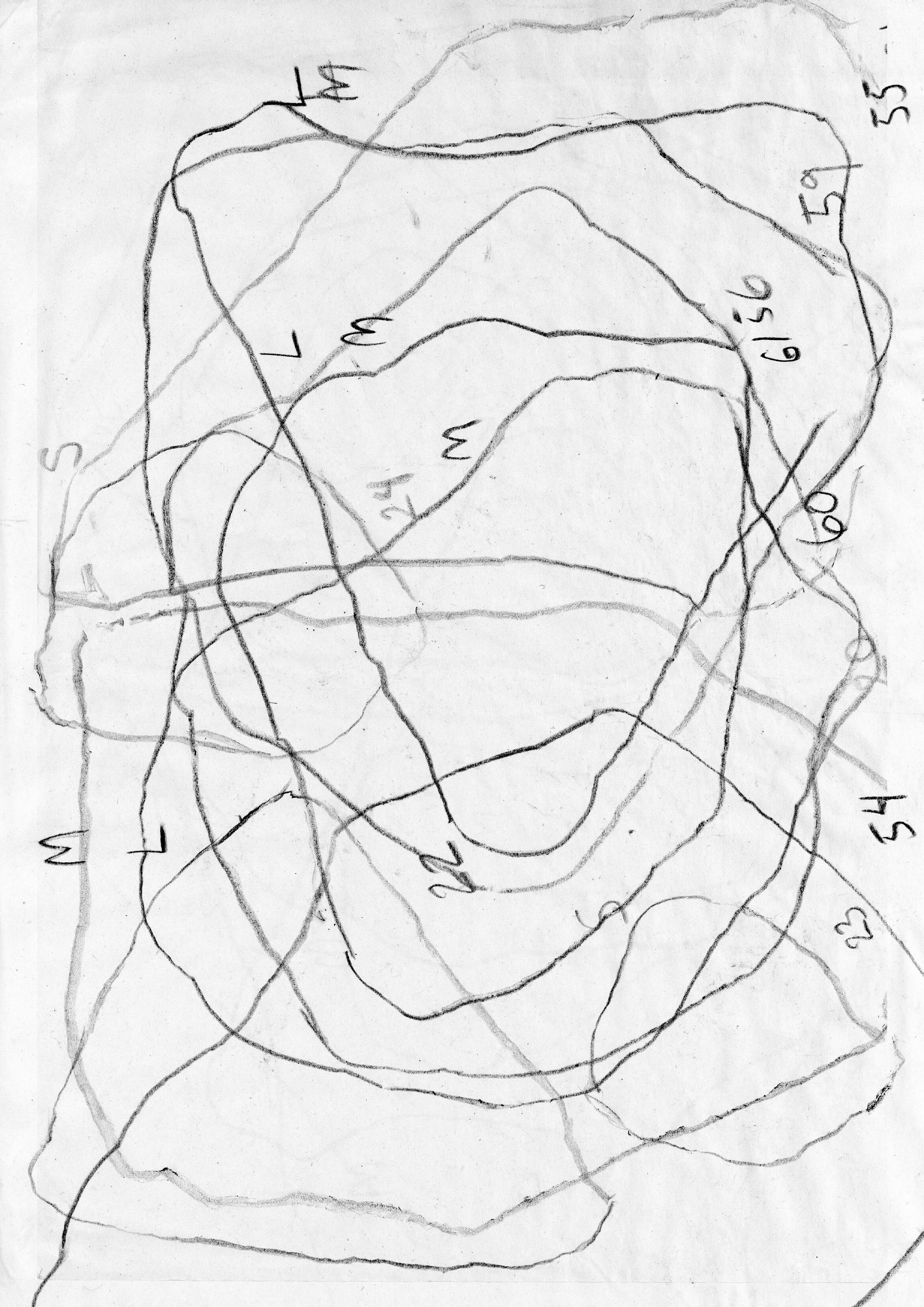

Dissolving the Picturesque Frame:

Representing Landscape and Redefining Wilderness

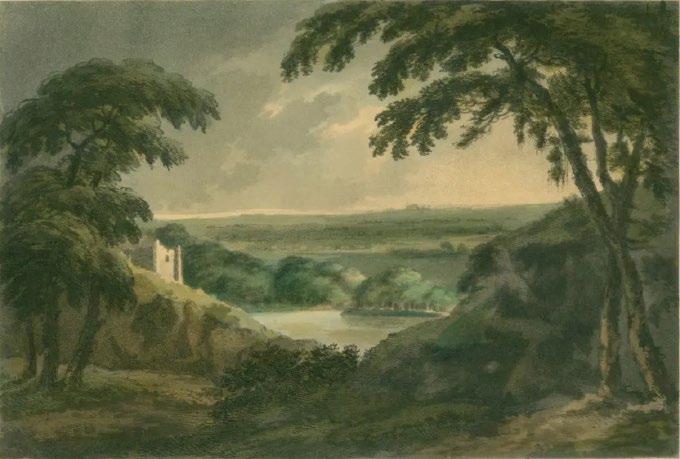

The 19th century European Romantic movement saw the division of landscape into three categories: the sublime, the picturesque, and the pastoral. These seemingly benign designations emerged from a violent framework of the categorization of people, plants, animals, and land, that was an imperial imperative. Land was categorised in terms of productivity and exploitability, translating into the degree to which they were considered scenic, and thus merited conservation.

The romantic era found beauty in the domesticated agricultural landscape of the English countryside and sublimity in untamed, “wild” landscapes, deemed closer to God and beyond the scope of human comprehension.

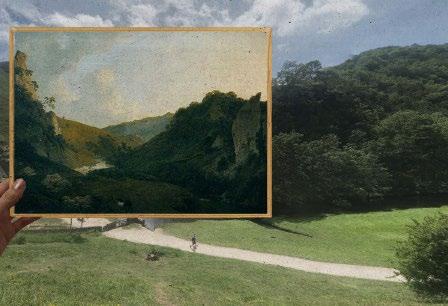

The picturesque movement, made popular by artists such as William Gilpin with his 1782 book “Observations on the River Wye,” commodified landscapes for their painterly qualities. In it, he acknowledged the distortions of the picturesque, declaring that nature ”is seldom so correct in composition, as to produce a harmonious whole,” so the role of the painter is to tastefully manipulate the view, for example in “the addition of a few trees; or a little alteration in the foreground.” Though the picturesque view is by instruction an artistic construct, these fabrications continue to inform conservation efforts.

Walking was the ideal way to experience the Romantic landscape. Picturesque tours became a popular activity for the wealthy in the late 18th century, and remain vital to the countryside’s recreational identity, where travellers visit viewpoints painted by the likes of Gilpin.

The picturesque becomes fluid as the image transposes onto the landscape. Watercolour brushstrokes merge into swatches of pastoral land seen through satellite imagery. These Romantic landscape imaginaries were not contained within Europe: they became key to the colonial project of terraforming, where conquered landscapes were transformed into neo-Europes.

In the United States, pre-colonial land was perceived as an entirely wild terra nullius. As land was seized, divided, and rendered property, productive pastoral landscapes emerged, transplanted from the English countryside to create rural America. A hierarchy of landscapes emerged, based on how productive land was assessed to be, and how easily it could be commodified.

The colonial frontier existed within binary conditions of known and unknown, near and distant, conquered and conquerable. The frontier was the domain of the wild; the settled the domain of the pastoral. It was the frontier, then, that fuelled conservation efforts: the desire to preserve – and to frame - remnants of empty terra nullius. The drive to form national parks coincided with the end of the colonial frontier, as Westward expansion extended the nation from coast to coast. As land was charted, measured, and conquered, the wildness defining the frontier dwindled.

What happens when the image meets the landscape?

If we are to take seriously western conservation’s colonial legacy, reject the human-nature dichotomy, and refuse the commodification of land and life, this will radically reshape the meaning of conservation in terms of both representations of and relationships to the land. What happens when the frame becomes a mirror, and we recognise the wilderness within ourselves? landscape?

Here lies a paradox of the wilderness: while the sublime implies a certain degree of humility, where the human is at the mercy of magisterial nature, the wilderness park encloses sublimity, containing the uncontainable within legislated boundaries. This paradox exposes wilderness as an ideal, closer to morality than reality. As William Cronan wrote is his seminal text, “The Trouble with Wilderness,” wilderness is an “impossible geography,” created in large part within the frames of pictorial representations.

Just as photographers, painters, and writers campaigned for their imaginaries of wilderness in the United States, Romantic-era artists were key to the conservation of land in the UK. Poet William Wordworth is famed for his calls to preserve picturesque landscapes, which he described as “a sort of national property, in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy.” Thus, the construct of property and ownership of land is central to conservationism. This provides an interesting point of comparison between British and American national parks,

where British national parks are primarily privately owned, and American ones are publicly owned. These differing ownership strategies emerged from two border regimes: the frontier on one hand, and enclosure of the commons on the other. Unlike the frontier conservation of wilderness in the United States, the sublime wilderness was never fully separate from inhabited land in England. Moorlands, perhaps, were an exception, deemed untameable and inhospitable. But most moorlands too became swallowed by farmland, mirroring the process of the frontier.

In the National Parks of England, we see the wild and the pastoral merge: the Peak District is made up of a patchwork of privately-owned pastures. Public access to them was not a given: it was fought for, such as in the Kinder Scout mass trespass in 1932.

01. Landscape, William Gilpin, 1794

02. Sheffield from Crookesmoor, William Ibbitt, 1856

03. Moorland scene, Derbyshire, Charles Thomas Burt, 1889

01. George Smith, Peak District Landscape, date unkown (presumed 18th or 19th century) 02. The enclosures act as invisible walls in the landscape, creating barriers to access.

Romantic-era landscape paintings of Derbyshire gave the illusion of far-reaching ‘wild’ landscapes, masking the reality of enclosure and privatisation. The English National Park, then, is an attempt to restore access post-enclosure without the commons , where conservation becomes an authoritative blanket covering a privatised landscape.

The Enclosures drastically altered the moorland landscape, defining its edges with farmland in clearly parcelled boundaries and changing the open-field pattern of long, thin strips into more regular, larger rectangles. Thomas Jeffrey’s 1772 map of Yorkshire (below) gives a glimpse into a moorland landscape pre-enclosures.

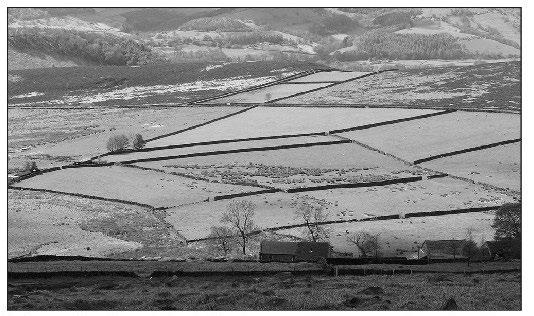

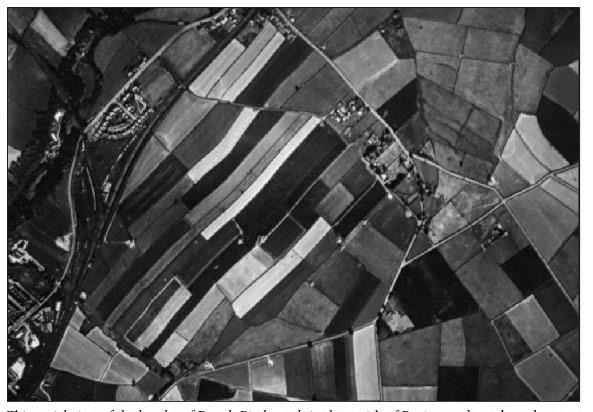

Common opne-field pattern of thin strips compared to larger rectangular fields from the enclosures. Image from History of the Peak District Moors by David Hey

Enclosed fields in the Dark Peak near Hathersage. Image from History of the Peak District Moors by David Hey

Peak District Timeline:

1000 1800

(1600s-1860)

Domesday Book (1086)

1900

Parliamentary Enclosure acts affecting Peak District region (1925) Land

Crown Estate established (1862)

The first attempt to completely record land ownership across Britain (1215)

Common Land first enshrined in Magna Carta (1860)

The Common, Open Spaces and Footpath Preservation Society founded (1760)

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest and Natural Beauty is founded (1899)

Land Registration Act (1873)

Return of the Owners of the Land / Modern Domesday (1895)

UK Gamekeepers Association founded (1876)

Local Government Act amended, giving some rights of way

Beginning of the right to roam movement (1912)

Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves founded (1894)

(1919) Forestry Commission woodlands deforested (1926) Council England (1925) Law way

(1925)

Land Registration Act

(1952)

5624 acres owned by Duke of Devonshire on Southern Kinder signed over (1961) Crown Estate Act (1982)

National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act

Kinder Scout Mass Trespass (1939)

Access to the Mountains Act passes (2005)

Sheffield Clarion Ramblers’ Winnat’s mass trespass (1932)

High Peak trail opened (1927)

Law of Property Act gives right of way access to commons (1973)

Council for the Preservation of Rural England formed (1942) Scott Report examines problems in the countryside and makes the case for National Parks (1972)

National Trust buys Kinder estate (1990) Survey shows over 70% Peak District privately owned (2002) Land Registration Act (1990) Rights of Way Act (2000) Countryside and Rights of Way Act

Peak District woodlands designated as open access (1949)

National Environment and Rural Communities Act (2019) Landscapes Review Report published (2021) Nature for Climate Peatland Grant Scheme (2024) Landscape Recovery Scheme (1926)

Peak District National Park’s Ranger Service founded (1968) Countryside Act (1981) Wildlife and Countryside Act (1951)

National Park Authorities created (1986) 4900 acres bought for conservation by NPA (1954)

Commission founded to restore deforested during WW1 (1995) Environment Act (2006)

Peak District designated as England’s first National Park (1925)

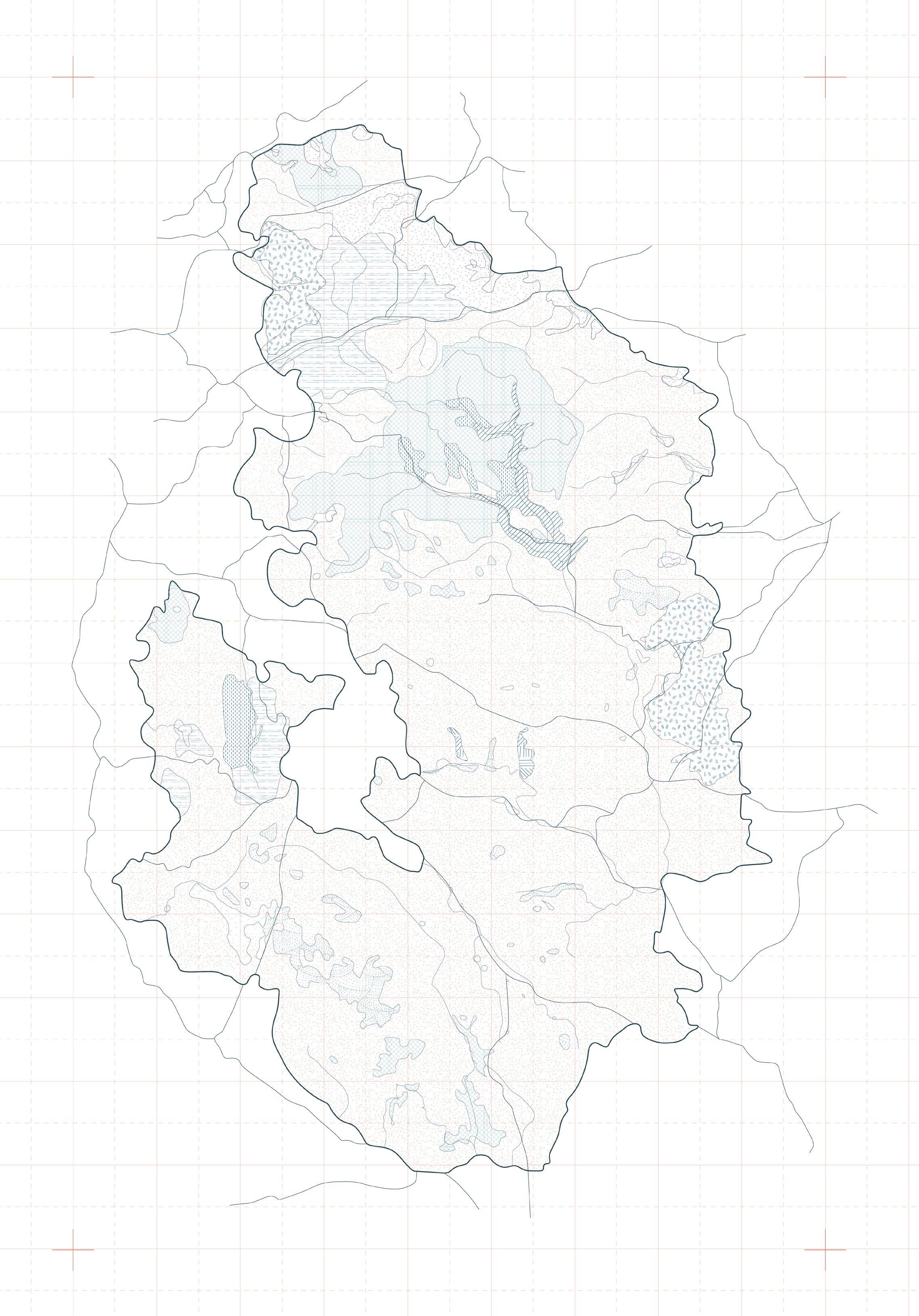

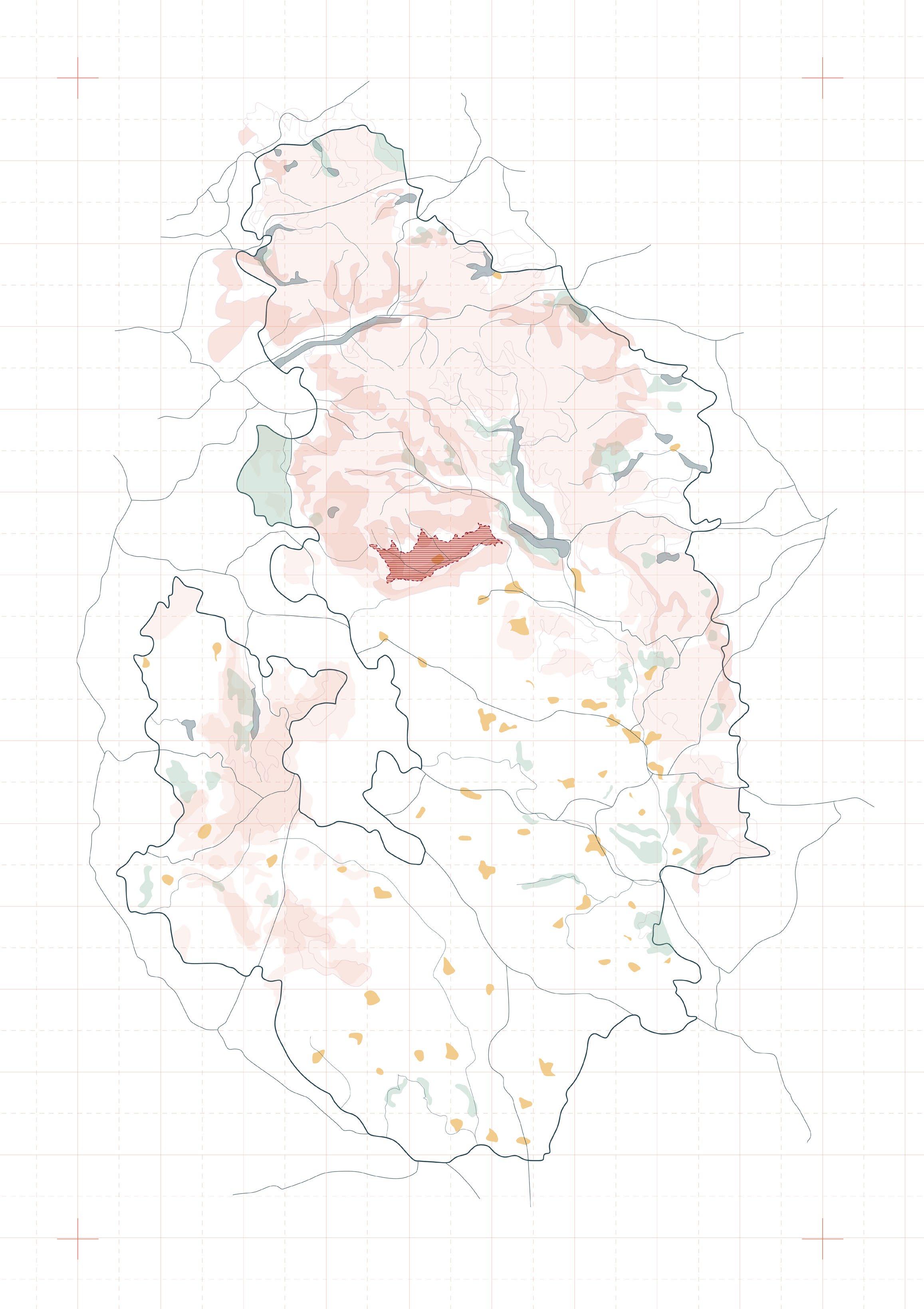

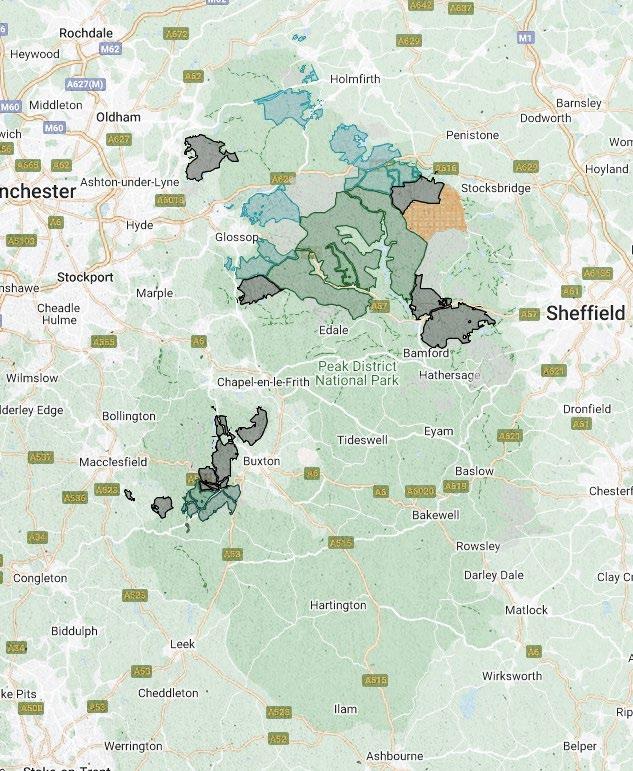

Current Land Ownership

Of the Peak District National Parks’ 1,348 km 2 , 90% of the land is privately owned. This contrasts to the North American national park, which is publicly owned. The British national parks were created nearly a century after the American and Canadian ones, and rather than focusing on conservation, they were formed to give access to the privatised countryside. Though extensive areas of the park are publicly accessible, they remain in the hands of wealthy individuals, water companies, and conservation agencies, among other bodies. The National Trust is currently the largest park landowner, possessing 12%.

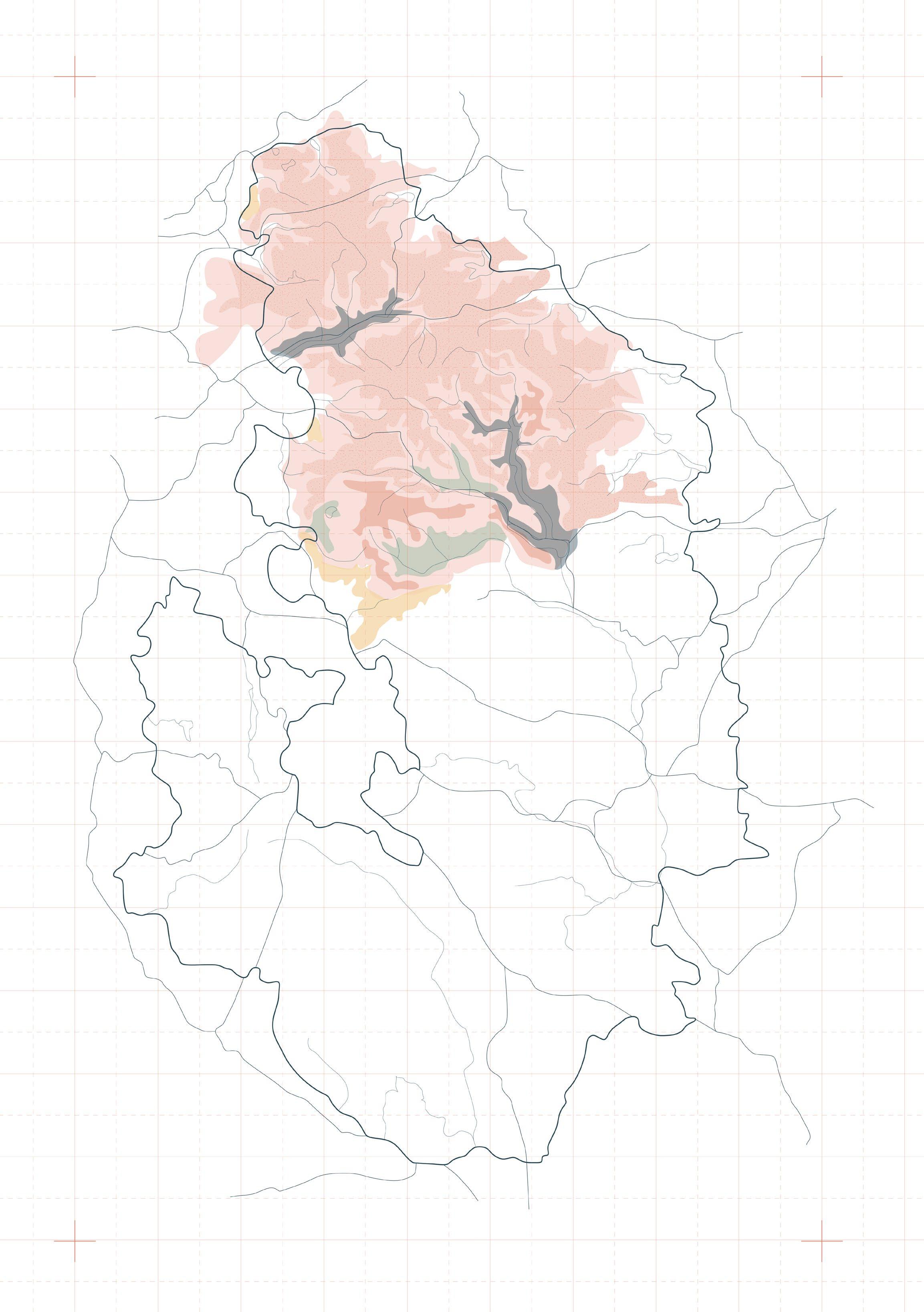

As Guy Shrubsole found in his research for Who Owns England?, data on land ownership is highly secretive and hard to come by. This map uses data provided by the National Parks Authority, but much of it is unattributed. These regions are largely held by private individuals and estates.

Land ownership key

National Trust

National Nature Reserve

Derbyshire Dales

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB)

Staffs Wildlife Trust Areas

Yorkshire Water

Severn Trent

United Utilities

Peak District National Park region Forestry Commission

National Parks Authority

Thesis Terminology: What is Convivial Wildness?

Tools for Conviviality, Ivan Illich Wildness, Kimberley Ward

“I intend [‘conviviality’] to mean autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment ; and this in contrast with the conditioned response of persons to the demands made upon them by others, and by a man-made environment. I consider conviviality to be individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such, an intrinsic ethical value.”

“In the endeavor of developing more positive and socially-just conservation practice in rewilding we can valorise Wildness, rather than Wilderness to renegotiate our understanding and relationships with non-human nature in ways that are not dualistic, exclusionary, or indeed, loaded with cultural baggage (. . .) Wildness is abiotic, biotic and a social relational achievement within human and more-than-human worlds.

The project addresses a crisis of the imaginary that separates humans from nature, calling for a redefinition of wilderness. Problematized by thinkers such as William Cronan, the idea of wilderness as sublime untouched nature is exposed as construct. Cronan terms this an “impossible geography,” an imaginary fabricated in large part by Romantic-era photographs and paintings.

Instead, the project draws from Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality, where convivial at its root means to live together, and from Kimberley Ward’s notion of wildness as “abiotic, biotic and a social relational achievement within human and more-than-human worlds.” Connecting the two, I propose the term convivial wildness, where wildness is understood not as pristine or remote nature, but as entangled networks of living beings sharing the land.

Commoning within convivial wildness, then, means practicing ways of being collectively with each other and with the morethan-human realm, making space for alterity while recognising our entanglements with one another.

Commoning through convivial wildness is not only a social or ecological question: it is an epistemic one, where landscape is a form of pedagogy that invites situated knowledges to emerge.

In Haraway’s writing on situated knowledge, she calls for the dissolution of the god-trick for “a view from a body, always a complex, contradictory, structuring, and structured body, versus the view from above, from nowhere, from simplicity.”

Commoning as Experimental Geography

Experimental geography, Trevor Paglen

“Experimental geography means practices that take on the production of space in a self-reflexive way, practices that recognize that cultural production and the production of space cannot be separated from each another, and that cultural and intellectual production is a spatial practice. Moreover, experimental geography means not only seeing the production of space as an ontological condition, but actively experimenting with the production of space as an integral part of one’s own practice.”

The project reframes situated practice—as an alternative to top-down neoliberal conservationism—as experimental geography, a form of space-making by being-in-place.

This section investigates various modes of experimental geography and cartography, such as walking and imprintmaking as mapping methods. Commoning is a process, not an event or end destination; it is by necessity experimental and open to change.

Experimental geography posits that geographers, in any sense of the word, do not merely study places, they make places. This sense of agency is absent from the top-down map. Instead, embodied mapping practices—where drystone construction is in itself a form of map-making — embrace the agency of the cartographer.

Walking is space-making; drystone is space-making; simply being in a place is a form of affecting it: these are some of the guiding principles behind the project, and ones that offer a powerful counter-narrative to the distanced view of the picturesque or the omniscient gaze “from nowhere” of the ordnance survey.

Forms of Commoning

What does commoning the English wilderness look like when we redefine wilderness as relational wildness? In wilderness, relationality between humans and the more-than human realm is heightened, because difference is more evident. This sense of difference recognises all beings as distinct and with their own life-worlds. Wilderness, rather than epitomising humans as outside of and other than ‘nature,’ holds the capacity for many life-worlds to co-exist, making space for the unknown and the unknowable. The project reconstructs the Peak District’s wilderness as relational wildness, where wildness is understood not as pristine or remote nature, but as entangled networks of living beings in a landscape assemblage.

Diverse woodland

Re-mossing peatland

Eliminating slash-and-burn

Seasonal rituals

Sharing labour

Collective walking

Negotiation

Acts of care

ECOLOGICAL

Convivial rewilding

Multispecies interactions

Multispecies inhabitation

Agroecology

From monocultures

Situated

Breaking human-nature

Folklore and storytelling

Diasporic imaginaries

Narratival knowledge interactions rewilding monocultures to polycultures inhabitation

Collective building

Learning collaboration

Knowledge of drystone construction as craft

Situated knowledges

human-nature dichotomies

EPISTEMIC

Sharing knowledge

Shifting mindsets: from ownership to obligations

Trespass as a Commoning Catalyst

How can trespass be a tool of direct action that challenges the privatisation of the landscape?

The first catalyst for commoning is trespass as the direct reclamation of land. This is where the act of temporarily inhabiting and building in the landscape becomes a transgressive one. By navigating by stone markers rather than the OS map, access boundaries are rendered illegible.

If property lines drawn on a map make visible private land ownership, and the picturesque view bypasses ownership regimes, this thesis proposes challenging the privatisation of the landscape through convivial rewilding practices, where property lines are illegible to the rocks, mosses, wildlife, and commoners taking part in rituals of repair.

This shift away from ownership structures requires a new paradigm: one of obligations. Through commoning the moorland, visitors to the landscape have a sense of obligation to care for the land and the beings surrounding them. This paradigm shift is incommensurable with a private property regime predicated on viewing land as an inert resource.

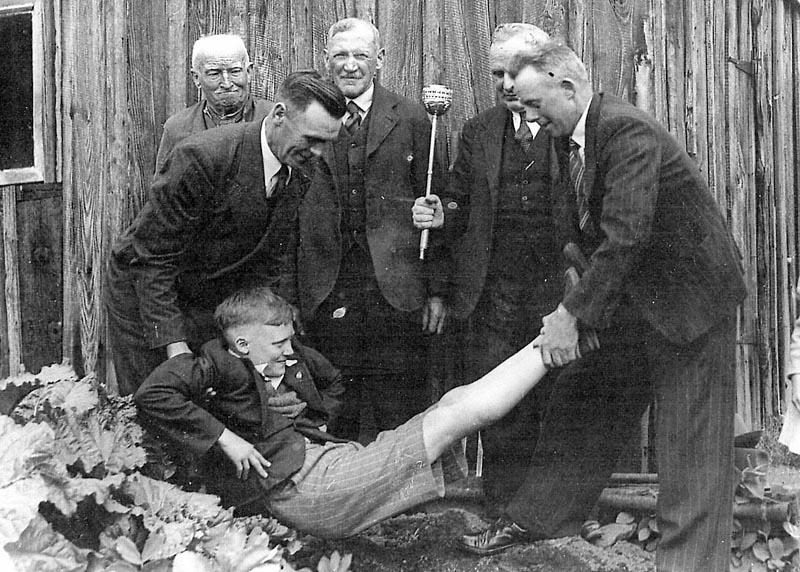

Opposite: The author trespassing in Edale valley, and in doing so taking part in a bourgeoning movement for reclaiming land rights.

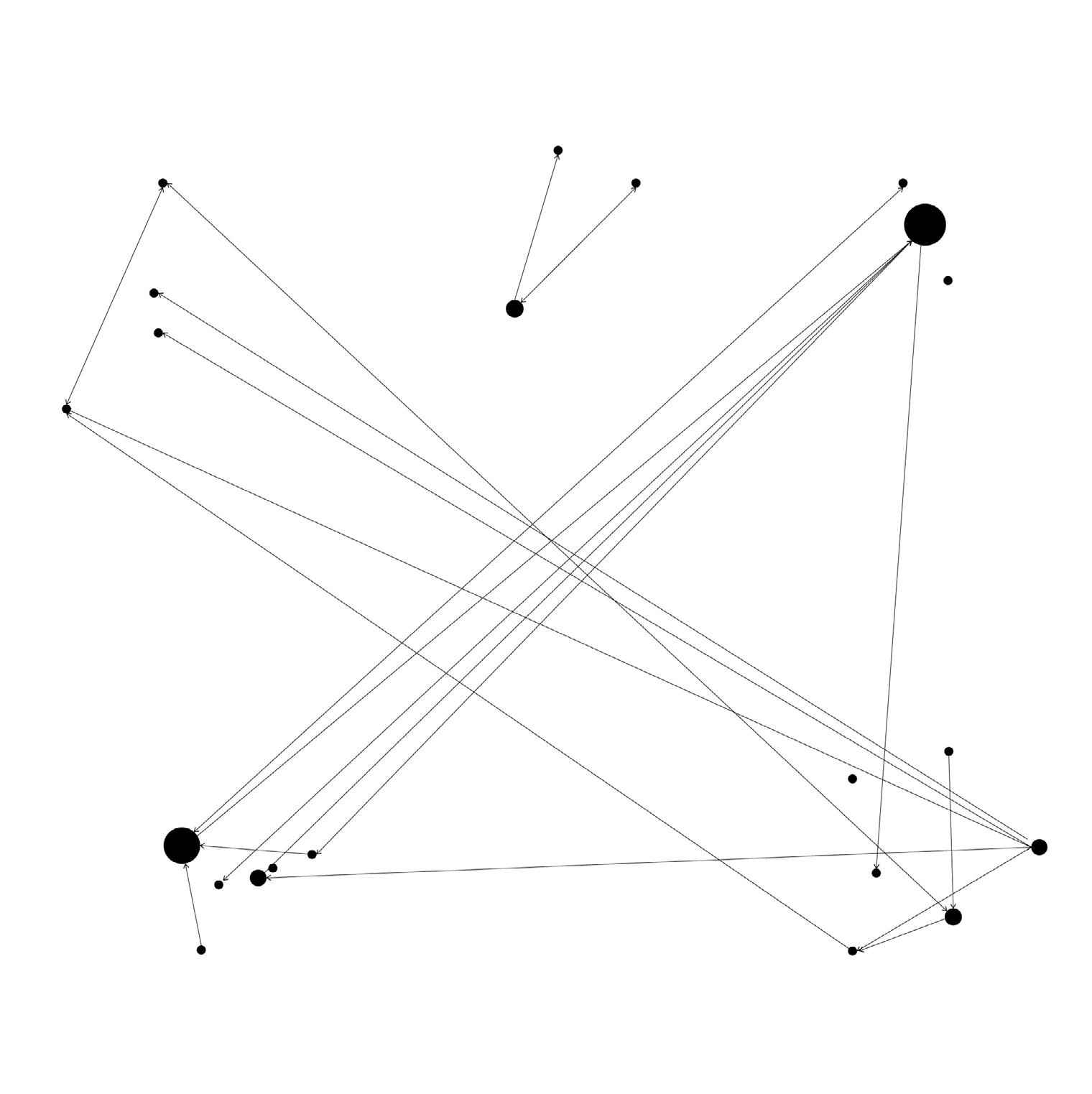

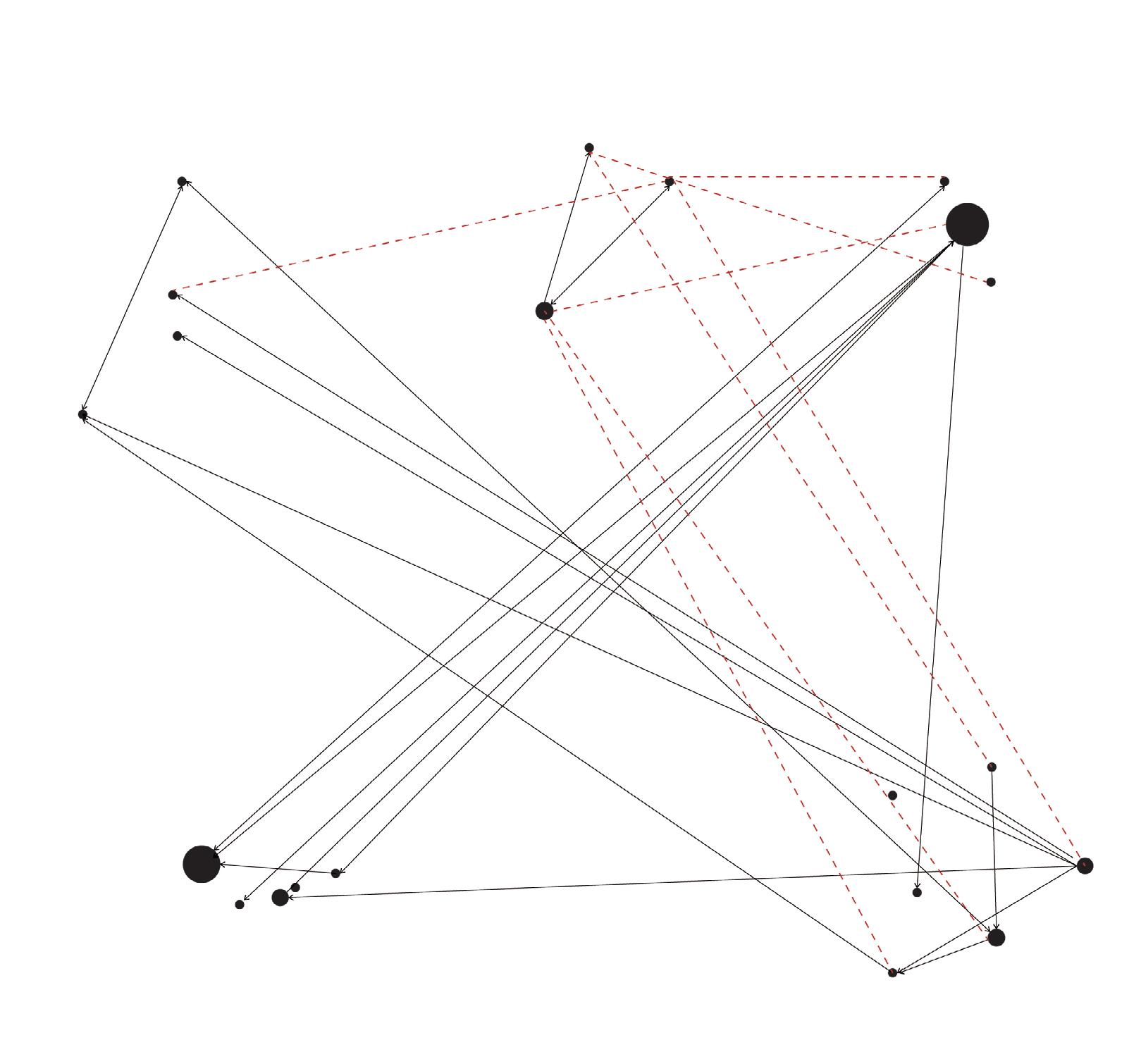

Shifting Stakeholders: Transient Commoners

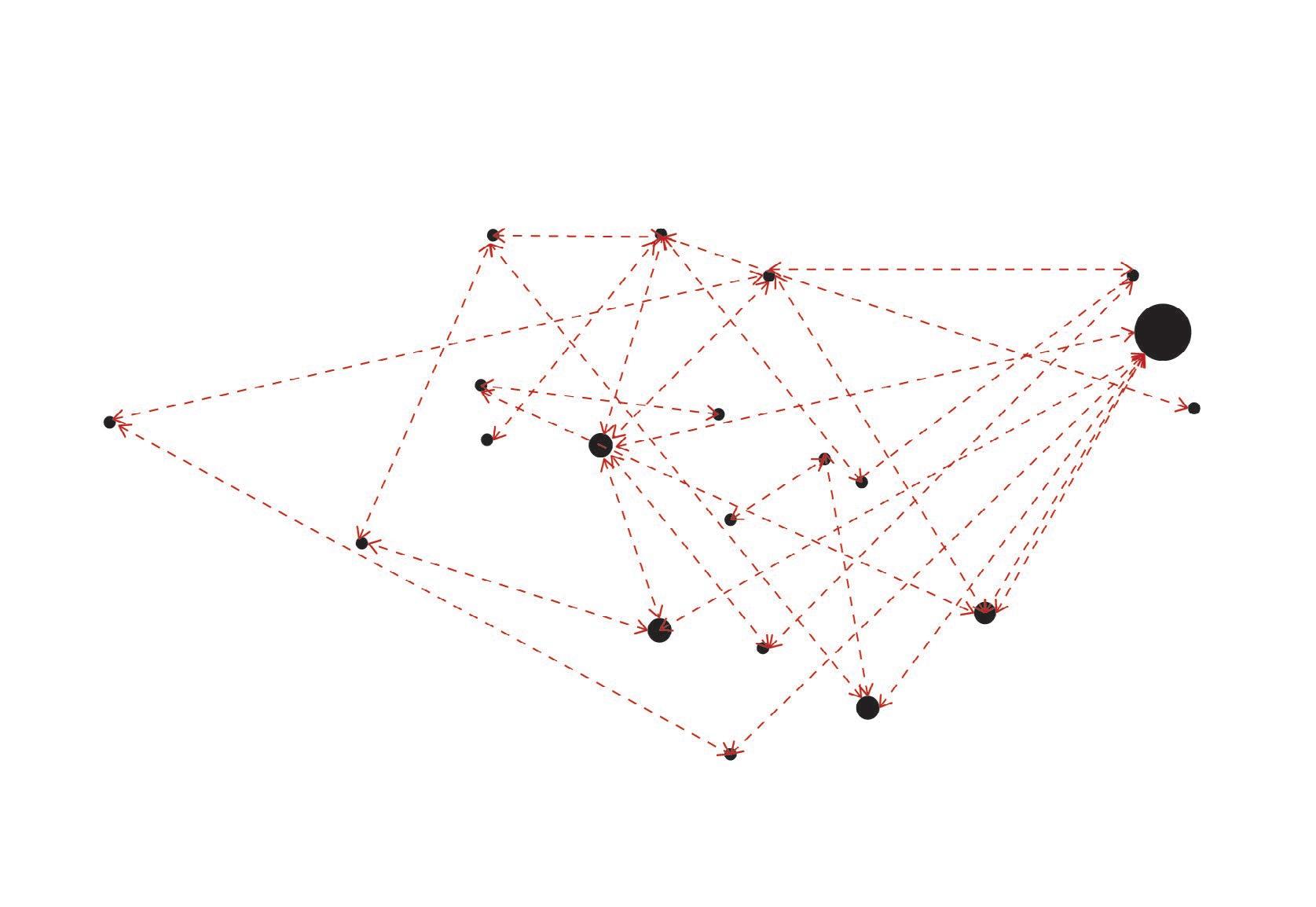

This series of diagrams shows communication between various stakeholder groups. Transient commoning images how visitors can engage with local actors in ways that are non-extractive, blurring the categories of conservationists and commoners as ecological repair dissolves the grouse hunting industry and challenges the privatization of water.

Conservationists

01. Current stakeholder configuration, where the larger the circle means the more people invovled, and the arrows indicate directionality of interactions. Diagram adapted from “Learning from Doing Participatory Rural Research: Lessons from the Peak District National Park” by A. Dougal, E. Fraser, and J. Holden et. al

02. Initial stages of commoning the moorland through engaged visitation, where transient commoners form relationships with other stakeholders

03. Well into the commoning process, the privatisation of land has dissolved, and with it the privatisation of water and the grouse hunting industry. Monocultural and capitalist farming practices are replaced with agroecological ones.

Grouse managers

Water industry

Grouse managers

Transient commoners Agricultural community

Water commons

Transient commoners

Conservationists

Agroecological community

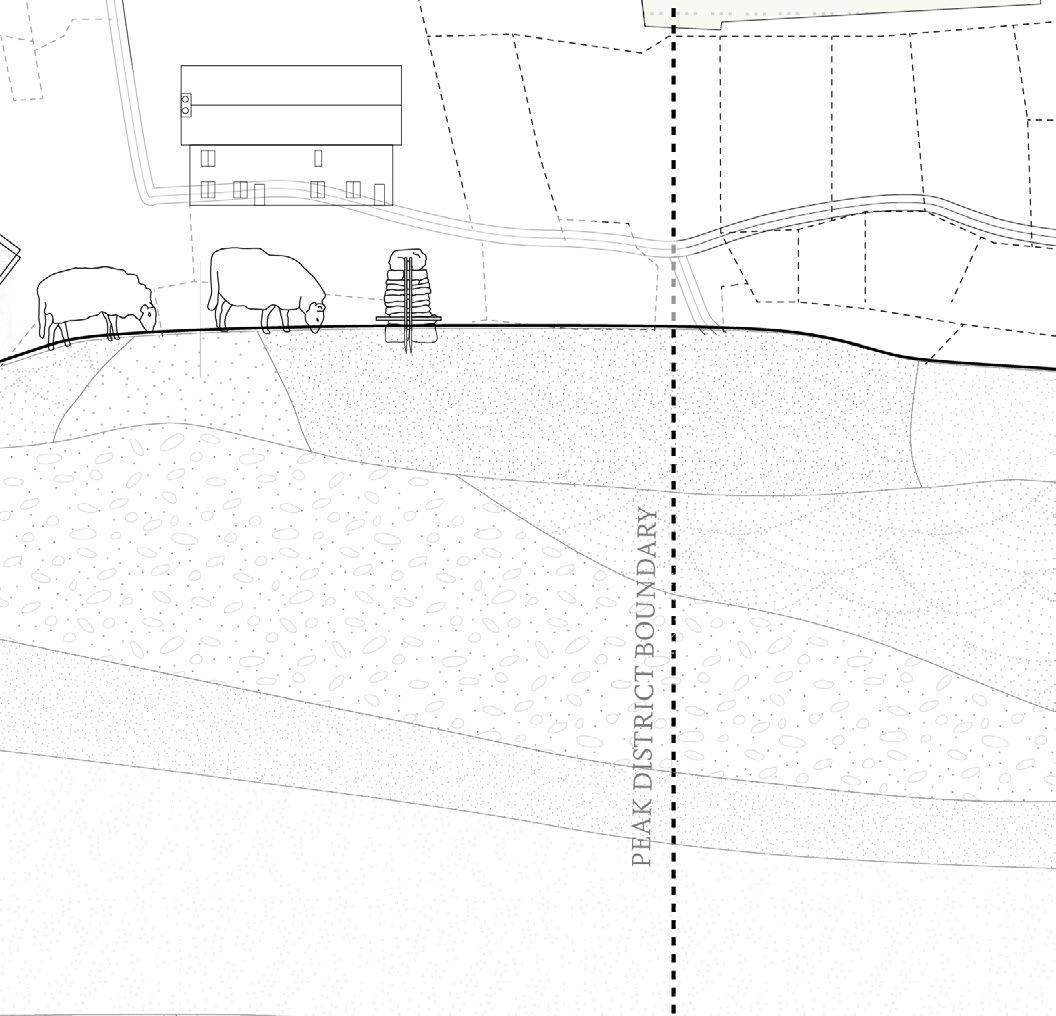

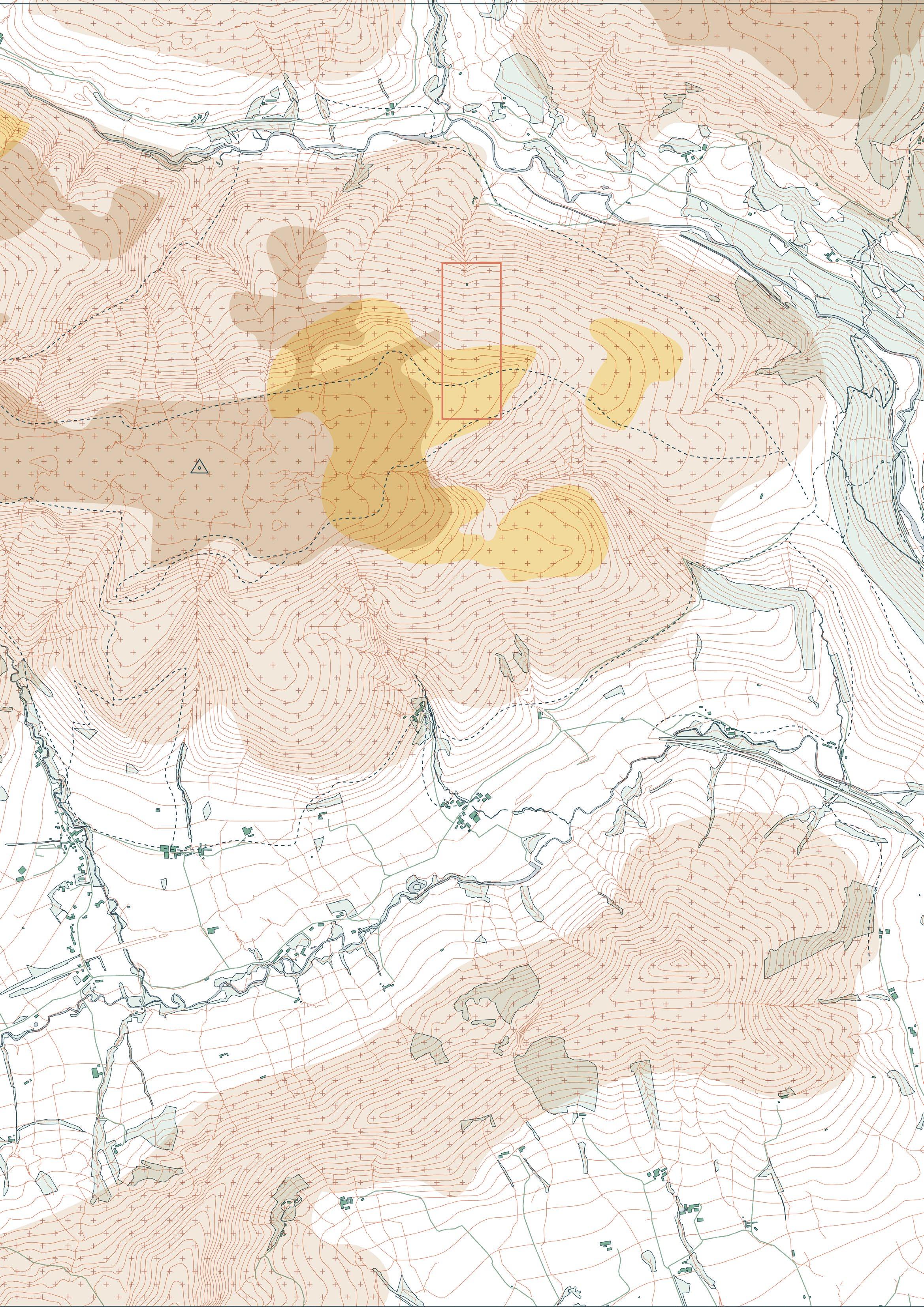

Region of Focus: Dark Peak Moorlands

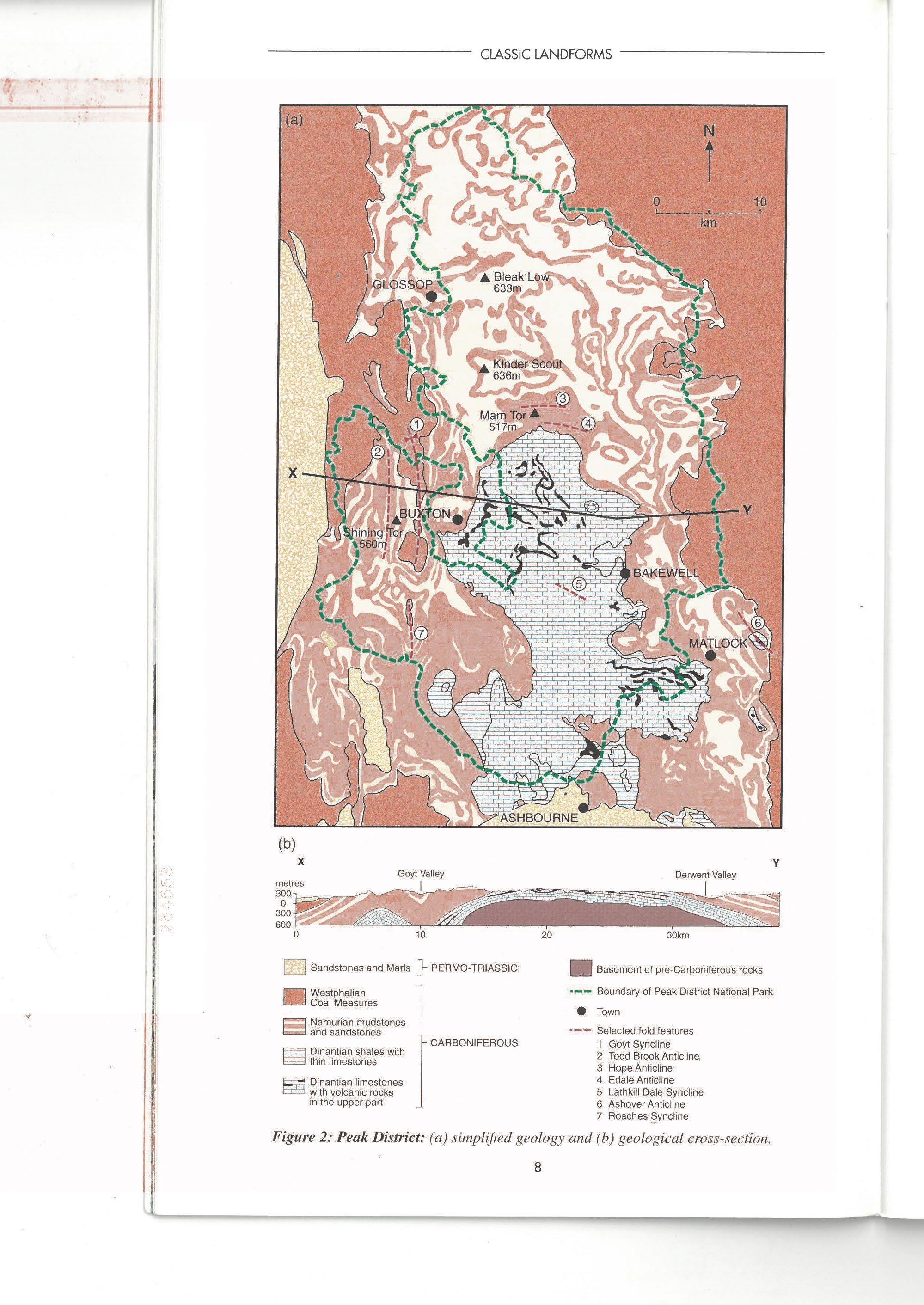

The Peak District is divided into two prominent regions: the Dark Peak and the White Peak. This refers to the geologic makeup of each, where the Dark Peak is primarily gritstone, and the White Peak is predominantly limestone. The dark peat soils of the moorlands are also important features of this area, in places reaching over 4m in depth. The Dark Peak has fewer settlements than the White Peak and fewer enclosed areas, though drystone walls are still ubiquitous. The region is known for its dramatic gritstone tors and high peaks, such as Kinder Scout, which reaches 636m. The landscape is carved by streams into cloughs and valleys, creating fertile environments for mosses, lichens, tree, and bird life.

The landscape has long been shaped by humans, with traces of early stone age settlements still visible in places. Valleys have long been agricultural and used for grazing, while the peaty moorlands have been cut for fuel—one of the rights of the moorland commons, though an ecologically damaging one. Large constructed reservoirs are another definitive element, created in the mid 20th century to provide drinking water to the growing urban centres around the national park.

Dark Peak Landscape Regions

Moorland slopes and cloughs

Open moors

Enclosed gritstone uplands

Upper valley pastures

Dark Peak moorland regions

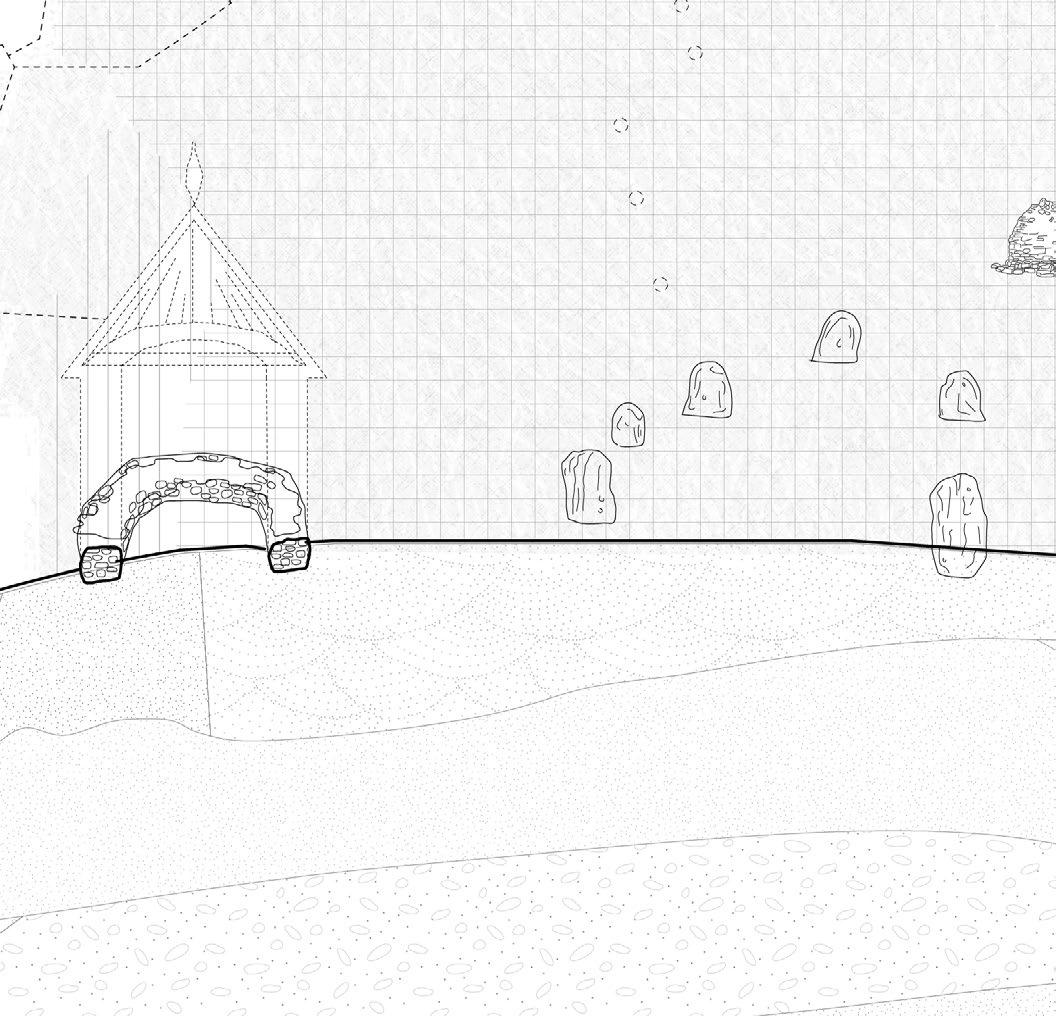

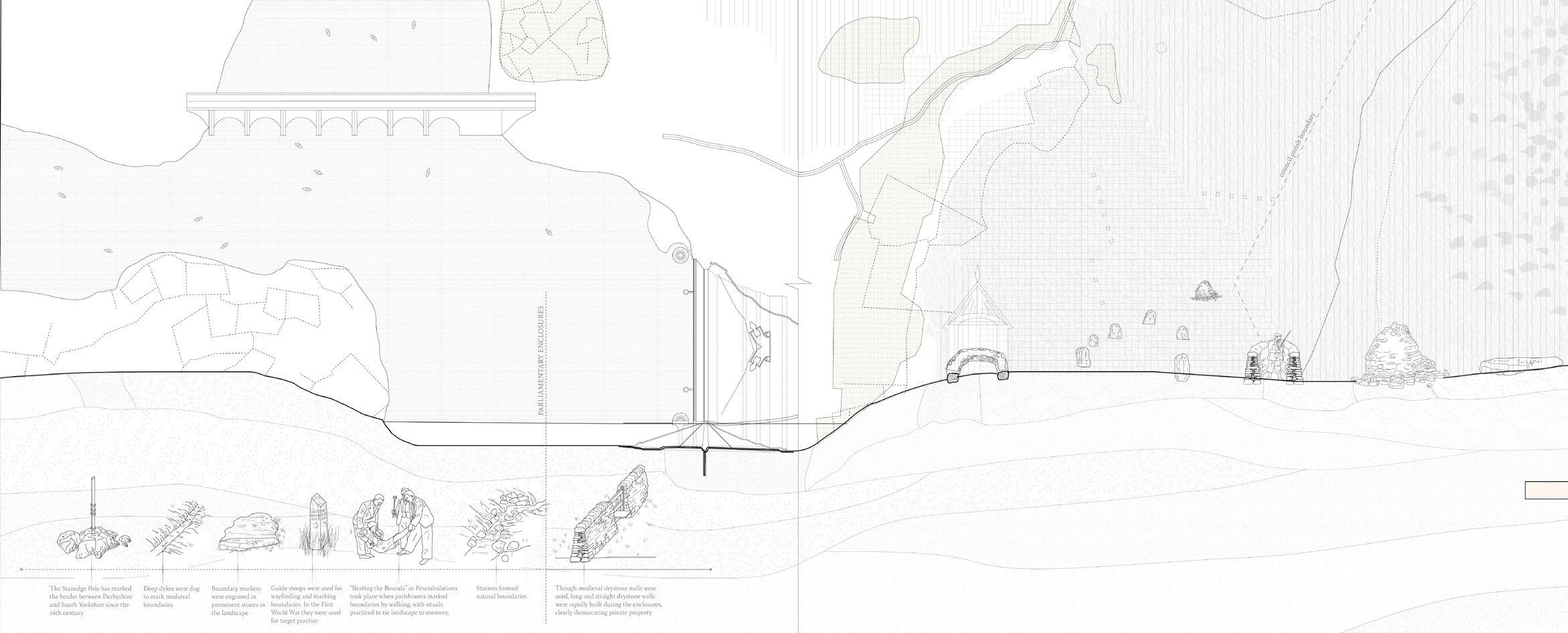

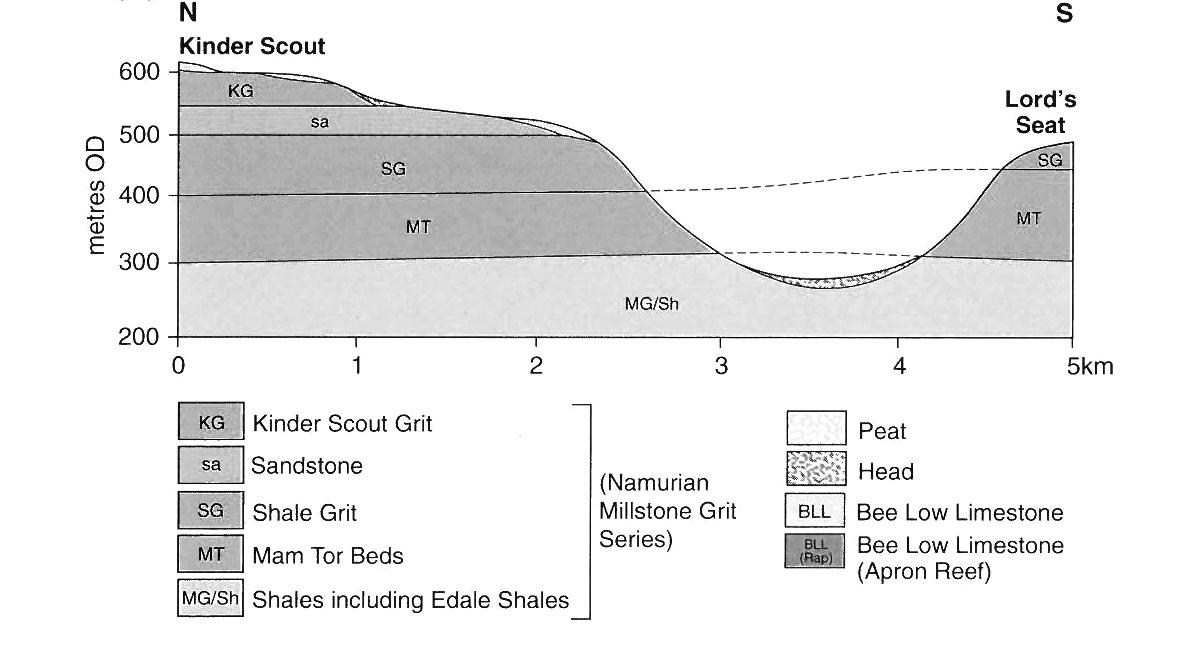

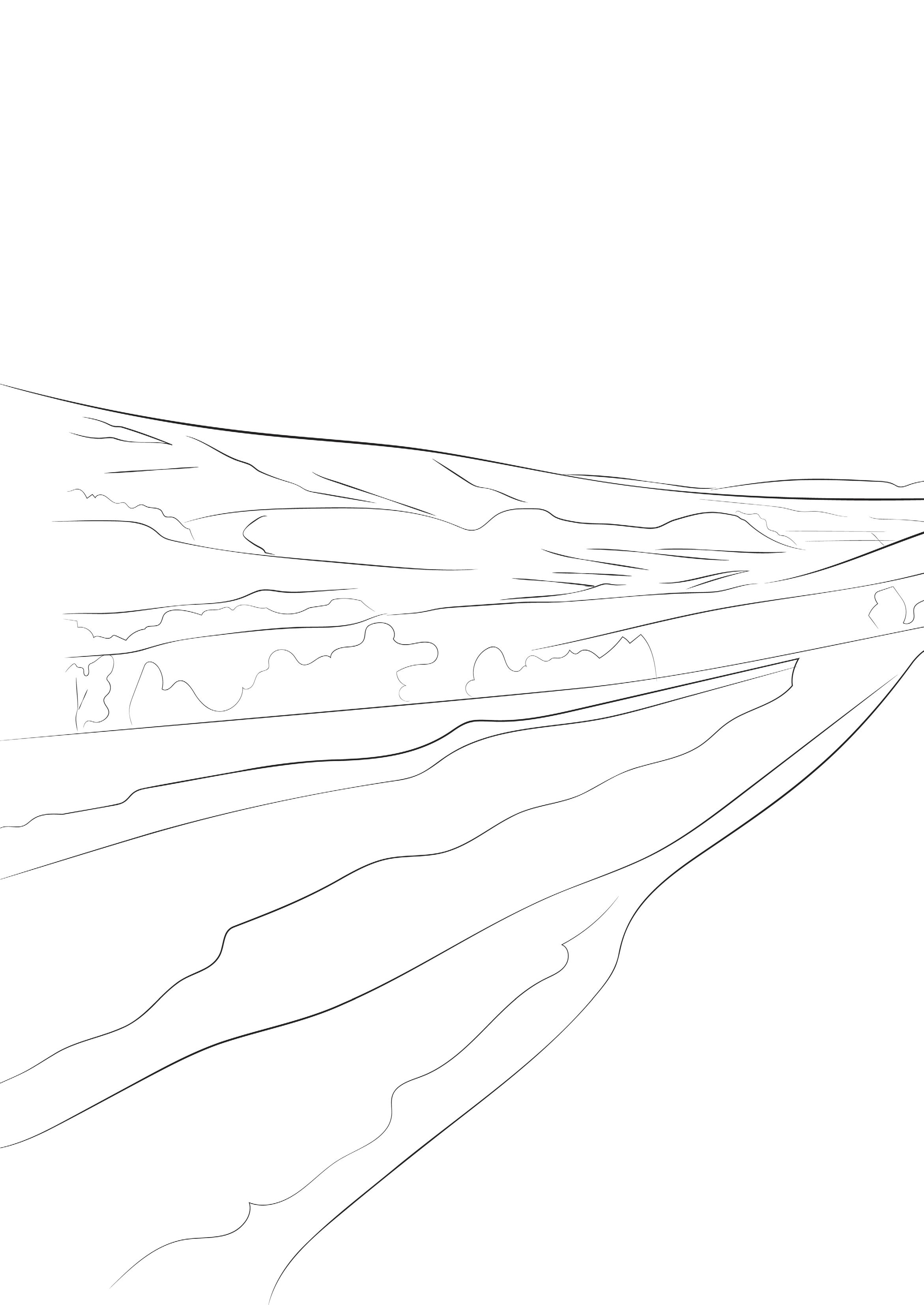

Section through the Dark Peak

The project is situated in the Dark Peak region in the northern half of the national park. This section analyses some of this area’s most distinctive elements, viewing the landscape as an assemblage of interrelated parts that are in constant dialogue with one another.

01. Vast reservoirs were constructed in the mid 20th century to provide drinking water to the rapidly growing cities surrounding the Peak District. Villages such as Ashopton were flooded and covered during the construction of these fabricated lakes and dams.

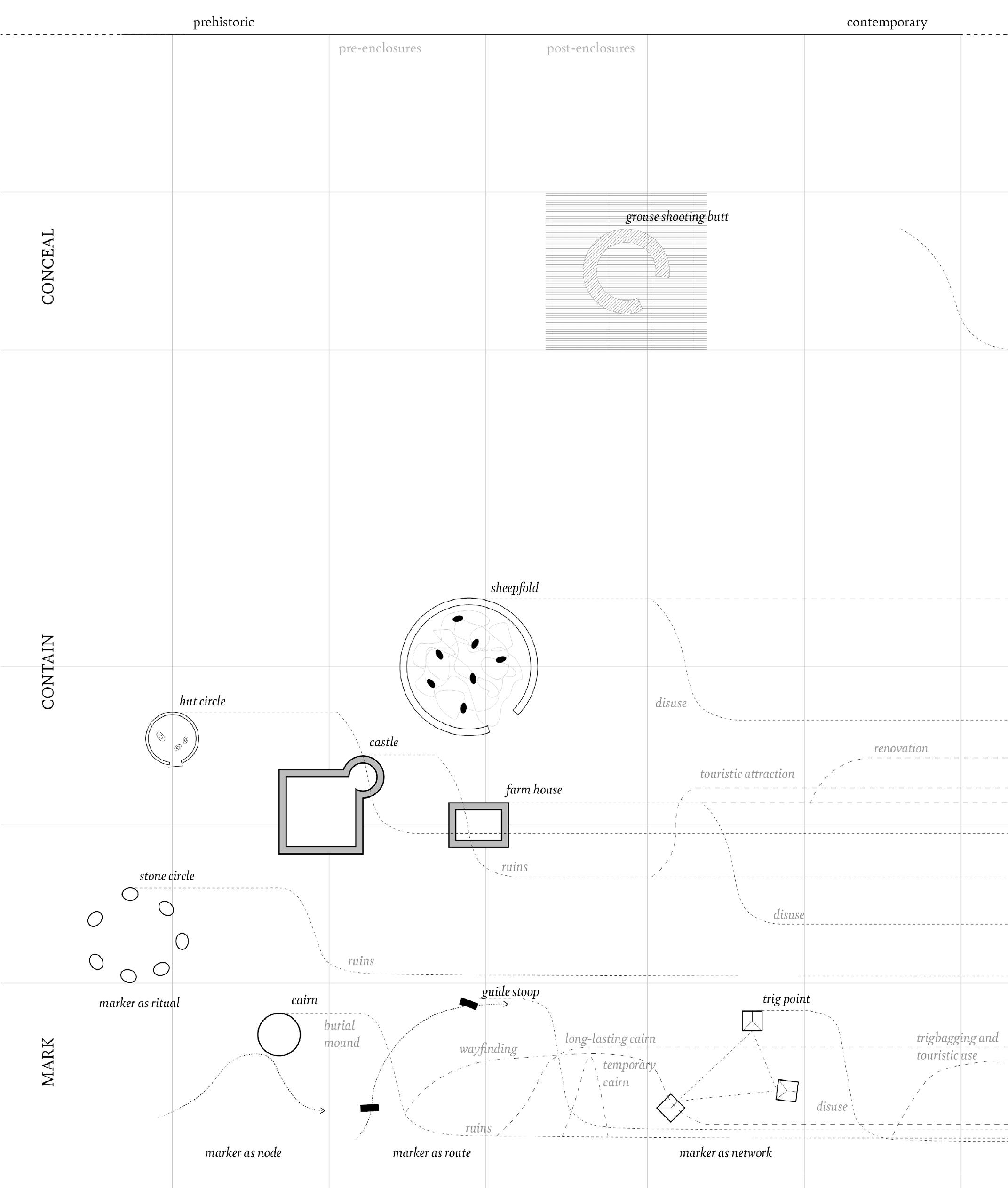

02. The landscape is dotted with stone structures both ancient and contemporary 19th- and 20th century grouse shooting butts sit adjacent to prehistoric stone circles.

03. The Peak District is an industrial landscape straddled between Manchester and Sheffield, two key cities in the Industrial Revolution. Beneath its surface are extensive mining networks, while quarries scar the rocky hillsides.

04. The national park boundary, demarcated in maps and legislation, is nearly invisible in the landscape, often passing through farmland.

Fieldwork Site and Area of Focus: Edale Valley and Moors

From April 7th- 11th, I stayed in Edale, spending time getting to know this particular landscape in the Dark Peak.

Situated between Kinder Scout and Mam Tor, Edale has long been a popular hiking destination. Human settlement in the valley dates back millennia, but the current landscape has been greatly shaped by agricultural, industrial, and recreational purposes. During the feudal system, sheep farming was the primary economic activity, with land owned by lords or monasteries. Edale was one of the first railway connections into the Peak District, allowing easy access for hikers arriving from urban centres.

Settlements

01. Edale Valley 02. Ladybower Reservoir 03. Manchester 04. Sheffield

Dark Peak moorland

Moorland slopes Forested areas Reservoirs

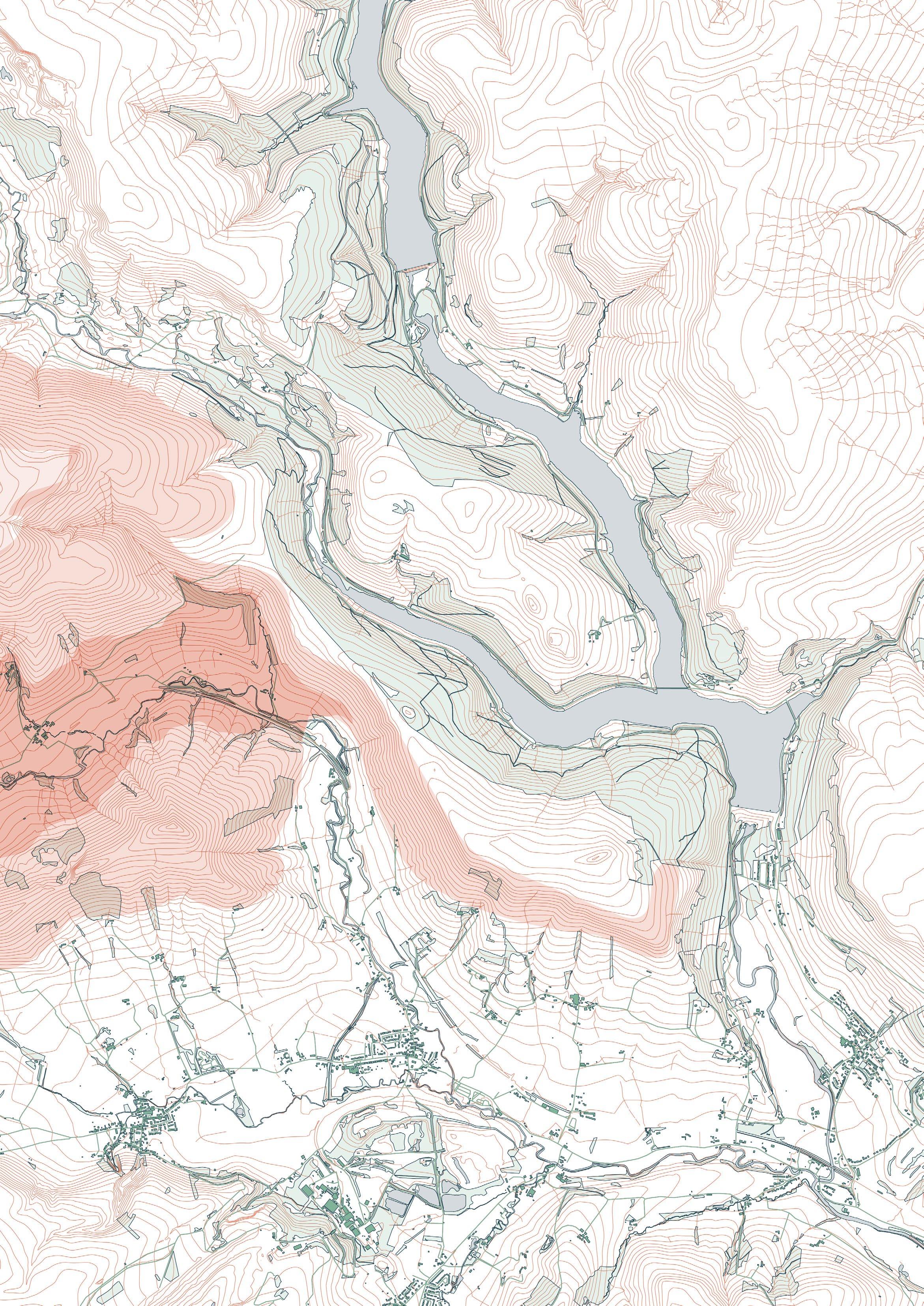

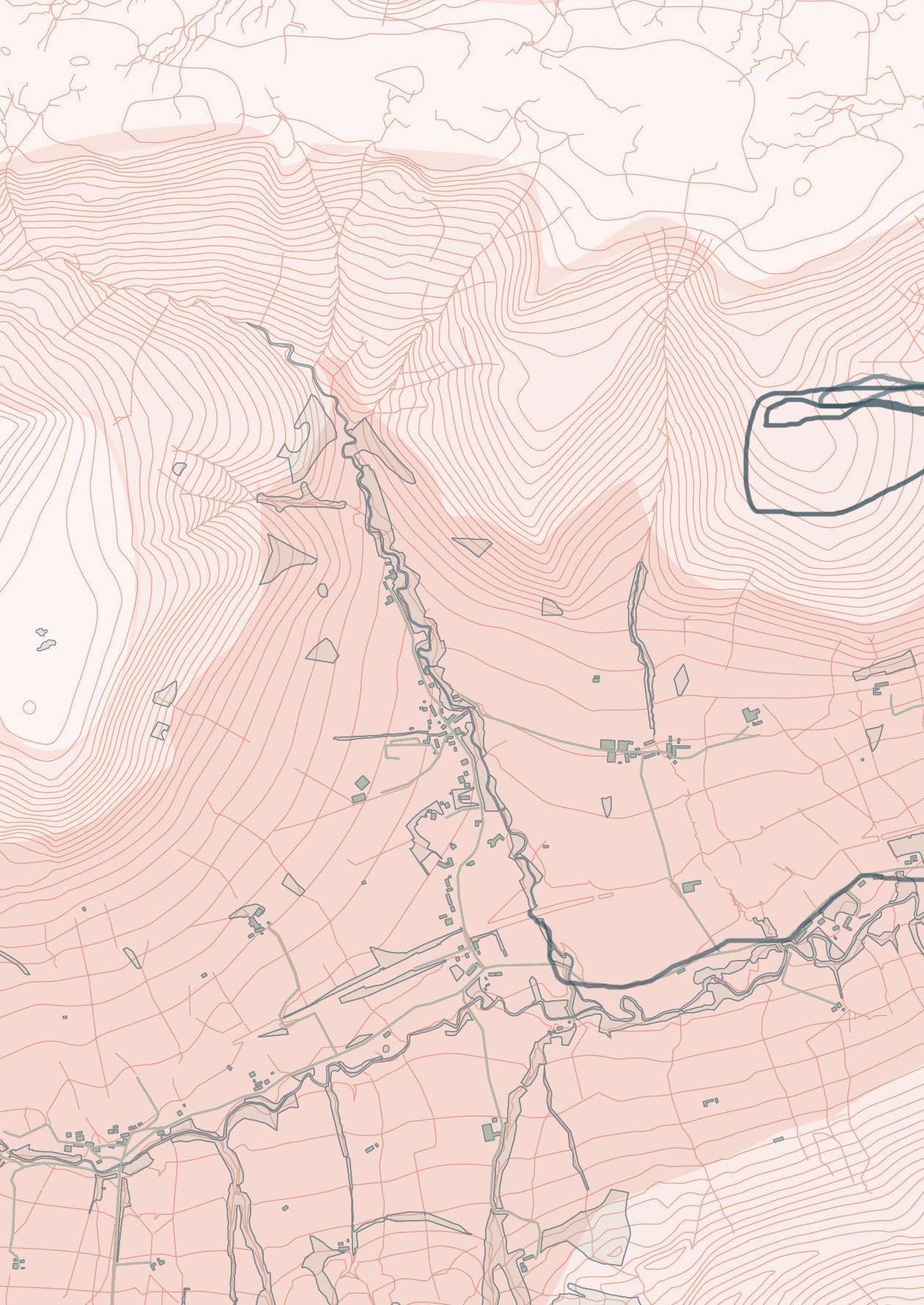

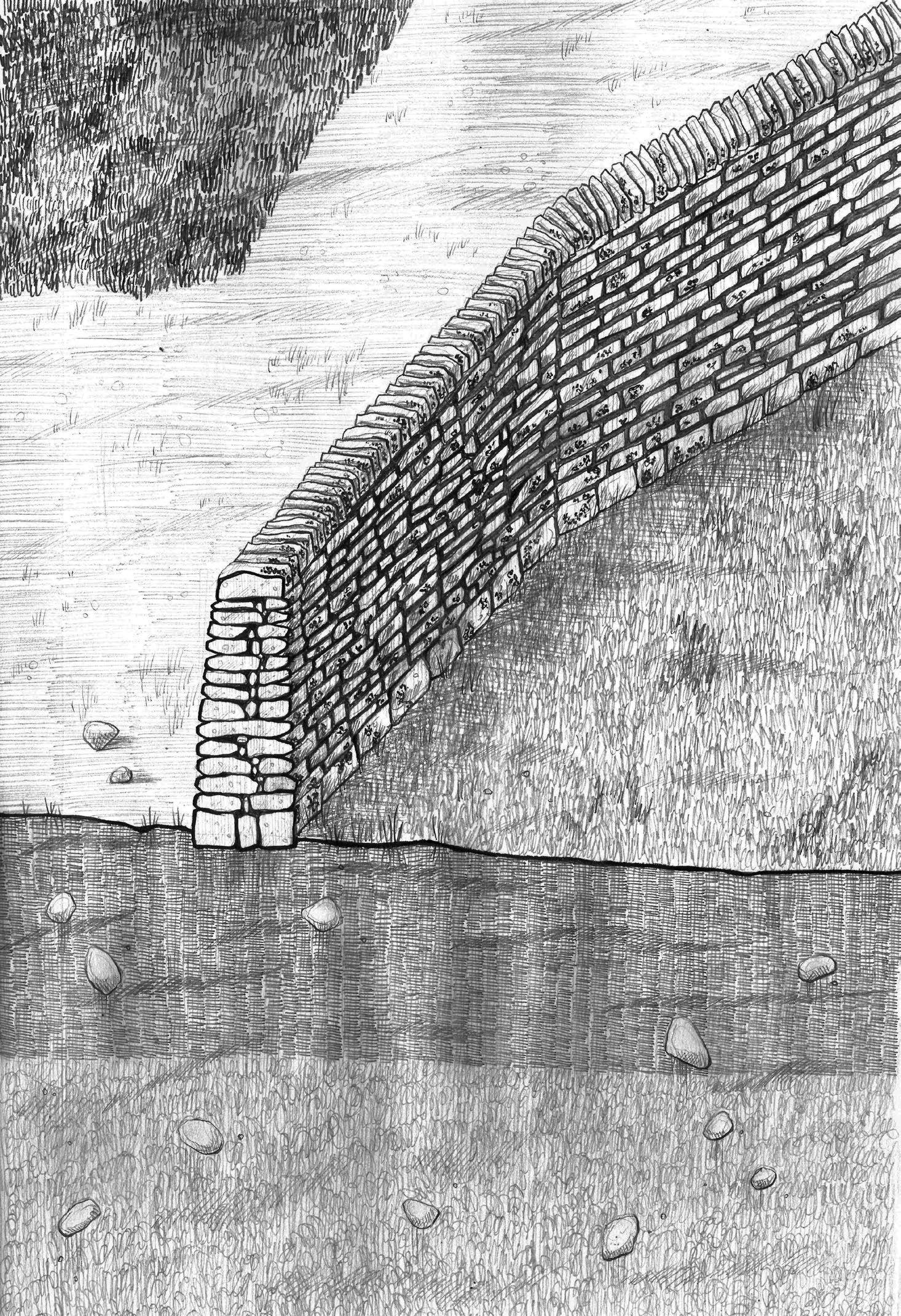

This archaeological survey of drystone walls in Edale valley shows legacies of enclosure and private land ownership clearly demarcated in the landscape. It tracks boundaries present, removed, and added between 1839/1848 and 1880 specifically. This survey clearly shows the implication of the parliamentary enclosures of the 19th century, where common land was parceled into relatively even private farms.

Boundary Wall Emergence

The survey of boundaries present, added, and removed between 1808/1839 and 1839/1848, compared to the previous survey to 1880, shows the rapid increase in wall construction during the Enclosure Acts of the second half of the 19th century.

By overlaying the ownership map surveyed in 1993 with the boundaries, we see how each property parcel grew over time, rendering old boundary walls obsolete. These are often the walls that are left to crumble and decay. Given that these surveys were hand drawn, they do not align perfectly.

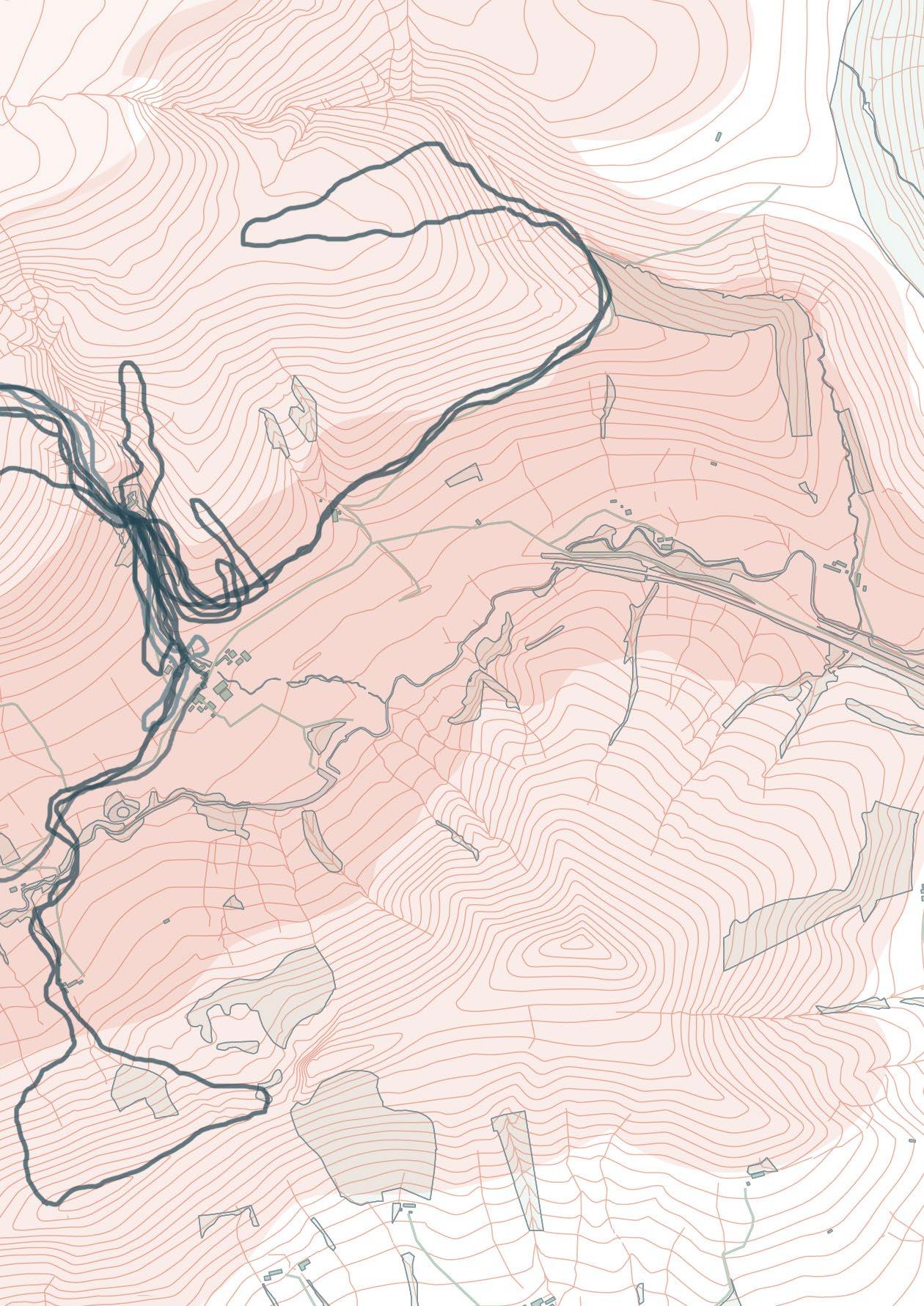

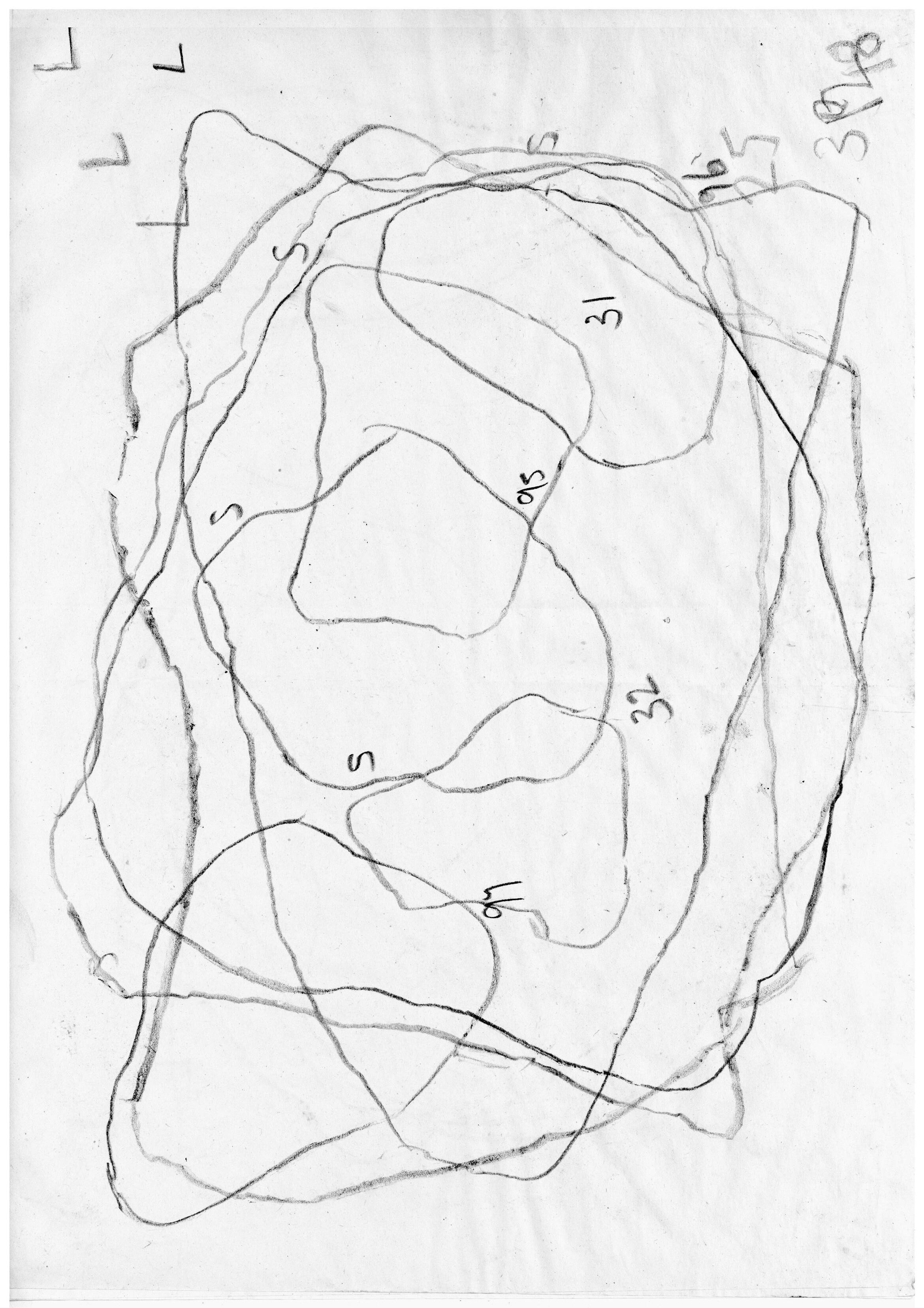

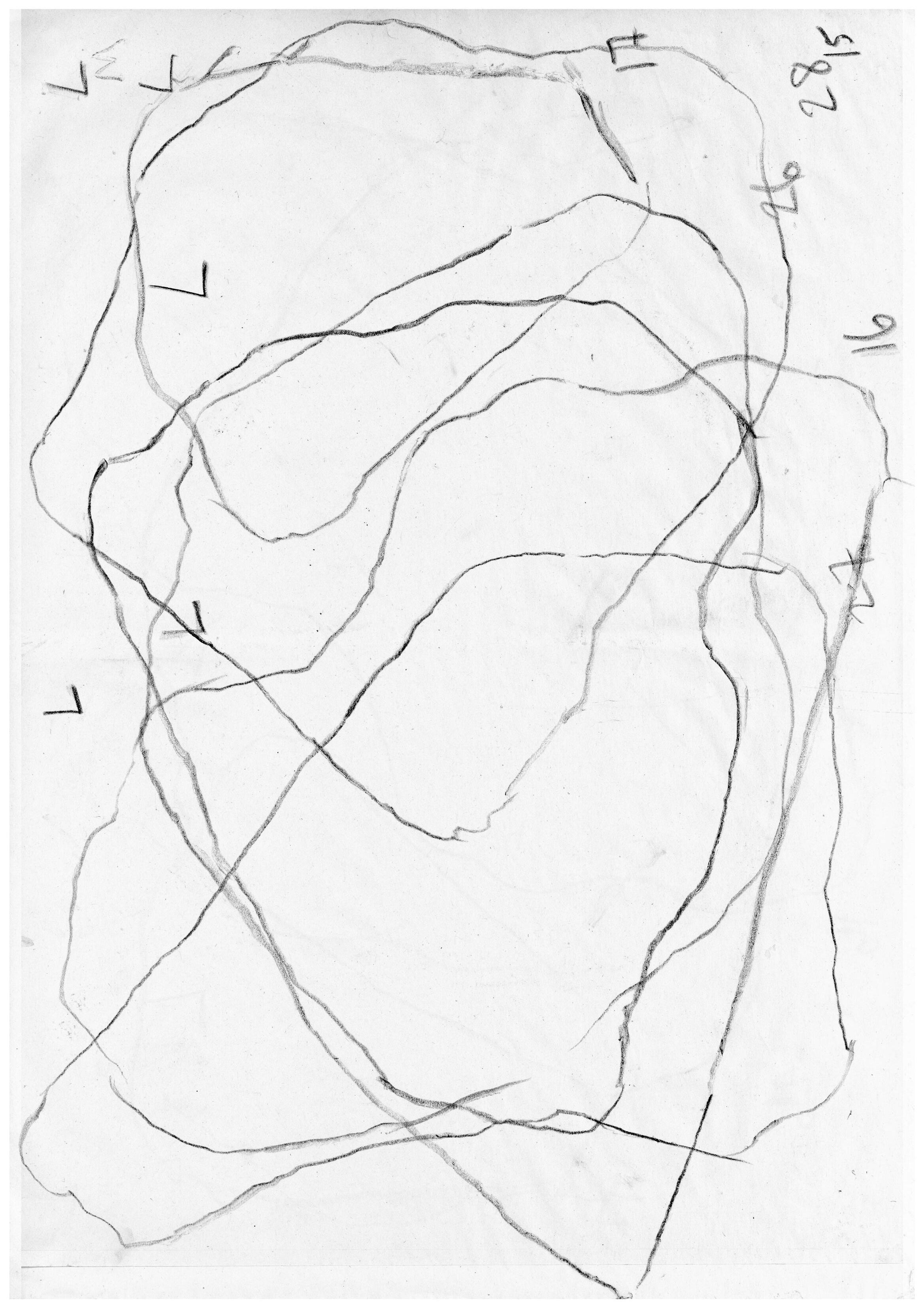

Fieldwork in Edale Valley and Moors: 07.04.24 - 11.04.24

I stayed in the YHA Edale

02 This circle demarcates my maximum walking radius

Edale valley: open pastures

Moorland slopes and cloughs

Open moors

Reservoir

Woodland

Walking Routes

The lines demarcate the walks I took during my five days in Edale. The density of lines shows that I often didn’t stray far from the hostel, and frequently returned to several locations of interest.

April 11, afternoon Sunny and warm

April 9, morning Windy and rainy

April 7, evening Windy and

April 11, morning Sunny and warm

evening drizzly

April 8, morning Sunny and cool

April 9, afternoon Windy and rainy

April 8, afternoon Sunny and warm

April 10, morning Cloudy and drizzly

April 9, evening Occaisional clouds

April 7, afternoon Windy and rainy

April 10, afternoon Windy and drizzly

GEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY:

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN SURFACE AND SUBSURFACE

This section examines the geology of the Dark Peak, the northern region of the Peak District where much of the moorland is found.

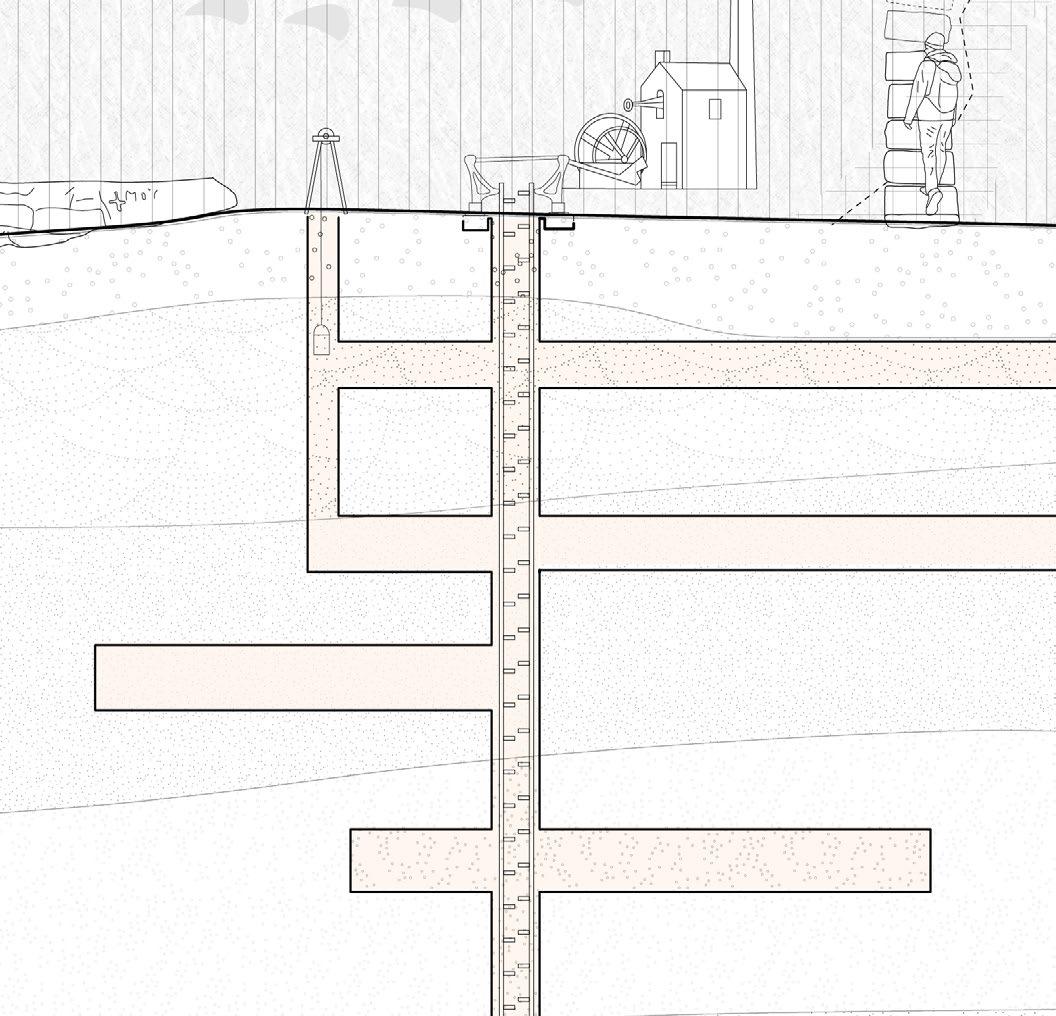

This thesis views geology as not static but the framework of an ever-shifting landscape. Building with drystone is to build with the fabric of the land itself, a re-assembly of the surface and subsurface conditions as built form. In doing so, humans inevitably encounter the agency of the rocks themselves, and the act of making becomes one of collaboration.

We are all geological.

Sub-question A:

+ How does the geologic makeup of the moorlands provide the ‘ingredients’ for drystone construction?

Preamble: Becoming Geological

Dark Peak Geology

Dark Peak Geologic Timeline

Dark Peak Geology

Gritstone Formation and Properties

Dark Peak Ecology

Dark Peak Flora and Fauna

Dark Peak Mosses and Lichens

Dark Peak Landforms and Lifeforms

Nether Booth Overlooking Upper Moor

Back Tor

Hollins Cross Overlooking Castleton and Hope Valley

Backtor Farm Overlooking Edale Valley Landforms as Windforms

Moorland Peat Ecologies

Peat Formation and Degradation

Moorland Grouse Industry

Problematising Heather Burning

Moorland Filmic Mapping

Grouse Moors and Land Ownership

Preamble: Becoming Geological

Experiments in Learning-with Stone

“We are in a knot of species coshaping one another in layers of reciprocating complexity all the way down”

“If we appreciate the foolishness of human exceptionalism then we know that becoming is always becoming with, in a contact zone where the outcome, where who is in the world, is at stake.”

- Donna Haraway, “When Species Meet”

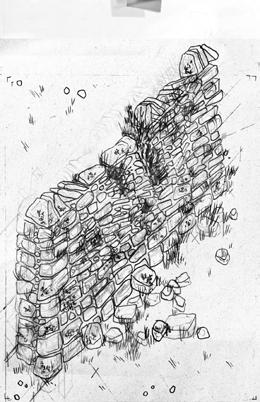

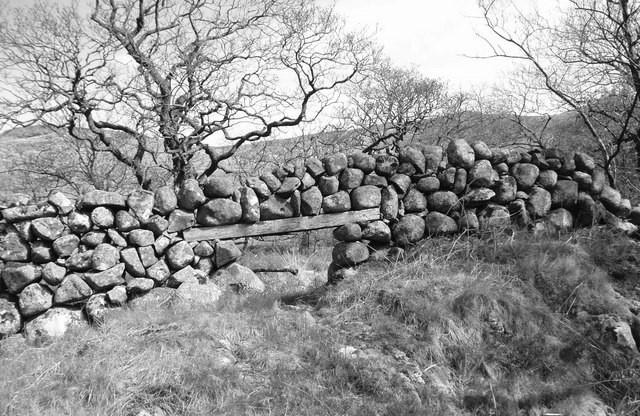

What might it mean to see oneself in relationship to stones? What might the implications be of seeing stones as living beings? Spending time with the drystone walls around Edale, I kept feeling their ‘alive-ness.’ Covered in mosses and infused with lichens, drystone structures are mineral conglomerates, food sources, homes, barriers, geologic entities, and expressions of the evertransforming landscape. Never static, they exist at a slower timescale than the human one, despite being built by human hands. As they crumble, rocks return to the earth’s surface, imprinting the land and confusing the binary condition of “wall” and “not-wall”. In this series of images, I developed a relationship with the stone walls by fitting my body into the gaps left by broken stones, attempting to merge with the wall. These were also attempts in forming situated knowledge, specific ways of knowing that are tactile and collaborative between myself and the stones.

Dark Peak Geologic Timeline

25,000,000BCE 1,800,000BCE 700,000BCE

EARLY PLEISTOCENE

MIDDLE PLEISTOCENE

Carboniferous Period (359-299 million years ago)

A shallow sea covers the Peak District. The remains of the sea creatures eventually form sediment deposits after millions of years

Upland Britain is formed, Carboniferous bedrock is exposed, sediments deposited 150m above current ground level, Peak Distict landmass is gradually uplifted

Uplift continues, pre-Pleistocene landscape erodes, valleys are carved out

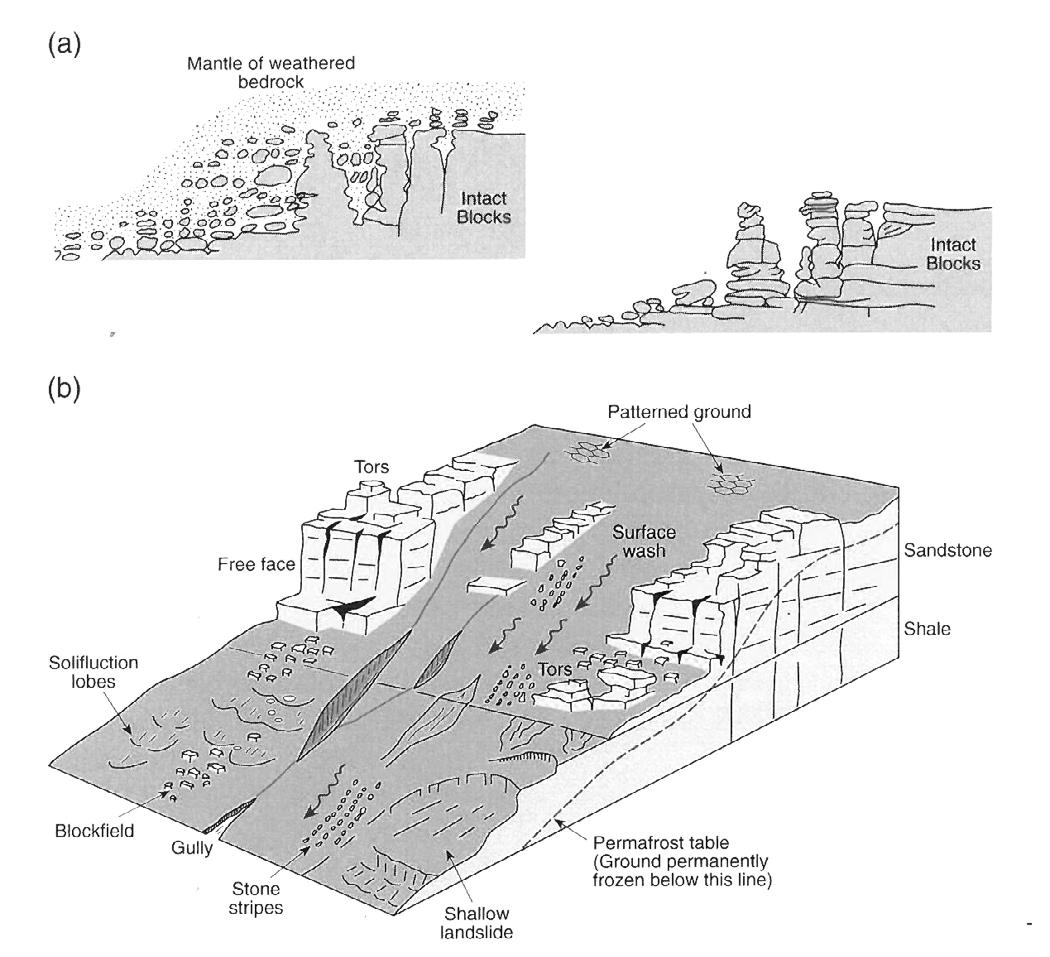

Cold and temperate cold period brings bedrock and till patterns are formed; brings about the loose rocks in Deep

Seasonal thawing and freezing (periglacial conditions) cause degradation and weathering, scree and tor formation, landslips, slow flow of saturated soil (solifluction), valley ridges level out, valleys carved out by seasonal streams, glacial ice material (till) deposits, meltwater channels form

Erosion of glacial deposits along valley ridges (interfluves), increased sediment (aggradation) in main valleys, bedrock weathers

Glacial Period

valleys and dales are carved into the landscape

temperate climate fluctuations; brings glacial erosion of till deposits, current drainage formed; temperate period the formation of weathered soil (regoliths)

Stream patterns are re-established between glacial periods, modern floodplains form, soil and vegetation cover develops, slopes stabilise, peat forms

Peat formation

Decayed plant material in wet conditions accumulated to form thick layers of peat in the moorlands,acting as valuable carbon sinks

Bee Low Limestone Formation: Limestone

Bee Low Limestones Formation (apron-reef): Limestone

Millstone Grit Group: Mudstone, siltstone and sandstone

Shale Grit: Sandstone

Mam Tor Beds: Siltstone and sandstone

Millstone Grit Group: Mudstone, siltstone and sandstone

Bowland Shale Formation: Mudstone, siltstone and sandstone

Above: Map adapted from the BGS Geology Viewer, https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/ Left: Diagram from “Classic Landforms of the Dark Peak” by R. Dalton, H. Fox, and P. Jones

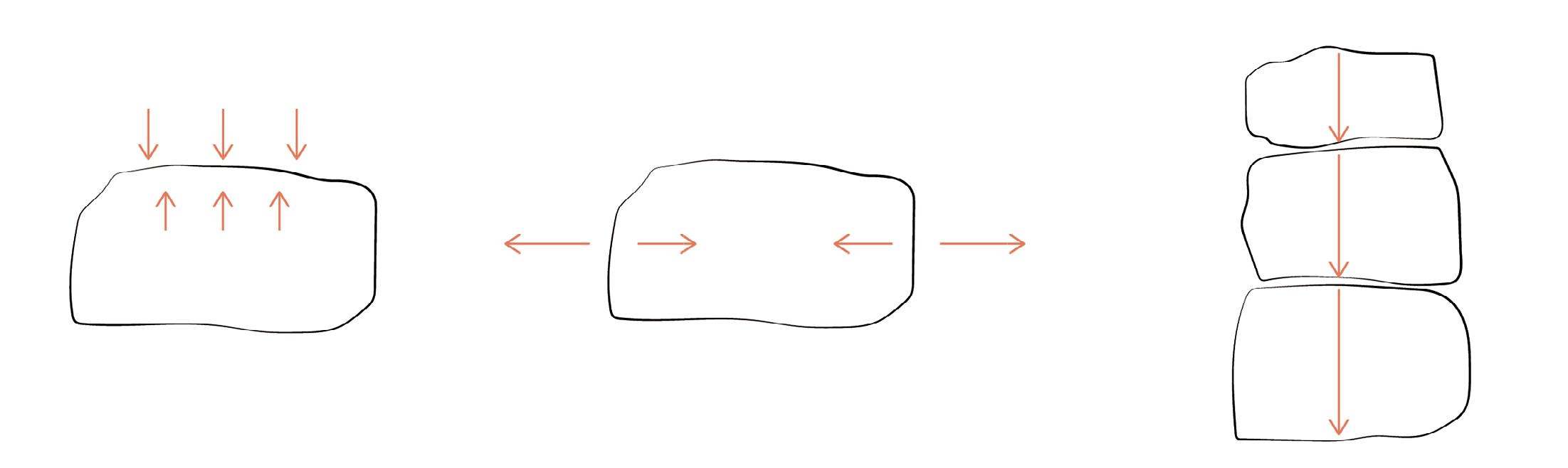

Gritstone Formation and Properties

01. Sedimentation

A shallow tropical sea covered this region during the Carboniferous period, causing sediment to accumulate on the sea floor over millions of years. Rivers, currents, and marine organisms deposited sediments such as sands, silts, and clays.

02. Diagenesis

Diagenesis is a process of sediment compaction that took place over millions of years. The pressure from the overlying sediments causes the grains of sand to become tightly packed and the pore spaces between them to decrease.

03. Cementation

As the sediment compacts, minerals such as quartz, feldspar, and calcite precipitate out of groundwater and fill the remaining pore spaces between the sand grains. These minerals bind the grains together and turn loose sediment into solid rock.

04. Lithification

The previous two processes transformed loose sediment into sedimentary rock. In the case of gritstone, the rock characteristic to the Dark Peak, the sedimentary rock that formed was sandstone. Gritstone can be identified by its coarse grain size, high quartz content, and resistance to weathering.

05. Uplift and Erosion

Over many millions of more years, tectonic activity uplifted sedimentary laryers, raising them to above sea level. Erosion further shaped the landscape into its distinctive valleys and tors, exposing underlying gritstone bedrock.

Qualitative properties

Grain size: coarse grain

Fracture: conchoidal

Streak: white

Porosity : high porosity

Luster: dull

Resistance: heat resistant, pressure resistant, impact resistant

Quantitative properties

Hardness: 6-7 (out of 10)

Compressive strength: 70.00 N/mm 2

Density: 2.2g/cm3

Specific heat capacity: 0.92 kJ/Kg K

Varied shapes and sizes of gritstone

Gritstone in a broken drystone wall

Dark Peak Flora and Fauna

*An asterisk indicates plants and animals I encountered in and around Edale in April

PLANTS

Eriophorum*

Cottongrass

Vaccinium myrtillus

Pteridium aquilinum*

Oreopteris limbosperma

FUNGI

Calluna vulgaris*

Huperzia selago

Viola palustris

Empetrum nigrum

Calvatia booniana

Porpolomopsis calyptriformis

Bracken

Heather Fir clubmoss

Lemon-scented fern

Marsh violet

Bilberry

Sphagum something

Giant puffball

Pink waxcap

MAMMALS

Lepus timidus

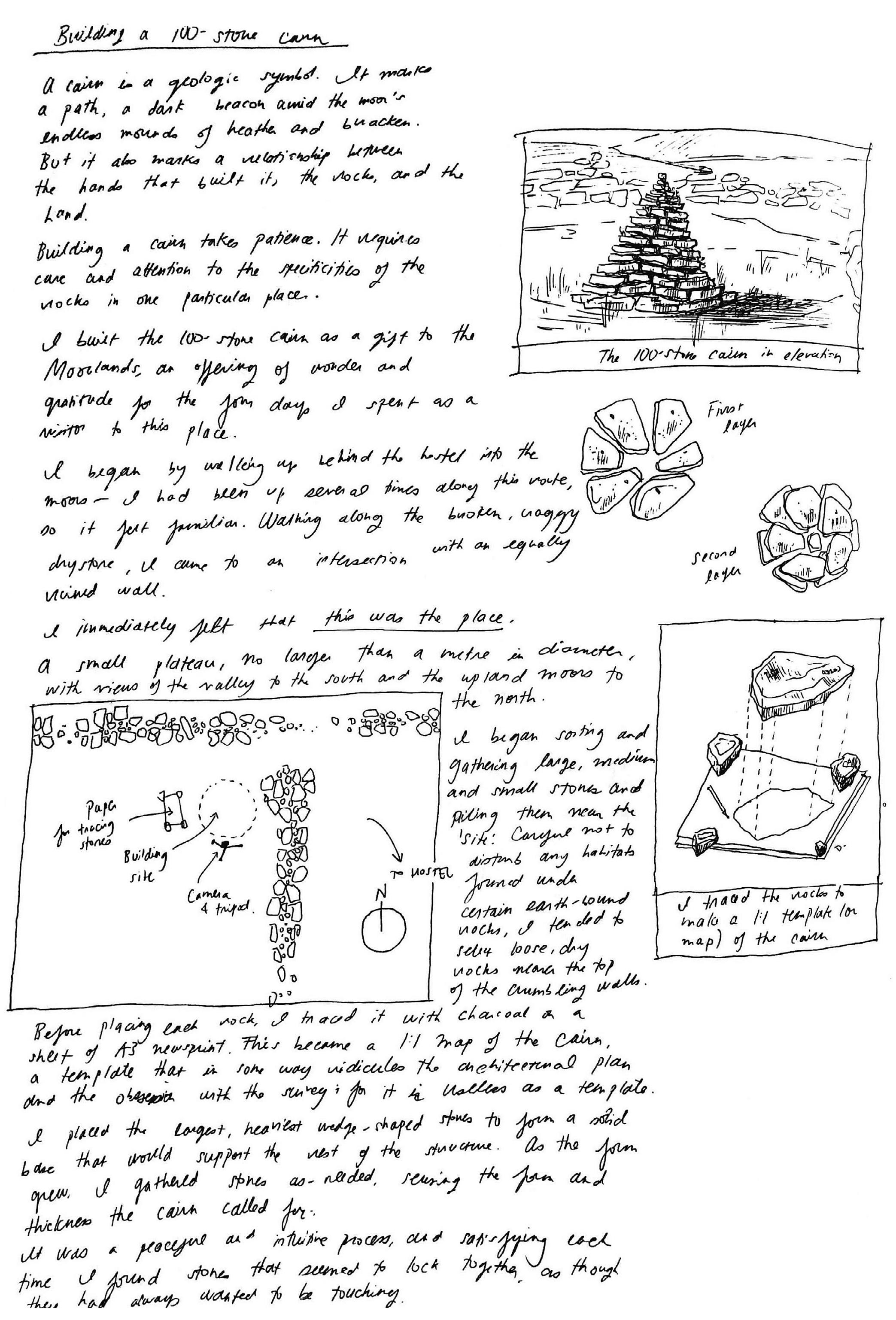

BIRDS

Pluvialis apricaria

Lagopus lagopus scotica*

Anthus pratensis

INSECTS

Lasiocampa quercus

Cervus elaphus

Turdus torquatus*

Numenius

Asio flammeus

Troilus luridus*

Red grouse

Golden plover

Curlew

Short-eared owl

Ring ouzel

Red deer

Mountain hare

Meadow pipit

Northern eggar

Bronze shieldbug

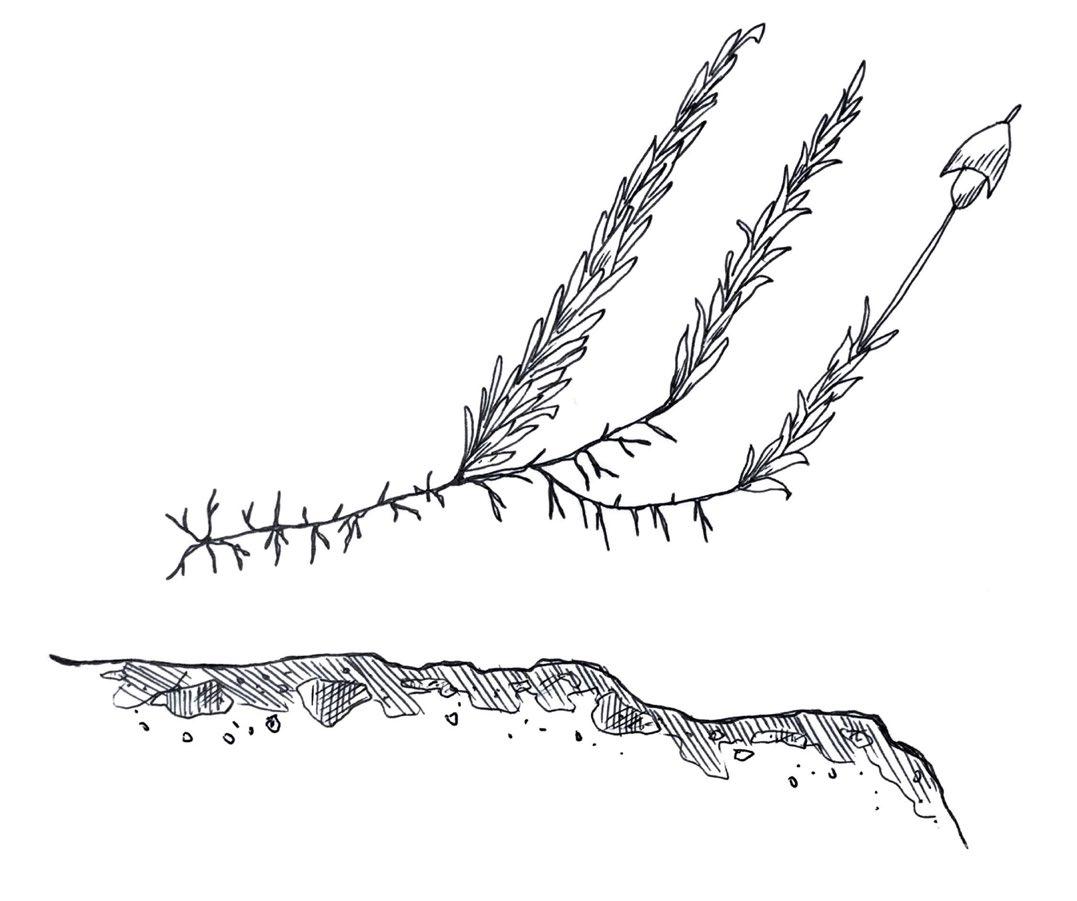

Dark Peak Mosses and Lichens

Hypnum cupressiforme

Sphagum something

Plagiothecium undulatum

Pleurozium schreberi

Sphagum something

Schistidium crassipilum

Sphagum something

Fissidens taxifolius

Sphagum something

These are the mosses and lichens that I encountered while in and around Edale Valley in April 2024.

Sphagnum austinii

Sphagum something

Polytrichum commune

Sphagum something

Dicranum scoparium

Sphagum something

Sphagum something

Sphagum something

Sphagum something

something

Polytrichum formosum

Parmelia saxatilis

Lecanora muralis

Cladonia chlorophaea

Aspicilia calcarea

Campylopus pyriformis

Sphagum

White crustose lichen

Dark Peak Landforms and Lifeforms

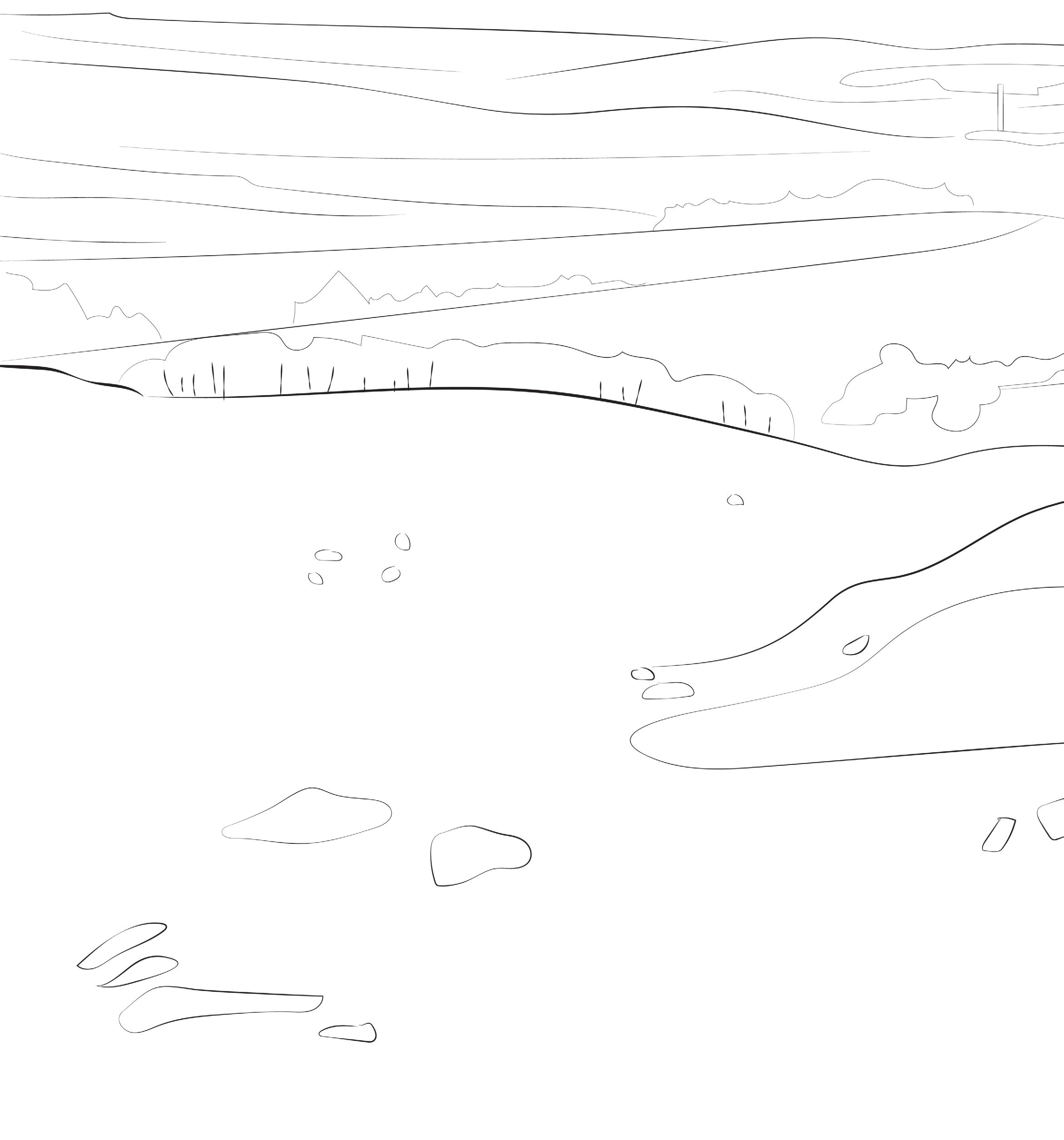

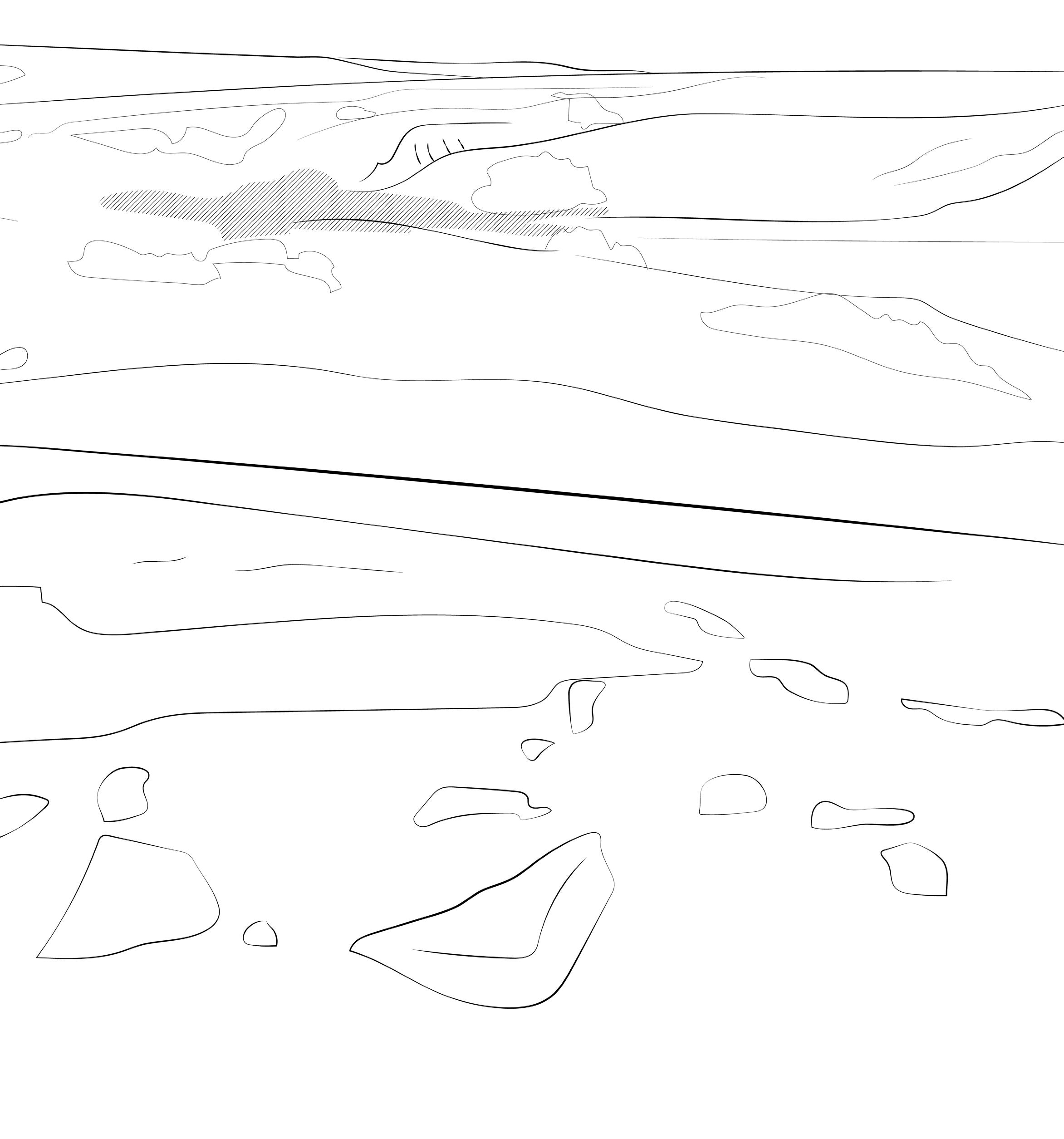

The following series of photographs and illustrations sheds light on the geologic and ecological story of the Edale moorland and valley region.

“The disintegrating rock, the nurturing rain, the quickening sun, the seed, the root, the bird - all are one.”

- Nan Shepherd

Nether Booth Overlooking Upper Moor

Grasses, Heather, Mosses

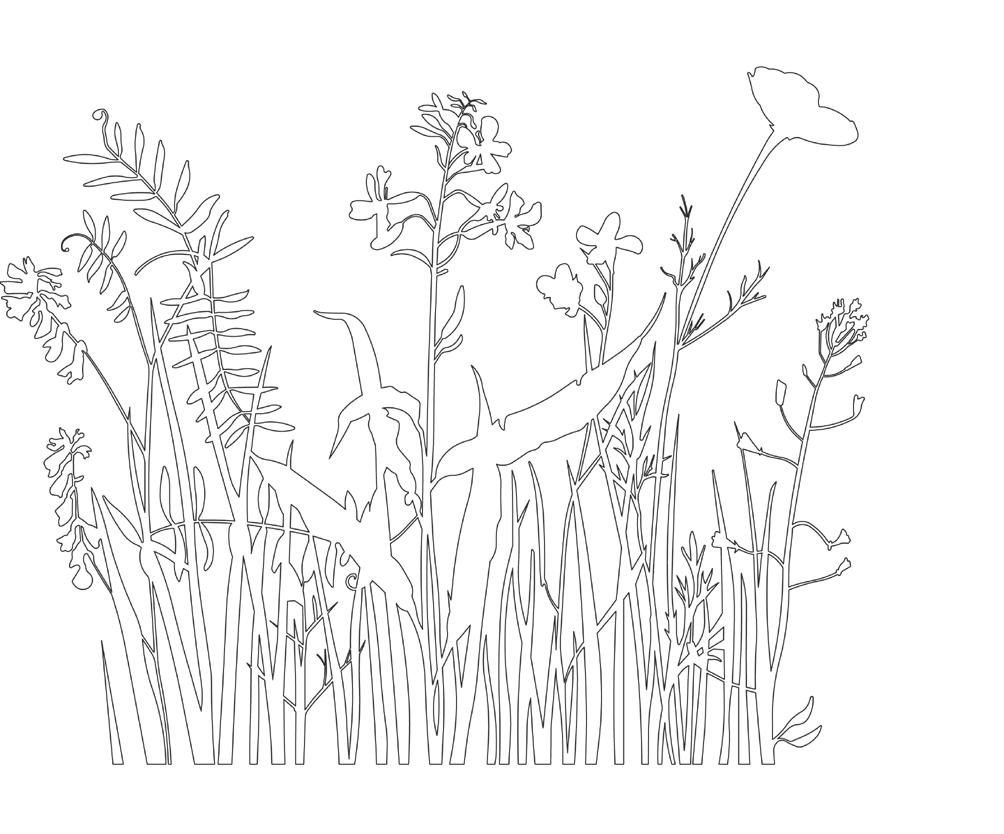

The moorlands feature a diversity of plant life, including many types of grasses, sedges, ferns, heather, mosses, and flowering herbs.

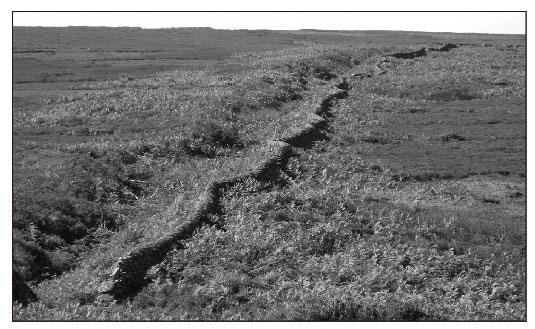

Possible Peat Sledway

Sledways were paths cut into sleep slopes to allow for the transportation of cut peat into the valley.

Bracken

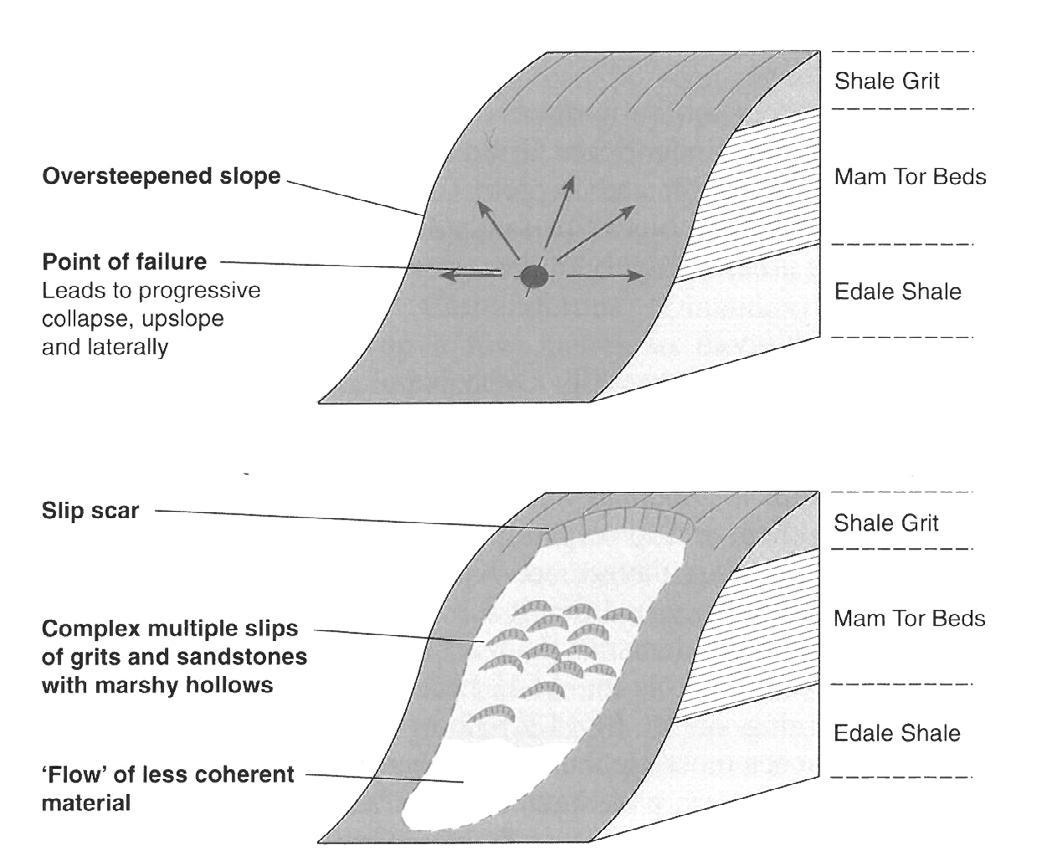

Steep slopes show evidence of landslips, caused by unstable rock strata. This terrain is difficult to navigate and cultivate as agriculture.

Bracken is the most common form of fern that dominates the moorland, turning a reddishbrown colour over winter as it dies back. It is poisonous to livestock and small mammals. A resilient plant, it tends to outcompete other species and spread rapidly across the landscape.

Waterfall and Lady Booth Brooke

A larger, fast-moving brooke cuts through the interfluve, leading into Edale valley. The mountain brookes and streams all lead to the River Noe in Edale valley.

Peat bog

Meandering stream

Small streams cut through peat along the mountainside to reveal bedrock below. These create gullies or cloughs of various depth, carving channels into the steep mountain slopes.

The open upland moors are characterised by peat bogs, possessing thick layers of peat soils created by the continual accumulation of dead plant matter, primarily sphagnum mosses. Blanket bog contains peat of two to three metres deep, and has been cut for fuel from medieval times, though this practice has stopped in recent years.

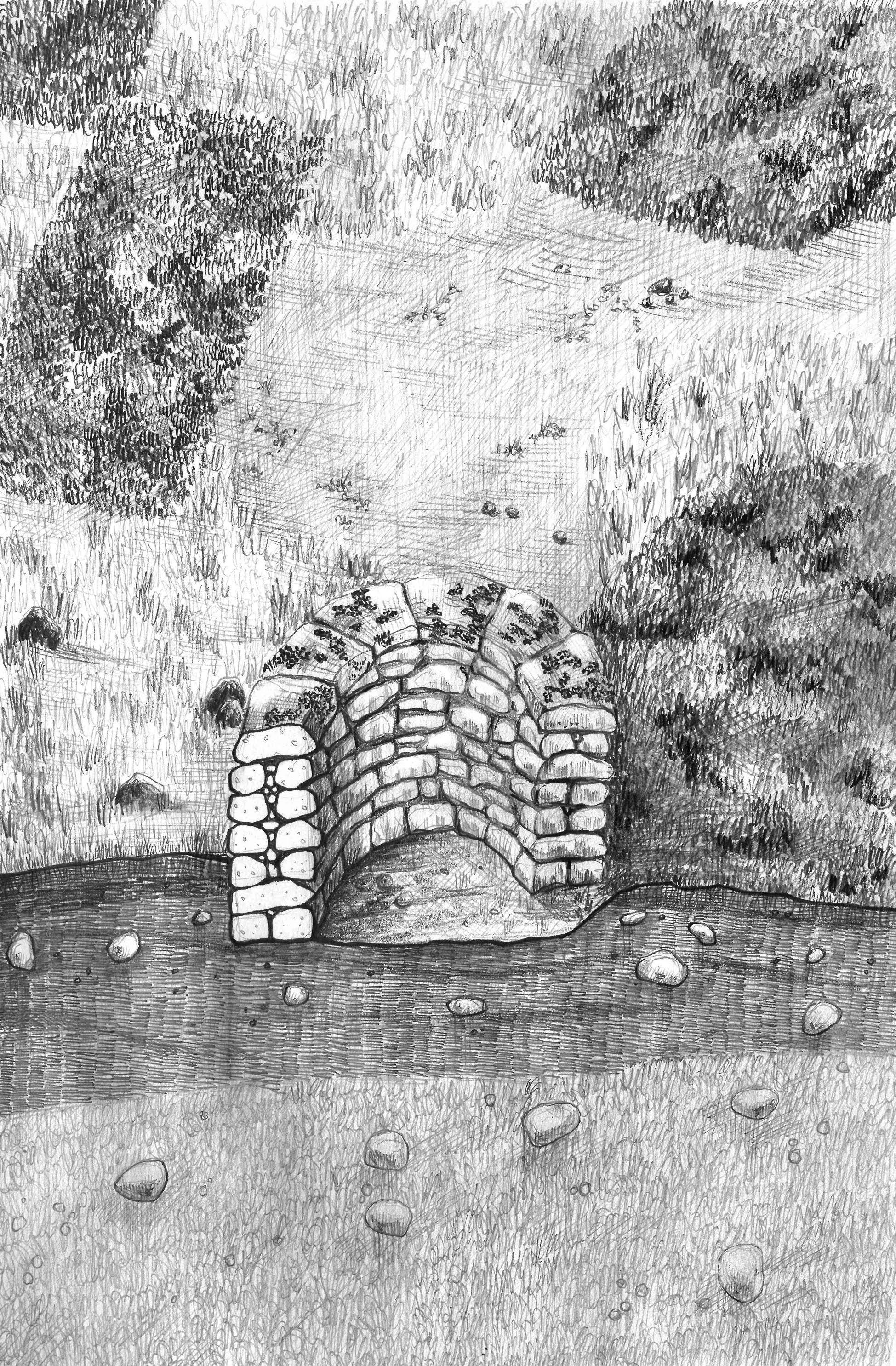

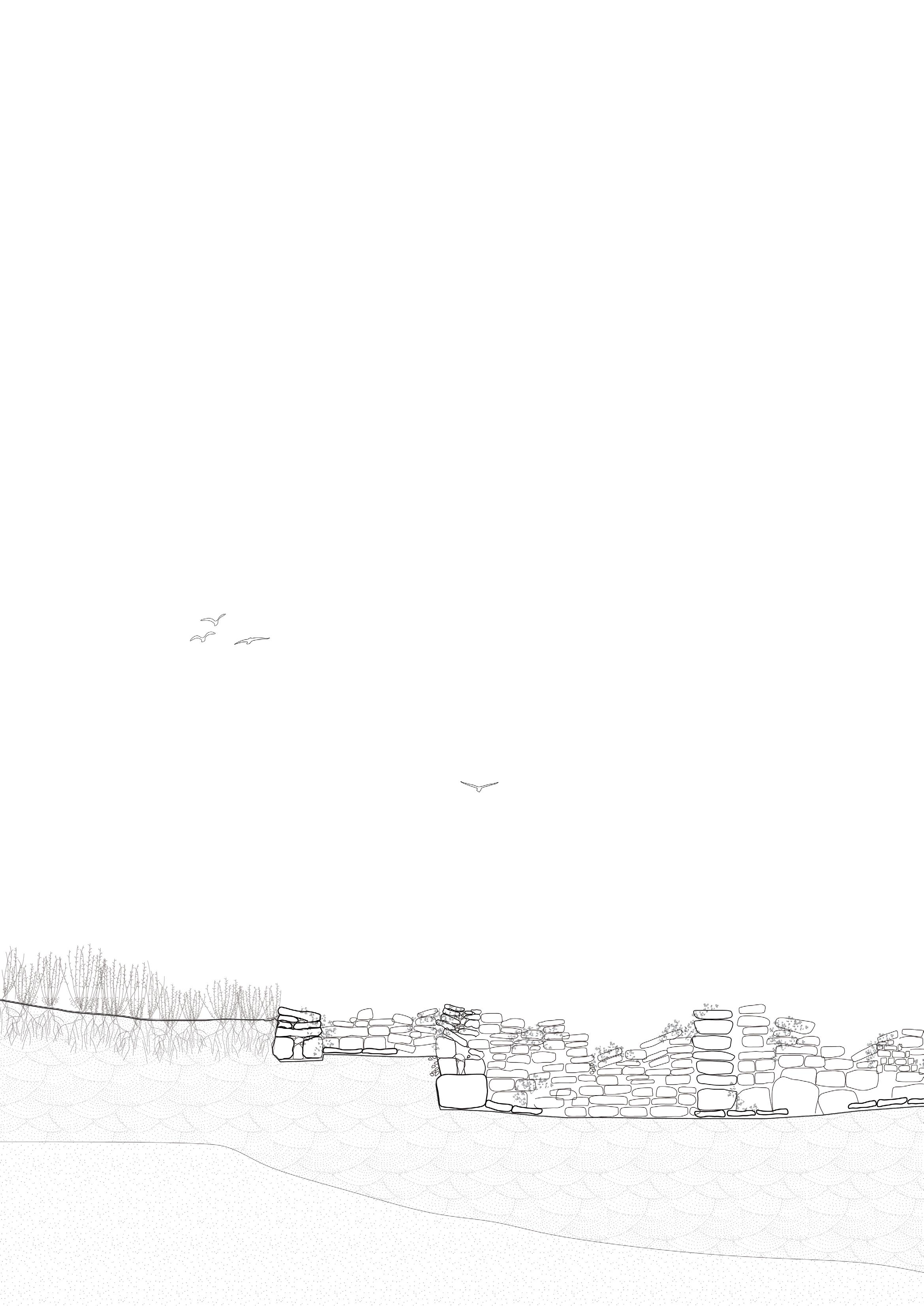

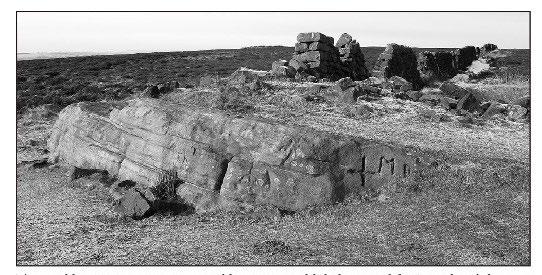

Ruined Drystone Wall

Many moorland drystone walls have fallen into disrepair, no longer maintained or required by the shrinking number of farmers in the region.

Exposed Gritstone Outcropping Conifer Plantation

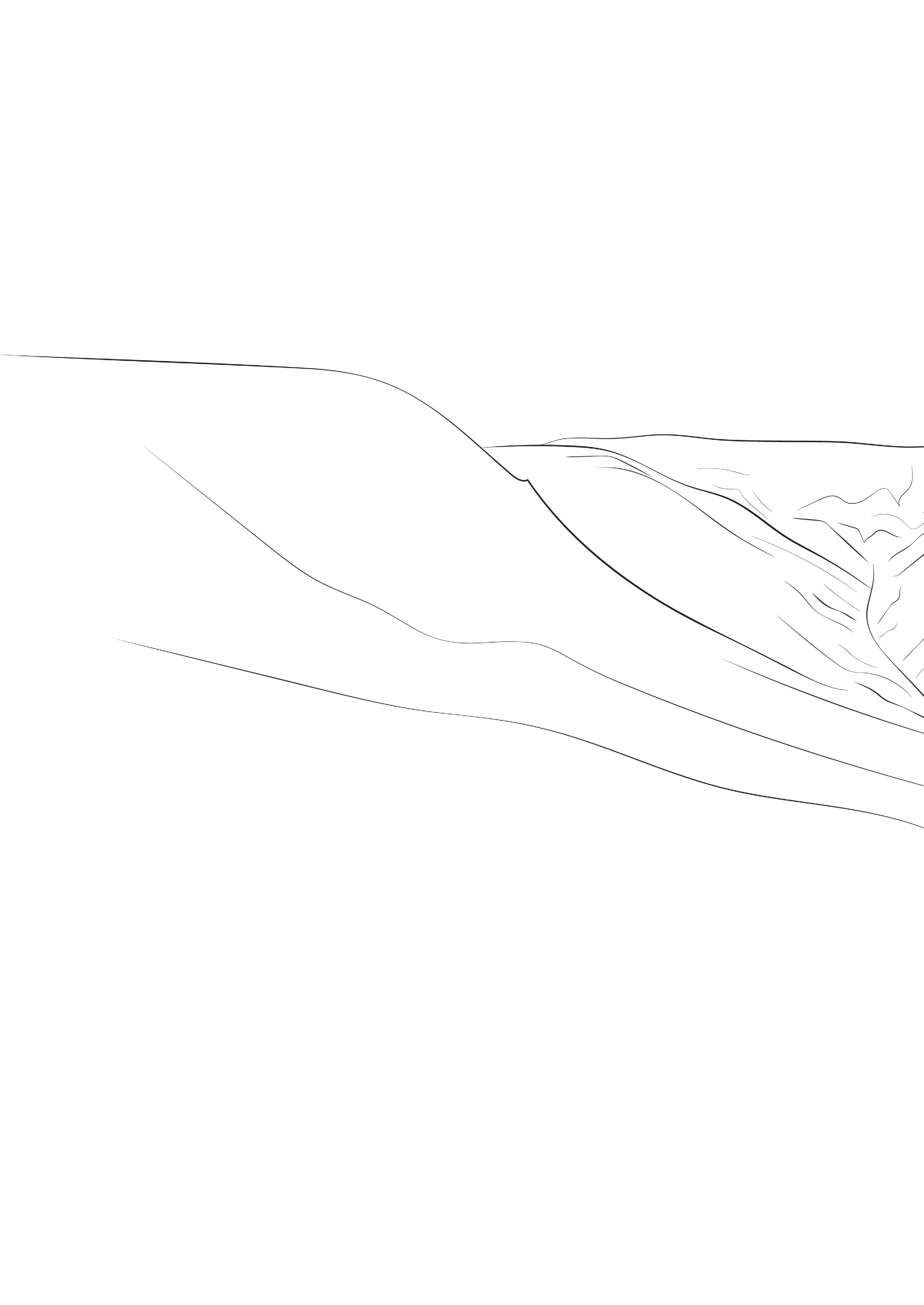

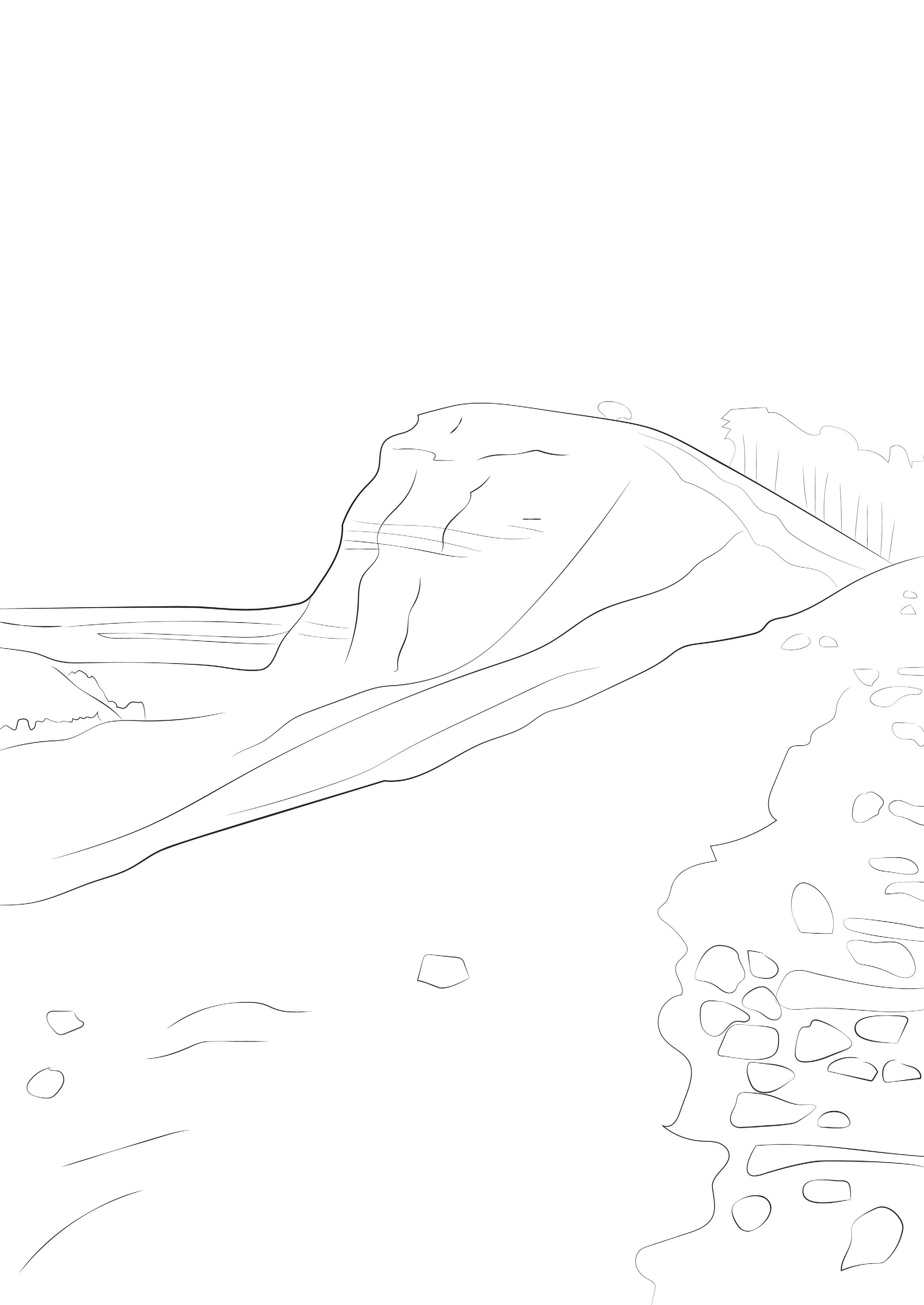

Back Tor is a gritstone formation developed through the Carboniferous period. Its current form is created by continual erosion and weathering.

Theories of Tor Formation

01. Resulting from intact blocks emergingsfrom a mantle of weathered bedrock

02. Resulting from the retreat of a free face under periglacial conditions Diagram from “Classic Landforms of the Dark Peak” by R. Dalton, H. Fox, and P. Jones

By the 1950’s, tree cover in the UK reached its lowest of approximately 5%. Postwar reforesting efforts focused on conifer plantations in this region, with monocrops limiting biodiversity and ecological resilience.

Hollins Cross Overlooking Castleton and Hope Valley

Enclosed fields

Drystone walls and rows of trees clearly demarcate the enclosure of the landscape into privatised parcels of agricultural land.

Cultivated Land

Farming in the Edale and Hope valleys was first recorded in the Domesday book. Given relatively poor soil conditions for growing crops, agricultural land is primarily for sheep grazing.

Landslip Formation

Diagram from “Classic Landforms of the Dark Peak” by R. Dalton, H. Fox, and P. Jones

an industrial landscape dotted with mines, and factories. This chimney is a prominent marker in the landscape, belonging to a factory built in 1929.

Castleton Village

Gritstone boulders are scattered across the landscape, dislodged through erosion and human activity. These form the building blocks for drystone construction.

Though Castleton was first settled by the Celts, the village developed alongside Peveril Castle, settled by the Normans arriving in the Royal Forest of the Peak in the 12th century. The Forest of the High Peak was not a dense woodland, but a region of land designated for hunting by royalty.

Backtor Farm Overlooking Edale Valley

Edale Valley Wall as Ecological Border

This deep upland valley was formed by glacial movement and melt water over the Carboniferous period. The River Noe, flowing through the base of the valley, has contributed to carving out the U-shaped landform, and continues to cut into the basin. The valley slopes have fertile land that are continually washed and weathered through slope erosion.

This drystone wall demarcates a clear division between the cultivated, grassy lower slopes and the moorland scrub of the uplands.

Vale of Edale Stratigraphy

North-south cross section showing layers of rock in the Edale valley.

Diagram from the British Geological Survey, taken from “Classic Landforms of the Dark Peak” by R. Dalton, H. Fox, and P. Jones

This drystone wall is reasonably maintained and demarcates Back Tor Farm. It also prevent them wandering Wall as Demarcating

Demarcating Ownership

reasonably well demarcates land owned by contains sheep to wandering up the slopes.

Acid Grassland

The acid grasslands thrives in nutrientpoor soils. Centuries of sheep grazing has actively shaped both landforms and lifeforms in the Edale valley, creating and maintaining the grassy lower slopes. Overgrazing can cause lack of species diversity.

Small Stream

Streams of various sizes and depth transverse the steep slopes.

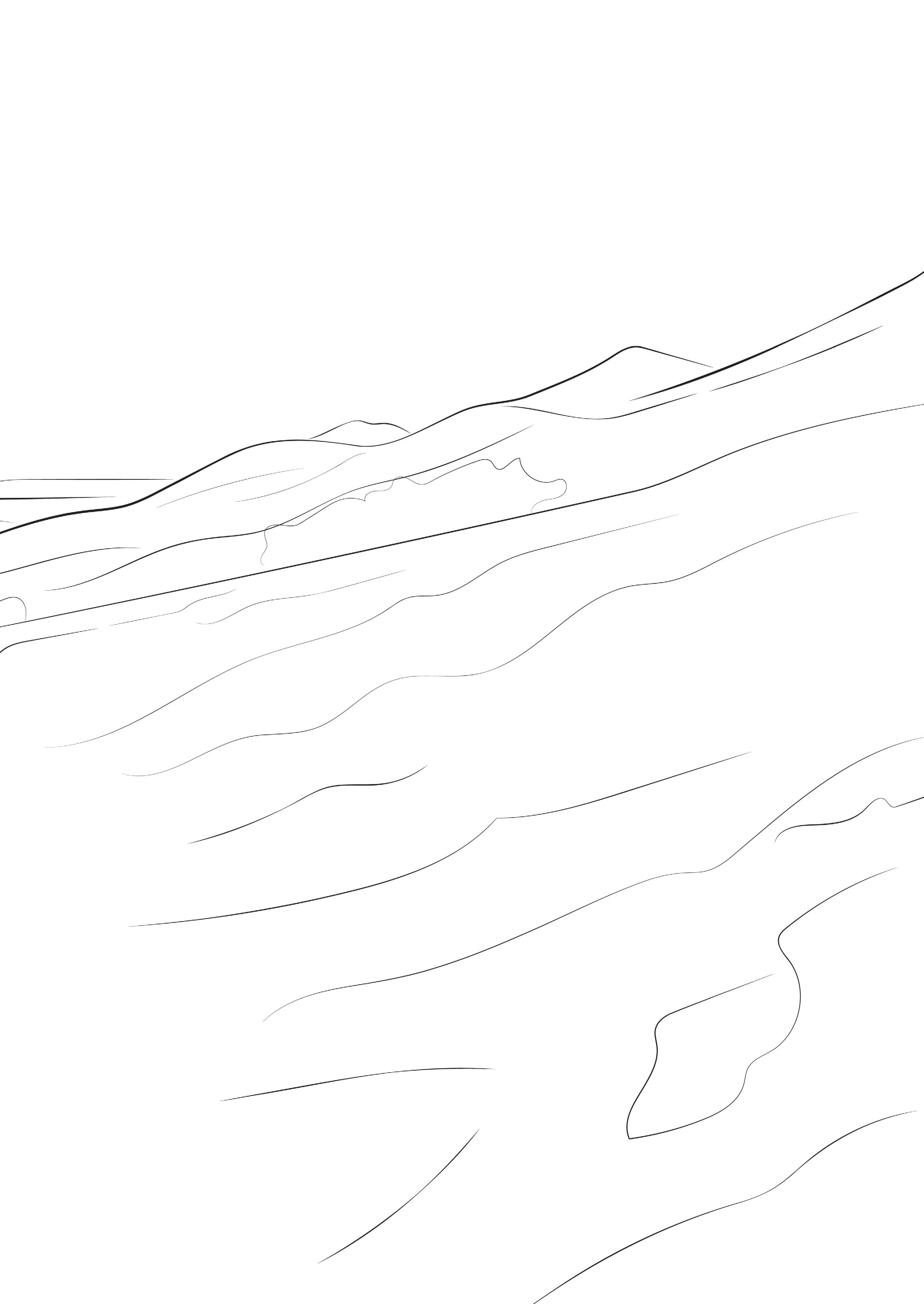

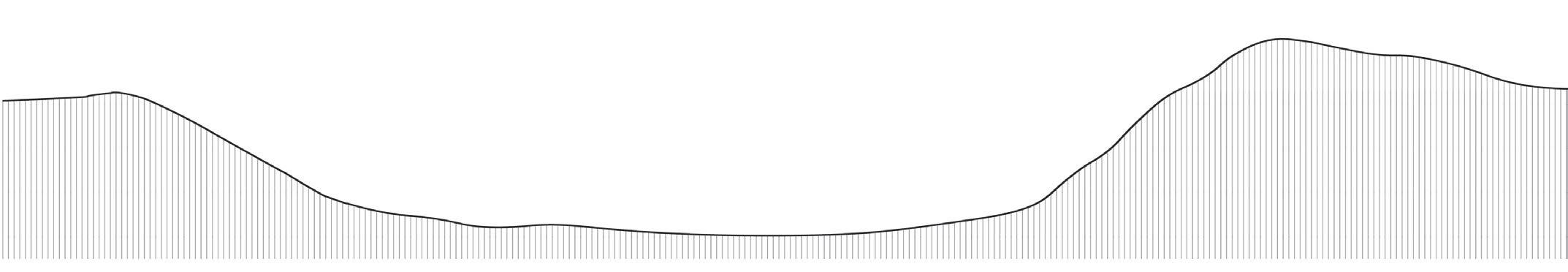

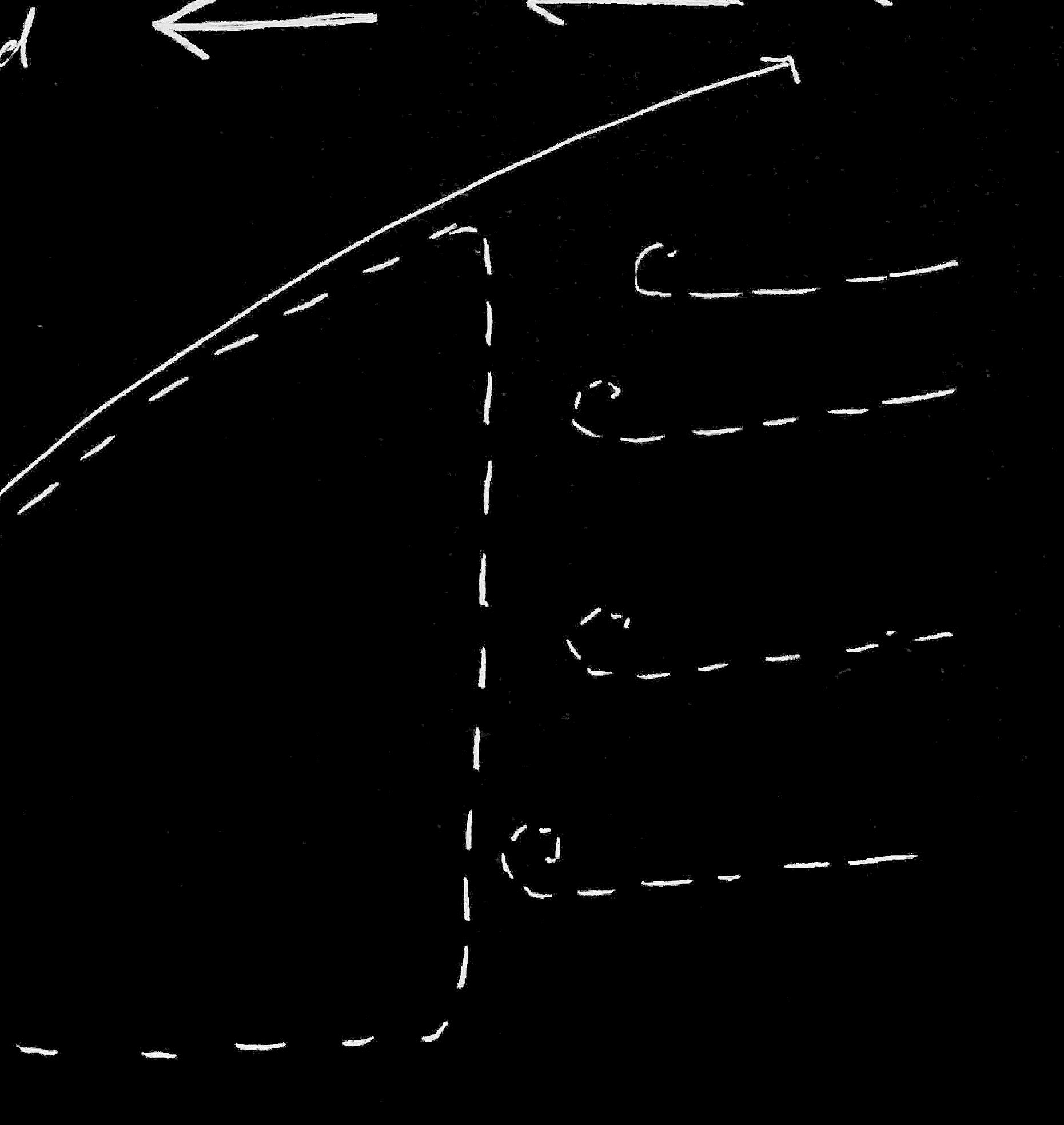

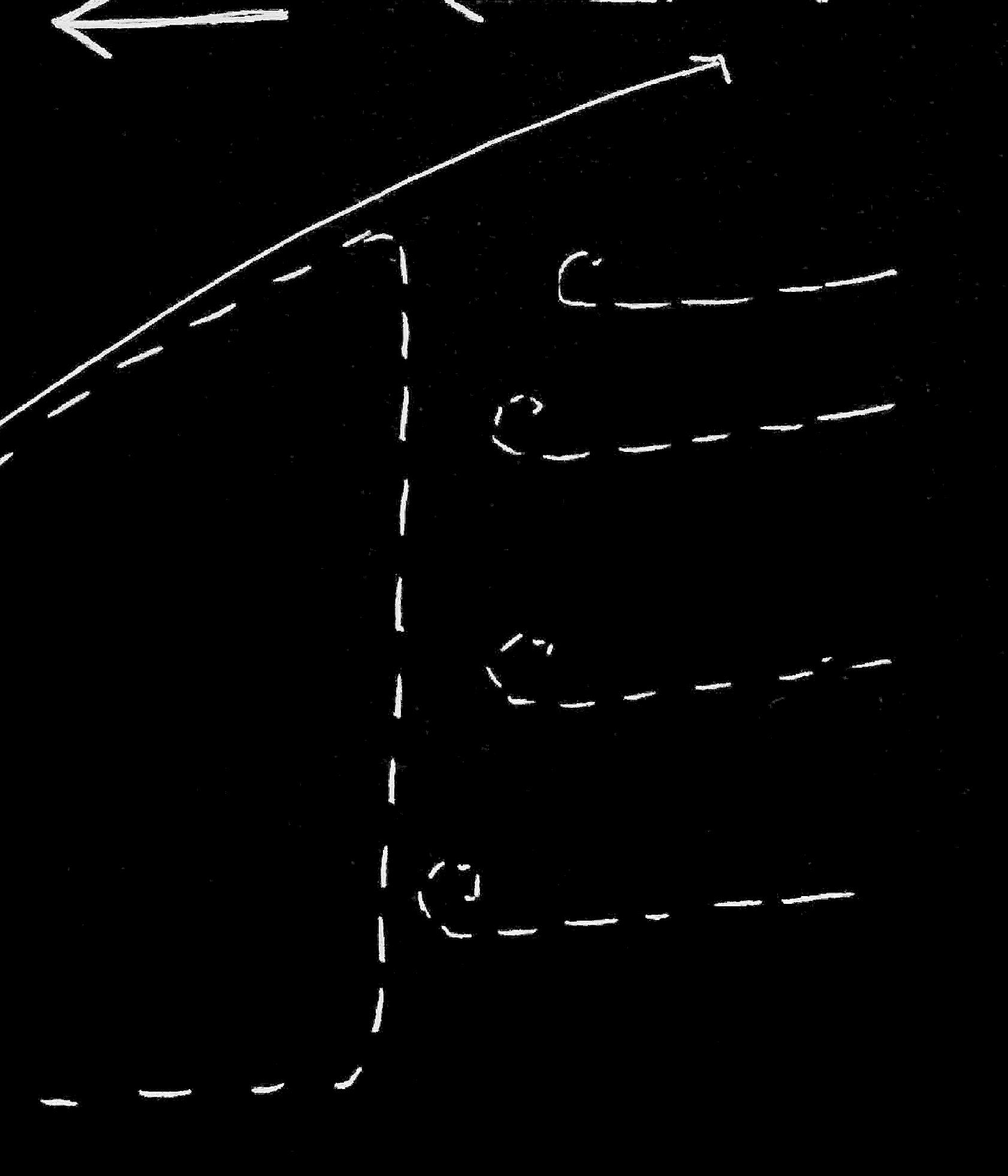

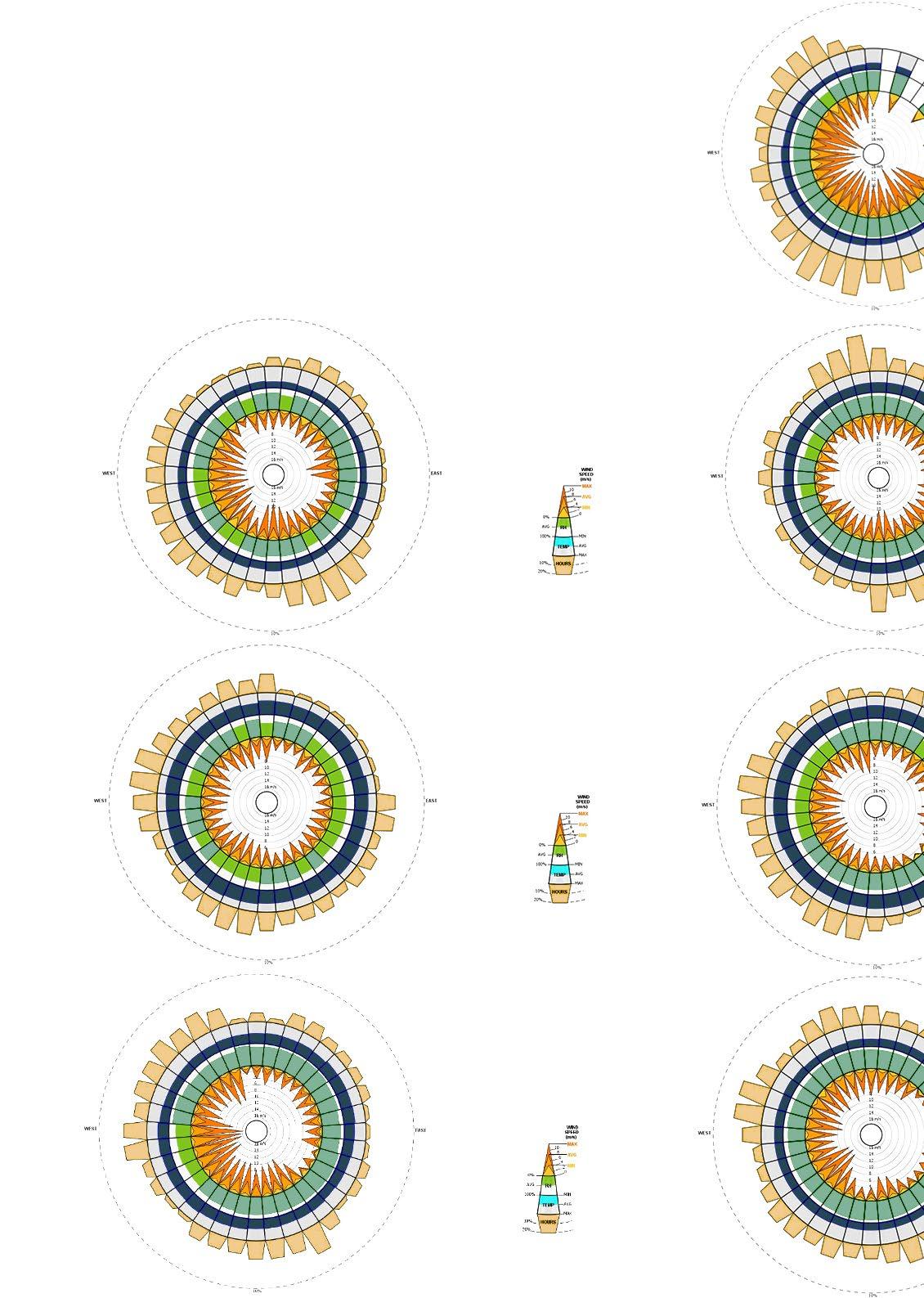

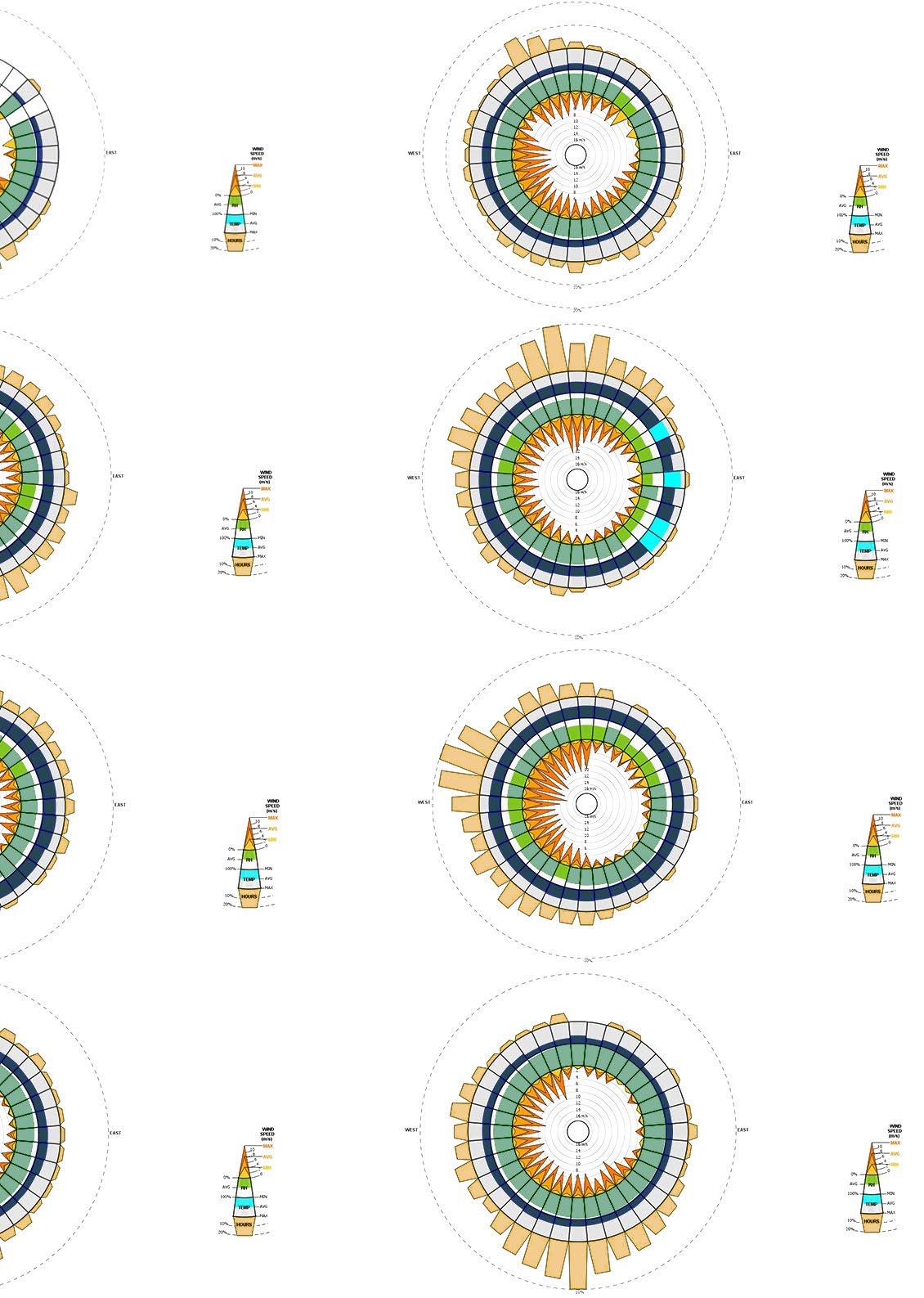

Landforms as Windforms

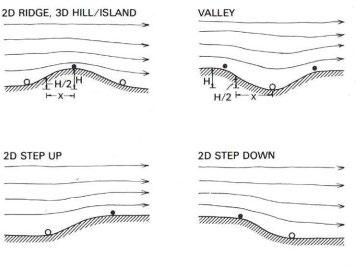

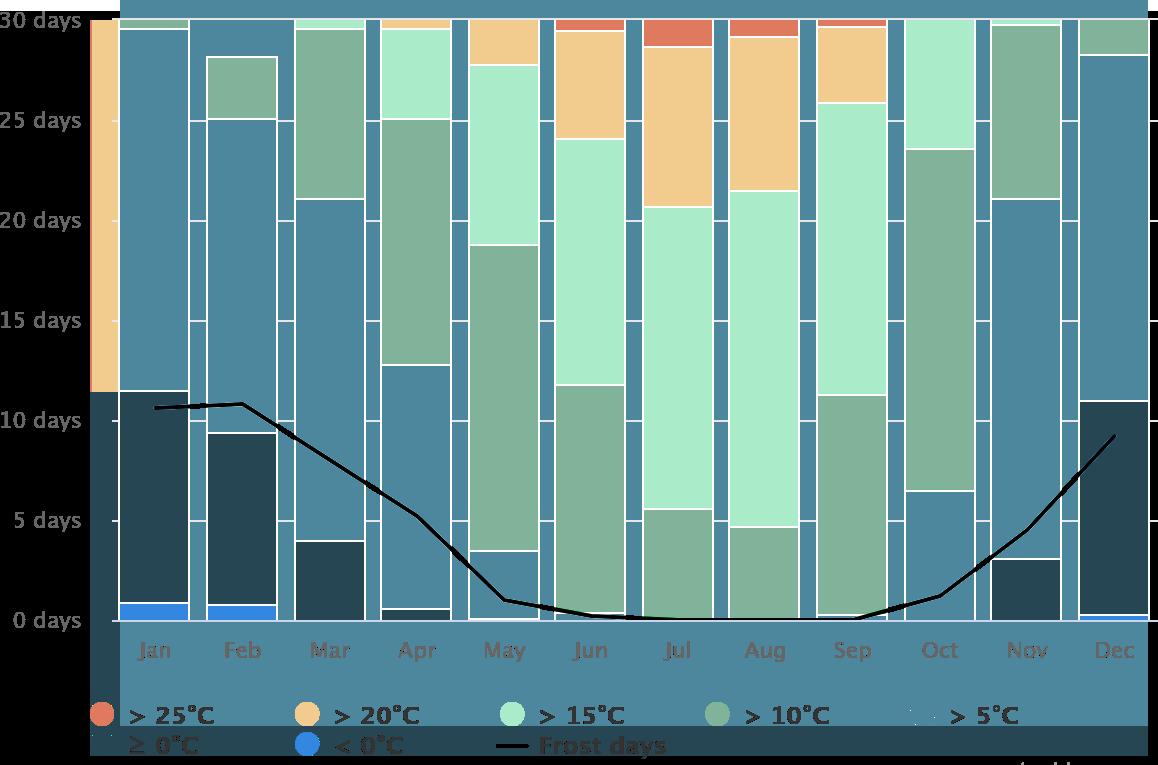

Wind is a constant presence in the Peak District. Though invisible, this force entirely alters and shapes one’s perception of place, and one’s ability to build within it. The Edale valley creates a basin guiding valley and anti-valley winds. The prevalent wind direction is eastward (a further wind analysis can be found in the following section on drystone construction). Topography plays an important role in influencing the direction and speed of wind. These factors should be kept top of mind in the design and construction of drystone. Though drystone acts as a wind break, its porous nature will always let some air through.

Typical windflow patterns affected by topography. Diagram from Boundary Layer Climates by T. R. Oke

01. Eastward valley wind

02. Edale valley basin

03. Anti-valley wind

Valley cross section showing daytime upslope breezes (anabatic)

Valley cross section shwoing night downslope drainage breezes (katabatic)

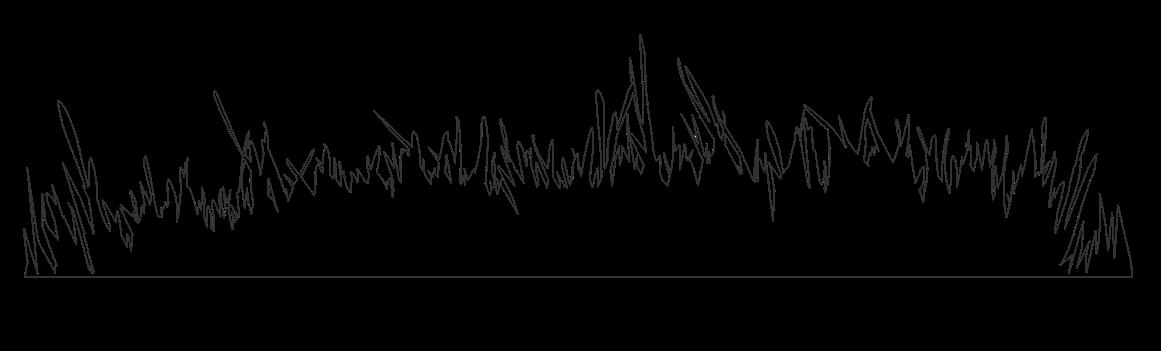

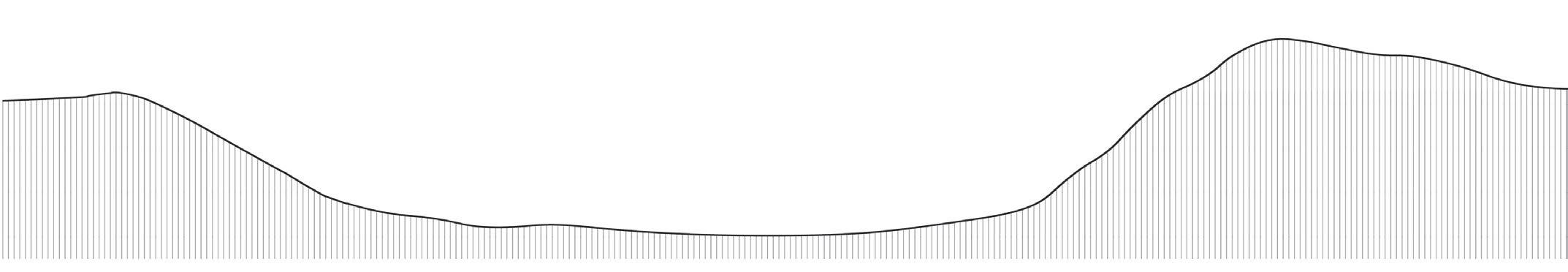

Moorland Peat Ecologies

The following section analyses the formation and degradation of peat soils, examining how the grouse hunting industry has drastically shaped moorland ecologies.

The heather, grasses, mosses, and small puddles of the grouse moors form a landscape-within-a-landscape. Looking down is to imagine a forest with the heather as autumnal trees and the puddles as great reflective lakes.

Peat Formation and Degradation

million years ago

5000-8000 years ago: peat formation begins

+ Peat forms over thousands of years under waterlogged and acidic conditions. With no oxygen, bacteria and fungi cannot act to decompose plant matter, so it preserved as it is compressed.

+ Over time, layers of sphagnum mosses and other plant matter accrues. As this accumulation increases in weight, it compacts the material below, and over time, this turns into peat.

Compressive forces compacting dead plant matter

+ Burning heather dries out peat soils and expells sequestered carbon into the atmosphere. This practice is particularly harmful when it occurs on thick peat bogs.

+ Peat cutting is an ancient practice, where cut peat is burned for fuel. It was also one of the “rights to the common” because it was a form of subsistence. Though it is currently illegal to burn ‘deep peat’, this practice continues. Another factor causing peat degredation is pollution from the industrialisation, retaining the Peak District’s industrial history in its very soils.

Several hundred years ago until present

Roman period until past century

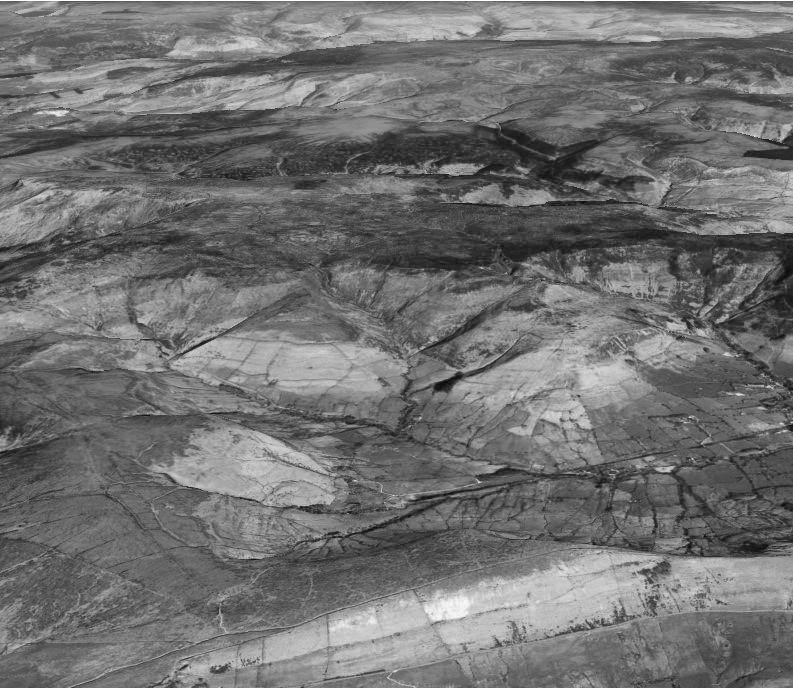

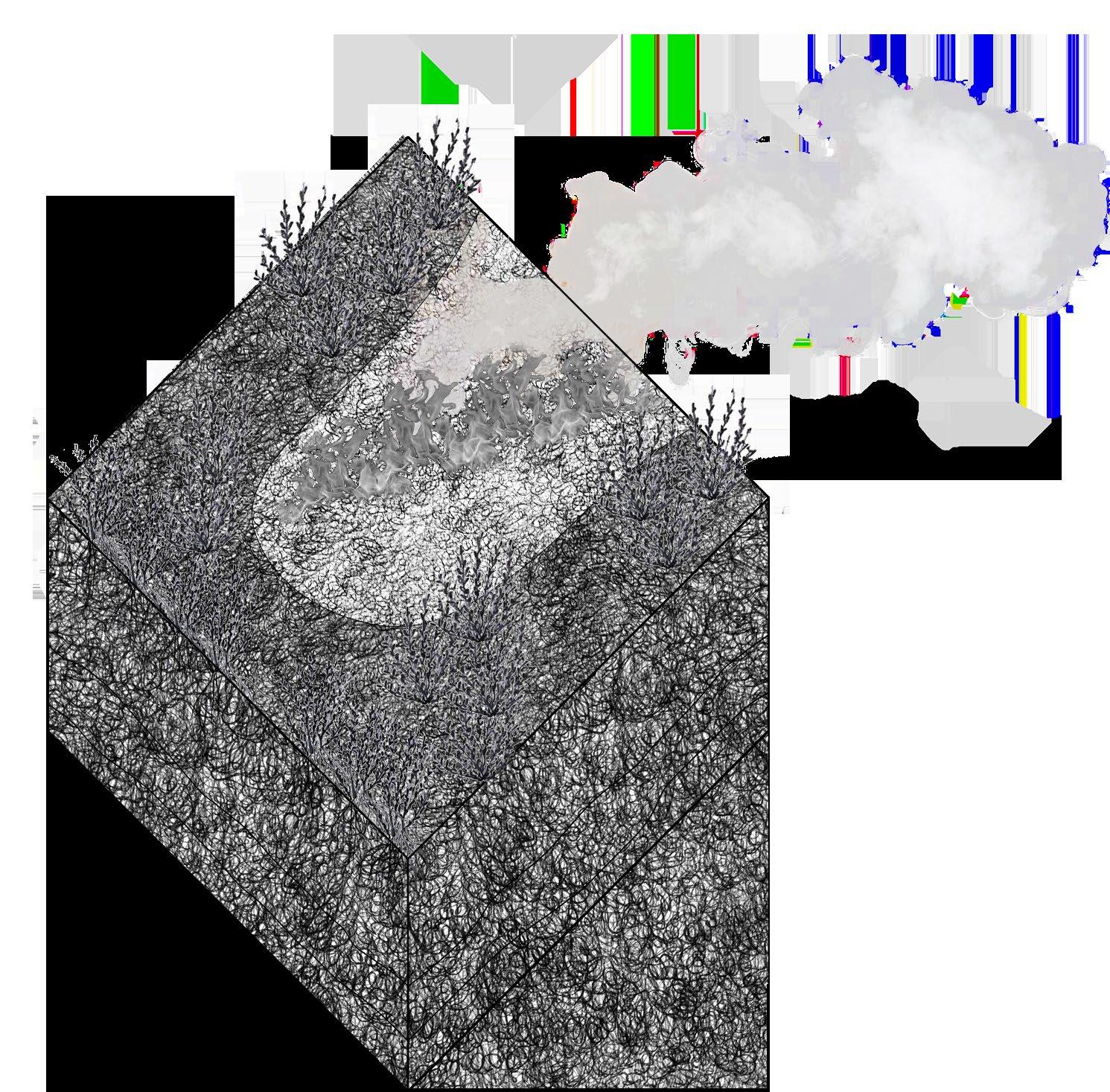

From a satellite view, much of the moorlands registers as a patchwork of irregular lighter rectangles on a darker surface. What causes this intriguing pattern, not unlike paintbrush strokes?

These are the marks left behind by the grouse hunting industry, traces that reveal vast tracts of land still owned by these estates and rooted in elitist and environmentally destructive practices.

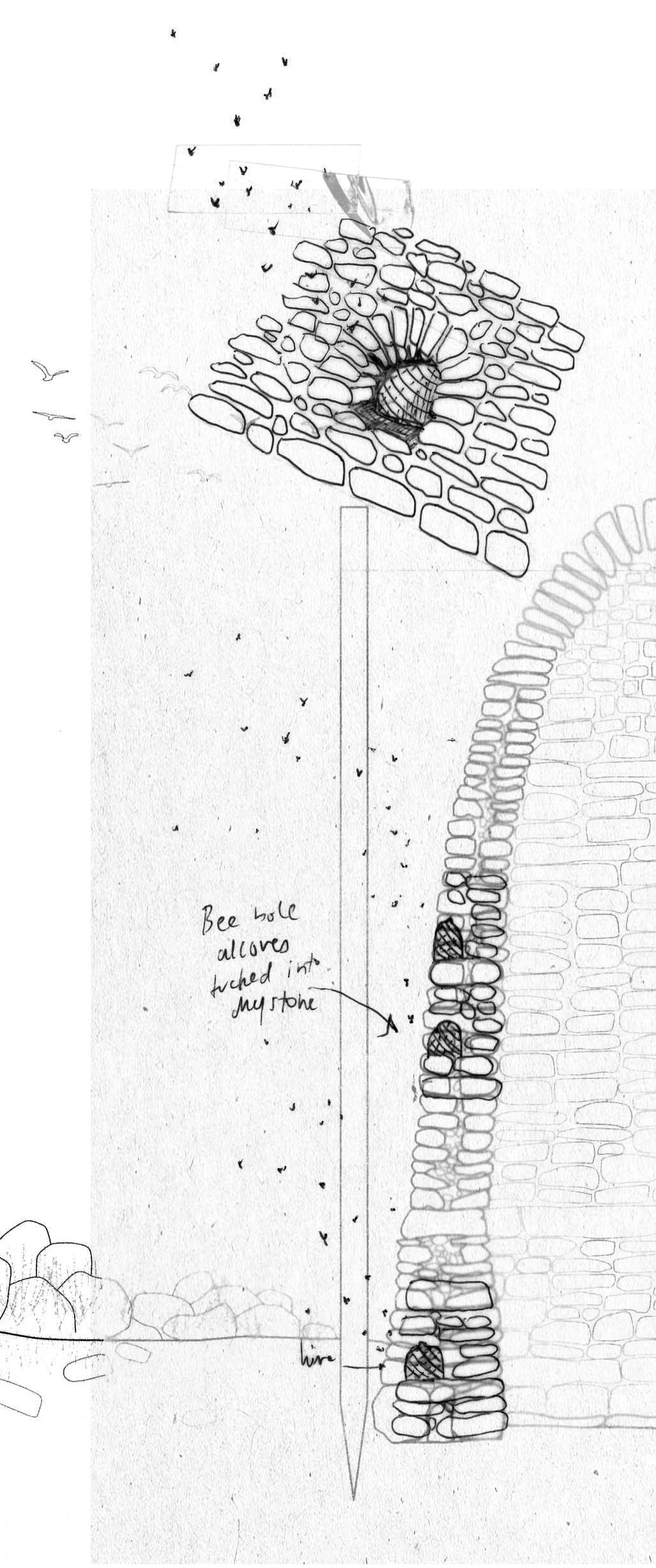

Moorland Grouse Industry

Red grouse are one of the few bird species indigenous to the northern British Isles, having inhabited this landscape for many thousands of years. The grouse hunting industry began in the early 19th century, though it emerged as a popular sport among the aristocracy and landed gentry in the 1880s. With the installment of railways, grouse shooting became ever more popular, and served as a source of income for large moorland estates. Grouse butts—further discussed in the chapter on drystone construction—were built as semi-permanent structures to disguise hunters. The ‘sport’ was commercialised, with wealthy men renting out use of a moor for one or several months at a time.

The annual shooting season runs from August 12th to December 10th, but the grouse moors are managed year-round by gamekeepers. Competitor species such as foxes, stoats, and crows are trapped and killed and new heather growth is encouraged as food for grouse using a slash-and-burn method. Grouse shooting continues to this day, though typically it is paid for by the day. The cost to hunt is expensive, ranging from several hundred to the thousands of pounds. A season of modern shooting typically results in the death of approximately 500,000 grouse, shot for around 75 pounds per bird.

Grouse hunting is contested: animal rights activists, environmentalists, and conservationists alike are calling for its permanent end. I argue that in addition to the concerns outlined by these groups, at the root of the hunting industry and its injustices lie the issue of private property. While large tracts of moorland are owned by private, wealthy individuals, land justice is unachievable.

As Guy Shrubsole notes in his investigation, “Who Owns England?” the grouse industry owns massive tracts of land, a remnant of aristocratic and elitist hunting traditions that are in turn expressions of patriarchal and colonial world-systems.

I go further, placing grouse hunting as not only a crisis of the peat lands, but a crisis of the ecological imaginary. The hunter’s gaze sees the moorland and the other-than-human beings held within it as resources to be extracted, killed, and conquered.

Slash-and-burn is an expression of this mode of landscape management dictated by control. Though it has been banned in many places, the practice continues to shape the Peak District’s landscape, made evident in satellite imagery.

Grouse hunting in the 19th century

Grouse hunting in the 21st century

Problematising Heather Burning

Heather burning is practiced by grouse shooting estates as a way of managing the moorlands to maximise grouse propagation. By cutting back and burning older heather growth, fresh heather is encouraged to grow. This provides food for grouse as well as grazing livestock: it is a practice of cultivating a landscape dedicated to the rearing—and subsequent killing—of a single bird species. As such, diversity of both flora and fauna is undesirable.

Slash-and-burn has severe ecological concequences. In setting fire to heather growing on peat soils, the peat itself dries out, releasing the carbon it stores back into the atmosphere. This is a series issue given the immense carbon sequestration that takes place within peat bogs. According to the government’s Committee on Climate Change, more that 18.5 million tons of carbon are released yearly due to damaged peat: more than the oil industry.

“Grouse moor estates cover an area of England the size of Greater London –some 550,000 acres – and are propped

up by millions of pounds in public farm subsidies.”

- Guy Shrubsole, Who Owns England?

Moorland heather burning

This ‘filmic mapping’ exercise shows frames from a walk in a grouse moor above Nether Booth at 10 second intervals, showing the dynamism and diversity of the landscape. The primary absence in these images is the wind: raging, fierce, relentless, piercing, howling across the open moors.

00:40

01:20

00:10

00:50

01:30

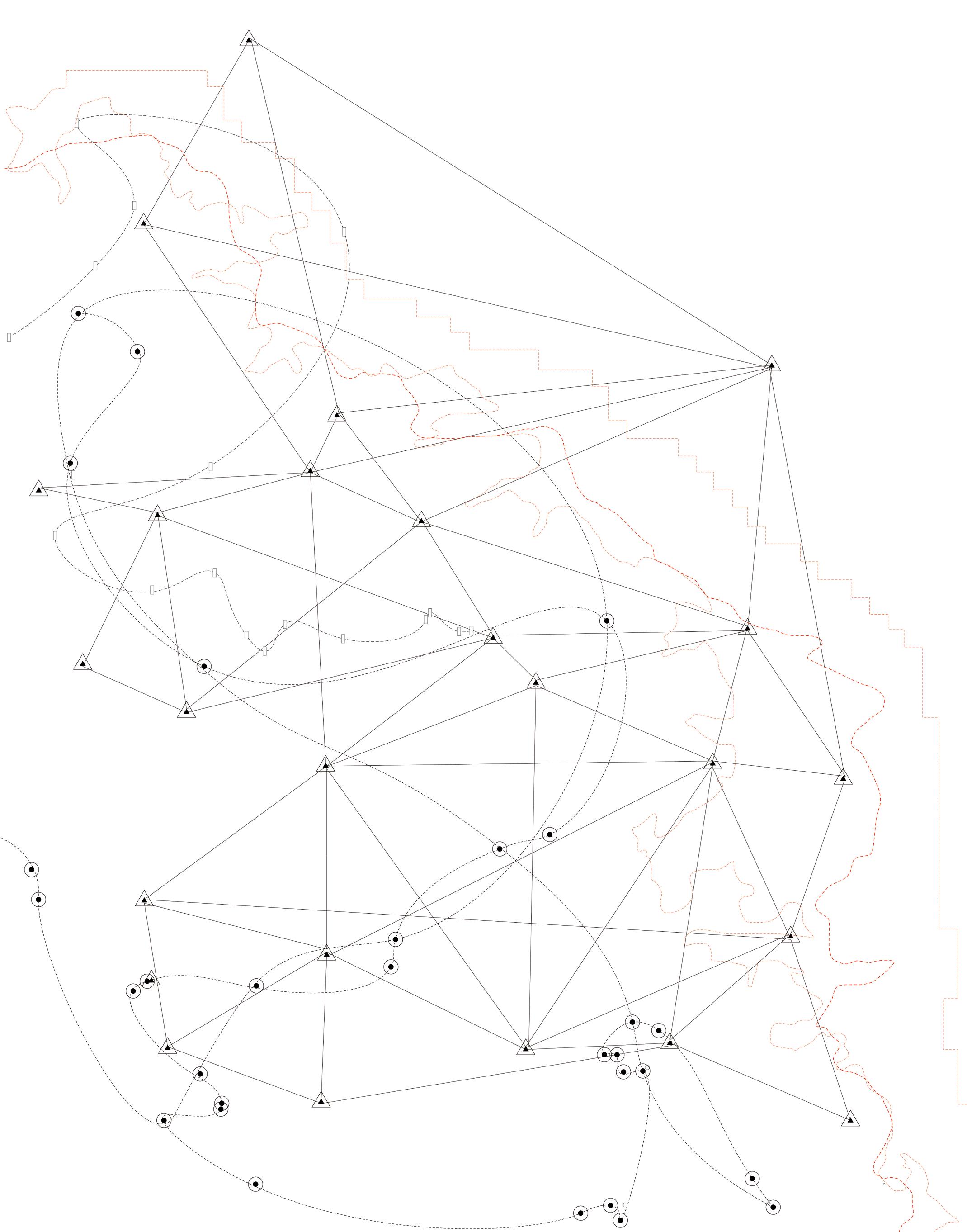

Grouse Moors and Land Ownership

Grouse moors and land ownership by the wealthy few go hand in hand. The project, in ‘commoning the moorland,’ challenges private ownership of land that is predicated on extractivist and capitalist ways of relating to the morethan-human realm.

Multispecies commoning asks, how can we re-orient ourselves as part of the land, holding obligations to it, rather than seeing it as a framed view to be admired from a distance or a resource from which to profit? By centring the entanglements of sphagnum mosses, grouse, and peat soils, we shift perspective away from the human construction of ‘landscape.’

Above: Grouse moors bearing slash-and-burn marks around Edale valley

Below: Grouse moors identified by Guy Shrubsole in northern England

Who Owns the Peak District’s Grouse Moors?

01. Wessenden Head Moor Owned by Yorkshire Water 3,410 acres

02. Buckton Moor Owned by Enville & Stalybridge Estates 3,500 acres

03. Snailsden Moor Owned by Yorkshire Water 2,023 acres

04. Thurlstone Moor Owned by Yorkshire Water 1,349 acres

05. Ladycross & Langsett Moors Owner unknown 3,187 acres

06. Peaknaze Owned by United Utilities 3,237 acres

07. Hope Woodlands

Owned by National Trust 8,876 acres

08. Broomhead Estate Owned by Ben Rimington-Wilson 4,237 acres

09. Hurst & Chunal Moors Owner unknown 2,304 acres

10. Park Hall Owned by National Trust 1,611 acres

11. Moscar Moor Owned by the Duke of Rutland 6,049 acres

12. Coombes Moss Owned by Harris & Sheldon Group Ltd 1,275 acres

13. Goyts Moss Owned by United Utilities

3,113 acres

14. Crag Estate Owned by Lord Derby

6,500 acres

15. High Moor

Owned by Richard & Anne May, Lionlike Ltd

750 acres

Opposite: Grouse moors identified by Guy

in the Peak District

Shrubsole

DRYSTONE CONSTRUCTION

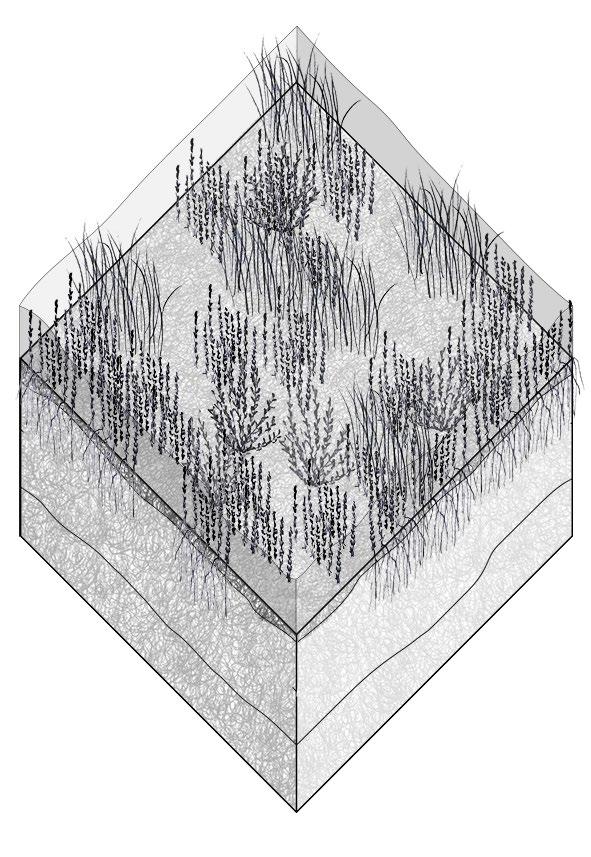

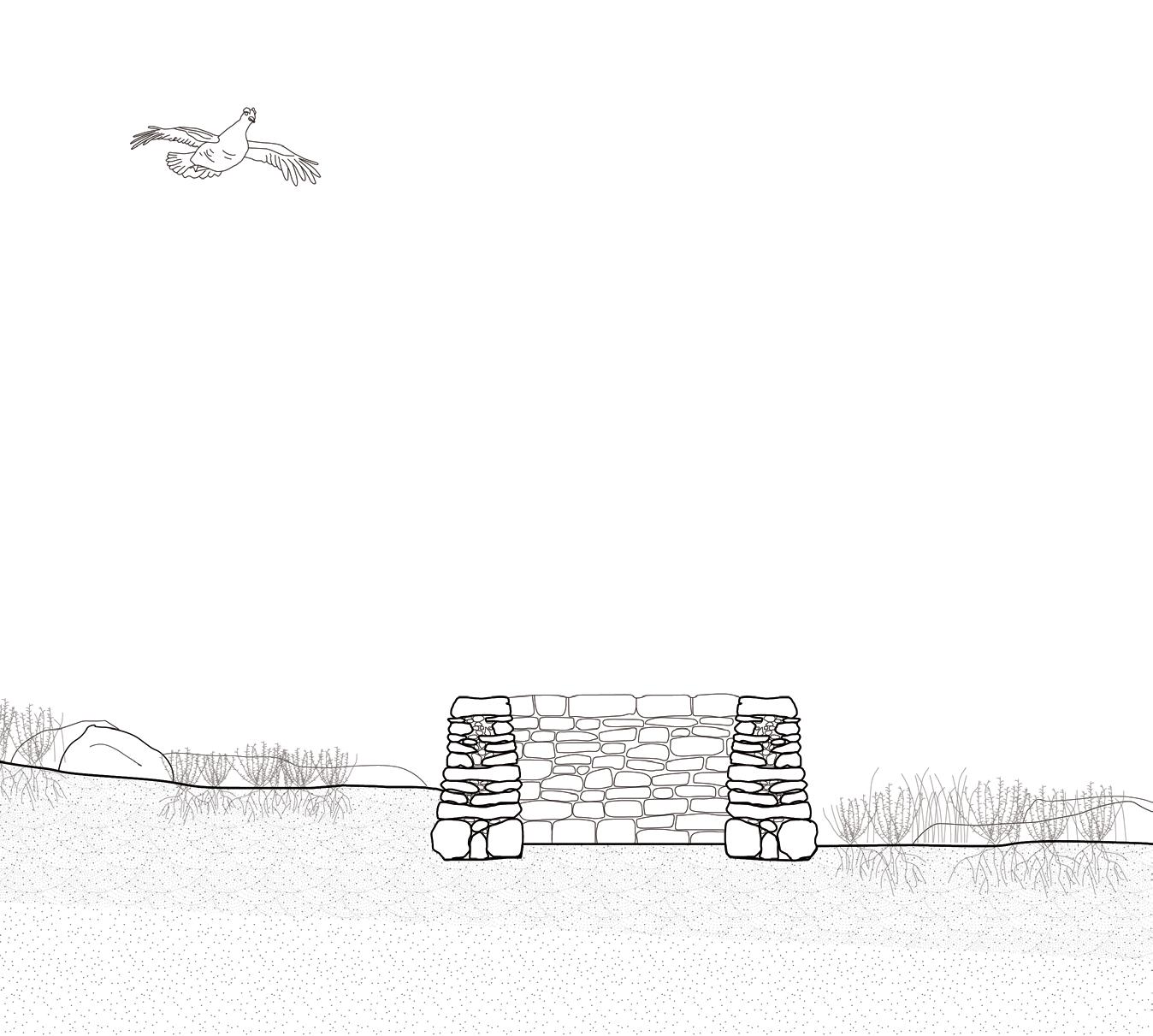

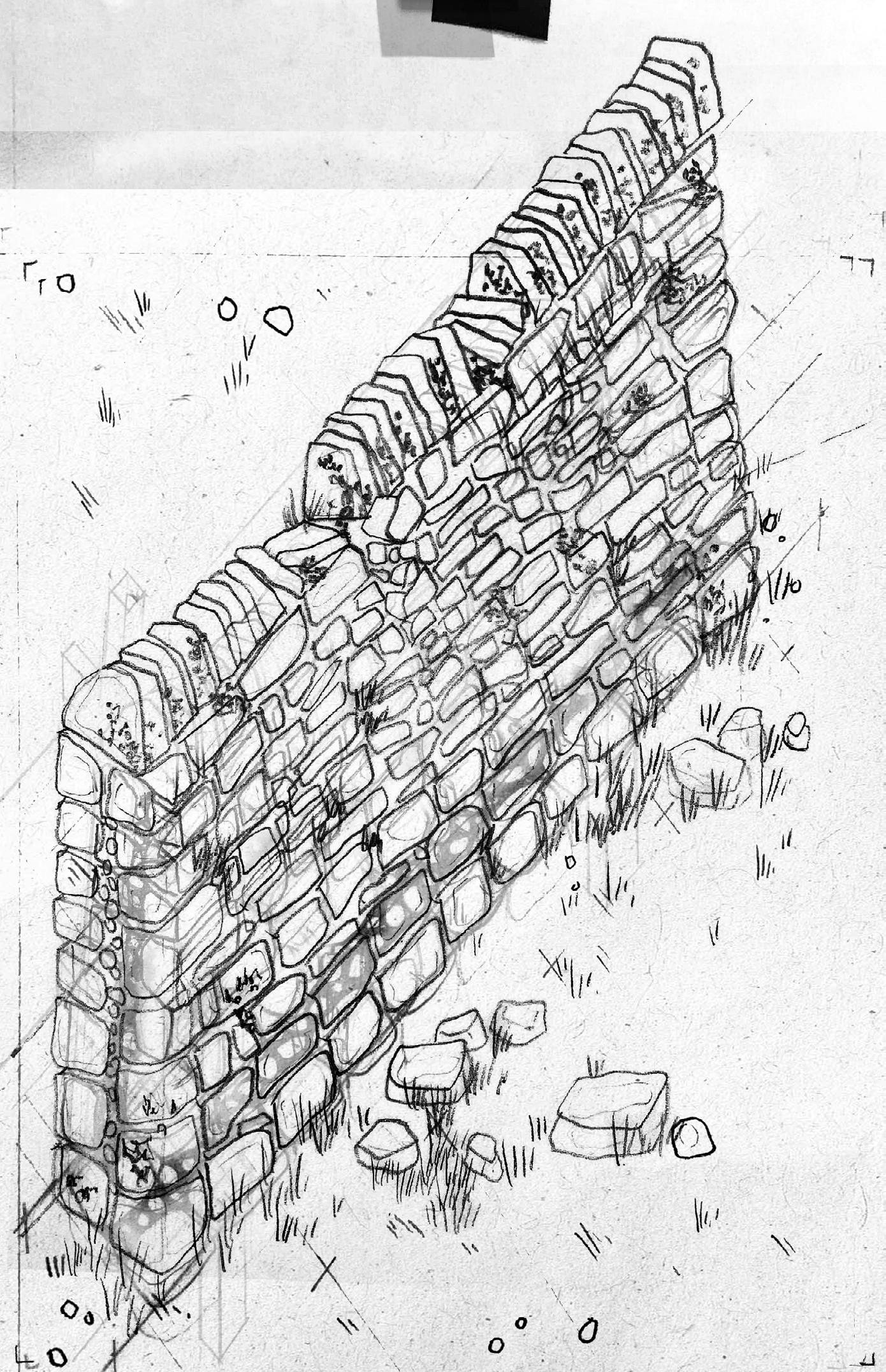

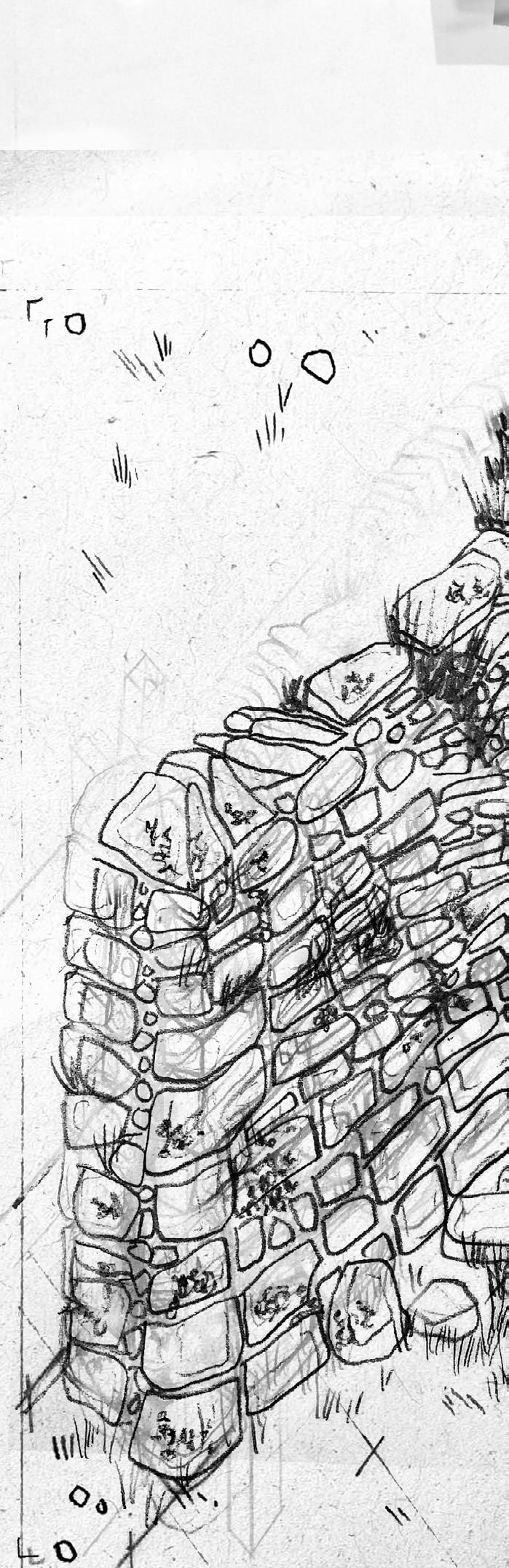

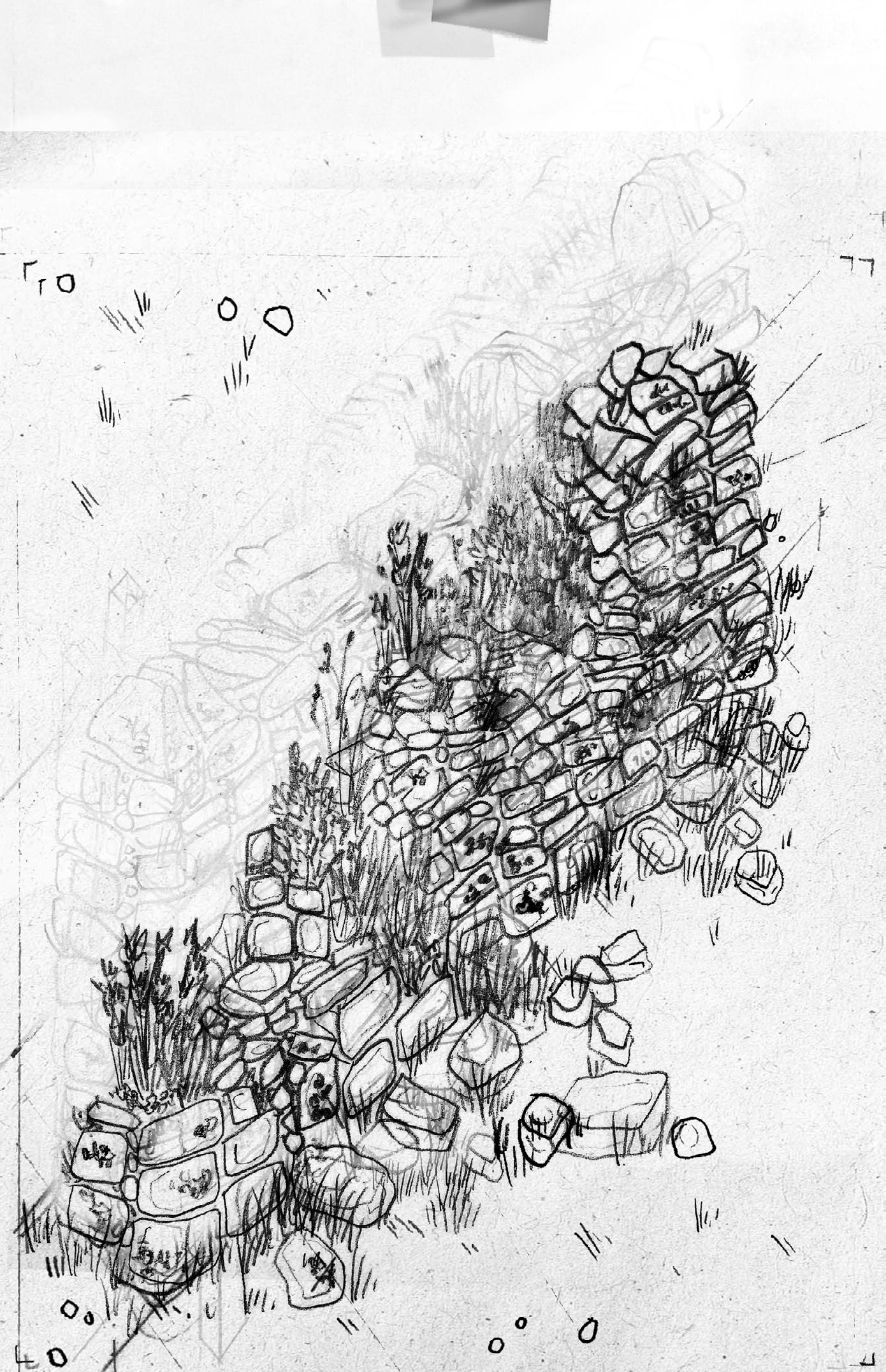

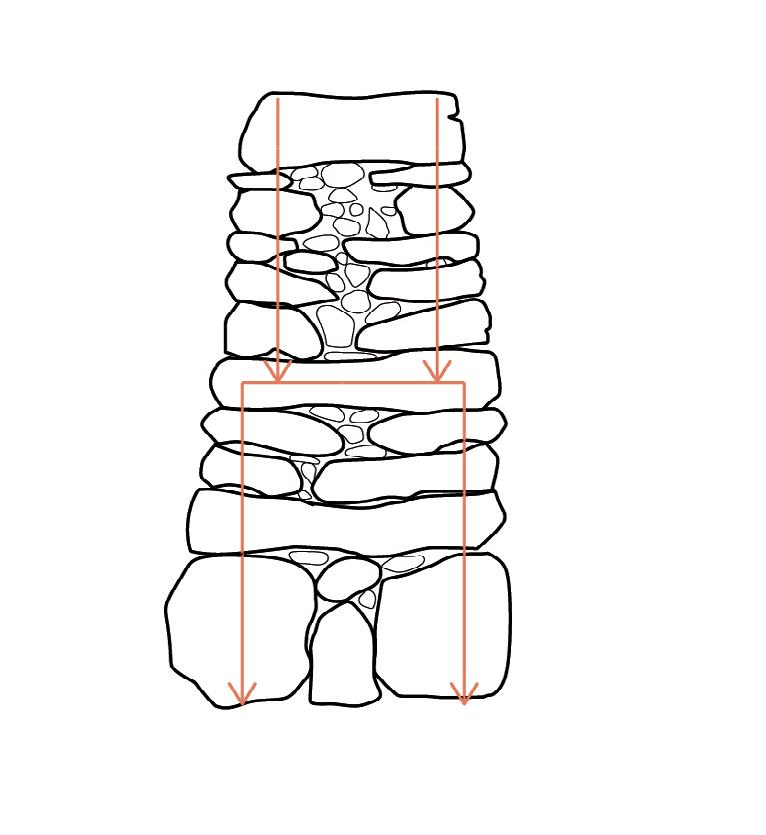

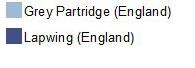

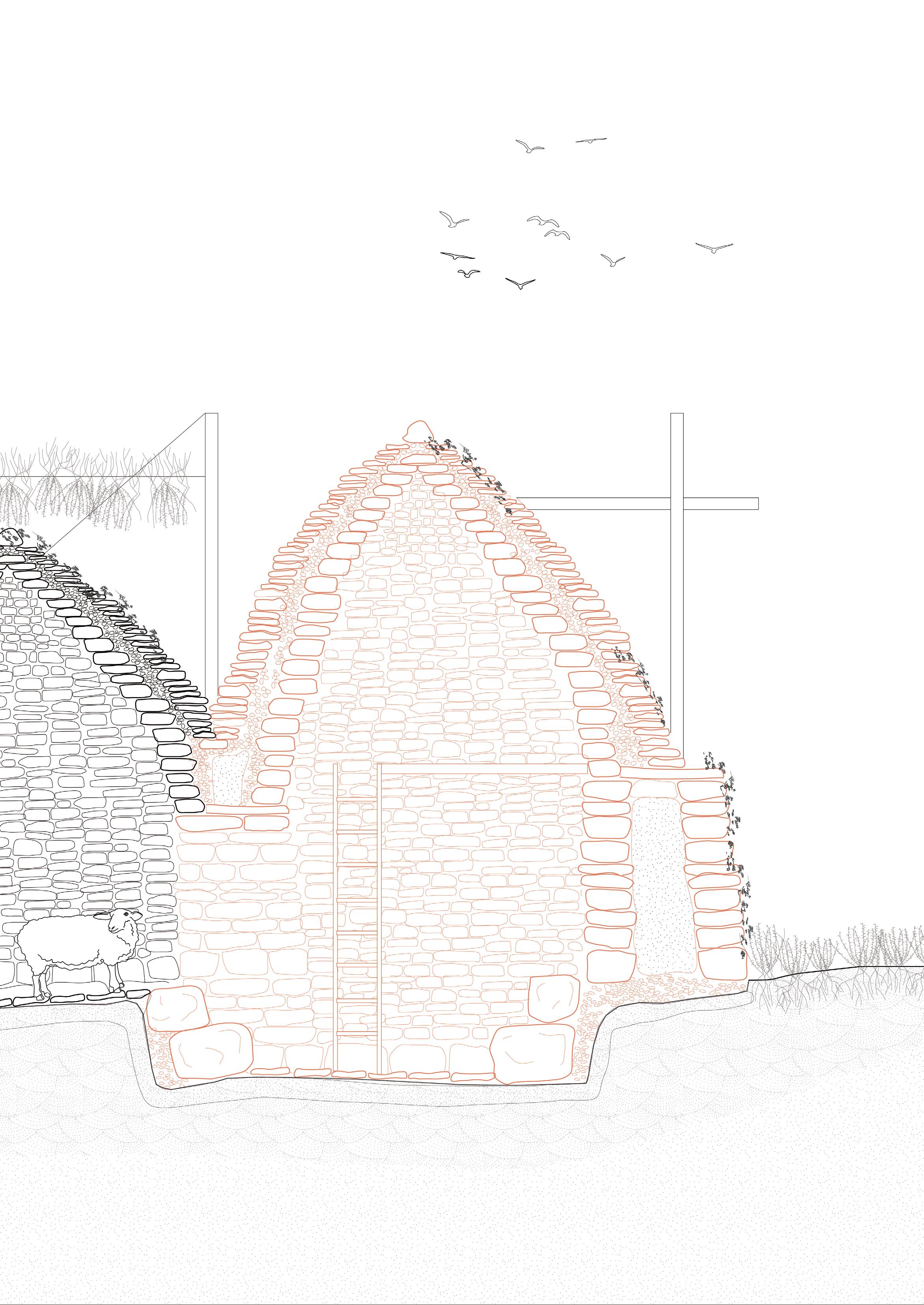

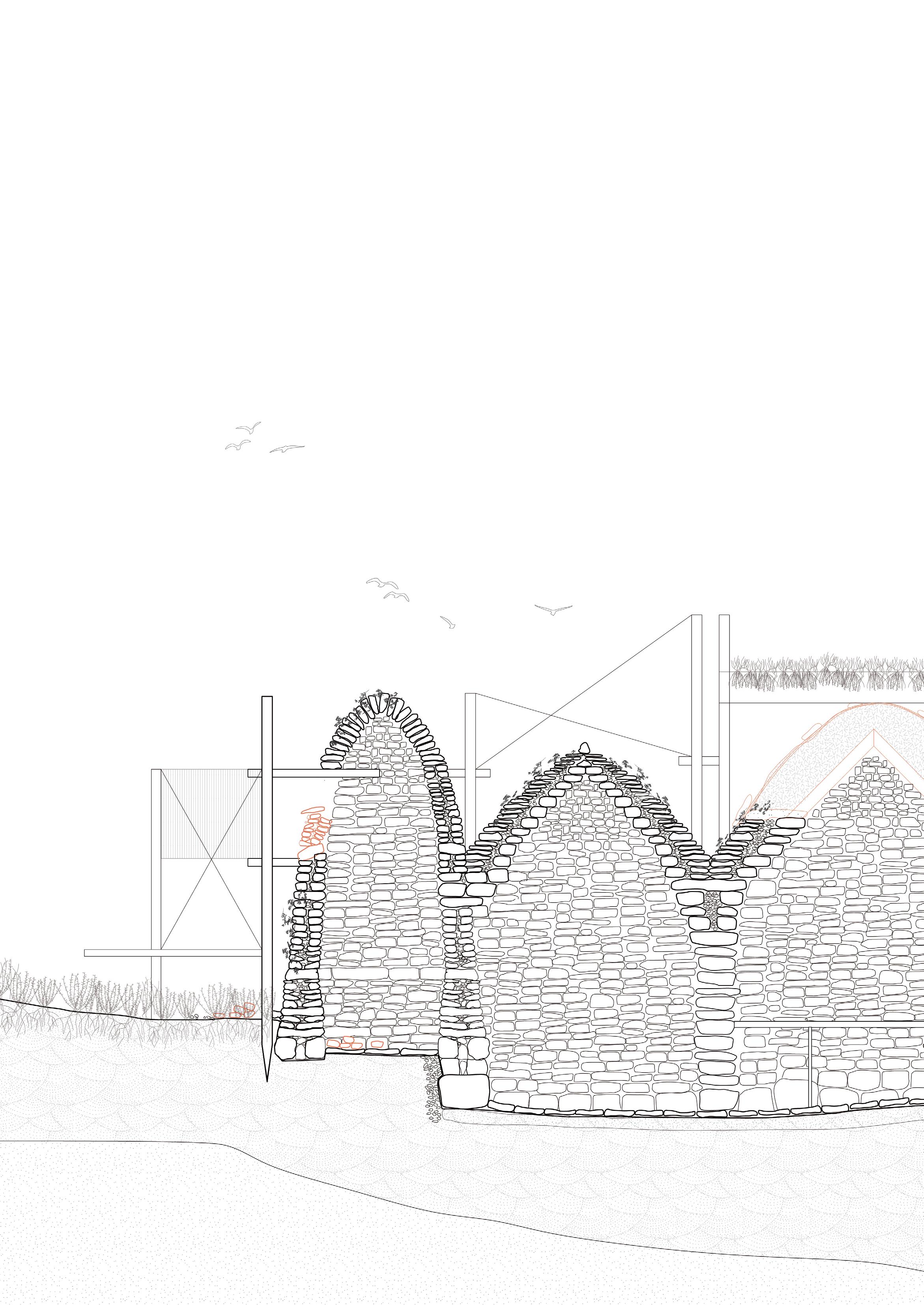

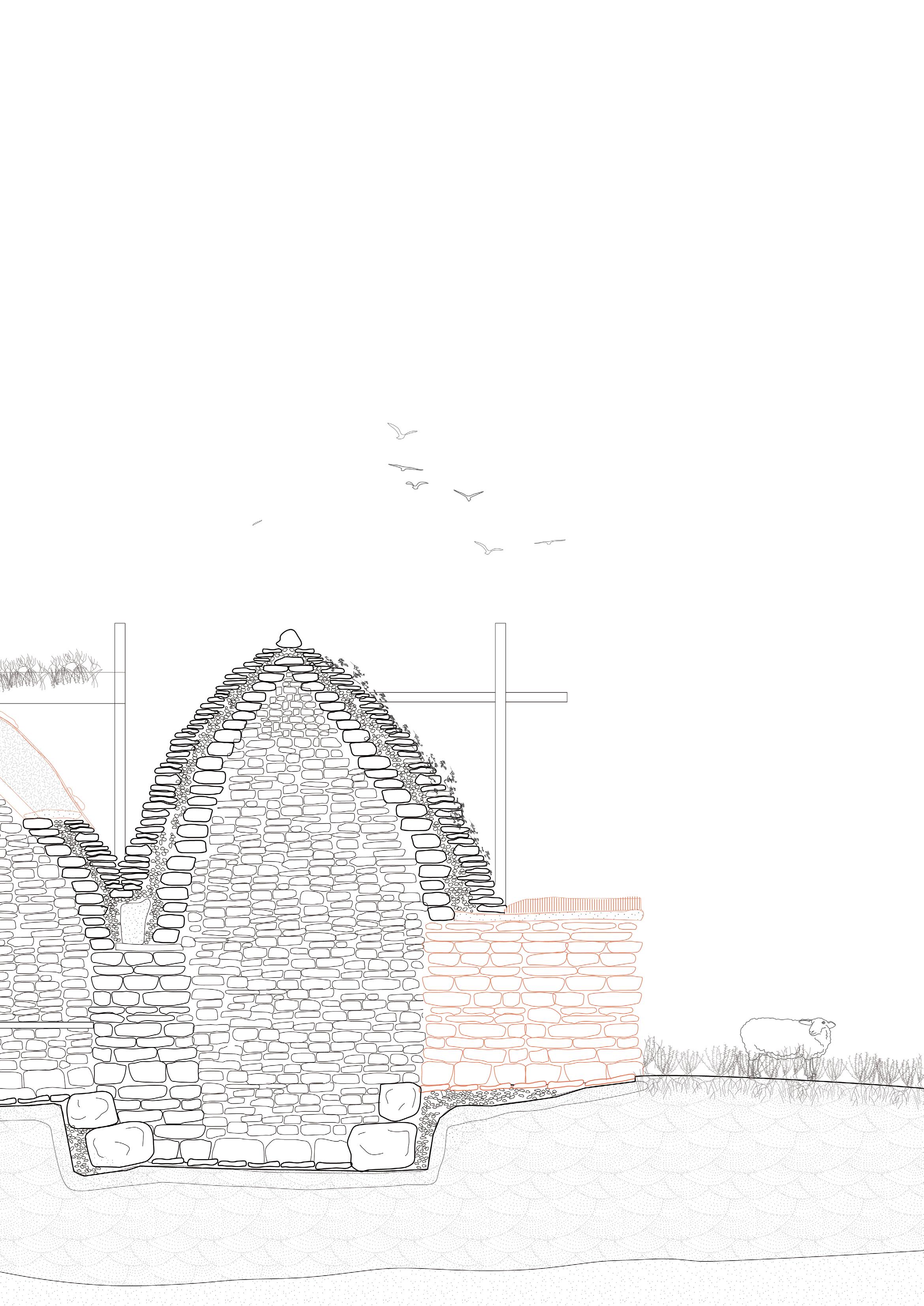

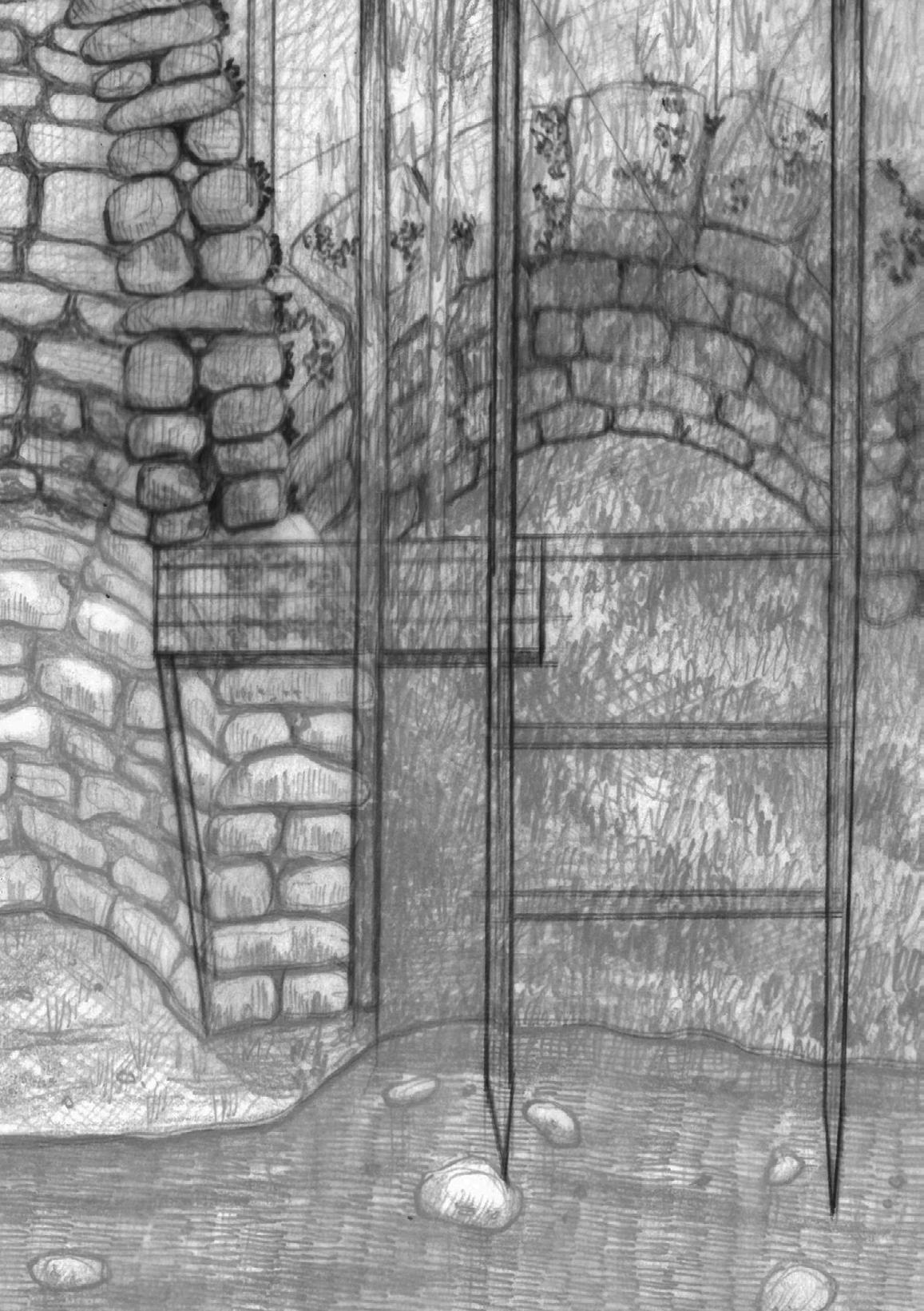

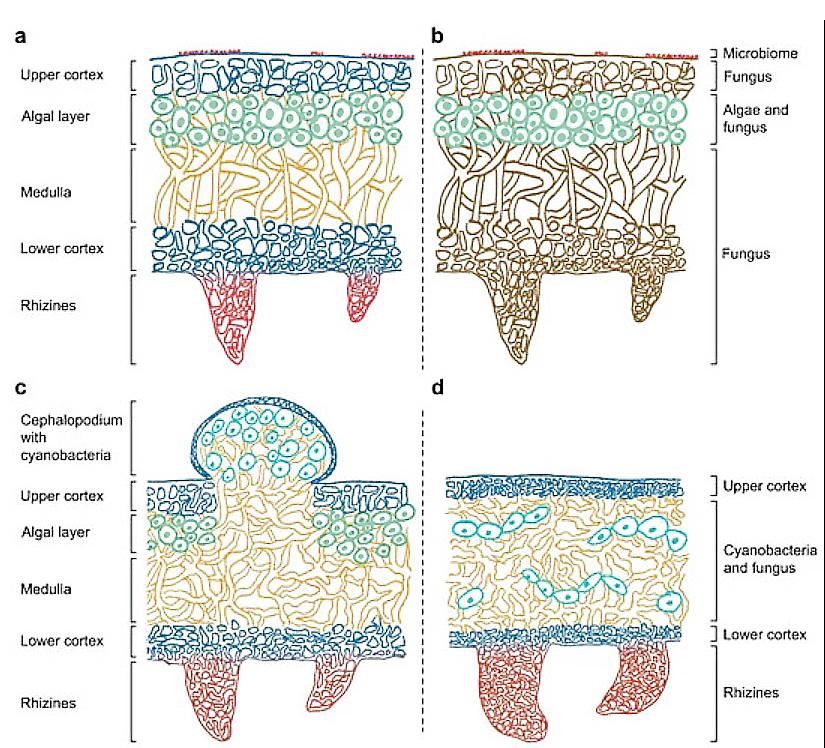

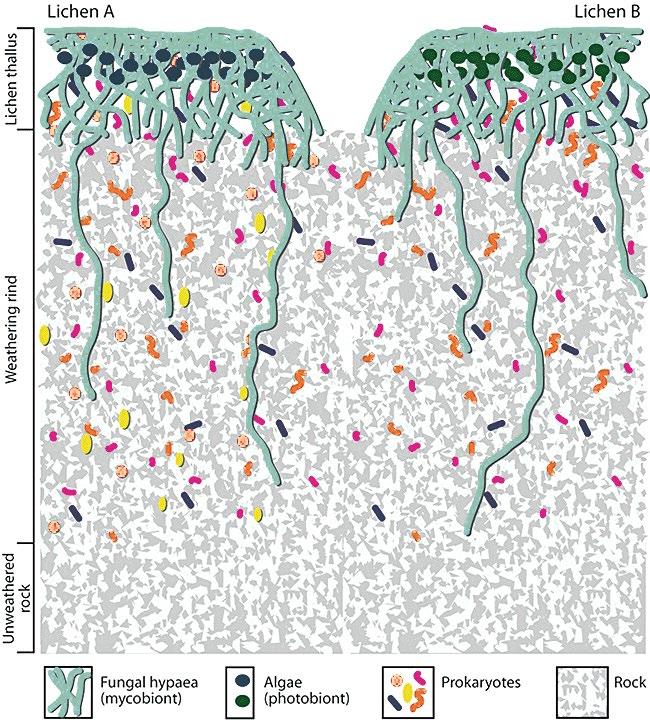

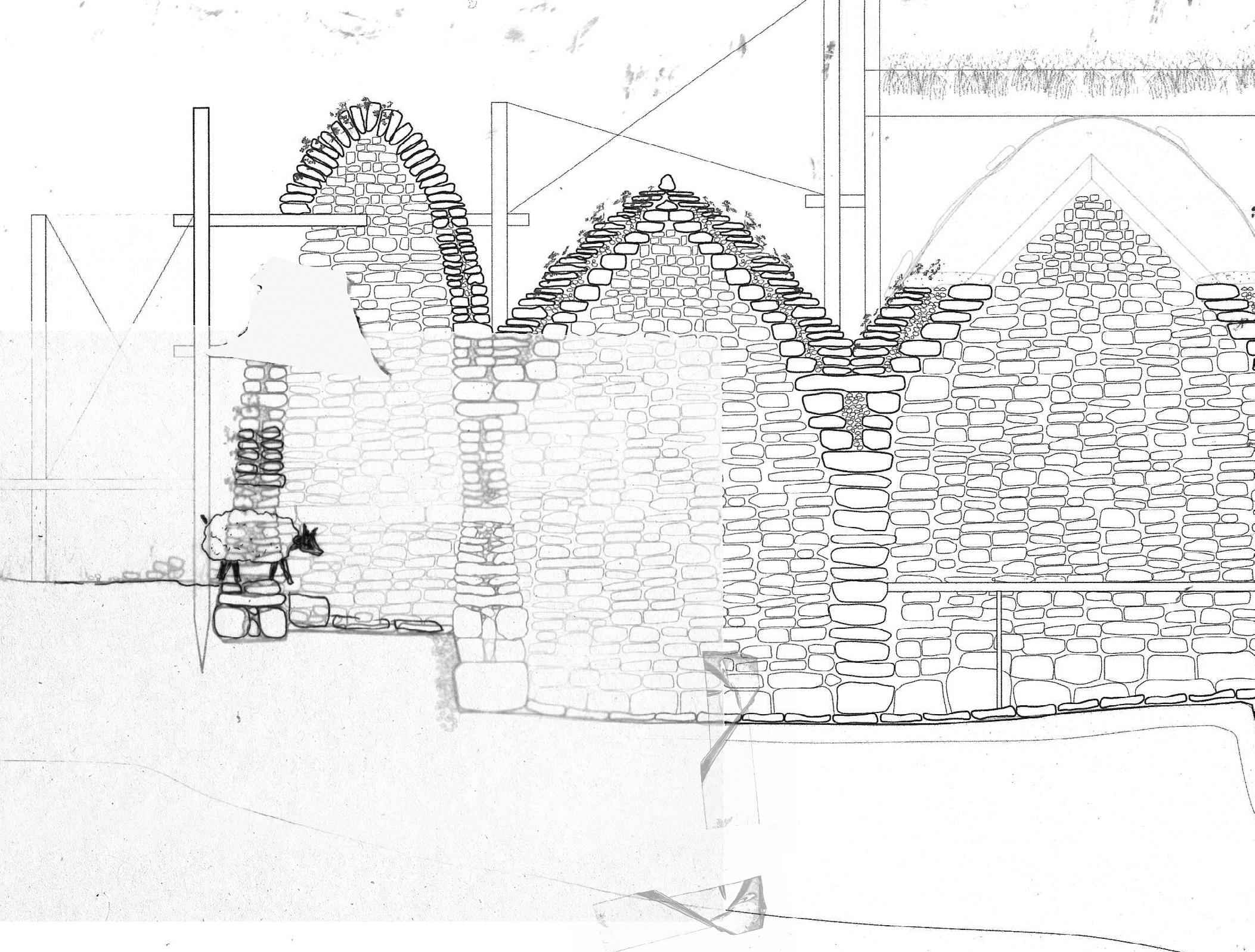

This chapter examines drystone case studies and construction methods—typically used for enclosure walls demarcating property boundaries—in order to imagine new possibilities for drystone construction as a collective practice, a form of “living” conservation, and a site for multispecies inhabitation. Thus, special attention is paid to the way in which mosses, lichen, insects, mammals, and birds interact with stones, and the way in which drystone falls into decay over time, returning to the geologic landscape.

Sub-question B:

+ How can drystone become a collective building practice that takes into account multispecies inhabitation, existing stone infrastructure, design for repair, and the constantly transforming landscape?

Design Question

Case Studies + Context Analysis

Case Studies of Drystone Enclosures

Case Study: Trulli, Italy

Case Study: Kažun, Croatia

Case Study: Blackhouse, Scotland

Stone Structures: The Moorland Vernacular

Drystone Purposes

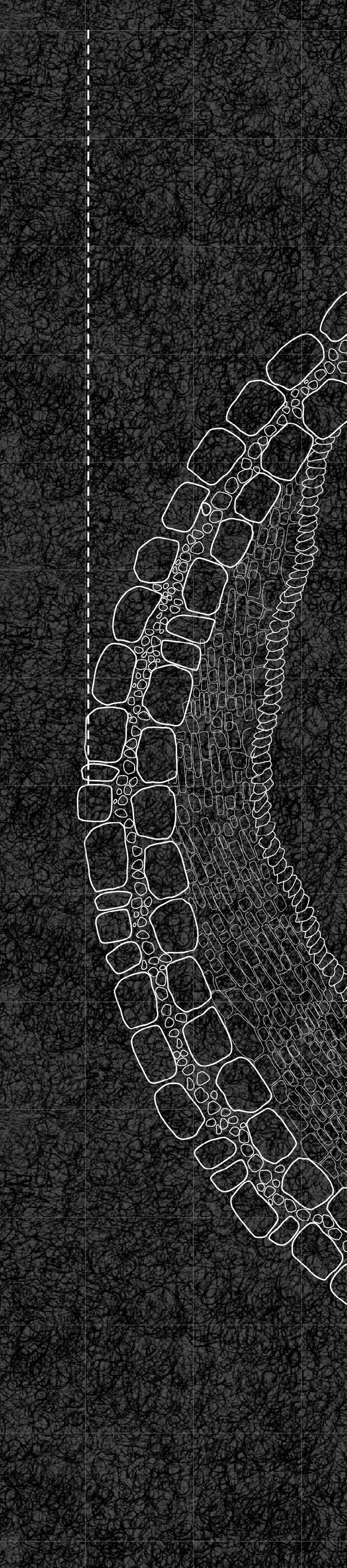

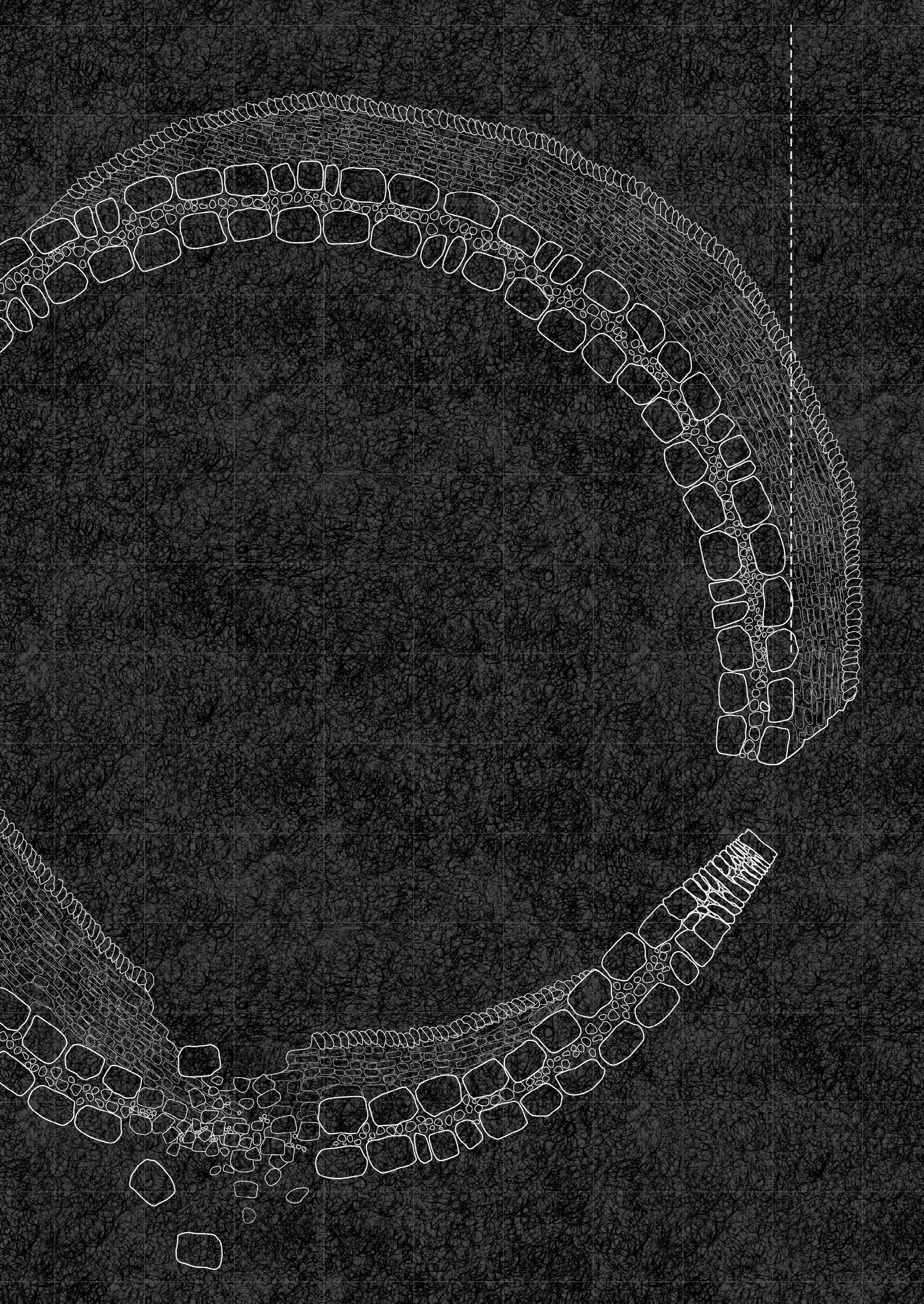

Sheepfold: A Moss-Eye View

Dark Peak: Stone Architectures

Existing Drystone Wall Forms

Stiles: Building in Access

Geologic Porosity

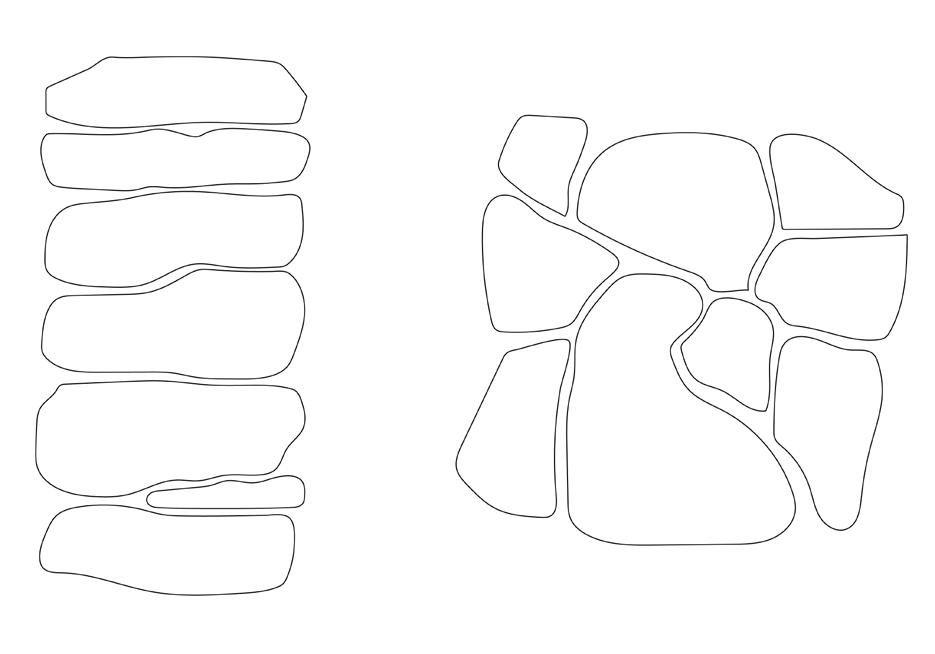

Drystone Analysis

Drystone Over Time

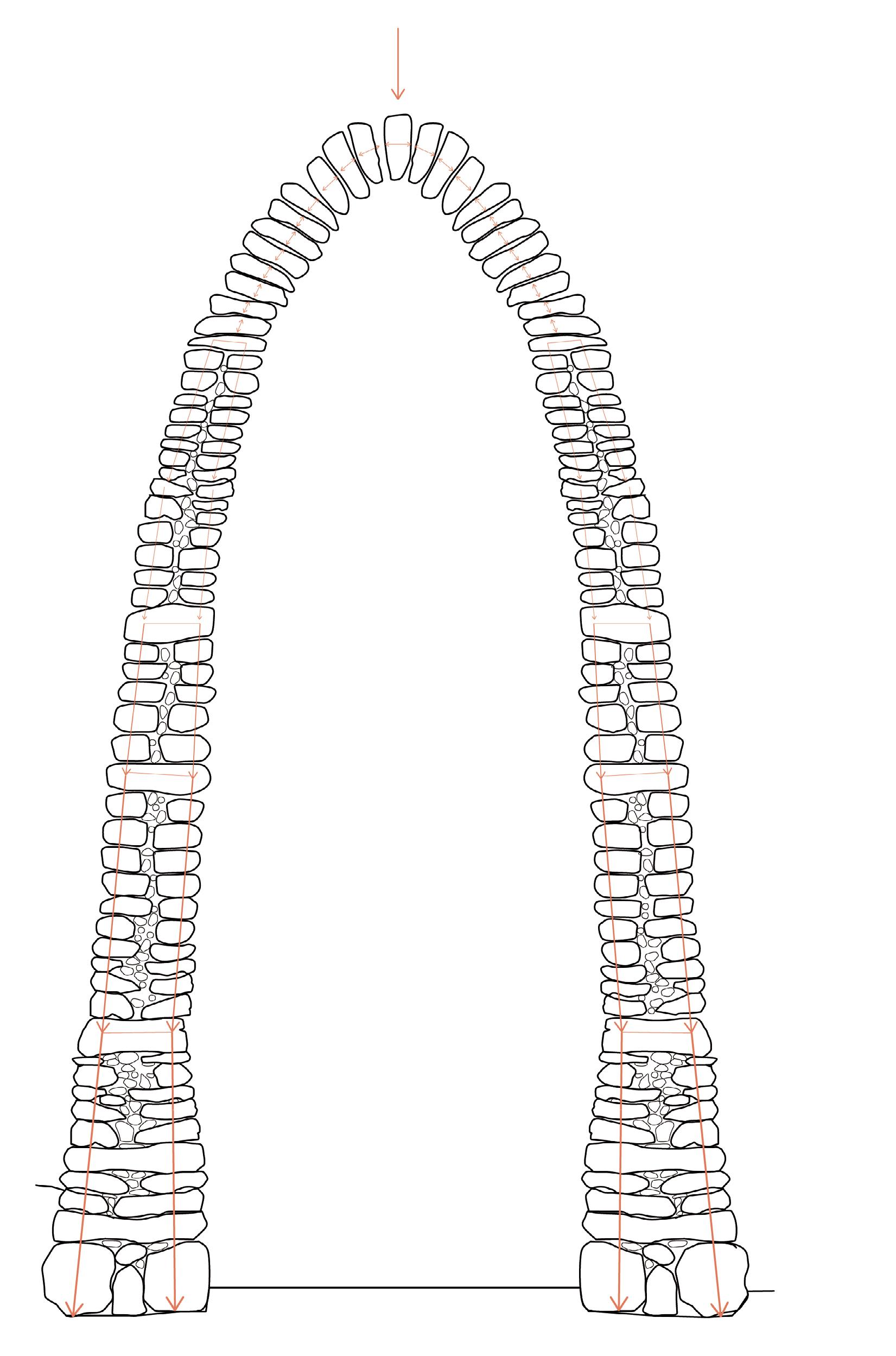

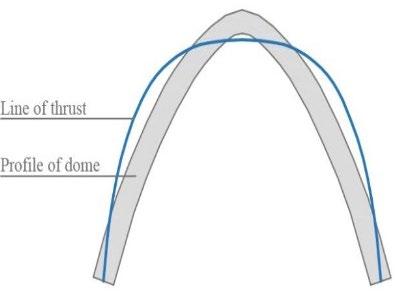

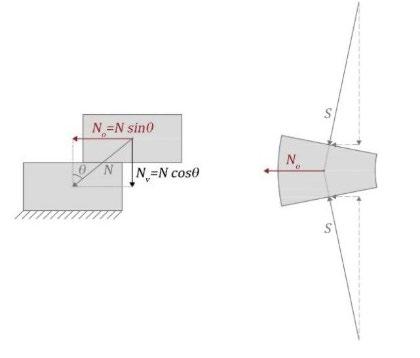

Structural Analysis

Corbelled Stone Domes

Structural Limitations

The Challenges of Drystone Construction and Inhabitation

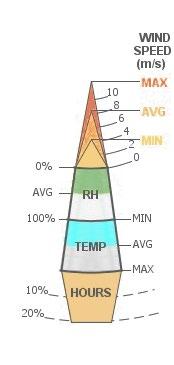

Charting Wind Form: Drystone Microclimates

Site Criteria and Analysis

Criteria for Choosing a Site

Design scenario: Crookestone Knoll Field Station

Climate Analysis

Wind Analysis

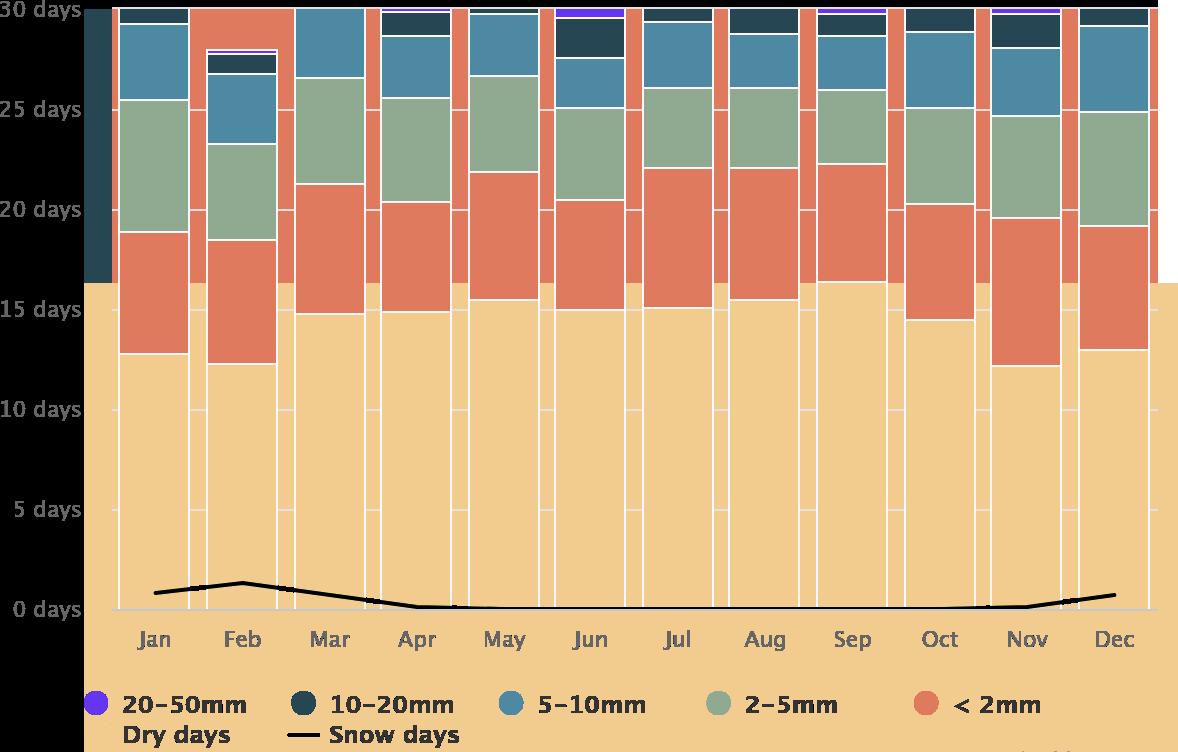

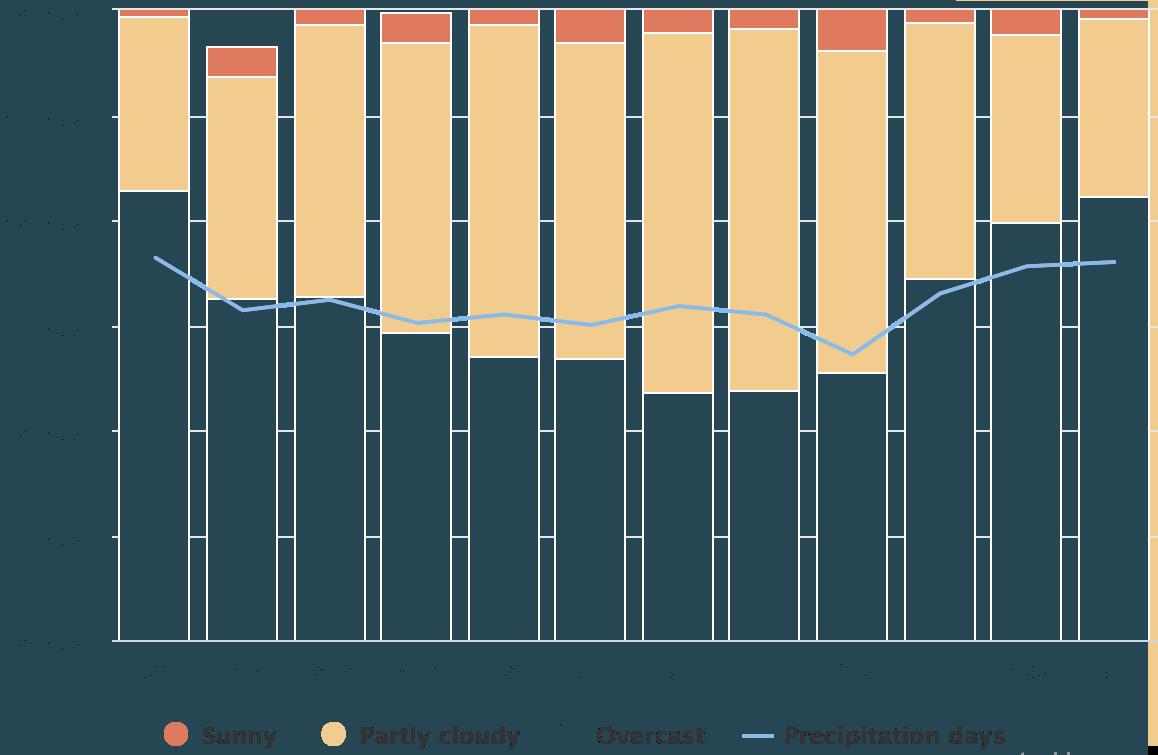

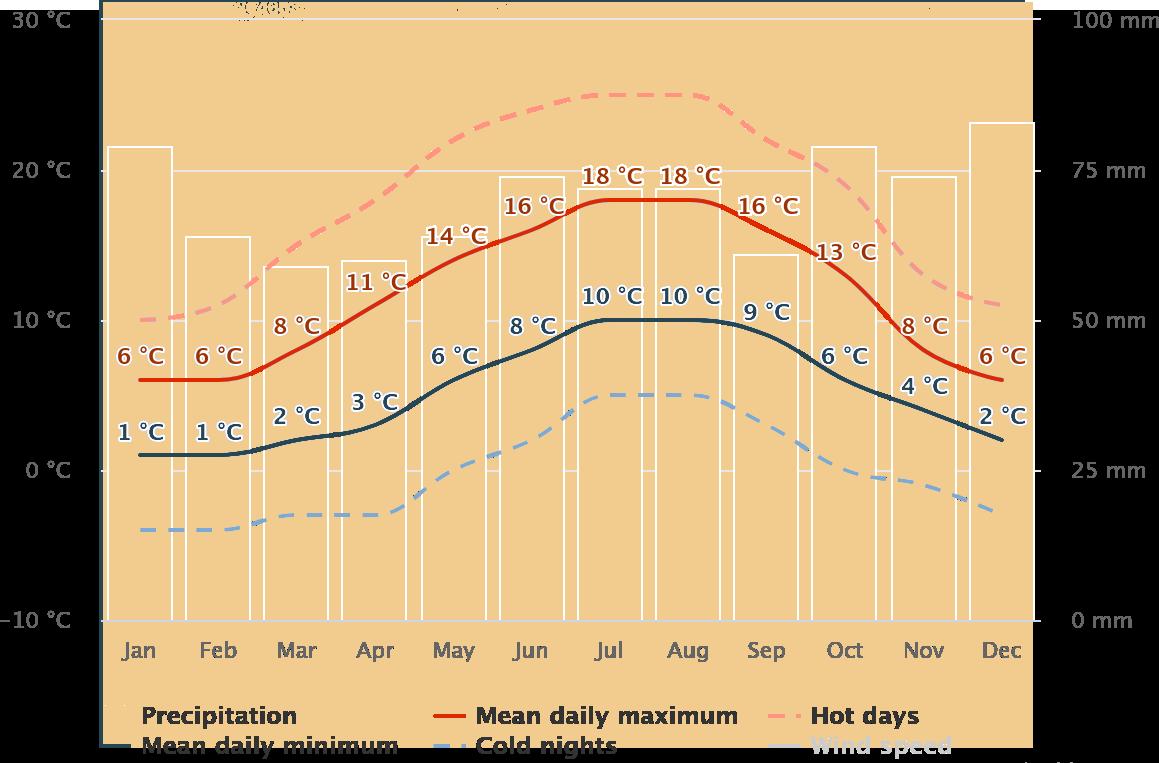

Edale: Temperature and Precipiatation Analysis

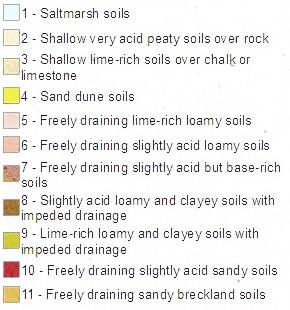

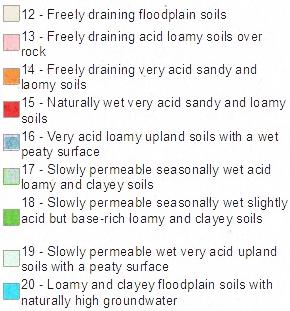

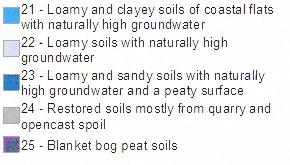

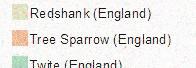

Soil Types

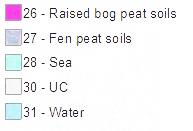

Bird Habitats

Drystone Construction Tests

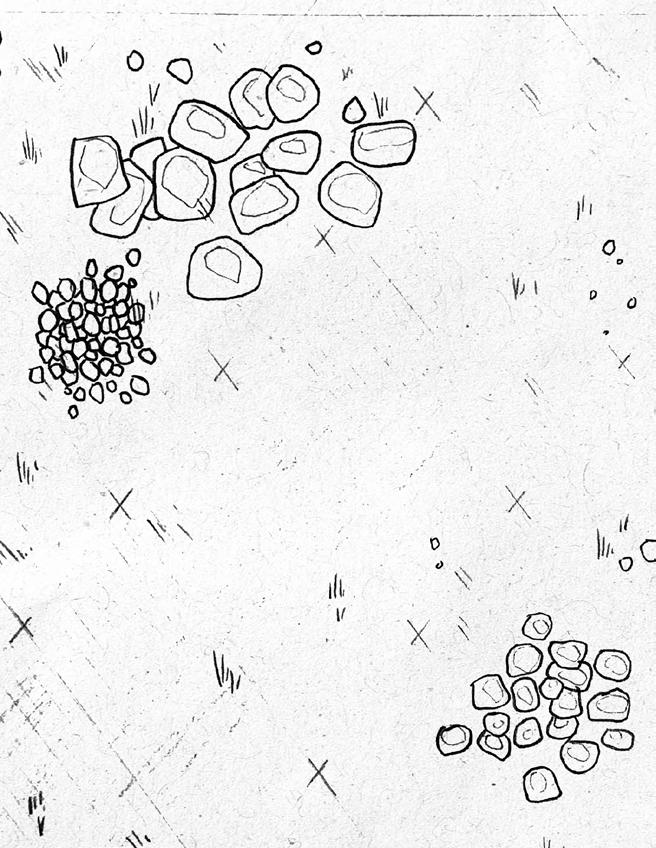

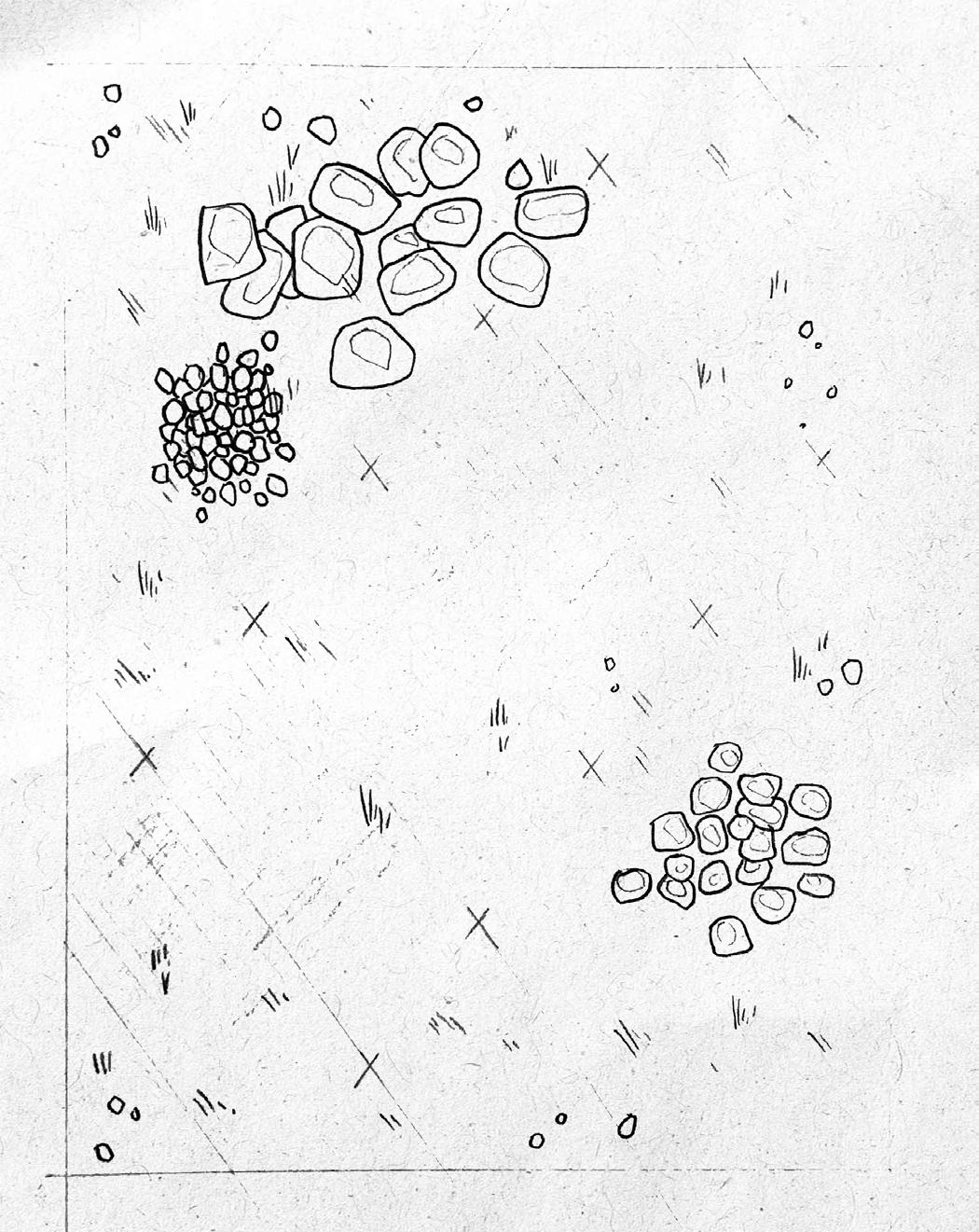

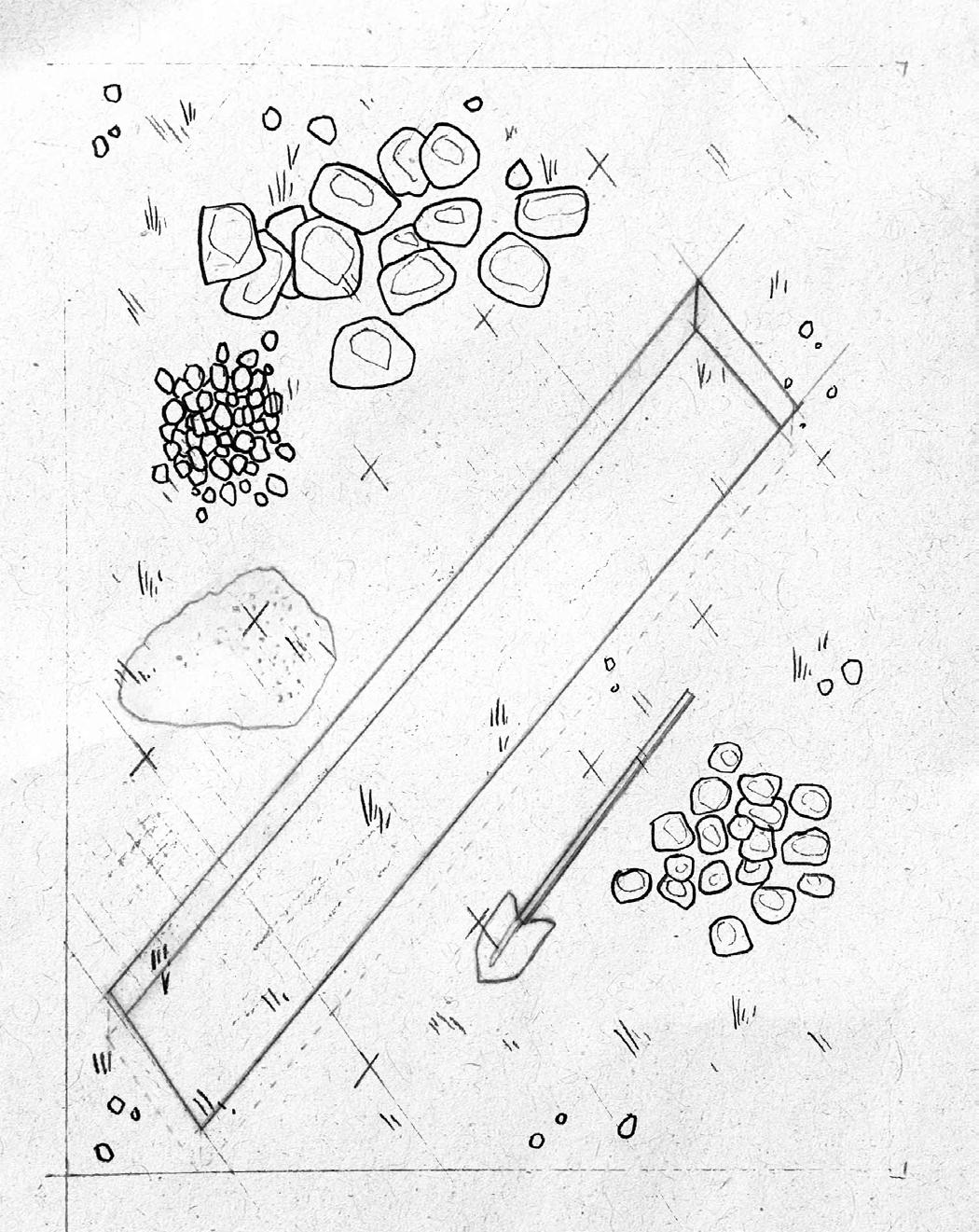

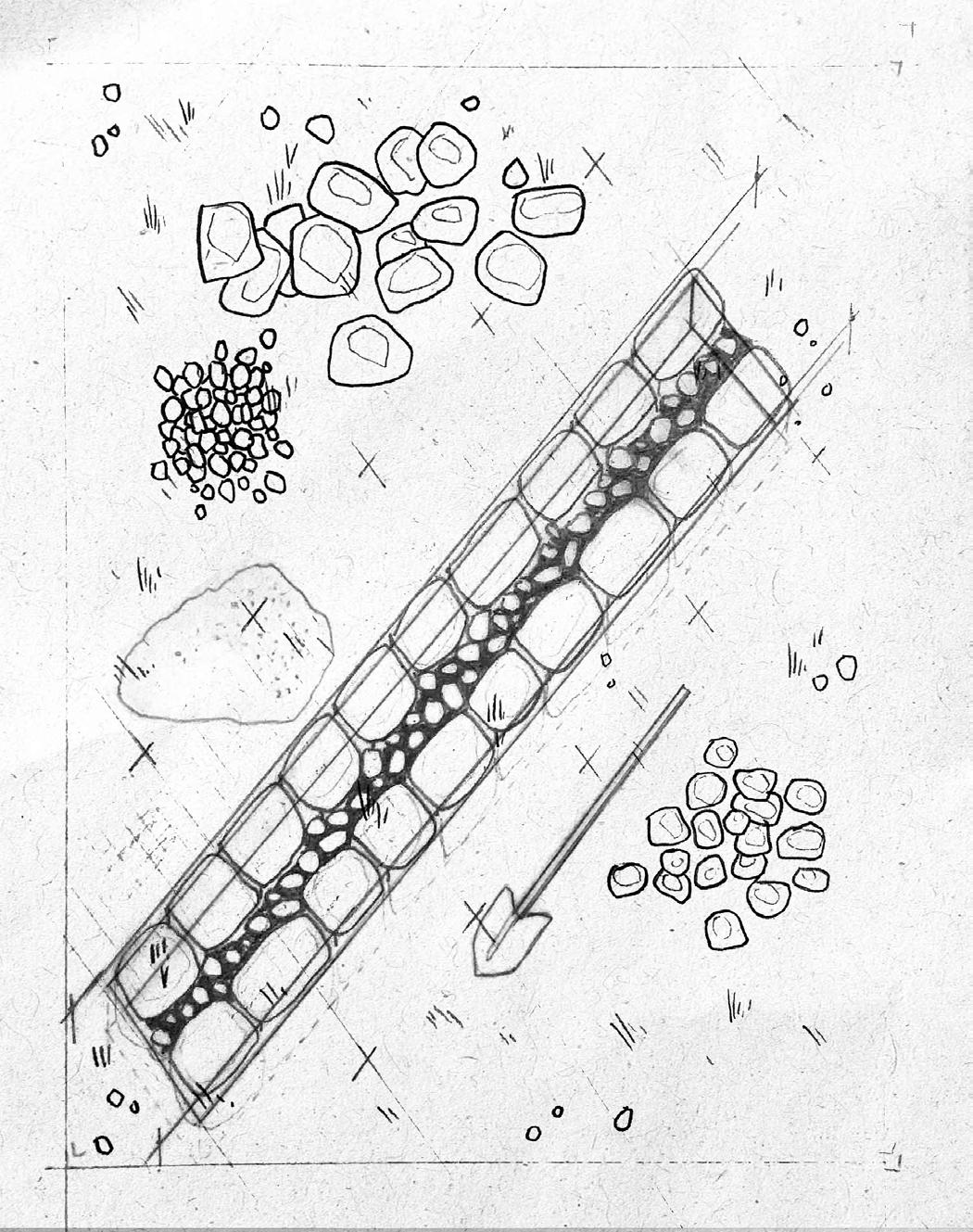

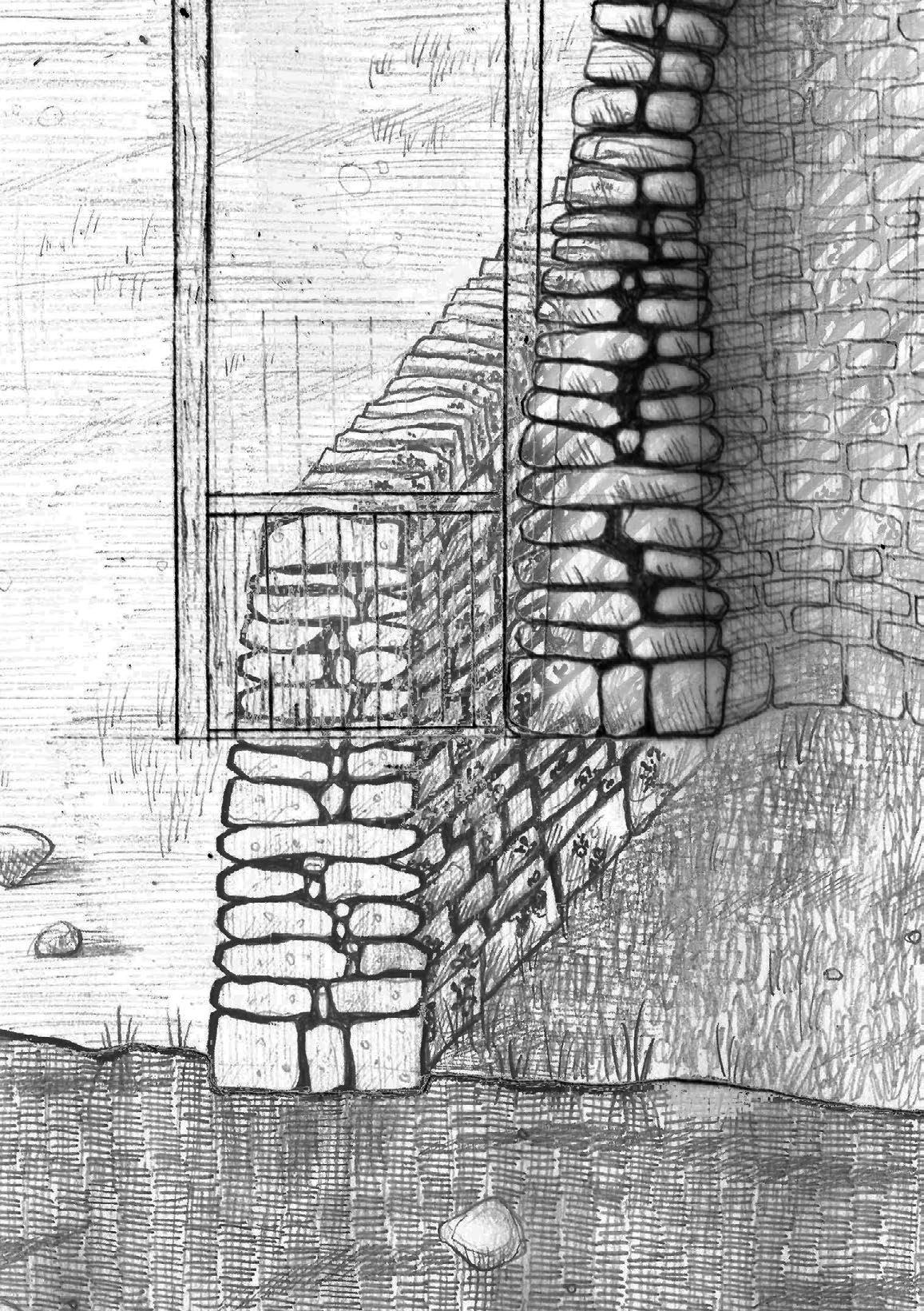

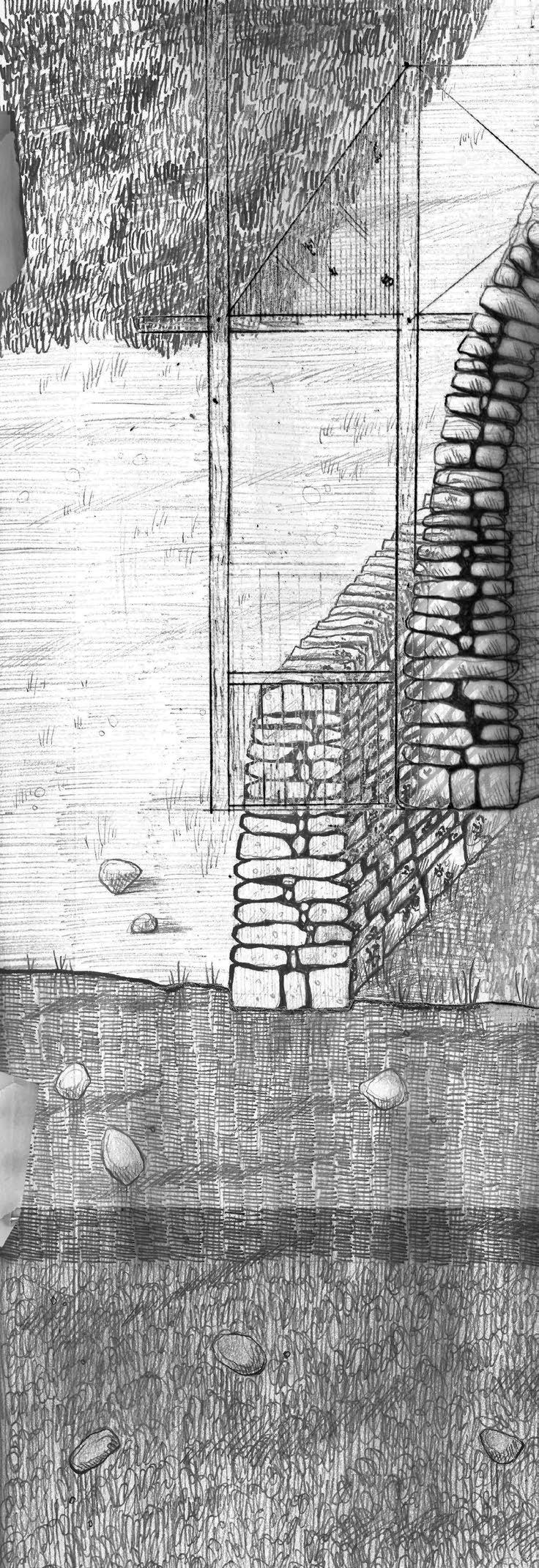

Design Strategy: Repurposing Broken Drystone

A Landscape of Broken Walls

Fallen Stones as Habitats

Form Follows Rock: Reimagining Construction as Fieldwork

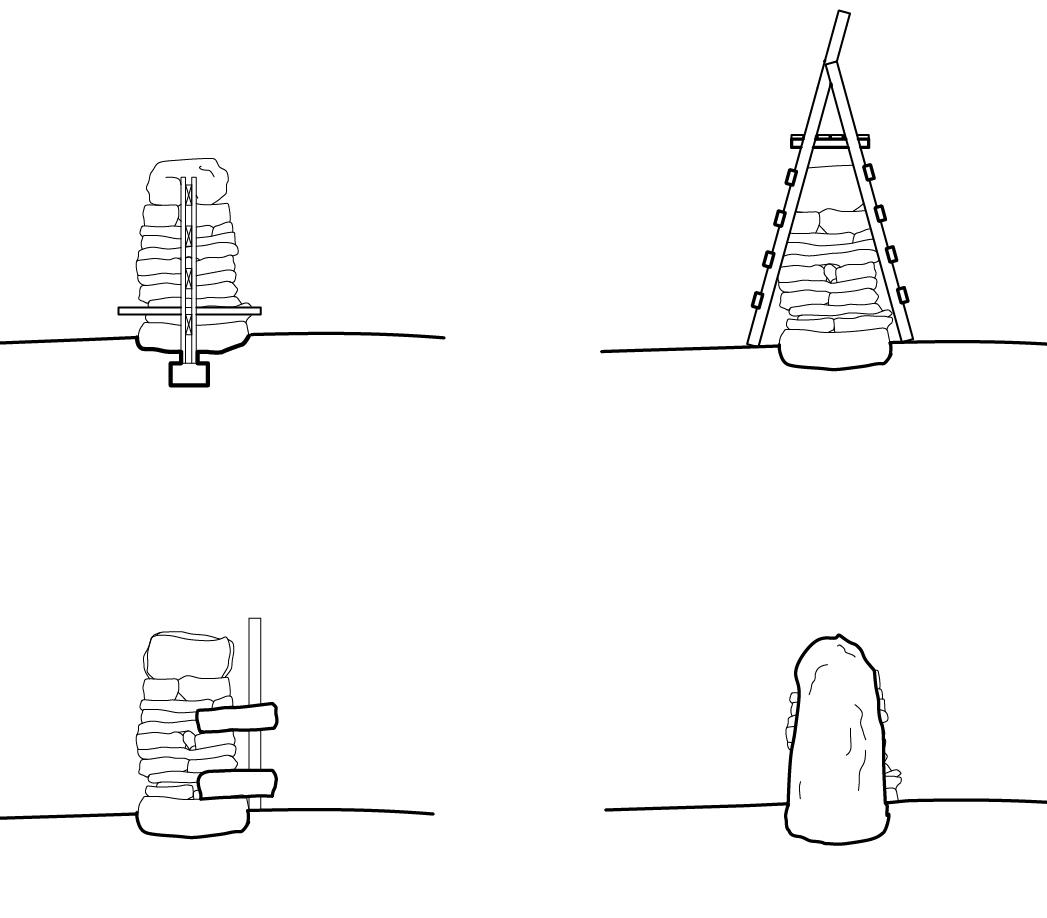

First Cairn: Testing the Ground

Second Cairn: Scaling Up

Third Cairn: An Offering to the Land Template for the 100-Stone Cairn

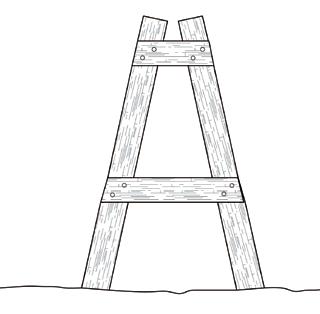

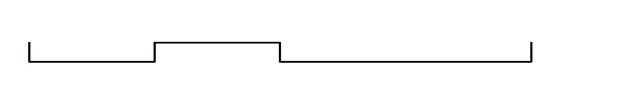

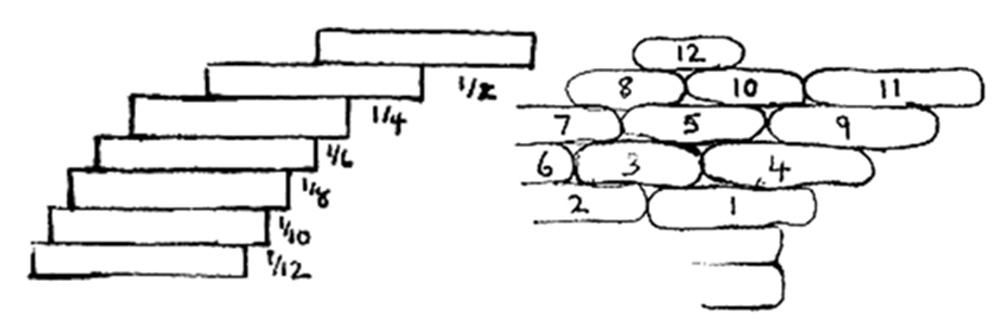

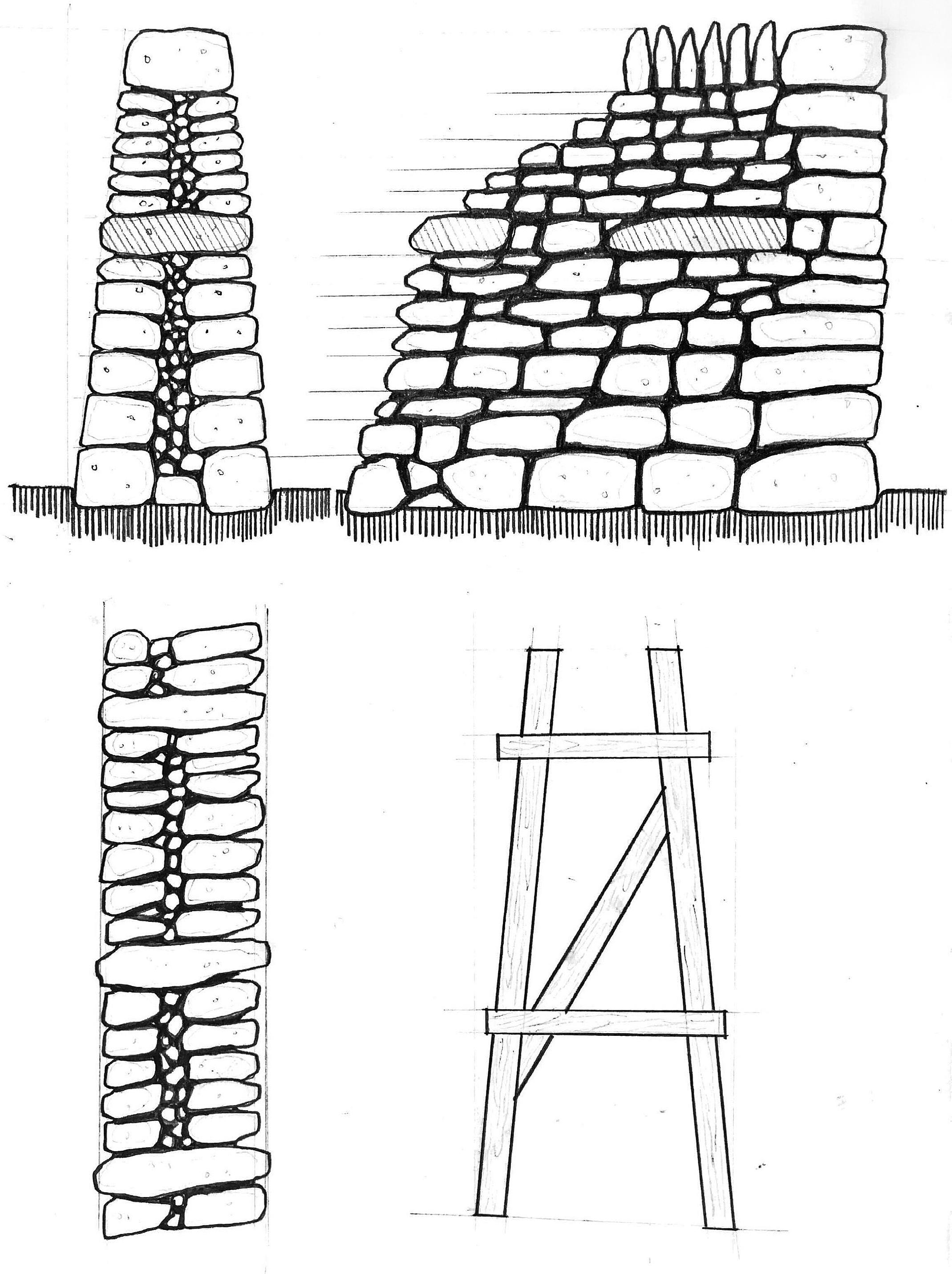

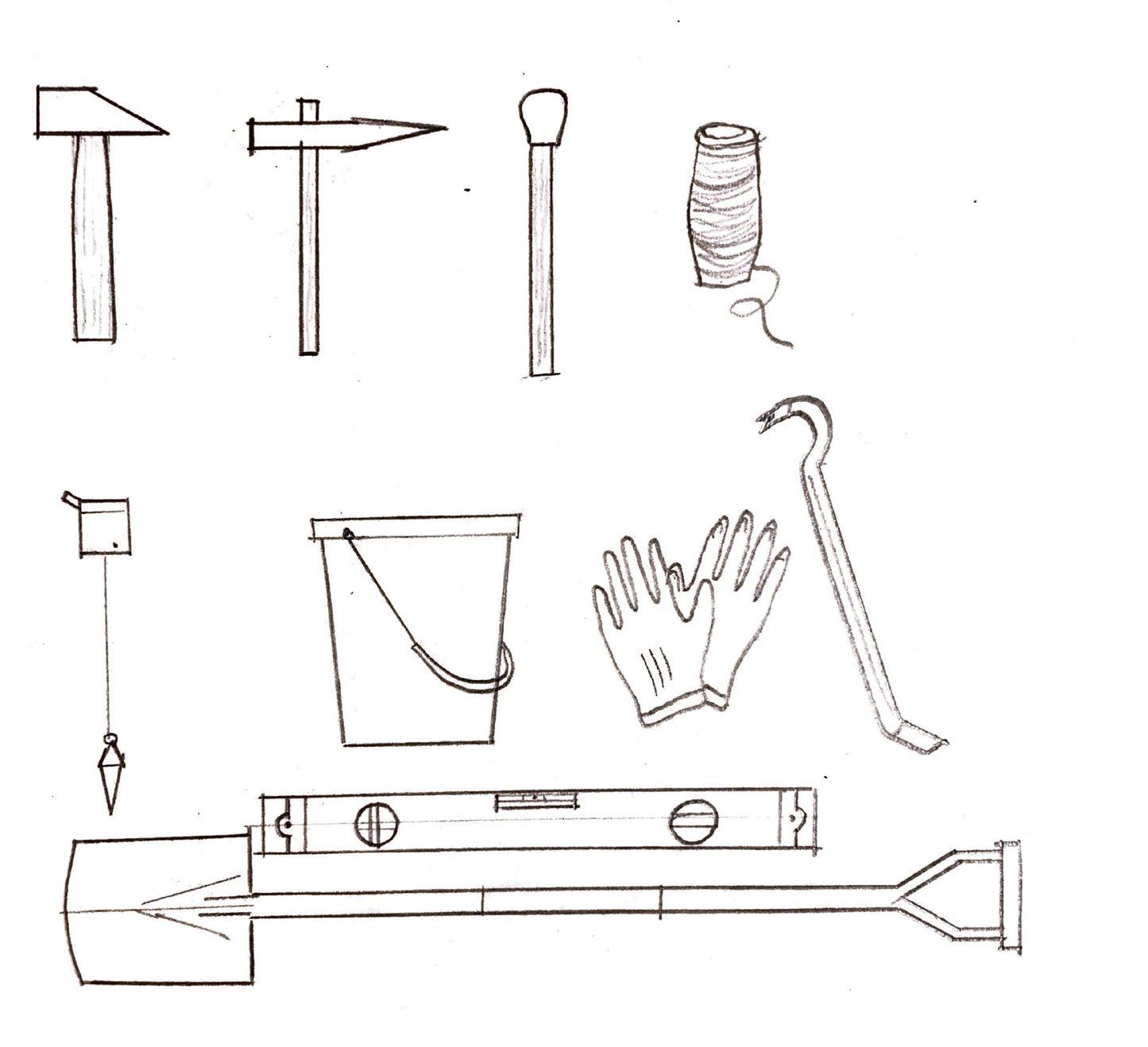

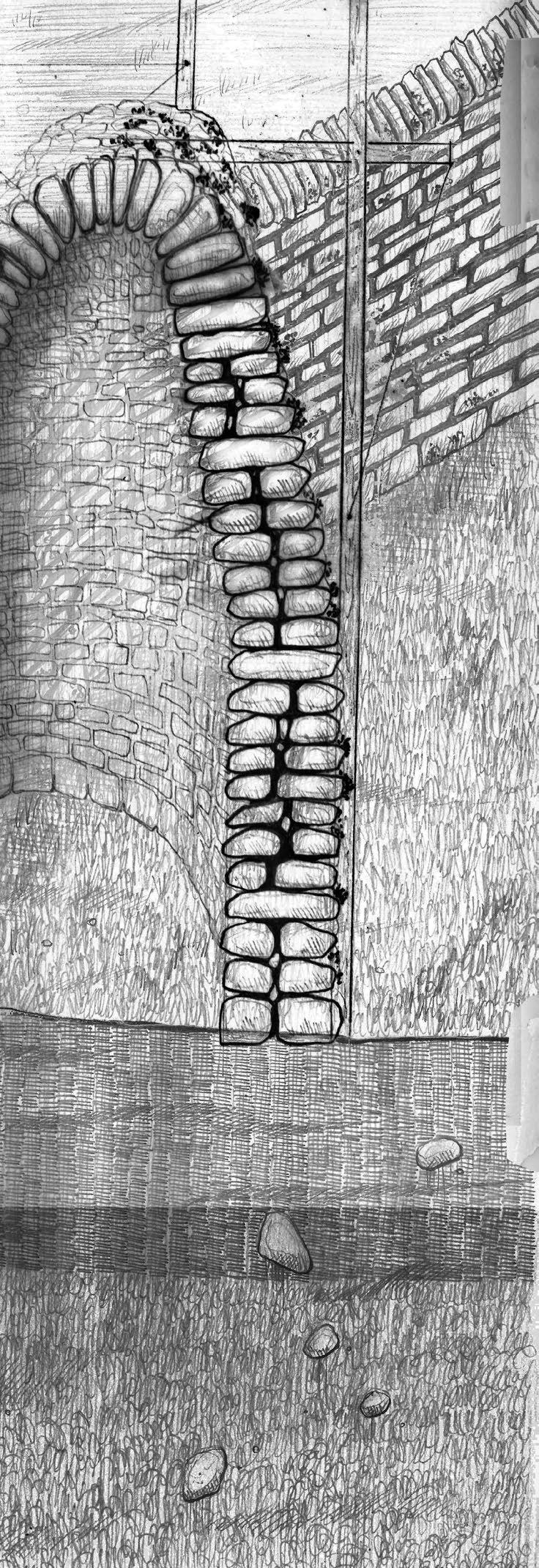

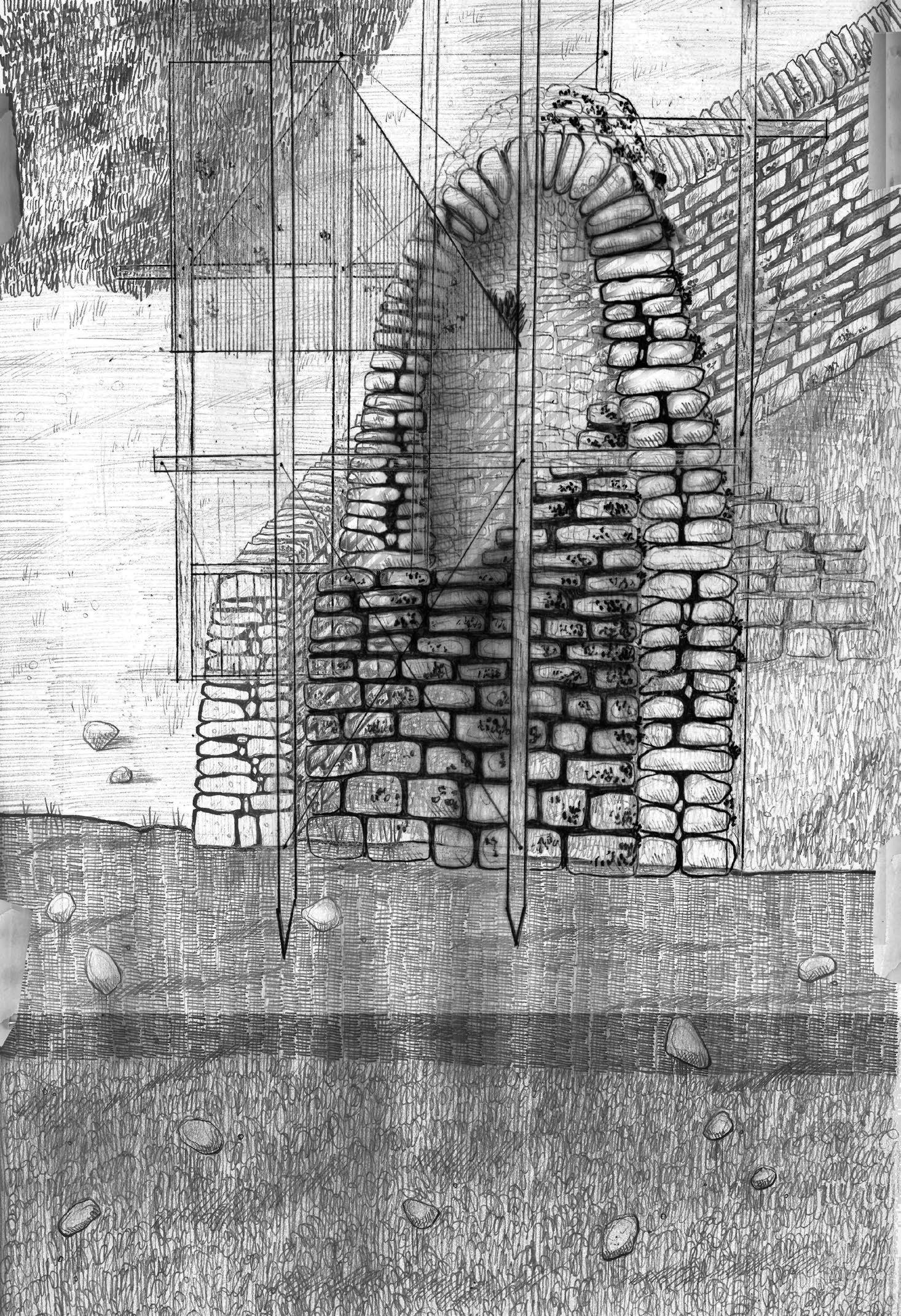

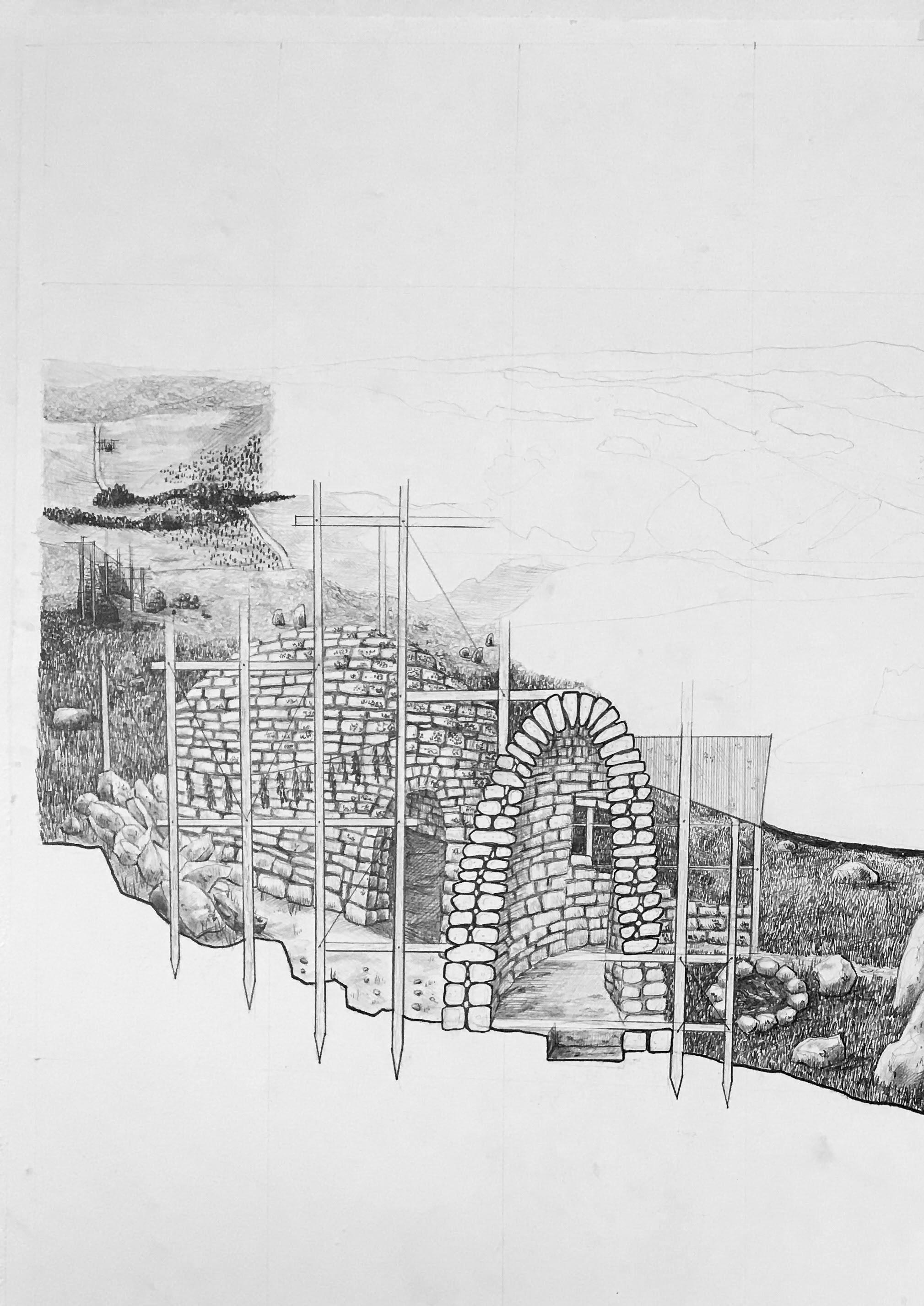

Constructing Drystone

Drystone as Craft

Building a Drystone Wall

Design Scenario

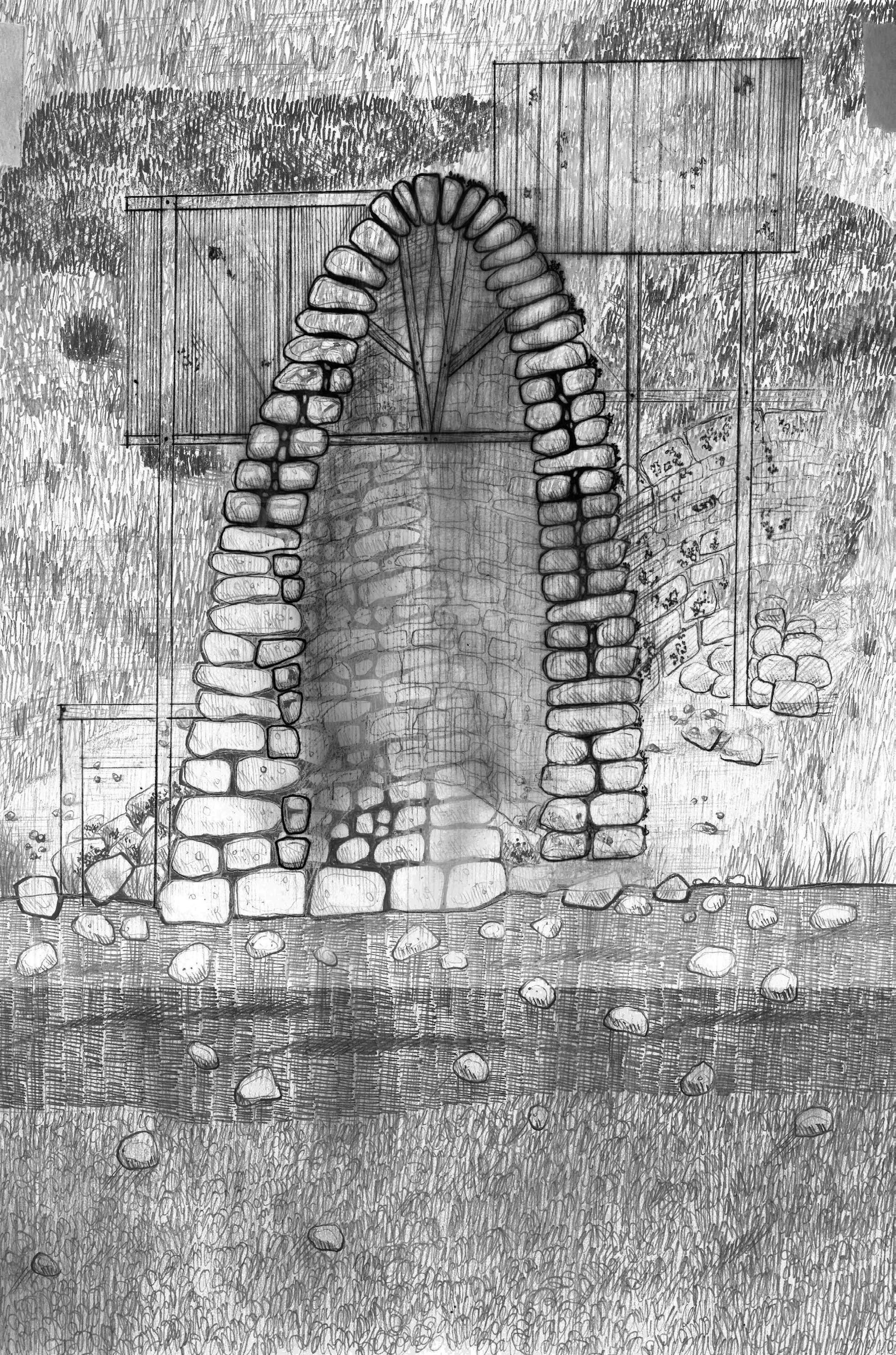

Design Strategy: Appropriating Grouse Butts

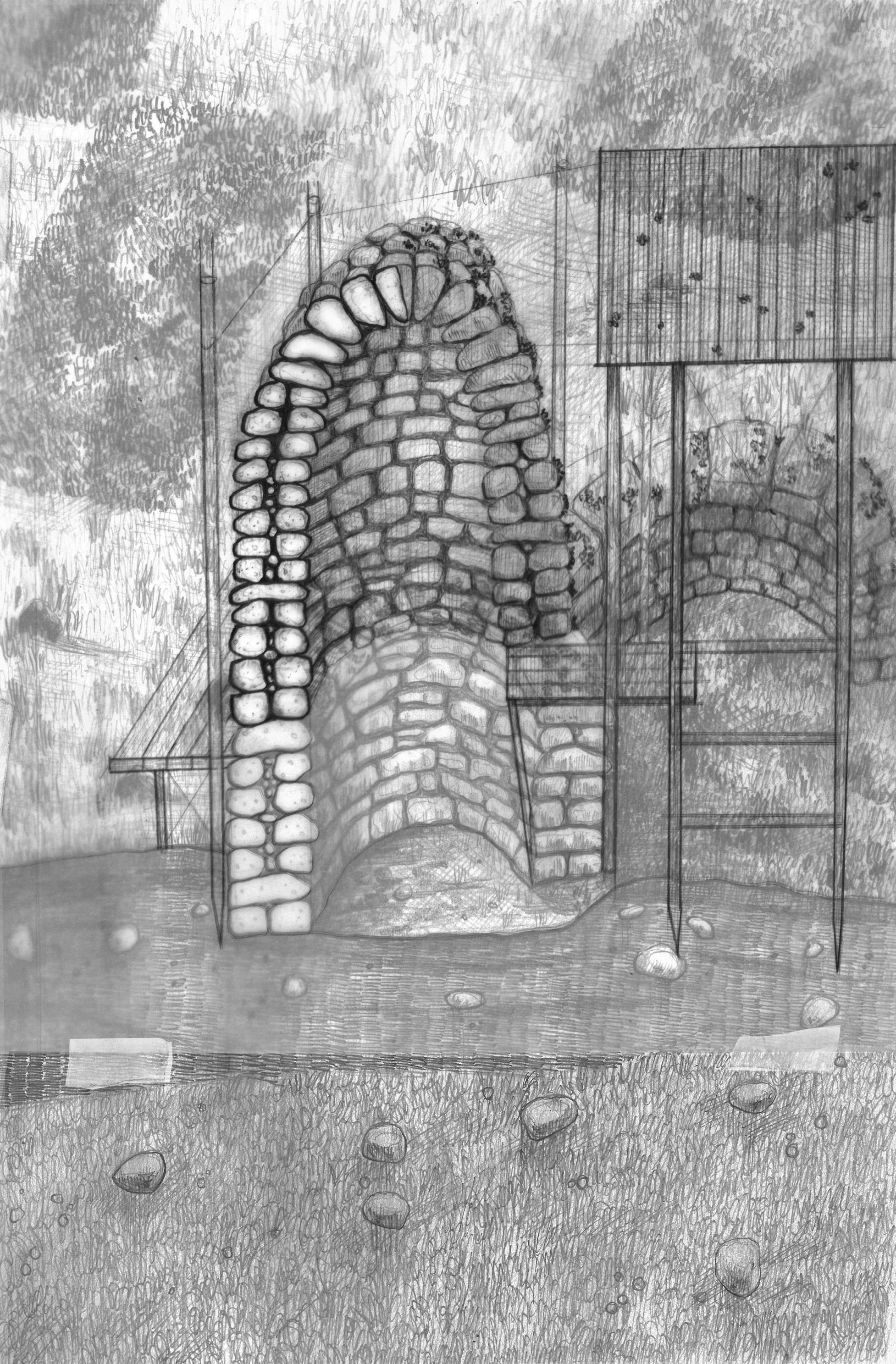

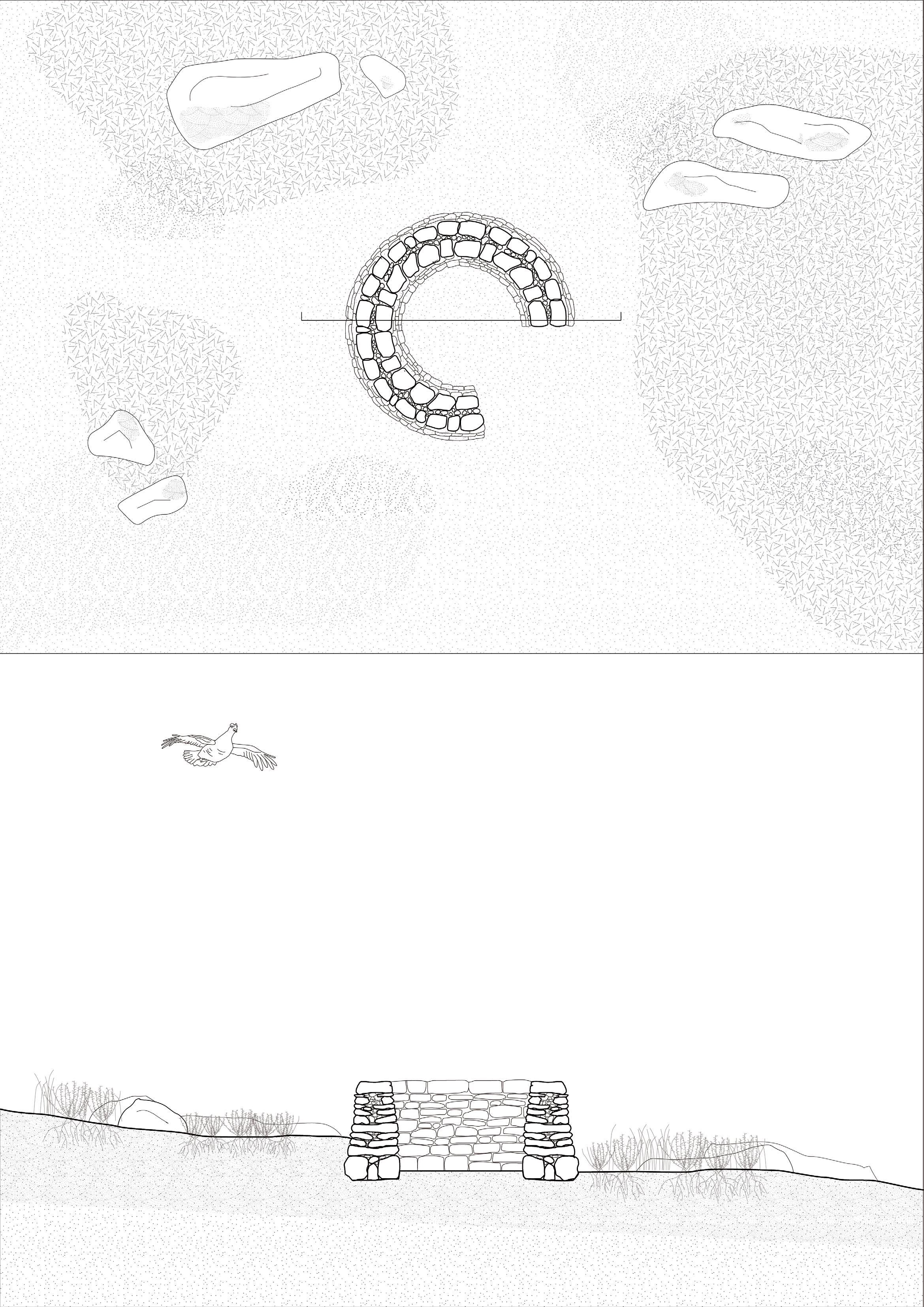

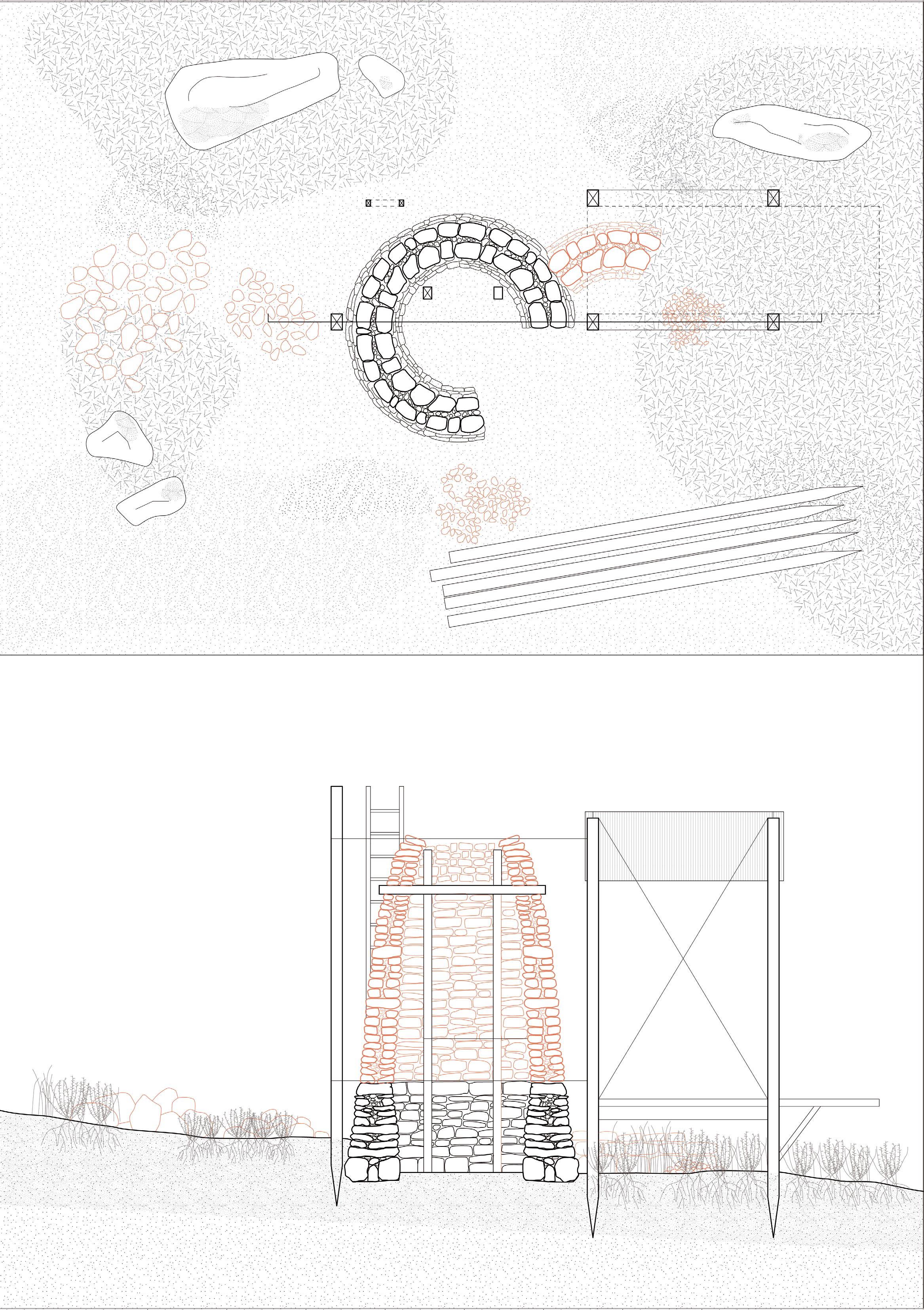

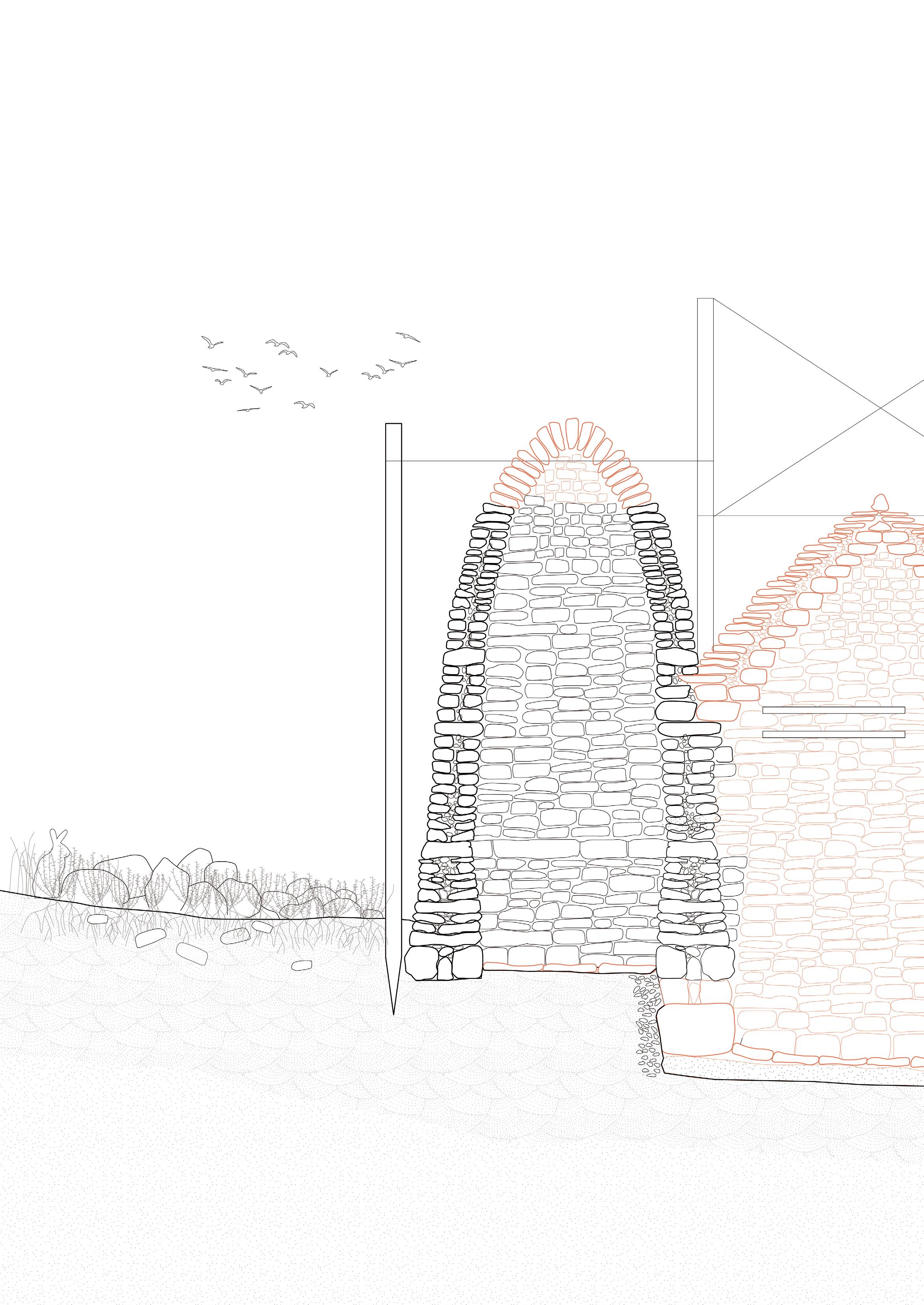

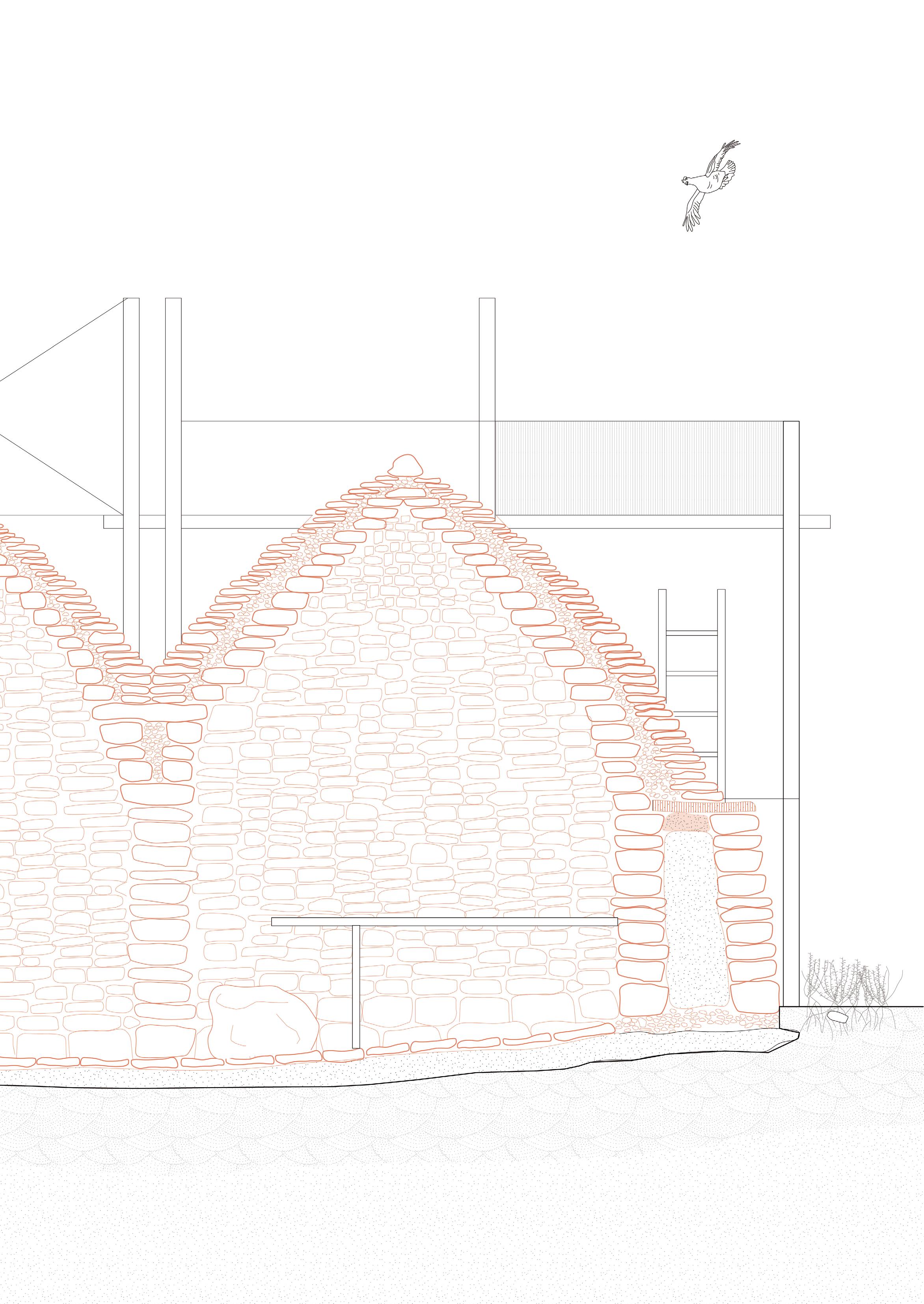

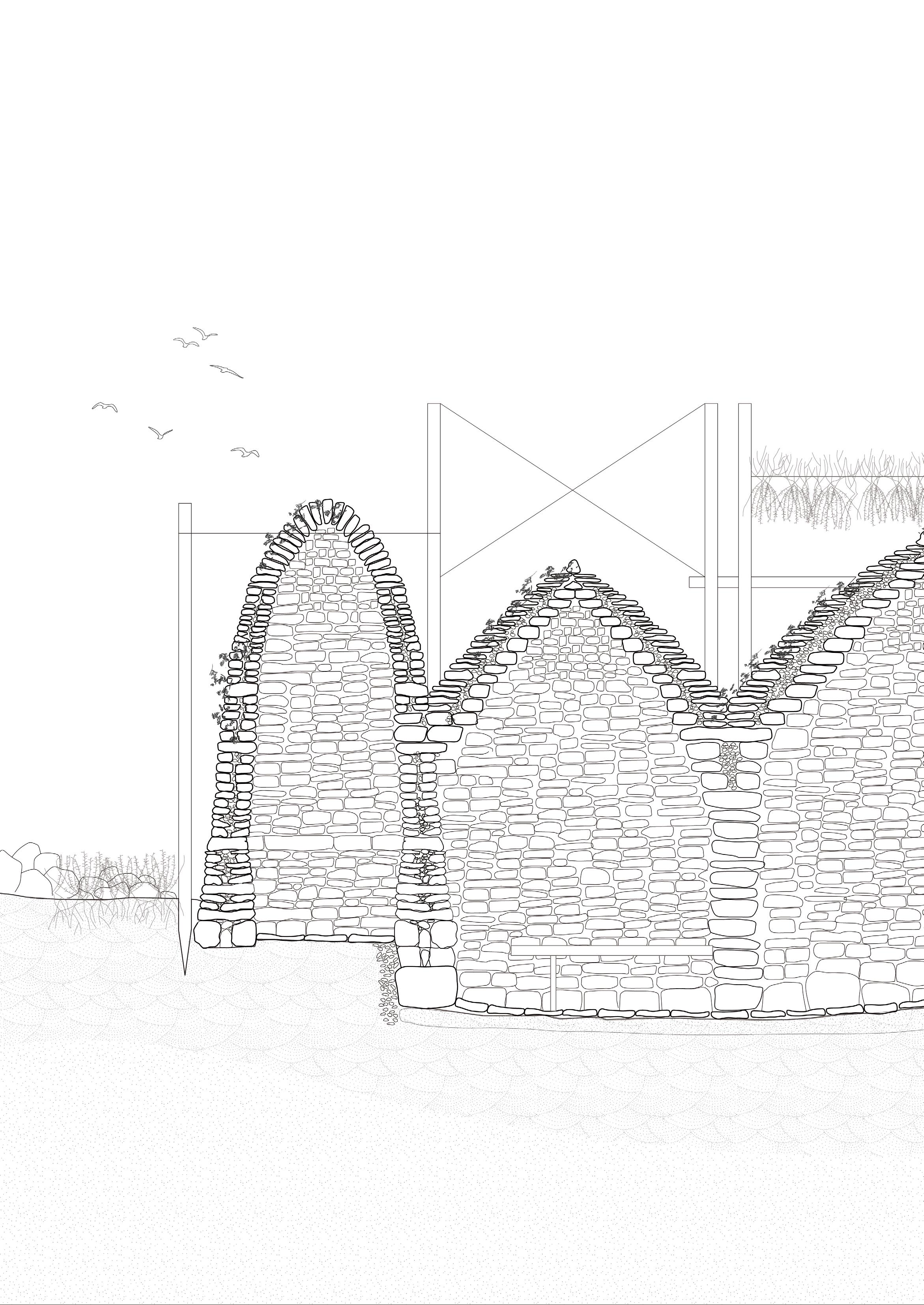

Design Stages 0-6

Drystone as . . . A collective design and construction process

Quantifying Effort: The Labour of Drystone Construction

Collectivising Drystone Construction

Construction Roles

Drystone as . . . A continual practice of repair and maintenance

Drystone Repair and Maintenance as a Commoning Practice

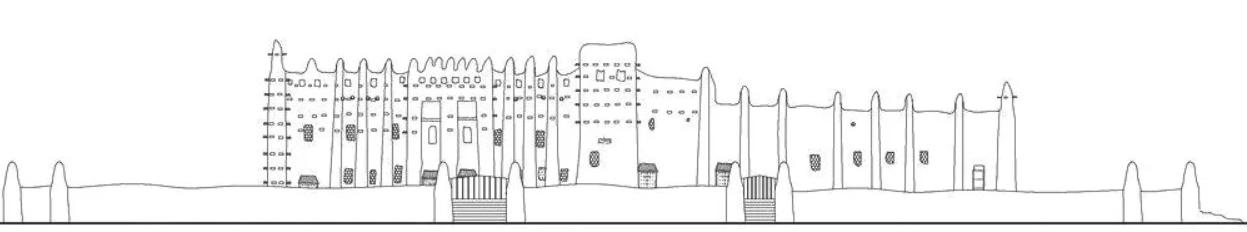

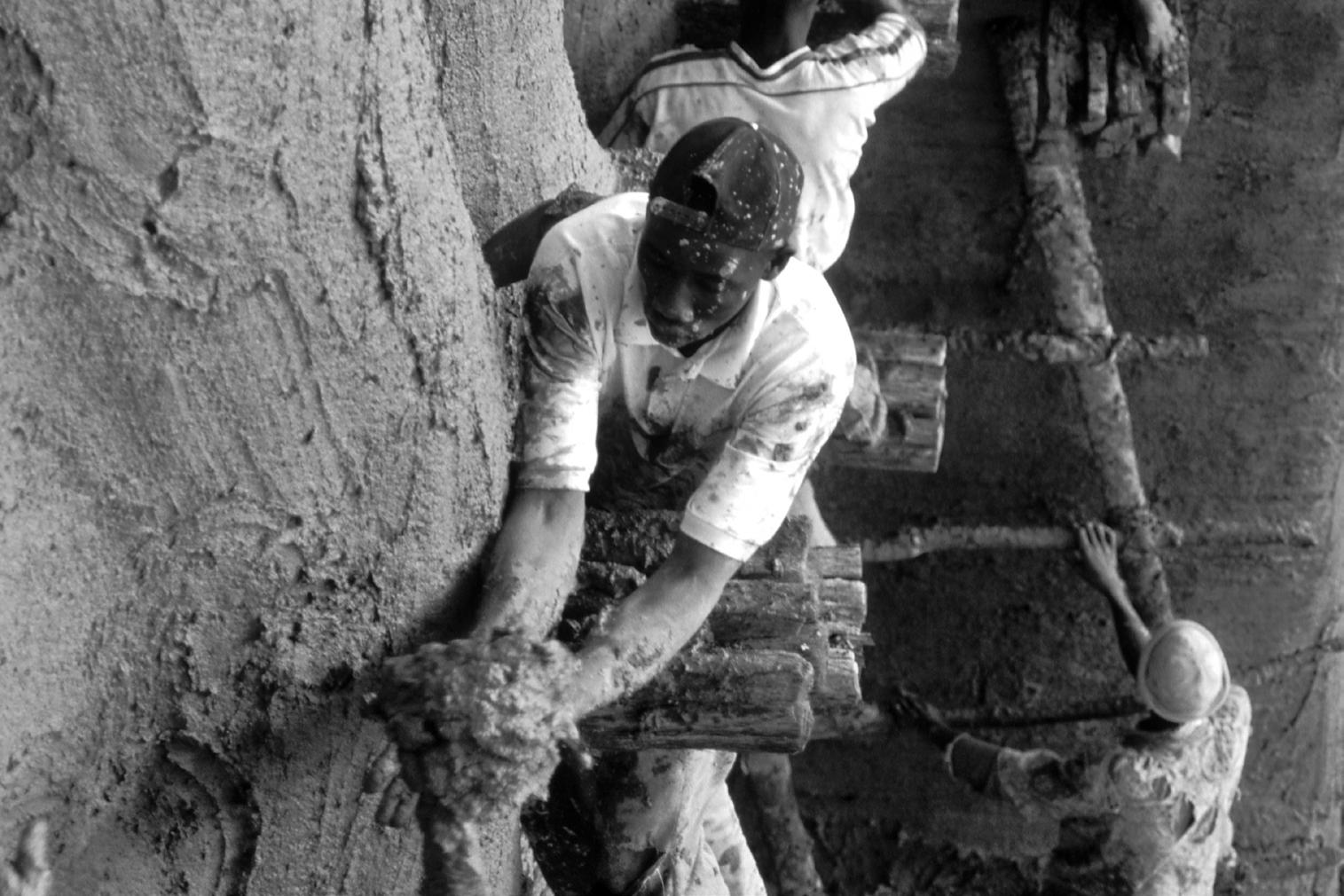

Case Study: Crépissage, Great Mosque, Djenné, Mali

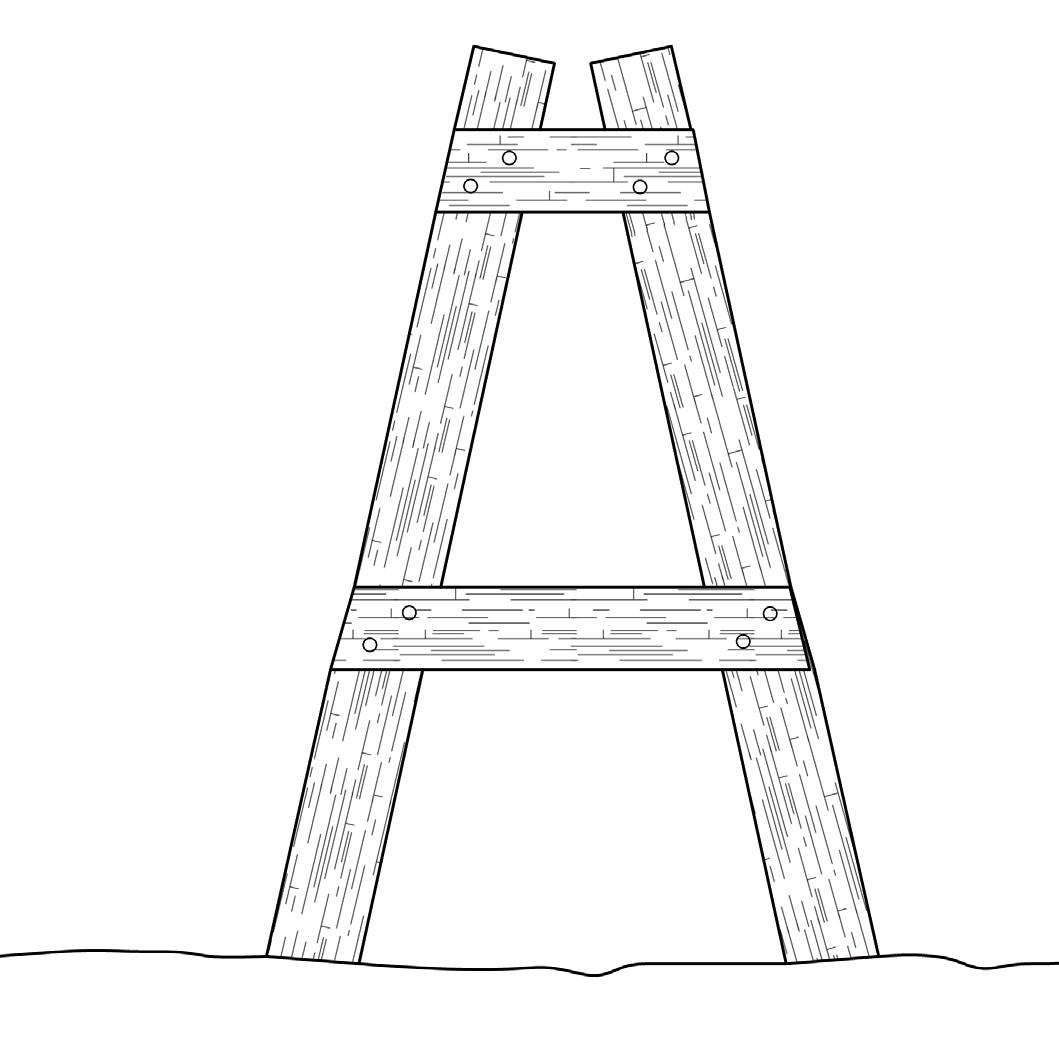

Scaffold for Construction and Repair

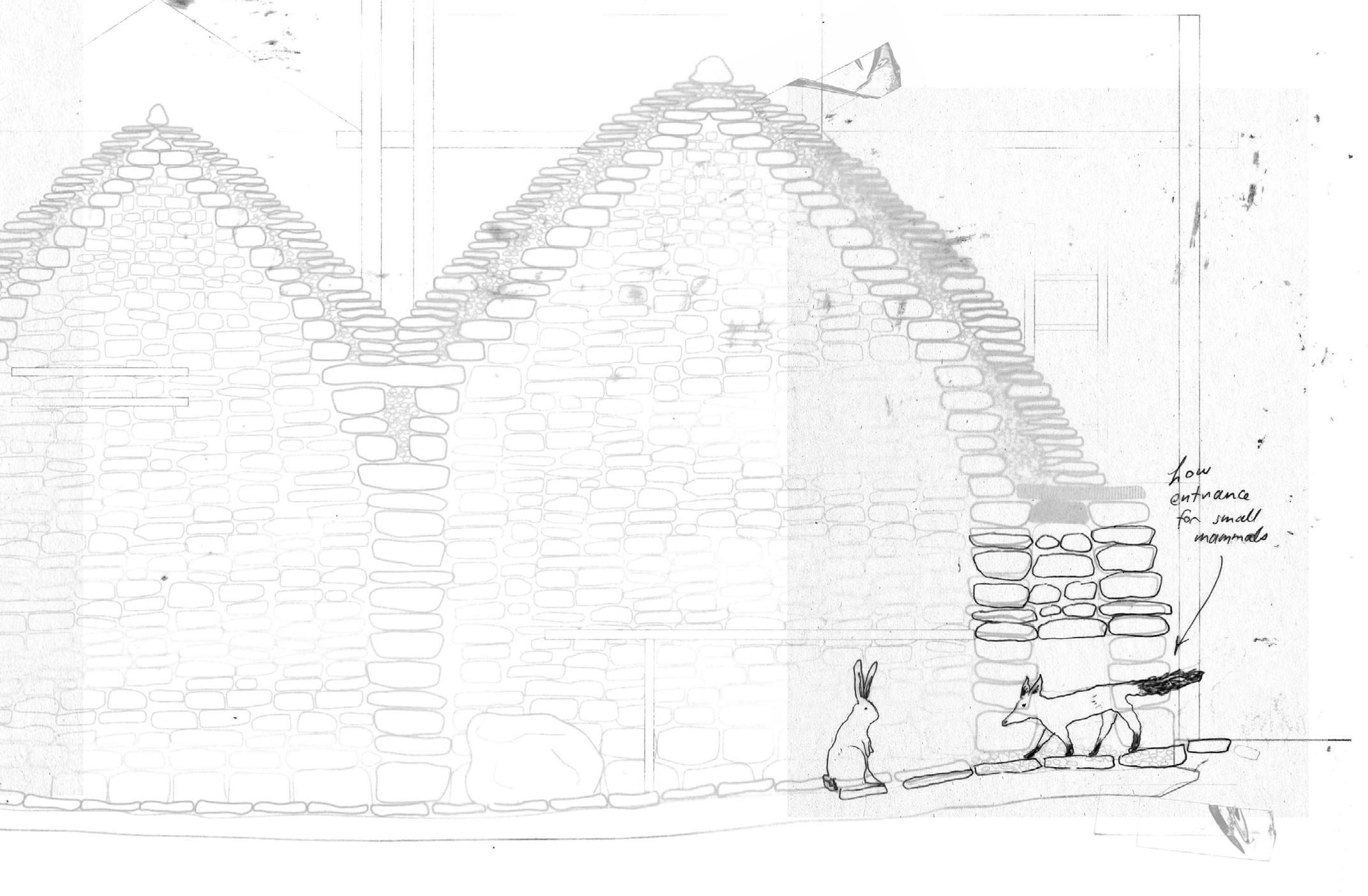

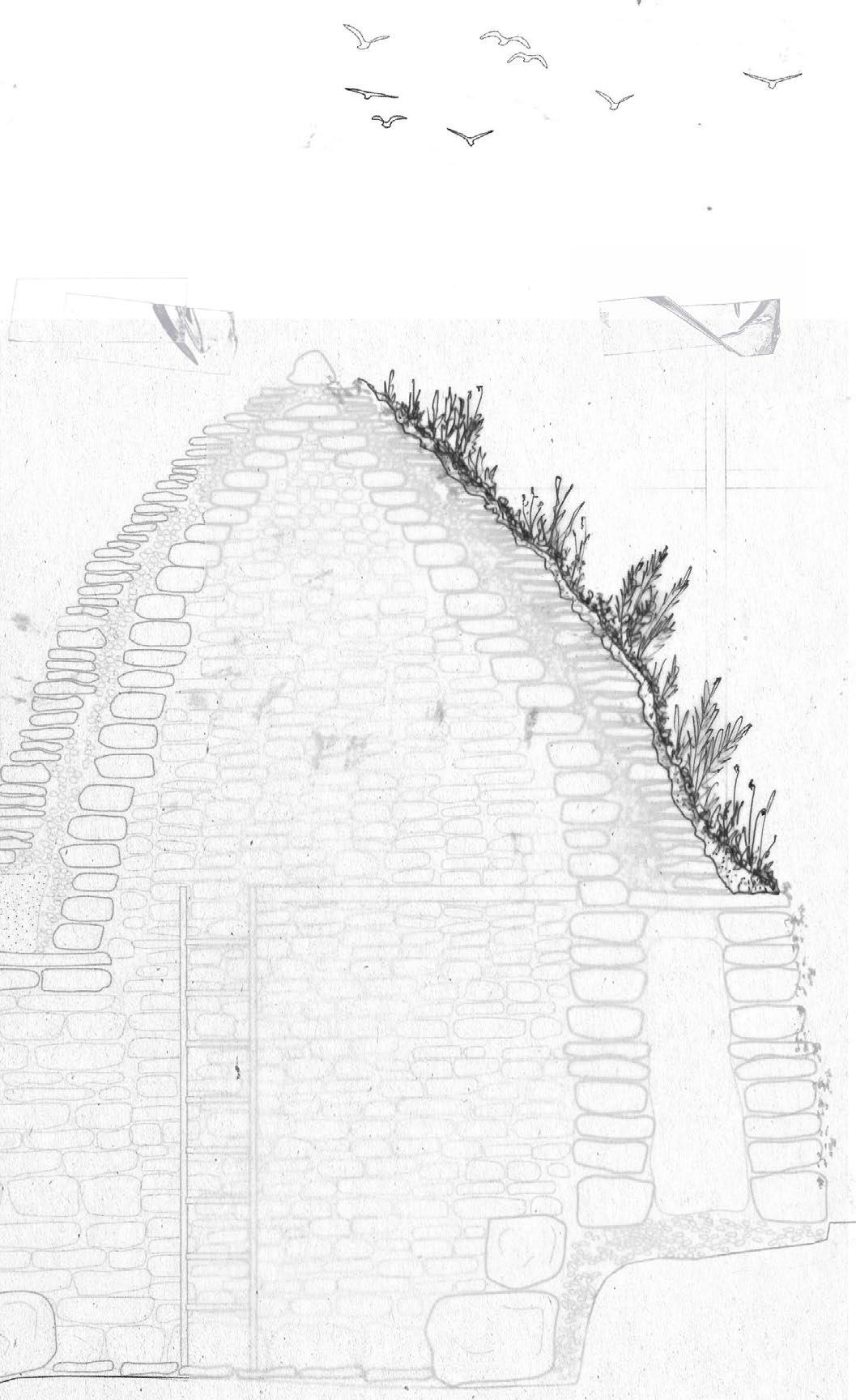

Drystone as . . . A site of multispecies interaction

Commoning Cairn

Drystone as a Scaffold for Moss and Lichen

Moss and Lichen Growth on Gritstone

Types of Multispecies Inhabitation

Design Question

How can broken drystone walls and existing stone structures be appropriated as building blocks for the collective construction of drystone enclosures?

This chapter tests construction methods to transform existing drystone into a moorland field station.

It examines collectivising drystone construction, design for repair strategies, and multispecies inhabitation.

Existing drystone structure Broken stones +

Drystone field station

Case Studies + Context Analysis

The following section examines case studies of drystone buildings, using these as precedents for the design strategy.

A context analysis of existing drystone structures in the Dark Peak sets the stage for the design of drystone field stations.

Case Studies of Drystone Enclosures

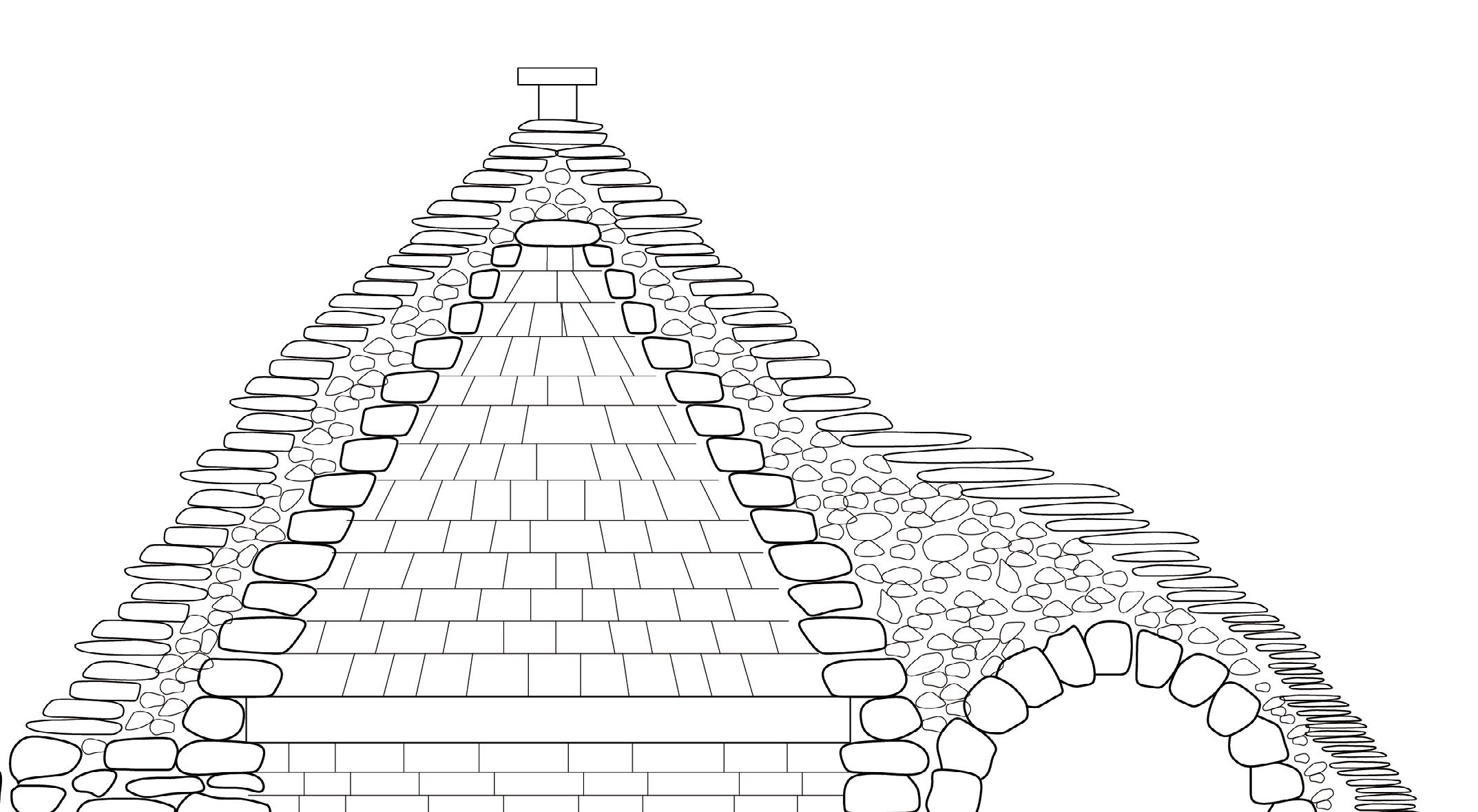

For thousands of years, drystone construction has defined vernacular architectures around the world. From the burial court cairns of Ireland to the pyramids of Giza, drystone makes use of locally found or excavated rock to create durable enclosures whose structural integrity relies on the interplay of stone and gravity. With no other materials required, drystone is perhaps the simplest of building methods, but it is also a skilled craft that takes decades of practice to perfect.

The following case studies examine forms, scales, and methods of drystone construction in a variety of contexts. In understanding the scope and potential of drystone, these case studies give a glimpse into possible trajectories for my own design of drystone field stations in the Peak District moorlands.

01. Drystone is Sobrarbe-Pirineos UNESCO Global Geopark 02. Drystone monastery at Sceilg Mhichíl, Ireland (6th-13th centuries CE)

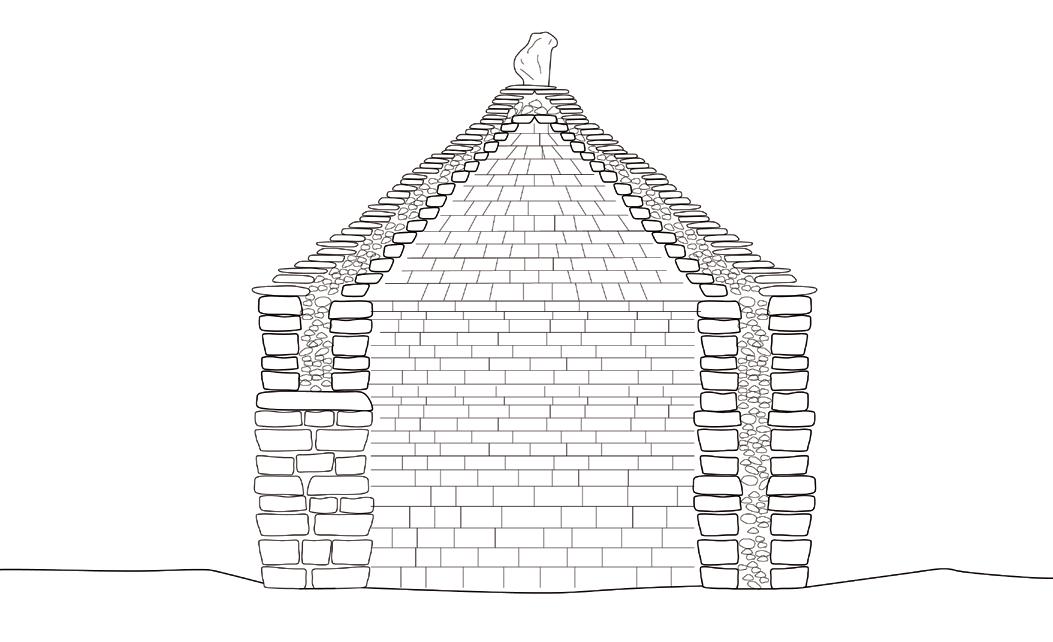

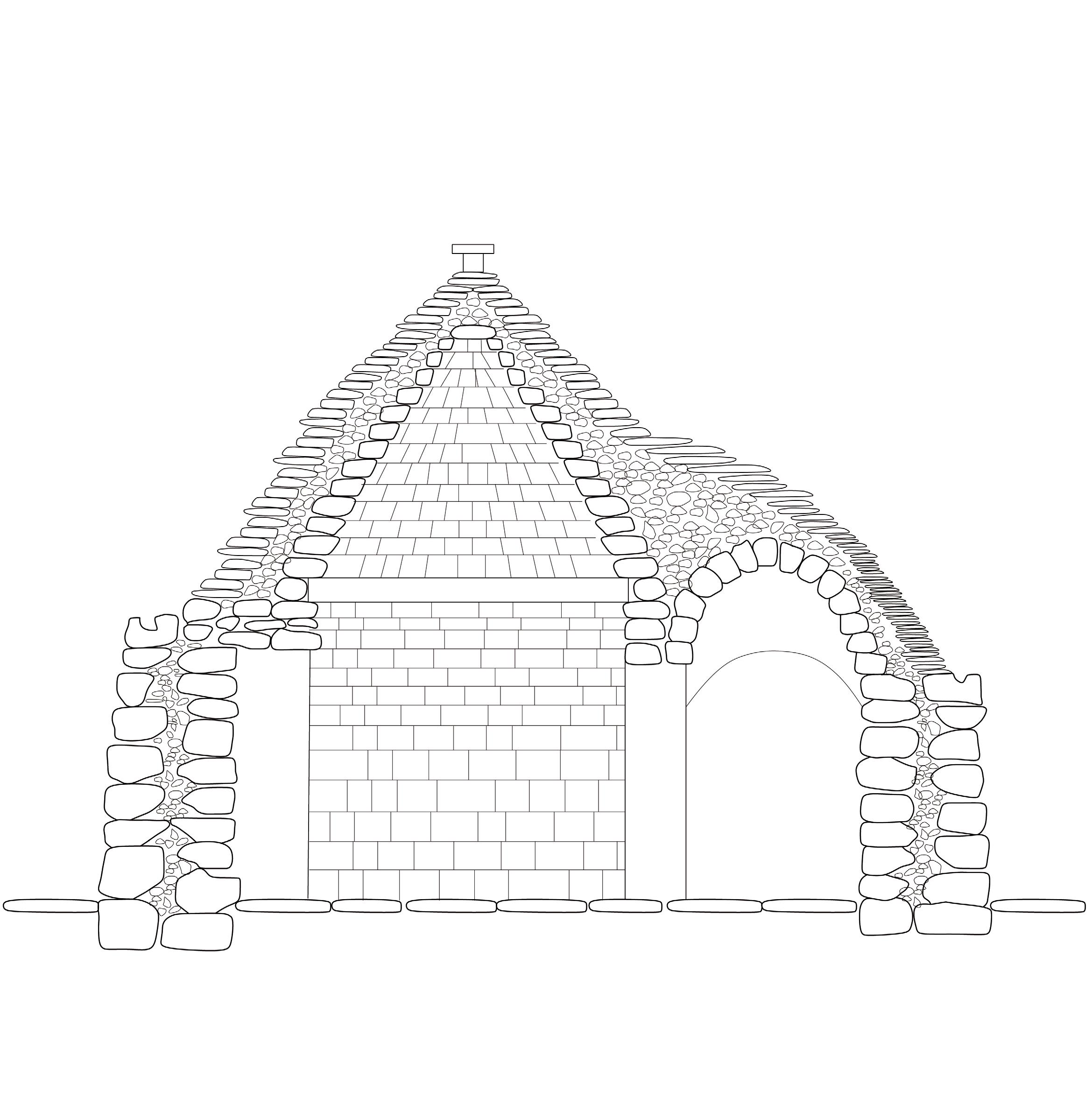

Case Study: Trulli, Italy

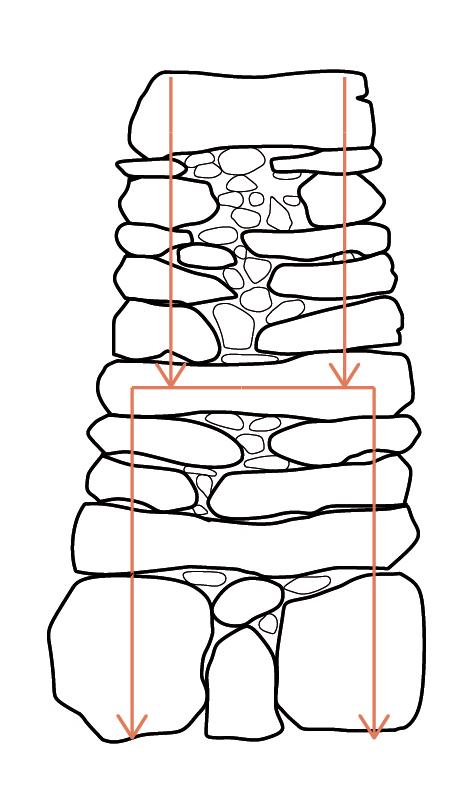

Trulli are drystone enclosures found in the Apulia region of southern Italy. Their high-pitched roofs employ a double layer of drystone with a pebble infill, and the walls are often whitewashed. The roof laying technique is called corbelling, where each layer is successively nudged inward to create a conical and durable form. Trulli may have originated in the medieval period as shelters for farmers or for storage, but they evolved to become permanent dwellings for local residents. The thick stone walls have good insulation properties, providing a cool interior space during the hot summer months. Interestingly, trulli are often adorned with symbols, carrying ritualistic or religious meanings.

Trulli provide a useful case study in understanding the structural properties of drystone. Though the type of stone found in southern Italy is different to the Peak District’s gritstone, a similar method of stacking could be used to create an enclosed, durable, and weather-proof roof.

01. Double-layered drystone wall

02. Thin and flat c0rbelled roof tiles

03. Chimney

04. Channel carved from top stone for water drainage

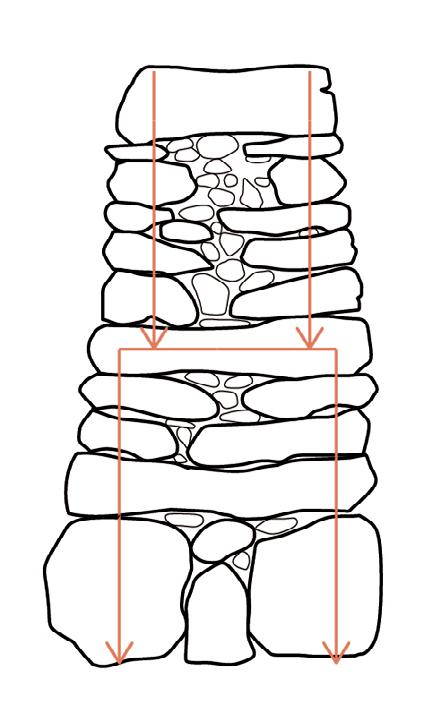

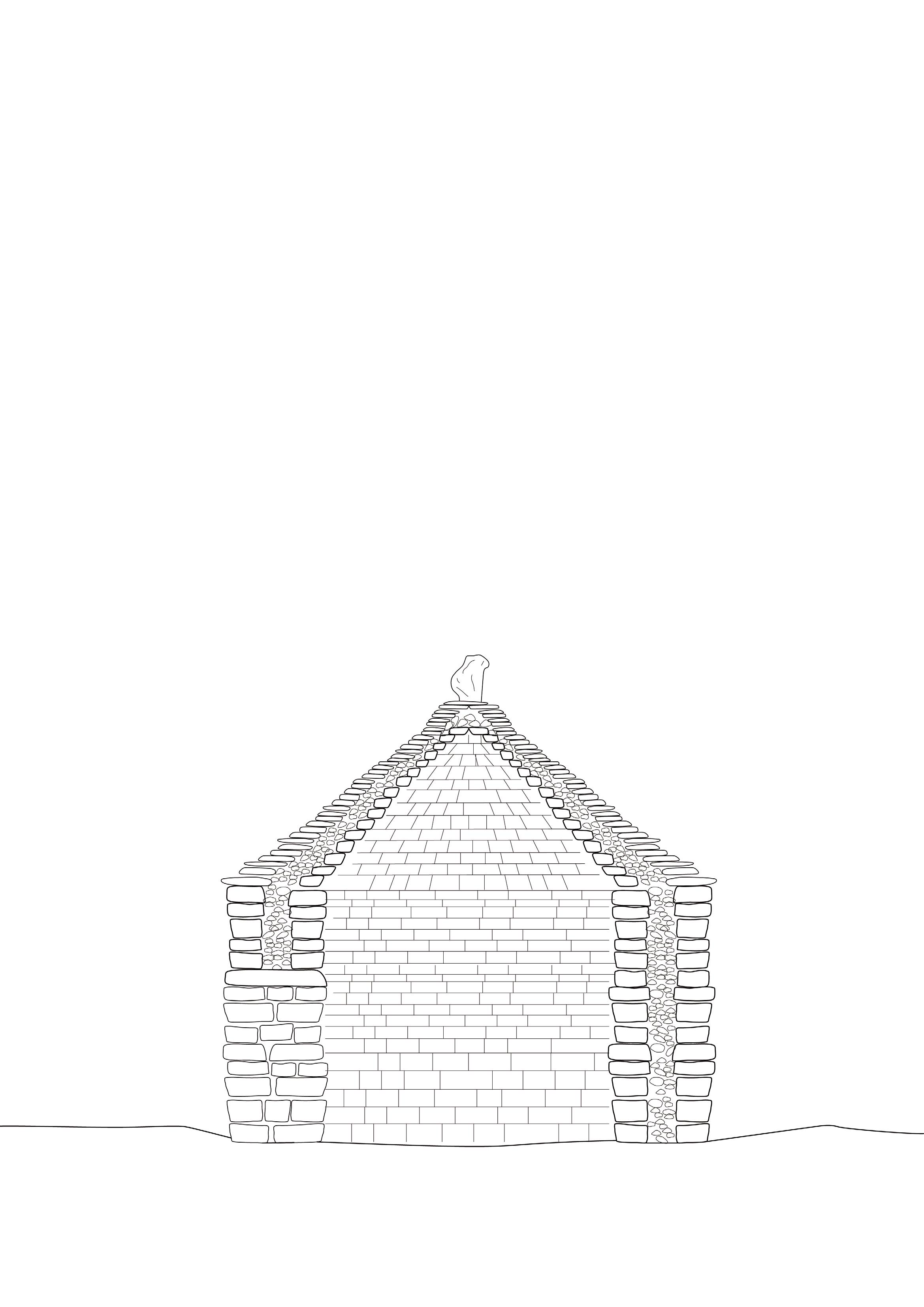

Case Study: Kažun, Croatia

The Kažun is a vernacular building found in the Istria region of Croatia. It is an ancient method of building, predating ancient classical civilisations. Made entirely of drystone, kažuni were built from stone—typically limestone—found when clearing fields for farming. It encloses a single round room, suitable for temporary shelter or storage. Over 3000 huts can still be found in the Vodnjan region.

The kažun shows how ‘waste’ rock—rock found or excavated when clearing land for farming—can be repurposed into a shelter for shepherds, farmers, or passers-by. In the Peak District, farmers often repurposed rocks dug up in clearing the land into enclosure walls. Kažuni ingeniously use a double layer of drystone with a pebble infill to provide both structural support and protection from wind and rain. With a steep incline, the stacked flat rocks create a durable roof structure.

01. Lintel to create door in the drystone wall

02. Double layer of drystone

03.

04. Flat, wide stones are stacked to create an external roofing layer

05.

at the top weighs down and secures the roof

Pebble or small stone infill

Large stone

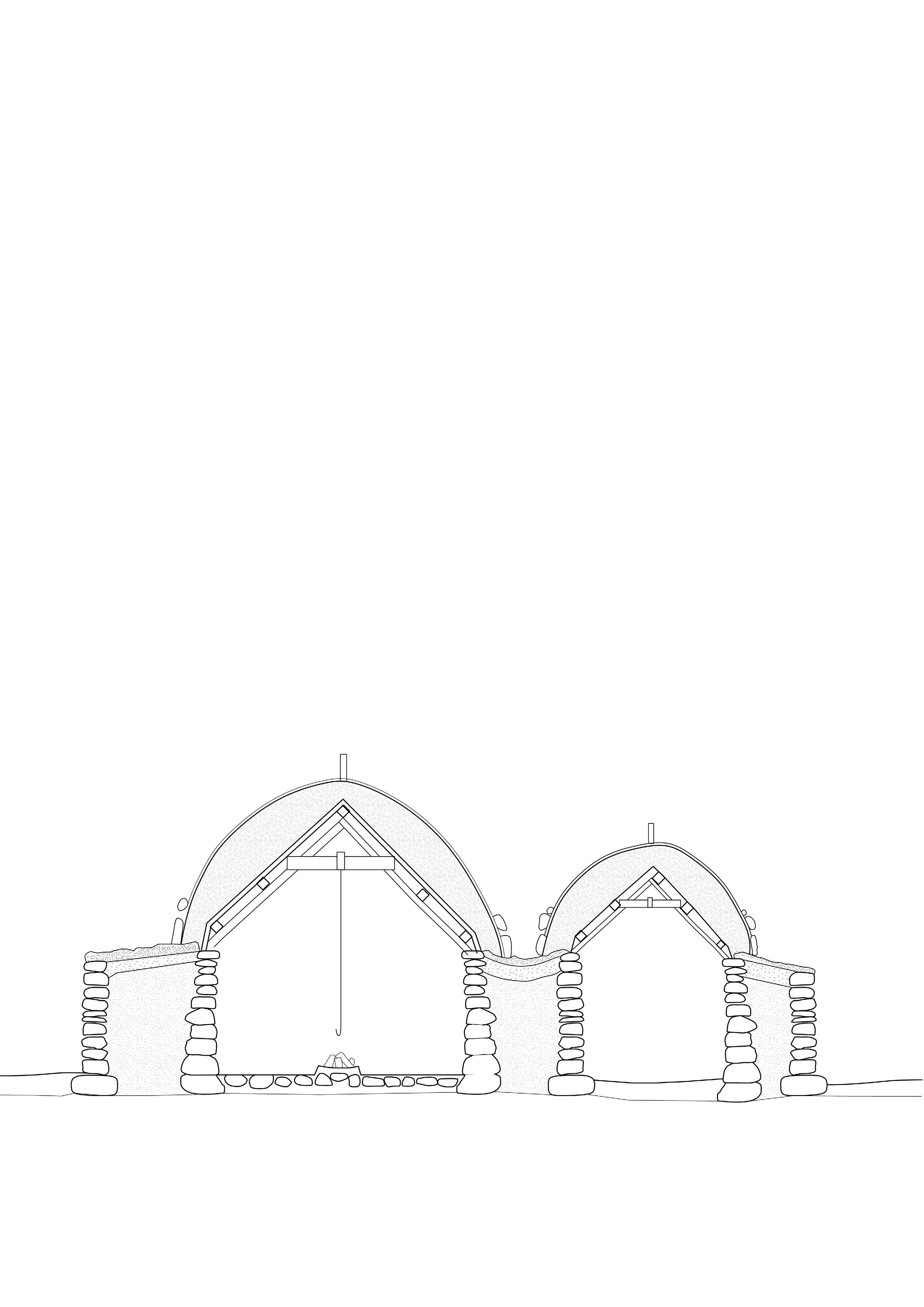

Case Study: Blackhouse, Scotland

The blackhouse, or Taighean, is a vernacular form of architecture found in Scotland. With drystone walls separated and packed thick with peat, the blackhouse provides protection from cold northern winds. The stones do not extend above the tops of the vertical walls; rather, timber frames support thatching. Blackhouses were built on clay, with a layer of pebbles supporting the weight of the drystone above. The two layers of drystone are topped with clay to prevent water leakage, then finished with a layer of turf, which also helps to absorb water. The timber used on the interior was typically taken from driftwood. In the case of the Peak District, local timber from the conifer plantations could be utilised. Given the windy conditions the blackhouse is built for, a rope net is often placed over the thatch to prevent it from blowing away. This is then weighed down with rocks. Chimneys protrude from the thatch to allow for cooking to take place indoors.

An interior fire would keep the blackhouse warm, but it would also blacken the interior walls, hence the name of this building type. The maintenance of the thatch was completed communally, with thatching and re-thatching a collective activity.

The blackhouse, though found in conditions further north than the Peak District, uses similar materials available in the moorlands, and provides an exceptional degree of shelter from wind and rain that other forms of drystone structures do not. In the following design exercise, I draw from the blackhouse’s layering of peat and thatch to provide additional protection from the moorland rains and winds.

01. Drystone wall

02. Turf roof covering

03. Layer of clay

04. Peat soil to provide insulation between drystone

05. Stones to weight down thatch in heavy wind conditions

06. Rope to tie down thatch

07. Thatching

08. Timber framed interior to support thatch

Stone

Under the moorland’s heather, moss, and peat lies gritstone. Stone structures dotting the landscape reflect a constant process of reshuffling the terrain, an exchange between surface and subsurface. This is where geologic, human, and plant timescales converge.