A Note on Positionality

My research on and fascination with the role of plants in the British colonial project emerged last year through my project “A Field Guide to the Botanical Imaginary: An Anti-Colonial Walk in Kew,” undertaken as part of Diploma 13: Experiments in Reparations. My interest in the intersection of plants and power precedes this, however. Growing up as a settler on Turtle Island, or so-called Canada, I began to take seriously questions of decolonisation in the last few years of my undergraduate degree. Books such as “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Wall Kimmerer, and courses I took such as “Indigenous Land Sustainability in the Carolinian Forest,” taught by Anishinaabeg professor Andrew Judge, were formative to my thinking, and I am grateful to the many teachers and knowledge-keepers from whom my work draws upon.

As an architecture student, I apply a spatial lens when encountering and learning-with disciplines beyond my formal education. Though my thesis closely relates to the emerging field of critical plant studies, it draws from archival studies and decolonial, feminist, social, and critical theory lenses. Beyond the traditional architectural interest in archives and botanical gardens, my exploration of Kew’s botanical archives seeks to contextualise them within a broader framework of British colonialism. I see them as concentrated nodes that both stored and created botanical knowledge, materially and epistemically linked to an expanding empire. My interest lies in relationality: in the constructed, experienced, and complex, relationships between plants, humans, landscapes, and territories.

I would like to thank Merve, George, Merce, Dena, Aris, Lina, Marleen, and Sue, among many others, for their guidance, insights, and support in this project.

Note: Following Jason W. Moore’s capital-n Nature, Marleen Boschen’s ‘nature,’ and others, I place emphasis on the term nature using quotation marks to show it as a construct that in its definition operates external to humanity, a notion I wish to challenge throughout this thesis.

1. Richard Harry Drayton, Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the “improvement” of the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), p. 194-5.

2. Lucile H. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens (New York, NY: Academic Press, 1979), 157.

Introduction

“Machines did not merely run on coal, they consumed cotton, wool, dyes, and vegetable oils, and the strength of the peripheral populations which provided these (…) There was, in short, a concern with economic botany across the British Empire.”1

Theft!

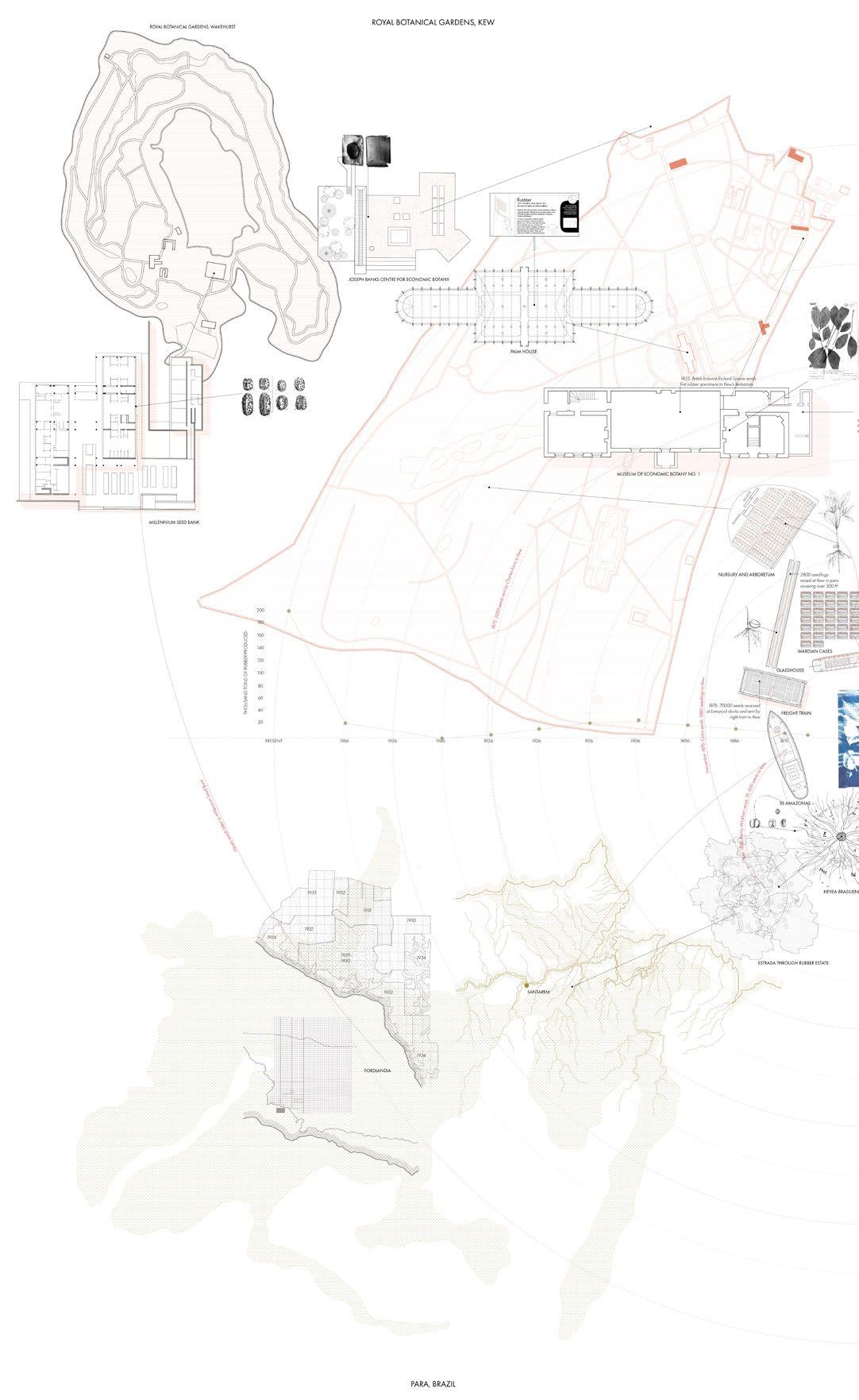

In June 1867, English plant ‘collector’ Henry Wickham leaves the port of Santarem, Brazil, on a steamship laden with 70,000 stolen seeds. With the aid of local peoples, he has painstakingly harvested these seeds from the rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis, found only in the Amazon rainforest. His destination is the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, a critical landscape in the British imperial project. Wickham has been commissioned by Kew to undertake this covert operation, hustling seeds out of the port under false pretenses. Little does Wickham suspect, these seeds will change the world as he knows it.

Kew’s director, William Hooker, is surprised by Wickham’s success. He arranges for the seeds to be sown in glasshouses, a new building technology that allows the fabrication of tropical climates in suburban southwest London. Wickham is delighted, writing of this “pretty sight—tier upon tier—rows of young Hevea plants—seven thousand odd of them,”2 unfurling in Kew’s seed pit. But the seeds will not stay long in London: they are destined for Britain’s colonies in Asia. The Hevea seedlings set sail, carefully placed in thirty-eight Wardian cases. These wooden terrariums, an invaluable imperial technology, enable plants to survive transoceanic voyages, acting as transportable micro-climates.

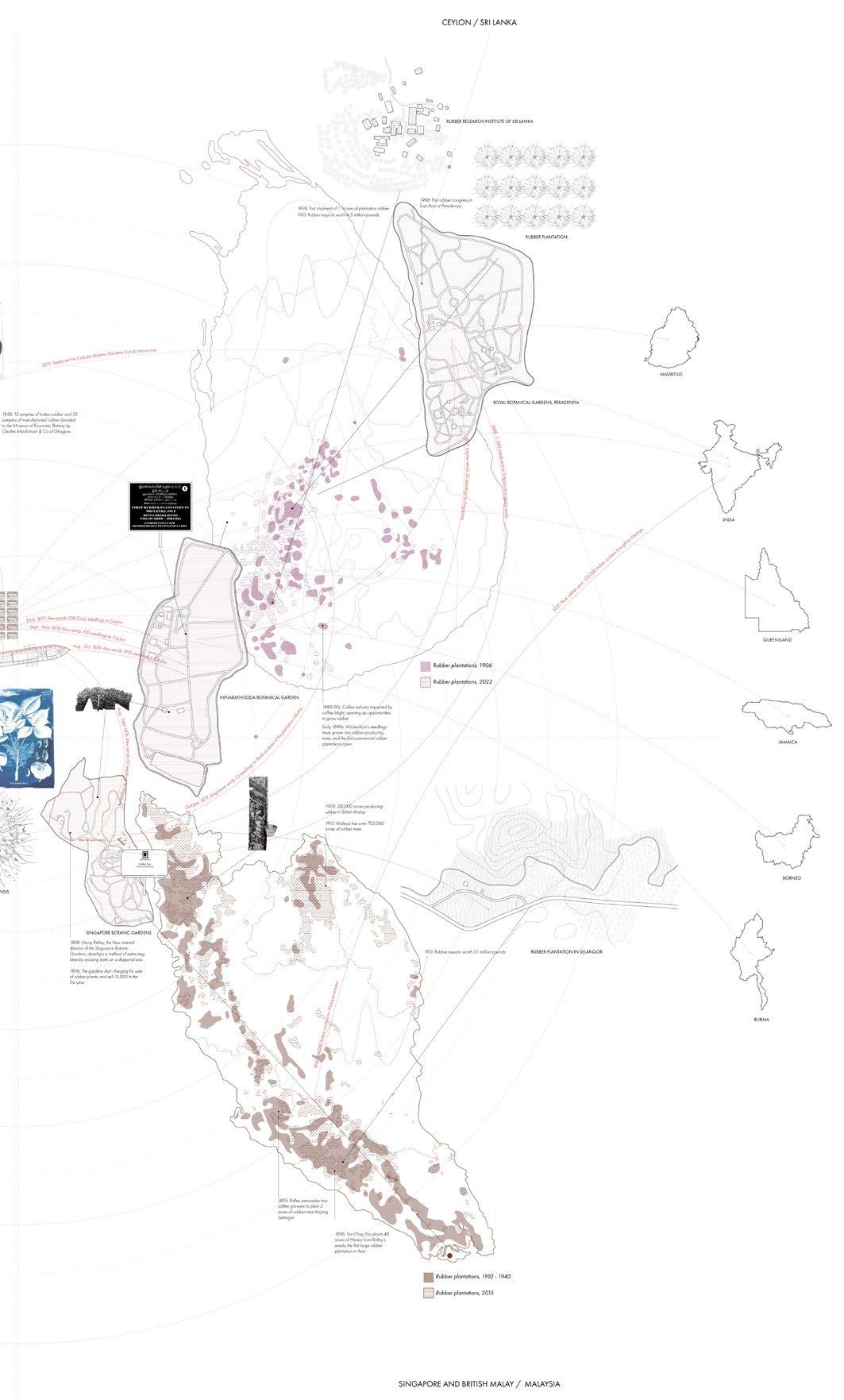

The Wardian cases are unpacked in botanical gardens in Singapore and Ceylon. Though many do not survive the journey, these newcomer plants will soon transform entire territories into rubber plantations. The story of the rubber transfer—one of many colonial plant transfers conducted by Kew—speaks to the enormous power held in the extraction, possession, and control of plant life. It is a story of botanical colonialism, an oftenoverlooked engine of the British colonial project.

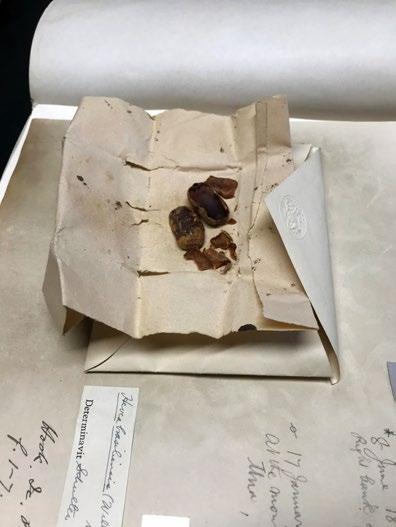

Figure 2. An original Hevea seed transported by Henry Wickham. Photograph by the author from Kew Archives, 2022.

Kew: Seeding Empire

The story of the rubber tree illuminates the power held by plants. Human history is entangled with the vegetal realm, where we have always relied on plants for food, clothing, materials, medicine, and even pleasure. If European imperialism was a world-encompassing project of control over people and land, it was also a project of conquering plant life, an effort to control, own, and propagate plants useful and profitable to Empire. This process can be referred to as ‘botanical colonialism,’ a term I borrow from critical plant studies scholar Catriona Sandilands, who describes the purposeful and unforeseen transit of plants as essential to human colonisation.3 I further define this phenomenon in two parts:

a. the commodification, extraction, representation, and instrumentalization of plant life to power colonisation

b. the inadvertent transport of plant life—primarily seeds—in colonial processes

3. 362. Kamea

Chayne hosts “Catriona Sandilands: Botanical colonialism and biocultural histories” Green Dreamer (podcast), 2022, https://www. greendreamer.com/ podcast/catrionasandilands-queerecologies.

Richmond.

This thesis is primarily concerned with the first definition, particularly in understanding how the co-production of space and knowledge within imperial archives created the conditions under which botanical colonialism was possible. In understanding botanical colonialism as a violent process that played a significant role in shaping our current intersecting crises of climate, biodiversity, and social justice—what Amitav Ghosh terms the planetary crisis4—the thesis addresses its key mechanisms of operation: the classification, commodification, and extraction of plant life. It argues that Kew’s archives designed and enabled these mechanisms in their collection, curation, and dissemination of botanical knowledge.

Kew’s links to empire began with its inception in 1759, when Princess Augusta transformed part of her pleasure garden in Richmond into a botanical garden.5 Prominent naturalist Sir Joseph Banks soon became Kew’s unofficial director, beginning his affiliation with the gardens in 1868 when he sent back seeds collected on his voyage to the south Pacific alongside Captain Cook.6 Kew rapidly became important in the growing field of botany, establishing itself within a network of botanical gardens collecting and studying plants necessary to empire. Banks was a key figure linking botany to imperialism: as Richard Drayton makes the case in his book Nature’s Government, Banks saw

4. Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (London, UK: John Murray, 2021).

5. Ray Desmond, The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (London: Kew Publishing, 2007).

6. Drayton, Nature’s Government.

Figure 3. Rocque, J. 1754. An exact plan of the Royal Palace Gardens and Park at

7. Drayton, Nature’s Government.

8. Ibid, p. 98.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid, p. 172.

11. “Our Collections,” Kew, accessed October 1, 2023, https://www. kew.org/science/ collections-andresources/collections.

the expansion of botanical knowledge and agricultural production as vital to the ‘improvement of the world,’ part of the colonial ‘civilising mission’ and both a moral and an economic imperative.7

With Banks’ death in 1820, however, Kew fell into unstable times, and the gardens lay stagnant. Finally, in 1841, Kew was transferred from the Crown to the government, opened to the public, and placed in the hands of botanist William Hooker.8 Between 1841 and 1873, Hooker and his son, Joseph, transformed Kew into not only a participant in but an active driver of the British imperial project.9 Kew became imperial within a complex chain of realities that saw the emergence of scientific professionals as integral to colonial expansion.10 Kew’s archives, then, were key to the advancement of botanical science, concretising the garden as fundamental to the functioning of the British Empire.

Kew’s Archives as Agents of Deterritorialisation

As a collection of living plants, a botanical garden can itself be thought of as an archive. Within Kew’s ‘living collections’—the 300-acre garden—are a series of nested archives. Kew currently holds eleven collections, including a fungarium, illustrations collection, library, DNA and tissue bank, and microscope slide collection, as well as its formal documentary archive.11 Each archive orders plants in a specific way, together recording, storing, and coproducing botanical knowledge. The evolution of Kew’s archives thus mirrors the development of scientific botany.

Botanical archives grew from different—but interlinked—modes of recording, representing, displaying, and preserving nature. As Kew’s role in the British colonial project expanded, so too did its need to enlarge its collections beyond displays of living plants. Live plants, though important for botanical study, were difficult to transport and grow, and held limited capacities toward the advancement of the rapidly expanding discipline of botany. The dried plant specimen and the botanical illustration, alongside the live plant, formed a triad of botanical knowledge, allowing botanists to comprehend different aspects of the plant.

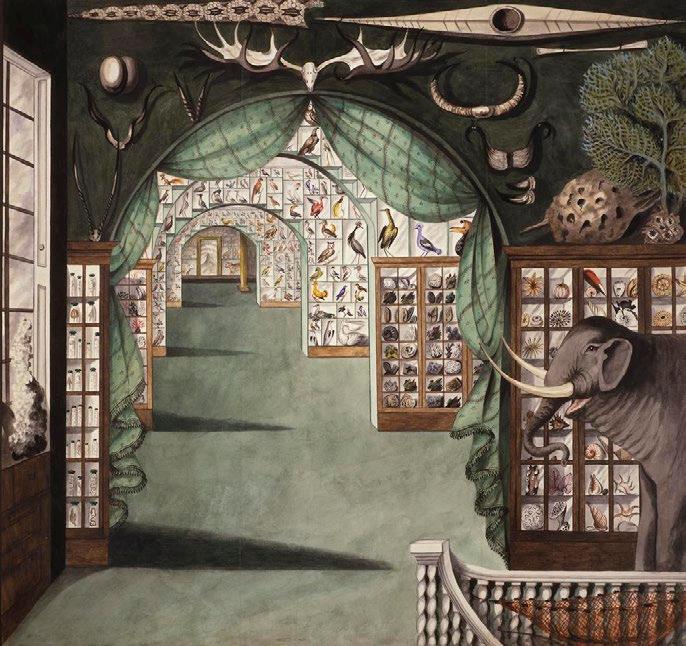

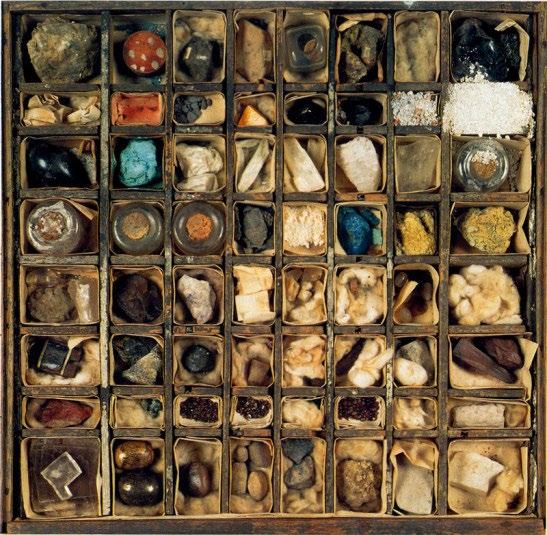

Early botanical archives emerged from the tradition of the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of

Figure 4. Hevea seedlings ready to be planted. Photograph by the author from Kew Archives, 2022.

curiosities, made popular in 16th and 17th century Europe. Notable Irish naturalist Hans Sloane’s collection of ‘Vegetable Substances’ is a clear example of a botanical Wunderkammer, a testament to European nations’ growing interest in obtaining control over plants to power colonial conquests.

Botanical colonialism is a territorial project, premised on the definition of mappable regions of land to be annexed or controlled for the creation of plantations, where plantations became both means of financing empire and of controlling colonial subjects. The botanical archive, which can be defined as any collection concerned with the classification, conservation, and storage of plants and plant-related matter, is an agent of deterritorialisation: the stripping of plants of situated ecological entanglements and their subsequent placement within contexts previously unfamiliar to them. In defining deterritorialisation, Deleuze and Guattari used the term ‘territory’ to imply a social relation;12 here, I take the term to mean both the physical territory, as a region of demarcated land, as well as epistemic territory, as the demarcation of the limits of a certain knowledge system.

12. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983).

The botanical archive constitutes a new territory, becoming a testing ground for the colonial imaginary. Borrowing from the American land artist Robert Smithson, the space between deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation can be named as the non-site.13 The non-site, belonging to nowhere, is the antithesis of emplacement. The archive as a non-site preserves and constructs ‘nature’ in the image of the plantation, the ultimate deterritorialized landscape. When a plant is deterritorialized into the archive, it becomes property: measurable, ownable, tradeable, and replicable. Deterritorialisation is thus a technology of mastery, a way of abstracting plant from place so as to assert control over it.

Deleuze and Guattari differentiate between absolute and relative deterritorialisation, where absolute deterritorialisation renders reterritorialisation impossible. Botanical colonialism is a form of absolute deterritorialisation, for it fundamentally destabilised ecological and social systems in its terraforming project, in large part through the formation of plantation systems. The non-site archive became a testing ground for the colonial imaginary, creating the conditions of possibility under which plantation worlds could emerge.

13. J. Flam, Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings (Berkeley: University Of California Press, 1996).

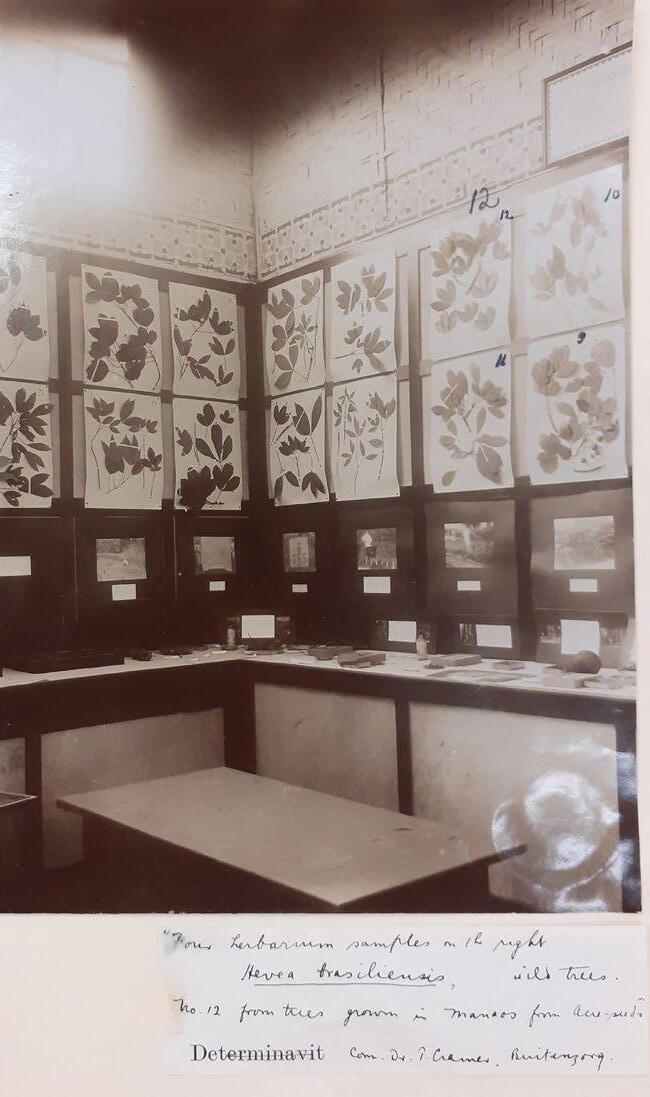

Figure 5. Inside a Museum of Economic Botany at Kew. Photograph by the author from Kew Archives, 2022.

13. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion

14. Ibid.

15. Donna Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin,” Environmental Humanities 6, no. 1 (May 1, 2015): 159–65, https://doi. org/10.1215/220119193615934 and Maan Barua, “Plantationocene: A Vegetal Geography,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113, no. 1 (August 25, 2022): 13–29, https://doi.org/1 0.1080/24694452.20 22.2094326.

Plantation as Territory and Epistemology

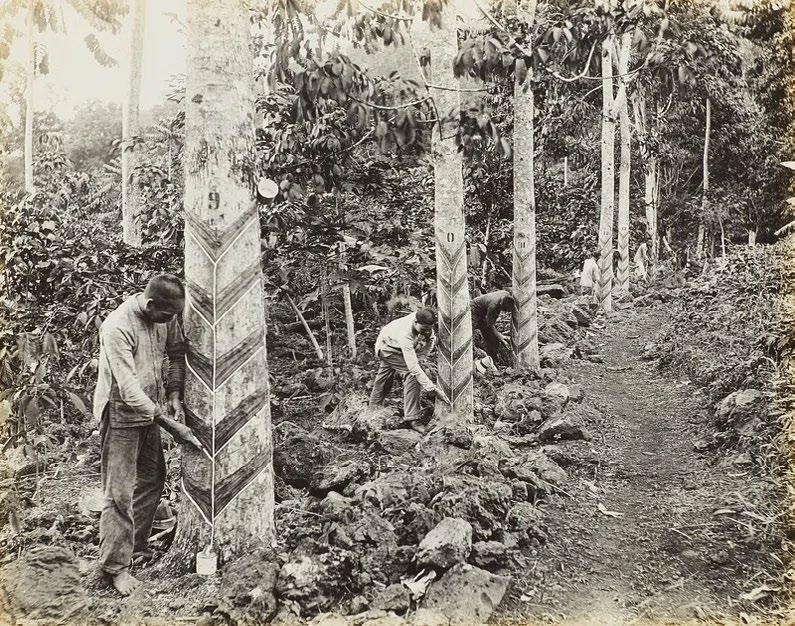

The rubber tree’s story begins to reveal the complex global operation of the plantation industrial complex: the terraforming of entire landscapes into sites of production, dedicated to the propagation and extraction of single crops. With Hevea’s introduction to Ceylon and British Malay, the tree was mechanised as a productive unit for the extraction of latex. By the early 20th century, hundreds of thousands of acres of Hevea plantations spread across Britain’s Asian colonies, soon followed suit by other European empires.13 The plantation economy was socially and ecologically brutal, requiring the labourpower of indebted workers from China and India,14 and devastating ecologies by replacing complex ecosystems with identical crops planted millions of times over.

The plantation has played no small role in deterritorialising the Earth. It is a project of terraforming, of shaping the world into a globally functioning machine.15 In his 1986 book EcologicalImperialism, Alfred W. Crosby argues that European colonisation was a project of transforming land into neoEuropes.16 This required the large-scale transfer of organisms—people, plants, animals, and microbial life—to the colonies, reminding us that “colonialism is a multi-species process.”17

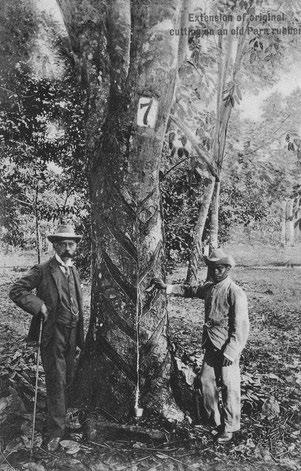

Figure 6. Henry Ridley, director of the Singapore Botanical Gardens, by a rubber tree scarred from tapping. Wycherley, P.R. (1959). “The Singapore Botanic Gardens and Rubber in Malaya” (PDF). Gardens Bulletin, Singapore. 17: 175–186.

With its focus on the vegetal realm, this thesis employs the term ‘Plantationocene’18 as an alternative to the human-centric term Anthropocene to frame a discussion of botanical colonialism’s role in creating the current socio-geologic era. The plantation, with its vast enclosed monocrops reliant on the labour of exploited or enslaved peoples, is landscape as factory. It is the site of multi-species displacement, where hyper-commodities are forced to interrelate, causing friction.19 A violent phenomenon, it represents the ultimate vision of human control over nature which Haraway deems “radically incompatible” with “the capacity to love and care for place.”20 Kew’s botanical archives were instrumental in the formation of the Plantationocene, where the collection, classification and distribution of ‘useful’ plants, and knowledge about them, informed the design of colonial plantation landscapes.

Though plantations attempt to create fixed, uniform environments to maximise efficiency and profit, they are incredibly fragile. Monocultures lack the resiliency of complex ecosystems. In reducing

16. Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

17. Chayne, “Catriona Sandilands: Botanical colonialism and biocultural histories.”

18. Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene.”

19. Gregg Mitman, “Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing Reflect on the Plantationocene,” Edge Effects, October 12, 2019, https:// edgeeffects.net/ haraway-tsingplantationocene/.

20. Ibid.

Figure 7 (above). Rubber tappers at work. From the album: Samoa (circa 1918) by Alfred James Tattersall, https://www.rawpixel. com/image/13029883/ photo-image-jungle-adult-album.

Figure 8 (below). Rubber plantation in Cambodia, 2019, https://socfin.com/en/ aerial-view-of-our-rubber-plantation-at-coviphama-cambodia/.

21. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion

22. Ibid.

23. Helen Anne Curry, “Gene Banks, Seed Libraries, and Vegetable Sanctuaries: The Cultivation and Conservation of Heritage Vegetables in Britain, 1970–1985,” Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 41, no. 2 (November 26, 2019): 87–96, https://doi.org/10.1111/ cuag.12239.

24. Marìa Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” Hypatia 25, no. 4 (2010): 742–59, https://doi. org/10.1111/j.15272001.2010.01137.x; Gayatri Spivak, “Can the subaltern speak?” Marxism and the interpretation of culture (1988): 271313.

25. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London, UK: Zed, 2021), p.68.

plants to commodified specimens, they are made vulnerable, particularly to epidemics and climactic changes. Hevea offers an example of the plantation’s precarity. As rubber became vital to the automotive revolution, Henry Ford attempted to construct ‘Fordlandia’, a massive plantation complex in Brazil in the 1920s.21 However, as Brazilian authorities were well aware, rubber plantations in the Amazon were destined to fail, falling subject to fungal infections. Ford’s hubris gave way to the forest’s ecological forces, and Fordlandia was abandoned in 1934.22

Given the difficulty of establishing plantation agriculture, the botanical archive emerged as an important site to research and test plantation crops, striving to identify the perfect type-specimen resilient to disease and changing climates. The cold-store seed bank, for instance, was initially designed to facilitate the reproduction of crops for easy propagation in monocultures; only later was it adopted as a site of biodiversity conservation.23

This thesis argues that the plantation is not simply territorial: it is an epistemic question. Just as diverse landscapes were razed to allow for the repetitive planting of a single species, the plantation mindset required the de-valuing and erasure of non-rationalist epistemologies and the propagation of a singular mode of thinking about—and relating to—plants. The plantation mindset epitomises the human-nature or nature-culture dichotomy that emerged from Enlightenment rationalism, where humans were seen as superior to wild, untamed ‘nature.’

It is important to note that ‘humanity’ only referred to European men, while women, people of colour, and Indigenous peoples were designated part of irrational ‘nature.’ The coloniality of gender and the persistent Othering of colonial subjects has been examined by scholars such as Maria Lugones and Gayatri Spivak in their decolonial feminist analyses.24 In understanding ‘nature’ as both gendered and Othered through imperial epistemologies, the thesis aims to include plant life as central to decolonial discourse. The role of Cartesian dualism within the colonial project cannot be underestimated, and thinking through the nature-culture dichotomy informs the following analysis of Kew’s archives. Botanical archives construct ‘nature’ as an entity and force external to human society; through their spatial organisation, they both order and assert control over ‘nature.’

The Epistemic Violence of the Archive

This thesis is concerned with the role of botanical epistemology within the British Empire, where, as Linda Tuhiwai Smith notes, “The production of knowledge, new knowledge and transformed ‘old’ knowledge, ideas about the nature of knowledge and the validity of specific forms of knowledge, became as much commodities of colonial exploitation as other natural resources.”25

The thesis frames Kew’s botanical archives, in their collection, curation, and dissemination of botanical knowledge within the British imperial project, as sites of epistemic violence, constructing imaginaries of ‘nature’ shaped by mastery. What, however, constitutes epistemic violence? Within the context of botanical archives, I conceive of epistemic violence as auniversalising knowledgesystempredicatedonmastery,Othering,andreplicability. I build on Julietta Singh’s conceptualisation of mastery as a force that “relentlessly reaches toward the indiscriminate control over something—whether human or inhuman, animate or inanimate”26 and Gayatri Spivak’s conjuring of epistemic violence as “the remotely orchestrated, far-flung, and heterogeneous project to constitute the colonial subject as Other.’”27 As built expressions of a totalising classification system—the Linnaean system—any way of knowing or being-with plants that are absent from the archive constitutes an Other. Thus, I position the botanical archive as a spatial system of Othering and mastering ‘nature.’

The thesis further argues that the specific epistemic violence of Kew’s archives is inextricable from the violence of the plantation. In attempting to measure, order, classify, and commodify plants as replicable units, the totalising epistemology of the plantation is rooted in a desire for control. Kew’s archives, too, ultimately seek the ability to replicate, through the type specimen in the herbarium; the standardised product in the EBC; and the seed-copy in the MSB. Though replicability in itself does not constitute epistemic violence, the process of constructing a universal type denies and destructs other ways of knowing and being. Violence lies in epistemic supremacy, of asserting one way of knowing plants as the only way.

In following Kew’s history into the present day, the thesis views epistemic imperialism as an ongoing process, where the institution’s shift to conservationism continues to replicate archival epistemic violence. In analysing how each collection adapted and transformed over time, I argue that neoliberal conservation regimes that do not challenge the nature-culture dichotomy remain beholden to the Plantationocene.

The Spatial Construction of Botanical Knowledge

Spatial analysis has been largely neglected in discussions of botanical colonialism, yet the enclosure of space to both create order and control climates was fundamental to imperial expansion. The colonisation of land was also a colonisation of climate: the ability to meticulously measure, regulate, and recreate climactic conditions to control the propagation of plants. While the top-down map of the world allowed climates to be charted and compared, the enclosure of space created microclimates that fostered the controlled conditions under which plants could be known and measured.

26. Julietta Singh, Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), p.10.

27. Spivak, “Can the subaltern speak?”

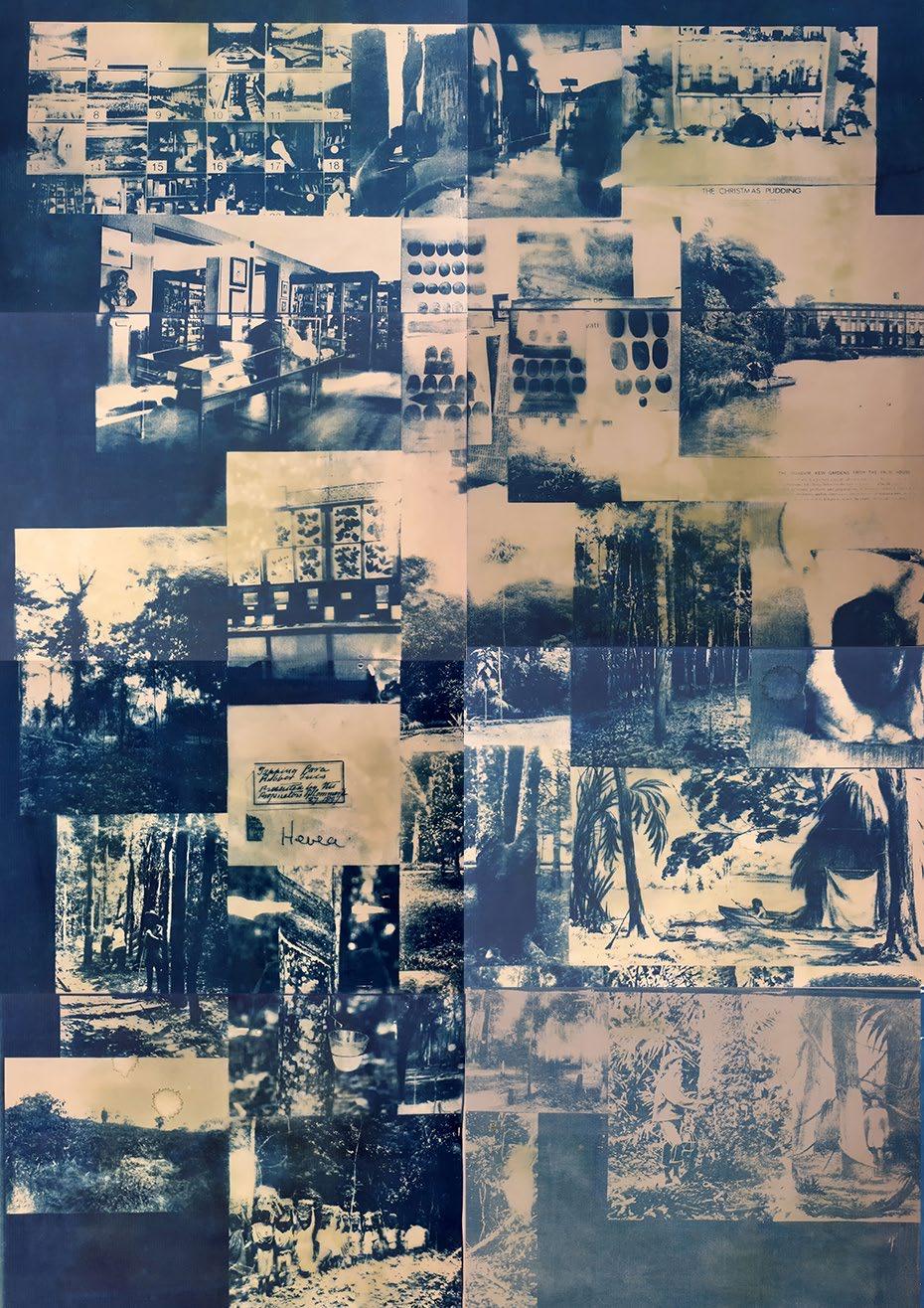

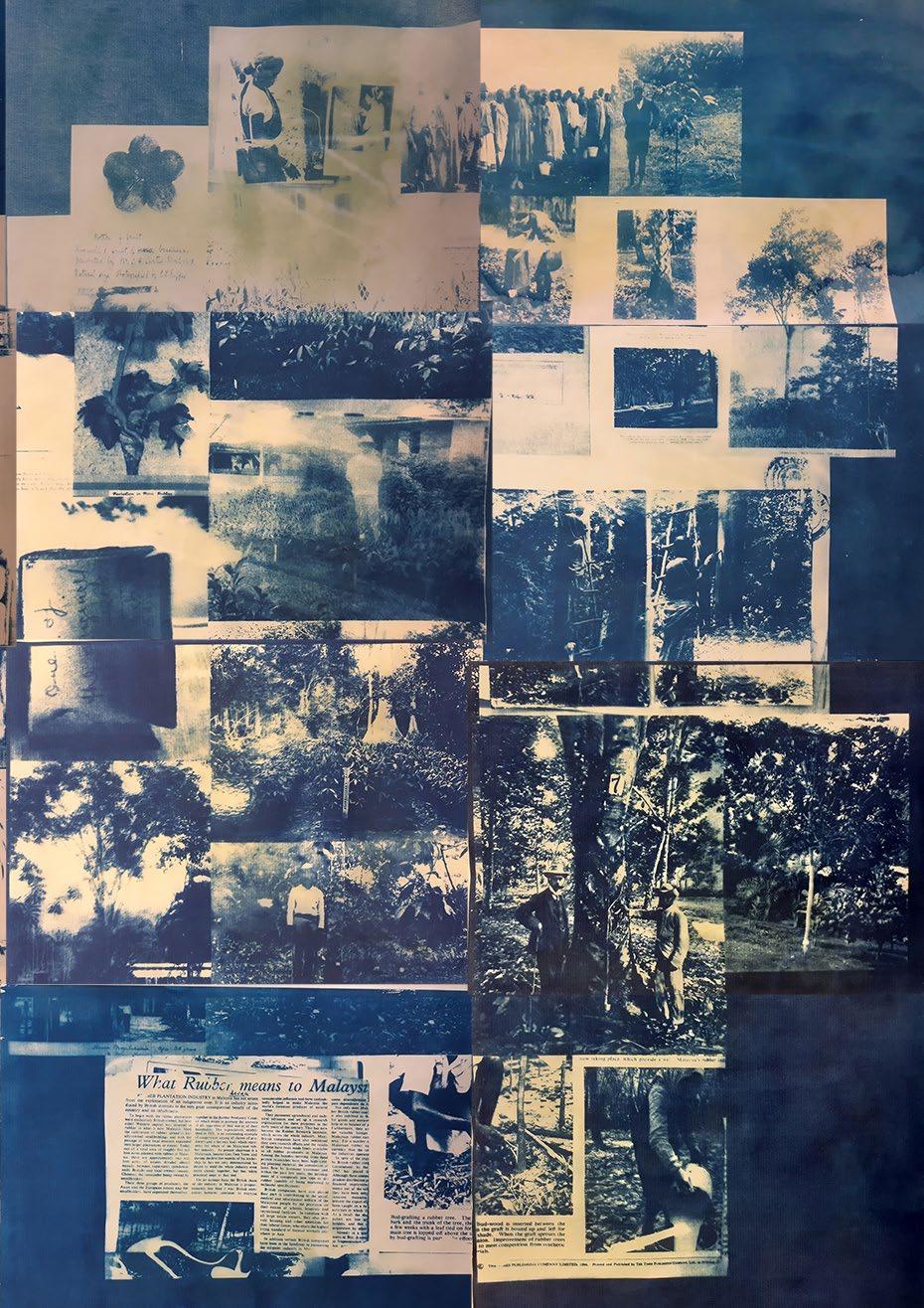

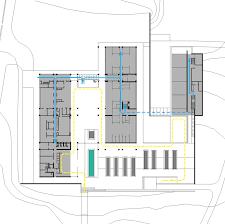

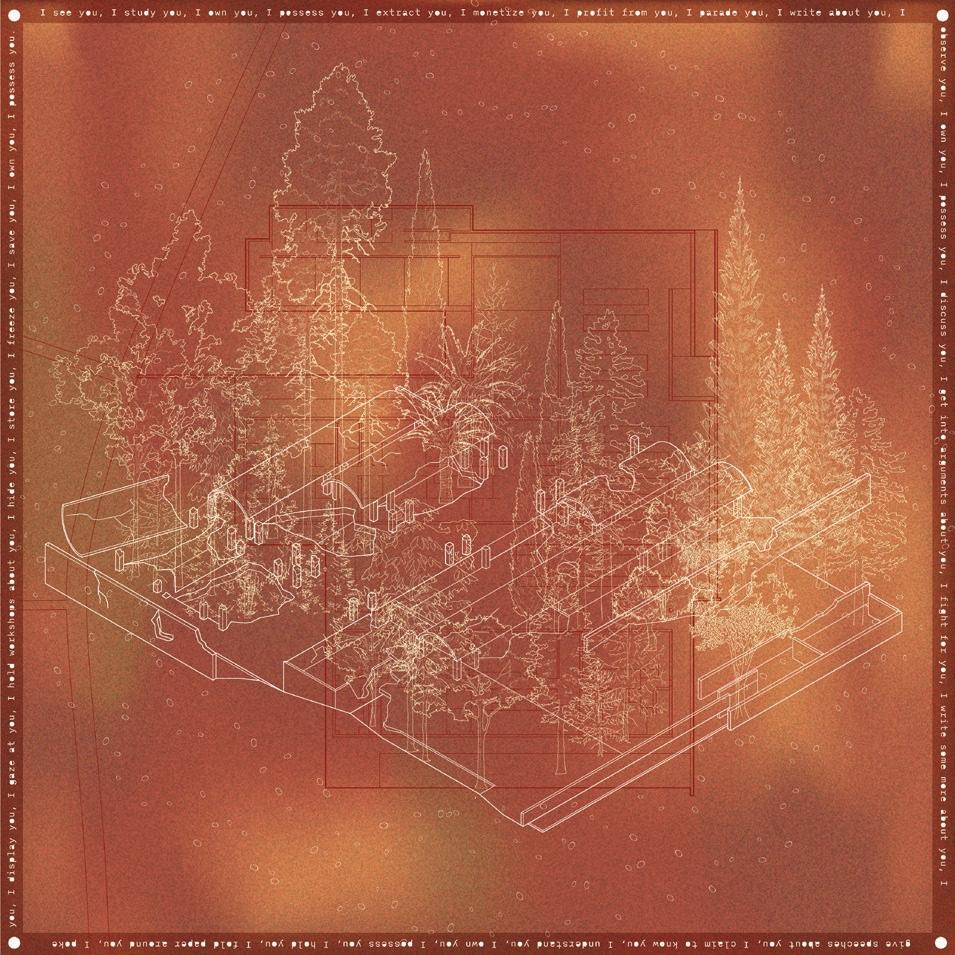

>> Following spread: Figure 10. Drawing depicting the disparate spatial fragments connected by Hevea’s journey. By the author, 2022.

The Wardian case and the glasshouse are two prominent climactic architectures that, in enclosing space with glass, created tropical microclimates. Yet Kew’s non-living collections are also climactic enclosures: even the Herbarium requires a stable temperature to prevent the decay of dried plants glued to paper. In fact, all archival spaces—whether containing living plants, seeds, illustrations, paper records, herbarium sheets, or plantbased products—required regulated climates to preserved archival matter. The thesis argues that controlling and reproducing climates within botanical archives was essential to the development of a universalising epistemology.

Spatial analysis is also useful in understanding botanical colonialism— and the imperial project at large—in terms of networks rather than isolated instances. The spread of botanical knowledge, such as the use of a standardised taxonomical system, required the reproduction of botanical archives. Botanical garden outposts in the British colonies were essential testing grounds for the introduction of plants, particularly those destined for plantations. The more important garden outposts, often directed by Kewtrained botanists, held herbaria, glasshouses, and even economic botany collections. This archival network—with the gardens themselves archives of living plants—transmitted both plants and knowledge through a process of constant exchange that complicates the notion of Kew as a centre directing colonial peripheries. Botanical knowledge was created multi-directionally, often involving the selective appropriation of Indigenous knowledge while simultaneously discrediting and erasing it.

The following sections will examine the co-production of space and knowledge within three key archives—the Herbarium, the Economic Botany Collections, and the Millennium Seed Bank—reading these collections as a cross-section of Kew’s history from imperialism to conservationism.

Figure 9. A horticulturalist packing a Wardian case. Wardian Case: Botany Game Changer, December 6, 2019, RBG Kew, https://www. kew.org/read-andwatch/how-wardiancase-changed-botanical-world.

28. Diane Bridson and Leonard Forman, The Herbarium Handbook (Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens, 2013), p.3.

29. Ibid.

30. Drayton, Nature’s Government.

31. Bridson and Forman, The Herbarium Handbook, p. 4.

32. Staffan MüllerWille, “Linnaeus’ Herbarium Cabinet: A Piece of Furniture and Its Function,” Endeavour 30, no. 2 (June 2006): 60–64, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.

33. “Linnaeus and Race,” The Linnean Society, accessed April 14, 2024, https://www. linnean.org/learning/ who-was-linnaeus/linnaeus-and-race.

34. Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality,” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (March 2007): 168–78.

35. Cedric J. Robinson et al., Cedric J. Robinson: On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance (London: Pluto Press, 2019).

Herbarium: Ordering ‘Nature,’ Spatialising Taxonomy

The first botanical archive was perhaps the herbarium: a collection dried plant specimens that creates, orders, and encloses taxonomical knowledge. If taxonomy is “the frame or base by means of which all other plant data can be related,”28 then the herbarium is the physical structure for this frame. Taxonomy underpins botanical knowledge and consists of three parts: identification, nomenclature, and classification.29 This process strips a plant from its situated entanglements, deterritorialising it into a type-specimen. The spatial configuration of the herbarium co-produces the taxonomical system, where systems of ordering space facilitate plant classification. In effect, the herbarium is a series of nested types, where the type specimen is held within an architectural typology, permitting both epistemic and spatial replicability. This chapter will provide a brief account of Kew’s herbarium, in reference to Linnaeus’s, examining how space and knowledge construct ordered ‘nature’ as a totalising system, pointing to the epistemic violence of botanical nomenclature and classification.

Classification—the governing system of the archive and the lynchpin of botanical science—is not a neutral system. It is an active process of selection by the classifier onto the classified. Botanical classification serves a purpose: to order plants for their utility to humans.30 Plants are categorised for their productive utility, as materials, medicine, food, or for ecological benefit, and for their aesthetic utility, as ornamental or curious. As Kew’s institutional priorities have shifted within the context of its herbarium, we see that the regime of utility remains much unchanged, but definitions of utility have evolved. Until the development of synthetics, plant material fed, healed, and constructed the world. With the advent of conservationism, utility morphed into monitoring and preventing biodiversity loss, yet the desire to control plants as productive and aesthetic commodities has only increased with the expansion of global capitalism.

Figure 11. Inside Kew’s Herbarium. McRob, A. 2023. Kew’s Herbarium. Available at: https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/relocating-kews-herbarium.

The Herbarium’s Origins

Originating from Italy in the 16th century and initially referred to as a ‘hortus siccus,’ or dried garden, the herbarium co-evolved alongside botanical gardens and the development of scientific botany.31 While early herbaria were bound in books, influential Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus—the father of the Linnaean classification system— organised his herbarium in loose sheets filed in a cabinet.32 As herbaria became institutionalised archives, Linnaeus’

cabinet multiplied to the scale of a building.

Linnaeus is a key figure in the history of taxonomy. His hierarchical system situated individual species within a tree of life, illuminating links between them and differences that kept them apart. Though presented as an objective, rational model, taxonomy is itself a biased projection onto the world, where classification is a means of control. In designating all living beings into distinct categories, life itself becomes compartmentalised into knowable subjects. This is exemplified in Linnaeus’s 10th edition of SystemaNaturae, where he taxonomized humans into four racial ‘varieties,’33 forming a basis for scientific racism that was imperative to the development of racial capitalism and colonial modernity, as elaborated in the work of Annibal Quihano34 and Cedric Robinson.35 His system was also gendered, categorising plants based on binary ‘male’ and ‘female’ reproductive organs inside flowers.36

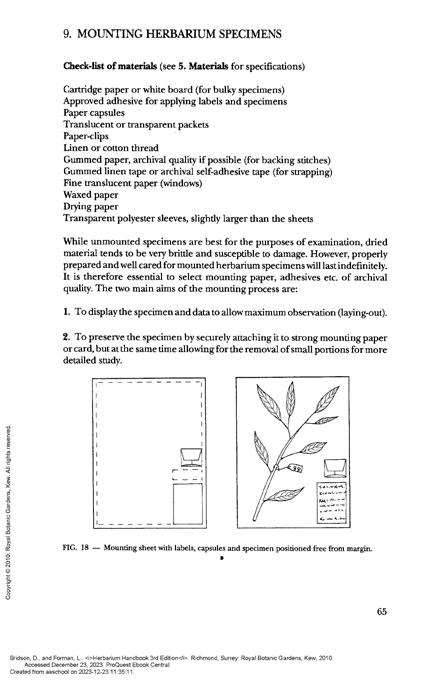

Linnaeus’s herbarium cabinet served as a prototype: he designed it to be replicable, the most effective model for his classification system.37 His PhilosophiaBotanica detailed its exact dimensions to accommodate 6000 sheets: a height of 7.5 feet, width of 16 inches, and depth of 1 foot.38 If his specific design was followed, he promised that “any plant can be pulled out and produced without delay.”39 Scientific advancement—Linnaeus’s goal— required efficiency, and efficiency necessitated standardisation.

As interest in scientific botany rapidly grew, botanists recorded and preserved specimens haphazardly. Linnaeus, frustrated with this lack of coherency, attempted to regulate the creation of herbarium sheets.40 While botanical illustrations had long existed, including in many non-western cultures, Linnaeus was adamant that herbarium sheets were “better than any picture, and necessary for every botanist”41 He described a specific process for creating a herbarium sheet, remarkably similar to current methods practiced over two centuries after his writing.42

Botanical classification generalises and orders plants as types. The most important herbarium sheets are type specimens, called holotypes: the first of their species to be categorised, acting as a reference point for future specimens.43 The standardised format of plant classification is Linnaeus’ binomial system, a two-part name including genus and species; the rubber tree is thus named ‘Hevea brasiliensis,’ while her complete classification is registered as follows:44

36. Uriel Orlow and Shela Sheikh, Theatrum Botanicum (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018), p. 231.

37. Müller-Wille, “Linnaeus’ Herbarium Cabinet.”

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid, p. 63.

40. Müller-Wille, “Linnaeus’ Herbarium Cabinet.”

41. Carl Linnaeus, Philosophia Botanica (1751), p. 18.

42. Bridson and Forman, The Herbarium Handbook.

43. “How Is the Collection Organised?,” HerbWeb - How is the Collection Organised?, accessed April 14, 2024, https://apps.kew. org/herbcat/gotoHowPlantsOrganized.do.

44. USDA plants database, accessed April 14, 2024, https://plants. usda.gov/home/classification/76316.

Figure 12. Linnaen Society of London, Linnaeus’s cabinet circa 1907.

45. Joe Jackson, The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Power, and the Seeds of Empire (New York: Penguin Books, 2009), p.22.

46. Ibid.

47. 1. Richard Evans Schultes, “The History of Taxonomic Studies in Hevea,” The Botanical Review 36, no. 3 (July 1970): 197–276, https:// doi.org/10.1007/ bf02858879, p. 199.

48. Ibid.

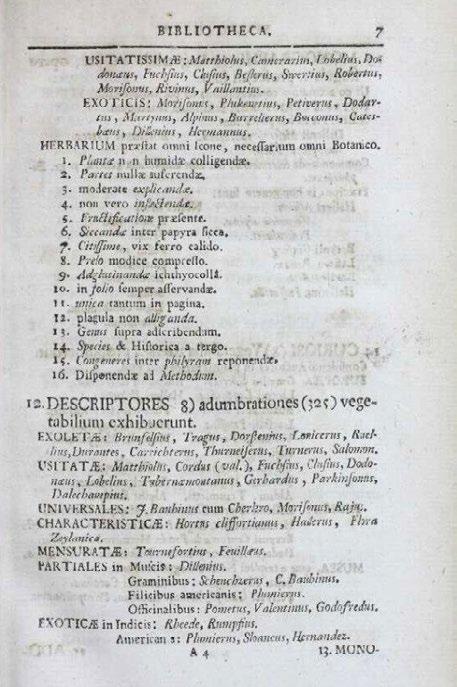

Figure 13 (left). Herbarium Handbook, Bridson and Foreman, 2013, p.65. Figure 14 (right). Philosophia Botanica, Linnaeus, 1751.

Kingdom: Plantae (Plants)

Subkingdom: Tracheobionta (Vascular plants)

Superdivision: Spermatophyta (Seed plants)

Division: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants)

Class: Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons)

Subclass: Rosidae

Order: Euphorbiales

Family: Euphorbiaceae

Genus: Hevea

Species: Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg

Classified as such, a plant is no different from a book shelved under the Dewey decimal system. The scientific classification locates the plant in space: it becomes a reference point within the constellation of taxonomy. Through this system, the rubber tree was granted a singular name, Hevea brasiliensis, the name by which no other name would be necessary.

Yet external to the archive, Hevea has a multitude of names past and present, some recorded, others erased or lost. The French name for rubber, ‘caoutchouc,’ can be traced back to the Spanish ‘cauchu,’ derived from the Indigenous name ‘cao o’chu,’ meaning ‘weeping tree’.45 Charles Marie de La Condamine, the first European to take note of Hevea while traveling in Brazil, recorded the Omaguas name for the tree’s resin as ‘cahuchu,’ while other tribes called it ‘Kaaocho,’ meaning ‘cry of the plant’.46 The Latin name itself comes from an Indigenous name in Ecuador, ‘heve’,47 with the complete binomial Hevea brasiliensis first used in 1824.48

Figure 15. Inside Kew’s original herbarium. Photograph by the author.

49. Edouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 1997, https:// doi.org/10.3998/ mpub.10257.

50. Quijano, ‘Coloniality and Modernity/ Rationality,’ p. 176.

51. Glissant, Poetics of Relation, p. 190.

52. Syed Hussain Alatas, “Intellectual Imperialism: Definition, Traits, and Problems,” Asian Journal of Social Science 28, no. 1 (2000): 23–45, https:// doi.org/10.1163/030 382400x00154, p. 24.

53. Ibid, p. 25.

54. Ibid, p. 26.

55. Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), p.194.

Naming is a powerful act. To name something is to establish a relationship with it, often one of possession. In theorist Eduard Glissant’s text TheRighttoOpacity, he links the desire to know something entirely with a desire for control.49 Total knowledge is a violent act: it requires dissection. To taxonomise a plant within the herbarium, it must first be cut, flattened, and stripped of its entanglements. Decolonial theorist Anibal Quijano expands on totality as “a product of colonial/modernity” and “a dream of the total rationalization of society.”50 Rejecting this, Glissant suggests a right to be unknown and different, “giving up this old obsession with discovering what lies at the bottom of natures.”51

The totalising system—the plantation system—requires a mastery of ‘nature,’ and mastery requires order. The taxonomical system, embodied by the herbarium, reflects a form of intellectual imperialism, defined by Syed Hussain Alatas as “the domination of one people by another in their world of thinking.”52 This variety of imperialism thrives on the extraction of knowledge as a kind of raw material, where Indigenous peoples are “used mainly as informants.”53 Appropriated knowledge is then standardised to be regulated, sold, and traded globally. Importantly, intellectual imperialism, as part of a civilising mission, “assumes the monopoly of, and dominance in, the affairs of science and wisdom.”54 Taxonomy in and of itself is not violent; it becomes violent when it is imposed as the only and superior way of understanding— and relating to—‘nature.’ The absence of Hevea’s other names within the herbarium speaks to taxonomy’s universalising system: by reducing each plant to a single name, countless other ways of knowing them are silenced.

Linnaeus had no qualms about proclaiming the superiority of western naming systems, particularly his own, stating that “The names bestowed on plants by the ancient Greeks and Romans I commend, but I shudder at the sight of most of those given by modern authorities: for these are for the most part a mere chaos of confusion.”55 The Latin standardised system indeed proved effective in ordering and governing ‘nature’, facilitating the imperial project. In effect, the Latin binomial is a form of epistemic deterritorialisation, where the plant name is dissociated from a plant’s situated agencies and relationalities. This epistemic deterritorialisation is mirrored in the nonsite territory of the herbarium. Kew’s herbarium, the largest in the world, exemplifies the need for spatial order to facilitate taxonomical order.

Kew’s

Herbarium

On a grey January day, I meet Sue at Kew’s herbarium. Trained as a taxonomist, she has worked in the building for nearly forty years; this year is her last before retirement. She guides me through the brick three-storey building. With its wrought-iron columns and wooden cabinets, Kew’s original herbarium appears to have little changed since the Victorian era. Housed

across four wings, peripheral alcoves around a central atrium are lined with white cabinets not unlike school lockers, each carefully labelled. Currently holding over seven million species, the plants—dried, pressed, and annotated— are filed neatly in the cabinets.

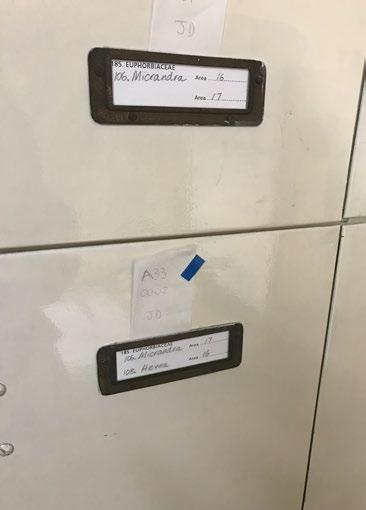

We enter a wing from the mid-20th century: this is where Euphorbiacae are held. Sue explains the building’s organisation to me. The cabinets are organised first by family, then by genus, then by geography. They are further designated as either native or cultivated; Sue notes that the cultivated category is elusive, meaning both deliberately planted crops—such as in plantations—and plants spread unintentionally, such as those growing on a roadside. The family number orders the cabinets from left to right, while the geographical number—the location where the plant was collected—dictates the vertical organisation. Within the white wooden cabinets are stacks of green archival-grade boxes, and inside the boxes are folders. These folders hold the specimens.

Red folders demarcate type specimens. Sue emphasizes their importance in “stabilising the world of plant names.” She uses the term ‘stabilise’ several more times throughout the visit. In creating a worldordering taxonomical system, stability is a means of control. An unstable condition creates unknowability. “Each plant can only have one name,” Sue says; multiple names create confusion. The type-specimen, after asserting a single name, becomes replicable, a case study to which incoming plants are matched.

From the box to the cabinet to the building’s organisation, the herbarium typology is structured by the taxonomic system. One cannot exist without the other; Sue notes that even now, taxonomic work cannot be

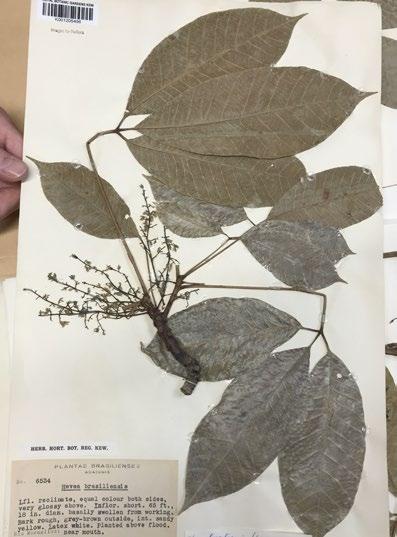

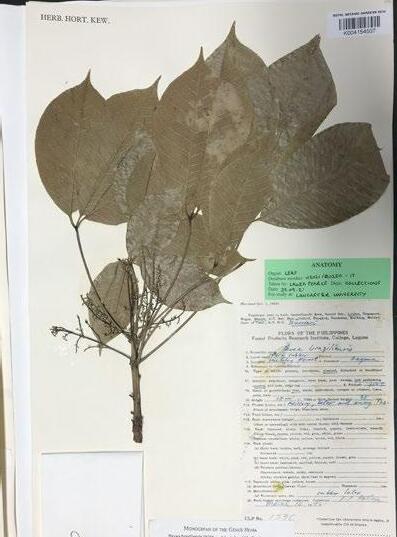

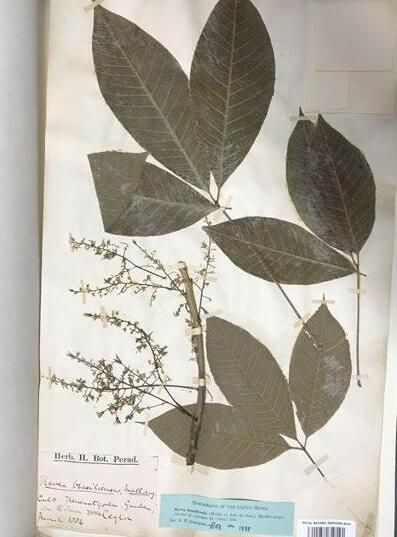

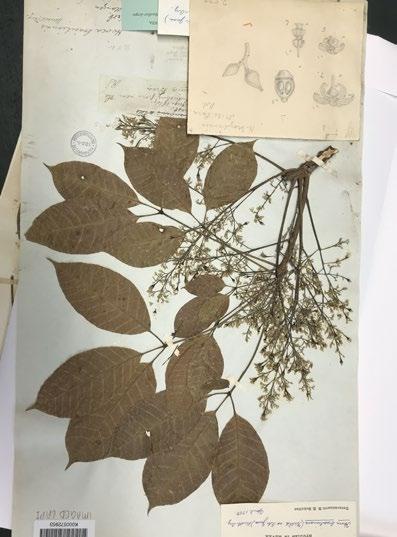

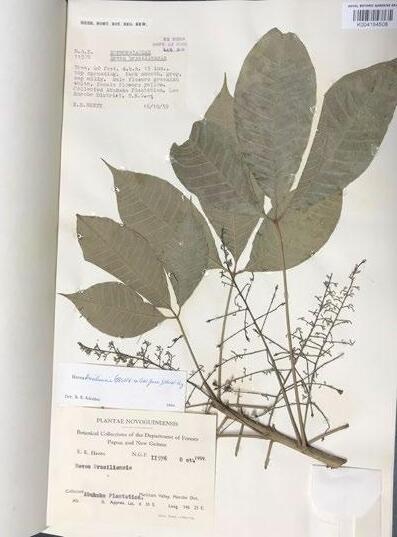

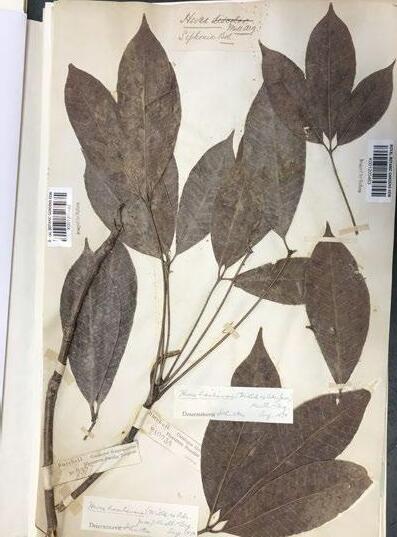

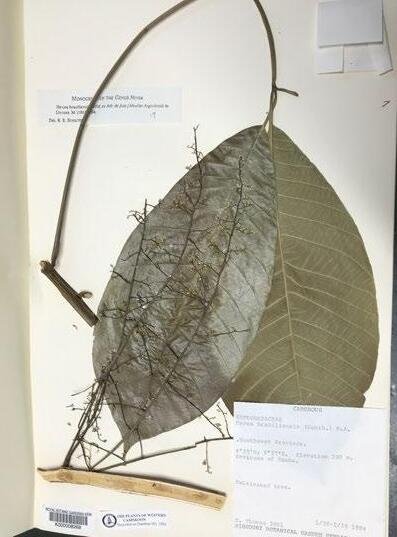

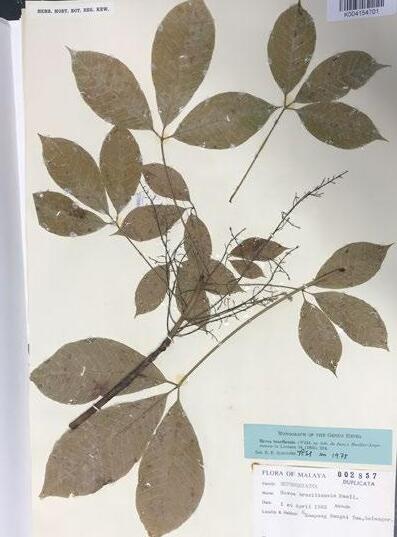

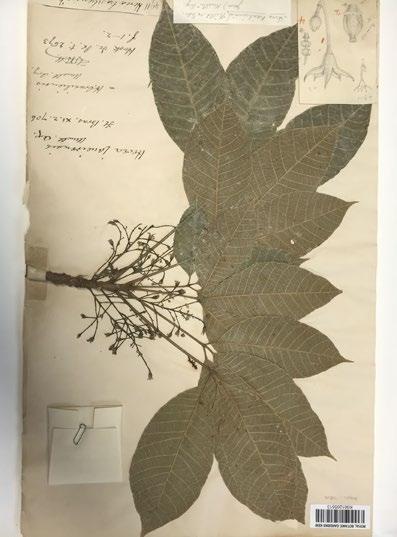

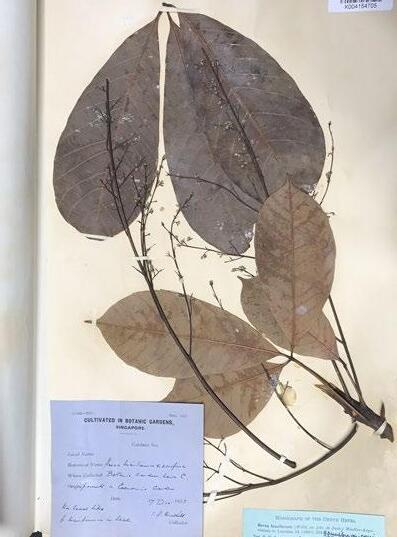

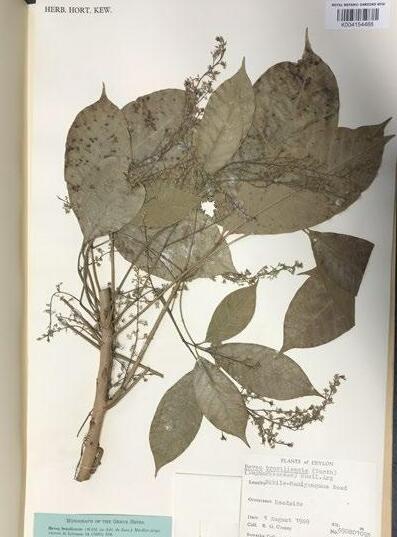

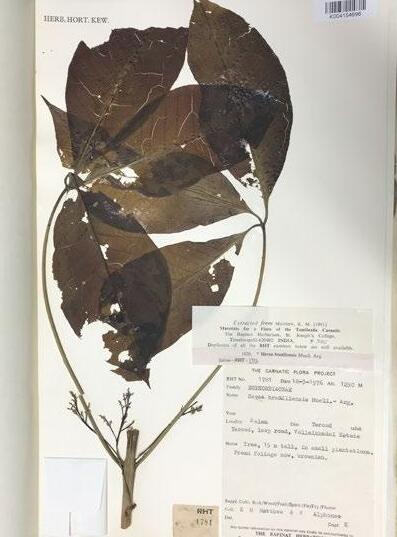

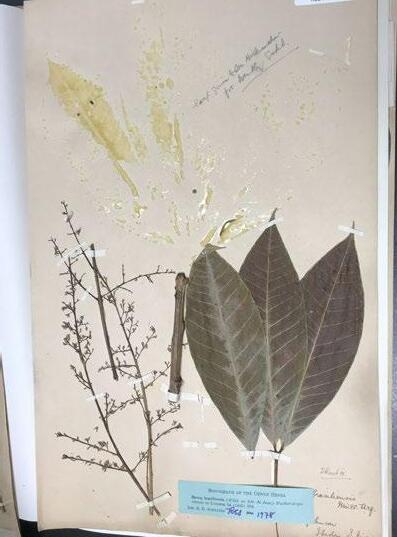

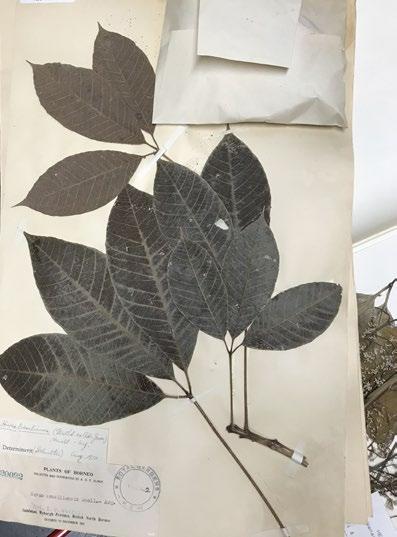

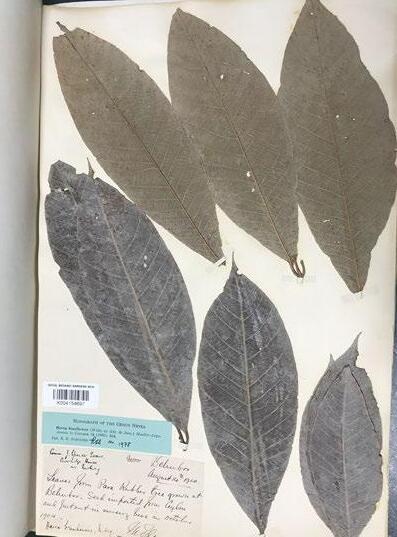

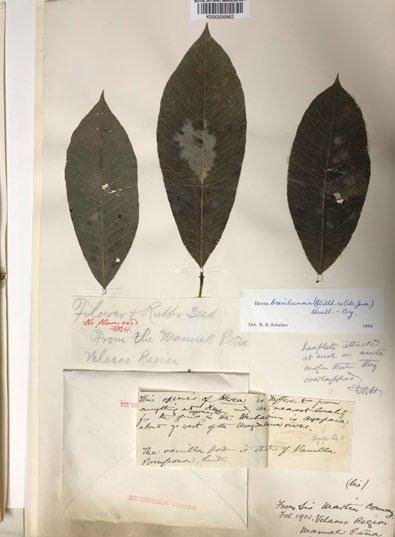

>> Following spread: Figure 19. A selection of Hevea herbarium sheets shown to me by Sue at Kew’s herbarium. Photographs by the author.

Figures 16, 17, and 18. Left to right: labels on a herbarium cabinet, folders inside a herbarium cabinet, a stack of boxes containing Hevea herbarium sheets. Photographs by the author.

Leela Keshav

56. Bridson and Forman, The Herbarium Handbook, p. 12.

57. William Milliken, “Mobilising Richard Spruce’s 19th Century Amazon Legacy,” Kew, accessed April 14, 2024, https://www. kew.org/read-andwatch/mobilising-richard-spruce-legacy.

58. Schultes, “The History of Taxonomic Studies in Hevea.”

59. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, “Occurrence Record: Herbarium:K000572953,” Record: Herbarium:K000572953 | Occurrence record | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, accessed April 14, 2024, https:// data.kew.org/records/ occurrences/ff71111d0915-4994-8312549644f85b8d.

done if herbarium facilities do not exist. This is why Kew continues to hold so many specimens: its size legitimises its importance as a collection, where more specimens mean more points of comparison, hence more accurate identifications.

Not unlike Linnaeus’ specifications, Kew’s Herbarium Handbook outlines the ideal conditions for collecting and storing herbarium sheets. While Linnaeus’ cabinets were wood, the Handbook describes metal cabinets, with “shelves which are at least 2cm. deeper and wider than the herbarium sheets and approximately 15cm. apart.”56 The continuation of herbaria methods in the present day raises the question: have imperial modes of collecting, naming, classifying, and archiving plants lingered, too? To probe this question, I will compare two herbarium sheets that reflect early and recent methods.

Specimen 1: Hevea Brasiliensis, Catalogue No. K000572953

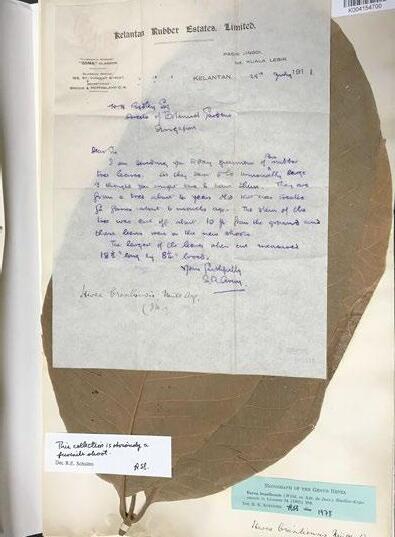

This herbarium sheet dates to August 1, 1849, an early example collected in Seringueira, Brazil, by prominent English botanist Richard Spruce (Kew, n.d.). Spruce travelled through South America from 18491864, departing just three years before Wickham’s theft. He collected over 14,000 herbarium specimens, many of them named ‘new’ species.57 American ethnobotanist Richard Evan Schultes noted that Hevea species were particularly challenging to differentiate, with eleven species recorded in 1874, fluctuating to twenty-four in 1906 and only nine in 1970.58 While the specimen remains fixed, taxonomic categorisation is under constant revision, reflected in the palimpsest of annotations on the herbarium sheet. Spruce’s tag notes that he collected this sample from a “lofty handsome tree, branching from near the base,” and it appears to be his 136th sample.59

This sheet provides three additional tags—called ‘determinavit slips’— to Spruce’s original. All three, from 1950, 1964, and 1978, were added by Schultes, making note of changes in the name or, in the case of the blue tag, an instance when Hevea was re-identified in the publication Monographof the Genus Hevea. The tags that appear most modern are current herbarium standards: a barcode with the catalogue number linking the sheet to its digitised copy, a colour grid to identify tones, and a scale bar. The clipping of Hevea is attached with small strips of tape to the paper, her leaves drained of colour.

What purpose might this herbarium sheet have served in Hevea’s journey from Brazil to colonial plantations? A single sheet is less important than the collection, where the sheets together form a body of botanical knowledge. In collecting, transporting, and shelving Hevea specimens, the herbarium asserted itself as a library of plant conquests, a collection of plants useful for the design of plantations. As herbarium samples continue

Figure 20 (above left).

Sue showing me a Hevea seed pod found in an envelope attached to herbarium sheet. Photograph by the author.

Figure 21 (above right). An opened envelope containing Hevea seeds. Photograph by the author.

Figure 22 (below). A series of boxes containing Hevea seeds and larger dried plant specimens in the herbarium. Photograph by the author.

60. Luciana Martins and Lindsey Sekulowicz, “The Herbarium as a Workshop,” TEA: The Ethnobotanical Assembly 8 (2021).

61. Schultes, “The History of Taxonomic Studies in Hevea,” p. 213.

62. “Kew Science - The Herbarium,” YouTube, July 26, 2016, https:// www.youtube.com/ watch?v=u_x15hIPgME.

63. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, “Occurrence Record: Herbarium:K001378541,” Record: Herbarium:K001378541 | Occurrence record | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, accessed April 14, 2024, https:// data.kew.org/records/ occurrences/32a3e6ce6ab9-4710-819a813e8ee6c327.

64. “About Us,” Darwin Initiative, accessed April 14, 2024, https:// www.darwininitiative. org.uk/about-us/.

65. Desmond, History of Kew, p. 350.

to accumulate into the present day, taxonomical knowledge is generated and updated, reflected in the layers of tagging. Fixity, then, is an illusion within the herbarium: mobility and revision are embodied within the sheets.60

My visit to the herbarium made visible the chaos behind the order. The totalising system only attempts to be totalising; the reality is that the herbarium is riddled with unknown plants, mistaken labels, forgotten specimens, and half-finished projects. Sue tells me that though the task of the taxonomist is to fill in gaps, delineating clear boundaries between where a species starts and ends is no easy task, exposing the illusion of quantification. This confusion is mirrored in the spatial system, where unidentified boxes are stacked in dusty corners, and misplaced folders befuddle taxonomists. Order may be designed, but the material reality manifests messier.

Taxonomical designations are often subject to heated debate; Hevea’s own naming underwent several iterations and contestations through the 19th century.61 Samples such as this one marked the ‘discovery’ of species, broadening a botanical imaginary based on the ordering of the ‘nature’ according to utility. Herbarium sheets, brought back to Kew, acted as material evidence for the existence of previously unknown species, more credible than illustrations. Currently, conservation researchers use copies of herbarium sheets in the field. In a Kew video of a fieldworker using a seed collecting guide in Mozambique, we see the journey of the plant collected, turned into an herbarium specimen, brought to Kew, digitised, then returned to its habitat as an image.62

Specimen 2: Hevea Brasiliensis, Catalogue No. K001378541

This Hevea sample was collected on May 8th, 2015, from the Tahuamanu Research Station in Bolivia.63 A small pouch in the bottom left corner contains seeds. The tag is in Spanish, noting a general description of the tree as “12m tall and 14.7cm DBH [diameter at breast height],” its specific coordinates, and its habitat, including surrounding trees. At the bottom, it reads (translated to English) “Museum of Natural History. Noel Kempff Mercado [National Park] (USZ) Royal Botanical Gardens (Kew) Financed by the Darwin Initiative of Reino Unido.” The Darwin Initiative is a UK government grant that “helps protect biodiversity, the natural environment and the local communities that live alongside it in developing countries,”64 and referred to by Desmond as a demonstration of Kew’s expertise, which “is now being tapped to assist the conservation and sustainable use of the planet’s resources.”65 Though nearly identical in format to Spruce’s sample collected 166 years earlier, this herbarium specimen shifts focus to conservation, from the funding that sponsored its collection to the information included on the sheet. For example, some emphasis is placed on surrounding plants—a feature entirely absent from Spruce’s sheet. This reflects growing scientific understanding of ecological interconnectivity, such as described in Merlin Figure 23 (opposite). Kew Herbarium Specimen No. K000572953. 1849, https://apps.kew.org/ herbcat/navigator.do

66. Smithsonian Magazine, “When Scientists ‘Discover’ What Indigenous People Have Known for Centuries,” Smithsonian.com, February 21, 2018, https:// www.smithsonianmag. com/science-nature/ why-science-takesso-long-catch-uptraditional-knowledge-180968216/.

67. “Unearthed: Journeys into the Future of Food,” Kew, accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.kew. org/about-us/virtual-kew-wakehurst/unearthed-kew-podcast.

68. Milliken, “Mobilising Richard Spruce’s 19th Century Amazon Legacy.”

69. Ibid.

70. Ibid.

71. Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso, 2019).

72. Marleen Boschen, “Carrier Seeds: A Cultural Analysis of Care and Conflict in Four Seed Banking Practices,” Carrier Seeds: A Cultural Analysis of Care and Conflict in Four Seed Banking Practices (thesis, n.d.).

73. Donna Haraway, “Encounters with Companion Species: Entangling Dogs, Baboons, Philosophers, and Biologists,” Configurations 14, no. 1 (March 2006): 97–114, https:// doi.org/10.1353/ con.0.0002.

Sheldrake’s 2020 book EntangledLife, though these entanglements were known to many Indigenous peoples long before this western scientific turn.66

It is interesting speaking to Sue; deeply knowledgeable, she is well aware of Kew’s colonial legacy. She goes as far as questioning the very task to which she has dedicated her life, saying that she sometimes wonders whether imposing a binomial system onto the plants of the world is in fact a good system, if this is an entirely artificial fabrication. Sue helps me search back through the stack of Hevea sheets for any mention of Indigenous uses. In the hundreds of sheets, we find all but one brief note. This absence perhaps speaks more than all the material present within the archive, for it is in this absence that the epistemic violence of the herbarium is made evident.

Though Kew claims to have put its imperial legacy behind, colonial terminology lingers. Terms entrenched in the human-nature dichotomy, such as ‘plant hunting,’ ‘plant explorers,’ ‘target specimens,’ and ‘natural resources’, preserve extractive human-vegetal relationality that mirrors the language of conquest.67 Without changing its imperial methods of extracting, drying, and preserving plants-as-specimens, Kew seamlessly shifted its herbarium from a library of conquest to a “resource being used to tackle the global challenges of our time,”68 namely crises of biodiversity and climate.

How does the herbarium remain relevant? According to Kew botanists like Sue, it allows for the accurate identification of plants according to the Linnaean system, providing a “wealth of information: its distribution, its uses and its ecology” which is vital to “effective conservation” and “sustainable use of natural resources.”69 The herbarium sheet, then, is “a complex piece of data,”70 forming an expanding body of scientific knowledge, preserved ex situ, and allowing for the identification of endangered species. In tracking species collection dates and locations, plant dispersion can be mapped, tracing habitat loss.

Figure 24 (opposite).

Kew Herbarium Specimen No. K001378541. 2015, https://apps.kew.org/ herbcat/navigator.do.

The herbarium sheet is analogous to a passport, registering an incoming plant as a botanical citizen-subject. The western imperial archive is integral to the creation of nation-state identities,71 but it also constructs nature-culture relationships based on mastery, commodification, and extraction. The intersection of the two is what Marleen Boschen72 calls national natures, a useful term in considering the botanical archive’s role in the British imperial project, as well as its position within British conservation efforts. Though herbarium sheets may well inform researchers of endangered species, many ways of becoming-with73 Hevea are unknowable to the herbarium. In stripping a plant of plural names for the singular binomial, it is deterritorialised from specific places and histories. Perhaps it is time to move beyond the standard name to the pluriversal narrative, for unarchived names hold stories and complex meanings that cannot be held within the deterritorialised space of the archive.

74. Mark Nesbitt and Caroline Cornish, “Seeds of Industry and Empire: Economic Botany Collections between Nature and Culture,” Journal of Museum Ethnography, May 31, 2019, https://www.academia.edu/25767383/ Seeds_of_industry_and_empire_economic_botany_collections_between_nature_ and_culture, p. 56.

75. Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life (London: Verso, 2015), p. 298.

76. Schiebinger, Plants and Empire, p.11.

77. Drayton, Nature’s Government.

Economic Botany Collections: ‘Nature’ Commodified

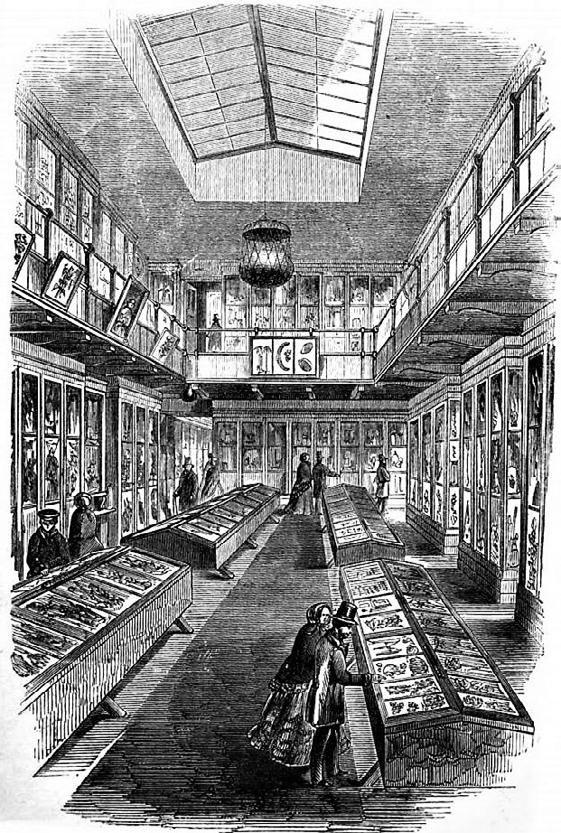

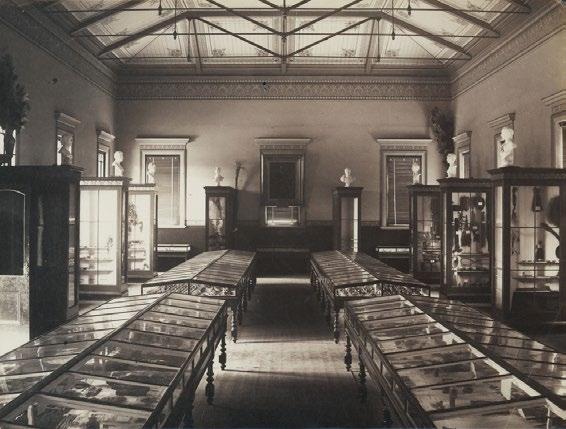

As seen in the herbarium, the development of natural science was integral to colonial modernity. This section will discuss the botanical archive’s role within a political economy predicated on extractivism. Kew’s Economic Botany Collections (EBC) reveal the prioritisation of useful ‘nature’ as a constant throughout the institution’s history. Economic botany renders ‘nature’ a resource, muting and devaluing plant-human relationships not beneficial to extractive commodification. Complicating the clear separation of culture and ‘nature’ seen in the herbarium, the EBC positions nature-for or nature-into culture, “in which both nature and culture [form] part of a single plant-based continuum.”74 This hybrid nature emerged through the commodification of plants as useful products, set apart from ‘wild’ plants in their domestication and transformation into manufactured goods. Developing conceptions of property, such as those propounded by John Locke, were fundamental to the idea of ‘owning’ nature, where plants themselves became property upon entering the institutional gates of the archive.

As a vast collection of plant-based products, the EBC makes explicit Jason W. Moore’s definition of capitalism as “a way of organising nature.”75 I argue that when plants are rendered commodities—products that can be traded, bought, replicated, and sold within a capitalist economy—they are stripped of relational ontologies, constituting another form of archival violence. Unlike the herbarium’s internalised ordering system, the imperialera EBC was public-facing, with museums designed to trumpet Kew’s role in the improvement of the world. The spatial organisation of Kew’s Museums of Economic Botany, from the sequence of rooms to the modes of display, constructed for the public eye a sequential, progress-oriented imaginary—a plantation imaginary—of plants as profitable products. Here, commodification became a way of knowing plants, another totalising epistemology coconstructed by Kew’s archives.

Economic botany—the practice of identifying, collecting, and growing profitable plants—emerged as Kew’s priority under the Hookers’ purview (Drayton, 2007). On colonial expeditions, plants with material, medicinal, and food uses were identified as important to Empire. Botanists, acting as ‘agents of empire’,76 flagged these species as important to control and maintain access to, informing key plant transfers across botanical garden networks. By directing its capabilities toward economic botany, Kew played a considerable role in financing Empire.

Kew opened four Museums of Economic Botany in the 19th century, exhibiting their plant-based conquests from across the colonies.77 In the tradition of the World’s Exhibitions, the museums displayed plant matter to astonish and amuse—and from which to profit. Desmond writes, “Hooker saw the Museum (…) as complementing the living collections in the Gardens

Figure 25. Categorising life in a natural history museum’s grid. Stone, S. 1835. Interior of Leverian Museum; view as it appeared in the 1780s, https:// www.britishmuseum. org/collection/ object/E_Am2006Drg-54.

Figure 26. Hans Sloane’s Vegetable Substances collection, https:// maceramicrrbarwell. wordpress. com/2016/02/15/ sir-hanssloane-1660-1753/.

78. Desmond, History of Kew, p. 191.

79. Caroline Cornish, “Nineteenth-Century Museums and the Shaping of Disciplines: Potentialities and Limitations at Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany,” Museum History Journal 8, no. 1 (January 2015): 8–27, https://doi.org /10.1179/193698161 4z.00000000042, p. 9.

80. Drayton, Nature’s Government, p. 196.

81. Caoutchouc and Gutta Percha (London: Printed for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1852), p.1.

82. Ibid, p. 14.

by exhibiting examples of products derived from them,”78 exemplifying the way in which Kew’s archives co-constructed the concept of ‘nature’ as a commodified resource. While the herbarium organised type specimens and the gardens exhibited the physical and temporal properties of living plants, the Museums of Economic Botany directly linked plants to utility in agriculture, pharmacy, craft, and manufacturing, among other purposes, facilitated in large part by the design of the museum exhibitions: “The display, with its botanical specimens accompanied by textual inscriptions, illustrations, and ethnographic artefacts, furnished the botanist, the grower, the importer, the retailer, and the general public with the botanical, geographical, commercial, and cultural knowledge necessary to translate a hitherto unknown South American shrub into an imperial opportunity.”79 By linking plant, image, and text in a particular sequence, the visitor was guided toward a particular understanding of plants—an epistemology of commodification.

Economic botany extended beyond utilitarianism: it was closely tied to religion. According to Drayton, Victorian ‘natural theology’ instilled a sense that “plants, animals, and everything in nature, had been placed there by God for the use or instruction of human beings.”80 Kew’s museums, then, were akin to temples of the God-given right for humans to make use of plant life. The 1852 book CaoutchoucandGuttaPercha, published by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, singled out rubber’s utility as a sign of God’s good will toward humanity. The book opens by stating “The vegetable world provides us with a few instances of products so important to Mankind, whether in a state of civilisation or otherwise, as to impress the strongest conviction that they were directly created for his use.”81 Describing rubber, it details La Condamine’s ‘discovery’ of rubber’s utility in his observations of Indigenous practices, where it “gave promise of becoming one of the most useful and valuable substances.”82

Figure 27. Map showing the locations of the four Museums of Economic Botany. Found in Nesbitt, M. and Cornish, C. (2016) ‘Seeds of Industry and Empire: Economic Botany Collections Between Nature and Culture’, Journal of Museum Ethnography, (29), pp. 53–70.

Thus, the moral imperative of economic botany was part of the imperial civilising mission, and economic growth—requiring the increased extraction and production of the plant in question—was a ‘natural’ consequence of civilised progress. Conceived of as a ‘white man’s burden,’83 the civilising mission of economic botany had a duty “in making its knowledge available to ‘all the world,’” where Kew

Figure 28 (left). Kew’s Museum No. 1. Museum: Interior of the Principal Room, from Sir William Hooker’s ‘Museum of Historic Botany,’ 1885, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Museum_of_Economic_Botany,_Kew_%281855%29.jpg.

Figure 29 (above right). Santos Museum of Economic Botany, Adelaide. Opening of the Museum of Economic Botany, 1881, https:// sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/places/museum-of-economic-botany.

Figure 30 (below right). Kolkata Economic Botany Gallery, https://indianmuseumkolkata.org/gallery/botanical-gallery/.

“took a stand against ‘the aggressions and intolerance of all sorts of selfish mystification and humbug.’”84 The Museums adopted the role of displaying the growing economic botany collections, a theatrical declaration of Kew’s importance on the international stage where “visitors might discover their nation’s place and purpose, at the centre of the world.”85

For Kew took its role in the colonial project seriously: William Thistleton-Dyer, Kew’s third director from 1885 to 1905, declared to the Governor of Madras, “We at Kew feel individually the weight of the Empire as a whole, more than they do in Downing Street.”86 Though Kew felt that it was doing the world a service by publicising the rubber tree’s useful properties, control over and access to the plant itself were firmly safeguarded in imperial control and guarded by scientific experts.

Kew’s Economic Botany Collections have grown and shifted into and out of public view. Four museums opened between 1846 and 1910, at the peak of imperial economic botany. The first two museums were organised

83. “The White Man’s Burden,” The Kipling Society, April 7, 2024, https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poem/ poems_burden.htm.

84. Cornish, “Nineteenth-Century Museums,” p. 9.

85. Drayton, Nature’s Government, p. 196.

86. Desmond, History of Kew.

87. Cornish, “Nineteenth-Century Museums,” p. 11.

88. Ibid.

89. Desmond, History of Kew, p. 193.

90. Nesbitt and Cornish, “Seeds of Industry and Empire,” p. 282-3.

91. “The Botanical Gallery in the Indian Museum.,” The Free Library, accessed April 14, 2024, https:// www.thefreelibrary. com/The+Botanical+Gallery+in+the+Indian+Museum.-a0571836882.

92. Alexander Parsons, “SA History Bank,” Museum of Economic Botany | SA History Hub, January 1, 1876, https://sahistoryhub. history.sa.gov.au/ places/museum-of-economic-botany#:~:text=Opening%20 in%201881%20in%20 the,ensured%20a%20 wealth%20of%20content.

93. Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, p. 71.

taxonomically; walking through them “in the prescribed order was in effect to perform the ‘natural’ system of Swiss botanist Augustin Pyrame de Candolle.”87 As the collections grew, Hooker opened two additional museums, one containing items from the 1862 London International Exhibition— particularly empire timbers— and using a similar geographic method of display, while the other was dedicated to forestry.88 To walk through the Museums was to glimpse the scope of empire.

No doubt influenced by Hans Sloane’s earlier ‘Collection of Vegetable Substances,’ Kew’s EBC in turn sparked an interest in plant-centric museums in the colonies, such as the Museum of the Raw and Manufactured Products of India89 and the Museum of Economic Botany in Adelaide, Australia. In St. Louis, Missouri, a replica built to Kew’s Museum No. 1’s floor plan was erected in 1860,90 making explicit the Museum of Economic Botany as a replicable typology, an architectural equivalent of a type-specimen. Like herbaria, this collection and display method operated as a knowledge network, enabling the development of plantation territories.

In comparing images of Kew’s Museum No. 1 (1846), Adelaide’s Santos Museum of Economic Botany (1881), and Kolkata’s Economic Botany Gallery (1901), the semblance is striking. All three contained rows of glass vitrines through which visitors viewed economic specimens and products. The gaze of a visitor through the glass and onto the plant-turned-product entailed not only a form of voyeurism but constructed new understandings of the plants themselves. Each museum was configured to narrate a specific ideology of progress, from the ‘wild’ plant to the profitable plant-product: a replicable commodity and form of financial asset.

In Kolkata’s museum, peripheral displays classified useful specimens labelled in English, Hindi, and Bengali, while central cases showcased factory-produced products made by these same plants, such as cotton cloth, paper, and matchboxes.91 Similarly, Adelaide’s Santos Museum used displays modelled from Kew’s to show a progression from plant-specimen into useful commodity. The gallery included a section on Indigenous cultural objects and foods,92 showing the selective appropriation of Indigenous knowledge into the colonial archival-epistemic system. Upon entering the museum, certain Indigenous knowledges were made accessible and acceptable to the European gaze; as Linda Tuhiwai Smith notes, “the cultural archive with its systems of representation, codes for unlocking systems of classification, and fragmented artefacts of knowledge enabled travellers and observers to make sense of what they saw and to represent their new-found knowledge back to the West through the authorship and authority of their representations.”93

Both the Kolkata and Adelaide museums were tied to Kew, receiving shipments from the London gardens. Together, they co-constituted an expanding network of botanical knowledge that operated under the same

episteme. From the scale of this network to the scale of the display case, economic botany produced and disseminated the rationalist doctrine of colonial modernity. The glass case became a vessel of objectivity, forcing distance between the viewer and the plant being viewed. The fiction of the plant-commodity requires distance to maintain subject-object relationships rooted in mastery; if the glass dissolves, we risk seeing ourselves in relation to the plants as beings with agency of their own. Like the herbarium sheet, the museum’s encasement of plants is another attempt to fix ‘nature’ as static and entirely knowable.

Exhibiting Rubber

As Hevea was commodified through economic botany, she became a proto-currency, a tradeable financial asset that swayed entire stock markets.94 After Britain seized control over the growth of Hevea and rubber production, in large part due to Wickham and Spruce’s transfers, Brazil’s rubber monopoly came to a halt.95 In the first half of the 20th century, rubber production soared, becoming one of the most valuable plant-assets enabling the industrial and automobile revolution.96 As Brockway recorded, rubber mania reached the extreme from July 1909 to April 1910, when “there was such wild speculation in rubber stocks on the London Stock Exchange that the chairman proposed closing the exchange so that brokers and clerks could keep up with the orders. One office boy made a coup of £19,000 in rubber shares.”97 The stocks, too, were deterritorialised, where the investors “neither knew nor cared whether the rubber was to come from Brazil, Mexico, Africa, or Malaya.”98

In a visit to Kew’s main archive, I came across two images of Hevea displayed in one of Hooker’s Museums. It uses a composite approach in its display,99 creating a linear narrative of progress where ‘civilised culture’ emerges from ‘wild nature’. The herbarium

94. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion.

95. Ibid.

96. Ibid.

97. Ibid, p. 152.

98. Ibid.

99. Nesbitt and Cornish, “Seeds of Industry and Empire,” p. 56.

Figure 31. Archival images photographed by the author. Illustrative series exhibit of Hevea brasiliensis herbarium sheets, photographs, and product samples. Location unknown, date unknown. I came across this image in Kew’s archive, November 2022.

100. Ibid.

101. “Flask of Para Rubber - Specimen Details,” Kew science, accessed April 15, 2024, https://ecbot. science.kew.org/read_ ecbot.

102. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion.

103. 1. Randolph R. Resor, “Rubber in Brazil: Dominance and Collapse, 1876-1945,” Business History Review 51, no. 3 (1977): 341–66, https://doi. org/10.2307/3113637, p. 346.

104. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion, p. 149.

105. Ibid; Resor, “Rubber in Brazil.”

sheets are descriptive templates to read the raw plant samples, while the rubber-based items display ‘Man’s’ ingenious transformation of plant into product. This display method, called an illustrative series, is process-oriented, focusing on how utility can be most effectively extracted from the plantspecimen.100

A quick search for Hevea brasiliensis on the Economic Botany Collections web page gives 142 results of products made from various parts of the plant. In analysing three objects collected in different time periods and locations, I will discuss ways in which Hevea’s commodification evolved, serving various purposes depending on who interacted with the plant.

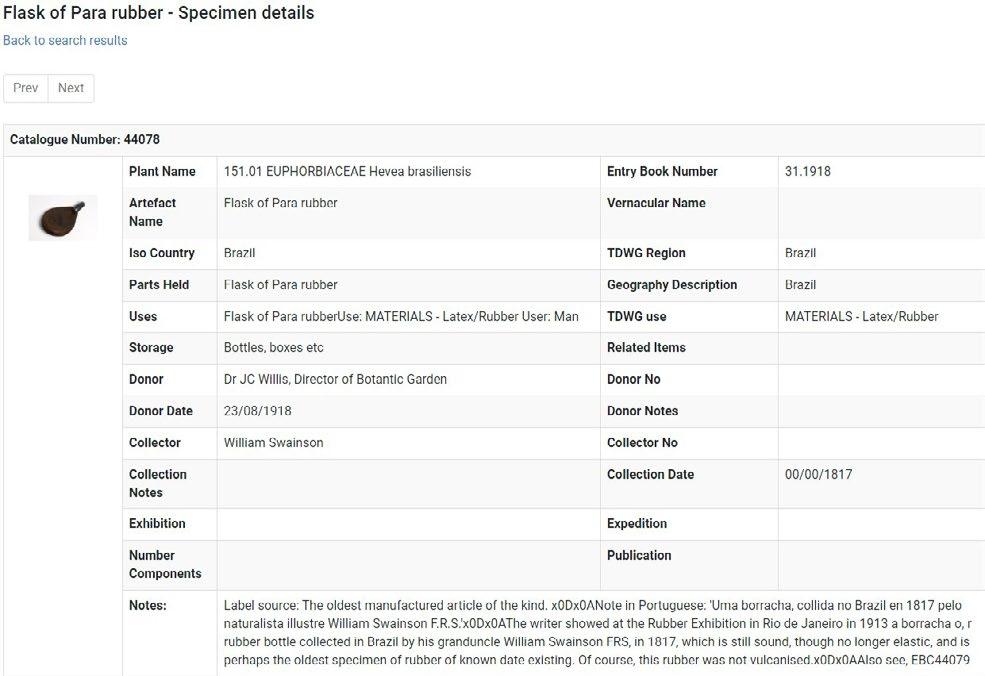

Item 1: Flask of Para rubber, Catalogue No. 44078

This reconfiguration of Hevea’s sap takes the form of a rounded pouch with a metal nozzle. Its scale is unidentifiable in the provided image. The dark brown-red rubber is imprinted with a floral pattern, not dissimilar in appearance to Hevea’s leaves. It appears well-crafted and little used. The sparse information on the EBC database notes Specimen 44078 as “perhaps the oldest specimen of rubber of known date existing.”101 Collected in 1817 by William Swainson, the catalogue records that it is “still sound, though no longer elastic,” as it was made prior to Goodyear’s invention of vulcanisation 1939, which revolutionised rubber’s utility.102 This flask was also made before the period of Brazil’s rubber boom, where colonial barons enslaved Indigenous peoples in the Amazon to work on their ‘estradas,’ looping paths connecting Hevea trees in the rainforest.103 Working under horrifying conditions, this was a genocidal regime, leading to the extinction of over 45% of Indigenous tribes in rubber extraction regions.104

The pouch’s use is noted as “Materials” and its user as “Man,” showing the EBC’s form of bioculture as nature-for-humans—specifically, European men. It is curious that this is named the ‘oldest specimen,’ given that it is well recorded that Indigenous peoples have for thousands of years made all kinds of products from rubber, including balls, ponchos, shoes, and bags.105 Does ‘oldest specimen’ mean oldest to the EBC? Or oldest specimen ‘collected’ by a European? Or is it perhaps the oldest example of rubber transformed into a specimen—a manufactured commodity?

Figure 32 (opposite). Flask of Para rubber, Kew Economic Botany Collection, online database, https://ecbot.science. kew.org/read_ecbot. php?catno=44078&search_term=44078&search_type=name.

How did Swainson obtain this pouch, and from whom? The word ‘collect,’ pervasive within museums and archives, is a neutralising force, obscuring the actual conditions under which something was taken. Little more can be gleaned from the EBC’s database. Who made this pouch? Which tree did the latex come from? Is there any meaning behind the ornamentation? Did it have a ceremonial purpose? Who drank from its metal nozzle? These are some of the unanswerable questions created by the imperial archive. The worlds that created this pouch were muted with its objectification in the EBC.

106. “Six Rubber Shoe Sole Patterns - Specimen Details,” Specimen image, accessed April 15, 2024, https:// ecbot.science.kew.org/ main_image.php?imageid=EBC_90918.

107. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion

108. Ibid.

109. Balloon and Dipping Former / Gloves - Specimen Details,” Kew science, accessed April 15, 2024, https:// ecbot.science.kew. org/read_ecbot. php?catno=75952.

110. Desmond, History of Kew.

111. “Economic Botany Collection,” Kew, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www. kew.org/science/ collections-andresources/collections/ economic-botanycollection.

Item 2: Six rubber shoe sole patterns, Catalogue No. 90918

Donated by the India Rubber, Gutta Percha & Telegraph Works Co. in 1885, these samples were exhibited at the International Inventions Exhibition in London that same year.106 Only nine years after Wickham’s theft, colonial rubber plantations were still in early stages. At this point, Brazil’s ‘wild’ rubber production, though struggling to meet rising global demands, held strong to its monopoly.107

Rubber had long been used by Indigenous peoples in the Amazon to make shoes, given its durable and waterproof qualities.108 These finely crafted sole patterns were likely catered to the British elite who would be keen to sport this trendy, modern material. Within the EBC, they present Hevea’s sap as useful for everyday products: a hallmark of economic botany. Moulded by the European Homo faber, the raw ‘natural’ rubber becomes a cultural artefact, able to be mass produced as a standardised sellable unit.

Item 3: Balloon and dipping former / gloves, Catalogue No. 75952

This micro-collection, donated in 1998 to Kew by a unit of the Rubber Research and Development Boards in Malaysia,109 consists of a plastic bag of colourful rubber balloons, a form-mould used to create the balloons, and a pair of white latex gloves. While such products seem ubiquitous and unremarkable, their presence in the EBC reminds us that they are plant-based products. Balloons are botanical. In 1998, production of natural rubber had drastically dropped, reflecting the surge in synthetics. Still, Asian plantations continued to extract latex; Malaysia still produces about half of the world’s rubber.

Conserving Economic Botany

Figure 33 (opposite above). Six rubber shoe sole patterns, Kew Economic Botany Collection, online database, https://ecbot.science.kew.org/ main_image.php?imageid=EBC_90918.

Figure 34 (opposite below). Balloon and dipping former, Kew Economic Botany Collection, online database, https://ecbot.science.kew.org/ read_ecbot.php?catno=75952.

By the 1980s Kew’s last museums closed: the purview of economic botany had shifted from production to conservation, notably of seeds. The EBC moved out of public view to a research store, and eventually into the basement of the Joseph Banks Centre for Economic Botany, built in 1990.110 However, the collection, containing upward of 100,000 items, continues to expand annually.111 If space and knowledge are co-constructed, then landbased conservation efforts continue to develop economic botanical knowledge and technologies.

Economic botany arguably remains Kew’s domain of expertise, a guise through which the institution maintains both credibility and relevance. From financing imperialism through plantation development to green capitalism through neoliberal ‘nature’ conservation programmes, economic botany continues to link plants to profit. This is no bold claim; even Desmond’s

112. Desmond, History of Kew, p. 350.

113. Ibid.

114. “Plantas Do Nordeste,” December 2000.

115. Ibid.

116. William (Bill) Adams and Martin Mulligan, Decolonizing Nature: Strategies for Conservation in a PostColonial Era (Florence: Taylor and Francis, 2012).

117. Drayton, Nature’s Governement, p. 236.

118. Ibid.

119. Adams and Mulligan, Decolonizing Nature; Shela Sheikh, “‘Planting Seeds/The Fires of War,’” Third Text 32, no. 2–3 (May 4, 2018): 200–229, https://doi.org/10.108 0/09528822.2018.14 83899.

120. Ramón Grosfoguel, “Colonial Difference, Geopolitics of Knowledge, and Global Coloniality in the Modern/ Colonial Capitalist World-System,” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 25, no. 3 (2002): 203–24, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/40241548.

121. Quijano, Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality, p. 169.

seminal history of Kew states plainly that “economic botany still ranks high among Kew’s priorities.”112 Natural theology, too, exists today as nature is deemed a ‘resource’ or ‘natural capital.’ To admit that humans do not have a pre-ordained right to take infinitely from plants threatens capitalism’s need for constant growth. While economic botany remains Kew’s governing doctrine, it continues to perpetuate extractive and masterful relationships to plant life.

More recent ventures in economic botany show its continued relevance within a ‘green’ capitalist-conservationist framework. In 1992, Kew launched its Plantas do Nordeste project, an example of economic botany reborn within a conservation framework.113 Working with communities in northeastern Brazil—Hevea’s native habitat—this Kew initiative shows the close ties between western development ideologies and community-based conservation in ‘developing’ nations. Funded by a 1-million-pound grant from the Weston Family Foundation,114 the programme aimed to identify useful plants and their distribution, sharing this scientific and technical information with poor rural communities.115 Though I was unable to determine specific outcomes of the programme for the communities implicated, it is important to question the power dynamics inherent such projects, risking paternalistic, controlling, and saviourist attitudes.

In fact, conservation’s colonial roots have been well recorded.116 The concept of ‘nature’ preservation emerged from the notion that Indigenous peoples were over-using plants and driving them to extinction. Drayton exemplifies this in his discussion of India-rubber gatherers in Central America, where an 1884 article in the The Globe cautioned that “unless the natives can be prevented from destroying the trees, only one result can attend this Gladstonian activity.”117 The solution to this was state control led by scientific experts, who were more capable of managing ‘natural resources’.118 Current western conservation efforts risk replicating similar dynamics: when Global North conservation bodies enforce ‘nature’ protection strategies in Global South countries, they all too often replicate colonial forms of land management and knowledge extraction.119

The persistent desire to ‘develop,’ integral to the capitalist worldsystem,120 replicates European supremacy, where “cultural Europeanisation was transformed into an aspiration (…) to reach the same material benefits and the same power as the Europeans: viz, to conquer nature – in short for ‘development.’”121 This points to a common dilemma in Kew’s conservationism, which often employs developmentalist ideologies: how can reciprocal, equal partnership be achieved when such power imbalances are at play? Under the doctrine of ‘development’ via economic botany, it seems unlikely that human-vegetal entanglements can evolve beyond an epistemology of commodification.

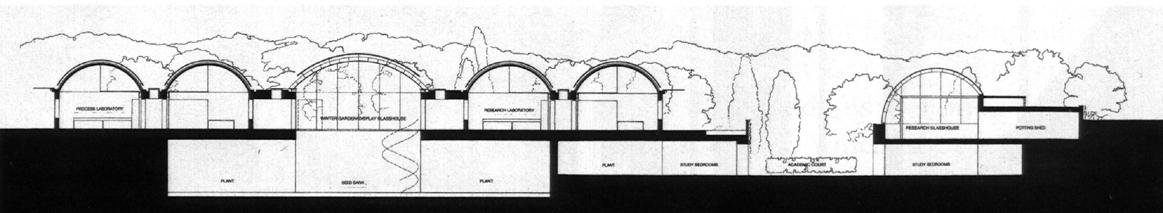

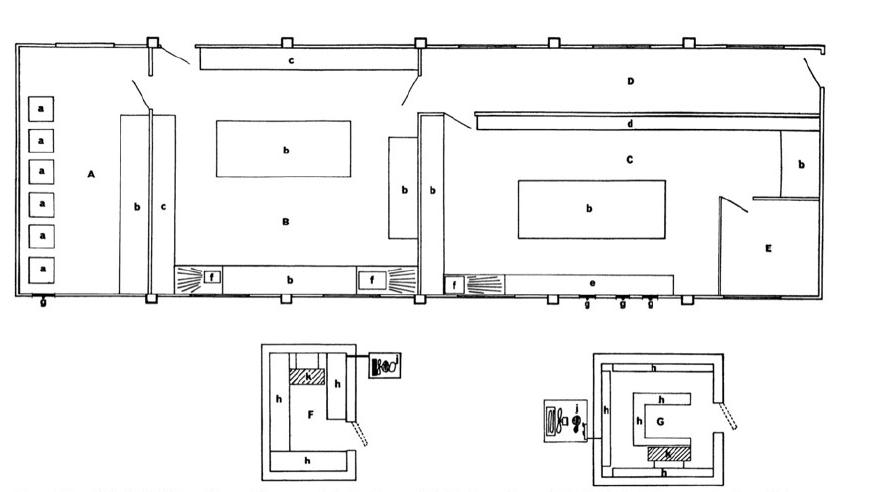

Economic botany, through its archival ordering of replicable plantproducts, initiated the very idea of ‘nature’ as something to be owned, bought, and sold: a way of knowing plants essential to the formation of plantation worlds. While Kew’s Museums of Economic Botany created a public consciousness of plant utility, the collections continue to inform the paradigm of plant-as-commodity. Today, Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank has perhaps replaced the EBC as the institution’s most prized collection, where economic botany is remade as seed conservation. Under neoliberalism, and aided by scientific advancements, scales of commodification have grown increasingly fine-grained: even a genome is subject to property laws, patentable under certain conditions.

Sowing Futures: The Millennium Seed Bank

The Herbarium and EBC may have adapted to Kew’s conservation agenda, but the seed bank poses a relatively new form of botanical archive created solely for conservation efforts. If the Herbarium and EBC created plantation epistemologies through replicable types and commodities, the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) acts a defence mechanism responding to the imminent collapse of the plantation industrial complex in its creation of replicable seeds. A key development in Kew’s turn toward conservationism, the MSB is the world’s largest seed bank, housing over two billion seeds in underground cold storage. This chapter unpacks the deterritorialisation of seeds and seed-related knowledge as an effort to maintain stability and control over ‘nature’, pointing to the continuation of epistemic mastery reborn through neoliberal conservationism