Lambton Musings

www.heritagelambton.ca

www.heritagelambton.ca

Genevieve Buchanan, Forest Museum

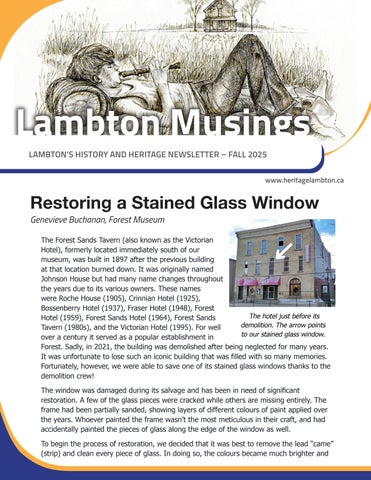

The Forest Sands Tavern (also known as the Victorian Hotel), formerly located immediately south of our museum, was built in 1897 after the previous building at that location burned down. It was originally named Johnson House but had many name changes throughout the years due to its various owners. These names were Roche House (1905), Crinnian Hotel (1925), Bossenberry Hotel (1937), Fraser Hotel (1948), Forest Hotel (1959), Forest Sands Hotel (1964), Forest Sands Tavern (1980s), and the Victorian Hotel (1995). For well over a century it served as a popular establishment in Forest. Sadly, in 2021, the building was demolished after being neglected for many years. It was unfortunate to lose such an iconic building that was filled with so many memories. Fortunately, however, we were able to save one of its stained glass windows thanks to the demolition crew!

The hotel just before its demolition. The arrow points to our stained glass window.

The window was damaged during its salvage and has been in need of significant restoration. A few of the glass pieces were cracked while others are missing entirely. The frame had been partially sanded, showing layers of different colours of paint applied over the years. Whoever painted the frame wasn’t the most meticulous in their craft, and had accidentally painted the pieces of glass along the edge of the window as well.

To begin the process of restoration, we decided that it was best to remove the lead “came” (strip) and clean every piece of glass. In doing so, the colours became much brighter and

clearer. There are two methods practiced when creating a stained glass window. This window was originally done with the “lead came method”, but for the restoration we decided to use the “Tiffany/copper foiling technique”.

The window with its original lead came, before restoration.

In consideration of the missing pieces, we reached out to Sunrise Stained Glass Inc. in London, Ontario. We showed them the glass we needed to match and they were able to give us more information about it. Two of the missing colours were made with a diamond pattern and they informed us that this texture is no longer produced. Our only option was to find the closest colour and accept that the textures wouldn’t perfectly match.

An interesting fact about stained glass is that each colour is created due to different metallic compounds. These compounds are added while the sheets of glass are made. For example, the blue pieces in this window were coloured with a copper compound (most likely copper oxide). Red is known to be the most expensive colour of glass because it is created by using gold chloride. Consequently, stained glass artisans will often buy “flashed glass” as a cheaper alternative. This is a technique done when creating a glass panel that involves making a very thin layer of coloured glass on a thicker pane of clear glass. This way, less of the metallic compound is used while still achieving a beautiful colour.

We eventually made a trip to the stained glass shop to find our replacement pieces and selected the closest colours we could. Once we had those, it was time to cut the pieces and wrap them all in a copper foil tape. The copper is what allows the pieces to be soldered together, providing the structure of the window. Once these steps are complete, the window will be set back into its original, repainted, wooden frame from the hotel.

Some may think it’s odd to save and restore an old window from an abandoned building, but the preservation of artifacts serves a greater purpose. By restoring artifacts, we save a tangible element of the past that people are then able to connect with. The restoration of this window symbolizes the importance of museums and the role they play in the community.

This process can be an expensive one when factoring in the cost of glass, copper foil, solder, along with the other tools and supplies that are needed. We would like to thank all who have contributed so far toward this restoration. If you are interested in making a donation to this project, come visit our museum or contact us at museum.forest@gmail.com. In the very near future we plan to have an unveiling of our restored window, which will be on permanent display in our museum.

Note: Genevieve Buchanan is a member of our summer staff. She has been assisted in the stained glass window restoration by fellow staff member, Amy Jennings.

This year marks a remarkable milestone in Lambton County history — the 175th anniversary of the first Agricultural Fair held in Moore Township. Sponsored by the Moore Agricultural Society, the inaugural event took place in 1850, the same year the first township council met.

Just a year earlier, the County of Lambton had been officially formed. Before that, the “District of St. Clair” was governed by a council meeting in Sandwich, with delegates walking long distances to fulfill their duties. Moore and Enniskillen were jointly represented by James Bâby. In the early 1800s, the region was sparsely settled, with more pioneers arriving in the 1830s. By 1850, Moore Township had been divided into school sections, and two small villages — Froomefield to the north and Sutherlands (between present-day Mooretown and Courtright) — had begun to emerge along the St. Clair River.

Life for early settlers was demanding, but they took pride in their achievements in farming and livestock. That pride inspired the first Fair, held at Reilly’s Tavern on Lot 26, Concession 8. Far from the large-scale exhibition it is today, the early Fair was a modest, male-only gathering.

In the years that followed, the Fair expanded and moved to various locations as the community grew. The arrival of the Canadian Southern Railway between St. Thomas and the St. Clair River spurred greater development. Two new villages — Corunna and Mooretown — flourished, and the Fair became an increasingly important community event.

By 1884, the Fair was held in Mooretown for the final time, moving to Courtright in 1888. A year later, a group of farmers and businessmen secured a permanent home for the event. They purchased a 15-acre tract just south of Brigden and rented it to the Moore Agricultural Society as Fair grounds. The Fair, now known as the Brigden Fair, had found its place.

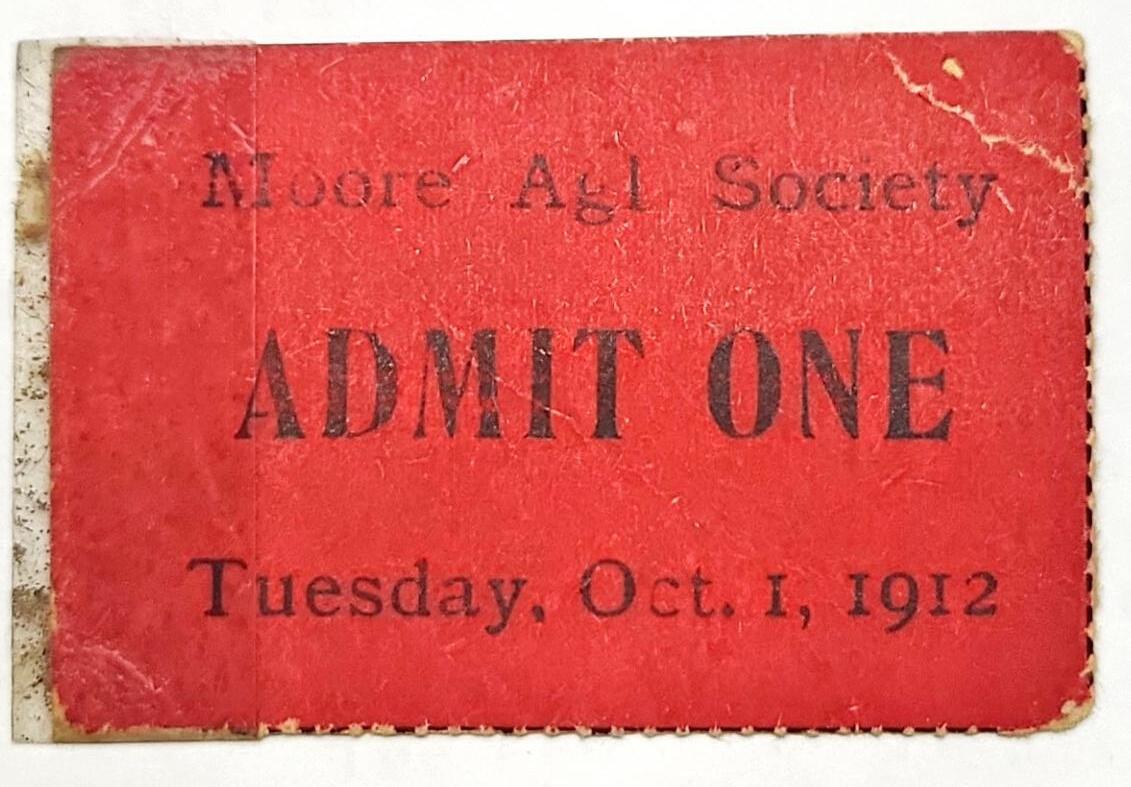

Ticket to the fair, dated October 1, 1912, from the collection at Moore Museum.

In 1915, the Agricultural Society purchased the land outright. Seeking growth and broader competition, the Society decided in 1928 to open the prize list to entrants from “around the world” — with the exception of the Children’s Department. Year after year, reports praised the Fair’s success, with gate admissions covering prize costs and then some.

While women did not participate in the earliest years, their role soon became central. By 1900, two directors oversaw the Ladies’ Department; by 1949, that number had grown to 24. Displays showcased domestic needlecraft, home arts, fine crafts, and more, with expert judges brought in to evaluate entries. The range and quality of exhibits reflected the community’s talent and dedication.

To celebrate the Fair’s 100th anniversary, the Society built a new exhibition building, equipped with modern amenities to host diverse displays. It officially opened in 1980, symbolizing both tradition and progress. Today, the Brigden Fair remains a proud celebration of rural life and community spirit — a tradition rooted in 175 years of resilience, innovation, and shared heritage.

Colleen Inglis, Lambton Heritage Museum

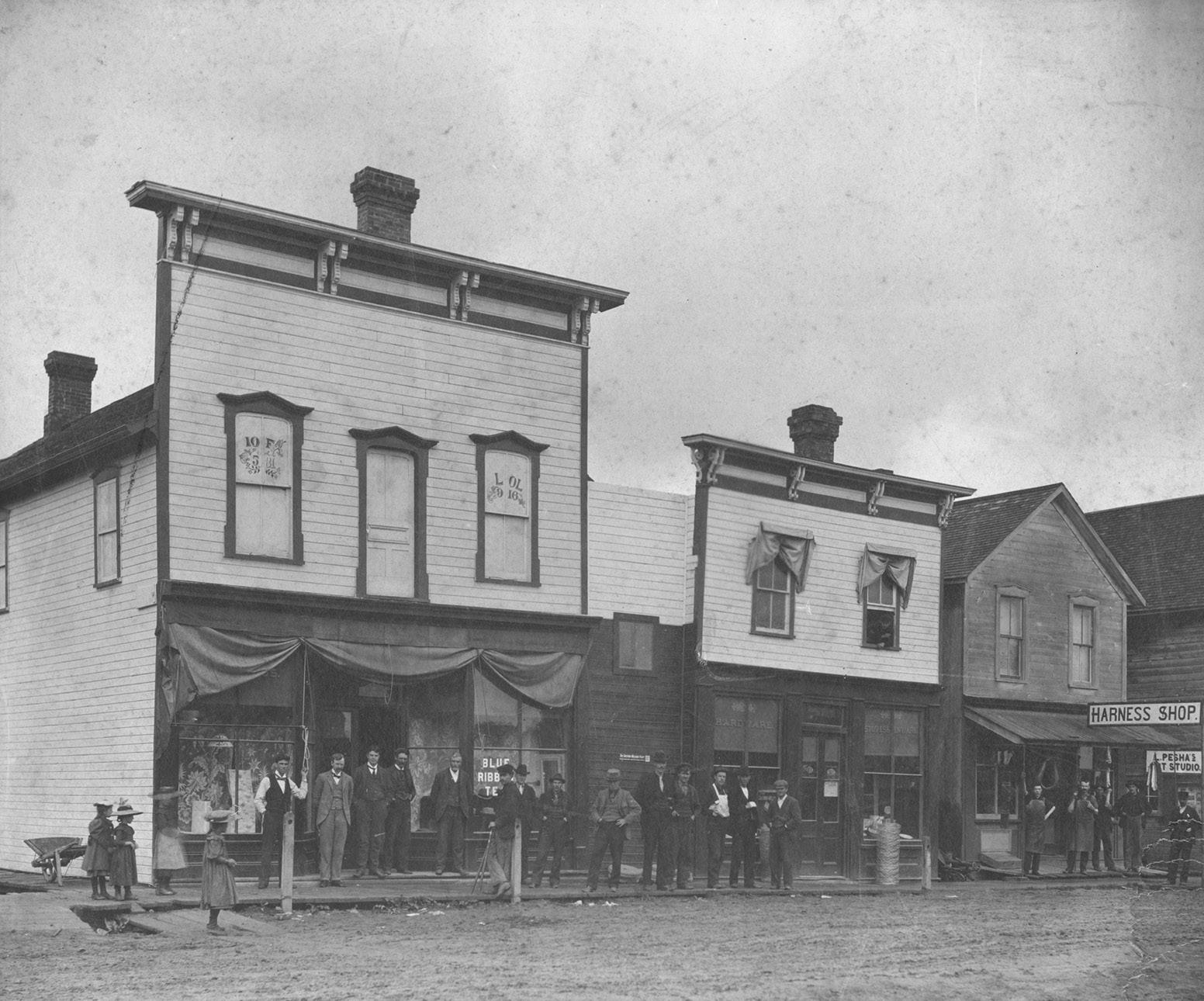

Pesha Postcard of Hotel Bedard in Courtright.

Louis James Pesha was a prolific Lambton County photographer. He created more than 8,000 images before his tragic death. He specialized in real photo postcards of ships and landscapes in southwestern Ontario, Michigan, and beyond.

Pesha was born August 11, 1868, in Euphemia Township to James Pesha and Elizabeth Ward. His paternal grandparents, Louis Picher and Julie Fénix, came to Euphemia Township from Quebec. His maternal grandparents, George Ward and Huldah Hicks, lived in Dawn Township.

Pesha grew up on a farm north of Shetland with three younger siblings. He started out farming his parents’ land and they sold him 50 acres for one dollar after he turned 21. Pesha married Lena E. Faucher of Battle Creek, Michigan in Sarnia on August 29, 1892. They sold the farm for $1,500 on November 11, 1898. Assessment rolls place them in Oil Springs in 1900. Their daughter Lorraine was born the same year.

Pesha learned the photography trade before 1899. He was active in Oil Springs at that time. His early business was in portraits. His Oil Springs studio was on Kelly Road just south of Oil Springs Line. A spur line connected Oil Springs to the Michigan Central Railroad. By 1901, Pesha was using this line to reach branch studios in Alvinston and Brigden.

His business ruffled some feathers. There was extensive damage at the Alvinston studio after a break-in. An anonymous letter in the Alvinston Free Press threatened Pesha with more danger unless he raised his prices. In an unrelated incident, Pesha’s Brigden studio was destroyed by fire in January 1901. The blaze consumed an entire block on Brigden Road.

Pesha and his family moved to Marine City, Michigan in 1901. His studio on Water Street included the family’s living quarters and a basement workshop/garage. Pesha set up his camera on a platform outside and photographed ships as they passed on the St. Clair River.

In the early 1900s, a photographer would take a picture and develop the corresponding negative. The negative was then placed on photosensitive paper and exposed to light to create a positive contact print. For real photo postcards, the photosensitive paper was a standard 3 ½ by 5 ½ inch size that was pre-printed with a postcard back. The design of the postcard back helps to date it, particularly the stamp box. Most Pesha postcards are captioned, numbered, and labelled “Pesha Photo.”

Lewis Miller worked for Pesha in Marine City. In Gareth Lee McNabb’s biography of Pesha, Miller described Pesha as an active man of few words. He was friendly, not especially social, read extensively, and enjoyed tinkering in his basement. Pesha was tall and thin, a snappy dresser, and always wore a derby hat. As a Seventh-day Adventist, his business was closed on Saturdays.

Pesha’s wife Lena supervised the postcard printing. Miller and others worked in dark cubicles where they placed photosensitive postcard paper against a glass negative. They used sunlight or a lantern to expose the prints. When the exposure was complete, they removed the paper and dropped it into a chemical bath in a developing tank. After the appropriate amount of time, Lena would remove the paper for rinsing and fixing. Each worker earned one dollar a day.

By 1910, Pesha’s business was booming. He bought a steam car built by the White Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Pesha loved to drive the large, powerful, and luxurious car around town. Unfortunately, the car proved to be his downfall. Pesha died in a car accident on October 1, 1912, at age 45. Pesha, Lena, and Lorraine had stopped to visit family in Euphemia Township on the first leg of a road trip. Pesha went for a drive with his brother-in-law John McAuslan and nephew Lancelot McAuslan. When John got out of the car to open the gate at Pesha’s parents’ home, the car started to

roll backwards. Pesha reached for the wrong lever, or the correct lever failed to respond. His heavy car shot backwards down an embankment, fracturing Pesha’s skull and pinning his body underneath. Lancelot escaped.

Duffy Atkin responded to the call for help. He vividly remembered Pesha lying on the floor while Pesha’s mother swept the floor around her son’s body. Beatrice (McAuslan) Chapman, cousin of Lancelot, recalled staying at home to babysit while her mother hurried to the Pesha farm. Pesha’s funeral took place at his parents’ home October 4, 1912, with interment at Shetland Cemetery.

Lena kept the Pesha Art Company going and was joined by her second husband, Daniel Conrad Miller in 1918. They offered portraits, local views, and enlargements. About 1922, Durrell J. Butterfield took over. The business moved to Detroit and eventually closed.

There are more than 130 real photo postcards by Pesha in the Lambton Heritage Museum collection. They provide some of the best images of our towns and villages in the early 1900s. We are incredibly fortunate that he was active in our area.

Alan Campbell, Lambton County Branch OGS Newsletter Editor

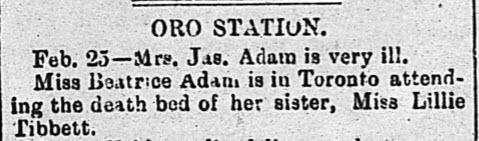

While searching a newspaper for an obituary, I came across the following article which grabbed my attention:

“Miss Lillian J. Tibbett, one of the nurse’s [sic] of the Sarnia General Hospital, passed away Sunday evening after a six week’s illness from typhoid fever. Miss Tibbett contracted the disease while attending a patient and although she made a gallant struggle for life, passed away as above stated at the early age of 23 years, in the presence of her mother, brother and sister, who were summoned here owing to her serious illness. Deceased was a favorite with the hospital staff and her death is deeply regretted. The body will be shipped to Guelph tomorrow by G. L. Phillips for interment.”

Lillian’s death registration noted her date of death as February 24, 1901, at the age of 23, at Sarnia General Hospital. The cause of death was recorded as pneumonia. Apparently, typhoid and pneumonia have similar symptoms which could explain the differing cause of death recorded. No parents’ names were given but her birthplace was recorded as England.

Questions came to mind. Who were her mother, sister and brother who came to be at her death bed? Where in England was she born? Where did she train to be a nurse? Why was her body shipped to Guelph?

A baptismal record for a Lillian Julia Tibbitt, born December 26, 1875 at Kensington, St. James Parish Norland, Middlesex, England records her parents as Joseph and Julia Tibbitt residing at Clarendon Place.

An 1881 England Census captured the family of Joseph Tebbitt, age 28, librarian’s assistant; his wife Julia, age 26; daughter Julia, age 5; son Alfred, age 3; and daughter Beatrice, age 5 months.

Calamity struck the family in 1888. A news article in The Kensington News and West London Times, dated September 8, 1888, reported that Joseph had been charged with embezzlement from an Oddfellows lodge and committed for trial. According to A Calendar of Prisoners Tried at the September, Adjourned Sessions of the Peace, Joseph was received into custody August 29, 1888, tried on September 26, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to “12 calendar months” at Pentonville Prison. According to records created by the Charlotte A. Alexander Home, Joseph contracted smallpox which led to the loss of his job and then to the embezzlement.

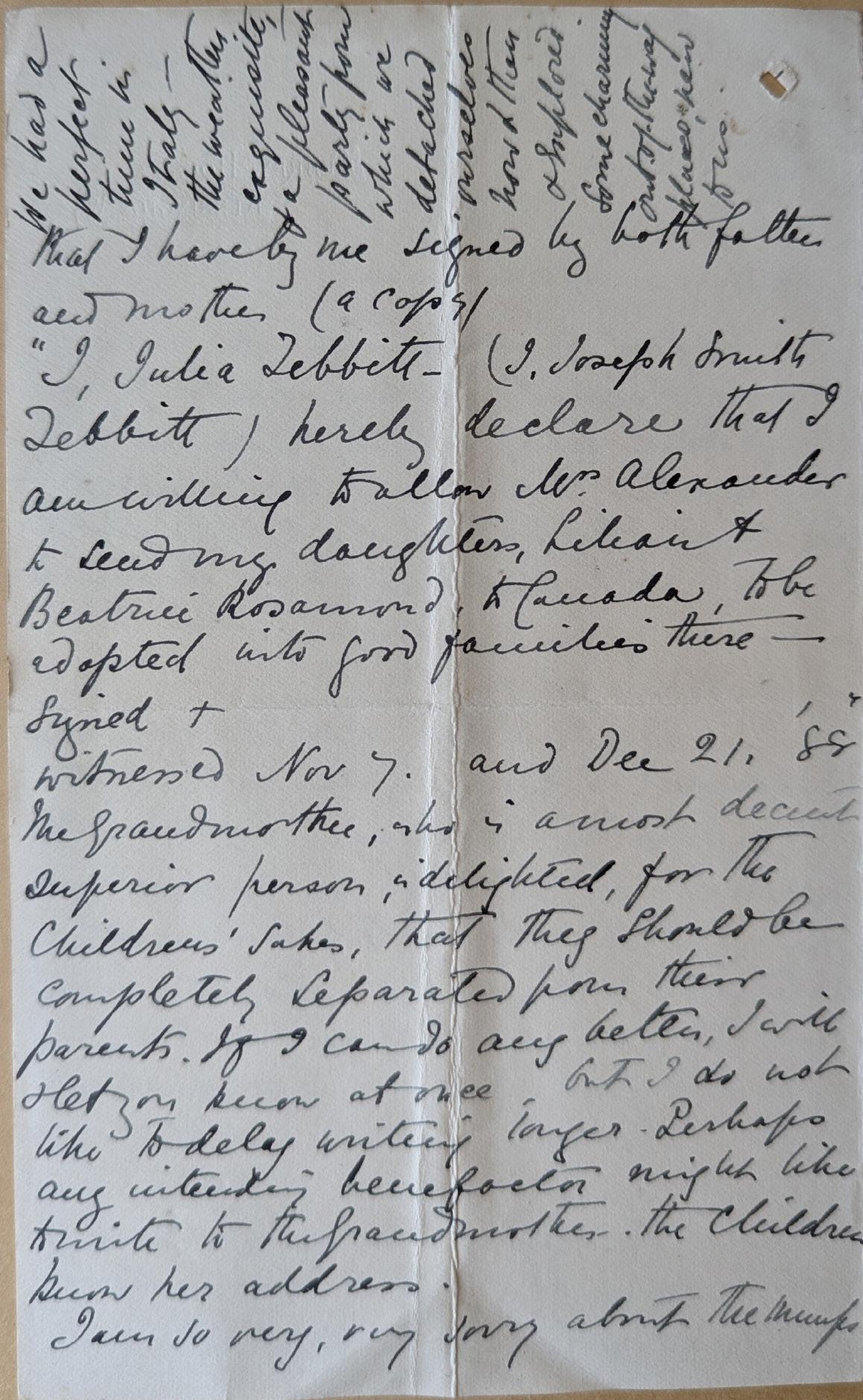

He and his wife Julia gave up Lillian and her sister Beatrice to the Charlotte A. Alexander home. Julia left Joseph to live with someone else. Lillian spent a good deal of time with her grandmother Tebbitt, a “most respectable“ person, according to the records. A letter from Aubrey House in Kensington, England to Miss Alexander, presumably in Canada, dated June 22, noted that the Tebbitts had not formalized the adoption of their children but had signed an agreement November 7, 1888 [Julia] and December 21, 1888 [Joseph].

The Tebbitts give up rights to Lillian and Beatrice. Courtesy of the Charlotte A. Alexander Fonds, Library and Archives Canada.

“I, Julia Tebbitt hereby declare that I am willing to allow Miss Alexander to send my daughters, Lilian & Beatrice Rosamond, to Canada, to be adopted into good families there.”

Lillian and Beatrice travelled as part of a group to Canada on the Assyrian from London on May 2, 1889. Lillian was recorded as age 13 and Beatrice as age 8 on the ship’s list. The ship arrived in Quebec May 17, 1889 after which the group probably was sent to the distribution centre, the Charlotte A. Alexander Home in Toronto.

The initial placement for Lillian was with Frances (Fannie) Knowles and her husband Frank who lived at 449 Glasgow Street in Guelph. The inspector who kept track of her recorded that “Lillian very happy quite like daughter in family…” At this point in time Lillian was in this home on an annual agreement. Lillian could send letters to Miss Alexander and Beatrice but was not allowed to send letters to her parents. If she wished to send a letter to her grandmother Tebbitt, it had to go through Miss Alexander.

In a letter dated July 26, 1889, written to Miss Alexander, Lillian wrote that she was “…getting along nicely with her music now. I practice from one hour to five hours a day.” She mentions her brother Eddy.

In 1890 the Knowles family moved to live with Frances’ sister, Eliza Scott, on Jarvis Street in Toronto. The inspecting person recorded that Lillian was going to spend a month with Beatrice who was living with James Adam’s family. She also noted that the Knowles were going to move to Peterborough.

The inspector’s report for 1891 noted that Lillian’s behaviour was not positive; “Lilian been going to school & not improved since spring. Forgetful, not obedient. Not fond of domestic work.” Even so, Frances signed an agreement that she would act as a guardian for Lillian and would “… make suitable provision for her in all ways, till she marries or comes of age & is earning her own living.”

Lillian was captured in The Toronto City Directory 1897 as “Miss Lillian Knowles,” a lodger at 203 Jarvis Street the home of Eliza Scott, sister of Fannie Knowles. Lillian could have trained as a nurse at Toronto General Hospital or in Sarnia at Sarnia General Hospital. To date no records of her training have been found.

Lillian’s brother Alfred lived with an uncle during the time of the family breakup and then immigrated to Canada October 5, 1901.

The Barrie Examiner, in its February 28, 1901 issue, reported as part of the Oro Station news that “Miss Beatrice [Tebbitt] Adam is in Toronto attending the death bed of her sister, Miss Lillie Tibbett.” Other than the incorrect location for Lillian’s “death bed,” this would indicate that Beatice went to Sarnia. The mother who attended her was most likely Fannie Knowles and the brother could have been Edward W. Knowles or Harry Knowles from her adoptive family. Lillian’s burial site is still unknown so further research is required.

18 & 19, 2025

Cash Admission 12 and Under Free Hwy 21, South of Grand Bend

Kalea Pottle, Oil Museum of Canada

Letter writing during World War I was incredibly valued by soldiers and their home communities. This is evident from a collection of letters in Oil Museum of Canada’s collection. They were originally sent to the Oil Springs Patriotic League, an organization of women on the home front who sent care packages to active-duty soldiers from Oil Springs. The care packages were a source of physical support to the troops. Writing letters back to the Oil Springs Patriotic League gave soldiers an emotional outlet, and shared war news with the small community.

Over 600,000 Canadians served in the First World War, and approximately 50 of these men were from Oil Springs. Most enlisted and served from 1917 onward and were part of various battalions seeing action in Belgium, Germany, England, and France.

Mail during the First World War was highly regulated. Letters soldiers wrote were screened by officials for fear of enemy interception and gaining information, and complaints sent home led to a decline in voluntary recruitment. This led soldiers to self-censor their writing. Information such as one’s exact location, grave health, or harsh living conditions were strictly forbidden. The overall tone of letters home had to be reassuring. They wrote about their general health and location, the local weather, and harmless gossip.

Letters written by Oil Springs soldiers were detailed, honest, and frequent. They wrote around the censorship. For example, on December 8, 1918, Private J. Melton wrote while in Germany, “you will notice by the above address where we are… about as welcome as the flu” (see Figure 1).

Letter from Private J. H. Melton. Additional information on him is unknown, but his letter mirrors the tone and information given in a usual letter from someone on active duty.

Being able to communicate with Oil Springs proved to be a great comfort for soldiers. Giving them a space to express their feelings in a way that was widely preferred over keeping a diary because of the human interaction that happens with letter writing. On February 28, 1918, Private Thomas Truan wrote to the Patriotic League, “you may be surprised to hear I’m in hospital but nothing very serious… I took pneumonia, getting along fine… but I don’t know when I will be sent to the camp. They won’t let me go to France and it makes a person feel rotten when the rest of the boys leave for France. Without any joking I sit in the huts and cried when the boys I knew left and I was still stuck.” Truan was only 18 at the time of his enlistment and wrote to the League often.

Care packages sent from the Oil Springs Patriotic League were a piece of home for soldiers overseas. These parcels contained raisins, knit socks, tobacco, jam, chocolate, tea, coffee, sugar, gum, maple candy, and around Christmas, fruitcake. Every known soldier from Oil Springs was on the League’s mailing list, even if they had moved away from home. This surprised many soldiers, such as Private E. K. Crosbie. In a thank you letter after receiving a package, he wrote, “You people at home, I don’t think, really realize what pleasure you give us when you remember us with a parcel or some other way. I always considered myself an Oil Springs boy, even though I had been away from there for some ten years, and often wondered whether I was included with the boys of Oil Springs who came over.” Private William John Lumley expressed immense thanks for considering him as well, writing to the League, “I was sure surprised and also very glad to get [an overseas parcel]. I thought that now when my people have moved away from there that you wouldn’t think of me. But I guess I had better start thinking different.” Lumley, 19 at the time of enlistment, served on the front lines in France.

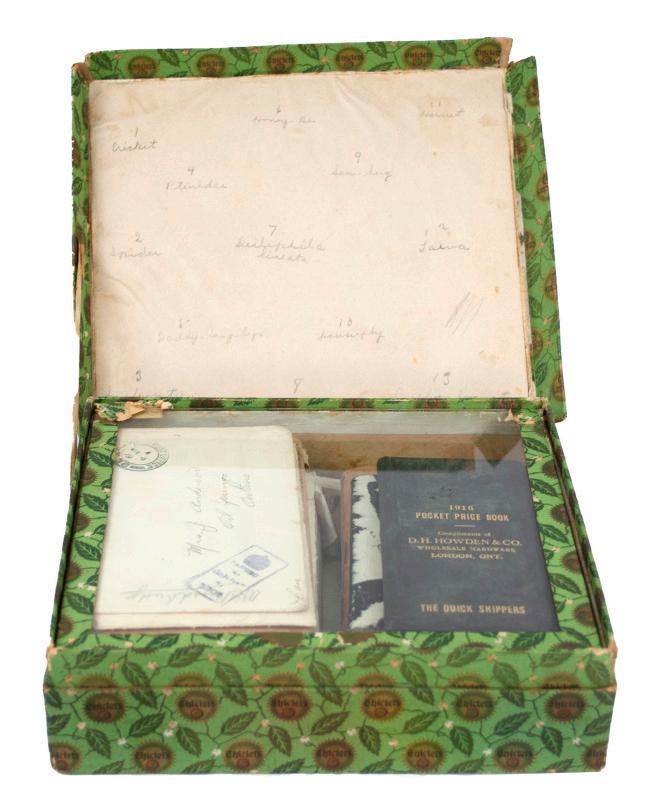

This box was used by the Oil Springs Women’s Patriotic League to store the letters received from soldiers. The box was donated to the museum along with other records from the League, all of which are still used today for research and are currently being digitized.

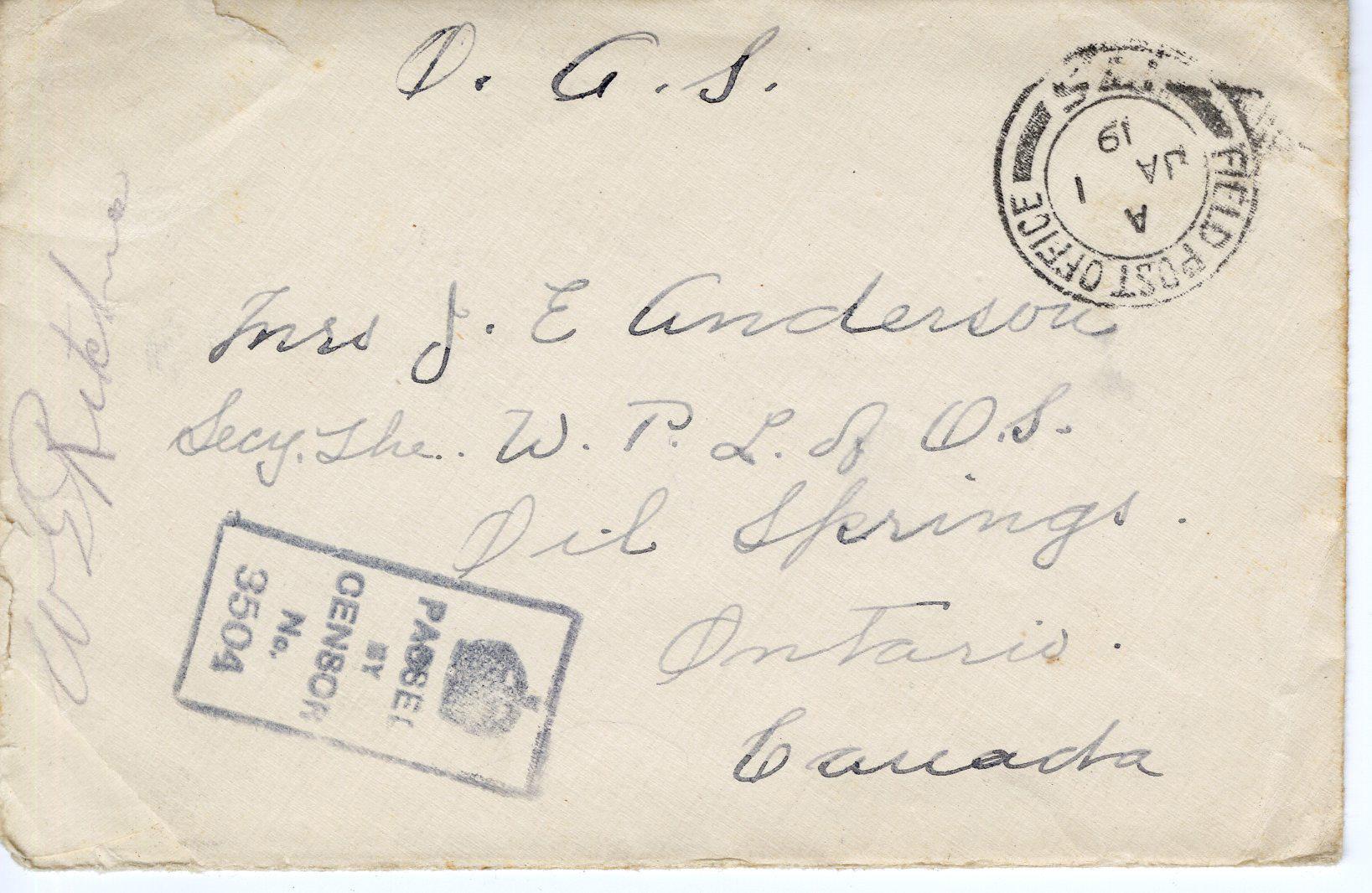

Figure 2: H. Ward envelope

Pictured is the envelope of a letter from Howard Ward on December 27, 1918 to the Oil Springs Patriotic League, thanking them for the socks they sent for Christmas in Belgium. This is a standard envelope sent by a Canadian soldier during World War I. All envelopes were stamped with “passed censor” and the signature of the approving officer (seen on the left). Other requirements included a stamp stating the post office and date the letter was sent, and an indication showing the letter was from a Canadian soldier on active service (here it is marked with initials O.A.S). Letters to Oil Springs were often addressed to Mrs. Anderson, who served as President of the Oil Springs Women’s Patriotic League.

Packages sent from Oil Springs supported other troops as well. The Oil Springs soldiers shared items year-round because they got packages regularly. Private Thomas Ward, a long-time Oil Springs resident, was one of these men writing on June 17, 1918, “I gave a pair of socks to one of the boys that needed them much more than I do, for you all keep me well supplied.” The League began sending double packages to each soldier, asking them to give the extra to a soldier who needed it. Private W.H. Littice of the 47th Canadian Infantry wrote on December 5, 1918 “… sox [sic] received today and passed on to a lonely soldier as requested.”

Colleen McLean, Lambton

Clipping from The Toronto Star, March 28, 1958, p. 33.

This Historic Recipe comes to us from the book Popular Recipes, compiled by the Shetland Women’s Institute in 1970 (second printing 1981). It was submitted for that project by Jitsuko “Dickie” (Sada) Moorhouse.

“Dickie” Jitsuko Sada was born in 1922 in Vancouver. During World War II hundreds of Canadian citizens of Japanese descent were relocated to Alberta, including Dickie. In 1944, she moved to Hamilton, Ontario, where she worked in a camera shop and began her work with colour photography. It was through this position that her talent was recognized and in 1956 she was hired by Berkeley Studio in Toronto and was put in charge of the Graphics Division. At Berkeley she became colleagues with Anson C. Moorhouse.

Rev. Anson Carlyle Moorhouse was the son of Rev. Anson E. and Minnie (Powell) Moorhouse. He was born on March 12, 1908 in Shedden, Ontario and was one of three children. His brother was Rev. Hugh E. Moorhouse and his sister, Muriel Niece. Anson C.’s first marriage was to Alice Bradley on October 24, 1935 in Windsor. Anson and Alice had a son and daughter together. On August 28, 1973 Alice passed away in Toronto and was laid to rest in the Shetland, Ontario cemetery.

Anson was an award-winning film maker. After spending most of his adult life in Toronto, he retired as Director of the Department of Audio-Visual for Berkeley Studio (United Church of Canada). He decided to build a new home in Shetland, as this where his parents were from.

Reverend Doctor Anson C. Moorhouse and “Dickie” Jitsuko Sada married in 1974 and lived in the home Anson built in Shetland. Anson became a fill-in minister in the area and from 1978 to 1981 he was the minister at Shetland United Church. He and Dickie had a theatre/music room in their home and they continued travelling, showing films and guest speaking.

Jitsuko “Dickie” (Sada) Moorhouse passed away in 1989. Rev. Dr. Anson Moorhouse who, at the time of his death was a resident of London, Ontario, passed away on March 5, 1994 at St. Thomas-Elgin General Hospital. Dickie and Anson were laid to rest at the Shetland Cemetery.

Ingredients

Meatballs:

1lb. ground beef

¼ lb. sausage meat

2 tbsp. chopped onion

1 tbsp. snipped parsley

1 tsp. garlic salt

1/8 tsp. ginger or curry powder

¼ cup fine bread or cracker crumbs

1 egg

1 tbsp. soya sauce

Sauce:

¾ cup brown sugar

¼ cup corn starch

½ cup vinegar

2 tbsp. ketchup

½ tsp. powdered ginger or 1 tbsp. grated fresh ginger

1 tin pineapple (chunks or sliced)

hot water

Combine all ingredients well and form into 1” balls. Bake about 20 minutes in 350 degree oven on ungreased baking sheet.

Sauce: Drain juice from pineapple and add enough hot water to measure 2 cups liquid, and heat. Mix rest of ingredients, except pineapple, to a smooth paste with ½ water and gradually add to hot liquid. Cook over low heat stirring constantly till thickened.

Add cooked meatballs and pineapple chunks and simmer in sauce for 15 – 20 minutes or put in covered casserole in 350 degree oven for 30 – 35 minutes. Serve with rice.

Moore Museum

94 Moore Line, Mooretown, ON N0N 1M0 226-784-3340

Facebook Page

Plympton-Wyoming Museum

6745 Camlachie Road, Camlachie, ON N0N 1E0

Facebook Page

Lambton Heritage Museum

10035 Museum Road, Grand Bend, ON N0M 1T0 519-243-2600

Facebook Page

Oil Museum of Canada

2423 Kelly Road, Oil Springs, ON N0N 1P0 519-834-2840

Facebook Page

Arkona Lions Museum and Information Centre

8685 Rock Glen Road, Arkona, ON N0M 1B0 519-828-3071

Facebook Page

Sombra Museum

3476 St. Clair Parkway, Sombra, ON N0P 2H0 519-892-3982

Facebook Page

Lambton County Archives

787 Broadway Street, Wyoming, ON N0N 1T0 519-845-5426

Facebook Page

Forest-Lambton Museum

8 Main St. North, Forest, ON N0N 1J0

Facebook Page

The Ontario Genealogical Society, Lambton Branch

Facebook Page