REVISTA N'OJ

LATINX RESEARCH CENTER AT UC BERKELEY

FEATURING GUEST EDITOR QUETZAL RUVALCABA

DISABILITY JUSTICE · ISSUE 6 · FALL 2023

table of contents

Page 2: Letter from the Guest Editor

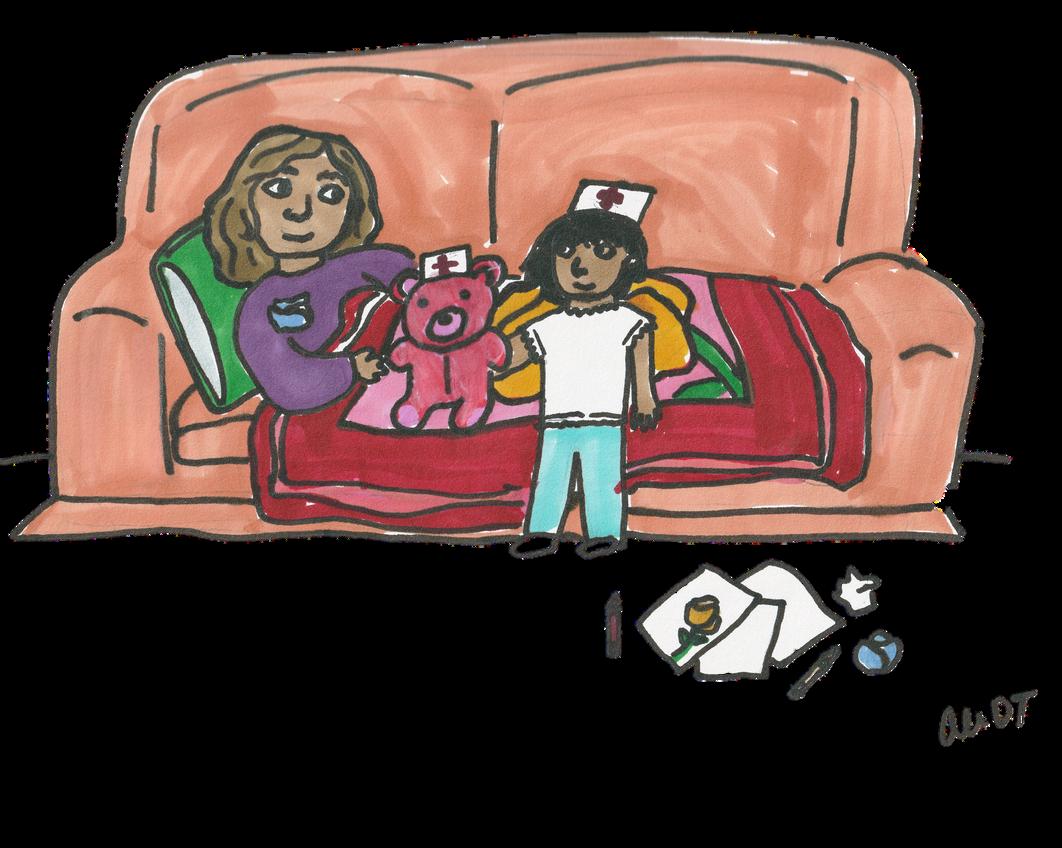

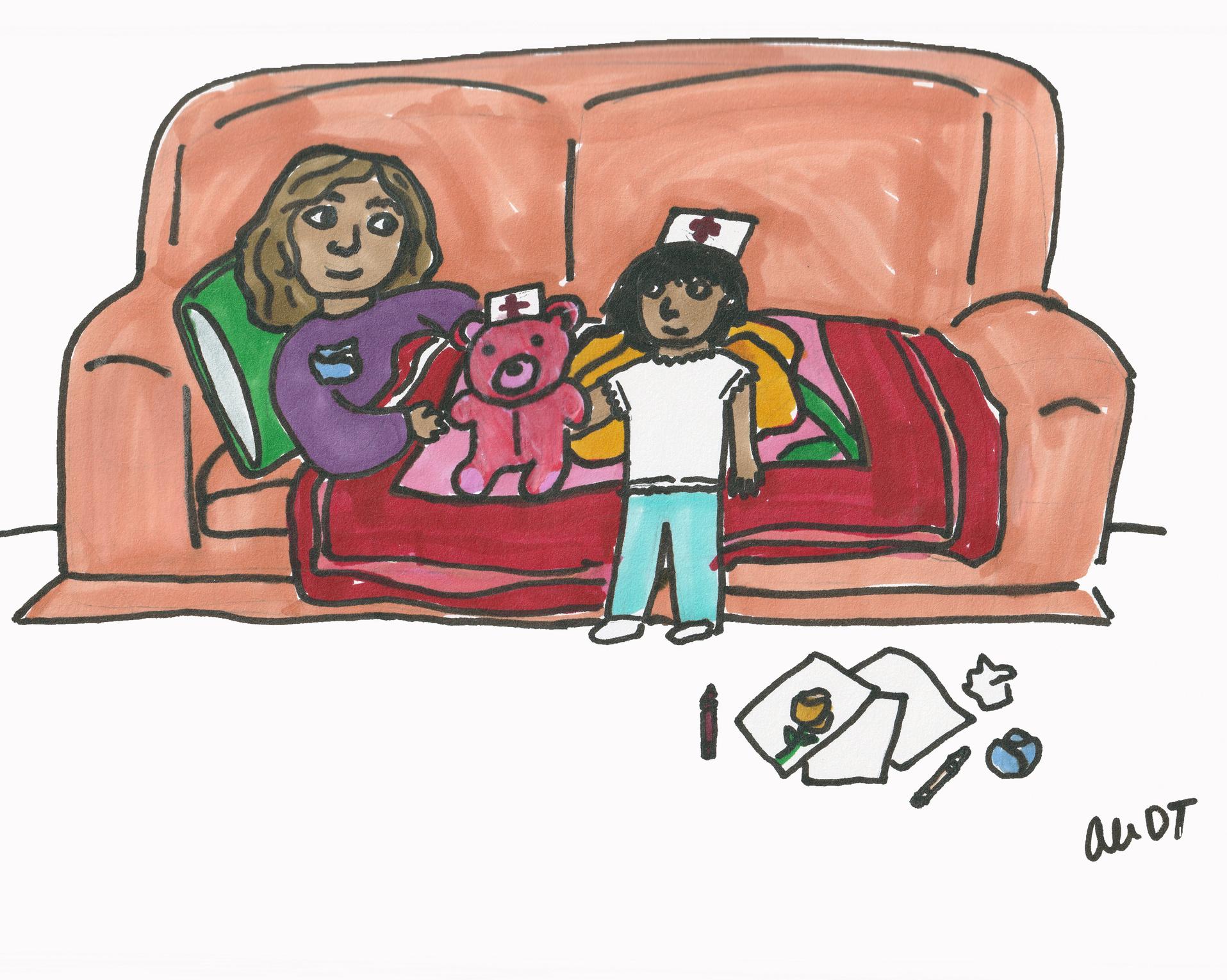

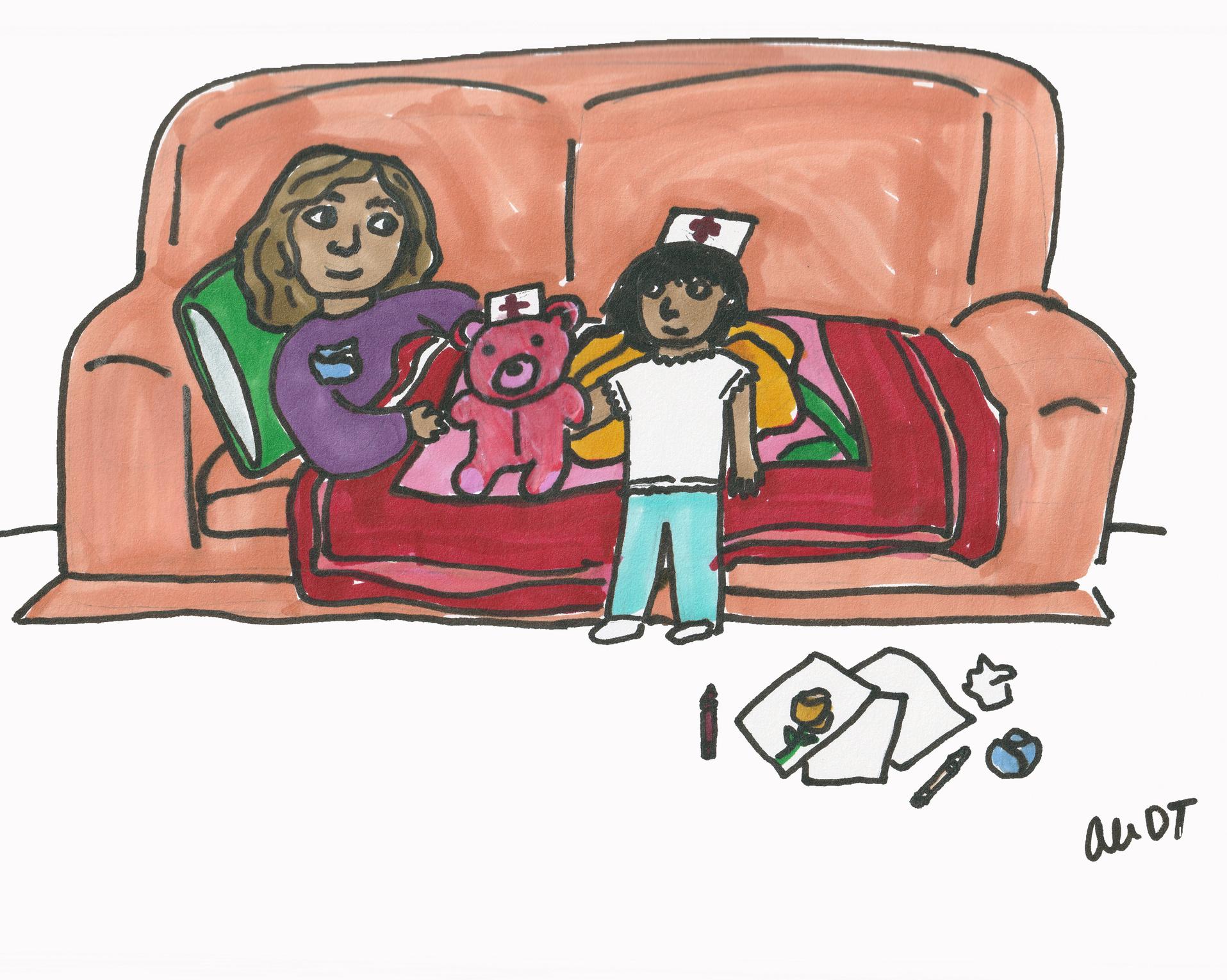

Pg. 3-4: Mami's Nurses by Ali Diaz-Tello (featured in cover art)

Pg. 5: My Location You Ask by Rainbow Alvarez

Pg. 6: Illusory World by Cindy Esperanza Sanchez

Pg. 7-8: Response to call out email by Naomi Ortiz

Pg. 9: In Your Garden by Cynthia Salazar

Pg. 10: Wired by Aura Valdes

Pg. 11-12: About the Contributors

Pg. 13: Image Descriptions

Pg 14: Works Cited + Disability Justice Watch & Reading List

Access the Audio Journal! spotify link: 1

“My Body Doesn’t Oppress Me, Society Does.” -Stacey Park Milbern

The state has a history of designating certain bodies as disabled in order to isolate, exploit, and exterminate them. During colonialism, any physical body that did not conform with that of the white masculine settler was deemed deviant and defective, including that of BIPOC laborers who were seemingly unproductive, women who were ‘unchaste,’ people that embodied racial-sexual differences, etc By ascribing value to people based on their level of productivity and proximity to hegemonic white behavior, colonialism set the terms for ableism

The colonial targeting of people marked as disabled is reproduced to this day, especially against those with physical and neurological impairments. Disabled people continue to experience violence, segregation, and sterilization in the United States and our Latinx communities/countries. Consider that people with disabilities represent about 50% of the incarcerated adult population and that the forced sterilization of disabled people is legal in most states. These conditions of violence and disposability are further entrenched under capitalism, which places the highest value on those people that live and work independently, and devalues those it deems “unproductive” and interdependent

If ableism is the product of colonial violence and capitalist isolation, then the project of Disability Justice must necessarily be an ANTICOLONIAL labor of love and interdependence. It is a worldbuilding project: it calls on us to build reciprocal relationships and intimate community networks which enable disabled folx to practice autonomy. It rejects individualistic definitions of autonomy and access because ableist paternalism/control is usurped when we collectively “transform the conditions that created inaccessibility in the first place ” It insists that time spent resting and caring for one another is generative, not counterproductive It rejects capitalist associations of value with commodity production and disposes of ableist constructions of beauty and wholeness It necessitates collective agency and care in place of state-sanctioned violence and ostracization.

It is also intersectional: Disability injustice is not an isolated issue; it is inextricably tied to racial and gendered notions of ‘deservingness’ and ‘redeemability.’ The work of Disability Justice is informed by Queer, Trans, and BIPOC organizations and leaders such as Sins Invalid, Mia Mingus, Alexa Arani, and Talia T.L. Lewis – who demonstrate that disability justice is about more than just access and education; it’s about confronting the carceral, class, racial, and gendered boundaries which construct our disabled bodies as ‘unwhole’ and ‘undeserving ’ It is also informed by a history of resistance in which generations of disabled QTPoC have asserted the wholeness of their bodies, and have worked to sustain one another in the face of ongoing colonial violence.

Therefore, this issue of Revista No’j is a love letter: it is a celebration of the deep love that we hold for our bodyminds. It is a site of recognition for the pain and vulnerability which makes us beautifully human. It is a record of the Disability Justice praxis that we engage in every day as we care for ourselves and one another

2

letter from the guest editor

6 4 1 2 3

Quetzal Ruvalcaba Guest Editor of Revista N’oj Issue

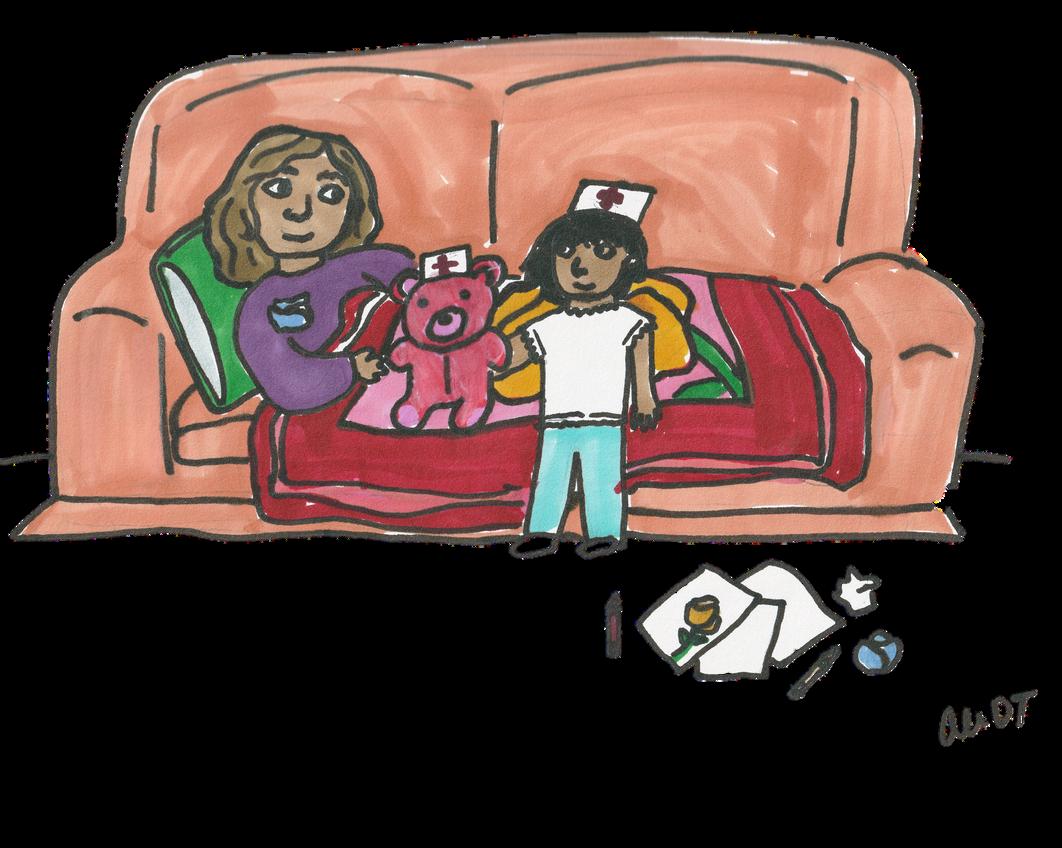

mami's nurses

by ali diaz-tello

3

artist statement

This illustration is a depiction of the healing we find in family. When I was a child and my mom had periods of being bedridden, I would make a nurse hat for my pink bear ‘Baby’ and for myself. We would stay by her side as her loving care team when she needed us.

My mom is of a generation and learned culture where being strong often entailed putting on a show and acting like nothing is wrong. However, I believe that sustainable strength comes from existing in vulnerability with others and allowing them to support and witness our healing. To this day, the days of Baby and I being my mom ' s nurses are core memories my mom and I still bond over.

d ote – my mom ’ s name is Rosie, and true to her he’s well known in our family for her knack for oses out of anything. Most notably, when I was often used lint from the dryer to craft roses, ctured next to me in the illustration. Roses are a mbol of resilience and beauty among hardship, which fits her perfectly.

4

my location you ask by rainbow alvarez

There are moments when I stare violently at the ground

In hopes that it will swallow me whole

To return to the comfort of the earth

Return & never be again birthed

But here I am fueled by the warmth of the sun

Looking for the guide within me

Trusting in the feelings that stir at my core

I will no longer seek truths outside of me, for those truths have run me ragged

When things calm in my mind & I close my eyes

I can see the cosmic energy that I am made of Covered in soil and sprinkles of gold, the armor of warriors before

5

illusory world by cindy esperanza sanchez

Never-ending pain. Nerve-ending pain.

I was a Brown girl gone white to the blood color of my oppressors. There was no amount of sunshine, vitamins, or love that could pause it. My disorder might not be terminal but God… do I wish it could kill me?

It brings out the worst in me. I stopped writing, painting, laughing. I snap, yell, and cry when all my elders want to do is love… love, understand, care for me. I am a “Brown” girl gone white to the blood color of my oppressors trying to live.

I’m sore, sore, sore… SOAR! I want to soar!

to fly over that rainbow and land in another world. A world where I have access to life, warmth. Sometimes my soul travels there. Is this the quantum nonlocality we speak about? the reason my bones ache? Help.

I just need help to get up every morning and brush my teeth.

I want sunshine. I need sunshine. My muscles are gray; my hair is tangled. They yell at me “reclaim! return! recover!”

I want copal to envelop me; take my breath away forever. How do I reclaim my body when it has a mind of its own?

It has scars I never asked for. It’s feeling pain even when I say “NO!”. My damaged cells, damaged tissues… They don’t listen to me. What happens if I surrender and reincarnate back? Forgive me. I have failed you in so many ways.

I swallowed the colonizers' poison and what little liberation I found, drifted away. The treacherous dangers disabled people endure every day is horrendous. This first-world space was meant to make you blind. I’m remembering how to write, paint, and love. I am

a Brown girl embracing Brown, watering our resilience.

4 5 6 6

by naomi ortiz

Intersectionality is such a radical goal for disability community because to be disabled in our society is still seen (by all communities) as a legitimate reason for segregation/se pa ra tion/exclusion. Many oppressed communities have, historically and currently, use disability to push away from. To differentiate their overall worth. For example, the women ’ s movement insists that pregnancy and menstruation is different than disability. Historically, then leveraging this difference to push away from disabled people, as a reason as to why they could work in the same jobs as men. (Obviously, not equating something like parental leave/maternity leave with accommodation.)

“I’m just X, I’m not disabled.”

I personally rarely talk about my family’s journey with being undocumented. Not because dominant culture has told me not to, but because folks who are part of undocumented organizers have pulled me aside and asked me not to or have publicly rebuked me as to not be associated with a “drain on society.”

Responsetocalloutemail

7

There are also several books, essays in academic journals, online writing, and discussions taking place about pathologizing racism as a disability. Or to a lesser extent equating ignorance and hatred with having an intellectual or psychiatric disability. These opinions/assertions, often coming from communities of color, queer community, Latin American immigrant communities, etc., as well as, mainstream society/dominant culture cause disabled people harm. As a disabled person to be included as part of my cultural communities (festivals, house parties, protests, organizing movements, art shows) requires addressing issues like access, desirability, work and productivity, vulnerability. Currently, cultural communities often automatically respond to these issues with defensiveness, hostility, and disdain.

Intersectionality work is radical because it is taking our place as disabled people within our other identity/cultural groups, asking to be embraced versus used as leverage would be a radical shift. For our cultural communities to align with vulnerability would challenge the standards of productivity, attractiveness, and the value of human life.

Intersectionality, including disability communities actually creates a foundation for collective liberation.

8

in your garden

by cynthia salazar

I would sit outside on my little garden chair and watch you talk to your plants

“

¿Mami, por qué le hablas a las plantas?”

s amigos.” You would tell me with a big grin. ched you admire your plants as a sign of love

Watering them growth

Talking to them for strength

As I got older, and your garden grew were moments when you stood in our kitchen And you carried this blankness in your eyes And off you went to your garden. When I noticed the same blankness in myself I went to your garden and hoped that I could find the love and growth

That your plants got from you. I didn’t.

Because along with all the herbs you planted, you planted your depression Deep into the ground.

You told me that your mother did the same, and her mother did the same. The blankness in our eyes was a connection to a line of women who struggled For recognition. Recognition in a world that told us that we had to bury our sorrows and our pain. That we were the outcasts in our feelings

.

As I start my own garden, I plant your herbs. I plant love and growth. I plant the resistance we both deserve.

9

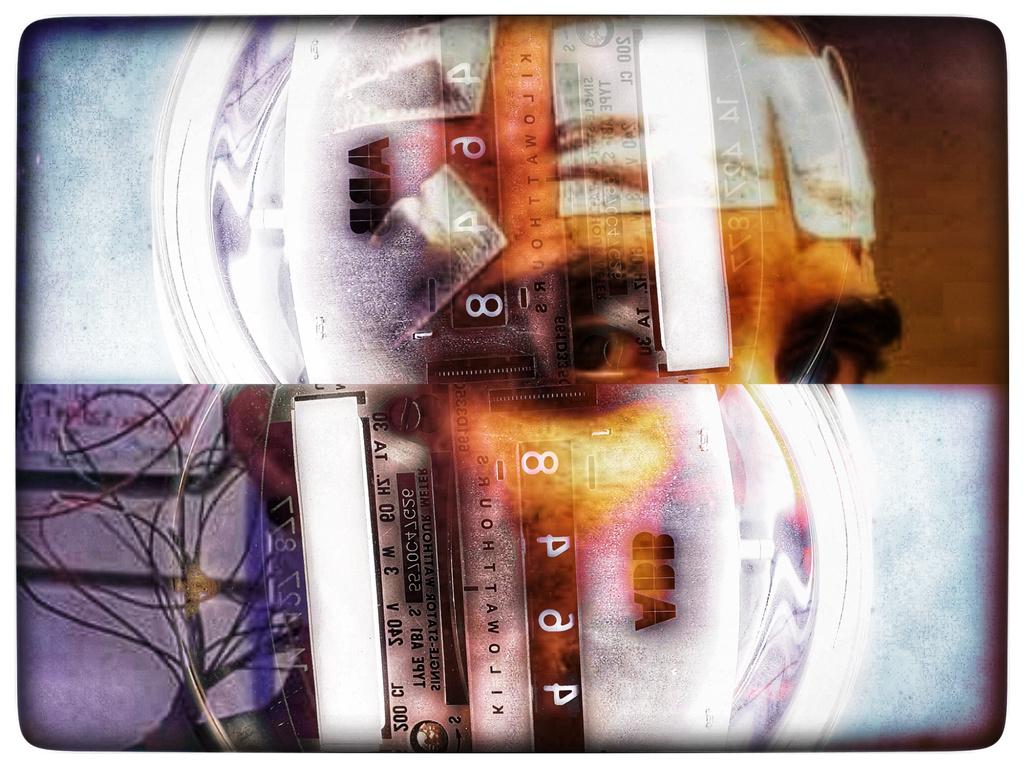

wired by aura valdes

What means interrupt ?

What means posterior ?

What means hemisphere ?

What means Sit ?

What means Queer?

What means fast ?

What means medication ?

What means Spike ?

What means Drowsy ?

What means amount abundant ?

What means abnormal ?

What means Queer?

10

about the contributors

Quetzal Ruvalcaba

Quetzal Ruvalcaba is a fourth year Ethnic Studies student at UC Berkeley She is particularly interested in the ways that the logics of coloniality are manifested in law, economy, and the criminal “justice” system. She was born with one hand and spent much of her youth denying her identity as disabled, frustrated by the infantilization (“pobrecita!”) and comments about her being “ an inspiration” that would follow whenever her disability was brought up in conversation. Studying Disability Justice has liberated her, teaching her that she does not need to be independent to be autonomous, and that the interdependence and care we show one another are the framework for a future free from colonial violence and capitalist prescriptions of worth. She celebrates her identity as a disabled Chicana, and dedicates this issue to her friends, family, and community who uplift her through gentle and reciprocal care.

Ali Diaz-Tello

Ali Diaz-Tello is a Mexican-Cuban-American graphic designer and artist with a special interest in the decolonization and destigmatization of mental health. She believes in the healing power of art and family, and her art can be found at @tia ali art on Instagram.

Rainbow Alvarez

Rainbow Alvarez is a senior at UC Berkeley and a transfer student from East Los Angeles Community College. She is majoring in Gender & Women's Studies. She identifies as a first-generation, DSP, EOP, system-impacted, re-entry student with dependents She boasts a strong background in community organizing for incarcerated folx and has worked as a service provider in the fields of domestic violence, human trafficking, and substance abuse While at Berkeley, she intends to bridge her experiences as a system-impacted and domestic violence survivor with her academics to destigmatize and uplift the communities she identifies with

Cindy Esperanza Sanchez

Cindy Esperanza Sánchez was born and half-raised in South Central/South East Los Angeles by a wonderful, loving, disabled Salvadoran mother Sanchez is a 5th-year senior transfer at UC Santa Barbara majoring in Chicanx and Spanish Studies Sanchez contends that her/their disenfranchised background enabled her/them to experience and understand hegemonic social dynamics from a young age As a result of living through these experiences, Cindy began to search for a cathartic way to heal and find community. Cindy is currently trying to care more for themselves and their community by practicing decolonial love in both soft and tough ways.

11

In order of presentation

about the contributors

In order of presentation

Naomi Ortiz

Naomi Ortiz (they/she) interrogates self-care, disability justice, and climate action through their poetry, writing, and visual art Ortiz is the author of Rituals for Climate Change: A Crip Struggle for Ecojustice (Punctum Books) and Sustaining Spirit: Self-Care for Social Justice (Reclamation Press). As a 2022 U.S. Artist Disability Futures Fellow and 2021-2023 Reclaiming the US/Mexico Border Narrative Grantee, Ortiz, a Disabled Mestize, explores the relationships between self, community, and place in the Arizona U.S./Mexico borderlands. www.NaomiOrtiz.com

Cynthia Salazar

Cynthia Salazar is a queer, Guatemalan, first gen, low-income, and re-entry transfer student at Cal from Fresno, CA Before transferring to Cal as a Gender and Women's studies major, Cynthia attended Fresno City College where she earned an AA in Law, Public Policy, and Society, and became a Cal-Law Scholar Cynthia has worked as a Social Media and Events Manager at Lush Cosmetics, where she curated social media posts and events that highlighted important issues such as immigration rights and reducing our carbon footprint; through this work found the importance of community engagement. Cynthia has supported asylum seekers as a volunteer at Esperanza Legal Services, where she assisted clients in completing their applications and preparing for trials. As a domestic and sexual abuse survivor, Cynthia has dedicated healing time to writing short stories and poems and hopes to continue doing similar work as this while at Cal. She hopes to self-publish a book of short stories and poems on this topic.

Aura Valdes

Aura Valdes is a Krip poet and Queer activist living in Tucson Arizona They are the host of QueerTrans summer, a virtual series for LGBTQIA community to explore rest, art, & creativity Aura has been featured at Tucson poetry fest, Gender Unbound Festival, Trans Symposium at University, and the first Disability Pride Festival in Tucson Arizona. In a recent piece, Aura writes "My work pieces together a narrative of queerness. My body was built for the in-between spaces and I am an expression of that."

12

image descriptions

Cover page

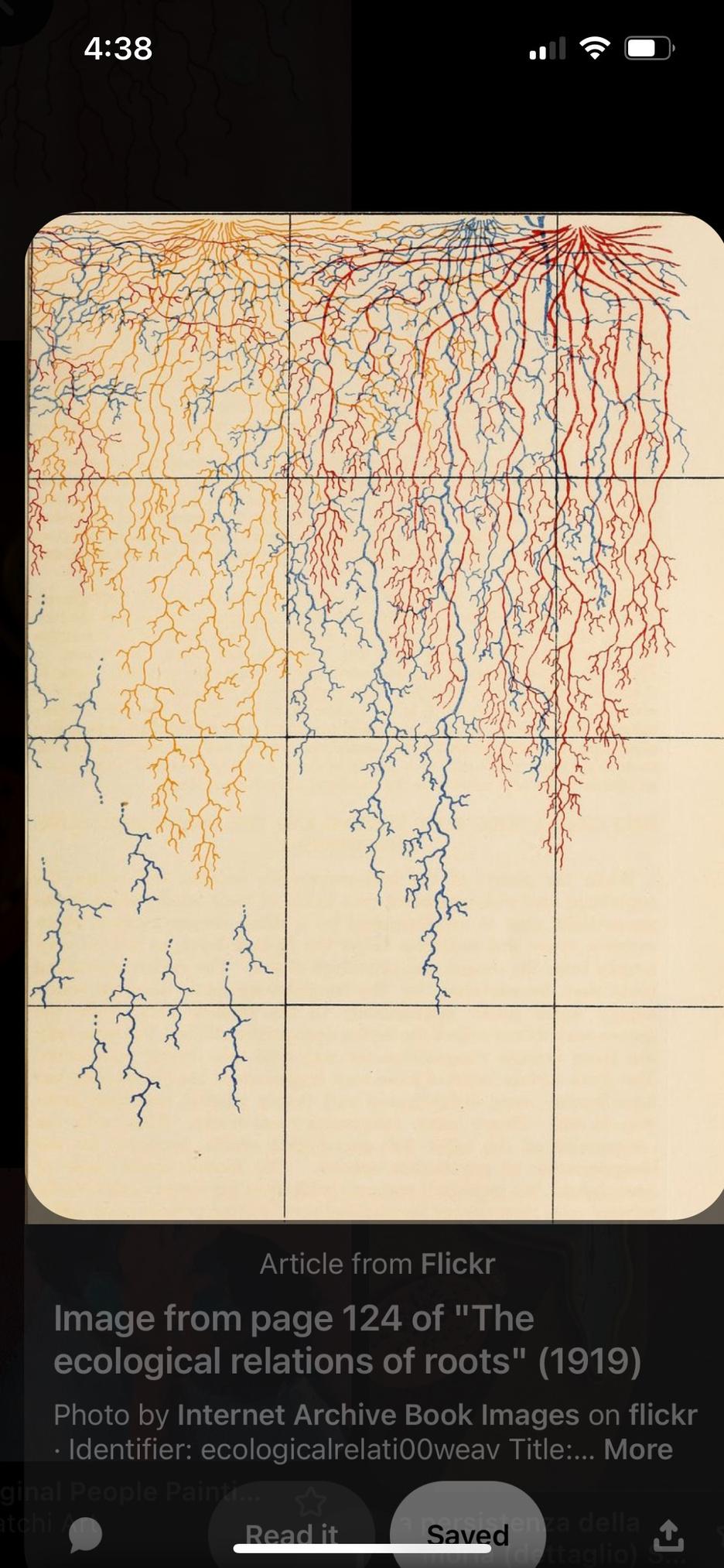

The cover page centers a collage with el sagrado corazón, Matisse’s Dance, a bouquet of yellow roses with a cempasúchil, a drawing of a demonic figure, a prosthetic arm, and a melting clock. The central image is the “Mami’s Nurses” drawing (see below). Underlying these images is a graph of intermixing root systems

Page 3: Mami's Nurses

The drawing features a woman lying under a blanket across a couch. A child, wearing a nurse ' s cap (white with a red cross), hands a pink teddy bear to the woman. The teddy bear also wears a nurse ' s cap. On the floor in front of them lies scattered pieces of paper, one with a yellow rose drawn on it. Next to the pages lies a blue rose constructed from dryer lint.

Page 5: My Location You Ask

The photo depicts a Pukapukara, an Incan fortress in Cusco, Perú The stone fortress is nestled between a lush green valley and a blue mountain range.

Page 6: Illusory World

The photo depicts a bright orange sunset over a green valley in Cusco, Perú

Page 9: In Your Garden

The image is of a bouquet composed of a sprig of white sage (with purple blossoms) and a single cempasúchil.

Page 10: Wired

The image depicts a face obscured with several measurement tools, including one which reads “killowatthours.” These tools obscure the back of the person ’ s head and their mouth entirely, with their eyes remaining uncovered. A number of twisted wires appear behind the figure’s head

13

Presley, R. (2019, October 29). "Decolonizing the Body: Indigenizing Our Approach to Disibility Studies " The Activist History Review https://activisthistory com/2019/10/29/decolonizing-thebody-indigenizing-our-approach-to-disability-studies/

Lewis, T (2020, October 6) "Disability Justice Is an Essential Part of Abolishing Police and Prisons." Medium. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://level.medium.com/disability-justice-is-an-essential-part-of-abolishing police-and-prisons-2b4a019b5730

Mingus, M (2017, April) Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice Paul K Longmore Lecture on Disability Studies San Francisco State University Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://leavingevidence wordpress com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-anddisability-justice/.

Moraga Cherríe, Anzaldúa Gloria, & Moraga, C (2015) "For the Color of My Mother " In This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (4th ed.). Essay, SUNY Press.

Miranda, D. A. (2022). Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir. Heyday.

Moraga Cherríe, Anzaldúa Gloria, & Moraga, C (2015) "La Guera " In This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (4th ed ) Essay, SUNY Press

works cited disability justice watch & reading list

watch list

Barnard Center for Research on Women, & Sins Invalid (2017) Political Education Video Collaborations with Barnard Center for Research on Women Sins Invalid Retrieved November 2, 2022, from https://www sinsinvalid org/politicaleducation

reading list

Arani, A (2022) "Abolitionist Care: Crip of Color Worldmaking in the U S -Mexico Borderlands " UC San Diego Retrieved from https://escholarship org/uc/item/2r2255zt

Berne, P , Morales, A L , Langstaff, D , & Invalid Sins (2018) "Ten Principles of Disability Justice " Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46(1/2), 227–230 https://www jstor org/stable/26421174

Kafai, S (2021) Crip kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid Arsenal Pulp Press.

Lewis, T. (2020, October 6). "Disability Justice Is an Essential Part of Abolishing Police and Prisons." Medium. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://level.medium.com/disability-justice-is-an-essential-part-of-abolishing police-and-prisons-2b4a019b5730

Mingus, M. (2017, April). Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice. Paul K. Longmore Lecture on Disability Studies. San Francisco State University. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-anddisability-justice/.

14

4 5 6

1 2 3