UPSHIFT MAGAZINE beyond driven limits

The Epic Journey of Frank Baker and Gérard Fabry

EDITOR’S LETTER

As summer ends, we reflect on a vibrant season and upcoming automotive celebrations.

SHIFTING

PERSPECTIVES

Meet our new exhibit through April 2026.

Learn about the Museum’s history 4 6

THE COMEBACK KID

The “new” Mini: global roots, iconic design, collectible sport models, and a growing enthusiast following.

Expanding the Museum’s reach to New England and beyond! 26

MOTOTOURS

ABOUT THE MUSEUM

TRACKING YOUR DAILY

Listen to Ana discuss continuous driver development, coaching, and consistent practice, both in and out of the car.

STARVING FOR CONTENT

A hidden gem in coastal New England: Sakonnet Gardens, a serene, meticulously crafted plant paradise. 16

The Volvo 122/Amazon offers classic style, dependability, and fun at an affordable price for enthusiasts. 20

AFFORDABLE CLASSICS

The Epic Journey of Frank Baker and Gérard Fabry 28

DRIVEN BEYOND LIMITS

THE CROWN JEWELS

Monterey Car Week auctions feature the world’s most glamorous, rare, and expensive collectible automobiles. 40

Rob restores a 1969 Lotus Elan +2, connecting with its past owners. 22

THE LOCAL HACK

REVIVING A CLASSIC

Aston Martin AMV8 Volante receives drivetrain upgrade at RS Williams, boosting power, performance, and driving experience. 51

Executive Editor

Sheldon Steele

Editor-in-chief

Andrew Newton

Art Director

Jenn Corriveau

Contributors

Andrew Newton

Ryan Phenegar

Rob Siegel

Stefan Lombard

Paul Knutrud

Ana K. Malone Oliver

Jenn Corriveau

Cover Photo

Jenn Corriveau

Photo Contributors

Ana Malone Oliver

Volvo

Ethan Pellegrino

Jenn Corriveau

Paul Knutrud

Rob Siegel

Clarus Multimedia

Dreamweaver Presents

Josh Sweeney

The Estate of F.E. Baker

Hagerty

RM Sotheby’s

Broad Arrow, Mecum

Gooding Christie’s

UpShift

Quarterly Publication of the Larz Anderson Auto Museum

Larz Anderson Auto Museum

Larz Anderson Park 15 Newton St. Brookline, MA 02445 | larzanderson.org

617-522-6547

UPSHIFT MAGAZINE

FROM THE EXECUTIVE EDITOR

As summer’s long shadows stretch into autumn, we at the Larz Anderson Auto Museum find ourselves reflecting on a season that has been nothing short of extraordinary. Our Lawn Events rumbled in with enthusiasm, none more so than an absolutely stellar Tutto Italiano, a celebration of Italian style, design, and spirit that left the Carriage House lawn shimmering in red, white, and green. This year’s Italian Car Day reminded us just how deep the passion for motoring runs in our community.

In this issue of UpShift, we turn our attention to stories that span the past, present, and future of the automotive world. From Affordable Classics that still stir the soul without emptying the wallet, to the painstaking beauty of an Aston Martin Restoration by one of our friends, to the crystal ball gazing of Future Classics, there’s something here for every enthusiast. The ever-entertaining Hack Mechanic returns with his signature blend of wit and wisdom, while our Monterey Auction Preview offers a tantalizing look at the machinery crossing the block on California’s most prestigious automotive stage.

Closer to home, we celebrate the artistry and engineering of our Japanese Car Exhibit, a fresh perspective on a segment of automotive history too often overlooked by some. Shifting Perspectives invites you to see the familiar in new ways, while Starving for Content and Tracking You Daily bring sharp, thoughtprovoking takes on car culture’s constant evolution. UpShift is, as always, the perfect mix of educational and entertaining, in other words, truly edutaining!

And the excitement doesn’t stop at the turn of the page. In the months ahead, the Carriage House will host a whole series of presentations, talks, and special programs that promise to inspire, inform, and ignite conversation. Whether you’ve been with us all season or are planning your first visit, I encourage you to join us, not just for the cars, but for the stories, camaraderie, and the shared passion that makes the Larz Anderson Auto Museum so unique.

See you on the Great Lawn, in the Carriage House, or on the road at a car event near or far!

Sheldon Steele Executive Editor Larz Anderson Auto Museum

MEET THE NEW EXHIBIT

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVES

CELEBRATING THE JAPANESE CAR REVOLUTION

WORDS: Ryan Phenegar |

PHOTOS: Jenn Corriveau

In the aftermath of World War II, Japan was economically devastated, but a spirit of resilience and innovation fueled its recovery. The automotive sector, supported by strategic government initiatives, became a pillar of industrial revitalization. Japanese automakers, initially seen as imitators of American and European brands, gradually forged a unique identity centered on efficiency, quality, and technological precision. At the heart of this revolution was the Toyota Production System, an approach that emphasized just-in-time manufacturing, continuous improvement, or kaizen, and empowering workers to halt production when problems were detected. This system revolutionized global manufacturing by proving that high quality could be achieved with less waste and greater adaptability.

Unlike many of their Western competitors, Japanese carmakers prioritized reliability, fuel efficiency, and affordability, qualities that became especially valuable during the 1973 oil crisis. While American automakers were producing large, gasguzzling vehicles, Japanese companies were ready with compact, efficient cars that met the new consumer demands. Cars like the Datsun 240Z, Subaru 360, and Honda Z600 quickly gained popularity, not just because of their economy, but because of their reputation for durability and minimal maintenance. These vehicles challenged the perception that affordability required

compromising quality. Over time, Japanese brands not only gained significant market share but also reshaped consumer expectations about what cars should deliver.

Japanese automakers also began to challenge traditional luxury brands with the launch of Lexus and Acura, proving that they could compete not just on price and efficiency, but on refinement, design, and technological sophistication. End products like the Lexus LFA and Acura NSX redefined the supercar market, merging high performance with Japanese reliability and steep price discounts when compared to their European competitors.

The legacy of the Japanese car revolution is seen in nearly every modern automobile factory. Principles such as lean manufacturing, total quality management, and employee involvement have been adopted worldwide. Japanese automakers didn’t just build reliable cars; they introduced a new philosophy of production, one that valued long-term thinking over short-term gains, and customer satisfaction over aggressive marketing. Stop by the Larz Anderson Auto Museum to see these automotive icons with our new exhibit, Shifting Perspectives: The Japanese Car Revolution, running from May 2025 to April 2026!

ABOUT THE MUSEUM

STEP INTO THE HISTORIC CARRIAGE HOUSE, HOME

TO “AMERICA’S OLDEST CAR COLLECTION,” AND EMBARK ON AN IMMERSIVE JOURNEY THROUGH THE RICH HISTORY OF AUTOMOTIVE INNOVATION.

The Larz Anderson Auto Museum is located in the lavish and original 1888 carriage house on the grounds of the former Weld Estate, now Larz Anderson Park, in Brookline, Massachusetts. The building was inspired by the Château de Chaumont-Sur-Loire in France and designed by Edmund M. Wheelwright, the city architect of Boston. First constructed as a working stable, it later served to house and maintain the Andersons’ growing collection of motorcars.

Larz and Isabel Anderson began their love affair with the automobile before the turn of the century. In 1899, soon after they married, they purchased a new Winton Runabout, a true horseless carriage. From 1899 to 1948, the Andersons purchased at least 32 new motorcars in addition to numerous carriages, thus creating “America’s Oldest Car Collection.”

As each car became obsolete, it would be retired to the Carriage House. By 1927, the Andersons began opening the building to the public for

tours of their “ancient” vehicles. When Isabel Anderson passed away in 1948, it was her wish that the motorcar collection be known as the “Larz Anderson Collection,” and that a separate non-profit organization be created to promote the mission of preserving the collection and automotive history. The grounds of Larz Anderson Park include a romantic pond, a picturesque view of the Boston skyline just four miles away, acres of lush open space with walking paths throughout, and an ice skating rink that is open to the public during the winter months. Today, the Carriage House is on the National Register of Historic Places. A landmark within the community and both a cultural and educational hub in the automotive world, it continues to house and preserve the fourteen motorcars that remain in the Larz Anderson Collection.

SECRET TO FAST LAPS

growth beyond the gas pedal

WORDS: Ana K Malone Oliver | PHOTOS: Clarus Multimedia Ana K

Malone Oliver & Dreamweaver Presents

The secret to improving lap times not only lies in fast tires and car upgrades but continuous driver improvement through coaching, out-of-car learning, and the application, practice, and repetition of new techniques. The mind of the driver needs to be modified and improved just like a car, and our goal as drivers should be to perform as optimally as we expect our cars to. My not-so-secret approach to becoming an advanced driver quickly–and continuing to improve even after earning that title–is that I’m always in the mindset, even outside the car: “What else can I learn? How else can I improve?”

One method that recently helped to boost my skills dramatically was a program through Porsche Car Club (the group I track with the most) called “ADX,” which stands for Advanced Driver Education. ADX is designed exclusively for advanced drivers, with a primary focus on stepping back from lap times to instead emphasize the goals of the driver, progress their skills, and hopefully, as a result, set faster lap times. ADX pairs drivers with a coach throughout a track weekend. Together, they will set goals, formulate a plan (which could include activities like the coach riding along for a session or on-

track driving exercises), and engage in debrief conversations following focused deliberate practice sessions where the driver executes specific advanced techniques or exercises that emphasize the driver’s sensory awareness, the car’s load transfer, or braking methodologies, just to name a few. Full completion of the ADX program occurs over two consecutive track weekends. For me, ADX kicked off the track season at my first event during Memorial Day weekend at Thompson Speedway, and then several weeks later, my second ADX session occurred at Palmer Motorsports–Clockwise.

My track season began shakily because I was relearning how to drive my car after upgrades made over the winter. The most significant change to the GTI was the conversion from the front single piston stock “big-brakes” to Neuspeed 6-piston calipers. This modification was necessary because the previous calipers needed rebuilding or replacement, and after years of troubleshooting overheating front brakes, I needed a new solution. Therefore, upgrading to the Neuspeed 6-piston calipers was a logical choice. This upgrade dramatically changed

First track weekend of the year at Thompson Speedway, CT. Photo courtesy of Clarus Multimedia.

Top: Personal Best data from the final session of second ADX weekend at Palmer MotorsportsADX (using the Garmin Catalyst).

Bottom: econd session ADX at Thompson Speedway. In this photo, you can see I am in the passenger seat and there are red gloves on the steering wheel. The coach was driving my car to test a theory (was the master cylinder the problem)? He drove the car perfectly. I was the problem. Photo courtesy of Dreamweaver Presents.

the pedal feel while driving on track. With the previous calipers, the pedal travel was long; now, it was minimal, forcing me to retrain muscle memory from scratch. But, most importantly, I had adapted my driving style to compensate for the old brake’s overheating: trail-braking every corner, lifting and coasting on long straights, and braking extremely early. Now, I could brake “normally”, but I had to relearn what that meant for the car.

The first ADX weekend was frustrating because I wasn’t utilizing my coach fully. Instead, we were revisiting basic braking techniques as I struggled like a “newbie” with my car. My driving was sub-par, far below the level I was accustomed to. It took three full days before I could confidently and smoothly brake at an advanced level. The second ADX weekend, though, was a success. I was once again driving my car with confidence and precision. My coach assigned several driving exercises, starting with vision– what am I looking at on track? Where should my eyes be? Are they looking up and ahead down the track? When I reliably kept my eyes up and down the track, I consistently gained speed.

Next, we selected three corners to improve and collected baseline speed data, known as “Vmin” (minimum velocity). The goal was to raise Vmin by initiating braking earlier and applying a lighter, longer brake. The exercise was very successful, as I did increase my Vmin in these corners. As cornering

speed increased, the car began to move and shift–almost dance-and for some drivers, this can feel unsettling because these movements sometimes require correcting oversteer, understeer, or loss of traction. However, in advanced driving, these car movements indicate the driver is operating at or near the vehicle’s limits–an ideal state for maximizing speed, provided you’re not sliding or drifting.

After completing these exercises, I was eager to test my skills and attempt a personal best. Due to circumstances beyond my control, my attempt occurred during the final session on the last day, far from ideal timing for a PR. Therefore, I planned to stay calm on track, keep my eyes up, practice my new skills, and see what magic might unfold.

Magic did indeed unfold.

The moral of the story? Driving is a journey of constant selfdevelopment–an ongoing push for improvement. We’re never finished learning. The art of driving on track is a continuous process of research, education, application, and practice. With dedication, determination, and devotion, magic can happen.

AVI provides bespoke performance car audio and video. We are capable of providing you with the latest technology and styles available for your vehicle You may add new components to your system or have it rebuilt from the ground up Our professional staff performs custom work at competitive prices

Locally owned and operated, AVI truly has all of the quality products and experience you need to personalize your car We pride ourselves on personalized service and helping make your automotive dreams reality.

We are open Monday through Friday from 8:00am to 5:00pm. Premium consultation services available on Saturday by appointment only.

FUTURE CLASSICS

THE COMEBACK KID with a union jack

It’s sort of fitting that the classic Mini—largely unchanged for 40 years— wrapped up production in 2000, just in time for the new one to start rolling off the line a year later.

WORDS: Andrew Newton | PHOTOS: Mini

If the original BMC Mini of 1959 was an icon of mid-century British-ness, then the “new” Mini of the early 2000s is perfectly emblematic of our current, globalized twenty-first century. These Minis of the new millennium played up their English heritage and rolled out of a factory in Oxford, but they had a German corporate parent (BMW). Their looks smartly echoed the original, but the shape came from a Moroccan-born, Spanish-American designer (Frank Stephenson). Its engine went in the same place as before, but it was one developed in part by both BMW and Chrysler, and it was assembled in Brazil. Even with all the corporate moves and its mixed heritage, though, it made an identity for itself, and Minis are still cars with personality. The first of these “new” Minis is also very close to turning 25 years old, which is usually around the time when an enthusiast car makes the transition from “used” to “collectible.”

In 1994, BMW bought out the Mini’s then-parent Rover Group, and by the 2002 model year was ready with its completely new version. While significantly more massive than the original, it was still conspicuously small by 2000s standards. Especially on the roads of the United States, where it

would be the first Mini officially sold since the ‘60s. “Retro” styling was a real trend in car design during the 1990s and 2000s, and while some of these retrostyled cars were little more than cynical nostalgia plays, the Mini was particularly well-executed, striking a fine balance of echoing the past while still being fresh enough to look contemporary. Its interior, too, with quirky details like the massive tach above the steering wheel and the roll cage-like door panels, was playful and has aged better than the dark, drab, plastic-and-cloth affairs of the German and Japanese cars the Mini competed with.

For our own market-focused purposes here, the Minis viewed as potential “classics” or “collectibles” in the future are going to be the sportiest models, namely the Cooper S and the John Cooper Works (JCW). The Cooper S came with a supercharger for its 1.6-liter four-cylinder, good for 163hp and 155 lb-ft. Not much in 2025 numbers, but right up there with the established sport compact cars of the day, and plenty to have fun with (0-60 in under seven seconds) while enjoying the whine of a supercharger and the tossable nature of a tiny hatchback riding on a short wheelbase. The Cooper S could be had with an automatic, but the 6-speed manual will be more desirable, more

fun, and likely more reliable. The JCW model, meanwhile, boosted things to 200-plus hp and came with John Cooper Works badging, and while the very first batch of JCW upgrades could only be had as a kit installed at the dealer, the JCW package soon became available straight from the factory. All were a bit pricy, though, and clean JCW cars are fairly rare. The first generation of the “new” Mini, aka the “BMW Mini,” got a facelift in 2005, but a second generation model came out in 2007. These models ditched the supercharger for a turbo in the Cooper S, a move which some enthusiasts lamented.

Early Minis are not exactly Civic-reliable and parts for them can get expensive, but a clean one can be a rewarding modern classic, and Minis have a fairly large, passionate, knowledgeable, and young fanbase of owners. At current values, it’s also hard to see them getting any cheaper. It would honestly be tough to find one for sale asking more than somewhere in the mid-teens, and solid ones with a little more wear and tear can sell for under five figures. The JCW commands a sizable premium of several grand, but they’re still solidly entry-level cars for the time being. Few properly fun cars offer the same kind of performance and style at such a low price, and as the supply of clean Minis dwindles from attrition, demand—and values—may just start to climb.

a secret garden, by the sea

Nestled in Little Compton, RI, and tucked by the sea lies a secret getaway called Sakonnet Gardens. This hidden gem sits quietly among native coastal fields.

WORDS & PHOTOS: Jenn Corriveau

Let me rewind. The drive to this storybook place is about an hour doorto-door from northern Rhode Island. It was a fairly uneventful trip, even on a summer Friday heading toward the beaches.

Once I got off the highway, the scenery began to change. The roads and homes were exactly what you’d picture when someone mentions a “coastal New England town.” There were narrow winding roads, antique houses clad in weathered gray cedar shakes, and impeccable landscaping.

Before arriving, I made a pit stop at a café in Tiverton called Groundswell. More compound than café, it includes a market, gift shop, and home goods store along with the Parisian-inspired café. When I arrived, I pulled into a crushed stone parking lot and wandered first into the market. Inside, I found an eclectic but carefully curated mix of books, artisanal cooking sauces, cheeses, and gifts. But as fun as it all was, I had one mission: coffee.

I meandered over to the café, and it was buzzing. People were grabbing food before heading to the beach, friends were catching up at bistro tables, and

the energy was warm and inviting. I ordered a vanilla latte, an açaí bowl, and a croissant. The coffee was rich, strong, and delicious. The açaí bowl wasn’t the frozen store-bought kind. It seemed homemade, garnished with fresh fruit, granola, and even flower petals. I loved it. But the croissant? Hands down, the most buttery, flaky, perfect croissant I’ve ever had. A true 10/10. I’m already planning my next visit. My favorite part? No laptops or tablets allowed. They want you to relax, breathe, and enjoy the moment.

Caffeinated and happy, I set out for the garden. It was only about 10 minutes away, but I drove by it three times because the sign is tiny. After finally spotting it, I pulled right in. It is a secret. As I walked toward a small group of people, three corgis greeted me. After getting acquainted with the cutest little guard dogs I’ve ever seen, I checked in with the owner, who, since I signed up early, knew my name right away. Pro tip: If you want to visit, sign up early. You can always adjust the time later. Admission is $25 per car and driver, with an additional charge for passengers. The parking lot is small, and the garden is only open Thursday through Saturday.

After a warm welcome, they told me to wander, so wander I did.

The garden began in the 1970s as a natural thicket of autumn olive trees, oriental bittersweet, and local arrowwood viburnums. Today, it spans over an acre, designed with “rooms” of different plants and species that evolved from the original growth.

This magical space is the long-term creation of John Gwynne (JAG) and Mikel Folcarelli (MF), along with Addie Kurz (John’s energetic sister) and Ed Bowen of Issima Nursery. John, a landscape architect, is deeply involved in global conservation education and local meadow restoration, while Mikel, a store design and brand identity consultant, manages much of the project and interior spaces.

As noted on their website: “Semi-hardy, zone 7 plants grow outdoors here due to the Gulf Stream proximity and high hedges and stone walls, which we hand-built to enable microclimate modifications. This is our personal and quixotic test garden. Thousands of rarely grown plants have been planted, moved, coddled, or weeded out in the last 35 years.”

Honestly, it’s one of the most beautiful places I have ever visited. It almost feels like being indoors, yet surrounded by nature. Benches are strategically placed throughout, offering perfect spots to pause and take it all in. Every plant is meticulously cared for, growing in a way that feels both natural and artful, some climbing over fences or spilling across benches.

The winding wooden paths, reminiscent of boardwalks at the beach, weave through the woods like a maze, always looping back to familiar trails. It’s clear this garden is the product of 50-plus years of vision and care.

If you’re ever in the area and want to experience a museum-quality garden that feels both secret and timeless, I can’t recommend Sakonnet Gardens enough.

SAKONNET GARDENS

A private garden located in Little Compton, RI. Reserve tickets at sakonnetgarden.net.

AFFORDABLE

CLASSICS

SEATBELTS & SWAGGER

MEET THE VOLVO AMAZON

WORDS: Andrew Newton | PHOTOS: Volvo

Volvo is perhaps best known in this country for the indestructible bricks it built from the 1970s to the 1990s, or for the understated yet graceful luxury vehicles it builds today. Sports car fans might also remember the svelte P1800 series from the ‘60s … and lament that 1800s just aren’t as cheap as they used to be. There is a sweet spot among vintage Volvos, however, in a car that offers lovely looks and proper fun with classic Swedish run-forever dependability, all at an affordable price. It’s the 1956-70 122 series, known in its home country and to Volvo nerds as the Amazon, after the race of lady warriors from Greek mythology.

The Amazon replaced the venerable PV544 in the Volvo lineup, offering more interior room, better visibility, and a much more graceful and curvy shape, reminiscent of a 1950s Chrysler, albeit on a much smaller platform. Body styles consisted of a two-door sedan, a fourdoor sedan, and a station wagon, while the B-Series four-cylinder overhead valve engine grew from 1.6 to 1.8 and finally 2.0 liters. Volvo had already built a reputation for selling rugged and dependable cars with models like the PV444 and PV544, and the Amazon furthered its reputation for safety by becoming the first automobile fitted with a three-point seatbelt as standard

equipment.

Dependability and seatbelts aren’t exactly sexy stuff, but the Amazon packed some surprising excitement under its steel Scandinavian skin. Testing one for a British newspaper shortly before he died in 1959, F1 champion Mike Hawthorn quipped: “Have you ever gulped at your glass of honest, sober ginger ale to discover that you have picked up someone’s neat Scotch by mistake? Well, that’s the shock I got when I tested a Volvo 122S the other day … The Volvo is a sensation of a car, and about as typical of its background as a battleship called Buttercup.”

Five decades and nearly 700,000 units later, the 122/Amazon remains a great entry-level classic. The moving parts are dependable, the cars enjoy reasonable parts availability, and there are specialists out there who work on and supply them. Being from a snowy country, vintage Volvos are also better rust-proofed than

most European cars from the 1960s. As for what to pay, the rarest and most valuable variants are the wagons and the factory sporty coupe model, called the 123GT. Very clean ones will sell for somewhere around $30,000, and driver quality ones in the low- to mid-$20K range. The standard two-door car carries similar but slightly lower values, while the four-door sedan can be had for under $20,000 in all but the very best condition. Few European cars from the swinging ‘60s have this level of look and fun factor combined with easy-to-live-with simplicity and an entry-level price point.

THE LOCAL HACK

WORDS & PHOTOS: Rob Siegel

As I wrote about for Upshift last year, on Halloween 2024, I bought what, for me, was a dream car—a 1969 Lotus Elan +2. I already owned a Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special (about which I spoke in a talk at Larz in 2022), but the first time I went to a Lotus event, I saw an Elan +2 and was instantly captivated. The car is not, as its name implies, simply a stretched Elan with a back seat. It is instead a different car, not just longer, but wider, and with a different body, glass, and interior. More than that, the +2 looks nothing like the Elan other than sharing the characteristic vintage Lotus grin. It instead looks, well, Italian, particularly the rear ¾ view.

Part of the lesson of reviving my Europa (which cost me $6000 to buy, I now have a total of $23,000 in it, and on a good day, it’s worth maybe half that) is that there’s no pretending that reviving a basket-case Elan +2 wouldn’t cost me similar. And there didn’t seem to be anything between basketcase +2s and the $25k market price. But I found one. It was being sold in southern NH by an estate-sale guy for the widow of the owner, who unfortunately had passed away in March 2024. When I asked him to tell me about the car, he rattled off its history back to four owners. He said that the late owner had bought it from his best friend, who had home-restored the car in 2011. The two of them drove the car multiple times to events at Lime Rock and at Larz Anderson, where, one year at British Car Day, it was voted Best Lotus. The car needed some recommissioning after having sat for a few years, but in addition, when I drove it, I found that it stank of mice, which gave me an opening to make an offer that put the car within reach. I never expected the widow to accept the offer, but the Larz connection turned out to be pivotal: When she heard my name, she said that her husband and his restorer friend had come to my Lotus

talk at Larz in 2022 and had chatted with me afterward, and that he’d be thrilled if he knew the car went to me.

I spent much of the winter sorting out the car. To de-mouse it, the heater box had to be removed and cleaned, but fortunately, the contamination hadn’t spread to porous areas like the rug, insulation, and headliner. The rest of the sort-out wasn’t bad. Once I replaced a bad universal joint in a set of aftermarket rear half-axles, I began driving the car in ever-widening circles around my home in West Newton to find out what else it needed. A hot-idling problem required more powerful electric fans to be mounted on the radiator. A no-spark problem that left me stranded was traced to a bad set of ignition points that only had 300 miles on them. (I then installed electronic ignition, as I do with most of my vintage cars.) A bevy of thunks, clunks, and rattles were identified and rectified. Pretty soon, I was venturing as far as I-495 and back again in the pretty little +2. It was beginning to feel

Just tell me that that doesn’t look like it should be wailing around Lake Como.

like a real car, not a project.

When I received the email about British Car Day at Larz Anderson in late June, I was all in. I left home early in a drizzle to get a good spot. Rather than panic about my pampered +2 getting wet, I instead loved the little slice of experience of what using the car as a daily driver would’ve been like 55 years ago.

By the time I arrived at Larz, the rain had stopped. I had brought a printed sheet listing the car’s two previous owners who’d been there many times, and put it on the dashboard, not realizing that there was a numbered card in the registration packet that I was supposed to use.

As Lotus Row filled in, I found myself between two screaming yellow scalpels that looked like they were going to carve and eat my little red jewel. But even flanked by high-dollar track weapons, the Elan +2 got a lot of attention, not just because it’s gorgeous, but because, even at British Car Day, people honestly didn’t know what it was. They didn’t ask “Which Lotus is this?” They asked, “What is it?” Part of this is because 50 years ago, cars weren’t designed for the goal of brand identification at the distance of a football field (okay, maybe Mercedes were), and the Lotus badging is subtle.

But the main reason the Elan +2 continues to not be well known, even in the vintage British car world, is that they didn’t sell a lot of them here. It’s believed that about 5200 Elan +2s were built from 1967 to 1975. The cars were sold in the U.S. through Lotus dealerships, but the exact number isn’t known. It’s likely multiples of orders of magnitude less than other ubiquitous marques like MG, Triumph, and Jaguar. And the number currently still on the road in the United States must be tiny.

As people swarmed the car, I told the story over and over of how I bought it, the tie-in to Larz Anderson, and how an Elan +2 is not a stretched Elan. And I allowed them to try it on. A 6’ 2” friend of mine showed up in his Europa, from which he needed to unfold himself reverse-origami style. He sat in the +2, stretched, smiled at the amount of room, and said “This is niiiiice.”

Halloween 2024 was a very good day for me.

But my favorite part was at the end of the day when a fellow parked next to me in an Elan roadster. Suddenly, I didn’t need to lecture people about how the +2 is a different car from the Elan. Everyone could simply see it. Even the pop-up headlights are a different shape.

The +2 didn’t win Best Lotus (though it might have had I remembered to put the card with the registration number on the dashboard). But I didn’t care in the least. The car felt like it had come back home to the place that made it happen.

It’s too bad I only met the previous owner that one time. But the chance meeting here at Larz that, three years later, led to me purchasing his pride and joy is the kind of automotive resonance you can usually only dream of.

I love your baby, Henry. It’s in good hands. —Rob

(Rob Siegel has been writing the column The Hack Mechanic™ for BMW CCA Roundel Magazine for almost 40 years, and is the author of eight automotive books.)

Left: This bucolic scene in Lincoln was marred by the fact that the hood was up because the ignition had died. Right: It’s important to be true to your roots.

Rain, rain go away!

Left: Definitely not your usual 2+2.

Right: Evora to the left of me, Emira to the right, here I am.

MOTOTOURS

AT THE LARZ ANDERSON AUTO MUSEUM

Expanding Our Reach to the Greater New England Area

WORDS: Ryan Phenegar | PHOTOS: Josh Sweeney

The Larz Anderson Auto Museum’s MotoTours have long extended the museum’s reach far beyond the Boston area, connecting the joy of motoring with the beauty of New England’s roads. Each year, our driving events team curates experiences that celebrate the automobile, not just as a machine, but as a bridge to people, places, and unforgettable moments. From single-day cruises through Massachusetts to multi-day excursions to the Northeast’s finest resorts, every tour offers something special, whether you’re a seasoned enthusiast or simply someone who loves the open road.

This year’s tours demonstrated the power of these drives in building community. The first route wound from Concord, MA, to Barre, MA, following scenic state routes and winding back roads until we arrived at Stone Cow Brewery, a 1,000acre dairy farm operating since 1938. Over craft beer and hearty food, drivers swapped stories, compared notes from Subaru BRZs to vintage Porsche 911s, and reflected on their favorite stretches of the route. It was more than just a drive; it was the creation of shared memories. The second tour began at Garage42 in Acton, MA, and carved its way to Jaffrey,

NH, threading through forested twisties and rolling hills. From a stately 1970s Maserati to nimble Mazda Miatas and sleek Ferrari F8 Tributos, the eclectic lineup underscored how accessible these tours are for all. At the Dublin Road Taproom, overlooking the Shattuck Golf Club with Mt. Monadnock rising in the background, the conversations naturally shifted to when and where the next drive should be. The desire for more was unanimous.

That desire will be fulfilled in grand style with the 2025 Annual Tom Larsen Moto Tour, an all-inclusive journey through northern New England that promises luxury stays, gourmet dining, historic stops, and exhilarating driving. Kicking off September 6 in Burlington, Vermont, the adventure begins with an exclusive tour of Beta Technologies’ electric airplane factory, followed by an evening at the Von Trapp Family Lodge in Stowe. The days ahead will bring group hikes, cheese tastings, legendary mountain roads, and a grand banquet at the historic Omni Mount Washington Hotel, the same venue that hosted the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference. The finale, a sweeping run through the White Mountains and along the Kancamagus Highway, will close with a farewell lunch at a friend’s farm in southern New Hampshire.

Year after year, the Larz Anderson MotoTours remind us that the true magic of driving lies not just in the road beneath us, but in the friendships we forge along the way. In 2025, that magic will be alive again, rich with history, scenery, and the shared joy of the journey.

DRIVEN BEYOND LIMITS

The Epic Journey of Frank Baker and Gérard Fabry

WORDS: Stefan Lombard | PHOTOS: The Estate of F.E. Baker & Hagerty

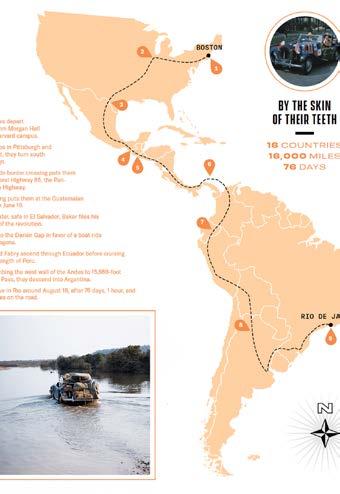

By June 19, 1954, the day Frank Baker and Gérard Fabry arrived in their MG TD at the northwest border of Guatemala, the wet-season rains of the Southern Hemisphere were in full swing. All the first-year Harvard Business students wanted was to get to Brazil, but their timing could not have been worse. Already 16 days and 5000 miles into their trip, as they idled in the downpour at the guard station, the real adventure was just beginning—one that would press their and the car’s limits. What happened next is a story that has outlived them both.

The particulars of the conversation are lost to time. But we know that as Baker and Fabry walked together across campus one crisp autumn day in 1953, they discussed the idea of legacy, of challenging themselves to do something important before their adult lives took over.

Baker, an American, and Fabry, a Frenchman, were 24 years old, each naval veterans of their respective countries, so they had already done plenty that mattered. They were both car guys, too, and in the early 1950s, before the construction of vast, interconnected highways, driving anywhere far still carried the promise of the unknown and a whiff of danger.

We know that their conversation

concluded with an agreement to forgo the usual B-school summer internships at J.P. Morgan or Procter & Gamble and instead do what felt important: In the spring, they would drive to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Both were interested in learning something about Latin America, and they believed they might help to educate others upon their return. A story published at the time of their journey in the Boston Globe noted they hoped to “compile information for a book, lectures, and articles.” “But mostly,” the story concluded, “they just want to be the first ever to succeed in driving from the United States to South America.”

The publicity wasn’t incidental: Some 50 years before anyone had thought of becoming a social media influencer, they set out on a full-blown campaign of letter writing, phone calls, and handshakes to get the whole enterprise off the ground. They enlisted Baker’s undergrad roommate, Bruin Hall, to help promote them to the press, and a Boston speakers bureau, Lordly & Dame, to book speaking engagements upon their return. Baker, an editor of the Harvard Lampoon, got himself an International News Service (INS) press pass, with plans to post stories along the way. They applied for all the entry and exit visas they’d need. And they secured sponsorships from the American Automobile Association, from Dunlop Tires, and from MG, from which they purchased a 1953 TD.

By the early 1950s, MG had cemented its reputation in America for building spartan, diminutive sports cars that did everything well (barring, perhaps, weather protection). The right-handdrive TCs that had followed American GIs home across the Atlantic after World War II soon evolved into the left-hand-

drive TD for 1950. Power came from MG’s tough-to-kill 54-hp 1250-cc XPAG four-cylinder; rack-and-pinion steering, a rarity on contemporary American cars, helped to make it nimble, just the thing for the racetracks and jungle tracks of the Western Hemisphere.

Yet the little sports car also appealed to the duo for all that it lacked. “Going down with any comforts is like climbing Mount Everest in a helicopter, or fishing for brook trout with deep-sea tackle. It just isn’t sport,” Baker told the Boston Traveler, in a piece published 10 days before the trip commenced.

Throughout the winter of ’54 and into the early spring, the Harvard men mapped out a route that included 10,000 miles of unpaved roads and 400 miles of roadless jungle, through a total of 16 countries. Baker would serve as mechanic and Fabry as interpreter. They reckoned the trek would take 100 days, at a cost of roughly $3000 apiece (about $35,000 in today’s dollars).

On June 3, 1954, sporting pith helmets and smoking pipes, before a small gathering of friends and classmates, Baker and Fabry departed from Harvard’s Morgan Hall in their British sports car, which was cloaked in the crisp, bright flags of the Americas and loaded to within an inch of its life with a two-person Army tent, a gas stove, four 15-gallon jerrycans of fuel, four spare Dunlops, 5 gallons of water, essential spare parts, a shotgun, and a machete. If ever there was an ideal “Before” photo, this was it.

The Boston Traveler warned, “This journey probably sounds like a lead-pipe cinch, a real joy ride. Don’t be fooled. First of all, this is a special jaunt no one has yet attempted. The boys have only a few maps and AAA descriptions to

rely on…”

“Among hazards they will face,” added a piece in the Brazil Daily Times (that’s Brazil, Indiana, of course), “are stretches of scorching deserts, tropical storms, poisonous insects, and the heavy snows of the Chilean Andes at an altitude of more than 15,000 feet.” Pre-trip prep included inoculations for tetanus, typhoid, epidemic typhus, smallpox, and yellow fever. “They are continually popping anti-malaria pills down their throats,” said the Traveler. Failure was not an option: “This is one course we expect to pass,” Baker stated.

The initial part of the journey, in the United States, seemed to have been largely uneventful. Though America was still two years from the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act—which would give us the 45,000-mile Interstate Highway System that today connects everyone to everything—by 1954, crosscountry travel wasn’t quite the roughand-tumble experience it had been just a few decades earlier. From Boston, they

passed New York, crossed Pennsylvania, and spent the first night in Pittsburgh, where the Pittsburgh Press reported that “clothing for each is limited to two shirts, two pairs of pants, tropical hat, dust mask, and a heavy jacket… Food will consist of Army C-rations supplemented with whatever edibles are obtainable en route.”

In Cleveland the next day, where the Plain Dealer provided coverage, Baker and Fabry “paused here long enough to have their pictures taken, leave their press statements and visit a handy television station before plunging into the darkness toward Chicago.” From Chicago, they turned south to pass through St. Louis and Fayetteville, Arkansas, to Dallas, San Antonio, and, finally, the border at Laredo.

They crossed onto Mexico’s Federal Highway

85, part of the Pan-American Highway network first proposed in 1923, which ran, tentatively and incompletely—but always with grand plans—from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to Tierra del Fuego in Argentina. Mexico had completed its section of the route in 1950, the very same roadways that hosted the fifth and final Carrera Panamericana race later that year. Baker and Fabry’s grand plan had always been to average 160 miles a day, and this route would have helped them do that. Through Mexico, anyway.

Southwest to Monterrey they went, then to Mexico City and Oaxaca, and on into the mountains of Chiapas, where they crossed the Continental Divide before arriving at the southern border town of Tapachula. From there, Baker steered the stout TD into Guatemala, where—for reasons neither could have foreseen—their adventure would begin in earnest.

In 1954, Guatemala was in its infancy as a democracy. Four years prior, Jacobo Árbenz had become the country’s second democratically elected president, and he continued to carry out and expand the social reforms enacted by his predecessor, namely allowing public debate and workers to organize, growing wages, and expanding voting rights. Árbenz, a moderate capitalist, also initiated major agrarian reforms, which had been a key platform of his candidacy. In a country where 2 percent of the population owned 70 percent of the land, he began to expropriate uncultivated tracts from large landowners in exchange

for compensation. He then redistributed the land to nearly half a million peasants, many of them displaced Indigenous peoples.

The biggest landowner Árbenz came up against in his noble doings was United Fruit Company, the American corporation that controlled the banana trade and 3.5 million acres throughout Central America. In Guatemala, it owned 42 percent of the land, as well as the rail lines and telephone and telegraph systems. Shouting at the top of their corporate lungs the era’s most in-vogue accusation—many of the May/June news stories about Baker and Fabry’s trip shared real estate on the page with updates on the Army-McCarthy hearings—the banana republicans at United Fruit appealed directly to good friend President Dwight D. Eisenhower for help in dispensing with that Communist in Guatemala.

And so, on Friday, June 18, one day before the MG-shaped pack mule carrying Frank Baker and Gerry Fabry crossed into the country from Mexico, Operation PBSuccess saw CIA-trained rebels (reports vary between 150 and 480 men) follow a disgruntled Guatemalan military officer named Carlos Castillo Armas into the country from the east. Accompanied by

strategic American bombing and strategic American propaganda, Armas and the rebels were able to take Guatemala City in just nine days. Árbenz went into exile, and by early July, Armas had declared himself president.

While the rebel march to the capital was relatively easy, as the teeth of the revolution bit down on them, Baker and Fabry had a considerably harder time getting there. Baker’s account, dictated to the INS wire via telephone, was picked up by papers large and small across America.

“I have just driven through the western part of war-torn Guatemala,” Baker began,

“and along with a companion have been arrested, manhandled, and put under almost constant police guard among trigger-happy police and peasants…

“The customs men made us drive into a big, dark building. They stood on a platform above us with guns, machetes, and knotted rubber hoses in their pockets.

“They pulled everything out of the car. They frisked us, even examined the lining of our coats.

“We explained to them that we were

‘just college guys on a vacation.’” Baker said they were allowed to keep their cameras but had their pocketknives confiscated, and “after many hours of questioning and examination of our papers, they let us into the country with a warning that ‘North Americans are not wanted in Guatemala.’”

They might not have been wanted, but for reasons we’ll never know and can only surmise—namely, grit—the two young men were undeterred, and it seems turning back never entered the equation. Over the next couple of days, as Baker and Fabry tried to get to Guatemala City, about 175 miles away, similar scenarios played out dozens of times—roadblocks operated by wary barefoot peasants loyal to their president—“citizens committees”—searching them, searching the car. “They were dressed in rags but were armed with revolvers, tommy guns, and double-edged machetes,” Baker said. “The way some of the wilder ones would wield those machetes close to your head, you’d wonder if you’d ever see home again,” he added in a later report.

In one stretch of countryside, they were shot at. In a small town, they were taken to police headquarters and questioned for two hours by the chief, who informed them they had no constitutional guarantees and could be arrested at any time by anyone. “All towns are guarded,” he told them. “No one is allowed to drive across the country.” Then he kept them under house arrest for the night, questioning them once more and again in the morning before letting them go.

They weren’t allowed to drive across the country, but that is exactly what they did: Very slowly and with great difficulty, the TD soldiered on. In Antigua, they were fired upon again. “When we stopped, the police pulled us out of our car and shoved us down in the dirt,” Baker reported. Again, they were searched, again the car was searched, again they were dragged away to a headquarters to be questioned for hours and then put under house arrest for the night. Again, they were allowed to leave in the morning.

They did their best to dodge patrols, but the entire country was on patrol, and 5 miles from Guatemala City, they were caught again, this time by government troops. This time, when questioned, however, Fabry lied and told them they were both French. Sacre bleu! Much to the great delight of the young men, it worked, sort of. “The regular troops agreed to give us protection to get into Guatemala City,” Baker said. “We were given a police escort the rest of the way, and these men turned us over to the city police, the Guardia Civil.” Once released, the two weary travelers took a room at the Hotel Florida, determined to figure out their next move as Guatemala collapsed around them.

In the capital, the threat of bombing from enemy (that is to say, American) planes was ever-present, even though Baker said it never happened. Still, Baker told the Boston Traveler in a later interview, “In one three-day period, the Communists shot off a thousand rounds of ammunition a night. They would shoot up and down the streets at anything that moved…” Often, he added, “you’d see long black cars charging from embassy to embassy at 80 miles an hour.” Baker had been snapping photos for much of the journey, and now that they were off the road, finally able to breathe and get their bearings, he brought some film to a place to have it developed, which proved to be a mistake. “The fellow who ran the developing shop turned us in,” Baker told the Boston Traveler later that fall. “Fabry and I were taken to the chief of the secret police.” There they were searched, then escorted back to the hotel, where two police officers ransacked their room.

Right about then, mid-morning on June 22, there was a knock on the door.

Fred Sparks was a swashbuckling foreign correspondent for the Chicago Daily News who cut his teeth covering the American occupation of Germany in the wake of World War II. He bounced around then, contributing stories both serious and humorous to various outlets, including Esquire magazine. He was one of six journalists to win a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his early coverage of the Korean War. A 1994 New York Times story claimed that Sparks “rarely missed a revolution”—and that he was rarely without an umbrella. “After covering a good many revolutions,” Sparks once told a young reporter, “I’ve noticed that no one ever shoots at a man carrying an umbrella.”

Naturally, Sparks and his umbrella were in rainy Guatemala City in June 1954 when the fledgling democracy went sideways. And naturally, his reporter’s nose led him (along with a fellow reporter, Briton Patrick Catling) to the Hotel Florida on the morning when Frank Baker and Gerry Fabry were holed up in their humid, tiny room, under the watchful gaze of the local constabulary.

“We wanted to chat with a Harvard student named Frank Baker, who had just arrived from the Mexican border on an automobile tour of Latin America,” Sparks wrote in his syndicated dispatch, which was framed as a chummy letter to his boss. He referred to Baker as “a 6-foot husky.”

“As we walked into Baker’s room, we found him sitting on his bed with his driving companion, a young Frenchman. Two plain-clothesmen were in the room. I asked them, ‘Who are you?’ One of the men stepped forward and flashed a small badge. It looked like the kind of detective badge you get for 100 box tops and a dime.”

Sparks reported that all of the young men’s things were spread out across the room, much of it—their tent, their combat boots—the kind of things one could get at an army surplus store for camping. “But stretched out here in Guatemala on the floor of the Hotel Florida under the suspicious eyes of those two plainclothesmen, it sure looked like military gear.”

It didn’t help that much of Baker’s gear was stamped “U.S. Navy,” courtesy of his time in the service. “They thought we were American soldiers, or at least aides of Castillo Armas, the insurgent leader,” he told the Traveler. “They were convinced I was connected with the American ‘fifth column,’—that I had been dropped from a plane.”

Despite the deep suspicions of the two cops in the room, Sparks noted they were at least respectful and added, “After all, how would we have acted in 1941 if we’d picked up a couple of Heidelberg U. boys touring the USA in similar circumstances?” As material shortages had already begun to grip the country, however, he also noted they took two rolls of toilet paper before they “invited” Baker, Fabry, Catling, and himself to accompany them to the police station.

Sparks was detained for half an hour. “But the police liked my pictures so much they kept the film.” For their part, Baker and Fabry were bailed out by an American embassy attache whom Sparks knew, and that seems to be the last the men saw of each other. Sparks went on to grab dinner at a nearby restaurant, which was interrupted by a power outage and then gunshots. “We thought we’d better hit the floor,” he told his boss, “but I do digest poorly on the floor.”

Baker and Fabry, on the other hand, were told in no uncertain terms by “the Communists” to get out of the country, which was far easier said than done. They were issued a safe conduct pass to the border,

which they put no faith in, given the difficulties they’d already faced. And they knew it was no guarantee to get them over the border and into El Salvador once they’d arrived. If they arrived. But Fabry, ever resourceful, had noticed a pile of exit visas sitting unguarded in the customs office at the embassy and pocketed one. That, they hoped, would get them out.

The only thing standing in their way was 120 miles of hostile road between the capital and El Salvador. That evening, as they reorganized and repacked all their belongings in the Hotel Florida, their MG was a curious sight parked out front. Thunder rolled in, and it began to rain again. Hard.

With the entire city under blackout and a tropical storm pounding the country, three hours before dawn on June 23, Baker and Fabry crept out of the hotel, hastily loaded up the MG, and made their way east. In that direction lay El Salvador, but also, quite inconveniently, the brunt of the rebel siege making its way toward the capital. Fuel had been shut off, and Americans were forbidden from traveling—but, as Baker reported in a story titled “Two Students Run Civil War Gantlet” that was picked up by the Lubbock Morning Avalanche on June 26, “We took this opportunity because police patrols would be indoors.”

All the main roads were heavily fortified and reserved for military traffic, so they stuck to back roads, the MG’s skinny tires slicing through mud, its tiny windshield wipers struggling to keep up as they sped along in the night. The area they traversed had been under attack by enemy planes, and now and then the men craned their necks beneath the TD’s feeble top to look skyward, but darkness and the cloud cover prevented them from seeing much. They pressed on, counted their blessings, and hoped not to get strafed.

Eventually, even the back roads led to heavily guarded fortifications. For a time, at least, so long as Baker kept silent, Fabry spoke French, and they flashed the

safe conduct pass, the combination was enough to get them through. Their luck ran out at Jutiapa, about 25 miles from the border. “This town was expected to be the first target of the rebels,” Baker said. “It had received considerable bombing. We were caught approaching it and taken to the colonel in charge,” a tall mustachioed man who “wore cavalry boots and carried pearl-handled pistols.” The colonel had been educated in America and spoke good English, and although he explained that many rebels were trying to get into the country disguised as tourists, he believed them when they said they were only students passing through. To help them on their way, he ordered guards to escort them to the border—and to ensure they “did not take any pictures or see too much.” “Many boxes of ammunition were stacked against the sides of buildings along the route,” Baker noted, with sandbags and rock piles erected as interior defenses and sentries carrying foreign-made automatic weapons. Below Jutiapa, all the villages he could see had been barricaded with rocks and logs, and all the people in them stood by on high alert, armed with machetes, knives, and pistols to defend their homes. “Local villagers trust no one,” Baker reported. “We would never have gotten through without the guards. If you are a foreigner, it is enough to start them swinging machetes.” Even still, at each successive barricade, “about 50 men would rush at the car” and tear apart the men’s baggage looking for weapons. “The guards would let them do this but kept them from harming us.”

Finally, they reached the border, and a guard there asked for their papers. Baker presented the exit visa Fabry had swiped the day before. “He looked at the seal and the signature but did not check the name. He waved us on, and we burned

up the road getting to the El Salvador side,” Baker said. “It felt mighty good to be out of the revolution.”

If Guatemala had been a gauntlet, and indeed it was, then certainly the remaining 10,000 or so miles that still lay ahead for the MG of Baker and Fabry would be a relative Sunday drive, rainy roadless jungle notwithstanding. But for a bent muffler and a leaky transmission housing brought on by impact with a rock, the MG remained ever reliable. At some point, they picked up a roll of chicken wire to unfurl as a traction device in particularly sticky situations, and they were back to camping out roadside in the two-person tent and cooking over the single-burner gas stove. Through El Salvador they went, where, like Mexico, the entire section of the Pan-American Highway was paved. They stopped in San Salvador, the capital, just long enough for Frank Baker to file his harrowing account of the previous week’s events via telephone. They then crossed into Honduras, rounding the Gulf of Fonseca, and went over the border into Nicaragua, where they would have passed through Managua on a brief paved section in the east and then driven the long shoreline of Lago Cocibolca before entering Costa Rica.

By the 1950s, for citizens with means, the cars of Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler dominated the roads of Latin America. Big Three ubiquity had been one of the primary goals of the PanAmerican Highway, and as a result, Ford had been building cars in Brazil since 1919 and in Mexico since 1925. GM was up and running in Brazil by 1925 and in Mexico by the mid-1930s, which is also when Chrysler began its Mexican operations. By contrast, Volkswagen didn’t open its first plant in Brazil until 1953.

Outside of cities, most of the citizenry lived in poverty and got around on foot, on horseback, on bicycles, perhaps aboard the occasional small-bore motorcycle. What a sight it must have been, then, to see the laden MG trundling along among the Tudors and old Ts, the Fleetlines and Capitol Express trucks, the Cranbrooks and DR sedans of the day.

“Most of the roads are about one car wide and follow along steep hills,” Baker later told the Boston Traveler. “If a car comes in the opposite direction, you blow your horn, stop, and get out with your machete to discuss who goes ahead. There is prestige in a big machete,” he continued. “The sign of peace is to put the instrument on the ground. All the ones we met were reasonable, fortunately.”

It was jungle and more jungle through Panama, and more than once, they enlisted locals (and their beasts of burden) to help pull them through stretches of muck that had defeated the chicken wire and threatened to swallow the car whole. Elsewhere, they waded the car through flooded crossings, sometimes hundreds of feet long. Given the low-slung stature of the TD and the requisite height of its door sills, it’s not hard to imagine soaked footwells, sodden feet, and booming laughter at the ridiculous fun of it all. And all the while, the chugging four-cylinder up front gave no complaints.

After what must have seemed like an endless, slow-going slog through the tropics, Baker, Fabry, and the MG entered Panama City and, rather than continuing south, most likely they hung a left and took the transisthmian route up to the coastal Caribbean city of Colón.

They had only barely survived the trek through Guatemala; they had no interest in rolling the dice again through the Darién Gap. Then as now, the Darién Gap is a roughly 70mile section of unnavigable, mountainous, swampy, unstable Panamanian jungle that adjoins Colombia’s equally uninviting Chocó region, with the border lying somewhere in between. To date, this area remains the only place in the world where two neighboring countries lack a single road that connects them. For decades, everhopeful politicians and overly confident developers dreamed of getting a road in there to link the Western Hemisphere end to end, to complete the Pan-American Highway at last, but the efforts were blocked for various reasons over the years (the sheer squishiness of the earth, for starters) and petered out for good by the late 1970s, thanks ultimately to legal arguments that the Gap served as an effective deterrent against the spread of hoofand-mouth disease.

Inaccessibility and viral contagion had never been a part of Land Rover’s vocabulary, and the marque’s 1971–72 effort to drive a pair of new Range Rovers the 19,000-mile length of the PanAmerican Highway, including the Darién Gap, is its grueling feat. In all, it took the British TransAmericas Expedition 96 days to traverse the Gap, accompanied by 64 men cutting a path and heaveho-ing, plus 30 horses hauling supplies and also probably heave-ho-ing in particularly sticky spots.

In 1954, our intrepid explorers had no men, they had no horses, and they certainly didn’t have that kind of time. What they had instead when they reached Colón was petty cash and crossed fingers, and there they engaged a crew with a dockside crane to load the MG onto a small wooden cargo boat, aboard which they secured passage for themselves and the car out to a coastal steamer for a ship-to-ship transfer, before riding it across the Caribbean to arrive a few days later in Cartagena, Colombia.

Once off-loaded, the pair made their way back to the Pan-American Highway in Medellin and headed south out of Colombia, ascending to the Ecuador border, into the Andean foothills, and Quito just beyond. A long, gradual descent into Peru would have taken them just about to sea level, where they had the mountains on their left, the Pacific on their right, and shimmering fresh pavement for 600 miles, from Piura to Lima, the capital. Here they turned inland and climbed.

“From Peru, they cut over the west wall of the Andes,” reported the Boston Traveler in a recap story published that November. It was winter in the mountains, sunny and dry but chilly, and “the roads were like corkscrews…” Up they went, sometimes digging their way through rock slides, the TD’s hardy four huffing and puffing but persevering, carrying them ever upward from the sea to the 15,889-foot Anticona Pass. Both men battled altitude sickness. Both got sun- and windburned in the thin, dazzling air. At night, they drained the radiator into one of the jerrycans and slept with it between them in the tent to keep the water from freezing. Somewhere among the Indigenous people who have called the Andes home for thousands of years, Baker discovered a real disdain for llamas. “They don’t carry much and are easily the most obstinate animal in the world,” he told the Traveler. “When they sit down and don’t want to get up, they can’t be prodded, beaten, or set on fire. The natives simply sit down and flip pebbles at the animal until he becomes annoyed and bounds off.”

It was on the descent, as they negotiated a dry riverbed, that the MG finally gave in to the forces being lobbed against it and broke a rear spring. Crudely, creatively, Baker shoved a chunk of wood into the space in such a way as to prop up the back of the car and they limped ahead for 10 miles, over the border into Bolivia, around the southern shore of Lake Titicaca, and into the port town of Guaqui.

“There was a fiesta in progress,” Baker said, “and both the town’s blacksmith and mechanic were borracho, or drunk, as just about everybody was. We finally got some broken springs from the village priest, bent them with stones, tied them with baling wire, and went to La Paz, the capital, at the rate of 10 mph.”

Whether or not Baker and Fabry were able to source a proper set of rear springs for the TD in La Paz is unknown, but we hardly think they would have kept on without first making the car roadworthy at more than a crawl. Nevertheless, down into Argentina they rolled, through the Jujuy and Tucumán provinces and across the broad pampas west of Buenos Aires, where the frigid southwest winds—the pamperos— coming off the Andes buffeted and stung them incessantly. They veered northeast, up through tiny Uruguay before crossing the border into Brazil on August 12, less than a thousand miles to go.

Baker and Fabry rolled into Rio de Janeiro on or about August 18, 76 days, 1 hour, and 30 minutes after they’d departed from Boston. They were well ahead of schedule, and just as planned, they’d done it in the most sporting way possible—no fishing for brook trout with deep-sea tackle for these two.

In Rio, they cleaned themselves up, got haircuts, shaved, bought suits, and then met with members of the Automóvel Clube do Brasil (ACB) to share stories of their adventure.

Gerry Fabry flew home to Paris to spend the remainder of the summer with his family, while Frank Baker stayed behind to make arrangements to have the car shipped back to the

States. Perhaps at the invitation of the ACB, he and the TD also paced a local race in Rio with the first Miss Brazil, Martha Rocha, alongside.

The end of the journey did not, as it happened, bring the end of witnessing political intrigue: Baker was still in the capital on August 24, when Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas, embroiled in controversy and having lost the faith of his cabinet, shot himself in the chest. His suicide note was read over the radio within hours of his death, and it sent the country into a riotous frenzy. The following day, making one last use of his INS press pass, Baker talked himself into the Catete Palace and was in one of the reception rooms when Vargas’ body was brought out in a glass-topped coffin for display to relatives and close friends.

“Vargas’ youngest son started shouting the national anthem, waving his arms,” Baker reported. “The mob went wild with hysteria. The room started to vibrate, and plaster began falling off the ceiling. A chandelier then fell and knocked me cold. I came to with a woman’s foot in my face. Soon, the other chandelier came down, throwing the room into complete darkness. That was a rough experience. I ended up with four stitches in my forehead.” He took a final photograph, though.

Baker flew back to the States shortly after, and both men returned to Harvard in the fall. There was no book, but Baker did make several speaking appearances, which helped recoup some of the money they’d spent to fund their incredible, important odyssey. They completed their MBAs in 1955, and following graduation, Gérard Fabry returned to France and joined industrial gas supplier Air Liquide before getting into banking, first with Lazard Frères and then Crédit Mobilier Industriel

(Sovac), from which he retired as director general. Frank Baker had a short stint at Arthur D. Little consulting before starting a venture capital firm. He retired from the electronics manufacturing firm Andersen Group after serving as CEO for 30 years.

The two men remained close friends throughout their lives, and their families became friends as well. Frank Baker died in 2017, Gerry Fabry in 2020. Their adventure, however, lives on through their descendants (who, in turn, shared it with HDC magazine along with the accompanying photos).

“I remember key pictures from the trip in his den, like he and Gerry standing in Rio, along with a Spanish newspaper cover about Guatemala,” said John Baker, Frank’s son. “I remember finding the slides in the attic as a kid. They were well boxed and had metal edges, which made them incredibly cool.” John credits his father with his love of vintage cars and boats, not to mention a bit of wanderlust. “I’ve taken jobs that have taken me all over the world,” he noted.

Although the whereabouts of their magnificent MG remain unknown, so tough was the TD, so easy to maintain, that Baker and Fabry’s car may still be out there somewhere, puttering around back roads on sunny weekend days in the hands of a loving owner oblivious to its remarkable history.

This story first appeared in the May/June 2025 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine.

crown jewels the

FIFTEEN LEGENDARY CARS TO WATCH AT THE AUCTIONS AT MONTREY CAR WEEK

Monterey Car Week doesn’t host the largest auction event in the world, but the sales held on this Central California peninsula are the most glamorous and, when it comes to average price, the most expensive. Here, you will see more cars selling for seven (and occasionally eight) figures than you will anywhere else in the world all year. And it happens in the span of a few days.

WORDS: Andrew Newton

PHOTOS: RM Sotheby’s, Broad Arrow, Mecum, Gooding Christie’s,

In terms of total sales, the high point of the Monterey auctions was in 2022, when over $471M worth of collectible automobiles changed hands. Average total sales there for the last 10 years are roughly $371M, and the 2025 auctions are set to once again roll some of the world’s rarest, most significant, and valuable vehicles across the block. There are almost too many desirable cars to keep track of, so below are 15 of the most serious ones, their presale estimates, and why they’re so important.

1968 ALFA ROMEO T33/2

RM Sotheby’s

Estimate: $1,700,000 - $2,000,000

Alfa Romeo’s Tipo 33 (T33) was a sports racing prototype, continually developed throughout its competitive career from 1967 to 77 with multiple bodies, engines, and chassis designs. The highlight of a group of a dozen 1960s-70s Alfas dubbed the “Quadrifoglio Collection”, this car is one of approximately 10 T33/2s reported to still exist. It took sixth overall at Daytona in 1968 with Mario Andretti behind the wheel, and was holding onto second place at the Targa Florio before it crashed out. Repaired in time for the Nürburgring 1000km, it took seventh there, then eighth at Monza and sixth at Spa. It had a second life, raced by Portuguese privateers in Angola (a Portuguese possession until 1975). After multiple victories in Africa, they fled to Portugal and left the Alfa behind, but the car returned to Europe in the 1980s and was restored. If it sells, the Tipo 33/2 will be one of the most expensive postwar Alfa Romeos ever sold at auction.

1962 SHELBY COBRA 260

Broad Arrow

Estimate: $1,500,000 - $2,000,000

Building most of the early Shelby Cobras basically went like this: AC in England would ship a painted and trimmed car— sans engine and gearbox—to Shelby in Los Angeles, where the Ford bits went in (specifically a 260-cubic-inch V-8 and BorgWarner four-speed). Final assembly was completed there, in California. For the earliest batch of cars, however, Carroll Shelby hadn’t yet set up his full operation. Luckily, an early backer named Ed Hugus stepped up to assemble the first handful of production Cobras at his dealership in Pittsburgh. This one—CSX 2003—was part of that first batch, so it’s one of the first Cobras ever built. After completion, it also went to Ford in Dearborn for evaluation and road tests by company engineers. Henry Ford II even took a turn behind the wheel. The current owner has had the car since 1989, and even drove it daily for a while. Broad Arrow’s presale estimate puts it among the most expensive small-block (260cid and 289cid) Cobras ever sold.

1935 DUESENBERG

MODEL J TORPEDO PHAETON BY WALKER-LAGRANDE

RM Sotheby’s

Estimate: $4,000,000 - $5,000,000

Model Js wore a dizzying array of bodywork from the era’s best coachbuilders on both sides of the Atlantic. Although almost all are gorgeous, some are rarer and better-looking than others, and this car is represented as one of just five original “Torpedo Phaetons” designed by the famous Gordon Buehrig, as well as the first offered for public sale in two decades. Noted for its folding dual windshields and disappearing top, this Torpedo Phaeton boasts its original, matching numbers chassis, engine, firewall (Duesenbergs do have a firewall number), and coachwork. If its $4M-$5M estimate is a bit rich, the same auction will also offer a more common Model J Convertible Sedan with an estimate of “just” $2.3M-$2.75M.

1967 CHEVROLET CORVETTE

L88 COUPE

Mecum

Estimate: N/A

One letter and two numbers—L88—will perk up any Vette fan. The never-promoted, semi-secret option package loaded up a Corvette with trick competition equipment and a special 427 engine while deleting every creature comfort possible. L88s were only offered from 1967-69, and 1967 is both the only L88 on the C2 body style and the rarest with just 20 built (80 sold in ’68, and 118 sold in ‘69). This Rally Red on red coupe is one of those 20. Back in 2014, it became the most expensive Corvette ever sold at auction when it crossed the block at $3.85M (that record has since been beaten). It resurfaced on the auction scene this year, but was a no-sale at a $2.5M high bid in Kissimmee, and was a no-sale again at a $2.7M high bid in Indianapolis. It will hope for better luck and deeper pockets in Monterey.

1995 FERRARI F50

RM Sotheby’s

Estimate: $6,500,000 - $7,500,000

Once somewhat underappreciated compared to the F40 that came before it and the Enzo that came after, the F50 is rarer than both. It has surged in value in recent years, though, and is currently the most valuable of the three. Current prices for them are effectively six times what they were 15 years ago. This one is reportedly one of just two U.S. spec cars in this eye-catching Giallo Modena color, and its first owner was none other than Ralph Lauren, who kept it for eight years. The current world auction record price for an F50 is $5,532,500 for a car sold earlier this year.

1952 JAGUAR C-TYPE

Gooding Christie’s Estimate: N/A

The C-Type brought Jaguar two of its five victories at the 24 Hours of Le Mans during the 1950s, but this one spent its early life as a road car. No racing glory, then, but its lack of competition history also means that it avoided a hard life on track. It was never crashed or cut up, and has a clean and well-documented history. Just 53 C-Types were originally built, and though good replicas regularly sell in the neighborhood of $100,000, the real deal is worth millions, and one hasn’t been offered at auction in a couple of years.

1961 FERRARI 250 GT SWB CALIFORNIA SPIDER

Gooding Christie’s

Estimate: $8,000,000 - $10,000,000

A desirable short wheelbase (SWB) version of the Ferrari California Spider, this car was delivered new to a Milanese publisher before selling on to its second owner, the famous Italian singer and actor Antonio Ciacci, aka “Little Tony”. It even starred in one of his films, racing against a Lamborghini Miura. It’s Nocciola over Tobacco color scheme is unusual but lovely, and potentially the only knock against this car is its open headlights. California Spiders were available with more attractive covered lamps, and, believe it or not, that setup translates to a price tag several million dollars higher. Regardless, this one still has the potential to be one of the most expensive cars of the week.

1989 RUF CTR1

‘YELLOWBIRD’

LIGHTWEIGHT

RM Sotheby’s

Estimate: $4,500,000 - $5,000,000

Bespoke 911s are en vogue if the Monterey consignments are any indication, as there are half a dozen RUFs and multiple Singers on offer this year. This one is one of RUF’s all-important “Yellowbirds” from the late 1980s, with this specific one dubbed the “Redbird” for its one-of-one Bordeaux Red paint. It is also one of just six Lightweight versions built, and was reportedly used as Alois Ruf’s personal car for a while. Ordered new and extensively optioned by a German doctor, it boasts 18,900 km (R11,745 miles). Made famous by their breakthrough performance in Road & Track’s “World’s Fastest Cars” test, Yellowbirds rarely come to market, but with two huge auction results for them so far this year ($4.68M and $6.06M), it’s natural for another one to pop up for sale.

1971 FERRARI 365 GTB/4 DAYTONA SPIDER

Broad Arrow

Estimate: $2,500,000 - $2,800,000

The 365 GTB/4 Daytona was a solid seller for Ferrari, with 1284 examples rolling out of Maranello from 1968-73. A far, far rarer sight was the 120 or so additional Daytona spyders. These drop-top Daytonas quickly became so desirable that more than a few of the standard coupes had their roof cut off by independent shops back in the day. This one is the real deal, though, documented with three owners since new and 34,360 original miles.

1973 FERRARI 365 GTB/ 4 DAYTONA COMPETIZIONE

Gooding Christie’s Estimate: $8,000,000 - $10,000,000

Even rarer than the Daytona Spyder are the competition versions of the bullet-shaped berlinetta. One of 15 official competition Daytonas built by Ferrari, this one raced at Le Mans in 1973 and ’74, but the highlight of its racing career was second overall and first in class at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1979. Luigi Chinetti’s famous North American Racing Team (NART) campaigned it, and it also ran at Watkins Glen and Sebring during that period.

1955 FERRARI 375 PLUS SPYDER BY SUTTON

RM Sotheby’s

Estimate: $5,500,000 - $7,500,000

A 375 Plus won Le Mans in 1954, and Ferrari built six original examples as well as two additional cars that got the same massive 4.9-liter V-12 but with a different chassis dubbed “Tipo 102 Plus”. One was a road car ordered by the King of Belgium, and the other was this racing spyder. Carroll Shelby, Dan Gurney, and Ken Miles all raced it in period, and Shelby reportedly called it “the lightest, fastest Ferrari I ever knew.” It was also rebodied in period by West Coast builder Jack Sutton with this still very Italian-looking shape. Restored in the 1980s, it has been with its current owner since 1996.

1969 LAMBORGHINI

MIURA

P400 S

Mecum

Estimate: N/A