Extraordinary for Landscape Architects

Product: Cliffhanger Terraces Project: Seattle, United States Architect: Hewitt Landscape Architecture

Planning beyond growth

Since the general election, the UK’s planning system has been eagerly positioned front and centre of the Labour government’s ambition to drive economic growth through the development of new housing and infrastructure.

In the rhetoric across government, industry and the public can be found a tension between economic growth and environmental sustainability: How can we ‘get Britain building’ in such a way that drives green growth and delivers the homes we desperately need, while also addressing the very real challenges we face in climate change, biodiversity loss, and public health?

“By taking a landscape-led approach,” says Ian Phillips CMLI MRTPI (p8) in his introduction to the issue – and this is the premise on which much of what follows is built.

We present, and critique, emerging government policy seeking to integrate nature into development and make better use of our land, including contributions from the Better Planning Coalition (p14), Natural England (p20), and the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission (p44). We focus on the peri-urban edges where the most impactful projects could manifest, from the newly designated ‘grey belt’ (p52) to new towns (p62), and gain perspectives from across the devolved nations (p49). We highlight the ongoing necessity of vital landscape policy instruments such as Biodiversity Net Gain (p38), sustainable drainage systems (p40),

and Landscape Character Assessment (p56), and highlight the public sector skills gap that could compromise their effectiveness (p33). As well as looking at what all of this means on the ground with case studies from the north and south of England (pp24,28), we also bring you the latest from the Landscape Institute, with news on our Standing Committees (p67), and a look ahead to our new corporate strategy (p70).

With nature having been unfairly pitched as the blocker to development and growth, this edition of the Journal seeks to reestablish it as the enabler, and very foundation, of long-term social, economic and environmental value. As LI Director of Policy & Public Affairs, Belinda Gordon, points out: ‘LI members are the ones who can cross this divide’ (p12).

Josh Cunningham Managing editor

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931 darkhorsedesign.co.uk studio@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Saira Ali FLI, Team Leader, Landscape, Design and Conservation, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

Stella Bland, Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes CMLI, Director, Allen Scott Landscape Architecture

Sandeep Menon, Landscape Architect and University Tutor, Manchester Metropolitan University

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape Architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Landscape Architect, Allies and Morrison

Jane Findlay PPLI & FLI, Director FIRA Landscape Architects

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Managing Editor and PR & Communications

Manager: Josh Cunningham josh.cunningham@landscapeinstitute.org

Technical Copy Editor: Romy Rawlings FLI

Proof Reader: Johanna Robinson

President: Carolin Göhler FLI

CEO: Rob Hughes

Head of Marketing, Communications and Events: Neelam Sheemar

Director of Policy & Public Affairs: Belinda Gordon

Landscapeinstitute.org

@talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

Print or online?

Landscape is available to members both online and in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: my.landscapeinstitute.org

from

(Environmental

and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accepts any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it. Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914

© 2025 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design.

Southgates masterplan. © BDP

The new planning system should recognise that economic growth should be delivered by working alongside communities and landscapes to maximise benefits to the environment, health and the economy.

Cllr Alex Ross-Shaw, Portfolio Holder – Regeneration, Planning & Transport at Bradford Council Find out more on page 24

The Better Planning Coalition takes stock of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill

Lessons from Bradford Natural England Landscape solutions

How to meet the growth agenda while supporting nature recovery

Government nature advisor sets out the importance of Local Nature Recovery Strategies

Building for growth, planning for nature in one of the UK’s most rapidly expanding cities

FEATURES

Clearer guidance is needed to enhance biodiversity The foundations

How the government’s ‘grey belt’ proposals underline a tension between growth and nature

Key characteristics

Local planning authorities must prioritise Landscape Character Assessment to shape positive change

What can the history of new towns tell us about building such ambitious projects today?

Learnings from the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act

All voices must be heard

What impact will planning reforms have on the role of communities in shaping new development?

Introducing the LI’s four new Standing Committees, putting members at the heart of our work

President Carolin Göhler FLI looks ahead to a new corporate strategy for people, place and nature

Landscape solutions

Built development doesn’t need to come at the cost of the environment and local places. By taking a landscape-led approach, the government can successfully meet its growth agenda while supporting nature recovery and high-quality, sustainable design.

1. The Southgates masterplan creates a vibrant gateway around the Grade I-listed Southgates in King’s Lynn.

2.

¹ https://labour.org.uk/ missions/

² https://labour.org.uk/ plan-for-change/

³ https://www.gov.

uk/government/ publications/uks-2035nationally-determinedcontribution-ndcemissions-reductiontarget-under-the-parisagreement

⁴ https://jncc. gov.uk/our-work/ uk-biodiversityframework/

⁵ https://stateofnature. org.uk/

⁶ The healing power of landscape, Landscape, the journal of the Landscape Institute, Winter 2024

⁷ https://www. landscapeinstitute.org/ policy/policy-focus/

⁸ https://www.gov.

uk/government/ publications/letterfrom-the-deputyprime-minister-to-localauthorities-playingyour-part-in-buildingthe-homes-we-need

Ian

CMLI MRTPI

A fresh wave of planning reform is unfolding in the UK under a new government, driven by an acute housing crisis, persistent economic stagnation, the Labour Party’s electoral mandate to build more homes and create more jobs and the political imperative for the new government to make swift progress on key domestic priorities.

Labour’s pathway to government was forged on a mission to “kickstart economic growth… rebuild Britain, support good jobs, unlock investment, and improve living standards across the country”.¹ After a landslide victory in summer 2024, ministers soon began to implement a ‘Plan for Change’² that included a commitment to deliver 1.5 million homes in England during the Parliament and to approve at least 150 major economic infrastructure projects. Such a plan has significant implications for landscape, with reforms now set to reshape how development is planned, delivered and integrated into the wider built and natural environments.

Running in parallel to the government’s growth agenda are the interrelated challenges the UK faces in addressing climate change, biodiversity loss, and public health. Under the Paris Agreement and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, the UK is committed to cutting greenhouse gas emissions and halting nature’s decline.3, 4 These commitments are set against the sobering reality that the UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world,⁵ and its National Health Service is under increasing strain from the health consequences of poor-quality living conditions, characterised by air and water pollution, inadequate resilience to climate change and limited access to nature and green space.⁶

This convergence of pressures presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is to align

housing and economic objectives with those on climate, biodiversity and public health, to deliver long-term, sustainable value for people, place and nature. In a context where speed and delivery are being prioritised, it is a legitimate concern that both established and current environmental considerations may well be undermined.

This should not be permitted –especially when there is a way forward that enables development and nature to thrive together. The fundamental purpose of the planning system has always been to balance the broader interests of the public against the narrower focus of the developer. The system has long recognised the importance of landscape planning, design and management in addressing and reconciling these competing priorities and applying this approach directly to development. By recognising the role of landscape treatment as a multifunctional resource, and not merely as an aesthetic feature, such an approach ensures that land use change can deliver concurrent social, economic and environmental value. It’s about bringing the issues that currently run in parallel together to provide integrated solutions.

The Landscape Institute (LI) sees nature-based solutions as fundamental to this vision, and to the long-term

health, sustainability and value of built development. A landscape-led, nature-based approach creates sustainable, liveable, climate-resilient and attractive places. It makes good use of natural capital, integrates biodiversity and water management, improves health outcomes and supports economic growth. This was the vision we set out in 2024 in our ‘Recommendations for the next UK government; a landscape policy agenda for people, place and nature’.⁷

Within three weeks of entering government, Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, Angela Rayner, had launched an overhaul of the planning system in England, beginning with an updated National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). Further reforms included the introduction of new Spatial Development Strategies and new methodology for setting mandatory housing targets, with stronger emphasis on delivering social and affordable homes. Also included was a commitment to reviewing the green belt and the introduction of a new concept of ‘grey belt’ land alongside brownfield land, with local authorities expected to release appropriate land to meet housing and commercial needs. Additional measures were given to the development of ‘growth-supporting infrastructure’,⁸ including transport,

Phillips

Climate-ready Edinburgh SuDS pond and wildflower meadow. LI Awards winner 2023.

Atkins

energy and data networks. Further reforms, including a national housing strategy, a series of new towns, changes to Environmental Impact Assessments and the flagship Planning and Infrastructure Bill, with its novel proposals for Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs), are also set to play a key role.

From a planning policy perspective, these reforms have far-reaching implications for how landscape is incorporated into the development process. The updated NPPF,⁹ for example, seeks to integrate some environmental priorities at the national level, but much depends on how policy is implemented at regional and local levels. The Planning and Infrastructure Bill10 introduces significant changes, underpinned by new policy instruments such as Environmental Outcomes Reports (EORs), while the Development and Nature Recovery working paper11 further proposes the establishment of a Nature Development Fund (NDF) that aims to finance nature restoration in tandem with new development. EDPs, managed by Natural England, are proposed to provide a framework to ensure nature-based objectives are addressed through strategic investment and planning. Local Nature Recovery Strategies are also promoted as essential tools to integrate biodiversity planning across administrative boundaries. However, the potential strategic benefits of these proposals to offset nature recovery through the payment of a financial levy

may result in a lack of any significant onsite environmental provision. There is little clarity on how this separation between development impact and its mitigation will evolve and it creates a real risk that areas of poorly designed and unsustainable development may potentially be mitigated by remote and distant nature reserves. It is clearly a matter of public interest that all development, including infrastructure, is context sensitive and incorporates good landscape treatment. Failing to address this may result in new areas of environmental and social degradation and the creation of places that are unfit for living.

In addition, devolved and crossboundary decision-making is being advanced in England, supported by proposals for a national land use framework. These measures collectively indicate a shift towards more strategic, system-wide thinking about how development interacts with the natural environment. However, the mechanisms for delivery remain in flux, and the government has yet to fully answer how these new tools will safeguard nature in practice. The resource, skill and funding implications for both local planning authorities and government bodies are also legitimate concerns: does the UK have the right skills in the right places to build the green growth the government has set out? Early results from the LI’s investigation into workforce issues in the landscape sector suggest not.12 Proposals in the recent immigration white paper13 aim to wean organisations off the employment of non-UK workers and to meet skills needs domestically. This may work in the mid to long term, but it threatens to increase skills shortages and growth in professional areas (such as landscape) where training to high standards takes years.

When Prime Minister Keir Starmer articulated a ‘Plan for Change’ at the start of the year, he spoke of “taking

3. Hagshaw Energy Cluster: Co-location of renewable energy generation and storage technologies delivering optimisation from suitable land within the cluster. LI Awards finalist 2023.

© Richard Carman

4. Pydar river path illustration. LI Awards winner 2023. © PRP

9 https://www.gov. uk/government/ publications/nationalplanning-policyframework--2

10 https://www.gov. uk/government/ publications/ the-planning-andinfrastructure-bill

11 https://www.gov. uk/government/ publications/planningreform-working-paperdevelopment-andnature-recovery

12 Landscape Institute workforce and skills research to be published later in 2025. It will also be the focus subject of a journal edition

13 https://www.gov. uk/government/ publications/restoringcontrol-over-theimmigration-systemwhite-paper

5. Otterpool Park Garden Town. LI Awards finalist 2023.

© Arcadis

6. Warners Fields, Birmingham. LI Awards finalist 2022.

© Dandara Living

14 https://www.gov. uk/government/news/ prime-minister-clearspath-to-get-britainbuilding

15 https://www.gov.uk/ government/speeches/ chancellor-vows-togo-further-and-fasterto-kickstart-economicgrowth

16 https://www.gov. uk/government/ publications/planningand-infrastructure-billimpact-assessment

17 https://www. landscapeinstitute.org/ policy/consultationresponses/

18 https://www. landscapeinstitute. org/news/industrybodies-call-ongovernment-to-set-aprecedent-for-naturepositive-developmentin-joint-letter-toprime-minister-andchancellor/

19 https:// defraenvironment.blog. gov.uk/2025/05/16/ planning-reformprotecting-naturewhile-supportinggrowth/

the brakes off Britain by reforming the planning system so it is pro-growth and pro-infrastructure”.14 With so much of the government’s proposed reforms still lacking clarity over the environmental implications, Chancellor Rachel Reeves has also said, “we are reducing the environmental requirements placed on developers … so they can focus on getting things built, and stop worrying about bats and newts”.15 However, the government’s own impact assessment has been able to cite very little evidence that environmental requirements delay development.16

In response to the prevailing growth vs nature rhetoric, the LI has responded to numerous consultations,17 engaged with parliamentarians and joined with organisations across the built and natural environment to raise concerns.18 We are writing to relevant ministers and meeting government and civil service officials to address planning policy issues and taking a collaborative approach to improvement.

As this edition goes to print, the government has acknowledged that questions have been raised over

whether the bill could jeopardise nature protection.19 In response, Defra continues to point to the NDF and EDPs as a means to adopt a strategic approach, reduce delays for developers and ensure environmental outcomes are delivered more effectively.

Nevertheless, the LI remains concerned about unresolved aspects of the reform agenda, particularly the risk that biodiversity could be displaced off-site, rather than embedded within the places where people live and work, and close to the communities that need access to green space the most.

We believe that landscape-led planning and the appropriate use of nature-based solutions are key to resolving this tension, and we look forward to working with the government, civil service and stakeholders across the industry to drive this approach. By designing with nature, not against it, planning reform can help to deliver the government’s growth agenda and shape a lasting legacy of healthy, sustainable and inclusive places that are fit for living.

Ian Phillips CMLI MRTPI

is Chair of the Landscape Institute Policy & Public Affairs Committee

Landscape Institute policy priorities

Director of Policy & Public Affairs, Belinda Gordon, sets out an LI policy agenda focused on bridging the gap between builders and blockers.

The Landscape Institute and its members are in a unique position in relation to the government’s housing and infrastructure development agenda. We bridge the ‘builders v blockers’ narrative that has developed, unfairly pitching nature concerns as preventing development.

LI members are the ones who can cross this divide, ensuring we get the housing and infrastructure we need and crucially that this development is high quality, creating new landscapes and places that deliver for people and the environment for the long term.

The policy team at the LI, ably supported by members and staff with policy, technical and communications expertise, has been working to exploit this unique position and expertise. Here I set out some of the ways we’ve

been doing this and our future approach to influencing policy.

Strategy

Given both planning and environmental policy are devolved, we have the challenge of influencing four administrations with limited staff resources. To do this as effectively as possible, we are moving our activities upstream, from responding to written consultations (by when many decisions have already been made) to engaging more directly with government sooner. With this in mind, the team have been building links with government officials, agencies and partners, as well as developing some focused policyinfluencing priorities to use as a way in and to build out our broader message about the importance of all landscapes and the vital role of landscape professionals.

Given the emphasis the government is placing on built development, our priorities for this year all relate to that agenda – in order to have impact, we can’t spread our resources too thinly.

To help deliver this approach, we have renewed the LI’s Standing

Committees, establishing a new Policy & Public Affairs Committee, chaired by Ian Phillips CMLI, and a Knowledge & Practice Committee, which will ensure members guide these areas of work. We were delighted by the response to our call for members to get involved and by the quality of applicants. The new Committees are now established and providing strategic oversight of our work.

Action

To begin to deliver this approach, the team have been busy meeting organisations such as Natural England (on biodiversity net gain (BNG) as well as broader landscape issues), the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) (to discuss both design and broader planning policy), Defra (on sustainable drainage systems (SuDS)), Northern Irish government and partners on design, the Scottish Government Planning Division; connecting with partners such as the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) on planning, the Construction Industry Council on skills and

Belinda Gordon

Policy-influencing Priorities

A landscape -led approach to built development is essential for delivering costeffectively for people, place and nature

immigration, Northern Ireland Environment Link, Historic Environment Scotland and the British Association of Landscape Industries (BALI) Scotland on skills and training needs, Learning through Landscapes, the Wales Landscape Group and the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA) on Environmental Outcome Reports; and working with the Better Planning Coalition on the Planning and Infrastructure Bill.

We have continued responding to critical consultations such as the Land Use Framework, Energy Planning Guidance Notes and the creation of a new national park in Scotland.

We have gathered data on the landscape workforce (an update to our 2022 Skills for Greener Places Report) to be published later in the year. And we have published an evidence-based briefing setting out why a landscapeled approach to built development is essential. Aimed at developers and policy makers, it was launched at UKREiiF in May, and will be the focus of our next Journal edition.

High streets

Green infrastructure / Parks / Access to greenspace

Wider planning – Bill, green / greybelt, design guides

Plans for Scotland, NI and Wales will focus on these examples but also cover 1 or 2 local priorities

Championing all landscapes, use of Landscape Character Assessment

Planning: EORs –England initially

BNG / Planning delivering biodiversity

SuDS & NBS & NFM

Landscape Skills & Workforce: LI Policy & LI Education staff working together

SuDS – Sustainable Drainage Systems NBS – Nature Based Solutions NFM – Natural Flood Management

Impact

It is too early to be able to judge our impact – it is clear that in Scotland, where we have strong links with the government, we have influenced policies such as Scotland’s Flood Resilience Strategy. In England, we are getting on the government’s radar and have been invited to various fora – such as a newly formed MHCLG Design Sector Forum and various National Energy System Operator groups.

Based on our refreshed brand identity, Corporate Strategy and case for a landscape-led approach to development, our visibility and impact will grow and we will have more tangible policy ‘wins’ to outline in future.

Coming up

In the next few months we’ll be delivering plans for each of the policy-influencing priorities outlined above, with input from the new Committees, including pushing hard for a landscape-led approach as being essential to build quality developments and new towns. As part of this, we will also be raising the profile of landscape workforce issues and focusing on

influencing the rapidly changing planning agenda in England – from Environmental Outcome Reports, to BNG exemptions, and another set of changes to the NPPF, to be consulted on shortly.

We are also delivering conferences around the UK, with a focus on housing and regeneration – the first being in Birmingham on 2 October, as well as webinars and masterclasses that support members on vital issues.

Get involved

We are dependent on member expertise to help guide and inform our policy work. We will be recruiting another set of members to our new Policy & Public Affairs Committee next year, but in the meantime we are looking for members for our Task & Finish groups on issues such as planning. If you’d like to help with this, please contact the policy team at policy@ landscapeinstitute.org.

Peat

Footing the bill

Towards a planning system fit for climate, nature and people? The Better Planning Coalition’s Richard Hebditch takes stock of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill and looks ahead to where improvements could be made.

No one should have been in any doubt of the Labour government’s intentions to change the planning system. In opposition, Keir Starmer said he would “bulldoze through planning laws” and Labour’s manifesto set out their proposals for radical change.

In the months since coming to power, the government rewrote the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and commenced reviews of all the national policy statements that guide the planning system. Working papers were published on further changes to the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIP) process, on how planning committees operate, on a new nature restoration fund to

replace Habitats Directive-derived protections for nature, and on new ‘brownfield passports’. Housing targets have been increased, meaning many local plans are obsolete as their five-year housing land supply is no longer sufficient for the higher targets.

Alongside this, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) has been pursuing wider reforms to local government, publishing the English Devolution White Paper in December 2024. This proposes a more uniform suite of Strategic Authorities across England who, among a range of powers and duties, will have to produce a spatial development strategy. In addition, they will have development control powers similar to the Mayor of London, as well as influence over Homes England on housing and local councils on transport.

Much of the work over the last year is about making planning and local government more logical as viewed from Westminster. The focus is on helping ministers deliver their national

policy aims (including the 1.5 million new homes target) by removing blockages and making it easier for them to set policy that local government then has little choice but to implement. But it’s also about enhancing the state’s (including local planning departments), capability and capacity. Changes include the ability to recover costs through

Councils, housing associations and development corporations need the powers and finances to deliver housing themselves

Richard Hebditch

setting their own planning fees, creating the new strategic planning layer and strengthening development corporations.

After this flurry of activity from MHCLG, from the start of 2025 we’ve seen the rhetoric ramp up.

In spring came the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, which put these competing policy narratives into legislation. The bill is broad ranging and aims to achieve the following:

– Streamline the NSIP process with changes beyond those for transport and electricity infrastructure planning and permitting processes

– Allow councils to retain income from planning fees

– Create national rules restricting the planning applications that elected councillors (as opposed to officers) will be allowed to decide through a national scheme of delegation

– Set out what should be included in spatial development strategies for the new strategic planning level

– Introduce Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs) where developers can pay a levy to help deliver EDPs in

place of site-specific mitigation or compensation measures under the Habitats Regulations – Strengthen the role of development corporations

So where does the bill fall between the two visions within government for planning: one that tries to sweep planning out of the way and one that sees a reformed planning system as the way to deliver housing and infrastructure objectives?

To some extent, we don’t yet know. Much of the bill will be implemented through future guidance and regulations. Ministers have promised that they will consult on the new national scheme of delegation and that Natural England will start piloting EDPs while the bill is still making its way through Parliament. But at the time of writing, there is still no sign of these assurances.

The first part of the bill covers major infrastructure. The NSIP process has a problem with proposals taking longer and longer to get through the system, so tackling the causes of delays is reasonable. But there are

risks around quite how much freedom is given to ministers through these changes. For instance, one change will allow the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government to move applications from the NSIP process into other planning processes. This is likely to include the Town and Country Planning Act, Highways Act, or Transport and Works Act regimes but could include the use of Local Development Orders or simplified planning zones. This removes the need for much oversight of developments, along with certainty and clarity on how major infrastructure will be determined, and could open to abuse.

The bill’s move to allow local planning authorities to set their own planning fees and to amend the planning fees model is welcome. This investment should help local authority planning departments reinvest fee income from planning applications directly back into their services and recover from over a decade of cuts. In addition, 97% of planning departments report planning skills gaps and, even in

the last year, departments were twice as likely to report that their workforce was decreasing rather than increasing.

The move to reintroduce strategic planning is also positive. Land is in short supply and we must plan strategically to manage the many competing demands upon it.

Effective strategic planning will be essential to ensure new developments are located in the right place and designed to both reduce car dependency and support healthy communities.

We welcome that the bill allows for strategic authorities to specify the amount or distribution of housing, including affordable provision. This will allow authorities to respond to the range of local needs rather than relying on housing developers’ proposals, which focus on the most profitable housing and force negotiation for the inclusion of affordable housing within a restrictive viability test.

However, planning reform alone is not enough. Councils, housing associations and development corporations need the powers and

finances to deliver housing themselves. Otherwise, they are reliant upon a limited number of volume developers who have strong financial reasons to manage a limited pipeline of housing delivery to maximise profits.

We hope that ministers will say more about the links between strategic planning in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, the forthcoming English Devolution Bill and the Land Use Framework being consulted upon by Defra. Strategic planning will not succeed if strategic authorities, and local government more generally, lack the ability to make decisions around new transport services, infrastructure to support new development or areas to protect for nature.

The bill will also give the Secretary of State the power to set a national scheme of delegation for local planning decisions. Councils will not have the freedom to decide themselves which planning applications should be decided by officers and which should go to a planning committee. Delays to a limited number of major schemes is

97% of planning departments report planning skills gaps

not sufficient to justify excluding elected councillors from key decisions. The welcome measure of ensuring mandatory training of councillors on planning committees is a more proportionate response. The weakening of green belt protection in the revised NPPF, local government reorganisation and more decisions being taken behind closed doors by officers alone could lead to growing resentment rather than building public support for new development.

EDPs backed by a Nature Restoration Levy to require developers to fund nature recovery, offer potential for some environmental issues. But there are risks that, without

safeguards, these proposals could cause significant harm to wildlife. In the rush to develop the proposal, the bill as it stands lacks safeguards as it potentially withdraws the protections derived from the Habitats Directive without guaranteeing a system that will deliver improvements in practice. The Secretary of State’s power to unilaterally amend EDPs lacks key safeguards and could see improvements watered down. The bill includes a viability test where the rate of the levy cannot be set if it threatens the profitability of the development; this could result in an underfunding of the necessary improvements needed to outweigh harm from a development.

In particular, the bill should require benefits to significantly outweigh harm. Evidence from Biodiversity Net Gain and other offsetting schemes is that the anticipated benefits in a plan are not necessarily realised on the ground, so there is a need for legal underpinning to require significant environmental improvement.

Better planning is not only about procedural changes but also the outcomes it enables. A statutory purpose for planning should be the foundation of the government’s reform agenda and demonstrate a clear determination to refocus the system on renewal and sustainable development. Making clear the purpose of planning through a new clause in the bill could tie together all the strands being developed separately. This integrated approach would ensure key elements –biodiversity, water management, landscape and visual impacts, health and wellbeing, transport and climate targets – are considered from the outset. This would help ensure that new infrastructure and built environments contribute positively to our economy, society and environment.

The bill is now going through its committee stage and then to the House of Lords, where it’s likely to face tougher scrutiny. We hope that ministers recognise the concerns from parliamentarians and the public alike over the potential weakening of the

planning system. There must be recognition that delivering the government’s objectives needs a strong and capable system that works in the public interest, rather than one that is weakened, sidelined and weighted in favour of private developers.

Richard has been coordinator of the Better Planning Coalition since February 2025. He has worked in external affairs for a range of NGOs, as well as in the Cabinet Office, working to improve relations between the government and voluntary sector.

Landscape Institute response to Development and Nature Recovery

In spring 2025, the government consulted on a Planning Reform Working Paper for Development and Nature Recovery to dovetail with the implementation of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill. The Landscape Institute acknowledges the aim of simplifying the process for developers, but we are concerned that nature recovery may be treated as separate from development, rather than being fully integrated into planning and placemaking.

The proposed Nature Restoration Fund may be attractive to developers due to its simplicity and certainty of cost. However, this approach risks isolating nature recovery in designated areas, rather than embedding natural systems as fundamental components of development. This would miss opportunities for delivering integrated, multifunctional landscapes that support biodiversity, climate resilience, and community wellbeing.

The fund may provide benefits in high-density, small-footprint developments – such as urban highrises – or in addressing cumulative impacts from incremental development. However, it is less suited to large-scale, low-rise housing schemes, where green infrastructure, open space, and community access are integral to good design.

We are also concerned about

the delivery capacity of responsible agencies. Many lack sufficient funding, multidisciplinary expertise, and access to reliable ecological data. While capital investment may enable the development of initial habitats, long-term monitoring and management are essential to securing lasting environmental benefits and must be properly resourced.

Furthermore, the proposal to substitute on-site mitigation with financial contributions risks undermining the established hierarchy, which prioritises avoiding and minimising harm before restoration or offsetting. It risks normalising offsetting, creating a disconnect between impacted communities and the benefits of nature recovery. The scale of mitigation should be based on relevant landscape character and catchment area assessments and may well cross political boundaries.

To be effective, the proposals must demonstrate genuine environmental net gain and ensure measurable improvements to community wellbeing. The current approach does not yet achieve this.

Scan here to read the working paper and the Landscape Institute response in full.

Rooted in SustainabilityThe Benefit of British-Grown Trees

Supplying trees to landscaping projects, local authorities and private estates across the UK.

trees.hillier.co.uk

Proven, High Impact, Low Maintenance SuDS

Wildflower SuDS Turf tried and tested in hundreds of interventions for flood resilience projects

Rapid Establishment

Pre-grown, dense roots deliver quick bank stabilisation

Verified Infiltration Rates

Tolerance for waterlogging and drought stress

Sustainable Design

100% peat-free product with no plastic netting

Stunning Visual Impact

100% flowers, long-flowering mixes for urban settings

High Ecological Impact

Natural England: the government advisor perspective on putting nature at the heart of development

Marian Spain, CEO of the government body responsible for the natural environment in England, explains that Local Nature Recovery Strategies are central to putting nature at the heart of local development.

1. Marian Spain.

© Natural England

2. Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspace (SANG), Shinfield.

© Natural England

1 https://www.gov.

uk/government/ publications/naturalenglands-strategicdirection-2025-2030/ recovering-naturefor-growth-healthand-security-naturalenglands-strategicdirection-2025-2030

2 https://www.gov.uk/ government/ collections/ biodiversity-net-gain

3 https://publications. naturalengland.org.uk/ publication/6414097 026646016

4 https://naturetowns andcities.org.uk/

5 https://www.gov.uk/ government/ publications/theplanning -and-infrastructurebill/factsheet-naturerestoration-fund

The government has set out an ambitious plan for kickstarting the economy and our transition to green energy. Planning reforms are key to speeding up the delivery of 1.5 million new homes, quadrupling the energy from offshore wind and reinstating onshore wind farms in England. The reforms include a raft of different measures including the Planning and Infrastructure Bill and Nature Restoration Fund; the introduction of Strategic Authorities and Spatial Development Plans; a review of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF); and the New Towns Task Force and Future Homes Accelerator, to name a few.

In Natural England’s recently published Strategic Direction, Recovering Nature for Growth, Health and Security,1 we set out how nature underpins our nation’s growth, economy, health and security. The current value of nature to the economy is estimated to be over £1.8 trillion.

Putting nature at the heart of new housing, infrastructure and renewable energy projects attracts greater investment and builds in resilience to climate change. Nature is integral to making great places for people to live, learn, work and play. It brings multiple

Case Study

Thames Basin Heaths Strategic approaches are delivering beneficial results for nature, greenspace and development. In the Thames Basin Heaths for example, Natural England worked with local authorities and developers on providing 2,000 hectares of alternative greenspace for residents to use, unlocking the 50,000 homes and enabling populations of Dartford warbler, woodlark and nightjar to increase.

benefits for businesses, communities and the economy: clean water and air, reduced flood risk, delivery of net zero targets and mitigation of extreme heat and drought. Connecting with nature also provides spaces for people to be refreshed and revitalised spiritually, mentally and physically.

But while there are many good elements to the current planning regime, it hasn’t been able to secure sufficient enhancements for nature to reverse the long-term loss of species and habitats. There are multiple inefficiencies in the current system, including delay, sub-optimal workarounds at site level in the absence of strategic solutions, lack of joined-up delivery and missed opportunities to deliver economies of scale.

Our vision Natural England has a clear ambition to support the government’s planning reforms by making a substantive shift in our planning advice work towards a more strategic space. After all, the restoration of our natural world is best achieved at scale, rather than in small increments.

Pivoting on Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS)

Central to putting nature at the heart of planning and development are Local Nature Recovery Strategies

(see diagram overleaf). Co-developed through local partnerships, these strategies provide the backbone for all things nature: setting out where nature is, providing opportunities for more nature and highlighting priorities for its creation and restoration. All local planning authorities have a legal duty to have regard to the relevant strategy for their area and it may be a ‘material consideration’ in the planning system. New Spatial Development Strategies and LNRSs will function at the same tier and this brings a significant opportunity for synergies to build nature into placemaking at a strategic level. Underpinning LNRSs are tools such as mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain2 and internationally recognised Green Infrastructure Standards. These will be key to creating accessible greenspace, nature recovery and increasing tree canopy cover. Tools like Natural England’s Environmental Benefits from Nature3 tool can aid the design of habitats to maximise wider benefits, for example for managing flood risk, air quality or water supply. New approaches, such as the Nature Towns and Cities4 accreditation (which is based on the Green Infrastructure Standards), will recognise and reward those places that have an ambitious vision to put nature at the heart of towns and cities.

The emerging Nature Restoration Fund (NRF),5 planned for launch

Marian Spain

in 2026 under the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, offers a unique opportunity to simplify the developer user journey and deliver better outcomes for nature recovery. The NRF will allow us to assess impacts and develop mitigation, compensation and restoration for habitats and species at a strategic level, rather than at site level. This will in turn allow us to better manage environmental pressures such as nutrient pollution, enable faster delivery of housing and infrastructure and result in on-theground improvements for nature at scale. The government is working to refine the legislation and prepare for launch. If done well, the NRF could be a significant means of delivering LNRS ambitions.

– What can the sector do to support planning reforms?

– Engage with the government on the reforms;

– Support efforts to address workforce issues, particularly in local planning authorities;

– Align LNRSs and new Spatial Development Strategies;

– Take a landscape-led approach to masterplanning and make use of nature-positive tools;

– Use digital tools like Natural

Nature in plans and development

Local plan / Masterplan

3. Sheffield: grey to green. © Peter Neale

4. Eddington, Cambridge. © Peter Neale

5. Nature in plans and development.

Natural England

Houlton, Warwickshire

The Houlton housing development, east of Rugby in Warwickshire, will create design with high-quality green infrastructure at its core. With 50% green cover including natural play spaces, footpaths and green and blues spaces, there is plenty of opportunity for outdoor recreation. It showcases well the success of Natural England’s Accessible Greenspace standard and the Urban

Greening Factor standard. With meadowlands and ecology corridors designed in from the outset, it is achieving 27% Biodiversity Net Gain.

Working in partnership with parish councils, community groups, elected members and neighbouring residents, a place has been created that truly fits with Rugby and its existing communities, and meets the needs of residents, 95% of whom expressed a preference for living close to greenspace.

England’s Impact Risk Zone tool to streamline consultations; and – Engage Natural England early on high-risk/high-opportunity developments to ensure highquality applications that can be assessed quickly.

The current appetite for reform that will enable both development and nature recovery is a significant opportunity for positive change, provided we work together across central and local government, nature organisations, developers, infrastructure providers and businesses, for environmental recovery that benefits us all. Landscape architects, working alongside ecologists and planners, in both the public and the private sector, are ideally placed to help meet the government’s agenda, bringing vital expertise on the planning, design and management of land as a multifunctional resource.

This is a significant opportunity to re-shape the way development and nature work together to achieve benefits for people, nature and climate.

Marian Spain is CEO of Natural England

6. Mayfield Park in Manchester – the first new park in Manchester city for 100 years, putting green infrastructure at the heart of the city.

© Natural England

7. Houlton, Warwickshire. © Urban and Civic

Building for growth, planning for nature: Lessons from Bradford

A collaborative approach, aligning strategic ambition with local needs, supports a landscape-led approach to both growth and nature recovery in one of the UK’s most rapidly expanding cities.

The UK’s planning system is undergoing its most significant transformation in a generation, with the government’s commitment to building 1.5 million homes in England setting the stage for rapid development. However, this ambition raises a fundamental challenge: how do we ensure that economic

growth and housing expansion do not come at the cost of our landscapes, biodiversity and communities?

Bradford provides a compelling case study in this national debate. As one of the UK’s youngest, most diverse, and fastest-growing cities, it faces acute pressure to deliver housing while safeguarding its rich natural assets, including the South Pennines’ designated nature reserves and Special Protection Area. Through examining planning decisions in Bradford, and linking them with wider regional strategies such as Nature North, we can explore how a landscape-led approach, grounded in partnerships and collaboration, ensures that development supports both people and nature.

The challenge of balancing growth and nature

Bradford’s emerging local plan will seek to set out an ambitious vision for delivering homes, jobs and infrastructure while protecting and enhancing the environment. However, as in many parts of the country, this vision is tested by the tension between housing demand and the need to protect green spaces.

Bradford’s commitment to a landscape-led approach is not just about shaping places – it’s about shaping healthier lives. By embedding nature into city planning, Bradford’s landscape team are creating sustainable, healthy and equitable communities.

The revised National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the upcoming Planning and Infrastructure Bill place increasing emphasis on ‘brownfield-first’ development, but in areas like Bradford, viable brownfield land is limited. Developers often look to the green belt for expansion, which raises concerns about urban sprawl, biodiversity loss and increased flood risk. And the pressure is not only for housing and commercial growth, but also renewable energy developments such as large wind and solar farms or battery storage facilities in sensitive landscapes like the South Pennines.

A landscape-led approach offers a way forward. By designing developments that integrate nature-based solutions (such as green corridors, wetlands and urban tree planting), and by responding to local landscape character, Bradford can deliver housing and other types of development that enhance rather than erode the natural environment.

Professor Rosie McEachan, Director, Born in Bradford

Saira Ali FLI

Working alongside Bradford’s landscape team and our planning and landscape consultants has allowed us to integrate green spaces and nature into the very fabric of the city’s regeneration.

Simon Dew, Development Director, Muse Places

Nature North: A regional vision for growth and green recovery Nature North, a collaboration of environmental and economic partners, advocates for nature-led regeneration across the North of England. Its strategy aligns with national ambitions for economic growth but emphasises that investment in the environment should go hand in hand with development.

The relationship between Nature North and Bradford’s planning framework is key. The city’s strategic location, at the heart of a region rich in natural assets, positions it as a prime example of where nature recovery can be integrated into economic and housing growth. Through Nature North’s vision and investment priorities, Bradford can:

– Prioritise nature recovery in development – ensuring that new housing contributes to biodiversity gain and climate resilience

– Unlock funding and partnerships – working with landowners, businesses, and environmental organisations to implement landscape-scale restoration

– Enhance green infrastructure (GI) networks – connecting urban areas with surrounding natural landscapes, improving access to nature for communities.

Local plans, landscape-led approaches, and partnerships Bradford is already demonstrating how a landscape-led approach based on Nature North’s strategy can shape the city’s future. The council is taking proactive steps to embed this regional framework across a range of different planning scales, including:

– Bradford Local Plan: The council’s work on a new local plan is taking a landscape-led approach from the outset. It seeks to ensure connectivity of green spaces and other important GI assets through new development. This work is supported by an updated Landscape Character Assessment and a Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy that set the high-level context for a landscape-led approach to inform the policies in the local plan and choice of development sites.

– Homes and Neighbourhoods: A guide to designing in Bradford. This supplementary planning document guidance aligns with Nature North’s call for nature-integrated development, to ensure that housing projects actively contribute to GI.

– Transforming Cities Fund: A recently opened multi-million pound scheme that supports Nature North’s ambition for greener urban centres by introducing new public spaces, tree planting and active travel routes.

– Bradford City Village: A council-led scheme, working in partnership with developer Muse, Homes England and Legal & General, to deliver a vision for a new sustainable neighbourhood of up to 1,000 homes.

– Southern Gateway regeneration area: 140 hectares of underutilised commercial space on the southern edge of the city centre. The site offers one of the largest regeneration opportunities in the UK.

– Ilkley Flood Alleviation Scheme: Using tree planting and river restoration to reduce flood risk and deliver ecological enhancement, this scheme exemplifies Nature North’s emphasis on landscape-led water management, using nature-based solutions to address climate resilience and biodiversity loss.

1. Active travel infrastructure with integrated SuDS, Hall Ings, Bradford.

SWECO

These projects highlight how a collaborative approach – engaging environmental organisations, developers, government agencies, local businesses, and regional bodies like Nature North – can significantly strengthen landscape-led development.

Strengthening local planning capacity

Despite these ambitions, local planning authorities face significant resource constraints. Cuts to local government funding have reduced the capacity of planning teams, making it difficult to fully implement forward-thinking strategies. Bradford’s experience reflects a wider national issue: how can local authorities be better resourced to deliver high-quality, sustainable development?

One solution lies in strengthening the role of landscape professionals within the planning system. By embedding landscape-led approaches early in the planning process, we can ensure that new housing developments contribute positively to the local environment, enhance biodiversity and promote health and wellbeing.

Aligning planning policy with industrial strategy and transport investment

For a truly sustainable approach to growth, planning policy cannot operate in isolation. There is a pressing need to ensure that the planning reforms introduced by the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) are aligned with the strategies of other government departments such as the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) and the Department for Transport. For example, the promotion of investment in green industries by DBT should be directly linked to spatial planning frameworks that prioritise sustainable land use. This will integrate economic growth policies with landscape-led development principles to ensure that new development enhances both

At present, planning policy remains largely reactive to market forces, rather than proactively shaping the kind of development that balances economic, social and environmental priorities. Bradford’s partnership approach offers a template for national policy, demonstrating how growth and nature recovery can be integrated from the outset.

It is key that nature is seen as critical infrastructure. Bradford’s landscape-led approach is an excellent example of this, integrating nature and it benefits across policy and decision-making such as transport, health, visitor economy and climate resilience.

Dr Colm Bowe, Development Manager, Nature North

local character and environmental resilience.

2. Bradford City Village.

© 5 plus Architects / Dematerial

3. Norfolk Gardens, Bradford.

© Balfour Beatty

2.

Devolution and the future of regional and strategic planning

The role of devolution in shaping planning policy is critical. The new West Yorkshire Combined Authority (WYCA) has increasing control over regional investment, yet strategic spatial planning powers remain limited compared to devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales.

WYCA is already the responsible body for strategic policy such as the Local Nature Recovery Strategy, and it has produced a Climate and Environment Plan in response to the climate emergency. Bradford is aligning local development projects and strategies with these goals.

However, to maximise the benefits of a landscape-led approach, greater powers should be devolved to regional authorities like WYCA, to:

–

Develop regional green infrastructure strategies, ensuring that nature recovery is embedded into long-term planning

– Coordinate cross-boundary nature-based solutions, especially for flood resilience, habitat restoration, and active travel networks

– Secure sustained funding for green regeneration initiatives, linking economic growth with environmental enhancement

A fully integrated approach, where local and regional planning decisions align with national strategies like Nature North, and sectoral policies from DBT and MHCLG, must be the ambition. This would ensure that landscape-led regeneration is not simply a local ambition, but a core element of national economic and environmental policy.

A future vision for Bradford and beyond Bradford’s approach demonstrates that growth and nature restoration do not have to be at odds. Through a combination of strategic planning, investment in nature recovery and a commitment to high-quality design, the city can be a model for sustainable development in the UK.

For this vision to succeed, planning reforms must empower local and regional authorities with the funding, skills and flexibility to make informed decisions. The new planning system must recognise that economic growth should not come at the expense of our landscapes and communities: it should work with them.

The new planning system should recognise that economic growth should be delivered by working alongside communities and landscapes to maximise benefits to the environment, health and the economy.

Cllr

Alex Ross-Shaw, Portfolio Holder – Regeneration, Planning & Transport

Bradford’s experience highlights the importance of a landscape-first approach to planning. If properly resourced and integrated into policy, this approach, supported by regional strategies and strengthened by devolution, can help shape not just a more sustainable Bradford, but a greener, more resilient future for our communities across the UK.

Saira Ali FLI is Team Leader of Bradford and Metropolitan District Council Landscape Design and Conservation Team

Read ‘Investing in Nature for the North: A Strategic Plan for a Nature Positive Regional Economy’ at www.naturenorth.org.uk

at Bradford Council

Law of nature: Clyst Valley Regional Park

Leaders of a new landscape-scale green infrastructure network in Devon argue that a strategic approach to nature recovery is welcome, but new delivery mechanisms proposed in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill must not undermine existing environmental law.

1. Clyst Meadows sketch.

© Phil Watts

2. River Clyst, Honiton.

© East Devon District Council

Paul Osborne FLI

The Clyst Valley Regional Park (CVRP), on the eastern edge of Exeter, will provide a connected, multifunctional green infrastructure (GI) network that links existing historic villages and internationally important landscapes with the rapidly growing new community at Cranbrook, Exeter and the East Devon Enterprise Zone. The strategic approach to nature recovery proposed in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill offers the potential for a step change in the delivery of this vision to enable the creation of a nature-rich landscape that benefits the rapidly growing community. However, it is vital that the existing environmental protections from which CVRP has benefited to this point are not undermined by new mechanisms for nature delivery.

The vision for the Clyst Valley is to restore its landscape to create a tranquil haven for people and wildlife, with clear running waters nourishing new woodlands and wetlands, and an embedded resilience to climate change. The concept of the CVRP originates from LDA Design’s 2009 Green Infrastructure Strategy, which identified the importance of Clyst Meadows. These follow the River Clyst from Topsham on the Exe Estuary through Clyst St Mary and Broadclyst, to the National Trust’s 2,500-hectare Killerton Estate. The CVRP Masterplan1 sets out a vision and objectives for the Clyst Valley to create a multifunctional GI framework that provides space for people and nature, alongside a range of ecosystem services.

East Devon is one of the fastest growing districts in the country, with 8,000 homes completed, alongside significant employment growth, and plans to deliver a further 14,500 homes and a total of 26,000 jobs by 2040. The CVRP is essential to provide multifunctional ecosystem services, including water quality enhancement, flood storage, tree canopy cover, food production, habitat connectivity,

accessible green space and mitigation of the impacts of development on nearby European protected wildlife sites.

The South East Devon Habitat Regulations Partnership (comprising Exeter City, Teignbridge, and East Devon District Councils, with Natural England) has a track record of supporting the delivery of housing through a strategic approach to mitigating the impact of recreational impacts on internationally important locations. These include the Exe Estuary, Pebblebed Heaths National Nature Reserve, and Dawlish Warren. The South East Devon European Sites Mitigation Strategy2 sets out on-site measures, which include Wildlife Wardens (a coordinated parking and signage strategy), and ‘Devon Loves Dogs’3 (a free scheme for dog owners to promote responsible dog walking on these sensitive habitats). In addition, it promotes off-site measures, most notably Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspace (SANG). These are funded through a rigorously tested and clearly set-out funding regime, through developers’ contributions from planning agreements (typically Section 106 or Unilateral Undertakings), direct delivery (for larger developments) or Community Infrastructure Levy contributions.

This approach has secured significant areas of developer-led SANGs at Cranbrook and other larger-scale housing schemes that provide high-quality natural green space for residents and the wider community within the Clyst Valley. Clyst Meadows, currently being established on-site, will be the first SANG delivered by East Devon within the CVRP and will provide a 10-hectare country park for recreational use and biodiversity enhancement.

1 The Clyst Valley Regional Park Masterplan was the overall winner of the RTPI South West Awards for Planning Excellence

2021. The masterplan was also the winner of the Awards Category

‘Excellence in Plan

Making’ and highly commended in the RTPI South West Chair’s award for ‘Health, Wellbeing and Inclusivity’.

The vision for the Clyst Valley is to restore its landscape to create a tranquil haven for people and wildlife, with clear running waters nourishing new woodlands and wetlands, and an embedded resilience to climate change.

The Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) and Environmental Development Plans (EDP) proposed in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill⁴ have the potential to supercharge this existing approach to mitigation, potentially enabling a forward-funded, strategic and multifaceted approach that could unlock landscape-scale nature recovery. However, there are concerns about the weakening of existing environmental protections in the bill as it is currently worded.⁵ The Office for Environmental Protection has advised the government that while they commend a more strategic approach to issues such as nutrient overloading, they are concerned about aspects of the bill that reduce the level of environmental protection provided for by existing environmental law.⁶ If EDPs are implemented, it is vital that they are evidence-based and integrated with Local Nature Recovery Strategies to ensure they protect key species and habitats and truly deliver nature recovery.

An EDP for the Clyst Valley could support the CVRP masterplan objectives, ensuring equitable access to nature by providing more accessible natural greenspace close to people’s homes – particularly as many nature-rich places in Devon are difficult to visit without access to a car.

3. Clyst Meadows heart tree planting.

© Max Redwood

4. Clyst Valley Regional Park boundary.

© East Devon District Council

2 https://www.southeastdevonwildlife.org.uk/

3 https://www.devonlovesdogs.co.uk/

4 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ the-planning-and-infrastructure-bill/guide-tothe-planning-and-infrastructure-bill

5 https://www. wildlifetrusts.org/news/ gaps-planning-infrastructure-bill-deeply-concerning-say-wildlife-trusts

3.

5.

6 https://www. theoep.org.uk/ report/oep-gives-advice-government-planning-and-infrastructure-bill

The structure of the NRF and EDPs is not yet clear, nor is the role Natural England will take as the designated delivery body, but the potential for existing delivery partnerships (such the South East Devon Habitat Regulations Partnership) to share learning and build upon these successful mitigation strategies should not be lost. For CVRP, and many more similar projects around the country, there is a clear opportunity for a strategic approach, underpinned by protection of our important landscapes and habitats, to restore nature and enable sustainable development. The successful delivery of landscape-scale strategies such as the CVRP masterplan, and wider outcomes such as nutrient neutrality, carbon capture and health and wellbeing benefits, relies on existing levels of environmental protection not being reduced.

Paul Osborne FLI is Green Infrastructure Project Officer for East Devon District Council. All views are his own.

Tree planting with Broadclyst Primary School.

1 https://www. publicpractice.org.uk/ reports/recruitment-

Research shows public sector lacking in essential landscape skills

If the UK government is serious about integrating nature recovery strategies alongside ambitious housebuilding and infrastructure programmes, more landscape architects must be recruited and given meaningful roles across development, parks and regeneration departments.

Despite our famed love of gardens, the UK is one of the most biodiversity-depleted environments in the world. Since the introduction of the Environment Act 2021, it has been a legal requirement for every Defraappointed responsible authority in England to produce a Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) to mitigate against biodiversity decline, address escalating climate change threats, and deliver improved natural environments for citizens.

But pressure on housing has driven the current government to declare an ambitious target for 1.5 million new homes, the construction of which threatens to undermine precious natural ecosystems and landscapes. Local authorities, whose planners will need to ‘have regard’ for the LNRS when preparing local plans, require the right skills in-house to make informed decisions. A UK-wide, 2024 Recruitment & Skills Insight Report¹ that we conducted with more than

400 public sector officers identified landscape architecture as one of the most needed, yet most lacking, skills, in public sector placemaking. Other gaps exist in ecology, biodiversity and environmental sustainability. Of 420 respondents, 69% identified landscape architecture as a skill their team doesn’t have enough of.

Public Practice is a not-for-profit organisation, founded to address the critical shortage of planning and placemaking skills in local government. In 2018, we launched the Associate Programme, a pioneering initiative that works with local authorities to place talented, mid‐career, built-

environment professionals into public sector roles, for a minimum of one year. The success of the programme is evidenced by the many who choose to stay beyond that first year, and whose ongoing input has been welcomed within their respective teams. We have now placed over 350 Associates in around 100 public sector organisations. Over 80% of them had never worked in the public sector before, and approximately 75% remain in place two years after the initial 12-month contract ends.

The roles for which Public Practice recruits are wide-ranging, from architects working in town-centre

Pooja Agrawal

1. Public Practice spring 2024 cohort. © Benoît Grogan-Avignon

With the right skills in-house, local authorities can confidently lead this change by engaging stakeholders, holding housebuilders to higher standards and embedding nature at the heart of policy.

2. Allocating the right resource in the right places.

© Abbie Jennings

3. Grassington, North Yorkshire.

© Abbie Jennings

economic developments to engineers working on large-scale infrastructure projects. We have recruited landscape architects into roles ranging from steering county-wide LNRS strategies (see p35), to coordinating landscape and maintenance departments or advising within planning and regeneration teams.

There is, of course, variation in the level of support for, or understanding of, landscape architecture within each authority. Helen Sayers, for example, moved from a landscape team within a London-based commercial architecture practice (PRP) to join the Greater Cambridge Shared Planning Service. Helen is one of five landscape architects within her team, which works within a wider group of technical specialists in urban design, heritage and the natural environment. She says: “We work as an advisory service to planning officers, providing specialist landscape design and planning input on strategic sites, the emerging local plan and the landscape design elements of planning applications. A large part of the role is contributing, with colleagues, to pre-application discussions with developers.”

Helen adds: “Cambridge has always had this team, even when the

two planning services were separate. Cambridge is economically thriving, with many interesting developments and infrastructure projects emerging, and the planning service is well resourced and well structured.” She is now a permanent team member.

Lee Heykoop is another Associate with a background in landscape architecture. She joined Tower Hamlets in 2021 as a regeneration project manager. She says: “Tower Hamlets had two different landscape and maintenance teams in two separate directorates. The excellent parks landscape team was a marked contrast to the maintenance team, who were driving down use and biodiversity in pocket parks and roadside green spaces.” Lee put together a strategy document to improve joint working between these services, and has since gone on to another public sector role, this time with Homes England, which carries the potential for even greater strategic impact.

However, even in the most enlightened planning departments, there are challenges. Helen cites a lack of understanding around how to implement landscape works on the part of both contractors and

developers: “For example, in South Cambridgeshire, there are a lot of housing schemes that have a Section 106 agreement for open space and those are very poorly implemented… Developers and main contractors don’t have in-house expertise, and so planting often fails and has to be replanted.”

With pressure increasing on local authorities around the provision of new housing, and new requirements such as Biodiversity Net Gain and Strategic Development Strategies on the horizon, the need for landscape architects in the public sector has never been greater. With the right skills in-house, local authorities can confidently lead this change by engaging stakeholders, holding housebuilders to higher standards and embedding nature at the heart of policy. We are committed to bringing more talented and motivated landscape experts into the public sector and empowering them to have the broadest possible impact.

Pooja Agrawal is an architect, planner and co-founder and CEO of the not-for-profit organisation, Public Practice.

Public Practice in practice: The essential role of landscape architects in developing Local Nature Recovery Strategies

Landscape architect Tim Johns signed up as a Public Practice Associate in October 2022. As Senior Policy Officer for North Yorkshire Council, he has been devising a deliverable Local Nature Recovery Strategy.

My role as a landscape architect within the local planning authority of North Yorkshire Council is about building bridges between the technical world of nature specialists and a broad group of stakeholders, including farmers, residents, managers of rivers and woodlands and the Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Park Authorities. The aim is to synthesise an understanding of what a good nature recovery programme might entail across such diverse landscapes and communities.

The role requires initiative, collaboration, problem-solving and communication: working on the Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) has been about negotiating lots of hurdles and I’ve had to use all four skills in the pursuit of a successful outcome. There is plenty of

collaboration, due to the involvement of many different parties. There is also a lot of problem solving. And everyone we talk to around LNRS is on a spectrum: some people know a hell of a lot about nature, some a lot less. Because we have all these different interfaces, we need to adapt our message to each one.

North Yorkshire, the UK’s largest county, has seen a significant decline in wildlife due to loss of habitats caused by a variety of factors: from pollution and pesticide use to development and climate change. Given that the county is 70% farmland, it is reassuring to see how willing some farmers have been to collaborate. Several joined the six workshops the LNRS team ran in spring 2024, with each focusing on a specific habitat. We had a lot of goodwill in the room, which has informed the LNRS proposal that was put out for statutory consultation in May and will be finalised in autumn 2025.

Having had my initial 18-month contract with North Yorkshire Council extended to three years, I hope to be able to play a part in this vital opportunity to create a network of nature-rich sites that are more joined-up across both the county and the country.

Tim Johns is Senior Policy Officer at North Yorkshire Council and a landscape architect and urban designer with experience working across transport, education, housing, health, and infrastructure.

Tim Johns CMLI

1. Sutton Bank.

© Abbie Jennings 1.

Not all wildflower turf is created equal

The difference between success and failure is in the roots.

Other growing systems

Use a felt-like matting

Lab analysed UK seed.

Well-balanced species ratio.

Scientifically engineered substrate. Root network suppresses weeds.

Biodegradable netting. Easy for roots to penetrate.

Roots kept intact.

Limits root penetration, stresses plants, causes some species loss. Requires more watering.

Want to know more? Scan here for a free expert session!

Cut the roots

More grasses added in order to lift turf. This grass will outcompete flora.

All roots are cut at harvest. Slow to establish and some species loss.

Digital frontiers

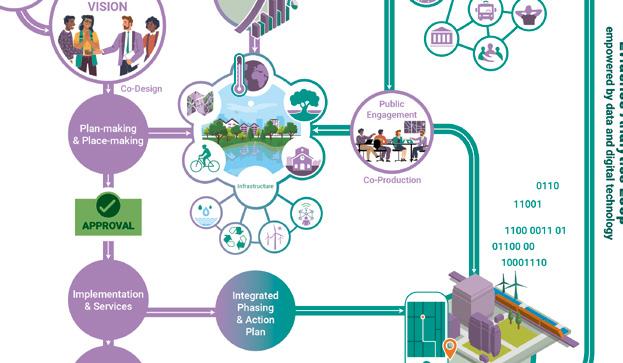

The new planning system must utilise digital technologies to efficiently integrate landscape benefits into development

Tracy Whitfield

As the planning and landscape sectors confront the prospect of supporting the delivery of 1.5 million homes and critical infrastructure, it is evident that digital technologies are indispensable. The Landscape Institute (LI) continues to play its part in driving this transformation, championing the integration of nature and communities into the digital future of planning.

Key to this work is the development of the LI’s Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) database – a robust, accessible resource

designed to help authorities and developers make new development sensitive to local people and places. By aligning with Natural England and other devolved bodies, the LI is ensuring this tool supports planning processes with insight on landscape heritage, data and impact.

In parallel, the LI’s involvement with the Digital Task Force for Planning and engagement with the New Towns Taskforce highlights our efforts to embed landscape values into the delivery of new homes and infrastructure. Working together, stakeholders must harness the digital planning ecosystem to model land use, optimise green infrastructure, and foreground nature-based solutions in strategic decision-making.

Digital Task Force for Planning

The Digital Task Force for Planning is a not-for-profit enterprise that positions spatial planning at the forefront of addressing grand challenges and envisions a planning profession

Tracy Whitfield is Technical & Research Manager at the Landscape Institute. Visit to view the LCA database: landscapeinstitute.org/ technical-resource/landscapecharacter-assessment-lca-database.

equipped with new digital tools, expertise, and improved data.

The first project to be delivered is the Digital Planning Directory, including a range of UK digital planning service providers for community engagement, visualisation, mapping, sustainability, design, plan-making, artificial intelligence, and more. Our goal is to unlock the full potential of spatial planning in the digital era by acting as a convenor, facilitator, and enabler of digitalisation in spatial planning practice and education.

The future of built and natural

environment practices should be interdisciplinary and digitally empowered, and the contribution of landscape professionals will be essential for shaping a digital future that benefits people, nature, and society.

Dr Wei Yang is Co-Founder and CEO of the Digital Task Force for Planning and Chair of Wei Yang & Partners.

Find out more in the ‘Digital’ edition of Landscape (Autumn 2024).

Dr Wei Yang

1. Digital planning system structure.

Digital Task Force For Planning

BNG: Bringing landscape architects into the conversation from the outset

Without early engagement with landscape architects and a framework that values ecologically valuable sites, BNG risks becoming just another compliance box to tick.