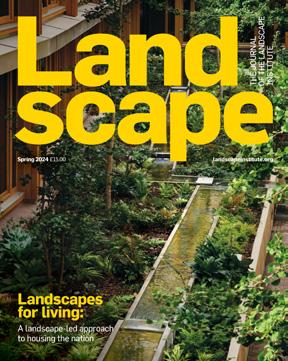

A landscape-led approach to housing the nation

landscapeinstitute.org Spring 2024 £15.00

living:

Landscapes for

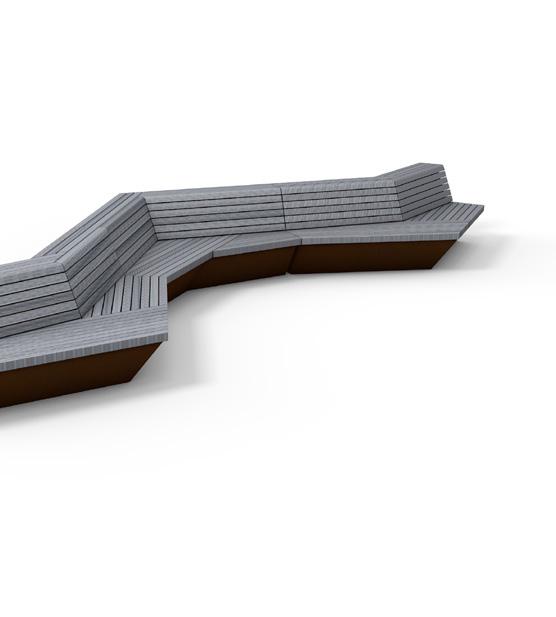

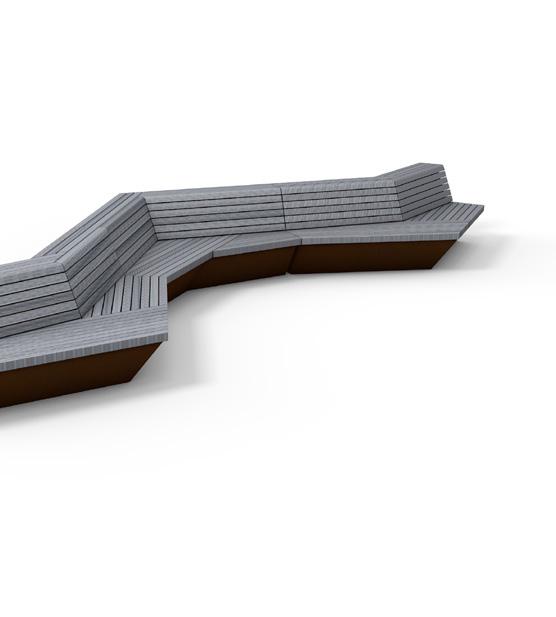

Products: Solid Skirt Benches & Solitude Benches Project: Kings Cross Gasholders, London (UK) by Townshend Landscape Architects enquiriesUK@streetlife.com I www.streetlife.com I t. +44 (0) 20 30 20 1509 I FSC® license number: C105477 Extraordinary for Landscape Architects

beam size: 7 x 7 cm -certified hardwood or Accoya

and armrests

Big Green Bench

Grey (recyclate) Green Circular Skirt Benches Solid Wing Bench Cloudy Grey (recyclate) TWIN NEW Green Screen System with cantilevered Rough&Ready Benches TWIN NEW NEW

Product Range: Solid Series,

Back-

Drifter

Lava

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931

darkhorsedesign.co.uk

tim@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Saira Ali, Team Leader, Landscape, Design and Conservation, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

Stella Bland, Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes CMLI, Director, Allen Scott

Landscape Architecture

Sandeep Menon, Landscape Architect and University tutor, Manchester Metropolitan University

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape Architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Landscape Architect, Allies and Morrison

Jane Findlay, PPLI, Director FIRA Landscape Architects

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Editor: Paul Lincoln

Copy Editor: Jill White

Proof Reader: Johanna Robinson

PR & Communications Manager:

Josh Cunningham

President-elect: Carolin Göhler

CEO: Rob Hughes

Head of Marketing, Communications and Events: Neelam Sheemar

Landscapeinstitute.org

@talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

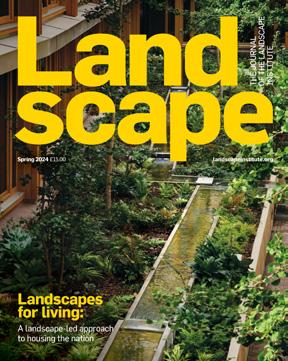

An election about housing must include a debate about landscape

Housing is set to be one of the key issues in the general election due at the end of this year. Election rhetoric often focuses on promises to build a million homes in one parliament or fears about damaging the green belt. This edition of the journal offers a more nuanced focus which highlights the creative relationship between landscape architect and architect, and the role of the public sector client.

We open with the nature-led regeneration of Thamesmead by Peabody, and conclude with an interview with Saira Ali, landscape team leader at Bradford City Council and winner of the 2023 LI President’s Award. The value of the public sector commission continues with a look at landscape-led urbanism in public housing and a reimagined almshouse, Appleby Blue, which shows how good landscape design is beneficial at every stage in a life.

We examine the rebirth of a housing estate in Barrow-in-Furness and consider how allotments are struggling for space alongside housing. We pay tribute to the legacy of Mies van der Rohe; investigate the power of the pocket park; look at the dreams of self-build pioneer Walter Segal; and consider how to safeguard a sense of place in new developments.

The focus on post-election promises considers the delivery of garden cities and the expanded research section looks at maintenance, water resilience, cohousing and how to retrofit an urban forest.

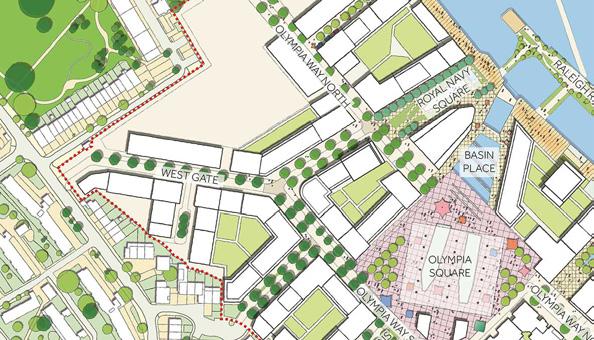

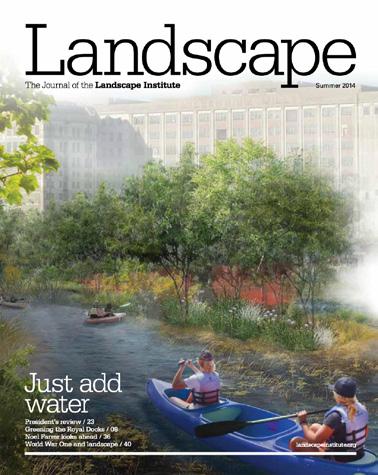

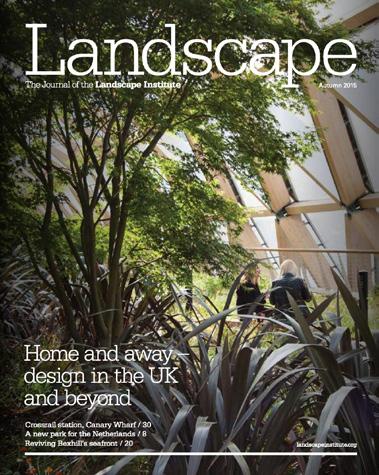

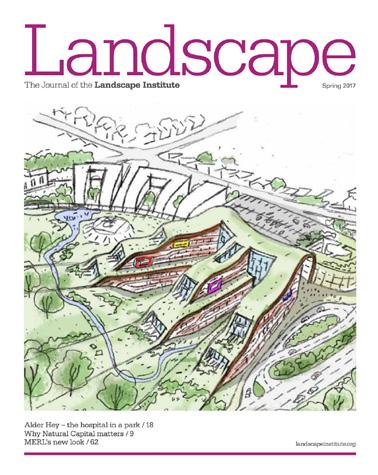

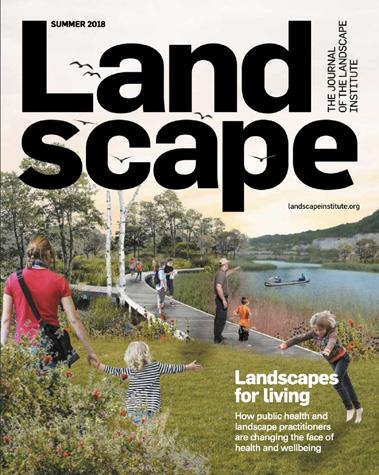

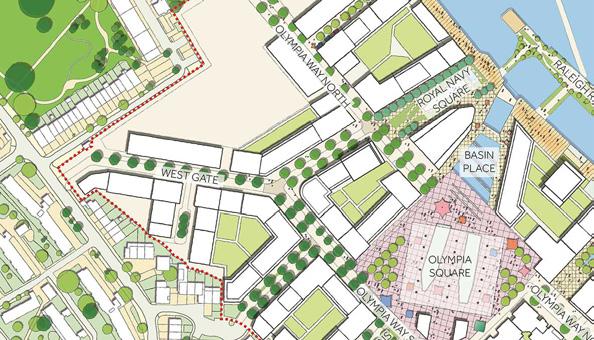

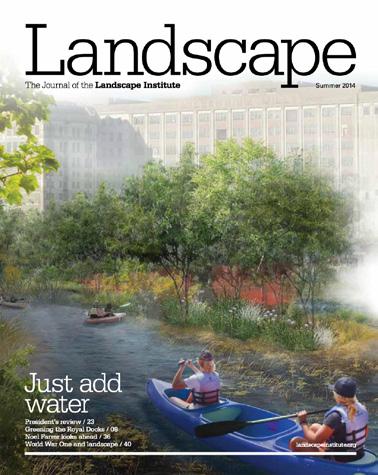

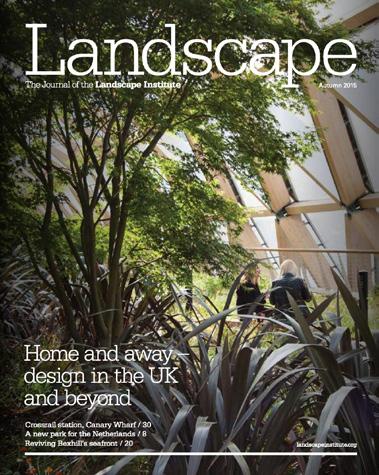

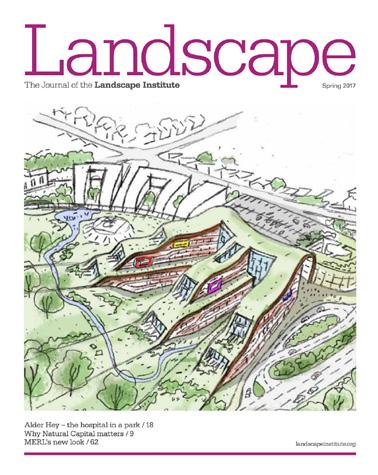

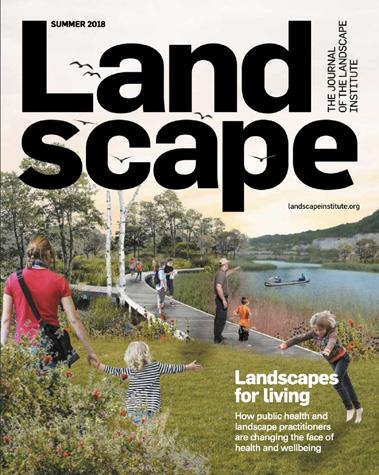

As I retire as editor of the Journal, I want to offer my huge thanks to the

many members and supporters of the LI who have been not just readers but also writers. I want to thank the Editorial Advisory Panel which has offered guidance and support throughout my time at the LI, and I want to thank Jill White who has been both a member of the EAP and for many years, copy editor. Darkhorse Design have published the Journal over the past twelve years. There is a creative dialogue between landscape design and graphic design celebrated by the catalogue of front covers illustrated overleaf, all of which can be enjoyed in detail through the online archive.

Paul Lincoln

Editor

Editor

WELCOME Landscape is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing. The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it. Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914 © 2024 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design. Cover image: The Garden Court at Appleby Blue, London. © Philip Vile

Landscape is available to members both online and in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: my.landscapeinstitute.org

or online? 3

Print

Contents 4 6 A 12-year partnership Explore the Landscape online archive 16 Lafayette Park, Detroit The legacy of Mies van der Rohe and Alfred Caldwell 27 Modern Hospice Design A landscape architect response 35 Allotments and food strategies How food growing competes with the demand for housing 8 Brutalism and biodiversity The landscape-led regeneration of Thamesmead 20 Housing, health and landscape Appleby Blue – reimagining the almshouse for the 21st century 29 Barrow-in-Furness The benefits of retrofitting the landscape 37 Home Sweet Home Safeguarding the sense of place in new developments 13 A new era for public housing New thinking in council-led schemes 24 Courtyard and garden The landscapes of palliative care 32 Plan the street as well as the sky How to respond to a tall building at the foot of the tower 40 Home Truths Ten years on from England’s first zero carbon estate

42

45

48

51

53

56

59

62

64

73

FEATURES

The power of the pocket park The threat to Crabtree Fields

The Sayes Court Project Community development by the river in Deptford

pioneer in a challenging landscape

Walter Segal Self-build

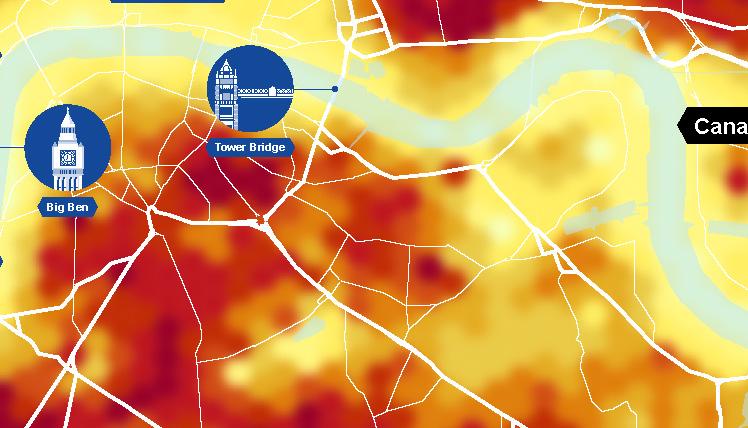

Climate advice Focus on housing schemes

Post-election

Ensuring that housing is part of the election debate RESEARCH

promises

Finding

Water resilience Maintenance matters

landscapes of cohousing Designing resilience into housing developments How not to deprive people of the benefits of GI TECHNICAL

Getting SuDS right The impact of making SuDS mandatory LI LIFE

Saira Ali interview Meet the winner of the President’s Award

common ground

The

67

70

CAMPUS: Learn from anywhere RESEARCH

Building

Retrofitting

into social housing 5

the urban forest

urban forests

Celebrating a 12-year partnership between graphic design and landscape design

2024 marks the 12th year that Landscape, which has been in print since 1934, has been designed and published by Darkhorse Design. The back catalogue is available to download free of charge from issuu.com/landscape-institute.

FEATURE

September 2012 March 2013 June 2013 September 2014 December 2015 March 2016 June 2016 September 2016 December 2016 December 2014 March 2015 June 2015 September 2015 September 2013 December 2013 March 2014 June 2014 6

FEATURE March 2017 September 2018 January 2020 April 2021 July 2021 October 2021 February 2022 July 2022 November 2022 March 2023 June 2023 September 2023 January 2024 March 2020 July 2020 October 2020 January 2021 January 2019 April 2019 August 2019 November 2019 June 2017 September 2017 September 2017 May 2018 7

Brutalism and biodiversity

FEATURE

8

Thamesmead is a remarkable town with a fascinating backstory. A draft masterplan approved by the Greater London Council in 1966 envisaged an alternative to London living, defined by brutalist architecture, spacious homes, elevated walkways and considerable open space. Built on former Thames Estuary marshland, the original homes in Thamesmead were designed to be above ground level to reduce the risk of flooding, while a network of

The regeneration of Thamesmead offers a unique opportunity to restore and revive an important post-war estate through a focus on biodiversity and landscape.

picturesque lakes and canals, sitting alongside green corridors, were created to retain and divert surface water. Hailed as the ‘town for the 21st century’, the first residents moved to Thamesmead in 1968 to much excitement.

However, the 1966 masterplan was never fully realised due to a range of factors – site constraints, insufficient amenities, inconsistency in governance and wider socioeconomic circumstances.In 2014, Peabody took ownership of two-thirds of the

Thamesmead. This meant that for the first time in a generation, much of the town’s housing, community investment activities and land would be managed by a single, wellresourced body. Working with local people and partners, we’re now aiming to improve, grow and look after the town for the long term. With a vision to realise Thamesmead’s full potential, we’re taking a ‘whole place’ approach to the regeneration, investment, and management of the town, which includes managing the town day-to-

FEATURE

Phil Askew 1.

1. Southmere Lake. © Phil Askew, Peabody

9

day, providing better quality homes and amenities, making culture a part of everyday life, supporting communities, and – my area of work – maintaining and enhancing Thamesmead’s extraordinary natural assets. This is set out in detail in our Thamesmead Plan, our core governing document, which is reviewed every five years.

Prioritising the landscape

The landscape of Thamesmead is unlike anywhere else in Greater London. Its sheer extent and variety of green and blue spaces offer us a significant opportunity to bring positive change to local people and the natural environment at scale. To drive this

Peabody owns 65% of the land in Thamesmead – a total area 7km² –and is now steward of:

– 240ha of green space – 5 public parks – 5 lakes

– 7km of canal and waterways – 5km of river frontage – 53,000 trees

– 15 community buildings

forward over the long term, we’ve put in place a green and blue infrastructure strategy, Living in the Landscape. This strategy sets out our approach to making the most of Thamesmead’s outdoor spaces, with a particular focus on the existing landscape’s potential to reduce health inequalities, mitigate the impacts of climate change and create habitat for a wide range of species. Developed with LDA Design and a consortium of experts in topics such as ecology, planning, economics, and sustainable urban drainage systems, it sets out five key programmes for change:

– The Big Blue – making more of our lakes and canals

– Wilder Thamesmead – enhancing biodiversity through design and a biodiversity action plan

– A Productive Landscape –volunteering, gardening and food growing, landscape activation

– Active Thamesmead – play for all, sport and an active landscape

– Connected Thamesmead – active travel using the landscape as a connecting thread

The strategy is invaluable to us, underpinning every aspect of our work

– from informing project briefs to commissioning services, tracking our progress and measuring success.

Day-to-day stewardship

Many of the opportunities identified in Living in the Landscape will be achieved through improved landscape management approaches and working with our Peabody in-house Environmental Services team. In tandem with Living in the Landscape, we’re developing our approach to landscape management through a detailed Estate Management Plan, working with Land Management Services. To this end, we’ve focused on upskilling the team through training with Capel Manor College, a specialist in environmental education. Our aim is to equip them for more nuanced approaches to looking after the land – thinking as horticulturalists rather than simply cutters or mowers.

Recent investment

Over the last five years we’ve focused on developing more detailed approaches to managing the landscape of Thamesmead. In South Thamesmead, where the original brutalist homes sit, we’ve overseen a number of large-scale changes. They include the development of a masterplan by Turkington Martin landscape architects to improve water quality and biodiversity at Southmere Lake, which had previously endured decades of decline. Our investment of £2.5m saw the dredging of 7000m³ of silt to create extensive new reedbeds and floating islands elsewhere in the lake. In doing so, we’ve deepened and therefore cooled the water, lessened anaerobic microbial activity in the bed of the lake, and improved water flow, all of which has improved the water quality and encouraged greater biodiversity. This work, along with better access to the water’s edge, lakeside planting, wooden viewing platforms, a 23m water fountain and a nature trail, has transformed the look and feel of the lake and its immediate surroundings.

We’re now working with Thames 21 and the London Wildlife Trust to help improve water quality in Gallions Lake and our extensive canal network.

With a vision to realise Thamesmead’s full potential, we’re taking a ‘whole place’ approach to the regeneration, investment, and management of the town, which includes managing the town day-today, providing better quality homes and amenities, making culture a part of everyday life, supporting communities.

2. Aerial view of Thamesmead.

© Peabody

3. Archive image of Thamesmead at time of opening.

© Thamesmead Community Archive

2.

FEATURE 10

3.

Courtyard before new planting.

© Phil Askew, Peabody

5. Courtyard after planting.

© Phil Askew, Peabody

6. Southmere Lake.

© Phil Askew, Peabody

7. SuDS planting scheme.

© Phil Askew, Peabody

Within our floating reedbeds we’ll be introducing freshwater mussels, which provide natural filtration. As they retain contaminants, they can potentially help us monitor the health of the water over time.

Greening the grey

We’ve also invested heavily in the spaces directly outside people’s homes in South Thamesmead.

Working with Land Use Consultants (LUC) and Levitt Bernstein Associates (LBA), we’ve transformed around two hectares of public realm in the Parkview and Southmere estates. Here, the designs are sympathetic to the original layout but introduce contemporary elements.

Improvements involved ‘greening’ the grey walkways and enhancing open spaces right outside people’s front doors. Changes included replacing trees that were too big for green courtyards with better-sized, diverse mature trees; installing above-ground planters; planting climbers along parts of the walkways; and introducing beds in the hard and soft landscape. The beds were planted with colourful, textural and biodiverse

perennials, including bulbs and herbaceous plants. Some were designed as attractive raingardens, acting as sustainable urban drainage systems (SuDS). Other improvements to the estate included new lighting, play and seating areas.

Completed in 2020, this has transformed a large area of the original estate and has been well received by residents. Idverde landscape contractors carried out the works during 2019 and 2020, and went on to win a BALI National Landscape award for their involvement. In 2021 the Southmere estate was commended as a runner-up in the Landscape Institute’s award for horticulture and planting design.

Working with the community

A second phase of this work, known as the South Thamesmead Garden Estate, is now underway. This will see more than three hectares of underused green space, including a green walking route stretching from Lesnes Abbey ruins to Southmere Lake, transform into flourishing parkland and other welcoming spaces.

Crucially, this phase of the programme is being co-produced by a group of local people, known as the Community Design Collective. Recruited, trained and paid a part-time living wage, they’ve invested more than 1,000 hours in design conversations, site visits, and client and contractor meetings since the project began in 2018. Moving towards a more democratic approach to design has been challenging and rewarding in equal measure. It’s an approach that we’re constantly learning from and that we hope to replicate.

Alongside these significant programmes of investment and others elsewhere, we’re providing opportunities for local people to participate in nature-based activities and events across the town. Through our community programme, Making Space for Nature, there’s now a growing movement of local naturelovers getting involved in all kinds of outdoor projects – including habitat creation, woodland coppicing and tree planting across the town. Our work has taught us that that small-scale

projects can be as valuable as large-scale changes, so long as what is being delivered responds to the needs of communities and the local environment.

This article provides a snapshot of what we’ve achieved in Thamesmead, thanks to the ongoing support of local people and our partners. But to appreciate the full extent of the changes, Thamesmead is well worth a visit. Seeing is believing. If you’d like to hear more about our work or take a tour of Thamesmead’s neighbourhoods, please go to www.thamesmeadnow.org.uk and get in touch.

Dr Phil Askew is Director of Landscape & Placemaking at Peabody. He is a landscape architect, urban designer and horticulturalist. Prior to his current role he led the design and delivery of the London 2012 Olympic Park at the Olympic Delivery Authority and its transformation into the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

4.

4.

6.

7.

FEATURE 11

5.

FEATURE 1. 12

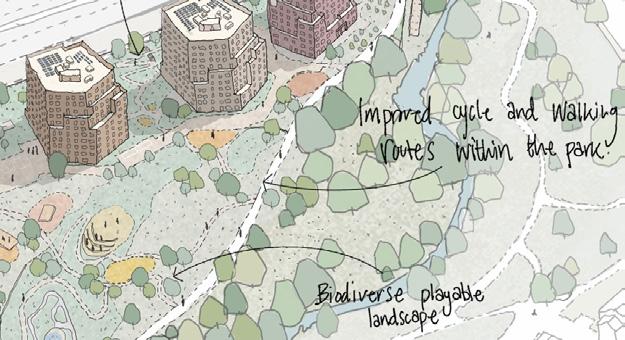

Led by residents, these urban rambles provide an opportunity for design teams to learn from their local experiences and better understand their sense of identity and the issues as they see them.

A new era for public housing and landscapeled urbanism

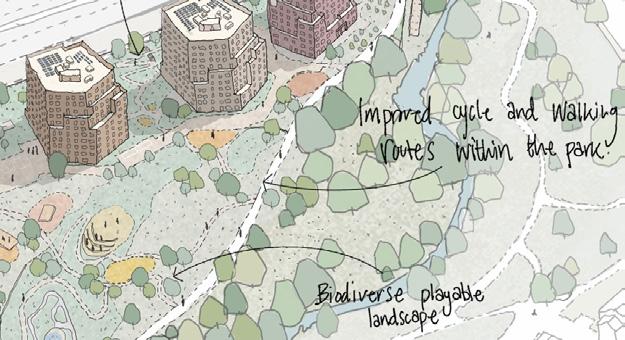

The landscape of public housing is under pressure to be multifunctional and to provide amenity, recreation, shade, ecology and biodiversity. Three projects from Karakusevic Carson demonstrate new thinking in council-led schemes.

Landscape within the realm of public housing estates has long been contested. Post-war neighbourhoods possess a visible generosity of it: a strong legacy of the modernist-inspired planning of our cities, when acres of green space were created to promote communal forms of living and offset new densities.

However, neglect, a sense of insecurity, species monoculture and hostile nearby uses such as car parking and busy roadways have rendered many landscapes unusable. Despite their generosity and original intention, some estate open spaces can play an active role in partitioning communities and severing neighbourhoods.

Today, as some councils embark upon programmes of housing and estate renewal, a new era of landscape-led urbanism has emerged. As a practice working within these environments, our brief is to provide new and ever greater numbers of homes. As part of this process, green spaces are impacted, so a positive

relationship between architecture and landscape – and architect and landscape architect – is key. In all our projects we work collaboratively to ensure the creation of new dwellings, but also maximise the potential of landscape to create spaces that will support residents’ quality of life and the future resilience of our cities.

All our council clients have declared a climate emergency and realise the need to rethink neighbourhoods to increase their resilience and improve the lived experience of residents. Typical challenges for estates include a lack of ground floor activity, poor quality pedestrian environments, a lack of cycling links, the dominance of cars, a lack of bin and cycle storage and underutilised but valued green spaces. To support positive change and help mitigate climate impacts, there is significant pressure on landscape and civic spaces to be multifunctional and to provide amenity, recreation, shade, ecology, biodiversity and sustainable drainage, as well as support physical and mental wellbeing.

As we embark upon any project, we look for strategies to improve connections and forge links between existing assets and the rest of the city. London is blessed with lots of green spaces and many of our estate projects, for example Kings Crescent in Hackney, Broadwater Farm in Haringey and St Raphael’s in Brent,

border existing large public parks. However, the mere presence of a park does not guarantee active use of or participation in it. In response, we ensure routes are purposeful and that buildings frame key civic spaces in a positive way, maximising views out for residents, creating open and generous backdrops, while promoting engagement with existing assets such as mature trees often found within post-war estates, but which are frequently uncelebrated.

To understand the role of open space in the neighbourhoods in which we work, we carry out site walks. Led by residents, these urban rambles provide an opportunity for design teams to learn from their local experiences and better understand their sense of identity and the issues as they see them. These walks can reveal neighbourhood stories, anecdotes and characters that can often be surprising and challenge assumptions.

Public realm is typically a key priority for residents on public housing estates. We undertake numerous thematic workshops to inform co-design processes and engage specific groups to discuss potential ways to improve green spaces. As part of these sessions, we take time to work with young people and girls in particular, who often feel excluded in public space and are less likely to

© Karakusevic Carson Architects

1. St Raphael’s Estate Masterplan Axonometric aerial view.

FEATURE

Paul Karakusevic and Abigail Batchelor

13

spend time outdoors. The broad range of workshops for specific groups like children, young adults and old people ensures we capture as many views and experiences as possible, in order to design for flexibility and a variety of needs, aspirations and user groups.

Additional excursions with housing estate maintenance teams and sometimes local police also inform the landscape and masterplan approach. Ongoing pressures on council budgets means money needs to be spent wisely to future-proof landscapes and minimise costly maintenance. Working with clients and collaborating with others we prioritise the development of initiatives that are simple, practical, multipurpose and flexible and so provide ecology, play and amenity simultaneously.

Kings Crescent Estate

Approved in 2013, our masterplan for the 1960s Kings Crescent Estate in Hackney was an early exemplar in promoting alternative approaches to estate renewal and new and experimental landscape. Renewal of the neighbourhood is ongoing

with phases one and two delivered in 2017. At the heart of change are new mansion block buildings that provide mixed tenure homes and work with existing estate buildings to create a series of courtyards. Developed in close collaboration with muf architecture/art, the strategy for landscape across the estate is twofold.

At the heart of each of the three communal courtyards created are a series of discreet and intimate responses intended to bring residents in both old and new buildings together with young child play space, small planted gardens, quiet seating areas, allotments and growing spaces to promote interaction and engagement with nature. The main articulation of the new neighbourhood however is its central east–west street – a linear axis designed to open the estate and improve connectivity to adjacent amenities, but also be a civic space in itself – a sociable, active and consciously playful space to linger rather than simply pass through. The traffic-free space is lined with trees and is full of new planting and playful installations to encourage imaginative

responses from people of all ages, including a huge table for impromptu open-air gatherings. Supporting the life of the space, front doors and the communal entrances to the new buildings all open out onto the space ensuring regular use by and visibility of the community. The generous high-ceilinged lobbies feature large openings that provide views from the street through to the courtyard landscapes. Elsewhere, non-residential uses at ground level at key locations, such as retail and community use, brings activity to occupy and spill out into this public realm.

Broadwater Farm Estate

Completed in the 1970s, the modernist landscape of the Broadwater Farm Estate features extensive areas of green, but much of it is a visual resource rather than an active space. Dominated by car park undercrofts beneath residential buildings, pedestrian movement about the neighbourhood was originally separated to upper decks, which also meant a separation between people and their local landscapes. Following demolition of connective upper-level walkways in the 1990s, residents were left without defined pavements or routes through the estate.

Collaborating with What If projects and East Landscape architects, we prepared an Urban Design Framework that establishes five core principles that, alongside providing new homes, will transform the landscape and the experience of the estate over more than ten years. Developed with the community they include the creation of safe and healthy streets, a focus on welcoming and inclusive open spaces, more active ground floors and enhancing the existing character of the neighbourhood.

To ensure a coordinated approach to neighbourhood change, the framework seeks out synergies between existing assets and new interventions. One of the central proposals is the creation of a new route through the estate following the line of the culverted river Moselle. This connective artery aims to better link the neighbourhood to the adjacent Lordship Recreation Ground,

The main articulation of the new neighbourhood however is its central east–west street –a linear axis designed to open the estate and improve connectivity to adjacent amenities, but also be a civic space in itself – a sociable, active and consciously playful space to linger rather than simply pass through.

2.

2. Kings Crescent Estate Phase 1 & 2. View of new buildings looking west along Murrain Road.

FEATURE

© Jim Stephenson

14

but also provide the axis for new residential buildings and new civic spaces. Elsewhere, the framework includes the retrofitting of existing communal entrances and simple measures, for example encouraging diverse planting regimes in existing spaces and proposing less frequent lawn cutting to allow wild flowers to thrive and carbon to be sequestered.

A common critique of post-war estate landscapes is their overpermeability. Our work with the community at Broadwater challenged this perception and residents demanded that the openness of the numerous courtyards be retained to minimise loss of public space and prevent the privatisation and securitisation of the area. In response, our framework retains routes through the network of courtyards, whilst prioritising key connections to aid wayfinding. Desired accessibility of landscape has also informed the design of a new residential building that is conceived as an open courtyard and a building in two parts, echoing the existing organisation of the estate.

St Raphael’s Estate

Bordering the meandering landscape of the River Brent and the extensive Brent River Park, our work at the 1960s St Raphaels’ Estate in Wembley with Periscope landscape architects revealed a surprising misconception about open space that has directly influenced the masterplan now being taken forward. One of the main outcomes of our extensive consultation with the community was that the generous open space nearby was seen as a place of concern and potential danger, rather than one that was readily valued or celebrated. Homes physically turned their backs on the space, and it was evident that most people did as well, in particular young women and girls.

Through co-design conversations we together developed six residents’ principles that informed an estate-wide strategy for change. This included the provision of new affordable homes, new community facilities and improved access to the estate, ensuring all streets are safe and welcoming and improving the existing green areas and the park adjacent to the estate.

To achieve this vision our masterplan involves the creation of infill homes within the footprint of the existing estate, but also by building along the edge of the park on an area bordering the busy North Circular Road. This approach was not without controversy. London-wide policies prohibit building upon open space; however, the evidence from the community, the existing condition of the park and proposed benefits persuaded the council to adopt a different, but very site-specific position which was endorsed by the Greater

London Authority (GLA).

Conceived as elements nestled within topography, the three new landscape-led apartment buildings will directly balance loss of space, by introducing new activity, with new homes providing new life and contributing to physical park improvements that will increase safety with new pathways and new lighting, promote biodiversity through new wild flower meadows and planting, support resilience through the addition of flood attenuation basins and promote new use through growing spaces, seating areas and play amenities including an outdoor gym and skate park.

In creating new and adapting existing housing for the future, landscape has a fundamental role to play. Well-designed, meaningful and well-loved spaces engender ownership and provide opportunities to improve wellbeing and for communities to come together.

Within the realm of the public housing estate, the pressures upon councils to introduce new homes can seem overwhelming. The integration of estates and neighbourhoods through new connectivity and spaces with common purpose is key. Through our work in public housing we have learned that the development of strategies through collaboration and co-design is the best way to better understand communities, to challenge and interrogate assumptions and ensure lasting legacies.

Paul Karakusevic is Founding Partner and Abigail Batchelor is Associate Director at Karakusevic Carson Architects

3.

5.

4.

3. Broadwater Farm Estate Illustrative view of Willian Road towards the Civic Space.

© Jim Stephenson

4. Broadwater Farm Estate Axonometric showing the UDF network.

© Karakusevic Carson Architects

5. St Raphael’s Estate Masterplan; View across Brent River Park towards the new neighbourhood.

FEATURE 15

© Slab Ltd

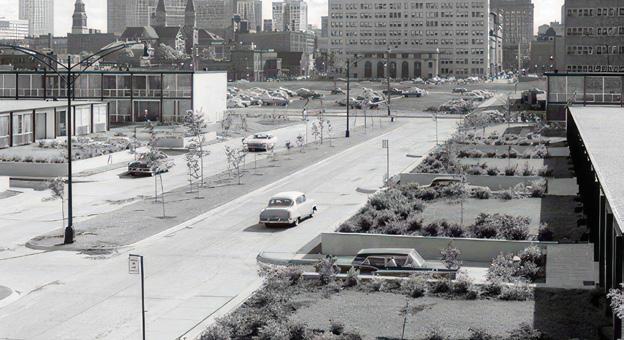

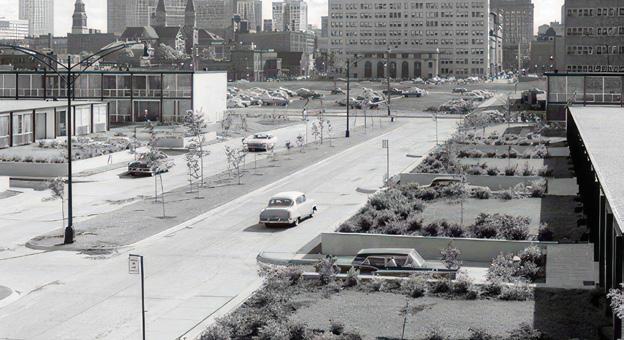

The landscape legacy of Lafayette Park, Detroit

Howells’ David Henderson pays tribute to the work of Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Alfred Caldwell in the design of two East London housing schemes.

1. Townhouses in Lafayette Park in Detroit. Constructed between 1956 and 1959, Lafayette Park contains the world’s largest collection of buildings by Mies van der Rohe. © Alamy

2. Lafayette Park on completion.

David Henderson

FEATURE

1. 2.

16

At Howells, the sites we build on and the residential typologies we work with cover all scales and densities. There is no one-size-fitsall and, particularly in London, near public transport nodes, we are building housing of significant height. The questions we face include establishing appropriate scale and ensuring that there is always a close and meaningful relationship to the landscape, as has often been the case historically.

In the early 20th century, the idea of the garden city tended towards a low-rise, detached suburbanisation, which threatened the very landscape that made living there an attractive idea in the first place. As Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, architects of the Barbican in London, said, ‘We strongly dislike the Garden City tradition, with its low density, monotony and waste of good country, road, kerbs, borders and paths in endless strips everywhere.’¹ By the time of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse urban planning concepts, the pendulum had swung towards proposed highrise dwelling units seeming to float disconnectedly above an indeterminate salad of greenery.

While the proximity to green infrastructure is important, and the

need to build taller and more densely is an increasing necessity, neither extreme offers an answer to the kind of challenges we are faced with now. However, one mid-century development in the US incorporated elements of both philosophies to good effect.

Surprisingly, given its scale, Lafayette Park in Detroit was a commercial enterprise, with the central parkland and street landscape developed by Howard Greenwald, working together with architect Mies van der Rohe, urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer and landscape architect Alfred Caldwell. They shrewdly appreciated this would add significant value to the real estate in exactly the tradition of London squares and parks of the Georgian period.

When Lafayette Park was newly completed in 1963, it looked to be somewhat sterile, dominated by parking, roads and hard surfaces. Now, however, after a period of 60 years, the landscape has matured and what seemed an abstract flexible pattern of development is now a highly valued place. The project has fairly high densities and incorporates a mix of building scales, from townhouses to flats up to 22 storeys, and this variety of scale, alongside its landscape, is what provides its quality and interest.

The scheme is distinguished from its contemporaries by a clear sequence of densely landscaped spaces, moving progressively from open parkland to private courtyard via a network of green streets and pathways.

It is a dwelling experience that is immersed in nature, a humane civilised compromise that recognises both the attractiveness of the garden city ideal and the need for increased density, but which treats the landscape as a key component in a legible sequence of spaces, not just as background scenery.

In its recognition of the value of landscape to housing development, Lafayette Park draws on a historical narrative which still has contemporary relevance. It has a collection of buildings designed by one of the acknowledged masters of 20thcentury architecture, and yet it is the maturing landscape which ultimately gives it its quality. In its mix of scales and multiple uses it could almost be seen as a prototype for what the 15-minute city is now.

Although it has a very different context, Howells’ project at Royal Wharf – a new Thameside district in east London of over 15 hectares – addresses many of the same challenges as at Lafayette Park.

We believe that the key to

FEATURE

3.

¹ Chamberlin,

& Bon,

15 January 1953 17

3. Drawing Sheet P-1, Planting Plan, from the Lafayette Park Construction Documents Set of 1958.

Powell

Architects’ Journal

successful places are mixed demographics, housing types and tenures – with streets and homes that people aspire to live in as a vital part of balanced and strong communities. Looking to the urban characteristics of typically successful residential districts forged in the 19th century, we investigated a new urbanism for this district, which is in the London Borough of Newham, focused on grid densities, building heights, road and pavement widths and people-to-gridspace ratios.

Reinterpreting traditional terraced housing for the 21st century, the townhouses were among the first buildings at Royal Wharf, leading the way in demonstrating a familiar urban streetscape of three- and four-storey terraces, screened by front gardens with hedges and bookended by taller mansion blocks and residential towers.

Looking at the wider area, we analysed the river context several miles east and west of Royal Wharf’s Thames frontage, exploring ways for a new community to experience London’s river. Understanding that the key to a sustainable neighbourhood

was to look beyond the site’s high-value frontage, we analysed local networks of green spaces, community infrastructure and transport stretching from Canary Wharf to the Thames Barrier.

We were fortunate to benefit from two significant established green spaces nearby in Lyle Park and Thames Barrier Park. We integrated these, along with our own newly created Royal Wharf Gardens, into the development, with a high street running through the site.

This high street connects adjacent communities with the river, a new Thames Clipper stop and inland Docklands Light Railway stations. Royal Wharf’s high street also gathers essential local amenities, including dentists, doctors and food shops. A new primary school for 420 children, a nursery with 60 places and a community centre located at the heart of Royal Wharf lay the groundwork for a cohesive and socially connected community.

Another of our masterplans, London City Island, presented a different set of challenges and opportunities. London City Island (LCI)

is a new residential and culture-led neighbourhood located in Canning Town in the heart of east London, with distinct public spaces and a maturing soft landscape edge to the River Lea. The masterplan includes 1,706 homes, shops, restaurants, cafés, offices, an energy centre and new spaces for both English National Ballet and Queen Mary and Newham College.

London City Island was a brownfield site where all evidence of its former use had been erased. A key driver in the development of the masterplan was the dramatic meander in the River Lea, creating access to an almost continuous waterfront while allowing for a less structured urban geometry. Proximity to a major public transport interchange and wider amenities at Canning Town was achieved by providing a new lifting bridge, allowing us to develop more densely while also greening and rehabilitating the previously industrial waterway.

Historically, the buildings on site had been undistinguished other than the original house and orchard, a memory of which survives in the

We were fortunate to benefit from two significant established green spaces nearby in Lyle Park and Thames Barrier Park.

FEATURE

4.

4. Royal Wharf. © Greg Holmes

18

In all three projects, the housing design was preceded by the creation of a destination: the park in Detroit; the boulevard connecting new and existing green spaces at Royal Wharf; the garden and river edge at London City Island.

street name, Orchard Street. The surrounding presence of water therefore offered an opportunity to develop a new narrative of riverside buildings surrounding a central garden, an arrival square fronted by the new spaces for English National Ballet and a new landscaped water’s edge.

The landscaped spaces, one intensively planted and the other more formally surfaced, are critical in creating a liveable environment, a meeting place, a connecting point between visitors, students and

residents and leading through to new vantage points around the extensive waterfront. We were able to cluster the tall buildings fairly closely together without compromising daylight, privacy or views, by carefully aligning and angling facades away from each adjacent block. This created a relatively tall and dense but extremely liveable development with daylight reaching deep into the central green spaces.

The buildings share a language of brick architecture distinguished by bold use of colour but acting as a foil

to the greenery of the waterfront park. Overall, the collective has a greater impact than the sum of its parts, like a mini-Manhattan.

The common thread between Lafayette Park and our two projects has been the understanding that, for the project to be successful, it cannot simply adhere to an abstract idea (à la garden city or Ville Radieuse). In all three projects, the housing design was preceded by the creation of a destination: the park in Detroit; the boulevard connecting new and existing green spaces at Royal Wharf; the garden and river edge at London City Island.

At Lafayette Park, the landscape has been a 60-year investment in the quality of the dwelling experience. At Royal Wharf, and London City Island, after about five years, it is already apparent that the green spaces are becoming well established and we hope that in due course these two new places in London will mature in the same way.

David Henderson is an architect and Partner at the London studio of Howells

FEATURE

5.

6.

5. London City Island.

© Hufton + Crow

6. London City Island.

© Hufton + Crow

19

Housing, health and landscape

Appleby Blue is a development reimagining the almshouse for 21st-century living. Grant Associates’ Keith French explains the vital role of landscape in the project –and outlines three other schemes that show how the practice incorporates nature into housing environments.

Appleby Blue, a social housing development of 57 almshouses in Bermondsey, south London, recently opened its doors to welcome its first 63 residents. Managed by United St Saviour’s Charity, the building provides independent living with a resident support model for over 65-yearolds in Southwark.

During the early stage of the project, we visited the charity’s existing almshouse community at Hopton’s Almshouses in Southwark, where residents explained to us the role of the garden for them: the importance of seasons and the joy of watching birds and wildlife, space to garden and a sense of a mini oasis while still living in the heart of the city. We were also advised how vital it is for the almshouse experience to feel comfortable for visitors. With loneliness and social isolation on the rise – especially for retired people –the almshouse should also appeal to families with young children seeing their elderly relatives. It was therefore important for us to create inviting

social spaces and gardens for the whole family.

From the outset of the project, in close collaboration with Witherford Watson Mann Architects, the landscape and architectural design was developed to create a close fit between the building uses and a distinctive and seasonal landscape across different levels. The landscape was never considered as a cosmetic addition, but rather as an integral part of the overall design, use, atmosphere and wellbeing of the community.

Central to the landscape concept is the idea of time and seasonality which is reflected in the two primary garden spaces. The gardens frame the living environment at different

Keith French

1. The Garden Court at Appleby Blue, London.

© Philip Vile

20

1.

Extensive research studies show how gardening benefits the wellbeing of communities, from reducing stress and lowering disease risk to increasing life satisfaction and promoting learning.

levels, bringing the changing colours, textures, sounds and light of the seasons into the residents’ and local communities’ everyday experience. Conceived as an abstract woodland glade, the Garden Court provides direct and indirect views of the garden spaces as you move through and around the building, with a raised and gently cascading linear water feature running between a grove of gingko trees and an understory of seasonal woodland flora including ferns, sedges, hellebores and foxgloves. The acoustics of the Court, coupled with the sound of the water feature, create a sanctuary space for socialising and relaxing in peace and quiet.

The Garden Court links to a double-height indoor Garden Room. This light-filled area invites the neighbourhood to engage in the array of intergenerational activities in this new community space, including the community kitchen, set to deliver culinary events based on upskilling and nutrition as well as using the herbs and produce grown on the roof terrace. Extensive research studies show how gardening benefits the wellbeing of communities, from reducing stress and lowering disease risk to increasing life satisfaction and promoting learning.¹ We were keen to enable this on the secondfloor roof terrace space, where there is more direct sunlight and residents can enjoy views out. The Productive Garden features a series of interconnecting raised beds for growing herbs and vegetables, as well as a planting mix of herbs, fruits, vegetables and companion planting.

Raised beds, using pre-cast board-marked concrete, have enabled recreational gardening activities to maintain accessibility despite residents’ potential loss of mobility. Some of the beds were left prepared for residents to garden, while others were planted with a mix of fennel, rosemary, thyme, sage, mint, marjoram, wild strawberry, rhubarb as well as local apple and pear tree varieties. Adjacent to the raised beds, potting tables and storage spaces for residents’ gardening tools make it comfortable and practical.

Both gardens will be managed by a local gardening group, with United St Saviour’s working alongside Bournemouth University research partners to explore how multigenerational, socially inclusive activities can be co-created with older people around food growing, cooking and meal sharing to improve their health, wellbeing and social connectedness.

The almshouse is designed to encourage residents and non-residents to come together through its open nature and progression of places

to share, extending from the busy public high street to the more intimate walkways, to the different garden spaces – cultivating a strong sense of community and reducing loneliness. The Appleby Blue development sets a new benchmark for the provision of older people’s social housing and brings nature into the heart of the living environment. Designed specifically for today’s generation of older people who want to lead an active life in the heart of the inner city, it is creating a community hub for them in central London.

FEATURE

¹ Soga et al., 2017, Health benefits of urban gardening: improved physical and psychological well-being and social integration

2. The Productive Garden on the roof terrace at Appleby Blue, London.

© Philip Vile 2.

21

Accordia, Cambridge

Accordia in central Cambridge is a large-scale housing project, and a pioneering collaboration between Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, Alison Brooks Architects, Macreanor Lavington and Grant Associates.

The relationship between the homes, the landscape, trees and different kinds of external space was central to the project. The ‘Living in a Garden’ landscape concept inspired different gardens throughout Accordia, each with a function or theme: the ‘Kitchen Garden’, the ‘Long Walk’ and the ‘Central Lawn’. All spaces are linked by a network of paths and clearly defined by walls, hedges and boundaries, featuring mature trees and new planting.

Today, 15 years on, Accordia boasts beautiful public gardens, garden streets and planted mews spaces, food and play gardens, well-connected pedestrian and cycle routes, and discreet, integrated cycle and car parking for all dwellings. The diversity of planting and well-established trees stands as a testament to the thoughtful selection of species,

supporting biodiversity and creating an ever-changing tapestry of colour and texture of the public spaces.

What none of the team originally foresaw was Accordia’s dramatic success in generating a sense of real community. We began to observe this anecdotally, but it was interesting to see research by Cambridge University, which focused on the incidence of wellbeing as defined by the New Economics Foundation.²

Researcher Jamie Anderson looked at the attitude to neighbourhood life and the use of the community outdoor space provision at Accordia, compared with a similar but more traditional neighbourhood. The 2015 study found that living in a neighbourhood with a higher ratio of communal gardens is associated with higher levels of wellbeing and community.

‘Living in a communal garden’ associated with well-being while reducing urban sprawl by 40%: a mixed-methods cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 3:173. doi: 10.3389/ fpubh.2015.00173

FEATURE

² Anderson J (2015)

Case Study

3. and 4. Accordia, Cambridge.

© Tim Crocker

22

3.

4.

Extensive research studies show how gardening benefits the wellbeing of communities, from reducing stress and lowering disease risk to increasing life satisfaction and promoting learning.

Case Study

New Islington, Manchester

Grant Associates’ approach to New Islington was always people-centred, planning for an existing and new community of people and incorporating waterways linking the historic navigations between the Rochdale and Ashton Canals to give the new neighbourhood an identity of waterside living and parkland.

Located to the east of Manchester city centre, the vision was to take this unloved, low-density area of the city fringe and transform it into a Copenhagen-inspired dense urban neighbourhood. Today New Islington has transformed the area, with Manchester Evening News calling it an ‘oasis’ for Manchester.

Cotton Field Park, the 1.5ha epicentre of New Islington has established a focus and landscape identity for the neighbourhood, and gives residents a unique relationship with the canal network. The park consists of a new body of water, a landmark grove of Scots pines around an urban beach, with a boardwalk that links together several distinctive islands. The extensive planting includes an orchard island, wetland edges and reed beds, and community

Case Study

gardens. The combination has helped not only appeal to a new population of human residents, but other species too, including the many Canada geese who call Cotton Field Park home.

The 20-year regeneration of New Islington has been transformative – for Urban Splash the developer; for Manchester; and for us as a

Brabazon, Bristol

Brabazon is a new peri-urban neighbourhood for Bristol, bringing the historic 142-hectare Filton Airfield site back into use. The green and connected, low-carbon masterplan sets out a vision for a high-density, sustainable, new district for Bristol.

From the outset, the vision for Brabazon was to be a green, leafy place where pedestrians have priority. Planned on a framework of

15-minute neighbourhoods, the masterplan’s sense of place and identity is very much shaped by its landscape, public spaces and sense of aviation heritage. Two kilometres of pedestrian and cycle routes link a series of linear parks and gardens, as well as a new 6ha destination park and landmark lake adjacent to a potential new entertainment venue at its heart. The site incorporates a Heritage Trail which connects the new districts with the Aerospace Bristol

practice. It gives the UK a great example of urban development done differently and sets a pioneering precedent for the role of green and blue infrastructure, with a neighbourhood filled with green space, water, wetlands, islands wooden sculptures, and a canal marina.

Museum and the historic, listed Hangar 16U, which is set to be a new local, social hub for the community.

The phased growth of Brabazon is linked to key sustainable travel milestones to lower car usage. Car parking is provided off-street, and the streets are at a scale that prioritises pedestrians. The streets – lined with trees and rain-gardens – will offer seating and play space to encourage community and interaction among residents.

A theme in each of these projects is human connections with the environment around them and finding new ways to bring people closer to nature. There’s a sense that if you develop the right environment, you nurture a community of people who like their setting and are therefore more likely to look after it. That’s been an interesting theory that has proved to be very true among these projects that we’ve worked on – all are linked by a strong sense of community and ownership, and a commitment to looking after our collective world together.

FEATURE

5. New Islington Cotton Field Park, Manchester © Urban Splash

6. Brabazon, Bristol

© YTL/FCBS/Grant Associates

6.

23

5.

Courtyard and garden: landscapes of palliative and social care

More than any other event in recent years, the Covid-19 crisis revealed how many vulnerable older people spent their last years confined in residential care homes – and how poorly managed and routinised life in such homes had become. In recent decades, a number of radical initiatives have recast residential and therapeutic care, offering hope for the future.

At the heart of these initiatives is a more imaginative relationship between building design, landscape enhancement, and the connectivity of both to the ongoing life and culture of the communities they serve.

The development of the modern hospice movement from the opening of St Christopher’s Hospice in Sydenham in London in 1967 has been a UK success story and has also expanded the ways in which we think about care. Originating as a response to the shocking conditions

in which many people died in geriatric wards, the public quickly adopted local hospices as their own. In doing so, communities have learned how to live with the dying in more supportive and generous ways. First designed as small inpatient units, hospices have evolved into ‘open house’ therapeutic settlements, offering a wide range of support services as well as short-term residential care, with people coming and going, thus turning them into what one architect termed ‘a living village’. Now other not-for-profit initiatives

First designed as small inpatient units, hospices have evolved into ‘open house’ therapeutic settlements, offering a wide range of support services as well as short-term residential care.

FEATURE v

Ken Worpole

1.

8. Orchard Garden at rear of St Wilfrid’s Hospice, Eastbourne, enclosed by waterretaining bund of wildflower grassland. © Ken Worpole

Ken Worpole introduces the updated version of Modern Hospice Design, which addresses both architecture and landscape.

8.

24

© Ken Worpole

First-time visitors may be surprised to find that the central feature of the new hospice is a large public ‘street’, a place where the public are welcomed in, and the café busy at all times.

in palliative and social care are following suit, imaginatively integrating uplifting design with landscape and garden elements to greater therapeutic effect.

St Wilfrid’s, designed by Nic Hoar of RH Partnerships and landscape architect Rick Rowbotham (Studio Loci), was completed in 2013, and is just one of a number of fantastic examples included in Modern Hospice Design. It has 20 inpatient beds, with 250 – 300 admissions a year. The average length of stay in the IPU (Inpatient Unit) is 20 days, with around 30% of inpatients discharged back to their home or to a care home, symptoms under control. Additionally, nearly 1,500 patients are currently supported where they live, whether this is a domestic residence or a residential care home, though many will use the hospice regularly for consultations and therapies.

Sited close to a main road, and adjacent to a large supermarket and

college, this was not the ‘sheltered, rural retreat’ that some supporters hoped for or expected ‘but it was perfect for a new hospice wanting to actively engage the community and change attitudes,’ former CEO Kara Bishop told me. An ‘open house’ philosophy is soon evident. First-time visitors may be surprised to find that the central feature of the new hospice is a large public ‘street’, a place where the public are welcomed in, and the café busy at all times. This long, double-height linear atrium runs from the entrance to the far end of the building, with large rooflights providing natural lighting. For the hundreds of people who come here daily – as patients, visitors, family members or staff – it is a ‘home from home’.

The gardens are an integral part of the hospice’s ethos and support. The Courtyard Garden sits in the centre of the inpatient unit and is primarily for use by patients and their visitors, with the facility to move patient beds easily

into the open air: a haven of peace and tranquillity. The Orchard Garden at the rear of the building has patient rooms facing onto it and is a riot of grass meadow and wildflowers at its banks, looking down to a star-shaped planted area, gazebo and beehive. This garden has been structured as a bund from soil excavated from the site, capturing water for the impressive apple orchard and more formal gardens at ground level, for use by patients and staff. The Wellbeing Garden at the front of the building is a mix of trees, herbaceous borders and planters and is used by outpatients and general visitors to the hospice, as well as staff and volunteers.

The value of natural landscapes and those of the built environment have long been recognised as having a profound impact on a person’s sense of wellbeing, and here these effects are seen in abundance. Between them, Rowbotham and Hoar have created a new kind of public health

FEATURE

9. Curtilage garden at Maggie’s Southampton.

Building architect: A_LA , garden designed by Sarah Price Landscapes.

9.

25

Hospice design essentials from Rick Rowbotham, landscape architect at St Wilfrid’s Hospice.

– A landscape-led masterplan determining the disposition of built structure within a site-wide landscape

– A design narrative that is poetic, engaging and familiar

– A predominately ‘green floriferous’ outlook for calming impact

– A hierarchy of spaces from the public, to semiprivate to private

– The use of intimate enclosure and courtyard spaces, for privacy, contemplation and sanctuary

– A secular space for meditation and prayer

– Private outer space accessible to bed-bound IPU patients

estate, a place of reflection and hope for the many thousands who use its facilities at one of the most difficult times in life.

On a contrasting site in Bermondsey, south London, architects Witherford Watson Mann (WWM) recently completed Appleby Blue Almshouse, another of the hospices to feature in Modern Hospice Design.

Writing in Wallpaper magazine architectural critic Giovanna Dunmall says, ‘There is no doubt that Appleby Blue will become a blueprint for the provision of older people’s social housing.’

WWM took their inspiration not from conventional residential home typologies, but intriguingly from the liveliness and courtyard culture of Bermondsey’s long history of coaching inns. Other recent historical precedents were influential too. The area was famous in local government history for having a municipal Beautification Department in 1921, combining public health, housing and recreation in one programme, underwritten by an extensive network of new parks, playgrounds and green spaces. Chaired by the legendary Mayor Ada Salter, Bermondsey

– Sheltered external positions to offer protection during inclement weather

– Provision for all users from family members who will be the primary users, to patients, staff and visitors. There should be unimpeded visibility between internal and external space

– Private space for staff members

– Use of running water and reflective water

– Planting design for seasonality, colour and smell

– Animation of the site through biodiverse landscapes to attract wildlife, birds, and insects

became an international watchword for ambitious public design, which United St Saviour’s Charity has revitalised with this outstanding project, along with Southwark Council support.

Having visited Appleby Blue on four occasions now, I admire its open sightlines and bold patterning of access levels and inner connectivity, agreeing with the Guardian’s architecture critic, Oliver Wainwright, who has described its interior glazed corridors and terraces as those of an Alpine spa. There is also a touch of the Globe Theatre and the South Bank (if not a whiff of the Thames) to the Garden Court as a performative space, as there is to the gardens at St Wilfrid’s, where their designer Rick Rowbotham saw their function as offering a place of ‘intimate enclosure, privacy, contemplation and sanctuary’, as do the gardens in Shakespearean theatre. On my last visit to Appleby Blue, only weeks after the first residents moved into their new homes, it was clear that the building had already settled down and was buzzing with life. It would be good to think that the old assumptions

about residential care as a retreat from life are finally changing.

Ken Worpole’s Modern Hospice Design: the architecture of palliative and social care, was published by Routledge in October 2023.

There is no doubt that Appleby Blue will become a blueprint for the provision of older people’s social housing

FEATURE

26

1. Macmillan Cancer Care, Hereford.

© Fira Landscape Architects

Jane Findlay

Jane Findlay

Death is an unusual topic of conversation for a landscape architect. We usually discuss the benefits of landscape for improving our health and wellbeing. The way we design our urban and rural landscapes to promote a healthy population and even the design of hospitals, where the landscape can aid the healing process, is a concept pioneered by Professor Roger Ulrich.¹ But while death is something that we don’t talk about much publicly, or perhaps think about on a day-to-day level, it’s a feature in all of our lives.

Where do you want to be when you die? Chances are, a hospital isn’t top of your list. Hectic places, stressful, with stark fluorescent lighting and hardly any privacy or dignity. Few of us (less than one in ten, in fact) would prefer to die in hospital.² No wonder around two-thirds of us would like to be where we live, with the people we love, at the end of life. But, for a whole host of reasons, that isn’t always possible.

How do we make sure the place where we do die is the best it can be for supporting a ‘good death’?

¹ https://www. healthdesign.org/ knowledge-repository/ view-throughwindow-mayinfluence-recoverysurgery#:~:text= Patients%20 with%20nature%20 window%20 views,pain%20 medications%20 such%20as%20 narcotics.

² National Survey of Bereaved People (VOICES): England, 2015

³ ‘Introduction to Maggie’s Architectural Brief’, Maggie’s Centres, London, undated

Answering that question is Ken Worpole in his book Modern Hospice Design: The Architecture of Palliative and Social Care, in which he assesses the needs of people living with a terminal illness and looks at the places that support them, both today and in the past. He advocates care settings that, in the words of Maggie Keswick Jencks, ‘rise to the occasion’.³

Historically, humans used to place a great deal of importance on death and the rituals associated with it. However, in contemporary society there has been a distinct shift. Instead of embracing it as a natural part of life, there is a tendency to conceal and

Jane Findlay responds to some of the issues raised in the Modern Hospice Design book and looks at what they mean for landscape practitioners.

distance death within unremarkable, sterile institutions. A hundred years ago, we were likely to die of infectious diseases like pneumonia; ill health would be short. We tended to die at home, in our own beds, looked after by family. The 20th century saw a revolution in healthcare. We developed new medicines like penicillin to treat infectious diseases, for example, and new medical technologies were invented. Because they were so big and expensive, they were housed in large, centralised buildings, shaping our modern hospitals. Post-war universal healthcare systems, like the NHS, allowed everyone easy access to the treatment they needed. The result was that lifespans extended from about 45 at the start of the century to almost double that today.

We now overwhelmingly die of degenerative diseases, like cancer and heart disease. It means that people tend to have a long period of chronic illness at the end of their lives in which they will spend a significant amount of time in hospitals, hospices, and care homes. These buildings are widely regarded as being awful places to be, not just because people are there for a negative reason, but also because the buildings and their surroundings tend to be institutional and often uninspiring, with miles of long corridors, no natural daylight, and a feeling of loss of control for the patient.

Dying well, or what constitutes a ‘good’ death will mean different things to us all. Most people express a wish to die at home, but often care for the chronically ill can be too complex for

FEATURE

27

1.

families. Can we make the end of life as meaningful and enriching as the beginning, not just for the patient but for families too? Worpole suggests that a careful blend between a homely and supportive environment with architectural and landscape interest that is imaginative and bespoke can be achieved in the new generation of supportive facilities, developed in response to the increasing anxieties about ageing by patients and their families. They are also an essential part of the care system to relieve the pressure on our hospitals.

Worpole uses the example of Maggie’s Cancer Care Centres as exemplar projects. Although not hospices, they are a hybrid of beautiful, imaginative and homely facilities with gardens and nature at their heart; to support the person and family during their most difficult time.

For decades my practice, Fira, has been designing healthcare environments, from large acute hospitals which are highly technical to small, homely hospice and care units. The concept that contact with nature can positively contribute to patient recovery is accepted by the medical profession and is essential for palliative care. By combining a consultative approach to form a detailed understanding of the needs of patients, staff, family and visitors, we place people at the heart of the project. The design brief, as Worpole states, is essential to a successful scheme.

The feedback and post-occupancy evaluation bears this out. We are continually surprised and moved by the letters of thanks from patients, families, and staff on our hospice and Macmillan Cancer Care projects.

They appreciate the care and attention to detail, such as access to beautiful gardens, the sounds of nature, the smells, uplifting colours, allowing choice at a time when there is little control over their medical needs.

The learnings from these small schemes continue to influence our approach to large healthcare projects, but they also influence the way we design healthy and beautiful places where people live, work, learn and play. Most importantly it raises the important question of how we design so that we might grow older in our own homes, within supportive communities.

Jane Findlay is past president of the Landscape Institute and founding director of Fira Landscape Architects.

FEATURE

For further information on our versatile products visit woodblocx-landscaping.com or telephone 0800 389 1420 Sustainable timber solutions for the built environment with limitless design potential The world’s #1 modular timber system Street Furniture | Raised Planters | Free Design Service LIJ Advert 2023.indd 1 23/3/2023 7:54 pm 28

Retrofit first in Barrow-in-Furness

and 2. View of estate before work started and on completion. © Farrer Huxley FEATURE 29

1.

Noel Farrer

Barrow is my largest local town. I first became aware of the tenement blocks on Barrow Island through a Landscape Institute competition that took place in 2013. I could see why I had not visited before. It is unnervingly quiet and feels a little unsafe, with unoccupied run-down tenements overlooking degraded and car-dominated streets. When we visited the flats, we found ourselves pushing through heavy cobwebs on the communal staircases, indicating that whole floors were deserted. Six hundred homes were mostly empty and forgotten.

The tenements were built in the late 19th century to house the workers of the nearby dockyard and steelworks. Through engagement with residents, we understood that many Barrovians started their lives in the flats. Many who lived here as children fondly described the sense of community shared by everyone. These

Retrofitting a new landscape has not only benefited existing residents but also encouraged a new generation to move in.

homes were often the first rung on the ladder for those coming to Barrow for work and were an important starting point for many people living here now.

Changes in the nature of the work, with manual labour and riveting replaced by a greater focus on engineering skills, contributed to the closure of the steelworks in 1963. The dockyard workforce also steadily declined. People were also prepared to live further afield and travel by car. The flats were no longer desired becoming part of one of the most deprived wards in the UK. We began work in a place with little direction or prospects and where drug- and drink-related issues gripped the community.

The deterioration of urban housing is not confined to Barrow. Many towns are blighted by the loss of large-scale employment and redundancy. This climate of economic decline results in house prices so low that traditional development is not an option. At Maritime Streets, the flats were selling at auction for between £8,000 and £20,000, with the investment needed to bring them to a habitable level much greater than this. As the flats are all privately owned, and the council only own the surrounding roads and open

space, investment in the landscape was the only option for change. A grant for £1.3m was approved, with the measure of success for the landscape being simply the investment in and reoccupancy of the flats.

There was a recognition that a big change in perception was needed to attract people to the neighbourhood. The design of the landscape needed to work hard to achieve a level of desirability that would encourage investment and occupancy. We were clear that achieving this would demand a high-quality and high-impact landscape, designed, detailed and built with thoughtfulness, consideration and care.

However, with improvements needed across the whole site, the limited budget would be spread too thinly to make meaningful change. This meant difficult decisions and prioritisation. A resourcing study was undertaken to identify which changes would make the biggest impact. Investment was deliberately targeted at the most visible and used spaces, with some areas left as they were. This was tough, but we also believed that funding for other areas was likely to be prompted by the successful delivery of a high-impact scheme.

At Maritime Streets, the flats were selling at auction for between £8,000 and £20,000, with the investment needed to bring them to a habitable level much greater than this.

3.

Planter detail.

FEATURE

© Farrer Huxley

3.

30

High quality was key to demonstrating that this is a place we care about, enabling others to care about it too. Our conviction was reinforced by the kindness, support and passion found within the existing community. Building on this local capacity, the ambition was to create a place which needed to be looked after. We invited residents to care for the space with a view to establishing ownership, belonging and neighbourliness. This also addressed the issue of limited maintenance resource, without creating a hardened and sterile place.

The vision was for a new community space, where people could come together, play, socialise and get to know each other. A place that felt safe for all to enjoy.

The design narrative is one of connections, inspired by the block typology. We designed the garden with a network of paths, which link the communal staircases leading to people’s homes. The intention was to draw people into the space and create opportunities to glimpse and bump into neighbours. The bold pattern created by crossing pathways was intentional, creating a surprising contrast with the surrounding streets. The unexpected green oasis, not typically found in Barrow’s harsh coastal landscape, was made possible by the shelter and microclimate provided by the tenement blocks.

With the aim of generating interest and anticipation, we issued images to the local press showing what the Maritime Streets courtyard would look like. This was successful; the care showed for this place and simply the expectation of investment was driving interest in the flats. We met with stakeholders and potential investors. When a single buyer expressed interest in acquiring some 320 of the flats, we invited them to our offices to talk through the scheme. By the time we had completed the works, the purchase was made and investment in the flats had begun. The auction prices for some of the other flats were double what they had been. The outcome we had hoped for was being realised.

More than 450 empty flats have been refurbished and are now lived in,

many for affordable rent. This provides much needed housing for those working in the expanding shipyard or elsewhere. The £1.3m investment in the landscape has catalysed a much greater investment in the flats, through the creation of a healthy and loved new space.

Each home generates, on average, around £500 per month of expenditure into the local economy.1 On this premise, the £1.3m investment and re-occupancy of 450 empty properties is delivering £225,000 a month to Barrow’s economy. The entire cost of the scheme has in effect been reinvested in the first six months, after which local spending contributes to the regeneration of services and amenities in the town, promoting more jobs, and there is more to do. And so it goes on.

What we as landscape architects

have seen at Maritime Streets is healing, the re-emergence of a healthy urban community.

The fact remains that the conversion and use of existing housing stock is a pragmatic and sustainable goal. The work here demonstrates the role that landscape can play in unlocking it. It evidences the benefits and importance of investing in the outdoor spaces where people live. Landscape architects can make an essential contribution to the future success of moribund urban housing, bringing well-located homes back to life, rather than building new ones in our green fields.

Noel Farrer is past president of the Landscape Institute and director of Farrer Huxley Landscape Architects.

1

The reference is an estimate based on the Office for National Statistics (ONS) census information for family spending (workbook 3).

5.

4.

4. Planting scheme.

© Farrer Huxley

5. Scheme detail.

FEATURE 31

© Farrer Huxley

Plan the street as well as the sky

What causes more debate – how tall buildings look, or what happens at their feet?

Skyline eye candy seems to trump the ground floor every time, which is curious because it will be the public realm that does all the heavy lifting when it comes to making community. It is where lives overlap, and people get to know their neighbours. Not a square metre can be wasted.

Inspired by a conversation with Scott Carroll from LDA Design, illustrator and architect Anna Gibb has explored how to make the most of the foot of the tower.

FEATURE

32

No 1 Public realm is where the character of the place is expressed. Design for people and nature; don’t let vehicles dominate.

No 2 You want residents to linger instead of heading for the lift. With the right activities, local people will join in too.

No 4 Tailor spaces to create favourite spots. Sometimes, we want quiet. Other times, table tennis and a pizza oven.

No 3 Sunlight governs street life, especially in spring and autumn. Create natural anchors in sunny areas, from benches to coffee carts.

No 5 Help people forge connections with nature, whether it’s a tree canopy or planted podiums screening off floors above.

No 7 Remember, nature doesn’t have to be naturalistic. A wildflower meadow with straight edges will still come alive with pollinators.

No 6 When solutions are identified early on, even tricky things like wind can be properly addressed, ensuring open space is never sacrificed.

No 8 Public realm has to feel welcoming and safe from day to night. Make it cosy, like a living room.

No 9 Whatever our age, we love play along the way. Even if we’re watching rather than jumping. All part of making spaces diverse and convivial.

FEATURE

33

Allotments and food strategies

Food growing is increasingly popular but now it has to compete more than ever with the growing demand for housing developments.

Martin Lee

The supply of allotment space has been on a steady decline for decades, as more public land is turned over to the provision of housing. It is imperative that we, as designers, can integrate food growing opportunities within new residential schemes. This could work by designing growing gardens with resilience and longevity in mind. We believe outdoor growing space can also contribute to a sustainable food ecosystem.

It is commonly accepted that growing food is innately good for our mental and physical health, as well as nurturing community values. Yet many do not have access to growing food, particularly those living in densely populated cities. We should look to alleviate the demand by integrating sustainable food systems wherever we can. How can we do this? By implementing a food strategy at a neighbourhood and masterplan scale and foregrounding the role of local food growing within food systems.

Landscape architects are trained to fulfil client briefs and policy requirements, while having to face a myriad of apparent and inextricably linked crises (i.e. biodiversity, climate and energy) at once. Furthermore, the ripple effect from Brexit and Covid-19 exposed the fragility of our food systems, as captured in

the Government’s Food Security Report in 2021.1 Since then, we have experienced a cost-of-living crisis affecting basic needs of food, heating and housing. Despite these revelations, food growing is severely overlooked within UK planning policy. Is it time to challenge the status quo and reframe the narrative of food?