2022 Issue 3 landscapeinstitute.org Designing for gender

Celebrating 100 years of women in landscape architecture

equality

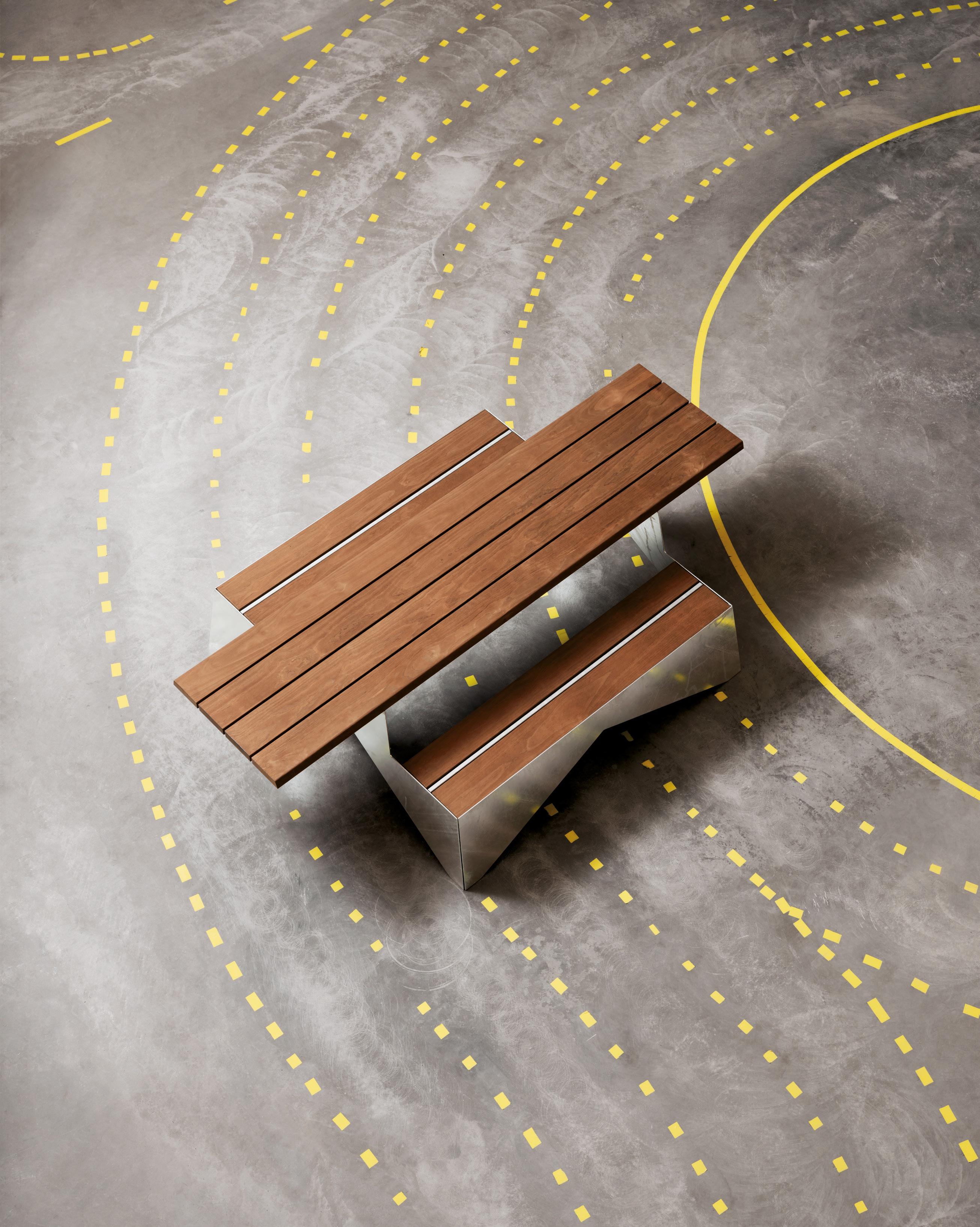

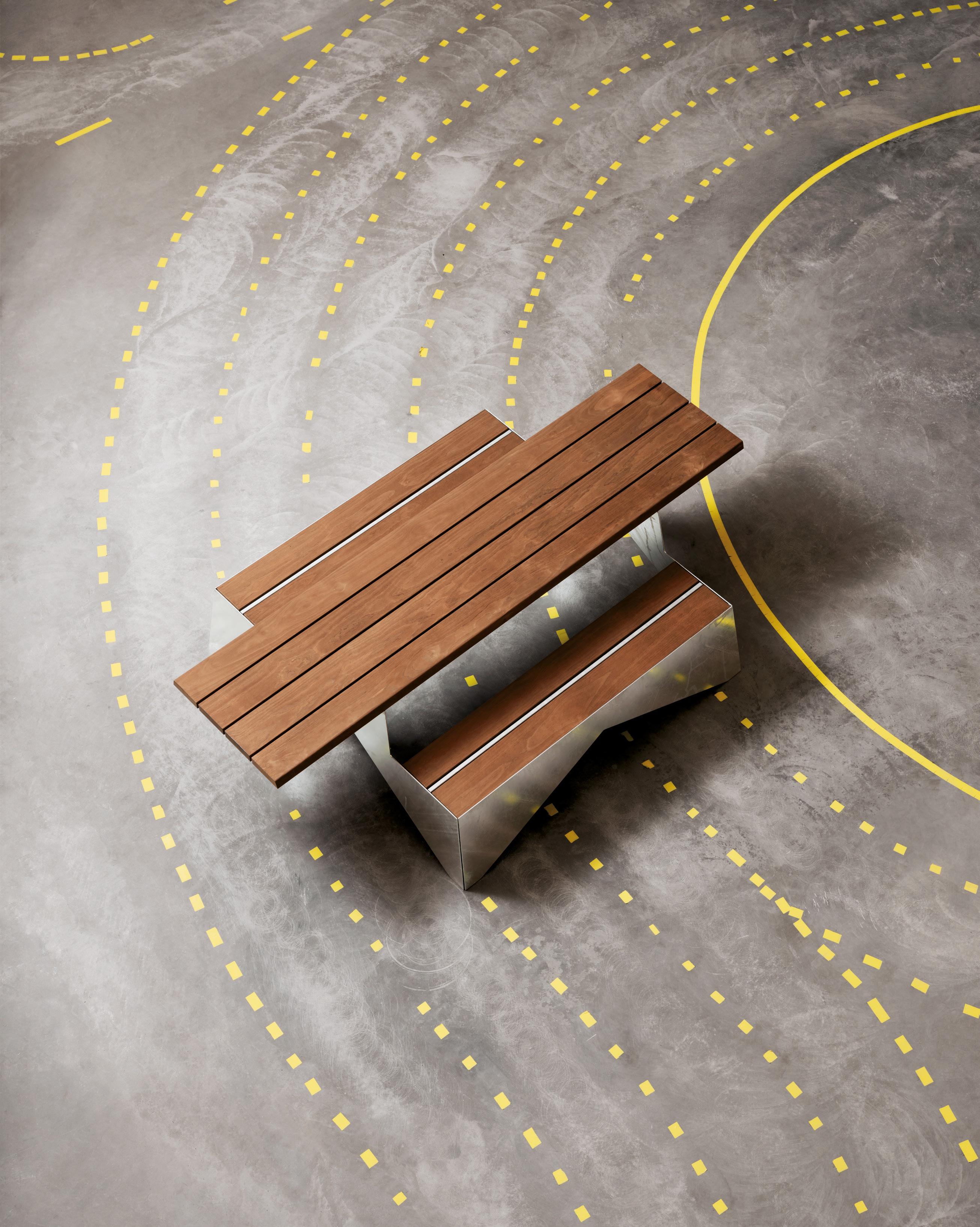

Stoop DESIGN TANK PHOTO EINAR ASLAKSEN Location The Plus Designer Julien De Smedt Produced in Scandinavia vestre.com Lifetime anti-rust warranty 200 RAL colours

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931

darkhorsedesign.co.uk tim@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Saira Ali, Team Leader, Landscape, Design and Conservation, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

Stella Bland, Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes CMLI, Landscape Architect, Allen Scott Landscape Architecture

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape Architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Senior Landscape Architect, BBUK Studio Limited

Jo Watkins PPLI, Landscape Architect

Jenifer White CMLI, National Landscape Adviser, Historic England

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Editor: Paul Lincoln paul.lincoln@landscapeinstitute.org

Copy Editors: Jill White and Evan White Immediate Past President: Jane Findlay PPLI CMLI

CEO: Sue Morgan

Head of Marketing, Communications and Events: Neelam Sheemar

Landscapeinstitute.org @talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

Print or online?

Landscape is available to members both online or in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: mylandscapeinstitute.org

Landscape is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it.

Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914

© 2022 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design.

Women and landscapea special edition guest edited by Jane Findlay

As we were preparing this edition of the journal, the death of Queen Elizabeth II was announced, and it made me pause for thought. The period of mourning and watching the historic news reels of her reign reminded me just how much our lives have changed since her accession to the throne during the period of postwar austerity.

Her reign of 70 years and 214 days – the longest of any British monarch – means she has presided over seismic changes in planning, design and construction in the UK, from the brave new world of architecture and the post-war rebuilding of Britain to the built environment’s response to the climate and biodiversity crisis. Now, the built environment sector has changed beyond recognition.

Queen Elizabeth II cut her fair share of red ribbons, opening numerous public buildings across the UK and the Commonwealth in her role as head of state. Many of us in the built environment sector will have met Her Majesty at an opening ceremony. Having worked extensively on public sector projects, I had the pleasure of meeting her on several occasions. The joke on site was that the Queen

always thought that all buildings smelled of new fresh paint, as construction teams would be working late into the evening before her visit.

At a time when men still wielded all the power, the young Elizabeth was a vital role model. It meant at least one female in official photographs. The Queen could never be described as a feminist, but her accession to the throne was a significant marker on the road to second-wave feminism and she was the ultimate role model for women - strong and dignified.

It is, therefore, appropriate that in this edition, dedicated to Women and Landscape Architecture, we look back at those women who have led the profession, assess where we are today and how we can break down the structural barriers that hold women back, and support women to achieve success in the future.

I would like to thank all of those who have contributed to this edition of Landscape. Let’s hope the Carolean Era is one where women can blossom in our profession.

Jane Findlay CMLI

Immediate Past President of the Landscape Institute

WELCOME

2022 Issue 3 Designing for

equality Celebrating 100 years of women in landscape architecture Cover

–

Des

Raums (Score

gender

image from Ringstrasse Concept

Aspern Die Seedstadt Wiens, Partitur

Offentlichen

of Public Space) Gehl Architects, 2009.

3

Contents 4 Introducing the Women of the Welfare Landscape project 10 Celebrating the ‘not-seen’ Just 14% recognise women and none are awarded to a landscape architect 17 Blue Plaque Blues Immediate Past President Jane Findlay reflects on her presidency 20 A President for the unprecedented Investigating the Aspern neighbourhood of Vienna 35 Designing for gender equality Three practitioners consider the barriers to progression 44 The impact of gender on career progression Evaluating the transformation for women landscape architects 38 The changing relationship in Chinese landscape Why ‘New Lives, New Landscapes’ by Nan Fairbrother remains required reading 46 New life for a classic The importance of reimagining collective histories and mythologies 41 Reimagining the past Lynn Kinnear on her thirty-year career Advocating for Design 30 6 Reflecting on seventy years The ‘Elizabethan Age’ in landscape architecture BRIEFING: REFLECTIONS FEATURES Three past presidents discuss life, landscape and the future of the profession Past Perfect 25

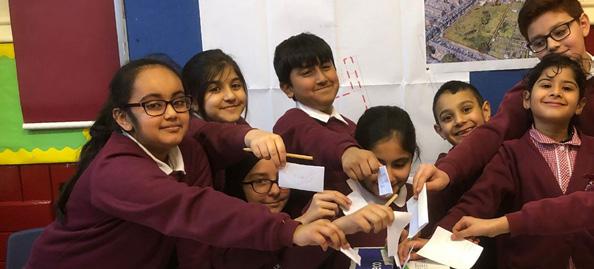

FEATURES 48 Post-natal depression 52 Cultivating culture How Bradford is creating green and safe spaces 50 Seeing the world through the eyes of a child Amplifying female voices to create more equitable landscapes Making the world inclusive using landscape design CASE STUDY 54 Safer by Design Making our streets and public spaces safer for the most vulnerable OPINION 56 New models for running landscape practices The former chair of Policy at the LI considers new approaches REFLECTION 58 Access to nature - my life in landscape Personal reflections and a family picture album raise some big questions PRACTICE 60 Gender inclusive design EDLA showcases its work and philosophy RESEARCH 67 Improving women’s safety in public spaces A new report from Marshalls challenges the industry to make improvements RESEARCH 64 The Landscape Skills and Research Project Highlights of the LI’s new research programme 70 LI LIFE CAMPUS: Learn from anywhere 5

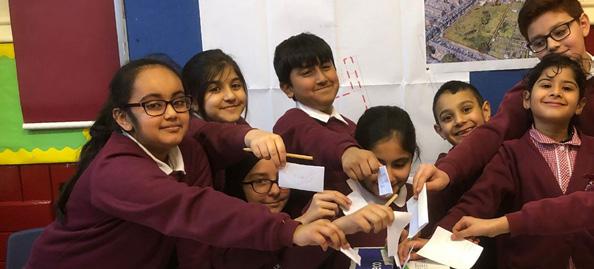

1.

Reflecting seventy years of landscape architecture

It will take many years to evaluate the impact of the ‘new Elizabethan age’ on the built and natural environment. Landscape invited a number of past presidents to choose a significant moment.

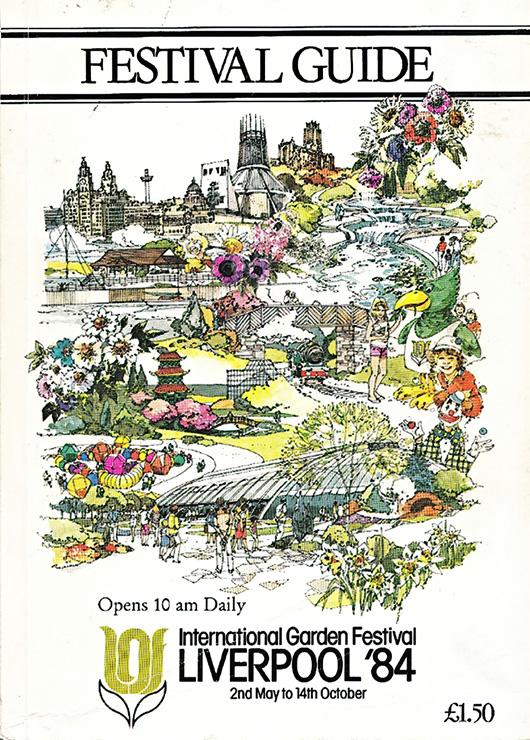

1. In October 1981, Brian Clouston and Partners were invited by the Merseyside Development Corporation to lead the Riverside Reclamation Team. The official opening of the International Garden Festival was held on May 2 1984.

© Liverpool Echo.

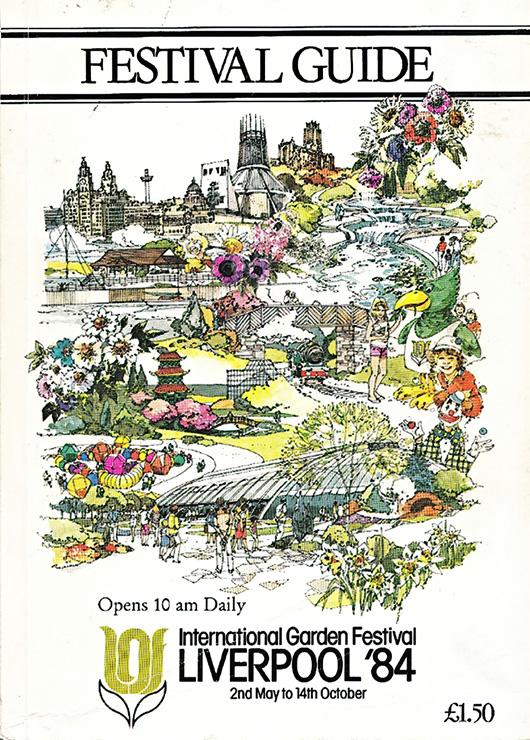

2. Liverpool International Garden Festival ’84 guide, designed and produced by Brunswick Publishing.

BRIEFING: REFLECTION

6

BRIEFING: REFLECTION

2. 7

Liverpool International Garden Festival

BRIEFING: REFLECTION 6.

5.

4. 3

Thamesmead

8

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

Ministry of Defence Executive Headquarters at

BRIEFING: REFLECTION 7. 3. Opening

© LLDC 4. Opening

© FIRA 5. A visit

© Thamesmead

Archive and London Metropolitan

6. RHS

©

7.

©

of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park 2012.

of the Ministry of Defence Executive Headquarters at Abbey Wood, Bristol designed by Jane Findlay IPPLI.

to Thamesmead in 1980.

Community

Archive.

Back to Nature Garden at Chelsea Flower Show, 2019. Codesigned by the Duchess of Cambridge, Andree Davies and Adam White PPLI.

Adam White

Opening of the newly-designed Jubilee Gardens on London’s South Bank, 2012.

South Bank Employers’ Group

Jubilee Gardens

RHS Back to Nature Garden at Chelsea Flower Show

9

Abbey Wood

Celebrating the ‘not-seen’:

FEATURE

1.

10

An introduction to the Women of the Welfare Landscape

A major new Arts and Humanities Research Council funded research project uncovers women’s contribution to post Second World War landscape architecture and looks at the role of the women who helped to establish both the profession and the Institute.

11

2021 marked the 70th anniversary of Brenda Colvin becoming first female president of the Institute of Landscape Architects (today’s Landscape Institute), this year celebrates the 100th anniversary of the founding of her joint practice, Colvin & Moggridge. 2023 will see the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA), in which Colvin also played an important role.

Among these milestones of the profession and professionalisation of landscape architecture, it is crucial that we gain a more thorough understanding of its history, and of the key people who shaped its development, including a number of female professionals whose contribution to landscape architecture in a variety of forms and practices –such as writing, campaigning, teaching, working in policy or professional organisations as well as design – is often ‘not seen’.1

While the work of key female professionals such as Brenda Colvin, Sylvia Crowe, Lady Allen of Hurtwood or Jacqueline Tyrwhitt are relatively well known, the Women of the Welfare Landscape project sets out to go beyond understanding their individual contribution, and instead aims to look into women’s collective impact on landscape architecture, both in terms of design, and beyond. As Sylvia Crowe wrote in a letter to Geoffrey Jellicoe, “team-work is the only possible solution in a profession that covers such a wide range of subjects, many of them requiring not only a different training but a separate set of capabilities, and a different type of mentality.”2 Collaboration between leading thinkers and designers in the post-war period was manifested in a variety of different ways. In their book Women and the Making of Built Space

in England, Darling and Whitworth argue that “the mythologization of the design process”3 and the focus on the design product hides the contribution of many other thinkers and actors. Writers, campaigners and educators get much less attention, than their successful contemporaries with design careers. In this short introduction to this ongoing research project, the focus will be on collaboration within and beyond the field of design, to start painting a more nuanced picture of the ways landscape architecture can be practised.

In 1929, when the Institute of Landscape Architects (ILA) – originally the British Association of Garden Designers – was established, two founding members were female: Lady Allen of Hurtwood, at the time working as garden designer in collaboration with Richard Sudell, and Brenda Colvin, who by then was running her own independent garden design practice. Their vision for a changing, independent profession hugely shaped the discipline’s future, and their work through the Institute was a catalyst for this development. As Colvin wrote: “The wider applications of landscape architecture are those of regional planning. While the main work of members may be at present laying out medium sized gardens, we had to remember that our most important contribution to the life of the nation would be in the wider field.”4

Allen and Colvin both served the Institute in a variety of roles, including playing an active part in various committees and the Council, as well as Lady Allen serving as honorary VicePresident between 1939-46 and Colvin as President between 1951-1953. Soon after the establishment of the Institute, they were joined by other

1. Lady Allen of Hurtwood

© Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick Library.

2. Brenda Colvin

© MERL Brenda Colvin Collection.

3. Sylvia Crowe

© MERL, Brenda Colvin Collection.

3.

2.

visionaries such as designer and author Sylvia Crowe; designer, author and educator Madeleine Agar; landscape architect, urban planner and educator Jacqueline Tyrwhitt; and architect and landscape architect Sheila Haywood, then working with Geoffrey Jellicoe.

In an article for the ‘Your Daughter’s Future’ section of the Evening Standard in 1936, Lady Allen described landscape architecture as “one of the newest professions for women” and highlighted, that, “as in all growing professions that are not fully

1 Darling, Elizabeth (2020) ‘The Not-Seen’ https:// www.sahgb.org. uk/features/the-notseen-ggz64

2 Letter from Crowe to Jellicoe MERL SR LI AD 2/2/1/25

3 Darling, Elizabeth & Withworth, Lesley (2007) ‘Introduction: Making Space and Re-making History’ in Women and the Making of Built Space in England 1870–1950 London: Routledge p. 3

4 Rettig, S (1983) The Creation of Professional Status: The Institute of Landscape Architects between 1929 and 1955. Unpublished manuscript p. 3 MERL SR LI AD 2/1/1/28

FEATURE

Dr Luca Csepely-Knorr

12

5 Hurtwood, Lady Allen of (1936) Your Daughter’s Future. 1. Landscape Architecture Evening Standard, Monday, September 21. pp. 24-25.

6 Interview with Sylvia Crowe. Published in: Harvey, Sheila (ed) (1987) Reflections on Landscape. The lives and work of six British landscape architects. London: Gower Technical Press. P. 34

7 Gibson, Trish (2011) Brenda Colvin. A career in landscape. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. P. 124

8 Jellicoe, Geoffrey: The Wartime Journal of the Institute of Landscape Architects. In: Harvey, Sheila & Rettig, Stephen (1985) Fifty Years of Landscape Design. London: The Landscape Press pp. 9- 26 . 22.

9 Jellicoe, Geoffrey (1979): ‘War and Peace’ Landscape Design February 1979 p. 10

recognised, a woman of ability and push must at first actually devise new avenues for the expression of her work.”5 Her comment and article in general sheds light on two equally important aspects of the profession shortly before and during WW2. Firstly, that it needed to establish itself through a growing membership, professional standards and education. And secondly, that women found many ‘new avenues’ throughout this process, without which the LI and the profession would look very different today.

Allen’s article describes the different educational pathways to becoming a landscape architect, including the route she and many other women took: training in horticulture. Lady Allen herself held a Diploma in Horticulture from the University of Reading, Brenda Colvin and Sylvia Crowe studied at the Swanley Horticultural College under Madeleine Agar (herself a Swanley graduate under Fanny Wilkinson), while Jacqueline Tyrwhitt had RHS qualifications. This background was significantly different from the majority of (male) members, holding qualifications in architecture or town planning. As Sylvia Crowe remembered, “most of our members were architects and/or town planners and to get them to realise that landscape architecture was a third different profession was not always easy.”6 With membership numbers being small, the idea to merge with larger, more respected institutions, like the Town Planning Institute (today RTPI) or the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) was a recurring question before and during WW2. In 1934 at the Town Planning Institute’s annual conference and summer school at St Peter’s Hall in Oxford, Gilbert Jenkins, himself a member of the Institute, recommended the merger of the two.7 Between 1943-1945, the next question – whether the Institute should assimilate with the RIBA – was dominant. As Geoffrey Jellicoe, then President of the ILA who led the discussions described it, “The choice was not easy. On the one hand lay security within a body whose prestige, expertise, resources and powers of

patronage were immense; on the other hand, a dangerous road of independence in a world where the Institute numbers were still infinitesimal.” In the description of the events Jellicoe recalled that “at the Council meeting prior to the decisive meeting the architecturally-minded majority favoured amalgamation and empowered the President to meet the RIBA special committee to inform them that the ILA Council had declared itself sympathetic; and to report back as to whether negotiations could begin.”8 The Council minutes and the other resources in the Archives of the Institute highlights two main opponents to the idea: Brenda Colvin and Sylvia Crowe, who were tirelessly arguing for the importance of an independent Institute to secure strong enough professional emphasis on the biological and ecological aspects of the profession as well as questions of large scale rural planning, including forestry. Retrospectively, Jellicoe recalled the contribution of the two women as a “famous outburst”, and that it was

“thanks largely to those two Furies (‘the friendly ones’ to the Greeks) that the warm embrace of the RIBA had been resisted.”9

Deciding to take the ‘dangerous route to independence’ meant a renewed effort to establish the Institute and the profession’s reputation. Building links with other professional bodies in the field was a key goal in this process. According to Geoffrey Jellicoe’s recollections, in 1946 not long after the decision by the Institute to keep its independence, at a council meeting, “Joan [Lady] Allen had popped up and said ‘let’s call an international meeting, and possibly have an international federation arising from it’. We all agreed – it sounded awfully easy – and the motion was passed.” Organising an international conference and exhibition wasn’t awfully easy. However, the ILA found an extremely capable member to undertake the task. Returning from active military service, Sylvia Crowe was asked to take on the position of Chairman of the International Conference

FEATURE

4. Wylfa Power Station idesigned by Sylvia Crowe © Luca Csepely-Knorr.

4.

13

Committee.11 The conference and the associated exhibition was held in the London County Council’s County Hall in August 1948. After the conference a meeting was convened of the representatives of 14 countries in Jesus College Cambridge on 14th August where the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) was established. Not surprisingly, the presidential post was given to the British – as convener of the conference, and Geoffrey Jellicoe became its first lead. Brenda Colvin was nominated as representative of ILA, and Sylvia Crowe became Honorary Secretary. Crowe held the position for two years, during which time the constitution of the Federation was written and accepted. She stepped back after two years but had a seat for life on Council. In 1953 she was elected Vice-President, and was Secretary General between 1956-59 (while also acting as President of ILA).

Colvin, Crowe and Jellicoe saw IFLA as a key achievement, and in 1976, when the Institute was considering leaving the Federation, they strongly argued for it, when they stated that IFLA is “essential for us to break out of insularity into a very much wider world than that of our daily experience” and that the Federation is “a power for peace”. As they argued, the aims of the founders were “first, to promote understanding and knowledge throughout a war-shattered world through the common language of landscape; second, to raise universally the prestige of landscape in the public mind; and third, to enable member countries to keep abreast of world ideas”12 – a vision and dedication that could not be more important in our current global crises. As Crowe said in 1979, at the occasion of the Institute’s 50th anniversary, “We have contributed much, gained much and still have a vital role to play”.13

Maintaining and strengthening the independent Institute and its international standing was one way to establish a recognised profession, but education and educational standards – another key aspect discussed in Allen’s 1936 text – was equally important. Establishing educational standards has been a key goal of the

5.

5.

Colvin and Madeleine Agar were both members of the Women’s Farm and Garden Association (WFGA), through which Colvin – together with Jacqueline Tyrwhitt – launched a course to train female gardeners who could not afford tuition fees for horticultural colleges. The 6-month course specialising in food production started in 1942, and the collaboration of the two of them led to further educational projects. In 1942, Colvin started to teach landscape architecture in the Regent Street Polytechnic to architecture and planning students and Tyrwhitt taught the history of town planning. A year later Colvin started to teach surveying and drawing to Diploma students at Studley

Horticultural College for women, and also started to teach for the renowned Architectural Association. Her famous book, Land and Landscape was developed from her lecture notes. Here, she taught an intensive course on trees, as well as design studios and history of landscape architecture. The same year – most probably on the basis of their experiences in architectural schools – she and Tyrwhitt embarked on their next joint project: a book, that only two years after the first publication was already in its third edition. Trees for Town and Country described 60 trees suitable for general cultivation in Britain aiming to show them in different periods of their growth.

FEATURE

5. Evening Standard Article. Warwick University Archive © Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick Library

14

The intention was to help visualise how trees would look as they matured, for the benefit of professionals with no education in planting or horticulture but who might oversee strategic tree planting, including architects and planners.

Together they also organised a postgraduate evening course through the School of Planning and Research for National Development (SPRND) that Tyrwhitt was leading throughout the War. The SPRND course led to the final examination that allowed students to enter both the Town Planning Institute and the Institute of Landscape Architects, and Colvin worked as a lecturer there until the 1950s.

Writing about the legacy of Sylvia Crowe, Jack Lowe recalled that “Full training for the landscape qualification in the years immediately after the Second World War was not easily found. Only one British school offered a comprehensive course and there was no longer a pupillage system. For students already qualified in related professions and studying to pass the entry exams, the greatest hurdle was in design subjects – suitable tuition, books, and journals being scarce. It was in that void that the writings of Sylvia were eagerly sought; and they were highly influential not only among the emerging landscape profession, but in sending clear signals to the world outside.”14 If we add to this Peter Youngman’s statement, that Brenda Colvin’s Land and Landscape was a pioneer book which had an enormous influence in “spreading the wider view of landscape” whilst also considering Tyrwhitt’s many publications, like the Town and Country Planning Textbook and Planning and the Countryside, the understanding of their educational profile and their role in creating a common understanding of what landscape architecture is, becomes even more profound.

In her 1936 article for the Evening Standard, Lady Allen argued that “if it is left too exclusively to men, the rehousing of our people may result in towns where too little regard is paid to those whose lives are spent in the home”, and that “for those who can succeed, it is a profession which is not only one of the most delightful in the

6.

world, but one that offers a great contribution to the happiness of mankind.”

Brenda Colvin, Sylvia Crowe, Lady Allen of Hurtwood, Jacqueline Tyrwhitt and their collaborators continued to advocate for the profession of landscape architecture throughout their careers. Brenda Colvin designed landscapes across the country at every scale from private gardens to power stations and New Towns. She went into partnership with Hal Moggridge in 1969, establishing Colvin & Moggridge, which is the longest running landscape practice in the country today, with a greatly varied portfolio of projects.

Sylvia Crowe authored several books, and also ran a successful design practice as well as working closely with the Forestry Commission. She co-authored her last book with landscape architect Mary Mitchell.

Lady Allen’s work and advocacy for children’s welfare and adventure playgrounds saw her to become an important member of the International Playground Association, as well as working with the UN. Her many books and articles as well as talks benefitted hugely the development of children and children’s play.

Jacqueline Tyrwhitt worked extensively with CIAM, and taught planning and urban design in Canada and at Harvard. She was remembered as a hugely influential teacher as well

as someone whose organisational and editorial skills were crucial in the formation of international networks and publications.

Allen, Colvin, Crowe and Tyrwhitt collaborated very widely and contributed to the development of British landscape. While this short summary can only give a glimpse into some of their activities, the Women of the Welfare Landscape project will uncover their work and most importantly their networks in more detail. We aim to learn more about women’s agency and contribution to the landscape profession and understand more about how they contributed to ‘the happiness of mankind’ by creating landscapes for the welfare of all.

Dr Luca Csepely-Knorr is a chartered landscape architect and art historian, researching the intersections of the histories of landscape architecture, architecture and urban design from the late 19th century to the 1970s. She is leading the AHRC funded ‘Women of the Welfare Landscape’ project, and is Co-Investigator of the project ‘Landscapes of Post-War Infrastructure: Culture, Amenity, Heritage and Industry’. She is incoming Research Chair in Architecture at the Liverpool School of Architecture.

FEATURE

6. Drakelow Nature Reserve, designed by Colvin & Moggridge.

© Luca Csepely-Knorr

15

‘Women of the Welfare Landscape’ is an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) supported research project that commemorates the network of women and their collaborators who have had a major impact on shaping the post-war designed landscapes of the British Welfare State. The research focuses on understanding Brenda Colvin’s networks and collaborations and through these the wider questions the role of women in the creation of the landscapes of the Welfare State. The project aims to shift attention to the women’s role as educators, campaigners or advocates; and projects of the everyday: landscapes in service of communities. It will analyse landscapes of public housing, public and country parks funded by municipalities and landscapes of infrastructure commissioned by publicly owned, nationalised industries, as material examples of landscapes for social benefits and ‘fair share for all’: a key objective of Welfare Planning.

A travelling exhibition is designed to return the work of Colvin & Moggridge to the communities they designed for. By taking it to the universities in Edinburgh, Reading, Birmingham, Sheffield, Manchester, Belfast and London the exhibition will be a

Further reading:

Darling, E & Walker, N (2019)

Suffragette City: Women, Politics, and the Built Environment (London: Routledge)

Darling, E & Whitworth, L (eds) (2007) Women and the Making of Built Space in England, 1870-1940. London: Ashgate; Darling, E & Walker, N (eds) (2019) Suffragette City. London: Routledge

Duempelmann, S. (2004) Maria Theresa Parpagliolo Shephard (19031974). Ein Beitrag zur Entwicklung der Gartenkultur in Italien im 20. Jahrhundert (Weimar: VDG); Duempelmann, S. and Beardsley J

freely accessible event allowing the local community, staff and students of each institution to engage with the research. The places to hold the exhibition were chosen to facilitate a discussion between the past of landscape architecture and its future: all of the partnering universities are centres for training landscape architects. Through collaboration with the Modernist Society, The Gardens Trust, the Garden Museum, the Museum of English Rural Life and Historic Environment Scotland, the exhibition will also feature in public galleries and spaces, such as East Kilbride Library, in the centre of Colvin’s first New Town project in the 1950s.

At each stage of the travelling exhibition, public-facing events are being organised in tandem with a ‘Show and Tell’ event to collect visual resources (family photos, postcards etc.) and memories of the landscapes of Colvin & Moggridge and the post-war period. The collected materials will be organised and publicised on a crowd-sourced HistoryPin archive.

Through a series of widely accessible online and blended public symposia organised in collaboration with educational charities such as the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain (SAHGB), TGT and

[eds.] (2015) Women, Modernity and Landscape Architecture (London: Routledge)

Gibson, T (2011) Brenda Colvin: A career in landscape (London: Frances Lincoln Publishers).

Mozingo, A and Jewell L. (eds) (2012) Women in Landscape Architecture: Essays on History and Practice (London: McFarland & Co)

Powell, W. & Collens, G. (eds) (2000) Sylvia Crowe (London: The Landscape Design Trust)

Shoshkes, Ellen (2013) Jaqueline

Tyrwhitt: A Transnational Life in Urban Planning and Design (London: Routledge) Way, T. (2009) Unbounded Practice.

international research networks such as the Women in Danish Architecture Project, ‘Women of the Welfare Landscape’ will widen the discussions to involve international audiences.

In partnership with the LI, a series of online CPD events will be organised to help students and academics, as well as chartered members of the Institute, to gain a better understanding of methodological and theoretical questions for researching post-war Welfare Landscapes.

If you would like to learn more about our activities, please follow us on:

Twitter: @WomenWLandscape Instagram: @women.welfare.landscape HistoryPin: https://www.historypin.org/en/ women-of-the-welfare-landscape/ pin/1173722/

We would like to hear about projects, memories, photos etc. that you think might be relevant to this project. Please do get in touch with us through wowela@gmail.com

Dr Luca Csepely-Knorr & Dr Camilla Allen

Women and Landscape Architecture in the Early Twentieth Century (Charlottesville & London: University of Virginia Press)

Campaigns and projects: ‘Women Taking the Lead’ campaign by The Cultural Landscape Foundation: https://www.tclf.org/women-takinglead

MOMOWO: Women’s creativity since the modern movement 1918-2018 http://www.momowo.polito. it/#3/17.39/-3.25

Women in Danish Architecture project https://www.womenindanish architecture.dk/?lang=en

FEATURE

16

the mark of a good landscape scheme is where you cannot readily see where the landscape architect had been at work.

Blue Plaque Blues

In 2018, Blue Plaques were turned down for Dame Sylvia Crowe and Branda Colvin. If successful, the plaques would have been placed on the office that they had shared in Marylebone in west London.

Blue Plaques in London have been awarded by English Heritage since 1986 (previously they were awarded by the Royal Society of Arts, London County Council and Greater London Council). The scheme started in 1866 and has been replicated with similar schemes across the country. Outside London, local authorities and civic societies across the UK award Blue Plaques, some schemes of which are registered with English Heritage, such as the Gateshead scheme.

In London, the Blue Plaque scheme identifies the buildings in

which ‘notable figures’ from the past lived and worked. Key criteria for proposing a Blue Plaque are that twenty years must have passed since the candidate’s death, at least one building associated with the nominee must exist within Greater London (barring the City of London, which has its own scheme) and in a form that the nominee would recognise, as well as being visible from a public highway.

The Blue Plaque scheme welcomes proposals from the public, which are then considered by their Panel. The current Panel is made up of 11 individuals who will consider proposals, though from cursory research it is unclear whether an English Heritage staff team assess and shortlist nominations in advance of the Panel seeing them. The proposal forms ask for information about the ‘the life and achievements of the person’ being proposed, as well as why the proposer believes ‘this person deserves a plaque, and how they meet the following selection criteria’.

The selection criteria cover the nominee’s contribution to human welfare and happiness;

their exceptional impact in terms of public recognition; and the grounds for their being regarded eminent and distinguished by a majority of members of their own profession or calling. And in items one and two of this list lies the rub for a landscape architect.

It is both the point and the frustration of the vast majority of landscape architects’ work that, at its best, it does not call attention to itself and therefore their work is highly unlikely to meet the condition of public recognition. Not for the landscape architect, the edifice that reaches to the sky or that shimmers with endless panes of glass. Instead, in Sylvia Crowe’s own words, “the mark of a good landscape scheme is where you cannot readily see where the landscape architect had been at work.” Furthermore, “we are trying to make a land which people can enjoy, a land, too, where wildlife can flourish.”1

The impact of these two landscape architects on the built environment and on the profession is not in doubt. However, for the wider public, the breadth and scope of their work,

FEATURE

Just 14% of Blue Plaques have been awarded to women and within this number, none has been awarded to a landscape architect.

Sabina Mohideen

17

from private garden to townscapes and infrastructure landscapes, and their legacy in terms of thinking and practise, must be preserved and promoted.

However, as it currently defines value of public recognition, there is a long road to travel before these two truly extraordinary landscape architects get the respect they deserve with a Blue Plaque. Making your mark in a way that the public will confer fame and/or value is not, currently, within easy scope of a landscape architect’s work.

There are, of course, exceptions. Charles Bridgeman, Capability Brown, John and Jane Loudon and Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe all have Blue Plaques marking where they lived in London. While there is no ‘landscape’ category, they each fall under the ‘gardening’ one, with only Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe being identified as a landscape architect, and the others being associated with landscape gardening. This is problematic in itself – if the only way to recognise a landscape architect’s work is through seeing it executed within the field of gardening, how should work like forests, woodlands, reservoirs, and large infrastructure sites be acknowledged that does not fall within that category?

While it is impossible to know what evidence of ‘impact in terms of public recognition’ and ‘contribution to human welfare and happiness’ was provided in their proposals, there is a clear commonality across the work of all of these individuals. They all designed landscapes attached to the homes of the wealthy and landed gentry – in short, their gardens.

Even Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, while not primarily known among the landscape profession for his work in this area, has the rose garden at Cliveden, St Paul’s Walden Bury, Hartwell House and Sutton Place listed among his key works.

Unlike the majority of open spaces that landscape architects design, in keeping with Sylvia Crowe’s maxim of work that does not call attention to itself, these grand places are designed to be admired, in craft and impact, even when using the artifice of ‘appearing natural’ to achieve

this effect. This approach is most humorously summed up in Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia, when the fictional character Lady Croom says of her Brown-designed landscape ‘Sidley Park is already a picture, and a most amiable picture too. The slopes are green and gentle. The trees are companiably grouped…The rill is a serpentine ribbon peaceably contained by meadows on which the right amount of sheep are tastefully arranged – in short it is nature as God intended…’.

Aside from the attention-calling character of these landscapes, there is another aspect to why designers of these places invite notice and acclaim more easily. They are the landscapes we are biased to appreciate. In a previous issue of Landscape 2, I quoted Kofi Boone, Professor of Landscape Architecture at NC State University, who points out that “...we have an implicit professional bias toward not only European landscape, but privileged European landscapes.” I would argue, however, that it is not just a professional bias, it is a societal one. We are conditioned to give value to the gardens of a stately home or private squares of a West London borough in a way we would not dream of ascribing value to the functional, landscapes of a nuclear power station or the everyday landscape of a muchloved local park.

This is not to say that neither Sylvia Crowe nor Brenda Colvin designed for the wealthy and the prominent properties of the UK, or that Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe’s equally notable work that did not involve such landscapes were not recognised. But there is an additional hurdle that women have to clear. And that is the simple fact of being a woman at all.

Since the scheme’s inception in 1866 ... 14% of Blue Plaques have been awarded to women.

It has long been identified that women’s work goes unnoticed and, therefore, unrewarded. The traditional

reputations/sylviacrowe-1901-1997.

2 Black Landscapes Matter pp.70-71, Landscape, Issue 1-2022

FEATURE

18

plaques-to-tellworking-classstories/ 4 https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Fanny_ Wilkinson

roles of care giving, child raising, and home making are all taken entirely for granted – unremunerated and most certainly not celebrated. Giving birth, dressing, washing, tending to the sick and vulnerable, cooking, feeding and cleaning were, and still are for many households, just natural facts of life that ‘happen’. The immense dedication, skill, commitment and practiced expertise involved is taken entirely for granted. It is work we overlook because it is so much a part of our everyday, and so vital to our survival, we default to thinking it happens naturally and requires no effort at all, much like the planning, design and management of our landscapes.

Even where women have blazed what should be paths of glory in fields, they have historically been kept from entering, any kind of public acknowledgment has been withheld. (Ada Lovelace anyone? Or Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson whose mathematical skills helped NASA win the space race? Not to mention potentially millions of others lost to history). And we see this again with the decision not to award Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin Blue Plaques when they were nominated for recognition.

This 2018 decision is a matter or real regret and, as this article hopefully makes clear, the impact is that an opportunity has been lost to make a wider public aware of their considerable contribution to the profession, to England and society. While I maintain that there should be persistence with this, by reapplying when possible, I would also argue that it is time that we no longer rely on long-established processes and bodies alone to help tell landscape architects’ stories.

We now have more power than ever in which to ensure that legacies are not just recognised but made. Websites such as Wikipedia, blogs and podcasts and posts on social media – put power in the

hands of people to celebrate the individuals they decide deserve time and respect. Ada Lovelace may not be in the mainstream but has long been recognised through patient campaigning. Similarly, the book, followed by the film, Hidden Figures brought the stories of Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson at NASA to a mass audience. It was through a video on Tik Tok that I discovered that Hedy Lamarr was an inventor, whose work is incorporated into Bluetooth and GPS technology, including the invention of WiFi.

We can wait for the Blue Plaques scheme to catch up with what the landscape profession knows about the value of celebrating Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin but we can also ensure that while we wait, their story, and that of other brilliant people are told in a variety of public-facing ways.

And there is hope here. This year, when the Blue Plaque scheme ‘aims to tell the stories of London’s working class with its 2022 awards’3 Fanny Wilkinson will be recognised as Britain’s first professional female landscape gardener. Her achievements include public gardens across London – she served as landscape gardener to the Kyrie Society, which aimed to ‘bring beauty to the lives of the poor’.4 While perhaps a patronising sentiment, there is no doubt that it is wonderful to celebrate the practice of someone whose work had its greatest impact on those without financial advantage and privilege. Someone extraordinary, using their skill and creativity to create public benefit for the ordinary. Someone just like Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin.

Sabina Mohideen is a freelance programme manager, with a background in EDI, events and change management.

FEATURE

19

Since the scheme’s inception in 1866 ... 14% of Blue Plaques have been awarded to women.

1.

A President for the unprecedented

It’s strange to think that three years have passed. So much has happened and how different the world was when we gathered for the LI-90 Festival of Ideas at the Olympic Park, where Dr Wei Yang, the then RTPI Vice President, announced that I would be the next President Elect.

I remember being thrilled: thrilled that so many women had stood for election, after research had shown a widening gulf between male and female leaders in the profession. Thrilled that more members had voted than at any election since 2011. And thrilled that those members had put their faith in me. It gave me a deep sense of responsibility to do my best.

Back when I was campaigning to become President, I could never have foreseen what the next three years would bring. It has been unprecedented on so many fronts. Of course, we were all wise previously to the challenges we faced and that we still face today - in particular those of

climate change and biodiversity loss (in fact, the temperature outside whilst I’m writing this article has reached a staggering 39 degrees). The relationship between human health and nature was a guiding principle of my manifesto – looking at the evershifting relationship between health and nature, and how we can turn our cities into places where both can thrive. The fact is that designing healthy places for people is not just a nice idea, but an achievable reality. In order to be elected, I prepared a manifesto outlining the issues that I believe were important to our profession; the balance of the built environment and nature; the relevance

Immediate Past President and guest editor of this edition of the journal reflects on her presidency.

Jane Findlay

1. Working from home during lockdown © Phil Champion

Immediate Past President and guest editor of this edition of the journal reflects on her presidency.

Jane Findlay

1. Working from home during lockdown © Phil Champion

FEATURE 20

of our profession; skills; encouraging young people to join us; developing role models and leaders to champion our profession; support for our registered practices; and growing a strong supportive and modern professional Institute.

This is how I truly believe our profession can march in from the verges and take a leading role in delivering infrastructure. It’s the key intersection between the art and science of landscape: between the intangible and the tangible; the expressive and the evidenced; the beautiful and the biophilic. It’s what has underpinned my every agenda priority: the knowledge that with a strong, skilled, supported workforce, we are the profession best equipped to build a world where human health and environmental health could co-exist. Little did I know when I was elected how important the topic of health would become. COVID hit, lockdown came, and just like that, everything I’d expected of the coming two years was out the ‘attic window’. But had the vision really changed?

I’d wanted to improve the LI’s influence and relevance. When COVID gave us uncontested proof of just how valuable green spaces are to people, our work became more important than ever. I’d also wanted to improve diversity and inclusion in landscape. When COVID highlighted such stark inequality of access to nature, it

became immediately clear that the people who plan and design our public places need to champion, and represent, all the communities we serve.

I’d also wanted to build a strong and supportive LI. When the business, learning, and welfare pressures of life under lockdown became apparent, it was clear the LI had to do everything we could to support our members through a difficult time.

The status quo shifted –dramatically – but the goals remained the same. My time as ‘Lockdown President’ is unprecedented and the way I had to work changed along with everyone else. It has been a challenging two years, adapting to these new ways of working with new colleagues from the LI team working remotely and connecting virtually with the membership. Conducting my formal role of chairing Board of Trustees and Advisory Council has been more challenging, those adhoc conversations and the relationshipbuilding we take for granted when meeting in person is more difficult when we are working remotely.

If I had to do it all again, I probably wouldn’t do everything the same. But overall, I’m very proud of what we’ve achieved as an Institute in that time. We’ve created new opportunities for people to enter the landscape profession. Together with the Trailblazer group, the LI launched

Level 3 Technician apprenticeship and is working with delivery partners on the Level 7 Landscape Professional apprenticeship, both a fantastic way to future-proof the landscape sector.

We’ve transformed our digital offering overnight to deliver CPD, networking events, Pathway to

Chartership exams, and more online. We’ve held two fully online Awards ceremonies – and by making them free and accessible to all, massively broadened the scope of how we showcase the very best of our wonderful profession.

We’re returning to the Troxy this year to celebrate in person – but we’ve learned a lot from the past two years and will make sure people can continue to access and enjoy the Awards online.

We’ve produced landmark policy work, including our Greener Recovery paper and Landscape for 2030, that demonstrate to decision makers the enormous benefits that landscape-led projects bring.

COVID has had a huge influence on the way I have been able to perform my role and responsibilities, it has also presented many opportunities. My presidency is perhaps not as dramatic as others have been, but I may have been more visible than previous presidents and I have been able to really focus on the message, the link between healthy places and healthy people. The digital world has made the President more accessible to members through online conferences, webinars and digital coffee mornings than ever before, it is one of the positive outcomes of COVID and I have enjoyed meeting so many of you.

The LI CPD conferences in digital format have attracted a formidable list of influential speakers and have

2. Design for Planet event at COP26

© Design Council

3. Panel discussion at the President’s Reception in May 2022.

FEATURE 21

© Ron Gilmour

2. 3.

probably been one of the more enjoyable and exciting parts of my role as president. I have been privileged to share the company of some very impressive women, including Dame Fiona Reynolds (former DG of the National Trust), Baroness Brown of Cambridge (member of the House of Lords and chair of the Climate Change Committee’s Adaptation SubCommittee), Carolyn Steel (architect and author) and Kotchakorn Voraakhom (Thai landscape architect and influencer).

I like to be on the front foot, so for each conference I will carefully prepare

with a morning coffee just as we go live, posters falling off the wall, internet outage, speakers dropping offline and having to adlib, or our recently adopted dog performing ‘zoomies’ behind me. I have learnt so much during my tenure as LI President, it is the best CPD I have ever done, and it’s been great fun!

As soon as the world opened up last September, I took every opportunity to speak at conferences, sit on panels and chair in-person events to champion our profession. The LI went to COP26, where we championed the fundamental importance of an integrated, landscape-led approach to securing a sustainable future. We attended MIPIM and put green at the heart of the debate at the world’s leading property conference.

Smaller crowds than in previous years led to a different kind of MIPM experience with different priorities and successes. The published programmes were pretty much the same as they’d always been. By the time March arrived, the conversation had shifted fundamentally with environmental, social and governance (ESG) suddenly rising to the top of the agenda. Social value, nature-based placemaking, sustainable design were everywhere.

Investment and Infrastructure Forum as a partner at the Beyond Net Zero pavilion. The LI was also represented at the first ever Footprint Plus conference in Brighton, to continue making sure that policymakers and investors know the value of naturebased solutions. I spoke about the benefits and the importance of parks and green open space on national radio, attending industry awards to celebrate the best the sector has to offer. Meeting with CEOs and presidents of other built environment institutes enabled me to build relationships and emphasise the importance of professional collaboration to solving the challenges we collectively face.

Even through the final month of my presidency I continued to champion the relevance of our profession as creative problem solvers, banging the landscape drum to the very end!

These last two years haven’t all been plain sailing – at times it has been quite a stressful and demanding personal challenge for me, for example working with three different CEOs during my term in office, would be disruptive and challenging for any organisation. Historically and in recent years the Landscape Institute has experienced a higher turnover of staff, elected officers, trustees, staff and volunteers, as well as a higher than usual number of internal disagreements and complaints on issues which relate to aspects of governance and operation of the LI.

5.

by researching each speaker and formulating questions I think the audience would like to hear answers to. But things don’t always go to plan; the awkward entry of my husband

In fact, by day 3 it was all MIPIM News talked about, and we were on hand to have those important discussions with the decision makers, developers and financiers.

We attended the UK’s Real Estate

For the future of our Institute and the welfare of the staff and volunteers it was imperative that the Board of Trustees addressed the regularly occurring issues surrounding governance and member behaviour. We commissioned an independent review to ensure that the LI was fit for the future, to make us a more equitable and stronger organisation. Completed towards the end of 2020, this significant piece of work involved consultation with a wide range of individuals across the LI. It made recommendations to improve our ways of working and to improve longstanding issues that continue to hamper the work of the LI and successive presidents. I’m pleased to

4. Arit Anderson CMLI, CEO Sue Morgan and Advisory Council member Wing Lai CMLI at the Presidents’ Reception. © Ron Gilmour

Collaboration with other built environment institutes - with Timothy Crawshaw President of the RTPI.

4. 5. FEATURE 22

© Ron Gilmour

report that the first phase of this work has been completed despite a challenging couple of years and many of the recommendations are now business as usual. There is a two-year change programme to deliver the more complex improvements to operations, strategy and more.

This last couple of years have been a wake-up call for humanity. Not only did we realise that nature was so important to us – we realised that human activity was so detrimental to nature. COVID changed how the last two years played out. But it didn’t change what matters.

No matter the crisis, no matter the variables, no matter the ever-shifting ecology of today’s world, human health and environmental health are the same. We humans are, and always have been, part of our biosphere.

Every negative effect we have on our environment is a negative effect on us.

The world needs planners, designers, managers and more who work with nature, not against it. Whose projects make a difference not just in one area, but across multiple areas. That is us, that is our domain and I’ve said it many times before, and I’ll say it again: our time is now. And key to our success is healthy collaboration with organisations in the built environment sector.

Anyone who feels that the profession has either lost or is losing its way needs to watch the footage of the online awards ceremonies. Many of the acceptance speeches were made by the younger members of our profession. It portrays a profession that is confident in itself and in its message. Yes, we still need wider recognition within the general public, but you are never going to convince people of your value if you don’t have a feeling of self-worth.

For the first time in my career, I feel that the profession is finally emerging as a force in its own right. What we all need to do is support the enthusiasm, vigour, and ability to see

things through fresh eyes, which is evidenced by our younger members.

The role of President is ephemeral, our time at the helm is short. I have merely scratched the surface and, with other challenges we have faced over the last two years, there is never sufficient time to complete the job. That is why continuity is crucial, driving forward the LI strategy and not losing sight of the goal of the LI to lead and inspire the landscape profession, to ensure it is equipped to deliver for the benefit of people, place and nature, for today and for future generations.

Our apparent difficulty in making ourselves heard and influencing is something that has long dogged our profession and will not change if all our efforts are channelled into regular “governance navel gazing”. It’s not what most of our membership want. They need a dynamic, modern professional institute that supports them on their career journey, that will champion our sector, grow our profession and ensure the highest standards.

We are passionate about our work, our profession, and our legacy but we are poor at self-promotion. Kathryn

6. 2022 Graduation Ceremony.

© Andrew Mason

7. The LI attended COP26 in Glasgow working with Scotland branch chair Rebecca Rylott.

FEATURE 7. 23

© Sue Morgan

6.

Gustafson sums it up beautifully, “Landscape Architects are a shadeloving species.”

Landscape Architects need to become advocates. We need to ‘convince our elected leaders that this (landscape) is important stuff’.

So, what should we prioritise for the next 20 years?

Leadership Landscape architects are “generalists” in nature and have a broad understanding of climate change, social inequalities, the built and natural environments. We need to use this knowledge to work with allied professionals by leading and uniting teams to create greater environments for people. By becoming leaders, we will create and greatly improve the environments and places that allow everyone to thrive.

We should encourage and support the next generation, those young leaders and role models, through development and mentoring programmes to become leaders of our profession. They must be helped and encouraged to become involved in the LI and to stand for election on Advisory Council, an honorary officer role, or to volunteer for a position on a committee.

Political Leadership

We need a strategy for placing more landscape architects into the elected, appointed, and bureaucratic offices where the big decisions about how to

plan, design, and manage the land are made. This is how we construct a positive feedback loop between private and academic practice, which can bring invention and creativity, and government, which offers a tremendous scale of impact.

Education

For landscape architects to become changemakers, we must change how they are taught. Landscape schools should create more opportunities within their programmes to: Develop the ability and capacity in students to engage in the political process to create change; understand better the language and systems of power; accept the responsibility of professionals as engaged citizens and as members of a democracy.

Build knowledge and capacity beyond the traditional core of the profession; engage in collaboration on research, teaching, and service with other disciplines; learn from how other fields generate, disseminate, and apply knowledge, and how they engage the public and advance their agenda.

Encourage more red-brick universities to provide accredited courses to cover all aspects of landscape.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

We are fortunate to work in a broad profession that attracts people from all walks of life. The gender balance of

those at the start of their careers has always been even and today there are more women entering the profession than ever before. However, there’s still a long way to go before women are represented equally at the more senior levels as practice principals and business owners.

It’s one of the LI Strategic goals, but we are not there yet. The LI must actively promote a profession that is balanced, diverse and inclusive, representing the communities we design for and which addresses the dearth of black practitioners.

Landscape architects and landscape professionals are holistic – we understand both natural surroundings and built environment, and the interface between them. With our skills and expertise, we are positioned to handle the questions of how we plan and design our urban and rural spaces the face of the monumental problems we face. Our contribution to society is pivotal and vital as we address both the built and natural environment. We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity for our profession to excel - landscape professionals “must become a sun-loving species.”

I’m truly proud to have served as your President. And I’m confident that, with passion, skill, and support, our Institute will continue to go from strength to strength.

8. Jane is one of the founding Directors of Fira with offices located in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter.

8. FEATURE 24

© FIRA

1. Jane Findlay, Sue Illman and Kathryn Moore.

© Paul Lincoln

Days after the Commonwealth Games, Jane Findlay, Sue Illman and Kathryn Moore, all past presidents of the Landscape Institute, met in Birmingham to discuss landscape, life and the future of the profession. Their conversation was recorded by Paul Lincoln.

FEATURE

25

Past Perfect

How did you become a landscape architect?

Jane Findlay (JF)

I was inspired by Dame Sylvia Crowe through someone I knew at the Forestry Commission. Although he didn’t suggest going into forestry – he thought it wasn’t a career for a woman – he suggested that I should become a landscape architect mentioning Sylvia Crowe, who worked for the Forestry Commission designing forests and large-scale landscapes. This ticked all my boxes with its combination of arts and science. I was lucky to come across landscape architecture before completing my A-Levels. I went to Leeds where I met my husband Phil who is also a Landscape Architect. He found a job in Birmingham, and I followed him to the city where I started with Percy Thomas Partnership, a large architectural practice, working on projects healthcare projects and schemes that were the catalyst for the regeneration of Birmingham.

Sue Illman (SI)

When I left school, I had a place at university to study law, but had second

thoughts and decided against it. I studied accountancy for three years, which, as I was good at maths, was OK, but I became bored by it. So, one day I went to a careers office and picked up a leaflet on landscape architecture. And I just thought, ‘that’s everything I want to do.’ It was towards the end of September, I called the university in Cheltenham on a Monday, went for an interview on the Tuesday, was accepted on the Wednesday and I started the following Monday, joining in week six of the course. I’ve never looked back.

Kathryn Moore (KM)

I had never heard of landscape architecture. What inspired me was being driven back from Manchester University one day by my father. We were on the A449, which is an exceptionally beautiful road and the landscape around it is extraordinary. I thought I want to do something with landscape. I had been planning to do a course in geography after completing a foundation course in art and design, but I found a leaflet that said if you're interested in art and you like geography, then landscape architecture may be the career for you. This led to me doing the master’s course in Manchester University.

How has the profession developed during your time as a landscape architect?

JF It’s changed profoundly since I started my degree at Leeds

Polytechnic. In the early years of my career, we often worked ‘for architects’, there were fewer landscape-led schemes and there were some master planning projects – we didn’t work as strategically as we do now. Information technology has completely transformed our world and the way that we work especially how we collaborate with other construction professionals. We’re also gaining the credibility that we’ve often looked for. I think we do have something important to offer that wasn’t recognised in the past. We are perhaps ‘a shade-loving species’ [Gustafson] as we rarely promote our work and talk about what we can do and how great an impact we could have, but I think our time is now. It’s not just about climate emergency, it’s about our existence, our health and wellbeing. If we don’t look after the planet, we’re not looking after ourselves. There is a danger that people think of themselves outside of the ecosystem, that the natural world just carries on without us. If we’re going to be healthy and comfortable, we have to look after our planet, our reserves, our natural resources. None of this can be ignored anymore.

SI When I first started, we were very much second-class professionals, asked to fill in spaces around buildings once the architecture had been designed. Today, a landscape-led approach is normal, and we rightfully have our place at the table. The majority of developers and their design teams understand and respect our approach these days. Now, we are generally allowed the broadest of scopes where its required. However, we still have a job to do in terms of selling our full skill set and helping the client to understand how much more they can get out of each of their projects, if they allow us the scope to show what we can do.

KM Practice is expanding beyond the purely technical. We recognise that working with the processes of nature and addressing climate the emergency are now givens in any kind of practice. We recognise that whether our practice is primarily concerned with ecological design, SuDS, urban design

2.

Jane Findlay, Sue Illman and Kathryn Moore

2. Sue Illman in her fern garden.

FEATURE 3. 26

3. Jane Findlay, Sue Illman and Kathryn Moore. © Paul Lincoln

Today, a landscape-led approach is normal, and we rightfully have our place at the table.

or planning, developing policy, or landscape management or any other mode of practice, it all has a spatial dimension one way or another. This needs to be shaped well, with care and expertise. What is created plays a fundamental role in shaping the relationship people have with the territory they occupy, work in, move through, remember or cherish.

Seeing the bigger picture is repositioning landscape practice beyond the provision of green infrastructure or blue infrastructure. The challenge now is of a greater magnitude – we are beginning to recognise landscape as the infrastructure upon which we all depend, culturally, economically and ecologically, a vital resource to be harnessed if we are to address global challenges effectively and at scale. Understanding the immense restorative capacity of landscape (in its widest sense) to support the green recovery, the construction and transformation of our cities is a fundamental part of the West Midlands National Park (WMNP) Awards being run by the WMNP Lab at BCU.

How do you think the landscape profession needs to adapt over the next 30 years?

JF We are generalists, which makes us very holistic in the way we approach our work. We have to realise that we can’t operate in our own little sphere, we have to be open to collaborations. I think we have to be self-sufficient and skilled; we are highly competent professionals with the confidence and the ability to be able to deliver highly skilled, creative work. It’s important that we focus on all the issues of climate change, biodiversity, net-gain, health, and well-being – all these have got to be streams that feed into our projects at all stages, which I think as a very diverse and holistic professional we can do, as we are good at pulling all these threads together.

SI We’ve always worked with the environment as a fundamental part of what we do. And now those messages around adaptation are being

heard loud and clear, and not only from us. However, we’ve got to be so much more vocal about what we do, and how we can effect positive change. We are all beset by issues around flooding and problems with water resources, and as a profession, we can make a major contribution to tackling this. We need to think about resources, the environment and how we’re going to create places for people that are liveable in our changing environment, and how within that context, we will monitor and adapt to deliver the ongoing change that we need.

KM The most important thing we must do is stop dividing nature from culture and thinking of nature as something that’s out there and that culture is something elsewhere. Natural systems do not stop when you enter the building.

Education needs to respond by encouraging the exploration of ideas, to encouraging students to constantly see the bigger picture, and to understand the role of economics and governance. One of the things I try to encourage students to take on board is to become political.

Addressing the challenges expressed through the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the other guidance and commitments are a crucial part of our work. As a special envoy for the International Federation of Landscape Architects [IFLA] I was invited to co-author a policy paper “Roadmap to a Just and Regenerative Recovery” for the UN Habitat Professional Forum. Presented

at the UN Urban Forum in June, it is timely. Over the last two years, more than $1 trillion dollars has rushed into Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance investment funds in the US, according to the Harvard Business Review (2022). In the UK, investors are looking for suitable ESG projects. The significance of the HPF Road to Recovery is that it moves landscape more firmly towards the economic realm – and as we know, you’ll only persuade people to take things seriously if there is a clear understanding of its long term social, environmental and economic value. This is what we need to adapt to.

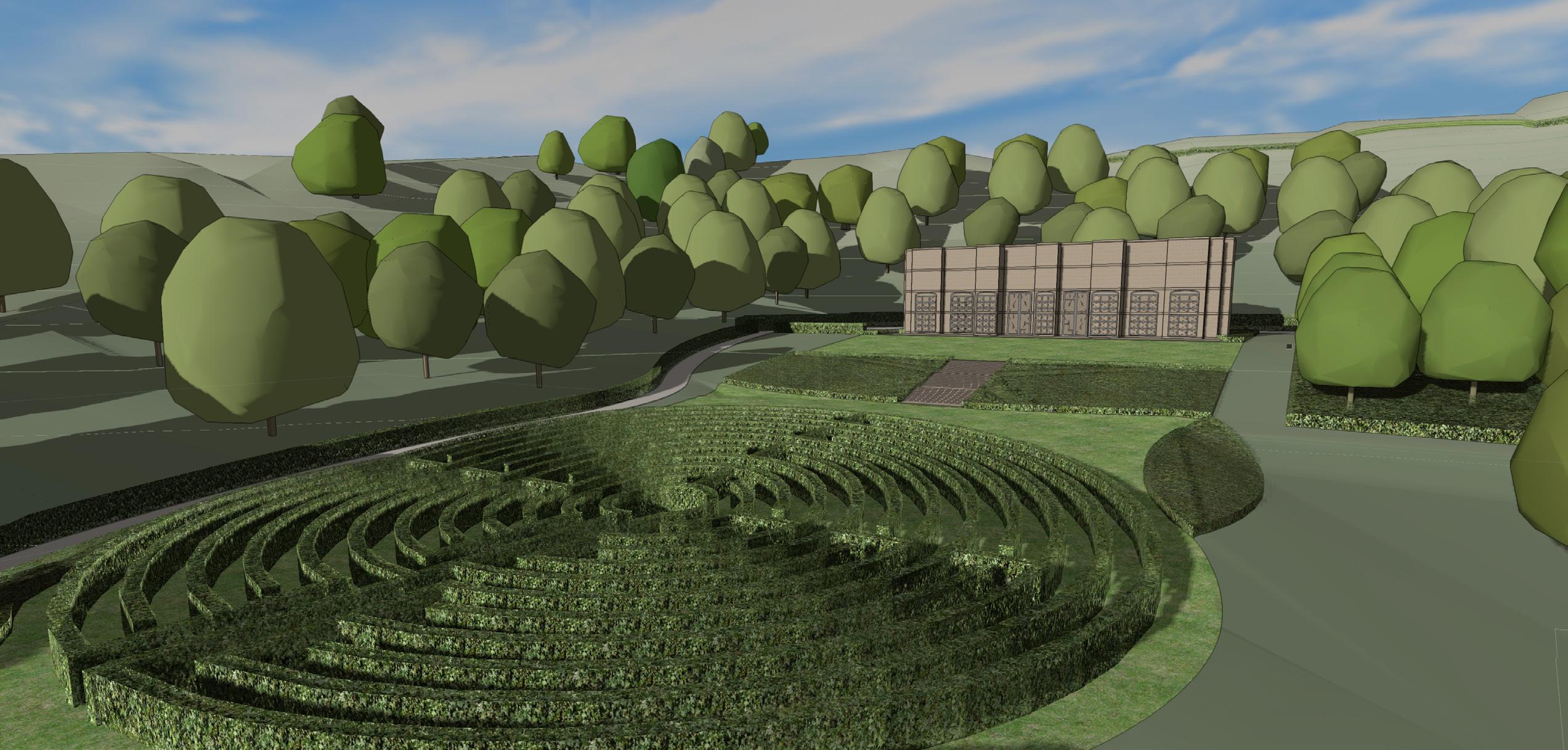

Tell us about one project you’re working on at the moment that really excites you

JF I’ve been working for a decade or more on the National Memorial Arboretum, the home of remembrance, and of the Armed Forces Memorial. It commemorates and celebrates the efforts and sacrifice that people have made for this country. It was the idea of David Childs back in the late 1990s. He was inspired by a visit to Arlington Cemetery and the National Arboretum in Washington DC, and wanted to create a year-round national centre of remembrance here in the UK. It’s in the National Forest, who provided the funding. We originally worked on the new masterplan for the site. Our latest project is on land donated to the Arboretum by Tarmac from their adjacent sand and gravel extraction works. It will expand the site by another 25 acres. Our plans are to transform the existing scrubland and silt pond into an inspirational and restorative landscape, where people can gather to reflect and contemplate the impact of the pandemic and remember loved ones who have died as a result.

© BCU FEATURE

27

4. Kathryn Moore.

4.

5.

Find out more about the National Memorial Arboretum https://www.thenma.org.uk/

SI In recent years, I haven’t focused on design, but I have spent a great deal of time on policy work and training. So that’s really been the big focus of what I do, as well as coordinating a number of larger design projects. Sharing knowledge and trying to inspire others to understand the scope of what we can do has focused on water management, as this is such a fundamental part of life now. Enabling people to understand why we need to do it, and how we need them to engage with it, is so important. We see so much SuDS work which is just atrocious. Most of the people I’m training are civil engineers, highways engineers and facilities management people. By explaining the principles, and illustrating good and bad practice, we can help them understand what good looks like, and the important role of landscape. We need to encourage the professionals we’re working with to approach the job properly, to get it right, and to maximize the benefits for all. We’ve needed water management policy to change for a long time, and now it finally is.

Find out more about the Updated Guidance on Flood risk and coastal change published on 25th August 2022

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ flood-risk-and-coastal-change

KM I argue that redefining theories of perception, design, and landscape has implications far beyond the academy. My current work investigates the nature of these implications. The potential for HS2 as a social, environmental and economic catalyst

for all the communities along the route, builds on the work carried out for the Black Country Consortium in 2004/5. The study for North Warwickshire funded by the Environmental Agency in 2016 shows the relationship between the communities of the West Midlands plateau and the rivers and streams, the canals, geology and topography as a powerful connective tissue across the region that could have immense social and ecological benefits.

These projects led in turn to the idea of creating West Midlands National Park (WMNP), formally launched in 2018 at Birmingham City University (BCU). Having since built widespread support with institutions, authorities and communities across the region and nationally, it is a strategic project for BCU. Supported by Andy Street, the Mayor for the West Midlands Combined Authority and Birmingham City Council (recipients of a WMNP Award in 2021 for its vision, “Our future City Plan”), the WMNP Foundation is chaired by Dame Fiona Reynolds.

masterplanner and has delivered complex public realm projects for residential, infrastructure, higher education and biomedical sectors, and is particularly experienced in design for healthcare. Jane is a sustainability advisor on the University of Warwick Estate & Environment Committee and a landscape advisor for the National Memorial Arboretum.

A past President of the Landscape Institute and Honorary Fellow of both the Society for the Environment, and University of Gloucestershire, Sue Illman is a practicing landscape architect and a specialist in historic landscape conservation, with a long-term interest and expertise in hard landscape construction and planting design. Sue is a passionate advocate for Sustainable Drainage Sytems (SuDS) as a key element in sustainable design practices. She has extensive experience in both lecturing and the delivery of training about SuDS and also speaks about the wider subject of sustainability, of which water is a key part.

5. National Memorial Arboretum

© Credit

6. Topography, rivers, canals: the centre of Birmingham on the high ground overlooking the Rea and the Tame valleys.

6.

Find out more about the West Midlands National Park https://www.bcu.ac.uk/newsevents/news/the-westmidlands-national-park-unveilsprojects-to-change-the-region

Jane Findlay is the founding director of Fira Landscape Architecture & Urban Design and the Immediate Past President of the Landscape Institute. She is an experienced

Professor Kathryn Moore, Former President of the LI and IFLA, has published extensively on design quality, theory, education and practice. Her book ‘Overlooking the Visual: Demystifying the Art of Design’ (2010) redefines theories of perception, providing the basis for critical, artistic discourse, and setting a new way of looking at landscape, putting it at the heart of the built and natural environment. This work informs her teaching, enabling a more democratic way of teaching design, equipping students with the confidence and skill to become designers. Her radical proposal for the West Midlands National Park (WMNP), based on over 25 years of research was applauded in the 2020 UK Government Review of Landscapes. Reimagining the region from a spatial landscape perspective to drive inclusive social, economic and environmental change, the WMNP is attracting considerable support nationally and from UN Agencies.

FEATURE

© Kathryn Moore

28

Bespoke street furniture, planters and retaining walls. Sustainable timber solutions for the built A 100% FSC Manufacturer www.factoryfurniture.co.uk design+ make+ collaborate

- Ridley Road, Hackney Planter seats in concrete, FSC Cumuru and corten steel 29

Photo

Advocating for Design

Hattie Hartman (HH)

Why did you decide to study landscape architecture and how did you select the Edinburgh course?

Lynn Kinnear (LK)

I’m from Edinburgh so it was on my doorstep. My grandfather was a builder and he was quite keen for me to study architecture.

HH Did you come to London straight after you finished the course?

LK Initially I worked for Gillespies on the Liverpool Garden Festival and the reclamation of the Lanarkshire Steel Mills. They brought me down to London to work on master plans. When their master planning work dried up, I moved to SOM to work on Canary Wharf. SOM was a very disciplined environment and I learned a lot. I was paid very well and racked up lots of overtime. So I went traveling for a year to Australia, India and other places. When I came back, I worked for Jo when she had her first baby.

Jo Gibbons

(JG)

While I was having Miles, Lynn kept the jobs going.

LK Then I took a teaching job at University of Greenwich and set up the practice. My first projects, were from

the London Docklands Development Corporation, whom I’d previously worked for at Gillespies.

HH How would you describe your USP when you first set up?

LK I wanted to work with local communities to effect change to their public space.

HH Even after all the large-scale master planning that you’d been doing?

LK I’d learned that that didn’t work. SOM’s accomplished Beaux Arts approach to master planning didn’t adequately address local communities. For me, the ultimate project was Norman Park in Fulham. Engagement funding had kicked in, and we set up

1. Brentford High Street - The reclad timber sheds create a light destination on the canal and advertise the history of Brentford as a crop growing place for London.

Recently appointed a Mayor’s Design Advocate, KLA's Lynn Kinnear reflects on her career and the challenges of juggling a demanding practice and motherhood in conversation with university friend Jo Gibbons of J&L Gibbons and Hattie Hartman, Architects’ Journal sustainability editor.

Hattie Hartman

1. FEATURE 30

© Grant Smith

2. Walthamstow

community groups across the social divide and taught them how to be clients. In many of those early projects, we funded the engagement ourselves.

JG Engagement is never adequately funded. But you do it anyway because the deeper and the better you do it, the better the outcome.

HH How many people have worked with you over the years?

LK I’ve always kept it small, say three or four, because it’s a teaching practice. We bring in specialists, as needed. I like to employ people straight out of university and take them all the way through. I see teaching people as part of my role as an employer. It’s one of the things I really enjoy.

Andrew Grant working on large land reclamation and ecology-based projects – he was a year ahead of us. And Gross Max, which is Bridget Baines and Eelco Hooftman and the German and Dutch practices, like West 8 and their spinoffs. In the UK, there’s a tendency to think of us as an offshoot of architecture.

JG Either that or gardeners.

LK My last big project was 200 hectares. We deal with the landscape and it can be very large-scale. That’s what we’re trained for.