New attractions in NYUNGWE Forest

National Park, Rwanda

With new attractions including one of East Africa’s longest zipwires and a wonderful eco-lodge that places guests at the heart of the ancient rainforest, there’s never been a better time to visit Nyungwe Forest National Park. Mark Edwards finds it a magical place for animal and aerial adventures.

Iam being propelled by gravity at a speed of 60 kilometres per hour, the wind roaring in my ears. Around 50 metres below me – when I pluck up the courage to look down – I see the verdant canopy of one of Africa’s oldest rainforests intersected by jagged ravines and a rushing waterfall.

This unforgettable, adrenaline-charged experience is provided by the Nyungwe Zipline, which was opened to the public in May this year as the latest visitor attraction in Nyungwe National Park in Rwanda’s south-west corner. It’s my first time visiting the park and when my picturesque five-hour car journey from Kigali (RwandAir offers flights from the capital to Kamembe, the closest town to the park’s western edge, if you’re in a hurry) reaches its final stages on the smooth paved roads that wind through the mountainous terrain here, I am transfixed by the floating layers of mist that seems to hold the forested peaks in a magical embrace.

Around an hour later, having received my zipline safety briefing at the 2,400-metresabove-sea-level Uwinka Visitor Centre where the ride begins, I am hurtling through that very mist, wrapped up in its magic and feeling its moist air kiss my skin. The zipline is made up of three sections, with each subsequent section longer, higher and faster than the previous one. The first section, ‘Monkey’, is 335m, the second, ‘Chimpanzee’ is 580m, and the last, ‘Gorilla’, is just over a kilometre-long and connects facing cliff tops across the spectacular rainforest valley. The names for the individual rides not only reflect their ascending size, but also Rwanda’s diverse primate population. While Volcanoes National Park in the north-west of the country is one of only three places in the

world to see mountain gorillas in the wild, Nyungwe is known for its chimpanzees and many species of monkey. Nyungwe harbors around 6 percent of Africa’s primate species, or about 12 percent of those found on the African mainland, making it a vital stronghold for primate conservation.

As it comes first when you’re not sure what to expect, ‘Monkey’ was the one to give me pre-ride jitters. I am nervous around heights – I have to mentally prepare myself to ride an escalator – and I could see that the ground below the zipline soon plunged away into a deep crevice. Fortunate then that I had Jean-Paul – my driver and guide for my three-day adventure in Nyungwe designed by Rwandan-owned tour company Shalom Safaris Rwanda – to offer encouragement. Along with many other young Rwandans working in the local hospitality industry, Jean-Paul had recently been given the opportunity to ride the zipline before its official opening to the public. He tells me he was nervous, but he loved the experience, ending up riding each section twice. “Face the fear and do it,” is his advice. “It will be worth it.” He proves right.

By the time I was riding ‘Gorilla’ all nerves had gone and I was able to relax and soak up

Nyungwe harbours around 6 percent of Africa’s primate species, or about 12 percent of those found on the African mainland”

the stunning views. It took just 45 seconds to whizz along the final section’s 1,020 metres, but I relished each one as a moment of pure freedom. That sense of emancipation was to remain throughout my time in Nyungwe. The national park is Rwanda’s largest tract of mountain rainforest, covering 1,019 sq km, and there were times when I felt like I had it all to myself. The Unesco World Heritagelisted Nyungwe doesn’t yet attract the visitor numbers of Rwanda’s national park headliners, Volcanoes and Akagera, while the towering natural landscapes can create a feeling of being enveloped in a private, serene world.

I feel that immersion in nature walking the Igishigishigi Trail back up to the visitor centre from the last zipline station with the route shrouded by an abundance of the giant tree ferns the trail is named after in Kinyarwanda. One of the three guides who oversaw my zipline rides accompanies me back along the trail. Like the other young

locals that will steer my explorations over the next few days, he has been trained by the Rwanda Development Board (RDB) –the government body that has managed Nyungwe since 2010 and has shared the running of the park with international conservation organisation African Parks since 2020 – and is impressively knowledgeable and passionate about the diverse ecosystem here.

Over the 2km trek he shares a host of insights – among them that the Igishigishigi ferns are believed to be among the oldest plants on the planet with fossils found that predate the dinosaurs; that the tiny holes he somehow spots in a slope of soil in the mountain side were dug by predatory ant lion larvae to trap other insects; and that a cluster of tiny yellow flowers in the dense overgrowth of the forest floor belong to the more than 250 species of orchid to be found in these parts. Our trek also takes us past the canopy walk. Like the ziplines,

this 160-metre-long bridge suspended 70 metres above the ground offers exhilarating panoramic views of the rainforest, but it has been around far longer. It was built in 2010 as the first of its kind in East Africa.

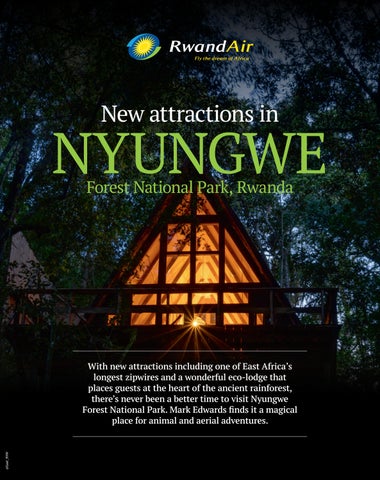

My accommodation while in Nyungwe is Munazi Lodge. As the first and only hotel built within the national park, the new eco-lodge – it was officially opened in June, and I am privileged to be among the first guests – is just a 5km drive from the Uwinka Visitor Centre. The last kilometre is a private dirt track that hugs the mountain side before revealing Munazi deep within the forest with its nine wooden A-frame chalets elegantly blending in with the natural surrounds.

Almost all of the lodge’s impressive wooden infrastructure and furniture – from the boardwalk that connects the chalets to the central lounge area right down to the tree slices used as tablemats in the dining area –is handmade by local builders and artisans. Assistant manager at Munazi Lodge Marie Solange Umotoniwase points out that all the wood used is from invasive trees cut from Nyongwe to allow for the natural regeneration of indigenous plants in the national park. Nyungwe is one of the oldest forests in Africa with mountain streams considered the most remote sources of the Nile and Congo basins. The park’s high rainfall

and numerous rivers create a network of microhabitats, leading to the evolution of species found nowhere else. Today 70 per cent of Rwanda’s fresh water originates here. Prioritising the growth of indigenous trees is key to preserving this vital ecosystem.

Run by RDB and African Parks, Munazi Lodge is aligned with the park management team’s drive to conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of Nyungwe. As well as the use of sustainable building materials, Munazi’s low impact living includes site-wide solar-powered energy, and a kitchen creating wonderful dishes from locally sourced produce. As in the rest of the park, no plastic bottles are allowed. Glass carafes in the rooms are refilled daily with chilled water sourced from a mountain spring and filtered on-site using high-quality, approved filtration systems.

The elevated chalets make the most of their forest views with floor to ceiling windows that open onto a large veranda complete with hammock. The height of the A-frame structure allows for a cosy mezzanine level

bedroom. My room was a double but there are two chalets designed with families in mind that offer extra beds. The downstairs living area is spacious with banquettes to stretch out on and soak up that view, a workspace (there is wi-fi), a kitchenette, and en-suite shower room.

I head to the communal area for dinner. It’s a cavernous space, but artfully divided by two log fires, which were lit each evening for welcome warmth – it gets chilly in the evening at this altitude. The fires’ accompanying chimneys demarcate a large dining area as well as two more intimate spaces, including a snug corner library with highbacked armchairs and a good selection of books that I came to cherish.

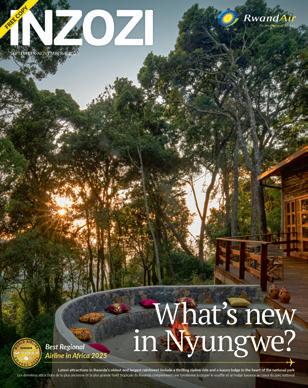

Outside there is a large veranda with a fire pit surrounded by a semi-circular stone seating area ideal for story-swapping with fellow guests after your day’s adventures. The views across the valley from here are impressive. The hotel’s food and beverage manager Ishimwe tells me Lake Kivu is visible on a clear day. He also identifies a line of towering trees just metres from the veranda as waterberry, named after its edible fruit that is much loved by the park’s monkeys and baboons. The waterberries blossom in October with guests getting a ringside seat as the primates tuck in.

Human guests will also find plenty of food to enjoy at Munazi Lodge. Stays here are full-board and meals are inventive, artistic and nutritious. The hotel’s charismatic chef, Pacifique Niyonkuru, crafts a delicious threecourse dinner that begins with homemade guacamole and chapati chips followed by steak fillet with mustard sauce on a bed of dodo, a type of spinach that thrives locally, and rounded off with a heavenly homemade chocolate pudding.

Stomach satisfied, I return to my chalet, which feels a little chilly compared the fire-warmed lounge. However, when I pull back the duvet of my bed, I find housekeeping has left two ‘bush babies’ – the name the hotel gives to its complimentary hot water bottles – to warm the sheets. Toasty

Nyungwe is the first natural site in Rwanda to be featured on the UNESCO World Heritage list”

again, I fall into a sleep so deep I don’t even hear the raucous calls of the tree hyrax – a rabbit-sized mammal that hotel staff have warned me dominates the nocturnal forest soundtrack.

I’m up at six the next day to meet Jean-Paul. Who knows what time Pacifique woke up because he is waiting for me in the lounge, having created an amazing breakfast involving a selection of freshly baked pastries, a fruit platter including tangy local favourite the tree tomato, and a plate of sausage, bacon and eggs.

After breakfast, Jean-Paul and I head to Gisakura Visitor Center in the park’s western corridor. As well as a café and a campsite, the centre now has its own tree-top obstacle course that includes rope walks, balance poles and mini-ziplines to test your ape-like agility. We, though, our heading on a hike to one of Nyungwe’s hidden gems, the Kamiranzovu waterfall. Jean-Paul shows me the fall’s starting point first, stopping the car on a mountain road so we can look down on a vast, almost circular expanse of high-altitude wetland. This is the Kamiranzovu swamp. Its Kinyarwanda name derives from ‘kamira’ (to swallow) and ‘nzovu’ (elephant) as its ooze is believed to have claimed the lives of elephants unfortunate enough to test its depth. It was actually poaching that led to the extinction of elephants in Nyungwe in 1999, but the shameful practice is well guarded against here now and there are plans to reintroduce a population of tuskers soon.

We begin our hike to the falls at the Gisakura tea plantations on the edge of the park where the fields of tightly packed tea bushes are a shade of green so lush they shimmer. Near the entrance to luxury hotel One&Only Nyungwe House we find the start of the trail and immediately drop down into forest cover. The enormous variety of plants in Nyungwe – the national park is home to at least 1,000 species –amazes me. Such density of growth means plants are engaged in a fight for light with some employing dirty tricks to survive. Our guide Jack points out a strangler fig that

has wrapped its roots around the trunk of another tree – a deadly embrace that will starve the host of resources.

Jack knows his flora – he also points out a cluster of towering munazi, the tree my lodge is named after, and which is also known as ‘the broccoli tree’ because of its floret-like evergreen crown of leaves – but his real passion is birds. The 6km hike to the waterfall offers an excellent opportunity to see some of Nyungwe’s 275 bird species. Stand-out spots include yellow-eyed black flycatcher and blue-headed sunbird, both endemic here, as well as great blue turaco, Neumann’s warbler, and red-throated alethe. Jack encourages the birds to come close by imitating their calls. When he sees a bird not in his impressive repertoire, he plays the call through an app. It’s an effective tactic and gives us an intimate audience with the park’s diverse avian population.

We hear the falls before we see it, which adds to the anticipation. Soon the trail grows slick with water spray and there it is: a torrent of crystal-clear water bursting from rocks 20 metres above us. It feels like our hike has uncovered a treasure hidden deep within Nyungwe. This moment of communion with wondrous nature is ours alone – the three of use shrouded from the outside world by sheer slopes of forested mountain. I am surprised by the purity of water given its source, but Jack informs me the swamp acts as a natural filter with its vegetation trapping sediment. By the time the water reaches the waterfall it has been significantly cleaned.

Mark Edwards

@Gael_RVW

It took just 45 seconds to whizz along the final section’s 1,020 metres, but I relished each one as a moment of pure freedom”

The steep uphill return journey is happily broken up by more bird sightings, including a soaring African harrier-hawk. Back at the plantation, I am given a crash course in tea picking by a mother and daughter team. They are among the more than 1,000 residents of Gisukura village – 530 pickers and 700 to clear the bushes of weeds – employed at the farm. It’s a dependable job – tea can be picked all-year-round here – and employees get help with school fees and health care. I am taught the ‘plucking’ technique that involves grasping the tea plant between thumb and forefinger before snapping it off. I am woefully slow, struggling to differentiate between young tender shoots ripe for picking and older leaves that should be left to continue to grow. In contrast, my two teachers are a vision of delicacy and speed. Working with both hands, they have soon filled their baskets and, pityingly, begin filling mine as well.

The next morning at 4am, Jean-Paul and I are heading back to the Uwinka Visitor Centre for the start of a chimpanzee trek. Unbelievably, by this time I have already had a three-course breakfast lovingly prepared by Pacifique. When does this man sleep? I’m thankful for the fuel because chimp trekking is more intense than your standard hike. There are around 400 eastern or mountain chimpanzees in Nyungwe, but they are constantly on the move and build new tree-top nests in new locations each night. Trackers have been out ahead of our trek and have found the latest nesting site of a community of habituated chimps deep in the forest. However, the chimps rise at dawn to begin foraging for food, and they move fast and cover large distances. Hence the early start and why I and seven more tourists on the trek are frantically trying to keep up with the lead ranger as he sets out at pace from the village of Banda. Our guide Clare has told us that seeing the chimps cannot be guaranteed and we don’t want to miss out. Once in the jungle, the path steepens and we are crossing streams on rocks and battling through dense foliage at near head-height. I stay close behind

the ranger and can hear crackling reports on the chimps’ location come through his walkie talkie. We are moving faster than ever now.

Suddenly, the ranger instructs us all to stop and stay silent. The forest’s symphony of natural sounds – cicada chirp, the gentle murmur of a stream, and the wind blowing through the trees – comes into stark relief. Then, the peace is broken by a chorus of grunts that build into high-pitch screams. It’s so loud – reverberating through the forest – and such a primal and thrilling noise to hear in the wild. This is the famous ‘pant-hoot’ of excited chimpanzees. The reason for their excitement is a stand of fig trees filled with ripe fruit. The team of trackers point out the chimps high in the branches. They are joined for breakfast by a troop of mountain monkeys and greycheeked mangabey monkeys. There is some fighting over food with the chimps – apes, not monkeys with bigger bodies and no tails – benefiting from their size advantage. However, the mangabeys, with their coats so dark they look like acrobatic living shadows, give as good as they get. A chimpanzee trek permit – which must be booked through the RDB in advance – allows the holder one hour to observe the animals once located. The time flies by. There are few things more joyous than watching playful chimpanzees swing from branch to branch before you. This community of chimps is habituated so used to human presence, but there was one mangabey that didn’t seem to appreciate having their morning meal disturbed by us, displaying their displeasure by flinging the weighty fruit shells of the African crabwood tree in our direction.

The chimp trek marked the end of my time in Nyungwe, but I hope to return soon for more adventures. The park’s vast network of trails allows for guided multi-day hikes with accommodation in wooden huts along the route. This seems an ideal next step in embracing the freedom of this wild, magical work. I’ll also be having a second ride on that zipline.

Soon, the trail grows slick with water spray, and there it is: a torrent of crystal-clear water bursting from rocks 20 metres above us”

Mark’s travel and Nyungwe tour itinerary was curated by Shalom Safaris Rwanda, a family-run tour company that specialises in creating we specialize in creating personalised tours across the country and East Africa. For more details on their tours and destinations, visit https://shalomsafarisrwanda.com/

To book a full-board stay at Munazi Lodge, visit http://visitnyungwe.org/munazi-lodge or email munazi.lodge@africanparks.org or edwardb@africanparks.org