OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO

“The Day of Heaven and Hell”

“The Day of Heaven and Hell”

Guillaume Houzé

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel p. 5-7

OPERA I

“House party” p. 9

OPERA Ⅱ p. 17

INTRODUCTION

Elsa Coustou p. 28

OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO

“The Day of Heaven and Hell”

ACTE I

“Drowning” p. 39

UNE CHAMBRE POUR TRIPER Kemi Adeyemi p. 40

ACTE Ⅱ “Irradiate” p. 39

UN ANIMAL NOCTURNE Charlie Fox p. 84

BIOGRAPHIES p. 154

LISTE DES ŒUVRES p. 156

PREAMBLE

FOREWORDS

Guillaume Houzé

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel p. 5‒7

OPERA I

“House party” p. 9

OPERA Ⅱ p. 17

INTRODUCTION

Elsa Coustou p. 28

OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO

“The Day of Heaven and Hell”

ACT I “Drowning” p. 39

A ROOM TO FREAK (OUT) IN Kemi Adeyemi p. 40

ACT Ⅱ “Irradiate” p. 39

A NOCTURNAL ANIMAL Charlie Fox p. 84

BIOGRAPHIES p. 154

LIST OF WORKS p. 156

« Nous

Orlando, Virginia Woolf

Éloge de l’ombre, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

, Virginia Woolf

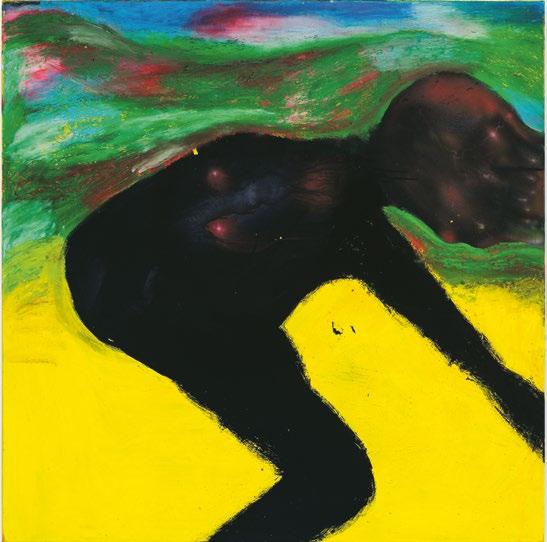

L’œuvre de Pol Taburet se loge dans les territoires de la nuit, de l’espace domestique, de la spiritualité ou encore de l’intériorité, des lieux de l’intime, dissimulés, imperceptibles ou inaccessibles. L’artiste y décèle des images d’une grande puissance où s’expriment craintes, fantasmes, rêves, désirs et pulsions, entre le plaisir et la colère d’être au monde. Son travail accorde ainsi une importance primordiale à nos imaginaires, à la manière dont ils fabriquent l’expérience, tangible ou hallucinée, que nous faisons de l’existence. Finalement, Pol Taburet célèbre les zones d’ombre, les territoires plus difficiles à raconter, plus complexes à décrire, plus délicats à partager, propres à l’aventure humaine et à sa relation à l’invisible. On retrouve dans sa peinture les gestes et les obsessions pour le monstrueux d’un Bacon ou d’un Goya, qui rencontrent les mondes magiques du jeu vidéo ou du night-club. Ses sculptures, présentées pour la première fois, poursuivent son obsession d’un intérieur domestique hanté par une forme d’absurdité, que les artistes Robert Gober ou Dorothea Tanning ont aussi pu explorer avant lui. C’est un honneur de présenter les œuvres de Pol Taburet pour sa première exposition monographique dans une institution à la Fondation Lafayette Anticipations, que les équipes et sa commissaire Elsa Coustou ont pu accompagner. Tous mes remerciements vont à Pol Taburet pour sa confiance, aux prêteurs, aux auteurs et autrices de cet ouvrage, à ses galeries, ainsi qu’à toutes celles et ceux qui ont contribué et contribueront à faire résonner l’œuvre de ce regard hors du commun. Pol Taburet’s work is embedded in the territories of the night, of domestic space, of spirituality, or even of interiority – places of intimacy which are hidden, imperceptible, or inaccessible. The artist reveals images of great power through which fears, fantasies, dreams, desires, and impulses are expressed, somewhere between the pleasure and the anger of being in the world. His work thus gives primacy to our imaginations, to the way in which they produce the experience, whether tangible or hallucinated, that we have of existence. Finally, Pol Taburet celebrates the grey areas, the territories that are more difficult to recount, more complex to describe, more delicate to share, specific to the human experience and its relationship to the invisible. In his paintings, the gestures and the obsessions for the monstrous of a Bacon or a Goya meet the magical worlds of the video game or the nightclub. Exhibited for the first time, his sculptures extend his obsession with a domestic interior haunted by a form of absurdity, which the artists Robert Gober and Dorothea Tanning explored before him. It is an honour to present the works of Pol Taburet for his first solo exhibition in an institution at the Fondation Lafayette Anticipations, put together by our team and the curator Elsa Coustou. I would like to thank Pol Taburet for his trust, the lenders, the authors of this book, his galleries, and all those who have contributed and will contribute to making the work of this extraordinary artist resonate.

“The unseen for us does not exist.” In Praise of Shadows, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

« La vie est un rêve, c’est le réveil qui nous tue. »

tenons pour inexistant ce qui ne se voit point. »

“Life is a dream. ‘Tis waking that kills us.” Orlando

Quels souvenirs, quels récits, quels rêves participent à la construction de notre être ? Quelles sont les forces qui nous meuvent et celles qui nous accompagnent dans notre passage sur terre ? Dans son exposition OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell”, Pol Taburet nous fait entrer dans l’intimité que ces questions soulèvent et nous invite à un voyage vers les profondeurs humaines. Ce sont nos peurs, nos fantasmes, nos liens les plus étroits avec les personnes et les choses de notre quotidien que nous voyons exposés, incarnés par des personnages et mis en scène. Dans la continuité des deux expositions précédentes OPERA I (2020) et OPERA Ⅱ: “House Party” (2021), OPERA Ⅲ interroge la manière dont les mythes et les croyances viennent nourrir notre compréhension du monde, la place des fantasmes et des pulsions dans la relation à l’autre, et par là même, les dynamiques de pouvoir entre les êtres. Les trois OPERA de Pol Taburet sont des œuvres de l’intime : elles pénètrent les corps comme des rayons X pour nous révéler les émotions qui les animent (OPERA I), les intérieurs domestiques protecteurs des passions qui se jouent dans le privé (OPERA Ⅱ) ou encore le monde psychique (OPERA Ⅲ).

de la mère, l’accouplement et la création, la mort et la question de la vie après la mort.

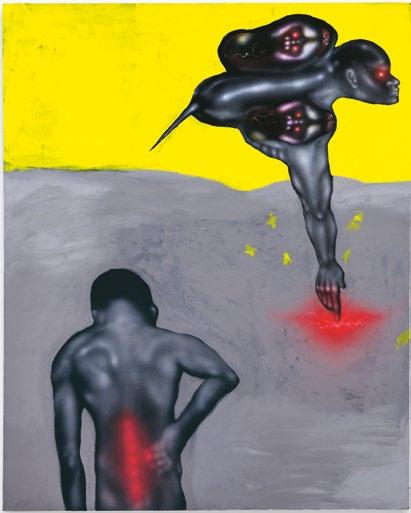

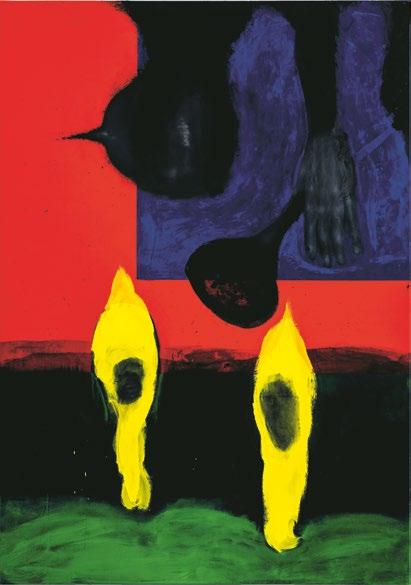

Au fil de l’exposition se dessine le portrait d’un être à travers un récit qui peut être lu comme une autofiction, tout à la fois le portrait de l’artiste, d’un personnage fictif et le nôtre. Un récit qui décrit l’expérience du corps et la violence – réelle ou potentielle – qu’engendre la confrontation de notre monde intérieur, de ses pulsions, ses besoins, ses traumas, avec le monde extérieur, de l’autre. Deux actes divisent l’exposition : le premier est tourné vers ce monde de l’intérieur, de l’obscur, lieu de l’inconscient, des pulsions et de la jouissance, celui qui va de la naissance à l’adolescence ; le second est orienté vers le monde de l’extérieur, de la lumière, de la pleine conscience de l’âge adulte.

Plusieurs tableaux d’OPERA Ⅱ sont inclus dans OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell”, créant ainsi de nouvelles narrations entre les œuvres existantes et celles produites pour l’exposition. Pour la première fois dans sa carrière, Pol Taburet a créé un groupe de sculptures pensées comme une extension de sa pratique de la peinture. Celles-ci forment la colonne vertébrale de l’exposition et la structurent en épisodes qui illustrent les grands passages marquant l’avancée dans la vie et dans le monde d’un être : ce qui nous est transmis par nos ancêtres, le séjour dans le ventre

autobiographical fiction – at once the portrait of the artist, of a fictional character, and of ourselves. A story that describes the experience of the body and the violence – whether real or potential – that is generated by the confrontation of our inner world and its impulses, needs, and traumas, with the outer world, with the other. The exhibition is divided into two acts: the first is turned towards this world of the interior, of darkness, the place of the unconscious, of impulses and pleasure, the one that extends from birth to adolescence; the second is oriented towards the world of the exterior, of light, of the full awareness of adulthood.

Le récit que nous propose Pol Taburet s’appuie sur de nombreux mythes dont la fonction première est de rendre compte des origines de l’humain et de donner un sens au monde qui l’entoure. La transmission orale des récits fondateurs est fondamentale, comme le montre Sunset Ⅱ (2021, p. 38), tableau d’une bouche grande ouverte placé au seuil de l’exposition. Les pointes lumineuses qui font briller les dents, en demi-cercle, rappellent la couronne d’épines du Christ, symbolisant ainsi la violence et la souffrance corporelles. Cette bouche évoque aussi le cri du nouveau-né et le souffle vital. Elle est l’organe qui relie l’extérieur et l’intérieur (par l’ingestion ou le vomi), et qui, dans certaines croyances, conduit à l’âme. Dans la mythologie grecque, l’âme des défunts est gardée par le chien Cerbère, mythe que Pol Taburet revisite dans la première salle de l’exposition pour interroger la manière dont l’âme de nos ancêtres continue de vivre chez leur descendance. Dans un intérieur domestique baigné d’une couleur jaune, les cinq What are the memories, the stories, the dreams that contribute to the construction of our being? What are those forces that move us and those that accompany us through our time on earth? In his exhibition OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell”, Pol Taburet takes us into the private sphere that these questions relate to and invites us on a journey into the depths of humanity. Our fears, our fantasies, our closest connections with the people and objects of our daily lives are exposed, embodied by characters, and staged. Following on from the two previous exhibitions OPERA I (2020) and OPERA Ⅱ: “House Party” (2021), OPERA Ⅲ questions the way in which myths and beliefs shape our understanding of the world, the place of fantasies and impulses in our relationships, and by the same token, the power dynamics between beings. Pol Taburet’s three OPERAs are works on the inner world. They penetrate bodies like X-rays to reveal the emotions that animate them (OPERA I), the domestic interiors that protect the passions that are played out in private (OPERA Ⅱ), or the psychological world (OPERA Ⅲ).

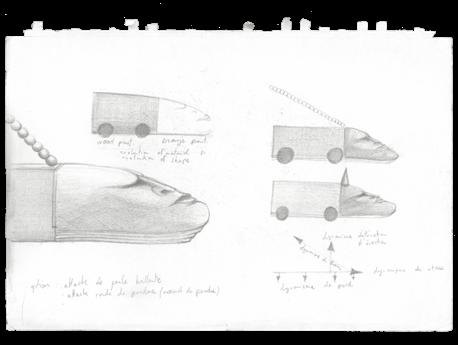

Several paintings drawn from OPERA Ⅱ are included in OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell”, thereby creating new narratives between the existing works and those produced for the exhibition. For the first time in his career, Pol Taburet has created a group of sculptures as an extension of his painting practice. These form the spine of the exhibition and structure it into episodes that illustrate the great passages that mark a being’s progress through life and through the world: that which is passed down to us by our ancestors, the time in the womb, mating and creation, death and the question of life after death. Throughout the exhibition, the portrait of a being is drawn through a narrative that can be read as

The narrative created by Pol Taburet is based on many myths whose primary function is to give an account of the origins of the human being and to give meaning to the surrounding world. The oral transmission of foundational stories is fundamental, as shown by Sunset Ⅱ (2021, p. 38), a painting of a wide-open mouth placed at the entrance to the exhibition. The luminous spikes that make the teeth glow, positioned in a semi-circle, recall Christ’s crown of thorns, thus symbolising bodily violence and suffering. This mouth also evokes the cry of a newborn and the breath of life. It is the organ that connects the outside and the inside (through ingestion or vomiting), and which, in some beliefs, leads to the soul. In Greek mythology, the souls of the deceased are guarded by the dog Cerberus, a myth that Pol Taburet revisits in the first room of the exhibition to question the way in which the souls of our ancestors continue to live on in their descendants.

In a domestic interior bathed in yellow, the five black sculptures Soul Trains (2023, p. 49) are composed of a bronze head, sculpted from the artist’s – deformed – face

sculptures noires Soul Trains (2023, p. 49) sont composées d’une tête en bronze, sculptée d’après le visage – déformé – de l’artiste, qui est accolée à un wagon de petit train pour enfant en bois. Le titre de cette œuvre rend hommage à l’influente émission de télévision étasunienne du début des années 1970, la première à accueillir des artistes africain·e·s-américain·e·s. Il inscrit ainsi les Soul Trains dans l’histoire décoloniale et soulève la question de l’héritage des traumatismes issus de la violence raciale systémique.

Peut-être ces sculptures veillent-elles, comme Cerbère, à ce que les âmes des défunts ne s’échappent de leur royaume, protégeant ainsi les vivants des traumatismes des morts ?

Les têtes de ces êtres fusionnent avec le petit wagon sur roues, montrant des corps engloutis par l’industrialisation construite sur l’esclavage, le déplacement et le déracinement. Toutefois, comme leur forme rappelle celle d’un obus, elle en fait des objets dangereux et pénétrants constitués d’une matière extrêmement robuste qui rend par là même ces êtres tout aussi résistants.

contraste des matières dans les installations. Au cœur du premier acte, Belly (2023, p. 63), une fontaine en bronze rouillé présentée dans une salle d’un bleu profond, reprend l’iconographie de l’Aphrodite sortant des eaux dans une forme épurée et circulaire. Une pointe allongée et tranchante forme sa tête ; sa poitrine et ses hanches sont figurées par des protubérances tout en rondeurs ; ses jambes sont posées sur une soucoupe, telle un coquillage flottant sur l’eau, écho lointain à La Naissance de Vénus (1485) de Sandro Botticelli. Pourtant, comme la sculpture monumentale Maman (1999) de Louise Bourgeois, Belly est à la fois protectrice et menaçante : le ventre peut être tout autant celui qui porte l’enfant que celui qui engloutit. La fontaine, à l’origine nourricière, est ici asséchée, évoquant la mort prochaine plutôt que l’immortalité.

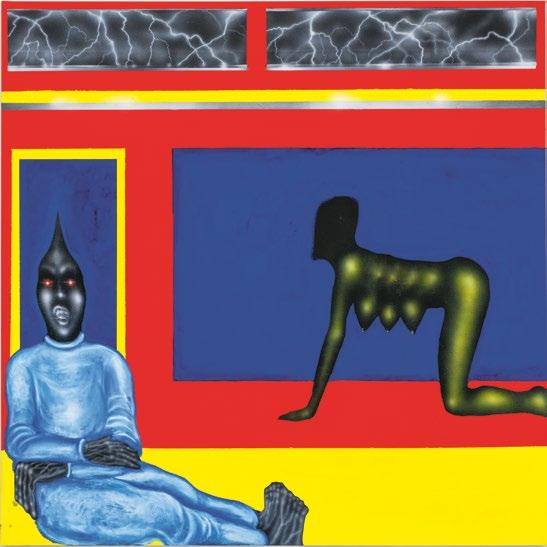

La relation à l’autre est à la fois source de plaisir sensuel et de danger. Dans la peinture Götterspeise (2021, p. 43), la figure mythologique de la louve nourricière est elle aussi détournée dans une relation cannibale, ou du moins qui menace de l’être, avec le personnage représenté à ses côtés. La menace d’engloutissement, donc de mort, est présente dans le couple et les rapports amoureux, comme le montrent les tableaux Jumping out the womb like my daddy is the devil (2022, p. 80-81) où la mort accompagne l’imminente mise au monde d’un être, Parade (2022, p. 101) qui s’inspire du mythe d’Orphée et Eurydice et de leurs retrouvailles joyeuses au destin tragique, ou encore A Couple, (2021, p. 51) which is attached to a wooden toy train carriage. The title of this work pays homage to the influential American television show of the early 1970s, the first to programme Black artists. In this way, Taburet situates Soul Trains in decolonial history and raises the question of the legacy of trauma from systemic racial violence. Perhaps these sculptures, like Cerberus, ensure that the souls of the dead do not escape from their realm, protecting the living from the trauma of the dead? The heads of these beings merge with the small carriage on wheels, showing bodies engulfed by industrialisation built on slavery, displacement, and uprooting. However, their shape reminiscent of an artillery shell transforms them into dangerous and penetrating objects crafted from an extremely robust material that thereby makes these beings just as resistant.

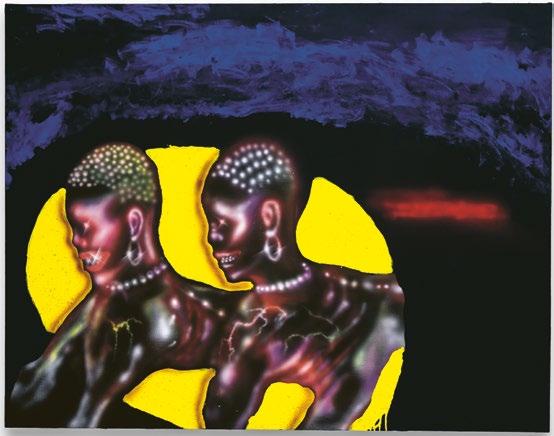

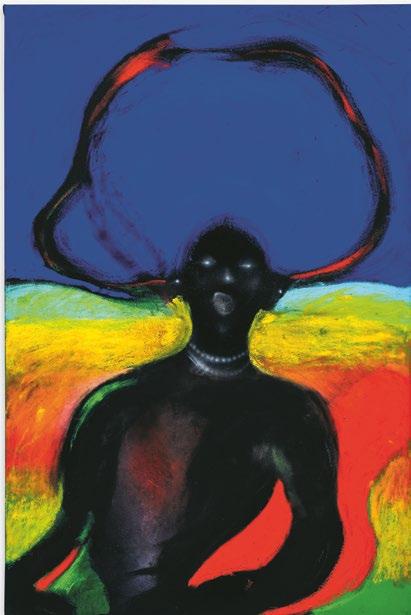

Cette ambivalence imprègne les œuvres de l’exposition et caractérise les dynamiques de pouvoir qui y sont exposées. Elle se traduit par l’utilisation de la couleur et des contrastes, notamment par la juxtaposition dans la peinture de figures gris-noir sur des aplats de couleur vive ou par la délimitation très nette, dans la composition entre les personnages et les décors, de zones qui cadrent le sujet et accentuent leur opposition, ou bien le

This ambivalence permeates the works in the exhibition and characterises the power dynamics on display. It is reflected in the use of colour and contrast, notably in the painting’s juxtaposition of grey and black figures on bright blocks of colour, or, through the composition between figures and their surroundings, of a sharp delineation of zones that frame the subject and accentuate their opposition, or in the contrast of materials in the installations. At the centre of the first act, Belly (2023, p. 63), a rusty bronze fountain presented in a deep blue room, takes up the iconography of Aphrodite emerging from the waters in a refined, circular form. Her head is formed by

an elongated, sharp point; her breasts and hips are represented by rounded protuberances; her legs rest on a saucer like a shell floating on the water, a distant echo of Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1485). Yet, like Louise Bourgeois’s monumental sculpture Maman (1999), Belly is at once protective and threatening: it can both carry the child and swallow it up. The fountain, originally nourishing, is here dried up, evoking imminent death rather than immortality. The relationship with the other is both a source of sensual pleasure and of danger. In the painting Götterspeise (2021, p. 43), the mythological figure of the nurturing shewolf is also distorted into a cannibalistic relationship, or at least one that threatens to be so, with the figure depicted beside her. The threat of being swallowed up, and therefore of death, is present in the couple and in intimate relationships, as shown in the paintings Jumping out the womb like my daddy is the devil (2022, p. 80–81), where death accompanies the imminent birth of a being, Parade (2022, p. 101), which is inspired by the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice and their joyful reunion with a tragic fate, or A Couple (2021, p. 51), and its couple that are “devouring” each other with their eyes, mouths wide open. In the installation Ô... Trees (2023, p. 77), the oblong sculptures, like shells, form a small forest in a green space. Their shape is inspired by the cypress tree, a symbol of immortality often found in cemeteries in Mediterranean countries, and by Constantin Brancusi’s Bird in Space (1941), a sculpture of a mythical

avec ce couple qui se « dévore » des yeux, bouche grande ouverte. Dans l’installation Ô… Trees (2023, p. 77), les sculptures oblongues, telles des obus, forment une petite forêt dans un espace de couleur verte. Leur forme est inspirée du cyprès, symbole d’immortalité souvent présent dans les cimetières des pays méditerranéens, et de L’Oiseau dans l’espace (1941) de Constantin Brancusi, sculpture d’une figure fabuleuse et d’un corps animal. Par cet hommage et ses références à l’histoire de l’art, Pol Taburet interroge l’acte d’ingestion intellectuelle et artistique, forme de filiation et de relation au monde. Flanquées du visage d’une muse qui paraît nous regarder et regarder au loin, à travers nous, vers le passé ou vers le futur, ces sculptures totémiques sont à la fois protectrices et menaçantes. La forêt représente un lieu de fantasmes, de rencontres amoureuses et d’inversement des rôles comme chez Shakespeare, ou encore le lieu du subconscient comme chez les surréalistes. Teintées d’érotisme, les sculptures ressemblent désormais aussi à d’imposants godemichés vivants.

figure and animal body. Through this homage and its references to the history of art, Pol Taburet questions the act of intellectual and artistic ingestion, a form of filiation and relationship to the world. Endowed with the face of a muse who seems to be both looking at us and into the distance, through us, towards the past or the future, these totemic sculptures are both protective and threatening. The forest represents a place of fantasies, of the amorous encounters and role reversal of Shakespeare, or the place of the subconscious as for the surrealists. Tinged with eroticism, the sculptures now also resemble towering living dildos.

Je suis allé au jardin de l’amour Et j’y ai vu ce que je n’avais jamais vu : Une chapelle était construite au milieu, Là où je jouais autrefois sur l’herbe.

Les portes de la chapelle étaient fermées Et « tu ne dois pas » était écrit sur la porte. Alors, je me tournai vers le jardin de l’amour D’où naissaient tant de jolies fleurs.

Et je vis qu’il était envahi de sépultures Et de tombeaux là où il devrait y avoir des fleurs. Et que des prêtres en soutane noire y faisaient leur ronde, Enchaînant avec des ronces mes joies et mes désirs.

William Blake, « Le jardin de l’amour » Chants d’Innocence et d’Expérience, (traduction de Marie-Louise et Philippe Soupault), Paris, Éditions des Belles Lettres, 2021

I went to the Garden of Love, And saw what I never had seen: A Chapel was built in the midst, Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut, And ‘Thou shalt not’ writ over the door; So I turn'd to the Garden of Love, That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves, And tomb-stones where flowers should be: And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds, And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

William Blake, “The Garden of Love” in Songs of Innocence and of Experience (London: privately printed), 1794 and 1826.

Au cœur du deuxième acte, une haute boîte blanche érigée sur un sol vert gazon, telle un temple, renferme une table de salle à manger couverte d’une épaisse nappe blanche sous laquelle surgissent les deux larges pattes d’un sphinx, toutes griffes dehors. À la fois très réalistes et cartoonesques, seules les pattes en silicone beige laiteux du chat sont visibles, comme si l’animal avait fusionné avec la table, qui en devient monstrueuse. Elles semblent prêtes à se jeter sur leur proie – en l’occurrence nous, le·la visiteur·euse. La sculpture My Dear (2023, p. 95) incarne la menace de la prédation et de la mise à mort. La table de salle à manger autour de laquelle on prend ses repas en famille devient-elle ici un autel sacrificiel ? Marque-t-il un passage, celui de la vie à la mort, de l’enfance à l’âge adulte ? Ce temple dans lequel on ne peut pas entrer, est-il la maison d’un être défunt réincarné ? Les anges et les esprits qui peuplent l’exposition l’animent d’une présence surnaturelle liée à l’extérieur. Ils s’immiscent dans l’intériorité domestique et psychique des personnages que l’on rencontre au fil de l’exposition. Ce sont des têtes sans corps sur un fond de couleur unie, comme dans Heads et Head I (2021, p. 99 et p. 125), Jumping out the womb like my daddy is the devil et My Eden’s Pool (2022, p. 111), ou bien ces êtres dont une partie du corps a fusionné avec un objet. Telle une forêt d’objets décimés, Fork Melody (2023, p. 121) est composée d’un tas de clous géants tombés au sol, abîmés par le temps et l’usage. Le titre évoque les

At the heart of the second act, a tall white box erected on a grass-green floor, like a temple, contains a dining room table covered with a thick white tablecloth under which the two large paws of a sphinx emerge, claws bared. At once realistic and cartoonish, only the cat’s milky beige silicone paws are visible, as if the animal had merged with the table, which thereby becomes monstrous. They seem ready to pounce on their prey – in this case us, the visitor.

The sculpture My Dear (2023, p. 95) embodies the threat of predation and killing. Has the dining room table around which we eat our family meals become a sacrificial altar? Does it mark a passage, from life to death, from childhood to adulthood? Is this temple, into which one cannot enter, home to a deceased being that has been reincarnated?

The angels and spirits that populate the exhibition animate it with a supernatural presence linked to the exterior. They intrude into the domestic and psychological interiority of the characters we encounter throughout the exhibition. They are heads without bodies on a solidcoloured background, as in Heads and Head I (2021, p. 99 and p. 125), Jumping out the womb like my daddy is the devil and My Eden’s Pool (2022, p. 111), or those beings whose body parts have merged with an object.

Like a forest of decimated objects, Fork Melody (2023, p. 121) is composed of a pile of giant nails that have fallen to the ground, damaged by time and use. The title evokes the threatening and disturbing sounds of a fork penetrating

sonorités menaçantes et dérangeantes d’une fourchette qui pénètre dans la chair des aliments : les clous sont-ils pris dans le piège d’un·e prédateur·rice, ou au contraire sont-ils protégés par cette mélodie ? Rouillés et tordus, les clous ont été retirés si violemment de la surface à laquelle ils étaient intimement fixés qu’ils en portent les blessures sur leur corps plié. L’œuvre invite à réexaminer les traumatismes et les regrets que nous portons en nous et laissons dans un recoin de la psyché. Il y a toutefois une forme de résistance dans ces clous qui, malgré leur aspect fatigué, gardent une pointe affûtée et tranchante sur un corps au matériau extrêmement robuste. Le corps anatomique se transforme ainsi en corps politique. Dans les dynamiques de pouvoir qu’OPERA Ⅲ met en scène se dessine un corps collectif, résistant. Les sculptures de groupe Soul Trains, Ô… Trees et Fork Melody évoquent la force de révolte des corps instrumentalisés, la riposte armée, la puissance du bronze et de l’acier. La lutte est aussi celle du dieu de la guerre dans Mars (2021, p. 72-73), représenté avec une tête à pointe menaçante. Symbole de violence et de résistance, ce personnage à tête pointue présent dans Götterspeise, Belly, Our Turf Heads et A Couple revient souvent, comme une armée disséminée parmi les œuvres.

Cette force est aussi celle de la destinée, puissance que l’humain ne contrôle pas et qui est mue par certains êtres : les anges, les esprits, les déités, ou encore certains événements. OPERA Ⅲ peut être lue comme une tragédie, avec la

the flesh of meat: have the nails fallen into a predator’s trap, or are they rather protected by this melody? Rusty and bent, the nails have been so violently removed from the surface to which they were intimately attached that they bear the wounds on their bent bodies. The work invites us to reexamine the traumas and regrets we carry within us and leave in a corner of our psyche. There is, however, a form of resistance in these nails which, despite their worn appearance, retain a sharp, cutting edge on a body of extremely robust material. The anatomical body is thus transformed into a political body. In the power dynamics that OPERA Ⅲ stages, a collective, resistant body emerges.

The group sculptures Soul Trains Ô… Trees , and Fork Melody evoke the force of revolt of instrumentalised bodies, the armed response, the power of bronze and steel. The struggle is also that of the god of war in Mars (2021, p. 72–73), represented with a threatening spiked head.

A symbol of violence and resistance, this pointed-headed figure, present in Götterspeise, Belly Our Turf, Heads, and A Couple , recurs frequently, like an army scattered throughout the works.

This force is also that of destiny, a power that the human being does not control and that is moved by certain beings – angels, spirits, deities – or even certain events.

OPERA Ⅲ can be read as a tragedy, with death as its horizon. Objects are deprived of their primary function: the little wooden trains are too big for a child to play with and

mort pour horizon. Les objets sont destitués de leur fonction première : les petits trains en bois sont trop grands pour qu’un·e enfant joue avec eux et bien trop lourds pour rouler ; la fontaine, habituellement source de vie, est ici asséchée ; la table de la salle à manger, plutôt que d’accueillir des convives, est prête à les dévorer ; les clous, tordus, sont inutilisables. Les unions amoureuses et érotiques sont impossibles : les deux figures du couple de A Couple sont chacune figées dans un socle qui les tient à distance ; celles de Götterspeise se trouvent dans deux espaces picturaux distincts qui ne communiquent par aucune entrée, rendant leur rencontre impossible ; le couple de Parade, comme Orphée et Eurydice qui se retrouvent aux Enfers quelques instants seulement avant de se perdre à jamais, semble déjà sur le point de se séparer avant que chacun·e retourne dans son monde respectif.

Pol Taburet invente une nouvelle mythologie qui puise dans les récits fondateurs et dans l’histoire de l’art. L’image de la bouche et la métaphore filée de l’ingestion rendent cette expérience à la fois effrayante et joyeuse : elle s’apparente aussi bien à la dévoration qu’au plaisir sensuel et érotique. Les œuvres de l’exposition se nourrissent de références artistiques, notamment de celles qui évoquent les fantasmes, entre rêves et peurs : les visions prophétiques et fantastiques de William Blake, les apparitions fantomatiques et féériques de Johann Heinrich Füssli, les créatures dévorantes de Francisco de Goya et celles de Francis

far too heavy to travel; the fountain, usually a source of life, is here dried up; the dining room table, rather than welcoming guests, is ready to devour them; the twisted nails are unusable. Romantic and erotic unions are impossible: the two figures in A Couple are each rooted to a pedestal that keeps them at a distance; those in Götterspeise are in two distinct pictorial spaces that do not communicate with each other through any entrance, making their meeting impossible; the couple in Parade, like Orpheus and Eurydice who meet in the Underworld for a few moments before losing each other forever, seem to be on the verge of separating before they each return to their respective worlds.

Pol Taburet invents a new mythology that draws on foundational stories and the history of art. The image of the mouth and the extended metaphor of ingestion make this experience both frightening and joyful: it relates as much to devouring as to sensual and erotic pleasure. The works in the exhibition draw on artistic references, particularly those that evoke fantasies, between dream and fear: the prophetic and fantastical visions of William Blake, the ghostly and fairy-like apparitions of Johann Heinrich Füssli, Francisco de Goya’s devouring creatures and those of Francis Bacon, the surrealist scenes of Salvador Dalí and the frightening ones of Dorothea Tanning, the body and sexuality of the works of Louise Bourgeois, and the dark and hallucinatory reality of David Lynch. The exhibition pulls us into a world that is both familiar and fantastical, populated

Bacon, les scènes surréalistes de Salvador Dali et celles, effrayantes, de Dorothea Tanning, le corps et la sexualité des œuvres de Louise Bourgeois, la réalité sombre et hallucinée de David Lynch. L’exposition nous plonge dans un monde à la fois familier et fantastique, peuplé d’esprits et d’objets animés, de personnages dédoublés qui font naître un sentiment d’inquiétante étrangeté 1. Par cette ambivalence et ce dialogue avec les œuvres et récits d’un passé récent ou lointain, Pol Taburet nous invite à repenser notre rapport au monde et convoque nos propres récits, ceux de nos expériences vécues et imaginaires. ✺

by spirits and animated objects, and by recurring characters that bring about a feeling of the uncanny. Through this ambivalence and dialogue with works and stories from the recent or distant past, Pol Taburet invites us to rethink our relationship with the world and summons our own stories, those of our lived and imaginary experiences. ✺

1 « L’inquiétante étrangeté », traduit par Marie Bonaparte et E. Marty, in Sigmund Freud, Essais de psychanalyse appliquée, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, 1933, p. 163-211

1 “The ‘Uncanny’”, in Sigmund Freud, Collected Papers, trans. Alix Strachey, vol. 4 (London: Hogarth, 1925), 368–407.

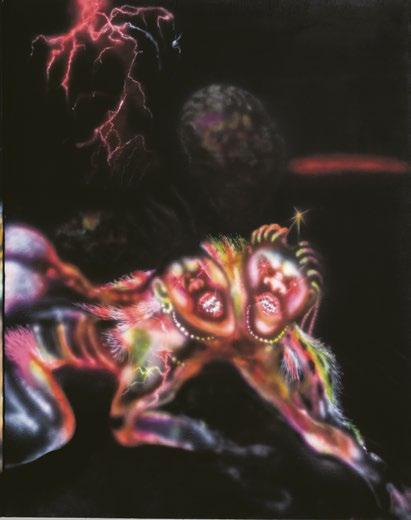

Si vous êtes déjà rentré·e chez vous après une nuit de clubbing, vous connaissez le cycle d’émotions par lequel on passe quand, après tant d’euphories, la jubilation du dancefloor cède la place à la dure réalité de la descente. C’est un véritable moment de vulnérabilité où l’on a particulièrement conscience de son corps. Les vestiges de la fête se matérialisent dans la sueur qui sèche lentement sur votre peau en continuant de se mélanger à celle des autres danseur·euse·s. Vous sentez le poids de vos vêtements légèrement défaits et l’impression de danser serré·e contre quelqu’un persiste. Pendant plusieurs minutes, plusieurs heures, voire plusieurs jours, la musique et les cris bourdonnent encore dans vos oreilles. Vous pouvez encore sentir la chaleur, la transpiration, le parfum. Vous avez aussi moins conscience de ce qui vous entoure quand vous sortez du club et retournez à des considérations plus prosaïques. Ce décalage avec les attentes sensorielles de la vie post-club peut être assez dangereux quand on a tout donné à l’émotion et qu’on n’est pas prêt·e à réfléchir à la suite. C’est là que Pol Taburet intervient. La collection de tableaux et de sculptures qui constitue OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell” construit des structures fantasmagoriques où le corps physique, le monde matériel et les excès de nos vies psychiques semblent devenir plus poreux. L’ensemble donne à voir la frontière incertaine de ce qui pourrait être un trip, un rêve, un cauchemar ou une généreuse réunion avec le monde des esprits. Nous rencontrons des humanoïdes auxquels il manque différentes parties du corps, quand celles-ci ne sont pas allongées ou multipliées ; nous découvrons des personnages aux attributs humains et animaux, d’autres qui sont composés de matière organique et inorganique, brouillant la limite entre personne et objet. Il y a des

métamorphes, des fantômes, des anges et des démons. La viscéralité des sujets charnus, qui pourraient aussi être des objets ou des esprits ne vivant que dans notre imagination (ou par-delà notre conscience), a largement de quoi perturber et la palette de couleurs parfois sombre de Taburet peut d’autant plus vous nouer l’estomac. Pourtant, le grotesque est avant tout une convention esthétique que l’artiste utilise pour donner du sens à une autre proximité avec l’incertitude, à laquelle on ferait autrement face avec les drogues (autorisées ou pas), le recul et la distraction de la médiation (écrans, etc.), et/ou en nous tournant vers des objets qui permettent d’accueillir cette incertitude plus près de notre être (accessoires érotiques, idoles). Les étranges tableaux de Taburet nous offrent l’occasion de nous réorienter en fonction des possibilités de l’incertitude – et, plus spécifiquement, en fonction des peurs du genre, du sexe et du spectral qui animent une grande partie de son œuvre – et d’habiter des psychés sensorielles de façon inédite.

A ROOM TO FREAK (OUT) IN

À travers l’attention minutieuse qu’il accorde à des espaces comme les chambres à coucher, les clubs de striptease, les ascenseurs ou des appartements entiers, l’artiste structure les différentes formes de désorientation qui définissent, et pourraient autrement écraser et surdéterminer, l’expérience d’OPERA Ⅲ. Le tableau Götterspeise (2021, p. 43) fait référence au dessert gélatineux allemand qui doit son aspect répugnant à sa couleur fluo et à son tremblotement, mais qui n’en est pas moins recherché pour son goût sucré. Les personnages du tableau représentent ce réseau de dégoût et de désir tout en s’y débattant : un personnage féminin sans visage, doté de plusieurs paires de seins, marche à quatre pattes vers – et semble prêt à manger – une forme masculine assise dont If you’ve ever come home from a night of clubbing, you know the range of feelings you cycle through when the euphoria of the dance floor meets the harsh reality of coming down from multiple highs. This is a really vulnerable space where you feel most attuned to your body. The remnants of the party materialize in the slow-drying sweat that sits on your skin, where it continues to mingle with that of other dancers. You feel the weight of your slightly dishevelled clothing and the sensation of being gripped up with someone lingers. For the next minutes, hours, and even days your ears still ring from the music and shouting, and you continue to catch the whiff of heat and sweat and perfume. You also have a dulled awareness of your surroundings as you transition into the pedestrian reality beyond the club’s doors. This can be a quite dangerous moment of being at odds with the sensory expectations of post-club life, when you have given too much to the feeling of feeling and are now unprepared to think about what might come next. This is where Pol Taburet begins.

The collection of paintings and sculptures that make up OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell” build phantasmagoric structures where the physical body, the material world, and the excesses of our psychic lives feel most porous. The work gives into the uncertain boundary between what might be a trip, a dream, a nightmare, or a generous convening with the spirit realm. We encounter humanoids with variously missing, elongated, or multiplied body parts; there are figures with human and animal attributes, and those that are made up of organic and inorganic material, blurring the lines between person and object. There are shapeshifters, ghosts, angels, and devils. The viscerality of fleshy subjects that may also be objects

or spirits that live only in our imagination (or on the other side of our consciousness) can certainly be unsettling and Taburet’s sometimes grim colour palette may make your stomach sink even further. But the grotesque is above all an aesthetic convention the artist thinks with to make sense of a different proximity to uncertainty, which we might otherwise manage with drugs (legal and otherwise), through the distance and distraction of mediation (screens, etc.), and / or by turning ourselves towards objects through which to welcome that uncertainty close to our being (sex toys, idols). Taburet’s eerie tableaux provide the opportunity to reorient ourselves in relation to the possibilities of uncertainty – and, specifically, to the fears of gender, sex, and the spectral that animate much of his work – and to inhabit sense-psyches in new ways.

Through a careful attention to spaces such as bedrooms, strip clubs, elevators, and entire apartments, the artist gives structure to the various forms of disorientation that underscore and could otherwise overpower and overdetermine the experience of OPERA Ⅲ. The painting Götterspeise (2021, p. 43) references the gelatinous German dessert that appears repulsive with its neon coloration and the way it moves, but is nonetheless desired for its sweet softness. The figures in the painting represent and grapple with this network of disgust and desire: a faceless female figure with multiple breasts crawls toward – and seems poised to eat – a seated male form with arms crossed covering his genitals. His red eyes burn like the flash of lightning at the top of the frame. Their unnerving relation is set against the mundane surroundings of the red, blue, and yellow room – a similar room to that in Buried on a Sunday (2021, p. 23), both of which are perhaps located within the

les bras croisés recouvrent les parties génitales et dont les yeux rouges brillent comme les éclairs dans la partie supérieure du cadre. Cette relation perturbante est illustrée dans l’environnement banal d’une pièce rouge, bleue et jaune – une pièce qui ressemble à celle de Buried on a Sunday (2021, p. 23), toutes deux se trouvant peut-être dans le même immeuble que Fertilizer / Neg (2022, p. 96-97), où une forme féminine dépourvue de torse et de bras patauge dans une mare de sang devant une figure masculine décapitée qui monte la garde sans pouvoir bouger. La composition de ces œuvres, qu’on retrouve comme un écho à travers les tableaux de Taburet, évolue entre perspective linéaire et plate, produisant une impression de « proximité distante » entre les figures (im)matérielles représentées.

Parallèlement, de nombreuses compositions de Taburet incluent des points de sortie qui suggèrent le mouvement des personnages dans le cadre tout en montrant les allées et venues du fantasme dans nos propres psychés. Dans des œuvres telles Our Turf (2021, p. 70), Jumping out the womb like my daddy is the devil (2022, p. 80-81) et Buried on a Sunday, les portes et les fenêtres ouvrent un passage pour – et entre –les vivants et les morts. Certains tableaux représentent des espaces intimes comme la chambre ou le salon, tandis que d’autres sont situés dans des lieux publics impersonnels où l’on se retrouve seul·e au milieu des autres. C’est le cas de A Sacred Pit (2021, p. 152), où une bouche béante et remplie d’or s’ouvre en grand, qu’elle soit saisie par le plaisir, la

terreur ou simplement en train de crier. Ce tableau est un instantané de ce qu’on éprouve au milieu du dancefloor et de la nuit, quand on se sent soit piégé·e, soit soutenu·e par la masse des autres danseur·euse·s, en proie à l’extase de la drogue ou à ses coups violents. Cette hésitation est illustrée par les portes d’ascenseur qui encadrent la bouche, et capturée dans l’impression que l’image, la bouche et tout ce qui en sort passeront bientôt de cet état à un autre.

L’artiste façonne des architectures expérientielles tout aussi surréalistes dans des sculptures qui construisent des habitats en trois dimensions, où le fantasmagorique apparaît dans des espaces familiers et à la fois étranges. My Dear (2023, p. 95) matérialise les intersections entre l’objet et la forme charnue que Taburet dépeint dans ses tableaux tout en montrant le malaise qui imprègne sa pratique. La table est recouverte d’une épaisse nappe blanche sous laquelle émergent les griffes acérées d’une créature d’aspect félin. Comme un avertissement à ne pas trop s’approcher, ses pattes sont aussi menaçantes que les pieds pointus de la table. Dans cette œuvre, l’artiste fait se côtoyer l’animal et l’objet dans un environnement que nous pouvons vraisemblablement comprendre – une table autour de laquelle on pourrait se réunir pour manger –, mais la nature incomplète de cet animal, de surcroît étrange, entrave le possible réconfort qu’un objet ou une scène aussi ordinaire pourrait nous apporter.

Même si la figure grotesque ou l’objet métamorphe semble same building as Fertilizer / Neg (p. 96–97), where a female form without a torso or arms wades through a bloody pool as a decapitated male figure stands watch, unable to move. The composition of these works, which echoes throughout Taburet’s paintings, walks the line between linear and flat perspectives, producing an estranged closeness between the (im)material figures in question.

At the same time, many of Taburet’s compositions have such exit points that suggest movement for the figures within the frame while underscoring how the phantasm may come and go in our own psyches. In works like Our Turf (2021, p. 70), Jumping out the womb like my daddy is the devil (2022, p. 80–81), and Buried on a Sunday, doors and windows provide passage for and between the living and the dead. These paintings are sometimes staged in intimate spaces such as the bedroom or the living room whereas others are located in impersonal, public spaces where we find ourselves alone yet amongst others. This is the case in A Sacred Pit (2021, p. 152), where a yawning mouth opens wide, filled with gold, gripped by either pleasure, terror, or the sheer release of a shout. The painting is a snapshot of the feeling of being on the middle of the dance floor at the height of the night, where you can feel either trapped or held up by the crush of other dancers, in the grips of the ecstatic release of intoxication or of its crushing blows. This vacillation is captured by the elevator door that frames the mouth and the sense that the image, the

mouth, and the feeling of whatever escapes it, will soon pass into another state.

The artist fashions similarly surreal architectures of experience in sculptures that build three-dimensional habitats where the phantasmagoric can be encountered in familiar though somewhat surprising spaces. My Dear (2023, p. 95) materializes the intersections of the object and the fleshy form that Taburet depicts in his paintings, while also drawing out the dis-ease that suffuses his practice. The table is draped by a heavy white tablecloth beneath which the sharp claws of a cat-like being emerge. Its paws are as menacing as the sharp-tipped legs of the table itself, warning us to not get too close. In this work, the artist poses the animal near an object within an environment that we can seemingly wrap our minds around – a dinner table around which we might congregate – but the partial nature of the animal, and a strange one at that, disrupts any possible comfort we might take in such an ordinary object or scene. For all the ways the grotesque figure or shape-shifting object seem to take precedence in Taburet’s work and although the exhibition might require us to sit in the shock to our senses, OPERA Ⅲ is also deeply engaged with the discipline of art history. A Couple (2021, p. 51) riffs on Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930), translating the scepticism within the work into an electric connection between the two figures painted with Taburet’s signature pointed heads. His depiction of a dead figure in Sleep (2021, p. 44) converses

passer avant tout le reste dans l’œuvre de Taburet, et bien que l’exposition puisse provoquer un choc sensoriel, OPERA Ⅲ s’intéresse aussi à la discipline de l’histoire de l’art de manière approfondie. A Couple (2021, p. 51) revisite le tableau American Gothic (1930) de Grant Wood en traduisant le scepticisme présent dans cette œuvre sous la forme d’une connexion électrique entre deux personnages peints avec les têtes pointues caractéristiques de Taburet. Sa représentation d’un mort dans Sleep (2021, p. 44) dialogue avec l’intensité dramatique d’Edgar Degas et d’Andrea Mantegna tout en mettant en scène une alternative au controversé Open Casket (2016) de Dana Schutz et en nouant une conversation plus étroite avec la représentation du meurtre de Philando Castile par Henry Taylor, THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! (2017). Ces explorations de l’intimité, de l’aliénation et de la mort permettent à Taburet de rester fidèle à la gravité qui imprègne une grande partie de sa pratique, et pourtant, au moment nous arrivons à Sleep, le corpus d’œuvres semble presque réaliste dans la mesure où l’hallucinatoire est peut-être le seul domaine permettant de comprendre la quantité de violence physique, architecturale et psychologique qui conditionne la vie des Noir·e·s.

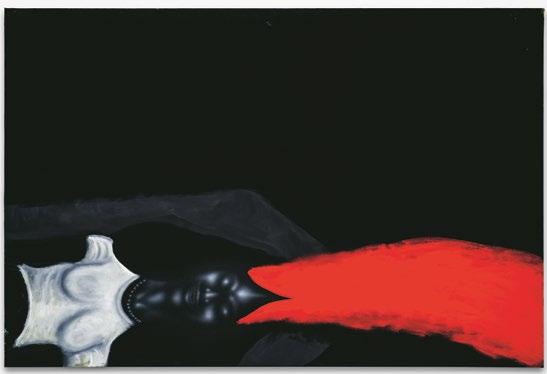

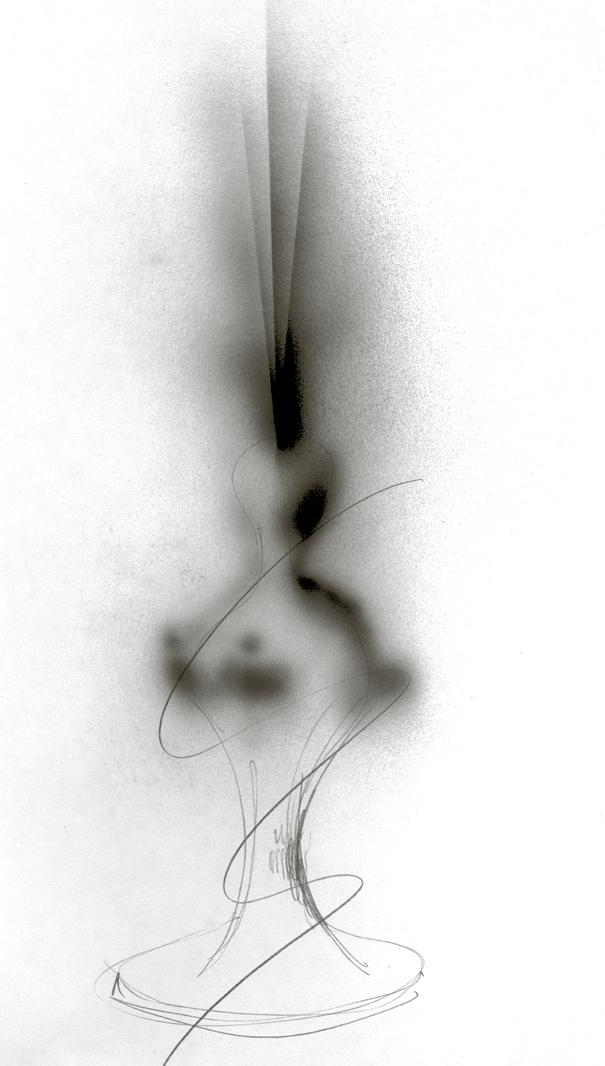

appliquant d’abord une couche de peinture acrylique noire sur la toile brute en lin marron – un refus total du blanc (et de la blancheur) comme prémisse et condition de la possibilité d’un tableau. Les œuvres peuvent ensuite mettre un certain temps à se matérialiser car Taburet passe des heures et des jours à imaginer ce qui pourrait émerger de tant de noirceur, avant de créer des formes d’abord abstraites au moyen de résine colorée avec des pigments et de peinture mélangée d’alcool à 95°, puis d’appliquer de la peinture acrylique à l’aérographe et, enfin, du pastel à l’huile. Le fait de partir d’un fond noir l’oblige à travailler autrement – dessiner les formes sur une telle profondeur exige une patience particulière et beaucoup de soin. Pourtant, à tout moment, il peut rapidement repeindre en noir une partie ou la totalité du tableau en cours pour recommencer à zéro.

Le processus matériel de Taburet établit une intimité avec les confins de notre psychisme, là où nous n’avons généralement pas envie d’aller, ou alors seulement sous l’emprise de la drogue. Pour l’artiste, ce processus débute toujours dans le noir et la noirceur. Il construit ses tableaux en

kind of patience and care – and yet, at any point, part or all of the painting-in-process can be quickly repainted black and Taburet can start over.

Ce processus est une astucieuse démonstration de la matérialité de la noirceur, dense et indéterminée, et un reflet de la méthode de l’artiste basée sur l’absorption. Chaque œuvre résulte de l’absorption de l’histoire de l’art telle que Taburet la détourne. Chaque œuvre résulte aussi de l’absorption réelle et imaginaire de drogues, de l’intégration des visions, sons, textures et mouvements de la piste de danse dans le psychisme. Surtout, OPERA Ⅲ montre également l’absorption de la culture noire américaine dans la vie et la pratique de Taburet. C’est peut-être le plus évident dans les sculptures anthropomorphisées de Soul Trains (2023, p. 49) – un titre inspiré de l’emblématique émission de télévision with the high drama of Edgar Degas and Andrea Mantegna while staging an alternative to Dana Schutz’s controversial Open Casket (2016), sitting in closer conversation with Henry Taylor’s depiction of the murder of Philando Castile, THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! (2017). Such examinations of intimacy, alienation, and death allow Taburet to stay true to the grimness found in much of his practice and yet, by the time we arrive at Sleep, the corpus of work feels practically realist in that the hallucinatory is maybe the only realm in which we can make sense of the sheer amount of physical, architectural, and psychological violence that conditions Black life.

Taburet’s material process establishes an intimacy with the furthest reaches of our psyches, those we don’t typically want to encounter, or only when under the influence. For the artist, this process always begins in blackness. His paintings are constructed by first applying a base layer of black acrylic paint over raw, brown linen canvas – refusing white(ness) altogether as the premise and condition of possibility for a painting. The paintings can then take quite a long time to materialize as Taburet takes hours and days to imagine what might come from such blackness, eventually giving shape to initially abstract forms by applying pigment-dyed resin and 95° alcohol-infused paint, acrylic airbrush paint, and lastly oil pastel. Starting out on a black background compels the artist to work differently – drawing form and shape from such depth requires a particular

The process is a shrewd demonstration of the materiality of blackness, dense and indeterminate, and a reflection of Taburet’s absorption-as-method. Each work is an effect of the absorption of art history, which Taburet twists on its head. Each work is also an effect of the real and imagined absorption of drugs and the incorporation of the sights, sounds, textures, and movements of the dancefloor into one’s psyche. But importantly, OPERA Ⅲ also demonstrates the absorption of Black American culture into Taburet’s life and practice. This is perhaps most visible in the anthropomorphised Soul Trains sculptures (2023, p. 49) – a title which riffs on the iconic Black American television show – that walk the line between children’s toy and Cerebrus-like guardian keeping the dead at bay. There is a particularly important genealogy in Taburet’s Black milieu, however: the Atlanta strip club culture that has been a major influence in Southern hip-hop which has, in turn, defined the landscape of global hip-hop for decades. The painting Parade (2022, p. 101) reflects how diverse diasporic Black spiritual and cultural practices are routinely enmeshed with Taburet’s obvious love for this strain of Black American cultural production. Here, the strip club transforms into mas as the ancestral figures, their bodies and faces warped by travelling the astral

afro-américaine – qui se situent à mi-chemin entre le jouet pour enfant et le gardien à la Cerbère tenant les morts à distance. La généalogie a néanmoins beaucoup d’importance dans l’environnement noir de Taburet : la culture des clubs de strip-tease d’Atlanta a exercé une influence majeure sur le rap du Sud des États-Unis, qui à son tour a défini le paysage du hip-hop mondial pendant des décennies. Le tableau Parade (2022, p. 101) montre que les diverses pratiques spirituelles et culturelles de la diaspora noire jouent systématiquement un rôle dans l’amour que Taburet porte à cette partie de la production culturelle noire américaine. Ici, le club de strip-tease se transforme en lieu de procession quand les figures ancestrales, dont le corps et le visage sont déformés par le voyage dans le plan astral, se réjouissent du culte que nous leur vouons, le tout sur la consistante rythmique trap que l’on peut presque entendre en arrière-plan. Ce culte se poursuit jusqu’à For Our Children (2022, p. 102-103), où l’on voit la moitié inférieure du corps de deux femmes en talons hauts glisser de haut en bas ou de bas en haut sur une barre verticale imaginaire. En dessous, on retrouve l’être chimérique récurrent dans l’œuvre de Taburet, un tapir humanoïde au long museau d’où jaillit la même électricité que celle qui s’enroule autour des jambes des strip-teaseuses. L’étrangeté des personnages est compensée par le choix de composition, où le rectangle jaune et le rectangle vert à l’arrière-plan confèrent paradoxalement à l’image un côté simple et accueillant : dans ce strip club, pas de tape-à-l’œil,

they can actually deceive us. In fact, Taburet has already ordered the chaos for us. By descending into the artist’s uncanny valleys, we are given the chance to take on the sensory labour of determining the porousness between reality and otherwise, heaven and hell, ghoul or loved one – and the time to reconsider and perhaps reconfigure the work we do to protect us from fear and uncertainty. Drop yourself into the zoo, invite them in; you’ll get your bearings if you get close enough, if you can stand the beat long enough, if you can look at the beast long enough. ✺

de glamour ni même de sexe – en revanche, il y a une porte derrière laquelle se réfugier si on se sent submergé·e. En effet, tout club se doit de posséder un endroit pour faire une pause – des toilettes, une backroom, un parking ou un recoin où passer un moment seul·e. Une fois que vous avez réinvesti la physicalité de votre corps et de votre esprit, vous pouvez retourner sur le dancefloor avec les autres corps, la drogue ou le martèlement rythmique que vous avez eu temporairement besoin de fuir. Le trip fantasmagorique d’OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell” nous fait vivre et revivre ce cycle où nous atteignons des sommets et vivons des moments de retour à nousmêmes dans un corps particulier à un instant particulier. L’exposition ne se contente pas de nous plonger dans un chaos de perceptions semblable à un zoo pour embrouiller nos sens et nous rappeler à quel point ils peuvent nous tromper. Taburet a déjà organisé le chaos pour nous. En descendant dans les inquiétantes vallées de l’artiste, nous avons la chance de pouvoir entreprendre le labeur sensoriel qui consiste à évaluer la porosité entre la réalité et le reste, le paradis et l’enfer, le démon et l’être aimé, ainsi que le temps de reconsidérer, voire de reconfigurer, le travail que nous faisons pour nous protéger de la peur et de l’incertitude. Enfoncez-vous dans le zoo et invitez-le à l’intérieur ; vous trouverez vos repères si vous vous approchez suffisamment, si vous pouvez tenir le rythme et regarder la bête assez longtemps. ✺ plane, celebrate our worship of them, all to the thick trap beat we can almost hear in the background. This worship carries through to Four Our Children (2022, p. 102–103), where we see the bottom half of two women in heels as they either ascend or slide down an imagined stripper pole. Below them lies a chimeric being found throughout Taburet’s work, a humanoid tapir with a long snout spouting the same electricity that wraps around the strippers’ legs. The eerie nature of the figures is settled by the compositional choice to render a yellow and a green rectangle in the background, which gives the image a paradoxically homey feel: this is a strip club devoid of glitz, glamour, and even sex, and there is even a door we can go through should we feel overwhelmed.

Indeed, every club needs a place where you can take a break – a bathroom, a back room, the parking lot, or a corner where you can stand alone for a while. Once you have re-anchored yourself in the physicality of your own body and mind, you can go back out onto the dancefloor with the bodies, the drugs, or the pounding beats that you needed a momentary break from. The phantasmagoric trip of OPERA Ⅲ: ZOO “The Day of Heaven and Hell” works us through this cycle of reaching highs and providing moments to return to ourselves in this particular body at this particular moment, over and over again. The exhibition does not merely drop us into a zoo-like chaos of perception to scramble our senses and remind us how