Number 9

August 2019

Thurston County Homefront During World War I

Lingo from a Tin Pants Show $5.00

Thurston County Homefront During World War I

Lingo from a Tin Pants Show $5.00

Number 9

August 2019

Thurston County Homefront During World War I

Lingo from a Tin Pants Show $5.00

Thurston County Homefront During World War I

Lingo from a Tin Pants Show $5.00

The Thurston County Historical Journal is dedicated to recording and celebrating the history of Thurston County.

The Journal is published by the Olympia Tumwater Foundation as a joint enterprise with the following entities: City of Lacey, City of Olympia, Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation, Daughters of the American Revolution, Daughters of the Pioneers of Washington/Olympia Chapter, Lacey Historical Society, Old Brewhouse Foundation, Olympia Historical Society and Bigelow House Museum, South Sound Maritime Heritage Association, South Thurston County Historical Society, Thurston County, Tumwater Historical Association, Yelm Prairie Historical Society, and individual donors.

Publisher

Olympia Tumwater Foundation

John Freedman, Executive Director

Lee Wojnar, President, Board of Trustees

110 Deschutes Parkway SW P.O. Box 4098 Tumwater, Washington 98501 360-943-2550

www.olytumfoundation.org

Editor

Karen L. Johnson 360-890-2299

Karen@olytumfoundation.org

Editorial Committee

Drew W. Crooks James S. Hannum

Erin Quinn Valcho

The Journal does not offer a subscription service. To get your own copy, join one of the heritage groups listed at the top of this page. These groups donate to the publication of the Journal, and thus receive copies to pass on to their members. Issues are also available for purchase at the Bigelow House Museum, Crosby House Museum, and Lacey Museum.

One year after print publication, digital copies are available at www.ci.lacey.wa.us/TCHJ.

The Journal welcomes factual articles dealing with any aspect of Thurston County history. Please contact the editor before submitting an article to determine its suitability for publication. Articles on previously unexplored topics, new interpretations of well-known topics, and personal recollections are preferred. Articles may range in length from 100 words to 10,000 words, and should include source notes and suggested illustrations. Submitted articles will be reviewed by the editorial committee and, if chosen for publication, will be fact-checked and may be edited for length and content. The Journal regrets that authors cannot be monetarily compensated, but they will gain the gratitude of readers and the historical community for their contributions to and appreciation of local history.

Opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the Olympia Tumwater Foundation

Written permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication.

Copyright © 2019 by the Olympia Tumwater Foundation. All rights reserved.

ISSN 2474-8048

Number 9

August 2019

2 Thurston County Homefront During World War I

Jennifer Crooks

Jennifer Crooks

38 Lingo from a Tin Pants Show

Karen L. JohnsonBack Cover

Who/What/Where Is It?

On the cover: The “Invincibles” team (Lucille Stanger, Muriel Hoage, and Ruth Adair) of the Olympia I Kan Kan Club competed at the Yakima State Fair in 1916. The woman on the far left is likely Myrtle Setchfield, adult leader of the club. The club formed in 1915 at Olympia’s Washington School; Setchfield became county leader of school agricultural clubs during World War I. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Crooks.

In the background is a border from a World War I poster promoting food conservation. Lithograph, 1917, from the Willard and Dorothy Straight Collection, New York State Food Supply Commission. Image courtesy of Library of Congress. See article on page 2.

The year 2018 marked the centennial of the end of World War I. This conflict had a huge impact upon Europe and the United States; many historians consider it the most important event of the 20th Century. Although far away from the war and isolated from its major effects, Thurston County offers an interesting window into how World War I affected the lives of ordinary Americans.

Official United States involvement in World War I lasted only eighteen months, from April 1917 to November 1918, but the war in Europe began three years earlier. The conflict was between the Allies, consisting of Great Britain, France and Russia, and the Central Powers, which were made up of Germany, Austria-Hungry, and the Ottoman Empire. This conflict erupted from long-simmering tensions that had divided Europe for decades. The war was sparked by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir apparent of the Austria-Hungarian Empire, in Sarajevo by a Serbian nationalist. A tangled web of treaties

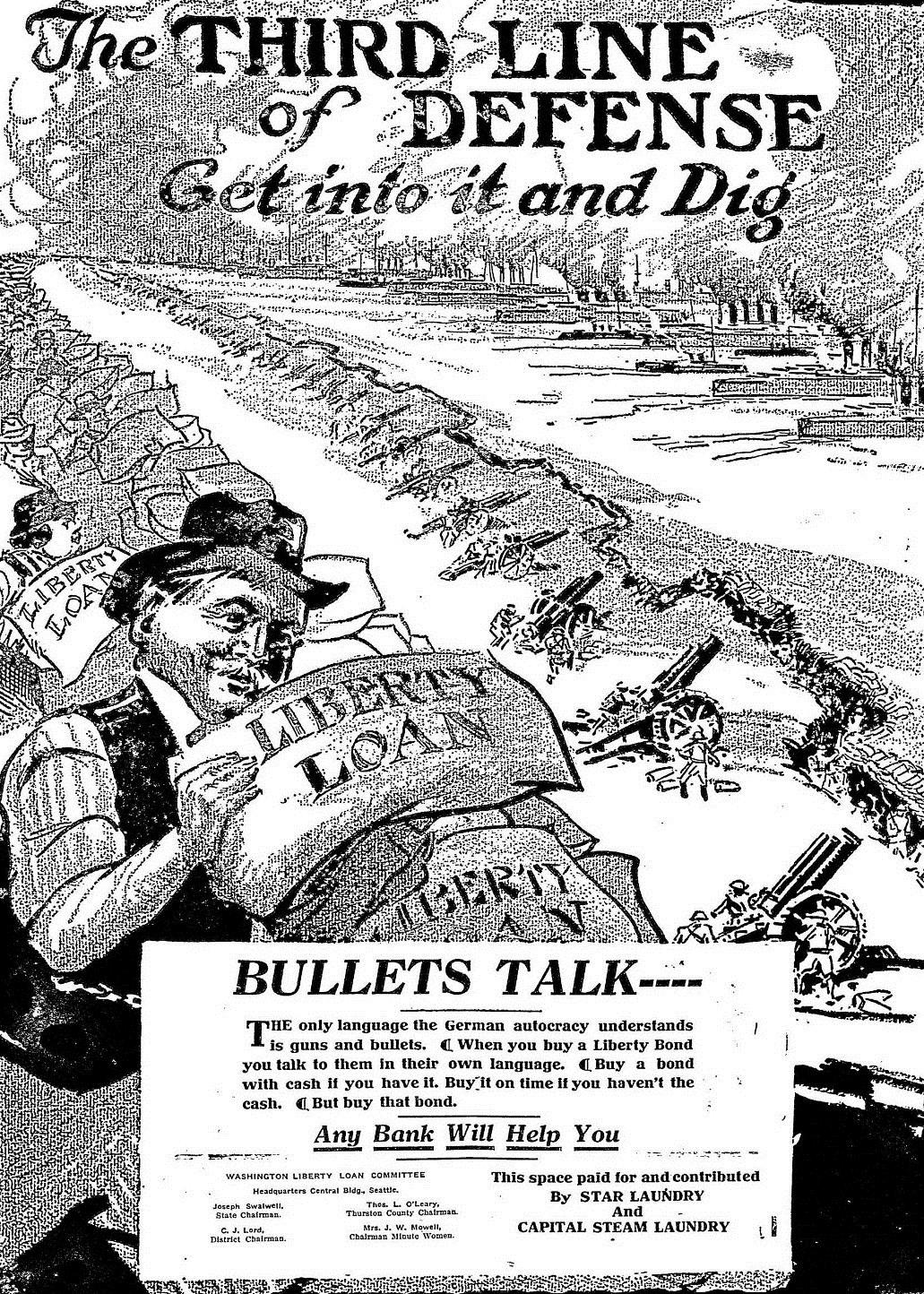

Local businesses sponsored Liberty Loan advertisements in local newspapers. This ad from the April 23, 1918 issue of the Morning Olympian was sponsored by Star Laundry and Capital Steam Laundry. It shows a man using Liberty Loans as a last line of defense along the American coastline.

brought other powers into the conflict and the fighting soon bogged down in Russia and northern France. Trench warfare and deadly weapons such as the tank, airplane, machine gun, and poison gas kept the war in a bloody stalemate with no clear end in sight.

Far from the battlefields, America was initially officially neutral. The conflict was a distant one and although most Americans were sympathetic to the Allied cause, others were more ambivalent. Many Irish-Americans were angered at Britain’s indefinite cancellation of Home Rule in Ireland and by the harsh British response to the 1916 Easter Rising, a rebellion against the British government in Ireland. Socialist radicals argued that the war was driven by capitalists and bankers and therefore American workers should have nothing to do with the conflict.

Moreover, more than ten million people of German descent, many within thriving ethnic communities, called America home. Most German Americans in Thurston County were well integrated into communities. Local residents were even excited to see a German naval cruiser, the Falke, anchored near Butler Cove (northwest of Olympia) for a few days in September 1905. Most of the crew of 163 men and officers spoke only German and stayed aboard ship. State officials, as well as many local people, took launches to tour the ship. Visitors noted that all the sailors ate well and had bottles of Olympia Beer.1

Had they left the ship, the German sailors would have found a number of German-Americans in the county. Prominent Thurston County Germans included a number of business and political leaders. One important German-American was Tumwater’s Leopold Schmidt, founder of the Olympia Brewing Company. His business was an economic mainstay of the community before and after Prohibition. Another important German-American was artist Edward Lange. Immigrating to America in the 1860s, he and his family moved to Olympia in 1889. Lange drew communities, businesses and homes throughout the Pacific Northwest using Olympia as a base.2 (Both Schmidt and Lange died before the advent of World War I.)

Prior to the war, Thurston County reflected national ambivalence about the European conflict. Many people probably doubted that the United States would become involved. Reflecting these feelings, the pacifist epic film Civilization played for two days in September 1916 at Olympia’s Ray Theater with a special orchestra and singers accompanying the film.3

During a 1915 Olympia Chamber of Commerce membership campaign, the Olympia Daily Recorder newspaper called Joseph Reder, a respected grocer of German parentage, the “Von Hindenburg of Olympia”4 for his aggressive promoting of the drive.5 During the war, Reder became the county’s Food Administrator,6 overseeing food conservation policies in the area.

His son and grandson, Carl Reder and Joseph Reder, later became leaders of the Olympia Tumwater Foundation.

As the United States drifted closer to intervention in the war, groups (including some in Thurston County) began to advocate for “preparedness,” which meant strengthening the military for potential conflict. Reasons for eventual American involvement in the war were complex. America had closer social, historic, and economic ties to the Allies than to the Central Powers, including lending billions of dollars to the Allies. Moreover, Americans were outraged by a series of deadly incidents such as German submarine attacks on American ships and the sinking of the British passenger liner Lusitania. The Zimmerman telegram in January 1917, promising German aid to Mexico for retaking the American southwest in case America became involved in the war, was another factor. The resumption of unrestricted German submarine warfare led to the official declaration of war on Germany on April 6, 1917.

remained the best way to travel long distances. World War I hit county residents hard. Historians consider this America’s first “total war,” meaning that almost every aspect of public and private life was expected to help win the conflict.

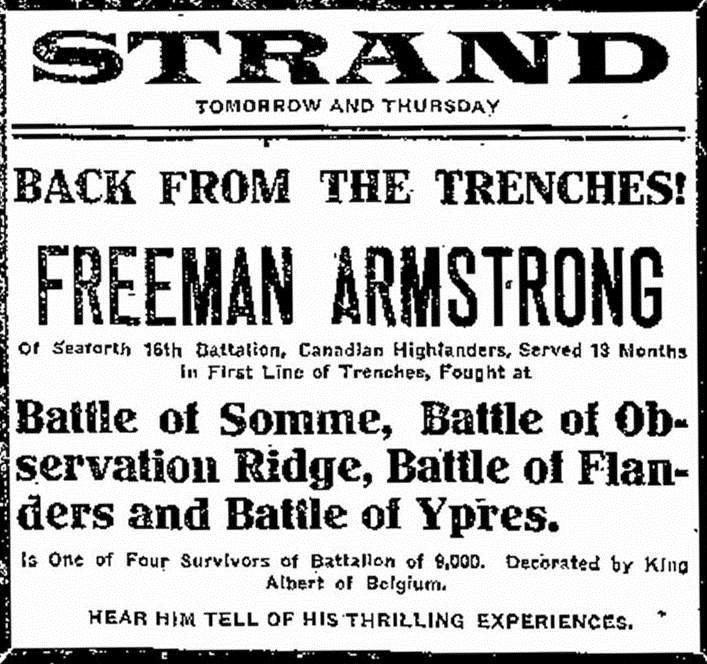

The declaration of war in April 1917 was greeted with a tidal wave of enthusiasm in the county. Thurston County businesses sold out of flags in the week after the declaration of war as families, individuals, businesses, clubs, and offices put up flags to show their patriotism.9 Residents flocked to Olympia’s Strand Theater to hear Freeman Armstrong, a recentlyreturned Canadian veteran, talk about his war experiences.10

Thurston County in 1917 would be almost unrecognizable to people today. Residents numbered only about 22,000, most of them in rural areas.7 Automobiles were becoming popular and even common among the upper and middle classes. (The speed limit in downtown Olympia was only twelve mph.8) However, ship and train travel

This advertisement from the Morning Olympian on April 10, 1917 urged people to hear Freeman Armstrong talk about his wartime experiences. Attendance was boosted by America’s entry into the war only days earlier.

Another outlet for this excitement was a major parade on May 1: “Dewey Day,” which marked Commodore (later Admiral) George Dewey’s victory at Manila in 1898 during the SpanishAmerican War. That conflict was a rallying point for Americans as the country took a more international role.

Taking weeks to organize, the Dewey Day parade involved a long list of organizations such as the Tenino Gun Company and the Home Guard units of Olympia and Tenino as well as fraternal organizations and their female auxiliaries. Veterans from the Civil War and Spanish American War led the parade. Heading the parade column was Frank Kenney, a SpanishAmerican War veteran who had coined the Olympia brewery’s slogan “It’s the Water.”

The parade was held in the evening; stores lining the parade route in downtown Olympia kept their lights on and hung up bunting and flags to demonstrate their patriotism.11

Nationally, the most important preparedness group in America was the Council of National Defense, which was created in 1916 by Congress to coordinate war activities. Later, councils of defense would form at the state, county, and local levels.12 The Washington State Council of Defense was appointed by Governor Ernest Lister

in May 1917;13 across the state, local groups formed county councils with women’s auxiliaries. Female members at all levels in this state were named the “Minute Women” and assisted with Council activities. They ended up running the day-to-day work for the bulk of the Council’s projects.14

The Thurston County Council of Defense was formed on July 13, 1917.15 Local councils of defense were set up later that month.16 Each county and local council, as was common throughout the state, had one female member who was chair of the Woman’s Work Committee and thus the leader of the Minute Women in her area. For most of the war, Ada Sprague Mowell was head of the Thurston County Minute Women.17

The Minute Women divided Olympia by ward and precinct and the rest of the county by school district.18 These districts roughly coincided with both incorporated and unincorporated county communities. Each school district and community was led by a captain. The “considerable” towns of the county (except for Olympia) were assigned a councilor as well. Rochester, Gate, Rainier, South Bay, Grand Mound, Little Rock, Tumwater, Yelm, and Tenino all had councilors. Smaller communities did not have councilors participating in the Minute Women. Lasting Minute Women auxiliaries did not form at Hunter’s Point, Tono, Zenkner Valley, Lackamas, Lacey, Rocky Prairie, Cat Tail, and Oyster Bay, which Mowell later blamed on

organizational misunderstandings, conflicts, and lack of motivation.19

In an attempt to organize contributions to the confusing, often competing legion of war funds that sprang up during this period, the Thurston County Council of Defense established a central Council of Defense fund to finance all requests for money by national and state organizations except the Liberty Loan and approved Red Cross drives. Estimating its budget at $2,000 a month, the Council asked “every person in the county over the age of 15 to give at least 10 cents a month.”20 The Minute Women collected pledges and contributions house-to -house. These funds proved insufficient to pay expenses by early fall 1918, so the Council planned to create a “war chest” of $5,000 to meet all financial requests. However, the plans were quickly abandoned because the Armistice ended World War I not long afterwards.21

The Minute Women collected pledged contributions and gifts that ultimately totaled $7,013.45. After paying for its office and secretarial expenses, the Council of Defense doled out funds to the Y.W.C.A., Home Guard, Salvation Army, American Bible Society, and Armenian and Syrian Relief.22 The pledge drive was considered a great success despite signing up only part of the Thurston County population.23 The Minute Women were tasked with collecting the donations. Evidently it was a tiresome task because in June, the Minute Women urged that the July

and August subscriptions be paid two months early “to relieve the Minute Women from making collections during the summer months.”24 They also tried to streamline collections by making a “complete” list of families in the county so that “government patriotic campaigns” could be more easily conducted. Their effort created an index of families, some complete with maps and diagrams of locations.25

The Council of Defense also organized “Four Minute Men” speakers to give patriotic speeches around the county. A national group, they earned the name from the amount of time it took to change reels at movie theaters, during which they gave many speeches. However, not all “Four Minute Men” were male; Olympia’s Clara Van Etten served as one of the local speakers. For example, she spoke at movie theaters during the Red Cross Christmas Membership campaign in 1918.26 Van Etten came to Olympia in 1900 and became a deputy in the State Department of Education during Governor Rogers’ tenure, where she compiled a textbook on civics. After the war, she served two years overseas helping with Near East relief efforts,27 assisting in running an orphanage in Smyrna for Armenian boys who survived the Ottoman’s genocides of Armenians and Assyrians.28

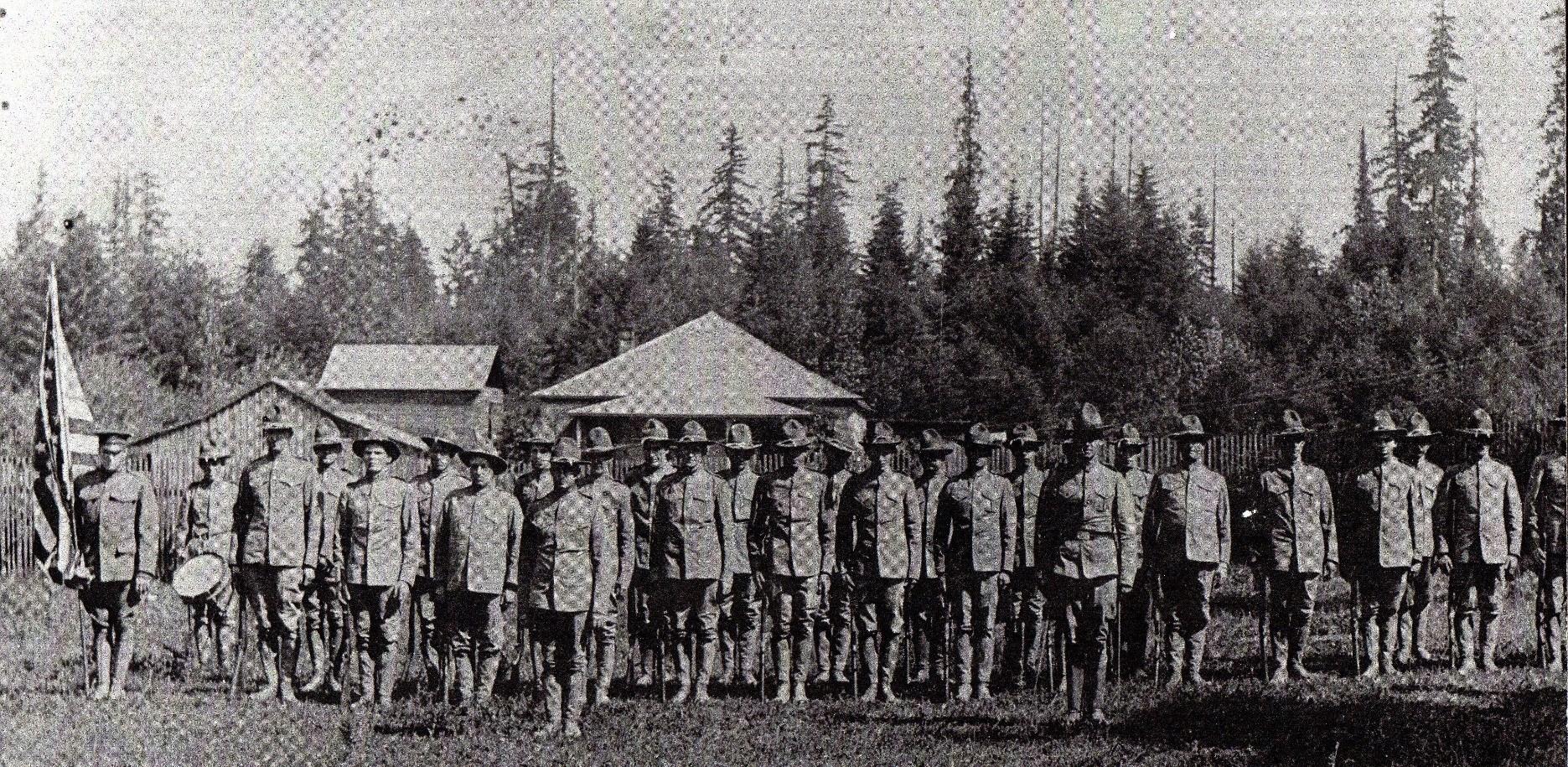

Another more unusual homefront group was the Home Guard. These were semi-official militia groups made

up of men over draft age, which drilled on evenings and weekends, and served as defense against internal disturbances. The Olympia Home Guard formed at the Chamber of Commerce on March 31, 1917, a week before the American war declaration29 and held a swearing-in ceremony with Superior Court Judge Mitchell.30 The group soon grew to over 40 members.31 Other organizations such as the Elks32 and the Knights of Pythias formed their own home guards. All Olympia home guard units were consolidated in the summer of 1917. Other communities such as Tenino33 and Yelm formed their own Home Guard units.

were more homespun. For example, W. J. Cook, a Tumwater grocer, decided all on his own that Thurston County needed a mounted cavalry. Having cared for horses in the military, he wanted people to lend horses to form a supplemental mounted patrol. In May 1917, thirty people attended a meeting at the Tumwater School, but nothing ever came of it.34

IBERTYAmong the most remembered wartime programs were Liberty Bonds and War Stamps, which both helped finance the war. Business leaders were major proponents of bond sales, and the Minute Women canvassed house-to-

The Home Guard units were semi-official militia groups made up of men over draft age, meant to defend against internal disturbances, which fortunately never occurred. In Thurston County, groups formed in Olympia, Tenino, and Yelm. Here, the Yelm Home Guard gathers for a portrait in 1917. Photo courtesy of Yelm Prairie Historical Society.

house. Speakers visited businesses, especially sawmills and logging camps, to solicit funds for the bonds.35

Although nationally the Woman’s Liberty Loan Committee was separate from the Woman’s Committees, at least in Washington State the Minute Women were the same as the Women’s Liberty Loan Committees in the counties, which made Ada Mowell the chair in Thurston County.36 While the actual financial transactions were handled in area banks, the Minute Women were prominent in promoting the purchase of these bonds.

In total, there were five Liberty Loan campaigns, including the post-war “Victory Loan.” The Third Liberty Loan drive was oversubscribed days before the end of the campaign in Thurston County with $1,080,900 in bonds purchased by 3,021 subscriptions. It was a massive campaign promoted throughout the area. For example, the Reverend R. Franklin Hart addressed the workers and employers at the N. & M. Mill near Rochester.37 Thurston County Minute Women also aided in the Fourth Liberty Loan campaign. After the war, they assisted with the Fifth Liberty/Victory Loan campaign, although they did not canvas for it.38

nor Ernest Lister (who hosted the event) and state officials gave speeches. Ada Mowell also spoke, urging women to encourage husbands and neighbors to support the war and buy Liberty bonds, telling people, “Do not be afraid to offend your neighbors. If we are loyal nothing we can say will offend the person of similar leanings, which should mean all Americans worth the name.” And the governor stated, “There are no party lines, no democrats or republicans, just one great American party. Those not members are traitors.”39

On “Liberty Day,” October 31, 1917, the Minute Women ward captains lit “Liberty Bond Fires” as part of a nationwide celebration. The first bonfire was started in Washington, DC. Our state’s contribution to the DC fire was a piece of the wooden foundation of the Isaac Stevens home, donated by his son Hazard Stevens.40

Liberty bond campaigns typically opened with much fanfare and excitement. Mass meetings and rallies encouraged people to contribute. The Second Liberty Loan campaign opened at the Olympia Elks Club on October 1, 1917 with a chicken dinner. Gover-

Later Liberty Bond campaigns were even more strongly promoted, probably because people were becoming weary of buying bonds. Many groups throughout the county promoted their sale. Businesses and individuals were quick to show that they were loyal and supported the war by sponsoring bond advertisements in the local newspapers, selling bonds and stamps, and forming “thrift societies” to encourage the purchase of war stamps. Labor unions also bought bonds as a group.41 County schools participated by assigning students an essay contest in which they wrote about why

people should buy bonds and war stamps. May Wasson, an eighth grader at the Tumwater School, won $20 and a bronze medal shaped like a dollar with the inscription: “Liberty Loan Essay Prize.”42

Businesses and groups paid for advertisements in local newspapers. Advertisements for the Third Liberty Loan, for example, were paid for by the Knights of Pythias Capital Lodge No. 15 of Olympia, Capital National Bank of Olympia, Olympia Oyster Growers and Dealers Association, Buchanan Lumber Company, Olympia Lodge No. 1, International Order of Freemasons, Olympia Council of the Knights of Columbus, Olympia Gas Company, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks No. 186, and Aerie No. 21 Fraternal Order of Eagles.43

Others carried out more creative advertising strategies. At Olympia movie theaters, Four Minute Men speakers gave short talks on the Liberty Loan and led audiences in singing sentimental and patriotic songs such as the “Long, Long Trail,” “Love’s Old Sweet Song,” and “America.”44 The Olympia police department even offered thrift stamps as rewards to children for bringing in stray dogs that damaged war gardens.45 The first recipient of a reward

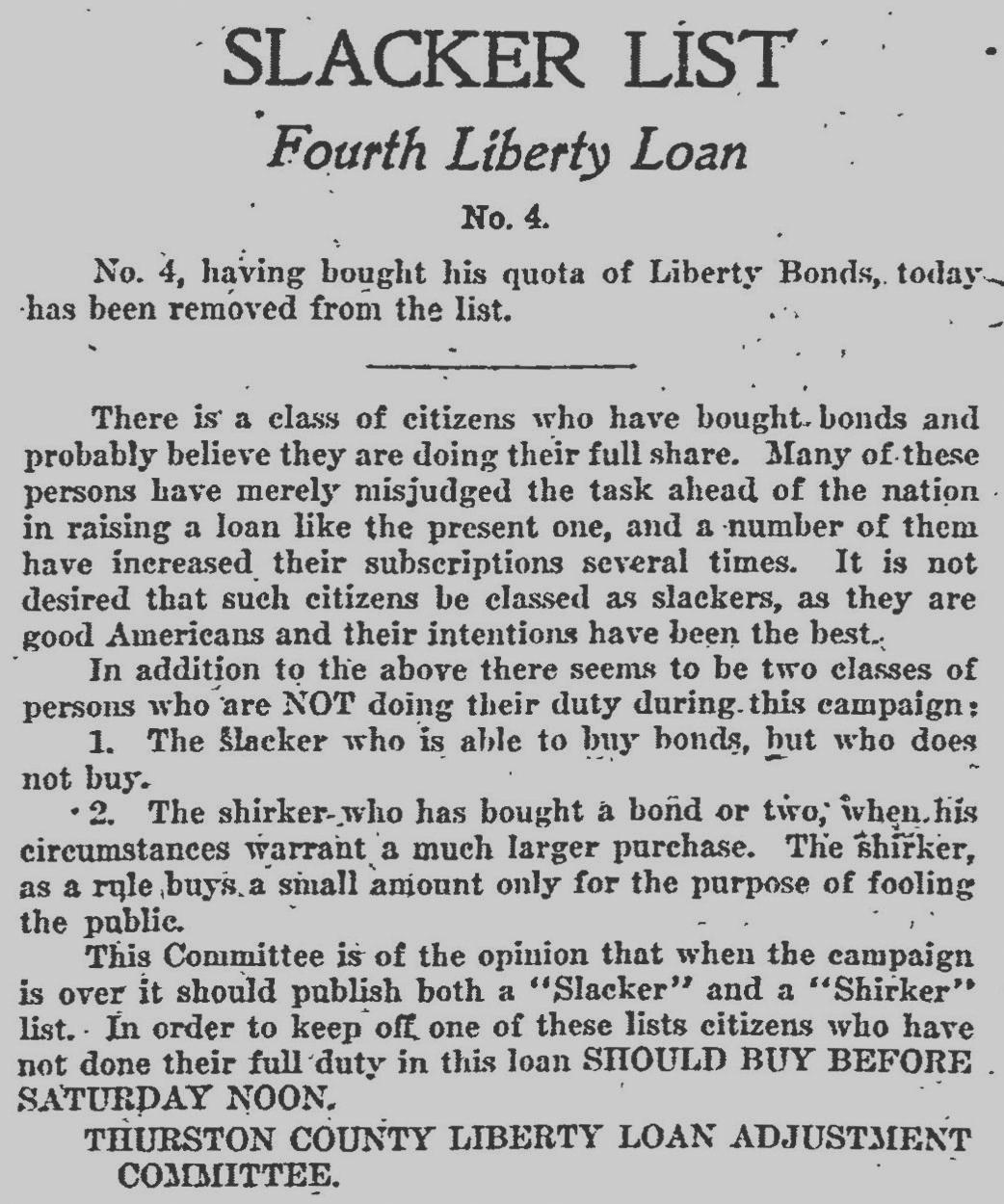

Although all bond drives were oversubscribed in Thurston County, people who for any reason refused to buy bonds (“slackers”) or buy bonds in the amount others thought they should (“shirkers”) were harassed. In October 1918, the Olympia Daily Recorder and Morning Olympian newspapers published a series of “Slacker Lists,” naming and shaming these people. The above ad was printed in the October 18, 1918 issue of the Olympia Daily Recorder.

was twelve-year-old Theda Stokes. She brought in a shepherd dog that had attacked her puppy, claiming a 25cent stamp as a reward.46

became bitter when people refused to buy bonds at all, or in the amount that their neighbors thought they should. Those who did not buy Liberty Bonds in Rochester were publicly listed by the local Minute Women, a plan that Ada Mowell urged other communities to adopt.47 Local newspapers published “slacker lists” which went beyond listing names to humiliate the non-complying people.48 For example, the Thurston County Liberty Loan Adjustment Committee declared that Americans (like a local dentist) who were not in favor of the war were “entitled to the Kaiser’s iron cross.”49 Another protested that since America was a free country he did not have to buy bonds if he wished not to; he was told that to show his appreciation of freedom he had to buy Liberty bonds.50 The Committee reminded that those who wanted off the terrible lists “SHOULD BUY BEFORE SATURDAY NOON” (capitalization in the original).51 The following week Olympia newspapers listed five more “slackers” (who had not bought any bonds) and several “shirkers” (who had not bought the amount of bonds the Adjustment Committee thought they should have).52

Administration led by future president Herbert Hoover. Unlike during World War II, people were not issued ration books, but laws limited how much of certain foods people could purchase at one time. People were encouraged to have meatless and wheatless days and limit their consumption of sugar.

A good summary of the food conservation rules came from a poem by Ruth McDowell, a sixth grader from Olympia’s Garfield School:

“Don’t eat this and don’t eat that, Try to get thin instead of fat. Hoover says to save all we can; Do this and we’ll help some soldier man.

Whether we’re short or whether we’re tall,

We’ll help the soldiers one and all. Corn can be used instead of wheat. Fish can be used instead of meat.

If we waste we’ll help the Huns

So of corn let’s make our buns.

We can eat rice and crisp corn flakes And use less sugar in our cakes; If we do all this without a grunt

We’ll help the soldiers at the front.”53

Much more was done on a daily basis to encourage what people of the time called “food conservation.” During the war there was a great effort to conserve food for soldiers and shipment to the Allies. This amounted to a voluntary rationing system under the Food

The Minute Women were active in getting people to pledge to obey food conservation rules. The first food pledge campaign began in late October 1917. The campaign met with an initially enthusiastic response from both the community and the Minute Women,54 but was ultimately a failure, as only 2,000 people (half of the quota) signed the pledge and sent it to the Olympia

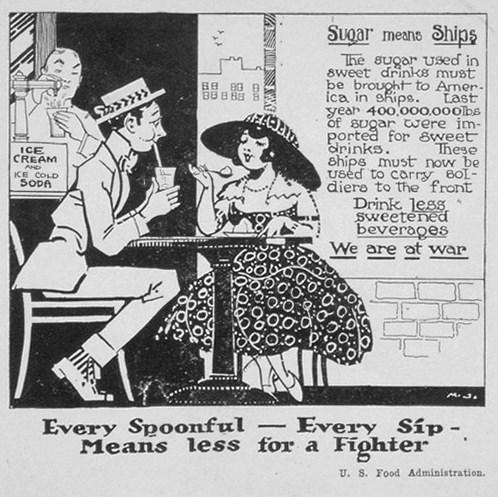

World War I propaganda posters encouraged people to support the war effort. This poster admonished people to use less sugar and thus free up ships to carry soldiers to Europe. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Chamber of Commerce.55 Further campaigns in Thurston County succeeded in signing up more people, but

never included everyone in the county. In a January 1918 campaign, over 2,800 pledge cards were completed

(from a quota of 4,000).56 Another campaign was held in early March— the Minute Women were instructed to get signatures as well as distribute recipe pamphlets and “home cards” outlining the conservation schedule to display in the home. Sixty percent of state households had signed earlier,57 but that still left hundreds in Thurston County who had not signed the pledge.58

Many people participated in planting and maintaining “war gardens.” The Olympia Chamber of Commerce even listed vacant lots available for farming.59 This was fairly successful, but police had to issue warnings for children to keep off the new garden plots on which they used to play baseball.60 Local newspapers routinely published recipes. For example, after speaking about Food Conservation at the Chautauqua in July, Edith Wilson Roberts published several recipes in the Morning Olympian including cottage cheese cakes, cottage cheese and liver salad, cottage cheese and nut loaf, tamale pie, steamed brown bread, and raw potato griddle cakes.61 Other groups helped popularize food conservation rules. School children were encouraged to grow gardens and join canning clubs. These clubs held public demonstrations about food conservation.62

States Food Administration in April 1918, chief librarian Elizabeth Southwaite described how the Olympia library had a bulletin board displaying food conservation posters and newspapers clippings, updated regularly. Lists of war food-related items in the library’s collection had been distributed by door-to-door solicitors for the food card pledge campaign. Books on the subject were displayed at the office of two lawyers, Harry Parr and James Marts, at 5th and Washington Streets.

Southwaite also described how the library had sponsored a food conservation display in the window of J. F. Kearney’s grocery store in downtown Olympia. The store provided food which was then cooked and put on display by girls from the Home Economics Department of Olympia High School. The girls also typed up recipes cards to give shoppers. Kearney’s employees decorated the window with “Joan of Arc (from the Food Administration poster), holding a large flag in the background, and ‘War Substitutes’ printed in cornmeal in the foreground.”63

Olympia’s public library, housed in the historic Carnegie Library building, partnered in efforts to spread food conservation. Writing to the News Letter of the Washington State section of the Library Division of the United

The Red Cross was another important group during the war. It provided support for soldiers and Allied civilians. The Red Cross was formed in Thurston County in February 1917.64 Headquartered first in the Kneeland Hotel’s vacant lobby, it relocated to 526 Main Street in the summer of 1917 where it remained for the rest of

the war. The Red Cross had auxiliaries throughout the area and at local schools; official groups were at Nisqually Valley, Little Rock, Maytown, Yelm, Grand Mound, South Union, Rochester, Lacey, Spurgeon Creek, Rainier, Union Mills, Hays, South Bay, Brighton Park, Pleasant Glade, Lackamas, State School for Girls (Maple Lane), Eureka, McLane, Gate, Tumwater, Fairview, Schneiders Prairie, Roadside, Rocky Prairie, and Riverside (Independence). Tenino and Tono originally had an independent joint chapter but were later annexed to the Olympia group. Various women’s church groups, lodges and clubs also assisted by regularly meeting to sew and knit. Schools also had Junior Red Cross units. After the war, Olympia Superintendent Chauncey E. Beach estimated that all Olympia schoolchildren were members and that about half of county children were as well.65

Over the months of the war, the Red Cross held many drives, but by far the largest and most important Red Cross campaign was its membership drive during the Christmas season. This campaign began in mid-December 1917 with the slogan “Every man, woman and child in Thurston County a member of the Red Cross.” The Minute Women assisted in canvassing the county, signing up new members and renewing current memberships, raising thou-

This poster, created circa 1917, encouraged Americans to join the Red Cross. Lithograph by Potomac Lithograph Manufacturing Company, Washington, D.C. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

sands of dollars across the area.66 Small communities collected much money for their size. Union Mills (a logging community near Lacey) raised $1,177 in May 1918.67

While many people were more than happy to join, Red Cross membership

was often socially mandatory. “There is not a home in the district,” reported Flora B. Gunstone of the Minute Women in Independence, “but has responded nobly to the Red Cross Christmas drive or the war fund. The little folks as well as the big ones were eager to add their contributions to help swell the war fund, not withstanding most of the residents had become members of the Red Cross a few months previous.”68

The Red Cross also used other types of events to raise money. The Schmidt family lent their Tumwater Club for free. Dances for soldiers were held there every weekend. They soon overwhelmed the club’s capacity and dances had to be held at the Central and Masonic Halls in downtown Olympia. Organizers held several raffles to benefit soldiers; raffled items included a red, white and blue quilt and a goat, which netted about $100 for both prizes. The goat was taken to Camp Lewis and served as a unit’s mascot for a time.69 Other areas also had Red Cross dances. For example, on May 14, 1918 the Chambers Junction group held a Red Cross benefit dance, raising $25 for the Olympia Chapter of the Red Cross as part of the Second Red Cross War Fund.70

bandages. They even took over a courtroom in the Temple of Justice, dubbing it the “moss room,” and made bandages there for a time.71 In total, they produced about 12,000 moss surgical pads. The Olympia Red Cross and its auxiliaries made some 27,145 surgical dressings, 10,000 gauze masks, and 5,092 knit garments for soldiers and refugees. Some items went to the base hospital at Camp Lewis. Individuals often contributed heavily. Mary Prickman, for example, knitted 73 sweaters for the Red Cross by March 1918, 38 of which she gave to the Red Cross and the rest to naval relief projects.72

The Red Cross also produced many items for soldiers. Volunteers knitted socks, sweaters, and mittens. Women sewed hospital gowns, made towels out of rags, and donated used clothing for refugees. People gathered sphagnum (peat) moss in the woods to make

To raise interest in knitting, State Commissioner of Agriculture Edwin F. Benson, a sheep farmer from Prosser, donated two ewes, each with two lambs, to the Olympia Red Cross, hoping to encourage people around the state to graze sheep on spare lots and yards. To do this he had them graze in the parking strips of Sylvester Park, in front of the Capitol.73 (The idea of publically grazing sheep during World War I was not unique and in May 1918 President Wilson put a herd on the White House lawn.) Things went well in Olympia until it started to rain and Benson received an avalanche of calls and letters accusing him of animal cruelty and giving him advice on how to better care for the sheep. Lieutenant Governor Louis F. Hart ordered umbrellas for the animals.

Many people loved the sheep. The ewes were named Mary and Maude.

Their lambs were called Lizzie, Lottie, Timothy and Titus. Local newspapers received sheep-themed poems but they did not print them.

Some people objected to the constant noise the sheep made. A group of sixteen state house employees signed a carefully worded petition and submitted it to the July 19, 1918 Olympia Daily Recorder. Benson blamed children for causing much of the noise by feeding the sheep cake, popcorn and cookies. This was unhealthy for the sheep, who now begged passersby for food. A few weeks later the lambs were sold by raffle at a carnival held by the Elks. The total raffle netted $475. The proceeds went to the surgical dressings department.74

In total, the Red Cross collected $27,679.78 in its first War Fund and $32,588.32 in their second. They recruited 4,284 new members during their 1917 Christmas Roll Call and 7,022 annual members the next Christmas. They sent 350 bath towels, 700 hand towels, 500 handkerchiefs, 175 sheets and 40 napkins in a “linen for France” drive. In 1917, volunteers sent 335 Christmas packets to soldiers at Camp Lewis; the packets included candy, apples, pencils, postcards, envelopes, scrapbooks, cards, writing pads, and cigarettes. The Red Cross had less luck with used clothes, collecting 6,362 pounds (quota 2 tons), 7,043 pounds (quota 3 tons) and 3,770 pounds (quota 6 tons). At Union Mills, Japanese employees (most of whom were ineligible for citi-

zenship due to racist laws) were noted for their generosity during Red Cross drives.75

Perhaps one of the most complicated aspects of the World War I era in Thurston County is the story of Olympia’s two shipyards. They have been seen either as a complete failure or as a great success. Both viewpoints are misleading. While the county has had a strong maritime connection, commercial boat building has never been a viable local industry. Other cities such as Aberdeen and Tacoma were much better locations for shipbuilding.

In 1916, seeing increased wartime demand as an opportunity, local investors created the Olympia Shipbuilding Company in September and its first keel was laid the next month.76 The company built its yards at what is now the Port of Olympia. The company in Olympia was part of Aberdeen’s Grays Harbor Shipbuilding Company. In January 1917 the Sloan Shipbuilding Company also set up a shipyard in Olympia.77 This firm had plants up and down the West Coast. Neither the Olympia nor Sloan Shipbuilding Companies would long survive after the war. They did not built warships, but wooden auxiliary vessels. Sloan had a contract with the government for several ships while the Olympia Shipbuilding Company contracted with a Norwegian company to build motor auxiliary schooners as cargo ships.78

Much confusion surrounds Olympia’s two wartime shipyards, the Olympia Shipbuilding Company and the Sloan Shipbuilding Company. Olympia Shipbuilding delivered all of its ships. The popular legend that Sloan Shipbuilding never delivered any of its ships is mistaken; government records show that several Sloan ships built in Olympia were sold and sailed for decades after the war. This photo shows the Sloan yards. Photo courtesy of the Port of Olympia.

Both shipyards initially seemed to prosper and employed hundreds of people.79 Sloan went through a period of rapid expansion, driving piles for new slips in June 1917.80 It purchased the Capital City Iron Works81 for which noted local architect Joseph Wohleb designed a building expansion.82 Sloan even felt confident enough to promise a seven percent annual bonus for all workers.83 The Olympia Shipbuilding Company leased

a dock from the Olympia Oyster Company to build ships84 and constructed temporary offices, also designed by Wohleb.85

People celebrated the shipyards as a patriotic venture. Kate Young of Littlerock was proud to provide a 27-inch ship knee (a large, naturally curved piece of wood used as a brace): “I feel that every timber I contribute toward

the making of an American ship is just one more blow delivered in the cause of my country at this time of supreme need.”86 Ship launches were widely attended. At the launch of Olympia Shipbuilding Company’s first ship, the Wergeland, in July 1917, thousands watched the ship slip from the way (a structure on which a ship is built). The company hosted a banquet at the Elks Club for the ship’s crew and its owner, C. J. Brock of Trondheim, Norway. Over two hundred people attended the banquet. Governor Ernst Lister was invited but was unable to come.87 The Wergeland went on a maiden voyage to Sydney, Australia, with a load of lumber from Port Blakely, taking along as ship mascot and captain’s companion a stray dog rescued from Olympia’s pound.88

In total, the Olympia Shipbuilding Company yards built three ships: the Wergeland, General Pershing, and Korsnaes. 89 All these vessels were completed in Tacoma and received by their respective owners. Sloan built a number of ships including: the Coolcha, Cethana, Challamba, and Culburra90 as well as the Himoto, 91 Hynannis, 92 and Conewago. 93 Only some of these were delivered to their owners.

ly declared that paydays would be moved to the 5th and 20th of the month, with five days pay held back, rather than having payday once per week. In addition, they would discontinue double pay on Saturdays. The manager argued that these changes would save time and money in the office. In response to these radical changes, workers went on strike.94 However, the regular bowling games between the shipbuilders and local businesses continued unabated95 and some work continued.96 This strike lasted several months and there were also later strikes.97 The Olympia Shipbuilding Company also experienced disruptions with accusations of fraud, delays in production, and false insolvency claims.98

Despite the pride civic leaders felt for the city’s shipyards, the veneer of financial solvency and harmony was very thin. In mid-October 1917 all but four watchmen at the Olympia Shipbuilding Company walked off the job. They cited several grievances for this action. The plant manager had recent-

Both shipyards closed soon after the war. The Olympia Shipbuilding Company dissolved in July 1920.99 Sloan’s ships at Olympia and Anacortes were seized by the Federal Shipping Board in December 1917, alleging fraud and mismanagement.100 Work on ships continued, but after much litigation, the Sloan Company closed and remaining ships were sold as scrap. After all machinery and quality wood was removed, the ships were sold to a junk dealer for $1 each, dismantled and burned in 1920.101

Many people in Thurston County feared spying and sabotage, especially from German-Americans. Local historian Gordon Newell once wrote, “In

Olympia, as in the nation as a whole, the World War I years became a glorious opportunity for busybodies, snoopers, frustrated fascists and the self-righteous to bask in the glow of patriotism and public approval.”102

The Thurston County Council of Defense had a Committee on Disloyalty, chaired by Frank M. Kenney. According to the final report of the Council, although most people in the county were “loyal,” the committee investigated “a great many” cases brought in by the general public. A few were found guilty and punished, “but in the majority of cases reported the words and deeds had been enlarged upon in the telling.”103

People panicked about a plane, seen by farmers on Bush Prairie, whose occupants sang “My Old Kentucky Home.”104 Others panicked about a grumpy man working a radio at Priest Point Park across from the shipyards.105 However, most of the anger and suspicions was directed at German-Americans.

German-Americans had been an important part of the county’s population. Prior to World War I, Germans were one of the largest white ethnic minorities in the Pacific Northwest. At the beginning of the war, many in Thurston County were quick to defend German-Americans from criticism and suspicion. Announcing that the city would now record gun and ammunition sales, Olympia Mayor Mills assured the public that “There is no

cause for worry in Olympia. We have a number of German-born citizens here who are loyal to the [American] flag. They may regret that the United States is at war with Germany, but they are Americans clear down the line and will make a lot of native born Americans ashamed of themselves before the war is over. They are mighty good, patriotic citizens.”106

Non-citizen German-Americans were required to register as enemy aliens. This angered Abbot Oswald Baran of Saint Martin’s Abbey in Lacey, whose family had immigrated from the Austrian-Hungarian Empire when he was a small child. Writing to his friend and mentor Abbot Peter Engel of Minnesota’s Saint John’s Abbey and University, Baran stated, “I registered as an enemy alien. It may not have been necessary but I wished to avoid or preclude any trouble. I was always convinced that my father had taken out his citizenship papers but I have no proof for same. I am getting busy now to find out what country I owe allegiance! Fine state of affairs after having voted and spent nearly all my life in the United States.”107

This anti-German sentiment also affected schools. German was a popular language to study nationwide and was the top foreign language taught in Washington high schools.108 Arguing that school administrators were tolerating teachers’ pro-German, pacifist or “un-American” ideas, nativists made language an issue over widespread concerns that teachers were some-

Oswald Baran (1866-1928) was the first abbot of Saint Martin’s to be elected by his fellow monks. Elected abbot in 1914, Baran had been Saint Martin’s College’s first director (18951900). Unsure about his American citizenship status, Abbot Baran registered as an enemy alien during World War I. Baran Hall (a student dormitory) and Baran Drive on the university campus are named in his honor. Photo courtesy of Saint Martin’s University Archives.

larly German language instructors. Nativists and nationalists used the issue to promote their vision of a united and assimilated American nation which spoke only English. Washington was unique in both its late movement to ban the German language and in the disproportionate (yet comparatively moderate) anti-German sentiment in education without overt violence. The situation was different elsewhere. For example, anti-German attitudes in other states were more violent with numerous incidents of Germans suffering beatings, floggings and attempted lynchings for failure to participate in the war effort, such as refusing to join the Red Cross.109 Similar incidents were much rarer in Washington.

In April 1918, the State Board of Education passed a resolution that the German language could remain an elective in high schools, as preparedness for possible overseas service, so long as the teachers who taught it were clearly loyal and supported the American war cause.110 In August of the same year, however, the State School Board requested that all schools ban German instruction completely.111

times promoting pro-German attitudes. These concerns about disloyalty resulted in increasingly intense scrutiny of textbooks and teachers, particu-

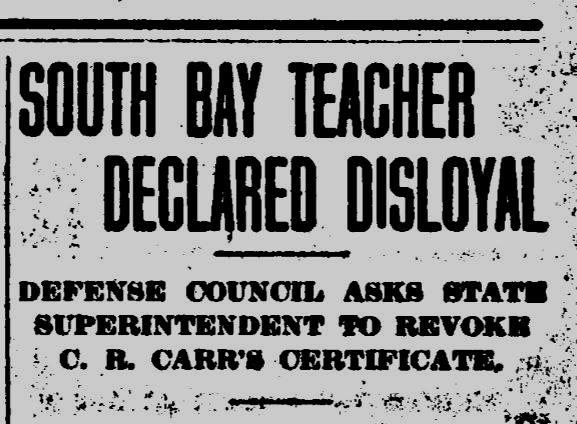

Some teachers faced dismissal and reprimand if perceived to be anti-war. Charles R. Carr, a teacher in Thurston County, was fired for making anti-war remarks. Carr had worked in the county since 1908, teaching at the South Bay School and nearby McLane

School.112 A Christian pacifist and a socialist, he was accused in 1918 by his school board of being disloyal to the United States and the war effort. After the board fired him, then reinstated him, and then fired him again, the Thurston County Council of Defense asked the Washington State Su-

Charles Carr’s teaching license was revoked after his pacifist attitude was deemed “un-American.” This headline appeared in the January 25, 1918 issue of the Washington Standard.

perintendent of Public Instruction to rule on Carr’s case. They had three main charges against the teacher: calling the war unholy, unrighteous and “wholly for commercial purposes” at a Liberty Bond meeting; telling a few men that he would not assist in shipbuilding and other war activities; and discouraging students from selling, buying, or writing essays about the second Liberty Loan.113

pia, Carr defended himself and had a lawyer. He argued that he meant only that the war had commercial origins, not that America had commercial interests for joining the war, and that he was interested in helping in the homefront war effort, but not in killing. His pastor also defended Carr, arguing that he was a pacifist and not disloyal. Several members of the audience of the Liberty Loan meeting testified. The court swore in some of Carr’s students, aged eight to ten, but they did not testify and romped around the Speaker’s desk the entire time. A local woman brought a petition from district residents (250 of them who attended the hearing) arguing that Carr was an excellent teacher, urging his reinstatement and stating that the true issue was a conflict between Carr and the principal of the school.114

Preston revoked Carr’s teaching license, arguing that his “un-American and unpatriotic remarks” were deplorable and unprofessional.115 At first Carr tried to appeal to the State Board of Education, but he dropped the appeal in June.116 He later moved to Idaho for work, where, struggling with depression, he committed suicide in 1922.117

At a hearing before Washington State Superintendent of Public Instruction Josephine Preston held in the Senate Chamber of the State Capitol in Olym-

During World War I, numerous women supported the war effort. Some women had joined the National League for Women’s Services before the Minute Women were created.118 The National League formed in early April 1917 be-

fore the war declaration and continued despite the ascendance of the Minute Women. They became less prominent than the Minute Women, but remained active.119 The National League for Women’s Service was not disbanded with the creation of the Woman’s Committee,120 but was partially absorbed by the new group.121

As mentioned before, the Minute Women of Thurston County helped with the Liberty Loan, food conservation and other jobs but perhaps the most unusual project for them was participating in the “baby weighing” project of the Children’s Year programs. Believing that since many young American men would die in the war, it was imperative to lower childhood mortality, women’s groups such as the Minute Women implemented programs to encourage child welfare. This included weighing and measuring young children to gain knowledge of national health.

Across the nation, five million children were examined by thousands of volunteers in over 16,000 communities in July 1918.123 Thurston County Minute Women asked that children ages five and under be brought to the Olympia Chamber of Commerce at times assigned by ward.124 After the first day of tests, the newspaper noted with pleasure that the children seemed to be healthy.125

action against them during the war era. After the conflict ended, Ada Mowell reported that “insult was often the portion given” to the women collecting the Council funds. She also complained that their “biggest task”, the family census, “was not appreciated by the people.” Mowell alleged that “The usual tales were told by the traitors in our midst of the per. cent [sic] received for collecting monies, etc., but these were absolutely untrue” because the Minute Women were not paid.126 Perhaps some people were tired of the Minute Women who, as the Morning Olympian noted, “laid siege to every home until a membership card appears in the front window.”127

The Minute Women claimed to be a good, helpful organization. A March 1918 newspaper article quoted Mowell: “There is a mistaken idea in some districts about the Minute Women. They are not secret service operatives. They are not engaged in any campaign to run down slackers or to get information as to the loyalty of Thurston County citizens. They are taking it for granted that everybody is loyal and true. They work on that principle. Of course, sometimes they find outright disloyalty and they report such cases directly. But those cases are few. I believe that if everybody understood the work of the Minute Women the workers would have no difficulty.”128

The Minute Women were not always well received by the public. Indeed, they recorded a substantial hostile re-

The end of World War I in November 1918 caught the county at a pause.

County homefront groups had cancelled meetings when the communities banned all public gatherings during the deadly flu pandemic, and the war ended before the ban was lifted.129

Across America, people celebrated the Armistice a little early on November 7 because of misleading newspaper accounts. Thurston County was no exception. Olympia and other communities resounded with cheers, flu masks were thrown off, and an impromptu band concert of makeshift instruments and an official demonstration were held in Sylvester Park in the evening. The Olympia Home Guard assembled for the event as well.13

The real Armistice on November 11 was a bit anti-climactic, but businesses closed and Governor Ernest Lister gave a short speech on the capitol steps. Cars drove up and down the streets dragging along tin cans and honking their horns amidst cheers.131 Tenino held an Armistice Day parade with a Liberty Bell float. The Tenino Home Guard and mothers of soldiers had places of honor. Cannons were sounded off and fireworks lit up the night. Tenino’s William H. Mullaney even composed a song for the occasion.132

The war was now over, but Thurston County residents participated generously in post-war relief efforts, especially the United War Work Campaign, which ran November 11-13, raising a total of $23,158.99.133 In December, the Red Cross Christmas Membership

As part of a campaign to provide food to war-torn Europe, the Woman’s Club of Olympia, in conjunction with the Daughters of the American Revolution, raised money to revitalize France’s poultry population. A 25-cent donation provided one chicken for France and one stylish button for the donor. Image courtesy of blog.dar.org.

Drive planned to renew the 4,990 members and add the remaining 2,990 potential members. They wished to “send a Christmas cablegram to the men in the American and Allied armies telling them there is a full Red Cross membership in every home in the United States.”134 The Woman’s Club of Olympia also raised money to “rechickenize France,”135 an effort to restock the poultry population which was decimated by invading soldiers.

But things did not remain the same

now that the war was over. The Washington State Council of Defense disbanded on January 9, 1919,136 and the Thurston County Council of Defense dissolved on January 1.137 Despite being created only for the war period, the Minute Women were determined to continue and the Minute Women Association of Washington was created in 1920.138

By March 11, 1920 a branch of the state group, the Minute Women Association of Thurston County, formed. The new group accepted members who had received their captain’s and county councilor’s recommendations “as having done loyal and faithful work while serving as Minute Women during the war.” After the charter roll closed the next November 11, “only the lineal descendants of the signers will be allowed to become members.”139 Bi-annual meetings were set for March and September.

The Minute Women Association’s constitution proclaimed that: “The object of this association shall be to perpetuate the fellowship of service and the memories of the Great War; to engage in such community service as the Association may determine; to familiarize its membership with the new ideals and responsibilities of America; to further by all means in its power a thorogoing [sic] Americanism among all classes of people; above all to guard the memory of our heroic dead and to hold as sacred trust the freedom safeguarded by their sacrifice.”140

Statewide, the Minute Women Association of Washington became inactive in 1930, but continued to exist.141 Despite the advent of World War II, the State Association faded away and folded by 1943.142 World War II revitalized the Thurston County Minute Women and they regularly volunteered as hostesses at the Olympia USO Club.143 They also started a “cookie jar” project for soldiers, enlisting the aid of local woman’s clubs and published recipes in The Daily Olympian. 144 Indeed, the Thurston County Minute Women kept going into the early 1950s.145

Sometimes lost in the homefront story are those who served in the military. Although no official statistics exist, hundreds of county men served in the military. Prior to official American intervention in the war, some county people had served with the Allies. When the war broke out in 1914, several German reservists were recalled to Germany but were unable to pass the British naval blockade.146

After America declared war on Germany, many young men enlisted. Others were drafted under the Selective Service Act. The first draft contingent from Thurston County received much fanfare. The state capitol provided cars to ferry the 56 men from the county courthouse to Camp Lewis. Home Guard paraded and presented arms as they left. The Red Cross packed them lunches.147

The county had close ties to Camp Lewis (now known as Joint Base Lewis -McChord). The construction of the post in Pierce County employed thousands of laborers and the need for food created an economic boom for area farmers. The Thurston County Dairy and Farm Products Association sold massive amounts of milk and vegetables to Camp Lewis.

Soldiers visited Olympia on leave from Camp Lewis. Military police accompanied the weekend excursions.148 The Chamber of Commerce offered dormitories to soldiers and arranged for them to have dinners at private homes, including on Thanksgiving. The Olympia Public Library increased its hours149 and the YMCA held an open house with music and games. The Red Cross hosted dances at the Tumwater Club, Central Hall and Masonic Lodge.

For their part, soldiers seemed to like Thurston County. One soldier patient said to a doctor, “Sir, the Olympia people know how to put the ‘hospital’

into hospitality.” At least he was only sick from overeating and not from food poisoning.150

County soldiers kept close touch with the folks back home. In August 1918, Captain C. Chase, who was serving with the engineer corps near the front lines in France, sent his father (State Hydraulic Engineer Marvin Chase) a German gas mask. The mask was put on display in the window of the Talcott Brothers’ store in downtown Olympia. The horror of the mask attracted many an onlooker.151

Although there are no official statistics for the number of soldiers from Thurston County who died in the conflict, it appears to be over 30. Some of them had enlisted in the military of Allied nations before American intervention. Robert Banner of Alberta, son of former resident Joshua Banner, died in the war.152 Joseph Collins of Little Rock enlisted in Canada, was gassed and spent six months at an

English hospital before returning home.153

A number of war dead were buried in Thurston County, part of a government policy to return soldier remains to their families upon request. This proved so expensive it was not repeated during World War II. Harold J. Tibbets from Littlerock was the first fatality to be returned to Thurston County. He had perished in a scarlet fever epidemic in Brest in January 1918 and was given a military funeral by the local American Legion in Tumwater’s Masonic Cemetery.154

In November 1919, Olympia’s American Legion post held a memorial for all

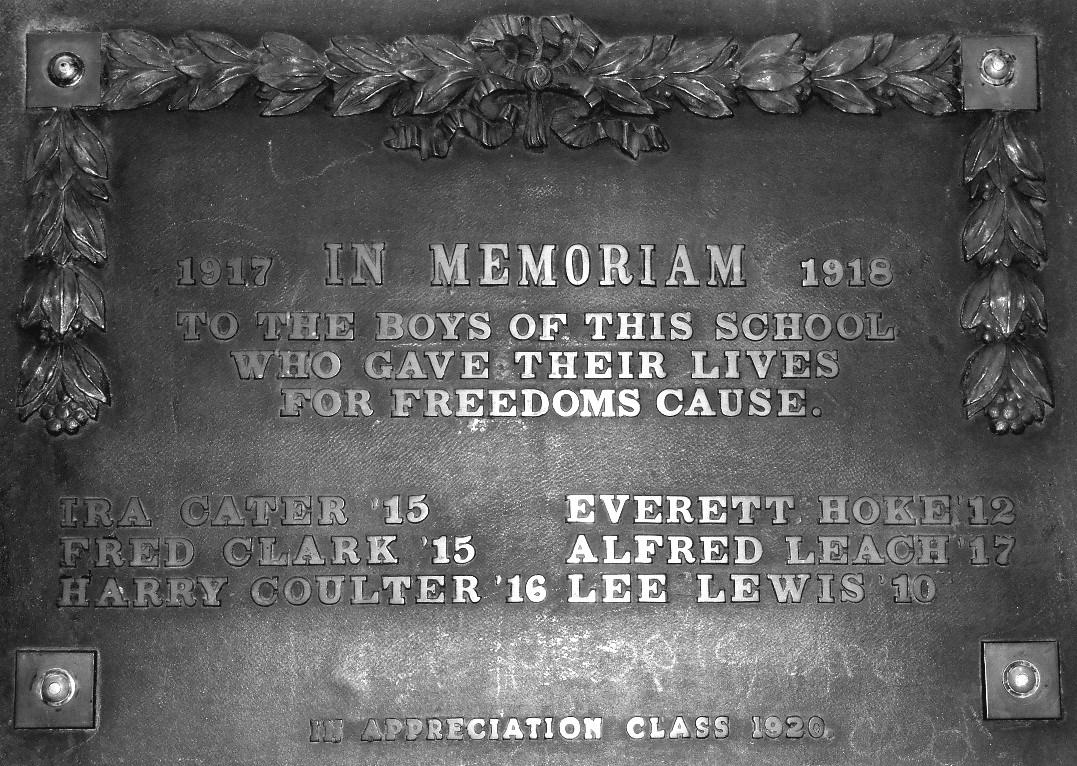

county soldiers who died in the military, whether from war or disease: Earl M. Belden (Yelm), Leon B. Beege (Rochester), Charles C. Cady (Rochester), Charles G. Cady (Rochester), David R. Carr (Kamilche, Mason County), Ira H. Cater (Olympia), Arlough E. Cole (Olympia), Don W. Clark (Bordeaux), Cecil H. Dooley (Littlerock), Frank E. Gilliland (Tumwater), Charles B. Hart (no town listed), Elijah B. Hays (Olympia), Harry Hobson Coulter (Olympia), Purnell M. Jacobs (Olympia), Otto Albert Kingery (Olympia), Alfred W. Leach (Olympia), Lee C. Lewis (Olympia), Frank Malpass (Kamilche, Mason County), Jacob B. Miller (Lacey), Will Melaney (Tumwater), Lawrence O’Neal (Delphi), Samuel N. Parker (no town listed), Henry Risse (Rochester), Adolph A. Schirmer (no town listed), William Henry Shaw (Olympia), Harold J. Tibbets (Littlerock), Hugh R. Williams (Rochester), William Roy Wiltson (Olympia), and Rowen W. Wood (Rochester).155 In the book Soldiers of the Great War, Oscar R. Benson (Yelm), Gabriel Haas (Olympia), Gustave P. Prenzlau (Tenino), Walker A. Nelson (Olympia), William T. Mullaney (Tenino), and Martin V. Charleston (Bush Prairie) were also listed as fatalities.156

Olympia High School students dedicated a plaque to OHS alumni who died in World War I. The plaque has moved as new buildings have replaced old. During the war, the school kept a service flag with stars for all alumni who were serving in the military. Some students graduated early in order to enlist. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Crooks.

Thurston County veteran’s organizations named their posts for World War I dead. Olympia’s American Legion Post chose the name William Leach, a graduate

of Olympia High School. The Veterans of Foreign Wars Post took the name of Ira Cater, who was also an Olympia High School graduate. Leach is buried in France, but Cater’s body was returned to his family and is interred at Tumwater’s Masonic Cemetery. Tenino’s American Legion Post named itself for William Theodore Mullaney, son of Tenino poet William H. Mullaney, who died of heart complications from shell shock and was buried in Tenino.157

anchored in Olympia September 1315.

2 Drew Crooks, Edward Lange: An Early Artist of Olympia and Washington State. Olympia: Tenalquot Press, 2012, page 1.

3 “The Film Sensation ‘Civilization’ Coming.” Morning Olympian, September 26, 1916.

In many ways, Thurston County and the United States after World War I were very different places from what they had been before the war. Perhaps some innocence was lost. Former Minute Woman leader Mrs. Ada Sprague Mowell seemed to believe so. “Into the midst of our busy life,” Mrs. Mowell reflected decades later, “came World War I and overnight everything changed. Olympia went all out for war work, Red Cross work, Minute Women, Council of Defense, etc. When it was over life had changed and never quite resumed its old tenor.”158 Now over a hundred years later, it is a good time to remember the conflict and its effects upon history and society.

4 Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who commanded the German Army from 1916 to the end of the war in 1918. He later served as president of the post-war Weimar Republic.

5 “Thumb-Nail Sketches Prominent Olympians: Joseph Reder.” Olympia Daily Recorder, May 14, 1915.

6 “Reder Says County Holds High Record.” Morning Olympian, April 6, 1918.

7 “Population Washington Table 9 Composition and Characteristics of the Population, for Counties,” in “Fourteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1920 Volume III: Population 1920 Composition and Characteristics of the Population by States. Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census, 1922, page 1090.

1 “Falke in Harbor.” Morning Olympian, September 14, 1905, page 1. “Falke to Go Today.” Morning Olympian, September 15, 1905, page 1. The ship was

8 ”Former Chief Caton Reminds Council That State Sets Auto Speed.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 6, 1917.

9 “Flags Go Up in Price as Demand Increases.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 3, 1917.

10 “Back from the Trenches!” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 10, 1917.

11 “All Olympia to March in Parade.” Morning Olympian, May 1, 1917.

12 Ida Clyde Clarke, American Women and the World War. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1918, page 17.

13 Washington State Council of Defense, Report of the State Council of Defense Covering Its Activities During the War, June 16, 1917 to January 9, 1919. Published by the 16th Legislature in Compliance with Governor’s Recommendation. Olympia, WA: Frank M. Lamborn (Public Printer), 1919, page 5.

14 State Council, Report, page 112.

15 Gertrude Marsland, Report of the Thurston County Council of Defense 1919-1920. Olympia, WA: np, circa 1920, page 1.

16 “Select Shipbuilding Branch of County Defense Board.” Morning Olympian, July 24, 1917.

17 Marsland, Report, page 1. Ruby Fromme held the position briefly before Mowell.

18 Minute Women Association of Thurston County, Minute Women Association of Thurston County Charter Roll and “True” Wartime Minute Women. Minute Woman Association of Washington Papers, MSSC 72 Box 2, Folder 23, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, WA.

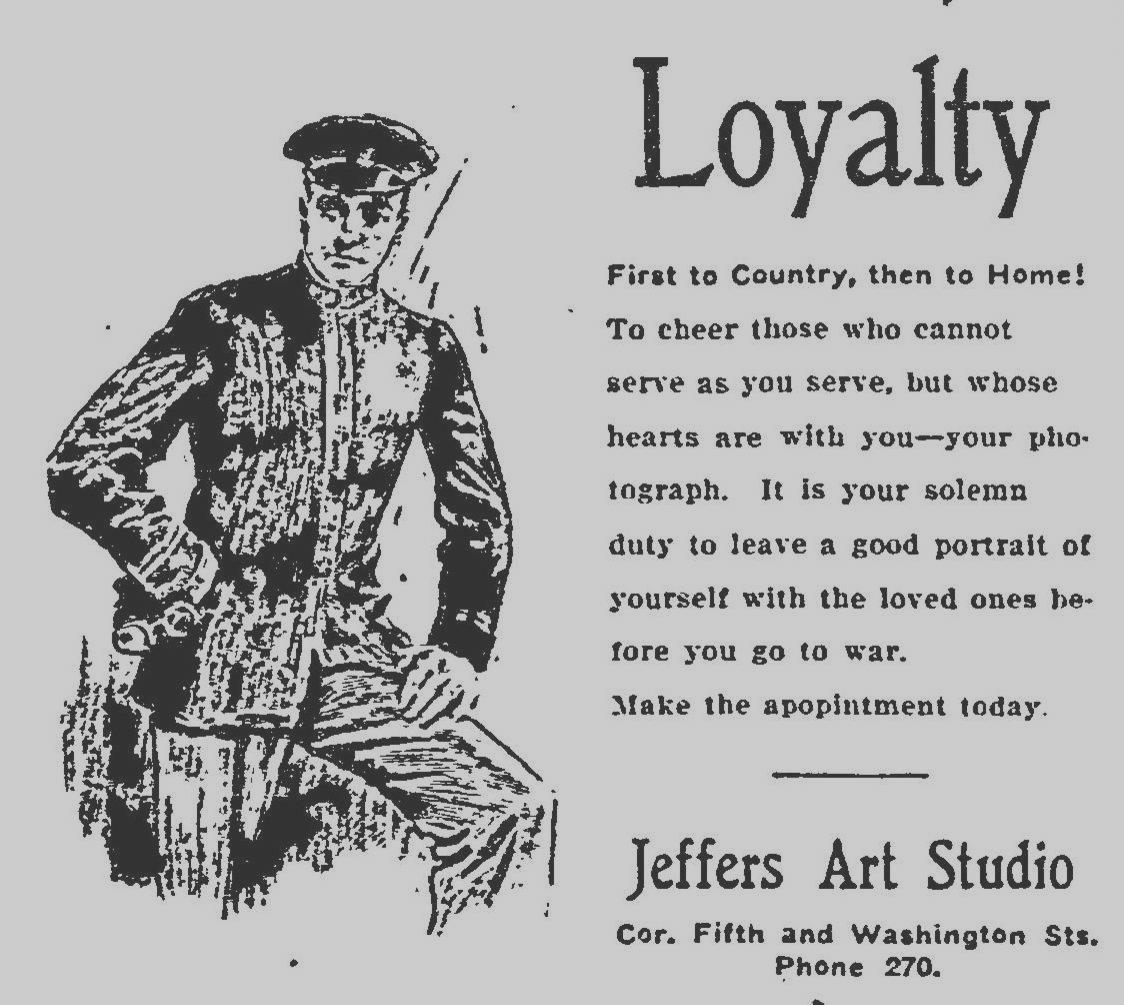

Olympia’s Jeffers Studio was run by photographer Joseph Jeffers and later his son Vibert. Here the studio encouraged military men to give their families portraits before leaving for war. This advertisement from the July 14, 1917 issue of the Morning Olympian was published daily for weeks.

19 Ada Sprague Mowell, Final Report [Of County Councilor Chairman of Women’s Work In Council of Defense], Minute Women Association of Washington Papers, MSSC 72, Box

2, Folder 23, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, WA, pages 1-2.

20 County Council of Defense, “An Appeal to Patriots.” Morning Olympian, February 8, 1918.

21 Marsland, Report, pages 6-7.

22 Marsland, Report, page 6.

23 “More Money is Needed for War Drives.” Olympia Daily Recorder, January 31, 1918.

24 “Minute Women to Help Commercial Economy.” Olympia Daily Recorder, June 25, 1918.

25 “Get Family Census.” Olympia Daily Recorder, March 14, 1918.

26 “Chairman Savidge Thanks Assistants in Roll Call.” Olympia Daily Recorder, January 30, 1919.

27 “Mrs. Van Etten is Taken by Death.” Daily Olympian, March 21, 1931.

28 “Returns From Armenia.” Washington Standard, July 6, 1920.

29 “27 Men Sign Home Guard Roster Roll.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 2, 1917.

32 “Elks Organize Their Own Guard.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 17, 1917.

33 “Tenino Has its Guard.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 23, 1917.

34 “Twenty Horses Ready for Tumwater Home Guard.” Morning Olympian, May 22, 1917.

35 “Predict Loan Will be Oversubscribed.” Morning Olympian, May 4, 1918.

36 State Council, Report, page 121; State Council, Report, page 125; “Pay Your War Bills.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 6, 1918 and Morning Olympian, April 7, 1918.

37 “Predict Loan Will be Oversubscribed.” Morning Olympian, May 4, 1918.

38 Mowell, Final Report, page 1.

39 “Loan Drive Gets Enthusiastic Sendoff.” Morning Olympian, October 2, 1917.

40 “Women Organize for Liberty Day Effort.” Morning Olympian, October 21, 1917.

30 “Home Guard Hold 1st Drill Saturday.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 6, 1917.

31 “Protect Capital is Guard Object.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 7, 1917.

41 “Every Member of Olympia Union Bought a Liberty Loan Bond.” Morning Olympian, July 13, 1917.

42 “Liberty Loan Essay Contest Award of Prizes Announced.” Morning Olympian, November 20, 1917 and “Essay

In the 1920s, veterans in Olympia planted trees such as these along Legion Way. Over the years, the trees have been topped (a severely damaging procedure) and some have died. Recently a few young trees have been planted along the street to honor more recent veterans. Photo of the intersection of Legion Way and Boundary Street, 2015, courtesy of Jennifer Crooks.

Contest Won by May Wasson.” Morning Olympian, November 28, 1917.

43 “Pay Your War Bills.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 6, 1918 and Morning Olympian, April 7, 1918; “Your Hiding Dollars Are Traitors to that Flag.”

Olympia Daily Recorder, April 9, 1918; “Lend Your Eagles to Liberty.” Morning Olympian, April 10, 1918 and Olympia Daily Recorder, April 10, 1918 (“Eagles” refer to dollars); “Youth!”

Olympia Daily Recorder, April 11, 1918; “Subscribe to the Third Liberty Loan.” Morning Olympian, April 13,

1918 and Olympia Daily Recorder, April 13, 1918; “At Your Door!” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 16, 1918 and Olympia Daily Recorder, April 18, 1918; “This War Must be Fought on European Soil.” Morning Olympian, April 18, 1918 and Olympia Daily Recorder, April 18, 1918. “Only A Bit o’ Celluloid BUT.” Morning Olympian, April 12, 1918; “Win We Must Or .”

Olympia Daily Recorder, April 19, 1918.

The annual Veteran’s Day event at the State Capitol on November 11, 2018 also commemorated the centennial of the World War I armistice. At 11:00, Peter Lahman, flanked by members of the AEF Northwest living history group, rang a bell eleven times as part of a program to ring bells across the country to commemorate the end of the war. The locomotive bell was loaned by the DuPont Community Presbyterian Church in DuPont, Washington. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Crooks.

44 “Community Singing at Theaters Tonight.” Morning Olympian, April 18, 1918.

45 “Beware! For Fido Danger is Waiting.” Morning Olympian, March 23, 1918.

46 “Girl Wins Stamp by Catching Dog.” Morning Olympian, March 26, 1918.

47 “Minute-Women Sell Many Liberty Bonds.” Morning Olympian, April 28, 1918.

48 Thurston County Liberty Loan Adjustment Committee, “Fourth Liberty

Loan Slacker List.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 26, 1918 and Morning Olympian, October 27, 1918.

49 Thurston County Liberty Loan Adjustment Committee, “Slacker List, Fourth Liberty Loan No. 1.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 15, 1918 and Morning Olympian, October 16, 1918.

50 Thurston County Liberty Loan Adjustment Committee, “Slacker List to Fourth Liberty Loan No. 3.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 17, 1918 and Morning Olympian, October 18, 1918.

51 Thurston County Liberty Loan Adjustment Committee, “Slacker List Fourth Liberty Loan No. 4.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 18, 1918 and Morning Olympian, October 19, 1918.

52 Thurston County Liberty Loan Adjustment Committee, “Fourth Liberty Loan Slacker List.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 26, 1918 and Morning Olympian, October 27, 1918.

53 “By a Young Poetess.” Morning Olympian, April 19, 1918.

54 “Food Saving Drive Winning in County.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 31, 1917.

55 “Housewives Slow in Signing Pledge Cards; County Falling Behind Quota.” Olympia Daily Recorder, November 5, 1917.

57 “Every Loyal Housewife to Sign Pledge During Conservation Campaign.” Morning Olympian, March 8, 1918.

58 “Third Food Pledge Card Drive Planned.” Olympia Daily Recorder, March 12, 1918.

59 “Help Make Olympia Prepared Tonight.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 19, 1917.

60 “Small Boys Object to Farming ‘Ball Parks;’ Will Be Warned by Police to Keep Off New Gardens.” Morning Olympian, May 9, 1917.

61 “Recipes.” Morning Olympian, July 21, 1918, page 4.

62 “Canning Exhibition is Complete Success.” Morning Olympian, June 28, 1917.

63 U.S. Food Administration, Washington State Library Director, News Letter (April 1918). A clipping is at the Olympia Timberland Public Library special collections. Parr and Marts are specified in “Library Displays New War Volumes.” Olympia Daily Recorder, November 20, 1917, page 4.

64 “Red Cross Chapter Began in Wartime.” Morning Olympian, November 5, 1922, page 8.

56 “2,829 Food Pledge Cards Are Signed.” Morning Olympian, January 15, 1918.

65 Louise Ayer, “A History of the Thurston County Chapter American Red Cross February 18, 1917 to August 1, 1919.” From Washington State Historical Society. America Red

Olympia resident Elizabeth M. McDowell created “Allie-Patriot Games” with brotherin-law Frederick Mellor. The “thoroughly patriotic” game rivaled modern strategy games, with 40 pages of instructions. This advertisement from the December 19, 1917 issue of the Morning Olympian described how McDowell began creating the game before America entered the war. She filed for copyright, but the game was not a success. No copies of the game are known to have survived. In May 1918, Lt. Governor Louis Hart appointed McDowell as Washington State’s representative to a Philadelphia meeting of the League to Enforce Peace, a group that supported peace efforts such as the League of Nations. Image courtesy of the Washington State Library.

Cross, Thurston-Mason Chapter Records MS 108. Box 1, Folder 1 (Report Thurston-Mason ARC Historical Notes for 1917-1924.)

66 “Red Cross Xmas Drive to Start.”

Olympia Daily Recorder, December 11, 1917.

67 “Red Cross Drive Now Aimed After Double Minimum.” Olympia Daily Recorder, May 25, 1918.

68 “[No Title].” Olympia Daily Recorder, December 22, 1917. Mrs. Gunstone’s first name comes from the 1920 United States Federal Census.

69 Ayer, “History.”

70 “Red Cross Benefit a Success.” Morning Olympian, May 15, 1918.

71 “Thirty Angels of Mercy Work on Dressings that Will Bind Men’s Wounds.” Morning Olympian, February 21, 1918.

72 “Mrs. [Robert] Prickman on Her 73rd Sweater.” Morning Olympian, March 28, 1918.

73 “Two Ewes and Four Lambkins Arrive On State Lawn to Fatten and Thrive.” Olympian, May 10, 1918.

74 Jennifer Crooks, “Wool on Legs: The State Capitol’s World War I Sheep.” thurstontalk.com. Posted July 29, 2018.

75 Ayer, “History.”

76 Gordon Newell, Rogues, Buffoons and Statesmen: The Inside Story of Washington’s Capital City and the Hilarious History of 120 Years of State Politics, Olympia: Hangman’s Press, 1975, page 277.

77 “New Ship Plant Locates Here.” Morning Olympian, January 24, 1917.

78 “Sloan Shipyards to Build 12 Ocean Boats.” Morning Olympian, May 23, 1917.

80 “Improvements at Sloan Yards to Begin at Once.” Morning Olympian, June 10, 1917.

81 “Fire-proof Building for Capital City Iron Works.” Morning Olympian, May 18, 1917.

82 “Improvement is Begun at Capital City Iron Works.” Morning Olympian, June 28, 1917.

83 “Seven Per Cent Bonus For Workers.” Morning Olympian, May 27, 1917.

84 “To Outfit Ships Here.” Washington Standard, May 4, 1917.

85 “Shipyard Allowed to Build Offices.” Morning Olympian, October 17, 1917.

86 “Sloan Yard to Get Biggest Ship Knee.” Morning Olympian, November 29, 1917.

87 “Great Wooden Ship Takes First Dip.” Morning Olympian, July 22, 1917.

88 “Fido, Spotted Setter, Finds Home on the Schooner Wergeland; Will Sail Soon for an Australian Port.” Morning Olympian, January 13, 1918; “Wergeland Is Ready for Maiden Voyage.” Morning Olympian, March 5, 1918.

79 “Three Boxing Bouts at Shipyard Smoker.” Morning Olympian, January 27, 1918.

89 Greg H. Williams, The United States Merchant Marine in World War I: Ships, Crews, Shipbuilders and Operators Jefferson, N.C.; McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017, page 259.

90 Williams, Merchant Marine in World War I, page 269.

91 “‘Himoto’ Launched From Sloan Yards Yesterday.” Morning Olympian, December 20, 1918.

92 “Recent Launchings” in The Nautical Gazette 95 no. 18 (May 3, 1919), page 296.

93 “Recent Launchings” in The Nautical Gazette 95 no. 21 (May 24, 1919), page 344.

94 “Employes [sic] Go Out at Shipyards Over Wages.” Morning Olympian, October 17, 1917.

95 “Shingle Weavers Win.” Morning Olympian, October 18, 1917.

96 “Situation at Yards Gets No Change Yesterday.” Morning Olympian, October 18, 1917.

97 “Workmen Return to Work at Sloan’s.” Morning Olympian, February 19, 1918.

98 “Fraud is Charged in Shipyard Hearing.” Morning Olympian, October 19, 1917.

101 “Sold for $1 As Junk $180,000 Hull Sinks Sullenly in Harbor.” Morning Olympian, February 7, 1920.

102 Newell, Rogues, Buffoons and Statesmen, page 286.

103 Marsland, Report, page 5.

104 “Airplane Over Bush Prairie Seen Daily,” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 10, 1917 and “Farmer [Nate Trosper] Declares He Sees Airplane.” Olympia Daily Recorder, April 9, 1917.

105 “Wireless Station at the City Park?” Morning Olympian, June 13, 1917.

106 “Will Make Record of Powder Sales.” Morning Olympian, April 9, 1917.

107 John C. Scott, O.S.B., This Place Called Saint Martin’s 1895-1995: A Centennial History of Saint Martin’s College and Abbey. Lacey: Saint Martin’s Abbey, 1996, page 95.

99 Williams, Merchant Marine in World War I, 259.

100 “Sloan Shipyards Suit Dismissed By Federal Court.” Morning Olympian, October 6, 1920.

108 Edwin Twitmyer, “High School Inspector’s Report: Enrollment in High School Subjects from Reports of 330 High Schools,” in Washington State Department of Education, TwentySecond Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction for the Biennium June 30, 1914. Olympia, 1914, page 52.

109 Mark Sontag, “Fighting Everything German in Texas, 1917-1919.” The Historian 56 no. 4 (August 2007), pages 655-670, 667.

110 “State Board of Education Proceedings: High School,” in Washington State Department of Education, Twenty-Fourth Biennial Report of Superintendent of Public Instruction for the Biennium Ending June 30, 1918. Olympia, 1919, page 52.

111 “State Board of Education Proceedings: High School.”

112 “New Teachers Are Engaged.” Morning Olympian, July 12, 1908.

113 “South Bay Teacher Declared Disloyal.” Washington Standard, January 25, 1918.

114 “Review Carr Case.” Olympia Daily Recorder, February 4, 1918.

115 “Revoke Carr’s License.” Olympia Daily Recorder, February 12, 1918.

116 “Carr Drops Appeal.” Washington Standard, June 21, 1918.

117 Death Certificate for Charles Carr, March 11, 1922, Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics, Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, State of Idaho.

118 “Women Prepare for Service of Country.” Morning Olympian, April 5, 1917. Early members included future Minute Women Mrs. Fred Guyot and Mrs. R.L. Fromme.

vas for a statewide canning census. The article also listed Mrs. M. J. Chadwick (a Minute Woman) as chairman for the league the previous year. Mrs. Chadwick is included as a member in the Thurston County Association, “Member List,” page 2.

120 Barbara J. Steinson, American Women's Activism in World War I. New York, NY: Garland Publishing, 1982, page 377.

121 Steinson, Activism, page 325.

122 Blair, Report, page 82.

123 Virginia R. Boynton, “ ‘Even in the Remotest Parts of the State’: Downstate ‘Woman’s Committee’ Activities on the Illinois Home Front during World War I.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 96, no. 4 (Winter 2003/2004): pages 318-346, 346.

124 “Uncle Sam Asks Measurements of Babies.” Morning Olympian, July 23, 1918.

125 “Olympia Babies O.K.” Olympia Daily Recorder, July 25, 1918.

126 Mowell, Final Report, pages 2-3.

127 “Women Campaign for Signers on Food Pledge Cards.” Morning Olympian, November 3, 1917.

119 “Take Canning Census.” Olympia Daily Recorder, March 29, 1918. A different article stated that the group was planning a house-to-house can-

128 “Third Food Pledge Card Drive Planned.” Olympia Daily Recorder, March 12, 1918.

129 Marsland, Report, page 8.

130 “Olympians in Celebration.” Olympia Daily Recorder, November 8, 1918.

131 “World Celebrates End of Great War.” Washington Standard, November 15, 1918.

132 “Tenino’s Big Peace Demonstration.” Tenino News, November 14, 1918. The song was to the tune of “Battle Cry of Freedom:” “Oh! The Prussians started out to conquer every land, Shouting for Kultur and Kaiser. But when they struck the Yanks they had too much on hand

Shouting for Kultur and Kaiser!

Chorus: U. S. forever! They cannot put us down! No more the nations will tremble at the frown

Of the War Lord Kaiser, for he had lost his crown

To the scrapping Yanks and their Allies.

Oh, the Kaiser abdicated, it was his only chance

Shouting for the Yankies [sic] and their Allies

The red flag flies in Hamburg, the Stars and Stripes in France

Shouting for the Yankies [sic] and their Allies!”

134 “Minute Women to Aid Red Cross Campaign.” Olympia Daily Recorder, December 14, 1918.

135 Marsland, Report, page 8.

136 State Council, Report, page 2.

137 Marsland, Report, page 8.

138 Stevenson, “Minute Women.”

139 “Organization of County Minute Women Formed.” Morning Olympian, March 11, 1920.

140 Minute Women Association of Washington, Constitution. Minute Woman Association of Washington Papers, MSSC 72, Box 1, Folder 1, Washington State Historical Society Collection, Tacoma, WA, Article II, Section 1.

141 “Twelve Years of Patriotic Work Ends.” The Seattle Daily Times, October 31, 1930.

142 Stevenson, “Minute Women.”

143 For example, “USO Hostess Calendar.” The Daily Olympian, November 4, 1942, “USO Hostess Calendar.” The Daily Olympian, August 4, 1943 and “USO Hostess Calendar.” The Daily Olympian, April 2, 1945.

133 “Report Shows How Funds Were Raised in Campaign.” Morning Olympian, November 30, 1918. This was mostly in cash rather than pledges.

144 “Cookie Jar Arranged For New USO Building.” The Sunday Olympian, February 15, 1942.

145 Crooks, Jennifer, “Patriotism & Paranoia: The Thurston County Mi-

nute Women of World War I,” Columbia 31 no. 3 (Fall 2017): pages 22-26, 26.

146 “Germans in Olympia Are Called Home.” Morning Olympian, August 4, 1914 and “German Soldier To Return Here.” August 13, 1914. They were George Schutt, an employee of the Mottman Mercantile Company, and Ernest Glaser, nephew of Leopold Schmidt. Glaser even traveled to New York to catch a ship. He later served in the National Guard and became an American citizen. “In Love With America, Prepares to Fight For Ideals After 4 Year Residence.” Morning Olympian, September 5, 1917.

147 “Third Draft Contingent Goes Today; Elaborate Demonstration.” Morning Olympian, October 3, 1917.

148 “Soldiers Will Help Keep Olympia Clean.” Morning Olympian, December 6, 1917.

149 “Let Soldiers Know Library Keeps Open.” Morning Olympian, December 5, 1917.

150 “Soldiers Suffer from Hospitality.” Morning Olympian, January 23, 1918.

151 “German Gas Mask Reaches Olympia.” Morning Olympia, August 30, 1918.

153 “Homeward Bound After Serving Two Years in France With Canadians.” Morning Olympian, February 20, 1918.

154 “Thurston County’s First Soldier Dead Sent Home.” Morning Olympian, May 11, 1920.

155 “To Honor Men Who Gave Lives During the War.” Olympia Daily Recorder, October 27, 1919.