JApplPhysiol 138:720–730,2025. FirstpublishedJanuary20,2025;doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00396.2024

JApplPhysiol 138:720–730,2025. FirstpublishedJanuary20,2025;doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00396.2024

AnnekaE.Blankenship,1,2 RileyKemna,1,2 PaulJ.Kueck,1,2 CaseyJohn,1,2 MichelleVitztum,3 LaurenYoksh,4 JonathanD.Mahnken,1,4,5 EricD.Vidoni,1,2 JillK.Morris,1,2 and PaigeC.Geiger1,6

1UniversityofKansasAlzheimer’sDiseaseResearchCenter,UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter,Fairway,Kansas,United States; 2DepartmentofNeurology,UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter,KansasCity,Kansas,UnitedStates; 3KUDiabetes Institute,DepartmentofInternalMedicine,UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter,KansasCity,Kansas,UnitedStates;

4DepartmentofBiostatisticsandDataScience,UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter,KansasCity,Kansas,UnitedStates;

5FrontiersClinicalandTranslationalScienceInstitute,UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter,KansasCity,Kansas, UnitedStates;and 6DepartmentofCellBiologyandPhysiology,UniversityofKansasMedicalCenter,KansasCity,Kansas, UnitedStates

Abstract

Impairedglycemiccontrolincreasestheriskoftype2diabetes(T2D)andAlzheimer’sdisease(AD).Heattherapy(HT),viahot waterimmersion(HWI),hasshownpromiseinimprovingsharedmechanismsimplicatedinbothT2DandAD,likebloodglucose regulation,insulinsensitivity,andinflammation.ThepotentialforHTtoimprovebrainhealthinindividualsatriskforADhasnot beenexamined.ThispilotstudyaimedtoassessthefeasibilityandadherenceofusingHTincognitivelyhealthyolderindividualsatriskforADduetoexistingmetabolicriskfactors.Participantsunderwent4wkofHT(threesessions/week)viaHWI,alongsidecognitivescreening,self-reportedsleepcharacterization,glucosetolerancetests,andMRIscanspre-andpostintervention. Atotalof18participants(9males,9females;meanage:71.1±3.9yr),demonstratingmetabolicrisk,completedtheintervention. Participantadherenceforthestudywas96%(8missedsessionsoutof216totalsessions),withonestudy-relatedmildadverse event(milddizziness/nausea).Overall,theresearchparticipantsrespondedtoapostinterventionsurveysayingtheyenjoyedparticipatinginthestudyanditwasnotaburdenontheirschedules.SecondaryoutcomesoftheHTinterventiondemonstratedsignificantchangesinmeanarterialpressure,diastolicbloodpressure,andcerebralblood flow(P < 0.05),withatrendtoward improvedbodymassindex(P ¼ 0.06).Futurestudies,includinglongerdurationsandathermoneutralcontrolgroup,areneeded tofullyunderstandheattherapy’simpactonglucosehomeostasisandthepotentialtoimprovebrainhealth.

NEW&NOTEWORTHY

Ourpilotstudydemonstratedpromisingresultsforheattherapy(HT)viahotwaterimmersioninolder adultsatriskforAlzheimer’sdiseaseduetometabolicfactors.Despitearelativelyshortintervention,significantimprovementsin meanarterialpressure,diastolicbloodpressure,andcerebralblood flowpostinterventionwereobserved.Highparticipantadherence,overallsatisfaction,andminimaladverseeventssuggestHT’sfeasibility.These findingshighlightHT’spotentialasan effectivealternativeinterventionforcardiometabolicdysfunctioninat-riskpopulations.

Alzheimer’sdisease;glucosemetabolism;heattherapy;hotwaterimmersion;metabolicdysfunction

Alzheimer’sdisease(AD)isthemostprevalentneurodegenerativedisorderandby2060,thenumberofaffectedindividualsispredictedtoreach13.8millionworldwide(1).Although theetiologyofADisnotfullyunderstood,mechanismssuch asimpairedenergymetabolism,cellularbioenergeticdysfunction,reducedintracellularproteinhomoeostasis,andinflammationareallpotentialcontributors(2–6).Thelinkbetween metabolicdysfunctionsandAD(7),particularlyimpairedglucosemetabolism(8),suggestsacriticalintersectionbetween metabolichealthandneurodegenerativediseaseprogression.

Elevatedglucoselevels,forexample,correlatewithincreased cerebralamyloiddeposition ahallmarkofAD andreduced amyloid b (Ab)catabolism,indicatingthatinterventionstargetingmetabolichealthcouldplayacrucialroleinmanaging ADrisk(9–13).Arecentlycompletedexercisepreventiontrial incognitivelyhealthyolderadultsatriskforADshowedthat longitudinalincreasesinfastingglucoseoveroneyearwere associatedwithregionalincreasesinbrainamyloid(10).This researchsuggeststhatglucoseregulationmaybeanimportant therapeutictargetforAD.

TraditionallifestyleinterventionsforADfocusonsymptommanagementandslowingdiseaseprogression.Aerobic

Correspondence:P.C.Geiger(pgeiger@kumc.edu). Submitted28May2024/Revised26June2024/Accepted9January2025

8750-7587/25Copyright

exercisehasshownefficacyinimprovingfunctionalabilities andpotentiallyenhancingcognitiveoutcomesinindividuals withADbymitigatingassociatedriskfactorssuchascardiovasculardisease,obesity,andtype2diabetes(T2D)(14–18). Thebenefitsofaerobicexercisetrainingonbrainhealth likelyoccur,atleastinpart,throughincreasedcerebral blood flow(19),acriticalvascularmeasurethatdeclineswith age(20, 21).However,thelowadherenceratestoexercise, particularlyamongolderadults withonly14%engaging sufficiently limititswidespreadapplicability(22).

Heattherapy(HT)viahotwaterimmersion(HWI)has emergedasapromisingalternativetherapeuticstrategy.From theinitialworkbyDr.Hooperin1999(23)demonstratingthat threeweeksofHWIsignificantlyloweredbloodglucoseand glycatedhemoglobin(HbA1c)inasmallgroupofindividuals (fivemenandthreewomen,agerange43–68yr),thereare nowanumberofstudiesdemonstratingbenefitsofHTonglucoseregulation.Interventionsrangingfrom2–10wkofHTvia HWIresultedinreductionsinfastingglucoseand/orglucose responsetoanoralglucosetolerancetestinindividualswith obesityand/ortype2diabetes(23–25).Obesewomenwithpolycysticovariansyndromedemonstrateddecreasedfastingglucoseandimprovedglucosetolerance,aswellasreduced sympatheticactivityandimprovedcardiovascularriskprofiles followingrepeatedsessionsofHWI(24, 26).HWIhasdemonstratedsignificantmetabolicandcardiovascularbenefits acrossvariouspopulations(24, 26–32)andhasbeenshownto haveanti-inflammatoryeffects,includingacuteincreases inbeneficialcytokines(33).HWIimprovesfastingglucoseand insulinlevelsinwayssimilartotheeffectsofexercise(34), makingitparticularlyattractiveforindividualsunabletoparticipateintraditionalphysicalactivities(23, 33).Amongtheelderlypopulation,ademographicatheightenedriskforAD, HWIhasbeenshowntobesafeandwell-tolerated.Ina12-wk study,elderlyindividualswithperipheralarterialdiseasewho underwentHWIshowedimprovementsinwalkingdistance andrestingbloodpressure(28).

ConsideringtheimpactofsystemicmetabolicdysfunctionsonADpathogenesis,andthedemonstratedbenefitsof HTonglucosemetabolism,thispilotstudyaimedtoevaluatethefeasibilityandadherenceforaregimenofHWIheat therapyamongcognitivelyhealthyolderadultsatmetabolic riskforAD.WehypothesizedthatHTviaHWIwouldbea feasibleinterventionforthispopulationwithheatresulting inimprovementinperipheralglucosemetabolism,blood pressure,andanthropometricoutcomessuchasbodyweight andbodymassindex.Our findingssuggestheattherapymay beaviablealternativetotraditionalexercisemodalitiesfor individualsatriskforAD.

TrialDesign

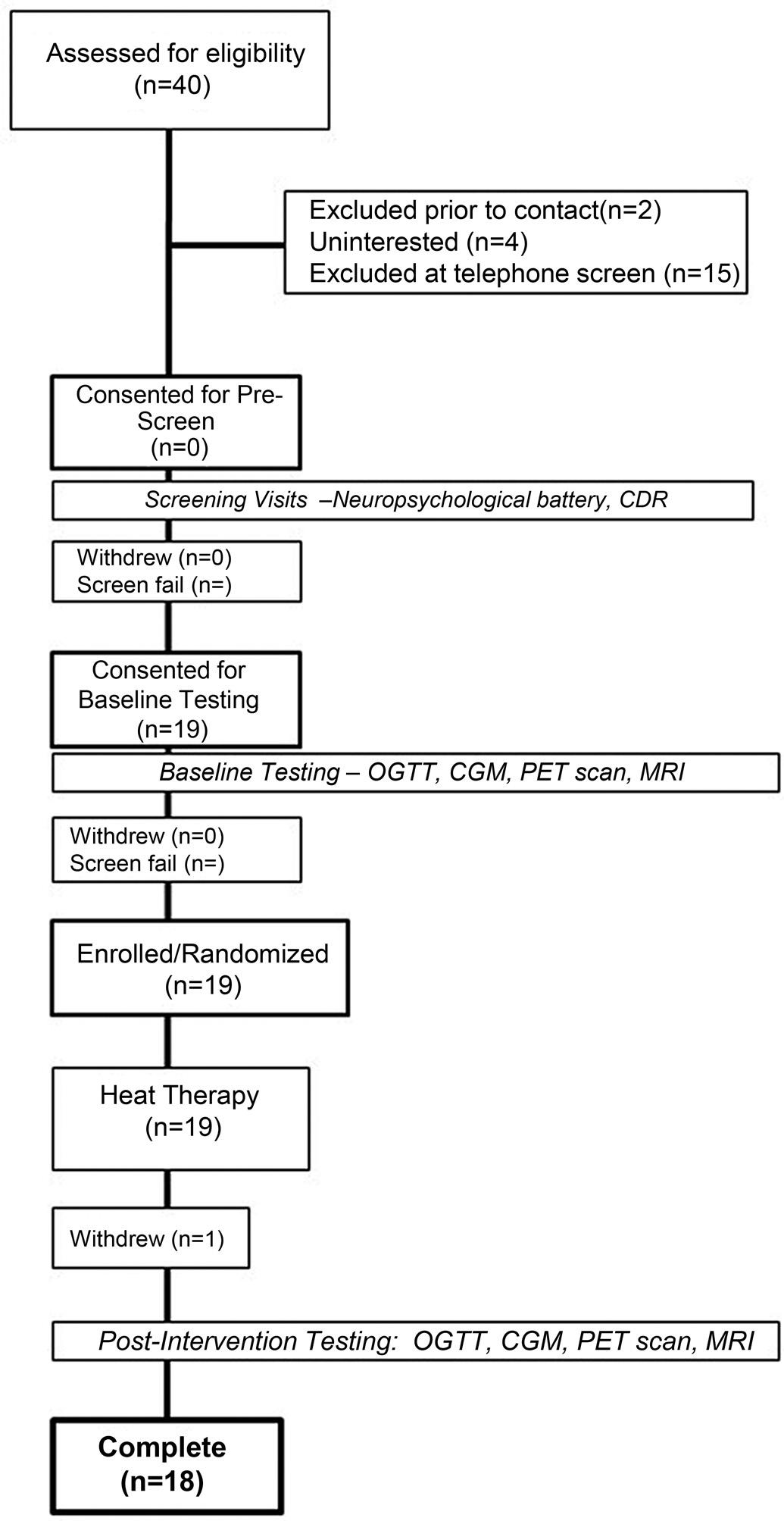

Thisinterventionalpilotstudycharacterizedthefeasibility ofandadherencetoHTincognitivelyhealthyolderadults (65 þ yr)whoareatriskforADduetometabolicfactors. Figure1 presentstheCONSORTdiagram,whichoutlinesthe flowofparticipantsthrougheachstageofthestudy.Allparticipantswererequiredtohaveastudypartner(someonewho routinelyinteractswiththeparticipantmorethan fivetimesa

Figure1. CONSORTdiagramshowingthe fl owofparticipantsthrough thestudy,includingrecruitment,screening,enrollment,intervention,and follow-up.CDR,clinicaldementiarating;CGM,continuousglucosemonitor;MRI,magneticresonanceimaging;OGTT,oralglucosetolerancetest.

week)tobeavailabletospeakwiththestudyteamviatelephoneabouttheprospectiveparticipant’sfunctionalperformanceduringtheQuickDementiaRatingSystem(QDRS) questionnaire(35).Thestudypartnerwasconsentedoverthe phone.Followingprescreening,informedconsent,andenrollmentintothestudy,participants(n ¼ 18)underwentafasting blooddraw,oralglucosetolerancetest(OGTT),andamagneticresonanceimaging(MRI)scan.Followingthispreinterventionevaluation,participantsreceivedHTthreetimesa weekforfourweeks.Afterthecompletionofheattreatments, subjectsrepeatedthesameassessments.Activitieswerecondensedintothefewestpossiblevisitstoreduceparticipant

burdenandtoallowthecaptureofkeymarkersintheirtemporalrelationshipfollowingarigorous,time-sensitiveprotocol.The flowofthestudyisillustratedin Fig.2

Outcomemeasures.

Thecoprimaryoutcomesofthispilottrialwerefeasibilityof theintervention(numberofHTsessionsattended)andadherencetotheintervention(numberofHTsessionscompletedoncestarted).Secondaryoutcomesincludedchanges inperipheralglucosemetabolism,bloodpressure,andanthropometricoutcomessuchasbodyweightandbodymass indexfollowingtheintervention.Exploratoryoutcomes includedneuroimagingmeasuresofbrainblood flowand self-reportedsleepcharacterizationforpreliminarycharacterizationofintervention-relatedchanges.

ParticipantswererecruitedthrougharegistryofvolunteersattheUniversityofKansasAlzheimer’sDisease ResearchCenter(KUADRC).Writteninformedconsentwas obtainedfromallparticipantsaftertheyreceivedbotha verbalandwrittenbriefingofallexperimentalprocedures onthedayoftheir firstvisit.Eligibleparticipantswereaged 65yrandolder,hadnoreportedhistoryofcognitiveimpairment,andhadahistoryoforcurrentmetabolicimpairment [i.e.,adiagnosisofprediabetesorT2D,oratleasttwoofthe followingcriteria:hypertension,dyslipidemia,bodymass index(BMI) 30].Additionalinclusionandexclusioncriteriaaredetailedin Table1.Thisstudywasapprovedbythe InstitutionalReviewBoardattheUniversityofKansas MedicalCenter(IRBSTUDY00147446).

Thelistofproceduresateachstudyvisitisgivenin Table2. Participantsunderwentaphonescreeningthatincludedthe QDRSquestionnaireandthecollectionofbasicdemographic information.Oncedeemedeligible,participantscompletedall subsequentscreeningproceduresandtwoin-personpreinterventionstudyvisits(OGTTandMRIscan).Aftercompleting thepreinterventionvisits,individualsattendedapproximately threeHTsessionsperweekfor4wk,totaling12sessions, beforecompletingtwopostinterventionstudyvisits(OGTT andMRIscan).Allvisitswerecompletedwithinapproximately 5wk.Eachstudyvisitisdetailedbelow.

Preinterventionvisit1.

TheOGTTvisitwasscheduledforthemorningafterparticipantshadfastedovernight.UpontheirarrivalattheKU ClinicalandTranslationalScienceUnit(CTSU),fullyinformed, writtenconsentwasobtainedforthein-personvisits.Their medicalhistorywasthencollected,alongwithcurrentmedicationsandanthropometricmeasures,includingheightand weight,beforestartingtheOGTT.Participantswereaskedto restquietlyandseatedfor5min,duringwhichheartrateand bloodpressureweremeasured.Subsequently,anintravenous catheterwasinsertedforbloodcollectionthroughoutthestudy visit.Tomaintainconsistencyacrossalltrialsandaccurately recordanydeviationsfromtheplannedschedule,allvisit activitiesweretimed.

Afterplacingtheintravenouscatheter,abaselineblood samplewastaken.Participantswerethengivenacommerciallyavailableoralglucosebeverage,containing75gof glucose,whichtheyconsumedwithin5min.Timingbegan

temperature increasesby 1°C

and coretemperaturemeasuredpre-interventionat rest,every10minutes duringintervention,and postintervention atrest.

BloodDraw OGTT (upto72hpost finalheat therapy intervention)

(atleast7 days following finalheat therapy intervention)

3x/weekfor4 weeks

Figure2. Study flowdiagramfortheFIGHT-ADpilotstudy.Followingconsent,participantsunderwentpreinterventionevaluations,includingafasting blooddraw,anoralglucosetolerancetest(OGTT),andamagneticresonanceimaging(MRI)scan.Participantsthenreceivedheattherapythreetimesa weekfor4wk.Eachheattherapysessionbeganwiththeparticipantfullyimmersedinthehotwateruptoshoulderleveluntiltheircorebodytemperatureincreasedby1 Cor30minhadelapsed,atwhichpointimmersionwasreducedtowaistlevel.Heartrate(HR),bloodpressure(BP),andcoretemperatureweremeasuredbeforeenteringthehottub,every10minduringimmersion,and10minafterexiting.Uponcompletingtheheattherapyregimen, participantsunderwentthesamesetofevaluationstoassesspostinterventionchanges.AD,Alzheimer’sdisease.

JApplPhysiol doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00396.2024 www.jappl.org

Table1. Studyinclusion/exclusioncriteria

InclusionCriteria

ExclusionCriteria

InformedconsentClinicallysignificantchronicdiseaseb Menandwomen65yrandolderACSMriskscorestratificationof “High” unlessclearedbytheirphysicianbeforeparticipation

Stablemedicationdose(>1mo)Diagnosisoftype1diabetesmellitus Postmenopause(females)InabilitytoundergoMRIscan Diagnosisofmetabolicimpairmenta

Diagnosisofrecentmyocardialinfarctionorsymptomsofcoronaryarterydisease(<2yr)

Neurologicaldiseaseimpairingcognitionorbrainmetabolismc Clinicallysignificantdepressivesymptomsthatmayimpaircognition

Useofpsychoactiveandinvestigationalmedications

Significantvisualorauditoryimpairment

Orthopediccomplicationsthatwouldprecludeindividualsfromsafelyenteringahottub Untreatedhypothyroidismordiseasesassociatedwithheatintoleranced

Priordiagnosisofcognitiveimpairment

Contraindicationfortemperaturepillingestione

ACSM,AmericanCollegeofSportsMedicine. aThisincludessuchdiseasesasmetabolicsyndrome(atleasttwoofthefollowingcriteria:hypertension,dyslipidemia,BMI 30),prediabetesortype2diabetes; bThisincludesdiseasessuchascancer,HIV,oracquiredimmunodeficiencysyndrome; cThisincludesdiseasessuchasAlzheimer’sdisease,Parkinson’sdisease,strokedefinedasaclinicalepisode withneuroimagingevidenceinanappropriateareatoexplainthesymptoms; dThisincludesdiseasessuchasGraves’ disease; eThis includesdiseasessuchasinflammatoryboweldiseaseorrelated.

immediatelyafterthey fi nishedthebeverage.Bloodsampleswerecollectedatintervalsof30-,60-,and120-min postconsumption.TheOGTTconcludedwitha10-minobservationperiodfollowingthe fi nalblooddraw.TheSleep/ Circadian[PittsburghSleepQualityIndex(PSQI)]and GeriatricDepressionScale(GDS)surveyswereadministeredtoparticipantsduringbothOGTTvisits,beforeand aftertheHTintervention.

Preinterventionvisit2.

MRIscanswereperformedpre-andpostintervention(Skyra, Siemens,Erlangen,Germany).AT1-weighted,three-dimensional(3-D)magnetization-preparedrapidgradientecho (MPRAGE)structuralscanwasacquiredfordetailedanatomicalassessment[repetitiontime(TR)/echotime(TE) ¼ 2,300/ 2.95ms,inversiontime(TI) ¼ 900ms, fl ipangle ¼ 9 , fi eld ofview(FOV) ¼ 253 270mm3 ,matrix ¼ 240 256voxels, voxelin-planeresolution ¼ 1mm2,slicethickness ¼ 1.0mm, 176sagittalslices,in-planeaccelerationfactor ¼ 2,acquisition time ¼ 5:12].Apseudo-continuous,backgroundsuppressed,3Dgradient,andspinechoarterialspinlabeling(pCASL) sequenceprotocolwasacquiredtomeasurecerebralblood fl ow(TE/TR ¼ 22.4/4,300ms,FOV ¼ 300 300 120mm 3 , matrix ¼ 96 66 48,postlabelingdelay ¼ 2s,4-segmented acquisitionwithoutpartialFouriertransformreconstruction, readoutduration ¼ 23.1ms,totalscantime5:48,2M0images). ThepreinterventionMRIscanwasperformedbeforetheuse ofingestibleheatsensorsandthefollow-upscanwasperformedatleastsevendaysfollowingthe finalHTsessionto

allowforthe finalcoretemperaturesensortopassthrough thegastrointestinaltract(GI)tract[see Heattherapyinterventionvisits(4wk)].Theparticipantwascheckedusingtherespectivereceivingdeviceforanyingestedtelemetricpill.

MRIanalysisprotocolshavebeendescribedpreviously (36).Briefly,wecreatedindividualizedgraymatterregions ofinterest(wholebrain,hippocampus,andcerebellumasa referenceregion)foreachparticipantusingtheStatistical ParametricMappingCAT12(neuro.uni-jena.de/cat,r1059 2016-10-28).Wemotion-correctedlabeledandcontrolpCASL imagesseparately,realigningeachimagetothe firstpeer imagefollowingM0imageacquisition.Cerebralblood flow (CBF)wascalculatedwithsurroundsubtractionofeach label/controlpairwithoutbiopolargradientswhichwere thenaveraged.Subtractionimageswerethencoregisteredto theanatomicalCSFsegmentedimageandsmoothedusinga 6-mmfull-width,half-maximumGaussianwindow.

Heattherapyinterventionvisits(4wk). ParticipantsattendedHTsessionsthreetimesweeklyfor 4wk.AteachvisittotheCTSU,coretemperaturewas monitoredusinganingestibletemperaturesensor(telemetricpill,HQInc.,Palmetto,FL).Onceingested,thepill traveledthroughtheGItractandtransmittedtemperature toareceivingdeviceoutsideoftheparticipant’sbody.The pilltypicallypassedthroughtheparticipantwithin2– 3 bowelmovements.Ateachsubsequentvisit,thecoretemperaturesensor’saccuracywascheckedagainsttheparticipant ’sprevioussessiondata.Ifthesensor’ssignalwas

intact,nonewsensorwasprovided.Whennosignalwas present,anewsensorwasingested,followedbya30-min restperiodtoensuresignalstabilitybeforeproceeding. Duringthesession,participantswereimmerseduptotheir shouldersina40 Cwatertherapybathuntiltheircore bodytemperature(Tc)increasedby1 C,or30minhad elapsed.Althoughthereissomevariabilityintheincrease inTcbetweenparticipants,the30-minmaximumtime fortheinitialheatingmaintainedamaximalheatdose throughoutthestudy.Participantsthenremainedinthe hottubsubmergedtowaistleveltomaintaintheirTcfor anadditional15min,totaling45min.FollowingHT,participantsexitedthehottubandweremonitoredfor10min oruntiltheirTcreturnedtobaseline.

Signsandsymptomsofheat-relatedillnesswerecontinuouslymonitoredbystudystaff.Heartrateandbloodpressuremeasurementsweretakenevery10minduringthe interventionsessiontoensureadequatehydrationandcirculation.Ifaparticipant’sheartrateincreasedbymorethan60 beats/minaboverestingorincreasedbymorethan20beats/ minwithina5-minperiod,theparticipantwasmovedtoa seatedpositioniftheywerepreviouslyfullysubmerged,or removedfromthehottubiftheywerealreadysittingup.If thebodytemperaturereached39.5 C,ortheparticipant experiencedsymptomsofheat-relatedillness,a “Rapid CoolingProtocol” wasimplemented.Participantswere allowedtodrinkwateradlibitumduringthesession.Ifthe participant’sTcwasaffectedbydrinkingwater,repeatmeasurementsweretakenuntilthetemperaturenormalizedto ensureaccurateTcreadings.Bodyweightwasmeasured beforeandimmediatelyafterHTinallsessionstomonitor hydrationlevels.Participantswhodidnotdrinkenough watertocompensateforsweatloss(bodyweightloss > 1%) wererequiredtodrinkadditional fluidstomakeupthisdifferencebeforeleavingthevisit.

Postinterventionvisits.

UponcompletionoftheHTintervention,apostinterventionOGTTwasperformedaspreviouslydescribed.The postinterventionOGTTwasperformedwithinapproximately3daysofcompletingthe finalHTintervention visit.Atthisvisit,participantsprovidedfeedbackthrough asurveyregardingtheirperceptionoftheHTintervention (see TableA1 forsurveyquestionsandresults).TheMRI scanwasperformedonaverageninedaysfollowingthe fi nalHTinterventionvisit.

Atthebaselineblooddrawduring visit1 preintervention, wholebloodwascollectedinanacidcitratedextrose (ACD)yellowtopvacutainertube(8.5mL)specifi callyfor apolipoproteinE4(ApoE4)genotyping.ApoEgenotyping wasperformedasdescribedpreviously(36 ).Subsequently, atbothbaselineandthreeadditionaltimepointsduring eachOGTTvisit,bloodwasdrawnintoEDTAlavendertop vacutainertubes(10mL)usedforplasmacollection.Our previouslyreportedoptimizedsamplecollectionandprocessingprocedurestoensureaccurateandconsistentcollection ofbothplatelet-richplasma(PRP)andplatelet-poorplasma (PPP)wasused(37).PRPwasgeneratedbycentrifugingwhole

bloodat1,500 g for10minat4 C,followedbycarefulplasma removal.PPPwasobtainedfromanaliquotofPRPthroughan additionalcentrifugationstepat1,700 g for15minat4 C,performedduringthebaselineblooddrawateachOGTTvisit. GlucoselevelswereimmediatelyanalyzedinPRPusingaYSI analyzer,whereasHbA1clevelswereanalyzeddirectlyin wholebloodfromtheACDtubeusingtheSiemensDCA VantageAnalyzer.Afterprocessing,aliquotsofwholeblood, PRP,andPPPwereimmediatelyfrozenandstoredat 80 C forfutureanalyses.

TheSimoaHD-X(Quanterix)wasusedtoquantifymarkers ofADneuropathology,includingplasmaamyloid b 42/40ratio(Ab42/40),phosphorylatedTau181(pTau181),neurofilamentlight(NfL),andglial fibrillaryacidicprotein(GFAP). PlasmaAb42/40isanestablishedproxyforbrainamyloid(38, 39),andplasmapTau181isknowntocorrelatewithADseverityandbrainimagingmarkersoftaupathology(40–42).NfL isaplasmamarkerofneurodegeneration(43)thattrackspositivelywithage.Earlyastrocytosissecondarytoamyloid-b pathologyisdetectedbyplasmaGFAP(44).Forthisstudy,we usedthepTau181(v2)andneuro4plexE(N4PE)kitsfor fluid biomarkeranalyses,withN4PEusedspecificallytoanalyze Ab42/40,NfL,andGFAP(Quanterix).Thegoaloftheseanalyseswastoprovideabaselinebiomarkercharacterizationof thecohort.Allanalysesfollowedthemanufacturer’sinstructions,includingtheuseofappropriatestandardsandquality controlsamples(37).Allsampleswereprocessedinduplicate, andthemeanconcentrationofbloodbiomarkerswasrecorded foreachsample.ELISAmethodologyisusedtoanalyzemetabolicmarkers(insulin).

Primaryoutcomes.

Datawascollectedandanalyzedfor19subjects.Onesubject withdrewfromthestudyforreasonsunrelatedtothestudy’s requirements,andthedatacollectedonthatsubjectbefore droppingoutwasnotincludedinsubsequentanalyses.

TheprobabilityofasubjectattendingasingleHTsessionwasestimatedandaClopper – Pearsonexact95% con fi denceintervalwasconstructedfortheestimate.The probabilityofasubjectattendingall12HTsessionswas estimatedsimilarly.Wald95%con fi denceintervalswere alsoconstructedfortheestimatesofthesetwooutcomes.

One-samplepaired t testswereconductedforeachsecondaryoutcometoassessthedifferencesbetweenpost-HT andpre-HTvalues.Changevariableswerederivedbycalculatingthedifferencebetweenpost-HTandpre-HTvaluesforeachsecondaryoutcome.Ordinaryleastsquares regressionwasusedtomodelthechangeineachsecondaryoutcomeasafunctionofageandsex.Eachchange scorewasalsomodeledtoobtainanestimatedage-and sex-adjustedinterceptforthemodel,usingtheaverageage andtheproportionofmalestofemalesspeci fi ctothatsecondaryoutcome.AllanalyseswereconductedusingSAS Version9.4.Thefulldatasetwillbemadeavailableon HarvardDataversefollowingpublication.

Oneoftheinitial19recruitedparticipants,onewithdrew fromthestudyduetounrelatedeventsafterfourvisits.Itis noteworthythatthewithdrawnparticipantattendedand successfullycompleted100%oftheirvisits.Subsequent analyseswereconductedwiththisparticipantexcluded fromthedataset.Amongtheremaining18participants,the meanagewas71yr,and50%werefemale.Thecohortexhibitedconsiderablediversity,with28%identifyingwitha minoritizedracialorethniccommunity.Allparticipants wereclassifiedasbeingathighmetabolicrisk,evidentfrom averageHbA1cvaluesof48.5mmol/mL,averageBMIof 29kg/m2,and15outof18participantsusingantihypertensivemedications.Inthiscohort,ATNmarkersweremeasuredtoconfirmbaselinecognitivefunction,yieldingaverage valuesof0.07pg/mLforAb42/40,2.49pg/mLforpTau181, and18.30pg/mLforNfL.Allparticipantswereinitiallyidentifiedascognitivelyunimpairedduringrecruitment;however,aftertheadministrationofaGeriatricDepressionScale (GDS)questionnaireprovidedattheOGTTvisit,twoparticipantsscoredhighonthescale.Subsequentexclusionanalysesdemonstratedthattheseoutliersdidnotsignificantly impacttheoverallresults.Detaileddemographicinformationforthestudyparticipantsispresentedin Table3

Outofthe12scheduledHTsessions,theestimatedprobabilityofparticipantsattendinganygivenHTsessionwas 96.3%,withanexact95%confidenceintervalof92.8%to 98.4%.Outofatotalof216HTsessions,only8sessionswere missed.Onlysixparticipantsmissedoneormoresessions duetoextenuatingcircumstances:oneduetoasnowstorm,

Table3. Demographicandclinicalcharacteristicsof studyparticipants(n ¼ 18)

PatientCharacteristicsValue

Age,yr(means±SD)71.06(3.87)

Malesex, n (%)9(50.0)

Race, n (%)

Asian2(11.1)

BlackorAfricanAmerican2(11.1)

Anotherracialidentity1(5.6)

White13(72.2)

Hispanicethnicity, n (%)2(11.1)

Education,yr(means±SD)16.28(1.99)

ApoE4carrier, n (%)8(44.4)

Hypertensionmedication, n (%)15(83.3)

Diabetesmedication, n (%)11(61%)

HbA1c6.5%orgreater9(50%)

TotalQDRSscore(means±SD)0.72(0.84) NfL,pg/mL(means±SD)18.30(7.84) pTau181,pg/mL(means±SD)2.49(2.02)

Ab42/40,pg/mL(means±SD)0.07(0.01)

Thistablepresentscomprehensivedemographicandhealthrelatedcharacteristicsofthestudyparticipants.Meanage,educationlevel,totalQDRS(QuickDementiaRatingSystem)score,NfL (neurofilamentlight),pTau181(phosphorylatedTau181),and Ab42/40(amyloid b 42/40)arereportedalongwithcorresponding standarddeviations(SD)orpercents.Inaddition,thetable includesinformationonthedistributionofparticipantsbasedon sex,race,ethnicity,ApoE4carrierstatus,andtheuseofhypertensionmedication.

anotherbecauseofaminorcaraccidentthepreviousevening, andathirdmissedtwosessionsduringaCOVID-19isolation period.Allotherparticipantsattendedall12oftheirscheduledHTsessions.Thelikelihoodofattendingall12sessionswasestimatedat66.7%,witha95%con fi dence intervalrangingfrom41.0%to86.7%.TheWaldcon fidenceintervalsfortheseprobabilitiesweresimilar,at 93.8%–98.8%forattendanceatanysessionand44.9%–88.4%forfullattendance.Onceasessionwasinitiated,it wascompleted100%ofthetime.

Throughoutthestudy,fouradverseeventswerereported, ofwhichthreewereunrelatedtothestudyprotocol.The onerelatedadverseeventwasmild,characterizedbylightheadednessandnauseaduringoneoftheHTsessions. Overall,feedbackfromapostinterventionsurveywaspositive( TableA1 ),withparticipantsexpressingenjoyment andsatisfactionwiththeirinvolvementinthestudy.Most reportedthatparticipatingwasnotburdensomeontheir schedules,highlightingthestudy ’sminimalimpacton theirdailylives.

Thesecondaryoutcomesfromthepilotstudy,summarized in Table4,showedfavorablechangesinvascularmeasures, consideringageandsexdifferencesamongparticipants. Specifically,meanarterialpressure(MAP)significantly decreasedbyanaverageof6.6mmHg[standarddeviation (SD) ¼ 9.8, P ¼ 0.009]frompre-HTtopost-HT,measuredat restbeforetheparticipantsenteredthehottubatboththe firstandlastHTsessions,asshownin Fig.3A.Acute decreasesinMAPwerealsoobservedduringtheHTsession whileinsidethehottubatboththeinitialand finalvisits,as depictedin Fig.3B.Similarly,diastolicbloodpressuresignificantlydecreasedfrompre-HTtopost-HTbyanaverageof 6.8mmHg(SD ¼ 6.9, P < 0.001).

Postintervention,afteradjustingforageandsex,additional trendswerenoted.BMIpresentedaborderlinesignificant associationwithanaveragereductionof0.27kg/m2 (P ¼ 0.06).Bodyweight(BW)alsotrendedtowardanassociation, withadecreaseof0.67kg,thoughthistrendapproachedbut didnotachievestatisticalsignificance(P ¼ 0.09),again adjustedforageandsex.

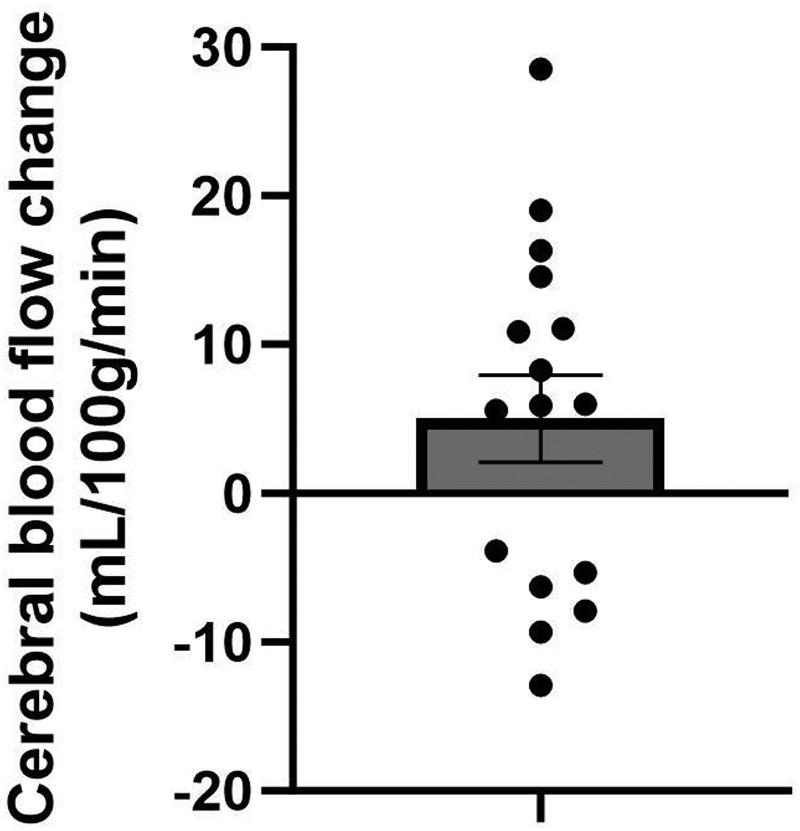

Intermsofexploratoryoutcomes,wholegraymattercerebralblood flowsignificantlyincreasedfrompre-HTtopostHT,averaging3.7mL/100gtissue/minincrease(SD ¼ 7.0, P ¼ 0.032),asdetailedin Fig.4.

UnderstandingthemetabolicimplicationsofHTiscritical giventherisingprevalenceofADandthelimitedsuccessof conventionaltreatments.ThispilotstudyexploredthefeasibilityandadherenceofHTinolderadultsatmetabolicrisk, addressingthegapinalternativeinterventionsforthisvulnerablecohort.Thecurrentcohort,equallysplitbetweenmale andfemaleparticipants,raciallyandethnicallydiverse,and 44%beingApoE4carriers,enhancesthegeneralizabilityof

Table4. Summaryofpre-andpostheattherapy interventionmeasurementswithchanges(D)and correspondingP-values

CONDITIONOVERALLP-VALUE

MAP,MMhGPre94(5.13)0.009

Post87(8.59)

D 6.62(9.83)

GLUAUC,MG/DLHPre26,200(6,070)0.359

BMI,KG/M2

Post27,100(7,320)

D 927(3,780)

Pre29.1(5.44)0.064

Post28.9(5.49)

D 0.270(0.556)

BW,KGPre82.7(19.9)0.089

Post82.0(19.9)

D 0.672(1.47)

HBA1C,MMOL/MOLPre48.5(7.2)0.229

Post46.1(9.5)

D 1.8(5.7)

SYSTOLICBP,MMhGPre131(8.34)0.125

Post125(15.4)

D 6.28(17.3)

DIASTOLICBP,MMhGPre76(5.96)0.0008

Post69(6.48)

D 6.78(6.91)

PSQIPre7.39(3.96)0.106

Post6.39(4.13)

D 1.00(2.63)

InsulinAUCPre2,057.5(4,854)0.335

Post2,536.6(4,840)

D 210.4(1,998)

HOMA-IRPre1.30(9.7)0.307

Post1.16(12.2)

D 0.24(1.9)

Thistablepresentsthepre-andpostinterventionmeasurements alongwiththechanges(D)observedforvariousparameters.Thevaluesrepresentmeans(standarddeviation)foreachcondition.The P valuesindicatethestatisticalsignificanceofthechangesobserved betweenpre-andpostinterventionmeasurementsadjustedforage andsex.Negativevaluesformeanchangeindicateadecreasepostintervention,whereaspositivevaluesindicateanincrease.MAP(mean arterialpressure),systolicBP(systolicbloodpressure),diastolicBP (diastolicbloodpressure)weremeasuredat firstheattreatmentsessionandlastheattreatmentsessionatrestbeforeenteringthehot tub.BMI,bodymassindex;BW,bodyweight;GluAUC,glucosearea underthecurve;HbA1c,glycatedhemoglobin;HOMA-IR,homeostaticmodelassessmentforinsulinresistance;PSQI,Pittsburghsleep qualityindex.

our findingsacrossadiversepopulationatriskforAD.The HTintervention threeweeklyHWIsessionsover4wk mirrorspotentialreal-worldapplications,addressingbothmetabolichealthandpotentialbarrierslikeexerciseadherence.

Key findingsdemonstratedahighprobabilityofparticipantsattendingHTsessions(96.3%),withonly8outof216 sessionsmissed.Notably,participantsfacingextenuating circumstances,suchasasnowstormorCOVID-19isolation, missedonlyafewsessions.Thisisconsistentwithprior studiesshowingexcellentadherencetoHT(45, 46),emphasizingitspracticalityandacceptance.Thebroadandinclusivenatureofthiscohort,coupledwithoverwhelmingly positivefeedbackfromparticipants,furthersupportsthat HTisnotonlyfeasiblebutalsowell-toleratedandenjoyable,crucialfactorsforlong-termadherence.

InthebroadercontextofHTliterature,thecurrentstudy demonstratesthefeasibility,adherence,andpotentialcardiometabolicbenefits particularlyintermsofbloodpressure withinahigh-riskpopulation.Despitethebrief4-wkintervention,signifi cantchangesinMAPanddiastolicblood pressure,aswellasslightchangesinbodycomposition, wereobserved.These fi ndingsreinforcethevalueofHTas aninterventionandsuggestthatitcanimpartmeaningful benefi tsevenwithinacondensedtimeframe.

ThereductionsobservedinMAPanddiastolicbloodpressurefollowing4wkofHTareconsistentwithimprovements inendothelialfunctionreportedinpreviousstudies(47–49), suggestingthatHTmaycontributetoenhancedvascular relaxation,reducedarterialstiffness,andprotectionagainst endothelialdysfunction.Individualswithhighmetabolic riskoftenexhibitimpairedendothelialfunction,commonly duetohypertensionorinflammation(50).Endothelialcells, whichlinebloodvessels,playacrucialroleinregulatingvasculartoneandprolongedinflammationcanimpairendothelialfunction(51).Priorstudiesindicateenhancedendothelial functionfollowingHT(52–55),whichcouldbeimpactfulfor olderadultswithcompromisedmetabolicfunction(24, 56–59).Ourresearchgrouphasmadeasignificantcontributionto theliteraturedemonstratingthebenefitsofHTinpreclinical models(60–65),andpotentialmechanismssuchasdecreased inflammation,improvedinsulinsignaling,andenhancedmitochondrialfunctionasaresultofheatshockprotein(HSP) activationneedtobeexaminedinhumans(66).

AnadditionalbenefitofHTassessedinthecurrentstudyas anexploratoryoutcomewasimprovedcerebralblood flow. Priorworkfromourresearchgroupdemonstratedthatina populationofbothAPOE4carriersandnoncarriers,anacute boutofaerobicexerciseincreasedcerebralblood flow(36).In addition,inolderadultswithpoorcerebrovascularhealth, hippocampalblood flowrapidlyincreasedfollowingabout

Figure3. Effectsofheattherapyonmeanarterial pressure(MAP). A:individualparticipantsatthe resting(outsideofthehottub,seatedrestbefore enteringthehottub)MAPvaluesattheinitialand finalheattherapysession.RestingMAPsignificantlyreduced(final-initial)followingtheheat therapyintervention. B:acutechangesofMAP whileinsidethehottub(showingtheeffectof heattherapyonbloodpressureacutelyduring thesession).Thereisasignificantdifferenceof MAPwithtimespentinthehottub. P < 0.05.

Figure4. Effectsofheattherapyoncerebralblood flow.Pre-topostchangeinwholegraymattercerebralblood flowmeasuredusingarterial spinlabeling.Barrepresentsmeans±SEwithindividualdatapointsplotted. n ¼ 16individuals.

ofmoderate-intensityexercise(67).Thebrainbenefitsof chronicaerobicexerciselikelyoccur,atleastinpart,through increasesincerebralblood flow(19).Theobservedincrease incerebralblood flowinthecurrentstudysuggestsapotentialforenhancedcerebraloxygenationandmetabolicsupportfollowingHT,whichcouldbeparticularlybeneficialfor olderadultswhomayhavecompromisedcerebrovascular health.This findingisconsistentwithpreviousresearch demonstratingmodificationofcerebrovasculardynamicsin responsetothermalexposurewithandwithoutexercise(68–70).However,comparisonsaredifficultaspriorstudies examinedthecerebralblood flowresponsetoacuteboutsof HWIandusedmeasuresofinternalandexternalcarotidarteryconductanceand/orshearstressusingultrasonography. UnderstandinghowHTinfluencescerebrovascularfunction, anditspotentiallong-termbenefitscouldprovidevaluable insightsintotherapeuticstrategiesforenhancingbrain healthinagingpopulations.Alargerclinicaltrialinthis samepopulationisongoinginhopesofaddressingtheseimportantoutcomes(Clinicaltrials.govNCT06023407).

AlthoughbaselinemeasurementsofAD-relatedbloodbiomarkers(Ab42/40,pTau181,NfL,andGFAP)werereportedto assessparticipants’ cognitivefunction,theirroleinunderstandingtheoverallimpactofHTonmetabolichealthremains animportantareaforfutureresearch.Moredetailedanalyses ofthesebiomarkersbeforeandafterHTareessentialtoelucidatepotentialbenefitsoncognitivehealth.Futurestudies shouldinvestigatetheimpactofheattherapyonATNbiomarkerstounderstandunderlyingneurobiologicalchanges andpotentialrisksofneurodegenerativediseases.

Limitationsofthepresentstudyincludeasmallsample size,theabsenceofacontrolgroup,andtheshortinterventionof4wk.Thesefactorsmayaffectthegeneralizabilityof theresultsandtheobservationoflong-termeffects,however, thisstudycohortexhibitedconsiderablediversity.Duetoa relativelysmallsamplesizeandthepilotnatureofthetrial, theabilitytoexploreadditionalfactorssuchassexwaslimited.Futuremorewell-poweredstudiesshouldinvestigate

theimpactofsexonmetabolicoutcomes.Thepotentialinfluenceofhydrostaticpressureoncardiovascularfunction,as wellasnonspecificeffectsrelatedtofamiliaritywithrepeated interventionsand/orbenefitsofsocialinteractions,require considerationandfuturestudieswithcontrolgroups(e.g., thermoneutralwatertub)toisolatepassiveheatingeffects fromotherinfluences.

Inaddition,nosigni fi canteffectsofHTonglucosetolerancewereobservedinthecurrentstudy.Thisoutcomeis consistentwithElyetal.( 24 ),wheresigni ficantimprovementsinglucosetoleranceinindividualswithpolycystic ovariansyndrome(PCOS)werenotobserveduntilafterthe midpoint(5wk)oftheirstudy.Inaddition,Qiuetal.(71 ) showednochangeinfastingglucoseorimprovementsin glucosetoleranceafter4wkofHWIinpatientswithvaryingdegreesofstenosis.Althoughseveralstudiesshowed improvementsinfastingglucosewithonly2 –4wkofHWI (23 , 25 , 33 , 72 ),itisdif ficulttocompareacrossthesedifferentstudypopulationsandadditionalresearchexamining HWIinlarge,diverseparticipantgroupsisneeded.

ThecurrentpilotstudydemonstratesthepotentialofHT asapotentialtherapeuticapproachforolderadultsatriskof ADduetometabolicfactors.Specifically,HTviaHWI,was notonlyfeasiblebutalsoenjoyable,achievinghighadherenceratesamongparticipants.Theseoutcomeswereespeciallynoteworthygiventhelimitedexerciseengagement typicallyobservedinthisdemographic.Thefeasibilityand highadherenceforHTsupportitsuseasanalternativeor supplementtoexerciseinmanaginghealthrisksassociated withmetabolicdysfunction,aknowncontributingfactorto cognitivedecline.Consideringtheintertwinednatureof metabolicandcognitivehealth,particularlyinthecontextof agingpopulations,furtherresearchisessential.Futurestudiesshouldaimtoaddresscurrentlimitationsandexplorethe broaderimplicationsofHToncognitivefunctions,including itspotentialroleinpreventingormitigatingneurodegenerativediseasessuchasAD.

TableA1 showsthesurveyquestionsandresultsofthe postinterventionsurvey.

Thestudystaffexplainedthestudypurposeand procedureswithclarity

Receivingheattreatment3timesaweekwasnota burdenonmyschedule

Receivingheattreatmentforanadditional6wk wouldnotbetoolong

Myheattreatmentwaschallengingbutnotpainful1

Theingestibletemperaturesensorwasnoharder toswallowthanamultivitamincapsule

OverallIenjoyedparticipatingintheFIGHT-ADstudy1–54.8(0.5) FollowingtheHTintervention,participantswereaskedtogive ratingsusingaLikertscalewiththefollowingvalues:stronglydisagree(1),disagree(2),neutral(3),agree(4),stronglyagree(5).AD, Alzheimer’sdisease;HT,heattherapy.

doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00396.2024 www.jappl.org

from journals.physiology.org/journal/jappl at Univ Kansas Med Ctr (169.147.005.091) on July 3, 2025.

Datawillbemadeavailableuponreasonablerequest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Wegratefullyacknowledgetheresearchvolunteersfortime andparticipationinourstudy.

ThisstudywassupportedbyaDevelopmentalProjects ProgrampilotgrantthroughtheKUAlzheimer’sDisease ResearchCenter(P30AG072973)andtheauthorshavebeen supportedbyR01AG081304.

Noconflictsofinterest, financialorotherwise,aredeclaredby theauthors.

C.J.,E.D.V.,J.K.M.,andP.C.G.conceivedanddesignedresearch; A.E.B.,R.K.,P.J.K.,C.J.,andM.V.performedexperiments;A.E.B.,R.K., P.J.K.,L.Y.,J.D.M.,E.D.V.,J.K.M.,andP.C.G.analyzeddata;A.E.B., P.J.K.,J.D.M.,E.D.V.,J.K.M.,andP.C.G.interpretedresultsof experiments;A.E.B.andJ.K.M.prepared figures;A.E.B.drafted manuscript;A.E.B.,P.J.K.,L.Y.,E.D.V.,J.K.M.,andP.C.G.editedand revisedmanuscript;A.E.B.,E.D.V.,J.K.M.,andP.C.G.approved final versionofmanuscript.

1. Alzheimer’sAssociation. 2023Alzheimer’sdiseasefactsand figures. AlzheimersDement 19:1598–1695,2023.doi:10.1002/alz.13016

2. ArvanitakisZ, WilsonRS, BieniasJL, EvansDA, BennettDA. DiabetesmellitusandriskofAlzheimerdiseaseanddeclineincognitivefunction. ArchNeurol 61:661–666,2004.doi:10.1001/archneur. 61.5.661

3. JansonJ, LaedtkeT, ParisiJE, O’BrienP, PetersenRC, ButlerPC. Increasedriskoftype2diabetesinAlzheimerdisease. Diabetes 53: 474–481,2004.doi:10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474

4. LeibsonCL, RoccaWA, HansonVA, ChaR, KokmenE, O’BrienPC, PalumboPJ. Riskofdementiaamongpersonswithdiabetesmellitus:apopulation-basedcohortstudy. AmJEpidemiol 145:301–308, 1997.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009106

5. OttA, StolkRP, vanHarskampF, PolsHA, HofmanA, Breteler MM. Diabetesmellitusandtheriskofdementia:theRotterdam Study. Neurology 53:1937–1942,1999.doi:10.1212/wnl.53.9.1937

6. ProfennoLA, PorsteinssonAP, FaraoneSV. Meta-analysisof Alzheimer’sdiseaseriskwithobesity,diabetes,andrelateddisorders. BiolPsychiatry 67:505–512,2010.doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.013

7. MorrisJK, HoneaRA, VidoniED, SwerdlowRH, BurnsJM. Is Alzheimer’sdiseaseasystemicdisease? BiochimBiophysActa 1842:1340–1349,2014.doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.012

8. O ’ SullivanJB. Agegradientinbloodglucoselevels.Magnitude andclinicalimplications. Diabetes 23:713–715,1974.doi:10.2337/ diab.23.8.713

9. AkhtarMW, Sanz-BlascoS, DolatabadiN, ParkerJ, ChonK, Lee MS, SoussouW, McKercherSR, AmbasudhanR, NakamuraT, LiptonSA. Elevatedglucoseandoligomeric b-amyloiddisruptsynapsesviaacommonpathwayofaberrantproteinS-nitrosylation. Nat Commun 7:10242,2016.doi:10.1038/ncomms10242

10. HoneaRA, JohnCS, GreenZD, KueckPJ, TaylorMK, LeppingRJ, TownleyR, VidoniED, BurnsJM, MorrisJK. Relationshipoffasting

glucoseandlongitudinalAlzheimer’sdiseaseimagingmarkers. AlzheimersDement(NY) 8:e12239,2022.doi:10.1002/trc2.12239

11. MacauleySL, StanleyM, CaesarEE, YamadaSA, RaichleME, PerezR, MahanTE, SutphenCL, HoltzmanDM. Hyperglycemia modulatesextracellularamyloid-betaconcentrationsandneuronal activityinvivo. JClinInvest 125:2463–2467,2015.doi:10.1172/ JCI79742

12. MorrisJK, VidoniED, WilkinsHM, ArcherAE, BurnsNC, KarcherRT, GravesRS, SwerdlowRH, ThyfaultJP, BurnsJM. Impairedfastingglucoseisassociatedwithincreasedregionalcerebralamyloid. Neurobiol Aging 44:138–142,2016.doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.04.017

13. TaylorMK, SullivanDK, SwerdlowRH, VidoniED, MorrisJK, MahnkenJD, BurnsJM. Ahigh-glycemicdietisassociatedwithcerebralamyloidburdenincognitivelynormalolderadults. AmJClin Nutr 106:1463–1470,2017.doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.162263

14. MorrisJK, VidoniED, JohnsonDK, VanSciverA, MahnkenJD, HoneaRA, WilkinsHM, BrooksWM, BillingerSA, SwerdlowRH, BurnsJM. AerobicexerciseforAlzheimer’sdisease:arandomized controlledpilottrial. PLoSOne 12:e0170547,2017.doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0170547

15. PiepoliMF, HoesAW, AgewallS, AlbusC, BrotonsC, CatapanoAL, CooneyMT, CorraU, CosynsB, DeatonC, GrahamI, HallMS, RichardHobbsFD, LochenML, LollgenH, Marques-VidalP, PerkJ, PrescottE, RedonJ, RichterDJ, SattarN, SmuldersY, TiberiM, Bart vanderWorpH, vanDisI, MoniqueVerschurenWM. 2016European Guidelinesoncardiovasculardiseasepreventioninclinicalpractice. RevEspCardiol(EnglEd) 69:939,2016.doi:10.1016/j.rec.2016.09.009

16. TomotoT, ZhangR. Arterialagingandcerebrovascularfunction: impactofaerobicexercisetraininginolderadults. AgingDis 15: 1672–1687,2024.doi:10.14336/AD.2023.1109-1

17. CastellanoCA, PaquetN, DionneIJ, ImbeaultH, LangloisF, CroteauE, TremblayS, FortierM, MatteJJ, LacombeG, FulopT, BoctiC, CunnaneSC. A3-monthaerobictrainingprogramimproves brainenergymetabolisminmildAlzheimer’sdisease:preliminary resultsfromaNeuroimagingStudy. JAlzheimersDis 56:1459–1468, 2017.doi:10.3233/JAD-161163

18. LiuL, GracelyEJ, ZhaoX, GliebusGP, MayNS, VolpeSL, ShiJ, DiMaria-GhaliliRA, EisenHJ. Associationofmultiplemetabolicand cardiovascularmarkerswiththeriskofcognitivedeclineandmortalityinadultswithAlzheimer’sdiseaseandAD-relateddementiaor cognitivedecline:aprospectivecohortstudy. FrontAgingNeurosci 16:1361772,2024.doi:10.3389/fnagi.2024.1361772

19. PereiraAC, HuddlestonDE, BrickmanAM, SosunovAA, HenR, McKhannGM, SloanR, GageFH, BrownTR, SmallSA. Aninvivo correlateofexercise-inducedneurogenesisintheadultdentate gyrus. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA 104:5638–5643,2007.doi:10.1073/ pnas.0611721104

20. AlwatbanMR, AaronSE, KaufmanCS, BarnesJN, BrassardP, WardJL, MillerKB, HoweryAJ, LabrecqueL, BillingerSA. Effects ofageandsexonmiddlecerebralarterybloodvelocityand flowpulsatilityindexacrosstheadultlifespan. JApplPhysiol(1985) 130: 1675–1683,2021.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00926.2020.

21. XingCY, TarumiT, LiuJ, ZhangY, TurnerM, RileyJ, TinajeroCD, YuanLJ, ZhangR. Distributionofcardiacoutputtothebrainacross theadultlifespan. JCerebBloodFlowMetab 37:2848–2856,2017. doi:10.1177/0271678X16676826

22. FederalInteragencyForumonAging-RelatedStatistics(Forum). OlderAmericans2020:KeyIndicatorsofWell-Being.Washington, DC:U.S.GovernmentPrintingOffice,2020.

23. HooperPL. Hot-tubtherapyfortype2diabetesmellitus. NEnglJ Med 341:924–925,1999.doi:10.1056/NEJM199909163411216

24. ElyBR, ClaytonZS, McCurdyCE, PfeifferJ, NeedhamKW, ComradaLN, MinsonCT. Heattherapyimprovesglucosetolerance andadiposetissueinsulinsignalinginpolycysticovarysyndrome. AmJPhysiolEndocrinolPhysiol 317:E172–E182,2019.doi:10.1152/ ajpendo.00549.2018.

25. KoçakFA, KurtEE, MilletliSezginF, S as S, TuncayF, ErdemHR. Theeffectofbalneotherapyonbodymassindex,adipokinelevels, sleepdisturbances,andqualityoflifeofwomenwithmorbidobesity. IntJBiometeorol 64:1463–1472,2020.doi:10.1007/s00484-02001924-x

26. ElyBR, FranciscoMA, HalliwillJR, BryanSD, ComradaLN, Larson EA, BruntVE, MinsonCT. Heattherapyreducessympatheticactivityandimprovescardiovascularriskprofileinwomenwhoareobese

JApplPhysiol doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00396.2024 www.jappl.org Downloaded from journals.physiology.org/journal/jappl at Univ Kansas Med Ctr (169.147.005.091) on July 3, 2025.

withpolycysticovarysyndrome. AmJPhysiolRegulIntegrComp Physiol 317:R630–R640,2019.doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00078.2019

27. JamesTJ, CorbettJ, CummingsM, AllardS, ShuteJK, BelcherH, MayesH, GouldAAM, PiccoloDD, TiptonM, PerissiouM, Saynor ZL, ShepherdAI. Theeffectofrepeatedhotwaterimmersiononinsulinsensitivity,heatshockprotein70,andinflammationinindividualswithtype2diabetesmellitus. AmJPhysiolEndocrinolPhysiol 325:E755–E763,2023.doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00222.2023.

28. AkermanAP, ThomasKN, vanRijAM, BodyED, AlfadhelM, Cotter JD. Heattherapyvs.supervisedexercisetherapyforperipheralarterial disease:a12-wkrandomized,controlledtrial. AmJPhysiolHeartCirc Physiol 316:H1495–H1506,2019.doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00151.2019

29. RicheyRE, HemingwayHW, MooreAM, Olivencia-YurvatiAH, RomeroSA. Acuteheatexposureimprovesmicrovascularfunction inskeletalmuscleofagedadults. AmJPhysiolHeartCircPhysiol 322:H386–H393,2022.doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00645.2021

30. BruntVE, MinsonCT. Heattherapy:mechanisticunderpinningsand applicationstocardiovascularhealth. JApplPhysiol(1985) 130: 1684–1704,2021.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00141.2020

31. AminSB, HansenAB, MugeleH, WillmerF, GrossF, ReimeirB, CornwellWK, SimpsonLL, MooreJP, RomeroSA, LawleyJS. Wholebodypassiveheatingversusdynamiclowerbodyexercise:a comparisonofperipheralhemodynamicprofiles. JApplPhysiol (1985) 130:160–171,2021.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00291.2020

32. EngellandRE, HemingwayHW, TomascoOG, Olivencia-Yurvati AH, RomeroSA. Neuralcontrolofbloodpressureisalteredfollowingisolatedlegheatinginagedhumans. AmJPhysiolHeartCirc Physiol 318:H976–H984,2020.doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00019.2020

33. HoekstraSP, BishopNC, FaulknerSH, BaileySJ, LeichtCA. Acute andchroniceffectsofhotwaterimmersiononinflammationandmetabolisminsedentary,overweightadults. JApplPhysiol(1985) 125: 2008–2018,2018.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00407.2018

34. KrankelN, BahlsM, VanCraenenbroeckEM, AdamsV, Serratosa L, SolbergEE, HansenD, DorrM, KempsH. Exercisetrainingto reducecardiovascularriskinpatientswithmetabolicsyndromeand type2diabetesmellitus:howdoesitwork? EurJPrevCardiol 26: 701–708,2019.doi:10.1177/2047487318805158

35. GalvinJE. Thequickdementiaratingsystem(QDRS):arapiddementiastagingtool. AlzheimersDement(Amst) 1:249–259,2015. doi:10.1016/j.dadm.2015.03.003

36. VidoniED, MorrisJK, PalmerJA, LiY, WhiteD, KueckPJ, JohnCS, HoneaRA, LeppingRJ, LeeP, MahnkenJD, MartinLE, Billinger SA. Dementiariskanddynamicresponsetoexercise:anonrandomizedclinicaltrial. PLoSOne 17:e0265860,2022.doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0265860

37. GreenZD, KueckPJ, JohnCS, BurnsJM, MorrisJK. BloodbiomarkersdiscriminatecerebralamyloidstatusandcognitivediagnosiswhencollectedwithACD-Aanticoagulant. CurrAlzheimerRes 20:557–566,2023.doi:10.2174/0115672050271523231111192725

38. LiD, MielkeMM. Anupdateonblood-basedmarkersofAlzheimer’s diseaseusingtheSiMoAplatform. NeurolTher 8:73–82,2019. doi:10.1007/s40120-019-00164-5

39. VergalloA, MegretL, ListaS, CavedoE, ZetterbergH, BlennowK, VanmechelenE, DeVosA, HabertMO, PotierMC, DuboisB, Neri C, HampelH; INSIGHT-preADstudygroup,AlzheimerPrecision MedicineInitiative(APMI). Plasmaamyloidbeta40/42ratiopredictscerebralamyloidosisincognitivelynormalindividualsat riskforAlzheimer’sdisease. AlzheimersDement 15:764–775,2019. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.03.009

40. JanelidzeS, MattssonN, PalmqvistS, SmithR, BeachTG, Serrano GE, ChaiX, ProctorNK, EichenlaubU, ZetterbergH, BlennowK, ReimanEM, StomrudE, DageJL, HanssonO. PlasmaP-tau181in Alzheimer’sdisease:relationshiptootherbiomarkers,differentialdiagnosis,neuropathologyandlongitudinalprogressiontoAlzheimer’s dementia. NatMed 26:379–386,2020.doi:10.1038/s41591-0200755-1.

41. LanteroRodriguezJ, KarikariTK, Suarez-CalvetM, TroakesC, KingA, EmersicA, AarslandD, HyeA, ZetterbergH, BlennowK, AshtonNJ. Plasmap-tau181accuratelypredictsAlzheimer’sdisease pathologyatleast8yearspriortopost-mortemandimprovesthe clinicalcharacterisationofcognitivedecline. ActaNeuropathol 140: 267–278,2020.doi:10.1007/s00401-020-02195-x

42. MielkeMM, HagenCE, XuJ, ChaiX, VemuriP, LoweVJ, AireyDC, KnopmanDS, RobertsRO, MachuldaMM, JackCRJr, Petersen

RC, DageJL. Plasmaphospho-tau181increaseswithAlzheimer’sdiseaseclinicalseverityandisassociatedwithtau-andamyloid-positronemissiontomography. AlzheimersDement 14:989–997,2018. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.013

43. MattssonN, AndreassonU, ZetterbergH, BlennowK; Alzheimer’s DiseaseNeuroimagingInitiative. AssociationofplasmaneurofilamentlightwithneurodegenerationinpatientswithAlzheimerdisease. JAMANeurol 74:557–566,2017.doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.6117

44. PereiraJB, JanelidzeS, SmithR, Mattsson-CarlgrenN, Palmqvist S, TeunissenCE, ZetterbergH, StomrudE, AshtonNJ, BlennowK, HanssonO. PlasmaGFAPisanearlymarkerofamyloid-b butnot taupathologyinAlzheimer’sdisease. Brain 144:3505–3516,2021. doi:10.1093/brain/awab223

45. FlynnB, VitztumM, MillerJ, HouchinA, KimJ, HeJ, GeigerP. Feasibilityandpilotstudyofpassiveheattherapyoncardiovascular performanceandlaboratoryvaluesinolderadults. PilotFeasibility Stud 9:86,2023.doi:10.1186/s40814-023-01314-1

46. ThomasKN, vanRijAM, LucasSJ, CotterJD. Lower-limbhot-water immersionacutelyinducesbeneficialhemodynamicandcardiovascularresponsesinperipheralarterialdiseaseandhealthy,elderly controls. AmJPhysiolRegulIntegrCompPhysiol 312:R281–R291, 2017.doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00404.2016.

47. LaukkanenT, KunutsorSK, ZaccardiF, LeeE, WilleitP, KhanH, LaukkanenJA. Acuteeffectsofsaunabathingoncardiovascular function. JHumHypertens 32:129–138,2018.doi:10.1038/s41371017-0008-z

48. NeffD, KuhlenhoelterAM, LinC, WongBJ, MotaganahalliRL, RoseguiniBT. Thermotherapyreducesbloodpressureandcirculating endothelin-1concentrationandenhanceslegblood flowinpatients withsymptomaticperipheralarterydisease. AmJPhysiolRegulIntegr CompPhysiol 311:R392–400,2016.doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00147.2016

49. TeiC, HorikiriY, ParkJC, JeongJW, ChangKS, ToyamaY, Tanaka N. Acutehemodynamicimprovementbythermalvasodilationincongestiveheartfailure. Circulation 91:2582–2590,1995.doi:10.1161/01. cir.91.10.2582

50. MatsuzawaY, LermanA. Endothelialdysfunctionandcoronaryarterydisease:assessment,prognosis,andtreatment. CoronArtery Dis 25:713–724,2014.doi:10.1097/MCA.0000000000000178

51. DeanfieldJE, HalcoxJP, RabelinkTJ. Endothelialfunctionanddysfunction:testingandclinicalrelevance. Circulation 115:1285–1295, 2007.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652859

52. HemingwayHW, RicheyRE, MooreAM, Olivencia-YurvatiAH, KlineGP, RomeroSA. Acuteheatexposureprotectsagainstendothelialischemia-reperfusioninjuryinagedhumans. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrCompPhysiol 322:R360–R367,2022[Erratumin AmJ PhysiolRegulIntegrCompPhysiol 323:R278,2022].doi:10.1152/ ajpregu.00336.2021

53. KiharaT, BiroS, ImamuraM, YoshifukuS, TakasakiK, IkedaY, Otuji Y, MinagoeS, ToyamaY, TeiC. Repeatedsaunatreatmentimproves vascularendothelialandcardiacfunctioninpatientswithchronic heartfailure. JAmCollCardiol 39:754–759,2002.doi:10.1016/ s0735-1097(01)01824-1

54. MartinZT, AkinsJD, MerlauER, KoladeJO, Al-DaasIO, Cardenas N, VuJK, BrownKK, BrothersRM. Theacuteeffectofwhole-body heattherapyonperipheralandcerebralvascularreactivityinBlack andWhitefemales. MicrovascRes 148:104536,2023.doi:10.1016/j. mvr.2023.104536

55. BruntVE, HowardMJ, FranciscoMA, ElyBR, MinsonCT. Passive heattherapyimprovesendothelialfunction,arterialstiffnessand bloodpressureinsedentaryhumans. JPhysiol 594:5329–5342, 2016.doi:10.1113/JP272453

56. BruntVE, Wiedenfeld-NeedhamK, ComradaLN, MinsonCT. Passiveheattherapyprotectsagainstendothelialcellhypoxia-reoxygenationviaeffectsofelevationsintemperatureandcirculating factors. JPhysiol 596:4831–4845,2018.doi:10.1113/JP276559

57. HafenPS, AbbottK, BowdenJ, LopianoR, HancockCR, Hyldahl RD. Dailyheattreatmentmaintainsmitochondrialfunctionand attenuatesatrophyinhumanskeletalmusclesubjectedtoimmobilization. JApplPhysiol(1985) 127:47–57,2019.doi:10.1152/ japplphysiol.01098.2018

58. HafenPS, PreeceCN, SorensenJR, HancockCR, HyldahlRD. Repeatedexposuretoheatstressinducesmitochondrialadaptation inhumanskeletalmuscle. JApplPhysiol(1985) 125:1447–1455, 2018.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00383.2018

59. RomeroSA, GagnonD, AdamsAN, CramerMN, KoudaK, Crandall CG. Acutelimbheatingimprovesmacro-andmicrovasculardilator functioninthelegofagedhumans. AmJPhysiolHeartCircPhysiol 312:H89–H97,2017.doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00519.2016

60. GupteAA, BomhoffGL, GeigerPC. Age-relateddifferencesinskeletalmuscleinsulinsignaling:theroleofstresskinasesandheatshock proteins. JApplPhysiol(1985) 105:839–848,2008.doi:10.1152/ japplphysiol.00148.2008

61. GupteAA, BomhoffGL, SwerdlowRH, GeigerPC. Heattreatment improvesglucosetoleranceandpreventsskeletalmuscleinsulinresistanceinratsfedahigh-fatdiet. Diabetes 58:567–578,2009. doi:10.2337/db08-1070

62. GupteAA, BomhoffGL, TouchberryCD, GeigerPC. Acuteheat treatmentimprovesinsulin-stimulatedglucoseuptakeinagedskeletalmuscle. JApplPhysiol(1985) 110:451–457,2011.doi:10.1152/ japplphysiol.00849.2010

63. GupteAA, MorrisJK, ZhangH, BomhoffGL, GeigerPC, Stanford JA. Age-relatedchangesinHSP25expressioninbasalgangliaand cortexofF344/BNrats. NeurosciLett 472:90–93,2010.doi:10.1016/ j.neulet.2010.01.049

64. RogersRS, BeaudoinMS, WheatleyJL, WrightDC, GeigerPC. Heatshockproteins:invivoheattreatmentsrevealadiposetissue depot-specificeffects. JApplPhysiol(1985) 118:98–106,2015. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00286.2014

65. VonSchulzeAT, DengF, FullerKNZ, FranczakE, MillerJ, AllenJ, McCoinCS, ShankarK, DingWX, ThyfaultJP, GeigerPC. Heat TreatmentImprovesHepaticMitochondrialRespiratoryEfficiency viaMitochondrialRemodeling. Function(Oxf) 2:zqab001,2021. doi:10.1093/function/zqab001.

66. VonSchulzeAT, DengF, MorrisJK, GeigerPC. Heattherapy:possiblebenefitsforcognitivefunctionandtheagingbrain. JApplPhysiol (1985) 129:1468–1476,2020.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00168.2020

67. PalmerJA, MorrisJK, BillingerSA, LeppingRJ, MartinL, GreenZ, VidoniED. Hippocampalblood flowrapidlyandpreferentially increasesafteraboutofmoderate-intensityexerciseinolderadults withpoorcerebrovascularhealth. CerebCortex 33:5297–5306, 2023.doi:10.1093/cercor/bhac418

68. SatoK, OueA, YoneyaM, SadamotoT, OgohS. Heatstressredistributesblood flowinarteriesofthebrainduringdynamicexercise. JApplPhysiol(1985) 120:766–773,2016.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol. 00353.2015

69. BainAR, NyboL, AinsliePN. Cerebralvascularcontrolandmetabolisminheatstress. ComprPhysiol 5:1345–1380,2015.doi:10.1002/ cphy.c140066

70. AminSB, HansenAB, MugeleH, SimpsonLL, MarumeK, Moore JP, CornwellWK3rd, LawleyJS. High-intensityexerciseandpassivehotwaterimmersioncausesimilarpostinterventionchangesin peripheralandcerebralshear. JApplPhysiol(1985) 133:390–402, 2022.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00780.2021

71. QiuY, ZhuY, JiaW, ChenS, MengQ. Spaadjuvanttherapy improvesdiabeticlowerextremityarterialdisease. Complement TherMed 22:655–661,2014.doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2014.05.003

72. OlahM, KonczA, FeherJ, KalmanczheyJ, OlahC, NagyG, Bender T. Theeffectofbalneotherapyonantioxidant,inflammatory,and metabolicindicesinpatientswithcardiovascularriskfactors(hypertensionandobesity)–arandomised,controlled,follow-upstudy. ContempClinTrials 32:793–801,2011.doi:10.1016/j.cct.2011.06.003.