High Density

Can buildings threatened by demolition become donor buildings for mass housing?

Can buildings threatened by demolition become donor buildings for mass housing?

Erik Stenberg

Helena Westerlind

Mulaika Samphani

Oscar Harmsen

Editors Teachers Cover and layout

Haukur Hafliði Nínuson

Marthe Nordmo

Natalia Szczepaniak

Printed by

Universitetsservice US-AB

KTH Campus

Drottning Kristinas väg 53B 114 28 Stockholm

October 2025

Resource efficient mass housing through reuse

The catalogue that you are looking at is the result of a seven week project called “High Density, Low Carbon” in the KTH Housing Studio researched, compiled and presented by twenty-three Masters level students. The project places its origin in the findings of a recent report by Public Housing Sweden. The report states that: “The housing market is undergoing change. After several years of widespread housing shortages, a growing number of municipalities and housing companies are now reporting that there is a balance – or even a surplus of housing. Vacancies increased sharply between 2023 and 2024, as well as continuing long queues in large cities and some municipalities near large cities. There are now two opposing realities with different challenges existing side by side.” En tudelad bostadsmarknad (2025) P. 31 (https://www.sverigesallmannytta.se/document/ en-tudelad-bostadsmarknad-marknadsrapport-omefterfragan-vakanser-och-kotid/). To address this new surplus of modernist mass housing in some Swedish municipalities and the urgent need to reduce the environmental impact of demolition, the Housing Studio project investigated and mapped buildings deemed obsolete. Group and archival work was used to find, analyze, and digitalize information of existing housing areas threatened by demolition. The original typology, production and construction of the housing was studied at three scales: as a structure, as elements and as materials.

The Housing Studio also explored the effects of resource efficiency through material and reuse strategies in mass housing design. While the separation of design tasks in the building process was historically considered essential for optimizing construction of mass housing, the shift toward material reuse (once again) calls for a more integrated design approach — one that challenges the divide between architecture and engineering. Through the theme of resource efficiency, the Housing Studio therefore explores the architect – engineer divide and fosters an empathetic attitude for the complementary roles of the architect and engineer in the design, production, and construction of mass housing. The studio further studies the living conditions of mass housing as a design driver by asking the critical questions: For whom? And Why? In general, the studio proposes a process of designing mass housing as it relates to structural and material methods intimately tied with a cultural - historical perspective while critically engaging in today’s housing debates. Following the mapping project, students will design new mass housing with the reuse of structures, elements, and materials as a prerequisite. The individual projects will explore the effects on (and results of) an architectural design process including reuse of structural components, the architect - engineer divide, and living conditions in housing. By moving designing with reuse from the scale of a pilot (single unit or single building) to the scale of mass housing (with sixty or more apartment units) the Housing Studio will, in addition, explore how reuse can contribute towards a sector shift in low carbon construction.

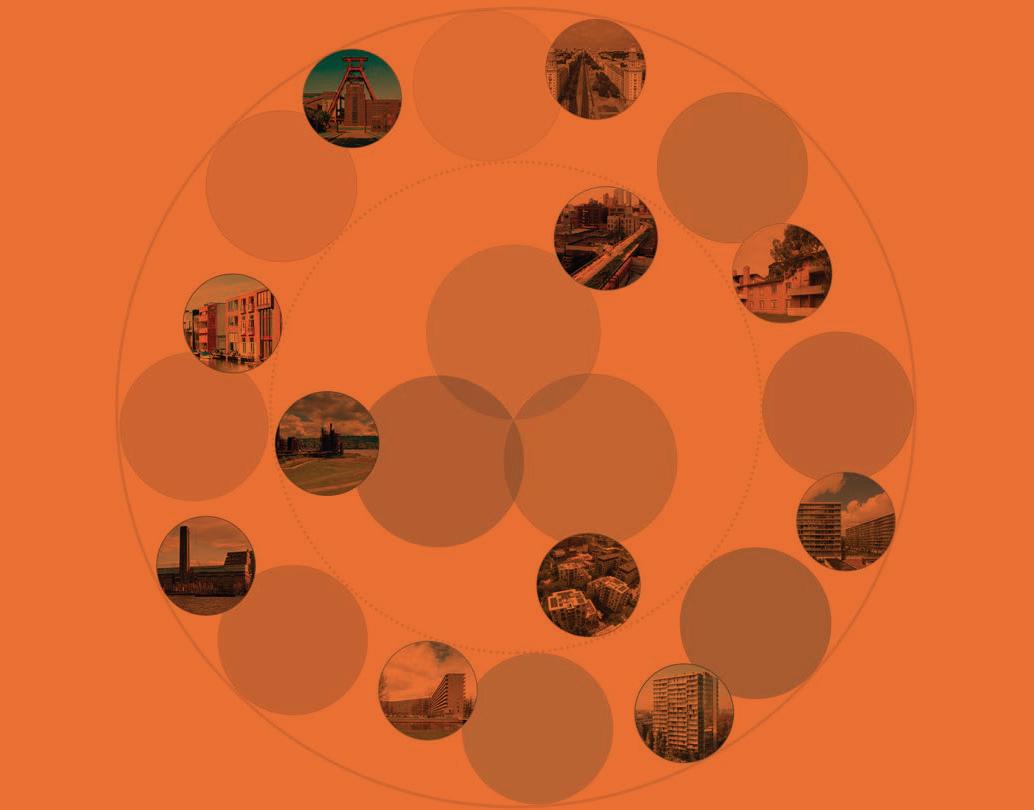

Themes and cases

Both mass housing and climate related issues in architecture have already been studied from many angles and there are many conflicting forces at play. The Housing Studio believes that the role of the architect in a contemporary practice requires an understanding of these histories and hurdles. The second part of the project was to explore a number of the themes related to the High Density, Low Carbon topic. By exploring the discourse through written resources and specific case studies of architecture, the students gained a more precise vocabulary. The themes for High Density were: The Housing Question, Mass Housing Histories, Renovation, Adaptation, Alteration, and Remodeling, and Housing as Heritage. The themes for Low Carbon were: The Environmental Question, Circularity, Reuse, and Material Flows. These themes are in one sense arbitrary and in many cases overlapping. They are not intended to cover all issues related to the topic but more to act as doors to enter a deeper discourse through. Key concepts and an overall perspective of the theme have been collected through readings. They are displayed as diagrams and as sources for further reading. Since it is was an impossibility to read all the texts and study all the case studies, the catalogue in front of you now serves as a curated source of information for further studies and reading on the topics.

In the first part of the project, the studio divided itself into smaller groups of two to four students who studied a specific geographic region of Sweden. Each region was made up of two to three counties which in turn each had many municipalities. The responsibility for providing housing (bostadsförsörjningsansvaret) is located at the municipal level by law (Lag 2000:1383). The teams of students were tasked with the mapping of housing threatened by demolition in municipalities with a surplus of housing as stated in the above mentioned report. However, they soon expanded their search to include other typologies such as offices and hospitals and, maybe even more importantly, buildings threatened by demolition in municipalities with a housing shortage. Through the research, it became clear that a main driver of demolition in Sweden is urban development in expanding municipalities, not vacancies in shrinking municipalities. A set of strategies for identifying obsolete buildings was crafted. The main source of information turned out to be demolition permits provided by the technical offices of the municipalities. There have been hundreds of demolition permits issued and the challenge here was how to filter them for relevance. Another source was the direct contact with the municipal housing companies. They were, however, not always inclined to point out specific buildings for demolition, even though they are experiencing a surplus. A third source were other maps such as Rivningskartan (https://www.rivningskartan. se/karta) and 08demolition (https://08demolition. se/downloads). Both of these sources are ongoing mappings but with slightly different limits compared top the Housing Studio exercise. A fourth strategy was to scan the internet and local newspapers to identify threatened buildings by discussions of urban planning or demolitions. The debate is usually quite local and vocal. In total, these strategies led the students to hundreds of buildings threatened by demolition all over Sweden. The further selection process (as shown in the catalogue) was guided by the intention to find donor buildings of a sufficient size for the planned large scale reuse in the design of mass housing.

Katarina Lundgren

Linnea Lindh

Alexander Lind

Zofia Andrzejewska

Matilda Marcström

Emilie Reinhall

Natalia Szczepaniak

Per Åström

Beata Schück

Jakub Gasek

Erik Boström Wallin

Oscar Harmsen

Axel Kullin

Ksenia Iorzh

Haukur Hafliði Nínuson

Mulaika Samphani

Nina Lagerkranz

Marthe Nordmo

Victor de Keijzer

Isa Larsson

Flavie Bernard

Lovisa Risberg

Gabriel Voltaire

Erik Stenberg

Helena Westerlind

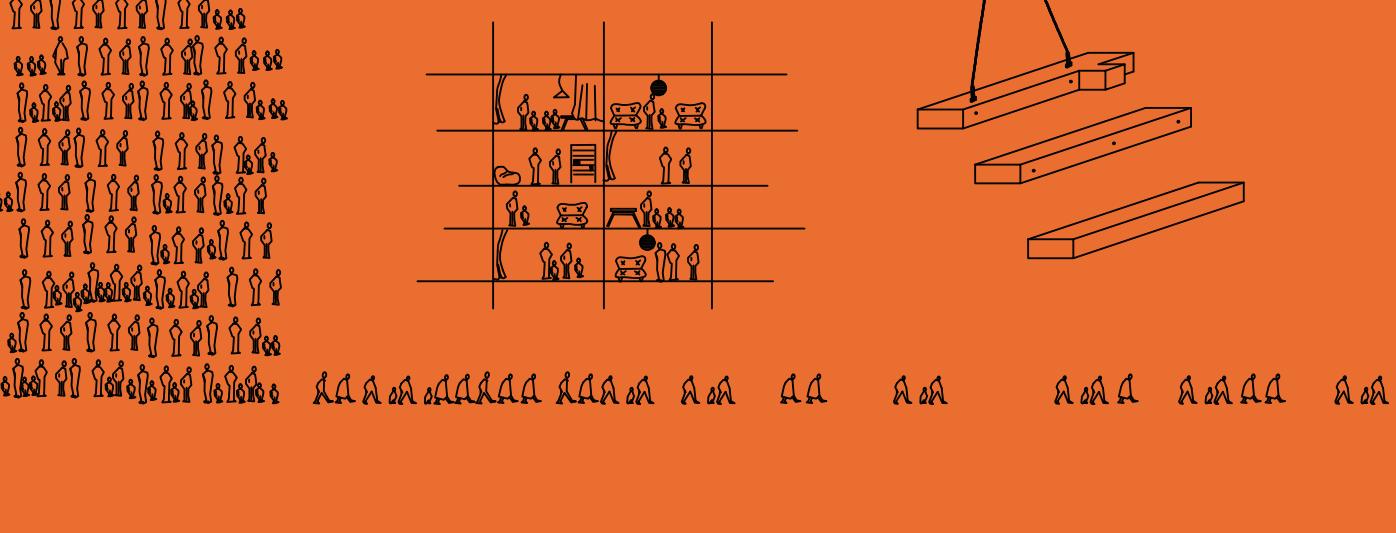

LEGENDMETHOD DIAGRAM

A1_____ Stockholm

Uppsala

Sörmland

A2_____Östergötland

Jönköping

A3_____Kronoberg

Kalmar

Gotland

A4_____Blekinge

Skåne

Halland

B5_____Västra götaland Värmland

B6_____Örebro Västmanland

Dalarna

B7_____Gävleborg Västernorrland Jämtland

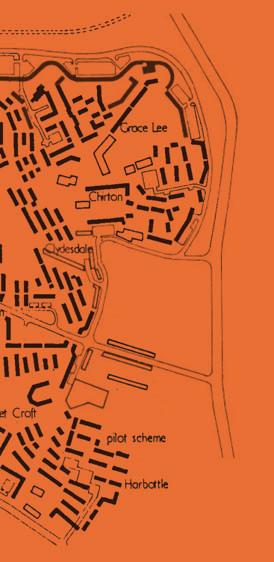

This diagram shows how the studio has identified threatened buildings, by demolition, around Sweden. Most have been most successful using the same method, contacting the municipalities and requesting demolition permits from 2023 onward. When it comes to bigger cities, Rivningskartan has proven to be the most effective tool, compared to smaller towns.

Stockholm Uppsala Sörmland

Östergötland Jönköping

Kronoberg Kalmar Gotland

Blekinge Skåne Halland

Örebro

Västra götaland Värmland

Västmanland Dalarna

Gävleborg

Västernorrland Jämtland

How did we get the information? Rivningskartan _____________Threatened buildnings

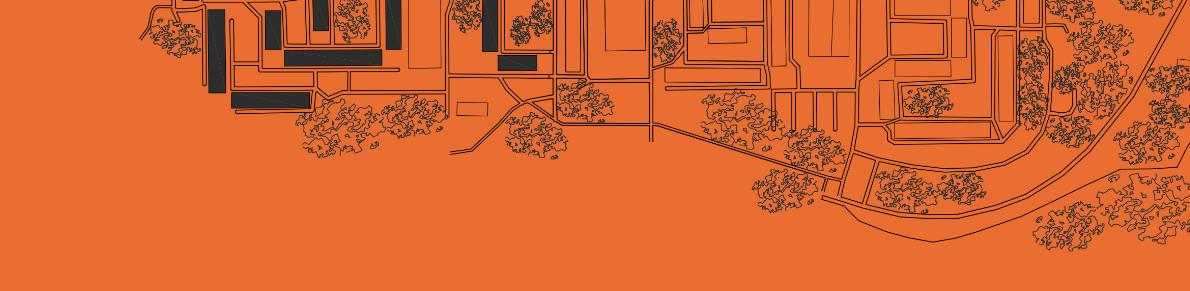

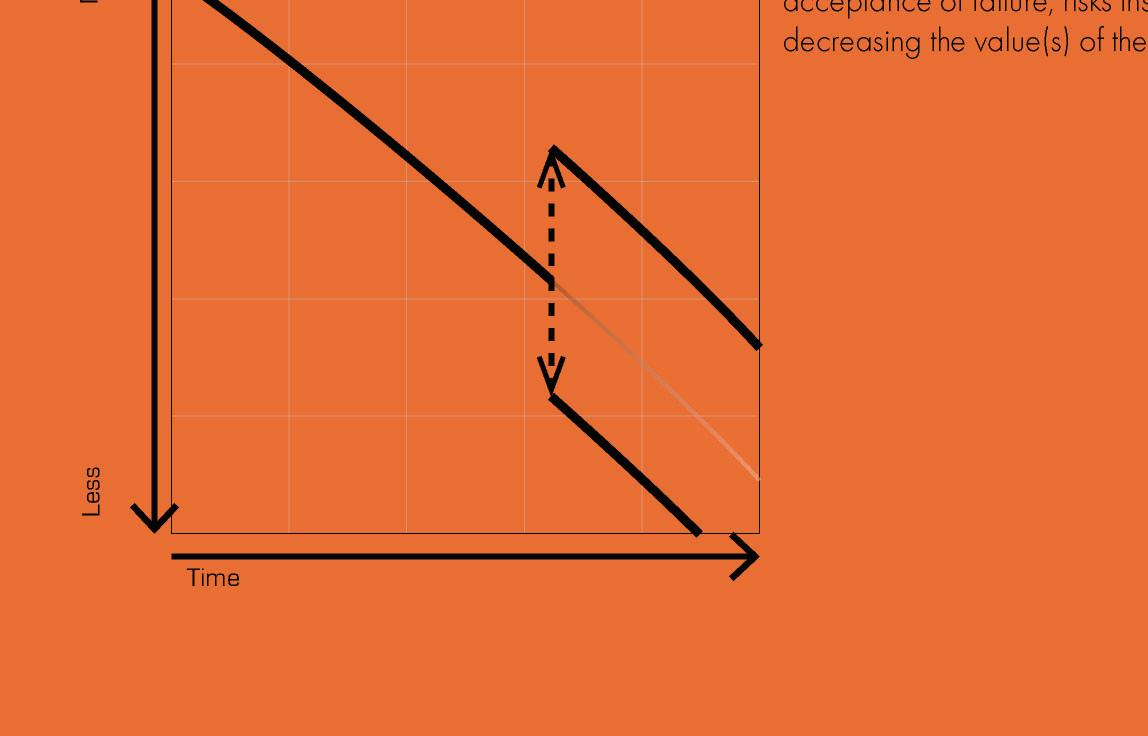

This diagram aims to describe the selection process the studio has gone through, where a big selection of potential buildings from all municipalities in Sweden have been carefully understood and evaluated for the potential of serving as a donor building. The studio has then gone through a selection process of municipalities and their buildings, ending up with a final selection and inventory for the catalogue and following design project

The diagram describes the selection process in a chronological order from left to right, where the section line through Sweden is placed furthest to the left, giving a north to south direction on the Y axis, where the counties and all municipalities from the beginning of the selection process are placed accordingly

Each municipality has an indicator providing insight into if it has a surplus or deficit in housing, or if it’s balanced

Each municipality has then been contacted through various means, and the ones that have been able to provide potential buildings have moved on to the next step of the process. These municipalities are also shown along the section line of Sweden to the left Each building from the selected municipalities, where some have multiples, are shown and categorized with different line variations under First Selection. These buildings have then been selected or disqualified for the next step through an evaluation of different parameters. This is the Second/final Selection. The final selection is then presented along with names and dates

built

END OF PROCESS

ELEVATION OF MUNICIPALITY

HOUSING DEFICIT -

HOUSING BALANCE - WHOLE MUNICIPALITY

HOUSING SURPLUS - WHOLE MUNICIPALITY

VÄSTERBOTTEN

VÄSTERNORRLAND

JÄMTLAND

GÄVLEBORG

DALARNA

UPPSALA

VÄSTMANLAND

ÖREBRO

VÄRMLAND

STOCKHOLM

SÖDERMANLAND

ÖSTERGÖTLAND

VÄSTRA GÖTALAND

GOTLAND

KALMAR

JÖNKÖPING

KRONOBERG

HOUSING INDUSTRIAL COMMERCIAL

HEALTHCARE OTHER

HALLAND

BLEKINGE

SKÅNE

UMEÅ KIRUNA

VINDELN

ÅRE LULEÅ BODEN PITEÅ ARVIDSJAUR

BRÄCKE HÄRNÖSAND ÖRNSKÖLDSVIK

MORA SÖDERHAMN BOLLNÄS

AVESTA

LUDVIKA

FILIPSTAD

NORBERG SALA ÖREBRO LAXÅ VÄSTERÅS SÄFFLE

LIDINGÖ

STOCKHOLM

HUDDINGE ENKÖPING

ESKILSTUNA

OXELÖSUND LINKÖPING MOTALA

TROLLHÄTTAN

MÖLNDAL GÖTEBORG UDDEVALLA

NÄSSJÖ

LAHOLM

HULTSFRED HÖGSBY VIMMERBY VÄSTERVIK LJUNGBY

KARLSKRONA

ÖSTRA GÖINGE OSBY

LUND

MALMÖ

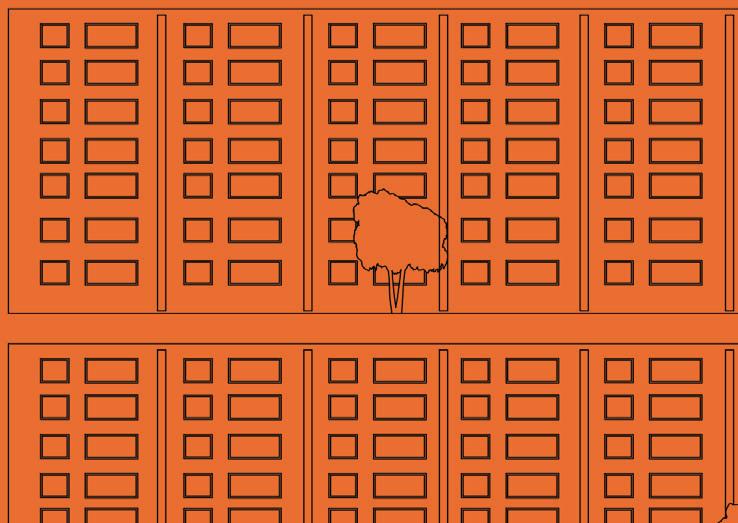

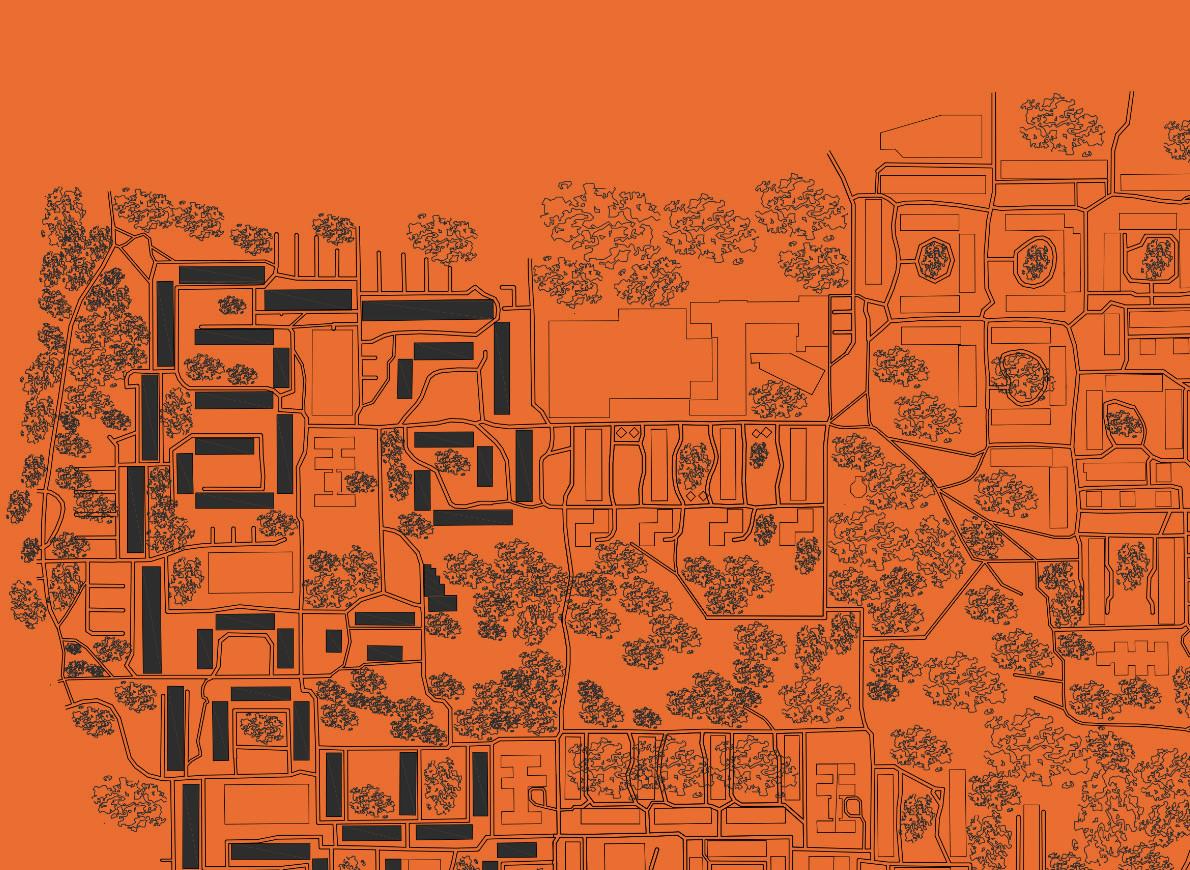

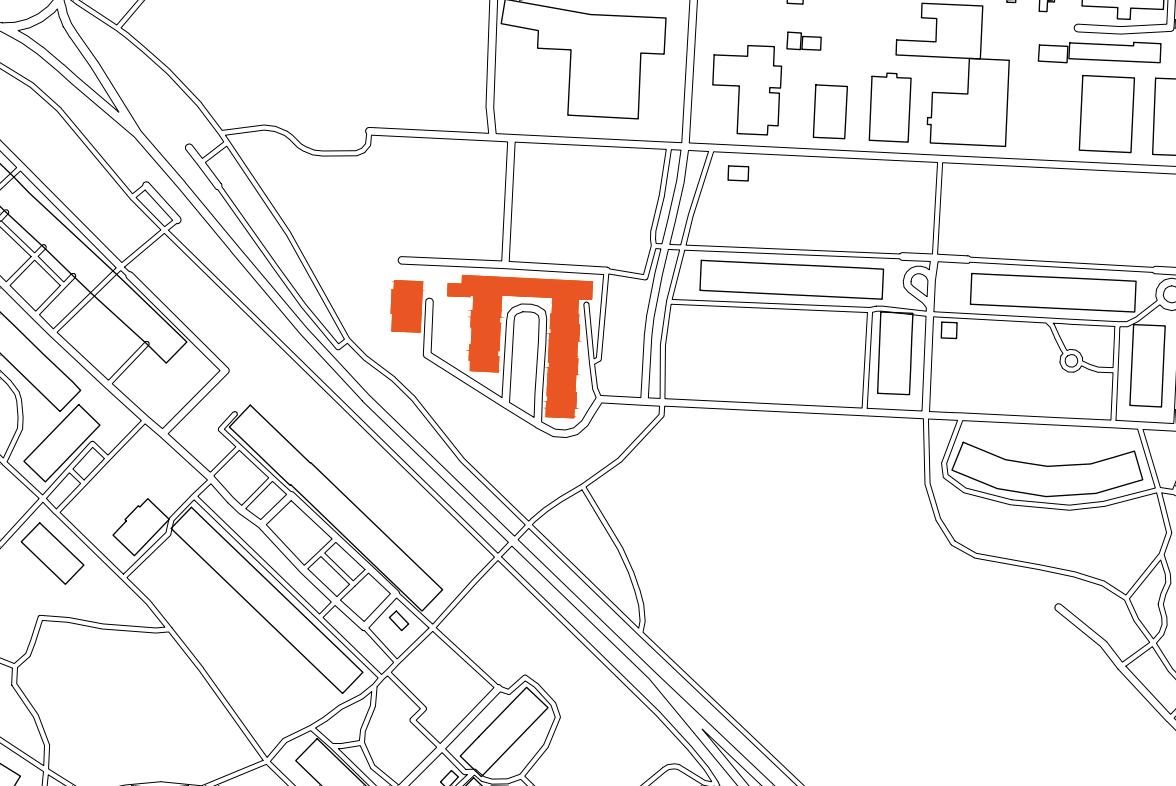

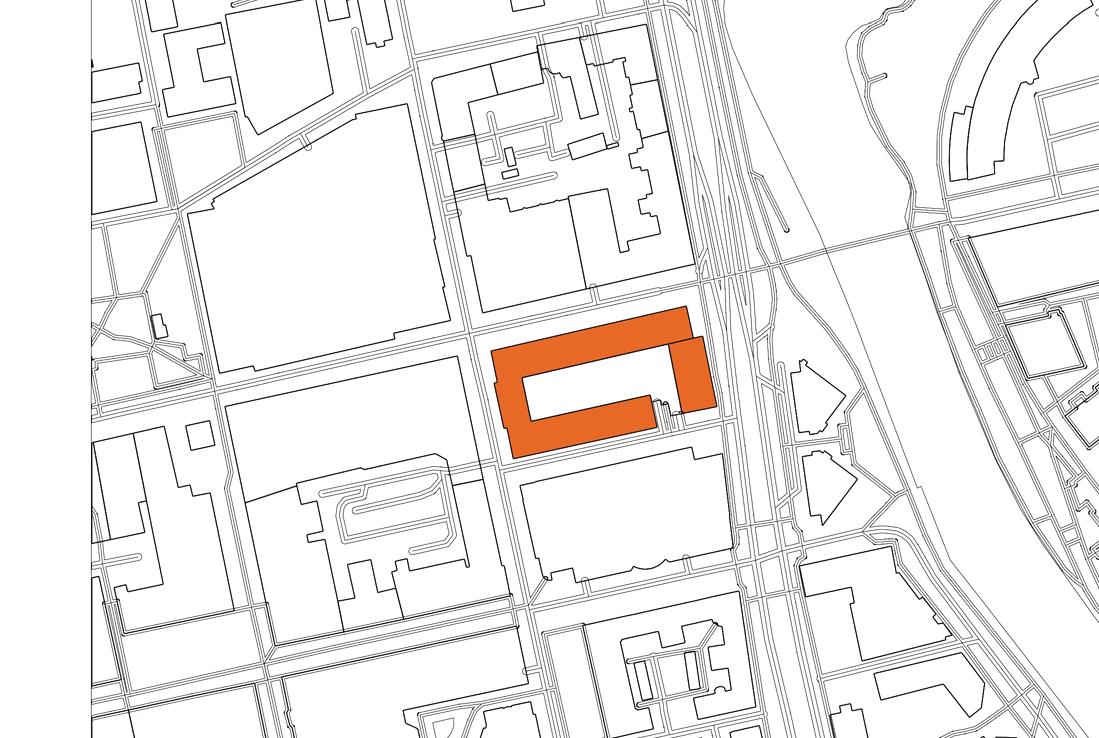

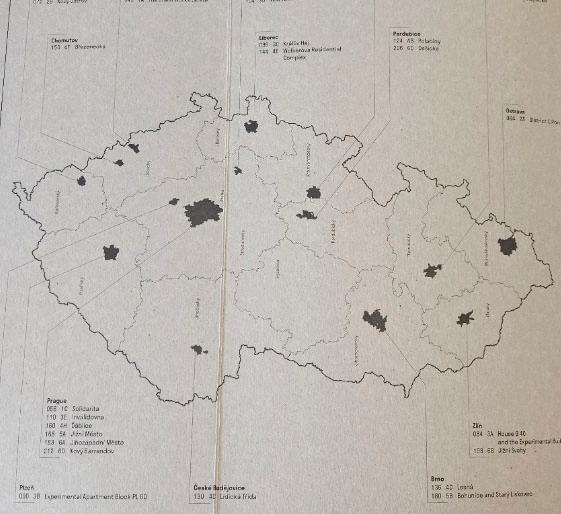

This map compiles buildings across Sweden that have been identified as threatened to be demolished. Both confirmed and speculative cases have been documented during the research process. The mapping was carried out through a nationwide scan, moving from north to south, and the findings have been investigated as potential donor buildings for future housing projects.

Each point on the map marks a site with a building, or in some cases several buildings within the same complex, currently facing the risk of demolition. The number on the map corresponds with a list on the following spread containing building identifiers. A distinction has been made between potential donor buildings and selected donor buildings, highlighted in a separate color, that has been subject to further analysis regarding their potential for reuse on a structural as well as component scale. Donor buildings, highlighted in a separate color, represent larger structures selected for subsequent design investigation.

Norrbotten 1–14

1. Bergmästaregatan 10 swimming pool

2. Skolgatan 28 residential

3. Trädgårdsgatan 6 commercial

4. Leveäniemi 1 industrial

5. Kvarntorpsvägen 1 school

Kiruna

Kiruna

Kiruna

Svappavaara

Niemisel

6. Sundomsvägen 543A residential

7. Unbyn 306 school

8. Laboratorievägen 16 educational premises

9. Regnbågsallén 5 educational premises

10. Hemmansvägen 6 residential

11. Storgatan 46 gas station

12. Stationsgatan 44 sport facility

13. Hammarvägen 32A industrial

14. Stationsvägen 20 residential

Västerbotten 15–16

15. Storgatan 30 residential/ office

16. Sågverksgatan 10 industrial

Luleå

Boden

Luleå

Luleå

Luleå Arvidsjaur

Arvidsjaur

Öjebyn Hällnäs

Umeå Holmsund

Västernorrland 17–21

17. Björnavägen 2A industrial

18. Myrängsvägen 8 industrial

19. Vetevägen 12 kindergarten

Örnsköldsvik

Örnsköldsvik

Domsjö

20. Arkivvägen 3 construction building

Härnösand

21. Matrosgatan 5 warehouse/storage

Härnösand

Gävleborg 29–39

29. Tegelbruksvägen 5 industrial

30. Vänortsvägen 17 residential

31. Edelsbergsvägen 25C Bollnäs school

32. Polacksgatan 4-6A residential

33. Regementsvägen 5-7 residential

34. Hammarvägen 39 residential

35. Norrberget 180 residential

36. Enrisvägen 1 A-B nursing home

37. Stationsgatan 31 storage hall

38. Kilafors Riksväg 35 car repair service

39. Brunnsvägen 6 residential

Dalarna 40–44

40. Fredsgatan 14 office

41. Rottnebyvägen 20 residential

Bollnäs

Bollnäs

Bollnäs

Bollnäs

Söderala

Söderala

Söderhamn

Söderhamn

Kilafors

Kilafors

Ljusne

Mora

Falun

42. Sulfatvägen 15, 17, 23 industrial

43. Oxborvägen 7 library

44. Dillners väg 8 industrial

Värmland 45–48

45. Skolgatan 34 residential

Avesta

Saxdalen

Grängesberg

46. Skummeråsvägen 2 residential

47. Allégatan 8 residential

48. Industrigatan 10-12 residential

Västmanland 49–50

Lesjöfors

Filipstad

Filipstad

Säffle

56. Hannebergsgatan 41 residentail

57. Högsätravägen 2 communal building

58. Karlbergsvägen 77-81 office

59. Odengatan 69 offices

60. Birger Jarlsgatan 31 commercial

61. Torsgränd 3-27 residential

Solna Lidingö

Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm

62. Gustavslundsvägen 151B offices

63. Segelbåtsvägen 13 offices

Stockholm

Stockholm

64. Högalidsgatan 26-28 residential

65. Polhemsgatan 50 hospital

66. Ripsavägen 38 communal building

67. Gymnasievägen 3 school

Stockholm

Stockholm

Bandhagen

Södermanland 68-72

68. Sictoniagården Flygel nursing home

69. Frejastråket 2 hotel office and storage

70. Bellmansgatan 1-8 residential

71. Brogatan 5 hotel

72. Oxelögatan 26 school

Örebro 73–76

Huddinge Strängnäs Strängnäs

Eskilstuna

Flen

Oxelösund

73. Södra Grev Rosengatan 18 hospital

Örebro

74. Södra Grev Rosengatan 15 office

75. Skvadronvägen 15 industrial

76. Von Boijgatan 16ABCD residential

Örebro

Örebro

Örebro

Jämtland 22–28

22. Järnägsgatan 16 storage building

23. Åkersjön 234 hotel

Strömsund

Föllinge

24. Indalsvägen 1 residential buildings

25. Gällö skolvägen 6B,D educational premises

26. Furugränd 17 school

27. Herrgårdsvägen 5 hotel

28. Tjärngatan 5A row houses

Duved Gällö

Bräcke

Ljusnedal

Sveg

49. Bolagshagen 1-5 residential

50. Wijkmansgatan 7 industrial

Uppsala 51-54

51. Huddungevägen 2 residential

52. Ulleråkersvägen 44 communal building

53. Skolvägen 5-31 residential

54. Hamngatan 3

Stockholm 55–67

Kärrgruvan

Västerås Heby Uppsala Örsundsbro

Enköping

55. Solhems hagväg 2-51 residential

Spånga

Östergötland 77–83

77. Lindövägen 72 residential

78. Ulaxgatan 57C school

79. Margaretagatan 27 residential

Norrköping

Motala

Söderköping

80. Danmarksgatan 19D residential

81. Storgatan 6-16 residential

82. Söderleden 35 municipal building

83. Kisavägen 37 residential

Linköping

Linköping

Linköping

Ydre

Jönköping 84–87

84. Myrgatan 24 A-B residential

85. Eksjöhovgårdsvägen 6 residential

86. Växjövägen 5 residential

87. Norrgatan 5 residential

Avesta

Sävsjö

Vrigstad Rörvik

Västra Götaland 88–98

88. Bastiongatan 14 municipal building

89. Göteborgsvägen 6 sports facility

90. Mjölnaregatan 1 office\industry

91. Valhallagatan 3 sports facility

92. Valhallagatan 1 stadium

93. Södra Vägen 37 parking garage

94. Dicksonsgatan 2 museum

95. Renströmsgatan 4 library

96. Bäckstensgatan 5 offices

97. Gärdesvägen 5 sports facility

98. Kindsvägen 11

Kalmar 99–109

99. Hamnen 1 industrial

100. Präststigen 3 nursing home

101. Tändsticksvägen 8 Warehouse

102. Kvillgränd 21-23 residential

103. Parkvägen 1A residential

104. Parkvägen 1B residential

105. Ringvägen 1-5, 7-11 residential

106. Kyrkogatan 33 residential

Uddevalla

Uddevalla

Trollhättan

Göteborg

Göteborg

Göteborg

Göteborg

Göteborg

Mölndal

Hovås

Svenljunga

Gamleby

Gamleby

Västervik

Storebro

Silverdalen

Silverdalen

107. Bruksgatan 13A,15, 17 residential

108. Östra Långgatan 9 residential

109. Vitsippvägen 1–10 residential

Virserum

Fågelfors

Fågelfors

Ruda

Ljungbyholm

Kronoberg 110–121

110. Fridhemsvägen 3A residential

111. Bruksvägen 3 industrial

112. Storgatan 51 grocery store

113. Skolgatan 6 preschool

114. Sjögatan 2 industrial

115. Forsdalavägen 1 industrial

116. Blädingevägen 23 office

117. Kyrkogatan 2 hospital

118. Lasarettsgatan 3 preschool

119. Björkstigen 9 preschool

120. Replösavägen 4 preschool

121. Delary bruk 2 old factory

Blekinge 122–123

122. Polhemsgatan 28 residential

123. Snapphanevägen 1 residential

Skåne 124–135

124. Hällebäcksvägen 10 residential

Ljungby

Alvesta

Alvesta Alvesta

Ljungby

Ljungby

Ljungby

Ljungby

Älmhult

Karlskrona

Karlskrona Laholm Osby

125. Tommahultsvägen 16 industrial

126. Torggatan 1 residential

127. Stobygatan 10 residential

128. Kvingevägen 27-29 residential

129. Halabacken 15 preschool

130. Repslagaregatan 14 residential

131. Bruksgatan 10 industrial

Sibbhult

Hässleholm

Hanaskog

Eslöv

Eslöv

Eslöv

132. Landsdomarevägen 1, 3, 5 residential

133. Smedjegatan 5 parking

134. Uppsalagatan 2A residential

135. Eric Perssons väg 5 stadium

Lund

Malmö

Malmö

Malmö

Torpsbruk

Uppvidinge

Uppvidinge

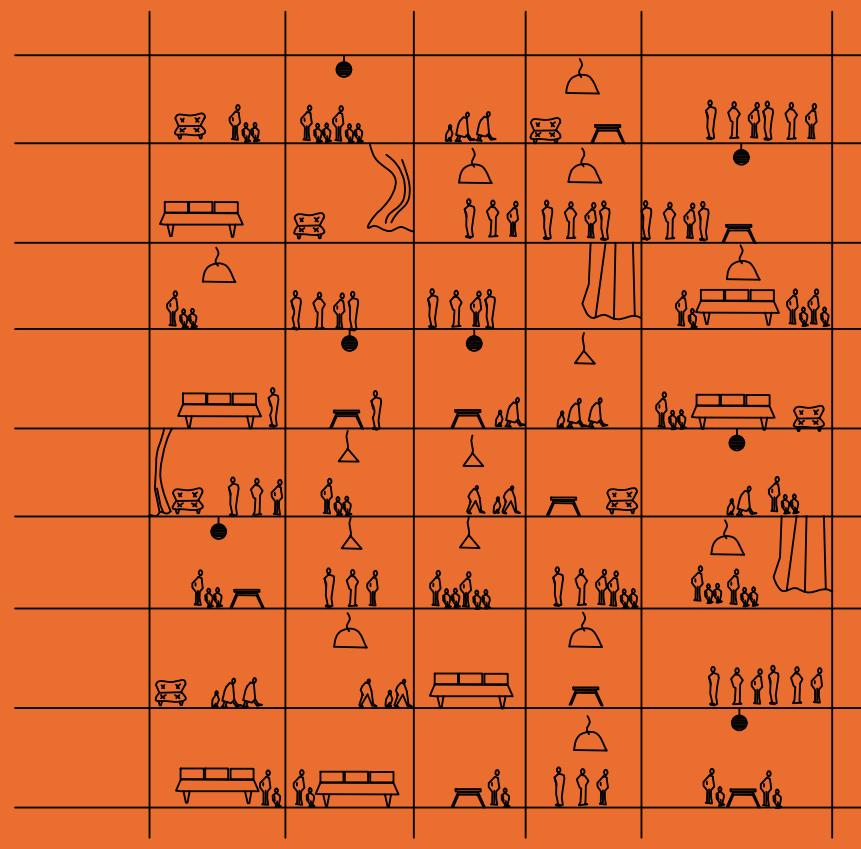

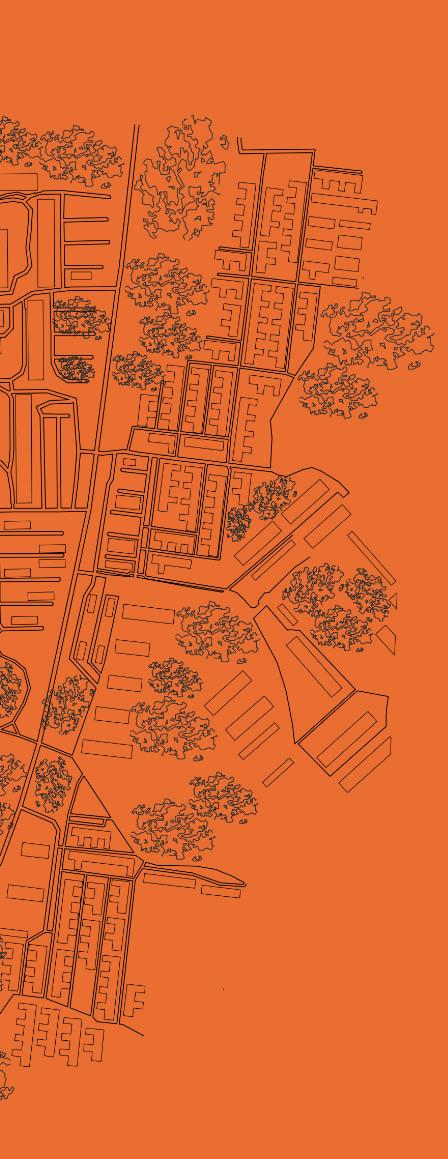

The function diagram reveals that residential buildings make up the largest proportion of buildings threatened with demolition in Sweden, with housing being the primary category. This is followed by commercial buildings, specifically grocery stores and offices. Education buildings, including schools and kindergartens, also represent a significant portion of the buildings threatened with demolition. This suggests that urban areas in Sweden face challenges related to outdated or surplus buildings, particularly in residential and commercial sectors, which could be undergoing redevelopment or repurposing.

Donor buildings (21)

Size diagram

Silverskopan 3

Tallbiten 1-5 & Trasten 1

Esbjörn 1

Klockaren 18

Alabastern

Druvan 22

Cypressen 2

Hulingsryd: 14:67

Läkaren 6

Sjundekvill 1:193

Riksvapnet 3

Ringen 1

Virket 8

Hermes 14-15

Bastuban 1

Regionsjukhuset

Virkeshandlaren 11

Kallmora 2:46, 2:49

Omformaren 6

Vallmon 12

Hamre 2:45

Quality

Affordability

Sustainability

Politics

The housing question refers to how people can be ensured access to safe and affordable homes. It highlights the economic and social inequalities that arise when housing goes from user value to exchange value and is being managed as a market commodity rather than a human right. It describes a historic change in systems that affects mainly the middle and working classes as housing shortages and rising rents prevent people from finding adequate homes. Therefor the housing question is not only about homes, but also about equality, civic rights and economic systems.

1850s-1870s

Industrialisation drives mass migration from rural areas to cities across Europe (Belgium, France, UK, Germany, and later Stockholm, London). Stockholm’s population trebles from 93,000 to 300,000. Overcrowding, slums, poor sanitation, and high mortality become widespread. In Sweden, rural population rises from 1 to 3 million, urban from 2 to 4 million. Over 40% of families live in 1–2 room apartments, often in unhealthy conditions.

First debates on the “housing question”; early reform ideas emerge, linking housing with public health and social order.

Friedrich Engels publishes The Housing Question (1872), framing housing as a structural social issue inseparable from inequality, not just a shortage of dwellings.

Rural-to-urban migration intensifies; housing crises in cities like Stockholm. Apartments severely overcrowded, with rents consuming over half of tenants’ income. Poor living conditions fuel disease and social tensions.

Industrialisation -rapid rural-to-urban migration causes severe housing crises in major cities (Stockholm’s population triples to 300,000).

Overcrowding, slums, poor sanitation, and disease widespread 40%+ of families live in 1–2 room apartments; rents consume more than half of tenants’ income.

1914 Government Housing Commission Report: Swedish housing more expensive and lower quality than in other industrialised nations.

By late 1920s: 70% of Stockholm homes lack bathrooms; 60% lack central heating.

1940s-1950s1960s-1970s

Post-war period: urgent need for mass housing

Early suburbs (1930s) with linear blocks considered monotonous, failing community needs : Old stock dominated by outdated “one room + kitchen” flats, inadequate for growing families

1942 Rent Regulation Act keeps rents affordable but insufficient.

Economic boom migration to cities Labour shortages in construction, housing shortages persist.

1925

1904: Riksdagen introduces national loans for rural smallholders and urban homeowners’ associations to stabilise settlement and discourage U.S. emigration

Architects, hygienists, and engineers tackle housing with rational, hygienic, and reform-driven designs

1921: Report Praktiska och hygieniska bostäder recommends rational small apartments (40–45 m²), three-floor blocks, light, courtyards, staircases

1923: Stockholms Kooperativa Bostadsförening (SKB) foundedhousing cooperatives become key players

1930: Stockholm Exhibition- Functionalism declared Swedish way forward

Acceptera manifesto ties housing to modern society’s transformation. Functionalist designs: standardisation, hygiene, rational layouts, linear blocks with green space

Per Albin Hansson presents vision of folkhemmet (“the people’s home”) -housing as social equality foundation

Competition for low-income mass housing begins; public sector steps in

Collective Housing Experiments: Inspired by Soviet communal housing and U.S. gender debates. Aimed to free women from domestic burdens and balance family with community. Criticised as a threat to the nuclear family, but pioneered future cohousing models.

1950

1944: Hemmens forskningsinstitut (HFI) founded -research on ergonomics, gender roles, and efficiency in home life

1946–47: Final Reports of the Social Housing Commission - call for universal housing policy, serving all citizens, not only the poor 1947: Parliament adopts universal housing policy - housing recognised as a right for everyone

1948: National Housing Board replaces earlier loan agency - stronger state coordination

General Municipal Plan strengthens municipal role in urban planning - focus shifts from family/society to community scale

1945–1960: Housing Boom

-Around 700,000 dwellings built -Families move into 2–3 bedroom modern flats with bathrooms, central heating, and functional kitchens

-Everyday housing begins to embody the folkhemmet vision - equality, modernity, and collective welfare.

1950s: Prefabrication experiments (e.g., Järnbrott, Gothenburg, 1953) 1960: Byggforskningsrådet founded to modernise building sector

1965–1974: Miljonprogrammet launches - goal: 1 million dwellings in 10 years

Result: Sweden builds 100,000 units/ year, adds ⅓ to housing stock

Features: spacious apartments, prefabricated systems, rational layouts, green space, neighbourhood

1975

Global crash hits Sweden hard: soaring unemployment, falling birth rates

Housing still inadequate; families suffer

Social transformation of the 1920s— industrialisation, rising wages, electricity, mechanisation—had raised expectations of better living standards. 1900-1940

2000s

2008: ROT deduction introduced -mainly used by highincome households, fuels inequality. New housing construction drops to 20,000 units/ year lowest since WWII. Population grows by +1 million (2000–2016), adding pressure.

2013–2016: 300,000 refugees granted asylum worsens overcrowding

Increasing rents, privatisation, and low-quality refurbishments

displacement, segregation, homelessness.

2010s

2012–2023: Overcrowding increases from 9.2% - 13.6%

2015: If food rose like housing in UK -chicken would cost 670 SEK

2017: Discrimination & black-market dealingsexploitative rents, more reliance on allowances

2017: Regulations encourage cheap, short-lifespan building materials

2020s

2020: Debt-toincome ratio ~200% (2nd highest in Europe)

2020: Riksbank buys mortgage bonds -44,000 SEK per citizen spent to keep prices high

2022: “The work line is dead” -housing price per m² - 800% since 1996 (general inflation only 33%)

2000 2025

1984: ROT Programme (repair, alter, extend) improve postwar housing & Miljonprogrammet stock

1979–80s: Social-cultural projects (e.g., Blå Stället, Angered) to address segregation

1988: Planning & Housing boards merged into Boverket

1991: Conservative gov’t closes Ministry of Housing subsidies cut, municipalities forced to privatise stock.

Neoliberal shift: Housing treated as a market commodity, speculation rises

DEFINED BY OWNERSHIP

Rental housing, privately or municipally owned.

Condominium, owned share in a housing association.

Owning, housing where the occupier owns the property.

Cooperative, association rents from a property owner or multiple people own together.

Other, special forms; student housing,

senior housing, staff housing, etc.

DEFINED BY TYPOLOGY

Detached, single family villas

Linked, semi detached single family townhouses, rowhouse or duplexes.

Low rise, multi-family residential rental apartments and condominium buildings.

High rise, multi-family residential rental apartments and condominium buildings.

Annexes, secondary housing units connected to a primary residence like guestthouse etc.

Slums, informal and unplanned housing areas with low standards.

Miscellaneous, specialized or temporary housing like barracks, temporary pavilions or house boats.

DEFINED BY SIZE DEFINED BY FUNCTION DEFINED BY USE

Small buildings, 1 - 10 units (single-family homes, small apartment buildings).

Medium buildings, 11 - 59 units (mid-sized apartment buildings, townhouse clusters).

Large buildings, 60 - 200 units (larger apartment buildings, small housing estates).

Very large complexes, 201+ units (large housing estates or multi-building developments).

according to demand.

Community housing, non-profit organisations meeting housing need through affordable rental and home ownership options.

Municipal owned housing, rent controlled and, in principle, available to everyone.

Permanent housing, Holiday homes or second homes, Student housing, Senior housing or assisted living,

Market based, housing that is built and priced dwellings intended for all year around use used seasonally/ occasionally for recreation or leisure.

Supportive housing,

accommodation specifically designed for students. housing adapted for older, sometimes with care or support services. housing for people with special needs or requiring social support.

30

Zollhaus, Zürich

Zollhaus is a housing complex located in Zurich designed by Enzmann Fischer partner in 2021. It constitutes of affordable apartments in various forms of housing, together with a mix of commercial premises. The first three floors work as a meeting point for the various areas of use, while the upper floors are private housing. The common areas and meeting points create an inclusive area both for the residents and for people working in or visiting the building.

Zollhaus project is a cooperative housing project showing how the housing question can be handled in terms of the concept of the theme. Social quality and community are being created through common areas and various forms of housing. The project offers housing at affordable rents in the otherwise expensive city, which challenges the housing market. It is an example of how the city and its inhabitants can promote housing as a social right. Further, the building is energy-efficient and emphasizes social integration, uniting people, the environment and the economy.

Gamla Östberga

Lars-Magnus Giertz designed the neighbourhood of Gamla Östberga in 1957-1959. It was the first on a larger scale to be prefabricated in Sweden and was, at the time of its construction, seen as a modern and experimental building. The project was part of Sven Markelius new city plan, and the three to four-storey high buildings were arranged around Stamparken, a car-free zone that became an important meeting point for people of all ages.

Built between 1957-59, Gamla Östberga in Stockholm is an early example of handling the housing question of the time through modernity, planning and social sustainability. As one of the country´s first prefabricated projects, it showed how industrialization could create affordable and modern housing for more people. The housing quality was emphasized through light apartments with common green areas. Stamparken contributed to safety and community, creating both social and environmental sustainability. Further, the project shows how housing politics, techniques and city planning cooperated in order to meet the needs of affordable and functioning housing.

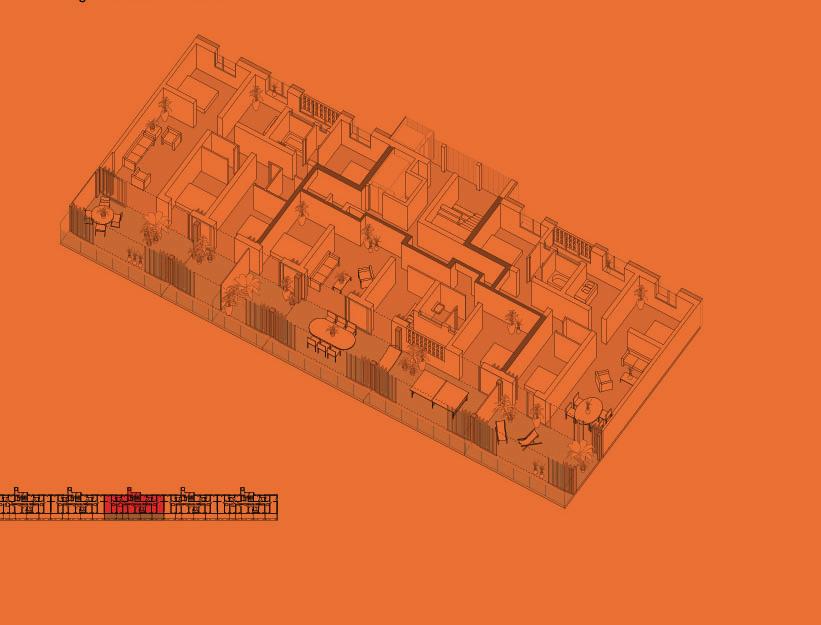

5. Exploded floorplan with mapped functions.

Authors

Linnea Lindh

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors

Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1981

High-rise, multifamily, residential

Cast-in-situ

144

9 15000 m²

Riksbyggens

Arkitektkontor

County Stocholm

Municipality Stockholm Iän

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Torsgränd 3-27, Stockholm Afa Tjänstepension

Project description

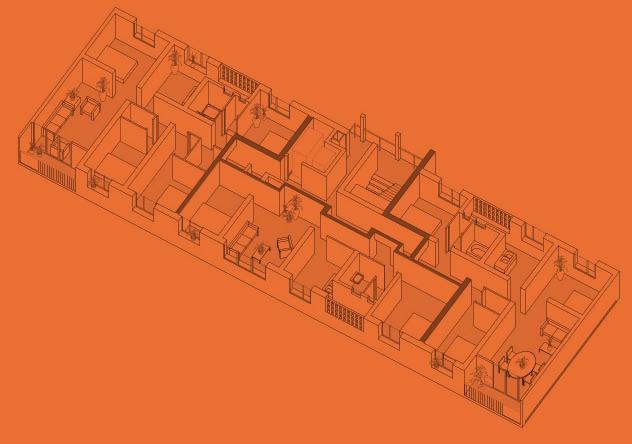

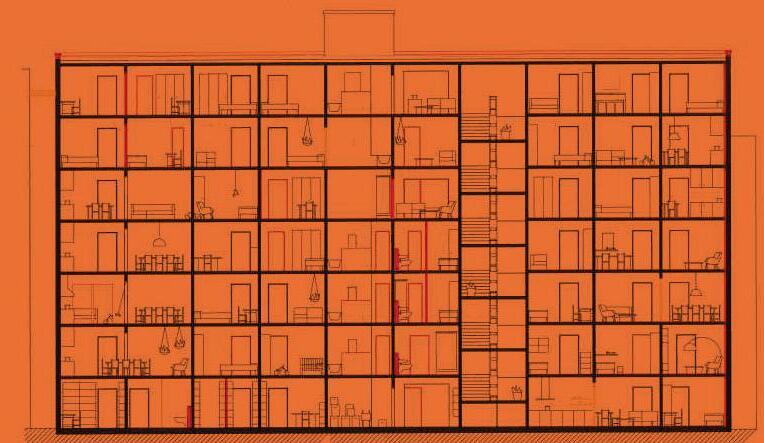

Silverskopan 3, formerly called Sabbatsberg 22, is located at Torsgränd 3 in Vasastan, Stockholm. Built in 1981 by Riksbyggen’s architectural office, the prefabricated concrete building is typical of its time. Over the years it has developed serious issues with its indoor environment and outdated technical systems. Because of these problems, the owner, Afa Tjänstepension, is planning to demolish the property. The demolishion will be in stages, allowing tenants who want to remain in the neighborhood to stay during the redevelopment. The City of Stockholm has approved a new zoning plan, which is currently under appeal, to reshape the site and surrounding blocks. The plan includes around 300 new apartments, a preschool,

local shops or community spaces, and a parking garage. The new buildings, designed at six to eight stories, aim to create a livelier and more connected streetscape along Torsgatan with the character of Sabbatsberg intact The house is carefully designed in a southwest-facing arch that recalls the brick gas clock that stood on the site until 1970. It has also been nominated once for the Kasper Sahlin Prize, Sweden’s most prestigious architectural award in 1982. The new design proposal is made by Alexander Wolodarski the sam architect that was working with the project for Riksbyggens arkitektkonot only 40 years ago.

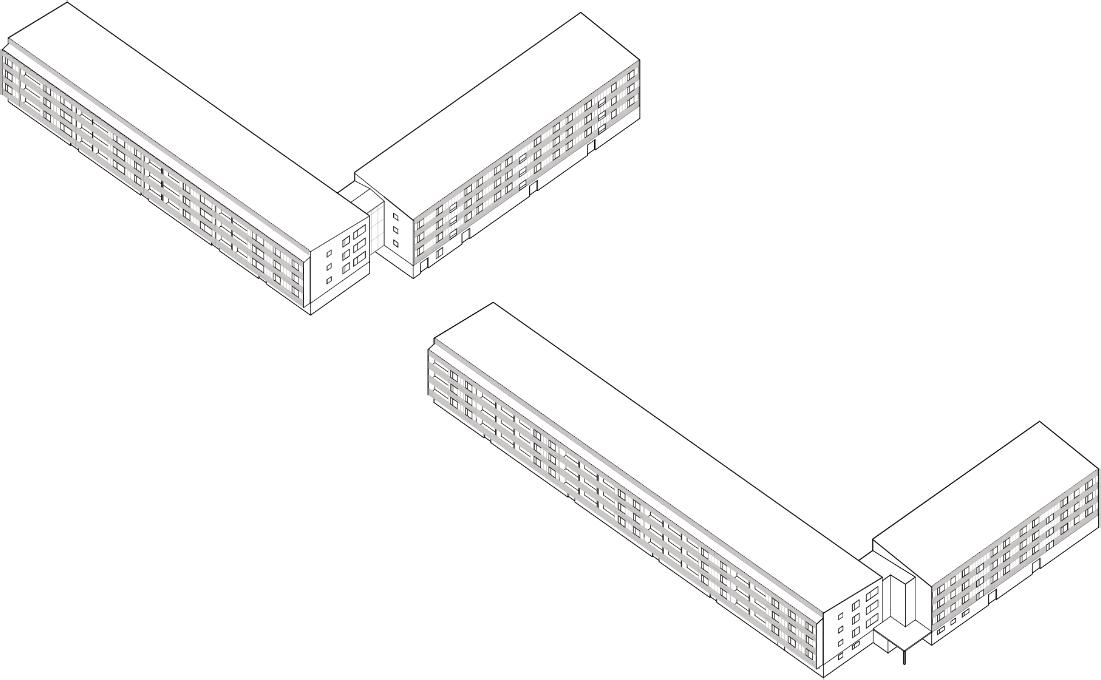

70. Tallbiten 1-5 & Trasten 1

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

High-rise and low-rise, multifamily, residential Bookshelf

1961 560 4-8

25 000 m²

J. Höjer - S. Ljunqkvist

CountySörmland

MunicipalityEskilstuna

Address

Collected documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Bellmansgatan 1-8, Eskilstuna Kfast, Eskilstuna kommunfastigheter

Project description

Brunnsbacken is located just south of Eskilstuna’s city centre, between the downtown area and the Vilsta recreational park. The neighbourhood was built in the early 1960s and mainly consists of apartment buildings, both lamella blocks and point houses and with flats ranging from one to five rooms and a kitchen.

There are about 560 apartments here, owned by the municipal housing company Kfast. Many of the flats have balconies, and there are also a couple of care homes for the elderly nearby as well as schools, preschools, shops, and health centres. Green spaces and playgrounds are spread among the buildings.

Several apartments in Brunnsbacken are worn out and in need of extensive renovations. Maintenance costs are high, and political proposals have been made to demolish the site instead of renovating. At the same time, there is opposition from residents and politicians who argue that demolition would take homes away from people and that it would be better to renovate as much as possible.

Socially, Brunnsbacken struggles with several issues. Problems with vandalism, carfires, open drug dealing and violent crimes have been reported. Residents also express concerns about empty apartments and financial constraints affecting both upkeep and living conditions.

Load-bearing

Load-bearing

55. Esbjörn 1

Year

Building category

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1973

Low-rise, multifamily, residential 96 Bookshelf 2 826x12 m²

AB Stockholmshem Ernst Grönwall

CountyStockholm

MunicipalityStockholm

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Solhems hagväg 2-51, Spånga

Project description

Esbjörn 1, at Solhems hagväg 2–51 in Spånga, Stockholm, consists of 12 two-story slatted houses and one service building with a laundry and meeting room. Designed by AQ Arkitekter and built in 1973 by AB Stockholmshem, the neighborhood includes 96 apartments of two, three and four rooms.

The buildings su er from major technical issues: counter-fall roofs have caused recurring leaks, drainage pipes made of brittle ABS plastic are failing, energy use is high (246 kWh/m² A-temp), radon levels are elevated and access to roofs and foundations does not meet work environment standards.

Stockholmshem therefore plans to demolish all buildings and redevelop the area with 300 new rental units in 3–5 story apartment buildings and smaller townhouses. A new public square will face Spånga kyrkväg. The City of Stockholm approved the start-PM in 2022, and public consultation is scheduled from September 30 to November 11, 2025.

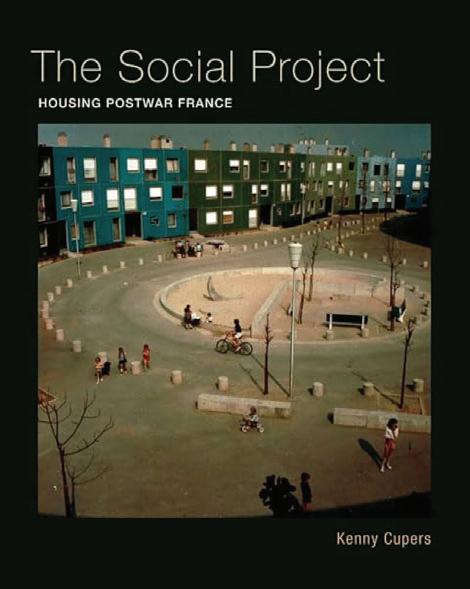

Modernism

Social project

Standarisation

Identity

Abstraction

Linear typology

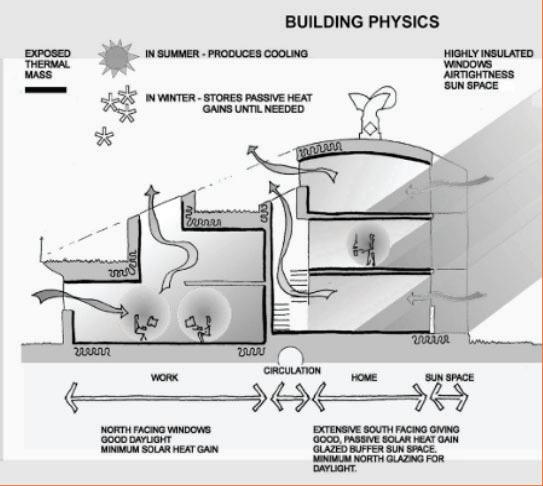

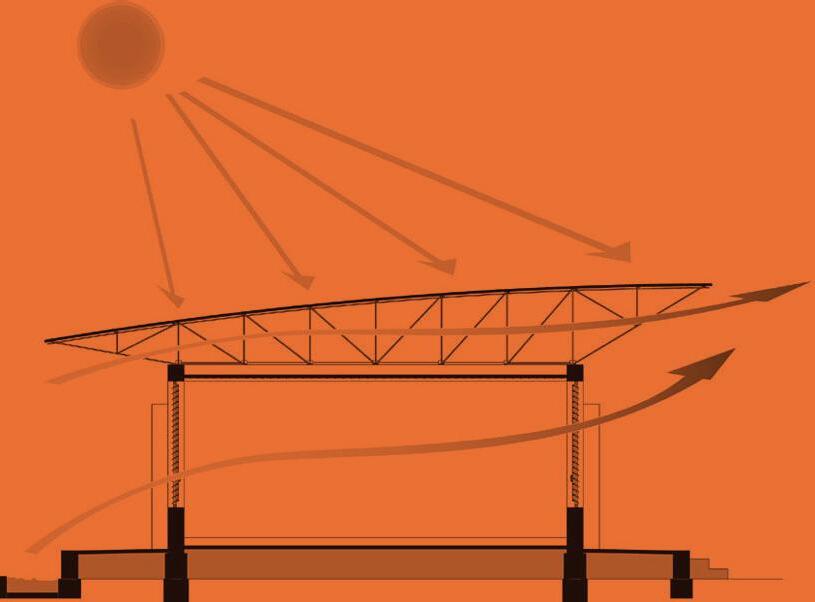

Segregation

The housing shortage, driven by rapid population growth, limited land, and restrictive zoning, has prompted modern architecture to adopt prefabrication, open floor plans, and industrial materials for faster, cheaper construction. Cities also encourage modular and “missing middle” housing to boost density and affordability, addressing the urgent need for functional, sustainable homes.

In the 1960s, it was a widespread lack of affordable and adequate homes caused by rapid urbanization, population growth, and insufficient construction to meet demand.

The pursuit of efficiency became central to housing production. New technologies like, prefabrication and modular construction enabled rapid, cost-effective, and standardized responses to the housing shortage.

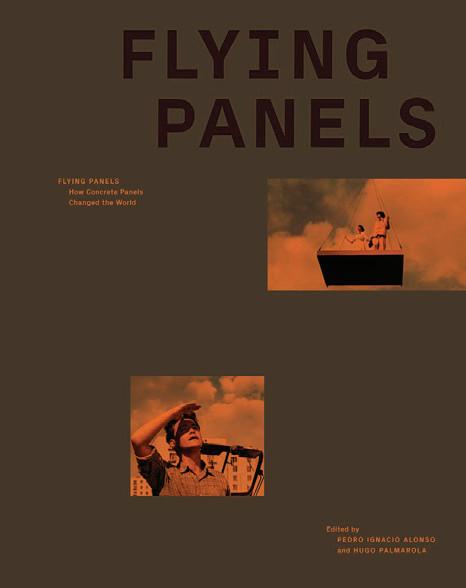

PREFABRICATION AND STANDARDIZATION

The arrival of prefabrication drasticly transformed the construction industry. It introduced standardized components and modular systems, allowing buildings to be assembled faster and more efficiently. This shift challenged traditional craftsmanship and reshaped the workforce, creating a new industrialized approach to housing production

REPETITIVE /MONOTONY

Paradoxically, the housing shortage also stimulated innovation, pushing architects and engineers to develop new technologies and rethink large-scale housing design.

URBANISATION SOCIAL PROJECT

EXPANSION-REGULATION

Rapid industrialization and urban migration created overcrowded, and unsanitary slums. Governments and philanthropists began building affordable housing for workers. The 1919 Housing and town Planning Act (UK) established government responsibility for housing provision and encouraged large-scale house construction, introducing an early standardization in housing design and quality control.

After World War I, many countries in Europe faced a severe housing shortage. Millions of soldiers returned home, populations grew rapidly in cities, and construction had been almost entirely stopped during the years of the war. The demand for affordable housing far exceeded the supply, leading to overcrowding and poor living conditions. Governments began to recognize housing as a social issue, which led to early public housing programs and new urban planning policies aimed at improving living standards.

The housing programs expanded with subsidies and slum clearance policies. Standardized building regulations and quality assurance organizations emerged to improve consistency. Rising homeownership aspirations led to suburban growth alongside social housing efforts.

Urbanisation peri-urbanisation

Modernism experimental approaches, sociopolitical and cultural contexts

Demolition

the role of ruin in reflecting on modern architecture.

Reduction and abstraction searching for the pur essence of architecture

After World War II, many cities were heavily damaged, and the housing shortage became even more critical. Governments launched large-scale reconstruction and social housing programs to respond to the urgent need for homes. This period saw the rise of modernist architecture, influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas of efficiency, standardization, and collective living. Prefabrication techniques and industrial materials were used to build quickly and economically. Across Europe and North America, entire neighborhoods of high-rise housing estates were developed to provide modern living conditions for working families.

Massive demand due to war destruction and population growth in the cities prompted housing construction to act rapidly. To develop new towns and large housing estates. Prefabrication, modular building systems, and industrial materials like concrete, and steel. This became widespread, and represented architectural modernism principles. Social diversification began as housing policies aimed to accommodate varied social groups, though often in segregated large estates

Decline of mass social housing construction with increased focus on homeownership. Housing associations rose as new actors in affordable housing provision. Urban regeneration and mixed-use, mixed-tenure developments aimed at social integration and diversity. Continued innovation in construction types to address affordability and sustainability.

Industrialisation

Its redevelopment in the modernization of postwar societies

Contemporary building methods critique and decline of panel housing: Requestioned

Standardization symbol of modernity and social progress

Identity

Modular and typological construction systems

Social project multiplicity of actors

44

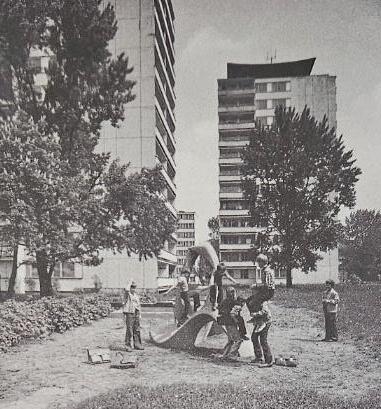

Vollsmose, Odense, Denmark

Vollsmose is a large municipal housing district in Odense, Denmark, built mainly in the 1960s and 70s as a modernist “new town” with high-rise blocks, generous green spaces, and a focus on welfare ideals. Isolated by main roads and later associated with high immigrant populations and social problems, it was listed on Denmarks “Ghettolist”, comparable with Swedens map of vulnerable areas. Today, a major redevelopment aims to integrate Vollsmose with the city by demolishing some public housing and adding diverse urban functions, connecting streets, and more sustainable housing, reflecting current Danish policies striving for social mix and urban revitalisation.

Connection to the theme

It exemplifies the postwar welfarestate drive for large-scale, modernist housing solutions in Denmark. Vollsmose followed international trends-concrete prefabrication, open green spaces, and functional zoning-to answer housing shortages and reflect ideals of social equity and collective life. Over time, as elsewhere in Europe, Vollsmose became a symbol for both the ambitions and criticisms of mass housing: its scale and planning expressed welfare optimism, but also led to debates about segregation, community, and the adaptability of such estates in changing social contexts.

The project is part of the most ambitious municipal housing initiative in the Swedens history. It embodies the ideals of postwar welfare urbanism—standardized prefabricated buildings and abundant green areas, and complete local services - to provide affordable, modern living for thousands of residents. Like other mass housing estates across Europe. It’s located in Haninge, south of Stockholm, and was built during the 70’s as a part of the swedish “Miljonprogrammet”.

Connection to theme Brandbergen, Haninge, Sweden

This project is one of Swedens most ambitious municipal housing iniative. Today, it’s listed in the police in Swedens map of “vulnerable areas”, which is to identify areas in Sweden with high segregation and criminality The list is categorized in three subcategories; vulnerable, especially vulnerable and areas that are in risk. Brandbergen illustrates both the optimism of large-scale industrialized buildings and its long-term challenges, such as social segregation, monotony of design, and the later need for renewal to adapt to the changing urban and social realities.

Authors

84. Klockaren 18

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1956

High-rise, multifamily, residential 35 Wallframe, slab 4 1097

Lindén Fastighetsbolag

Johannesdahl Arkitekter

CountyJönköping

MunicipalityNässjö

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Project description

Klockaren 18 is one of three buildings on the same plot currently threatened with demolition. The buildings status is today “under consultation”. In 2021, Lindéns fastighetsbolag decided that Klockaren 18, Klockaren 17 and Ringaren 13 would be demolished in two stages. These buildings are located in Bodafors, a smaller locality with approximately 31,000 inhabitants. In june 2024 the demolition process was suddenly paused after the property owner terminated their contract with the demolition contractor. According to the owner, the decision to demolish the appartments were based on several factors: The buildings condition, outdated layouts and a weak rental market. Lindén argued that

the apartments and the building are in bad state and will be in need of total renovation, which makes it more cost effective to construct new housing. The new housing structures that were/are planned are row houses, aimed for older residents in Bodafors who are looking to downsize from their single-family houses. This case has received significant media attention which has led to antiquarian statements. These reports indicate that the building posses high cultural values, due to among other things the preserved details in the buildings. They state that the building is in good condition, but are in need of some upgrading in the ventilation, heating, water and sewage installations.

Lightweight frame

Cast-in-situ walls Cast-in-situ floors

basement

Alabastern

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1958

Low-rise, multifamily, residential

Wallframe, slab

35 apartments

3 floors

925m2

Botrygg fastigheter

Lennart Ekenger

CountyÖstergötland

Municipality

Address

Collected documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Linköping

Danmarksgatan 19D

Linköping

Project description

The project consists of a complex of three brick buildings, connected at the front by a row of shops. It is a 1960s construction imitating the industrial style. The structure is made of concrete blocks and floors, topped by a wooden frame. The bricks on the facade allow for the use of a structure made from less expensive materials. The three buildings are part of a rapid and low-cost construction approach, typical of the rapid construction context due to the housing shortage of those years. Each module consists of three floors, including one basement level, which is half underground. At ground level, the building is suddenly covered with facing bricks. The layout is repeated from floor to floor, accommodating apartments ranging

from studios to three-room units. The aim is therefore to house single people and couples, excluding families and shared accommodation. The profiles of the residents are diverse only in terms of age. The site is very well connected to the city and offers a large green space that separates it from the road. Due to its location, the project is set to be completely demolished to make way for a primary school. Work was due to begin in 2021, but Botrygg is participating in the early stages of a detailed planning process. The demolition is explained by the desire to replace this old industrial style in order to revitalize this suburban area.

Druvan 22

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

Residential, office and commercial

70 Concrete load-bearing

8 10605 m2

Castellum1962

CountyLinköping

MunicipalityOstergotland

Address

Collected documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Storgatan 6-16, Linköping

Project description

The donor building Druvan 22, constructed in the 1960s, is located in the city center of Linköping and follows a clear block structure in the area. The highrise building contains private residences, except for the ground floor, which is dedicated to retail spaces. Other buildings feature retail shops, restaurants, and a car repair shop on the ground floor facing the street, with office spaces on the upper floors. Additionally, the building has an underground parking garage. The total area of the building is 10,605 square meters.

The new development will include approximately 70 residential units, along with 19,100 square meters of retail and office space. The entire block of Druvan 22,

excluding the underground garages, will be demolished as part of the redevelopment. The facades today consist of white and yellow sheet metal and copper sheets, as well as a single-story building with a yellow brick facade. The ground floor of the block is clad in slate and all buildings have flat roofs.

The reason for demolishing the existing building is to create a connection between the current city center and the area east of Stångån. This aims to complement the city center in a well-balanced way. The demolition is planned to begin in 2025 at the earliest.

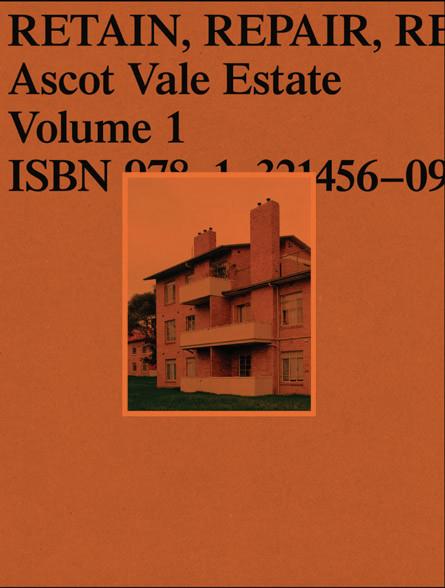

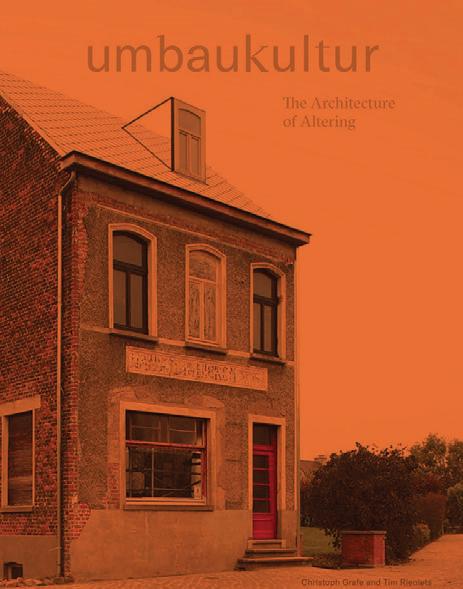

Conservation

Renovation

Remodelling

Alteration

Adaptive reuse

Transformation

Umbaukulur

Retain Repair Reinvest

The theme explores a spectrum of interventions that balance preservation and transformation. Renovation upgrades a building while keeping its structure intact, alteration makes precise adjustments without altering identity, and remodelling reshapes both form and character. Adaptation extends these processes by giving new purpose to existing structures. Together, they reflect an approach grounded in sustainability and continuity, where transformation is understood as a way of caring

The

Repurposing

Protecting

A

Retain, Repair, Reinvest (RRR)

of

Community & Social Value

Renewal that strengthens residents’ lives, health, and networks, not just the physical fabric.

Authenticity & Age Value

Recognizing

Renovation

Repairing,

Environmental Suistainability & Resource Awareness

Viewing

Remodeling

A

Alteration

Umbaukultur: The Architecture of Altering

Pre-Industrial Era

Buildings seen as valuable resources (labour, materials, embodied energy).

Adaptation and repair were normal practice to extend lifespan

Retain, Repair, Reinvest - Ascot vale Estate

Before 1940’s Race-course

Post-WWII reconstruction

Adaptive re-use: Strategies for Post-War Modernist Housing

Ascot Vale estate built

2 600 homes. Flats, maisonettes, houses)

Between 1950s - 1970s Focus on fast housing and infrastructure via new builds. Mass estates and industrial buildings lacked cultural value 1926

Neue Heimat founded in Hamburg as a non-prot housing company

Bombings and demolitions of buildings and cities in all of Germany during WWII.

Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage

Timeline

Based on case studies and key texts, traces adaptive reuse from early heritage awareness to a central sustainability strategies over time.

Architecture and conservation began to move closer together as a number of important architects began to show increasing interest in working with historic buildings

Prefabrication Factories

Built 1962

Project: Transformation of 350 dwellings.

Architects: Lacaton & Vassal. Frédric Druot, Christophie Hutin

1980s–1990s

Activists promoted reuse of industrial architecture. Iconic projects (e.g., Tate Modern, Neues Museum) proved reuse could inspire

Renewal program announced (demolition & rebuild)

2010’s

Neue Heimat had build 187.000 apartments, representing 1/3 of all apartments constructed since the Federal Republic of Germany was founded 1966

2016: Completed renovation. New facade and balconies with winter gardens

Reduce/Reuse/Recycle introduced as architectural principle. Post-war modernism revalued; economic debates expose hidden costs of new builds

RRR Strategy introduced Retain, repair, reinvest

In response to the announcement, a group of residents formed Save Ascot vale Estate (S.A.V.E)

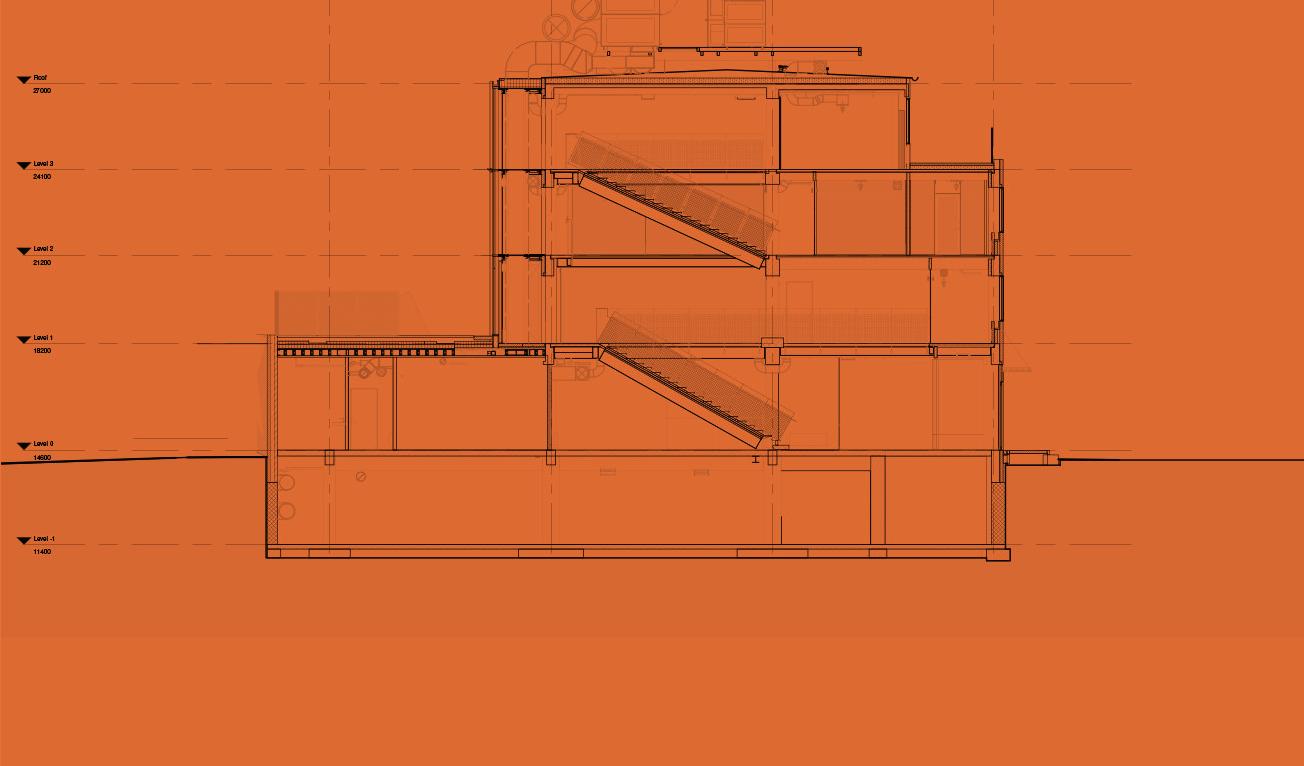

Section of the proposed refurbishment Image by OFFICE

1975 book “New Uses for Old Buildings”

Cantacuzino, pioneering research on adaptive reuse, study of churches, industrial and residential buildings

1975-1980´s

Gårdsten is classed as one of Swedens problem areas. Coupled with criminality and exclusion, the long rows of housing with monotonous facades led to unsafe passageways/areas

Gårdstens bostäder implements new ideas of economic, social and ecological strategies 1975-1980´s

Architects: Lacaton & Vassal

Location: Bordeaux, France

Year originally built: 1962

Renovation: 2016

Typology: multifamily residential blocks.

Materials: prefabricated, reinforced concrete The renovation added winter gardens and balconies (glazed, sliding doors), insulated façades.

Number of Buildings: 3

Number of Apartments: 530

Project description

The Transformation of 530 Dwellings is a social housing renovation project in the Grand Parc estate, carried out by Lacaton & Vassal together with Frédéric Druot Architecture and Christophe Hutin Architecture. The strategy was not to demolish, but to transform existing modernist housing blocks (buildings G, H, and I) built in the early 1960s. The aim was to dramatically improve the quality of life for residents without displacement, by adding extensions (winter gardens and balconies), enlarging windows, reworking facades, improving thermal performance, upgrading services (electrical, bathrooms, vertical circulation), and upgrading common/public spaces (stairwells, access halls, gardens). The result is generous, lightfilled apartments, better connection to outside, improved energy performance, and enhanced comfort all around.

The transformation focused on renovation without demolition. The existing concrete structure was kept, while new extensions, winter gardens and balconies, were added to expand apartments and improve light and comfort. Works were carried out with residents still living in their homes.

Architects: Oliver Clemens, Anna Heilgemeir

Location: Berlin, Germany

Year originally built: 1976

Renovation: 2015

Typology: Office building tuned into apartments

Materials: prefabricated, reinforced concrete

Number of Buildings: 1

Number of Apartments: 55

Project description

2.

WiLMa19 in Berlin-Lichtenberg is a pioneering collective housing project that transformed a former state office building into affordable, communityoriented living spaces. Organised under the Mietshäuser Syndikat model, the project is protected from speculation and managed collectively by its residents, ensuring long-term affordability and self-determination.

The seven-storey building accommodates a wide range of household types, from compact single apartments to large shared flats and family units, reflecting a deliberate social mix. Renovations were carried out on a modest budget, reconfiguring interiors to provide both private homes and generous communal areas. Shared gardens, event rooms, and common spaces encourage interaction among residents and open connections to the wider neighbourhood.

Adapting Wilma19

WiLMa19 exemplifies renovation and adaptation by transforming a former state office into affordable, community-focused housing. Through modest interior alterations and collective ownership under the Mietshäuser Syndikat, the project reuses existing structures sustainably while fostering social connection and long-term affordability.

Architects: Liljewall + CNA + White

Location: Gothenburg, Sweden

Year originally built: 1972

Renovation: 2006

Typology: multifamily residential blocks.

Materials: prefabricated, reinforced concrete, added glazed glass facades, Number of Buildings: 50

Number of Apartments: 2700

Gårdsten is a large housing area in north-eastern Gothenburg, built in the late 1960s and early 1970s as part of Sweden’s million program. Like many areas from that era, it consisted of long concrete slab blocks, standardized apartments, and underused outdoor spaces. Over time, it faced technical and social challenges, including deteriorating buildings, high energy use, and segregation. In the late 1990s, Gårdstensbostäder AB launched ambitious renewal plans, including the “Solar Houses,” which added solar collectors, glazed balconies, and shared facilities. Later projects rescaled blocks, renewed facades, and improved courtyards and pathways. Today, Gårdsten is a nationally recognized model of sustainable and socially inclusive renewal, with multiple national and international awards.

Gårdsten illustrates rescaling as both a physical and social process. By breaking down large slab blocks, redefining courtyards, and improving spatial connections, the renewal adjusted the neighborhood’s scale to human interaction. This transformation balanced architectural proportions with community life, turning an oversized modernist plan into a more livable urban fabric.

Ellebo Garden Room

Architects: Adam Khan Architects

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

Year originally built: 1963

Renovation: 2013 - 2020

Typology: multifamily residential blocks

Materials: load-bearing concrete frame, new prefabricated timber structures, glazed facades, metal cladding

Number of Buildings: 4

Number of Apartments: 260

Project description

Ellebo Garden Room is the renovation and extension of a 1960s estate in Copenhagen, Denmark. Typical of its time, the estate enjoyed generous landscape and good transport links, but suffered from poor thermal performance and comfort, weak spatial hierarchy, lifeless open spaces, and a concentration of elderly and low-income residents. A superficial 1980s renovation added colour but left the real issues unresolved.

This project took a more radical approach, working at several scales and challenging the then-dominant push for demolition. Blocks were extended in length and height to increase density and housing variety, while clearly framing the courtyard and giving it a sense of neighbourly enclosure. New lifts and direct garden access strengthened the buildings’ connection to the courtyard.

New highly insulated façades gave each apartment winter gardens, while minor internal adjustments created larger, dual-aspect homes.

Transforming

By retaining the concrete structure and adding lightweight timber extensions with glazed winter gardens, the project improves living quality, energy performance, and social interaction. It turns the estate into a vibrant “society of rooms,” demonstrating how thoughtful adaptation can regenerate both buildings and community life.

Authors

Year

Building type

1966

Low-rise, multifamily, residential

Number of apartments

Number of floors

Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect Structural system

75 Crosswall load bearing

4 6871 m²

AB Hultsfred bostäder Anders Sjunnesson

CountyKalmar

MunicipalityHultsfred

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Ringvägen 1-5, 7-11

Hultsfred

Project description

The building was constructed in 1966 and designed by architect Anders Sjunesson. There are four buildings on the plot, each consisting of three floors and a basement. The structural system is a crosswall loadbearing type with cast-in-place concrete elements. The decision to demolish the buildings was based on several factors, including high vacancy rates, extensive maintenance requirements, and the property’s low energy classification. Although some tenants consider the buildings to be in relatively good condition, the analysis indicated that the long-term costs of renovation and maintenance would be too high to be economically viable.

However, the existing structures contain significant material and spatial potential. By studying their construction logic and component systems, opportunities may arise for selective reuse of materials or structural elements in a new proposal guided by circular principles.

Hulingsryd 14:67

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1960

Low-rise, residential, multifamily

8 Bookshelf

4,5 560 m

AB Hultsfred bostäder Nils Johansson

CountyKalmar

MunicipalityHultsfred

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Parkvägen 1A, Silverdalen

Project description

Parkvägen 1A is one of two residential buildings on the same property in Silverdalen that are scheduled for demolition. Neither building has been rented out as housing for a long time, which has resulted in a lack of maintenance and led to their use as storage instead. According to the justification for the demolition, the purpose is to reduce the number of vacant apartments owned by the municipal housing company.

The building is a typical example of 1960s residential architecture and can be categorized as a lamellhus, a common post-war typology in Sweden characterized by long, narrow volumes arranged in rows. These structures were designed

to maximize light, ventilation, and access to green spaces, often forming part of larger housing developments built during the Million Program era.

The buildings on Parkvägen are just a few of many in Hultsfred that are planned to be demolished as part of a wider effort to reduce the number of empty apartments and manage a shrinking housing demand in the municipality.

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect 117. Läkaren 6

Erik Carlberg 1956 HospitalWallframe, slab 8 3500 m²

CountyKronoberg

Address

Collected Documentation MunicipalityLjungby

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Kyrkogatan 2, Ljungby Region Kronoberg

Project description

Building 1A at Ljungby Hospital was originally home to the eye clinic, administrative offices, and the ambulance station. Over time, changing healthcare needs and technical standards made the building increasingly unsuitable for modern hospital use. When renovation plans were initiated, extensive investigations revealed serious structural problems dating back to its original construction.

Several floor slabs had been cast too thin, and sewer pipes had been embedded directly in the concrete instead of in a separate layer. As these pipes corroded, they weakened the structure, causing cracks and uneven floors, and in some areas the pipes were the

only elements holding the slabs together. Some loadbearing walls were also made from façade brick, and the low ceiling heights left little room for modern systems such as ventilation and sprinklers.

Renovation was deemed neither technically nor financially viable, as the cost would have reached hundreds of millions of kronor without meeting current hospital standards. Region Kronoberg has therefore decided to demolish the building and construct a new seven-storey hospital wing in its place. Departments have already been relocated to temporary modular buildings, and demolition is planned to begin after the summer of 2026.

102. Sjundekvill 1:193

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1968

Low-rise, multifamily, residential 23 Bookshelf 3 2155 m²

Lars Erik Magnusson

CountyKalmar

MunicipalityVimmerby

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Kvillgränd 21-23, Storebro Vimarhem AB

Project description

Built in 1968, this linear apartment block in Vimmerby exemplifies a typical postwar Swedish housing model. Owned by Vimarhem AB, it forms part of a local surplus of underused dwellings and is currently slated for demolition.

In 1996, the building was reconfigured into a co-living prototype, testing how a standardized typology could accommodate contemporary forms of communal living. Later, during the migration crisis of 2015, it was repurposed by the Swedish Migration Agency to provide temporary housing. After six years, the tenants moved out, and since then, the building has stood vacant.

Vimarhem AB now plans to demolish the structure, citing high maintenance and renovation costs, as well as a lack of demand for this housing typology in Storebro and Vimmerby Municipality.

Structurally, the building follows the “bookshelf method”, where transverse load-bearing concrete walls form the “shelves” and the floor slabs span between them. This system allows for flexible internal divisions, which were previously adapted to create shared kitchens, communal living spaces, and private rooms.

Culture Heritage

Heritage listing

Preservation

Renovation

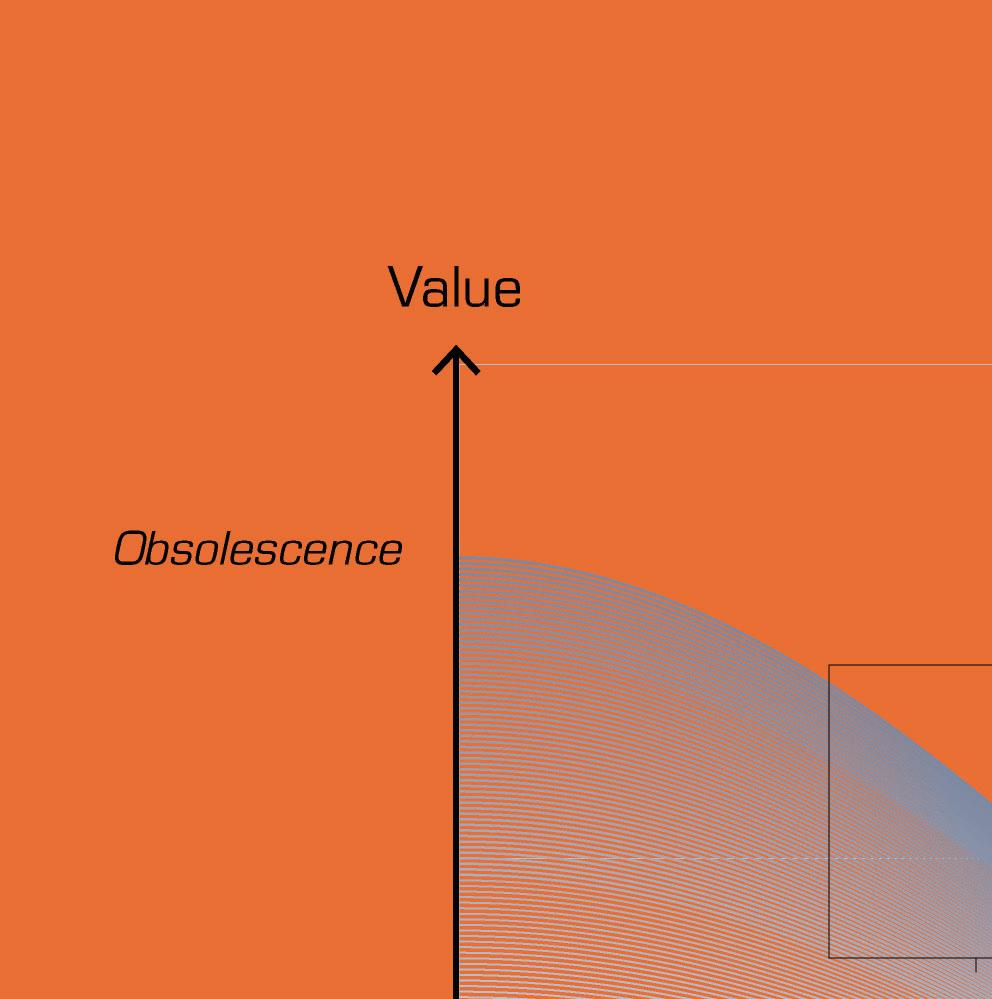

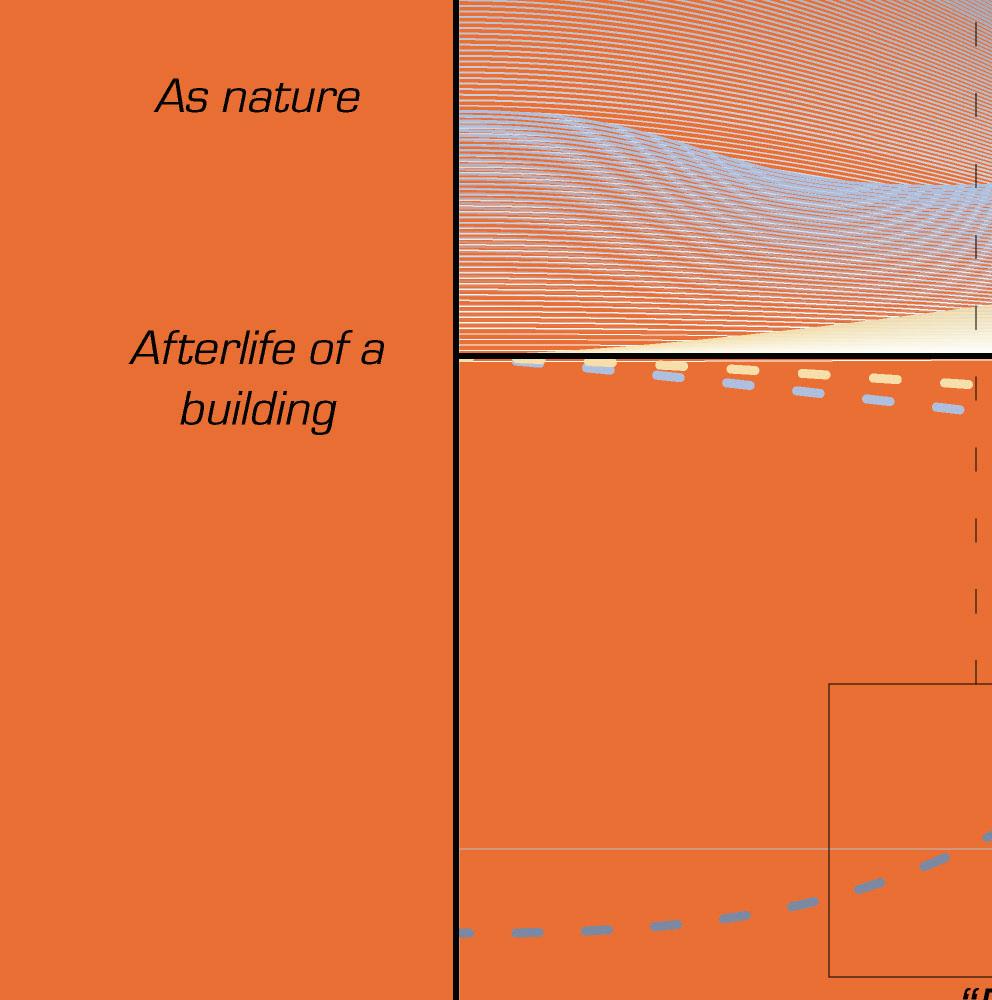

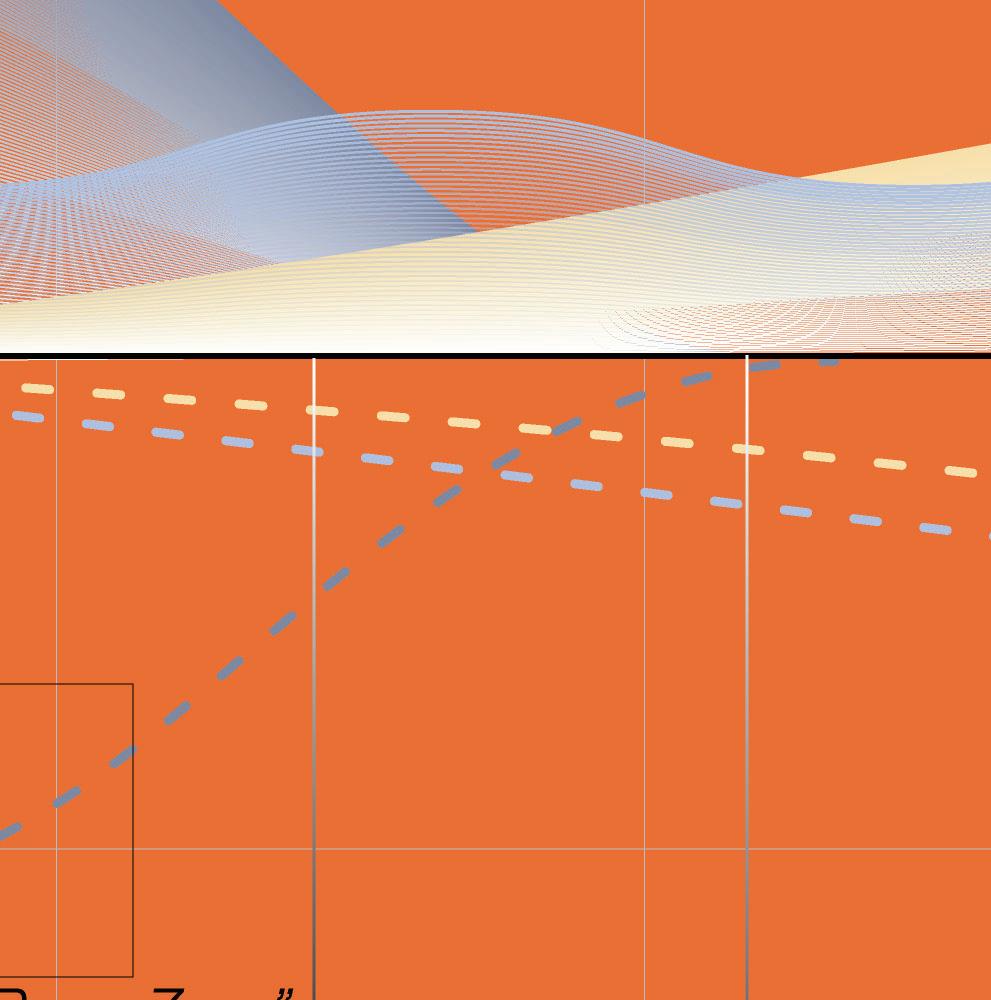

Afterlife

Obsolescence

Architecture as nature

The built environment and housing constitute a large part of our heritage. While we want to preserve and promote these for future generations, we also want to ensure that they are accessible and usable for everyone. This leads to a series of contradictions that we must resolve. Key questions are why, what and for whom? What is to be preserved and become cultural heritage and what different methods can we use?

Architecture as complete, perfect and permanent

Heritage listing

Expert-driven preservation

Preservation of solitary objects

Positioning through dichotomies

By identifying dichotomies in the text and taking a position on them, we can determine a course of action and potentially a method for the specific case.

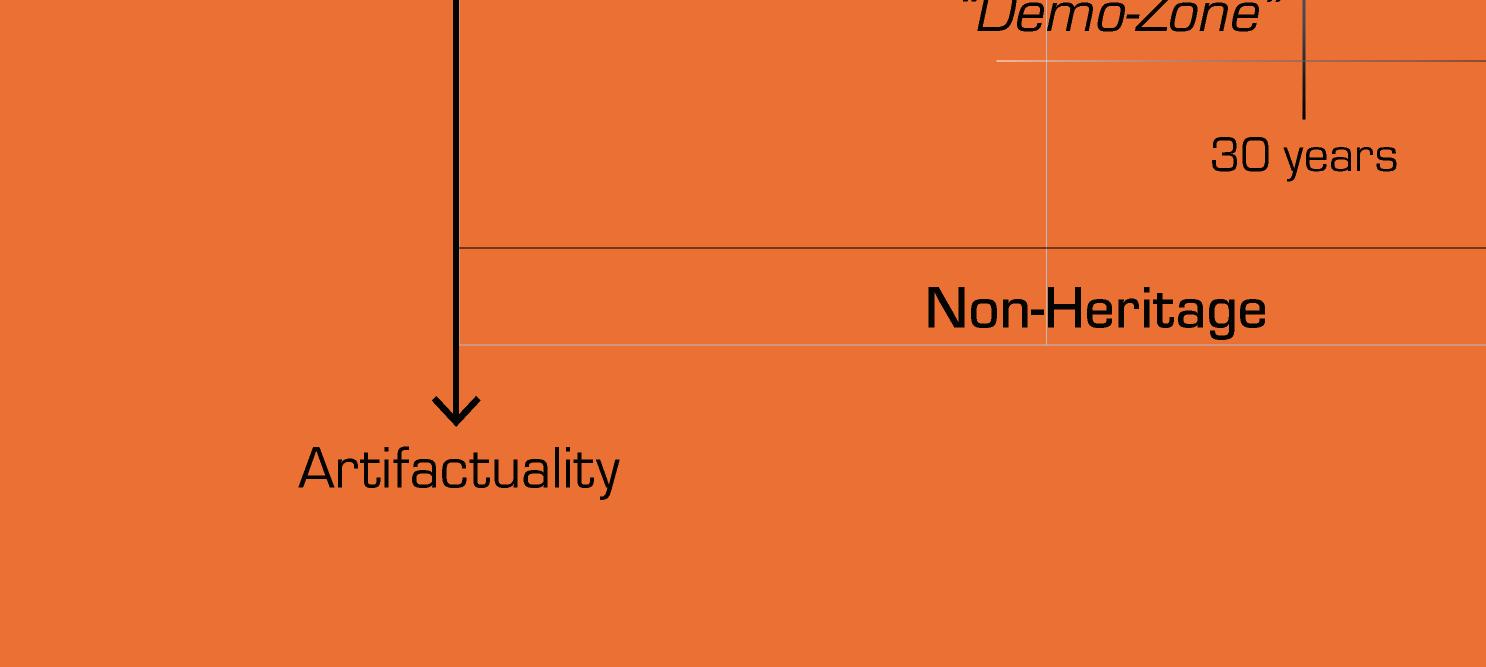

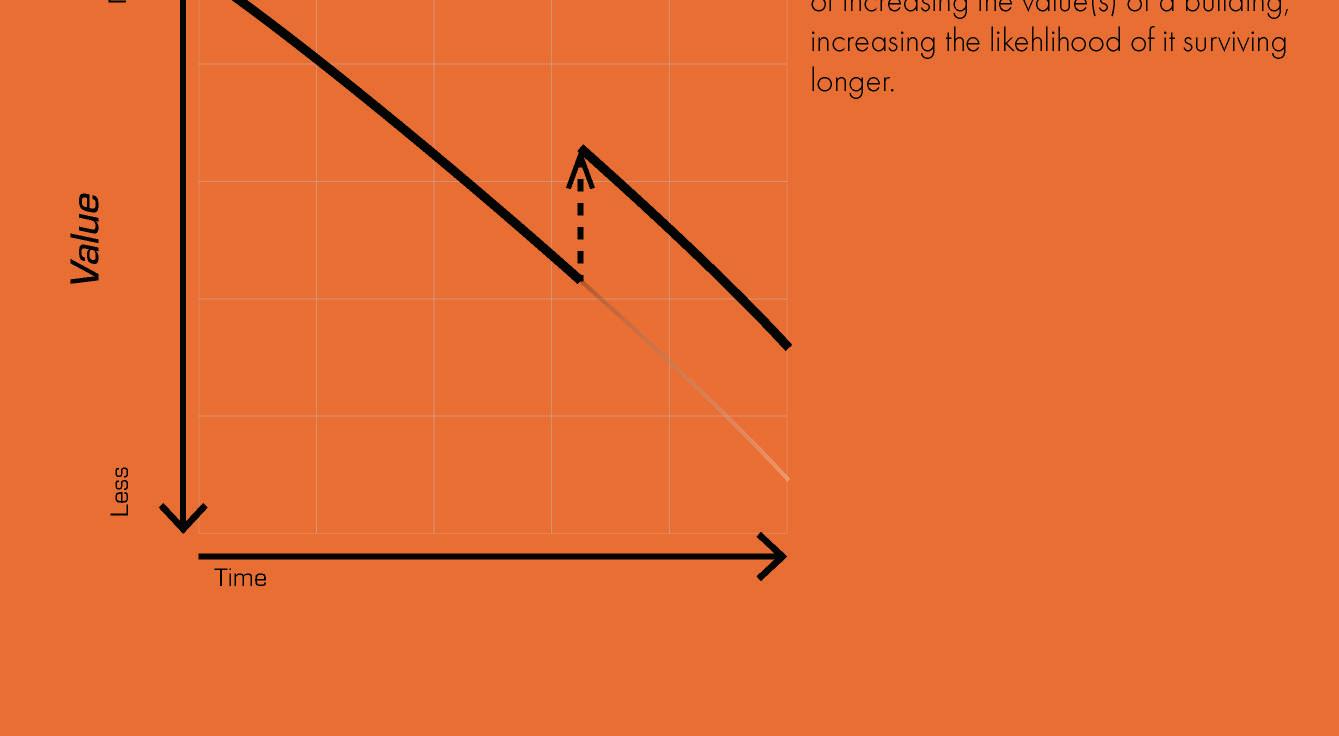

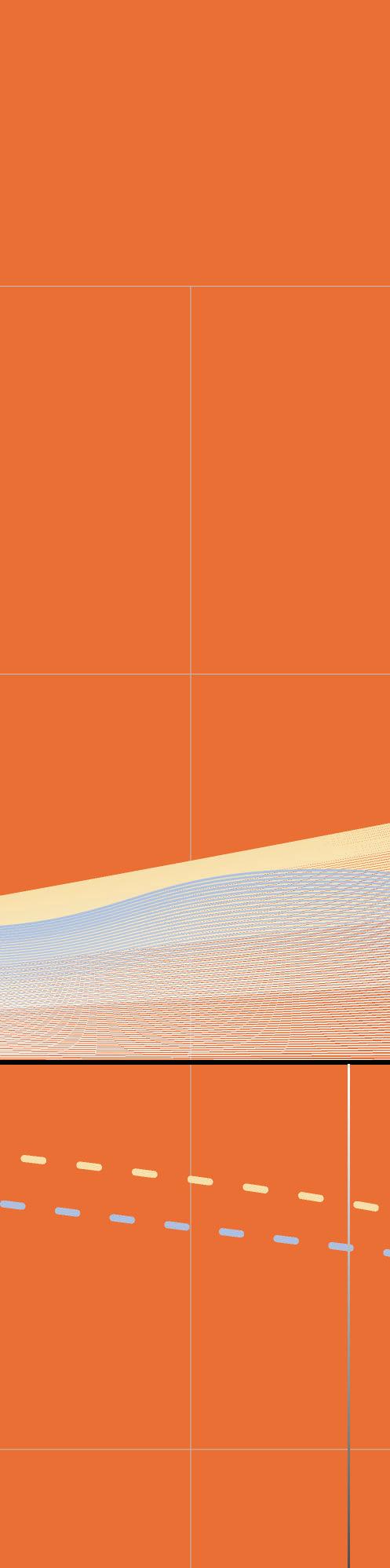

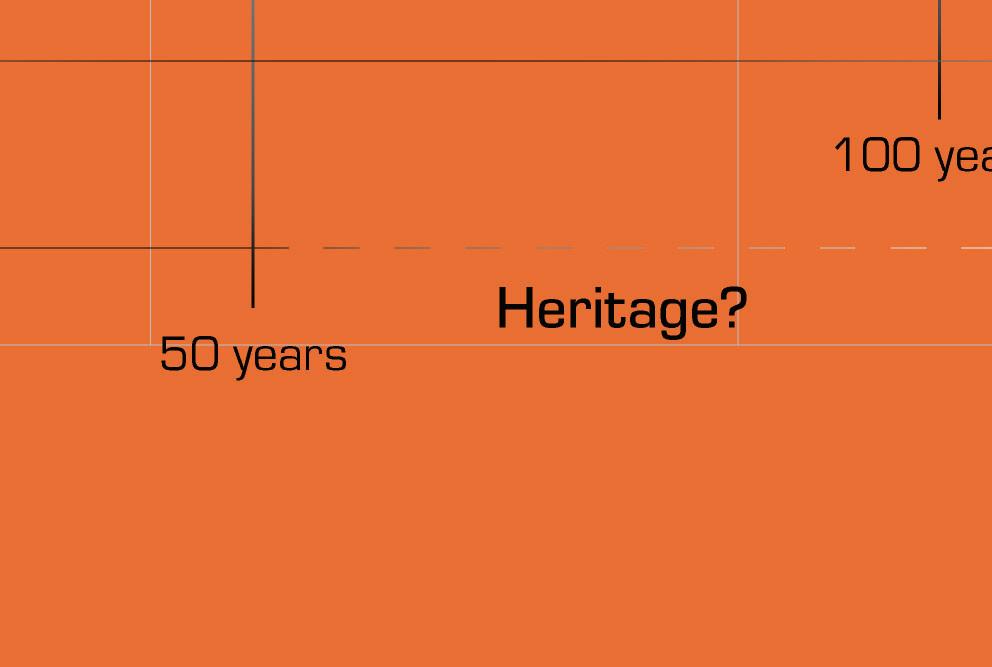

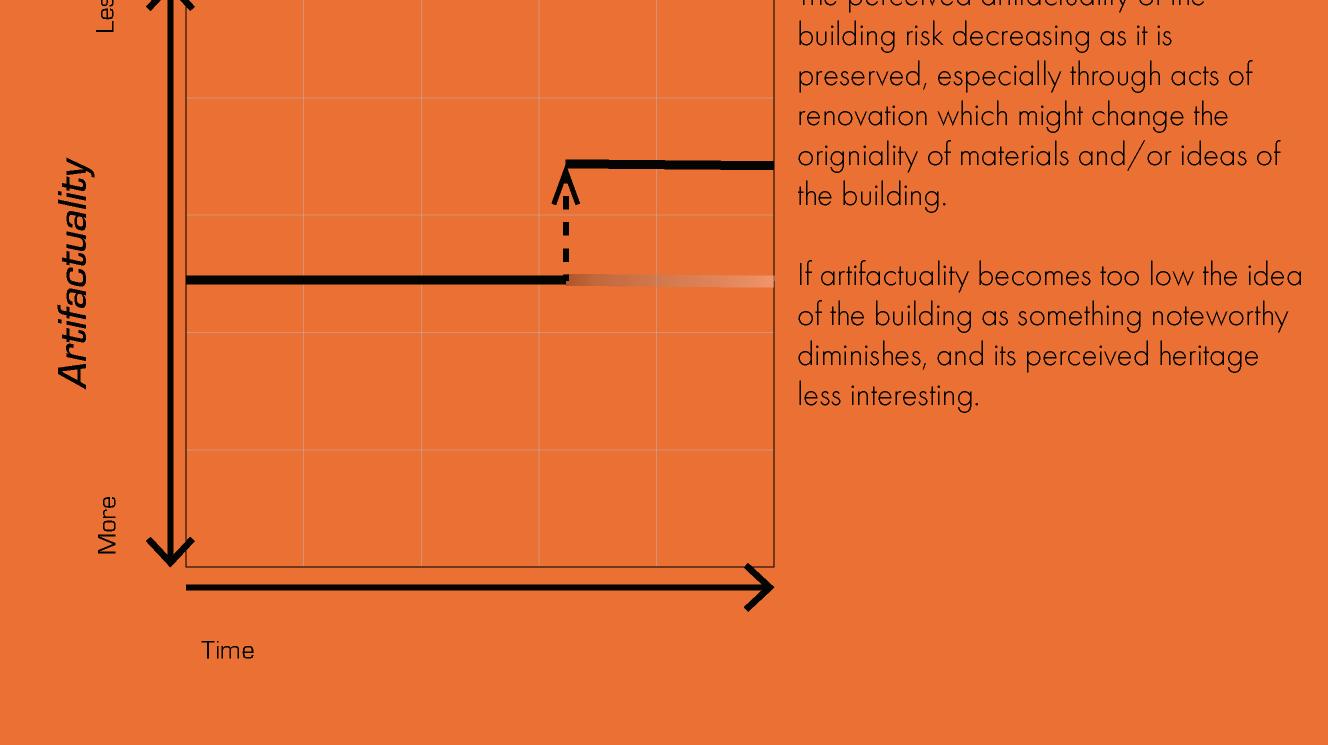

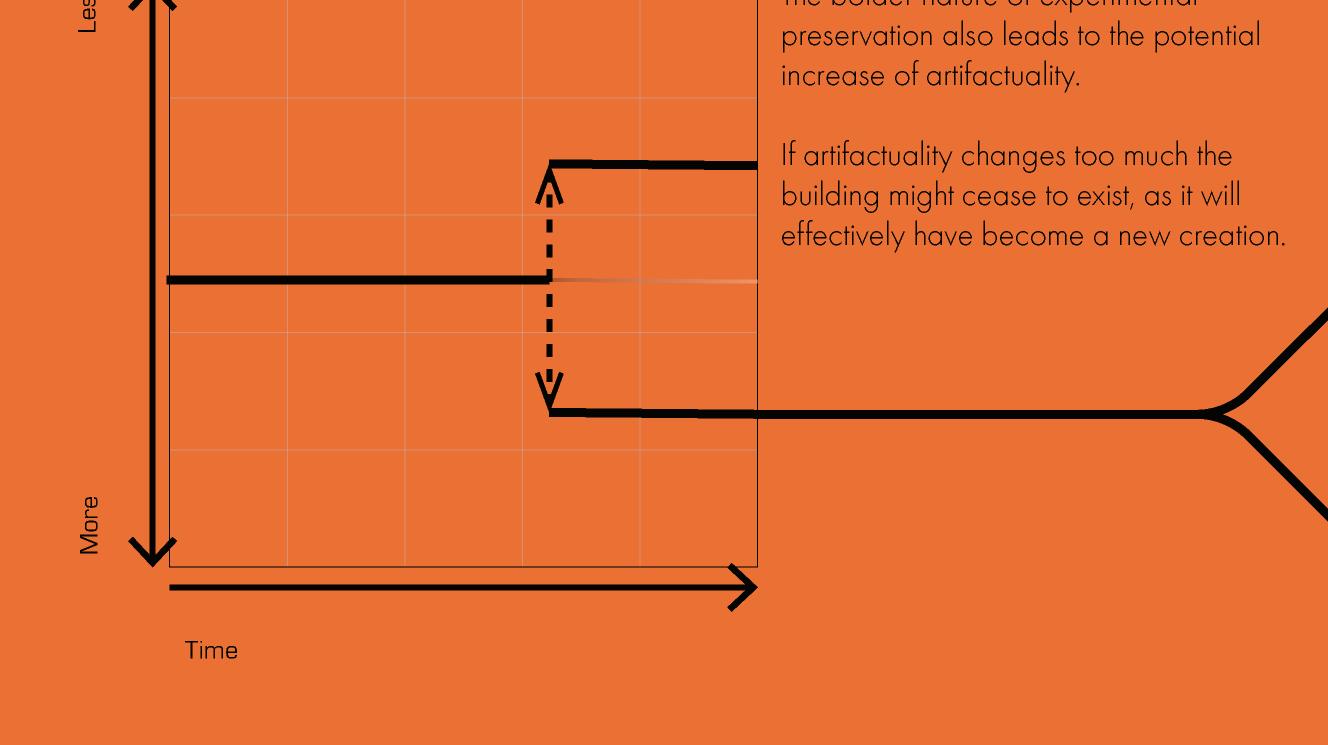

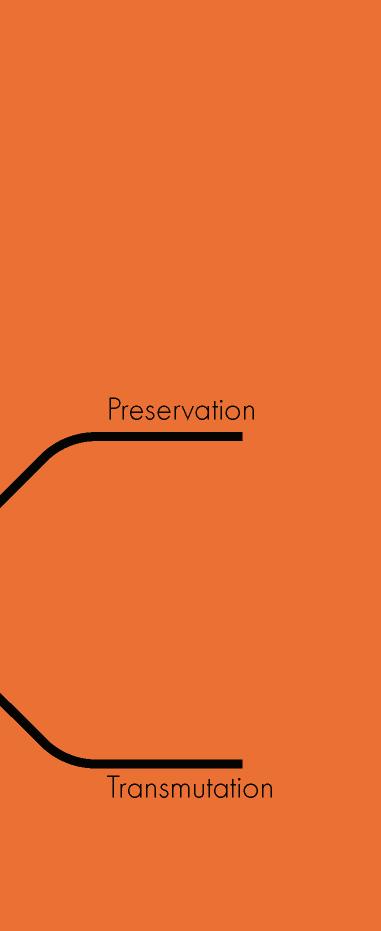

Different readings covering the subject of heritage visualised as value/artifactuality over time.

Effects of preservation vs experimental preservation on value/artifactuality.

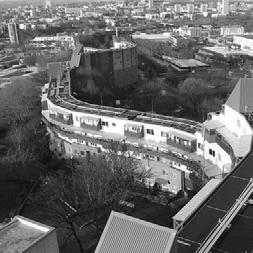

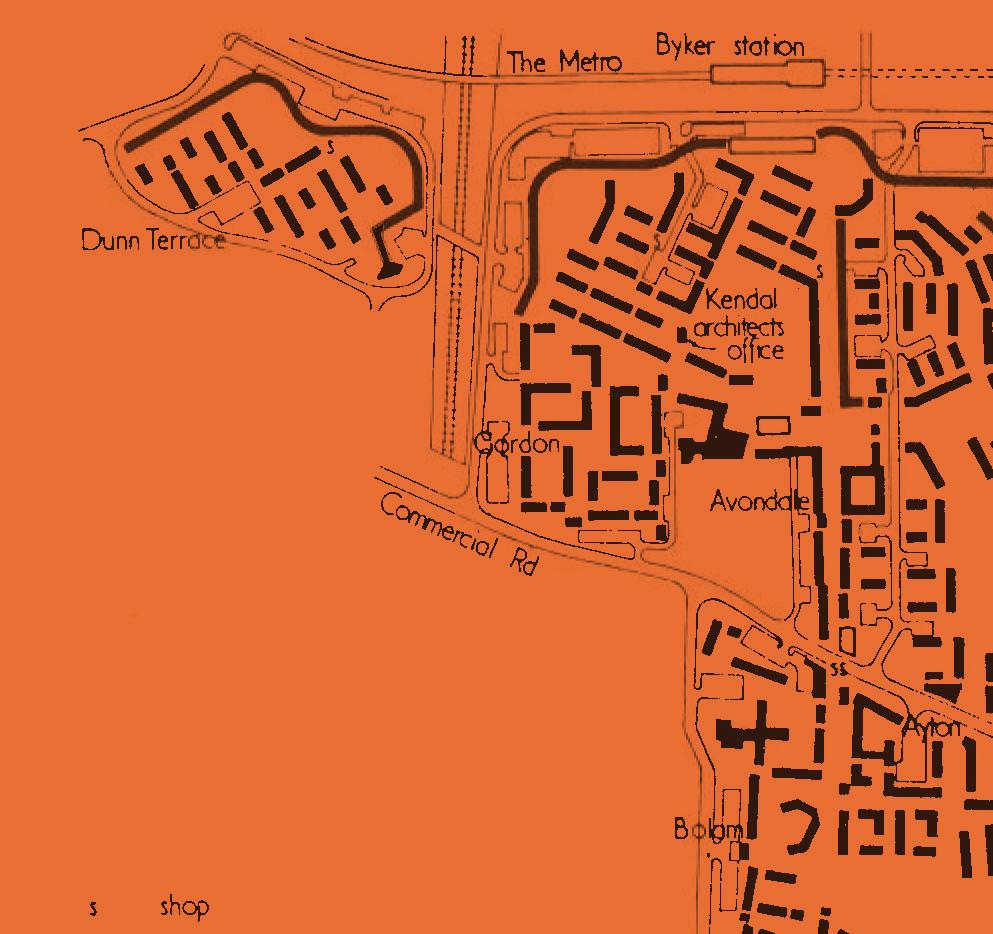

Byker Wall

Newcastle upon Tyne, England, Great Britain

Ralf Erskine 1969-1982

The Byker estate has a Grade II heritage listing in recognition of its outstanding architecture. Byker Wall is also on UNESCO’s list of outstanding 20th-century buildings.

Traffi c separation over time

The original site plan for the Byker Estate shows that the area was divided into separate traffi Compared with images from Google Earth in 2023, it appears that this has changed. What was once a garden or courtyard is now a car park. This illustrates how the area has evolved and adapted to new needs and ways of life over time.

With the large scale destruction of Europe after the second world war, and the fierce competition between the US and the Soviet aligned nations during the cold war, the rebuilding and urbanisation of countries led to an unrivaled scale of construction. Mass housing especially became a predominant concept. The ideas of mass housing however tend to move further than the building itself. To appreciate the concepts require a more hollistic approach. The predominant ideas of what constitutes a building with “heritage” cant really be applied to the ideas of mass housing (estates). At the same time so many people today have some kind of direct relationship to a mass housing estate that it cannot not be considered a part of our heritage?

Where Byker Wall and Stjärnhusen achieves their heritage listing through a single-faceted artifactuality, the housing estates contain a multi-faceted approach to artifactuality not usually considered.

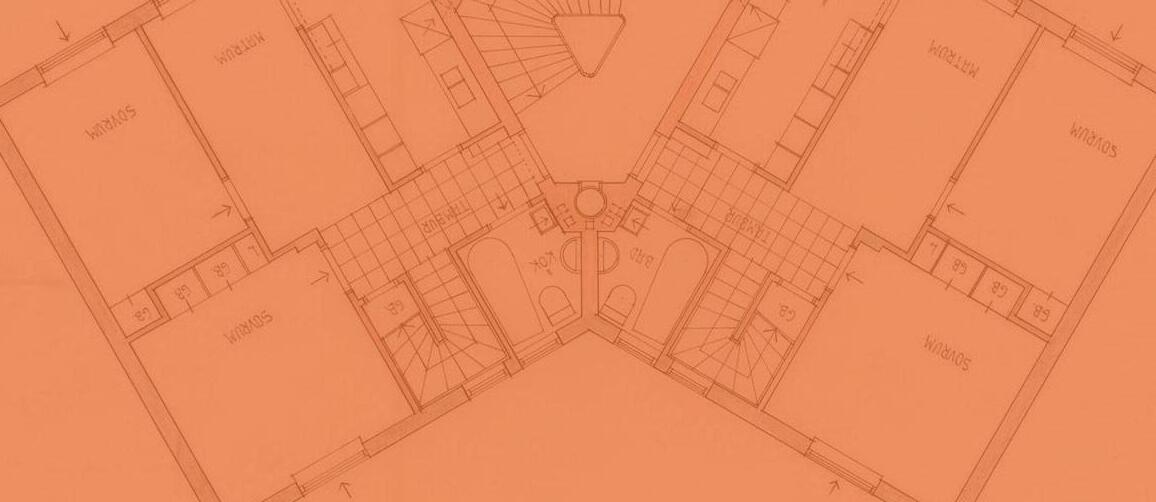

Stjärnhusen

Stjärnhusen are a residential complex in Gröndal, Stockholm. The houses were groundbreaking for their innovative design, designed by Sven Backström and Leif Reinius and built during 1944-46, more star houses and a terraced house were built in 1950s and 1960s. The star shaped typology feautures a central stair core with several radiating wings. “Stars” can be connected to other stars by the wings gabels. Backström och Reinus also designed terraced houses Gröndal. There are also star houses in Rosta.

In contrast to Byker Wall the artifactuality of Stjärnhusen is achieved through a repeating individual house shape.

Authors

Year

Building type

1968

Low-rise, multifamily, residential

Bookshelf

Number of apartments

Number of floors

Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect Structural system

County

Municipality

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

60

3

5600

Project description

Carl-Ossian Klingspor

Skåne

Lund

Landsdomarevägen 1, 3, 5

Lund LKF

The property consists of three almost identical rows of two story apartment houses built in the 1960s. The apartments are generally small, around 45 sqm each.

The buildings are facing demolition due to plans of building 5 point houses instead, ie the municipality is looking into increasing the exploitation of the area.

The houses are built using a concrete structure, made in-situ but with a large collection of prefab elements used for the access balcony. Built using the bookshelf method of supporting cross going concrete walls.

128. Ringen 1

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1964

Low-rise, multifamily, residential

111 Bookshelf

3

15.000 m2

Göingehem AB Bo Lundgren

CountySkåne län

MunicipalityÖstra Göinge

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Åkesvägen 5

Kvingevägen 27-29, Hanaskog

Ringen

“Ringen” is the local nickname for the group of apartment blocks: Kviingevägen 27, 29 and Åkesvägen 5. The complex originally had 111 apartments in 8 houses

In June 2021, Göingehem’s board together with Östra Göinge kommun decided to demolish the entire complex in steps, with first residents moving out in January 2021 and demolition starting in September that year. Then either one or two houses were and will be demolished in the next few years. As of today, only three remain. The whole demolition project is estimated to take five years.

There seem to be hints of future development on the site, however, no designs or plans have been released yet.

The current floor plans for the Ringen are mostly the same throughout the complex, with minor differences between buildings. The dimensions of apartments are fixed and the buildings are made of a modular bookshelf structure. No construction drawings were available but we assume that the buildings has modular sandwich walls.

Cast in situ slabs

Cast in situ load bearing walls

Pre-cast facade elements

Year

Building type

Structural system

Number of apartments

Number of floors Size (BTA)

Building owner

Architect

1991-2023

Non-residential, Institutional, health

35 Bookshelf

6 3500 m2

Hemsö Fastigheter AB

Stefan Törnquist at Fritz Jaenecke Architects

CountySkåne

MunicipalityMalmö

Address

Collected Documentation

Demolition Permit

Demolition Plan

Construction Drawings

Architectural Drawings

Material inventory

Uppsalagatan 2A, Malmö

Project description

Virkesvägen 8 was designed 1991 by architect Stefan Thörnqvist at Fritz Jaenecke Arkitektgrupp AB in 1990–1991 as a retirement home for Kullenberg Fastigheter. A building designed by Carl-Axel Stoltz in 1935 was demolished to make way for the retirement home. In 2015, the building was renovated and converted into a home for people with substance abuse problems. The building is designed in a postmodern style with a concrete frame and brick facade. The building’s demolition was scheduled for 2021, but the process was delayed. While the City Planning Office initially considered the building to be of historical value, a preliminary study by the consulting firm WSP concluded that it had low cultural and historical

2, 1:300

significance. Other reasons given for demolishing the building, which was just over 30 years old, were the low ceiling height of 2.4 metres and the building’s wear and tear after its time as a home for substance abusers. However, the building was not demolished due to poor condition, but rather because it was deemed unsuitable for the property owner’s plans for the site.

The new property, designed by Space Arkitekter AB and planned for completion in 2027, will feature restaurants and other amenities and is expected to invigorate the Södervärn area. Additionally, the development will include a school, a health centre, and a dental clinic.

Holistic perspective

Interconnected systems

Interdisciplinarity

Environmental justice

Regenerative design

Distributive design

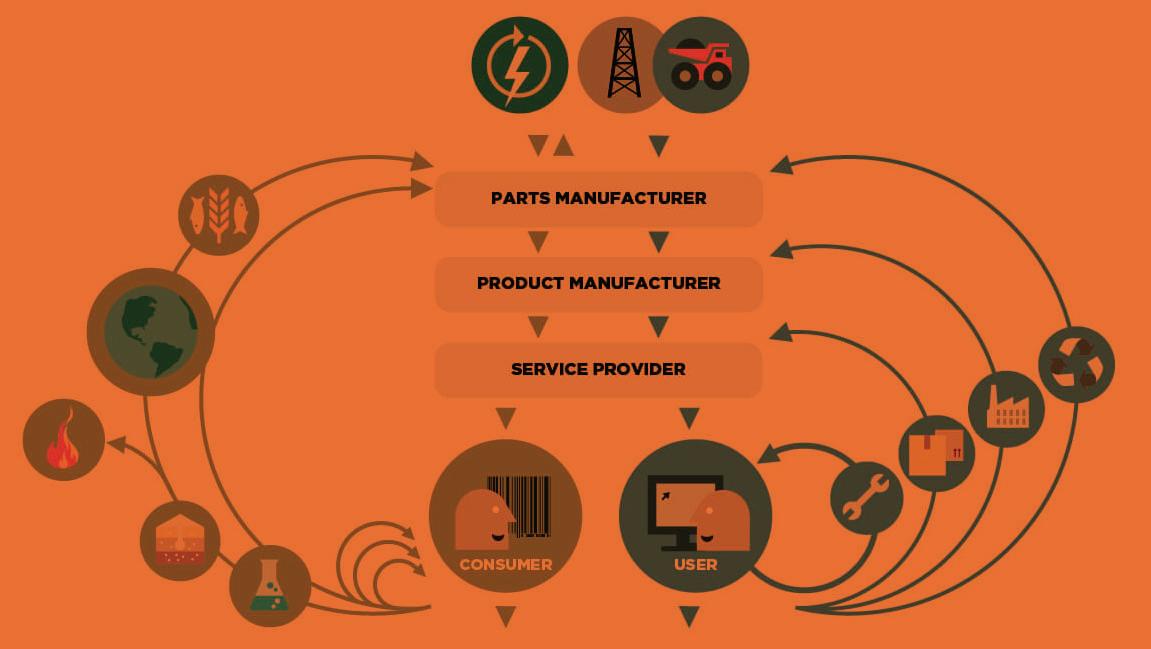

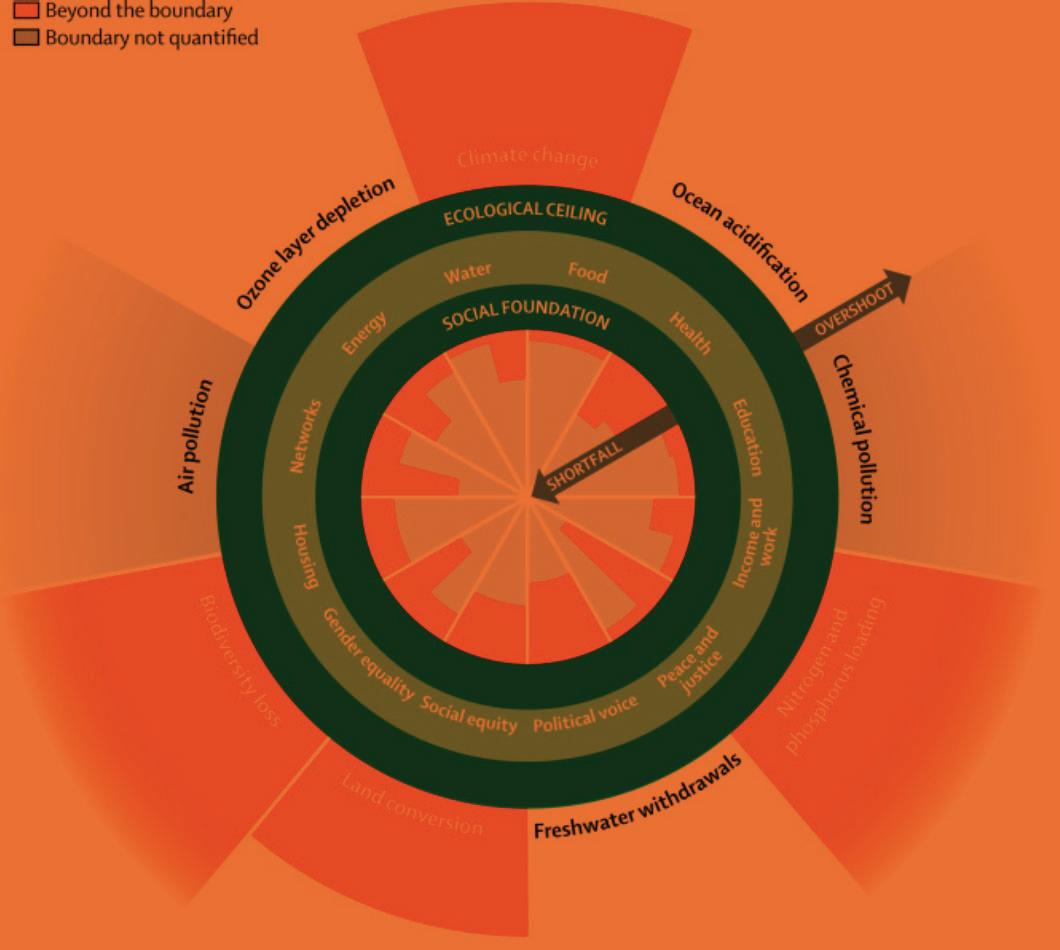

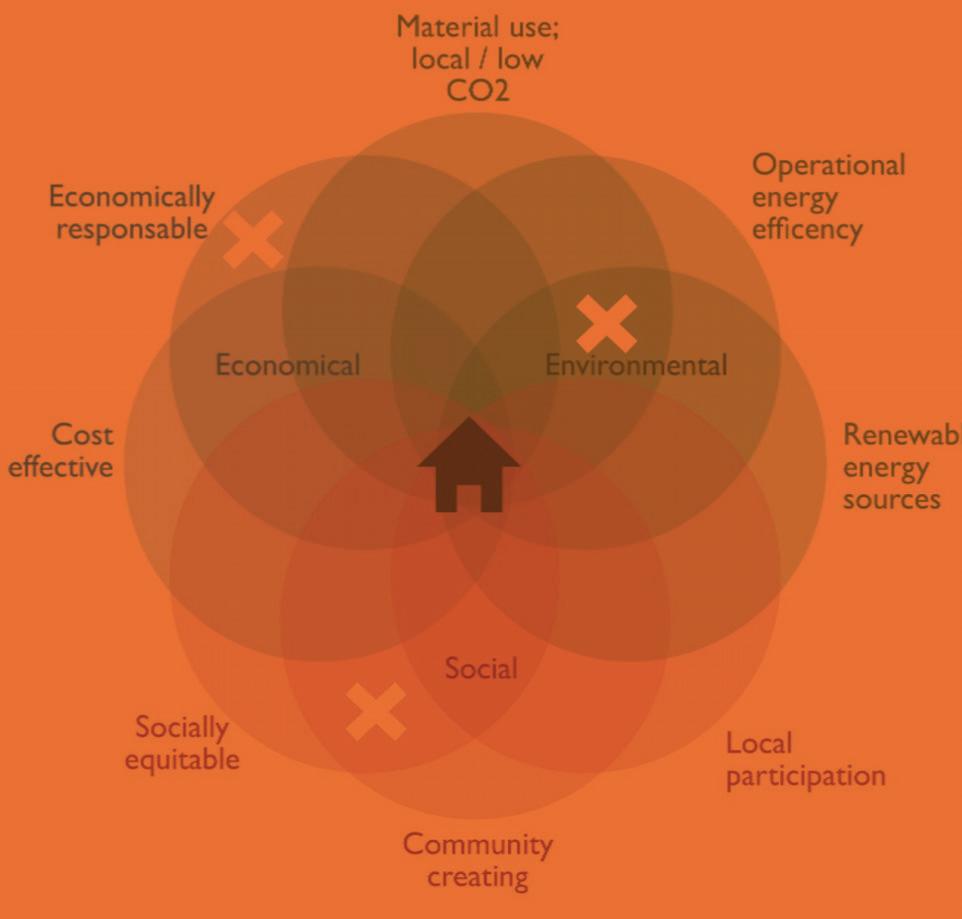

With the building sector responsible for about 37% of global greenhouse gas emissions, addressing environmental issues in design is crucial. Planetary boundaries define the safe limits to human pressure on nine key earth systems—seven of which are already exceeded—highlighting the urgency for low climate impact design solutions. This means shifting from the traditional “take, make, use, lose” model toward a restorative and regenerative approach.

CLIMATE CHANGE

BIOSPHERE INTEGRITY

LAND-SYSTEM CHANGE

STRATOSPHERIC OZONE DEPLETION

CHANGE

Core earth systems

All planetary boundaries relate to two core earth systems:

Key objectives for design

Innovation pursuits in building design can thereby be focused with two key objectives to scale impact within panetary limits:

BIOGEOCHEMICAL FLOWS

HEALTHY ECOSYSTEMS

ATMOSPHERIC AEROSOL LOADING

ACIDIFICATION

PROJECT, SUPPORT AND REGENERATE NATURE AND BIODIVERSITY

Universal recycling symbol

Designed to raise awareness of environmental issues. The arrowsrepresents three different stages of recycled productCollection, Processing, Reprocessing.

Key principles

Reduce by consuming less

Reuse by using items multiple times

Recycle materials into new products

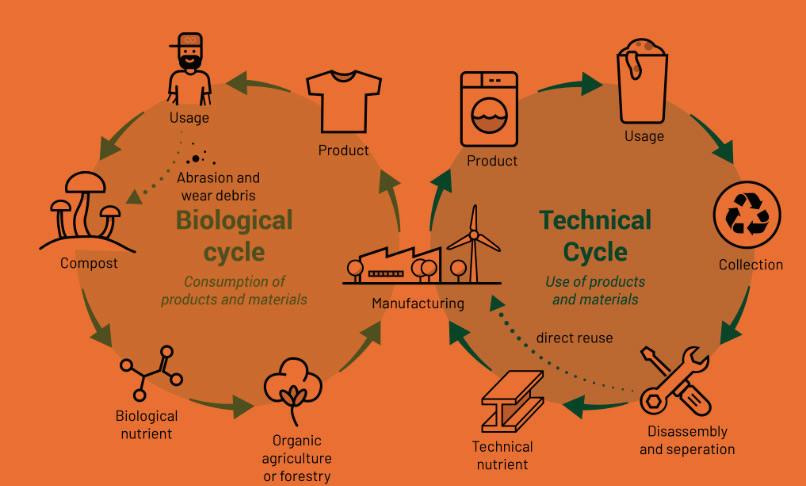

Promotes the safe and potentially infinite circulation of materials in closed systems, the technical and biological cycle. The model is treating all products as natrients for future processes, rather than as waste.

Key principles

Everything is a resource for something else

Use clean and renewable energy

Celebrate social, cultural, and ecological diversity in local context

Based on the Cradel to Cradel method. It Illustrates the continuous flow of materials in a circular economy with two separate closed-loop flows for biological and technical materials.

Key principles

Eliminate waste and pollution and rethinking how products and systems are created

Circulate products and materials (at their highest value)

Regenerate nature

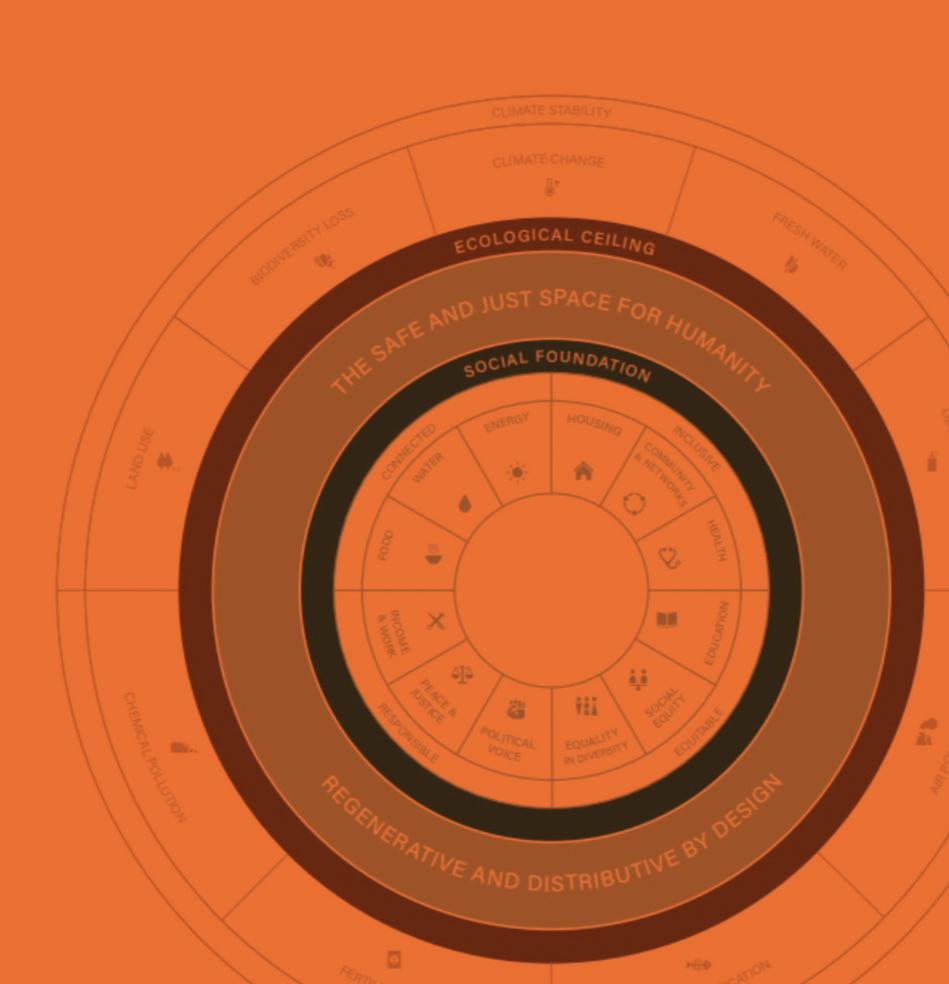

Doughnut for urban development 2017

The doughnut of social and planetary boundaries

The doughnut shape represents a safe and just space for humanity, with an inner ring representing the social foundation of basic needs and an outer ring representing the ecological ceiling of planetary boundaries.

Applies Doughnut Economics principles and provides a pratical toolkit for cities to apply the global doughnut principles to their specific urban context.

Key principles

Redefining the goal of growth within planetary limits

Understanding interactions between economic and ecological systems

Regenerative and cyclical

Key principles

Sustainable development that serves both social well-being and planetary health

Considering social equity, human well-being, ecological restoration, and economic sustainability in urban devenopment

Awareness of global and local connection

Connection to the theme

The operational energy efficiency of the buildings is not only beneficial from an environmental point of view; it is also economically sustainable since it significantly reduces the residents´ heating and electricity bills. In the BEDZed there is also a strong sense of community through, for example, shared outdoor spaces and a communal car club, which in addition reduces greenhouse gas emissions from travel. In this way the project is an example of sustainable design from a holistic perspective, with ecologically sustainable solutions also having a positive effect on social and financial factors. he dis se on, ar O2 be he ng ed he ht, us or